Democracy

Democracy

Meeting the moment:

Ask the ancestors

Unequal pandemic, unequal recovery

John Cartwright / 18

Katherine Scott / 15

The pandemic wreaked havoc on hotel workers

The rise of zany conspiracy theory politics

Luke LeBrun / 22

Alice Mũrage and Michelle Travis / 21

From leader to laggard

Sheila Block earns prestigious award

We Saskatchewan public libraries. Policy-makers should too.

Sheila Block / 12

Simon Enoch / 9

Another banner year for CEO pay— and income inequality—in Canada

Free contraception a win for all Katherine Scott / 13

David Macdonald / 10

Viewpoints

Niall Harney / 25

If you value democracy, stop expecting free news

Antonia Zerbisias / 25

Minimum wage workers need a raise

Canada’s failure to adequately address the Israel/Palestine crisis

Clare Mian / 39

Christine Saulnier and Jenna MacNeily / 12

How to fix Canada’s housing crisis

Democracy:

When “survival” jobs become “essential” work

The oligarchs are at the gate

Trish Hennessy / 26

Catherine Bryan and María José Yax Fraser / 27

Canada should withdraw from Safe Third Country Agreement

Kirsten Bernas and Shauna MacKinnon / 42

Jon Milton / 13

Bolder moves needed to tax the rich

Running on empty— the care economy / 28

What if we stop knowing what’s true from what isn’t?

Trish Hennessy / 28

A timeline: The pandemic’s impact on women in the workforce

Marc Lee and DT Cochrane / 44

Hitting a new low: Ontario well-being is lowest in Canada

Carolina Aragão / 15

source of progressive policy ideas. The CCPA began publishing the Monitor magazine in 1994 to share and promote its progressive research and ideas. The Monitor is published four times a year. The print version is mailed to all supporters who give $35 or more a year to the CCPA.

Understanding the methods of the far right in Canada

Katherine Scott / 32

Stéphane Leman-Langlois, Aurélie Campana, and Samuel Tanner / 30

Canadian cities could raise tens of millions of dollars with one tool: a local income tax

Time to lean in to the foundational values of democracy

David Macdonald / 5

Molly McCracken / 32

Tax cuts favour men

Jess Klassen / 6

Let’s reimagine our political future, together

Chi Nguyen / 34

Faster internet as slowly as possible

Randy Robinson / 7

View of democracy from its smallest cog

Craig Pickthorne / 35

Why a capital gains tax on the rich makes sense

David Macdonald / 8

ESTABLISHED BY OTTAWA POLICE

Up Front

FEBRUARY 18, 2022

Policy innovations

Trish Hennessy / 10

CCPA BC’s Ben Parfitt retires Ben Parfitt / 11

Economic populism: A carbon copy of failed right-wing policies

Marc Lee / 5 12 radical ideas to counter Trump’s tariff wars

Hadrian Mertins-Kirkwood and Marc Lee / 7

HIGHWAY 417

Artist uses photography and visualization to bond with her Indigenous ancestry

Viewpoints

Emily Zarevich / 45

Interprovincial trade barriers: a convenient myth

Columns

Stuart Trew / 37

Inside trade

Stuart Trew / 38

The Omatsu Files: It’s time to end the precarity that comes with tipped work

Books

Luis Ernesto Pineda Gomez / 38

Gutting our civil service for consultants undermines democracy

The richest 10% are driving Canada’s carbon emissions

Simon Enoch / 50

Nicolas Viens and Andrew Jorgenson / 40

Corporatization of cannabis allowed profits to trump public health

Bruce Campbell / 51

Celebrating a win: Historic labour laws in Manitoba

Kevin Rebeck / 42

Summertime and the reading is easy: What we're reading this summer / 53

Science fiction author coins term for online digital decay + solutions

Amanda Emms / 55

Taking the initiative to learn: My immersion in Indigenous contemporary literature

E.R. Zarevich / 46

Book review: Leadership in a time of uncertainty

From the Editor 1 / Letters 2 / New from the CCPA 3

John Cartwright / 50

Hennessy’s Index 37 / Get to know the CCPA 48 / CCPA Donor Profile 49

The good news page by Elaine Hughes 56

From the Editor 1 / Letters 2 / CCPA in the spotlight 3

Hennessy’s Index 36 / Get to know the CCPA 44 / CCPA Donor Profile 45

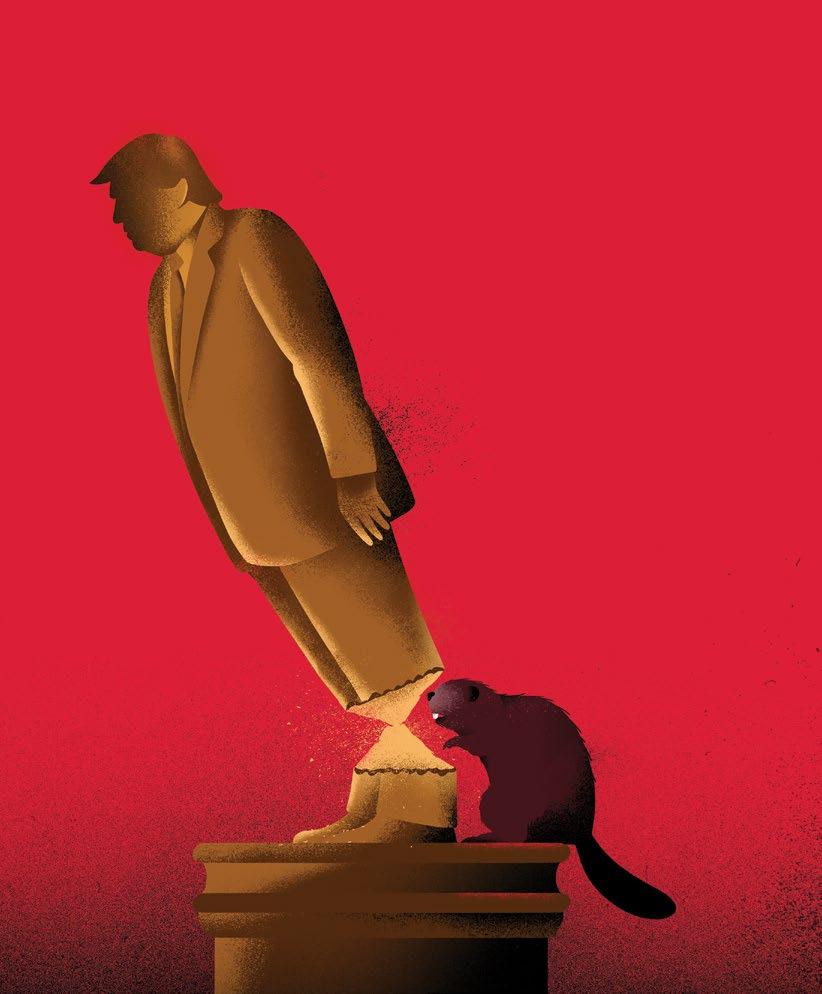

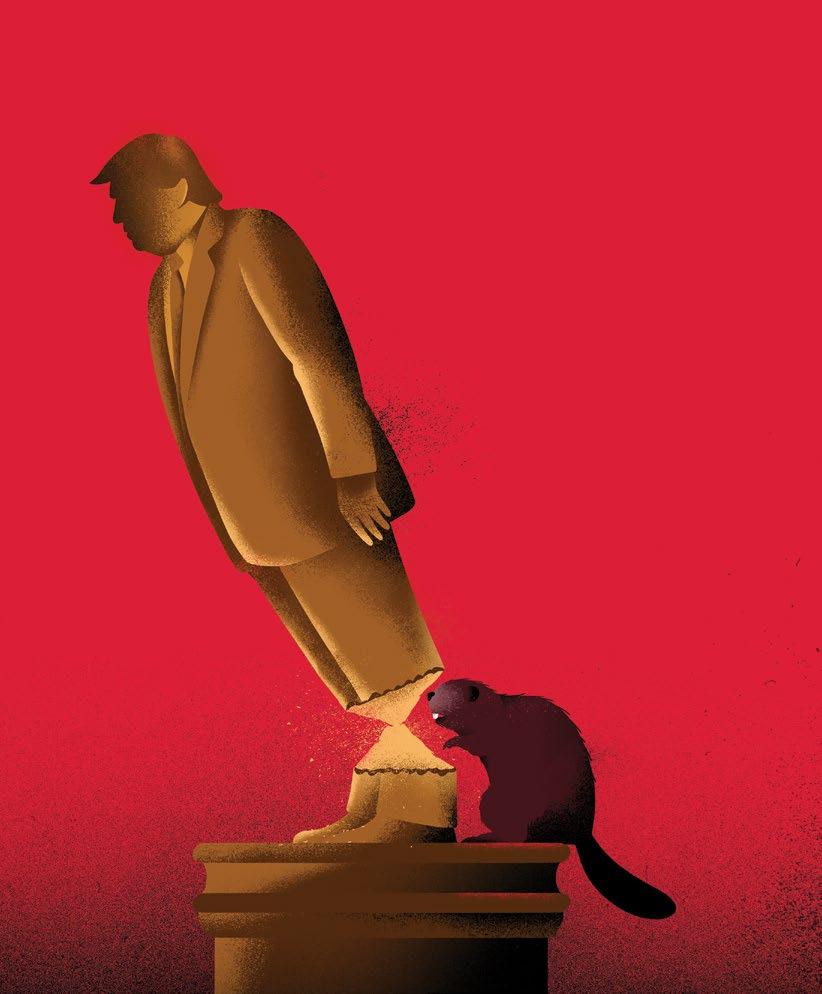

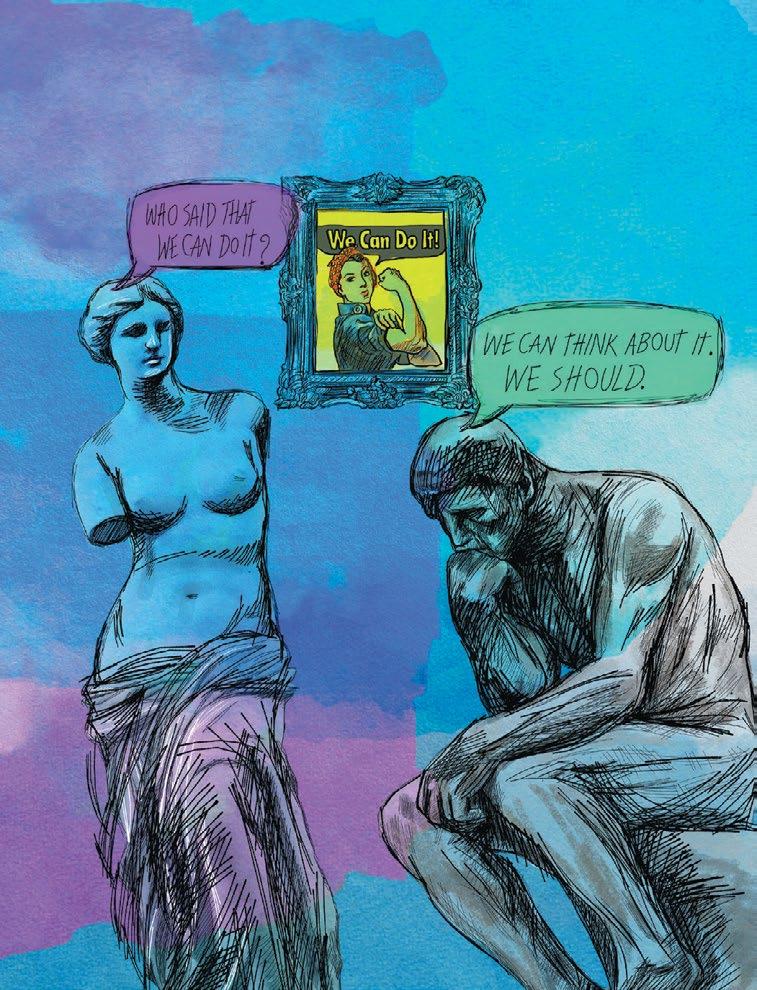

Cover illustration by Sébastien Thibault

The good news page by Elaine Hughes 52

Based in Matane, Quebec, Sébastien Thibault creates illustrations that provide ironic or surrealist visions of political subjects or current news. He uses graphic shapes, simplified forms, and intense color to create symbolic images for publications like the New York Times, The Guardian, and the Economist

Cover illustration by Sébastien Thibault

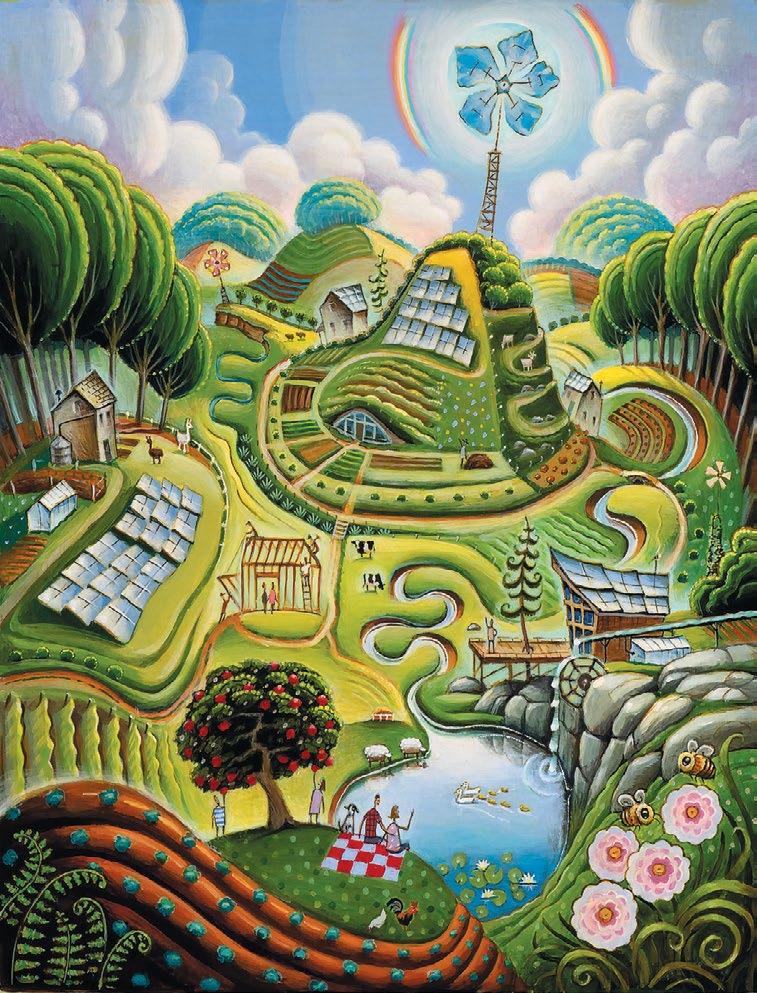

Centrespread design Joss Maclennan, illustrations Sébastien Thibault

Founded in 1980, the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives (CCPA) is a registered charitable research institute and Canada’s leading source of progressive policy ideas, with offices in Ottawa, Vancouver, Regina, Winnipeg, Toronto and Halifax. The CCPA founded the Monitor magazine in 1994 to share and promote its progressive research and ideas, as well as those of like-minded Canadian and international voices. The Monitor is is published four times a year by the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives and is mailed to all supporters who give more than $35 a year to the Centre. Write us at monitor@policyalternatives.ca with feedback or if you would like to receive the Monitor

UNIVERSITY OF OTTAWA

You can gift the Monitor to a friend or family member, view previous issues, and read more free, timely content at www.policyalternatives.ca

The opinions expressed in the Monitor are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the CCPA.

ISSN 1198-497X

Canada Post Publication 40009942

The opinions expressed in the Monitor are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the CCPA.

Editor: Trish Hennessy

Associate Editor: Jon Milton

ISSN 1198-497X

Canada Post Publication 40009942

Senior Designer: Tim Scarth

Layout: Susan Purtell

Editor: Trish Hennessy

Associate Editor: Jon Milton

Senior Designer: Tim Scarth

Layout: Susan Purtell

Editorial Board: Catherine Bryan, Simon Enoch, Sabreena GhaffarSiddiqui, Jon Milton, Jason Moores, Erika Shaker, Trish Hennessy

How to contact the CCPA

Letters to the editor monitor@policyalternatives.ca

Editorial Board: Catherine Bryan, Lisa Akinyi May, Simon Enoch, Sabreena Ghaffar-Siddiqui, Jon Milton, Jason Moores, Trish Hennessy, Erika Shaker

CCPA National Office 141 Laurier Avenue W, Suite 1000 Ottawa, ON K1P 5J3 613-563-1341

ccpa@policyalternatives.ca

CCPA National 141 Laurier Avenue W., Suite 501 Ottawa ON K1P 5J3 613-563-1341 1-844-563-1341 ccpa@policyalternatives.ca

www.policyalternatives.ca

CCPA BC Office 604-801-5121

CCPA BC ccpabc@policyalternatives.ca

ccpabc@policyalternatives.ca

CCPA Manitoba Office 204-927-3200

CCPA Manitoba 204-927-3200 ccpamb@policyalternatives.ca

HIGHWAY 417

ccpamb@policyalternatives.ca

CCPA Nova Scotia Office 902-240-0926

CCPA Nova Scotia 902-943-1513 ccpans@policyalternatives.ca

ccpans@policyalternatives.ca

Based in Matane, Quebec, Sébastien Thibault creates illustrations that provide ironic or surrealist visions of political subjects or current news.

Centrespread design and illustrations by Jamileh Salek and Joss Maclennan Joss Maclennan is the creative director of Joss Maclennan Design. She combines a passion for clear, simple language with a strong visual sense. Her background is mainly in design, but includes painting, drawing and illustration as well. Decades of experience help her find the central message and the way to convey it.

Jamileh Salek is an Iranian-Canadian artist, writer and illustrator. Pattern, colour and art making was part of her childhood and life in Tabriz and Tehran. This rich Persian heritage shows in all her work. Themes of migration, culture, and the shape of women's lives are woven into her painting, textile art and books.

Joss Maclennan is the creative director of Joss Maclennan Design. She combines a passion for clear, simple language with a strong visual sense. Her background is mainly in design, but includes painting, drawing and illustration as well. Decades of experience help her find the central message and the way convey it.

CCPA Ontario ccpaon@policyalternatives.ca

CCPA Ontario Office

ccpaon@policyalternatives.ca

CCPA Saskatchewan ccpasask@sasktel.net

Located east of downtown in the Vanier neighbourhood, the Coventry camp was established by the end of the first week of the occupation. It quickly became a fortified encampment and home of the infamous saunas. It was not removed until February 20.

CCPA Saskatchewan Office 306-924-3372

ccpasask@sasktel.net

Trish Hennessy

Progressivenews,viewsandideas

Progressivenews,viewsandideas

Progressivenews,viewsandideas

Progressivenews,viewsandideas

These days, there are many reminders to hold on to this one precious thing: our democracy. Not just ticking a box at election time, but working in between elections to protect the systems in place to safeguard our democracy.

As this edition of the Monitor lays bare, our democracy is on trial. A global geopolitical shift is underway as America crumbles under the weight of tech bros, billionaires, oligarchs, and Trump himself. Leonard Cohen would say “America is the cradle of the best and the worst.”

Now it is chaotic, duplicitous, ruinous. The North American stability that we’ve enjoyed for generations is no longer something we can count on.

That stability did allow us to become complacent. Trade deals offered cheaper goods and services while governments traded the social safety net for an agenda of tax cuts that appealed to our power as consumers—not as engaged democratic people.

The hard truth—the bitter pill we must all now swallow—is that cheap is no longer a guarantee. Lettuce will cost more, if we can access it at all. California lettuce, certainly, is a thing of the past. That was inevitable. The climate emergency already guaranteed that California lettuce, oranges and other produce were never going to be as accessible in future.

We have arrived at that future. We will continue to be forced to think hard about what we consume, about where we buy, about need vs. want.

Seriously, how long has the system felt rigged to you?

Now the threats are real and the agenda of a salivating far-right has been laid bare. In the U.S., obviously, but in Canada too. Emboldened by the role billionaire tech bros like Elon Musk have played in the early days of the Trump administration, Canada has its own class of wealthy tech bros wanting to organize here too.

Recharging North America

In fact, one of our first collective acts of resistance to Trump’s destabilizing economic warfare on Canada and his reckless threats to make us the 51st state of America has been to boycott American products and buy Canadian. Consumerism.

To be honest, I held out this glimmer of hope in 2008-09, when a U.S.-led banking ponzi scheme crashed the world economy. Like many other countries, Canada fell into a sharp recession. Greece was forced by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to make extreme concessions to public services and supports in order to deal with the debt crisis the ponzi scheme created in that country.

Build Canada is an initiative backed by Canadian tech executives, including from Shopify and Wealthsimple. Among other things, they’re advancing a business-friendly agenda that includes deregulation and AI—an agenda that puts corporate profits ahead of Canadian well-being, consumer safety, and decent work.

There is power in that, yes. But the irony is not lost that it was consumerism and the cult of cheap that made us complacent in the first place. Access to cheap goods made us feel more middle class. Made us detach, decade by decade, from any sense of working class awareness and solidarity.

It seemed then that it was the jolt we needed to clearly see the hard limits of intertwined globalization and capitalism. My optimism was not rewarded by reality.

The 99% Occupy movement came and went. Banks were bailed out but the most vulnerable people weren’t. And things just returned to “normal.”

These are all variations of a neoliberal theme. None of this is about protecting our democratic rights. That job comes down to us. This issue of the Monitor examines our democracy on trial and the role that you and I can play—working together with progressive movements—to advance transformative change that puts people’s well-being first. It invites you to become an active participant in this transformation, to embrace our collective power. M Trish Hennessy is Monitor editor.

At $35, gifting the people in your life with an annual subscription to the Monitor is a win-win—we make gifting easy and you help to enlighten loved ones while supporting the CCPA. Gift the Monitor here: policyalternatives.ca/givethemonitor or contact Patrick Hoban at 1-844-563-1341 x309 or phoban@policyalternatives.ca

Remember that normal tolerates—indeed, ignores—income and wealth inequality, racism, the harmful impacts of colonialism, the rights of Indigenous Peoples, racialized people, migrant workers, women and gender-diverse people, people with disabilities…

The future of food I read, with great appreciation, Darrin Qualman’s article in the Winter 2025 Monitor. The author gives a very realistic appraisal of the current Canadian perspective of the future, and the current dilemma that we find ourselves facing around food insecurity in Prairie agriculture.

The uncertainty due to climate change and economic factors is truly frightening. Along with the elements contributing to the crisis that food systems are facing, there is another, unmentioned in the article. The effects of foreign ownership of agricultural land are an important consideration in developing plans to address food security.

Loss of the agriculture land base to foreign interests continues to

erode our ability to plan and accurately assess food production. Outside of the Prairie agriculture region on which the article focuses, agricultural potential is also being eroded through urban encroachment and industrial development. Soil depletion and other factors add to the uncertainty that shadows our future prospects of food security.

While the reality of climate change is upon us, the very real consequences, such as food insecurity, have not yet been realized by many people. Please continue to raise awareness among those who listen to reason in your excellent publication, the Monitor. Robert Hunter Kamloops BC

The January 2025 Monitor edition focusing on food is appreciated but sends mixed messages about food access. If the goal is to provide a platform for diverse views, it succeeds. However, as a discussion of social justice and food as a citizen right, it is confusing. Some articles advocate for transformative changes to the food system, while others support minor adjustments to the status quo. The CCPA’s stance on food access remains unclear.

The articles highlight the tension between food security and food sovereignty. Food security, rooted in market-driven systems, views food access as a privilege based on ability to pay. In contrast, food sovereignty emphasizes local control

of food production and distribution, viewing food as a human right. Articles by Oickle and Yanful, as well as Hennessy, align with the latter, stressing the need for community-driven decision-making and municipal involvement.

Qualman warns of climate-related threats to food systems. He calls for fundamental change. He notes this will take courage. Research shows that prioritizing food as a commodity benefits corporations and perpetuates inequalities, while food sovereignty challenges these structures, advocating for food as a public good.

Achieving transformative change will require municipal policy reforms, education on local food systems, and public engagement. However, corporate influence and resistance to change can be expected to present significant hurdles. The Monitor articles show that advancing food justice and climate resilience will require overcoming entrenched “conventional” thinking if access to food is prioritized as a right, not a privilege.

Murray Hidlebaugh Saskatoon, SK

Thanks for the timely articles on where food comes from and what it really costs us, our kids, and the planet.

Qualman (“Breadbasket no more”) chose to clarify causes of food grain problems rather than discussing solutions. That gives me a chance to alert readers to truly

revolutionary work done in the last 40 years by The Land Institute in Salina, Kansas. Starting with native Prairie grasses that have annual tops and deep-rooted perennial bottoms, they developed a commercially viable grain called Kernza. To the land, that means no yearly bare-soil exposure, little erosion, no irrigation infrastructure, and no artificial fertilizer inputs. To farmers, it means that 1,000 acres can yield the same net income as 100,000 acres under machine-dominated farming methods. Low capital costs and little debt give farmers the flexibility under ever-changing Prairie climates to find niches for small holdings where now-outdated “modern” methods haven’t a chance.

The myth of cheap and plentiful grains brought us stumbling on the brink of disaster. Groceries were never cheap and plentiful to everyone, despite our conscious choice to ignore human enslavement and costs to Gaia. And then there was the “trickle down” myth…

Oickle and Yanful assert (“Building a just food system in Canada”) that “Food justice is a human right, not a commodity. Surely such a right exists only when human consumption leaves enough for the health of all the other life that makes human existence (we are Earth’s most voracious predator!) possible. Otherwise these rights will be the death of us.

Bob Weeden Salt Spring Island, BC

latest research from the CCPA

Bring back CERB and make it permanent

“Economic uncertainty is here to stay,” as CCPA Senior Researcher Ricardo Tranjan, who is based in Ontario, wrote in the Toronto Star. Whether it’s U.S. economic warfare, climate change, AI, new viruses (like the bird flu), there are plenty of sources for destabilization in Canada. “Meanwhile, the two pillars of Canada’s social safety net are a federal Employment Insurance (EI) program that fails most workers and provincial social assistance programs that sentence

families to deep poverty,” writes Tranjan. “We must do better, and we know how.”

Early into the COVID-19 pandemic, the federal government quickly replaced EI with CERB. Among the advantages of CERB over EI:

• Lower eligibility requirements.

• Higher benefits.

• Streamlined application process.

• No two-week waiting period before applying.

• Self-employed workers were included.

• It was generally more accessible to low-wage and precarious workers.

Tranjan’s bottom line: The federal government must permanently change EI, bringing back many of the CERB features while learning from some of the shortcomings of the pandemic-era benefit.

“While external factors are driving economic uncertainty, it is up to Canadian governments to strengthen our safety net,” Tranjan says.

As part of their Manitoba Research Alliance research project, Mapping Colonial Harms: Social emergencies in northern Manitoba First Nations, Jonathan Meikle and Elizabeth Comack conclude social emergencies aren’t unforeseen—they’re predictable.

“Social emergencies relating to deaths caused by suicide, violence, drug misuse/poisoning, community fires, and/or health-care services have been declared in northern First Nations in Manitoba and, in some communities, multiple times,” Meikle and Comack write.

That’s not accidental.

“They are rooted in colonial conditions that have left many First Nations in dire straits,” the co-authors write. “Social emergencies are a clear sign that the myriad harms generated by colonialism—impoverished living conditions, disconnection from Indigenous cultural traditions and ways of being, the impacts of forced relocations, and historical and intergenerational trauma—have reached a breaking point.”

The mapping problem makes clear the roots of colonialism in social emergencies. As the authors write: “Without that understanding, responses on the part of governments will fall short and social emergencies—and the tragedies that prompt them—will only continue to occur…provincial and

federal governments—and all settlers—have a responsibility to ensure the success of this decolonizing process.”

The CCPA Manitoba Office is a part of the Manitoba Research Alliance.

B.C. must maintain its climate policies, tariffs or not

“British Columbia’s exports to the United States, in particular natural resource exports, are at risk,” writes CCPA Senior Economist Marc Lee, who is based in B.C.

“There will be a time when Trump is no longer in office,” Lee writes. “As climate change related crises get worse, the world must not lose the momentum towards clean sources of energy. One bright light in recent years is that renewables have become much more competitive on the margin relative to fossil fuels, and that advantage will only increase over time.

“The fight against the Trump tariffs must be balanced with an industrial policy aimed at decarbonization. Digging deeper into fossil fuel expansion and simply seeking alternative markets than the United States is not a long-term win for Canada—or the world.”

Nova Scotia has recorded its highest single-year increase in child poverty in the 35 years since the federal promise to eradicate child poverty.

The 2024 Report Card on Child and Family Poverty in Nova Scotia: Swift Action is Needed for Child and Family Wellbeing—a report by CCPA Nova Scotia Office—shows the child poverty rate in Nova Scotia increased from 20.5 per cent in 2021 to 23.8 per cent in 2022, an increase of 16 per cent.

Nova Scotia still has the highest child poverty rate in Atlantic Canada and the fifth highest in Canada (third highest among provinces).

“Child poverty was swiftly and dramatically reduced in 2020 because of income security benefits sufficient to bring families over the poverty line,” says Dr. Lesley Frank, Tier II Canada Research Chair in Food, Health, and Social Justice at Acadia University, co-author of the report and research associate with the CCPA-Nova Scotia. “The choice to return to insufficient support by 2022 negated all progress—meaning the rise in child poverty was by design and predictable.”

Dr. Christine Saulnier, co-author of the report and director of the CCPA-Nova Scotia says: “We know what changes in policies and systems work. The current approach only softens the blow of poverty and props up community charity. We applaud the government for indexing income assistance rates to inflation, and we urge them to go further and raise the base rates ensuring that these families have enough

income to provide for what their children need.”

What are the roots of rural resentment?

The rise of right-wing populism throughout the western world has been linked to the idea of “rural resentment.” CCPA Senior Researcher Simon Enoch, based in Saskatchewan, presented a talk as part of the University of Saskatchewan’s Political Studies Speaker Series focusing on this issue.

While many see the growth of rural resentment and right-wing populism as a recent phenomenon, the political history of Saskatchewan over the past 40 years is replete with examples of politicians attempting to stoke these kinds of resentments for political gain, says Enoch.

“Indeed, the shifting politics of the province, from social democratic to conservative, as well as the success of the Saskatchewan Party and demise of the NDP, can best be explained through the lens of rural resentment and the use and abuse of populist themes from the 1980s to the present,” says Enoch.

Fast-rail project should be in public hands

The federal government announced on February 19 that it will pursue an electrified high-speed rail project from Toronto to Quebec City.

A national infrastructure project of this size will have numerous economic, social and environmental benefits that has the

potential to profoundly improve transportation patterns in Canada’s most populous region, Simon Enoch and Hadrian Mertins-Kirkwood write in their analysis of the proposal.

“Unfortunately, the government’s decision to pursue a public-private partnership (P3) to design, build, finance, operate and maintain this vital service could jeopardize the ability to realize many public benefits,” they write.

Building high speed rail in the Toronto to Quebec City corridor will profoundly transform the region. Cutting travel times between Canada’s two largest cities to three hours will likely drastically reduce short-haul airline flights and trips by car and their associated carbon emissions. Evidence from other countries show demonstrable reductions in fossil-fueled based travel when high-speed rail is an option.

The Madrid-Barcelona high-speed rail line opened in 2008, passenger volume for rail increased by 1,380,000 people in the first year of operation—and by

more than 500,000 in the second year. Air transport between the two cities, on the other hand, lost 800,000 passengers in the first year and more than 1 million in the second year. Similarly, for auto travel, California’s high-speed rail system estimates that, if and when it is finally built, it will reduce vehicle miles of travel in the state by 10 million miles each day.

To maximize these benefits, the high-speed rail system must be able to sustain high ridership through affordable fares to entice travellers to make the switch to rail.

“Passenger rail is a notoriously unprofitable enterprise,” write Enoch and Mertins-Kirkwood.

“Allowing the private provider to set fare rates will no doubt price-out a large segment of the population that would otherwise be predisposed to choose rail over other travel options.”

While there is no doubt that the high-speed rail line can be a public good, the only way to ensure it remains a public good is if it is in the hands of the public. M

Marc Lee

With a federal election in the offing, eyes are on federal Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre, who managed to rise in popularity as Justin Trudeau’s popularity tanked.

Much of Poilievre’s commentary has been centred around trash talking Canada and blaming everything on Trudeau and the federal Liberals. While that makes for good populist politics, it’s far from clear what he actually stands

for and what Canadians can expect should he become the next prime minister.

We can read the tea leaves of Poilievre’s statements to the media and in interviews. His hour-and-ahalf interview with the controversial Jordan Peterson outlines his takes and positions on a number of issues.

Beyond capitalizing on the unpopularity of Trudeau, there is not much that is new in Poilievre’s

small-government, free-market rhetoric. Ideologically, he cites the hard-right economist Milton Friedman as his inspiration. He claims his views have changed very little since he was a young man who wrote an essay about what he would do as prime minister.

That type of ideological rigidity should be cause for alarm, given how much the world has changed in the more than two decades since. Moreover, for someone who so worships the free market, he has spent his adult life working as a politician. Despite targeting his message to disaffected youth and the working class, he remains among the elite, including time as a cabinet minister in the final years of the Harper Conservative government.

The Poilievre economic agenda is mostly to double down on the same old conservative policies of deregulation, cutting taxes and public services. This, we are told, will unleash the power of the private sector, leading to surging new growth and closing the productivity gap between Canada and the United States. That, plus a house you can afford, clean streets and getting on Donald Trump’s good side—or so he says.

Canadians have already been there and seen the disastrous results. Tax cuts, deregulation and free trade have all been invoked by past federal governments to close Canada’s productivity gap with the U.S.. There is no reason to believe that cutting taxes for the wealthy or large corporations will stimulate broad-based economic growth. If anything, the benefit of these tax cuts will flow to the wealthiest Canadians while households struggling to get by will be faced with the burden of public spending cuts needed to pay for upper-income tax cuts.

The bait-and-switch on affordability is illustrated by Poilievre’s attacks on federal carbon pricing. It has taken several years for the federal minimum carbon price to rise beyond symbolic levels and now (at about 18 cents per litre at the pump) they are contentious.

But a key plank of the federal policy has been to flow all carbon tax revenues back to households and small businesses through the Canada Carbon Rebate. The upshot is a vast majority of households get back more from federal carbon rebate than they pay in carbon taxes. Cutting this system will make people worse off, not better.

Abandoning carbon pricing abrogates our responsibility to do our part to cut the flow of greenhouse gas emissions that are now tearing the planet asunder with flame and flood. Worse, it would

Bringing in tax cuts and growing military expenditures while balancing the budget imply massive federal spending cuts

Missing: a plan to address overarching challenges

Ultimately, Poilievre’s smallgovernment mindset fails to address the overarching challenges facing Canadians. The reason the Liberals won in 2015 and subsequent elections is that they spoke to important issues facing the nation, like climate change, the soaring cost of housing, homelessness and stagnant wage increases for ordinary households.

These issues remain top of mind because, in classic Liberal fashion, the Trudeau government was big on election talk, and slow on action. Our book, The Trudeau Record, looks at the failed promises of the Trudeau era in a number of areas and finds that reality has failed to live up to the hype.

boost the fortunes of the oil and gas sector, which shattered its previous all-time profitability records during the inflation of 2022 and 2023.

If the Trudeau Liberals deserve heat on affordability, it’s for failing to tax these excess profits back then, not for its carbon pricing.

Poilievre positions the Trudeau Liberals as the enemy of Alberta and the oil and gas industry. Certainly, any action to reduce emissions must include the oil and gas industry that is causing the problem of climate change in the first place. The extraction and processing of oil and gas accounts for more than 30 per cent of Canada’s emissions (and much more if we count the carbon embodied in fossil fuel exports).

Capping oil and gas emissions is a necessary step, but one that has been too slow in implementation. Since the Liberals took power in 2015, the production of oil and gas has surged (oil up 27 per cent in 2023 compared to 2015 and gas up 14 per cent). To help the industry, the feds bought the Trans Mountain Pipeline to the B.C. coast and spent $34 billion to triple its capacity, all for export.

The Poilievre campaign puts the blame on Trudeau Liberals for the wrong reasons and promises that our pressing problems will be solved by doing even less.

Consider housing, where Poilievre has been keen to position the Conservatives as beneficiaries of the Liberals’ failure to dent unaffordable ownership and rental housing. But rather than bolstering the National Housing Strategy, Poilievre would withdraw the limited funds that have been put towards providing genuinely affordable housing.

In terms of solutions, so far all Poilievre has to offer is a cut in the GST on new housing (rental housing and student residences are already exempt) and to push municipalities to approve more housing supply (which the federal Liberals have already done through the Housing Accelerator program).

In the face of big challenges, we need a strong public sector to reduce extreme inequality and ensure we have the infrastructure and public services that share the wealth and provide a base for sustainable economic development.

Big military spending could be on the way

Poilievre’s hard-right conservatism can be seen in verbal attacks on “socialists” who “want free stuff for everyone” and a massive state. A big plank of his economic agenda is aimed at cutting back the size of the federal government. One important exception is that he would support a major increase in military spending. It’s not at all clear how Poilievre will make the fiscal math work since he also decries Ottawa’s budget deficit. Bringing in tax cuts and growing military expenditures and balancing the budget together imply massive cuts in federal spending.

What would Poilievre cut? Most federal spending is for transfers to individuals (such as seniors’ and children’s benefits) and to provinces/territories (to support health care, post-secondary education and social services). Discretionary spending by federal departments is a fairly small part of federal revenue. Defunding the CBC would save little but would be very unpopular and undermine an already weak media sector.

Putting away the broadsides, social-democratic programs are popular in Canada and are built into our social safety net, from income support programs to public health care and education, and other public services, Crown corporations and infrastructure. All of these collective enterprises are key parts of a dynamic mixed economy.

If anything, the federal Liberals have done too little to deepen public services and invest in areas where the market is not delivering. Public dental care and the beginnings of a national pharmacare system are sensible directions and, if anything, the government has not gone nearly far enough.

New public investments in child care have greatly reduced out-of-pocket costs for families with young children, and have generally been supported by pro-business groups. The case for public support can be made in terms of advancing women’s ability to participate in the labour market along with benefits to young children. Again, we need more public investment, not less.

While Poilievre is clearly tapping into a general malaise that the Canadian economy is not delivering for everyone, his small-government approach to economics suggests he won’t be the standard bearer of working Canadians. It’s just a recipe to funnel even more income to those at the top.

Marc Lee is a senior economist at the CCPA, based in B.C.

Hadrian Mertins-Kirkwood and Marc Lee

The belief that economic integration with the United States—epitomized by the 1989 Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement, the 1994 North American Free Trade Agreement and finally the Trump-led 2016 CanadaU.S.-Mexico Agreement—would protect Canadian commercial interests from arbitrary political interference has been exposed for the myth that it always was. Here are 12 measures Canada could take to respond forcefully to this existential threat.

1 / Impose an export tax on energy products of at least 15 per cent. An export tax would force U.S. consumers and businesses to shoulder the full cost of Trump’s measures while generating Canadian public revenues for emergency social support.

2 / Implement export quotas and bans for strategic resources. The U.S. counts on Canada for its supply of many critical resources, including oil, potash, uranium and various metals. Canada should prepare limits on the volume of resources that may be sent south of the border—and consider outright bans.

3 / Repatriate U.S.-owned assets, especially in the resource industry. As long as Trump wages economic war against Canada, American assets here should be considered forfeited. Simply freezing those assets as a first step would send alarm bells ringing across corporate America. Going one step further and taking U.S. companies and capital under public control would mark a powerful turn toward independence.

4 / Curtail U.S. patents and copyrights. Restricting U.S. patents in Canada through compulsory licensing and other policy tools would hurt large U.S. companies and make Canadian companies in those industries more competitive.

5 / Target U.S. oligarchs and Trump enablers. The billionaires cheerleading Trump’s musings about Manifest Destiny cannot be permitted to operate and propagandize in Canada. American companies tied to Trump’s inner circle, such as Elon Musk’s X, Starlink and Tesla, should be blocked, frozen or punitively taxed, as appropriate. Imposing heavy financial penalties or outright bans on X and Mark Zuckerberg’s Meta, in particular, would serve the dual purpose of hitting Trump’s allies directly while insulating our media environment from obvious foreign interference.

6 / Enact “Buy Canadian” procurement rules and consumer programs. Wherever possible, Canadians and Canadian governments should be buying goods and services that are made in Canada. That goes double for governments, which should immediately halt procurement contracts with American firms wherever feasible and prioritize Canadian options moving forward. Canceling defense contracts with U.S. arms companies is especially important—Canada has imported more than US$1 billion in U.S.-made weapons in the past decade.

7 / Review and tax new foreign investments in Canada. As the Canadian dollar falls against the U.S. dollar, there is a risk that investors from the U.S. and elsewhere try to sweep in and buy up Canadian companies at fire sale prices. Triggering more reviews would allow Canadian governments to keep U.S. investors from controlling strategic sectors.

8 / Deepen economic ties with non-U.S. trading partners. Canada has existing trade relationships with the UK, the EU, Japan and other countries that will also be affected by Trump’s rampaging on the world stage. A common front to deepen trade linkages away from the U.S. would be in everyone’s interest. Mexico remains a vital ally that Canada cannot throw under the bus.

9 / Make the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) permanent. Reviving and making permanent the CERB program could mitigate the human cost of the “Trump Bust” that will be concentrated in tradeexposed sectors and regions.

10 / Enact price controls on essentials. Price controls need not be permanent, but, in the short term, they can blunt the effect of Trump’s aggression on Canadian consumers. These measures could include an expansion of Canada’s supply-managed agricultural sectors, such as dairy and eggs, to ensure domestic production for the Canadian market.

11 / Strengthen domestic media and cultural industries. Canada requires a reinvigorated public voice, which could be achieved through a combination of regulations, such as CanCon, and investments in the CBC, independent local media and the arts.

12 / Develop and implement an aggressive green industrial strategy. The federal and provincial governments must aggressively support a state-led expansion of strategic green industries that reduces Canadian dependence on U.S. trade and the volatile fossil fuel industry more broadly. Such a strategy could build on several of the measures outlined above, such as the repatriation of parts of the oil industry.

Nobody wins a trade war. The preceding measures are ambitious and not without their costs, but they would resist U.S. imperialism, insulate Canadian workers, households and communities from the worst of the economic consequences, and set up the economy for a long-term pivot toward independence. The future of Canada may depend on them.

Hadrian Mertins-Kirkwood is a senior researcher at the CCPA, based in Ottawa. Marc Lee is a senior economist at the CCPA, based in B.C.

Simon Enoch

Public libraries continue to be a treasured public space and resource for residents of Regina and Saskatoon.

Far too often, policy-makers who may not actually frequent public libraries view them as an anachronism—thinking of them as mere repositories of books, ignorant of the vast array of services and programming that modern libraries currently offer.

Recall the government’s justification for the proposed elimination of library funding in 2017 when then Education Minister Don Morgan cited drops in items checked out as the rationale for making multi-million dollar cuts to public libraries across the province. Public

outrage and protests over the cuts ultimately forced the government to back down, with Premier Brad Wall admitting the proposed cuts had been a “mistake.”

Let’s compare public library usage to attendance at major sporting events in Saskatchewan. The numbers don’t lie—Regina and Saskatoon libraries are significantly more popular than some of the province’s biggest sporting events. The chart below demonstrates the continued value of a public library system that often must beg and plead for public funding versus sports stadiums and event centres that are often showered with public money even when public support for these projects is muted, at best.

Regina residents endured a dedicated mill rate increase of 0.45 every year for 10 consecutive years to pay for a new Mosaic stadium that many simply cannot access due to the rising cost of ticket prices. Despite these public subsidies, the stadium continues to be a perennial money loser for the city.

Seeing the disparity between public usage of libraries versus stadiums and arenas might make us contemplate what kinds of public venues are most deserving of taxpayer support.

Some will argue that such a comparison is faulty because libraries are free while sporting events are not. This is obviously true—sports events cost money to attend and are not accessible for most of the year as libraries are. However, this argument misses the point.

If sports venues were entirely financed with private money, we wouldn’t be having this debate. But these venues suck up significant amounts of public money that could go to other priorities—and they are often of dubious economic value.

Indeed, if there is anything like a consensus in the economic profession, it is that public funding of arenas and stadiums is a poor economic development strategy and that franchises, stadiums, and arenas may be harmful rather than beneficial to the local community,” according to a 2015 study.

The economic impact of libraries, on the other hand, is undeniable, but in ways that may escape those that are unfamiliar with the services and programming available in a modern library system.

Libraries are central to our communities

Obviously, libraries continue to play a vital role in fostering early literacy and childhood development. But libraries are also vital hubs for job-seekers, with many libraries providing job information, technology training and other career services. They are vital to new immigrants, offering English language courses, tax filing information sessions and adult literacy programs to help newcomers navigate their adopted country. Many libraries also host small business programs to support local entrepreneurs. No other venue can generate the kind of foot-traffic that public libraries can, directly benefitting local business in the area.

We need to appreciate the economic, social and cultural impact that public libraries bring to our communities so that they receive the same kinds of enthusiasm for public investment that sports arenas and stadiums do.

Simon Enoch is a senior researcher with the CCPA and is based in Saskatchewan.

David Macdonald

At 10:54 a.m. on January 2—the first work day of the working year—the 100 top CEOs in Canada had already made the salary of the average Canadian worker of $62,661.

In 2023, the top 100 CEOs in Canada took home an average of $13.2 million in total compensation. This equates to 210 times the salary of the average worker.

Workers have been fighting back this year, seeing a wage gain of seven per cent over last year. One solution to rapidly rising prices is to get a raise so you can afford those higher prices. On the other hand, a tear will be shed in corporate boardrooms now that inflation has come back to normal. They may never again be able to raise prices like they did in 2022-23 and reap

the bonuses that resulted from those profits.

Certainly CEOs have always made more than the average worker, but the gap has grown tremendously. In the 1980s, CEOs made 50 times the average worker. By the late 1990s, it was 100 times and now we’re solidly over 200 times.

CEOs would have you believe they got the CEO position after intense international competition. But the reality is much more mundane: 76 per cent of the top CEOs in Canada were hired into a lower position and worked their way up. On average, they’d been with the company 21 years, or half their career. They’re company men—yes 97 per cent are men—whose value is in knowing a particular company. Corporate Canada prefers internal hires.

In the 1980s, CEOs made 50 times more than the average worker in Canada. Now they make 210 times more.

What does it say about Canada that the benefits of economic growth are distributed so unevenly? As record-breaking numbers of people are living in the street and food banks are being pushed to their absolute limits by increased need, a small class of corporate executives is living like kings.

We’ve made a number of small wins in the past few years that have helped cap growth on out-ofcontrol CEO pay. In 2021, the federal government capped tax deduction for those paid in stock options, a common form of bonuses for CEOs. This led to a substantial fall in stock option use by CEOs.

And as of June 2024, people who make massive annual profits

on stocks and real estate—over $250,000—now pay a tax rate slightly closer to what workers pay. Incredibly only five CEOs on our list owe over $800 million more in taxes due to this one change. This shows not only how concentrated wealth is in Canada, but also how concentrated the impact is of the June change.

That said, they won’t pay that tax until they sell their shares, so they’ll likely just hold out for a friendlier government to cancel the change. This speaks to the need for a wealth tax that charges these amounts annually and attacks entrenched wealth hoarding head on.

These measures are obviously welcome, as is anything that attempts to make the CEO class pay something closer to their fair share. But there’s still a lot of work to be done to address the growing wealth gap in Canada.

It’s time we ask many of the people who have profited the most from the various crises Canada is living through—the climate, affordability, and housing crises, U.S. economic warfare—to start financing solutions. Why shouldn’t real estate barons have to help finance a massive public housing construction program, and why shouldn’t fossil fuel magnates have to finance transition to a green economy?

This article will take the average reader about two minutes to read. By the time you’ve finished reading it, the top CEOs will have about $105 more than they had when you started.

David Macdonald is a senior economist at the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives.

Christine Saulnier and Jenna MacNeily

Minimum wage workers in Nova Scotia can expect a 50-cent increase as of April 1, 2025 (to $15.70), followed by another increase of 80 cents in October 2025 (to $16.50), representing an increase of about 8.5 per cent. These are undoubtedly welcome increases for these lowwage workers. However, this is still not enough.

These minimum wage increases hardly begin to bridge the gap between the minimum wage and the living wages calculated by CCPA Nova Scotia. The 2024 living wage report indicates that this minimum wage falls significantly short of what is necessary to make ends meet across the province. The highest living wage in 2024 was in Halifax, at $28.30. Even the lowest rate—$24.00 in Cape Breton—is considerably higher than the provincial minimum wage. The weighted average for the province was $26.53, with living wages in the Annapolis Valley, Northern, and Southern regions at $26.20, $24.90, and $25.20, respectively.

Those who oppose significant increases to the minimum wage

argue that this work is primarily done by young people with few expenses and lots of family support. However, the reality is that teenagers are far from the only ones working in low-wage jobs. As highlighted by CCPA-NS, data from Statistics Canada showed that 35 per cent of workers in Nova Scotia earn $20/hour or less. Furthermore, the data show that 85 per cent of these low-wage workers were over the age of 20, 82 per cent were not students, and the majority were in full-time, permanent positions. We also should not overlook that young people and their families face considerable costs. With Nova Scotia university tuition coming close to the $10,000 mark this year, and student debt averaging $39,100 (2020), they also deserve a living wage. To be clear, everyone deserves to earn at least a living wage.

How did the government determine the amount for the minimum wage increases? The first increase follows the Nova Scotia Minimum Wage Order, which states: “Effective on and after every April 1, beginning in 2025, the current hourly minimum

wage rate for employees will be adjusted by the percentage change in the projected annual Consumer Price Index for the calendar year immediately preceding the year in which the adjustment occurs, plus an additional 1%, and rounded to the nearest $0.05.” The average CPI annual increase in 2024 was 2.4 per cent across Canada; plus one per cent is a 3.4 per cent increase by April 1.

According to the government, the second increase is to help these workers with the cost of living. The formula should factor in real-time costs in the province more carefully. For example, rent rose 7.9 per cent in Nova Scotia in 2024 compared to 2023; rent takes up the most significant portion of low-wage workers’ budgets, and for some of these workers, these increases will be swallowed already.

Bridging the gap between the cost of living and low-wage employment requires government action on both sides of the equation. One solution is to increase the minimum wage to $20. Making life more affordable also requires substantial public investment to lower people’s out-of-pocket costs for essentials. This includes expanding access to key universal public services, like child care and health care, and increasing the amount directed to non-market affordable housing, public transportation, post-secondary education and food security.

With a provincial budget around the corner, we draw your attention to the alternative budgetary choices the government could make to build a green, diversified economy and just society. We look forward to hearing more about the new government’s plans and urge it to be transparent about them, as respecting democracy requires.

Jenna MacNeily is a graduate student at Dalhousie University, completing her Master of Social Work and Dr. Christine Saulnier is the Nova Scotia director of the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives.

Jon Milton

On his first day in office, U.S. President Donald Trump declared war on migrants. That might seem like hyperbole, but it’s barely an exaggeration—in one of the many anti-immigrant executive orders he signed on day one, he officially declared that irregular migration to the U.S. is an “invasion” and assumed wartime presidential powers to stop it, including the unprecedented move of deploying the military on U.S. soil to “secure complete operational control” of the border.

Trump plans to build a massive machine of surveillance and repression in the United States to root out migrants, including stripping migrants of legally acquired citizenship. He plans to send millions of U.S. residents to countries across the world, some of whom have not seen “their” country since they were children, in order to fulfill his campaign promise of mass deportations.

The situation is bleak, and Canada has responsibilities—both moral and legal—to act. The first thing it should do is immediately withdraw from the Safe Third Country Agreement with the United States.

The Safe Third Country Agreement is a bilateral agreement between the U.S. and Canada, which was signed in 2002 and went into effect in 2004. It regulates refugee claims between the two countries. According to the terms of the agreement, a migrant applying for refugee status must do so in the first “safe” country that they arrive in.

That means, for example, a migrant arriving from Haiti via Mexico cannot cross through the

United States and then apply for asylum in Canada. Because the hypothetical migrant arrived in the United States first—and the U.S. is designated as a “safe country” by the terms of the agreement—they must apply for refugee status in the United States. The same would apply to a migrant who arrives in Canada first—they cannot then apply for refugee status in the U.S.

The initial agreement only covered official points of entry, such as land border crossings, airports, and marine ports. It did not cover the vast majority of the U.S.-Canada border. So when Trump first took office in 2017 and began to implement his anti-immigrant vision, migrants began fleeing to Canada through irregular crossing points.

The most famous of those crossings was at Roxham Road.

Located between Champlain, New York, and Saint-Bernard-de-Lacolle, Quebec, Roxham Road became the site where migrants fleeing deportation in the U.S. would arrive and cross into Canada. Because Roxham was not an official point of entry, it allowed migrants to legally apply for refugee status in Canada despite having previously been in the “safe country”—the U.S.

Between 2017 and 2023, around 100,000 people crossed the border at Roxham Road to apply for asylum—over 90 per cent of the total of irregular crossings into Canada.

In 2023, during then U.S. President Joe Biden’s first official visit to Canada, he and Trudeau announced that they had renegotiated the Safe Third Country Agreement. Now it would apply to the entire border, not just official points of entry. Roxham Road was closed—and so was a key

legal path to asylum in Canada for migrants fleeing the U.S.

Back in 2007, a judicial review of the Safe Third Country Agreement triggered by Amnesty International, the Canadian Council of Refugees, and other human rights groups— found that the agreement was unconstitutional and failed to live up to Canada’s obligations under international law to protect the rights of refugees. It found, in short, that the United States could not reasonably be considered a “safe country” for refugees due to its non-compliance

with the Refugee Convention and the Convention Against Torture.

The decision was overturned by an appeals court on procedural grounds—but even in the overturning decision, the court did not find that the U.S. was a “safe country.”

That was 2008, years before Trump became the dominant figure in American politics by stoking anti-immigrant hate. Today, the immigration environment in the United States is significantly worse.

to section 208 of the Immigration and Naturalization Act, which allows for asylum claims.

A family disembarks from a taxi at the end of Roxham Road just south of the US-Canadian border near Champlain, NY, despite signs prohibiting crossing it here, and request asylum in Canada. / Wikimedia, Daniel Case

One of Trump’s day-one decrees was to completely suspend the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program (USRAP), the program through which all refugee claimants must pass to enter the United States, for 90 days “pending review.” If the program comes back at all, it will likely be significantly more restrictive. Trump also suspended access

It appears that, for now, there is essentially no way to make a legal refugee claim in the United States of America. The idea that such a place can be considered a “safe country” for refugees in this context is completely and obviously absurd. Canada, though, continues to maintain this fiction as a signatory to the Safe Third Country Agreement. Pretending that the U.S. is a safe country means that Canada continues to lock out asylum seekers who have legitimate fears of persecution in their home country—and, increasingly, in the United States itself.

America’s Department of Homeland Security has been given a mandate to use “all legally available

resources” to construct detention centres for migrants, and America’s federal government is setting up task forces in every state to manage the mass deportation of millions of people. The president of the United States has expressed plans—some of which are blatantly unconstitutional—to strip legally acquired citizenships. It would be reasonable to interpret the U.S.’ war on migrants as a form of persecution in itself.

If Trump actually does even half the things he has promised to do to migrants in the United States, it will trigger a humanitarian crisis—and Canada has the responsibility to act to protect people fleeing persecution.

When governments attempt to close migration routes, migration doesn’t stop—it just moves to more dangerous areas. When the U.S.

“closed” the border with Mexico in the 1990s, more migrants moved into the dangerous terrain of the southwest desert. When Europe “closed” land migration routes coming from Turkey and elsewhere, more migrants chose to take the perilous journey across the Mediterranean in small and crowded boats.

In the past 10 years, over 31,000 migrants have “gone missing” in the Mediterranean while attempting to cross into Europe. Another 10,000 are “missing” along migration routes in the Americas during that same period, with the majority of those deaths being in the desert along the U.S.-Mexico border.

Canada has largely been insulated from these waves due to geography. It only shares a single land border with a country that it designates as a “safe country” for refugees, justifying a blanket refusal of asylum claims. But what happens when that country is no longer safe?

Like most countries, Canada is a signatory to the Convention on the Status of Refugees, an international agreement that outlines the legal responsibilities signatories carry towards asylum seekers. The convention is clear—refugees have a right to asylum from persecution, and they have the right to access such asylum even if they enter a country irregularly.

But the most important arguments in favour of scrapping the Safe Third Country Agreement aren’t legal—they’re moral. Do we, as a country, want to bear the weight of thousands more migrants dying while searching for lives of dignity?

During the Holocaust, a high-level Canadian government official—likely either Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King or his immigration minister—was asked how many Jews Canada should admit to the country as they fled Nazi persecution. They responded by saying that “none is too many.”

Let’s not say the same thing to refugees today.

Jon Milton is associate editor of the Monitor.

Aragão

Recent estimates of life satisfaction from Statistics Canada reveal a troubling reality about the well-being of Ontario residents. Compared to all other Canadian provinces, Ontario ranks lowest in reported levels of life satisfaction, in a stark contrast to neighbouring Quebec, where 58.4 per cent of residents report high levels of life satisfaction, compared to 45.4 per cent of Ontarians.

While several aspects can influence life satisfaction, including cultural and individual characteristics, a closer examination shows that Ontarians don’t have many reasons to be joyful. Additional estimates from Statistics Canada show that, compared to the national average, Ontario residents are more likely to report financial strain, express distrust in their education system, and report poor mental health—portraying complex combinations that systematically erode quality of life.

Indeed, paying the bills has become a challenge for many Ontarians. Housing costs in Ontario are among the highest in Canada, prompting an increase in the number of individuals experiencing housing instability and homelessness. The growing cost of keeping a roof over one’s head has also intensified a food insecurity crisis, leading over one million Ontarians to seek the assistance of food banks between 2023-24.

Times are getting tough, and the public safety net is not there

By province

Individuals reporting high life satisfaction rank their life satisfaction 8 or higher on 1-10 scale

to support the population. As the CCPA has systematically documented, the chronic underfunding of public services in Ontario is a structural issue. Despite boasting a substantial $1.05 trillion GDP, Ontario falls $3,863 behind the national average per capita spending, allocating about 75 cents for every dollar invested in public programs by other provinces.

There are also no indications that the provincial government is doing anything to change this scenario. The spring 2024 provincial budget ignored this troubling trend, seemingly indifferent to mounting social challenges inflicting the population. The budget included explicit cuts to areas such as post-secondary education and justice spending. In addition, while the nominal budget for areas such as education, health care, and social services increased, our estimates show that when inflation and population growth are accounted for, we see a decline in provincial public spending.

Cuts to social programs have been systematic in Ontario. In education, the government has employed strategic accounting techniques to mask significant cuts to classroom resources, such as the “planning provision”, which comprises 4.85 per cent of core education funding and cannot be spent at school boards’ discretion. As a result, the province effectively reduced per-student funding by $1,500 between 2018-19 and 2024-25. Changes to the funding system have consequences: classrooms across Ontario have 4,990 fewer educators than they would have if these cuts had not been implemented.

Proposed changes to Ontario’s health care system are also not making things better. Ontario’s plan to expand publicly funded surgeries in for-profit facilities poses significant risks to public health care, with the potential to compromise patient safety, create financial conflicts of interest in medical decision-making, and entice private investors to permanently alter Ontario’s health care infrastructure.

It’s no surprise Ontarians are gloomy. As the province continues to systematically underinvest in its people, the human cost becomes impossible to ignore.

Carolina Aragão is a researcher with the CCPA, based in Ontario.

John Cartwright

The election of Donald Trump on November 5, 2025 shocked people across Canada and the world. Americans chose him as their 47th president and rewarded Republicans with effective control over all levels of the federal government. Analysis of the Democratic defeat and the role of culture wars and billionaires will fill media platforms for months to come, but it comes down to this: faced with a choice of someone who represents the status quo and a system that many feel is letting them down, or a life-long scrapper who promises to shake up that system, a clear majority voted for change.

The entire world is watching as things unfold. Mass deportations, tax cuts for the wealthiest people on the planet, slashing environmental standards and public services, Ukraine’s independence, the Middle East condemned to relentless violence, and so much more...

As we learned immediately, the consequences for Canada are deeply troubling. While Trump threatens

massive tariffs and speaks of the 51st state, influential figures in corporate Canada feel emboldened to dismantle any previous consensus on climate action, social programs or human rights for refugees, all while demanding increased military spending and integration with the U.S. economy. The “Premier of Petroleum,” Danielle Smith, took her show to the U.S. to deliberately sabotage any sense of Canadian unity in the face of Trump’s aggression.

Conservative politicians are awash with funds from Bay Street financiers, mining magnates, land speculators and Alberta oil barons. Pierre Poilievre was taking the right-wing playbook written by Steve Bannon for Trump and riding a wave of discontent towards certain victory. And then Donald Trump swept to power, and, as Naomi Klein noted in the title of one of her books, This Changes Everything. What does this moment mean for the rest of us? People want answers they believe will make a difference in their lives. For those who are despairing or

feeling hopeless, an answer can be found by using our heart to inform our hands. In Steven Spielberg’s movie Amistad, the most powerful words came from the leader of the enslaved Africans who rose up to take the ship from their captors. The American lawyer who was at the Supreme Court arguing for their freedom faced certain defeat in his legal case. He asked his clients for advice and received eternal wisdom: “we ask our ancestors.”

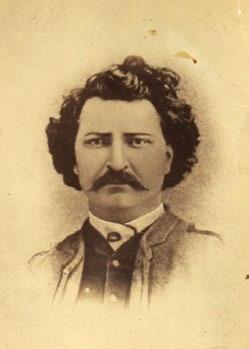

We can look back on our own history and “ask the ancestors.” Not simply the fathers of Confederation, but people like Louis-Joseph Papineau, Louis Riel, T. Buck Suzuki, Agnes McPhail, Viola Desmond, Gerry Gallagher, Charan Gill, Art Manuel, Carol Wall, and Murray Sinclair. Not all these names are well known, but they deserve to be. How did these heroes and so many others harness the energy and spirit to succeed against overwhelming odds? How did they project a vision of a more just society while building the power necessary to challenge the economic and political elites of the day?

I was blessed by learning at the feet of incredible leaders of the working-class movement, most of whom were never profiled in the history books. They were natural leaders who were thrown into struggle by the events of their day and helped forge mass movements—for racial justice, affordable housing, environmental action, women’s equality, gay rights, and for respect at work and in society. I heard women who had sustained a peace movement through the cold war expressing their joy at a 1970s rally that “the young people are joining us to carry on the message of peace.” I marched beside Cesar Chavez and Marshall Ganz in their effort to win dignity and a union for California farm workers. I will never forget the humble dignity of that movement that could force the

most powerful opponents to yield. I saw the same sense of purpose in the disarming smile of Pura Velasco as she led the fight for migrant domestic workers.

I think of Italian and Portuguese immigrants fighting the Compensation Board to win benefits for their injured bodies. Of the brave African Canadian leaders like Daniel Hill and Bromley Armstong who fought tenaciously to dismantle systemic racism before that was a phrase in our vocabulary. Of Cape Breton miners, or Winnipeg strikers, tenants fighting for rent controls and affordable housing, of young South Asians who organized to resist physical violence by racist thugs, and women from every background struggling against endemic sexual harassment or domestic violence.

There is a monument in Toronto to the 14,000 Chinese Railroad workers who came from Guangdong in the1880s to blast through the Rockies and complete the Canadian Pacific Railway. Hundreds died at work and many more were injured. A century later, their descendants and community allies forced the government to apologize for the infamous Head Tax and the Chinese Exclusion Act that followed. The Japanese Canadian community sought reparations for the savage internment program of the Second World War and decided that the money should be used to create the Canadian Race Relations Foundation—to help educate young Canadians about the impact of xenophobia and bigotry.

There are many lessons from intense struggles for justice, but there is also much to be learned from other kinds of community building that is also necessary for a caring and inclusive society. Those who volunteer for charitable causes are also essential for the social solidarity we need. From the United Way to newcomer settlement agencies, to seniors’ services and mental health networks. The people in churches, mosques and

synagogues who offer shelter to those in distress, and the countless others who sponsor refugees fleeing famine and war.

There is a beautiful statue in Toronto’s Regent Park of Pam McConnell, a community activist who used her role at city council to spur a massive investment in decent housing and urban renewal. Arms outstretched, she invites us to “look at all we have done.” Not just the physical space of fine buildings and community amenities, but the tapestry of people from diverse origins and backgrounds who have come together to create a better future. If only we made sure that, as working-class Canadians, our stories and achievements are being chronicled and shared.

But here is the reality. “Power concedes nothing with demand. It never has, and never will.” Those words of African American abolitionist leader Frederick Douglass in his visits to Canada in the 1840s are as true today as they were at that time. How do we build power today in the time of global corporate empires, billionaire funders of

Louis Riel / Wikimedia

fascism, and a wave of disinformation that dominates every screen? If we ask our ancestors, what do they tell us?

Marshall Ganz, the fellow I met through the Scarborough grape boycott committee 50 years ago, has become one of the foremost social justice educators in the world. He recently published a summary of his life’s work entitled People Power Change. It describes using the power of narrative to help ordinary people discover their own inner strength and build deep relationships with others. His “five practices of democracy” are: building relationships, storytelling, strategizing, acting and structuring. It’s not about finding “kumbaya” moments, it’s about intentional relationships that become the basis of organization and mobilization.

Ganz provides a unique but powerful definition: “Leadership is the ability to allow others to act in common purpose in a time of uncertainty.” It’s quite a different approach to the strong man politics that is sweeping our world today, or the strong leader culture that informs many of our movements. But it is what we will rely on to get us through the dark days ahead. There is another aspect of his craft. He often reminds the reader that every faith tradition is rooted in the questions of how we discover and affirm our common humanity. It is done through storytelling that paints a

picture of a people committed to each other. Someone once referred to that as “the vision thing.” It is what holds people together in times of distress, of endurance and when asked to take risks.

The California farm workers told a story rooted in the traditions of Mexican culture, Catholicism, the Mexican revolution and everyday life of people in the fields. At the same time, we in Canada were grappling with our relations with the United States, our sovereignty (either in Canada or Quebec, or for Indigenous Peoples) and resistance to being drawn even closer into the American empire. A wave of nationalism sparked the move for a clearer Canadian identity, arts and culture, and a reckoning with the dynamics of a branch-plant economy. The Council of Canadians became the standard-bearer for the widespread yearning for an independent Canada.

If progressive Canadians are clear about what we stand for today, we all have a much better chance of defending what we have won in the past. And in the face of the adversity to come, our commitment to building a stronger future together must be seen and believed by Canadians from all walks of life, in every part of this country.

But there is something missing today. We don’t have a coherent progressive movement. We have lots of good organizations doing good work on their individual issues. Lots of volunteers—from the youth of the Fridays for Future and Black Lives Matter to the veterans of the Urban Alliance on Race Relations and Seniors for Climate Action.

Compared to the ascendant conservative movement, whose inspiration comes from the Tea Party and whose energy was sparked by the Freedom Convoy, the progressive movement has no shared “playbook” in the way that Steve Bannon created for Donald Trump, and leading conservative operatives translated into Canadian. Ontario Proud was funded by the development industry furious with the Liberals for the Greenbelt policies. Together, they helped create a momentum that wiped out the “natural governing party” of Canada’s largest province. In British Columbia, John Rustad’s Conservatives came within a hair’s breadth of taking office—with a party that had barely existed a few years before.

These guys have a playbook, and we don’t. Sure, some folks want to aspire to “strategic voting” as a solution. But that lasts about as long as the first debate between party leaders as each seeks to find advantage in the other’s weakness. And frankly, the Liberal Party in both Ontario and Canada is scurrying back to the centre to try to repair their relations with Bay Street and the Rideau elites. The NDP are unlikely to form a government east of the Manitoba border without a mass movement to propel them there. And there is no mass movement today that is building power for the 99 per cent.

I always smiled at a cheeky poster that my Guyanese friends brought from back home to explain this issue in the clearest terms: mobilization without organization is like bark without bite. So, my friends, how does our side do organization?

Think back to another group of ancestors, across the ocean. Nelson Mandela, Moses Kotane, Soe Slovo and Ruth First, Desmond Tutu. How did they and millions of South Africans sustain a struggle over decades against the ruthless apartheid state backed by the wealth and weapons of the UK, the U.S. and Israel? They built unity by creating the Freedom Charter that could serve as a common vision for many disparate groups, and then coordinated mass actions through a network of inspiring leaders. In his 1999 book Developing Organizational Capacity, Alan Kaplan drew the lessons of this long journey.

His approach was summarized by Rob Fairley for the Toronto & York Region Labour Council as it sought to build its own capacity at the start of this century. There are two aspects outlined: first, how to identify an organization with capacity, and second, what steps to follow to build such an organization (see sidebar).

Kaplan speaks of how to build a single organization, but surely the same concepts can apply to the entire progressive movement. It’s time for us to get our act together and start building the kind of power that once forced capital to accede to demands in the past: public health care, public pensions, unemployment insurance and social benefits, non-market social housing, pay equity, women’s and queer rights. The list is truly impressive when you count up all that previous generations of Canadians have won through political bargaining—and add on a national pharmacare program secured in the last year.

They made tough decisions to build solidarity that was never easy. I would say that, in 2025, we are all called to replicate their determination and vision. In the words of one of those ancestors, we should dream no small dreams— and then commit to each other to model the spirit of Marge Piercy’s immortal poem “To Be of Use.” M

To Be of Use

I love people who harness themselves, an ox to a heavy cart, who pull like water buffalo, with massive patience, who strain in the mud and the muck to move things forward, who do what has to be done, again and again. I want to be with people who submerge in the task, who go into the fields to harvest and work in a row and pass the bags along, who stand in the line and haul in their places, who are not parlor generals and field deserters but move in a common rhythm when the food must come in or the fire be put out. —Marge Piercy

John Cartwright is the chairperson of the Council of Canadians and former president of the Toronto & York Region Labour Council.

• Is an autonomous, self-aware entity that defines its own sources of inspiration, focus and direction

• Is able to learn from its experience

• Is able to respond with flexibility, innovation and adaptability to changing circumstances

• Has a strategic outlook that enables it to act decisively to impact and change its circumstances and social context

• Motivates, inspires and develops its members

• Concentrates on developing a robust capability

• Is sustainable—organized for the long haul, rather than for the capacity to perform a particular task at a specific time

• Create a shared assessment, a shared conceptual framework of the organization’s situation in the world

• Develop an organizational “attitude” (stance) and identity (sense of itself) which enables the organization to act confidently and effectively on the world

• Create a vision, an understanding of what the organization intends to do, by exploring internal and external constraints and possibilities

• Develop a strategy—the “how” by which the organization intends to realize its vision

• Nurture an organizational culture with norms and values which are self-critical and self-reflective

• Structure the organization to suit its culture, implement its strategy and achieve its goals

• Take the time to develop the organization’s members and organizers—it is not enough to train them

• When the organization faces a scarcity of material resources, harness organizational ‘attitude’ to overcome the scarcity

iStock.com/tupungato

Luke LeBrun

British Columbia has long had a reputation as Canada’s most progressive province.