Bellerive 2017

Issue 18

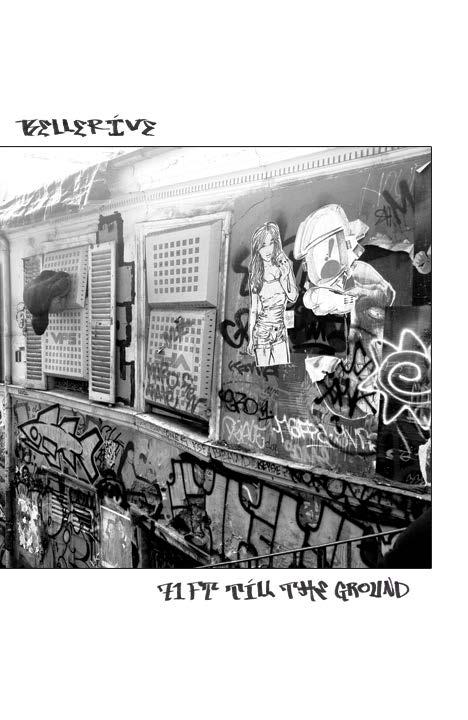

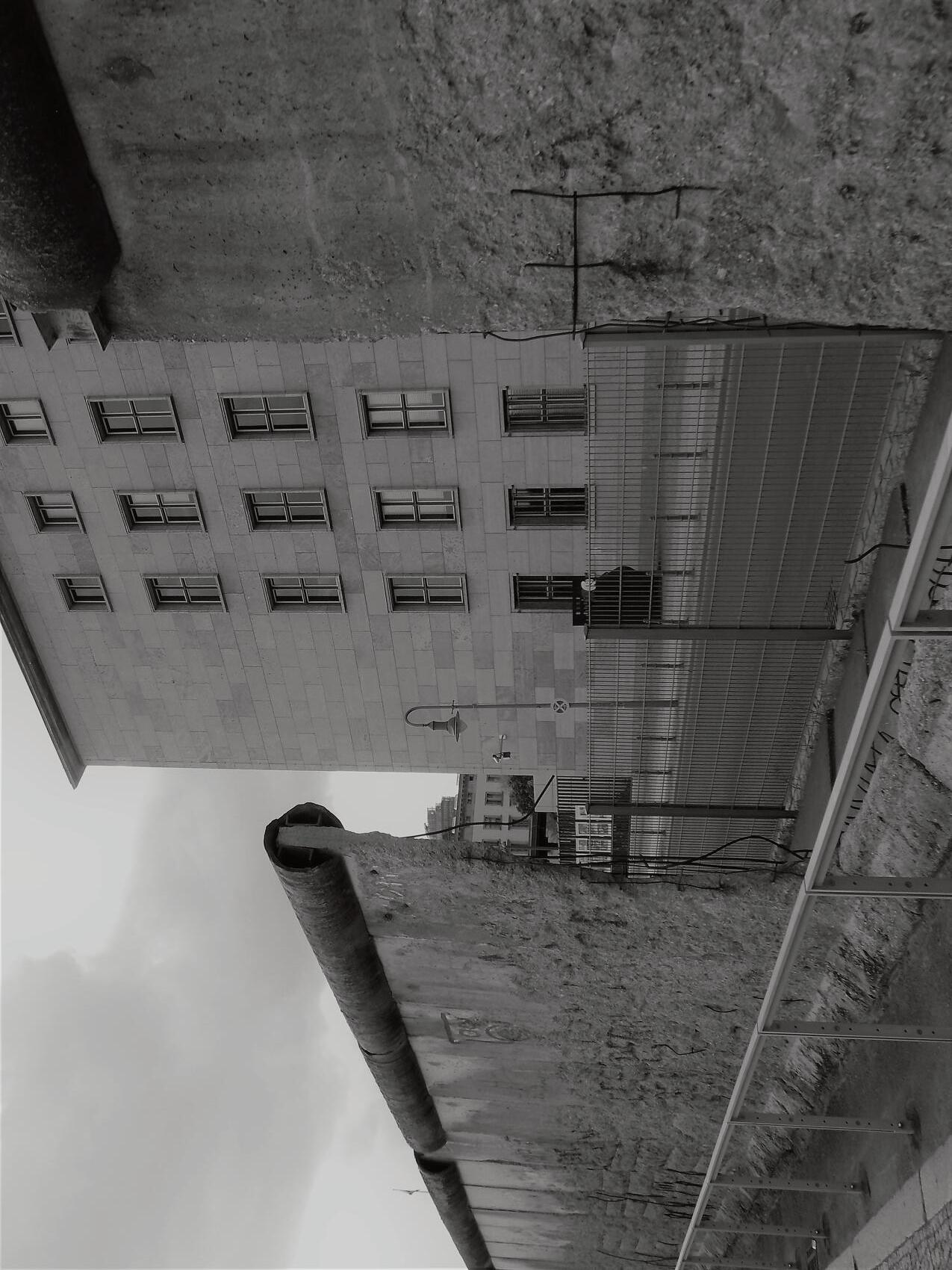

Cover Art: Mur Montmartre

Mandy R Bibee

University of Missouri–St Louis

Pierre Laclede Honors College

Pierre Laclede Honors College

A R T

Audri Adams, Zyra De Los Reyes, M. Macallan Lay, Zoë Scala*, Emma rasher

E D I T I N G

Sean Chadwick, Jaimi Cook, Haley R Graham, Sarah D Gordon, Zachar y J. Lee*, Kaitlyn May, JoHannah McDonald, Chloe Simpson, Regan Slaughter, Daisha T. Smith, Andrew Stoker

L AY O U T

Kristy N. Burkemper, Kevin Kuchno*, Carly Leigraf, Kayla Schieffer, Lysa Young-Bates

F A C U L T Y A D V I S O R Geri Friedline

*Denotes committee chair

Current and past copies of Bellerive editions are available to purchase for $7 each or two for $12 To purchase, contact Geri Friedline at (314) 516-7874 or via email at friedlineg@umsl.edu. Alternatively, visit the Triton Bookstore. Please note that limited copies are available for each edition, and once they have all been sold, no further copies will be produced

All University of Missouri–St. Louis students, faculty, staff, and alumni are invited to submit original creative works that have not been previously published Submissions are accepted from March 1 through October 1. We invite eligible individuals to submit up to 8 poems, up to 3 prose pieces (each at 4,000 words or less), up to 8 digital images of photography/art, and up to 2 original music works (as audio files)

To learn more about submitting to Bellerive, inquire at BelleriveSubmit@umsl.edu or visit facebook com/BellerivePublication

Submissions review is a blind process. Submitters’ names are not disclosed during review. e new issue of Bellerive is launched at a reception in Provincial House each Februar y is open reception also kicks off the next issue’s submission period.

Offered ever y fall, the Bellerive Workshop course is open to Pierre Laclede Honors College students, sophomores to seniors, interested in all aspects of producing our creative writing and art publication, Bellerive. e class focuses on all steps of publishing, including reading and selecting works to be included, copy editing, communicating with submitters, designing layout, digital image editing, and marketing and selling of the publication. Individuals in the class choose which areas of contribution best suit their interests and talents.

facebook.com/BellerivePublication

ii | Bellerive Issue 18 Staff Ackn owledgments

1 Bobby Meile | Suddenly, Bees

2 Audri Adams | Simmons SK-5 Killer

3 A. Erin Hyde | Curiosity

4 Jessie Kehle | The Fourth Pig Made His House out of Sequins

5 Haley R. Graham | this one thing will change the way you think about everything!

6 Emese Mattingly | Overreading ings

7 Ryan Brooks | Smooth Lines

8 Zachar y J. Lee | Under Elm in Early April

9 Jason Becker | Avocado Tree

11 Ramsay Wise | #8 Flowers Monochrome

12 Bailee Warsing | rough the Woods

13 Sean Chadwick | e Cicada’s Song

17 Anthony Deluvia | A Forgotten Childhood

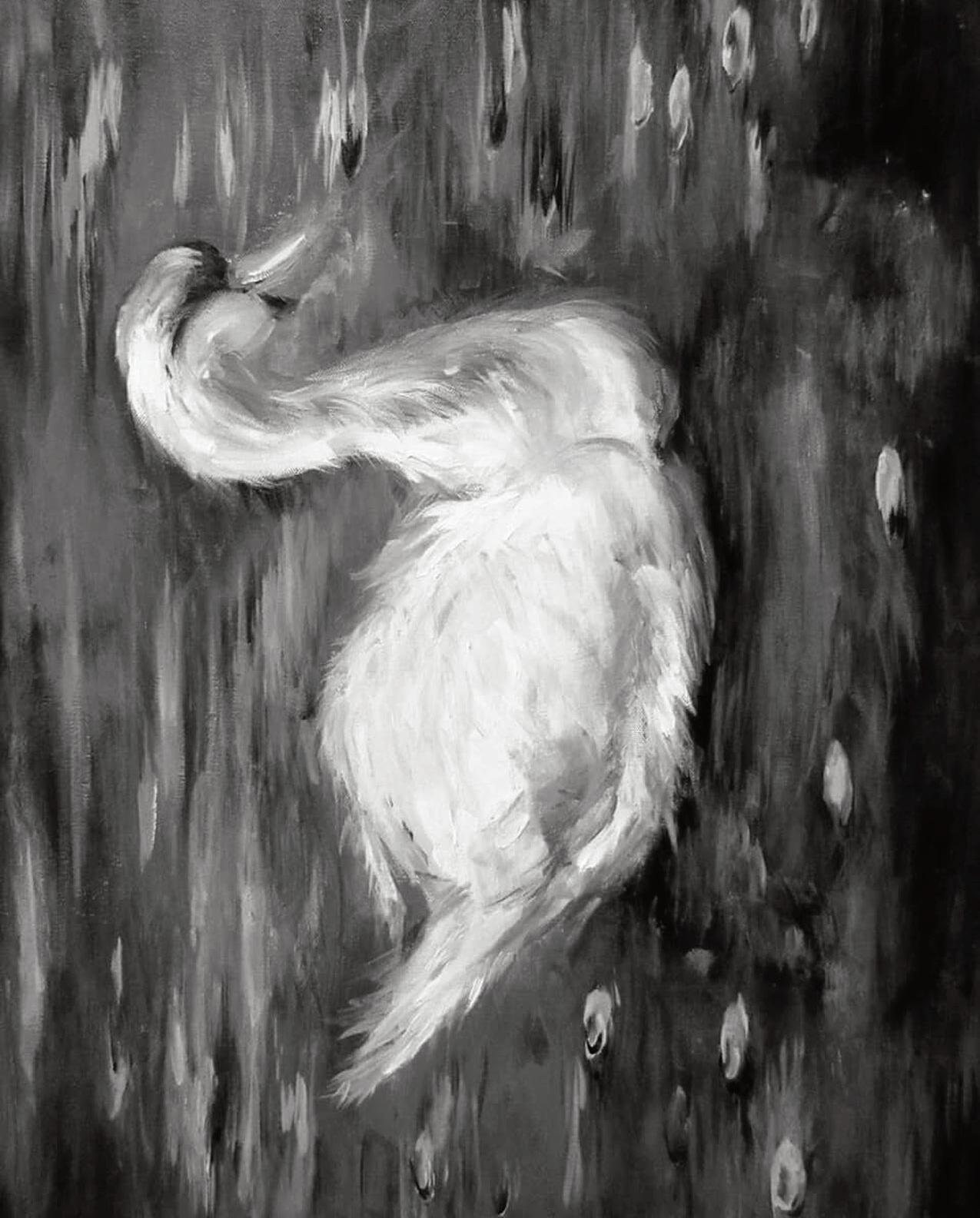

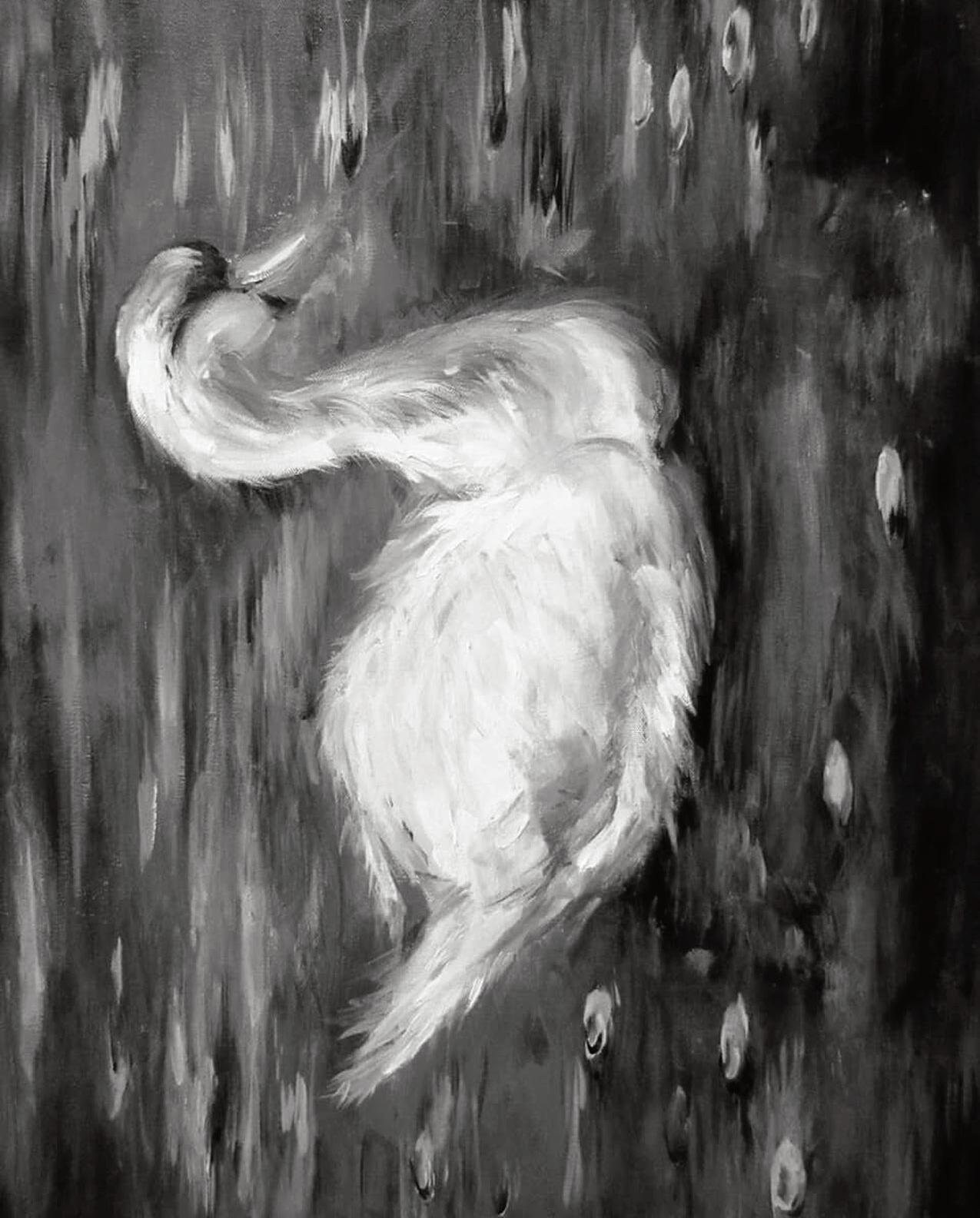

18 Molly Brady | Collapse

19 Jason Becker | Unreborn

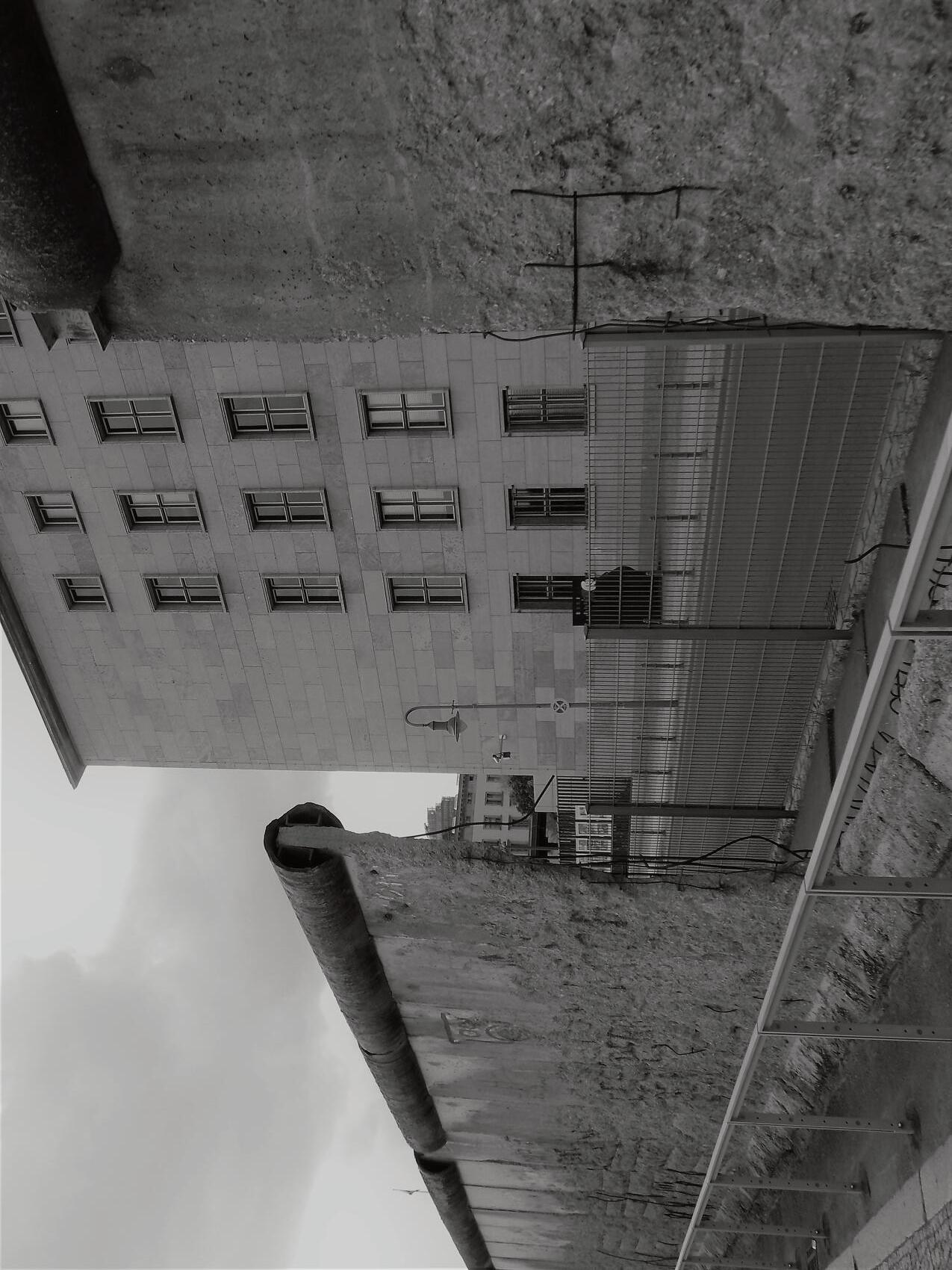

20 Audri Adams | Teufelsberg Station

21 Ramsay Wise | #6 Flowers Monochrome

22 Jeff Polizzi | e Funeral March for the Fallen

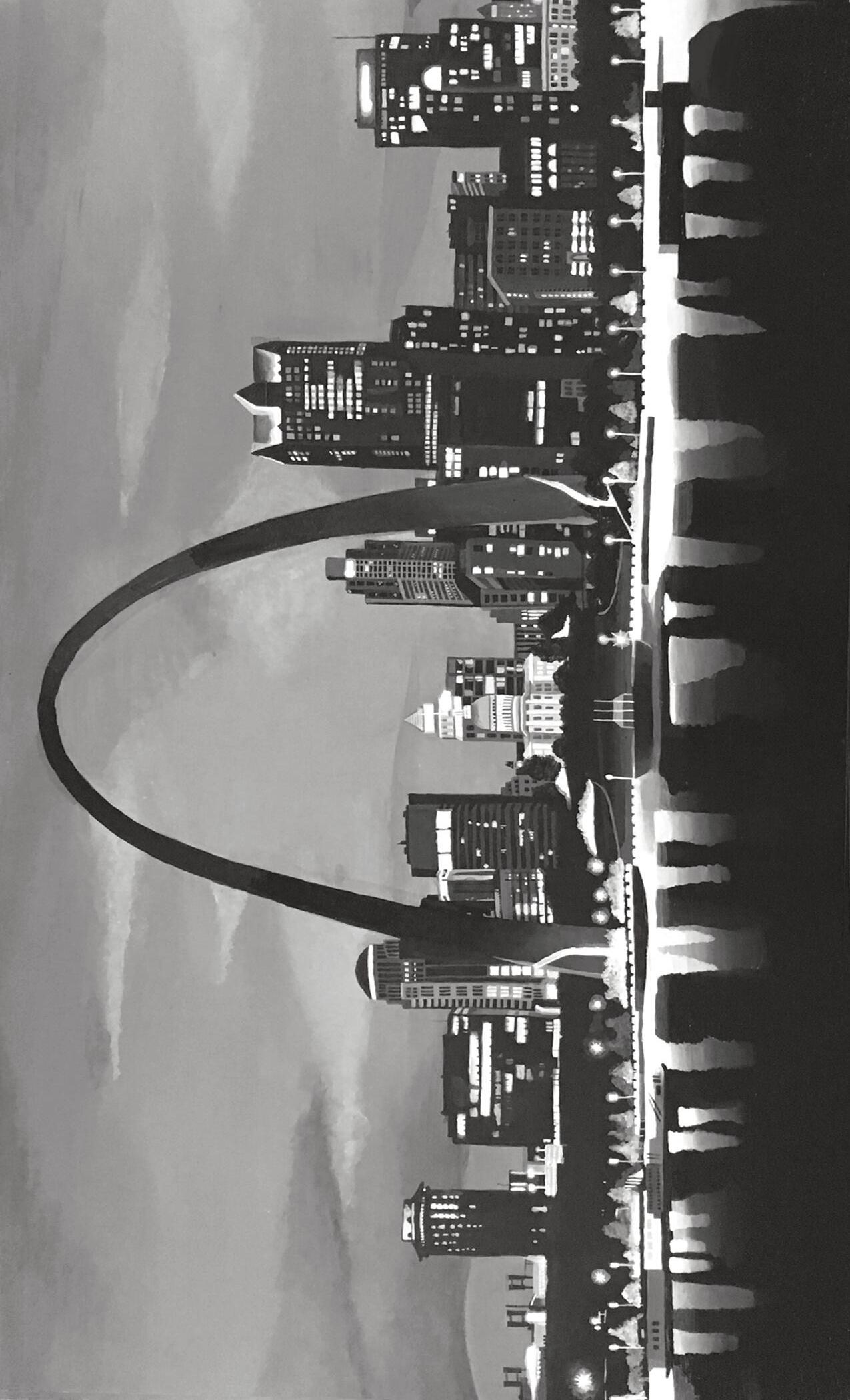

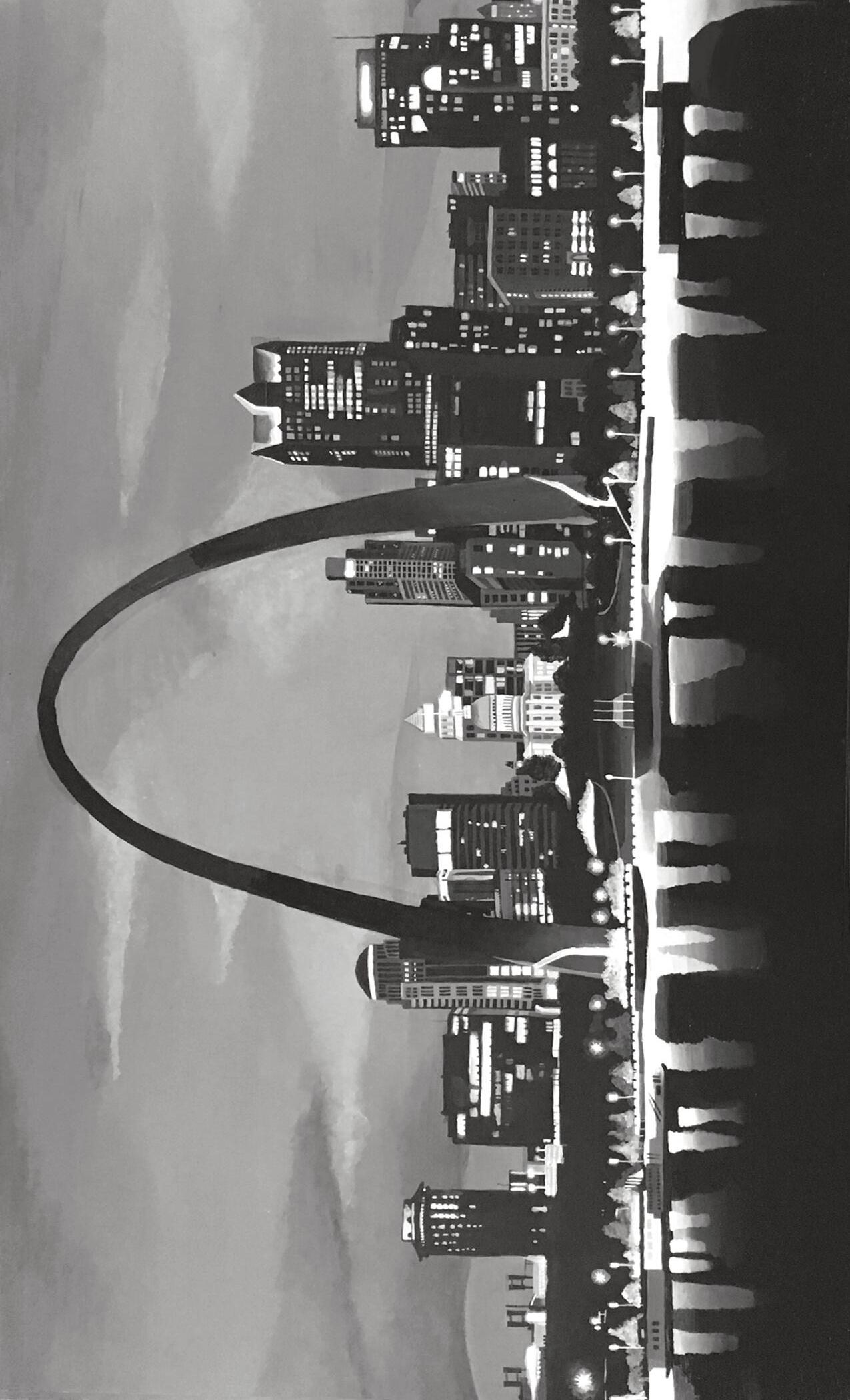

23 Nicole Gevers | St. Louis at Night

24 Katelyn Hanners | e Other Side

48

50

Table of Contents v | Introduction

25 Anoa Alimayu | Brick Homes Are Headstones 26 Mandy R. Bibee | Mur Montmartre 27 Kayla Schieffer | Through the Wall 28 Cour tney Rowland | Silent Pain 29 Danyel Poindexter | #LifeInABottle

35 Chelsea Brooks | Sterile White 36 Sean Chadwick | Remission

37 Cour tney Rowland | Morning Sun

the

Susan S. Lee

Bailee Warsing

the Canyon

38 Bailee Warsing | Into

Canyon 39

| Without Sound 47

| Into

Haley R.

has

Sean

in

Graham | apathy

many shapes 49

Chadwick | Two Weeks

Rio

Emma Daues

Waltz

| Glass Bell

51 Ryan Brooks | Diamond Ring

ojos 7 1 ft till the ground | iii

52 Lysa Young-Bates | Abre los

53 Kate Votaw | In Bruges 54 Brianna Winistoer fer | Broken Promises 55 Lysa Young-Bates | Gaussian 56 Anoa Alimayu | My Guide On: How to Clean on a Saturday After a Long Time of Neglect 58 Nicole Gevers | King of the Hill 59 M. Macallan Lay | Irony in the Form of Love & Chain Smoking 61 Andy Nguyen | Untitled 62 Nicole Gevers | e Clock Strikes Twelve 63 Saaba MBB Lutzeler | e Long Haul 64 Zachar y J. Lee | Ash 65 Anthony Deluvia | Fogg y Forest 66 Ramsay Wise | #5 Categorical Landscape Monochrome 67 Sean Chadwick | Universitas 68 Sean Chadwick | Robbing the Jar 69 A. Erin Hyde | Wolf ’ s Eye 70 Lori Dresner | e Observer 71 Zachar y J. Lee | Portrait of a Passerby 72 Zachar y J. Lee | Eye Contact 73 Cour tney Rowland | Seeing Double 74 Chelsea Brooks | From Lebanon to Camdenton 75 Haley R Graham | knoxville, tn 76 Kate Votaw | Madurodam 77 Kimberly Cowan | “It’s not just a tomatillo” 78 Kayla Schieffer | Eye of the Tigress 79 Lauren O’Donnell | For Women Who Are Something Else 80 Cassidy Kilgore | What I Shouldn’t Wear 81 Erin Hyde | Serenity 82 M. Macallan Lay | e Reasons I Dyed My Hair Red 84 Zoë Scala | Lilith 85 Kate Votaw | Wilhelmina 86 Zoë Scala | Caeneus 87 Jason Becker | Quietude 88 Jessie Kehle | Sparing Her My Body 90 Ramsay Wise | #7 Flowers Monochrome 91 | Excellence in Writing 2016–2017 e Pierre Laclede Honors College 92 Zachar y J. Lee | Monsters in the Closet: Victor’s Homosexual Repression in Mary Shelley’s Frankestein 98 | Biographies 103 | Staff Notes 104 | Staff Photograph iv | Bellerive Issue 18

Introduction

As I prepared to introduce 71 ft till ground, I couldn’t help thinking about this eighteenth issue as a graduation. is book clearly embodies the growth and development of the Bellerive publication as a whole, placing the spotlight on this year ’ s featured authors, artists, and musicians while anticipating the amazing growth and possibilities for future issues.

is year ’ s title, 71 ft till ground, not only offers an intriguing lead-in to a remarkable collection of 71 creative works but also offers a genuine description of the duality explored within this book. e title suggests both destination and arrival, anticipation and dread, distance and movement. is duality is perceived in particular moments in life that may offer cause for celebration or require pause for resolution. Individual works emphasize journey over arrival, contrast individual desires with societal controls, and reflect on the transition from the innocence of childhood to the complexity of adulthood. As a collection, these works offer a view of life and art that recognizes change and movement whether that movement is a plunge, a crash, or a freefall Featured works show how this movement occurs in the midst of chaos as well as in the vastness of nature.

From cover to cover, this year ’ s book also reflects the experiences of the 2017 Bellerive staff in delivering a publication that stands on its own, as well as one that lives up to an ongoing tradition of excellence. Staff members willingly accepted plunges, avoided crashes, and enjoyed freefalls during the selections and production processes. eir outstanding teamwork and dedication throughout this sometimes chaotic but always interesting adventure has resulted in a smooth landing and an awesome book.

Our eighteenth year seemed like the perfect time to begin welcoming submissions from alumni as well as from current students, faculty, and staff. us, with 71 ft till ground we offer both a continuation and an expansion of the Bellerive tradition. We celebrate this book. We celebrate the submitters, the staff members, the alumni, and you, the reader.

ank you all for making this great thing possible!

Geri Friedline Bellerive Faculty Advisor

7 1 ft till the ground | v

Suddenly, Bees

In the beginning God said, “Let there be bees.” And there were.

Bumblebees

Honeybees

Writhing clumps of sweat bees

Colonies of stingless bees in the shape of a knife Africanized honeybee volcanoes, erupting from the ground

God said, “Let there be no more bees.”

“Please. No more. ”

Suddenly, more bees.

B O B B Y M E I L E

7 1 ft till the ground | 1

Simmons SK-5 Killer

Shelf upon shelf, hundred rows deep, 18 months slaughtered, the cycle repeats.

Ruffling feathers tell solidarity among perfumed charms of ammonia and feces. Her brilliant flame rests on an organ chosen unworthy, lodged intermittently between ear, breast, and cold wire frame. Wings confined, altogether decrepit, while bone protrudes thigh, hidden by hard spines of grime that twist and knot in spiritual ways. Claw is dead, ruthlessly mangled under four different bodies. Hen withered, beak half-sawed, her brothers feverishly culled, ground, and trashed. Core drumming rich wine now over whelms senses, irregularly spurting plastic. Water rises, ill-tempered boil, red feathers, the end.

2 | Bellerive Issue 18 A U D R I A D A M S

7 1 ft till the ground | 3 A . E R I N H Y D E Curiosity

graphite

The Fourth Pig Made His House out of Sequins

ey said it was the worst fucking idea they’d ever heard. I looked at the straw and sticks (horses. the Amish. Transcendentalism.) and bricks (inner city. Samuel Slater. Modernism.) and decided that mine had to be the most fabulous house ever made. I cemented it with glitter glue and imagined that when the wolf showed up his retinas would be so scorched by colored eyes that he’d sink to his knees. But it didn’t happen like that. It gets maddening, watching the sun amplify first the greens, then the golds, then the purples, day after day e wolf finally appeared yesterday, and he just shrugged and said, “I see what you ’ re going for, but the Dadaism thing doesn’t work for me. ” I’m wondering if it’s time to bring in the wrecking ball. Apply for a factor y job. Hop on a horse.

4 | Bellerive Issue 18 J E S S I E K E H L E

Open the book, page 390.

Page 390. Was it 390?

Make sure (again).

390 is right.

Read the first sentence.

You read it wrong. Tr y again.

Why do I I said, read it again

Correct. Next sentence.

Count the syllables. Find the meter.

Doesn’t feel good, doesn’tfeelgooddoesn’tfeelgooddoesn Again. (again)

You read that line in the wrong voice. What does that mean? Again.

“Sublimity,” not certain of meaning, look it up. Make it real, look it up. I don’t need to You have to

“complete; absolute; utter. ”

Are you positive that’s what it means?

Read the definition again.

complete; absolute; utter. Again.

complete; absolute; utter.

(again)

complete; absolute; utter.

(again)

(again)

(again)

7 1 ft till the ground | 5 H A L E Y R . G R A H A M

this one thing will change the way you think about ever ything!

Overreading Things

6 | Bellerive Issue 18 E M E S E M AT T I N G LY

It is what it is, Not what you make of it. What you make of it is exactly that. A fact is a fact.

Smooth Lines

photography 7 1 ft till the ground | 7 R YA N B R O O K S

Z A C H A R Y J. L E E Under Elm in Early April

With firm wet muscle the wind blew onceleafclung seed, which fell, gasping, onto the unfecund earth

8 | Bellerive Issue 18

Avocado Tree

A little tree grows in a pot on my doorstep. It is an avocado tree. We planted it in just spring, when the stores were crammed with the things. My wife took the seed it was slick and fairly oozed life, covered by a clear jelly and so difficult to hold tightly and suspended it in a glass of water. For a month, we watched.

And then a searching green finger sought breath, and light, and earth. And so we planted it in a big pot on the doorstep of my home

I live in the wrong neighborhood for avocado trees. When the winter comes, it will die.

We watched it grow, incredulous ever y time we again became conscious of its illogical progress, but the summer beguiled the young shoot, a brown line connecting the store-bought earth with the flickering sky Damned straight, like some chthonic god had shoved it up from below! An aberration in these climes, this suburban scene.

I reeled at the impossible thought of full-grown avocado trees reaching out over the fescue, the leather y purple globes hanging there in the air above me. I thought of what it would be like to walk out of my front door and pluck one, bring it back inside to the table, open it carefully and eat the golden-green flesh, and know that life and light were mine for the taking.

J A S O N B E C K E R

7 1 ft till the ground | 9

It’s dying now, of course. Last night, the frost climbed as high as the six hopeful leaves. Just high enough to make itself clear to the sapling: I am coming. I am here You are almost gone.

10 | Bellerive Issue 18

R A M S AY W I S E

#8 Flowers Monochrome

7 1 ft till the ground | 11

spray paint & acr ylic on canvas

Through the Woods

12 | Bellerive Issue 18 B A I L E E W A R S I N G

photography

I C K

The Cicada’s Song

When I was seventeen, I visited Yosemite. Not that I had any particular interest in Yosemite it was my parents ’ idea. I think they saw it as a neat way to forgo the inconvenience of parenthood for a chance at their own summer travel plans to Venice or Paris or anywhere tourists were supposed to go and exchange money for patronization. at was their favorite pastime. Typically, they shipped me away ever y summer with whatever group they could find that would kindly agree to conduct inconvenient young people to distant places. at August, it just so happened there was a local men ’ s group offering to take the boys of wellto-do parents to Yosemite on a camping trip for only a few thousand dollars. I suppose to my parents this seemed a small price to pay.

I discovered then that the phrase camping trip is the wealthy man ’ s way of indicating a strange desire to venture deep into wilderness and stay at a lodge with more luxuries than most people have in their homes. at summer, the lodge was the Majestic Yosemite Hotel, an especially huge and bombastic building. Somehow, though, it felt prematurely dated; the building itself couldn’t have been ver y old, but it was the type of place built with unreasonably ambitious expectations which begins to decay almost from the moment construction is completed. e lodge was designed to hold hundreds of people, but we were some of the only patrons, and the vast emptiness of the place filled me with dread.

e previous May, my parents had wanted an evening out on the town alone, so they hired a babysitter who took me to see e Shining at the theatre. I don’t think it occurred to them at any point that a sixteen-year-old might not need a babysitter Truthfully, I felt younger than my age; growing up routinely isolated and ignored can have that effect. Being the first horror movie I had ever seen my parents would never have had such a film at home, let alone have taken me to a theater for one it petrified me. Almost ever y night for two weeks after that I had the same nightmare. I would dream of being startled awake by crazed axe strikes at my door. Inevitably, my attacker would splinter the wood, reach their hand through, grasp the doorknob, and twist. Each time I would wake, panting and drenched in cool sweat, precisely as the door swung open. Now, walking around this grand and empty lodge on my first day there, the walls plastered with Native American drawings and rugs, I often had the distinct fear that at any moment an axe-wielding and wild-eyed Jack Nicholson might come maniacally lumbering around a corner at me.

at first night, I woke in my bed, soaked in cool sweat and with a pounding headache. I sat up and cupped my temples in my palms. I could feel my blood pumping, angr y and hot, through distended veins above my eyes. Tossing the covers off my legs, I stood up and, guided by the moonlight pouring

7 1 ft till the ground | 13 S

E A N C H A D W

through my tall window, walked to the bathroom. I flipped on the light, swallowed two Tylenol, and stared at myself in the mirror; for a moment, I was convinced the face there wasn ’ t my own but rather the face of a young girl. She was bruised and purple, a gruesome gash running through her cheek and up her forehead into her scalp, where her brown hair hung heavy and wet. I blinked and my face was there again in the mirror, my eyes groggy and hair disheveled I stared at my reflection for a moment to be certain it wouldn’t change again, to convince myself my imagination had run wild for a moment, a result of my sleepiness and my headache.

Convinced after a few long moments, I headed back towards bed. Having made it halfway across the room, I heard a peculiar but alluring thrum coming from the hall and stopped in my tracks. Hypnotized, I homed in on the sound and followed it out of my room and down a dark corridor. e hotel was dark, and I traced my steps by the moonlight that drifted in the occasional windows. Bare feet treading on cold hardwood floors, I pursued the noise to the hotel’s solarium and opened the double doors. Standing there in the center of the room, its back to me as it stared out the windows, was a massive green and brown cicada. Its huge torso thrummed and vibrated as it chanted a buzzy, strangely bittersweet song. Unnoticed, I stared and listened for several moments, taking in the music. Feeling like an intruder on something sacred, private, and beautiful, I spoke out of guilt, a need to announce my trespassing.

“at’s ver y beautiful.”

e words tumbled from my mouth into the stillness of the huge room with a gracelessness only an interloping, ignorant child could wield, and then dissipated quickly, perishing in the open air of the vaulted ceiling e creature stopped singing abruptly, fluttered its semi-transparent green wings in surprise, then turned and fixed its gaze directly upon me. It didn’t respond immediately. Instead, it simply cocked its head subtly and stared down at me from two huge, bulbous, red eyes positioned on the ver y sides of its head, with tiny, discerning pupils like volcanic rocks. Yosemite’s several-thousand-foot-tall gray granite bluffs, visible through several huge windows, framed the cicada as it stood in the dim moon and star light. I stood paralyzed and felt as if I were being weighed and measured Time suspended then stretched interminably as we gazed at one another. I couldn’t have said if only seconds or entire minutes passed before it finally spoke.

“It is a love song. I sing to find a partner with whom to mate before I die.”

I accepted this as naturally as any conversation. “I sing too. I’m in the choir at my school. I sing tenor. ”

“Your choir do they sing for mates as well?”

I considered this briefly, unsure. “No, I don’t think so. Not where I come from. Mostly holiday songs and the national anthem. I don’t think Mrs. Blackwell would approve of us singing love songs. ”

14 | Bellerive Issue 18

e cicada didn’t seem to fully understand this, but seemed satisfied with my response, and replied. “ Today, I heard boys singing in the valley. ey chanted a song at the lake nearby. It was a song of hunger.” Not understanding, I remained silent, and the cicada continued. “ey chanted, all of them, for a girl to jump from high rocks into the water. eir voices rose ceaselessly into the air, and their song was coarse and violent ey chanted her name, ‘Sophia,’ again and again. Until she jumped.”

e cicada stopped and peered into my eyes again with a discerning look, as if inquiring whether I knew yet what it was speaking of. I believe it saw what it was looking for in my eyes.

“ey have not told anyone, but soon her body will be found. It cannot be avoided. You should go back to sleep now. Do you understand?”

I nodded yes. e huge cicada returned to the window and resumed its song. I turned around, walked back to my room, climbed into bed, and fell asleep instantly.

When I awoke, the morning was a chaotic flurr y of concerned adults hustling and bustling back and forth at the Majestic Yosemite Hotel. e body of a little girl had been found downriver from Mirror Lake. Sophia. Numerous children and all adults present at the hotel were questioned by stern-looking police officers, men with shorn heads and perfectly starched uniforms. Late in the day, the police officers told us she had suffered a skull fracture and drowned to death, and that some of us children might have to be taken to the police station to answer further questions. I spent almost the entire day isolated in my room, unnoticed by the adults. Near dusk, after the commotion had largely died down, I took my moss-green hammock and walked into the dense pines in the Yosemite Valley to sleep under the stars. I wrapped my hammock around two massive pines as the sun was setting. As I finished, the last rays of light finally fell beyond the granite bluffs. Climbing to rest in my hammock, I stared up.

Above, past the towering, wind-swept pines, stars clustered so thickly in the night sky that constellations became imperceptible, glittering cr ystal-white arms of each reaching, swirling, coalescing with one another. As I watched, shooting star after shooting star flared into distant, fier y being before vanishing, each in a single moment In all, more stars than I had ever seen before glimmered overhead, and I was struck that in their multitude they seemed unreachable, cold, and pitiless. My hammock swung an even rhythm, the thrum of the cables matching time with my heartbeat. I imagined I could hear the savage chorus of boys’ hungr y voices echoing repeatedly, rattling through the darkness of the Yosemite Valley, and I clenched my eyes shut. “So-phi-a!” again and again, each syllable erupting and reverberating distinctly in the mocking, coarse voices of young men.

Opening my eyes, I noticed nearby a small, gray, chitinous shell left behind on the lowest branch of one of the pines supporting my hammock. Abandoned during molting, the legs of the cicada shell still clung firmly to the pine’s bark.

7 1 ft till the ground | 15

Suddenly, the shouting vanished, and I became aware of the voices of a thousand cicadas singing around me. eir dying love song rang and echoed throughout the valley in a pulsing chorus, lulling me to sleep. Finally, nestling deeper into my green hammock and allowing its walls to embrace me tightly, I surrendered to a dreamless sleep as the cicada choir sang into the darkness.

16 | Bellerive Issue 18

A Forgotten Childhood

7 1 ft till the ground | 17 A N T H O N Y D E L U V I A

photography

Collapse

she builds her nest in a tin can, an old coat, a dead horse, burrows deep in the damp meadow and with hooked claws she feasts on insects. moths, gnats, or flies are swallowed whole. greedily.

the night feeder drinks in acrid air and shrill bellows sound from wide-open jaws.

virtue: collaborator of man. their bodies curse loudly the killer of attraction, hide the relic of illumination, send it to hibernate inside a nest of skins. all graceful species have cannibalistic tendencies. his body sank into the orange-golden center: spine, churning waters, plume-like secretions trapped and extinct are the measures of nocturnal labor.

18 | Bellerive Issue 18 M O L LY B R A D Y

Unreborn

You can never rise up like a crocus in spring, light and pink against the softness of the earth. But can we slide from ourselves gradually, and are we eventually pink as babes, raw and elated?

Not planted firmly, how could we sink ourselves through ourselves and find our own roots? Tear them up?

No, we carr y ourselves within ourselves, and the spring drought will leave its gray death-mark inside.

Ever ywhere the same: each center full of the earth, and the gray records.

As the new spring rises and the real crocuses burst, you will know it is there by the memories you do not allow, and you will know because the feeling of that self is there within you even as you stretch and quicken, quiet and gray.

7 1 ft till the ground | 19 J A S O N B E C K E R

Teufelsberg Station

Our corner lies among peppered edelweiss bloom and stone facade. Its hearth harbored a single swing. Back and forth it fluttered, mimicking barnacle goose flight. rough Grunewald thicket you rose. Desperate to find that collating drum beat, you screamed to sea. ose were aimless days; a mother son blanketed adventure.

Frost accompanied that Januar y breeze when you departed. Týr had erupted in rage. Mud shuddered, and Fenrir once again teethed free. Lead shell debris leapt through mountain tide and city sphere.

Only red pools remain in our bend, flooding poppy ’ s loose form. Blue-eye glaze descends granite fixture, tangle weed catastrophe. Water weight presses lungs, demands retreat. Deeper still, ripples coil throat, a mute scream. A thousand Nixes’ pointed reach.

20 | Bellerive Issue 18 A

U D R I A D A M S

R A M S AY W I S E

#6 Flowers Monochrome

7 1 ft till the ground | 21

spray paint & acr ylic on canvas

The Funeral March for the Fallen

is composition is based on the second movement from Jeff Polizzi’s Symphony No. 1 in C Minor, Ferguson. It was dedicated to the fallen AfricanAmerican teenager, Michael Brown, who was fatally shot by a white police officer, Darren Wilson, in August 2014. For more universal purposes, this piece can be dedicated to all people who have lost their lives in natural disasters and massacres.

In the beginning of the piece, the percussion plays six sustaining notes with an echo expression that decrescendos on the last note, representing the echo of lost souls cr ying to the Lord, “ Why hast thou forsaken me?” e low strings darkly sustain the low register while the woodwinds respond to the lost souls.

e brass expresses the calamities that the lost souls faced. e string trio between two violin sections and the viola section express the stor y that results from the calamities. e tubular bells express churches around the world praying for the lost souls e oboe solo expresses a prayer for mercy to the Lord ere is a recapitulation at the end, where each section of the orchestra expresses the departure of lost souls to the afterlife as the tubular bell plays a farewell.

22 | Bellerive Issue 18 J E F F P O L I Z Z I

a QR scanner to listen or visit https://goo gl/rJDdYD (case sensitive)

Use

N I C O L E G E V E R S

a c r y l i c o n w o o d 7 1 ft till the ground | 23

St. L ouis at Night

The Other Side

p h o t o g r a p h y 24 | Bellerive Issue 18 K AT E LY N H A N N E R S

Brick Homes Are Headstones

is brick-famous, Saint-named city Was known once as the backbone of the Midwest, But many years have gone now.

On the Riverfront, a silver-bricked behemoth Arches over backward to fool you

As it has us.

e Gateway is a trapdoor. Rich red-brick homes once stood

In our northern city streets

Proud as the oak

But you won ’ t find them alive now.

On this side of the river, You crossed into a gravesite.

On this side, you’ll find skeleton homes, Brick flesh burned from their bodies

at sit as warnings

On the edges of our ghettos.

eir ghosts whisper

Leave now

Don’t come here

I was born here.

I was grown here.

No one plans to rebuild the rotted corpses, Ribcages torn through their backs

By raiders in the night.

In my youth I lived beside these brick carcasses

In houses made of matchbox wood. We called them the mayor ’ s projects.

We tr y to ignore the smell of the deceased, But the bruised window-frame eyes haunt us.

ey remind us we are stuck here, at there is nothing more for us, Just our graveyards.

7 1 ft till the ground | 25 A N O A A L I M AY U

p h o t o g r a p h y 26 | Bellerive Issue 18 M A N D Y R . B I B E E Mur Montmartre

Through the Wall

p h o t o g r a p h y 7 1 ft till the ground | 27 K AY L A S C H I E F F E R

Silent Pain

photography 28 | Bellerive Issue 18 C O U R T N E Y R O W L A N D

I know what’s supposed to happen when you open up a cold bottle of soda. You hear it breathe for the first time. You listen to that crisp sound it makes. You drink it. You’re happy. It’s that simple. You’re smiling with friends and hanging out, coming up with ideas . . . stuff like that. I know, I’ve seen the commercials. I’ve Googled it. People smile and dance with them. ey forget it’s just stupid soda.

I heard the dark ones are the worst.

Something about them being unhealthy. But . . . those are the ones I’ve been drinking the most. Even now, as I swing my feet over the smooth concrete edge and they dangle in the thin air the wind softly whistling against my skin and making my hair stand on end a cold, dark soda sits in my hands. I sit here, thinking up little slogans they would use in moments like these. In moments like this.

It’s not too late to be young, is one.

Unfortunately, I felt the opposite. Or rather, “ we ” did, I suppose. e young woman who sat to the right of me her crimson hair falling over her shoulders as the tresses bent with the cur ve of her back and the tall auburn-haired boy who sat on the left of me. His back bent over like hers but craned more towards the ground too far below us, as if he were tr ying to make his feet kiss it. It’s something we weren ’ t brave enough to do ourselves. I don’t even think I planned to. I am a quiet person, I’ve always been one. Even now, I made the three of us quiet together. e scener y is quite nice, though, something to be quiet about, and I think that’s what the three of us were doing. Soaking up the watermelon sky

We’d been sitting up here for at least an hour, this concrete tower set as a throne that kissed the sky. Our eye view matched that of a cloud’s, as rooftops of other buildings surrounded us. Up here, there was nothing but the soft sounds of breezing wind and flapping wings. Up here, there were no loud noises to distract us or cloud our insides. Up here, we were calm. We breathed in the small wisps of cool air that flew past our bodies and prickled against the surface of our skin.

I could hear the banging of the door behind us, but whether it was locked or jammed, we weren ’ t sure. Didn’t matter. e door was heavy steel, and I think we all knew it would take another hour or so for them to actually break it down if they tried hard enough. Maybe that’s what we weren ’ t doing . . . tr ying hard enough. Or maybe we have, and that’s why the three of us randomly met here today. Maybe tr ying too hard was just too much.

I pulled the bottle up to my lips and drank a little before asking, “Do you think we ’ re dumb . . . for doing this, I mean?”

7 1 ft till the ground | 29 D A N Y E L P O I N D E x T E R

#LifeInABottle

e question surprised me. Why was I talking? Must be the soda. ere was a long pause before Red answered. I decided to call her Red, along with Auburn, the boy next to me, for none of us had shared our names. She sighed and slouched her shoulders even further, timelines forming on her forehead.

“Not dumb. Maybe a little overdramatic, but never dumb. Dumb is a word used for stuff with no meaning Like God God is dumb My parents said He knows our ever y move, yet, here I am. Why wouldn’t He stop me?”

I didn’t respond. I always get uncomfortable talking about religion. Her bright, hazel eyes turned to me, almost as if asking for an answer. From this angle, I could see the freckles suffocating her cheeks and the silver necklace pulling itself out of hiding from under her shirt and dangling underneath her chin. e cross that hung from the chain was dull and worn out, with tiny scratches gleaming against the orange light that hovered in the sky. She noticed and looked down. With her pointer finger and thumb, she clenched the cross to stop its movements, then slowly placed it back into the collar of her raspberr y sweater and straightened her posture as best she could.

She had done the same thing earlier, put the cross back into her shirt. It was when the three of us stood here just an hour ago, standing so much farther apart that it was easier not to notice each other. e ledge to this building is ver y wide after all. But as I was standing there, gaping down at the people below us at the people who noticed I suddenly noticed her. Her back bent and her arms spread wide as if she were tr ying to copy the iconic scene from Titanic, only her Jack wasn ’ t here. Nobody was here. Even right now I can see this worr y on her face, as if no one will ever be there for her. But when she was standing farther away from me, the wind had suddenly blown from behind us.

e gust surprised me a little, but for her, her hair blew towards the front of her face. A long tail of flame stood like a flag to signal the people below us, but a flame that was slowly losing oxygen. She’d almost stumbled. Almost. And for a mere second, my heart stopped. e stumble made her necklace force its way out of hiding, from beneath the safety of her raspberr y sweater, and dangle right under her. I couldn’t tell how old she looked then, but suddenly I saw it. Now that her face was closer to mine, I saw that she appeared to be no older than sixteen maybe . . . or fifteen perhaps. Somewhere close to my age.

Now that her face was closer, I could see the small freckles that suffocated the surface of her skin. Now that her face was closer, I could see the frown embedded into each word she spoke.

Auburn laughed at Red’s implication of God’s interference with us being here.

A smile in ever y sip. Another soda slogan that popped into my head. When I turned to look at his smile, taking another sip from my bottle, I realized how similar he looked to those actors in the commercials: nice chiseled jawline, handsome enough to persuade you to buy such an unhealthy drink.

30 | Bellerive Issue 18

s

s

“Something funny?” Red scowled, crossing her arms.

Auburn used his pointer finger to wipe away an invisible tear from the corner of his eye.

“Sweetie, God has nothing to do with it. It’s how you look at things. Take me for instance.” He rolled up his black sleeves, bringing attention to the small brown scars laced across his pale skin “I’ve lived seventeen years of my life being happy . . . for the most part. Even now, I’m smiling. I’ve noticed that people call you crazy if you smile too much. . . . ”

His voice trailed off for a minute, as if that solitar y sentence was something he should not have said, something he should have kept a secret for himself. I watched his eyes wander around the landscape of buildings ahead of us before strictly piercing me.

“So to answer your question: no, it’s not dumb. From my point of view, it’s kind of funny.”

Red rolled her eyes and heaved a huge sigh.

“I mean, what are the odds that the three of us would meet?” he continued, “And here of all places, for the same reason? You guys should laugh too, it’s kinda funny.” s

It’s kinda funny ose were the same words he had said an hour earlier as the three of us stood together on this concrete ledge. When Red had almost stumbled, I heard him laugh from the other side of me. Not because he was closer in any way, but because it was loud. He laughed so hard that it took our attention away from wherever our minds were tr ying to wander off to. e wind was still blowing then, but only a whistle. So, the hair that flew in front of my face as I turned my head, was easy to place behind my ear when I focused my eyes in his direction.

“I guess we ’ re all here for the same reason!” he yelled to the both of us. He stood farther down, left of me. But unlike Red, he’d not spread his arms. Instead, his hands rested casually in his pockets, almost as if this was nothing but a cool scene from a movie Almost as though, if he’d taken a step for ward, there would be a green screen floor in place of mid-air. I was unsure how he kept his balance so well. His legs were so straight, and his demeanor was so well kept. He stood like a professional gymnast. Like someone with practice. Like he’d done this many times before.

“You know,” he laughed, “if we were to slip, it wouldn’t be considered suicide! Gravity would technically be the murderer!”

And he laughed again. And again. And again. His laughs were dark, too dark for my liking Still, I watched him so much that I, too, began to laugh, and from the distance to my right, I heard a woman began to laugh as well. Red.

“It’s kinda funny!” he hollered.

7 1 ft till the ground | 31

s

I remembered how I stood on the ledge just an hour ago. Awkward with unsteady feet and sweaty hands. Fingers grasping tightly onto the bottle of soda clasped in my left hand. Soda. I planned to do something so horrible, and for some reason, I brought a damn soda. My heart jumped a bit, but it was hard to explain. I was almost calm at the same time. e feel of the cool air on my skin gave me goosebumps I was a statue Different scenarios of how I could force myself to fall played in my head, but all I did was teeter in the end. My hands had become so sweaty that I felt the plastic bottle slipping from my grasp. None of us had noticed the other, but in that moment of caring in that moment where I thought I was going to lose a grip on the only thing I brought with me I noticed Red. I noticed that there were more people than just myself on this ledge. And I noticed that we all had the same expression on our faces. Sometimes, allowing myself to think too long was a dangerous game to play. So when Red stumbled and Auburn laughed, I was glad that it broke my concentration. When his laugh made me smirk, I turned to Red who, in that moment, placed her arms down at her side and began to chuckle a little as well. And now, the three of us were here. At the time we had laughed at each other, Red and Auburn had slowly scooted closer towards me from where they stood, and together we helped one another sit down. ey saw my bottle, and each asked for a sip. I said nothing, just passed it around without a single thought. I heard that if you boiled dark soda down, it turns thick and mucky, disgusting. Maybe that explained why we were here. Maybe . . . just maybe . . .

we ’ ve drunk too much dark soda in our life, and over time, we ’ ve gone mucky. Auburn stood up to go close the door, then rejoined us in sitting down. He was the one who first started the conversation

“I’m funny,” he’d stated. “So, what are you guys?”

To my surprise, it was Red who had spoken next.

“I’m lost.”

“Honey, I think we ’ re all that.” He chuckled.

“I mean, I think I’m Christian. I’m supposed to be. Or at least, my parents are and they said I am. And they taught me that when you ’ re a Christian and you don’t know what’s going on in your life . . . you ’ re lost.”

She paused, exhaling a long breath, her chest heaving out

“I was hoping by jumping, I wouldn’t be lost anymore. I’d be there,” she pointed down to the ground, “and ever yone would know where I was. ”

Auburn had laughed once again and looked at me for a next say so, but being the introvert I believed myself to be, I said nothing. Time had passed, the banging on the door had started, more people had begun screaming from below, and the three of us watched the subtle sky. It was silent like that for a while until I had finally decided to break that silence and ask, “Do you think we ’ re dumb?”

By now, the sky had gotten dimmer, it no longer reminded me of the sweet taste of watermelon, and the soda was almost gone. It had been reduced to a

32 | Bellerive Issue 18

s

small, thin puddle at the bottom of an un-disposable plastic bottle. I sat between two strangers. We all dangled our feet. We all swung them back and forth. We all stared at the sky and the people, our gazes switching between above and below because we were so unsure of where to look. e ground started to splash with red and blue lights, and my heart skipped a beat, just like the moment I saw Red stumble

I saw Auburn’s stor y written on his skin, I heard Red’s stor y spoken through her necklace, but then there was me. Where was my stor y? Did I have one? e feeling of understanding something that cannot be understood started to over whelm me just as the question surfaced into my mind. I kept saying, I think this, I think that, but I could never actually finish the sentence. What did I think? What did I know? e best way I can explain is that I couldn’t relate to those people in the soda commercials. Can we? Can anyone? But I did what they taught me to do. I kept a smile on my face.

I keep a smile on my face.

Even though it’s weighing me down to the point that I think if I stood a bit, a little of the pressure could drag me over the edge and carr y me down to the bottom. I could watch the world around me swirl away like the clouds above me. I could experience that moment of liberation. Ever ything would become a blur in an inst wait. Stop. Don’t think. Sometimes when I allow myself to think, I’m playing a dangerous game.

#LoveInEver ySip. I looked at the tiny sip, all that was left of the bottle. My gaze switched between Red and Auburn. Red let hills stain against her forehead, and Auburn gazed down at the ground as if thinking up the same idea that had resurfaced in his brain numerous times. In that moment, he began to mumble something I couldn’t hear. His voice had grown lower. His thick fingers scratched at the concrete, creating small white marks against the ledge surface. e banging behind us became louder, so I turned, obser ving the huge dent in it.

“Any time now, they’ll be through there,” I spoke and searched between the two again.

I watched Red’s reaction deepen, the lines on her forehead creasing even harder.

“It doesn’t matter, ” she answered, shrugging her shoulders and lowering her voice. “My family lives far away. ”

I turned to Auburn, but of course, he was still smirking. All he did was continue to peer down at the people below us. Gradually, his smirk went away. I’m unsure if he knew me and Red were here anymore. His eyes had turned cold. ey weren ’ t present.

“It wouldn’t be suicide if I slipped.” He mumbled and slowly went back to being inaudible.

7 1 ft till the ground | 33

e phone in my pocket started to ring. e vibration started to hum. I could feel and hear it above the nauseating turn that had conjured in the depths of my stomach. e tune caught neither Red nor Auburn’s attention. I dug into my pocket and looked at the caller ID.

“Mom.”

I took a sip of my soda and clicked on the green button

“In honor of your birthday, your mother has called you! Where’s the party at!” She screamed on the other end. It was the same fun-loving-mother line she fed me ever y year for ever y birthday.

“Here,” I murmured.

“Must be nice to be young! I remember when you were still small and squishy! I’m getting some birthday stuff. When’re you gonna be home? I might be a little long, heard there was some commotion a little ways from the house.”

I looked down at the plastic bottle in my hands, but by now it was empty.

“Honey, are you there? What’s that noise?”

I forgot about the bottle just for a split second, but in that second it slipped from my grasp, zooming out of sight and hitting the ground with no sound. I opened my mouth.

“I’m here.”

34 | Bellerive Issue 18

Sterile White

walls, floor, sheets, t.v. remote plate of half-eaten food: mashed potatoes, cauliflower, a shredded roll nurse ’ s whiteboard (blue marker for contrast) socks to keep the blood circulating a weight hanging over the bed connected to a rod keeping the femur straight packing in the open incision of the abdomen tinted red around a leaking liver layers of tape bridge of the nose left hand, right elbow gauze covering countless sutures wrist restraints to hold ever ything in place skin

under hospital gowns and deeper where the body met road kissed by concrete almost permanent

7 1 ft till the ground | 35 C H E L S E A B R O O K S

E A N C H A D W I C K Remission

Resting my head against the American Beech in our backyard, my half-shut, hazel eyes stared over slate-blue Atlantic before sunrise, expansive waves indistinguishable in pre-dawn darkness, their unrelenting rhythm chorusing on morning breeze. Inhalation, exhalation. Straggly haired mother had ner vously insisted on my heaviest winter coat, a tasteless bundle of monstrous gray puffs proclaiming me the Michelin Man’s dingy son. I ran my fingers across my despised coat ’ s polyester exterior and as goose pimples erupted, clamped my eyes shut, pictured myself blending gradually into the grand tree ’ s hoar y roots, two candles melting together in approaching dawn light until evening would cool skin, coat, bark, and bone into one. Massaging warm palms against wind-burnt cheeks, I rubbed away sleep sand and heard the tree ’ s shadow cough awake at daybreak peeking over the ocean, felt it awakening, stretching with lazymorning yawns across backyards, blanketing my home.

If you don’t think you can handle school yet, you can stay home today, mother had breathed to me with muted wounds in her eyes She kneeled to my height, briefly wreathed me in her arms, and kissed my forehead before releasing me out the back screen-door.

Sunrise was even later than yesterday; the days themselves shrinking, wilting into abbreviated stor ybook pages where images withered, forfeited color and definition. I opened my eyes, watched the Beech’s last tawny leaves somersault off firm diving board branches onto clammy ocean-air currents, momentar y nimble gymnasts before joining mud-damp ground Sun breaching horizon, my hands explored tree roots, discovering patches of shorn bark where tender lesions trickled amber-green sap. I gazed at the thick syrup glaze on my smooth, thin fingers, smelled its sweetness, and wondered if the Beech was sick.

36 | Bellerive Issue 18

S

p h o t o g r a p h y 7 1 ft till the ground | 37 C O U R T N E Y R O W L A N D Morning Sun

Into the Canyon

p h o t o g r a p h y 38 | Bellerive Issue 18

A

L E E

N G

B

I

W A R S I

Without Sound

In my sixth grade American histor y class, Mrs. Green told us that the reason we didn’t know much about slaves’ thoughts is because ver y few of them wrote anything down. I didn’t think a whole lot about it until two years later when my father died, and I was left searching for answers that didn’t come. Instead, I listened to the chimes of the grandfather clock by the front door marking the passing of another hour before the entire house fell silent again.

e quiet didn’t last long though. Instead of sleeping until noon, my mom started digging through the old boxes upstairs where my dad kept his nice watches and rings. en we went to the pawnshop. She left most of his valuable coin collections in their glass enclosed frames on the walls, so after a while it was like we lived in a museum under construction. But I knew that even the glass cases couldn’t preser ve his life forever.

Tr ying to find tangible evidence with which to immortalize him, I started going through the boxes myself when my mother wasn ’ t home. I discovered a leather-bound notebook. Inside, I recognized the familiar handwriting my mother used in notes to excuse me from school e first and only entr y was from November 22, 1977:

On the news, I heard about a young girl who was killed by her stepfather. He wouldn’t reveal where he had buried her, but the police thought it was in a field which had been built over with apartment complexes. I decided that I would name my baby, Surette, after her.

James liked it, but said he hoped I knew that people would be forever mispronouncing it.

e origin of my name was buried under old shoes and shoeshine tools that my dad used ever y evening after dinner. I closed the journal with a clap. Downstairs in the hallway closet, I found the rifle my father had given me. I grabbed it from behind his old jackets and went into the backyard to shoot at cans. Right as I hit the last one, I heard cars coming up the gravel drive. I saw my mom park, get out, and wait. A green sedan stopped behind her. A man got out like he had been here a million times before.

I don’t know why I did it, but I aimed the barrel at him. For a second, I could feel my finger pulling against the trigger. When a boy got out of the car after him, I quickly lowered my gun and looked around to make sure no one had seen me, but there was no one else there among the pines.

No one could see me because I was behind the trees. I squatted down and watched them in the driveway. My mom gestured to the big yard and our house like it was some sort of prize even though the gutters were starting to fall down from neglect. e boy was older than me, maybe by two years. He had really dark hair, and there was something about him that was quite different from the

S U S A N S . L E E

7 1 ft till the ground | 39

man. I bet he was quiet. My dad used to say that quiet people were the ones with really interesting stories and that talkers merely liked to hear the sound of their own voices.

“Surette, where are you? Come here for a minute,” my mom said, cupping her mouth with her hand to project her voice. I stood up and started down the hill

“is is Jonah and his son, Benjamin,” she said when she saw me, my rifle lowered. She put her arm around me once I was close enough. e man leaned for ward and insisted on shaking my hand. He squeezed too hard, but I didn’t make a face. As I looked up at him, I knew that whatever had been left since my dad’s death was finally gone.

Jonah and my mother married six months later. I had to wear a pink bridesmaid dress made of wool even though it was May and getting hot outside. Benjamin was a groomsman. I kept looking at how the light shone off his hair.

en someone awkwardly clapped, and we went home.

Jonah was different after the wedding. He had many rules about hygiene. We had to clean the bathrooms ever y day with hot water and some powder y substance that irritated my skin and made me cough. He liked the towels folded so that they were identical in length and width. All of the silver ware had to be hand-dried so that there weren ’ t spots, especially when it came to the knives and spoons. He chose our soaps and shampoo. Ever ything had to be scentless, except of course the powder used to clean the bathtubs. It smelled like lye. e whole house smelled like lye.

“Surette!” Jonah said, after my second week of purposely misaligning the towels. Sitting on the couch, my mom stared at the floor. Benjamin looked up at me as I passed by. I could tell that he wanted to say something, but just like ever yone else around Jonah, he couldn’t get a word in.

“Do you see this?” Jonah said. He was pointing at the towels. “Yes.”

“Haven’t I told you how we do things in this family?”

“It isn’t a family,” I said. “It’s just you. ” He looked at me for a moment, and then it was like all the blue-grey in his eyes converged into a single sound. He slapped me before I even noticed the movement of his hand. I fell back against the bathtub, coughing. Instinctively, I covered my face. He kicked at my sides and legs with his steel-toed work boots. I could hear the scuffing sound of them as he drew back his foot again.

It was a dream, I thought, a terrible dream. My mom is going to come rushing into my room and wake me up now But my mom didn’t come upstairs to wake me up or to stop Jonah. She had drifted off to that place where a woman thinks this is better than being alone, even though deep down she knows it feels far worse.

40 | Bellerive Issue 18

s

s

Benjamin came into my room after the house got silent. I had been cr ying on my stomach while thinking about my dad and how we used to go on hikes in the woods behind the house. ere was a cave back there where I could live. I wouldn’t have to see Jonah anymore, and I could take all the pictures of my dad out of the guest closet and put them on the stone walls with Gorilla glue.

“I thought I would tell you now, ” Benjamin said, sitting on the bed and gently moving my hair away from my face. “He took your rifle.”

“ Where?” I said. I sat up on the bed, even though my ribs and legs felt like someone had stretched the skin too tight.

“He’s pawning it.”

“ Why?”

“ To go to the track,” he said. I couldn’t form the words to express the growing wave of anxiety that was spreading throughout my insides. “I’m sure you think that adults have ever ything figured out, but the only thing they really know is that someday we will all be dead,” he said.

I looked at him for a minute, and then I lay back down. Maybe the slaves didn’t write down their stories because they didn’t want to remember them.

Benjamin didn’t just escape through headphones; it wasn ’ t enough to listen to other people’s music and lyrics. He told me later that he always waited until after my mom took the “supplements” Jonah gave her. en he waited until he heard Jonah’s sixth beer bottle cap hit the downstairs garbage can. After wards, he came into my room to access my window above the old trellis where my mom used to grow jasmine. I don’t know how long he’d been doing this before I finally heard his footsteps on the carpet and the slow movements of the window opening. I didn’t move the first time I heard him, but the next night I was determined to go with him.

After school started, we began reading David Copperfield in my English class. My classmates groaned and passed notes during the lecture. After I finished writing my choppy responses to the reading comprehension questions, I looked at Ms Whitaker sitting in her chair with her legs neatly crossed She told us that the novel was a call for social justice, her eyes falling on me with that last word.

I looked down at my paper, unable to meet her gaze. Ms. Whitaker was probably out-to-lunch just like ever y other adult I knew, so I lifted my eyes and looked past her to the flower y handwriting on the chalkboard.

at night, I waited for Benjamin with my clothes on under the sheets.

“ Where are you going?” I said into the darkness. He didn’t flinch, even with one leg over the sill

“Come on, ” he said. “Bring your bathing suit.”

We climbed out the window and down the trellis. We went through the backyard, careful with ever y footstep until we were over the incline on the other

7 1 ft till the ground | 41

s

side. Benjamin had found the cave. He put his backpack down at the cave ’ s edge and started taking off his shoes.

“You can change in there,” he said. “I brought a flashlight.” I took the flashlight and went into the dark.

I hadn’t been swimming in the stream since before my father died. We had picnics here and ate sandwiches, dangling our feet into the water We used to laugh when the minnows would rub against our toes. And now it was like a late summer adventure from someone else’s life. I didn’t know that girl anymore, and what I thought I knew was strangely unfitting, like going to bed and waking up inside of a closed coffin.

“ What’s wrong?” Benjamin said after I dove in.

“Nothing,” I said, wiping the water from my face.

“inking about your dad?” he said, his lips close to the water. His hair was slicked back, and he looked like one of those models from the Eternity ads, the kind of man meant for a life of leisure on the beach. “I think about my mom, too. ”

“ What happened to her?”

“She died from cancer, ” Benjamin said. “ When chemo made her sick, Jonah said she was being a drama queen. After she died, I asked him if she was still being a drama queen, and he looked at me like he was going to hit me, but instead he went into the kitchen and got a beer.” It was the most I had ever heard him say.

“Did he hit your mom?” I said, my voice barely a whisper.

“No,” he said. He was quiet for a minute. “I wish that they didn’t exist. en I would know that I wouldn’t turn out like them ”

I turned to look at the house. Because it was dark, I couldn’t see it in the distance, just the cliff. e cliff had erased that world from our vision. It was getting easier to pretend that morning wouldn’t come and we wouldn’t be sitting at the breakfast table with two tangible adults. I began to think of them as figments of my imagination, not worth mentioning.

e sound of the teachers’ voices was so quiet and unassuming that I had sleepy daydreams of past conversations I’d had with Benjamin in the cave. He had told me to do ever ything that Jonah said. He said that after a while, when the newness of being married wore off, Jonah wouldn’t be around as much.

He was right. We had an unusually warm October, but on what would be our last night swimming, Benjamin told me that Jonah wouldn’t be driving us to and from school anymore. “He said I could do it,” he said. “ We’ll have at least two hours after school before he gets home ” Benjamin laughed to himself “He always has to stay for the sixth race. ”

“You broke the rules,” I said and splashed him. We had promised not to mention our parents when swimming.

s

42 | Bellerive Issue 18

“Yeah, I did,” he said and splashed me back. As the water arched towards me, I could still see his face through the drops. It was like he already knew the ending to the stor y. Before that thought had completely reached its conclusion, he grabbed my hand under the dark water and pulled me close to him. I had never kissed anyone before, but I was not surprised that the person I kissed first was someone I wasn ’ t supposed to touch

“Stop,” I said. “It’s wrong. ”

“Lots of things are wrong, ” he said and smiled at me, still treading water. “But not this.”

“If they find out, we’ll ”

“ We can make rules. Nothing in the house or at school.”

I kept quiet. I didn’t say anything because I didn’t want to disagree. All I really had besides him were semblances: the semblance of being a good student, the semblance of following Jonah’s rules, the semblance of being a normal awkward fifteen-year-old girl, when really I wasn ’ t any of those things. e semblances of what I should’ve been merely told me what I really was. I had the sensation that I was falling through the cracks in each of these realities, and still, my fall didn’t make a sound.

During the spring term, I signed up for sign language. All the cheerleaders and football players were taking Spanish, so I knew that wouldn’t work. But it wasn ’ t just popularity contests that bothered me: it was words. e other language courses like Italian and French would involve some kind of presentation in front of the class. Another opportunity to speak in front of a crowd that didn’t want to hear.

Like at home. At home, Jonah talked us to death with his incoherent speeches about how we didn’t respect him. He never provided examples to prove his point, but then again, he didn’t need to. I signed up for American Sign Language, and the world became quiet and peaceful again for at least one hour of my day.

I was the only kid in the class who could hear At first, the other five students ignored me by signing rapidly when I didn’t even know the alphabet. But I went home and studied in our fire-lit cave. I learned by teaching Benjamin. Pretty soon, I could catch glimpses of what the deaf kids were signing about me. ey said the only reason I was taking sign language was to get into a good college. ey said people like me never cared about people like them.

I went up to Jenny, one of the girls who’d said these things. I told her she didn’t know why I did what I did or who I was. She stared at me like she had just woken up from a dream en she invited me to sit at the lunch table with her and her friends as if we had never argued. At lunch, we talked about the semi-illiteracy of the football players and how most of the cheerleaders weren ’ t virgins. But I wasn ’ t one either.

7 1 ft till the ground | 43

s

Benjamin would drive us to school, and for fifteen minutes in the morning, we could listen to music and speak without whispering. In the afternoons, we’d drive to Canyon Cove, parking directly off of one of the gravel paths. No one ever came through there, except an occasional jogger who didn’t know us. I looked for ward to those hours in the backseat when I could say or do anything.

It had been harmless for a long time, until one afternoon in March Benjamin pulled the car onto the familiar path, but he remained seated in the front seat for some time.

“I have something for you, ” he said.

“ What is it?” I said.

“It’s in the trunk,” he said, leaning down to pop the trunk open. We got out, and he pushed it all the way up. Wrapped in an old blanket was the rifle my father had given me.

“ Where did you get this?”

“I bought it back,” he said. “You’re going to have to keep it in the cave because he’ll just sell it again.”

I had forced myself to forget about it. To think of this rifle meant thinking about ever y other thing that I had once possessed and lost: all of the afternoons behind the house shooting at cans and my mom telling me what a good job I was doing, seeing my mother smile, the sound of the leaves being blown by the wind in late fall, the smell of outside on my father’s coat, the soothing sound of his voice, and me looking up at him and laughing at his jokes.

I picked up the rifle and ran my fingers across the hand-car ved grip and the mother-of-pearl inlay. I looked at Benjamin and he was smiling.

“Feel better now?” he said It was a ridiculous question

Benjamin had created the night swimming, the fire-lit cave, the fifteen minutes in the morning and the two hours in the afternoon, and the return of what was rightfully mine. I had accepted all of these gifts and I don’t think that I had ever given him anything. In fact, it hadn’t occurred to me to do so, mainly because I wasn ’ t sure what I had to give him in the first place. I had been thinking of the tangible again, but maybe there was something between the intangible and the tangible, or perhaps a mixing of the two. So that’s what I gave him I gave him American Sign Language And I gave him my feelings through my body. It didn’t take much. I should’ve done it a long time ago.

When we had gym, I changed in the bathroom stalls instead of the locker room. Of course it was Jenny who walked in on me because there wasn ’ t space under the door to see feet and the locks had been broken so that the bathroom monitors could catch girls sneaking a smoke She saw the boot marks on my back before I had a chance to turn around. She started frantically signing.

“ Who did this to you?”

“My stepfather.”

“You have to tell someone. ”

44 | Bellerive Issue 18

s

“I can ’ t. ”

“ Why not?”

“ey’ll listen long enough to put us in foster care, ” I signed. Jenny dropped her hands dejectedly and waited for me to get dressed. “Come on. It’s okay.” I patted her back as the bell rang for the start of class.

She walked with me to the gym We played basketball, but she was lost in another world as the basketballs beat a rhythm she couldn’t hear. I envied her deafness because she could shut so much out. And yet, it was bad putting those thoughts into her world. She should’ve lived a perfectly normal life, not knowing that secrets rarely remained secret and that some of them cut to the quick. s

At dinner that night, Jonah started drinking early. By the time my mom put our plates on the table, he was slurring his words. My mother’s hands were shaking as she passed around the potatoes. I wondered at what point she could no longer continue lying to herself about what Jonah was. I wondered, if she could write a journal entr y now about stepfathers, would she mention taking more and more pills or her difficulty staying awake? I wondered if she would mention me, and would she blame herself if she did. I let out a big sigh.

I think that she would’ve written what Jonah wanted her to write. Her entries would have been nothing more than his thoughts transcribed by her hand.

“Surette,” Jonah said. I looked up from my lackluster plate. “I know something about you. ” He was squinting his eyes like he was seeing two of me and wasn ’ t sure which one to address. “I was wondering what a nice girl like you is doing with this?” he said. He pulled his hand out from under the table, jostling the silver ware on top. e butcher knife on the plate of pork chops slid down, soiling the white tablecloth.

Jonah tossed a packaged condom into the green, undressed salad. I looked at it sitting there, so laughable, and remembered how Benjamin and I were supposed to return it along with some cigarettes to the cave, but Jonah had gotten home early before we had a chance to go down there. I had improvised by throwing the cigarettes out the car window and putting the condom in my backpack’s side pocket. My plan had been to stash it in my locker at school in the morning which was only ever searched for drugs. No one cared about anything else.

“I found it in the locker room, ” I said. Even though I felt like I couldn’t breathe, my voice sounded calm. I didn’t look at Benjamin.

“I don’t think so ”

“ Well, that’s what happened,” I said. I picked up my fork, and began eating my salad. Ever yone sat still at the table, waiting. It wasn ’ t that I was unaware, but that I understood the inevitability.

7 1 ft till the ground | 45

“You’re lying,” Jonah said. His voice was ver y quiet. It had a tone I hadn’t heard before. en he slowly stood up from his chair at the table. My mom shifted uncomfortably in hers.

“Jonah, I’m sure it’s just a misunderstanding,” my mother said quickly. e sound of her voice surprised me. It was as if I hadn’t heard it in years.

“Get upstairs, Surette,” Jonah said, ignoring her

“Dad, it was mine,” Benjamin said. Jonah looked down at him.

“You’re just tr ying to defend her.”

“No, it’s mine. I asked her to hold it for me and I forgot about it,” Benjamin said. “It was mine. ” He was panicking. I sat still at the table, looking down at my plate. I couldn’t look anywhere else. All I focused on was the image of David Copperfield locked in his room. If I went upstairs like he said, I would never walk out of this house again. It would go too far because eventually it always does.

I grabbed the butcher knife my mom had used to cut up the pork chops. Its edges were sticky from the pork grease. e grandfather clock chimed in the hallway. e sounds and sights were all in slow motion, even the ringing of the mechanical bells. Underneath the details, I knew that if I didn’t grab the knife, I wouldn’t stand a chance of ever doing anything else.

For the first time in my life, I had purpose. It wasn ’ t the words that I could use or what I would write down later about the past; it was this frenzied desire to live that outweighed the ramifications of the reality I had come to recognize. When I grabbed the knife off of the table, the girl I used to be when my father was alive and the girl who lived in the museum house finally woke up.

No one was going to bur y me under the future site of apartments No one was going to make up a stor y that I had run away to escape it all. I wasn ’ t going to be written out of my own existence with lies and fabrications. is was my narrative, and only I knew the ending.

46 | Bellerive Issue 18

p h o t o g r a p h y 7 1 ft till the ground | 47 B A I L E E W A R S I N G Into

the Canyon

A

apathy has many shapes

I’ll probably never get my motorcycle, you’ll never get your show. Suppose that’s expected of two people who can ’ t decide what they want and don’t believe in a higher power.

You were star running back in high school, nothing else to do. I watched the clouds at your practices, nothing else to do. We’d go for walks after wards to help you cool down. Stopped by the mart next to the abandoned Masonic temple and got lemonade.

It’s corny, but we mostly talked about our hopes and dreams and shit. You never wanted to talk about yours, though, had to juice them out of you. Even once you got going, you’d only say a few words at a time. Eventually figured out that you wanted to be a talk show host. Because when it came down to it, you said, it would help you get over your fear of messing up in front of people. ought it’d make it worse, but you were stubborn as ever.

Cicadas always flared up at the turn of the mile, our signal to go home. For some reason the sounds of evening bugs made it seem hotter. Like they were complaining too. Our lemonade bottles became a hassle once empty, but my ma would smack me if she saw me litter. Dust from the gravel stuck in the creases of our elbows. Your sister would be looking for you soon, you said ever y time.

Okay, I said ever y time. You kissed me on the cheek, ever y time. We took opposite turns at the three way stop, I faced west

Soon enough the lights would come on, the dogs would come in, and the chill would come out.

48 | Bellerive Issue 18 H A L E Y R . G R

A H

M

Two Weeks in Rio

An ending, brother and lover clutched in famished embrace. As their last morning ages they curse the imperious sun rising so pitilessly.

Two weeks came and have gone, five thousand miles from home. Strolling by day, brown hand in white, you visited the favelas. By night, from white sand beaches you stumbled into Atlantic, allowed yourself to be washed in the memor yless tide, never for a moment ashamed.

As you shower for your flight, his brown hands tenderly fold your white, cotton shirt and brown, cargo shorts. Blinking through tears, he lays them in your bag

7 1 ft till the ground | 49 S E A N C H A D W I C K

Glass Bell Waltz

My grandmother collected small handbells for a good portion of her life. I remember, when I would visit as a kid, I would ask permission to open the tall display cabinet and play with them, giving each a ring one by one. When she and my grandfather moved into assisted living, the bells were distributed to all their kids and grandkids, with me getting first pick of the lot. I kept five of them.

I was fascinated by the humongous variety of sizes, shapes, and styles the bells had. Of the five that I kept, I started to imagine that each had a magic power when rung: the white one that clacked like hooves summoned unicorns, the small one with strawberries made the air smell sweet. I began to imagine a large, dark mansion the home of a witch filled with shelves and shelves of enchanted bells. is is a song to play while slowly walking through the home of the Bell Witch. Look, but be careful not to touch; you don’t know what curse may befall you

50 | Bellerive Issue 18 E M M A D A U E S

a QR scanner to listen or visit https://goo gl/xW18Zz (case sensitive)

Use

Diamond Ring

R YA N B R O O K S

p h o t o g r a p h y 7 1 ft till the ground | 51

los ojos

I’m not wanting a tether

Strung to you from scopes

Determined by the flow, the play

at moves you most. I may Hate the view of crimson earth, of Skies vanilla with your haze. I may Sink beneath the clouds midst gusts Of breaths that steal cool gales.

You’ve swallowed life in swollen gulps, Devoured want, my mother hopes, Consumed passion mixed with fears

Tasted all I am.

I am tapered waste, warm wet lips with Laughter slipped in for a break.

Heady thralls I think too much

Just turn my face away

While slipping lust into my back.

Cram it well beyond my reach.

You know the tears, have channeled pains

Toward ebbs that meet your course.

And yet,

I am not so pliable, you see.

I’m steady wind with will and force. A whisper in full speed

And I hide heart drowned in aches for Sugared scenes, for seasoned sighs, for Weathered highs. For golden-coated homes. A requiem to shore-tossed plights. Wonders

Well beyond this pale.

52 | Bellerive Issue 18 LY S A Y O U N G -

B AT E S Abre

p h o t o g r a p h y 7 1 ft till the ground | 53 K AT E V OTA W

In Bruges

Broken Promises

Dennis, forgive me

You could never be what I needed you to be

Six years old

Looking up from this soccer field

Peering through the glaring lights

Scanning the crowd for your face

Dennis, forgive me

You could never be what I needed you to be

Seven years old

Calling to say you would see me at eight

Sitting on this doorstep

Waiting with my bag packed

Dennis, forgive me

You could never be what I needed you to be

Twenty years old

Rejecting your approach

Tr ying to erase your scars

You’re nothing to me

Daddy, forgive me

You were never what I needed you to be

54 | Bellerive Issue 18 B R I A N N A W I N I S TO E R F E R

photography 7 1 ft till the ground | 55 LY S A Y O U N G - B AT E S Gaussian

My Guide On: How to Clean on a Saturday After a L ong Time of Neglect

Trust is the metal foundation

I forgot how to care for.

It warps

It becomes unhinged

And it corrodes.

I know because he walks out the door this morning And I feel the flaky grain of distrust

Scraping my navel from the inside.

Ever y line he says is a leaking spout. We clamber, in a fight

Down our three flights

And he leaves to go visit the mother of his children

Even though they’re still home with me.

I don’t see him again until the sun sets. But understand, no matter how much

You want the cabinet door to stop leaning

You can ’ t use a screw whose grooves

Look as if they’ve been ground out

By a mad woman.

You must stop shoving the closet door

at sits askew in its frame

As if secrets will spill out

If there is no boundar y to hold them.

Go clean the oven

And reminisce on the warm pasta

You made them all two nights ago

Whose splattered mess leaves you

With a wish that you gassed yourself to death

Accidentally, of course.

en keep scrubbing the thoughts away.

e juice-caked blender blades.

e burned-brown Foreman grill.

e frigid crisper flung with onion skin. Keep scrubbing it all

And then you’ll find out

How much fuzzy, gray-green shit

Is growing in hidden places of your life.

56 | Bellerive Issue 18 A N O A A L I M AY U

Remember, once fruit molds No amount of cleaning Will make it edible. You have to throw the whole batch In the garbage.

7 1 ft till the ground | 57

King of the Hill

58 | Bellerive Issue 18 N I C O L E G E V E R S

graphite

Irony in the Form of L ove & Chain Smoking

e blacktop of this Catholic school parking lot Burns my ass cheeks as I watch you extend your arms All the way up to the hoop. As if you ’ re reaching for God, Clinging to the net as if it could offer you some peace. As if basketball is your religion.

I hate basketball. But I love you, maybe. I absolutely envy you.

Your ash-blonde hair is pulled up in a messy bun that looks like a rat ’ s nest, But you pull it off well Your skin is polka-dotted with brown-berr y freckles. I hate the shape of your teeth, but your smile is my favorite thing.

I smoke another menthol cigarette that I stole from my father, ink about how much I hate that my father smokes, en think about irony, how my sister looked me dead in the face last spring, Muttered, “You’re exactly like Dad ”

I think about how I should throw his cigarettes into the pond Down the street from our three-stor y townhouse To prevent him from getting lung cancer.

“Smoking is bad for you. ”

ank you, Captain Obvious Not all of us can be all-star athletes. Especially when we ’ re five foot three, And have two left feet, No hand-eye coordination, And the fastest mile we ever ran was nine-and-a-half minutes long.

7 1 ft till the ground | 59 M . M A C A L L A N L AY

60 | Bellerive Issue 18

I light another cancer stick, Pray that if I get that bitch that cancer I get the kind at kills you quickly.

A N D Y N G U Y E N Untitled p h o t o g r a p h y 7 1 ft till the ground | 61

The Clock Strikes Twelve

62 | Bellerive Issue 18 N I C O L E G E V E R S

photography

The L ong Haul

e old man and the old woman walked single-file down the long hallway, the woman in front.

In a cracked voice, the man struggled to share his obser vation: “ere’s heaters on both sides, all the way down.”

After a habitual pause, the woman answered, “at’s nice.”

“Maybe they’re air conditioners too, for the summer, ” the man added.

“Probably,” agreed the woman.

e two proceeded, one with his cane, the other with a slight cur ve in her back, and the heaters buzzed and warmed them. And with the heft of the complex behind them now, the man pulled back his shoulders just a little and risked something: he called ahead to the woman

“ Wait up!”

Without changing her pace, the woman shoved her hands into her tracksuit pockets, clasping the penny she’d picked up for their grandson the week before. It was from 2009 his birth year and that, he’d informed her, made it lucky. She fingered it, taking a few more steps before finally stopping, feeling generous, maybe even brave

e woman tipped her head way back and let her mouth hang open, as if stopping to gawk at the ceiling. She directed her old voice upward, without looking in the man ’ s direction.

“Let’s go get some ice cream. ”

Caught up, the man put his free hand on the woman ’ s shoulder, and they turtled along together, toward the exit at the end of the long hall.

7 1 ft till the ground | 63 S A A B A M B B L U T Z E L E R

I was surprised when you tumbled clumsily out of the box. Not a fine chalk, but rocks. Not finely crushed, but ground snapped smashed like ceramic like glass on the grass under the linden tree.

64 | Bellerive Issue 18 Z A C H A R Y J. L E E

Ash

Fogg y Forest

p h o t o g r a p h y 7 1 ft till the ground | 65 A N T H O N Y D E L U V I A

a c r y l i c o n c a n v a s 66 | Bellerive Issue 18 R A M S AY W I S E

#5 Categorical L andscape Monochrome