Bellerive 2012

Issue 13 penumbra

1. A space of partial illumination between shadow and full light.

2. A fringe region. 3. A place where light and shade blend.

Cover Art: Tracks

Jeremy E. Cheuvront

Pierre Laclede Honors College

University of Missouri-St. Louis

The Labor Camp at Nordhausen

Ogre Style

Irony

Game Over Forget It, Jake

On Using the Names of Plants (in Poetry)

1944

Tranquil Moments

Drawn in Your Eyes

Excavation

Stanzas on the Shore

Dragging Off

Sons of Singleton

Lauren Kenney

Christopher Lahr

Robert Bliss

Dana W. Townsend

Emily Spak

Mary High

Charlie Diehl

Christopher Lahr

Lauren Kenney

Brian Farrar

Dana W. Townsend

Sam J. Imperiale

Mary High

William Morris

Joe Thebeau

Christopher Lahr

Amanda Wells

Sam J. Imperiale

Laura Schuhwerk

Sarah Myers

Jason N. Vasser

Robert Bliss

Andrew L. Mills

Jeremy E. Cheuvront

Ken Wolfe

Ellen Huppert

Aladeen Stoll

Jessica Duncan

Nicholas Brune

Anya Glushko

Michael Wense

William Morris

Christopher Lahr

Jason N. Vasser

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 14 15 16 17 18 20 21 22 24 25 26 28 29 30 31 33 38 39 42 43 44 45 46 47 53 55 56 Sparks Art Therapy

fuck you up, your mum and dad” Anticipation Summer Yard magnolia

Baked Potatoes Takeout The Breakup Dinner Genocide and Jailbait Barbies From Infinity Garage Sale iron and vine Upon Being Rejected

Town in a Bust Economy Finishers

“They

Cheesy

Boom

Cruel Summer Crumpled Paper 9th Street Tunnel Pondering the Gateway By Definition

Canopy the strength of a tree Ambrosia Untitled Queen Anne’s Lace N-ICE Reflection Paper Cranes Stilted Flight Shhhh War Mongers Pickled Liver Trail of Beers Three Hands in Prayer A Silver Spoon Afternoon in Paris As Skinny Feels

Contest Winners Damsel in Success: Defending ‘Beauty and the Beast’ as a Model for Female Empowerment

Notes

Photograph Emily Spak Mary High William Morris Timothy Boettcher Michelle Radin Seymour Sarah Myers Aladeen Stoll Lauren M. Ewart Emily Spak Laura Schuhwerk Lauren M. Ewart Brian Farrar Rebecca Siefert Jessica Duncan Ellen Huppert Lauren Kenney David Von Nordheim 57 58 59 60 61 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 80 81 82 83 95 103 106

Essay

Biographies Staff

Staff

Faculty Advisor

Art Committee

Gerianne Friedline

Lauren M. Ewart, chair

Emma Figueroa

Michael Goers

Layout Committee

Brian Farrar, chair

William Morris

Sara Maxine Novak

Public Relations Committee

Heather L. Goodwin, co-chair

Caryn Rogers, co-chair

Alex Hale

Sharon L. Pruitt

Editing Committee

Emily Spak, chair

Brice J. Chandler

Courtney Henrichsen

Lauren Kenney

Greg Mueller

Casey L. Rogers

All members of the staff participated in the selection process.

What if I allowed my car to glide cleanly into yours? To slowly shift into oncoming traffic and smash into your Subaru, making real sparks fly between us? Vertigo would carry the public blame, but the screams you wouldn’t hear— private screams deafened by the airbag— would tell you it was purposeful.

We would be connected forever: metal wrapped around our bodies, glass protruding from tangled limbs, seatbelts serving as straitjackets. Our tombs would be joined so closely I could tunnel over to yours if the engine wasn’t in the way. Our names would appear together in every newspaper obituary as though we were married, and the freak accident took us together.

But the only freak in this scenario is me.

— 1 —

Sparks

Lauren Kenney

— 2— A r t T h e r a p y

Christopher Lahr

[Philip Larkin, “This be the verse”]

One senses this must be so.

Heavens though, you were perfect, Philip, Like most of your ilk, at first spank, womb-fresh creation.

What else could they do?

Now your perfect poems limn the wrongs they wrought and salve our wounds.

— 3—

Robert Bliss

“They fuck you up, your mum and dad”

Anticipation

Dana W. Townsend

The once vibrant hall loomed dark and ominously silent. Christmas break had cleared a space for my racing thoughts, and her. Dim, yellow light welcomed me into a room with spongy brown carpet and a single lamp glowing in the corner. As she floated down onto the worn, scratchy couch, I caught the scent of her perfume— silky and sweet like the dew-covered roses I used to comb through for Japanese beetles when I was still just a boy. My throat tightened and my pulse began to crescendo like crashing waves of young anticipation.

I smeared slippery palms across my thighs to hide my damp unease. Then she leaned gently into me.

I wrapped my arm around her shoulder, and as I drew her closer, the tension seeped out through my toes.

— 4—

Summer Yard Emily Spak

Dandelion, sweet and yellow, is shining up at me, A reminder of what summer is—what it ought to be. You started as a young white puff, waiting to set out. A huge gust of wind lifts you up and flies you all about. Through fields and over streets, wherever shall you land?

Tossed around and driven like a wave upon the sand. All settled down and cozy, you soon begin to grow. You sprout the big white puff and let your children go. Once more you send up a shoot, as bright as the yellow sun, Attracting bees for food and children for make-believe fun. The heat has dwindled as the first frost settles in. You’re withering—I’ll see you next year, my friend.

— 5—

— 6— Mary High magnolia

Cheesy Baked Potatoes

Charlie Diehl

The summer before Mother died, I remember her pulling the car over on the shoulder of this windy country road on the way to Grandma’s and telling me to get out. I sat frozen in my seat, but when she unbuckled her seatbelt and opened her door, I quickly did the same so she wouldn’t spank me even harder.

Walter and I had been arguing over my new Batman action figure. Walter had stolen Batman when I wasn’t looking, and he sucked on it and got it all slobbery. As if that wasn’t bad enough, when I tried to get it back, he just started wailing. After a long week at work, the last thing Mother wanted was to drive for an hour with screaming kids in the back. But still, I was surprised because usually she yells at me first, threatens to pull the car over, and then pulls the car over and spanks me. I remember thinking that I must have been in for it if she was skipping to step three already.

She had pulled over right in front of this drive to this house that was set back a little from the road, and I wished that maybe the country folks would come outside or arrive home or anything so maybe Mother wouldn’t hit me. I said a little prayer while Mother walked around the car, and somebody must’ve heard me, because she just pointed at the flower bed around these country folks’ mailbox and said, “Alice, will you pick some of those tulips for Grandma?”

I was so prepared to get spanked that I didn’t move. And then when Mother didn’t say anything or do anything else but stare at me, I started crying because I couldn’t think of anything else to do.

“Honey, what’s wrong?” she asked, squatting down to my level. She brushed a few fallen hairs behind my ear. “It’s okay. It’s okay.” She kissed my forehead. “Mommy was so rushed to get going over to Grandma’s that she forgot to get Grandma some flowers. Will you just pick a few of those tulips for Grandma? They’re gorgeous tulips.”

I looked into her eyes to see if this was a trick. “They’re not ours.”

“I know, Sweetie. But they have so many. You don’t think they’d miss a couple of them, do you?”

I looked at the tulips and then back at her.

“They have so many. They won’t even notice,” Mother said.

“But they’re not ours. It’s wrong.”

— 7—

“You remember a couple days ago when I was trying on that dress? You remember? What’d I say?”

“You got mad because I said it made you fat.”

“No.” Mother caressed my cheek. “I said that sometimes it’s okay to tell a little lie if it makes someone happy. If it’s going to make someone you love happy, then it’s okay to do little wrongs. This is the same thing, Honey. You want Grandma to be happy when she sees us, don’t you?”

I nodded.

“Of course you do. Look, they’re not even home. Their lights aren’t on. They’ll just think a deer ate them.” She brushed my hair again, but it wasn’t in my face that time. “And Grandma will be happy.” She smiled. “I will be happy.”

I looked at the house. I looked at the tulips and again at her. I picked one of every color except red, because that’s my favorite, so I picked two of those. Mother smiled again.

“Wow—almost as beautiful as my granddaughter,” Grandma said when I handed her the tulips. “Why don’t you and me go find a pretty vase for these?” I looked back at Mother unpacking some groceries from the trunk, and I wasn’t sorry to make her do all the work.

Inside, Grandma’s house smelled like potatoes. We were Irish and German and some other things and we ate potatoes at every meal. She was digging in a high cabinet for a vase when I sniffed too audibly.

“I’m baking them. We are going to have baked potatoes, salad, buttered bread, and spaghetti. I know how you love spaghetti.” She looked back.

I smiled. I liked when Mother melted cheese on my baked potatoes at home, but Grandma never served them that way.

Mother usually picked us up from daycare before the sun went down, but as the days got shorter, she wasn’t as reliable. On days when it wasn’t too cold yet, they let us older kids go outside. Some kids played kickball or swung, but my action figures and I liked the sandbox. When I saw Mother pull up, I pretended not to see her.

“Hi, Sweetie. How was your day?”

Batman lay on his back, and I started pushing sand on top of him.

“Alice?” Mother stood behind the wooden beam of the box.

“It was boring,” I said.

— 8—

Mother watched me cover Batman with more sand. His arms, which stuck straight out in front of him as if he was preparing for a hug, were the only things left uncovered. “Why are you burying Batman?”

“Batman lost.”

“Why?”

“Because there are lots of bad guys, and Batman only has Robin.” I looked up at her as if she was the stupidest mother ever, and she stared back at me as if my tone or my words were the most horrible burden ever. She looked away and then at her watch.

“Let’s go get your brother now.”

Walter and the other babies had to stay inside in the baby room and sit there while the staff watched the news. When we walked in, the ladies greeted Mother. Walter relaxed in his carrier, and while Mother chatted with the staff, I went over to watch him. Mother had finally bought Walter his own action figure. He just had G.I. Joe. I don’t think he really cared what character he had, as long ashe could put it in his mouth.

On the way home, Mother seemed strange but joyful. “What’s for dinner?” I probed for more than just an answer.

“I don’t know. What do you want?”

“Mac ‘n’ cheese!”

“Sounds great. We’ll have mac ‘n’ cheese and hot dogs.” She glanced back at me to judge my reaction. I’m not sure if Mother was just really good at understanding what kids like to eat or if maybe she never grew out of eating kids’ food herself.

While Mother was making dinner, Walter and I played Batman on the dining room table. Walter was more like a prop than a player. He sat there sucking on G.I. Joe while Batman fought Penguin and Joker around the edges of his carrier. Before either side could win, Mother swooped in from behind and hoisted me up by my armpits. Without a facial expression, I could not judge whether this was a positive trip or if I was in for it. I kept my mouth shut. She put me down, turned me around, and grabbed my hand. I couldn’t hear any music, but Mother started dancing anyways. Batman remained crushed in between our hands as we slow danced. She swayed back and forth to the smooth jazz still stuck in her head from the car ride home. “I love you,” she said. She looked into my eyes and smiled.

“Don’t burn the mac ‘n’ cheese,” I replied.

— 9—

Grandma lived near the wineries, and occasionally Mother would stop off and pick up a bottle on the way. On Thanksgiving Day, Mother pulled into the biggest one, probably the only one that was open, and bought her favorite wine. Grandma never drank wine, and Mother didn’t like Aunt Jill enough to consider her opinion. Right as we pulled out of the parking lot, I saw a messed-up animal on the side of the road. “Ewww. Mother, what is that?”

“It’s a dead animal,” she said.

“Which animal?”

“I don’t know. A possum or something.”

“Oh.” I watched it get smaller as we gained speed.

“A car hit it,” she said, guessing my next question.

“Why didn’t the car move?”

“Then the people in the car would have gotten hurt.”

“Oh.”

I told Aunt Jill all about the possum when we got to Grandma’s. Aunt Jill and Uncle David brought me and Walter our Christmas presents on Thanksgiving because they were from Massachusetts and spent Christmas with Uncle David’s family out there. They gave me Two-Face. Aunt Jill had obviously asked my mother what to get me because the previous year they got me a doll and a crib, but that’s still in the box.

“What’d you get?” Grandma asked, stirring the garlic mashed potatoes.

“Two-Face!”

“Cool. Is he your favorite?”

“No,” I answered. “He’s a bad guy. But I don’t have him yet.”

“Oh. Here, put this on the table,” Grandma said, handing me the potatoes.

During dinner, Aunt Jill tried to help feed Walter. Mother let her go for a while but then laughed and said, “Alice could do a better job getting Walter to eat his turkey, couldn’t you, Honey?”

“I don’t like turkey,” I answered.

“So that’s why you haven’t finished your plate yet?” Mother asked.

I nodded.

“Eat your turkey, Alice.”

“I tried. I can’t eat anymore.”

— 10

“Alice,” she said.

“I don’t like turkey.”

“Alice, don’t,” Mother said. “Alice. You want to make Grandma happy, don’t you? Grandma spent all day making that turkey for us.”

I pushed the remaining turkey around with my fork.

“Alice, eat your turkey. You want to make me happy, don’t you?”

“But...”

“Don’t you?”

“I want to make you happy,” I said.

“Good. Finish your plate.”

I thought of ways to get back at Mother, but no good plan came to mind. Mother saw that I was still upset, so when my plate was finally empty, she came up behind me, kissed the top of my head, and pulled me to my feet. Right there as Grandma was cutting the pie and Aunt Jill was exchanging glances with Uncle David, Mother started waltzing me around the table. Music always seemed to have a hold on Mother, and in certain moments she had no choice but to let it out. As we danced through the dining room, we squeezed her wine glass between our hands, Mother too careless to know it was there and me too careful to tell her otherwise. I was still angry, though, so I didn’t warn Mother when she was about to bump into the counter. The glass stayed between our fingers, but the wine jumped over the side onto the edge of her dress. “Shit,” she swore. “Why did you let me bump into it?”

“I’m sorry.”

“This is ruined. It’s completely ruined,” Mother said, holding her dress.

“Don’t worry. It’s just a dress,” Grandma said. “At least you’re both okay.”

“Alice, my dress is ruined.”

“I’m sorry, Mother.”

“We have to go now. Get your things, Alice.”

“I want to stay.”

“Calm down,” Aunt Jill said, rising from her seat.

“There’s no need to go,” Grandma added.

“Alice. We’re leaving.”

— 11

That winter the snow was pretty heavy, so we were glad the snow was light enough on Christmas Eve that we could make the drive out to Grandma’s for dinner. Walter had started to move on to books during car rides. Obviously, he had no idea how to read or even really how to interpret the pictures, but he loved to hold them. Almost the entire ride, we played this game where I would grab a Little Golden Book and hold it in front of him until he snatched it. After he had a good grip on it, I’d let go and grab another Little Golden. I’d hold this new one in front of him, then he’d throw his old one on the seat, then take the new one from me and burst into a small fit of giggles. Then I’d pick up his thrown-away book and start all over. Mother wasn’t angry. The back of her head almost made it look like she was smiling.

When we arrived, Mother handed me some poinsettias to give to Grandma. I ran to the door, and Grandma opened it before I could knock. “Perfect,” she said as she took the poinsettias. She placed them on the mantle above the stockings she hung for each one of us.

Walter and I played with his baby toys while Mother and Grandma prepared dinner. After I became too hungry, I went in the kitchen to find out when dinner would be ready. “Not too much longer,” Mother said. Mother handed me a bunch of silverware, and I set the table. Soon Grandma was transferring hot dishes and platters to the table.

As we sat down to eat, Mother rose quickly, saying, “I almost forgot.”

“What?” Grandma asked.

Mother didn’t respond as she fiddled with the oven. “Alice likes her baked potato with cheese melted on it,” Mother finally answered.

After dinner we watched It’s a Wonderful Life until Mother saw that it was starting to snow harder. She knew I wanted to get home, because she had me convinced Santa would only come if I was asleep in my own bed. Grandma offered us pie, but Mother insisted we leave before the roads got too bad.

The country roads hadn’t been plowed yet, but everyone was inside, so Mother just drove slower, and we were fine.

On our way home I recognized the house we got the tulips from, and Mother must have, too, because when she finally saw the deer, she swerved to the right, and we tumbled down a hill.

— 12

Later, I realized that I must have been thrown from the car, because I was lying in the snow, and I was struck by the high beams. I made my way to the overturned car, and I found Walter still buckled inside. He wasn’t crying, and I knew that could only mean one thing.

I remember Mother lying next to a tree some ways off, calling me to her side.

“Alice.”

“Mommy.”

“Alice. Don’t cry, Honey. Mommy’s going to be all right.” Through all my tears, I tried to believe her.

“Alice. Where’s Walter?”

“Mommy.” I didn’t have to shake my head.

“Alice. Don’t cry.”

“Mommy.”

“Don’t cry, Alice.”

“Why?”

“Because I don’t want you to. And you want to make me happy, don’t you?” When I didn’t answer, she repeated, “Don’t you?”

“Yes, Mommy.” I stopped crying. Mother smiled and didn’t say anything else. The snow was beginning to cover Mother. After no one came for awhile, I began to push snow on her chest until it was completely covered. Then I did her legs. The sky took care of her face, and I held her hand. I started crying.

— 13

— 14

Christopher Lahr

Takeout

The Breakup Dinner

Pour water into medium-sized pot and boil. Boil until the water temperature feels as hot as your red cheeks. Boil until the bubbles pop and overflow like tears onto the stove top.

Dump in uncooked pasta and stir, being more careful with the noodles than your last lover was with you. Drain when soft and watch it all fall away. Add four tablespoons of butter because no breakup dinner can be prepared without it. Add more butter because it’s good. Add more butter because you can. Add more butter because it’s the only thing you can bear to spend your night with.

Pause and mentally note that should you expire tonight, you would prefer to die with butter.

Fold in milk and neon-orange crack packet. Stir quickly and stop remembering how handsome he looks when he’s writing. Serve while hot and eat with a reckless abandon reserved for those who will not be seen naked anytime soon. No side dish required. Any available wine recommended. Chocolate ice cream for dessert.

Lauren Kenney

— 15

Genocide and Jailbait Barbies

It starts as children. A Barbie on your second birthday. The model of a perfect woman, blonde, with big breasts and a plastic face. Until you look like her, no one, especially not the boys, will remember your name.

Ph.Ds sit in boardrooms—stripping teenage girls of their young faces. A month’s worth of meetings condensed into a thirty-second commercial—raping them of any self-confidence.

Now, as you wait for your Ken, you can work on your tan. Soon the cancer will set in, but you’ll look so damn pretty until then. Just remember that bald Barbies don’t turn on most men.

Brian Farrar

So don’t pretend you’re Barbie, because he’s no Ken. But if you find someone like Dan, maybe you can be his Roseanne.

— 16

From Infinity

Out of cool, still air my mother returned to me from celestial heights.

Dana W. Townsend

— 17

Garage Sale

Come one—Come all!

Buy the remnants of a life! Two dollars each or three for five! Place the sign of desperation At the entrance to my vanquished kingdom!

Welcome, circling vultures, To memories leaping from dead carcasses. Priceless treasures—once, Now picked through like refuse. My blood in a jar to be bargained for.

Grandma the expert negotiator And Grandpa the fast-talking auctioneer. A stain on the beautiful dawn! Arms outstretched with tainted offerings. The decaying body of liberty and happiness On a rusty card table.

Nickel and dime prices

Written across my soul with a magic marker. The American Dream Evaporating like a cloud over the desert— With no hope of rain. Only the parched reality of a few trinkets That separate us from the inevitable demise.

The ghost of a dead Middle Class, Which haunts Saturday mornings. A buyer’s paradise for some, Evil tidings of a future, Screamed by innocent signs.

Blessed noon— And a few crumpled bills To ease the pain,

— 18

Sam J. Imperiale

Washed down with remorse. What remains—packed away For another tragic day. The door is shut, and any sign of despair Is pulled from the earth.

— 19

Mary High i r o n a n d v i n e — 20

Upon Being Rejected

A liquid despair

Slides down my chiseled figure And I rebuke my stony hands And feet

At every crack. What’s worse?

A cardinal rests Upon the carved marble That is my hair And I can hear The thunder roll.

— 21

William Morris

Boom Town in a Bust Economy Joe Thebeau

She was second mermaid

At the Aquarama in 1968

Her pal Judy was first and got her the job

Three shows a night

One matinee

Choreographed skits

In an eighty-five thousand gallon tank

The pay was good

The costumes even better

Chasing AquaBeatles and James Bond

Spies in sexy swimsuits

Hold your breath and dance underwater

Until they raise the curtain of bubbles

Yes this was a promotion to be sure

From skating waitress at the Steak ‘n’ Shake

Where the tips were good

But nothing compared to summertime tourist applause

They treated the mermaids like stars

Osage Beach was a boom town then

And she was just a kid

With California dreams and Everything as a possibility

Today she’s working the register

The locals still need groceries

Thank God

The pay is enough for the rent

But the house is gone

Just like the second husband

She’s not complaining

It’s better than nothing

Which is what her brother’s got

Now that the drywall business has dried up

In this bust economy

— 22

It’s not such a bad gig

Now that they have the barcode scanners and Some kids to bag the groceries and bring in the carts

She used to have to do all of that and run the register too

So maybe things are getting better

But it’s never going to be as good

As three shows a night and one matinee

In an eighty-five thousand gallon tank

That might as well have been Broadway

— 23

F i n i s h e r s — 24

Lahr

Christopher

Cruel Summer

We grew up wildflowers among the fractured gray cement— too much runoff heaving, wash out, cleaving to tainted soil. Still coronas reached toward open sky in late summer heat.

We left weeds in shadow to die slow deaths of the anti-phototropic. Woven crowns of clover and thistle placed upon our heads, thorny-blossomed blessings—

never mind the pricks to spite our reverie—

pronounced ourselves divine, danced curves in cyclic moon as only we can, my blood, my sister.

Our passion this pleasure pain our saving grace:

To dance in humid, thick summer night after rain, knowing a reprieve beyond deserted months—

nothing left to thirst save for this nectar, our stolen season’s offering.

Amanda Wells

— 25

(An Ode to St. Louis)

As I lay in this gutter dying, A brief letter I am compelled to write, An epitaph of sorts—a story, maybe, About this city—and a little bit of life.

All I have is this one piece of paper And a discarded pen that I found. The words that are left in me Struggle to describe this town.

St. Mary’s seems like a paradox now, She gave and took so many lives. Clayton Road became a highway To both pain and paradise.

I still feel as if I am riding That elevator at Famous Barr, The poor child’s roller coaster With fried pretzels cooked in lard.

Art Hill was Heaven when it snowed, And Hell was July with trains as black as coal. Who knew that moments were golden then? Certainly the child I was did not know.

I saw the last segment set On that silly silver coat hanger, Watched Gibson on the mound When there was something to cheer.

Cruised our own inland sea Aboard the mighty silver beast, Coins turned kids into kings and queens, But the brown river still smells. Red, White, and Green fire hydrants, And a half-pound of Volpi Salami,

Paper

J. Imperiale — 26

Crumpled

Sam

Shotgun houses, and Missouri Bakery cannoli, Mama Tuscano still makes the best ravioli.

A final word to our sponsors: Johnny, I could care less That you own your building and lot. Ted, that icy muck has made millions fat. Imo, no offense, but I really hate provel cheese.

Ah!—my last impression must sadly be This lousy pot-hole in front of me. How long I wonder to fix this one, And how many did I hit in my day?

I doubt these scribbles mean anything to you. I crumple this paper and cast it aside, Writing it not to say that I had died, But to say that I had lived—

This city was my home. The sweetness and the sadness All part of her magic—her charm, Although I am dying—she lives— And with her a part of me lives on.

— 27

9th Street Tunnel

I sat in that old 9th Street tunnel waiting for the Metro to come and drag me away from my mindless voyeurism back to work—the place surrounded by half walls made of fiberglass or cardboard or years of droning circumstance

That old tunnel reminds me of some past orange lights glowing every ten feet or so and old tracks that look like they belong below Soho, not St. Louis

Laura Schuhwerk

The brick arches even seem to have some ghostly voice telling me to jump on a train to the northern airport and fly off to southern skies and borders, strange of labored days

And all I picture is Casablanca, black and white movie moments, seeming so easy to walk away but here it’s the muddy river and the green street signs that tie my feet to the tracks where I sit in the 9th Street tunnel waiting for the Metro to drag me away

— 28

Pondering the Gateway

— 29

Sarah Myers

By Definition

(In the style of the Villanelle)

Eternity is merely a matter of moments spent leisurely, eagerly doing things cherished or not, eventually wondering where all of the time went,

without equity, our time is but a small room we all rent listening to syncopated tunes admiring the lot, eternity is merely a matter of moments spent,

and without flaws, our journeys are certainly meant to allow fellows to appreciate all of what they’ve got, eventually wondering where all of the time went,

Jason N. Vasser

and without effort, words move about like letters sent through pathways hidden in memory sentenced, without a dot, eternity is merely a matter of moments spent,

knowing those moments by the heavens are graciously lent to allow ladies to appreciate all of the what they’ve got, eventually wondering where all of the time went,

from vine to wine, time is best enjoyed in a tent of the company best suited for better times than not, eternity is merely a matter of moments spent eventually wondering where all of the time went.

— 30

The Labor Camp at Nordhausen

Robert Bliss

Dad’s Magnavox, splendid in mahogany, brought us Toscanini on some Sundays. A green keyhole signed the signal’s strength.

Oftener, he spun the seventy-eights bought before marriage, Europe, war. Heavy, black, breakable. Beethoven by Bruno Walter, Mozart’s Prague, and Rachmaninoff’s piano. (He sort of knew Sergei).

Or he’d play my yellow kids’ disks with “A Little Night Music” that was my delight, or “Peter and the Wolf”, where I took fright at the French horn, or Franz Lizst’s march that sent me stomping round the room while dad batoned the beat..

What did the music mean?

I now think he wanted me to speak to break his grief.

I had not lived enough to know any answer.

— 31

But he, who’d seen too much, said (of Mozart) that “these men thought their world would never end.” And then he knew it did.

— 32

Andrew L. Mills

The park was a little less populated than George was used to. Normally when he brought his lunch to the city park, there were joggers, picnickers, and parents supervising their kids on the playground. He tried to think if there was anything unusual about today. Maybe there was a parade somewhere, or a ball game. Sometimes a ball game would keep people glued to their television screens or elbow to elbow at the stadium. He couldn’t think of anything in particular, so he concluded the weather was the cause. It had been raining all morning, and the sky was still overcast and occasionally let loose a few sprinkles here and there. It was hard to tell the difference between what fell from the sky and what fell from the trees. It was one o’clock in the afternoon, and a little bad weather would not stop George from having his usual bologna-and-cheese sandwich. He wiped away as much water as he could from his favorite bench before sitting. He liked this bench because every Friday after twelve a girl about his age would jog through the park and pass right in front of it. George had never spoken to her. He thought it was better to just enjoy the view. Some things are better left to the imagination; they are less likely to go wrong that way. George wiped away a few droplets of water that landed on his nose from the tree limb above. The leaves were a lively green, which was normal for April. Spring was his favorite season, not just for the rain, but because he liked to watch things grow and bloom.

George opened his blue lunch bag; removed his sandwich, a large cloth napkin, and a diet soda; and set the bag aside. He unfolded the napkin and spread it across his lap before he unwrapped the sandwich and placed it in the center. The sandwich was cut into two triangles, and all the crust had been trimmed away, just the way he liked it. He took the first bite from his lunch and enjoyed the taste of the yellow mustard asit squished over his tongue. As he chewed his food, he couldn’t help but wonder if the girl would still jog today, given the weather. He took another bite and heard laughter from the jungle gym, which was further down the sidewalk. He recognized them immediately: three local gang members, a few years older than George. All three were the rough and tumble type. He didn’t know their names and didn’t want to. They bullied everyone from small children to old folks

— 33

Ogre Style

taking a stroll. Now that the rain had mostly stopped, they had probably returned to make sure no one was trying to play on their jungle gym—why, no one knew. There was a rumor spreading that the oldest boy stabbed someone to death with a screwdriver. George watched the cops arrest him once in the park, but a few weeks later the three boys were back on the jungle gym with a vengeance. George never went near them and they left him alone. He was never much of a fighter, nor was he a fan of confrontation, or pain, for that matter.

George was startled by the sudden sound of his cell phone ringing. He quickly shoved the remaining portion of the first half of the sandwich into his mouth, nearly choking on its size, while he dug his phone from his left pocket, careful not to dump the rest of the sandwich from his lap. He held the screen up to see who was calling as he chewed the lump of sandwich. It was his friend, Bryan. He probably wanted to know whether George was going to make it to their session of Dungeons and Dragons. He was the Dungeon Master, and it was his duty to rally everyone for each session as well as invent the story and setting for the players. George swallowed hard to force the partiallychewed lump painfully down his throat. Finally able to speak, he answered, “Hey, Bryan, what’s up?”

“Hey, Ogre! You’re going to make it tonight, right? The others are counting on you,” said Bryan. He always called George after the character he role-played during the game, O’gar, a mild tempered but brutish ogre that relied on giant strength and a massive club over wit.

“Yeah, I’ll be there. What are we battlin’ tonight?” asked George.

“You know I can’t give you all the details,” said Bryan. He was notorious for not being able to keep his story lines a secret. This was because he would get so excited about the game and his genius plots. Surprisingly, even though George knew what lay ahead in the story, Bryan still managed to keep it suspenseful and fun.

“You don’t have to give away the good stuff; just entice me a bit,” said George with a smile, knowing Bryan only needed a little nudge to give up his secrets.

Bryan laughed. “You know me too well, but not this time, Ogre. It’s a surprise, and you won’t see it coming! No hints.”

“You are killin’ me, man,” said George.

“I’ll see you later, dude. I still have to call Sara and Chancy.” Chancy earned his nickname years ago from playing a gambling-ad-

— 34

dicted rogue; his real name was Robert.

“See ya, man,” said George. He put his phone back into his pocket, excited for the next gaming session.

George was about to take a bite from the second half of his sandwich when he heard a twig snap a short distance away. There was debris scattered across the park, mostly dead tree limbs and leaves knocked loose from the storm. He looked up to see a rain-soaked mutt looking for food in the trash. George had seen this stray in the park often. It was common to find food scraps in the park on nice days when people would have picnics, but today Teeth Face would not be so lucky. George had named the stray after O’gar’s animal companion. Teeth Face sniffed around one of the park’s trash cans with a prominent limp. The mutt had an injured back leg, which hindered its mobility. George raised the remainder of his sandwich to his mouth, but his conscience wouldn’t let him take a bite and dismiss the poor animal. He stuffed his napkin into his lunch bag and walked carefully toward the dog with the sandwich in hand; it’s what O’gar would do. Teeth Face eyed George carefully as he slowly approached, holding the sandwich before him. “Here, boy, are you hungry?” asked George. He could sense that Teeth Face wanted to run, so he squatted lower to the wet ground to be less intimidating, which gave the desperate animal enough courage to stretch its head forward and sniff at the bologna sandwich. George couldn’t help but wonder if the dog had rabies or a taste for fingers. He then realized Teeth Face didn’t trust him, either, and his desire to keep all of his fingers inspired him to toss the remainder of his lunch to the mutt’s front paws. Teeth Face took one last sniff and then picked up the morsel with its teeth and chewed furiously as small bits of bread fell from its jaws. George watched as the mutt carefully licked up the remaining bits of bread from the wet grass and wondered if he had made a new friend. George inched forward and stretched his arm out to bring his hand less than a foot from the dog’s nose. Teeth Face sniffed at George’s fingers hoping to find more food while George looked away with closed eyes, convinced he was about to lose his hand to a hungry animal with rabies. Suddenly, Teeth Face growled, and a startled George fell back on his butt and expected to be eaten alive. George instantly regretted helping the mutt.

Teeth Face growled again, and George opened his eyes to see the animal growling not at him, but at something over his shoulder. George twisted his neck, afraid to see what lurked behind him. The

— 35

three gang members from the jungle gym approached. George quickly scrambled to his feet; his every instinct told him to run away as fast as he could. It was unlike George to stumble into a predicament such as this, given his careful nature.

“It looks like we have our first trespasser of the day, guys! Should we break his nose or make him limp like that mangy mutt behind him?” The other two chuckled, although whether it was out of nervousness or humor, George couldn’t tell. The gang leader reminded George of Teeth Face and its limp. George wouldn’t put it past them to hurt an animal. It wouldn’t be the first time he had seen them kick and throw rocks at someone’s pet. “I have an idea,” said the gang leader as he lifted his shirt to reveal a screwdriver tucked into his pants. George suddenly recalled all of the vicious rumors and looked over his shoulder for support, only to find Teeth Face running away as fast as a dog with three good legs could, leaving George with a bad taste of betrayal. “Look, he’s so scared he’s speechless. Even the dog has more sense to run!” continued the leader. As the gang came closer and closer, George became painfully aware that the park was still empty and there wouldn’t be anyone to help him. He began to wonder if the screwdriver was a flat-head or Philips and which would hurt more. He wanted to apologize and ask for forgiveness and promise never to go near their territory again, but he had seen other victims do the same, and it only seemed to make things worse. He needed to run, but his legs felt like they had turned to lead. “He looks like he’s about to piss his pants like a little girl!” The bullies continued to taunt him, but George was barely aware of what they were saying, too busy trying to figure a way out of his predicament. Suddenly he thought, If O’gar got himself into this mess, he could surely get himself out. What would O’gar do?

George quickly scanned the wet ground around him. He spotted a fallen branch about as long as his arm and as big around as his wrist no more than a few feet away. George couldn’t help but smile at the level of insanity he was about to embrace. He quickly snatched up the branch and held it high with both hands. At the top of his lungs, George shouted, “I am O’gar Bonesmasher! That my Teeth Face! You go now, or I break you face!” George bared his teeth and snarled the way O’gar would to intimidate his foes during the game. The gang was stunned, not sure how to handle the amount of crazy that stood before them. They were used to people being afraid or at least unwilling to risk a fight when outnumbered by the three of them, especially with the — 36

leader’s violent reputation. Although the gang didn’t come any closer, they didn’t retreat, either. Before they had a chance to regain their composure and remember they outnumbered him, George snarled and charged at them, swinging his club wildly through the air in ogre style. The gang was not able to process what was happening, and the three retreated instinctively to the far side of the park as quickly as they could, occasionally tripping and falling over each other. “And don’t come back!” added George for good measure.

The rush of adrenaline left him trembling as he collapsed to the ground in disbelief. Common sense told him that his crazy act should not have worked. This was not a game. George let go of the branch and realized for the first time that his menacing club was rotted and would have most likely crumbled to pieces had he actually hit anything with it. He was overwhelmed with relief as he sat on his knees in the wet grass.

“Are you okay?” asked a young woman. George didn’t hear her. She came closer, startling him as he recognized the jogger. “They didn’t hurt you, did they?”

— 37

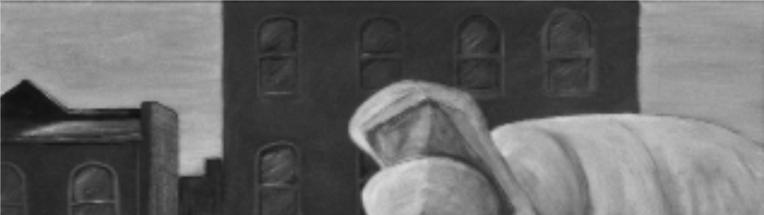

Jeremy E. Cheuvront I r o n y — 38

Game Over

Mom says for me to go outside, to get off my butt, to turn it off.

Mom says I need to play with friends, to kick a ball, to socialize.

Mom says my video gaming will rot my brain, stunt my smarts, make me a loser.

Mom doesn’t know. She doesn’t play.

See—

In life, I run laps. Wheezing. Feet flapping. Lungs ablaze. Getting passed by everyone. Collapsing. Last.

On screen, I run miles. In heavy armor. With massive rifles or wicked swords, I leap crazy far. I throw myself from great heights and crack the pavement with steady boots. Sword drawn. Guns locked and loaded.

I unleash dire consequences on waves of demons and Nazis, one after another after another.

All of this, without my inhaler.

In life, Mom decides where I go and how quickly. My teacher decides what I do and how quietly. My coach decides how high I jump and how many times.

Ken Wolfe

— 39

My enemies decide what hallways I can use and when I can safely use the toilet. My life submits to their whims.

On screen, the whole world pauses for me when I move my thumb a millimeter and press a tiny button.

Then—

Bullets hang, sizzling in mid-air.

Gargantuan beasts balance silently on hind legs. Evil swords freeze in the hands of stupefied villains. Explosions become still like fiery oil paintings while I scratch my nose or get more snacks and settle in again.

Oh, yes. I make them wait. Sometimes for hours.

In life, I watch my back.

If I drop my guard, the wedgies come from behind. Mystery feet hook my ankles and I find the floor. Phantom hands drop wet, nasty things down my shirt.

No one sees anything.

No one knows.

Alibis for all.

On screen, I whirl ‘round to face enemies and give ‘em what they’re asking for, give ‘em what’s coming to ‘em, make ‘em pay!

I punish evil. I answer insult with force! Bloodied, they regret their insolence!

In life, at home, I hide the bruises from my parents.

I try not to fold when they ask, “How was your day?” If I say more than, “Fine.”

I’ll show that I’m not.

— 40

In life, everything is dangerous and volatile: the teacher’s hidden bad mood that bursts into edged sarcasm, the bully’s roaming attention that pulls into harrowing focus, the politics of friendships, the economy of loyalties, the fragile, shifting alliances. Nothing predictable. Rules don’t apply across the board.

On screen, there are rules, there are tutorials, there are patterns, there are combos, there are power-ups, there are health packs, there are checkpoints and saves.

In my life, there’s just me.

— 41

F o r g e t I t , J a k e — 42

Ellen Huppert

On Using the Names of Plants (in Poetry)

AladeenStoll

Sometimes spring smells like fall leaves: layered and moist, retained along chain link fence bottoms, and slowly peeling back slick surface after slick surface to reveal fertile earth.

And sometimes spring smells like a blossoming dogwood.

— 43

You can’t see what I see. When the clouds will part And the rain falls like acid On our open eyes And melted faces.

When worse comes to worst, You’re gone like the wind.

This home is broken. The cracks drain the evil that You have been rooted in. You only see shit like this in the movies.

In the tiny window at the top Of the stairs. That’s where they got her.

A single ring around her neck, The rope burning hot Like a reddened ember. Her eyes closed Like a mourning, morning angel.

Her skin glowing white and blue. Her wings wrinkled on the floor.

Don’t trust all you see. Don’t ever pity me.

— 44

1944

Jessica Duncan

Tranquil Moments

I wanted to return to that place, the calming ocean, the glassy sand, the wooden beach house filled with memoirs.

I was thinking of the soul, not the physical lustiness of her appearance, but the deep romantics that run through brains, tempt the mind, explore the contours of [her] heart. The seagulls follow the boat, free of mind, as they reflect on the wakes of depth’s mystery.

The boy studies his father, questions his integrity, and wonders why it’s never mom anymore.

Nicholas Brune

— 45

Drawn in Your Eyes

— 46

Anya Glushko

Out of the corner of his eye, Steve saw Danny bite at his fingernails. He spat them down onto the ground with a soft pfft sound that Steve couldn’t help but notice. Are you paying attention? he wanted to ask. If you’re going to get anything out here, you need to watch. You need to be alert. The words were there, but if he wasn’t careful, they’d come out too strong. You come off so harsh sometimes, Luanne had said, years ago.

Danny scratched at the spot on his neck where his orange vest had shifted, brushing against his skin. He tried to put it back, but as he moved the tree stand made a squeak, and he stopped.

Steve almost shushed him. He tried to let it go, but he could feel the sound rising up through his throat. Instead, he swallowed a gulp of coffee from his thermos. Luanne’s voice, already fading after two months, eased him down from the high orbit of his temper. He could almost hear her. This is only the second time you’ve taken him, she would’ve reminded him.

He shook his head and set his eyes forward. After a moment, Danny went back to scratching at his neck, trying to adjust the nylon vest. The heavy camouflage jacket he wore made it impractical.

“If you need to fix your vest, Danny, just do it,” Steve whispered. He didn’t think it came out that strongly, but he caught Danny’s nervous, slightly startled look. Danny put his hands in his lap.

The cooler had put Steve in a bad mood. “Don’t forget to throw it in the bed of the truck,” he’d told Danny just before they left. But in the cab, when Steve had just passed the last of the early morning gas stations, Danny had quietly confessed. Steve tried to understand, but his mind kept repeating, I just told you before we left.

In the woods before them, the faint September light seeped through the trees. Steve let his eyes scan across the distance. He settled into a rhythm of long breaths. Occasionally, Steve checked to make sure Danny’s gun was upright. He half expected to see it angled down, but there it stood in Danny’s tight grip, swaying just a little with the breeze. Danny sat looking as though he were sleeping with his eyes open.

If Danny had forgotten anything but the cooler, Steve might have laughed it off. But the coffee he’d brought would be cold by nine, and without lunches, their hunting trip might end up as more of a hike.

— 47

Excavation

Michael Wense

Sometimes he couldn’t help but imagine Danny’s head as one of the deer mounted on the den walls—hollowed out, for show. He could detail the specifics of the Second World War, about howitzers and the Battle of the Bulge, but asking him to help fix a drain pipe meant Steve might as well do it alone. Danny had been lucky to get his boots on his feet that morning.

Steve tried to tell himself that he was just anxious for the deer. It’d been nearly a year since he’d been out here, ever since other things took priority. Now, he felt the two deer tags in his pocket against his leg. He itched to bring something in, something to put on the wall, like he would’ve done before everything fell apart.

Back home, he felt as though they had fallen from something and it was his duty to get them back where they were before. But without Luanne, it was like struggling through a strange land, directionless and without language. Here, the world around them stood still. All Steve could hear was birdsong. He tried to focus on that. Through the gaps in the trees, he could see the clouds moving slowly overhead.

Steve kept thinking that he might speak. He didn’t want to risk scaring anything away, but the desire kept coming up. Vague questions formed. Small talk pressed at his lungs like breaths needing release. But then Danny shifted next to him, and Steve exhaled.

“Quiet out here today,” Danny whispered.

Steve nodded.

His hope was that the sun might get the deer moving. After an hour, though, the sky was still overcast. The air ran with a chill. And if there was anything to be had from today’s trip, Steve started to wonder if it would come. He reached around to scratch his back, and he remembered Luanne resting her hand there once when they’d checked in on newborn Danny in his small room.

Steve had to take a drink of his cooling coffee, unscrewing the cap of the thermos so quickly it made a squeaking sound. He focused on the taste, the bitterness, to distract him from the tightness in his neck and stomach.

“I’m gonna go take a leak,” Steve said. “I’ll be right back.”

Climbing down from the tree stand, he sensed that the ground had gone absent beneath him, almost as he had when the doctor broke the news. Steve moved behind the tree stand, but he didn’t really have to pee. What he wanted was another taste of the coffee, its sharp flavor, but he doubted it would work a second time. Just beneath his eyes,

— 48

he could feel tears starting to well up.

At the hospital, he’d cried. And at the service, he’d cried again. But ever since then, he could feel things built up inside of him, like something caught in his throat that he just couldn’t get out. He often wished he could climb out of his sadness as if it were a pit. All he would have to do was find a sturdy hold, a root or a rock, to grip. He could save himself, then reach down and help pull Danny out, too.

Away from the stand, Steve cleared his throat and unzipped his fly. His father had always used empty bottles to keep the scent from traveling, but he didn’t have much choice now, so he let out a weak stream of urine at the base of a tall oak. When his bladder quit, he bore down again to force another short stream.

When he looked back at the stand, he watched his son. Danny pulled off his orange cap and then slid it back onto his head. He glanced around, searching as though the deer might be swarming the woods around them, sneaking, weaving in between the trees. He still looked like a child, Steve thought.

He wished he knew how to help Danny handle the loss. He never imagined having a son who was such a mystery.

Years ago, Luanne, in the same hospital she would return to later, handed Danny over to him. He could touch his fingers to a flame and feel nothing longer than anyone he knew. Bent into an engine block, he could feel out ratchets and wrenches when he needed them by touch alone. But Danny was a puzzle. There had been so many times throughout the course of his fatherhood that Steve thought he might break him with his rough, imprecise hands. Danny always seemed— even now, as a teenager—so fragile.

Luanne had always been the nurturer. If it had been me who’d gone, Steve thought, she would’ve known what to do. She could have patched Danny’s cracked feelings, just as she had when the kids in school stomped his glasses into shards or slammed him into the hallway walls.

“Boys will be boys,” the principal had said when Steve and Luanne sat down with him. Steve recalled the fierceness he’d seen in Luanne, the way her cheekbones seemed to stand out beneath her narrow eyes.

He remembered saying, “Those boys do this again, I’ll kick their asses myself.” But he also remembered agreeing with the principal—somewhat, anyway. That was a part of nature, the way the world

— 49

was. He himself had done similar things in school, and when they had happened to him, he had pushed back. At home, he had said to Luanne, “He needs to stand up for himself. I can’t always take care of him.”

There in the woods, looking up at Danny, the thought of climbing rung after rung back up to the stand made him feel weak. But he moved silently back to the stand. You’ve got to climb back up, he told himself.

He let the thought of getting the deer push him, but even as he brought himself farther and farther from the ground, he started to wonder if they even had a chance of seeing a deer today, let alone getting one.

Back in the stand, next to Danny, Steve let himself dream of the deer. It would be big, the largest he’d ever seen, with a rack so impressive that no one would believe their story until they saw it mounted on the den wall. That would bind them, set them square—the shared story of their triumph, their accomplishment.

Steve could feel his lungs filling with the desire to express himself, to open his mouth and give himself over to the rise of words he could feel somewhere inside him. There were questions he could ask Danny—about his life, about girls or school or music. Steve could tell him about the hunting trips with his own father, the way he felt when he drove his first car, or when he met Luanne. There was so much to share, Steve realized.

Too much, maybe.

The things he could say, the questions he could ask, they all stuck in his mouth like pieces of hard candy, rolling around over his tongue, and if he tried to speak, he thought everything might come tumbling out. The more he tried to find the right thing to say, the more he wanted the deer, the more he became certain that the deer could start to solve everything.

But time passed. He didn’t realize his hunger or his thirst as the morning crept away. Together, he and Danny waited.

When the brush rustled in front of them, Danny’s elbow touched his arm. Steve realized his mind had been drifting, and he cursed himself for losing focus even as his hands went to work raising the rifle, disengaging the safety with a soft click, and settling the gun’s weight into his shoulder.

— 50

He swallowed hard, bringing the barrel in line with the movement and starting to tense his finger on the trigger.

It was difficult enough to see into the brush, and Steve found himself repeating, Thank you, thank you, at the fact that the breaking sun hadn’t yet crossed in front of them. He had to strain his eyes enough as it was.

And then a doe emerged. Her ears twitched as she stepped out. She wasn’t what Steve had imagined. But she’ll have to do, Steve thought. As she moved, he kept the rifle trained on her, waiting for a clean shot. He would bring her down, and Danny would dress her right here in the woods, just as Steve had done when he was younger. He could hear Danny’s finger itching against his thick pants. As his own finger started to squeeze the trigger, easing it back just enough where firing the shot wouldn’t skew his aim, he realized he wasn’t breathing.

Don’t let it get away, he told himself. Come on, take the shot. The doe’s hooves made soft sounds in the leaves. Steve could feel his heart thumping inside his chest. And then he fired.

The doe started to go down. Steve let himself breathe again, grasping at breaths as if he had accidentally thrown a handful of change into a wishing well rather than a single intended coin. He closed his eyes for a second.

“You got it,” Danny said next to him. “You got it.” When he laughed, it came out nervous and startled.

Steve climbed down from the tree stand and started toward the spot where the doe had stood, gaining speed until he was running over the uneven ground, its crunching leaves, and struggling to catch his breath again.

When he got to the tree, he looked around for the body. He expected to see it lying there, but it was gone. Following the trail of blood, darker red against the crimson leaves, he panted. His mouth felt dry as he drew in the cool air. The smell of the woods took on an alltoo-rich quality, its sweetness cloying in his nostrils as his legs burned and his lungs moaned.

But there was no body, no deer. Only the sounds, now that his panting started to subside, of the birds as they settled back into the trees.

And in a moment, behind him, he heard Danny’s running foot-

— 51

falls. Then there he was, standing next to him. He had his rifle slung up on his shoulder, pointing up at the sky. His vest still rubbed against his neck, and, coming closer, he scratched at the spot again. His eyes had an uneasy look, as if at any moment he might be expected to jump into bloody celebration, even as he searched for the body.

Steve turned back, looking for the doe. She has to be here, he thought. He was sure he’d gotten her, but now he couldn’t find her.

“Is she gone?” Danny asked, coming closer.

Steve could feel that low boil, that steam, frantic now, rising up through him. The deer was gone. She’d crawled away. She’d never really mattered much, he realized. The world seemed to spin. Once again, he felt as though the ground beneath him had vanished, and he fell.

Landing on his knees, he slid back onto the seat of his pants. Pulled into their unaccustomed position, his leg muscles lit up with surprise and then pain. Steve put his fingers through the leaves. He tore them into the tough ground as if something important had been buried and all he had to do was claw through to it and dig it back up. All he wanted was something—the words, the doe, the roots, even—to help him start to build himself again. But his fingers found only tiny, loose stones and hard bits of earth. He started to cry.

Danny kneeled beside him. “You okay, Dad?” Fear lined his voice like the inside of a coffin. He put his hand on Steve’s shoulder. Steve’s mouth fumbled sounds until he finally started to settle. Exhausted, he let out a long sigh.

There were words buried below. He could feel them. Later, in the cab of the truck or back at the quiet house, beneath the dusty deer on the den wall, he would dig; he would keep digging until dirt packed itself beneath his fingernails and fell from his rough, frenzied hands in clumps. He would dig until he uncovered the words and felt their ease and effortlessness. He would commit himself to the digging. But for now, he reached for Danny’s outstretched hand, squeezing it, feeling its surprising strength. “Danny, help me up,” he managed to say. And as he sensed Danny’s arm begin to tense, Steve moved his legs, preparing to push, ready to rise.

— 52

Stanzas on the Shore

Against the shore, countless waves beat A fluid rhythm under silver light. Their song is sung in the dark, out of sight, When the sun has set and lost its heat. The coarse brown sand, stained by the water’s heart, Has heard this chorus ever since the start. Still the waves break the shore With the song sung in poet’s lore.

As gentle day comes climbing from behind the hill, Quick, the water calms to match the skies, And the sand grows warm as it dries!

Sun is up, day is new, all Nature must be still Where men may come to feel at peace and live serene; Where blankets, laid across the sand, set the lovely scene Of a picnic when the weather’s fair, And women are found reading there.

So many hours spent in peace! The Lines of Wordsworth make them stop To look about as tears may drop Just like the page when they reach Keats. When the too-soon-setting sun Lets men know their day is done, They quickly pack up and drive away With plans to return another day.

When all are gone and think of how the sun had shone, The water comes again to meet the shore Where they have met so many years before, And they embrace, by the moon, when they are alone. Oh the song that they sing!

In the wind and everything; Though man cannot hear this, but through the throng; The mass of voices that all sing his song.

— 53 William Morris

Still in the night, I listen close With the hope that I may hear the voice From wind or within, but only noise

Clamors my ears to inspire prose

About the worthlessness of bustling When all Life can be heard in rustling. I cannot hear! I cannot speak! Alas, I fear I am too weak!

Curse Shelley and Coleridge for what they did! They found within and about everlasting muse So lovely and so perfect, I wished I could use. I may sit upon this beach, dejected, But they drank the waves And met their graves Upon the shore, Heard forevermore.

— 54

Dragging Off

Christopher Lahr

— 55

Sons of Singleton

The Cornell Seven fashioned—old gold and black, lived with unconquerable souls, against ice cold attacks from those similar, though not the same, odd fellows of their time, ancient as Cheops in an Egyptian desert, though fresh as a spring rain.

If, out of the dark that covers, the test of a man succeeds in unwavering faith, led blindly by the light of a drinking gourd let him free his chains, for is he not a man and a brother whose mother fed lady fingers and coffee in demitasse?

Jason N. Vasser

To bed they went, with Neapolitan dreams of things to come, providing the mind’s light to shine in darkness—like jewels buried beneath. The youth, they march onward and upward through the Middle Passage, to cotton fields, and on to Ivy League.

— 56

Onward I climb to the tops of the trees. What will I do? I’ll do as I please!

A scrape on the knee, a slap in the face, I’ll put this tree back into its place. I reach the summit, and I look out yonder. A little log cabin. What goes on there, I ponder. I scurry down as fast as I can.

One fell swoop and there’s no more branch in my hand. I tumble down and down: thump, oof, thwack.

The wind is knocked out of me, and I’m flat on my back. My eyes flutter open. The fog begins to clear. It seems that I’ve been having this problem all year. When will I learn my lesson? Will I change my ways?

No. I’m determined to repeat myself all of my days. My success has been low, but I keep on trucking, As I attempt to perfect my love of climbing. For miles I can see, and I feel so free. But why do these trees always have it out for me?

— 57

Canopy

Emily Spak

Mary High t h e s t r e n g t h o f a t r e e — 58

That ambrosia does not fall on us.

No, not in June, when Sweat-stained skin Recalls Nature’s gift

With wetted lips.

Starved fingertips

Point west in distress

And, in Summer’s stillness, Wish for Rain’s ambivalence.

That ambrosia does not fall on us.

No clamor in the wind when Dust-dried corpses

Remember April skies

With some foreign form of reverence. Woe is the desert wind—

More harm than hand

Of help to dying men

Who wished for sun on days of rain.

That ambrosia does not fall on us.

— 59 William Morris Ambrosia

Untitled

— 60

Timothy Boettcher

Queen Anne’s Lace

Michelle Radin Seymour

I snuck away through the tall white flowers. My loudmouth sister was still screeching, but I kept crawling, and soon I didn’t hear her mad, yelling voice. My knees got all scraped up on sticks and twigs. There was a piece of glass pushed into the dirt. Who would put glass in the woods? I pushed up to spy and couldn’t even see my yard. That’s when I knew I was safe.

I wiggled down on the ground, not too bumpy, just hard. My hands were my pillow, and I rested on my back. The flowers were green on their underneath part, up there waving above my head. They looked like they were saying yes over and over. Nobody says yes that much. I rolled over and closed my eyes. The cicadas were loud and pushy. They was all we could hear at my house. Even the TV wasn’t loud enough to hide them. In the night, when the light was off and I tried to sleep on the bottom bunk, the house filled up with the squeaky-creaky sound of those big, loudmouth bugs.

I stood up, and the flowers were around my waist, just like my sister’s tutu skirt she got from Walmart. She wouldn’t ever let me touch that skirt. I rested my hands on the flowers. They looked soft as the lace on Mama’s church dress but felt scratchy instead. I pulled a few of those flowers out of the ground for Mama. She likes those flowers.

Connie Miller sighed as she pushed aside her faded kitchen curtain and looked out into the overgrown vacant lot. “Crap,” she muttered. Pushing the curtains closed, she went to her favorite kitchen chair. The green daisy print had disappeared long ago, but the seat fit her behind just right. When the knocking started, she groaned. She waited, hoping the little beetle would go away. But the knocking, tapping, and calling continued. Pushing to her feet, Connie shuffled to the back door. She wrenched it open and peered down. “What do you want?” she asked.

“I wanna come in,” the dirty child in front of her said. “You ain’t invited. I told you before, you should wait to be invited.”

The little girl shook back dark blond wisps of hair from her face and said, “You never invited me. I’da had a wait forever.”

Connie glared at the unwanted visitor. She noticed the strag-

— 61

gling Queen Anne’s lace in the girl’s hand. “That for me? I don’t want weeds in this house.”

The girl put the flowers behind her back. “No. These are Mama’s. Mama likes these flowers.”

“Then go give ‘em to your mama. Go home, little girl. I’m busy and don’t need kids bringing dirt and weeds into my house.”

“I’m not going home. I am not. Mandi is mean, mean, mean. I hate her.”

“What did she do that was so mean?” Connie rubbed her forehead. “Never mind. Just go home.” She put her hand on the child’s shoulder and tried to guide her back out the door. “Go make up with your sister.”

“No.” She pushed the hand off.

“Fine.” Connie gave up and settled back into her kitchen chair. She pulled a cigarette out of an almost empty pack on the table and lit it with her American flag lighter. She took a deep pull before turning to look again at the little devil. Noticing a purple mark on the child’s face, she asked, “What happened to your cheek?”

The small girl sat down on the cracked linoleum floor and put her hand on the mark. “This ain’t a house, anyways—Mandi says you live in a trailer.”

Connie exhaled to the ceiling, rolling her eyes. “Fine, little smartass. It’s a trailer. It’s a double-wide. Did your smarty-pants sister tell you that?”

One shoulder shrugged. She placed the white flowers on the floor, arranging them by length. “Do you have snacks?” she asked without looking up.

“No.”

“Pop?”

“No.”

“I’m hungry. I took a long walk through the woods. The trees wouldn’t talk to me, but the cicadas wouldn’t stop. The bees buzzed but only near the flowers. I don’t get near the bees. They will sting you bad.

One time Mandi stepped on one, and her foot swelled and swelled. Mama had to give her medicine. She cried all night.” Finished with her flower design, she stood up and began opening and closing cabinets.

“Hey, stop that.” Connie ground out her cigarette in the green melamine ashtray on the table. “Fine, I will get you a snack. Sit at the table and pretend you have some manners.”

— 62

Pushing her hair out of her eyes, the child pulled out a chair and climbed into it. “How do I pretend?”

“Put your hands in your lap and shut up. That’s how, missy.”

Connie picked up a loaf of Wonder bread off the counter and put a piece on a paper plate. She spread grape jelly on one side and peanut butter on the other. Folding the sandwich in half, she took the plate to the child.

A glance down at the sandwich and a frown. “I don’t like folded sandwiches.”

“Well, that’s what you’re getting, missy,” Connie said.

“My name isn’t Missy. My name is Annemarie. Why do you always call me ‘Missy?’” She poked her finger into the soft bread of the sandwich. “Who is Missy? One of your kids?”

Connie rolled her eyes again. “No, not one of my kids. You know my kids’ names.” She lit another cigarette.

“I do?” Annemarie tugged the crusts off. “Like Daddy? His name was Michael, right?”

Connie rubbed her left eyebrow with her thumb, the trailing smoke from her cigarette hovering around her gray and brown perm.

“Yeah.”

“You got other kids, too? I never saw them. They dead?” Annemarie licked grape jelly from the palm of her hand.

“No, they ain’t dead.” She tapped the ashes from her cigarette into the ashtray. “They’re up in St. Louis with their families.”

“Oh. Mama says we’re gonna visit St. Louis someday, when she gets some time off from the diner. Mandi says she ‘members going there once, but she’s a big liar.”

“She ain’t lying. She did visit. Your Grandma Mitchell lived in St. Louis. Your mama used to go back and visit every now and then.”

“Grandma Mitchell? Who that?” Annemarie stuffed the last bite in her mouth.

“Your mama’s mama. She died when you was a baby. She came down here to visit after your daddy—” Connie stopped. She stood and pushed her chair back.

“When my no-good daddy went and left?” Annemarie put her small palms on the table. “When he upped and run away? She came to visit Mama and little Mandi and baby me. She probably liked to hold me when I was a baby. She probably sang me songs so I’d stop crying about that bastard leaving.”

— 63

Connie’s hand slammed on the counter. “Your daddy is not a bastard. Where did you hear such lies? No. Don’t tell me. I know.” Connie grabbed the paper plate from the table and stuffed it in the trash.

“Time for you to go home, little girl. I don’t want to hear any more.”

“I’m not going home.”

“Yes, you are.” Connie put her hands on her hips.

“No, I’m not, ever!” Annemarie jumped down from the chair and ran out the kitchen door, yelling as she went, “I’m gonna live in the woods.” The door bounced but didn’t close.

I slammed her door hard ‘cause I knew how much she hates that. I heard “Hey!” from inside, but I ran away again into the deep woods.

I found my favorite tree, the one with the green needles. Not the sharp sticky kind like at my house. My favorite tree had soft green needles. Those needles turn brown and fall on the ground. It’s like a carpet or a blanket. I scooted down under those low branches. They hung all the way to the ground. Underneath made a good fort.

The soft brown needles smelled clean. Better than that stuff Mama uses to clean the bathroom. That stuff says it’s pine-scented, but it’s a liar. My tree made a real pine scent. I sat under that tree. For hours, maybe.

“You’re my only friend, tree. Everyone hates me.”

The tree kept the cicada sound far away. By now the sky was dark, and I shivered even though it was as hot as ever. I heard noises out there in the woods that sounded like someone was coming. The creaky cicadas got louder, swelling like a stomachache just when you think it’s gone away.

Someone pushed a branch aside. I woulda screamed, but I saw my sister’s purple jean shorts. She found them at the Goodwill. I only found stained shirts when I looked. When I showed Mama the stains, she said, “They’re fine for all the playing in the dirt you do.”

“Annemarie, what’re you doing under here?” My sister crawled under a branch and crouched next to me. Her long legs folded up under her chin. Mandi’s hair is orange like the orangutan we saw at the zoo a long time ago. I think I was almost a baby. She has long monkey arms, too.

“Living. I’m gonna live here.” I smoothed the needles with my hand.

— 64

“You can’t. Mama’ll never let you.”

“I don’t care. She won’t even be home.”

My sister put one of her skinny arms around my shoulders. I shrugged it off. She wasn’t getting off that easy after being so mean and loudmouth. She put her hand back in her lap. Pulling at one of those orange hairs growing out of her freckled arm, she said, “You can’t blame me for that.”

I shrugged again. “You like being the boss.”

“You think I wanna hang around at home all the time? You think I like babysitting you every second? I don’t even have friends ‘cause I’m stuck with you all the time.”

“Go away! Get out of my house.” I pushed her away from me. She fell a little ‘cause she didn’t know I was gonna do that.

“Stop being such a brat.” My mean sister grabbed my arm so hard I felt it come out of the socket and snap back in just like I did one time to Mandi’s Ken doll. His leg popped right out. I popped it back in, but she was still mad. “We’re going home, Annemarie. Mama’ll be home soon, and she’ll freak out if we’re not there.”

“So what? I don’t care.” I picked up one of Mama’s white flowers and started pulling it into little tiny pieces.

Mandi didn’t say one word. She just sat there for a minute. She picked up a flower and began ripping it like me. We threw those little bits that used to be white tutu flowers away from us.

“She shouldna hit you like that, Annemarie. She was just tired and cranky, and you was being a stink.” Mandi put her freckled hand on my ankle. “But a mama shouldn’t hit.”

I put my hands over my ears and screamed as loud as I could. I screamed so long I could feel my throat ripping apart like the shredded bits of white flowers all around me. In front of my eyes, I saw purple and red. I felt arms closing around me. I hit and bit at those arms, those monkey arms. But they held tight. Those bright hurting colors all mixed and smoothed out into deep blue. My long scream floated into my tree’s needles. Those needles pulled my scream right into themselves. I saw them turn brown and fall.

Mandi’s neck was clean when I rubbed my forehead on it. Her long arms squeezed me tight. I was eight years old, not a baby, but I cried. I cried into my sister’s neck so much that her shirt got wet spots on it. Then I pushed away from Mandi and wiped those dumb tears off my face. I picked up the last few flowers, and I ripped and ripped until

— 65

they was all just scraps on the ground. Mandi helped me. Then we covered those scraps with the soft brown needles.

The two girls emerged from the trees hand in hand and headed up the sidewalk toward home. Connie let the curtain drop.

— 66

N-ICE Reflection

Sarah Myers

Sarah Myers

— 67

Paper Cranes

With care, he pressed their folds and strung them, a needle up through their square middles— shades of red through orange, precious few a gayer yellow.

He made a canopy above our bed, a wide chandelier the hazy colors of the sun where I come from. Stretched rays of paper cranes and I can’t tell him; even a thousand folded birds won't keep me warm.

Aladeen Stoll

— 68

Stilted Flight — 69

Lauren M. Ewart

He strolls by the stream, searching for the elusive animal he seeks. A rustle behind him diverts his attention; he sees nothing. A flash of movement captures his roving eyes. Momentary joy courses through his body; alas, it’s merely a squirrel. Suffering from disappointment, he continues upstream. He steps on seemingly solid stones, damp from water splash, and pauses, basking in the solemn solitude. With the next step, his torso steady, his foot slips, and the rock slides, sending him tumbling. Sure hands stop his face from smashing. Yet the fall brings him to what his eyes longed to see. He is nose to nose with the slit-pupiled beast. Its tongue flickers. Its body strikes.

— 70

Shhhh

Emily Spak

War Mongers

By dust they bear death with their need to watch beauty dry and they say in a thousand whispers come see the sky break into the sea

Laura Schuhwerk

— 71

Lauren M. Ewart Pickled Liver — 72

Trail of Beers

An older gentlemen hikes the same gravel trail from nine to five as I drive to and from my own. I’m not sure what name he’s dragging, so I just call him “Hops.”

He probably sleeps in whatever basement or couch his friends will lend him for the night. Maybe a ditch here and there too.

His jeans are littered in sleeping cigarette ash scars.

Some days, I want to pull over and walk alongside him. As we’d talk, Hops would explain to me how walking is faster than driving if you’ve got no place to go.

We could pool our money and spend the rest of the day spoiling our livers.

Some days, it seems like the stress of homework, wedding rings, dirty diapers, and social security checks is harder than the need for inebriation or hikes ending in highs.

Brian Farrar

— 73

Siefert T h r e e H a n d s i n P r a y e r — 74

Rebecca

A Silver Spoon

Jessica Duncan

It wasn’t that I didn’t love yogurt—it just didn’t seem like the right thing to be eating when my parents were lying dead on the kitchen floor. So when people ask why I set the half-eaten container of it back in the fridge before calling the police, just let them know that it’s only because I didn’t want to waste it. After all, black cherry is my favorite flavor, and it was the last one we had.

Also, I didn’t feel like it was okay to eat yogurt with a spoon that had my parents’ blood on it. So when the psychiatrist asks why I decided to wash a few dishes before covering my parents’ bodies, just tell them I was only trying to keep things clean; it’s what my mother would have wanted.

I also thought it was rather rude when my sister Christi entered the room, yelled, “Good God, Karen, what happened?” and then began to scream and cry like a maniac. I mean, here I was, doing her daily chore, and she didn’t even have the decency to thank me for it. I don’t know. I guess it was just a little rude is all I’m saying.