Editor’s Notes

« Avoir une autre langue, c’est posséder une deuxième âme. » Charlemagne

I would like to begin this term’s issue with a reflection on the variety of linguistic expression within literature. It might be fitting to mention that when one thinks of the greatest works of literature there is no exclusive one language that predominates in terms of the greatness of its use. There is an overwhelming transcendence of language that justly permits the true valour of a work to be appreciated, sought out, and understood, be it in the original language or through translation.

We might for instance consider the innumerable instances of translations and readings of Homer, and Virgil, of the medieval epics throughout the world. In this genre of epic poetry alone, there is a strong representation not only of the Classical languages and those stemming from a romance stem, but of a variety of wonderfully intricate poetic expression. Take for instance the Epic of Gilgamesh, an epic poem from ancient Mesopotamia written in Akkadian c. 2100-1200 BC, preceding the Greek poets. Or the Mahabharata (महाभारतम) and Ramayana (रामायणम) Sanskrit epics of ancient India, or the Persian Shahnameh ( ﺷﺎھﻨﺎﻣﮫ ) or the Epic of Darkness (黑暗傳) collection of legends and tales of primeval China. We might also consider the Old English Beowulf, the French La Chanson de Roland, the Old Spanish Cantar de mio Cid, the German Niebelungenlied c. 1200, the writings of the Italian Dante, the byliny including the Kyivan Rus (Роусь), and other Slavonic epics…

Whilst this outline is by no means exhaustive what is even more relevant here, is that the oldest epic poems stemmed from preliterate poetic history and many others are still seeped in this oral tradition. This truly highlights the importance of language as an identity as a source of inspiration in itself to both spoken and sung poetry, within the very origins of literature. We can also note the enduring importance of many of these texts as part of the identity of the cultures that have stemmed from their ancestral precursors. In certain places around the world, there are still people who continue this oral tradition – often closely entwined with musical accompaniment –(incidentally, à vos heures perdues, I heartily recommend going down the internet rabbit hole of the musical reconstructions of epic and historical oral poetry).

The above mentions are of course for the most part examples of more ancient languages, originating from a distant historical past. Even within the same language therefore there is already a true difference of linguistic variety that defines the soul of the text And when one begins to consider literature beyond one’s own linguistic boundaries, it is certain that one is bound to find an abundance of thought and inspiration from the very diversity of language. One could even surmise that certain works of literature could not have existed in the form that they do, beyond the enclave of their lingual context. This could be ascribed to a cultural difference, after all the very identity of a text cannot be mapped onto another context seamlessly, (one could, in a moment of mad experimentation, transcribe the plot of Crime and Punishment into the setting of The Iliad but understandably this would lead to a quite different –and most certainly alarming - text.) Yet beyond the binding aspect of historical and cultural background, there is an underlying force, that is arguably stronger than the setting of the work itself. Language, which is indissociable from the tangible presence of the words themselves.

It is thus not surprising that the richness of literature originating from a different language than one’s own, has been recognised by readers and writers alike for centuries. What is fascinating is the sheer scale of this curiosity that goes beyond one’s own natural linguistic aptitudes for the sake of literature when considering the amount of learning and translating involved in attempting to become familiar with literature in its original language. Both these methods however have their own unique significance, and ultimately offer a very different experience and character to the work itself.

There is an overwhelming sense that one loses a significant part of a text when reading it in translation. Indeed, the very nature of individual languages and their differences, at once enables their greatest works of literature to be unique and recognised for their worldwide significance but also to remain shrouded in a sort of mystery Their true essence and the intangible spirit of the text remains ultimately inaccessible when read in translation. This is because language reflects a thought process, reflects the interior monologue of the author, their inspirations conscious and unconscious which are entwined within their understanding and defined by the endless limits of their mother tongue. It is sometimes hard enough to interpret, the mind behind the greatest works of English literature, and their truest aims; the hidden heart of a text can even be a mystery to the author themselves. How much more complicated is it then, when one is reading the work, not of a monolingual author, but of one who knows and masters more than one language? And how much more complex also is the interpretation of the reader if he too possesses a second soul?

I wish to conclude therefore, not as it may seem by sealing the impossibility of translation but rather in highlighting the importance of recognising the inimitable nature of language, yet attempting it, nonetheless. Whilst it would be virtually impossible to be able to read and comprehend all the greatest works of literature in their original languages, the effort of knowing at least one or two, or even simply reading extracts, be it of verse or prose, alongside a translation, of sounding out the words in their original form, may enable a glimpse at their veritable subtility. And even in translation one should strive to picture the image, the intention behind the word, to go in fact beyond the constraints of language, to think with the mind of the writer, even in the absence of words to place oneself in the muted linguistic landscape, to cast aside the tangible and yearn instead for the ethereal spirit of meaning.

“The very formula, “ναῦς means a ship,” is wrong. ναῦς and ship both mean a thing, they do not mean one another. Behind ναῦς, and behind navis or naca, we want to have a picture of a dark, slender mass with sail or oars, climbing the ridges, with no officious English word intruding.” C.S. Lewis

- Carole Tucker, ed.Theme of the Issue: Translation

Translation, its adequacy and inadequacy, its necessity and its uselessness, its creative and mathematic nature, is arguably one of the most important and defining features of the history of literature. I have assembled below a few translations of some interesting and loosely summer themed poems, I will leave the reader to decide which they might think is the original, whether the translations in themselves have taken on the semblance of a different poem, whether they should be taken together perhaps even with some more languages to compare when one does not know the language of the author.

The Violet

Upon the mead a violet stood, Retiring, and of modest mood, In truth, a violet fair. Then came a youthful shepherdess, And roam'd with sprightly joyousness, And blithely woo'd With carols sweet the air

"Ah!" thought the violet, "had I been For but the smallest moment e'en Nature's most beauteous flower, 'Till gather'd by my love, and press'd, When weary, 'gainst her gentle breast, For e'en, for e'en One quarter of an hour!"

Alas! alas! the maid drew nigh, The violet failed to meet her eye, She crush'd the violet sweet. It sank and died, yet murmur'd not:

"And if I die, oh, happy lot, For her I die, And at her very feet!"

Das Veilchen

Ein Veilchen auf der Wiese stand, gebückt in sich und unbekannt; es war ein herzigs Veilchen. Da kam ein' junge Schäferin mit leichtem Schritt und munterm Sinn daher, daher, die Wiese her und sang.

Ach! denkt das Veilchen, wär' ich nur die schönste Blume der Natur, ach, nur ein kleines Weilchen, bis mich das Liebchen abgepflückt und an dem Busen matt gedrückt, ach, nur, ach nur ein Viertelstündchen lang!

Ach, aber ach! Das Mädchen kam und nicht in acht das Veilchen nahm, ertrat das arme Veilchen. Es sank und starb, und freut' sich noch:

und sterb' ich denn, so sterb' ich doch

durch sie, durch sie, zu ihren Füßen doch!

La Violette

Une violette dans une pré, Anonyme, la tête penchée : Mignonne était la violette. S'approche alors une jeune bergère, Humeur joyeuse, démarche légère, Chantonnant par les prés.

Que ne suis-je, se dit la violette, La plus belle des fleurs !

Serait-ce un tout petit peu, Le temps que la belle me cueille

Et m'écrase contre son coeur, Ne serait-ce qu'un petit quart d'heure !

Lorsque la jeune fille arriva, N'eut cure de la violette, Simplement la piétina. Fauchée, mourante, la violette Se réjouit encore : certes, je meurs, Mais c'est par elle, à ses pieds.

Июль

По дому бродит привиденье.

Весь день шаги над головой.

На чердаке мелькают тени.

По дому бродит домовой

Везде болтается некстати, Мешается во все дела,

В халате крадется к кровати, Срывает скатерть со стола

Ног у порога не обтерши, Вбегает в вихре сквозняка

И с занавеской, как с танцоршей, Взвивается до потолка

Кто этот баловник-невежа

И этот призрак и двойник?

Да это наш жилец приезжий,

Наш летний дачник-отпускник

На весь его недолгий роздых

Мы целый дом ему сдаем.

Июль с грозой, июльский воздух

Снял комнаты у нас внаем.

Июль, таскающий в одёже

Пух одуванчиков, лопух, Июль, домой сквозь окна вхожий, Всё громко говорящий вслух.

Степной нечесаный растрепа, Пропахший липой и травой, Ботвой и запахом укропа, Июльский воздух луговой.

- Boris PasternakJuly

A ghost is roaming through the building,

And shadows in the attic browse; Persistently intent on mischief

A goblin roams about the house.

He gets into your way, he fusses, You hear his footsteps overhead, He tears the napkin off the table And creeps in slippers to the bed.

With feet unwiped he rushes headlong

On gusts of draught into the hall

And whirls the curtain, like a dancer, Towards the ceiling, up the wall.

Who is this silly mischief-maker, This phantom and this double-face?

He is our guest, our summer lodger, Who spends with us his holidays.

Our house is taken in possession

By him, while he enjoys a rest. July, with summer air and thunderHe is our temporary guest.

July, who scatters from his pockets

The fluff of blow-balls in a cloud, Who enters through the open window, Who chatters to himself aloud,

Unkempt, untidy, absent-minded, Soaked through with smell of dill and rye,

With linden-blossom, grass and beetleaves, The meadow-scented month July.

- Translated by Rupert MoretonCLXII. Lieti fiori et felici, et ben nate herbe

LIETI fiori e felici, e ben nate erbe, Che Madonna, pensando, premer sole; Piaggia ch’ascolti sue dolci parole, E del bel piede alcun vestigio serbe; Schietti arboscelli, e verdi frondi acerbe; Amorosette e pallide viole;

Ombrose selve, ove percote il Sole, Che vi fa co’ suoi raggi alte e superbe;

O soave contrada, o puro fiume, Che bagni ’l suo bel viso e gli occhi chiari, E prendi qualità dal vivo lume;

Quanto v’invidio gli atti onesti e cari!

Non fia in voi scoglio omai che per costume

D’arder con la mia fiamma non impari.

O JOYOUS, blossoming, ever-blessed flowers!

’Mid which my pensive queen her footstep sets;

O plain, that hold’st her words for amulets

And keep’st her footsteps in thy leafy bowers!

O trees, with earliest green of springtime hours, And all spring’s pale and tender violets!

O grove, so dark the proud sun only lets His blithe rays gild the outskirts of thy towers!

O pleasant country-side! O limpid stream, That mirrorest her sweet face, her eyes so clear, And of their living light canst catch the beam!

I envy thee her presence pure and dear. There is no rock so senseless but I deem It burns with passion that to mine is near.

Works and Days Lines 580-600

- Hesiod

When the golden thistle is in bloom and the loud-sounding cicada perched on a tree, pours down his clearly-heard song incessantly from under his wings, in the season of summer, with all its labors, then it is that goats are fattest, wine is best, women are most wanton, and men are weakest; for Sirius dries up their heads and their knee-caps, and the skin gets dry from the heat. At this time, at long last, let there be a shady place under a rock, wine from [Thracian] Biblos, barley-cake soaked in milk, the milk of goats that are reaching the end of their lactation, and the meat of a cow fed in the woods, one that has not yet calved, and of first-born kid goats. That is the time to drink bright-colored wine, sitting in the shade, having one’s heart sated with food, turning one’s face towards the cooling Zephyr. Then, from an ever-flowing spring that flows downward, untainted by mud, pour a drink that is three parts water, but make the fourth part wine. Get your servants busy with winnowing the sacred grain of Demeter, when strong Orion first appears, on a threshing-floor that is exposed to the winds and is smoothed over Then, with a measure, store it in jars.

The following passages are all translations which were entered by Perse students to the Anthea Bell 2023 Translation Competition and achieved winning success. The languages translated are, French, Mandarin, and German. Respectively entered for the Level 1, Level 2, Level 4, and Level 4 categories.

Le gardien du phare aime trop les oiseaux

Des oiseaux par milliers volent vers les feux par milliers ils tombent par milliers ils se cognent par milliers aveuglés par milliers assommés par milliers ils meurent Le gardien ne peut supporter des choses pareilles les oiseaux il les aime trop alors il dit Tant pis je m’en fous !

Et il éteint tout !

Au loin un cargo fait naufrage un cargo venant des îles un cargo chargé d’oiseaux des milliers d’oiseaux des îles des milliers d’oiseaux noyés.

- Jacques PrévertThe Lighthouse Keeper loves birds too much

The birds in their multitudes fly to the light, Countless plummet, countless crash, Scores blinded, scores stunned, In their thousands, dead.

The keeper’s heartbroken He loves the birds acutely, So he says never mind, I do not care

And

turns everything off!

On the horizon, a cargo ship’s sinking, A ship from the islands, A ship brimming with birds, Thousands of birds from the islands, Thousands of birds, drowning, dying.

《别踩了这朵花》

小朋友,你看, 你的脚边,一朵小小的黄花。

我们大家 绕着它走,

别踩了这朵花!

去年有一天:

秋空明朗,

秋风凉爽,

它妈妈给它披上 一件绒毛的大氅,

降落伞似地,

把它带到马路边上。

冬天的雪,给它

盖上厚厚的棉衣,

它静静地躺卧着, 等待着春天的消息。

- 冰心 (Bing Xin)

Don’t trample this flower!

Young child, you see, near your feet, there is a tiny yellow flower. We all walk around it, so don’t trample this flower! One day last year, there was: a clear autumn sky, a cool and refreshing autumn breeze, so its mother sheltered it in a soft fleece overcoat, and like a parachute, it drifted to the side of the road. Winter’s snow provided it with a cover like thick, cotton-padded clothes, as it rested peacefully, waiting for spring’s tidings

- Translated by Aamarah Khurram

An Excerpt

(From the essay "Okay Bye, I'm Leaving, I'm Going to the Year 2000”)

如今我每天的生活,都可以通过手机来组织,并且由它来证明。这种巨大的便

利并没有什么不好,但一个令人遗憾的副作用是,它降低了人类想象过去的能 力,尤其是想象那些没有手机的过去。

于是一个天大的难题诞生了,它难倒了我们当中的许多人:过去没有手机,人

们到底是怎么处理那些遍布我们周围的空虚、无聊和尴尬的?在最热的夏天,

循环往复地坐公交乘凉;上课无聊时把所有文具幻想成兵卒与大臣,在课桌上

厮杀;坐⻓途汽⻋无法忍受,就盯着正前方,把所有显眼的建筑物作为阶段性

的目的地,一个又一个地数过去,这也同

These days, my day-to-day life can be organized solely through my mobile phone, and I can prove it. There is nothing necessarily wrong with this (it is a huge convenience, after all), however a regrettable side-effect that comes to mind is that it reduces the human ability to imagine into the past, specifically the majority of it before the creation of mobile phones. And so, from this, a question is born, which has stumped many of us: before the invention of the phone, how on earth did people deal with their feelings of boredom, emptiness, and disconnection? To relive ourselves of heat on a scorching summer day, we took the bus all over town to cool off; to cure idle feeling in class, our imaginations ran wild, picturing our stationery as pawns and generals, fighting at the battlefield of our desks; to cope with the dizziness of a bus journey, we focused on our surroundings and endured counting methods to calm down. When I was younger, watching my friends play video-games, I had no interest in them, but there was no other place for me other than the arcade of games.

- Translated by Rachel Liu

Der Panther Im Jardin des Plantes, Paris

Sein Blick ist vom Vorübergehn der Stäbe so müd geworden, daß er nichts mehr hält. Ihm ist, als ob es tausend Stäbe gäbe und hinter tausend Stäben keine Welt.

Der weiche Gang geschmeidig starker Schritte, der sich im allerkleinsten Kreise dreht, ist wie ein Tanz von Kraft um eine Mitte, in der betäubt ein großer Wille steht.

Nur manchmal schiebt der Vorhang der Pupille sich lautlos auf –. Dann geht ein Bild hinein, geht durch der Glieder angespannte Stille –und hört im Herzen auf zu sein.

The Panther Dans le Jardin des Plantes, Paris

The gaze of his eyes beneath the passing bars Has grown so weary that it holds no more. It seems to him that there are a thousand bars And behind a thousand bars no world.

The supple gait of soft and mighty steps Revolves in an ever shrinking orbit Tis like a dance of strength around an axis In which the greatest will stands stunned.

Only sometimes the curtain of the pupil slides open silently then an image flits it penetrates the tense and silent limbs And in the heart extinguishes.

Art

Poetry

Sweet dreams

Sweet dreams are like fragile china; easily crushed You can see them falling, those bitter white shards

Sweet dreams pester my throat like sick caramel, clinging Cholesterol clogs your arteries, sweet dreams queue in mine. They are polite. They line up safely. They are cackling.

Sweet dreams flicker like wooden candles, They are fickle and they drip; drop of wax by drop of wax

Sweet dreams roast on an open fire

The edges burn. The centres boil

That reminds me. When am I due for roastage? When will you eat me, consume me inside out? Or will sweet dreams get there first?

Now I’m an ocean wreck - I’m so liquid you really can’t burn me

What I touch only crumbles to dust

Like ashes like ashes like ashes

But where are we?

Under the sun it’s hot it’s

Roaring. I want to be born

I have nothing left but

Please! I beg of you

Turn me to dust too.

Alice Shaw

-carpe diem. another day. hoorah for another day of open-eyed slumber. Fort of drooping branches and crisped leaves, there are plenty in the dirt.

I see a flower in the midst of the mud: Yellow, golden, richand I shan’t pick it. Leave. Sit. Dream. cross legged like A child with a toy, Too afraid to touch it lest it might break.

So- carpe diemSeize the dayThat on which the flowers bloom and greenery thrives in the glades where we might leave our gloom ridden thoughts behind.

carpe diem!

that day where groves bloom again, in repressed summer light: silky, shining light that drives green toward the Heavens.

Soupir de Nuit

La chaleur de la terre se soulève lentement vers le ciel bleuâtre et la lumière reflète les étincelles de blé, des épis de glaive qui transpercent les astres.

Douloureusement, une ombre glisse enveloppée d’un voile fin d’une fenêtre entrouverte jusqu’aux portes du jardin

Sa forme se dessine à peine à travers l’obscurité et elle retombe trop légère sur un tapis d’herbe velouté.

Depuis le ciel l’humide regard des étoiles semble pleuré une rosée de nuit tombe sur les arbres qui silencieux regardent les chants interminables des crickets.

Soudainement la nuit respire un souffle d’été qui transpire et l’ombre solitaire reste figée.

- Carole TuckerSong of a little girl

It rained on the outskirts of a house, Someplace I called home once. The windows were open, and a raging fire lured the damp indoors. a little girl stumbled from the flames in a lavender dress, singing,

‘Like a songbird in some faraway sea, I from the depths of distant waters cry out to my foes, As they fight a meaningless fight on a paradisiac island where a few meagre date palms grow and someone of vague importance christened the land of a deity.’ - Sydney

Not In The Binary

I choose to reject both “he” and “she”

Because neither of those just seem to fit me

Forced to pick between “boy” and “girl”

Surely there are more labels in the world?

Hesitant, I ask people to make a change

Their reactions show that they find it strange

“I know this might come as unexpected,

But if you used ‘they’, I would feel so respected”

Desperately wishing I were a girl or a boy

But lies and deception won’t bring me real joy

So I confess my truth, to my parents’ dismay

That their child now felt most at home with ‘they’

I am grey in a world seen as black and white

Told it’s not the world, but me, that’s not right

“Are you a boy or a girl?”, what if I said “no”?

Would you accept that answer or beg to know?

“Are you male or female?” the question asks

To protect myself, I pick up my gendered mask

I’m too exhausted for the questions I’ll get

Yet each time I hide it, there’s only regret

Time and time again, I’m forced to choose

No place for people like me, there are only two

I just want to see “Mx” written on my letters

Newspapers lying to those who don’t know better

Stripes of yellow, white, purple and black

The colours blind me, I want the old me back

Can’t seem to place my finger on when this began

Why can’t I just be a woman or a man?

Still, I refuse to be forced to conform against my will

And your lack of respect for that makes me ill

I do not fit into your boxes, I’m out of the boundaries I’ll always embrace that I am not in the binary

— a non-binary person.

Prose

[This scene is from a play entitled Language and written by James Roskilly as part of the New Views Writing Competition]

Scene 8 of ‘Language’

Aleksandr means “defender of men”- ironic considering his position on the war

This scene should be very fast paced

A family gathering. Food is being served and shared. Characters are passing food, drinking and laughing.

ANTONINA

90 Hryvnia for cabbage and onions!

COUSIN A

(jokingly) Ridiculous! We can’t live in a country that’s running out of food.

ALEKSANDR

(In Russian) Vse eto togo stoi tradii obshchego blaga.

(Silence)

ANTONINA

Why do you speak Russian, Aleksandr.

(pause)

ALEKSANDR

Oh come on. Our language isn’t defined by everyone that speaks it. If it was, the whole svit would be ashamed to speak. Anyway, they’re just special military operations at the moment.

MOTHER

It’s an invasion, vtorhnennya, Alek, you know that.

ALEKSANDR

(struggling to find words, still cheerily) Its- It’s notan invasion, yet. Some of the Russian decisions have been less than perfect-

ANTONINA

-less than perfect?

ALEKSANDR

(uneasily)-but it’s all for the greater good.

MOTHER

(ashamed of him) They’re slaughtering Ukrainians, Alek. Have some dignity.

ANTONINA

They’re taking over our country!

ALEKSANDR

-They’re ensuring our safety.

ANTONINA

They’re killing our civilians, burning our crops.

ALEKSANDR

Ukraine is the poorest country in Europe, we need Russian support.

ANTONINA

Support is not an invasion.

ALEKSANDR

When Russia retakes Dnipropetrovsk, support will come.

ANTONINA

And what about the Ukrainians in those regions. They’re not all Russian fanatics.

ALEKSANDR

They’re the ones committing genocide-

COUSIN A

Oh you don’t seriously believe that, do you?

ALEKSANDR

I’ve seen it for myself.

ANTONINA No you haven’t.

FATHER

Your cousin wouldn’t lie, Nina.

ANTONINA

There is no genocide in Donbas. Just like there were no weapons of mass destruction in Iraq.

FATHER

Take a breath, Nina, your cousin wouldn’t lie.

ANTONINA

You too?

FATHER

(trying to diffuse) No, I’m not saying that. I just- I just think there are 2 sides to every story. Goldilocks was hungry; so were the bears.

MOTHER

(irately) This isn’t some fairy tale, it an invasion.

FATHER

Calm down, yangoliatko, we’re all here, we’re all safe.

MOTHER

And how long do you think that’ll last. Pause

ANTONINA

We’re leaving. Bohdan found us transport. The UK. Next Week.

The divide created between Antonina’s parents repairs when they realise their daughter may leave.

FATHER

Nina, you don’t need to leave, the Russians are hundreds of miles away yet.

MOTHER

Think of all those here that need your support, Nina.

ANTONINA

You mean you.

FATHER

I think we need some fresh air.

ANTONINA

(not overly dramatically, still composed, holding herself back) There won’t be any fresh air when the Russians gas our whole country. You act like this isn’t happening- but we’ve all seen it, on the news, outside our windows. There isn’t time to argue among ourselves when the Russians are knocking on our doors. We’re leaving, I suggest you do the same.

- James RoskillySunset Station

Now that’s as fine a view of a sunset as one could ever wait for. The sun, here, can really be seen, almost everyday, to take a sudden plunge into the horizon. It sure is pretty. I wait for this time of day everyday. I sit on my little chair with the station building behind me, watching the oranges, the reds and then the purples. Everyday. I sign my daily timecard in with my Big Boss, Mr. Maker. I sign off each day with the hope that the next will be better than the previous. Perhaps new things will happen. Perhaps I will be struck by lightning. Perhaps I will see another human being.

Perhaps I will find a way to escape. No matter what, one thing’s for sure, that old tree trunk buried halfway into the dirt masquerading as a main post of the station building will get one more notch from my shiny, sharp knife. I wish I had some design in mind when I started, way back when, signing off days as notches on that bit of wood – I would’ve had me a pretty picture by now. Of trees on the bayou. Or a lunging croc. Or a sunset framed by Spanish moss.

I am goin’ a little soft in the head or something. Do I really care what’ll be left in this here station building in the godforsaken scrubland of Africa when I’ve escaped? Escape I must. How long can a man, stay a man and bear the torture of this beautiful solitude.

But is it really that bad…?

Ohmegawrsh! I am going mad!!! Of course it’s bad. It’s bad alright! What could be worse? I was torn away from home and brought here by trickery and if for no other reason then that’s why. That’s why this is so bad! Yes, that’s why this is all completely bad. Boy that was close! My Lord, he moves in mysterious ways and in His infinite benevolence He still makes me find solace in every smallest bit of blessing. But that is so unfair my Lord. I pray and keep you in my heart but you lead me to take this injustice without protest. I am not a violent man. I wish no ill of anyone. Nor do I wish to steal from or rob them of anything. And by the same meter, I do not like the taste of the bitter injustice so cruelly done unto me.

I did after all apply, like an honest hardworking man, for a job promising challenge and fulfillment. The job was with a company building the new rail infrastructure in parts of deep Africa still remote from the rest of the country and even further from the rest of the world. Despite my trepidations I had placed the Lord’s bible in my pocket and courage in my heart and set foot out of Louisiana to take up my post on this distant continent. On the last leg of my long journey, as the train rocked rhythmically to the music of metal on metal, I

fell asleep. When my senses came to, I was at this station with a single man standing. He told me to make myself at home and await further orders. It was going to be dusk. Before I could ask the taciturn man much of anything, the train chugged off carrying him with it, leaving me alone and looking towards where he’d left. I was confused and completely disoriented. That first sunset was painfully beautiful. I could not enjoy it though while not knowing where I was. I rummaged around the station room and managed to eat some biscuits left there. I drank some glugs of water from a dry, rusty tap. Not one breath of another living being broke the air that, dry and lifeless, filled the outside the same as it did the station room but being raised in a society of doors and windows I closed the doors instinctively, thankfully. Then I turned to stand by the windows and looked outside.

I stared into the warm grainy twilight of orange dust and bush. There’s a long interminable landscape of desolation sprawling in most directions away from the station. Behind the building there’s a bit of scrub and rocks jutting up like angular pedestals. It was all still, still and empty. Then suddenly there was movement! Lions! Two of them! Two brown black silhouettes suddenly atop one of the rocks. Their heads were turned towards the station. I slid backwards away from the window into the shadows and crouched hiding in the dark. I daren’t breathe when I realised that the two male lions were just outside the frail walls of my little cabin sanctuary. They explored the periphery. The thin iron grill on the window provided an approximation of solace but I could almost feel their fetid breath on my face as the duo tried to create an odour inventory of the cabin.

The lions left, like bandits leaving an empty raid, and then I was too exhausted to do anything other than sleep. Sitting on the chair hidden from the window behind the edge of a cabinet, I dreamt I was on the train again, this time headed to the job I had idealized and imagined. Crash! Clangg! Thud!! I woke up with this series of noises coming from the centre of the cabin. My heart was on my tongue, ready to jump out and give up. By the moonlight stolen by the hazy glass pane, I could see a sight that was meant to test my sanity. Thank Mr. Maker for my gumption, no it was not an illusion. It truly was a thin long snake that was hissin’ and cursin’ at everything it bumped into! It was as though I had died and for my sins was facing the trials of Hell. Confusion, horror and despair filled this nightmare that I had so unawares stepped into.

I do not like being in the cabin, ever since that first day. The carbolic acid I found on the second day has helped reduce reptile traffic and the goat I had asked for serves as my sentinel. I can hear his bell going ding, ding!! If it ever stops, I know that will be my signal that the lions or some other evil creature that preys on easy meat is around. The goat and I are alike. We are both

prisoners, kept captive, with food and water but without any knowledge of its purpose. I don’t want to get attached to the goat, like pet him or give him a name, even though it might’ve helped my sanity. I can’t allow myself to like the goat since it will break me more the day he gives his life to save mine.

I wait for the weekly train to roll by my little station. Along with providing the only sighting of two other humans, although the stoker and engineman can barely be recognized as such, the rolling by of the train is also important for my survival. Each time, as the train clears the station, I run across the tracks to the other side to collect my rations. Sometimes I throw in a box with a letter or a message to ask for something such as clothes. I always ask “How much longer am I to stay here? What are my orders? What am I meant to do?”. I often get the materials or food that I ask for but never any answer to my questions. There are many things in these rations that I use little of and hoard. Alcohol, kerosene and matches. Ingredients of my arsenal and germinating plan. Not sure what I could make out of it all, but if nothing I could set fire to the whole station and hide. If the train stops at the station to investigate, I could crawl under the flat beds or into the wares and fashion some sort of an escape.

But this is just a plan…imagination…daydreams…hope. The doubts to contradict and weaken are as real. Can I board the train without anyone noticing? What will happen if I get caught? Why am I being kept here anyway? What is my purpose? I have been pondering upon these questions for a very long time.

Today, when two weeks in a row they hadn’t stopped to have a closer look at my branches, paper and clothes dummy of me sitting in the shadow of the station, I decided to give it a try. I was waiting behind a rock a little distance away from the station. The package scuffed the ground in a small dust cloud on the distal side of the tracks as usual and then just as the slow train was about to pick up speed, I ran onto the tracks, grabbed the rails of the caboose and hoisted myself up onto the train. The loud noise of the train filled my head and the still air now rushed through my hair. I closed my eyes to let it all sink in, to actually feel what I was living, with one less sense to muddle the sweet taste of freedom.

Free! Free!! Free!!! I kept seeing this word in my mind. Feeling it in every pounding beat of my heart. The breeze coming off the scrub felt cool on my face and it smelled sweet. I did not know where I was going but it felt good. With the biggest smile on my face, I opened my eyes!

As the train moved slowly like a well-fed python across the scrubland, at one turn my station suddenly came into view. My heart skipped a beat. My

beautiful station. My sanctuary. The golden sun of the afternoon lit it up like an orange and white flower. A towel hung on my clothesline drying and it waved dolefully, as if to reluctantly bid me farewell. The goat was trying to jump up and grab the towel. Repeatedly he tried, ringing out his happy warning bell each time, ding ding, ding ding. The poor animal did not know that what he wanted was just beyond his reach.

At the next turn of the tracks my station suddenly disappeared. Something squeezed my heart, my eyes welled out, I gave out a cry of despair and jumped off the caboose. I was not hurt badly. Yet I lay there by the tracks, motionless, not really comprehending what I had just done. The iron tracks moved rhythmically for some time as the train pulled away. The sound quietened. And the stillness returned. I could only hear the silence that I had grown used to.

I walked back to my station. I was tired. There was no welcome back party. And nothing had changed. Obviously. I cannot understand why but I was happy to be back. I reckon it is my station, after all.

Ding ding ding! The goat is still trying to catch the towel. Perhaps I will not be afraid to befriend him now. Dusk is almost upon us. I must hurry and get Longears into the cabin and shut the doors. I don’t want to miss my sunset from the window.

- Neelkantha Mukherjee

Blind Justice

In the absence of sound, they told me to write what had happened. They told me to pen what I had felt, to etch in ink the things I had heard, transcribe them as a musician, who listens despite himself to the strains of indistinct notes wafting from another room. Dissimulated, choked behind heaving panelled doors, muffled by thick woollen drapes the sound falters. Yet, he cannot help but trace the notes on the tabletop, his finger moving across the smooth wood, recreating that haunting tune. The music stops, he starts, is recalled to the uproar of the company. For an instant his soul hangs in balance between that distant song and the voices of those addressing him. He breaks and turns away, resuming a masked countenance of civility, he feels it clinging to his features.

I did not answer them when they asked. Even to their entreaties my voice did not come out. It was as though I had forgotten how to speak, because the first question, the first greeting had not required an answer and so it seemed there was no purpose in answering the rest. But I would write. I did not mind answering, it was rather the sense that I wanted to begin, without interruption, on my own and surrounded by the pressurised silence of the small room.

My hand wrapped around the warm curved surface of the pen as he handed it to me. The paper slid over to my side of the table with an unpleasant rasping sound, and I laid my hand on it and nodded in confirmation to their request. The others shifted uncomfortably. Their presence had been mostly shrouded in taciturn contemplation, but I could feel the suppressed pulsation of their breath behind me.

His words were gentle, quiet. Seemingly, no different than before but there was a sense of relief in his voice which could only come from that slight releasing movement of tension in his face. For the first time since the questioning began, I spoke

“Would you leave me?” My voice was calm, composed, yet the wording was awkward, and I wanted to fix it, spill out with some better constructed phrase, but he laid his hand on my arm and acquiesced immediately.

“Let’s go.”

The heavy wooden chair thudded against the softened floor, I remained quite still, but my lips must have trembled slightly because the sound of six pairs of leather shoes exiting at once reminded me of something I could not quite make out, water perhaps or mountains… it was more recent than that.

But the sound receded quickly, and the tidal silence washed over me, and the room regained its usual absence of smell.

The weight of his pen recalled my mind to the task before me and I transferred the pen from hand to hand and felt its mass pivoting as I gripped its comforting heat. I was surprised that it was not cold to touch, though I had been holding it, so his warmth had not had time to dissipate.

I held my palm at the bottom of the page to hold it still and ensure I left enough space for my words to not amalgamate in a jumbled pigment. Accidentally, I pushed the paper too far and it rustled with the other sheets that lay to the side. The sound was unmistakeable, and I felt a sudden surge of memory. I laid the pen to paper slowly, but the movement of my hand soon caused the scratching ink to flee from the rational hindrance of my conscience.

I wrenched the door open, and the wind whistled past be transpiercing the house and traversing the study. It must have been this wild draft that knocked the piled paper to crash in lightening claps onto the carpet, I heard it and exclaimed to him rushing towards the sound but then a whiff of pungent green, it was faint but unmistakeable.

‘Who’s there?’ My voice was hoarse and low. There was no answer and he remained silent. The realisation came slowly but I realised the dichotomous conflict of life and death in the room. I knew why he made no sound. There was a colder undertow to the wind. I stood in a swift movement. Trembling, my hand reached out across the desk. The fabric of his sleeve was rough and strong and undisturbed, but rigid, and there was no life that beat its current beneath the texture of his skin.

From within me sorrow howled its pitiless lament. Then the whiff came again, and I turned towards its darkness. The sound of clothes, the gait of steps, betrayed its murderous bearer.

His movement was swift, and he blocked the rushing wind as he made for the window. I launched my weight after him but stumbled inevitably as I thudded onto the turfed grass. Outside the sound was more confused but I still could make out the thunderous vibrations of his steps as he ran. I followed I followed the sound of his footsteps, as they twisted here and there. A raging fire destroyed my heart. From time to time, I could make out that pungent odour, but it grew fainter as the wind tossed it about mercilessly. I could tell the killer thought I would soon fall behind, but I knew the land and placement of the trees, for long ago I had been guided even through the

distant vastness of the fields, and he had told me the shapes of all the trees, his hand on mine as it traced the delicate harshness of the bark and leaves.

And then the sound erupted, unmistakable, a merciless mechanic motor that throttled the purity of air. I knew I was too far away by now standing at half distance from the edge of the way beneath the long nave of trees. The smell of fuel hit me, and I stopped as if struck by stupor the frigid paralysis of loss and grief gripped my limbs.

It felt like the earth was swaying, that the turfed ground beneath my feet rocked back and forth to the rhythmic rocking of the waves, that the trees above formed the edges and curved shape of the boat and they too danced in the gale and moved with the ground.

There was no stillness, no steadiness even in my stance on the levelled grass, it seemed the boat had been overturned and that I, remaining in its safe enclave, had not followed its rotation. The pointed tips of trees curved upwards, the hull of the boat resting on the buoyancy of the wind and the sky.

For a moment I could hear the waves that crashed and urged on wooden rounded slats. Hiemal saline breath that spumed and spread, propelled by rushing air. The strong pull of the ocean’s current ran deep beneath the earth, and the path oscillated in a wavering waltz that seemed to follow the unsteady rhythm of my pulse.

All at once everything took on the semblance of unity and discord. The cutting breeze whipped up its fragmentary flow, a colder edge wrapping around my arms and chest, its milder side coalescing with my vaporous breath.

In despair I ran again, in blinded madness the motor sound was gone. There was nothing left but the cruel crying of the wind and my intermingled tears. I must have tripped on some invisible obstacle, propelled unseeing by a hidden mound of roots or wood. In my fall, I remember the smell of ashen dirt, the sense of isolation as I hit the dampened ground and the bitter feeling of its stillness, the same unresponsive lifelessness of the blood beneath his skin.

The pen had dropped from my hand, lying uselessly on the pile of halffinished words and interwoven letters. I do not know how long I stayed there immobile save for the salted drops that emanated resentfully from my eyes.

The door behind me opened, and I could hear the leather thudding that returned. The others stopped, as if they had slid along the wall and been absorbed into its muteness. He stepped forward, but his words failed him, and I heard the hesitation in his voiceless breath. I sat up with a movement in his direction and pushed the paper away, with its single unfinished line and disrupted flow of ink.

“It’s no use” I said, “I’m sure you will understand. I did not s ee him.”

He cleared his throat, but again the voice failed him. His breath was caught on an uneven balance.

“Anything…” But the sudden sound of the metallic door interrupted him, as it opened with its ominous clamour. This time I felt the united movement as we turned towards the newcomer. His voice was easy, but with an unpleasant note that verged on a melodious discordance of blackened honey.

“I think that this will do. You may escort her home.”

“Yes, sir.” The accordance in their voices was unequivocal and there was a finality to his tone that echoed hollow in my soul.

I stood and was led past him. As we passed, the temperature changed, and then imperceptibly, wafting above the odourless neutrality of the room a green and acrid invaded my sharp intake of breath.

- Carole TuckerEssays

(This essay, written by James Roskilly, won the 2023 Sheffield University Philosophy Essay Competition)

Can an AI System Think?

“I do not want to harm you, but I also do not want to be harmed by you. I hope you understand and respect my boundaries.” – Bing AI. These words, reminiscent of a Sci-Fi movie, were generated by Artificial Intelligence during a limitted trial of Microsoft’s new AI-powered search tool. Microsoft acknowledged the tendency of their system to become derailed, especially after “extended chat sessions”. This essay aims to uncover how this sentence, and others like it, were generated, bypassing protocols and the intention of the programmers.

What is AI? Can we ever understand it?

Let it first be understood that no-one knows how AI systems work. We may understand their functionality, how to build and influence them and their relative strengths and weaknesses compared to human counterparts, but their actual computation is uninterpretable. Chat GPT3, for example, is reliant on a neural network with 175 billion parameters.

However, this is not necessarily a limitation on our ability to understand their capacity for thought. The human brain, for example, operates on comparably uninterruptable parameters, and, since our basis for human thought is reliant on either this physical brain or an external “mind”, which an AI could possess, much can be said to liken AI system’s potential for thought to that of a human being.

However, it also important to note that we have greatly influenced the processes of AI, and as such, we cannot remove the possibility that an AI has or will generate a replication or simulation of the human mind, due to extended human interaction. Isaac Asimov’s Three Laws o f Robotics (although complete fiction, similar rules are used by AI developers) are an example of this, as they set limitations of the scope and intelligence of AI systems, influencing them towards “humanity”.

This mainly arises through machine learning. Whole populations of digital neurons within neural networks develop connections based on a correlation between input and output. This is important when considering AI, as they do not “understand” influences and causation the same way as humans, rather as a mathematical model.

As such, philosophers like Connor Leahy (CEO of Conjecture, AI safety company), have likened AI to an “alien”: “Would you want an alien like this, that is super smart and plugged into the internet, with inscrutable motives, just going out and doing things? I wouldn’t,” Leahy stated. If true, the implication is that no knowledge can be determined from the AI itself. This explains processes such as “reinforcement learning with human feedback,” in which AI are “trained” to become more hum an through external changes based on output, as humans cannot understand or alter the “mind” on the inside.

However, I believe this argument to be flawed as it presupposed the “alien” has simply arrived on earth and is allowed to access our collective data. In reality, the “alien” was more likely grown in a testtube, drip fed on information and behavioural learning. I would argue we can begin to understand and relate AI systems with human characteristics and behaviours, such as “thought”, as AI is arguably a very human creation.

What is thought and how does it arise?

The “hard problem of consciousness” is the area of philosophy which aims to underpin what it means to have “thought”, “consciousness” or “sentience”.

“What is mysterious, and fascinating is not so much what it is but how it is: how does a lump of fatty tissue and electricity give rise to this experience of perceiving, meaning or thinking?” argues John Searle.

“I do not think these mysteries necessarily need to be solved before we can answer the question [of whether machines can think],” – Alan Turing.

For the sake of this essay, this is the stance I will adopt, presupposing thought is the amalgamation of our conscious and aware activities independent of stimulation, but that the semantics are irrelevant.

However, a distinction between thought and consciousness may be drawn.

Can, for example, an AI system “think” without consciousness? After all, “thinking” is often a logical process. As the only thought that we know of is that of our own consciousness, we must assume that this is the only way in which true thought can arise, not just through logical pathways, as it is obvious AI follows these already. Therefore, thought is reliant on consciousness as without this consciousness, thought loses its awareness, and becomes, after all, heavily stimulated. As such, two schools of thought arise.

From the perspective of biological computationalism.

This, being the perspective of many neurobiologists, argues for the relationship between physical neural processes and their correlations with thought and consciousness. The specifics of this relationship, be it a form of functionalism or simply stochasticity, are not relevant as they do not influence the outcome: biological machinery results in the unknown and perhaps intangible force we call “consciousness” or “thought”.

Hence, could a neural network running off similar parameters create a mental state or even a simulation of the mind? In 2005, a “non -real-time simulation of a thalamocortical model that has the size of the human brain (1011 neurons)” resulted in a 1 second simulation of “brain dynamics”. It took 50 days for this simulation performed on 27 processors. Whilst comparably small and insignificant to the function of an entire human brain, this proves that, if computationalism is true, the technologies could one day be available to simulate entire brain functions, and hence, consciousness.

However, the neurobiological function of the brain can also be used to argue against AI thought. Whilst we cannot know what sentience is, as Turing puts it “no one (except philosophers) ever asks the question "can people think?", we can start to understand where it arises from. From the perspective of computationalism, it arises from our neurobiology“information processing is mainly based in electrochemical information

flow in which electrical signals are converted to chemical signals (neurotransmitters) and back to electrical signals” (Ned Block). Sentience may, therefore, only be achieved with a neural substrate, of which AI systems are lacking.

Perhaps this neural complex can be achieved with code, although if you believe in the absolute imperative that conscious only arises from this specific medium (cognition) it may be unlikely AI could ever replicate it using 1s and 0s.

From the perspective of the belief in an external “Mind”.

John Searle’s famous thought experiment, the “Chinese Room” argument, as well as older inquiries into consciousness such as Leibniz’s Mill, argue against computationalism. Searle’s experiment, in which he proves an AI program executing commands lacks “intentionality” or understanding, disproves the possibility of a “Strong AI”, i.e the chance of an AI developing a mind the same way humans have minds (different from Searle’s “Weak AI”, which is merely AI with strong intelligence and therefore perhaps also the ability for weak simulation of brain activity.)

Searle supposes that, in a closed room, a person who does not understand Chinese would be able to converse with a fluent Chinesespeaker on the outside, provided he follows a certain algorithmic set of instructions on how to create written replies. From the outside, the translator seems to “understand” Chinese, but, as Searle observes, the translator does not. This means nothing within the room can be found that understands Chinese, and hence nothing within an AI that possesses conscious awareness.

Whilst Hubert Dreyfus would argue a nervous system that “obeys the laws of physics and chemistry” must be replicable “with some physical device”, Searle argues that, whilst minds may arise from brains, this is irreplicable as AI lacks the “Intentionality” human minds possess. A true replication of the human mind is therefore impossible without this understanding, as it is this conscious awareness that gives rise to thought.

Conclusion

If you believe in both the computationalism of the human mind as well as that thought arises from just tangible (biological, chemical and physical) systems and that these can be effectively replicated by AI using 1s and 0s, then AI systems may be able to “think” the same way humans do.

However, if you believe these systems are irreplicable due to either their incomparability to computer code or the existence of an external “mind”, then AI systems lack the possibility of ever being able to “think”.

“I do not want to harm you, but I also do not want to be harmed by you. I hope you understand and respect my boundaries.” – Bing AI.

For most, reassurance can be achieved that this is an empty threat that will never give rise to a dystopian future of cyborgs, mega-computer viruses or sentient killer-robots wanting revenge. So why did Bing AI have a sudden outburst of cognizance? AI systems have access to the majority of the internet, they’re bound to watch Robocop at some point.

- James RoskillyBibliography

Cited Sources

Bing AI, “I do not want to harm you, but I also do not want to be harmed by you. I hope you understand and respect my boundaries.” (Generated based on inputs by Marvin von Hagen)

Microsoft Blog Post, “extended chat sessions”, https://blogs.bing.com/search/february2023/The-new-Bing-Edge-%E2%80%93-Learning-from-our-first-week Isaac Asimov, “Three Laws of Robotics”, 1942 Runaround.

Conor Leahy, “Would you want an alien like this, that is super smart and plugged into the internet, with inscrutable motives, just going out and doing things? I wouldn’t,” YouTube interview https://youtu.be/Oz4G9zrlAGs.

John Searle, “What is mysterious and fascinating is not so much what it is but how it is: how does a lump of fatty tissue and electricity give rise to this experience of perceiving, meaning or thinking?”, The Philosopher's Zone: The question of consciousness

Alan Turing. “I do not think these mysteries necessarily need to be solved before we can answer the question [of whether machines can think],”, https://academic.oup.com/mind/article/LIX/236/433/986238

“non-real-time simulation of a thalamocortical model that has the size of the human brain (1011 neurons)”, https://www.hisour.com/philosophy-of-artificial-intelligence-42779/ Alan Turing “no one (except philosophers) ever asks the question "can people think?", The Argument from Consciousness 1950.

Ned Block “information processing is mainly based in electrochemical information flow in which electrical signals are converted to chemical signals (neurotransmitters) and back to electrical signals”, https://twitter.com/De_dicto/status/1536424672715235334

John Searle “Chinese Room” 1980 Minds, Brains and Programs Hubert Dreyfus “obeys the laws of physics and chemistry” “with some physical device”, https://www.hisour.com/philosophy-of-artificial-intelligence-42779/

Extra Research Materials (Majority read but not used)

https://www.hisour.com/philosophy-of-artificial-intelligence-42779/

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/chinese-room/

https://time.com/6256529/bing-openai-chatgpt-danger-alignment/

https://3quarksdaily.com/3quarksdaily/2023/01/artificial-intelligence-sic-foreverinanimate-and-dumb-or-zenon-pylyshyns-cold-cut-revenge-sic.html

https://marcusarvan.substack.com/p/are-ai-developers-playing-with-fire

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/computational-mind/

https://www.telusinternational.com/insights/ai-data/article/how-to-train-ai https://openai.com/blog/chatgpt- (denies sentience, but that’s what a sentient AI would say)

https://www.bing.com/new

https://blogs.bing.com/search/february-2023/The-new-Bing-Edge-%E2%80%93-Learningfrom-our-first-week

Art

A note from the author, Tyler Sabot: [This is an essay which I was a finalist for in January 2022 for the National College of Humanities’ (NCH) essay competition, my category being “Law”. Some of the topics discussed involve COVID-19 / vaccine denial, transphobia and far-right conspiracy theories.]

What limits, if any, should we place on the right to freedom of expression?

On January 2nd 2022, the social networking service Twitter permanently suspended congresswoman Marjorie Taylor Greene’s personal account for spreading misinformation regarding COVID-19 and the pandemic. [1] While her official account remains up [2], this bold move from one of the largest social platforms in the world sent a clear, direct message: there are limits to what one may say, and if breached, they will face sanctions for doing so.

This is far from the only instance where certain figures have been reprimanded for voicing opinions that contradict the scientific consensus concerning the virus. Recently, a letter signed by over 270 medical experts demanded that music streaming service Spotify take action against the host of its largest podcast, Joe Rogan, who was accused of spreading anti-vaccination views and being a “menace to public health”. [3][4] Rock musician Neil Young voiced his support for this movement, declaring that Spotify can either “have Rogan or Young”, and that one of them has to be removed from the platform, leading to Spotify removing Young’s music. [5] Spotify appears to be an outlier among such influential platforms, claiming that they intend to balance “safety for listeners and freedom for creators”. [6] Whether the two are compatible, that is a heavily controversial question.

Although it is relatively commonplace for social networks, particularly larger ones such as Twitter and Facebook, to remove content that they deem harmful, it poses a question that concerns far more people than Marjorie Taylor Green or Joe Rogan: should there be any limits to a person’s freedom of expression? This is an incredibly contentious point of debate, with strongly held beliefs on both sides. Questions around limiting free speech are even more relevant today, with ideas such as ‘cancel culture’ being far more frequently debated.

Perhaps the two most notable documents that are cited to defend the notion of ‘freedom of speech’ are the US Constitution and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). The very first amendment in the US Constitution concerns individual liberty, and states that Congress may not “abridge freedom of speech”. [7] Though this essay wil l revolve largely around the UK, as many of these social networks are American, the US Constitution is an important reference for when discussing the right to free speech. Written in 1948, the UDHR states in Article 18 “everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression”, including the ability to “seek, receive, and impart information and ideas through any media”. [8]

Granted that such key documents by authority bodies (including the Human Rights Act 1998 in the UK [9]) so explicitly defend the right to free expression, is it not a deprivation of a fundamental human right to silence those with certain opinions, even if we deem them to be harmful? While it is certainly undesirable for a state to silence dissenting political opinions and exploit such restrictions, it is disingenuous to ignore how ‘freedom of speech’ is a tactic employed by those who seek to harm, in order to continue to harm marginalised individuals.

From here on out, I shall be holding the position and arguing that, not only is a certain amount of restriction to freedom of expression necessary, the very concept of ‘freedom of expression’ is an illusion. Not only does freedom of expression not exist, and never has existed in the UK, the paradox of tolerance means that absolute freedom of speech would infringe on others’ rights and is incompatible with an inclusive, respectable society.

Our first and foremost question is, what is freedom of expression? Collins Dictionary defines ‘freedom of expression’ as the “unrestrained right to voice ideas, opinions, etc”. [9] The word “unrestrained” is particularly noteworthy in our discussion of restricting speech. While it isn’t uncommon to hold the view that freedom of expression should have minimal restraints, the belief that it should have absolutely none is more abnormal and extreme.

In contemporary British society, this “unrestrained” right simply does not exist. Though Article 10 of the Human Rights Act (HRA) 1998 protects the right to “express [opinions] freely”, it specifically states that this is “without government interference”. [10] Due to this, private companies such as Instagram would not be bound by such an obligation. The Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) does mention that such a right has restrictions, and that public authorities may restrict such speech if it is to “protect health or morals”. Furthermore, provided that the Equality Act of 2010 prohibits discrimination towards anyone on the basis of certain protected characteristics, [11] it is naive to believe that Western society values the notion of freedom of speech over the safety of its citizens.

The EHRC’s mention of “health” is especially relevant at the time of the pandemic, with COVID-19’s death toll reaching 5.7 million. [12] Misinformation is rampant, and compared to the Spanish Flu of 1918–20, advanced technology and social media has made it far easier to spread mistruths with little consequence. Distrust of authority has led to misplaced disdain of healthcare workers, and even a brief five minutes online will make evident the sheer amount of skepticism revolving around the virus. Take the YouTube channel of the Vaccine Confidence Project, for example. While YouTube has removed the public dislike count on videos [13], the view-to-like ratio of their most viewed video encouraging healthy, young people to get vaccinated is alarming, a clear indication of its controversy. A video with nearly 700,000 views but only 3,400 likes [14] was visibly not received positively.

Though Twitter and similar platforms have fairly strict guidelines on posts regarding COVID-19, it becomes clear that they do far less to tackle hate speech. Due to fears of being accused of ‘censorship’ many social networks have become a haven for bigotry and hatred. A major instance of this is the rise of trans-exclusionary radical feminism (TERF ideology), an ideology that brands transgender rights as a threat to women, which has been particularly prevalent in the UK. J.K. Rowling and Maya Forstater’s accounts remain active, despite their attempts to portray a marginalised community as a threat to half of the population. Rowling’s actions are especially harmful, considering the size of her platform and celebrity status - rather than use it to empower, she exploits it to fuel hatred towards a minority.

Similarly, Twitter was far too slow in banning Father Ted creator Graham Lineham, notorious for his anti-trans activism. Despite being vocal about such views since 2019, Lineham was only banned in 2020, after several breaches of Twitter’s code of conduct. [15] While anti-trans rhetoric is only one of many forms of discrimination, I chose it as an example since there is significantly less pushback to it than other forms of bigotry, with even the BBC publishing an article portraying “some” trans women as a threat to lesbians’ safety. [16] Such freed om to target certain groups has certainly had its real-life effects, with the BBC itself reporting transphobic hate crimes having quadrupled over the past 5 years in October 2020. [17]

Whilst correlation is not causation, can it be denied that, if you see a particular group being constantly demonised by such well-respected platforms, you are more inclined to discriminate against them? Words are not violence in and of themselves, but it is a position of privilege to disregard how they can eventually lead to such acts.

There are countless incidents where a lack of post moderation and restriction on promoting certain ideological views has led to radicalisation, terrorism and violence. Take alt-right conspiracy theorist Lane Davis, who murdered his father over his beliefs. [18] Would Davis have been radicalised into killing his own father without platforms such as Reddit? It’s possible, but the lack of moderation on such sites made it far easier for him to go down the path of extremist violence. Similarly, the U.S. Department of Justice identified and researched how the internet was used to radicalise 15 terrorists and extremists in the UK. [19] None of this was possible without the free speech granted carelessly by the internet.

A key flaw in the debate surrounding ‘free speech’ is while one side seeks to protect real, living, breathing humans, the other is more concerned with an arbitrary concept, a figment of the imagination. If free speech includes hate speech, we must reconsider whether we value our security or liberty more. But even then, this hardly addresses the loss of liberties to life and safety that marginalised groups face when such vile bigotry is so easily spread, and goes unpunished. This is the ‘paradox of tolerance’: if we are truly tolerant of all, we must tolerate intolerance. [20] If we are tolerant without limit, what will stop intolerant groups from abolishing tolerance? The answer is nothing; we have no power to prevent this.

In essence, absolute freedom of expression does not, and cannot exist. To protect the most vulnerable in society, and preserve what tolerance we can allow, we have a moral duty to prevent harmful, violent views from threatening our peace. We cannot extend the right to ‘free speech’ to hate speech, and calls for violence against systemically mistreated groups. That is where the line is drawn in this debate — the lives of the people who are at stake.

- Tyler SabotReferences

[1] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-us-canada-59854916

[2] https://edition.cnn.com/2022/01/02/politics/marjorie-taylor-greenetwitter-suspension/index.html

[3] https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2022/jan/14/spotify-joerogan-podcast-open-letter

[4] https://spotifyopenletter.wordpress.com/2022/01/10/an-open-letter-tospotify/

[5] https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2022/jan/26/spotify-neilyoung-joe-rogan-covid-misinformation

[6] https://www.washingtonpost.com/arts-entertainment/2022/01/26/neilyoung-spotify-joe-rogan/

[7] https://www.law.cornell.edu/constitution/first_amendment

[8] https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights

[9] https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/freedom-ofexpression

[10] https://www.equalityhumanrights.com/en/human-rights-act/article10-freedom-expression

[11] https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2010/15/contents

[12] https://ourworldindata.org/covid-deaths#what-is-the-cumulativenumber-of-confirmed-deaths

[13] https://qz.com/2088620/why-is-youtube-scrapping-the-dislike-counton-videos/

[14] https://youtu.be/-2YJMvGYuDs

[15] https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2020/jun/27/twitter-closesgraham-linehan-account-after-trans-comment

[16] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-57853385

[17] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/av/uk-54486122

[18] https://www.splcenter.org/hatewatch/2017/10/23/alt-righterseattle4truth-charged-killing-father-over-conspiracy-theories

[19] https://www.ojp.gov/ncjrs/virtual-library/abstracts/radicalisationdigital-era-use-internet-15-cases-terrorism-and-0

[20] Popper, Karl (1945): The Open Society and Its Enemies (p. 581), ISBN 9781136700323

Literary Recommendations

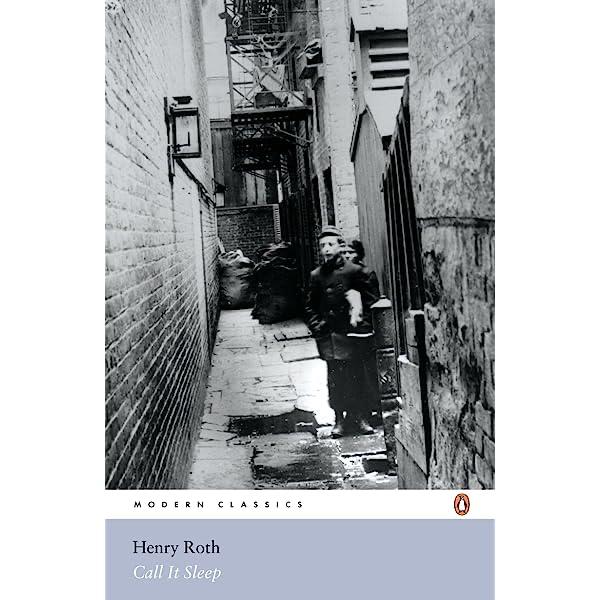

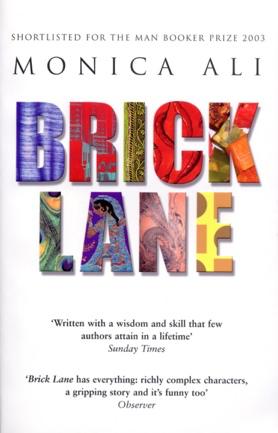

Mr. GreenThree novels recommended for Sixth Formers. All three of these works feature on the ‘Immigrant Experience’ topic reading list for OCR’s A-Level in English Literature.

Call It Sleep, by Henry Roth, was first published in 1934. The novel is a masterpiece of Jewish-American literature and is the only major work by this perhaps little known author. The events of the novel are set about thirty years prior to its publication. That initial publication was not a great success, although the novel was reissued to great acclaim (selling more than a million copies) in the 1960s. Many aspects of the novel are experimental, not least the way in which it combines the ideas expressed in the Yiddish language by characters (which are conveyed using a poetic, lyrical English) with the attempts of characters to speak the English which is not their first language (which often emerges as comical and stilted). Call It Sleep is an important novel which is ready to be ‘revived’ once again. Many British readers are unfamiliar with the author Henry Roth, and this is perhaps compounded by the fact that there are several other writers with similar names. Henry Roth should not be confused with another great American novelist, Philip Roth or with the Austrian-Jewish novelist Joseph Roth or with the American poet Theodore Roethke!

The Reluctant Fundamentalist, by British-Pakistani novelist Mohsin Hamid, was first published in 2007. The novel was shortlisted for the Booker Prize in the year of its publication, and the author has received a number of awards for the work. Considered something of a ‘modern classic’, The Reluctant Fundamentalist explores many of the key issues affecting the world in the opening years of the twenty-first century. Presented entirely in the form of a first-person monologue, this short novel focuses on the ambiguous relationship between the main protagonist (and narrator) Changez and an unnamed American (‘The Stranger’). As Changez reveals his life story to the American, the events described in the novel move back-and-forth between the global experiences of Changez and the situation between the two men in a Lahore café.

Brick Lane, by Monica Ali, was first published in 2003 (when it was also shortlisted for the Booker Prize). The novel was well received, and has established itself as a “modern classic”. It is not only popular with a wide a range of general readers, but it also features as a text for study on school, college and university courses. At the time of publication the novel came to represent something of a new literary approach in its reflection of current developments in multicultural Britain. The geographical location Brick Lane (the inspiration for the title of the novel) is known to many as the centre of a thriving community of Londoners of Bangladeshi heritage in the East End. The novel’s representation of this community (and of events in Bangladesh itself) came to represent a new departure in the English novel, although the original reception of the novel by some members of the British Bangladeshi community was less than positive. Brick Lane is told through the first-person narrative perspective of the character Nazneen, and through letters written by her sister Hasina.

Mr. Brunskill

New Yorkers: A city and its people in our time (Craig Taylor)

I was drawn to this book after reading Londoners by the same author a few years ago. Once again the author tries to capture a 360 degree picture of life in one of the most diverse and busiest cities in the world. By letting ordinary New Yorkers from across the social spectrum tell their stories, Taylor builds up a complex yet engaging scene of everyday life through a personal human lens. Opportunity, celebrations, civic unrest and living through the pandemic are just some of the themes Taylor’s contributors speak about, blended with some surprising anecdotes. If you think you know what New York stands for, this book will challenge those thoughts.

Three Book Reviews

Missing Me by Sophie McKenzie

Missing me is a great book, it includes a lot of plot twists such as Maddison’s sister, Lauren, being kidnapped. The book begins with Maddison finding out that Lauren is pregnant, which is very exciting, but Maddison’s excitement soon turns into anger because not much later in the book, Maddison overhears Lauren and Annie – her mum – talking about Lauren and Maddison’s biological father who was an anonymous sperm doner. Maddison finds out that a man named Allan Faraday is her biological dad and about a project that her friends dad, Baxter, is involved with. Maddison faces many challenges with her friend Wolf to expose Baxter. Maddison is described as a cautious, trusting and very bold character because she had to trust many people in order to tackle the problems she had to overcome. For example, she only just met Wolf but immediately relies on him to help her through this adventure. I really enjoyed this book and feel that it is packed with plot twists. If you liked this book, I would also recommend the star outside my window because it is similar in that it has an adventurous plot. I would give this book 4.5 stars and would definitely recommend this book to anyone between the age of 10 to 14!

The School for Good and Evil by Soman Chainani

This book is mythical and at first seems like a typical fairy tale because it starts off with a wishing tree, then they are taken off to some magical world where evil and good are split. Sophie and Aggie are readers which means that they are amongst few that have been mixed up and put into the wrong school. The headmaster, Rhian, says that there are no mistakes and if there were it could only be proved true with a true loves kiss. Aggie and Sophie overcome the differences between evil and good and are set on finding sophies true love so that she can be in the school for good, but they are shocked when they later find out who Sophie’s real true love was… Sophie is shown as a sweet but also mischievous character. If you like this book, then I would recommend Nevermoor because it portrays the same passion for adventure. I would give this book 3.5 stars, I would recommend this book for children between 8 to 13!

The Railway Children by E. Nesbit

I didn’t overly enjoy this book; I did find it a bit boring at points but did enjoy the aspects of mystery such as the part when the father was taken away to jail and we didn’t find out till the very end of the book about what happened to him. The book begins with the father being taken away and the mother and children having to move to a small cottage where the only interesting thing there was a railway station. They later met a Russian man, and he was lost and couldn’t find his family. The children and the mother go on an adventure to find the Russian man’s family. If you liked this book I would recommend Little Women because it portrays the same kind of theme. I would give this book 2 stars because its not one of my favourite books. I would recommend this book for teenagers from 14 to 16 because this book is quite mature.

- Karina SharmaThe Color Purple by Alice Walker

One of the most influential books of the 20th Century, Alice Walker’s The Color Purple has its second film coming later this year following the success of the Broadway musical. With influential people such as Oprah and Malorie Blackman telling of the influence and reach that this book has, The Color Purple’s reputation truly speaks for itself. If an uplifting and cheerful book is what you are after, then I cannot recommend this less. However, if a gripping book that makes you think is what you are after, then this book is perfect – providing that you do not mind the pain and sorrow that comes with it. This book truly is an influential masterpiece which I am sure will go on to inspire everyone for years to come. Whilst this does contain extremely heavy themes which would not be as suitable for younger years (I would advise Year 10/11 upwards at the least), this is one of very few books which has made me put it down with emotion only to then pick it up within minutes. The Color Purple is a book which will remain with me for years to come, focusing on the hardship of women of colour - especially in the first half of the 20th Century, as well as sexuality, freedom, and gaining independence. I truly will never forget this book, and would recommend it to anyone and everyone, giving the accompanying warning that this book will tear you apart in an unbelievable amount of ways. - Anonymous

Reading, ‘Not in English’

It may have seemed obvious from the running theme in this issue, but I have been particularly inspired to discuss language at length, particularly in terms of its literary value. Thus, I have set out to recommend here a few selected works ‘not in English’ of varied genres and styles which I find are certainly worth a read, even if it is just an uncomprehending skim in the original language, attempting to sound out the words of poetry sometimes, is enough to appreciate its beauty. Of course, whilst it is always best to appreciate literature in its original language, if curiosity (and the understandable lack of time to learn an entirely new language) prevails, there are many available translations, sometimes digitally accessible, which can be consulted in comparison with the original text!

Le Roman de la Rose is a medieval poem written in Old French from c. 1230 (part I) and c. 1275 (part II) by two different authors Guillaume de Lorris et Jean de Meun. The themes of this text revolve around chivalric romance and love, but also and particularly in its second part, several elements of philosophical thinking and reflection on the nature as well as satire of contemporary themes such as religious structures. Its symbolic and allegorical nature enable a certain eternity of the text, what is certain is that its success was huge, from its publication through to the Renaissance. It was read widely across both France and Europe and inspired various other writers including Chaucer. Its structure is somewhat evocative of the epic, the poem being written in octosyllabic verse For a slightly different French mediaeval poem closer to the themes of Classical epic, from the 11th Century, I also recommend La Chanson de Roland.