Phil Freelon Design Competition 2025― Hacking Health

Health Everywhere, for Everyone.

Devika Tandon, AIA

Hacking Health Design Competition

The healthcare landscape today is missing a crucial element—spaces dedicated to preventing illness, not just treating it. While hospitals are essential, they focus on illness, leaving the broader factors of health untouched.

The reality? Only 33% of our health is influenced by genetics and medical care—67% is shaped by our environment, behavior, and social factors.

Executive Summary

This challenge invited designers to rethink the built environment and create spaces that proactively improve health. Whether through small interventions or large, multifunctional hubs, the goal was to rethink how we live, work, learn, and move—empowering individuals to take charge of their health. Where could we make the biggest impact?

The “Hacking Health” competition was born from a simple but urgent insight: our built environment shapes well-being just as powerfully as medicine does. During the competition, multidisciplinary teams from studios around the world rapidly devised retrofit “hacks” of everyday places—malls, schools, streets, offices—to demonstrate that simple, high impact interventions can improve behavior, boost mental and physical health, and foster community. What emerged was a clear pattern: we have a wide range of opportunities to accelerate preventative care at scale, by reframing existing spaces as health-supporting venues.

This was part of our annual Phil Freelon Design Competition that is named after our late colleague and friend Phil Freelon. We also honored Robin Guenther with this year’s brief and focus on health. Robin was an avid advocate for health and for preventing health problems through design and transparency.

This white paper distills our key findings, illustrates them with project spotlights, and offers an eight point design framework.

Finally, we issue a call to arms: designers, public health advocates and policy makers must work together to embed health into every corner of our environment. The next steps are immediate and actionable—pilots, partnerships, metrics, open source toolkits—and they begin with a collective shift from “health at the end” to “health everywhere.”

Integrating health into our everyday is meant to be simple, accessible and to feel doable. That is the point. That is how we will make progress. In this paper, we zoom out and analyze the ideas presented in the competition submissions. This way, we can better learn from the variety of ideas presented and the different angles from which our designers tackled the problem. Why does the shopping mall makes so much sense as a health hub?

How can we better tap into the full potential of schools and what they can do for society?

A lot of what was proposed did not build new but repurposed what we have. Not only is this the most sustainable thing we can be doing now from a carbon and resources perspective, it also means we can intervene incrementally, and thus sooner rather than later.

Designing Bold Ideas for Healthier Futures

What was the competition?

Ideas Competition

We live in a world where healthcare often begins too late—at the onset of illness, rather than in the environments that could help prevent it. Research shows that only about a third of our health is determined by genetics and medical care; the majority is shaped by our behaviors, environments, and social conditions. Recognizing this, the 2025 Phil Freelon Design Competition, hosted by Perkins&Will, challenged designers worldwide to rethink how health can be embedded into everyday spaces we frequent—places like malls, schools, transit hubs, and streetscapes. By inviting teams to “hack” these environments with spatial, architectural, and service-oriented prototypes, the competition showcased how communities can reclaim their agency over health long before medical intervention becomes necessary.

68 diverse submissions revealed innovative ways to transform existing infrastructure, turning spaces that are often neutral or even

detrimental to health into active wellness supporters. These ideas ranged from small, incremental changes to broad systemic interventions. This white paper distills those insights into a narrative, presenting five key themes that emerged across the proposals, highlighting exemplary case studies, and offering a practical design framework that can guide future projects. Whether it’s retrofitting a parking garage into a wellness hub or creating nature-based play in schoolyards, the work demonstrates a path forward that is joyful, equitable, and deeply grounded in lived experience.

Our core message is clear: health does not need to be a distant destination or a special building. Instead, it must be integrated into everyday life and the spaces we inhabit. We call on designers, policymakers, and public health leaders to adopt the mindset of “health everywhere.” This paper provides the ideas and tools to start building that future today.

Why the Hack?

We are a sick society. We have more cases of cancer in younger people, more instances of attention deficit disorder, and more loneliness and mental health issues in youth and younger adults than ever before.

Today’s chronic disease statistics paint a stark picture: asthma, diabetes, obesity and anxiety are on the rise, and our traditional healthcare system—hospitals and clinics—are more reactive than preventive. Meanwhile, everyday we occupy a host of building types such as schools, malls, offices and streets. If our designers and planners could reimagine those environments to nurture well being, the potential impact would dwarf that of any single new hospital.

“Hacking Health” reframes this challenge as an opportunity to act with creativity. By defining a “hack” as a rapid, low resource retrofit or reprogramming of an existing space, we empowered teams to develop prototypes. This agile approach not only tests ideas fast but also sparks a playful, rebellious spirit—flipping conventions upside down, pushing boundaries, and inviting experimentation. The result is a suite of actionable interventions that any community can adopt to a diversity of projects.

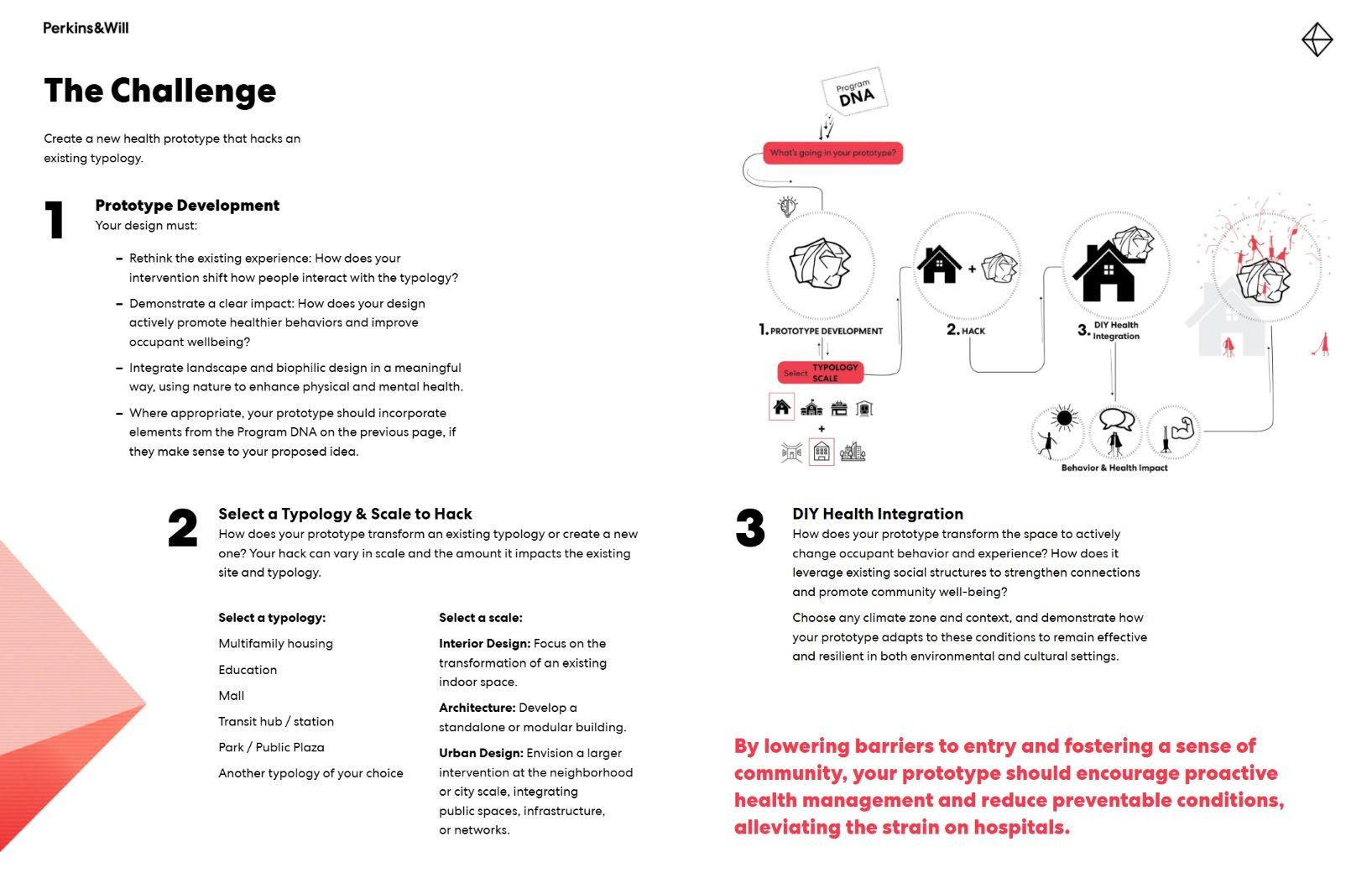

The challenge given to the teams was to develop a prototype. One where they were hacking a typology and scale of their choosing, and where they would need to demonstrate how their intervention would positively impact behavior and health of the occupants.

A Global Problem

Anywhere, Any Typology.

MAP OF PROJECTS

The graphic represents the variety of project locations we received. We can learn so much from various cultures, climates and typologies around the world.

Why no Site?

Rather than prescribing a specific building or locale, we issued an open ended challenge: choose any site, of any typology, anywhere in the world, and propose a prototype that measurably improves occupant health. This “no site, no typology” format celebrated our firm’s international diversity, from updated North American strip malls to Ayurvedic gardens in India, refugee housing prototypes in the middle east, and beyond. Teams drew on local context and cultural insights to surface health gaps unique to their communities, then shared those insights across the firm. The outcome was a rich dialogue of global viewpoints, united by the belief that health belongs in every space, everywhere. There is so much we can learn from the problems and solutions found in other cultures, climates, policies, environments.

A variety of typology options as suggestions provided for the competition

showcasing the diversity and variety of projects we received.

Health isn’t—and shouldn’t be—confined to the hospital.

Why Not Just the Hospital?

Why didn’t we simply assign a hospital for this challenge? Because health isn’t—and shouldn’t be—confined to the hospital.

Our expertise in healthcare architecture is deep, and it remains essential. Hospitals will always be necessary. But they are not enough. If we truly care about public health, we must look beyond the clinic and the emergency room. We need to consider how all the spaces people inhabit—every single day—can play a role in keeping them well.

The leading causes of death globally are noncommunicable diseases (NCDs): chronic conditions like heart disease, diabetes, and respiratory illnesses. These diseases are deeply tied to our lifestyles, our environments, and the degree to which we have access to preventive care. Hospitals can help manage these conditions, but they cannot reverse the years of influence from poor air quality, food deserts, sedentary lifestyles, and social isolation.

Health is made in the everyday moments outside the hospital. That’s why we challenged teams to rethink how design can “hack” health into daily life. Not by adding more hospitals, but by expanding typologies, merging programs, and creating environments where wellness is simply part of how the space functions.

We are missing a huge opportunity—and an underserved market. Every building, not just healthcare buildings, should support occupant health. That goes beyond highperformance HVAC or daylighting. It’s about programming, resources, access, and design strategies that nurture wellness in holistic ways.

If we limit our health practice to healthcare buildings, we’re reinforcing a system focused on treatment over prevention. We’re designing for illness rather than investing in well-being.

Wellness is multifaceted. The eight dimensions—physical, emotional, intellectual, social, spiritual, occupational, environmental, and financial—are all shaped by the built environment. How a space makes us feel, whether it fosters connection or isolation, whether it energizes or depletes us—these are as vital to health as clean air, low-toxicity materials, and circadian lighting.

Of course, design alone can’t solve every health issue. But the environment can provide a foundation—one that makes it easier to move, to eat well, to rest, to connect, and to care. And when spaces invite us to be better to ourselves and each other, that’s when we see true health equity begin to take root.

Abstract artwork representing health for all

Equity

It can be a privilege to walk into a hospital and receive treatment. But here’s the truth: around 75% of global deaths are caused by NCDs—chronic conditions like heart disease, diabetes, and certain cancers—that cannot simply be “cured” in a hospital. These are slowdeveloping illnesses deeply rooted in lifestyle, environment, stress, diet, and access to preventive care. Modern medicine can manage them, but it cannot undo years of systemic and behavioral neglect.

So why does our system place so much emphasis on hospitals? The most expensive, specialized health interventions are often reserved for people who already have the privilege—financial, geographic, or educational—to access them. Meanwhile, the upstream causes of illness—sedentary lifestyles, ultra-processed food, social isolation, and polluted environments—remain unaddressed.

Wellness needs to be decentralized. Practices like movement integrated into daily life, access to whole, unprocessed foods, opportunities for mindfulness, and social connection are not confined to hospitals, clinics, or even gyms. These should be embedded into the design of our everyday spaces—from workplaces to schools, from homes to transit stations.

Convenience is a silent killer. Our built environments often prioritize speed and efficiency over exercise, nourishment and rest. If we want to create more equitable health outcomes, we must prioritize wellbeing by design.

Hospitals are essential, but they are not where health is built. Healthcare buildings are expensive to construct, operate, and visit. Most of us don’t need a hospital every day. What we do need are public spaces, homes, neighborhoods, and workplaces that make healthy choices easy, accessible, and habitual.

Take the Blue Zones, for example—regions around the world where people live the longest, healthiest lives. These communities don’t rely on gyms or cutting-edge hospitals. Their secret? A lifestyle deeply embedded in their environments: walking or biking instead of driving, fresh home-cooked meals, gardening, daily physical tasks, multigenerational social networks, and a strong sense of purpose— especially into old age. These centenarians not only live long but live well, with autonomy and joy.

This is why the work of this design competition is so critical. It underscores the need to bring health expertise into every design discipline—not just healthcare. It’s not enough to specify healthy materials or monitor air quality. We need to rethink how people move, rest, connect, and engage within spaces. We must create environments that gently nudge people toward habits and behaviors that support lifelong wellness—especially in underserved communities, where the stakes are highest and the access to formal healthcare is most limited.

We uncovered urgent stories— about refugees, restrooms, and reimagined garages.

Key Themes

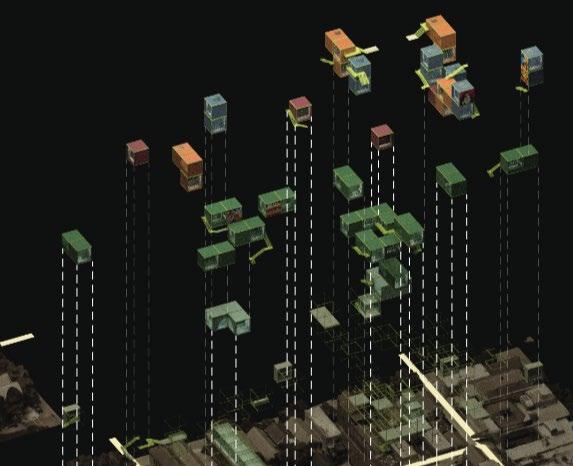

Out of 68 total submissions, teams explored a diverse range of spaces to embed health: there were 17 parks and plazas, 14 transit centers, 6 malls, 7 housing and mixed use projects, 8 that focused on education and learning spaces, 6 with a focus on mental health, 3 inbetween spaces tackling alley ways, and 3 parking garage renovations.

Despite the range of typologies, five themes surfaced again and again—cutting across geographies, programs, and design approaches: nature as a healer, joy as design driver, reclaiming the overlooked, community connection, and education as prevention.

Nature as Medicine

Outdoor Spaces

Outdoor spaces become more than scenery— they become active agents of care, connection, and renewal.

Simply put—proximity to nature improves our health. Aligning our lives with natural rhythms, allowing our environments to ebb and flow like the seasons, keeps us grounded and more deeply connected to our well-being.

This concept surfaced powerfully throughout the Phil Freelon Design Competition. Nearly every project acknowledged the role of the outdoor environment in shaping interior space. Even in regions with challenging weather, teams found ways to maintain this connection. Biophilic strategies—sun gardens, edible forests, multisensory landscapes—were not treated as luxuries but as essential tools for promoting mental clarity, physical activity, and sensory engagement.

Outdoor programming played a crucial role in bridging the built environment with nature, especially in dense urban areas where green space is scarce or often underutilized. The Urban Oasis project highlighted that while parks are essential, they frequently fall short of serving community needs. Too often, they lack diverse uses or thoughtful responses to seasonal change. The team based their project in Vancouver and emphasized designing year-round connections to nature—especially in winter, when sun exposure drops and depression rates increase. Drawing inspiration from successful examples like Bryant Park in New York, which remains active in colder months with ice skating, warming stations, and food kiosks, Urban Oasis advocated for parks that are adaptable, engaging, and resilient through all seasons.

Nature emerged as a form of medicine in the Flourish project, where growing food, communal eating, and outdoor play converged to promote holistic health. Centered around a school playground, the project demonstrated how education, movement, and nourishment could be seamlessly integrated outdoors. While therapeutic horticulture has long been practiced, recent studies have highlighted its cognitive and emotional benefits.

Nature-based design quietly restores health through movement, microbes, and immersion.

Gardening boosts physical activity—classified by the CDC as a moderateintensity exercise that burns approximately 330 calories per hour, similar to hiking or dancing. And when you grow your own vegetables, fruits, or herbs, you’re more likely to improve your diet—often increasing fiber intake, which supports digestion, reduces inflammation, and strengthens immune function.

Flourish also touched on the simple but profound impact of animal interaction. By incorporating a chicken coop into the schoolyard, the project offered children rare urban opportunities for gentle contact with animals and soil. These experiences not only build empathy and curiosity but also support immunity by introducing beneficial microbes and encouraging microbial diversity in the gut.

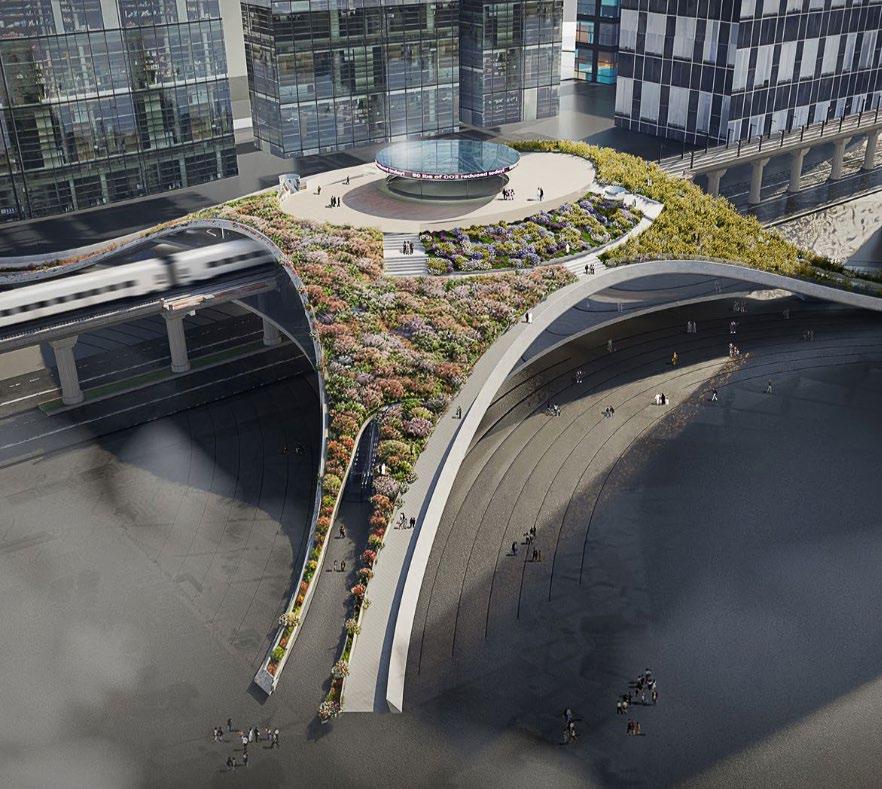

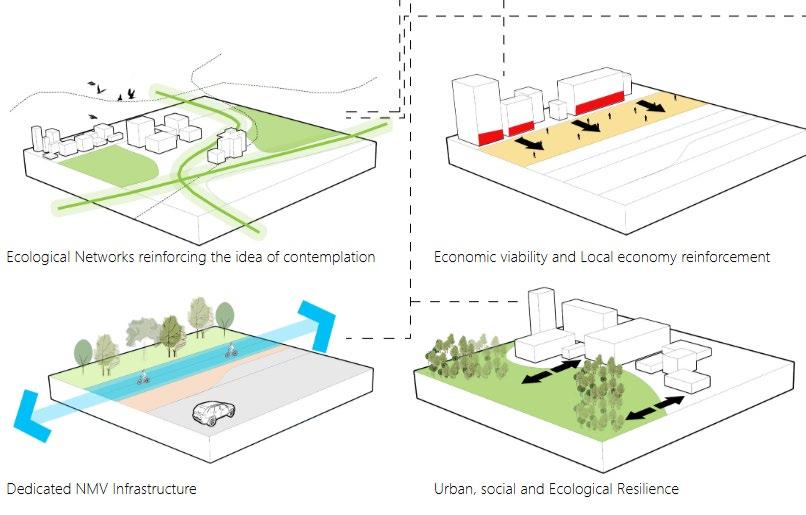

The Chronoscape project explored how to merge the best qualities of rural and urban environments. It proposed maximizing access to natural systems while preserving the density and infrastructure of the city. The design featured dynamic walking paths, cycling superhighways, and irregular terrains that created visual interest and movement. The team emphasized the restorative qualities of natural landscapes and suggested strategies for reintroducing those qualities into urban settings—through porous ground cover, plant-rich edges, and layered vistas that interrupt the monotony of concrete.

Grounding—while not explicitly addressed by the projects—also deserves mention. This simple act of physically connecting with the Earth (walking barefoot, sitting on natural ground) has measurable physiological benefits. The Earth carries a negative charge, and direct contact allows electrons to flow into the body, helping neutralize free radicals, reduce inflammation, and decrease oxidative stress. Designing safe, accessible places for people to connect with the Earth can be a subtle but powerful way to restore balance.

Finally, (n)ode to Life offered a poetic interpretation of outdoor programming as prescription. The project created sensory nodes tailored to specific health outcomes. For sleep enhancement, for example, the proposed node was a moon garden—a serene retreat immersed in flowing water, soft soundscapes, and gentle light. It supported circadian rhythms by reducing artificial light and technological overstimulation, creating a calming, immersive natural experience as a counterpoint to the modern pace of life.

Play

and joy are powerful for healing

Joy is not extra—it’s essential to health, connection, and longevity.

Play and joy weren’t mere embellishments but they were recognized as core ingredients of well-being. Health, in this context, was not portrayed as a burden or a clinical task, but as a source of pleasure, social connection, and daily engagement. Many interventions seamlessly wove play and movement into everyday routines, acknowledging that laughter, spontaneity, and physical activity are essential to wellness at every age.

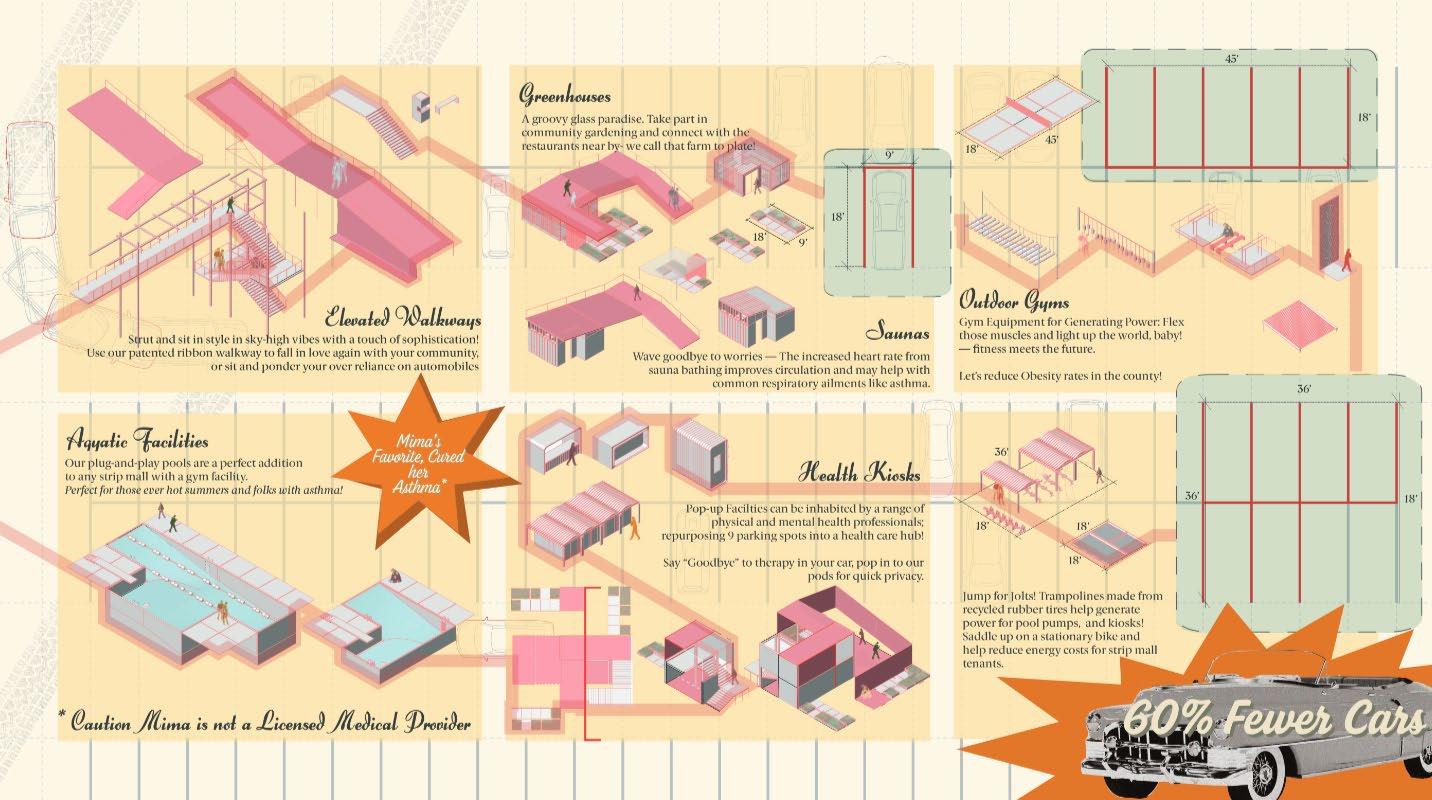

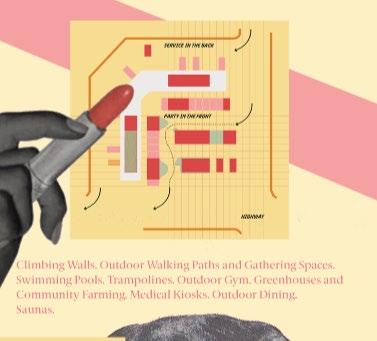

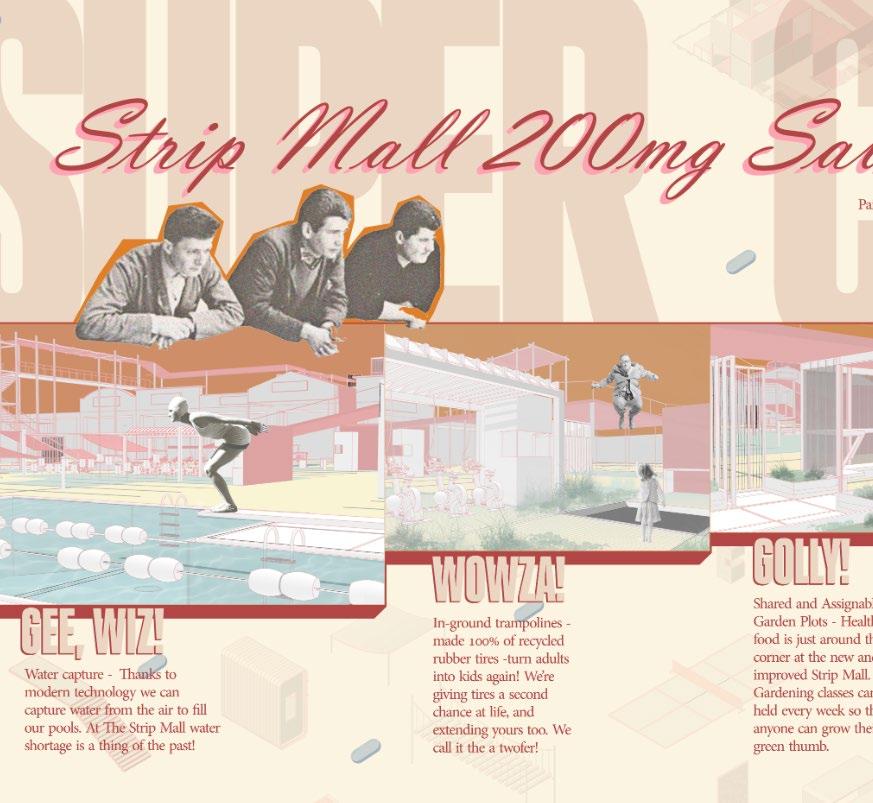

One of the most effective stress relievers is laughter. Rx Strip Mall 200mg cleverly embraced this by reimagining the strip mall—a tired and underutilized typology—as a place full of fun and delight. The team subverted the typical associations of healthcare as sterile or intimidating, instead creating an experience that was nostalgic, accessible, and engaging. Vintage graphics and narrative storytelling evoked playful memories, helping to ease anxieties around health and wellness. By working with a ubiquitous American

typology, the team reinforced the idea that systemic health challenges cannot be addressed by a single building. Instead, they proposed a modular, repeatable system based on the unit of the parking space—scalable and flexible enough to adapt across communities. The project also tackled loneliness, using the mall as a site for active and social programming to boost emotional and social wellbeing. Activities like climbing walls and trampolines gave adults the chance to move, laugh, and feel like kids again.

Flourish explored the importance of unstructured play, especially for children. Unstructured play allows kids to take initiative, learn from failure, and engage all areas of development. In an age of overscheduling and academic pressure, even 60 minutes of free play—particularly outdoors—can yield lifelong cognitive and emotional benefits. Animal studies show that play deprivation stunts prefrontal cortex development, and similar effects have been observed in cases of human

neglect. Moreover, self-directed play enhances neuroplasticity, fostering integration between emotion and cognition—key ingredients for healthy brain development.

Joy also stems from experiences that align with our values, goals, and sense of purpose. An 85-year longitudinal study on adult development found that strong relationships—often built through shared joy—are among the strongest predictors of longterm health and life satisfaction.

Joy naturally strengthens social bonds, from close friendships to broader community ties. Many of the competition entries reflected this truth, emphasizing that fostering joy and connection isn’t a secondary benefit of good design—it’s central to creating healthier lives and communities.

Reclaiming Space

Underused/Unsuccessful spaces

Many proposals focused on transforming underutilized or overlooked spaces—parking lots, strip malls, rooftops, and transit hubs—into vibrant, health-supporting environments.

A Tale of Two Alleys explored how neglected alleyways and underused pockets within two adjacent city blocks in Pilsen, a neighborhood in Chicago, could become an interconnected wellness hub. Taking a “neighborhood block” approach, the team envisioned a series of modular wellness spaces distributed throughout the site. Each module, derived from a flexible “kit of parts,” was designed using location-specific data via the open-source tool PRECEDE. Some focused on reconnecting residents with nature; others addressed urban challenges like the heat island effect.

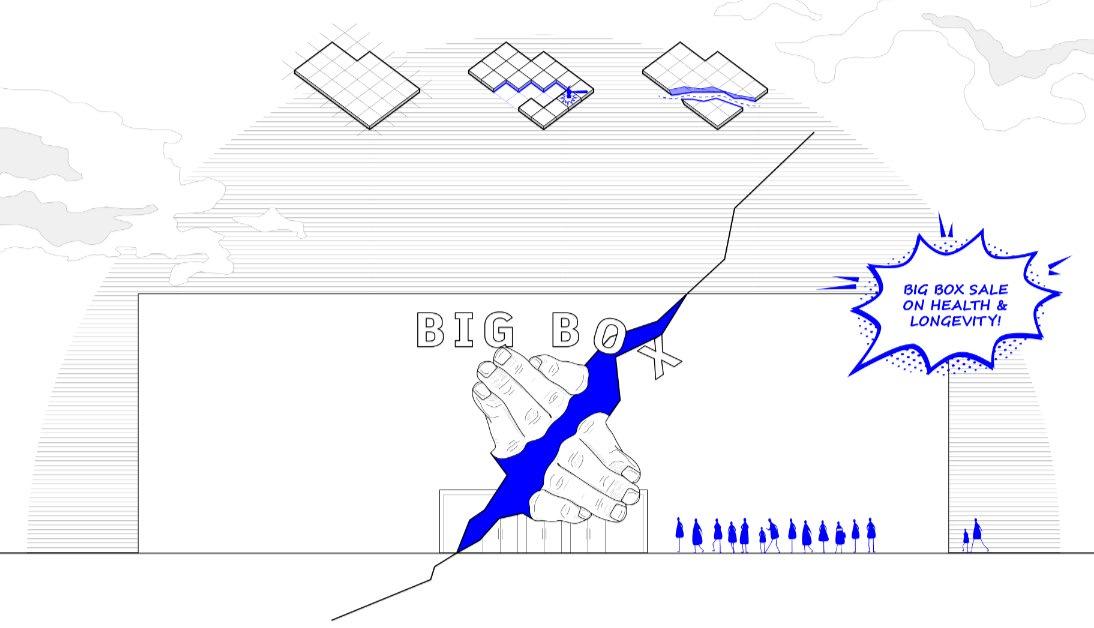

Big Box reimagined the widespread infrastructure of largescale retail stores in the U.S., proposing their adaptive reuse to support public health and everyday well-being. Notably, while approximately 80% of U.S. counties are considered health deserts, 90% of the population lives within 10 miles of a big-box store. This proximity presents a powerful opportunity to expand access to preventive care, health education, and community services—bringing better choices closer to where people already are.

A familiar space, radically rethought—public restrooms paired with adjacent hubs for care, nourishment, and community.

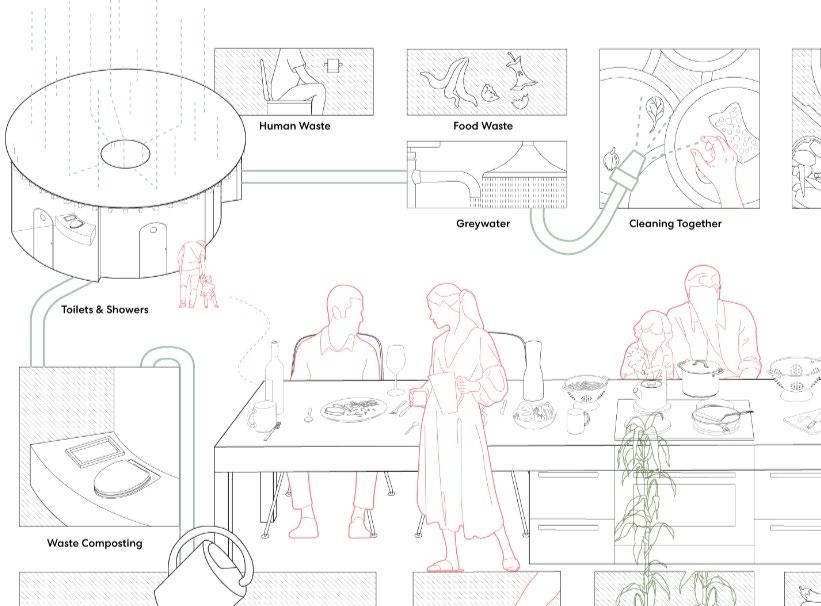

One often-overlooked but deeply familiar space is the public restroom—something everyone has searched for and often found disappointing. Beyond Necessity took this utilitarian space and reimagined it as a dignified, inclusive place for sanitation, nourishment, and social connection. These redesigned public restrooms, located in high-traffic areas, incorporated community pantries, seating and dining areas, and wellness programs—creating micro-hubs for both physical and mental health. The project also highlighted the value of intergenerational gathering, transforming the restroom into a space that brings people together at a fundamental, human level.

Reclaiming space and time.

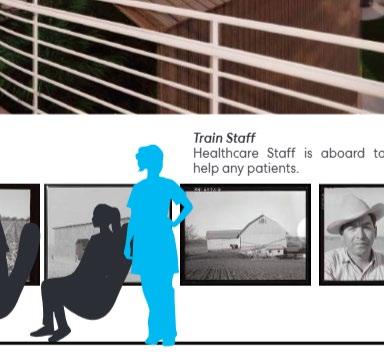

Transit spaces were another recurring focus. Several projects saw potential not only in the physical spaces near transit stations but also in the underutilized time people spend waiting or commuting.

Get Ground Go placed health check-up stations inside train stations, offering quick, on-the-go assessments for travelers. Hart Centers positioned health services, activity zones, and gardens near residential transit connections, emphasizing walkability and the proximity of care to daily routines. Kykloi capitalized on the often-forgotten space beneath sky trains, installing modular wellness pods that could be adapted based on community needs—an elegant example of using existing infrastructure to support flexible, localized care.

The Ranch: A Healthcare Community by Biologenius proposed bringing care directly into transit itself—through mobile train cars that not only provide healthcare on the move but also connect passengers to a rural health destination: The Ranch. This retreat-like setting offered abundant access to nature, animals, trails, and open space—amenities often lacking in dense urban environments.

A powerful sub-theme within these underutilized spaces was the reimagining of areas traditionally dedicated to cars. Parkitecture proposed converting Dallas’s parking garages into adaptive health hubs. Using the parking space module as a framework, the design allowed for incremental implementation—turning static, underused infrastructure into dynamic spaces for health checkups, community gathering, and physical activity. Importantly, the concept is scalable and replicable across cities, reclaiming cardominated land for human-centered purposes.

Finally, PulsePlay addressed the temporal underuse of school buildings. Recognizing that these valuable community resources sit vacant in the evenings, the project proposed opening schools after hours to host wellness programs, recreational activities, and social events—extending their purpose beyond education to support broader community health and resilience.

Connecting Community

Human connections and mental health

We’re more connected than ever, yet lonelier than before—design can address that.

Social isolation and mental health emerged as urgent concerns addressed through efforts to rebuild connection— especially between generations. We are increasingly disconnected not only from our neighbors and communities but even from our own families. As our lives become more entangled with technology—through remote work, constant notifications, and curated social media feeds—our opportunities for genuine, in-person connection continue to shrink. This shift is quietly eroding our mental health, leaving many of us feeling isolated, unseen, and without a true sense of belonging.

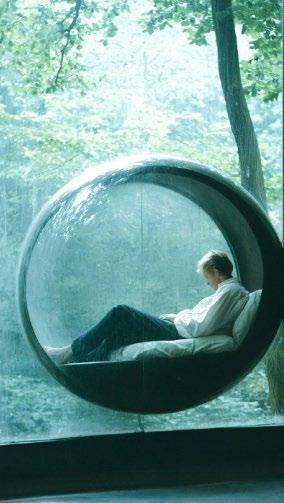

In a world of constant digital noise, the Disconnect to Reconnect concept offers a deliberate counterbalance. It creates a structured experience where individuals can temporarily step away from screens and distractions, engage in self-reflection, and ease into a more mindful and connected state. Combining solitude, sensory therapy, and community interaction, the space helps participants regain clarity, emotional balance, and a deeper connection to themselves and others. The mental health effects of constant screen time are especially acute in younger generations, where in-person socialization is declining, and attention spans are rapidly shortening. Encouraging moments of disconnection—especially in nature—can help rewire our minds for presence, calm, and focus.

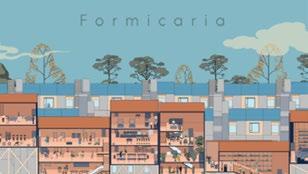

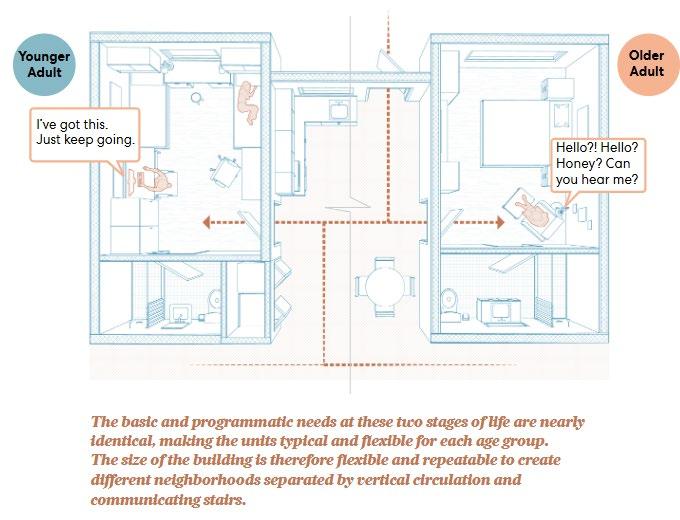

Today, fewer people interact with generations outside their own. As families are located farther apart, aging parents often live alone, and many young people move away for education or work. These trends leave large groups—especially the elderly and students—more vulnerable to loneliness, with limited access to everyday support. Formicaria addressed this gap by creating an intergenerational cohabitation model that connects college students with older adults. Students help elders with

errands, companionship, and conversation, while receiving wisdom, mentorship, and emotional support in return. The result is a mutually beneficial relationship that fosters belonging and shared purpose.

Research supports this approach: grandparents recover faster from illness when regularly engaging with their grandchildren, and intergenerational contact is linked to greater longevity and life satisfaction. However, with many people delaying childbirth, today’s aging adults are less likely to have grandchildren nearby, often aging in isolation. At the same time, studies show today’s college students increasingly need emotional and physical support—and don’t always feel safe or supported on campus. Formicaria’s model of connecting these two typically separate groups reveals powerful mental health benefits and stronger social cohesion.

Nudge theory suggests that subtle changes in our environment can encourage healthier behaviors without restricting personal choice. Over time, these small shifts can evolve into lasting lifestyle habits. The Conservatory explores how technology can support such environmental nudges— for instance, by monitoring daylight levels and adjusting indoor lighting to align with our natural circadian rhythms. The project also emphasizes community connection and engagement by incorporating shared spaces like gardens and rooftops, which help reduce isolation and support mental well-being. These outdoor amenities offer a healthy, accessible way to enhance daily life within an apartment complex. Importantly, the design encourages interaction across different household types—for example, by having a one-bedroom and a four-bedroom unit share a common open space. This subtle arrangement fosters unexpected, meaningful connections that may not occur when similar units are clustered together.

Anadroma reimagines the refugee shelter not as a temporary site of survival, but as a dynamic hub for healing, growth, and integration. Drawing from the term anadromous—referring to a return in stronger form—the project sees refugees not as passive recipients of aid but as active agents of transformation, both in their own lives and in the communities they join. By embedding education, economic opportunity, and cultural exchange into the fabric of the shelter, Anadroma reframes displacement as a journey toward empowerment.

Anadroma reframes displacement as a journey toward empowerment.

At its core, Anadroma champions connection as a foundation of health—connection to self, to others, and to place. The design fosters shared spaces and social interaction with host communities, encouraging collaboration, mutual understanding, and inclusion. Rather than isolating refugees, it weaves them into the broader social and economic fabric, building relationships that strengthen resilience, reduce stigma, and create a genuine sense of belonging.

Reimagining care as a collective, inclusive experience woven into the heart of community life.

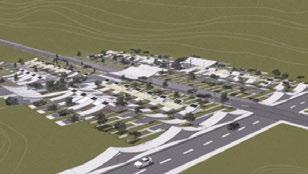

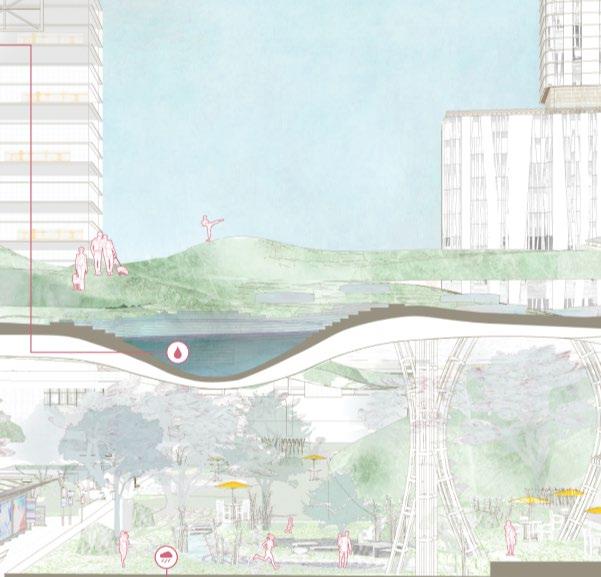

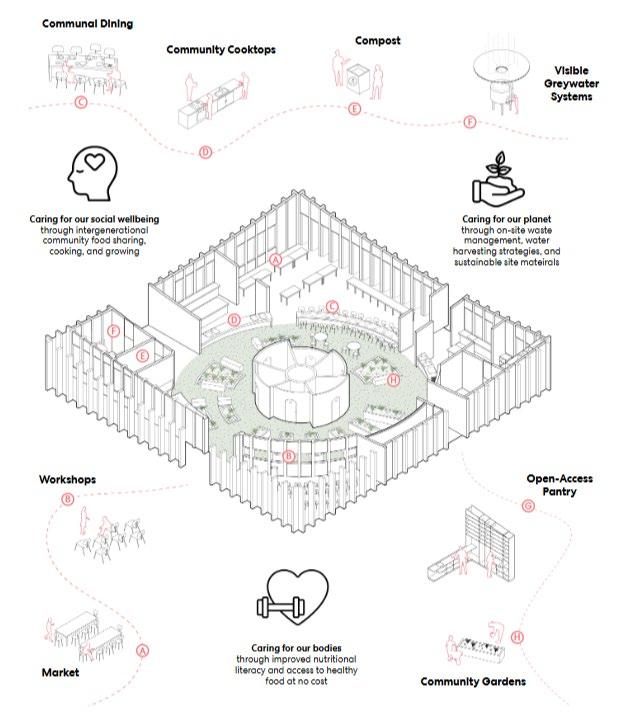

↑ Monumental Community Care

Monumental Community Care reclaims Detroit’s historic Michigan Central Station—a long-abandoned icon of disinvestment—and transforms it into a vibrant hub for collective healing, learning, and connection. Inspired by the concept of a “third place,” the project offers opportunities for people of all ages to engage in holistic well-being through nature, movement, curiosity, and culture. It acknowledges Detroit’s history of fragmentation and economic decline while imagining a future rooted in regeneration. Shared gardens, flexible learning environments, and intergenerational programming invite community members to gather, heal, and grow together. In this vision, restoring the station is not just about architecture—it’s about restoring community, connection, and care.

Across today’s healthcare systems, caregiving is often shouldered by one individual, while those needing care are siloed—confined to sterile nursing homes, hidden from public view, or left without accessible, inclusive spaces. What if, instead, care was reimagined as a shared responsibility supported by environments designed to meet physical, emotional, and social needs?

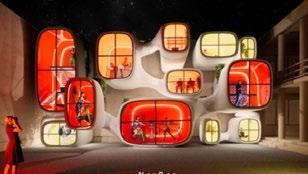

↑ Neuroinclusiv-City

Neuroinclusiv-City envisions an inclusive care ecosystem built into the fabric of everyday life. It rethinks health not as an isolated service but as a neighborhood-wide experience—one that responds to diverse neurological and physical needs. Rather than relegating care to the clinic, it distributes it across spaces that are warm, welcoming, and full of life. The project proposes a vibrant mosaic of places where people of all identities and abilities can thrive together, weaving neurodiversity and care directly into the community experience.

Anxiety and Screen Time

When neighborhoods trade screen time for shared gardens, bathhouses, and blue spaces, they transform isolation into belonging and stress into calm.

While projects like Disconnect to Reconnect and Formicaria respond to the erosion of community ties, the data behind this trend is sobering. Social media and screen-heavy lifestyles are strongly linked to rising rates of anxiety and depression, especially among youth. Excessive screen time replaces face-to-face interaction, shortens attention spans, and increases feelings of isolation. Even as online connections multiply, the depth of real-world relationships diminishes.

Research shows that teens and young adults who spend hours on passive digital engagement—scrolling, streaming, or multitasking—report higher levels of anxiety and loneliness than those with more offline social interaction.

Between July 2021 and December 2023, half of U.S. teenagers ages 12–17 logged four or more hours of daily screen time. Among these heavy users, roughly one in four reported experiencing anxiety (27.1%) or depressive symptoms (25.9%). The paradox is clear: greater digital connectivity often fuels anxiety, depression, and a weakened sense of belonging.

This is why many competition projects emphasized creating real-world opportunities for shared experience—gardens, intergenerational housing, neighborhood programs, and public gathering spaces. By designing environments that invite people to interact face-to-face, move, and participate in meaningful community life, we begin to counter the silent mental health crisis driven by isolation in a hyperconnected age.

Bathing Culture exemplifies this approach. The project reimagines the communal bathhouse, a typology that promotes health while fostering community. Beyond their cleansing function, bathhouses tap into the profound link between water and well-being. Water-based experiences— from hydrotherapy to simply being near water—are shown to reduce stress, improve mood, and prevent certain health issues.

“Blue space,” or proximity to water, offers measurable benefits: living within one kilometer of blue space significantly lowers the risk of premature death from multiple causes. Just 20 minutes near water can improve sleep, quiet racing thoughts—especially in people with anxiety or PTSD— reduce cortisol levels, lower blood pressure, and calm the nervous system. Even simply looking at water activates the prefrontal cortex, the part of the brain that regulates mood, focus, empathy, and emotional balance.

Bathhouses and other water-centered spaces also provide a rare chance to unplug. Time spent in water is time away from screens, opening space for reflection and face-toface connection. In this way, the project transforms a simple act of bathing into a catalyst for mental health and community resilience.

↑ Disconnect to Reconnect

Learning & Health

Education

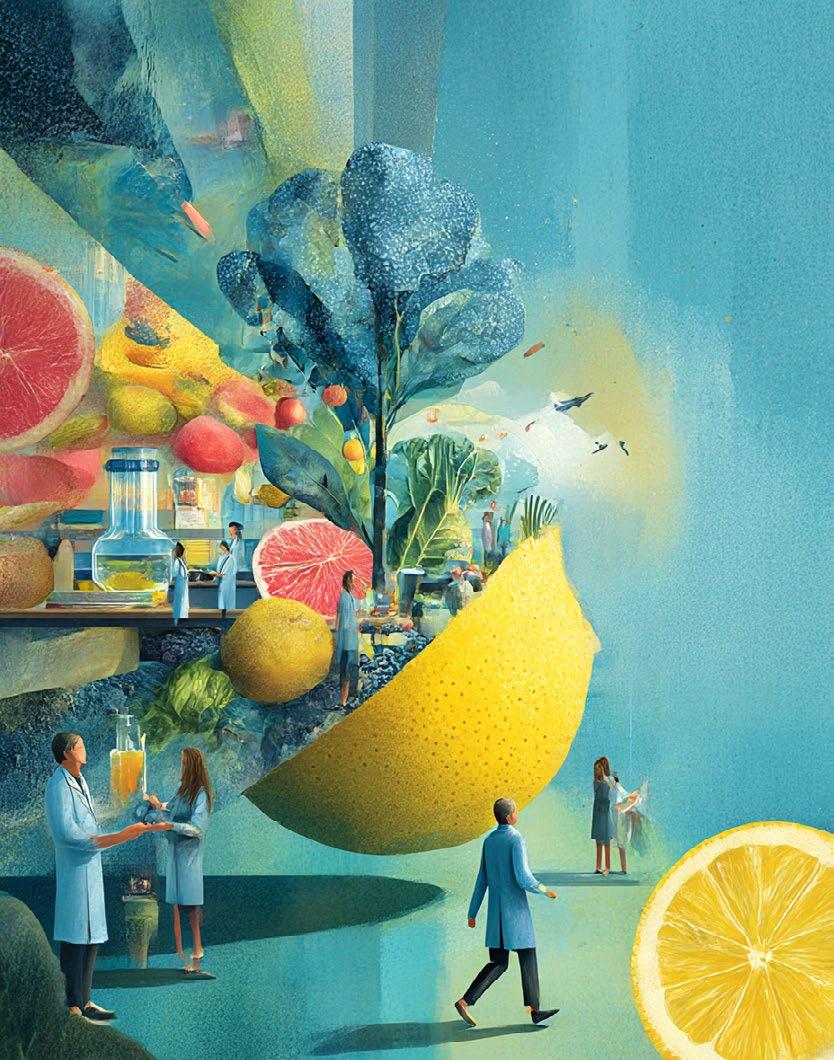

Several teams focused on reconnecting communities to food through gardens, food labs, and nutrition workshops embedded within schools, libraries, and community centers. These interventions empowered individuals through hands-on experiences and shared knowledge, encouraging sustainable eating habits and strengthening food literacy at the community level.

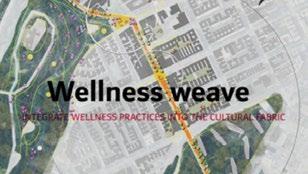

Wellness Weave took something as simple as walking and transformed it into a curated journey of wellness and education. The project proposed a scalable urban strategy that integrates learning, health, and community engagement directly into the city’s fabric. At the heart of the concept is the Cohesion Spine—a dynamic pedestrian pathway linking schools, parks, and public institutions through a network of wellness corridors, flexible health pods, and neighborhood hubs. This model encourages proactive health practices as part of everyday life, fostering social connection and expanding access to lifelong learning. Easily adaptable to different cities and contexts, the prototype envisions a future where walking becomes not only a form of movement, but a shared ritual of wellness and collective experience.

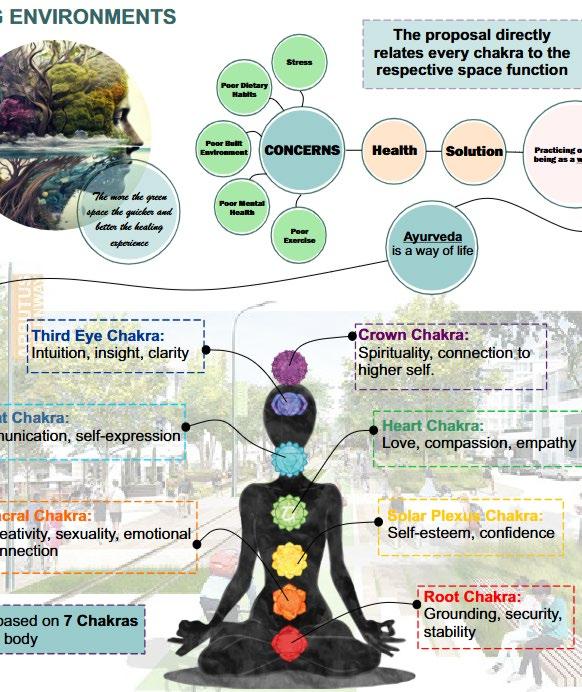

Healing Bridges drew on Ayurvedic principles, emphasizing wellness as a lifelong journey rather than a one-time intervention. The project highlighted the importance of reconnecting with ancestral knowledge—turning to elders, cultural traditions, and food practices that have historically supported health. Many of these practices are disappearing, especially as traditional diets shift toward more processed, Western patterns. For example, Indian communities historically shaped by famines and droughts have adapted biologically to store fat more efficiently—an advantage in times of scarcity, but now a potential risk factor when combined with sedentary lifestyles and modern diets. By understanding this kind of intergenerational and biological context, individuals can be better equipped to make informed decisions about their health. Healing Bridges encouraged communities to reframe health not as something external or clinical, but as something rooted in one’s history, culture, and way of life.

“In the end, we conserve only what we love; we will love only what we understand; and we will understand only what we are taught.”

Beyond the Bell emphasized why schools are such vital sites to “hack” for health and well-being. The project opened with a quote from Senegalese forestry engineer Baba Dioum:

“In the end, we conserve only what we love; we will love only what we understand; and we will understand only what we are taught.”

While originally referring to conservation, Beyond the Bell connected this same principle to health—arguing that our understanding, appreciation, and care for our own well-being must also be taught.

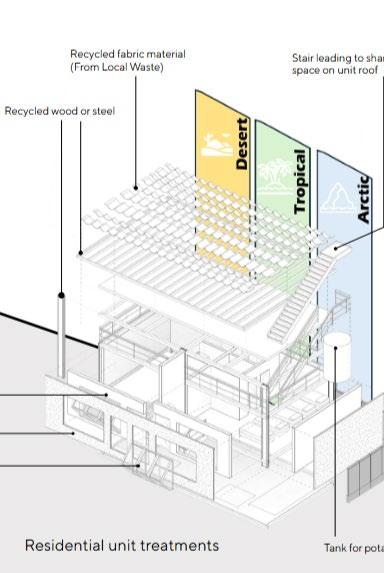

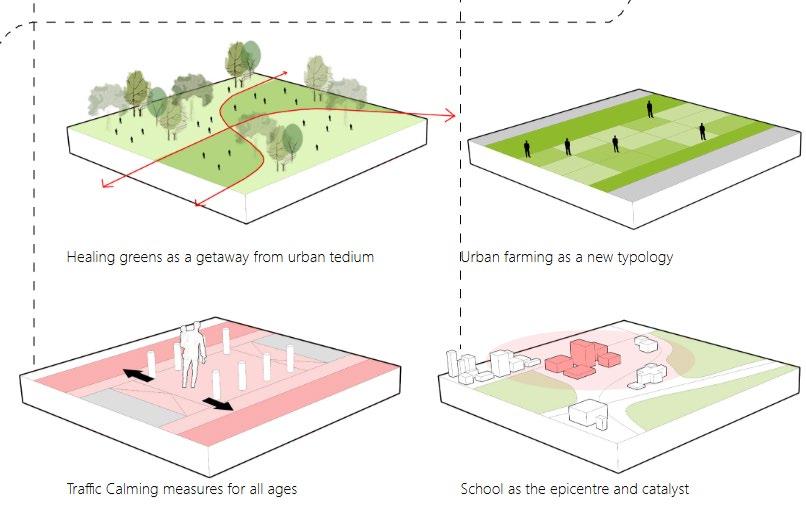

Like PulsePlay, the project proposed extending the school’s purpose beyond classroom hours. It focused on transforming underutilized outdoor areas—such as schoolyards and rooftops—into spaces for physical activity, community gatherings, and urban farming. The idea is simple but powerful: health starts with what we eat. By linking schools with urban agriculture and broader community uses, the project envisioned a mutually beneficial partnership between educational institutions and their surrounding neighborhoods.

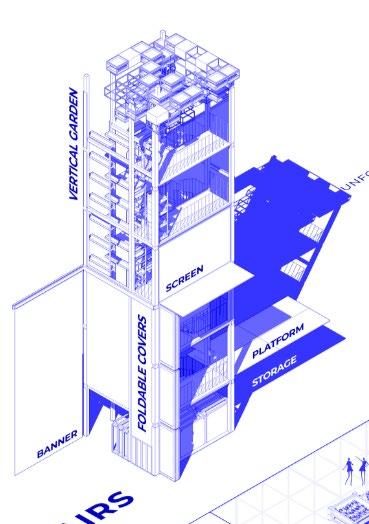

Institution as Urban Catalyst proposed a new school typology that integrates pedestrian networks and urban farming as a way to foster healthy lifestyles. The school becomes more than a place of learning—it becomes a sustainable hub for well-being and environmental stewardship. Urban farming sits at the heart of this vision, encouraging students and local residents to participate in growing their own food. With features like rooftop gardens, vertical farms, hydroponic systems, and community planting plots, the school extends beyond its walls, embedding healthy practices into daily life.

This model reconnects people with where their food comes from, bridging the growing urban disconnect from nature and agriculture. It becomes an educational tool that not only teaches academic subjects, but also instills habits that promote physical, mental, and environmental health. Education as Urban Catalyst thus becomes a driver of broader urban transformation. By incorporating principles from Blue Zones—communities known for longevity and well-being—the school becomes a model for future urban design. It nurtures and empowers communities through a holistic approach to education that combines human health, climate action, economic sustainability, and social unity. Ultimately, it equips the next generation with the tools to confront the intertwined challenges of climate change, chronic illness, and community resilience.

Around the world, there are powerful examples of how schools can teach lifelong healthy habits. In Japan, public schools implement Shokuiku—a national food education program that treats school meals as a living textbook for lifelong healthy eating. This approach emphasizes that education and health go hand in hand, and that schools are the first and most consistent place to instill healthy

habits, knowledge, and skills. As of May 2021, 99.7% of public elementary schools and 98.2% of junior high schools in Japan provide school meals, integrating nutrition, culture, and social connection into daily life.

France offers another example where school lunches are designed as communal, educational experiences that build culinary awareness and healthy eating habits. Students sit down together for four-course lunches during a 1.5 to 2 hour meal. More than half of these meals are prepared in-house, either in a school kitchen or a district-run satellite kitchen. These lunches are intentionally nutritious, balanced, and enjoyable, reinforcing the idea that eating well is a shared cultural value. Most primary and secondary schools in France offer this experience, making healthy, communal dining a cornerstone of the education system.

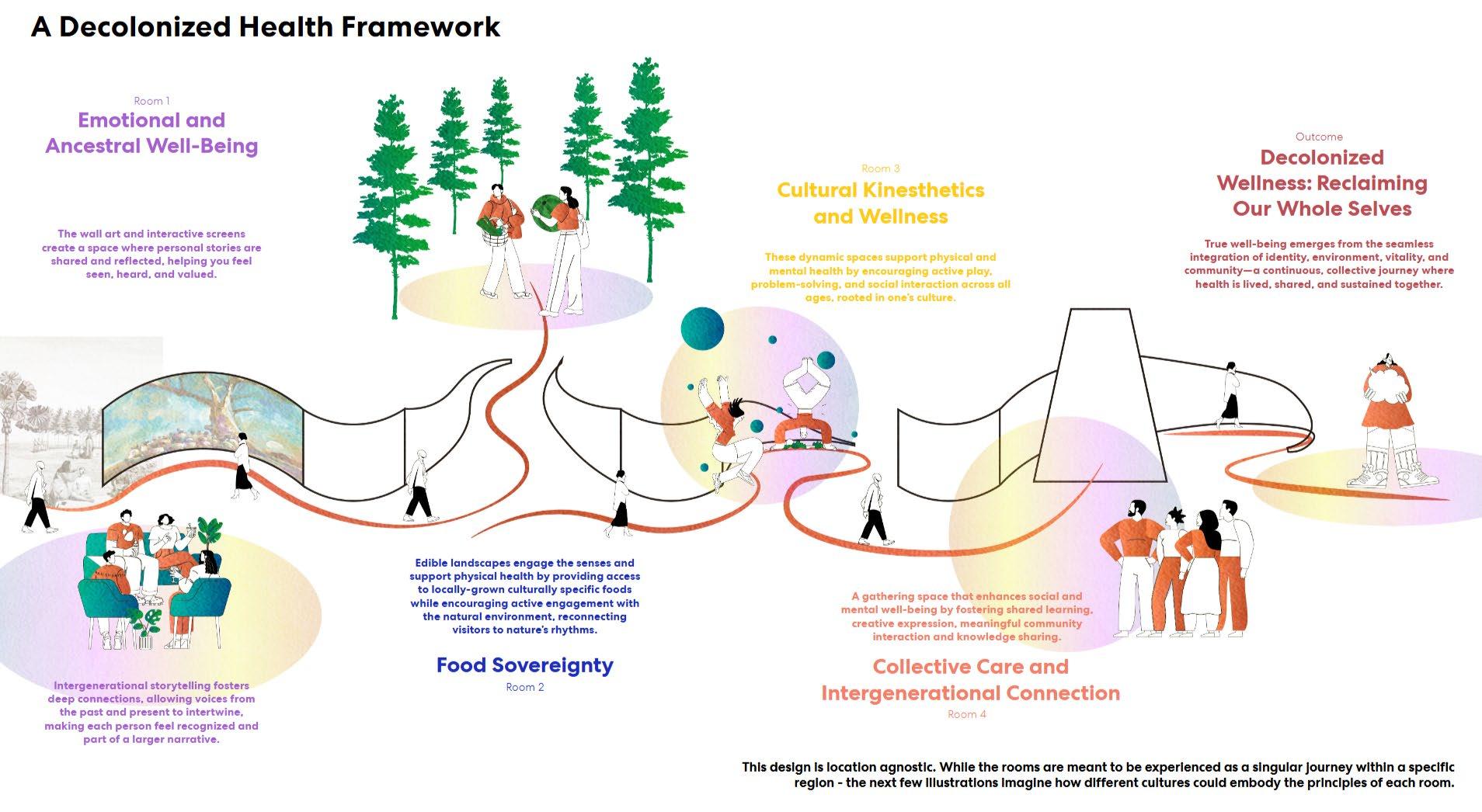

Decolonizing Health through Mythology explored the urgent health inequities faced by people of color and Indigenous communities in a globalized world. Disconnection from ancestral lands, cultural identity, and traditional support systems has contributed to stark disparities. For instance, suicide rates among Indigenous peoples are 2.5 times the national average, while Black Americans face a 77% higher prevalence of diabetes. These are just two examples of the many disparities impacting marginalized groups.

The project emphasized the healing power of cultural grounding—reconnecting to food sovereignty, community, and ancestral wisdom—as essential components of holistic health, often overlooked by Western paradigms. In this, it echoed the values of Healing Bridges, which also recognized how health and equity are deeply entwined with culture and place. These projects highlight the need to understand how different regions, histories, and identities shape the ways people experience and respond to health issues.

Education is the first prescription for preventive health—empowering people to understand, own, and transform their well-being at the root.

The link between education and health is crucial. It is within learning environments that mind-set shifts occur—often the first, most significant step toward preventive health. Education plants the seed for lasting change. Transparent and accessible information around health empowers individuals to understand the root causes of their conditions, whether those stem from family history, environmental exposure, or lifestyle. Rather than merely treating symptoms, education paves the way for people to take sustainable, informed ownership of their well-being.

Weaving Into Healthcare

A health ecosystem

The future of care blends hospital expertise with everyday environments designed to nurture well-being.

metaphor for health

Hospitals should represent just the tip of the iceberg in our broader health practice. While they will always be essential— especially when acute illness or injury strikes and preventive care is no longer enough—they should not be the only places where health is addressed. Now, we have the opportunity to consider how ideas from the competition might be woven into hospital environments themselves.

Many projects emphasized joy, connection to nature, and the integration of health into everyday spaces—places people regularly visit, move through, and learn from. They envisioned environments that adapt with the seasons and respond to human needs. They reconnected generations that have long been separated. These principles don’t need to stay outside the hospital—they can help reshape how we think about care, healing, and the environments that support both.

So, what can we learn from these projects? And how can we apply these principles to all the spaces we design moving forward?

A Design Framework for Health Everywhere

1. Nature & Connection to Outdoor Spaces

nj Thoughtfully program outdoor areas to meet diverse needs—spaces for gathering, reflection, play, food, or rest.

nj Design for all seasons and weather conditions. How can your design maximize time spent in connection with nature, even during winter or extreme heat?

nj Is there an opportunity to grow food? Consider how gardening can foster community, promote learning, and improve both mental and physical health. Think about connections to animals and biodiversity, and how these interactions support well-being.

nj Bring the rural into the urban. Use nature as a tool to realign people with their circadian rhythms.

2. Joy

nj Design opportunities for play and delight—for all ages, not just children.

nj Include informal spaces that support unstructured, creative play.

nj Remember that joy also stems from a sense of purpose, meaning, goals, and connection. Are your spaces nurturing this kind of joy?

3. Underutilized Spaces

nj Identify spaces that are currently underused. Can you maximize their impact through minimal interventions?

nj Think beyond typical typologies: parking garages, vacant storefronts, empty alleys, neglected public restrooms—how can these be transformed into places of health, activity, and connection?

nj Consider the rhythms of time: how do these spaces function throughout the day or across seasons? Could they serve new purposes in the evenings, or be activated during off-hours?

4. Connection

nj Are you creating opportunities for meaningful connection—especially across generations?

nj Consider how your design fosters community ties: with neighbors, between age groups, and by helping people disconnect from their screens to reconnect with one another.

5. Education

nj Embed learning into daily life—whether through signage, shared activities, or cross-generational exchange.

nj How can we design spaces that allow people to learn from one another, especially from the wisdom and lived experiences of older generations?

As you apply this framework, ask:

Who are you designing for? What are the unique risks to their health and well-being? Are there existing spaces that serve them (e.g., schools, elder care facilities)? How do these spaces align with—or diverge from—this framework?

And finally, consider time, scalability, and systems thinking. Does this project connect with other programs, site elements, or community needs in a meaningful way? Can the concept be repeated elsewhere? Are you creating something that others can learn from? And can your lessons—and your impact—extend beyond this one site?

Call to Action: Health Everywhere, for Everyone

Design has long influenced behavior. Now it must intentionally shape health. Waiting for specialized buildings or costly programs is no longer an option. Instead, we must start where we are—in the everyday spaces of offices, parks, schools, malls, and streets—and transform each into an opportunity for better health. This shift not only addresses immediate needs but also creates healthier systems that endure, are sustainable, resilient, and built to last.

Health doesn’t have to be a distant destination. It’s something we build into every day, everywhere. Join us in sharing health hacks, advocating for change, and embedding well-being into the very fabric of our environments and culture.

Credits & References

CONTRIBUTING AUTHORS

Devika Tandon, Project Designer, Ed Feiner Fellow

ACKNOWLEGDMENTS

Thank you to Casey Jones, Chief Design Officer, and Marie Henson, Global Health Practice Leader, for their guidance and support in shaping the development of this paper. Thank you to all of the participating teams for inspiring us with so much incredible work. Thank you to all the Juror Reviewers for their insights and comments on the projects.

PROJECTS REFERENCED

(n)ode to Life

Isidora Elcic, Una Bakovic

A Tale of Two Alleys

Megan Clevenger, Rafi Alam

Anadroma

Ahmed Zaki, Mahmoud Wael, Abdullah Kamalabdeen, Antony Ibrahim

Beyond Necessity

Abubakr Bajaman, Emily Chee, Chuhan Zhao, Miucci Yung

Beyond the Bell

Mohammad Qubbaj Nadia Abu Jbarah, Nayrouz Ali, Tarq Alrashdan

Big Box

Rachel Francescon Barroso, Julian Menne, Belle Marty, Liwen Shi

Chronoscape

Veronica Paulon, Victoria Wong

Conservatory

Margo Cochell, Lily Srouji, Jennifer Kim, Annika Olson

Decolonizing Health through Mythology

Sharvari Raje, Serena Lousich

Disconnect to Reconnect

Amr Hatem, James Chen

Flourish

Corey Phelps, Joshua Gripton, Luke Christensen, Joe Wilfong

Formicaria

Lisa LoGiudice, Marlen Veith, Prakriti Vasudeva, Amir Heydarpour

Get Ground Go

Taymour Zeineddin, Arunkumar Mariappan, Daniil Leover, Solan Horo

Hart Centers

Shreya Gera, Ayeh Aburayyan, Jiong Wang, Jett Misuraca

Healing Bridge

Aparna Varma, Aishwarya Divekar, Shivam Agrawal

Institution as Urban Catalyst

Tulsi Bhardwaj, Nikhil Salunke, Shraddha Nagotanekar

Kykloi

Luciano Siffredi, Kemeng Gao, Glenn Veigas, Chelsea Wu

Monumental Community Care

Dishaddra Poddar, Clare Coburn

Neuroinclusiv-City

Sarah Brophy, Ana Soterio, Sara Segura, Danielle Baez

Parkitecture

Junye Zhou, Jeremy Cheng, Carven Chen, Dahan Xiong

PulsePlay

Mohd Altaher Al Aeffi, Hamza Albustanji, Ibrahim Mreizeeq

Rx Strip Mall 200mg

Anne-Philippe Kakou, Samuel Orlando, Felipe Florentino, Joseph McKenley

The Ranch—A Healthcare Community by Biologenius

Joseph James

Urban Oasis

Douglas Peterson-Hui, Sandro Nanic

Wellness Weave

Reem Ehab, Salma Elseoudi

REFERENCES

• World Health Organization. (2016). Urban green spaces and health. WHO Regional Office for Europe. https://www.euro.who.int/__data/ assets/pdf_file/0005/321971/Urban-green-spaces-and-health-review-evidence.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023). Health and well-being of children. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/childrens-health

• United Nations. (2016). World health statistics 2016: Monitoring health for the SDGs. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/ publications/i/item/9789241565264

• Braveman, P., Arkin, E., Orleans, T., Proctor, D., & Plough, A. (2017). What is health equity? Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. https:// www.rwjf.org/en/insights/our-research/2017/05/what-is-health-equity-.html

• Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). (2022). Environmental justice. https://www.epa.gov/environmentaljustice

• National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2017). Communities in action: Pathways to health equity. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/24624

• Marmot, M., & Wilkinson, R. G. (Eds.). (2005). Social determinants of health. Oxford University Press.

• Galea, S., & Vlahov, D. (2005). Urban health: Evidence, challenges, and directions. Annual Review of Public Health, 26(1), 341–365. https:// doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144708

Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Health Services. Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Health: Our Mission & Community Garden.

Global Child Nutrition Foundation. (2024, June 26). Shokuiku – How Japan Leverages School Meals as a ‘Living Textbook’ for Lifelong Healthy Eating. GCNF.

• Canyon Ranch. LONGEVITY8™ Retreat at Canyon Ranch Resorts. Canyon Ranch.

• Salamon, Maureen. (2023, June 1). Sowing the Seeds of Better Health. Harvard Women’s Health Watch.

• Bevill, Lisa, and Becca Smith. (2023, March 23). Cultivate Joy to Improve Well-being. IE Insights.