The Age of Collaboration

Transformational Designs

The Third Act

FALL 2022

Welcome

The Fall 2022 issue of The Narrative captures compelling stories about Perkins Eastman people and projects around the world.

Perkins Eastman welcomed five firms into the fold over the last few years, spurring creative and strategic synergies with intriguing new colleagues. Our combined efforts are proving serendipitous in myriad ways (p. 2). In another story of collaborative endeavor, we mark the opening of the second and final phase of The Wharf in southwest Washington, DC, with personal anecdotes from our 16-year journey as the master architect of this vibrant new waterfront neighborhood, which has developed into an international destination (p. 14).

In a striking study, the American Institute of Architects reveals that renovations have surpassed new construction throughout the nation for the first time in the 20 years the institute has been tracking this trend. This focus on existing buildings holds tremendous potential for curbing climate change (p. 30).

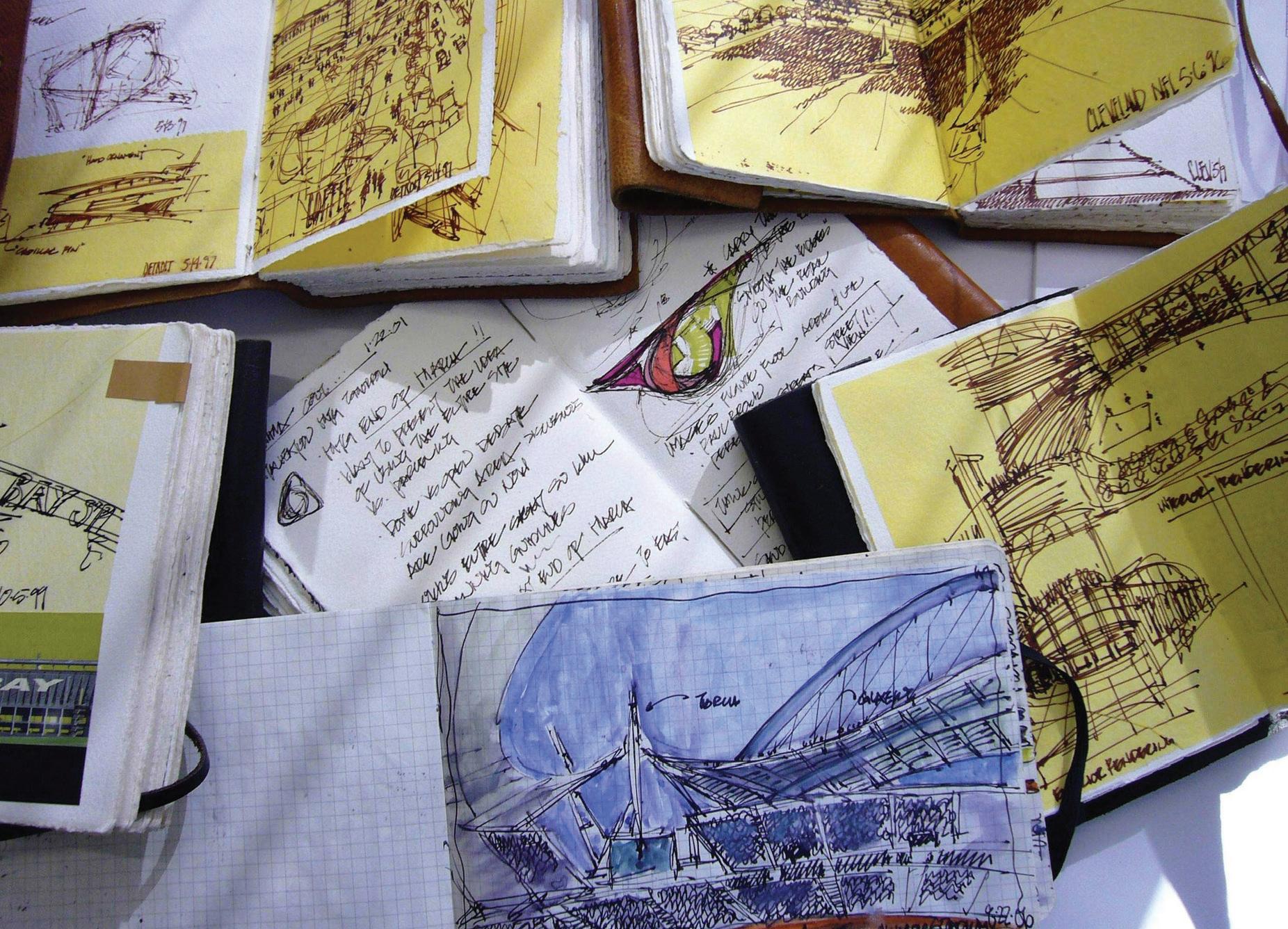

If you’ve noticed fewer architects sketching by hand, relying instead on digital tools, we have a refreshing story about Perkins Eastman artists who enjoy hand sketching so much they do it on and off the job (p. 24). Performing arts venues integrate and enliven patrons’ experiences in new ways. Read about the Shakespeare-inspired theater created from shipping containers, a beachfront amphitheater enhanced with VIP amenities, and a multipurpose theater on a dramatic campus site (p. 36). In terms of transit-oriented development, Perkins Eastman and our specialty studios are helping to catalyze a resurgence in downtown Raleigh, making Philadelphia’s century-old subway system accessible, and extending the SkyTrain in Canada (p. 42).

Six PEople from around the firm share their thoughts on architecture, inclusivity, mentorship, and more (p. 53). Inclusiveness is also a theme in the story about new senior living communities that represent seismic shifts as developers tailor housing to residents’ lifestyles. Feeling “understood and valued” is key (p. 48).

The Annual Excellence Portfolio, an inspiring celebration of Perkins Eastman’s talented staff members and the firm’s most outstanding projects of 2021, beautifully reflects our Human by Design ethos (p. 60). Our people-focused design thinking is also found in “Imagine a Perkins Eastman City,” a fictitious metropolis populated with projects from some of our 18 practice areas. Its skyline was a pure pleasure to create, and we hope it will be fun to explore (see insert)!

The Communications Team

EDITOR IN CHIEF

Trish Donnally

EXECUTIVE EDITOR

Abby Bussel

CONTRIBUTORS

Emily Bamford, Jennica Deely, Nick Leahy, Jennifer Sergent, Ling Zhong

GRAPHIC DESIGN EDITOR

Kim Rader

LET US HEAR FROM YOU

Please send questions, comments, or a story to share to: humanbydesign@perkinseastman .com

© 2022 Perkins Eastman. All Rights Reserved.

design

on the original submission by the

Christian Benefiel and Ryan McKibbin, who created the clock sculpture Time and Space, which hangs in the atrium of Benjamin Banneker Academic High School in Washington, DC (above).

Cover

by Kim Rader based

artists,

View of The Wharf Phase 2, which opened on October 12, 2022

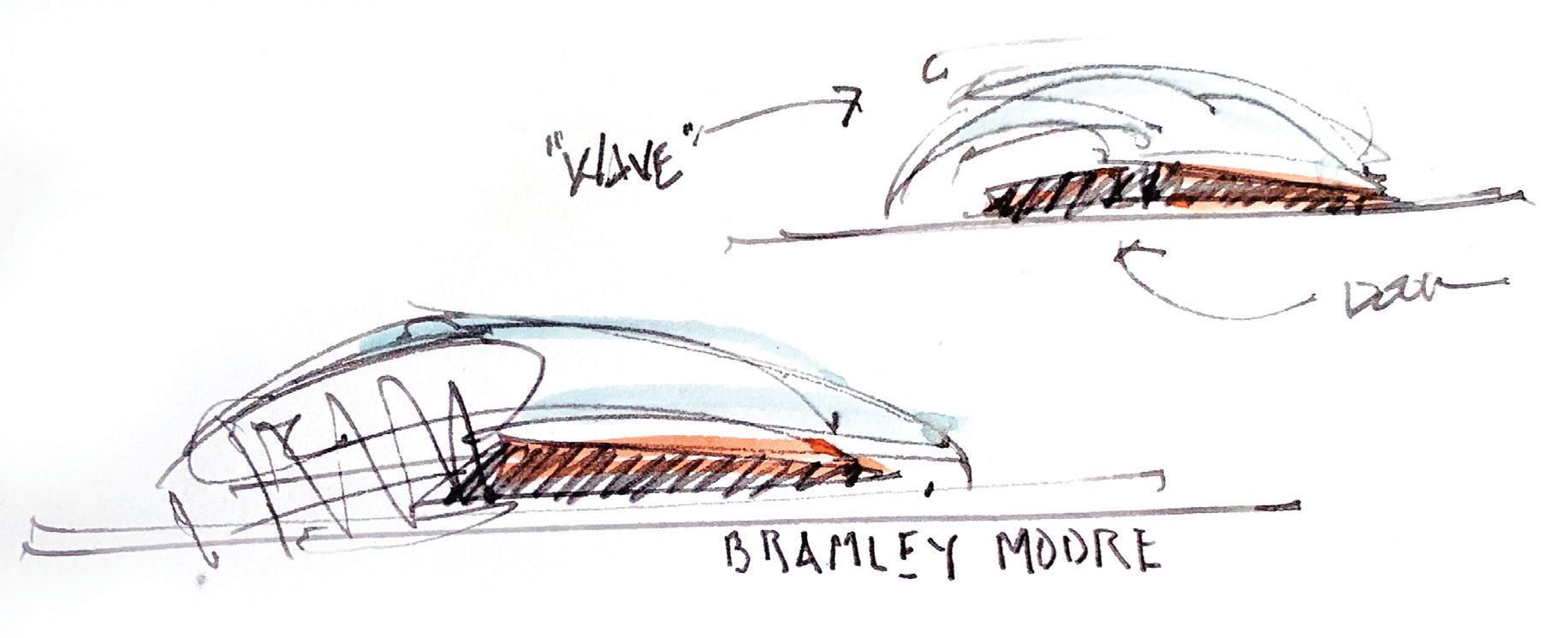

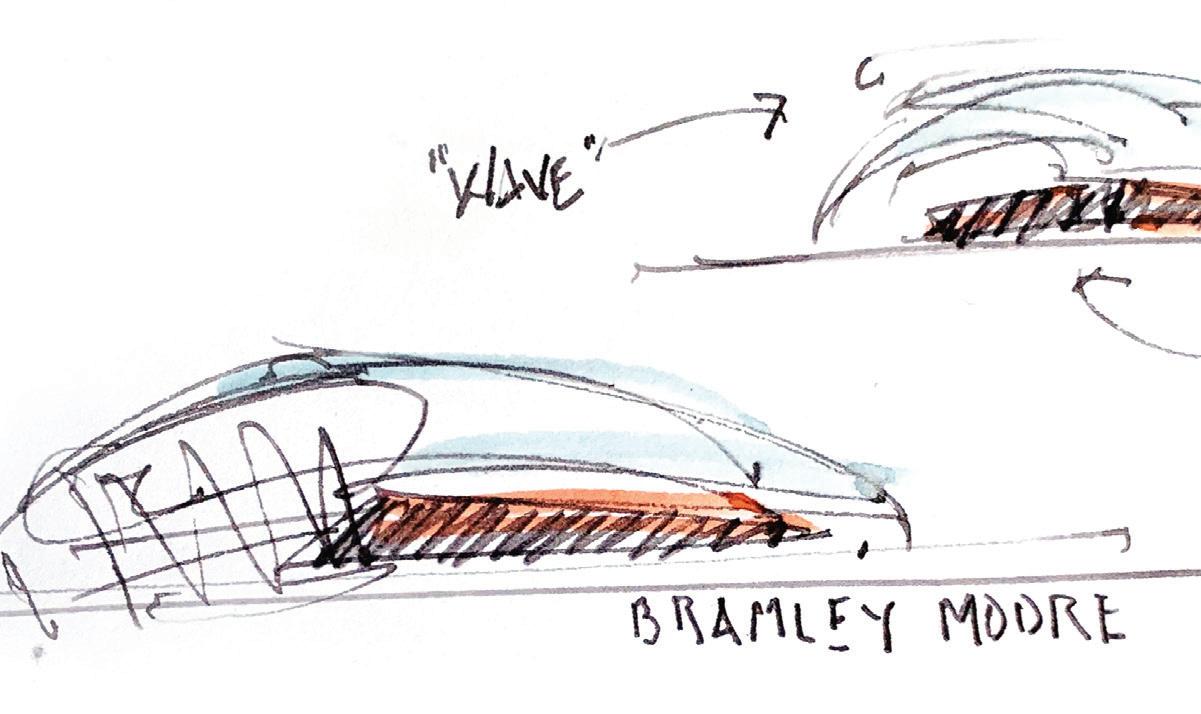

Everton Stadium sketch by Dan Meis

Benjamin Banneker Academic High School Learning Commons Atrium

Copyright Matthew Borkoski/Courtesy Hoffman-Madison Waterfront

Photograph Courtesy Dan Meis

Copyright Joseph Romeo/Courtesy Perkins Eastman

TABLE of CONTENTS

TABLE of CONTENTS

FEATURES

The Age of Collaboration | 2

Perkins Eastman’s strategic alliances spurring synergies

The Wharf—At Long Last | 14

Stories and memories from a 16-year odyssey

INTERVIEW

Take Five | 53

A Q+A on the life of an architect with PEople from across the firm’s studios

STORIES

Quick on the Draw | 24

The virtues of sketching by hand

Transformational Designs | 30

Reimagining existing building stock to confront climate change

It’s Showtime | 36

Agile and immersive venues for the performing arts

Park & Ride | 42

Urban designers making it easy to leave cars behind

Living Our Best Life: The Third Act | 48

Senior living communities reflect cultural identities

IN REVIEW

The Annual Excellence Portfolio | 60 Perkins Eastman’s new program and publication celebrating design

PANORAMA

Imagine a Perkins Eastman City

To view The Narrative online, go to www.perkinseastmanthenarrative.com

the NARRATIVE FALL 2022 1

COLLABORATION The Age of

2 Features

Perkins Eastman’s strategic alliances spur creative synergies.

COLLABORATION

By Trish Donnally

Since the summer of 2021, five exceptional firms have joined forces with Perkins Eastman. Pfeiffer Partners, VIA Architecture, MEIS Architects, BLT Architects, and Kliment Halsband Architects have become Perkins Eastman studios. Merging talents has reaped big benefits, producing projects where vision, resources, and expertise have coalesced into exciting new designs and collaborative opportunities.

“It isn’t surprising that fi rms are merging at the level they are now. Architecture has become so increasingly complex, and we have entered the real age of collaboration,” says Robert Ivy, former CEO of the American Institute of Architects (AIA). For the last 30 years, Ivy notes, the roster of people who’ve been necessary to achieve what clients and projects have demanded has grown exponentially—from the architect, engineer, landscape architect, planner, and perhaps a graphic designer to a list of consultants that might be 35 fi rms long. “What single entity can contain all of those experts in one house? Almost none.

“The merger motive and movement,” as Ivy refers to it, “allows companies to enjoy the resources and strengths that any particular fi rm or group might bring to the entirety. What a wonderful idea.”

When various disciplines and resources are rolled together, projects can be approached at radically different scales, Ivy continues: A fi rm like Perkins Eastman can [plan and design] an entire city, a waterfront, a neighborhood, an individual project, or a dwelling unit. . . . Part of the beauty of the entire merger idea is that you don’t have to cast about between projects for the next job and the next company to ally yourself with. Instead, you’ve essentially built a network of trusted partners and co-workers who can work and reciprocate through the existing network. There’s no due diligence required; there’s no familiarity to be achieved. The level of trust is enhanced. Therefore, the whole has a greater opportunity, one hopes, for a better outcome. Merging fi rms creates an automatic level of knowledge and trust in the resources of our colleagues. It’s a maturity that’s been happening in the marketplace for a long time.

Creating Symbiotic Relationships

Perkins Eastman, now one of the largest architecture fi rms in the world with more than 1,150 professionals, has grown steadily over

40 years, in part through uniting with fi rms such as Larsen Schein Ginsberg Snyder, Ehrenkrantz Eckstut & Kuhn, LBL Architects, and ForrestPerkins. Several years ago, Perkins Eastman’s leadership strategized to expand its presence in California and the Northwest as well as in Texas and the Southeast.

“We almost always fi nd a respected regional fi rm to give credibility and an understanding of the region where we want to be,” says Brad Perkins, co-founder and chairman of Perkins Eastman, who has led the realization of several successful unions. Another strategy is to open a studio with select professionals, spread the word, and prepare for organic growth, as Perkins Eastman did in Pittsburgh, Raleigh, Austin, Dubai, and, most recently, Singapore.

“Our goal is to establish design studios that are strong locally and regionally, and have national stature that can be part of a larger practice,” says Perkins Eastman Co-CEO and Executive Director Shawn Basler. He underscores other vital qualities when joining forces. “The cultures have to align. We want fi rms to join us that believe in our culture and are compatible with us. This not only expands our business opportunities, but enhances our culture,” Basler says. “That’s what all fi ve of the fi rms that joined us in the last couple of years do.”

Basler also emphasizes combining a talent pool and leadership to create a portfolio that neither fi rm could have fostered independently.

“What can we be doing together that we can’t do separately?” he asks. “Maybe it’s expanding our core markets, expanding geographically, or expanding into project types that a combined portfolio helps us get into.”

Chemistry counts too. “Portfolios are one thing, but jobs are won by people and how well they work together,” Basler stresses. “You can have the best story in the world on a portfolio, but if the people in the interview going after a project aren’t in harmony, it doesn’t work. Close collaborations are something we’ve strived for, and they’ve been working.”

the NARRATIVE FALL 2022 3

“An Absolute Dream Come True”

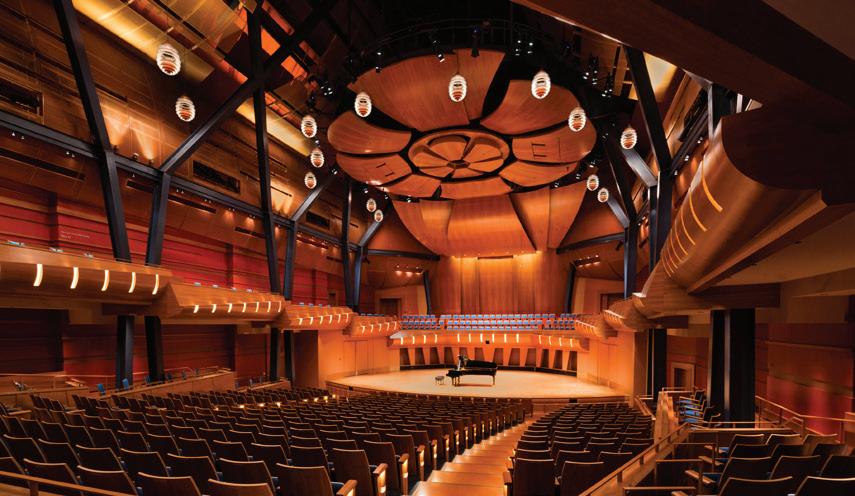

The recent competition win to design Wuxi Taihu-Bay International Culture and Arts Exchange in Wuxi, China, a city some 85 miles from Shanghai, crystallizes the success of the collaborative effort between Perkins Eastman and Pfeiffer, a fi rm founded in 1969 and known for its expertise in performing arts, libraries, historic preservation, and civic design.

“Wuxi would never have been a win for us without having a merger. This project is almost literally what we had hoped for coming into the merger,” says Alberto Cavallero, design principal of Pfeiffer— A Perkins Eastman Studio.

In fact, Perkins Eastman won the opportunity last spring to design the Wuxi Taihu-Bay International Culture and Arts Exchange after a Herculean twomonth effort that involved Pfeiffer’s studios in Los Angeles and New York and Perkins Eastman’s studios in New York and Shanghai. The effort included working long hours through a lockdown in Shanghai. The winning design concept, “Moonrise,” mixes culture and civic life. The design radiates from the stage of its world-class, 1,500-seat symphony hall. The

cultural program includes other music-performance sites and a public-engagement zone. Altogether, this curated arts and retail venue creates a unique cultural, leisure, and entertainment destination—and a civic place—for Wuxi’s new Xinfa District.

“We [Pfeiffer] had hoped to expand the reach that we already have in the arts world regionally and size-wise. What we were thinking then, and it still applies, was to expand . . . [in the] east,” Cavallero says. “We just weren’t expecting to expand this far east—to China!”

The merger also strengthened Perkins Eastman’s ability to compete and win in Wuxi, given that a significant portfolio of work in the performing arts was an expectation to create a cutting-edge acoustic space for the city. “Conversely, I don’t think Pfeiffer, independently, would have been considered—we may not have even heard about this kind of endeavor.

We didn’t have the strong Shanghai office that we have [now through Perkins Eastman].” Having a strong Chinese presence was a given for entering the competition.

4 Features

“This has been an absolute dream come true to win and execute, and we hope to parlay this into other major cultural projects,” Cavallero says.

“Expansion of our horizon is really the biggest benefit of the merger. It’s opened up other worlds to us that we couldn’t have [otherwise],” says William Murray, a Pfeiffer principal based in Los Angeles. Murray considers Perkins Eastman’s 24 worldwide studios another strong asset. “The idea that you can say to a potential client, ‘We have a Charlotte office, or we have a Raleigh office, or we have a Pittsburgh office’ . . . is a great opportunity.” He adds, “I was just talking to a person at VIA about a performing arts center I’ve been working on for years in Bellevue, WA, and when that starts up . . . it will be great to tell the client, ‘We have an office just across the lake in Seattle.’”

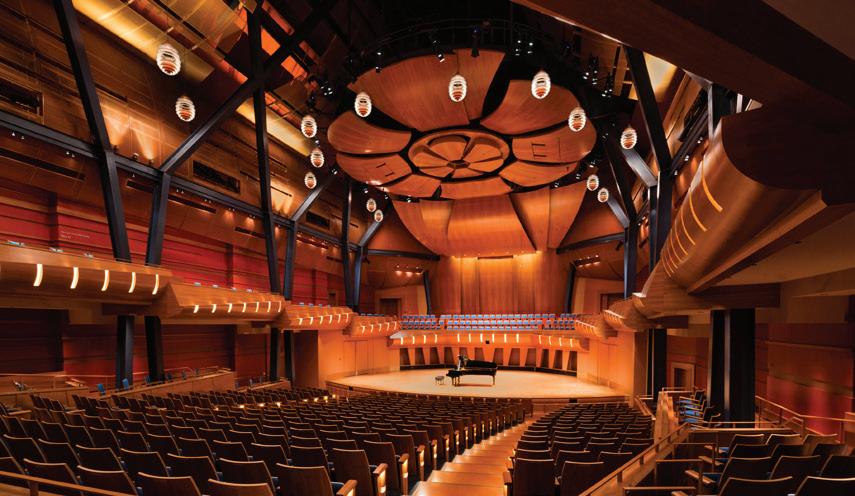

“All aspects of our professional lives have, by and large, improved,” says Jean Gath, who was Pfeiffer’s comanaging principal before she assumed an expanded role as co-managing principal of Perkins Eastman New York. “This is the perfect meld, because we don’t do science, we certainly don’t do healthcare, we don’t

do senior living—things at which Perkins Eastman excels. In turn, Perkins Eastman doesn’t do, to the same extent as we do, performing arts or academic libraries. Our two fi rms are coming together in ways that really complement each other without getting in one another’s way.”

For Pfeiffer’s team, the transition from a staff of 37 to more than 1,000 has required some adjustments. Making decisions could be expedited with a small group, for instance, but the benefits have outweighed the challenges. In particular, Gath has been pleasantly surprised by Perkins Eastman’s culture. She credits Brad Perkins and Mary-Jean Eastman, co-founders and chairman and vice chair respectively, for building a global fi rm while maintaining the culture of a smaller one. “They’ve kept that homegrown, familiarity culture that fi rms of this size typically don’t have. It’s far less bureaucratic than we expected. Brad said, ‘We’re bringing you in to do what you do, why would we want to change what you do?’ That’s one thing for Brad to say, but another thing to actually have it be the case,” Gath says.

Opposite Page Above

Pfeiffer—A Perkins Eastman

Studio renovated and expanded the iconic Griffith Observatory in Los Angeles by almost 40,000 sf, most of it below grade. Copyright Tim Griffith/Courtesy Pfeiffer

Opposite Page Below

The Mount Royal University

Taylor Centre for the Performing Arts, designed by Pfeiffer, is a concert hall that provides high-quality instructional and performance spaces in Calgary, Alberta, Canada. Copyright Ema Peter/Courtesy Pfeiffer

Left Perkins Eastman and Pfeiffer joined forces, competed in, and won an international competition to design Wuxi Taihu-Bay International Culture and Arts Exchange in Wuxi, China.

Rendering Courtesy Perkins Eastman and Pfeiffer

the NARRATIVE FALL 2022 5

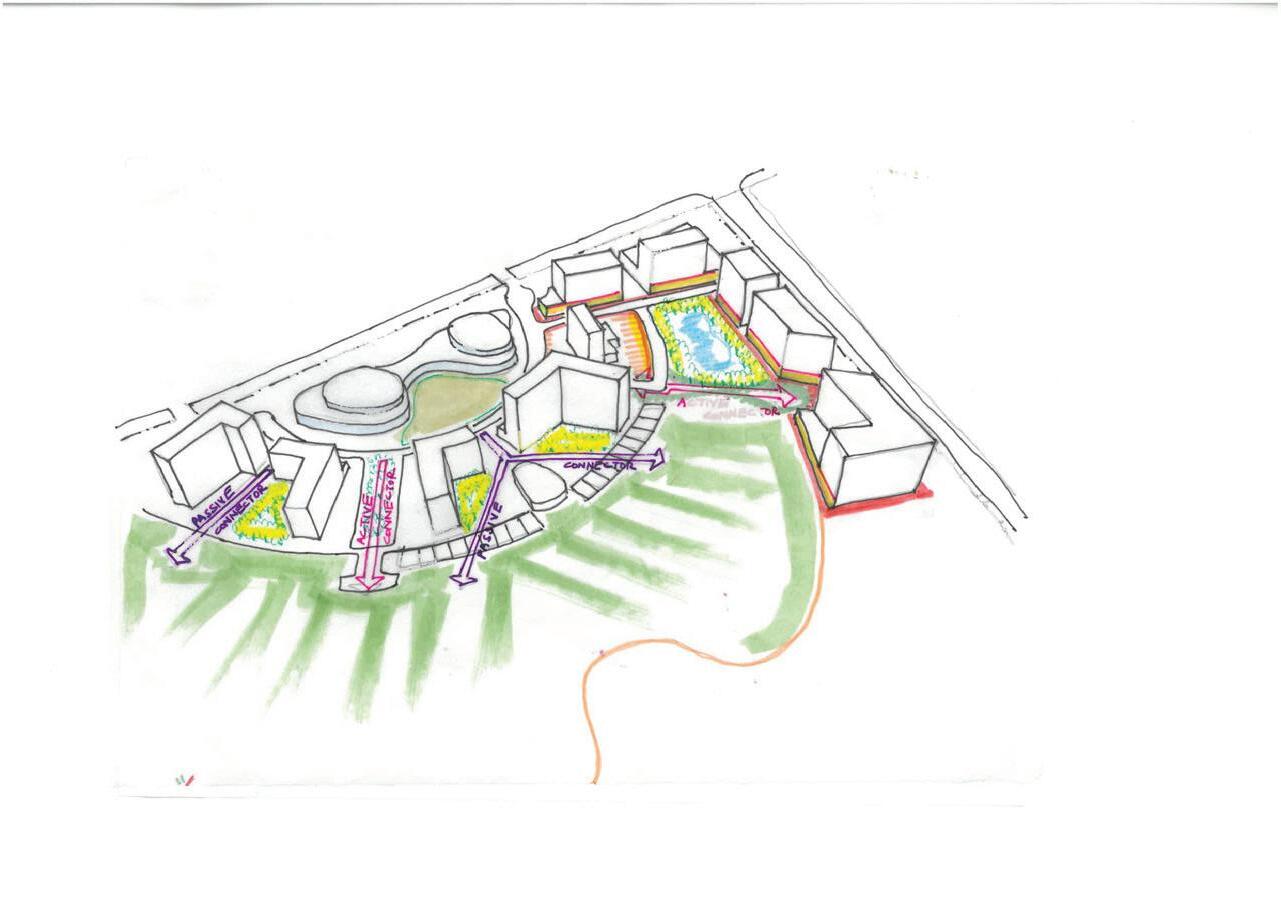

Satisfying Intellectual Curiosity

Mergers do not happen overnight; timing is everything. “We consciously started talking to VIA over fi ve years ago,” Perkins says. “We wanted to have a respected presence in the Northwest. They have experience and expertise in areas such as transit facilities, infrastructure, and multifamily residential. And we’re always interested in fi rms with strong planning components, which VIA has. We’re often involved in projects where we do the planning before any architectural projects begin, and we often end up doing planning, consulting, and building.” VIA, established in 1984, has 70-plus employees with studios in Seattle, WA; Oakland, CA; and Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

“The main thing that compelled us to do this is that we saw a similar culture,” says Seattle-based Wolf Saar, managing principal of VIA—A Perkins Eastman Studio. “We like the idea of thinking of the fi rm as one entity rather than as siloed profit centers. That’s a very successful model; that’s the way we operated with three offices, so that was a positive.” Saar notes that expanding on the West Coast has created unexpected opportunities. “The fact that Pfeiffer was joining was an added value to us and the same for MEIS here

on the West Coast. It made for larger critical mass of personnel, offices, and reach. And we’ve already found that we’re working very well with our West Coast brethren.” For example, VIA staffers have been working on Pfeiffer performing arts and college and university work as well as K-12 projects with Perkins Eastman in Costa Mesa and Oakland.

“We’re diving into new markets,” adds Lauren Hamilton, managing principal of VIA, who is based in Vancouver. “I couldn’t have imagined the depth of opportunities for cross marketing and expansion of markets.” Hamilton highlights the common culture many West Coast teams share, which has created a bond among the eight studios that span from Perkins Eastman in Costa Mesa to VIA in Vancouver. “It comes out really strongly in terms of looking for work together, and we’ve had some success stories there.”

Hamilton emphasizes another unexpected benefit she extolls as “hugely positive.”

“Coming out of the pandemic, morale was down here, across the board, across the industry, and across the world. People had their heads down, waiting to see what would happen next, and afraid to make any

6 Features

moves for such a long time,” she says. But, as things started to pick up, Hamilton leveraged the benefits of being part of a larger constellation of studios: What people really needed was a sense of power to make changes in their lives. VIA would have lost a lot more people had we not been able to say, “This is a whole new change. Look, you can now go work on a senior living project in San Francisco, you can work on a hospital project in Los Angeles.” People got the experience of change, and feeling even some ownership, because we said, “Hey, do you want to go work on this? What would be exciting to you?”

Julia Bartmanska, an architectural designer at VIA in Vancouver who previously lived and worked in Poland, is among the people embracing change. Since joining VIA in 2019, she’s focused on multifamily housing and urban design. After the fi rm became part of Perkins Eastman, however, she says her opportunities broadened from her base in Canada to new collaborations with colleagues in San Francisco on senior living projects in California. “I had personally never worked on senior living residential projects,”

says the designer, who is happy to be expanding her repertoire.

Bartmanska has since traveled to San Francisco to work alongside her new team members in person. “It defi nitely helps with pushing the design process faster,” she says, and “it’s nice to develop stronger connections.”

Having new options has made Bartmanska and other VIA staff members want to stretch their design muscles. “It has satisfied a lot of the itchiness in the intellectual curiosity that was tamped down during the pandemic when people were just trying to hold steady and make it through,” Hamilton says. “People thought ‘I need some change, I want some change, I want to assert some new agency in my life,’ and this [union] came at the right time to be able to offer that to people, while keeping them here.” People were missing the chance to travel, to interact socially, to challenge themselves. “We had nothing to stimulate us for two years. And the job became the easiest way to do it. Only because of this merger have we been providing depth and variety,” Hamilton says.

Opposite Page Above

VIA—A Perkins Eastman Studio, which specializes in transit work among other practice areas, designed Metrotown SkyTrain Station Renovation in Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada. Copyright Ed White Photographics/Courtesy VIA

Opposite Page Below

VIA designed this floating horizontal entrance canopy for the Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) system on Market Street in San Francisco. Many more entrance canopies are planned based on this prototype.

Copyright Mike Sanchez Photography/Courtesy VIA

Left

VIA designed Spire, a 440-foottall luxury condominium tower that enhances downtown Seattle’s recent building boom.

Copyright Francis Zera/ Courtesy VIA

the NARRATIVE FALL 2022 7

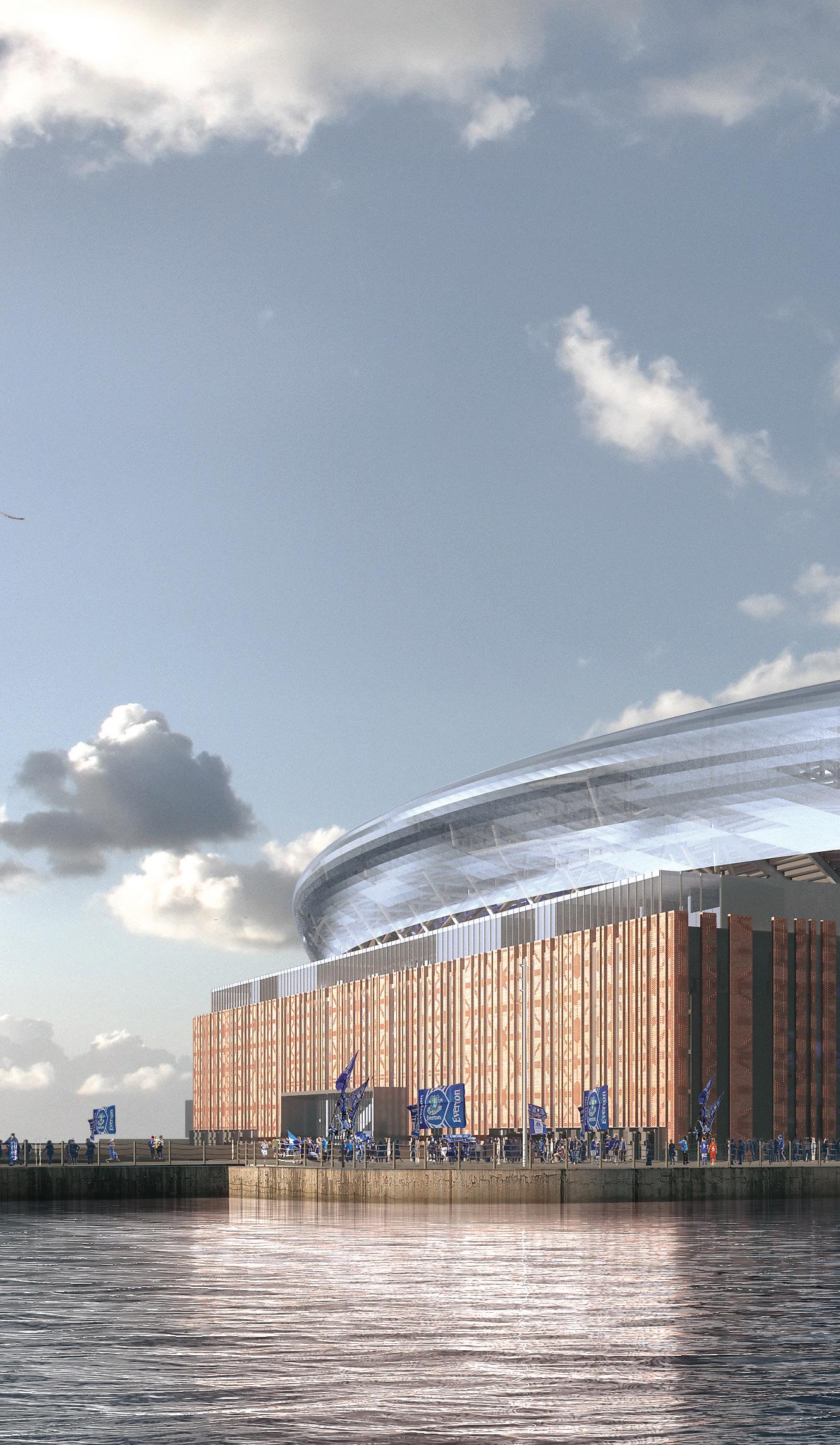

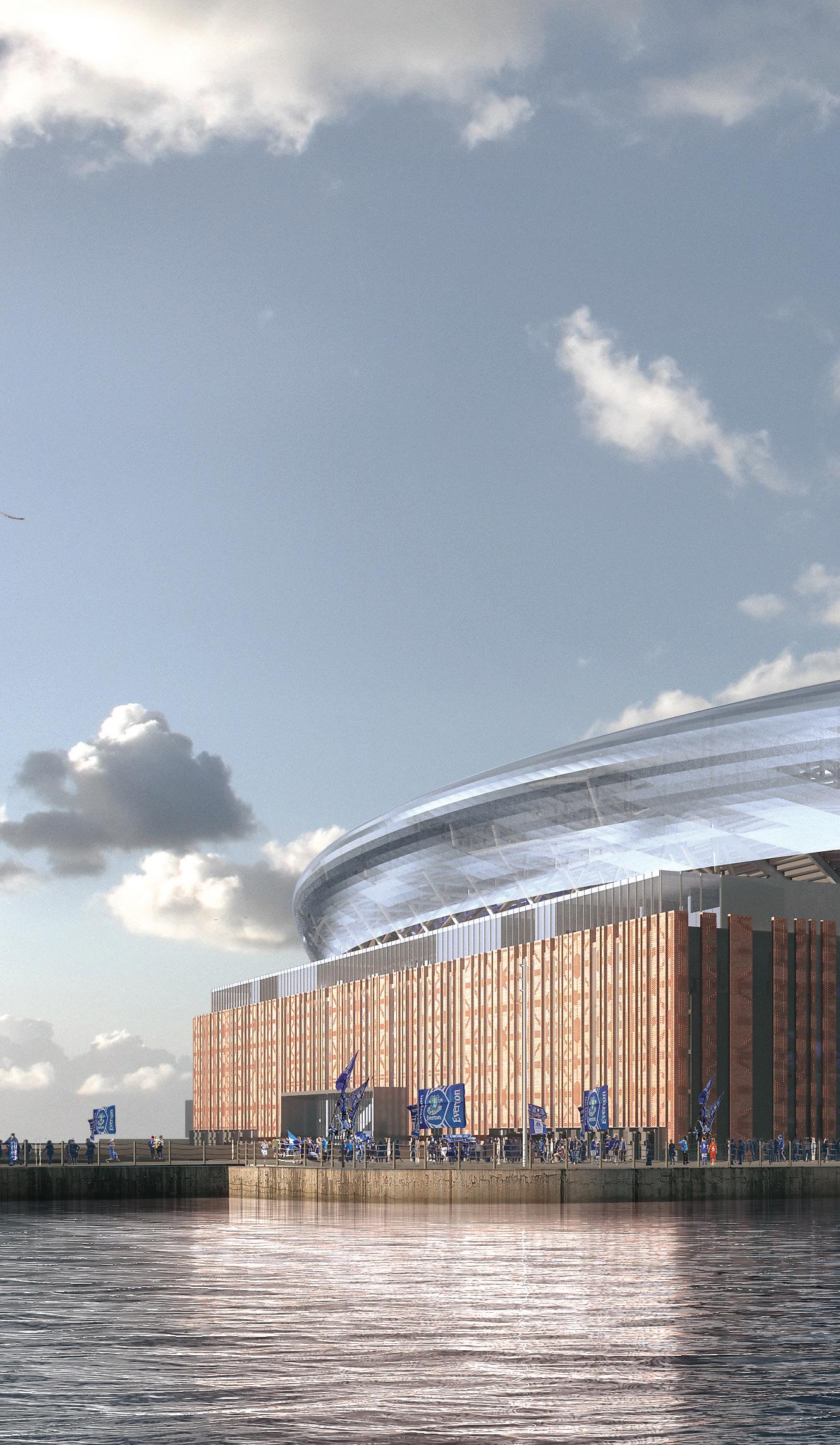

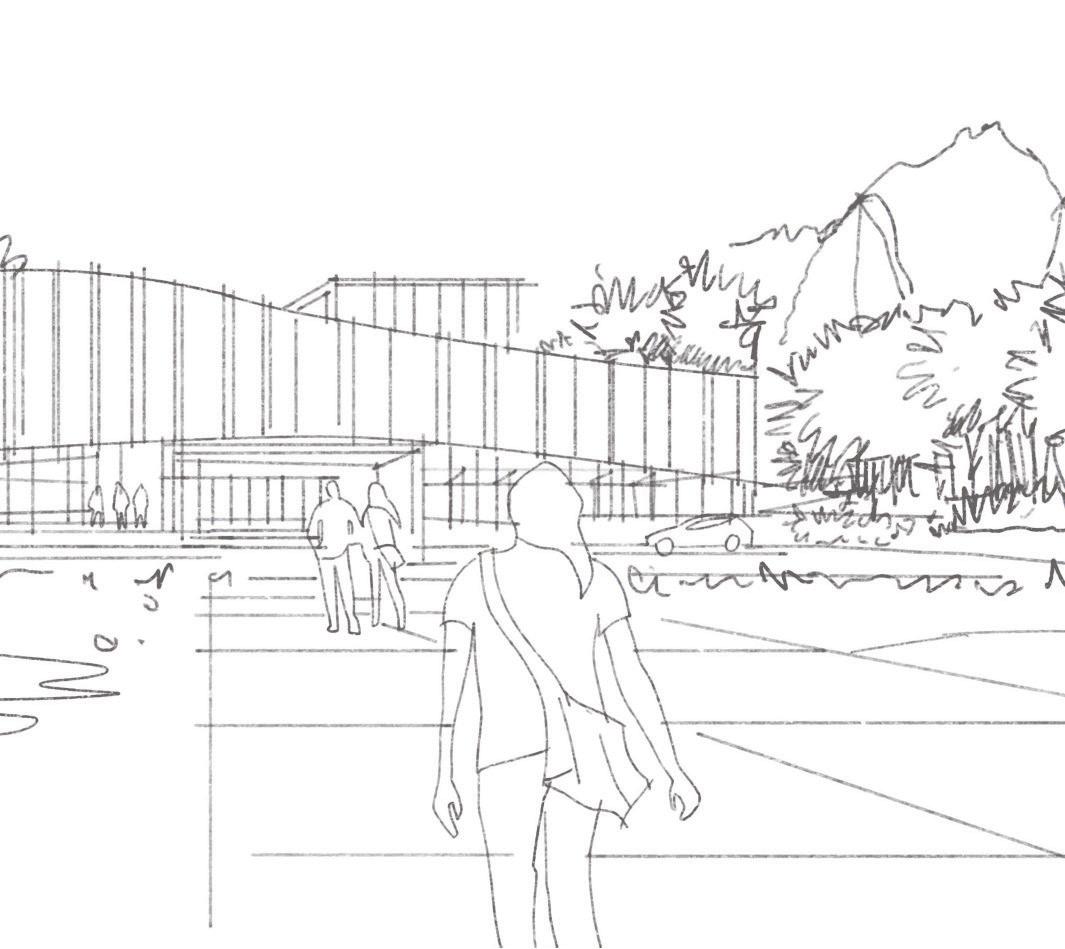

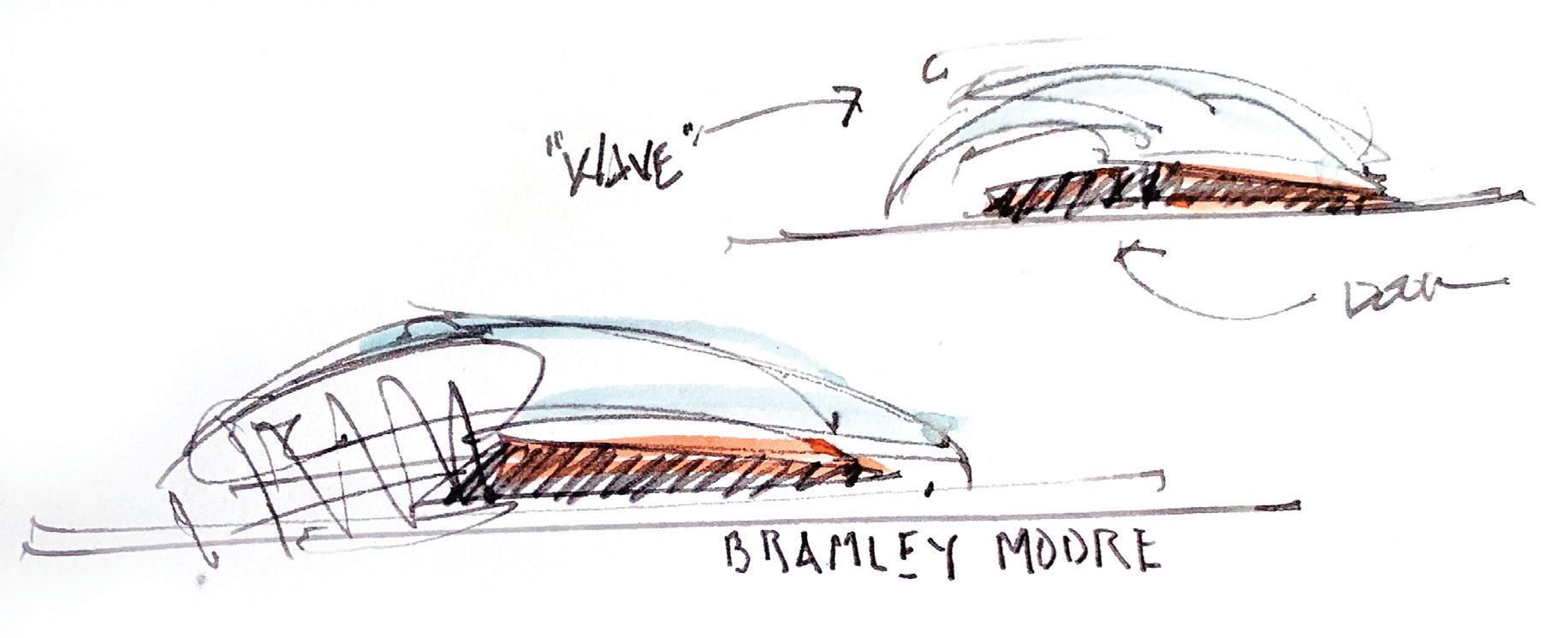

Playing with a Deep Bench

MEIS—A Perkins Eastman Studio is a powerhouse sports and entertainment fi rm that specializes in the design of experience and spectacle. MEIS is known for activating entertainment destinations through placemaking and urban planning and creating environments that inspire people to gather and celebrate. Founder Dan Meis, whom Time magazine recognized among its “100 Innovators in the World of Sports” in 2001, leads the practice, which has studios in Los Angeles and New York. Current projects, among others, include the new Everton Stadium in Liverpool, England, and the renovation of the Crypto.com Arena, formerly the Staples Center in Los Angeles, which Meis designed in 1999. The latter is a game-changing project that consistently ranks among the highest revenue-producing buildings in North America.

“We could never get into large-scale sports without the portfolio and the brand name, and Dan Meis is just so well known in that arena,” Basler says. “It would have taken us decades to get there, and we gave him a larger platform to sell from, plus support. Having this platform has allowed us to accommodate the fast growth we’ve had. I don’t think any of us

expected how fast it would grow,” Basler adds. Perkins Eastman and MEIS had teamed up on pursuits prior to joining forces, and the strategic partners are currently collaborating on multiple projects as well.

“Dan’s been a great partner to bring in on a lot of other projects,” Basler says. Little Caesars Arena in Detroit is one example where space, including a large plaza outside the building, is being analyzed and reimagined. Meis says the project is sports related, because it’s outside an arena and similar to other projects he’s designed, but the client was also interested in the portfolio of Hilary Kinder Bertsch, principal and executive director of Perkins Eastman, and her extensive work with public realm design. “It was another time when the client was very vocal about, you know, ‘We see you guys bringing both sides of this equation together,’” Meis says.

“This is exactly why we joined each other,” Basler says. “You put our large-scale practice together with the sports practice and you think about the whole entertainment district. . . . It’s not just the arena or the stadium. It’s about what happens around it, and how that becomes seamless, because sometimes those

8 Features

[spaces] are designed independently, and being able to have an integrated approach inside and out makes a big difference.”

Another new—and confidential—project combines the talents of MEIS, Perkins Eastman, and Pfeiffer in an unexpected way. “It’s a fun project in New York. I don’t often get to do projects in my home base, whether it’s New York or LA. The venue hosts ultraelectronic music. It’s a rave kind of place,” Meis says. The combined portfolio of the three practices helped Perkins Eastman win the job. “It clearly was Dan’s relationship, but Dan’s relationship combined with Pfeiffer’s performing arts centers and understanding of them, combined with what Francisco [Tsai of Perkins Eastman] does, and his understanding of performance venues and sound stages. It all came together,” Basler says.

And that’s not all.

MEIS, Pfeiffer, and Perkins Eastman have also teamed up to create a master plan for the UCLA Easton Stadium. “I’ve never been able to really go after the college market because they always saw me as the guy that does big pro buildings, and it was kind of

a different market. Even though it was LA, that still would have been a struggle for me,” Meis says, so the team leveraged the relationship Pfeiffer’s Jean Gath had with UCLA. “They were interested in all of us. They had a history with Pfeiffer, they knew me in LA, and they were interested in Perkins Eastman and the kind of master planning the fi rm could bring to the project,” Meis says, referring to the growing college and sports practice led by Principal Scott Schiamberg. “It was a really good example of things we couldn’t have done individually,” Meis says. Plus, he adds:

It really shows the power of bringing the portfolios together, and it’s not just added capacity and added staff, it really exemplifies synergistic experiences. Joining Perkins Eastman was really about the belief that together we could do something we couldn’t on our own, but it was also important for me to be able to maintain a brand that has distinguished us in sports architecture from the other larger fi rms. The opportunity to approach clients as a global, diverse fi rm but with the identity and feel of a boutique specialty practice really sets us apart from our competition.

Opposite Page Above

MEIS—A Perkins Eastman

Studio is renovating the former Staples Center in Los Angeles. Originally designed by Dan Meis in 1999, the complex has been renamed the Crypto.com Arena. Copyright John Edward Linden/ Courtesy MEIS

Opposite Page Below

MEIS, Perkins Eastman, and Pfeiffer—A Perkins Eastman Studio, have teamed to create a master plan for the UCLA Easton Stadium. Rendering Courtesy MEIS

Left MEIS designed Everton Stadium for a waterfront site in Liverpool, England. It is currently under construction and due to open in 2024. Rendering Courtesy MEIS

the NARRATIVE FALL 2022 9

Hitting the Jackpot

BLTa—A Perkins Eastman Studio, as the fi rm is now known, commands a respected presence in the greater Philadelphia region, where it has completed more than 500 projects in 60 years. The integrated architecture and interior design fi rm of 46 professionals built its venerable business with expertise in multifamily residential work, higher education, historic renovation, adaptive reuse, and transit-oriented projects. BLTa also boasts an exceptional hospitality and gaming portfolio, but more on that later.

Perkins Eastman has long sought a robust partner in the City of Brotherly Love, and, in BLTa, the fi rm found like-minded colleagues with deep local roots who were ready to spread their wings. “The synergy for us is that we can take the things we do really well to a broader geographic platform, and Perkins Eastman can bring its expertise in healthcare, higher education, and senior living into the Philadelphia region,” says Eric Rahe, a principal of BLTa, who joined the fi rm in 1987. Perkins Eastman’s studio in Pittsburgh, established 27 years ago, provides a strong presence in Western Pennsylvania. Now, the addition of the studio in Philadelphia strengthens the fi rm’s presence in Eastern Pennsylvania.

Back to gaming. “BLTa has gaming experience, and that’s been huge,” Basler says. The fi rm’s casinos and hotels include Borgata Hotel Casino & Spa, The Water Club, and Ocean Casino Resort (formerly Revel), all in Atlantic City, as well as Live! Casino & Hotel Philadelphia, and Live! Casino Pittsburgh. The fi rm designed several amenities, including an event center, poker room, beer garden, and sports book for Parx Casino in Bensalem, one of the top-rated casinos in Pennsylvania, and the architecture and interior design for Parx Casino in Shippensburg, also in Pennsylvania. Currently under construction, the Shippensburg casino is due to open this winter.

Rahe especially enjoys the variety of programs involved in gaming projects, because they are often integrated with a resort. “Gaming is so broad, we get to work on so many different project types,” he says, mentioning hotels, spas, ballrooms, meeting spaces, and restaurants as examples. “It is not uncommon to have a dozen restaurants in these gaming venues,” he says. Non-gaming hotels in the BLTa portfolio include the Marriott Philadelphia Downtown, Philadelphia Airport Marriott, Philadelphia Loews Hotel, and Canopy by Hilton, among others.

10 Features

Michael Prifti, a principal who joined BLTa in 1982, says the fi rm now has many more opportunities and resources to do the things they’ve long aspired to do. “From our point of view, we gained access and relationships to a tremendous number of capable professionals, design professionals, but also folks in the more administrative line of work,” Prifti says.

Perkins Eastman’s Women’s Leadership Initiative (WLI), a program Mary-Jean Eastman launched within the fi rm in 2014, has inspired BLTa’s existing Women in Architecture group, modeled after the AIA. Engaging with the larger, fi rm-wide Perkins Eastman WLI group has helped the BLTa members expand their network, share lessons learned, and make meaningful connections across the fi rm.

Perkins Eastman’s expertise in sustainability exemplifies another expanded resource Prifti appreciates. “In a smaller fi rm, more people are generalists. We have at least one person who is LEED-accredited on every team, but now our green team liaises with Perkins Eastman’s broader sustainability group across multiple studios,” he says.

Milton Lau, senior associate of BLTa, brings a unique perspective. Lau worked for Perkins Eastman in New York City for six years before relocating with his family to Philadelphia and accepting a position with BLTa. “The big takeaway for me is when I was at Perkins Eastman 10 years ago, I worked on big, large-scale projects,” Lau says. His work took him on trips to India, where he worked on The Indian School of Business, in Mohali, and Antara Dehradun, a senior living community in Uttarakhand. He also worked on a TV broadcast station in Qatar and a master plan for Hanoi, Vietnam. When Lau joined BLTa, however, he began focusing on the local vernacular through the particulars of local zoning, construction methodologies, material supply chains, and market demands. Now that’s he’s back under the Perkins Eastman umbrella, Lau has the opportunity to work on national and international projects again.

“I’ve enjoyed the beauty of working locally and knowing the folks in the community, and now I’m enjoying the beauty of being connected to Perkins Eastman and its global resources, global clients, and global expertise,” Lau says. “All of these are opportunities that broaden my perspective while helping me appreciate what’s right under my feet.”

Opposite Page Above

BLTa—A Perkins Eastman Studio has done extensive work in downtown Philadelphia, including East Market, which spans an entire city block.

Copyright Philly by Drone/ Courtesy BLTa

Opposite Page Below

BLTa transformed a historic office building, formerly known as the United Gas Improvement Company Building, into One City, a multifamily residence.

Copyright Jeffrey Totaro/ Courtesy BLTa

Left Live! Casino & Hotel Philadelphia is but one example in BLTa’s extensive hospitality and gaming portfolio. Copyright Jeffrey Totaro/Courtesy BLTa

the NARRATIVE FALL 2022 11

The Sky’s the Limit

Celebrating its 50th anniversary this year, Kliment Halsband Architects (KHA) and its staff of 17 joined Perkins Eastman in the K-12 and Colleges and Universities practices. This distinguished fi rm earned the AIA Architecture Firm Award, the highest honor the AIA bestows, in 1997. KHA, renowned for its institutional work, has designed projects for Columbia, Yale, Brown, and Johns Hopkins among many other universities, as well as numerous K-12 private schools in New York.

Frances Halsband, a founding partner of KHA and a principal of Kliment Halsband Architects—A Perkins Eastman Studio, became the 61st Chancellor of the AIA College of Fellows on December 9, 2022. She’s delighted with the people she’s been meeting since joining Perkins Eastman and co-locating at 115 Fifth Avenue in New York City.

“I have met some amazing and wonderful people here, and it has been exactly as I had hoped,” Halsband says, offering an example. “We have a university client that we have worked with for years, and we have a wonderful relationship with them,” Halsband says. “They came to us this spring and said, ‘We have this [historic] academic building that we want to work with you on, and we know you’d be perfect for it, but, of course, we want it to be passive house.’” Halsband paused, and thought, “We can do a lot of things, but we can’t do that.” After researching a bit, she was introduced to a passive house expert in Perkins Eastman’s studio in Washington, DC. “Ryan Dirks came with us to the interview, and he was fabulous, and the client said, ‘Great, you’re hired.’ But not only that, now that we’re working with him, Ryan really is terrific.”

Halsband provides another example of a potentially symbiotic relationship.

“We’re working on a master plan for a college in St. Petersburg, FL. They have an unused piece of land at the edge of the campus. They kept saying, ‘We should do something with this land that could benefit us, we could monetize it, there must be something,’” Halsband recalls. Then, at a meeting in New York, she met Joe Hassel, a Perkins Eastman principal and Senior Living practice leader. “I said, ‘Joe, what do you know about doing something like that in Florida?’ And with that, he had a whole story about how colleges reach out and create housing for older alumni, and how the alumni become part of the college community.” Halsband again thought to herself, “‘This is exactly the kind of person and relationship that I’d hoped to fi nd.’ These

two examples are very vivid to me as exactly what we thought should happen,” Halsband says.

Basler cites another example. “Where we had dropped off a little bit in the K-12 private school market, which is very hard to get into, KHA brought its portfolio and relationships to the private-school world in New York City that we didn’t have. They also brought relationships to certain universities that we didn’t have,” he says. Leveraging the KHA relationships with the larger Perkins Eastman platform has already proven successful. While collaborating, the two fi rms have won a project at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, and have been shortlisted for a confidential project on an Ivy League campus. “We couldn’t have done those projects without them,” Basler says.

“The great opportunity here is that we’re not competing with each other,” Halsband says. “We’re different enough in what we know and who we know,

12 Features

we’re going after jobs together.” She notes, “In all of the marketing conversations, we have yet to have a single one where somebody has said, ‘We want to go after that, and you can’t.’ It’s really the opposite. . . . These are opportunities that we never could have taken advantage of on our own.”

“KHA is a wonderful group of people who bring a lovely spirit to the New York office, and have proven to be good partners to work with—no egos, and terrific team players,” Basler says. “There’s a lot more potential. It’s still very early with KHA. The few things we’ve done together already have been very different than what we’ve ever done, and there’s a lot to build off of there.”

Halsband looks forward to the future too. “I have a lot of fun putting people together to make things happen,” she says. “I feel like there are 1,100 people here I’ve yet to meet, but we’ll see what we can do.” N

Above Left

The living green wall in the lobby of New York University’s School of Global Health, designed by Kliment Halsband Architects—A Perkins Eastman Studio, sets the tone for the building’s healthful interior environment. Copyright Ruggero Vanni/Courtesy Kliment Halsband Architects

Top Right

Kliment Halsband Architects designed this glass-enclosed entrance structure for the Long Island Rail Road at Penn Station in New York City. Copyright Cervin Robinson/ Courtesy Kliment Halsband Architects

Bottom Right

The Pratt Institute Manhattan Center Gallery is among many projects Kliment Halsband Architects has designed for the school. Copyright Ruggero Vanni/Courtesy Kliment Halsband Architects

the NARRATIVE FALL 2022 13

By Jennifer Sergent

AT LONG LAST The

Wharf

The Perkins Eastman team and developer Monty Hoffman share stories and memories from a 16-year odyssey.

14

Features

The excitement was palpable on October 12, 2022. Five years to the day after opening the first phase of The Wharf in Washington, DC, its developers, designers, contractors, and city officials returned to open the second and final phase of the project, completing what Washingtonian magazine has termed “the glittering mile of southwest waterfront” that has become home to some of the city’s marquee businesses and top restaurants, apartments and condos, and hotels.

“The assemblage of so many talented professionals in one place created what The Wharf is today,” said Shawn Seaman, president of The Wharf’s developer, Hoffman & Associates, during a ceremony that preceded fireworks and The Killers’ sold-out concert at The Anthem. He was standing in front of the new Pendry Hotel, a spot that for more than 40 years had been occupied by the three-story Channel Inn, one of a smattering of low-lying buildings and parking lots along the marina. Few beyond the inn’s guests and the boat owners ventured out to the paved walkway that bordered the water then. Today, the development draws thousands of DC residents and tourists daily.

Seated in the audience that October evening were several Perkins Eastman leaders who had been involved in the project for a decade or more. As The Wharf’s master architect, the firm oversaw dozens of other architects, landscape architects, engineers, builders, and consultants who contributed to the $3.6 billion endeavor that has reimagined the water’s edge along the Washington Channel of the Potomac River, stretching between the city’s historic Municipal Fish Market and the Fort McNair army post. “I’d like to acknowledge in particular Perkins Eastman, the master architect, the glue that held all the design teams together for both phases of the project,” Seaman noted in his speech.

“That feels great,” says Perkins Eastman Principal Jason Abbey. “It’s not often in the developer world where we’re literally getting hugs from the developer and the client team. To see that happen after the end of such a long run is amazingly gratifying.” A long run is right. The city issued its first request for proposal (RFP) to redevelop this stretch of waterfront in 2004. Principals Stan Eckstut and Hilary Kinder Bertsch, who were with the firm Ehrenkrantz Eckstut & Kuhn (EE&K) before it merged with Perkins Eastman in 2011, served as the initial design partners for Hoffman & Associates in the RFP response that won the project in 2006. The 16 years of work that followed have resulted in one of the city’s liveliest neighborhoods and a world-class destination. Its impact, however, goes much deeper in the lives of the Perkins Eastman professionals who helped bring it about as they worked side by side with developer Monty Hoffman and the constellation of other firms that would ultimately send up to 2,000 workers to the site every day once construction began in 2014. These are their stories.

In the Beginning

It all started, of course, with Monty Hoffman. “Back in 2006, no one—[not] even the District of Columbia— knew what lay ahead. I knew I was getting into something big, but it was an abstraction,” Hoffman says. The first three years were spent acquiring the land and water rights from the city and the federal government. The ensuing years would see 14 rezoning applications, 1,200 community meetings, 1,700 permits pulled, 4,000 inspections, and the largest construction loan in DC history. Not to mention the four Acts of Congress that were required to make it all happen. “I knew the journey would be difficult, but I did not think it would take 16 years.”

Under Eckstut’s vision, which Bertsch aided and managed through to completion, their team wrote the regulations and requirements for the public realm that surrounds the new buildings along The Wharf, in addition to designing several of the key buildings in Phase 1. “Stan has a way of thinking about how a layperson can relate to things,” says Associate Principal Stephen Penhoet, The Wharf’s project manager throughout the initial planning and entitlement phases. “He wanted to create this messy environment down at The Wharf,” where cars, delivery trucks, pedestrians, and cyclists occupy the same network of spaces. “One of the challenges was trying to convince people that messiness was a virtue.”

Opposite Page

Much of The Wharf’s success is the result of its commitment to public placemaking, which is rich with landscaping, shaded lanterns, and chandeliers.

Photograph Courtesy HoffmanMadison Waterfront

Above

The newly completed Wharf, years in the making, fits beautifully into its waterfront context in southwest Washington, DC. Copyright Matthew Borkoski/Courtesy Hoffman-Madison Waterfront

the NARRATIVE FALL 2022 15

The developer and his team were open to it. “In the formative design stages, we held small group meetings—five people or less—that I would describe as intellectual food fights. We wanted to hear and learn from all perspectives,” Hoffman says. For Principal Omar Calderón Santiago, the project’s point person for The Channel Apartments and The Anthem, “that experience, to me, was significant in my growth as an architect. Monty is very hands-on and he has a great design sensibility.” But unlike many developers, he adds, Hoffman wasn’t looking for everyone to agree with him. As the developer explains, “it was an accretive adventure where design outcomes were greater than anybody could have imagined on their own. I loved it.”

The Process

“It’s not often you get to build cities, and at the waterfront in the nation’s capital? My goodness,” Calderón Santiago says of his career-changing experience at The Wharf. But he’s quick to point out that “the process overall was not without its horrors,” an observation many shared as they described the project’s rocky, uncertain path from start to finish. Calderón Santiago identifies his most humbling moment as when the US Commission of Fine Arts sent his designs for the Channel and Anthem’s exteriors back to the drawing board. “In the words of one commissioner,” he recalls, “‘This is not how we do buildings.’ It was painful to go through that very public process,” although he now recognizes that the commission’s rebuke was not a failure, per se, but “just part of the iterative process of design.”

Perkins Eastman Associate Principal Douglas Campbell, the project manager who led the construction phases,

calls it “the gauntlet project.” He directed a team of 30 Perkins Eastman staff who occupied four trailers on the construction site for five years, and he oversaw a consultant team that included more than 100 people. “This was eight times bigger than anything I’d ever done before,” he says. “You have to be the opposite of being a designer who focuses on one big idea. Your job is to execute across a bunch of different projects,” he adds. “Part of doing a large project is learning what the people on your team can do and letting them go do that. There’s always some other crisis. There’s always some other phone call. You have to broaden your vision.”

Abbey had his own trial by fire. When he joined Perkins Eastman in 2015, he moved directly into the trailers to help Campbell manage the contractors. On his first day, he was greeted with a stack of 146 RFIs, or requests for information, from contractors seeking clarification on one matter or another. Addressing them became his daily existence. “They literally had a line of contractors every day for us to answer questions,” he says. It was a ritual performed to the soundtrack of pile drivers ramming piers and bulkheads into the water to underpin the new development. And, as they say, that’s not all: As the architect responsible for the 1.5 million square feet of below-grade structures that now span the development and protect it from the Washington Channel, Abbey and the Perkins Eastman team had to coordinate with all the architects (including their own) and builders who were designing and constructing the site’s 13 buildings. They accommodated how each one, with its own design and program, would connect to the foundation below. “We had to support and adapt to all the structures upstairs,” Abbey says. “We engaged with all the other entities. We were on the phone with

16 Features

Above Developer Monty Hoffman, founder of Hoffman & Associates, celebrates the completion of The Wharf in a ceremony at The Pendry Hotel on October 12. Copyright Dan Swartz/Courtesy HoffmanMadison Waterfront

every single person for every single parcel to make sure they were getting what they needed for their buildings to work.”

Hoffman, meanwhile, was going through a gauntlet just to keep the development financed. “The Great Recession drove some of my partners into bankruptcy. So I self-funded for a few years,” he says. “In that environment, there are many predators. And honestly, with all the hurdles to be jumped, I probably wasn’t a good ‘bet’ in the beginning.” Yet by the time Phase 1 opened in 2017, the developer had established a capital partner in PSP Investments, one of Canada’s largest pension investment managers, which gave The Wharf the “certainty for both development and long-term ownership” that it needed to reach completion, Hoffman says.

Bertsch says she’ll never forget the night before Phase 1 opened on October 12, 2017. Members of the Perkins Eastman and Hoffman & Associates teams gathered to celebrate on what is now the Recreation Pier. There was a collective sense of relief in the air. “They had a countdown clock, and had booked the Foo Fighters years in advance for the opening day. That was the date. There was no blinking,” she says. “There was so much going on. I don’t think the Hoffman & Associates team slept much during that last month. Two million

square feet came online in one day. This whole Wharf neighborhood—it didn’t exist, and then it did!” As they gathered that evening, she says, “that moment, it was life-changing. This was the last moment we would have it to ourselves. We were giving it to the world the next day.”

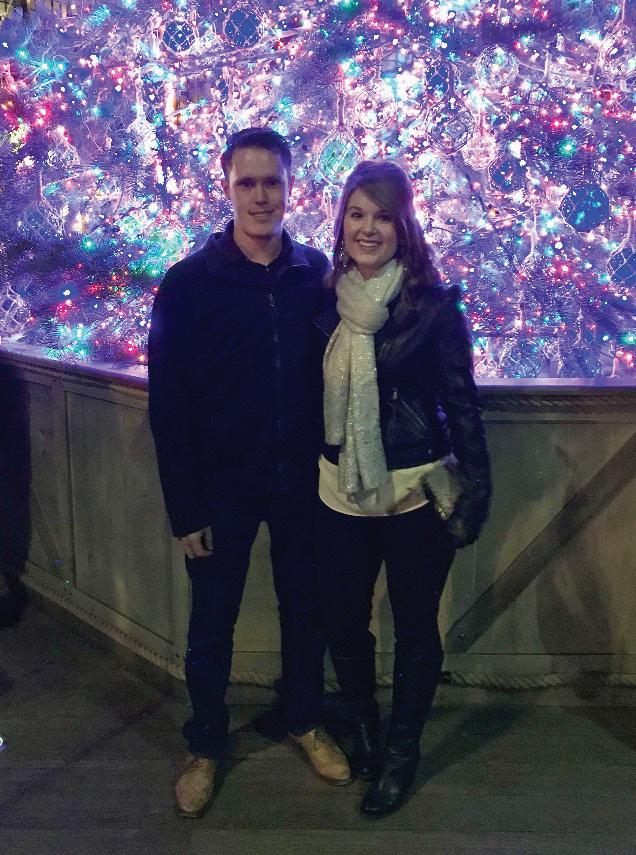

Life Changes

Babies became teenagers in the time it took to develop The Wharf—including Shawn Seaman’s twin girls, who were born in 2010. As Campbell describes the 16year endeavor, “it was a percentage of our lives.” It was a time that saw people get engaged—Perkins Eastman Associate Jake Bialek met his wife, Lindsay Scott, while she was working as a receptionist for Hoffman & Associates at the trailers—but it was also a period that saw tragedy. Perkins Eastman’s Blair Phillips, a young architect who was passionate about The Wharf, died in a ski accident in 2013. “He had the sun, the moon, and the stars ahead of him,” Penhoet says. He was so popular at the firm that grief counselors were called in to help his colleagues cope with the loss, and a fountain on the waterfront esplanade was dedicated to him.

Phillips’ parents visited The Wharf after his death, and Monty Hoffman met with them in one of the trailers. “Right then and there,” Campbell says, Hoffman

Below

Vehicles and pedestrians share the same “messy” space at The Wharf. Placemaking features such as shaded lanterns, trees, and a huge firepit made the Wharf Street esplanade an instantly popular destination when Phase 1 opened in 2017.

the NARRATIVE FALL 2022 17

Photograph by Andrew Rugge/ Copyright Perkins Eastman

also decided to rename the alley behind the fountain Blair Alley.

The Wharf was deeply personal for those who grew up in the area. “This project has a lot of emotional significance to me,” says Principal Gary Steiner, who co-manages the Washington studio with Principal and Executive Director Barbara Mullenex. The Rockville, MD, native remembers visiting the Municipal Fish Market as a child to purchase crabs with his parents. “At the time, it was a pretty seamy experience. It was pretty gritty,” says Steiner, who built the teams that worked on the new development. “Seeing this thing happen in a place that I was familiar with was pretty significant.” Associate Ricardo Hemmings, who worked on the below-grade elements for four years, remembers moving with his family from Jamaica to Washington, DC, when he was 19. His parents quickly

found the Municipal Fish Market because it was the only place in the city that sold fresh fish, which is how they bought it in the Caribbean. Nearly every Saturday since then, they’ve come to the fish market— even during The Wharf’s construction. “When we got here initially, there were very few things that we felt connected to,” Hemmings says. The Caribbean community along Georgia Avenue in Northwest DC was one of them—and the fish market was another. “When [my parents] found out that I was going to be doing Phase 2, my mom was gushing to everyone about it. I was like, ‘Mom, I’m doing the garage!’”

The project was even more pivotal to Perkins Eastman as a firm. There were about 40 people in the DC studio when it merged with EE&K and began work on The Wharf in 2011. With Perkins Eastman’s overall size and expertise in big buildings, the merger allowed

Eckstut

Above Left Perkins Eastman Principal Stan Eckstut and Principal and Executive Director Hilary Kinder Bertsch on a rainy Phase 1 opening day. Photograph courtesy Hilary Kinder Bertsch

Above Right Hoffman & Associates team members gathered to celebrate with Perkins Eastman colleagues the night before the Phase 1 opening. Left to right: Yasmine Doumi, former development manager; President Shawn Seaman; and Senior Development Manager Lane Gearhart. Photograph courtesy Hilary Kinder Bertsch

18 Features

Right The Phase 1 opening day saw widespread delight. The Foo Fighters inaugurated The Anthem with a sold-out concert. Photograph courtesy Barbara Mullenex

and Bertsch to go past the planning and strategic phases and into the architecture and construction space. In turn, Perkins Eastman secured one of its biggest commissions to date. “Nobody [here] had ever done anything nearly as large before, either personally or as a firm,” Steiner says. “The Wharf was the seminal project that put us on the map.” With more than 120 people at the DC studio—and still hiring—Mullenex says, “the size we are now is the size where you can do anything as a firm—and The Wharf was the ticket.”

Signs of Success

Phase 1 was completed with largely local architecture firms responsible for its structures. The Wharf’s immediate success, however, paved the way for national and international firms to enter the mix and design office and residential buildings for Phase 2. Celebrity chefs such as Gordon Ramsay are opening restaurants there, and “insane luxury condos,” in the words of Washingtonian, are expected to sell north of $12 million. Yet in his speech at the Phase 2 opening, Hoffman emphasized the spaces in between the buildings—the public realm that Perkins Eastman

designed along this mile between the fish market and Fort McNair. Hoffman pointed to the “warm and soft” wood where people walk along the piers, the trafficcalming cobblestones, and the energy that surrounds the development’s multiple “town squares.” He noted the trees and plantings that provide shade and the chandeliers over the streetscapes that have dimmers “so they make you look good at night.” There are outdoor firepits to gather around and small stages where artists perform as visitors walk by and spill out of the restaurants and hotels.

“I talk a lot about the tenacity of vision,” Bertsch says, explaining that the public realm brings connection and order to everything else. “It’s the integrity of the place,” knitting the city to its waterfront. “If you keep the fabric of the environment, there is continuity in that spirit.” That’s the placemaking theme Hoffman was after, he says. “We traveled all over the world to visit and study public realms and waterfronts. We wanted to learn what worked and what to avoid in creating The Wharf. Today, we give tours to people from all over the world who come to The Wharf to study and learn how it works. It’s kind of a poetic full circle.”

Below

Perkins Eastman designed The Wharf’s public realm to bring the development’s massive size down to human scale. It features myriad vignettes such as a shaded seating and play area.

Copyright Jeff Goldberg/Esto/ Courtesy Perkins Eastman

the NARRATIVE FALL 2022 19

Above Right

The Perkins Eastman and Hoffman & Associates teams gathered to celebrate the opening of Phase 2 at The Wharf on October 12. Left to right: Perkins Eastman DC Associate Principal and Project Manager Douglas Campbell; Colin Gdula of Hoffman & Associates, who handled field construction; Perkins Eastman DC Principal Jason Abbey; landscape architect Paul Josey of Wolf Josey, who worked under Perkins Eastman DC; Perkins Eastman Principal and Executive Director Hilary Kinder Bertsch; Senior Development Manager

Lane Gearhart of Hoffman & Associates; Perkins Eastman Associate Belen Ayarra, the project architect for ground plane; Hoffman & Associates Vice President of Development

Matthew Steenhoek; Hoffman & Associates Development Manager Christopher Kirchner; and Hoffman & Associates Senior Development Manager

Anthony Albanese. Photograph

Catherine Page/Courtesy Perkins Eastman

Center

The Perkins Eastman and Hoffman & Associates teams celebrated the Phase 1 opening in 2017. Left to right: Perkins Eastman Associate Principal Douglas Campbell; Perkins Eastman Principal and Executive Director Barbara Mullenex; retired Perkins Eastman Principal Douglas Smith; Perkins Eastman Associate Josh Eisenstat (seated above); Hoffman & Associates President Shawn Seaman; former Perkins Eastman design architect Evan Smith (seated above); Perkins Eastman Principal and Executive Director Hilary Kinder Bertsch; former Perkins Eastman Associate Sarah Watling; and Perkins Eastman Associate Principal Mathew Hart. Photograph courtesy Hilary Kinder Bertsch

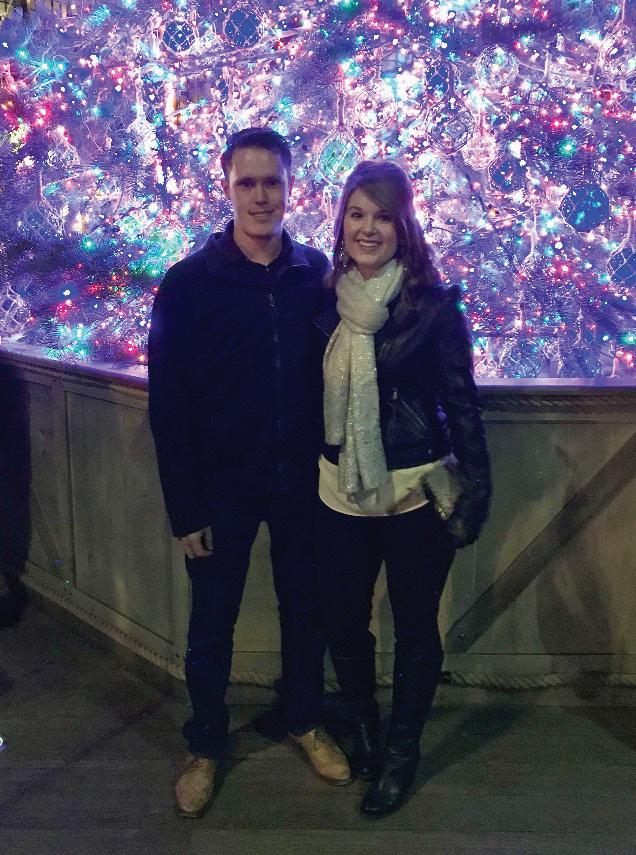

Left Perkins Eastman Associate Jake Bialek and his wife, Lindsay Scott, posed at the Christmas tree on The Wharf’s District Pier in 2017. Photograph courtesy Jacob Bialek

Right

A fountain is dedicated to the late Perkins Eastman architect Blair Phillips. Photograph by Andrew Rugge/Copyright Perkins Eastman

20 Features

Five years to the day after opening Phase 1, fireworks go off beyond the Transit Pier, which Perkins Eastman designed, to celebrate the completion of The Wharf’s second and final phase. Copyright Dan Swartz/Courtesy HoffmanMadison Waterfront

the NARRATIVE FALL 2022 21

BUILDINGS + STRUCTURES Perkins Eastman

The Channel Apartments and The Anthem: The 12-story, two-tower apartment building embraces The Anthem music hall—an unorthodox scheme that disguises what would otherwise be a large, windowless box.

800 Maine Avenue: The 11-story office building, directly across District Square from The Channel Apartments, includes street-level retail and restaurants.

Pier House: This freestanding building is located in the center of District Square between Maine Avenue and Wharf Street. Besides housing the popular ilili Restaurant, it also provides a mask of sorts, enticing visitors to move through District Square, walk around the building, and discover the water’s edge on the other side.

Dockmaster Building: An assembly and event space, with views of the water and national monuments, tops the dock manager’s office at the end of District Pier.

Transit Pier: This multipurpose structure houses the box office for The Anthem, accommodates ticketing and loading for the Potomac Water Taxi, offers public amenities such as tiered outdoor seating and public bathrooms, and hosts the rooftop bar Cantina Bambina.

22 Features

Kiosks: These small vendor stands are scattered along the water side of Wharf Street. All photographs on this page Copyright Jeff Goldberg/Esto/Courtesy Perkins Eastman

The Hidden Wharf

Invisible design interventions were critical to allow the smooth functioning of The Wharf and its buildings:

• Under Principal Stan Eckstut’s vision, pedestrians and vehicles share the same “messy” spaces; there were to be no curbs or gutters separating them. That meant engineering four different types of drainage, including rain gardens on Maine Avenue, conventional drains in the alleyways, trench drains on Wharf Street, and large-scale, landscaped planter beds by the water. They all convey stormwater through separators to filter out waste and on to four huge, custom-designed underground cisterns, which supply water to all the buildings’ cooling systems.

• T he Wharf continues to be a working wharf with a large marina and a live-aboard houseboat community. All those boats need fuel. Amid the tight confines of the two-level underground parking garage that Perkins Eastman designed to stretch underneath the entire Wharf complex, there are tanks containing 25,000 gallons of gas and diesel fuel to service the boat traffic, in spaces engineered to remain secure from storm events.

• I nitially, PEPCO—the local power utility—insisted that 23 electrical transformer vaults were required along Maine Avenue, which would have interrupted a streetscape experience that includes a bike path, trees, building entries, commercial storefronts, and street lamps. Perkins Eastman’s team spent a year developing a design to ventilate the vaults through the garage spaces, resulting in a sidewalk with minimal utility intrusions, and in the process, reduced development costs. N

Top Two-level garages and other underground structures run the length of The Wharf. An exit at District Square is welcoming and ceremonious, instead of hidden away from the action.

Bottom Perkins Eastman’s design to place utility transformer vaults underground made way for an unobstructed pedestrian experience on Maine Avenue, which includes sidewalks and a bike path separated by rain gardens.

Photograph by Sarah Mechling/ Copyright Perkins Eastman

the NARRATIVE FALL 2022 23

Photograph by Andrew Rugge/Copyright Perkins Eastman

QUICKDraw on the

Perkins Eastman promotes hand sketching as an invaluable design tool that technology cannot replace.

By Jennifer Sergent

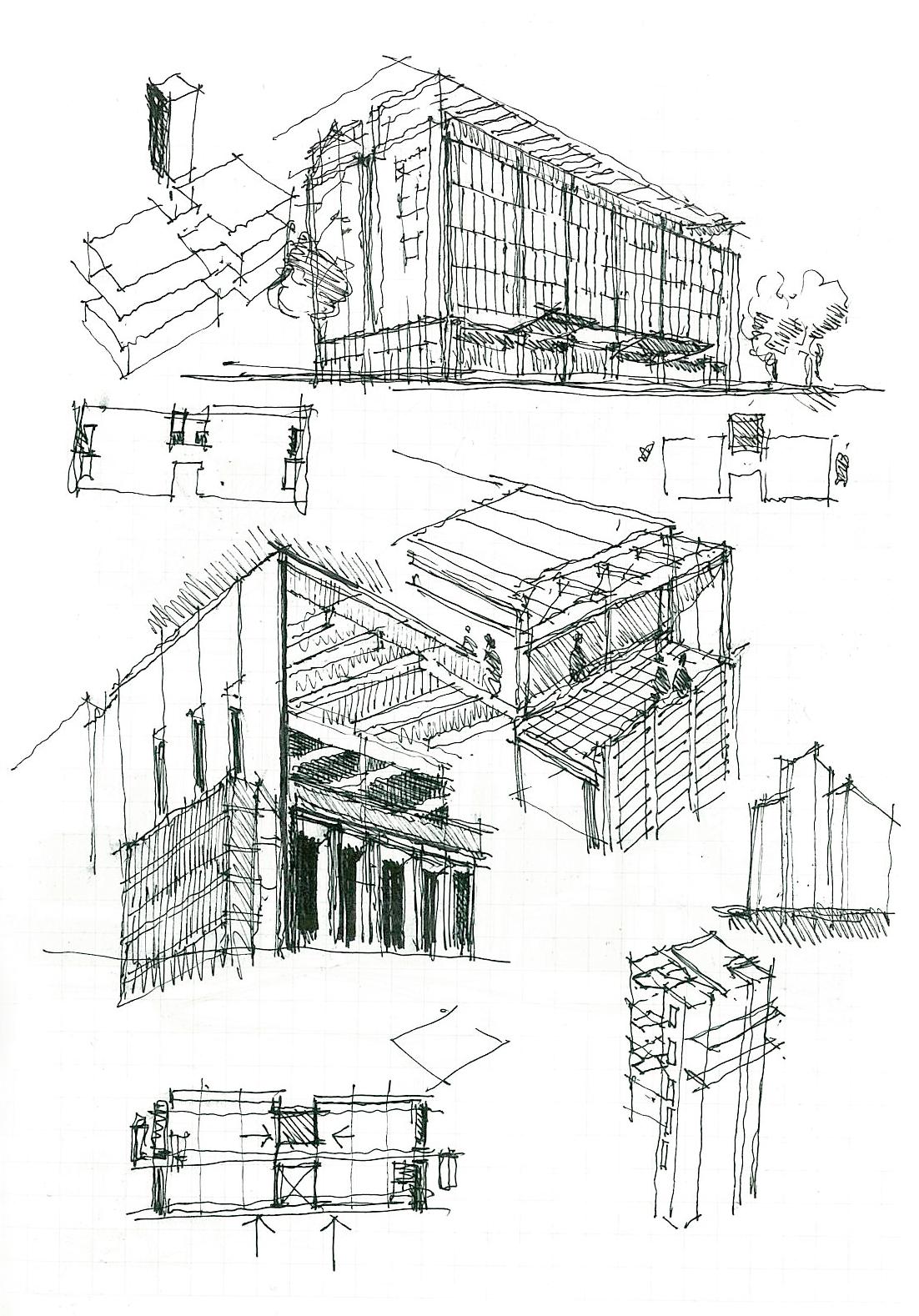

Decades after graduating from Pratt, Perkins Eastman Associate Principal Ty Kaul says his most influential instructors taught by drawing. “They would sit down and analyze your project with a few simple sketches that clarified the idea.”

In practice, Kaul adds, the fi rst sketches of a project— imperfect and incomplete though they may be—can provide that spark of inspiration from which a building will emerge. “When you draw, you are in a special place. You are in a separate nation—the imagination.”

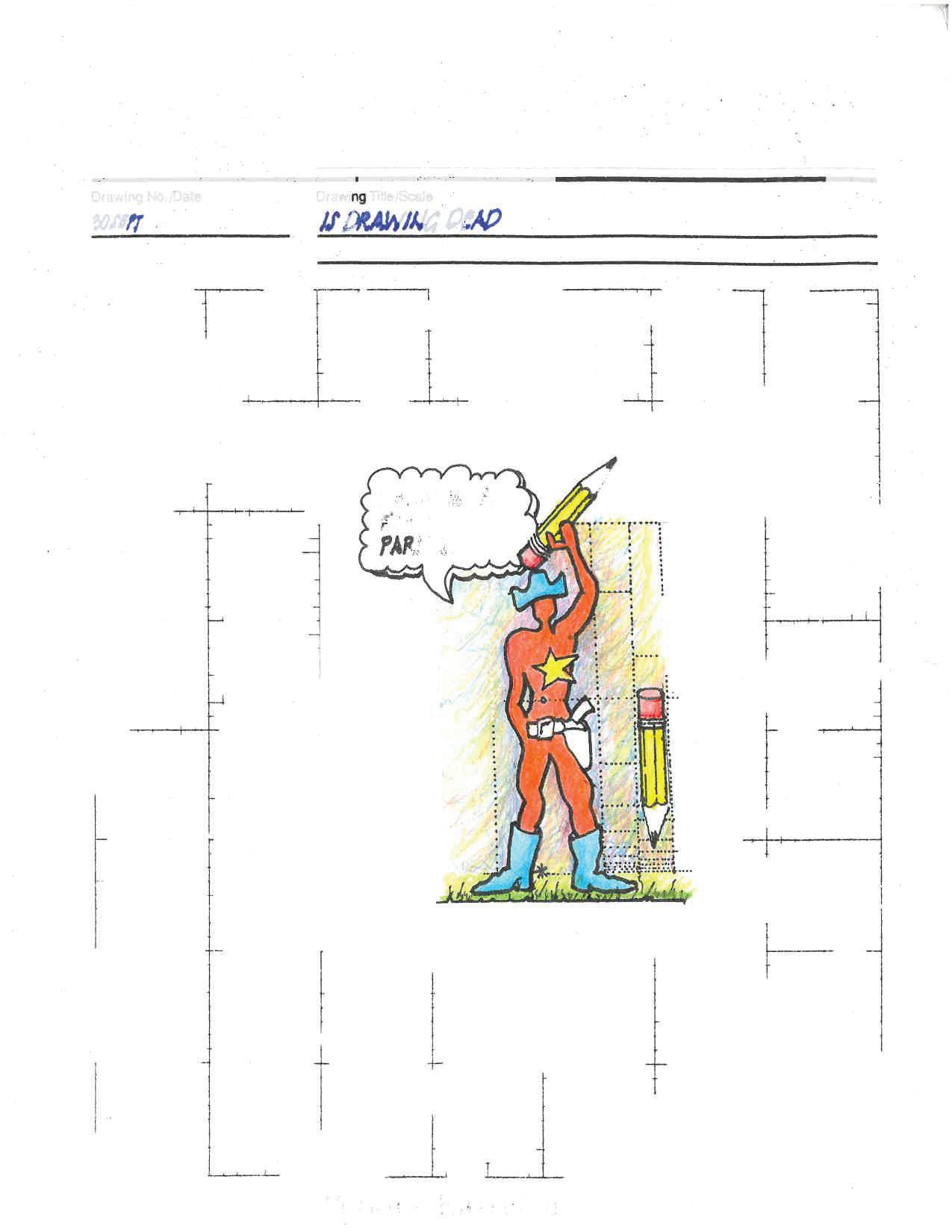

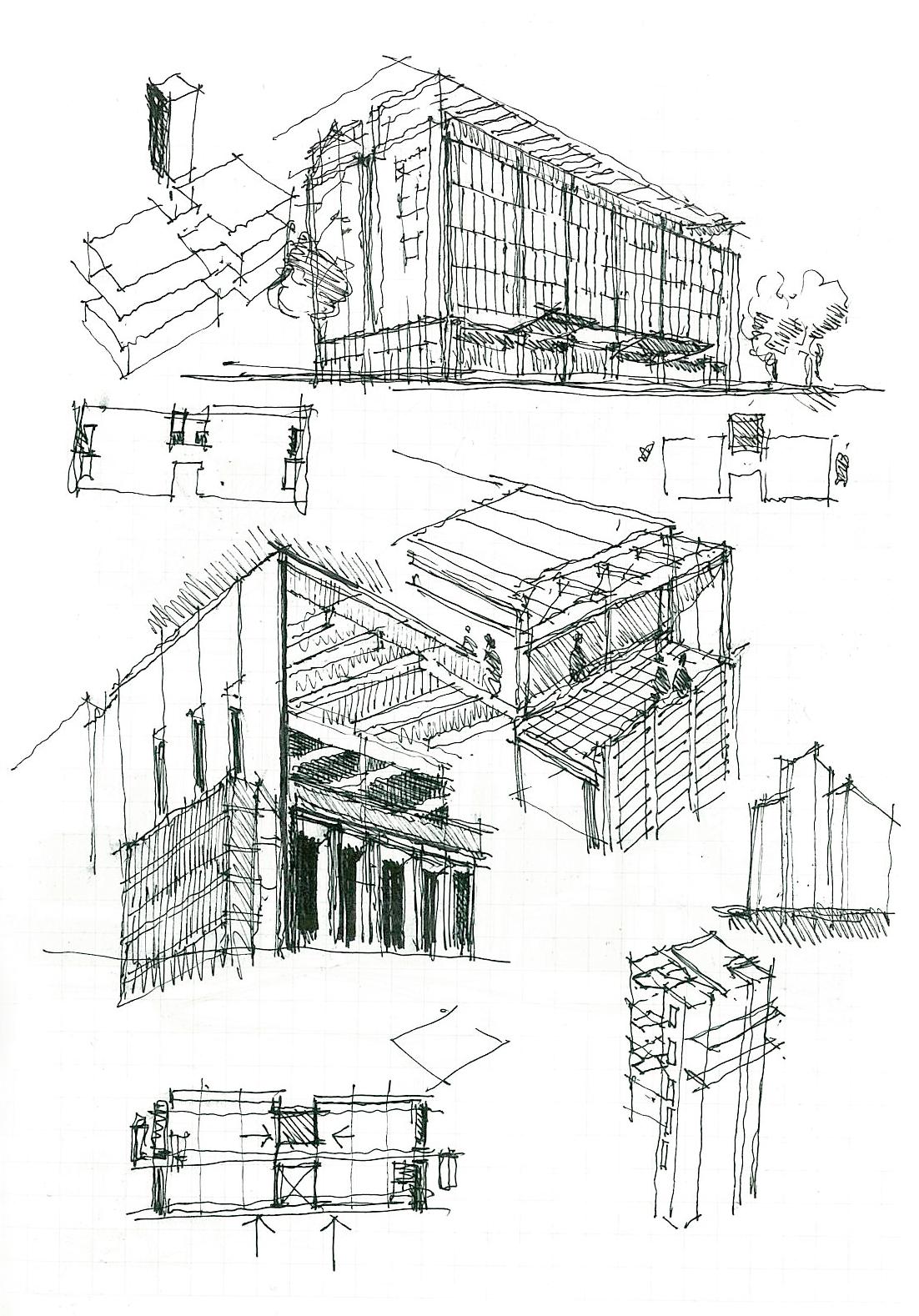

Now that digital technology has become the default design tool among architects, some question the usefulness of drawing by hand. The Yale School of Architecture even hosted a symposium back in 2012 that was provocatively titled “Is Drawing Dead?” Yet Kaul and many of his colleagues in the New York studio and across the fi rm remain steadfast adherents.

Power of the Pen

Omar Calderón Santiago, a principal in Washington, DC, sees “a quiet revolution” afoot that’s reviving the power of sketching. “People are responding to the immediacy and the intimacy that a hand drawing gives you,” he says. Calderón Santiago and members of the K-12 Education practice team recently arrived at a client interview with nothing but sketches to demonstrate their work. “They were so appreciative and thankful that someone took the time to draw by hand,” he says. Associate Principal Christy Schlesinger, who also works in DC, explains why: “It’s a tool you

24 Stories

use during a meeting to show that you’re listening— that you’re translating their words into something they can see.”

Architects also sketch to work through their own ideas. Co-CEO and Executive Director Nick Leahy describes this essential process in the updated edition of Eric Jenkins’s Drawn to Design: Analyzing Architecture through Freehand Drawing, which was published this fall: “The bodily, physical interaction that occurs through a drawing instrument literally helps architects ‘feel the weight of things’—a feeling that cannot be carried over using a keyboard, mouse, or tablet.” In a conversation for this article, Leahy adds, “When you’re drawing, it focuses the mind.”

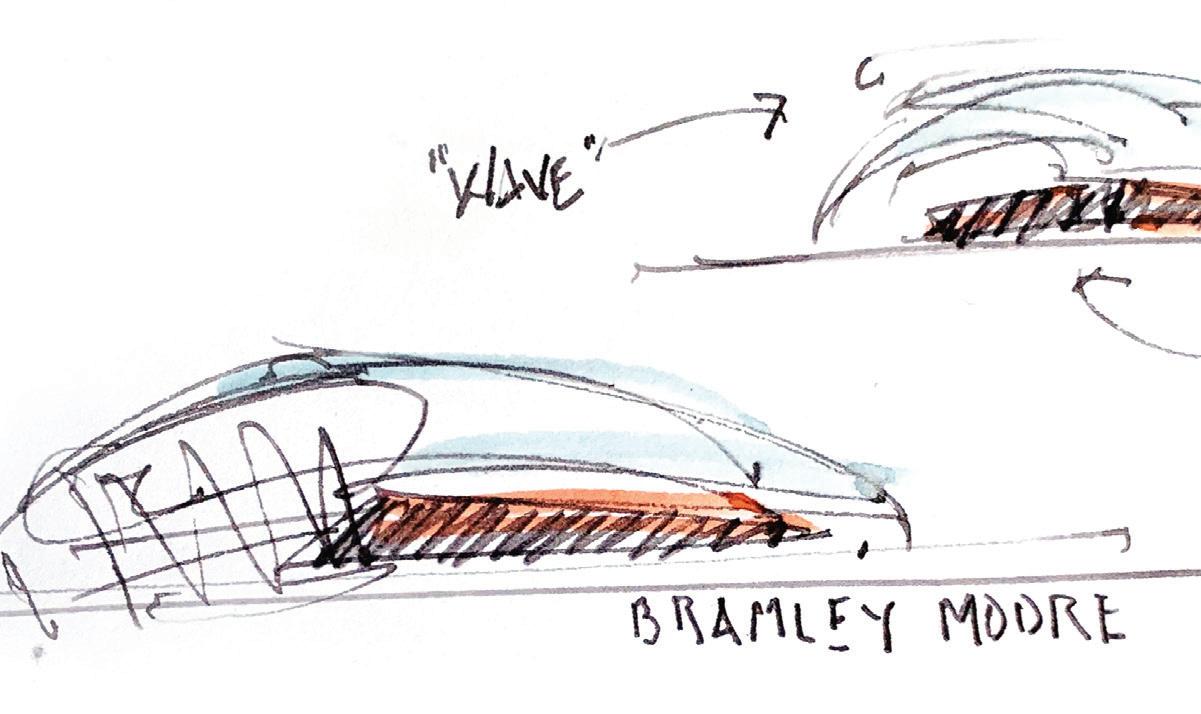

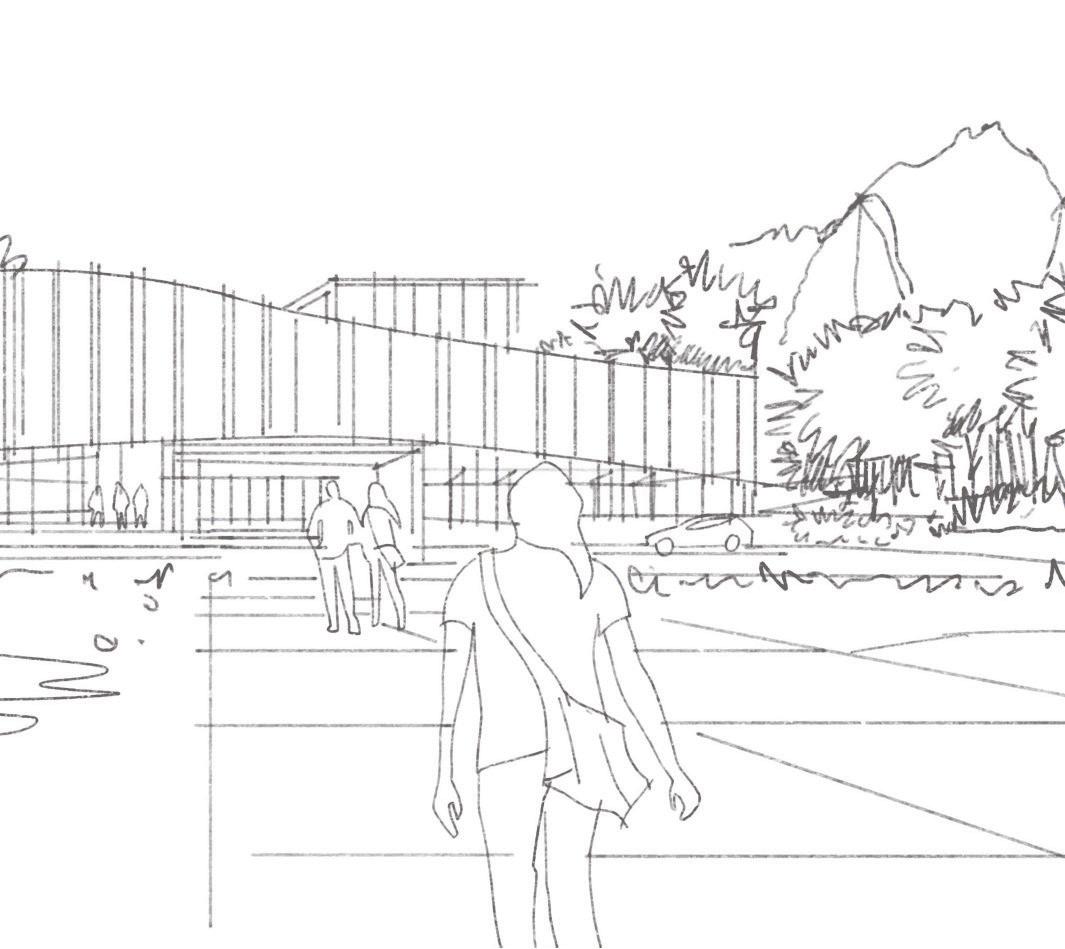

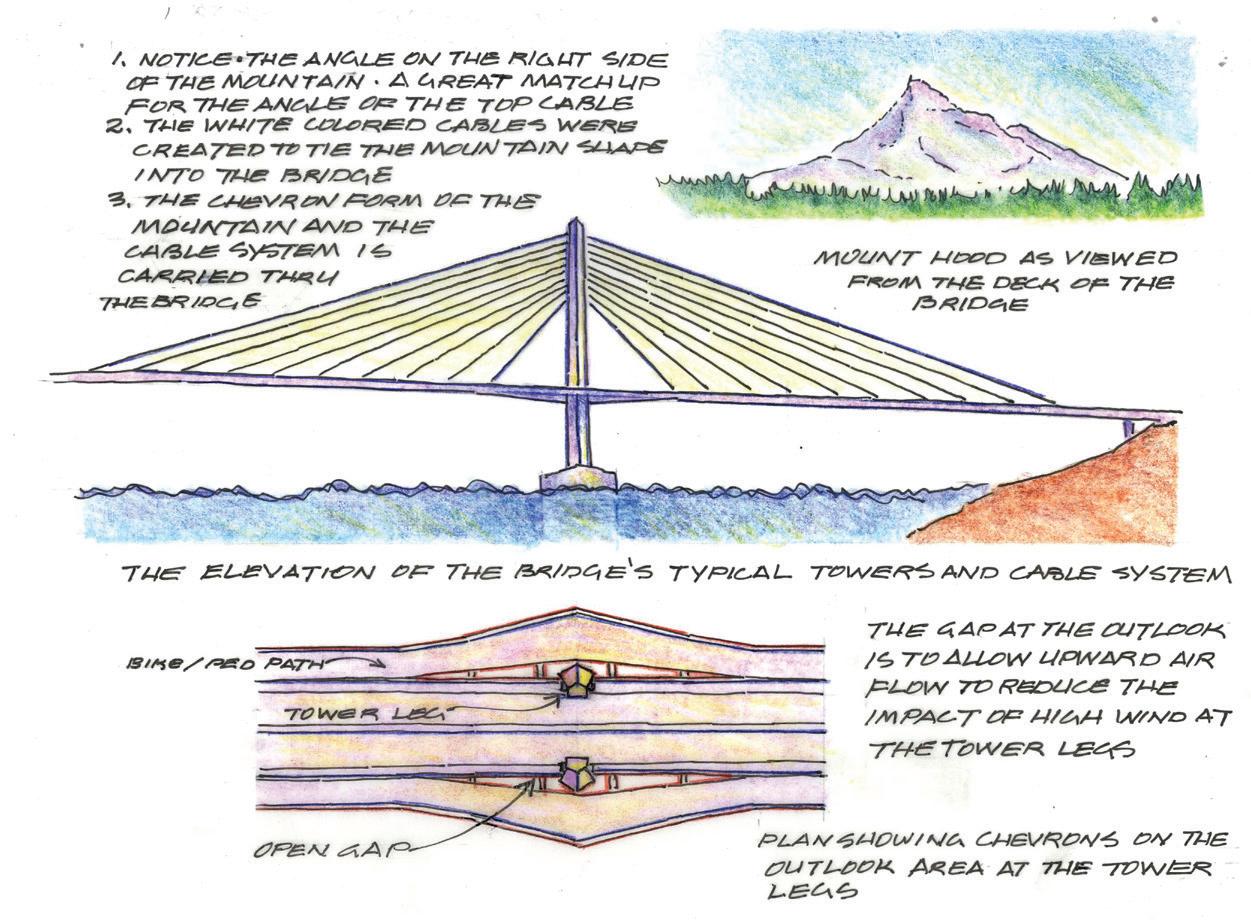

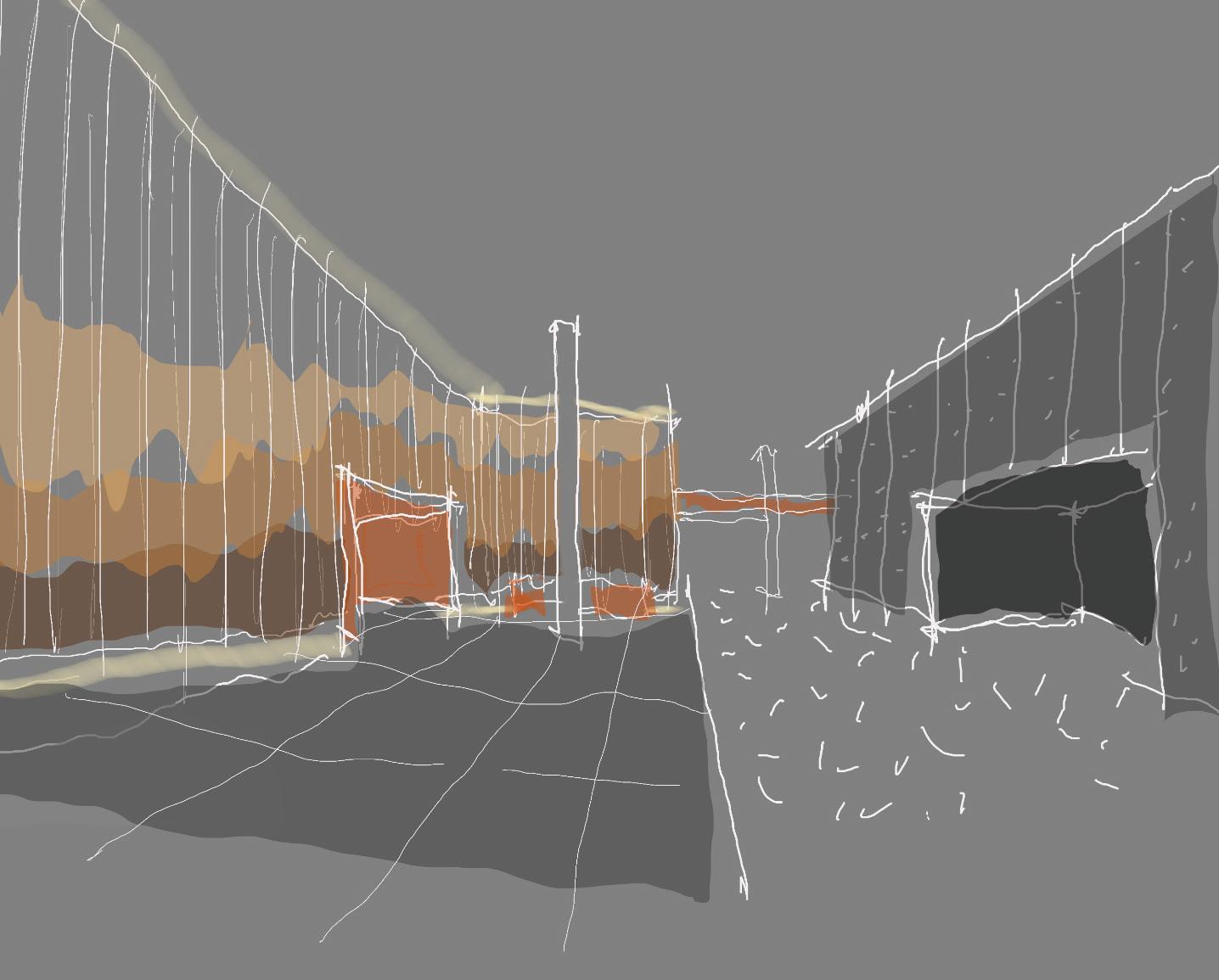

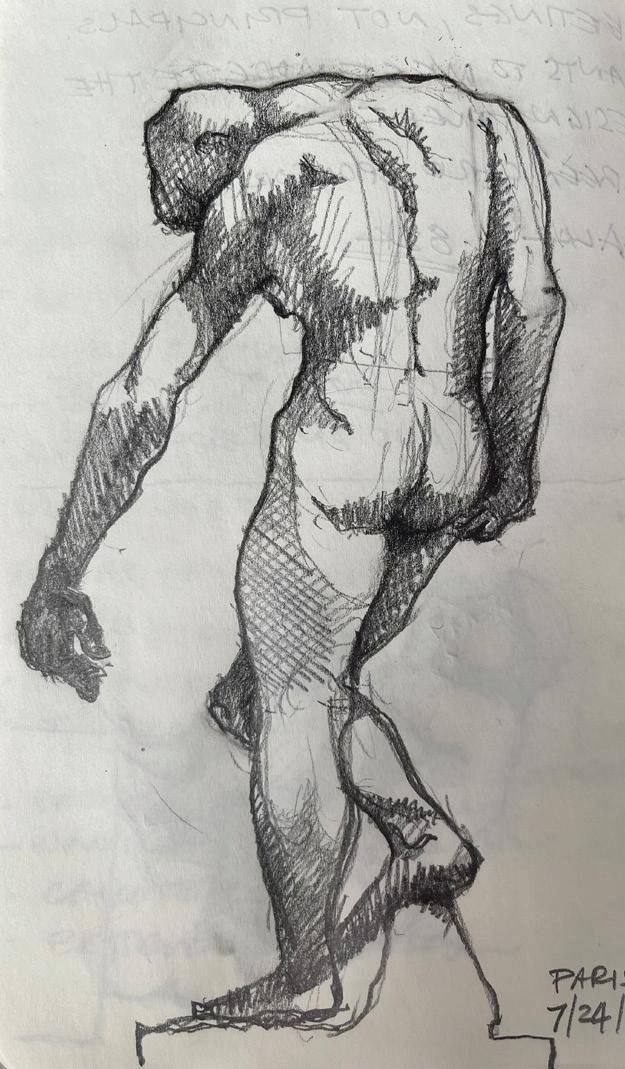

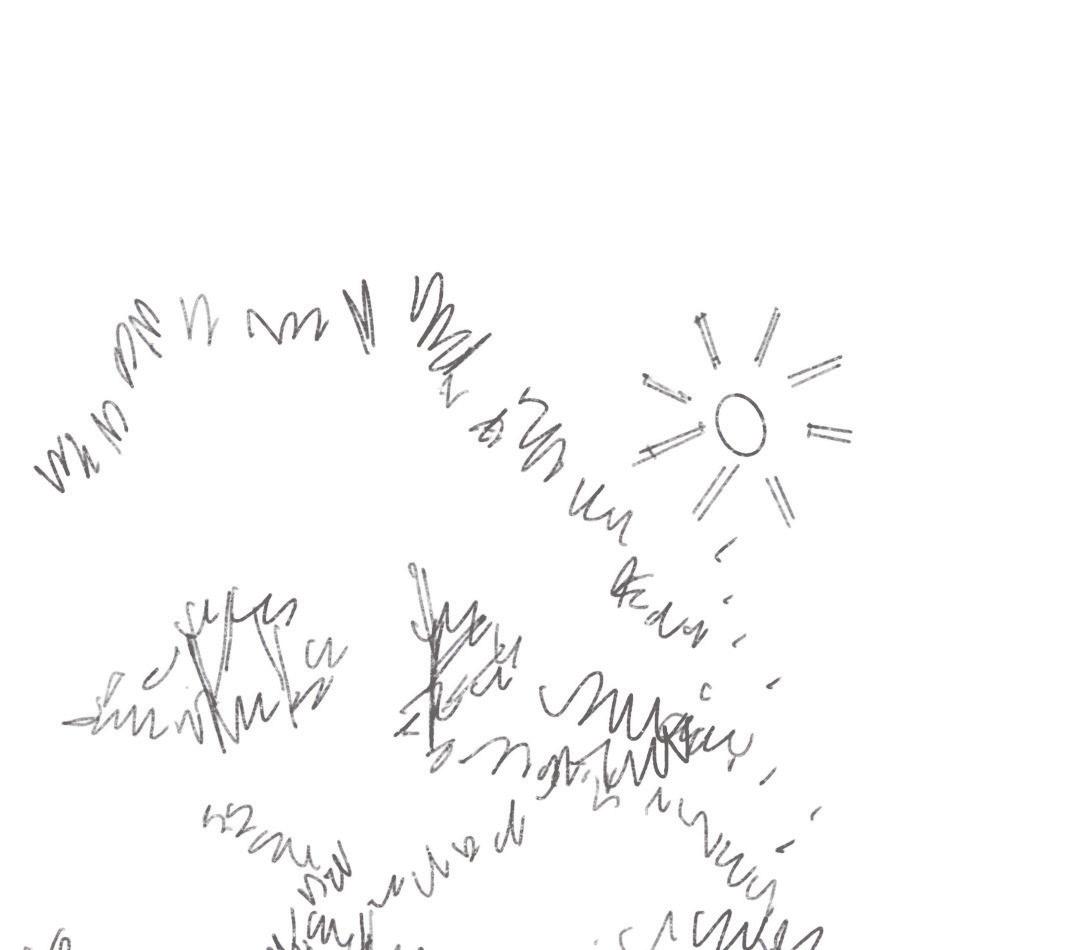

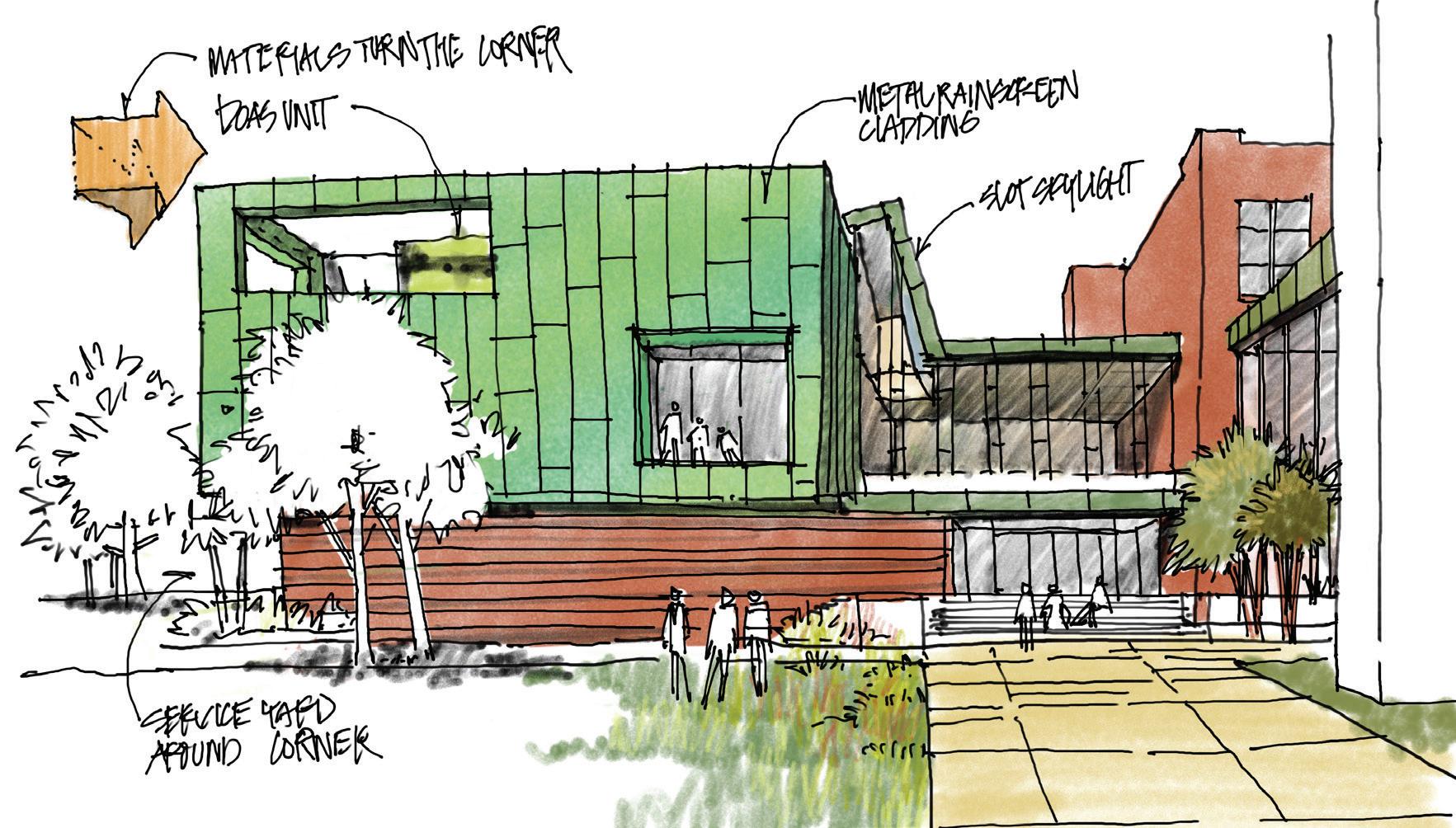

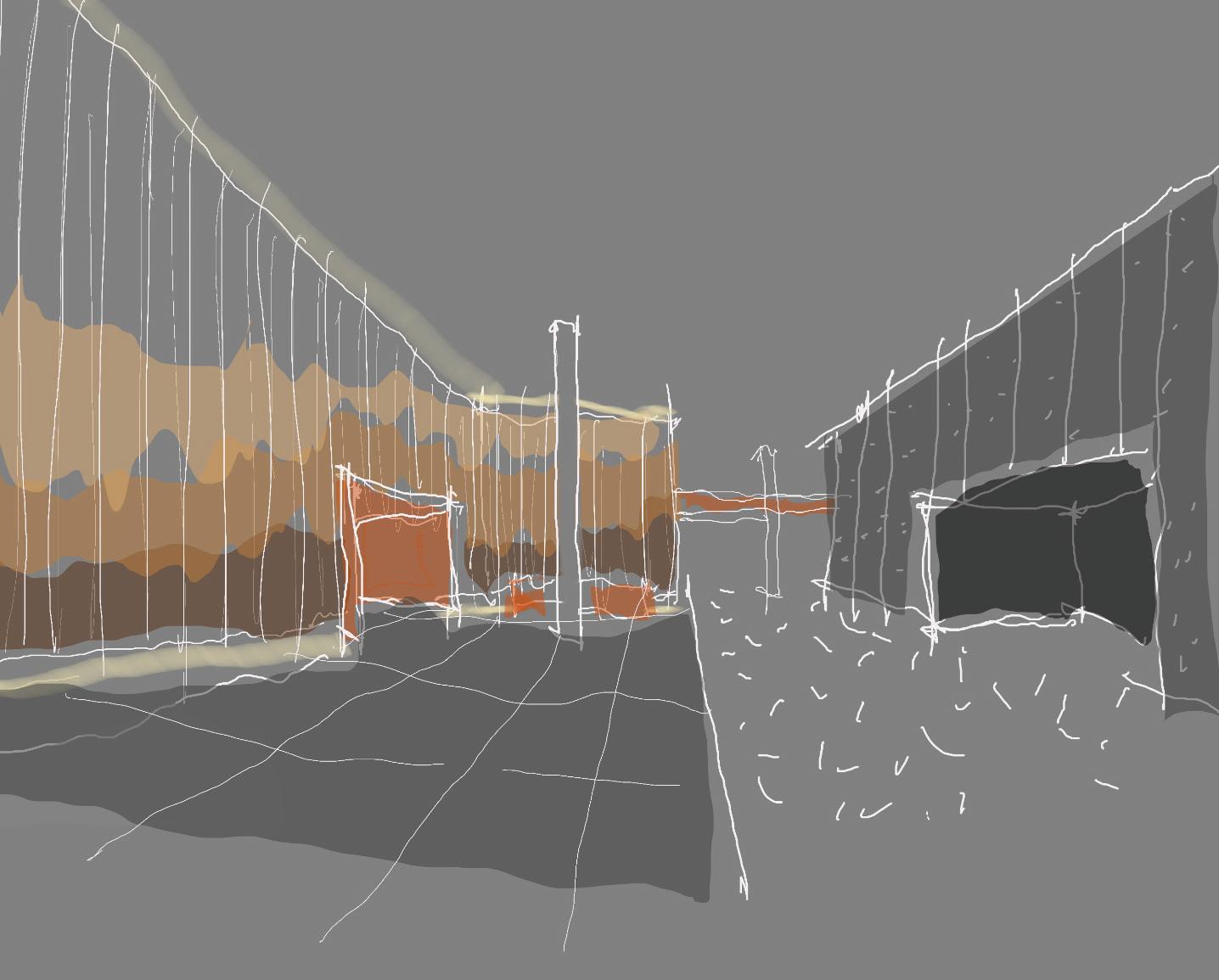

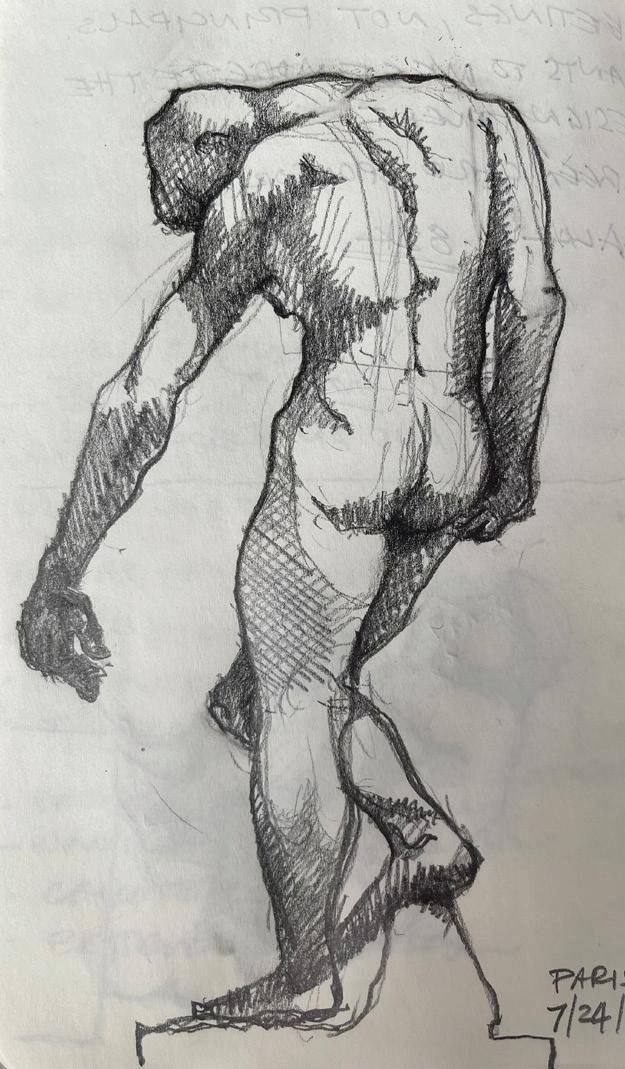

That concept played out on a grand scale in Liverpool, England, where the new Everton Stadium is rising from the historic Bramley-Moore Dock on the River Mersey. When Dan Meis, a principal and founder of MEIS—A Perkins Eastman Studio in Los Angeles and New York, first met with the chairman of the Everton Football Club, his instinct was for the stadium design to evoke the rough-hewn, gritty history of the former coal-handling dock. Yet his client preferred a sleeker, more modern profile. In an attempt to bridge the two concepts, Meis later sat down with his sketchbook, exploring new configurations as they emerged from his pen. In the end, he produced a sketch that looks like a cresting wave is washing over the stadium. “The chairman has been 100-percent sold on the design ever since,” Meis says, noting that the plans call for a

curved, glass-and-steel “wave” over a rugged brick base that looks as if it’s always been part of the dock. “If you sketch for the client, they feel like they’re part of the process. They see the thinking behind it,” he says. In contrast, a beautiful computer rendering can look like a fait accompli, with no room for further alteration, imagination, or participation. Giaa Park, an associate principal in New York, compares it to cake decorating—pretty on the surface, but there’s no way to know what’s underneath. “It often results in losing its abstract value, because computer graphics can overpower the idea and be presented—prematurely— as a final project,” she says. “A sketch is an intuitive thinking tool searching for a solution to the essence of what a building should be.”

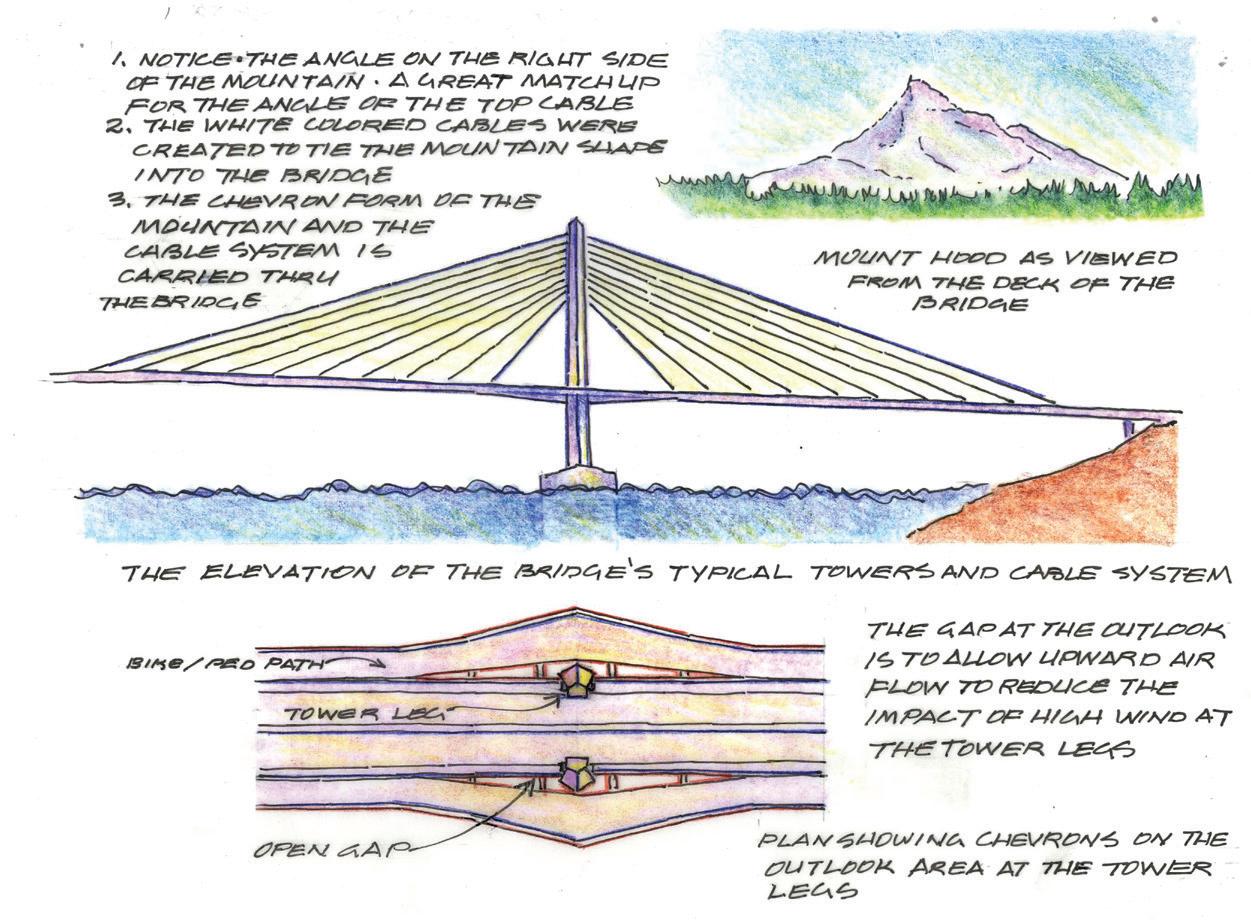

The benefits of sketch-driven client presentations also extend to public meetings, says Don MacDonald, founder of Donald MacDonald Bridge Architects— A Perkins Eastman Studio in San Francisco. “I always find it’s better to start out with a sketch at a public hearing,” he says. “When we’re done, everyone feels like they’ve had some say in the process.” That approach brought him success in Portland, OR, throughout a series of 15 hearings to develop the design for Tilikum Crossing, a bridge for pedestrians, cyclists, and public transit that crosses the Willamette River. “I did [the hearings] with drawings,” says MacDonald, who later included them in a book he wrote about the crossing, which is also known as the “Bridge of the People.”

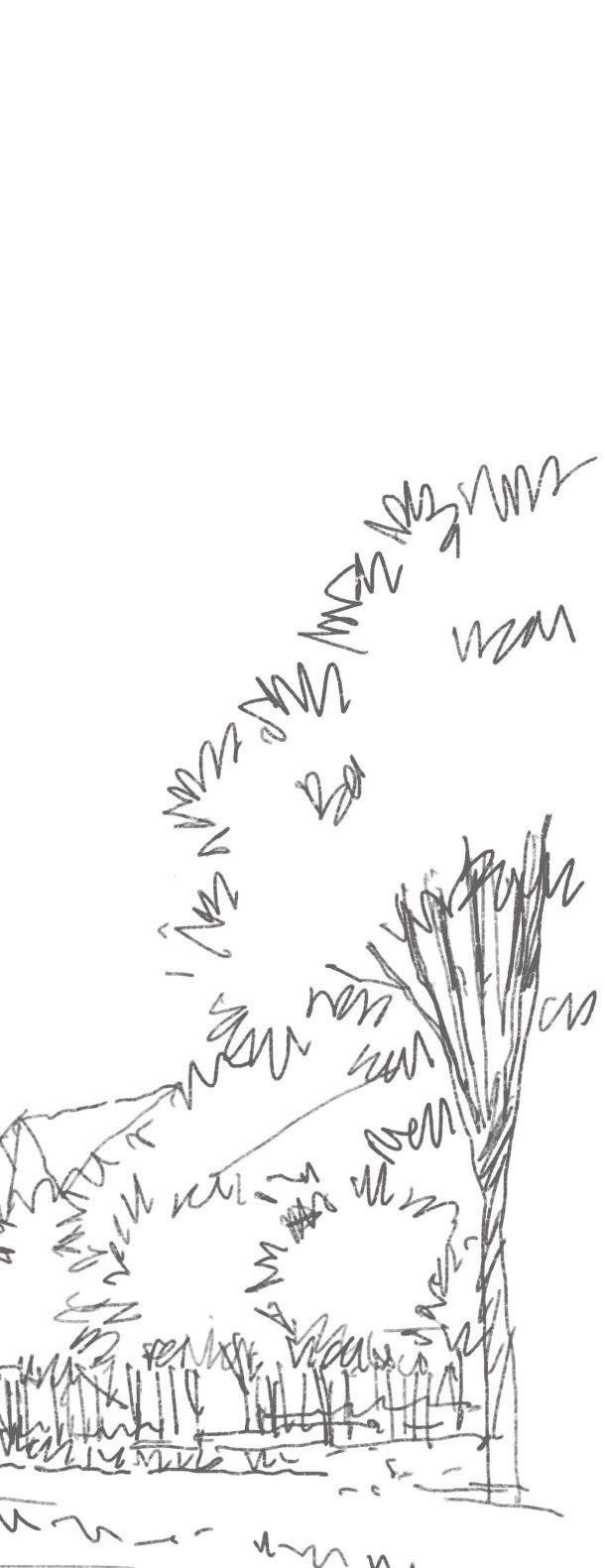

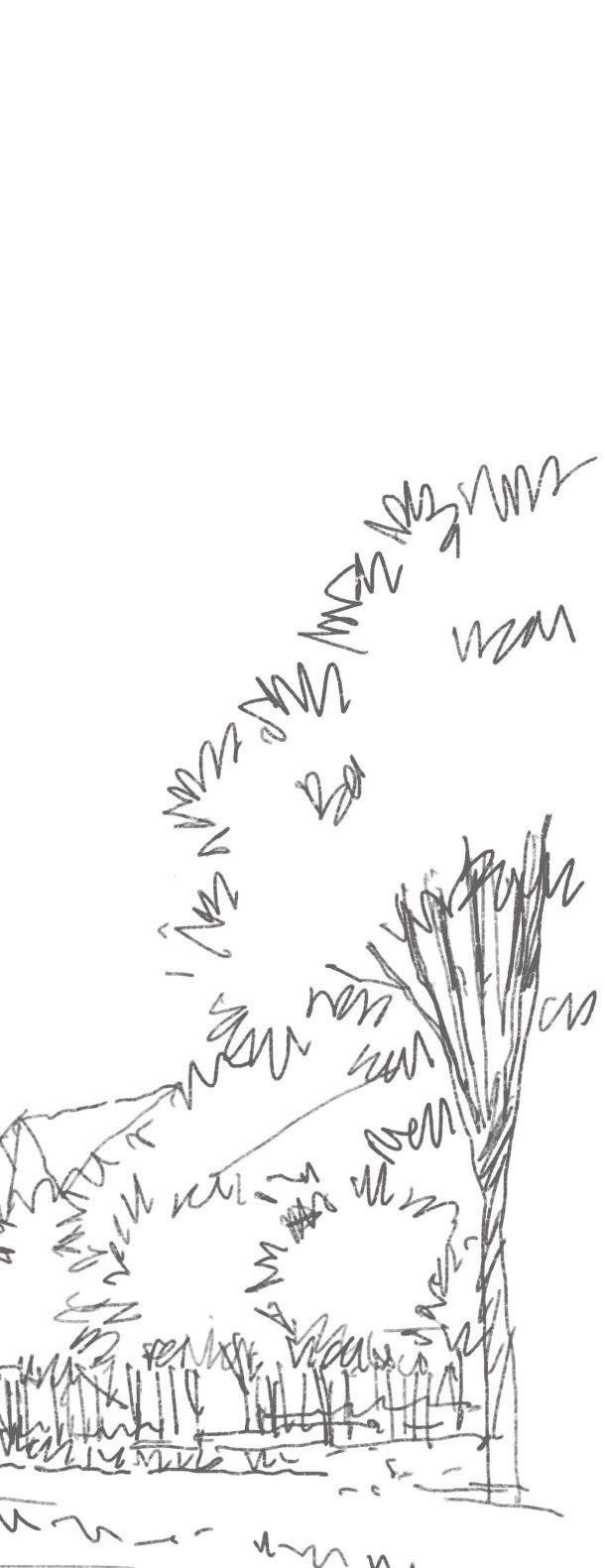

Opposite Page

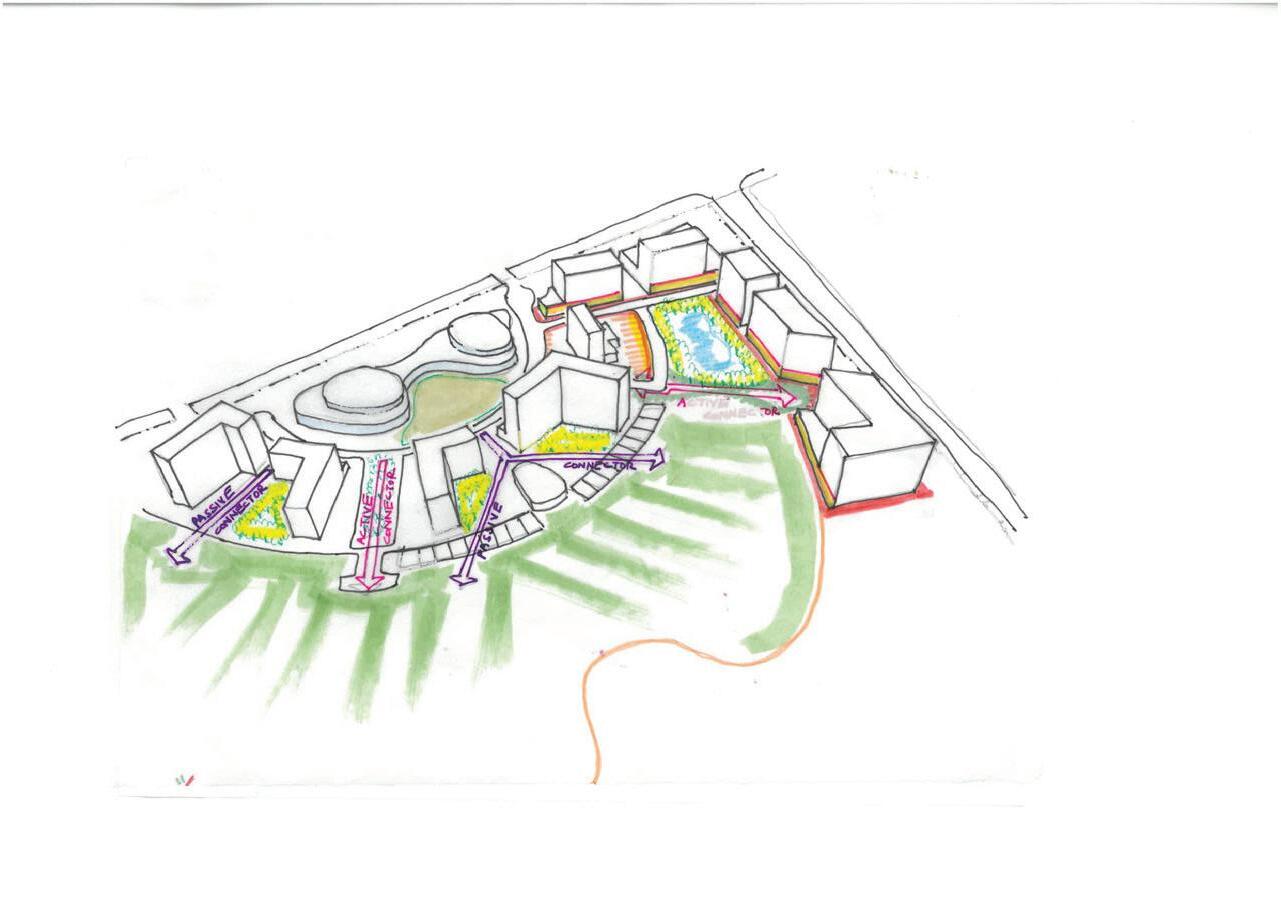

Principal Omar Calderón Santiago included this sketch, featuring the campus green and main library, in a 2022 competition entry for the Huzho University of Technology in Huzho, China.

Left Calderón Santiago drew a concept sketch for an expanded community space at the School Without Walls at Francis-Stevens for early-childhood through middle-school students in Washington, DC.

the NARRATIVE FALL 2022 25

26 Stories

Conflict Resolution

From a practical perspective, notes New York-based Principal Andrés Pastoriza, “I’ve always valued [sketching] as a tool to communicate ideas more clearly.” On a construction site, he points out, a design detail can be clarified with a pencil sketch on an unfinished wall. In the studio, he often asks his colleagues to sketch their feedback directly onto a printout of a blueprint, computer model, or rendering. “It’s a challenge to communicate ideas on any of those digital platforms in the same way,” he says. “It just works better when you can do it in real life.”

Chhavi Lal, an associate principal in Mumbai, shares a breakthrough moment she recently had with a new designer to the studio who was having trouble with a plan detail she was trying to develop in a computer program. Lal asked her to take a break from the screen and start drawing. “Somehow, the whole plan just came together. That is the power of hand work,” she says. “You don’t want to get inhibited by a computer graphic.”

Principal Cristobal Mayendia, who is based in New York, also emphasizes the benefits of moving from screen to paper, recalling a notable example with a hospital client in Atlanta who was eager to see more progress on the computer-generated massing models for their project. Mayendia suggested a daylong sketching session to work things out. “It was all pen and paper,” he says. Through those drawings, the client team could see the building truly come to life, embracing the curvature of the planned landscape design and facilitating a seamless flow of people in and out. As Mayendia describes it, “you have to draw a lot to understand space, the human body, cityscapes, buildings, and details.”

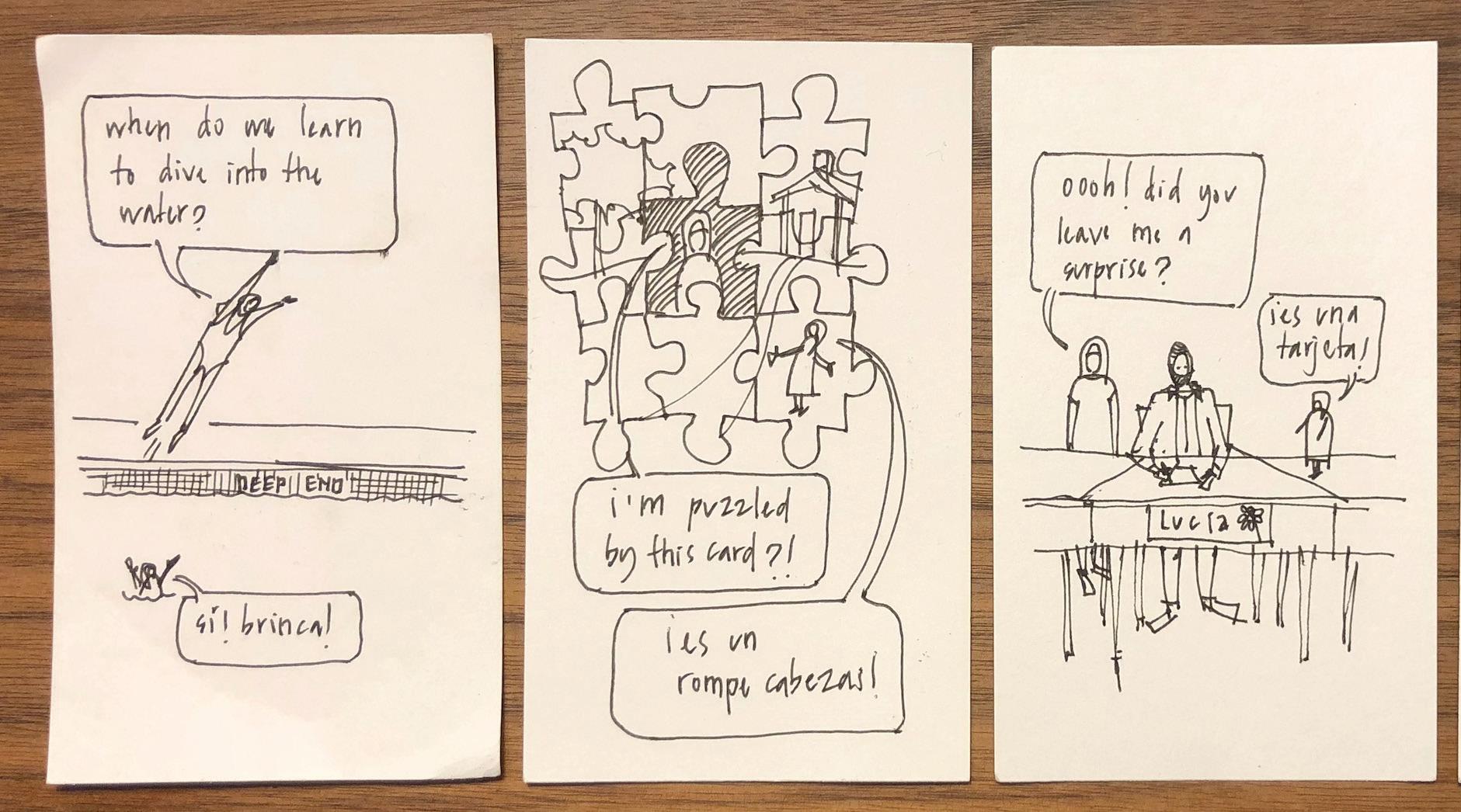

And if you draw with a sense of humor to break the ice, even better, says Associate Ling Zhong, who is known for his fanciful cartoon drawings. “I tend to make things silly,” says Zhong, who spent downtime during the pandemic shutdown sketching images of New York from Google Street View, then adding cartoon animals into the cityscape for fun (right). “I can turn very serious situations into a relaxed context with cartoons,” he says. At its core, drawing is “not about the blocky building. It’s about the stories that flow through the building.”

Blending Both Worlds

Luckily, the iPad—along with many sketching and illustration apps—is allowing architects to blend the art of sketching with the oomph of computing. “It has made my work go to the next level,” says New York Senior Designer and Senior Associate Amit Arya, who calls programs such as Morpholio Trace “Photoshop for the hand.” Using an iPad and Apple Pencil, he can sketch on top of computer models to adjust or build upon what’s already there—or create something new—and instantly share it with his team. “If you had 10 ideas” for a project, he says, it could take up to three days to model them all in a computer program such as Rhino, but with sketching software, “you can produce it all within a day.”

Calderón Santiago bought his first iPad during the pandemic, and the device has permanently changed the way he works. With apps such as Morpholio Trace, Procreate, and SketchUp, he says, “I still have the ability to connect my brain to my hand,” and, like sketching on paper, “there’s an immediacy there that’s been transformative for me.” He’s not alone in this regard—these widely accessible apps have enabled a growing circle of architects, illustrators, and artists to celebrate and share each other’s designs—and the apps themselves promote the best ones on their platforms. Calderón Santiago hopes this thriving community will swing the pendulum back from the almost exclusively digital education that most architecture schools now offer toward a better balance between hand drawing and computer-generated design.

“If drawing is thinking with a pencil, schools are not teaching students to think,” says Kaul. Plus, he continues, sketches are just plain memorable: “You can make a napkin sketch to explain something to a client,” he says, and what you end up with is a hand-drawn design concept that someone can put in their pocket. “It’s a much more productive exchange than, ‘Here’s the flash drive—it’s all complete.’”

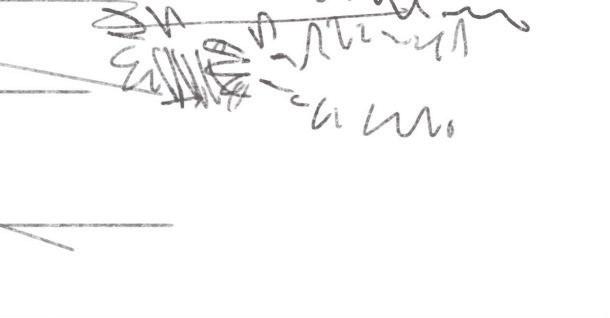

Above Principal Dan Meis’s initial sketch provided the design foundation for what would become the Everton Stadium in Liverpool, England.

Opposite Page

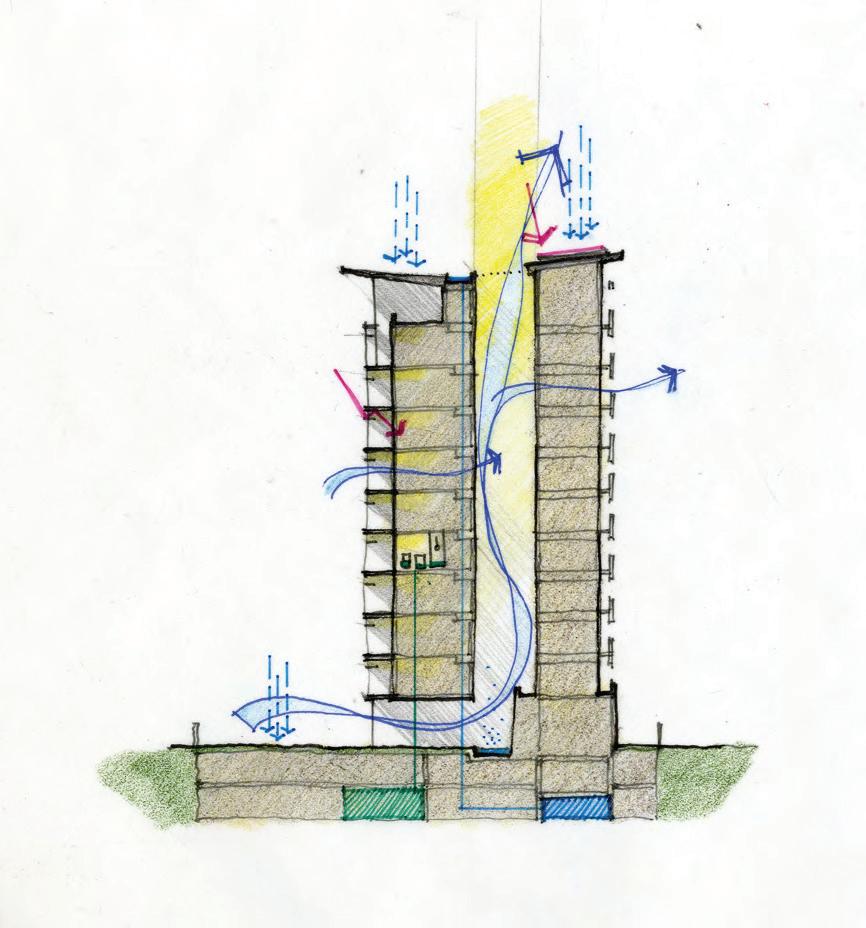

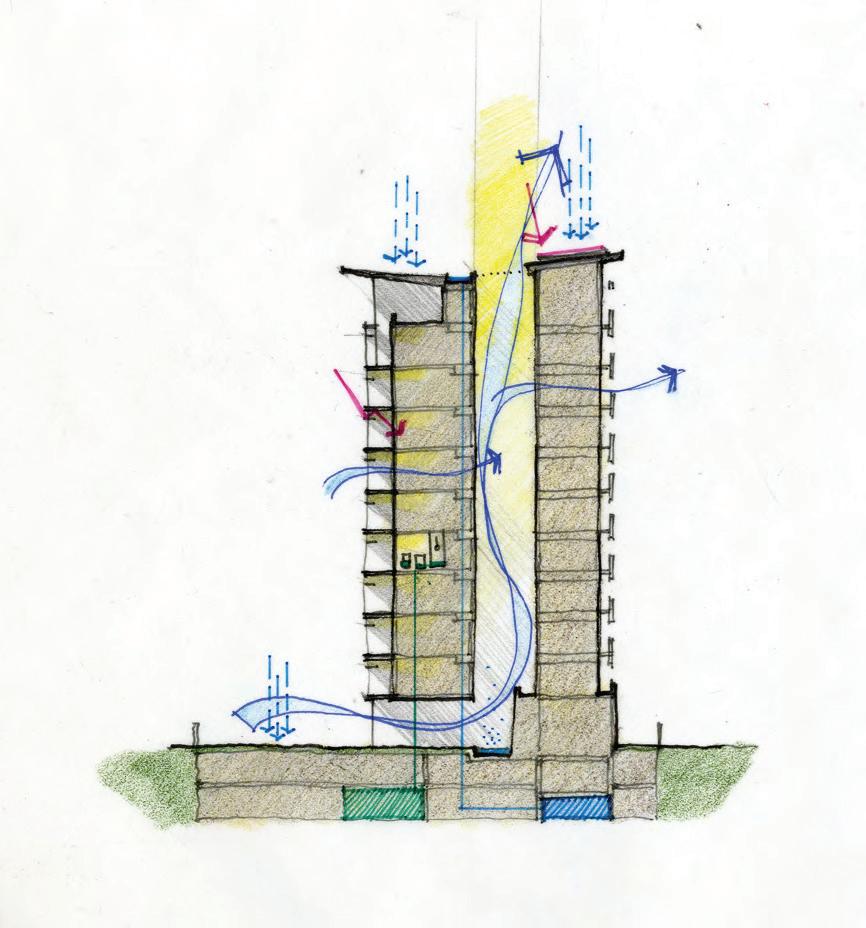

1. Principal Andrés Pastoriza uses color to illustrate concepts in his sketches, such as the passive design features of a residential tower in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic.

2. Don MacDonald, principal and founder of Donald MacDonald Bridge Architects—A Perkins Eastman Studio, used a drawing to demonstrate how a new pedestrian and public-transit bridge in Portland, OR, would complement the profile of Mount Hood, visible in the distance.

3. For the Raycom Infotech Park in China, Co-CEO and Executive Director Nick Leahy produced a series of explanatory sketches to describe the campus’ gateway buildings to the client.

4. Senior Associate Amit Arya used this sketch in a presentation to the town planning commission in Dublin, Ireland, for a communal work/live project. The intent was to show the open, neighborly welcome the building would offer in its urban context.

5. Associate Principal Chhavi Lal produced a sketch to show how Earthspace, a mixed-use development in Surat, India, features public green space on the campus’ perimeter that facilitates views of the surrounding golf course.

6. Associate Principal Christy Schlesinger makes quick sketches for clients to test out ideas and concepts. This one, for the lobby design of a Washington, DC, government agency building, features a rammed-earth wall.

the NARRATIVE FALL 2022 27

PURSUITS Personal

Omar Calderón Santiago likes to do subject sketches when he’s out and about. “Sometimes I get a kick out of drawing people I see on my commute,” he says. “I have also been known to draw my unsuspecting colleagues while on a Teams or Zoom call.”

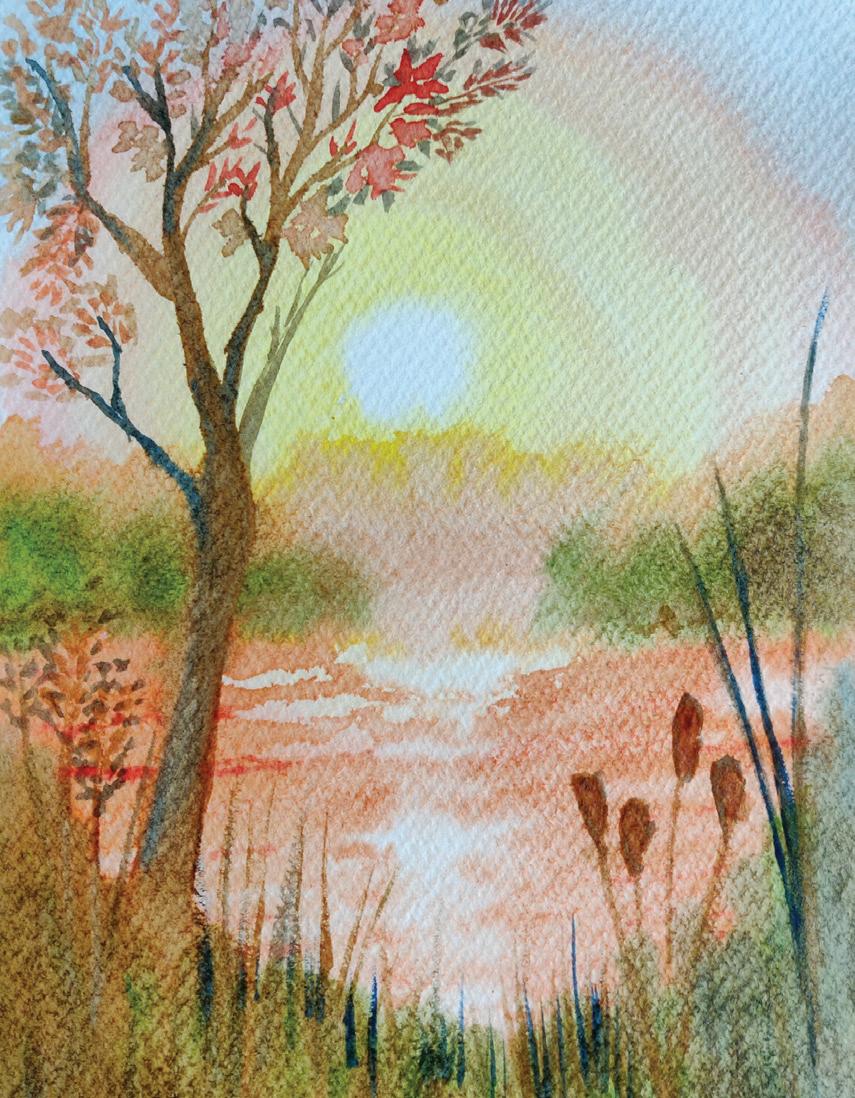

Chhavi Lal turns to her watercolors after work, painting landscapes as a way to unwind. “I’m completely focused for those couple of hours—cut off from everything else. It’s just so meditative.”

Ling Zhong loves to draw with his nine-year-old daughter, a budding artist in her own right. She’s lefthanded and he’s right-handed, so they can sit side by side and draw the same thing simultaneously. He also draws with his five-year-old son: “Right now, I’m a pro at drawing dinosaurs.”

Ty Kaul used drawings to help his drafting students when he taught at the New York Institute of Technology, just as his professors did for him. He frequently used a sketch of Le Corbusier’s famous “Modulor Man” dressed as a cowboy: “Just like the gunslingers of the Wild West, the one who draws the most and the fastest usually ‘lives’ in design studio to design another day.”

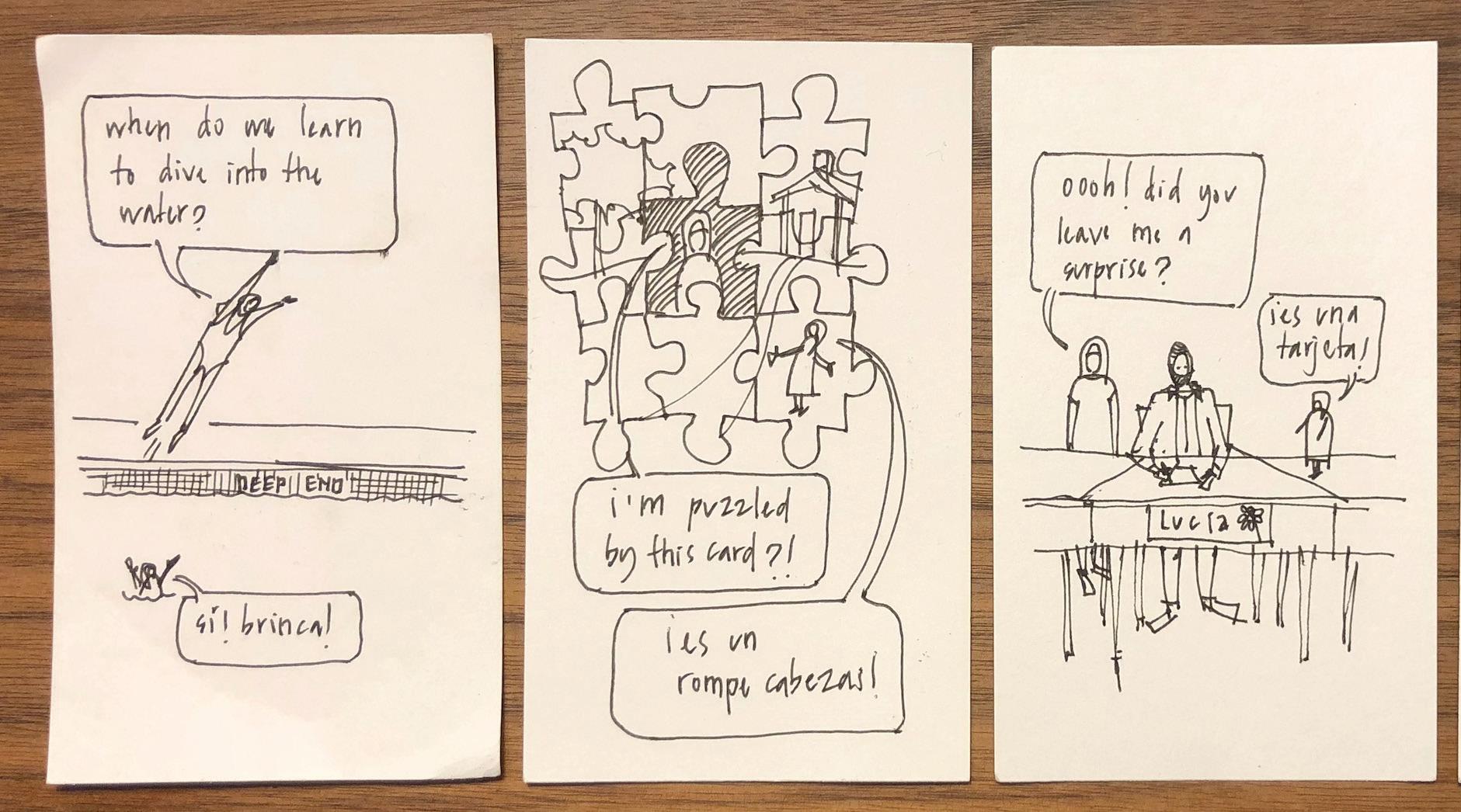

Andrés Pastoriza paints watercolors on the weekends with his daughter—“just some art time to let loose,” he says. “I also do a series of cartoons for her school snack box that are more personal, but have become a daily activity two years running. It’s a nice visual diary of what was happening in our family that day.”

Cristobal Mayendia prefers drawing memorable scenes to photographing them. “I feel like when we travel, we go too fast. Drawing is a way to slow down.” His fondest memory of a trip to Paris last summer is sketching with his daughter in the garden of the Rodin Museum.

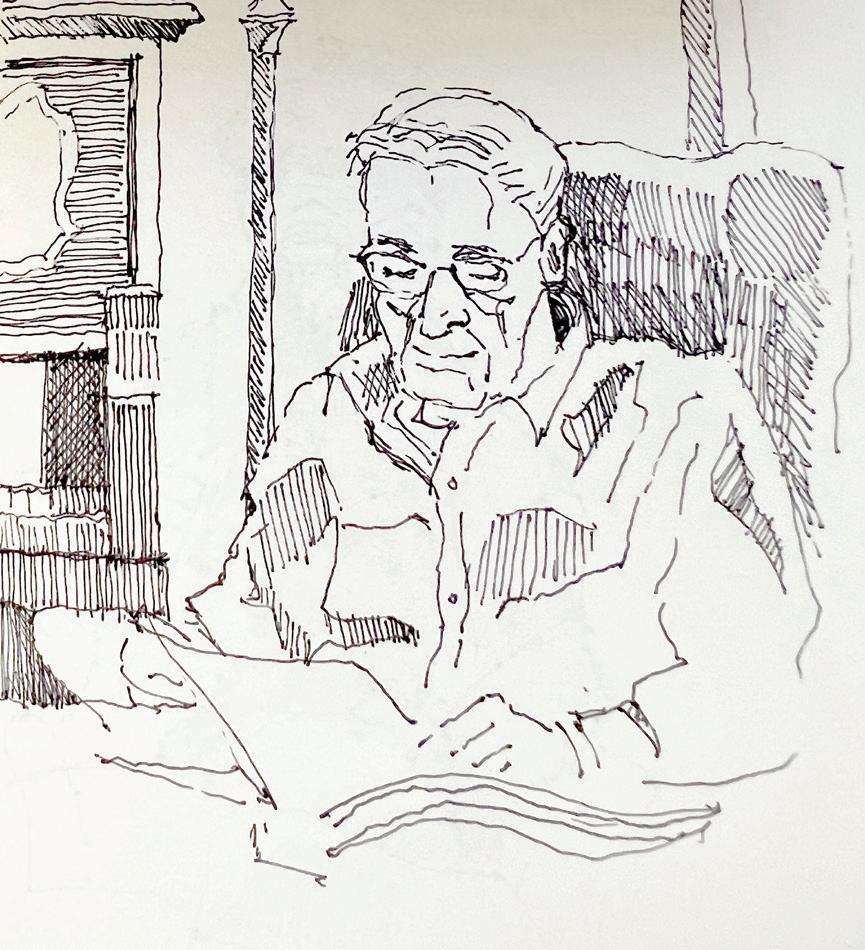

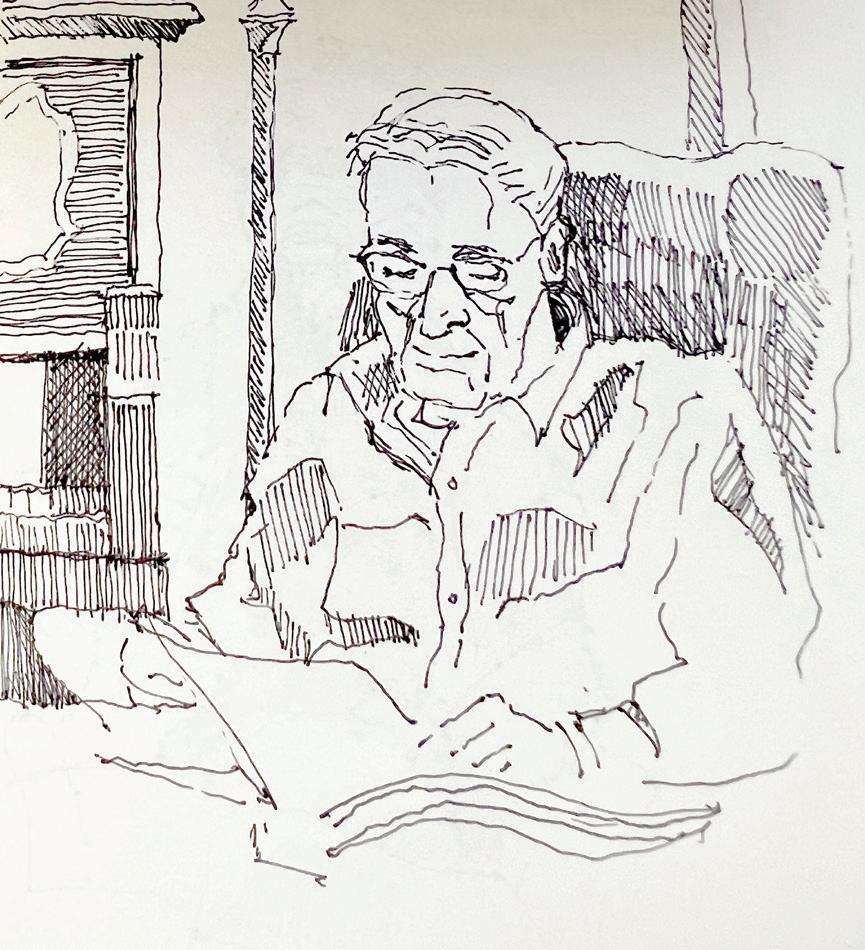

Nick Leahy is never without a sketch pad, and he fills it with all sorts of observations, from a vase of flowers to the people he sees on a Teams screen. He recently did a study of his father-in-law, Roger Stemen, during a visit to Stemen’s apartment.

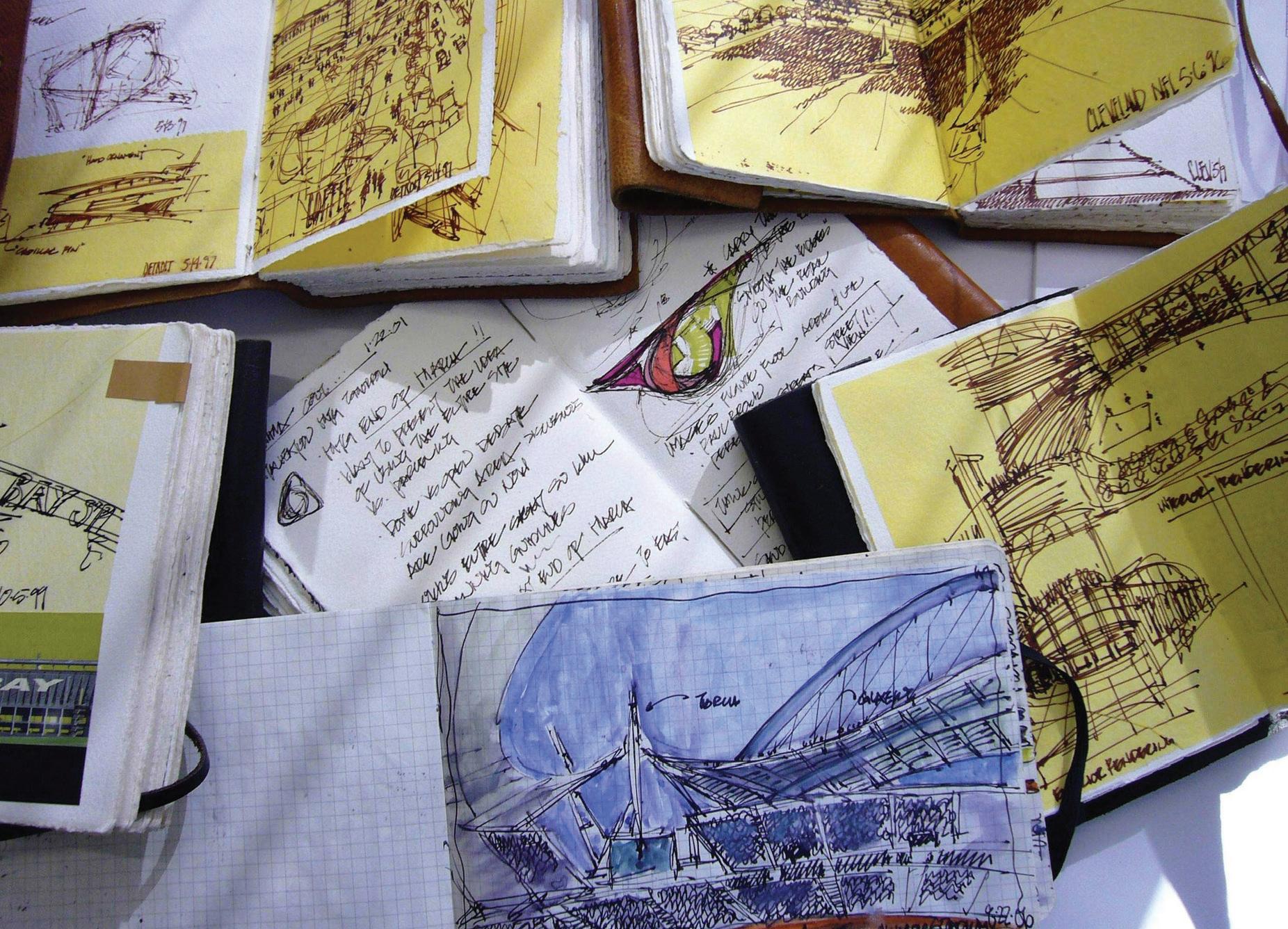

Dan Meis has kept every sketch he’s ever made, and he’s talking to a publisher about compiling them into a book. He also helped raise money for World Elephant Day this year by promising to send a sketch of Everton’s new stadium to anyone who matched his own $500 pledge. “I ended up making more than 30 sketches!” N

28 Stories

the NARRATIVE FALL 2022 29

30 Stories

Transformational

DESIGNS

Reimagining our existing building stock is key to reducing the country’s carbon footprint.

By Trish Donnally

Renovations have surpassed new construction in the US for the first time in the 20 years since the American Institute of Architects (AIA) began tracking renovation, retrofitting, restoration, and reconstruction. A recent Bloomberg story calls the trend “One Nation, Under Renovation.” According to an AIA report from last May, “Renovation claims 50 percent share of firm billings for the first time.”

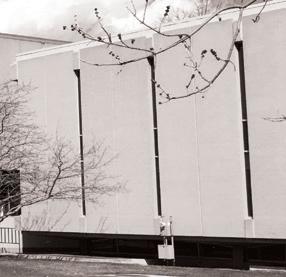

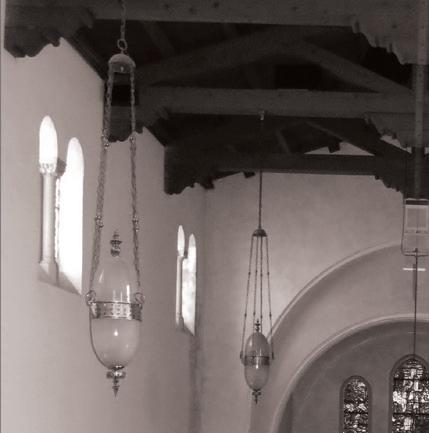

Atascadero City Hall In 2003, after sustaining severe damage during the 6.5-magnitude San Simeon earthquake, historic Atascadero City Hall in Atascadero, CA, built in 1918, was in dire need of repair. With a shared goal of rehabilitating while repairing, Pfeiffer—A Perkins Eastman Studio embraced many of the historic elements while simultaneously updating the space. The design team repaired and rehabilitated the structure, reprogrammed the building, created a museum, and transformed the first-floor rotunda. Surprisingly, the rotunda’s original interiors were all white. “They didn’t paint anything inside; they just left it. Whether that’s because they ran out of money or whatever, we don’t know,” says Stephanie Kingsnorth, a principal at Pfeiffer. The design team developed a new color palette for the inside of the building, transformed the rotunda into a glorious public gathering space, and restored Atascadero City Hall as the centerpiece of the community. The exquisite building is on the National Register of Historic Places and is a California Registered Historical Landmark. (Opposite Page) After Photo Copyright Tim Griffith/Courtesy Pfeiffer. Before Photo Courtesy Atascadero Historical Society

BEFORE

the NARRATIVE FALL 2022 31

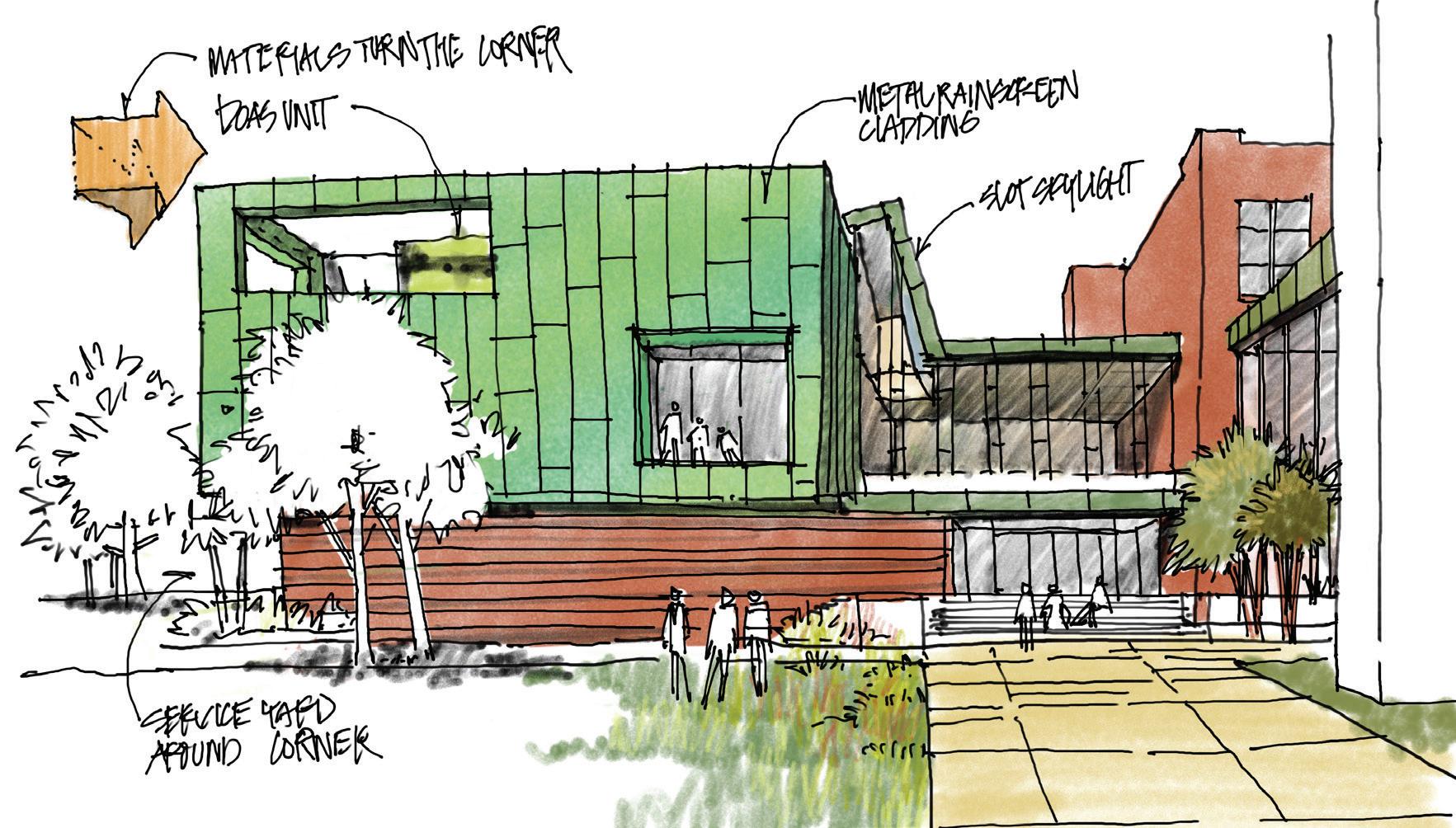

Charles L. Tutt Library at Colorado College While renovating the main library at this liberal-arts college in Colorado Springs, CO, the Pfeiffer team combined preservation, rehabilitation, and new construction while simultaneously achieving net zero energy (NZE). This made it the first academic 24-7 library to achieve NZE in the nation. The team preserved certain elements and the intent of the original architect, Walter Netsch, who designed the library in 1961. “We treated him as a partner, but we drastically modernized the interior environment while keeping most of the exterior,” Kingsnorth says. “The concrete on that building was gorgeous. It had a waffle slab and the exposed coffers were just beautiful. It was some of the crispest, cleanest concrete we’ve ever seen. But then everything that was overlaid on top of it was 100 percent modern,” Kingsnorth says. For the exterior, essentially a concrete box, Pfeiffer removed some of the precast panels and opened the building up to daylight and views of the Rocky Mountains. “And, we put an addition on it that literally wrapped the original building like a ribbon. That harmonized the new and the old.” (Above) After Photo Copyright

“I think we are, as a country and as design construction industries, fi nding that the opportunities to adapt or renovate what we already have is at least as appealing as starting anew,” AIA’s Chief Economist, Kermit Baker, says in a recent report. This perspective represents a sea change from the reaction the late architect and sustainability champion Lance Hosey received when he wrote “Stop Building. Now.” for Huff Post in 2013. Hosey’s proposal to cease all new construction in the US drew a wave of criticism within the architecture industry.

It was also prescient—at least in spirit. “As his article lays out, we have an overabundance of vacant buildings, and Lance suggested that if a new-construction moratorium were enforced, we’d be forced to look deeply at the existing building stock and seriously question what we need and how we could get there,” says Perkins Eastman’s Director of Sustainability Heather Jauregui, who is based in Washington, DC.

The New Frontier

Currently, buildings are responsible for about 40 percent of the world’s fossil-fuel carbon-dioxide emissions (CO 2). “But that number can be greatly reduced by limiting the embodied carbon of our building materials. Embodied carbon—the CO 2 released during material extraction, manufacture, and transport, combined with construction emissions—will be responsible for 74 percent of all CO 2 emissions of new buildings in the next 10 years. And unlike operational carbon, which can be reduced during a building’s lifetime, embodied carbon is locked in as soon as a building is completed and can never be decreased,” according to the AIA.

Embodied carbon reduction is the new frontier in green building.

“It’s the elephant in the room that we know relatively little about, compared to operational carbon, and research and tools are being developed in droves to help architects across the world be able to understand and tackle the embodied carbon challenge in their work,” Jauregui says.

“The embodied carbon conversation led to an increased focus on the reuse of existing buildings, because the carbon that we spend now—embodied—is going to determine the extent of global warming,” Jauregui says in reference to the 2015 Paris Agreement on global warming. “We still have a long way to go.”

BEFORE

Steve Lerum/Courtesy Pfeiffer. Before Photo Copyright Stephanie Kingsnorth

32 Stories

Shattering the misconception that existing buildings can’t achieve high levels of efficiency is one challenge. New legislation, however, is spurring action. New York City passed the Climate Mobilization Act in 2019, which requires owners of structures 25,000 sf or larger to reduce emissions or pay a substantial fi ne. The legislation’s goal is to reduce carbon output by 40 percent. Currently, according to the AIA, nearly 70 percent of New York City’s emissions come from buildings. The District of Columbia’s Building Energy Performance Standards (BEPS) Program, designed to reduce emissions and energy consumption by 50 percent by 2032, is beginning to force existing buildings to meet thresholds of performance too. “Climate-related legislation will both drive down operational carbon, and then increase the amount of existing building upgrades that are required to maintain compliance, and thus increase the market for building reuse,” Jauregui says.

Embodied Carbon and Character

Accepting the premise that any building can be transformed is another issue. The buildings that “everyone wants to demolish, that appear to have the largest problems, still have value—both in terms of embodied carbon but also in terms of community history and context that’s worthy of trying to preserve. Yes, it may be more challenging than going to new construction, but it can also lead to much more rewarding results,” Jauregui contends.

Los Angeles-based Stephanie Kingsnorth, a principal of Pfeiffer—A Perkins Eastman Studio, concurs. “If you simply save the exterior envelope of a building in the primary structure, you are reducing your carbon footprint by essentially 50 percent,” she says. “We can’t go around tearing everything down. We need to focus on energy utilization, embodied carbon, all of these things.”

And the decision, she believes, should not be based on aesthetics. “Some people will say, ‘Oh, I hate midcentury buildings, or I hate brutalism, . . . oh, it’s just so ugly, it looks like a concrete box. That doesn’t matter, you can change it. Again, the embodied carbon that’s in that concrete is something that really needs to be carefully considered before you just take all that down.” Before tearing down a building, Kingsnorth notes, developers and their architects should determine what percentage of material is recyclable, and how much of it will have to go to a landfi ll.