Project Storybook

Final Executive Summary

December 23, 2022

Riddhi Batra Transportation

Kelly Cary Housing + Community

Alex Charnov Housing + Community

Mia Cherayil Technology + Data

Lynn Chong Housing + Community

Madeline Csere Transportation

Henry Feinstein Technology + Data

Robby Hoffman Development

Nata Kovalova Transportation Anastasia Osorio Environment

Yuchen Wang Urban Design

Marquise Williams Land Use + Transit

Shawn Li Development

Nell Pearson Environment

Riddhi Batra Transportation

Kelly Cary Housing + Community

Alex Charnov Housing + Community

Mia Cherayil Technology + Data

Lynn Chong Housing + Community

Madeline Csere Transportation

Henry Feinstein Technology + Data

Robby Hoffman Development

Nata Kovalova Transportation Anastasia Osorio Environment

Yuchen Wang Urban Design

Marquise Williams Land Use + Transit

Shawn Li Development

Nell Pearson Environment

Page 2

Nando Micale Instructor Danielle Lake Instructor

Statement of Purpose

In Fall 2022, a Studio group of a dozen students in the UPenn Masters of City & Regional Planning program focused their study on the eight-mile stretch of Anacostia River in Washington, DC from US Joint Base Andrews property at the Southeast to the District’s boundary with Maryland to the north. For the purposes of this project, the area is referred to as the Anacostia River Corridor or the River Corridor.

Running directly though the River Corridor is a 6-mile stretch of DC-295, which is D.C.’s only state highway. The highway serves as an important regional and local connector, but is also a significant barrier for nearby residents.

The premise of this studio is to look critically at the future of transit and development in the Anacostia River Corridor, with a focus on creating an equitable and resilient alternative to the highway. The materials produced for this Studio provide the D.C. Office of Planning (DCOP) and the D.C. Office of Energy and Environment (DOEE) with the preliminary materials needed to start an advocacy planning process in the Anacostia River Corridor.

The UPenn students worked closely with instructors — Nando Micale, Principal with the Philadelphia studio of LRK, and Danielle Lake, LRK architect and urban planner/designer and UPenn alumni — on developing this plan. The Studio also benefited from input from select members of the District’s Office of Planning (DCOP), Office of Energy and Environment (DOEE), and the larger Anacostia Waterfront Corridor Working Group (Working Group).

Page 3

How to use this interactive document

The Anacostia River Corridor team prepared this document as a summary of the plan’s final proposed recommendations. Designed for digital viewing and sharing, and to spark discussion and interest, in some places this summary may appear light on detail. Behind these recommendations, however, is a wealth of research and resources that the team organized within a series of 10 technical memos which we have called “deep dives.”

Within this document, interactive hyperlinked markers appear on the first pages of each topic with a relevant deep dive memo. To access the deep dives, you may click on any of the document covers shown on this page, or click on the markers throughout this document for more information on each topic area.

The following memos to provide additional information on topics that deserve a deeper dive. These are referenced throughout the document using this interactive, hyperlinked marker.

Click here to explore Deep Dive on this topic * Page 4

Contents

Regional + Planning Context

History of the River Corridor

Framing the Problem

Highways Past & Future

Why now?

Connectivity

Ecology

Development

Why a Boulevard?

Walk Down the Boulevard

Benefits for Connectivity, Ecology, Development

Example Site Area Plan

Concerns about Traffic

What is Bus Rapid Transit?

Addressing Gentrification

Project Timeline + Impacts of Construction

Community Process

Planning Workshop Kit

Page 5

River Corridor Context 1

Study Area

The geographic focus of this project is a portion of Washington D.C. that spans from U.S. Joint Base Anacostia-Bolling in the south to the D.C.Maryland border in the north. For the purposes of this project, the area is referred to as the Anacostia River Corridor or the River Corridor.

The Anacostia River Corridor contains multitudes. It includes the neighborhoods of Barry Farms, Anacostia, Fairlawn, Dupont Park, Greenway, Mayfair, Eastland Gardens, and Kenilworth. It also constitutes most but not all of Wards 7 and 8. The area interfaces with metro transit, freight rail, and numerous bus routes, and contains low-, medium-, and high-density residential areas as well as industrial and brownfield sites.

Running directly though the River Corridor is a 6-mile stretch of DC-295, which is D.C.’s only state highway. The highway serves as an important regional and local connector, but is also a significant barrier for nearby residents.

Though its history of disinvestment remains clear, the river corridor still sports a wealth of assets and a strong community.

Page 8 River Corridor Context

As of 2020, there are 136,653 residents living in the River Corridor, which accounts for about one fifth of the entire District of Columbia population (701,974). Despite being a large portion of the overall population, demographics across the Anacostia River look notably different across income and race.

The median income of households in Anacostia ($37,803) is significantly lower than DC ($82,604), as is the number of people living in poverty, with 28 percent in the study area versus the District’s 15 percent.

The study area is predominantly Black and AfricanAmerican, accounting for about 90 percent of the total population, compared to the District’s even share of White and Black residents (roughly 45% each).

28% below the poverty line vs.

15%

17% bachelor’s or advanced degree

About 27 percent of the River Corridor’s population falls under the age of 18 and only 12 percent are above the retirement age of 65. Almost half of the population (49 percent) falls between the ages of 18 and 54. The District sees less children under the age of 18 (18 percent) and about the same residents over the age of retirement (12 percent). Both populations’ single largest age category from ACS data is between 25 and 34 years old, with 17 percent for the study area and 23 percent for the District.

Educational attainment numbers show that about 40 percent of the study area’s population over the age of 25 has graduated from high school as their highest form of education, with only about 10 percent of the population with a Bachelor’s degree and 9 percent

with a master’s, professional, or doctorate degree. Data for the District shows that 17 percent of the population graduated from high school as their highest attainment, with 25 percent graduating with a Bachelor’s and 35 percent with a Master’s degree or higher.

As the significant differences in racial makeup, income, and educational attainment demonstrate, the Anacostia River Corridor stands out from the rest of the city. The history of segregation and disinvestment covered in the introduction reveals itself in this demographic overview, further highlighting the importance of addressing the harm I-295 has caused this long-standing D.C. community.

Demographics

D.C.’s

D.C.’s

vs.

63%

D.C. River Corridor 91% 45% Share of Black Residents $37,800 $82,600 Median Household Income D.C. River Corridor Page 9 River Corridor Context

Median Household Income by Census Tract. Source: United States Census Bureau (2020 ACS 5-Year)

History of the Anacostia River Corridor

Industrial Waterfront

Anaquash

The indigenous Nacotchtank inhabited what is now D.C. for an estimated 10,000 years before the arrival of English colonizers. In the early 1600s, about 300 tribe members lived in villages mostly along the eastern banks of the Anacostia River. The river was referred to as ‘Anaquash,’ or ‘village trading center’.

Agrarian Transformations

John Smith’s arrival in 1608 heralded the rapid settlement of the land east of the Anacostia by English landowners.

The Anacostia River offered the potential for deep-water ports and was poised for significant harbor development Dredging, dumping, and walling the Anacostia ensued.

1600 8400 BCE 1800 1900

Marshy low-lands

Army Corps Of Engineers, Map of Anacostia River, 1891

“Area to be filled shaded in red.”

Navy Yard Bridge, 1865

Page 10 River

Context

Anacostia flats July 20, 1912

Corridor

Parks & Parkways ”

The “reclamation” of the silted river, and the destruction of wetland habitats, to create a public park took several decades.

Highway Boom Corridor Restoration

Anacostia highway is conceived by the NCPPC in 1950. Ground is broken in 1958. Nearby neighborhoods including, Anacostia and Fairlawn, are separated from Anacostia Park. Neighborhoods including Kenilworth and Barry Farm are severed.

Meaningful efforts to restore the river and its surrounding communities begin. The Six Point River Restoration plan is adopted in 1991. The Anacostia River Clean Up and Protection Act is passed in 2009. But the highway remains omnipresent. Anacostia Freeway 11th Street Interchange under construction, 1964

Contaminated sites show history of the District’s treatment of eastern neighborhoods as disposable. The district openly burned trash in Kenilworth Park from 1942 -1968. In 1966-in one of the earliest environmental justice protests in US history-residents laid down in the street in an attempt to stop the trucks, but the city’s dumping and burning continued.

1950 1990 2020 2050

“

Example of the collapsing riprap walls along the Anacostia River

Breaking ground for Anacostia Park, 1923

New cultural landscape

Black Power activists visiting Barry Farms in 1967

Frederick Douglass housing project, 1942

Page 11 River Corridor Context

-- Krista Schlyer, River of Redemption

DC-295 Highway

DC 295 is the only state route within the District of Columbia. It measures 4.9 miles total and is mainly composed two segments:

• 2.3 miles of Kenilworth Avenue Freeway that runs from the Maryland state line to north of East Capitol Street, which sees an annual average daily traffic count of about 100,905 vehicles.

• 2.7 miles of Anacostia Freeway that connects I-295 south to Richmond up to East Capitol Street, which sees an annual average daily traffic count of about 127,762 vehicles.

295 serves as a regional connector north to the Baltimore-Washington Parkway via Kenilworth Avenue, south on I-295 towards Richmond, and provides access to downtown Washington DC for Ward 7, Ward 8, and Prince Georges’ County MD. It also provides local connections for employees and visitors to the Joint Base Anacostia-Bolling, DC Department of Employment Services building and DC’s Department of Housing and Community Development building.

Currently improving pedestrian safety and mobility throughout the I-295/ DC 295 corridor and across the Anacostia River has been the focus of DC’s Department of Transportation. Most notably the opening of the Fredrick Douglass Bridge allows for improved bike space into Anacostia Park and for a safer direct crossing experience into the Navy Yard & Buzzard Point.

MoveDC, the District’s Long-Range Multimodal Transportation Plan, identifies a number of communities with the greatest transportation needs, based on proximity to frequent transit, access to jobs and amenities, and safety risks. Many of these areas are also home to historically under-served communities of color, lowincome residents, and people with disabilities. The Anacostia River Corridor falls at the intersection of both these considerations, thus calling for a greater focus in transit equity to improve the corridor’s options for multimodal connectivity.

Page 12 River Corridor Context

Planning Context

The deliverables produced by the Anacostia River Corridor Studio are congruent with previous planning efforts conducted in Washington D.C.

Of the plans represented on this page, some are district wide, some are at the “waterfront” level, and some are for small areas like Poplar Point. This plan fits in between the district wide and small area scale, and is most aligned with the Resilient D.C. initiative established by Mayor Bowser.

The Anacostia River Corridor Studio strives to address the goals laid out in the Resilient D.C. plan, which aim to situate D.C. as a countrywide leader in equitable climate action.

In Fall 2021, another group of UPenn City Planning students sought to rethink systems that create resiliency as they envisioned a future for Poplar Point in Washington, DC for a studio course. In collaboration with DCOP, the project team envisioned the redevelopment of Poplar Point within the context of the Resilient DC initiative and other planning goals District-wide, as well as the site’s history, culture, and challenges.

Page 13 River Corridor Context

The Story of Highways 2

Why remove the highway?

Since the DC-295 highway was built, our values have changed. Today, we are striving to create a more environmentally just future. We recognize that transportation infrastructure like this does more to divide than it does to connect. The big fundamental underlying question here is who does this highway serve? Our research shows it’s not really the residents of southeast DC, and further, that for them it is a barrier blocking access to the parks, river, and greater DC.

Page 16 Story of Highways

River Culture

Southeast residents have important cultural ties to the Anacostia River, it is high time they had ease of access as well.

We’re so inspired by personal stories like this. This is Rodney Stotts, whose recently published memoir, Bird Brother, chronicles how when he got involved with the Anacostia River cleanup efforts at the Earth Conservation Corps, his encounters with wildlife and nature on the river completely transformed his life.[1] We think this opportunity to enjoy interacting with nature and communicating with wildlife is a fundamental human need that some communities have been cut off from. This project can serve as a vehicle to address that issue.

Rodney Stotts

“The Anacostia River still weaves its way into my dreams.”

On the Anacostia River, William Mitchener catches his first fish with cousin Byron Coleman. Photographer: Krista Schyler, author of River of Redemption

Page 17 Story of Highways

Rodney Stotts with Agnes, a Harris’s Hawk. Photographer: Greg Kahn

1951 City before highway

Highways Past: Environmental Racism and Displacement

Highways were constructed to serve convenience for a few, at the expense of environmental health and the well-being of the many.

America has a long and shameful history of constructing freeways through low-income neighborhoods; as highways were intended to serve white populations moving out to the suburbs while invariably displacing entire urban communities and creating areas of highspeed traffic and pollution that continue to affect the health and safety of those who live there.[2]

The economist Matt Yglesias put it this way: “Highways beget corruption of the city core: they make it less pleasant to live downtown, at the very same time they make it easier to live farther away.”[3]

Anacostia Freeway 11th Street Interchange under construction, 1964

Page 18 Story of Highways

Highways Present: Negative Public Health Impacts of

Highways

We also now understand highways to have many negative public health and ecological impacts.

The American Lung Association estimates that as many as 35-40% of all urban populations in North America live near a highway. Risks posed to those living within half of a mile of a highway include risks for serious chronic health conditions, impaired lung function, cardiovascular disease, childhood asthma. Risks posed to those living within 300 meters of a highway also include higher risks for decreased brain function, dementia, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in older adults.[4]

In addition to these public health impacts, highways cause stormwater runoff to increase and have a number of ecological downsides. DC’s equity-based approach to resilience planning must be deployed to improve environmental and public health while mitigating negative externalities such as green gentrification.

The area most affected by risks of impaired lung function, increased risk of death from cardiovascular disease, and the onset childhood asthma is roughly the band within 0.3 miles of the highway.

(American Lung Association, 2022)

Adults living closer to the road—within 300 meters—have higher risk of dementia as well as developing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

(Anderson et al., 2011)

DC-295 During Rush Hour

Page 19 Story of Highways

Highways Future: A Global Movement to Reimagine Highways

The idea of highway removal or conversion is coming from a worldwide movement where many cities are asking, “What can we do with the space of this highway that no longer serves our needs and no longer serves the kind of future we want?” Renewed calls for social and environmental justice are bringing the highway issue to the forefront of national conversation, resulting in this movement to reclaim the space of highways for the city for people.

According to the Congress for New Urbanism, “18 American cities have either removed, covered, or committed to transform urban highway corridors.”[5] We’ve studied these precedents carefully and incorporated lessons from all these different places as much as possible into our plan.

Notably, in a lot of these places, the removal of the highway has been a catalyst for new investments and new developments. The following three case studies highlight these impacts in detail:

The Park East Freeway in Milwaukee, Wisconsin was a one-mile freeway spur leading from I-43 to downtown Milwaukee. They found it was actually less expensive to tear it down than it would have been to rebuild it. The city demolished the freeway in 2003, for a total cost of $25M, where it would have cost $100M to rebuild the freeway as is. And so that was part of the value proposition here, and it opened up immense tracts of land for new development, which has now seen over a billion dollars of development happen, with more coming down the pipeline. Since the removal of the freeway, the Park East Corridor has seen over $1.06 billions of private investment in development projects, with the potential for an additional investment of $250 million on the few remaining undeveloped parcels.[6]

ROCHESTER SYRACUSE NEW ORLEANS BOSTON

Page 20 Story of Highways

Boston’s Big Dig involved constructing a 1.5-mile tunnel and rerouting I-93 through central Boston. The tunnel and rerouting were completed in 2007 and cost $14.5B. Original plans for the Big Dig included many mass transit investments, including a transit tunnel to connect South Station and Logan airport, connections to existing subway lines, and restoration of historic streetcar service. As of 2022, however, only the new transit tunnel is built and operational. Despite the challenges and giant budget, this project did have some success, including the establishment of a heavily used linear park running along the former highway’s footprint.[7]

The Cheonggyecheon Highway in Seoul, Korea was removed from 20012005. In the 1990s, the Cheonggye area recorded the highest levels of noise and congestion in Seoul. However, in 2001 the plans for highway removal began as part of a plan to transform Seoul into a tourism hub. The final budget of the project was $323M and was expected to attract $9.2B of private investment. The project was centered on revitalizing the Cheonggyecheon Stream by removing the highway and creating a central plaza and multimodal roads. The project included increased bus routes around the area, as well as increased parking fees and stricter control over parking generally. It was also designed on a 200-year flooding interval assumption. The project is largely considered a success, attracting 64,000 daily visitors, an increased number of businesses, and reduction in the urban heat island effect.[8]

PROVIDENCE SEOUL

MADRID

MILWAUKEE

PARIS SAN FRANCISCO

Page 21 Story of Highways

= substantially completed or implemented project

Why now?

After reviewing the story of highways, we have seen their historic and present harms, as well as how highwaysto-boulevards projects can serve as powerful tools for revitalization. However, the other question to address is “why now?” - Why is now the right moment to explore a project like this? We outline five reasons in the following pages.

Page 22 Story of Highways

Health impacts are happening now.

Despite significant environmental restoration gains and advocacy efforts made in the past 40 years, today, Anacostia River Corridor residents are still disproportionately impacted by environmental hazards including air pollution, as well as the impacts of climate change, especially flood risk and extreme heat. Although air pollution levels in DC are considered within safety standards, around 20% of residents in Ward 8 (which is partially included in the Anacostia River Corridor), suffer from asthma compared to 12% in DC as a whole.[9] This difference can be tied closely to the presence of the highway.

Similarly, lack of accessible and sufficient medical care forces these residents to travel across the river to get to hospitals. However, missing public transportation links and low car ownership in some neighborhoods makes this difficult and leads to a cycle of worsening health outcomes. The removal of the highway will provide an opportunity to enhance connectivity and public transportation options to facilitate these connections.

Unsurprisingly, data shows that temperatures are relatively higher in census tracts along the highway compared to those further east. These tracts also contain less tree cover. The Heat Sensitivity Exposure Index, which provides information about which tracts are most vulnerable and exposed to extreme heat indicate that these census tracts are least likely to be able to cope and adapt to heat.[10] These conditions will play a role in how we think about environmental equity in the plan.

20% Rate of asthma among Ward 8 residents

DOEE Monitoring sites in Ward 7 record higher averages of particulate matter, carbon dioxide, and nitrogen oxide than other sites in the District.

0.6 - 0.7

Score on the Heat Vulnerability Index (with 1 being the most) vulnerable

1-

Page 23 Story of Highways

Environmental risks are increasing.

This plan focuses on creating sustainable and flood-resistant infrastructure, which will be critical as DC prepares for worsening flooding over the next 15 to 30 years. Due to global warming, sea levels are projected to rise over the coming decades to levels not seen for more than 10,000 years. Since the Anacostia is part of the greater Chesapeake water system, as the sea level rises, simple high tides will result in local flood conditions for sustained time periods.

Another effect of climate change will be worsening storms. Due to aging and overburdened infrastructure, flooding from stormwater in the interior of neighborhoods is already a significant concern in DC. The issue of stormwater overflow into the Anacostia River has for a long time contributed to the heavy pollution of the waterway, but stormwater also affects low-income neighborhoods east of the river in the form of basement backups, surface flooding, and impaired roadways.[11]

According to the Union of Concerned Scientists' 2014 Encroaching Tides Report, The mid-Atlantic coast is expected to see some of the greatest increases in flood frequency. Washington, DC can expect more than 150 tidal floods a year.

11.9” in sea level rise by 2045

400 Predicted number of flooding events per year by 2045 in DC

2-

Page 24 Story of Highways

Development pressures threaten housing security

A project at this scale presents a remarkable opportunity to address DC’s housing crisis. As will be covered later in this plan, a lot of land can be opened up for new development with the removal of DC-295. The implications of this could affect the supply of affordable housing within the corridor if managed appropriately.

Currently, homeownership rates in the Anacostia River Corridor are low, and the existing homes are older than elsewhere in DC. Also, as of 2020, more than half of the residents in the Anacostia River Corridor were rent burdened, meaning they spent more than 30% of their income on rent.[12] At the same time, the Anacostia River Corridor has seen more development pressure in recent years as millions of dollars have been invested in the neighborhoods directly across the Anacostia River on its western waterfront. [13] This all means - if development is done inequitably and rents go up more than they have in the past, then there is a very real risk of displacement for current residents.

This tone is one shared by many residents. For example, In an article about DC’s rising housing affordability, Kimberly, who is now a former resident of SE DC, stated that as a 3rd generation Washingtonian, it’s hard to see people struggle to live in the city. With this in mind, DC has already recognized the urgency of preserving housing affordability in the area.[14]

$318,400 +10%

Home values increase from 2010-2022

Our Housing Policy Toolkit deep dive examines The District’s Housing Equity Plan which aims to raise the share of dedicated affordable units from 16 percent in 2020 to 21 percent by 2050.[15] Equitable development on new land opened up by the highway’ removal has the potential to increase the supply of affordable housing and programs that support existing residents which can transform housing in the area at a crucial time.

53% Rent burdened households +7%

$1,024 Avg. gross rent increase from 2010-2022

3-

Page 25 Story of Highways

The future of mobility is multimodal.

The removal of DC-295 offers an opportunity to push both the Anacostia River Corridor and DC towards a multimodal future. While ARUP forecasts the total urban vehicle count to increase by 3% annually, the proportion of cities’ population growth is moving at a much more rapid pace, bringing a shift in design paradigm from designing cities for cars to fitting vehicles into cities.[16]

Many experts believe now is the time to reimagine roadways that could include power generation to charge electric vehicles on the go, adaptive speed limits and narrower lanes to better control traffic, and connect to technology.[17] Similarly, creating an integrated ecosystem of shared micro-mobility among existing transportation options and hubs will encourage modal shifts from driving to other forms. DC is a leader in the e-scooter and bike-share revolutions and is now discussing ways to create a more equitable and connected future of transportation such as making public Metrobus rides free and subsidizing MetroRail rides for DC residents.[18]

In our Future of Mobility deep dive we explore these possibilities and more practices that discourage owning a private vehicle and the reliance on traditional highways for transportation.

4 -

Integrated ecosystem of shared micro-mobility among existing transportation options.

Reduced vehicle miles traveled from adoption of automated vehicles and ride-sharing practices.

Reimagined roadways that include power generation, adaptive speed limits, and narrower lanes promoting safety and affordability.

DC is already incentivizing transportation mode shift.

Page 26 Story of Highways

There’s $$$ on the table.

From a transportation perspective, federal funding will support Highway to Boulevard efforts through the Reconnecting Communities pilot program. The program provides $1B over five years to reinvest in transportation infrastructure that better connects communities to economic opportunities.[19] For example, California recently announced $150M in state funding for a parallel program as well, with other states potentially following suit.[20] These funds can be distributed via planning grants to explore area-specific options that work for respective communities, making this the perfect time to begin exploring concrete alternatives to DC-295.

However, there are also a number of federal funding sources available from Federal Agencies like FEMA, EPA, and HUD to support building community resilience with nature-based solutions. These include the Coastal and marine habitat restoration grants, national coastal resilience fund, hazard mitigation assistance grants, and the community development block grant program.[21] Finally, if we layer into this project’s green-blue infrastructure that help deal with ecological issues we can add funding from other sources that support such projects.

5-

D.C. expects to receive more than $3.3 billion in federal infrastructure funds.

Reconnecting Communities Pilot Program = $1B for Urban Highway Removals

Page 27 Story of Highways

+ Grant programs for flood mitigation, environmental restoration, affordable housing through FEMA, EPA, and HUD

3

What can this movement achieve?

Three Frameworks Connectivity

Bringing down the highway offers opportunities to largely reshape the river corridor in several ways. The effort to imagine this generates important questions about how to balance sets of priorities.

In the course of our research, we identified three frameworks which capture the range of opportunities presented by a project of this size. They are Connectivity, Ecology, and Development. In this section, we will discuss how these frameworks served as a guide to ensure our proposal met the corridor’s most pressing challenges.

Good connectivity means the entire area is connected by an active, accessible, and diverse transportation system.

Ecology

Development

The development framework is all about how to create conditions for sustainable, inclusive growth, and an equitable quality of life.

The ecology framework describes how human and ecological processes can coexist, supporting the natural systems that maintain breathable air and drinkable water, mitigate heat, and provide habitat for wildlife.

Page 30 Goals & Frameworks

Connectivity

Existing Conditions

Connectivity arose as a framework for this advocacy plan due to the regional and local importance of DC-295. Regionally, the segments of the Anacostia Freeway & Kenilworth Avenue connect to Suitland Parkway and help residents of MD and VA commute to downtown DC from the west. It also allows drivers to pass through the district from I-295 south towards the Baltimore-Washington Parkway going north.

Locally, it provides access to the rest of the District for Wards 7 & 8 and also provides local connections for employment nodes at Joint Base Anacostia-Bolling military base, the DC Department of Employment Services building, and the DC Department of Housing and Community Development building.

Despite its regional and local significance, there are connectivity challenges that the highway presents. The highway encourages a heavy reliance on driving, however, transit and other modes of travel are important for residents of the Anacostia River Corridor. Only 40% of households have access to a vehicle.[22] As a result, 2 out of every 5 corridor residents rely on transit to get to work.[23]

40.3% of households without access to a vehicle

4-mile

The Pedestrian Friendliness Index accounts for the physical state of sidewalk infrastructure

Source: MoveDC

Metro and Circulator Station Walksheds showing a barrier to travel for corridor residents

Page 31 Goals & Frameworks

Transit gap stretching from end-to-end of the corridor

2.5-mile

barrier to pedestrian crossing across into Anacostia Park

Although many residents rely on this transit for traveling, there is a 4-mile transit gap in the corridor. With nearly 94% of residents leaving the area for work, many face challenges just to merely complete their daily commute. [24] The highway compounds these barriers created by a lack of transit access by physically blocking access to the park and limiting travel between neighborhoods. Particularly concerning is the 2.5 mile stretch in the central portion of the corridor, which lacks any pedestrian crossings over or under the highway.

Infrastructure enabling safe crossing of DC 295 on foot is limited to 5 pedestrian bridges and 7 underpasses with sidewalks.

View from inside a pedestrian bridge crossing DC 295 near the Minnesota Ave metro station

View from inside a pedestrian bridge crossing DC 295 near the Minnesota Ave metro station

Page 32 Goals & Frameworks

Good Hope Rd SE, looking towards Anacostia Park. This is the closest access point to the park on foot from downtown Anacostia.

To create safe and welcoming ways to access the riverfront park - for residents of all ages and abilities

Connectivity Goals

With these existing circumstances in mind, this advocacy plan emphasizes goals based upon improving connectivity in the corridor: To improve connections between neighborhoods East of the River, and ensure more equitable access to goods and services

To enhance access to and from jobs, opportunities, and attractions in the Greater DC area

A portion of the DC 295 across from the Anacostia Metro Station in Southeat, DC (Ward 8).

A portion of the DC 295 across from the Anacostia Metro Station in Southeat, DC (Ward 8).

Page 33 Goals & Frameworks

Ecology

Existing Conditions

The River Corridor has enormous potential. The area boasts over 1,800 acres of parkland along the Anacostia River. By comparison, New York’s Central Park offers only 843 acres.[25] Boston’s Emerald Necklace sweeps in six linear miles around the city, compared to the Anacostia River Park’s nine-and-a-half mile circuit around both sides of the river. This waterfront includes more than 700 acres of water and wetlands, including the stunning Kenilworth Aquatic Gardens.[26]

Flood modeling

Although it is a serious and escalating problem, there is no single authoritative mapping of flooding in the District. So we wanted to do our own exploratory analysis of the hydrology system in the area. We looked at where water tends to accumulate, the patterns for the direction of the flow of water, and combined this with soil drainage , slope and elevation to create a high-level flood risk model. Unsurprisingly, we see that areas closest to the river are most vulnerable to flooding but there are also pockets in the interior where risk is significant. For more information, refer to the Climate Resilience deep dive.

Identifying areas for new stormwater infrastructure using flow analysis

610

buildings currently in flood hazard zones

26%

20% of household in this study area stay in their homes longer than 30 years, 33% stay for over 20 years.

If a household is living within a 1%-annual-risk flood hazard zone, that means over a 30-year span there is a

likelihood that their home will flood while they are living in it.

Interior Flooding on Anacostia Avenue in July 2021 (NBC4 Washington).

MLK Ave and Good Hope Rd - Entrance to the Anacostia Park

Minnesota Avenue and Benning Rd Mayfair Area

Page 34 Goals & Frameworks

According to analysis of existing flood maps, today there are over 600 buildings within flood hazard risk areas inside our study area east of the Anacostia. Estimates also show that by 2080 the areas of flood risk could more than double in size.

Page 35 Goals & Frameworks

Resiliency hubs

Climate Ready DC and Resilient DC are supporting a pilot Resilience Hub in Ward 7, with the intention of supporting “communities to become more selfdetermining, socially connected, and successful.”[27] Modeled after programs in Baltimore and Los Angeles, the Resilience Hub will serve people during one-time disaster events as well as meet day-to-day needs.

The Resilience Hub Community Committee (RHCC) envisions there should be a center within walking distance of every Ward 7 resident. Some initial efforts have been running out of the Faunteroy Community Enrichment Center.

Advocacy efforts

The River Corridor has benefited from robust advocacy and stewardship conducted by community groups, regional coalitions, and federal agencies. Several organizations today are taking unique approaches to improving water quality while promoting environmental stewardship and community engagement. These include the Anacostia Riverkeeper, Earth Conservation Corps, Anacostia River Society, Urban Waters Federal Partnership, among many more.

2032

Page 36 Goals & Frameworks

On track to render the river fishable and swimmable by

Use new roadway infrastructure as a vehicle for capturing water.

Ecology Goals

This advocacy plan emphasizes goals based on the enhancing ecological health of the corridor:

Bake-in resilience strategies to any development that is triggered by the highwayto-boulevard intervention.

Connect more people to more nature through better park and recreation access.

Page 37 Goals & Frameworks

Development

Existing Conditions

In terms of development, the River Corridor has already seen a lot of construction activity in recent years. In the Historical Anacostia area alone, 2,600 new units of housing are in the pipeline, which outpaces the number of new units slated for many other parts of D.C.[28] Relatedly, median home values and average rents have continued to rise over the past decade. At the same time, the study area has a low homeownership rate and an aging housing stock. A fifth of the River Corridor has lived in their homes for 20 or more years and more than half of residents are considered cost burdened, spending more than 30% of their income on rent.[29]

Neighborhoods in the River Corridor are in a precarious position as development attracts while current residents continue to struggle with housing cost and quality. While this advocacy plan is not a housing equity plan, there are clear gentrification and displacement risks in the area, which could be exacerbated by removing the highway if not addressed preemptively.

2,600+ new units

of housing already in the development pipeline, in the Historic Anacostia area alone, a third of which are designated as affordable

1.8 million sq ft of potential developable land opened by this project

Allowing for the creation of approximately

1,633 new units of housing

Page 38 Goals & Frameworks

Proposed

Locations

Example of typical single family detached housing.

renderings for a future develompent.

Credit: Redbrick LMD

Example of typical single family detached housing.

renderings for a future develompent.

Credit: Redbrick LMD

Page 39 Goals & Frameworks

of Affordable Housing in the Anacostia River Corridor

Increase housing stock while maintaining affordability and alleviating cost burden

Development Goals

The goals for the development framework are first and foremost to build a better Corridor for the people who already call the area home. Ensure new development is climate resilient and zoned for responsible land use

Ensure new development expands upon neighborhood character and amplifies existing assets

Italian Row in Historic Anacostia

Italian Row in Historic Anacostia

Page 40 Goals & Frameworks

A holistic solution for the Anacostia River Corridor

With all of these goals established, the question became: what does it actually look like to achieve all of these goals along the entire corridor? What moves have to be made to lessen the barrier that the highway poses, along the entire corridor? The character of the corridor differs widely, with development, connectivity and ecology intermingling in different ways. You can see some of this variation illustrated in these sections - one from the north and one in the south.

It is clear that to achieve all of the framework goals along the whole corridor, interventions will have to account for the changing neighborhood character along the five miles of highway, while still treating the corridor as an interconnected whole.

Anacostia High School

Anacostia Recreation Center DC-295 Chamberlain Elementary School District Yacht Club

Section through Anacostia Recreation Center

PEPCO

MetroRail

Section through PEPCO and National Arboretum

Site National Arboretum

Atrium Apartments Senior Housing DC-295

Page 41 Goals & Frameworks

Imagine a boulevard 4

Case Study Research Highway Removal Alternatives

Tunneling or Burying + Capping Conversion to Boulevard Removal + Conversion (Park or New Development) Before and After: The Big Dig, Boston Before and After: Bonaventure Expressway, Montreal Before and After: Cheonggyecheon, Seoul Page 44 Imagine a Boulevard

In considering the Anacostia River Corridor and the advantages and challenges of each approach, the boulevard approach appears to be best suited for the local context and for advancing connectivity, resilience, and equitable development in the communities that surround DC-295.

Highway removal precedents around the world reflect three main ways to remove a highway: reroute the highway into an underground tunnel, convert the highway into a boulevard, and replace the highway entirely with a new or restored street grid. The table on this page lays out benefits and challenges of each approach.

A boulevard would retain the corridor’s role as a highercapacity north-south connector yet still serve to reconnect neighborhoods to the riverfront park and one another. In addition, a boulevard can take on many different forms, which offers the flexibility for the removal of DC-295 to adapt to changing local conditions along the corridor. Lastly, a boulevard approach takes advantage of the existing momentum surrounding the Highways to Boulevard movement.

The boulevard approach is one amongst many possible methods to transform the DC-295, and has been chosen by our studio as a basis for imagining alternatives for the Anacostia River Corridor.

Tunneling or Capping Boulevard Removal + Conversion

Benefits

• Traffic going north and south through the corridor remains continuous

• Improve health equity through removing pollutants, mitigating heat, and reducing flood risk

• Restore open space that increases biodiversity gains and improves climate resilience

• Increase access to public amenities, recreation, and active transportation

Challenges

• Highest cost and longest time to implement

• Does not shift travel behavior away from polluting, private vehicles

• Likely requires high-end/luxury development to recoup project costs which does not fit in with goals of equitable development or the existing neighborhood fabric

Benefits Benefits

• Maintain a high level of travel capacity throughout the corridor

• Create smoother connections to the riverfront recreation spaces

• Shape development along the boulevard, contributing to placemaking and re-knitting efforts for the community

• Increase opportunities for resilience through the use of blue-green infrastructure assets lining boulevard and a depressed median

• Eliminate infrastructure barriers to open and recreational space for the community

• Expansive multimodal transit corridor investments would create new highcapacity connections north-south between existing neighborhood transit nodes, routes, and trails

• More green space and stormwater interventions to address flood risks, air quality, and urban heat effects

• Catalyze development that amplifies existing assets and preserves neighborhood character

Challenges Challenges

• Will require some former users of DC-295, especially those who use it for through travel, to shift away from driving motorized vehicles or take new routes

• Non-motorists could still face issues safely crossing at busier stretches of the boulevard

• Will require the largest change in travel behavior away from driving alongside the largest investments in transit

• Biggest change from what exists today

Page 45 Imagine a Boulevard

What is a Boulevard?

Boulevards can take many forms from pedestrian-oriented main streets to higher capacity downtown thoroughfares. Some boulevards like State Street in Madison, WI function as pedestrian-oriented main streets with bicycles, transit, and vehicles sharing lanes and traveling at low speeds. On the other hand, downtown boulevards like the Bonaventure Expressway in Montreal have a dedicated right-of-way for transit and wide medians that serve as parks and bike share station locations. However regardless of their context, boulevards have a few important things in common.

Common features of a boulevard include:

• Multimodal travel lanes

• Wide range of vehicle capacity

• Frequent crossings to maximize connections

• Traffic calming measures like crossing islands, curb extensions, and visible crosswalks

• Mixed commercial and residential development on one or both sides

Together, these features prioritize people over cars. This section considers typical boulevard elements in the context of the Anacostia River Corridor to imagine what a boulevard in place of DC-295 could look like. One common element across segments would be a new high-capacity transit option. A new bus rapid transit system, for instance, could run north and south between Anacostia and Deanwood Metro stations, filling in existing transit gaps and providing new ways to travel along the corridor without needing to get in a car. For more information on bus rapid transit (BRT) systems and why one could work well in the Anacostia River Corridor, check out the “Bus Rapid Transit” deep dive.

The local conditions differ throughout the Anacostia River Corridor, which suggests the boulevard will have a different configuration depending on the corridor segment.

Bonaventure Expressway, Montreal, CA

State Street, Madison, WI

Bonaventure Expressway, Montreal, CA

State Street, Madison, WI

Page 46 Imagine a Boulevard

Imagine a Boulevard in Place of DC-295

Potential segments

Proposed boulevard segments

Proposed Bus Rapid Transit

Existing bike lane

Existing bike share station

Existing Metro station

1 Six-lane multimodal boulevard

2 Parkway

3 New bridge

4 Four-lane multimodal boulevard

Page 47 Imagine a Boulevard

Imagine a Boulevard

Six-lane multimodal boulevard: River Terrace to Kenilworth

The northern portion of DC-295 sees the most traffic today with residential neighborhoods and businesses sitting along both sides of the highway. As a result, this busy stretch of highway could lend itself well to a six-lane multimodal boulevard. The boulevard could continue to serve as a high-capacity connector to greater DC and other parts of the river corridor, however, unlike DC-295, this boulevard would accommodate all types of travelers, not just those in private vehicles.

By enabling more access points to and across the road, especially for pedestrians and cyclists, the boulevard could also create opportunities for new commercial activity and a larger development at the PEPCO site.

Proposed features:

• Dedicated bus rapid transit (BRT) in inner lane each way

• Two lanes of vehicle traffic each way

• Two-way cycle track on west side

• Retention median

• Sidewalks on both sides

• Development on both sides except where boulevard approaches CSX rail

Proposed boulevard section (Streetmix)

Cycle track in Seattle, WA

Existing Conditions of DC-295 at highlighted section

Proposed boulevard section (Streetmix)

Cycle track in Seattle, WA

Existing Conditions of DC-295 at highlighted section

0 0.25 0.75 0.5 1.0 Mile Existing bike lane Proposed Bus Rapid Transit Proposed boulevard segment Existing bike share station Existing Metro station 1

Page 48 Imagine a Boulevard

Imagine a Boulevard

Parkway from D St SE to Capitol St SE

After E Capitol St SE, DC-295 curves into the park, at which point the new boulevard could look more like a parkway. Today, there are no connections between DC-295 and the park. In the future, the parkway could run at grade with several crossing points to ensure this segment, like the others, reverses DC-295’s role as a barrier between neighborhoods, the park, and the river.

This portion could narrow into two lanes of traffic in each direction, slowing vehicle speeds down as the boulevard leaves the mixed commercial and residential areas. A cycle track, wide sidewalks, trees, and park space would line both sides of the parkway, creating a new space for residents and visitors to enjoy the park.

Proposed boulevard segment

Proposed features:

• Dedicated bus rapid transit (BRT) in inner lane each way

• Two lanes of vehicle traffic each way

• Two-way cycle track on west side with a connection to the river trail

• Retention median

• Sidewalks on both sides

• Park on both sides, no development

Proposed Bus Rapid Transit

Existing bike lane

Existing bike share station

Existing Metro station

Green Street in Nashville, TN

Eastern Parkway in Brooklyn, NY

Existing Conditions of DC-295 at highlighted section

2

0 0.25 0.75 0.5 1.0 Mile

Page 49 Imagine a Boulevard

Imagine a Boulevard

Bridge Connecting Southeast Blvd to New Parkway

Today, there is a long stretch between Pennsylvania Avenue and E Capitol St without a connection over the Anacostia River. While there is a CSX railroad bridge around where Massachusetts Avenue meets 30th St SE, there are no opportunities for vehicles, pedestrians, or people on bicycles to cross. Additionally, the existing CSX railroad bridge is extremely low new and prevents any boat larger than a canoe from crossing. The conversion of DC-295 into a boulevard could present an opportunity to address this gap with a new bridge that connects the boulevard to Southeast Blvd west of the river. A new elevated bridge that carries the CSX rail and the boulevard could not only increase the accessibility of D.C. to nearby residents but also allow boats to move up and down the river again. Like other segments of the boulevard, the new bridge should make space for people without a car, and feature wide sidewalks like D.C.’s Frederick Douglass Bridge and dedicated lanes for cyclists.

• Splits off from the parkway segment and connects to Southeast Blvd west of the river

• Runs parallel to the CSX rail bridge

• Two lanes of vehicle traffic each way

• Wide sidewalks on both sides to accommodate pedestrians and cyclists

0 0.25 0.75 0.5 1.0 Mile Existing bike lane Proposed Bus Rapid Transit Proposed boulevard segment Existing bike share station Existing Metro station 3 Proposed features:

Existing Conditions of DC-295 at highlighted section

Fredrick Douglass Bridge in Washington, DC

6th Street Bridge, Los Angeles, CA

Page 50 Imagine a Boulevard

Île-des-Sœurs Bridge in Quebec, CA

Imagine a Boulevard

Four-lane boulevard from Barry Farm to Greenway

4

In the southern portion where DC-295 runs between the park and the residential neighborhoods, a lower capacity four-lane multimodal boulevard that emphasizes connections between the surrounding residential neighborhoods and the park could fit well into the existing neighborhood fabric. Today, residents have limited options to cross the highway and must use lengthy pedestrian bridges or low-quality sidewalks along underpasses. With the Anacostia Park on one side and newly developable land on the other, this segment of the boulevard could not only facilitate better connections to the park but also provide new amenities to the park itself.

• Dedicated bus rapid transit (BRT) in inner lane northbound and in outer lane southbound

• One lane of vehicle traffic each way

• Two-way cycle track on west side

• Retention median

• Sidewalks on both sides

Bus Rapid Transit

Existing bike lane

Proposed boulevard section (Streetmix)

Existing Conditions of DC-295 at highlighted section

Existing Conditions of DC-295 at highlighted section

Proposed

Proposed

• Mid-rise residential development east of the boulevard, park space west of the boulevard segment

boulevard

Existing bike share station Existing Metro station

0 0.25 0.75 0.5 1.0 Mile

Proposed features:

Page 51 Imagine a Boulevard

Suburban artery turned Main Street in Huntsville, AL Green street in Nashville, TN

Page 52 Imagine a Boulevard

The Cheonggyecheon highway converted to a boulevard in Seoul, South Korea

Benefits of a Boulevard

Converting DC-295 into a boulevard would benefit the connectivity, ecology, and development potential of the entire Anacostia River Corridor.

Improved Connectivity

Ecological Benefits Benefits for Development

• Investments in transit to address long-standing accessibility and congestion issues

• Traffic calming and safe crossings to improve pedestrian safety and park access

• Expanded bike networks to create new recreation and commute opportunities

• Green infrastructure assets to increase flood resilience

• Pollutant removal to improve health equity

• Smoother connections to increased equitable access to public open spaces

• Capitalize on newly developable land to increases housing supply and alleviates cost burden

• Ensures that new development is zoned for responsible land use

• Builds mixed-use density around new transit nodes to create more accessible homes and services

Page 53 Imagine a Boulevard

Improved Connectivity

A boulevard that prioritizes people over cars and that is responsive to local conditions will significantly enhance connectivity for surrounding communities. The map to the right shows possible corridor-wide interventions that, together, would achieve the following connectivity benefits.

Better accessibility and less congestion

A bus rapid transit system carrying people north and south along the corridor could address long-standing accessibility issues for residents traveling between neighborhoods east of the river, while also reducing congestion. Extending the existing streetcar line down Benning Road to Benning Road Metro station could further enhance the transit network.

Safety for all

Traffic calming and safe crossings throughout the corridor could improve pedestrian safety and park access. Although converting the highway into a boulevard will bring vehicle speeds down along the corridor, to achieve safe and equitable connections for the surrounding communities, traffic calming measures should extend to nearby arterials like Minnesota Avenue as well as major roads that intersect with the new boulevard.

More connections to the park

Expanding bike share and bike lanes to link together the areas’ vast amount of park land with the new boulevard could create a network of new recreational and commuting opportunities.

Proposed boulevard

Bus Rapid Transit along the boulevard & streetcar extension on Benning Rd

Traffic calming Land bridge

Pedestrian-oriented crossing

Proposed bike lane

Proposed bike share station

0 0.5 1 0.25 Mile N

Page 54 Imagine a Boulevard

Improved Connectivity

Bus Rapid Transit

Bus Rapid Transit or otherwise known as BRT is a “high-quality bus-based transit system that delivers fast, comfortable, and cost-effective services at metrolevel capacities.”[30] It achieves metrolevel capacities through the provision of dedicated lanes, stations that are typically aligned to the center of the road, off-board fare collection, and fast and frequent operations.”[31] The proposed bus rapid transit system in this plan would run in dedicated lines between Anacostia Station and Deanwood Station. The system would be the first north-south high-capacity transit line east of the river.

Streetcar extension

Streetcars are “lightweight passenger rail cars operating singly (usually two-car trains) on fixed rails in a right of way that is not separated from other traffic for much of the way.”[32] Washington D.C.’s streetcar, DC Streetcar, currently runs on H Street NE and Benning Road between Union Station and Oklahoma Avenue.[33] This plan proposes extended the streetcar line down Benning Road to Benning Road Metro Station to provide additional transit options east of the river.

Traffic calming

Physical design measures that slow vehicle speeds and improve conditions for nonmotorists.[34] Examples of traffic calming include speed humps, roadway narrowing, curb extensions, and crossing islands.

Pedestrian-oriented crossings

Crossings that elevate the importance of non-motorists at traffic intersections through measures like high-visibility crosswalks, pedestrian crossing signals, signage, and crossing islands. In addition, pedestrian-oriented crossings can have amenities like benches and landscaping that make the intersections more pleasant to use.

Land bridge

A land bridge is a “cap” or a “lid” over a roadway that reclaims land that was lost in previous transportation projects.[35] A land bridge over the CSX rail just south of Benning Road would allow for residents east of the railway to access the boulevard, new amenities that come out of developing the PEPCO site, as well as the riverfront park.

Proposed bike lanes

Bike lanes are dedicated lanes for people riding bicycles and are often separate from vehicle traffic with a physical buffer. Buffers can range from a painted zone on the road to plastic flex posts to landscaped medians. Bike lane infrastructure east of the river is limited, so this plan proposes building out a more comprehensive network of separated bike lanes that connect Ward 7 and 8’s many green spaces as well as along the full length of the new boulevard.

Proposed bike lanes

Capital Bikeshare is Washington D.C.’s bikeshare service with 600+ stations across Washington D.C. and nearby jurisdictions.[36] The proposed bike share station locations in this plan are intended to improve accessibility of bike share by adding more stations along the boulevard and nearby arterials.

Van Ness BRT in San Francisco, CA (Source: Mattsjc via Wikimedia Commons)

Van Ness BRT in San Francisco, CA (Source: Mattsjc via Wikimedia Commons)

Page 55 Imagine a Boulevard

Proposed land bridge in downtown Pittsburgh, PA (Source: Urban Design Associates)

Ecological Benefits

A boulevard in place of DC-295 could facilitate healthier, cleaner movement, among other environmental benefits, to the surrounding communities. The map to the right shows possible corridor-wide interventions that could improve the ecology of the Anacostia River and the Anacostia River Corridor.

Increased flood resilience

The ability to layer-in new blue-green stormwater infrastructure – in parallel with the new boulevard as well as any new development that the boulevard triggers – presents an unprecedented opportunity to mitigate the risk of flooding in neighborhoods east of the Anacostia, while also restoring long-lost wetland habitats and improving river health.

Improvements to health equity

Removing the highway infrastructure and reducing the through-traffic that whizzes by the neighborhood will reduce dangerous pollutants in the air, reduce the urban heat island effect, and create a more walkable environment that supports active, healthy lifestyles for people of all ages and abilities.

Constellation of green

These neighborhoods are blessed with an abundance of park spaces, but these currently feel disparate and moving between them is not easy. As barriers like DC-295 fall, and connectivity and activation improve, the hope is that south- and northeast areas embrace a new identity as neighborhoods of lush parks and gardens, streams and ponds, that create an interconnected constellation of green space.

Proposed boulevard

Expand living shoreline and restore floodplain

Daylight streams and restore wetlands

Land elevation

Build new retention ponds

Retention median Blue-Green crossings

Existing FEMA BRIC study area

Existing bike lane

Existing bike share station

Existing Metro station

0 0.5 1 0.25 Mile N

Page 56 Imagine a Boulevard

Ecological Benefits

Expand living shoreline and restore floodplain

Continue to remove deteriorating concrete channel walls and riprap barriers; replace with 150 ft wide riparian buffer (approx. distance between Anacostia Drive and current coastline), consisting of softened slopes made of sand and rock, stabilized by native tidal-wetland planting.

Daylight streams and restore wetlands

Restore connection between the river and tributaries that were drained, relocated, or buried over time by daylighting streams and reintroducing native marsh vegetation to protect against erosion.

Elevate land out of floodplain

Elevate land to a level that removes any new riverside development from the 500-year or 0.2% chance projected flood hazard, also accounting for sea level rise – estimated to be between 7 to 16 ft above ground level. This strategy fits a dual purpose for site remediation where necessary to cap contaminated land with new soil.

Build new retention ponds

Install new larger-scale retention ponds at 3 key areas identified along the boulevard, where water seeks to flow into low-lying areas of vacant or publicly-owned land.

Retention boulevard

A retention system anchored around the boulevard will buffer riverine flooding and provide routine mitigation of stormwater runoff. The retention boulevard roadway slopes towards depressed green medians and/or swales at outer edges, where water drains down to stormwater pipes and cisterns located at intervals along the length of the boulevard.

Blue-Green crossings

To enhance connectivity from neighborhoods to the river edge use the paths of daylighted streams to trace new connections that cross the boulevard and traverse parkland. Expand or install new open culverts for streams to flow unobstructed under the boulevard, fill with native planting, and add educational signage to mark each bluegreen boulevard crossing, highlighting site ecology and water quality improvements.

Activate park with water-based recreation

Enhance visitor experience in the park and connectivity to the river by investing in water-based recreation facilities, including fishing, boat launches, and splash pads; and installing pedestrian pathways and/or floating boardwalks along daylighted streams and over restored wetland areas. Punctuate new installations with educational signage celebrating the natural ecology of the area and community stewardship efforts

Existing FEMA-BRIC study area

Coordinate with ongoing FEMA-funded community efforts to examine flood risk along the Watts Branch tributary, especially as regards potential buyout programs, land-swaps, or new mitigation strategies.

Floodplain management

In line with Climate Ready DC Resilient Design Guidelines, restrict development in flood-prone areas, and require any new developments triggered by the boulevard transformation to be built in a way that reduces the risk of flood damage.

A living shoreline project at Pine Knoll Shores, NC

(Source: North Carolina Coastal Federation)

A living shoreline project at Pine Knoll Shores, NC

(Source: North Carolina Coastal Federation)

Page 57 Imagine a Boulevard

Lady Bird Lake in Austin, TX (Source: Johannes Schneemann via Visit Austin)

Benefits for Development

The removal of DC-295 will has the potential to catalyze more equitable development east of the river. The map to the right shows possible areas of new development following the conversion of DC295 to a boulevard. The benefits of a new boulevard to equitable development are listed below.

Larger housing supply and lower cost burdens

The biggest benefit of a boulevard conversion for development is that such a project would open up large amounts of developable land and provide an opportunity to increase the supply of housing, while maintaining affordability and alleviating cost burden.

Responsible zoning

Taking down a physical barrier allows new development uses to be focused on connecting Ward 7 and Ward 8 residents to the river. By incorporating this goal into local zoning policy, the conversion of DC-295 into a boulevard could ensure that development expands upon existing neighborhood character and supports existing neighborhood institutions.

More accessible homes and services

Emphasizing multimodal options within a boulevard conversion opens up the possibility of building true density around transit nodes, which does not yet exist in the area. Greater density near high-quality transit in turn could create more accessible homes and services for the Anacostia River Corridor.

Existing bike lane

Existing bike share station

Existing Metro station

1 2 3 4 5 6 0 0.5 1 0.25 Mile N Proposed boulevard Residential development opportunity Commercial development opportunity Kenilworth development triangle Expand neighborhood fabric PEPCO redevelopment Minnesota transit hub Anacostia transit hub The Bridge District Special Purpose Zone Eco District Zone 1 4 2 3 5 6

Page 58 Imagine a Boulevard

Benefits for Development

Residential development opportunities

Kenilworth development triangle: Currently wedged between DC-295 and the CSX rail, this area primarily contains auto-oriented businesses, a self-storage facility, and towing storage lot. With the conversion of the highway, the area would no longer be isolated from the Kenilworth neighborhood by DC-295 and could be the site of new residential development.

Expand neighborhood fabric: Today, the highway’s footprint takes up all of the space between Fairlawn Ave SE and Anacostia Park at this section of the corridor. Removing DC-295 here would free up land for mixed commercial and residential development lining the east side of the boulevard.

Commercial development opportunities

PEPCO redevelopment: This site presents 3.5 million square feet of development potential. Energy providers, including PEPCO, are already undergoing significant changes in their operations, and this site provides the opportunity to reimagine an industrial site along the new boulevard. Development at this site could not only provide new commercial amenities to residents but also improve access to the river and nearby river trail.

Minnesota transit hub: Dense, walkable, mixed-use development near transit can create more vibrant, connected, and equitable communities, especially when coupled with affordable housing.[37] The Minnesota Avenue Metro station is situated near several large government buildings but the area is otherwise largely residential. The boulevard could help catalyze more commercial development and help the area realize the benefits of transit-oriented development.

Anacostia transit hub: Dense, walkable, mixed-use development near transit can create more vibrant, connected, and equitable communities, especially when coupled with affordable housing.[38] The Anacostia Metro station is not currently well integrated into downtown Anacostia. With the conversion of DC-295 to a boulevard, commercial development near the metro station could help to better connect the transit center to the surrounding neighborhood

The Bridge District: An existing residential and retail development with a focus on sustainability and creating and sustaining local jobs and businesses that broke ground in mid-2022.[39] Converting DC-295 into a boulevard would enable the removal of the on and off ramps to Suitland Parkway from DC-295, opening up additional developable land in this area.

Special purpose zone

Changing the PEPCO site to ‘Special Purpose Zone’, which is intended for single large sites that require a cohesive, self-contained set of regulations, can allow maximum density close to transit stops, as well as consistent design standards and an opportunity to preserve affordability.

Eco district zone

An ecodistrict is a neighborhood that centers environmental and social wellbeing in planning processes.[40] Physical infrastructure (ex: public transportation, green space) as well as social and cultural networks constitute the district. There is an established framework that provides key goals and objectives for these districts, which includes three overarching priorities (equity, climate resilience, climate protection), as well as six key priorities (place, resource restoration, living infrastructure, connectivity, health & wellbeing, prosperity). This framework could be incorporated into existing development plans for Poplar Point to help align the initiative’s goals with the goals for removing DC295 in the broader corridor.

1 2 4 3 5 6

Page 59 Imagine a Boulevard

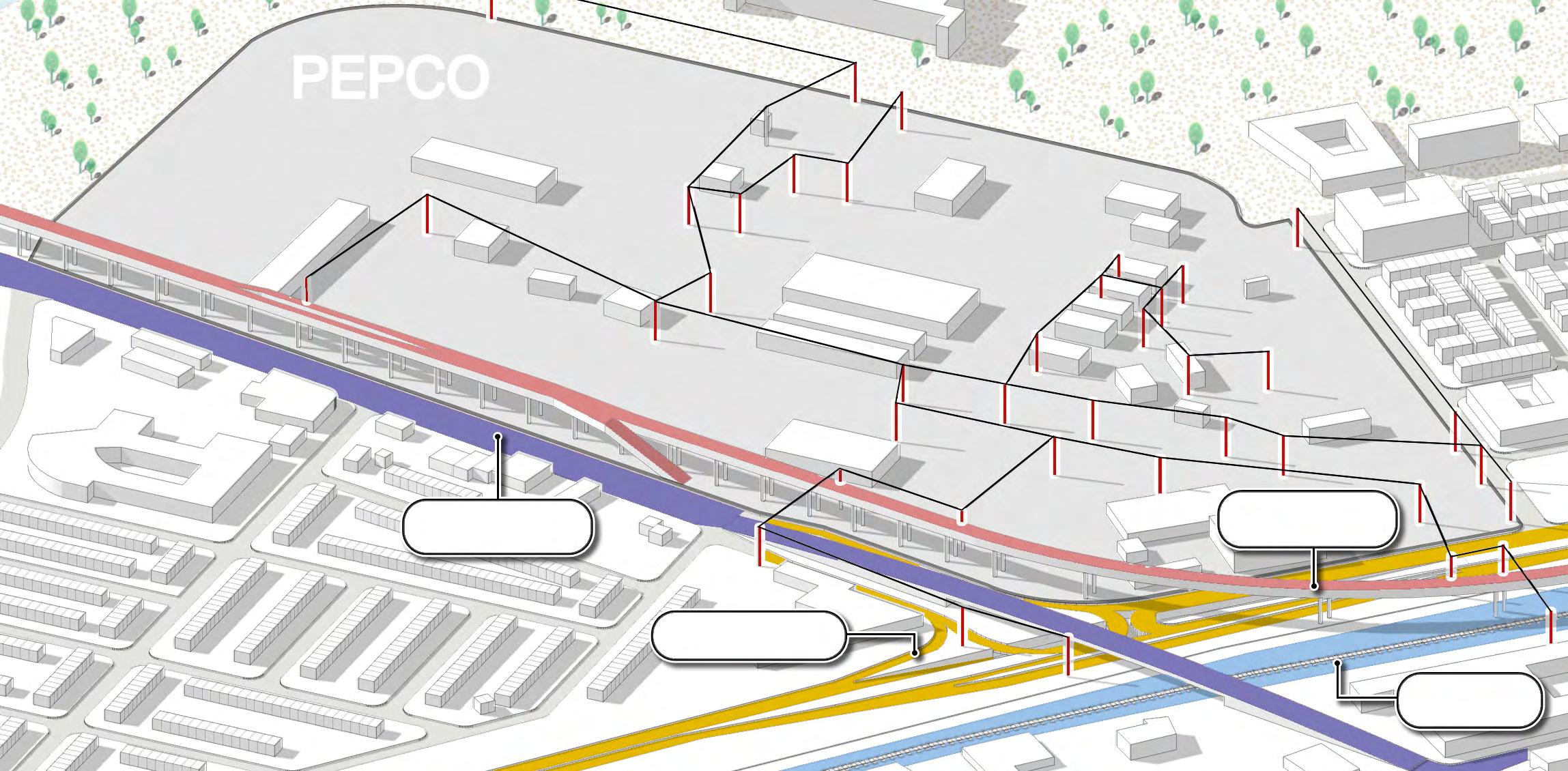

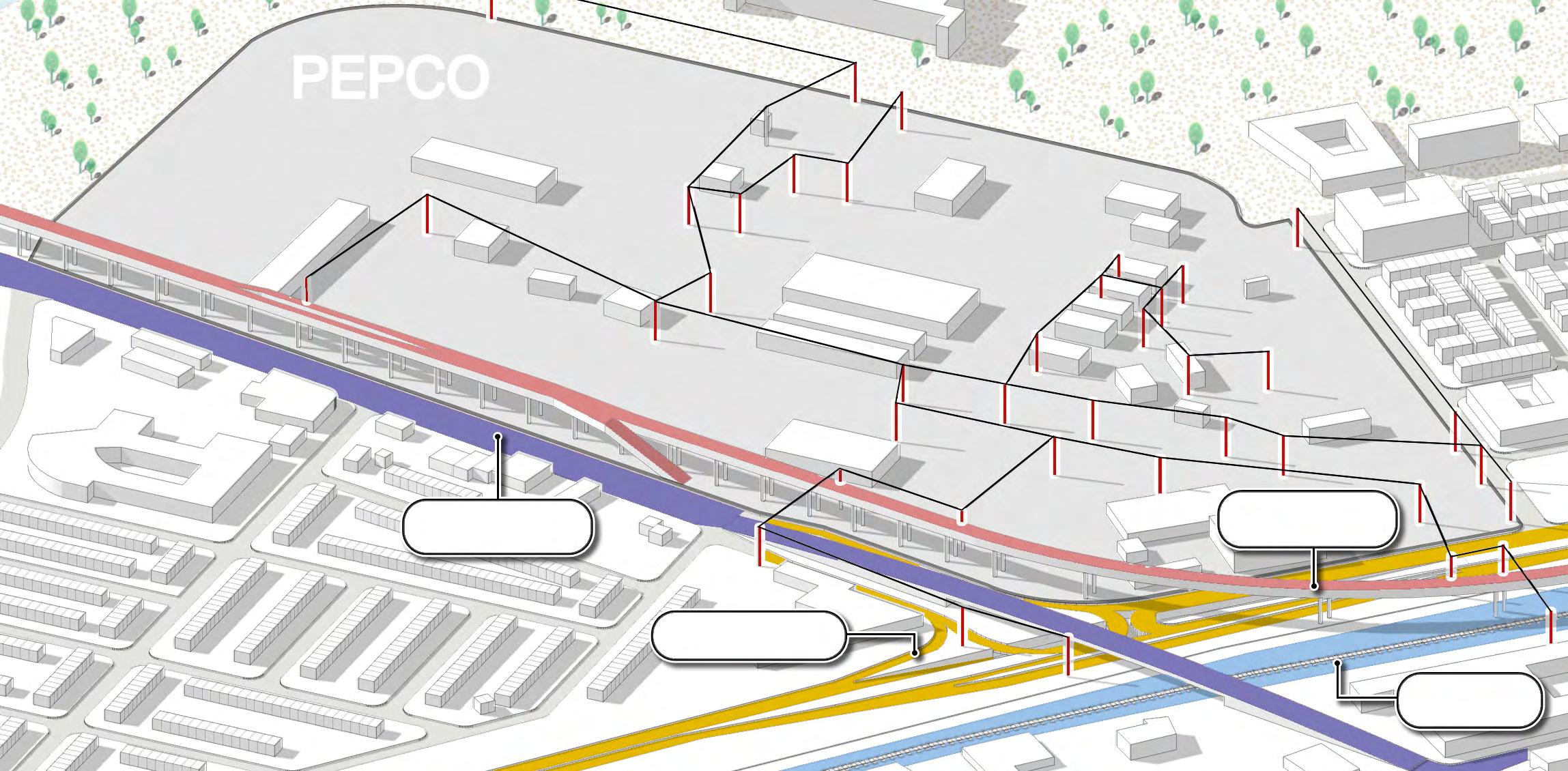

The PEPCO site located towards the northern segment of DC-295

Exploring the PEPCO Site

How can a boulevard conversion can catalyze development - and not just any development, but equitable development? While this project is mainly about the highway conversion itself, it is useful to imagine how a lot of these ideas would ideally play out at a smaller scale through the example of one specific site.

To do this, we explored the PEPCO site located in the northern portion of our boulevard where Benning Road and DC-295 intersect. Within this small area plan, we wanted to achieve certain outcomes that align with the connectivity, ecology, and development frameworks we presented on earlier. These include: planning for a multi-modal future of mobility, creating new river connections and increasing accessibility to amenities, and increasing the corridor’s housing supply through a mixed-income neighborhood model.

This is by no means a final plan, rather, a suggestive imagination of equitable development that would be subject to change and evolution if taken through a rigorous process of community engagement and feedback. Our deep dives include materials for community members to run their own planning workshop at this site, similar to how we conducted ours.

The PEPCO site currently exists as 3 million + sq-ft of Production, Distribution, and Repair (PDR) land for DC’s electrical utility company, with large warehouses, pylons, and surface parking.

Page 60 Imagine a Boulevard

The PEPCO site situated towards the northern segment of the DC-295, adjacent to the Anacostia River and Parkside, Benning, and River Terrace neighborhoods.

Why this site?

Interaction with boulevard

The site interfaces directly with the proposed boulevard, and provides an opportunity to explore how the boulevard could affect future development.

Environmental reparations

Hosting non-renewable energy production and a trash-processing facility without proper controls of limiting pollution, the site has a history of environmental injustice and is a brownfield, providing the opportunity to explore ways to transform a polluted site into a community asset.

Access to Anacostia river

Sitting along the waterfront, PEPCO is a good location to explore how highway removal and equitable development can improve access to the river and river trail.

Over 3 million sq-ft of land

The site represents nearly 3.5 million square feet of development potential, which is an unprecedented amount of land and gives a lot of room for imagining possibilities.

Rethink industrial uses

The existence of crucial energy infrastructure on the site provided an interesting and timely development constraint. Energy providers, including

PEPCO, are already undergoing significant changes in their operations, and this site provides the opportunity to explore those changes in the short term.

Adjacent residential and commercial land use

The site is adjacent to varying residential and commercial typologies, meaning the site gives us the opportunity to think through what it would look like to develop with existing neighborhood characters in mind.

4 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 5 2 6 3

Page 61 Imagine a Boulevard

Existing Conditions

Road

Lines

Lines Page 62 Imagine a Boulevard

Benning

DC-295 MetroRail

CSX

Opportunities and Constraints

Opportunities

1. Proximity to Anacostia Riverfront

2. Direct access from Benning Road & DC-295

3. Adjacent to existing residential land uses

4. Close to Minnesota Ave station

5. Defunct CSX line in site

6. Brownfield remediation potential

Constraints

7. Floodplain

8. Existing roads and metro lines

9. Auto-oriented industrial land uses

10. Active CSX lines

11. Existing trash processing facility

12. PEPCO infrastructure

The planning process began with an identification of opportunities and constraints. This site presented challenges of a complicated intersection at Benning Road and DC-295, PEPCO’s electricity infrastructure, a trash facility at the northwest, and a storm surge line that cuts into the site. Conversely, it provided opportunities to better connect the neighborhoods of Parkside and River Terrace, strengthen the uses of developable land as community assets, and protect the river’s natural ecosystem.

Through our planning process and outcomes, we reiterate that the communities of and around this site know their needs best.

1 6 2 2 3 3 3 4 5 7 11 12 8 9 10 Page 63 Imagine a Boulevard

Extend transportation networks, move site boundary out of floodplain, and open up developable land

To continue the boulevard all the way through the corridor, it needs to be brought to grade with Benning Road at the place where they intersect. To bypass the existing metro lines running overhead and CSX lines below, we designed the road to curve into the site at the southeast corner. This would create large areas of developable land with unique opportunities for transit-oriented development.

We propose an extension of the H Street streetcar line across the Anacostia River down to Benning Metro Station with two additional transit stops: one on 34th Street at the main entrance to the site, and another at the Benning Road/Boulevard intersection. With this dedicated streetcar lane, Benning Road would get a Complete Streets treatment including protected bike lanes and pedestrian friendly infrastructure. To strengthen connections to Minnesota Avenue Metro Station, a station entrance should be added near Parkside, connected to existing MetroRail infrastructure through a short underground corridor.

Based on our research, we determined it was feasible to condense PEPCO utilities to about 750,000 sq ft in the middle of the site, retaining most existing transformers and buildings. We also made the decision that there would be no development built within the floodplain and buildings would be built accordingly to prepare for rising sea levels and storm surges. This still leaves a large amount of land for development surrounding the condensed PEPCO site.

Programming land uses to provide for mixed-use, mixed-income development

To develop the land to provide for mixed-income groups and create opportunities for upward mobility, a mix of uses catering to Wards 7 and 8, as well as DC at large is included. Entering the site through 34th Street at the south are dense, mixed use areas, which can be mid-rise buildings with mixed income apartments on top and retail at ground level. This is complemented with additional mixed use community assets closer to the waterfront - including affordable apartments, a health clinic and a small business incubator. Many of the commercial spaces on the site can be held for participants of the incubator program who need affordable space to grow their business ideas, such as restaurants, salons, and other small businesses.

Across Benning Road, a more unified commercial corridor with zoning regulations to restrict certain industrial related uses is proposed. This proposal accommodates existing auto related companies as part of a wider business retention strategy by consolidating footprints and creating a green buffer between them and the adjacent residential community. Lastly, an anchor grocery store would be located at the corner of the new intersection, making it accessible by car, transit, and bike from surrounding communities.

Reimagining PEPCO

A B

Page 64 Imagine a Boulevard

Planning for transit-oriented development and a spectrum of housing communities

To capitalize on transit-oriented development, the curved portion formed by the boulevard would be used for high-density, mixed-use buildings with commercial and hospitality, which is currently lacking east of the river. With an activated ground plane, this site can connect to neighborhoods across the CSX lines through thin “land bridges”.

To extend the boulevard’s philosophy of providing for people, place, and nature, green street networks are integrated across the site. The abandoned CSX rail that currently enters into the site would be extended into a wheelchair and bike accessible trail - directly connecting Minnesota Avenue Metro Station to the waterfront through the site’s green and public spaces. A community garden, farmers market, and tool library would anchor the eastern corner, directly accessible to Parkside and surrounding communities.