Reimagining Shophouses for Bangkok’s Urban and Heritage Resilience 4 x 4 x 4

Living:

Abstract

Shophouses, buildings combining ground‑floor retail with upper‑floor dwellings, have long shaped urban life across Southeast Asia. In Bangkok, many such buildings, once family‑owned, are now vacant, poorly maintained, and underutilised, suffering from inadequate natural lighting, ventilation, safety, and operational conditions. Largely unlisted and politically unplanned, shophouses occupy extensive areas of city centre prime land and are facing growing pressure for demolition amid the city’s rising housing costs, rapid sprawl, inadequate public transport, regular flooding, and lacking green space.

Leveraging the author’s long‑term residence in Bangkok, this study asks how shophouses can adapt to meet climate, urban, housing, and conservation needs. Using Banthattong Road within the “Sam Yan Smart City” as a pilot and adapting Peter Swinnen’s “policy whispering,” the research produces an illustrated “off‑white paper” of strategy and policy propositions addressing to the Property Management of Chulalongkorn University (PMCU), the sole landowner whose decision would affect hundreds of shophouses on the pilot site.

Results indicate that a strategic approach to conservation could be affective in preserving shophouse heritage while enabling incremental redevelopment that improves affordability, climate resilience, and social cohesion. Based on these findings, the research recommends establishing an organisation to pilot shophouse heritage stewardship together with outlining initial steps for developing guidelines that could steer Bangkok’s shophouses, and potentially those in neighbouring countries, toward a more holistic and sustainable future.

x 4 x

Table of Contents

Abstract

Table of Contents

List of Figures

Glossary and List of Abbreviations

Introduction

Methods

Context and Problems

Background

Historical Origin

Current Pressure

Bangkok in Focus

Bangkok’s Shophouse

Lessons from Elsewhere

A Chance to Rethink

Reframing Conservation

Prototype: The New Shophouse

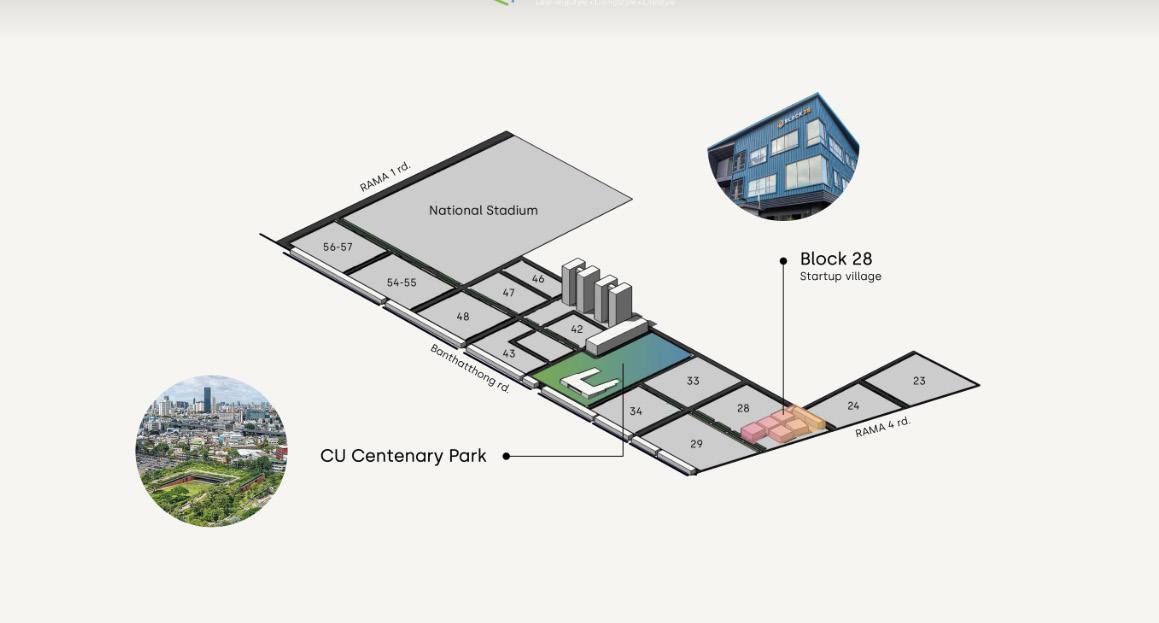

Testing Ground: Sam Yan Area

Why Sam Yan

Transport and Connectivity

Demographics and socio-economics

Cultural and Public Realm

Environm

Fit for Prototype

The [Off] White Paper

From Prototype to Policy

Conclusion

Reference

Bibliography

Interview Records

Photographic Records

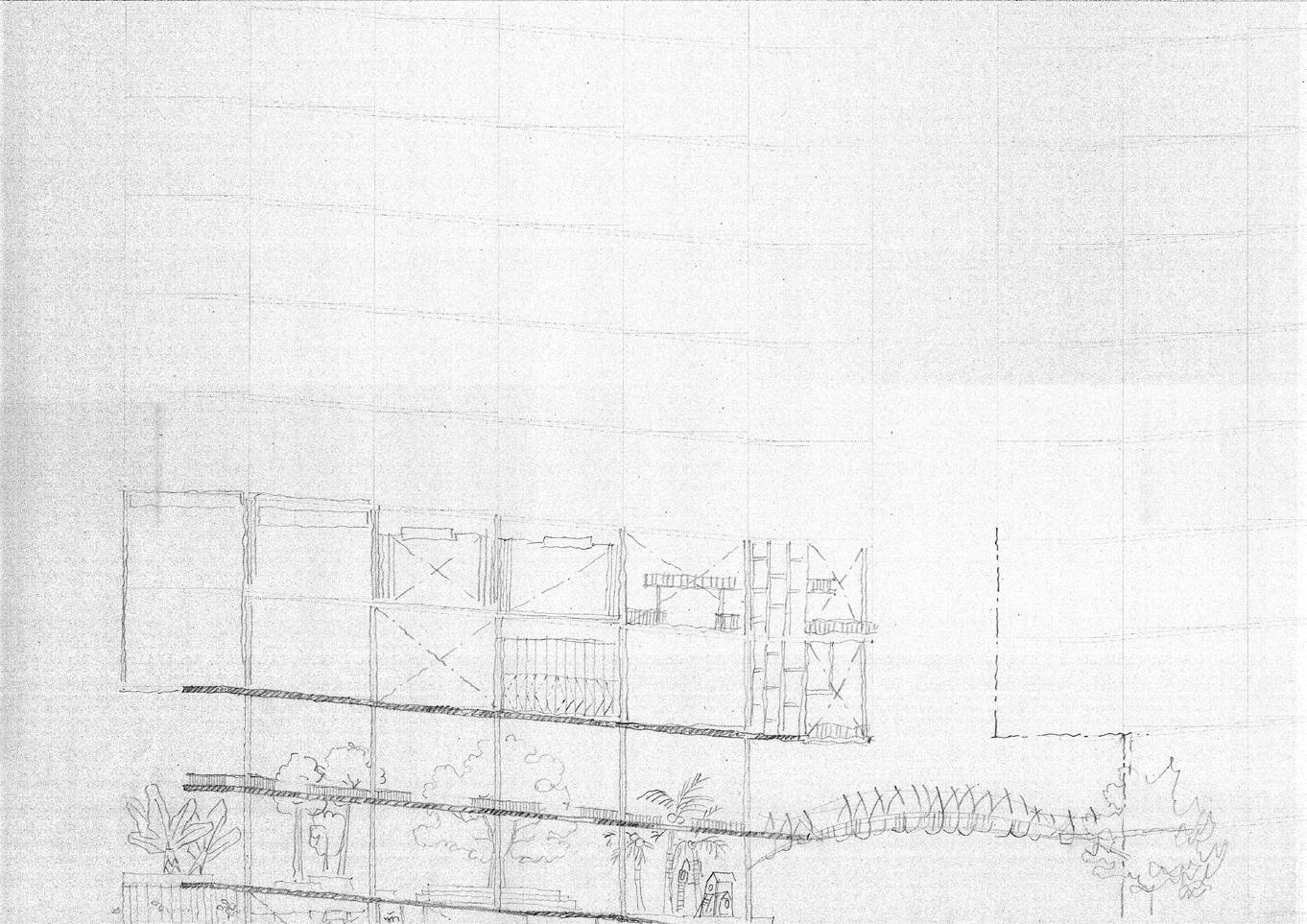

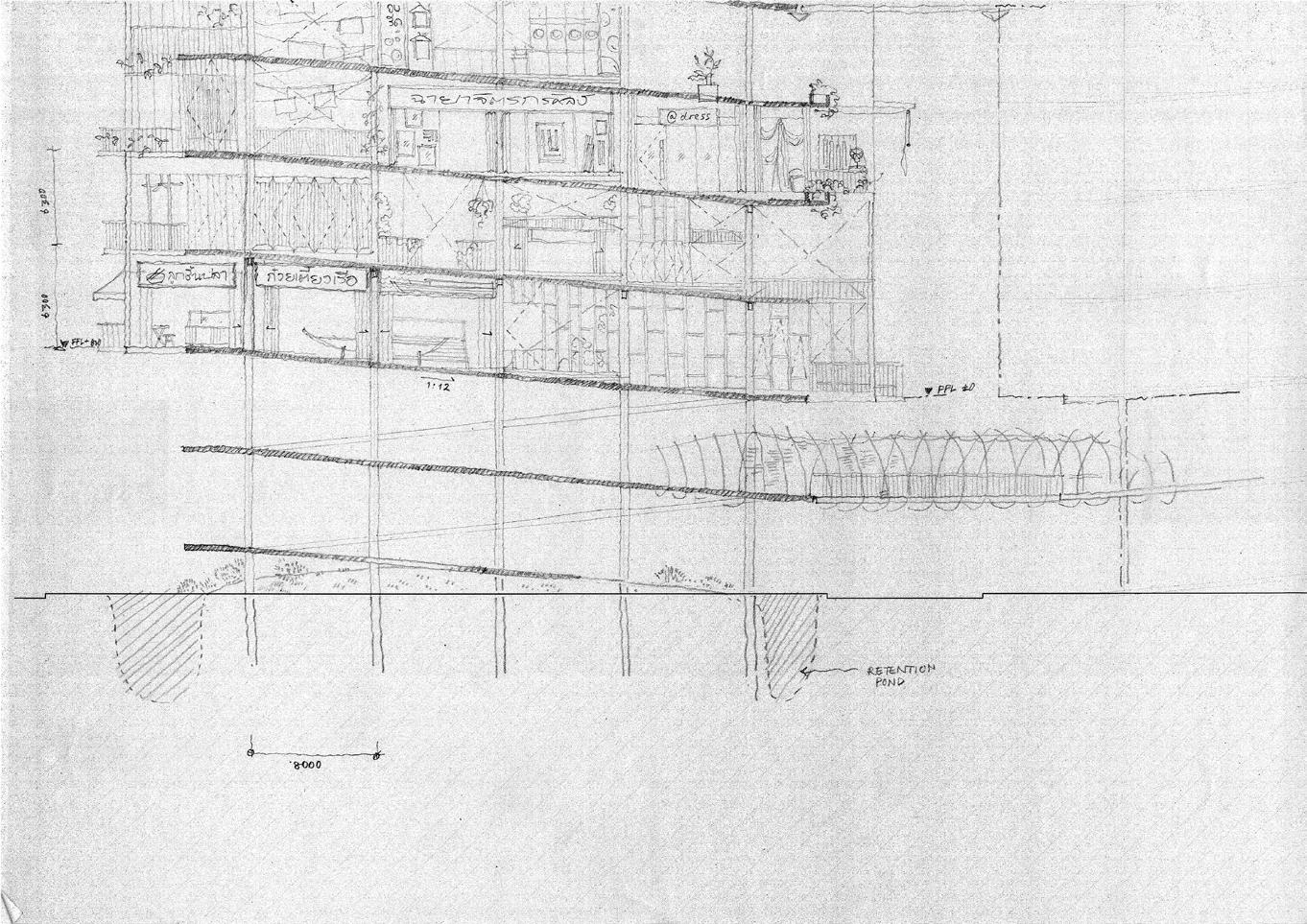

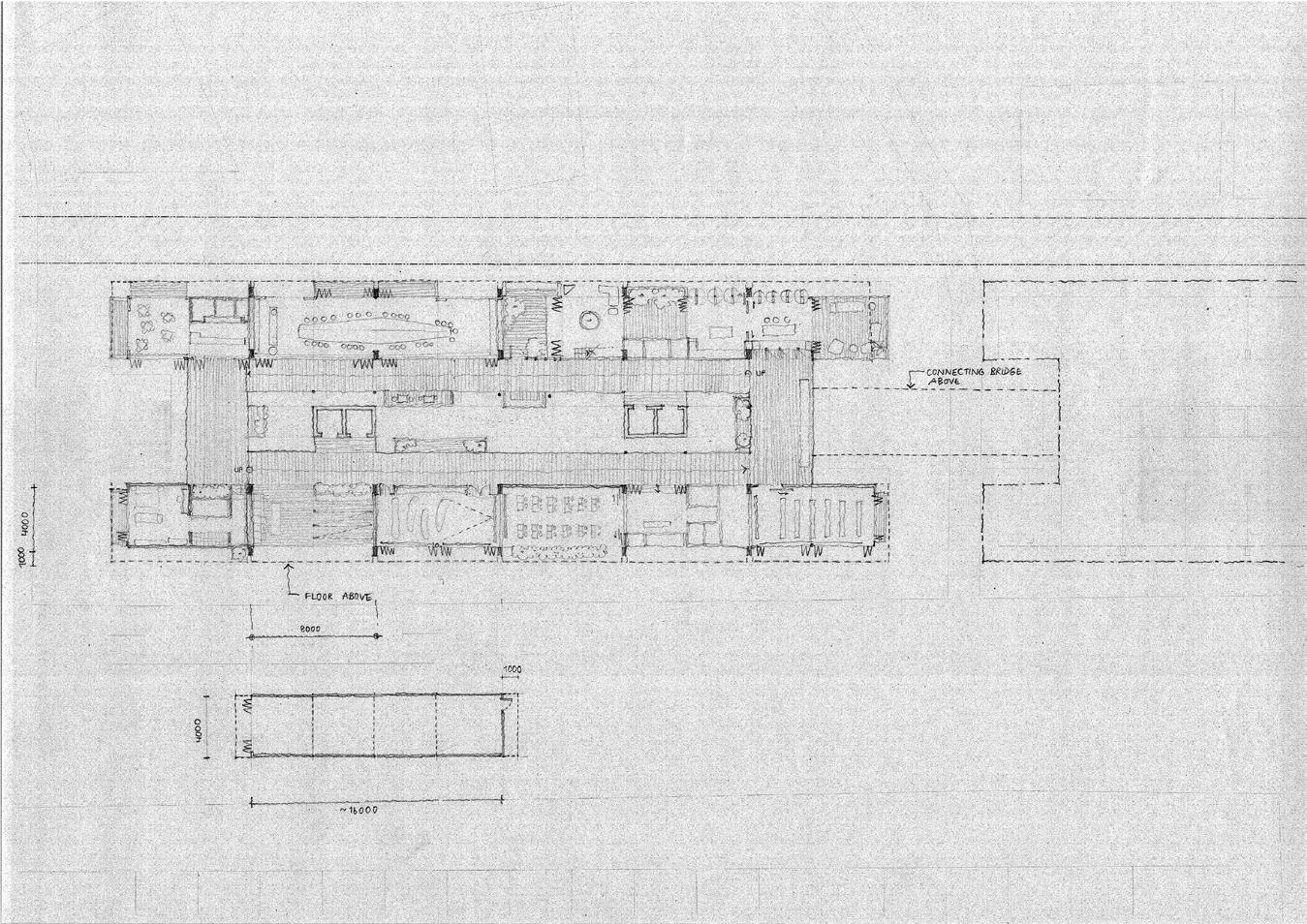

Development of Design Idea: Sketch

Possibilities and Precedents

Appendix

Appendix 1: Shophouse Guardian Collective Organisational Model

Appendix 2:

Historical and recent maps of commercial zone of Chulalongkorn University

Appendix 3: Shophouse Conservation Situation in Bangkok Review

List of Figures

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

Fig. 3

Fig. 4

Fig. 5

Fig. 6

Fig. 7

Fig. 8

Fig. 9

Fig. 10

Fig. 11

Fig. 12

Fig. 13a

Fig. 13b

Fig. 13c

Fig. 14

Fig. 15a

Fig. 15b

Fig. 15c

Unlisted shophouses are threatened by new development.

Shophouses is modern vernacular architectecture heritage in Bangkok and South East Asia

Frequent flood problems in Bangkok, a result of urban growth and climate change.

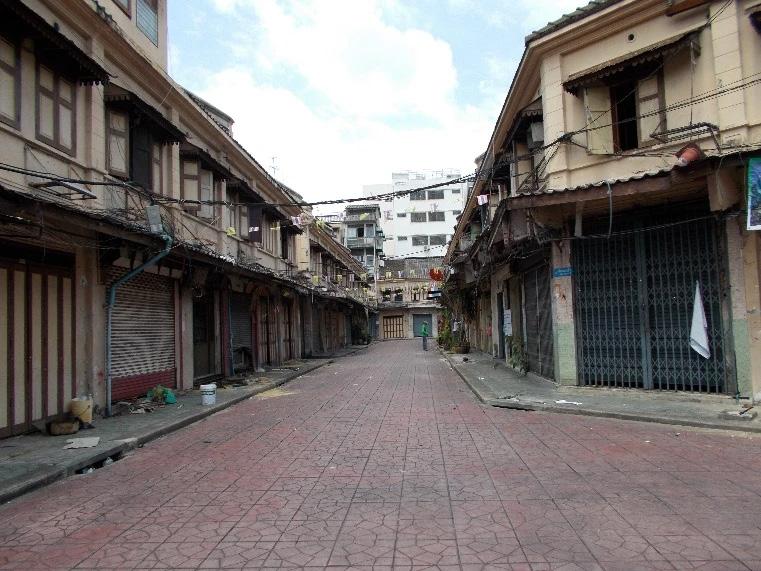

Shophouses in the Talat Noi neighbourhood.

Bangkok traffic

Spillout activity in shophouses

Unlawful canal settlements

Bangkok shophouses in old city area

Bangkok pollution

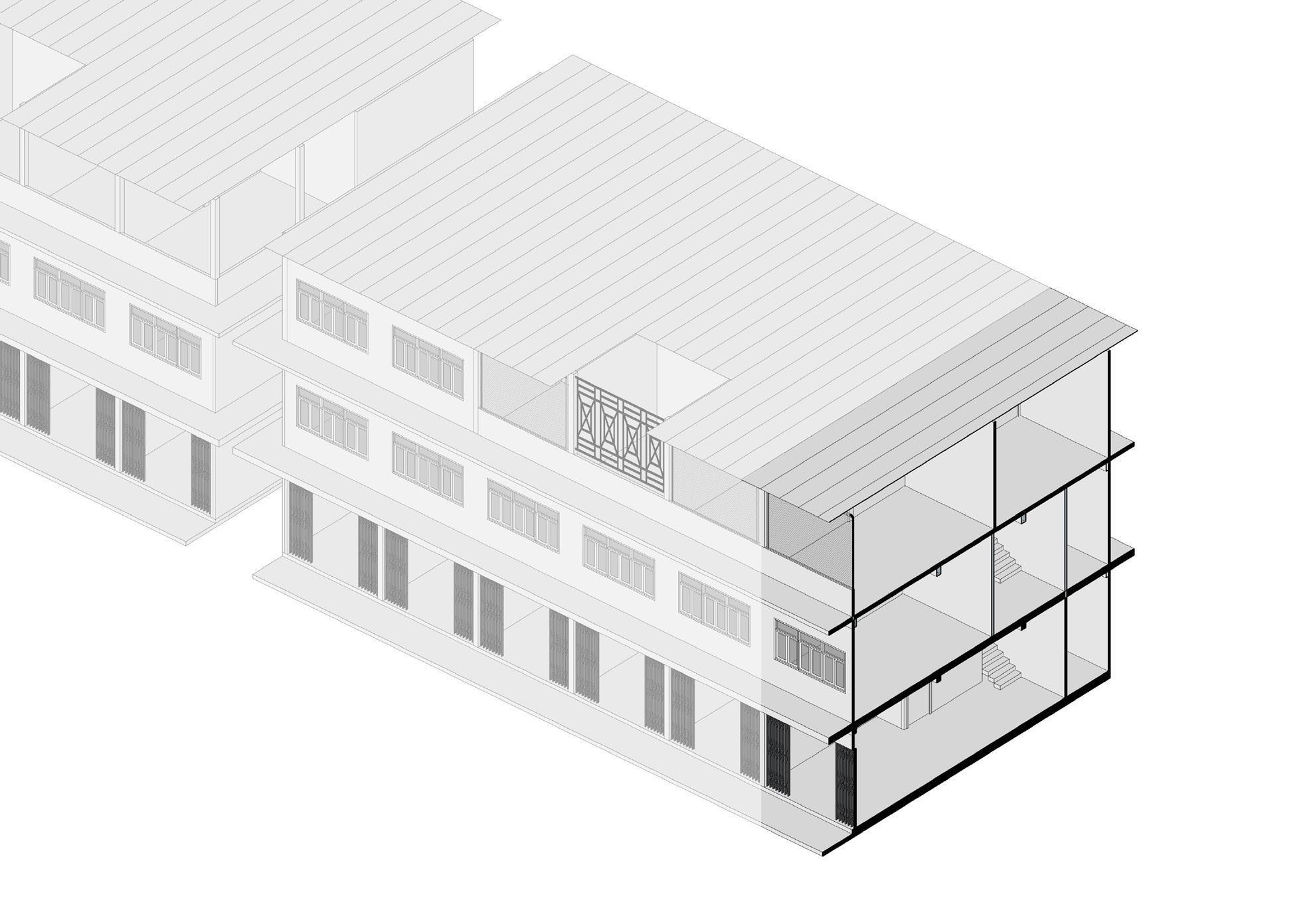

A sectional axonometric showing the interior spatial arrangement of a shophouse.

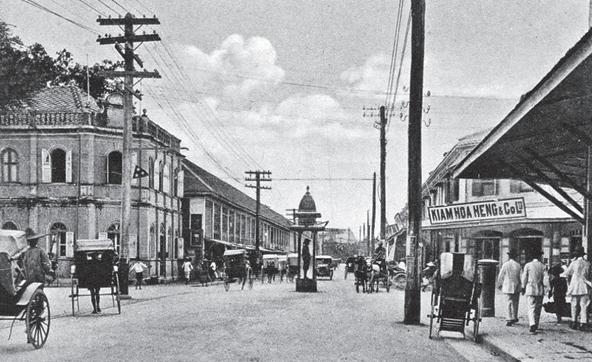

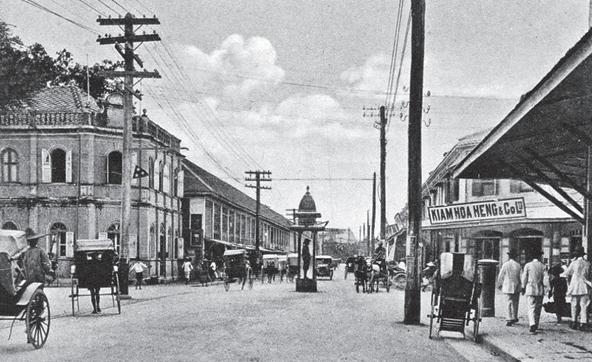

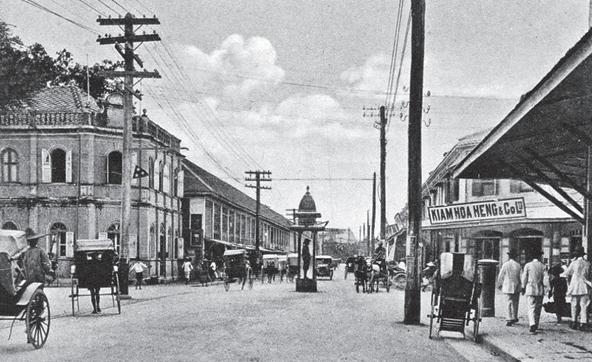

A timeline showing how shophouses emerged in Bangkok

Singapore’s six shophouse façade styles

Mid‑century shophouses distinctive utilitarian character in Ratchaburi

Mid‑century shophouses distinctive utilitarian character in Bangkok

Mid‑century shophouses distinctive utilitarian character in Nakhon Sawan

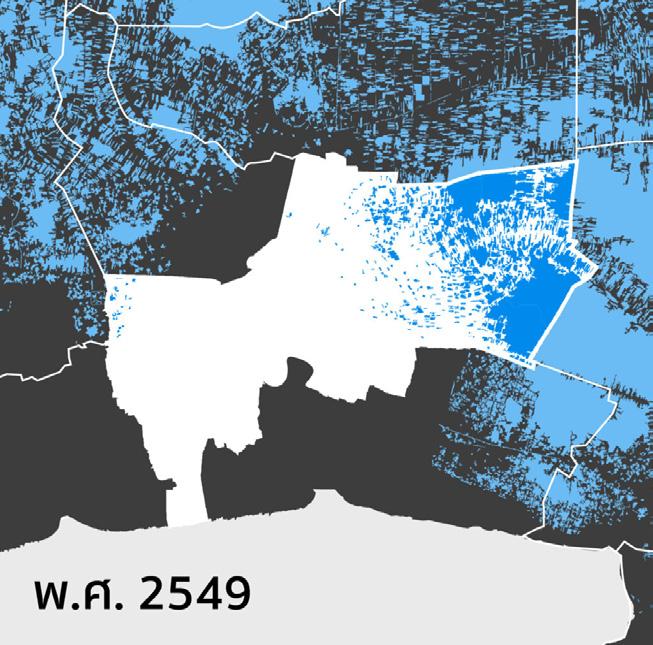

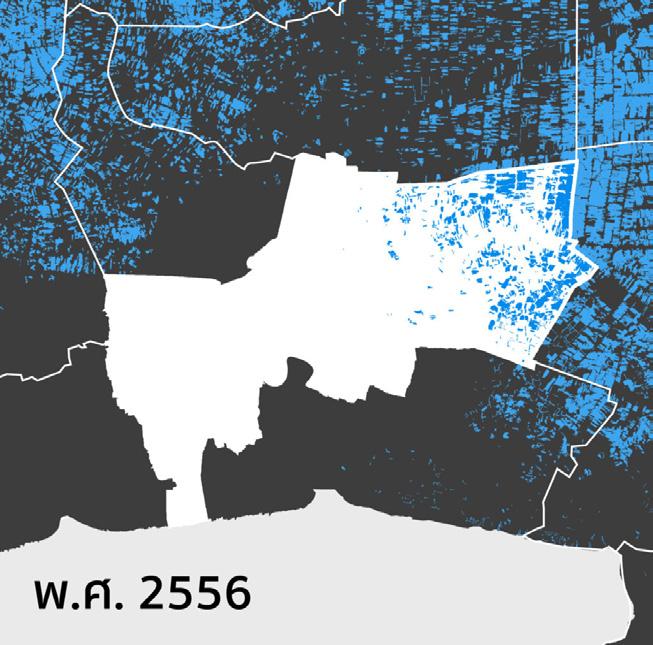

Bangkok’s Flood Map in 2006, 2011, and 2013

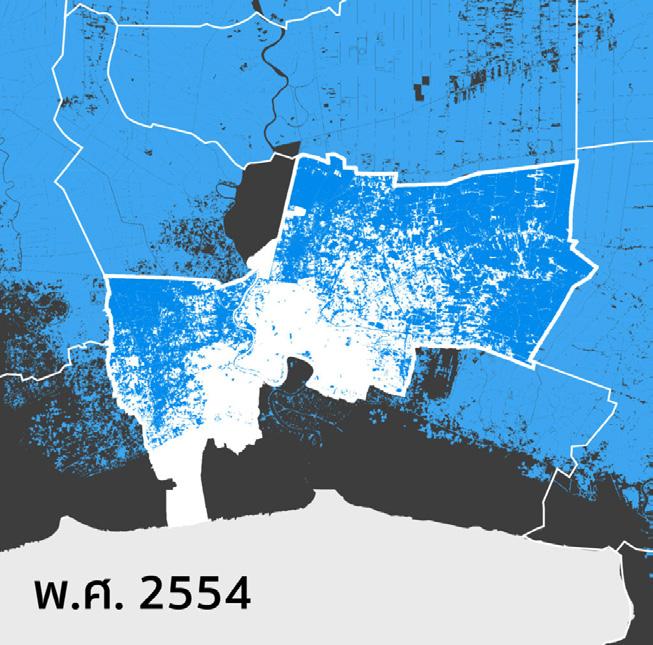

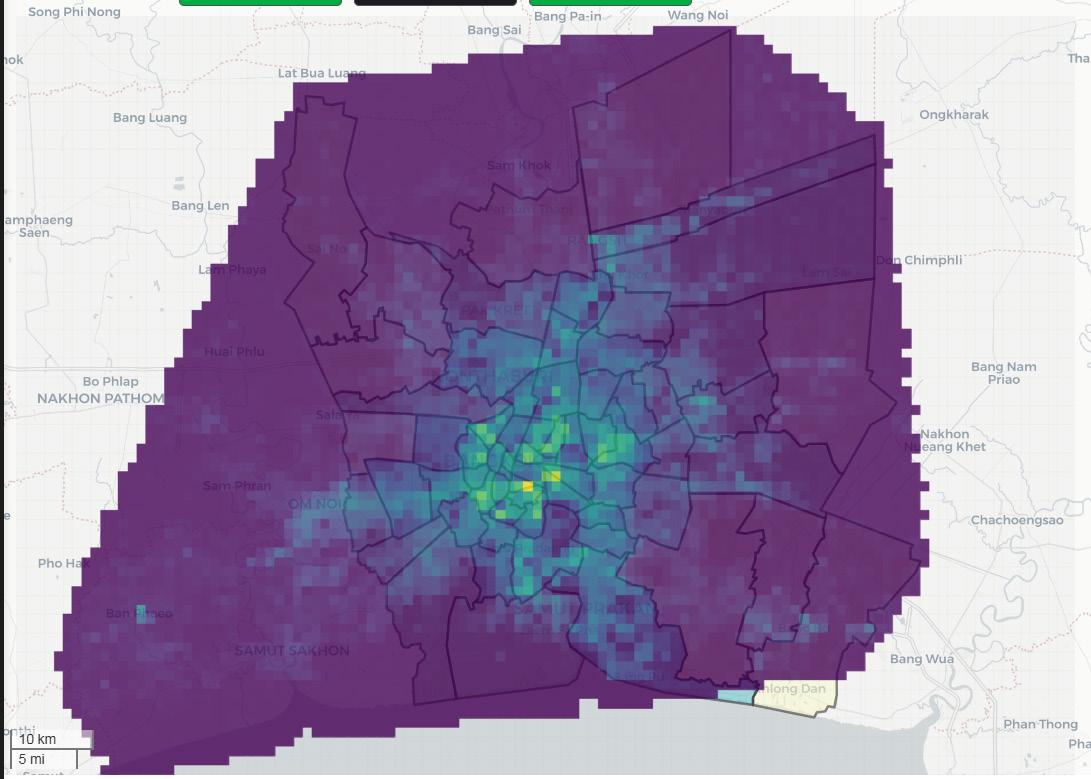

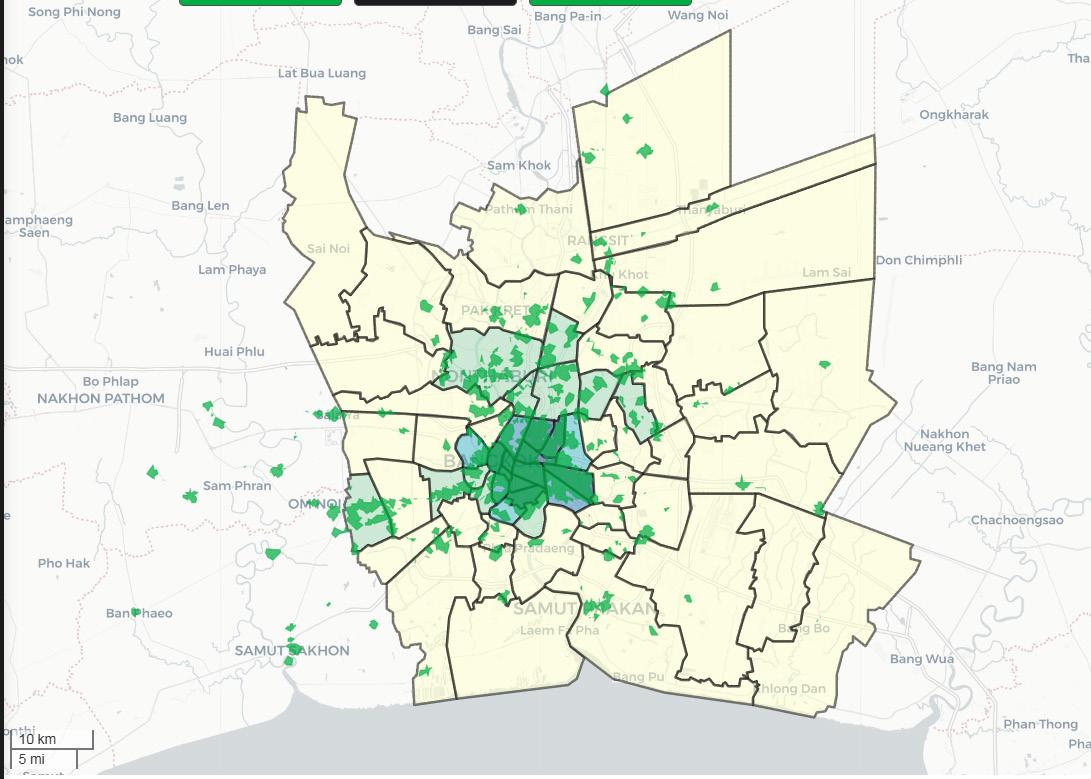

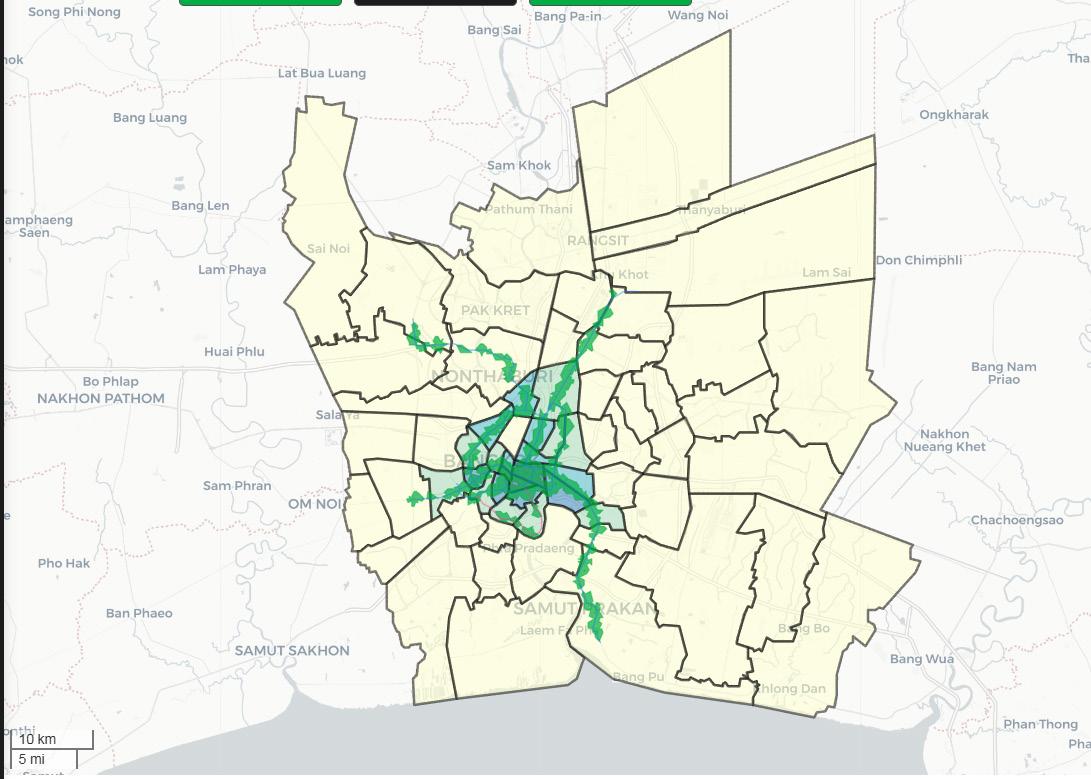

Map showing population density in Bangkok in 2024

Map showing people near services in Bangkok in 2024

Map showing people near rapid transport in Bangkok in 2024

16a

Fig. 16b

Fig. 17

Fig. 18

Fig. 19

Fig. 20

Fig. 21a

Fig. 21b

Fig. 22

Fig. 23

Shophouse renovation elements: internal atrium

Shophouse renovation elements: internal atrium

Shophouse renovation elements: ventilation bricks

Shophouse along Upper Cross Street inSingapore’s Chinatown

Shophouses coexist with high-rise in Singapore

Pilot site aerial map

Development phase of Sam Yan Smart City (2022)

Development phase of Sam Yan Smart City (2037)

Sam Yan area in 2017

A diagram showing how to read the [Off] White Paper

List of Figures

Appendix

Fig. 24

Fig. 25

Fig. 26

Fig. 27

Fig. 28

Fig. 29

Fig. 30

Fig. 31

Fig. 32

Fig. 33

Fig. 34a

Fig. 34b

Fig. 35

Deteriorating condition and pattern of use of Shophouses in Sam Yan area (2025)

Changes in Banthatthong shophouses

Varied uses and adaptability of shophouses

The Pelip Housing in Cape Town

Park Hill Estate in Sheffield

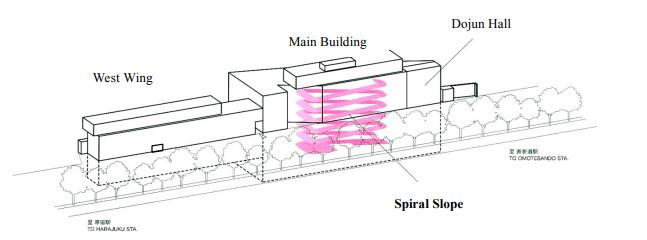

Omotesando Hill axonometric view

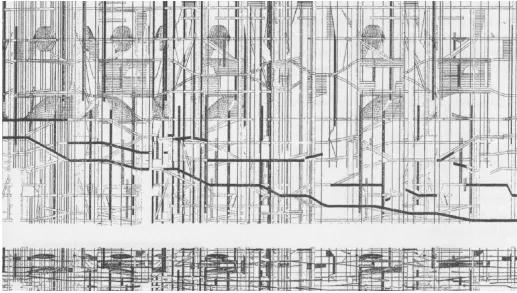

Jussieu Libraries ramp system diagram

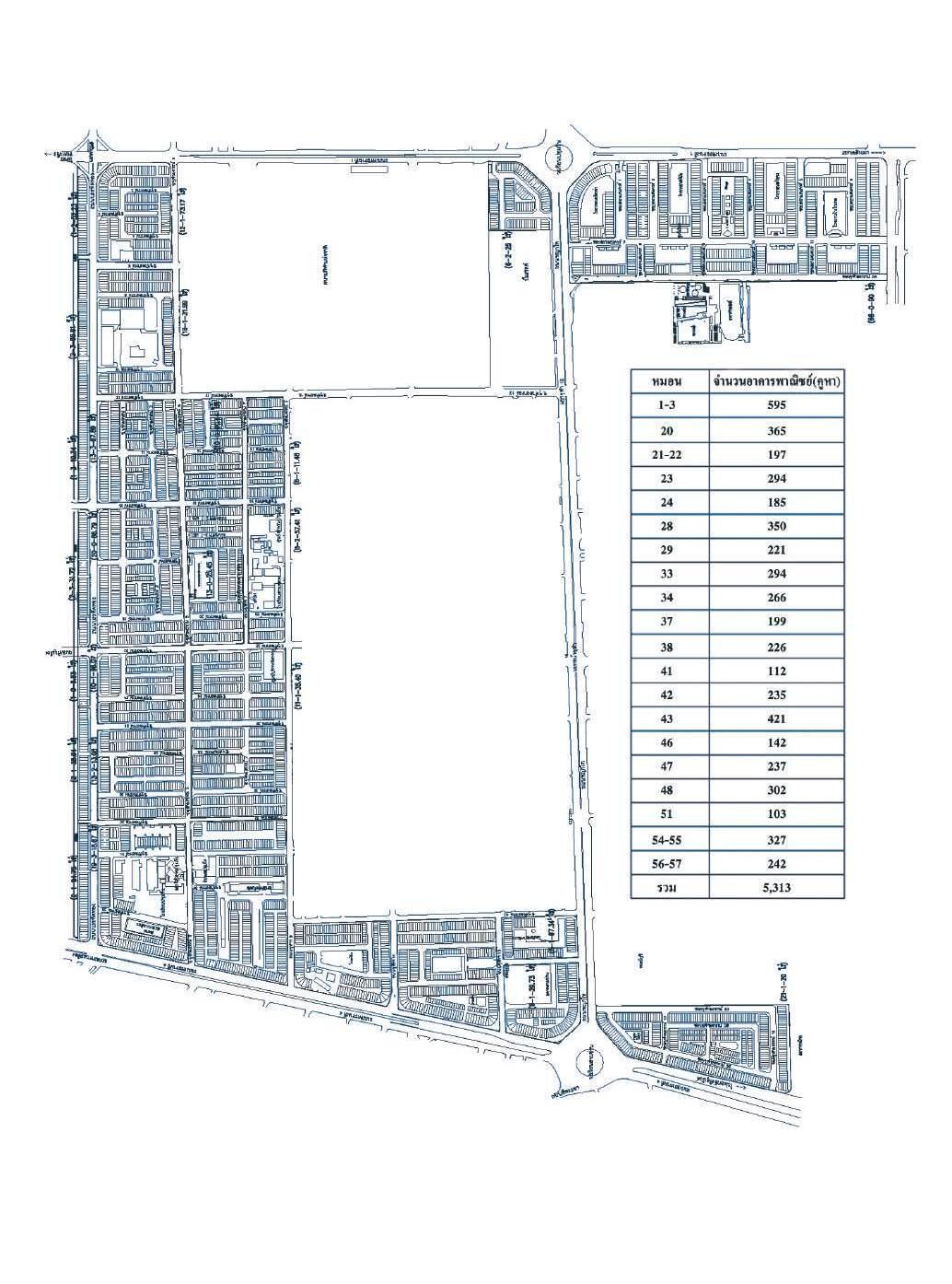

A historic map of commercial zones of Chulalongkorn University, showing 5,313 shophouses in the district

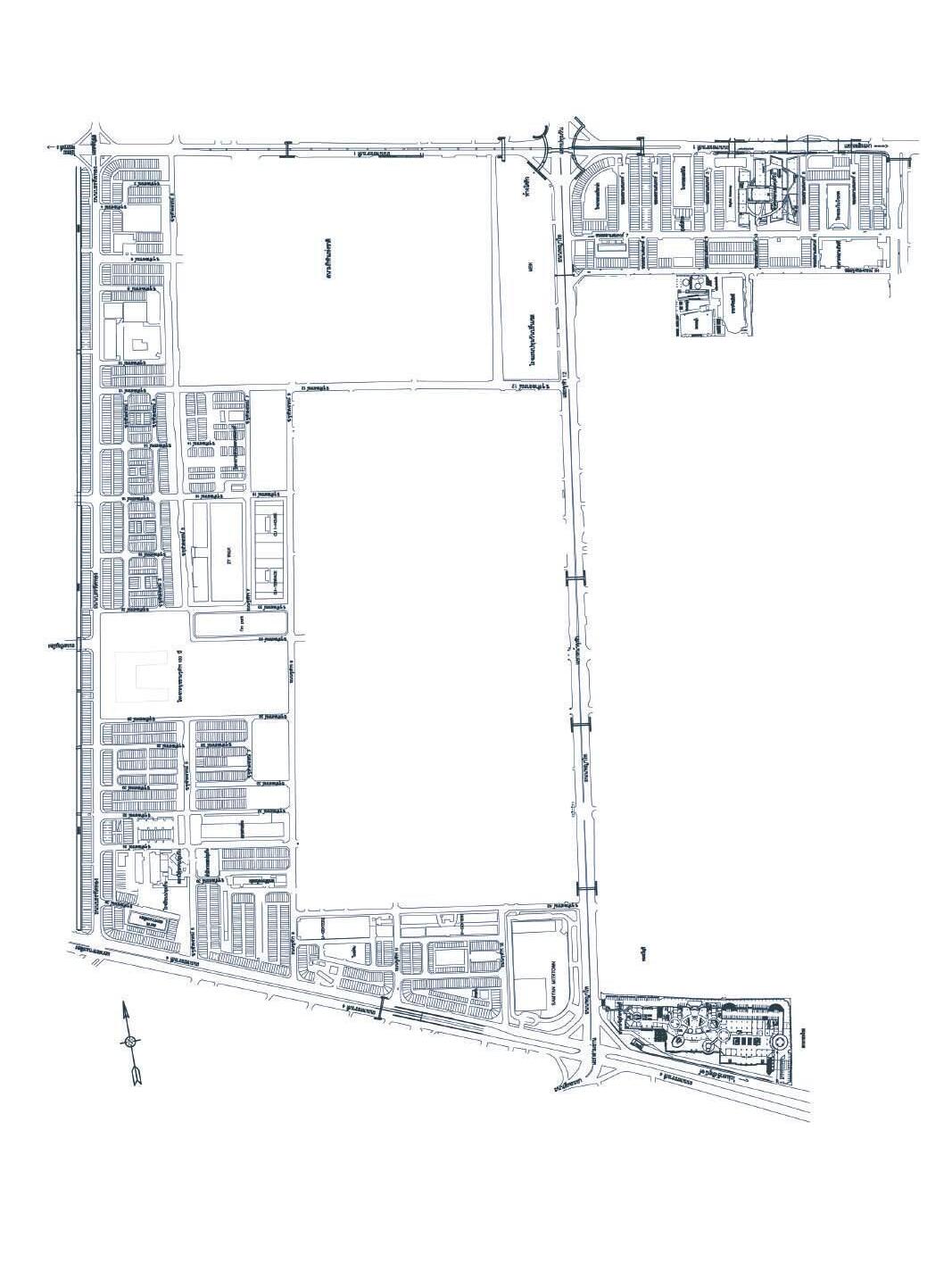

A recent map of commercial zone of Chulalongkorn University (estimate between 2015 2017)

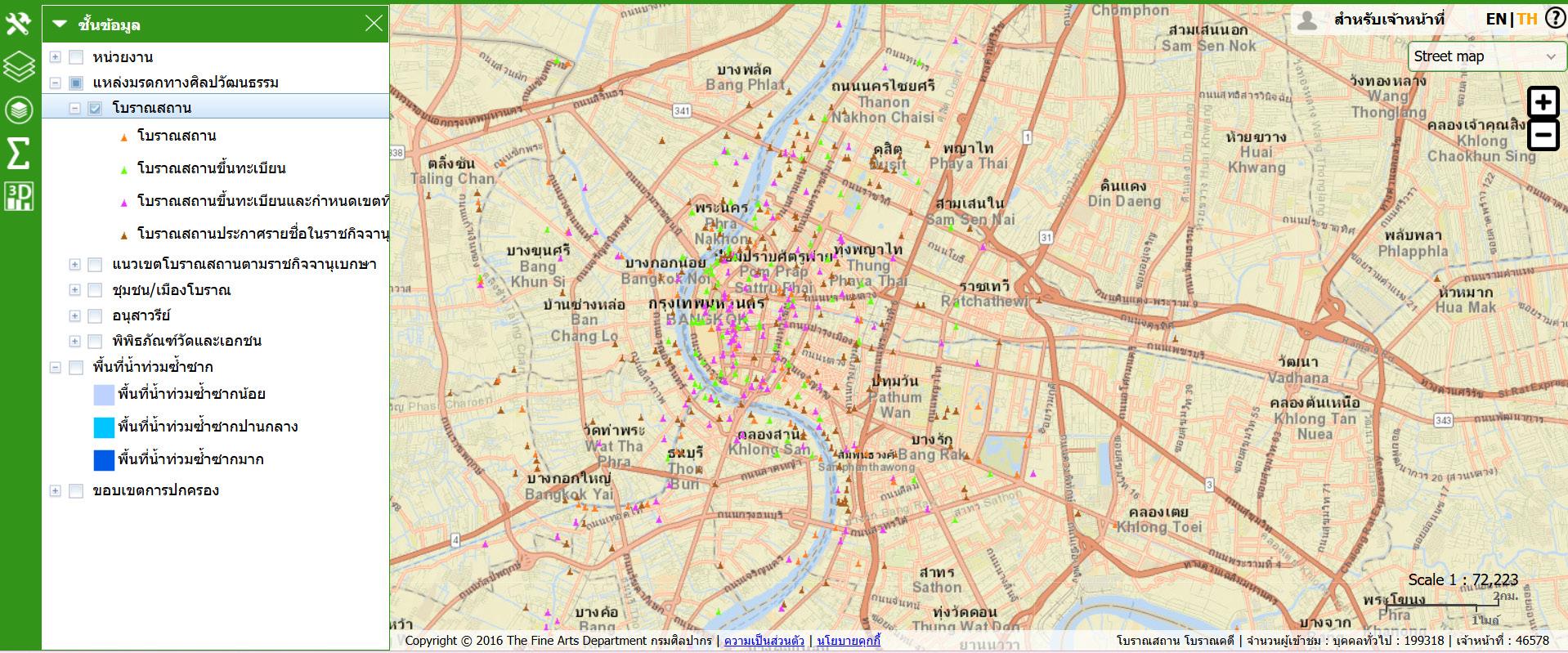

The GIS map indicates archaeological sites in Bangkok

Luen Rit shophouses in a deteriorating condition despited being liste

Luen Rit shophouses in a deteriorating condition despited being liste

Corner shophouse at Song Wat Street in a deteriorating condition despited being liste

Glossary and List of Abbreviations

Association of Siamese Architects under Royal Patronage

Bangkok Metropolitan Administration

Bangkok Mass Transit System (Skytrain)

Crown Property Bureau

Chulalongkorn University

Fine Arts Department

Metropolitan Rapid Transit (Underground)

National Housing Authority

Property Management of Chulalongkorn University

A professional organisation that promotes architecture, cultures, history, arts, and heritage conservation of Thailand and Southeast Asia.

The municipal government responsible for the administration, services and urban planning of Bangkok, oversees local infrastructure, public works, permits and many city-level regulations.

The elevated rapid transit system serving central Bangkok and adjacent districts.

An agency responsible for managing the King of Thailand’s assets

One of Thailand’s leading public universities, located in central Bangkok.

A government department under the Ministry of Culture responsible for managing Thailand’s cultural heritage.

The underground and elevated metro network in Bangkok.

A government agency responsible for planning and providing public housing and affordable housing policy programs across Thailand. Its initiatives impact housing supply, low-income housing projects and related regulations.

The university unit that manages Chulalongkorn University’s real estate assets, campus property developments and related commercial activities.

The national urban planning and land conservation authority of Singapore, responsible for strategic land-use planning and guiding the country’s physical development.

Source: CNA Insider

4 x 4 x 4

Source: Thiti Wannamontha / BKKTribune

Introduction

The concept of combining retail and dwelling into a single building is common in many cities worldwide (Davis, 2012, 1). Similarly, the shophouse emerged in Southeast Asia as a response to urban needs: social, economic, and architectural (Weinberger, 2010). Uniform in appearance and built en masse, with family owned retail on the ground floor and dwelling above, many shophouses in Bangkok have become vacant, poorly maintained, and underutilised (Imam, 2022), with main living condition issues in natural lighting, ventilation, safety, and operations (Li, 2018; Thinnakorn et al., 2025; Boonyachut et al., n.d.). Largely unlisted and politically unplanned, and occupying large areas of prime land near the city centre, they are increasingly threatened with demolition for urban renewal.

On the other hand, Bangkok faces significant housing challenges shown in high housing price-to-income ratio and rising real estate prices (Market Research Thailand, 2022; Rujirapaiboon, 2025). The city’s rapid urban sprawl and disconnected public transportation network, lack of green space and regular flooding, and potential submergence of the city are also pressing issues. In what ways can Bangkok shophouses evolve to meet the demand of the city, responding to climate and urban challenges, live-work needs, and heritage concerns?

The author believes effective answers require collaborations involving multiple stakeholders: government authorities, planners, designers, heritage consultants, private developers, shophouse residents, and community members. To explore the possibilities, the author draws on Peter Swinnen’s architectural ‘policy whispering’ praxis to create an ‘off white paper’, an illustrated variation of the conventional white paper presented as a two-sided concertina booklet, resembling traditional folding manuscripts, a historically shared writing medium across mainland Southeast Asia, addressing to the Property Management of Chulalongkorn University (PMCU).

Banthattong Road, the pilot site, lies within the area of ‘Sam Yan Smart City’, where PMCU is the sole landowner. As the sole unit responsible for managing and developing the university’s extensive real‑estate assets, PMCU is well placed to shape the future of local shophouses and to draw on interdisciplinary university expertise. The author’s familiarity with the area, gained during university study and through firsthand observation of its transformation, informed the analysis.

Research is conducted through a combination of literature review and primary data collection such as interviews and site visit, with the design of strategy approaching the issue serving as another research method. A series of speculative design propositions, visually illustrated, are used to prompt questions and discussion of the new approach the author advocates.

Informed by professional architectural experience and by long-time residence, understanding, and deep care of Bangkok, the author brings an integrated perspective that situates shophouse heritage within the broader urban, social, and organisational context. At this crossroads, the prevailing lack of formal recognition renders shophouses particularly vulnerable; however, this condition also presents opportunities for timely architectural and policy interventions that could steer many Southeast Asian cities toward a more holistic approach.

Methods

This research employs a mixed qualitative method framed by design inquiry: site observation, semi‑structured interviews, document review, complemented by “what‑if” speculative design scenarios as a research tool.

Site Observation

Site observation combined repeated in‑person visits with extensive Google Maps walkthroughs. This provided photographic documentation of existing shophouses (façade, occupancy signs). Observations focused on physical vulnerability (self initiated additions, alterations in response to climate), patterns of use (occupancy, spillout activities)

Interviews

Semi‑structured interviews were conducted with stakeholders including local shop owners, residents, a community architect, a heritage practitioner, and an urban planner. Interview topics covered tenure arrangements, perceived threats/opportunities, attitudes and reactions toward redevelopment and specialist perspectives

Document and policy review

Relevant regulations, policy and archival materials were reviewed to situate a proposed pilot scheme within regulatory and landholding frameworks: Bangkok building and conservation codes, and precedent studies of architecture, heritage conservation initiatives and guardianship scheme. Secondary sources include academic literature, books, historic maps, prior surveys and media reports.

Speculative Design as research

Speculative design propositions were developed from findings. Architectural drawings, and an “off‑white paper” booklet were produced to prompt open-ended discussion dialogue with stakeholders and to offer possible directions for those engaging with the proposals.

Limitations and reflexivity

This study focuses on a single site (Banthattong Road) and draws on a limited number of interviews and site visits. As such, the findings are exploratory and meant to inform the development and adaptation of a similar model for other sites or cities rather than to be directly generalised. The proposed model relies heavily on place‑specific authenticity and local identity and therefore requires contextual adaptation where it is implemented. Its outcomes will also depend on the particular stakeholders involved and on evolving local conditions; the model is therefore inherently site‑specific and contingent on changing participants and circumstances.

The author’s position shaped the research. Prior familiarity with Banthattong as well as the land owner helped with contacts and understanding, but it could also bias what was noticed. Part of the fieldwork was carried out remotely, with a local research assistant collecting photos and conducting interviews. Remote data collection made the study possible, but it can miss everyday details, casual conversations and rhythms that come from long‑term, in‑person observation.

Source: Author (2025)

Context and Problems Background

Shophouses are multiple-unit buildings constructed in rows, typically combining commercial ground floors with residential upper floors (Fusinpaiboon, 2021). They are an enduring and vibrant form of Southeast Asian urban heritage, reflecting everyday modernity and the aspirations of ordinary people across the region (Fusinpaiboon, 2021).

Shophouse Literature: Bangkok History

(Crawfurd, 1828) NA

1850s

Bangkok was a water city relying on rivers and canals as transportation routes

There were amphibian habitats facing water and water markets.

Historical Origin

The shophouses emerged as Bangkok has become terrafirma

Modeled after the shophouses in Singapore to showcase Thailand’s countries,

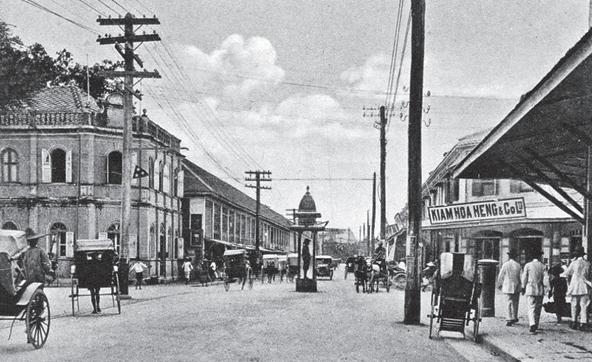

The concept of combining retail and dwelling in a single building dates back over a thousand years, with examples such as the insulae in Rome (Davis, 2012, 1) the stoa in Greece (Chantawarang, 1986). In the East, shophouses originated in China and were introduced to Southeast Asia, including Japan, Korea, Vietnam, Malaysia, and Singapore, through maritime trade and the activities of merchants (Chantawarang, 1986). Under pressure to present the Kingdom of Siam as a modernised nation amidst colonialism power in Southeast Asia, Bangkok transformed from a water city of floating houses and shops, where canals served as the main transportation arteries, into a land-based city. Alongside the construction of roads, the city introduced its first shophouses, inspired by those in Singapore (Thai Historical Commission, 1982; Davis, 2012, 20), which proliferated until their popularity began to decline in the 1980s (Fusinpaiboon, 2021). By the 1960s shophouses made up over half of new construction in Thai cities (Sternstein and Daniell, 1976). These “ubiquitous” shophouses, which follow traffic routes, form a pattern that later contributed to a high level of underutilised land (Askew, 1993).

3-5 ชน นอกจากนยงมการวางแผนผงในรปแบบของกล

: chinatownyaowarach.com

งถนนซงมกถกควบคมเรองท จอดรถยนตเนองจากปญหาการจราจร และตกแถวทรวม

ญหาจากความซบเซาหร อ

ดโดยเฉพาะอยาง

กแถวต อง

งพาณชย

กถ ก นยม

กตอ

อถอนเพ อ

กอสรางอาคารพาณชยหรออาคารอยอาศยซงเปนอาคาร

สงหรออาคารขนาดใหญขนทดแทน

: chinatownyaowarach.com

และเรอนแถว ตามขอมลจากสามะโนประชากร และเคหะของประเทศไทยซงไดเพมขนจาก 1,302,569 ครวเรอน หรอคดเปนรอยละ 10.6 ของครวเรอนทงหมด

ในป พ ศ. 2533 เปน 2,256,145 ครวเรอน หรอคดเปน

รอยละ 11.1 ของครวเรอนทงหมดในป พ ศ. 2553 และ

อาจเหนไดอยางชดเจนถงครวเรอนทอยอาศยในตกแถว

ห องแถว และเร อนแถวในเขตเทศบาลซ งมส วนแบ งถง รอยละ 41.1 และ 78.9 ในป พ ศ. 2533 และป พ ศ 2553 ตามลาดบ ในสวนของกรงเทพมหานคร

กอสรางอาคารพาณชยหรออาคารอยอาศยซงเปนอาคาร สงหรออาคารขนาดใหญขนทดแทน

also buildings designed to attract crowds, such as fresh markets, cinemas, shopping malls, and transportation merged into large department stores, which no longer served as residences for the business operators within those buildings.

2.1. Literature review and observation: typical features, limitations, and problems of shophouses

พ จารณาได จากจ านวนคร วเร อนท อย อาศ ยในต กแถว

stories. Small companies sought space in shophouses to establish their businesses. This led to the emergence of commercial areas with similar types of businesses, collectively known as trade districts or business clusters.

หองแถว และเรอนแถว ตามขอมลจากสามะโนประชากร

และเคหะของประเทศไทยซงไดเพมขนจาก 1,302,569

ครวเรอน หรอคดเปนรอยละ 10.6 ของครวเรอนทงหมด

ในป พ ศ. 2533 เปน 2,256,145 ครวเรอน หรอคดเปน

รอยละ 11.1 ของครวเรอนทงหมดในป พ ศ. 2553 และ

อาจเหนไดอยางชดเจนถงครวเรอนทอยอาศยในตกแถว

to traffic

clusters of shophouses frequently encounter problems of stagnation or closure, particularly for attractions like fresh markets and cinemas. This situation activities and the quality of living in these shophouses. Consequently, many shophouses have been neglected and fallen into disrepair.

that the simple design and construction of most shophouses built during the 1960s and 1970s was aimed at reducing the cost but resulted in a repetitive and noncreative design, unlike those built in the 1980s onwards that started to have a greater level of variety (Tiptus and Bongsadadt, 366; Hinchiranan 1981, 21).

Current Pressure

The typical features, limitations, and problems of shophouses built during the 1960s and 1970s in Bangkok were identified. There were two main parts. Firstly, both the primary and secondary sources showed typical features of shophouses built in this period in terms of their physical and characteristic developments. Secondly, published and unpublished research studies illustrated the typical limitations and problems of shophouses from this period. Visual surveys of existing shophouses in Bangkok confirmed what the literature recorded and were incorporated.

ห องแถว และเร อนแถวในเขตเทศบาลซ งมส วนแบ งถง

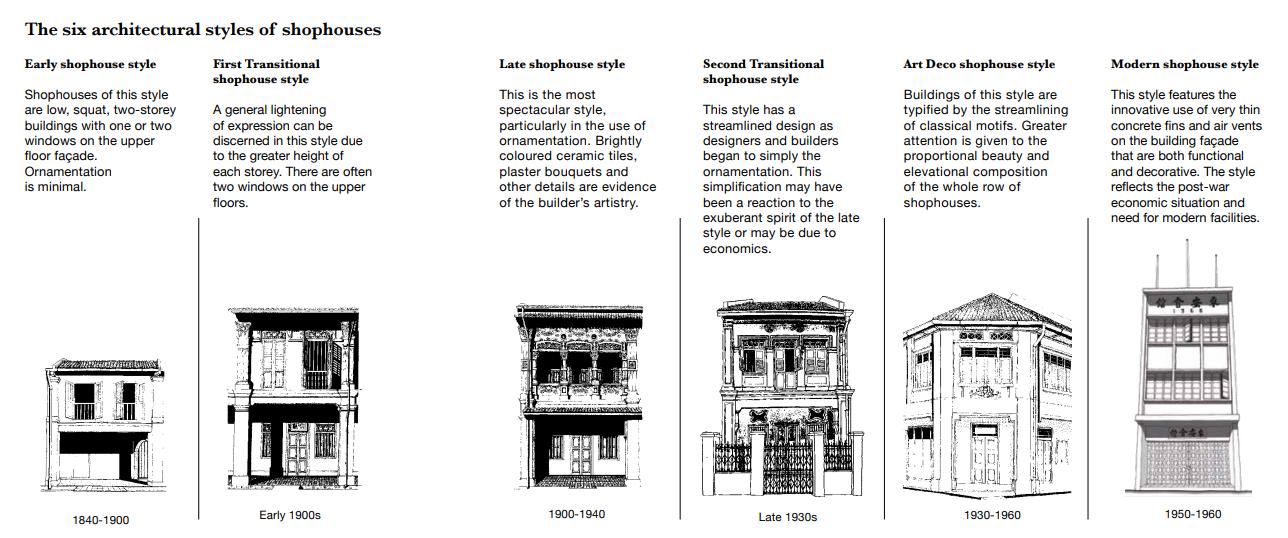

Distinct shophouse characters and generations coexist in Bangkok. In Singapore, the URA (Urban Redevelopment Authority) categorises shophouses into six styles (see Fig. 12). No equivalent official guideline has been identified for Bangkok (author); however, one researcher has informally divided Thai shophouses into three broad eras (Fahim & Mou, 2025): Early style (1862–1896), Transitional stage (1936–1980), and Modern stage (1980–present).

รอยละ 41.1 และ 78.9 ในป พ ศ. 2533 และป พ ศ 2553 ตามลาดบ ในสวนของกรงเทพมหานคร มครวเรอน ท อย อาศ ยในต กแถว ห องแถว และเร อนแถวจ านวน

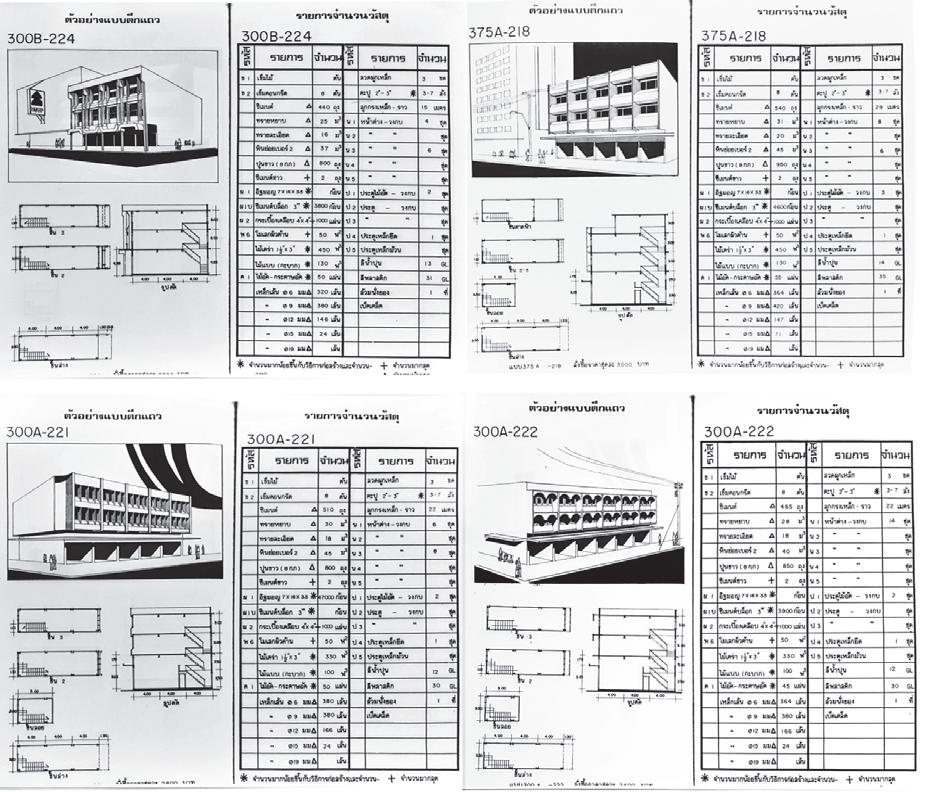

2.1.1. Typical features of shophouses built in Bangkok during the 1960s and 1970s During this period, shophouses in Thailand were mainly built in what could then be called a modern style, usually characterised by compositions of simple forms and spaces. Scholars in the early 1980s observed

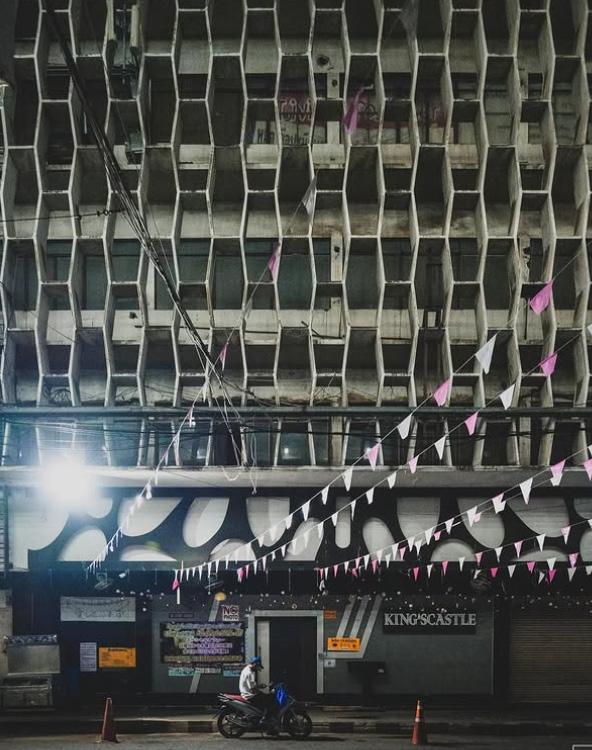

The ornate, older shophouses in inner-city historic town are readily recognised for their architectural value and are more likely to benefit from formal conservation.1, 2 By contrast, the newer, more utilitarian mid-century concrete shophouses, typically about 4 m wide, 12–16 m deep, and 2–5 stories tall (Chantavilasvong, 1978), were often built outside the old town district and now face demolition and displacement pressures from higher‑value redevelopment. This research concentrates on these at‑risk properties (see Fig. 13).

1 Thailand’s heritage conservation has been handled by two main ministerial bodies. The Department of Fine Arts (Ministry of Culture) registers archaeological sites and monuments, while the Department of Public Works and Town & Country Planning (Ministry of Interior) designates conservation areas and regulates land use in historic towns and their surroundings (Prin, 2009). See Appendix 3.

2 The Department of Fine Arts’ Geographic Information System for Cultural Heritage Resources (GIS) indicates a small number of archaeological sites located outside the Rattanakosin Old Town District (Department of Fine Arts, GIS: https://gis.finearts.go.th/ fineart/). See Appendix 3.

A row of shophouses from this period is normally comprised of a repetition of a 3.5–4 m wide unit with a depth of 12–16 m and a height of 2–5 stories (Chantavilasvong 1978). The height of the ground floor is usually about 3.5 m and the other floors are about 3 m. Eaves, of about 1 m long, normally cantilever from the front façade, especially on the ground floor. Shophouses are built with reinforced concrete columns and beams, the floor structure is either reinforced concrete or wood, and the walls are non-loadbearing brick masonry.

Being simple, standardised, and practical in their original plans and construction, many shophouses, however, have attractive sun-shading elements, either cast in concrete or assembled with concrete blocks, on their facades. They increase the level of privacy and shade interior spaces from the tropical sun and rain. Elaborate iron grills are always added for security. All these features are not only pragmatic, but also serve as decorative and symbolic purposes (Suwatcharapinun 2007, 2015), not unlike aggregate wash or mosaic finishes on some of the shophouses’ surfaces. These are elements that add beauty, unique characters, and

A study (Imam, 2022) indicates social changes and urban space usage, the emergence of new shopping areas, shifting concepts of living and housing, the migration of younger generations, parking issues, and management challenges, such as weak regulations regarding vacant buildings, have contributed to numerous abandoned shophouses in Bangkok. These vacant shophouses have become ‘cancer’ (Chula, 1958) for the neighbourhood and surrounding development areas. Data from REIC (2005) show that in 2005 shophouses accounted for only 0.04% of all horizontal-construction building permits in Bangkok, indicating very low demand. With their unlisted status, remaining shophouses lose strong economic incentive and are often demolished to make way for higher-return commercial and high-rise residential projects.

4 x 4 x 4 Living:

Reimagining

Fig. 12

Singapore’s six shophouse façade styles were identified by the Deputy Chief Planner at the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) in around 1989, as a way to explain conservation in terms that the public and policymakers could understand. In doing so, he demonstrated that each style corresponds to a specific historical era and that, collectively, they contribute to the distinctive character of districts as a whole.

Source: URA, 2020

Source:

Bangkok in Focus

Bangkok, a dynamic and densely populated metropolis of 11.4 million people (World Population Review, 2025) faces rapid urbanisation, high population density and chronic traffic congestion driven by limited road space (9% of land versus 20–30% in many Western cities), rising car ownership, and incomplete mass‑transit coverage. Although rapid transit expanded from 59 km (2010) to 108 km (2023), only ~40% of residents have convenient access to public transport (Limsaarnphun, 2018; Asian Transport Observatory, 2024).

Housing provision by National Housing Authority (NHA) is misaligned: government housing is often peripheral and poorly connected (Lerdrat, 2022), while central condominiums target higher-income buyers, leaving low‑ and middle‑income groups with long commutes and reliance on private vehicles. Over half the population faces flood exposure and Furthermore, by the 2030s coupled with extreme rainfall events could inundate 40% of the Thai capital and almost 70% of Bangkok by the 2080s. (World Bank Group, 2013). Public green space in the city is limited, estimated at roughly 1.47–7 m² per person, well under the WHO’s minimum guideline of 9 m² (JLL, n.d.). These factors make central affordable housing urgent; shophouses therefore represent both heritage and remaining affordable stock.

Fig. 15a , 15b, 15c Maps (in sequence) showing population density, people near services, and people near rapid transport.

Source: The Atlas of Sustainable City Transport, The Institute for Transportation and Development Policy (ITDP), 2024

Bangkok area had a total urban population of 18,724,611, and the average density experienced by urban residents was 12.4k people per square kilometer. (ITDP, 2024).

20 % of Bangkok urban residents live within a 1km walk of both healthcare and education services (ITDP, 2024).

(ITDP (2024) explains, People Near Services measures the percentage of an area’s population living within walking distance (1km) of some form of both healthcare and education services. Proximity is the first requirement for walkability. In a city where people live within a 15 minute walk of their daily needs, they will be able to live without a car.)

13% of urban residents of The Bangkok lived within 1km of a rapid transport station (ITDP, 2024).

1% people within 1km of a bus station

Bangkok’s Shophouse

Research on shophouses spans many disciplines; to inform their future we must consider them not only for their historical value but also from architectural, urban‑planning, and social perspectives.

Architecturally, shophouses are characterised by their long and narrow design with shared walls, allowing for openings only at both ends. This layout affects living quality, particularly in terms of light and ventilation. Additionally, their proximity to the street contributes to street noise and pollution. The lack of open space is also a result of shophouses being constructed in full rows to optimise land use. According to the Building Control Act of 1936 and the Building Control Act of 1979, shophouses can be constructed in a row of no more than 10 units, with at least 4 meters of space between rows. However, the self initiated extension of buildings, particularly in the side and rear spaces of shophouses, has worsened the lack of open space (Nopanant et al., n.d.).

To address these issues, renovation architects often create atriums in the center of the house to provide green space and allow natural light in, or they employ elements that facilitate airflow, such as ventilation bricks. However, renovations are not feasible for all owners or occupants.

From an urban perspective, shophouses block the development of land behind them and contribute to the already severe traffic congestion in Bangkok. Shophouses are not legally required to provide parking, which affects their ability to operate commercially and provide quality housing. Unlike most other Southeast Asian cities, where shophouses are accessed via secondary roads (Fahim & Mou, 2025), Bangkok shophouses are built adjacent to main streets. This design leads to congestion as customers often park in front of the shops when making purchases. Additionally, sidewalks are commonly used as informal storage areas for goods from shops and street vendors, which forces pedestrians to walk on the road and exacerbates traffic slowdowns (Nopanant et al., n.d.).

From a social perspective, the poor physical and management conditions of many shophouses have encouraged their conversion into low‑cost rental units (Nopanant et al., n.d.). This shift often accelerates physical deterioration and generates social problems that prompt neighbouring owners to relocate. Short-term leases, commonly used by owners who intend to sell to developers, further discourage both landlords and tenants from investing in maintenance, worsening neglect and instability in these neighbourhoods.

along Upper Cross Street in Singapore’s Chinatown.

Markets

Lessons from Elsewhere

Conservation and gentrification are closely intertwined. International examples show conservation works best when legal protection, public-realm upgrades, tenant‑sensitive measures, and active programming are combined. Singapore’s precinct approach and pedestrianisation, Penang and Malacca’s street‑activation strategies, and Hong Kong’s hybrid façade‑retention plus infill development all offer tactics adaptable to Bangkok, while also warning of commodification and affordability loss if revenue is not recycled to protect local occupants. (Yung, 2014; Nopanant et al., n.d.) Although Singapore’s precincts are well preserved,3, 4 shophouses have become investment assets sought by foreign buyers, the new “quality tenants” replaced the original hybridity of shop and residence (CBRE, 2024; Knightfrank, 2024).

3 Singapore is a recurring reference in this study because the author is familiar with the city, having lived and worked there; shophouse conservation in Singapore happened alongside rapid national urban renewal (URA, 2020); the useful strategies from that context are discussed in the following chapters.

Street in Singapore’s Chinatown. for Bloomberg Markets

4 The Singapore Tourism Board also played a key role in conservation. Preserving historic districts was a strategic part of the 1986 Tourism Master Plan, alongside development of man‑made “tourism products” such as Sentosa, the Botanic Gardens, Fort Canning Park, Jurong Bird Park, and the Night Safari (URA, 2020). Bangkok could learn from this: for the conservation to be effective and sustainable, strategy and implementation had to extend beyond heritage bodies.

11

coexist with high-rises in Singapore.

a

A Chance to Rethink

Opportunities around Bangkok’s shophouses are inseparable from their threats. On the one hand, rapid redevelopment driven by economic incentives, developer interest, and zoning changes threatens to erase the distinctive shophouse economy that McGee (1967, pp. 57–59) identified as central to Southeast Asian urban identity; market‑driven demolition, gentrification, and piecemeal conversion to low‑cost rentals further accelerate physical deterioration, social problems, and displacement.

Thailand’s legal gap compounds the problem: the Ancient Monuments Act covers archaeological sites but not landscapes, or shophouse rowscapes (A. Kittimethaveenan, personal communication, 3 September 2024). Institutional responses have been narrow and uneven. Preservation efforts focus on a handful of inner-Bangkok areas designated as historic city zones (Song Wat, Phraeng Phuthon, Nang Lerng and Tha Tien) and concentrate on façades and fabric rather than broader streetscapes (Nopanant et al., n.d.). The wider stock of shophouses is left without coordinated improvement strategies, and research into scalable urban‑design interventions remains limited.

At the same time, opportunities exist: acknowledging the intrinsic social, economic, and architectural value of shophouses alongside their problems opens space for balanced policy. It is therefore essential to evaluate shophouses carefully. Those with historic or architectural value should be retained, while non‑significant buildings may be considered for replacement, but these decisions must be made by qualified experts. Without expert assessment and transparent processes, the public or private actors may demolish indiscriminately and risk losing valuable urban fabric.

Therefore, to design effective strategies, we must move from broad typologies to the city scale and think of a strategy combining selective conservation and urban-design-led replacement. This approach can protect historical identity and preserve key affordability even as Bangkok adapts to evolving lifestyles and market pressures.

Reframing Conservation

The urgency of city issues affecting shophouses makes preserving every shophouse as a detached, static, pristine heritage object unrealistic. There is a need for forward‑looking strategies that are both relevant and resilience‑oriented, ones that align cultural preservation with contemporary urban needs. After all, is it not the memories, stories and lives they contain that we ultimately wish to preserve in our attempt at building conservation?

Shophouses could be viewed as living systems that combine housing, work and street life in ways that foster economic resilience, social cohesion and public vitality. In this section the author identifies a way forward that leverages shophouses’ key strengths: live‑work hybridity, flexibility, connectivity and street vibrancy. Paired with a pragmatic strategy and policies for supporting micro-businesses and local residents, this approach can sustain shophouse attributes and unlock their tourism value, making conservation financially viable.

Live-work Hybridity

The practice of living above the shop predates industrial urban commuting patterns (Cutting Edge Planning Design, 2005). The daily commuting became the norm only after people had to go to work, and made working at, or close to, homes become privileged and sought after.

The shophouse arrangement offers valuable opportunities for those wishing to run a business from home rather than from separate commercial premises.

According to proprietary data from The Instant Group, demand for flexible workspaces in Thailand is forecast to increase by 43% in 2024 compared to 2023, indicating a strong market need. However, finding suitable premises remains a significant barrier for many small businesses. Working from home can help alleviate these costs by eliminating the need for separate business spaces and reducing commuting expenses.

By combining dwelling and workspace, shophouses cut overheads and commuting time, helping households manage care responsibilities (for example, a parent with a toddler or an owner with a pet can work downstairs while attending to the home upstairs). Their central locations further reduce travel demand and strengthen local economic ecosystems. In these ways the shophouse model supports economic resilience and social sustainability, enabling small-scale entrepreneurship, keeping spending local, and lowering transport‑related costs and emissions (Aranha, 2013).

Most shophouses were built speculatively to generate financial returns, which encouraged simple, economical layouts and straightforward construction methods. Their open plans, rectilinear forms and repetitive bays make them inherently adaptable: interiors can be reconfigured, subdivided or combined with minimal structural intervention, enabling a wide range of functions from residences and workshops to restaurants, offices, salons and studios.

It would be beneficial for housing design to intentionally embed this adaptability so occupants can construct, modify or expand units to meet present and future functional, economic and cultural needs. Equally important is the capacity for personalisation: within the shophouse’s consistent framework, residents have traditionally been able to express individual taste through internal layouts, and modest built details. This combination makes the shophouse a straightforward yet adaptable urban housing model.

Connectivity

The dual role of residents as both business owners and customers in shophouse neighbourhoods creates a distinctive social and economic tie that strengthens local connectivity. Everyday transactions and repeated, face‑to‑face interactions weave residents into reciprocal relationships—shopkeepers know their neighbours’ needs, customers exchange information, and services circulate within walking distance—producing a network of social ties and economic exchanges that conventional separated land‑use patterns rarely achieve.

As McGee (1967) observes, this close human–economic connection was once common in the West before the Industrial Revolution. In Bangkok’s shophouse streets it persists, supporting informal social safety nets, public safety through natural surveillance, and resilient local

Contribution to Street Vibrancy

“The everyday experience of cities is made up of a continuous sequence of moments” (David, 2012, p.9). Bangkok’s shophouses animate those moments: each unit; shop, or home, contributes distinct sights, sounds and activities that together form a rich public life along the street. Jane Jacobs (1961) argued that continual pedestrian flows are essential to a lively street, and Kevin Lynch (1981) identified vitality as a core dimension of urban quality: a vital street meets basic human needs while creating a sense of safety through activity and watchful presence.

The aesthetic and social value of shophouse streets can be understood through Francis Hutcheson’s idea of “uniformity amidst variety” (1753): beauty arises where order and diversity are held in balance. Shophouse blocks exemplify this principle — a coherent building rhythm and consistent street edge provide visual unity, while the countless small variations in signage, display, uses and daily routines supply variety and interest. As Aratha (2013); by contrast, mass housing often sacrifices local identity through monotonous repetition. In short, the combination of consistent form and diverse uses makes shophouse streets inherently vibrant, resilient, and pleasurable places for everyday urban life.

Viewed as living systems, shophouses become assets for inclusive urbanism rather than relics to be frozen. Policies and design practices that emphasise hybridity, adaptability, connectivity and street vitality can sustain their material fabric and the social lives they enable. With targeted support for micro‑businesses and housing‑sensitive regulation, conservation can be both culturally meaningful and economically viable.

Prototype: The New Shophouse

Overview

Aiming for conservation approaches that protect social value as well as physical fabric, the author proposes adaptation and adaptive reuse to unlisted shophouses with historic or architectural value, while non‑significant buildings may be considered for replacement. Without heritage expert assessment and transparent processes, however, the public or private actors may demolish indiscriminately and risk losing valuable urban fabric.

A new shophouse typology, the “Smart Shophouse” presented in the [Off] White Paper, is proposed as a prototype for shophouse replacement. This model retains the existing intangible characteristics of demolished shophouses while optimising land‑value economics, supporting revitalisation, and increasing housing density. Revenues generated by the model (from leases, and real estate investment) would circulate back into site management, conservation and adaptation of other historic shophouses.

The Smart Shophouse model operates under a city‑wide collective, The Shophouse Guardian, that manages and cares for at-risk shophouse properties across Bangkok, and facilitates collaboration and coordination between public and private partners.

Objectives

While trying to remain practical within current land‑value conditions come with shophouse, this design test aims to:

1) Sustaining respective area’s local assets, particularly small‑scale commerce and street vibrancy.

2) Protecting shophouse attributes; flexibility and connectivity between residents; and

3) Initiating a broader historic shophouse network across the city.

5 Adopting a citywide perspective enables conservation without foregoing development. For example, Singapore was able to retain much of Chinatown’s historic shophouses because intensive development was accommodated elsewhere, most notably through land reclamation at Marina Bay (URA, 2020).

Target user groups:

1) Existing long‑term small businesses

2) New and diverse residents; students, office workers, artists, and other creative professionals seeking central, affordable accommodation

3) Visitors and day‑time users whose spending supports local businesses and activates public spaces

Programming Operational Model

_Rehousing and mixed uses: Rehouse existing shophouse households into a new shophouse typology whose units are adaptable for shops, residential use, and shared public amenities (for example, a library, communal laundry, and multi-purpose community space). Flexible unit layouts will enable changing uses over time and support micro‑enterprises.

_Climate resilience and landscape: Introduce multifunctional green infrastructure on the former shophouse footprints that double as retention basins during storms. This could provide leisure space, improve microclimate, increase permeability, and reduce flood risk.

_Revenue diversification: In addition to rental income from residential and commercial units, provide spaces for venue hire, commercial rental, and short‑term creative residencies. These activities can generate higher revenues while supporting local affordability when programmed to prioritise community access and subsidised rates for local users.

The model proposed situates the ‘smart shophouse’ within a city‑wide collective that manages and cares for heritage and non-heritage shophouse properties across Bangkok.5 Drawing on examples6 such as M8 Real Estate and Figment, the collectives would treat historic shophouses as investable assets to generate revenue. By activating underused buildings for income‑generating uses; long‑term leases, short‑term tenancies and venue hire, the collective can create a revolving fund. That fund would finance conservation assessments, ongoing maintenance, and restoration of shophouses heritage.

In the UK, property guardianship is an arrangement where individuals, called property guardians, live in vacant residential or commercial buildings at a reduced cost in exchange for providing security and maintenance for the property. A property guardianship company acts as a middleman between the property owner and the guardian, managing the arrangement and granting the guardian a license to occupy the property.

Inspired by Bow’s Art Guardianship scheme, a leasing program with volunteer opportunities could be introduced in the proposal. This initiative could attract individuals from creative backgrounds, provide affordable housing alternatives, and foster activities and movement around shophouses.

5 Adopting a citywide perspective enables conservation without foregoing development. For example, Singapore was able to retain much of Chinatown’s historic shophouses because intensive development was accommodated elsewhere, most notably through land reclamation at Marina Bay (URA, 2020).

6 There are many real‑estate firms specialise in Singapore shophouses. Examples include R8 Real Estate and Figment, which rents shophouses as boutique homes, and agencies such as Shophouse Collective and theSGshophouse, that advise investors on purchases. Major consultancies such as Knightfrank and CBRE have also published studies and market notes specifically on shophouses. While shophouses offer strong potential, government support, through conservation policies, incentives such as buying and leasing schemes, has helped enhance their attractiveness and market value.

Train Station

Testing Ground: Sam Yan Area

Why Sam Yan

Sam Yan areas a timely and appropriate pilot site7 for a shophouse guardianship scheme. The area is currently subject to a master plan that aims to transform it into a “Sam Yan Smart City” with predominantly commercial and residential intensification (UddC, 2017). That redevelopment has raised persistent concerns about impacts on long-term residents, small businesses, and historic buildings; debates over displacement and gentrification continue as communities and heritage sites are relocated.

CHaoPhraya River

Historically a mixed residential-commercial quarter, Sam Yan has evolved into a high‑intensity urban node where older low-rise fabric, student life, mid-century shophouses and new high‑rise development coexist. Chulalongkorn University is a dominant landowner.

Transport and connectivity

The area benefits from excellent connectivity. Sam Yan MRT station (Blue Line) provides rapid links to central business districts and transit corridors; major roads (Rama IV, Henri Dunant and Rama I nearby) give vehicular access, though they also generate congestion.

Demographics and socio-economics

Sam Yan’s population mix is diverse: low‑ to middle‑income households, students, and office and short-term workers. Small shopkeepers and service providers predominate at street level, while an increasing number of knowledge-economy and hospitality jobs appear in newer developments (ddproperty, 2019).

7 A pilot allows testing ideas, demonstrating feasibility, and building support before wider rollout. For example, to persuade skeptical decision‑makers during Singapore’s urgent period of housing, infrastructure, and urban renewal, the URA restored a single “crummy‑looking” shophouse on Neil Road as a four‑month pilot project to show its potential. (URA, 2020)

Cultural life and public realm

The area’s street life is animated by market trade, food stalls, student activity, and small cultural venues. Shophouse streets deliver a dense, mixed‑use environment that supports everyday interactions and local economies (Aranha, 2013). Public spaces are limited in size and quality; Sam Yan has few generous parks.

Climate

Bangkok has a tropical monsoon climate, characterised by hot, humid conditions year-round with three main seasons: a hot season, a rainy season with heavy convective downpours and frequent flooding, and a cooler, somewhat drier season. High humidity, intense solar radiation, and occasional tropical storms influence urban comfort, infrastructure and building design in the city.

4 x 4 x 4 Living:

Fig. 21a

Sam Yan Smart City: Development phase of Suanluang Sam Yan & National Stadium (2022) indi cates mostly low rise buildings in the area (grey plots).

Source: Sam Yan Smart City (n.d.). https://www. samyansmartcity.com/en/about.

Fig. 21.2

Sam Yan Smart City: Development phase of Suanluang Sam Yan & National Stadium (2037) showing complete replacing of low rise buildings, mostly shophouses, except along Banthatthong Road.

Source: Sam Yan Smart City (n.d.). https://www. samyansmartcity.com/en/about.

Fit for Prototype

Strategic pressure point: The ongoing “Sam Yan Smart City” initiative makes the neighbourhood an ideal site to test redevelopment alternatives.

Diverse stakeholders: Presence of the university, students, long-standing shop owners, and new developers enables iterative testing of governance and stewardship models that must work across interests. The sole landowner (PMCU) is a well‑resourced and well-connected actor whose people and institutional relationships are pivotal to realising the proposal.

Urban challenges to address: The site exhibits issues central to the proposal, housing affordability near the CBD, recurrent flooding, environmental degradation, and contested redevelopment, that the model is targeted to mitigate.

Heritage and everyday value: Sam Yan retains vernacular shophouse fabric and street life whose social and economic value can be demonstrated and measured through a pilot.

The [Off] White Paper

To convince Property Management of Chulalongkorn University (PMCU), an administrative department responsible for managing and developing the university’s extensive real estate assets of the selected site, the author draws on Peter Swinnen’s architectural ‘policy whispering’ praxis to create an ‘off white paper’, an illustrated variation of the conventional white paper to offer observations and recommendations for a potential approach to dealing with shophouses on the pilot site.

In contrast to conventional white papers that usually follow a problem solution structure, the [Off] White Paper uses a two-sided, linear reading format. Readers can engage with the material from either direction. A useful exercise would be to have local residents and decision-makers read opposite sides at the same time to reveal differing perspectives and spark a conversation. Additionally, the format draws inspiration from traditional folding manuscripts, a historically shared writing medium across mainland Southeast Asia, creating a link between the medium and the subject (shophouses).

On one side of the [Off] White Paper, discuss the current “Sam Yan Smart City” masterplan, which largely replaces shophouses with mixed-use development. It highlights gaps in the plan, and suggests possible actions to address them. The other side offers an alternative strategy that treats shophouses as an asset: it poses “what‑if” scenarios to provoke conversation about feasible futures for the area as built in this research and prompts consideration of ongoing challenges such as recurrent flooding, climate risks, and residents’ quality of life.

The [Off] White Paper is intended to demonstrate that the issues raised are complex and cross‑sectoral; progress will require collaboration among multiple stakeholders. Collaboration between differences is essential for making progress. To amplify impact across Bangkok, the author proposes an organisational model: a public–private partnership collective to coordinate and oversee shophouses in Bangkok (See Appendix 1). For wider application beyond the test site, four government bodies are identified as central to the proposal: Bangkok Metropolitan Administration (BMA), the local government that manages the city, the National Housing Agency, a state enterprise under the Ministry of Social Development and Human Security, the Fine Arts Department, a government agency under the Ministry of Culture responsible for managing the country’s cultural heritage, and Tourism Authority of Thailand (TAT).

A

how

Source: author (2025)

From Prototype to Policy

The action could begin by establishing a collective and conducting rapid surveys while putting immediate protections in place for at‑risk shophouses and tenants. Use the survey findings to create an open database and co‑design pilot projects with the community. At the same time, run public engagement activities, test business feasibility, and carry out policy planning to prepare for implementation and scaling. Below are action steps divided into three phases: Immediate, Long-term, and Ongoing.

Immediate

Form ‘Shophouse Guardian’ Collective

Establish a core project and advisory panel, and establish a shophouse collective8 to steward the process (local tenants and shop owners, landowners, BMA/ heritage officers, heritage professional, academics).

Public Engagement

Launch outreach to tenants and shop owners to raise awareness of disappearing shophouses. Set up a clear reporting channel so tenants can notify the Shophouse Guardian about planned demolitions or threats. Invite and provide a registration for tenants/micro businesses who wish to be considered for rehousing.

Value Assessment and Policy Review

Commission heritage led condition and value assessments, including both physical fabric and intangible community. Put in place immediate tenant safeguards.

Long-Term Foundation

Create ‘Shophouse Inventory’: a shared open-sourced shophouse database9 with layered data: flood risk, ownership/tenure, land value, building condition and character-defining elements (CDE), environmental risk, etc.

Convene co-design workshops with affected communities and stakeholders to develop pilot prototype.

Feasibility Study and Business Analysis: business-plan work and economic study for the pilot prototype.

Policy and Interventions: rehousing mechanisms, rent support, and regulatory measures to enable the prototype and protect livelihoods.

Concurrent and Ongoing tasks

Create ‘Shophouse Alliance’: a network across citites and disciplines, to strengthen the recognition of shophouses, advocacy and knowledge sharing.

Ongoing public programs: exhibitions, artist residencies, business case competitions, and student–microbusiness partnerships, design competition.

Bangkok needs these careful first steps that build long term resilience to heritage while responding to the city’s urban pressures. It is hoped that the ideas in this research can be developed into a formal guidebook to inform other cities facing similar challenges, potentially across Southeast Asia.

This strategy will evolve as more viewpoints are included, so adaptation is expected. After all, discussion is the first crucial step.

8 See Appendix 1 for the collective operational model 9 Case study: ‘Colouring Britain’ is a research led, free public resource offering open spatial data on Britain’s buildings and natural environment. It is a collaborative open‑knowledge initiative created for and by academia, communities, government, industry and the third sector. All data extracts and code are freely available under open licenses. Contributions to the platform are welcome; new data and features are added regularly. Accessed from: https://colouringbritain.org/

Conclusion

Through this research, the author aims to understand and evaluate the tension between preserving heritage and the necessity for the city to grow and evolve. The focus extends beyond the physical and characteristics of the built heritage to the essence of shophouses; the hybridity of living and working, the flexibility, the distinctive community ties between businesses and residents, and the contribution to the street vibrancy. These seemingly intangible aspects are often overlooked by policymakers and developers, yet they hold great social and economic value.

A lack of recognition and formal protection for many shophouses, combined with pressures from rapid urbanisation and development, risks the irreversible loss of both built fabric and the communities that animate it. Given the intense urban issue, traditional conservation approaches would be unrealistic. For this reason, the research proposes a pragmatic, selective strategy: replace some deteriorated shophouses with a new type of “shophouse” that preserves and amplifies key attributes: live work hybridity, flexibility, connectivity and contribution to street vibrancy, while addressing affordability, climate resilience, and social cohesion.

As the issue spans across heritage, urban planning, environmental and social resilience, an open, multi‑stakeholder dialogue is essential: landlords and owners, tenants, academics, private sectors and government agencies and local authorities including the Bangkok Metropolitan Authority (BMA), Department of City Planning, National Housing Authority (NHA), the Fine Arts Department, and Department of Public Works and Town & Country Planning (DPT), Tourism Authority of Thailand (TAT).

The study concludes by proposing the formation of a collective to steward and manage unlisted shophouses, with actionable steps including heritageled value assessment, creating a network for advocacy, developing a data mapping, and targeted policy proposals. Implemented in partnership with public and private sectors, the pilot prototype is intended to evolve into a practical guide that other cities facing similar challenges can adapt.

Reference

Aranha, J. (2013). The Southeast Asian Shophouse as a Moel for Sustainable Urban Environments. International Journal of Design & Nature and Ecodynamics, 8, 325 335.

Asian Transport Observatory. (2024). Bangkok transport sector profile. https://asiantransportobservatory.org/ documents/245/Bangkok_transport_sector_profile.pdf

Askew, M. (1993). The making of modern Bangkok: State, market and people in the shaping of the Thai metropolis. Background report for the 1993 Year-End Conference:Who gets what and how? Challenges for the future, December 10-11, Ambassador City Jomtien, Chon Buri, Thailand. Victoria University of Technology.

Askew, M. (2002). Bangkok: Place, Practice and Representation (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi. org/10.4324/9780203005019

Boonyachut, S., & Tirapas, C. (n.d.). Shophouse: Quality of Living and Improvement. King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi.

CBRE. (2024). CBRE viewpoint: Singapore conservation shophouse market.

Chotiphatphaisal, N., & Thanakitkoses, S. (2024, May 23). Sam Yan shows need to save history. Bangkok Post. https://www.bangkokpost.com/opinion/ opinion/2797814/sam yan shows need to save history

Cunha Borges, J., & Marat Mendes, T. (2019). Walking on streets-in-the-sky: structures for democratic cities Journal of Aesthetics & Culture, 11(1). https://doi. org/10.1080/20004214.2019.1596520

Cutting Edge Planning Design. (2005). Does live/work? Problems and issues concerning live/work development in London. London Borough of Hammersmith & Fulham.

Davis, H. (2012). Living Over the Store: Architecture and Local Urban Life. Routledge. ddproperty. (2019, March 15). A deep look at Sam Yan DDproperty.

Fahim, M. R., & Mou, I. Z. H. (2025). A comparative analysis of traditional shophouse and its subsequent diffusion in Southeast Asia. International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science, 8(12), 3015 3030. https://doi.org/10.47772/ IJRISS.2024.8120250

Fusinpaiboon, C. (2021). Strategies for the renovation of old shophouses, built during the 1960s and 1970s in Bangkok (Thailand), for mass adoption and application. Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering, 21(5), 1697–1718. https://doi.org/10.108 0/13467581.2021.1942880

Hutcheson, F. (1753). An enquiry into the original of our ideas of beauty and virtue (5th ed.). London: A. Millar.

Imam, N. (2022). Vacant shophouses in Bangkok: Root causes and policy implications. Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Faculty of Architecture, Chulalongkorn University.

ITDP. (2024). The Atlas of Sustainable City Transport. https://itdp.org/publication/the atlas ofsustainable city transport/

Jacobs, J.M. (1962). The Death and Life of Great American Cities.

Jauslin, D. (2023). Two libraries at Jussieu, Paris. Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/97538835/ Two_Libraries_at_Jussieu_Paris

Jhearmaneechotechai, Prin. (2009). Conservation measures for ancient towns in Thailand.

Kapp, P. H., & Armstrong, P. J. (2024). Reimagining live-work in postindustrial cities: how combining living and working is transforming urban living. Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/175 49175.2024.2337153

Knight Frank Singapore. (2024). Singapore shophouse market update H1 2024: Shophouse — Modernising shophouses, gentrifying neighbourhoods. Knight Frank.

Lerdrat, V. (2022, March 31). Secure rental housing for everyone: Solutions to urban housing problems. The 101 World.

Li, S. (2018). Ecological design of lighting and ventilation in traditional shophouses in urban Southeast Asia (Doctoral thesis, Cardiff University). Welsh School of Architecture.

Limsaarnphun, N. (2018, August 17). Bangkok traffic nightmare. The Nation. https://www.nationthailand. com/in focus/30352400

Litchfield, W., Whiting, M., Panero Associates, & Thailand. Krom Phænthī Thahān. (1958). BangkokThonburi city planning project. Royal Thai Survey Dept. Retrieved August 28, 2025, from http://nla.gov.au/nla. obj 2936850524

Lynch, K. (1981). A theory of good city form. MIT Press.

Market Research Thailand. (2022, September 26). Affordable housing in Thailand:What is holding it back? Retrieved April 30, 2025.

McGee, T. G. (1967). The Southeast Asian city: A social geography of the primate cities of Southeast Asia. London: G. Bell & Son. Retrieved from https://archive.org/ details/southeastasianci0000mcge/mode/2up

Reference

Mori Building Co., Ltd. (n.d.). Omotesando Hills: Concept and history. Retrieved from https://www.mori. co.jp/en/projects/omotesandohills/background.html

Mumford, E. (2017). Golden Lane: Alison and Peter Smithson. In Companion to the History of Architecture, H.F. Mallgrave (Ed.). https://doi. org/10.1002/9781118887226.wbcha140

Pensri Chantavaranang. (1986). Shophouses : the transition of mixed-use building in Bangkok metropolis [Master’s Thesis in Architecture, Chulalongkorn University]. Chulalongkorn University Intellectual Repository. https://doi.org/10.58837/CHULA. THE.1986.689

Rahman Fahim, Mashudur & Mou, Ishrat. (2025). A Comparative Analysis of Traditional Shophouse and its Subsequent Diffusion in Southeast Asia. International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science. VIII. 3015 3030. 10.47772/IJRISS.2024.8120250.

Real Estate Information Center. Accommodation statistics in Bangkok in 2005 [Report page]. Real Estate Information Center.

Rujirapaiboon, T. (2025, March 17). Can public housing bridge Bangkok’s affordability gap? JLL. Retrieved April 30, 2025

World Economic Forum (2019). The Global Risks Report 2019, 14th Edition.

The Urban Idiot. (2018, January 17). Streets in the sky. The Academy of Urbanism.

Thinnakorn, W., Srimuang, K., Kaewtawee, R., Pinich, S., Mohd Razif, F., & Garcia, R. (2025). A novel approach to analyse indoor daylight quality in heritage shophouses: a case study in Nakhon Si Thammarat, Thailand. Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/13467581. 2025.2546396

Tang, X., & Turingan, G. (2024). Faith and rights in the smart city: Preserving the significance of the Chao Mae Tuptim shrine amidst gentrification of the Sam Yan neighborhood of Bangkok. Thai Journal of East Asian Studies, 28(2), 51–73. retrieved from https://so02.tci thaijo.org/index.php/easttu/article/view/272119

United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN‑Habitat). (2016). World cities report 2016: Urbanisation and development: Emerging futures. UN-Habitat. https://unhabitat.org

Urban Redevelopment Authority. (2020). 30 years of conservation in Singapore since 1989: 30 personal reflections and stories

Weinberger, N. (2010). The shophouse as a tool for equitable urban development: The case of Phnom Penh, Cambodia (Master’s thesis). University of Pennsylvania.

World Bank Group. (2013, June 19). Warmer world will keep millions of people trapped in poverty, says new report. World Bank.

Yung, E. H. K., Langston, C., & Chan, E. H. W. (2014). Adaptive reuse of traditional Chinese shophouses in government led urban renewal projects in Hong Kong. [Article].

Bibliography

Regulations and Conservation Laws

Building Control Act B.E. 2522. Ministerial Regulation No. 55 (B.E. 2543)

The Ancient Monuments, Antiquities, and National Museums Act B.E. 2504. Amended and supplemented by the Ancient Monuments, Antiquities, and National Museums Act (No. 2) B.E. 2535

Housing, Renting, Leasing and Home Buying and Guardianship Scheme

Singapore. Housing and Development Board. (2001/2). Annual report (pp. 6, 10). Singapore: Housing and Development Board. Call no: RCLOS: RSING 711.4095957 SIN [AR]; Lim, L. (2002, May 19). HDB scraps queue system for its flats. The Straits Times, p.1,; Chua, C. (2001, March 22). Get ready for the where when what flats. Today, p. 1. Retrieved from NewspaperSG.

Ministry of National Development. (2025). New flat classification framework: Standard, Plus, Prime. Retrieved from https://www.mnd.gov.sg/our work/housing a nation/bto classification

London Housing Zones Brochure (October 2015). Greater London Authority. Retrieved from https:// www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/housing_zones_ brochure_october_2015-2.pdf.

UK Government. (2022). Property guardians: guidance. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/ publications/property guardians fact sheet/property guardians-a-fact-sheet-for-current-and-potentialproperty-guardians

RentCafe. (n.d.). Live work play developments: A snapshot of the rental market. Retrieved August 27, 2025, from https://www.rentcafe.com/blog/rental market/market snapshots/live work play developments/

MOORE, Russell and GOODCHILD, Barry (2022). Gentrification and inequality in Bangkok: Housing pathways, consumerism and the vulnerability of the urban poor.

Sojourn: journal of social issues in Southeast Asia, 37 (2), 230 261. [Article]

White paper and Policy related

Royal Institute of British Architects. (2023, January 11). RIBA education white paper. RIBA.

Perkins Eastman. (2025, May 1). Someplace Like Home: Unlocking the science of hominess in open-plan, free-address environments. Perkins Eastman. https://www. perkinseastman.com/white papers/someplace like home/

Giraldo, A., Fusco, A., & Perkins Eastman Design Research. (2022, May 12). Adaptive reuse and senior living: Can existing buildings provide an integrated, authentic, and vibrant lifestyle for older adults? Perkins Eastman. https://www.perkinseastman.com/white papers/adaptive reuse and senior living/

Swinnen, P. (2023). 66 years later: A policy whispering praxis — Fall semester 2023 (KUL / Campus Sint-Lucas Brussels) [Course brochure/white paper].

Archfondas(2017, Oct 30). Peter Swinnen The Architects as Policy Whisperer [Video]. (2018). Vimeo. https://vimeo.com/240575054?share=copy

Shophouse

Esther H.K. Yung, Craig Langston, Edwin H.W. Chan, Adaptive reuse of traditional Chinese shophouses in government-led urban renewal projects in Hong Kong, Cities,Volume 39, 2014, Pages 87 98, ISSN 0264 2751, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2014.02.012.

Kuo Yi Mei Centennial. (2024, December). Origins and transformations: A landmark Dachaocheng trading house

Ruehl, M. (2025, August 31). Singapore’s shophouses — hotter than Fifth Avenue? Financial Times. https:// www.ft.com/content/e1a53cb8 5bf0 408a 91a0 bcdd738c0f11

Trial Site: Sam Yan, Pathumwan District and Bangkok

Digital Economy Promotion Agency (DEPA). (2024). Samyan Smart City: Proposal for a smart city development plan.

Urban Design and Development Center. (2017). Intelligent Chula City (Smart City For Everyone). Retrieved August 29, 2025, from https://en.uddc.net/ ud project06

Thanavanichkul N., Rungcharoenkij, K., & Lattanan, P. (2024). Public perceptions and expectations of smart city development: A case study of Rama 4 Smart City and Sam Yan Smart City. Journal of Liberal Arts, Thammasat University, 24(3), 459–488. Retrieved from https:// so03.tci thaijo.org/index.php/liberalarts/article/ view/279293

Patsawut. P. (2024). Development of a smart city: The case study of Sam Yan Smart City (Master’s thesis, Chulalongkorn University). Chulalongkorn University Theses and Dissertations (Chula ETD), 11460. https:// digital.car.chula.ac.th/chulaetd/11460

Heritage and Conservation Initiatives

ICCROM. (2025). Baan Luang Rajamaitri Historic Inn. Cultural Heritage for Inclusive Growth in Southeast Asia.

ICCROM. (2025). Luenrit community conservation and rehabilitation project. Cultural Heritage for Inclusive Growth in Southeast Asia.

Interview Records

Shophouse Resident (F)

Can you describe your daily routine and your relationship with your shophouse?

_ I’m a tenant — renting from Chulalongkorn University. I’ve rented here for 40 years. I sell goods and walk around — normal trading. A grocery-style shop and I also do deliveries.

_ This building has three floors. The ground floor is for business, the upper floors are residential.

_ Before COVID things were okay, but after COVID it has steadily declined and hasn’t improved. It depends on each profession — some got better, some worse. It changes with the times. It’s different from our generation when we sat and chatted together. Students’ behavior has changed a lot too. They go to tech places, pubs. Very different.

_ For meals, I buy food outside — made-toorder dishes, noodles, things like that. Mostly go out to get what I want.

What do you enjoy most about living/working in a shophouse, and how does it differ from living/working in other types of homes?

_ The safety is good. And the transport connections — you can go many places by different routes — buses, vans — there are options.

How do you feel about the community and neighborhood around your shophouse?

_ I know them to some extent, but I don’t talk much. We know each other but only small talk about trade or general topics — not personal issues, to avoid problems. Small talk and business — “How are things? Are sales okay?” — that’s the usual conversation.

_ People’s lifestyles have changed. eating and living habits change. People order in; I order too. People don’t go out wandering and sitting at shops like before.

What challenges do you face living in a shophouse, particularly regarding space, privacy, business, noise, light, heat, ventilation, safety?

_Being in a shophouse, privacy isn’t much. Sometimes there’s noise when people repair things — banging. I live a nocturnal life because I deliver until late and sleep late; those who live daytime sometimes do repairs and it gets loud. But I understand — this is how it is living here. It’s not like a detached house.

How do you feel about the demolition of the shophouses in your area? What impact do you think the demolition will have on the community and local culture?

_ Not exactly here yet, but every time they renew the lease they raise the price. They renew every two years and when renewal comes they raise the rent more and more. If it rises a lot we can’t afford it, we have to leave. It’s sad — we’ve been here 40 years. I lived here with my child — my child was born here, delivered at Huachiew hospital — I worked here while pregnant and gave birth here. We’ve been here a long time and are attached. I like the safety; coming home late I don’t have to be afraid. I’m familiar with the place and people. I know who comes and goes. The architecture students is like an anchor here.

_ I think maybe it should be our right to stay, I want to stay, but the rent is unbearable because we have to pay everything ourselves — rent, taxes, property tax — we pay those; it’s included in monthly expenses. Now it’s over 30,000 baht. It used to be 8–9,000 back then; now it’s over 30,000. Imagine how many houses you could build with that money. If it were money for building houses, it would be many houses. It’s just too much. I can’t keep up. I think next year I’ll probably leave because it’s gotten quiet — people have moved away.

Do you have any thoughts on what should replace the shophouses, or how the area could be developed in a way that respects its history?

_Listen — as an older person I prefer the old style. It’s okay if buildings are newer, but I’d like them to remain commercial like before. In the past it worked very well — many people, many shops, Chiang Kong (the old community before expropriation).Back then it was very crowded; all the Chinese food shops were delicious. Now… Only Isan food remains. The old, really tasty shops are gone. In the past, the streets were full and people closed the road to sell — it was lively and fitting of the Sam Yan name. But now look what’s left. Just new restaurants, mostly Isan food — many of them. Go look at Suan Luang area — so many som tam shops.

_ If they redeveloped here and allowed previous tenants to rent again, whether I would be interested depends on the price. If it’s like that — no, I wouldn’t want it if they take everything. If they do it and there’s nothing left for us, it drains us. The economy matters; even if you rebuild, people’s lifestyles have changed.

Can you describe your daily routine and your relationship with your shophouse?

_ It’s an old-style hair salon because the owner is old and doesn’t do much work now.

_ There’s one floor above as a bedroom. I sleep here. If you want three floors you have to add them yourself. Chulalongkorn only allows two floors.

_ I wake up and do business. If a customer comes for hair I do their hair. I have to do many things because the rent is very high.

_During meal time, I buy nearby. If I have ingredients at home I cook. Mostly my husband buys bagged food from Suan Luang (Suan Luang Square) because it’s cheaper. This area is expensive — understand that high land costs mean higher prices.

_ In the past there were no malls and this spot did well in the evenings — a meeting point to pick up kids and eat, because it’s near a chool. My child graduated that too. My child is almost 30 and is attached to the school.

_ I do hair and sell lottery tickets and other items. During COVID we weren’t too badly hurt because we sold other items; shops that only did hair had to close. So we must do many things, not just one. My husband works outside; in the morning we help each other. Sometimes we sell bananas from the village — regular customers know we come from the village, so being long-term helps. But rent is so high we can’t save. Fortunately my child graduated; timing was lucky.

What do you enjoy most about living/working in a shophouse, and how does it differ from living/working in other types of homes?

_ Everything is fine. It’s clean, you don’t have to be afraid of theft, it’s clean and orderly. I like it a lot. Transportation is convenient so my child never thought of living in a dorm because it’s easy to commute. It’s

How do you feel about the community and neighborhood around your shophouse?

_ Neighbors are fine. I know most neighbours, but most of them are new — the old ones have left because they couldn’t afford it. Rent is high. New places change hands often. Long-standing shops survive because they have regular customers. For example, that made to order food stall in front survives because of longtime customers; new shops don’t last long. If you don’t have deep pockets you can’t stay.

What challenges do you face living in a shophouse, particularly regarding space, privacy, business, noise, light, heat, ventilation, safety?

_None at all. The weather is natural — no problem. I’m used to it.

How do you feel about the demolition of the shophouses in your area? What impact do you think the demolition will have on the community and local culture?

_ The rumor has been around for about 10 years and keeps coming up. We’re anxious every time the lease is renewed. Chulalongkorn renews short two‑year contracts, so we don’t expect much — every renewal we worry about how much the rent will increase. Shocked, because we’re attached here and it’s our livelihood.

_ Everyone is upset, but if they’re serious [PMCU] they’ll take it because it’s their land. I hope something of the old character will remain — preserve identity and uniqueness. Many people say the shophouses should be conserved.

_ There are a lot of young people coming and some small businesses behind. Everyone here is anxious about when they’ll be evicted.

_ The shrine (San Thapthim) is very sacred — people dare not touch it. Some say they’ll [PMCU] keep it and build around it.

Do you have any thoughts on what should replace the shophouses, or how the area could be developed in a way that respects its history?

_ The area has already been improved — look at the sidewalk; it used to be much more sunken and they fixed it. If they only refresh the building appearance it might be enough. But if improvement increases rent, nobody will want it.

_If they redevelop the area, it will be more expensive. Would customers be the same? No — things have changed, it won’t be the same. We couldn’t stay even if they invited us because our business can’t operate in a fancy place; our local character sells local community goods. Where would we get money to pay 40,000 baht rent? Ask people around there.

_ They should at least finish condos first and see if they survive. Then we can have more customers.

Can you describe your daily routine and your relationship with your shophouse?

_ I’ve rented the space for about 18 years. Not the least is two years each time.

_ It’s my workplace. I use the upstairs sometimes. Upstairs is the home, it’s the room. I stay there sometimes.

What do you enjoy most about living/working in a shophouse, and how does it differ from living/working in other types of homes?

_ Not having to travel far

How do you feel about the community and neighborhood around your shophouse?

_ I know the neighbours. I use their services mostly food shops.

What challenges do you face living in a shophouse, particularly regarding space, privacy, business, noise, light, heat, ventilation, safety?

_ The air has some issues in certain parts. No noise disturbance.

How do you feel about the demolition of the shophouses in your area? What impact do you think the demolition will have on the community and local culture?

_ We’re worried. We don’t know how long they will let us stay. If they tell us to move, we’ll have to move.

Do you have any thoughts on what should replace the shophouses, or how the area could be developed in a way that respects its history?

_Just improve them—develop the roads and the area, the electrical system. Make it better and brighter.

Interview Records

A Heritage Practitioner

Arpichart Kittimethaveenan is a registered architect, independent researcher and current PhD candidate based in Bangkok. He has professional experience as an architectural conservation specialist and as a lecturer in architecture, and holds an M.Sc. in Conservation of Monuments and Sites from Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Belgium (2021). Arpichart is active in international heritage networks, including ICOMOS EPWG, CIPA Heritage Documentation Emerging Professionals and Future for Religious Heritage.

Conservation Practice in Thailand