Oral History Memoir

Conducted by Randy Gaddo and David Piet

September 9, 2002

Collection — Peachtree City: Plans, Politics, and People, “New Town” Beginnings and How the “New Town” Grew

Project — Peachtree City Oral History

Peachtree City Library

Copyright 2024

201 Willowbend Road

Peachtree City, GA 30269

Phone: 770-631-2520

library@peachtree-city.org ptclibrary.org

This material is protected by US Copyright. Permission to print, reproduce or distribute copyrighted material is subject to the terms and conditions of fair use as prescribed in US copyright law. Transmission or reproduction of protected items beyond that allowed by fair use requires the written and explicit permission of the copyright owners.

Scholarly use of the recording(s) and transcript(s) of the interview(s) with Joel H. Cowan is unrestricted.

If you have questions about whether your intended use qualifies as fair use, please contact us at library@peachtree-city.org. Also, please let us know if you are using our interviews in scholarly work, as we like to keep track of this data and promote the use of our collection.

The recordings and transcripts of the interview were processed at Peachtree City Library, Peachtree City, Georgia.

Interviewers: Randy Gaddo and David Piet

Transcriber: Sharon Ayers

Editor: Molly Stinson

Final Editor: Jill Prouty

The Peachtree City Oral History Project at Peachtree City Library includes interviews with city founders and their families, elected officials, and other community leaders.

The Joel Cowan History Room at Peachtree City Library follows the transcription style guide developed by Baylor University Institute for Oral History as well as The Chicago Manual of Style

Joel Cowan History Room at Peachtree City Library

Interview Abstract

Interviewee: Joel H. Cowan

Interviewers: Randy Gaddo and David Piet

Collection:

Peachtree City: Plans, Politics, and People, “New Town” Beginnings and How the “New Town” Grew

Project: Peachtree City Oral History

Interview #: 1

Interview date: September 9, 2002

Interview location: Peachtree City, Georgia

Recording medium; duration: Cassette tapes, digitized; 1.39 hr.

Abstract

Joel H. Cowan was born and raised in Cartersville, Georgia. As a student at Georgia Tech, he began his career in real estate development and investment under the tutelage of Peter Knox Jr. In 1958, he graduated from Georgia Tech with a degree in industrial management. He is credited with founding the City of Peachtree City in 1959, serving as its first mayor from 1959-1963. He also served as CEO and Chairman of the Board for two of Peachtree City's early development and investment companies, Peachtree Corporation of Georgia and Garden Cities Corporation. He is also credited with developing the first upscale shopping center in the South—Phipps Plaza.

Cassette 1A (p. 1):

Introduction, genesis of oral history program |00:02:10|; Cowan’s files, need for broader effort to fill in gaps |00:05:34|; discussion of file contents, newspaper clippings, timeline |00:09:13|; creating CD to be shared, process for adding to timeline |00:11:57|; how Peachtree City got its name, Byrd & Associates |00:13:34|; ties to Atlanta, wording on legislative bill |00:16:01|; Pete Knox [Peter Jr.], “new towns” |00:20:25|; Denny purchases land in Fayette County |00:23:06|; Denny sells property to Knox, description of other Knox developments in Atlanta area |00:24:51|; background on land districts and lots, intrastate stock issue |00:26:25|.

Cassette 1B (p. 17):

Creation of Fayette County Development Corporation, breakfast conversation with Pete Knox [Peter III], first meeting with Pete’s father |00:02:01|; visit to Knox home in Thomson, overseeing property in Fayette County |00:04:25|; inexact property lines, job offer from Knox upon graduation |00:06:23|; decision to create a city, board meetings at Shorty’s |00:07:59|; lack of funding to secure land |00:09:12|; property owners selected for first Council, moving to

Peachtree City |00:11:38|; marriage, builds house on Shakerag Hill |00:13:22|; gas station and store owned by T.C. “Cleo” Collier |00:14:54|; commute to Atlanta before and after Interstate 85 |00:18:13|; interest in property from James F. Riley Jr. |00:20:56 |; Riley agrees to visit area |00:22:03|; writes letter with option to purchase, plans Riley’s visit |00:23:46|; Riley’s visit |00:25:32|; relationship with Riley, Bessemer purchases 12,000 acres, Peachtree Corporation of Georgia formed |00:28:26| debt paid to farmers, visits Atlanta banks |00:30:32|.

Cassette 2A (p. 33):

C&S Bank deposit, experience working with father in Cartersville |00:01:11|; industry focus, Clayton McLendon of C&S |00:02:35|; building relationships as first mayor |00:03:54|; attractiveness of lake community |00:05:04|; protecting road frontage |00:06:56|; land around Golfview Drive, Dr. McDaniel |00:08:07|; purchases land with Griffin Bell as attorney |00:09:45|; early plans for lake north of Highway 54 |00:11:07|; uses dynamite to clear beaver dams |00:12:20|; finding new location for dam |00:13:40|; sole authority on decisions |00:14:53|; lack of downtown city center |00:16:05|; question of density |00:18:26|; attitudes about density |00:19:54|; creation of Flat Creek Country Club |00:22:12|; building Lake Peachtree, flood of ’61 |00:23:48|; spillway design |00:25:33|; structure fails, dam moves downstream |00:27:22|; discovers design flaw |00:29:45| designs replacement concrete structure |00:30:41|.

Cassette 2B (p. 51):

Builds new concrete spillway with help from Chip Conner |00:02:07|.

Name clarification: Notes have been added to the transcript where needed to differentiate between Pete Knox Jr. [Peter Jr.] and his son, Pete Knox III [Peter III]. Where the name “Knox” or “Mr. Knox” appears without notation, the speaker is referring to Peter Jr.

Joel H. Cowan

Oral History Memoir

Interview Number 1

Conducted by Randy Gaddo and David Piet September 9, 2002

Joel Cowan History Room, Peachtree City Library Peachtree City, Georgia

Project Peachtree City: Plans, Politics, and People, “New Town” Beginnings and How the “New Town” Grew

GADDO: This is the first interview in a series of interviews by the Peachtree City Historical Society as part of the oral history program. This interview is being conducted on nine September 2002 by Dave Piet and Randy Gaddo. The interview is being conducted in the Joel Cowan Room in the Peachtree City Library and the interview is with Joel Cowan, who is senior, Joel Cowan Sr. who is one of the original founders of Peachtree City.

(Librarian Jill Prouty checks microphone)

GADDO: Alright, we’re hot. I’m Randy Gaddo. I’m the director of leisure services for the City: that’s parks, recreation, library services. Retired marine, retired army, so

COWAN: Oh, a rivalry, eh?

GADDO: (all laugh) No, no, no. We um actually, the reason we are doing this oral history program is because of that pair of boots back there and the gear that are sitting back there. M.T.

[M.T. Allen, library manager] and I were sitting there one day, and I saw those, and I asked her about them, and she said the boots are the boots that were worn in the Chief McIntosh play at the amphitheater and the gear was an original gear off the Flat Creek Mill.

COWAN: You mean Tinsley Mill?

GADDO: Yeah. So that got us started and then the folks who were in the room started telling stories about Peachtree City and I said, “We’ve got to get this down.” So that is kind of the genesis of the oral history program. So this is the first interview of that series of what is to be a continuing series interviewing many, many people who had a part in bringing Peachtree City to what it is today.

1A |00:02:10|

PIET: And I’m David Piet and I’ve been here since ’86, Joel, and I retired from the army back right after Desert Storm in ’92, ’93, and was on the Planning Commission for a few years and don’t ever plan on leaving here and same kind of thing, we sat around one time and said you know, this city is going to be one hundred years old someday and people will look back and say, Gee, doesn’t it have wonderful character, I wonder how it got the way it was? And then everyone will look around and they’ll have this big effort to try and figure out, well, how did we get the way we were? So it seemed like a nice idea while the folks that were involved in it are still around, to get their slant on it, so that a hundred years from now somebody who is interested in seeing how we got the way we are, that that information would be available and somebody could

document it if they cared to and that the citizens who came, would know how we got this way.

GADDO: Now these tapes will be transcribed and categorized and cataloged and will be kept here in the library so that someone can really do some organized

COWAN: Well as I told you, and I think I sent you, I have had a lot of research done and that, uh manifests itself in about that much [referencing present physical documents] which basically tracks news reports and then what I’ve done is put in the special things that only I know how they were in my mind, and that kind of thing. My thought with this is to cut a CD or something with it. The written part is not so informative at that point, but what I was hoping to do then was to circulate that around to people who can fill in the City’s gap from the mid-70s until now, people like Francis Meaders and a lot of others around because it helps if you have that timeline. You can say, “Oh yeah, I remember that.” That’s what I had to do. I had to get that done to go back and figure out

PIET: Right, and the passing around might jar your memory again, you remember some things that you overlooked or didn’t consider particularly significant at the time.

COWAN: So that was the purpose of that and really to make it a broader effort. I was pleased to hear that somebody had really taken it on that could do it.

GADDO: Well, of course, like we talked about, once you get that, it could be part of the research material that we would put together, so

COWAN: Well, I think you can put it down, but I’ve got only a few more that I know about to add to it. But even like it is now, it would help get you through to where you are—

PIET: Are you saying that you would be willing to share that with us at this time?

COWAN: Oh yes, sure.

PIET: Well, that would be great because we could do some homework before we start interviewing these other folks and have some better background ourselves as to what to ask and what to clarify as we are going along.

1A |00:05:34|

COWAN: Yeah, I sent it to Randy, and because it’s better—it’s so long, what I’ve done—just, I don’t know if you need to record this part of it, but just trying to find a unique way to organize it. And what I’ve done is to put keywords (paper rustling) like this over here, the written keywords, but then at the end of each one of these paragraphs—this in caps—you know— (??). Then you put it into the computer, you know, and it works fine and (crosstalk) pick that up. And then it’s all by date.

GADDO: Is that in Word already?

COWAN: Yeah. It’s already in Word.

GADDO: Can you send it to me?

COWAN: Yeah, I did send it once.

GADDO: Oh, you did? I never got it.

COWAN: You didn’t?

GADDO: Unh-uh, unh-uh. Sure didn’t.

COWAN: And then what I’ve done here, these are my recollections [referencing documents].

PIET: That’s not quite as good. Is that kind of free thought there?

COWAN: It’s supposed to be. Well, a lot of it’s in here and then I just put this—like a particular industrial plant, that one we didn’t get. And, uh, a bank there, and just a lot of(??) lakes there (unintelligible crosstalk) a lot of stuff like that.

PIET: Well, that’s the kind of thing we’re looking for.

COWAN: How I got the first school—[referencing document]. Now, I was just going to copy

that and put them in the timeline, but what I was trying to do is to separate—my recollections, you might say, from the timeline so that anybody can look at the timeline. But this all comes out of newspapers.

GADDO: Okay, yeah. Okay, gotcha.

COWAN: Some of which were wrong, and I mean (Gaddo laughs) corrections— You know, a person writing a later story would hear about something and get it out of sequence

_________(??) remarkably not. Not bad, by the way. So that’s, a, uh—

GADDO: A good resource, yeah.

COWAN: I think it will be a fantastic resource.

PIET: Absolutely, because again—we weren’t here, so it will give us a clue as to how to keep track of things as we’re going through all of this.

COWAN: But then if you send it to many, many people around, they’ll say, Oh, I remember something—

GADDO: Um-hm.

COWAN: —and they can put it in that time sequence.

PIET: Well, we’ll take care of that (crosstalk)

COWAN: —recollections. I had Ginger Blackstone do all this and I’ve got all of the original clippings—she’s filed all that, which I’ve got in boxes, which—my hope was they will be transferred here, either uh—

GADDO: Yeah, once we get this—

COWAN: microfilmed or whatever.

GADDO: Yeah, yeah, once we get this all set up, we can keep going __________(??) resource.

COWAN: —because there are news clippings and things like that—not necessarily on me, but one of the things is the paper did every year for a review and it said, “this industry, this industry, and this industry—” Otherwise, I’m not sure you’d have it. ___________(??)—everything, simply because the newspaper did an annual review, and then typically the mayor spoke to the Rotary Club, and then that was an article—

PIET: Kind of a “State of the City,” or—

COWAN: You can then put it in a chronology which I think helps a bit. So that was that. And if you’re working on it, as I said, I can give you this—

GADDO: Yeah, if you could—

COWAN: as it is.

1A |00:09:13|

GADDO: I don’t know why I didn’t get that. I remember when we talked about it and then, uh—

COWAN: Every time I pick it up, you know, I find I was making little, tiny little editorial things—not substantive. What I’ve tried to do is keep the news report. In other words, if I had a comment about that, I’d make a separate ____(??) so that I didn’t try to change the news—as much as I’d liked to have. (all laugh)

GADDO: Well, what we’d like to do then, right now, is kind of—from what we’ve researched already—we’ve got some questions which are pretty basic questions, and we’d like to get them on tape and kind of get your perspective on it, so if it’s okay now—I’d like, if you could try again, and email that to me.

COWAN: Yeah, you have a—is it on here?

GADDO: Um—Randy Gaddo. I see my number there. I don’t see the email, but I can write down there if you don’t mind.

COWAN: Yeah. Write it right in there.

GADDO: d-l-s hyphen city, dot org. That’s a d-l that’s an l lowercase l d-l. Director of leisure services.

COWAN: What I would like to do, is for you all to keep it where you can use it for this until we get it where we want it.

GADDO: in its final form.

COWAN: Well, it’ll have to be it’ll never be final. (Gaddo laughs) But until we get it um, so we don’t have multiple copies floating around, and then

GADDO: Right, this is just for research.

COWAN: If we put it on a CD, then you can give that to somebody, which they can’t change that. Hopefully, they would then write back something and then one of you or whoever would sort of accept it or not or say what we need to clarify, we don’t want to put it in just like it is. And that’s what I was hoping to do is get my part finished. Then what somebody else does, that’s what they do.

GADDO: It’s ambitious.

COWAN: Well, and it’s pretty expensive (Gaddo laughs) to hire somebody to do it. I think most of the work that and the grunt work there is done, so the fun work, you know, ought to be doable that way.

1A |00:11:57|

GADDO: Yeah. Okay. Well, if we can get started off then, I’ve got a question that might kind of it’s something I’ve always been curious about. I’ve heard a story about it and want to see if it is true. How did the city get the name Peachtree City?

COWAN: Well, that’s written in here, like I said, “It’s in the book.” When we had this I think around here somewhere is a little original, red kind of a red-covered brochure that was the very first thing (unintelligible)

GADDO: The history of

COWAN: I think I still have one. No, it’s a it’s a big thing like this, with a maroon cover, spiral bound. And it had a rendering and it was the earliest thing back when we were originally

GADDO: She [Prouty note: M.T. Allen??] might have it. She keeps a lot of stuff in there.

COWAN: But it’s we were looking for a name and I was postponing doing that and that

name, Peachtree City, was floated by Willard Byrd who was the land planner in the original effort. That name had been used as a reporter in Atlanta then, that was called “Mayor of Peachtree City.” That was his, sort-of, byline. Conceivably, that’s where Willard got it but I don’t know that. But it was fairly common right then.

1A |00:13:34|

GADDO: Who was Willard?

COWAN: Willard Byrd b-y-r-d was a land planner, Willard Byrd and Associates.

GADDO: Ah, okay.

COWAN: I think he may be still alive. He was a young land planner that they had hired. In our early meetings in Atlanta, he was always there, he was on the board of the old Fayette County Development Corporation. But we didn’t have to get serious about that. I thought of a lot of names. I had Prosperity as one and I’ll have to think later, think of the ones that had surfaced then. But it wasn’t serious until 1958, when we were broke at that time we didn’t have any money. I wasn’t on the payroll even though I ran it. And uh, we I decided to go and incorporate it as a city, which meant you had to prepare a bill for the legislature. Then kept that, and so then I had to pick a name, of course. So I seized on that [name], because it was it told you, anywhere you were in the nation everybody knew where it was. My biggest aim at that point was industrial development. It wasn’t people at that point. Chicken or an egg, you know, which

comes first? I felt we could get the jobs here. Even though that was highly competitive and difficult, I thought we could do it. So I was interested in a name that would go well if you were in New York or Chicago, or someplace like that looking for industry. And, by the way, that worked. I never liked the “city” aspect because legally—and I only learned that when I prepared the bill for introduction to the legislature “City of Peachtree City,” that’s the way they like it. City of Atlanta, City of so-and-so(??). The name is Peachtree City. The City of Peachtree City (??). But any other name and without a lot of publicity or a big advertising budget, you just couldn’t hope to get the same bang for the buck. I honestly believe that Peachtree Center, Portman’s development [Cowan note: John Portman], would [have] probably been named Peachtree City had we not preempted the name in that case.

1A |00:16:01|

GADDO: Did you feel that that was associated with Georgia?

COWAN: Yeah—or Atlanta, which obviously leads to Georgia _________(??). Atlanta was the key target.

GADDO: Well, that mirrors what I heard.

PIET: Basically, I think most folks around know the general story that you grew up here in Georgia and you had a roommate, and you were hired by his dad, but having been around awhile, I scratch my head. You’re a young guy fresh out of college—

COWAN: Well, in college.

PIET: In college. We have this thing that most people think was a pretty great vision. Two-part question: how did the original founding fathers, now these are corporate, envision fifteen thousand acres being something special, and to be perfectly honest, what did they see in a young man in college to be the one to steward this into being what it is?

COWAN: Well, for that, you’d have to get an idea of who Pete Knox [Peter Jr.] was. He was in Thomson, Georgia, which is not even in Augusta it’s a small town outside of there. He was a Davidson graduate, a very liberal arts-type major, devout Methodist but a visionary in the extreme. He would see something, and probably if I were to characterize myself, I’d probably be in the same mold. Because typically somebody like that me included when you have an idea and that kind of thing and you go around and find who might do something, but in terms of you doing it, you know, you’re not very good at it, frankly. Not a good executive, not just getting in there and grinding it out day-by-day kind of thing, so he was clearly that way. His son [Peter III], by the way, was the reverse the one that I knew, although he is dead now, but he went on to Harvard Business School and was very successful, but very specific.

GADDO: Detail type

COWAN: Yeah. But the father like that he, Tom Cousins that’s the way Cousins got his start same office, same guy, same thing. [Cowan note: Tom Cousins, former CEO of Cousins

Properties Inc., initially sold prefab homes at Knox Homes.] And many others, and they were all young, and they would find something. Now what he would do, it was either successful or failed, that was your business. And if it failed, well that happens it went on. It went on. He had read a book about uh Toward New Towns, or The Satellite Cities of England it was a name about like that. Because those cities after the war, London was on the shrinking mode you have too many people here and you need to disperse them. But I’m sure you all have traveled there, and you know, the land is all tied up, you can’t just sprawl, you know, when you walk outside the city limits, you’re in the country. It’s not another farmhouse, another house, and this kind of thing, like it is here. So that was a conscious effort to have a green belt and then go out and create all of the infrastructure; in that case, a ring of parks and all of that, in advance, and major things and then the city just filled in around that infrastructure, which you could argue is a good way to do it. There was a town in the US called Greenbelt, Maryland, which goes back, back far I mean further than that. So in the twenties, there was sort of the idea of new towns. Now what is a new town? Is it just a large development? You know, what is the distinction there? But in any case, he [Knox] knew about what it was.

1A |00:20:25|

The funny thing was he didn’t say, “Well, let’s go find a site. Atlanta would be a good place, this would be a good place, let’s go out and acquire the land.” He didn’t do that. This fellow Denny, Earl Denny, who at that point was seventy years old and he had a partner named Golden Pickett, and they were both retired from something else. Denny was a chemical engineer, had traveled all over the world. And so, he was in real estate, and they were based in College Park and so they

had _______(??) went south, naturally, and so he started trying to do a land business and he, as much as—probably more than anybody—cooked up this large piece of land, and he was trying to figure out a way to sell it. Just coming down the road, he ran into the bank up there at Tyrone, the brick building in front of the seed house, where Floy was the manager. [Denny said] “Who could I see about buying land around here?” Floy directed him to Bob Huddleson. Mr. Bob had—Mr. Bob or Uncle Bob, depending on what you choose to call him—he owned probably three thousand acres of land—twenty-five hundred to three thousand—but he had a mortgage on a lot more. Typically, the way he would do that, a friend or somebody would get married, and they wanted to buy this hundred-acre farm, and he would lend them the money that may be five dollars an acre, or eight dollars, or ten dollars an acre. But he would lend the money, they would build a house, and then typically they wouldn’t pay any more. So it may be twenty years later that he hadn’t been paid anything, but he had the mortgage and the land and only way he could collect was for it to be sold. And the only way we could buy it was to leave that house out, so we would leave typically a house and four acres out—around that—and buy it and then let them cut the timber. And in those cases, let them continue to farm it under a lease which paid practically nothing, but—you have to remember, we were broke then, and we didn’t have money and we owed these farmers because we bought it, when it was bought, it was bought with a down payment and then this note, and these farmers were pretty smart themselves, you know. (Gaddo laughs)

1A |00:23:06|

COWAN: They had no idea this guy, Denny, knew what he was talking about because he would

just talk about things in South America and he was kind of a Teddy Roosevelt kind of guy, and he would, uh so they didn’t believe him. But when he brought a down payment, they took the down payment figuring they’d get the land back anyway. So, you know, who can say? So he got a core group of properties under option and then started trying to find who to sell it to and he found Knox. Knox owned a lot of land over in East Georgia, [but] not much here. He had done development on Lakewood, Stewart-Lakewood Shopping Center. And then if you go north up Stewart Avenue and see those stores, I actually built those for Knox. That was some of my later work with him. I built those. But behind that is a thing called Perkerson Woods, which was a residential development that he did years ago, and so the commercial land he had out there was just a by-product that he had left over and that’s when I brought the first discount store called Zayre’s down here. That was, not the first, but the first here, but it was a sidelight, but it goes back to sort of a relevance of all of it. So Knox said yeah, well, he may have come I’m not clear myself on whether because this predates me a long time, what I’m telling you now he may have come out here or he just came generally, because the truth is Denny didn’t know where the land was. And all or most of the landowners didn’t know.

1A |00:24:51|

There were deeds in there that said go to the creek where there is a hickory tree (Gaddo laughs) or a horseshoe hanging in the limb and that was the corner, and then there were militia districts like the Shakerag voting district that’s a militia district. And, of course, there are land districts, and we are all in the seventh or the sixth district land district and there are land lots. Well, the deeds over the years got confused with that, so sometimes they would put the militia district

number in and others the right district, so it was just—and we didn’t have the money, of course, to survey it. None of this was surveyed. We surveyed the piece around the house, but not the land at all—which became significant later on when we got money. So, uh, that—Knox got sort of interested in it. Well, now you have to go to the trend of the times. The law was different. You could have what is called an intra—i-n-t-r-a—state stock issue, not in-ter-state, without going through a lot of registration. Well, Herman Talmadge, Senator Talmadge back when he was really popular as governor and that kind of thing—created a company called Georgia International Life Company, life insurance. They prepared a prospectus and sent the suede shoes out _____(??) in his name and they raised a lot of money across Georgia, and they—

pause in recording as cassette tape 1, side 1 ends; side 2 begins

PIET: We have some learning to do to get organized for all this.

COWAN: So—as I was saying about these stock issues, so this group who created what’s called the Fayette County Development Corporation, a Georgia company. I still have the seal and a lot of the records. But he created that and had some of his pals to put up some money—and by money, that was $175,000 total—first trunk(??). Then they sent the suede shoe boys out, but they only sold $50,000 worth of stock, which was deemed a failure. But one of the significance about that is that is how I found about it because they put an article in the paper, which I’ve got—in the Atlanta Journal, and it was on that morning, which was in May, in the fraternity house at breakfast, that we were reading the paper and saw the article with Mr. Knox’s picture on it. It said, “New Town to be Built in Fayette County.” So I read it and I turned to Pete [Peter III], I

said, “Your dad may need a mayor.” I literally said that. I said, “Does your dad need a mayor for that town?” We talked a little, but not more than that. It was only a short time, a couple of weeks later, his dad was in town and asked me to lunch with Pete—he called him Peter at the Atlanta Athletic Club, on the 5th floor. Quite (??) with the tablecloths and everything. (Gaddo laughs) So we, uh—well, we talked on and that’s how he met me and proposed the question that we discussed.

1B |00:02:01|

GADDO: So that was the first you’d met him?

COWAN: The first I’d met him. As we were leaving, we’re standing up, lunch was over, and he said, “Joel, Peter tells me you’re a whiz.” Those were his exact words. I can’t remember much, but I do remember those words. Of course, I didn’t respond. Then he said, well, he would like to talk some more—so that was the end of that, and then some time later, I got an invitation to come over to stay at their house in Thomson, which was a big mansion-like place. So we made the deal there, which doesn’t answer that question, but—____(??) more together, to—I had one more year to go in college. They didn’t have any money to pay me, but they just said, We’ll give you stock. But we’ll pay some expenses; you can have some money to pay some expenses. So I rented an efficiency apartment in Darlington Apartment[s], which was the only high-rise apartment. That was sort of where I lived and my office.

GADDO: Where was that?

COWAN: In Atlanta. It’s out on Peachtree Road—right, almost across from the Piedmont Hospital. That and the Howell House were the only two [high rise apartments], but—I think I actually lived there once before. While I was in college, they didn’t have dormitories to speak of, so after your freshman year you moved out and lived all over Atlanta. So, in any case, that’s what I did and set up shop there. And I spent some of that summer coming down and meeting all of these people and learning to sit around at Dave’s [McWilliams] store over here. I couldn’t chew tobacco or spit, (Gaddo laughs) but that’s what you’d do around the pot-bellied stove. But basically, the mission was to keep them from foreclosing and keep the options alive on the property and you know, the things like forest fires because they didn’t have good coverage—

GADDO: Right fire with fire(??)—

COWAN: any coverage. But someone would call and I’d actually have to come down here in the middle of night. Course at night, you could single-handedly put one of those things out.

1B |00:04:25|

PIET: (crosstalk)—because you could see it.

COWAN: —which I did. Well, you could see it and then the moisture in the air—over the line like that (??), but I didn’t do that. But Knox still hadn’t been down here to see the property. And the other was to find—like I’d go out with a farmer, and they’d say Well, this

property is here, and I’d say, “Well, where?” (Gaddo laughs) and I’d say, “Could you use a pin or something?” Well, there was not a pin and I said, “Let’s get out of the car. Would you go stand on where you think the corner is?” (all laugh) Because that was the closest thing it was an important thing to know where that property was.

GADDO: So there it was pretty much dead reckoning?

COWAN: Yeah, and of course where a hedge row had been built or a road or you know, you can see, but see those things deteriorate over years because this guy, when he’s turning his tractor, you know, keep going and first thing you know he’s over here [another property] if the guy doesn't care. That’s where most of Georgia property law was built, just resolving those kinds of disputes. Honestly, the acreage was very inexact in that sense. We tried to put that together and so during the my last year at school that’s what I’d do come down here and, meanwhile, study everything and see just what could be done. When I graduated in 1958, I didn’t have a job because I didn’t go to any of the job interviews nothing. I just had in mind that’s what I wanted to do and so he [Knox] offered me a job for $600 a month in Atlanta and I could keep doing this but do these other jobs for him including the one on Lakewood and bid on some of the military bases where they build housing.

1B |00:06:23| I bid on some of those projects (unintelligible) for him. And it was during that period that I you know, kept we had to have the money, meanwhile, because the public stock failed. The

original guys put up another $125,000, I believe—about $300,000 or $350,000 plus the $50,000 from the public—that was all that ever went in it basically, all of which was spent on the down payments here. We didn’t spend it on anything else. We kept going and during that fall, well, I decided on a city. We’d have a board meeting—ask Floy to come on board up there to sort of represent the local group here. We’d meet up there and have dinner at Shorty’s Grill on uh— that’s on Decatur Street just beyond Five Points—because the Knox office was there, where Georgia State’s office is now, at Pryor Street and Decatur Street. So we’d meet and go into Shorty’s. Shorty would fix up a place. There was a liquor store on the other side of that and Mr. Knox would buy some Scotch and (Gaddo laughs) bring that into Shorty’s. So that is the way we’d have a board meeting or try to decide what to do, what we wanted to do with it.

1B |00:07:59|

GADDO: So when you say “trying to decide,” was that when you were trying to figure out how you were going to conceive this city, or how—

COWAN: Well, you know, that was the last of the thought is what the city would look like. It was a matter of how you were going to buy the property and finance it—that drove everything. So that’s—that’s apropos (??) clearly, but you can go in and have a plan, but you’ve got to get the money first. That’s the key element, and that was also the hardest part.

PIET: So going into the first government, the security of the land itself was still an issue. You still hadn’t—didn’t have the resources. That is an interesting perspective because I think a lot of

people, and certainly myself, thought that we had some high rollers. These guys weren’t poor, but I mean obviously this was a poorly funded project, not a robustly funded project. This wasn’t somebody’s start peeling off money, bought fifteen thousand acres, peeled off some more money and said, “Build me a plan,” peel off some more money, start building roads.

1B |00:09:12|

COWAN: Yeah, I mean, none of this is the kind of thing you could do now. You’d never even think about it now. But, that’s true, and after I moved down here and up on Shakerag Hill there and when we were putting that bill through legislature, as soon as we got the deed, I went to these same property owners, the ones we owed the money: Mr. Bob Huddleston and his son Hugh Huddleston, Albert Pollard and Johnny Robinson—that's the one Robinson Road was named after—and asked them to be on the council. The truth is, had I not asked them, we wouldn’t have gotten it [passed]. Grady Huddleston, Mr. Bob’s other son, was in the legislature, and Harry Redwine was a senator. They had the Redwine Funeral Home over there, and his grandson is the one that ran for county commissioner this time—(unintelligible) [Prouty note: Thomas Stephens]. It was his grandson—Harry’s grandson. Harry Redwine was different from Hill Redwine, and they were kin back up here, but they—

PIET: They were so far apart down here, right?

COWAN: Well, they were politically and a lot of other ways ________(??). They did own this piece of property that had been zoned in the south end of the county, I mean the city, right across

Flat Creek actually, it straddles Flat Creek. They had two hundred and something acres that I— never was able to buy—and they just kept—and that is what is being developed down there now [Wilshire Pavilion]. We never bought it; it was never in the city—that and International Paper had another piece of land near there that we didn’t buy, but I had a way of getting that. So, uh, it was uh—that’s the way we got that part (??). So I moved here. Actually, it was a little late, I thought I had—nobody was counting—I think I moved in on January the second or third. We started the house December first. We built it in thirty days. Actually, there’s a picture around somewhere—the carport was propped up and we pulled into that, but my wife and I moved in then.

1B |00:11:38|

GADDO: Well, you look great(??)

COWAN: Well, I got married my senior year, halfway in December [1957]. So she moved into my little apartment. She was working at Lockheed, and she brought the regular paycheck in. (Gaddo laughs) So we lived in that same little apartment.

GADDO: Now where is your property here? Are you on the same property?

COWAN: Well, now I live down on the lake. I traded that. What they did, you know when I said they gave me stock? Well, the stock didn’t mean anything at that point, so they didn’t get it. But when I was getting the house, he [Knox] said, “Well look, we’ll just give you some land and you

could build on that.” So they gave me sixty acres that we bought from Mr. Johnny Robinson. It was a strip, you know, Highway 54 sort of running northeasterly—after you go beyond McDonald’s—through there. But at the top of that hill, Shakerag Hill, there is a new development [Peachtree City Promenade] right where the house was. It has been graded in— there’s a Waffle House and I’ve forgotten the name of that, but the house was there. The hill went on like that and I built the house where I could look over most of the valley, so to speak, there.

GADDO: And there was nothing else—

COWAN: The land went back along that road that Ts off Robinson Road. It goes straight back— the funeral home, straight on across there. The land lay on that side of it and the Barbers had land to the north of that. So it was out of the development, you might say, except for the part [where Cowan lived] that stuck in.

1B |00:13:22|

GADDO: Was there anything else around you when you moved in(??)?

COWAN: No, there was a store. Mr. T. C. “Cleo” Collier had a little gas station and a store that was about the size of this history room here. His name was Cleo; that’s what we called him. He was what was called in the old railroad days a “butch,” the guy that went up and down the cars selling candy bars and that kind of thing. So when he retired from the railroad he came down with his wife, whose name was Musetti—was crazy, mentally ill, you would say. Then they said

“crazy,” (Gaddo laughs) now we say “mentally ill.” But she was, literally, and we never knew whether she was dangerous or not. He kept her a pack of dogs, and by a pack I'm talking more than ten. When Musetti would wander, these dogs would all wander with her. (Gaddo and Piet laugh) Well, she was our closest neighbor, so often she would

PIET: Wander your way

COWAN: She’d wander over there, and she wandered over there when I wasn’t there. My wife, and at that time we had a maid they would see her coming and lock all the doors. And she would beat on the door and all of that kind of thing and would frighten them a good bit.

1B |00:14:54|

GADDO: Um-hm especially with all the dogs.

COWAN: Well, the dogs weren’t that bad, I guess because they kept fed, but sometimes, when we were away and we’d come back, at the back door there’d be something she’d obviously gotten out of his store, like ice cream melted and run right off across the patio (laughs) out there. Well, I digress, but

GADDO: You were on 54 was 54 there at that time?

COWAN: Yeah, 54 was there.

GADDO: What was it?

COWAN: See what 54 was the Redwine influence, as near as I can piece it together, fought having a road direct to Atlanta ___(??) having competition for labor and all that kind of thing. So 54 came from Jonesboro and across, so if you were leaving Fayetteville, which was the center of their universe, that’s the way you would go into Atlanta. You wouldn’t go up what is now 85 or any of those roads because they were all dirt. Now, 74 was paved—I’ve forgotten when it was paved. It was just an old road, and it was eighteen feet wide. I always thought that would be the way I’d die because that was ultimately the way I was commuting. When I started out, I’d go from here to Fayetteville and then Georgia 85, because there was no Interstate 85, and then of course, when Interstate 85 came, I switched and went up 74 right through Tyrone. A lot of people here can remember that. You remember going through Tyrone, of course.

PIET: Yeah, the first couple of years. It always seemed like such a great thing because the widening of 74 and cutting out Tyrone seemed to be ahead of its time, because when they first opened it up, traffic was wonderful. I mean, just a straight shot. It was wonderful.

COWAN: But by the time you got here, they had at least widened it. It wasn’t eighteen feet wide; it was twenty-four feet wide. When you—(crosstalk)

PIET: It was a real highway. (laughs)

COWAN: Course, I did have a fairly bad wreck on that one time, but I knew I’d get it because the farmers would come out. I found that if a person, be it farmer or otherwise, was coming to the main road and going across (??) turning into field here, they would pay no attention to oncoming traffic. It was like, Well, I’ve got a short distance to go there, boom—they’d pull out with a tractor, with a plow or something behind it, and I’d come usually too fast. Well, that’s the (??) the truth. (Gaddo laughs) But fortunately, we got it paved becoming four-lane and well, that makes the difference. But Knox came only one more time and that was when we were living in that house and we had had our first son, Joel, who was born July 30th of ’59. So he came in that fall perhaps, and maybe—I think it was the fall—that was probably the only time.

GADDO: Hm. He never actually—

1B |00:18:13|

COWAN: He couldn’t have told you where the property was at all, but he had fully the vision and everything about it. It’s not to denigrate his—you know, his credit. But when we went to the financing aspect, I’d be in his office, and I just started this and that’s how I learned networking the hard way. I would just go sit with anybody who would listen, just knock on desk(??), door after door. Eventually, a guy named Judson Ackerman heard about it and he asked to see me, and so—well, we met, and he looked like Mr. Sharpie, if you know what I mean. You just couldn’t put any credibility in him. But it turns out that he knew—and by the way, he got to me through another broker—so there were two on that side. He knew a guy with the William A. White Company in New York and that guy in New York knew a man named Howard Auerbach [Cowan

note: Auerbach also worked for the William A. White Company]. And the significance of Howard Auerbach is that his wife was a close friend of Blanche Riley. Blanche Riley’s husband worked for Bessemer, or the Phippses. He was the head land guy. Originally from Alabama. Riley Field is named after him and Riley Parkway.

GADDO: What was his name?

COWAN: James F. Riley Jr. He always kept the Junior even though— So, he originally came from Alabama and went to Florida in the twenties. And then, probably the early twenties went to work for the Phippses [Bessemer] down there. Then the Florida crash came in ’25 or ’26, somewhere in there, but the Phippses had plenty of money so his job was secured by the (??) jobs and that sort of thing. So he was their chief guy in Palm Beach, and then they had only recently moved into New York to liquidate properties, because they had—up above the UN— they just had thousands of cold water flats and property on Madison Avenue—Abercrombie and Fitch building, KLM, and some others up there—which, I later inherited that job and I did it. But in any case, he [Riley] told me that the reason he came was because of that friendship and Auerbach needed the money and he said, "I was just hoping to find something that he could sell me.” (all laugh)

1B |00:20:56| And so, he said, “Well, I’ll go down.” They were liquidating properties, not buying them, and they certainly weren’t buying here in Atlanta. I mean, they had no, there was no—nothing to

bring them here. They were Florida or New York, and that’s it. So uh, they kept it secret from me who it was, as though I would’ve known. I wouldn’t have recognized the name anyway. I mean, if it had been Rockefeller or something you’d know it. So, in any case, they said I had to give, uh—he wasn’t going to come, though, unless he had an option to buy it, because he would come, look at it, and like it, and then I wouldn’t sell. So I called Mr. Pete and said, “I think we got somebody who would at least come look at the property.” And at that time, Pete really had written it off because he had, in fact Tom Cousins told me, he’d actually asked him to try to sell it, you know, try to sell and get anything for the interest. So, in any case, he said, “Joel, you have carte blanche.” Well, I didn’t know what that meant, but I said, “Well, thank you.” (all laugh)

1B |00:22:03|

PIET: It wasn’t no, right?

COWAN: (laughing) Well, I got a dictionary and it said, “unlimited authority,” so I then write out this letter, or typed it up, giving the option of $225 an acre which was a lot of money because we had only paid $60 and $70 for what we had then. We owed and we were behind but nevertheless, with a purchase like that we’d come out well. And I included my house and sixty acres because—I didn’t know what would happen to me in that case. So uh, I wrote that letter—I wonder if I could find that letter—because here I was, just out of college, you know, and I had never done a thing like that. I called him back and said, “Do you want to see the letter or sign it?” and he said, “Nope, you sign it.” (laughter) So I signed it and sent it, and that got him(??) down. Of course, in planning for that trip, I was pretty nervous. I wanted everything to go just

right. There was no access. There was no Interstate 85. There was no—we had little Old 74. But you wouldn’t come that way; so you’d have to come down to Fayetteville and then across, and I said, “This would be the wrong impression.” So I got Knox to agree to charter a little plane—

GADDO: Fly him in.

COWAN: —but, of course, there’s no place to land. There was, but at Tyrone, right in the intersection of Palmetto Road and Old 74 on the west side of the railroad. That area was just a dirt area and they in fact, there was no point of base there—but they in fact, they would land planes there were no houses there or anything like that.

1B |00:23:46|

So I got Floy—I think he had a ’55—either a ’55 or ’57 Ford—and I got him to leave his car with the key in it parked there in case everybody(??) was ready to go look at the land. Well, as soon as we took off, I got air sick. I put him [Riley] up there with the pilot and I sat right behind him so I could point out things. And then the two brokers, Auerbach and Ackerman, were there and there was one more seat available it was a twin-engine plane. I thought I’d get sick, but I came prepared. (laughs) So I was directing him. (all laugh) I don’t know if he knew I was sick or not. In any case, he probably did know and landed to give me a little relief there. But we landed there on that strip, got in Floy’s car and then drove around. Well, after we drove around, I was okay. I could make my point for my case there. And so we left. Well, he was staying over the next day, which would be Saturday, but that night he said—Friday night he said, “Now,

tomorrow, Joel, what I’d like to do—” He took out a map. “I’d like to drive with you.” What he pointed out was to go down to Newnan and across to Griffin, up through Fayetteville, and back—he wanted go around all of it to get an idea of where the property was. Which was something of a relief to me, because at least they had roads. (all laugh) There was a way to get there on the pavement. That’s what we did. Then on Sunday he left back out.

1B |00:25:32|

And that was in February, as I recall, of ’59. Of course, I had the bill in the legislature then to incorporate it. But he was a grand guy and until his death, you know, it was almost a father-son relationship. In fact, the other thing he told me—it’s uh, braggadocio—but he said that uh—, “You know, we wouldn’t normally be interested in this, but we are interested in you.” He had visions of me going to New York—and later, by the way, they tried to do that—but I commuted. I got an apartment and commuted up there. But, uh—

GADDO: To New York?

COWAN: Yeah. They looked on it as twelve thousand acres of land, within(??) twenty-five miles of Atlanta, and it’s just got to be good some time. They had no interest in the—I mean, the development was okay. Well, the way I positioned that—and again, I was fresh out of school, and I didn’t have anybody to tell me what to do or how to do it. Of course, we were a public company, literally, and we weren’t where one guy could just make a decision. And I knew we couldn’t find all the shareholders. You know, they may have been down in Valdosta, a guy says,

“You want to buy a share of stock for five dollars?” Yeah. (all laugh) And you don’t find them. So, in any case, I needed to position it so that Bessemer got what it wanted, which was twelve thousand acres, but I got a shot at starting the development. Because I figured that once I got it started, it would go on—and I could then finance it. The way that worked out is we created a new company called Peachtree Corporation of Georgia and the old stockholders were going to own the minority of that, 49 percent, and Bessemer was going to own 51 percent. But the way the money worked—so they put cash in to buy that, so that was part of the cash. And then they bought the outside land—the land to the south and the land to the north—outright in a company called Henry Phipps Estates. Plural. No Inc., no company, no nothing, just Henry Phipps Estates, which was a screwy name for a New York company, and we have funny?? little deeds that just wasn’t the right way to write the deeds somehow. That was to be just put out and kind of forgotten about. So what that left was this center part that Peachtree Corporation of Georgia owned and about $435,000 cash, which was a lot of money.

GADDO: From them?

1B |00:28:26|

COWAN: Yeah. What they put, because see, they bought the land and that let us pay off the debt to all the farmers—and then put this money in the company with all of the free and clear land that was thereby clear, and it left us $435,000. And I had been to the bank—Trust Company, C&S, and First Atlanta to say: What would it take to get some attention on an industrial development—in the way of a deposit in the bank? So they said (unintelligible)—and I said,

“Would $100,000, quantify(??)?’ and they said, Oh yes, you’d get a lot of attention with that. So when we decided to go forward, they hired what’s now King and Spalding to represent them and us—and they were close to the Trust Company and the First National; and then I knew C&S pretty well. So, when “Mr. Big,” that’s Mr. Riley, came down and we were ready to do this, he was going to meet the top officials: George Kraft was chairman of the Trust Company, Jimmy Robinson was chairman of First Atlanta, and Mills Lane at C&S. And a little digression it happened to be Mr. Kraft’s golf day. I was just talking to, the other day, to an officer at that time that knew me and knew of me. And he said, you know here comes Mr. Big in and he got the bum’s rush from George Kraft. You know, “Nice to meet you,” and all this kind of thing.

GADDO: Yeah, (laughs) I got you.

COWAN: —and no lunch and all that kind of thing. And so, that was noted. And First Atlanta was much better, but they didn’t have the resources that C&S did. He got to C&S—

pause in recording as cassette tape 1, side 2 ends; cassette tape 2, side 1 begins

COWAN: —this was a perception with C&S. They got the big deposit, which was good because they had a guy named Clayton McLendon—they had a full-time industrial development guy— with whom I had worked from with my father, who was mayor of Cartersville. You had asked why they would pick me. In fact, all of my years before in college I had worked with my father who was mayor of Cartersville. But he was a merchant, a small-town merchant. He fought the establishment. Today you would say he was liberal like I am, or I’m liberal like he was. But

basically, his interest was with the common man. They were his customers. But up there, that’s a mill town, and you know in a mill town they’re interested in keeping labor cheap, other industry out, education down. That is just the way things were done back then, everywhere, not just there.

2A |00:01:11|

So he was fighting the establishment there but trying to bring industry in at the time the mills were trying to keep industry out, because they started bringing labor unions and that type of thing in.

PIET: (crosstalk) because they were bringing competition to the mills.

COWAN: Yeah. This guy, Clayton McLendon and dad he was really the first pioneer to actually go to New York and try to get industry. Well, Clayton and C&S were the ones to take him up there. So I had done that with him. I’d go to the airport and pick him up and then be with some of these industrial people when they were entertaining at dinner at the club and all of that kind of thing. So you might say I had a little background.

GADDO: A little training, yeah.

COWAN: Nobody had any real training, but I had as good as any. At least, I thought so. (Gaddo laughs) But the fact was, from his eyes, he was looking at it [thinking], Well, here is a reasonably bright young guy who is enthusiastic and at least salutes the idea. You know, if you are a

visionary, that is what you want first is somebody to say, “That’s a great idea, do you need any help?” Doesn’t matter what they can do, it’s just the fact that they support you and that’s probably what and it really didn’t cost him anything to speak of. But that was his style, literally Knox. He would give the chance and you could make something of it or not.

2A |00:02:35|

PIET: Now it’s February or so of 1959 and now you have secure financing.

COWAN: Well, we didn’t close that till July 30th which was the day my son was born, in fact.

PIET: Okay, so now it’s middle (unintelligible).

COWAN: He [Riley] came in February, but it took that long to get it ready to close.

PIET: You are already an incorporated city, teetering on the brink of bankruptcy.

COWAN: And now we have money.

PIET: But now you have money, come July.

COWAN: There’s no debt. We don’t owe anybody any money and all of a sudden people look at it. Today people think, well, you’re the first mayor. The important fact, you know, I kept the city

part down. First of all, I thought it was, you really couldn’t—that things have an inherent conflict in them and so I wouldn’t do anything as mayor. As a matter of fact, we didn’t have a meeting except we may have had one a year. But all of these people, you know, were just around; they were good friends, and they demonstrated their friendship and I had, too. So we had very strong relationships with them.

PIET: There weren’t very many of you. 2A |00:03:54|

COWAN: No, not many, that’s for sure. So, uh―you know, on this side of the county I was sort of “one of them.” On the other side of the county, it was a different story, I guess. You know, a fear(??) or generational kind of difference between west and east. Those are separate stories. So it was going, but I saw it—and I never saw it any other way—as being a long-term thing. There was a development called Norris Lake Shores, over—was it in Henry [County], or—no, it was further out [Prouty note: Gwinnett County]. But it was a big lake and was done as a resort and people were building these cabins and putting trailers and all that kind of thing. But I saw the attractiveness of the lake, you know, that just put you, kind of, on the map. That was before a golf course could do it. The lake was there and a few things, but I thought if you really spent the money—and we had money—on advertising, you could get—but you’d get a certain kind of people there, and you’d lose all of your frontage property, and you probably wouldn’t have anything to build a community around.

2A |00:05:04|

The job I saw then was building a community to get industry. And the people who would work at the industry, by the way, wouldn’t live here because they would be cheap jobs and they couldn’t afford a house. It was a question of what you could get built—a perception. The other thing I saw, even then, at twenty-three years old, I saw that if you made too flashy a start, then in ten years you’d look like a failure—five years, even(??)—simply because you had made a flashy start, and nobody could see anything. I was then very protective of road frontage. Consequently, we didn’t build anything on 54, didn’t build anything on 74. We didn’t have so much of the frontage on 74 as you can see up there [referencing a map]. Those were four-acre pieces we cut out. You can still see some of them all around the city. Later on, the ones who we bought we had to pay dearly, including where we are sitting right here. There’s another one on the other side who’d—the guy really troubled me because he came in and built a junk service station right in front of his house and I really had to pay through the nose to get that back and not use it. That’s the reason when you drive that way, when you get before the bank—the pharmacy here, but that big tree sitting out there—and it’s just there alone (unintelligible crosstalk) well, that was the house. If you happen to see a tree like that, that was the house. Here was one, just where the bridge lands—the pedestrian bridge there—there’s the one owned by the Whitlocks, across the way. So they were all along here and we just had to get [them] one by one.

2A |00:06:56|

Let me tell you one thing about the money. I had this $435,000 and my whole career and the

future of this city at stake. But there was a piece of land up here where the golf course started out Golfview Drive where all of those fine-looking trees that you can see are different from the tree cover in the rest of the city. That was a piece of land we were never able to buy. It wasn’t owned by the farmers. It, in fact, was owned by Dr. McDaniel. Doctor I’ve forgotten his first name. His office was in the old Loew’s Grand building where Georgia Pacific is today. And the theater went through where “Gone with the Wind” was you went through a tunnel-like, and the theater was in the back. But in the front was this old office building and that’s where Dr. McDaniel’s office was. Well, I had scouted him out and I knew a lot about him, but I felt like I had to have that piece of property because a) it was beautiful, and it was right in the middle of everything I wanted to do. I figured that was where we could start something. So I I had a cold one day, (Gaddo laughs) and so I had to go see a doctor.

GADDO: (laughs) had to go to the doctor.

2A |00:08:07|

And that's exactly what I did, you know, under pretense and that kind of thing. It turned out, you know, that we may have been distantly kin very distant, as it was but something could be constructed. “Oh, you’re the guy who owns that land,” and that kind of thing. I didn’t fool him though for a minute. Before the day was over, he said, “Now young man, I want two hundred and something dollars an acre” 250, 275 sticks in my mind. I know it wasn’t 300, but it looked like all of the money in the world. But it was all to me, because I had this 400 pot and now I was going to lose 175 or 200 for that one piece of property. He said, “But you’ve got to have a

contract back in here to buy this—” I think it was, like, three days. Back then, of course, we didn’t have FedEx, didn’t have fax machines, didn’t have anything to do. I called my boss up there and couldn’t get clear instructions, so I went down to the law firm and got Griffin Bell, who later turned out to be Attorney General of the United States. “I need you to sign this contract for me as attorney—” (unintelligible; Gaddo laughs) And lo and behold, he signed it. He said, “Joel, I hope this property is valuable because I may have just bought it.” (Gaddo laughs) But it was absolutely binding every way around.

2A |00:09:45|

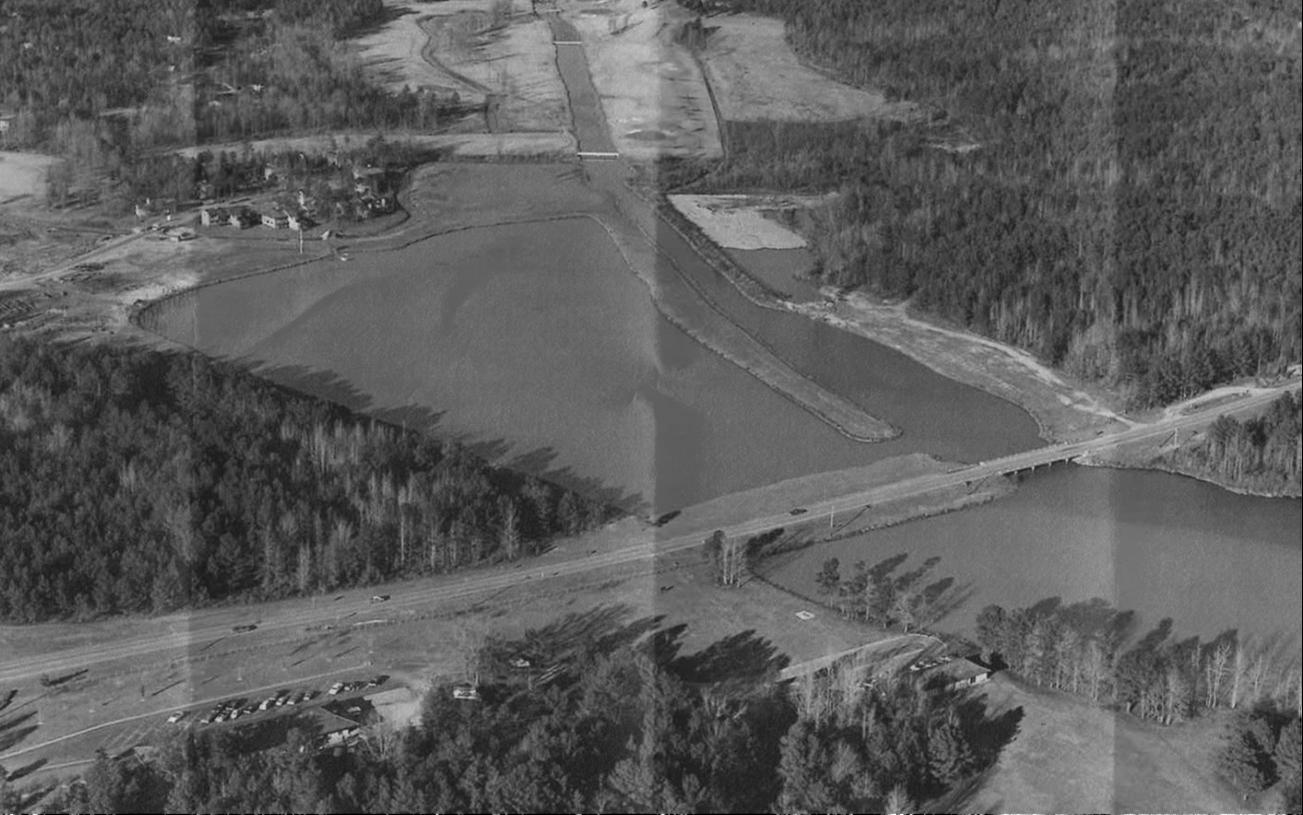

But it was one of those things we just had to have. So I did, but I got the property and it worked—and everything was paid for—provided the development was going forward. It if wasn’t going forward, it wasn’t worth anything like that. So I had lost part of my money in terms of convincing the Phippses to put up more money. That was my big issue there because when they looked at the land, they just listed(??) land. The lake is kind of interesting because—in that early theme that’s around here somewhere, there is a rendering of the city—what happens is that at Highway 54, there was to be a dam above it. And what’s now the golf course, and all of that area, was to be, probably—we thought—three or four hundred acres of lake up there. That is what was on the drawing—now remember, we never had the money to do any engineering. We didn’t have a topo map. We had these old coast and geodetic maps which had a ten-foot contour, so they were hopelessly inaccurate. So, I did a lot of work up there, in fact, myself.

2A |00:11:07|

I got somebody to teach me how to use ditching dynamite and I would go where there was just a big swamp back there, full of beaver dams and all that kind of thing. I was trying to figure out how to build a dam because they told me that you couldn’t—the cost to build a dam right here above Highway 54. You can see how wide it is and how swampy it is and that kind of thing. The state?? highway wanted you back away from it. It wouldn’t have been a smart place to put it, but that’s just where this original Williard Byrd, this original plan, had it; but again, without any real information. I went all through that swamp. I’d go take these beaver dams—I’d take a stick and stick this dynamite, two and three sticks, down one hole all through one of these dams and put a cap, pull a wire over behind a tree, (all laugh) then get over there and blast it. I mean, it would blast all over everywhere and stuff would rain down on me and that kind of thing. I did that all over. Of course, those beavers would build them back just as fast as you could (unintelligible).

But I went all through that swamp trying to figure a way to do it and finally just figured you couldn’t.

2A |00:12:20|

Well, I was sitting over at Dave McWilliams’s store, and Hugh Huddleston said—I was telling him what the about the problem I was having and that kind, and he said, "You ought to go down here south of 54,” and “there’s a place down there that I bet you could build a dam.” And then, you know how your mind works; I thought it was worth looking at. There wasn’t any road in there, so the way you’d go down, you’d go 74, which was on the other side of the railroad, down about—I guess beyond where Kelly Drive is now, because Bob lived down about where the

sewer office is. And so, you could get there, and then you’d park and then walk up. Now I got one of the old timers to go up there with me and look good and eventually got on the other side, because you couldn’t see through there (unintelligible). But sure enough, I found what’s now the dam site down there and when I saw it, I knew that was the place. Then I had to figure out where that would be in relation to flooding Highway 54. I had to pick a place there and you know, run it down to figure out how the dam would be down there. But it all worked out as you see it now.

2A |00:13:40|

GADDO: Was that in your training? I mean, was that something you just were jack-legging that, sort-of?

COWAN: That’s right.

GADDO: Wow. (laughs) That’s incredible.

COWAN: But you know, you just get an instinct for that kind of thing, and you can talk to engineers or anybody else. (Gaddo and Piet laugh)

GADDO: So when you were doing all of this, in your mind, did you still really envision the whole final picture in your mind?

COWAN: Yeah, the one disappointment and thing I couldn’t figure, and it’s interesting when you

see these cities and groups agonizing like where an airport should go like the airport we have down there. I had sole decision-making authority on that. Nobody in New York or anywhere ever questioned either doing it or where or anything like that. It just wasn’t something anybody was interested in. But it’s funny when you have sole authority, and you still can’t make (Gaddo laughs) a decision, you know, about where to put it.

2A |00:14:53|

But a downtown center I spent a lot of time and money trying of course, it originally was to be right north of 54 and on the shore of that lake and have a beautiful water feature, right where the conference center is now. That was to have been it. But, you know, it just never would work. I couldn’t there were a lot of reasons, but I just couldn’t make it work there. We looked at doing it over here [west of that area]. It was popular because all of these British new towns and others, this village concept was always, uh always popular. But you still wanted a center something to give you some (unintelligible). So, uh that and, again, like I said, the airport were two, kind of, tough decisions, but A regret is not having a center, you know, but arguably we may be under the current lifestyle we probably are better not to have it, but it is still hard for me to admit. We may be better not to not to have it.

2A |00:16:05|

GADDO: Why?

COWAN: I don’t know, you know we are sort of blessed that, what with the original plan, we stayed with it a long time. Typically, in any city, if you think generationally, then you don’t stay with it. Because we had planned in here. I knew you couldn’t do any kind of higher density, but we had planned for it, nevertheless, so everybody would know, right here is going to be six units here or ten units there, something like that. That is how the population numbers worked.

GADDO: It was up to eighty thousand, somewhere around the eighty thousand-mark.

COWAN: It was a perfectly logical idea and had you done it today, literally today and ten years in the future, that would be perfectly acceptable. But the misnomer and it’s one I absolutely knew back then, not now, but back then that it’s easy to say a master-planned city, but you still had to plan it within the context of what you could sell. And you certainly couldn’t sell that. Now, the question is could you reserve it and sell it later on, and of course the decision was made to cave in rather than in other words, every time one of those [population dense areas] came up, then it got beaten down. Even though it is zoned for it, you still have a certain political public responsibility. And much of that occurred after my time anyway, when you would start thinking about using this. But I think, let me see, Honeysuckle [Prouty note: neighborhood in Kedron Village] and those up there you know, those are nice developments, they just don’t need or want that much yard and so on to keep up with, provided you have the green space. You still end up with the same overall count, but you just have more green space to compensate for, which is something (crosstalk) societally we have to face today all over.

2A |00:18:26|

GADDO: But you had that in mind right from the beginning.

COWAN: Oh, yeah. I’ve actually got for some reason, in my sock drawer a tape of a speech I made in ’72 to the Decatur Rotary Club out there. You can hear every one of the ideas in that, and it wasn’t new then, as I’d done this back in ’69 and ’70 when I had done the Arthur D. Little plan which had the eighty thousand [count population]. That’s how Richard Brown you know, Leslie Mitchell’s husband not only moved down here, but he was part of that planning effort, and he has been since he left the area and went to Houston’s new town there I can’t remember the name of it but he carried out much of that out there. But you couldn’t do it there and you’d hear all of the complaints about density here, which is I understand both arguments, but it is one we will have to get around. We won’t here in this city, but we will in the region because people just have a different lifestyle now. They want different things. Except for here, there are not enough examples of true green space to make people understand it well enough.

2A |00:19:54|

The golf course was another thing that we tried to, uh we had this idea for it where it was and what it would do for us. The lake was defining where it was and that type thing. A golf course of that caliber on the south side Canongate had been built over there, just sort of out in the middle of nowhere by this wonderful guy, Bill Roquemore. And so we started, and I called him, and got him. We had a little guest house I built right down here [indicating below the library] and had a little place to entertain with people up there. We were instant friends and had a nice dinner

there together, and I just felt that he was somebody I could really deal with. What I didn’t want to do, because I had control of so many, many things, I didn’t want it to be perceived that I controlled the golf course because you get into all of these country club issues, (Gaddo laughs) like where the greens are, and I didn’t want people complaining to me on that. But yet, everybody advises you to keep control of that because the wrong person controlling it could ruin it; run a bad operation or charge too much or any of those things. But we haggled that out then and in subsequent meetings and so I said, “Let’s go on and build it. You do the turf grass and help give advice on building it and I’ll use your architect” a guy named Joe Lee, who is the one who trained Rocky [Bill’s son]. Rocky worked for Joe Lee, and that is how Rocky is a golf architect today. But, uh, Bill was just absolutely true [Cowan note: a true friend] in fact, I later did three other courses with him. After I was gone, we continued that relationship all over, years. But it [Flat Creek Country Club] was the right one; it fit us; it was not an elitist thing. Everybody could join and it runs, I think, very well.

2A |00:22:12|

GADDO: And it’s still the same. Still the same.

PIET: Yeah, I mean, it’s still in the same building

COWAN: It has always been a credit to the development. You know, I didn’t have but I always felt I had control against anything bad happening. It was usually just a telephone call. But I had a wonderful guy and a wonderful relationship.

PIET: I’m sure everyone here knows, but just for the record—the lake was built; when did you make your decision, what was about the time frame you made the decision—

COWAN: (crosstalk) It was during, uh—

PIET: (crosstalk) With the dam and the lake?

COWAN: Oh, that was in ’59 and we built the lake, probably, in early ’60, uh—maybe it was summer—I don’t know when it (??). The biggest event, of course, was in February—I want to say the 25th—’61; however, we had this big rain, a flood, and that—

PIET: (crosstalk) I bet that filled up the lake real fast.

COWAN: —it breached, what is called Huddleston Pond up here. You know, whoever built that thing had a crooked eye (unintelligible). It was low on one end, and when that flood breached it, it washed out and washed down into this lake and then ultimately washed out the main spillway. It was actually the equivalent of a dam break.

GADDO: What year was this?

2A |00:23:48|

COWAN: This was ’61. So I woke up and I was still living up there [Shakerag] because there was nothing down here. I had a Jeep. It was a terrible flood and somebody came up to the house and said that the water was about to go over Highway 54 down there. I knew I’d get the blame for that. (Gaddo laughs) So I went out I got the Jeep and came down and, sure enough, it was very high. But I’d been through all the engineering of this thing and that wasn’t supposed to happen. So, I made my way through all of the mud and all down to the spillway. The spillway was designed with that in mind. It was a hundred and yeah, a hundred and twenty linear foot concrete spillway, not the dam that you see there where the water intake and all that is what you now see going around it. Straight in line with the dam, if you look when the lake is down, you can see an old concrete structure at the bottom of that. And you’ll see the head wall of it even now, on this side on the dam side. But what had happened is that that thing was designed with these boards three feet boards across supported by iron pins. The idea of those were called “flashboards,” in engineering parlance, and so what happens is that was to hold the lake at a higher level. See, I wanted the lake to be a constant level, so I had them design it to accommodate that. Then in these floods, which are supposed to occur every twenty to twentyfive years those boards would break away and let the water through so you could have a higher lake level and still have that carrying capacity.

2A |00:25:33|

And that sounded like a nice idea, and it did what I wanted done but the problem was they didn’t break. So that four feet of water was going on top of that three feet and thus, backing it up. But worse than that the engineers at least should have accommodated that maybe happening so

the structure wouldn’t fail, but they didn’t. It got around that edge the other protected side and started channeling around it, and just ate away and ate away and ate away enough so that it moved one hundred twenty feet intact. This end stayed up here the dam was still there but it moved it down stream, so (unintelligible). That was a heartbreaker there. Funny thing you did, when you asked about engineering that day I called the engineers. In fact, I’ve got it written in here. His name is I think he just died named Ben Hall. I got him down water was still flowing. I took him down there in the Jeep. He was wearing a starched shirt. I’ll bet he had a tie on, but he was certainly (unintelligible) carried a cane. His whole life was hydraulics and here was the biggest of all going right before his eyes. It was like he was having an orgasm while I was having a heart attack, (Gaddo laughs) but we’d be walking along the shore and talking and occasionally he’d disappear. His cane would go down in the mud

GADDO: Whoa! (laughs)

COWAN: and he’d fall over, so I’d stand him up and we’d go on. It was something. I sued them, by the way. (Gaddo laughs)

2A |00:27:22|

Gaddo: Over that?

COWAN: (crosstalk) but we couldn’t find the real smoking gun. You know, you could say we didn’t inspect it, or those pins should have been tested. There were a lot of reasons, but the

lawyers basically said unless you’re playing dirty, you can’t collect anything suing. I thought we’d get some settlement or something. Back then, people were too gentlemanly to sue. I kept those plans in my office on a table there. I would just look at them occasionally. One day I just went over and looked at them, and all of a sudden, like a light coming on, it just jumped out at me right on the plan why it failed. Of course, nobody I had hired another engineering firm two others, to look at it and see what was wrong and nobody picked up what was wrong, but I found it. And when I found it, I called the engineers and said I wanted to talk to them. I carried the plans down there and pointed it out. They said, You got me just like that. And they settled. But the design wouldn’t have worked in any case. You couldn’t put a bulldozer through it.

GADDO: Well, what was it?

COWAN: Well, in the design remember I said there were boards with pins like this and they were tongue-in-groove boards that hold the water. And they uh, used a U-clamp around that pin.

You’d say, Well, there is nothing remarkable about that. But they laid it like bricks, like this [gestures overlapping]. Now at each one of these joints they put a plate and bolted it in and then here they bolted it. So it was like a brick wall, but at each overlap you had something holding it here so you could have put a bulldozer at either end and you couldn’t have pulled it apart. Literally, that thing, if it went, it had to go as one whole unit.

GADDO: The whole thing, yeah.

COWAN: The way it was designed to break out in the middle, and this, and this [gesturing] depending on how high the water got. It even had scores around the pin to make the center ones go first. You know, very scientific.

PIET: But they made the thing too strong.

2A |00:29:45|

COWAN: Yeah, they made it where it was just well, that was just the flaw right on its face. It could not have worked. Right there on the blueprints, the way somebody built it (??)

Worst part of that was—you couldn’t—I said, “Well we’ve got to rebuild it.” Well, that thing had washed out, sort of like the dam site up here. You couldn’t have a—you couldn’t—the structure was washed out. It was going to cost—in those days—I had a bid. I had a design and a bid, but we were going to have to build, from the ground up, a concrete—a full concrete structure like the Corps of Engineers dam. It was very expensive because it washed out. So I designed what’s there myself. I took it to engineers, and they said, We can’t tell you why that won’t work, but we are not going to put our stamp— pause in recording as cassette tape 2, side 1 ends; side 2 begins

COWAN: I actually built it myself, put the lever up, and Chip Conner was working for me then, and we actually built it. The way I designed it, which was, in essence, an earthen dam capped in concrete and—

GADDO: That’s what’s there now?