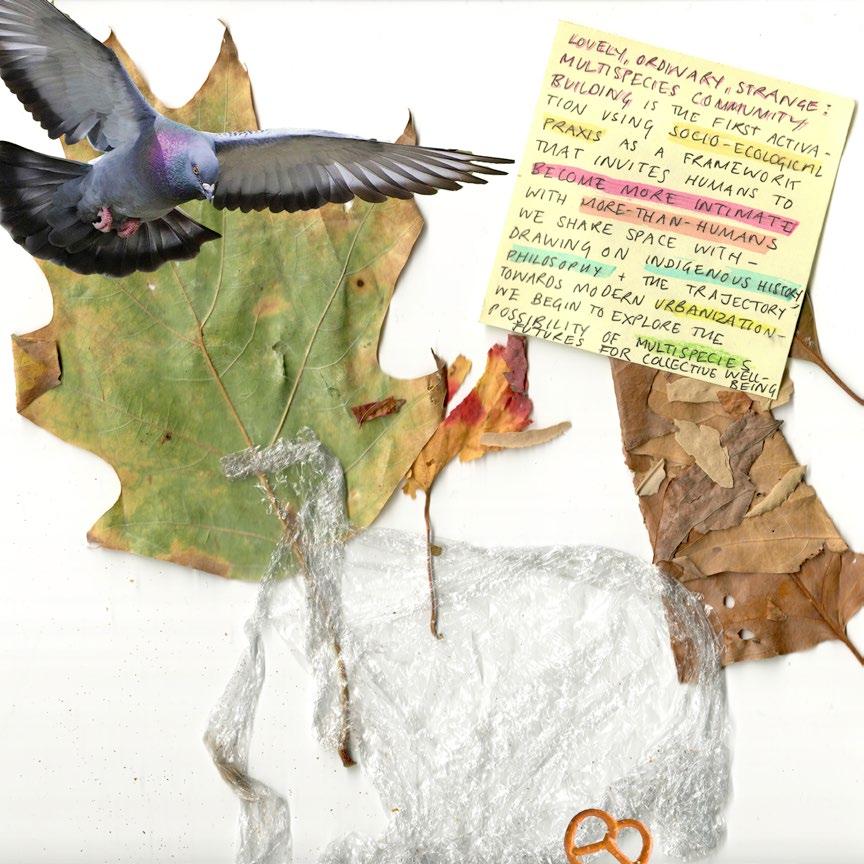

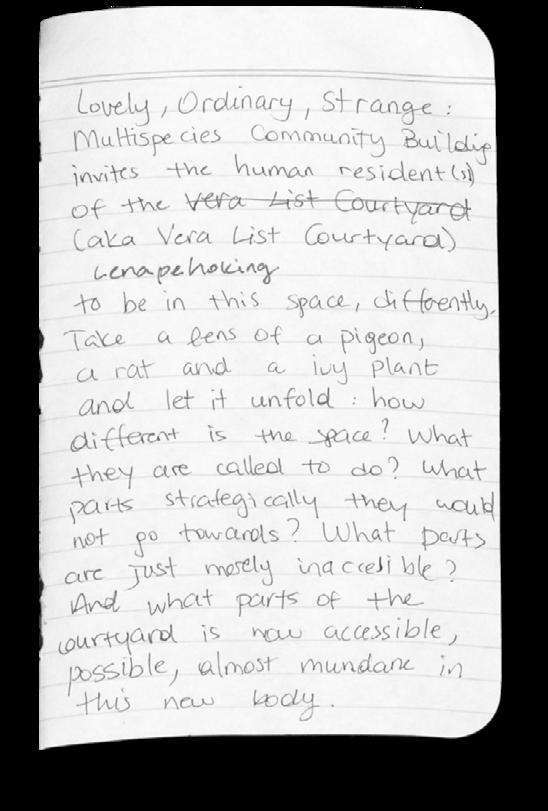

MULTISPECIES COMMUNITY BUILDING LOVELY, ORDINARY, STRANGE

IN VERA LIST COURTYARD

this zine documents some of the history and ideas that inspired a multispecies exploration of The New School’s only outdoor space on campus in october 2025 as part of the visible-izing care festival at the new school.

the zine traces the history of place, of species, and hints at potential shared futures where the most villified of non-human urban dwellers are recognized as intimately tied to our own histories and cultures as human beings.

it is inspired by the belief that shared knowledge and a sense of belonging that transcends species boundaries is vital to healing the crisis of relationship that underpins the so-called climate crisis,

by izzy groenewegen, urbanist, multispecies advocate, and alum of parsons.

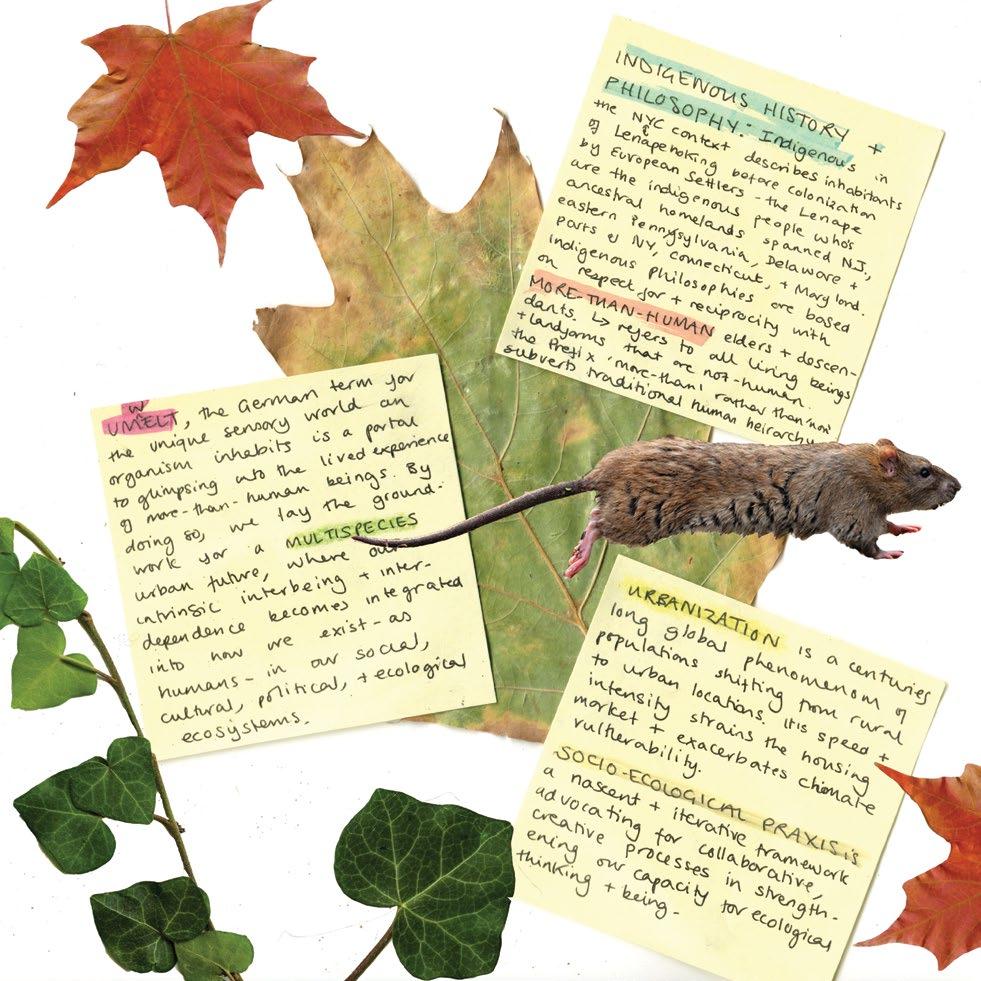

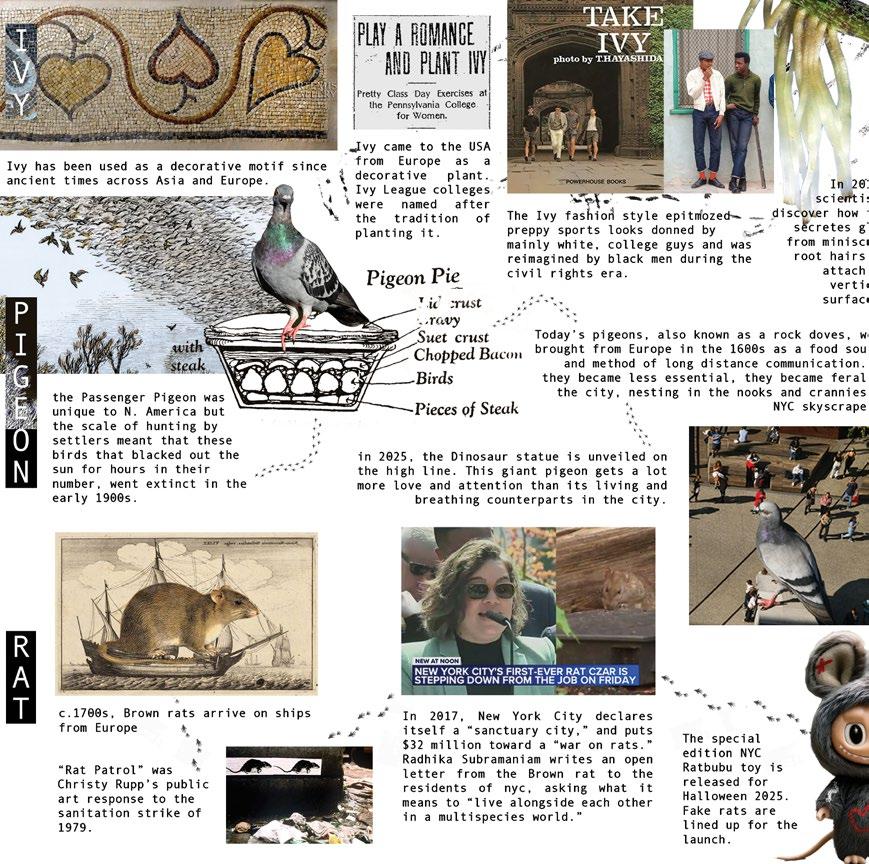

non-exhaustive, incomplete timeline of the ivy, pigeon, and rat.

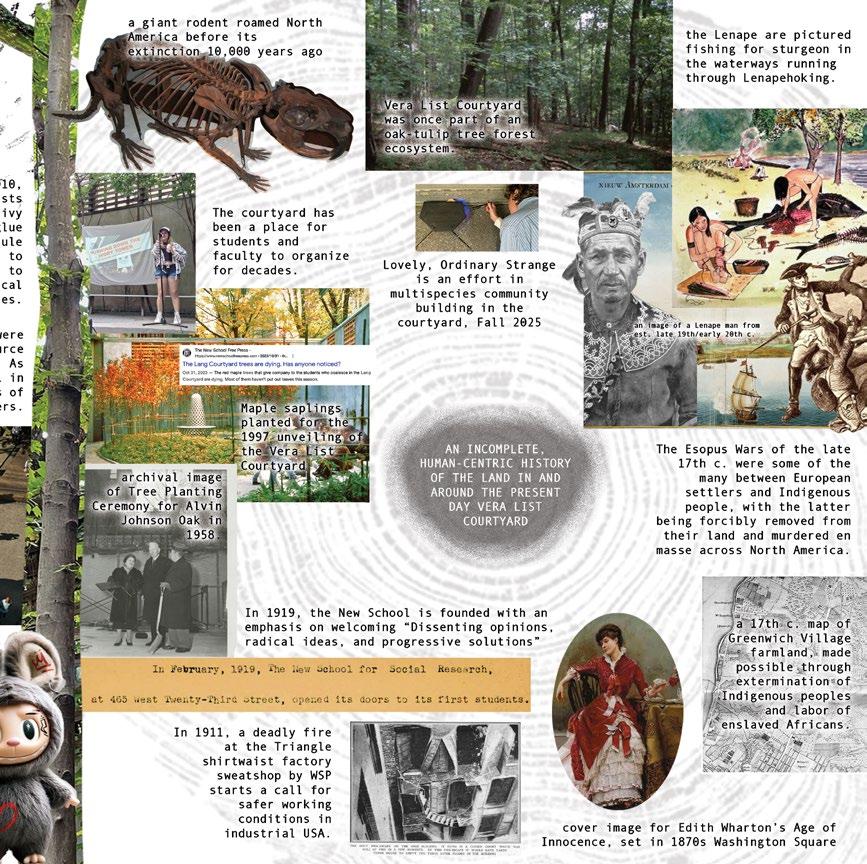

non-exhaustive, incomplete timeline of the land now referred to as lang or vera list courtyard.

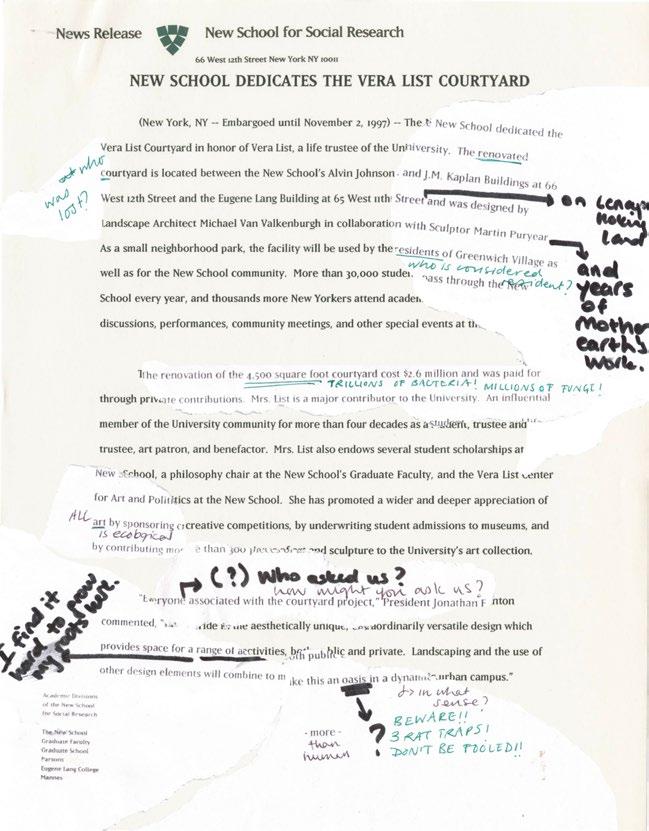

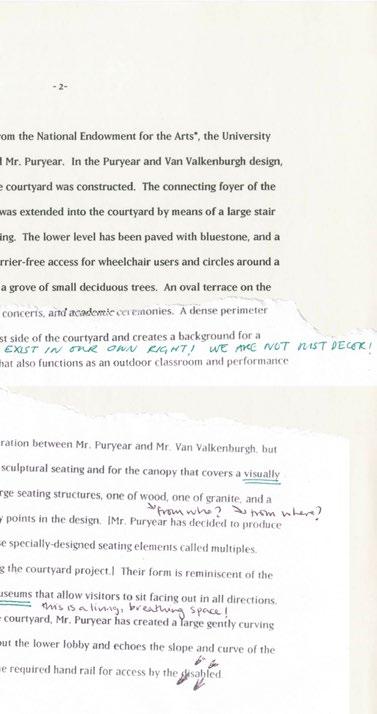

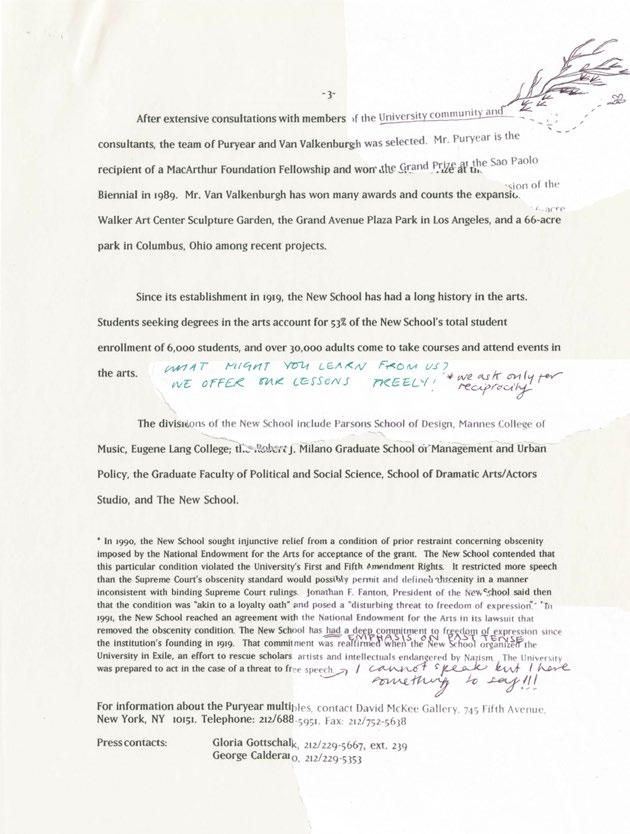

multispecies annotations on the vera list courtyard dedication, 1997.

invitation to explore the courtyard through the umwelt (see left) of more-than-human residents and visitors.

rat sensory profile and ways of glimpsing into its sensory worlds.

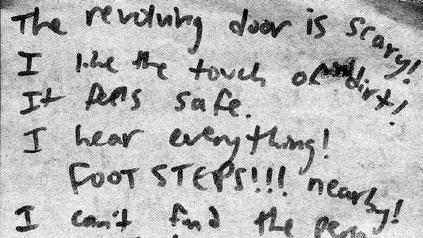

rat recordings from the lovely, ordinary, strange event in the courtyard.

pigeon sensory profile and ways of glimpsing into its sensory worlds.

pigeon recordings from the lovely, ordinary, strange event in the courtyard.

ivy sensory profile and ways of glimpsing into its sensory worlds.

ivy recordings from the lovely, ordinary, strange event in the courtyard.

interview with mark larrimore, religious studies professor and friend to the trees.

invitation to imagine multispecies urban futures at the new school.

walk “A stroll into unknowable worlds”

Familiarize yourself with some of the tools How might they aid you in experiencing another being’s umwelt? What else might you use?

Freely explore the courtyard through the umwelt of a selected species.

Use iNaturalist or another identification tool to aid your exploration, if you wish.

Notice how your imagination expands or if you feel blocked

In any and as many ways as you like, record your experience of glimpsing into the umwelt of another being.

walk prompt for the lovely, ordinary, strange activation

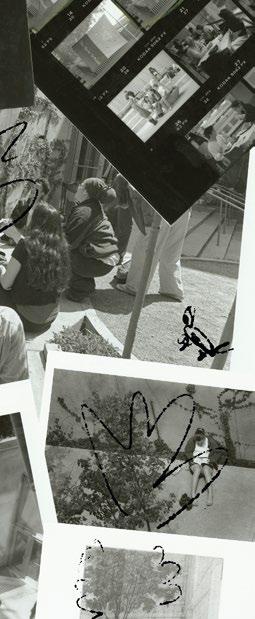

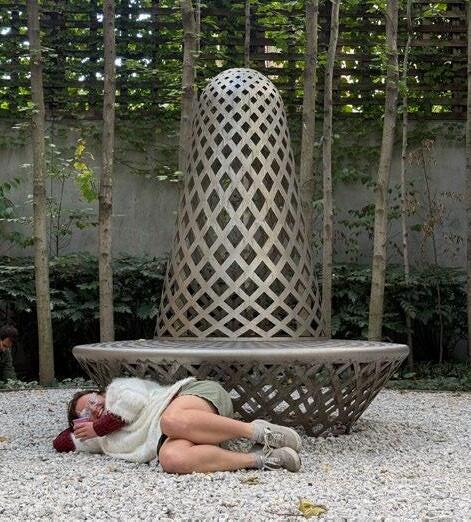

collage of archival images in the courtyard by ezgi eyigor

reflections by ezgi eyigor, lovely, ordinary, strange participant and collaborator

Massage the lobes of your ears to increase blood flow.

Use your imagination to turn up the volume and pitch of everything you hear.

Tune into the subtler sounds in your environment. Could you sense an electrical wire?

How does this impact your sense of surroundings? Your mood? Your orientation?

With over 1% of DNA devoted to odor detection, rats live in a galaxy of smells. Every surface, object, and whiff of air provides important information. Rats use their 2nd scent organ, the vomeronasal, to detect pheromones from other rats that signal re-

Most rat communication occurs beyond our hearing range. Humans can hear up to 20 kHz, but rats can hear up to 90 kHz, into the range of ultrasound.

The humming of electrical wires and distant traffic fall within a rat’s audible range, with the crinkling of a plastic bag causing major distress.

productive status, stress, and hierarchy. Research suggests that rats produce high pitch sounds to create clusters of particles that enhance their reception of pheromones and other smells.

Visualizing smells can help to improve your sense of smell.Use a shallow sniff to identify a particular smell.

Pay attention to surfaces, or objects you would not consider scented. How do these scents shift your sense of space?

Rats have two color cells: one for green and one for blue and ultraviolet light. Reds appear dark to them. Rats use ultraviolet to see urine marks from other rats, gaining information on territory, sex, age, social rank, and reproductive readiness.

Rats’ eyes are on the sides of their head and are able to move each eye independently - likely to see aerial threats from birds of prey. They cannot judge distance well. They bob their heads like pigeons, using motion parallax to take mental snapshots of their field of vision and estimate depth.

Rats do not see sharply. They are nocturnal and averse to bright light.

Imagine you can only see in shades of blue and green. Anything red becomes dark.

Lower yourself to the ground and reopen your eyes. Are there traces of past presence that might glow faintly to you? How might they transform your perception of privacy or ownership?

Keep one eye on what is above or behind you. How does this affect your comfort in exposed areas?

Imagine stitching your world together from fleeting snapshots. What might it feel like to construct depth with rhythm and motion?

A rat’s whiskers are more sensitive than our own fingertips, and are used as short-range sensors.

A rat perceives its environment by brushing its whiskers back and forth dozens of times per second against surfaces, objects, and other rats.

Rats prefer to run along edges where they navigate by whisker touch and are close to shelter.

Bring awareness to your outer layer of skin and pay attention to what it is in contact with.

Plan to move a short distance, with part or all of your body. Unfocus or close your eyes, using touch to orient yourself. You might try to reach an edge.

Make small repetitive movements to develop a detailed sense of a surface’s texture.

holly embodies a rat by scurrying around the courtyard, searching for hiding spots.

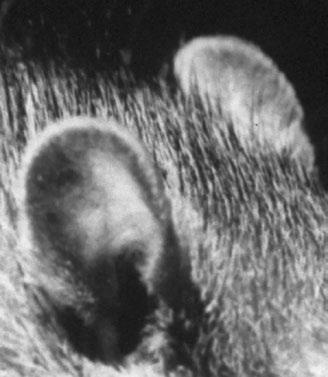

ultraviolet torches help us imagine the rat’s color spectrum.

peering into a rat trap with

rats use the courtyard in totally different ways to humans.

rat trap from the inside.

how a rat might see a leaf. imagining the rat’s courtyard experience with an ultraviolet torch.

blue light glasses covered in ceran wrap for a more rat-like blurry vision.

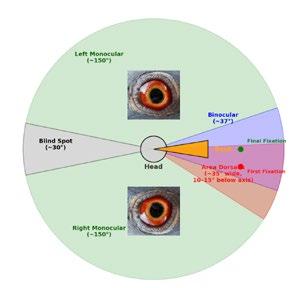

Pigeons have much better vision that hu- mans do and can see ultraviolet!

Pigeons can memorise visual landmarks, helping them create a mental map of fa- miliar areas.

They have a panoramic field of view of ~ 340 degrees.

Let your attention sweep in a wide cir- cle without moving your body. What shifts when you sense the whole space at once?

Tilt your focus forward. Imagine your beak as the center of a narrow field of vision where details sharpen. What details pull your eye?

When walking, a pigeon bobs its head to focus its vision.

The pigeon thrusts its head for- ward, then holds it still as its body moves, allowing its eyes to keep a stationary view of its surroundings.

This motion stabilizes the image on the retina, helping the pigeon see clearly.

Pigeons can detect infrasounds made by ocean waves and weather pat- terns that travel thousands of miles through the atmosphere, below the range of human hearing.

Try a small bob of the head. Hold still, then shift forward. Notice how nearby and faraway objects seem to move differently. How does this help you sense distance?

While humans can’t hear infrasound, we can feel it as physical vibra- tions.

Plant your feet or any other body part firmly on the ground. Can you ‘hear’ vibrations through the ground or atmosphere through your body? Can you imagine them?

How does this impact your sense of surroundings? Your mood? Your ori- entation?

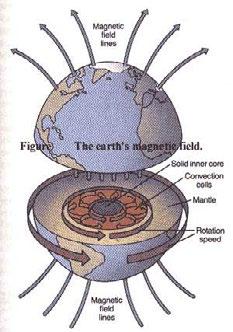

While scientists are not sure how, pigeons and other birds navigate by sensing the earth’s magnetic field. One theory is that they use magnetic particles in their head.

Some studies show that - like pigeons - humans can sense our planet’s magnetic field. Imagine you are navigating yourself towards home, where do you turn to?

Research suggests that pigeons create a map of environmen- tal and atmospheric odours over long distances, allowing them to return home by smell alone.

Take a deep breath. Imagine that each current of air car- ries a trace of directions and places. Where does your attention go?

a tongue and cheek illustration of a pigeon by a student participant in lovely, ordinary strange

an archival image of formed by the multicolor sion of a pigeon swooping

the courtyard transmulticolor and panoramic viswooping overhead.

it is thought the slur “rats with wings” was coined by parks commissioner thomas hoving, who was frustrated by the feral pigeons no longer needed for communication or food.

Relative to humans and other animals, plant movement is slow and growth-based, such as phototropism (growing towards light) and thigmotropism (response to touch).

Plants respond to environmental stimuli over hours and even days. Movements are generally measured in millimeters per hour.

Slow down your breathing and your heartbeat. Can you feel time differently?

While your growth is imperceptibly slow, you are full of motion. Can you feel air pass through your leaves, the constant flow of water through your veins?

Ivy prefers dappled, filtered light and gets burnt by direct sunlight.

Ivy seeks out non-reflective, dark, rough surfaces with a neutral pH to attach to, climbing up to 80 ft high. If ivy cannot find a vertical surface, it grows as ground cover.

Imagine your roots stretching out in all directions. What is it like to stretch out and take over a space?

Imagine yourself growing slowly and steadily towards a surface. What do you sense for?

As soon as ivy makes contact with a suitable surface, the plant’s roots change shape, increasing their area of contact.

The plant then excretes a glue to anchor it to the wall.

Tiny root hairs come into contact with the climbing surface.

They fit into minuscule holes in the wall and dry out in a spiral shape to locks the root hair into place.

Hook-like structures growing on the tips of the root hairs strengthen their hold.

Ivy flowers in autumn and is an invaluable late-season food source for over 70 pollinating insects, including butterflies, moths, flies, wasps and bees.

Other insect species visit Iiy for the prey attracted to the flowers. Many invertebrates also feed on the leaves and buds. Ivy supports species as forage, shelter and nesting habitat.

Ivy is the most abundant and widespread late-flowering plant, and considered a keystone species for flower-visiting insects.

Make contact with a surface. Which surfaces are you drawn to?

Use your sense of touch to discover small crevices in the smooth surfaces you see.

Imagine that as soon as your body makes contact with somewhere to adhere to, its form changes, fitting the grooves of the surface.

Feel how your roots shift and curl, seeking to anchor deeper.

Your body is blooming when most other plants are quiet. What signals are you emitting to those who come for their last feed until spring?

composition using pencil rubbings of ivy plants, close-up of courtyard wall texture, and image of the ivy flower.

I’m very fortunate to have an office on the fourth floor that looks out on the courtyard, so the trees are my office mates. I did a course called Religion of Trees a few times, and we spent a lot of time in the courtyard. And that was a time before this new planting; there were a whole bunch of the younger trees on the far wall, where those bushy green things are now, and several of them were clearly dead. And we figured out it’s because there’s another floor of offices and classrooms underneath it, so the trees only have about a meter and a half to put down roots. At one point, some of my students were sitting in the cafe (next to the courtyard), and one of them sent me a message saying they were taking the trees out. And several of the saplings were so completely dead that the maintenance people could just pull them out, and then for a while they were sort of lying there like logs, narrow little things. So, as a class, we decided we needed to do something, and we came down to improvise a parting rite for the trees, a farewell. That was a few weeks into Fall, so there were a lot of big yellow leaves from the ash tree across the way. We came down as a group and quietly wandered around. I’d said in the classroom beforehand, “Do we want to plan something?” The students said, “No, ab- solutely not. We just have to go there and sort of let the space speak to us. us.” So we went down there, and there were three holes where the trees had been, and one by one, people started picking up leaves and placing them around them in these little patterns. And then the pat- terns started to morph like kaleidoscopic things with yellows and reds, and some people found some roots, and then some- body connected one of them to the oth- er with this little train of leaves, and then before we knew it, with nobody say- ing a word to anyone about what we were doing, we had kind of stitched them all together. I’d like to offer a chance for something like that to happen again. When I was growing up, I heard about leaves changing color in books, but I never saw it. When I came to the East Coast, I was transfixed by the deciduous seasons, and then wound

up in this office when the maples were not as big as they are now. I’ve been here more than 20 years or something, so the maples reach just below my window. So now they sort of fill the entire window. And you see all kinds of things when you’re up there that you don’t get to see when you’re on the forest floor, like the tiny little buds that come out in the spring. And learn that the red maples are called red because of their stems, not because the leaves turn red. Lots of trees, lots of trees. I started teaching Religion of Trees after Suzanne Simard’s Finding the Mother Tree came out, and I started to see trees differently. Instead of seeing these solitary saints, I came to understand this incredible network of mutual care, which I think leads to its own kind of religion. There was just this sense - and I already had a sense from the maple trees out the window of the office - that they are people. I got from Robin Wall Kimmerer this un- derstanding of the trees as standing people, like, what would it be to un- derstand them as people? In one of my earlier classes, I encouraged students to read Robin Wall Kimmerer’s essay on how Nature needs a new pronoun. She suggests that English, by rendering everything that is animate - inanimate - and by forcing us to talk about plants and animals and so on, with a few exceptions, as just “it”, makes it easy to exploit and impossible to imagine a relationship with them. So she imagines what kind of a new pronoun we might come up with for living things, and ends up with syllable Ki, which is the last syllable of this long Anishinaabe word that an Elder offers to her. And she says, Ki’s good, you know, we can use it. It rhymes with ‘s/he’ and has an obvious plural in kin, which is very nice. So I’ve encouraged students to try to refer to the trees as kin. And some students take it very seriously, some people don’t, and the ones who do change the way we relate to kin. I have a sense of introducing new human people to the standing people of the courtyard in some way, not that I’m their spokesman, but that I am kind of an intermediary. I mean, it’s kind of like “you should meet these folks.” But I’ve also realized recently that I can’t actually remember what it was like not to see trees as people. Can’t remember if I ever sort of thought of them just as these automata, these little wood and leaf and fruit-producing

machines that just strive against each other for the sunlight in order to produce seeds and nuts so that they can produce more forever and ever, with no meaning and no relationship and no anything. I’m not sure if I ever did see them that way, but I certainly didn’t have the concept of them as people, in the sense that we sort of learned from Kimmerer. Part of being a people with other people is that there are relationships at the level of people. So human beings have relationships with standing people. So I’m not quite sure what the relationship is between that group of standing people over there and the human people who pass through here, but I’m quite sure it’s there. For me, it’s a personal practice, but I’m very happy to be able to initiate students and others into a discovery that New York City has a forest. There’s an urban forest of many different trees, and then, of course, oh, my God, street trees are so lonely. I was reading this book by this author, Joan Maloof, an ad- vocate for old-growth forests, although she calls them secondary growth because she’s like, any place will become an old- growth forest if you let it. So every county in the United States would sort of set aside some area for that. And she had this description of street trees that completely changed my view of them. She’s like, they’re all so young, they’re basically all orphaned teenag- ers who never get a chance to mature. The trees that we plant, we bring them in for a time, for some particular purpose, and then they no longer serve that purpose when they scratch the buildings, when their branches sort of fall down on things, then we take them down. If you go into a forest, it feels wonderful. None of those volatiles were intended for us us, and most of them were intended to sort of keep various other species at bay. And it’s just because we’ve arrived fairly late in their evolutionary history that we’re unharmed by them and can actually enjoy them. So I think there’s a kind of romanticism, a kind of colonial fantasy, about, “oh, here’s this land that just welcomes us, that’s just waiting for us to be sort of empty in it.” But I think city trees are completely different. Every city tree was planted by a human being. Every street tree is already part of a web of relationships with humans and other urban peoples.

this is a 1950s architectural rendering of an open plan, public version of the courtyard opening onto 6th ave. this did not happen.

Drawing inspiration from the previous pages and from your own imagination, how might you transform the courtyard into a public space that is welcoming to a multispecies community?