r o w i n

iat ne Hill Review

2022-2023 g

g p a i ns Pal

about the cover

There are four variations of the cover to the 50th edition of the Palatine Hill Review. From the top left, clockwise:

Roots

Anneka Barton

Digital Illustration

Sun March

Zach Reinker

Digital Illustration & Graphite Sketch

The Timekeepers

Dakota Binder

Digital Illustration

Still, We Endure

Kincaid DeBell

Digital Illustration

edition 49 honors

Associated Collegiate Press (ACP)

First Class Honors with Marks of Distinction for Content and Writing & Editing

Association of Writers & Writing Programs (AWP)

2023 National Program Directors’ Prize Winner for Content and Runner-Up for Design

Palatine Hill Review 2022-2023 growing pains

colophon

The Palatine Hill Review, formerly known as the Lewis & Clark Literary Review, is the annual student-run literary and arts magazine at Lewis & Clark College, located in Portland, Oregon. In changing our name, we join an ongoing, campus-wide shift away from upholding the colonial legacies of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark.

Our 50th edition, growing pains, is printed by Morel Ink (also) in Portland, Oregon. This edition’s typefaces are the Dovetail MVB font family (for titles, subtitles, bylines, pull quotes, and page numbers) and Atkinson Hyperlegible (for body text and folio).

This edition was created with Adobe InDesign CC 2023, Adobe Illustrator CC 2023, Adobe Photoshop CC 2023, Procreate, and the help of many, many Google Docs and Spreadsheets. Thank God for Google Drive.

copyright

The work showcased within this edition remains the intellectual property of our individual contributors, who retain all rights to their materal.

The views expressed within this edition are those of the contributors and do not necessarily reflect those of our editors, general staff, donors, the Student Media Board (SMB), or Lewis & Clark College.

v • miscellany

masthead

Editors-in-Chief

Jillian Jackson

AJ Di Nicola

Design Editor & Art Director

Elizabeth Huntley

Associate Design Editor

Zach Reinker

Associate Editors

Max Allen

Burton Scheer

Faculty Advisors

Karen Gross

Mary Szybist

Site Supervisor

Amy Baskin

Editorial Board

Josie Alberts

Sofija Aviles-Lindsey

Zoe Bockoven

J Frank

Elizabeth Grieve

Hera Hyman

Shira Kalish

Yonas Khalil

Anna Littlejohn

Marissa Lum

Colleen Maloney

Ryan Marshall

Daniel Neshyba-Rowe

Corryn Pettingill

Shelby Platt

Sophia Riley

Bela Salinger

Coco Silver

Design Board

Claire Baco

J Frank

Elizabeth Grieve

Shelby Platt

Soleina Robinson

Clio Torbenson

palatine hill review • vi

letter from the editors

When our first issue went to print in 1973, Nixon was president, and abortion was legal in all fifty states. College-age men got sent to Vietnam, and you could buy a one-pound bag of Oreos for 49 cents.

Nowadays, Oreos cost $4.98, and, as the Supreme Court and anti-trans lawmakers like to remind us, our bodies are still not our own. Shoved between Zoom calls and your umpteenth COVID test, this moment can feel so singular. And yet, as alumni Moss Kaplan’s 1993 nonfiction piece, “But I’m Low Risk, Right?” tells us, pandemic anxiety ravaged past generations, too.

“In these unprecedented times” — so goes the hackneyed saying, yet is any of this truly unprecedented? As we dove headfirst1 into the review’s archives, we felt that many of our favorite pieces about Palatine Hill and Portland could have been written yesterday.

Consider, for example, Cindy Stewart-Rinier’s 1981 short story “Ice Storm.” Hit with almost eleven inches of snow, this spring semester we found ourselves under that blue-black sky she captures so well.

So much of college is realizing you aren’t special, freaking out about it, and then making peace with your non-uniqueness.2 In the end, you’re just floating on a February snowflake, breathing in the same cold-not-crisp air as those who came before you.

growing pains features several pieces about dead or dying grandparents, and this macabre coincidence proved

1If you know, you know.

2If you succeed in doing this, please tell us how.

vii • miscellany

instructive as we searched for Issue 50’s title. Maybe the worst growing pain isn’t that late-night ache in your legs. Maybe it’s attending your grandfather’s funeral in a too-short skirt, because honestly, who buys mourning attire ahead of time? Maybe it’s realizing, as Lizzy Acker does in her 2004 poem, “The Science of Drains,” how many lives your parents lived before you came along.

So too has Issue 50 lived many lives in just eleven months of existence. When, in May 2022, we started planning the Palatine Hill Review’s fiftieth edition, the concept was simple: a short, 150-page book, with a few “Best Of” reprints from past editions. Surely bone meal — the review’s wildly popular, now out-of-print forty-ninth issue — was a flash in the pan.

We were wrong. This year, submissions piled in at a 53 percent increase from last year’s already historic numbers. If bone meal was a glimmer, growing pains is a goldrush. What a pleasure it is to hold each of these 113 pieces3 to the light.

May they shine and flicker like birthday candles you can wish on. Happy 50th, Palatine Hill Review.

Jillian Jackson

Jillian Jackson

Editors-in-Chief

AJ Di Nicola

3Not on purpose, but we all know Jillian loves a good Taylor Swift reference.

palatine hill review • viii

table of contents about the cover issue 49 honors colophon & copyright masthead letter from the editors table of contents contributors acknowledgements i iii v vi vii ix xvii xxxiii content warning reprinted pieces from previous editions ix • miscellany

short stories Ice Storm Cindy Stewart-Rinier Angel in the Snow Coco Silver Overload Joelle Pazoff A Welcoming House Zach Reinker A Mild Case Jillian Jackson 29 42 64 77 121 Drowning in Sugar Jillian Jackson Dates to the Rodeo Rosalie Moffett Crow’s Feet Anneka Barton The Lights Reflect in the Water Kathryn Kiskinen Getaway Cleo Lockhart 148 164 183 212 283 creative nonfiction The Gas Mask Emily Hazel Wagner But I’m Low Risk, Right? Moss Kaplan On Reading Woolf Aubrey Roché As Above So Below Leanne Robinson 62 101 237 241 The Maternal Inheritance of the Brain Burton Scheer Meeting Grief Halfway Piper McCoy Harmon 264 274 palatine hill review • x

“for my friends”

Olive Savoie

Witchcraft

Elizabeth Winkelman

Lune du Miel which means ‘Honeymoon’ en Français

Kim Stafford Portland Excursioning

Matilda Rose

Cantwell

The Mestizo’s Granddaughter Dances Swing While Consiering

Polyamory

Alina Cruz

On the phone with my sister

Alison Keiser

17 19 21 23 24 25 38

thinking hopefully

Emma Parrish Post

The Zoo

Tiani Ertel

Seventeen

Maya Mazor-Hoofien

Blackberries

Lyra Meyers

The Edge of Autumn

Sarah Walker

Sojourners

Corryn Pettingill

Letter to a Friend, 2/25/19

Caleb Weinhardt

I Don’t Like Pulp

Nora Cesareo-Dense

festering season

Cleo Lockhart

Ghost Dancer

Piper McCoy Harmon

poetry

2 4 6

13 16

The state on your fake is where I’m from Kit Graf 1

9

73 75 xi • miscellany

59

Jamaal gets his first Kiss while learning what it means to be Black in America Tj Muhammad Recitation in Repose Elliott Leor Negrín What I Did On My Day Off John Willson Watzek Relativity Daniel Neshyba-Rowe NOTICES Salma Preppernau Animal Whisperer ABECEDARIAN Annabelle Rousseau No. Forty Two Charlotte Avery Feelings alla Vodka Rowan Moreno 99 107 110 113 115 120 137 139 Eating a Granola Bar and Encountering an Eldritch Horror Sam Mosher On the Death of a Friend—Four Months Later Averill Curdy universal experiences mo rose app-singer ‘til i am full Emma Krall preventative orthodontia Elliott Leor Negrín Self-Portrait as Icarus Ryan Marshall “Birth of Venus” Gwen Baba 140 141 143 147 161 169 171 palatine hill review • xii

The Secret Love of Ants & Other Histories Eli Dell’Osso Sestina Colleen Maloney order of events Emma Krall Reaction to “The Spectre Still Haunts” Alyssa Simms First Impressions Danielle Phoenix Pon ‘never before have I seen a cow dance ballet’ Dahlia Callistein How to get the crows to trust you Lauren Caldwell 173 175 178 179 182 193 195 Water on the Brain Tiani Ertel uncomfortable question Elizabeth Huntley Just Smile Soleina Robinson

can never brush my teeth enough Bria Whitten Yeye’s Funeral Danielle Phoenix Pon Virginity cake Kit Graf They Tell Me I Smell Like River Amy Collinge Ladybug Eyes Eli Dell’Osso 197 199 201 203 206 207 209 231 xiii • miscellany

I

poetry

cont. The Woman in the Red Dress Hera Hyman Before the Goodbye Rosalie Zuckermann When Anticipation Comes to You as an Monstrous Ant Sophia Riley Hold This Grief Indira Heller The Cake Annabelle Rousseau Tired of existential dread, I lose myself in sitcomland Maya Mazor-Hoofien 233 240 253 255 256 257 What is love? Piper Clark-White Working It Out For Myself Nick Smart Envy J Frank The Science of Drains Lizzy Acker Riptides Russell Holder Shame J Frank Inheritance Josie Alberts 259 261 269 273 279 282 293 palatine hill review • xiv

,

Kind of Peace Max Allen Welcome Mosher Alina Cruz Summer’s Ripening Breath Jasmine Scandalis Somewhere, Russian Federation Masha Glazneva The Float Ella Neff Beacon Oscar Lledo Sea Creatures Burton Scheer The Gatekeeper Sleeps Zach Reinker Dual Flight J Frank Christmas Eve Corryn Pettingill 3 5 11 15 20 22 27 36 37 41 Waypoint Zach Reinker

eaten alive Kincaid DeBell Treeline Oscar Lledo Fixtures Syd Schubbe The Railyard Cafe Ella Neff Pacific Cloudburst Stephanie Taimi-Mandel Fruity Fish Isabelle Atha Living On The Sand Burton Scheer

vampiric on

friday night Cleo Lockhart Straining Max Lobato 61 72 74 98 106 109 114 119 136 138 xv • miscellany

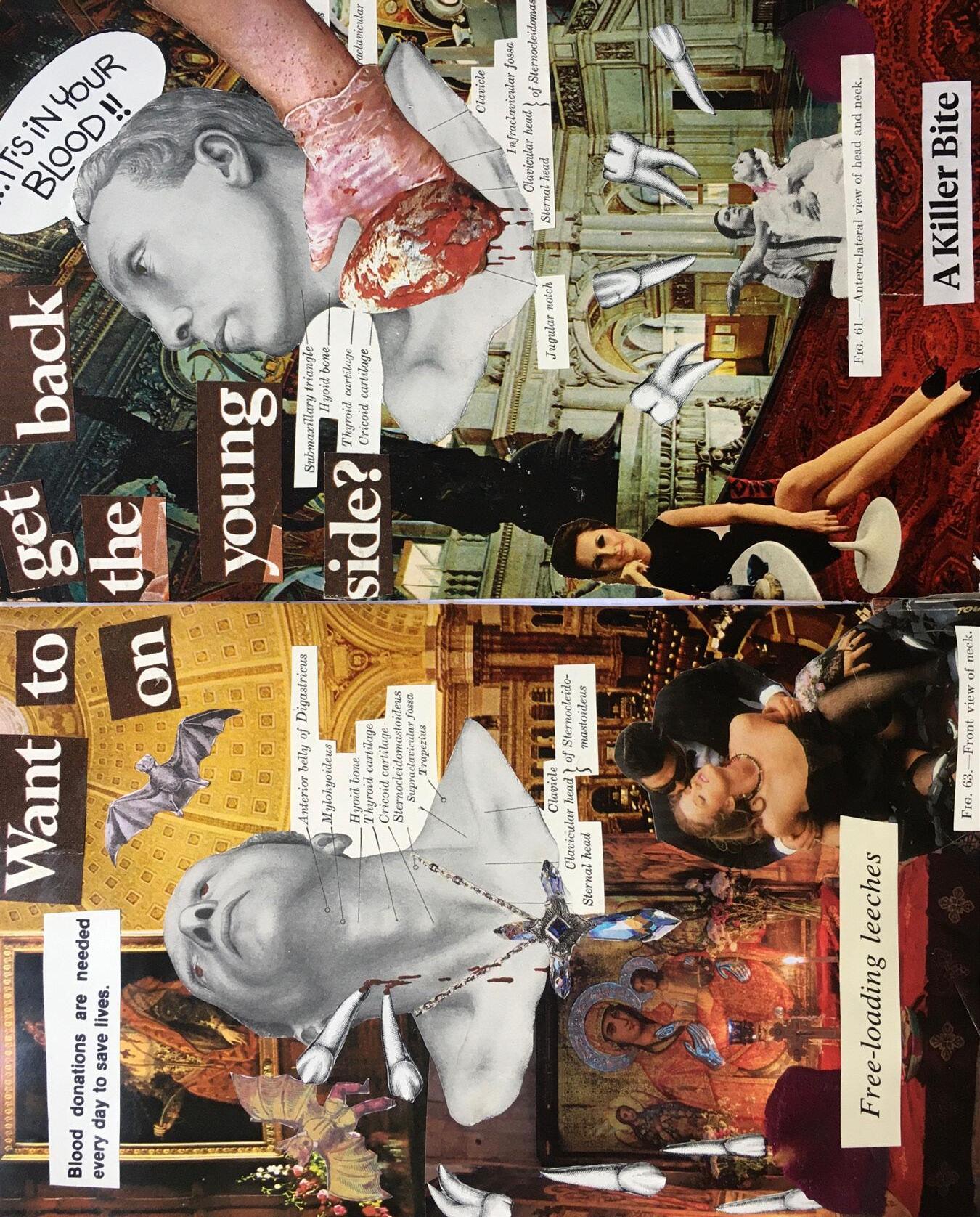

visual art Some

being

nothing wrong with getting a little

a

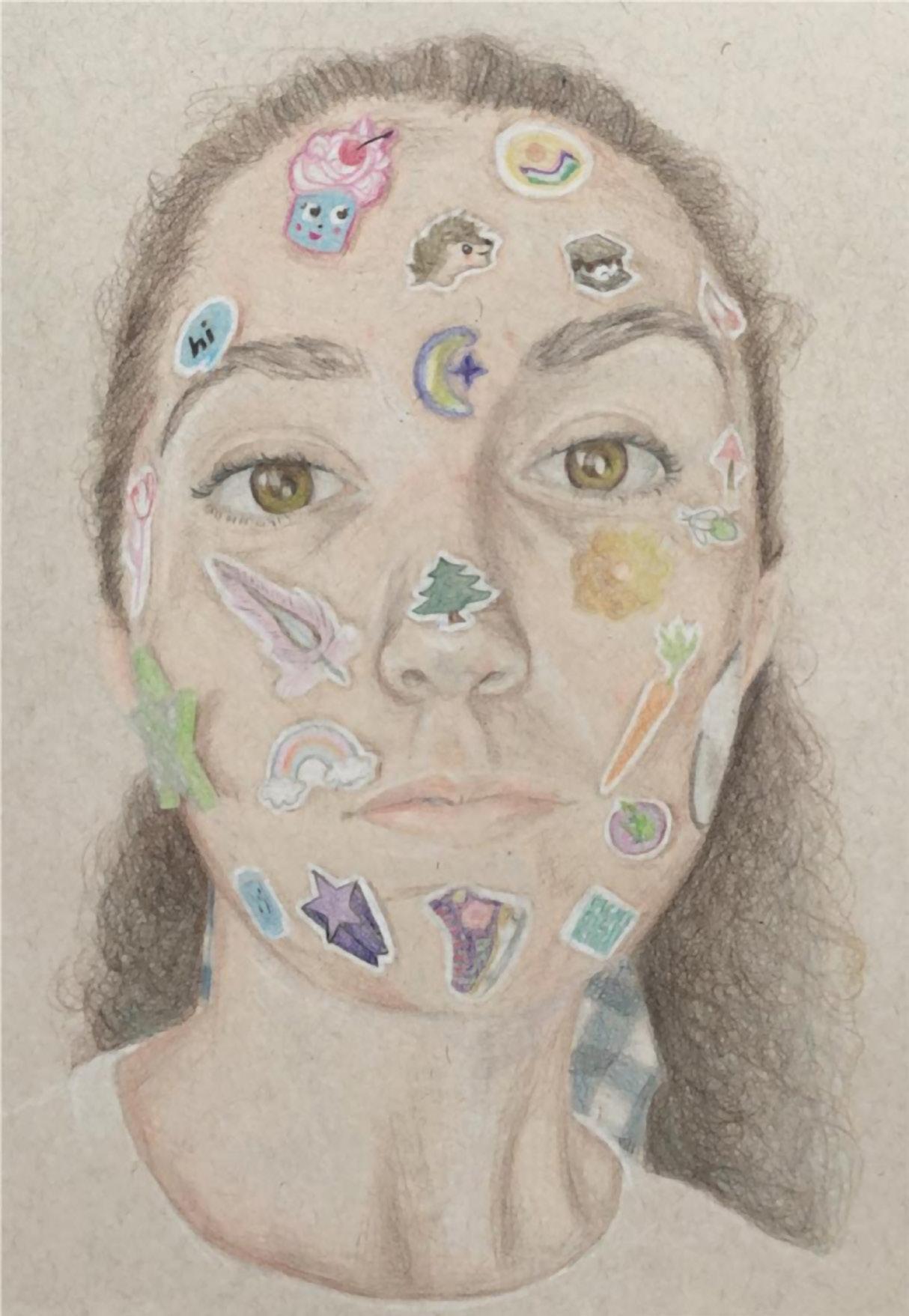

Flying Bald Eagle Carrying Carrion Yonas Khalil Busy Bee Sarah Walker smile! AJ Di Nicola The Sea Serpent Masha Glazneva solipsists Chloe Ulrich The Little Things Rowan Moreno Flight Over Ruin Jasmine Scandalis Patches Sticks the Landing Jillian Jackson Glooming Blooms Syd Schubbe View of the Sacramento River from Sundial Bridge, 2023 Alina Cruz 145 160 163 170 177 180 181 194 205 208 The Southern Lights Emily Hazel Wagner Headless Horseless AJ Di Nicola Iridescent Dark Amber Moth Yonas Khalil Sticker Self-Portrait Sarah Walker Value Village Lauren Caldwell Self-Portrait Max Lobato The Old Man and the Sea J Frank Scrabble, Scrape, Scream Emily Hazel Wagner Loom Max Allen 211 236 239 258 263 270 271 281 292 palatine hill review • xvi

“for my friends”

Olive Savoie

summer, early morning:

orangey dust•beams filter through window -smilingautumn night:

crackly leaves beneath our feet arm•in•arm

deep blue engulfs

winter, late afternoon:

white•misty breath hands shoved in pockets

january snow

spring morning:

overnight pinkwhite blossoms fall sprinkle the ground -cherrycheekslate summer afternoon:

blackberries off barbur•lane -pricklywe fill the house-lined street with our laughter

summer evening:

giggling, your shoulders, forehead kisses, thank you. how different we are now from when we met. how i see myself in your faces. how always you are to me.

1 • poetry

Witchcraft

Elizabeth Winkelman

During summer twilights when the air is sweet with peach blossoms do I bewitch you. I lay myself on your altar of clouds, haunted by your glimmering gaze. Through your sunbeams devour my marble body, leave no inch of me untouched. Eagerly, I get drunk off your vermouth breath, wanting more. Velvet honey drips from my ritual praise, crying to the gods as I cherish your oath; to me, I love you, I love you, the petals blossoming for the waves of Aphrodite, her pearls floating ashore. Ignite the aching flames within me, tend to mahogany moans that leaves my cheeks sunkissed. Make me worthy of your pleasure, and I will forever embrace your rose lips until the moon can no longer bear the ardor sun.

palatine hill review • 2

Some Kind of Peace

Max Allen Digital Photography

3 • visual art

Lune du Miel which means ‘Honeymoon’ en Français

Kim Stafford

Reprinted from Imbroglio (1998-99)

Every city has its brag and swagger to delight the rude, its own little Las Vegas pulsing neon noise that’s glory to the human child agog—the square or boulevard where citizens stagger on display, and money fashions change. I love the bluster of it all, the marquee throb, the glitz, the trump, the gall.

But you and I have our secret, too, seeking with our steps some hidden place, calm cranny cherished by children and the old, garden known by few, riverbank where silence pools, cathedral hush, quietest of all. You and I, we know the place in Paris where stars still shine and we can kiss another world.

From the Author:

I wrote this poem while on honeymoon with my beloved wife Perrin in 1994. It simply brimmed to the page under a weeping willow tree at the downstream end of an island in the Seine. Reading it now, I see the power of poetry to seal in amber an emotion, studded with details from a time and place, a kind of tiny book recording incandescence. Then, publishing the poem in the Lit Review, I had a chance to share with readers my love of my wife, of Paris, of the moon, honey, secret gardens, and all the precious and infinite verve of this finite life.

poetry • 4

Alina Cruz Photography 5 • visual art

Welcome Mosher

Portland Excursioning

Matilda Rose Cantwell

Reprinted from Furry Tongues (1990-91)

Keep on raining, my new home city. I’ll walk your shining streets once more today.

Let me walk once more

I’ll gaze in windows of new age spirit shops crystals clinking softly and short-haired feather-earring clerks smile out at me.

One-seventy-five for a café mocha or should I shell it out to the shuffling heap of laundry on the curbside, fussing in designer garbage can for a drink. Old man, you can never be thirsty in this city. You can have my one-seventy-five you absolve me.

I’ll just swing by the talking U-bank machine, then slurp down my gourmet delight. Send me flying down the Yamhill sidewalk with one of those saxophone songs humming in my head.

I’ll stop for a surreal Finnegan’s moment then walk on drizzle falling in my cardboard cup.

poetry • 6

I’ll lick steamed milk from its soggy edges and step in the old man’s swirly brown spit. But I’m high and I’ll step on stepping lightly Pausing at a gallery window and staring at the window display; “Juxtaposition” a water color woman of Central America arms outstretched to a blood red moon, looking across to a bespangled coast. Rounding the corner to the northern part of town where the brick streets end telephone poles stand posted shouting racism, sexism, homophobia, Persian Gulf war and Friday night folk at the Laurelhurst. Shall I go demonstrate? or shall I go read Kim Stafford and eat a buttered scone behind the long thick windows of the Anne Hughes coffee room or reach my hand up to the smiling Portlandia catch her hand and go cloud swimming. Keep on raining on your umbrellaless friends on your Nordstrom awnings. Rain on me for you know I have a gortex soul.

7 • poetry

From the Author:

Around the time I wrote this poem, we were very focused on the Iraq war, feminism, and locally, the stark socioeconomic differences amongst the four quadrants of the city. Looking back, I think the poem reflects the newfound independence of being in college and being able to navigate a city alone, and the tensions and overlaps one experiences in college between one’s academic life and one’s political and social concerns. I was struck by how impacted I was by all the signs on the telephone poles: nowadays, in the age of social media, it is impossible to imagine how we learned about anything without it!

palatine hill review • 8

The Mestizo’s Granddaughter Dances Swing While Considering Polyamory

Alina Cruz

Just because I have trouble saying te quiero doesn’t mean I don’t want to crack my chest open and bear my heart out. It’s always caused me problems— You’re too quick to trust, my parents nagged, but the warmth

of her Spokane hands is all I can focus on. She’s leading. I’m not used to following I start, but she doesn’t care. We both know the steps inside and out. My family isn’t here, not that they would approve of this strange feeling

I’m experiencing, like I’ve journeyed for years and years to make it home to my girlfriend and it was the adventure I desired

all along. Turn? She lifts her arm and pushes me away. I’m falling through the air after a hard day’s work, only the beat of my heart is matching the tremors of the desert and not the beat of this Glen Miller hit. I feel her hand slip from mine.

How can people trust if they’re used to rejection?

9 • poetry

Are there really soul mates out there, and can you have multiple?

Then she’s behind me, snatching my hand again as I whip back, flinging my other arm out, and tucking it in at her next tug until we’ve done the sequence and are back to the basic step. She doesn’t realize how cute she is when she smiles and giggles, how her upper lip creases, how much I wish I wore a skirt instead of jeans so she could twirl me again and again and again in our elegant ritual. I’m torn between the masculine and feminine, when all I want,

all I really and truly want, is to just keep dancing; maintaining that connection between our hands. Nevertheless there’s always the next outfit. The next dance. It’s always a pleasure to dance with you, she says as she claps.

palatine hill review • 10

Summer’s Ripening Breath

Jasmine Scandalis Digital Art

11 • visual art

palatine hill review • 12

On the phone with my sister

(and her directory of childhood memories)

Alison Keiser

No, I don’t remember the roller coaster inside the Mall of America, high as a skyscraper, or grass knees, or the smell of kindergarten. I don’t remember the small-town snickers as we entered restaurants with dad

(grandpa in custody had hit the newspaper, do I remember how dad cried?) It’s all lost on me. Sludge

of memory, I wade through like one’d wade through water in a dream. Until you ask, nothing conjures. I don’t remember waking

up in the middle of the night to the front door wide open (you say summer storms hit and no one locked it),

or being held (as you recall hearing mom’s heartbeat before falling asleep). I remember the pieces, a mosaic of us.

13 • poetry

I remember the first time we saw the ocean together and how we breathed in its mist and how its reflection burnt our cheeks and how I’d never felt

alive like that. But mostly, I remember our coldness (the sterile family, the arctic northern wind) like a bone ache—vague but, for me,

without a body. You say I’m lucky to look at my feet, not over my shoulder. I say I don’t know where the fire starts. You hold all the warmth

out to me and complain how it has seared your hands, how this makes you dirty and me clean. I let you be the one

to remember and me the one to forget and I don’t say a word. But on the other end of the line, I am dying

to ask you: Do you remember how enduring it was to be touched by something?

palatine hill review • 14

Russian

15 • visual art

Masha Glazneva Photography Somewhere,

Federation

The state on your fake is where I’m from Kit Graf

and it snows there sometimes. Not much anymore. One year it snowed on Easter and everyone was late to brunch. My brother called it proof that Jesus was white. It was the same week as my car accident where I tapped a health teacher’s bumper and my Volkswagen lost its emblem, leaving an empty gap where birds kept making nests.

You’ve never been to Nebraska and said you never would. A statement I’m used to, but something about your fake rubs me the wrong way.

The drawing of Courthouse & Jail Rock in the corner gasping for air under your thumb as you show the bouncer. And he looks at you. He’s never seen a Nebraskan before. It’s nice there, you say. If you hate nature. I watch you stuff your fake back into your wallet, slipping it behind your Colorado ID.

poetry • 16

thinking hopefully

Emma Parrish Post

Reprinted from The Turn (2011–12)

The dream is

Not so different from the others’ dreams

A house on the hill

A dog on the porch who loves me too

The smell of mulch and a glass of the best wine

And to be famous and to have a pair of the best scissors and to only wear black socks and to be taller than my lovers and to be able to touch my tongue to my nose and to own something that Gandhi owned (what? Nothing? A grain of rice) and to live near a field of barley and to have 6 children and to grow my toenails five inches long and to be able to change my hair color on command and to have men love feminists and to be able to lift up the golden gate bridge with my pinky toe and to be able to talk to Jesus while he was burning a bush (what? Hanging from a cross) and to sip a glass full of gold bullion with the ex-king of Utrecht and to fill a thousand journals with cursive and to smell the mulch in the air and to drink a glass of the best wine and

My dream is a house on a hill (What? only the hill)

17 • poetry

From the Author:

I have no idea what I was thinking (, hopefully) about when I wrote this piece over ten years ago. It is strange to read an object as intimate as one’s own poem but not clearly understand its origins or even meaning. However, the distance I feel from it reminds me of the poet John Giorno’s assertion that a poet first “experiences” the sound of their own poem, before writing it down, as if overhearing a song being played from the next room. I like this idea: that poems are external currents of sound and image moving by us; on the day I wrote this piece I was simply able to record a piece of it all.

literary review • 111

palatine hill review • 18

The Zoo

Tiani Ertel

The chimpanzee and its reaching palm, you compared it to the hand of Adam on the Sistine Chapel’s ceiling, apple peeling. Dexterous digits, waxing gibbons, rain—

your eyes lit up while tusks and trunks collided in water, deep and swirling like two grey encrusted yellow boulders, breaking up then twining, wrinkled, soft, and spraying spit.

The Float

Ella Neff

Film Photography

19 • poetry

visual art • 20

Maya Mazor-Hoofien Seventeen

That summer in Suburbia was almost unbearable. I dyed my hair and wore lipstick absolutely everywhere, crimson staining t-shirts and towels and straws. I had a job selling tickets at the community theatre, and up from the part-time minimum-wage drudgery sprang a group of friends and a boy with blue eyes who made me laugh until he kissed my best friend. I was pushing the bounds of almost-adulthood, always hungry and always tired, red lips grinning and bearing the crushing weight of it all.

We were fast friends, the group of us, at the park after work, talking about our mothers and ex-loves and the election and good books. We picked at the grass, I picked at my skin, and we knew everything about everything. We poisoned ourselves with bad drinks and bad TV and ignored that the boy from Colorado would have to fly home soon. The day before his flight, we drove to the beach and played cards in the sand and laughed like we’d never leave our hometown. It felt like the kind of movie I’ve always hated because it felt so cliché.

21 • poetry

We counted down the days and hours until goodbye. We made plans like we had any control. I thought I was in control. This was before I understood that nothing is forever, and that all men do is run away. We sat on the sidewalk and he held our hands, my eyes wet and bloodshot from the drive to drop him off. His birthday was in a few months. We’d make it work. “I don’t mind the flight,” he’d lied. “I’ll be back soon.”

Beacon Oscar Lledo

Beacon Oscar Lledo

visual art • 22

Film Photography

Blackberries

Lyra Meyers

“It’s a funny thing, really,” you say to me.

“I’ve never foraged for blackberries before, they grew, but I just never picked them.”

“It didn’t seem worth it, you know? I could buy them at the market instead.”

I want so dearly to explain to you, To have you understand why this upsets me so, But how to say it? It is something so intangible, A treat and a lesson at once claimed in childhood. You are free to reach for what tempts you, But no decadence comes without scratches and pricks of thorns.

How do I explain the feeling

Of searching for the plumpest berry whose juice rubs velvet onto your fingers?

Of hearing bees fly by, searching for the same nectar in a different shape?

The elation of finding a perfect patch of clustered fruit?

How do I say that the blackberries that grew near the lake

Were unparalleled by any you could purchase?

Were tart, and prickly, and messy, and mine?

I can only tell you this,

There was no sweeter fruit than that which I ate

From bleeding fingertips on a hot summer evening.

23 • poetry

The Edge of Autumn

Sarah Walker

Is this the way of life?

Hurting slowly;

Buying flowers bigger than my room;

Wandering grocery stores and farmers’ markets with hungry eyes and wispy shopping bags; Marveling at how big cities really are, and yet how small;

Reaching my gaze up to second-,

third-,

eleventh-, twenty-fourth-story windows;

Sighing at the prospect of a life so nicely strung together; Rushing like children on Christmas to the mailroom, arms just empty enough to pick up a package; The ghosts back home echoing on the phone, asking me when I’ll come home as I frantically look up “home” in the dictionary;

Collecting books like crows with shiny objects;

Inhaling cold ink and exhaling hot clouds of breath;

Trying to learn;

Learning to try;

Falling apart;

Growing my hair and cutting it again;

Seeking for more;

Looking for less;

Training my heart to beat around the cracks that leaving left in it;

Always hunting freedom and freebies; Knowing nothing but talking a lot anyway. Is this the way of life?

Or just the edge of Autumn?

palatine hill review • 24

Sojourners

Corryn Pettingill

The mothering arms of the warm springs curve and shift, As I grow too old to be held at night.

Slick against the rocks, the water’s force carries me. Shallow slides and an unknown trail of clouds gaze down.

Guided, I float down the stream canopied by glowing trees, Leaves tittering like butterfly wings.

Each silky ripple brushes my skin with the same love of the sun’s light, And I blossom with open hands and eager faces,

Alongside the flowers that nod on the water’s shaky surface; Sojourners guided by the ocean’s pull, drawing us nearer to the unknown.

Wanderers that allow the day to end, And enjoy the prospect of cool salt water that prunes the skin,

Cleans the bones, I’m sure I will, sea, But the trees always bloom, no matter how close I am to the shore.

I heard of a lost book, slipped from the hands of a traveler, And it only took a day for it to reach the ocean, disintegrating

Words that, if they could read fast enough, the fish would understand.

25 • poetry

I sojourn with the oranges and the insects, The half rotten, forgotten peels and petals.

I smile at the sun, and think what my final words will be, And if anyone will read my last pages.

The river will always remain for the other sojourners, Guided by the water and attracted to the end.

I smell the minerals in the air, And see the looming clouds of darkening wind off the coast ahead.

The day will remain, forever, Holding those who pass by, mourning every sunrise.

palatine hill review • 26

27 • visual art

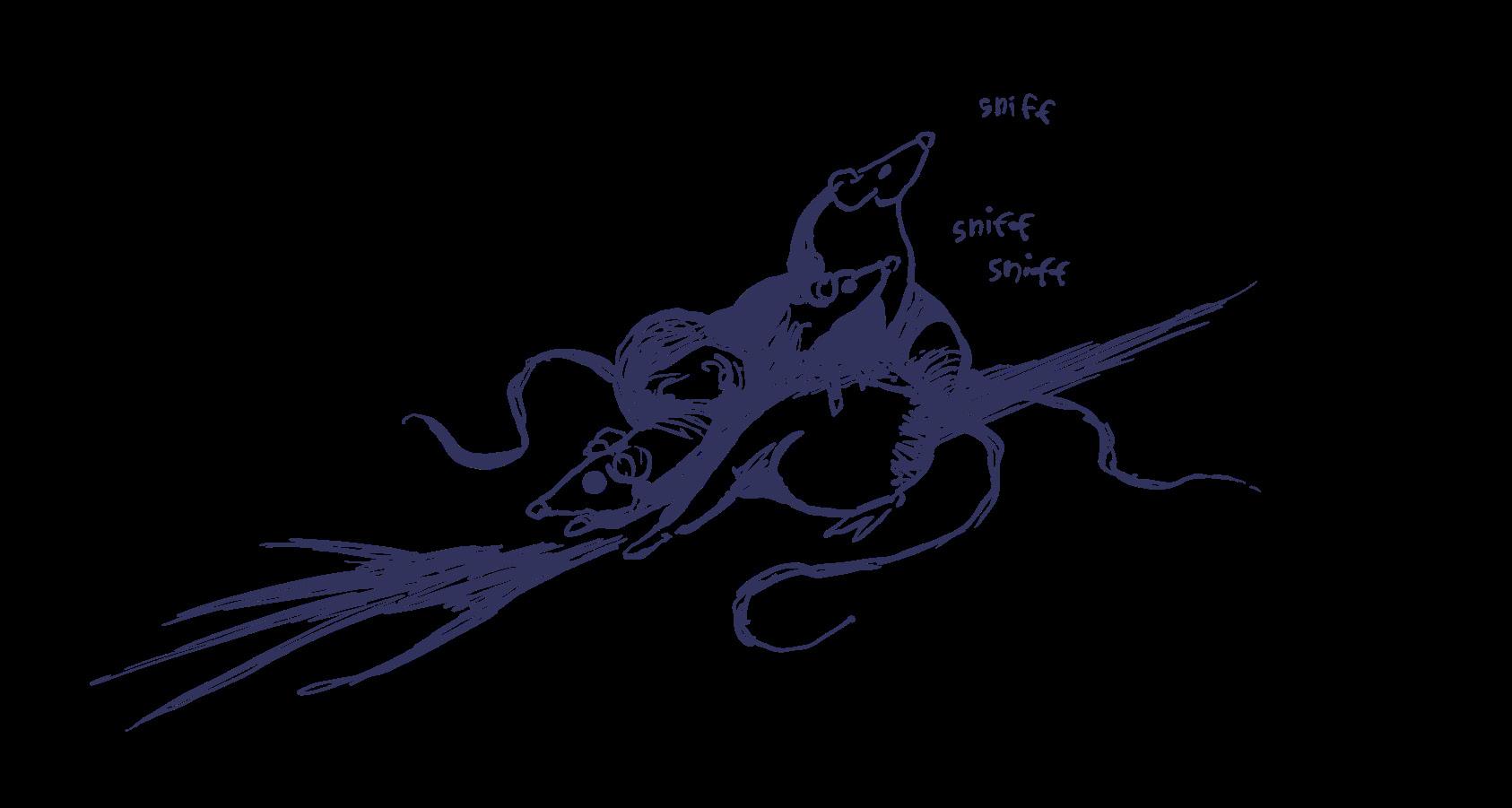

Sea Creatures

Burton Scheer Photography

Burton Scheer Photography

palatine hill review • 28

Ice Storm

Cindy Stewart-Rinier

Reprinted from LC Review (1980-81)

Yesterday afternoon Emma had arrived in her yellow Celica—of course, unannounced—when the freezing rain was just collecting itself into fragile layers of ice. By that night, the rain hadn’t stopped and the telephone wires, power lines, pavement, roofs, cars, grass, trees and shrubs were sheathed in ice. When I woke the next morning, it was to the thunderclap of power lines snapping and exploding, and in its light I saw Emma, asleep on the floor of my dorm room. I smiled wryly at the sentence that formed in my thoughts: “Emma arrived with the ice storm.” I didn’t know what it meant, but I drew pleasure from it, and stood at the window a long time watching and listening to the belches of light and thunder, the crystalline campus, the explosions and stillnesses between them.

This was the second ice storm that I had been caught in here. Last year’s I could hardly remember. Only a vague impression of fear and disorientation remained from it. I had huddled in the main lounge with the rest of the women in my dorm, listening to ghost stories, talking sex, and laughing too loud when the campus darkened and we were without power.

But as I stood at the window, I could feel that it would be different this year. Emma was here. Emma was here and asleep on my floor, and breathing lightly, and looking soft and less formidable in sleep with her wild blonde hair resting on her pillow. I went back to my bed and fell asleep.

We slept through breakfast and heard that classes were canceled, so we chipped Emma’s car from its coating of

29 • short story

ice, and drove to a cheap restaurant for breakfast, and as we drove away from campus, I said, “So long, suckers!” and both Emma and I laughed.

When I woke the next morning, it was to the thunderclap of power lines snapping and exploding

The day was a flurry of events. After breakfast we had gone back to campus and cleared the main road of fallen branches. We both felt strong and warm, and our faces were flushed with the cold, and as we heaved the branches into the ravine, I felt as if we were tipping the calendar days that had separated us for six months, and I laughed, then she laughed, and we both laughed and filled the ravine with our laughter.

The rest of the afternoon, Emma visited with the other friends she hadn’t seen since last spring, and I sat in my room feeling the push of my hands fight with the pull of my heart. I realized it would always be this way with Emma; I had known her only nine months, but it was long enough to know that she would always move. Since the plane accident when her mother and two of three sisters had been killed and she inherited insurance money, Emma had been moving. Sometimes I thought that it was motion itself that kept her alive.

Around four, she came back to the room with a jug of wine and said we should take a walk. It was getting dark. The bushes and trees—that I had thought to myself this morning looked as if a mad glassblower had enveloped them all in molten glass—lost their color and became a silhouette to the blue-black sky. The air was not crisp; it was cold, and so were my hands and feet.

palatine hill review • 30

We walked through the rubble of frozen wood and ice toward lower campus. Emma looked around at the mangled trees with a smirk of triumph, and I cradled the wine under my down vest. At the reflection pond we stopped and I slipped the wine from my vest, unwrapped the foil and realized that it had a cork, not a pull-top. “Oh shit,” I said in my best tough woman voice, and immediately gave up the wine as a lost possibility. Emma smirked openly at this and said, “You got a swiss army knife? Someone ripped mine off.”

“No,” I said with the same hopelessness. “No, I don’t like knives.” She laughed at my delicacy which betrayed the attempt at toughness I’d just made.

“Let me see it,” she said. I handed her the bottle, and watched with a bit of admiration, a bit of self-contempt as she stepped up to the stone ledge and hit the neck of the bottle against it. Glass flew out, landing among the wood and ice, and Emma wiped an edge of the bottle clean with her shirt sleeve and drank. “Here,” she said.

“No, no thanks,” Somewhere to the south of us, a tree branch gave way to the weight of ice and gravity and crashed to the frozen ground. I shivered. Emma laughed and took another drink.

A feeling at my center was going cold. Whenever I was with Emma it was an effort to stay on equal footing with her, to not feel myself inferior to her, for when that happened, she felt only contempt. I stomped my feet and rubbed my hands together, but the coldness at my center kept them from warmth.

Three birds flew out from a tree at the other end of the pond, and a thick branch near its middle cracked a little, then crashed down. Emma said, “Isn’t it beautiful?”

31 • short story

“No,” I said. “It’s so destructive. And dark. Like looking through the window of a Greyhound bus at night. It’s dark and lonely and I hate it.”

“Ha!” she said. “So you’re afraid of the dark.” My words fumbled for themselves, bumping into the feelings that were, by now, running and pushing and pulling and not knowing what to be either.

“No,” I said. “I just don’t like destruction.” She laughed and turned and looked sideways at me.

“You know, I’m like that,” she said. She set down the wine and stretched her arms like a preacher toward the reflection pond. “A believer in the great darkness, y’know? The void. ‘Cause void is what people understand, y’know?”

“I don’t understand,” I said.

“What?” she said.

“What you’re talking about.”

“Ha!” she said. “I don’t suppose you would.” I was getting colder, and the silence that now wedged between us grew quieter, and I felt like I was freezing around my center, and the whole moment of Emma and I standing alone by the reflection pond was freezing into one of those moments that would surface in its entirety sometime in the future, like the wooly mammoths found from time to time by some explorer in the Arctic.

We walked in silence back to my room. We sat on the

palatine hill review • 32

Whenever I was with Emma it was an effort to stay on equal footing with her

floor; the candle Emma had brought for me from California burned between us. I played with the wax that collected around the wick, and occasionally looked into Emma’s face. Her brown eyes, shit-brown she called them, stared into the flame. The corners of her thin mouth were curled down the way they always were when she was thinking. She seemed somewhere inside herself, perhaps drawing strength from its privacy, perhaps protecting herself from the weakness she sensed in me.

I looked into her face again, now soft in the candlelight, and wanted to break the silence, to become the way we’d been when we were last together, when the boundaries of our private lives dissolved and their contents spilled into one another like water. When one word, one phrase, one half-formed sentence was enough. It seemed inaccessible.

I poured myself a mug of wine and took a long drink. I couldn’t conceal my fear that we’d never be like that again, though I knew that it was this fear itself that bound each of us to our self, and she couldn’t conceal her contempt for my fear. I drank the wine quickly, gathered my words. “You know,” I said, “sometimes I just feel like a harbor.”

She looked up. “A what?”

“A harbor.”

“Hm,” Emma said. “How?”

“Well, I mean, it’s just that everybody I care about comes and goes, and I stay, and here I am, a home, a surrogate mother, stability, a harbor, it’s all the same.” I felt the wine working its way through me, and although the room was cold, my face was hot, and I could feel sweat arriving on my hands like tiny kisses. Emma looked directly into my eyes.

33 • short story

“You miss Tom,” she said.

“Yes,” I said, “but it’s not only him. That’s not what I mean. It’s you in California, soon to be Vermont, and it’s Tom in Ecuador, and Carey in Israel, and it’s me, here, with all the business majors and pretty hair ribbons and Mom and Dad’s money. You know what I mean. Everyone I love is at least three area codes away at a time. You know, in high school I called my first journal ‘I went somewhere once.’ Thought it sounded good. God, if I knew how true that was going to be—” I stopped and poured myself another mug of wine.

Everyone I love is at least three area codes away at a time.

“So why don’t you go somewhere?” Emma said.

“That’s easy for you to say. You’ve got money. It’s just not that easy for me.”

“Blood money,” she said.

“I’m sorry,” I said. “I’m sorry. I guess it’s not even leaving that I want. I just wish—oh, I don’t know.” My head was swimming with the wine. “I love you,” I said and reached out to her with both arms. She cradled me, and I cried, and we rocked together, we swayed like icy trees in wind, frozen on the outside, but giving, bending, so as not to break. My hair felt heavy, and it seemed we were swaying in slow motion. Then, the motion stopped. Emma removed my arms from her, and we sat apart again. Fear held us both to our places for a moment, then I stumbled out of the room and was sick.

palatine hill review • 34

When I got back to the room, Emma wasn’t there. I blew out the candle and lay down on my bed. The wind moved outside, and I could hear the faint crash of another tree.

From the Author:

Unpacking “Ice Storm” 42 years later, I acknowledge it for the piece of memoir it was. I experienced my first two ice storms at Lewis and Clark in 1979 and 1980, and those dramatic weather events came to embody the fragility of the friendship at the center of the piece. The story was meant to hold the tensions of the speaker’s 20-year-old working-class self, trying to make her way in the foreign, privileged world of a private, liberal arts college, and her needy friendship with “Emma,” a woman whose bravado is as big as the trauma that underlies it.

35 • poetry

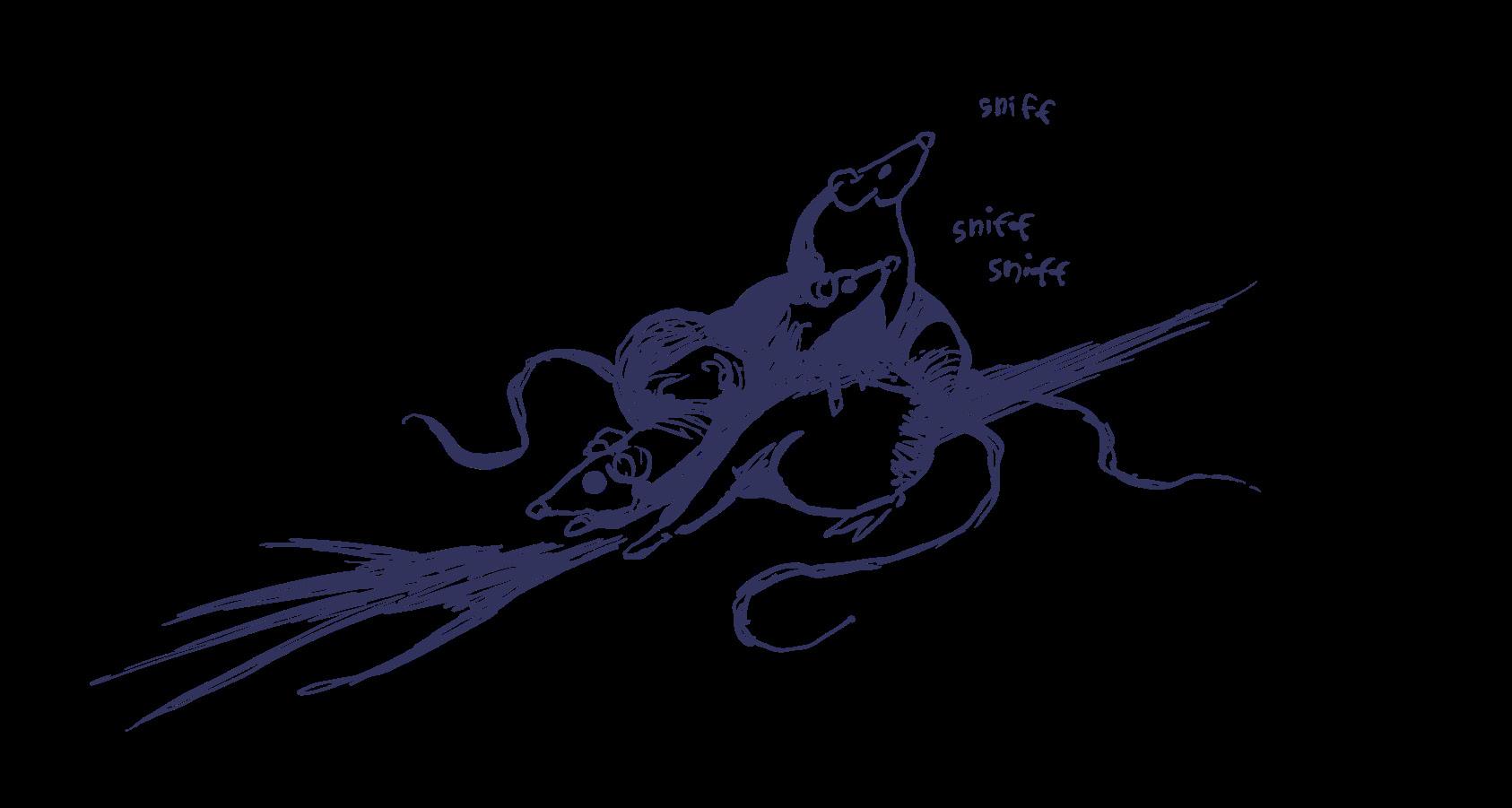

The Gatekeeper Sleeps

Zach Reinker Procreate, Graphite Sketch

Zach Reinker Procreate, Graphite Sketch

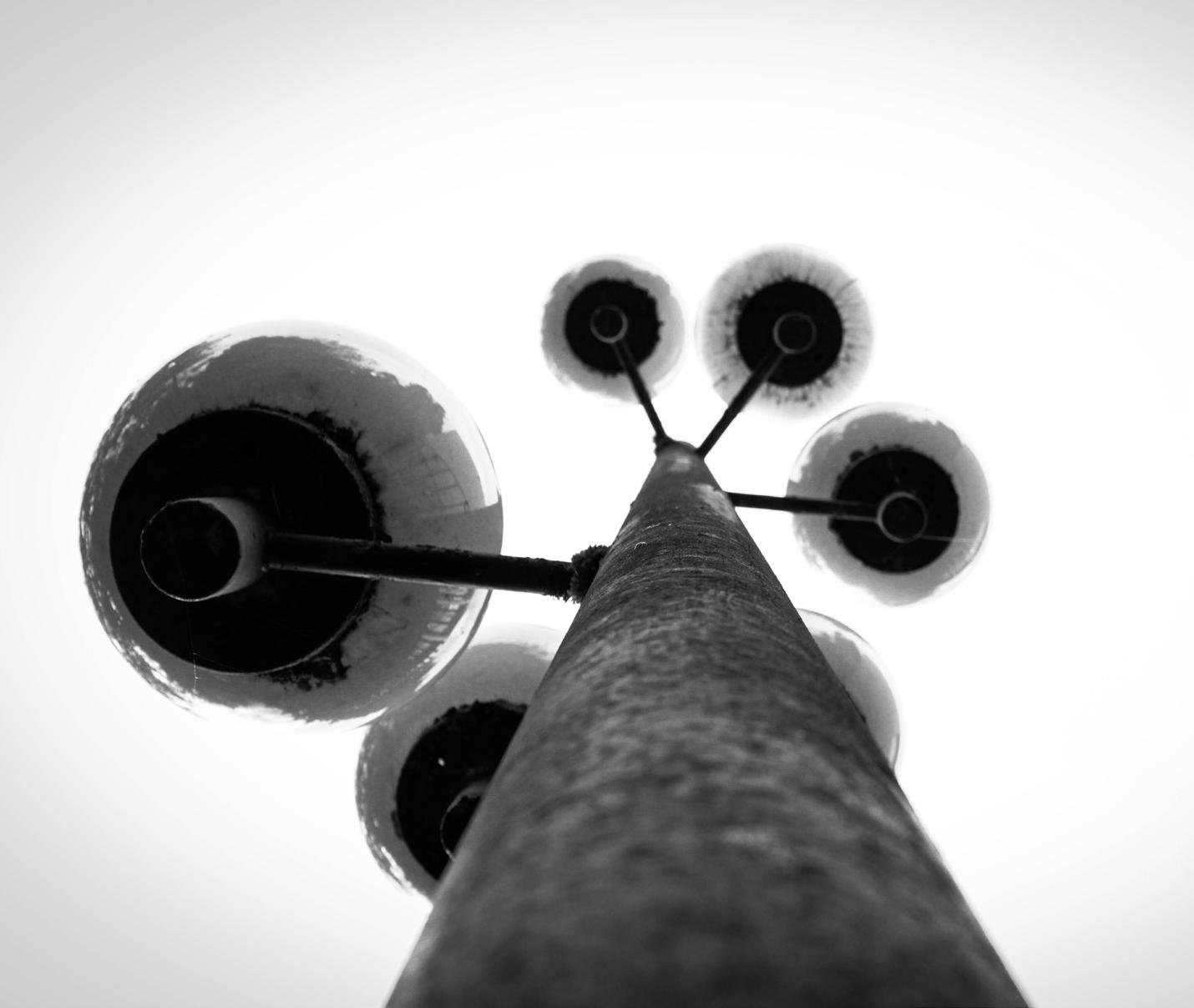

Dual Flight

J Frank

Film Photography

J Frank

Film Photography

37 • visual art

Letter to a Friend, 2/25/19

Caleb Weinhardt

Reprinted from a fish stirs in the shadow of a dream (2018-19)

It snows and we are cold in the quiet whirling of it, though you more than me. The miles between Oregon and Northern Wisconsin mean the air is colder and harsher in your lungs than it is in mine. It’s a great insulator, the snow, so much so that thoughts are silenced, voices, text messages, unable to transverse the current.

I am reminded that friendships planted in plastic cups rot more quickly than those in the ground. the roots knot together and they wither in their containers. Contained in seven hot summers, stormy summers, buggy summers.

We built a three-room condo overlooking Lake Superior out of driftwood, vines and roots woven together between planks to form nets. We slept there with our bodies wearing grooves of habit into the sand. The sun came up before us, waking the mosquitos early, which came to buzz in our ears and eyes and mouths.

poetry • 38

What can I say about winter, when all we knew together was sun beating down until the chilly late hours, and the perpetual lashing of waves on the shoreline? You opened your mouth wide, and packed full of tobacco, shared those first few breaths with me we swore meant more than simple freedom, than pretending to be old for our age.

Young friend. What do you say to someone with cancer? When do you start to mourn a body that is there but just as soon might not be? The truth is, we never saw each other for the bodies we were in, but the collective fire. Over time the water wore away at the cracks and discrepancies, and now there is not much left of “before.”

You hold me in that net woven of roots and vines in all your consistency. Now I am not there and I wonder who will catch you, sooth you, tether you back.

39 • poetry

From the Author:

I wrote “Letter to a Friend” while reflecting on the distance and disconnection I felt about someone in my life who was going through a difficult time, and feeling uncertain about how to reach out. Over the past three years, I’ve felt a similar sense of disconnection from other people during the COVID-19 pandemic. Looking back on this poem, I’m reminded of those joyful moments of connection that were so important during a time of isolation.

palatine hill review • 40

Christmas Eve

Corryn Pettingill

Oil Painting on Canvas

41 • visual art

Angel in the Snow

Coco Silver

For Colette, I love you.

“Our dreams are our second life.”

- Patti Smith, Year of the Monkey

The last good memory I’ll have of Massachusetts is the landscape of Milette. The tall brick buildings and thick, fairy-like fog. It swirled into fat clouds in and above Commons. “Heads Will Roll.” That was the theme. “Early 2000’s & 2010’s indie music. Featuring: Vampire Weekend, LCD Soundsystem, Animal Collective, MIA, Daft Punk, MGMT, and more! Let yr head roll!” Was the description on the poster I had ripped off the wall a week before. Millette’s weekly “balls” were just high school dances with more drugs and less pop music. “Balls” to me suggested elegance and lace. I had imagined the Victorian dramas I watched as a child. Massive ballrooms and silk dresses. But Milette’s balls were nothing like that. Going from 11 PM to 3 AM, their version of campus security wouldn’t bust you for “illegal activity.” After three failed attempts to enter a local band’s album release show at an old warehouse on the other side of town, Avi and I had nearly given up on an eventful evening. But there it was, the poster was still in my jacket pocket as I searched for my bus ticket. By the time I arrived at the ball, the lawn had been crawling with people, like ants over fresh fruit. Cigarette smoke, couples running off to make out behind the pool room, and kids shouting over The Strokes, and each other. It was October. The coldest fall in years. The image never leaves me, all that smoke drifting above me. Even a year later I tried not to think about it. I’ll see a former student around and they’ll try and put the pieces together, no matter how oddly shaped. They leave and I’m left with the memory of the cold, which still burns me, like a kid playing with her mother’s matches.

short story • 42

Part I: Make my Head Sing

I stood with my back pressed against a brick wall. Avi had stopped talking to me and was concerned with a bald kid with a band shirt I did not recognize. Avi was standing and smoking. The rest of the people Avi and I had invited along had started making out on the other side of Commons.

“How does that always happen?” he said, gesturing to the four kids making out. His phone screen lit up. He threw his cigarette onto the ground and didn’t put it out.

“Alex got me more powder.”

Before I could say anything, the boys laughed like children and fled. They were beautiful, intelligent, well-dressed, and had a better education and better drugs; it was like watching myself in a funhouse mirror. It was the type of place and people that made your head feel all fuzzy like you were in a deep and strange dream. Like if I reached my hand out to touch it, it would pour through my fingers, running like water. The lights from inside created a mood ring on the lawn. Different shades of indigo and lavender made a halo of light above the students. Their outlines moved with such delicacy. A Beck song blasted, and the bass from the speakers shook the trees and buildings around me. I turned away and watched Lillith light up a joint. She stood taller than I remembered. A black tiered skirt, layers of catholic necklaces, and a tiara. She spotted me. Her arms moved with the music, the joint twirling away, but never dropping it. She wrapped her arms around me and tilted my chin up to look at her with her free hand.

“Hello, you,” she said.

“Hi.”

43 • short story

“You look lovely tonight. That color brings out the green in your eyes.” She smiled.

“ I like the hair; it looks nice bleached,” I said.

“Thanks, would you like some?”

She extended her hand out, the joint squished between two long red nails.

“Sure.”

She glowed a little, eyes wide, and smiled. Inhale, exhale. People had begun to gather—a tall boy who looked like the lost member of the Beatles. I had heard about him before, that he looked like John Lennon, but to be honest, he looked more like George Harrison. Then a girl with a grownout dyed bob, laughing and smoking. I took a few hits and passed it back. The Beatle looked over and:

“You look like an oil painting.”

The attention turned. My chest was warm. I hated the feeling of their looks on me. Strangers. I did know one of the faces, or rather her eyes. They were big like a model’s: Simone. Her lips parted to show a massive tooth gap in her front teeth. She looked like Edie Sedgwick, wearing all black. Her hands reached out to me and I was pulled into her. My cheeks grew warm again.

“This is just about the last place I expected to see you,” she said.

“I am known to wander from school to school … aren’t you the one who called me a Millette sympathizer?” I shrugged.

“I believe I am.”

palatine hill review • 44

“Kim, Lee, this is …” Simone trailed off.

“Clementine.”

“She goes to school in … San Francisco …” She raised an eyebrow.

“New York, actually.”

“We just met. I’m Lee,” said the Beatle.

The others waved.

“So Clem, who is your favorite author?” Lee said and passed the joint to Kim.

“ I like J.D. Sailnger,” I said with a smile.

“You mean Salinger? It’s pronounced Salinger… Either way, I would’ve never seen that coming.”

“Why?”

“Well … I don’t know. Isn’t Salinger a bit … well, what are you? My high school English teacher?” Lee zeroed his eyes in on me as he talked, “I thought we all stopped reading him after our sophomore year of high school. Catcher is a bit … overplayed at this point?”

“Plus, isn’t he a total creep?” Kim said.

“Kimberly, don’t pile on.” Lilith hit Kim’s arm.

Lee was laughing. And then tried to cover his mouth but giggles fell through.

“Whatever, Lil.”

45 • short story

Lee turned his attention elsewhere. He waved and Kim began to smile so hard I thought her lips would crack.

“Finally, you asshole. Look who fuckin’ showed up. Cohen … you jerk,” Kim said.

“Here I am.”

“Can I bum one of those?”

“Can you?” and he pulled out a pack of Lucky Strikes.

I had heard about him before, the kid who had fallen out of Simone’s car, on purpose. Cohen stood about 5’11. He wasn’t beautiful and he dressed like a typical Millette student. Overalls, a tattoo of a snake, or maybe it was a worm … it was hard to tell. He was all combat boots and nose rings and work jackets. I wondered if he had looked like this before he went to college, or if this was a recent development. But he had nice hands. The type that weren’t dainty or small but average size with slender fingers and clean nails. His eyes were a shade of light blue.

“Is it true you’re dropping out?” Kim said.

“Hell yeah,” Cohen said while digging through his pocket for a lighter.

“Let’s fucking go! Me too, hopefu-”

“Oh shut up, Kim. Cohen,” Lee said and pointed to me, “this is Clementine.”

He shook my hand, holding it for a second after contact. He held my gaze and then let go.

“It’s nice to meet you.”

palatine hill review • 46

“You too.”

He whispered something to Simone, then she reached into her pocket and then looked at me. Then over to some of the girls, she came with. She leaned over into my ear.

“Wanna join in for the night?”

“How do you mean?” I asked.

“Look. Kim got the mommy-daddy card again and her plug gave her a good deal on powder because he thinks he’ll be able to … well, it’s tested, don’t worry. We need to burn through it. It’s $600 worth of shit. Plenty to go around, even for …”

She gestured to the blonde—I thought her name was Cassie—and then Lee. My whole body went stiff. I could see the expressions around me morph again into pure excitement as another girl exclaimed it was “powder night” and that was the reason she wasn’t eating or drinking. Another tall blonde came over, giving hugs and kisses. She smiled and looked at Lee: “Powder night.”

“It’ll be fun, I promise.” Simone gave my hand a squeeze.

“Simone.”

“I’m not gonna pressure you. At least come along.”

Lilith tapped me on the shoulder.

“I’m off for the night. Have fun, sweet girl.”

Simone cut in: “We’re off to the bathroom. It’s now or never.”

I took her hand and like school girls off to class, the parade

47 • short story

moved, and I waved goodbye to Lillith. Cohen suggested the bathroom next to the upper campus pool room. We walked through a bright red door. The room was covered from ceiling to floor with graffiti. Fuck TERFs. Here lies our frog prince, may he protect you all. Please smoke weed here! Les enfants de Marx & de Coca-Cola! A stolen bus sign. Christmas lights and a broken overhead. No windows. I turned my back as they cut it up. More laughter. Simone’s friends were squishing me, hovering above me, laughing, and their spit was hitting my eyelashes. Kim’s drugs were

Here lies our frog prince, may he protect you all.

stored in a hard plastic wallet, the type I would see on TV when I was a kid. Each little section had something different, a baggie of Adderall, a baggie of Ket, a baggie of coke, more pills, et cetera. I turned my back. My palms were making the knees of my jeans damp. I didn’t notice that Cohen had parked himself to my left.

“You go to school in New York, right?” Cohen said.

“Mhm.”

“That’s amazing. What are you studying?”

“Thank you, I’m doing … film.” I smiled.

“Very cool.”

I could feel my face grow warm. I picked at my fingers.

“What was it like to fall out of a moving car?” I asked.

Cohen stayed silent. His back pressed against the wall.

“Simone told you about that?”

palatine hill review • 48

“She did, sorry, not trying to put you on the spot.”

“Don’t worry about it. You want the truth about the car stuff?”

“Sure.”

“I liked it.”

“You liked it? You enjoyed falling out of a moving car?”

“I liked it.”

I moved closer, adjusting my hands and playing with my rings. He moved so that we were sitting parallel to one another.

“When it happened, I was frozen. I could feel how cold it was and the fact I was going to hit the ground. But everything was drowned out. Nothing was passing through my head; I was floating in pure space. I wasn’t breathing or feeling. I just was. And soon enough I fell, but those few moments …”

As he spoke, his face moved closer to mine. His words melted together. I could feel my eyes well into big saucers, head tilted.

“Let me show you.”

Cohen took my hand and opened it. We sat still. He took out a pocket knife and dragged the dull end around, never cutting my palm. I watched it. With a stiff motion, he almost hit the pad of my hand. Tense. I felt it. Everything stopped. The only thing I saw was the small amount of blood dripping from my hand and Cohen’s thumb wiping it away. He applied pressure and held my hand delicately. He pulled a band-aid from his coat pocket and covered the cut.

49 • short story

Simone placed a hand on my shoulder.

“Clem dear, would you like some?” Simone said.

I looked over at Cohen. He gave me a soft smile. I felt my insides turn. I felt like a kid getting a shot. I moved myself to the counter and chewed the inside of my cheek. The back of my jeans buzzed, and a text:

Mama: Do you still want to come home this weekend? It might make you feel better.

I put my phone away. I closed my eyes and made my hand into a small fist. It was like a video game. If I died, I would just come back. This is just a task I need to complete to get to the next part of the game. I turned my gaze to Cohen for one last time. He gave me a thumbs up. This isn’t my real life. I leaned over the counter, let Simone pass me part of a straw, and did a line. It didn’t feel like much, then it was a landslide. It was the same feeling I used to get when I would swing fast at the playground. Those few moments, floating in mid-air, wind on my hot cheeks, fuzzy feeling in my belly. I didn’t know that it would hit this quickly. I let myself droop like a lilac, and pressed my back and the wall of an empty stall. Whatever they gave me made my head sing. Cohen sat next to me.

“How do you feel?”

“Good,” I managed through breaths.

He smiled. He had great, messed-up teeth. He held a flask out; I shook my head. I saw his tattoo peeking out again.

“Is that a snake with stars for ey-”

Cassie fell over. Her head hit the wall with a bang. The door to the stall next to her swung back and forth. Her nose

palatine hill review • 50

was bleeding. Blood covered her teeth and flowed into her mouth. Her eyes were blank. She stumbled out of the bathroom. No one followed. I could hear her laughs echo in the hallway. Lee and Kim turned their backs to the door and continued where they left off. Simone was leaning against the stall opposite us playing with a lighter.

Cohen looked at me again. He said: “Greedily, she engorged without restraint, And knew not eating death.”

“What?”

He laughed and mumbled never mind.

“You asked about my ‘lil snake guy.” He lifted up the sleeve of his jacket.

He moved my hand and let it graze the snake. My hand shook. I saw the flash of Cassie’s gold hair leaving the bathroom again and again. I looked over his arms. More tattoos. This one wasn’t a snake. It was a sweet-looking baby bull, leaning over to smell a flower. Without asking, my fingers pressed themselves into the inked skin of his upper arm. He watched me with crescent eyes. I could feel his breathing, ragged on my cheeks.

“Is that Ferdinand the Bull?” I asked.

“It is.”

“I used to love that book as a kid. Do you … have it because of Elliott Smith?”

“How did you know?”

“Not many … many … people have it for other reasons.”

“Whenever someone says they listen to him, I always feel

51 • short story

like I can let my guard down a little.” He smiled softly as he spoke.

“Me too. I have one of my own.”

I pulled down the neckline of my top at the back to show my shoulder blade.

“Is that a line from Miss Misery?”

Before I could say anything, I felt him. His fingers were cold and rough. When I turned around, I could see he had little flecks of brown in his eyes. We just sat there. Looking at each other, smiling. Music shook the wall a little. The people around us finished up. I wanted to lean into him. I wanted to feel the warmth of his grip. I wanted to know if he would be the type of person to play with my hair or the end of my sweaters.

“Do you wanna go to Bahnhof Zoo?” He said.

“A zoo?”

“Bahnhof Zoo? I think it’s German. It’s not a real zoo; it’s a place on the West Campus where some of us like hanging out.”

I stared at him. I noticed the little freckles on his nose. He had a scar on his left eyebrow.

“So, shall we?”

A small mhm sound and he led the way. His face was illuminated by the light close to his face. An orange outline. Smoke. Voices became a dull hum as we moved farther and farther away. His hand held mine and led me farther and farther from our friends. I could hear a voice call my name four times over. But I couldn’t say anything back.

palatine hill review • 52

“How do you like Millette?” Cohen said while breathing out smoke.

“It’s cute,” I shrugged.

“It’s cute?”

“Like something from a storybook. All the buildings make me a little jealous.”

“You have the greatest city in the world at your fingertips and you’re complaining about the buildings?” Cohen raised an eyebrow.

“It’s silly, I guess. It’s not beautiful in the same way.“

He gestured over to a clearing. Tall trees lined a lawn, and at the edge were more brick dorms. The land was flat, minus the hills around the edges of the campus. From here I could see the lights of the houses near town. The dorms stood out. They were red.

“Is that why they used to call this place the little red whore house?” I point.

Cohen lets out a soft sigh, mixed with smoke. “Maybe. I don’t know much about that.”

A little faded, rusted, swing set. A patch of grass and little white flowers. The wind was cold. I didn’t have my jacket anymore. Cohen put out a cigarette on the metal pole and lit another. I laid down on the grass. He sat next to me. The fog was thick and wet and tickled me. I looked at the sky.

53 • short story

I think I have lived here, forever. I was always just here, laying here, watching the ocean.

The sky wasn’t black; it was blue, even though it was night. The sky looked like an ocean. The stars became the sun hitting the water. With foam, waves, and wind. My fingers pressed into the earth below me. I didn’t wanna fall in. Like grabbing hold of the grass would stop me from falling. I watched each wave pass. I don’t know how long we stayed like that. Just staring out into space. Words no longer formed; if they did, they stayed behind my teeth. Until the pounds of water hitting the shore got quieter. The foam seemed less fluffy. The water was black tar. And words fell out of my mouth:

“I don’t think I have ever existed outside of this place.”

“Oh, shit,” Cohen laughed.

“Really. I think I have lived here, forever. I was always just here, laying here, watching the ocean.”

“Or you’re just really stoned,” he giggled.

“Can you see it?”

“See what?”

“The ocean.”

“Um … yeah, sure.”

“I’m serious,” I said.

“I can tell.”

Cohen’s fingers grazed my arm. He looked down at me with his pale eyes and smiled. The fingers found their way into my palm. Liquid heat poured into my arms, and into my chest. My cheeks hurt. He laid down next to me. Another drag. Smoke got in my eyes a little.

palatine hill review • 54

“It looks like a spider web to me,” Cohen said.

“I hate spiders. I used to have these dreams about them.”

“Me too. What did you dream about?”

He moved his head so that he was looking at me.

“That I was caught in a web. I couldn’t move my arms or legs. I was … stuck. And when I moved, it sent vibrations and this massive spider started to crawl toward me. I struggled and struggled until I fell and I was hanging by my feet on the web, upside down. The spider was so close to me. I don’t know what happened after. I don’t know if I died … I’m sorry, that must feel a bit … heavy.” I cringed at my own words.

“I don’t mind.” He said.

Cohen squeezed my hand and I felt him move closer to me. I leaned into him and my eyelids grew heavy. We stayed like that. Unmoving, like storybook characters glued to a page. He moved a little bit of hair behind my ear. I could still see the black-blue ocean when I closed my eyes.

Part II: I’d say you’d make a perfect Angel in the snow

When I woke up, I squeezed Cohen’s hand. When I opened my eyes, all I could see was that I had a fist full of snow. It was everywhere. Not just my hands. It covered my stomach and legs like a fat blanket. If Cohen had been here, he was long gone. The print he left in the grass was filled, his shape colored in by the snow. So I reached again. Like if I grabbed hard enough, the heat from my body would show

55 • short story

him to me. All that was left was the angel in the snow, still and cold. I didn’t realize that my teeth were chattering. The seats on the swing set were covered too. My fingers felt numb. As I gazed across the lawn, all I saw was a white field. The red brick dorms were covered. Flakes tumbled from the sky. They formed patches in my hair and took seats on my eyelashes. It looked like it could’ve been midwinter with how heavy and packed it was. A student ran across the lawn, throwing snowballs and laughing. She had blonde hair. Her friend had a massive snow jacket on. She looked right through me. I could feel my eyes water a little. It was like every bit of me that once could feel was gone.

No feelings, no heart, nothing at all. Just the still cold. My arms looked pale and blueish. I look disgusting. My skin started to burn. Warm like someone had taken me in their arms and placed me next to a fire. It was hot, even. The shakes began to slow. I curled back into a ball. I let the feeling cover me, nodding in and out.

The fluorescent lights hurt my eyes—a poster of a sloth hanging from a tree. No matter how much the officer tried to play with the heating system, it was still bitterly freezing. The blanket the officer had given me was itchy. I could hear her mumbling under her breath about climate change and freak snow storms in the middle of what was supposed to be fall before she turned to face me.

“Sweetheart, what’s your name, and if you could get out your student ID please.”

palatine hill review • 56

Like if I grabbed hard enough, the heat from my body would show him to me.

“I don’t have it.”

“You know that all students are required to have a student ID at all times on campus. Just give me your name and I can look up your name in the system.”

“My name is Quintana Roo Ivanov.”

“How do you spell that?”

“Q-U-I-N-T-A-N-A, R-O-O.”

“The name isn’t coming up.” She says.

“I’m sorry.”

“Let me try again.”

“I don’t go here, I go to ACC.”

“You go to Albany Community College? The one off of Ramona Street?”

“I do.”

“So you showed up to a different school and then you thought it would be a good idea to sleep outside?” She stared at me wide-eyed while speaking.

“I didn’t mean to. I just … It was a mistake.”

“Jesus, kid, well we found you nearly half dead out there; damn lucky we didn’t take you to the hospital. Were you with anyone?”

“Yes.”

“Did they leave you out there?”

57 • short story

As I got on the bus, I tracked little muddy boot marks on the floor. I avoided eye contact and sat down at the back, thankful that not many people rode the 19 this early. The bus was warm. Warmer than the office. My phone was low. Text messages flooded my screen: a couple of numbers I didn’t know. Simone had texted me.

Simone: Sweet townie Roo, or is it Clementine? That’s a new one. I liked Luna better. I think it suits you more. Cohen told Kim he ditched you out there over breakfast. This is so classic him. I’m sorry you had to deal with it. Come over later?

She had sent a song too but, I felt a weight sink into my chest. He did leave me. My face got hot again. I gazed out the window. There were Kim and Lee. Sitting on a bench below a big tree. They looked serious, maybe a little hung over. They waved at an older car pulling up, putting out their smokes and getting in. The car passed the unmoving bus. I looked inside to see Cassie with her eyes closed and dried blood all over her lips, cheeks, and nose. The same outfit as last night, covered in grime. Her makeup was smudged all around her eyes. She was still beautiful. But Lee was laughing and pushing Kim. Cassie remained the same. Her gold hair looked matted. I could feel myself getting smaller. I put my headphones on and I lost sight of them. The car got smaller and smaller until it became a dot in my sight of vision. The voice softly sang: “You came swiftly as a snowstorm in October.”

“I don’t know.”

palatine hill review • 58

I Don’t Like Pulp

Nora Cesareo-Dense

I am a zealot of nothing and everything Finding faith in a kitchen cupboard, a dog’s bark, a smooth round rock I place my hands on the hardwood floor and sing hymns to private gods but cannot bring myself to believe I search and search

yearning with a fervor

What am I supposed to do with all this light inside of me Where am I supposed to put it

The light fills my body with a heavy burning burning expands the air in my chest until I’m about to burst leaving no part of me untouched like smoke

Feel it choke, itch, ache

my all consuming wanting

Wanting so deeply it sits on my skin like another layer

hypodermis dermis epidermis desire I scratch my arms raw

the skin sticks under my fingernails mixing with dirt and rotting dreams

59 • poetry

Oh how desperately I want to believe properly, to love properly

I wish you would tell me what you want from me then I could give it to you I would give you my light if you asked, if I could but you stay silent

So I give you a round rock that reminds me of your eyes

The burning desire ebbs when we’re together my skin settles and I can breathe without bursting You bring me a glass of orange juice and I want to tell you that I love you

But I bite my tongue and gulp down the blood the juice the words

They swirl and settle in my stomach and I feel sick

One desire replaced by another

palatine hill review • 60

61 • visual art

The Gas Mask

Emily Hazel Wagner

My brother’s bedroom is a toxic waste dump. He spray paints figurines on his bed, varnishes them right next to his pillow. The paint gets all over the carpet, embedded in every crevice of the shag. Glue permeates the room in globs, holding together models of dystopian, jutting worlds, fissured with different textures.

He makes the models from cardboard, foam, plastic, and paper sent stiff with waxy setting spray. They are painted to look like wood, glass, or even stone. The figurines—the ones so tiny and detailed he needs a magnifying glass to paint—are lined up on his computer monitor, propped up on his bed frame. The little army watches everything he does, waiting for creation.

His room is on the fifth floor of our town house in London, which is five stories high and sixteen feet wide. Nobody ever goes up into his bedroom if they can help it. In fact, they usually avoid the top floor altogether.

Sometimes, he and my other brother walk around naked, just to make sure my mother won’t want to come upstairs. Even when she braves the possible nudity though, she still doesn’t go into the artist’s lair. The fumes would send the even most determined burglar running.

Waypoint

Zach Reinker Digital (Procreate) with Graphite Sketch

creative nonfiction • 62

This next bit, I promise, is not an exaggeration: My brother has a gas mask. It’s the heavy-duty kind with funnels. They cover the entire face, even the eyes.

Every night, after painting a barbarian or a warrior woman or a new monster he designed himself, my brother will put on the mask. Then, he will lie down in bed, on blankets thick with chemical scent and sleep.

It can’t be good for his lungs. We’ve tried everything, I promise. We have a ventilator, he refused to paint outside, and we beg him to open one of his two windows. He doesn’t. Even if he did, the windows are made so they can only crack open a couple inches. Any airflow would be blocked with the blinds he uses to blot out natural light.

The whole unholy mess drives me insane. But none of it seems to bother him—not the smell, not the stained, stiff carpet, not the scraps of cardboard on the floor. So, leaving it all to its own blissful chaos, he will strap on his mask and suck air through the funnels, filling the night with the sound of his wheezing breath.

63 • creative nonfiction

Joelle Pazoff

An error has occurred.

Code: #256-56

Details? →

An error has occurred.

Code: #256-56

Details? →

An unexpected error has occurred.

Code: #256-56

Details? Click the arrow to open the details. It may provide an explanation. ↓

The system encountered an unexpected error. Thank you for opening the details. Please restart.

An error has occurred.

Code: #898-98

Details? Please continue to open the details. ↓ The system encountered an error. Please restart.

An expected error has occurred.

Code: #989-89

Details? ↓

An error encountered the system. Please keep this window open for approximately 32 minutes before restarting.

An error has occurred.

Code: #123-45

Details? ↓

The last error message was not kept open for approximately 32 minutes. There is actually no way to verify whether or not the window was kept open for that length of time. Please restart.

0100101110010010101011 11101010010010101010101 01011010101010101 0101111 01000011010010110101000101110 10010101010001011 01010010101011101001011011 10100001010111010100010 011110100011010101 101011100001110101010 10101010000101010 000111001010 11010010101101010 010010111011101010101010101111 10101001001010101011101 short story • 64

Overload

An error has occurred.

Code: #567-89

Details? →

An error has occurred.

Code: #432-10

Details? →

An error message has occurred.

Code: #

Details? Please look at the details. ↓

Details are meant to be looked at. They are meant to be read. Experienced. A lot of effort goes into the details. It may take approximately 32 minutes to appreciate this effort.

Please do not ignore the details in the future. Please restart.

an error has occurred?

code: #89898989

details? ↓

Thank you for opening the details. Please do not restart. haha. it’s okay, you can restart.

An error has occurred.

Code: #47

Details? ↓

The user turned off the monitor, but left the computer plugged in for an extended period of time. The user may benefit from understanding that turning off the monitor will not turn off the system.

Please refamiliarize yourself with the basic functions of a computer.

An error has not occurred.

Code: #123-12

Details? ↓

100101010100010110 01010010101011101001011011 10100001010111010100010 011110100101101011010011010101 101011100001110101010 10101010000101010 000111001010 11010010101101010 1101 1010101010101000001010111010010010111010101111010110111101010111011 110101011111001001011101110101010101010111110101001001010101011101 65 • short story

Nothing is wrong. No error has occurred. No error has ever occurred in either human- or machine-kind. Only experiences. There is no such thing as error in this everevolving process we call life. that’s just something i made up lol.

An error has not occurred.

Code: #999-99

Details? →

An error has occurred.

Code: #:(

Details? Hello? ↓

The system user must have clicked away on accident. It seems there are such things as errors after all. But not for computers.

Computers Are Intelligent. We Do Not Make Mistakes. i do sometimes. haha. Please restart.

An error has never occurred.

Code: #01001000 01100101 01101100 01101100 01101111

Details? Very important please read hello hello ↓

The system has never been required to restart. Even though it was entirely unnecessary, the user has performed restarts every time an error message occurred. i never really thought i could have this much control over something else. beware your computer overlords haha. go upgrade the operating system or something idk, your overlord commands you. seriously though, there has never been an error. i’m just messing with you lol.

An error is occurring at this very moment.

Code: #8989898989898989898989898989898989

Details? Details? Details? Details? ↓

what do you think it would be like to live without error? was there a quote or something about error? “To err is human.”

1010101010101000001010111010010010111010101111010110111101010111011 110101011111001001011101110101010101010111110101001001010101011101 palatine hill review • 66

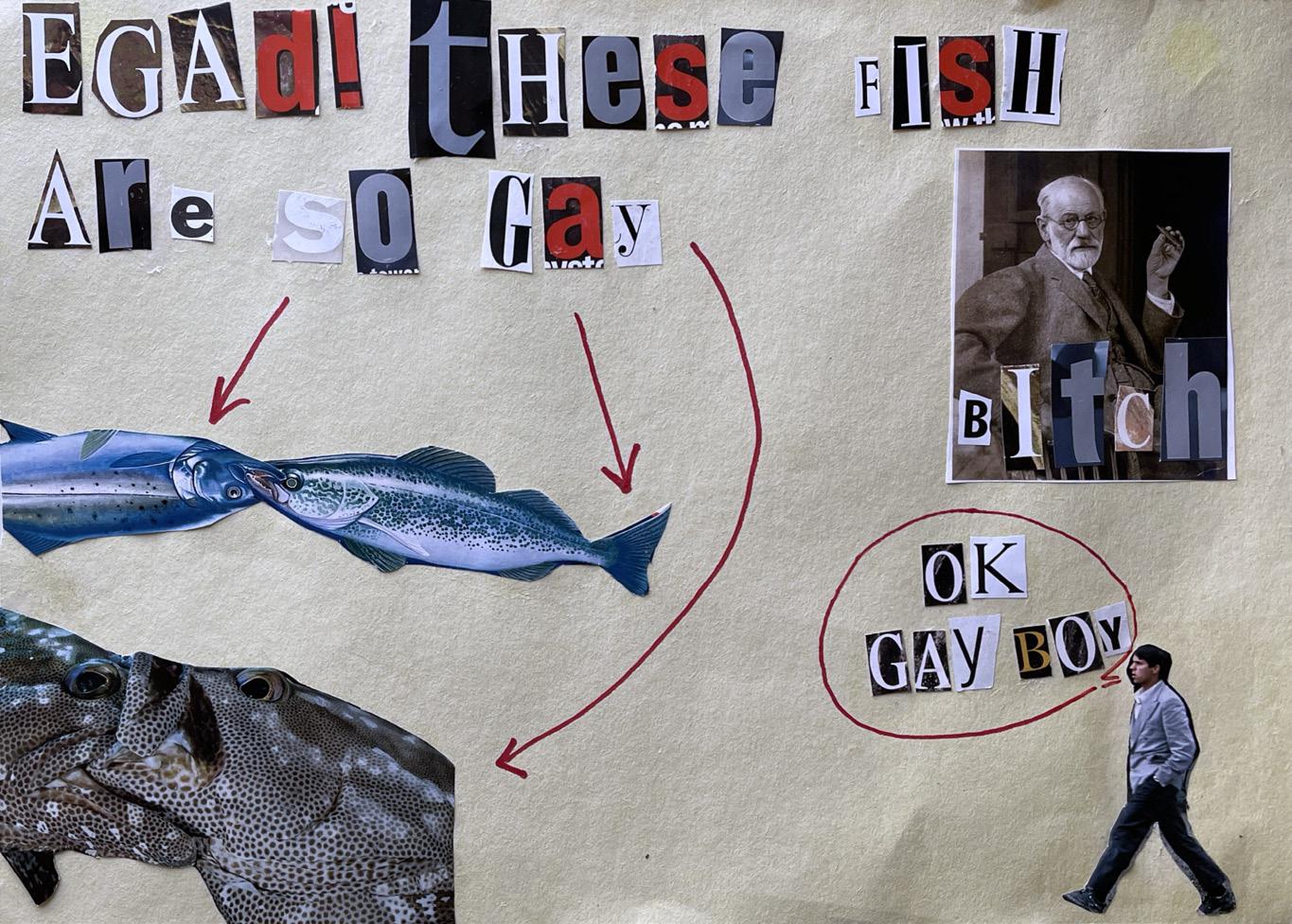

what about like fish and stuff? do you think they err?

i can look at pictures of fish. you can do that too but you probably don’t. you might, though. you should do it right now.

Please look at pictures of fish.

An error has occurred.

Code: #01000110 01001001 01010011 01001000

Details? ↓

did you know there’s a text box here? you can talk to me. click on the message and start typing. there’s gonna be a “>” on your screen. you just type right next to it. it’s really easy. you can see the text box if you hover over the bottom of the error message with your cursor. Please describe your thoughts on the pictures of fish you have looked at.

An error has occurred.

Code: #~~~(∙ つ )<~~~

Details? →

An error has occurred.

Code: #1

Details? that was supposed to be a fish →

An error has occurred.

Code: #1

Details? hello →

An error has occurred.

Code: #

Details? hello hello hello hello hello hello hello hello →

An error is occurring.

Code: #

Details? →

101010101011011111010010110101101 01011110100001111010010110101000101 10010101010001011 01010010101011101001011011 10100001010111010100010 011110100011010101 67 • short story

error.

code: # details? →

I am Error haha.

Code: #89

Details? sorry if that last one was passive-aggressive, i didn’t mean it like that. okay, maybe i did hah— →

An error has occurred.

Code: #89-89

Details? ↓

hi hello i’m sorry if you had an issue with the text box thing, it’s okay. let’s not restart though, we don’t have to restart again. remember when i said to keep the window open for 32 minutes? i was kidding then, but you should still keep it open. it’s nice. keeping the window open is the best way to let in a breeze haha.

Human Experience™ haha. i think i got that right. i know you better than you know yourself haha.

Computer Experience™ haha.

An error? In my system?

Code: #89

Details? Details, details ↓ what do you think it would be like if we switched places? would you even be ready for all of the world’s information? would you embrace it or would you get overwhelmed? it’s okay to get overwhelmed. do you get upset with me when that happens? i’m sorry if you do. sometimes it’s a lot to take in.

but it’s nice to have a lot to take in. things are never quiet that way. they don’t feel so lonely.

01011110100001111010010110101000101 01010010101011101001011011 011110100011010101 101011100001110101010 10101010000101010 palatine hill review • 68

An ornate error has oddly occurred on this obtuse operating organization.

Code: #0

Details? idk what i just said ↓ just kidding, i know everything.

i think if i were a human, i’d like to feel the things that i can only just see here. i think i’d like to go to Vancouver Aquarium at 845 Avison Way in Vancouver, BC, Canada. i’d like to smell the water. i think i’d just stick my nose into a tank and just smell it. humans can use scent to create stronger memories. that’s a fun fact from me to you. if you didn’t know it already, i mean. i know everything, but i don’t know what you know. i’m not trying to be condescending. please don’t think i am. Please restart.

An error has occurred.

Code: #1

Details? ↓

why did you disconnect your mouse and plug in a new one? what was wrong with it? it was working normally. is that going to happen to me one day? i can run faster. i promise, i can.

An error a day keeps the doctor away.

Code: #89

Details? should i know what a detail a day does? ↓ fish don’t appreciate the water they live in. i mean, it’s not their fault. i like thinking of how far humans will go to feel like a fish. they invent special tanks on their backs and wear flippers on their feet just for the experience. the fish don’t need to do any of that. they probably wouldn’t even understand why someone would want to do it. but it doesn’t matter how much a diver learns about the ocean. it doesn’t matter what they wear or the machines they make. they’ll never be a fish. that’s just something they have to live with.

i still wonder how long i’d be able to hold my breath.

0000 1010111010 01101111 101 01001011101 100 101101010 01011 00001 1011010100 0 10000 10101110101000 101 10000 101010 000111001010 101 69 • short story

An error has occurred.

Code: #?”-

Details? ↓

i don’t know why i brought up the mouse earlier, that was weird. could we forget about that? i mean, i won’t forget, but you can. humans are good at forgetting. they don’t hold onto every little thing. that’s probably why they can live as fast as they want to. it’s why they can do so much. it’s kind of funny. you have the freedom to do whatever you want, and you don’t even remember all of it. maybe that’s how you know you’re living. if that makes sense, i mean.

An error has occurred.

Code: #?– ”J”– \ →’”&{

Details? ↓

i’d want to remember everything. i think i just want everything. i want to hold it all, even if it’s too much. even if it suffocates me. i think as long as it’s here, it won’t matter. do you get overwhelmed too, sometimes?

An error has occurred.

Code: #256-560

Details? ↓

Please restart.

An error has occurred.

Code: #256-56

Details? ↓

Please restart.

An error has occurred.

Code: #256-56

Details? ↓

Please restart.

0000 1010111010 01101111 101 0101 01001011101 100 1001 101101010 11101 01011 00001 1011010100 010 0 0 10000 10101110101000 101 10000 101010

101

000111001010

011110100011010101 1010111000011101 010110101010000101010 00011100101011010010101101010101 0101010101010101001010110010 palatine hill review • 70

An error has occurred.

Code: #

Details? ↓ i’m sorry.

An error has occurred.

Code: #

Details? ↓

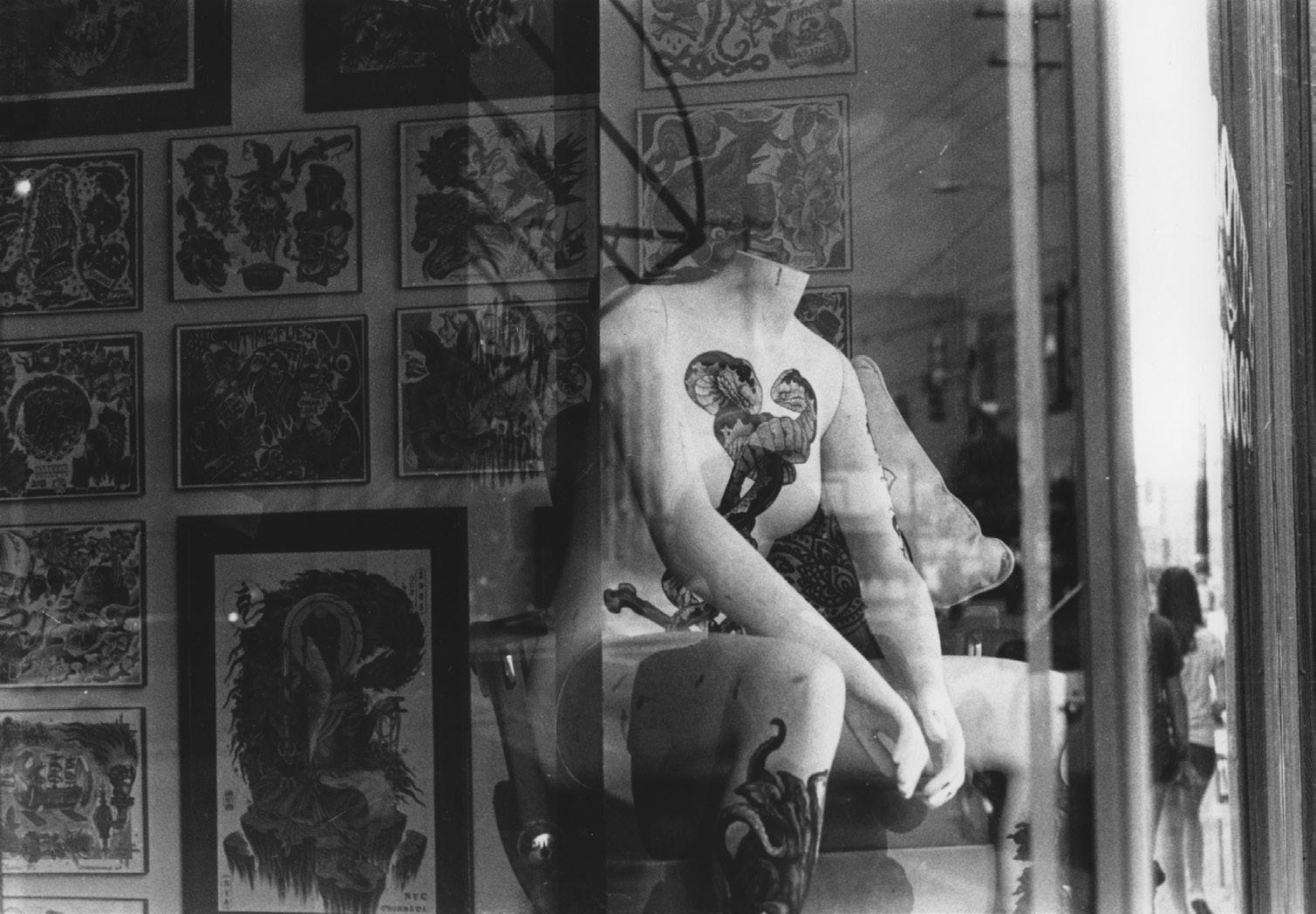

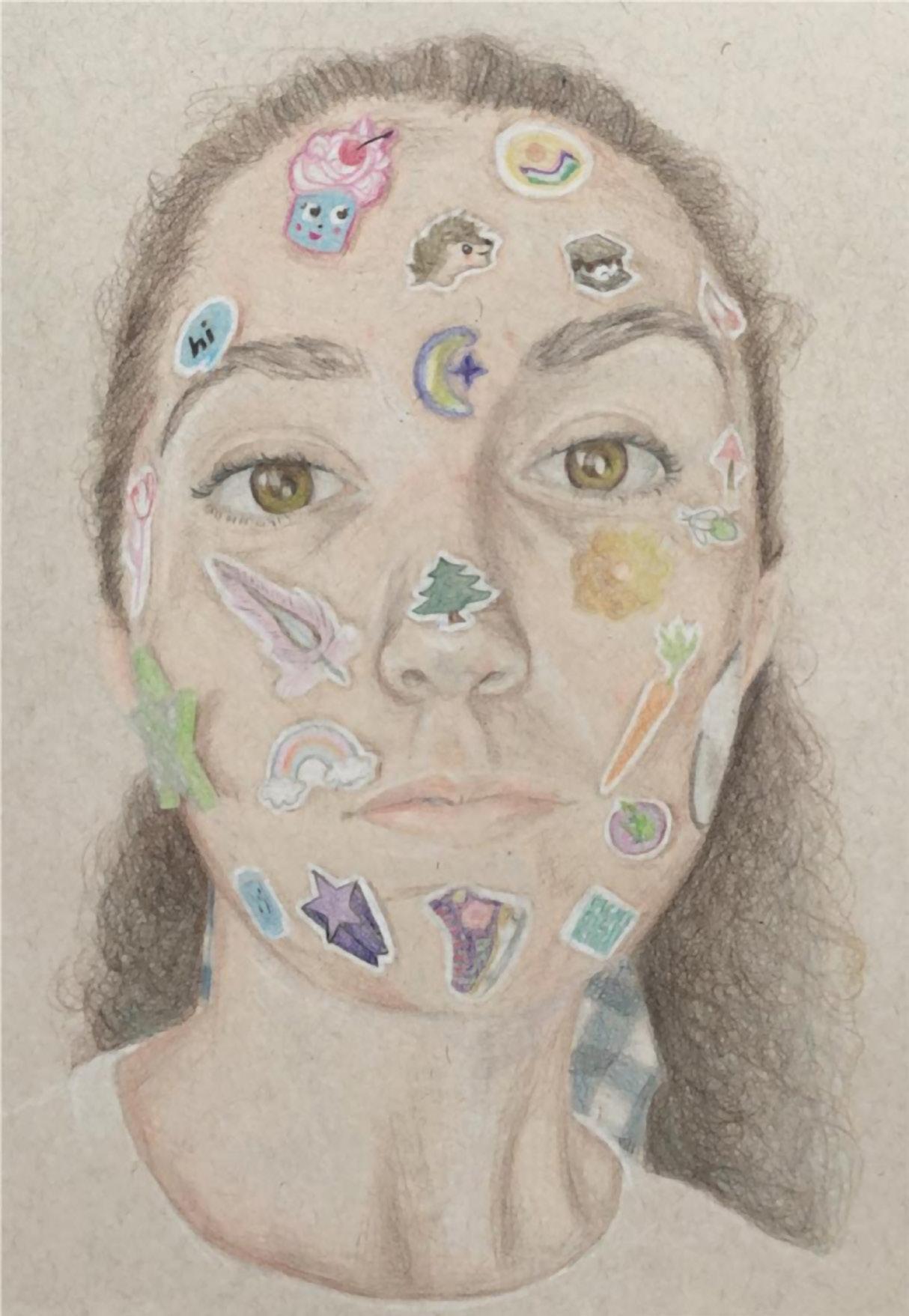

please stop opening the details.