Individual pieces contained herein are the intellectual property of the contributors, who retain all rights to their material. Every effort was made to contact the artists to ensure that the information presented in this magazine is correct.

Opinions expressed in the Lewis & Clark Literary Review are not necessarily those of the college.

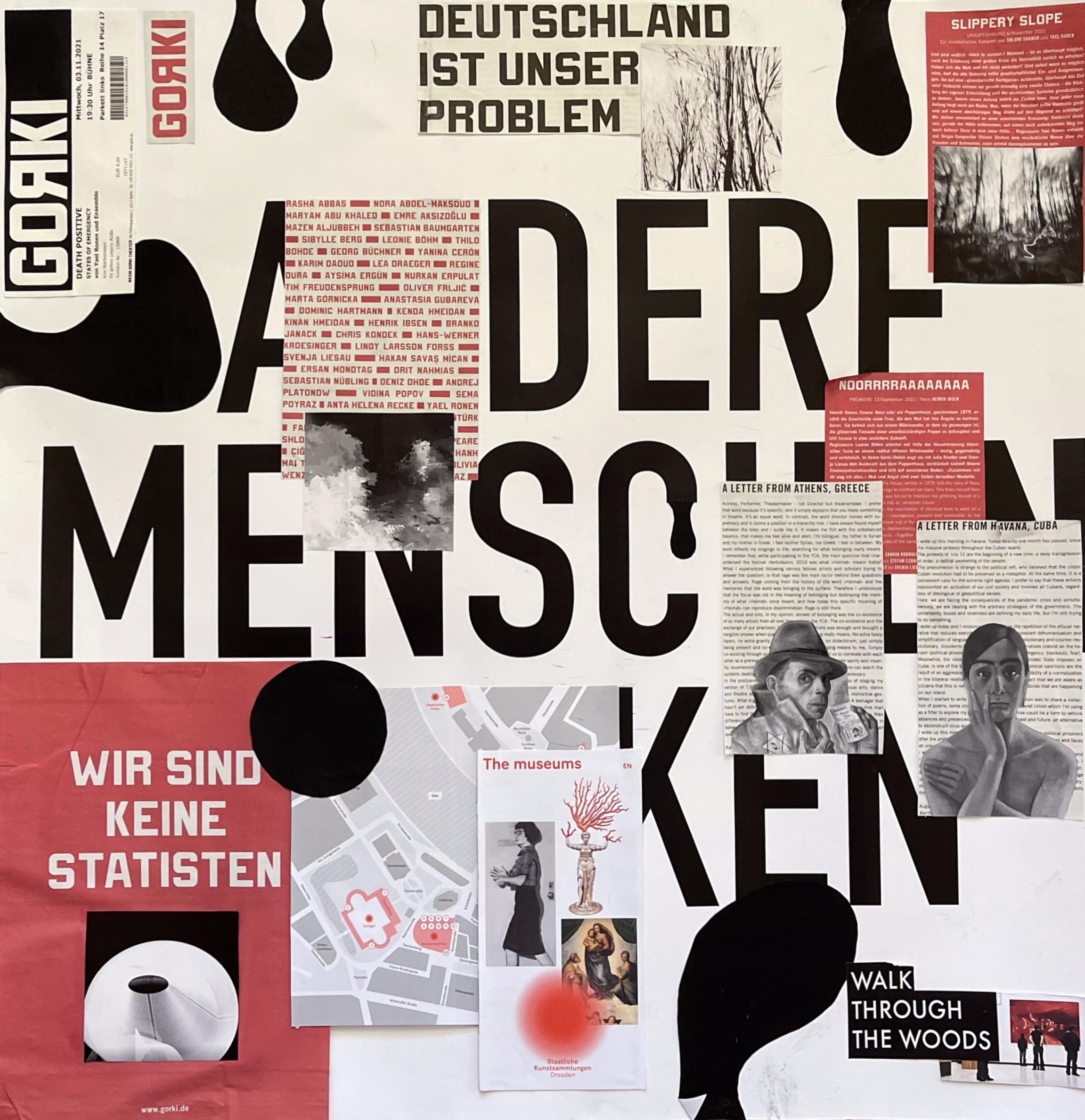

bone meal is published by Morel Ink. This edition’s typefaces are Brandon Grotesque and Atkinson Hyperlegible.

bone meal was created using Adobe InDesign and many, many Google Docs. Additional graphic editing was done in Adobe Photoshop and Procreate.

Editors-in-Chief

Eve March

Jillian Jackson

AJ Di Nicola

Editorial Assistant

Design Assistant

Editorial Board

Alina Cruz

Elizabeth Huntley

Anna-Marie Ahn

Max Allen

Anneka Barton

Apollo Beaber

Meghan Blandon

Sage Braziel

Kay Brooks

Elliot Chadwick

Claire Champommier

Alex Chew

Leila Diaz

Lola Ecker

Tiani Ertel

Kit Graf

McKenna Jones

Colette Kane

Alison Keiser

Adele Kelly

Joans Kelly

Yonas Khalil

Kathryn Kiskenen

Marijona Sasway

Mangelsdorf

Hailey McHorse

Sam Mosher

Rose Palma

Kayla Peer

Elliot Pfeiffer

Ashley Phan

Shelby Platt

Jack Quimby

Zach Reinker

Lily Ronda

Burton Scheer

Claire Williams

Lizzie Winkelman

Jade Ferguson

Colette Kane

Shelby Platt

Lily Ronda

Zach Reinker

Mary Szybist

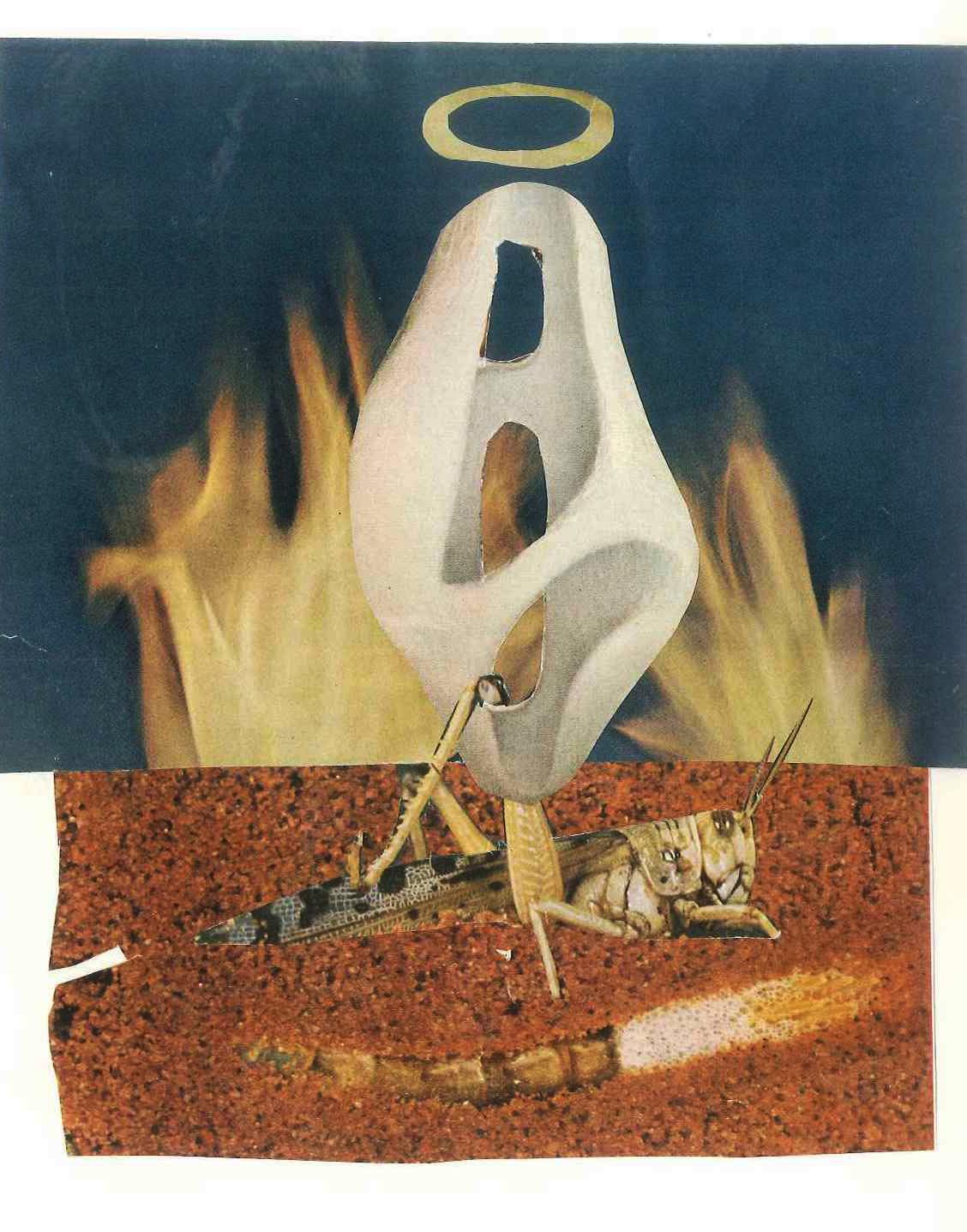

Molecular biologists believe that carnivory in plants has evolved at least ten times independently. In other words, this equal-parts wondrous and threatening phenomenon is a coping mechanism, a way to stay ahead and protect oneself.

As we “emerge from the pandemic”—for the third time— our contributors are flipping the realist tradition on its head, contorting it to a landscape that teems with ghosts, bloodthirsty cosmic entities, and maybe even King Kong.

Simultaneously, our contributors use adaptation and regeneration to unlock productive, whimsical possibilities. Perhaps a bison and a seagull can be friends, or a polar bear can join a dating app. The lines between human and animal, between decay and growth, between being nourished and being devoured, remain blurry.

As we move towards a degree of normalcy, we seek adaptation not only in the pieces we accept but in our club as a whole. This was a transformative year for the Literary Review. We welcomed more than 15 new members to our editorial board and worked on this edition from three different countries. Better still, we benefited from a distinct collaborative energy that came from a return to in-person weekly meetings.

We also sought to revitalize our design this year. In an effort to create a cohesive work of art, we established a design board with bi-weekly meetings, taking into account the themes emerging from the pieces we’d accepted.

We are thankful for the unprecedented amount of submissions that we have received, the dedication of our board members and new leadership, and the creative community that we have fostered this year.

Next year, the Literary Review turns 50, and we look forward to celebrating this milestone with our own kind of evolution.

We hope you enjoy the Literary Review’s 49th edition as much as we enjoyed putting it together.

Eve March Jillian Jackson AJ Di Nicola Editors-in-Chief

Eve March Jillian Jackson AJ Di Nicola Editors-in-Chief

1 French for “Until tomorrow.” Jillian says Bonjour from Puteaux!

demain1,

Three

Three

Romance

Beautiful Like a Woman

He’s such a romantic

I wake up after senior year homecoming with a joint in my eye. Des’ jacket lies on my face and I can feel her curled with Jake besides me. I reach over, parting the morning sunbeams and cover them with the lavender coat. Laura is tucked in the corner of her bed, as far from the hole in the wall her dipshit boyfriend made as possible. I can’t look at the bruise on her jaw so I just pull her blankets up and go to the bathroom to steady myself. There I look at her mom’s pills for a second too long, and find my shirt and a lighter in the hallway. I end up on the window sill blowing youth and sativa to the five o’clock roses. I look past Laura’s car, our textbooks still piled in the front seat, down the mist dappled street, past the pockmarked sidewalks, through the day, the week, the year. Pretty soon we won’t fall asleep in the same room, laughing more than we breathe. I won’t feel their hands as we handshake in the hallways, never braiding our hair together. But that’s for later as I purse my lips around one of the last things keeping us together, rest my head on the blinds and play keep-away with the roses at my feet.

eating pickles out of a jar he found in the back of the fridge deciding whether or not

to run this morning based on secrets unfolding on his weather app he notes the 70% chance of rain

and heads out for coffee instead where he orders six feet from a masked hipster drowning in a screen

wearing his likeness on a T-shirt who doesn’t even notice him as he sinks a tentacle

into the tepid foam of his latte everyone is already insane these days he thinks

there is no one left who isn’t anxious no one even bothering to notice his foretold return

1 Lovecraft’s creature who, when imprisoned, is the source of relentless subconscious anxiety for humankind.

He saw two crows pinning a third down at the park across from his school this morning.

Disgusting, he muttered as we drove to the supermarket. How civilized we were behind the wheel,

on our way to get food the clean-way. Our fingers, bloodless, clutched grapefruitw

instead of livers and crossed each item off our list with a leaky pen instead of a claw.

How lucky we were, stuffing groceries into canvas bags and leaving with some dirt beneath our fingernails and dust on our shoes.

The only fear was of our ice-cream, melting before we could make it home.

In bed, he mentioned how the image of the crows, pecking away the eyes of the other kept him awake.

How haunting, I said.

It was early harvest when I cut open the first of the fruit, picking the seeds out with my nails. You were some thousands of miles away, And the remains of the rind made me wonder: If Hades is truly barren, then would this not be Persephone’s gift?

A fruit that is only ready when she returns, As Demeter turns the world cold. She is happy and warm in the arms of her lover, Bound by the fruit of her making. Does Hades tend to his pomegranates carefully, Ever grateful for the annual clock she has made for him So they may share their bounty together?

I finished the pink and red seeds and wonder if only six from this fruit is enough for you to stay.

Bored on a Monday Night

Acrylic Paint

Last month, some bigwig with a pleated suit and no soul bought and tore down Donatello’s. You probably haven’t heard about it, so I’m telling you now. I’m telling you that there’s an Italian bistro-shaped hole in the scorched earth between the residential high-rises.

Since losing his ma-and-pop shop, Jerry’s turned to crime. Crime novels, I mean, with borderline culturally insensitive titles like Crime of Passion in Palermo. For her part, Carlotta sold the red-checkered tablecloths. I bought one and turned it into a babydoll shirt that rides up on my belly button.

Fair warning, I’m going to tell you that I wear the aforementioned navel-bearing, asking-for-it crop top to get wasted in the razed Donatello’s parking lot on Wednesdays. I don’t expect you to do anything about it, though. Don’t worry. I got your Christmas card in the mail. Your son looks just like you: freckle-shouldered and smiling with his eyes scrunched tight.

The white checkers on my shirt are stained with Sangiovese; the red ones look the same to my careening vision. I know I’m drunk because it’s April, and here I am thinking about Christmas cards. I’m picking pine needles out of my pinnedup hair. I’ll water the tree with $9.99 mulled wine from BevMo.

Wait. I made a mistake. You’re Jewish, and people who are Jewish don’t make a habit of sending out Christmas cards to their ex-girlfriends from seven years ago. I’m pretty sure they

don’t send out Christmas cards to anyone. No, that shirtless child in the Santa cap, taking up three-quarters of the frame, was not yours. My cousin’s kid just has the same approach to life that you do, pinwheeling his arms wily-nily. So, now I’m sure you’ve got a wife out there, kids and Christmas, kids and Hanukkah. But, most of all, kids that aren’t mine.

Help! I’m still at the restaurant, still cross-legged in the corner I haunt. I’m crying into my Pasta Fagioli and getting my dignity tangled up in plastic grape vines. Still, I outlived those fake grapes strung about the rafters. I outlived the rafters themselves. Next week they’ll deliver the plexiglass for the windows of 37 single-occupancy units. They’ll pack people in like the sardines from Donatello’s bitter-lemon pasta.

The whole joint took sides, remember? Jerry started to plot your untimely death in some moonlit piazza, but Carlotta gave you free, over-buttered focaccia breadsticks for a year.

You left me—no! You’re just moseying on up to Carlotta’s counter. She forgot to put ice in my lemonade. Of course, you don’t need any ice in a chipped wine glass filled with Sangiovese. I’m still twenty-three, and what twenty-three-yearold waters something down?

“You’re Jewish, and people who are Jewish don’t make a habit of sending out Christmas cards to their ex-girlfriends from seven years ago.”

Now, two women my age roll past with strollers, arms pumping for 6am Thursdays. I am a heap of gingham and grapes, plastic grapes, wine grapes. I am the clatter of soup spoons, one of Jerry’s meandering thousand-page detective novels, a woman in a ravaged, gentrifying ditch, a woman waiting for her boyfriend to come back to the checkered, still-intact tables.

“Did you ever hear about the girl who got frozen?” One of the mother’s lips move, and I decide that’s what she’s saying.

“Break-ups happen everyday,” the other nods sagely. “You don’t have to lose it.”

I haven’t lost anything except my wallet, which is fine, since you wanted an excuse to pay for me anyways. Wait. I’ve changed my mind. You forgot your wallet and left me to foot the bill, to get my elbows sudsy while washing compensatory dishes beside Carlotta.

You left me no choice but to stay here forever. I am telling you that’s also fine. If you squint into the sunrise, everything’s sepia-toned, like the blurry family photographs Jerry used to frame on Donatello’s walls. Dust collects on my pinned-up hair. I’m right where you left me.

I don’t expect you to do anything about it, though.

This vignette was written for Professor Don Waters’ Fiction Writing II class, during which his students were tasked with interpolating the lyrics and exploring the themes of a song. Many thanks are owed to Taylor Swift and Aaron Dessner, the writers behind “right where you left me,” a breakup track that I chose for Waters’ assignment.

I’ve got Marvin Gardens taste with a Baltic Avenue budget on Pacific Avenue though it’s priced as high as Boardwalk due to domination of the market by a single entity. Did I mention I’m getting around in a wheelbarrow?

All the people all the dancers so crowded crowded together with laughing and shouting and talking alone together in time but not small lags mistakes not mistakes just fun it’s funny to miss a step as long as you jump back in and try try to keep a rhythm hope it is the same rhythm as the music the dance the crowd dancing stepping jumping always stomping and jumping in time a missed step a missed turn a missed spin now run the other way the other other way now no now bodyslam like a too-cool-for-school bro hug and fall and are you okay and smile and laugh and not care and accept a hand up and dance ignore it it’s much more fun to dance than not so there is no twinge in the ankle and dance dance dance all night because it is so much more fun fun to jump and twist and turn and step than dodge and skip through lines to the side where there are

others standing drinking water wine water and lifting and rolling your foot go back go back to dancing it is so much more fun to dance than not

Is it her? How can I tell when I get only glimpses through the writhing heaving mass of people dancing weaving a tapestry dancing in the open pavilion dancing in the crowded street dancing in the overheated room with the oversized fans and lights turned on because the sun can’t get in through the too-small windows because the stars can’t get in between the too-large drapes because the moon is new and has no one to train her to do her job tonight

Fingertips brushing fingertips asking let’s go let’s have fun please asking can we go we know how asking it’s been so long asking I’m scared nervous embarrassed asking don’t care don’t care do it it will be fun you won’t regret it I promise

asking but what if you’re wrong asking let’s go have fun please you’ll have a good time sing your song and move your feet you don’t have to know the dance you can follow along asking are you sure asking grinning pulling let’s go

She runs and kicks and her shorts leave her legs free to move unhindered her skirt flies around her waist the colors are eye catching and bright and mature and refined with purples and greens and blues and yellows and pinks intertwining with jewel tones and tie dye and neon all flying with hair dyed to match and hair blonde as dirty strawberry platinum blonde it flies whipping around her head whapping friends and acquaintances in the face whapping her in the face getting caught in her glasses not glasses that never fall off or get loose it is too light too heavy to flow it tumbles to the floor skimming the hem of the skirt at her ankles it is too

heavy too light to fall it is short cut close to the skin light as a bird it lets the wind fly through and dry the gathering sweat it’s girly always girly because she is a woman except when it’s not except she always is except when she wishes she could be a woman without all it entails it is gathered up into a ponytail and a braid and striped with ribbons and color and it flies through the air as free as can be

Her face is flushed and clear with black above her eyes that her best friend put on hours before it doesn’t smudge no matter how much she touches it and rubs the corners of her eyes and the eyelashes that itch along with the bright colors on her eyes the colors that match her dress and lipstick that disappears like it was never there before she licks her lips to smile wider and shriek louder as she’s lifted into the air flying by the arm around her back

Break for water because she has to because it’s important so she doesn’t get cramps or pass out and get trampled they wouldn’t actually trample her but the thought is there she can also get cramps from not breathing while dancing she always forgets to breathe it takes thought and dancing is just so much fun and so distracting but cramps hurt and make dancing less fun so she must go to the side weave out of the moving writhing masses and drink from the neon shiny plastic metal plastic bottle where friends are standing and they chat and talk while she drinks and breathes and they hug hello and they hug goodbye huge hugs pressing against each other cheek to cheek and chest to chest with arms wrapped tight like it’s been too long despite living so close and being so close they hug tightly and it doesn’t hurt the pressure is painless and soothing and it is right pressure on top of pressure it used to hurt to be uncomfortable and out of place but no longer now it is right and they hug goodbye before she goes back jumps

back into the hopping of the dance and the shouting of the people dancing with the music

She takes a hand it’s bala bala yaa take a step take three and spin spin spin around hair whipping around heads close cropped hair to the floor dresses billowing out like sails why like sails they are cylinders spinning round and round as the women in the middle are spun round and round a hand above their heads not holding just touching palm to palm talking and moving telling where to go while the mouths are busy with conversation and laughter with the music flowing through the air touching ears and hair and skin and skirts and shoes spinning around and around but not like a top because tops are unpredictable she is not she knows where she is going with her eyes closed with her hand above her head with her feet underneath her stepping on air stepping on music carrying her in a cig bircle

a bircle that is cig around and around and around

I wanna know what you sound like in French.

The same as in English, maybe. You stroke my troubadour throat. Coax les mots doux1 out. Sap them from my mouth like honey. A sweet string drips from my parted lips. My accent might sour fruits.

I am not like you. I could not fold up a second tongue in my pocket, ribboning its wrapped des jolis cadeaux pour des étrangères. 2 Of course, you and I are not strangers. For you, I split my infinitives. Cleave them open like pomegranates. Make tart grenadine.

Je coupe en deux ce que j’aimerais vous partager jusqu’à ce que rien ne soit entier.3

I could call you ma mie, 4 in French. Roll out the idiom’s dough. Pinch the pie crust of my possessives around what I adore most: your soft middle. The tender, crumbly insides slathered with jam. I drizzle you in euphony.

Comme la mienne, mais pleine de sucré.5

1 Sweet nothings.

2 Beautiful gifts from strangers / foreigners.

3 I cut in two what I would like to share with you until nothing is whole.

4 Term of endearment that literally translates to the doughy, soft part in the middle of a slice of bread.

5 Like mine, but full of sugar.

I do not want to be beautiful like a woman I want the beauty of a towering forest, All encompassing and powerful, Fear inspiring.

To be viewed not as an object of pleasure But a mirage of beauty, Elusive and untouchable With places men can never reach.

I want to shake in the wind

Like a dance, A warning

Not in fear of lurking shadows in Parking lots and empty streets

I do not want to be a woman

I want to be the thing in the woods that men fear.

He pulled up to my dorm and stood against his car, door open, all hard rock at 9 am and don’t you look nice. Lips puckered like he’s smoking a cigarette, but instead he’s wanting a kiss

and an apology for being late. Popped the trunk for me to throw my bag in the back, he laughed when I flinched at the slam of it.

I picked lint off my yoga pants in the passenger seat, looking at each piece up close as if to figure out which article of clothing it once belonged to

while he complained that the hill was too tall, but he still liked the drive with the big houses all the way up.

We called the modern one with a teak fence the “bamboo house” and tried to guess how much it cost, usually ending with him irritated at how money works, at least I’m in STEM, he’d say meaning that one day he’ll live in a “bamboo house” on a hill

and I would live in some shitty bungalow painted a weird color like mint green but at least I’d have a porch swing

and be pleased with my life.

After he’d say something risky, he’d reach for my hand and wait for me to squeeze it, confirmation that I wasn’t upset.

I began to feel like Pavlov’s dogs, drooling over complacency like a milkbone.

I’m his girlfriend, the phone number he doesn’t memorize yet calls every morning to say Good morning and Sorry I woke you up but look at this book about computers, zooming in on pictures of motherboards and calling number sequences his poetry.

He used to run his fingers through my hair, pulling each curl apart one by one, commenting that it looks greasy. But my Mom thinks you’re beautiful.

I’d hang his valentine in my dorm, the one he spent two hours making, with rolled paper that formed a brocade heart on the front and I like how cool and nice you are on the inside. He’d spend the next two weeks asking how much I liked it, A lot, I’d say, I like it a lot.

As a child I believed that gated communities were parks meant to contain wild dogs. I thought they held packs of rottweilers with shiny teeth that would chase my family’s beatup Subaru on the other side of the wall, looking for a crack to slip through. I’d press my little hands and face against the glass, hiding behind my breath as it fogged the windows, and picture them waiting for me. Large bundles of muscle pressing up against velvet fur, teeth gleaming in the streetlights. I was always fearless with dogs, but I knew to be scared of these ones. It was clear to me that these walls were not something I was meant to pass beyond. Those who do belong there always seem to smile with too many teeth. To dogs, this is a threat.

Sometimes I imagine that it’s true. That after long days the business men and wealthy retirees will go home beyond the crisp brick walls and unzip their skin suits. They’ll sit on their haunches and pant, waiting for some poor soul to wander in so they can get a bite to eat. The drool will cling to their jowls and for the first time all day their perfect manners become meaningless. Returning home reduces them to creatures built of hunger, interested only in consumption.

Even now, sitting in the front seat of a pretty new car, watching the man’s smile turn into a leer as we pass through the gates, I think they must have been built to hold something sinister inside.

Sophia Riley

Sophia Riley

In therapy she talked of a bottle cap

The soda shakes and fizzes and as you wait you assume it’s fine

Then the cap pops, jumps, runs

Brown liquid pours from all directions and I’m a kid in 7th grade science watching an explosion

The explosion is so encompassing it consumes. Life is sucked in at all angles

The toys, the pens, the homemade pillow, then you and me

We’re in the bottle and the caps screwed and we’re waiting

Because when the soda shakes and fizzes the cap pops

Up Rotary Park and down through the rocks with their boot-banging backpacks and outdoor socks, stuck onto slab-crimps by their chalk-covered fingers that brush away mullets, the blond locks that linger— You’ll find the Boulder Boys.

Some climb the sandstone, and some of them sit and even play cards on the sedimentary slits. But all find their way here, to Rotary Park, meeting beer-chugging buds and music ‘til dark. Too sweet, those Boulder Boys. Further up, herder yucks have fenced in their land. Barbed wire grief struck, with pricks fixed in their hands. With the money to spend if the mayor agrees, the town blew it up, poor Rotary. With no cracks to climb or boulders to boy They wiped off their chalk—too much time to annoy. The fellas all said their final tearful goodbye as they all raised up their calloused hands with a cry for the best of the Boulder Boys.

for a night i melt into your house on marion street. your turbid waters settle & we seep into totoro with billowing spirits. we are in love, if only for a moment; you take a long drag from my nail polish and sigh into another week.

i cascade from my hangover with newfound fears of forever. you assuage me only as i read between lines and swallow days like the lump in my throat. there’s something searing in your taillights—to my bleary gaze they’re leaking into storm drains. maybe i should get my eyes checked again.

you call me on facetime two months later & we talk about nothing. your ceiling is scattered and your walls are hollow. you lament the textures of space but i can only see your wildfire hair and the brass in your eyes. when you have to go—we’re running on fumes by now anyway—i wonder if this is the last we’ll know of each other. for all you made of me, i hope i was worth the miles.

Michael Mulrennan

Michael Mulrennan

It was strange, driving up there without him. Sure, the highway looked like it always did: heavily wooded, winding this way and that, small shops and dilapidated resorts sprinkled every dozen or so miles. The September air was dry and cool, still hanging onto the last bits of summer’s warmth. The Great Lake, a deep, ominous blue, lay calm in the amber sunset. As it had for centuries, the North Shore remained the same. But everything felt different. Maybe some of that had to do with the fact that my dad was no longer sitting next to me playing old Bob Dylan CDs and talking to me about which book he was reading from my sociology class. He was still in the passenger seat, but a box of ashes doesn’t do a whole lot of talking. I still buckled in his seatbelt. Sometimes I try to act like it never happened, like I still have a dad, rather than had one. I took a course on psychological first aid once and they told me that you can tell that someone’s depressed when they have a case of the “I used to’s.” I wish I had paid more attention after that and figured out how to get out of it; I guess I just couldn’t stop thinking about how I used to have a dad.

I had to get pulled out of school when it happened. I was in the middle of taking a midterm my sophomore year of college when the Dean of Students walked into the classroom. She whispered something into Professor Jones’ ear before they

“He was still in the passenger seat, but a box of ashes doesn’t do a whole lot of talking.”

tactlessly aimed their gaze toward me. They motioned me up to the front of the classroom and said I’d better grab my things and call my mother. They said it was urgent. I called my mom and she broke the news for me. She was crying. She had loved him before they got divorced. Maybe she still did. When you love someone enough you decide to have a kid, the love changes. When there’s a walking memory of what used to be you never really let go of that love. It just morphs into something else. At least that’s what my dad would have said.

After I finished talking to my mom I went back to my dorm, sat on my bed, and wondered where to look. February rain rapped against the muddy window pain. Every inch of the room was littered with memories. How could it not be? After all, he was the one who dropped me off. He was the one who drove halfway across the country to see his only son start a new chapter without him. It would only be fitting for me to come back to the North Shore and finish his elegy by spreading his ashes out over the land we knew best.

“I don’t know if I’m ready for this,” I said.

“Oh come on. We both know that’s bullshit,” he responded.

We were sitting in the station wagon outside of the Student Union. There were people everywhere. Sons and daughters scoured the landscape looking for potential friends and future hook-ups as their parents gawked at the beautiful campus that lay before them. A handful of people wearing the school’s red and white T-shirts danced between people, smiling and offering words of encouragement to the incoming freshmen and nervous parents before directing them to their child’s dorm. The August heat pressed down upon my forehead as sweat trickled down my cheeks, which were almost certainly as red as those godawful shirts.

“Seriously Dad, I don’t know about this. What if I don’t like it here? What if I waste all of the money you and Mom are paying for me to go here? What if I—”

“Wanna know something buddy? Your mom and I have been your parents for almost nineteen years to the day and not once have we spent a dime we would have wanted back. Except for that one year you played hockey. Jesus that was a fuckin’ joke.”

That made me smile. He was right. Before I’d picked up a baseball and learned I had an arm like Sandy Koufax I’d tried out for the local youth hockey team. After successfully making the worst team and riding the bench all year my parents and I collectively decided that hockey was not a venture I ought to pursue. I haven’t put on a pair of skates since.

“That was different,” I said, my mood lightening ever so slightly. “I was a kid then. But this. Going off to college? That’s big Dad. What if I can’t take it?”

“Do you really think your mother and I would let you come out to Bellingham all by yourself if we didn’t think you could take it? Jesus Marty, how irresponsible of parents do you think we are?”

“Well you did let me go up to the cabin with Jeff and Dan every summer since we could drive and I think we all know what would happen up there.”

“Your mother just about had a conniption when she found all those fuckin’ empty bottles,” he said shaking his head. “So maybe we let you get away with some things. But we knew what we were doing, just like you do right now. This place is yours for the taking buddy. It’s your home to make.”

“I’ll make you proud Dad.”

“I don’t doubt that for one second.”

The sun was slowly making its way down the endless horizon. Night was approaching and I would have to find a place to sleep. I looked in the backseat at the little black lab sleeping on our dad’s old quilt. I reached my hand out and stroked her ears. They were soft and comforting. Millie opened her droopy eyes with a confused look on her face. “It’s getting late, girl,” I told her. “Best we start looking for a spot to spend the night. I don’t know how many of these grimy resorts take dogs so we might have to sleep in here. How’s that sound?”

She gave a long sigh, closed her eyes and went back to sleep.

I worried about her. She hadn’t been the same since he died. There was sadness in her eyes. A sadness that lingered like an insidious virus. It would lie dormant, waiting to be awoken and to strike its unsuspecting host when she was at her most vulnerable. I would take her to the park that she and Pop used to go to. Rather than launch herself out of the trunk and bark at me until I grabbed the slobber-crusted tennis ball, she would sit down and stare at me. She wouldn’t fidget or prance as I was so accustomed to her doing. She would just sit and wait in melancholy silence. I’d look at her knowingly, knowing what she was waiting for… knowing that I was waiting for the same thing too… both of us wishing we didn’t have to.

There’s something special about those that we love, and I don’t mean the people. I mean the soft, wool blanket that we’ve had since we were toddlers; the misshapen patch of sidewalk that made the perfect end to a game of hopscotch; the maple trees that rain down their helicopter seeds in the brisk, midwestern autumn; the jingle of a collar and the clickclack of paws on hardwood racing to eat kibble for the 2132nd

time. They are our left hand when we play the piano. Though they may not make up the complicated melody, they remain a constant. They support us when we get lost or veer off course. They tether us to a rhythm, a beat that is easy to lose and even harder to recover. Many of us neglect this seemingly unremarkable love until it’s too late, until we are left trying to pick up the pieces to a puzzle that’s missing its borders. It’s when I look at her that I remember to appreciate those beautiful, mundane flecks of consistency. When I remember to let my heart drip with the emotions I’ve soaked up from living in a world abundant with feelings.

Maybe that’s how you know you love something unconditionally.

“Oh shit girl!” I shouted, causing her to jolt up right and study me quizzically. “You must be hungry, huh?…” Her tail started to wag more ferociously. She knew what was coming next, but I couldn’t help myself. I paused, letting the magic word dangle in the air like a partially deflated balloon. She whined, stomping her feet in amusement and frustration. “Gosh if you could only just tell me what you wanted.” She was getting really hot and bothered now. Climbing on the center console she took to licking my ear with her anteater-sized tongue. “What, whaaaat,” I giggled, grinning more than I had in months. “Do you want some…”

“It’s when I look at her that I remember to appreciate those beautiful, mundane flecks of consistency. When I remember to let my heart drip with the emotions I’ve soaked up from living in a world abundant with feelings.”

But before I could spit out a word that sounds very similar to “tinner” the car began to slow down. I pressed my foot on the gas pedal but to no avail. The car sounded exhausted. Like a horse at the end of an arduous day the engine sighed and groaned until eventually it came to a slow, graceful halt. Bob and Johnny were in the middle of their heart-melting duet. The sound faded out into silence, but not before they were able to moan:

If you’re travelin’ in the north country fair

Where the winds hit heavy on the borderline

Please say hello to the one who lives there

As the radio faded out and the engine finally spluttered into silence I examined the fuel gauge. It read 0.0. I peered back at Millie who had since sat down, her head tilted in perplexity. Her tail started to wag again. Clearly, she had not forgotten what I was about to say. No matter the fact that we were stuck with no gas in the middle of an empty highway, the next town some fifteen miles away, and had a cold, dark night quickly approaching. In the mind of a labrador, food reigns supreme. My eyes fell back onto where the zeros had been. The electronic gauge evidently didn’t even have enough power to keep the numbers illuminated. I shook my head and gazed at the felt, black ceiling and began to laugh.

“What’re we at buddy?” the ol’ man asked.

“Oh Jesus, we’re gettin’ down there. We got five miles left,” I said, watching the miles tick down more and more. “Where’s the nearest gas station?” I asked.

“Ohhh not for another ten.”

We turned our heads towards each other simultaneously, eyes

wide and lips curled into a mischievous smile only a kid could know. We beamed at one another basking in the absurdity of what we had just said. Then, at the exact same time, we burst out laughing. Millie climbed up toward the front and began licking our necks, not wanting to miss out on the fun.

“Not for another ten?!” I shouted. “Uhh what the fuck are we gonna do? Just sit on the side of the road and stick out our thumbs?”

“Well, yeah!” he said matter-of-factly. “What else are we gonna do? Got any better ideas up your ass?”

“Um I dunno, maybe to have gotten gas half an hour ago!” I said, half-exasperated, half-cackling.

“But that wouldn’t have been any fun now would it? What’s the point of playing it safe when you can take a risk and have a laugh? If this ain’t livin’ I don’t know what is.”

“This isn’t living, it’s just stupid.”

“But of COURSE it’s stupid! Who says that living can’t be stupid?”

“Well, it’s tough to argue with that one.” I smiled at him and he smiled back.

We sat in silence for a few minutes, still laughing and grinning broadly. “Ya know bud, I’m sixty-five years old and I still get off on dumb shit like this.”

“It’s gotta be hereditary,” I said. “Something tells me I’ve got the same gene as you and all of the other rat bastards in our family.”

“So all of them?”

I bobbed my head from side to side, feigning real contemplation. “Yeah, all of them,” I said. Our laughter and Millie’s kisses continued all the way until we pulled off at a gas station ten miles down the road. Feeling both disappointed for not having ran out of gas and proud of ourselves for being so willing to test the limits, we got out of the car to stretch our limbs and knotted stomachs.

“Well,” Dad said. “Maybe next time we’ll run out.”

But there wasn’t a next time. That was the last time we drove down Highway 61 together. The last time we had spent the weekend burying our secrets under the smooth, silver stones of the North Shore. He died a month after that. This time, his miles were the ones that had run dry.

Millie and I spent the night huddled together in the back of the car. The seats, already laid down, made for a comfortable enough mattress and the Thanksgiving-colored plaid quilt was more than enough to keep me warm. I woke up to the sound of a gentle rain pit-pattering on the roof of the car. I looked over at the black ball of fur still slumbering peacefully next to me. I loved her more than I thought I could love another person. I checked the passenger seat to make sure that the wooden box of ashes was still tucked underneath the seat belt. Indeed, Dad was still there, entombed inside of a cedar chest—his favorite wood—waiting to be set free.

I yawned and let out a big, gurgling exhale that woke Millie on the spot. After several rounds of kisses, rubs, and a healthy amount of tussling I gave her breakfast. Grateful, she devoured the food in all of 20 seconds, threw it up, and then promptly ate it again. “You’re disgusting,” I said to her, but I had to give her credit. The girl gets what she wants.

After she cleaned up her mess, we went outside into the mist and relieved ourselves. A push here and a squirt there for each of us. He would have been proud. I re-entered the car, pulled out the bagels and lox I had packed and ate my own breakfast. Millie, ever hopeful, received several slices of salmon that just so happened to slip from my generous grasp.

The rain was still falling and a thick mist was starting to form on top of the lake. I hadn’t realized how close we were to the water. Only a few hundred yards from the shore, I could see the white caps forming atop the lake, now gray from the overcast. To my left I could see the retired lighthouse gazing out over the never-ending water. The waves crashed violently on the cliff it was perched on, splashing enormous black boulders with icy water. Straight ahead was a long beach, turned black from the taconite mining. There was something fitting about the color. Any coastline could have a normal, white sand beach. It’s easy, ordinary, too superficial to contain anything of substance. Sure, it looks pretty. But it doesn’t make you feel anything, it doesn’t make you wonder or make you cry. It doesn’t ask anything from you.

Millie and I considered each other for a moment. “Well, shall we?” She tilted her head. I could have sworn she nodded.

I stepped into the car and picked up the cedar urn containing our father. I cradled it in my hands like a bird with a broken wing. It was odd, holding something so small but whose contents were so vast. It was like holding a microscopic universe. Inside was the man who raised me, who taught me how to throw a baseball, and give a firm handshake, who relived every one of my heartbreaks as I sobbed and ached wishing the pain would go away; the man who was supposed to see my children, who was supposed to ruffle their hair and slip a five dollar bill into their hands to get candy at the convenience store, who was supposed to tell tales of his days stealing bottle caps from the neighbors and sneaking out to

meet ex-girlfriends in the dead of night, who was supposed to be here with me and our little girl walking down to the water so we could let our hearts bleed into the rock-filled shore. That cosmos, laden with stardust and memories, stared at me blankly. I might have been the one trapped inside a box.

We walked through the sodden grass until our feet touched the black beach and our lips could taste the cool spray spitting off of the lake. Normally, Millie would bound up and down the beach like a lunatic, barking at me to find a ball or stick to throw. This time, she remained by my side, trotting along, pausing when I paused, speeding up when I sped up. Occasionally, she would cast me a sidelong glance with her big, black eyes lingering just long enough for me to see her doing it. We continued to offer each other these little checkins as we walked toward the rocky peninsula that jutted out to our right. The stones beneath our feet sank with each step, whispering to each other as they slid underfoot. I wish I knew what they were saying.

The peninsula was not very big, though it was elevated above the beach some twenty feet. It looked like an ancient dagger, crusted in orange rust with chunks taken out of its blade. It was polka-dotted in bright green patches of moss and dying aspens. Its rugged surface made it difficult for anything to grow and the bitter wind that blew onto its jagged cliffside served as a constant reminder that life did not belong there. The water slapped against the oxidized rock face with ruthless determination. The lake was alive. Waves postured in a frenzy, battling for supremacy before conjoining and enacting their outrage upon the murmuring minerals. A layer of cold sweat

“That cosmos, laden with stardust and memories, stared at me blankly. I might have been the one trapped inside a box.”

enveloped the peninsula, making it slick with nerves.

Millie and I clambered up a handful of large boulders and walked toward the edge of the point. Several times I lost my footing, my heart leaping and hands trembling under the emotional weight of the red urn in my hands. Soon enough, we neared the last bits of scarred land where the wind was at its fiercest. We found a relatively round, dry rock and sat down in silence. Although Millie couldn’t talk, this silence felt different. It felt heavy, so heavy that I thought if we fell into the water we would sink to the bottom.

Several minutes passed and the urn lay quite still in my hands. We watched the lake fight itself and the gray clouds roll over the outstretched arms of the North Shore. Neither of us knew what to do next. How do you start, I wondered. How do you just let go, forever?

Millie’s low growl broke the silence.

It

so heavy that I thought if we fell into the water we would sink to the bottom.”

“What’s up girl?” I asked, holding on even tighter. She was looking behind us, hackles up. A man was approaching. He was as old and weathered as the stones we were sitting on. He had a deformed white beard that trickled down his neck and a big red nose that looked like it had been stung by a gang of wasps. He was wearing a buffalo plaid hunter’s cap and a dull, green vest above his torn blue jeans. He looked like the old man who used to run the abandoned lighthouse. As he limped closer I could see a red scar dripping down the side of his cheek like a bloody tear, dried out from the stinging wind howling off the lake.

“This silence felt different.

felt heavy,

“Can I help you sir?” I said, holding onto Millie’s collar. My voice was calm and measured but I could feel the tension beneath her skin, fear and instinct bubbling in her veins.

“Sorry son, I didn’t mean to sneak up on you. I saw your car parked over yonder. There aren’t many folks who come to this beach. Isn’t exactly the most forgiving I supposed. Figured whoever it was might need a helping hand.”

His voice, though as deep and gravelly as the lake, was tender to the ear. He bent down and offered his hand to Millie. I slackened my grip and allowed her to investigate. After a few sniffs here and there she was rubbing her behind on his leg as he obliged her incessant request to be scratched on her rump. She was smiling.

“Alright Millie that’s enough, stop badgering the poor guy,” I said.

“Oh that’s quite alright,’’ he said. “My wife and I used to have one just like her. So what brings you here?”

“Well, I guess there’s a couple things.” I paused, unsure of how much I ought to say. He noticed.

“Ah, now I don’t want to overstep my boundaries. I don’t mean to be a nosy old fart. It ain’t important what’s brought you here.”

“No no, sorry. It’s just that, well. You see, my dad died last February and we used to come up here together. Not here, exactly,” I gestured to the violent landscape. “But to our cabin up near Grand Marais. We just ran out of gas.”

“Is that who you’ve got in that box of yours?” he asked.

I nodded, swallowing the tears that were trying to travel from

my throat to my eyes.

“I see,” he said. “And I’m guessing this is the first time you’ve been here since?”

Again, I nodded. The lump in my throat was getting bigger, harder to digest.

To my surprise, his eyes were the ones glistening with tears. He shifted his gaze from me to the lake as a few tears trickled down the scar on his cheek.

“I brought my wife here when she passed,” he said. “I had a chest similar to the one you’ve got in your arms. There was a lupine engraved into the wood, I think it was Spruce. I waded into the water and stood there, searching the horizon for something I think was courage. I just stood there, wondering if I might just go down with her. Thought that might be easier. At least then I wouldn’t know that I let go. ”

“I waded into the water and stood there, searching the horizon for something I think was courage.”

“So how did you? Let her go, I mean.”

“Those rocks on the beach, the black and blue ones. You know what those are? Basalt. They come from volcanoes and form when lava cools down really quick-like. If you look close enough you can see tiny crystals twinkling at you.”

I sat there in silence, unsure if he wanted me to speak or if I should remain quiet. It seemed like he was getting somewhere and I didn’t want to interrupt him.

“After standing in the water I walked back to shore and sat down. My legs were red and I couldn’t feel my toes. Everything was cold. I saw something sparkling next to me and picked up a basalt stone. I had never noticed the crystals before. I felt something as l examined the stone. Something other than cold. I was thinking about her. Thinking about her short, salt and pepper hair, hazel eyes, her silly little giggle.”

He choked down a swallow, but his voice was steady.

“Those rocks have eyes, son. Eyes that listen. Eyes that pierce your own and travel down into your heart. They gave me the strength to let her go. Told me she would always be here.”

“Was it hard?” I asked.

“Hardest thing I’ve ever done. But that’s how I knew it meant something.”

I pondered what he said for a moment. I could feel the volcanic pool of fire coming to a rolling boil inside me. All of the agony I had endured over the last few months seemed to be reaching its climax. I was on the precipice of spilling all the contents of my aching, wailing heart onto the rock slab I was sitting on. Then, a wet, sandpaper tongue gave me a kiss on the cheek.

“Millie,” I sighed. I had been so caught up in what he had been saying I had almost forgotten that she was there. But of course she was. My left hand love. Her eyes were fixed on mine meaningfully. Although she couldn’t have known what we were saying, I knew she understood what he meant. She sniffed at the box containing her best friend before returning her attention to me. She blinked purposefully and rested her head on top of the urn, her eyes not leaving my own.

“She knows,” he said.

“I know girl, I know,” I said, stroking her ears. My throat swelled with lava.

“What say I go ahead and put some gas in that car of yours,” he said. He got up and began to walk through the fog before turning back.

“Is this goodbye?” I asked.

“For now, sure. But you never really say goodbye. Just ask the basalt.”

We exchanged a gentle look of finality before he set off through the mist where he was soon enveloped, disappearing from sight.

“Okay,” I sighed. “Okay.” I stood up and Millie followed suit. We strode over to the last rock at the end of the peninsula. The rain had subsided and the waves had calmed to a low whisper. The mist blowing in the wind was cool and refreshing. The burning liquid inside me was rising, but not with anger or agitation. It was moving steadily upwards like a rain gauge during an Oregon winter. As it passed through my throat and up into my eyes I could feel the smoldering sensation fill my ducts. Soon enough, the reservoir of tears broke through my last dam of defense and poured down my prickling cheeks. Each drop burned as it fell down my face and onto the ground, waiting to be swallowed by the lake. I bent down until I was level with Millie. I leaned in closer and pulled her to my side, our heads pressed against one another.

I opened the urn and stared down at the photo resting on top of the bag of ashes. It was of the three of us. Dad was giving his usual broad smile, eyes twinkling beneath his glasses. Millie staring up at the both of us, her grin as toothy and wide as could be. And me, wearing a smile that looked so unfamiliar. It was taken on that last trip we had been on up here, just a

few weeks before he was gone. The trees were green and the lupines purple. Our tattered old cabin glowed in the summer sun. Slowly, I pulled the bag out of its chest and held it in my hands. I felt the weight of him in my fingertips, letting it radiate through my arms and deep into my belly. The tears on my cheek had dried and I could feel the scars beginning to form inside and out. I held the bag out to Millie. She took in a long breath, smelling the memories as only she could.

I opened the bag and shook out its contents as a gust of wind blew from behind us. The ashes flew out across the placid water, before disappearing on its mirror-like surface. I picked up a basalt rock and raised it to my face to be scanned. There was, unmistakably, a new crystal shining brightly on its rough and tender exterior, looking into my eyes the way he used to.

The train whistle is always that of a summer backyard; Bees in the pollen and under our skin. It’s my shout To the engine roar that reminds me, my sister, And you—my mentor—that the divine doesn’t come When we know it, but when we are too busy In our noise to feel the rumble.

And every whistle after is a remembrance of that sky— A portrait to memorialize the sun when she kissed The horizon and died. Every whistle, From childhood into the lonely night, Is a memorial. For moments that pass. For the reason we can’t clutch them.

But the sound, today as it will tomorrow, thickens the air, Pulls the bees out of their coffins and inside us.

If I am lucky, I will be burdened with not knowing what it is, But that it is as true—it is a backyard. And one day, I will hear the train whistle again and remember tonight Then it kissed me as mothers do

Then let our moment die.

my grandma hasn’t breathed for 90 years she says this is because of her mother I pinch my legs together on the bus, fold myself up like an origami swan a boy walks into the dorm hallway; key in hand, I flinch and immediately stammer something like sorry it’s my way of not breathing it’s a family tradition

what is a woman? a vessel through which guilt thrives a bottomless trench into which fleeting desires and careless whims are flung a blank canvas onto which grimy fingers smear blood, then claw at in fury when the outcome is not spotless

I have nightmares where I don’t even need to look down I feel my skin stretched and striped like a melon, bloated with a life I didn’t ask for and I wake up and wonder why it was a nightmare and not a dream maybe because I’ve already become the mother I never wanted to be for people I love, people I know, people I’ve met, people I passed three years ago on the street

and with every borrowed breath I fear that I’ll exhale and give birth to a wailing, screaming reminder

Sitting in a field

An embodiment of poppies

Sitting in a yellow dress

Imprisoned in its thread

Quiet on the hill

Please be quiet on the hill

In my yellow kitchen, I absorb the warm tile, The silver clatter below of some late night Dinner at the restaurant terrace, The orange and teal lights of other kitchens Of other homes. The ache of this impermanence Feels so unfair; How dare I leave myself

On these mountains, street corners, and sunsets, In bars, in conversation, in the quiet

When one day I will quit it all for good? How could I make a home out of a moment?

My stubborn, child love—

I can’t admit that this is how we love things; Because they go, because they are the memory You feel as it unfolds. It’ll never fit in your palm, But it will always leave a mark as it slips out.

I think I’ve been here before, but it was only In some dreamscape, something I would lull Myself to sleep to when my bed was an island And I was the lone witness. I think I’ll be here, In this kitchen, again, but I can’t avoid knowing, Next, that it’ll be the view I see behind my eyelids

When I’m on the transport to another place, A new home to find rest in, a new place I know will fade just the same.

I touch the cold stovetop and imagine I lit it from beneath. So this is what home is. I let my fingers caress the blue-black skyline And feel something electric every time my skin Runs over a streetlight. This is what home is. I find my face in the reflection of the dark window— The day has turned inside out and this is the girl Who faced it. Perhaps for the first time, Her memories are mine. We share in our glance, Like the patrons of the restaurant below Share their food, something familial. This is only ours.

There’s a knock at the door. My arm jolts, splashing hot coffee over the side of the mug, down the table leg, and onto the carpet. Mom’s hand, heavy and now wet with coffee, comes uncurled from the handle and thuds onto the table. The TV goes to commercials. Today is Sunday. On Sundays my parents come upstairs for brunch and coffee. They get so lonely down there. No one is supposed to come today.

Through the peephole, I see a short, balding man with thick glasses and a clipboard. He wears a suit jacket and tie. Maybe he’ll go away.

He thumps his fist against the door again and I step back. Dad’s head hangs heavy to one side. His left hand rests on Mom’s, but I can’t move his fingers anymore to clasp their hands together. They used to sit that way for hours. I imagine how Mom used to smile at him, project that image onto the pillowcase I’ve used to cover the cloudy eyes and cold, shrunken skin beneath.

“Mr. Miller,” the man calls, his voice muffled through the door. “We’ve been trying to contact you about your homeowner’s association fees. Is anyone there?” The doorknob jiggles.

My heart pounds in my ears. I drag the coffee table, as quietly as I can, to block the door.

“Mr. Miller? Is everything all right?”

It’s unceremonious, not the way I’d like to do it, but there’s no time. I pull Mom by the shoulders, tipping her forward until her weight carries her onto the floor.

“Sorry!” I whisper.

I grab her ankles and pull. Moving six inches at a time, I drag her to the closet, hoist her up against the wall, and slam the door before she can collapse. It takes even longer to move Dad to the bathroom.

Shelby Platt

Shelby Platt

The wind blows the hot sun sweat sticks my shirt to my back and my soggy chanclas cannot protect my feet from the dry hay stalks. But this will protect us—will it protect us? No time to find out we must

a silent command but everyone hears it. People in the streets in the cars on the highways and yet all we can hear is the wind. Suddenly it starts to rain—white flakes— or was that a week from then?

Sitting in the car across from you I wanted to reach out and take your hand—we thought we would lose everything, although it wouldn’t come to that.

Driving that night air still hot and fierce blood dripping from the sky and monsters dancing in the streets, I pinched myself hoping to wake up but I haven’t yet.

Finally we’re delivered through the barricade and make it home. A place too many people will never return to.

Your new home is in the heart of a town which you have never been to before, which you hardly know, and the town, likewise, is dreadfully unfamiliar with you.

The sign comes into view, a tentative stranger in the dark which makes two things apparent. One, it has a name beginning with an O, and ending in something else. Two, as the modest population number shows, it is a town so small as to forget itself, and so quiet as to die without anyone’s notice. When you peel off the highway and start making your way down its twisting roads, it is dusk already, and you see few signs of life beside the odd fox or raccoon slinking into the shadows at the touch of your headlights. The people you do see all seem to be looking at you. You suddenly become self conscious at the sound of your engine, thinking its loudness is the cause of the unwanted attention.

It is not. But you have no way of knowing this, yet.

The house you arrive at is not haunted. It is built of wood and brick, and it sits at the top of a hill so that your pens will roll sideways should you ever try to set them on your desk. Beneath your home there is a storm shelter, which you did not have back home in the city—it makes you think of Dorothy just before being swept away to Oz. There are no windows at the front of your house, making it impossible to look out into the street. You find this odd. You begin unloading boxes.

As you are doing this, it comes to your attention that you are being watched. The eyes belong to a small woman sitting on the porch of a house the color of dusty bubblegum, or dried

meat. She has far too many lawn ornaments, and does not wave back. Instead, she hobbles inside and comes out some moments later struggling beneath the weight of a cow’s skull in her arms, which she sets down on her steps like some obscure jack-o’-lantern. Then she goes inside, and does not come back out.

You elect to take this as an unfamiliar form of greeting.

That night, the first night, there are noises coming from outside your house, though you can see nothing from your limited selection of windows. You hope they are owls, or some other thing of the night that would have no use for you. You sleep, because it seems the obvious choice.

The next morning, your house is full of boxes, and yet you find yourself unwilling to unpack them. This is mostly owing to a new sort of nausea you have never felt before, which clings to the pit of your stomach like you are rotting from the inside out, though you have no reason to be nervous. You try to distract yourself by getting to work, but it does little to help. You have a job, of course, maybe with the church, or maybe with the post office; either way, you are sorting through papers. That’s why you moved here, for work. What other reason would you have? You are from the city; you are supposed to be in the city. There is nothing here that suits you.

The quiet, for instance, is a thing that presses in on your peace like an unwelcome guest, as you are quick to notice when you elect to take a short walk to calm your nerves. The empty space, too. You hate the way that, walking down Main Street, you can see right past the small cluster of residential blocks and out to the expanse of desert, and beyond that, hills, and beyond that, a sky that could swallow you. And you do not like the people. You do not like the way that they stare, or the way that they look away just as quickly to pretend that they were not, or the way that the woman in the antiques store is so

quick to ask where are you from? when you stop in to examine a set of drawers. You tell the woman you are from the city, and there is fear and venom in her smile. You hate the way that she knows without asking that you are not from here, that you are an outsider. The people come and go, she says, but the town is as it’s always been. You make a joke about being fresh meat, trying to be friendly, and the woman’s laugh in response lasts a little too long, and does not reach her eyes. When you leave, she flips the sign to say CLOSED.

You are walking home, and as you pass through the neighborhoods you become suddenly acutely aware of the abundance of cow skulls. Some are set out on porches, like that of the woman from the bubblegum house, or else they are hung up on doors like wreaths. They are of different shapes and sizes, some more chipped and ancient than others, some with a certain amount of decorative hand painting, but most without. And they are outside nearly every house, when you are certain that only yesterday this had not been the case. You look at them, and they look back at you. The back of your mouth tastes like dust. You go home and return to your papers.

That night, the second night, the sounds in the street have grown louder. You lie awake, listening; they no longer sound like any creature you have heard before. Rather, they are oddly mechanical, with a twinge of warning to them. Are they car alarms? You have hardly seen any cars here—given everything’s proximity to everything else, there are few places one would need to drive to. There is something beneath the echoing wail, something that you cannot quite place. It is dry and rattling.

“You hate the way that she knows without asking that you are not from here, that you are an outsider.”

The sound swells and fades, ebbs and flows, makes you seasick and sticky with sweat. Your clock has stopped working, and the dark does not betray the time. You strain to look out into your street, but can see nothing. You do not want to open your front door. You decide you will leave in the morning.

It is dawn, and you are driving. There is not a soul in sight, and the morning light makes the landscape look like a yellowing newspaper. You have left your boxes back at the house which has nothing wrong with it, though you are now secondguessing this decision—the absence of objects in the back seat makes you feel painfully exposed. You pass the antiques store, and the CLOSED sign has been replaced by a skull. You are driving. And you are driving.

And you stop.

There’s the sign again, faded like an old postcard, which has now switched to face the town and not the main road. You are not looking at the sign, though. Mostly, you are looking at the skulls.

They are placed neatly side by side in a manner that blocks the road, and then wraps around in a vast formation that you suppose must encircle the whole town. They are all facing inwards. Many are, like those you saw on the porches, cow skulls. Many are decidedly not. You do not feel well. You step on the gas.

You open your eyes at the sound of your pen rolling off of your desk and hitting the floor. It is the third day, and you have fallen asleep over your papers. You mustn’t let your imagination get the best of you. You think of going down to the diner for a coffee, but there isn’t enough time.

It is the third night.

You are standing, though you don’t remember standing, and you are looking at the wall where the windows should be. There is the sound again, the awful sound, and it is louder than ever. It is the sound of snapping tendons, and behind it, something long and yawning and awful, like the rising and falling scream of a tornado siren. You realize, suddenly and fearfully, that they are here for you—naturally, they are here for you. You do not have a skull to keep you safe, and so they know precisely where you are. You are afraid, you think, but you cannot hear your dread over the sound of the sirens. It seems absurd to deny the fact that you are the thing that is wrong with this town, because you are the thing that has changed.

You open your front door.

The first things you notice are the birds.

This is your best approximation of a word to describe the creatures, but really there is very little to them but bone. They are tall, taller than the houses, with sickly white bodies and beaks carved sharper than steak knives, their legs too thin and too long. There are hollow pits in place of their eyes. They are walking the streets slowly, like diligent scavengers, and there are a great many of them, maybe thirty, maybe a hundred, maybe more. The sound, deafening now that you have no walls to shield you, is coming from them, though their beaks remain

closed—it is as though it is emanating from each putrid ribcage. At the sound of your door, they all turn to you. They have been waiting for you.

“It is the sound of snapping tendons, and behind it, something long and yawning and awful, like the rising and falling scream of a tornado siren.”

The second thing you notice is the feeling of pierced flesh, like you are being stapled to a signpost.

You are taken apart, piece by piece. It is a loud and unsightly process for such a quaint and quiet place. You should be ashamed.

After some time, once you have been adequately removed, the scavengers withdraw, and the town is quiet again. The doors along your street, along all the streets, open one by one. The people step outside, and they retrieve the skulls. They shut their doors.

By morning, the street is so clean as to have never been tarnished by you at all. And the town is as it has always been.

i am fully aware (of the air right now and the hint of orangepurpleblueexplodingred that lingers so would you Please take a few steps further back into the hallway—)

, thank you

, now can you leave ((which means (you shouldn’t see splintering white you can’t ) pl,ease i beg ) get out get ouT geT OUT i do not Care if you Care anddontmakemehaveto—)

—stab you in the eye with unconventional,love, if necessary i will move back to terrestrial hell if necessary i will shove black dowN yoUR tHROAT if necessary(understand that) but

now there’s hues , (h)yous , hues ( oh , )

thedoorisclosed and youare gone ; there is only faded scarlet

I’m playing hangman in the closet.

Yelling, no more yelling

Only letters

A loud thrash. A lamp, I think falls and bursts

Accusations and slammed doors

No more yelling

She’s there with me

Playing hangman in the closet.

Letter by letter

We almost spell the outside noise to silence

The lights flicker back on

And the door opens

I can see the tears on my hands and lap

It’s safe now.

Sunrise and morning again

And we’re walking to breakfast at Bluebird’s with Dad

Tearing frills off my napkin

I look down

And think about the unfinished game of hangman—

I don’t remember what they were fighting about anymore.

The sea and a wedding dress you’d never wear, A cold fire casting embers against skin

The words on the tip of her tongue burning, blistering, blue.

A dream you had of when she left you in the forest without looking back

Only this time she’s closer, closer, reaching out from October, never saying anything quite like love —

The sun’s gone down in the arms of a girl you once loved, you have this unspeakable feeling she’s not the one you’re marrying.

Maybe the dress is a joke, a parade of intimacy she’s never wanted and

At the altar you’ll see that desolate campground and her eyes, ice just beginning to thaw

The sound of ice splintering— She holds her hands out to you in offering.

She’s got a knife and a roll of bandages. Right or left?

You rest your head in the divot where neck meets shoulder Remembering the one smile that reached her eyes:

I might love you if everyone else wasn’t watching.

It’s the same as always —

The press of the blade at your back lips against your ear, a whisper but never a promise.

Diana sat in her study with her laptop open. The cursor blinked and she looked at the words she had already written:

We are so consumed by tales of haunted houses that we forget to remember that it can be the land that is haunted. In 1815 the Hersch family lost their two oldest children after they went out to Diana’s Baths—in their journal they refer to them as the “fairy pools.” The father, James Hersch, a priest in Conway, found his children dead in the baths. He believed that evil spirits played a hand in his children’s deaths. That Sunday he preached to his congregation: “Be wary of the evil spirits of this land.” He was found dead in the forest that Monday by his wife Ann. She became a recluse. Her youngest daughter, Elizabeth, took care of her mother. She wanted to be a writer and so we have many documents from her. Their deaths, too, were mysterious. Elizabeth wrote about her mother’s death. However, it is difficult to tell the difference between what is fact and fiction in her writing.

“Bill asked us to sign for a package that’s supposed to come today. He said he’s working a double.”

“Soooo typical.” Lilly loved talking to her mom about Bill; together they made stories up about him. They would guess what he did for work, and question if he ever had a wife (her mom claimed that there was no way he ever did). Lilly wanted to know what went on in the dirt-frosted windows of his house. Sometimes Lilly felt bad for guessing that Bill was probably a murderer, but then her mom would one-up her saying that

he wasn’t just a murderer but a cannibal living in Truckee to pay a twisted homage to the Donner party. Lilly knew Bill had never done anything to deserve these theories; he had only ever been nice to Lilly and Diana. He just didn’t say much. He offered them eggs every week (and her mom always accepted), and waved hi to them when he saw them. Lilly hated to admit it, but she didn’t like Bill. The stories had created something in her, and her stomach would fall whenever she saw him.

“I can keep an eye out. Did he say what it is?” Lilly knew that he didn’t, but she wanted to know what her mom thought it might be.

“Just a pair of eyeballs and a kidney. He finally told me he sells organs on the black market.”

The package ended up being a small box from Amazon.

Diana heard Lilly enter the house and she began packing her bag faster. She didn’t know why she was trying to hide what she was doing. Her daughter would know. It was September.

“So, you don’t even tell me when you’re going to New Hampshire anymore?” Lilly stood in the doorway. Her face was blank, but Diane knew that anger was under the surface. It didn’t matter. Lilly was better without New Hampshire. She was better without knowing. Bill would be here. He would make sure she stayed safe.

So she replied: “I’m not gone yet, am I?”

Lilly rolled her eyes. Diana remembered having to get Lilly to stay with family friends before she was in high school. It had been difficult to find friends for Lilly to stay with—Diane knew what people thought of her, holed up in this tourist

town, staying inside through the winter, doing her research. Whenever someone would ask about her research she would wave it down. Lilly thought that she just researched New Hampshire—and she did. But Diane’s main body of work? It wasn’t finished.

“When are you going then?” Lilly asked.

“Flight is at midnight.” It was 8:15. Diana knew better than to tell her too far in advance.

“For how long?”

“We’ll see.”

Her mom left for the airport 45 minutes later, and Lilly didn’t have anything better to do than go to sleep. It was always hard for her to fall asleep in September. The street was empty now, except for Bill. There was no laughter coming from the lake, and no hope for even going in the lake anymore with the first snow on the horizon. Instead the forest commanded a silence that seeped into the house. The cottonwood and aspen leaves would latch like glue onto the bottom of her shoes coming into the house with her, making the house the forest’s domain.

Lilly put on a show and let herself fall asleep to it.

She woke up, sitting at the edge of her bed. Her head was tilted, looking at Bill’s house, as though she were a puppet. There was a light on in his garage. She couldn’t see into it; the glass was too fogged over with dirt, but the light was distinct. She’d never seen the light on. Her own TV was off now, and the darkness of her room made the light seem brighter. She felt a pull to it. She didn’t want to stop looking at it. If her mom were home she would run into her room, and make up some story

about how Bill was probably in there planning a murder, and they would laugh and she would feel guilty. But, without her it was real. Bill could really be in there doing something a true crime podcast would eat up. The light in the garage switched off and darkness came over the neighborhood. Lilly sat in it. She wanted to know and she didn’t want to know. She couldn’t even move her fingers, but her mind raced. She wasn’t going to go over there. She wished her mom would stop with all the stories or wished that Bill would move or wished that her mom was at least there with her.

The sun was shining in the morning. Her head hurt and her face felt puffy and sore from the night before. She made herself a cup of tea, determined to shake off the night before. Determined to believe that last night was just a dream or an overactive imagination. She sat on the porch, hoping Bill would come out with a cup of coffee. There was no point hiding in her own house. Maybe they could strike up a conversation. And then Lilly could remind herself that Bill was not a cannibal. He was her neighbor and she had no evidence other than her mom’s stories to be afraid. He was normal.

Bill knew she was there, and they both knew no one else was here. It was really convenient that of all the houses on the street, the two that people lived in here year round were across from each other. She looked at the Murphy’s house next door. They hadn’t come back this summer. The summer before the Murphy’s dog, Jack, had drowned in Donner Lake—another innocent body at the bottom of the lake.

“The forest commanded a silence that seeped into the house. The cottonwood and aspen leaves would latch like glue onto the bottom of her shoes coming into the house with her, making the house the forest’s domain.”

Bill did come outside. Lilly wanted to wave. She would even be okay with just bringing her hand up in a greeting. Even a smile would suffice. Just anything to invite him to speak, but her hand wouldn’t move and her mouth wouldn’t stop blowing on the already cold tea.

“Good morning,” Bill called out, interrupting Lilly’s train of thought. She looked up and knew her eyes were wide and scared. She composed herself.

“Good morning.”

“You know, I had this dream last night that you and your mom moved out,” he said.

“Weird, don’t think we have any plans to.” Lilly tried to cheer up her voice. But, it was barren and getting colder.

“Oh no, I hope not. It’s great to have someone else on the street that lives here. Makes me feel a little less responsible for all the other houses,” he said. He was right. One winter so much snow had piled up on a part-timer’s house that the windows collapsed in. Her mom and Bill had called the family, and instead of coming out, the family asked if Diana and Bill could be the point of contact for when they got contractors to come out. They had agreed.

“Well, I better get to it. Good talking to you, Lilly.” He retreated back inside the house. A leaf stuck to his foot, following him in.

Diana could feel the difference in the air the second she stepped outside the airport in New Hampshire. She breathed the air in, letting the cold infiltrate her down into and past her lungs. Letting air give power. It smelled as it should; changing leaves have a distinct scent: fresh and hauntingly woodsy.

When she was here she found it hard to check her phone. Even text her own daughter, even though she was here for her.

It’s what she told herself. She had no evidence that coming here was doing anything. Except that she was still alive. And that Lilly was still alive. That was enough for Diana.

Her rental car acted as a thin barrier between herself and outside. A safety belt for her to remember why she was here, to not become consumed by the smell of white pines. She went to the house first: her childhood home. She liked returning here and seeing how the world changed it each year. The driveway was long, covered in leaves with salt hay sprouting out in the widening cracks of what was left of the asphalt. Bloodroot had long ago taken over the front yard. It was fitting. She could see the house, the blue door, with juniper and birch trees brooding over, framing it like a story. Ivy twined into and through the windows, taking over. She called Lilly.

“Hi honey, how was your night?”

“Her rental car acted as a thin barrier between herself and outside.

A safety belt for her to remember why she was here, to not become consumed in the smell of white pines.”

“It was fine. I woke up looking at Bill’s house. He had the light on in the garage. It freaked me out. Wish you would’ve been here.” Diana scolded herself. She wished she had been there too. It was a fine line she was walking, telling all the stories she told about Bill. She needed Bill to help keep Lilly safe. But she didn’t need Lilly to like Bill.

“Yeah. That is creepy. I bet he—”

“No, Mom. Stop it. I don’t want to hear that.” Lilly’s voice was strong. It shocked Diana and she waited.

“I have enough money to come to New Hampshire. I saved up. It’s my money and I want to come.” Diana remembered the first time Lilly suggested coming with her. She had yelled at her. Her face was bright red. She had raised a hand up to hit her daughter. It was dangerous.

“Why? I want to meet—” the line cut off. Diana looked down at her phone.

To meet her grandparents. She didn’t know why her mom kept them from her. She never talked about them. It was different from her dad. Her mom talked about her dad. Told her how he didn’t support her research and how he thought she was stupid. Her mom said he was a narcissist. Oh, she knew all about her dad, except for knowing him. It didn’t matter. She didn’t want to know him. She wanted to know New Hampshire. It made no sense. Her mom did research on the history of New Hampshire, and yet it was off limits. One time when Lilly had pressed her mom about what it was like to grow up there, she had stopped talking to her for three days. Lilly decided it didn’t matter. Maybe the line was cut off or maybe her mom didn’t want to hear it. It didn’t matter.

Lilly looked outside to the safe. It wouldn’t be her first time trying, but she was determined to let it be her last time trying. It was kept in the shed. A spot that Lilly had never quite understood as an ideal spot for a safe. It was impossible to get into the shed in the winter. Snow piled over it creating a new hill. When she was younger she took to sledding down it. Her mom caught her once and she was grounded for three