Schrodinger’s fund

The more this fund changes, the more it stays the same

By Zain Naeem

There are a few anomalies in the capital markets that are difficult to understand and even more difficult to explain. One such dichotomous example is a fund called Habib Growth Fund. The fund is currently listed on the stock exchange which means that it is a closed end fund quoted on the exchange. In addition to that, this is listed as HGFA which stands for Habib Growth Fund (A) which shows that it has been carved out from a previous fund. Throwing so many terms in quick succession can confuse a reader who has little knowledge on these technical terms. Lets start by unpacking the basics of mutual funds before explaining how this fund is existing in two states at one time.

Mutual funds 101

Amutual fund is an investment vehicle where an asset management company (AMC) collects the funds from a group of investors and then invests in different asset classes. Based on the nature of the risk appetite of the investors, the AMC is given a mandate on where to invest these funds.

A 65 year old pensioner would want to supplement his income by investing in income generating assets which provide a stable and constant income to him at his old age. He has little to lose in terms of his investment and would want his investment to yield a return. He will invest in an income fund which invests in government securities or corporate debt which has little risk and an average return.

On the other end of the spectrum would be an 18 year old who can lose a part of his savings as he is not dependent on them to cover day to day expenses. He will be willing to invest in a stock fund which can yield higher returns, however, there is a chance that he can see his initial investment lose value as well. He will be willing to invest in a stock fund which will give him a higher yield compared to the income fund.

The main task of the AMC would be to gather the funds from different investors and then to manage these funds by investing them in the appropriate asset classes. Collecting the funds is just the start of the whole process as the real job begins when it has to invest them in the right assets.

This is the differentiating factor which separates the funds from each other. The AMC has to appoint an investment committee who is responsible for deciding where the funds are invested. A good investment committee carries out the necessary due

diligence based on experience, resources and market expertise. A good investment committee does not mean that they will always make the right call. There will be times when their pick will not yield the returns that it is supposed to. The adaptability and response of a good investment committee would mean that they will be able to realize their mistake and change strategy rather than try to recover their losses.

This means that an investment committee acts as the brain of the AMC making the right decisions and picking the right asset classes while the funds circulating through it are the lifeblood of the whole operation.

So what does the AMC get for running and managing these funds? For every fund being managed, the AMC is able to get a fixed percentage of fee on a daily basis which is dependent on the assets that are owned by each of the funds. The more assets being managed, the higher the fee and the more revenue that is earned by the AMC from each of their funds.

Now that the core of the mutual fund has been understood, there is a need to add additional information on top of that. Funds can be closed ended or open ended. In an open ended fund, the investor goes directly to the AMC and hands them over their investment. Against these funds, the AMC issues them units in the fund they are interested in. In an open ended fund, the primary interaction is carried out between the investor and the AMC. In case of issuance or redemption of fund units, the investor contacts the AMC alone.

In a closed end fund, the fund size is closed and the units are floated or listed on the stock exchange. In case of any investor willing to invest in a fund, they buy the shares from another investor in the market who is willing to sell. In a closed end fund, the number of units stays the same and investors have to contact other investors if they wish to buy or sell their units.

Getting back to HGFA

After that explainer, it would have become clearer that HGFA is a closed end fund which is listed on the stock exchange and is managed by Habib Asset Management as is obvious in the name Habib Growth Fund. However, the fund was known by another name since its inception.

Habib Growth Fund used to be called PICIC Growth Fund in a previous life and was managed by the PICIC Asset Management company limited. PICIC AMC was a wholly owned subsidiary of PICIC Commercial Bank which came into existence in 1993 as Schon Bank Limited. The ownership changed hands when Al Ahlia Portfolio securities com-

pany bought the majority shareholding and changed the name to Gulf Commercial Bank Limited. In 2001, the bank was acquired again and the name was changed to PICIC commercial bank. The bank was bought again by the NIB Bank in 2007 after which the bank went out of existence.

The lasting legacy of the bank was its AMC which was still running PICIC Growth Fund and PICIC Investment Fund with some of its other funds as well. The success of the fund can be gauged by the fact that throughout its history, the fund had a stellar record in terms of giving out cash dividends on a regular basis which shows that the fund was able to generate an ample return on their investments.

WIth the success of these funds, Habib Asset Management decided to merge these funds into their own AMC and applied for the merger to be carried out. The Securities and Exchange Commission of Pakistan (SECP) allowed the merger to go through in August of 2016. Based on this merger, PICIC growth fund would now become Habib Growth Fund. This was another change in the history of the bank and the AMC which would be carried out. The merger meant that the ownership and management of these funds would now be handed over to Habib Asset Management from PICIC AMC.

The last change that was going to take place was the conversion of PICIC Growth and Investment Fund from closed end to open end funds. In February of 2017, it was announced that the merger stipulated that these two funds had to be converted into open end schemes and due to that requirement, the board approved the conversion to take place.

Frozen portfolio adds to the complexity

In line with this conversion, a whole conversion plan was required. Why was this extra complexity added on top? Well that is due to the way the investments had been carried out. PGF had invested in certain shares which were substantially owned by the government.

The fund had invested in the shares of Pakistan State Oil (PSO) and Sui Northern Gas Pipeline Limited (SNGPL). When this investment was carried out, an initial consent agreement had been made between the Government of Pakistan and PICIC AMC in October of 2005 which meant that these shares could not be sold by the AMC according to the privatization policy of the Government of Pakistan. In case the AMC wanted to sell these shares to a strategic investor, they had to get approval from the government to do so. Until this approval could be given, these shares would be assumed to be part

of a frozen portfolio. Due to this, PGF was split into two different funds. One fund was going to be HGFA which was going to have the frozen portfolio as part of its assets and it will remain a closed end fund which could be traded in the exchange. The other part of the funds would be HGFB which would comprise the unfrozen portfolio and would become an open end scheme.

At this point in time, the whole fund had almost 16 million shares of PSO which made up 46.27% of the fund and held almost 10 million shares of SNGP which were around 7.8% of the fund. The remaining 45.96% of the fund had unfrozen shares in its portfolio.

The valuation of a fund is known as Net Asset Value or NAV. NAV is the value of assets after the liabilities have been paid off and then divided by the number of units that have been issued. After the conversion was carried out, the NAV of HGFA was valued to be around Rs 17.41 per unit.

Divergence between NAV and market price

From the time that the new fund was listed on the exchange in July of 2018, there has been a pattern of divergence that has been seen in the market price and the NAV of the fund. On the 3rd of July 2018, the market price for the fund was Rs 16.41 while the NAV of the fund was Rs 25.18. This meant that the investors were buying one unit of the fund for Rs 16.41 while the fund had net assets of worth Rs 25.18. This represents a liquidity premium of around 65%. What the market is saying is that they are selling and buying a unit for a discount of 35% as the investor will get a right to own a fund worth much more.

The catch, however, is that they will not be able to get the full amount until and unless the frozen portfolio can be sold. In order to attract the investors, the market is giving a certain return of 35% on their investment being carried out right now. The only thing in the way of this payout is the inability of the fund to be able to sell their portfolio, get the proceeds and then pay back the investors their due amount.

The need to attract the investors is engrained in the market price being quoted and the final price that they can expect to get at the end. Tracking this premium from the inception, it was seen that it hovered between 40% and 65% from July 2018 to December 2020 after which it started to fall between the range of 40% and 25% till July of 2023. After July of 2023, this ratio started to recover back as it reached a high of 40%. Over time, however, as the NAV has continued to increase, the ratio has fallen to an all time low of around 20%.

From the lofty heights of 65% to 20%, it can be seen that the discount has increased from 35% in 2018 to 80% in 2025. This shows two trends side by side. The first trend is that the NAV and the market price has fallen out of lockstep as they should be moving in congruence to each other. The ratio increasing over time shows that market forces are holding back the market price while the NAV has kept increasing. The second trend it shows is that PSO and SNGP have increased in market value which has not been mimicked by the market price of the fund.

SNGP and PSO are two companies which have been impacted by the circular debt issue that has plagued the country. Due to loss of recoveries, both these companies have seen their balance sheets grow in terms of receivables and payables that they have not been able to pay off. The impact of that has been that even though they have been earning a good amount of profit, there is a question mark around the fact that whether they will be able to make these recoveries or not into the future. Due to the question mark around their payables, the market started to value these companies at a lower price.

SNGP has seen its price plummet to Rs 25.88 in May of 2022 which has recovered to Rs 126.42. The recovery in the price of the stock revolves around the fact that the government has carried out reforms in this sector in order to reduce the circular debt. There have also been measures taken to address this circular debt which has led to the prices increasing by almost 500% from the lows. Similarly, PSO saw its price fall below Rs 100 due to the circular debt issue which has now recovered to Rs 445.2 in recent times. Due to the rebound seen in the market prices, the NAV of HGFA has increased while its market price has remained depressed.

It can be expected that once the fund is given the permission to sell their frozen portfolio, the liquidity discount will start to dissipate and the market price will start to near the NAV of the fund.

Complaint against the AMC

But the conversion of the fund into a frozen and unfrozen portfolio raises a new question. A complaint was lodged with the SECP which said that the management at the fund was charging management fee, selling and marketing expenses to the fund which had become passive in nature. The complaint contended that, even though the fund had a passive portfolio which it could not influence, it was still charging management and marketing fees to the fund when the portfolio of the fund could not be changed.

Based on the complaint lodged and replies from HBL AMC, the SECP advised the AMC to take up the issue with the Ministry of Energy, Petroleum Division for the betterment of the unitholders. The purpose of this communication would be to get a better understanding of the consent agreement carried out between the government and the AMC in relation to selling their portfolio. The AMC was also asked to cease collecting the charging of selling and marketing expenses as they were deemed unjustified. In regards to the management fee, the AMC was asked to raise the matter in its board of directors meeting and look to lower this fee as the portfolio was passive and did not justify the management fee being charged.

The complaint that had been lodged looked to protect the unitholders from seeing their returns being deducted for unjust fees that the AMC was charging. The complaint alleged that the AMC had earned an income of Rs 293.6 million in 2019 from the fund from which nearly 60% was paid off in expenses. For the first 9 months of 2020, nearly 90% was paid in fees. The complaint was being made as a plea to stop this from happening and to protect the interest of the unitholders. The complaint also highlighted a past precedent where the SECP allowed the JS AMC to see its frozen portfolio and allowed HBL AMC to do the same. Five years later, the issue has raised its ugly head again as State Life recently sold their 20 million shares in PSO allowing it to liquidate its investment. It seems that State Owned Enterprises (SOEs) are allowed to sell their shares in the oil giant while AMCs looking out for the interests of the unitholders cannot do so. If this opportunity was given to the unitholders, they will gladly take it and earn a 75% gain in their investment if it is sold at the current prices.

The double whammy for these shareholders is that they see their investment being locked in while the AMC looks to take out fees from these funds while the fund needs no active management to be carried out.

Based on the conversion of the funds being carried out, it can be seen that the unitholders of HGFA and HIFA seem to be locked in a Kafkaesque purgatory. At one end, they own units in a fund which has been frozen and cannot be sold allowing them to make a return on their investment. On the other hand, they are being charged fees by the AMC which is not actively managing the fund but collecting all the fees and expenses that they charge it. Not being able to liquidate their investment and seeing their income slowly disintegrate in front of them, they have no other option but to sell their units at a heavy discount. The only remedy they have is to call for the SECP to step in and provide for an exemption to help in their case. n

By Farooq Tirmizi

If you have read about the 2025 India-Pakistan war in the global press recently, you will have noticed the narrative around the fact that India is not just a larger country than Pakistan by just about any measure, but that it is also one that is doing significantly better economically.

The India-Pakistan economic divergence

How and why it happened, and why it is likely to narrow once again

Of course, it is not just a narrative, it is the truth. India is, by any measure, better off economically than Pakistan is right now, and this trend has been ongoing for at least the last two decades, and started even earlier. There is simply no denying Pakistan’s current relative weakness with respect to India.

At the time of writing, India and Pakistan have begun a low-grade war that is threatening to go into high gear any minute now. This is a time of jingoism, nationalism, and choosing sides. This publication considers itself staunchly Pakistani patriots, but we also believe in being a delivery vehicle of the cold, hard facts. When others’ blood runs red hot, ours remains ice cold. Both have their virtues, but this is the role we choose to play.

And so in this piece, we write the story of how India overtook Pakistan economically, with a focus on perhaps some less commonly examined underlying economic variables, specifically its demographics. The historical data shows how India rose and outpaced Pakistan. The forward-looking projections, however, indicate that perhaps Pakistan’s recent phase of relative weakness may soon end.

Even in this moment on the verge of war, we will not wish India ill. When the bombs stop falling, we will both still be here and still have to live next to each other, and we hope that can one day be on friendly terms. This is not about trying to find weaknesses in India, but merely to say that Pakistan’s fortunes are likely to turn soon.

India’s rise

“I

n 2023, Indian per capita income ($10,200 in purchasing power parity terms) was about 70% higher than Pakistan’s ($6,000). Fewer than half of Pakistani women are literate. The country ranks 27th on the Fragile States Index, between Eritrea and Uganda. An Asian Development Bank report last year warned that Pakistan’s population could reach 400 million by 2050, straining the government’s ability to provide basic services.

India’s population of 1.45 billion is about six times Pakistan’s, and its $4.2 tril-

lion economy is about 11 times as large. The market capitalization of a single Indian conglomerate, Reliance Industries ($225 billion), is more than four times that of the entire Pakistan Stock Exchange. India produces nearly 27 times as much steel each year as Pakistan. India’s $86.1 billion defense budget dwarfs Pakistan’s $10.2 billion. And India has more than 80 chess grandmasters, while Pakistan has none.”

The above two paragraphs were written by Sadanand Dhume, an American commentator of Indian origin writing in The Wall Street Journal. All of it is true.

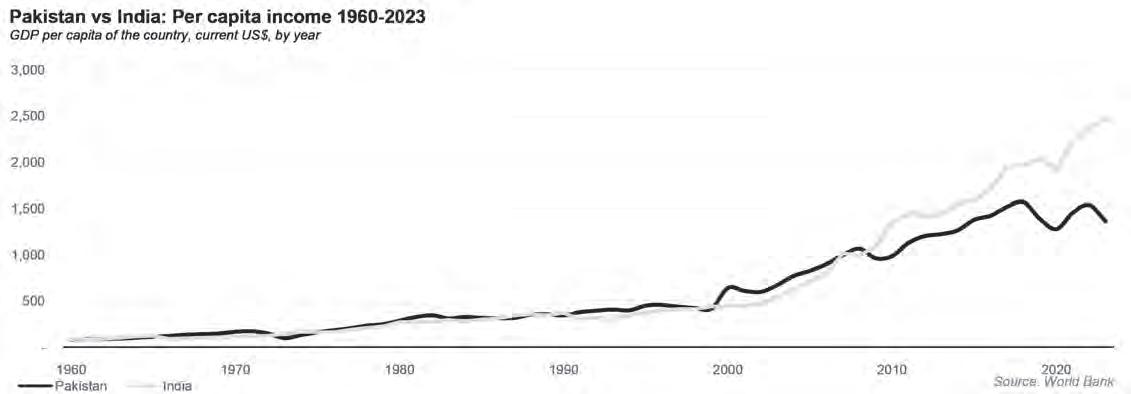

India has always been a larger country than Pakistan on an absolute basis, just by virtue of having more people spread over a larger land mass. But even measuring on metrics that are per capita, India has handily been outpacing Pakistan. For instance, that per capita income that Dhume cites: Pakistan used to be ahead of India for decades, until about 2008 when India overtook Pakistan, and then just never looked back.

How did India overtake Pakistan? The standard answer involves the market-friendly economic reforms that took place in 1991

after India’s economic crisis that year that forced that country to seek its first – and only – bailout from the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

That answer, of course, holds merit and is certainly a reason for why India’s economic growth picked up pace. But the fact of the matter is that Pakistan has been – and probably even now still is – a more market-friendly economy than India. The market reforms, while critical in jumpstarting Indian growth, do not explain the extent to which India has been able to not just overtake Pakistan, but continue to outgrow it almost every year.

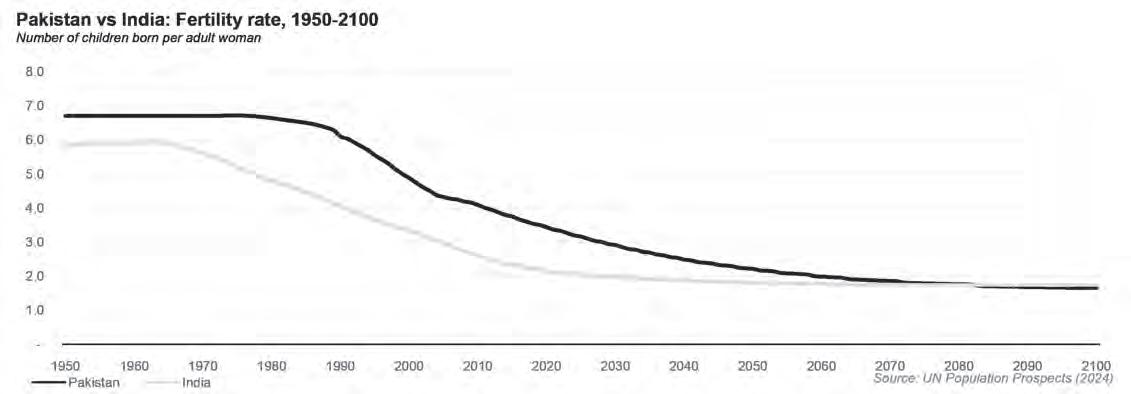

We contend that one factor that helps explain many of the shifts is India’s demographics – specifically its household size – which started shifting only slightly earlier, but did so much faster than Pakistan.

The demographic shift

At Partition, Pakistan started off with a slight disadvantage relative to India. Literacy was low in both countries, but was slightly higher

in India than in Pakistan. Family size and fertility rates were high in both countries, but again, slightly higher in Pakistan than in India, making Pakistan the poorer country.

On the economic front, India effectively ceded that advantage by pursuing socialist policies under Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, which sought to impose egregious state control over the economy and effectively strangled the country’s entrepreneurial ambitions. On the other hand, the socialists tendencies did have the effect of directing government resources towards educating the population, so India’s literacy rate not only started off at a higher point, but continued to improve its lead over Pakistan.

The dichotomy between the investment in education and the stifled economy is best illustrated by the fact that as many as 80% of the graduates of the prestigious and world class Indian Institutes of Technology (IIT) in the 1970s and 1980s left India to pursue careers outside the country.

But that higher literacy rate – and higher public investment in education relative to Pakistan – had consequences that shaped Indian society.

Consider a young Indian graduate of a prestigious college in India. He can move to Delhi and work at the offices of any of the major American or European technology companies’, working not just in back-office roles anymore, but rather a more integrated part of those companies’ core workforce. He can move to Mumbai and get a job at any blue chip financial services institution that might have its headquarters in London or New York, and do the same kind of work that might be done in those financial centers. Or he can move to Bangalore and live in one of the most exciting entrepreneurial cities in the world, where top software engineers command salaries that are comparable to any rich American city outside San Francisco.

This is obviously not the experience of the average graduate of a prestigious Pakistani university, who functionally has to move outside Pakistan to access these opportunities. Within the country, it is working for the staid old banks, the consumer goods companies, maybe an industrial conglomerate, or working as a freelancer online.

The universe of opportunities is narrower, and far less likely to be on the cutting edge of any field. And that difference in sets

of opportunities is starting to have physical consequences.

Watch Bollywood movies even into the early 2000s, and the cityscapes portrayed look familiar to the average Pakistani. But since the 2010s, it is clear that the average Indian city has started to look and feel different than the average Pakistani city. Indians still complain about infrastructure problems, so it is easy to convince ourselves that we live in similar conditions. But we do not. India’s major cities now have more of life’s physical comforts than Pakistan’s cities do.

A shifting future

India is accelerating, perhaps not as fast as the East Asian economies did over the past half century, but nevertheless moving forward at a considerably faster pace than Pakistan. The average Indian is now about 60% or more richer than the average Pakistan, a difference made starker by the fact that they were roughly the same about 20 years ago.

The future, however, may not necessarily be one of diverging paths. Pakistan may have fallen behind India, but it remains on the same path economically, even though the countries

have significant differences in political structures and regimes of governance. India may be faster for now, but Pakistan’s catch up period of more rapid growth may soon be about to begin.

Pakistan’s demographics are finally turning more favourable, and as we have previously noted, it is not just that family sizes are being reduced, it is also the case that the increased savings from a smaller family size is being spent on educating children in private schools when inadequate or absent public schools fail to do the job.

This means that Pakistan’s working age population is expanding, both in absolute terms as well as relative to the total population. And it will be educated enough – just barely – to be able to begin the process of industrialization and the march towards greater economic prosperity.

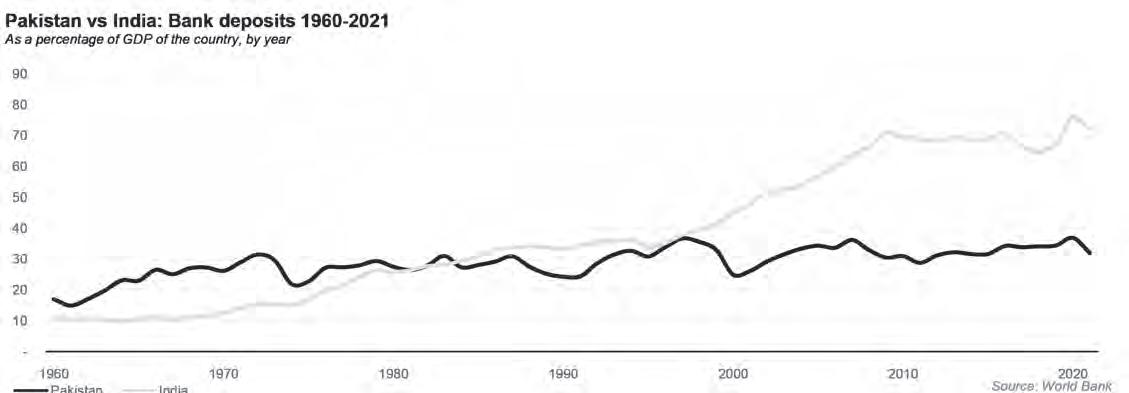

The same 15-year run of banking sector deposits as a percentage of GDP that hit India between 1995 and 2009 is likely about to start for Pakistan around the year 2030, which will result in a significant expansion of domestic capital available for economic expansion in the country.

Will Pakistan ever be as significant for

the rest of the world as India is? Never, but Pakistan is nonetheless a significant country in other respects, and the expansion of domestic savings – which will then result in lower cost of capital and therefore more funding available for the growth of both established and new businesses – will mean that foreign money will have active local investors to follow.

Then there is the sheer size of the demographic dividend itself. Between 2025 and 2050, Pakistan will add about 96 million people to its prime age (ages 15 to 64) workforce, which is one of the largest absolute increases in workforce size anywhere in the world during the next quarter century. For comparison, India’s prime age population will increase by 143 million people during that same period: larger, but not as much larger as the proportionate difference in populations might have implied.

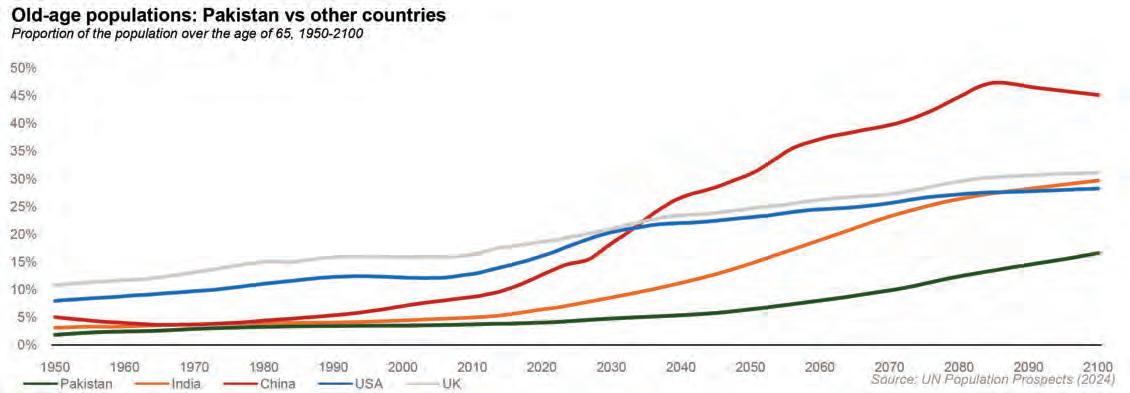

Crucially, Pakistan’s slow start may end up meaning that Pakistan can avoid some of the pitfalls that other countries are likely to face, the biggest risk of which is that they grow older before they get rich.

The “getting old before you get rich” trap

Japan is a society that is old, with far fewer children being born than the number of people who die off every year. The country’s population is declining, the average age is growing, and Japan increasingly looks like a place where people are waiting to die. Innovation happens much slower there than in decades past. Japan is sclerotic. But at least this is happening to the country after it already became rich. Imagine the same situation, but in a country that is much poorer. That is a risk run by many a developing country that is growing rapidly but has not yet become rich while at

the same time facing collapsing fertility rates as fewer young people choose to have children at all. That society does not just face the prospect of economic slowdown, it will never become rich.

To advance economically requires growth, and growth requires vigour and an ever increasing supply of young people to come up with new ideas and pursue them with hard work.

An expanding workforce as a percentage of the population means that a country has the right mix of people at every stage of the skills and income levels.

You need young, hungry people in their late teens and early 20s entering the workforce to do the grunt work, people in the late 20s and early 30s to be the immediate supervisors to those, and then people in their late 30s and early 40s to be the next level up. And finally, we need people in their late 40s through early 60s to be at their peak savings level so that we can generate the capital needed to invest in the expansion of the economy’s productive capacity.

Pakistan’s dependency ratio peaked in the 1990s almost entirely because of children, and we are now in a position to reap the benefits of those children aging into the workforce. This means that Pakistan’s prime age working population as a percentage of the total population will continue to expand from its low point of around 33.7% in the late 1990s well into the 2090s, peaking somewhere around 51% in the 2090s if current trends hold. A child born this year will be retiring in their 70s in a Pakistan where the workforce is still expanding.

Will Pakistan be a rich country by the year 2100? Maybe, maybe not. But it at least has a chance.

Even dynamic countries like India, however, run the risk of aging too fast and closing off the possibility of getting rich before they get too old. India’s dependency ratio started

declining much earlier than Pakistan’s but as a result, it is declining a bit too fast.

India’s fertility rate has fallen before the replacement rate of 2.1 though it remains to be seen if this is a temporary dip or part of a larger trend. However, what is clear is that Indian society is growing older, and the lack of a sufficient number of young people coming into the workforce means that India’s dependency ratio will hit its lowest point – the fewest number of dependents per working adult – in the year 2035, after which it will start rising again.

This time, however, the rise will not be because of young people who will eventually grow older and become contributing members of the economy, but instead it will be because people are getting older and retiring and can no longer work anymore. It is the most expensive, irreversible kind of dependency.

A factor that Pakistan will not have to think about for the next 75 years, India will have to start confronting within the next 10 years.

If you are young and poor, you can work hard and get rich. If you are old and poor, that is it. You will die poor.

India is unquestionably more dynamic and faster growing and richer than Pakistan right now, and there are justifiable reasons for Indians to turn up their nose at Pakistan. But Pakistan also has a healthier set of forward-looking vitals and may soon begin the path towards faster economic growth that –at least based on current projections – looks like it will be more sustainable, and therefore longer-lasting.

Will Pakistan be richer than India ever again? Maybe, maybe not. But it will, within the next two decades, cease to the kind of economy that is stagnating and failing its own people. And perhaps that is something worth remembering as we find ourselves unfavourably compared to our more successful neighbours. n

Cement industry riding a profit boom but bracing for a softer quarter

Eid tends to slow down construction activity, but after a rough few years, the industry finally has some breathing

room

PProfit Report

akistan’s 15 publicly listed cement makers closed the January to March 2025 quarter (3QFY25) with after tax earnings of Rs33.7 billion, up 89 percent year on year but 3 percent lower sequentially, according to a sector update circulated by Topline Securities last week. The disconnect between a spectacular year on year surge and a modest quarter on quarter dip is emblematic of the push and pull forces shaping the industry: better fuel economics and rising exports on one side, softer local demand and easing selling prices on the other.

Dispatch numbers tell the same story. Total sales volume slipped 7 percent QoQ to 11.0 million tonnes as the post winter construction lull arrived earlier than usual, yet was still 4 percent higher than the same period last year thanks to a 19 percent YoY jump in exports.

Sector revenues fell 15 percent QoQ to Rs168.2 billion even though they inched 6 percent higher YoY. The culprit was a pull back in average bag prices in the dominant North zone, down to Rs1,360 from Rs1,447 in the preceding quarter, as mills competed for shrinking retail demand once public sector projects hit funding constraints. Southern mills held the line at Rs1,382, barely a whisker below the previous quarter.

Gross margins nonetheless expanded 2.9 percentage points YoY to 29.7 percent, cushioned by cheaper coal and a more diversified fuel mix – northern plants leaned on Afghan and local coal while southern peers

tapped South Africa’s Richards Bay cargoes that have slipped another 5 percent QoQ.

Lucky’s blockbuster quarter owed less to bags of cement than to dividend cheques: it booked Rs10.9 billion of other income, mainly payouts from group ventures Lucky Electric, Lucky Motors and chemical subsidiary LCI. Maple Leaf, by contrast, did it the hard way – a 35 percent gross margin on the back of higher retention prices and a nimbler kiln that can burn Afghan coal blended with lignite.

Only Dewan Cement stayed in the red ( Rs31 million) as its ageing plant at Hattar struggled with energy downtime.

It has been a roller coaster decade for the industry. In 2015 17, it was a boom time: record low interest rates, CPEC motorways and a private housing frenzy drove domestic dispatches past 40 million tonnes. Plants ran flat out and ordered new lines. Then came 2018 19 and the capacity shock: eleven new kilns came on stream almost simultaneously, swelling national capacity from 45 million to 69 million t p.a. just as demand cooled. Utilisation plunged below 70 percent and pricing power evaporated.

In 2020 came the pandemic pain: Covid 19 halted construction, but the government’s amnesty fuelled housing package unleashed pent up demand in 2H2020. In 2022, a 55 percent currency slide and $340 per tonne South African coal slashed margins to single digits.

Finally, in 2023 24, global coal prices collapsed, and mills began blending cheaper Afghan and Thar lignite. Gross margins rebounded into the high 20s.

Those cycles leave today’s firms with

stronger balance sheets – sector leverage is below 0.4 × EBITDA – but also with installed capacity topping 70 million tonnes, or twice normalised domestic demand.

The cement story stretches far beyond the latest quarter. At independence Pakistan hosted four modest wet process kilns producing 470,000 t p.a. Nationalisation in 1972 created the State Cement Corporation, but capacity only really exploded after the 1990s privatisation wave lured private capital and Chinese engineering. Today’s market is dominated by six groups – Lucky, Bestway, DG Khan, Fauji, Maple Leaf and Kohat – accounting for 75 percent of production.

Fuel makes up 55 60 percent of cement variable cost, so the 40–50 percent slide in Richards Bay API4 prices since mid 2024 has been transformational. Plants in Sindh’s south have locked in long term supply agreements indexed to the South African benchmark, while northern peers truck in Afghan and local coal now trading at Rs33–35,000 per tonne, 8 14 percent cheaper YoY.

The pivot to indigenous fuels is structural: three kilns have switched part of their diet to Thar lignite, and almost every major producer has installed waste heat recovery turbines to shave energy bills. The industry’s coal blend is now roughly 45 percent imported, 35 percent Afghan and 20 percent local versus 70 percent imported just two years ago.

Domestic sales remain king, claiming 85 percent of tonnage, yet they are fickle. In the first seven months of FY25 local dispatches fell 7.6 percent, hurt by public sector austerity and a pause in private real estate launches. Exports, however, jumped 31 percent as a cheaper rupee made Pakistani clinker competitive again in East Africa and Sri Lanka.

Export tonnage is still only one sixth of production capacity, but it provides a safety valve when the local market stalls. Lucky and DG Khan have invested in purpose built

loading terminals at Port Qasim while Bestway charters Panamax vessels direct from its Kallar Kahar plant via the Karachi Lahore rail corridor.

Despite a bruising oversupply episode five years ago, the engineering queues are lengthening again. Three projects worth a combined 6 million t p.a. are under construction – Maple Leaf in Punjab, Power Cement in Sindh (brownfield) and Attock Cement’s new grinding mill at Basra, Iraq, its first offshore foray. If all commission on time, national nameplate capacity will exceed 75 million tonnes by 2026, compared with a domestic market that rarely tops 50 million.

Management teams argue that modern dry process lines can still pay back in five years provided export channels stay open and energy efficiencies are realised. Lenders appear convinced: the sector’s weighted average cost of debt fell to 13 percent after the State Bank cut its policy rate in February, slashing 3QFY25 finance cost 38 percent YoY to Rs6.5 billion.

The cement sub index has out performed the KSE 100 by 22 percentage points year to date, riding the earnings momentum and lower interest rates. That said, Topline’s strategist notes that cement still trades at 6.3 × forward earnings, a 12 percent discount to its five year mean, partly because investors remember how quickly margins can evaporate when coal spikes. The sector also provides about 9 percent of KSE 100 earnings, behind banks and oil but a growing slice nonetheless.

Topline expects aggregate sector profit to shrink QoQ in 4QFY25 as two long Eid breaks in April and June shave at least 1.2 million tonnes off domestic dispatches. But on a year on year basis earnings should still improve thanks to:

• Continued low coal costs;

• Firm North zone bag prices once construction restarts in July;

• Sustained export orders as Kenyan and Tanzanian infrastructure pipelines gather pace.

Consensus models foresee FY25 full year earnings of around Rs122 billion, up 45 percent YoY, but only single digit growth in FY26 as cost tailwinds fade.

Among the risks to the sector are the potential for an energy shock. A sudden rebound in global coal or a disruption in Afghan supply routes could add Rs120–150 per bag in variable cost.

A mooted hike in Federal Excise Duty to fund the FY26 budget would be margin negative unless mills pass it on. Every 10 percent rupee depreciation against the dollar costs the sector roughly Rs45 per bag in imported spares and logistics. And if the

proposed levy materialises without offsetting tax credits, sector EBITDA could contract 6–8 percent from FY27.

The cement industry’s ability to post record profits at a time when the broader economy is muddling through stagflation is a tribute to its relentless cost re engineering and willingness to hunt for export niches. Yet the same structural overcapacity that

plagued the sector in 2019 has not gone away – it has merely been masked by low fuel prices and a weak rupee.

History suggests the party ends when either demand disappoints or energy costs surge. For now, though, Pakistan’s grey powder giants have earned a breather, and investors can count on at least one more bumper year before the cement cycle turns again. n

Fasset brings tokenized gold ownership to Pakistan

Can Fasset’s tokenization strategy unlock bullion’s billions for the masses?

By Hamza Aurangzeb

From ancient agricultural societies to contemporary modern ones, gold has been revered as one of the most valuable commodities in human history that has symbolized wealth, power, and stability. Across cultures, civilizations and eons, this yellow metal has been used for a diverse range of purposes from building tombs for emperors, serving as a means of exchange, developing alluring ornaments or simply accumulating savings in the form of bars.

The unique characteristics of gold along with its historical significance, and uniform fondness across cultures led to the establishment of the Gold Standard, which played a pivotal role in the expansion of international trade for a significant period until 1971, when the fiat monetary system was introduced after the NIxon Shock, which suspended the convertibility of US dollars into gold.

However, despite the end of the gold standard in the 20th century, the value of gold has remained resilient. Its demand continues to soar, whether due to its appeal in producing enchanting jewelry or its role as a safe haven during economic uncertainty. In Pakistan, gold not only symbolizes affluence but serves as an integral part of our wedding rituals and cultural practices, which propagates its perpetual value, while for investors, it offers a unique combination of stability, diversification, and a hedge against inflation, making it a sought-after asset in times of market volatility, such as the contemporary era in Pakistan. Fasset has launched a new gold tokenization scheme in Pakistan under SECP’s regulatory sandbox leveraging decentralized finance and the blockchain. It has introduced an innovative way for the masses to invest in gold, providing access to fractionalized investments without the need for large capital. Nevertheless, the million dollar question remains, whether this emerging investment scheme will harness the power of gold to build wealth for Pakistanis or would it just prove to be another gimmick that may go out of fashion.

Tokenization and asset ownership

Tokenization is the process of converting ownership rights in both real-world assets and virtual assets into digital tokens stored on a blockchain.

These tokens act as secure, digital certificates that represent real-world assets like gold, real estate, stocks, or bonds, as well as virtual assets like cryptocurrencies and digital art. Tokenization allows people to buy, sell, and transfer these assets digitally and instantly without having to deal with complex paperwork or physical exchanges.

When an asset is tokenized, its ownership is divided into digital units, or tokens, each representing a fraction of the whole. For example, a gold token might represent one gram of gold held in a certified vault. These tokens are issued on a blockchain — a decentralized digital ledger that records every transaction permanently and transparently. This ensures that every token has a clear, traceable link back to the real-world asset it represents.

The use of blockchain is crucial as unlike traditional databases, blockchain is decentralized, which means no single entity controls it. It provides immutable records and once data is added, it cannot be altered. This makes tokenization highly secure and allows for real-time tracking of asset ownership. Whether it’s gold changing hands or a share in property being sold, every movement is recorded transparently, which helps in reducing fraud, disputes, and hidden costs.

The strategy of tokenization has a wide range of benefits. First, it brings liquidity to traditionally illiquid markets. Assets like real estate or art, which usually take time and effort to sell, can be divided into tokens and traded instantly. This enables owners to unlock value and gives investors the flexibility to buy and sell portions of assets with ease.

Second, since tokenization enables fractional ownership, it lowers the barrier to entry for small investors. Thus, people can invest small amounts by purchasing fractions through tokens instead of needing large sums to buy property or commodities. This opens up wealth-building opportunities to a broader segment of society, particularly in emerging markets.

Perhaps most importantly, tokenization enhances transparency and traceability. Every transaction is permanently recorded on the blockchain, allowing both regulators and investors to track the history of an asset. This improves trust in markets where transparency has often been a challenge and helps ensure compliance with financial regulations.

The applications of tokenization are ex-

panding rapidly. In finance, the strategy is being used for trading tokenized stocks, bonds, and commodities, while in real estate, properties are turned into tradable digital shares. The strategy is being utilized even for carbon credits and renewable energy assets to enable more efficient tracking and increased trading. Tokenization is transforming how the world invests — making markets more open, efficient, and trustworthy by combining the transparency of the blockchain with the flexibility of decentralized finance.

Fasset and DeFi

In the world of tokenization, Fasset is a digital asset platform, which aims to promote financial inclusion across emerging markets in the world by empowering individuals and businesses to invest in both digital assets and real world assets through leveraging decentralized finance (DeFi). It utilizes tokenization and online distribution to make digital assets like cryptocurrencies and real world assets like stocks, bonds, commodities, and precious metals more accessible to the masses.

The company aims to dismantle traditional barriers to entry by leveraging the transformative power of decentralized finance (DeFi) and blockchain technology in order to make wealth-building opportunities more accessible to the masses — particularly in regions where access to global financial markets has long been limited.

The platform was founded in 2019 by Mohammad Raafi Hossain, a former UN advisor and fintech strategist, along with Daniel Ahmed, an expert in investment management. Fasset has raised $26.7 million in funding thus far from investors like Liberty City Ventures, Investcorp, and Gobi Partners. Moreover, the company has received regulatory approvals to offer tokenized assets in various countries, including the UAE, Indonesia, Malaysia, the EU, Turkey, and Pakistan among others.

The cornerstone of Fasset’s strategy is using asset tokenization to bridge the gap between digital innovation and tangible economic progress. Through the process of tokenization, it converts physical and financial assets into digital tokens on the blockchain, allowing users to invest in fractional shares of assets that would otherwise be inaccessible to many due to the high ticket size. The platform not only enables investments in cryptocurrencies but also unlocks access to other assets such as stocks,

bonds, commodities, and precious metals.

Till now, Fasset has successfully raised $26.7 million in funding from global investors including Liberty City Ventures, Investcorp, and Gobi Partners. It has also secured approvals to offer tokenized assets in a growing number of jurisdictions, including the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Indonesia, Malaysia, the European Union, Turkey, and Pakistan, among others.

Inside Fasset’s gold tokenization scheme

Fasset has launched Pakistan’s first gold tokenization solution, licensed under the Securities and Exchange Commission of Pakistan (SECP)’s Regulatory Sandbox. Fasset’s innovative platform is turning gold into accessible, digital tokens that are backed 1:1 by physical gold of 23.88 Karat Gold Quality, securely stored. Currently, the service is in the testing phase under SECP’s sandbox framework. However, once the service is validated for its systems, user experience, and scalability, Fasset plans a full nationwide rollout, which would bring gold tokenization to millions across Pakistan, from major cities to underserved regions.

Raafi Hossain, CEO of Fasset while talking to Profit stated that “We’re testing our gold tokenization solution under the SECP’s Regulatory Sandbox, focusing on validating its processes, scalability, and user experience. It’s an exciting step toward making gold investment accessible, and we’re preparing for a broader rollout pending regulatory approval.”

Each gold token will be backed by certified, investment-grade physical gold. This will ensure that every digital token directly corresponds to high-quality gold securely stored in partnered vaults. Nevertheless, users must meet a minimum withdrawal threshold to convert digital holdings into physical gold.

The facility will be unavailable during the testing period, while the company focuses on providing an elegant user experience to early adopters. However, users will be able to convert their digital tokens into physical gold in the future, where Fasset’s trusted local partners will handle the secure custody and delivery of physical gold, ensuring that users receive genuine and certified bullion.

Fasset’s fee structure is designed to be transparent, competitive, and affordable for the masses. While discussing fees for the service, Raafi revealed, “We’re keeping fees low and transparent, including 0.5% of transaction fees + standard sales tax charges. We’ll share full details as we get closer to the nationwide launch.” This simple and upfront approach of Fasset aims to make digital asset access as straightforward and cost-effective as possible, where users always know exactly what they’re paying, with no hidden charges,

One important thing to note, this service is open not just to residents within Pakistan but overseas Pakistanis—including those in the Gulf, Europe, and North America—can use the service, which will allow them to invest in Pakistan’s gold market digitally while benefiting from blockchain’s security and transparency. All customers can register through Fasset’s platform, complete KYC verification remotely, and manage their gold investments in real time from anywhere in the world.

With a clear plan for national rollout, robust gold standards, local partnerships for secure logistics, and inclusive access for overseas investors, Fasset’s gold tokenization solution is poised to reshape gold investment in Pakistan and beyond.

The potential roadblocks for Fasset

Fasset has an ambitious plan to transform access to investment avenues of the masses in Pakistan. However, the plan faces significant regulatory, structural and technological impediments that pose a threat to the pace and scale of its success.

At the regulatory level, the landscape remains incomplete. Pakistan’s Securities and Exchange Commission (SECP) is still in the process of developing clear frameworks for the tokenization of assets, a necessary foundation for legal compliance and investor protection. The absence of robust regulations for tokenization limits Fasset’s ability to roll out its services at a large-scale across the country.

However, apart from the regulatory uncertainty. There is a persistent digital divide in Pakistan due to asymmetric and inequitable broadband infrastructure development, which has left the masses unconnected to the world of internet. Pakistan has the third-largest broadband usage gap in the world, where a staggering 140 million people live within areas that have mobile broadband coverage areas but are not connected to it, which signifies a major disconnect between availability and adoption.

Moreover, an estimated 17% of Pakistan’s population still lacks access to any form of mobile broadband. Among those who are covered, service levels remain subpar compared to the rest of the South Asian region. Only 74.9% of the population falls under 3G coverage, and 4G reaches just 83.6% — both trailing the South Asian averages of 88.1% for 3G and 90.9% for 4G connectivity.This inadequate infrastructure poses a real challenge for a platform like Fasset, which relies on widespread internet access to onboard users and facilitate transactions. In regions where even basic connectivity is unreliable, expecting rapid adoption of sophisticated digital financial services is unrealistic.

Beyond broadband infrastructure, digital security emerges as another critical concern

which could undermine Fasset’s mission of financial inclusion. While tokenization can eliminate the physical risks associated with trading assets like gold, it exposes investors to cyber threats such as hacking, phishing, and malware attacks, particularly users from Pakistan’s underdeveloped areas, which have limited digital and financial literacy.

Now coming towards the tech-enabled youth, which is often celebrated by throwing numbers like 20 million crypto users. While Pakistan’s young population has developed an enthusiastic culture for digital assets like cryptocurrencies, however much of this engagement is driven by speculative trading. The appeal for these young individuals lies in the potential for quick profits, not in the stability of real-world assets like tokenized gold. Hence, it would be an arduous task for Fasset to persuade these users to pivot from high-risk speculation to lower-yield, long-term investments, this fundamental shift in mindset would be a challenge that should not be underestimated.

Nevertheless, Fasset’s ambitions extend beyond gold. The company has outlined plans to tokenize over $1 billion in U.S. equities, including shares in major global tech giants, ETFs, and REITs — an unprecedented move which could make such assets accessible to Pakistan’s retail investors. Moreover, the company plans to expand into commodities, bonds, and Shariah-compliant instruments like Sukuks.

Fasset aims to promote financial inclusion in Pakistan through offering a comprehensive investment platform, beginning with the gold tokenization scheme. However, history reveals that several ingenious investment and wealth management apps have attempted to reshape the investment landscape of Pakistan but only a handful have succeeded. Whether Fasset can overcome these structural, technological, and cultural barriers to become a bedrock in the investment landscape of Pakistan remains to be seen.

A precedent in Pakistani history

There is one business that points to the potential for Fasset’s success: ARY. The jeweller in Pakistan rose to fame by becoming the first entity to sell high quality gold bars in very small sizes to help people save their money in gold without having to first save up large lumps of money to then buy a jewelry set that may depreciate from its purchase price.

In effect, it was tokenization in the pre-digital world, and it was a massive success. Of course, it relied on illegal smuggling rings whereas Fasset is coming in through a legal, regulated route, so the differences are likely to play out in Fasset’s favour in being able to build trust with the Pakistani market over time. n

Why Pakistan’s Rs16 billion cheese market is expected to double in the next five years

A few small home-based cheese manufacturers are introducing fresh, authentic cheese to the Pakistani market. Will they be able to compete with international brands and local FMCG giants?

By Nisma Riaz

Cheese has long been a quiet but persistent presence in Pakistan’s culinary landscape, although its roots here are relatively recent compared to its ancient legacy elsewhere. Traditionally, dairy in Pakistan meant milk, yogurt, butter, and ghee, rich staples of everyday life, while cheese, in the European sense, remained a novelty. It was during the British colonial era that cheese was first formally introduced, with varieties like cheddar and processed cheeses finding their way into British households and cantonment clubs across the subcontinent. For decades after independence, cheese remained largely confined to imported brands or basic processed slices, treated more as a luxury or an add-on rather than an artisanal food in its own right.

In recent years, however, Pakistan’s relationship with cheese has evolved. The Pakistani cheese market today is a mix of well-established international brands and dominant local players. Imported names like Happy Cow, Puck, and Almarai have long catered to consumers seeking processed and spreadable cheeses, offering familiar flavors and convenience. On the local front, brands such as Adam’s, Nurpur, and Olper’s have built strong footholds, supplying a range of processed cheeses, mozzarella, and cheddar geared toward everyday use. While these brands have successfully popularised cheese across the country, most products are heavily processed, leaving a gap for artisanal, natural cheeses, a space that small local cheesemakers are beginning to fill.

The cheese market in Pakistan

Even though cheese is not a huge part of Pakistani culture, the dairy byproduct is slowly consuming local palettes and consequently pushing the cheese market in Pakistan to experience a period of rapid expansion.

According to data by Euromonitor, the retail value sales of cheese grew by 30% in 2024 to reach Rs15.7 billion. This growth reflects broader changes in culinary habits, driven by the rising popularity of Western cuisine and fusion dishes. Cheese varieties like mozzarella, cheddar, and feta are becoming staple ingredients, integrated into pizzas, pastas, salads, and a variety of gourmet recipes. Looking ahead, the market is projected to sustain strong momentum with a forecasted compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 17%, potentially reaching Rs35 billion by 2029, according to the same source.

Upon a closer look, you will notice

that the market is divided across several key categories. Spreadable cheese leads in terms of absolute retail value with Rs7.1 billion in sales, followed by processed cheese, excluding spreadable variants at Rs4.7 billion. Hard cheese, while smaller in absolute terms at Rs2.6 billion, has demonstrated the highest growth rate in 2024 at 37%. Soft cheese remains a niche segment, accounting for just Rs1.3 billion, a value much smaller than that of other categories.

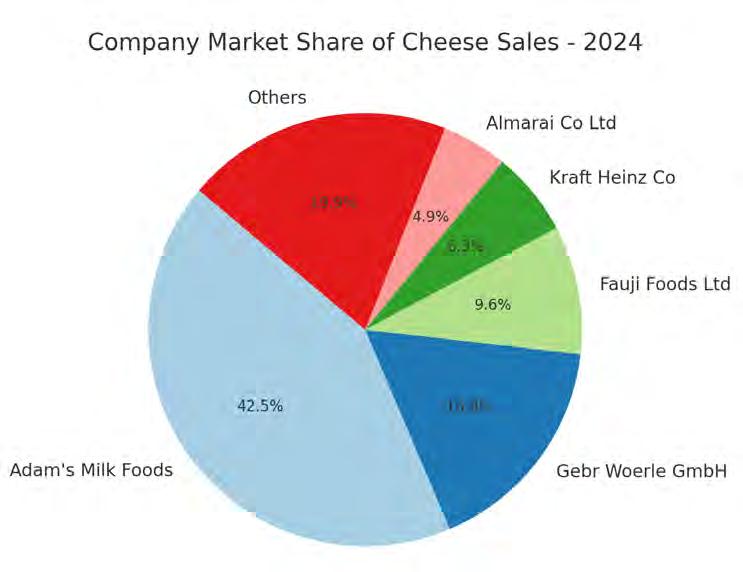

In terms of company market share, Adam’s Milk Foods (Pvt) Ltd overwhelmingly leads the competition, capturing 42.5% of the retail value share. Gebr Woerle GmbH follows with a significant but notably smaller share of 16.8%, while Fauji Foods Ltd’s Nurpur cheese holds 9.6%. Other competitors such as Kraft Heinz Co and Almarai Co Ltd maintain 6.3% and 4.9% shares respectively. Smaller players like Arla Foods Amba and Cottage Foods account for 4.4% and 2.8% respectively, with Bel Groupe and other minor companies making up the remaining 12.5%.

Brand-wise, Adam’s continues to dominate the market, mirrored by Happy Cow and Nurpur as leading challengers, though none come close to matching Adam’s commanding presence.

Cheese sales have surged from minimal levels in 2010 to PKR 15.7 billion in 2024 and are

cheeses that local consumers rarely have easy access to.

Tahira Saeed, founder of The Artisan Cheese Factory, sat down with Profit to share how her cheesemaking journey began. “The inspiration for starting The Artisan Cheese Factory was deeply personal. As a mother passionate about providing healthy, natural food for my children, I became increasingly concerned with the lack of quality, preservative-free dairy products available in Pakistan. Frustrated by processed cheeses packed with additives, I began experimenting at home, crafting small batches of fresh, wholesome cheese using traditional methods.”

Founded in 2010, The Artisan Cheese Factory emerged from Saeed’s passion for traditional cheesemaking and her desire to offer preservative-free alternatives in a market saturated with processed products. Largely self-taught, she honed her craft through rigorous trial and error, online research, and selective short training courses both locally and abroad.

“There was no market at all back then. I picked up some literature, started studying about it, got a few ingredients from the UK, and began experimenting. That’s how I was learning both cheese making and business at the same time, figuring it all out through trial and error. I started by giving the cheese to my family

forecast to approach PKR 35 billion by 2029, as shown in the graph above.

A story numbers don’t tell

While multinationals and large local conglomerates continue to dominate Pakistan’s cheese market, a handful of small businesses are working hard to carve out a niche for themselves — offering artisanal

members, and that’s really how I first made and introduced it. Luckily, they liked it, and around the same time, organic farmers’ markets were starting to catch on here. That gave me the idea to display my cheese at one of those markets, and that’s really where it all began, turning it into a proper business. It was so encouraging because it was something completely new for people, and from there, many businesses and restaurants started contacting me.”

Initially, Saeed focused on mastering

basic, familiar cheeses like mozzarella and cheddar, adapting them to local conditions and experimenting with fresh milk. Over time, as her confidence and skills grew, she expanded into more sophisticated, traditional cheeses such as brie, tomme, and ricotta.

The venture started modestly, with a tiny production space outfitted with basic equipment, borrowed vats, and a handful of recipes developed through perseverance. Every aspect of production was hands-on, from stirring curds to individually wrapping and labeling each cheese wheel.

“The focus was always clear, to deliver cheeses that honored the richness and quality of local milk while maintaining strict artisanal methods, celebrating the natural diversity brought forth by the changing seasons,” Saeed shared.

Profit also spoke with Farmers Cheese Making (FCM), another artisanal producer founded in 2011. Their spokesperson recounted a similar origin story, with the venture starting from a home kitchen driven by a passion for producing high-quality, non-processed cheese in Pakistan.

“The idea stemmed from the lack of locally produced, non-processed artisanal cheese. Initially, the business faced challenges related to consumer awareness, sourcing high-quality milk, and perfecting traditional cheesemaking techniques in a local setting. Scaling up production and maintaining consistent quality while educating consumers were among the biggest hurdles in the early years,” they explained.

Meanwhile, Karachi-based YayyCheese entered the scene more recently with a slightly different genesis. “It is a COVID-born business,” Co-founder of YayyCheese Sadaf Furqan told Profit. “During COVID, we saw a huge gap in the market as imports of artisanal cheeses became scarce. We started to study, research, and experiment with different kinds of cheeses to fill that market gap.”

She added, “As a young population, our fast food industry is growing exponentially, and restaurants are always looking for good quality cheese. We wanted to solve this problem.”

When asked about their journeys from inception to profitability, the companies revealed distinct but overlapping trajectories.

Since its founding, The Artisan Cheese Factory has seen steady, organic growth, evolving from a small, home-based operation into one of Pakistan’s most respected artisanal food producers.

“The early years were marked by financial challenges and the need to educate a skeptical market,” Saeed said. “But our commitment to quality and community engagement gradually built a loyal customer base. Participation in farmers’ markets and free tastings, further helped by word-of-mouth marketing,

lead to a consistent upward trend in both sales and profits.”

Saeed recalled how she started from a very small scale but her business expanded overtime, “I started with 10 litre pots, then I went to a 50 litre pot, then to 100 litre, and this is how growth started happening. One restaurant led to another, and gradually people started reaching out to me, it was a very organic and natural growth.”

“Now, at this stage, I produce many liters every day, starting from just 10 liters. We’ve also moved out of the home kitchen into a small factory setup but everything is handmade, and now we have more space and better equipment to control the environment, which is critical for certain cheeses,” Saeed shared.

Though specific sales figures are not publicly available, FCM has also demonstrated steady growth since its establishment. From a modest startup in 2011, it expanded into a full-fledged factory by 2020. The broadening range of cheese varieties and B2B collaborations suggest that business has remained strong.

Yayy Cheese, on the other hand, preferred not to disclose revenues or profit margins but confirmed that the company is profitable and growing.

How local cheesemakers are raising the bar

Behind every wheel of cheese produced by Pakistan’s local cheesemakers lies a philosophy shaped by passion, patience, and a deep respect for tradition. For these entrepreneurs, making cheese isn’t

just about business, it’s about preserving craftsmanship and celebrating local ingredients.

Saeed said, “Our philosophy is simple but uncompromising, respect the milk, respect the process, and respect the environment,” Saeed told Profit. “The milk we use is not just an ingredient, it’s the soul of our cheeses.”

The company works closely with a network of local dairy farmers who emphasise animal welfare and pasture-based feeding. From there, everything is done by hand. “We hand-ladle the curds, age in custom-built caves, and avoid chemical ripening agents. It’s all natural,” Saeed explained.

Saeed emphasised that local identity is key. “We’ve experimented with local herbs, spices, garlic and even edible flowers,” she said. “We also reduce salt content in halloumi to make it more palatable for local consumers.” For her, innovation means staying true to local flavors, not just like Europe, but something their target audiences can also appreciate.

“When you are eating a clean cheese that has no chemicals or preservatives, it is obviously not harmful to you. It’s not heavy on your stomach, and instead, it provides health benefits,” Saeed said.

At Farmers Cheese Making (FCM), a similar spirit of craftsmanship guides production. Founder Imran Saleh relied heavily on self-learning, constant experimentation, and informal training to build his cheesemaking skills. “While Saleh’s exposure to European cheesemaking traditions likely influenced his approach, his expertise was largely honed by adapting those methods to the local Pakistani environment, perfecting recipes through years of practice and refinement,” the spokesperson

shared.

YayyCheese, another rising name in Pakistan’s artisan cheese scene, takes a slightly different path. Furqan emphasised the importance of mentorship and formal education, “We’ve been fortunate to receive guidance from cheesemakers in the US and Australia,” Furqan shared, adding, “They taught us how to make the best possible cheese using the resources and ingredients available locally, and they continue to mentor us. We’re also in the process of pursuing formal cheesemaking certification from Europe, which will help us further refine our craft.”

Together, these three stories illustrate a common trend; a commitment to authenticity, but also rooted in deep respect for tradition, an openness to learning, and a profound love for local ingredients.

The cheese catalog and local innovations

When it comes to making cheese locally, the production goes well beyond simply replicating traditional European styles. They are not just making cheese, they are innovating with flavors, techniques, and ingredients that reflect local tastes and conditions, while still respecting the core principles of authentic cheesemaking.

At The Artisan Cheese Factory, diversity and creativity shape the product lineup. Saeed shared that the company offers a wide range of cheeses, each crafted to honor time-honored techniques while appealing to Pakistani palates.

“Our cheese selection includes fresh varieties like low-fat, low-moisture mozzarella, plain and flavored cottage cheese, high-protein ricotta, plain and flavored cream cheese, mascarpone, burrata, and both crumbly and creamy feta; hard cheeses such as cheddar (including orange cheddar), parmesan, and gouda; specialty options like lower-salt halloumi and marinated cheeses (feta and mozzarella in herb oils); and complementary products including flavored butters, nacho cheese sauce, pesto sauce, marinara sauce, and Greek yogurt.” Saeed shared.

Their approach blends tradition with local identity. “We’ve adapted our cheesemaking to suit the Pakistani palate without compromising on technique,” she explained.

“I realised that the local palate here is not very suited to sharp and pungent cheeses, so I had to adapt accordingly and keep the cheeses purposefully on the mild and medium side, not with a very strong aroma. Then I added chilies because people here want a bit of a kick; they don’t like anything too plain, so we have to give them flavors. In cottage cheese, I made it with olives and chilies so that people could eat it as it is, unlike the very low-fat and bland cottage cheese normally available in the market. In

cream cheese, I created a jalapeno dip and an herb and garlic cream cheese, which has become very popular. For marinated cheeses, I marinated feta and mozzarella in chili oils and herbs.”

Continuing, she explained, “In curd cheeses, I made flavors like garlic. Even in hard cheeses, I added flavors like cumin with herbs and garlic. I also made two types of feta, one that is hard and crumbly, just like the traditional Greek style, and another that is soft and creamier, which is now very popular. For halloumi, as I mentioned, I reduced the salt content to make it more palatable for local tastes.”

“In butters, I introduced flavors like herb and garlic butter, honey and vanilla butter, and parmesan garlic butter. I started with low-fat, low-moisture cheese so that when you bake it on a pizza, the oil and moisture won’t ooze out. When cutting hard cheeses, a few leftover chunks remained, and I thought I didn’t want to waste them, so the idea came to make sauces and dips from them. I made pesto sauce with it, and complementing my mozzarella, I also made marinara sauce, which has become very popular. Sometimes when producing low-fat cheese, you are left with extra cream, and that led me to create flavored butters. I also realized that mascarpone was not available here for desserts, so I made that cheese myself. In cheese making, nothing goes to waste except the leftover whey.” Saeed concluded.

Farmers Cheese Making (FCM) has also embraced diversity in its offerings. Speaking to Profit, they shared that the company currently produces over 50 varieties of artisanal cheeses, including fresh, matured, and cream cheeses, along with specialty products such as goat cheese, desi ghee, and even camel cheese, a rare innovation that, according to Saleh, is the first and only camel cheese produced in the world. As consumer demand has grown, so has FCM’s product portfolio. “The demand for quality cheese in Pakistan is steadily increasing, driven by changing dietary habits, the rise of cafés and restaurants, and an overall shift toward healthier, gourmet food options,” they said.

While mass-market brands dominate the general cheese market, FCM continues to find strong opportunities in the niche for premium, artisanal products, and is slowly expanding into broader consumer segments.

Meanwhile, Karachi-based YayyCheese took a more focused approach. Furqan told Profit, “We are currently making four types of aged cheeses, Red Cheddar, White Cheddar, Pepper Jack, and Camembert, and three types of fresh cheeses: Halloumi, Greek Feta, and Ricotta.”

YayyCheese’s journey started with just one product: Halloumi. “As Halloumi received great reviews from the market, we started to look into making aged and mature cheeses,” Furqan explained. However, the transition was

not easy. “We faced a lot of struggles when it came to aged cheeses. There were times we had to throw out entire batches, made with a lot of effort and hard work, because of our completely manual setup at that time and due to poor quality or hygiene of the milk we sourced.” Despite the setbacks, Yayy Cheese remained committed to research and development, and around two years ago, successfully launched their first mature cheeses, which have since been well-received by clients.

Challenges in local cheesemaking

Scaling up production while maintaining quality is a significant challenge for local cheesemakers. At The Artisan Cheese Factory, Saeed shared that early resistance from the market was one of their biggest hurdles. “Consumers accustomed to low-cost, mass-produced cheese questioned why their artisanal 200-gram wheel was priced higher than a large block of supermarket cheddar. Recognising the need for education, we began offering free tasting sessions, factory tours, and hands-on cheesemaking workshops to demonstrate the labor, time, and passion behind each cheese.”

Another challenge arose from adapting traditional cheesemaking processes to Pakistan’s climate. “We have to offer flavors, and I did work on that. But when it comes to cheeses like blue cheese or brie, I realised they require a lot of care. They look beautiful and appealing, but they demand months of attention, sometimes five to six months for just one type of cheese, where you have to constantly pamper and cater to it. After all that effort, if there’s no demand, it becomes difficult. For example, a restaurant might want to use a small amount of blue cheese to make a dip, and they would only need about 200 or 300 grams. For such a small quantity, it’s not feasible to go through the whole process. Even though I developed expertise in making those types of cheeses, because the demand in the market is so limited, it’s not practical to keep producing them.”Saeed shared.

At YayyCheese, Furqan noted that the quality and fat content of local milk present unique challenges, despite the overall cheesemaking process remaining similar globally. “Although fresh milk supply is good, a significant amount is wasted due to inefficiencies in the supply chain. Selecting farms with high hygiene standards is crucial, as poor milk quality and hygiene issues have led to the disposal of entire cheese batches in the past.”

Furqan also highlighted that the market for artisanal cheese is growing, with more consumers transitioning from processed to artisanal varieties. This growth is further fueled by consumers who, after purchasing imported cheeses, are now seeking locally produced alternatives.