07 Jazz has been trying to sell its towers for seven years. Why do they keep failing?

11 America is threatening sanctions over the Iran-Pakistan Gas Pipeline. Let it

20 Russian authorities just stopped a contaminated consignment of Pakistani rice. Are we looking at a ban?

23 Tech funding might be recovering in the US, but the trickle down effect will take its sweet time getting to Pakistan

Profit

CONTENTS

07 11 23 07 23 11 Publishing Editor: Babar Nizami - Editor Multimedia: Umar Aziz Khan - Senior Editor: Abdullah Niazi Editorial Consultant: Ahtasam Ahmad - Business Reporters: Taimoor Hassan | Shahab Omer Zain Naeem | Saneela Jawad | Nisma Riaz | Mariam Umar | Shahnawaz Ali | Ghulam Abbass Ahmad Ahmadani | Aziz Buneri - Sub-Editor: Saddam Hussain - Video Producer: Talha Farooqi Director Marketing : Mudassir Alam - Regional Heads of Marketing: Agha Anwer (Khi) Kamal Rizvi (Lhe) | Malik Israr (Isb ) - Manager Subscriptions: Irfan Farooq Pakistan’s #1 business magazine - your go-to source for business, economic and financial news. Contact us: profit@pakistantoday.com.pk

Jazz has been trying to sell its towers for seven years.

Why do they keep failing?

The first attempt to sell their towers and go asset light fell through in 2018. A second deal was struck in 2022 and has continued to drag along with no updates

By Ahtasam Ahamd and Shahnawaz Ali

During the 18th-century Industrial Revolution, railways were deemed the backbone of the rapidly evolving global economy, playing a pivotal role in connectivity and facilitating trade. Fast forward to the 21st century, the importance of railways may have diminished significantly.

Instead, a new form of infrastructure has emerged – digital railroads, spearheading the evolution of connectivity. The telecom sector serves as the cornerstone of this infrastructure, functioning as a multisectoral pass-through point and delivering great value to modern economies.

In Pakistan, the sector appears to have become entangled in its own array of issues, significantly impeding progress. While this situation may apply to multiple sectors considering the economic conditions over the past two years, the deterioration in the telecom sector began long before that time.

This crisis has prompted numerous players, including Cellular Mobile Operators (CMOs), to weigh their choices. These options

vary from exiting the market (case in point: Telenor’s departure from Pakistan) to divesting assets to improve cash flow.

The latter has been a focus area for many players with Jazz being the flag bearer of the movement.

The telecom giant established a subsidiary company, Deodar, in August 2016, which assumed ownership of Jazz’s tower sites. The intention behind creating a tower company for Jazz was evidently to prepare it for sale. In pursuit of this objective, the telecommunications company engaged in an agreement with Edotco, one of the largest tower operating companies, in 2018. However, the deal encountered a setback when the regulator intervened and withheld approval for the transaction.

Then it took Jazz four more years to find another suitable buyer which it eventually did in 2022 in the shape of a consortium formed between the Pakistani conglomerate TPL and UAE based TASC Towers Holding. But almost a year and half later, there is a deafening silence on the deal.

The deal appears to have fallen through once again, and this time, the regulator may not be the reason behind it. Let’s delve deeper and figure out what is holding back Jazz from going “asset-light”.

Surviving the telecom sector, a task and a half

Before diving into what became of the tower deal, it is essential to first grasp the context in which it was being carried out.

As per the 2023 sector analysis published by VIS credit rating, “The telecom market in Pakistan reflects a diverse landscape dominated by key players. Jazz emerges as the leading operator, commanding a substantial market share of 36.8%. Close behind are Zong and Telenor, each holding approximately a quarter of the market share at 24.0% and 24.2%, respectively.”

While the industry revenues present an upward trend, it is a slightly misleading picture in terms of the feasibility of operating in the sector. The average revenue per user (ARPU) has grown at a much slower pace not keeping up with inflation and customer acquisition costs.

The case for Jazz is not much different. On the face of it, things seem to pan out really well. As per VEON’s annual report, “In FY23, total revenue grew by 19.9% YoY and EBITDA grew by 4.9% YoY. Normalised for one-off recorded in 2022, FY23 total revenue growth of 23.0% YoY and EBITDA growth of 23.6% YoY

07 TELCOS

were supported by Jazz’s successful execution of its digital operator strategy.”

However, one thing needs to be understood. Multinationals like Veon (Jazz’s parent company) evaluate the performance of their local subsidiaries in dollars and this is also the currency in which the subsidiaries will be valued so any significant devaluation of domestic currency would have ramifications for local subsidiaries. This is exactly the case with the Pakistani rupee and Jazz. In dollar terms, the revenue in Pakistan was down by 12.9% in 2023 compared to 2022, and the EBITDA was down by 23%.

Further, the ARPU in dollars also paints a contrasting picture when compared to the same in rupee.

So a very rational response to this would

Source: PTA

be to invest aggressively in growth of product and service delivery to maximise ARPU while also protecting cash flows through going “asset light”.

“Infrastructure sharing holds significant importance for Pakistan amidst various economic challenges such as inflation, low ARPU, escalating fuel prices, revenue constraints, and the substantial capital investment required for the integration of emerging technologies such as 5G. The imperative to extend connectivity to underserved regions, deploy cost effective strategies to meet burgeoning capacity demands, deliver social benefits, and achieve nationwide coverage further underscores this necessity,” reads the VIS report.

For Pakistani CMOs, the logical first step

Source: PTA

towards infrastructure sharing is tower sharing.

The tower business in Pakistan

In the world of telecom, a company owns and manages the physical infrastructure used for wireless communication, such as cell towers and related equipment. When CMOs set up shop in Pakistan, they did not compete on price, or services, rather they chose to compete on something that was an automatic choice for Pakistan’s diverse terrain; coverage. Each company spent billions in making its network as accessible as possible. Towers were set up far and wide, all across the country.

While Pakistani telcos outspent each other, setting up new infrastructure, the world was moving towards more elegant solutions. Telecom companies realised that the capital expenditure that went into setting up their proprietary tower infrastructure was massive and was not likely to pay dividends quickly. Therefore, telecom companies around the world devised a way to share this infrastructure. Such that one company could use the towers of another company to transmit and multiple companies could use one tower as well.

This led to the emergence of infrastructure sharing companies that started erupting left and right. Companies that would set up a portfolio of properties on which they rented space to multiple telco operators. This resulted in mobile operators relaxing their grip on their network infrastructure via ad hoc arrangements by operators to sublet space on their sites.

The primary advantage of tower sharing is cost reduction. Building and maintaining a cell tower infrastructure can be prohibitively expensive, especially in densely populated urban areas or remote rural regions where demand for connectivity may not justify the investment. By sharing towers, telcos can pool their resources, share the financial burden of infrastructure development, and achieve cost savings through economies of scale.

Furthermore, tower sharing promotes infrastructure optimization and environmental sustainability. It also contributes to network performance enhancement and service quality improvement. By sharing infrastructure, telcos can strategically deploy equipment on existing towers to optimise coverage, capacity, and signal quality. This enables more efficient use of spectrum resources, reduces interference, and enhances the overall reliability and performance of mobile networks.

“When we were building most of our sites back in the 2004-2008 period, there were no tower sharing companies. Therefore, we had to build our own infrastructure but now we are sharing and we are sharing quite substantial numbers,” the then CEO of Telenor, Irfan Wahab, told Profit in an interview in 2022.

08

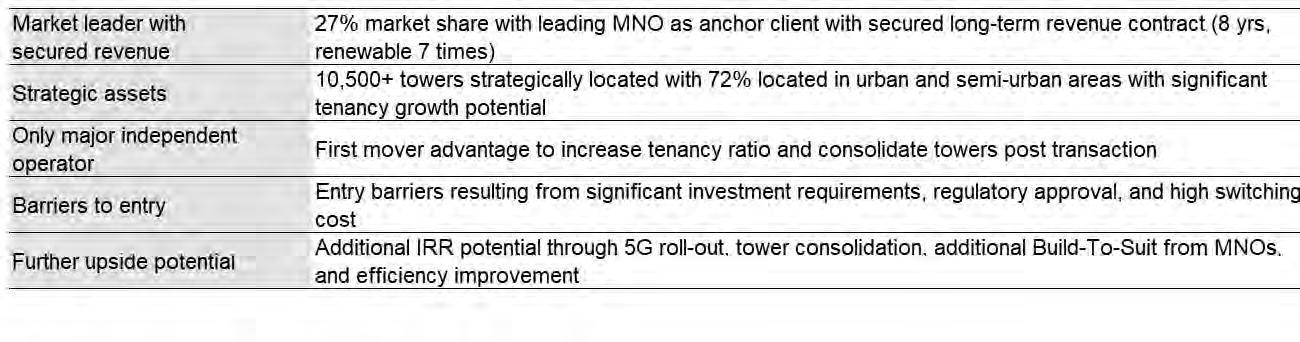

Currently, the industry’s market share is distributed among four major players: Engro Enfrashare, Edotco Pakistan (Pvt) Ltd, Awal Telecom, and Associated Technologies (Pvt.) Limited (now under the ownership of Tower Power (Pvt) Limited). In the country, as per VIS credit rating, there are around 42,000 towers installed, with approximately 6,000 managed by TowerCo companies.

These figures indicate significant potential for growth in this sector, as well as investor’s interest in participating. Jazz sought to capitalise on this opportunity and managed to secure a great deal.

Deodar; an attempt to sell

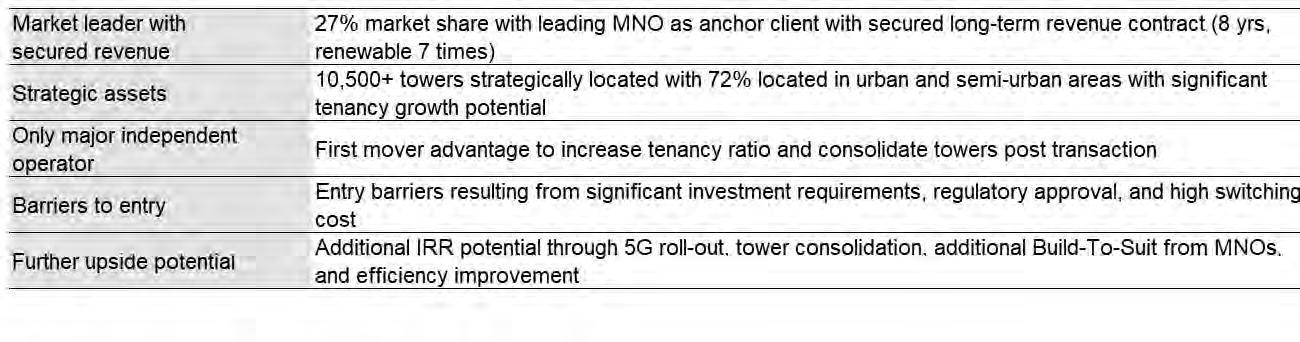

In December 2022, it was announced that Jazz had conditionally agreed to sell its 10,500+ towers. The successful bidder was a consortium of TPL REIT Management Company (TPL RMC) Limited and UAE-based TASC Towers Holding (TASC). The estimated deal size at the beginning of the negotiations was approximately $600 million.

In terms of the deal structure, the owner-

ship of Deodar was intended to be transferred to a holding company Veon Pakistan Tower Holding B.V (VPHL), incorporated in the Nether-

Source: VEON’s financial results

lands. Jazz in its extraordinary general meeting held in July 2022 provided approval for the sale of 100% shares of Deodar (Private) Limited to VPHL, subject to regulatory approvals.

During Q3-22, a Share Purchase Agreement (‘SPA’) was also signed between PMCL & VPHL setting out the arrangement for the transfer of shares for a purchase consideration of Rs 100,000.

On the buyer end, the TPL-TASC consortium aimed to establish a special purpose vehicle (SPV) in Abu Dhabi and a feeder fund in Pakistan. The SPV was planned to invest in the feeder fund, in conjunction with local investors, to ultimately acquire Deodar’s assets.

The offshore entities for Jazz and the buyer were established to facilitate transactions outside of Pakistan and mitigate potential liquidity concerns.

The buyer consortium had a clear roadmap on how to execute the deal and the massive benefits they were deriving from it were quite evident.

“TPLP is all set to launch the Digital Infrastructure REIT Fund to facilitate the transaction of selling and leasing back 10,500 cellular mobile towers from Deodar . The compa-

Source: VEON’s financial results

TELCOS

2021 2022 2023 Engro Enfrashare 48% 50% 51% Edotco 43% 42% 34% Tower Power 8% 7% 14% Awal Telecom 1% 1% 1%

Company name

TowerCo market share by VIS

Source: VEON’s financial results

ny is in discussion with the regulatory body to finalize the procedural modalities of the project. Commencement of this project would benefit TPLP through investment management fees. We think that the combined synergy of TASC and TPLP will improve the tenancy ratio and IRR that would increase the fund’s NAV and thus management fees of TPL RMC. Moreover, the partnership may further consolidate tower assets across the country and internationally through its Abu Dhabi subsidiary,” read an analyst note by Ktrade.

A sale not to be

However, despite the robust execution plan, the sale never materialised, and Deodar’s assets were not transferred to VPHL.

Sources familiar with the situation have

indicated that Jazz’s management has put the transaction on hold due to political instability in the country and the devaluation of the Pakistani Rupee. They also mentioned that Jazz’s management is hopeful that once the IMF-related matters are resolved, the transaction can progress. It is anticipated that the transaction will be finalised approximately within a quarter after the signing of a long-term IMF program.

Given the prevailing forex crisis and the difficulties faced by companies to repatriate profits, any investor is likely to have its reservations while investing in the country.

A concern reiterated by Telenor’s global CEO, “It’s very challenging to do business in Pakistan right now. That’s one of the reasons why we have decided to exit. If an investor cannot repatriate profit from a country, then the investor probably will, over time, leave.”

Sources privy to the development also state that the sale of Telenor also plays a big role

Source: TPLP investor presentation

in the pricing of Deodar’s deal. The Norwegian parent company of Telenor Pakistan, sold its entire business, including brand equity and non-technical assets for around $490 million, an amount less than what Jazz is demanding for Deodar. This prompts a comparison between the deal value for any potential buyers.

Although the TPL-TASC consortium remains involved in the sale discussions, other industry players are reportedly engaged in negotiations with Jazz, seeking to reach a middle ground for the acquisition of Deodar’s tower assets.

Profit reached out to Jazz for more information regarding the deal. “Jazz is continually exploring opportunities to enhance our strategic position and engage with various stakeholders in the industry. However, we do not comment on specific discussions or potential engagements unless there is a definitive outcome to share,” the CMO responded. n

Source: TPLP investor presentation

10 TELCOS

COVER

11

STORY

Pakistan’s need for an reliance on natural gas has only increased as our reserves have fallen. A cheap and convenient solution is staring us in the face. But will geopolitics let it take root?

By Abdullah Niazi

When Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi landed in Islamabad last week, the weight of the world would have been on his shoulders. His country had just ordered missile strikes inside Israel in retaliation for the bombing of Iran’s embassy in Syria by the Israelis.

Pressure and condemnation from the Global North was immediate and powerful. All of this at a time when the Genocide in Gaza has captured global attention. Already a pariah, the Iranian President was arriving in Pakistan at a time when the world’s ire was focused upon him. To make matters worse, Iran and Pakistan had been caught in a tit-fortat airstrike exchange not four months before the visit.

One could say that the visit was at a tense time.

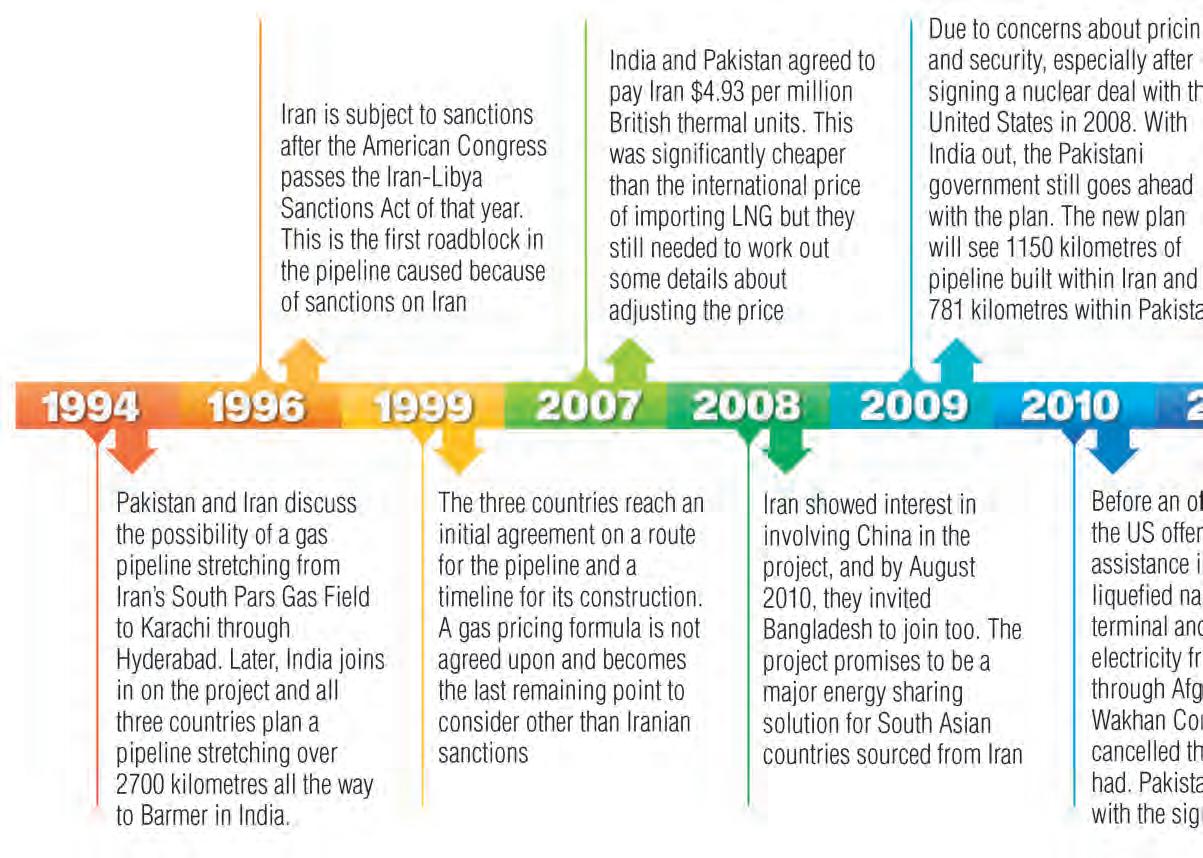

Yet somehow the missiles, the airstrikes, and war in the middle east and Europe were not the most awkward points of conversation between President Raisi and the Pakistani government. That was reserved for the Iran-Pakistan Gas Pipeline project. First proposed in the early 1990s, the pipeline remained a pipedream for the first couple decades. The idea was for a gas pipeline to run from Iran, through Pakistan, and all the way to India. It would give Iran buyers for its vast gas reserves and provided a steady and reliable supply of cheap gas that wouldn’t need to be imported through sea-ports.

Things haven’t quite gone according to plan. India dropped out of the plan in 2009 but Pakistan and Iran went ahead with the deal. Since then Iran has built its side of the pipeline but Pakistan has time and again delayed its participation in the project out of fear of sanctions from the United States. But it isn’t so simple. By not holding up its end of the bargain, Pakistan risks being slapped with a massive fine.

That is the equation that stands before the government of Pakistan. Risk having to pay an international fine or risk the ire of the United States and the economic difficulties of a sanction. So what should the Pakistani government be doing in such a situation? The answer depends entirely on what they plan to do with the gas.

An idea that stayed an idea too long

In the 1990s, Iran was looking for avenues to sell its gas. The sanction-stricken country had by then discovered it had some of the largest natural gas reserves in the entire world. They were able to give cheap rates, but because of international relations, they had no buyers. Normally, there are a few ways to go about exporting natural gas. The preferred method is by liquifying the gas (LNG), transporting it in special vessels across the sea, and unloading it in special floating ports that convert the gas and eventually transport it to pipelines.

But because international markets were unavailable to Iran, the other possibility was to sell to their neighbours. The idea was to set up a gas pipeline that would run from Iran and transport gas from their reserves to Pakistan and possibly onwards towards India. Not only are gas pipelines convenient, they also make transportation significantly cheaper and reduce the cost of the gas. Since building the pipeline is a one time investment, and maintenance is cheaper than one would expect, such a project with neighbours essentially cuts the transport cost out of the equation entirely.

Although these pipelines have associated concerns like inflexibility in delivery points and risk of sabotage, the econom-ics of overland gas pipelines have justified their presence in almost all continents. Existing literature has extensively documented this. The consensus is that natural gas pipelines are economical over shorter distances. When it comes to very large distances, such as over 4000 kilometres, the LNG option has the advantage. For distances under about 3200 kilometres in particular, pipelines are less expensive than LNG, and the network characteristics of pipelines also ensure added reliability and economies of scale for gas pipeline transportation.

A pipeline coming from Iran through Pakistan and all the way to India was perfect for this. The gas would come from the South Pars Gas Field. Easily the largest gas field in the world, ownership of it is shared between Iran and Qatar. To understand the geography of it better, the field actually exists 9800 feet below the seabed — a distance that is one third the size of Mount Everest.

From here the gas would be transported through the South of Iran, run through Baloch-

istan via Gawadar, and then go on to India. But to get the ball rolling, a level of cooperation was required that didn’t exist between the three countries. Many different plans were also made. In 1993, India and Iran discussed a bilateral arrangement to commission a pre-feasibility study in early 1995 for a shallow water offshore pipeline from Iran to India. At the same time, India also explored its options including deep-sea pipelines from Oman and Qatar. However, these did not materialise due to high costs and political hiccups.

The only project that made sense was building a pipeline from Iran through Pakistan to India.

Initial feasibility studies for this showed great potential. The plan for the Iran-Pakistan-India (IPI) pipeline dubbed the “Peace Pipeline” was that Iran would build from its gas field a pipeline 56 inches in diameter over an area of over 1000 kilometres. It would have its offtake point in Hyderabad Pakistan, around 800 kilometres from the Iran-Pakistan border. It would then extend up to Barmer in India, and a further 250 kilometres into the third country. The total length from the South Pars field in Iran to Barmer in India would be around 2700 kilometres, which would make it just the right size to be economically viable.

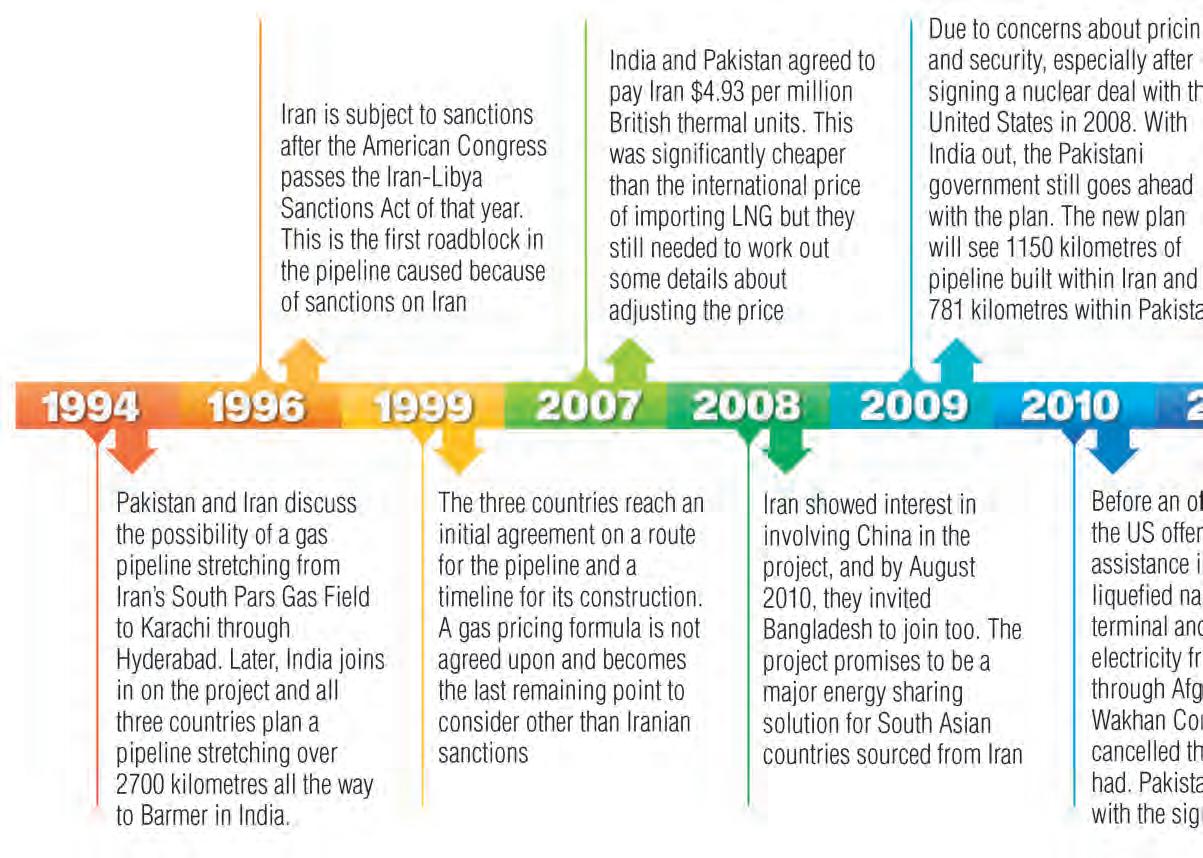

The hiccups of timing

The only problem was the numerous hurdles. For starters, in 1995 Pakistan refused to grant access for a feasibility study. This was at a time when diplomatic relationships with the Americans were at an all time low and tensions were high with India. Pakistan feared they would support India in a conflict. At the same time, Iran came under sanctions in 1996 when the US Congress passed the Iran-Libya Sanctions Act in response to the Iranian nuclear program and Iranian support for Hezbollah, Hamas.

This meant that only Iran was sanctioned, Pakistan was also going to have a hard time finding financing for the pipeline since international banks and lenders were not going to participate in business with the Iranian regime given the recent sanctions.

Despite this, an initial agreement between the three countries was decided on in 1999. But then the matter stalled for a while and no progress was made.

By February 2007, India and Pakistan

12

agreed to pay Iran $4.93 per million British thermal units. This was significantly cheaper than the international price of importing LNG but they still needed to work out some details about adjusting the price. In April 2008, Iran showed interest in involving China in the project, and by August 2010, they invited Bangladesh to join too.

This was clearly a project they were keen on and wanted to expand.

However, India backed out of the project in 2009 due to concerns about pricing and security, especially after signing a nuclear deal with the United States in 2008. With India out, the Pakistani government under the PPP administration of President Zardari signed an agreement with Iran to build the pipeline anyways between just the two countries.

What followed was Iran enthusiastically jumping on the agreement. The new agreement held that a length of 1150 kilometres within Iran and 781 kilometres within Pakistan was to be implemented by each country in their respective territories. The first gas flow was to start from 1st January 2015. Iran has completed construction of over 900 kilometres within Iran. Meanwhile Pakistan has continued to stall them.

Why has Pakistan been stalling?

The agreement between Pakistan and Iran was signed in 2010. Even as the two countries reached an accord the pressure from the United States was palpable. The US went so far as to offer assistance in constructing a liquefied natural gas terminal and importing electricity from Tajikistan through Afghanistan’s Wakhan Corridor if Pakistan cancelled the deal like India had.

The Zardari administration went through with the plan. The agreement envisaged the supply of 750 million to a billion cubic feet per day of natural gas for 25 years from Iran’s South Pars gas field to Pakistan to meet Pakistan’s rising energy needs. But over time Pakistan consistently kept stringing Iran along.

For example, while both countries broke ground on the project in 2013, Pakistan did not even acquire the land on which the project was going to be constructed let alone start working on it. In May that year, Iran through official channels wrote a letter to the Pakistani government expressing its concern over the lack of commitment on display. Pakistan, on the other hand, was hesitant to get things started because of the threat of US sanctions. The Zardari administration rode out its tenure and was voted out of power.

In 2013, when the government of Nawaz Sharif came to power, he assured Iran allayed

any fears regarding the abandonment of the project and said that the Pakistani government is committed to the fulfilment of the project and targets the first flow of gas from the pipeline in December 2014. The premier also stated that his government is planning to commit to the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India gas pipeline project as well. Still, because of sanctions, it was going to be hard to find financing for the project.

So in 2014, after delaying everything for the time being, Pakistan made it clear that it was being indecisive by asking Iran for a 10 year waiver in breaking ground on the project. There were also reports that Saudi Arabia, a country Pakistan was relying heavily on to manage its debt situation, had expressed its concerns regarding the pipeline being built. And from 2014 up until the beginning of this year that was that. Shahid Khaqan Abbasi, then the petroleum minister, said in parliament that sanctions meant the project was being hit with delays.

Some hope was revived in 2016 when sanctions were lifted on Iran and the then President Rouhani visited Pakistan, where the gas pipeline was under discussion between him and Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif. With the sanctions gone, Pakistan decided to go ahead with the project after securing funding from Chinese institutions. China was providing 85% of the total financing for the LNG pipeline project and wanted to emulate the same model for building the remaining portion of the pipeline from Gwadar up to the Iranian border.

But by 2016, the Iran Nuclear Peace Deal seemed destined to be doomed. Brokered by US President Obama, his successor Donald Trump took the US out of the deal by 2018 and reimposed sanctions on the country. Pressure was once again exerted on countries doing business with Iran and the pipeline project was once again under scrutiny and came to a halt. At the time, there was also a great lack of political will. Nawaz Sharif had been ousted, Shahid Khaqan Abbasi had seen a brief premiership, and Imran Khan had just come to power. It was now the new PTI government which would continue or stall work on the project.

What they did instead was follow the same will-they-won’t-they attitude that the previous governments of the PPP and PML-N had adopted. In 2019, Pakistan urged Iran to explain in-writing its interpretation of sanctions that resulted in a massive delay in completion of the mega Iran-Pakistan gas pipeline project. The problem was Pakistan could not abandon the project at this point.

Tehran says it has already invested $2 billion to construct the pipeline on its side of the border, making it ready to export. - Paki-

stan, however, did not begin construction and shortly after the deal said the project was off the table for the time being, citing international sanctions on Iran as the reason. The 10-year extension Pakistan had asked for in 2014 ended in January 2024, and Iran was once again knocking at Islamabad’s door. Reports started coming in that if Iran took Pakistan to international arbitration court, the country could be fined up to $18 billion for not holding up its half of the agreement.

The potential of the fine set things straight. A meeting of the Cabinet in February finally approved the construction of the first 80 kilometres of the Pakistani side’s pipeline to avoid the fine. Reports started coming in that Russia was providing funds for this initial construction which would cost Pakistan somewhere around $160 million. But the response from the United States has not been favourable, and the US has threatened consequences in the shape of sanctions.

The state of electricity in Pakistan

The only question that really matters is just how badly Pakistan needs this gas. The answer lies in how the government intends on using this gas. If the purpose is to provide cheap gas to households for domestic consumption then the rewards for taking on the risk of US sanctions is quite high. But if the purpose is to generate electricity, provide it to industrial customers, produce goods and decrease Pakistan’s import bill then it might make sense.

In the early 1990s, it wasn’t quite apparent that Pakistan was heading down a path that would lead to an energy crisis. At the time, a majority of the country’s electricity generation was coming from hydroelectric power through the Mangla and Tarbela dams. But the government was also on an expansionary path.

The problem for Pakistan was finding a source of energy that could be used to make cheap electricity that could then be used by commercial and domestic consumers.

In the 1980s, the government of Pakistan did start setting up oil-fired power plants.

At that point, with international financing difficult to procure owing to Pakistan’s poor relations with the United States, the government instituted a policy that allowed for more private sector players to set up independent power plants (IPPs) that were reliant mainly on oil. Over the next decade, this increased Pakistan’s reliance on imported oil as a fuel for its electricity generation.

In the early 2000s, the Musharraf Administration decided to convert at least some of that thermal power generation capacity from imported oil to domestic natural gas,

COVER STORY

A timeline of the Iran-Pakistan gas pipeline

14

under the assumption that Pakistan had abundant domestic reserves. This assumption was wrong and it didn’t require great foresight to know that it was wrong. As early as 1995, the government of Pakistan had access to estimates that suggested that Pakistan’s natural gas production was predicted to peak in 2010 and precipitously fall thereafter.

It was the Nawaz Administration in 2013 that pursued a solution to part of the problem, and actively sought to commercialise power generation in Thar, replace the waning domestic natural gas with imported liquefied natural gas (LNG) from Qatar, and above all, incentivize the private sector to build lots and lots of thermal power plants, while simultaneously embarking on a massive government

COVER STORY

spending spree on increasing hydroelectric power generation. Those policies are now bearing fruit, and after nearly a decade and a half of almost consistent decline, the domestic share of primary fuels for electricity generation in Pakistan rose substantially in fiscal year 2023, and may continue to rise in the coming few years.

Over the past 10 years – since the Nawaz Administration began dramatically altering Pakistan’s electricity generation mix – the country has increased its power generation output by 42%, from 98,655 gigawatt-hours (GWh) in fiscal year 2013 to approximately 140,493 GWh in fiscal year 2023. The aggregate increase, however, is not the full story. During that time, imported LNG replaced imported oil, and imported coal replaced the decline in natural gas.

And when we say replace, we mean that almost literally. Between 2013 and 2023, electricity generation from oil-fired power plants declined by 29,162 GWh, and that generated by LNGfired power plants went up by 29,282 GWh, an almost exact one-to-one replacement. Power plants run on domestic natural gas saw production decline by 12,942 GWh and replaced almost exactly by an increase of 12,457 GWh in imported coal-fired power production.

Now, the addition of cheap Iranian gas into this mix would not just increase power generation capacity but also provide a cheaper energy mix. The only trouble is that Pakistan has managed to find alternative sources for this energy at home. While Iranian gas might have been a game changer in 2014, the past nine years have not been quite bad. For starters there is Thar Coal. From 2013 to 2023 power plants run on domestic natural gas saw production decline by 12,942 GWh and replaced almost exactly by an increase of 12,457 GWh in imported coal-fired power production (which itself is now being replaced at least partially by Thar coal).

Then there is nuclear energy. As recently as 2009, Pakistan got less than 2% of its electricity from nuclear energy and now that number is above 17% of the total electricity

generated in the country, largely on the back of Chinese-backed nuclear power plants at Chashma, and a substantial increase in the generation capacity at the nuclear power plant in Karachi. So important is nuclear to Pakistan’s increase in electricity generation that the net amount of nuclear energy added to the grid is about equal to the total added by Thar coal, wind, and the new hydroelectric power plants combined.

This means that while gas from Iran could be used to bolster Pakistan’s electricity production, the country has found other ways to do this. As such, it is not so important that Pakistan should risk its ties with the United States for, particularly at a time when Pakistan is dependent on the IMF and others to fulfil its external debt obligations.

Natural gas supply

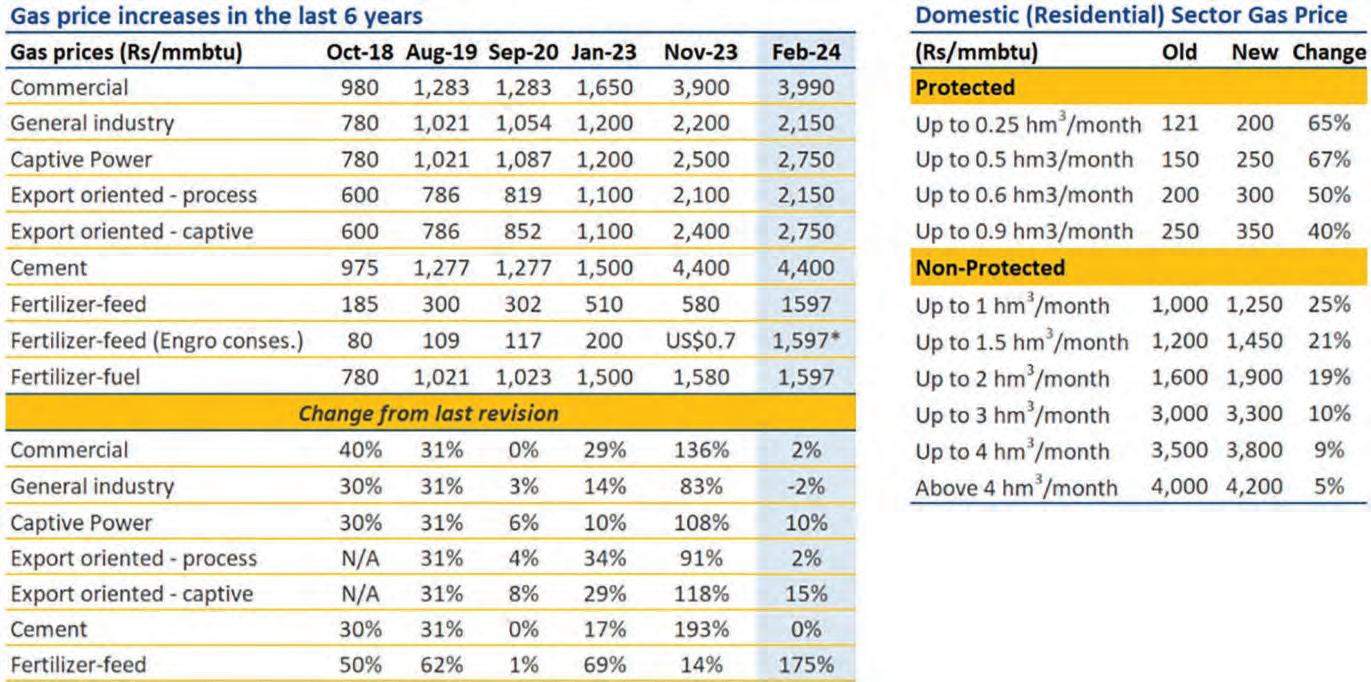

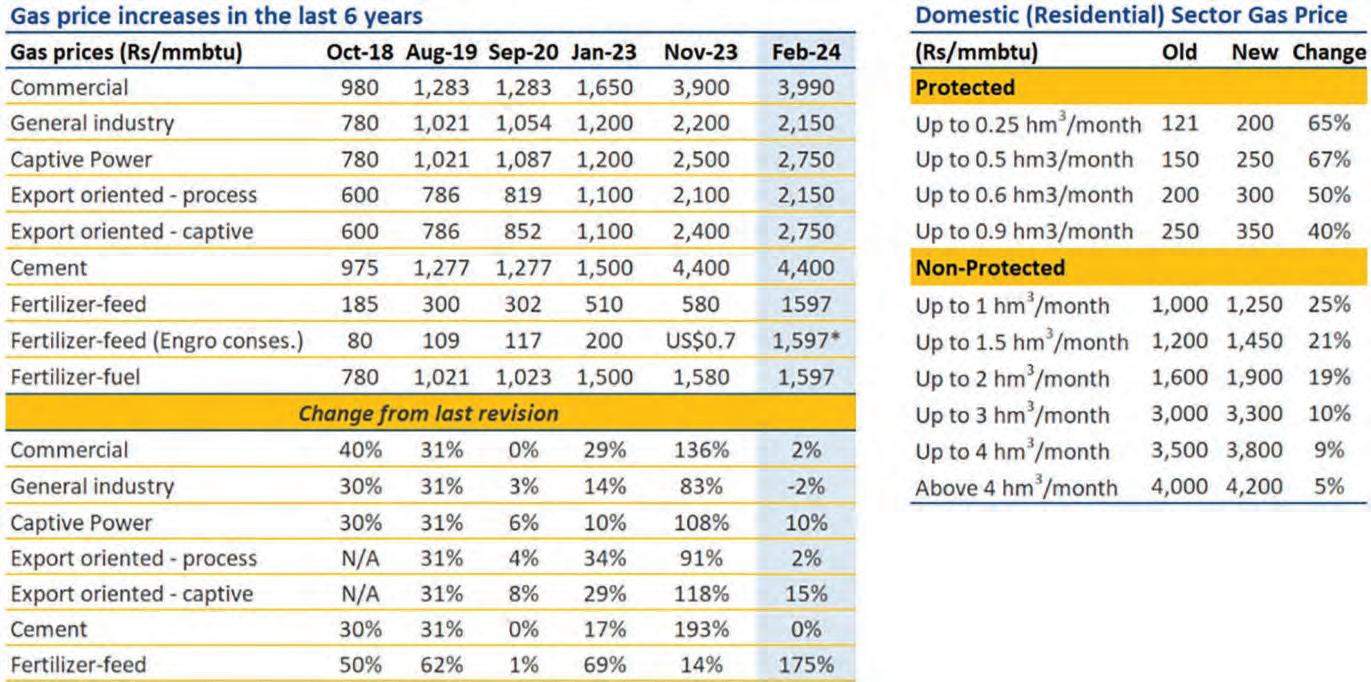

But the importance of cheap gas cannot quite be understated. Just look at the crisis that has been ongoing in Pakistan’s gas sector since the start of the year on the instruction of the IMF.

There is a reason the IMF wants to increase gas prices in Pakistan. Very briefly put, Pakistan does not have a lot of gas but we use it like we do. The IMF, as part of the ongoing programme, wanted to increase the price of gas for all domestic and commercial consumers. You see, Pakistanis have gas cross subsidised. This means that the natural gas we produce is given to different consumers at different rates. There is one category of protected consumers which get it at the cheapest possible rate.

These are small domestic consumers that use gas below a certain amount and tandoors that make rotis. Even within this protected category there are slabs and everyone is charged differently based on how much they consume. Essentially, bigger consumers end up subsidising smaller consumers.

And while this is a people friendly policy and popular for political decision makers, it is also unproductive. Because we don’t have a lot of gas available, the IMF and other bodies

such as the World Bank have always felt that gas should be used by industries for productive purposes rather than by domestic consumers to power stoves and heat water. This particularly becomes a problem in the winters, when the domestic need for gas increases, governments end up cutting it to industrial users. The gas industry circular debt is a relatively new situation caused by rising LNG costs and delays by the government in announcing the new and higher tariff consistent with the international gas price hikes. Another contributing factor is the government’s inefficient utilisation of this commodity coupled with untargeted subsidies.

The fundamental cause of the circular debt is the unpaid government subsidies intended for residential and export-oriented consumers for the consumption of LNG. This has hampered Sui Northern Gas Pipelines (SNGPL) and Sui Southern Gas Company’s cash flows (SSGC) as they are not able to recover the actual cost of importing LNG from their respective customers. To make the point clear, LNG costs a lot more than domestically produced gas, therefore naturally the price should be set at a level that would allow the recovery of the costs. But that is not the case as the government diverted the expensive LNG to domestic consumers which cannot afford to pay for it. This has resulted in ballooning receivables from the twin gas distributors on the balance sheets of energy exploration corporations, primarily the Oil and Gas Development Company (OGDC) and Pakistan Petroleum Ltd (PPL). To summarise it, the government has not paid up the subsidy amount it owes to SNGPL and SSGC for providing gas at lower rates than what it actually costs. The debt is parked within other state owned enterprises, as is the common practice of the government.

Because of this, the IMF ideally wants gas to come to its original price instead of being cross subsidised, which might result in domestic consumers in particular switching to electricity. In fact, one of the most ideal scenarios for the IMF and indeed for industrial

16

consumers is that domestic consumers switch from using gas to cook their food and heat their water to using electricity. The only problem is that domestic consumers are used to cheap gas. Electric cooking ranges, for example, are a rarity in Pakistan. Similarly electric geysers and water heating systems have simply not developed. This is despite the fact that at their real prices, and particularly with solar solutions, electricity is much cheaper than gas. The gas price hikes reflect this. Just take a look at how the prices have increased. Domestic protected consumers and tandoors have had their rates hiked by up to 70% in some cases. Similarly the non-protected category has seen an increase in prices of up to around 25%. But the real shift is in the subsidies that were being provided to industrial consumers.

The first round of gas price increase took place back in November 2023. Back then commercial connection rates were raised by 136%, and the biggest increase was in the cement sector which saw a hike of around 193%. The fertiliser industry was still protected, however. This particular price hike has been gentler on these sectors and has instead focused on the fertiliser industry which has seen an increase of 175% in gas prices.

A big part of why these changes were implemented were the constant insistence of successive governments to provide gas to domestic users at cheap rates. If the government intends on importing gas from Iran for this purpose, then it would be folly. However, if the government can ensure that every unit of gas coming from Iran would be used for its most

productive purpose then it might be worth it. The gas could be provided to captive power plants, to the fertiliser sector without subsidies and could help ease inflationary pressures.

Furthermore, there is the issue of supply security. While LNG prices are anticipated to decrease in the future with an influx of supply expected after 2025, Pakistan may still face challenges competing with larger consumer nations for this surplus supply. This competition may result in Pakistan continuing to pay elevated prices due to oil-indexed contracts and high credit risk.

This scenario unfolded in 2020 when LNG spot prices plummeted as a result of the economic repercussions of COVID-19. Despite the market conditions, Pakistan honoured its long-term supply agreements and paid a premium price. Locking in additional supply under the same conditions may impose a financial burden on consumers that could be unsustainable.

Going the waver route

So what exactly does Pakistan do in this situation? On the one hand there is the risk of sanctions. On the other hand Pakistan could be slapped with a massive fine twice the size of its foreign exchange reserves. The first step, which even the government of Pakistan is not incompetent enough to not to take, is attempting to ask the US for a special waiver.

Back in March when they started work on the project, the US immediately expressed its displeasure. Last month, Donald Lu, the

US assistant secretary of state for South and Central Asia cautioned Pakistan against importing gas from Iran, as it would expose it to US sanctions.

In response, Pakistan’s Foreign Office spokesperson Mumtaz Zahra Baloch made a case for national sovereignty; since the pipeline is being built within Pakistani territory, “we do not believe that at this point there is room for any discussion or waiver from a third party”, she said. Nonetheless, Thomas Mont-gomery — the acting US mission spokesperson in Pakistan — offered the following words of caution: “We advise anyone considering business deals with Iran to be aware of the potential risk of sanctions.” The US has been pushing Pakistan to seek green alternatives; through its development agency it has helped add almost 4,000 MW of clean energy to Pakistan’s grid since 2010.

The government also said they would seek a U.S. sanctions waiver for the pipeline. However, later that week, the U.S. said publicly it did not support the project and cautioned about the risk of sanctions in doing business with Tehran. And as reported in the international media, “Washington’s support is crucial for Pakistan as the country looks to sign a new longer term bailout program with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in coming weeks. Pakistan, whose domestic and industrial users rely on natural gas for heating and energy needs, is in dire need for cheap gas with its own reserves dwindling fast and LNG deals making supplies expensive amidst already high inflation.”

COVER STORY

The choice ahead

Pakistan must choose carefully what it does from this point on. There are many benefits to going ahead with the Iran gas pipeline project. The gas can help in electricity generation and can also be a major source of relief for export oriented industries. The goal, however, must be to ensure that it is used in the most productive and efficient manner possible.

Because if different governments start providing cheap gas to domestic consumers as a publicity gimmick there will be very little point to risking sanctions from the United States. It is a path Pakistan has gone down before and it does not end in a pretty destination.

The matter from this point onwards needs to be handled diplomatically. Iran has shown great patience over the past two decades and has persisted with the pipeline project. They have done so because they have to, but policymakers would do well to remember that it is looking like Tehran is running out of patience. If they choose to go to international court, Pakistan will be staring down a very steep penalty. The best bet is to get the United States on board, but the timing is particularly bad because of the war in the middle east and condemnation of Iran coming from America

and its allies.

Up until now, Pakistan has tried to maintain a balance. President Raisi received a very warm welcome from Islamabad but the issue of the pipeline remained one talked about in hushed tones and no formal statement was made. One can assume that this means no decisions have been made up until now. But if the economic benefit is in building the pipeline,

Pakistan should not fear US sanctions and needs to instead present its case diplomatically and lobby for an exemption from sanctions. Ideally the case for building the pipeline should be presented by India and Pakistan together, but it is unlikely that prevailing diplomatic tensions will allow that. In the absence of this joint strategy, Pakistan’s diplomatic corp have some brainstorming to do. n

COVER STORY

16 18

Food security revolution: National Foods grows Pakistan’s future ‘One Ingredient at a Time’

Imagine a world where a global crisis doesn’t cripple your dinner table. For Pakistan, a nation deeply woven into the fabric of culinary delights, the COVID pandemic was a game changer in many aspects. It all began as a response to the pressing need to address global supply chain constraints, particularly in the food sector. One key ingredient, tomato paste, a seemingly ordinary staple, symbolized a larger challenge – dependence on imported food supplies.

Seeing this challenge as an opportunity to transform the nation’s food value chain, National Foods Limited, a Pakistani powerhouse, embarked on a remarkable journey – a journey not just for a single ingredient, but for the very soul of Pakistan’s agricultural landscape, one seed at a time.

Born from Crisis, Driven by Innovation: The Seed to Table Initiative

‘Seed to Table’ by National Foods is a transformative project redefining the country’s agricultural landscape. Pakistan currently imports nearly $10 million worth of tomato paste annually, highlighting the need for localization of this raw material. The initiative is more than just an initiative; it’s a commitment to fortify the tomato value chain, seizing import substitution opportunities, and reshaping the agricultural sector positively.

Through formal partnerships with progressive farm-managing companies, National Foods Limited set out to empower local farmers and strengthen the tomato value chain.

Empowering Farmers, Strengthening the Value Chain

National Foods understood that achieving this ambitious goal required collaboration. They partnered with farm management companies like Ibtida Ventures, Kevlaar, Indus Acres, and Vital Green. These partnerships not only provided access to 500 acres of land for tomato cultivation but also leveraged the expertise of these established players in optimizing farming practices.

Farmdar and FarmEvo brought expertise in farm management and drone services, crucial for large-scale, efficient farming. Salaam Takaful provided crop insurance, offering much-needed security to farmers. Syngenta’s partnership ensured access to high-quality seeds and valuable agronomy expertise.

Weather Walay provides invaluable weather advisory services, allowing informed decisions to optimize crop yields. This holistic approach to farming improved yields and ensured long-term sustainability.

Finally, Al Rahim, their trusted tomato processor, ensures that the fruits of their labor are transformed into high-quality tomato paste, ready to enrich tables nationwide.

These collaborations are crucial in addressing challenges such as the quality of seeds, water availability, and stakeholder identification in the farming sector. With such meaningful partnerships, they’re optimizing farming practices and ensuring sustainability.

Return on Initiatives - ROI

Since the project began in August 2023, National Foods Limited has adhered to its deadline. They have followed their program with unshakable determination, from cultivating seeds in September 2023 until transplantation in October 2023. The harvests started in February this year have yielded around 8,000 tons of premium-quality tomatoes.

“The revolutionary ‘Seed To Table’ project has already saved USD 2mn with a realized localization potential of around USD 10mn. It presents us with the opportunity to export in a USD 10bn+ market,” said Abrar Hasan, Global CEO of National Foods Limited (NFL).

“By taking control of the entire supply chain, we’ve ensured a consistent supply of high-quality fresh tomatoes directly to NFL’s production facilities. We are dedicated to building upon the success of the ‘Seed to Table’ project by replicating this model with other key ingredients like red chilies, further strengthening domestic agriculture, and reducing reliance on imports,” he added.

A Model for the Future: Beyond Tomato Paste

The success of the Seed to Table program extends beyond immediate benefits. It serves as a model for the future of Pakistan’s agriculture. National Foods’ commitment to innovation, collaboration, and sustainability has paved the way for a more resilient food supply chain.

Building on this success, National Foods is already exploring opportunities to cultivate red chilies, another crucial ingredient. This expansion signifies their long-term vision of strengthening Pakistan’s food security and promoting sustainable agricultural practices across various crops.

This initiative by National Foods Limited represents a strategic and impactful approach to addressing supply chain constraints. By localizing the production of essential raw materials, National Foods has ensured a stable supply chain, empowered local farmers, and contributed to the country’s food security efforts. n

19 PARTNER CONTENT

Russian authorities just stopped a contaminated consignment

Pakistani rice. Are we looking at a ban?

of

Pakistan is trying to make its mark in the international rice trade at a time when India has stopped its export of rice. Will this be detrimental?

By Ghulam Abbas

Anasty surprise awaited the Russian port authorities when a consignment of Pakistani rice arrived at port on the 15th of March. The consignment of white rice had the presence of an insect Megaselia scalaris (LOEW), commonly known as “scuttle fly” or “coffin fly.”

Normally, the presence of minor insects would not be a major deal breaker in the international trade of food commodities. Countries regularly have pest control and fumigation protocols for all imported food. The only problem was that the particular kind of fly that was in the consignment is not native to Russia, and as such a fast reproducing pest such as the coffin fly could wreak havoc on Russia’s ecological integrity.

To fend away such a situation, Russia has strict controls against it in place. This, of course, is a blunder of great magnitude. Pakistan is currently at a crossroads in the international market where its rice is high in demand because of India ending its export of different kinds of rice. To send a consignment to a high-profile country like Russia that has not been properly vetted and contains a foreign pest will send shockwaves in the effort to make Pakistan a major rice exporter.

It takes glaring inefficiency to make a mistake of this magnitude and possibly harm trade ties between the two countries. What makes this worse is that this is not the first time this has happened. Pakistan faced a similar situation with Russia back in 2019 and had to face a ban from the country. So what effects will this latest mishap have on Russia-Pakistan food trade?

While talking with different sources with the government departments and other stakeholders, we tried to understand the whole episode and reasons behind such incidents which harm the country’s exports. And why, at a time when Pakistan needs exports to balance its current account, are regulators shooting themselves in the foot.

A story of Russian interception

Under the Article VII of International Plant Protection Convention (IPPC), the importing country has sovereign right to “regulate the entry of plants and plant products and other regulated articles and, to this end, may prescribe phytosanitary measures including ban on import of goods from any trading country with

20

the aim of preventing the introduction and/or spread of regulated pests into their territories.” This is mainly because invasive pests may be detrimental to the agriculture industry of an importing nation once introduced, developed and spread.

Rosselkhoznadzor - Federal Service for Veterinary and Phytosanitary Surveillance (FSVPS) is a National Plant Protection Organization (NPPO) of Russia under the Ministry of Agriculture of the Russian Federation it is responsible for biosecurity of Russia.

Originally, “biosecurity” was mainly used in defence regarding the control of biological weapons. Later, due to its growing importance, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Biosecurity defined it as a strategic and integrated approach that encompasses the policy and regulatory frameworks (including instruments and activities) for analysing and managing relevant risks to human, animal and plant life and health, and associated risks to the environment.

Rosselkhozdanazor has sent a ‘Notification of Non-compliance’ to Department of Plant Protection (DPP), National Plant Protection Organization of Pakistan, under Ministry of National Food Security and Research (MNFSR) on violations of international and Russian phytosanitary requirements at deliveries of regulated products from Pakistan to the Russian Federation on 17th March.

The notification has been served by Rosselkhozdanazor to DPP (NPPO) in connection with provisions of the International Standard for Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures, (ISPM-13) prescribed by IPPC to whom Pakistan and Russia also signatory. In the notification, Rosselkhozdanazr has provided DPP necessary information regarding intercepted rice shipment and requested to conduct an investigation into the matter and take measures to prevent this violation, and inform the Rosselkhoznadzor about the measures taken in the shortest possible time.

Notification reveals that the intercepted white rice consignment was exported by M/s Garribson Pvt. Ltd. in Karachi through MSC MARITINA V on 10th of January. The consignment arrived at the big port of St. Petersburg of Russia on 15 of March after a two month voyage. Coffin flies were detected in the shipment by Rosselkhozdanazor during inspection.

According to Pakistani documents, prior to leaving from Pakistan, the consignment was disinfected by M/s Prince Pest Control Services, Karachi, a vendor selected and arranged by the exporter. Hafiz Muhammad Zohaib, an Entomologist from DPP conducted the inspection and declared it free from pests and approved its phytosanitary certificate.

Mr. Muhammad Shaukat Hayat, Minister (Trade & Investment) in Embassy of

Pakistan, Russia translated and forwarded this notification to DPP and warned DPP that in order to avoid any possible ban on rice exports from Pakistan to Russia, an investigation into matter of sending non-compliant rice shipment to Russia should be conducted and shared its results with FSVPS immediately.

However, his remarks regarding a possible ban on Pakistani rice exports to Russia, something that was reportedly not hinted at in the Rosselkhoznadzor letter, has created panic and unrest among the rice industry. According to the rice industry they are already facing very strict phytosanitary import measures for export of rice from Pakistan to Russia that allow only 19 rice establishments and companies including the non-compliant company (Garribson), to export rice. The panic was justified because precedent suggests that in the past FSVPS has banned import of rice from Pakistan in 2006 and then in 2019 intercepting infested rice shipments.

According to International Sanitary and Phytosanitary standards, when a country intercepts an import at its port, that has a harmful organism, it has three options; confiscation and destruction of consignment; disinfestation and deport the consignment; or emergency disinfestation treatment and releasing of the consignment in the country.

It is revealed that despite the notification sent to the DPP by FSVPS, the FSVPS had given clearance to the intercepted consignment after treatment onshore instead of deporting or confiscating and destroying the consignment.

Interestingly the notification of non-compliance issued by Rosselkhoznadzor mentions India as a country for the issuance of the phytosanitary certificate accompanying the consignment. The notification hence mistakenly attaches a certificate issued on 29th of March with notification that was itself served on 15th March 2024. The DPP states that this might need clarification from Rosselkhoznadzor by DPP.

According to Schedule XI of Pakistan Plant Quarantine Rules, 2019, the registration of M/s Prince Pest Control Services, Karachi is necessary to be suspended. Since, interception has occurred due to defective fumigation. Therefore unless it is established in investigation that the container had been opened after treatment by any other agency, the registration will remain suspended.

Disciplinary action is also provided against Hafiz Muhammad Zohaib for issuing phytosanitary certificate to infested consignment based on faulty and inept inspection, unless it is established that the containers were not opened by any other one or agency.

It is pertinent to note that this investigation and phytosanitary actions are pending since 17th of March.

While the news of any ban on Pakistani

rice has been categorically denied and is found out to be nothing but an undue remark added during translation by Mr Shaukat Hayat, it sparks a new debate regarding the issuance of these notifications to Pakistan. The officials at DPP do not receive the notification with an open heart. Their discontentment, however, is not based on phytosanitary standards but rather on other factors such as courtesy. They claim that they have never dared to reciprocate similar strong action, such as a “notification of non-compliance”, against Russia despite repeated interceptions of Russian wheat and grains with harmful insects.

Rather, the DPP opts to conduct emergency disinfestation treatment to Russian goods on arrival after detection of biosecurity risks and gives them biosecurity clearance. Why does Pakistan afford such leniency to Russia despite its biosecurity misconduct? God knows. But is that reason enough to expect Russia to do the same, even the DPP fails to answer.

DPP; A bureaucratic nightmare

According to insiders the major issue causing negligence on the part of the department is lack of relevant and technical officials running the department. As per the available information, DPP is currently operating without a regular head of department i.e., a Director General, a Plant Protection Adviser and a Director Technical. In their absence the Deputy Director Quarantine, and Entomologist Quarantine (H), both BS-18 and BS-17 officers respectively are reluctant to take actions for want of jurisdiction.

However, it is revealed that even when the positions were occupied the Director General and Director Technical, were hired on a political basis. Against precedent promotions and hiring of individuals without due procedure has been the norm at the DPP.

The post of Director General has been vacant since 9th April 2024 after the Sindh High Court ruled that the appointment of a preferred Director General by the Federal Government in DPP under Civil Servant Act, 1973 and Civil Servant (Appointment, Promotion & Transfer) Rules, 1973 (the CSA,1973 Act & CSR, 1973) had been made without lawful authority and jurisdiction as such appointment could not be made when an eligible senior most officer was already available.

In June 2022, the Federal Government temporarily appointed Mr. Allah Ditta Abid as the Director General, instead of Dr. Muhammad Tariq Khan, the senior most officer without specifying any reason. Tariq Khan who then challenged the appointment before the high court, got the decision in his favour.

AGRICULTURE

The court ordered the appointment of an eligible officer as Director General, on a regular basis by promotion by holding a meeting of the Selection Board immediately. The ministry has not complied with the order so far.

The officials also believe that the appointment of favourites overlooks their technical qualification and relevant experiences in most cases. As a result the DPP collects all muds and burdens of wrong policies and actions introduced and spread by the temporary appointments.

An insider revealed that the former secretary of the ministry proposed the appointment of retired army officers in DPP to regulate import and export of agricultural commodities with respect to sanitary and phytosanitary measures. This shows that he was not aware that as per international guidelines and conventions signed by the Federal Government, technical manpower is required for inspection and certification of regulated agricultural goods. An unqualified candidate would not be able to carry out the job and nor would he be acceptable for the importing countries. Such policies lead to total disaster of these departments and invite restrictions on import of agricultural goods from Pakistan.

Another example of these hirings is an officer appointed by the most recent caretaker government Mr Muhammad Qasim Khan Kakar on the post of and Director Admin in DPP without requisite qualification and experience. While in service he was given additional charge, on mere verbal order of the outgoing secretary, MNFSR of the post of Director Technical (Quarantine), overlooking the regulation that additional charge could not be given against a filled post.

The decision proved to be fatal for the department resulting in case after case of corruption and outright incompetence. The officer was later recommended for suspension for the clearance of a highly infested shipment of chickpeas lying at Karachi port without proper inspection and testing and on fake documents. Earlier, in 2022, the whole top brass of the DPP was investigated by the FIA for alleged corruption in the Methyl Bromide case. The department allegedly preferred one company to import the substance and use it for fumigation purposes. The case resulted in Pakistan’s meat exports to be flagged as substandard by major importer destinations like the United States and Europe.

Another reason behind poor working of DPP, as per officials of the department, is the shortage of necessary infrastructure and modern gadgets of inspection. The officials have admitted that presently, the number of DPP experts are too few to conduct proper inspection and certification, so, they have to release many importable high risk consignments daily without inspection and appropriate treatment.

Custom, and exporter agents are wisely manipulating this situation for their own benefits.

Just how important is DPP?

The effects of these problems are far reaching. They have allowed the introduction and spread of a welter of invasive biosecurity risks in Pakistan. The increasing pest complex in crops, orchards and forests has increased the use of pesticides to control and this has soared the pesticides import bill of Pakistan from 30 billion to 130 billion during the last 12 years and despite indiscriminate use of pesticides, Pakistan’s production is declining due to invasive pests.

If the recent interception is an example of the diligent work of Rosselkhoznadzor (FSVPS) that quarantine specialists do on a daily basis, this interception is a classical paradigm of poor work done by the experts of DPP, responsible for the biosecurity of Pakistan.

The export products of the country have become infamous for being intercepted and face stringent restrictions from importing countries. This has caused a substantial dip in Pakistan’s exports. It is a big blow to an agricultural country like Pakistan whose fragile economy depends upon enhanced export of agricultural products and a reduced import of agricultural products.

While for now, the call for a ban may have been a wolf cry, insiders suggest that if investigation and corrective actions remain pending and more consignments are intercepted in Russia, Pakistan may face ban from Russia and other countries for sending non-complying goods.

The problem of being under-resourced to DPP however, is not new. The federal government has failed to provide requisite manpower and build infrastructure for the most key National Plant Protection Organization, DPP in Pakistan since 1990

Today DPP’s manpower and infrastructure has been reduced manifolds since its inception.

The policy and actions of MNFSR have always been more experimental and temporary rather than serious and permanent regarding its attached department including DPP, Federal Seed Certification and Registration Department (FSCRD) and Animal Quarantine Department (AQD) since long. Sometimes, MNFSR blames the Planning Commission, other times the Finance Department, and mostly, the Establishment Division for their pity and irrelevant objections in the way of strengthening of DPP, AQD and FSRD.

Ban from Russia in 2006 and 2019 was also imposed on Pakistan when it was headed by non-qualified and non-experienced temporarily appointed officers.

The timing

All of this comes at a time when Pakistan is anticipated to achieve a record high in rice exports by June, driven by India’s decision to limit its own shipments. The move has redirected buyers to source more rice from Islamabad, where prices are at their highest point in almost 16 years.

Normally India would be the Big Kahuna in the rice export field, but due to domestic troubles, the Indian government put a ban on the export of rice and raised the price of Basmati rice. With India out of the market, buyers are switching to Pakistan, and local prices are gradually rising despite higher production, said Hammad Attique, director, sales & marketing at Lahore-based Latif Rice Mills. Pakistan is offering 5% broken white rice at around $640 per ton and parboiled rice around $680 per ton, up from $465 and $486 respectively a year ago. Pakistan currently exports non-basmati rice mainly to Indonesia, Senegal, Mali, Ivory Coast, and Kenya and premium basmati rice to the European Union, Qatar and Saudi Arabia, dealers said. In India’s absence, Vietnam, Thailand, and Pakistan are trying to fill the gap. However, Pakistan’s relative proximity to buying countries in the Middle East, Europe and Africa is providing it with a freight advantage, said a Mumbai-based dealer.

Pakistan’s rice exports are expected to reach 5 million metric tons in the 2023/24 financial year, up from 3.7 million tons the previous year. Some industry officials are even more optimistic, suggesting that exports could reach 5.2 million tons, given the significant improvement in production this year. Pakistan is projected to produce 9 to 9.5 million tons of rice in 2023/24, rebounding from the previous year’s 5.5 million tons, which was impacted by floods. In December alone, Pakistan exported approximately 700,000 tons of rice, with higher production and elevated global prices enabling rapid exports. Basmati rice exports are expected to increase by 60% to 950,000 tons, while non-basmati exports could surge by 36% to 4.25 million tons. Traditionally, India offered non-basmati rice at a lower price than Pakistan.

However, with India withdrawing from the market, buyers are turning to Pakistan.

Local prices are gradually rising despite higher production, with 5% broken white rice priced at around $640 per ton and parboiled rice at around $680 per ton, up from $465 and $486 respectively a year ago. Pakistan’s current export destinations for non-basmati rice include Indonesia, Senegal, Mali, Ivory Coast, and Kenya, while premium basmati rice is exported to the European Union, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia, as reported by industry dealers. n

AGRICULTURE 22

Tech funding might be recovering in the US,

but the trickle down effect will take its sweet time

getting to Pakistan

23

Amidst this dreadful funding winter, can local capital be the nurturing source for Pakistan’s tech scene?

By Nisma Riaz

It will be a long winter for the budding tech industry of Pakistan. Although bursting with potential, the global funding crunch has nipped most efforts of local startups and VCs to raise capital in the bud. While it looks like the American market stands at the cusp of a revival in funding, with the rest of the world eagerly anticipating any positive development, the landscape for startups and entrepreneurs seeking investment across the globe remains a challenging one.

Some are speculating that AI is quickly becoming the catalyst for a funding comeback, however, still unsure whether it can save the entire ecosystem or not.

But what is happening in the rest of the startup economy and what does that mean for Pakistan?

What is happening in the land of opportunities?

The American economy serves as the cornerstone of the global financial system, influencing markets and policies worldwide. Developments within the US, whether in trade, technology, or monetary policy, reverberate across borders, consequently shaping the trajectory of economies globally. Therefore, any shifts in the American economy hold profound implications for businesses and investors worldwide.

That is the reason why, currently, all eyes are on the American tech landscape and the expected recovery of tech funding in the US.

Earlier this month, Peter Walker, the head of Insights at Carta, wrote on LinkedIn, “Funding to VC startups might be rising soon.” Carta is a US-based technology company that helps companies, investors and employees manage their ownership.

According to Walker’s LinkedIn post, in January 2024, VC funds on Carta requested more money to invest than they have since mid-2022, signalling a boost in VC funding. This increase in capital calls, along with a successful Reddit IPO, proves to be a positive sign for the larger American tech scene.

Needless to say that this news brought some semblance of hope to tech professionals globally.

But are these funding calls enough to

revitalise, not only American, but also global tech funding?

Well, according to the Financial Times (FT), VCs are encountering difficulties in raising funds, indicating the conclusion of an era characterised by “megafunds”. The numbers have been quite bleak recently, projecting a deceleration in start-up dealmaking in the forthcoming years.

Has global venture capital funding finally reached its lowest point?

Based on the latest data from PitchBook, global VC funding totaled $95.7 billion in Q1’24. While it remained steady year over year, there was a 14% recovery compared to the previous quarter.

Nevertheless, the number of deals continues to decline consistently, marking the 7th consecutive quarter of decrease. In Q1’24, it plummeted by 37% year over year, reaching less than half of its peak levels. Even when factoring in the estimated 2,702 undisclosed deals, this figure represents the lowest since Q4’20.

On a global scale, venture firms secured $30.4 billion from university endowments, foundations, and other institutional investors in the initial three months of this year. According to reports by PitchBook, this marks a noticeable slowdown compared to 2023, which itself represented the poorest year for fundraising since 2016.

FT also reports that Limited partners have moderated their expenditure over the past couple of years, adopting a more cautious stance as interest rates have risen, start-up exits, including public listings and sales, have decelerated, and returns from venture fund managers have plummeted.

Kaidi Gao, a venture capital analyst at PitchBook, told FT that a revival in initial public offerings or sales would enable limited partners to regain their invested capital and reinvest it. That is, if there are no significant enhancements in the exit market, Gao anticipates enduring challenges in fundraising, which will consequently exert downward pressure on dealmaking.

24

The essence of venture investments is growth and that attraction won’t go away. However, right sizing of capital deployment in this space over a long-ish horizon is happening. It had a hyped upward swing and now perhaps a little over correction because of macro factors, and micro or VC specific learnings we’ve experienced

Ahsan Jamil, Founder of sAi Venture Capital

However, there’s a caveat. Or two.

According to Farooq Tirmizi, founder of fintech startup Elphinstone, “Carta is an American organisation, while the Financial Times reports from a European perspective. So, the US might be on the verge of welcoming a new wave of funding but it will take time before the effects of it reach Europe and even longer till we see improvements in developing economies like Pakistan’s.So, these two sources are not contradicting each other, rather talking about two different markets at different stages of recovery.”

Tirmizi highlighted how historical trends show that the American market is the first to get hit with funding droughts, however, it is also the first and fattest market to recover. He associates this trend with certain salient features of the US market, “”It is much easier to make money in the US and consequently, risk adjusted returns are higher in the US.” This is why American startups are more likely to receive funding during a time like this.

Eventually, funding trends trickle down from America to the rest of the world, with Europe and the developed Asia experiencing recovery before markets like Indonesia, Bangladesh and Pakistan.

Tirmizi speculates it to be a “very long winter” for Pakistan. “I would say it will take a good five to 10 years before Pakistan benefits from the current anticipated boom in the US,” he concluded.

The second caveat is that only a specific sector is observing an influx of capital.

William Chu, co-founder of SparkLabs Fintech, told Profit, “What Carta is referring to is a very recent occurrence. Yes, there is hope because the American market has been seemingly healthier than before in the past few months. However, investors have just been aggressively funding AI companies, which cannot be used to describe the state of the overall startup ecosystem. Startup funding is still very much at a standstill.”

FT backs this claim, reporting that

according to Venky Ganesan, partner at Silicon Valley firm Menlo Ventures, “VCs are now gambling that a boom in artificial intelligence will provide a generational opportunity and help ‘overcome the sins of 2020 to 2022’. Every venture firm is chasing the AI unicorn. Some are going to get it and will thrive, those who don’t will be sent to the dustbin of history.”

Chu divulged that there has been a dynamic shift in the global investment community. VC and private equity investments were characterised by very low interest rates, which has now changed due to tough macroeconomic conditions worldwide. “There is a slim chance of interest rates coming down soon, however, investors have stopped pursuing the same kinds of risks they did when interest rates had been low.”

So, the very essence of VC investment, which was precisely the risky nature of these investments, has seen a shift.

Can local capital be the saving grace of Pakistan’s tech industry?

It would be an understatement to say that Pakistan’s tech sector has seen better days. In an article for Techshaw Notes, Zahid Lilani writes that there has been absolutely no deal activity in Pakistan in the first quarter of 2024. Or at least no official announcements of deals have been made, other than that of Abhi, which raised an undisclosed amount earlier last month.

The startup funding has seen a drastic drop in Pakistan. From its peak of over $380 million in 2021, startup funding dropped to $332.4 million in 2022 and stood at a meagre $75.6 million in 2023. As the second quarter of 2024 has kicked off, no new funding deals have been announced so far and investors and founders predict a bleak funding outlook for the entire year.

This has led to dark clouds of layoffs

TECH

Yes, there is hope because the American market has been seemingly healthier than before in the past few months. However, investors have just been aggressively funding AI companies, which cannot be used to describe the state of the overall startup ecosystem. Startup funding is still very much at a standstill

William Chu, co-Founder of SparkLabs Fintech

and shutdowns and one slightly desperate exit looming over the sector. This would likely linger on for a while as the raising capital from abroad still looks difficult. Local VCs on the other hand do not have enough financial heft to invest millions of dollars in startups all by themselves in absence of rich foreign VCs.

According to a local VC investor Profit spoke to, local funds possibly did not fully deploy the money they had from the funds they had closed before the downturn kicked in because the pipeline was not solid. But they did support their existing portfolio companies with follow-on investments in the downturn. “From a VC perspective, the deal pipeline is still not solid for new investments at the moment.”

On top of that, the current environment requires a certain type of startups to be funded. These are the ones that have strong fundamentals. This further shrinks the number of startups that can be funded.

As the downturn continues, some of the local VC firms are also reportedly struggling to close new funds. Some of these local VCs have taken massive hits with important portfolio companies shutting down because of the downturn and otherwise. This would have certainly dampened local VC confidence.

But it’s not all gloomy for the Pakistani market either. None of the local VCs have decided to wrap up and leave. As one investor puts it, local VCs being cautious is just them following the global investment cycle.

The exits are going to come a few years down and until then, local VCs just have to hold fort.

On the bright side, the caretaker government has launched a Rs2 billion Pakistan Startup Fund that would underwrite risk for foreign VCs, encouraging them to bring investment into startups in the country. That is besides Rs 500 million allocated by the same caretaker government to fund startups for international incubation. On the other hand, PSO has allocated 1% of its pretax profits for investments in startups and currently has Rs1.7 billion in the VC fund.

The way forward

One thing is for sure; we might not be getting any foreign funding, or at least not a sizable amount, in the near future. And it won’t be a surprise if people started packing up their things and moving away, to markets where there is more hope and better opportunities.

We asked Ahsan Jamil, managing general partner and founder of sAi Venture Capital, to put in perspective the state of the industry and a possible way forward. He said, “The essence of venture investments is growth and that attraction won’t go away. However, right sizing of capital deployment in this space over a long-ish horizon is happening. It had a hyped upward swing and now perhaps a little over correction because of macro factors, and micro or VC specific learnings we’ve experienced.”

He added that the trickle effect of global adjustment will happen as VC funding stabilises because of the digital journey ahead.

“But what would be really exciting is making startups in Pakistan a choice destination for risk capital. For sAi, we’ve always believed in analysing and developing fundamentals with venture upside, hence our focus on Frontier Technology for almost 2 years. When this focus is coupled with localised business models, and local capital deployment, it is likely to attract global capital. We don’t need to be oversubscribed with global capital but rather focus inwards with global standard technology,” Jamil concluded.

Jami’s argument holds weight, especially because seeking lesser investment locally is obviously better than sitting around and waiting for foreign investors to come save us. Or worse; giving up on the sector and going back to our plain old corporate nine to fives.

Even though there is money in the country, a lot of it actually goes to unproductive and oldschool sectors like real estate. This money can be put to much better use and result in much lucrative returns, if in -

vested in building a local tech infrastructure.

But there’s a catch.

Chu, whose first accelerator in Saudi Arabia has seen a great response since its installation late last year, says, “Even though local government funding in Saudi has been robust, along with their help in creating incentives for hiring and dealing with taxes, it is extremely important to welcome offshore investors to enter the region.”

Chu quotes role modelling for building standards as the reason for this. International investors bring more than just their dollars to the table. They bring decades of experience, a stellar network necessary to excel in the global tech landscape and, well, of course the capital, as well.