08

08 Exchange companies: The putsch against the dollar continues

15 Will Olpers’ cartoon ploy work?

20

20 Inside the high returns of the Meezan Sovereign Fund

24 Living on the edge Asif Saad

26

26 What went down with Pakistan’s meat exports to the UAE?

29 “We are listening” : based on the latest T-bill auction, the market has realigned with the central bank’s stance

Publishing Editor: Babar Nizami - Joint Editor: Yousaf Nizami

Senior Editor: Abdullah Niazi

Executive Producer Video Content: Umar Aziz - Video Editors: Talha Farooqi I Fawad Shakeel

Reporters: Taimoor Hassan l Shahab Omer l Ghulam Abbass l Ahmad Ahmadani

Shehzad Paracha l Aziz Buneri | Daniyal Ahmad |Shahnawaz Ali l Noor Bakht l Nisma Riaz

Regional Heads of Marketing: Mudassir Alam (Khi) | Sohail Abbas (Lhe) | Malik Israr (Isb)

Business, Economic & Financial news by 'Pakistan Today'

Contact: profit@pakistantoday.com.pk

In early September, the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) made a decisive move, signalling that it had had enough. It unfurled a sweeping set of reforms targeting exchange companies. These reforms were not just about tightening the reins on the open market; they were a strategic endeavour to bolster governance, enhance internal controls, and elevate compliance standards to new heights.

The SBP’s actions were fueled by apprehensions that exchange companies were failing to provide foreign currency to customers when it was available while also carrying out off-thebooks transactions, resulting in substantial disparities between interbank rates and those offered by these companies.

Under the umbrella of these structural reforms, the SBP has given exchange companies three months to increase their paid-up capital and consolidate into a single category. It has also "encouraged" top banks to open exchange companies (more on that later).

The burning question is: What does this mean for the currency markets — is the central bank simply trying to rein in illegal activity and increase oversight of the open market, or does it plan to eventually phase out the open market completely?

There are two legal currency markets in Pakistan: the interbank market which is made for and participated in by banks, and the open market which comprises exchange companies. According to the Standby Agreement signed with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in June, the difference in the rates cannot exceed 1.25% for more than five consecutive days.

This is because the central bank intervened in the interbank market in the past, including last year, to control the rupee's depreciation by imposing an artificial cap on the dollar to rupee exchange rate. This makes imports cheaper and exports expensive, leading to a widening trade deficit and pressure on foreign exchange reserves. The IMF believes the open market is more difficult to coerce and so, by demanding that the rates align closely with each other, it was hoping the interbank rate would remain closer to the market reality.

However, between August 28 and September 4, the difference in the market rates widened to an alarming extent both in absolute and percentage terms. For instance, on September 1, the interbank rate was Rs 305.46 per dollar while the open market rate was Rs 333 — a difference of Rs 27.54 per dollar or

8.27%. It appeared that the open market, which is less heavily regulated, was out of control. This is when multiple agencies launched a crackdown on illegal foreign exchange trade. They ramped up monitoring, placed officials at certain branches and raided offices of exchange companies suspected of being involved in conducting “off-the-books” deals that added to the exchange rate volatility. Consequently, the exchange rate started dropping from a high of Rs 334 on September 4. At the time of writing (September 28), the open market rate stands at Rs 289 per dollar. [You can read further details of the crackdown in Profit’s September 11-17 issue].

The crackdown was followed by structural reforms unveiled on September 6. Under these reforms, the SBP encouraged leading banks actively engaged in the foreign exchange business to establish wholly owned exchange companies to cater to the legitimate needs of the public.

There are two categories of exchange companies, A and B. According to the SBP, there are 27 category A exchange companies of which two are subsidiaries of banks — Habib Bank Limited (HBL) Currency Exchange (Pvt.) Ltd. and National Bank of Pakistan (NBP) Exchange Company (Pvt.) Ltd. There are also 21 category B exchange companies. Additionally, there are also franchises.

Previously, exchange companies in category A had a higher minimum capital requirement — Rs 20 crore — while those in category B had a lower minimum capital requirement of Rs 2.5 crore. The latter could only act as money changers.

Under the reforms, all exchange companies in categories A and B along with franchises of exchange companies will be consolidated and transformed into a single category with a well-defined mandate.

The minimum capital requirement for exchange companies for category A has been bumped up from Rs 20 crore to Rs 50 crore, free of losses.

Category B exchange companies have been given three options: merge with an existing exchange company, upgrade to full exchange company status, or consolidate with other category B exchange companies to form a unified entity. They must approach the SBP within one month for a no-objection certificate (NOC) for one of these choices. After receiving the NOC, they have three months to meet regulatory and legal requirements for formal licensing, failing which, their licences will be cancelled.

Meanwhile, franchises of exchange companies have been offered two options: either merge with the franchiser exchange company

or sell the franchise to it. In either case, the franchises will have one month to approach the central bank for approval of the merger or sale. If they do not, their licences will be cancelled.

Profit spoke to three treasury officials from three leading banks, and two officials of a bank-owned exchange company to understand what necessitated the reforms and what the SBP hopes to achieve.

(We will refer them as treasury official 1, 2 and 3)

Treasury official 1 said the SBP and the law enforcement agencies involved in the recent crackdown had "ordered" the top 10 banks to open exchange companies. While the NBP and HBL already had exchange companies, Meezan Bank Limited, Allied Bank Limited, Habib Metropolitan Bank, Bank Alfalah Limited, Faysal Bank Limited, Askari Bank Limited and Bank Al Habib Limited were also ordered to set them up. The orders "came from the very top", the source said. Many of these banks have already made announcements in this regard.

In the coming months, exchange companies in category B will cease to exist and those in category A will find it very difficult to continue operating due to higher capital requirements and punishments for minor infractions, the treasury official said. Most exchange companies are small businesses whose profits come primarily from "off-the-books dealings", and they are very hard for the SBP to regulate. This is why the central bank wants them to be phased out and replaced by larger, more regulated exchange companies led by banks, he commented.

According to treasury official 1, the SBP has directed banks to send letters of intent within one month, assuring them that licences would be granted within the next three months. These banks would then have between 10-12 months to set up at least 10 branches, or separate booths in existing branches, dedicated to foreign exchange dealings. The banks would also have internal oversight of these exchange companies.

"The market will eventually be heavily regulated and banks will handle the know-your-customer requirements much better than the existing exchange companies. Walkin customers will also be allowed to sell or purchase foreign currencies provided they have the correct documentation, including possibly tax returns for higher amounts. The purpose of [these reforms] is to ensure that all foreign exchange dealings are done cleanly, legally and on the books."

Meanwhile, treasury official 2 recalled that when incumbent caretaker finance minister Shamshad Akhtar was the SBP governor, she came up with the ideology of 'big five banks' —

those "too big to fail".

The idea is that when your paid-up capital is high, you have a significant financial investment in the business. Consequently, you cannot afford to engage in any wrongdoing because you have a substantial stake in the company. For example, if your capital is only Rs 2.5 crore, it may not make much of a difference. However, if you are required to invest Rs 50 crore, the paradigm shifts, the scale increases, and the business becomes much more professional. In such a scenario, you can no longer afford to engage in questionable activities or operate without proper adherence to regulations.

Moreover, the problem with category B exchange companies and franchises is that compliance controls have regrettably shown a tendency to be less stringent. This, understandably, raises red flags for the regulatory authorities, particularly in light of their commitment to meeting the rigorous standards set forth by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF).

Therefore, to strengthen control and compliance, the regulator and the government want to phase out category B exchange companies and franchises. And the regulator has taken this job very seriously. In less than a month, the central bank has suspended or revoked the licences of four exchange companies.

Profit reached out to the SBP's Exchange Policy Department for more clarity on its plans but an interview could not be arranged at the time of writing.

The effects of the agencies-backed administrative measures and the resulting sentiment-driven market forces are already visible. The rupee has fallen below the Rs 300 mark in both the interbank and open markets and the premium is within the IMF-mandated range.

PKR does not drop by too much during any particular day.

For example, on Monday the market closed at 290/292. The following day on Tuesday, there is an inflow of exports and inward remittances that is well above the amount of imports and outward remittances. This means that banks cannot fully offset these inflows against their outflows and will therefore have to sell dollars in the interbank.

Most banks these days are facing the same predicament and therefore the interbank is flush with supply of dollars, and if left unchecked, such liquidity can cause the dollar value against rupee to fall considerably. So what the SBP does is that it enters the interbank market and buys up this liquidity at 289.50/290.50, Rs 1.50 less than the previous day’s closing rate. By doing this, it sort of mops up the excess dollars at a rate below the previous day’s lowest rate. This restricts any major downward dollar movement in a single day.

“While the central bank is looking to take the USD/PKR down to a certain level, it does want to do that too rapidly as it would not only irk exporters but also encourage importers to open more LCs and those ‘dollar investors’ to start buying and hoarding again if the rate goes too low too fast”, explained treasury official 1.

Following the rupee's appreciation, exporters have rushed to bring back their export proceeds [they tend to hold their proceeds or payments abroad if they expect the rupee will depreciate and they will get more Rupees; under SBP rules, the time limit for bringing export proceeds back is 120 days]. They have booked forward proceeds amounting to $1 billion so far, according to treasury official 1.

Let's say that an exporter has sold clothes worth $10 million dollars to its buyer in the US. The exchange rate on the day that he sends out his shipment — called spot or ready

money instead. If, for example, the spot rate two months later is Rs 290, he will have lost 50 paise per dollar.]

Exporters across the country have repeated this process multiple times. This indicates that they expect the rupee will continue to appreciate, at least in the short term. This is why the maximum period of these export forwards is just two months as opposed to six months; this recovery, in exporters’ view, is not going to last more than a few weeks.

The mood among exchange companies is far from content. The recent decision to grant banking licences for exchange companies has rattled the industry, sparking strong resistance. Exchange firms view the entry of banking giants into their domain as an existential threat, with their very survival hanging in the balance.

Profit spoke to Malik Bostan, chairman of the Exchange Companies Association of Pakistan (ECAP) and Zafar Paracha, general secretary of ECAP.

Paracha expressed his concerns bluntly, stating, "The way things are, it seems that exchange companies might be forced to shut down. If the government believes that the private sector should not exist, they should inform us, and we will close our business. The SBP doesn't even need to provide us with a roadmap."

Bostan lamented the crackdown on exchange companies, asserting that every sector has its "black sheep", and tarnishing the reputation of all exchange companies is unwarranted.

Paracha expressed his views on having the currency exchange business owned by banks. “This model will fail,” Paracha put it

he rupee's appreciation is also gradual this time around, instead of volatile. It has also been very consistent, around Rs1-1.50 daily. This suggests that the recovery of the rupee is being managed in a very controlled manner, and for good reason.

Because there is excess supply of dollars in the interbank, the SBP purchases these at a certain rate (Rs1-1.50 below the previous day’s closing rate) every day to remove that liquidity from the market and arrest any further weakening of the dollar during that day’s trading. What happens as a result is that the USD/

rate — is Rs 288. He is set to receive payment for his export in two months. However, he expects the rupee to appreciate further in that time, which means he could possibly be getting Rs 278 per dollar. To protect himself from the appreciation, he goes to a bank to book forward proceeds. The bank offers him a premium of Rs 1.5 per dollar. This essentially means that the exporter has agreed to sell his dollar proceeds (due at a later date) to the bank today, at a rate of Rs 289.5 per dollar. [There is a downside to this - the rupee may depreciate in the coming two months and he may lose

bluntly. He argued that shutting down exchange companies could pave the way for the rise of an informal market or "grey market" for foreign exchange, which would be more prone to manipulation.

Bostan also asserted that banks have a history of manipulating exchange rates, alleging instances where banks purchased dollars from exchange companies and subsequently charged customers higher rates, artificially inflating the dollar rates. This underscores apprehensions regarding the potential consequences of sidelining exchange companies in the foreign exchange landscape.

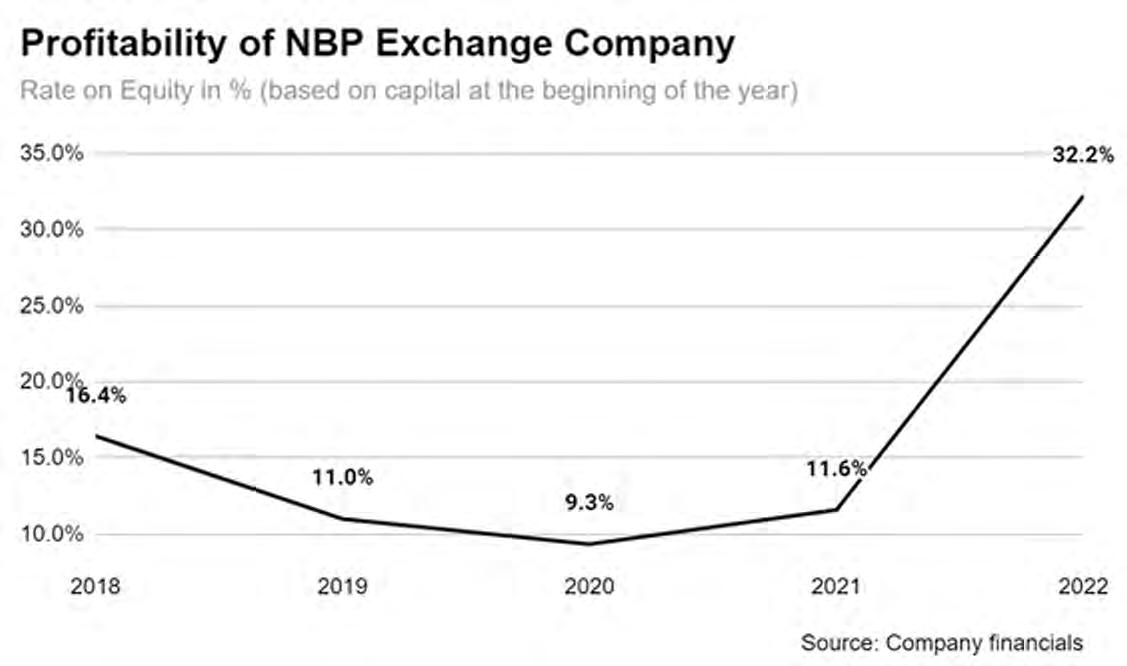

According to Bostan, bank-owned exchange companies haven't seen much success.

In a swift response to the central bank's recent reforms, United Bank Limited wasted no time in announcing its venture into the exchange company arena on September 12, six days after the reforms were rolled out. UBL's move triggered a domino effect, with a lineup of other banks swiftly joining the fray. Meezan Bank Limited joined the list three days later. In the following weeks, more banks followed suit which included MCB Bank Limited, Bank AlHabib Limited, Allied Bank Limited, and Faysal Bank Limited. HBL and NBP already had an exchange subsidiary as mentioned earlier.

An official from a bank-owned exchange company that Profit spoke to stated “this was long overdue”, “logical” and a “positive development”. He also added that they see the exchange companies and the banking sector from a treasury perspective coalescing together.

While speaking to Profit, both Bostan and Paracha claimed that the banks have not been successful in the exchange

company business. An official from a bank-owned exchange company disclosed that “they hardly make any revenues”. He added that “we have maintained a conservative position”. However, their return on equity exceeds 22%.

We also looked at the financial statements of the NBP Exchange Company. In 2022, it recorded the highest-ever return on equity of more than 30%.

What about the new entrants? Will they be just as successful? According to treasury official 3, it is very likely that exchange companies of banks will be successful. He cited two reasons for this — first, the foreign exchange business is generally a lucrative one because banks (and exchange companies) usually have customers on both sides of the trade and they earn from the spread in both transactions, and second, better management of cash flow positions. In addition, the costs will be lower for banking exchange companies as they would be operating out of the current existing branches of the banks and most of the required hardware and software would already be present in the branch, he commented.

One of the primary sources of revenue for the bank-owned exchange company is the standard spread of buy and selling rates. These rates are set

by the ECAP daily, typically at 1%. This spread serves as a limited source of income.

The other source is through positioning. The SBP permits category A exchange companies to maintain a portion of their paid-up capital in foreign exchange. This means that they can hold up to 50% of their capital in foreign currencies. This provision enables these companies to actively engage in currency trading. When the value of the dollar increases, they can generate gains due to their currency positions.

Conversely, if the dollar's value decreases, the exchange companies resort to reducing their position by selling the greenbacks to banks’ treasury to minimise potential losses.

One of the most significant expenses incurred by the exchange company is related to Cash in Transit. The company purchases various foreign currencies like riyal, dirham, pounds, euros, and damaged cash dollars received at its counters, consolidating them at central locations — typically Karachi, Lahore, or Islamabad, depending on flight availability. These physical currencies are then sold in Dubai and Abu Dhabi, with the proceeds converted into dollars and deposited into the exchange company's NOSTRO accounts (these are essentially dollar accounts held with foreign banks).

Originally, electronic dollars in these accounts were used for settling credit card payments. However, the game changed in June when the SBP granted banks the authority to purchase US dollars from the interbank market for settling cross-border card-based transac-

tions. As a result, the exchange company now sells various currencies, including dollars, to banks and individuals for this purpose.

Electronic dollars aren't just sitting around, though. They are also withdrawn from NOSTRO accounts and handed out as physical cash to individuals. Moreover, these electronic greenbacks are used for settling imports and conducting treasury operations with other banks, being transferred to other banks' NOSTRO accounts as needed for various financial transactions.

Let's break it down: Imagine you're running a franchise or a category B exchange company, and suddenly, you're told to take your capital from a modest Rs 2.5 crore to a whopping Rs 50 crore in just three months. Realistically, that's a tall order, and for many, it's a challenge they might struggle to meet.

So, what happens next? Well, category B exchange companies and franchises would either merge or be forced to shut down. This would leave a gap in the market. To bridge this gap, regulators have encouraged banks to step in and play a role in this space.

Does this mean that only banks will remain in the exchange business? The short answer is no. An official of a bank-owned exchange company told Profit that it is premature to assume that banks will outright dominate the landscape of exchange companies at this juncture. Instead, the vision is one of coexistence, where both bank-owned exchange companies and other category A players operate on a level playing field.

Moreover, if we look through the lens of paid-up capital - currently, there's a club of 27 category A exchange companies, and interestingly, just two of them are bank-owned. Now, here's the fascinating part: the majority of these category A companies boast capital ranging from a substantial Rs 50 crore to an impressive Rs 1 billion.

What does this mean in the grand scheme of things? It's a clear sign that the exchange company sector won't be exclusive territory for banks, as some market sentiments may have suggested.

However, bank-owned or not, all category A exchange companies have to follow stringent conditions if they want to keep operating.

The survival of these businesses teeters on their ability to navigate this regulatory maze. One standout requirement demands an unrelenting 24/7 recording of transactions. These recordings encompass both audio and video footage of personnel working at the exchange

counters. Companies must maintain recordings for the past six months, readily accessible at any given moment. Failure to comply with this crucial provision can result in a suspension of transaction privileges at their counters. Adding to the scrutiny, audits conducted by the SBP include meticulous examination of these recordings. The SBP cross-references recordings with transactions, demanding explanations in cases where discrepancies emerge.

Moreover, conducting currency exchange transactions beyond the registered place of business is now strictly off-limits unlike in the past when one could ring up an exchange company and a company representative would deliver currency to your location or office. The emphasis is crystal clear: only those companies meticulously adhering to compliance processes will be permitted to continue operations.

The future of the open market and its potential convergence with the interbank market has been a subject of curiosity since banks have been rapidly establishing exchange companies. While some questions persist, here's what three insiders shared with Profit.

According to an official of a bank-owned exchange company, the open market is expected to continue to exist. However, there's a crucial caveat: it will continue to exist within the framework of rules and regulations mandated by the government and regulators, something that it was not made to do very diligently by the regulator in the past. Therefore it will take some getting used to.

Treasury official 3 elaborated on this, emphasising that the foreign currency cash market and the interbank market are distinct entities. While it's expected that rates will converge and the cash foreign currency market's volatility will diminish, they won't become identical. This disparity stems from various additional costs inherent to cash market transactions. One notable cost is the cost of cash in transit which arises when cash foreign currency is transferred to the NOSTRO account of the bank.

Conversely, Bostan believes that the gap between the open market rate and the interbank rate could potentially widen. This divergence is expected because people may choose to refrain from bringing foreign exchange into the market.

The net result of all of this are some very encouraging news reports of the Pakistani Rupee being on its way to claim the ‘best-performing currency

title in September’. That is all well and good but this thumping victory of the rupee over the dollar must be taken with a little more than a pinch of salt.

Yes, these gains are impressive, but are they sustainable? As we have mentioned in our previous articles, all the measures being taken are administrative in nature and they have created a sentiment in the market that the rupee will continue to make strides against the greenback, but only to a point.

The interim federal minister for industries Gohar Ejaz, who also happens to represent the largest representative body for exporters, APTMA, feels the dollar will bottom out at 260. Others feel it will be 250. But from that point onwards there will be a gradual move in the opposite direction.

Why? Because our fundamentals remain intact and unchanged. We have to make loan repayments in dollars and we have to import oil, in dollars, both of which are major outflows. And while these are being taken care of by exporters rushing to sell their dollars at the moment, there will come a point, not too long from now, that these proceeds will dry up. We are after all a net importer of goods and services.

Additionally, a weaker dollar means our exports have become expensive and therefore, there will be shrinkage in volumes as booking deals with foreign buyers will become more difficult. As far as remittances go, the rupee amounts will be getting lower as the dollar weakens in the coming weeks, so perhaps some people hold off on those as well for a bit.

Add to this the fact that a lot of export proceeds that were going to be coming in after two months and add supply to the interbank have already been factored into the market as exporter have book forwards in droves (almost $1 billion we are told). So a slight recovery by the dollar within 60 days will coincide with very little export proceeds coming in, thereby putting added pressure on the rupee-dollar parity and possibly on the current account deficit as well.

The policy to move exchange company business from the under regulated ‘fast and loose’ open market to the over regulated banking industry may not be very well liked by the open market, but it is somewhat necessary. And even though banks are not very keen on doing this, one thing is for sure, they will make it work financially for themselves and play within the confines of the SBP regulations. This will introduce much-needed formality to the currency exchange market.

But let us not fool ourselves. The vulnerabilities of our currency market remain intact. And once tested again, they will become very visible, very quickly. It remains to be seen what the ‘shot-callers’ do then. n

By Daniyal Ahmad and Nisma Riaz

By Daniyal Ahmad and Nisma Riaz

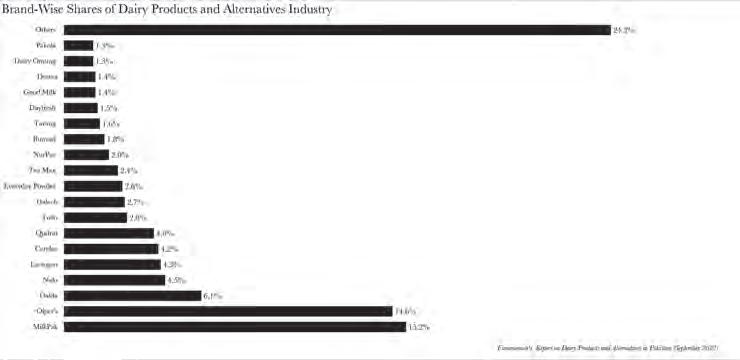

Engro-FrieslandCampina, henceforth referred to as Friesland for the sake of brevity, has had a good year. The dairy titan finally surpassed the Rs 60 billion threshold in terms of sales and its flagship brand, Olpers, has come neck and neck with Pakistan’s largest milk brand — Nestle’s Milkpak.

Normally this would be cause for celebration for any company. And while the good people over at Friesland will be happy with their recent performance, the mood at HQ might be slightly sombre. Despite surpassing the Rs 60 billion mark and firmly being in second place in the country’s market for dairy and its alternatives, Friesland is far behind its closest competitor. In the world of dairy Nestle is King and with sales worth over Rs 120 billion there is a lot of catching up left for Friesland to do.

So what is with the disparity? The story of packaged milk in the country and how the

dairy industry has evolved in Pakistan is well recorded. It has been chronicled in quite some depth by this publication as well. Very briefly put, Engro and Nestle have had their horns locked in a battle for supremacy.

Read More: The next phase of the Milk Wars

But over time Nestle has come out on top simply off the back of their very diverse product range. While Nestle’s Milkpak and Friesland’s Milkpak may be at par in terms of sales, Nestle simply makes far more things and is twice the size of Friesland. Besides their dairy division, Nestle has also diversified far beyond just dairy products with their juices and other food products. Meanwhile in their attempt to bolster Olpers, Friesland may just have hit the maximum sales capacity of its flagship Olper’s brand.

The twist in the tale is that Nestle remains unperturbed. Nestle’s sales are bolstered by a product portfolio as expansive as one could fathom. Amidst this backdrop, one might anticipate Friesland to introduce a plethora of products ranging from infant formula to juices in an attempt to bridge this gap. However, none of this appears to be on the horizon.

Instead they have decided to pick a different segment within the milk market to dominate: flavoured milk. And they are trying to conquer it with a strategy that is not new but has fallen out of use in recent times: Cartoons.

At first blush, this decision may seem innocuous. Yet, this is not Olper’s maiden voyage into the realm of flavoured milk. The company discontinued the product in 2014. Its resurrection in 2020 should have raised eyebrows, but it slipped under the radar. At that juncture, it was unclear whether it was here for the long haul or not. With a dedicated cartoon in its arsenal, it is clear that Friesland is doubling down on this venture. While it may initially appear that Friesland aims to monopolise the flavoured milk market to bolster its sales figures, there may be a more nuanced strategy at play.

What are we insinuating? Friesland has sent Olper’s into battle. Almost a decade after the initial iteration of Olper’s flavoured milk fizzled out, Friesland has armed it with the vibrant hues of happy subha. By bestowing upon

it a cartoon of its own, it has tasked it with capturing market share from segments where the dairy behemoth has no foothold.

The crux of the matter is that Friesland needs its flavoured milk to infiltrate markets and augment its sales figures without taking the risk of deviating from its core competencies in order to keep pace with Nestle.

But there is a problem. Nestlé’s dairy division is a behemoth, twice the size of Friesland. This has been the status quo for over a decade, with Nestlé even ballooning to thrice the size in parts of the previous decade.

when you incorporate Nestle’s other products such as baby formula into the equation, its competition becomes non-existent.

The most straightforward strategy for Friesland would be to introduce infant products. It does have infant centric products in its global lineup but the local market is stringently regulated. Advertisements are heavily controlled. It necessitates direct selling to doctors — almost akin to the pharmaceutical industry.

This means that it would take Friesland years, even decades to catch up with Nestle, if they were to tread into the formula milk category in Pakistan to bridge the proverbial gap.

So, why has flavoured milk of all things become Friesland’s pièce de résistance?

The competition, however, is fierce even within this niche. Brands such as Dayfresh, Pakola, Shakarganj, and Nestle’s renowned Milo are but a few of the contenders. Intriguingly, Olper’s has consciously chosen not to vie for dominance within the flavoured milk market.

“Rather than targeting market share gains within the existing, rather small, flavoured milk market, our ambition is to accelerate the growth of the category,” elucidates Faisal Amanat Khan, General Manager of Marketing at FrieslandCampina.But who, one might wonder, is Olper’s zeroing in on? Juices? Sodas?

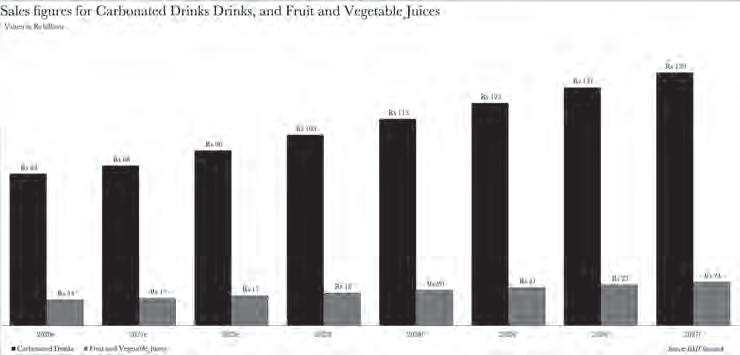

Assuming they were, it wouldn’t be a bad idea in all honesty. Whilst neither of the two aforementioned categories match dairy sales in any capacity, the two are sizeable on their own. Carbonated drinks are set to clock in sales of Rs 105 billion in 2023, whilst fruit juices will be hitting Rs 18 billion. Both are also poised to grow at compound annualised growth rates (CAGR) of 7% till 2027 to hit sales volumes of Rs 139 billion and Rs 24 billion respectively.

Slices of either wouldn’t be the worst thing to happen to Olper’s, but could a cartoon of all things help them if they were to choose to go down that route?

However, this dominance of Nestlé masks a crucial detail. Nestlé simply manufactures a broader range of products than Olper’s, thereby granting it an overarching supremacy in Pakistan’s dairy and alternatives sector. It boasts a commanding lead of 35%, dwarfing Friesland’s 18%.

The disparity is most conspicuous when examining the brand-wise split of the dairy and alternatives sector. Friesland’s Olper’s, Tarang, and Dairy Omung all trail their Nestle counterparts by a hair’s breadth. However,

In the grand scheme of things, the flavoured milk sector may not be the most expansive arena for a company to stake its claim. Friesland’s estimation places the category at a modest 60-65 million litres annually, a mere drop in the ocean when juxtaposed with the behemoth that is the fruit drinks sector — a market tenfold in size according to Friesland.

First things first, why is there a cartoon? Well this isn’t exactly a new strategy. Cartoons have been used to promote products before in this country as well. Perhaps the first to do it and do it successfully was Safeguard soap’s Commander Safeguard which became not just a good method of advertising but also proved to be a popular show that is still a cultural reference point from the pre-cable era. Caltex during its brief stay in Pakistan promoted itself through a comic book about cricket called Supa Tigers and Tetra Pak also introduced Tetrapak Milkateers which proved less popular than Commander Safeguard despite having a higher budget.

In Pakistan, you’ll see when companies are trying to market to kids, the easier thing they see is, you know, to sort of build up a cartoon in it. You’ll see lots and lots of bigger brands

Remember, these are not cartoonish mascots that many products have but actual cartoon productions meant to be aired. The goal is to get kids interested in the show so that they then want to buy the product. It might seem silly but it works.

“About a year and a half ago, we engaged in research to understand the reasons behind the category’s limited growth. It concluded that this is due to the fact that it is not tethered to a consumption occasion,” Khan explains. “Association with a relevant consumption occasion helps brands and categories become more relevant to consumers by naturally fitting into their existing habits,” Khan expands.

The occasion that cartoon is aiming to become synonymous with? Children’s lunchboxes. There’s a general focus on children’s health altogether, with Olper’s being in more than one place but the flavoured milk looks to have taken aim at children’s lunchboxes.

So, how does Friesland aim to make Olper’s a more prevalent category in the lunchboxes?

Intriguingly, Olper’s stands firm in its resolve not to indulge in comparative advertising that nudges customers to favour their product over another brand or an alternative product. However, advertising can be more sophisticated than just attacking your competitor outright.

Let’s look at a fun fact.

Contrary to popular belief, Milo is not a flavoured milk — it’s a malt. Does this distinction matter? Well, yes and no. Loyal consumers of Milo will continue their consumption regardless. However, Olper’s is on a quest to champion health and one cannot help but wonder when questions about the nutritional value of Olpers’ competitors are brought into question by those who watch the cartoon?

Friesland also doesn’t have anything in its Olper’s portfolio at least that could be termed unhealthy, and subsequently eulogising health through the cartoon won’t lead to flavoured milk cannibalising any of Olper’s existing sales. In short, Olper’s can, and might, have a field day promoting health. What does that mean for it’s not so nutritional competitors? Well, that’s their headache for all Friesland might care.

“With the growing discouragement towards juices due to heightened awareness levels, the brand is strategically leveraging the health and energy benefits of milk (think Milo), specifically targeting children,” explains Emaad Ishaq Khan, Executive Director at Synergy Dentsu & Synite Digital.

“The cartoon is ingeniously designed for children to recall and accept the flavoured milk. It aims to foster recognition and comfort so they don’t reject it. It also aids in

weaving relevant narratives and forging a strong association with the children. This makes it easier for mothers to offer it to their children with the reassurance that it’s a healthier alternative,” Ishaq Khan elaborates.

The reality is that lunchboxes do not operate within intricate dynamics. In the absence of an expansion in the average physical size of a child’s lunchbox or a surge in the parent’s income, curating a child’s lunchbox inevitably morphs into an exercise in prioritising certain products over others.

What could possibly be a more effective way to assist mothers in this lunchbox conundrum than by relentlessly emphasising the paramount importance of nutrition?

There’s no necessity to explicitly declare that other products are nutritionally inferior to yours; however, accentuating the benefits of a healthy lifestyle for a child while simultaneously emphasising that your product is healthy does seem like subtle competition cloaked in health benefits.

“In Pakistan, you’ll see when companies are trying to market to kids, the easier thing they see is, you know, to sort of build up a cartoon in it. You’ll see lots and lots of bigger brands playing with cartoons,” explains Arfa Syed, Senior Vice President at OULA.

Animated mascots such as Knorr’s vivacious spices, Tetra Pak’s Milkateers, and Bisconni’s Coco and Mo, all leap to the forefront of our minds. Yet as we’ve mentioned earlier with the exception of the Mikateers these are all mascots not actual productions. Only P&G’s Commander Safeguard achieved that status. And the success of that show was based on making a quality product that the target demographic would be interested in.

“The heart of the matter is that even when we dare to delve into the world of cartoons, we do so in a somewhat lacklustre fashion. They’re typically 2D characters. We don’t invest adequately in the brand. You

With the growing discouragement towards juices due to heightened awareness levels, the brand is strategically leveraging the health and energy benefits of milk (think Milo), specifically targeting children

Emaad Ishaq Khan, Executive Director at Synergy Dentsu & Synite Digital

can’t advertise enough for a cartoon to seep into mainstream consciousness. Then your entire existence is precariously balanced on the television commercial (TVC), and that TVC is also rather diminutive,” Syed expounds.

It goes without saying that a cartoon confined solely to YouTube will face an uphill battle. Especially if your target audience has the option to watch Cocomelon of all things, and is being incessantly targeted by YouTube’s algorithms.

That’s not to dismiss the potential for children’s cartoons. “There are Hindi dubbed cartoons that mothers may not necessarily want their children to watch, and then there are English cartoons whose storylines may or may not resonate culturally with us,” elucidates Syed. “There’s a significant opportunity to do cartoons right if you’re incorporating local context and languages,” Syed adds.

However, it’s not as if Friesland is oblivious to all this. Khan provides a detailed explanation, “If we just host it on social media, only a few consumers might end up watching it as most digital tools will serve other international content to the audiences” he begins. “We drove initial awareness through a digital reach and advertising plan.”

“We used 15 and 30 second trailers. The audience would simply click on the trailers

and be redirected to Olper’s flavoured milk’s social media page where they could watch it,” Khan articulates FrieslandCampina’s digital advertising strategy.

The cartoon makes perfect sense when viewed through a wider lens. Looking at Olpers’ portfolio from a panoramic perspective, they’re emphasising the benefits of breakfast and healthy living in general. A part of a child’s breakfast routine inevitably involves deciding what will go into their lunchbox for school.

Now, one might think that we’re reading too much into this. Perhaps we are, but that doesn’t mean the creators of the cartoon don’t comprehend portfolio strategy.

Want an example of all this? Look at the discontinued box of Olper’s flavoured milk, and the current one. One is clearly more in tune with the conventional milk brand than the other. In its defence, the discontinued one might even look more fun but that’s not how Olper’s is going to be able to take a shot at their only real competitor.

Let’s tie everything back together. At the time of penning this piece, only a single episode of the cartoon has been released. Consequently, it would be premature to pass judgement on the potential success or failure of the series. The cartoon itself, however, is arguably the least captivating aspect of this

entire thing. Instead, it’s the myriad opportunities it presents for Olpers’ that truly pique one’s interest.

We’ve previously established that our investigation involved scrutinising the cartoon, and we’ve underscored the fact that flavoured milk isn’t the sole product from Olper’s featured in the animation. This is crucial, as it ties into our discussion on synergies. That was merely the inaugural episode. For all we can predict, subsequent episodes may spotlight Olper’s cheese or their dairy cream. Friesland has the potential to pepper the entire series with their comprehensive product portfolio, should they choose to do so. They could even leverage it as a launchpad to cultivate the brand equity required to introduce the aforementioned infant products.

Consider this:

Friesland has a choice. It could just sit back, and do nothing — or it could seize the opportunity, and make history. Friesland’s dairy business has been outshining Nestle’s for the past six years, growing at a CAGR of 9% compared to Nestle’s 6% from 2016 to 2022.

One might contend that this higher CAGR is merely a consequence of Friesland’s lower base in 2016, when it had just stopped being Engro Foods, and that it only regained its previous sales volume the following year. This contention, however, crumbles when we examine the data from 2020 to 2022, when Friesland was back to its normal Rs 40 billion in sales that it saw across the 2010s. During this period, Friesland grew at a staggering CAGR of 28%, almost doubling Nestle’s 15%. The company clearly did not rest on its laurels.

Now, ceteris paribus, Friesland will inevitably overtake Nestle if both companies continue operating in their normal capacities. Based on a simple projection of the two CAGRs from 2016 to 2022, Friesland will eclipse Nestle in 2050, when the company will have a total sales volume of Rs 666 billion compared to Nestle’s Rs 655 billion. If we instead use an exponential growth formula of y =b*m^x for both companies, then the timeline shortens to 2038 as the tipping point for Friesland.

These assumptions, however, are based on historical data, and disregard the likelihood that Nestle will fight back. That would be uncharacteristic of a company that managed to create that Rs 60 billion gap in the first place. Assuming then, that Nestle does not do anything at all to challenge the status quo, does Friesland want to wait for two to three decades until it can finally claim the dairy crown? Or does it want to start shrinking that gap as soon as possible? n

By Zain Naeem

By Zain Naeem

It is one of those strange ironies. Most people that ask the question “what is a mutual fund” are usually the ones that need them the most. You see, for most working professionals not involved in the world of finance, terms such as mutual funds are often distant and confusing.

The reality is that mutual funds are investment instruments for individuals who feel that they lack the expertise on how to manage their own money.

Essentially, you put some of your savings in a mutual fund which is composed of a vast number of similar investors. So for example ten different people could put their money in the same mutual fund offered by a bank which would then use that aggregated money to invest in different projects. The profits on those investments would be returns on those mutual funds.

Pretty simple concept, right? Not exactly. The problem is that there are plenty of mutual funds out there. And since mutual funds are usually for people that don’t quite know how to invest their money, it isn’t always easy for these investors to pick the right mutual fund.

Take the example of Al Meezan Invest-

ments’ Meezan Sovereign Fund. On the 18th of September this fund introduced by the investment arm of Meezan Bank had earned an annualised return of 20.40% for the month of August. The investments that the fund had made in its assets gave them a return of 1.7% for the month alone. When these returns are annualised for the year, they translate to a return of 20.4 percent.

Compared to this, an average return on the market (what we would call benchmark — more on that later) at the same time in the market was around 7.8%. So how come Meezan’s Sovereign Fund is doing so well? And why are investors making a better return compared to other investments that can be made in the market.

The answer might not be quite as simple as it seems. But first, a bit about the basics.

Mutual funds are investment opportunities in which people hand their money over to an expert in the hope that they’ll be able to give them good returns. When many people go to the same expert, this money can be pooled into a ‘mutual’ fund. Different mutual funds can have different demographics

in mind and have different levels of risk and other characteristics.

The benefits are that the mutual fund managers are responsible for the investments and actively look to maximise the returns of the investors. The clients benefit from the skills of the money managers and are able to invest in assets which might be difficult to understand or comprehend.

The cost of this management is that the experts take a fee for the service they are providing in return for managing the investments. The money managers feel that based on their ability, skill and expertise, they need to be compensated and they derive a certain percentage of assets under management as a fee. Consider it to be some of the cream off the top of the milk bowl.

Now, mutual funds are tailored to the needs of the clients. An 18 year old who is working a job will have different investment goals compared to a professional on the verge of retirement.

{Editor’s note: As things stand in today’s day and age, an 18 year old with a successful YouTube channel might have a lot more money to play with than say a career marketing professional entering their 60s}

One might want to invest in the stock market to get variable and high returns and

Al Meezan Investments wants to grow your wealth and is offering high returns. Is there a catch?

can handle his investments making a loss from time to time. The retired man cannot see a fall in his income as he depends on the investment to supplement his income.

In essence, a stock market fund looks to invest in the stock market. It will own securities of companies that are listed and will look to earn a return that is far higher than compared to an income fund. At the core is risk that is involved. Stock market funds are risky as they can have no return or even negative return. In order to make it attractive, it can give a return that is higher than an income fund as well.

Similarly, an income fund invests in assets which provide risk free constant returns. There is little change that returns will fluctuate and investors who do not want to take too much risk will look to invest in it. The securities that this fund invests in are mostly bonds and interest yielding assets which are low in risk and provide a constant stream of income.

All the remaining investors fall in between these two extremes and can pick and choose a fund which provides them a steady return while having some investment in the stock market as well which can grow the value of their investment. There are many asset management companies (AMCs) which provide different types of mutual funds that suit their specific needs.

With many different asset and money managers being present in the market, it can be difficult to gauge the performance of one AMC to another. If one opens up the website of Mutual Fund Association of Pakistan (MUFAP), they can be inundated with a series of numbers that can confuse you further. MUFAP and SECP have developed a policy to use benchmarks in order to compare performances of mutual funds.

“(In Pakistan), benchmarks are not chosen by the funds but are set by the SECP and MUFAP on the fund themselves based on the categorisation of the fund” says Mustafa Pasha, Chief Investment Officer at Lakson Investment Limited. These benchmarks can help better understand the performance of a fund compared to the benchmark that has been designated for the specific investment objective of the fund.

Consider the example of Mutual Fund A which has an equity based fund. This means that such a fund can invest all of its funds into the stock market. This fund was able to earn a return of 4 percent while another fund was able to earn a return of 6 percent. Based on just numbers, it is evident that Mutual Fund B performed better.

When a third fund is added to the mix,

we can say that it earned a return of 10 percent. This one shows that Fund C was able to perform the best as it has the highest return. What if the benchmark shows a return of 20 percent for the same period? This would mean that Mutual Fund C performed the best and that it gave a considerable return of 10 percent. However, the benchmark was able to outshine all the funds.

But before you get any smart ideas, it is important to remember that lagging the benchmark does not necessarily mean that the fund managers were wrong and that they failed. They did their best and that should count for something. A trend lower than benchmark returns would, however, mean that the fund is lagging the market and it would be better to invest in a fund which is able to equal or perform better than the benchmark. Dial away my friend.

Another aspect of benchmarks is that they need to measure an asset class which is close to the fund that is being measured against it. A stock fund will have the KSE-100 index which is being used as the benchmark while an income fund is compared to the risk free rate or discount rate prevailing in the economy. A benchmark makes sure that apples are compared to apples while oranges are compared to oranges related benchmarks.

Now back to the sovereign fund at hand. A glance over the promotional material that Meezan has shared reveals that Meezan Sovereign Fund (MSF) was able to earn an annualised return of 20.40 percent while the benchmark was 7.8 percent. It is vital to understand here that MSF is an income fund which means that it is low risk and an Islamic Banking approved method to earn a considerable profit.

Such a large return is not an extraordinary occurrence. It is pertinent to note here that there are conventional banks which are providing annualised returns even higher than 20.4 percent. Go to term deposits or saving accounts of some conventional banks and they are much higher

than the one being provided by MSF. Fund Managers Report (FMR) of Faysal Funds (AMC under Faysal Bank) shows that its Sovereign Islamic Fund was able to earn an annualised return of 20.76 percent while the benchmark was 7.8 percent as well for the month of August 2023.

The problem is not with the return that is being advertised. There are other AMCs which have similar funds which are providing better returns and are higher in some cases as well. A return of more than 20 percent when the base discount rate is 22 percent is normal and expected to a certain respect. The angst that is seen in this regard is connected to the benchmark being used.

For equity based funds to outperform their benchmark is one thing. It can be expected that good managers will be able to select stocks and make investment decisions which will be able to beat the market or the KSE 100 index. Great managers will be able to do it consistently and they will advertise this feat as they have the knowledge to be able to beat the market on a consistent basis.

MSF is an income fund which is supposed to be consistent on a long term basis and is not expected to beat the market by a huge margin. As it is risk free, there should be little to no variability in terms of the return and the fund should not be beating the benchmark by such a large number.

Even if we see the past performance of

the fund itself, from FY15 till FY 22, it can be seen that the fund beat the benchmark by around 1 to 5 percent maximum. So what happened in FY 23 that MSF was able to outperform by such a huge margin of nearly 14 percent?

Alas, it can be seen that the real devil is in the details. Or, if it’s too Haram for a story on Al Meezan, then the essence is in the details. The benchmark that is used for sovereign funds is supposed to be PKISRV (Pakistan Islamic Revaluation Value).

This is a rate that is quoted by six brokerage firms that have been selected by the Financial Market Association of Pakistan. The Financial Market Association of Pakistan (FMA) selects six brokerage houses and asks them the price that is being quoted for conventional and Islamic bonds issued by the Pakistan Government.

The FMA averages these rates and based on these rates it decides what the PKRV (Pakistan Revaluation Value) and PKISRV rates are going to be. These rates are provided to the SBP (State Bank of Pakistan) and are released daily.

As the PKISRV is the closest proxy that is present for a sovereign fund, the SECP and MUFAP mandates that 6 month PKISRV needs to be used by the mutual funds when they have to release their performance data for income funds investing in sovereign debt. This is the best proxy that can be used in this case.

The issue that was created in the benchmark rate of sixmonth PKISRV in recent times was that the Pakistan government did not issue a sukuk or ijarah in the last few months. As no such Islamic security issue was carried out, this created a gap in the market. There could be no comparable return or benchmark that could be used for the time being.

Usually what happens is that at the start of every month, just like there is an auction for treasury bills (T-bills) and Pakistan Investment Bonds (PIBs), the government also issues Sukuks and Ijarahs (Islamic bonds). This takes place every month which means that values derived from these bonds can be used in other fields.

When reached for comment, the management at Al Meezan stated that there was a dissonance in the markets as the government had not issued any Islamic bonds. Trying to use old or unrelated data to calculate benchmarks would not be advisable in such circumstances. This has been stated by the management at many of the other AMCs as well as they were told to change this benchmark. In such a case, the SECP asked the funds to change their benchmark to the deposit rate being offered by 3A or higher rated Islamic banks.

At this point, it is important to understand that Islamic and conventional banks differ from each other in one very important aspect. The Minimum Deposit Rate (MDR). SBP has mandated that conventional banks have to give a minimum deposit to their depositors which is in line with the discount rate.

There is no such mandate for Islamic banks and so Islamic banks can choose a deposit rate based on their own decision making. This means that Islamic banks and specially A- rated Islamic banks can provide a deposit rate which is much lower compared to their conventional counterparts.

“There is a stark difference between the benchmark rates being used for conventional funds and Islamic funds at least. When it comes to bank deposits, Islamic banks do not have any MDR making their rates much lower compared to conventional banks.” says Pasha elaborating on the gap that exists in the Islamic conventional banking.

Due to the special dispensation given by the SECP, it meant that rather than using PKISRV rates which would have been much higher, the benchmark fell to the rates which have been quoted by companies like Al Meezan.

To put things into perspective, it was seen that PKRV rates recently have hovered around 22 percent while PKISRV rates have not been available for the same period. As the SECP had allowed for exceptions to be made, the benchmark which was chosen was persisting around levels of 7 to 8%. This created a huge gap between the return of the fund and benchmark which has been seen in the advertising material.

Muhammad Ali Bhabha, Chief Investment Officer at HBL Asset Management states that the benchmark return is supposed to be 6 month PKISRV rate and “since no instruments were available in the market…..(it) was replaced with 6 month deposit rates of 3 A and above rated scheduled banks selected

by MUFAP. Since 8th September…..GOP IS (Islamic) issue is available now.” Based on this issue, it is expected that the benchmark rates will be approved and converge around 20 percent.

At this juncture it can be stated that there needs to be a benchmark that should be able to represent the situation in a better manner. Most of the time, rates move in conjunction with each other and as there had been no fresh issue, the rates had become disjointed.

As the PKRV is hovering around 22 percent and the government is giving a return of more than 20 percent on its ijarah and sukuk bonds, the PKISRV can be revised accordingly and should be nearer to the PKRV rate. If the benchmark was around that rate, it would show that the actual return that the fund was able to earn was not that much greater than the benchmark and that the fund was tracking the benchmark as it should for an income fund.

It is important to note here that Islamic AMCs are showing high returns in their sovereign funds while their benchmarks are low. This is a special case in the market which will be rectified when a fresh issue of sukuk or ijarah is carried out. As this month has seen an issue take place, the situation is expected to go back towards normality.

Still, trying to imply that the fund is beating the benchmark by such a large margin is a misrepresentation of facts as the fund returns have increased while the benchmark has been changed on a temporary basis.

Maybe it would be better if Al Meezan gave the complete picture and stated in the promotional material that the benchmark is lower than expected and this was a special case.

This misrepresentation led to anger being felt by many people on X who felt that it would have been better to state all the facts outright. It seems that Al Meezan has had an error of omission by not stating all the facts and should have made a disclaimer. This would have appeased some of the people as the true picture would have been represented in the mutual funds industry. n

Pakistani start-ups face a difficult future as international venture capital funds dry up

As the business world comes to grips with the change in the global economic cycle, the situation faced by Pakistani start-ups is no different from the rest of the world. At the conference titled “Paklaunch Unconference 23.2”, held last week, in London, this was the major theme that resonated with the attendees, which included the top Pakistani start-ups as well as the venture capital firms who have invested in many of these start-ups.

Things are difficult not only due to the peculiar situation in Pakistan – that holds for everyone in the country and is taken as given by those who manage businesses here. However, start-ups face a particularly difficult situation due to the fact that global venture capital funding has shrunk significantly over the last few years as the interest rate regime has changed globally, driven by the escalation of interest rates in the US and other Western markets.

With free money no longer available, venture capital firms are having to ask start-ups to improve profitability, an unprecedented turn, as the start-up model has historically prioritised revenue and scale!

However, the message this time, for the start-up businesses, was to sit tight, not burn excessive cash and try to survive through these difficult times.

The writer is a strategy consultant who has previously worked at various C-level positions for national and multinational corporations

It was heartening to note that the Venture Capital firms, those represented by successful Pakistani expats as well as international investors, are keen to continue investing in Pakistan and understand that the country has long-term potential. Start-up eco systems as well as the technology infrastructure required for success, take time to build.

The investors mentioned that Pakistan is no different from many other markets, including Egypt, Nigeria and Mexico. In fact, Pakistan’s GDP growth rate for each preceding decade has been 5% per annum, which is better than many countries.

With Pakistan basically being an informal economy, businesses which are able to capture the informal markets are setting themselves up for success. Hence, Venture Capital looks for a business model which has a long-term strategy and would like to invest in category-winning companies, meaning that they want the businesses they fund to lead the particular markets they compete in.

But they normally stay away from capital-intensive businesses as well as ones with thin margins.

Venture Capital funds understand that they operate in the high-risk start-up world where failure is expected. They would like to back ambitious founders who can learn lessons from failures and not worry much about negative public reactions associated with failure.

As for the founders, there were a number of outstanding entrepreneurs in the room – from retail B2B, and fintech to EV producers to pure information technology and software companies. These founders have exciting ideas, are ambitious and seem to be good leaders with the ability to manage risk.

The situation they face in Pakistan is not easy. The slide of the Pak rupee has made business goals in terms of USD returns much more challenging as political instability continues to hurt the economy. Expanding overseas may be an option for some but without a stable base in their home market, it would be a bigger challenge.

Tapping into the domestic market for funding via listing on the PSX is also unlikely in the short term, given the short history and unproven profitability level for most start-ups. However, finding some form of local financing would be a suitable way out for all stakeholders, as mentioned by various participants during the conference.

Despite these issues, it was interesting to note the cultural transformation that many of the founders are implementing within their respective businesses. They hold themselves accountable and believe they can be replaced as leaders if they do not perform well. Sharing success with employees via stock ownership plans is also a positive cultural driver and very much a

part of the start-up DNA.

This is a positive change from the traditional Pakistani family business model where the business owner remains irreplaceable.

However, with most businesses still early in their life cycle, time will tell how many of these founders are able to pivot when the situation demands and display resilience in the face of adversity.

The sense of camaraderie and good chemistry between the Venture Capital funds and the founders of businesses was evident. VCs support founders in all aspects of the business but mostly provide guidance on governance and strategy. They listen to founders carefully as the founders understand the opportunity much better.

There was much discussion on founder integrity and how Venture capital funds deal with this subject in an economy like Pakistan.

The consensus was that this is no different from managing any business in Pakistan and similar markets. VCs do their due diligence and make sure they understand the founders’ motivation before writing the cheque. But sometimes terrible things do happen which is part of the business risk.

Having said that, good founders are difficult to find and once VCs find them, they tend to stick by them. Or as one of the VC reps says “It is often that founders pick the VC firm they would like to work with”

On the sidelines of the event, one got the sense that most Pakistani start-ups are still at an early stage of building their respective toplines. They need time and capital to continue building the business. But they are a bit far from achieving sustainable profitability.

Given that the global economic cycles can be 10-15 years long, these businesses will

struggle to build scale and become viable without the required funding.

Although Venture Capital firms hope for a quicker correction of the global markets and for the correction to also be visible in Pakistan, one dreads to think of this as wishful thinking. For the sake of some savvy investors and capable founders, one can only wish to be wrong in this assessment.

Finally, a word about the conference organizers.

Originally formed as a WhatsApp group by San Francisco-based Aly Fahad, Paklaunch has grown into a sizeable start-up community focused on Pakistan. It is great to see Aly’s dedication and commitment without which it would not be possible to bring together people from such diverse backgrounds and geographies.

Kudos to the Paklaunch team!

The UAE has banned fresh meat exports from Pakistan coming via the sea. How is the meat industry responding?

By Saddam Hussain and Shahab OmerIt was complete chaos after a notification from authorities in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) quietly announced that Pakistan will not be allowed to export fresh or chilled meat via sea to the UAE up until the 10th of October at least.

So what in the world is going on?

Put very briefly, the UAE does not trust the Pakistani meat industry and possibly for good reason. To make things very clear this does not mean Pakistani meat can no longer be exported to the UAE or anywhere else in the Gulf. It simply means that the export of fresh meat from Pakistan has been banned and that too through sea routes.

Early in the month, a fungal contamination was detected in a shipment of meat from Pakistan to the UAE. Within a country’s domestic market this would be considered a case of a bad batch and simply disposed of. The problem in exporting is that host countries bringing in food items from foreign countries need to be very careful. Fungi that could have originated from

Pakistan might be entirely new in an area like the UAE. This would mean resistance to this fungus in the Emirates would be next to nothing and it could have dire implications for the food supply in the country. This is why export quality food products need to be packaged in very particular ways and in line with international regulations and standards.

As detailed in a notification dated September 19, 2023, by the UAE Ministry of Climate Change and Environment, fresh or chilled meat from Pakistan is now required to adhere to specific packaging standards.

These include vacuum-packing or modified-atmosphere packaging and a prescribed shelf life of 60 to 120 days from the date of slaughtering to qualify for import.

The meat consignment in question had been sent by a Karachi-based company by sea and the whole shipment was destroyed by the UAE authorities, while a ban was imposed on all further imports of frozen meat from Pakistan through maritime channels at least up till Oct 10.

Meat exports by air will continue without any break. Pakistan exports meat worth around $144 million per year to the UAE of which, $12 million worth is transported via sea routes.

Pakistan’s current meat production stands at approximately 49 lakh tonnes, with only around 2 percent (equivalent to 95,991 tonnes) destined for export. The principal export destinations encompass Gulf Coopera-

tion Council (GCC) states and select Far East countries.

Over recent months, various Pakistani companies have effectively secured export agreements with China, Egypt, and Indonesia.

A total of 18 Pakistani companies have received endorsement from the UAE Ministry of Climate Change and Environment for the import of fresh and frozen meat. These approved companies include Zenith Associates, P.K. Livestock and Meat Co. (Pvt) Ltd, Organic Meat Co, Tata Best Foods, K&N Food Co, Big Bird Foods. Pvt. Ltd, Halal Meat Processing, Al Shaheer Corporation (Private) Limited, Fauji Meat Limited, Hamza Meat and Poultry, Al–Rahim Farming Meat, Tazij Meats and Food Co, Abedin International Pvt. Ltd, Asia Livestock and Meat Company, Pakistan Food Products, Meat World Pvt. Limited, and Hamza Halal Food.

However, because of the one consignment, the entire meat industry is facing the ban.

A recent report published by Salaam Gateway, a Dubai-based news and insights platform specializing in the global Islamic economy, underscores that the global halal food and beverage industry is presently valued at $415 billion. The top 10 exporters of halal meat collectively account for a total trade value of $14.04 billion. Notably, the top three halal meat exporting countries—Brazil, Australia, and India—are non-Muslim-majority nations. In contrast, Pakistan ranks 19th among the

world’s largest meat exporters, with annual exports exceeding $400 million.

Due to its geographical proximity to the Middle East, Pakistan stands poised to capitalize on the Halal meat industry, offering significant potential to enhance the country’s overall economic security. However, several challenges have restrained Pakistan from fully harnessing this sector’s potential.

Despite notable progress, Pakistan trails behind, holding only a 0.4 percent market share in global Halal meat exports. The majority of Pakistan’s Halal meat exports are destined for UAE, Saudi Arabia, Uzbekistan, and Kuwait, with beef constituting over 80 percent of these exports.

Pakistan’s meat industry already exports very little and much of this is because foreign markets have a trust deficit in doing business with Pakistan. The opportunity, as we’ve illustrated, is huge. Meat producers are now worried that this one bad consignment could have detrimental effects on their fledgling industry.

Talking to Profit, Faisal Hussain, CEO of the Organic Meat Company Limited, has clarified that the UAE has not halted meat imports from Pakistan altogether. Instead, they have temporarily suspended fresh meat imports via sea routes and mandated packaging upgrades until October 10. This measure is not expected to significantly disrupt Pakistan’s overall meat imports.

Traditionally, fresh meat had been shipped wrapped in cloth, but in recent years, importers have increasingly favored vacuum packaging and refrigerated containers for fresh meat. Hussain noted that these packaging upgrades may lead to increased expenses for companies involved in meat exports.

In addressing the issue of contaminated meat in the consignment, he emphasized that it appears to be a supply chain-related concern. He stressed that assigning blame to any specific company without a thorough investigation would be premature and refrained from

disclosing the company’s name. Meanwhile the Trade Development Authority of Pakistan (TDAP) also put out a statement in response saying they were actively working to resolve the recent ban imposed by the Ministry of Climate Change and Environment in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) on the export of fresh chilled meat from Pakistan via sea.

The preliminary investigations conducted by TDAP officials suggest that the compromised meat quality may be linked to issues with the refrigeration systems within the reefer containers. The responsibility for these systems lies with the shipping lines involved in the transportation of the goods. It has been revealed that the affected exporters have initiated legal proceedings against the shipping companies responsible.

In response to the ban, the Pakistani Consulate in Dubai has proactively engaged with various stakeholders to gain a deeper understanding of the root causes behind this unfortunate incident. They have also requested a formal meeting with the UAE Ministry of Climate Change and Environment to present Pakistan’s perspective and comprehensively address the concerns raised. The mission’s primary objective is to alleviate the concerns expressed by UAE authorities while strongly advocating for the withdrawal of the ban.

They said that TDAP is firmly committed to promoting fair trade relations between Pakistan and the UAE while upholding international quality and safety standards.

“We are optimistic that through constructive dialogue and cooperation, both nations can find an amicable resolution that allows the resumption of fresh chilled meat exports from Pakistan to the UAE. TDAP is closely monitoring developments in this case,” they concluded.

Meat exporter Nasib Ahmed Saifi has clarified that the restrictions imposed by UAE authorities are temporary measures and not permanent. These restrictions will remain in effect until Pakistani meat exporters adhere to the protocols recommended by the UAE for the transportation of future meat shipments. Saifi explained the significance of following

these protocols, which require exporters to vacuum-pack their meat before shipping it in refrigerated containers via sea routes.

He further explained that the meat shipments, which were found to have fungal issues, had been improperly packaged in cloth, resulting in damage to Pakistan’s reputation during the export of that specific consignment.

Abdul Hanan, Chairman of the All Pakistan Meat Processors and Exporters Association, expressed that the restrictions on sea routes are not expected to significantly affect export numbers. He highlighted the advantage of exporting via air routes, which allows for the shipment of fresher meat in a shorter time frame, expediting the export process. Hanan firmly stated that Pakistan maintains excellent meat quality, and any misconceptions regarding subpar quality based on one isolated incident are unfounded.

According to data provided by TDAP, Pakistan produced 52.996 million tons of meat during the 2021-22 period. The majority of this meat is consumed domestically, with only about 2% being exported. Total export earnings from meat in the last year amounted to USD 333.4 million. Pakistan’s primary meat products include beef, mutton, poultry, camel, and goat meat.

Pakistan ranks 11th in global poultry meat production. The country’s extensive cattle and goat farming are supported by the availability of pastures in Northern Areas, Cholistan, and Thar, along with natural animal rearing capabilities, meat-producing breeds, and favorable climatic conditions. Primary meat exports are directed to six GCC countries, Vietnam, Afghanistan, Indonesia, and China.

As per TDAP, Pakistan is internationally recognized as one of the leading meat producers and exporters. Over the past decade, it has experienced remarkable growth in meat exports, particularly to Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries. In January 2023, bovine meat exports from Pakistan amounted to $31 million, reflecting a substantial 29 percent increase compared to the same period in 2022. n

They have temporarily suspended fresh meat imports via sea routes and mandated packaging upgrades until October 10. This measure is not expected to significantly disrupt Pakistan’s overall meat imports

Faisal Hussain, CEO The Organic Meat Company

Cut-off yield for 3-month T-bills in Sept 6 auction was 24.49%, indicating an expected rate hike. But after the latest policy announcement, the cut-off yield went down to 22.78%

By Urooj Imranhen the results of the last market treasury bills (T-bills) auction were released on September 6, it seemed the market expected policy rate, which was at 22%, to be hiked up by 200 basis points (bps) to 24%. This was because the cut-off yield — the highest interest accepted — for the three-month T-bill had already gone up to 24.49%.

However, when the State Bank of Pakistan’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) met on September 14, it decided to maintain the policy rate at 22%. Subsequently, in the latest T-bills auction held on September 20, the cutoff yield for the three-month tenor decreased to 22.78%

Why did the yields go down? Was the SBP now ahead of the curve, with the market now aligning itself after receiving a “clear” message from the central bank? Had the finance ministry pushed for a rate hike in the

last auction? (After all, while the SBP issues tenders for the T-bills auction, the ministry decides the cut-off). Profit explains.

T-bills are short-term government securities, with tenures not exceeding a year, that are issued by the government and distributed in the primary and secondary markets by the SBP. These highly liquid government securities have sovereign guarantees and a fixed rate of return, which is also known as a yield. T-bills are a tool for raising short-term cash by governments.

Banks are allowed to hold this security in an Investor Portfolio of Securities account for their customers. Investors can buy these securities in a competitive auction in the secondary market, or a non-competitive auction in the primary market.

On auction day, primary dealers, such as banks and brokerage houses, offer bids for T-bills with a certain yield. This yield is determined by policy rates, market sentiment and future expectations. A certain cut-off

yield is announced that accepts all bids at that rate or below. The dealer pays the SBP a discounted amount for the bill, which is returned in full at maturity factoring in the yield of the T-bills. So, for example, a T-bill’s maturity value is Rs1,000, yield is 22% per annum, and maturity is three months. You can buy the T-bill at a discounted rate, say Rs950. At the end of three months, you will get Rs1,000 plus the yield which is the interest you have earned.