09 MG’s take two: Are we in for the long run now?

14 What’s all the fuss about | corporate farming?

20 Ufone dabbles into unchartered territory with ONIC, but what is there to gain?

25 Re-orienting consumption

Ammar H. Khan

27 Some brokerages pay their CEOs very well. But do their numbers justify the remuneration?

Publishing Editor: Babar Nizami - Joint Editor: Yousaf Nizami

Senior Editor: Abdullah Niazi

Executive Producer Video Content: Umar Aziz - Video Editors: Talha Farooqi I Fawad Shakeel

Reporters: Taimoor Hassan l Shahab Omer l Ghulam Abbass l Ahmad Ahmadani

Shehzad Paracha l Aziz Buneri | Daniyal Ahmad |Shahnawaz Ali l Noor Bakht l Nisma Riaz

Regional Heads of Marketing: Mudassir Alam (Khi) | Zufiqar Butt (Lhe) | Malik Israr (Isb) Business, Economic & Financial news by 'Pakistan Today'

Contact: profit@pakistantoday.com.pk

By Daniyal Ahmad

By Daniyal Ahmad

Acar that had everything at the time. Sleek black racing seats. Ambient lighting that shifted colours like a mood board. Massive headlights that cleaved the night. A car that linked its roots back to one of Pakistan’s most treasured tourist havens. All whilst being most routinely found on our roads in a frosted red colour. The MG HS demanded attention.

It was also a car that seized a once-in-a-generation opportunity. It came

at a time when car buyers were hungry for something new, something different, something exhilarating. If the KIA Sportage was the spark that lit the fire at the altar of the sedans, then the MG HS was a pyromaniac. But before it could pour the gasoline, it encountered internal and macroeconomic troubles.

The car vanished. Like the escapade it promised to those who sat in its seats and pressed the bright red super sport button, the MG HS just got up one day and left the scene. Like a ghost, it receded from the spotlight. There were whispers and rumours of what had transpired with the company, and many

surmised that they had seen the last of it. Until late last year. The company defied the odds and finally launched its locally produced HS. Perhaps this alone would have been enough to put an end to speculation of its future. However, the company has since been on a charm offensive like no other. So much so that it has literally organised cross-country concerts, amongst other events.

So, the question arises: Is MG back? And are they here to stay this time?

Trip down memory lane

To proclaim that MG hit the ground running would not be hyperbolic.

MG hit the jackpot with their timing when it stormed into Pakistan in the winter of 2020. The KIA Sportage had dedicated the better part of the year preceding MG’s launch to familiarising automotive customers with the crossover sports utility vehicle (C-SUV) market and prying them away from the sedans that had been omnipresent up until then. When Hyundai revealed its Tucson a mere four months prior to MG’s launch, Pakistani customers had experienced an epiphany: C-SUVs were here to stay. And MG had no qualms about going all in on this realisation.

Not only did it present the Pakistani market with the regular internal combustion engine variant of the HS, but it also introduced a plug-in hybrid vehicle variant. Moreover, it launched the younger sibling of the HS — the ZS — which was accompanied by its own unique engine combinations. The brand’s launch seemed perfect.

“I am of the belief that their strategy was astute, and shrewd, which is why they sold 12,000 completely built-up (CBU) units in Pakistan,” asserts Suneel Sarfrz Munj, Co-Founder of Pakwheels.

Whilst the cars sold like hotcakes, MG also hit a wall very early on.

To begin with, there were delivery issues. Genuine customers faced extensive delays waiting for their cars.

According to Shaheel Shahzad, Co-Founder of BloomBig OverDrive, a perception had been formed in the market that MG was only delivering cars on time to dealers who were perhaps profiteering from this early access to MGs.

Additionally, there were problems with clearing imports. Since all MGs were CBUs, the company was heavily import- dependent. There were news reports as well, suggesting that the hundreds of MGs were standing idle at Karachi port waiting to be cleared.

The market started questioning whether or not a company that could not produce locally had any future in Pakistan.

“There was a global shortage in semiconductors, and MG was not immune to the dis-

ruptions in the global supply chains,” explains Syed Asif Ahmed, General Manager of Sales and Marketing at MG Motors. “We ensured we were in constant communication with all of our customers 24/7.

MG was not the only one that had delayed its deliveries because of the aforementioned shortages. However, what was unique was that all the anger customers had for their delayed C-SUVs, irrespective of the brand, was somehow directed towards MG,” Ahmed adds.

Perhaps a case of suffering from its own success? The honeymoon period was clearly over. In a rather unprecedented move, MG even issued a public apology in May of 2021. It reached out to explain the predicament it was in, and reassure its customers whilst accepting that they had fumbled.

To follow it up, the company went on record and publicly stated in September 2021 that it would actively combat what it perceived as targeted propaganda against the company by those who sought to leverage its constraints. However, it would take another year, and a half, for the company to come back to its critics.

What happened in the meantime?

Shahzad, who professes to be familiar with a plethora of individuals who had purchased an MG, elucidates how MGs did not retain their value in the secondary market as opposed to other vehicles in the same category. According to him, MG cars prices had either dwindled or had not escalated as substantially.

“I still maintain that there is a degree of disillusionment among these individuals. Those who have invested in an MG are now cognisant of the issues it presents. Nonetheless, when queried about their satisfaction with their purchase, these individuals assert that — given the opportunity to choose anew — they would still opt for an MG,” Shahzad said, based on a survey of MG owners who have been in possession of their respective cars for two to three years.

Perhaps that is what truly matters. Despite initial missteps, those who had actually bought the car remained enamoured

with it, and MG was cognisant of this fact. This brings us to Act Deux.

We’ve covered some history and now find ourselves back at square one. In December, MG unveiled the completely knocked down (CKD) HS, christened the HS Essence. Since then, the company has taken the country by storm, hosting concerts from Islamabad to Karachi. Yet, the trump card up its sleeve is something it has kept under wraps – a move tantamount to bringing a gun to a knife fight amidst the current C-SUV melee in Pakistan’s automotive landscape.

What are we alluding to? The price.

At present, the MG HS Essence retails for a staggering Rs 87 lakh. A hefty sum indeed — until one realises it is one of the most economical options in its category. The notion of MG being a bargain is nothing short of bewildering. After all, it is an exceptional vehicle and its brand is built upon offering more than its competitors. So, what gives?

When the MG was first introduced, it was a CBU, and therefore more expensive than its competitors. The difference wasn’t a lot; one would have to pay Rs 6 lakhs more for an MG as compared to a KIA Sportage. It was still pricier nonetheless. After introducing the CKD unit, they are more affordable than the Sportage.

“I believe it’s commendable that they’re offering an affordable vehicle. Had they not done so, it would have raised questions about the very purpose of localisation,” ponders Munj.

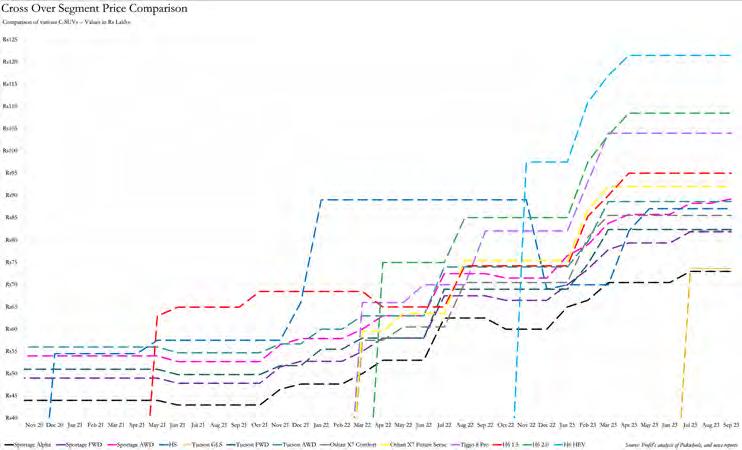

If we were to simply examine vehicle prices since the launch of the MG HS, Munj’s argument becomes all the more cogent. The price of the MG HS has indeed benefitted from localisation after traversing its own rollercoaster of a pricing journey.

However, there is one snag. If we were to disregard the period between December 2021 and December 2022, we would uncover

While other players and they have rigid separation of earnings as part of their agreements, sometimes having to just rely on part sales and other after-sales services for their profit margins, our relationship with SAIC enables us to reap benefits directly from the pricing decision

some intriguing price revelations at play. For context, this one-year period is when the MG HS retailed for Rs 89 lakh. Yet, no one actually purchased it at that rate because it was never available in the showroom at that price. This is when MG encountered the aforementioned supply chain issues.

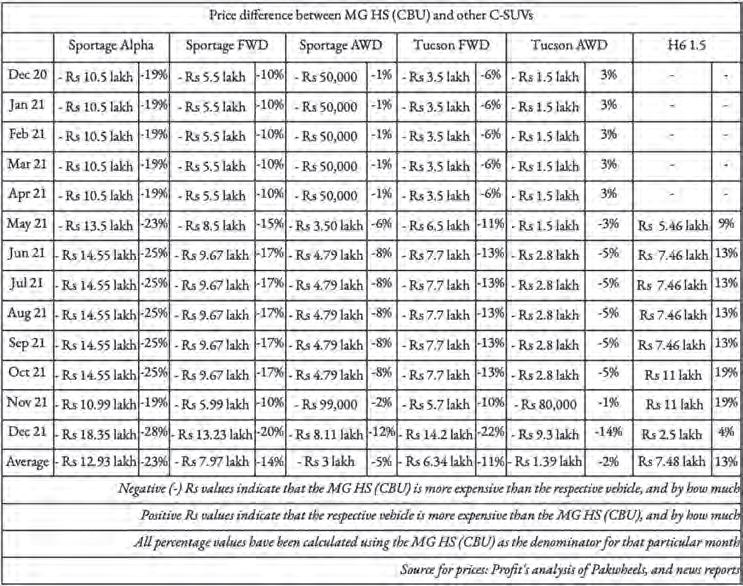

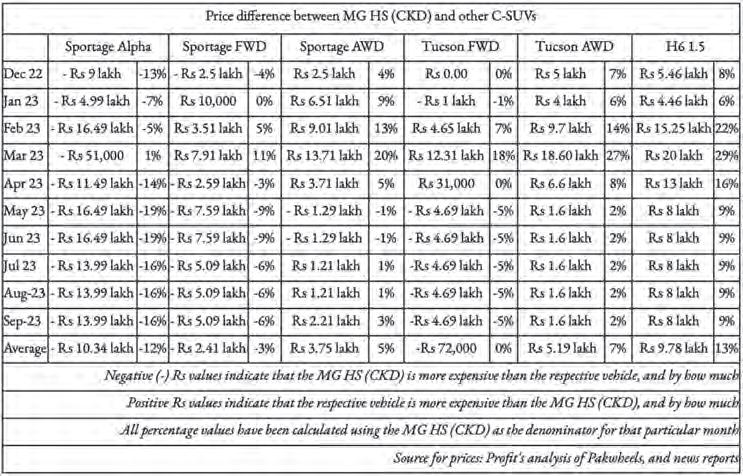

Examining the prices in the C-SUV segment from December 2020 to December 2021, the MG HS (CBU) was pricier than all variants of the Sportage and the Tucson on average. Haval’s H6 was the only vehicle that retailed at a higher price. The H6 was Rs 7.48 lakh on average more expensive than the MG HS (CBU) over that time period.

Now fast forward to December 2022 till now.

The MG HS Essence (CKD) has been cheaper than three out of six of those vehicles on average. In instances where it is still more expensive, that margin has diminished. It is now only 12% more expensive than the Sportage Alpha compared to its CBU counterpart being 23% more expensive. Similarly, whereas it was previously 14% more expensive than the Sportage FWD, it is now only 3% more expensive.

“Our pricing decision is influenced by our affiliation with SAIC, MG’s global parent company,” explains Ahmed. “Unlike many of

our competitors, we are not constrained by a technology licence agreement (TLA). SAIC owns 51% of MG in Pakistan.” Ahmed continues, “While other players have rigid separation of earnings as part of their agreements, sometimes having to just rely on parts sales and other after-sales services for their profit margins, our relationship with SAIC enables us to reap benefits directly from the pricing decision.”

“The principle (SAIC) deems to be the price of the vehicle,” Ahmed adds, “and subsequently this is the price that we will charge.” And therein we might have it.

This is a price that MG is willing to sustain. It is also a price which, based on Ahmed’s comments, is something that MG and its parent are still reaping profits from. However, MG’s pricing decision is not in isolation. When viewed in the broader context of the market, it poses challenges for competitors.

The on-road price for the HS is approximately Rs 90 lakh (comprising taxes and other expenses). The price point is indeed a favourable one, as you could contrast the HS with sedans as well. For instance, the HS might be a feasible alternative, given the price, if you’re looking at the Toyota Corolla Grande, the Honda Civic 11th Generation, the Hyundai Elantra, and perhaps the Sonata as well — its 2.0 variant.

MG’s pricing enables it to vie with both sedans and C-SUVs. This is the same triumphant strategy that the KIA Sportage employed back when it first launched. MG may not have the same brand loyalty as the Sportage does, but neither did the Sportage when it first pulled this off. MG does, however, come equipped with an arsenal that has perhaps everything one could desire except the advanced driving assist braking — for which customers cheered it and the rest of the industry to get rid of.

Furthermore, MG does this at a time when cars are readily available in the market. This, though not as unprecedented as the shift from sedans to CUVs, is an infrequent occurrence. One of the Sportage’s key advantages over the rest of the industry is its manufacturing ability whereby it can provide a car to the customer faster than everyone else due to its deviation from the just-in-time production model.

This has been one of the keys to its success; however, what happens when your competitors just have stock lying around? With the industry leader having one of its key advantages neutered, and everyone else being either pricier or lacking in features, the MG HS might have its deus ex machina moment.

Now, would it hold a candle to the competition if everything was just lined up and available for immediate delivery?

Munj did not comment on this particular

aspect. Shahzad, however, put it succinctly. “In my opinion, the MG HS is second only to the Haval H6 HEV. Haval’s H6 line is the only one I would also compare it to. However, they are more expensive”.

So, now that we have explored MG’s initial journey, and examined their current strategy, the final question is: are they here to stay? This is a pertinent question, as the one-year crisis did offer them the chance to withdraw from an industry that is no longer as profitable as when they first entered. It was as good of an opportunity, if there ever was one, to go gently into the night.

“In an industry-wide symposium, we’ve collectively envisioned the trajectory of our sector,” Ahmed reveals, his words echoing the shared

optimism. “A unanimous consensus forecasts a surge to 500,000 sales by the dawn of 2030.” He concedes that this is a recalibrated forecast. “Our initial projection anticipated this milestone by 2025. However, the economic tumult of the past year necessitated a refinement of our estimates,” he elucidates. But why does the broader industry data hold significance for MG, especially when it should be primarily focusing on its own figures?

Ahmed perceives an immense potential for expansion within the sector. He cites the motorisation index, a key indicator suggesting a shift from two-wheelers to four-wheelers once a nation achieves a per capita income of $2,500. Currently, Pakistan’s per capita income hovers around $1,500-$1,600.

He is of the firm belief that the industry’s growth is a tide that lifts all boats.

“Escalating volumes will inevitably lead to increased localisation, thereby making vehicles more affordable for everyone. Predom-

inantly, the cost of materials we frequently use will see a downward trend. This, in turn, enhances the viability of offering consumers a wider array of enticing models at various price points,” Ahmed articulates.

This is where MG puts its money where its mouth is. It has initiated the process of accepting reservations for its pair of entirely electric C-SUVs: the MG4, and the MG ZS MCE. Mirroring the assertive pricing blueprint adopted for its HS, the two vehicles will retail at a price oscillating between Rs 1.1 to Rs 1.5 crore.

While these figures may initially induce a gasp, it’s crucial to bear in mind that this is the only price range where you can acquire Haval’s hybrid if you’re seeking an alternative to the traditional internal combustion engine. Moreover, it’s worth noting that this was the initial price point for the Audi e-tron when it made its debut in Pakistan.

It was at this price that the car’s popularity soared, becoming a common sight on the bustling streets of Islamabad, Karachi, and Lahore. However, with the depreciation of the rupee, the e-tron’s value nearly tripled, leading to a noticeable dip in purchases. Currently, MG finds itself in a neck-and-neck race with DFSK to see who can introduce their electric vehicle to the market first. Yet, amongst the two contenders, only MG has started accepting bookings.

At the time of writing this piece, both vehicles are yet to hit roads, so any judgement or commendation is being held in abeyance. After all, MG does have a track record of announcing vehicles that never quite make it to production. Perhaps these two models warrant their own dedicated article upon their official release.

However, this time around, things seem different. So, one might wonder: how has MG managed to transition from being virtually absent for nearly two years to potentially outpacing everyone in terms of technological advancement?

“Given our arrangement with SAIC, we feel here at MG that we are especially poised to introduce newer models because we have an opportunity that is not available to most other competitors,” Ahmed declares.

What is this arrangement that Ahmed has vaunted innumerable times now? It’s the aforementioned lack of a TLA, and 51% shareholding by SAIC. So, what do these two things even mean and why is MG so bullish because of them?

Nonetheless, when queried about their satisfaction with their purchase, these individuals assert that — given the opportunity to choose anew — they would still opt for an MG

Shaheel Shahzad, Co-Founder of BloomBig OverDrive

A TLA is a contract that outlines the terms and conditions of a licensing agreement between a company and a party purchasing the use, reselling rights, or rights to modify a particular product or intellectual property of that company. In the automotive sector, TLAs are crucial because they allow companies to use or resell specialised property by another party. 51% ownership means that SAIC International is the primary party operating MG in Pakistan.

The absence of a TLA affects two key aspects in the case of MG: pricing and models. With 51% control of MG Pakistan, SAIC has managerial control and an active stake in MG, fostering a more harmonious relationship between the two — if they so wish. In this instance, it looks like they seemingly do.

In terms of pricing, SAIC could offset the reduced cost of the HS by participating in the profits from other parts of MG’s operations in Pakistan, in return for assisting MG in managing the cost of the vehicle.

Pricing is a subsequent joint decision between SAIC and MG Pakistan. This allows them to find more common ground for joint profits than would be possible for those of MG’s competitors operating strictly via TLAs. That is because MG’s competitors would not have the support of their parent companies to that degree, and without convincing them would have to bear the costs of competitive pricing on their own and subsequently recoup them as well. In contrast, SAIC and MG Pakistan operate in unison rather than at arm’s length. That is why the pricing is what it is.

Now the latter of the two major points: the models of vehicles available.

Ahmed explains in simple terms. “A TLA means that I have a licensing agreement, and I can back out anytime. If I don’t have a deal with you, then I won’t bring you the product,” he says. This principle, he explains, directly impacts the availability of certain models in Pakistan.

To underscore how this impacts the

availability of certain models in Pakistan, he highlights the paucity of diversity in the portfolio of companies operating in Pakistan. Despite the fact that some of these companies possess models that have instigated groundbreaking transformations in their respective domains and are considered trailblazers on a global scale, these innovative cars remain unattainable in Pakistan. The reason?

The parent company shows no inclination towards a TLA to supply these cars here. This scenario underscores the significant influence of TLAs on the automotive industry and the choices available to consumers.

He then juxtaposes this with MG’s predicament. He asserts that MG’s parent company is more committed to Pakistan than other companies’ progenitors are. “If you were to scrutinise any of the automotive companies in Pakistan, and ascertain where their parent is the most prominent outside of its native country, then it is in those countries where they operate directly — where they have the preponderant shareholding — where they do not depend on a local ally,” Ahmed says.

He clarifies that he is not dismissing the benefits of having a local partner. “I am not saying that there aren’t any benefits to having

a local partner. There are most definitely pros and cons to any arrangement,” Ahmed adds.

Ahmed concludes by reiterating his confidence in MG’s potential in Pakistan. He says that MG and its parent are serious about tapping into this market. “I cannot comment on my competitors, but the principle having direct purview on the Pakistan-based operations speaks far more volume than I can emphasise,” he proclaims.

A point of interjection: It is relevant to note that Suzuki Pakistan is mainly owned by Suzuki International — 73.09% to be precise, based on their latest annual financial statement. However, this is not their story.

There we have it. The HS Essence has given MG a rare opportunity to atone for their previous missteps and reclaim not only their estranged customers but new ones as well. It is a second chance at life, really. It is a serendipitous twist of fate that a global semiconductor shortage was what crippled their supply chains previously, but the current economic crisis is what has levelled the playing field for them again. The challenge remains the same as before — to lure prospective customers to just take a seat inside the vehicle. However, that is a task that MG knows all too well. n

I am of the belief that their strategy was astute, and shrewd, which is why they sold 12,000 completely built-up (CBU) units in Pakistan

Suneel Sarfraz Munj, Co-Founder of Pakwheels

The Pakistan Army has had enough. For a very long time the country’s military leadership has been sharing power with their civilian counterparts. Over time this complicated relationship has arrived at a general understanding by which the military is allowed to independently run its own affairs while having a sizable influence on Pakistan’s foreign policy. In exchange, civilian setups have every now and then been allowed to run the economy and policy in areas such as health, education, and other service sectors with relative independence. There is much to be said simply in terms of historical fact about how we got here. But let us set that aside for the sake of ease, security and understanding. Let us forget matters of what should be and what shouldn’t be. Of right and wrong, and of constitutional and unconstitutional and instead focus on realities. What we do know is that even in periods where military dictators were directly exercising executive power they largely relied on technocrats, bankers, and economists to manage the country’s finances for them.

That is until now.

Over the past six months the military leadership has played a key role in trying to stabilise the country’s ailing economy. And there is nothing more indicative of this newfound interest in financial management than the Special Investment Facilitation Council (SIFC) that has been designed, spearheaded, and launched by the country’s military leadership.

What exactly does the SIFC do? It is supposed to be a council composed of civil and military leadership that operates almost like a second, empowered, commerce and investment ministry. The council provides opportunities and easy terms of investment and cuts through the inefficiencies with a vast array of powers. It is, essentially, a way to ensure consistent economic and business policies for foreign and domestic investors.

You see, the government of Pakistan has developed a bit of a bad reputation as a business partner. Foreign investors in particular have regularly been left scratching their heads over the legal and regulatory quagmires they

have to navigate through to invest in Pakistan. On top of this, inconsistent policies and constant political upheaval makes the country a highly risky place to park your money.

With the SIFC, investors are supposed to know that any dealings with the council take place in a realm outside politics and vested interests. So have the investors been biting? While nothing concrete has come to fruition yet, the council is quite confident that investments worth tens of billions of dollars could be coming in any minute now through the auspices of the recently Christened council.

But what exactly are these investors putting their money into?

The SIFC, it seems, has picked two key avenues for finding foreign investment. The first is natural resources such as mines and minerals. The other is agriculture. Now, with mining the matter is harder to achieve but a bit simpler. Investors can come in, assess the potential of a particular mining project, buy the lease and get cracking. In the case of agriculture, it is a bit different.

Pakistan is solidly an agrarian economy. That means in the case of agriculture, the SIFC is not just looking to find investors but also solve one of the biggest problems plaguing Pakistan at the moment — food security. The council’s plan is to use uncultivated land owned by the government and make it cultivable through corporate farming. To do this, the council is partnering with all of the provincial governments with the initial projects kicking off in the Punjab. The council and their enthusiastic partners claim this will bolster the country’s food production. Critics claim that the move could end up creating a new system of corporate feudalism and do little to alleviate rural poverty. So what is the reality? We start, as all good stories do, at the beginning.

Corporate farming is a pretty vague term. Corporate Agriculture Farming is a practice usually undertaken by large companies looking to enter

The military leadership is taking the economy into their own hands. Agriculture is the biggest component of that economy. What are their plans?

the agricultural sector. They purchase or lease land on a grand scale and then develop farms for experimentation and sometimes to grow products that they might need for their other businesses. A manufacturer of cornflakes, for example, might want to grow corn.

The idea itself is nothing new for Pakistan. In fact, former President Pervez Musharraf during his time in office had drawn up a plan for the lease of over 2000 acres of undeveloped land to the Chinese for Corporate Agricultural Farming. In 2009, building off this original plan, the government proposed to offer about 700,000 acres of land in Cholistan to potential investors probably from Saudi Arabia and the UAE.

The term corporate farming caught wind in March this year when a letter surfaced. In the letter, the military’s land directorate was asking the Punjab Government to hand over 42,000 acres of land for the development of corporate farming in Bhakkar, Khushab, and Sahiwal. This raised some eyebrows as a number of people wondered what the military had to do with using unused land of the provincial government for farming. Concerns were exacerbated when it was discovered that the transfer of 42,000 acres that was mentioned in the letter was only the first part of an overall request for over 10 lakh acres of government land.

Now remember, this surfaced back in March 2023. The SIFC was not formed until the 17th of June later that year. Clearly the idea of corporate farming has been one that the military has been interested in for a while. Even back then, the armed forces clarified that they would only play the role of facilitator in this and not reap any benefits from the project. At least 40 percent of the revenue generated from the cultivation would go to the Punjab government, 20 percent would be spent on modern research and development in the agriculture sector, while the remaining would be used for the succeeding crops and expansion of the project. The military’s land directorate was

Taimur Jhagra, Former KP Finance Minister

conducting the project in partnership with the Punjab government and the other private parties interested in corporate farming.

The idea was that the government owns land that nobody is using. The army basically extended an offer to the government of Punjab to develop this land, auction it off to a private party on lease, have them come in and use progressive farming techniques to grow crops on it and increase the country’s overall agricultural output. The profits would be split three ways with most of it being reinvested in the farms.

The matter, however, was taken to the Lahore High Court (LHC). What followed were tricky arguments where petitioners claimed that a caretaker government did not possess the mandate to enter into such an agreement and that the armed forces were going beyond their constitutional jurisdiction as well. You can read more about the entire fiasco here but very briefly put, the LHC struck down the transfer of the lease to the armed forces on the 1st of April 2023.

The next two months went by quietly. Then in June 2023, then Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif announced the formation of the SIFC. Underneath this council, foreign investors would be facilitated and given preferential treatment to make Pakistan an easier environment to conduct business in. Within days the PM was posing with the military’s top leadership and announced the “Green Pakistan Initiative” (GPI) with the Army Chief by his side. The plan was for the SIFC to be the vehicle that would bring tens of billions of dollars worth of investment into Pakistan. A big part of this, which was advertised in the early days, was through mining minerals and other natural resources. However there was always a plan to also bolster agriculture through corporate farming.

The SIFC would create plans that would allow corporate farming models along the same lines that the army had tried to do with the Punjab government. The council quickly began announcing projects under the GPI. This

included opportunities to invest in livestock farms with over 20,000 animals, camel farms with a herd of over 10,000, and feedlot farms with over 30,000 animals. Other than livestock, investors also had the opportunity to start corporate farming in Cholistan on an area of 50,000 acres.

On the 17th of July 2023, exactly a month after the establishment of the SIFC, the Punjab Government also won an appeal in the LHC which ended up reversing the court’s decision to transfer the 42,000 acres of land in Punjab. It has still not become clear if the project in Punjab for corporate farming will now possibly be managed by the SIFC as well or not but it means that corporate farming is about to kick off in the country on a very large scale. So how exactly does it change Pakistan’s agricultural landscape?

This is where things get really interesting. As has already been explained, the SIFC’s vision is to acquire land from provincial governments that is not being used and prepare it for cultivation. So for example the SIFC plans to prepare millions of acres in Cholistan by providing basic infrastructure for water and electricity as well as manpower to potential investors that might want to cultivate the land. Their main goal is to look for foreign investors that can bring in foreign exchange, and to that end their immediate goal is to use 15 lakh acres of such land for corporate farming and modernise an additional 50 lakh acres that are already being cultivated.

“We have estimated about $5-6 billion [investment from Gulf nations] for initial three to five years,” says Major General (r) Tahir Aslam speaking to the media. The General is the CEO of FonGrow, which is a company set up under the umbrella of the Fauji Foundation in 2022 meant to promote the interests

As a result of middle men and inefficient land divisions our agriculture sector continues to underdeliver because of a vicious cycle of poor agricultural practices, unavailability of technology and finances, poor inputs, low investment, low yields, low productivity, poor quality and poor profitability. This cycle needs to be broken at a scale disruptive enough to make a difference, and while controversial, corporate farming may be one disruptive way of challenging these problems from the demand side

of corporate farming in Pakistan. “We are engaging with several Saudi companies like Al-Dahara, Saleh and Al-Khorayef to attract investment in the corporate farming sector,” he said without elaborating on what stage the discussions had gone to.

FonGrow is the company that is managing initiatives under agriculture being undertaken by the SIFC. Of course, the problem is that there has been no solid commitment from a foreign investor so far. Currently, the SIFC is offering a number of perks to investors that put their money in corporate farming. Foreign investors are allowed to own 100% equity in these projects and are also being given tax breaks of up to 25% on these projects. Despite this, interest has been passing.

Where it has come from however is domestic companies. Profit has been informed by reliable authorities that Fatima Fertilisers, Unity Foods, Roshan Packages, and also some large conglomerates such as possibly Descon are stepping up to the plate and investing in corporate farming.

“As things stand, a number of companies have entered into MoUs with the SIFC even if not in final contracts. Everything is being managed through the FonGrow company they have founded. It seems that foreign investors are a little harder to convince right now but we are hearing good news is right around the corner,” says Zaki Ajaz of Roshan Packaging, which is getting into corporate farming through the SIFC.

As he explains it, around 3 lakh acres of land has already been set aside for local companies to set up their farms on. The cost of setting up on this land, most of which is in Cholistan, is around Rs 5 lakhs per acre. This means that if the SIFC has managed to lease out around 3 lakh acres of land, that is an injection of around Rs 150 billion into corporate farming in Pakistan.

According to the SIFC’s own estimations, this business model demonstrates the feasibility of corporate farming on a large scale culturable wasteland in Cholistan with a front-

load cost of Rs. 37.55 billion to cultivate 50,000 acres. This estimate is a bit higher than the one provided by Mr Ajaz of Roshan Packaging but is within the same Rs 150-200 billion ballpark range. The problem here is that all of this investment is in rupees.

“Currently around 3 lakh acres are being given to selected companies to start work on corporate farming but the demand is much higher than they anticipated. In reality there might actually be a demand for around 7-8 lakh acres right now,” says Zaki Ajaz.

But why such high interest?

On top of this, the companies that are going for this all have something or the other to do with the agriculture business. One such company that is entering corporate farming is Fatima Fertilisers. One of Pakistan’s largest fertiliser companies, Fatima has a clear interest in wanting a corporate farm. Pakistan already has excess capacity that is not being utilised in the fertiliser industry and if unused land was to start being used there would be a higher demand for fertiliser.

Unity Foods has a similar interest since they could then grow a lot of their own raw materials. Similarly Roshan Packaging would also diversify into food packaging and enter the agriculture supply chain along with corporate farming. This means companies like this can synergise their businesses by having the ability to lease their own farms.

“We have no issue of rupee capital availability for our project because ultimately it will bring returns to Fauji Foundation,” says General Tahir. “There is a small challenge that we are facing basically, which is of foreign exchange because the irrigation systems and the tractors and harvesters that we have to import, they need foreign exchange.”

This is what we have up until this point. Pakistan’s armed forces have been interested in corporate farming as a concept for some time now.

Since at least 2021 they have been making attempts to acquire government land as part of a partnership and cultivate this land that is not being used. Under the banner of the SIFC, this vision is materialising. The Fauji Foundation has created a company to help manage corporate farming projects and while foreign investors are still deciding, plenty of local companies are signing MoUs.

But why does it matter so much? Mostly because Pakistan is at a crucial crossroads when it comes to agriculture. The current situation is such that the country’s population is growing at a higher rate than the rate at which food production is growing. In an international ranking of the Global Hunger Index (GHI) this year, the country ranked 92 out of 116 nations, with its hunger categorised as ‘serious.’ Pakistan currently faces a scenario in which it is largely food sufficient but not food secure.

Despite Pakistan being ranked at 8th in producing wheat, 10th in rice, 5th in sugarcane, and 4th in milk production, a 2019 report of the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) showed that nearly 37% of households in Pakistan are food insecure. In the three years since the SBP’s report, matters have only worsened. Food price inflation in Pakistan has been in double digits since August 2019. The cost of food has been 10.4-19.5% higher than the previous year in urban areas and 12.6-23.8% in rural areas, according to figures published by the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics.

And these are statistics from before the past year in which the country has been hit by wave after wave of inflationary pressure. To put this into perspective, food Inflation in Pakistan averaged 10.45 percent from 2011 until 2023, reaching an all time high of 48.65 percent in May of 2023.

The SIFC’s proposed solution to this is to increase the amount of land we have under yield. Pakistan has a geographic area of 79 million hectares (1H=2.47acres). Out of that, a mere 15.7 million hectares are cultivated. Besides, more than 8.2 million hectares are

As things stand, a number of companies have entered into MoUs with the SIFC even if not in final contracts. Everything is being managed through the FonGrow company they have founded. It seems that foreign investors are a little harder to convince right now but we are hearing good news is right around the corner

Zaki Ajaz, Non-Executive Director Roshan Packaging

classified as culturable waste (uncultivated farm area that is fit for cultivation). But is it a viable solution?

It sounds like a pretty neat solution. Pakistan doesn’t have enough food. The population is growing which means the demand for food is growing as well. So what do you do? Lo and behold the government has lots of free land that is not being used but is cultivable. You take that land, start developing it, lease it out to third parties that will grow crops on it and then the food supply in Pakistan will increase. If you get enough of an area cultivable the difference will be big enough that you can fulfil your own needs and even export the leftovers.

Right?

It is a little more complicated than that. For starters, a lot of the state owned land being leased out for 30 years or more, in some cases, is land that could be protected forest area. Since no clear demarcation has been made of what lands are going to be part of this, there is still very little clarity. Even in areas we know such as the Cholistan desert, there are a lot of questions that can be raised. After all, it is very easy to simply draw a circle around Cholistan and say it is a wasteland that can be better used but it is a biodiverse ecosystem that hosts many species and indigenous communities. And that also brings us to the bigger question in Pakistan pursuing corporate farming on such a massive scale.

Who will work the land? Pakistan’s land owning patterns are abysmally inequitable. With an average farm size of just over 2 hectares (5 acres), over 90% of landowners in Pakistan owning farmland of less than 12.5 acres; and only 3% of landowners having land-ownings of more than 25 acres; the agricultural landscape is dominated by subsistence farming, and a small number of absentee large landowners, all dealing with aarthis or middlemen.

“The idea of Corporate Farming or Large Scale Contract Farming has been around for a while, and the government says it is one of the primary potential avenues for investment in the country,” says former KP Finance Minister Taimur Jhagra. According to him, if agriculture improves through corporate farming it can be a great avenue of export particularly to the Gulf countries which have bread basket problems.

“As a result of middle men and inefficient land divisions our agriculture sector continues to underdeliver because of a vicious cycle of poor agricultural practices, unavailability of technology and finances, poor inputs, low investment, low yields, low productivity, poor quality and poor profitability. This cycle needs to be broken at a scale disrup-

tive enough to make a difference, and while controversial, corporate farming may be one disruptive way of challenging these problems from the demand side,” he adds.

“In fact, perhaps in addition to the GCC countries and China, it is worth pursuing companies like Coke, Pepsi, Nestle, and chains such as Carrefour and Metro, to see if they are willing to invest more in the sourcing of more local ingredients for their products, investing in value addition, and creating value chain partnerships with farmers and markets.”

Essentially, you have a situation where there will be labour shortages and on top of that, even if enough farmers are convinced to relocate, they will not know how to work this new land. The SIFC is encouraging progressive farming techniques for corporate farming. They have asked their partners to use the latest seeds, mechanise the farms to at least a certain extent, use drip irrigation, and many other modern methods and techniques. They are developing applications and other predictive technologies to ensure maximum yield on these lands. Partners have to conduct soil and water studies before planting and report back to the SIFC with the results. And while all of these measures are positive signs, there are serious questions about who will make it happen on the ground.

On top of this, corporate farming will do very little to alleviate rural poverty. According to Syed Muhammad Ali, an academic and author, the probability of military-operated corporate farms being able to help address rural poverty remains limited at best. “While land ownership patterns vary significantly across different districts, a lingering cause of rural destitution is highly skewed land ownership patterns,” he writes.

“The idea of external investors using finite land and scarce water resources to grow crops for export when the country itself

is facing water scarcity and food insecurity remains contentious. Rural areas in Pakistan are much poorer than its cities, and recent climate-induced stresses such as water scarcity and increasingly severe and frequent floods are making matters worse. While land ownership patterns vary significantly across different districts, a lingering cause of rural destitution is highly skewed land ownership patterns.”

This is really what it boils down to. Pakistan stands in the midst of complete economic peril. One can make many arguments about where and when the rot set in. Currently, the situation is being handled by a group of people that can very broadly be defined as establishment. There is much to be said simply in terms of historical fact about how we got here. This teetering understanding between civil and military authority first came about in the 1990s when a faltering democracy desperately tried to take root in Pakistan. It can be traced back through a history of multiple coups, war, and political engineering. But what matters at the moment is that major initiatives are being taken and it is still worth looking at what the cost and benefit will be to these.

In the case of corporate farming, Pakistan’s agricultural output can very well increase. But will it result in a net improvement for the most vulnerable segments of society? Or will it instead create a new feudal class backed by the powers of progressive, modern, mechanised farming? Only time will tell. The current pattern being followed of awarding lands and leasing them out to be developed comes from a very colonial mindset, and it isn’t particularly difficult to imagine which way the cookie will crumble. n

The idea of external investors using finite land and scarce water resources to grow crops for export when the country itself is facing water scarcity and food insecurity remains contentious. Rural areas in Pakistan are much poorer than its cities, and recent climate-induced stresses such as water scarcity and increasingly severe and frequent floods are making matters worse. While land ownership patterns vary significantly across different districts, a lingering cause of rural destitution is highly skewed land ownership patterns

Syed Muhammad Ali, Academic and Author

What is a digital telco brand? What is the need of one? And what additional value does it offer customers already using a conventional network provider?

By Shahnawaz Alihen an average Pakistani is asked about what they remember about telecom companies from the 2010s, most of them would recount the iconic Ufone television ads. But what most people do not remember is what other telcos were doing at that point in time.

Other than trying to beat the Ufone ads with their own “diss-track-TVCs”, these companies were employing another business strategy of ‘divide and conquer’.

Despite having their names out in the open, companies were operating by the means of brands. Djuice by Telenor, Indigo and Jazz by Mobilink and Glow by Warid are just some of the examples of Pakistani telecoms diversifying their brand names. These brands were often designed in a way to provide different demographics of consumers with an alternative option. With packages and plans more curated to that demographic’s needs and wants.

However, since the last 6-7 years, none of the telcos have initiated this type of brand

Wdiversification. Some have disappeared, while others merged into their companies’ single brand name sims. But all of a sudden, one telecom company in Pakistan has taken a new step. Reminiscent of the old age business tactic, Ufone 4G’s company PTML (Pakistan Telecom Mobile Limited), has decided to launch a brand called “Onic Pakistan”.

A company that, except for its one attempt called Uth, never dabbled much into the mix of different brands to begin with, has decided to give it a go much later. With a new digital telco brand Onic, Ufone (Formally PTML) has stepped into what is going to be uncharted territory for them. But what is a digital telco brand? What is Onic? How is it different from other brands? And who is its target audience?

For a layman, the definition would be pretty hard to understand, and the reason is that there is no one definition in particular. A telecom brand that has, in essence co-opted digital solutions to stay ahead of the curve is loosely categorised as a digital telco. Here is how it all started.

Over the last 20 years, telcos have seen a massive rise and fall in their revenues and profits. What was once the newest and most innovative business in the late 90s, became outright obsolete by 2020.

So much so that the growth of telecom brands is currently sitting at an all time low. The core telco revenue streams such as voice and SMS are being replaced by digital and OTT (Over The Top) services, these services include household tech ecosystems and streaming services.

Meanwhile the profit margins on mobile data continues to narrow on the back of downward price pressures and competition. A simple example of this is that as a consumer, you would not take a single second to jump onto a whatsapp call if the cost of the voice call goes beyond a certain margin. Similarly one would jump to WiFi if their “mobile data” is expensive or slow.

So this is where the problem lies. Pricing cannot be up to speed with the rising cost of doing business and a weakening rupee; hence the telco is forced to take the hit. As of February 2023, average revenue per user for a telco in Pakistan came to $0.8/month. Meaning that every individual who uses a mobile phone provides less than a dollar in profit to

their telecom company. The same statistic ARPU stands at almost $3/month for India and $30/month for USA.

So the incentive to branch out into a different revenue stream makes sense for Pakistani telcos. But this is not just a problem for Pakistan.

According to a recent report by Kearney, the average revenue growth across global telcos has also continued to decline. From 4 percent average growth between 2011 and 2016, to 0.2 percent between 2016 and 2022. Simultaneously, telcos’ efficiency initiatives have started yielding diminishing returns after years of progress. And meanwhile, these initiatives leave the telcos with a looming Capital Expenditure (CapEx) disaster, driven by rapid data consumption growth and eventual migration to 5G, demanding expensive infrastructure and yet no clear commercially viable use cases.

As margins continue to be squeezed, the more circumspect telcos started embracing digital businesses as a saving grace. This meant that they would indulge into a wide variety of digital businesses. What were these businesses? They range from things that were entirely in a telco’s domain to things that… just got the cash rolling.

For example; Digital telcos often bundle telecom services with other digital offerings, such as streaming content, cloud storage, or smart home services. These telcos also form partnerships with digital ecosystem players and content providers like OTT (Over The Top) platforms and IoT (Internet of Things) service providers. A lot of these services give them a penetration and are easy to do because of their access to user data.

Other than that, these companies employ data analytics, automation and AI to make agile operations, improving and automating the user experience. So where you’d spend hours to get a response on your email, a digital chatbot will solve your query

right away with its integrated manual. These brands also tend to make use of up and coming technologies like 5G computing and network slicing. These technologies upgrade their services and take them a notch above the traditional telco. This falls in line with improving the technology on the back of which their voice and data services would also flourish.

Some of these latter services have already been adopted by traditional telcos, that don’t portray themselves as transitioning towards being digital telcos, nor have they announced a new brand. Calling yourself digital, hence, is akin to being aboard the ship of the digital revolution, making it a lot more about brand optics.

In an attempt to privatise PTCL, the state in 2005 sold 26% of its stake in PTCL to UAE telecom e& (previously known as etisalat). Being a wholly owned subsidiary of PTCL, PTML was hence also as much under e&’s influence.

Upon rebranding itself as e& from Etisalat last year, one of the key objectives of the group was to become a technology companies group, rather than just being a Telecom group. In the process they have introduced their ventures e& life, e& enterprise and e& capital over the years. e& has been making strategic investments in tech companies. e& life, for example, is categorised as a financial super app meant to revolutionise the fintech space.

The UAE state-backed e& not only has the access to a virtually bottomless balance sheet in the form of the UAE government, but also to some of the biggest telecom brands of the Middle East, and North Africa, and through them an unlimited access to user data.

In the same stint of revolution and modernisation, e& entered into a partnership with a Singapore based Startup, Circles. A startup founded by a Pakistani amongst others, Circles offers digitisation services to telcos. Circles’ understanding with e& is to “empower its network of Mobile Network Operators (MNOs) and other operators based in the region to launch digital telco brands that deliver delightful digital experiences for the digitally savvy generation.”

In this newer understanding, all the portfolio telco companies under e& are making, or expected to be making similar headways in the future. What is interesting to note here is that, e& despite being a mere 26% stakeholder in PTCL, and subsequently PTML, is ready to serve up its direct deal with Circles Life to PTML.

However, being a “part” of e&, these steps are being taken by PTML and Onic is a manifestation of the e& goal. As per the spokesperson of PTML, “e& Int’l is an established global player in this domain, therefore, their collaboration with PTML will usher in a world-class user experience to our segment of data savvy urban customers.”

When Onic first started marketing itself mere weeks ago, it rang alarm bells across the board. People started to think that a new company had been given a licence to operate as a telco in Pakistan. The rumour became so widespread that the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority (PTA) had to do a press release in which it had to clarify that Onic was not a new company, but a “new digital product, to cater for digital segment of the market who prefer convenient digital engagement instead of traditional service delivery”.

The Press Release clearly suggests that

Onic’s customers predominantly are digital natives, who are avid smartphone and digital apps users. They consume a lot of data and are deeply immersed in a digital lifestyle that extends to both work and leisure activities. They are also distinct due to their higher service expectations. Therefore, Onic promises an improved digital experience to enable this unique segment and to drive the vision for Digital Pakistan

Amir Pasha, Spokesperson PTML

Onic is another Ufone “product”. And that is exactly what it would have been perceived as, provided that no new licences were issued. However, according to the Linkedin header of one executive employee at Onic, they were “Building Pakistan’s First MVNO (Mobile Virtual Network Operator)”, on the back of which tech blogs dug into Onic. When asked about the entity’s legal status, the spokesperson from PTML confirmed that Onic was indeed just another brand of PTML, much like “Ufone 4G ‘’, and not an MVNO. Therefore Onic is to PTML, what Indigo was to Mobilink.

It is important to note here that an MVNO is required to obtain a licence worth $5 Million from the PTA, an obligation that a “brand” or a “product” is devoid of. This rang alarm bells for a lot of people when they saw Onic being called an MVNO on the internet.

What is an MVNO? According to the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), “it is an operator that offers mobile services but does not own its own radio frequency. Usually, this operator has its own network code and in many cases issues its own SIM card. The Mobile VNO can be a mobile service provider or a value-added service provider.” This means that it could be an entirely different ecosystem altogether using an MNO’s (Mobile Network Operator) spectrum of cellular mobile services.

This gives rise to another pertinent question. How does a regulator differentiate between the two? This takes us in a different direction albeit an important one. It turns out that it is as confusing as differentiating between a digital telco and a non digital telco. The definition of what an MVNO is, is not even consistent across countries. The PTA obligates an MVNO to sign an agreement with an MNO (Mobile Network

Operator) before starting operations, but can the MNO own the MVNO? Commercially, it makes no sense.

Why would a company that already owns a spectrum of cellular mobile services and has its own licensed radio frequency go through the tardy process of registering a new entity, obtaining an expensive licence to do the same under a different name. Especially when they could already do that under their own company. The licences do not belong to Ufone, they belong to PTML. So just like Ufone, Onic is another brand of PTML.

Often, whenever the other telcos would release their new “brands” in the market, it had the same design language, the same colours, or sometimes a watermark of the company or a sister brand, making it obvious as to where they were coming from. Glow, for example, was officially called, “Glow by Warid”.

By giving no indication to where it is coming from, Onic avails a distinction upon the much older Ufone, something that only a new entrant would have been able to achieve.

In Onic’s defence, this could be entirely a move by PTML to redefine themselves, leaving all the negative equity of the past behind them. Ufone, afterall, was the last in Pakistan to obtain 4G capability, a fact that does not espouse the greatest amount of trust in the younger user.

Is there a use case of regulating the amount of “brands” a single telco can have? Yes. Is the regulator or the Competition Commission ahead of the telcos in this respect?

No. If it ever comes to one telco enjoying an unprecedentedly large share of the consumer pie, the government is sure to react, but will it preempt this? History does not suggest so.

Like a university student from a small town, on the face of it, Onic looks nothing like its “family”. The brand’s logos exude more sparklets than the historically state-owned PTML has ever done. An ad campaign strictly limited to digital platforms and social media apps, as of yet, Onic is proudly “digital”. Starting off with a teaser billboard campaign, Onic hired top models and celebrities before people even found out about it being a telco. The company has done mass-grabbing comical videos, no TVCs or sponsorships, it wouldn’t be a surprise if Onic were to sponsor MUNs in universities before it sponsors a soap opera on Prime Time Television.

All of the flashy and edgy design could mean only one thing, and that is that Onic is trying to acquire the allegiances of the younger audience, the Gen-Z. An age demographic that is the largest in terms of phone users. According to PTA, 77% of smartphone users in Pakistan are between the ages of 21-30. The technologically literate, TikTok and Instagram addicted generation has the internet down there with water and oxygen in their Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

Talking to Profit on the subject, PTML spokesperson, Amir Pasha said that, “Onic’s customers predominantly are digital natives, who are avid smartphone and digital apps users. They consume a lot of data and are deeply immersed in a digital lifestyle that extends to both work and leisure activities. They are also distinct due to their higher service expectations. Therefore, Onic promises an improved digital experience to enable this unique segment and to drive the vision for Digital Pakistan.”

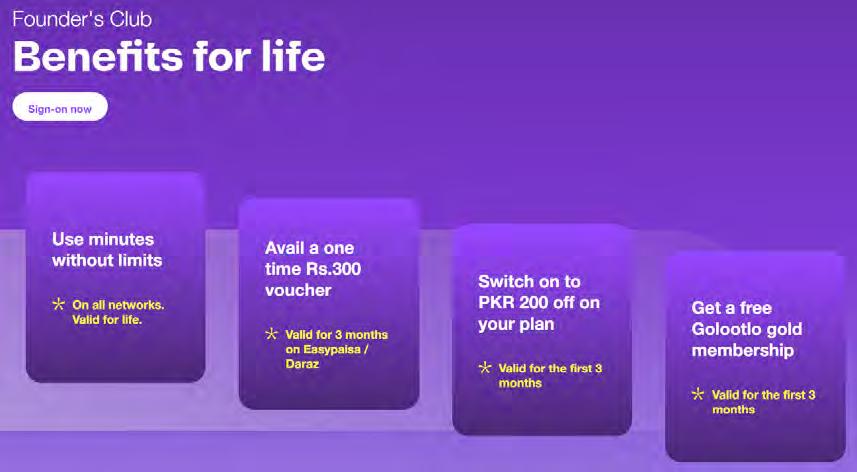

Perhaps the most important question that arises here is, how is Onic different? As per Onic’s website, it is said to provide its founders (founding customers) Off-net liberty, Home delivery, Hassle free onboarding, Swift assist, Fast activation, Carried data and a sign-on to founder benefits. As commendable as these steps are, all of them seem to be catered towards, user experience and onboarding. And even though user experience is one aspect of a customer’s needs, it is not their entire need.

When asked about this, an Onic spokesperson said that, “Unlike traditional telco brands, Onic operates entirely in the digital realm without any physical outlets. It offers a comprehensive range of services through its Digital App. For instance, customers can order SIM cards and have them delivered at a time and place of their convenience.

Additionally, Onic provides the convenience of e-SIM functionality. Onic aims to bring services directly to the customer’s time and place of convenience, eliminating the need for visiting physical stores while also offering hassle-free digital recharge options”

Sounds like just a bunch of corporate talk, right? Other telcos, including Onic’s sister brand no less, Ufone, do all this already. Both Jazz and Telenor sims can be ordered online. Ufone itself offers an e-sim. And all biometrically issued SIMs since the last 5 years are Pre-activated. It is difficult to comprehend how much faster can Onic’s “Fast activation” then be, that it defies chronology itself.

When it comes to being native on digital platforms, all Jazz, Telenor and Zong have Jazzworld, My Telenor and My Zong apps respectively, where a range of services, including subscriptions, recharge and packages are available. Infact, Telenor and Jazz, both of which are Digital Bank and EMI (Electronic Money Institution) Licence holders respectively, don’t just bring an in-app recharge option for their user, but in essence, an entire bank.

When asked about the technological advancements in Onic for the provision of better telecommunication services of voice, SMS and data, Pasha said, “Onic uses a state of the art IT platform for optimum quality, efficient service delivery and alliances with digital platforms”.

Onic denied delving into any OTT and IoT service provision in the future, something that digital telcos across the world aim to do. Infact Tamasha, Pakistan’s largest OTT and streaming service is a part of Jazz’s arsenal of digital service apps. So in a way, Jazz tends to be a step ahead in embracing the digital revolution. If anything, the other telecom brands offer a range of digital services, while simultaneously having a physical presence.

Another issue is that of network avail-

ability. Onic is only operational in Karachi, Lahore and Islamabad at the moment. This means that for many, an additional mobile network operator’s connection will be required to have nationwide coverage.

One thing that the younger customer does not have a lot of is disposable income. If Onic is to be their secondary sim, it needs to make a lot of financial sense.

Comparing Onic’s prices, it was found that not all telcos were more expensive than Onic. Onic currently offers 3 hybrid plans for its “digital natives’’, all of which are on the heavier side of mobile data volume. Its smallest plan offers 30 GB internet and additionally 5000 All-network minutes along with SMSs. The other 2 plans have 100 GB and 200 GB with the same amount of voice minutes and SMSs.

Compared to that 30 GB offer, Telenor 4G, offers similar deals that are at least 20% cheaper in the form of its easycards. Telenor’s Easycard 850, offers 24 GB in data and 5400 minutes (5000 On-net and 400 off-net) in Rs 850. Compared to this offer, Onic’s plan is just at par. However, Telenor’s monthly extreme, which offers 50 GB in 1100, takes the lead in both voice minutes and mobile data. With 50 GB data and 8100 minutes (7500 On-net), the offer is at least 20% cheaper than Onic in its per GB cost.

Similarly, Ufone 4G, PTML’s other brand, also offers good hybrid deals. However, Ufone’s Super Card Gold at Rs 1199, with 30 GB data and 8100 minutes (7500 On-net) stands just a touch more expensive than Onic. Intuitively, both Jazz and Zong have more expensive plans with Jazz’s Monthly Premium Plus giving 20 GB and 3500 minutes in Rs 1250, and Zong’s Monthly Super giving 30 GB and 5400 minutes in 1299.

The only major difference that Onic is able to create is the 5000 all-network minutes that it offers, as opposed to the hassle of Onnet and Off-net minutes.

In voice calls, companies differentiate between on-network and off-network calls. If the caller and the recipient of the call are using the same telecommunications network providers, it is On-network (on-net), whereas if the caller and the receiver are using different telecom networks, it is an Off-network (off-net) call.This means that while with other networks, the consumer has to be mindful of what network’s number they are about to dial, and whether they have enough minutes left to call that particular network, Onic’s customers can call anyone without bothering with the receiver’s network or their remaining quotas. For some, this counts as a blessing but for others, who have had their friends and family to move to one brand, the higher on-net minutes prove to be a better deal.

Regardless of the first plan, Onic was found significantly cheaper than the competition, in high volume data packages. It offers 100 GBs and 200 GBs along with 5000 all network minutes for Rs 1290, and Rs 1990 per month respectively. Other brands do not offer this volume of monthly data however, they only do so in the case of MBB devices (Mobile Broadband). Even for MBBs a 200 GBs Zong Package costs Rs 3300, while a 100 GBs Jazz package costs Rs 2400.

So is Onic as revolutionary as it would have the people believe? Not really. It seems like a compact, better worded, and better marketed version of Ufone. Whether to use Onic or not, invokes the same debate as a good UI/UX fintech digital wallet does. Is it important to have one if you already use a traditional one? Not really. But it is 100% the customer’s choice to opt between the seemingly cooler or the traditional looking product.

Onic is definitely positioning itself as a market leader in offering high volume data packages at a reasonable price, but what other things does it have under the belt? As of now, the brand’s team refuses to comment on their future ideas. n

More than one-third of all energy consumption in Pakistan can be attributed to the transportation segment, covering motorcycles, automobiles, trucks, etc. Pakistan’s biggest import for the last many years is oil and associated petroleum products. Any sharp rise in oil prices eventually leads to a crisis in Pakistan, as higher oil prices translate into an expanding current account deficit, a depreciating Rupee, and eventually higher inflation. In the first round of inflationary impact, the price of petroleum products increases which bumps up inflation. In the second round of inflationary impact, prices of other goods in the economy increase, as the Rupee also depreciates, and businesses incorporate the higher cost of fuel in product prices. As inflationary effects start to settle, another round of oil price shocks reverberates through the economy again, further fueling inflation like clockwork.

Over the last five years, Pakistan has imported more than US$ 73 billion in fuel, making up 28 percent of total imports. Despite increasing import bills, per capita consumption remains largely unchanged given the increase in population. This implies that due to increase in prices, affordability has also gone down, resulting in flat consumption of energy, and largely muted economic growth.

It is estimated that there are more than four million cars in Pakistan, and more than twenty-four million motorcycles. Almost 40 percent of all fuel consumed in the country is effectively in motorcycles. Similarly, movement of goods in the country is primarily through diesel-powered trucks, rather than more scalable, and fuel efficient solutions, such as rail. Movement of people, and goods essentially consumes a significant quantity of our total oil imports – making its consumption relatively inelastic. As the price of oil increases, disposable incomes after adjusting for fuel expenses also decline, leaving fewer resources for reallocation to other essentials. A pro-people energy policy would focus on improving affordability of transport, enabling access to transport more equitable, while striving to reduce energy intensity of the economy.

The core objective ought to be to reduce reliance on imported fuels, while also improving affordability, and making transportation more efficient. Productivity gains, and their contribution to the GDP can only be realized through improved efficiency. There exists a strong case for aggressively rolling out public transportation options across the country. Over the last few years, there have been a few projects, but a lot more needs to be done.

As an example, the Karachi Green Line, which is a massive infrastructure project serving more than one million commuters on a monthly basis was established at a cost of PKR 35 billion. Meanwhile, the fuel subsidy that was given in 2022, that wrecked the economy, cost the national exchequer more than PKR 450 billion. Effectively, this subsidy could have potentially funded dozens of large-scale public transportation infrastructure projects across the county. These projects would not have just increased mobility of people, but also improved affordability of transport, and reduced reliance on oil imports.

The country needs a public transportation emergency, that not just improves efficiency, but also reduces reliance on imported oil, while improving disposable income for households. The federal, and provincial governments need to roll-out public-private partnership schemes for public transportation infrastructure through a reverse dutch-auction process, with the government eventually becoming an enabler to support growth of public transportation rather than a capital provider.

The transition away from imported oil is largely a policy issue, rather than a capital issue. The government can crowd in private capital and enable development of transportation infrastructure, eventually phasing out private consumption of oil with more efficient public consumption. In addition to a transition towards public transportation, it is important for the government to have a forward-looking outlook. Oil is a fuel of the past, it is electricity that will drive transportation in the future. There exists a strong case to set ambitious targets to phase out petrol and diesel powered cars with electric cars. The government can essentially mandate that by a certain targeted date any new cars sold need to be electric cars, thereby encouraging investment in automobile manufacturing facilities for the same.

In parallel, the existing network of petrol stations can gradually transition towards electric charging stations. Moreover, the public transportation emergency can simply mandate usage of only electricity buses for public transportation as the lowest hanging fruit in accelerating transition away from imported oil. It is essential to note that Pakistan has surplus electricity generation capacity, and more capacity is under construction to be added over the next few years. Moreover, Pakistan’s electricity generation mix is skewed towards more local indigenous sources, including hydro, nuclear, and Thar coal. It is possible to generate greater quantities of electricity through indigenous sources, such that it can electrify our automobile and transportation infrastructure. Through such a maneuver, it will be possible to wean off dependence on consumption of imported oil, while increasing reliance on indigenous resources. A key blocker here is a horribly inefficient electricity transmission and distribution infrastructure which leads to significant line-losses and high costs for the consumer. Fixing the energy puzzle also requires reforming the transmission and distribution infrastructure – without which it may be impossible to achieve any productivity gains through efficiency.

A trade imbalance cannot be fixed till we fix reliance on imported oil for transportation purposes, which effectively drives consumption. A pro-people policy would aggressively roll-out public transportation, and electrification of transport, while reforming the transportation and distribution network. More than five years of flat growth continues to erode real incomes of people, and it is time that necessary efficiency gains are also realized, while spurring an increase in overall real incomes. A transition towards an electrified transportation regime, heavily reliant on public transportation infrastructure will not only improve overall household economics, and purchasing power, but also reduce external deficits, and keep inflation under check.

We can either make policies for the future, and for the betterment of the people of this country, or we can continue using a fuel belonging to the last century, and keep transferring household wealth to oil exporting countries. n

Looking

By: Zain NaeemThey say never ask a man’s salary. So we will not. But what about the people who are supposed to disclose it in their financial statements? It is not asking if these figures can be found in the companies’ own disclosures. Profit carries out an exhaustive analysis of more than 200 brokerage houses operating in Pakistan and sees how much the CEOs are actually being valued by the companies they are running.

Before the story delves into the numbers and figures, let’s quickly discuss what the role of a CEO actually is. Imagine a captain of a ship. The ex-

pertise of the captain is not how to steer the ship or even how to power the ship towards its destination. The real expertise of the captain is to provide direction and a sense to the whole crew to pull together.

The task at hand of the captain is to make sure that the whole crew works in unison with each other and to provide a vision that needs to be fulfilled. Mind you, that does not necessarily mean that he will be successful. Far from it. The role of the CEO is to bind the team into one. Before setting out on the journey, the captain does not know how many storms will have to be weathered and what challenges will be faced. The singular purpose is to make critical decisions that will help reach the common goal at the end.

Similarly, the CEO of the company has to provide a common purpose to the company which will lead to success in the future. The CEO is elected by the board of directors and

the shareholders of the company and carries the mandate to drive the company towards success. The CEO is answerable to both the shareholders and the board and is the liaison between the management running the company and the board of directors to make sure everyone is onboard with the vision of the company.

When a CEO is appointed or elected by the shareholders through the board of directors, the matter of salaries or remuneration is assigned to the board of directors. Based on the judgment of the board, the remuneration is decided upon by the board. Sometimes, a committee can be

at any CEO’s salary in isolation is sort of pointless. It has to be contextualized against performance. We attempted to do exactly that

created under the board which opines over the decision and then sets the remuneration of the CEO that will be paid out at the end of the year.

This compensation package of a CEO can be broken down into different elements. The first part of the salary will be basically an amount that is categorized as the managerial remuneration which the board allots. On top of that, the board can provide additional allowances which form a part of the compensation that is given.

The board of directors can hand out a bonus to the CEO or give some commission based on the performance of the CEO. This is a measure of how well the CEO has performed and is pegged to a metric that the board decides.

In addition to that, medical allowance, house rent allowance, utilities allowance, car allowance, traveling and boarding allowance can also be given to the CEO in addition. Lastly, a contribution to a provident or retirement fund can also be made by the company for the CEO and a listed company might also consider compensation in terms of stock options as well.

In simple terms, the goal of any brokerage house is to be the middleman in the market who facilitates buyers to meet sellers.

Once the two sides come together and a transaction takes place, the broker is able to earn a small part as commission. Imagine a market where millions of trades are taking place. As the broker keeps adding these small commissions, they end up becoming a big amount at the end.

In order to maximize their revenues and profits, brokerage houses can also invest in money market instruments like T-Bills or equity instruments which provide capital gains or provide dividends to shareholders. Big brokers can also provide underwriting services to help their corporate clients during IPOs or carry out consultancy for them. Based on this, the revenue model of a brokerage house comprises earning brokerage commission on trades they facilitate, dividend income, interest income and any other consultation fees that the broker might have collected from its corporate clients.

In order to carry out this research, the complete list of brokers registered and licensed by the Pakistan Stock Exchange was taken. Of the more than 200 brokers who are registered, 100 companies were extracted for whom the relevant data could be

found. The data consisted of the performance of the companies for the last two years based on their assets under management (AUM), equity, revenues and compensation of CEO only.

BMA Capital Management Limited, Foundation Securities (Private) Limited and Topline Securities have not disclosed the notes pertaining to the CEO compensation which is why they have not been included in the analysis. Representatives at these companies were asked to provide this information, however, they failed to provide these details.

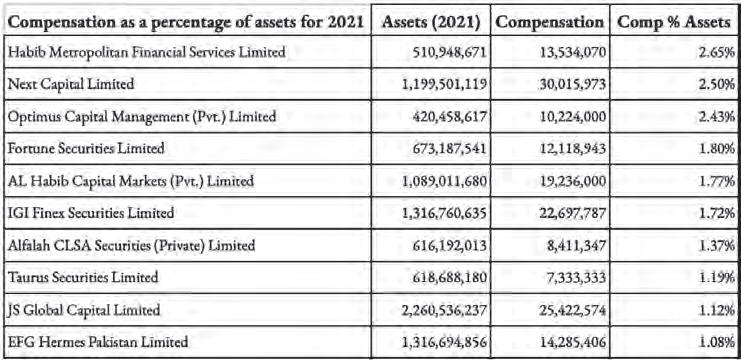

Once this had been done, the compensation of the CEOs was taken as percentage of the AUM and the following table was generated.

Metropolitan Financial Services Limited led with a payout of 2.65% of its assets in terms of its compensation for its CEO. It was followed by Next Capital, Optimus Capital Management (Private) Limited and Fortune Securities with 2.50%, 2.43% and 1.8% respectively.

In absolute rupee terms, it can be seen that the highest paid CEO in 2022 was from Next Capital earning a staggering Rs. 69.432 million while the second highest was Rs. 22.8 million from Al Habib Capital Markets and IGI Finex Securities Limited was third with Rs. 17.9 million in compensation. The compensation paid out by Next Capital was more than the compensation paid out by the next four brokerage houses combined. For 2021, the highest paid CEO was again Next Capital

Based on a brief snapshot, it can be seen that Next Capital gave out more than 6% of its assets as compensation to its CEO while the next highest compensation was 3.19%, 2.71% and 2.45% for Habib Metropolitan Financial Services Limited, Al Habib Capital Markets (Private) Limited and Fortune Securities respectively.

When a similar analysis is carried out for the previous year, it can be seen that Habib

earning Rs. 30 million with JS Global Capital paying its CEO Rs. 25.4 million and IGI Finex Securities Limited were third paying out Rs. 22.7 million compensation.

In terms of revenues earned by each of the brokerage houses, the analysis shows the following

It can be seen that Habib Metropolitan Financial Services paid out an eye-watering 48% of its operating revenues as compensa-

tion to its CEO. This means that for every rupee the company earned, it gave out 48 paisas to its CEO.