10

10 Dollar Danda: The taming of the Open Market

16 Sugar rush — Why are prices so high?

18

18 Some government employees are enjoying free electricity. Should they continue to do so?

23 Non-filers by choice

26

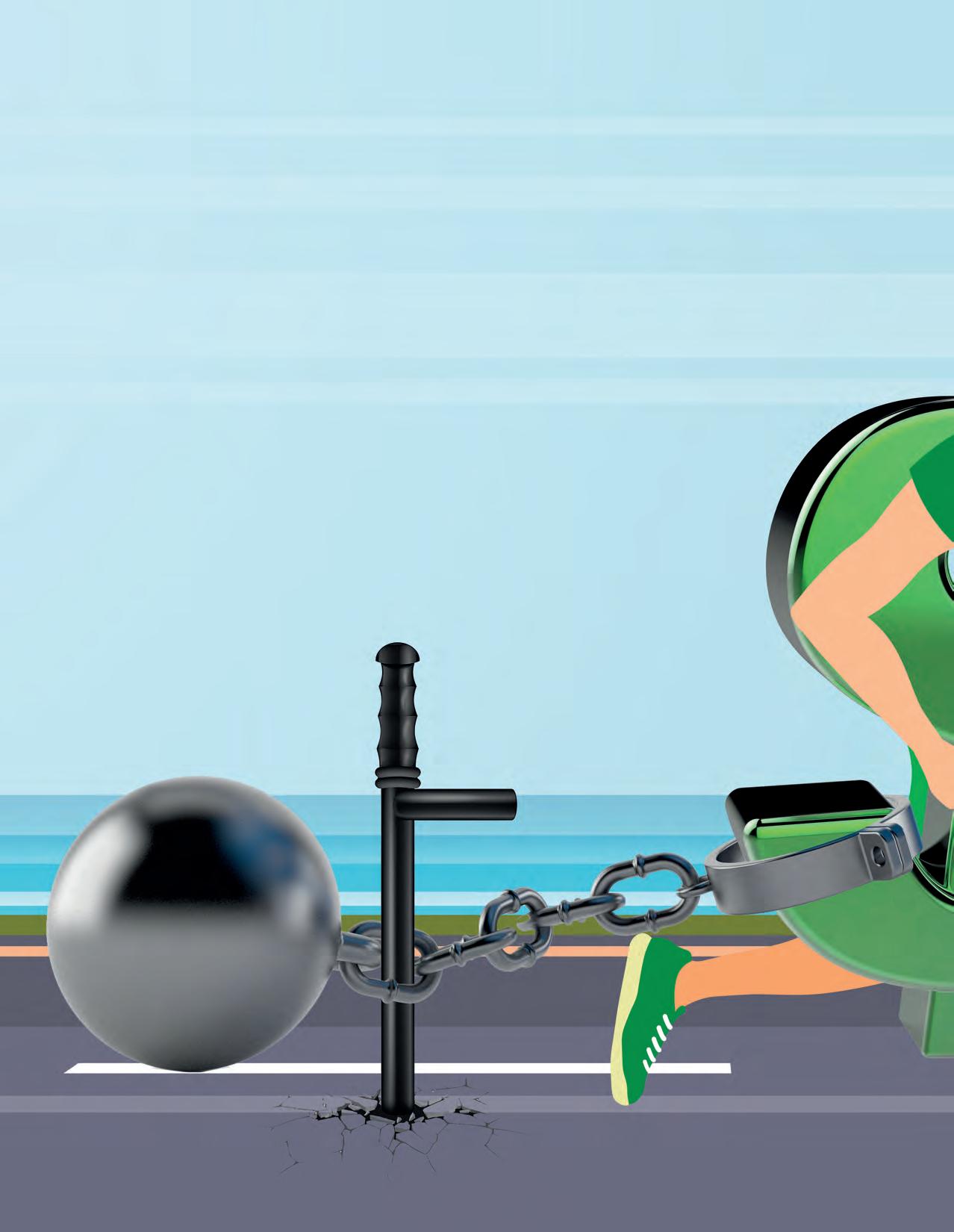

26 Why are Pakistani startups incorporating HoldCos abroad?

28 Governance system for local governments - Part 2 Ishrat Hussain

Publishing Editor: Babar Nizami - Joint Editor: Yousaf Nizami

Senior Editor: Abdullah Niazi

Executive Producer Video Content: Umar Aziz - Video Editors: Talha Farooqi I Fawad Shakeel

Reporters: Taimoor Hassan l Shahab Omer l Ghulam Abbass l Ahmad Ahmadani

Shehzad Paracha l Aziz Buneri | Daniyal Ahmad |Shahnawaz Ali l Noor Bakht l Nisma Riaz

Regional Heads of Marketing: Mudassir Alam (Khi) | Zufiqar Butt (Lhe) | Malik Israr (Isb) Business, Economic & Financial news by 'Pakistan Today' Contact: profit@pakistantoday.com.pk

The crassness with which the Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI) makes world cricket dance to its tune is matched only by the complete deference of other cricket boards.

The recent announcement that a Super Four game between India and Pakistan in the ongoing Asia Cup would have a reserve day has made a complete mockery of any semblance of equality in world cricket. For the reader unaware of how cricket tournaments work, this gives an undue advantage to both India and Pakistan in the tournament.

Reserve days as a concept in cricket are only ever used for big matches such as world cup finals. So why is a reserve day being set for a group stage encounter in a tournament not half the size of the world cup? Mostly because no matter where in the world it happens or under what circumstance a clash between India and Pakistan is the most watched event in the world.

With billions of people regularly tuning in to watch the high-voltage encounters the sheer economic power of this rivalry is massive. Yet this potential is ridiculously ignored only because of the BCCI’s continued insistence on politicising cricket and punishing Pakistan for the antagonism in foreign relations between the two countries.

Just look at the ruckus created by the BCCI around the Asia Cup even before it began. Pakistan was supposed to host this year’s Asia Cup under a tournament hosting rights division drawn up by the International Cricket Council. This would be the first major tournament hosted in Pakistan in decades and would bring significant broadcasting and marketing money for the Pakistan Cricket Board (PCB).

But the BCCI’s secretary Jay Shah, also the son of India’s home minister and Prime Minister Modi’s right-hand man Amit Shah, was more than happy to play spoilsport and announced India would not be travelling to Pakistan for the Asia Cup in 2023. Normally you’d think the country with the hosting rights would give this a “fine-by-us” and continue making arrangements. In fact if it had been Afghanistan, Bangladesh, or even Sri Lanka throwing a tantrum of this nature, the PCB would have snubbed them back.

But in the world of cricket India gets what India wants because it controls the pursestrings. With a cricket economy worth tens of billions of dollars (only the broadcasting and media rights for the IPL were worth more than $6 billion) the BCCI is more powerful than the entire ICC combined. Thanks to this financial muscle, almost every cricket board in the world, including other big fish like England, Australia, and South Africa, depend heavily on the rich spoils that they get from bilateral series with India.

Since consolidating its position as head honcho of the cricket world over the past 16 years, India has gone on a concentrated effort to

strengthen its relationships with other big boards such as Australia and England and systematically turn Pakistan into a pariah. The last time the two neighbours played a test series was in December 2007 in India. Since then, other than one short-format bilateral series hosted by India in 2012, the two arch-rivals have exclusively faced off in larger tournaments such as the cricket world cup. Pakistan’s players have also been excluded from the IPL since at least 2010 after the Mumbai Attacks.

Despite this, Pakistan cricket has persisted. Successive PCB administrations have managed to galvanise efforts like the Pakistan Super League, earn profits, and easily become one of the biggest boards in world cricket after India, England, and Australia. The biggest element in this has been the HBL Pakistan Super League which has been a great economic success but has also helped bring cricket back to Pakistan after the disastrous attack on the Sri Lankan cricket team in 2009. Since the beginning of the tournament South Africa, New Zealand, England, and Australia have all toured Pakistan as well.

The PCB has proven, not by any virtue of their own vision but simply out of necessity, that it is possible to not just survive but thrive without the BCCI. At the same time other boards have stayed quiet over the injustices and regular snubs suffered by Pakistan because they have been surviving off the scraps of Indian cricket. Pakistan had no choice but to exert its independence and it has managed to do so with aplomb.

Despite this resilience it is important to acknowledge that Pakistan cricket has suffered from this pariah status. The reason behind this has obviously been the antagonism of the Indian Cricket Board but Pakistan has also rarely made a good case for itself. There has been a particular lack of effective leadership because the PCB is run from the sidelines by the country’s political leadership.

The PCB has tried to modernise as an organisation but this process has been hampered by the fact that the Prime Minister remains the patron-in-chief of the board and appoints its chairman. Quick changes in leadership have all meant Pakistan has failed to appeal to the rest of the international cricket community. Remember, it was Najam Sethi who negotiated the current Asia Cup cycle and he was out of office by the time the tournament started leaving Zaka Ashraf to manage the fallout.

India too is a politicised cricket board. Jay Shah is the son of Amit Shah who is the right hand man of Prime Minister Modi and often his vocal attack dog. Jay Shah’s provocative statements have also been political in nature. Ideally cricket boards should be separate from the government and have the involvement of players’ unions. The Pakistan-India cricket rivalry holds great potential for both countries to make money. But until the politics are set aside there is little hope of recovery.

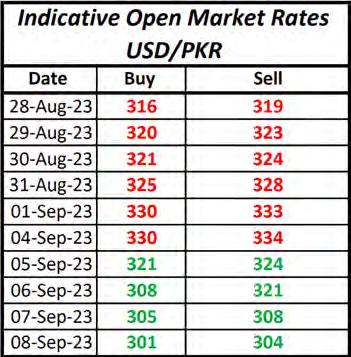

There is volatility and then there is madness. What happened in Pakistan’s currency open market in the past two weeks falls squarely in the latter category.

The unprecedented fluctuation saw the dollar go from 319 to 334 in six days and then from there, down to 304 in the following four days. Some quickly attributed this to news of twin $25 billion potential investments, from UAE and Saudi Arabia, over the next 2-5 years. This makes some sense but not enough to explain a Rs 30 appreciation against the US dollar.

the needs of dollars for the banks’ customers. Let’s say, for example, a textile exporter has received payment of $100,000 against the denim jeans he sold to a customer in the US. The exporter will receive this payment at his bank and as per rules, is now ready to exchange these dollars for rupees.

He will call up his banker and ask for the highest dollar rate possible. The banker gives him the prevailing interbank buying rate, there is some negotiation and an amount of $100,000 in export proceeds is settled at a rate of Rs 305 per dollar. The exporter gets his Rs 3 crore and 5 lacs in his Rupee account with the bank and for all intents and purposes, his transaction is done.

Note that the bank in question has effectively bought $100,000 from the exporter and added these to its dollar position. Depending on the circumstances, the bank can now do one of two things with these recently bought dollars. If there is a pending import payment of an equivalent or larger amount, it will use the amount from the export transaction (inflow) to pay for the import payment of another client (outflow). This means the bank will sell the $100,000 to its client, say a chocolate importer at the interbank selling rate of Rs 305.5 and transmit the dollars to the country from which the chocolates were imported from.

million. During such instances the interbank rate tends to go up since supply is being removed from the market.

Major inflows in the interbank market include export proceeds, home remittances, dollar encashments at branches and Foreign Direct Investments (FDI). Major outflows include import payments, outward remittances, profit repatriation of foreign companies and any payments and fees to be paid to foreign companies selling in Pakistan (think payments to Amazon, Netflix and Google or Airlines).

A combination of all these inflows (supply) and outflows (demand) takes place on a daily basis and banks along with the SBP and of late the Finance Ministry do a delicate dance of managing these various transactions to keep the interbank market and the exchange rate generated by the activity in it, in check.

Banks are heavily regulated and treasuries cannot play outside the parameters set by the regulator. They do as they are told; you can’t make money in banking if the regulator is consistently unhappy with you.

Most market experts believe and what is more plausible is that,“danda chal gaya”. There were warnings prior to it, the move was swift, fast and most importantly, clearly very effective.

What problem needed fixing? How was it created, what measures were taken to introduce such a massive correction and what new problems could this create? Who did it? Profit explains.

But before we dig deeper into the issue at hand, it is important to understand the workings of the interbank and open markets and how they are related.

The interbank is essentially a market exclusively made for and participated in by banks. Each bank, through its treasury department, accesses the interbank market to buy and sell rupees, US dollars and rupee-denominated investment instruments as well. For the purposes of this article, we will only focus on the US dollars.

There are various purposes for which banks would want to use the interbank market. One primary objective would be to fulfill

However, if on that day the bank in question does not have any import payment to offset against the export proceeds, the bank will go to the ‘interbank market’ and sell the $100,000 to another bank at the interbank rate. This other bank will buy these dollars because it needs to make an import payment but does not have enough dollars of its own. The reason banks will typically sell this amount to other banks, rather than keep it on their books, is because the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) does not allow banks to do this unless they absolutely have to.

Think of it like this: there is a minimum limit that a bank must have on its foreign exchange book. Anything above that has to be justified; otherwise it should be sold in the interbank. Anything below that and the bank has to go and buy from the interbank to cover the shortfall. Such transactions determine the ‘interbank exchange rate’.

There can be other variations of this. Perhaps a bank has to make a larger import payment for oil of around $1 million. Now, in a market such as ours where dollars are usually in short supply, the interbank foreign exchange desk will start buying dollars in batches in advance, before the payment date.

The bank’s treasury will inform the SBP that there is a pending oil payment for which buying of dollars is being done daily and nothing is being sold back into the interbank market because there is a requirement of $1

The open market comprises exchange companies (EC) who partake in trading of foreign currencies. The major inflow into the open market is through ‘inward home remittances’ that are transferred by expatriate Pakistanis to foreign currency (FC) accounts that are held by ECs in domestic banks. The other inflow is individuals selling foreign currencies to exchange companies at their brick and mortar locations across the country. These could be travelers coming to Pakistan from abroad etc.

Exchange companies fall into two categories. Those in category A have higher minimum capital requirements of Rs 20 crore and can perform a broader range of functions. Exchange companies in category B have lower minimum capital requirements of Rs 2.5 crore and can only act as money changers.

However, after the recent crackdown, the SBP has ordered all exchange companies to consolidate into a single category with a minimum capital requirement of Rs 50 crore.

One outflow of dollars from ECs is the demand for dollars for physical currency by individual buyers. However, there are many restrictions on the demand side of this market. More on this later.

ECs are also allowed to make outward remittances but only to personal accounts of individuals i.e. personal financial transactions and not those related to an individual’s trade or business requirements. The volume of these transactions cannot exceed 75% of the inward remittance business. Volumes are usually quite low in this regard.

Additionally, there is the option of exporting physical foreign currency, with a restriction on US dollars. This too would therefore not account for any major outflow.

The open market is a much simpler operation than the interbank with much lower volumes with simpler transactions. Theoretically speaking it isn’t big enough to have a major effect on the economy from a fundamentals point of view. An individual buying $20,000 of physical currency from an EC or someone remitting the same to Pakistan is not going to have an effect on inflation or the current account deficit.

Why all the fuss then?

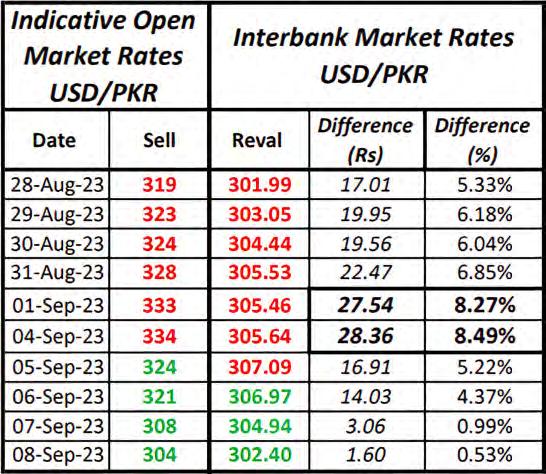

The International Monetary Fund (IMF), under the ongoing US$3 billion Stand-By Arrangement requires Pakistan, among various other conditions, to maintain the gap between the interbank and open market rates at maximum 1.25%. The idea behind this condition is simple. IMF suspects that SBP in the past has been coercing the banks into keeping the dollar rate artificially low in the interbank market. IMF does not like this, as this encourages imports and discourages exports, making the dollar reserve situation even worse . IMF, it seems, also believes that the open market is much more difficult to coerce and by requiring the rates in the two markets to be close to each other, it was hoping to keep the interbank rate nearer to the market reality.

But not only was this condition not being met, the delta was so high that even if the IMF was not making us do it, such a wide gap was abnormal. The chart below clearly shows that the open market and the exchange companies that are its main drivers had gone

berserk.

It shows the difference in the selling rate of the open market and revaluation rate (average rate in the interbank market after each day’s end of trade) in both absolute and percentage terms.

The interbank market was clearly less volatile than the open market. It is more heavily regulated and compliant. The open market on the other hand was exploding because it wasn’t being looked at with the same level of oversight.

The 1st and 4th of September are days when the gap widened to levels that were enough to warrant immediate action. Something had to be done. One option was for SBP to remove or at least relax the import curbs from the interbank market and let the dollar rate increase to around Rs 330 in the interbank as well. The other was to somehow bring down the open market rate. The second option was politically ideal. But how to do it? If SBP could do the job, it would have done it by now.

So in the days that followed, ‘Big Brother’ stepped in. And the rate in the open market was brought down to below the IMF-stipulated limit, where it remains at time of writing.

But how was it done exactly? Three major measures were taken.

How does the dollar rate in the open market go from Rs 319 to Rs 334 in a matter of 6 days? In short, ‘off-the book’ trades, a parallel market being run by ECs. Something that can only happen in the open market.

As per the SBP, individuals looking to purchase more than $500 have to present a valid visa, passport, airline ticket, biometric to prove they are buying dollars for travel purposes. They also have to pay for these dollars from their bank account into the EC’s bank account. If one fulfills all these requirements, they can buy their requisite amount and get an official receipt of the purchase. But what if one does not fulfill the requirements and still wants the dollars really bad?

Profit spoke to multiple ECs in Lahore to understand what has been happening. Let’s go through this step by step; here’s a hypothet-

ical that most likely happened, multiple times across the country.

An individual with a demand for $10,000 cash walks into an EC’s branch. He has the rupees to make the purchase but not the requisite documents.The person at the counter where the rate is displayed on a screen as Buy/ Sell, 315/318, says they cannot entertain his request. The buyer says he is willing to pay a premium. The person at the counter directs him to his ‘manager’, sitting in the back.

The manager offers to sell the $10,000 at a rate of Rs 328, Rs 10 above the prevalent open market sell rate. The deal is done. But apart from the rate, another major difference is that this transaction is not noted in the ECs formal ledger that is declared to the SBP, rather a parallel one that is maintained for transactions done on cash and without any official receipt: off-the-books.

So how does this push the rate upwards?

That’s the technical bit.

Once the EC has sold an amount of $10,000 at Rs 328 while the market is at 315/318, he has created enough room between the rate at which he is buying currency, Rs 315 and the rate at which the unofficial sale has taken place 328, that is Rs 13, to earn a higher spread.

Later, another customer, looking to sell $10,000 goes to the same EC. The rate displayed on the counter is still 315/318, but the seller would want to get the maximum rate possible. What does the EC do? Now that he has that Rs 13 room, he can buy the $10,000 from the new customer at a higher rate so that he doesn’t lose this business. So, he offers to buy the amount at Rs 317, Rs 2 higher than the prevailing buying rate of Rs 315. This transaction will be recorded on the formal ledger that is reported to the SBP and the seller will get an official receipt as well.

The SBP requires ECs to maintain a maximum 1% spread, i.e. the difference between buying and selling rates, which works out to roughly Rs 3 currently. So once the EC has bought $10,000 at Rs 317, in order to maintain that 1% spread, his official selling rate now goes up to 320.

In short, that unofficial off-the-books Rs 328 selling rate at which the first customer bought $ 10,000 pushed the official rate from Rs 318 to Rs 320.

Now imagine hundreds of such transactions happening daily across all ECs. This is how you go from 319 to 334 in 6 days.

But how do you take it back to 304 in 4 days?

The first measure put in place was to stop this off-the-books parallel dealing of dollars. A coordinated operation was conducted against all ECs involved in this practice when the rate shot up to the 335 level. According to a number of ECs that Profit spoke with, who wished to remain anonymous for obvious reasons, officials from multiple agencies put in place strict mon-

itoring measures such as placing men at certain EC branches while listening in on recorded lines as well.

This sent a clear message to ECs across the country, that the practice of off-the-books dealings would no longer be tolerated. Within the next few days, the market started to recede downwards, closer to the interbank rate, as only buyers who fulfilled the SBP criteria were being catered to at official market rates. Demand for investment purposes was eliminated. While some ECs may still be carrying out off-thebooks transactions, they are far fewer and not enough to move the market upwards in any significant way.

“The reason that this operation has been so successful is that for the first time ‘agencies’ led the effort. Most of the raids were against category B ECs and some category A ECs as well. The rest of the market got the message loud and clear and stopped what they were doing,” explained the owner of an ECs in Lahore on condition of anonymity.

Last week Forex Association of Pakistan Chairman Malik Bostan said that ECs had ‘surrendered’ $20 million. This was the second measure that was taken, to move dollars from the open market into the interbank.This practice has been used before, but very sparingly. The last two instances were in 2019 and 2021, as per reports. There are essentially three ways in which this was done. In this case too, ECs were ‘made’ to do this as part of the larger effort to rein them in.

ECs surrender physical cash dollars to banks. These were probably the same off the books dollars that were bought by EC’s to sell at a higher rate. These amounts become part of the banks’ FX book and they are able to utilize these funds in the interbank. This way, there is an injection of fresh dollars into the interbank market.

All ECs maintain FC accounts with domestic banks. They simply make outward remittances to banks’ FC accounts held with foreign banks. These accounts are called NOSTROs. Bank treasuries use these NOSTRO accounts to receive and make FC payments on behalf of their clients. What happens as a result is that banks get fresh funds that they can use in the interbank.

Instead of using FC accounts held with domestic banks, ECs use their FC accounts in foreign countries to transfer funds to banks’ NOSTRO

accounts. The effect is the same as the outward remittance ECs make.

Remember the ban on the opening of L/Cs by the SBP to restrict imports? Banks would have to get prior approval before opening any fresh L/Cs. The practice continued for some time, starting in mid-2022 until January of 2023 when the SBP issued a circular that it had lifted the ban on imports.

Since then, as per multiple commercial bank treasury officials and corporate bankers, the SBP has verbally said that it had ‘taken back’ that particular circular and banks would have to use their ‘cautious discretion’ when opening L/Cs.

But wait. How are imported items still making their way to grocery stores? In fact, even when the ban was in full swing unlike now, you may have noticed that there wasn’t really a severe shortage of your favorite imported items. What was going on? In short, smuggling.

Officially speaking, Afghanistan uses Pakistan as a transit route to import items for its own use. Here’s how it happens, or at least is supposed to happen.

An importer in Afghanistan places an order with a Chinese company for printing inks. The importer makes an ‘advance payment’ to the Chinese company. The goods will be shipped to Karachi port by the Chinese company from where a trucker, with the proper paperwork showing that the goods are bought and paid for by the Afghani importer, will drive the goods across the Pak-Afghan border to the owner of the goods in Afghanistan.

Naturally, no duty is charged to the Afghani importer since the goods aren’t meant for Pakistan.

But what is actually happening here is much different. The printing inks are not meant for Afghanistan at all. In fact, there is little to no demand for these inks in Afghanistan as they don’t have a lot of printing presses there; the goods are for the Pakistani market.

Once the inks arrive in Afghanistan, they will make their way back into Pakistan through the same Pak-Afghan border. This naturally requires on-ground ‘help and understanding’ which is easily bought. (Editor’s note: Due to the current state of freedoms in Pakistan, we are unable to state the name of the government agency whose officials man these borders). When stopped for checking to assess duty charges, the trucker bringing the inks back into Pakistan says that it is coal or some other commodity on which duty is either exempted or is very minimal under the Afghanistan–Pakistan Transit Trade Agreement.

The actual importer of the inks in Pakistan now has to pay the Afghani who made the advance payment to the Chinese seller. This is done through ‘hawala/hundi’, the FC grey market, as it were.

The Pakistani importer will pay cash rupees, equivalent to the dollar amount payable to the Afghani at a rate much higher than the prevalent open market rate, to say an EC located somewhere in Peshawar as it is closer to the Pak-Afghan border. The hundi rate is higher as there is a premium for the service being provided.

Following this, the hawala/hundi facilitator will send physical dollars across any of the many weak spots along the porous Pak-Afghan border to settle the payment. These cash dollars are being sourced from the open market, which not only leads to supply problems but also leads to rate hikes (refer to the earlier example of an off-the-book trade).

The net effect of this sort of import, that should more accurately be described as smuggling, is that the Government of Pakistan misses out on much needed revenue from duties and taxes on imported goods. Additionally, precious dollars are leaking out of the open market into Afghanistan.

The third measure that has been taken is against the hawala/hundi companies operating across Peshawar who are partaking in this business of currency smuggling. The ‘danda’ has been used quite extensively there, if reports are to be believed. Simultaneously, the Pak-Torkham border was sealed shut as well, presumably to arrest the smuggling of goods.

So everything is hunky-dory now? It is not that simple.

You see Pakistani presses still need the printing inks and they will now go their bank to import it for them, legally. As a result of the twin measures of cleaning up of hawala/hundi from Peshawar and sealing of the Torkham border; the demand for dollars to settle import payments will shift to the interbank, which will lead to increase in the dollar rate in the interbank market if supply is insufficient.

To that, add duties that were previously being circumvented and you have more expensive imports, because of the duties that will be paid on it. However, for that to happen, import curbs on banks will have to be lifted first. If there are no imports, there’s no pressure on the interbank and there are no duties being paid.

But as mentioned earlier, banks are still not allowed to open L/Cs with the fluidity and frequency that businesses want. This leaves importers in a tricky situation. Their banks still won’t facilitate imports and the Afghan option

is good as done. This will lead to shortages of goods in the market. Businesses that depend on imports will start to close shop.

We have seen what the Afghan transit option is capable of doing to the currency market.

To sum up, there are three sorts of demand for US dollars in the open market. One; the buyer who has all the necessary verification to buy dollars from an EC to actually use for the purpose he is claiming, typically, traveling.

Second; the investor who wants to protect the value of his savings and perhaps also make a quick buck in the process when he sells the dollar he bought. This is the $10,000 customer who made the off-the-book transaction.

Third; the importer who is misusing the Pak-Afghan transit trade option needs to settle the payment. This leads to a demand for physical dollars in the open market by the hawala/ hundi facilitating the transaction. In some cases, the hawala/hundi itself might be a small shady EC company operating out of Peshawar.

The latter two demands have been curbed. Bostan has claimed on record that the Pakistan Army on instruction of COAS Asim Munir has led the effort. Former Federal Minister for Water Resources also credited the army for the massive correction in the open market while appearing on a talk show with Wasim Badami, going as far as to say that the ISI chief planned and handled the execution of the plan.

One immediate effect of the closing of the gap between the interbank and open market is that individuals with dollar accounts with domestic banks will start encashing their dollars in banks rather than the open market. This will increase supply in the interbank leading to increased exchange rate stability.

Previously, when the gap was wide, these individuals would withdraw US dollars from their accounts through checks and sell those in the open market as the rate was higher. Now that the gap is negligible, it is more convenient to just sell to the bank.

Now that the problems within the open market have been addressed to satisfy the IMF, the only question on everyone’s mind, especially open market currency dealers, those heavily invested in cash dollars and the importer getting goods through Afghanistan, is, how long will this last?

These are afterall, administrative measures. It is regulation that has been done with

force and conviction with zero leniency by an institution that is in no mood to play games anymore and has taken charge to ‘fix the economy’. But at the same time, this is not some political party being taken apart. It is a market and the economy and one unignorable fact remains; if the market players do not believe that this new rate is the true reflection of the demand and supply dynamic in the market, they will be willing buyers eager to pay an extra Rs10-15 per dollar and the investors who had bought at a rate much higher than the current open market rate will continue to hold their position. This indicates a sentiment that the open market will rally once again and reach the 325-330 plus levels.

However, if the market stays where it is

and remains relatively stable for 3 to 6 months, the dollar hoarders will perhaps be forced to cut their positions and sell dollars in the open market. The investor willing to pay a high premium will also vanish as his prospects to turn a profit will have diminished significantly.

Therefore, only time will tell which direction the currency market goes and how the players in this market behave.

Unfortunately, the larger picture is being ignored in all of this. The flaws and cracks in the fundamentals of our economy are being left unaddressed. There is no quick solution to our economic woes. Structural reforms are needed and sadly these are long-term in nature. But can the COAS control the markets till then with short-terms measures? Highly unlikely. n

There is a rot in Pakistan’s sugar market. The current prices of sugar in the country have shot above the Rs 200 per kilogram threshold reaching heights that the vital commodity has not seen before. While some of this increasing price can be attributed to general inflationary trends in the country, the main reason is a vicious cycle that the country’s commodity market is stuck in.

In the case of sugar the problem lies in historical supply chain issues that have plagued the country for years. The country’s sugar daddies use an intricate network of political clout and lobbying to manipulate the market and maximise their profits. Using racketeering, hoarding, and satta bazi they control

sugar supply and short the product from the domestic market. To understand the full story, we must go back to the beginning.

Much like many other industries in the country, partition meant a new beginning. In August 1947, there were only two sugar factories in the newly minted state of Pakistan. Most of the sugar mills set up in the colonial era were on the Indian side of the border, and the two in Pakistan were not nearly enough to meet domestic supply.

This was an opportunity. For the first few years of the country’s existence sugar had to be imported which was a major drain on a new state with very little trading power. At the

same time, sugar was a high-demand commodity in the subcontinent and plenty of sugarcane was grown in the new state. The 1947-48 production numbers for sugarcane in Pakistan were over 54 lakh tonnes. Nearly 75% of this sugarcane was grown in the Punjab. Since at the time the country’s landed elite were also its political elite, it became clear that many of these landowners that were growing sugarcane would now set up sugar mills, process the sugar and make more money.

Over time, politicians in particular adopted the sugar business and mills thrived. By the early 2000s those initial two sugar mills had become 91 sugar mills. The only problem was that Pakistani sugarcane was wildly uncompetitive. Production was low compared to the global average yields and so was sugar extract percentage. This meant imported sugar could actually compete with the local product.

To counter this, government policies placed tariffs on imported sugar and even banned it while giving subsidies to local sugar mills. As a result, the number of mills grew and so did the number of farmers growing sugarcane.

To put this into context Pakistan ranks 5th among the world’s sugarcane producing countries by cultivating sugarcane on 1.1 million ha and producing sugarcane of about 65.5 million tonnes with an average yield of 58 tonnes.

Quite encouragingly, however, most of the increase in Pakistan sugarcane production came through improvement in per ha yield. Despite these developments in sugarcane production, Pakistan still obtains 17% lower yield than the world average and much lower than in the main sugarcane producing countries. The recovery rate of sugar from sugarcane is also lower than the world average resulting in higher sugar production costs in Pakistan, and the gap

is even wider when the rate is compared with major sugar producing countries of the world. Ironically, the sugar industry pays lower sugarcane prices to its producers and charges higher prices of sugar from its domestic and international consumers. Under this situation, Pakistan export of sugar is mostly viable only under export rebate programs. Such rebates in India and Pakistan have in fact created a slump in the international sugar market and its price has become low at US$260 per tonne.

Now the only problem here is that the only way sugar producers in Pakistan can afford to be profitable is through subsidies. To this end the government gives generous support prices for sugarcane, they give exports to sugar mills in the form of low electricity prices to encourage them to export more. However, the concept is that the sugar mills be empowered enough to produce enough to first fulfil domestic demand and then export and earn foreign exchange for the country.

The problem is that the country’s sugar barons live in a lawless land. Just last month Profit reported on how the country’s sugar mill owners finally called a truce on a seven year old war to form political alliances. With their deep political roots these families manage to control every aspect of the sugar supply chain.

Think of it this way. Pakistan has this year imposed a ban on sugar export. That is because international prices of sugar are increasing. Since the government of Pakistan gives subsidies to sugar mills and encourages the harvest of sugarcane Pakistan produces cheap sugar. Traditionally, agriculture products such as sugar and wheat are highly subsidised in Pakistan. There are direct subsidies in the form of support prices, and then there are indirect subsidies in case of urea due to availability of cheap gas, and availability of subsidised water and electricity for all farm produce.

Now this sugar should mean Pakistanis gets cheap sugar. Instead what the sugar mills do is they hoard sugar, say they lost a lot in production and illegally send the rest out of the country through smuggling routes.

According to a recent report, the reason behind this is smuggling. Interestingly, the sugar official exports over the past two years are a mere 1.5 percent of the last two years’ production yet shortage on the domestic market remains rampant.

The other problem is unhinged inflation expectations and loss of confidence in the PKR. Dealers and investors operating in a cash economy are better off by hoarding non-perishable products such as sugar in anticipation of price rise and as a hedge against the depreciating currency.

So Pakistan’s sugar market is subject to the whims and profiteering wishes of its political elite. That is nothing new. What makes it worse is that this profiteering is taking place at the expense of otherwise economically productive crops.

The battle between the delicate white lint of cotton and the sugary sweetness of sugarcane is an unexpected but harsh one. Over the past two decades, however, cotton has taken a backseat with farmers shifting in droves towards growing the more profitable but water-guzzling sugarcane. Cotton has fallen out of demand, become internationally uncompetitive, and output has fallen by a whopping 65% from 14 million bales being produced in 2005 to 4.9 million bales being produced in 2023. Cotton producers are losing interest and prefer crops like sugarcane and paddy while the government continues to be disinterested in reviving cotton. Sindh has seen growth in the sugar industry in cotton-growing areas, especially in Ghotki, where five sugar mills have been set up.

As things stand the issue of rising sugar prices have become a point of political infighting. It began with the caretaker government claiming there was a problem of depleting sugar reserves. “Rising sugarcane prices and court orders were also seen as being behind the rising price of sugar,” read a government report.

Meanwhile dealers began to claim that the price of the commodity increased after the supply of sugar got suspended as vehicles got stuck on the national highways after the suspension of permits. Senator Taj Haider claimed that “Honourable Rana Sanaullah allowed 1.4 million tons sugar to be smuggled” and lamented how ex-planning minister Ahsan Iqbal had held his former cabinet colleague Naveed Qamar responsible for the crisis. Haider claimed that Pakistan’s former Commerce Minister Naveed Qamar had officially allowed the export of around 250, 000 tonnes of sugar to help the finance ministry earn some foreign exchange, and took exception to the insinuation that his party colleague was somehow to blame for the shortage.

Ahsan Iqbal also pointed fingers at Naveed Qamar who pointed them right back at Ahsan Iqbal claiming the decision had been taken in a meeting of the Economic Coordination Committee. The fighting has led nowhere but sugar prices continue to rise. Prices will go down eventually but the cycle will not be broken. Unless serious introspection leads to even more serious decisions the next time sugar prices rise on the international market we will see the same hoarding and shortages leading to the same kind of price increases. n

It takes an extraordinary degree of tenacity to stage a demonstration in Pakistan during the blistering summer months. Yet, within a matter of weeks, citizens from all corners of the nation have taken to the streets to vehemently denounce their leaders for what they perceive to be unjustifiable increases in their monthly electricity bills and a government that is woefully oblivious to their suffering.

The outrage sweeping the nation is palpable. Protesters are no longer appeased by the hollow gestures of solidarity from those in power who pledge to switch off their air conditioning. They demand that government officials be stripped of their access to free electricity and be made to pay the same rates as ordinary citizens.

It would be unwise to intervene in any of these demonstrations and inform the protesters that their call for an end to electricity privileges may not yield the desired results. But that may well be the case. No unit of

electricity is truly ‘free’. In fact, revoking access to these units for certain individuals may even increase the government’s expenses and burden the very same protesters with additional taxes.

This is not to say that their anger is unfounded. It is difficult not to feel incensed when some are able to enjoy the luxury of air conditioning while others are forced to adjust their business hours. However, not all ‘free units’ are even equal — and tackling the behemoth that is our crumbling electricity sector is a far more complex task than we

Some government employees are enjoying free electricity.Hamed Yaqoob Sheikh, former Secretary of Finance to the Government of Pakistan

might imagine.

So, how many people in Pakistan benefit from free electricity? The answer is not straightforward. Due to a lack of transparency and data, it is difficult to estimate the exact cost of free electricity being provided to government officials, power sector employees, the judiciary or the military.

The Power Division estimates that 15,971 employees from BPS 17-21 consume 7 million units of free electricity per month, and 173,200 employees from BPS 1-16 consume 330 million units of free electricity per month. Sadly they do not provide a more granular look into the matter.

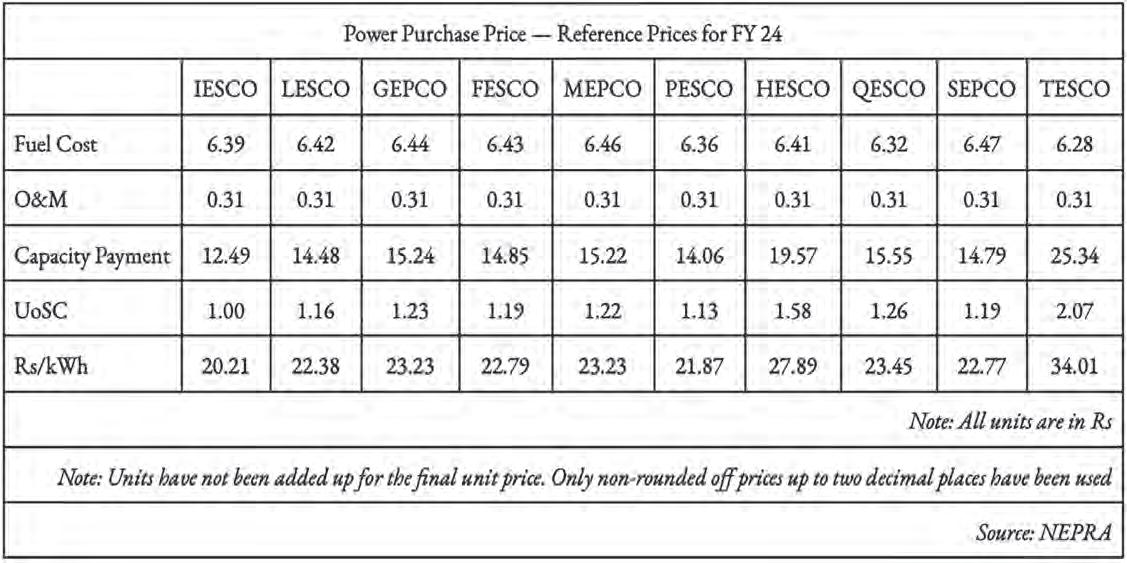

According to the National Electric Power Regulatory Authority’s (NEPRA)

State of Industry Report for 2022, serving and retired employees of power distribution companies (DISCOs), generation companies, the National Transmission & Despatch Company (NTDC), and the Water and Power Development Authority (WAPDA) are entitled to free electricity units.

The amount of free electricity provided amounted to Rs 6.4 billion in fiscal year 2022 (FY). This figure, however, excludes the electricity provided to WAPDA employees. How much do they consume? No one knows. NEPRA is yet to conduct that exercise.

The report also reveals that electricity consumers are paying for the pension benefits of retired employees of these power companies. The report elucidates on the total pension benefits, including free electricity, of six DISCOs located in Gujranwala, Quetta, Hyderabad, Sukkur, Multan, and Peshawar.

Across these six DISCOs, the benefits in terms of just electricity units given to retired

employees stand at an average of Rs 664 million per year from 2017 to 2025.

However, the true scale of the numbers remains elusive. The report misses out on the larger DISCOs such as those located in Faisalabad, Islamabad and Lahore.

All the numbers that we’ve discussed till now are in one way or another paid for by the average Pakistani. However, in different ways. Let’s start with the ones whose perks are directly financed by our monthly bills: power sector employees.

“The cost of the electrical units provided to all employees across Pakistan’s energy infrastructure is incorporated

I believe there is a need to scrutinise and analyse all the perks being granted by the public sector. It would be more prudent to monetise these privileges and pay individuals upfront for housing, electricity, and so onDr Fiaz Ahmad Chaudhry, Director of the LUMS Energy Institute and former Managing Director of the NTDC

into the operations and maintenance (O&M) charge, as part of the electricity tariff,” informs Dr Fiaz Ahmad Chaudhry, Director of the LUMS Energy Institute and former Managing Director of the NTDC.

Now this O&M charge might come as a surprise to most of us, because we don’t actually see it in our bill. So, what is it?

“Essentially, all companies across the generation, transmission, and distribution supply chain receive a margin for these costs, which they can bill as part of the tariff for the electricity they provide. The O&M charge is embedded into the base tariff of the electricity we consume,” explains Chaudhry. How much does the O&M charge add to the current sky high tariffs?

NEPRA tentatively estimates that these electricity infrastructure employees cost us approximately 30 paise per unit per month on average across FY 24 through their free units.

Examining NEPRA’s reference power purchase price (PPP) across all DISCOs, excluding K-Electric, the O&M charge remains consistent at approximately 30 paise throughout FY24. Now, what on earth is the PPP?

The PPP encompasses the cost of generating electricity, the capacity charge, transmission costs, and market operator fees. It represents nearly the final tariff of electricity without taxes. The only additional costs are distribution and supplier margins, and any prior period adjustments. However, it accounts for 90% of the final tariff without those two costs.

For reference, the current peak price per unit is approximately Rs 42, while the off-peak price is approximately Rs 36. “People seem more intrigued by the cost associated with free electrical units than with the staggering Rs 2 trillion in circular debt,” muses Chaudhry.

Even if we were to double the O&M charge, it would still only be approximately 60 paise of the tariff. Removing it may not be easy and could have far-reaching consequences beyond just the O&M cost.

Before we delve into that, let’s discuss another public sector that receives these units — arguably the more glamorous, and one that people seem eager to strip this privilege from.

The exact specifics of the free electricity units allotted to every office holder in Pakistan remain a mystery. While rough estimates

As long as a department pays their bill to the electricity sector, why should we worry about how much of its funds it allocates to this?

exist for individual offices, no large-scale exercise has been conducted to uncover any meaningful data.

However, let’s begin with a startling revelation: not all public sector employees receive free electricity units.

“There is no universal provision of free electricity units for government employees. However,

some public sector companies/corporations, including the power sector, may have extended this facility to their employees,” clarifies Hamed Yaqoob Sheikh, former Secretary of Finance to the Government of Pakistan.

“The Secretaries of Provincial Governments authorised a utility allowance that has remained stagnant at Rs 30,000 ever since it was granted in the 2000s. This amount covers utilities (electricity, gas and NTC/ PTCL bill). The officers are not allowed to withdraw the allowance and are reimbursed. Any remaining funds at the end of the month lapse and cannot be carried over or withdrawn,” Sheikh adds.

“The Chief Secretary, Chairman Planning, and Senior Member of the Board of Revenue across the provinces are the only ones whose entire utility bills — electricity, gas and NTC/PTCL — are fully paid for by the government,” Sheikh continues.

It is worth noting that under Shahbaz Sharif, the provincial government did introduce a similar utility allowance for BPS 1-16 cadre employees, albeit at a lower and variable rate.

However, a simple internet search reveals that information on the free electricity units received by the President of Pakistan and Judges of the High Court and Supreme Court is readily available. Numerous other individuals can also be found. So, who is footing the bill for them alongside the individuals highlighted by Sheikh?

These expenses are budgeted as part of the annual Budget. Sheikh explains that the Ministry of Finance pays a lump sum, which relevant Departments are then free to allocate as they see fit. They pay energy companies for the units used by individuals to whom they have allocated the allowance as part of their department-specific compensation packages.

Should we care about this expense if it doesn’t appear on our monthly bills?

“As long as a department pays their bill to the electricity sector, why should we worry about how much of its funds it allocates to this?” posits Chaudhry.

The issue is not so simple. These are public office holders, not private companies doing as they see fit. “Yes, there is a conflict when compensation packages lead to

a widening disparity between employees of certain organisations and cadres and the rest of society,” Chauhdry continues.

Ultimately, with this set of individuals, it becomes a conversation about public sector remuneration packages.

However, what if the Government were to wake up tomorrow and abolish this particular privilege? That is, after all, what the caretaker Prime Minister seems to be contemplating.

Let’s start with the genesis of free electricity units.

“In 1974, WAPDA concocted this scheme for its employees as a mere accounting expedient,” highlights Chaudhry. He adds, “At that time, they surmised it would be more convenient to remunerate employees by allocating electricity units rather than incessantly revising their pay scales.”

“There was also an aspiration to deter employees from resorting to fraud or pilferage in any way,” he further reveals.

WAPDA’s innovation was perhaps the epiphany that Pakistani human resource managers needed, as the rest of the country soon emulated them.

However, at its core, this scheme is simply an accounting facility that liberates human resource departments from the onus of constantly updating pay scales for their employees K-Electric does not provide its employees with these units, but their human resource department might be more comfortable with this accounting exercise than its public sector counterparts. That’s not to say it cannot be done.

“I believe there is a need to scrutinise and analyse all the perks being granted by the public sector,” proposes Sheikh. He suggests, “It would be more prudent to monetise these privileges and pay individuals upfront for housing, electricity, and so on.”

Herein lies the quandary. These privileges could be abolished, but we would then need to monetise them to avoid risking individuals simply renouncing their jobs.

The Government of Pakistan can still deliberate over how much it wants to monetise perks for non-power sector employees. After all, these perks are funded by the aforementioned annual budget, which is sanctioned by Parliament.

The argument becomes more intricate when it comes to power sector employees. Not only do we risk employee resignations, but there is also the possibility of a general

commotion. Allow us to explicate.

Profit conversed with a very senior individual at WADPA who outlined their remuneration contract on the condition of anonymity.

They confirmed that there is nothing precluding the Government of Pakistan from terminating access to free electricity units at any time since these are not baked into base compensation.

They further confirmed that employees could not take legal action against the Government since this perk is not part of their base pay.

However, they did confirm that WAPDA employees could take legal action against the Government on grounds of discrimination. They rightly pointed out that all public sector companies in Pakistan compensate their employees through privileged access to the final product they produce. For example, Pakistan International Airlines provides free or discounted tickets.

Their argument in court would be: why are they being denied access to the final product when no one else is?

Mind you, this is on top of any possible resignations that might ensue.

So where does this leave us? At the end of the day, even if free electricity units are removed, the Government of Pakistan will foot the bill one way or another. The only scenario where this does not seem to be the case is one where mass resignations occur due to the Government ending this privilege altogether without providing similar compensation.

This is on top of potentially upending the entire public sector utility remuneration system.

There is a moral argument for the Government of Pakistan contemplating this option. After all, it’s difficult to sympathise with a protestor debating whether or not to turn on their fan when your air conditioning is paid for by someone else.

And the thing is, if they want to, the Government of Pakistan could do it.

“Change always hurts,” Sheikh expounds, “But that’s the Government’s job: to manage change. If it is to be done, it should be done in one fell swoop with consistency.”

The economic argument is dubious. The paltry 30 paise in our tariffs for the remainder of FY 2024 are the only tangible savings we can identify.

Yes, half of our electricity bills are just taxes to fund an irresponsible sovereign and reducing the spending by the agents of the sovereign would be beneficial. But over Rs 5 trillion of our Rs 7.3 trillion budget for FY 2024 is just debt servicing — so are we missing the forest for the trees? n

Under any tax code of the world, citizens are classified as filers and non-filers. In literal terms, non-filers are people who are breaking the law by not filing their annual tax returns and should be punished to a degree. Even individuals who have failed to file a tax return in a given year are seen as being non-filers.

ind you, non-filer does not necessarily mean that the person is not paying any taxes. In cases where a return has not been filed, a salaried individual might still have his salary deducted at source, and still be termed a non-filer. Same individuals will also end up paying higher taxes as they will be seen as non-filers under the law. This story is not related to them as they are still depositing something to the exchequer and should be reaping the benefits of doing so. Their laziness is leading them to paying a fine which they can easily avoid.

This story concerns people who actively circumvent the tax code by wanting to maintain their non-filer status. Since 2014, the government has also looked to codify this status which gives these people legitimacy by paying a small fine which allows them to break the law. For many, this is a price they are willing to pay. Profit is here to try to make your blood boil.

Former PM of the country, Shahid Khaqan Abaasi, stands in front of a crowd at the “Reimagining Pakistan” Summit and claims that not even the parliamentarians of the country are filers. Rather than this statement being countered with derision and angst, the statement is meant with a murmur of laughter from the audience.

Experts on the tax code of Pakistan state that there is clear evidence that parliamentarians, bureaucrats and many government officials have huge amounts of assets and are able to bear huge expenses, however, the Federal Board of Revenue (FBR) fails to go after them. There are actual concessions that are provided to these non-filers that are not even available to mere mortals when they should be taxed to high heaven.

This leads to burning questions being asked in terms of why this category has been created and what is the cost of these non-filers to the country?

Pick up any tax code from around the world and you will see that the term non-filer is used to describe an individual who is either not expected to file their taxes or are tax dependent on someone else who is liable to pay tax. In Pakistan, the

meaning of the same word is much different. Here, a non-filer is someone who is legally bound to file a tax return but is not filing one. This can include people who miss the deadline to file their return. Lumping both these people together can seem a little harsh as the people who missed the deadline are not actively looking to stay non-filers.

These people have an intention but due to difficulties, they get to miss out on filing their return in time. These people actually have to suffer a double whammy at the end. They are being taxed in the form of their income being deducted at source and they cannot claim it as they have failed to file a return. In addition to that, as they are non-filers, they end up paying higher tax on transactions like cash withdrawals from banks.

The anger that should exist in the context of Pakistan is over the blase attitude that people have to filing their taxes. This has further been codified under the law as there is a strata of citizens who are filers while others are non-filers because they choose to be so. This attitude is due to the fact that the people are least bothered to become filers while the state machinery and institutions also do not do enough to change the status quo.

It seems that the government has little intent to change the situation and is actively looking to provide rationale for non-filers to exist. The passing of the Finance Act of

The term non-filer exists all over the world but in Pakistan we have non-filers by choice rather than circumstance. Why is that?

2014 was the last nail in the coffin for the government in terms of its seriousness to correct the situation. This passing signaled the last effort that the government could have made to persuade people to become filers.

In simple terms, the government admitted that it could not go after the non-filers. This was the waving of the white flag which showed that rather than carrying out a tax reform in the country, the government will take paltry steps to make filing voluntary rather than force people to come under a tax regime formally.

An approval of their failure was the passing of the Act which added the definition of filer and non filer into the Income Tax Ordinance of 2001. This was nothing more than a band-aid that was placed over the gaping wound ailing the economy. The government was going to legitimize the existence of non-filers and charge them a little extra for not complying with tax laws of the country.

The terms of filer and non-filer were codified into the Income Tax Ordinance 2001 with a stroke of a pen and the government was patting itself on the back that non-filers were going to be “penalized”. The word in quotes has to be emphasised and read with a tinge of sarcasm as the government felt that they were levying a huge burden on the individuals who did not want to come under the tax laws. The truth of the matter is that these taxes are levied on income and expenses which are small in comparison to income many of the non-filers earn which is not taxed.

On top of that, the government was creating more undue burden on the withholding agents who now had to check the status of the individuals before these withholding taxes were applied. Now it was the job of withholding agents like banks to check whether the person was a tax filer or not and charge varying rates of tax on them. The government was not only legitimizing the existence of non-filers but increasing the burden on the withholding agents to determine the tax and then collect it from the filers and non-filers.

The government brought in a new regime as a last ditch effort that was carried out to give a slight push to the tax revenues while incentivizing people to become filers. Anyone can guess what happened after this measure was passed. Non-filers chose to stay non-filers even if it meant they were paying higher taxes on certain items. They carried out a cost benefit analysis for themselves and saw that they would rather pay the higher charges compared to becoming filers.

In order to make such a strategy work,

Mohammed Sohail, CEO Topline Securities, feels that every year, the government should look to tighten the noose around non-filers by increasing tax incidence on them. This will make it arduous to avoid taxes and will incentivize more people to become filers.

While many citizens are able to stay non-filers and evade paying taxes that should be imposed on them, the government has a simple solution to plug the budgetary gap that exists. In order to meet their tax targets, the government continues to impose higher tax rates on people filing their taxes while not looking to tap into the potential taxpayers who should be brought into the net.

“A collection of tax where it is not due is as detestable as its non-payment when it is due’’ says Dr. Ikram ul Haq, a professor of taxes. In a developed country, tax payers are seen as being responsible citizens of the country who pay the dues accrued on them. This gratitude is extended to withholding agents who collect taxes on behalf of the government and the government allows them to deduct their expenses that they have incurred for the collection to be carried out.

In Pakistan, the roles are reversed. On one hand, the withholding agents are humiliated and insulted while taxpayers are penalised for asking for their rightful refunds. This all goes on while the taxation system looks to eek out the last rupee from the people who choose to be filers. The pressure and scrutiny which should be reserved for non-filers is actually taken out on the filers and taxation policy is used to penalize these people. Numair Liaqat, Country Economist for International Growth Centre Pakistan, states that “the underlying reason is that there are no actual incentives to become a tax filer in Pakistan.” He states that there are actual disincentives which need to be looked into.

Most of the blame for the mess has to be placed on the shoulders of FBR in this case. Experts state that people are indifferent in terms of registering themselves as taxpayers and actively avoid doing so in the first place. They know that once they do become part of the system, FBR will do everything they can to make their lives miserable with unlawful orders, inhuman attitude and illegal demands.

People have lost faith in tax officials. They want to avoid becoming involved in this Kafka-esque tragedy where they have to follow up in courts and appellate benches. With FBR not tightening their noose around the non-filers, filers bear the brunt of the audits and checks.

In addition to not following through on their duty, the role of the FBR is to sit on the sidelines and hand out the duty of collection of tax to withholding agents. An estimate is that 90 percent of the tax revenue collected is through the withholding agents which means that the machinery is only able to do a measly 10 percent by its own efforts.

What makes the efforts of the FBR even more draconian is the fact that they hold the people responsible to pay income tax in advance. This means that they need to hand over a portion of the income even before they are able to determine their taxable income at the end of the year. This shows that there is a move to keep harassing the people who are willing and able to give these taxes rather than go after the people who choose to stay non-filers.

To a certain extent, the attitude of the non-filers can be considered as tax filers are harassed to such a degree. FBR looks to do all that is within its own powers to target and go after the filers. Seeing the treatment handed out, many non-filers feel that they would rather pay the higher rate of tax applicable on them. “Once you become a filer, the tax authorities will keep a close eye on you. Those not filing their taxes won’t face any such scrutiny.” states Liaqat.

Once you become a filer, the tax authorities will keep a close eye on you. Those not filing their taxes won’t face any such scrutiny

Numair Liaqat, Country Economist for International Growth Centre Pakistan

Experts also believe that the complexity of filing a tax return means many people either cannot file themselves properly into the system or as the importance of filing is diminished, many feel that filing is not a necessary part of their civic duty. Making it easier to file taxes and facilitating them will encourage them to be part of the taxation system.

The government has designed incentive based schemes for filers and people do not even know their taxes are being deducted at source. There is a lack of knowledge and once they gain an understanding of the system, they will be able to file the taxes that are already being deducted from their salaries, phone bills, electricity etc.

Tax amnesty schemes have been introduced in the country at different stages in order to bring people into the tax net and make them filers in the future. These schemes are given by the government in order to facilitate the citizens to declare any assets, accounts and income that they have hidden from the government. Once these assets have been legalized, the government is able to levy direct taxes on these people based on the income that they have declared.

Such schemes are beneficial in the short run and can lead to some boost in tax collection for the immediate future, however, these schemes can only be made successful if subsequent action takes place once the scheme has elapsed. Structural reforms are a requirement for the country where the tax code needs to be revised and overhauled. With investments being parked in tax havens, there is no incentive for the government to reach these bank accounts or look to make its tax code more efficient.

Such amnesty schemes are a slap on the face of tax paying individuals who are abiding by the law while non-filers are given special dispensation from time to time after breaking the law. Rather than improve or work on the deficiencies of the system, the best course of action is always to provide an amnesty scheme, show a jump in tax filers for the year and move on. This is not the first amnesty scheme that has been given.

It is interesting to note that the first such scheme was given in 1958 by the Ayub Khan regime. This shows that the issue of taxation management has plagued the country since the last seven decades. This scheme was able to add 266,183 to the roll of tax filers and a total of Rs 1.12 billion was raised. At the end of the scheme, Pakistan’s tax to GDP stood at less than 10 percent. Subsequent tax amnesties were given out in 1997, 2000, 2001, 2008, 2012, 2013, 2016, 2018 and 2019. Time after time, these schemes have been used in order to boost tax revenues and allow the country to collect a higher amount of tax. Sadly,

Dr. Ikram

most if not all of these schemes have failed. The failure of these tax schemes is rooted in the fact that tax payers know that another scheme will be introduced at regular intervals while the FBR will do little to nothing to make non-filers compliant. This will happen while business community will be harassed which has become part of the tax net

Even when steps have been taken to bring part of the economy into the tax net, there are concerted efforts to make sure such steps are unsuccessful. The fate of providing CNIC for purchases above Rs. 50,000 to be provided to retailers by the buyers in the PTI government faced severe protest. This led to the measure being revised to Rs. 100,000 and then scrapped altogether shows that there is an active movement to make sure no such measures are put into place.

The PDM government also faced the same results when they tried to introduce tax on electricity bills of shopkeepers in order to boost revenues and they failed as well. Any strict measure that has been put into place by any of the governments has faced outcry before being scraped in the end.

Whenever a measure is set to be introduced to make people fall into a tax net or to make them accountable within a tax regime, the participants look to protest and create an issue around the fact rather than pay their fair share. The recent uproar around tax on immovable property has also been criticized by the real estate industry and it seems this tax will see a similar fate of being slashed or eradicated totally.

The cost of non-filers becomes apparent when reports come out which suggest that the salaries class of the country are paying a whopping 200% more tax compared to exporters and retailers of the country. The amount of tax paid was

around Rs. 264.3 billion in FY 2023 which was 40% higher than the amount collected in the previous year.

The brunt of the taxation, hence, falls on the people who earn salaries as companies employing them are made withholding agents. This means that the withholding of tax falls on the company as an institution rather than the responsibility being on the individual to declare their income. As more and more pressure is piled on the salaried class, the Salaried Class Alliance (SCA) states that the country is “killing the goose that lays the golden egg.”

According to FBR’s own data, the salaried class is paying a total of 42 percent of income tax while it constitutes only 15 percent of total registered taxpayers. Compared to this the agriculture sector which contributes 20 percent to the GDP and pays less than 1 percent of income tax. Similarly, the real estate and retail sector can yield an additional Rs. 500 billion and Rs. 234 billion respectively, however, this area is left untaxed or under taxed at best.

As retailers are given additional relief, the government keeps withdrawing the relief given to the salaried class. With income being taxed at a higher rate and people facing unprecedented unemployment and inflation, it seems like something has got to give and the salaried class will soon not be able to bear this burden any longer.

With exporters, retailers and wholesalers making up 20 percent of the economy and paying less than 2 percent in their share of income tax, there is a case to be made for better tax management to be carried out. With the finance minister clarifying that no additional tax will be placed on real estate and agriculture, it is obvious that no structural changes are on the books for now.

Another setback that has impacted the government is the fact that the super tax levied in the Finance Act 2023 has been struck down by the Islamabad High Court and petitions will be heard in the Supreme Court now. This will lead to a prolonged legal battle. This simply means that the salaried class will again be on the chopping block. n

A collection of tax where it is not due is as detestable as its non-payment when it is due

ul Haq, Professor of taxes

Considering the preconceived notions about holding companies abroad, what are the implications of this policy?

By Areeba FatimaPakistan is generally not considered a good business environment, but the State Bank’s February 2021 regulatory framework allows Pakistani residents and firms to make equity-based investment in entities abroad on a repatriable basis, subject to some terms and conditions. This has generated considerable chatter that things may be changing for the better.

The large sums of venture capital in seed funding acquired by a number of Pakistani startups has certainly contributed to the optimism and led to a greater public interest in how these startups are progressing, but then pivots and shutdowns also come under stricter scrutiny. Due to rampant cases of corruption at every level of governance and bureaucracy, one

might carry some preconceived notions about the role and purpose of a holding company. Interestingly, a number of startups have been launched in Pakistan, targeting Pakistanis, but are incorporated offshore… as well. This does not mean they aren’t ‘Pakistani companies.’ Firstly, because they aren’t even operational in the country they are incorporated in, and secondly they primarily operate in Pakistan. But this does raise curious eyebrows about the regulatory framework of startups and the role of offshore holding companies in it.

In an interview with Profit last month, CEO of Sadapay Brandon Timinsky confirmed that the FinTech startup is also incorporated in the UAE. He believed this is a step that helped him build greater confidence with investors abroad. Before the 2021 policy change, this was not a possibility for Pakistani residents, legally. A Pakistani tax resident

could not own shares in a company outside the country without prior approval from the SBP which was a long and arduous process. At the very least, it required the investor to have incorporated the firm for quite some time which was a difficult and often impossible task for a lot of start-ups.

First and foremost, this policy is only applicable for the incorporation of holding companies in countries which allow repatriation of profits, dividends and capital back to Pakistan (except equity investment in India, of course) and it is only for investors and firms which have no record of being involved in a money laundering or terrorism financing investigation. The policy’s intention is to help export-oriented

companies flourish.

A resident company (OpCo), is allowed to incorporate a holding company (HoldCo) abroad where an SBP assigned Designated Authorized Dealer (DAD) would allow an initial incorporation expense of under $10,000. After this, the OpCo shareholding pattern must be mapped on the HoldCo within 30 days by the founders acquiring shares in the HoldCo against transfer of shares in OpCo to the non-resident HoldCo on repatriation basis. Resident OpCo shareholders are allowed to purchase HoldCo shares by paying in PKR to OpCo and OpCo can issue an equal value of shares to the non resident HoldCo on repatriation basis.

Delivery Hero is a German multinational online food ordering company which owns Foodpanda through an arm incorporated in Singapore. This allows Foodpanda Singapore to function as a local start-up despite bringing

back home profits and dividends.

Similarly this policy allows repatriation of funds from abroad through equity or borrowing in Pakistan as equity-based investment in OpCp such that 80% of the funds raised on an annual basis up to $1 million are remitted back to Pakistan. And all this is supposed to happen through DAD, which is also supposed to ensure compliance.

Mubariz Siddiqui, Founding Partner at Carbon Law wrote a comprehensive Twitter thread in December 2021 explaining the policy and how it would work. “The point of the HoldCo is to act as a vehicle of ownership for the OpCo” he wrote.

“Look at it this way, consider you are job offers from both Singapore and Congo – you are more likely to take up the job in Singapore because there is little desire to relocate to Congo. Similarly, investors are concerned with a market’s reputation, its accessibility and its assessment as a destination for investing money,” Mubariz Siddiqui spoke to Profit discussing the need for this policy.

The logic is intuitive: if a global investor wants to invest, they are most likely to consider markets they have already or regularly invested in, or jurisdictions which are particularly favorable to foreign investors.

“Investors’ desire for a HoldCo represents that Pakistan is not a favorable jurisdiction, but this would still mean that at least Pakistan has a fighting chance at raising capital abroad, which is what the parameters of this policy safeguard,” he concludes.

Profit spoke to lawyer Abdul Moiz Jafferi about the need for this policy.

“It is a bureaucratic nightmare to have to answer for why you want to move money abroad especially in times like this when a conman like Ishaq Dar is a judge”, said Jafferi in response to a the same question, arguing that the policy provides a much-needed reassurance to foreign investors that their capital and profits will not be subjected to the winds of local political instability.

On the other hand, he accepts there is merit to the government’s concerns too, “Now the [government] is wary because whenever you allow legitimate operations abroad, what people do is they start hoarding their profits abroad and they start under-invoicing themselves”.

Jafferi explained to Profit how profits are hidden and withheld abroad.

“They set up a company in the gulf, they take all the real orders there, and then they set up another company in the gulf and

that company is not declared,” after which the company can begin to under-report their earnings, parking the additional wealth in the undeclared company abroad.’

“You will create this footprint abroad and then you start to under-invoice your own company, so if you are selling software abroad, and you got a contract for $10,000 in Dubai, instead of sending the entire $10k to your company back in Pakistan, you bill your own company a $1000, and you retain the $9k abroad,” he added.

This is the reason offshoring in this form was banned in the first place. The new policy addresses these challenges in a number of ways.

According to Jafferi, legitimate industry players argue that since the bigwigs have been investing abroad anyway, the government should create a legal framework that allows them to maximize their potential. This circular is a result of that demand.

It says that if you operate in the same sector in your country, you can invest a certain amount abroad, as long as you provide your financial statements for the last three years and meet some criteria. It also ensures that you are not just setting up a holding company abroad just to transfer money. The idea is to let people have their own presence abroad rather than relying on intermediaries. This policy is more relaxed for the IT sector, which only needs to show one year of operation, considering that startups are new companies and don’t have much history.

On the other hand, the monitoring is laid out as follows: the policy specifies what you can and can not do, and your audited accounts will reflect that. If you violate the policy, the tax authorities will detect it and charge you with money laundering, tax evasion or tax avoidance under the applicable tax laws.

Lawyer Mirza Moiz Baig told Profit that as long as structural reasons underlying the poor business environment are addressed, companies will continue to want to distance themselves from it. He opines that continuity of policy decisions is especially important, and the success of the circular will depend on the government’s ability to consistently implement it and improve upon it with time.

“There is an absolute need to ease a lot of restrictions into businesses and there is also a need for continuity of policies – you often see the govt issue an SRO and then a couple of months later the SRO is withdrawn so you need to have continuity of policy. You don’t just set up a manufacturing plant and start exporting tomorrow, first you set it up then you develop skills and expertise that will allow your products to thrive in the intl markets. So as an investor I would only invest if I know that there is going to be some continuity,” he said highlighting the importance of continuity. n