09 Lahore’s Spanish Inquisition

12

12 How Creek Marina went from being the next big thing in real estate to 19 acres of nothing

20 Our corn industry suffers from a ma(i)ze of problems, and it's set to miss out on a gold rush

24

24 The PMEX has grand plans, including digital gold trading. Can it be a success?

28 Creating a creators’ ecosystem. Can Daraz make its affiliate program work?

Publishing Editor: Babar Nizami - Joint Editor: Yousaf Nizami

Senior Editor: Abdullah Niazi

Executive Producer Video Content: Umar Aziz - Video Editors: Talha Farooqi I Fawad Shakeel

Reporters: Taimoor Hassan l Shahab Omer l Ghulam Abbass l Ahmad Ahmadani

Shehzad Paracha l Aziz Buneri | Daniyal Ahmad |Shahnawaz Ali l Noor Bakht l Nisma Riaz

Regional Heads of Marketing: Mudassir Alam (Khi) | Zufiqar Butt (Lhe) | Malik Israr (Isb)

Business, Economic & Financial news by 'Pakistan Today'

Contact: profit@pakistantoday.com.pk

PM Kakar’s cabinet will be in the driving seat for the foreseeable future. To do any good they must hold fast to their limitations

Two liberal-leaning economists with prior government experience to manage the finance ministry. One big-shot industrialist that can wrangle his fellow titans of business when needed and go out to bat for them when needed. And one pliant, sober, and affable politicians that can sit in a chair, take directions, and be their boss.

Stir well until mixed.

This is the perfect recipe for a technocratic dream-team to manage the economy. And that is exactly what we have gotten in the shape of Pakistan’s incumbent caretaker government. You have in the driving seat Prime Minister Anwar ul Haq Kakar. By all reports and estimations he is a good-natured and sensible man. He is also a founding member of the Balochistan Awami Party, has a good working relationship with politicians across parties, and is cosy with the establishment.

Handling the finance ministry is the duo of Dr Shamshad Akhtar and Dr Waqar Masood. In her second stint as caretaker finance minister, having also held the ministry in the last caretaker setup in 2018, Dr Akhtar is well-respected and possesses a steady head on her shoulders — a quality the finance ministry has been missing in recent times. She has also served as governor of the State Bank before this. By her side is Dr Waqar Masood, a former finance secretary who also served former prime minister Imran Khan in an advisory capacity and is neutral enough to have also been considered by Ishaq Dar for a position as minister of state. Together the two have the necessary capabilities to maintain the status quo and see

Pakistan through the current IMF programme.

And then finally there is Gohar Ejaz, who has taken over the commerce ministry. One of the most powerful industrialists in Pakistan, he is the patron of the All Pakistan Textile Mills Association (APTMA) and also has vast interests in real estate. His word carries weight in the business community, and he also has the stable temperament that is required for the job.

There is nothing particularly unique about this combination of people. You could replace Shamshad Akhtar with Abdul Hafeez Sheikh or Dr Ishrat Hussain and Dr Waqar Masood with another former bureaucrat and Gohar Ejaz with a different industrialist and pretty much guarantee that nothing would change except the faces.

Normally this is exactly what you want from your caretaker government. The concept of having a consensus-based government for a few months is archaic in itself. Developed democracies should have seamless transfers of powers with independent elections that cannot be manipulated. But when you have constitutionally stipulated caretaker governments, you want them to be as run-of-the-mill as humanly possible.

In normal circumstances a caretaker government comes in for a two-month stint and the entirety of the state machinery is so focused on conducting elections that the rest of the government runs almost on auto-pilot. In fact, other than the prime minister and interior minister’s posts, caretaker cabinet positions are mostly just a notch on people’s CVs. But the circumstances are far from normal.

By all indications the caretakers are here to stay. If the fawning praises by establishment-friendly journalists and espousing the qualities of ‘technocrats’ in cabinet were not enough of a sign, the Election Commission of Pakistan’s decision to conduct fresh delimitation of constituencies has made it all but a certainty that general elections will not be held within the constitutionally stipulated 90 days.

This puts Prime Minister Anwar ul Haq Kakar and his recently inducted cabinet in a peculiar position. Caretaker governments constitutionally have the solemn duty of ensuring free, fair, and timely elections. But at the same time they have the responsibility of running the day-to-day affairs of government that are necessary to keep the country afloat.

And while elections should be the only thing that any caretaker should very well be remembered for, all eyes will be on how he manages the economy.

The caretaker setup has come in at a time when Pakistan’s economy is facing a crisis that could be the worst in the country’s history. On the one hand prices of essential commodities are continuing to rise and inflation is spiralling out of control. The dollar has breached the psychological and historic barrier of Rs 300 which is worrying market sentiments. The rupee is expected to continue taking more beatings. On top of this utility prices are increasing and there is vast unhappiness over electricity prices. Reports of protests against high bills and people beating up linemen sent to cut connections are a cause for concern for the caretakers and their handlers.

The issue of high electricity prices, of course, is directly related to the agreement with the IMF. It must be remembered that on the 30th of June last year Pakistan failed to complete the last IMF programme it had entered and it seemed the country had no choice but to default on its external debts. However, prime minister Shehbaz Sharif managed to achieve a stopgap accord with the fund. The current deal Pakistan is surviving under is a $3 billion stand-by agreement that will last for a period of nine months and is higher than expected for Pakistan. Only the first tranche of this facility has been extended to Pakistan as of now. This stand-by-agreement ensured that whatever caretaker setup came in would not have to go beyond its constitutional limits and negotiate a programme with the fund. However, it also means that Mr Kakar must now ensure that the IMF’s conditions are met. As prices of petrol have been raised and are expected to be raised again. The gap between the interbank and open market rate of the dollar is quickly closing as per the IMF’s requirements. However, the entire burden of this is falling on Pakistan’s middle and lower classes. Instead of placing the responsibility for the circular debt problem on the people of Pakistan, a

better solution must be hammered out. Already the inflation problem raging through the country is continuing to hurt the weakest segments of society. People’s purchasing power is going down and with baseline inflation incredibly high the State Bank’s recent claims that inflation will slow down seem suspect. In fact, the SBP in its latest monetary policy maintained the interest rate at 22%. But with the SBP currently little more than an extension of the finance ministry and a former central bank governor at the helm in the finance ministry, it can be expected that this interim government will give us at least one MPC where the policy rate will be revised upwards — especially since that is what the IMF seems to want.

The current cabinet and PM Kakar seem to be committed to the cause of keeping things steady. In his three days in office the prime minister has mentioned the Special Investment Facilitation Council (SFIC) at least a dozen times as well as his resolve to complete the programme with the IMF.

The concept of ‘technocrats’ in power has been one that has regularly been fantasised about in Pakistan. The instability of democratic governments in the country and the seeming inefficiency of parliamentary procedure has long been considered a nuisance. The argument goes that instead of having bickering and volatile elected representatives calling the shots on technical affairs, it might be a good idea to put professionals in charge.

The only problem with this argument is that professional economists and money managers realise they do not have the mandate to be in positions of direct governance. For any democracy to develop the two key elements are stable institutions (this is where the ‘professionals’ must find their calling) and the will of the people (which can only be possessed by elected representatives).

As Pakistan goes forward it currently has the technocratic setup that so many have craved and wanted for a long time. Already this government is in constitutionally dicey territory if it overextends its stay by more than 90 days. But it is not unprecedented. In two months, Mohsin Naqvi will have been chief minister of Punjab longer than Pervez Elahi and Hamza Sharif combined. He has already served more than two 90-day terms which goes beyond the constitutional stipulations.

But with no other safeguard in place there is no knowing how long he will be at the helm of affairs in Punjab, or how long PM Kakar’s government will be in power at the centre. This is one area where the lines of constitutionality are already quite blurry. The caretakers would do well to, at the very least, not go beyond their other powers.

By Abdullah Niazi

By Abdullah Niazi

Allow us, for a brief moment, to take some liberties. It is not Profit’s place to comment on matters of style, taste, or aesthetic sensibilities. In fact, journalism is a famously dour field occupied by pests and pessimists in near equal numbers.

But despite our lack of expertise it would not be appropriate to write this story without commenting on what inspired it in the first place. Over the past few years, Lahore’s residential real estate market has seen an influx of a very particular kind of architecture.

The architecture in question is uniquely Lahori. It takes elements from classical and

European designs and mixes and matches different styles of architecture to produce a very particular kind of house. Most of these houses are characterised by their often golden, gaudy, and garish exteriors. And while students of architecture might nitpick and raise their eyebrows, the real estate market has largely lumped these houses into a category now known as “Spanish” style homes. The emergence of these Spanish houses has been obvious and fast. But exactly how prevalent are they? Who are the architects and developers behind this? And more importantly, what effect have they had on Lahore’s real estate market? Profit conducted an in-depth survey in Lahore’s DHA Phase 6 to determine how common this style of archi -

tecture has become in the past 10 years, what effect it has had on real estate valuations, and what the construction cost realities of this style of houses is.

Our results largely show that Spanish style houses are a trend that has taken off particularly in DHA and has since spread across the city. Of the more than 600 houses surveyed by Profit, exactly 192 had all the markings of “Spanish” design indicating that nearly a third of all new houses being made in this area fall under this style of design. Conversations with real estate developers and contractors have shown that these houses are not particularly more expensive to make but are highly in demand in the market and hence fetch a higher price than other styles of

architecture.

But before we get to the survey, let’s start with some history.

The Spanish style of architecture itself is nothing new for Pakistan. In fact, houses of the Spanish style have been made in Pakistan from the early 1950s and particularly in Lahore. The first batch of architects native to Pakistan graduated from the National College of Arts (NCA) Lahore in 1952. These contained some of the giants of Pakistani architecture such as Nayyar Ali Dada and others who have now become household names and are responsible for many of the country’s most iconic buildings.

Among this first batch of architects were people such as Aslam Khan, Raees Raheem, and Zaheer Khan. At the time the City of Lahore was still a bit of a silo. It looked nothing like what it does today and the concept of a modern urban city as the capital of Punjab was still fresh. Today the walled city of Lahore might seem like an ancient and antiquated reality, but up until 1839 Maharaja Ranjit Singh still ruled from the Lahore fort and the Sikh empire did not end completely until 1850. At the time of partition, it had not been a hundred years since the old city was the capital of a great empire.

In fact, it was only in 1850 after the defeat of Maharaja Duleep Singh in the second Anglo-Sikh war that the Lahore Cantonment was established by the newly reigning British empire. At the time it was set up as a garrison town and would only later, with the arrival of the Raj, take shape not just as a military cantonment but also as an upmarket residential real estate colony. This meant that around the time of partition, Lahore as a modern city was still taking shape.

“It was during the British period from 1849-1947 that Lahore, for the very first time, spilled over its fortified walls,” write professors N Naz and G A Anjum of the University of Engineering and Technology. Naz is a professor of architecture and Anjum teaches in the department of City and Regional Planning.

“Lahore for the very first time spilled over the fortified walls. Civil lines, the Cantonment, and the Model Town were developed to house the elite class segregated from the local population. Lahore Improvement Trust (LIT) soon after its inception in 1936 started preparing a Master Plan for the future development of Lahore. However, due to the Second World War, the task could not be accomplished. After Independence in 1947, there was brisk building activity in Lahore to accommodate migrants. Many schemes had to be launched to meet the housing Shortage.

From 1947-1958 there was aggressive building activity in Lahore and new colonies sprang up on the outskirts, notably Gulberg, Shad Bagh, Chauburji and Wahdat Colony.” commented Naz.

So when the first batch of architects emerged from NCA in 1952, they were setting their sights on a modern city in the making. Think about it. Model Town had been constructed in 1921 and was still developing. Gulberg was planned by S A Rahim from 1950-54. The concept of DHA did not yet exist. That is when these pioneering architects began to adopt their own signature styles. Among them was Aslam Khan who established his practice in Lahore’s cantonment where he started building houses in the classical European style influenced by Spanish and Mediterranean architecture.

By definition, these are houses identified by their airy, open exteriors and iconic smooth stucco walls and barrel roof tiles. Common features in these homes include the use of wooden beams, wrought iron, and warm tones. Originating from the Spanish coast of Amalfi, these homes were designed specifically for the climate and caught on in Lahore as well. At the time, these houses were simple, identified by their barrel tiles and expansive arches and one among many different styles of residential architecture popping up in Lahore. While these mediterranean homes caught on somewhat in defence, most architecture in the rest of the city took its inspiration either from local India architecture or colonial style homes. Model Town, the Hindu cooperative society set up in 1921, had its own regulations and thus developed a style of its own. Gulberg and other areas gave way to large driveways, massive lawns, and a general aversion to pillars and columns. For a while these styles were replicated as Lahore continued to expand. Block like houses made by contractors were the norm in newer housing areas. That is until recently.

So where does Spanish style architecture stand in Pakistan today? To get to the bottom of this Profit conducted a survey of over 600 houses. Our working theory was that a lot of houses built in affluent residential areas over the past 10 years have been made in the Spanish style. For this we had to pick a residential area that was relatively new and had mostly developed over the past 10-20 years, was affluent (the cost of a 1-kanal plot was over Rs 3 crore) and had access to good commercial markets. For this we chose DHA Lahore’s phase 6. To ensure maximum credibility, we picked three different blocks of phase 6 and

chose to sample 200 houses of 1 kanal or more in each block. Skipping any empty plots we decided to survey the first 200 homes in each block. To determine what counted as a ‘Spanish’ style house we spoke to a number of architects. They explained that some classical markers of Spanish houses are:

• Barrel Roof Tiles.

• Smooth Stucco Walls.

• Wood Support Beams.

• Arches and Curves.

• Wrought Ironwork.

While these are the markers of classical Spanish houses as understood by architectural textbooks, in Pakistan the term has taken on a new meaning. Markers of Spanish houses in Pakistan also include the following:

• Doric Columns

• Elaborate wrought iron gates

• Moorish Arches

• Heavy crown moulding work on the external facade

• Elaborate or colourful tile work on the floors

During the survey, we inspected the external facade of these 600 houses for all of these factors. If a house had at least 5 of these elements incorporated just in its external appearance, it would be checked off as a Spanish style house. The findings were overwhelming.

Of the 600 houses that were sampled, at least 192 met at least five of the 10 given criteria. Another 52 houses met at least four of these criteria. A vast majority of these Spanish houses were built on 1 Kanal land or less while a smaller proportion of these houses were built on 2 kanals or more. The prices of these houses on average, as estimated from demands made by local real estate agents and online listings, range from Rs 8 crore to Rs 16 crore depending on how elaborate the house is and whether it comes with a basement or not.

Generally, however, a 1 Kanal Spanish house without a basement was averaging at around Rs 8 crore. Comparatively, houses that were not Spanish in design with similar specifications (no basement, swimming pool etc) cost around Rs 50 lakh to Rs 1 crore less. For further context, 1 kanal plots in these particular blocks that were surveyed cost Rs 4 crore to 5 crore on average.

So what do these numbers tell us? For starters we can see that the Spanish style of architecture is currently dominating the market. Most of the houses being built are in this very distinctive style. Another observation we made but did not record in our official tally was that a lot of these houses are obnoxiously similar. The colour scheme is largely gold based, the gates all

carry similar designs, and the general layout of the houses is the same.

As we learnt through multiple conversations with architects, stakeholders, and other builders, that is because a lot of these houses are built mostly by contractors rather than by private individuals. This has been a story that has developed over the years in DHA Lahore. And perhaps the one person that has been the most influential in all of this has been the architect Faisal Rasul.

A 1992 graduate of NCA, Rasul did his masters from University College London before returning to Pakistan in 1998. Drive around any block of Defence and you will surely see a number of under construction or newly constructed Spanish style houses with the banner for “Faisal Rasul” designs hanging proudly. His firm, which he runs along with his wife, specialises in Spanish houses. Rasul designs and draws up the houses and his wife is an interior decorator who sets them up with furniture and all the other trappings.

Over the years he has partnered with many builders and been the biggest contributor to this trend of Spanish houses. His style has been widely accepted by the market and also widely replicated. So much so that there are plenty of houses that real estate agents will sell to you as “based on Faisal Rasul designs” — meaning replicas or copies of his style made by other architects.

“This entire thing started in Defence. When I came back to Pakistan the first house I made was my own in DHA Phase 4 on 1 kanal of land. At the time most of the houses being made in Defence were being made on what you would call the modern design look. I also started making these for some clients but took a chance on Spanish houses as well,” he tells Profit. Soft-spoken and articulate, Rasul clearly has a passion for what he does and is an ardent believer in his product.

This was of course the mid 2000s. By this point DHA Lahore had become quite developed. The Defence Housing Authority (DHA) was registered with the Punjab Government in 1975. This was the time when the Pakistan Army had set up DHA as a means to provide housing and accommodation to its retired officers and to the families of its martyrs. Development of DHA projects took time but by the 1990s construction in this area was on its way.

And with it the real estate landscape in Pakistan was forever changed. Out of nowhere you had a housing society that was gated, well maintained and was considered upper-class and respectable. The seal of the Pakistan Army meant that it was considered safe both to live in and conduct business in. Moreover, the chances of land fraud were low because the area was completely acquired and new so the land was not tainted by family disputes

and the like. This meant a lot of upper class families were moving to a new area and had the money to spend on constructing houses as well.

It was this class of people that these Spanish designs have appealed to. “Around 2005 when I first started making these houses other developers started noticing that people were asking for these kinds of houses. Initially it was only 1 Kanal house we were making,” he explained.

A possible reason for this is that it does not cost significantly more to make houses in Spanish style than in any other. The base cost of bricks, cement, and other materials is the same because these houses do not require more material; they are just built differently. But because there was novelty in this and the designs started getting glittzier because of Rasul’s particular style, a lot of people making 1 Kanal homes felt they were getting a more luxurious look for around the same amount of money.

The trend caught on as trends do. “By 2010 everyone seemed to want these houses. Whenever contractors would approach us they would want a Spanish design. Now even 2 Kanal houses and bigger ones wanted to be built in the same style and everyone wanted it grander and larger. We paid a little more attention to detail in our designs. We worked harder on making the house more beautiful and on things such as our marble floors and the crown mouldings we were using on the external facade and also on the internal walls.”, Rasul added.

This made Rasul’s designs more distinctive and more in demand. In addition to developers, his architectural firm started getting a lot of private requests as well and very quickly Faisal Rasul was on the map as a major up-and-coming residential real estate architect in Lahore. As time passed by, even though his practice was based in DHA, his designs started to find copies and demand in other areas as well.

“That is just how it works. The trend became quite big mainly because of developers but also private clients. Things that are made in Defence are then copied in other areas such

as DHA, Valencia, etc. The trend starts from DHA and spreads onwards,” he claims.

“People want these houses because they speak to their dreams. When they were little kids drawing pictures of their dream houses they were making them with slanted roofs, arches, chimneys and big doors. This style of architecture started on the Spanish coast before making its way towards South America and eventually towards the coastal areas of LA and on to Florida. Celebrity houses are often in this shape and style. These are the dreams that people have and it is the architect’s job to translate these dreams into reality.” he explained.

And this is what it boils down to. As mentioned before, the cost of building a house in the Spanish style is not particularly higher than the cost of building a regular house. Essentially, the grey structure of any two houses with similar covered areas and the like will very much be the same. It is simply that since Spanish houses are in fashion and are seemingly ‘fancier’ for lack of a better word people are willing to get to a higher price point for this.

“In terms of cost I think it is not particularly different,” says Faisal Rasul. “Spanish houses are a little difficult to make in terms of the drawings and the finishing which requires a little more detailing. We have made teams that have learned how to do things like moulding on the front elevation, cut work on marble flooring and there is no shortage of craftsmanship in this country. It is only a question of a little extra effort. Because the labour cost here is not that expensive and we have plenty of local material such as marble and plaster it is not very difficult. House becomes spanish not through the tiles or marble but through the arches, columns etc and those are things that can be managed at the same cost.”

Essentially the added price point of these houses is simply because they are in fashion. But there is a history behind how they came to this point. n

“By 2010 everyone seemed to want these houses. Whenever contractors would approach us they would want a Spanish design. Now even 2 Kanal houses and bigger ones wanted to be built in the same style and everyone wanted it grander and larger

Faisal Rasul, Architect

The companies regulator seems to have realised its mistake, but only after one business group allegedly tries to pull a fast one

In the unforgiving realm of the financial markets, it is the Goliaths that have things their way as opposed to the Davids. The ones that possess the means of production, end up on top, more often than not. They get to ride the waves and sometimes even control the currents. But does that mean that the smaller fish do not have a say?

The retail investor and minority shareholders, no matter how miniscule, are afterall a major part of the market. And to safeguard their interests is often in the best interest of the market itself. But sometimes safeguarding the interest of these smaller fish, means putting a hook on the bigger ones.

Such is the story of Securities and Exchange Commission of Pakistan’s (SECP) latest notification dated 18th August, 2023.

Through this notification SECP has informed that it plans to make some major amendments to its takeover regulations. These regulations, called the Listed Companies (Substantial Acquisition of Voting Shares and Takeovers) Regulations, 2017, in simple English, relate to the requirements when someone wants to become a substantial shareholder or acquire majority shares in a company that is listed on the stock exchange. The main change: it will be compulsory for in kind securities, offered as an acquisition settlement, to be highly liquid and for the acquirer to also offer a wholly cash alternative when offering securities to take over a company.

But why was there a sudden change of heart on the SECP’s part? Afterall, it was the same SECP that made completely opposite amendments less than a year ago in September, 2022. To understand this, first some background.

In its essence, the SECP is supposed to do its best to protect minority shareholders. That is one of the reasons why the SECP had mandated, anyone who wished to acquire majority stock in a company to make at least a market price offer to the minority shareholders of a company so that they could exit the stock, if they wished to do so.

This compulsion is not always in the best interest of the acquirer because it may land them with a more than required share of a company. Afterall one only requires 51% of a company’s equity to have controlling stake. Anything above that would just mean tying up their own money, unless that is what the acquirer wants.

But when the SECP in September last year, by the means of an amendment, allowed this settlement to be made with securities such as shares and bonds, that compulsion got complicated and created some loopholes which if exploited could lead to the acquirer not having to purchase more shares than they wanted, leaving the minority shareholders at a disadvantage. The JS group was apparently the first to pounce on these loopholes in its bid to acquire BankIslami.

In its attempt to acquire controlling stake in what would be the second commercial bank under Jahangir Siddiqui, the JS Bank had already struck deals with some big shareholders to cross the required 51% shares it needed to control BankIslami. But as explained above, according to the regulations JS Bank had to make a fair offer to the remaining 49% shareholders of BankIslami as well. And with the recent changes in the regulations it could make this offer in kind, and that is exactly what JS Bank tried to do. So instead of offering cash to these remaining shareholders, JS Bank offered shares of its two group companies, JS Global and JS Investments, to the other half of the minority shareholders.

Immediately after this announcement a number of voices in the financial industry alleged Jahangir Siddiqui and his JS Group of trying to shortchange the minority shareholders of BankIslami. According to them, there were at least three problems with the two shares being offered that made this offer a non-starter for BankIslami shareholders.

Firstly, the shares of both JS Global and JS Investments were largely illiquid, meaning it would not have been easy to sell them later in the market. Secondly, both these companies were not Shariah compliant, meaning offering such shares against shares that are Shariah compliant would have been a non-starter for many shareholders of BankIslami for religious reasons. Lastly, and probably most importantly, the price of JS Global shares had increased by an astonishing 4 times , while the price of JS investments shares had also increased substantially just months before they were offered to BankIslami shareholders. This meant that in an exchange, as shares of both these companies would have a higher value than usual, shareholders of BankIslami would have gotten fewer shares of JS Global and JS Investment now, had they opted for the exchange.

Profit covered the development as its cover story, highlighting the inefficiency and injustice this deal would apparently entail.

Following that story and strong advocacy by other minority shareholders, the JS

Bank finally succumbed on the 26th of April 2023, and agreed to pay cash instead of in kind payments to the minority shareholders of the BankIslami.

While the episode ended on a positive note for the minority shareholders, the saga brought to the fore regulatory inadequacies and potential pitfalls within the existing framework. As previously highlighted in in-depth reports by Profit in March and April 2023, the JS Bank deal unveiled vulnerabilities that it seems has prompted SECP’s proactive engagement.

The JS Group- BankIslami saga initially centred on JS Bank’s ambitious bid to establish a commanding presence in Pakistan’s banking sector by acquiring a controlling stake in another bank. However, this endeavour has been shadowed by reservations over potential conflicts of interest, stock price manipulations, and the exploitation of regulatory gaps, particularly to the detriment of minority shareholders.

A central concern that came to the forefront is the ability of acquiring companies, like JS, to offer minority shareholders compensation in the form of shares from other group entities, as opposed to cash. This mechanism raised alarm bells over the fairness and transparency of such transactions, as it could potentially lead to minority shareholders receiving less favorable terms or even coerced outcomes.

Amid mounting concerns, both market observers and regulatory bodies advocated for a comprehensive reassessment of the regulatory framework governing takeover transactions. It would not be unfair to say that the latest development came about as a direct response to the ongoing discourse surrounding the JS Bank deal and similar transactions.

The SECP has taken the initiative to launch a public consultation phase aimed at amending the Listed Companies Regulations. These proposed amendments, conceived with the input of diverse stakeholders, aspire to augment transparency, safeguard minority shareholder rights, and champion equitable practices.

Addressing the first problem pertaining to liquidity, in the BankIslami transaction the SECP proposes that only highly liquid securities would be deemed acceptable to be provided by the acquiring entity for meeting obligations under the public offer. To categorise any shares as highly liquid, the SECP has provided certain parameters.

These parameters state that the stock should have been listed at least 2 years prior to the offer. Moreover, it has to be a frequent-

After the publication of Profit’s news feature Jahangir Siddiqui will soon own two banks. Not everyone is happy ( https://profit.pakistantoday.com.pk/2023/03/19/jahangir-siddiqui-will-soonown-two-banks-not-everyone-is-happy/ )

JS Bank has filed a case of criminal defamation at a police station in Thatta, Sindh against us. Criminal defamation cases, as discerning readers might already know, require the accused to be physically present during hearings and investigations, making them a more calculatedly tedious affair than the civil defamation laws.

At a time when civilized societies are doing away with criminal defamation laws and making the matter entirely a civil matter, we are still stuck with laws that are clearly a tool to suppress independent journalism.

Would we have liked for the legal system not to be gamed against us, that too, more than a thousand miles away from our office in Lahore? Yes.

Would we do it all over again? Yes.

ly traded share for at least 180 days prior to the offer. As per amended definitions, a frequently traded share is one which has been traded for at least 80% of the trading days during any given time period. And during those 80% days, the average daily trading volume should not be less than 0.5% of its free float or 100,000 shares, whichever is higher.

The other major issue in the Bank Islami transaction was the shariah compliance and unwillingness to accept the JS Global and JS Investments stock. Addressing this issue, a very salient innovation of the proposed amendments is the provision for minority shareholders to opt for compensation in either cash or, if preferred, securities. In cases where the acquirer offers securities as compensation, and securities are chosen, an allcash alternative must be presented alongside the proposition.

Previously, the provision of a wholly cash alternative was absent. It is important to note here that this provision also provides the minority shareholder, to readily exit the trade making the process of acquisition more democratic.

The third, and possibly the biggest concern in the aforementioned example was the changes in price of the offered shares. To remove the possibility of price manipulation, the new draft proposes that the shares of listed company may be valued at the weighted average share price during 180 days preceding the date of the announcement of public offer.

For government securities the value is proposed to be calculated on the basis of applicable PKRV rates at the end of the day preceding the date of public announcement of public offer. PKRV rate is the average yield-to-maturity on government securities, on any given day, traded in the secondary market.

Apart from these changes, the SECP has also revamped the criteria governing accept-

able securities during public takeover offers. The refined criteria restricts eligible securities to shares of listed companies, listed debt instruments, and government securities with a remaining maturity of up to 364 days.

Additionally, SECP has also taken measures to articulate clear definitions for terms that were previously left ambiguous, cultivating a coherent and transparent regulatory environment. This includes definitions such as weighted average price of shares, and frequently traded shares, clearing up ambiguities about prices and liquidity of shares.

Many would be wondering why the SECP needs a public consultation to make a change? Therefore it is important to note here that the issuance of this Consultation Paper is to seek stakeholders’ feedback as required under section 169 of the Securities Act, 2015 on the draft amendments in the Listed Companies (Substantial Acquisition of Voting Shares & Takeovers) Regulations, 2017. The drafted amendments are also separately published in the official Gazette, and on the SECP website.

These changes will nevertheless come into effect after taking into consideration the objections and suggestions within 14 days of the posting of these draft amendments.

Those eager to delve deeper into the specifics of the proposed amendments, and wishful of proposing suggestions and amendments to this draft resolution, can head over to SECP’s website. SECP has published an all-encompassing consultation paper elucidating the key considerations underpinning these changes. This document, complemented by the draft amendments, is readily accessible on the official SECP website. n

K-Electric is the only privately owned and vertically integrated utility in Pakistan. The utility's heavy reliance on fossil fuels for power generation, and slow adoption of renewable energy has led to high electricity generation costs, requiring substantial government subsidies. Embracing sustainable alternatives earlier on could have had reduced costs, achieved greater self-sufficiency and would have provided relief to consumers.

K-Electric is the primary electricity provider to Sindh’s metropolitan capital and some surrounding regions. On the other hand, NTDC supplies electricity to all the other areas of Pakistan through its transmission network except the zone of K-Electric. The systems of NTDC and K-Electric have a tie-line which allows for K-Electric to import up to 1100 MW of electricity from the national grid at a very low cost. The total existing capacity of K-Electric is 4,485 Megawatt (MW), out of which 2817 MW is K-Electric’s own generation fleet, 526 MW is supplied by the Independent Power Producers (IPPs), and 42 MW is contributed by the Captive Power Producers (CPPs).

During FY 2022, about 45% of K-Electric’s energy demand was served by the electricity being imported from the national grid through the tie-line, indicating that the utility relies significantly on the national grid for its generation supply. It is important to note that the utility has been pursuing additional supply of up to 2050 MW from the national grid by building two new interconnections, which has not yet received approval from the government. This dependency on the national grid reflects poorly on utility’s efforts in the past to become self-sufficient by making timely and effective generation planning decisions.

Furthermore, the utility depends heavily on costlier thermal power generation plants, particularly gas/RLNG, furnace oil (FO), and imported coal. As of now, nearly 97% of the utility's total installed capacity is based on these thermal sources of energy. According to the Power Purchase Price (PPP) references set up by NEPRA for FY 202324, price for RLNG, FO, and imported coal is 51.42 Rs/kWh, 48.56 Rs/kWh, and 40.54 Rs/kWh, respectively. Therefore, this reliance on imported fossil fuels subjects the company and its consumers to fluctuations in international fuel prices, directly impacting electricity tariffs.

NEPRA attributes the high electricity generation costs in the K-Electric system to several factors, including the low efficiency of its newly added gas-based power plants as well as generation of power through furnace oil/RLNG using low efficiency steam turbine thermal power plants. The problem of expensive electricity generation in KE region is also reflected in the provision of subsidies by the federal government to bail out the consumers in Karachi. According to the federal budget, the total subsidy to pick up K-Electric’s tariff differential for FY 2022 alone was PKR 56 billion.

Moreover, the fact that renewable energy technologies, particularly solar and wind power, have witnessed significant advancements and cost reductions over the past decade cannot be overlooked. This has made them increasingly competitive with conventional fossil fuels.

Yet, looking at the generation timeline of K-Electric from March 2009 to March 2022, it is evident that renewable energy sources did not get the attention they deserved in the generation planning of the utility. Out of 2132 MW capacity that K-Electric decided to add in those thirteen years, more than 95% of it was fossil fuel based. Whereas, only two solar power plants (Gharo and Oursun) of 50 MW capacity each were added into the system. A large share of the fossil fuel based plants installed run on RLNG, which is currently the most expensive source of electricity generation in Pakistan (per unit cost of Rs. 51.42) and subject to international market volatility.

Zooming in on this, we can see that five different thermal power plants were installed in K-Electric’s system in just one year. KGTPS & SGTPS (both RLNG/natural gas based) in January 2017, FPCL (imported coal based) in May 2017, and SNPC-I & SNPC-II (both natural gas based) in January 2018. Based on the data available in NEPRA’s State of Industry Report 2022, these five plants generated a cumulative 1322 Gigawatt-hour (GWh) of energy during FY 2022, with a total cost $124 million approx.

According to an estimation, wind and solar power plants of about 460 MW capacity could supply more amount of energy (1326 GWh) than these five thermal power plants did in FY 2022 at a cost of only $53 million, a mere 43% of the latter’s cost. K-Electric could have saved its consumers nearly $71.2 million in FY 2022 alone by banking on renewable energy technologies.

The people of Karachi had high hopes from K-Electric when it first entered the market as a private entity. Yet in the 18 years since, it has neither solved the problem of load shedding nor been able to provide relatively cheaper electricity. Had K-Electric made timely decisions to diversify its energy portfolio, it would surely have been able to ensure cheaper electricity tariffs for its consumers, providing much needed relief to households, businesses, and industries across Karachi. However, there might still be a way forward. Embracing renewable energy now can pave the way for a sustainable and economically viable energy future for the utility and its consumers.

Real Estate is a very profitable investment in Pakistan, provided one knows what to buy when, have some holding power and sell at just the right time. The returns are very handsome; over 100% in some cases. There are protections and lack of oversight like no other. No wonder, it is a popular parking place for undeclared money, which is a vehicle of investment that not only hides such wealth but multiplies it as well. And then there are the periodic amnesty schemes announced by every new government attempting to address its fiscal woes.

However, there are also a plethora of fancy real estate projects that have turned out to be, to put it mildly, bad investments. That is not to say none of them had the intention of actually building and delivering what they had marketed to their clients within the stipulated timelines and quality standards. But there are some worrying examples of projects that have failed to do that, often with an intent to defraud customers. One such example, that has recently come to light as a result of an Federal Investigation Agency (FIA) investigation, is the Creek Marina Project.

According to an FIR submitted in Darakhshan police station in Karachi back in 2014 by Secretary DHA Karachi, Brig (Retd) Inam Kareem, in September 2004 an individual named Shahzad Nasim approached DHA Karachi, claiming to be the Managing Director and majority shareholder of Meinhardt, Singapore, a Singapore-incorporated company.

Nasim expressed his interest in establishing the Creek Marina Project at DHA Phase-VIII Karachi for public sale, with DHA going into an agreement with another one of Nasim’s companies, Marina Services Private Limited (MSPL).

The agreement was signed on September 27, 2004, laying the foundation for an ambitious development—an impressive high-rise residential and commercial complex situated on prime waterfront land in Phase VIII of DHA.

According to the key points of the agreement, DHA agreed to transfer approximately 92,000 square yards of waterfront land to MSPL. In return, MSPL was to allocate 15% of the net floor area of the Creek Marina Project to DHA. The responsibility of designing, constructing, marketing, and developing the project was entrusted to MSPL.

Initially, the project envisioned two

high-rise towers. As time passed, the project’s scope expanded, leading to the addition of more towers. To facilitate its execution, MSPL was required to establish a special legal entity (SPV) registered both locally and abroad. This agreement marked the beginning of the Creek Marina Project and established the framework for its development.

The project emerged as a promising endeavour. It boasted ‘luxury living on a waterfront development’ in the Karachi metropolis. It aimed to create an iconic landmark showcasing sophisticated architecture. Its vision revolved around transforming the picturesque waterfront into a property that set new standards for upscale living in Karachi. Nestled in Phase VIII of DHA, residents would savour breathtaking views of the Arabian Sea and the city skyline. At the heart of the project were the sleek high-rise towers.

State-of-the-art amenities, spacious apartments, private terraces, sky lounges, and rooftop gardens promised an ‘unmatched living experience’ was all promised. Furthermore, the project aspired to become a vibrant community hub, featuring high-end retail outlets, fine dining restaurants, boutique shops, and recreational facilities.

Moreover, the project was perceived as an economic catalyst, injecting fresh investment and employment opportunities into the local economy. The partnership with DHA added

How Creek Marina went from being the next big thing in real estate to 19 acres of nothing

The controversial project, once positioned to be the jewel in Karachi’s skyline, faces accusations of being a vehicle for money laundering

trust and credibility, attracting discerning buyers and investors seeking waterfront living at its finest. The developers emphasised their commitment to timely delivery, setting a nine-year timeline to complete the development by 2013. The excitement and anticipation from the city’s elite and real estate enthusiasts was promising.

According to the FIR, Nasim was able to collect ‘Rs 3,000,000,000 from the public’ for the project. Details on who these investors and buyers were is unknown.

As the project progressed, unforeseen challenges and controversies arose, casting shadows on its path. Allegations of financial impropriety and suspicions of money laundering, along with disputes with investors, threatened the future of the Creek Marina Project, leaving its future uncertain and the project entangled in legal complexities.

As per documents present with Profit, on the 16th of May 2023, Muhammad Mouz Ahmed Lone, submitted an application to the Federal Investigation Agency (FIA) revealing diverse and expansive detail of alleged fraud on part of the Creek Marina Project that affected him and other victims.

According to Lone’s application, the corporate labyrinth surrounding the Creek Marina Project was intentionally designed to deceive and obfuscate, employing numerous layers of companies and offshore entities to facilitate fraud, money laundering, and evade accountability.

This is where matters get a little confusing, seemingly intentionally.

Shahzad Nasim was the Managing Director and majority shareholder of Meinhardt, Singapore whose other company MSPL got into an agreement with DHA Karachi, but according to Lone’s application, at the heart of the project was Creek Marina Private Limited (CMPL).

CMPL, the seemingly local company, would be responsible for executing the ambitious project to develop high-rise towers on sought-after waterfront land. However, the ownership of CMPL remained shrouded in mystery.

Adding to this complex structure of corporate ownership, Lone’s application makes reference to records maintained with the SECP (Securities and Exchange Commission of Pakistan), which show that CMPL was nearly fully owned by a company named Creek Marina Singapore Pte Limited (CMSPL), an offshore entity registered and operating in Singapore.

The CMSPL itself was entirely owned by Swiftearn Holdings Limited (SHL), an entity nestled in the secretive off-shore company sanc-

tuary of the British Virgin Islands.

As each layer unfolds in the application to the FIA, the true beneficiaries of the Creek Marina Project become increasingly obscured from public view. The offshore secrecy afforded by CMSPL and SHL seemingly also provides perfect cover for concealing the identities of the actual owners. Allegedly, the accused parties exploited the confidential nature of offshore jurisdictions, engaging in money laundering through hawala/hundi and other untraceable channels to clandestinely transfer funds across borders.

Lone’s application also stated that the DHA made multiple amendments to the original agreement with MSPL. These amendments were necessitated by various changes and developments in the Creek Marina project and its execution. An addendum to the original agreement of 2004 was signed between MSPL/CMPL and DHA in July of 2005. This brought about several significant changes to the original agreement. Notably, it expanded the scope of the project to include eight highrise towers, each with 27 floors, instead of the initially planned two towers. Additionally, the project completion was divided into two phases, with Phase 1 (four towers) to be completed by December 2008 and Phase 2 (four towers) to be completed by December 2009.

DHA and Creek Marina entered into a first amendment to the contract in 2005, which outlined a two-phase project plan involving the construction of two towers instead of one. Following the agreement’s amendment, DHA proceeded to sub-lease 99 acres of land under the name Creek Marina Pakistan. However, despite these changes to the contract, the project remained incomplete.

A second amendment to the agreement was executed between DHA and Creek Marina on June 4, 2009. According to this revision, CMPL was obligated to pay Rs 12 Billion to DHA, and the net floor area was to be reduced from 15% to 3.75%. Under the terms of this new agreement, the project was to be completed in three phases. Creek Marina was responsible for finishing the first phase by June 2011, the second by December 2011, and the third by June 2012. However, the company failed to meet these deadlines.

According to Lone’s application, the project encountered severe delays, and despite CMPL having undertaken no work, DHA agreed to amend the main agreement once again. This required a second addendum, signed in June of 2009,

introducing one significant change: allowing CMPL to collateralize the 92,000 square yards of waterfront land with a bank.

According to documents available with Profit the intention behind this allowance made by the DHA was to regain some control and oversight over cash flow and accounts of the project.

The collateralization was to be done phase-wise, with MSPL/CMPL first committing 30% of the estimated cost of each phase and the loan could only be drawn down as per the agreed upon construction schedule.

Additionally, CMPL would open an Escrow Account with a commercial bank with minimum “AA” rating with clear understanding that the bank will act as an “Escrow Agent” as intended under the Agreement dated 27 September 2004. Evidently this part of the agreement was never fulfilled by CMPL in 2004, necessitating DHA attaching it as a condition to the collateralization.

Another clause that was seemingly ignored by CMPL in the original agreement was the appointment of ‘Renowned Chartered Accountants in consultation with DHA to verify/audit the cash flows both in and out of the Escrow Account as well as existing accounts’. DHA reiterated this in the 2009 addendum.

The 2009 addendum also made it mandatory for all money coming from new bookings to be deposited in the newly established escrow account with its account number for deposits printed on application forms.

It also made it compulsory for an independent engineering consultant to be appointed in consultation with DHA and the banks to certify payments to the contractors.

These efforts would ultimately prove futile however. As per sources in DHA, the construction on the project came to a halt in 2010.

Contrary to Lone’s assertions, both FIA and NAB have been unable to definitively confirm the involvement of Creek Marina’s owners in money laundering. Nevertheless, the documents received by the FIA clearly indicate that upon acknowledging the complaints from the victims, an investigation against the owners of Creek Marina has been initiated.

In June of this year, the FIA Commercial Banks Circle issued notices to the owners and stakeholders of the Creek Marina Project as well as various banks. A copy of the notice addressed to Naseem Ansari, Chairman of Creek Marina Singapore Limited.

As for Shahzad Nasim and his son Omer, the FIA has attempted to contact them but to no avail. Sources at FIA have confirmed that a letter will also be written to Interpol to track the accused, as there is so far no trace of them

in Pakistan.

As per an official of the FIA, the investigation is still ongoing, and the implicated individuals and banks are expected to cooperate fully with the authorities. While the FIA has initiated this investigation based on allegations and evidence presented, no conclusive confirmation of money laundering involving the owners of Creek Marina Singapore Ltd has been established as of now.

It remains to be seen how the investigation will unfold and whether further actions will be taken based on the evidence gathered during the course of the inquiry.

Funnily enough, Creek Marina’s website is still up and functional. The list of team members has Nasim listed as the Group Executive Chairman with an unmissable “THE MASTERMIND” superimposed over the profile.

Buyers in this predicament are plentiful across Pakistan as many projects showing similar promise have either come to a halt or were abandoned. The recent economic downturn leading to higher prices and import restrictions have only exacerbated the situation, making it difficult for developers to deliver projects on time. Profit did a detailed story analysing the new dynamics of the real estate market a few months ago, pointing out the difficulty some projects are facing.

For any project to begin, developers have to get necessary approvals leading to a ‘No Objection Certificate’ (NOC), from the relevant development authority to begin advertising and constructing a particular project.

However, according to Lahore Development Authority (LDA) spokesperson, Osama Mehmood, this stipulation is regularly violated.

“It’s a fact that a large portion of housing projects proceed without obtaining necessary approvals from the relevant authorities. These ventures engage in business without fear of consequences. In such instances, LDA and other development authorities in the country alert the public. We periodically update lists of unauthorised housing projects through advertisements and our website, explicitly advising the public to refrain from investing in such projects.”, he commented.

Developers, preferring to remain anonymous when speaking with Profit on the matter, however argue that the regulations are overly stringent, making it arduous for them to satisfy the numerous legal prerequisites mandated by development authorities or the government. Moreover, even if a developer manages to meet all these regulatory requirements, the red tape prevalent in most regulatory authority offices and the ‘methods’ to bypass them become hindrances in doing things ‘by the book’ and in a timely manner.

Mehmood argues that the regulator can only do so much; the buyers also have to be cautious.

It’s imperative for developers to adhere to stipulated regulations for projects, regardless of whether they involve high-rise buildings, residential spaces, or commercial properties. But the public should thoroughly evaluate all available information pertaining to the project before making an investment,” he said.

One would imagine that the requirement to get an NOC from a development authority would be enough of a disincentive to anyone looking to make a quick buck. Evidently not. As per an official at DHA, Creek Marina never had to go through many of the procedural requirements that most other projects had to because it had the backing of DHA Karachi, which was providing the land.

All this introduces excessive risk to the equation and discourages future genuine buyers, those who want to buy a home and build an asset over time with their life savings, to stay away from projects such as Creek Marina and similar largescale fancy projects whose bonafides are hard to establish when making the initial investment.

In 2016, India, in an attempt to address the same issues with its real estate development sector, established RERA (Real Estate Regulatory Authority). It was welcomed by the country’s homebuyers as a much-needed reform measure to make investments in real estate projects more secure.

For example, it introduced rules for developers that included builders having to put up 70% of the money they received from customers in a bank account separate from the construction company’s account that could only be used for construction purposes. Additionally, in the case of any delays, customers would receive payments as per a monthly interest rate against the money in the account.

Pakistan tried something similar. Enacting the ‘Islamabad Real Estate (Regulation and Development) Act 2020’, which led to the formation of the Islamabad Real Estate Regulatory Authority (RERA).

The authority enforces regulations that prohibit developers from selling properties without obtaining necessary approvals. Developers are obligated to demonstrate clear land ownership and present a comprehensive history of project delivery. Property sales are only allowed to be conducted by real estate agents registered with the authority.

Developers are also required to furnish regular updates to buyers, showcase plans and obtained approvals, and refrain from accepting advance payments. RERA (Pakistan) restricts the transfer of project rights without the consent of the majority of allottees, and provisions are in place to ensure refunds for projects left

incomplete or burdened with debt. Allottees are granted possession rights along with project maintenance oversight.

All this is very similar to the Indian RERA, both in terms of text and implementability. As per Indian news outlets, India’s RERA act has not yielded the desired results. It has struggled to ensure the punctual completion of ongoing projects, and buyers who had invested in such projects to secure homes have encountered the same difficulties.

One fatal flaw of RERA was that it was at the end of the day a non-judicial body, requiring the local administration of wherever a case was registered to sign off on the execution of orders.

Only ten percent of projects have reached completion, and there has been no noticeable increase in the number of home buyers.

Matters are much the same in Pakistan. No amount of laws will effectively address the problems at hand unless effective implementation is ensured.

The affected allottees have formed an action committee, the Creek Marina Action Committee (CMAC). have sought redress and the apprehension of Dr. Shahzad Naseem, Omar Shahzad, and other involved parties. They have made appeals to Prime Minister Shahbaz Sharif, the Army Chief, and the Karachi Core Commander, urging them to ensure justice and take decisive action against those implicated in the alleged crimes.

As per Lone’s application, the National Accountability Bureau (NAB) took note of the complaint filed by members of the Creek Marina Action Committee (CMAC) and initiated inquiries into the alleged financial embezzlement and fraudulent practices within the project. During the investigations, the NAB and other authorities uncovered questionable deals and irregular financial transactions within the project’s corporate structure.

Those who paid millions in booking fees and regular payments and never saw an inch of the property they were promised are understandably angry, frustrated and seeking some justice. That same money could have easily been sitting in a capital secured savings account in any bank of the country earning a healthy return.

But the fact that the project began almost two decades ago and was abandoned thirteen years ago, there is a plethora of evidence to sift through and make sense of by the FIA. This coupled with a very sluggish judicial system means any justice will take time to deliver. n

We’re surprisingly very good at it, but just not good enough for the largest buyer on a shopping spree

By Daniyal AhmadThere’s a remark often shared by fathers in Lahore that has woven itself into the fabric of local lore. It’s a sentiment echoed whenever one comes across the ubiquitous ‘challi wala’ — the street vendor might just be the smartest individual in the city. This is attributed to his remarkable achievement — he has harnessed the elemental power of fire within a portable wooden contraption of his own design.

These ‘challi walas’, or ‘bhutta walas’ as they are known to those from Karachi, are ubiquitous on our roads from Karachi to Kashmir. They have a knack for setting up shop in the most unlikely places — often the busiest and most congested parts of the road. Despite their relentless evasion of local authorities who attempt to dismantle their stalls, they persist — however, they might have now piqued the interest of a new patron.

This new patron is not one to quibble over whether the corn on offer is priced at Rs 40 or Rs 50. Instead, this buyer bought a

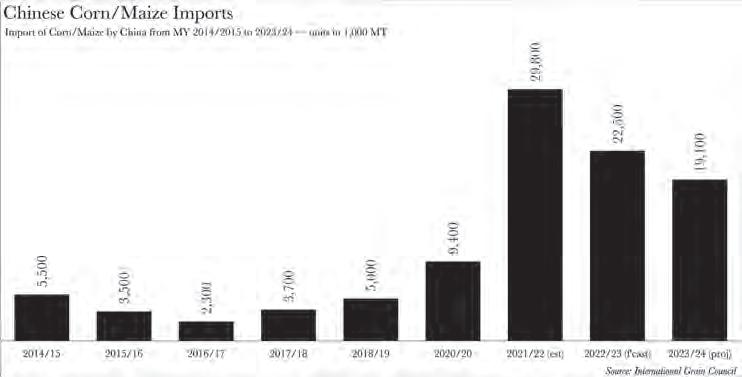

staggering $341 million worth of corn in April alone. It is the largest importer of the commodity: China.

One might ponder, what could the colossus to our East possibly want with our seemingly innocuous ‘chali wala’? The answer lies in the intricate web of international politics — specifically, the ongoing Sino-American trade war, which has thrust this humble crop into its crosshairs. As a result, Beijing is on an unprecedented shopping spree for new suppliers.

So, where does Pakistan fit into this intricate puzzle? Well, we’re actually quite proficient at cultivating this crop. The only caveat is that we’re not quite there yet. This is the story of how Pakistan is set to miss out on the gold rush for what could be termed as ‘the other gold’.

Corn, or maize as it’s also known, isn’t merely significant for the reasons that might spring to mind. Its true importance lies elsewhere

The poultry sector undeniably reigns supreme as the most voracious consumer of maize. Other contributors to the maize appetite include the realm of cattle farming. In addition, there exist 2-3 substantial corn processing behemoths akin to ours that significantly harness maize

Muhammad Saeed Akhtar, Director of Operations at Rafhan

— in its role as a fundamental component of animal feed.

Regarded as a primary ingredient in farm animal feed, corn constitutes approximately half of the feed composition. It serves as a dependable source of carbohydrates and is brimming with fibre, minerals, and vitamins. Beyond the grain itself, other parts of the corn plant — such as the cobs and stalks — are also utilised as animal feeding materials, supplementing other feed ingredients. Its prevalence is particularly noticeable in poultry feed. To put it into perspective, 75% of China’s and 40% of the USA’s corn is used precisely for this purpose, according to the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). As China’s standard of living increases, so does its meat consumption, and subsequently its poultry consumption.

There are two additional facets to consider: firstly, the USA holds the title for being the world’s largest corn producer; secondly, China stands as the world’s largest corn importer. The equation becomes clear — China has been fervently seeking new sources of corn throughout 2023, with Brazil and South Africa emerging as the most recent import destinations. It ordered 68,000 tons of Brazilian corn in January and 53,000 tons of corn from South Africa — in a first of its kind orders — and cancelled an order for 562,800 tons of corn from the USA in the last week of April. What in the world is going on?

China’s decision is inextricably intertwined with its escalating discord with the USA. This saga, a tit-for-tat tariff duel, traces its roots back to the inception of the trade war in 2018. It was during this tumultuous period that the USA — levelling accusations of unjust trading practices, and intellectual property pilfering against China — initiated an economic skirmish. Conversely, China — interpreting these actions as a calculated attempt by the US to stifle its ascension — began to decouple itself from the USA. This series of events has now culminated in this scramble for corn.

Ahh, globalisation.

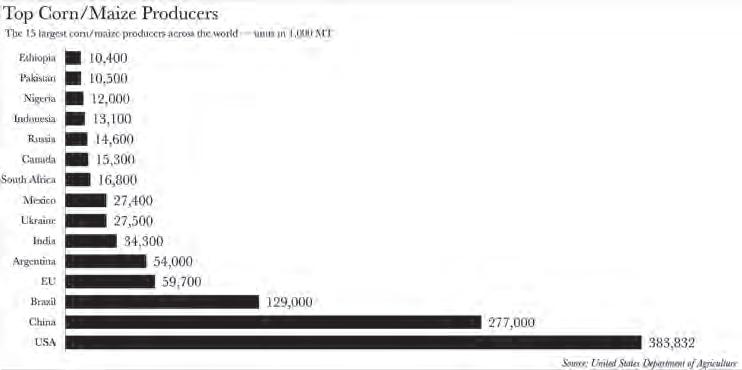

So, how does this global corn narrative affect us? Well, for starters, Pakistan ranks as the 14th largest producer of corn worldwide. More importantly, when we set aside absolute numbers and focus on relative figures, we’re actually quite decent.

And let’s not forget our status as an ‘iron brother’ to China — the world’s largest corn importer that is currently in need of new supply sources. A new supplier to potentially replace the $5.21 billion worth of corn it imported from the USA just last year alone.

“Maize is the best news to have come out of our agricultural sector,” proclaims Kazim Saeed, the Co-Founder and Strategy Advisor of the Pakistan Agricultural Coalition.

“In the two decades that have unfurled since the inception of the 21st century, maize yields in Pakistan have skyrocketed to unparalleled heights, tripling in magnitude. While the acreage has witnessed a modest augmentation, it’s predominantly the yield that’s been the

MaizeSaeed, and Strategy Advisor of the Pakistan Agricultural Coalition

driving force behind this astronomical rise. Last year, output surged to a staggering 10 million tons, catapulting maize to the coveted position of the second-largest crop in Pakistan, nipping at the heels of wheat,” Saeed added.

Saeed’s ebullience is well-justified. A scant two years ago, corn usurped rice to ascend to the throne as Pakistan’s second-largest crop. Although it still constitutes only half of wheat’s total yield, corn has undergone a formidable ascent over the past decade. According to data from the USDA, Pakistan’s corn production has burgeoned at a compounded annual growth rate (CAGR) of 8% from market year 2013/14 to market year 2023/24. This stands in stark contrast to rice’s modest 3% CAGR and wheat’s negligible 1% CAGR over the same period.

“You’re probably pondering how Pakistani farmers managed to orchestrate this re-

markable feat? The primary catalyst for this was the government’s decision to permit the import of hybrid seeds in 2001,” Saeed expounds.

“The potential for higher yield was then bolstered by domestic demand. The expansion has been entirely domestically driven — this is perhaps why you don’t hear much about the extraordinary strides we’ve made in maize production. The primary engine fuelling maize’s growth trajectory is the poultry industry. Estimates suggest that between two-thirds and three-quarters of total maize production is consumed by poultry feed,” Saeed elucidates. In effect, we witness the surge in maize production first-hand every day. Consider all the chicken in our biryanis, or the rise in fast food consumption — all these seemingly disparate threads intertwine back to the maize that nourishes the poultry sector.

Muhammad Saeed Akhtar, Director of Operations at Rafhan Maize, one of Pakistan’s oldest and largest corn refineries, agrees.

“The poultry sector undeniably reigns supreme as the most voracious consumer of maize. Other contributors to the maize appetite include the realm of cattle farming. In addition, there exist 2-3 substantial corn processing behemoths akin to ours that significantly harness maize. The remainder of the industry is an amalgamation of medium to petite players who exploit corn in accordance with their individual capacities,” commented Akhtar.

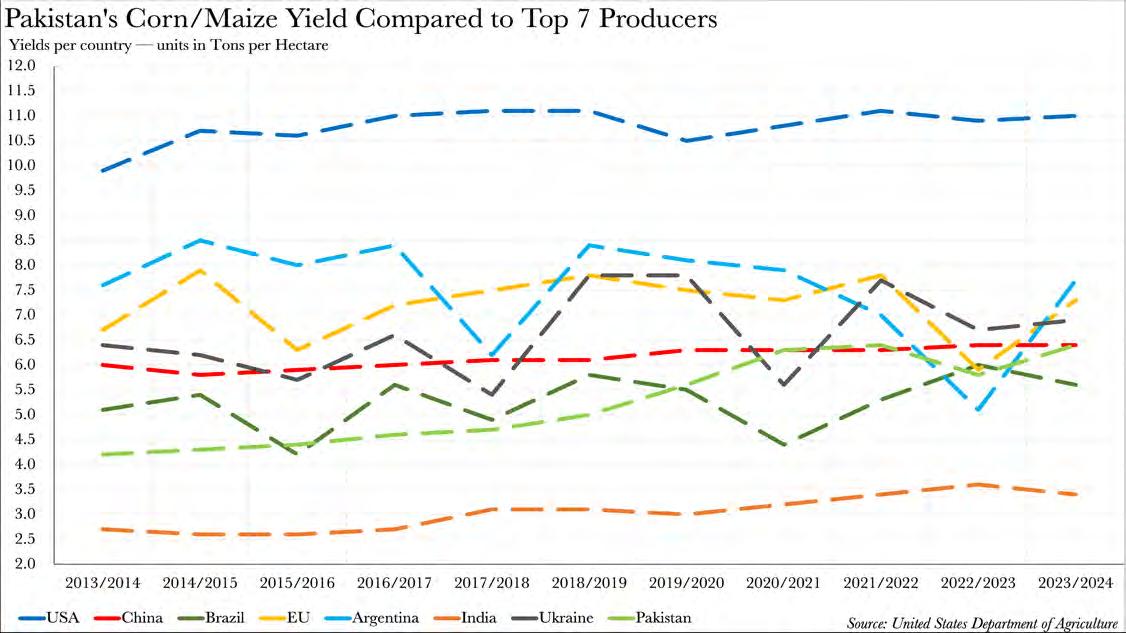

Looking at Pakistan’s yield in tons per hectare also paints a very pleasant picture. Of the seven largest corn producers in the world, Pakistan’s yield per hectare is better than two of them: India and the EU. Furthermore, it’s at

The potential for higher yield was then bolstered by domestic demand. The expansion has been entirely domestically driven — this is perhaps why you don’t hear much about the extraordinary strides we’ve made in maize production

Kazim

Co-Founder

the same level as China — the country we want to export to. At 6.4 tons per hectare, it also falls very shortly behind Ukraine’s 6.9 tons per hectare.

However, this is where our optimism comes to an end.

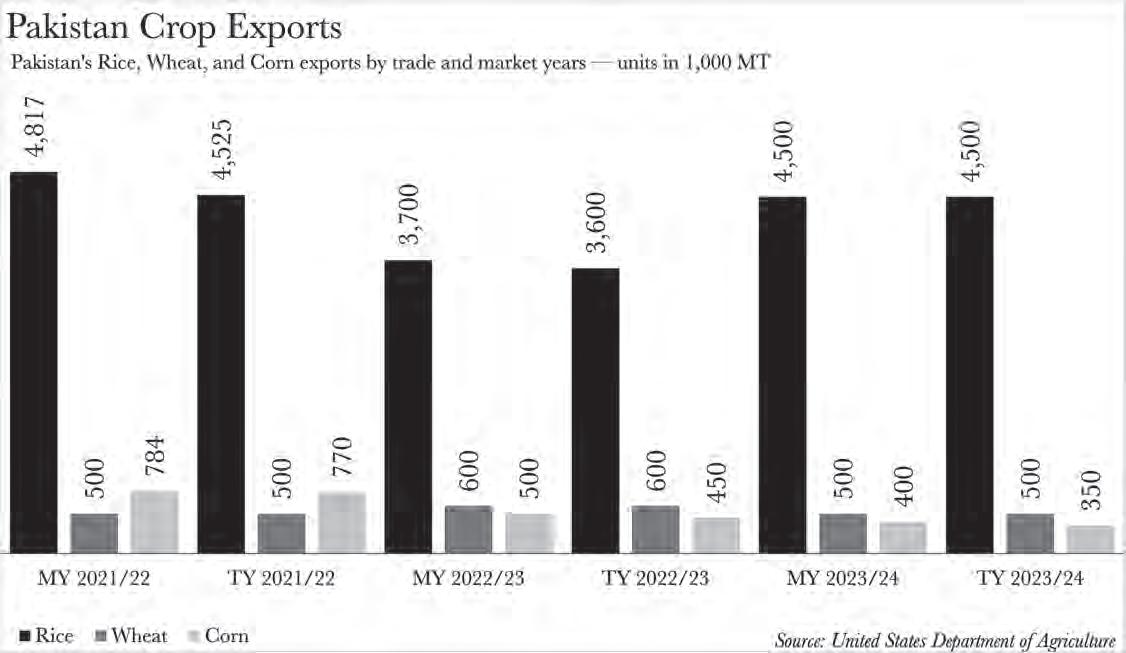

The export figures for corn in Pakistan, to put it mildly, are rather underwhelming. Our exports reached their zenith in 2021, surpassing 700,000 metric tons, only to experience a precipitous decline thereafter. This stands in stark contrast to wheat, which, despite not having breached the 700,000 metric ton threshold in recent times, has managed to maintain a considerably more stable export volume of between 500,000 and 600,000 metric tons. Rice, on the other hand, has consistently surpassed the formidable 3 million tons mark in terms of exports.

Given the current trends and market dynamics, these figures, particularly for corn, are unlikely to undergo any dramatic transformations in the near future.

In 2021, Pakistan’s maize fetched an average price of $287 per ton in the international market. This stands in stark contrast to the global price of $259 per ton. So why does

our crop command a higher price? Because of the conspicuous absence of genetically modified organisms (GMOs), and the cost of production.

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines GMOs, or genetically modified organisms, as organisms — be it plants, animals, or microorganisms — wherein the genetic material (DNA) has been manipulated in a manner that does not occur naturally through mating and/or natural recombination.

In recent history, in addition to traditional crossbreeding, agricultural scientists have used radiation and chemicals to induce gene mutations in edible crops in attempts to achieve desired characteristics. This means there are now possibilities of extracting genes from other organisms and including them in different organisms. For example, to make a certain maize crop more resistant to cold, scientists might extract a gene from a fish that swims in icy waters and inject it in the maize. By and large the scientific community has upheld that GMOs are safe.

Despite this, a continuous discourse surrounds the health implications linked with GMOs.The GMO question is one that haunts the entire agricultural industry of the world. This little fact benefits Pakistan. European markets do not accept modified maize and the Chinese market is also willing to pay a higher price for non-GMO maize. But then there is another issue. Because Pakistan is not using GMOs, our yield is low so there is less corn for us to export. On top of this, because our farms are not

mechanised and farmers are not highly skilled, the cost of producing this non GMO corn is very high. Labour is very expensive because of factors like manual sowing and inefficient methods.

“At the heart of the conundrum lies the contrast between the global market prices for the crop and our homegrown cost of production,” elucidates Akhtar, with a tone of concern.

An ideal situation would be to grow the high value non GMO corn but mechanise farms and provide farmers the right tools. This would essentially set Pakistan up as an important exporter that deals in high-quality maize. Separately, GMO corn could be grown in different regions aimed at markets more willing to accept GMO foods.

“One must contemplate how to render their sector sustainable. The prevailing discourse revolves around capitalising on the current opportunity presented by the Sino-American trade conflict. Analogous discussions emerged during the Russo-Ukraine war,” explains Akhtar.

“The inherent uncertainty of such opportunities is their unpredictable duration, which complicates long-term investment decisions. Formulating policies based on isolated events is impractical,” Akhtar ruminates.

Guess our challi walas aren’t going to be going to Beijing or Shanghai anytime soon then. n

The Exchange aims to offer smaller investors a “hassle-free” way to invest in gold without ever worrying about physical storage

hen you hear the word ‘trading’, your first thought will likely be about stocks or the Pakistan Stock Exchange (PSX). Few people will think of the lesser-known Pakistan Mercantile Exchange (PMEX). Fewer still will know that you can also trade gold, silver, oil, cotton wheat etc.

Unlike the PSX, the Pakistan Mercantile Exchange — a multi-commodity futures exchange — is more friendly for retail investors: non-professional market participants who invest smaller amounts compared to institutional investors. Any person interested in trading via the PMEX can open an account through one of the brokerage firms listed on their website, after which they can access the PMEX’s portal and trade on their own.

Investors can buy gold, silver, platinum, palladium and copper; crude oil and natural gas; cotton, corn, wheat and soybean; US and Japan Equity Indices; and certain currencies. However, despite being arguably more accessible, the PMEX has a very small number of investors — 35,000.

The Exchange’s managing director believes the number should be around 30 to 50 lakh. The PMEX is hence planning to expand across the country and launch some interesting initiatives including a global commodity trading platform and digital gold.

The love that Pakistanis, and South Asians in general, have for gold is already well-known. It is given at birth, on birthdays and other important occasions, and of course, no marriage is complete without a dazzling display of gold. However, the precious metal also serves a secondary purpose – that of a ‘safe’ investment, especially in times of turmoil.

With the rupee weakening against the dollar and the USD-PKR exchange rate crossing Rs 315 in the open market, buying the greenback appears to be a surefire way of protecting yourself against inflation, which conversely, is still near all-time highs. But what if, as is the case, there is a dollar shortage and you are unable to buy any? How else can you protect your hard-earned rupees and put them in something that is “guaranteed” to provide good returns? This is where gold comes in. The yellow metal’s price has only gone up in recent years, and it soared to Rs 240,000 per tola in Pakistan on May 11, 2023. While it has since come down from the re -

cord high, it has remained above Rs 200,000 since mid-March.

WThere is, however, a caveat. Pakistan’s domestic gold reserves are not enough to meet the country’s demand, which hovers around 150-200 tonnes according to estimates. This means that gold is smuggled into the country to meet that fresh demand that cannot be fulfilled by existing jewellery and gold bars. The country’s gold trade is largely unregulated, which means buyers can be sceptical about the authenticity and quality of the gold they want to buy. And if they are buying it for investment purposes, there are further concerns given the country’s street crimes situation — what if the gold gets looted and what would the safest place be to store it?

“If you buy gold from the market, you do not know whether it is real or fake. You will have to buy insurance, it may get robbed etc., so it is a hassle,” PMEX Managing Director Ejaz Ali Shah noted.

The PMEX plans to address these inherent risks with buying physical gold in Pakistan through the launch of digital gold. The concept of digital gold — buying the precious metal online without taking physical custody — may be novel but it is by no means a new idea. Companies across the world offer options to purchase gold in various quantities, including The Royal Mint in the UK and Augmont Gold Limited in India. In an interview with Profit, Shah explained how digital gold trading would be offered.

“What it means is that you can come to the Exchange and buy a certain quantity of gold, say one, two [or] five tolas, and pay the money at today’s rate. That quantity is then reflected in your PMEX account — an electronic entry is made and your gold stays there [in the PMEX’s storage].

“You come back to the Exchange after two or three years or whenever you are in the mood to get your investment cashed, and sell that gold at the prevailing rate. So, for instance, you bought gold worth Rs 200,000 back then and after three years, it is worth Rs 500,000. You can sell it and get Rs 500,000 in cash,” the managing director elaborated.