07 Climate Change ministry’s not-sobig reveal of the National Climate Resilience and Adaptation Plan 2023

10 Fresh out of A-levels? UBL has a job for you. But what’s in it for them?

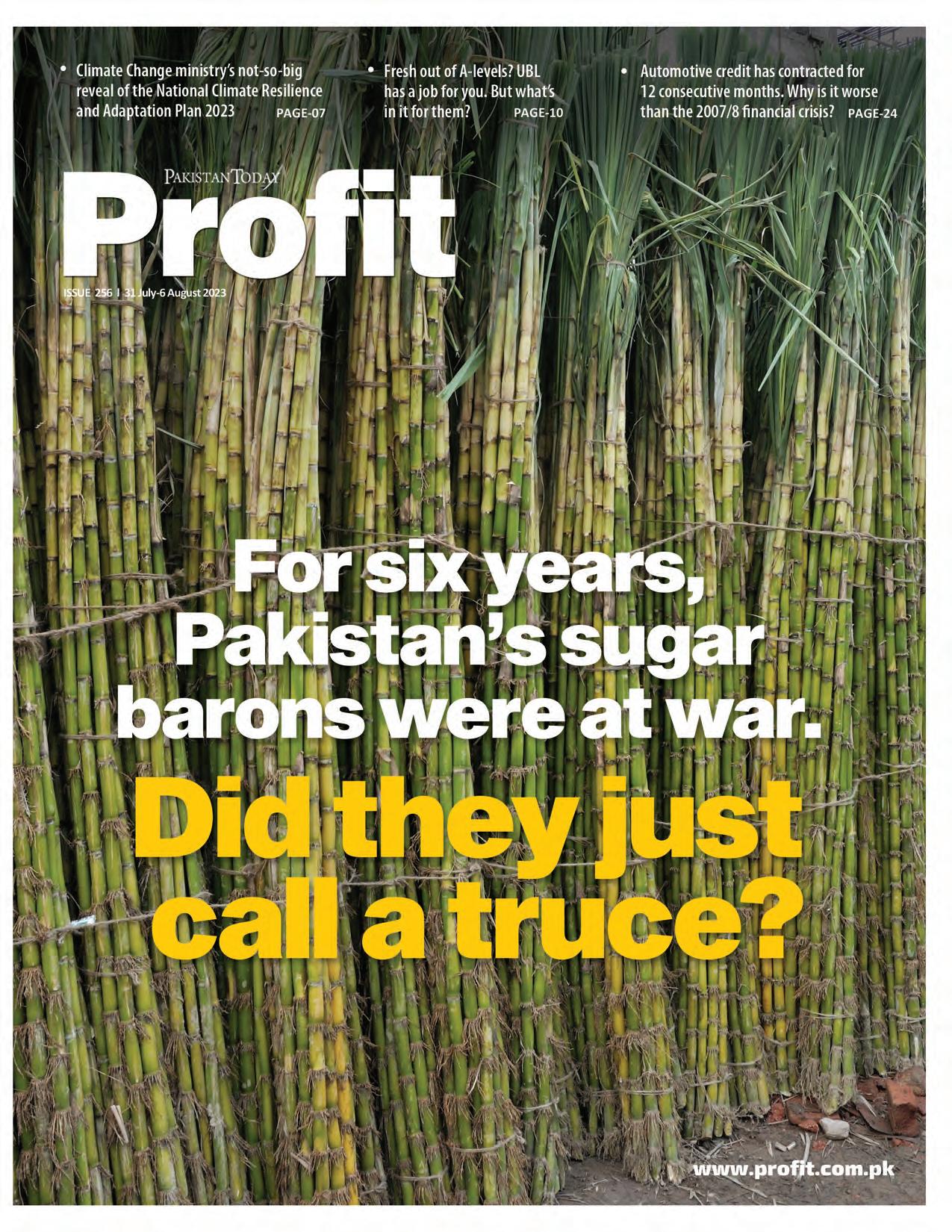

12 For six years, Pakistan’s sugar barons were at war. Did they just call a truce?

18 Fixing pay and pensions Taimur Khan Jhagra

22 The cascade effect MA Niazi

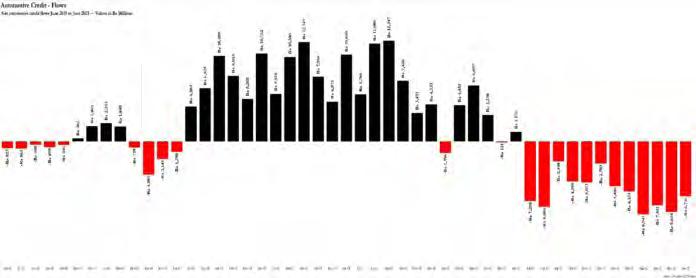

24 Automotive credit has contracted for 12 consecutive months. Why is it worse than the 2007/8 financial crisis?

26 Ultimate Finance Champion Zain Naeem

Publishing Editor: Babar Nizami - Joint Editor: Yousaf Nizami

Senior Editor: Abdullah Niazi

Executive Producer Video Content: Umar Aziz - Video Editors: Talha Farooqi I Fawad Shakeel

Reporters: Taimoor Hassan l Shahab Omer l Ghulam Abbass l Ahmad Ahmadani

Shehzad Paracha l Aziz Buneri | Daniyal Ahmad |Shahnawaz Ali l Noor Bakht l Nisma Riaz

Regional Heads of Marketing: Mudassir Alam (Khi) | Zufiqar Butt (Lhe) | Malik Israr (Isb)

Business, Economic & Financial news by 'Pakistan Today'

Contact: profit@pakistantoday.com.pk

On Wednesday, 26 July 2023

the federal cabinet approved the eagerly awaited National Adaptation Plan which is built with the focus on protecting vulnerable populations from the devastating impacts of climate change. Just a day before the approval, the Climate Change minister Sherry Rehman had tweeted a silent video of her discussing intently the contents displayed on a Macbook with her team at the MoCC office where everyone was more or less color-coordinated.

“Burning the midnight oil with the team @ClimateChangePK to leave behind a National Adaptation Plan that’s home-grown, inclusive and reflective of Pakistan’s growing challenges from mountain to delta. All such plans must be works-in -progress, but we must start somewhere, given the accelerated need for resilience.” she tweeted with the video.

After the January 2023 International Conference on Climate Resilient Pakistan, a lot of eyes in the world turned towards the Climate Change ministry’s ability to come up with a national adaptation plan. In March 2023, the UN Secretary-General António Guterres said in a video message for the press conference to launch the Synthesis Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), “Dear friends, humanity is on thin ice – and that ice is melting fast.” This statement best describes the stage of the climate crisis that Pakistan is in at the moment.

Floodwater has already inundated multiple houses in Ayun valley, Chitral and resulted in landsliding which has completely blocked entry and exit from Lipa valley this year. Earlier, in January the European Union approved a

Rs 7.86 billion grant for climate resilience and sustainability-based projects in Chitral, Gilgit-Baltistan and KP. But instead of diverting it to more sustainable and long-term projects it was announced that the grant will be used to build energy projects.

The United Nations Development Program (UNDP) has supported 35 countries, including Pakistan and all four of its neighbors, to advance their National Adaptation Plans processes with funding from the Green Climate Fund Readiness Programme. It grants funding for up to $3 million to support initiatives which strengthen their institutional capacities, governance mechanisms, and planning and programming frameworks towards a transformational long-term climate action agenda.

The “Pakistan National Climate Resilience and Adaptation Plan 20232030”, prepared by the Ministry of Climate Change, sets itself up in the executive summary to not only lay a groundwork of climate resilient ideas and address the gaps but also deal with preparatory elements, implementation strategies and evaluation of those strategies.

This document aims to provide a guiding framework for addressing the challenges and opportunities of climate change in Pakistan, and to outline the strategies and actions for enhancing the resilience and adaptive capacity of various sectors and stakeholders in 8 vulnerable sectors identified by the report as follows: Water Resource, Agriculture & Livestock, Forestry, Human Health, Biodiversity and other Living Ecosystems, Disaster Preparedness, Urban Resilience and Gender. The policy holds

the MoCC responsible for the complete implementation of this plan and the coordination and establishment of Pakistan National Adaptation Fund (NAF).

Chapter one of the policy, National Circumstances provides an introduction to the physiography, demography, climatic conditions, climate change impacts, issues and challenges, loss and damage, response and reclamation, and international environmental commitments and obligations of Pakistan.

NAP mentions, “There has been a significant rise in climate induced migration in the country, totaling at nearly 20 million people a lot of these migrations have also been a direct result of displacement”, says the policy paper. The katchi abadis of Islamabad, the housing settlements surrounding Gujjar Nala and Orangi Nala in Karachi, were evacuated after several decades of residents living there, although the reason that the authorities cite in the case of Karachi is urban flooding but this displacement is a man-made response to climate change, and a very ill-thought one.

In a 64:36 rural to urban population divide, Pakistan has the highest fertility rate (3.8%) in Asia. But the country falls at 154 in the ranking of 189 countries according to their human development index. The policy notes the need to establish early warning systems and build constructive rehabilitation policies despite making little attempt to demonstrate how. There was very little attention to detail, in fact a diagram explaining how the Natural, Economic, Social and Built environment needs to work in harmony for effective coordinated adaptation, was copied from a policy document from Australia.

The NAP 2023 highlights some key achievements of past governments and includes the Ten Billion Tree Tsunami Programme, Ban

on Polythene Bags and the National Hazardous Waste Management Policy. However, it has been clear over the years that these steps have not rendered the fruitful results as promised. In June 2022, it was noted that Karachi generates 472 gallons of sewage water every single day and more than 68% of it flows into the ocean, untreated.

After Imran Khan’s government announced the plan for the Ten Billion Tree Tsunami Programme in 2019, it was launched with the support of the United Nations Environment Programme. But environmentalists have claimed this to be an unsustainable and expensive waste of resources, citing reasons such as the lack of financial transparency, bureaucratic control over the natural environment instead of experts and environmental scientists, and the lack of consideration to tertiary environmental impacts such as diminishing grazing grounds.

NAP includes a comprehensive analysis of existing climatic data but it is only limited to 2010, there is a general lack of updated climactic records and statistics. This plan presents the observed and projected changes in temperature, precipitation, and extreme events in Pakistan based on historical data and global circulation

models. Pakistan has experienced a significant warming trend in the last 50 years, with more pronounced effects in winter and post-monsoon months, and in the southern regions. It also shows that precipitation patterns have become more erratic and variable, with shifts in monsoon onset and intensity. The plan notes the rise in extreme events such as heat waves, floods, droughts, cyclones, and glacial lake outburst floods (GLOFs), posing serious threats to lives, livelihoods, infrastructure, and ecosystems.

Chapter 3 of the plan identifies the key sectors that are vulnerable to climate change impacts in Pakistan, and proposes adaptation strategies and actions for each sector. The eight vulnerable sectors are: water resources, agriculture and livestock, disaster preparedness, human health, forestry, biodiversity and other living ecosystems, gender, and urban resilience. The proposal vaguely touches upon some action steps to execute but never really defines what these action steps mean, what kind of chainof-command will be set up to bring them about and what are the key areas within bureaucracy around the natural environment which need revamping. In the discussion on water resources, there is no acknowledgement of existing

systemic hurdles such as water mafia and the incapacities of water management authorities. The table of solutions in the categorization of ‘short’, ‘medium’, and ‘long term’ solutions, are descriptive sentences which any graduate student should be able to write with a few days of online research. Instead of discussing land reforms, better regulation on industrial usage of land, the plan focuses on the way in which the agriculture industry is causing pollution without including real and concrete examples or demonstrations on how to tackle that problem. Fortunately, in the case of disaster preparedness, the plan elaborates on how the NDMA has identified disaster-vulnerable districts but still fails to acknowledge or explain how the National Disaster Risk Reduction Strategy (2013) would be implemented differently to prevent the humongous loss of life and economy that Pakistan faced during the June 2022 floods. NAP lists down comprehensively the various kinds of natural disasters Pakistan has faced in recent years and intelligently notes the rise in trends. However, when discussing hurdles to biodiversity, the report conveniently ignores the various attacks on biodiversity in the name of unfettered and unfeasible development, the destruction of habitats in Thar by Sindh Engro Coal Mining Company, the devastation of the Kirthar National Park to build the Malir Expressway and the handing over of protected forests to the military in the name corporate agriculture farming. The plan proposes an Ecosystems Restoration Initiative (ESRI) which would develop model protected areas to conserve 7300 sq kms of land area and create 5000 green jobs. MoCC claims that through this initiative, Pakistan has expanded the protected area coverage to at least 17 percent.

A welcome news is that the MoCC explained the adoption of a monitoring, reporting and evaluation platform called ‘Pakistan Transparency Platform (RISQ)’, which is currently being developed by Global Climate Impact Studies Centre (GCISC) with the support of Centre Interprofessione Technique d’Etudes de la Pollution Atmospherique (CITEPA) France. Through this portal, citizens and researchers can hopefully keep track of the developments promised under NAP. The report mentioned

It was needed. It’s well written. And it explicitly speaks to the vulnerability of marginalised communities. However, it’s weak on plans to mainstream adaptation at the provincial and local level, and weak on how to leverage private sector finance

Ahmad Rafay Alam, Environmental activist and lawyer

various methods of engaging in public sector development projects, ensuring financing via opportunities such as Green Climate Fund (GCF). This plan approximates that from now on to 2050, around $6-14 billion will be spent on adaptation planning. “Currently, CC expenditure, both on mitigation and adaptation (investment and re-current) is to the tune of only US $5.0 billion. Apart from the existence of a narrow fiscal space, there are, however, many challenges related to the implementation of CC-related investments. These are: overriding and pressing governmental challenges such as security and energy supply, prioritization of CC responses, coordination and facilitation of CC across sectors and provinces, and the development of sector / provincial CC policies and strategies.” The plan notes.

Despite welcoming the decision, experts have voiced concerns regarding the feasibility of its implementation strategies. “It was needed. It’s well written. And it explicitly speaks to the vulnerability of marginalised communities. However, it’s weak on plans to mainstream adaptation at the provincial and local level, and weak on how to leverage private sector finance.” said Ahmad Rafay Alam, environmental activist and lawyer who spends his time filing important public interest litigation. Profit also spoke to Imran Saqib Khalid, Director Governance and Policy at World Wildlife Federation (WWF) Pakistan. “It has been years in the making. Ideally we should have developed it following our climate policy in 2013. But we waited for UNEP to fund this initiative. And then waited some more. What is truly needed are local level adaptation plans. It is at the District and Tehsil level where adaptation truly happens.”

It is safe to say that the most common criticism of the National Adaptation Plan is how it falls short on its ability to comprehensively

chart actionable steps for each identified goal and an authentic and genuine articulation of the obstacles that the state faces in their attempts to take these steps. “National plans can provide broad based guidance but unless and until there are concerted efforts to focus on local needs and local planning, we will remain at sea in terms of responding to the climate crisis. And there is no evidence to suggest that concerted efforts are afoot in this regard. Quite strange for a country that routinely reminds the world of its vulnerability to the climate crisis!” said Imran Khalid.

Chapter 4 of the NAP concerns the current climate governance framework and key institutions in Pakistan at the national and sub-national levels. It also reviews the existing policies, strategies, plans, and legal frameworks that are relevant to climate change adaptation. Moreover, it proposes a coordination mechanism and institutional roles for the NAP process that involves various actors such as the national focal point (NFP), sectoral climate adaptation cells (SCACs), national working group for cross-cutting national adaptation needs (NWG), regional climate cells (RCCs), civil society organizations (CSO) forum, Pakistan Climate Change Council (PCCC), and national steering committee (NSC). Despite pages and pages of explanation on the bureaucracy behind the implementation of NAP, there was little to now information regarding various non-governmental stakeholders, their responses and concerns or the mitigation of the same. “There is a need to ensure that the development of national level plans involves a detailed consultative process with all stakeholders. Consider the fact that not even the National Climate Change Council was kept in the loop before finalization of the document.” said Imran Khalid. “It is important to note that it is the process that defines the substance. As such, if the process is faulty, as was the case with development of NAP and many other national documents before it, then the substance itself becomes moot.”

Perhaps it would be wiser to understand

the recent key developments in these thematic areas rather than coming up with redundant phrases to define the same. Dr Nousheen Zaidi, with the help of Action Research Collective recently published a detailed study explaining how water in various parts of Lahore is contaminated due to a lack of regulation and basic expertise to even test the water adequately. Lead Exposure Elimination Project (LEEP) is a research endeavor undertaken by Aga Khan University which announced in February 2023 that the presence of lead is pervasive in paint, emphasizing that some paints contained 1000 times above the limit prescribed by the World Health Organization. Pakistan suffers from a history of ill-planning of urban settlements resulting in mass evictions, pushing urban poverty further towards the edge. Pakistan is the world’s second largest importer of refrigerant R-22 which has been banned in most parts of the world and being phased out in others.

Pakistan is faced not with just a lack of loosely framed open-ended adaptation policy, but what it needs is a consolidated understanding at each hierarchical stage of the bureaucracy and government that the ice is thin and it is melting fast and that if we do not develop a national war chest to deal with the climate crisis, there will be no nation left to save.

“The rate of temperature rise in the last half century is the highest in 2,000 years. Concentrations of carbon dioxide are at their highest in at least 2 million years. The climate time-bomb is ticking.” said António Guterres, humanity is on the brink of extinction and the climate crisis is now more significant than any national security threat – no stone must be left unturned. Pakistan’s carbon footprint is negligible compared to the first world countries but unfortunately we are prone to the worst effects of climate change. It is therefore crucial that we act now, for our sake. When it comes to climate catastrophes, there are no bailouts, like the ones we get for our financial woes. The only way to deal with it is preemptive timely action. n

National plans can provide broad based guidance but unless and until there are concerted efforts to focus on local needs and local planning, we will remain at sea in terms of responding to the climate crisis. And there is no evidence to suggest that concerted efforts are afoot in this regard. Quite strange for a country that routinely reminds the world of its vulnerability to the climate crisis!

Imran Saqib Khalid, Director Governance and Policy at World Wildlife Federation (WWF) Pakistan

in it for them?

One of the biggest banks of Pakistan is trying to tap into a new pool of talent

By Mariam Umar

By Mariam Umar

UBL is going old-school with their hiring. In a recent advertisement, the bank called on individuals between the ages of 18 and 24 to apply for an “Officer Grade IV Programme.” The catch? The applicants do not have to have educational qualifications beyond an intermediate level diploma.

That means if you’ve completed your FsC or A Levels and are looking for a job, you can apply to UBL and join the bank as a junior officer without having an undergraduate degree. So why is UBL hiring kids fresh out of high school? According to the bank it is an effort to provide individuals that may not have had opportunities for further education an oppor-

tunity to enter the banking sector. But beyond these generic statements, the bank’s initiative could have larger implications — both on the banking sector and the skilled labour market. For starters it may be a comment on the quality of higher education in the country. For a while now many employers across different industries have felt that the average quality of young graduates is such that they have to be trained from scratch no matter what varsity they are coming from. Banks in particular have this problem of hiring graduates with a four year degree from top universities but still having to train them in elaborate Management Trainee Programmes.

But beyond that it could also be a cost-cutting method. University graduates generally command higher starting salaries,

and since most big banks tend to hire management trainees from elite universities such as LUMS and IBA the fresh graduates that join their ranks each year are often paid highly and unskilled in the working of the banking sector. The programme that UBL is offering hires these intermediate students at the lowest grade possible for banking officers and will pay them accordingly.

So where does the reality of this programme lay?

Globally, there has been a great debate on whether degrees are more important than skills or vice versa when it comes to hiring new talent.

According to a Forbes article, in the United States, employers have started to focus more on specific skills rather than degrees. This is due to the increasing disruption caused by technological innovation in various industries. Digital skills are becoming essential in a wide range of occupations, and companies are restructuring their operations, necessitating changes in job tasks and descriptions. Moreover, traditional education systems have struggled to keep pace with these changes and provide the skills demanded in the evolving workplace. It has also led to a skills gap.

In Pakistan this is also a philosophy that has spread in recent times. People like Azad Chaiwala command massive followings and suggest that young students focus more on getting apprenticeships and learning skills rather than spending years getting a college education which will not prepare them for the practicalities of professional life.

Employers in Pakistan have also expressed similar views. In an interview with Dawn, Asif Peer, CEO of Systems Ltd said that there are only a few universities producing good graduates which is not enough for sustainable growth. He added, “Now with changes in technology, you don’t really need a four-year program if you have good IQ, critical thinking, and analytical capabilities.

If you can train them on specific skill sets — such as no and low code, configurations, and e-commerce — it doesn’t take them two years. It’s not an alternative, but this opens up the talent pool. We train them in specific areas based on our business requirements, say customer relationship management or e-commerce, assign them mentors and deploy them on practical projects. This can prepare a good resource in one year and is a win-win for both the employee and us.”

Intriguingly, this program deviates from the norm by eschewing university graduates altogether. Instead, it sets its sights on a special demographic: high school graduates. This unique opportunity is designed for those who have only studied up to the Intermediate/ A levels. The target age group is the population between the ages of 18 - 24. So why on earth would UBL choose high school graduates over university graduates who are equipped with business acumen and have a stronger grasp of finance? Is this some sort of a Corporate Social Responsibility stunt?

The advertising headline reads “Hamare naujawan, hamara mustaqbil” which literally translates to “Our youth, our future”. This also seems to be the first time that UBL has developed such a programme which triggers a thought-provoking question: Is this job opportunity a clever ploy by UBL to fulfil their corporate social responsibility (CSR)?

Profit reached out to UBL to seek answers. “This is the first time that UBL has introduced an OG-4 officer grade program,” affirmed Tariq Sayeed Khan, Senior Manager Marketing Operations. “However, UBL regularly introduces new initiatives to bring on board talented individuals and enhance its job pool,” Khan added. Nevertheless, UBL denied that it was merely a CSR initiative. Khan clarified, “This is not a CSR initiative. The new hires will perform tasks and services as per their role and will be compensated for their work like any other employee.”

As per UBL, the introduction of the Grade 4 Officer program for high school graduates is an effort to provide opportunities to individuals who may not have pursued higher education. Their contention is that just because one has not completed formal training from a university, it does not mean that they are unequipped or unable to handle working at a large bank.

They believe that with the necessary training and guidance, these new hires can enhance their existing skills to effectively take on the roles and responsibilities allocated to them. Through this program, they aim to tap into a different segment of the workforce and benefit from their unique skills and perspectives. But the burning question remains: Why does UBL want to tap into a new demographic? Could it be that university graduates are too expensive or less productive? Or is it a cost cutting measure?

UBL explained that their decision to introduce the program is not based on assumptions about the value or productivity of graduates from top universities. Rather, it signifies an expansion of recruitment options to include individuals with diverse educational backgrounds.

While UBL vehemently denies that this program is a cost-cutting measure, it is undeniable that university graduates generally command higher salaries compared to high school graduates. Additionally, the bank aims to reach a lower-income segment – individuals who lack the resources to pursue higher education. This group is more likely to accept positions with lower remuneration. Moreover, with relevant education and experience, university graduates are also more likely to jump ship and change organisations when offered a higher salary. This might not be the case for high school graduates who would have to face hurdles in negotiating a better package because of lack of formal education.

Probably, yes. But only time will tell. The introduction of the “Officer Grade IV Program” by United Bank Limited (UBL) marks a significant departure from the traditional degree-centric approach to hiring new talent. Ultimately, the success of the “Officer Grade IV Program” will be measured by the bank’s ability to effectively train and develop these high school graduates into valuable assets for the organisation. If successful, this initiative could potentially serve as a model for other companies looking to bridge the skills gap and adapt to the changing demands of the evolving workplace. As the world continues to grapple with the ongoing debate of degrees versus skills, UBL’s bold move demonstrates a willingness to explore alternative avenues for talent acquisition and invest in the potential of the nation’s youth to shape a brighter future. n

There is a battle unfolding in the heart of Punjab. Far away from the hustle and bustle of city centres, some of the most powerful people in the country have for the past few years been embroiled in a conflict that is seemingly over nothing more than the relocation of five sugar mills from central Punjab to South Punjab.

That is until now. Almost overnight the conflict seems to have ended, cases filed earlier have been withdrawn, and actions that had once meant the raising of war banners are now being ignored like a bad habit.

So what is going on? The reality is that these five mills represent control of the vast swathes of agricultural lands in the Punjab that are central to the economy and people of this country. And inextricably intertwined with this sugar economy are the interests of some of the most politically prominent families in the province.

The five mills in question, namely Haseeb Waqas Sugar

Mills, Chaudhry Sugar Mills, Abdullah Yousaf Sugar Mills, Abdullah Sugar Mills, and Ittefaq Sugar Mills, are all either owned directly by the Sharif family or by their extended relatives. Back in 2016, these mills relocated from different locations in central Punjab to districts in South Punjab near Muzaffargarh after getting special permission from the Punjab government.

The mill owners wanted to move from the water scarce central Punjab region to the much more fertile lands of South Punjab. The permission had to be taken because the government had policies against the construction of new sugar mills, but getting it wasn’t a problem largely because Punjab was then under the rule of Chief Minister Shehbaz Sharif.

And on this basis of alleged political favourtism the relocation of the five mills was challenged in the Lahore High Court (LHC), which quickly put a halt to the operation of these mills. Among the many complainants that took the case to the LHC were JDW Sugar Mills and Ashraf Sugar Mills — owned respectively by Jehangir Khan Tareen and Chaudhry Zaka Ashraf. Tareen at the time was General Secretary of the

PTI and Ashraf was and continues to be a PPP leader who is also a close personal friend of former President Asif Ali Zardari.

The fact of the matter is that Pakistan’s sugar industry is possibly the most powerful and influential lobby in the country. Almost all of the 91 sugar mills in the country are owned by household name politicians and their families, all of whom belong to different political parties. For the past six years, this powerful faction has been busy infighting because of politics. But a lot has changed in the past year. The disintegration of the PTI, the ouster of Imran Khan, and the alliance of the PPP and the PML-N has meant that once where the sugar lobby was divided by politics, it has now once again been united by it. The PPP and the PML-N are coalition partners and Jehangir Tareen’s newly formed IPP seems to be the league’s electoral partner in the Punjab. This has allowed all of these sugar barons to let by-gones be by-gones.

Lost somewhere in the middle of all this is the reasoning behind why the sugar mills were not allowed to relocate in the first place — the concerns of the textile industry and the fate of the fast disappearing cotton crop in Pakistan. The story is long, intricate, and complicated. To get to the bottom of it, Profit conducted an in-depth investigation involving analysis of court documents, interviews, and digging through financial statements to get to the bottom of the story. And the best place to start is the beginning — back in the 1980s when the sugar baron first roped the political elite.

Much like many other industries in the country, partition meant a new beginning. In August 1947, there were only two sugar factories in the newly minted state of Pakistan. Most of the sugar mills set up in the colonial era were on the Indian side of the border, and the two in Pakistan were not nearly enough to meet domestic supply.

This was an opportunity. For the first few years of the country’s existence sugar had to be imported which was a major drain on a new state with very little trading power. At the same time, sugar was a high-demand commodity in the subcontinent and plenty of sugarcane was grown in the new state. The 1947-48 production numbers for sugarcane in Pakistan were over 54 lakh tonnes. Nearly 75% of this sugarcane was grown in the Punjab. Since at the time the country’s landed elite were also its political elite, it became clear that many of these landowners that were growing sugarcane would now set up sugar mills, process the sugar and make more money.

The experiment was successful. Keeping in view the importance of the sugar industry, the government setup a commission in 1957 to frame a scheme for the development of the sugar industry. In this way the first mill was established at Tando Muhammad Khan in Sindh province in the year 1961. By 1962 there were six mills in the country and in 1964 the Pakistan Sugar Mills Association (PSMA) had been established and almost every single sugar mill in the country had a member of parliament on its board of directors.

The interests of the sugar industry were disproportionately represented in the legislature and the political patronage that came with this allowed the industry to boom. According to a report of the Competition Commission of Pakistan, the number of mills increased to 20 by 1971 during a period when cane cultivation was incentivized in Sindh through establishment of sugar mills. The size of the industry further increased to 34 by 1980.

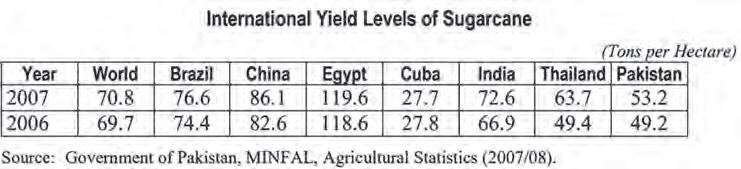

But by this point mills were facing a problem. Pakistan’s sugarcane was uncompetitive. Production was low compared to the global average yields and so was sugar extract percentage. This meant imported sugar could actually compete with the local product. To counter this, government policies placed tariffs on imported sugar and even banned it while giving subsidies to local sugar mills. As a result, the number of mills grew and so did the number of farmers growing sugarcane.

In fact, the number of mills grew at such a rate that the government eventually had to stop giving licences because of capacity maximisation issues. Through political patronage and protection through tariff and non-tariff restrictions on imports and generous subsidies, Pakistan went from 41 mills in 1987 to 91 by the mid-2000s before a ban was placed on the establishment of new factories due to excess installed capacity.

During this era in particular the Sharif family was prominent in entering the sugar mill business. They started with the Ramzan Sugar Mills and continued on to establish Ittefaq Mills and many others. There was a crucial

difference however. In the beginning, many of the mill owners had also been farmers. The Sharifs were hard-boiled industrialists with not a single green thumb in the entire family. This was also part of a rising trend of non-agriculturalists with political clout entering the country’s sugar industry. If one were to believe what was said in those days, the annual profit from one sugar unit in that period used to be more than enough for setting up a new one.

Of course, the problem was that most of this was a bubble. The fact that Pakistan’s sugarcane was uncompetitive was going to catch up with the mills at some point or the other. And that is when all of these sugar barons playing politicians were going to go to war with each other.

Now we fast forward. Up until the early 2000s there was no restriction on establishing a new sugar mill. However, around 2005 the government of Punjab decided that new mills could not legally be established. One reason for this was that a lot of the mills coming up were being set up in South Punjab near Muzaffargarh. This was a major part of Pakistan’s cotton belt — which the country’s largest export oriented sector, textiles, relied heavily on.

The other reason was that many of the South Punjab mills wanted to protect their turf. It was becoming clear around this time that sugarcane was not doing well in central Punjab. The region is water scarce and sugarcane is a water guzzling crop better suited for the South of Punjab which has better distribution of water. During the Musharraf administration during the early 2000s, a lot of the South Punjab mill owners were in government and hence lobbied for this. That is until Musharraf went into exile and democracy returned after 2008.

By late 2015, Shehbaz Sharif was solidly into the middle of his second stint as Chief Minister of the Punjab. With a thumping majority in the assembly and a knack for admin-

istration the younger Sharif ruled Punjab with an iron fist and he used it to his advantage. This was the time when five central Punjab mills moved operations from here to South Punjab. Ittefaq Sugar Mills Sahiwal, Haseeb Waqas Sugar Mills Nankana Sahib, Abdullah (Yousaf) Sugar Mills Sargodha and Abdullah Sugar Mills Depalpur shifted to regions such as Muzaffargarh and Bahawalpur. All of the mills were associated with the Sharifs.

JDW Sugar Mills, owned by former Pakistan Tehreek-i-Insaf MNA Jahangir Tareen, and others filed petitions against shifting of the mills. Chief Minister Shahbaz Sharif was also made party in the petition. The legal argument here was simple. The five mills claimed that they were not establishing new mills in South Punjab but were simply relocating existing mills to this region. The Tareens and others scoffed at this loophole claiming it was equivalent to establishing a new mill which was not allowed.

By October 2016 Justice Ayesha Malik, then of the LHC, stopped close relatives of Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif and his brother Punjab Chief Minister Shahbaz Sharif from shifting five of their sugar mills to new locations. The problem was that the Sharifs had already moved their mills and started the new ones in the Southern districts. Ittefaq Mills had shifted to Bahawalpur, Haseeb Waqas had gone to Muzaffargarh, and Chaudhry Mills had shifted to Rahim Yar Khan.

All of these mills were now set up but not operating. So what was to be done with them? The case went to the Supreme Court from here when the Sharifs appealed the decision of the LHC. The Supreme Court also struck down the appeal in 2018 ordering the mills to immediately move back to their original locations. “We do not find any merit in these appeals, consequently the petitions are dismissed,” announced Chief Justice of Pakistan Mian Saqib Nisar while closing the hearing of the appeals moved by Haseeb Waqas Sugar Mills Ltd, Chaudhry Sugar Mills Ltd and Ittefaq Sugar Mills.

By 2019 a review petition in the Supreme Court was also rejected and it seemed that the fate of these new mills was sealed — that fate being they would be sealed forever either to collect dust in anticipation of court relief or be converted for some other business venture.

Of all the sugar mills listed, the best illustration of their business woes can be gauged from Haseeb Waqas because it is a publicly listed company. Their latest annual report chronicles the state of the mill and the heavy losses they have suffered because of their mills being out of operation.

“It is in your good knowledge that the above situation arose due to the Supreme Court judgement about shifting of mills from

Most sugar mill owners are well known politicians who have had the good fortune of being elected to govern the country on a number of occasions. Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, his family and relatives own the Abdullah Sugar Mills, Brother Sugar Mills, Channar Sugar Mills, Chaudhry Sugar Mills, Haseeb Waqas Sugar Mills, Ittefaq Sugar Mills, Kashmir Sugar Mills, Ramzan Sugar Mills and Yousaf Sugar Mills. The Kamalia Sugar Mills and Layyah Sugar Mills are also owned by PML-N leaders. Former President Asif Ali Zardari’s family and PPP leaders are said to own Ansari Sugar Mills, Mirza Sugar Mills, Pangrio Sugar Mills, Sakrand Sugar Mills and Kiran Sugar Mills. Ashraf Sugar mills is owned by PPP leader and former Zarai Tarraqiati Bank Limited (ZTBL) President and current PCB Chairman Chaudhry Zaka Ashraf. Former Federal Minister Abbas Sarfaraz owns five out of six sugar mills in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP). Nasrullah Khan Dareshak owns the Indus Sugar Mills while former Secretary General, Pakistan Tehreek-i-Insaf and current IPP leader Jehangir Khan Tareen, has two sugar mills, the JDW Sugar Mills and United Sugar Mills. PML-Q leader, Anwar Cheema, owns the National Sugar Mills. Senator Haroon Akhtar Khan, special assistant to the Finance Ministry on Revenue, owns the Tandianwala Sugar Mills while Pattoki Sugar Mills is owned by Mian Mohammad Azhar. Former Governor Punjab and currently a prominent figure in the PPP, Makhdoom Ahmad Mehmood is a major shareholder in JDW Sugar Mills. Chaudhry Muneer owns two mills in Rahimyar Khan district and former deputy PM Chaudhry Pervaiz Elahi and former Minister of State for Foreign Affairs, Khusro Bakhtiar have shares in these mills.

Nankana to Ali Pur MuzaffarGarh,” reads the report. “The financial statements of the Company indicate that during this year, the Company incurred gross loss amounting to Rs.15 crores and net loss from operations amounting to Rs.3 crore and accumulated losses Rs.42 crores. Moreover, the current liabilities exceed current assets by Rs.378 crores.”

At the same time, however, the report seems hopeful. And not just corporate hopeful — genuinely hopeful. Indicating perhaps that with the change in political realities in the country, a truce might be in the offing as well. “We would like to inform you that there has been developed a positive scenario regarding the operations of the mills at its existing current location that is MuzaffarGarh. Recently the Punjab Provincial Assembly passed “The Punjab Industries (Control on Establishment and Enlargement) Amendment Act 2002 which after getting assent of Governor of Punjab on November 11, 2022 published as an Act of the Provincial Assembly of Punjab

on November 14, 2022.” So what were they playing at?

Let’s pause here for a second. What we have here up until now is that over the years the sugar industry has flourished under the watchful eyes of its political parents. In 2016, a major disagreement arose between major mill owners and sugar barons over the location and relocation of certain mills. Court cases dragged on and the mills under controversy remained closed.

But away from the politics, how good or bad is the sugar mill business for Pakistan’s agriculture? On the one hand one of the major issues raised over the relocation is that the mills would be moving to cotton districts. The battle between the delicate white lint of cotton and the sugary sweetness of sugarcane is an unexpected but harsh one. Over the past two

decades, however, cotton has taken a backseat with farmers shifting in droves towards growing the more profitable but water-guzzling sugarcane. Cotton has fallen out of demand, become internationally uncompetitive, and output has fallen by a whopping 65% from 14 million bales being produced in 2005 to 4.9 million bales being produced in 2023.

Cotton producers are losing interest and prefer crops like sugarcane and paddy while the government continues to be disinterested in reviving cotton. Sindh has seen growth in the sugar industry in cotton-growing areas, especially in Ghotki, where five sugar mills have been set up.

In an earlier interview with Profit, the son of Jehangir Tareen, Ali Tareen, had also agreed that a lot of farmers were shifting from cotton to sugarcane. The reason behind this, of course, is that sugarcane is much more profitable. Because the mills are around farmers, they have someone to sell to, unlike when they grow the cotton crop which is susceptible to disease and harder to sell.

“Rahim Yar Khan used to be a cotton growing area when we set up our mill,” says Ali. “Now it is the biggest sugarcane producing area in the region. That is because we came in and said from the get-go to the farmers that our goal is to have you grow lots of sugarcane for cheap and sell it to us at high rates. Before this, the relationship between the sugar mills and the farmers was that the mills would squeeze the farmers. Eventually, the farmers would simply stop growing sugarcane. And that’s why we provided cash loans, we gave seeds, we held training and sugarcane yield has never been higher,” Tareen told Profit in the earlier interview.

This is another issue. While water scarcity is an issue in central Punjab, many of the mills there had also gotten a bad reputation with farmers. The mills would make the farmers cue for hours to sell their crop and would not pay them on time. Deferred payments actually became a major bone of contention between farmers and mill owners.

But generally, sugarcane is a much safer bet than cotton. It is no wonder then, that sugarcane is seen as a ‘better’ alternative. Not only is it sturdier in the face of fluctuating weather, it requires less manpower in the fields. Revealingly, the sugar industry also enjoys the patronage of political elite and influential landowning families, and is therefore able to secure favourable policies.

And this is where we come back to politics. When the Supreme Court rejected the review petition on behalf of the Sharifs’ mills it seemed to be a case of game-set-match. The mills

would now have to move back to their original locations and the new buildings would have to be converted for some other business.

But the Sharfis were not going to give up that easily. In early 2021, a year after getting the final no from the SC, the mills decided to try again. They filed an application before the director general of industries, prices, weights and measures of Punjab under section 3 of the Punjab Industries (Control on Establishment and Enlargement) Ordinance 1963 for the relocation of Ittefaq Mills to Bahawalpur. Except this time they went with a different claim: they wanted to set up a “new” mill.

Even though the establishment of new mills was not allowed, this rule had been changed in 2016 when the relocation issue came to the forefront. Suddenly the case was a new one. While the relocation had been outlawed already by the SC, the Sharifs said instead of relocating they just wanted to set up new mills in South Punjab. Of course, at the time the PTI was in power in Punjab. The DG of Industries rejected the request citing the very clear decision of the Supreme Court on the issue but this was exactly the opening that the Sharifs needed.

They went back to the LHC against the DG’s decision which allowed a petition of Ittefaq Sugar Mills and set aside a decision of the director general (industries) with a direction to it to process the mills’ case further for the establishment of a new unit.

The case was successfully back in the courts. The Punjab Government also wanted to nip this second attempt in the bud and went straight to the Supreme Court against the LHC’s decision to allow the plea claiming it was against the SC’s original 2019 order. The SC was clearly feeling slighted and took it up. The matter was now once again in the SC with the Punjab government fighting back. And that’s when things started to change.

The SC took up the Punjab government’s case in mid 2022. Around the same time, PTI Chairman Imran Khan was removed from the office of Prime Minister through a vote of no confidence. Hamza Shehbaz also (briefly) became Chief Minister of Punjab. The reigns were suddenly back in the hands of the Sharifs. At the same time, they had come to power with the backing of the PPP which meant its leaders such as Zaka Ashraf were now also on the same side as the Sharifs. The PTI’s

former leader Jehangir Tareen also ended up not just parting ways openly but also allying his faction in the Punjab Assembly with the Sharifs. He has also recently announced his new political party — the IPP.

Once all of this added up, things were set for the Punjab government to take back their case in the Supreme Court. In February this year, the Supreme Court adjourned further hearing of petitions filed against the transfer of sugar mills to cotton areas till February 28. A three-member bench — comprising Justice Ijaz ul Ahsan, Justice Munib Akhtar and Justice Sayyed Mazahar Ali Akbar Naqvi — heard the case against permission to establish and relocate sugar mills in cotton growing areas.

To summarise, the Sharifs went back to the LHC to raise a new legal point and their petition was allowed. To oppose this, the PTI Punjab government went to the SC. Now, after the government is under different control, it has taken back the complaint it made earlier in the SC.

The Supreme Court expressed annoyance over the Punjab government for withdrawing the new case against the sugar mills. Justice Mazahar Ali Akbar asked why the provincial government wanted to withdraw the case. The Punjab Industries and Commerce Department representative replied that the problem of transfer of sugar mills had been resolved as permission had been given to the mills.

This permission was now labelled permission for a “new” mill instead of for a relocation which meant the SC’s old order could technically be flouted. Essentially, things have now returned to how they were in 2016 — with the Punjab government allowing the shifting of the mills, and since they have already been built they will begin operations and have already. Even though the Punjab government is under the control of Mohsin Naqvi as caretaker, it is an open secret that many matters in Punjab are run from Islamabad. On top of that, there is also no one there to oppose it.

Lost in all of this is the question of agriculture. What will happen to the cotton crop? How bad is the water guzzling sugar crop for Pakistan’s water scarcity problem? And will the sugar industry ever be released from the shackles of political engineering? n

If there is one reform that will unlock Pakistan’s from its state of perpetual inertia, it is the transformation of the public sector. While this article is primarily about transforming public sector pay and pensions; this is intertwined with bold, aggressive, and clear-headed civil service reform. And that is necessary not just because of what the public sector can do to support economic growth, but because as it is today, the public sector is a major barrier to reform in the country.

Look at Pakistan’s public sector revenue and expenditure numbers and there is one clear conclusion that will stare you in the face. While the government machinery in most states exists to serve citizens, in Pakistan our 250 million citizens seem to exist to finance the state.

Let me make my case.

Rs 3 trillion is the cost of public sector pays across the country. Rs 1.5 trillion is the national pension bill. Add the pays of all project employees, as well as the workforces at public sector companies and autonomous bodies are included; the total wage bill is closer to Rs 6 trillion. With the salary bill for the military added, we are now talking of a national wage bill of around Rs 7 trillion.

That is Seven Thousand Billion Rupees.

An additional Rs 7.3 trillion is simply the cost of debt servicing that must be paid. So even before we have spent a single rupee on the people of Pakistan who are not government servants, the state has spent over Rs 14 trillion. This figure of 14 trillion already exceeds total national revenue, which equals roughly Rs 13 trillion (Rs 12 trillion collected by the federal government and an additional Rs 1 trillion by the provinces).

This means that even to meet salary and pension expenses, the state needs to borrow up to a trillion rupees. This also means that every single rupee the government spends on anyone but itself is borrowed. Every rupee spent on the ordinary citizen, on you and me; to run schools, hospitals, and universities; to finance the equipment our jawans need to defend

our borders; to fund the operational cost for our police forces to keep the law and order; to repair roads; maintain the national electric grid; provide gas; every Rupee of that spend is financed through additional debt. 8 trillion rupees of additional debt, to provide exceptionally poor-quality services to the citizens of Pakistan.

Think about it. We do not have a single rupee to be able to finance the operating costs of the state.

Clearly, this needs to change. We need to create a public sector where the people we hire are productive and create value; and take decisions that allow citizens and firms in the private sector to create value for the economy. Given the state of the economy the reform should have happened yesterday, but with that not being the case, the best time to start is now.

Around 3 million individuals are permanent employees of the Government of Pakistan and the Provincial Governments (500,000 plus in KP; 700,000 in Sindh; 1,000,000 plus in Punjab; 250,000 in Balochistan; and around 600,000 in the Federal Government); if we include project employees and employees in autonomous institutions, we are talking roughly 5 to 6 million in total. Given that the total labour force is around 80 million, even accounting for a 700,000 strong army, the public sector employs less than 10% of the labour force.

In absolute terms, this is small.

But dig deeper, and we find a staggering number of people in roles that should not even exist. Certainly not as permanent employees who will draw a salary for 35 years and a pension for 20. For example, in KP, out of 565,000 permanent employees, you will find that roughly 200,000 employees are taken on as class 4 helpers, drivers, cooks, chowkidars, and in the roles of clerks, stenographers, private secretaries, and so on. By my estimate, this means that we employ well over a million plus people in such roles country wide. Nine out of ten are not needed.

The entire recruitment of lower grade employees has morphed into a patronage-based charade, not just for politicians but for senior and mid-level bureaucrats to try to push friends, relatives, and supporters as a favor. These people are employed not because the state needs them, but because we want to oblige favoured ordinary citizens with jobs. And what results is a public sector where the productivity we get from ten employees may not be the same as five in the private sector; less generous people would say one or two.

It is not how many people government employs, it is what they do, or more precisely, what they don’t do

The public sector as it is today, creates several challenges. These are financial; we cannot afford the cost of the public sector we have; as well as around capability, accountability, and productivity. There are several problems to solve.

1. We cannot afford to pay Rs 7 trillion in public sector wages and pensions: 10% of the workforce being employed in the public sector may be small in absolute terms, but when you have a Tax-toGDP ratio of just over 8%, and your Rs 13 trillion national revenue collection cannot cover debt servicing and wages, then it is indeed time to wake up and smell the coffee. We can’t reverse the past, but we need a different model for the future.

2. Many people get paid too little relative to their market value: Our best talent doesn’t get paid enough. The DMG and PMS officers who work; doctors; top tier academics; all our soldiers and policemen who risk their lives for us daily; IT professionals. In many government jobs, this impacts the quality of recruitment, and in almost all government jobs, it impacts job motivation and satisfaction.

3. But even more people get paid above the market: Almost all lower grade employees get paid significantly more than the market. For example, if a driver earns Rs. 30,000 employed privately, the equivalent pay in the public sector may be over Rs 100,000. But it is not just the lower grade staff. Because of the unified grading system, some professions just get overpaid. Teachers for example who may get paid Rs 60,000 at leading private school chains are likely to make twice that in the public sector. That would not be an issue, until you realize that outcomes in public sector schools are poorer than low-cost private sector schools where teachers don’t even earn a minimum wage. Can we afford to pay 3x the market rate to 1.5 million teachers’ country-wide and still not even get minimally acceptable student outcomes?

4. Everyone wants a government job: Clearly, in a system where you cannot reward great talent, but where you can provide job security to a lot of people for not working too much; public sector jobs will be in demand. Each politician knows this better than anyone, because our hujras, bethaks and offices are deluged with people wanting a little help whenever there is a recruitment opportunity; from that of a chowkidar or a driver, to that of a clerk or a stenographer. The demand for public sector jobs that come with a generous pension plan stunts the entire job market and not just the public sector and sets a very low bar for productivity. This must change.

5. Almost no one works: Of course, if you spend the money you have on jobs where people don’t need to work much, they will be

sought after. In my finance department, there was one secretary, two special secretaries, six additional secretaries, sixteen deputy secretaries, and 50 budget officers. Each budget officer was entitled to a senior clerk, a junior clerk, an accountant, a stenographer, and four to five helpers. The finance department consisted of around 500 people. At any time, maybe 50 really did the work. Can we afford wastage at this level?

6. Performance isn’t rewarded: Well, some people do work. In fact, they are brilliant. 20% of the teachers. 20% of the doctors. 10% of the DMG officers. The numbers should be much higher. But why aren’t they? Neither promotion nor financial compensation is tied to results. There is of course a risk that if you work, you will expose yourself to accountability processes. Not working doesn’t have a cost. Working might!

7. No one is punished, no one can be fired: Government processes to hold someone accountable for their misdeeds are so cumbersome, that it is almost impossible to take decisive action against anyone; this makes public sector employment even more attractive for the middle class that requires secure employment but has an impact on drawing talent away from the private sector.

8. The capability challenge: In an army of class 4 employees, clerks, stenographers, and accountants, as well generalist DMG and provincial officers; very few functional or sectoral capabilities are developed. No one is an HR expert. No one is an IT expert. No one is a public finance expert. We need space for functional and sectoral experts if we are to drive change in government thinking.

9. Nothing gets done: Not quite true. But let’s just say that the pace of work is slow. And if you want to create urgency, you must invest your own time, effort, and in doing so create more enemies than friends. Not where you want to be once you realize that your country has been on the verge of default for the last sixteen months.

10. The private sector also pays the price: Of course, with terms of service so generous in some respects, except for a very small upper echelon of the corporate sector, most people in the private sector aspire to government jobs, and the attractiveness of the inertia in the public sector to the average jobseeker creates a nation-wide culture of short-cuts, and of stifling desire for achievement and improvement.

What can we do to fix the public sector? As in many other areas, we have had studies, reports, and commissions

galore. In our government, there were two attempts at doing this holistically through a Pay and Pension commission. The first commission worked too bureaucratically. The second one gave its proposals just as the government changed. Those proposals are now in cold storage again.

The answers are not rocket-science. There are changes in recruitment, training, reward and accountability, promotion criteria, rules of business and several other dimensions that will transform our civil services into a more modern government machinery. More specifically, here are six shifts that will help our wage bill challenge; by reducing it; by moderating increases; or by increasing productivity. They will also go a long way in supporting the overall agenda of civil service reform.

1. Dismantle Universal Pay Scales (UPS): The belief that many in the public sector have, that we need to somehow equalize public sector pays, is wrong. Today, all permanent employees are mapped on a single Universal Pay Scale between Grades 1-22 (BPS 1-22). The Basic Pay for all employees in one grade is within the same band, and the compensation structure is then distorted by a deluge of allowances that make the UPS meaningless anyway, as well as making employee pay structure very difficult to understand. In KP, we counted 106 allowances in the pay structure!

The UPS also implies that DMG and PMS officers, doctors, teachers, engineers in the same grade have the same market value. They don’t. A doctor has a very different market value to an engineer, a DMG officer to a high school teacher to a bank CEO, and a rocket scientist or a computer programmer have skill sets that are even rarer. We just can’t treat different professions the same.

The UPS also results in a vicious cycle where provincial employees compare their pay structure to federal employees and vice versa, and financial managers spend the entire fiscal year trying to parry requests for increase in allowances and to manage strike after strike by powerful employee unions, by doling out money they don’t have, to too many employees, in increments that will never satisfy the needs of employees regardless.

The answer: dismantle the UPS and the BPS 1-22 system so that pay in provinces is decoupled from the centre and from each other, as well as from department to department, so that everyone can make their own decisions. Each department would keep the UPS until devising a pay scale in line with their budget and the market value of their professions. In the medium term, this would make pay much more in line with the market for all professions and allow for hiring good talent from the market.

2. Move towards Pay-for-Per-

formance: To compensate for the low basic pay of government officers, a deluge of allowances is added to basic pay. Some are substantial. For example, DMG and PMS officers get an executive allowance (150% of basic pay); doctors and engineers also get similar allowances in KP.

The allowance structure needs to be simplified and redone. Executive allowances, as well as functional top-ups to the basic salary can be converted into a performance-based variable allowance. The introduction of this could be in phases, but one can start with the Secretaries who are Heads of Department. One way of making this effective would be to force-rank peer groups on a six-monthly or annual basis. Every department could then roll out their own performance-based pay structure.

This change, done correctly, would mean that increased bonuses could incentivize or reward improved work outcomes by employees. In a system with no real means of reward, that could be transformative.

3. Reimagine employee benefits: If there weren’t such resistance to change, government employees could get a much better benefits package than they do currently, at no additional cost, or in cases, saving significant amounts of money.

Housing: Less than 1% of public sector employees are provided with housing. The rest get a meagre housing allowance. Ironically, senior officials with their own accommodation get a bigger “housing subsidy” than the “house rent allowance” provided to employees renting from the market. A revised allowance structure would have a market-based House Rental Allowance that would be revised upwards every three years based on a market survey. All employees could be eligible for a low interest loan to purchase land and build their own house or apartment. The government would exit from the business of building housing for their employees. If any housing projects are really required, these would be done as Public-Private-Partnerships (PPPs).

Vehicle Monetization: Similarly, there are around 20,000 vehicles in the possession of the KP government, and probably around 150,000 with governments across Pakistan. In KP alone, over Rs 2 billion a year is wasted on procuring new vehicles; up to another Rs 1 bln on maintenance; close to Rs 10 bln on fuel; this despite a so-called ban on the purchase of vehicles. The Punjab government recently procured vehicles worth Rs 2 billion for senior officials in one go. All this money could be put to better use, and a revised car monetization policy would minimize vehicles procured by the government (only to be done in departments such as the police that require pool cars); and all

government servants could have access to a vehicle lease-to-own scheme as happens in large corporations. Lower grade employees could lease motorcycles. As a one off, the sale of vehicles to respective owners could generate over Rs 20 bln in KP alone, and between Rs 100 bln and Rs 200 bln nationally, while significantly reducing recurrent cost.

Medical Coverage: Similarly, the very poor medical allowance given to government employees (Rs 1500 to Rs 5000) in no way provides any meaningful medical cover. At zero cost, this can be replaced by high end medical insurance, a top up to the existing Sehat Card. To finance this in KP, the Rs 15 billion spent on the medical allowance would be more than enough. The top-up medical insurance programme would have a one-time opt-out for employees, but it is highly unlikely anyone smart would take such an option. The new allowance would increase coverage from the basic Rs. 10 lakhs per family, to options of Rs 25 lakhs, Rs 50 lakhs, Rs 75 lakhs and Rs 1 crore per year per family. The programme would have medicine and OPD coverage on co-payment. Once rolled out, it could be scaled up as a top-up insurance programme that is offered to the public as well. The top-up insurance, because it would be funded, would also help to make the Sehat Card sustainable in the longer term. The work on this has all been done in KP, and the programme can be implemented immediately after the elections.

4. Embrace Contractual Employment and Outsourcing. Why does everyone in government need to be a permanent employee? They don’t. The job of government is to provide service to citizens, not to be an employment factory for those with a sifarish. Contractual employment and the outsourcing of services allows for the government to bring in talent on demand, as well as to allow the private sector to execute services that cannot be run well under the traditional public sector.

Very few positions require permanent employees; certainly not as many as we think. We need nowhere near the number of new clerks, accountants, stenographers, computer operators, assistants, helpers, telephone operators, or watchmen that are employed every year by the state, for 35 years, and then given a pension for another twenty.

Many functions in government can be outsourced. Chunks of the health and education system can be run in an outsourced manner. The hiring of doctors through the public service commission needs to be complemented by contract hiring of doctors (already done in KP); alternatively, staff can be provided by a third-party provider; rules for hiring in autonomous entities can be

made more akin to the private sector. And government departments need to be able to hire top tier talent from the market where it is needed; again, a blueprint for this exists in the way consulting talent was hired on performance-based contracts in KP Finance Department’s Internal Support Unit.

5. Everything else: Even if all of the above is put in motion, we will need ways to ensure how every person paid through the public exchequer provides productive service to the state and its citizens. We may need to think of retraining hundreds of thousands of people, given they are already employed. We may need to consider voluntary golden handshake programmes. Rules to dispose of staff not needed or required will need to be made more practical. The culture of regularization of employees must be stopped.

A leaner, more accountable government is a better government. During the early days of COVID, we realized that the government worked faster and more effectively with just 5% of the workforce coming to office. What does that tell you?

There are other things that could be done. Many quotas can be stopped; the employee son quota for example. The 4-day workweek could be a real option for the 80% of staff not required at the office every day. Work-from-home rules could save on fuel and electricity costs. More drastically, I would even seriously be in favor of allowing redundant employees to just stay at home and get a basic salary (no allowances), and not turn up to work. Why not? The system doesn’t need them, and it can’t fire them. Their turning up to office incurs cost and increases the risk of corruption. Think of the amount of rent-seeking that would stop as a result. And think of the state of our public sector if what I said is true.

Why hasn’t all of this been done, given the number of attempts to reform Pakistan’s civil service. Well, almost certainly because reform efforts have always been in the hands of the civil service themselves, and as they say, turkeys don’t vote for Christmas. We don’t have time though, and if Pakistan is to seriously embark on reform that strengthens its economy, civil service reform – and that includes public sector pay – will have to be at the top of the list. And it will have to be politician led.

Pensions are the other big part of the wage bill. I have publicly spoken a lot about pensions, because pensions are a critical issue to resolve, and

looking back over the last five years, I am proud to say that KP is the one government in Pakistan, federal or provincial, that has done real reform in this area. Our story on pensions, one of the most explosive reform areas to touch anywhere in the world, proves that real reform in Pakistan is possible. All that is needed is a will, some grit, thick skin, and a plan.

The cost of pensions nationally will be over Rs 1.5 trillion this year. Our pension bill is guaranteed to grow at 22-25% per year for the next 35 years, since we know almost exactly how many people will retire each year. The cost of inaction can be calculated from the fact that just 20 years ago, cumulative national pension payments were around Rs. 25 billion. Pensions have risen 50x in just 20 years! They double roughly every 4 years!

Unlike most countries, pensions in Pakistan are unfunded with terminal benefits defined (called Defined Benefit). Most countries have moved from unfunded to funded pensions and introduced Defined Contribution (DC) pension programmes. India did this in 2004 under a World Bank project; the same project in Pakistan failed, and the result is the Rs 1.5 trillion pension bill that must be funded through the budget.

Remember, without reform, within a decade, most pensioners will not be getting a pension. We simply won’t have the money. The reform actions listed below may be the only way to make the pension bill sustainable, and the good news is that much of it has been executed successfully in KP.

1. Introduce a contributory pension programme for new employees: It took a lot of work, but this has now been rolled out for all new employees in KP. The government contributes 12% and employees contribute 10%, and it applies to new government employees hired since July 1, 2022. The scheme is managed by third party providers, although in the longer term, the government can set up a pension management firm, provided it can get the right capacity.

2. Change the pension hierarchy: There are famously 13 tiers of pension beneficiaries in our pension rules. This seems to include everyone from the pensioner’s widow, children, parents, brothers, sisters, and even grandchildren! In KP, these have been reduced so that sensibly, only the pensioner’s widow, children and parents are entitled to benefit from the pension to a retired employee after his or her death. The federal government has recently followed suit, and other provincial governments should follow.

3. Increase the early retirement age: The minimum early retirement age remains 45 in all provinces except KP and Punjab, where it has been increased to 55. This should also be done across the board, including in the federal government. This

alone reduces the pension bill by Rs 20 billion annually in KP.

4. Streamline the Pension Rules: The spirit of the original Defined Benefit Pension Plan was simple. You get 70% of your last drawn pay. Over time, this rule has been bent. Many of the violations have also been fixed in KP. For example, all governments, through an illegal notification, were allowing employees to draw up to 120% or 130% of their basic drawn pay as their first pension. This has been reversed. Many employees were drawing double pensions (one for themselves and one for a relative), or a pay and a pension; These practices have been stopped through changes in rules. Additionally, the original way last drawn pay was defined was as the average of the last 3 years; it is now the pay drawn in the last month. This also needs to be reverted to the original definition, which is a fairer representation of the base pay on which a pension should be based.

5. Introduce a pension tax to cover Defined Benefit employees: Even with all the above pension reforms made, the real challenge is how to finance the unfunded pensions of employees on the Defined Benefit Programme. Remember that without a financing mechanism, the pension bill will grow for the next 35 years, even if all new employees are transitioned to a contributory pension programme. There are not too many solutions. One way is a pension tax deduction from employee pay, increasing progressively, so that the defined benefit programme is funded in a pay-as-you-go manner, with working employees helping finance the pensions of those that have left. In KP, a deduction of about 5% of pay is already applied as a pension tax for officers drawing executive pay. But given Pakistan’s tax shortfall, there is no justification for any employee who expects to draw

a pension, to not pay a pension tax.

6. Transitioning existing employees: Important as part of the overall pension strategy is to create pathways for existing employees. This will require both compensating and creating a transition pathway for early career employees; initiating golden handshake programmes; and making the existing pension programme more cost effective so that employees pay for it, and hence the cost benefit of the two programmes is equalized; and that most employees therefore are switching to the funded pension programme.

7. Increase retirement age: Finally, a short-term relief measure may be to allow an increase in the retirement age from 60 to 63 or 65 years, which will create a window of a few years in which the pension bill will not be added to.

Ultimately, as important as it is, Pakistan will not create the fiscal space it needs by just reforming pay and pensions. It will still need to raise significantly greater revenue. Tax-to-GDP will need to increase. Savings in other areas such as procurement and the development budget will still need to be found. But reforming pay and pensions will achieve four major objectives. First, it will help to create a more responsive and delivery oriented public sector that can help transform Pakistan. Second, it will and must stop the addition of more fat to an already bloated public sector system. Third, the pensions challenge alone, because it is unfunded, can sink our fiscal equation in the coming years, and resolving it will finance one of our most complex challenges. And finally, if we can reform pay and pensions, as political an issue as one can face in government, it will mean that we don’t need to shy away from any reform at all. n

This article is Part II in the series titled: There is an IMF standby agreement, but what next?

Perhaps the most dangerous IMF condition of them all is the raising of the power tariff, because it might finally unleash something which has been a nightmare for four decades in WAPDA, a cascade effect. That this is also coming at a time of transformation for the power sector means that WAPDA, which presently owns all of eight power distribution companies except K-Electric, may be rendered commercially unviable.

That tariff hike is set to begin this month, and even though the Rs 7.50 hike is massive, it is just the beginning. The tariff is expected to go up by Rs 50, which would lead to an average tariff of about Rs 75 per unit. It has already reached Rs 25, so what the IMF wants is a tripling of the tariff.

Even at lower tariffs, there have been power protests, with at least one incident of a distribution company office being attacked. There have also been cases of consumers driven to desperation and committing suicide. Of course, the attack was not because of bills, but because of a power breakdown in summer. As a sort of reminder that WAPDA is not just a power utility, but also deals with water, power breakdowns in the city also mean the water supply is cut, because Pakistan’s cities get their water from pumping groundwater by electricity-powered tubewells.

Actually, WAPDA is patterned on the Tennessee Valley Authority of the USA, a US New Deal project. It not only built nine

hydroelectric dams on the Tennessee River, but also controlled the river’s flooding, navigation, and led to reclamation. WAPDA was established not just to build storage dams along the Indus, but also to help irrigate large tracts of land, and to generate electricity.

Like the TVA, WAPDA became a power utility company. Today, the TVA continues to flourish as a utility, with nuclear, coal-fired, natural gas-fired, hydroelectric, and renewable and though still wholly owned by the US government, is essentially what in Pakistan is called a GENCO, or generation company. Its customers are mostly distribution companies.

However, WAPDA has not only been unbundled, but marked for privatization. WAPDA has only gone in for hydel projects, and for the last four decades, thermal projects have been in the private sector, the Independent Power Producers. One of the main issues with the power sector in Pakistan is that of capacity payments, which is related to the guaranteed rate of return for the IPPs, which was something they demanded before coming into Pakistan. It should not be forgotten that the guarantee has been made by the government, and thus is a charge on the revenues of the government. This makes the IMF very concerned whether or not the government can pay, and that too in foreign exchange.

Loadshedding has been as big a headache for Pakistani governments as it has been a tribulation for Pakistani consumers ever since the 1980s. With ever expanding demand, electricity generation in Pakistan has been unable to keep up. Governments build IPPs in a panic, and turn to such solutions as Thar coal generation (which would be a major pollutant, at a time when the world is trying to go green).

At present, furnace-oil generation places a heavy burden on the import bill. This was once balanced by exports from power-consuming industries and agriculture, but with the fall in exports, that argument does not work as well. Even if projections of increased software exports come true, though large numbers of computers will consume large amounts of power, they still have a long way to go before equaling the demand by the textile industry at full blast.

Furnace oil imports have also led to the development of circular debt. That debt is huge, about Rs 2.6 trillion in April, and keeps rising. The capacity payments have played their part. This is why the IMF wants the circular debt paid, and is making the consumer do so.

The idea of a tariff increase was thought of back when loadshedding started. The idea was that a higher tariff would lead to lower demand. However, the fear developed that if WAPDA put this into practice, a cascade effect might develop. The cascade effect is reasonably familiar in aeronautics, medicine and ecology, and postulates that an inevitable and sometimes unforeseen chain of events would occur due to an act affecting a system.

Going by the latest power tariff hike, the shape of things to come is ugly

Then as now, electricity was an essential, and thus it is price-inelastic, in that fluctuations in the tariff do not affect demand. If the tariff goes down, consumption will not go up. Conversely, if it goes up, consumption will not go down. However, there is a limit. At some point, consumers will simply refuse to pay. If enough do for long enough, consumers will be disconnected en masse. And at a certain point, WAPDA will no longer have enough consumers to be viable.