08

08 Wheat woes - Our need and inability to grow more

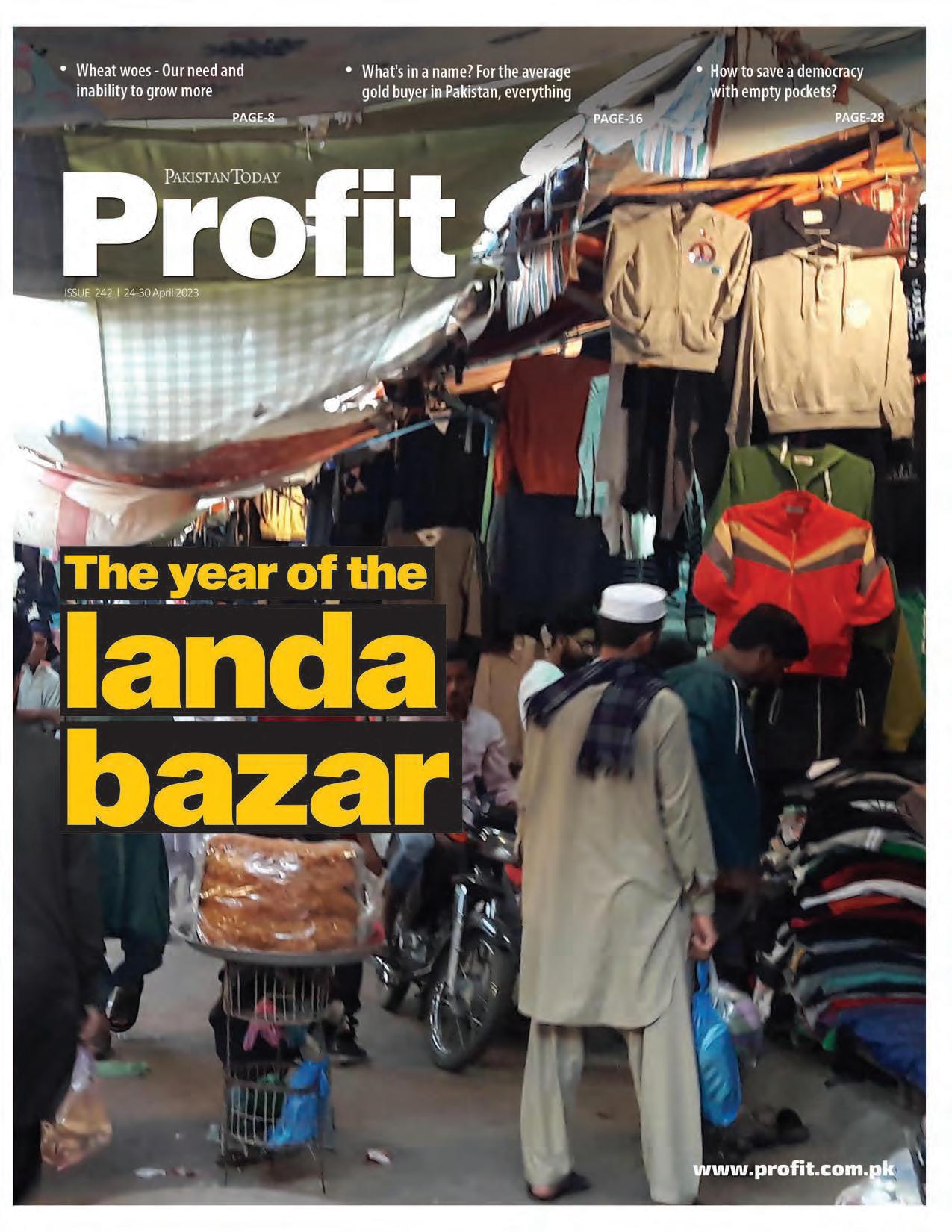

12 The year of the landa bazar

16

16 What's in a name? For the average gold buyer in Pakistan, everything

21 Private Solutions to Public Problems - Can Miftah’s education vouchers work?

24

24 The bad economics of cross-subsidizing fuel Ammar Habib

28 How to save a democracy with empty pockets?

Publishing Editor: Babar Nizami - Joint Editor: Yousaf Nizami

Senior Editors: Abdullah Niazi

Editor Multimedia: Umar Aziz - Video Editors: Talha Farooqi I Fawad Shakeel

Reporters: Taimoor Hassan l Shahab Omer l Ghulam Abbass l Ahmad Ahmadani

Shehzad Paracha l Aziz Buneri | Daniyal Ahmad |Shahnawaz Ali l Noor Bakht l Nisma Riaz

Regional Heads of Marketing: Mudassir Alam (Khi) | Zufiqar Butt (Lhe) | Malik Israr (Isb)

Business, Economic & Financial news by 'Pakistan Today'

Contact: profit@pakistantoday.com.pk

There is no crop in the world that is grown more than wheat. Covering almost one-sixth of the arable land in the world it is the food-crop with the highest demand globally that leads every other crop in the world including rice, maize, potatoes, and sugarcane.

In Pakistan, the story is not particularly different. Wheat and wheat based products account for 60-70% of all caloric intake in the country’s population. At 125 kilograms per year, Pakistan’s per capita consumption of wheat is one of the highest in the world. Correspondingly, the country is also the eighth largest producer of wheat in the world and one of the stated aims of the state has always been producing enough wheat to meet local demand and maintain a level of food security.

Yet these numbers pose a problem. Pakistan’s status as a wheat powerhouse is largely due to the vast amounts of cultivable lands in the country, particularly in Punjab. The reality is that for some years Pakistan has been unable to meet even its own wheat needs and has had to import the essential commodity which provides most of the caloric content for Pakistan’s population.

In November 2022, Pakistan approved a deal worth nearly $112m to import 300,000 tonnes of wheat from Russia to meet its domestic shortfall in the aftermath of the devastating floods that hit the country.

So what are the problems that Pakistan’s wheat crop faces? Largely, poor farm science has meant the yield of Pakistan’s wheat is far lower per hectare compared to other major producers. At the same time, a growing population has meant demand has risen at a faster rate than the amount of wheat we grow. On top of this, Pakistan has very serious issues with its agriculture supply chains — which at times have caused losses upwards of a billion dollars in crops forfeited because they could not be transported and stored in time.

Before we get into the details of wheat economics in the country, it is important to understand the state of the wheat crop in Pakistan over the past few years. Since 2020, the wheat crop in the country has seen a fast-changing landscape and serious ups and downs. Look at the following statistics:

• In 2020-21, Pakistan produced 27.4 million tonnes of wheat. This was up by more

than 2 million tonnes from the previous year and was the highest yield of wheat the country had ever seen. This was also significant because between 2008-09 to 2019-20 the annual wheat production in the country had stayed steady between 23-25 million tonnes.

• However in 2021-22, production fell again by a million tonnes but still clocked in at over 26 million tonnes. While this was a dip from the previous year, it was still higher than the yield in 2019-20 when just over 25 million tonnes of wheat was produced.

• This year, the crop’s status is finely balanced. A meeting of the Federal Committee on Agriculture (FCA) reported that Pakistan is estimated to produce 26.81 million tonnes of wheat during the ongoing Rabi season against the target of 28.4 million tonnes. Now, while the production is missing its target and the area under wheat cultivation also reduced from 9.3 million hectares to 9.1 million hectares, the production of 26.81 million tonnes of wheat this year reflects an increase of 1.6 per cent over the previous production year.

So what does all of this tell us? On the one hand, we can glean from this data that wheat production in Pakistan has been steady over the past few years. It has not been growing, but it has also not been significantly falling. However, this is not enough wheat for a country where it is the biggest source of nutrition for the population. In fact, even in 2021 when Pakistan got its record bumper crop of 27.4 million tonnes, it had to import 2.2m tonnes of grain to meet local requirements and build strategic reserves of 1m tonnes. Pakistan’s current population stands at 231.4 million people. That means in 2021 Pakistan produced around 95 kilograms of wheat for every single one of its citizens. However, the overall consumption of wheat per capita in the country is 120 kilograms per person — meaning every person has to consume around 25 kilograms of wheat that is imported.

The very next year in 2022, a 15 per cent drop in the domestic wheat yield due to shrinking acreage, poor application of fertiliser, water scarcity, limited certified seeds and the disruption of supply chain because of the floods, resulted in having to import wheat from Russia. This year, the government had predicted over 28 million tonnes of wheat production but is now looking at just around 26 million tonnes instead and like previous years will be reliant on imports. While the reliance on imports is nothing new, it is worth looking at why the government sets these targets and what role it has to play in the wheat cycle.

2021-22:

9.3 million hectares

2022-23:

9.1 million hectares

Of all the bad habits the government of Pakistan has, perhaps one of the worst is the one picked up by the Ayub Administration in 1958 from the Soviet Union of building a government that assumes that it operates in a planned economy, even as it presides over at least a semi-open market economy.

Since then, the practice has continued with the government announcing ‘targets’ every year for all manner of economic indicators, including many it has almost no control over at all. Profit has pointed out in the past how ridiculously high cotton production targets actually end up belittling the efforts of farmers. And much like cotton, wheat is another crop in which the bureaucrats stuck in the 1960s continue to announce targets for the commodity. This is despite the fact that the government of Pakistan does not own any wheat farms, nor most of the banks that do not lend to the farmers anyway, nor any of the companies that supply farmers with what they need.

What the government does do, however, is conduct a wheat planting campaign every year. Targets for planting and yields are set and procurement targets are agreed upon. Thousands of extension agents and agriculture students are instructed to fan out across the country to encourage and advise wheat farmers.

The results are mixed. On the one hand, with the help of better seeds, this system has helped increase wheat production. In 1990 production was 14.4 million tons and crossed 25 million tons in 2011 — an increase of 75% in about 20 years. However the inefficiencies of this system have been starkly exposed in the 12 years since. From 2011 up until now, however, it took 10 years before production hit a new

record of 27.5 million tons in 2021 (a 10% increase in 10 years) before falling back to 26.4 million tons in 2022.

“There is a looming shortage of wheat in the next fiscal year as well and the government will have to count on the import of wheat in order to meet the domestic requirements of staple food. The import of wheat is going to witness an upsurge at a time when the country is facing the worst-ever dollar liquidity crunch,” says one top government official.

“There will be no other option but to import 3-3.5 million tonnes of wheat for the next fiscal year in order to meet domestic as well as Afghanistan’s requirements. This is more than the import target of 2.6 million tonnes of wheat for the current fiscal year.”

This is where we stand. Pakistan between 1990-2010 increased its wheat production significantly (by 75%) but has since been stuck at the same level while the population and demand for wheat has been steadily increasing. This has taken Pakistan from being an exporter of surplus wheat to a net importer.

The difficulties of handling the wheat market became clear in 2019 when government estimates suggested a wheat surplus and some 500,000 tons were exported. But then, as domestic market conditions tightened, the government was forced to change gears and import some 3.4 MMT to meet consumer needs and help rebuild the country’s wheat stocks, at a much higher cost. The main reason behind this was that Pakistan’s agricultural supply chains were decrepit. There are many bottlenecks that make such losses inevitable. Pakistan desperately needs better storehouses, direct financing access to farmers instead of through exploitative middle-men, as well as better machinery for threshing. Most wheat is harvested by hand in the initial seasons but machines are needed for large scale harvesting. Most farmers have outdated equipment which results in significant losses.

Overall there needs to be a push towards financial access to farmers by collateralizing commodities for loans, and also creating strong incentives for crop testing, grading, and standardisation, proper storage, reduction in post-harvest losses, and preservation of crop quality for exports.

In a 2022 research article, Ghasharib Shoukat, the head of product at Pakistan Agricultural Research, and Daud Khan, formerly a UN staff officer, argue that slower growth in wheat production has made Pakistan increasingly dependent on foreign supplies. Two to three million tons — around 10% of needs

— have been imported in the last few years. However, high dependence on imported wheat is of some concern. International markets have been volatile and turbulent in recent times, and this may well be a continuing feature for the coming years if not coming decades.

“A good option for Pakistan would be to try to increase domestic wheat production. At present the average yield of wheat is around 3 tonnes/ha, substantially lower than other comparable countries. There is a huge scope to increase this yield through relatively simple changes in the production system such as reduced tillage, increased use of certified seeds, use of seed drills, a better match between fertiliser applications and soils, and application of micro-nutrients. There is also a large potential scope to reduce on-farm and off-farm losses through improved harvesting, bulk handling and storage in modern silos. Climate change poses problems for Pakistan as it does for many other countries. However, it also creates opportunities. Changing rainfall patterns have resulted in higher precipitation in some of the arid areas in Balochistan and Sindh. And this has expanded the potential area for wheat. With relatively minor investments, for example, in water storage (small dams) and water spreading technologies, these areas could, in a good year, get a reasonable wheat crop from post-monsoon residual moisture,” they write.

To improve our overall farm productivity for wheat, better farming techniques and seeds research is a must. But these are the obvious suggestions. One other way of going about it would be to possibly focus on provinces other than Punjab. In the current fiscal year, Sindh surpassed its sowing target of wheat as the staple food was sown on an area of 2.945 million acres as against the sowing target of 2.79 million acres for the current fiscal year. According to initial estimates, Sindh has harvested 25 percent of its cultivated area with per acre yield recorded as 40 tonnes. In KP, the wheat was sown on an area around 1.933 million acres as against the envisaged target of 2.22 million acres, achieving only 87.07 percent target. Balochistan achieved only 77.21 percent wheat sowing target as wheat was sown on 1.05 million acres as against the target of 1.36 million acres.

Even in 2021 when Pakistan recorded a record yield, a big part of pushing wheat over that threshold was increased yield in Balochistan and Sindh. Along with more research and better farm practices, if money is invested in the right place, Pakistan could once again become a net exporter of wheat rather than having to rely on imports and set lofty targets every year.

It is worth noting that this is very much possible. Wheat production in the country has increased from 3.35 to 25 million tonnes

2019-20:

25.2 million tonnes

2020-21:

27.4 million tonnes

2021-22:

26.1 million tonnes

2022-23:

26.81 million tonnes

(617%) during 1948 to 2011 whereas the increase in area was from 3.9 to 8.9 million hectare during this period (129%). Grain yield (Kg ha) has been increased from 848 (1948) to 2,797 (2013) with an increase of 317 percent. Over the past three decades, increased agricultural productivity occurred largely due to the deployment of high-yielding cultivars and increased fertiliser use.

A report of the Trade Development Authority of Pakistan has also pointed out how there has been an introduction of semi dwarf wheat cultivars. As a result, wheat productivity has been increased in all the major cropping systems representing the diverse and varying agro-ecological conditions. Improved semi-dwarf wheat cultivars available in Pakistan have genetic yield potential of 7-8 t/ ha whereas our national average yields are about 2.8 t/ha. A large number of experiment stations and on-farm demonstrations have repeatedly shown high yield potential of the varieties. National average yield in irrigated and rainfed area is 3.5 and 1.5 t/ha, respectively. The progressive farmers of the irrigated area are harvesting 5.5 to 7 tonnes wheat grain per hectare.

The slow-down has only really happened in the past 12 years and even then some of the lower yields have been attributed to climate change. There are some similar international examples at hand. From 1960 to 1980, Russia was a major importer of wheat requiring as much as 47 million tonnes in 1985. A major push after this has made Russia the world’s largest wheat exporter with overseas sales of about 40 million tons. With dedicated effort to improve growing and supply chain, a country like Pakistan with lots of cultivable land and favourable climatic conditions can very much see a turnaround of such proportions as well. n

One trader’s loss is another’s profit

If there was ever a time to go to the landa, it is this year. Let us explain. You see, most if not all of the clothes you find in flea-markets and thrift stores are hand-medowns that have been given away in charity by people in countries like the United States, England, Australia, Japan, and South Korea. And because the charities get these clothes for free, they sell them in bulk per-Kg at practically nothing. The clothes then make their way to thirdworld countries like Pakistan where they are sorted and sent to the market.

For example, the Catholic Church might collect a brand-new Ralph Lauren shirt as part of a clothes drive in Boston. Donors often think that the clothes will be shipped off to the third world to be distributed freely among people that need them. This is a common misconception.

In reality, charitable organisations end up collecting so many articles of clothing that it would be difficult and expensive to package and deliver them to the needy. Since charitable organisations get these clothes for free, what they do instead is find a retailer willing to buy the clothes from them at a set price per Kg and use the money from this to engage in other charitable activities.

Now, that brand-new Ralph Lauren shirt would have cost $110 at retail price in the US. But as part of a 50Kg bundle being bought by a used-clothes merchant at a rate of say $2 per KG, that shirt ends up costing literal cents. These bundles of clothes are then sorted, packaged, and shipped to third-world countries where they are sold at low rates. A shirt in the US that would have cost $110 in the US (Rs 31,000) will be available at a flea-market in Lahore for as low as Rs 1000-1500 ($4-5).

It is a classic example of the economic concept of arbitrage, in which you buy the same product in one market at a lower price and sell it in another market at a significantly higher price. But then why is this year going to be better for the landa? Normally, the thrifted clothes that arrive in Pakistan are so cheap that merchants from other countries such as Turkey, Afghanistan, and India buy these clothes from Pakistan at a slightly marked up price.

That’s right. Pakistan imports these landa-bound clothes at such cheap rates that they then sift through the clothes, find the most high-quality product in the best condition, and export them in a

strange case of double-arbitrage. Except this year things are a little different. Because of the continuing forex crisis in the country, the government has set a 300% import duty on these clothes.

As a result, the clothes will become too expensive to export, meaning the buyers from countries like Iran and Afghanistan have largely said they won’t be buying the clothes. This means two things: the first is that the clothes at the landa this year are bound to get more expensive and add to the inflationary trends in the country. The second is that because foreign merchants will not be picking up these clothes, the clothes will be of a better quality and be more in quantity. So how will this play out? To start, we need to get into the finer details of landa economics.

It is a pretty linear system. Charities, churches, and community centres collect clothes that people give away in foreign countries. The clothes are mostly hand-me-downs. As we mentioned earlier, charitable organisations do not have the time or the resources to sort and deliver these clothes to people that need them. Instead, they pack them up into huge bundles that weigh up to 60Kgs and sell them.

Who buys these bundles? There are retailers that have made a business out of hand-me-down clothing. In the UK, for example, there are enterprising Pakistani expats that store the clothes in warehouses. The first thing they do is open these bundles up and sort the clothes by categories. Pants on one end, shirts on the other, shoes in a different corner and so on and so forth. After this, each pile is sorted for quality, and by the end you have different kinds of items categorised by quality, age, and by brand. Out of this, the best quality products are sent off to thrift stores within the country. So if the warehouse is in Bradford, England — the best clothes will go to thrift stores in Bradford where they will fetch the best price.

The rest of the clothes are then exported. They are fumigated (this is where the infamous ‘landa smell’ comes from), once again bundled up (this time pre-sorted) and then shipped off to third-world countries. The market for this is massive, and Pakistan is one of the major importers of these clothes. According to a 2015 article in The Guardian, most donated clothes are exported overseas. A massive 351m kilograms of clothes (equivalent to 2.9bn T-shirts) are traded annually

from Britain alone. The top five destinations are Poland, Ghana, Ukraine, Benin, and yes, Pakistan. Low-income families then shop at these markets, where winter clothes are in high-demand.

The report estimated that globally the wholesale used clothing trade is valued at more than £2.8 billion. It is a textbook example of arbitrage. Donated clothes are sold dirt cheap in developed countries, but since they are not readily available to low-income families in the third world, their value is higher in that market. Arbitrage is essentially a risk-free way of making money by exploiting the difference between the price of a given good on two different markets. In fact, an example of arbitrage often cited in textbooks is that of vintage clothing, and how a given set of old clothes might cost $50 at a thrift store or an auction, but at a vintage boutique or online, fashion conscious customers might pay $500 for the same clothes.

Pakistan plays a significant role in this arbitrage, and in the past few years the demand for these clothes has only increased. According to data released by the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (PBS), during the last fiscal year (FY 2020-21), the import of used clothing increased by 90 per cent to $309.56 million and it weighed 732,623 metric tons. The year before that, there was an increase of 83.43 percent in terms of price. Pakistan imported 186,299 metric tons of pre-used garments during the first two months of the FY 2021-22 (July-August), which makes up for an increase of 283 per cent over the same period of last year, which translates to a spending of $79 million.

Now, this is where things get really interesting. You see, the shop-owners at the Landa are not the ones directly importing these clothes. Bulk importers get the clothes in massive quantities worth millions of dollars and bring them to Pakistan in containers. Land owners then buy these containers without seeing the contents inside — which means the quality of clothes you are getting depends on the luck of the draw.

“Be it an importer of pre-used clothes, a wholesaler, a shopkeeper or a wheelbarrow, no one has ever lost in this business. The main reason for this is that the price fix is only for the imported container and not for the preused clothes coming out of it. We take the preused clothes from the importer or wholesaler where the clothes are delivered in bundles and the price of the bundle depends on its weight, grading and type,” says Shams Khan. A native of Peshawar, he has been selling clothes to Lahore’s landa bazar for decades now.

According to him, there is no way anyone

can make a loss in this business because of how ridiculously cheap the second-hand clothes are. One needs to understand that these clothes are extremely undesirable in their home markets, and the traders that buy them there buy them from charities that want the masses of clothes off their hands and quickly, which means they settle for very cheap rates. “Very simply speaking, if I buy a bundle that has been tagged as B category, and the bundle weighs around 60 kilograms, then I have to pay RS 500 to RS 600 per kilogram for it. So this 60Kg bundle ends up costing me around Rs 36,000. Now, we take the example of t-shirts, then it takes around 18-20 t-shirts to make one kilogram. This means for Rs 36,000 I have hypothetically bought 1200-1800 t-shirts if that is all there was in the bundle,” he explains.

“When we sort the bundle approximately 500 to 600 shirts come out that look brand new and these shirts are of famous brands and easily sell for between Rs 300 to 500. Now if I sell 500 shirts myself for Rs 300, it becomes RS 150,000 and think for yourself, I bought this bundle for 36,000, so I have more than tripled my initial investment. The other aspect is that I do not sell these 500 shirts myself but I sell them to five different shopkeepers at the rate of Rs 150 per shirt. Even then I earn Rs 75,000 and make a profit. The rest of the 1000 shirts that were not as high quality I can sell to smaller shop owners or roadside merchants. At the rate of Rs 50 per shirt, I can earn another Rs 50,000. There is no losing here.”

There is no loss here because, as we have gone to painful lengths to explain, there is no loss in arbitrage. The shirts are so dirt cheap in the countries they come from because they are considered worthless. Even if they were given a price, no one would buy them since brand new clothes are not that expensive either. They are sold cheap according to weight, and since people here don’t have access to cheap new clothes, they buy the second-hand products for significantly less than what they would have to pay for new clothes.

The issue this year is the increased import duty of 300% that has importers up in arms. This increase is expected to increase the prices of used items, but due to the decrease in exports, market experts are also indicating that a large

number of these clothes will enter the market. That means even though prices will go up, the quality of the clothes will be better and people could find practically new clothes at second-hand rates.

“It is a 300 percent tax. Call it valuation duty or whatever but it is essentially quadrupling the price of the warm clothes that the poorest segments of society buy and wear, says Usman Farooqui, General Secretary of Pakistan Second Hand Merchants Association. According to him, a container of Landa clothes that used to cost RS 700,000 last year now costs Rs 2.7 million.

“The poor importer, who was already worried about the rising value of the dollar, is now further burdened by taxes. Landa is already subject to several taxes, including sales tax, in addition to valuation duty, due to which Landa's clothes are becoming more expensive,” he lamented.

“The previous government had increased the regulatory duty by 10%, and now the value has been increased from 36 cents to 1 dollar and with this increase, second hand clothing has become expensive, up to 300%, and has become beyond the reach of the poor. Due to this increase, hundreds of our containers remain at the ports and we continue to pay fines on the basis of detention. Imports of used clothes in Pakistan are worth around $100 million.

{Note from the editorial team: The $100 million is an estimation given by Mr Faroouqi. The latest figures available from the PBS are from 2021 and show an import value of $80 million. Figures for this year are not available yet.}

On the other hand, Faisal Memon, man-

ager of a company in Karachi, which has been in the business of importing and exporting Landa clothes for the past two decades, told Profit that due to unavailability of full stock with his company in winter he could not export as much as he was doing in the past.

“The increase in taxes and duties has not only affected the prices but also the export of these used garments from here. When the government increased the taxes, many importers did not clear their containers from the port because they thought that the government might withdraw or reduce the tax. Due to increase in taxes, the trend of importing containers of used clothes and toys is also decreasing,” he says.

“We have customers from Iran, Afghanistan, South Africa and Turkey. When the container is bought from the market, it is graded and the supply is sent to each customer in their country according to their demand. The market situation this time was that most of the foreign customers were willing to pay the asking price for used clothes and shoes, but due to non-availability of goods, many exporters could not meet their demand.”

Mian Fayyaz, a trader of Lahore Landa Bazaar, informed Profit that due to high duty and taxes on used clothes, the big merchants of Karachi are not able to supply these clothes to other cities at the moment due to which the business of the shopkeepers is also going down.

“Before the summer season started, I visited the importers in Karachi twice, from whom I have been buying for the last ten years, but they could not supply me what I wanted. These merchants do have used clothes but they are mostly old and of poor quality. These types of clothes are usually sold on carts in markets but since I am a shopkeeper and I have customers who are into used clothes and they demand from me a quality that is brand new.”

“In our market in Lahore, people are either selling the stock of the previous season or the clothes they are ordering from Karachi are of the previous season. In this situation, these used clothes will become very expensive and our business will slow down,” Mian added.

Ultimately, will anyone benefit from this? On the one hand, better clothes will hit the landa market this year. On the other hand, prices will go up. Importers, shopkeepers, and shoppers will all largely be unhappy. But there is one segment of the market that could reap the benefits if they play their cards right — Instagram thrift stores.

In the past few years, things in the landa have started to change. People from relative-

ly affluent backgrounds, mostly women, have started visiting the landa and sifting through the second-hand but branded clothes and buying them in bulk. They then sell them online through Instagram, marketing themselves as sustainable fashion brands dealing in ‘pre-loved’ clothes.

A big market is students. College going students need clothes, and a lot of the time they do not have the money to buy designer clothes that are a status symbol in elite universities. So for those students on a budget that want to keep up with their richer peers, the landa has been a saviour for decades. While the clothes might not be in the best condition, they are branded, comfortable and stylish.

Middle and upper-middle class sensibilities keep people away from the landa, because the market is dingy and there is a complex about buying used clothes. However, young people are able to traverse shabby markets and have less of an ego when they are on a budget. International brands are readily available at the landa and with some washing and sprucing up, entire wardrobes can be made for dirt cheap. These clothes are often even noticed by their high-rolling peers, who recognise the brands as not easily available in Pakistan. This was all there was to it, until of course, Instagram came about.

The trajectory has actually been quite ingenious, and the way some of these pages operate is truly enterprising. “I used to get almost all of my clothes from the landa since I started studying in Karachi,” says one student from IBA that runs a thrift store on the side when she isn’t busy with her studies. “I’ve always gotten compliments from friends and strangers alike for my outfits. It isn’t just as simple as going to the flea-market, you really have to have an eye for the right stuff and that means knowing about fashion.”

It is actually very enterprising work to be going to the landa and then selling clothes from there through Instagram. People do not like going to flea-markets, so these people with an eye for fashion and an understanding of landa dynamics go to the market for them. Many of these women then buy clothes and shoes in bulk, bring them back home, clean them or fix them if they need fixing, and after that photograph them aesthetically. Some of them even model the clothes themselves or get

their friends to model them for them. “There is barely any additional cost. There is the Careem fare that I incur going to and from the landa, and then sometimes I wash the clothes again, and then I put them on, set my camera on timer-mode and model them myself too. I upload the pictures and start getting DMs, my customers then bank-transfer me the payment and they pay for shipping too,” says the online thrift store owner we spoke to.

They brand their products as ‘preloved’ or ‘rescued’ and supporting sustainable fashion, which they claim is environmentally friendly. All of this coupled with well-done photography means that middle and upper-middle class people that see these pages are more than happy to buy from them, especially since they are so cheap.

And all of this is why this year could be big for the Insta thrift stores. For starters, they have a very good understanding of what products are high value and what brands sell better and go for better rates. On top of this, they have the added advantage of a clientele that buys sitting from home and not by going to dingy flea markets. As a result, people will be willing to pay more — especially for branded products.

A shirt that came to the landa at Rs 200 last year and was sold at Rs 500 was already selling at Rs 1100 on these online thrift stores within minutes of being posted. This year, people are more likely to buy a branded Rs 2000 shirt from an online thrift store rather than a Rs 800 shirt from the actual landa market. That is where the opportunity lies. And as soon as more containers start to be released and the clothes hit the market, it will be an opportunity worth cashing in on. n

In Pakistan, gold is more than just a precious metal - it’s a cultural powerhouse. A symbol of honour and wealth that binds relationships together with its glittering allure. Imagine having a Desi wedding without the dazzling display of gold jewellery visible from miles away. Unthinkable! And if you dare to try, you’ll never hear the end of it.

But gold’s value extends far beyond its cultural significance. In times of economic turmoil, it becomes a beacon of hope - a store of value that shields many from the harsh impacts of a rapidly depreciating currency.

As inflation skyrockets to unprecedented heights and the rupee plummets to all-time lows, there’s only one other currency that’s acceptable besides the highly coveted dollar - gold.

Picture our economy as a sinking ship. Dollars are the lifeboats, but they’re in short supply. What’s the next best thing? Gold. It’s the closest thing to a lifejacket in these treacherous waters. That’s how Pakistanis

see it as they scramble to amass as much gold as possible in a desperate bid to retain their purchasing power against the rapidly dwindling rupee.

Despite its limited foreign reserves, Pakistan’s population exhibits a strong affinity for gold. This fervent desire for the precious metal, coupled with the country’s lack of domestic gold reserves, necessitates a reliance on imports to meet the demand.

Investment-grade gold typically consists of 24-carat gold, the purest form of the metal. The most desirable sources of investment gold are found primarily in the Americas and the Middle East. It is customary for Pakistanis visiting Saudi Arabia on pilgrimage to purchase gold and bring it back for their relatives. Similarly, individuals returning from the United

States are often asked to bring back jewellery as a favour.

The New York Times reported on Pakistan’s gold trade, describing its coastline along the Arabian Sea as a popular destination for gold smugglers. In October 1993, during Benazir Bhutto’s second term as Prime Minister, Dubai-based bullion trader Abdul Razzak Yaqub (ARY) proposed that the government regulate the trade by issuing him an import licence. That licence was eventually granted under some very controversial circumstances. Profit did a detailed story on ARY’s beginnings in the gold to the media conglomerate it is today.

Despite this proposal, Pakistan’s gold trade remains largely unregulated to this day. As a result, buyers remain sceptical about the quality and authenticity of the gold they purchase.

Sarmaaya records the fluctuations in gold prices per tola.. Within the span of one week, the price of one tola of gold has gone from Rs 242,898 to Rs 231,939, as shown in the graph below. This shows that gold is a highly volatile asset.

Moreover, gold prices have consistently risen in the past five years. The price of gold per ounce was Rs 156,219 in April, 2018, soaring to Rs 569,386 in April 2023.

Profit will guide you on an exploration of how gold may emerge as the second most valuable or simply an acceptable currency if the country exhausts its dollar reserves.

Amidst hyperinflation in Pakistan, retaining the rupee’s value has precipitated a daily erosion of purchasing power for people’s wealth, provoking grave concern. In stable times, the focus is on achieving superior returns. However, during inflationary periods, concerns transcend returns and become a matter of survival. Pakistanis are habituated to an annual inflation rate of 8-10%. Panic remains contained as long as the rate stays within these bearable figures. However, when it exceeds these figures - in the current case, at a historical high of 35.4% no less- panic ensues.

So what is going on?

Nasim Beg, Director at Arif Habib Corporation, elucidated the current crisis for

Profit’s readers by outlining the trajectory that Pakistan has followed over the past 50 years, which has now brought it to the precipice of a possible default. “The situation is straightforward; Pakistan has inadequate foreign exchange earnings, rendering us incapable of purchasing the items we are accustomed to importing. Comparing imports and exports over the past 50 years reveals that we have consistently fallen short in meeting the cost of imports with the revenue generated from our exports.”

He continued, “In only six to seven years of these last 50 years have we seen a surplus. We have consistently borrowed money to pay for our imports, akin to using multiple credit cards to sustain a certain lifestyle without possessing the funds to pay off those credit card bills. Now all our credit cards have been maxed out and no one is willing to lend us more money to pay them off.”

The country therefore has had a perennial balance of payment problem for the past five decades.

According to Beg, “Friendly countries lent us money, artificially stabilising our currency. We received US aid during the Ayub, Zia and Musharraf eras. We can look back and say that our economy was robust. However, it

was like an athlete on steroids and now they are realising their body is quite dysfunctional.”

In essence, Pakistan never developed the capacity to earn dollars or pay for imports because someone would always bail us out. Now that America’s vested interest in providing aid has greatly diminished and others have recognised Pakistan’s pattern of dependency, all the usual suspects are hesitant to offer further assistance.

Beg also emphasised how our reliance on aid and loans has hindered our development of productive forces to generate dollars through sources other than bailouts. And now there is a shortage of forex, so demand for dollars is skyhigh while supply is negligible.

But how does gold fit into this equation between rupee and dollar?

Well, the government is desperately trying to hold onto the few foreign reserves that it has left, which is why it has taken some drastic measures (administrative and otherwise) over the past year to stop haemorrhaging the greenback. That leaves the open market, but there are restrictions there as well that hinder supply in addition to the bid/offer being not only wider but higher than the interbank rates. Another option is to utilise the hawala system. Beg explained how this might not be

The purchasing power of customers has suffered due to inflation and economic crisis. The gold we sell is predominantly in Dubai. Despite the imminent wedding season, jewellery is barely selling. We primarily sell gold bars, coins and nuggets to safeguard savings. With Eid and Ramadan coupled with hyperinflation, no one is in a position to spend on jewellery

Haji Haroon, CEO of Chand Gold

the best alternative either. “Some individuals may have the option to use the hawala system if they have a bank account in Dubai or a similar location. They can obtain foreign currency in exchange for their rupees without leaving a digital trail to track the movement of currency. However, not everyone has this luxury. Furthermore, the recently imposed FATF has made money transfers even more challenging, leaving people with no choice but to seek other ways to protect their wealth.”

This is where gold comes into play.

“The uncertainty surrounding the rupee and the unavailability of dollars is causing people to turn to gold, which has now become the only other acceptable currency after the dollar,” shared Beg.

But gold does not come with its fair share of challenges.

Pakistanis take the adage ‘not all that glitters is gold’ very seriously because we are cognisant of how easy it is to be duped into purchasing counterfeit or impure gold. Superficially, safeguarding your depreciating currency through gold might

seem like a million dollar idea. However, as we hail from Pakistan, we wouldn’t recognise a million dollars if it struck us in the face.

As we have already established, Pakistan’s gold market is not formally regulated. It is difficult to ascertain whether the gold you purchase is pure and authentic. Moreover, there is also the apprehension of being burglarised, so it is not secure to retain large quantities of gold in your home either. Nevertheless, people are still procuring it.

In order to safely invest in gold, people seek branded and trustworthy traders. This is where ARY enters the scene, but we will address that shortly.

Firstly, let’s examine why gold might be a precarious investment. Gold prices are highly volatile and, unlike the dollar, gold prices in Pakistan are not purely defined by its trade in the Pakistani market. The rates we obtain for gold here are directly linked to the international rates at which gold is trading. As a result, fluctuations in global gold prices also impact Pakistan’s gold market.

Beg informed Profit that “The international price of gold is elevated right now due to the war in Ukraine. If there is an armistice tomorrow, gold prices will dip. If gold is trading at $1,990.30 today and then plummets to $1,500, the international price will translate into the gold market in Pakistan. I will

awaken to discover that the gold I purchased for around Rs 570,000 is now worth Rs 426,000. I was safeguarding myself from the depreciating rupee but fluctuating international gold prices can still result in me being a loser.”

However, no matter how much gold prices may plummet, the downfall will not be as rapid or as significant as the rupee’s depreciation. But ultimately, gold is not the best investment.

What transpires when panicked masses all rush towards gold in a desperate attempt to evade going down with the rapidly collapsing economy? A shortage of gold emerges.

Haji Haroon, CEO of Chand Gold, informed Profit that “Our imports have ceased due to recent restrictions, lack of foreign reserves and the skyrocketing dollar rate.” He elaborated that it has become unfeasible to import non-essential products, resulting in a diminished supply of gold.

“Individuals are retaining their gold because it would be imprudent to sell when the rupee is anticipated to decline further,” Haroon shared.

He continued, stating that “The purchasing power of customers has suffered due to inflation and economic crisis. The gold we sell is predominantly in Dubai. Despite the imminent wedding season, jewellery is barely selling. We primarily sell gold bars, coins and nuggets to safeguard savings. With Eid and Ramadan coupled with hyperinflation, no one is in a position to spend on jewellery.”

Raihan Merchant, CEO of Z2C Limited, a prominent advertising agency based in Karachi, highlighted another reason for the current gold shortage. “Gold, over the last two years has become a commodity in which people can hoard money. Instead of keeping 20 crore rupees in cash in my house, if I can’t deposit that money into a bank account since it comes from

Gold traders will need to brand their gold, like ARY did, when the market is stagnant and they will need to engender demand. Then everyone will concentrate on brand building and advertising

Atiya Zaidi, Managing Director and Executive Creative Directorof BBDO Pakistan Director at

questionable sources or it is money that I haven’t declared in taxes, gold is a very easy way to park this money. Imagine the size and volume of that kind of money, it is not easy to store. When I keep it in the form of gold it becomes convenient and safe to store. So the supply is not just short because demand might be rising but also because many people also hoard gold to park their black money”, he explained, One thing is certain: what is transpiring in the gold market is expected and common in an economy headed towards default.

For anyone looking to make gold jewellery, it is typical to go with someone trusted whom they know to be authentic and good at the ‘making’ part of it. Similarly, a buyer purchasing pure gold as a means to preserve the value of his cash, will go with a reputable brand and ARY meets that requirement.

As with any brand, it takes time and money to develop. This is a major barrier to entry for other gold traders to replicate the ARY model, they don’t afford such a marketing exercise. ARY had the right idea at the right time and stuck with it.

‘Swiss’ is another brand of gold which is not local, not readily available and therefore open to counterfeiting, but is the only other name associated with gold bars, ‘biscuits’ as

they’re colloquially referred to here. This in turn gives ARY an added layer of authenticity and preference.

In the absence of trustworthy gold traders, people turn to the few branded and reliable sellers. ARY stands out with their branded gold bars featuring a scannable QR code, assuring customers of their gold’s purity and authenticity.

Profit asked Atiya Zaidi, Managing Director and Executive Creative Director of BBDO Pakistan, to explain ARY’s branding strategy. “ARY hasn’t done anything novel. It may be unprecedented in Pakistan, but globally even precious metals and gems have been branded. Take Tiffany & Co., for instance; research indicates that women’s heart rates escalate just by looking at those infamous tiny blue boxes!”

From a marketing perspective, ARY has essentially undertaken category development. “ARY accomplished this feat because it is already a renowned brand. Everyone is cognizant of it due to their media channels. They are reputed for veracity when it comes to news. So, ARY is not merely a gold brand or a jewellery store; it is a house of brands with an established image and reputation,” Zaidi shared.

Merchant had a similar response: “Purely from a branding perspective, when you want to engender trust with a product, you affix a brand name to it, which is precisely what ARY did. They have been doing it since 2000-2001. As ARY established its brand and became a

household name, they were able to augment their premium.”

“If you go to Dubai, no one will consider ARY gold to be the preeminent choice but gold from other brands, like Swiss, will be readily available and they levy an even higher premium than ARY. So, this phenomenon of ARY gold is specific to Pakistan because there aren’t many options to procure authentic gold,” Merchant concluded.

When asked why other gold traders have failed to brand their gold, Zaidi informed that previously gold did not necessitate branding because it would sell regardless. “Gold is perpetually in demand. You need advertisements where there is surplus supply and you need to engender demand for it. Gold is already in such high demand since it is an integral part of our culture that no one felt the need to brand it.”

Merchant echoed this assertion by saying: “Branding is costly. Brand building requires investment consistently over a time along, with lucid vision and positioning. ARY couldn’t levy the same premium as today 20 years ago. So you cannot simply commence charging a premium, without investing years of effort and money into it to first establish trust.”

Now that there is a need for branded gold because people are desperate but sceptical about what they are buying there is just one credible seller resulting in the current shortage of authentic gold bars in the market.

Zaidi highlighted that, “Gold traders will need to brand their gold, like ARY did, when the market is stagnant and they will need to engender demand. Then everyone will concentrate on brand building and advertising.”

Caught in a treacherous double bind, Pakistanis are desperately seeking to safeguard their savings from the rapidly depreciating rupee. But as the market’s dollars vanish before their very eyes, they are confronted with an insurmountable obstacle: The alarming decline in their ability to acquire authentic gold bars. The chaos of the current economic downturn engulfs them all in its deadly vortex of despair and hopelessness, leaving them reeling and gasping for air. n

The uncertainty surrounding the rupee and the unavailability of dollars is causing people to turn to gold, which has now become the only other acceptable currency after the dollar

Nasim Beg,

Arif Habib Corporation

The jury is split on whether or not conventional public education spending can be replaced with something better

By Bakht Noorhich country is Miftah talking about?” exclaimed Dr. Faisal Bari, an economist and Education specialist. “I can’t think of a country where primary and middle school education is not considered as part of government responsibility.”

This remark came in response to Miftah Ismail’s (a political economist and Federal Finance Minister from April-September 2022) suggestion that the government should provide PKR 3000 vouchers to parents who may enroll their children in low-fee private institutions, as the public education system is burning in flames. As the government is unable to sustain the public education system, it’s now devising new strategies to alleviate this burden and find shortcuts. One such shortcut is the outsourcing of education to private entities.

Presently, a PKR 100 billion is channeled into education per annum. However, given the abysmal student results, the amount doesn’t seem justified. How can one make more productive use of this money?

For Ismail, the answer is straightforward: more privatisation. He asserted, “this is not a time for ideology. Pakistan can’t be a leftist, socialist state. If private education is the answer, then be it.”

“What kind of a solution is this? If the judiciary is not functioning well, should we privatise that too? If the army is not functioning well, should we privatise that too?” Dr. Bari interrogated. “Our main focus should be

to improve the public education system, not aggravate it further.”

“The present education system is failing our students. Only a quarter of children end up at schools. Half don’t attend schools at all, and a good proportion attends madrassas. There are around 30,000-35,000 madrassas in the country, out of which only 12,000 are registered. Then, a segment attends private schools,” highlighted Ismail.

Now, when you think of private schools, elite top-tier institutions with exorbitant fees such as Aitchison, LGS, KGS come to mind. However, the ground reality is far different. You’ll find that most private education institutions have low-cost fees, around PKR 1000-2000. The quality of education there is no doubt questionable.

Nevertheless, Ismail elucidates that students in public schools are majorly failing.

“In math, they’ll typically score 27 and in science, 31. This means that the system is failing to educate them properly. Leave aside English, they can’t even write in basic Urdu. This is a sheer wastage of the PKR 100 billion that’s spent on education per annum,” asserted Ismail.

“In Pakistan, the education system is deeply fragmented and inequitous. Most private schools are the ones with low fee levels, around PKR 1000-2000,” Dr. Bari informed. “There are very few high schools under the private sector.For wider accessibility, reform

is warranted in the public school system, as students will have to be brought back to government schools as their years of education progress.”

Miftah Ismail propose a unique idea.

Just divide and disburse the government’s education budget through ‘vouchers’ to families who would have benefitted from the public education outlay.

Let them to decide where they want to send their kid to leave ABC the quickest!

Simple enough. However, one must ask. What does Miftah Ismali intend to achieve with this? Will the voucher system eventually replace the public school system in Pakistan or complement it?

“The intention is not to replace the entire system. But provide parents a choice to either enroll either in public or private, except that we’ll pay for the private. Pilot programs have already been done in Punjab and Sindh, with successful results. If needed, we’ll voucher increase costs for girls, as a means of giving incentive.”, he clarified Reforms can be made within the public education system as well; however, the system is deeply distressed according to Miftah- perhaps, damaged beyond repair.

“At the end of the day, the government has a singular purpose which is to provide education. Are public schools fulfilling this effectively? Absolutely not! They’re functioning as babysitting clinics, making students sit for

6-8 hours daily. They’re not providing education.”, Ismail argued,

“The state’s responsibility is to provide education to children. It doesn’t necessarily have to do that itself. We’re giving parents a choice here. No extra money is being spent. It’s just a more productive use of the PKR 1 billion that is presently being wasted on the education system,” he concluded.

Private sector schools mostly pay less than minimum wage to teachers, in fact, teacher salaries tend to be lower than the minimum wage, which is PKR 32,000. The privatisation solution will further increase the exploitation of teachers.

“Whoever wants to build a good career in Pakistan, why would they opt for teaching as a profession? Whenever I walk into a classroom and ask students what they wish to be when they grow up, they either shout “doctor” or “engineer.” Those who will raise and nurture the coming generation of Pakistan, nobody wishes to join them,” Dr. Bari elaborated.

Government salaries are better compared to those in the private sector, and that differential should be maintained to support the public school system in Pakistan according to Dr. Bari.

“It’s important that we think of building a good career path for our teacher, whether it’s the primary, secondary or tertiary level. They should build expertise in their niche area and have a rewarding career trajectory.”

“This is a serious matter as teaching is one of the highest filled professions in Pakistan. There are around 2-2.5 million teachers across the country. Yet, we face a consistent shortage of teachers as we don’t have mechanisms of making teaching into a lucrative profession. It’s nobody’s career choice. This must change.”

Why are the preexisting teachers not delivering well is another pivotal question.

According to Dr. Bari, it’s pertinent to oversee their entry requirements so that capable teachers enter the profession. Secondly, there needs to be a shift towards teacher licensing.

In most cases, an FSc, Metric, BA graduate is hired immediately after graduation, without any formal requirements. “We eventually need to introduce licensing for purposes of quality check, but this isn’t a short term solution, and will work over time. Then gradually with licensing , you can grade teach-

ers and differentiate rewards based on that. However, this isn’t possible at the moment,” explained Dr. Bari.

The private sector salaries issue is very complex. Due to poverty levels in Pakistan, most families can’t afford to pay high school fees for their children.Quality education will always cost money. The question is, who will pay for it?

Dr. Bari adds, “this is the biggest dilemma faced by private schools. If they’re acquiring a PKR 500-2000 fee per student, then how can they increase teacher salaries? They can barely meet the minimum wage. Therefore, If the education quality is to be ensured, the state will have to step in. Otherwise it’s simply not possible, the market alone can’t help this.”

It’s difficult to change the education quality if the circumstances of the teacher are not improved.

Ismail reminded of the enmeshment of politics with education.

“Education ministries’ sole purpose of existence is to provide jobs to political appointees. They are driven by votes and have absolutely no regard for education.”

This further stresses the usefulness of seeking more private solutions to the problems. However, Dr. Bari disagreed.

“I believe that this has changed to some extent, based on the data from the past 15-20 years particularly in Punjab and KPK. Nepotism and corruption in teacher hiring is not as prevalent as it used to be. The recruitment process has been made very objective now. If you have a good degree, there is very less we can do to not hire you and vice versa,” Dr. Bari clarifies.

“Yet, where the problem still persists is with the postings/transfers. Miftah’s case definitely stands here. Now, what can be the solution?”

“Firstly, let’s remind ourselves that both education and employment are not non-politicised anywhere, but they have to be made so. The non-politicisation of education is another question altogether. However, teachers’ postings/transfers can be non-politicised through various ways. If merit-based hiring occurs in areas such as the army, why can’t it be done here. Already, recruitment has been made largely non-politicised. Why can’t we do the same with transfers? We have already experimented with an online posting transfer system, which though was not good enough to satisfy everyone, can still be improved,” Dr. Bari suggested.

Solutions can be found through the system. Abandoning it altogether is not the answer.

There are 50,000 schools in Punjab, spread over its 36 districts. The biggest school system in the country, The Citizens Foundation (TCF) has merely 1500 schools, after 20 years of working. The Beaconhouse school system also barely has 400-600 schools in total.

“Look at the scale of the private sector,” Dr. Bari stressed, “TCF schools are only comparable to schools of one district. How can one expect private education to single-handedly take over this? It’s logistically not possible.”

However, Ismail wasn’t really bothered by this. According to him, scalability would evolve and improve over time.

“Education is the fundamental right of every child. The government must be involved in both its provision and financing. Even in the USA, which is the epitome of capitalism, most schools exist within the public sector. Private schools are considerably less in number and though voucher systems are present there too, most schools are public and of good quality,” explained Dr. Bari.

A rebuttal is that the USA is a developed country and therefore its example can’t be evoked in the case of Pakistan. However, Dr. Bari reminded that even developing countries such as Vietnam and Brazil have thriving public education systems. It’s inconceivable for them to shut down public schools or even allow them to deteriorate further.

Education reform is a time taking process, It doesn’t happen overnight.

“Since the inception of Pakistan in 1947, we have been resorting to shortcuts to meet challenges. If we had made long term plans and investments, we wouldn’t be facing such problems today. Whichever country sought to reform its education system was not always affluent. Take Japan for example. It was a poor country when it started its education reform back during the Meiji revolution in the 1870s.”

“The same case can be made for America. Its education reform started 200 years ago. If you rewind 100 years in time, you’ll find that the schools in America were of horrible quality. America wasn’t rich back then, but it had its priorities right. I could say the same for European countries, China, Singapore and South Korea.”

It ultimately boils to priorities and not money. These countries started reform when they were poor, and their current condition is a product of timely decision making and effective implementation. Despite all ideas proposed, we should perhaps start with the simple stuff first! n

The government comes up with a plan to subsidize fuel consumption of two and three-wheelers every few months. This time around they have even included four-wheelers as a sweetener. The intentions are certainly noble, but there remains a lot to be desired in terms of execution. The government recently announced that it will be providing petrol to two and three-wheelers, and 800cc automobiles at PKR 75 per liter. A noble task indeed, but the financing plan for the same remains non-existent, and largely depends on increasing fuel prices for all other consumers.

There are more than 25 million two-wheelers and three-wheelers officially plying the country's roads. Assuming daily consumption of a conservative 0.5 liters per vehicle, we are looking at subsidizing (or financing) 12.5 million liters. As the fuel would be available for the same at a much lower price, this will incentivize greater consumption hence resulting in increased demand. As demand for fuel increases, so will potential imports, thereby further draining precious supply of

foreign exchange liquidity.

Annually, such a cross-subsidy amounts to about Pak Rupee 450 billion. To keep things in context, the monthly amount that needs to be financed is roughly equivalent to the capital expenditure required for establishment of Green Line in Karachi. Instead of subsidizing fuel consumption, it just makes more sense to roll out public transit infrastructure across the country to solve the energy conundrum. Subsidizing fuel is the laziest and the most detrimental solution to a complex question.

Instituting two prices for a primary undifferentiated commodity creates more problems than it solves. It creates a parallel market for that commodity, while laying foundations of an informal shadow market. Given availability of such a massive arbitrage, it is entirely possible, and profitable for people to start selling their subsidized fuel quotas in the open market. This will also drive up consumption of fuel at a time when the country can barely scamper enough resources to meet even a fortnight of its import requirements. Such a pricing discrepancy would act as a fiscal stimulus, and increase demand for fuel, thereby resulting in even more pressure on already debilitating foreign currency reserves.

Execution of such an initiative effectively would require instituting quotas for two-wheelers and three-wheelers, that are linked with the identity numbers, which can then be accessed through existing payments infrastructure. Such an infrastructure is already in place, but how it can work seamlessly, and how it cannot be gamed remains a question unaddressed. This can ensure that any financing remains targeted, however, the creation of a parallel market, and a fiscal stimulus that further exerts pressure on the external reserves position will remain an unintended consequence.

We are at the precipice of a complete financial meltdown. Any more misguided adventures will ensure that we push ourselves over the edge instead of putting in an even half-hearted effort at course correction. Subsidizing fuel consumption at this stage of the global macroeconomic cycle is bad policy, and it will only take a few months till adverse results materialize, similar to what happened in the fuel subsidy that was given in the early part of 2021.

The scheme is guaranteed to derail the IMF program, and with that any potential bilateral funding, further pushing the country towards the edge. This is a badly thought out plan, and its unintended consequences will lead to creation of a booming informal market (resulting in lower tax collections), and may eventually lead to a complete fiscal disaster, while also derailing the IMF program at the same time. n

A bad idea that should be shelved, at least, for the time being

The supreme court orders the State Bank to release 21 billion but how will the State Bank do so?

By Shahnawaz AliSay there’s a bank account that is owned by a very powerful individual X, which has a certain amount of money in it. Another individual, Y, claims that X owes a certain portion of his account’s balance to Y. Y goes to court to claim his money and the court decides to rule in favor of Y. Now, because X is very powerful, he can choose to ignore the decision of the court without him going to jail (lets just say that even the police pay their bills with X’s money). But Y’s claim on the money is constitutionally valid, then what does the court do?

The court orders the bank to take money out of X’s account and give it to Y. A court can do that, there is no question about it but the question is, whether a bank can do that? What does the principal dictate and who dictates what the principal ought to be. Now take a spoonful of salt and put it in this analogy because even though this analogy is a good way to visualize the scenario, the matters of Public Finance are not as simple.

In the headliner news over the last weekend, the Supreme Court of Pakistan ordered the State Bank of Pakistan to pay the Rs. 21 billion required in additional funds to the election commission of Paki-

stan. These funds were meant for conducting the provincial elections in Punjab. But there is a categorical set of problems with the supreme court having to ask the central bank to “pay up”. First is the supreme court having to ask, the second is the precedent of the central bank being “ordered” to do something, and third is the treatment of SBP as a commercial bank that can “pay up” at will.

If someone has been living under a rock for the last one year, it is important for them to know the plot of the current season of the political soap opera of Pakistan. Feel free to skip the following summary if you are a constant consumer of the mainstream news.

Ever since former PM Imran Khan was ousted by a Vote of No confidence in April 2022, he has had one demand in general, and that demand is elections. Khan believes that his ravaging popularity amongst the people warrants him another easy win in the next general elections. Coupled with the current government’s handling of the economy it inherited, and the rising unpopularity that came as a result of being unable to handle it, Imran Khan naturally believes he has a good shot at winning a fair election.

In hopes that the provincial assemblies of Punjab and KPK would be landmine victories for the PTI, the assemblies were dissolved on the 14th and 18th of January respectively. What was not taken into account was the current economic crisis. And also the willingness of the current government to stand up and leave while the other party wins the race.

What could be a very apt excuse was exercised by the current government, that the government of Pakistan did not have enough money to carry out these elections at this time. And it is true, it does take a lot of money to hold elections. As per a 2018 report written by Dawn, the cost incurred per voter in the general elections of 2018 was around Rs. 198. Adjust that for the current level of inflation and that cost already exceeds Rs. 300.

Regardless, this unwillingness was taken note of by the Supreme court that came to its ultimate decision rather quickly. CJP Bandial taking a suo motu notice of the issue garnered a tirade of criticism from within the Supreme Court itself, making the apex court more controversial than it would ideally want to be.

As per the elections act, 2017, the election commission of Pakistan is liable to hold elections for a vacated seat within 90 days. While this may sound like an absolute condition, it is

important to know that being an institution of the state, the election commission receives its money from the federal government for its operations.

As per section 22 of the Public Finance Management Act, 2019, “The operation of the Federal Consolidated Fund and the Public Account of the Federation shall vest in the Finance Division under the overall supervision of the Federal Government” . The election commission also falls under the ambit of this fund.

Because the finance division had refused to provide the requisite funds to the ECP in the stipulated time, the Supreme court found it was only just to bypass the finance division. So the Supreme court directed the State bank to release funds to the ECP. This creates a problem. Can the SC do this? The legitimacy of the decision is in question here.

While the current decision is a short order, meaning the detailed decision will be made public later, it still states that the SBP should not bypass its constitutional requirement. Rather the approval from the finance division is to be made “Ex Post Facto” in this particular case by the orders of the Supreme Court.

Ex Post Facto means that the approval from the finance division would be taken after the release of the funds, by citing and providing the required paperwork. This is to say that, have the elections as soon as possible and worry about the money later.

Simply put, the final appellate court of a democracy such as ours, at least on paper, cannot and should not be directing an independent central bank in any matter whatsoever unless the latter is a defendant in a particular case. But the fact that the SBP in its current state is anything but independent makes it vulnerable to such unconstitutional instructions. The Dar-led Finance ministry is to blame for the weak central bank the country has to contend with currently.

Another important consequence of this decision is the international implications of the decision. A country like Pakistan which is a net debtor of a lot of entities already places a huge amount of pressure on its central bank. With State Bank being made vulnerable in such a manner opens a pandora box of possibilities for bond holders and creditors around the world.

Let us come to the viability of the decision in the face of the federal government’s defense. The government said that it cannot release the funds

because of the deteriorating economic conditions of the country. Does the supreme court’s decision really take that into account?

While it could be okay for the government to shift goalposts on its budgeted expenditures, the state bank operates in a completely different way. Its allocations, releases and statements directly affect the money supply, reserve ratio and investor sentiment. This in turn has a huge impact on the state of investments and inflation in the country. This is exactly why, other very valid reasons, that the SBP was made into an autonomous institution through legislation under the PTI government and Reza Baqirs governorship.

If the state bank pays up the money to the ECP upfront, from its current pool of money, it can do that in a number of ways. The first option is that the state bank auction’s an unscheduled bond which raises 21 billion in short term loans, increasing the public debt in the short run. Just because it has now been shifted to the backend does not mean it still doesn’t impact the economy. So this method does not debunk the argument made by the federal government which pertains to the economic condition of the country.

The other way in which the State Bank can achieve this goal is by injecting money into the economy, simply put, by printing cash. This again stands in contradiction with the bank’s aggressively tightened monetary policy.

It is important to note here that the state bank of Pakistan is not a commercial bank, nor will it get the money back, after the elections happen. It is a lender of last resort and the government’s banker. It’s role is well-defined as a monetary and fiscal policy making institution that has to keep the banking system of the country stable.

At time of writing, the unpleasant showdown between the legislators and the judiciary is at its peak. The State Bank has told the court that it has allocated the funds for the elections while the Standing committee on finance maintains that these funds cannot be released.

It is unfortunate that the central bank, that should remain apolitical and must be as independent and autonomous as possible to be an effective policymaker and implementer has been made into an active participant in the unending political circus the country currently faces.

That the SC can make the SBP do a lot of things, but that won’t be right or constitutional. It will forever plague the central bank however, which is exactly why it should resist in whatever legally viable way it can. n