08 Are local makeup brands really local? 14

14 The fool’s fuel plan?

21 Negative freight margins in the price of fuel ? 25

25 Finding Home in the City: Women’s Search for Urban Inclusion

29 From trainee to the boardroom

Publishing Editor: Babar Nizami - Joint Editor: Yousaf Nizami

Senior Editors: Abdullah Niazi I Sabina Qazi

Chief of Staff & Product Manager: Muhammad Faran Bukhari I Assistant Editor: Momina Ashraf

Editor Multimedia: Umar Aziz - Video Editors: Talha Farooqi I Fawad Shakeel

Reporters: Ariba Shahid I Taimoor Hassan l Shahab Omer l Ghulam Abbass l Ahmad Ahmadani l Muhammad Raafay Khan

Shehzad Paracha l Aziz Buneri | Daniyal Ahmad | Ahtasam Ahmad | Asad Kamran l Shahnawaz Ali l Noor Bakht l Nisma Riaz

Regional Heads of Marketing: Mudassir Alam (Khi) | Zufiqar Butt (Lhe) | Malik Israr (Isb)

Business, Economic & Financial news by 'Pakistan Today'

Contact: profit@pakistantoday.com.pk

By Nisma Riaz

By Nisma Riaz

Remember when you were a little kid and went makeup shopping with your mom? You probably stumbled upon a colourful display of Medora lipsticks and nail polishes, and couldn’t resist admiring every single tiny container, wishing you could buy them all. You wanted to grow up fast so that no one could tell you nail polish was bad for your nails, or that lipstick was for grownups only.

So you’re older now. And so is Medora. And so is the makeup game in Pakistan. And, it’s hotter than Karachi’s heat.

We’re talking big clothing retailers, like Sapphire, Bonanza, J., and Khaadi launching their own cosmetics lines, alongside a ton of high-end and low-end brands that have taken the market, excuse the cliche, by storm. And let’s not forget about the celebrities, beauty influencers, and makeup artists such as Atiqa Odho, Masarrat Misbah, Bina Khan, Sara Ali, Nadia Hussain, and Nabila, who have launched their own makeup brands and have become total game-changers.

And get this, despite the financial crisis, the demand for local makeup products is through the roof. We’re living in a makeup revolution, people! But hold up, let’s take a hot second to first understand what “local makeup” means. It’s most likely not

you’re thinking.

Beauty veteran Zainab Pasha, who has been in the beauty industry for over twenty years says there are two ways to go about it. “One can be local in the sense that production happens here in Pakistan, along with the brand identity and communication. There are very few such brands in Pakistan that are truly homegrown, though. Only Medora manufactures locally. They are the oldest and pioneers in Pakistan, and now there are many other brands that have come in at that price point, who have also been able to tap that particular consumer base.”

“The second meaning of local in our context is of brands that are owned by Pakistani entrepreneurs, with companies registered in Pakistan, the brand identity being local and sometimes packaging and distribution happening in Pakistan.” Pasha elaborated.

So, what is missing? Well, production.

“Most local brands, like Bina’s and Note by J. have contract manufacturing abroad, so they piecemeal it and bring it back here. None of the production happens here as such, mainly just the assembly. They rebrand and the branding is also done in international labs and manufacturing hubs,” Pasha explained.

Local is not synonymous with homegrown

Before we start talking about the rising popularity of local makeup, we first need to clarify what exactly we mean, in this article, when we refer to makeup brands as local. There are many brands, like Rivaj UK, Golden Rose, Lurella and what previously used to be called Sweet Touch Cosmetics (now ST London) that people initially thought were local brands, despite the UK and London in some of their names. However, these companies are registered and operate in the UK, Turkey and America, along with some having contract manufacturing in China.

Local, as we have clarified in the previous section, does not necessarily mean locally produced homegrown products, so when we say local, we mean companies that operate out of Pakistan, despite sourcing their product from abroad.

When enquired about the beauty industry worldwide and how production takes place, Pasha told Profit that. “There are only very few makeup manufacturers worldwide. So, if someone goes to buy a very specific product, they can choose from an assortment of economical to luxury ranges, and they can even get an optimised catalogue of products, since these manufacturers produce a range of different qualities and standards within the same product category. China and Europe have a few manufacturers. If you look at the beauty landscape worldwide, these same labs and manufacturing companies are producing worldwide, with varying ranges and quality that enables them to have both highend, as well as low-end companies as customers. Lastly, there are a few independent brands, which the US has been nurturing but they do everything in-house, in their labs.”

It is difficult to say what’s local and what’s international because everyone has a mixed manufacturing strategy, according to Pasha. “It really depends on the price point, imagery and how they’re planning to market themselves. I’m just saying that you cannot produce makeup in Pakistan.”

We can, however, assert that Turkey and Germany are two very popular destinations for local beauty entrepreneurs for finding b2b cosmetic manufacturers, who mass produce for other companies, usually on contractual basis. An industry source, who wishes to stay anonymous, shared that Note by J. is actually just Note in Turkey. It is a Turkish brand that J. represents here in Pakistan, so it’s something beyond white labelling even. Moreover, Masarrat Makeup has also been outsourcing production from Turkey. Meanwhile, Nabila’s Zero Makeup is manufactured in Germany and distributed from Dubai.

In conversation with Muneeb Sohail, marketing manager at Bays International, which is the franchise owner of Makeup City and ST London, Profit found that most local makeup is mass produced in China and then private labelled and sold in Pakistan under a local brands name. “Beauty is not just aesthetic but beauty is science. There is a whole bunch of science that goes into figuring out just the right pigment even and in Pakistan we don’t have that sort of quality control or technology,” shared Sohail.

He added that it is easy to have a company in Pakistan and source the product from China or Turkey, but it would take months, even years, to get your company registered and verified by the relevant authorities, if you want to produce locally. “It is easier for most of our local brands to get their product mass produced, rather than going through the quality assurance or concerns to set up a production plant here in Pakistan.”

There is one question that comes to mind. How has Medora been doing it then?

“Even though Medora makes its products locally, there are a few categories, such as their mascara that cannot be made in Pakistan. So, even those who are doing it locally, still require some outsourcing,” explains Pasha.

Another interesting point that comes up here is the huge unregulated market for makeup that we have. “If you go to any of the main bazaars, they will all have unregulated markets of products, where you will find a mascara for as low as Rs 300,” Pasha added. So, the competition is not simply between international and local players in the beauty industry, but also the unregulated market of smuggled and some not well known homegrown makeup brands.

One other reason for most of the production of cosmetic and beauty products happening abroad, according to Pasha, is “because we (Pakistanis) glamourise anything to do with the UK and it’s just the way of Pakistan, where you add that and it makes it look international.” Rivaj contracts manufacturing from China but the previous point explains why they have registered their company in the UK.

Can we manufacture makeup in Pakistan?

So far, we have laid the groundwork to prove that local makeup is, in fact, not so local afterall. However, that does not mean that it cannot be local. No, we are not contradicting ourselves. Some makeup brands told Profit that they are planning to begin production locally. In the very new future, apparently.

Several industries have suffered the brunt

of consistently rising inflation, the volatile exchange rate and the resultant import restrictions. Any item falling under the non-essential category has taken a hit and cosmetics are no different. Not only local makeup companies, but international ones, like the Body Shop are also under fire.

Saad Khan, country manager of the Body Shop, says that, “The import restrictions, followed by an almost 200% increase in duties and an 8% increase in GST from 17% to 25% has caused serious problems. We have an organised structure, therefore, almost eight months of backup stock that we had, saved us temporarily but we clearly asked government officials if they want us to wind up our business from Pakistan and shut down because we cannot run a business like this.”

He added that many attempts of bringing franchises of international companies to Pakistan have failed because it is a risky market. “We and others, require a conducive market to expand. Pakistan’s current state is risky in terms of both safety and scalability. Remember when during political riots, international franchises, like KFC would be under attack? No one wants to come to Pakistan.”

Khan continued, “And in terms of scalability, it is impossible to make profits at the moment, let alone expand and scale up. When our shipments are stuck at port, we cannot do much. The Body Shop is a management-run company, with women making over 60% of our workforce. We didn’t shut down or lay off people during the pandemic, we didn’t stop offering maternity leaves and we kept operating on losses… if things don’t improve, we will be forced to cease operations in Pakistan.”

According to Khan, the only solution is to import quality machinery and start producing cosmetic products locally. “We have an industry with great potential that is being wasted. The market is ready, and so is the industry. It is just the government… If they focus on bringing the right kind of technological innovation and set up production plants, we won’t have to rely on imports.”

This idea also resonated with Sohail,

who believes that we might even have the raw materials to make cosmetics locally.

Profit asked Mehrbano Sethi, CEO of Luscious Cosmetics, how they were impacted by the recent import bans, “Like everyone else, we are facing stock shortages, a decrease in revenue, and our supply chain has ground to a halt. We are waiting and watching for the situation to ease, while planning for domestic manufacturing which will take a couple of years to fully implement.”

When questioned about their production, Sethi shared that, “We have worked with manufacturing partners around the world, including Korea and Italy, since 2007. The situation has changed drastically in the last few years and it is now time to pivot to domestic production. The recent import ban and foreign exchange crisis spurred our decision to own our manufacturing after 16 years of contract manufacturing abroad.”

However, Redah Misbah from Massarat Misbah Makeup, who is also the Creative Director at Depilex (Pvt) Ltd, was slightly more optimistic. She told Profit, “All of our product ranges are made in Turkey. It’s developed, manufactured, and packaged there and comes to Pakistan as a complete packaged product. Our aim in the future is to make some product items in Pakistan and we are working on it. So, of course, with the import ban we had to suffer because we fell under nonessential products. Just like others, our container was not the priority but… our cargo and containers have been released. It’s a slow process but… I have a lot of faith in our country and I know things will improve.”

Despite the hope of things improving, Misbah clarified that they are not waiting patiently for things to magically fall in place and, therefore, they are also working on shifting to local production. “We have been considering going completely local for a long time and we have been working on some ranges that do get filled and packaged in Pakistan but the product is coming from Turkey. Our aim has always been to have it eventually made in Pakistan. As time passes we are gaining the expertise and experience for it to be possible. I can tell you there are labs and pharmaceutical companies that

I can tell you there are labs and pharmaceutical companies that have all the ingredients to make the best quality products.

I’ve seen them and been to them. We have been working very closely with them to make this ‘Made in Pakistan’ dream come true, which will happen soon InshaAllah

Redah Misbah, Creative Director at Depilex (Pvt) Ltd

have all the ingredients to make the best quality products. I’ve seen them and been to them. We have been working very closely with them to make this ‘Made in Pakistan’ dream come true,” Misbah disclosed. This shows that sooner or later, Pakistan’s beauty industry will be forced to innovate, in order to cater to the needs of the market. Now we just need to wait and see how long it takes to get there.

Pakistan’s beauty landscape

Industry experts, like Pasha, believe that Pakistan is a huge beauty player and has always been on the frontlines. It is one the most flitting categories, whereby people flit from one category to the other. For example, you like the mascara from one brand but you won’t be loyal enough to the brand that you buy a nail colour from them too.

Yet, it’s a category that relies on impulsive buying, meaning if it looks good it will be bought. According to Pasha, “There will always be a demand for makeup because Pakistani women love colour and we will always be loud and proud wearing it. It’s a feel-good, immediate gratification industry, and also a very resilient one. Beauty generally, across categories of makeup, hair colour, skin care, haircare and others are like indulgence. It’s something that women need to spend time on, especially in recession environments, it’s been bullet-proof. In recent years skincare is also taking a big peak in the selfcare industry and there’s only promises that it will grow leaps in months… if people find that importers have to increase prices… then there’s lots of more options on the table.”

“Along with the beauty industry being a popular one in Pakistan, women have also become more discerning, so there’s a growing educated consumer, who wants to take care and make sure she’s using products that are good, safe and compatible for their skin types, so that’s a reassuring facet, and a tipping point for the makeup industry, manufacturers or distribu-

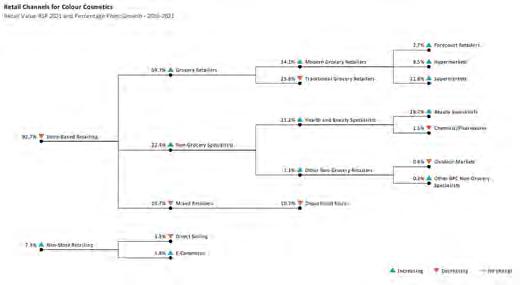

tors.” Pasha concluded. According to data collected by Euromonitor, the retail value of sales grew by 11% in current terms in 2021 to Rs 20.7 billion. It was found that colour cosmetics was the best performing category in 2021, with retail value sales growing by 12% in current terms to Rs 4.2 billion. According to the same source, L’Oréal Groupe is the leading player in 2021, with a retail value share of 25%. Moreover, retail sales are set to increase at a current value CAGR of 13% (2021 constant value CAGR of 7%) over the forecast period to Rs 38.7 billion. This data shows that Pakistan has a huge market for cosmetics, and entrepreneurs are realising this.

Do international companies consider local brands to be a worthy competitor?

The answer is no. Nope. Not at all. Or at least the Body Shop’s answer was a resounding NO. Khan believes that Body Shop is in a league of its own. “We are not a luxury brand worldwide but in Pakistan we somehow stand out as an expensive, almost luxury brand. We target

a different market entirely, which explains our price differentials, as well.”

He added that, “We are a sustainable and vegan brand. We source our raw materials through a fair Community Trade Programme, that protects labour laws and helps farmers source the materials in a more sustainable fashion. We have very strict quality controls and seriously condemn animal testing. Moreover, we are conscious of the carbon footprint we leave on the planet, so we don’t use plastic, but biodegradable wooden fixtures instead. Local makeup brands cannot even come close to the stringent procedures we have, so no we don’t think of them as competition.”

Similarly, ST London also seems confident that any new or old local players in the market are not a serious threat. Sohail defended that, “ST London focuses on introducing the right product, with the right technology. That’s what drives our growth. And coming up with a product that is suitable to your climate, skin tone, skin type, while also being cruelty free and sustainable has certain costs associated with it. We as a nation want a Gucci bag for Rs 500. Everyone has to play their part.”

He continued, “I have spent 17 years in the global beauty industry. I co-own a US-based brand and have consulted for beauty brands in the Middle East and around the world, where there is intense competition and market saturation. Pakistan is NOT a saturated market by global standards. There is opportunity at every level in consumer goods. We have a growing domestic market, where the demand will only go up.” Despite these companies refusing to admit that they have taken a hit from all the new and cheaper options available now, the market has something else to say.

A much-awaited mindset shift

Even those who do not frequently use makeup can tell that we are amidst a beauty revolution. Even 10 years ago, there were very limited locally owned

All the prices are justified, at least in my opinion as a brand owner, there is so much effort that goes into making a good product, there are bills to pay and so much more!

Laraib Rahim, Beauty Blogger and CEO of Organic Brown

The recent import ban and foreign exchange crisis spurred our decision to own our manufacturing after 16 years of contract manufacturing abroad

Mehrbano Sethi, CEO and Founder of Luscious Group

makeup brands, however, in the last few years, there has not only been an influx of newer local options, but also a mindset shift, whereby more and more consumers started experimenting with local brands.

For a nation that associates quality with anything that is imported and internationally manufactured, this shift towards using local makeup brands is heartening to witness.

It is not easy to assess the market value share of local brands, since most brands that Profit reached out to refused to share their sales performance. However, following a qualitative strategy to get an idea of their performance, Profit asked salespeople at Naheed Supermarket, Carrefour and Imtiaz in Karachi how local makeup brands have been selling, as opposed to well established international drugstore brands, such as Loreal, Maybelline, Rimmel, Essence, Color Studio and many others.

According to Nadia, who works as a beauty consultant at Naheed, “Sales depend on the kind of customer you have. If someone is shopping for their salon or for bridal makeup specifically, the foundation has to be the very best. Masarrat makeup’s foundation is the most popular among this category, which beats even Maybelline and Loreal! This might sound surprising but our local makeup has improved so much over these past few years that it has a better sales performance.”

“There are very high performing and extremely affordable local options, as well, like Sweet Face, Christine, Miss Rose and Vida. These things sell like hot cakes! And they might be cheap in price but they are not bad in quality. If you try the Sweet Face foundation, it is as good as Masarrat foundation.” Another salesperson at Imtiaz store shared.

Sara, a makeup consultant at Carrefour, couldn’t contain her excitement, when we asked to comment on local makeup brands and their sales performance. “They are just called local because of the brand. But they are as good as any international brand. I have used all kinds of cheap and expensive makeup and our local makeup is nothing short of amazing!” Sara exclaimed.

“I have been working here for five years and I can assure you, I have seen international

brands and their sales deplete, with new local options coming in. if you go for a branded mascara, you won’t get it for less than Rs 3000. We have local mascara and eyeliners that cost literally Rs 500. So, why would someone buy an expensive product when they have a cheaper one that’s just as good,” Sara elaborated. Social media influencers and makeup bloggers have similar sentiments, when it comes to the popularity of local makeup brands.

Dua Hamid, Digital Creator and model, said that, “I am a very loyal J. Note consumer. At one point I almost had their entire range in my makeup bag and on my dressing table. My favourites are hands down their lipsticks. I am also an avid user of the Zero Makeup Palette in the shade Honey. And recently I’ve also started experimenting with Top-face makeup and my experience has been absolutely lovely.”

Hamid continued, “The best feature is how well these brands understand our textures and skins and our colour palette better as being brown brands themselves. J. Note still dominates my entire makeup bag. They have the best formula, texture and the colour range for brown skins… Everything works so beautifully on my brown skin. The zero-makeup palette also holds a dear place in my everyday makeup bag… The products melt in your skin and just perfect it. The only thing I hold against it is its price range and product quantity.”

Laraib Rahim, Beauty Blogger and CEO of Organic Brown (a skin-care line that professes to be “obsessively safe and non-toxic with no artificial fragrances, synthetic ingredients, and chemical additives”), told Profit, “I remember when I started my makeup page, I used to have the Luscious makeup palette and I still have it. Most of the local makeup brands that I have tried have great potential.

Moreover, with the rising inflation, I believe these brands will soon be out-performing international ones, speaking from a price perspective. All the prices are justified, at least in my opinion as a brand owner,” Rahim concluded.

According to Sethi, this mindset shift cannot be ignored. “In Pakistan, the era of preferring imported beauty products has finally come to an end by the efforts of brands like Luscious proving consistent quality, supply and approachable price points.”

Misbah attributes the popularity of local brands to a larger reason. “It’s been 12 years since I’ve been working and Pakistan’s consumers, especially now, forecast what will look good and they aren’t far behind. We apply all the international trends and have been customising them to our needs. So, there is a global shift in consumers in terms of awareness in the world. Because of the ease of access to information about what is going on, on social, economical, and political levels, everyone knows what is going on.”

“Some 12 years ago I had clients who used to bring shampoos and conditioners from abroad and the packaging would say “with cinnamon extract” and such, and I used to laugh that the main active ingredients in these are all those that are present in Pakistan. But the consumers now ask if the product contains paraben, animal byproducts, or any harmful chemicals.”

Finally, Misbah also adds that because influencers, makeup artists, and local textile companies have entered the industry of beauty products and skin care, there is greater trust in the Made in Pakistan label.

We may have 99 other problems, but the boom in internationally-sourced makeup from local brands and its excellent reception goes to show the viability of a very promising industry in Pakistan, just waiting for the right kind of technological assistance. In the meantime, for those of us salivating at the sight of a new blush, or a bottle of hyaluronic acid at Al Fatah, just remember to put on some lipstick and pull yourself together. n

If you go to any of the main bazaars, they will all have unregulated markets of products, where you will find a mascara for as low as Rs 300

Zainab Pasha, Beauty Veteran and CEO of HERBeauty

For the past three months the federal government has been lying to you. What is worse, they’ve been telling you the same lie over and over again in a futile attempt to calm the nerves of a nation on the brink of complete economic collapse and already in the midst of a full-blown political and constitutional crisis.

The lie in question is that a staff level agreement with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) is just around the corner. Yet with every passing day the government’s mantra of “just a few days” has continued to ring hollow and their actions have become more erratic and difficult to make sense of. Perhaps nothing encapsulates this better than the announcement of a scheme to provide subsidised petrol to low-income families by slashing fuel prices for motorcycles, rickshaws, and cars under 800cc.

Already the IMF has said in so many words that a bailout is not coming until an understanding is reached on the new fuel pricing scheme. Cooked up in closed rooms, presented on lacklustre PowerPoint slides, and forced upon an industry partner with no choice but to comply there is a lot that can go wrong with this plan and very little that can work.

Profit set out to answer some basic questions:

• What exactly are the specifics of the scheme which the government claims will add no added spending burden on its budget?

• Is the basic mathematics behind the concept sound?

• What could possibly go wrong?

• What is the target audience for the scheme and is it worth the risk?

• Why in the world would they do this right now?

The answers have not been encouraging. Representatives of the oil industry have agreed to speak freely only off the record and have been wildly critical. Political opponents have railed against the move and most analysts and

opinion-makers have felt the introduction of the scheme is misguided and badly timed. And with the sword of the IMF hanging dangerously close to our heads, how will this play out?

The basics — what in the world are they trying to do?

At first glance, this is a pretty simple plan. The government wants to charge motorcycles, rickshaws, and cars with engines smaller than 800cc Rs 100 less per litre of petrol. But how do they plan on paying for this neat little plan? The government of Pakistan, in case you haven’t noticed, is broke and its lenders are knocking quite insistently on our doors.

After everything that has happened over the past year, the words “fuel subsidy” should terrify Pakistani governments like the boogeyman terrifies children. In this case, however, the government wants to implement what is known as a ‘cross subsidy.’ This means to provide relief to low-income families they will charge more from the rich. According to petroleum minister Dr Musadiq Malik, petrol for all cars that do not fit into the category of 800cc or less will be charged Rs 100 per litre more.

In his presser, Dr Malik was very careful to steer clear of the word subsidy and has since insisted that the scheme will only require logistical implementation and incurs no extra cost to the government. “In principle, the concept of a differentiated subsidy is better than an across the board one. No doubt about that,” said Taimur Khan Jhagra, Former Provincial Minister of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa for Finance, to Profit. Jhagra was part of the ruling PTI coalition that introduced the previous scheme, and therefore an acceptance that this scheme is different to that is a feather in the cap for the cross subsidy. However, that’s about it.

“We are implementing differentiated pricing on a product that is not traditionally sold in a way that lends itself to such pricing. This

raises questions about who will benefit from this strategy, and who will not. Moreover, it is important to consider the potential actions of petrol pump dealers, and whether this approach will lead to undesirable behaviours such as the emergence of informal markets where people purchase subsidised petrol and resell it for profit,” Jhagra continued.

And this is where the problems start to sneak in. Theoretically speaking, the scheme makes sense. “For one thing, the way the scheme is designed, its impact is fiscally neutral. The government is not using any of its own money to finance this subsidy. Instead, they are utilising money from one set of customers to cross-subsidise another. Theoretically, they are taking from the rich to give to the poor,” says Khurram Husain, a senior business journalist and former editor of Profit.

However, the scheme rests on very fixed assumptions in regards to its pricing mechanism.

“It’s not clear what amount of additional tax would need to be charged to large car owners to fund the subsidy for motorcycles and small car owners without understanding the elasticity of demand for petrol among all three groups. Without knowledge of demand elasticities, it is difficult to determine the technical specifics of the additional tax,” says Dr Ali Hasanain, Associate Professor at LUMS.

As of right now, the cross subsidy imagines a 50:50 split between those who will benefit from the subsidy, and those who will pay for it. “Look at how the ratio of customers changes once the cross subsidy comes into place,” says source number 1. It would be unfair to criticise the scheme to assume that there will be a massive increase in the consumption by low-income households as they will have to fork out the higher slab rates once they go beyond the subsidised threshold. However, a massive dip in the consumption by those paying for the subsidy might just leave a tab for which the government would need someone to pay.

“Overtime the price that you will need to charge large vehicle owners to maintain the

Khurram Husain, Former Editor of Profit and Business Editor of Dawn

The problem in implementing a scheme such as this is that electricity, and gas, are consumed through a single metre. An entire household obtains access through one metre, and thus identifying usage is easier there. Liquid fuels such as petrol and diesel in contrast are consumed through 10,000 pumps. Over there this is much harder to implement, if not impossible

We are implementing differentiated pricing on a product that is not traditionally sold in a way that lends itself to such pricing. This raises questions about who will benefit from this strategy, and who will not. Moreover, it is important to consider the potential actions of petrol pump dealers, and whether this approach will lead to undesirable behaviours such as the emergence of informal markets where people purchase subsidised petrol and resell it for profit

subsidy will change. It will change from time to time, and have to be recalibrated,” Hasanain continued.

What could go wrong? Everything

There is pandemonium in the petroleum ministry right now. Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif announced the plan for a fuel cross-subsidy on the 15th of March. On the 19th, Dr Musadik Malik walked out for a press conference, provided a rough plan, admitted that there were still flaws that needed to be ironed out and said the government had set a timeframe of six weeks to get the matter sorted.

Six months wouldn’t have been enough in a country that wasn’t going through one of its worst economic crises in history. The truth is that implementing a scheme of this sort raises serious logistical problems. Profit sought out some of the most senior sources in the industry to comment on the matter. Most refused to comment. Four agreed to speak under guarantee of anonymity. Dr Musadik Malik, Shahid Khaqan Abbasi, Dr Miftah Ismail, and Jam Kamal Khan were approached for comments on the matter. None of them responded to our request for comments.

First, and foremost, if the government were to utilise point of sales (POS) terminals in the administration of this subsidy then the plan is already dead in the water. “There are legally around roughly 10,000 pumps across Pakistan. Of these, only 2,500-3,000 have POS terminals. These pumps are primarily limited to tier 1 cities. Pumps in tier 2 and tier 3 cities, and roads beyond the motorways lack POS terminals,” said source number 1. There were similar reservations about the government’s utilisation of onetime passwords (OTP) with people’s mobile phones. “You basically make the delivery of the cross subsidy then, contingent upon the internet connection a person has at the time of filling their tanks. Is the internet reception equally

good around the country? What happens if the OTP does not come through because of the internet, and the staff at the petrol pump has filled the recipient’s tank? I can assure you that the pump staff will demand compensation either way,” continued source number 1.

What about the idea of having dual rates at the pump itself based on the type of vehicle that rolls up? This is particularly important as Malik highlighted this to be a viable option at a presser on March 20. He pointed towards the gas, and electricity markets as living examples.

“I think in principle it’s fine that they are thinking if we can charge differentiated rates in the electricity, and gas markets, then why not in the market for liquid fuels as well,” says Husain. “The problem in implementing a scheme such as this is that electricity, and gas, are consumed through a single metre. An entire household obtains access through one metre, and thus identifying usage is easier there. Liquid fuels such as petrol and diesel in contrast are consumed through 10,000 pumps. Over there this is much harder to implement, if not impossible,” says Khurram Husain.

“Of the 10,000 pumps across the country, roughly 200 are owned directly by oil marketing companies (OMC). The rest are owned by private dealers,” said source number 1. And therein lies a major bone of contention — Whether the pump owners will act in the interest of the government to deliver the subsidy truthfully. Source number 1 does not believe that to be the case. Source number 2, our only optimistic source, believed that it is unfair to discredit everyone of colluding in malpractice because these are allegations thrown at everyone across Pakistan. It is here that we find a compromise between the two in the form of source number 3.

“At the end of the day, all OMCs will want this subsidy to work, but our control over our pumps is very limited. I’m not going to say that our dealers, or those belonging to our competitors are bad at all. However, all the dealers are businessmen at the end of the day. They have other businesses that they need to

attend to. Even the best dealers that we have are not at their pumps 24/7. They too do not have complete control, as they devolve it. The more people you add to this chain, the messier it will get,” says source number 3. What exactly is the messy bit?

“What if a petrol pump owner, or someone at the pump takes a bribe, and puts the subsidised petrol in a vehicle not meant to be subsidised? What if I take someone along with myself who has a motorcycle or a 660cc vehicle, have them get their tank filled, and transfer the petrol to my car,” Jhagra muses.

Who does it even benefit?

So here is what we have. A scheme that works in theory but is a logistical nightmare and a possible powder-keg that could disrupt petroleum supply in the country. So could taking the risk be worth it? Let’s look at just who the cross-subsidy will actually benefit.

The Pakistan Social And Living Standards Measurement (2018-19) conducted by the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics identifies 54% of all Pakistani households to have motorcycles, and 6% of households to have cars. Assuming there is an overlap between the two, it is possible to say that 50% of Pakistani households do not own any motor vehicles. Thus, the poorest 50% of Pakistani households, those who cannot afford to purchase any motor vehicle, are simply ineligible to benefit from the cross-subsidy at all.

“This policy betrays a lack of seriousness on the part of the government to resolve Pakistan’s fundamental economic problems. We should be prioritising work to create a safety net for the most affected people which are not covered under this policy,” says Hasanain.

“At present, the scheme requires recipients to have motor vehicles registered in their name and also be registered as part of the Benazir Income Support Programme,” says Husain. “However, by the time you cross-check and

verify these requirements for recipients, many individuals who might actually need the subsidy may fall out of the scheme.”

“There will be blowback of all sorts once pumps charge an additional Rs 100 to people who may fall within the scheme’s parameters based on economic necessity, but fall outside of it due to any documentation problems,” says Husain. “In such an instance, many individuals may cause a commotion, believing they have been ripped off.”

As to who is eligible, and who is not for the cross-subsidy is an entirely new can of worms that the government has opened. For starters, the cross subsidy includes rickshaws. However, rickshaws are not necessarily used for personal use. They are commercial vehicles, with multiple owners at one time.

“Nearly one million motorcycles are employed for commercial use in Pakistan,” says source number 1. “Companies that utilise these motorcycle fleets, such as Foodpanda, add the cost of fuel they pay to their service charges. However, there is no guarantee that the cross-subsidy benefits the motorcycle riders rather than the companies, or whether the companies pass the benefit on to their end customers.”

Why now?

Now this is complicated. On the one hand, the scheme is a nightmare to implement and very few are happy about it. On the other hand, this has been the brainchild of Dr Musadiq Malik for a while. In fact, when the previous administration introduced its misguided fuel subsidy in 2022, one of the initial suggestions was to introduce a

targeted subsidy for smaller vehicles. This current plan even trims down on that spending and suggests charging larger vehicles more to fund less fortunate households. However, the great bone of contention here is why the government would introduce this plan at such a critical juncture in talks with the IMF.

So what is the government doing? The most obvious answer is that they are trying to provide relief to the public in the wake of elections that are due anytime this year. Already backed into a corner by Imran Khan who is riding a populist wave and unable to fix the ailing economy, the Sharif administration’s moves are growing in desperation with every passing day.

“The scheme runs several risks. There are several risks associated with the scheme, but the biggest one is its reception by the IMF. Their opinion will have a significant impact on its success” opines Jhagra. “What if the IMF would say that they will not sign a staff level agreement (SLA) until you can guarantee to us that this subsidy is workable. That it is indeed a cross subsidy, and so on, and so forth. Can Pakistan afford after all of the difficult decisions that have been taken to almost shelve that IMF SLA? There are all sorts of inadvertent things that need to be figured out when you are doing something as virgin as this,” Jhagra continues.

“Why would the government do this? Increasing that risk? The fact that this risk increases is an economic fact, and I think if the government has not thought this through, if they haven’t cleared it with the IMF in an environment where everyday counts,” Jhagra adds.

Husain provides a different perspective, “I don’t think the plan, as it was conceived, should have a significant impact on the SLA because

it is fiscally neutral. After examining it, the IMF may decide that it is acceptable and does not have any additional impact on the state of Pakistan itself, which is the real issue for them. However, we will have to wait and see. The IMF will need time to review the scheme, consult with the government, and understand all its intricacies,”.

However, Husain does concede that the timing is perhaps not ideal, “Right now everyday matters. That’s the situation we’re in. Even this scheme is a lot in terms of days added to the negotiations because it has inserted a new element in the middle of the talks,”.

What’s a nice middle ground to understand all perspectives relating to the IMF perspective then? We know there is a consensus on how bad the timing of this is. What about the severity then? “This lack of technical study suggests that there is a threat that the fuel subsidy on small vehicles will have to be funded by other means, which creates an irritant to IMF negotiations,” says Hasanain.

So where does all of this leave us? It was perhaps most succinctly put by one of our anonymous sources from the petroleum industry. “Bongi maari hai inho nai,” they said when given the guarantee of anonymity. “I am telling you that they have no mechanism to implement this, this scheme will be abused, Pakistan already has no money to pay for its existing petroleum imports, and now they will go on and create another balance of payments crisis.”

“Any mechanism designed hurriedly like the one on a timeline such as this will be vulnerable to cheating. There will be audit issues in the end, and this will just further exacerbate circular debt. This has the writings of disaster all over it.”

One of Karl Marx’s most well-known and frequently cited statements goes as follows: ‘Historical events occur twice, first as tragedy, and then as farce,’ describes how certain history may repeat itself in a different form. Often with a sense of absurdity or irony.

Or as this petroleum industry source put it, “Is mai aur pichli government nai jo bongi maari thi janay sai pehle, koi farak nahi hai. Wo agar Rs 50 ki bongi thi tou ye Rs 20 ki bongi hai.” n

This policy betrays a lack of seriousness on the part of the government to resolve Pakistan’s fundamental economic problems. We should be prioritising work to create a safety net for the most affected people which are not covered under this policy

Dr

Hasanain, Associate Professor at LUMS