6 minute read

Between claims and reality: the economy of Naya Pakistan

Imran Khan brought his own style of managing the economy. How do the results compare with his predecessors?

Dr. Shahram Azhar

Advertisement

As a pure imaginary, Naya Pakistan promised to be an era of institutional change and economic prosperity. From a political economy point of view, Naya Pakistan had one unique advantage that not many governments in Pakistan enjoyed: it was premised on a cooperative new political coalition; a “hybrid” power-sharing arrangement between the civilian government and the establishment, a new ‘political settlement’ that promised sustained institutional transformation and rapid economic development.

The proof of the pudding is in the eating. Leaving the lofty promises made at its inception aside, what can one objectively say about the economic performance and legacy of Naya Pakistan (2018-2022)? While a lot has been written in recent months on inflationary pressures during this period, a lot less attention has been paid to the issue of economic output. Specifically, what can one say about the evolution of the fundamental measure of the health of any economy - output

1a: GDP per capita (current USD) 1b: GDP per capita (constant 2015 USD)

Fig 1: GDP per capita before the pandemic

per capita - under the institutional setup of Naya Pakistan? The answer hinges on three major issues. Since these issues will ultimately shape the contentious discourse around the economic performance of Naya Pakistan, it is important to lay them out clearly before proceeding to see what the data suggests. In this article, for reasons described below, I offer readers a comparative/counterfactual approach by comparing the performance of Naya Pakistan with two regional economies (India and Bangladesh) during the same period.

Three things frame all discussions about the economy’s performance under Imran Khan. First, is the COVID pandemic. The pandemic presents an ‘exogenous shock’ to the system that will continue to be a key shaper of the political discourse around the global economy, as well as discussions within Pakistan. Understandably, the proponents of Naya Pakistan will tend to overestimate the ‘shock’, using it to justify everything that opponents claim went wrong. The opponents of Naya Pakistan, by contrast, will tend to underestimate the shock and place the entirety of the blame on the economic mismanagement of the government. Regardless, any discussion of the period will almost certainly be muddled by the virus.

Second is the inheritance. Although not strictly about the time-period (2018-April, 2022) under question itself, it nevertheless weighs on discussions of economic performance under Naya Pakistan with claims, critical or complimentary, about the situation of the economy before Imran Khan assumed office. While opponents of Naya Pakistan point to the demonstrably upward tick in GDP per capita during the 2014-18 period (Fig. 1), proponents of Naya Pakistan--- who disparagingly refer to this period as Daronomics--- argue that the economy was artificially ‘inflated’ via a ‘manipulated’ exchange-rate regime (Figure 4, notice the relatively stable line from 2014-17) that collapsed as soon as the transfer of power took place.

Finally, a third issue deals with the future effects, real or presumed, of any policies undertaken by the current regime that may have lagged policy-effects in upcoming years. In contrast to the first issue, in this case proponents will tend to exaggerate the prospective output gains while opponents will seek

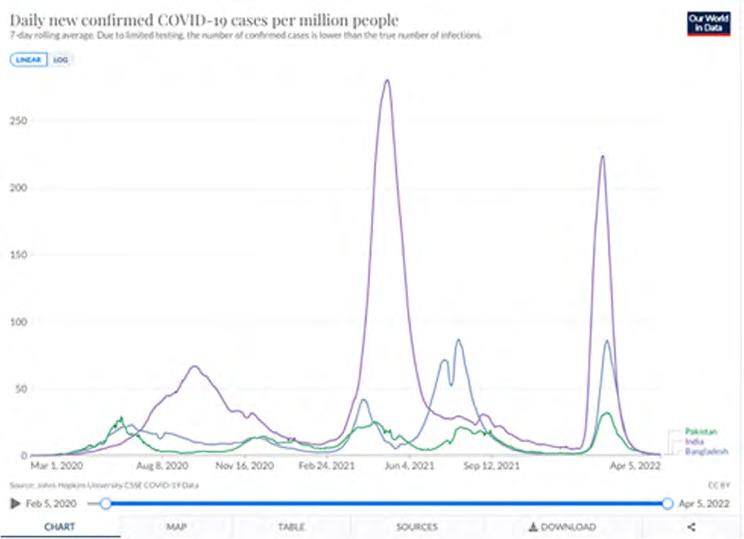

Figure 3- Disease Burden: Confirmed COVID cases per million

to undermine them. Given the political (and somewhat rhetorical) nature of these issues, there will never be a perfect approach to dealing with any of them.

One way of dealing with them is to compare the economic performance of Pakistan with two regional economies (India and Bangladesh) immediately before, during, and after the COVID pandemic. This allows the discussion to take place via the aid of some counter-factual with which the actual performance can be compared. Moreover, this must also be weighted in relation to the burden of the pandemic in each of the three economies (Fig 3). It is also crucial to remember that while the COVID pandemic hit the Chinese economy in November 2019, it was not before March 2020 that the rest of the world even began contemplating lockdowns.

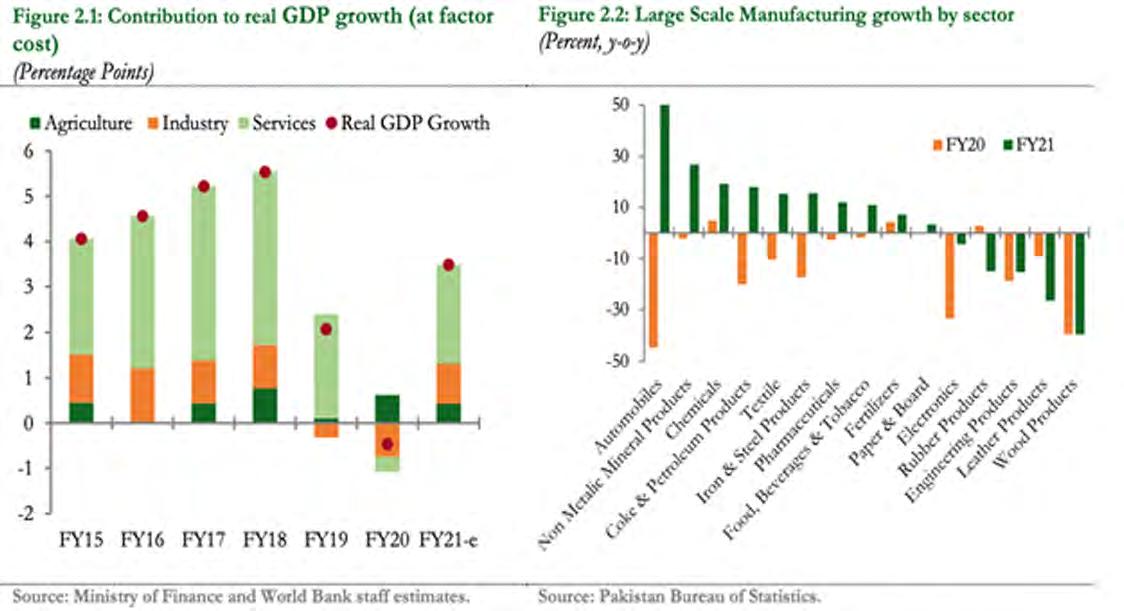

Figure 1 plots World Bank data on GDP per capita for Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh in current (panel 1a) as well as constant (panel 1b) dollars. As we can see, regardless of one’s opinion of Daronomics, both measures demonstrate that all three economies witness an increase in per capita GDP between 201417. While it is true that Pakistan’s growth lags behind India and Bangladesh during this period as well, it is nevertheless inching upwards alongside its South Asian neighbors.

A sudden divergence, a reversal, appears in this trend in 2018-19, that is after the inauguration of Naya Pakistan, and more than a year before the pandemic. Between 2018-19, Pakistan’s GDP per capita fell by 1% while India and Bangladesh continued to expand their per capita GDP by 3% and 7%, respectively. Between 2019-20, India’s output per capita declined by 8%, while Bangladesh continued to expand its per capita GDP, albeit at a slightly lower rate (3%). During the same year, Pakistan’s GDP per capita contracted by another 3% in constant dollar terms and 8% in current dollar terms, reflecting the immiserating effect of the depreciation of the Pakistani currency (Figure 4).

This overall decline in output can also be observed by zooming into the sector-wise changes to GDP growth (at factor cost) in Figure 2.1 and 2.2.

Moreover, since the economic impact of any exogenous shock must be assessed in relation to the quantum of the shock, it is also important to appropriately weigh our assessment of the economic impact of the COVID pandemic by comparing the disease burden per million across the three countries. This will also be useful when thinking about the speed and magnitude of the post-pandemic recovery. To do this, consider Figure 3 which presents a timeline of daily new confirmed COVID cases per million people between March 2020 and April 2022 using the Johns Hopkins University COVID dataset. As we can see, for most months Pakistan’s per million curve is lower, reflecting an overall lower disease burden.

Ideally, a lower disease burden should have translated into a much swifter and more robust economic recovery: the lesser the original shock, the quicker the recovery. Unfortunately, that has not been the case, either. A January 2022 World Bank Global Economic Prospects report (https://www.worldbank. org/en/publication/global-economic-prospects) estimates that despite the low-base effects associated with the 2020 downturn, Pakistan’s real GDP grew by a dismal 3.5% in 2021 (the government estimates a higher number); contrast this with the South Asian average (India estimated at 8.3% and Bangladesh at 5%).

If we now combine the three facts the conclusion is obvious: Pakistan’s economic downturn began before the pandemic and its economic recovery from COVID is significantly lower than India and Bangladesh despite the lower disease burden per million.

Finally, what can one say about the future trajectory of the economy in the aftermath of Naya Pakistan? Here too, World Bank estimates provide a rather grim picture. Estimates suggest that while India and Bangladesh will grow, on average, by 6-8% in 2022 and 2023, the Pakistani economy will grow at around 3-4% per annum. The depleting net reserves of the State Bank of Pakistan point to more economic hardship in upcoming years. Over the past seven months, the State Bank has been losing $1 billion a month of reserves. During the week ending on March 25th, the SBP witnessed the biggest weekly fall in reserves in Pakistan’s economic history. Once the political dust settles, a sobering conclusion awaits the judgement on Naya Pakistan: a stagflationary period with rising inflation, stagnating output, and a loss of competitive advantages to other regional economies. n

Figure 4: US Dollar to Pak Rupee