WINTER 2025

Land, Love, Legacy

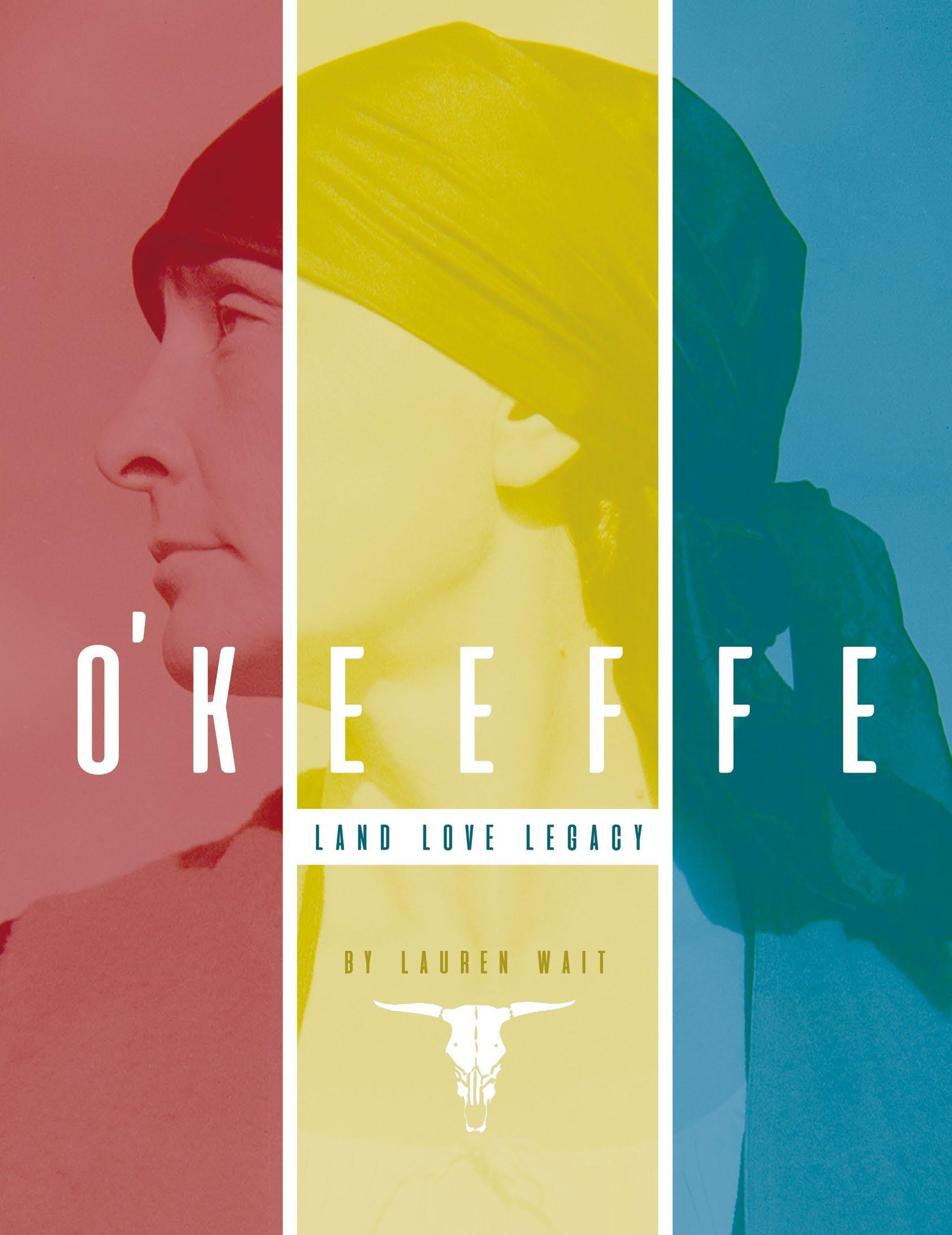

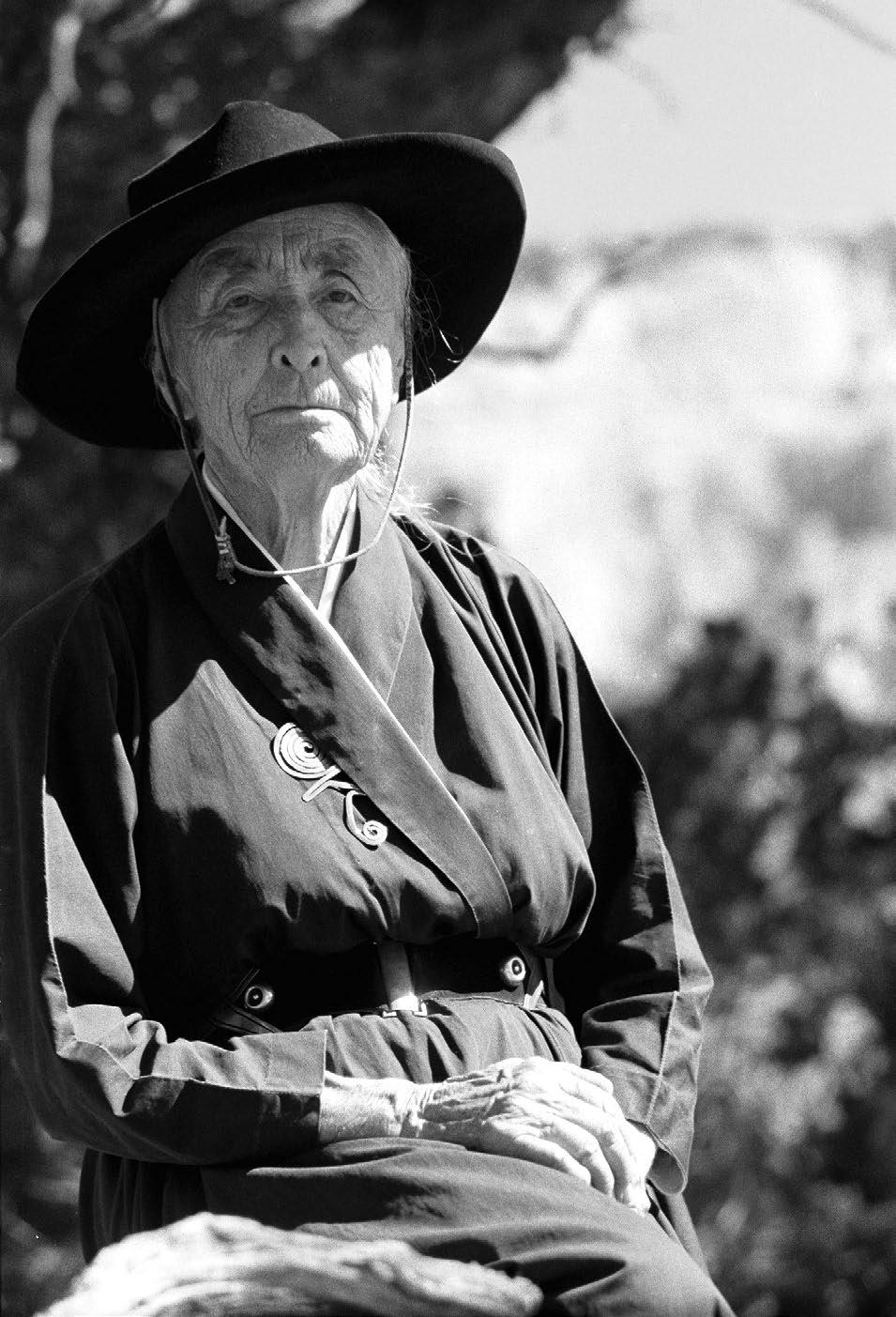

Georgia O’Keeffe, often referred to as the “Mother of American Modernism,” redefined how the world saw flowers, bones, and desert landscapes. Her bold use of form and color captured both intimacy and vastness, forever shaping the course of American art and influencing an art movement in New Mexico.

Radiating Charm Under a Blanket of Snow Nestled in the foothills north of Santa Fe, Tesuque exudes a quiet winter charm. Snow-dusted adobe homes, piñon-scented fires, and tranquil village lanes create a timeless atmosphere, where tradition, natural beauty, and serene stillness invite visitors to linger and savor.

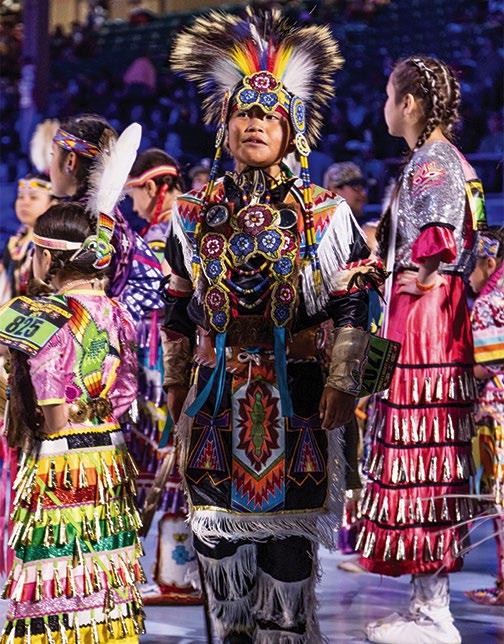

The Last Powwow, Not The Last Dance

The final powwow of the Gathering of Nations in Albuquerque in 2026 will pulse with drumming, dancing, and spirit. Thousands will gather in unity, celebrating Indigenous culture, tradition, and resilience. Experience this culturally significant event before it fades into history.

Augusta Sunshine Duran is as warm as her name, and her roots go deeper than the cottonwoods that line the streets of Taos. It’s not difficult to see how her drive to serve her community of Taos Pueblo is only eclipsed by her charming and contagious personality. We were fortunate to spend time with Sunshine to learn more about what motivates her to help create a better world.

WINTER 2025

52 Capturing the View From Here

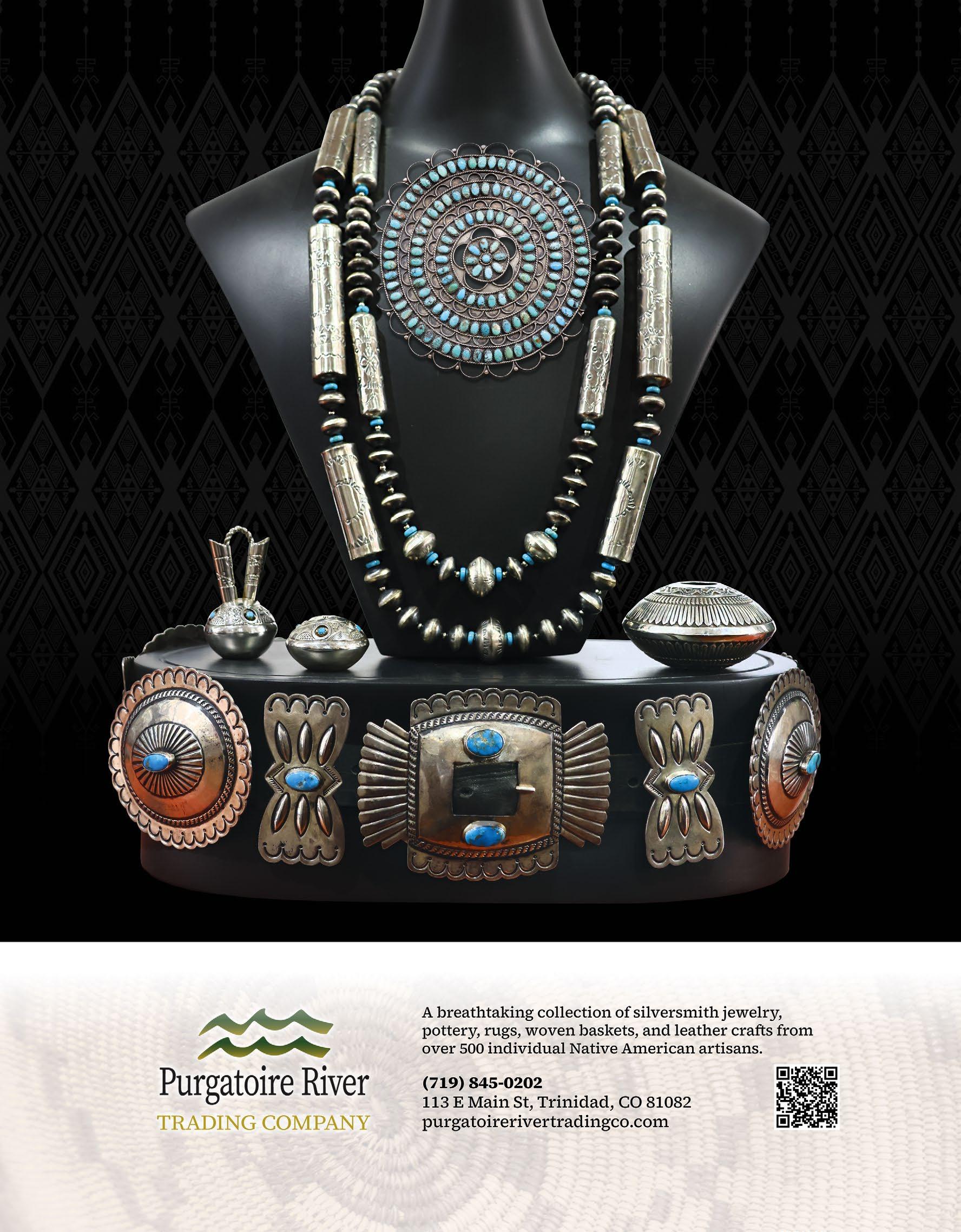

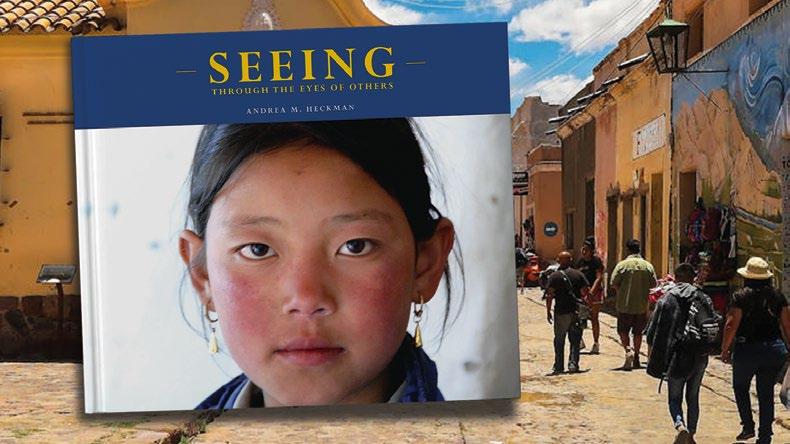

56 READ: SEEING Through the Eyes of Others

56 TOUCH: Santa Fe Bug Museum

56 LISTEN: New Mexico Wildlife Podcast

57 WATCH: Dark Winds

57 TASTE: Santa Fe Biscochito Company

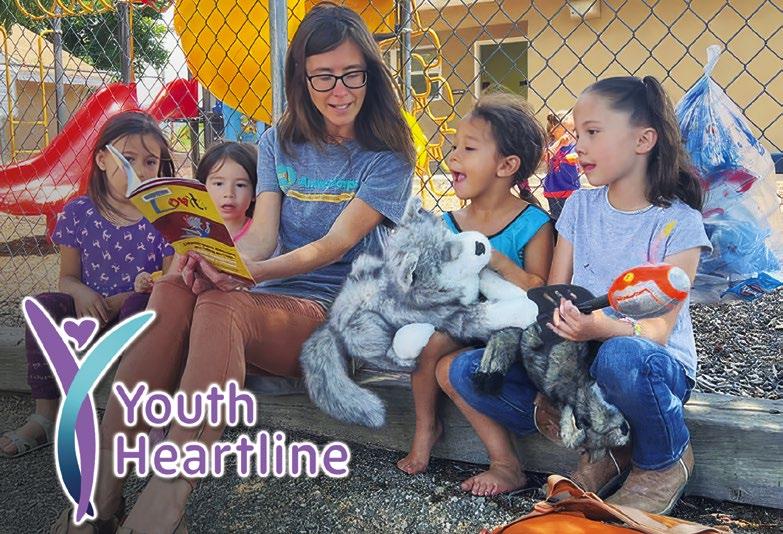

58 SUPPORT: Youth Heartline

58 SIP: Watrous Coffee House

58 STAY: Mabel Dodge Luhan House

62 CALENDAR: Featured Regional Events

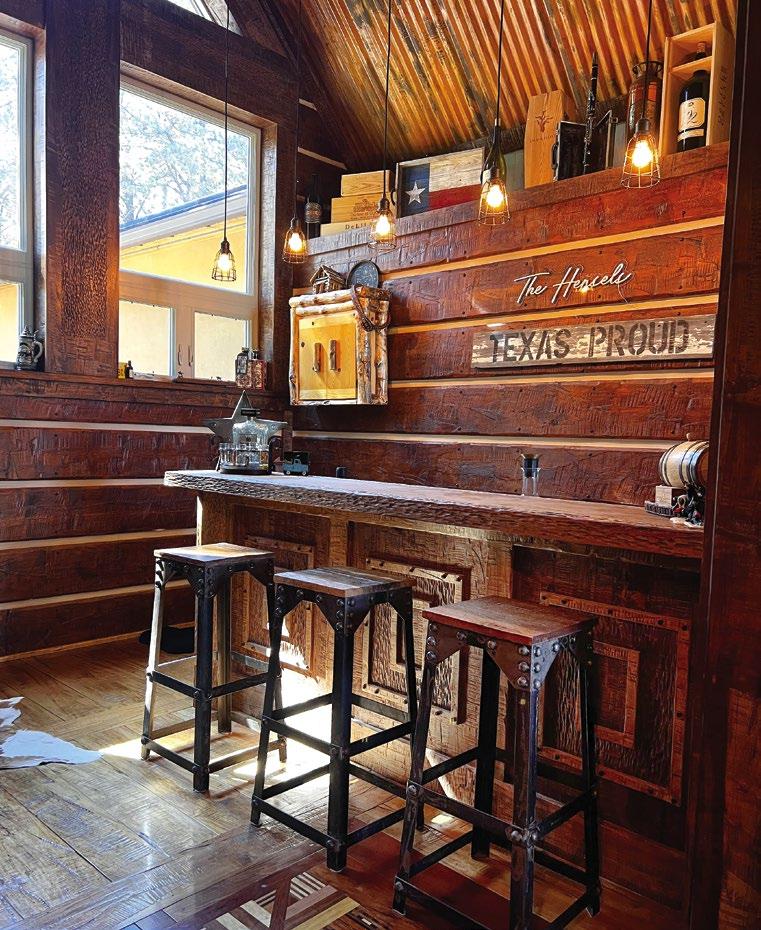

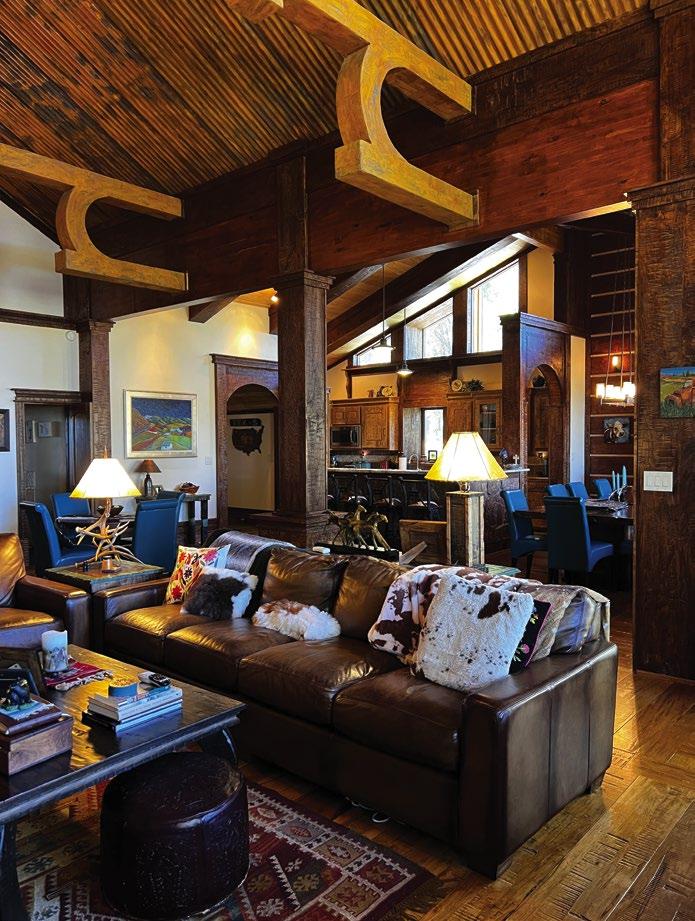

70 Regional Interior Design Masters

78 Voormi: The Future of Clothing

90 Sage Work Organics: An Intention of Hygge

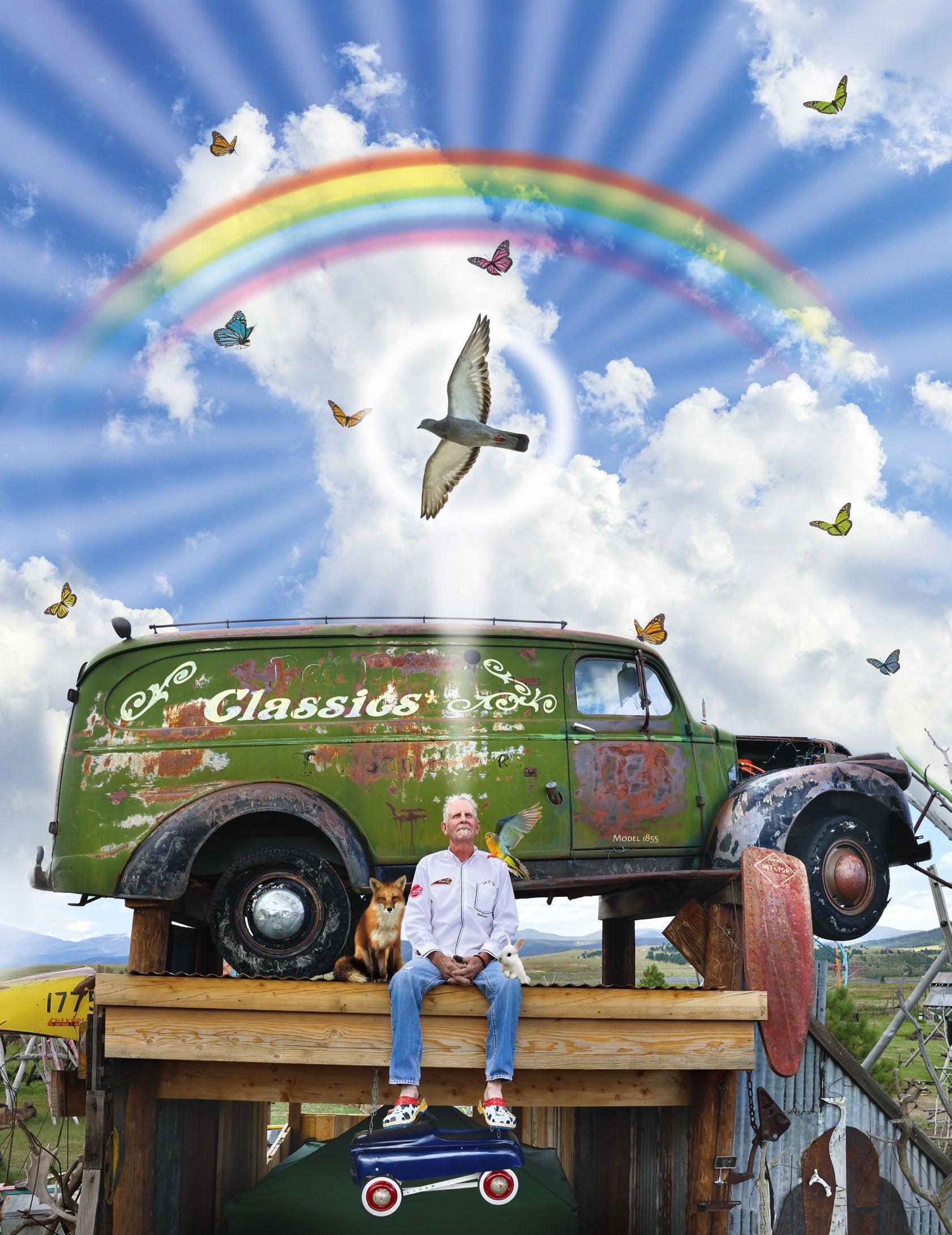

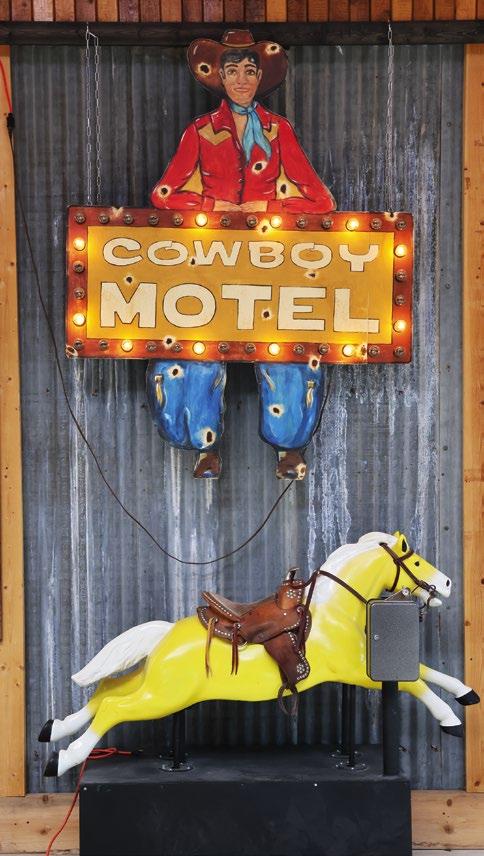

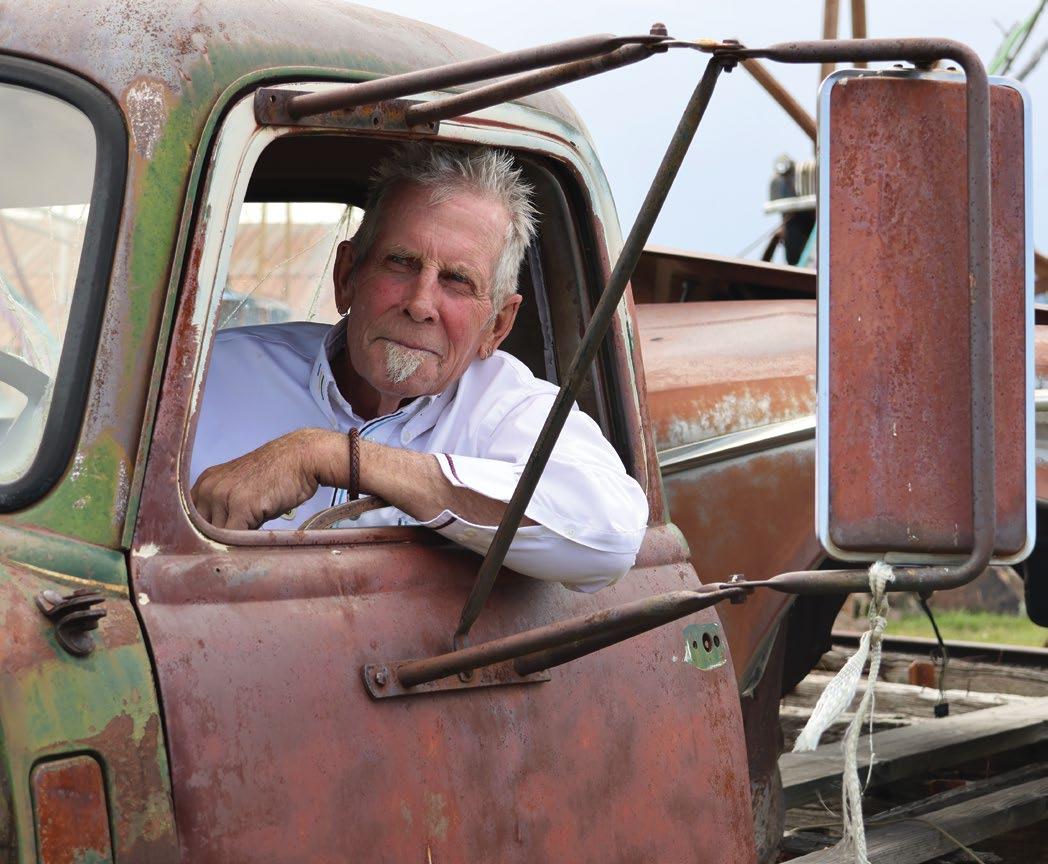

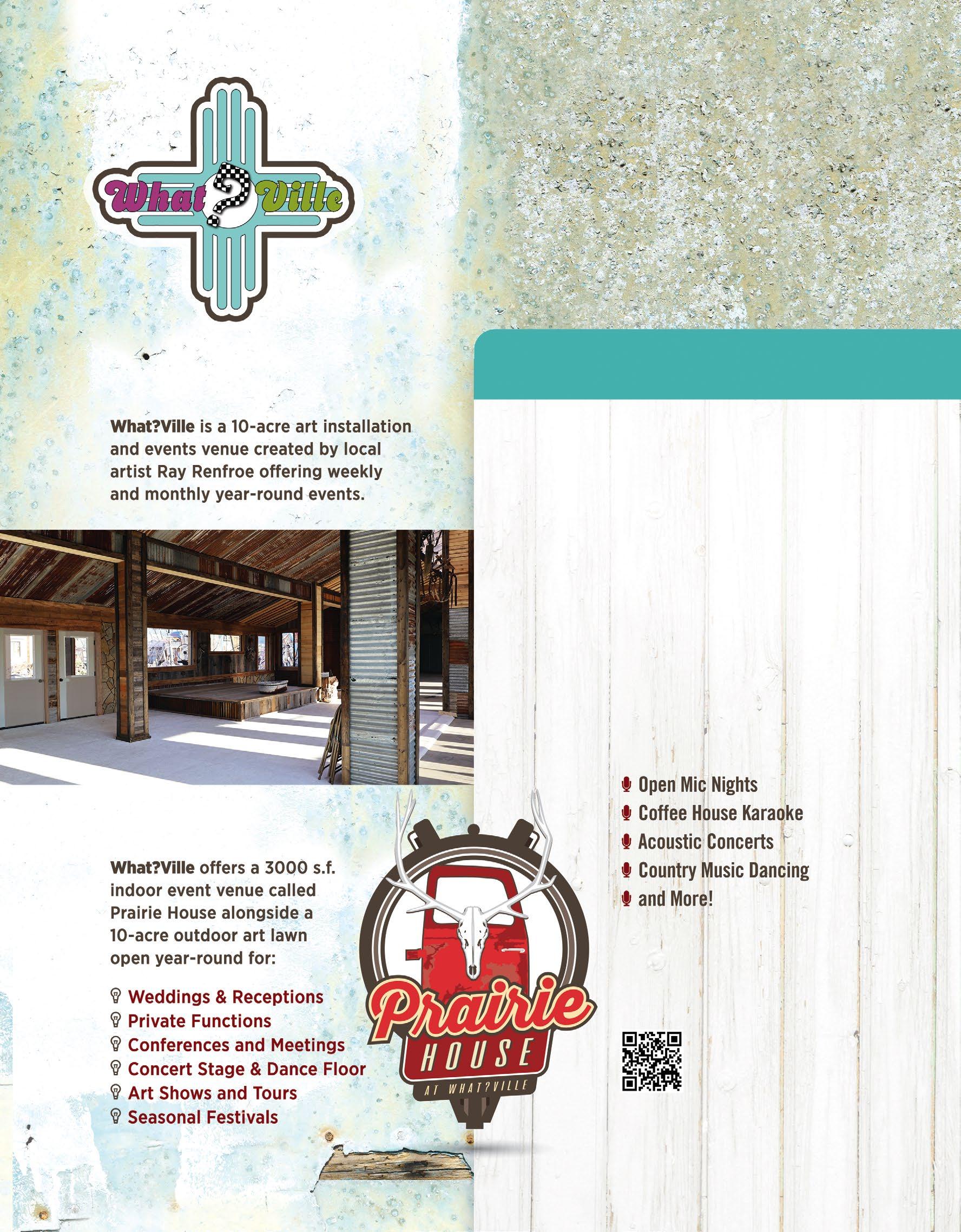

96 The Whimsical World of Ray Renfroe

108 A Trail of Two Cities

116 Sunshine Rising

124 Chimayó: A Pilgrimage of Remembrance

132 A.R. Mitchell Museum of Western Art

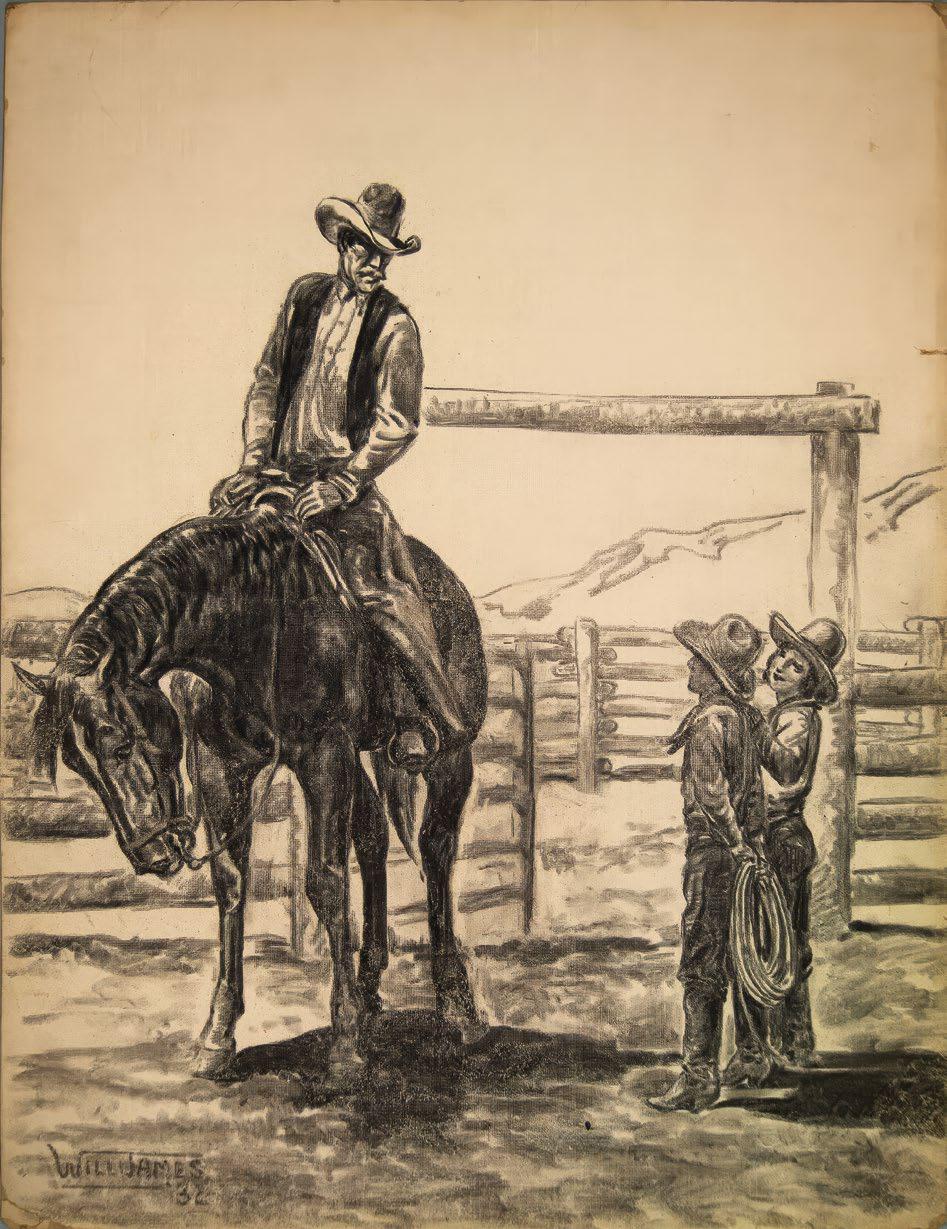

136 Will James: The Cowboy Artist

146 Magical Snowshoeing Adventures

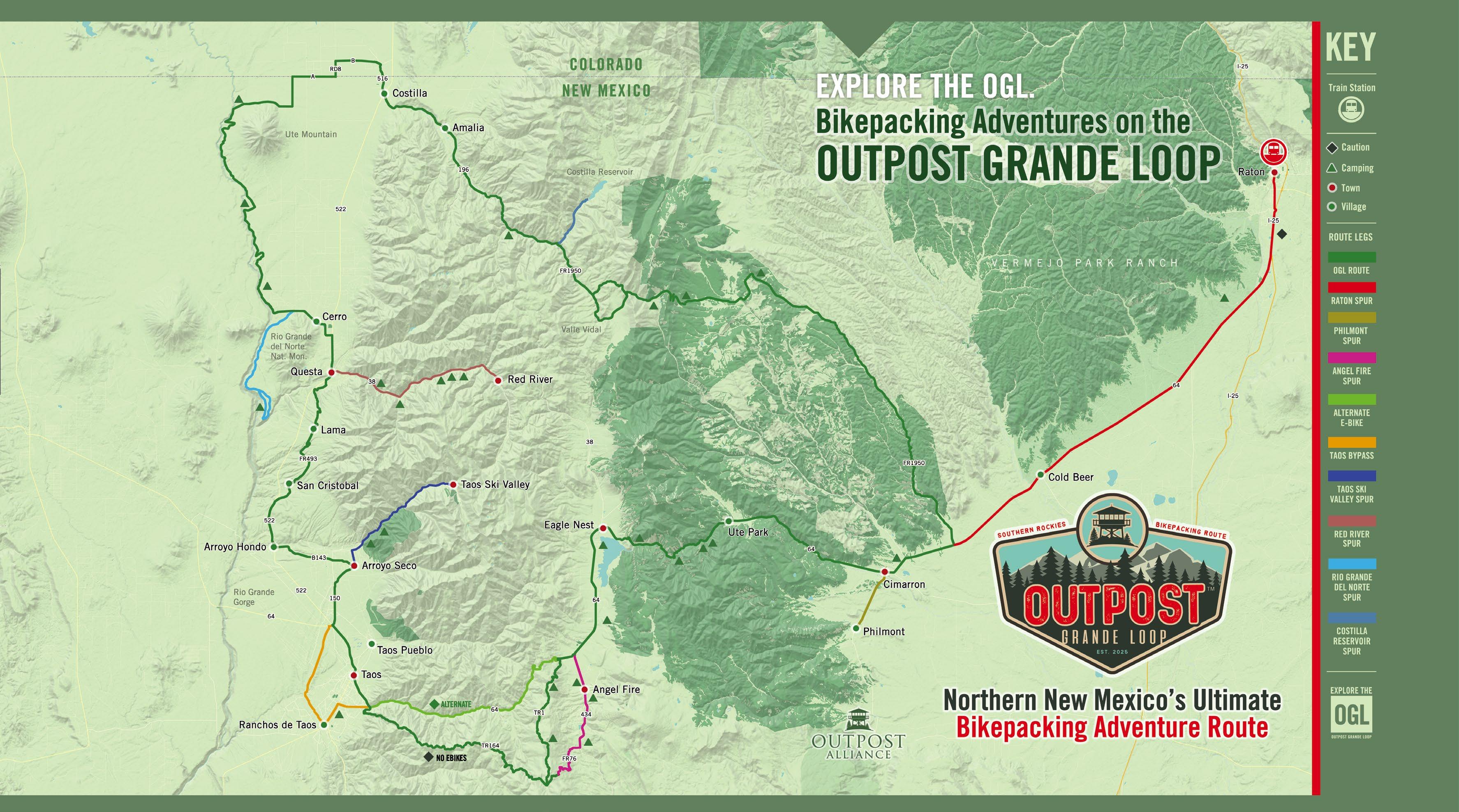

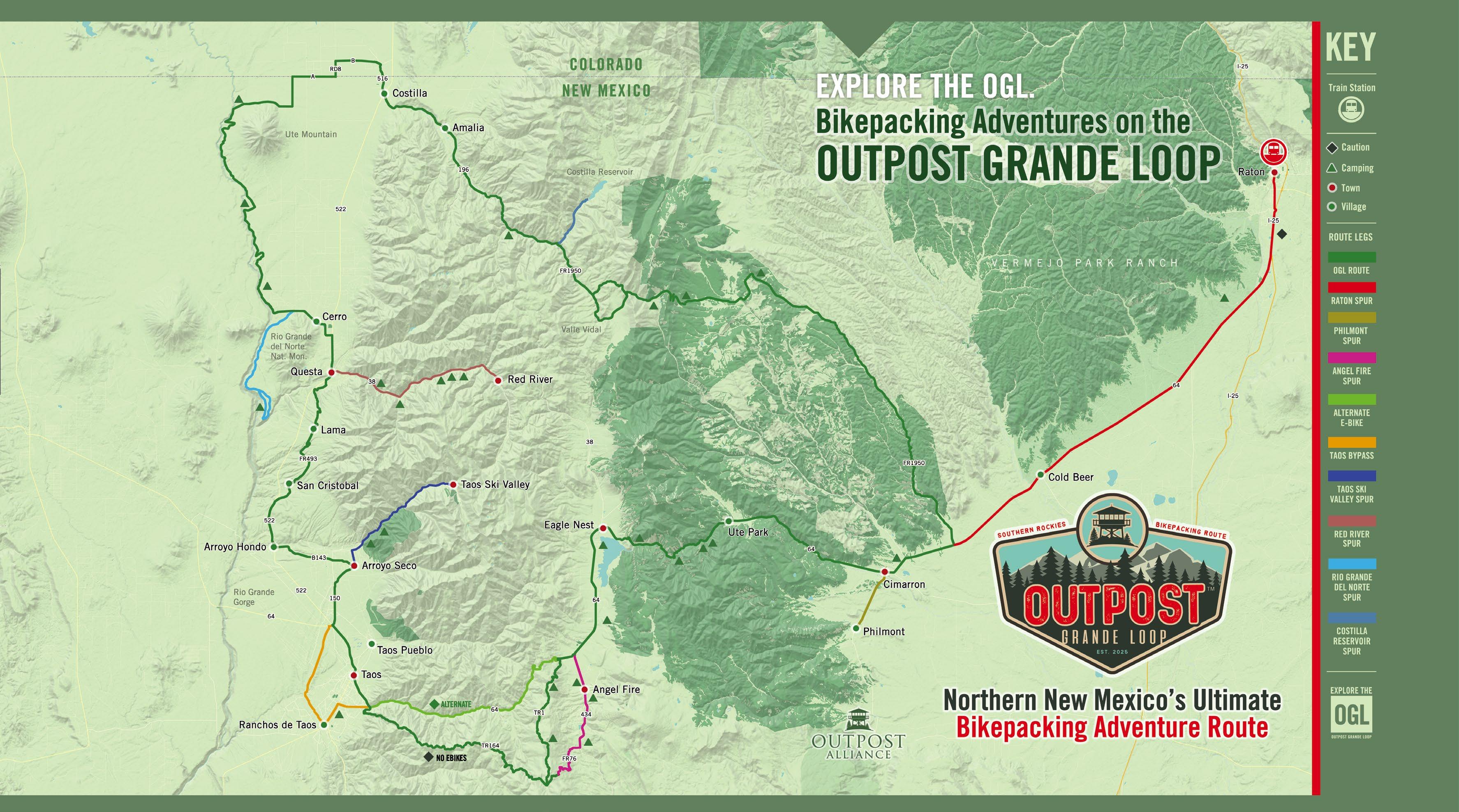

154 Bikepacking on the Outpost Grande Loop

170 Cold Rush: Race the Chama Chile Ski Classic

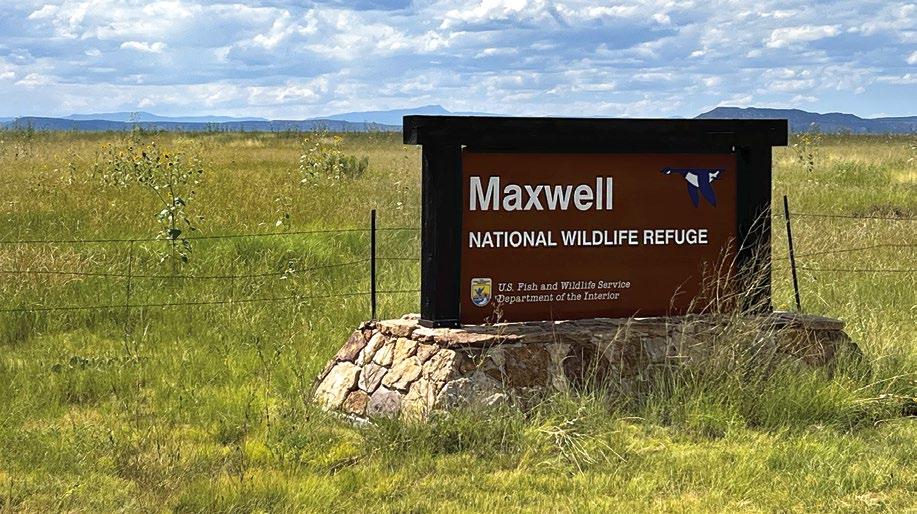

180 Maxwell National Wildlife Refuge

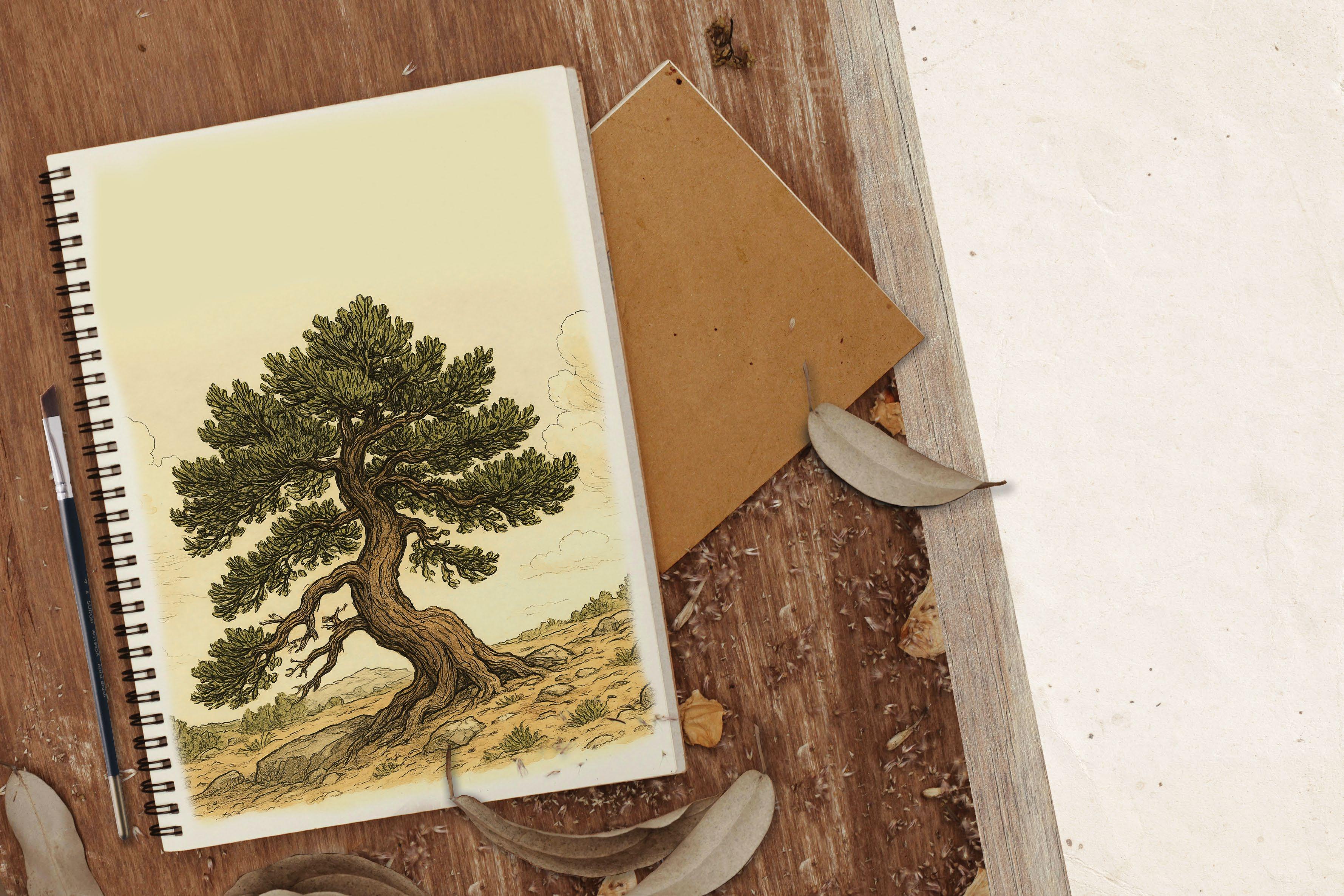

186 The Rocky Mountain Bristlecone Pine

192 A Crane Conversation: Celebrating Sandhill Cranes

201 A Last Look for the Season

The sport of Bikepacking has grown to become a refined, international adventure travel activity. We’re tapping into this growing popular culture with the introduction of a proposed route we’re calling the Outpost Grande Loop. This outdoor adventure route has the potential to bring an entirely new, organized experience to our region and expand our adventure travel offerings to enthusiasts around the globe. Learn more and get involved. Together we can bring the OGL to the world.

A word from the publisher.

When we set out to create an upscale regional lifestyle publication, our intention was to shed light on the rich cultural tapestry, the stunning landscapes, and the colorful people who consider this region their home. But the bigger initiative was to start a movement and play a role in driving new economic prosperity to the entire region we serve.

When I decided to move to northern New Mexico, one person I spoke to commented: “I’m not sure why you would want to move there, New Mexico is poor and riddled with crime and blight.” This comment was precisely what drove me to launch Enchanted Outpost magazine.

Although public perception of New Mexico—in a positive light—is a place where Indigenous and Hispano cultures and beautiful vast desert landscapes inspire spiritual connection and exhibit true la vita dolce, it is also seen as one of the poorest states in the country. And although the governor and her team work to improve the local economy through adventure tourism, a tech movement, film industry growth, and other key initiatives, it literally takes a village to bring prosperity to a village.

North of the border in Colorado—in the region of the state that we serve—those communities have one extra thing going for them: the word Colorado. Yet from our western outpost of Pagosa Springs eastward, we see vastly underserved communities. Towns like Walsenburg, Alamosa, and Trinidad work hard to bring visitors to spend money, but their efforts can only go so far.

We mostly receive rave reviews about the magazine and praise for our efforts. Public consensus leans heavily toward Enchanted Outpost being a “breath of fresh air.” Most municipalities in our region recognize what we’re attempting to do and support us however they can.

Yet, there are still people who strongly oppose the exposure we are generating. To them I say this: No matter what you do to attempt to stop the evolution of something, your attempt to stop it is still evolution. Things always move. Even successfully stopping development is an evolutionary change over time. Backwards is still forward evolution—eventually stagnating a community to the point where no businesses can survive. If you are a business owner here or provide a service, you likely love momentum. If not, maybe there’s a disconnect in understanding the dependency business owners have on more than local traffic. Because of that disconnect I can understand the initiative to stop or slow evolution. But that will only lead to the closing of the businesses that serve you. The world is changing exponentially. In a matter of a few years—whether acknowledged or not—technology and environmental issues will evolve every corner of the planet. Change is coming everywhere. Choose to fear change or embrace it.

There are three kinds of people: critics, talkers, and doers. It probably goes without saying that Heather and I are both talkers and doers. We talk the talk, and then walk the walk. We roll up our sleeves, put our heads down, and execute the things we set out to achieve.

We’ve spent countless hours speaking face-toface with hundreds of business owners across the more than forty communities we serve. We deeply understand the challenges real local people here face. Set aside the retired folks for a moment. Set aside the second home owners for a bit. The people here who are driven to create livelihood depend almost entirely on traffic through the door of their business, typically more so from visitors than locals. These are the people that connect our hearts

“I’m not sure why you would want to move there, New Mexico is poor and riddled with crime and blight.”

“This

comment was precisely what drove me to launch Enchanted Outpost magazine.”

to the region—the people who create the allure and ultimately the region’s identity. Through our conversations we understand, while they are deeply concerned about preserving a cultural identity, they also desire prosperity.

Prosperity to them is a consistent stream of customers, enough to maintain a simple yet comfortable life.

So, we set out to influence the inevitable evolution toward cultural preservation and respect while also driving economic prosperity. Our purpose is to bring to the surface as many hidden gems as we can—to showcase and honor the inspiring yet humble people who truly shape our culture. We believe in putting new businesses in empty buildings. We’re driven to blur the lines between high seasons and shoulder seasons. We’re motivated to disperse people from the economic centers people visit—like Santa Fe—into the smaller communities that equate to the full essence of our region. We’re here to harness the incredible momentum the City of Santa Fe has achieved to help all communities prosper.

Evolution is inherent. With every page of every issue of Enchanted Outpost, we’re choosing to influence that evolution toward real regional economic prosperity while inspiring cultural and environmental respect. With more than half a million estimated readers across our print and digital magazine, and countless comments of praise from both regional visitors and local readers alike, we believe we are achieving our mission.

Scott Leuthold PUBLISHER & COFOUNDER

Publishers and Cofounders

Scott and Heather Leuthold

Creative Director and Lead Designer Scott Leuthold

Copy Editor

Lauren Wise Wait

Advertising Sales

Collin Leuthold, Director of Sales advertise@enchantedoutpost.com

Distribution and Subscriptions

Ahnna Swanson, Director of Distribution distribution@enchantedoutpost.com

Photographers

Sarah McIntyre, Daniel Combs, Page Steed, Roland Pabst, Daniel Quat, Dustin English, Michael Candelaria, Scott Leuthold, Heather Leuthold, Collin Leuthold, Yellowstone Art Museum, Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, A.R. Mitchell Museum, and Library of Congress

To leave comments, make suggestions, or report errors, please complete the contact form on our website.

Visit us on-line at: enchantedoutpost.com

Enchanted Outpost is distributed through a variety of outlets in northern New Mexico, southern Colorado, and Texas and by mail through subscription service.

OUTPOST ALLIANCE, LLC and Enchanted Outpost PO Box 1650, Angel Fire, New Mexico 87710

©2025 Outpost Alliance, LLC. All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, digital scanning, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. For permission requests, please complete the contact form on our website.

Georgia O’Keeffe, photographed at her home in Abiquiú, New Mexico in 1950, was a prolific artist and transformative figure who significantly influenced New Mexico’s art culture.

PHOTO: Carl Van Vechten/ Library of Congress. Edited by Scott Leuthold with permission from Logan Esdale, Carl Van Vechten Trust.

Lisa Ragsdale

Lisa is a freelance writer living in Albuquerque, New Mexico. She loves being outdoors, hiking, backpacking, paddle boarding, and spending as much time as possible at her family’s property in the mountains near Angel Fire, New Mexico.

Collin Leuthold

Collin is a creative individual with a passion for music, short film production, vintage cameras, old cars, and outdoor adventure. Originally from Scottsdale, Arizona, and a graduate of Grand Canyon University, he now resides in Angel Fire serving as a Director of Enchanted Outpost Magazine.

Lauren Wise Wait

Lauren is an Arizonabased writer and editor who believes every great story has the power to connect and inspire. Her work has been published by VICE and LA Weekly. She loves to cook, travel, and teach her young son about desert critters and plants.

Shelli Rottschafer

Shelli lives in El Prado, New Mexico and Louisville, Colorado with her partner, photographer Daniel Combs, and their Pyrenees-Border Collie. She completed her doctorate in Spanish from the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque (‘05) and her MFA in Creative Writing from Western Colorado University, Gunnison (‘25).

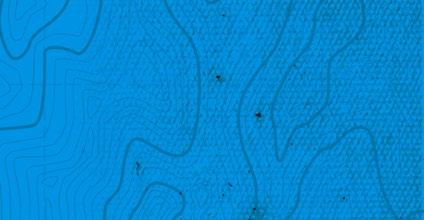

Our content and distribution region spans the state border and covers Pagosa Springs, Colorado east to Trinidad, Colorado and from Pueblo, Colorado to Albuquerque, New Mexico.

The locations of our subject matter in this issue of Enchanted Outpost are shown on the map to the right, illustrating our commitment to delivering unique stories from the 40+ communities we serve.

As an upscale, regional lifestyle magazine, we strive as a publisher to optimize our engagement with readers. To do so, you will discover opportunities with many of our articles to utilize your smartphone to extend the reading experience with interactive content. We employ the use of QR Codes to streamline the process of opening website links. As of the date of publication, all QR Codes resolved to their respective destination URLs.

QR Codes are easily read by most current model smartphone cameras. To read a QR Code, open the camera app on your phone. Point the camera at the QR Code. Your smartphone will recognize the code image and offer a link on the camera screen that you can tap with your finger. Doing so will open the website address in your smartphone browser. For further instructions, please refer to the owner’s manual of your mobile device.

We continually strive to improve the reading experience of our magazine with a goal of being the best regional lifestyle magazine in the country.

New Features:

• Added Guest Writer Contributors

• Added STAY to Waypoints

• Redesigned the interactive content areas of the articles.

• Improved maps

How one artist referenced the Southwest for then and now

On a summer night in 1929, Georgia O’Keeffe lay flat on her back beneath a towering ponderosa pine at the D.H. Lawrence Ranch in Taos. She looked to the branches arched overhead like cathedral ribs, framing a scatter of New Mexico stars. Instead of sketching the postcard mountains beyond, she tilted her gaze upward, capturing the limbs as they stretched into the night sky. The resulting painting, The Lawrence Tree, was radical not because of what it showed, but how it showed it: a ground-level perspective that transformed an ordinary tree into something cosmic. It married abstraction and reverence and was a literary nod as well:

D.H. Lawrence had written beneath that very tree.

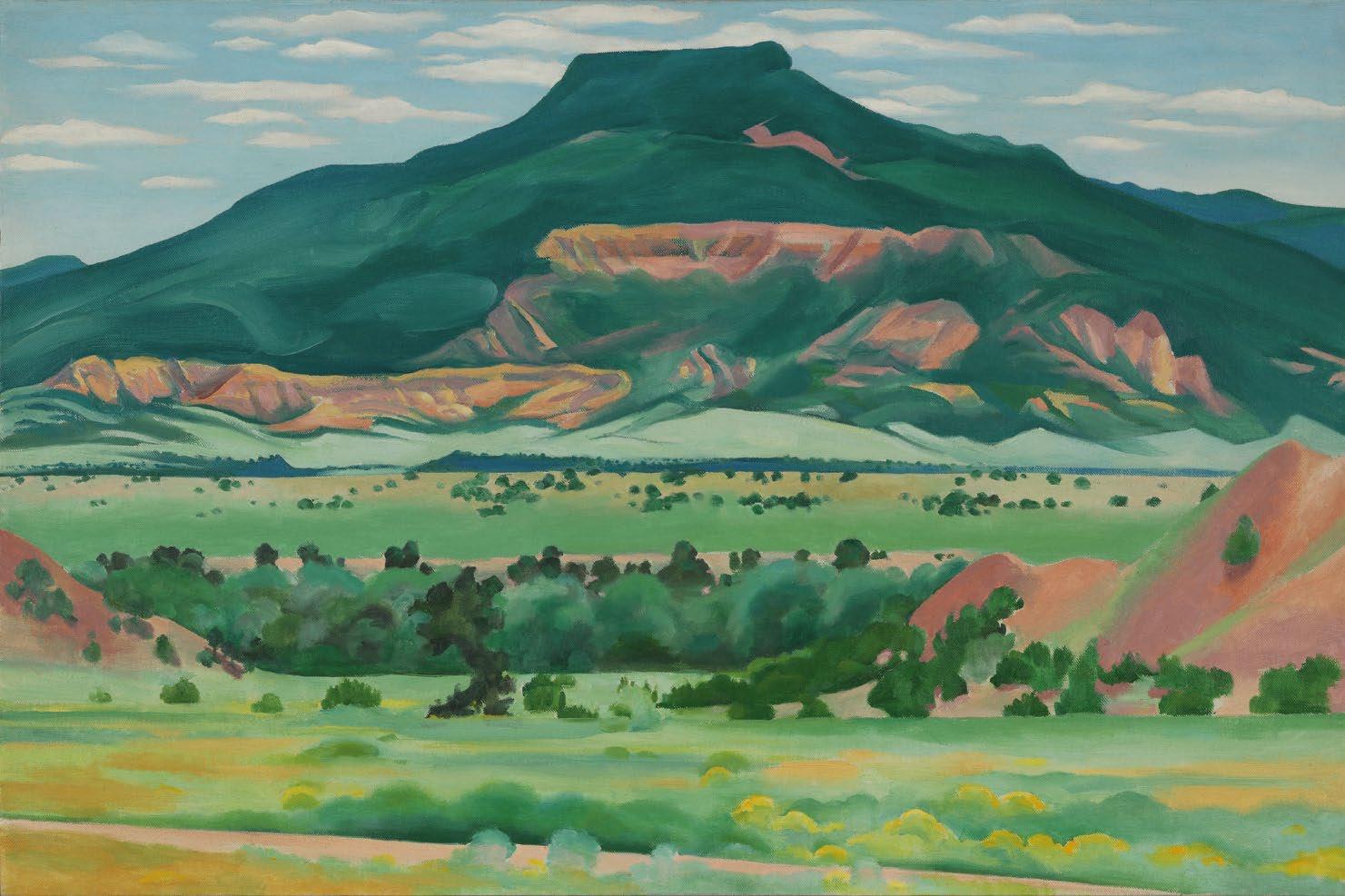

This shift—cropping, enlarging, editing the land into intimate fragments— became O’Keeffe’s signature. Her artistic language was born not from theory but from place: the red cliffs of Ghost Ranch, the white stone of Plaza Blanca, the adobe walls of Abiquiú, the flat crown of Cerro Pedernal. O’Keeffe didn’t just modernize the Southwest; she mapped a new way of seeing it, transforming land into language. As she once famously said: “I found I could say things with color and shapes that I couldn’t say any other way—things I had no words for.”

Born in 1887 to a dairy farming family in Wisconsin, O’Keeffe announced by

age ten that she wanted to be an artist. By her early twenties, after studying at the Art Institute of Chicago as well as in New York, O’Keeffe ran headlong into the stiff, rule-bound curriculum of art academies at the turn of the century. She stepped away from painting, believing she would never distinguish herself, and became a commercial artist.

Her creative rebirth came unexpectedly in 1912, during a summer course at the University of Virginia. There, she encountered the teachings of Arthur Wesley Dow, a proponent of Japanese aesthetic principles. Dow emphasized composition, line, and harmony—a dramatic shift from copying nature to interpreting it. Under his influence,

O’Keeffe began producing abstract charcoal drawings, and developing her unique style with watercolors.

In 1915, she sent a series of these drawings to a friend, Anita Pollitzer, who showed them to Alfred Stieglitz, a photographer and New York gallery owner. Stieglitz immediately recognized their brilliance, displaying them at his 291 Gallery. Stunned and intrigued, O’Keeffe confronted him for showing her work without permission but allowed the pieces to remain. It was a curious case of love at first sight.

The two kept in touch for two years while she taught at a Texas college, evolving from mentor/protégé to creative partner; O’Keeffe painted some of her most celebrated early watercolors during this time, including her iconic

Evening Star series and Abstraction, which evoke the starry Texan sky. She moved back to New York to marry Stieglitz in 1924, which spurred the start of her liberation into a modern woman and media personality: Fueled by the sensuous nude photographs of O’Keeffe that Stieglitz had taken and exhibited in 1918, her famous flower paintings were often interpreted and sensationalized as sexual metaphors, linking her sexuality and art.

But these flower paintings were also the early signs of her lifelong artistic mission: to find and depict the essential truth of a subject, pared down to form, color, and feeling. Her paintings were not records of what she saw, but equivalents for what she felt.

Through Stieglitz, she met a circle of

“I’ve been absolutely terrified every moment of my life and I’ve never let it keep me from a single thing that I wanted to do.”

—GEORGIA O’KEEFFE

American modernists who influenced her trajectory, but New York’s buzzing art scene never satisfied her. By the late 1920s, O’Keeffe was restless. Then the invitation that changed her life came from Taos patron Mabel Dodge Luhan, who routinely hosted a salon with writers and artists—a patronage without creative control. In 1929, O’Keeffe arrived with her friend Rebecca Strand, stayed in Luhan’s studios, and quickly

became enchanted with the land. The high desert, with its raw beauty and vast spaces, resonated with something deep within her.

At that time in New Mexico, the dominant artistic gaze was panoramic and romanticized. The Taos Society of Artists painted sweeping, sun-drenched vistas in the European realist tradition. But O’Keeffe took a different path, zooming in. Her canvases became

portals into a distilled world of flower centers, cloud formations, and adobe doorways. With each brushstroke, she told us that the spiritual essence of the desert could be found not in its grandeur, but in its details.

This edit of the land—this refusal to romanticize it—allowed her to turn mesas into minimalism, cliffs into color fields. In the process, she made the Southwest a key site of American modernism.

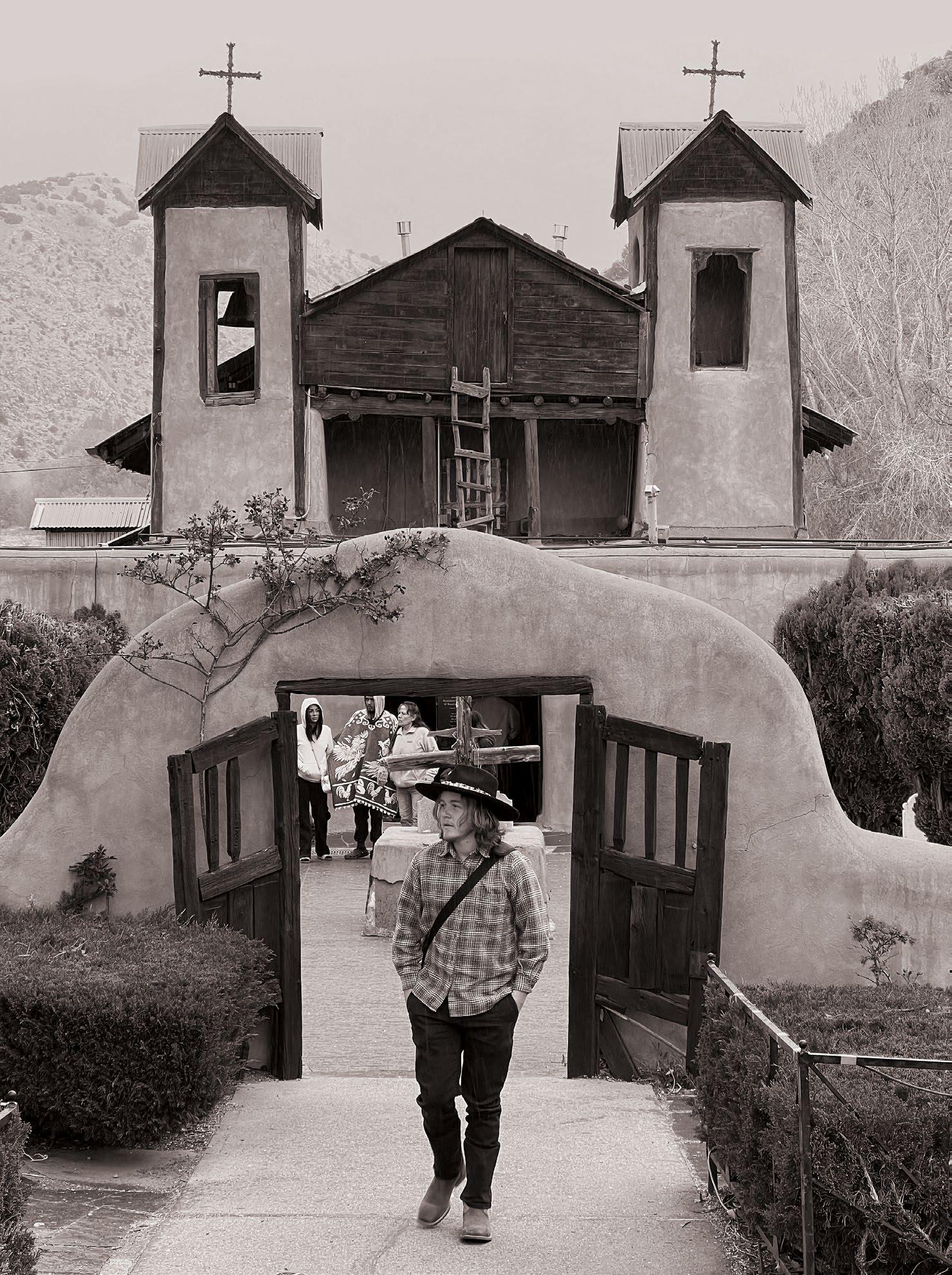

She painted the San Francisco de Asís Mission Church at Ranchos de Taos not in its entirety, but in cropped, minimal forms. The massive adobe structure became an abstract curve against a brilliant sky. She explored the ancient adobe of Taos Pueblo and discovered the morada of the Penitente brothers— all of which would become recurring motifs in her art.

Although she returned to New York after that first summer, O’Keeffe came back to New Mexico nearly every year, staying for longer periods each time. The desert wasn’t just a temporary escape. It was becoming her true home, and Luhan’s salons offered O’Keeffe access to a Western network and coastal tastemakers.

But what appealed to her most was the isolation. A loner by nature, she sought places where she could exist alone with her thoughts and paints. Ghost Ranch, north of Abiquiú, called to her.

By 1934 she staked her claim to a small house at Ghost Ranch surrounded by red and yellow cliffs. Later she acquired a crumbling adobe in Abiquiú. She spent years restoring it, eventually transforming it into a winter home and studio. The structure itself, with its clean lines and earthy textures, became a subject in her work. By 1949, after Stieglitz’s death, she left New York and made northern New Mexico her permanent home.

She roamed the land in her Model A Ford that she’d purchased and learn to drive in 1929, gathering bones, rocks, and dried flowers. These became central to her paintings. Summer Days (1936) features a deer skull suspended in the sky above a desert horizon dotted with wildflowers. These floating forms were not surrealist tricks but spiritual compositions—altars to the land’s mortality and mystery.

In the 2020s, her work feels startlingly current. In a world of digital overload and climate anxiety, her art invites us to slow down, to notice, to reconnect with the physical world.

Her landscapes from this period are among her most iconic. She once explained about the New Mexico landscape, “Such a beautiful, untouched, lonely feeling place, and such a fine part of what I call the ‘Faraway.’ It is a place I have painted before … even now I must do it again.”

Red Hills with Pedernal, the Black Place, and the White Place series showcase her mastery of simplification. The flat-topped Pedernal became her mountain—“God told me if I painted it enough, I could have it,” she said. She began making the architectural forms of her Abiquiú house subjects in her work and worked with photography, providing striking counterparts to her patio and door paintings. And over the years, she received many distinguished visitors at Ghost Ranch, including Charles and Anne Lindbergh, Joni Mitchell, and Ansel Adams. Her influence radiated outward. For

landscape painters, she legitimized abstraction, proving that cropping and simplification could express land more powerfully than realism. For a culture eager for myth, she helped reimagine the desert as a landscape not of scarcity but of revelation. And for women, O’Keeffe became proof that a woman could be both modernist and rooted in place. She broke free of strict gender roles and adopted gender-neutral clothing. Artists like Agnes Martin and Judy Chicago drew from her example, and a generation of women found the freedom to create in New Mexico. O’Keeffe had, by chance, arrived through a salon door opened by Luhan, and stayed because the land kept talking.

Santa Fe and Taos have become global art centers, in no small part due to O’Keeffe. Her presence drew attention, collectors, and curators. The Land Art movement of the 1960s and 1970s—with works like Walter De Maria’s The Lightning Field and Nancy Holt’s Sun Tunnels—extended her belief that the desert could be a cosmic canvas, sharing her view of land as sacred, stripped-down, and symbolic. Contemporary artists such as Yayoi Kusama and Cynthia Daignault continue the conversation she started. Today, the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe serves as both a shrine and a springboard, a place where her legacy continues to inspire new generations.

In the 2020s, her work feels startlingly current. In a world of digital overload and climate anxiety, her art invites us to slow down, to notice, to reconnect with the physical world. O’Keeffe asked (and still asks us) questions that matter: What does land mean? How do we live with it, not just on it? How does place shape who we are?

Her final decades were spent in near solitude in Abiquiú. Even as macular degeneration dimmed her eyesight

in the 1970s, she continued to draw, relying on memory and sensation. She passed away in 1986 at the age of 98. Her ashes were scattered at Ghost Ranch, the land she had made her own.

Ghost Ranch today is a 21,000-acre education and retreat center, where spiritual development and environmental stewardship converge. The logo, adapted from an O’Keeffe drawing, appears on T-shirts and signage. Her shadow is everywhere—not as a ghost, but as a guide. Today, artists still pilgrimage to her homes, study her work, and stand before the Pedernal, seeking the stillness and clarity that O’Keeffe found in the New Mexico desert.

Georgia O’Keeffe didn’t just paint the American Southwest—she reimagined how we see it. In doing so, she shifted the Southwest from backdrop to subject, from setting to spiritual core. Her artistic language of spare color, negative space, and off-center scale was born of place: Ghost Ranch, Abiquiú, Plaza Blanca, Cerro Pedernal. These weren’t just where she lived. They were her muses, collaborators, and finally, her legacy.

Nearly a century later, she still teaches us how to see. t

Learn more about Georgia O’Keeffe

Visit the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum to experience more.

Online: okeeffemuseum.org

Online: ghostranch.org

bakery counter, and coolers filled with unique items. In warmer weather, the outside patio offers umbrella-covered tables. Today, however, they are covered in a thick layer of snow, balanced atop like giant marshmallows.

Next door, visitors can wander through the sculpture garden at Glenn Green Galleries. This unique interactive art experience set among a stunning, lush oasis is a must-visit for those walking the area.

At the intersection of Tesuque Village and Bishops Lodge Roads, foodies can discover an eclectic pair of dining establishments: El Nido, an open-fire

Italian eatery, and Su Sushi, a specialty sushi dining experience. Other offerings farther south on Bishops Lodge Road include Tesuque Glassworks—a glass art studio and gallery established in 1975—and the reputable Santa Fe Institute—an educational institution offering undergraduate and graduate Complexity Science Research residency programs. These enrich the village with both creative and intellectual appeal.

Two of the finest luxury hotels in Santa Fe are nestled in the foothills of the Sangre de Cristos surrounding Tesuque Village. The Four Seasons Resort Rancho Encantado Santa Fe, located

north of the village along NM 592, and Bishop’s Lodge, located south of Tesuque toward Santa Fe along Bishops Lodge Road, both offer luxury accommodations and unique adventure-oriented activities for guests.

Tesuque becomes a painting, sepia dreams stitched with ivory thread.

The nearby Pueblo of Tesuque (for which the village is named) has a long history in the region. Tesuque is a Spanish variation of the traditional Tewa language name for “village of the narrow place of the cottonwood trees.” Though Tesuque Pueblo is one of the smallest pueblos in the state—encompassing some 17,000 acres—the Pueblo’s culture has influenced the region for more than 800 years. Today, the Pueblo offers one of the premier casinos in all of northern New Mexico. With its modern steel and glass architecture poised on the crest of a mesa above the valley, Tesuque Casino provides modern gaming and entertainment

with stunning views of the surrounding mountain ranges.

The world-renowned Santa Fe Opera is located just south of the casino, perched high above the valley. Spending an evening at the opera is considered one of the top activities when visiting Santa Fe.

Though Tesuque Village sits in the shadow of greater Santa Fe, the community offers something truly unique and all its own: the essence of authentic New Mexico. And if you’re fortunate enough to experience a fresh snowfall here, it makes for a most memorable experience. t

Tesuque Valley Community Association Online: tesuquevalley.org

Pueblo of Tesuque Online: tesuquepueblo.org

Tesuque Village Market Online: tesuquevillagemarket.com

Tesuque Casino Online: tesuquecasino.com

Santa Fe Opera Online: santafeopera.org

By Shelli Rottschafer

by Daniel Combs

In the Spring of 2000, I attended Gathering of Nations for the first time with a friend who grew up in Albuquerque. Held in The Pit—the University of New Mexico’s Sports Arena—we bought our tickets and descended the steep steps into the bleachers moments before Grand Entry.

As we took our seats, the Grand Entry drums guided dancers to the arena floor. Participants in full regalia paraded stepping and stomping to the beat of the drums and the wails of the singers. In response to the dancers lei-lei-ed in high pitched ululations, shouted war cries, and proceeded in an undulating circle around the dance floor. Seeing Grand Entry is powerful. The drums resonate through your chest; the wails bring goosebumps.

Gathering of Nations was first held in 1983. It was organized by University of Albuquerque’s Dean of Students, Derek Matthews. In 1984, the powwow was officially named “Gathering of Nations.” The powwow was established for the school’s Native American students to connect with their cultures. Although the University of Albuquerque closed not long after, the powwow continued. For two years the event struggled organizationally, then in 1986 it moved to The Pit.

Over the last four decades, Gathering of Nations has evolved and grown. Since 2017, it has been held at Expo NM where the Fairgrounds are located, and within Tingley Coliseum where the New Mexico Scorpions hockey team used to play. Over 70,000 people participate in Gathering of Nations whether as spectators, artists, dancers, or organizers.

On April 25, 2024, my partner Daniel and I went to Gathering of Nations. It was my second time over two decades later, and his first.

We arrived early to the Fairgrounds, and as we pulled into the parking lot other vehicles stationed themselves as well. Sliding doors open and lifting hatchbacks, people began setting boxes down on the asphalt, putting folding chairs and tables into place, setting up their dressing rooms for the day. Tailgaters with Coleman propane stovetops warmed up food, and heavy coolers were laden with sodas. Our car-neighbor began donning his fancy dancing regalia, bustles with eagle feathers, and leather moccasins.

Daniel and I stood in line, our pre-purchased tickets in hand. The line grew behind with visitors, extended family of dancers, and tourists. Volunteers behind the gate reminded everyone to stay hydrated—but also that Gathering of Nations is a sober event. We walked through the grounds,

taking it all in. There was a food court and food trucks selling everything from “Indian-Tacos” made with fry bread to elotes covered in mayonnaise and tajin to burgers with Hatch green chiles. The tent section of Expo NM held the artisan area with herbal remedies, parrot feathers and beads for regalia crafting, beaded earrings and necklaces, silver and turquoise jewelry, as well as dream catchers. Then we headed to Tingley Coliseum where the Grand Entry was about to start.

We took our seats in the bleachers. In front of us were tourists from Texas, and behind us was an extended family from Sandia Pueblo, cheering on family members about to dance. In the back rows were some folks resting in full regalia, their headdresses seated next to them before they made their way down to the floor.

Each Gathering of Nations begins with an opening ceremony. In our case, Miss World Indian looked over the floor as the drummers pounded. Their wide drums boomed and wails accompanied an honored dancer who began the procession by raising a ceremonial

staff. The beat drew in different groups of dancers in a clock-wise rhythm. Women dancers, senior and golden-age dancers circled onto the floor. In 2024, tribes representing all First-Nations in Canada, Natives throughout the United States, Indigenous Mexicans with Aztec-Nahuatl plumage-regalia, and international representatives gathered as waves of people trickled into the center.

Each powwow dancer is unique. Some men wear “grass dance” regalia with headpieces made of porcupine or deer hair and feathers. “The body of the outfit includes an apron with long fringe that mimics the action of grass blowing in the wind. The dancers themselves spin, turn, and shuffle their feet as if they are moving in tall grass, all to the beat of the drum” (Treuer 150). Other men wear “fancy dance” regalia of bright colors, double bustles, and eagle feathers. Their moves, “display rapid footwork [like] spinning, cartwheeling, and jumping” (150). Watching these athletic dancers was mesmerizing.

As women entered the arena some wore “jingle dresses” from an Ojibwe tradition. These are dresses made by the

dancer and her female family members, with 365 jingles—small metal cones— upon each dress, representing one for each day of the year. “The jingle part of the regalia is believed to have healing power” (Treuer 151).

Other women and girls wear “fancy shawl” and “ribbon skirt” regalia. “The attire involves a colorful dress and shawl. The dancer spins and moves her arms to mimic the actions of a butterfly coming out of its cocoon and flitting about the arena” (Treuer 156).

In 2024, during Grand Entry there were over two thousand traditional dancers on the floor. Seeing that number of people gathered, dancing in unison, brought tears to my eyes.

After Grand Entry we made our way down to the arena floor and joined other photographers who crouched on their knees to film the dancers. That’s when the children entered the arena. As drummers called they began their dancing steps. Each had a number on their sleeve, and judges swirled around the periphery with clipboards, evaluating their moves and agility. Some looked stern as they lofted feathers or staffs into the air. Some had smiles strewn across their faces. All proudly represented their families and communities as a member of a new generation.

After 43 years, the organizers of Gathering of Nations are billing the 2026 ceremonial celebration as “The Last Dance.” However, there are other similar events that are community-specific. For example, Taos Pueblo held its own powwow July 11-13, 2025. The dates for 2026 are to be determined. The Gallup Inter-Tribal Ceremony will be held July 31-August 9, 2026. While other dances are held throughout the year at the Pueblo Cultural Center in Albuquerque. t

References:

Treuer, Anton. Everything You Wanted to know About Indians But Were Afraid to Ask. Young Readers Edition. NY: Levine Querido, 2021.

Dr. Anton Treuer (Leech Lake and White Earth Ojibwe) is an esteemed scholar having graduated from Princeton and the University of Minnesota, who now teaches at Bemidji State University in Bemidji, Minnesota. He teaches Native American Studies and is an Anishinaabe Culture and Anishinaabemowin-Language Revitalization expert. He is the author of several scholarly works on Native American Studies, memoirs, and a young adult novel Where Wolves Don’t Die (2024). He lives with his family on his community’s traditional land upon the Leech Lake Reservation.

Visit: antontreuer.com

Anton Treuer comes from a family of activists, his mother Margaret “Peggy” Treuer was a Native Rights lawyer and Tribal Judge in Minnesota. His brother David Treuer is a Native American Historian and Nonfiction Author who has taught at IAIA: The Institute of American Indian Art in Santa Fe. He currently teaches English at USC. Visit: davidtreuer.com

Gathering of Nations, Ltd. 3301 Coors Blvd. NW, Suite R300 Albuquerque, NM 87120

Online: gatheringofnations.com

YouTube Video:

Gathering of Nations Powwow to end in 2026 after 42 years— a report by KOAT 7 News in Albuquerque.

DIGITAL CONTENT:

Capturing the view from here.

The setting sun casts a brilliant auburn glow against Squaretop Mountain located in the San Juan Range east of Pagosa Springs, Colorado. The natural feature exhibits a commanding presence over the surrounding valley below.

Microsoft—founded on April 4, 1975 by Bill Gates and Paul Allen—was originally housed in a strip mall office complex on the corner of Linn Avenue and California Street in Albuquerque, New Mexico. The multinational computer technology corporation operated from this location until 1979 and was established to develop and sell software, specifically a BASIC interpreter for the Altair 8800 personal computer. The company operated here until 1979, when it relocated to Bellevue, Washington to access a more robust computer programmer workforce. Currently, at the Albuquerque location, visitors can read a monument plaque that indicates the dynamic origin of one of the world’s most successful companies.

Andrea M. Heckman

Photojournalist, award-winning filmmaker, and Taos Ski Valley entrepreneur Andrea Heckman takes readers on a journey in SEEING Through the Eyes of Others. Based on years of travel photos and teachings organized by myth, pilgrimage, objects, and dance, this book brings cultural diversity and the human experience front and center with stunning images seen through the author’s lens while traversing remote locals around the world. Heckman is the owner of Andean Software, an Alpaca, fine textiles, and an international art retail store located in the central plaza at Taos Ski Valley. She began working with photography and fiber arts in California in the 1970s. By 1979, she had become a world traveler with annual trips to Peru, Ecuador, and Bolivia. She achieved her PhD in Latin American Studies in Anthropology and Art History—later teaching at the University of New Mexico. She’s resided in Taos since 1975.

Eyes wide open: stonecorralmedia.com/books

Fostering a connection between visitors and the natural world, this museum offers hands-on experiences and exhibits of unusual creatures, fossils, artifacts, and more. Founded in 2013 as the Harrell House, the organization has grown to serve more than 70,000 visitors. It features over a hundred live bug, reptile, and creature exhibits, where visitors are offered an opportunity to touch and interact with live specimens to help people have a better understanding of the environment.

Visit the Santa Fe Bug and Reptile Museum located at The Fashion Outlets near the intersection of I-25 and Cerrillos Road in Santa Fe.

The museum is open Tuesdays through Saturdays 10AM-6PM.

Bug out: bugandreptile.org

One of the fundamental rights as citizens of our great country is having access to wild places and the opportunity to witness wildlife in their natural habitat. Such experiences bring us closer to the land and instill a respect for nature and the planet—as well as offer a chance to provide for our families through honed skills in capturing and harvesting from our natural resources. Managing our natural environment is, in part, the responsibility of the Department of Game and Fish. Here in New Mexico, the department has forged ahead with an informative and entertaining podcast, hosted by James Pitman—the Information and Education Division Chief at New Mexico Department of Game and Fish—for coverage on all things outdoors in the land of enchantment.

Find nature: wildlife.dgf.nm.gov/home/publications/magazine

The AMC psychological thriller Dark Winds released its first episode in 2022. The multi-season series follows Lieutenant Joe Leaphorn, deputy Jim Chee, and Bernadette Manuelito, a Navajo Tribal police force who serve justice on the Navajo Nation in northern Arizona during 1971. As the posse works to solve violent crimes that escalate, their experiences force them to face personal challenges stemming from life on the reservation.

Dark Winds’ mostly Indigenous cast stars Zahn McClarnon, Kiowa Gordon, Jessica Matten, Deanna Allison, Rainn Wilson, and Elva Guerra. It’s executive produced by Robert Redford and George R.R. Martin and based on Tony Hillerman’s Leaphorn & Chee novels.

Though the story takes place on the Navajo Nation near Monument Valley, the sets were scattered around the Four Corners’ region, including locations in Arizona, Utah, and New Mexico. In New Mexico, film set locations include Gallup, Española, Santa Fe, Tesuque Pueblo, Cochiti Pueblo, and Abiquiú. Much of the show was produced at Camel Rock Studios, a state-of-the-art film production studio established in 2020 that’s owned and operated by the Tesuque Pueblo. At over 75,000 square feet, the facility has hosted Hollywood productions, including News of the World starring Tom Hanks. The studio is the first Indigenous-owned and operated film and TV studio in the United States.

Stream it: amc.com/shows/dark-winds--1053387

The Santa Fe Biscochito Company brings a rich New Mexican tradition to life with every batch of their handcrafted biscochito cookies and freshly brewed coffee. Made using time-honored recipes, their biscochitos are crisp, buttery, and delicately flavored with anise and cinnamon. Each cookie carries the warmth and heritage of generations past, offering a nostalgic taste of Santa Fe’s unique culinary culture. Red and green chilies add to the flavor palette for a range of choices. Gift baskets can also be ordered to gift a taste of New Mexico.

Paired with their locally roasted coffee, the experience becomes even more comforting. The coffee is bold and smooth, with a deep, earthy flavor that complements the subtle sweetness and spice of the biscochitos. The combination is both grounding and satisfying—and don’t forget to try the Biscookies, an ice cream sandwich favorite.

Owner and award-winning baker Richard Perea takes great pride in using quality ingredients and honoring traditional methods, while still offering a product that feels fresh and timeless. Whether you’re a lifelong New Mexican or discovering biscochitos for the first time, their cookies and coffee offer a connection to place, memory, and simple pleasures. It’s a treat that speaks to the heart of New Mexico and the Southwest.

B is for Biscookie: santafebiscochitocompany.com

Founded in 1991, Youth Heartline strives to reduce risk factors and remove barriers for underserved children and families. Their mission is to influence long-term outcomes and provide access to vital services.

One of the programs offered at Youth Heartline include court-appointed special advocates, safe exchange and supervised visitation, in-school and summer programs, Trauma Training, and youth and family navigation. The organization is the first and only court-appointed special advocates program for the Eighth Judicial District of New Mexico, including Colfax, Taos, and Union Counties. The Youth Heartline operates from offices in both Raton and Taos.

Help out: youthheartline.org

While traveling I-25 between Las Vegas and Raton, New Mexico, pull off the interstate into the community of Watrous for a most surprising discovery. This unassuming exit leads travelers through this tiny enclave before being welcomed by a tall green signpost for the Watrous Coffee House, a cozy inviting cafe situated in a beautifully renovated historic ranch-style home. Within, patrons discover an establishment that might otherwise be found in an urban community—we love it. Creative drinks, pastries, and other items are available weekly from a friendly, sophisticated staff. Stop in for a hot custom coffee, tea, or other flavorful drinks on your next journey through the area.

Warm up: instagram.com/watrouscoffee

Also known as the “Big House,” this property was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1991. The former home of arts supporter and writer Mabel Dodge Luhan, which is now used as a hotel and conference center, was a central hub for artistic salons in the early 20th century and hosted many well-known painters, writers, photographers, musicians, and emerging artists of the Taos Art Colony.

An exceptional example of traditional Puebloan construction, the main public space—the kitchen, reception office, and rooms—immerse the visitor in the historic charm of northern New Mexico architecture and culture. The outdoor decks and gardens are well-kept and serve as inspiring backdrops for recognized guest fine art painters, including D.H. Lawrence, Ansel Adams, Georgia O’Keeffe, Martha Graham, and Edward Weston. Bonus fun fact: the home was also owned by actor Dennis Hopper.

Stay well: mabeldodgeluhan.com

With each issue of Enchanted Outpost, we add our Waypoints to a new section we are building on our website. Use your smart phone or tablet camera and the QR Code below to discover these and other great picks we’ve featured in past issues.

Or Visit: enchantedoutpost.com/waypoints

Point your smartphone camera at the QR Code. Your camera will recognize the code. Tap your screen to visit the website.

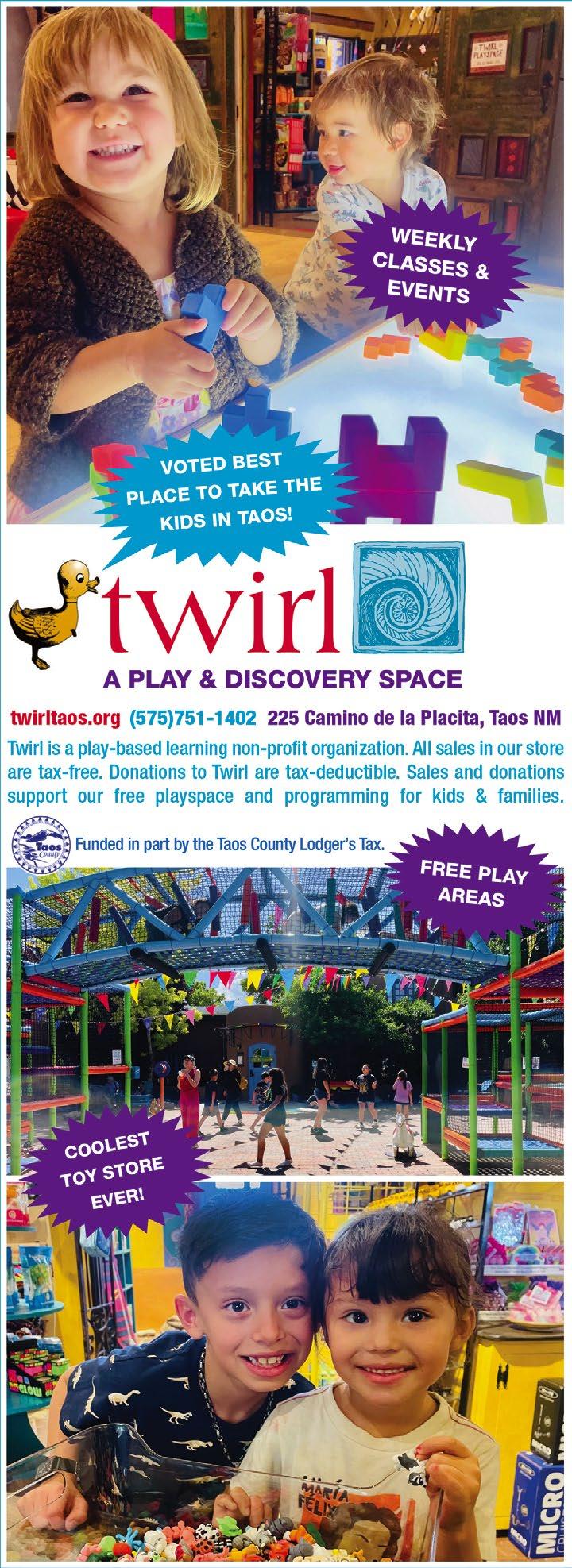

Attend Main St. Live in Trinidad, Colorado for the performance of Miracle on 34th Street adapted by Mountain Community Theater from the novel by Valentine Davies. Based upon the Twentieth Century Fox motion picture.

When: December 12-21

Where: Trinidad, Colorado Visit: mainstreetlive.org

1-4 Wolf Creek Ski Local Appreciation Day Pagosa Springs, CO visitpagosasprings.com

6-7 Winter Spanish Market Santa Fe, NM traditionalspanishmarket.org

12 Del Norte’s Hometown Holiday Del Norte, CO - delnortecolorado.com

13 Farolito Trail of Lights 5K Run Albuquerque, NM - irunfit.com

13 Alumbra de Questa Holiday Market Questa, NM - questacreative.org

15 Home for the Holidays Winter Gala Santa Fe, NM - santafesymphony.org

27 Cirque Musica Holiday Wonderland Santa Fe, NM - hiltonbuffalothunder.com

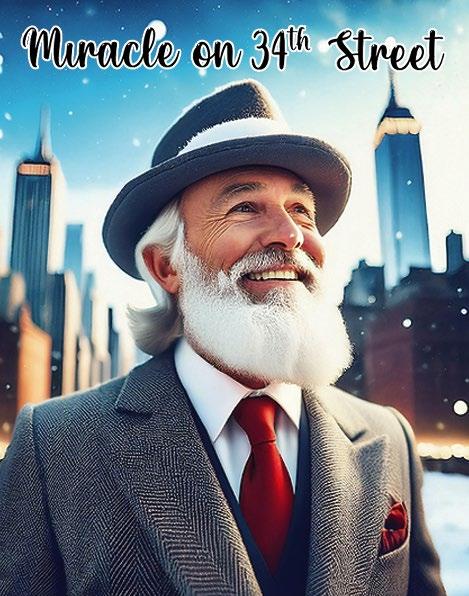

Rio Frio Ice Festival

Join in on the fun in Alamosa for the annual Rio Frio Ice Festival. The event includes a 5K winter run, ice carving demonstrations, disc golf tournament, kid’s zone, live music, vendors market, a cross-country luminaria walk and rounds out with a Polar Plunge.

When: January 23-25

Where: Alamosa, Colorado Visit: rioraces.com

2 ArtStop Market @ FUSION Albuquerque, NM - abqtodo.com

10 Cabin Fever Nordic Races Pagosa Springs, CO - pagosanordic.com

16-18 Albuquerque Comic Con Albuquerque, NM albuquerquecomiccon.com

17-18 Chama Chile (X-Country) Ski Classic Chama, NM chamachileskiclassic.com

22-24 Red River Songwriters’ Festival Red River, NM - redriversongs.com

30 Winter Warmup: Taos Opera Taos, NM - taosoi.org

30-31 Angel Fire Shovel Races Angel Fire, NM - visitangelfirenm.com

Enjoy 28 winery partners pouring their best wines alongside bites from great Taos restaurants. Bid at a silent wine auction including 40 wine lots. The event benefits Taos High School’s Great Chefs of Taos program. Sip and Support this great program for Taos students.

When: February 5-8

Where: Taos, New Mexico Visit: taoswinterwinefest.com

3-5 So. Rocky Mtn. Agriculture Conf. Monte Vista, CO - agconferencesrm.com

5-7 Quilt, Craft & Sewing Festival Albuquerque, NM - quiltcraftsew.com

7 Carlos Mencia – The Liberated Tour Santa Fe, NM - hiltonbuffalothunder.com

8 Artist Dinner, La Boca Santa Fe, NM - sfpromusica.org

12-17 Mardi Gras in the Mountains Red River, NM - redriver.org

13 The Conjurors: Performing Arts Raton Arts & Humanities Council Raton, NM - ratonarts.org

27-1 National Fiery Foods and BBQ Show Albuquerque, NM - fieryfoodsshow.com

Discover the Monte Vista Crane Festival in Colorado’s San Luis Valley — a vibrant three-day celebration of thousands of migrating Sandhill Cranes, engaging workshops, guided wildlife tours, and a lively craft & nature fair amidst majestic mountain scenery.

When: March 6-8

Where: Monte Vista, Colorado Visit: mvcranefest.org

1-2 Taos IFSA Qualifier 2 Taos Ski Valley, NM - ifsafreeride.org

7 Aaron Lewis American Tour Santa Fe, NM hiltonbuffalothunder.com

17 Happy Saint Patrick’s Day! Various Event Locations

20-22 Santa Fe Whole Bead Show Santa Fe, NM - wholebead.com

20-22 Treasures of the Earth Gem, Mineral and Jewelry Expo Albuquerque, NM - agmc.info

22 Women of Americana Music Tour Albuquerque, NM womenofamericanatour.com

Attend the largest Indigenous-led powwow in North America—to celebrate vibrant culture, music, dance, and community. Experience the Indian Traders Market, dramatic grand entry, crowning of Miss Indian World and the beautiful tradition of the powwow way.

When: April 24-25

Where: Albuquerque, New Mexico Visit: gatheringofnations.com

2-6 Chimayó Pilgrimage Chimayó, NM - holychimayo.us

4 Snowy Easter Egg Hunt and Potluck Eagle Nest, NM - eaglenestchamber.com

4-5 NM Renaissance Celtic Festival Edgewood, NM - nmrenceltfest.com

9 Shelby Means & Joel Timmons Concert Taos, NM - taoslifestyle.com

11 Rachel Barton Pine Violin Concert Los Alamos, NM - visitlosalamos.org

11-12 Southwest Chocolate & Coffee Festival Albuquerque, NM chocolateandcoffeefest.com

Founded in the 1950s by Los Alamos paddle boater and LANL employee, Jim “Stretch” Fretwell, this year marks the 68th annual race event on the Rio Grande River. Join in as a race course competitor or as a spectator. Get adrenaline either way you choose.

When: May 8-10

Where: Pilar, New Mexico Visit: mothersdaywhitewater.com

3 Santa Fe Pro Musica Season Finale Santa Fe, NM - lensic.org

15-16 Boots in The Park Music Festival Albuquerque, NM abq.bootsinthepark.com

15-17 Santa Fe Intl. Literary Festival Santa Fe, NM sfinternationallitfest.org

17 Elevated Baroque - Harwood Museum Taos, NM - harwoodmuseum.org

17 Dennis Hopper Day Taos, NM - robbyromero.com

22-25 Mayfest in the Mountains Red River, NM - redriver.org

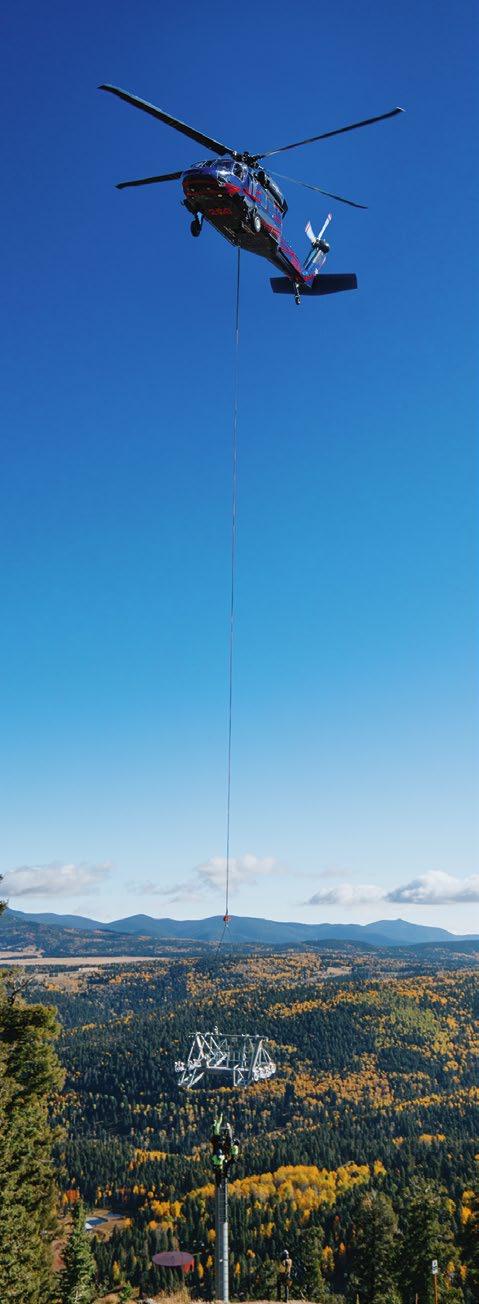

Tucked away in the majestic Sangre de Cristo Mountains of northern New Mexico, Angel Fire Resort has been a beloved alpine escape since 1966. What began as a modest ski area at 8,600 feet has evolved into one of the most dynamic year-round mountain destinations in the Rockies—offering adventure, luxury, and community without the crowds or prices of its northern counterparts.

In winter, Angel Fire’s 560 acres of skiable terrain deliver some of the Southwest’s best snow experiences— from gentle family-friendly runs to expert-only “Steeps” in the back basin. Boasting the longest ski run in New Mexico and the state’s only night skiing, the resort continues to grow, with a new fixed-grip quad lift (Rakes Rider) debuting in 2025 and New Mexico’s first high-speed six-pack opening the following season.

When the snow melts, Angel Fire transforms into a summer paradise. Its award-winning bike park offers 60+ miles of lift-served terrain across over 30 trails—one of the top-rated parks in the country. U.S. golfers enjoy a Paul Ortiz–designed championship course, winding through pine and aspen forests at the acclaimed Angel Fire Country Club. Tennis, pickleball, disc golf, and Monte Verde Lake’s kayaking and fishing make it a true four-season retreat.

The Village of Angel Fire is rapidly evolving into a vibrant mountain

community. The new Mountain View Events Center—complete with a stage, turf lawn, and festival grounds—hosts signature summer events like Cool Summer Nights, Bluews Fest, and Oktoberfest, drawing visitors from across the Southwest. Future plans include a downtown plaza and convention center, creating a lively hub for locals, visitors, and homeowners alike.

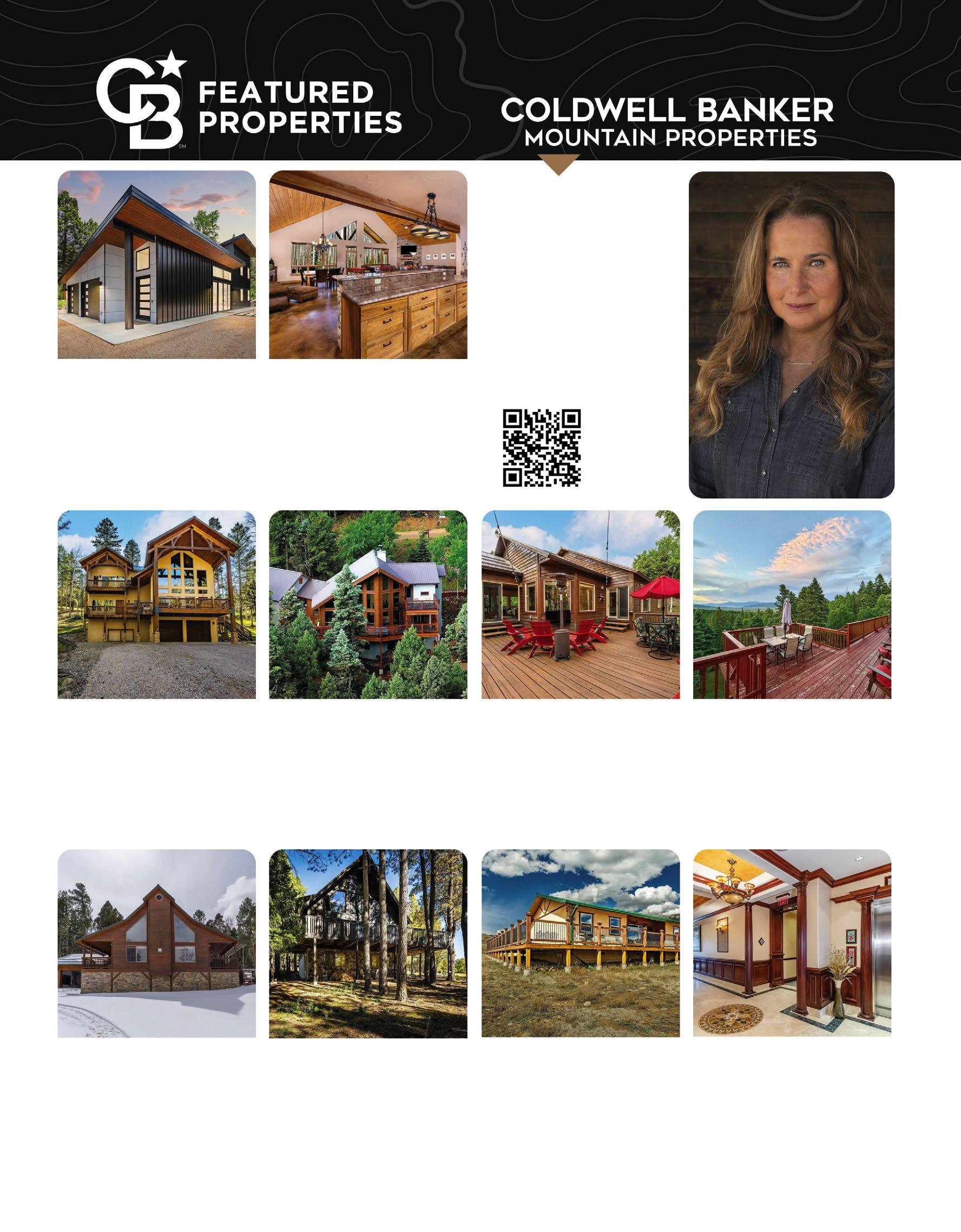

With over 18,000 acres of breathtaking scenery, the village is seeing an exciting wave of residential growth. Coldwell Banker Mountain Properties—Angel Fire’s premier real estate brokerage—is launching three exciting new residential communities:

Angel Fire Crossing

Affordable four, three, and two-bed-

room townhomes with one-car garages, starting in the mid-$400,000s.

Sangre de Cristo Townhomes

Value-packed, three-level, three-bedroom townhomes, one-car garage plus sports equipment storage priced under $500,000.

Base Camp Angel Fire

Luxury 4-story townhomes, within walking distance to the new six-pack chair, with private rooftop living and sweeping mountain views of Wheeler Peak, starting in the mid-$800,000s.

These projects will bring over 100 mountain home options over the next two years, offering attainable luxury at a fraction of Colorado’s resort prices.

“We’re seeing unprecedented demand for quality, well-priced mountain

Left: A helicopter lowers a tower on Rakes Rider to a team of installers. Above: Angel Express six-pack chairlift under construction at the resort base. Below: Expansion of the Tennis and Pickleball Center.

homes,” says Jeff Weeks of Coldwell Banker Mountain Properties.

With interest rates trending downward and major resort upgrades underway, Angel Fire is positioned for exceptional growth in the next decade.

“It’s the perfect storm of opportunity —strong demand, attractive pricing, and expanding amenities,” notes Kellie Buchanan of Highlands Residential Mortgage.

Easily accessible—just a five-hour drive from Denver, or a 25-minute flight from Albuquerque to Angel Fire Airport—this hidden gem in the Southern Rockies is finally stepping into the spotlight.

Whether you’re looking for a mountain getaway, a smart investment, or a place to call your mountain home, Angel Fire offers an unbeatable blend of accessibility, affordability, and mountain resort lifestyle.

Visit our property websites to learn more or contact local Broker, Jeff Weeks at Coldwell Banker Mountain Properties in Angel Fire at (505) 603-7311.

New Property Search

Angel Fire, New Mexico

Angel Fire Crossing

Priced from the mid $400,000s Online: angelfirecrossing.com

Sangre de Cristo Townhomes

Priced under $500,000 Online: sdctownhomes.com

Base Camp Angel Fire

Priced from the mid $800,000s Online: basecampangelfire.com

Regional Interior Design Masters | 70 Voormi: The Future of Clothing | 78 Sage Work Organics, An Intention of Hygge | 90

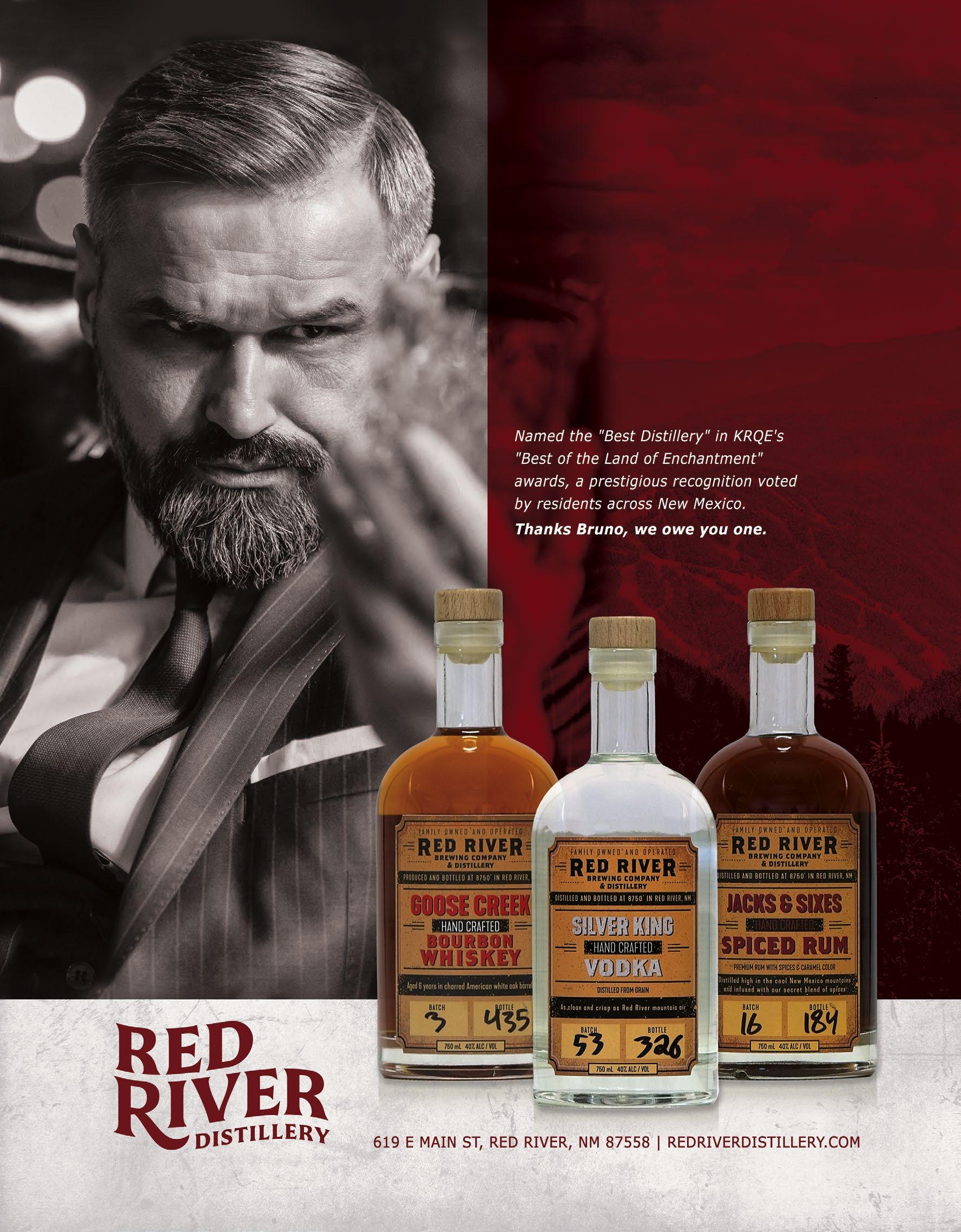

Voormi, an outdoor clothing company headquartered in Pagosa Springs, Colorado, develops high-performance, sustainable outdoor apparel and gear by merging advanced textile innovation with cutting-edge technology—and fashionable to boot.

By Scott Leuthold

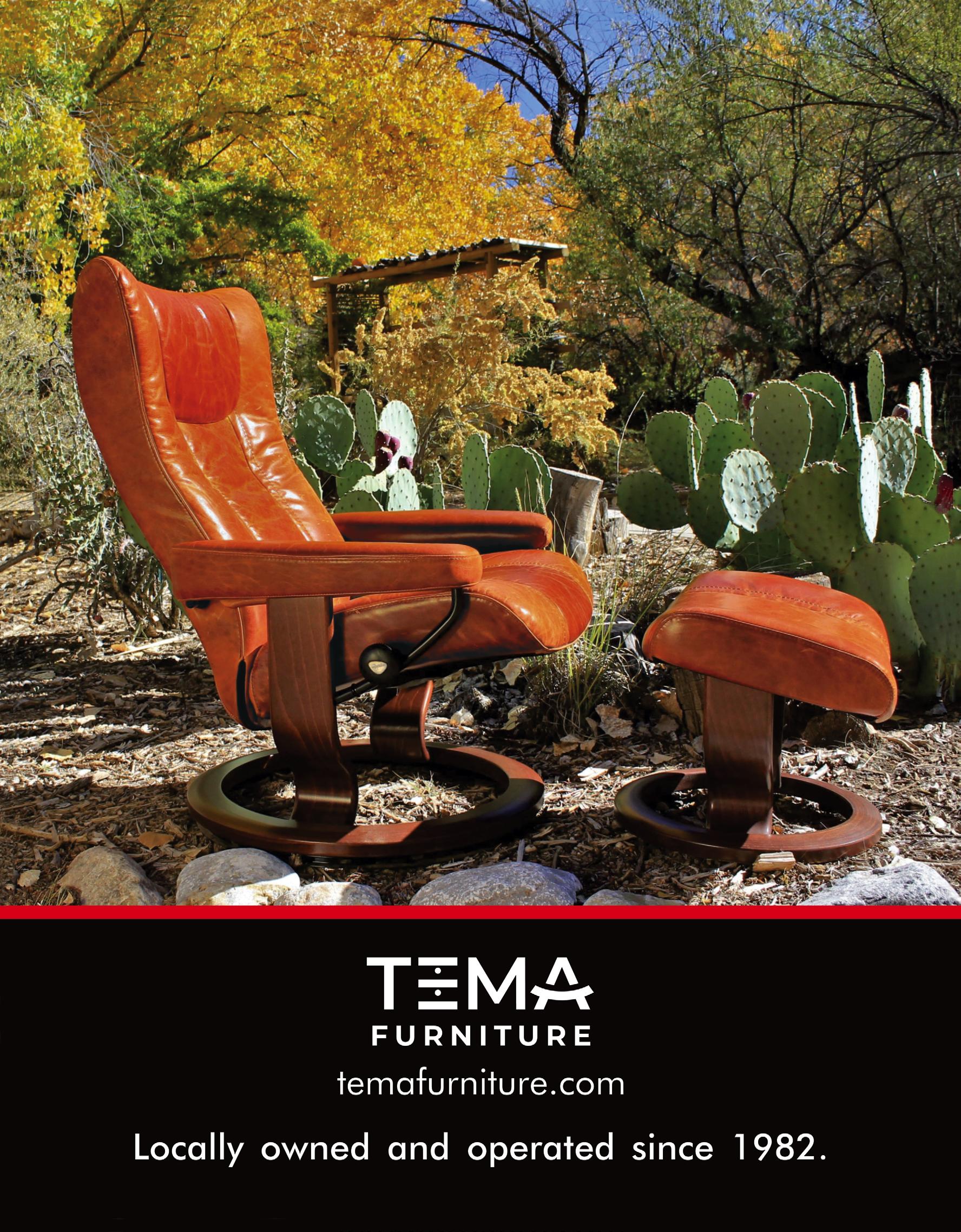

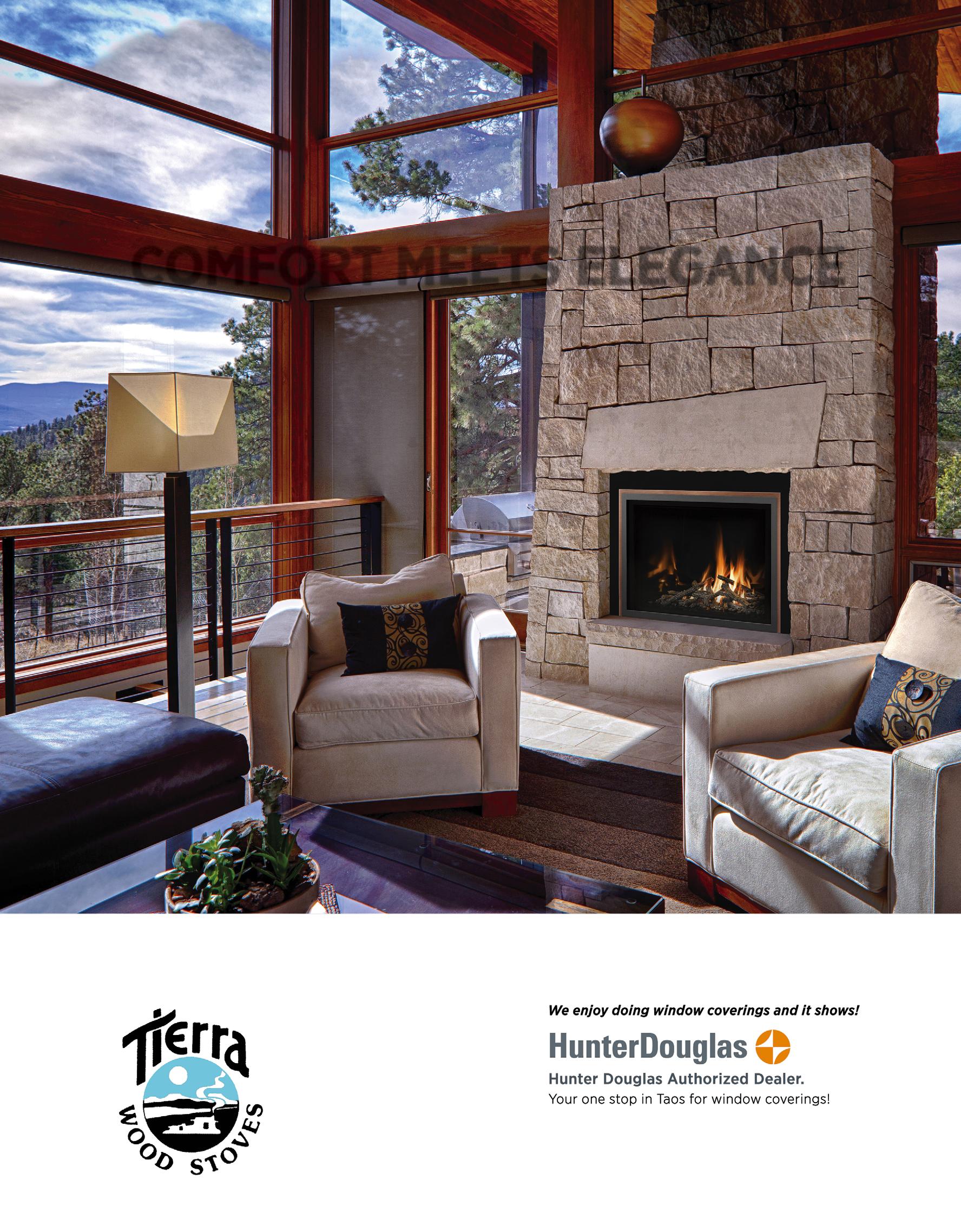

The interior design landscape of New Mexico and southern Colorado is a rich blend of cultural heritage, natural inspiration, and evolving modern trends. Rooted in the distinctive architecture of adobe homes, Pueblo Revival, and Territorial styles, the interiors of the region often celebrate earthy textures, organic materials, and warm, sunwashed palettes. Exposed wood beams, hand-plastered walls, and artisanal tilework reflect traditions that have shaped the Southwest’s visual identity for centuries. At the same time, contemporary design is weaving its way into the fabric of these spaces, with clean lines, minimalist furniture, and natural light, all used to balance rustic authenticity with modern comfort.

Demand for interior design in the region is on the rise, driven by a growing influx of homeowners seeking a blend of authenticity and sophistication. Many are drawn to the idea of creating interiors that mirror the rugged beauty of mesas, mountains, and desert landscapes, while still incorporating smart technologies and sustainable practices. From Santa Fe’s art-driven aesthetic to the mountain lodges of southern

Colorado, the region’s design trends reflect both a reverence for tradition and a willingness to innovate. The result is a distinctive design ethos—warm, grounded, and timeless, yet adaptable to modern lifestyles.

To understand how interior design is influencing the way our regional society dwells, we connected with five designers who serve astute clients, ranging from the high desert urban centers to our alpine forest communities. t

Kelly Davidson Pagosa Springs

Jamie Stoilis

Santa Fe

Joan Duncan Taos

Jenny Gordon

Albuquerque

Annie Jo Lindsey Angel Fire

From a young age Kelly was drawn to the world of design— whether it was interiors, fashion, or art, she always believed that if you loved one, you naturally loved them all. Growing up with a mother who was an interior designer, Kelly was immersed in a creative environment where color palettes, space planning, and finishes were part of daily life. She credits her mother for shaping her keen eye and innate sense of style.

Based in both Denver and Pagosa Springs, Kelly specializes in luxury residential projects with a strong focus on mountain homes. Her primary design style leans into the timeless appeal of Mountain Modern—a look that balances contemporary lines with the warmth and texture of natural materials. Drawing inspiration from her travels and the scenic beauty of the outdoors, her work blends modern simplicity with the rugged charm of mountain living. She brings a sharp eye and creative intuition to every detail of a space—but she’s especially known for her expertise in lighting design, color selection, and floor planning. She understands how thoughtful lighting can transform a room, how the right color palette sets the tone, and how smart layouts maximize both beauty and function. She also has a knack for crafting truly unique bathrooms, blending materials, textures, and finishes to create spaces that feel like personal retreats. Her approach is both practical and artful, resulting in interiors that are as striking as they are livable.

Kelly Davidson

Pagosa Springs, Colorado (719) 641-4417

Online: scenichomeinteriors.com

Instagram: @scenichomeinteriors

Jamie’s journey as a designer began at the Colorado Institute of Art, where she studied both interior design and architecture and graduated with honors at the top of her class. Coveted internships with a model home design firm and an international hospitality design firm led her to a full-time engagement immediately after graduation.

After shifting to residential work, she was hired by a European antique dealer with a high-end residential firm. The firm’s clientele includes many celebrities and overseas clients so, for almost a decade, Jamie was privileged to work on some of the most magnificent mountain homes in Colorado. These projects took her across the globe, sourcing pieces for each unique setting she helped create. It’s this sophisticated, international sensibility that informs all of her work.

J. Stoilis Design Associates, LLC opened in 2010, offering full-service interior design for both residential and commercial settings, supporting clients from the beginning stages through furnishing selections and the final finishing touches. Jamie relishes every aspect of the process and loves collaborating to create environments that reflect her clients’ identities. She makes it her mission to bring their dreams and vision into graceful, elegant reality. Her work spans traditional to modern styles with an emphasis on construction and interior architecture of luxury homes.

J. Stoilis Design Associates

Jamie Stoilis

Santa Fe, New Mexico (505) 467-8978

Online: jamiestoilis.com

Instagram: @jstoilisdesign

or more than 35 years, Joan Duncan has brought artistry, intuition, and heart to the world of interior design. After earning her BA in Art from the University of Texas, Duncan graduated from the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD). During her RISD years, she discovered Taos, New Mexico, a place she chose for a creative retreat long before making it her permanent home in 2000. Today, she is deeply rooted in Taos, often called the “Soul of the Southwest,” and has spent the last 25 years in Taos shaping interiors that resonate with the spirit of the high desert.

Duncan describes her style as eclectic, guided less by strict design categories and more by what brings joy to her clients. Though she has worked on commercial projects (including design for a resort), residential spaces are her specialty, with each project an exploration of personality, form, function, color, and materials. “Listening,” she says, “is my greatest strength.” By carefully tuning in to her clients—whether individuals or couples with differing tastes—she ensures their homes become reflections of their lives. Her process embraces the uncertainties of change, guiding clients through the journey of transformation with openness and trust. Whether navigating bold color choices or blending contrasting styles, Duncan thrives on finding common ground that creates harmony. The result is more than a designed space—it’s a home imbued with authenticity and soul.

Joan Duncan, ASID, Interior Architect Taos, New Mexico (575) 751-3030

Online: acreatrix.com

Instagram: @acreatrix

Jenny founded The Vibe Design Company in 2019 to help create spaces that owners feel passionate about. She believes that beautiful, welldesigned spaces make people feel good, which to her is an honorable endeavor. It is her mission to blend aesthetics and practicality to bring her client’s vision to life.

As a child, Jenny spent a great deal of time arranging furniture. She’s continually reimagining, decorating, and redecorating all the spaces she occupies. With a degree in business and marketing, her interior design is self-taught but comes from a place of deep passion.

Jenny’s design style is grounded in nature with a modern, warm Southwestern materiality and emphasizes interesting textures, earthy color palettes, and modern forms to convey her interpretation of contemporary Southwest design. She seeks inspiration in nature—especially in rock formations and naturally occurring color palettes.

She designs primarily for luxury homes and condominiums but has also completed commercial, retail, and office spaces, including an upscale salon and a boutique hotel. Working with a client, to her, is like ingredients of a collaboration soup. Her clients have their desires and needs, the space has its limitations and history, and Jenny has her design eye and experience. By blending shared experiences—putting it all into a pot and stirring it around— together they create something personal and original that the client feels a part of.

The Vibe Design Company

Jenny Gordon

Albuquerque, New Mexico (505) 369-2265

Online: thevibedesigncompany.com

Instagram: @thevibedesignco

nnie Jo moved to the mountains of Angel Fire at age twelve, and eventually opened her own hair salon at age nineteen. After running her business for more than twenty years, she transitioned into real estate in 2017. She shares this passion with her husband BJ Lindsey—who launched Lindsey Custom Builders in 2008—to delve deeply into every aspect of homes: Designing, building, buying, selling, remodeling, furnishing, and decorating.

Having become a premier builder in the area, the pair have combined their skills and shared vision to create Lindsey Land & Home, a real estate brokerage with a mission to help people find their own piece of paradise in the mountains.

In winter of 2024, Annie Jo launched Lindsey Living, a retail furniture and accessories boutique that serves as a staging area for her interior decorating projects. The space reflects the Mountain Modern style Annie Jo has become well recognized for. She incorporates a mix of modern metals with rustic wood textures, while utilizing palettes that combine neutral colors with pops of organic shades of greens or blues. To her, it’s all about combining the texture of the outdoors with the luxury of modern interiors.

Annie Jo specializes in luxury residential homes and condominiums, and has recently completed her first commercial project—Elevated Pour, an upscale wine bar next door to her retail store located in the Frontier Plaza in Angel Fire.

Lindsey Living

Annie Jo Lindsey

Angel Fire, New Mexico (575) 447-1248

Online: lindseyhomes.com

Instagram: @lindseyhomesnm

STORY BY LISA RAGSDALE

PHOTOGRAPHY BY DUSTIN ENGLISH AND VOORMI

After years of guiding clients up Denali, North America’s highest peak, and countless other adventures, Dustin English experienced first-hand how gear can catastrophically fail when lives are on the line. When facing unpredictable weather there’s no room for compromise, and after years of frustration, Dustin knew the industry couldn’t provide a solution. It became clear that clothing needed to evolve. VOORMI transforms clothing from passive protection into active partnership, creating gear that doesn’t just keep pace with your ambitions—it amplifies your potential and adapts to your world, whatever that may look like in the moment. To find out more, we reached out to Dustin and his team to learn about what drives their ingenuity and what’s next for the outdoorsenthusiast clothing line VOORMI.

EO: What inspired the idea to fuse technology with clothing?

V: It was late June 2009 on Denali, and Dustin was leading his team higher into the Alaska Range. At 10,000 feet, the mornings began bitterly cold. Breath froze instantly in the air. Water bottles turned solid in the packs. Everyone moved stiffly in their parkas, just trying to shake the chill out of their bones.

But a few hours later, the mountain flipped the switch. Under the thin air, high-altitude sun, and snow reflecting light from every angle, it felt like walking across the sur-

face of the sun. Jackets were stripped, sleeves pushed up, sweat pouring down faces. The swing from below zero to blazing heat happened almost daily, and there was no gear system built to keep up with these changes.

By 12,000 feet, the rhythm was set. Every water break turned into a scramble—someone shoving a down jacket into their pack or fumbling for a mid-layer, another peeling off gloves. What should have been a quick stop, stretched longer as the team wrestled with layers. As the guide, Dustin found himself less focused on the route and more on coaching people through their constant adjustments.

He felt it, too. One ridge brought wind that cut straight to the core. The next sheltered section had him overheating within minutes. Over and over, the cycle repeated: sweat, chill, swap, repeat.

By the time the team reached 16,000 feet, frustration was thick in the thin air. Morale dipped with every sweaty climb that turned into another shivering break. Dustin could see it: the mountain demanded their focus, but the clothing kept stealing it away. That’s when the thought crystallized: why are we adapting to our gear, instead of our gear adapting to us?

EO: Tell me about the brand name VOORMI. Where did it come from and what does it mean to you?

V: When we were searching for our brand name, we wanted meaning. During our extensive travels, we learned something fascinating: ancient legends spoke of mysterious, yeti-like beings called VOORMI who inhabited the harsh Arctic regions. These weren’t just mythical creatures, they were survivors, masters of their frozen domain who thrived in conditions that would defeat others. They had an almost supernatural ability to adapt. They didn’t just endure extreme cold; they flourished in it.

But there was another layer to our discovery. VOORMI, we learned, is actually a Dutch word meaning “For Me.” This wasn’t just coincidence, it was synchronicity. The Dutch translation represented our personal philosophy of gear designed with the individual in mind. This dual meaning became the foundation for everything we do, including our breakthrough technology MijTM, Dutch for “Me,” which continues this thread of personal adaptation and individual performance.

EO: How did your personal connection to the outdoors shape its beginnings?

V: VOORMI emerged from a fundamental frustration that every outdoor enthusiast knows intimately: the gear simply wasn’t designed for how we actually live and move in the mountains. As lifelong skiers, fly-fishers, Denali guides, and relentless outdoorspeople, we experienced first-hand the massive disconnect between what the industry is producing and what we actually need to perform and remain comfortable across diverse environments. We refused to believe that clothing had to

remain static while everything else in our world became increasingly more intelligent, adaptive, and revolutionary.

EO: Who do you partner with for research and development?

V: Our R&D philosophy is radically collaborative. Our highly skilled and diverse team works directly with national labs, textile scientists, and elite athletes who share our obsession with pushing boundaries. This approach has yielded breakthroughs, like our Ultralight collection, CORE CONSTRUCTION® technology, and our latest marvel: MijTM, the first successful integration of

biometric sensors directly into textiles. When MijTM won the innovation award at CES® 2025, it validated what we’ve always believed—that clothing has been sleeping through the technological revolution for far too long. Our tagline “The Future of Clothing” isn’t aspiration; it’s our commitment to revolutionizing the most intimate technology humans use every day. We’re not just a gear company; we’re pioneers of intelligent human-textile interaction.

With MijTM, we’ve achieved what sounds like science fiction: clothing that learns from your body, predicts your needs, and becomes an extension

of your biological intelligence. This is clothing as a living system, not dead weight. The best part, it is still as comfy as modern-day clothing!

EO: VOORMI emphasizes performance, sustainability, and local craftsmanship. How do these values show up in your day-to-day decisions?

V: Operational imperatives are hardwired into every decision we make. We deliberately stress-test everything to failure during development so it never fails when your safety depends on it. Every product must prove it belongs in our lineup.

Sustainability means building for lifetimes, not seasons. The most sustainable product is the one you never have to replace. Also, local craftsmanship keeps us connected to our process, our standards, and our community. We develop proprietary fabrics, manufactured domestically when possible. This control allows us to prioritize quality over quantity while staying rooted in the mountain communities that shaped our vision.

EO: What does “The Future of Clothing” mean to you—not just as a tagline, but as a philosophy?

V: “The Future of Clothing” captures something fundamental about our methodology and our core belief that clothing should do more. We recognized an absurd contradiction: while smartphones became supercomputers, cars learned to drive themselves, and homes became responsive ecosystems, clothing remained essentially unchanged for centuries. We were still putting on passive fabric that just hung there, waiting for us to adapt to it instead of the other way around.

This philosophy represents how we develop gear in the same unforgiving environment it’s meant to conquer, where every design decision gets

interrogated by reality, not theory. But more importantly, it embodies our relentless pursuit of clothing that actively enhances human capability, rather than just passively protecting. From the beginning, we’ve believed that gear should work harder than you do, adapting to your needs and amplifying your potential. This philosophy drives us to continuously push boundaries, from CORE CONSTRUCTION® to MijTM. We build it uncompromisingly, test it relentlessly, and never stop innovating toward clothing that truly does more. That’s the philosophy that fuels our vision for the future.

EO: How does the landscape of Pagosa and the Rocky Mountains influence your design choices and brand identity?

V: The high country is nature’s ultimate testing ground. Living and working at high altitude means our gear gets put through hell every single day—from bone-chilling mornings at 20o below to blazing midday sun to sudden afternoon storms that drop temperatures 30o in minutes.

Most importantly, this place keeps us honest. We’re proving performance in some of the most demanding environments on Earth.

EO: How do you balance innovation with tradition in your materials and manufacturing process?

V: True innovation doesn’t abandon tradition; it perfects and transcends it. CORE CONSTRUCTION® exemplifies this approach. Instead of accepting traditional membrane placement, we revolutionized it by embedding waterproof barriers between fibers rather than bonding them on top. This breakthrough delivers breathability and temperature regulation that outperforms everything else available.

Now we’re writing the next chapter

with MijTM, intelligent textiles that honor everything clothing has always done (protect, insulate, and endure) while introducing capabilities clothing has never possessed: learning, adapting, responding to human physiology in real-time.

This is innovation with integrity: respecting the craft while revolutionizing the possibilities.

EO: How do you see VOORMI contributing to the outdoor community—not just through products, but through culture and connection?

V: VOORMI contributes by staying au-

thentically rooted in the communities where outdoor life isn’t recreation—it’s identity. From Pagosa Springs to Bozeman, we’re not visitors; we are neighbors who serve as Emergency Medical Technicians (EMTs), Search and Rescue volunteers, trail builders, and mentors.

We collaborate with people who live and work at the edge: athletes, guides, creatives, and mountain folk who help us evolve our gear through real-world application. These are R&D collaborations with people whose lives depend on performance.

We’re fostering a culture where innovation serves adventure, where quality

trumps hype, where gear is built by people who depend on it. We support emerging talent with access, opportunity, and equipment that performs when it matters most.

EO: What type of feedback are you getting from customers or collaborators that has reaffirmed your mission?

V: The feedback that fuels us comes from moments when our gear enables experiences that wouldn’t otherwise be possible—the summit reached because our jacket held strong through a freezing storm, the guide who worked fourteen hours on water without sunscreen yet stayed cool and protected throughout.

The most electrifying feedback now comes from early MijTM testers. With MijTM, we’ve achieved something that seemed impossible: electronics and textiles merged at the thread level, seamlessly, invisibly, durably. Current testers include endurance athletes, engineers, and executives, and their feedback is beyond encouraging. It’s revolutionary. It’s the foundation of an entirely new relationship between human and textile. We’ll launch MijTM to consumers in 2026, and it will redefine what clothing can accomplish. You can see studies on our site in the Fall of 2025.

EO: What’s next for VOORMI—any new directions, materials, technology or partnerships on the horizon?

V: At VOORMI, there’s no finish line, only milestones on an endless journey toward clothing that truly amplifies human potential. While we’ll continue creating exceptional outdoor gear, our obsession extends far beyond: we’re pioneering the future of clothing itself.

MijTM is just the opening chapter. We’re exploring materials that respond autonomously to environmental changes, textiles that self-regulate temperature, fabrics that can repair themselves.

We’re building partnerships with researchers, athletes, and visionaries who share our conviction that clothing has been stagnant while every other technology evolved exponentially.

EO: If you could distill Voormi’s mission into one sentence, what would it be?

V: VOORMI transforms clothing from passive protection into active partnership, creating gear that doesn’t just keep pace with your ambitions, but amplifies your potential and adapts to your world.

EO: What legacy do you hope VOORMI leaves in the outdoor industry and in the lives of those who wear it?

V: VOORMI’s legacy will be the paradigm shift the industry desperately needed, a complete rejection of disposability in favor of gear that becomes integral to the wearer’s story, equipment that earns its place in life and keeps it for decades.

Let our legacy be this: We didn’t just build superior gear. We built the future of clothing, a vision born out of frustration and destined to revolutionize how humans interact with what they wear. t

Pagosa Springs 331 Hot Springs Blvd Pagosa Springs, CO 81147 (970) 264-2724

Bozeman 17 East Main Street Bozeman, MT 59715 (970) 264-2724

Online: voormi.com

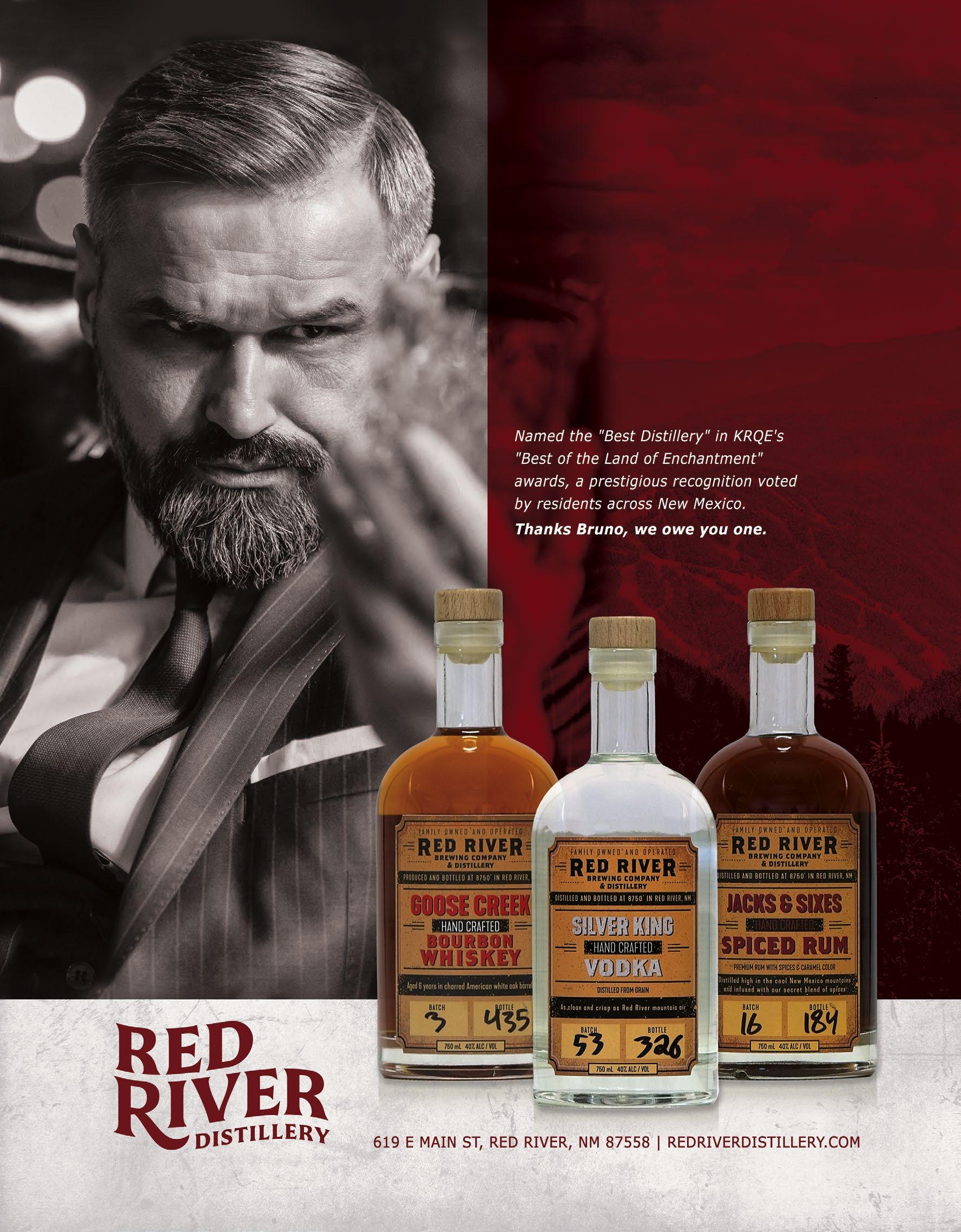

by lisa ragsdale

Native New Mexican, Michael Candelaria, first began helping people feel better as a massage therapist. Although he would often recommend natural, organic solutions to his clients with muscle pain, he says that people wouldn’t go buy them. So, he decided to make and sell them at his office. After an ACL injury sidelined his massage

therapy work, he turned his focus to his products. His inspiration came from a variety of sources: his massage therapy curriculum included classes on herbalism and aromatherapy, and his grandmother, a curandera traditional native healer, taught him herbal remedies. A curandera is typically a woman, found in Indigenous Mexican and Latin American cultures who practices curanderismo, a holistic healing system that addresses spiritual, emotional, and physical aspects of well-being.

In Duke City, Michael’s family was among the first settlers in New Mexico and owned land in the South Valley. These influences and his commitment to safe, organic products that are proven to work, resulted in Sage Work Organics, a small, family-owned and operated business that draws from generations of experience in herbs and natural formulations to provide products that elevate health and beauty from the outside in—as well as the inside-out.

The Sage Work Organics brand, as

well as the family’s product vision, incorporates a concept of hygge. Hygge is a Scandinavian word that evokes comfort and coziness. Think lying on a warm massage table with vibrant scents swirling in the darkened room and soft, relaxing music playing. Hygge reflects the cultural value of taking time away from the rush of daily life, to focus on relaxing and caring for yourself and your loved ones while taking the time

Hygge reflects the cultural value of taking time away from the rush of daily life, to focus on relaxing and caring for yourself and loved ones while taking the time to feel the comfort of good things.

to feel the comfort of good things. The cornerstone of Sage Work Organics’ pain-relief products is magnesium, which accounts for about 85 percent of their business. Magnesium plays a key role in muscle function, nervous system balance, energy production, and sleep. The Replenish Magnesium Butter comes in several varieties and strengths, including one for expecting moms, and one for kids.

Michael explains that almost everyone is magnesium deficient, and they don’t even know it. Oral supplements might help, but topical magnesium has better and faster absorption through the skin. A simple foot rub twenty to thirty minutes before bed will tell your nervous system that it’s time to rest. It’s also a great post-workout recovery to reduce inflammation and speed muscle repair. Sage Work’s small team handcrafts magnesium butter in small batches using high-quality, naturally sourced magnesium and botanicals.

Other offerings include bar soap, facial moisturizer, shave cream, aromatherapy candles, and eleven essential oils; deodorant spray and a natural bug spray are in the works. There’s also the signature 4 Thieves Essential Oil Blend which includes clove, cinnamon, eucalyptus, lemon, and rosemary essential oils that work together as an antiviral and antibacterial to ward off illness and improve mood.

One surprising offering I found on Michael’s site was gourmet kitchen spices, and I asked him about the connection between organic health, healing products, and the spices. But Michael just loves to cook, so he started reaching out to suppliers and testing blends. He’s had great outcomes there, too, so he started offering the blends and sharing a recipe or two on his blog. Recently, he shared a twenty-minute blackened salmon recipe using Sage Work Organics’ Blackening Seasoning, a blend of smoked paprika, cracked black pepper, cayenne, garlic, oregano, and citrus peel. Who can pass up a quick recipe that is full of flavor and ready for a weeknight meal or a dinner party in just a few minutes?