A GUITAR, A FOREST AND A CLIMATE LIFEBOAT

GALLERY: WHERE HOPE ENDURES REMEMBERING PAT WILLIAMS KEEP THE WEST WILD

THE ART OF BEING

A GUITAR, A FOREST AND A CLIMATE LIFEBOAT

GALLERY: WHERE HOPE ENDURES REMEMBERING PAT WILLIAMS KEEP THE WEST WILD

THE ART OF BEING

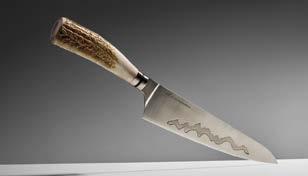

Black

43”

23 Karat Gold Gilding

Kevin Noble incorporates gold accents as a reimagining of Japanese Kintsugi’s golden mending technique, celebrating the bison’s dramatic resurgence from the edge of extinction.

For two decades, Svalinn has set the standard in elite protection dogs— combining instinct, intelligence and training to create unmatched guardians. Bred for loyalty, raised with purpose and trained for sociability, our dogs are more than companions. They are Family. Deterrents. Peace of Mind.

Join us in celebrating 20 years of excellence.

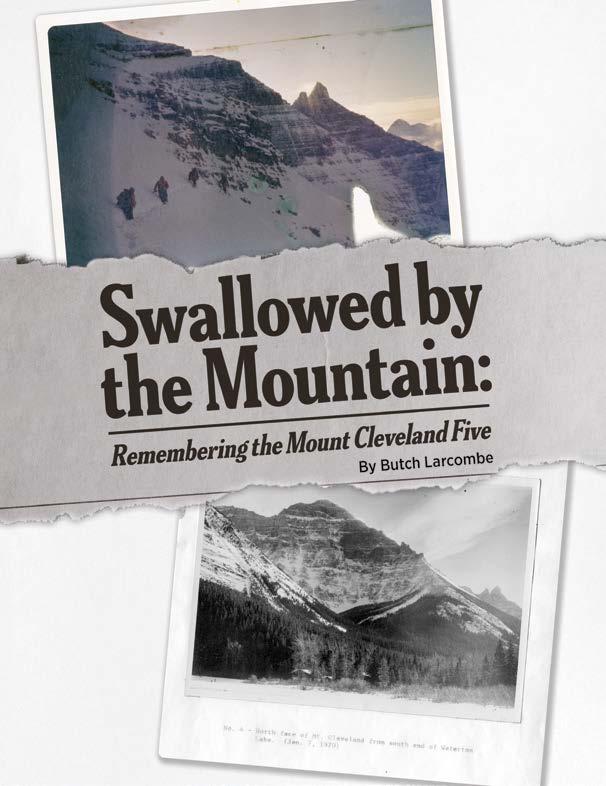

In December 1969, five young Montana climbers set out to make a winter ascent of Mount Cleveland, Glacier National Park’s highest peak. None returned home. Decades later, friends and searchers still wrestle with the loss — and with whether the climbers reached the summit before the mountain claimed them.

Across the Northern Rockies and beyond, LightHawk pilots take to the sky to reveal what can’t be seen from the ground. Their flights connect people to place as they help track wildlife, document change and show how vast, fragile and intertwined our landscapes are. From above, conservation becomes both more apparent and more urgent.

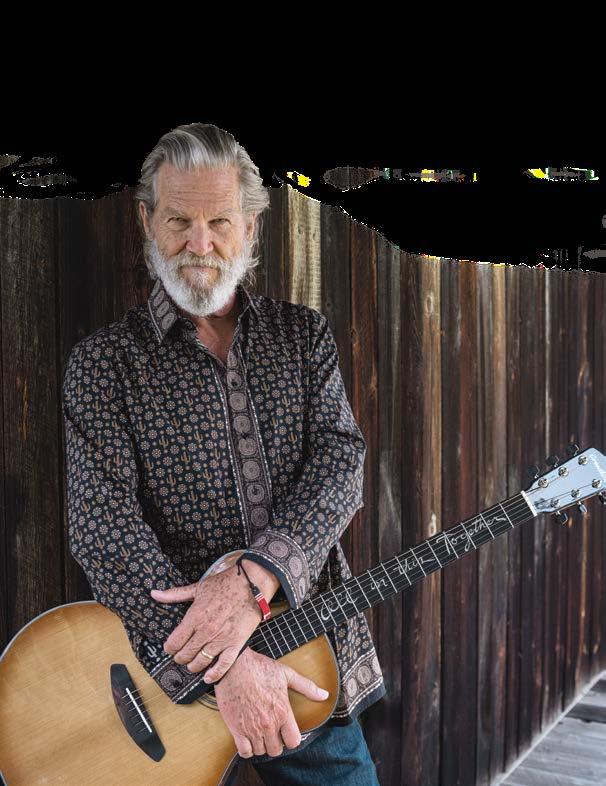

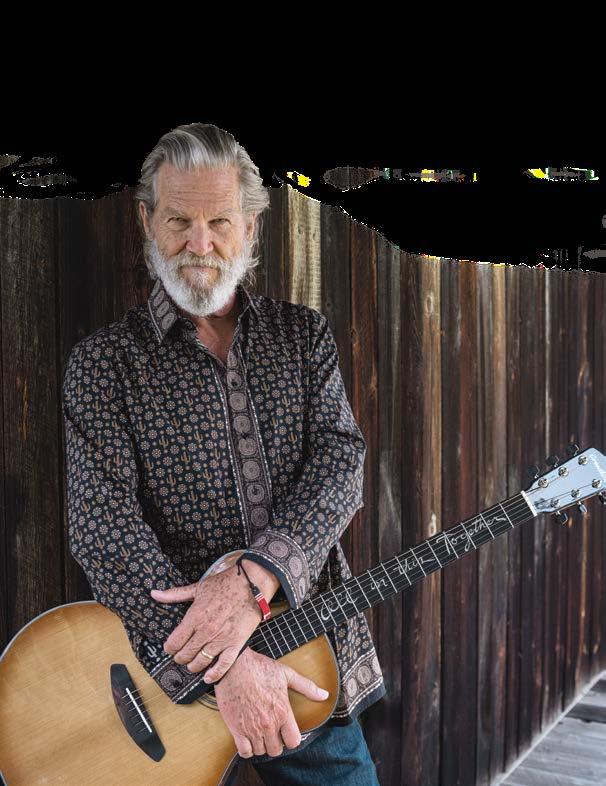

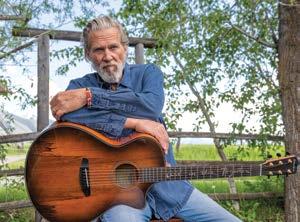

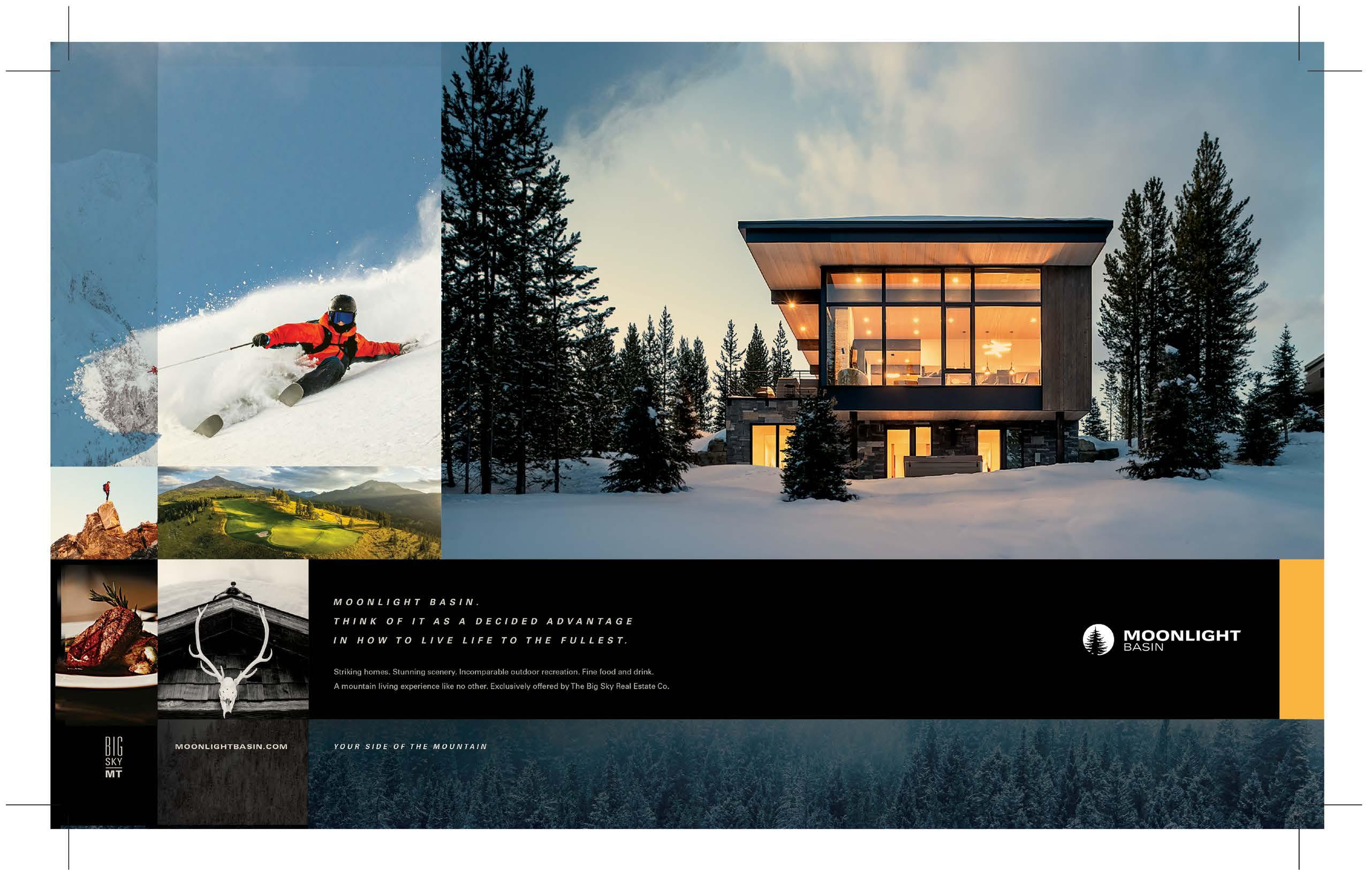

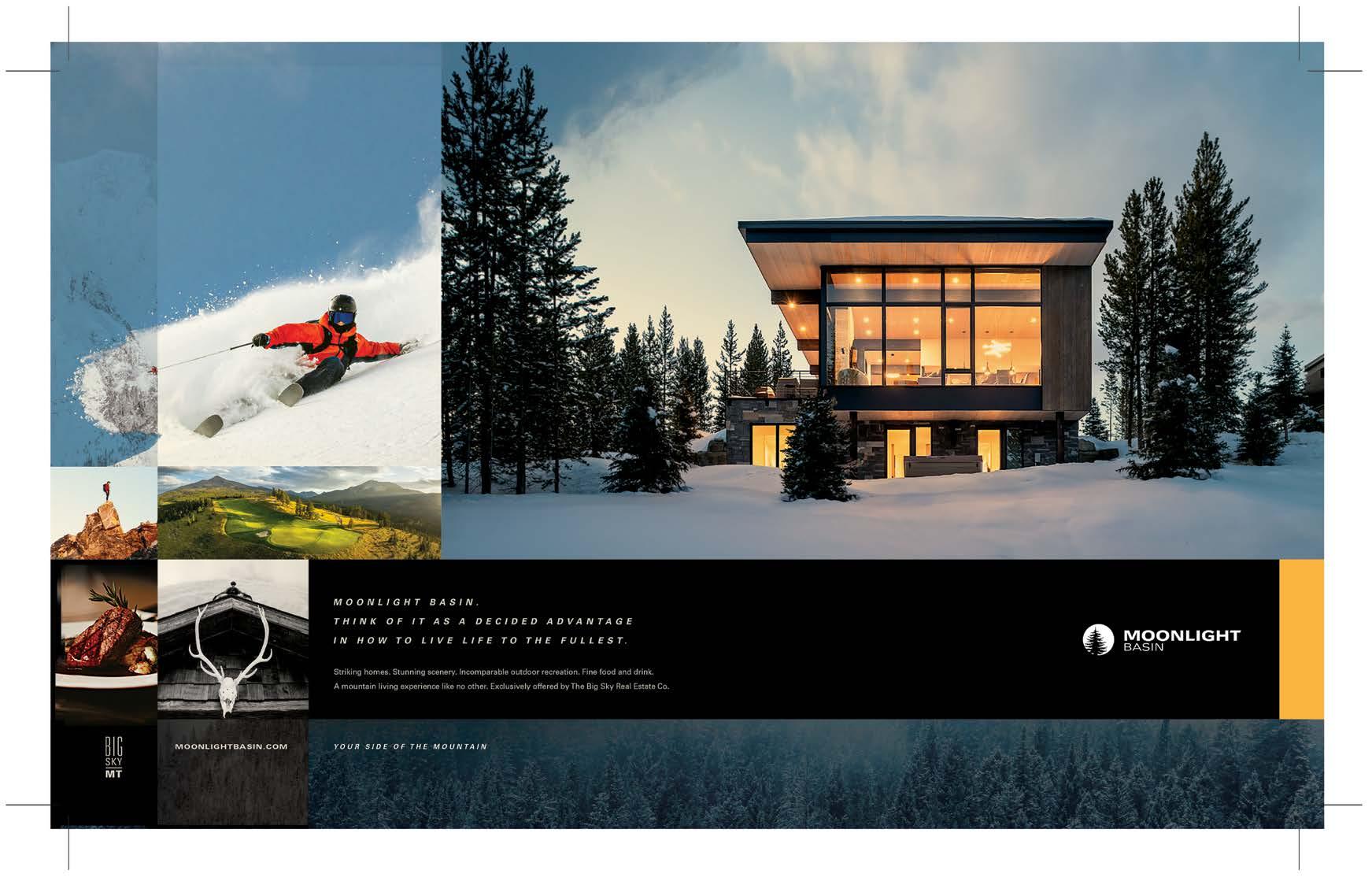

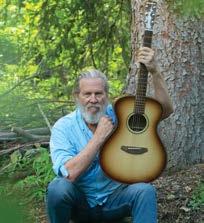

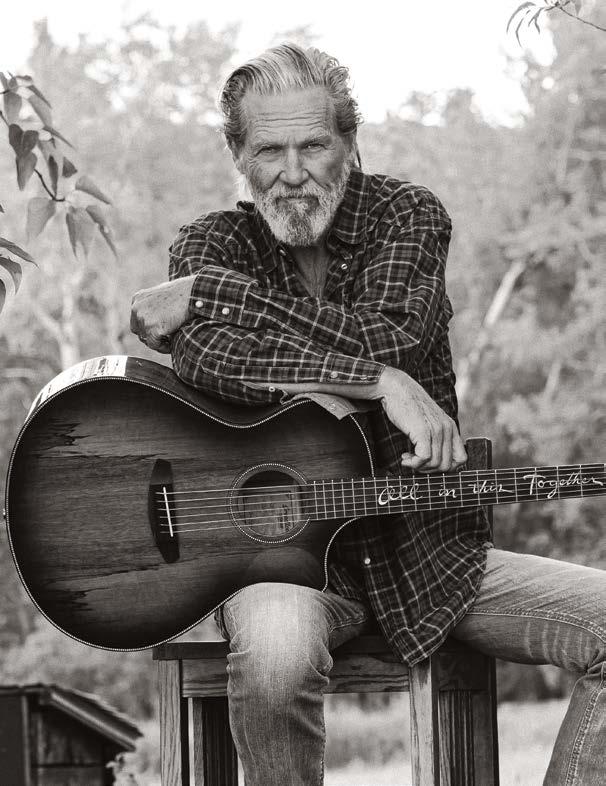

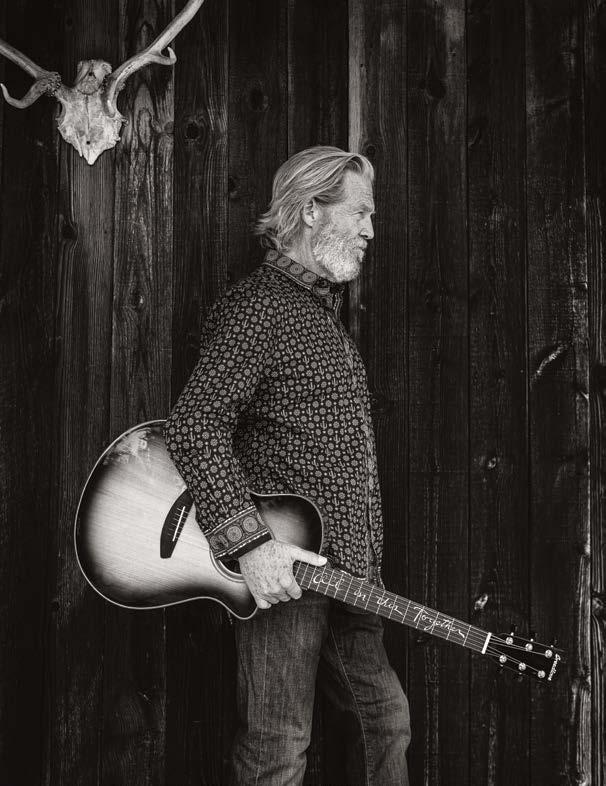

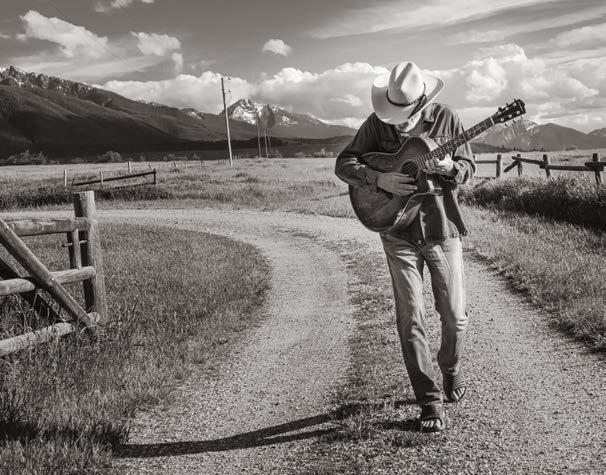

At his Paradise Valley ranch, Jeff Bridges reflects on a life spent between Hollywood and his home in Montana. The Oscarwinning actor and musician opens up about how the West shaped his sense of refuge, creativity and renewal, and how he’s still learning to live with grace, gratitude and a little bit of slow magic.

“BT Construction turned our dream into a reality as our recently completed Big Sky home is beyond stunning. We cannot stress enough the positive experience that Jacob and the entire BT Team provided throughout the build process.

From the quality of workmanship to the constant communication and level of professionalism, every part of the process exceeded our expectations. We would 100% recommend BT Construction to any future clients.”

~Big Sky Client

INSIDE OUTLAW

19 Letter Stories of refuge

FIRST TRACKS

22 Trailhead Our editor’s picks, from books to bites

27 Shorts GYE news in brief

30 Reviews In-depth takes on local media

34 Recipe Shan and North Bridger Bison pair up

OUTBOUND GALLERY

38 Where Hope Endures Images of an Arctic refuge

ADVENTURE

56 Adventure Guide Winter yurt camp in Yellowstone’s Hayden Valley

62 Swallowed by the Mountain Remembering the Mount Cleveland Five

70 The Mountain Within Reach Q&A with Everest climber Emma Schwerin

76 The Fragile Edge Navigating loss in the mountains

80 Seeing the Unseeable Ethical mountain lion photography

90 Poem A month alone in the Centennial Valley

94 Wings Above the Wild LightHawk takes on conservation from above

102 Heart of the Cedars Refuge in transition

CULTURE

108 Fully Rad Wisdom Getting to know Brendan Leonard

116 Songs From a Climate Refuge How a guitar is saving the Yaak

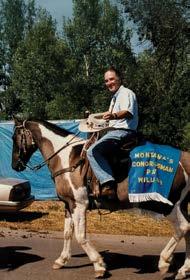

124 Montana’s Champion Remembering Rep. Pat Williams

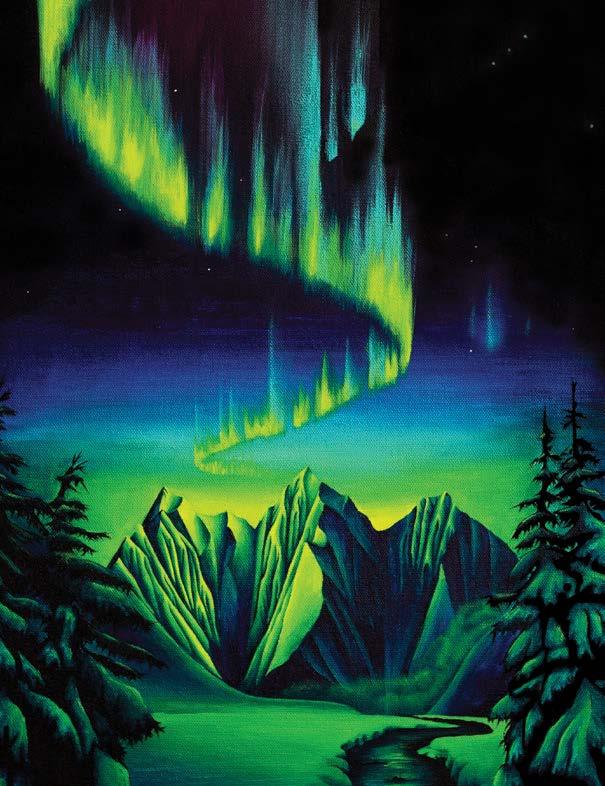

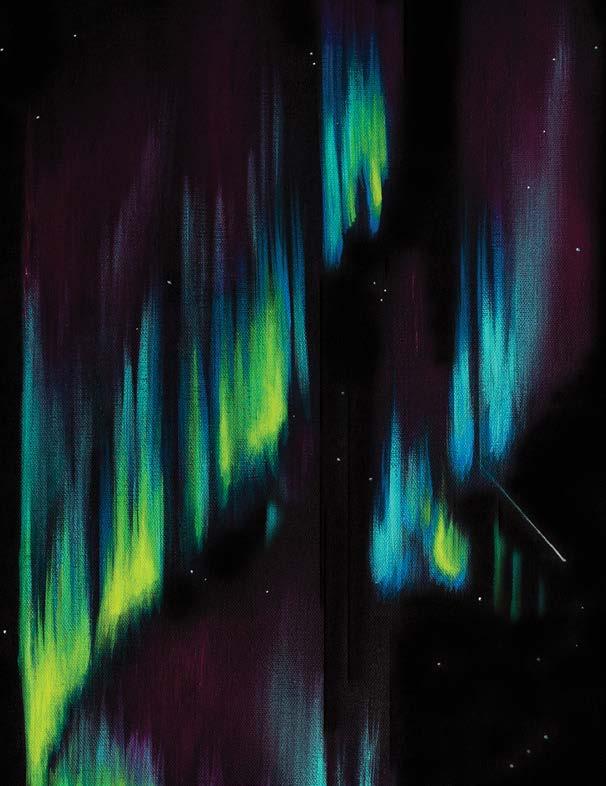

128 On Love and Space Weather The mystery of the aurora borealis

PUBLISHER’S LENS

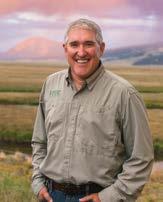

134 Keep the West Wild Honoring pioneers of conservation

FEATURED OUTLAW

152 Jeff Bridges’ Slow Magic Abiding in Montana’s Paradise Valley

LAST LIGHT

168 Refuge in rhythm

Owned and published in Big Sky, Montana

PUBLISHER

Eric Ladd

VP MEDIA

Mira Brody

MANAGING EDITOR

Sophie Tsairis

ART DIRECTOR

Robyn Egloff

COPYEDITOR

Carter Walker

ART PRODUCTION

Megan Sierra Griffin House

Radley Robertson

SALES & ADVERTISING

Ellie Boeschenstein

Ersin Ozer

Patrick Mahoney

ACCOUNTING

Sara Sipe

CHIEF OPERATING OFFICER

Josh Timon

CHIEF MARKETING OFFICER

Megan Paulson

VP DESIGN & PRODUCTION

Hiller Higman

DISTRIBUTION

Ennion Williams

Visit outlaw.partners to meet the entire Outlaw team.

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

Rick Bass, Chandra Brown, Lauren Burgess, Bella Butler, Jen Clancey, Madison Dapcevich, Maggie Neal Doherty, Sula Castilleja Griggs, Carli Johnson, Butch Larcombe, Savannah Rose, Matt Skoglund, Kathleen Smith, Emily Sullivan, Toby Thompson, Leath Tonino, Jarrett Wrisley

CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS/ARTISTS

Ralph Alswang, Lincoln Athas, RA Beattie, Chris Boyer, Taylor Burk, Sula Castilleja Griggs, Lindsay Coe, David Driscoll, Jacob W. Frank, Audrey Hall, Dave Hall, Henry Higman, Bobby Jahrig, Tyson Krinke, Butch Larcombe, Kevin League, Riley McClaughry, Holly Pippel, Kylie Paul, Jim Peaco, Erik Petersen, Bonni Willows Quist, Michael Reubusch, Savannah Rose, Tendi Sherpa, Kathleen Smith, Meg Smith, Anthony South, Emily Sullivan, Madeline Thunder, Laura Wells, Don Wolfe

Subscribe now at mtoutlaw.com/subscriptions.

Mountain Outlaw magazine is distributed to subscribers in all 50 states, including contracted placement in resorts and hotels across the West. Core distribution in the Northern Rockies includes Big Sky, Bozeman and Missoula, Montana, as well as Jackson, Wyoming, and the four corners of Yellowstone National Park.

To advertise, contact Ersin Ozer at ersin@outlaw.partners or Patrick Mahoney at patrick@outlaw.partners.

OUTLAW PARTNERS & Mountain Outlaw

P.O. Box 160250, Big Sky, MT 59716 (406) 995-2055 • media@outlaw.partners

© 2026 Mountain Outlaw

Unauthorized reproduction prohibited

Subscribe to and read Mountain Outlaw online.

Check out these other Outlaw publications:

ON THE COVER

Academy Award-winning actor, musician and environmentalist Jeff Bridges poses with a signature-edition Breedlove guitar he designed with Breedlove owner Tom Bedell as part of a close partnership with the Bend, Oregon-based guitar maker. Read more about Bridges, this issue’s Featured Outlaw, on p. 152. Photo by Audrey Hall

Butch Larcombe

Swallowed By the Mountain | p. 62

Butch Larcombe is a lifelong Montana resident who grew up in Malta, on Montana’s Hi-Line. He currently lives near Woods Bay, south of Bigfork. Larcombe has worked as a newspaper reporter and editor for the Missoulian, Great Falls Tribune and Helena Independent Record. He also served as editor and general manager of Montana Magazine for six years and worked in corporate communications for NorthWestern Energy from 2012 to 2019. Historic Tales of Flathead Lake was published in June 2024 by The History Press. Another nonfiction book, Montana Disasters: True Stories of Treasure State Tragedies and Triumphs, was published in December 2021 by Farcountry Press.

Emily Sullivan

Outbound Gallery: Where Hope Endures | p. 38

Emily Sullivan (she/they) is an award-winning photographer, filmmaker and writer focused on outdoor recreation, environmental wellness and community empowerment in the north. She was the recipient of the 2023 Climate Futures storytelling grant from High Country News and was a 2024 Artist-in-Residence at Singla Creative Retreat in northern Norway. She lives, works and recreates on Dena’ina Ełnena, the lands surrounding Anchorage, Alaska where she is a community organizer for climate justice, Arctic sustainability, and land issues. When not engaged in creative pursuits, she can often be found walking long distances on skis or picking berries on the tundra.

Seeing the Unseeable | p. 80

Savannah Rose is a full-time wildlife photographer and author who strives to capture evocative portraits of the most misunderstood and elusive creatures in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. Her journey began in Jackson, Wyoming, 10 years ago where she quickly fell in love with mountain lions and the pursuit of sharing their stories with the world. Savannah believes effective portraiture of wildlife brings a human connection with animals that often live their lives unseen and inspires people to want to conserve their habitat. Her work has been featured by the Natural History Museum’s Wildlife Photographer of the Year, Audubon, Nikon and The National Wildlife Foundation.

Rick Bass

Songs From a Climate Refuge | p. 116

Rick Bass has lived in Montana’s Yaak Valley for nearly 40 years. A former oil and gas geologist, he is the author of more than 30 books of award-winning fiction and nonfiction, and has won a Governor’s Award for the Arts. He co-founded the Yaak Valley Forest Council, where he serves as executive director, as well as The Montana Project, whose mission is to empower Montana artists in conservation measures. An avid hunter, he has served as contributing editor for magazines as various as Tricycle: The Buddhist Review and Contemporary Wingshooter. He teaches writing workshops nationally as well as at the Stonecoast MFA in Maine.

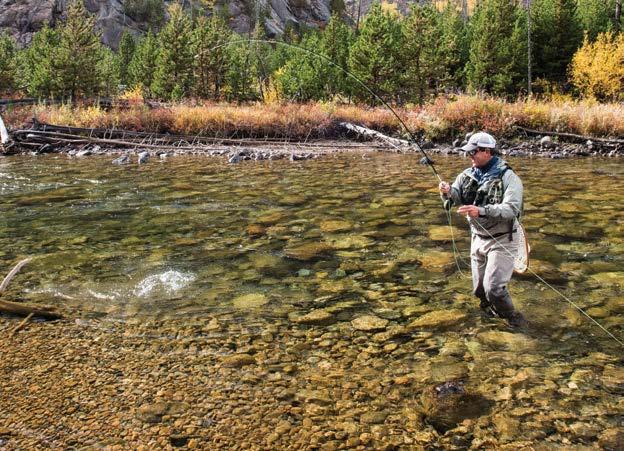

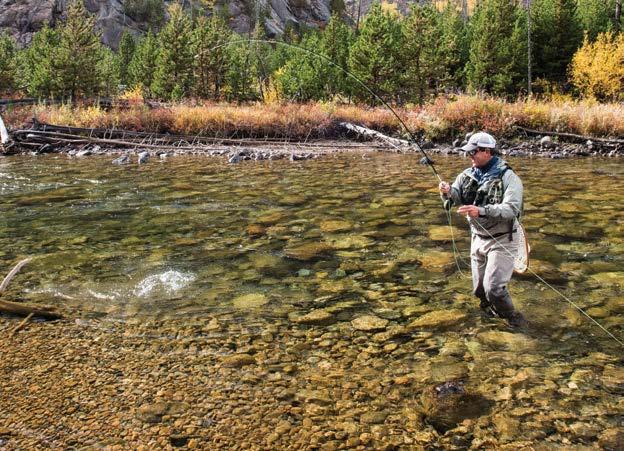

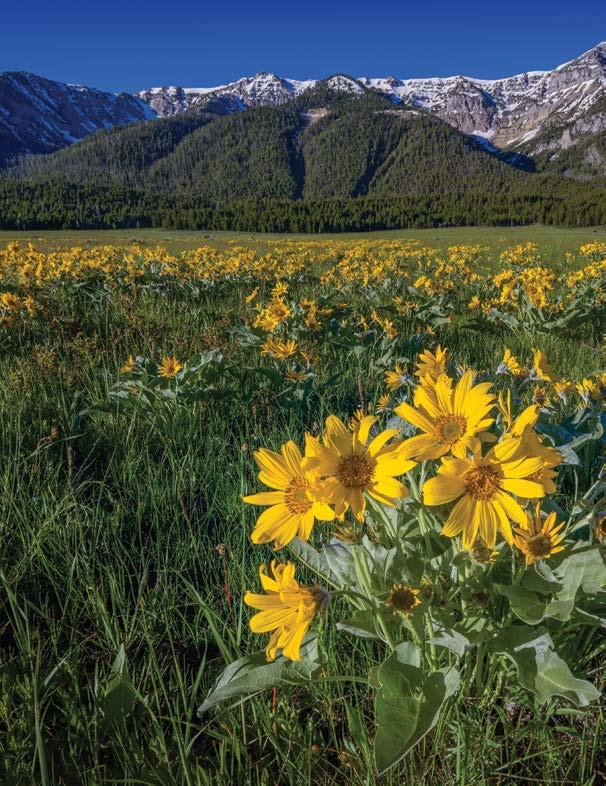

Fly Fishing in Montana can be a rugged, sometimes-tiring adventure—that’s why Madison Double R will be a welcome respite at the end of each day

Located on the world -renowned Madison River south of Ennis, Madison Double R offers first- qualit y accommodations, outstanding cuisine, exper t guides, and a fly fishing lodge experience second to none Contact us today to book your stay at the West’s premier year-round destination lodges

This July, students from the University of Southern Maine will make their way from Portland, Maine, to the most northern region of Montana, the Yaak River Valley, mapping old growth forests and absorbing the music of the ancients along the way (p. 116). Their goal is to raise awareness of climate refuges across the northern United States.

We often think of protecting wild places for the sake of those who cannot advocate for themselves, but we must also safeguard them for our own well-being and for generations yet to come. Refuge is not only about the land itself, but also about the act of caring for it, and for one another. And while these ecosystems are a vital lifeline on an ecological level, for biodiversity, for our climate’s stability and for thriving life, in this magazine we’ve discovered they’re also tied close to our human spirituality.

In this issue, our incredible writers, photographers and artists explore how refuge can take many forms. In the old-growth forests straddling the Idaho-Montana border, Sula Griggs finds her identity (p. 102). In Montana’s Red Rock Lakes National Wildlife Refuge Poet Leath Tonino finds solitude and inspiration during a month alone in the Centennial Valley (p.90), and in Featured Outlaw Jeff Bridges’ Montana sanctuary, he still abides, far from the noise of show business (p. 152). Even the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, recently reopened to drilling, remains, as the images in our Outbound Gallery remind us, a landscape and community where hope endures (p. 38). Refuge can be a mountain or a marsh, but also a neighborhood potluck, a friend’s kitchen table, a community that chooses empathy over fear. It is built in the small, intentional acts that make places — both wild and domestic — safe for all who seek shelter.

As you read through these pages, you’ll find stories of those working to protect what offers us both physical and emotional shelter, including the wild spaces, living systems and human connections that sustain us. Perhaps you will even recognize a version of your own

refuge here or be moved to help protect someone else’s. However, wherever we find it, refuge is not passive. It’s something we must create, nourish and safeguard together.

Thank you for being here, and for receiving and offering refuge when and where you can.

Let it snow,

Managing Editor

Mira Brody VP Media

E a r n M o r e a n d W o r r y L e s s .

im pe r ati v e . To thri v e, y ou n eed a c o m p a n y with a r e v en u e m a n a geme n t t eam c a p a bl e o f adjusting r a t es 2 4 /7 based on r e a l - time fl u ctuati o ns in m a r k et demand

W h y i s p ric i ng so impor t a n t? I

l o w , y o ur h o m e wil l b o ok but y o u ’ l l be l e a v i ng mo n e y on the t a ble. S et r a t es t oo h igh and y o u ’l l l o se book i ngs a l t o gethe r

N at u r a l R et r e a ts has m a de a m a ss i v e i nv est m e n t i n o ur R e v e n ue M anageme n t t ea m o v er the y e a r s. T he r esult? G r ea t er r e v en u e f or o u r h o me o w n e r s

Browse all Trailhead features online

Every great adventure starts at the trailhead. Our editors have curated some favorite discoveries across the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, spotlighting page-turning reads, delicious eats and more.

–The Editors

By Nick Triolo

In The Way Around, Missoulabased author Nicholas Triolo explores the transformative power of walking in circles, both physically and spiritually, as an antidote to Western goal-driven culture. After global travels and ultrarunning failed to ease his inner unrest, Triolo is inspired by the ritual of kora, or circumambulation. What follows are three deeply personal pilgrimages: around Tibet’s Mount Kailash, California’s Mount Tamalpais and perhaps most surprisingly, Montana’s Berkeley Pit. Triolo’s prose is both grounded and transcendent. It’s a meditation on how slowing down and walking with intention can reconnect us to place, to healing and to a more cyclical way of being.

By Jessica Hays

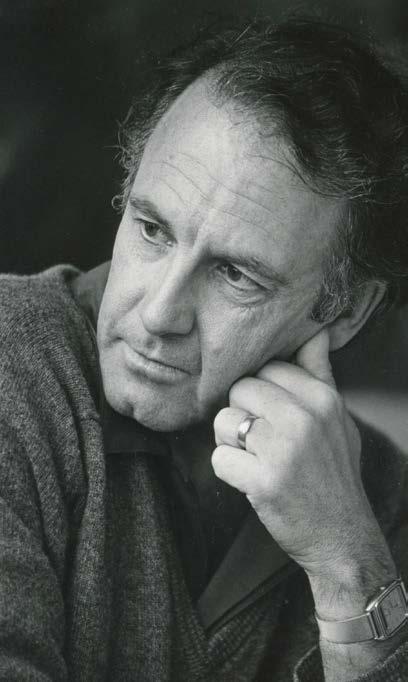

Bozeman photographer Jessica Hays has spent five years documenting wildfires across the U.S., capturing both the visual and emotional aftermath of climate-driven megafires. Her upcoming photobook, The Sun Sets Midafternoon, captures this devastation and its psychological toll, what she calls “solastalgia,” the grief tied to environmental loss. Through her work, she creates space for conversations around collective grief and how deeply people relate to and mourn damaged landscapes.

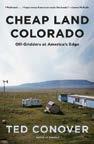

By Ted Conover

In Cheap Land Colorado, Pulitzer Prize finalist Ted Conover explores life on the fringes of American society in Colorado’s remote San Luis Valley. Living among off-grid settlers, he finds a diverse, selfreliant community shaped by independence, hardship and mistrust of the mainstream. Over four years, Conover witnesses their struggles, resilience and contradictions — people resisting authority yet reliant on aid and seeking solitude, yet tangled in their neighbors’ lives. Their stories reflect a fractured America where its edges increasingly define the center.

“Everything here is from scratch,” said Sally Schwartz, owner of Dilly Dally Donut Bar in Bozeman. That includes the hot chocolate, vanilla bean milk, cream and yes, the doughnuts themselves. Massive and in great variety, pastries range from classic glazed and sprinkle, to apple fritters made from Schwartz’s great-aunt Thelma’s recipe, beignets, kolaches and doughnut holes. Since opening in May, Dilly Dally has drawn sweet treat lovers to the far east side of Bozeman off Frontage Road to indulge in baked goods hot out of the oven. Go early, before the “sold out” sign lights up her shop window.

Still new to the growing Bozeman food scene, Shawarma Bus has carved out a space for itself in the modest but popular food truck court along Bozeman’s North 7th Avenue. The name says it all: “Shawarma” comes from the Turkish word for “rotates,” referring to the cooking method that forms the heart of every dish — thin-sliced lamb, chicken or beef carved fresh from the spit and piled into wraps or served as platters. While Shawarma is popular across the Mediterranean region, the bright red bus focuses on traditional Lebanese chicken and beef recipes the owners grew up enjoying.

Along Broadway Avenue in Red Lodge, Montana, sits One Legged Magpie, a bistro inspired by quality bites with local ingredients and craft cocktails, as well as the resilient, blue-and-white corvid for which it is named. Founders Mike and Kat Porco drew inspiration from a disheveled, one-legged magpie they encountered during a reflective moment in Pride Park in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, and it became a symbol of their vision to create a restaurant defined by grit and character. The bistro’s popularity is well-earned: One Legged Magpie’s executive chef, Chase Cardoza, will represent the state of Montana on the upcoming season 24 of Hell’s Kitchen: Battle of the States.

Armed with a name that has a natural ring to it, Teton Thai has long held a special place in the hearts of Teton Valley locals — and for good reason. The family-owned spot in downtown Driggs, Idaho, delivers vibrant, balanced flavors inspired by family recipes from Bangkok. After a day of deep powder turns at Grand Targhee Resort, relax and refuel in the historic building’s cozy dining room. We recommend their pad thai for noodle-lovers — a classic done exceptionally well — or their massaman curry, a rich, creamy, mildly spiced coconutmilk-based dish with potatoes, carrots, onions and peanuts. On the other side of Teton Pass? Never fear — Teton Thai has a second location in Teton Village, Wyoming — a personal favorite dining spot of famed snowboarder Travis Rice.

About Damn Time is a powerful documentary celebrating the pioneering women who navigate the Grand Canyon’s treacherous rapids in handcrafted dories. Produced by OARS, the film follows veteran guide Cindell “Dellie” Dale and the fierce women following in her wake. The film captures stunning canyon scenery but carries deeper currents. It documents the stories of women carving out space in a male-dominated river-running world. With resilience, humor and hardearned wisdom, they fight for their place on the river, and for the river itself as it is increasingly strangled by drought, politics and overuse. It’s both an exhilarating adventure and a poignant call to protect a river, and legacy, whose future remains uncertain.

Browse all Trailhead features online

Working Dogs for Conservation is a Bozemanbased nonprofit that utilizes rescue dogs to locate everything from invasive species to diseases in wildlife, offering a non-invasive, efficient and accurate alternative to traditional detection methods. Using an olfactometer, the dogs, most rescued from shelters, are trained to recognize specific scents and have achieved impressive results — like identifying 1,298 kit fox scat samples with 100 percent accuracy and covering more ground than human surveyors or cameras on many of their projects.

Alice Whitelaw, one of four initial co-founders, helped establish the organization 25 years ago to meet a growing need for non-invasive DNA collection through scat detection. Now operating in 45 U.S. states and 36 countries, their dogs have worked on global projects including rhino conservation in Indonesia and poaching prevention in Africa. Most recently, Whitelaw is training dogs to detect Mycoplasma bovis, a disease affecting bison in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. As the field grows, Whitelaw remains inspired by the dogs’ incredible abilities and their global conservation impact — far exceeding what she initially imagined.

The other Dayton, while lesser known than its Midwest cousin, is well loved by those who enjoy some quiet exploration into the Bighorn Mountains via U.S. Highway 14. Incorporated in 1906, Dayton, Wyoming’s history follows the veins of agriculture, timber and the Dayton Flour Mill. The town elected the state’s first female mayor, Susan Wissler, in 1911 and during World War II it was protected by an all-female volunteer fire department. Today, Dayton is the gateway to the beautiful Tongue River Canyon, home to many fishing holes and recreation trails that weave deep into the northern Bighorns. Stay along the river at Foothills Campground and grab an ice cream cone or bag of kettle corn at the historic Dayton Mercantile.

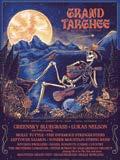

The beloved finger-picking fest in the Teton Valley, Grand Targhee Bluegrass Festival, is back in full swing. After a three-year pandemic hiatus, the festival re-emerged in 2023 with all the magic that made it a regional favorite. This past summer’s three-day lateAugust festival welcomed bluegrass names from near and far including the Kitchen Dwellers, Greensky Bluegrass, Yonder Mountain String Band, Brothers Comatose and Molly Tuttle. With available camping on-site, the event is a good time for the whole family, and it feels like it has found its way back to its roots: incredible live music paired with good company, fresh air and stargazing. This year’s festival is Aug. 7-9 with a lineup that includes Sierra Ferrel, The Brother Comatose, Mountain Grass Unit and AJ Lee & Blue Summit.

The Last Revel’s latest album, Gone for Good, marks a return for the Minneapolis-based Americana/indie-folk band after a brief, two-year hiatus. Produced by Dave Simonett of Trampled by Turtles, the 10-track album creates a marriage between “fast-grass” and strong storytelling familiar to their following, and touches on life on the road, love, loss and resilience. Standout tracks like “Solid Gone,” inspired by a near-tragic accident, and the fiery “Go On” showcase the strong four-piece harmonies The Last Revel has become known for. You can hear Gone for Good live in November as a part of their U.S. album tour in Missoula and Bozeman.

In 10 episodes, Wilder revisits the beloved Little House on the Prairie series with a refreshingly nostalgic yet critical lens. Hosted by Glynnis MacNicol and Elizabeth Stevens, the show explores Laura Ingalls Wilder’s beloved book series that made its way into almost every childhood home, examining both its enduring cultural impact as well as some of the damning historical truths glossed over, such as themes of manifest destiny and the government-issued land grants that the Ingalls family participated in on active Native land. Blending history, humor and sharp commentary, Wilder unpacks how these cherished stories helped shape American identity while diving into themes of race, gender and myth-making on the frontier.

// Words by Sophie Tsairis | Illustrations by Madeline Thunder

In an executive order issued July 3, the Trump administration directed the Interior Department to increase entrance and recreation pass fees for international tourists visiting national parks, with the revenue earmarked for park infrastructure and visitor services.

The fee hikes, which are not yet specified, will apply only to parks that currently charge admission, like Yellowstone and Grand Teton national parks.

The move aligns with a proposal from the Property and Environment Research Center, a Montana-based think tank, which recommended a surcharge for foreign visitors in a 2023 report.

Shawn Regan, PERC’s vice president of research, said a recent analysis focusing on Yellowstone found that a $20 surcharge could generate an additional $12 million for the park, an 84 percent increase in fee revenue overall, and with almost no impact on total park visitation. “We need to find creative ways to help sustain our parks for the future. Increasing fees from international tourists is a common sense way to do this,” he said.

National parks saw record attendance in 2024, with 331 million visits, including 14.6 million by foreign tourists. The revenue could provide much-needed support amid budget constraints.

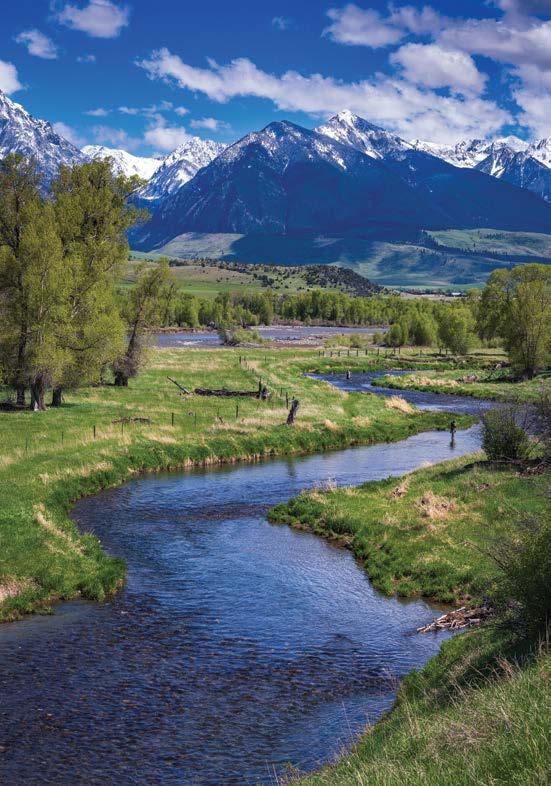

A new bipartisan bill from Rep. Ryan Zinke seeks to permanently protect nearly 100 miles of Montana’s Madison and Gallatin rivers by adding them to the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System.

The Greater Yellowstone Recreation Enhancement and Tourism Act would mark Montana’s most significant river conservation move in decades. Calling it a “Montana solution,” Zinke said the bill strikes a balance between conservation and multiple use. “These rivers support everything from family farms to fly shops, ranchers to rafters, and literally power our community.”

If passed, the bill would designate stretches of five rivers and creeks — including 42 miles of the Madison and 39.5 miles of the Gallatin.

Supporters like American Rivers and the Gallatin River Task Force say the move would safeguard water quality, block new dams, and preserve outdoor recreation. Sen. Jon Tester introduced similar legislation in 2024 — the Montana Headwaters Legacy Act, which would have protected sections of the Madison, Gallatin, Smith, Yellowstone and others under the Wild and Scenic Rivers System. That bill never made it out of the Senate, but conservation groups are optimistic that the GYREAT Act stands a better chance.

Sophie Tsairis is the managing editor of Mountain Outlaw

On April 11, 2025, Teton County, Wyoming, became the world’s first county to be certified as an International Dark Sky Community, a major milestone in efforts to combat light pollution and preserve natural night skies.

“It goes well beyond the aesthetics of a beautiful night sky to admire,” said Samuel Singer, founder of Wyoming Stargazing. “Reducing light pollution increases public safety, makes the nighttime environment healthy for all forms of life including humans, saves money, and reduces energy consumption.”

According to DarkSky International, a Dark Sky community is a town, city, municipality, or other legally organized community that has shown exceptional dedication to the preservation of the night sky through the implementation and enforcement of a quality outdoor lighting ordinance, dark sky education, and citizen support.

The county committed to retrofitting all public lighting to meet Dark Sky standards by 2030, and of 51 proposed lighting regulation changes, 49 were adopted by local officials.

Jackson Hole Airport also became the first airport in the world to receive Dark Sky status, while Sinks Canyon State Park earned designation as Wyoming’s first Dark Sky Park in 2023.

Madeline Thunder is a freelance artist based in Bozeman, Montana. When she is not creating, she can usually be found playing outside.

By Carli Johnson

Even as a renowned and successful scholar at the University of Chicago, Norman Maclean always found himself returning to the revered land of Montana. Raised in the rugged West and teaching in the bustling city of Chicago, he lived a dual life between academia and wilderness, between the classroom and the riverbank. Norman Maclean: A Life of Letters and Rivers by Rebecca McCarthy, is a catalogue of that life.

McCarthy, who first met Maclean as a teenager at her family’s cabin in Seeley Lake, brings both personal knowledge and thorough research to his life’s story. The result is an intimate portrait of Maclean as a scholar, teacher, writer, fisherman and family man. McCarthy traces the course of his life in ways that illuminate the roots of his writing and the legacy he left behind.

A man of tactfully curated words and slow-burning ambition, Maclean’s most notable works came late in life. A preacher’s son, a bereaved sibling and an eventual widower, he drew deeply from these relationships to craft stories that captivate an audience. His most celebrated work, A River Runs Through It and Other Stories, takes direct inspiration from his Montana upbringing and his brother Paul’s untimely death. Published when Maclean was 73, the book stands as a testament to the persistence and patience with which he pursued art.

“A storyteller,” Maclean wrote, “unlike a historian, must follow compassion wherever it leads him. He must be able to accompany his characters, even into smoke and fire, and bear witness to what they thought and felt even when they themselves no longer knew.” McCarthy follows this same principle, tracing the compassion that guided Maclean through smoke, fire and grief. She chronologically documents his life with both care and admiration, revealing the deep humanity behind his disciplined mind.

A Life of Letters and Rivers opens early: the Montana childhood, the young Maclean working for the U.S. Forest Service, the son of a strict Presbyterian minister whose lessons in language and discipline shaped Maclean’s writing. From his father he learned the rhythm of sermons, the power of narrative and the moral weight of words. Yet

his father’s approval remained out of reach. In a letter to a close friend while writing A River Runs Through It, Maclean confessed, “Writing is largely a matter of courage, or not knowing any better.” The admission reveals both his humility and self-doubt. Despite the breadth of his knowledge and education in literature, Maclean was famously hard on himself and his writing, a characteristic illustrated by McCarthy throughout the biography, perhaps best when she applies that discipline on the young author herself.

Readers accompany Maclean to Dartmouth, where he felt out of place among the Eastern elite. He would later find a sense of belonging at the University of Chicago, where, as he liked to say, “He and the university grew up together.” McCarthy paints him as both a formidable and generous teacher. “Norman was known as a fair, and supportive, attendant who wanted students to succeed, but he still managed to scare the bejesus out of some of them,” McCarthy writes.

Still, Maclean never fully left Montana behind. Teaching through the academic year and retreating to his cabin on Seeley Lake in summer, he found a balance that sustained him. That rhythm, McCarthy details, was his ideal life — one where he could be the Western outdoorsman and the attentive academic, the fly fisherman and the literature professor.

When A River Runs Through It was published in 1976, it made history as the first work of fiction ever released by the University of Chicago Press. That institutional milestone mirrored Maclean’s personal triumph: a man who had spent a lifetime teaching literature finally entering it himself. McCarthy explores the mix of humility and disbelief that accompanied Maclean’s success as he was suddenly hailed as a new voice in American literature.

In his final years, Maclean turned again to tragedy with Young Men and Fire, his account of the 1949 Mann Gulch disaster near Helena, Montana. Here, McCarthy’s themes of place and perseverance converge. The same Montana landscape that nurtured his youth and inspired his fiction now became the setting for his final work. Committed to the art, he continued to write even as his health declined.

By the end of McCarthy’s biography, the reader senses the completeness of Maclean’s circle: the boy from Missoula, the scholar from Chicago, the wise man returning home. Norman Maclean: A Life of Letters and Rivers is a record of how land, loss and a lifelong dedication to craft shaped his voice. McCarthy’s prose flows with the same patience and restraint that marked her subject’s own.

Carli Johnson is the social media coordinator for Outlaw Partners.

By Jen Clancey

After an Oct. 18 showing of the documentary Bring Them Home, co-producer Daniel Glick recalled the experience of filming buffalo. For directors Glick and the brother-sister duo Ivy and Ivan MacDonald, Blackfeet filmmakers, capturing still, breathtaking shots of the 1,000-2,000-pound mammals was surprisingly simple. “They look right at you,” Glick said.

Perhaps that’s why, sitting in the balcony of the theater, I felt I was seeing a new side of the iconic animals on the screen. Bring Them Home, or Aiskótáhkapiyaaya in the Blackfeet language, tells the story of the Blackfeet Nation’s ongoing fight to restore bison to their homelands and renew the relationship between its people and the iinnii (buffalo).

Narrated by Lily Gladstone, a member of the Blackfeet Nation and Golden Globe winner for Killers of Flower Moon, the film offers a profound understanding of the millenia-long connection between the Blackfeet and the buffalo.

Early in the film, viewers learn about the near-eradication of bison populations across North America as white settlers expanded westward. In 1870, an estimated 8 million bison roamed across what is now the United States. By 1890, fewer than 500 remained. Leaders were explicit about the violence, heartbreak, and harm this slaughter would inflict on Indigenous Nations. In 1867, a U.S. general reportedly encouraged the cull, saying, “Kill every buffalo you can. Every buffalo dead is an Indian gone.” These words open the section of the film recounting this history, followed by archival photographs of white men posed in front of mountains of buffalo skulls and bones.

“Without buffalo, our world collapsed,” Gladstone narrates. But for decades, a small group of Blackfeet community members have been leading efforts to bring the buffalo home, to heal from the trauma and genocide inflicted on both the Blackfeet people and the iinnii and revitalize the centuries-old relationship between them.

In one of my favorite moments from the film, Paulette Fox (Kainai Nation), co-creator of the Iinnii Initiative to restore buffalo to Native land, explains a vision she had at five years old when a herd of bison appeared to her. She notes what it felt like to be alive beside the iinnii, as the sun shone through

grassland. Like a foretelling, the image and feeling of being beside the relative stayed with her throughout her life and guided her work to reunite Blackfeet people and buffalo. But from the start, the effort faced challenges. In one scene, a 1993 attempt at buffalo restoration on the Blood Reserve in Canada, part of the three-piece Blackfeet Confederacy, faced resistance from Indigenous community members who didn’t have a say in the relocation decision. The truck carrying the newly purchased bison was turned away. Fox comments on seeing her people oppose the return of bison. Rather than dwelling on the frustration, she expresses her understanding that if buffalo do return, it must be a decision the Indigenous community supports wholeheartedly. She describes the moment as the community needing more time to prepare for the iinnii reunion.

On the timing of the restoration effort and the film process itself, Gladstone offered her perspective in a 2024 KUOW Puget Sound Public Radio interview: “I feel like when something is this big and this meaningful and it’s tied to something that is communal, which is our planet, it has its own timeline and it has its own animism and it comes about when it wants to, when it demands that it be there,” she said.

Community participation was and is central to the Iinnii Initiative, and through it, the return of a second herd gained traction. This time, the Tribe acquired bison that originally roamed Blackfeet land and lived in Canada’s Elk Island State Park following a series of forced sales. In 2016, Elk Island State Park calves were released onto Blackfeet land, a moment the film captures. On screen, Fox reflects that the relocation project was finally successful because it was done in “a loving way.”

As the years passed with original Blackfeet bison on tribal land, a final goal steadily took shape in the minds of Blackfeet organizers: a free and wild herd. Gladstone narrates that much like bison facing and moving toward a blizzard, the Blackfeet people sustained their momentum through events such as Iinnii Days and buffalo drives. Gradually, they negotiated and advocated to open northern Blackfeet lands bordering Glacier National Park to allow bison to roam freely at last.

Bring Them Home traces the ongoing renewal of the iinnii -Blackfeet relationship, and the collaboration and community-building required to return them on Blackfeet terms. Where nature documentaries separate the human from the mammal and the land, Bring Them Home reminds us of a different relationship with the beings around us, one that is familial, and crucial to survival.

“We know how to be patient. We know how to survive, endure,” Gladstone narrates, attributing these lessons to the iinnii

Jen Clancey is a staff writer at Outlaw Partners.

Introduction by Matt Skoglund

Recipe by Jarrett Wrisley

Photos by Henry Higman

I obsess over this work. “Good enough” isn’t acceptable here. In the name of “progress,” our food system has become industrialized and mechanized, often at the expense of animals, people, biodiversity, rural communities, and our health.

At North Bridger Bison in Wilsall, Montana, we believe there’s a better way. A way to raise food that honors land and life, increases biodiversity, treats animals and humans with dignity and respect, and improves both ecological and human health.

A few years ago, shortly after he and his family moved to Bozeman, I met Jarrett Wrisley. We had mutual friends, shared interests, and a similar outlook on the world. My wife, Sarah, and I went to one of his pop-up dinners, and we were blown away. His was a different kind of cooking, a different kind of experience.

As he prepared to open his restaurant, Shan, Jarrett was deeply intentional about sourcing ingredients from Montana farmers and ranchers that shared his values. He wanted to know who was raising food with integrity. We met multiple times, and I recommended to him some of the producers I admire most in the valley.

Jarrett opened Shan, and people went wild over it — so much so that Shan was named a finalist for the James Beard Award for best new restaurant in America.

Jarrett obsesses over the small details of his cooking. “Good enough” is not acceptable.

He took his entire team at Shan from Bozeman to Asia to experience the food and culture firsthand. He sources the best ingredients he can find, treats his team with dignity and respect, and leads with his heart.

In 2024, we had the honor of hosting Jarrett as the guest chef for our Outstanding in the Field dinner on our ranch, a dream come true for Sarah and me. Even with Shan in full swing, Jarrett poured himself into that dinner. We met to discuss the menu, and his brain was buzzing with ideas. He even came to the ranch to witness the field-harvest of the bison he would be cooking, wanting to honor the story behind the food.

The result was an extraordinary, one-of-a-kind meal for more than 200 people that blew everyone away. And he did it all with grace, humility, and a sense of humor.

It’s an honor to call Jarrett a friend, and it’s an honor each time he cooks our bison meat. It feels like a celebration of everything we believe in.

This larb recipe is out of this world; cook it and savor every bite.

Matt Skoglund is the founder and owner of North Bridger Bison, a bison ranch rooted in regenerative agriculture principles in Montana's Shields Valley. North Bridger Bison sells 100 percent grassfed, fieldharvested bison meat direct-toconsumer across Montana and all over the country.

Isaan-Style Bison Larb

Serves 4

Larb — or laab, as it’s pronounced — is an onomatopoeia for the sound a large knife makes as it cleaves through chunks of meat on the stump of a tamarind tree, the traditional cutting board of Thailand. Larb is something eaten across the Mekong River Basin in northeastern Thailand and Laos, usually seasoned with fish sauce and lime juice, herbs, chilies and toasted sticky rice powder. In Thailand’s north, there are raw and cooked versions that are reliant on dark, toasted spices, fried garlic and shallots, and lots of chili. (This is the northeastern version.) This dish is best eaten with sticky rice or steamed jasmine rice, along with a soup, a curry or maybe some stirfried vegetables. Or, just cut some cucumbers and serve it with crisp lettuce — we use Little Gem at the restaurant — and lots of fresh herbs like dill, cilantro, Thai basil and mint. I love using the Skoglund’s bison for Thai recipes — its leanness and grassy, natural flavor is not unlike that of water buffalo, often eaten in the Thai countryside.

Ingredients

2 tablespoons neutral cooking oil

20 ounces bison, either ground or, preferably, chopped very finely to a consistency like ground meat

2 tablespoons chicken or beef stock (or water)

5 tablespoons fish sauce

4 tablespoons freshly squeezed lime juice

3 teaspoons chili flakes (or more to taste!)

3 tablespoons rice powder (to make, toast raw jasmine or sticky rice in a pan slowly, until it is very brown on the outside, flipping it so as not to burn. Then grind in a spice grinder or crush in a mortar and pestle to a texture that is grainier than flour — sort of like finely ground coffee).

4 tablespoons minced shallots

2 to 3 tablespoons fresh mint, cilantro and green onions, all roughly chopped

Method

1. In a small saucepan, heat the oil and add the bison and cook through, over medium heat. You are not browning the meat but merely cooking it. Add the stock halfway through and continue to cook until the meat is no longer pink, then reduce whatever liquid is in the pot — roughly 5 minutes of cooking over medium-high heat.

2. Add the shallots and stir.

3. Next add the fish sauce, lime juice, chili flakes and rice powder and stir aggressively. Taste. You should have a nice balance of sour, salty and spicy. If you think it needs any more chili, lime or salt (in this case, in the form of fish sauce) add it now.

4. Finish by stirring in your herbs. Decant into a bowl and top with more rice powder and chili flakes, and a dusting of cilantro and mint. Serve.

Jarrett Wrisley is a chef, author and owner of Shan, in Bozeman, and two restaurants in Bangkok, Appia and Peppina. He spent two decades researching, cooking and writing about the foods of China, Thailand and Italy before returning to the United States in 2021.

Scanhere to viewoffers!

It’s the last day the sun will peek above the horizon in Kaktovik, Alaska, for the year — polar night begins tomorrow. Not far from town, I stand at the edge of the sea ice with Robert Thompson, taking in the view. The Brooks Range looms purple at the edge of the coastal plain, 50 miles south. Most of the next few days are spent bundled up, enjoying the long, lavender, midday twilight, and listening to Thompson’s stories. Over a lifetime of hunting, exploring, and guiding, the Iñupiaq Elder has had more adventures (and misadventures) than most can dream of.

When I first met Thompson in 2021, we were camped along the banks of the Hulahula River in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. I had heard his name many times — the former polar bear guide is well-known in environmental circles for his efforts to protect the Arctic Refuge from oil and gas exploration. Thompson lives in Kaktovik, the only community located on the refuge’s coastal plain. He has witnessed firsthand the impacts of climate change on polar bears, caribou, Dall sheep, and the ecosystems these mega-fauna rely on. Years ago, he dedicated himself to preventing further damage to the Arctic environment, and he has held steadfast in his commitment — traveling to Washington D.C. to lobby, granting interviews, and educating the public.

That same year, Thompson and I traveled to the Hulahula to take part in the Imago Initiative, a place-based dialogue between conservation advocates and Indigenous peoples aimed at progressing conservation through an Indigenous worldview. The program was created in 2020 by Karlin Nageak Itchoak, an Iñupiaq land protector from Nome and Utqiagvik. Camped in the river valley and surrounded by the Brooks Range, Imago groups learn about the land’s cultural importance while brainstorming equitable and just solutions for its protection.

The refuge’s northern coastal plain has been the topic of intense debate in Congress for four decades. Held sacred by the Gwich’in Nation, it’s the birthing grounds for the Porcupine Caribou herd. Despite repeated attempts by industry and pro-development lawmakers to open it to drilling, grassroots organizing and legal challenges have stymied

Previous page left to right: Polar night settles in over the village of Kaktovik from mid-November to late January. During this time, the sun never rises fully above the horizon. A polar bear stands nearby the village of Kaktovik, with the Brooks Range in the background. This page: The final sunrise of 2023, lightly obscured by frost in the air, lingers for a few hours as the sun barely peeks above the mountains of the Brooks Range.

these efforts, making it one of the most enduring environmental struggles in the United States.

There is no better place to brainstorm land protections than on the land itself. Each summer during the gathering, Imago participants hear from elders like Thompson, both Gwich’in and Iñupiat, about the changes they’ve seen in the land and wildlife. We learn about the challenges facing Indigenous communities today, which can be exacerbated by such approaches to conservation as dispossession of land, infringement on hunting rights, and more. We learn to hold the land, plants, and animals as equals and as relatives. We brainstorm strategies to ensure a healthy future for the coastal plain and the Porcupine Caribou herd. These yearly trips renew my hope for the future of the Arctic.

My friendship with Thompson is what brings me north to Kaktovik for a visit in November of 2023. Winter arrives early at 70 degrees north. As we sightsee near town, my mukluks crunch over unpacked snow. By now, the sea ice should be thick and solid, but it remains patchy. Open water is a stone’s throw away. Thompson explains that the changing ice forces polar bears to spend more time on land, limiting their hunting access to sea mammals. We watch as a sow and cub feed on a whale carcass close to town, and observe a massive, lone boar napping farther out on the ice. Thompson fears for their future — not only because of climate change, but also because of the threat of seismic testing for oil wells.

It’s a difficult time to remain hopeful for the Arctic. Threats to the refuge loom larger than ever. But when hopelessness creeps in, I remember Thompson’s steadfast commitment to the lands he loves and the animals his people rely on. I think of that last, golden sunset before polar night began, and remember that only a few months later, the sun would rise again on the Arctic Ocean. As industry continues to push for drilling, the future of the Arctic Refuge will be decided not just in the halls of Congress, but in whether we choose to stand with the Indigenous communities who have always fought to protect it.

Emily Sullivan (she/they) is a photographer and writer focused on outdoor recreation, environmental wellness, and community empowerment. Sullivan was the recipient of the 2023 Climate Futures storytelling grant from High Country News and was a 2024 Artist-inResidence at Singla Creative Retreat in arctic Norway. She lives, works, and recreates on Dena’ina Ełnena, the lands surrounding Anchorage, Alaska.

solutions for its protection.

Above left: A muskox stands on the banks of the Hulahula River. These ancient herbivores graze on grasses and willows, playing a vital role in the fragile Arctic ecosystem. Left: A young, curious caribou rests near camp on the Hulahula. The Porcupine Caribou herd makes the longest land migration of any mammal on Earth, traveling to the Arctic Refuge coastal plain each spring for calving. Above: A sow and cub polar bear approach the village of Kaktovik in search of food. As Arctic sea ice seasons shrink with warming temperatures due to climate change, polar bears face growing food scarcity and increased conflicts with humans.

The high peaks of the Brooks Range hold snow year-round. Here, the headwaters of the

River are illuminated by the midnight sun around 2 a.m.

56 Adventure Guide: Winter Yurt Camp in Yellowstone’s Hayden Valley

62

Feature: Swallowed by the Mountain

70

Q&A: Emma Schwerin

76

Essay: The Fragile Edge

By Kathleen Smith

When winter settles over Yellowstone National Park, the vast landscape takes a deep breath, the roads close, and some of the most amazing scenery and wildlife are left to be enjoyed by the few who are willing and able to access it. I should know: Working as a ski guide for Yellowstone Expeditions, a small yurt camp tucked away in Yellowstone’s Hayden Valley, I’ve experienced the magic of this winter wonderland in a way few ever do. From early mornings chipping ice off snow buster vans — passenger vans outfitted with track conversion kits for snow travel — to evening skis watching coyotes fight otters for a fish dinner along the Yellowstone River, to bison warming themselves in the steam of bubbling thermal features, yurt camp is a once-in-a-lifetime experience (or for us guides, once a year)! Blankets of snow insulate the park, providing solitude and a reprieve from the busy summer tourism season. With many of the roads closed in winter, wildlife roam more freely across the quiet landscape — yet the season still brings its own relentless challenges for survival. For those who venture in, winter in Yellowstone offers a rare, raw experience: a glimpse into the park’s wild heart when nature is both most vulnerable and most alive. Guests explore thermal basins, ski through vast meadows, canyons, and along steaming creeks, and listen to the howl of wolves echoing through the stillness.

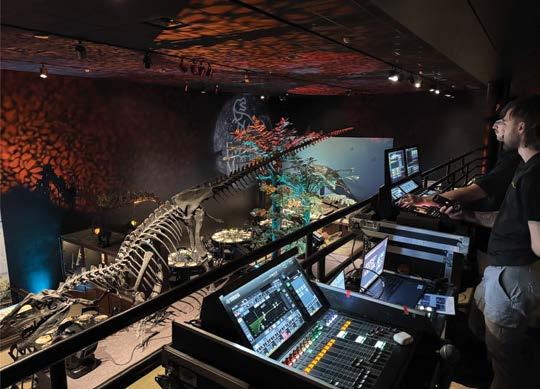

Near the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone River, Yellowstone Expeditions’ yurt camp is a haven where adventurous outdoor enthusiasts explore the park by skis, snowshoes, snowcoaches, or through photography. Guests work with guides to personalize their experience and plan routes and skis that are aligned with their goals and abilities. Upon arrival at yurt camp, hosts and guides greet the guests, welcome them to camp, and provide the appropriate gear for each person. Guests then embark on their first cross country ski, following a trail that provides access to the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone River. Guides lead adventurers to a viewpoint where the Lower Mesa Falls towers over 300-feet tall. In the cold winter months, the spray from the waterfall freezes and forms an ice tower at the base. Those lucky enough may see river otters playing and sliding around on the ice, showcasing the whimsical life that exists in Yellowstone’s winters.

Back at camp, guides are bustling, preparing appetizers and drinks in the main yurt. Guests, in groups no larger than 16 at full capacity, begin to get to know each other and chat with guides about goals for their stay in the park. Some hope to cover miles, test their endurance, and conquer long days on skis, while others are looking for casual ski outings exploring the thermal basins. Others aspire to track and photograph the Wapiti wolf pack and other wildlife, which are active and often easier to observe in winter.

The first step is to book a stay with Yellowstone Expeditions. This can be easily done online, but don’t wait; the experiences tend to book out a few months in advance! There’s a four-day and a five-day option for staying at camp. Guests meet in West Yellowstone at the park’s West Entrance, where the snowcoach picks them up to shuttle them to basecamp. For visitors coming from far away, West Yellowstone is about a two-hour drive from the Bozeman Yellowstone International Airport and offers a variety of lodging.

The accommodations at yurt camp are nothing short of magical — like the North Pole, stepping into Santa’s village. Two large traditional style yurts are connected to form a dining and kitchen yurt where guests enjoy hearty home-cooked meals and share stories from the day. The rest of the camp is dotted with small “yurtlets” designed after Scandinavian ice fishing huts, heated by individual propane stoves and providing a cozy private space for each guest. Throughout the winter, snow piles up between the yurts, muffling the sounds of any movement or chatter from neighboring yurts and accentuating the silence.

Winter in Yellowstone is one of the harshest climates I have ever experienced. Temperatures are rarely above 0°F, and sometimes plummet to −60°F. On days where temperatures are colder than −30°F, we wait for the sun to come out before we ski. Yellowstone Expeditions provides a great packing list before arriving at camp, but I have included a few recommendations for items I couldn’t live without during winters in the park.

+ Layers: Top and bottom base layers, fleeces, and insulated outerwear will keep you comfortable on the trail.

+ Extra gloves and socks: Cold feet/hands are the worst. Come prepared with extras of everything — but especially a second pair of warm gloves or mittens and more socks than you would think!

+ Thermos: A hot sip of tea, hot chocolate or coffee on the trail is a luxury in the harsh Yellowstone winter.

+ Cozy yurtwear: Slippers and warm, comfortable clothes to wear as you sit around the fire and enjoy the evenings at camp.

+ Something to document your trip: While we spend a lot of time basking in the moment, having a camera and/or a journal to keep a record of this special experience will help you enjoy it later. I know I love to flip through old photos from my time out here.

Kathleen Smith is an adventurous girl based out of Bozeman, Montana. She spends her summers as a whitewater raft guide, her shoulder seasons chasing rivers and her winters as a ski patroller. She loves all things water, frozen or melted!

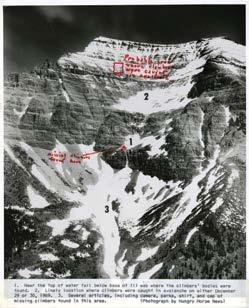

■ Above: A photo by Jim Anderson, recovered from the area seven months after the 1969 tragedy, shows the climbers traversing onto the west face of Mount Cleveland in Glacier National Park. Right: At 10,466 feet, Mt. Cleveland is the highest mountain in Glacier National Park. In December 1969, five young men died in an avalanche while climbing, or possibly descending the peak.

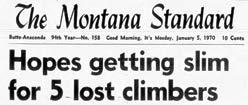

Mount Cleveland, 1969

At the southern end of Upper Waterton Lake — a body of water bound by imposing mountains that span the Montana-Alberta border — looms the tallest peak in Glacier National Park. At 10,448 feet, Mount Cleveland rises above the lake, an ominous sentinel of limestone presiding over a remote and dramatic landscape.

The massive mountain’s 4,000-foot, almost-sheer north face is described in the Climber’s Guide to Montana as “the greatest sudden piece of vertical topography in the lower 48 states.” The mountain, with its summit often blanketed in clouds, can be brooding and foreboding, especially in the winter months. From the final days of December 1969 to July 1970, Cleveland concealed its secrets deep in snow and ice.

That winter, on the day after Christmas, a band of intrepid college students and mountain climbers from Butte, Helena, Bozeman, and Bigfork left their families and the holidays behind and drove north to Glacier with a lofty goal — to scale Mount Cleveland via its imposing north face. If conditions precluded that route, Plan B was to climb the mountain’s more accessible west slope. Either line would be a first: There were no records of anyone reaching Cleveland’s summit by way of the north face, and the steep, avalanche-prone mountain had likely never been ascended by any route in the depth of winter.

It was a bold plan, and one that members of the climbing team had been working toward for several years. Jerry Kanzler, 18, grew up in Columbia Falls and had climbed extensively in Glacier and elsewhere with his father and older brother before enrolling at Montana State University in Bozeman. Jim Anderson, also 18, was from Bigfork, a fellow MSU student

with a love of climbing who had twice summited Cleveland in warmer months.

Mark Levitan, 20, from Helena also attended MSU and had reached the top of Wyoming’s Grand Teton. The remaining two, Clare Pogreba and Ray Martin, both 22 and students at Montana Tech in Butte were regarded — along with Kanzler — as the most experienced and skilled climbers in the group.

Pogreba, Martin and Kanzler, along with a few others, were among the members of an informal clan of climbers known as the Wool Sox Club. Pat Callis, a fledgling chemistry professor at MSU at the time, was also part of the club, and had climbed with the three a number of times. “It was an amazing group,” he recalled in the summer of 2025. “These kids were special.” Callis, now 87, said Pogreba had asked him to join the Cleveland attempt. Having recently returned from another climbing trip, he’d declined.

As they made their way to Waterton, the five students stopped to share their plan with Bob Frauson, Glacier’s St. Mary’s district ranger, a no-nonsense World War II veteran and experienced climber who had served in the Army’s famed 10th Mountain Division. The ranger checked the men’s gear and issued warnings about Glacier’s unpredictable weather, the slim odds of rescue if they got in trouble, Cleveland’s reputation for avalanches, and a recent storm that had left the mountain coated with ice. “I talked to them a long time about the danger,” Frauson said years later.

The five climbers arrived at Waterton Townsite in Alberta on December 27, and hired a man with a boat to ferry them and their gear up the lake to the Goat Haunt ranger station, near the base of Cleveland. The boat driver, Alf Baker, dropped the five men off; he was the last to see them alive.

The first hint that the climbers might have found trouble came just two days later when Bud Anderson, an older brother of the Bigfork climber, flew a private plane around Cleveland to check

■ Top: An aerial photograph from the Hungry Horse News, a weekly newspaper in Columbia Falls, outlines a possible sequence of events on the mountain's west slope. Photo courtesy Glacier Park archives, photographer unknown

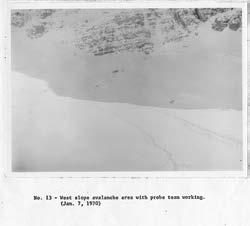

Above: Searchers combed the west slope of Mount Cleveland for almost a week in January 1970 in search of the missing climbers. Photo courtesy Glacier Park archives, photographer unknown

the team’s progress. He didn’t spot the young men. He did see tracks, maybe human, maybe mountain goat, on the mountain’s west slope. He also saw signs of a fresh avalanche near the tracks.

Two days later, Anderson, joined by a Waterton park warden, took a boat up the lake to search the area near the base of the mountain. They found only skis and snowshoes apparently cached by the climbers. The next day, searchers found an assortment of climbing and camping gear, possibly a base camp, below the mountain’s north face. Tracks believed to belong to the climbers led to the west.

Over the ensuing six days, would-be rescuers from Glacier and Waterton and expert alpine rescuers from nearby Canadian national parks and Grand Teton traveled to the slopes of the remote Montana peak. They were joined by volunteers including Callis and Peter Lev, an experienced alpine guide who was teaching a mountaineering course at MSU. At the time, Kanzler, Anderson and Levitan were among Lev’s students. Another Bozeman searcher was Jim Kanzler, Jerry’s older brother, an experienced and skilled climber and ski patrolman at Bozeman’s Bridger Bowl. Like Callis, he had spurned an offer to join the Cleveland climb, citing work and family.

belonged to Jim Anderson, resting in a gully. Shortly thereafter, they found other items, including Anderson’s camera. Hastily developed film showed the missing five trudging through snow toward Cleveland’s west slope.

For the next few days, the searchers combed the avalanche area using long probes and a magnetometer, a device that could detect metal buried deep in snow. They found no further traces of the climbers. On January 9, with a have thought they were rinky-dinking around, but these boys were dead serious. They studied Mount Cleveland from every angle.” In her eyes, there was no mystery about what motivated the young climbers. “They wanted to be first; this was the uppermost thought in their lives.”

While the early days of the search focused on a campsite near Cleveland’s north face, Callis, Lev and Jim Kanzler were dispatched to the mountain’s west slope where they found clear signs of potential tragedy. “It was obvious that the whole face had seen a number of avalanches — there were lots of broken slabs,” Callis recalled. “It’s just like the whole west face went.”

After several days searching, the three made a key discovery: a pack that

The loss of her son was the second family tragedy for Jean Kanzler in as many years. Her hard-charging

husband, Hal, who had introduced his sons to climbing and outdoor adventure in Glacier when they were young, had committed suicide just two years earlier. She had moved to Bozeman not long before the Cleveland climb to be near her sons. The search suspension brought a small measure of closure. “There are regrets, deep ones of course, but no real ones,” she said. “I couldn’t live Jerry’s life.” The mother also predicted that her son’s body would be the last to be found on the unforgiving mountain.

The hunt for the missing climbers resumed in May 1970, amid dicey conditions created by melting water, tumbling rock and snowslides. On May 29, searchers decided to climb to Cleveland’s summit following the route

likely taken by the missing men. Well below the summit, in a bowl area just above a waterfall, they spotted a body with a red climbing rope still attached. It was Ray Martin. That same day, the searchers reached the body of Jim Anderson attached to a gold rope. Using photos recovered earlier from Anderson’s camera, the searchers suspected they would find Mark Levitan along the path of the gold rope, followed by Clare Pogreba. They believed Jerry Kanzler was linked by the red rope to Martin.

With shovels, Pulaskis, and ice chippers, and later using a system that tapped water from a nearby natural pool, the recovery team used a highpressure stream to speed the removal of debris and snow more than 25 feet deep in places. On July 3, the searchers reached the remaining bodies and extracted them, along with the remains of Jerry Kanzler, who was, as his mother predicted, the last of the five to be ferried off the mountain.

The same day, in the Inter Lake, Glacier superintendent William Briggle, who flew in the helicopter that brought Kanzler’s body off the mountain, noted the sadness of the deaths but defended

the right of the young men to climb. “If they insist, there is nothing we can do about it. They have the right to make that attempt,” he said. As for future adventurers, “We will try to guide them in making their decisions. And we’ll tell them the story of five young men and 188 days . . . perhaps Mount Cleveland can speak louder than we can.”

In the coming days and weeks, Jerry Kanzler was buried next to his father in Glacier Memorial Gardens in Kalispell. Mark Levitan was buried in Home of Peace Jewish Cemetery in Helena. Clare Pogreba and Ray Martin found their final rest in side-by-side graves in Butte’s Mountain View Cemetery. The ashes of Jim Anderson were spread over Mount Cleveland, fulfilling an “if anything happens” request he’d made to his family. The Anderson family, with the support of families and friends of the other climbers, built a monument memorializing the five men in Yellow Bay State Park, next to a small creek that trickles into Flathead Lake.

In 1976, Jim Kanzler, Terry Kennedy, and Steve Jackson became the first climbers to complete a full ascent of Mount Cleveland’s north face, propelled in large part by the 1969 tragedy. Callis said he would have liked to have joined the climb but was out of town. He had returned to Cleveland in 1970, not long after the bodies were recovered. He has not been back since. Recalling the invitation to join the ill-fated climb, he said, “I’ve often wrestled with the question of whether I would have died along with them,” adding that there are elements of the long-ago tragedy “that you can’t let go.”

The ill-fated Mount Cleveland climb is the subject of The White Death: Tragedy and Heroism in the Avalanche Zones, published in 2000. Author McKay Jenkins, a college professor who lives in Maryland, first learned of the Cleveland story in 1997 after attending a presentation by Frauson during a trip to Glacier. Working over two years, Jenkins dug into the lives of the climbers and their families to capture what he describes decades later as “a really indelible story.”

In 2017, Kennedy, a longtime Bozeman physical therapist who grew up in Columbia Falls near the Kanzler

family, authored, In Search of the Mount Cleveland Five, chronicling the tragedy as well as a series of climbs with Jim Kanzler and others, including the 1976 successful Cleveland north-face ascent. Since then, Kennedy has climbed Cleveland four more times, conducting a personal investigation into the possible sequence of events that led to the climbers’ deaths. The official 1970 park report into the accident concluded that the young climbers were buried by an avalanche as they traversed the mountain’s west face well below the summit. The summit register retrieved by helicopter during the initial search didn’t include the names of the climbers.

Kennedy, relying on his recent climbs, the study of the entire series of Jim Anderson’s 30-some photos from decades ago and current images of the mountain, reached a different conclusion: “I think these guys reached the summit and were killed in the dark on the way down.” As for the summit register, he speculated the climbers had reached the top late in the day, were being pounded by wind and cold, and as darkness approached, chose to leave the peak quickly, forgoing the register.

The possibility that the climbers reached the summit admittedly offers little consolation to family or friends. Claiming the first winter ascent of Cleveland holds meaning in the mountaineering world, Kennedy said. Reaching the top would validate the effort and dreams of the young climbers.

While he still finds the deaths on Cleveland haunting, Kennedy says his investigation, more than five decades after the climb, has a practical motivation. “I decided somebody has got to do it, or otherwise the whole thing fades into nothing. It’s going to be lost to history.”

Butch Larcombe worked for 30 years as a newspaper reporter and editor and as the editor of Montana Magazine. His book, Montana Disasters: True Stories of Treasure State Tragedies and Triumphs, was published in 2021. His most recent book, Historic Tales of Flathead Lake, was published in 2024. He lives near Bigfork.

By Sophie Tsairis

On May 15, 2025, Bozeman resident Emma Schwerin stood at the top of the world. At just 17 years old, she reached the summit of Mount Everest at 29,032 feet above sea level, becoming the youngest woman ever to complete the Seven Summits — the highest mountain on every continent — and the youngest American woman to summit Everest.

Her size never defined her; her determination did. She went big. From 4-hour Stairmaster sessions to a mountaineer course in Bolivia, to carrying more than her bodyweight up Denali, her determination and focus never wavered. Encouraged by her family and accompanied by her father and their guide Tendi Sherpa — an 18-time Everest summiteer — Schwerin carved her name into mountaineering history.

Mountain Outlaw sat down with Schwerin before she headed back to her senior year of high school to find out what it takes, emotionally and physically, to accomplish such a big dream at such a young age. She reflected on what the mountain gave her — and what she hopes to give back.

Mountain Outlaw: What inspired you to take on a challenge as massive as the Seven Summits?

Emma Schwerin: I went to Headwaters Academy in Bozeman for middle school, and in English class, one of the units was on Mount Everest — super random, but it changed my life. We read Into Thin Air and The Climb, which are about a famous disaster on Everest. We also watched a documentary, and there was a scene in it that showed someone crossing a ladder on icefall, and I remember watching it and thinking, ‘That looks amazing.’ I was driving up to Big Sky to ski for my birthday, and I was with my dad — just the two of us — and he was

asking, ‘How’s your day’ and I was telling him about the unit we were doing in school and how cool it was and how it would be so awesome to do something like that one day. He was like, ‘Yeah that would be super cool — we should do that.’ So, we decided the next day. We booked a trip to go to Everest Base Camp, which is a two-week trek to get there and back.

MO: Which summit was the most challenging and which was your favorite?

ES: Mentally, Aconcagua [the highest peak in South America] was the hardest because of the wind. We almost didn’t get to summit — you don’t know if it’s going to happen until the last minute.

Everest was definitely the longest. It was 50 days, and it just kind of eats away at you emotionally — being so far from home for that long, waiting on weather. That part was really hard. Everest just kind of changes everything. It’s not like any of the other Seven Summits. The only thing you can really compare Everest to is other 8,000-meter peaks, just because there’s no other mountains that you have to spend two months preparing for and acclimating for. So Everest, it’s just like … it’s a crazy experience. And I mean, it was one of my favorite mountains. But Denali was the hardest mountain physically, for sure. You’re carrying a 60-pound pack and dragging a sled behind you, and your body just gets broken down. I think Denali was my favorite, even though it was brutal. It was just so beautiful and remote. It felt wild.

MO: Did you encounter people who didn’t think you could do it? What did your family think?

ES: Yes. That was something that I really struggled with. Denali was kind of the turning point for me. After I climbed Denali, whenever I showed up, I was able to say, ‘Well, I climbed Denali.’ Before that, it was especially difficult because people thought I was just this little girl who was saying, ‘I’m gonna climb the Seven Summits, and I’m gonna be the youngest woman to do it,’ and people would be like, ‘Okay, sure … yeah, oh, okay.’

After Denali I was also able to say I carried all my own gear — 120 pounds — so at least I could tell people that, and it would stop them from doubting me, I guess. But I mean, I had to believe in myself a lot, because pretty much no one else would. I mean, some people did, but a lot of people would doubt me. I would show up for a climb, and if I was in a group, people would look at me and see this girl who’s 4-foot-11, and assume that I was going to be the weak link, and that I was going to be the person holding everyone back. And so, it was really frustrating for me to know that when I showed up, people

already had an impression of me that wasn’t right, and it wasn’t true, and I had to change that.

I’m very grateful for [my parents]. I definitely couldn’t do it without them. I’m very grateful for my dad, because there were a lot of times when it was really difficult, and I was glad that I had someone who always believed in me from the start. And there were people, like all my friends on Everest, they believed in me a ton, but it was nice to have someone who believed in me before I proved in an actual concrete way that I could do it.

MO: What did your training consist of — the physical and the mental?

ES: I trained for two years, six days a week, anywhere from one to maybe five hours a day. So, it was a lot. The Seven Summits … those mountains were a small portion of the hard work. The training was really difficult. I go to boarding school, so my gym is in my high school, full of my high school peers. That was something that was very difficult for me, because I would go with my giant Denali backpack, which is taller than I am, walk in, and I would take the weights and put them in my backpack.

I was like, ‘People probably think that I’m stealing these weights right now.’ And then I would go on the Stairmaster for four hours with the pack. The nice thing was that the Stairmaster faced a window, and I couldn’t see anything behind me. So, I was like, ‘People are giving me weird looks, and that’s okay. I can’t see them.’

The mental training was a big thing too. I had to learn a lot, because I would get really nervous. And I was always way more nervous the weeks before I even left than when I was on the mountain. Every time I got to the mountain, I was like, ‘OK, this is fine. I can do this, because now I can’t train anymore. I can’t change anything. And I’m here, and this is it.’

I always thought to myself that it was going to be some level of hard — and it’s either gonna be hard right now, in my training, or it’s gonna be hard later. And I get to decide.

MO: Were there any specific moments of doubt? How did you get through them?

ES: A very different thing about Everest, is you have to go through the icefall. It’s between Base Camp and Camp 1, so it’s pretty early on. And we went through the icefall six times. So, you go up three times, down three times. I think that there were probably … there were only a few days on Everest that I was scared, and I mean, most of them had to do with the icefall.

I think of the night, the first time I went through the icefall. I think about the night that I had the most growth and that’s the same night as the night I was most scared. And I mean, summit night was great, I summited, and it was wonderful and there were challenges there, but I remember waking up the night before and pretty much knowing that I was going to summit, and so that was kind of different. But the night we went through the icefall for the first time, I was just very nervous.

A friend [on Everest] told me this quote: “If it wasn’t scary, it wouldn’t be big enough.” And, oh my gosh, it just, really changed my life, and I remember every time I heard an avalanche going through the icefall that night, I would just repeat it in my head. And I remember when he told

me that I was like, ‘Wow that really resonates with me,’ and I think that’s something I’ve learned from this whole thing is that if I’m not challenging myself to where I’m scared, I really could be challenging myself more. Because the other Seven Summits were also challenging, but the night that I changed the most and learned the most was the night I was most scared. And I don’t think that’s a coincidence. I think that because I was so scared, I was able to push myself and work through that.

MO: How did it feel to complete this huge goal?

ES: So, I mean, I guess if I told myself before I started the whole thing, that person would be very proud. But I worked every day for two years trying to accomplish [this goal]. And so, for me, it wasn’t really like, ‘Oh my God, I did it.’ It was relief because I accomplished it, and nothing got in my way. I was proud, but at the same time, I was confident by the end because I knew how hard I worked. I have three world records and that’s great, but it’s not crazy for me because I guess I lived it, and I couldn’t really work any harder. Yes, I’m very happy with it, but it’s also just like, the records — I never really did it for the records — they were nice, but … it was really just an extra challenge for me, and to me it just says how hard I worked which is more important to me than the actual numbers themselves.

Reaching the summit of Everest though, that whole thing felt like a dream — less in the moments where it was hard and more like, when we saw the sunrise, I thought, ‘This can’t be real, it’s so beautiful,’ … I was like ‘This is, this is a dream.’ And then I remember thinking, ‘I have to get down,’ because I sort of promised my mom that I wouldn’t celebrate until I got down.

MO: What has it been like returning to “normal life” after all of that?

ES: I think it is going to be hard for me to not be training towards something and working towards something, because I loved that I got to spend an hour or two each day, which isn’t that much in the grand scheme of things, training for something and then I was able to accomplish this insane thing. A lot of times people tell me, ‘Oh my God it’s so crazy that you climbed Mount Everest,’ but it’s similar to what other people do. I just decided to do this instead of something else. I know friends who spend an hour or two playing the violin each day, and they’re incredible at that. And so, I think that’s going to be hard for me to not be doing something small each day to work toward something big.

It’s my senior year, which is helpful because I’m trying to soak in all the fun memories of my last year of high school. I have plans [for the next adventure] already, just because that’s kind of who I am. I have to be working toward something. I’m trying to take a break for now, and just enjoy my senior year.

With the Seven Summits, it’s honestly, it’s super cool, but I also feel like I barely scratched the surface. People who don’t know a lot about it always ask me, ‘How are you going to do anything more? Haven’t you done all of them?’ But no. The tallest mountain outside of the Himalayas is Aconcagua, but that’s because all of the tallest mountains are in the Himalayas.

MO: What would you tell other young people — especially girls — who dream big?

ES: It’s really important to me to kind of be a role model for other girls and show them that even if you don’t have someone else to believe in you, you can believe in yourself. And that’s really all that matters. You can do crazy things — and you can be the girl who says she’s going to do something crazy and does it. I’m in this calendar actually… for this guiding company called AWE Expeditions … they sell calendars to help raise money for women, young girls’ scholarships to start mountaineering. And so that’s so fun for me; I get to help other girls do stuff like this.

Sophie Tsairis is endlessly curious, constantly humbled and inspired by what drives people to chase bold dreams. She is the managing editor at Mountain Outlaw.

This fall marks a remarkable milestone—twenty years of bison on American Prairie. Our herd, now over 900 in number, has already started to return and repair important ecological processes on the prairie. We look forward to the next twenty years.

To learn what you can do to support bison VisitAmericanPrairie.org.

Words by Lauren Burgess

For all they give us – vitality, identity, the taste of freedom – the mountains also take. Loss comes in layers: some wounds temporary, some weathering us down, some rupturing us forever. How do we live when not just what the mountains mean to us, but our inner landscape itself, has been forever changed?

We love the mountains for what they make of us. Grit applied to a dream – rubbed in with sweat, frostbitten breath, and stubbornness – becomes tangible. We love the rough-cut meeting of flesh and stone and snow. We love who we are “up there.”

Unburdened by deadlines, small talk, and cultural baggage, a backpack feels almost weightless. We call it being our best selves. Our true selves. Our purpose simple: What can I feel? What can I learn? What joy awaits?