Editor's Note

As I’m writing this, my surroundings are very different from Jackson, Tennessee’s usual hot summers. I’m surrounded by cypress trees and a cold, fresh spring-fed river that’s crystal clear. There’s birds chirping; the morning sunlight is glistening on the river in a magical kind of way. I’ve grown up coming here my whole life. We’re on family vacation in Florida, a place that makes me feel like a kid again no matter how old I get or the season of life I’m in. This week is the peak of summer, eating cherries and watermelon on the dock in the heat of the day or floating down the river at dusk.

I worked on the journal for some of the time I was in Florida this year. Creatively, it was a magical experience for me, as anything is when I do it at the river house. I noticed more when I was forced outside of my normal busy schedule of going from place to place in Jackson. This journal pops with vibrancy and color, with stories of growth, of what real community is to people, of how a craft is discovered and created from the ground up. This summer's ‘Made in Jackson’ journal is filled with some who have just moved to Jackson within the last few years, and others who can’t remember a day not in this town.

As I sat and read the stories again and again, with the sound of the river flowing in the background, I was struck by how much we can notice if we just step outside the norm of the everyday hustle and bustle of life. The stories we can see, the thoughts that flood our minds, or the quiet that can be scary, but healthy for our bodies.

Summer is always a busy season for me, as I know it is for many of you reading this. My encouragement to you this busy summer season is to find a moment — maybe it’s just in your kitchen or your backyard, maybe it’s driving to a park or a place that’s relaxing for you. Allow this journal to give you an excuse to find a few moments to sit, to read the stories of people making our community into what it is, and to learn from them. Be a ‘maker’ of Jackson right in your own circle, even if no one sees the work you’re doing. You matter to Jackson. It takes all of us to create a home.

MADDIE MCMURRY, EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

CONTENTS

6/MAKENZIE WINTERS

Crowned With Purpose

12/CATBIRD STUDIOS

Art Is Infrastructure By Margee Stanfield, Photos by Kristi Woody

18/LOVE YOUR BLOCK

The Sustainable Beauty of Restoration

By Gabe Hart, Photos by Mirza Babic

22/ESSAY

Community By Trey Thompson

28/STEPHANIE RILEY

Lucky To Have the Work

By Julia Ewoldt Stooksberry, Photos by Carrie Cantrell

34/SCOTT DONEY

Anywhere but Behind a Computer

42/SPONSOR FEATURE: COMMUNITY FOUNDATION OF WEST TN Rooted in Community, Growing With Purpose

48/CARITA COLE

The Dreamy Depths of Duality

By Trista Havner, Photos by Cari Griffith & Trunetta Atwater

56/POEM

Homestead Morning

60/ JASON REEVES

Tending Relationships Through the Garden

Story & Photos by Maddie McMurry

By Shelby Tyre, Photos by Darren Lykes & Bridgett Wright

By Truman Forehand, Photos by Maddie McMurry

By Evangeline Holmes, Photos by Cari Griffith

Crowned With Purpose MAKENZIE WINTERS

WRITTEN

BY

PHOTOGRAPHED BY DARREN

SHELBY TYRE

LYKES & BRIDGETT WRIGHT

MaKenzie Winters moves like she was born mid-performance — grace in her bones, purpose in every step. And somehow, the music’s only just begun.

Raised in Jackson, Tennessee, MaKenzie is quick to trace her roots through a childhood filled with motion — of the body, the spirit, the community that formed her before she even realized it. “I’ve played so many different sports growing up. And I went to church, so I had community all around me,” she said. She attended East Elementary, then Northeast Middle School, before enrolling in the Early College High program through Jackson State Community College. “If I was to describe what living in Jackson is like, it’s probably the people that I surround myself with that make it feel like home.”

From the very beginning, MaKenzie was learning choreography — sometimes in the form of drills or classroom routines, sometimes in the gentle cadence of Sunday morning services. But it was her mom who helped her find the rhythm of her own story. “If you could think of your biggest supporter, think bigger. That’s my mom,” she said. Whether it was driving her to practices, prepping with her for events, or sitting her down to choose between cheer and volleyball, her mom’s presence was both grounding and empowering. “She sees it in me, and she recognizes my talent, and she’s not scared to embrace that.”

If there’s one thing you should know about MaKenzie, it’s that dance has always been her throughline. She trained at Pat Brown School of Danc-

ing, a studio that became more than just a practice space — it became a kind of foundation. It was there she learned the language of movement and, for the first time, saw herself reflected in it.

As a Black ballerina in a majority-white environment, MaKenzie had grown used to being the only one in the room who looked like her — until she met Jennifer Whitelaw, a dancer and one of her instructors at Pat Brown. “She taught me for the first time when I was about ten, and I was so excited,” MaKenzie said. “It was just — seeing someone who looked like me, the passion was brought back into me.”

Jennifer wasn’t just an instructor — she was also the first Black girl to play Clara in The Nutcracker at Ballet Arts. Years later, MaKenzie followed in those footsteps, becoming the third. She would go on to play Clara twice, and during her second performance, Jennifer surprised her by showing up in the audience.

“When I say unique, it’s just experiences like that that make it feel like, okay, I’m in the right place at the right time. I’m supposed to be here.”

It was more than a role — it was a step forward in claiming her place in a dance she’d long been part of.

While ballet was her first language, pageantry came later — a different kind of stage, but no less demanding.

“Miss Juneteenth Jackson was my first pageant, and I was blessed enough to be able to participate here locally.”

MaKenzie won not only the crown, but also Best Talent, Best Essay, and Miss Congeniality. The experience lit a fire in her and gave her a powerful platform to stand on.

“I get the platform to represent what Juneteenth is, and I get to tell people about it — who do know, who don’t know — and I can expose different people to it,” she said. That legacy of liberation, of voice, of visibility — it pulses in her like music.

“If I was to describe what living in Jackson is like, it’s probably the people that I surround myself with that make it feel like home.”

She went on to win Miss Bronze, Miss Murfreesboro Teen Volunteer, and Miss Juneteenth USA 2024–2025. But through it all, her humility remained. Pageantry didn’t rewrite her; it simply gave her new choreography to move with confidence through the spaces she already belonged to.

She knows how easily people make assumptions, especially about pageant girls, but MaKenzie’s presence is quiet strength, not self-importance. “My

mindset and my perspective were fully changed by that first pageant. Being able to do that one as my first, rather than jumping straight into the longstanding system — it was definitely something I needed to take baby steps into.” Her confidence is a reflection of how deeply she’s rooted. Her radiance never feels performative. It doesn’t come from ego or applause — it comes from alignment. From muscle memory. From that deep understanding that she is dancing in step with something bigger. This presence she brings, this grounded poise, is rooted in purpose — a purpose shaped by the community that raised her and the stages that held her. “Growing up in Jackson meant knowing who you are and who’s in your corner — and that kind of sup-

"Her radiance never feels performative. It doesn’t come from ego or applause — it comes from alignment. From muscle memory. From that deep understanding that she is dancing in step with something bigger."

port never leaves you.”

The metaphorical crown she wears is heavy, and that’s on purpose. She carries it well, showing other girls, young artists, and dreamers that it can be done — with kindness and grace and love — all while holding the door open behind her.

MaKenzie’s platform centers around expanding access to the arts, especially for young Black creatives. “My platform promotes the arts with a specific emphasis on the performing arts as a way to infuse pride and accomplishment in young people and specifically minorities like myself who weren’t always exposed to the arts when we were kids.”

Her path forward is clear: finish school, dance professionally, pursue social work, and eventually open her own performing arts company — one that includes music, theater, and band. She’ll be taking the next step of that

journey at Howard University, where she was recently accepted on a full scholarship. But, no matter where that future unfolds, her heart remains tethered to Jackson.

When asked what scares her most about the future, she answered without hesitation, “My ambition. I just want so much for myself and the people around me. I want to put myself out there and try new things and make a difference.”

It’s that hunger, and that self-awareness, that make her “made in Jackson” in the truest sense. The stages she’s stood on, the dance floors she’s trained on, the pageants she’s entered, the coloring books she’s passed out at summer camps, they’ve choreographed not just where she’s been but the grace and power with which she’ll go.

The music may change, the stages may grow, but the rhythm that shaped her will carry her through.

CATBIRD STUDIO

Art Is Infrastructure

WRITTEN BY MARGEE STANFIELD PHOTOGRAPHED BY KRISTI WOODY

Stepping into Catbird Studio feels like stepping into a world of flourishing creativity. You might just be stopping in for a latte from J-Town Coffee and settling into a cozy seat in the Catbird living room, but your senses will undoubtedly be enveloped by so much more, revealing the fact that this space’s roots run deeper than you might have imagined.

In a sort of symphonic synchrony, various forms of art intersect in this one building. On a given day, you might hear all these sounds all at once: piano keys chiming, the strum of strings, the swish of paintbrushes, the clinking of one chess piece claiming another. Someone is on stage. Someone is having a voice lesson in the music room. People are dancing. Kids are learning. Ideas are blooming, and inspiration is flowing. It all comes together — not just coexisting, but connecting, in this space that allows creativity and the joy of art to flourish and seep into every nook and cranny.

It’s infectious.

“I want every single person that walks in here to walk out feeling encouraged to continue being creative,” Suzanne Gillis, Owner and Creative Writing Director of Catbird Studio, said.

Catbird Studio is multifaceted, and what it does can be hard to describe succinctly. Each team member I talked to described it in their own way.

“We're an art studio and event venue. We do basically anything creative you can think of, and we try to either teach those skills or help hone those skills during the daytime, and then we like to show off those skills for events at night,” Suzanne said.

“It's a place that you can come and be the most creative version of yourself. Even if you think you're not creative, there's something for you here,” Leigh Ann Barrios, Catbird Studio’s Art Director, said.

“It's a place for all kinds of creators: writers, actors, musicians, photographers — everything. However you want to do art,” Kristen McAfee,

Photography Director, said.

“Nothing like this has ever been in Jackson before. This type of space and environment is so unique. I call it my little unicorn,” Chrissy Taylor, Art and Piano Instructor, said.

Whether you’re five or 55, starting a new art form or honing an old one, eager or hesitant, there is a place for you here. You can find classes, parties, camps, photography sessions, concerts, and theatre productions, among other events, all at Catbird Studio. Whether it's engaging with someone else’s art or branching out and making your own, Catbird wants to see you — and Jackson — dive in.

“I want people to be able to not just create here — because that's the obvious thing that we do is create,” Suzanne said. “But I want people to feel like they can learn and connect and grow with other people and also with their craft.”

gonna bring the quality — we have to go to Memphis or we have to go to Nashville to get that kind of quality. When it comes to art, we don't have to,” Suzanne said.

Art is alive and thriving right here in Jackson; we just have to engage with it.

“I've had those moments where I just let myself get down and think, ‘I don't know if they'll ever embrace us the way I want them to,’ but also, we'll turn right around and have another event, and everybody will show up to it, and my energy and my passion and my love for what we're doing here is completely restored,” Suzanne said.

"Art is alive and thriving right here in Jackson; we just have to engage with it."

Catbird understands the power of art. Art can be a connective tissue and a seed for growth.

Art is not just entertainment; it's infrastructure.

The culture of a city can flourish or fade based on how it interacts with art and the people who make it. Whether we realize it or not, we are shaped by the art around us every day. And it is, in fact, all around us — even if some people in Jackson have yet to discover that reality. Some don’t think to engage with art at all. Others assume they have to leave town to find it.

“The conflict of it all is we're sort of set in our ways. I think it's still easy to maybe not trust that Jackson's

Chrissy painted me a picture that is frequently witnessed at Catbird and that all the team members have experienced in various ways. When one student first came to Chrissy for lessons, she was incredibly shy.

“Now to see her at this last recital that we had, she's so fiery and confident and just this big energy in this room now. And it just tore me up to pieces,” Chrissy said.

Confidence is just one fruit born of engaging with art — it also builds relationships. One of Chrissy’s greatest joys is having a student, like this one, simply share with her during a lesson what is going on at school or what they did last weekend.

“Being able to not just teach her, but also being able to be a connection for her outside of school and at home is something that is just … you can’t replace that,” Chrissy said.

Leigh Ann echoed this sentiment, having had the same experience.

She also spoke about why these moments here at Catbird — whether it is one between teacher and student, coworkers, or just art and artist — are so foundational.

“It's a safe place for them to talk and feel connected to somebody,” Leigh Ann said. “I feel like art is a way just to express yourself, to heal yourself through certain things. You don't have to become an artist because you enjoy art. But I think it kind of pours into the other things that you're gonna do in life.”

Catbird is seeking to be a space for art and creativity to thrive and expand in Jackson, and every day, it turns around and displays exactly why art is so important. Catbird proves the power of art. At Catbird, the confidence

of kids is blooming, strangers are becoming collaborators, and people are connecting on a deeper level through and beyond the art.

The catbird is one of the only birds that can mimic the sound of their predators and humans. They pursue a high vantage point so they can take in all of their surroundings from every direction and perspective. When danger threatens the vulnerable, they even use their talent to distract and protect. The catbird is creative, brave, and self-aware.

“We keep pushing forward and hoping that more and more people will learn about Catbird and learn about all the creative things that are happening in Jackson and just go from there,” Suzanne said.

The Sustainable Beauty of Restoration LOVE YOUR BLOCK

WRITTEN BY GABE HART

PHOTOGRAPHED BY MIRZA BABIC

Beauty is contextual; the definition is malleable to the point of elasticity. Is something beautiful because of its aesthetic quality? Is beauty found in spaces deeper than surface impressions? Can something be beautiful without a contextual, emotional connection to an object, person, or space? Yes and no. Beauty is subjective enough to be seen in each and none simultaneously.

Light spills down East Baltimore, scattering itself across lawns and roofs, towards Dr. F. E. Wright Drive. The houses on this block are roughly a century old. 100 years of history, transition, and light refracting east daily, forming shadows under trees, over empty lots, on repeat.

Time has pressed itself, subtly, on many of the homes in this neighborhood — paint chipping, wood rotting, ichnites of condensation on window panes. The surface blemishes symptomatic of deeper structural flaws.

Elvia Trejo, Neighborhood Spe-

cialist for the City of Jackson, carefully maneuvers a passenger van full of tools between parallel-parked cars on a narrow street in East Jackson. Slowing, then turning around in a driveway, the van's shocks well past their prime. She points to her left, focusing on three new windows with white trim beaming from the sunlight.

“If these windows stayed in the shape they were in, there would’ve been much bigger problems for the house. With the water and all the elements coming in, mold was just spreading. It was spreading through the wall, so we were able to replace those windows, fix all of that, and now their house is just fine. Now, the owners can also age in place,” she explained.

Along with Abby Palmer, Elvia works in the Neighborhood Services Department of the City of Jackson. Under the umbrella of this department, city residents can apply for grants for home improvement, borrow tools from a mobile tool shed, or complete a home

repair needs survey.

The cornerstone of this department is the Love Your Block (LYB) program — a high-impact volunteering initiative committed to reducing blight and inspiring neighborhood-driven change. LYB provides resources and funding for resident-led improvement projects, focusing on minor exterior home repairs, litter clean-ups, and neighborhood improvement.

Like beauty, love is also a subjective word. Love can be shown in a variety of ways — investment of time, intricate care, service to another person, to name a few. But what does it mean to love your block? To help meet the needs of your neighbors? Conversely, how much vulnerability and trust is required to ask for help when needed?

“We’ve had to be very intentional in building trust throughout the community with this program,” Elvia said. “People were skeptical at first. They didn’t understand how they could receive free repairs; they thought it was a scam.”

a free community refrigerator is accessible year-round for anyone needing something from it.

The genesis of LYB traces back to 2021 when Jackson was selected as one of eight U.S. cities to be funded by a grant program that brings city leaders and residents together to build stronger neighborhoods, one block at a time.

"I feel like in this day and age, we don't see a lot of neighbors that know each other, and I think that has been one of the greatest things that I've seen. Just people kind of slowing down, talking to us, asking, ‘What is this?’”

The first two years of the program focused on the physical aesthetics of homes that had aged precipitously over time. A fresh coat of paint on a front porch or a pressure-washed driveway can seem small on the surface, but each improvement restored a sense of pride in the homeowner and even inspired other homeowners on the street to make minor improvements to their properties. The surface beautification of these early projects helped establish LYB within the community and opened space for conversations between neighbors and neighborhoods.

Initially, the LYB program was relegated to East Jackson and provided only front-facing aesthetic work, but it has since expanded to every part of the city and now includes repair options for windows, siding, and partial roof repair. Along with minor home repairs, LYB commissioned multiple murals featuring past and present Jacksonians in downtown and East Jackson. Accompanying the mural next to JACOA,

“Once residents saw that we were raking leaves, cutting limbs, and things like that, the whole street transformed. So then, the following days, we saw people out there cleaning up on their own. And that has happened a lot when we are doing a house, other people will come out and they're like, ‘Well, I want to fix up my house too,’ and that has been really nice to see, because I feel like in this day and age, we don't see a lot of neighbors that know each other, and I think that has been one of the greatest things that I've seen. Just

people kind of slowing down, talking to us, asking, ‘What is this?’” Elvia said.

Today, the LYB program has evolved to include a mobile tool shed, a free lawn care service for qualifying residents, and mini-grants of $2,000 each to 20 homeowners for beautification and minor repairs. This program's importance reaches beyond cosmetic improvements; the deepest benefit LYB provides is the sustainability of property for longer periods, preventing irreversible damage. Most importantly, the program has allowed residents to stay in their homes.

One resident knows firsthand how vital LYB can be to a community.

“One of my windows was rotting around the trim. In the winter, I could feel the air coming through the windows. It was just terrible. I was worried the pane itself would fall out. I absolutely needed that window replaced, and I’m so happy I could get the help to do it.”

As LYB has grown, so has the need for volunteers. LYB contracts with Alpha Lawn Service for the yard maintenance program and a few contractors for minor repairs but still heavily relies on community members for work like painting, trash pickup, and pressure washing. Each provides opportunities for connection within the community, a soul-level beautification process of service and support.

Light will continue to scatter east from the west each evening, the sun setting on another day, the day to a week, the week to a month, and so on and so forth. Time will march, wood will rot, and paint will chip. Most of what LYB provides may easily go unnoticed by a passerby, but the beauty will always be found in the restoration, in the small details of sustainability and community.

COMMUNITY

ESSAY

& PAINTINGS BY TREY THOMPSON

This series is a tribute to the people who carry a place — often quietly, often without recognition, and often without asking for any. You’ve seen them. You might know their names, or maybe just their faces. They’re the ones behind counters, fixing things, feeding people, checking in, showing up. The ones who do what needs to be done because it needs doing.

The portraits in Community aren’t about status or accomplishment. They’re about presence. Every person here plays a part in holding their neighborhood together. Some lead with humor, some with grit. Some are tough as nails, some deeply tender. Many are both. What they share isn’t a personality type — it’s a choice to care. To make space. To do the work, seen or unseen.

They aren’t loud about it. Their impact doesn’t come from titles or speeches — it comes from consistency. From being the kind of person who knows what’s needed before anyone has to ask. The kind of person who remembers, who notices, who steps in. And when you see that kind of care in motion, it changes the way you move through the world. It makes you more awake to the quiet contributions that keep everything going.

I’ve tried to paint them the way they exist in the world: layered, textured, full of contradictions. Not romanticized or elevated, just recognized. Because that’s the point of this work — not to make these people into something more, but to reflect how much they already are.

But this isn’t just about them. It’s about what happens when we decide to look more closely. When we make space for people we don’t yet understand. When we choose empathy, even when it's inconvenient. A strong community isn’t built on agreement — it’s built on care. On the belief that everyone has value and that the small things matter. A kind word. A shared meal. A door held open. A neighbor checked in on. These things aren’t extra. They’re the foundation.

What I’ve learned from the people in these paintings is that you don’t need a platform to make an impact. You don’t have to be in charge to matter. You just need to be there — and be willing. The rest grows from that.

So let this series be more than a collection of portraits. Let it be a reminder. To be generous with your time. To look out for one another. To lead with understanding. Community isn’t built by grand gestures — it’s built by ordinary people choosing, every day, to treat each other like we belong to one another.

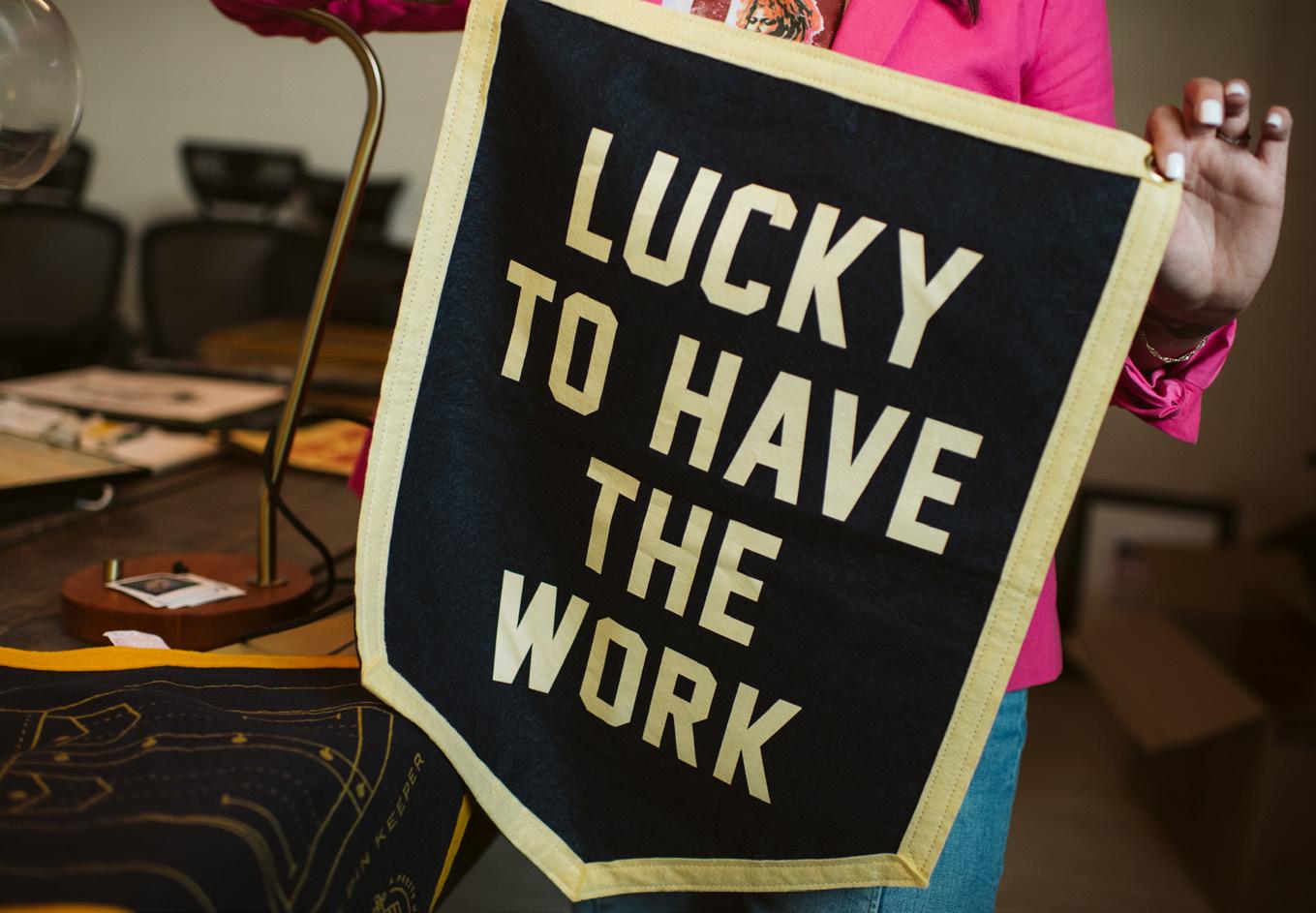

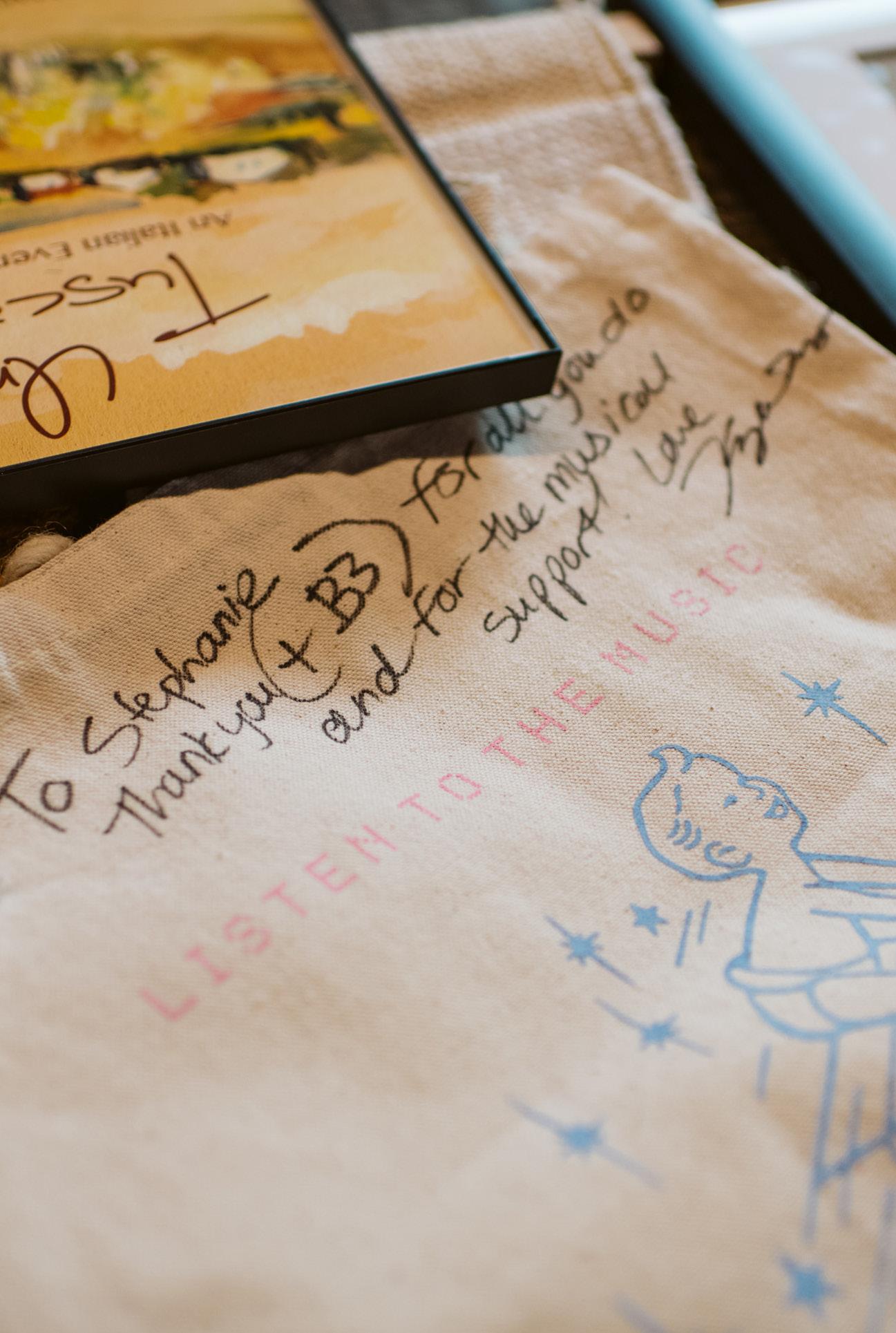

STEPHANIE RILEY

Lucky To Have the Work

WRITTEN BY JULIA EWOLDT STOOKSBERRY

PHOTOGRAPHED BY CARRIE CANTRELL

Her office is bright with afternoon sun. It still smells like fresh paint from the rich-blue walls and sunshine-yellow trim. Local, bold art is starting to adorn the walls. And the conference room table is cluttered with artifacts from jobs long completed.

It’s okay, though. It’s only her team’s first week in their new office.

Stephanie Riley holds up a felt pennant with the words, “Lucky To Have the Work,” from Jason Isbell’s song “Something More Than Free.”

Stephanie considers herself an artist and an entrepreneur. You may think the phrase “lucky to have the work” is a slight nod to that. It definitely is.

Stephanie Riley is the owner of B3 Creative Agency in Jackson, although she is originally from Union City. She first moved to Jackson after she worked for an area food-product supplier. From there, she started a design agency and then worked for a larger firm before building the business she has now.

As a third-generation business owner, she says her entrepreneurial spirit came directly from her parents and grandparents.

“In the fifth grade, I found an Oriental Trading catalog, and I thought, ‘Trolls are really in right now!’ and asked my mom to buy me 12 of the ‘troll rings’ they had for sale,” Stephanie said. “I marked them up 50 cents, and I charged my classmates $2.50 for ‘troll rings’ sold out of a little suitcase that said, ‘Going to Grandma's,’ on the front.”

Stephanie could have done anything with her inherited talent and spirit. But, already artistically inclined, she discovered Photoshop in high school.

“I had just gotten a computer. I

would take this thing home because the teacher didn't want to deal with it, and I was like, ‘Wow, Photoshop is cool!’”

Combining her two skills, Stephanie launched herself into a tough yet rewarding journey as both an artist and entrepreneur. But the longer she talks about her favorite pennant, the more clear it is that her “work” is much broader.

“I'm lucky to have the work because it means I get to be with these incredible people who love what they do and who are so talented,” she said.

Stephanie takes pride not only in her work (from national corporations to local festivals and startups) but also the 14 people she works with. Most of them are under the age of 30.

“That's what I'm the most proud of, the team we have here, the team that we built. That's what I think is different about us: truly caring about the people you work with and being very genuine and intentional. It makes it a really awesome place to work,” Stephanie continued. “I'm very proud to say every person in here cares about the dollars we receive, and they care about the work they do because they know it's not only a reflection of our company, but a reflection of themselves, and it's a reflection of their coworkers.”

Because of that, Stephanie views herself as just as much of a mentor to her employees as she does a boss.

Stephanie spoke about the phrase ‘safe at work,’ and she explained not just physical safety but emotional safety. With a young, growing team, this is essential to the growth of her business.

“They feel comfortable if they need to tell me they've made a mistake,” she said. “They are willing to take more risks. You know, if you are too scared to make a mistake, you're going to stay

by

in a box.”

Stephanie said she often finds her employees not just doing their jobs but also constantly collaborating to make their work better. They take the time to learn new techniques, and they feel supported to make mistakes.

“When people feel supported and truly valued, they feel more inspired to do a really good job, and then it's contagious.”

Now, what she is hoping to inspire in her employees is being repaid by her community, as she makes the transition from her office in North Jackson to a brand new space in Downtown Jackson.

The new-to-her space on the corner of Shannon and Baltimore is sprawling. It’s even complete with original green tile in the bathroom, a strange air-return vent turned into a table, and a spooky basement she plans on completing in the future (but isn’t quite sure what it will be yet).

“I've had to pause during this building process and just sit there and think about all the people who have been like, ‘I'm so excited about your

building. I'm excited it’s being done. You're going to be downtown. I can't wait to see it.’ And I thought, ‘Man, how awesome is that, that people care, that people are interested in what you're doing in the community.’”

The building also features a mural by Samantha Wood, highlighting B3’s work in arts, agriculture, and the Jackson community. It’s exactly the type of culture Stephanie wants to grow.

“It's the heartbeat of the community. We wanted to be a more creative agency. We belong downtown. I wanted to be downtown because I think it takes people investing and being downtown.”

Stephanie Riley made Jackson her home, and she is now encouraging and inspiring others to do the same. Her work is not only her career, but it is also the impact she is making in the community.

“I'm just very lucky to know the people I know, to have the community that we have, and lucky to have the work.”

photo

December Rain Hansen

“When people feel supported and truly valued, they feel more inspired to do a really good job, and then it's contagious.”

Join the Neighbors Club. HELP OUR JACKSON HOME CONTINUE INTO THE NEXT DECADE. MAKE A DONATION

SCOTT DONEY

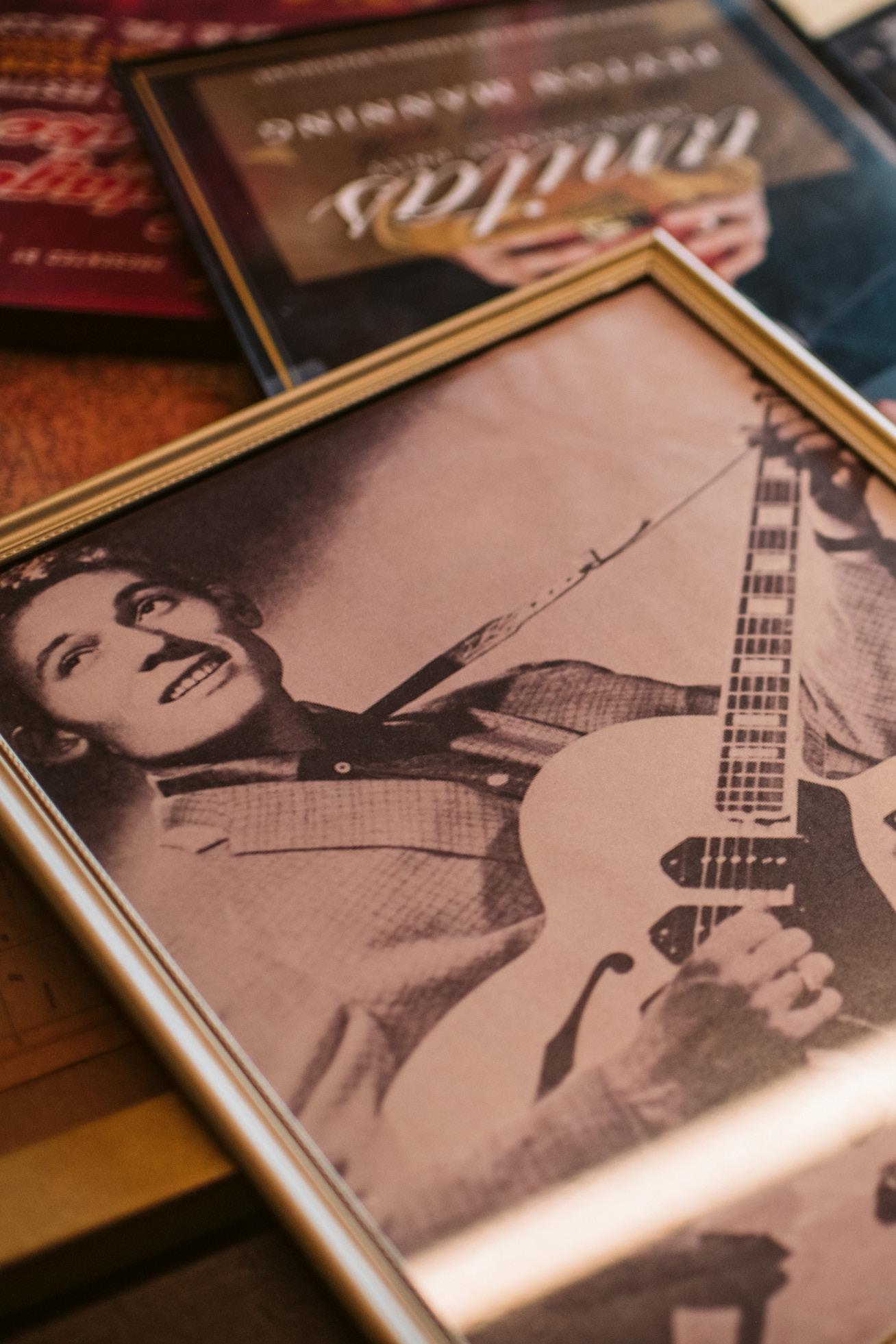

Anywhere but Behind a Computer: Continuing a 126-Year Legacy of Cobblery at James Shoe Hospital

WRITTEN BY TRUMAN FOREHAND

PHOTOGRAPHED BY MADDIE MCMURRY

East Main Street, Downtown Jackson, 1918. A broad, not yet paved street is populated with trolley cars on their routes throughout the bustling heart of a growing town. Men in short sleeves and vests with driving caps on their heads weave their way between the cars. Women in layered dresses and cloche hats stroll the sidewalks in the background alongside the rows of small shops. Somewhere out of frame, at the corner of East Main and Shannon, is James Shoe Hospital. This scene is displayed in a photograph in the Tennessee Room at the JacksonMadison County Library. And James Shoe Hospital, that same shoe repair shop, is still in business.

“It’s kind of a nostalgic thing,” Scott Doney, the current owner of James Shoe Hospital, said. “When you walk in, you're like, oh, okay, I know where I'm at. It smells like decades of leather and glue and polish and all that stuff. It's probably just infused deep inside these floors and walls.”

Doney has owned the shop for three years now, having bought it in 2022,

and the distinct smell he mentioned is often a new customer’s first impression of the place. It smells like a bygone era, like your grandfather’s dress shoes or your grandmother’s leather purse. DB James and his wife opened the shop together on the corner of Main and Shannon in 1899 and operated continually there through two World Wars and the Great Depression before moving to the current location on East Main around 1950. Johnny Lane started work there as a shoe delivery boy at the age of 16 in 1938 and continued until he left to serve in the war in 1942. He resumed work as soon as he got back from service, though now as a fully fledged cobbler — trained by James himself. Lane was the only person the Jameses trusted to take over the business in 1960 upon their retirement, and he operated it continually until ceding control to his son Tommy upon his own retirement in the 2000s. The younger Lane kept going, repairing shoes on East Main, until 2022. That brings us to Scott Doney and the present day.

Though the shop itself is old, the craft — working with shoes, or cobblery — is not one that Doney himself came to by heritage or family tradition. He came to it later in life as a second career, a pivot driven by a passion for a trade that was falling out of favor and had been for some time.

“You can’t find anybody that wants to learn this skill,” Johnny Lane told The Jackson Sun in 2004. “It takes time to learn it, and most young people today are more interested in computers.”

Ironically, the very technology that Lane feared would spell the death of his ancient craft is, in a roundabout way, what would bring the shop its new caretaker nearly 20 years later.

“I just couldn’t sit behind a computer anymore,” Doney said.

Now 47 years old, Doney says that working with computers was the only

job he had ever had before the shop. His dad purchased a home computer when he was a child, one of the first in their neighborhood in the 1980s, and he learned that skill early. In 2020, though, burnout and COVID-19 pushed him to consider a different lifestyle and a different perspective.

“During COVID, there was a lot of YouTube watching and stuff like that. So I ran across a bunch of those guys who were cobblers that were just kind of filming themselves, doing their thing and talking,” Doney said.

That duality of computers — both to push a man away from sitting behind one and to teach him the skills to do something else — might have saved James Shoe Hospital. After learning through YouTube and from an older cobbler in Memphis who acted as a mentor, Doney was interested in a long-term career shift.

“I saw that [Tommy Lane] was selling this shop, and I called him up,” Doney said. “I was like, I don't have a background in this. I enjoy it. Is it possible I could buy it and learn it like that? He said, ‘Oh yeah, come on up. I'll show you how it all works. I'll get you familiar with the machines.’ That was three years ago, and you know, knock on wood, it's going well. I really like it.”

The road that Doney took to learning the craft, however, would not historically have been how the trade was passed from one person to another. In fact, it would have looked a lot like the way that the previous generations of James Shoe Hospital handed it down. Johnny Lane was a longtime apprentice to DB James, and Tommy Lane learned the business under the tutelage of his father. The 21st century and the decline of handworking trades have changed the landscape, though.

That changing landscape can, of course, be attributed to a number of factors. Lane’s earlier complaint that technology is drawing away people who might otherwise learn a trade is echoed across many fields today. For cobblers specifically, though, it’s not just that the economy or the workplace has changed — shoes themselves have changed.

“Sometime around the ‘80s, there was a big push on basically glueconstructed tennis shoes that aren't meant to be resoled. You wear them until they wear out and you toss them and buy a new pair,” Doney explained. “I think a lot of cobbler shops probably suffered from that.”

"Because he cares so deeply, Doney does his best to keep up with what the elders of the trade have done and what he can continue to learn from them."

Because he cares so deeply, Doney does his best to keep up with what the elders of the trade have done and what he can continue to learn from them. Anytime he travels to a new town, he looks up the cobbler. And if there is one, Doney will visit their shop to sit, observe, and do his best to preserve the proud trade he has adopted.

“Cobblers, we're pretty few and far between these days,” Doney said. “I mean, at one time, there were a lot of them. But now I think I saw an article that said there were, like, 4,000 left in the US, which, when you think about it, is really not that many. Because New York has a bunch, Chicago has a bunch. They're concentrated. So when you get outside of those bigger cities, it gets pretty few and far between from shop to shop.”

“I hate that there's a lot of cobbler shops where the cobbler’s getting up in age and about ready to retire, and there's nobody underneath,” he said. “So once they retire and they close, that's it. Another one's gone.”

In that sense, James Shoe Hospital is an outlier. A cobbler shop that has operated continually since 1899 and is still going strong. In another sense, though, Doney is hopeful both for Jackson and for cobblery in a broader

sense. Just as the same new technology that could seemingly have doomed his craft is also what brought him to the trade, he sees it bringing other new faces and new voices. There is an online community of cobblers that is growing and thriving, keeping an old tradition alive through a modern medium.

“As old a craft as it is, there's always new stuff to learn,” Doney said. “So it's just neat to see what everybody's doing, and with YouTube and all that stuff, you can see that.”

The shoes he gets today look different from the ones that DB James worked on in 1918 or the ones that Johnny Lane worked on in 1960. There’s plastic, vinyl, nylon, glue, foam, and assorted synthetics. But

the innovation that has sustained the profession for centuries is still going strong. As the shoes have changed, so too have the solutions and repairs required: new glues, new stitching, new techniques. James Shoe Hospital’s daily operation is a meeting of the old and the new, of wistful nostalgia melding with the innovation necessary to thrive in the modern era, of working on 60-year-old cowboy boots one minute and six-month-old sneakers the next.

Newness and tradition live side-by-side. It’s important, then, that the shop is a family business, even if the actual family involved has changed over the decades and the turns of two centuries. Doney does not speak of himself, personally, as the owner of the shop,

but instead of being a collective “third family to own the shop.” His daughter Lena, on summer break before starting college in the fall, works behind the counter with him. The shop still bears the name of the original owners, of course, a detail that Doney said was a condition presented by the Jameses to Johnny Lane in 1960.

“They told him, ‘The only thing I ask is that you don’t change the name.’”

Over time, the name of the shop has come to be associated with the man behind the counter, no matter who he is.

“Probably daily, people come in and call me James,” Doney said. “And I just go, ‘Yeah?’”

He identifies with the shop, a gesture that makes sense for a man who works at a craft that involves putting some of himself into every pair of shoes he repairs by hand. The sands of time

have covered over this once essential profession, as shoes have become rebuyable instead of repairable, but for those who remain, it has only ever been a labor of love.

In the three years since he took over, Doney has seen foot traffic around the shop increase. He’s seen new shops open in previously empty buildings around his own, a change he welcomes for the increase in vibrance and people walking outside his doors.

East Main Street, Downtown Jackson, 2025. The trolley cars are gone, replaced by cars and trucks with computers in their dashboards on paved streets. Men and women walk together in sneakers and shorts and ballcaps. Somewhere, alongside new shops and this new increase of pedestrian passersby, is James Shoe Hospital.

SPONSOR FEATURE

Rooted in Community, Growing With Purpose

For 40 years, the Community Foundation of West Tennessee has been fueling some of the most meaningful work in Jackson and the surrounding counties. While you may not always see its name in headlines, you’ve almost certainly felt its impact — whether it’s in a backpack full of school supplies, a local arts project in your community, or a parent receiving legal help for their child.

Founded in Jackson in 1985 with a focus on healthcare, the Community Foundation has blossomed into a multifaceted support system for nearly every aspect of nonprofit life. Its mission is to strengthen the health and well-being of the communities we serve through support of philanthropic initiatives.

“A lot of people don’t even realize we’ve been around that long,” Beth Koffman, Chief Operating Officer, said. “I like to talk about our logo — it's a tree, because we're rooted in the community and have deep roots that are strong, but then also branching out and changing and growing as the community changes.”

What started as a way to assist patients and families has expanded into supporting education, housing, food

security, the arts, and so much more. One way the Community Foundation does this is through Community Project Funds, which allow groups to receive charitable donations for their causes through the foundation. These funds have helped them expand into so many areas of our community of West Tennessee.

For example, Heaven’s Cradle is a fund of the Community Foundation that was born from grief after a local couple lost a baby at birth. Today, it helps families access counseling and support they wouldn’t have had just a decade ago. Another example is a fund created by a husband to honor his wife, a schoolteacher, ensuring that her students never miss out on field trips or basic needs, like shoes that fit.

“We just want to remind people that these organizations are serving your friends and neighbors, making our city a more beautiful place to live, encouraging us to be kind and celebrate our differences,” Beth said.

Most of the time, the Community Foundation is behind the scenes because it’s funding the organizations on the ground doing the work. When the team gets to meet people and hear the stories of how funding has directly touched

people’s lives, it is moving. Funding from the Community Foundation could impact your neighbor, coworker, or even you personally. This organization has touched so many aspects of what makes Jackson a home.

The Community Foundation’s Community Impact Grants, which were launched in 2016 with just over $6,000, have since grown to $120,000 annually, directly funding organizations like West Tennessee Legal Services, All Saints Immigration Services, RIFA, Habitat for Humanity, and more.

“We just see a whole scope of issues in our community, and being able to take those grants and to get to see the work that these organizations are doing with this funding, I mean, that’s what is making Jackson a better place,” Haley Fortune, Community Impact Manager, said. “It’s incredible to see how that money multiplies through the work of local nonprofits.”

The Community Foundation also supports communities outside of Jackson and into the rest of West

Tennessee, with regional chapters in Humboldt, Milan, Trenton, and Henderson County. This allows it to make an impact on other communities while allowing the people who are living in those spaces to do the lifechanging work that is needed.

“I am a firm believer that problemsolving is not accomplished by people who are not actively affected by the issue making decisions for people who are. We believe problem-solving starts with the people closest to the issue,” Beth said.

One of the Community Foundation’s newer programs is 100 Women Who Care, a giving circle where every woman contributes at least $100 annually, then votes to decide which organization will receive the funds they’ve given. This group connects women of all ages, backgrounds, and circles in the community, allowing the impact to spread even farther. It also helps to make philanthropy less intimidating to the younger generation, as they can get involved within a group

of women from all ages.

“I feel like for a lot of people, especially the younger generation like myself, we can be kind of intimidated by philanthropy, but philanthropy doesn't have to be scary,” Haley said. “You know, even just giving $10 a month can really add up to make a big difference. And I think 100 Women Who Care highlights that, because $100 for a year may not seem like a lot, but when you take 100 women who are giving $100, you're maximizing that impact for the organization that's going to receive those funds. So we really want to make philanthropy more accessible for our younger generation.”

At 40 years old, the Community Foundation of West Tennessee is still growing. Still rooted. Still reaching out. And Jackson — and the region around it — is better for it.

“We’re not on the front lines, but we get to fund the people who are,” Beth reflected. “And that means we get to see the best parts of this community — the neighbors who show up, the leaders who step forward, and the small

ideas that grow into movements.”

“How can I get involved?” you may ask. You can always donate, and there’s a variety of ways you can give no matter what you feel called to do. You can give your time and connections by bringing community issues to the Community Foundation’s attention — they might have a solution or funding for that problem. If the foundation does not have an answer or solution to the problem, its team wants to connect you to someone who does.

“We turn visions into a reality for people,” Haley said passionately.

“I’m in the relationship business. Everything we do is built upon relationships — whether it’s with a donor, a partner agency, it’s all about building that relationship,” Beth concluded. “And it’s one of the greatest things because these aren’t just people I pass. These are people I’ve known for over a decade sometimes. It’s beyond just funding a project. We’re all members of this community, and we’re all working to make it a better place.”

CARITA COLE

The Dreamy Depths of Duality

WRITTEN BY TRISTA HAVNER PHOTOGRAPHED BY CARI GRIFFITH & TRUNETTA ATWATER

I shifted the cooler bag straps from one damp shoulder to the other and dug out a moderately cool Miller Lite from the rapidly thawing contents. The July heat was doing its best to melt every ice cube and individual standing on Division Street that afternoon. (Let me be clear — though Jackson seems to save its hottest twenty-four hours for the last day of July every year, I look forward to Porchfest with childlike anticipation.) We meandered, as one does in triple-digit heat, toward the fourth performance of the night and attempted to share the little pockets of shade where we could find them, collectively fanning in one methodical motion. But then the music began. A strong beat, the drummer collecting attention — the kind of music that compels you to bob your head and move your feet. And out came Carita Cole, donned head-to-toe in orange, with energy and passion and lyrics that had the whole crowd smiling and dancing and twirling hoops and

participating in no time. By the end of her set, Carita had us all — strangers and neighbors, young and old — experiencing a collective moment. That version of Carita Cole is what I knew of her until only very recently. Her journal feature was assigned to me and I was so excited to sit down and talk about music and the industry and inspiration for her lyrics, but the woman I interviewed was that artist I had seen two years ago and so much more. Carita Cole was born in Jackson, TN, the only child of her parents. Due to her father’s career in the Air Force, Carita and her parents moved to Glendale, Arizona, and then Texas, Nebraska, and even Izmir, Turkey, in the first decade of her life. She found that moving so often made it hard for her to make real connections with people and places. When Carita was ten years old, her family moved back to Jackson, and the adjustment to life in her hometown was initially uncomfortable. Moving so

"The term 'duality' is typically used to describe two opposing sides of the same subject, but I have found that duality is just a beautiful manifestation of the complexity and creativity and depth of a person. Carita proves my analysis. "

often made establishing roots anywhere nearly impossible, and now she was in a place that felt more permanent. That adjustment was not easy.

Shortly after moving back to Jackson, Carita enrolled in Tigrett Middle School. She was looking for belonging and was drawn to the band. She had desperately wanted to play the drums — with Carita being small in stature, the thought of her carrying drums on her body made her parents leery, so she settled on the trumpet. Music enamored Carita early on, and she was playing the keyboard by ear at seven, listening to her parents sing at church, even sneaking away to her bedroom to watch music videos on BET. Music both excited her and put her at ease. She excelled playing the trumpet and was first chair all three years at Tigrett. Band afforded her opportunities to play in places outside of Jackson and deepened her love of music.

Despite her musical success in middle school, Carita left band behind when she got to high school. She joined the track team and ran for both Jackson Central-Merry and North Side High School, with the goal of running her

way onto an Olympic team. She attended Western Kentucky University on a full track scholarship and majored in psychology with a minor in journalism broadcasting. While in college, Carita worked on her music in her spare time, writing and producing. Upon graduation, she moved back to Jackson with hopes of finding a job and settling into her career (music included). Jobs were hard to come by, however, and while she continued working toward her dream of running professionally, real life and real bills forced her into odd jobs that were not fulfilling.

In search of work that felt more in her wheelhouse, Carita took a position at West Tennessee Legal Services. She had always had a propensity for helping others however she could, and this new position offered a convergence of her skillset and educational background as she would be directing disabled clients to critical resources. As her role evolved, she moved even more into client advocacy and found her passion- educating the public about fair housing. Currently, Carita works more on the legal side of fair and equitable housing access, and she educates the public about their rights and benefits.

People tend to be multifaceted, and Carita is no exception. Before her interview, the only iteration I knew of her was rapper and performer. As she laid out her personal timeline, I began to see the duality of Carita, and this is the part of the interview process that always draws me in and keeps me writing about strangers. The term “duality” is typically used to describe two opposing sides of the same subject, but I have found that duality is just a beau-

tiful manifestation of the complexity and creativity and depth of a person. Carita proves my analysis.

Carita’s first experiences performing were in church. She grew up with strict, religious values but felt most comfortable rapping instead of singing. She found inspiration in Kirk Franklin and Missy Elliott (See? Duality!) but found that rapping was not accepted by the older churchgoers. Still, she continued writing rap lyrics throughout college and after graduation joined a gospel rap group called Radical for Christ that traveled all over the region. She made it her mission to win over both young and old with her positive lyrics, fearless delivery, and stage presence, and she reveled in the affirmations after her sets. But it was not easy

work. She advocated all week for West Tennessee Legal Services and wrote and mixed and recorded her own music at night. She would eventually leave the rap group in pursuit of her own music career and drop the title “gospel rapper” in favor of a more fitting title, “inspirational artist.” If you have heard Carita’s music, you have been inspired.

Having two passions can be exhilarating and exhausting, but Carita has found the energy to excel and enjoy her day job (a full-time job that requires much from her) while growing her music career at night. Over the last few years, she has recorded an album, released singles, and has been featured on multiple artists’ tracks. She has taken every influence and experience and created music that uplifts and enter-

tains and beckons her listeners to feel good. Her hope has always been that the music she creates is a vehicle for positivity and hope.

Carita Cole’s duality exists in the spaces where her passions overlap. And really, isn’t that true of all of us? Our most authentic yet protected selves, our most public yet sacred offerings, our most wearied yet tended-to sentiments are often the places where our value lies, both to ourselves and our neighbors. Communities and individuals alike exist on many different planes, and we are better for it. Carita

Cole’s duality is a microcosm of what we can all be if we put time and teeth into what makes us feel alive. An advocate by day and a performer by night, Carita is proof positive that when you lean into the work of doing something worthwhile and you love doing it, people notice.

Carita’s music can be streamed on Spotify and Apple Music, and you can find her music videos on YouTube. Her new self-titled album, “Carita,” was released on July 1st.

Homestead Morning

POEM

BY

EVANGELINE HOLMES

PHOTOGRAPHED BY

CARI GRIFFITH

Walking to the barn, pail in hand, and boots on feet, the cow in her green pasture, waiting there to greet.

Mooing when she sees you, glad that you are there, rubbing up against you, sniffing at your hair.

The frothy milk sings, as it swiftly hits the pail, the smell of elderflower is drifting in the air.

The jars now full, we walk inside, to put the milk away, cheese 'n butter 'n sour cream, will be made another day.

Evangeline is one of five siblings growing up and homeschooling on her family’s 8-acre homestead at Rose Hill, a historic house built in 1823 in Jackson. She loves to read, pick blueberries, and bake pies, and her favorite place is home.

Evangeline's Vanilla Ice Cream

"My favorite ice cream to serve with pie — or sometimes I add protein powder and have it for breakfast with fresh berries!"

2 eggs

1/2 cup of maple syrup

1 cup of milk

2 cups of cream

1 teaspoon vanilla powder or 1 tablespoon vanilla extract

In a blender, blend the eggs on low/medium for 1-2 minutes. Add in maple syrup and blend to mix. Add cream, milk, and vanilla; blend until combined. Pour into an ice cream maker and use the ice cream setting.

JASON REEVES

Tending Relationships Through the Garden

WRITTEN &

PHOTOGRAPHED BY MADDIE MCMURRY

“Gardening is so therapeutic… There's something about starting a little seed and ending up with something towering or beautiful. It’s like a little miracle in this tiny package,” Jason Reeves, Garden Manager at the University of Tennessee Gardens in Jackson, said.

Jason Reeves is many things — horticulturist, garden manager, educator, international tour leader, landscaper, and an advocate for community connection through plants. But if you ask him, the work isn’t about titles. It’s about educating people so they can find something meaningful in the garden and fall in love with getting their hands in the dirt.

Growing up, I watched my mom begin gardening when I was a young teenager. She began with a small raised garden bed and then expanded every year, producing lots of fresh produce in the summer. It quickly became a solace for her. A space where she learned lessons of life by the rhythms of the garden. I remember always having an abundance of juicy cherry tomatoes colored yellow and red to eat. I had forgotten what a real homegrown tomato tasted like until I recently bought some cherry tomatoes at our local West Tennessee Farmers’ Market.

I never realized how therapeutic working in the garden was for my

mom until she moved 9 hours away from me a few years ago. Gardening has been her safe place in a new home. It's grounding. It occupies her time and gives her something to nurture from the ground up. Her children are all out of the house, and summers as a teacher are a season with more free time, which she fills with hours outside — watering, weeding, keeping bugs and critters away, and all the other tasks involved in growing something from the dirt.

For Jason, being in the dirt is deeply ingrained in his blood. His childhood was spent on a family farm between Huntingdon and Clarksburg, and his formal training was at UT Martin, with a bachelor's degree in grounds management, and UT Knoxville, with his master’s in ornamental horticulture and landscape design. He also spent his time post-grad with internships at prestigious institutions including the Missouri Botanical Garden and Longwood Gardens, which is the largest garden in the United States.

“I grew up learning to love plants with my parents and my grandparents, who also lived on the farm with vegetable gardening,” Jason said, remembering his childhood fondly. “My mother and grandmother, we would grow flowers in the vegetable garden or just in rows with zinnias or strawflowers or gladiolus bulbs. That really got me

excited about horticulture. I'm 50 years old now, so I've been in it most of my life.”

Jason has even gardened abroad in New Zealand, a place he has visited multiple times and calls one of his favorite climates in the world. Even with his travels all over the world, Jason remains deeply connected to West Tennessee. He still lives near his childhood home and recently purchased a farm where he is slowly building a new garden of his own that will be open to the public seasonally. He’s already planted over 13,000 daffodil bulbs on the farm and many different trees, and he has plans to use some of the land for growing Christmas greenery.

Jason started working at the UT Gardens in October 2002 and was hired to create the public botanical gardens you see in Jackson today. The goal of the gardens is to show residents of West Tennessee what can grow in their area, to provide them a place to come and enjoy the gardens, and to provide research material for growers, land-

scapers, and nurserymen. The research associates at the UT Gardens are responsible for testing different plants to see how they grow in our environment. This helps local landscapers and nurseries to know what to plant in yards and businesses so that they will thrive for years to come.

They also have two large plant sales every year, one in the spring and one in the fall, and a summer celebration every other year. Their parking lot is uniquely designed with big island beds with plants labeled clearly, giving accessibility to those who may not be able to walk around the property but still want to enjoy the beauty of plants. They want every person to come and soak in the power of getting in the garden, in the dirt, in nature. The lessons someone can learn by just sitting in a garden are endless.

When I was interviewing Jason, he drove me around the property to see different areas where they grow plants or create spaces for people to enjoy. It was filled with the hustle of summer

interns who had just arrived, a school group there for an educational lecture, and several staff members pulling weeds and planting new flowers. People were learning, experiencing, growing.

What makes Jason’s work stand out isn’t just his expertise — it’s his generosity. Whether he’s designing low-cost, low-maintenance landscapes for first-time homeowners or teaching someone how to swap out one plant for another with fewer disease issues, he always brings it back to sharing knowledge. He believes that gardening is therapeutic, grounding, and something that can help people, especially those going through hard times, to find healing and hope.

“Sharing my experiences is very gratifying to me… You learn so much by doing. I can read all day in a book and sit in a classroom all day long, but until you are actually out there doing it yourself, you really don't know,” Jason said.

travel together,” Jason said.

Jason also has grown quite the following on his Facebook page, over 13,000 followers in fact. People all over West Tennessee have found a place to be educated simply by Jason posting his educational content on a public platform. He usually receives around 5–6 private messages a day that he tries to respond to. His advice is practical, encouraging, and always grounded in the thought that success in gardening is within reach for anyone if you’re willing to get your hands in the dirt.

“Gardening is so therapeutic… There's something about starting a little seed and ending up with something towering or beautiful. It’s like a little miracle in this tiny package."

“Having that community on Facebook has really made me slow down. If I'm typing something out or reading up on something, because I don’t know everything, it makes me learn. And when I'm taking photos of a plant to post, I have to slow down and really focus on that plant or flower,” Jason said enthusiastically.

Jason is also deeply involved in the Master Gardener Program, working with dozens of volunteers who give thousands of hours of service each year to make the gardens what they are. Jason has a group of Master Gardener volunteers they call the “greenhouse crew” who put in between 2,000–3,000 hours of service a year. For many of them, it’s more than volunteering — it’s friendship, mentorship, and community.

“A lot of those Master Gardeners have become very dear friends of mine, and we eat dinner at their houses or

Gardening connects people. It connects Jason to students, to Master Gardeners, to the community, to people across the world on garden tours. It’s about relationships, not just plants. Despite the wealth of knowledge Jason already has, he is quick to note how much he still learns every day — from successes, from failures, from others around him. He sees value in slowing down, paying attention, and letting the beauty of what is grown in the ground be both a teacher and a reward. And I would say, we could all learn the lesson of slowing down and enjoying the garden that is life, growing right around us day by day.

IN THIS ISSUE Contributors

MIRZA BABIC is a multi-talented creative, adept at weaving captivating narratives through both visual and written forms of expression. With a foundation in photography and content creation, Mirza brings stories to life with a keen eye for detail and a flair for engaging storytelling. Beyond the lens, Mirza's versatility extends to music, where a passion for music production and a commitment to excellence shine through. Mirza is dedicated to crafting compelling narratives and immersive experiences that leave a lasting impact.

CARRIE CANTRELL is a Milan native, boy mom and photographer. With a decade of experience in storytelling through her lens, she has a keen eye for capturing authentic moments. Balancing her role as a Community Engagement Specialist with her passion for photography, she values spending quality time with her sons, family, and close friends. Her love for exploring in nature, travel and enjoying live music serves as a source of inspiration and balance in both her personal and professional life.

TRUMAN FOREHAND is a lifelong writer and reader from Garfield, GA. He graduated from Union University in 2024 with a degree in journalism and

now works for Adelsberger Marketing. In his free time, he loves photography, going to National Parks, and being let down by every Atlanta sports team.

CARI GRIFFITH is a gardener and a photographer with a lifelong affection for seed sowing and storytelling. She lives a sweet life in midtown with her husband, Rob. She spends most of her time behind a computer or a camera, or teaching college students to appreciate the good light. Her most treasured moments are eating dinner with her friends both at home and afar.

GABE HART is an Instructional Coach at Jackson Central-Merry High School. A lifelong Jacksonian, Gabe is a product of the Jackson-Madison County School System and has taught English in JMCSS for 14 years. Along with contributing to Our Jackson Home, Gabe also writes monthly columns for Tennessee Lookout, weekly columns for The Jackson Post, and has been published in The Tennessean. When he's not in Jackson, he's most likely traveling with his partner, Laura, or spending time with her in her hometown of Philadelphia.

TRISTA HAVNER is a born-andraised Jackson girl, a mom, wife, and small business owner. She and her

husband, Charlie, have a charming local family business and are passionate about the history there. Trista can be found putting together frames in her family’s shop or lettering anything that will hold still. Her love for home grows daily, and she is passionate about being an agent of growth and positive change in her beloved Hub City.

EVANGELINE HOLMES is one of five siblings growing up and homeschooling on her family’s 8-acre homestead at Rose Hill, a historic house built in 1823 in Jackson. She loves to read, pick blueberries, and bake pies, and her favorite place is home.

ESTHER JONES is a Maryland native who moved to Jackson in 2019 to complete her English degree at Union University. She lives with her husband, Wesley, and their dog, Otis. Her favorite things are contemporary fiction novels and Pinterest vision boards, and she doesn't know what she would do without em dashes.

MADDIE MCMURRY serves as Editorin-Chief of Our Jackson Home and Communications Manager at theCO. She came to Jackson to attend Union University, where she graduated with a degree in journalism and decided to stay in Jackson and make it her home. She is a writer and photographer who loves telling real and authentic stories from behind the camera or on the page. In her spare time, she loves spending time with her husband, Zach, hosting people, traveling, and baking cakes.

MARGEE STANFIELD has lived in the Jackson area for the majority of her life and is currently a senior journalism major at Union University, where she serves as Editor-in-Chief of the school's student-run journalism publication. You can most often find her reading

a book or rewatching a Marvel or Disney film, a cup of coffee in hand, and her one-eyed black cat nearby.

JULIA EWOLDT STOOKSBERRY is a storyteller and marketing professional. While she’s always called West Tennessee home, she moved to Jackson in 2018. She and her husband live in a really old house in Downtown Jackson with their two dogs and cat. When she isn’t writing, you’ll probably find her in her garden or at the local brewery.

TREY THOMPSON is an acrylic painter based in Jackson, TN, whose work explores themes of connection, identity, and everyday life. Blending realism with abstraction, his paintings reflect an ongoing journey of self-discovery and a deepening awareness of the world around him.

SHELBY TYRE is a filmmaker, writer, and storyteller based in Jackson, Tennessee. She runs The Reel Collective and serves as the Festival Director of the Hub City Film Festival. With a passion for storytelling in all forms, she focuses on capturing and preserving meaningful narratives through film, writing, and community-driven projects.

KRISTI WOODY is a freelance photographer and storyteller. Her photography work spans from headshots for Jackson's finest to family portraits to food photography at local restaurants, but her specialty is weddings. She also works part-time in SEO marketing and enjoys the data and detail-oriented nature of that work. In her free time, Kristi enjoys reading and spending time with her husband, daughter and rambunctious beagle, Rhett, Liliana and Chipper respectively.