PHILANTHROPY VOL 8, ISSUE 2 FALL 2022

EDITOR’S NOTE

Our city recently dedicated a mural and historical marker to the late Gil Scott-Heron, a jazz musician, poet and activist who spent his formative years right here in Jackson, Tennessee. In the first pages of his memoir, he begins by talking about his childhood in Jackson, which included the experience of being among the first Black students to integrate Tigrett Elementary School. In the opening of his memoir, Gil speaks fondly of his time in Jackson, though riddled with the clear memories of segrega tion and hate. So when he sings, "I've seen everything there is to see/ And I know there is no sense in crying/ I know there ain't no sense in cryin'/ Yeah I think I'll call it morning," we get a glimpse of a kind of hope that has seen the worst yet still works for a better way.

Gil's legacy speaks to us today. Our responsibility is not to promote a blind positivity about our community, but to tell stories that encourage us to actually see the place we live and the people who live in it, and be moved to create a place where everyone can thrive.

It's from that kind of willingness to face reality that many of our city's most impactful philanthropists, non-profits, and more were able to build the programs that bring us so much pride in this place.

Thanks to our sponsor the West Tennessee Healthcare Foundation, in these pages we get to tell many of the stories of the people who were willing to take an honest look at the way things are and respond with action. It's an encouragement to all of us to follow in their path — to find ways to say with our money, actions, and time — it doesn't have to be this way. They inspire us, as Gil wrote, to say, "I'm gonna take myself a piece of sunshine/ And paint it all over my sky."

COURTNEY SEARCY, EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

EDITORIAL BOARD EDITOR-IN-CHIEF DESIGNER Courtney Searcy COPY EDITOR Olivia Chin CONTACT WEBSITE & BLOG ourjacksonhome.com PHONE & EMAIL 731.554.5555 courtney@attheco.com ADDRESS 541 Wiley Parker Road Jackson, TN 38301 CONTRIBUTORS FEATURED WRITERS Britton Crenshaw Lizzie Emmons Gabe Hart Lily K. Lewis Courtney Searcy Ginger Williams FEATURED PHOTOGRAPHERS Dan Battle Isaac Elliott Cari Griffith Hannah Gore Courtney Searcy A PUBLICATION OF OUR JACKSON HOME VOL. 8, ISSUE 2: PHILANTHROPY BROUGHT TO YOU BY THECO | WWW.ATTHECO.COM

2/EDITOR'S NOTE Creating our Community Courtney Searcy 6/STORY Around the Ring & Back Again Gabe Hart 16/STORY A House Built with Many Hands Ginger Williams 22/STORY Aging in Place Britton Crenshaw 26/FEATURE Giving the Arts a Chance Lizzie Emmons 32/ESSAY Strangers to Friends Courtney Searcy 40/PHOTO ESSAY Beauty in the Wayside Isaac Elliott 46/POEM Philanthropy Lily K. Lewis 48/SPOTLIGHT Freeges for All City of Jackson 52/SPONSOR SPOTLIGHT West Tennessee Healthcare Foundation CONTENTS

BY GABE HART PHOTOS BY DAN BATTLE

AROUND THE RING & BACK AGAIN

6 • OUR JACKSON HOME

Muhammed Ali made that phrase famous. In many ways, Ali changed the national perception of boxing by adding fluidity, grace, and artistry to a sport that had long been dominated by fighters who relied on heavy-handed brute force. That famous quote is longer than those eight words, however. There’s a second part that has fallen away over time.

“The hands can’t hit what the eyes can’t see.”

Ali knew there was much more to boxing than the relentless barrage of punches being hurled toward an opponent. Boxing requires thought and strategy and, yes, savage violence as well.

Boxing has always been a sport fraught with brutality; a sport whose popularity has greatly waned over the last quarter century even as more brutal forms of combat have risen in popular culture. From UFC to MMA, violent combat sports have forced boxing to the precipice of irrelevance –like a slow, heavyweight fighter gasping for air against the ropes.

Before the rise in the appetite of violence by the general public, boxing found itself at the pinnacle of the sports world in America. Like other professional sports, boxing combined strength, athleticism, and skill, but did so with much higher stakes.

In basketball, if a player makes physical contact with too much force, that player is penalized. In football, players wear armor to protect themselves and limit the damage to their bodies. In baseball, the vast majority of contact is between the ball and the bat. Boxing, however, is a siloed sport. It is a violent act played

out between two people in a ring with their only protection being their skill and their resolve.

Beneath the chaotic surface of what occurs in a boxing ring is what truly makes the sport beautiful. Boxing at its core is a harmonious and conflicting dance where every muscle in the body is acting in a rhythmic, graceful symphony in order to deliver a viciously devastating blow to an opponent. The legs and feet of a boxer are just as important as their hands. The legs are the accumulators in the body, where energy is stored until the fighter is ready to give the burst of torque to the upper body to deliver the strongest punch possible. The feet are light and delicate as they shuffle in a counted, metered way – up and back, left and right. A boxer’s hands are always curtained in front of the face to provide instant protection. There is a constant ebb and flow between intense violence and balletic grace.

Decades ago, Jackson was home to some of the best fighters in the country. Under the tutelage of Coach Rayford Collins these young men would train in Jackson and fight all over West Tennessee and beyond. Names like Jim Carmichael, Joe Morris, Michael Nunnaly, and the Beard brothers (Jackie, Obie, Rickey, and Aubrey) all trained at Collins’s gym and were part of the legendary Jackson Boxing Club.

In the original incarnation of the JBC, Coach Collins passed his love of the sport of boxing to any young man who had the desire (and toughness) to learn the lessons that the sport of boxing provided. Collins would train these young men at his gym and then take them to tournaments around the region. While winning was paramount, the camaraderie and opportunities for

“Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee.”

VOL. 8, ISSUE 2: PHILANTHROPY • 7

travel outside of Madison County and West Tennessee that were provided by being part of the JBC were where the memories and lessons of that time were ingrained in the young men who were lucky enough to be part of it.

Obie Beard was a member of that group and found a love for boxing as a teenager.

“Every weekend, we’d go to towns around Jackson to box, stretch it out to Memphis, to Nashville, and go to so many places. I was so wrapped up in boxing that I didn’t have time to get in trouble,” he recalled. “Boxing kept me locked down in the gym and traveling. This stuff took me all over the world.”

As Obie’s and his teammates’ love for the sport grew, their talent and skill in the ring also began to rise. The more they trained, the more breath they had in their lungs after three rounds of fighting. The more reps on the heavy bag they accrued, the stronger their punches landed on their opponents’ rib cages. The more they sparred with each other in the ring, the more intense those sessions became.

“Boxing is a sport where my teammates helped get me in shape. In that ring right there,” he said with a wave behind his head, “we had better fights in our training than we did in actual fights.”

Even for people in the boxing world that had been around the sport their entire lives, the intensity of the

practice sessions between teammates at the JBC was somewhat surprising. Obie recalled a time in Detroit when he and his brother were training in a gym for an upcoming fight and the gym’s trainer mistakenly thought a real fight had broken out during the sparring session.

“I was in Detroit, Michigan with one of the best trainers in the world. My brother and I were at this trainer’s gym sparring one day, and that man came running out of his office hollerin at us; he thought we were in a real fight. But I was taught that if you wanna be like Muhammad Ali, you gotta train like Muhammad Ali,” he said.

Ali was the gold standard for aspiring fighters in the 1960’s and 70’s. In many ways, it was boxing’s golden age in the world of sports, and Ali was the king. For Obie and his teammates to be like Ali they had to train like Ali. Through that training and experience fighting, the sport of boxing opened many doors for Obie.

“I was fortunate enough that when I graduated, the coach of the 1976 Olympic boxing team, Pat Nappi, got me a scholarship at Lane College. Boxing opened that door for me. When I left Lane, I didn’t owe them a dime,” he remembered.

Boxing gave Obie a free education and helped teach him those hard lessons that helped shape him and his teammates, but those hard lessons

“Every weekend, we’d go to towns around Jackson to box, stretch it out to Memphis, to Nashville, and go to so many places. I was so wrapped up in boxing that I didn’t have time to get in trouble,” he recalled. “Boxing kept me locked down in the gym and traveling. This stuff took me all over the world.”

8 • OUR JACKSON HOME

VOL. 8, ISSUE 2: PHILANTHROPY • 9

10 • OUR JACKSON HOME

"You have to keep your composure in the ring; you have to be considerate of people no matter how mad you are at them outside of the ring. Some people don’t have self-control, but boxing helps teach self-control.”

didn’t seem as appealing for everyone. Boxing was a sport that was dangerous and challenging.

“In order to learn boxing, you’re gonna have to get whooped. That’s where you learn,” Obie explained.

But Obie learned a lot more than when to slip a left jab or duck a right hook. Through countless punches to the face and the body, through the exhaustion of the constant movement, to his hands feeling like bricks, Obie still remembers the lessons that were literally knocked into him in the ring in East Jackson.

“I used to get beat up everyday in that ring, but iron sharpens iron. I learned more from getting hit in a ring than I did when I was doing the hitting,” he said. “Just because something bad happens or you get hit in the face, doesn’t mean you just have to go off the chain. You have to keep your composure in the ring; you have to be considerate of people no matter how mad you are at them outside of the ring. Some people don’t have selfcontrol, but boxing helps teach selfcontrol.”

As the overall popularity of boxing began to recede, less young men came to the JBC on a regular basis. Long after Obie and his teammates moved on from the JBC, Coach Collins continued to train new boxers but not the same number of boxers or with the same consistency. As Rayford Collins aged and interest in the sport dwindled, a decision needed to be made about the future of the Jackson Boxing Club.

There are circular patterns of completion and restoration throughout the physical world — endings of stories finding themselves in some of the familiar places they began; seasons rotating like hands on a clock with the

same rhythm as a boxer’s feet - up and back, left and right.

Muhammed Ali came full circle: loved as a young fighter, hated for his courageous political stances, and in the end, revered as one of the most influential athletes in our nation. Like his hero, Obie Beard had a circular moment in his life, too.

In 2015, Rayford Collins, in declining health, passed the mantle of Head Coach of the Jackson Boxing Club to Obie Beard. That same year, Coach Collins was given the first Lifetime Achievement Award from The Jackson-Madison County Sports Hall of Fame.

In 2016, Obie Beard was inducted into the Lane College Hall of Fame and later that year, Rayford Collins, the man who sparked Obie’s love for boxing, passed away at age 76. Obie was left with the memories and lessons he learned from Rayford, but also with the heavy responsibility of continuing a legacy that impacted so many young people in Jackson.

Every two minutes, a shrill, automated sound emanates from a box with red, yellow, and green lights alternating flashes. The box rests on a table next to the ring, across the room from where Obie and I are sitting. The box is an interval timer used for training fighters in timed rounds. Behind me, a young man is throwing heavy hooks into a weighted bag that hangs from the ceiling at the JBC which is now located just off North Royal on O’Neal Street. The sound of the gloves hitting the bag and a metallic chain rattling as it shook is familiar to Obie. He glances at the young man from time to time as we talk making sure his form is correct, that he’s throwing his punches with his

VOL. 8, ISSUE 2: PHILANTHROPY • 11

whole body and not just his arms.

“A lot of times, how you stand as a boxer affects how hard your punches are thrown,” he tells me. “We were taught to punch with our legs; you tryin' to go through and knock your opponent’s head off. It’s a wonderful sport,” he says with a smile.

There are pictures hanging in the gym of Obie’s former teammates. The pictures are in a straight line, high and near the ceiling, as if they’re observing what is taking place in the gym below them. Obie feels their presence, and Rayford’s presence, too.

“I think about our time with Rayford Collins and it’s a lot like Jackson — you don’t really know what you have here until it’s gone,” he reflected. “Some people think boxing is about making money, but that’s not what it is for me; it’s the opposite. I owe this town and this sport; I’m in debt to

it. I’m paying that back now. I want to pay that back.”

Most debts are burdensome and heavy, but this payment is a payment of love. It’s an involuntary sacrifice for Obie.

“Boxing taught me how to treat people; it taught me humility and selfcontrol. I’m trying to make the world better and not worse.”

Obie and the JBC are facing the same challenges that a lot of sports and clubs and even schools are facing when it comes to engaging kids in the year 2022 — a competition for their interests and trying to regain some normalcy since the pandemic. Obie says his numbers are sparse and attendance is inconsistent, but he thinks the best days for the JBC are ahead. He also knows that the main goal of the JBC isn’t winning tournaments, but giving kids a healthy outlet for exercise and fun.

VOL. 6, ISSUE 2: HOME & GARDEN • 12

12 • OUR JACKSON HOME

VOL. 8, ISSUE 2: PHILANTHROPY • 13

"I owe this town and this sport; I’m in debt to it. I’m paying that back now. I want to pay that back.”

“We don’t have a lot coming regularly right now. Some kids will come in when we open the doors up and some won’t,” he explained. “This sport can attract a lot of kids who are doing stuff they don’t need to be doing, but that’s a good thing because boxing is a great sport that gives guidance.”

With a partnership with the Jackson Police Department and burgeoning cooperation from community advocates, the JBC is building a support system for young people to reap the same kinds of benefits that Obie and his teammates received over thirty years ago.

“Even if we’re not quite boxing in tournaments, yet, I’ll take some of the kids who come here and we’ll go watch a fight in Paris, Tennessee or in Brownsville. I want them to see what it’s like and what they’re getting into,” he said. “If we don’t find kids something to do to keep them out of trouble, they’re gonna find something to do that might get them in trouble.”

The overlapping lessons learned in

the ring that are applicable to life are numerous and somewhat cliche, but those lessons are also true. The boxing ring is still the great equalizer, and if the sport is taught and learned correctly, it can be a place where brotherhood and sisterhood can truly be formed. Boxing is like a chess match with your fists — it takes thought, controlled impulsivity, strength, and grace. It is hard and taxing and extremely rewarding.

Obie is proof of all that boxing can provide a young person who wants to put in the work it takes to learn those lessons inside a ring. He wants to pay his debt back to Jackson; to help kids today learn what he learned so many years ago.

“I think this club could bring us together as a people. In that ring, it doesn’t matter what color you are. You’re teammates, you’re fighting to make each other better. I know what it’s like to be a kid that needs something and have someone step in and help me out. I want to be that for kids in Jackson.”

by December Rain Hansen

photo

14 • OUR JACKSON HOME

I think this club could bring us together as a people. In that ring, it doesn’t matter what color you are. You’re teammates, you’re fighting to make each other better.

I know what it’s like to be a kid that needs something and have someone step in and help me out. I want to be that for kids in Jackson.”

VOL. 8, ISSUE 2: PHILANTHROPY • 15

A HOUSE

BUILTWITH MANY HANDS

BY GINGER WILLIAMS PHOTOS BY COURTNEY SEARCY

A Jackson Police Department officer stares into the face of a woman working as a prostitute; his only option was to arrest her. He had no evidence or proof to arrest the man who was likely her trafficker. But where would the officer take her? Years later, this same officer would write a check to the Scarlet Rope Project, a home for survivors of sex trafficking.

This is how it started for many who have become involved with the Scarlet Rope Project’s new house, their own stories leading them to participate in building a place for others to feel safe and to heal.

Years ago, a Bible study teacher sat straight up in her bed one night while watching a Youtube video about sex trafficking and asked God, “What can I do to stop this?” She called her friend, a nurse who ran triathlons, to discuss what could be done. Six years later, those two friends, Debbie Currie and Julanne Stone, early leaders of the Scarlet Rope Project, led a tour of women through a partially completed house that will soon house survivors of sex trafficking in Jackson, Tennessee.

There are countless stories of people from all sorts of backgrounds

coming together to build this one house. Each contributor’s gifts are being used in ways they had not dreamed of. A realtor builds her first house, and begins to dream of the neighborhoods she could build one day. A young mom takes a leap to start her own interior design business and arranges furniture to make houses into homes. An attorney loses her husband and begins a journey of healing. An addict attends an AA meeting, celebrates one year sober and begins mentoring other addicts. Each of these stories have played a part in people becoming board members, advocates, counselors and builders for the Scarlet Rope Project. This spring, many of them stood together on a dirt plot on McCowat Street in Jackson, their individual stories culminating in this moment. They are building a house together that none of them will ever live in. The foundation has been laid and the studs are up for a house that will be a safe haven of healing for survivors of sex trafficking: The Scarlet Rope House. The current Scarlet Rope House, just down the street, has been housing survivors for several years. Inside, paint and plaster flakes off of the bathroom

VOL. 8, ISSUE 2: PHILANTHROPY • 17

Building a new house has given the community an amazing opportunity to be a part of helping sex trafficking survivors heal in a very real way.

18 • OUR JACKSON HOME

walls, the water coming out of one of the sinks smells like sulfur, and the A/C unit struggles on hot summer nights. Many donations and kind hands have made the house a home, but it’s old, crowded, and not always functional. The survivors will live there for a year or more depending on their situation.

One is now in college, and needs a quiet place to study. Another is still feeling the darkness of detox; she’s barely able to function. Another is meeting with the staff to work through more stories she’s just remembering. Two ladies sit at the kitchen table to plan meals for the week.

Outside, a survivor jumps out of her chair. Wide-eyed, she grips her cigarette and then quickly calms down realizing the danger isn’t coming. It’s just the wind blowing a shingle off of the roof. Every creak, backfire, sudden movement, car pulling into the driveway or meeting a new person; how long will it take to feel normal? What is normal? The things that have been done to her and over and over can’t be shared; after all, it’s her story. She stares blankly, and then a moment later she laughs at a joke shared in the group. Healing is a bumpy road; if we can even call it a road. She’s more than a victim; she’s a survivor.

“There are very few long term care facilities across the country for survivors; many have been through drug treatment facilities numerous times, but 30 days isn’t enough time to establish new habits and allow for deep layers of suffering,” said Julanne Stone, Nurse and Director of Scarlet Rope Project.“Yes, sex trafficking happens in Jackson, Tennessee. We aren’t just here to help stop trafficking; we are here to educate the community and to provide a long term facility that will give these

women a chance to heal and start living a new life. But, we couldn’t build a house by ourselves. We needed a lot of help.”

Melanie Bucholz, Attorney and Director of Survivor Services said, “From learning to cook and shop for the whole house, to budgeting and sleeping at normal hours, attending Bible study, counseling and having 24 care from trauma-informed counselors who have fought their own share of issues, Scarlet Rope Project provides a rich array of resources that the women need to heal. We also need a house that allows women to live here for a long time while accommodating different phases of healing.

We regularly get calls from people in the community who just want to help. But, we also have to protect these women whose vulnerabilities have been exposed in the worst ways. We only allow volunteers who are willing to make long-term commitments and go through trauma-informed training. Building a new house has given the community an amazing opportunity to be a part of helping sex trafficking survivors heal in a very real way.”

At the new house, builders and Bible study teachers used red sharpies to tattoo the studs with Bible verses. The survivors also wrote on the boards of the rooms that will be theirs in only a few months.

Light flows through the efficiently designed house with high ceilings and an open floor plan. From the oversized pantry to the study room and counseling room, the house has been specifically designed for those who will come through the Scarlet Rope Project Residential Program. The firepit encourages conversation; the in-home office keeps the staff near; the kitchen

VOL. 8, ISSUE 2: PHILANTHROPY • 19

20 • OUR JACKSON HOME

table is for community dinner. Every piece of furniture and every wall has been talked about, planned, prayed about and selected to make life in the Scarlet Rope House a home of healing.

So who is building the Scarlet Rope house? It’s complicated.

What does it look like when an entire city builds a house together? It means that the giving comes in layers. Aspell gifted the lot across the street from their campus. Donors gave money. The organization Eight Days of Hope built the frame. Many others poured over blueprints, furniture, budgets, grants, etc. making decisions for a house they will never occupy.

“I remember sitting down with Frank McMeen at West Tennessee Healthcare Foundation when they were still helping us do our books,” said Julanne Stone. “He has been a great resource. Also, when big donors, like Carl and Alice Kirkland, stepped forward, he made sure that their gift was handled correctly. There are so many others that have contributed by

fundraising, building, decorating and planning.”

There are too many to name and no one person contributes more than another. Instead, they’ve all jumped in with their resources and gifts to build a home for women they may never meet. Their own stories have intersected at this moment in history, leading them to this moment to make an impact on the story of someone else. They are building a home together; a home for survivors of sex trafficking. A home that will be in Jackson for years to come.

Who built the Scarlet Rope House? No one built it, and everyone built it. No one person will ever be able to take credit and, without the support of many, it would’ve never happened. Where do the survivors belong now? The old places are haunted, and they don’t fit there anymore. They are survivors and just passing through. They are welcome here, in a house built with many hands, the Scarlet Rope House. Learn more at www. scarletropeproject.com.

VOL. 8, ISSUE 2: PHILANTHROPY • 21

22 • OUR JACKSON HOME

Aging in Place

BY BRITTON CRENHSAW

Habitat for Humanity Jackson, TN Area, Inc. (Habitat Jackson) has been working to improve the Jackson community since 1986. Known for serving low-income individuals and families by constructing affordable housing solutions, Habitat Jackson continues to expand its impact through the Aging in Place program.

This program supports the continued safe residence of lowincome, older adult homeowners through the completion of nocost critical repairs. The program targets those age 60 and older who own their home and reside in Madison or Haywood County. The repairs improve the safety and accessibility of the structure for the homeowner, so they do not have to seek shelter elsewhere such as a temporary living facility or with additional family members. It also relieves the older adults of undue

financial burden later in life. New roofs, new floor beams, wheelchair ramps, handrails, doors, grab bars, shower transfer benches and more are the life-changing products of this program. One such person whose life was changed was Ms. Martin.

Ms. Martin recently had the roof on her 1959 home replaced. The new improvement brings safe shelter to a home that has long proved special to her and her family. Before Ms. Martin owned the home, it belonged to her aunt. “I have lived here since I was in third grade,” Ms. Martin stated. She remembered knowing everyone on her street and it being a family environment. “Everyone was family. We had three churches, Bible study, and activities for the whole community. Everyone looked out for one another,” she recalled. When her aunt got older, she became sick and eventually

VOL. 8, ISSUE 2: PHILANTHROPY • 23

24 • OUR JACKSON HOME

"I just enjoy living by myself and being able to be independent."

passed. Her aunt chose to entrust the home to Ms. Martin.

Ms. Martin continued to live in the home and raise her own children in the home. She and her children were able to attend the school only a block away from the home where she also worked as an assistant in a pre-kindergarten program. Today, a handful of her neighbors are some of the original owners and her lifelong friends. The neighbors continue to look after each other and know everyone’s grandchildren. Ms. Martin said the process of getting a roof was enjoyable and she appreciated how they cleaned up after themselves, and that she got to socialize with the workers while offering refreshments. She is most thankful for a roof that no longer leaks and the ability

to continue to live by herself.

“It is so comfortable to live in the same place since 3rd grade, and I just enjoy living by myself and being able to be independent,” she sai.

Aging in Place has been in operation since May 2019 and with over $263,000 invested in Madison County alone, it has been truly life changing work for all involved. Habitat Jackson began servicing this need as it sought to close the gap of services for our most vulnerable community members. As construction and living costs continue to rise, Habitat Jackson is seeking new, regular donors to support the work of the Aging in Place program and provide affordable housing solutions for all. Learn more at www.jacksonhabitat. com.

VOL. 8, ISSUE 2: PHILANTHROPY • 25

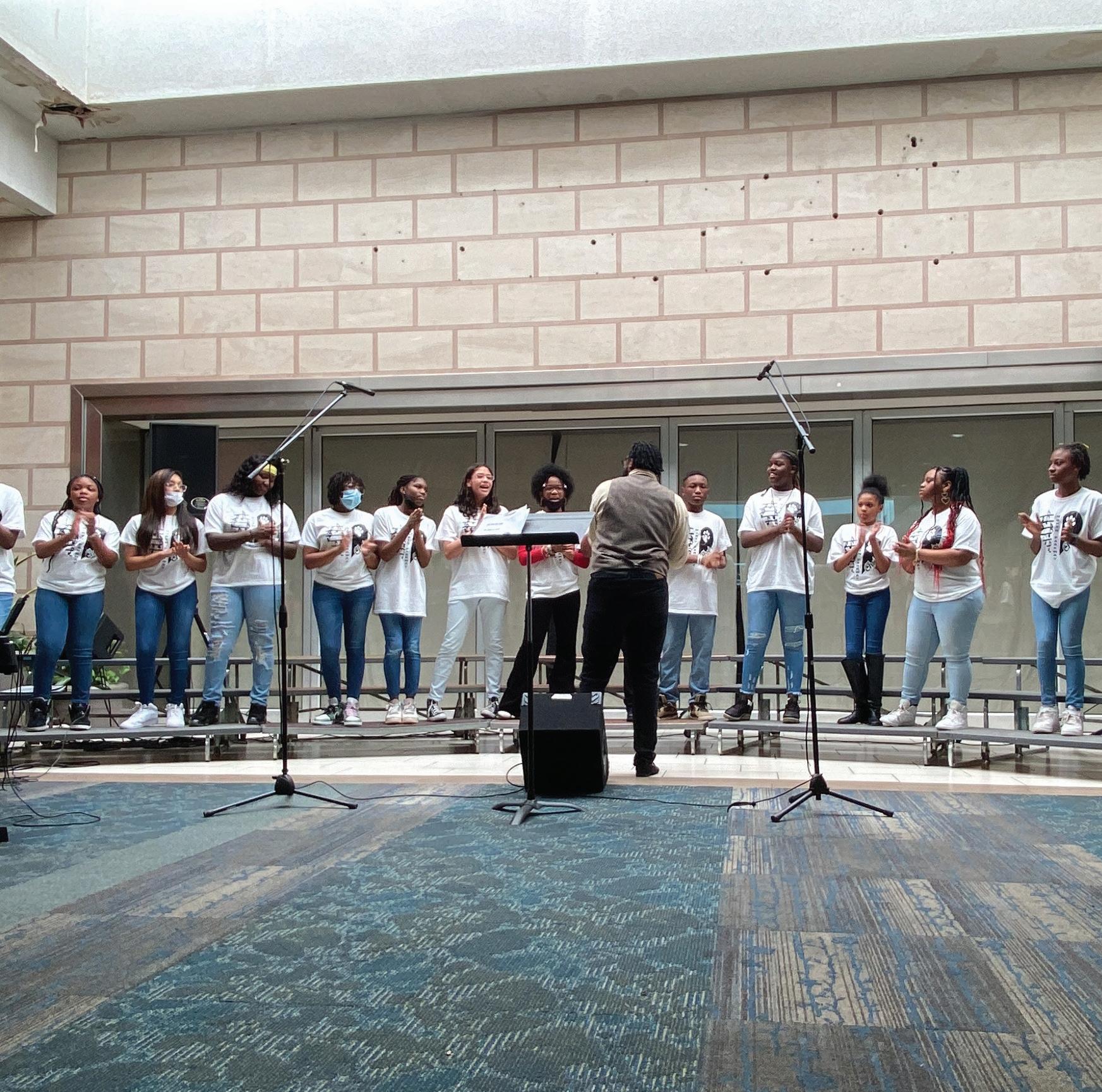

Giving the Arts a Chance

BY LIZZIE EMMONS

BY LIZZIE EMMONS

When we discuss the benefits of investing in the arts, we often talk about the beautification of our neighborhoods and the significant impact that the arts have on our economy. Although those are powerful ways that philanthropy directly impacts the arts that should continue to be robustly supported for the growth of all communities, we often overlook the critical benefits of providing arts access to students.

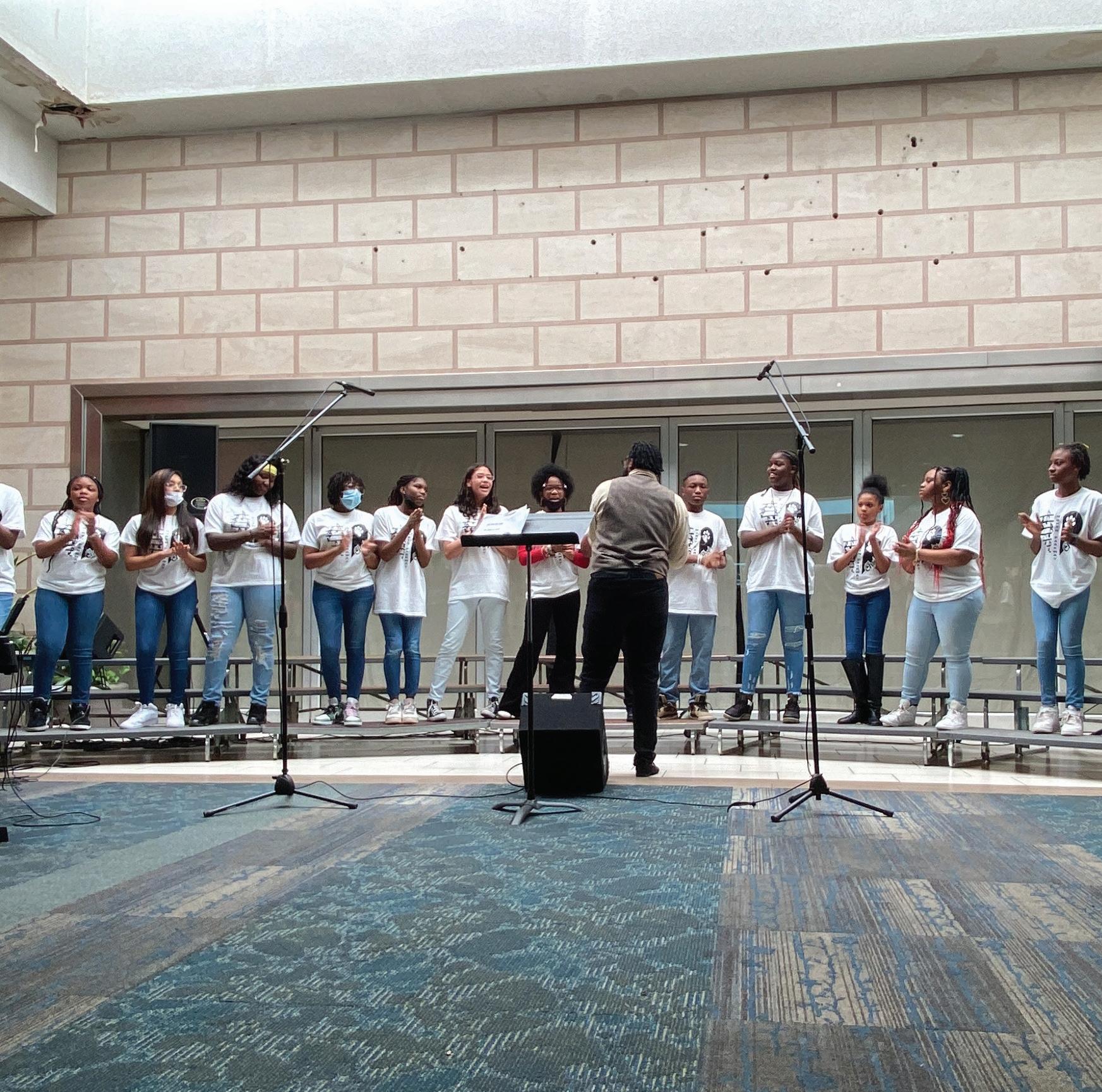

It’s no secret that when budgets get tight, the arts get cut. The arts in schools are often seen as extracurricular or optional. In reality, the arts are as essential as any other subject area with their own state and national curriculum standards taught by professionals with four year degrees or higher. Under the Every Student Succeeds Act signed into law in 2015, music and the arts are included in a well-rounded education. Time and time again, research shows that access to the arts for K-12 students improves academic performance, lowers dropout rates, reaches students with different learning styles, creates

schools that are exciting places for learning and discovery, and results in gainful employment, completion of college degrees, and creation of community volunteers after graduation. Despite the impressive research that proves the benefits of strong arts education programs, national support for arts education has declined in favor of other subject areas. When the arts are underfunded or cut completely, that leaves hardworking educators scrambling to find community resources for their students. That’s where philanthropy comes in to help. Locally, the Jackson Arts Council provides resources to support arts access to students both in and out of schools. The Arts Council’s vision is for every individual in the community to have impactful cultural experiences through engagement with the arts. One way that the organization sees out their vision is through grant funding that often supplements what is not provided in schools. There are 22 Jackson Arts Council grant recipients in 2022

26 • OUR JACKSON HOME

who will receive funds that directly provide arts access to students in the community either in or out of the classroom. These grant funds would not be possible without philanthropic support of the Jackson Arts Council. Many of the Jackson Arts Council’s grant recipients are independent arts organizations dedicated to providing arts access to K-12 students, including dance, theatre, visual arts, and music that rely on local philanthropy.

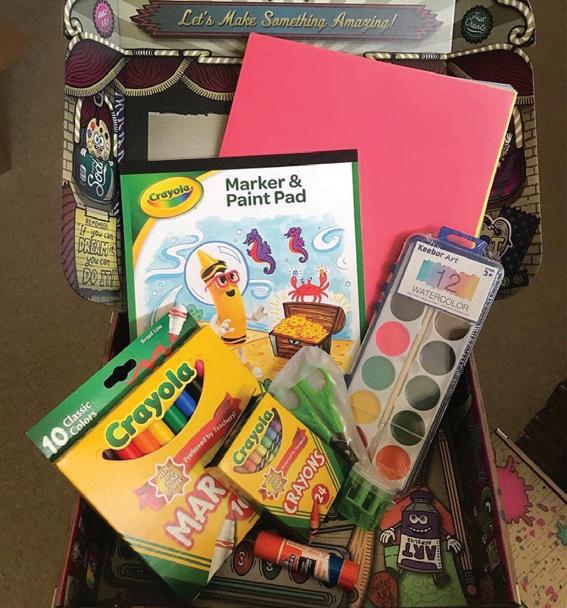

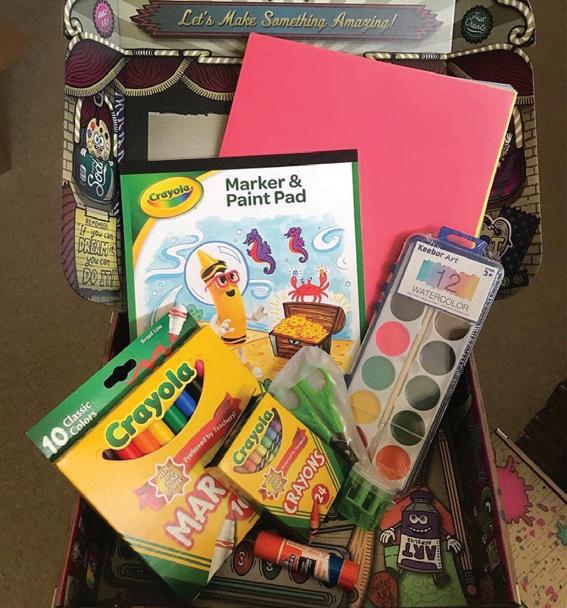

The Jackson Arts Council also launched a pilot project this year called the Jackson Art Box. This project provides free art supplies to students in the Jackson Madison County Public School System. School counselors were provided professional development training by an art therapist on how to use art as a means of expression. Free art supply boxes were delivered to school counselors at the beginning of this academic year. The Jackson Arts

Council knows that this new project provides two important services: one, it provides an additional tool for students to be creative and process emotions in a safe space with a licensed professional, and two, it removes barriers to artmaking by providing students with their own art supplies that they can take home.

Necessary funding for the arts at the local level and projects like the Jackson Art Box are only possible through philanthropy. When communities come together to invest in the arts through organizations like the Jackson Arts Council and other local arts groups, they are making a direct, positive impact on the lives of students. We know through proven research that removing barriers for students to participate in the arts creates pathways to success. When our students succeed, our entire community succeeds.

VOL. 8, ISSUE 2: PHILANTHROPY • 27

"We know through proven research that removing barriers for students to participate in the arts creates pathways to success. When our students succeed, our entire community succeeds."

28 • OUR JACKSON HOME

BALLET ARTS, INC.

“What we do doesn’t have any talking or singing — you’re telling a story with your movement. That can be really powerful for a lot of kids who struggle with how to express themselves.”

“Ballet teaches so much more than just movement. It takes hard work, dedication, repetition, responsibility, and builds a great work ethic in children. Even if they aren’t planning to dance for the rest of their lives, they have skills that ballet teaches them that they will keep for the rest of their lives.”

CAROLINE MEINERT Artistic Director

VOL. 8, ISSUE 2: PHILANTHROPY • 29

JACKSON MADISON COUNTY SCHOOL SYSTEM

“The arts in our schools always have to find other avenues of support to have more programs, more equipment, and more instruments for students. Special projects like the Jackson Arts Council’s grant programs help supplement needed resources to grow our music programs.”

“So many families cannot afford private lessons on their own. With funding for the arts coming to schools to provide private lessons instruction from the Jackson Arts Council, it becomes easier for students to have access to music instruction.”

KRISTY WHITE

District-wide Consulting Teacher - Music

30 • OUR JACKSON HOME

THE NED

GRAYSON HART Children and Teen Theatre Director

GRAYSON HART Children and Teen Theatre Director

“After school theatre programs provide safe, creative outlets that allow children to express themselves and find groups of like-minded, supportive people.”

VOL. 8, ISSUE 2: PHILANTHROPY • 31

32 • OUR JACKSON HOME

Strangers to Friends

BY COURTNEY SEARCY PHOTOS BY CARI GRIFFITH

If there’s one shared value Southerners agree on, it’s probably hospitality. Hospitality comes naturally to us when it comes to a dinner party, where our guests will be treated to an extra heaping of cobbler and a box of leftovers to take home.

In my mind, hospitality is defined by one memory: every major holiday, the living room at my grandparents’ house would be packed with family and anyone we knew who didn’t have family to share the day with. Even though there were guests I sometimes rolled my eyes to see, I understand the value of that space now. Eventually, one of those friends gifted them a sign that hangs at the door. It reads, “Enter as strangers, leave as friends.”

One of my favorite writers, Henri Nouwen, defines hospitality in this way: “Hospitality means primarily the creation of a free space where the stranger can enter and become a friend instead of an enemy. Hospitality is not to change people but to offer them space where change can take place. It is not to bring men and women over to our side, but to offer freedom not disturbed by dividing lines… The paradox of hospitality is that it wants to create emptiness, not a fearful emptiness, but a friendly emptiness where strangers can enter and discover themselves as created free; free to sing their own songs, speak their own languages, dance their own dances; free also to leave and follow their own vocations.

Hospitality is not a subtle invitation

VOL. 8, ISSUE 2: PHILANTHROPY • 33

to adore the lifestyle of the host, but the gift of a chance for the guest to find his own.”

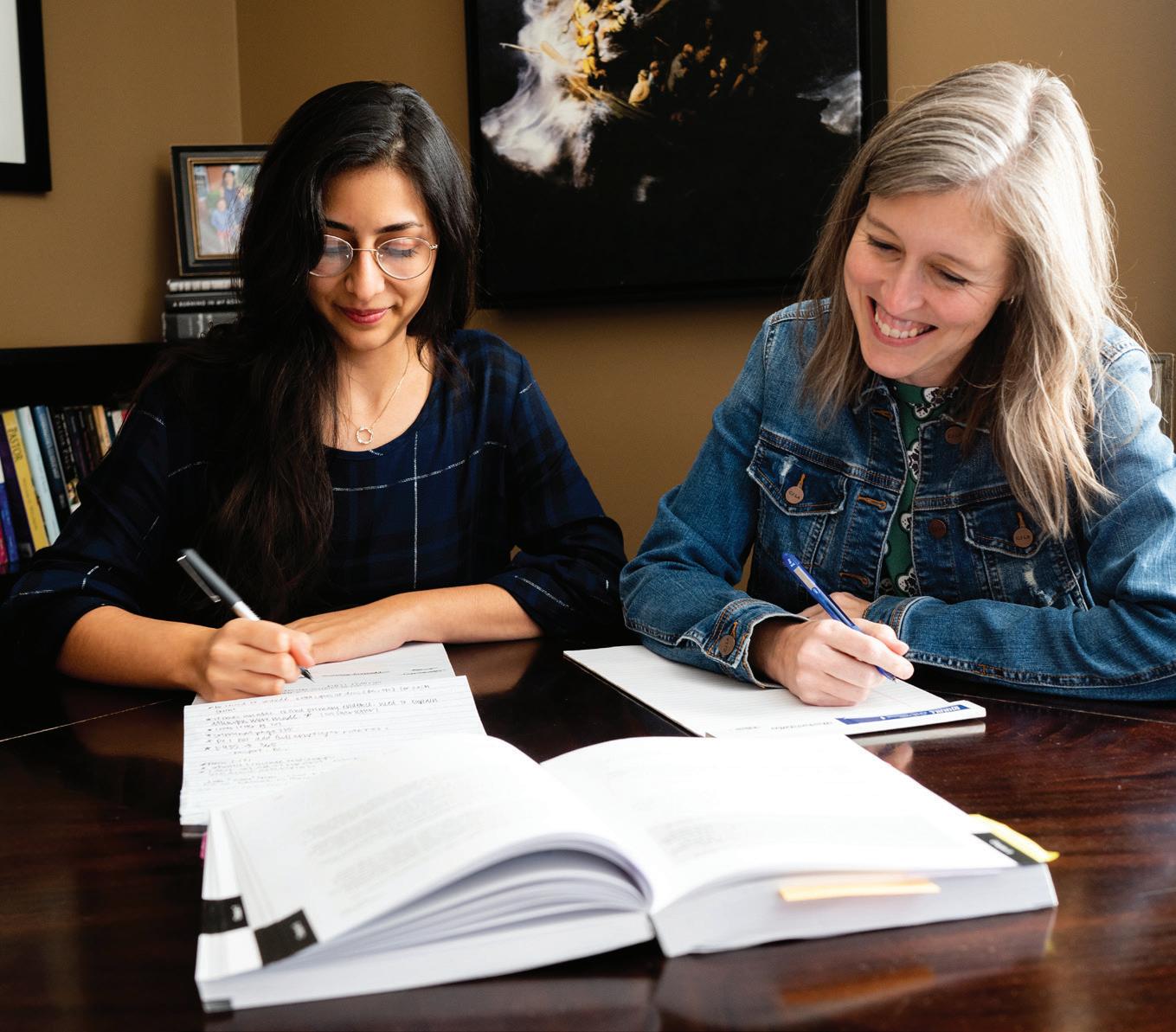

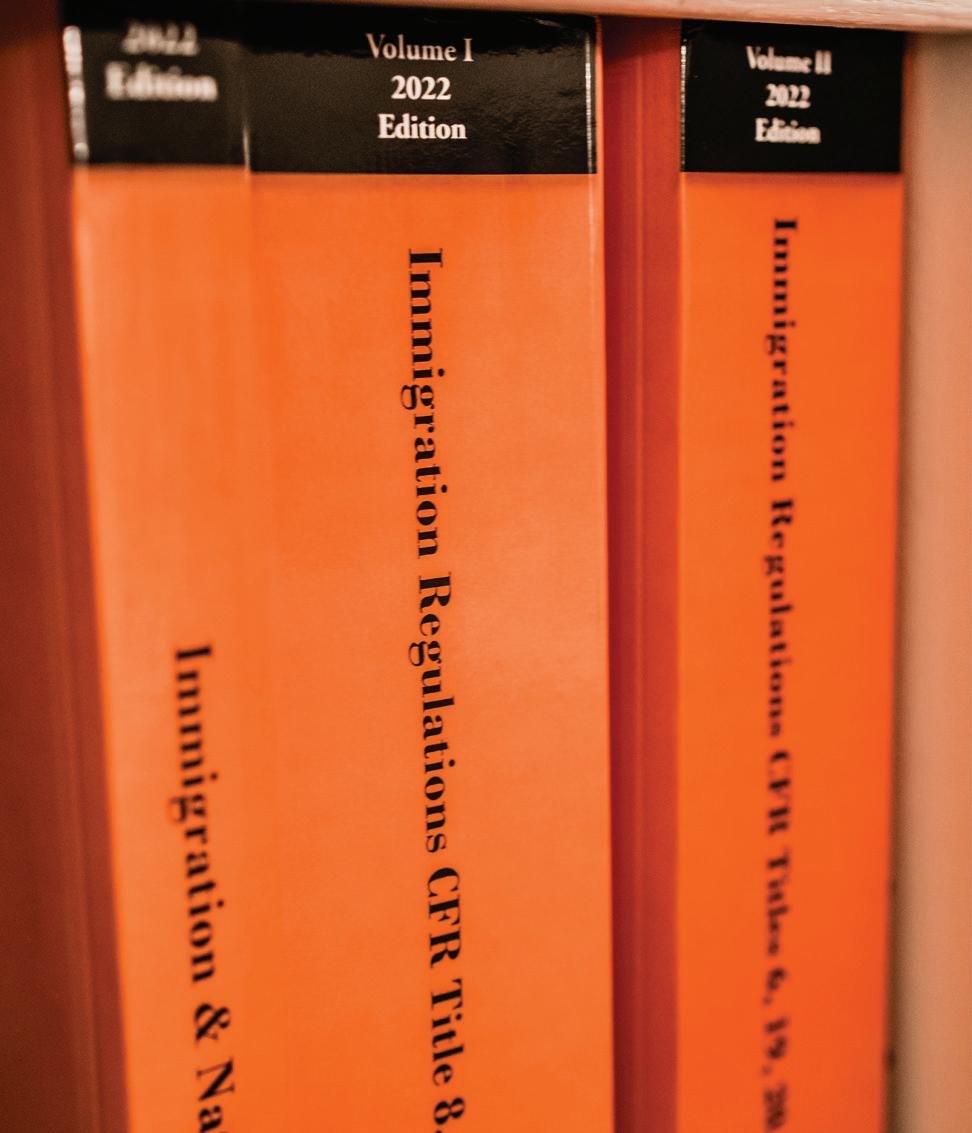

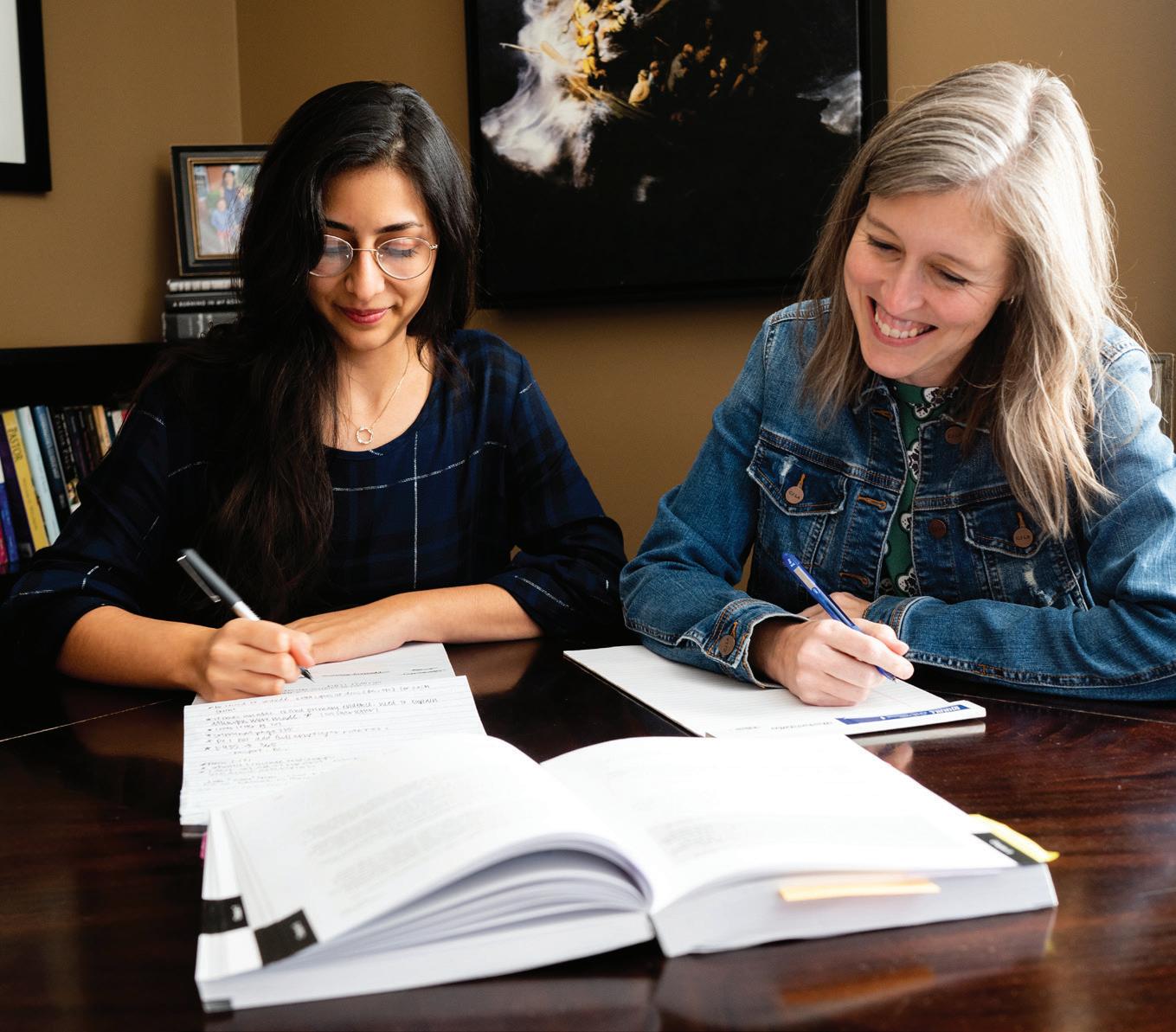

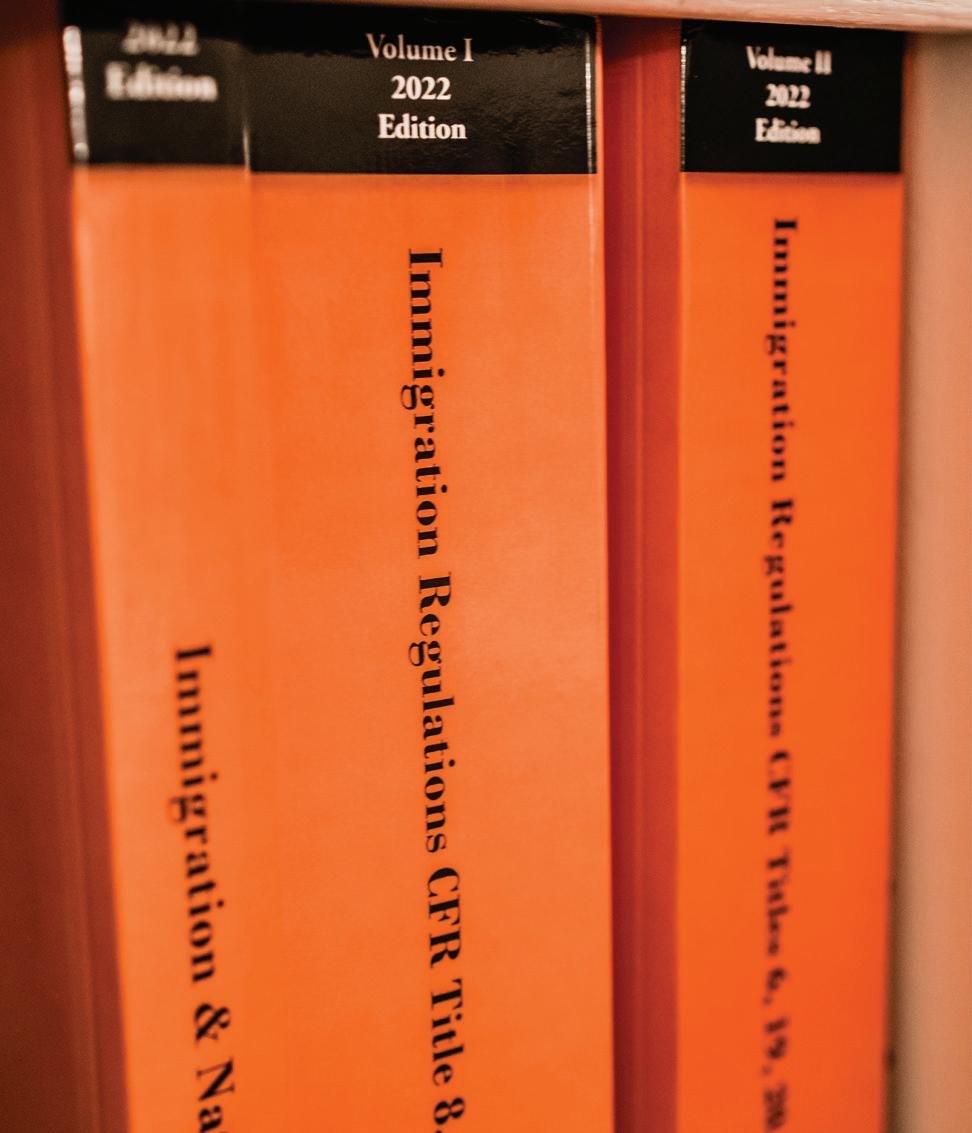

So our supposed value of hospitality becomes harder for us to extend in our daily lives. Once we step outside of the comfort of our homes, the barriers between us start to grow. Our cultures, languages, habits, and politics make it harder for us to welcome people outside of our normal circles into our lives. The greatest challenge for us then, might be knowing how to welcome a true stranger, someone who shares very little of our culture with us — an immigrant. But one local organization, All Saints Immigration Services (ASIS), is creating a more hospitable Jackson for immigrants navigating the legal system. They are guiding people in Jackson and West Tennessee through the process of immigration to become thriving and engaged community members.

The clients who walk through the doors of ASIS come from a variety of backgrounds and situations, with over 20 countries

represented among them so far. Some are fleeing violence or poverty, but they all share one thing: they left the place they once called home. With new languages, laws, and culture to navigate, where do they begin?

“We help provide legal access to help — it’s hard to find the information and very easy to be taken advantage of. You almost have to have an advocate,” Director Stacy Preston says.

The State of Tennessee estimates that there are 349,000 immigrants in Tennessee, compromising five percent of the population. ASIS estimates that roughly 15,000 of them are within a one hour drive of Jackson-Madison County. Before the opening of ASIS in November of 2020, there were no immigration services in Jackson-Madison County and the nearest non-profit legal services were in Memphis and Nashville. Furthermore, there is no law firm in our community devoted solely to immigration law work. What began with Stacy Preston and

34 • OUR JACKSON HOME

Lynn Binkley has grown to an organization that operates with two staff members, Stacy Preston and Dulce Maria Salcedo, as well as interns. Stacy and Dulce Maria are both certified by the Department of Justice to serve as legal advocates for the immigration process.

According to ASIS, “Four percent of Tennessee children live with at least one family member who is at risk of being deported or separated from their family. Yet immigration law assistance can cost tens of thousands of dollars, precluding people without significant resources from this type of help. When families have the security of legal status which provides the ability to legally work

and provide for their family, it contributes to much higher levels of mental health and well-being which directly impacts the JacksonMadison community. Families will be more likely to use health and social services, volunteer, learn English, and cooperate with local authorities instead of living in fear.”

Since they have been operating as a non-profit for two years, Stacy counts being able to hire Dulce Maria as a full time employee one of the greatest milestones in their time as an organization. Dulce Maria serves as a translator as well as an advocate, her own experience as a first-generation immigrant providing a layer of trust and understanding with clients. Dulce

VOL. 8, ISSUE 2: PHILANTHROPY • 35

Maria’s family made the difficult decision to move to the United States when she was just one year old.

“We didn’t want to leave our home, our friends, our community. Coming to the United States was our last choice — the economic situation was really tough… especially for my dad, who was a business owner,” Dulce Maria said.

Though it can be difficult to acquire, her family was able to qualify for a visa. It was not an easy process from there, although they had taken all of the correct legal steps. Shortly after that, their visa expired, and her father died after a battle with colon cancer. But before he passed away, her mother made a promise to him that she would

stay in the United States for her children.

In the following years, they spent thousands of dollars to get a chance, and for a long time, nothing worked to get them to a path of citizenship. Through these years, her mother encouraged Dulce Maria to focus on her education. She applied for a competitive scholarship, Golden Door Scholars, aimed to help non-citizen students receive a college education and was able to attend Rhodes College for her bachelor's degree. Her family has been able to obtain legal status and is in the process of gaining citizenship.

These kinds of long, frustrating, difficult, and confusing journeys are what the ASIS staff navigate every

36 • OUR JACKSON HOME

VOL. 8, ISSUE 2: PHILANTHROPY • 37

day. There are many misconceptions and misunderstandings among immigrants and the greater community regarding the immigration process.

“Sometimes when they come to us they have never met with us and so this is new information, or they have been given wrong information, or paid money for someone who did not actually help them,” Stacy said.

Much of their work involves dispelling misinformation, which often involves dissapointment. Some people may have to go back to their home country to start the process, or may be required to stay in their country for ten years. “They thought they would have a way forward and they just don’t,” Stacy said.

While ASIS exists to serve the immigrant population, they also

hope to serve as a resource for other organizations and businesses in Jackson who may work with immigrants in order to guide them to best practices regarding employment and other obstacles that may be faced.

They hope to help educate the community abut how much value immigrants bring to our community, and empowering immigrants in turn to contribute to the community.

Ultimately, this is the vision the office of ASIS is building, to create a hospitable path for immigrants to be thriving members of our community. They’re offering the truest form of hospitality, to open up a path for someone else to make Jackson and the United States home. Learn more at www. allsaintsimmigration.com

38 • OUR JACKSON HOME

brewing community.

300 EAST MAIN STREET | DOWNTOWN JACKSON

Beauty in the Wayside

BY ISAAC ELLIOTT

What’s special about photography is the unique eye each person has. In my work, I’m drawn to warmer tones, capturing the moment a perfectly-placed ray of sunshine makes a subject light up, or finding exciting scenes in a normal stroll down the street. Simple colors, light, and composition can make any shot one of great beauty, we just have to train our eyes to see it. My hope in sharing these photos is that you’ll begin to see more of what my eyes see, beauty in the wayside.

40 • OUR JACKSON HOME

VOL. 8, ISSUE 2: PHILANTHROPY • 41

42 • OUR JACKSON HOME

VOL. 8, ISSUE 2: PHILANTHROPY • 43

44 • OUR JACKSON HOME

VOL. 8, ISSUE 2: PHILANTHROPY • 45

Philanthropy

BY LILY K. LEWIS | PHOTO BY HANNAH GORE

A son buys his father coffee after an argument, A woman gives a dollar she did not have to give, A parent shows mercy when punishment is expected, Teaching a lesson of forgiveness. These are actions of compassion. A rich couple donates a hefty sum to an orphanage, A homeless man gives his jacket to a starving child, A pair of friends take the time to listen Though the time they have is limited. These are actions of generosity. These are actions of charity. These are actions of philanthropy because Philanthropy is the desire to provide for others; It is a way of living to show the people you love How much you love them.

Craving what is best for others and assisting them

In whatever way you can. That is philanthropy. Philanthropy is starting a non-profit for Those who are victims of their circumstances, yes, But most of all, at the heart of it, philanthropy Is freely using the gifts you’ve been given To uplift those who cannot empower themselves

In a way unique to you And special to every relationship you create, Every life you have the opportunity to impact.

VOL. 8, ISSUE 2: PHILANTHROPY • 47

48 • OUR JACKSON HOME

Freeges for All

The City of Jackson in partnership with JACOA and First Methodist Downtown recently opened two free community fridges at 900 E Chester St and 200 S Church St. This project is sponsored by the highly-competitive 2022 AARP Community Challenge grant, awarded to the City of Jackson as one of 260 quick-action projects out of 3,200 applications nationwide. These community fridges joined an international network of hundreds of community fridges, and will serve as a pilot program for expanding food access and addressing food insecurity in Jackson. More information on the network can be found at freedge.org or on the Jackson, TN Community Fridges Facebook page. The community fridges will be open to all residents of Jackson to take or donate food, with a 5 item limit per person when taking food. Produce, dairy, eggs, pre-packaged prepared food, beverages, bread items, yogurt, deli meat (cooked), and individual meals prepared in commercial kitchens are all accepted. Non-perishables, raw meat, expired food, or food prepared

in a private home can not be accepted. The Jackson Community Fridges will also be working in partnership with Give Back Jack to join the existing network of food donations and volunteers here in Jackson. As part of the AARP grant award, the City of Jackson received funding to stock the fridges once a week for 10-12 weeks. However, when this funding runs out the fridges will rely solely on donations from the community. We are looking to set up partnerships now to get local businesses and groups involved in creating a regular donation schedule. This could be once a month, once a week, or even for holidays. These community fridges are not meant to take the place of food banks or operate as a grocery store, but rather to help supplement a few items to help lower the cost of grocery bills. The intention behind the community fridges is to expand on existing mutual aid initiatives, which allow the community to share food and reduce food waste, while increasing access to fresh food items for those in need.

VOL. 8, ISSUE 2: PHILANTHROPY • 49

SPONSOR SPOTLIGHT

A Foundation for Community

WEST TENNESSSEE HEALTHCARE FOUNDATION

50 • OUR JACKSON HOME

Who is the West Tennessee Healthcare Foundation?

Merriam-Webster defines foundation as “a basis upon which something is supported or a body upon which something is built up,” and these descriptions encompass what the West Tennessee Healthcare Foundation is to our community.

Founded in 1985, The Foundation has always worked to improve the health of those in our service area, but over the past three decades, The Foundation has transformed from its initial role as a healthcare foundation into a community foundation with a solid emphasis on supporting our local health system. As we have adapted to the changing needs of our community, our focus has transitioned to serving as a catalyst for positive changes in healthcare, education, and the arts. We seek to strengthen the health and well-being of our community by supporting the physical health of our residents as well as their quality of life.

So much of what The Foundation does is behind the scenes. Home to almost 500 funds, The Foundation supports all aspects of the community from healthcare to the arts; education to animal welfare; housing and food security to equity and diversity. This can be found in the form of sponsorships, grants, scholarships, and direct support to agencies and individuals.

Our various types of funds make

it possible to increase our reach into all facets of our local area. Our community project funds function as micro non-profits meeting needs in the community where gaps in services exist. The Foundation serves as the fiscal agent for several state and federal grant programs providing additional support for homelessness, addiction, mental health, and aging. Donor-advised funds allow local philanthropists to support worthy causes both locally and internationally, and our more than $28 million in endowments ensure many of these causes will receive funding beyond the scope of our lifetimes.

Each year, The Foundation supports West Tennessee Healthcare through direct funding for health system needs as well as individual assistance for employees and patients, helping with housing, utilities, medication, and other necessities.

To extend our support of the health system, The Foundation embarked on its first capital campaign in 2021 to construct a hospice home. This facility will be the first and only of its kind in our rural nineteen county service area and will provide families with a vital option for end-of-life care. West Tennessee Healthcare employees along with individuals and organizations across the area have joined together to make this vision a reality by volunteering their time and giving financial support to provide mercy, comfort, and love

VOL. 8, ISSUE 2: PHILANTHROPY • 51

for those needing hospice care.

While access to healthcare is crucial to the overall health of any community, research has shown numerous influences outside the health system may play an even larger role in determining the health of its citizens. These influences are commonly referred to as social determinants of health, and strengthening these factors are the key to reducing health disparities and improving health outcomes. The Center for Disease Control has identified five domains in social determinants of health: economic stability, education access and quality, healthcare access and quality, neighborhood and built environment, and social and community context.

Our goal is to strengthen these five domains, which directly improve the health and well-being of our community. To achieve this, The Foundation supports a variety of initiatives focused on social determinants of health. Last year, The Foundation invested almost $3.5 million back into our local communities with more than $3 million of those funds distributed to other non-profits who are addressing each of these five areas.

Since 2016, The Foundation has awarded more than $205,000 in community grants to non-profits serving Madison County. This

year, $55,000 was awarded to the following six agencies to improve social determinants of health in our community. These awards are highlighted on the opposite page. Another unique way The Foundation engages with the community is through our largest annual fundraiser, The Charity Gala. This elegant two-night event brings together leaders from across West Tennessee to support projects and services directly connected to the health system. This year, the event benefits the Hospice Home and Ayers Children’s Medical Center.

In addition to raising money, The Charity Gala recognizes the achievements and impact of local individuals who are making our city and county a better place to call home through the Jackson Awards, Dr. A. Barnett Scott Award, and Tigrett Award.

Over the past 37 years, The Foundation has established strong roots in Jackson and Madison County. As we continue to grow, we want to provide the foundation where other great accomplishments are built in our community. By investing in local initiatives and non-profits as they impact the lives of those they serve, we continue to branch out and expand our reach to impact the future of West Tennessee.

52 • OUR JACKSON HOME

JACKSON ARTS COUNCIL

JONAH AFFORDABLE

HABITAT

SCARLET ROPE PROJECT $5,000 to fund trauma therapy for victims of sex trafficking. ALL SAINTS IMMIGRATION SERVICES $20,000 to fund a full-time legal representative allowing the organization to serve more clients needing immigration law assistance.

(RIFA)

to fund Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) fresh

boxes

distributed

$5,000 to fund the Jackson Art Box project to provide an art therapy outlet for students in the JacksonMadison County School System.

REGIONAL INTERFAITH ASSOCIATION

$10,000

produce

to be

through Jackson Housing Authority to lowincome senior adults.

FOR HUMANITY $10,000 to fund home repair projects for low-income senior homeowners.

HOUSING $5,000 to fund assistance for low-income to moderate-income tenants to obtain affordable housing and retain housing during hardships.

Contributors

IN THIS ISSUE

DAN BATTLE is a self taught photographer and filmmaker. He has the artistic ability to display beauty in unexpected places.

BRITTON CRENSHAW is the Resource Development Director for Habitat for Humanity in Jackson, Tennessee. A West Tennesse native resident and social worker by trade, Britton believes in making his community better for all by building strength, stability, and self-reliance through shelter.

ISAAC ELLIOTT is a local photographer who desires to capture light and color to show the resplendent beauty of every day life. He is currently a resident director at Union University where he lives with his wife, Brooke, and puppy, Bristol. He graduates with his masters’ degree in May of next year and is seeking to pursue ministry with college students in some way. Check out his Instagram @isaac.crtv

to see more of his photos and stay up to date on his photobook that is releasing soon.

LIZZIE EMMONS is the Executive Director of the Jackson Arts Council. She is a native West Tennessean from Dyersburg, Tennessee. Lizzie is a passionate advocate for the arts with experience in arts administration, graphic design, education, therapy, music performance and visual arts. She currently serves on the Board of Directors for ArtsEd Tennessee as the Board Secretary, and is also the vice-chair for the City of Jackson’s Public Arts Commission. Lizzie has a Bachelor of Arts in Music and a Master of Science in Education, both from the University of Tennessee at Martin, and a certificate in Arts Management from the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

CARI GRIFFITH is a gardener and a photographer with a lifelong affection for seed sowing and

54 • OUR JACKSON HOME

storytelling. She lives a very sweet life in midtown with her husband Rob. She spends most of her time behind a computer or a camera, and her most treasured moments are eating dinner with her friends both near and far.

GABE HART is the Chief Communications Officer for Haywood County Schools. A lifelong Jacksonian, Gabe is a product of the Jackson-Madison County School System and taught English in JMCSS for fourteen years. Along with contributing to Our Jackson Home, Gabe also writes monthly columns for Tennessee Lookout and The Jackson Sun and has been published in The Tennessean. He lives in Midtown Jackson with his daughter who attends high school at Madison Academic. When he's not in Jackson, he's most likely traveling with his partner, Laura, or spending time with her in her hometown of Philadelphia.

HANNAH GORE is a photographer from Jackson,Tennessee, who currently lives in the nearby town of Medina. She is currently working to earn her associates degree in mass communication at Jackson State Community College. Through her passion for authenticity, she seeks to capture the heart and soul of Jackson through the art of photography. When she doesn’t have a camera in her hand, you can find her in the corner of a coffee shop with a good book, learning a foreign language, or watching Korean dramas.

LILY K. LEWIS is a senior at Madison Academic, and she recently published her first book, “Everlasting Light.” When Lily isn’t at theater rehearsal, you’ll find her drinking coffee, writing, or baking something with chocolate. Lily believes that writing is a form of connection and always tries to embody that in her work.

COURTNEY SEARCY became the Program Director of Our Jackson Home at theCO in 2020, having contributed to OJH as a writer, photographer, and volunteer since 2015. Courtney serves as Editor-inChief for the blog and magazine and coordinates events and Our Jackson Home projects. She thinks the best things in life are good food, art, music, and friends to share it all with.

GINGER WILLIAMS is a lifetime Jackson resident, who has been a contributor and editor of the Jackson Business Journal, as well as one of the writers of the history book of Jackson: Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow and Our Jackson Home. She has spearheaded community events including the citywide water balloon fight on 731 Day; and created the Arts Backstage, a networking event for Jackson’s leaders to meet Jackson’s local artists. She has served on the board for the Jackson Arts Council and the Scarlet Rope Project. She is also a local real estate investor and top producer at Town & Country Realtors. She and her husband Matt, have two sons, Blake and Ethan.

VOL. 8, ISSUE 2: PHILANTHROPY • 55

Help Bring the First Hospice Home to West Tennessee. Learn More at www.hospicehome.org

BY LIZZIE EMMONS

BY LIZZIE EMMONS

GRAYSON HART Children and Teen Theatre Director

GRAYSON HART Children and Teen Theatre Director