LETTER FROM THE EDITOR

Asian American musician Lowhi once said “We are forever tethered to those we share a connection with, even after death.”

For us as Asian Americans, there are infinite lifetimes of experiences that find their roots within the word “connection.” From our parents, who sought to form connections within their immigrant communities as a way to reconnect with their heritage. And now, these stories continue with us.

For this month’s publication, we hope to explore how connection helps to define our culture. Whether it is those strained connections with our family or the lifelong connections that we develop within our communities, our Asian American identity is intertwined with how we connect.

As the end of the semester is slowly approaching, we wish you the best of luck with your final exams. During this holiday season, however, we hope that you remember the people around you. After all, we are only as strong as the connections that we form with one another, and we couldn’t have made it this far without them.

Once again, I want to thank everybody who helped make this magazine possible, including your support as a reader. We’ll be back next semester, and we can’t wait to show you what we have planned!

With

Love, ANTHONY NGUYEN | EDITOR IN CHIEF

Please contact me at ouaasa.gensec@gmail.com with any comments, questions, or concerns.

MITTEES

IF YOU HAVE ANY INTEREST OR EXPERIENCE IN ASIAN AWARENESS/CULTURE, EDITING/WRITING, GRAPHIC DESIGN & PHOTOGRAPHY ... JOIN THE OU AASA MAGAZINE!

BE A PART OF THE ASIAN AMERICAN STUDENT ASSOCIATION'S MAGAZINE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA FOR A GREAT OPPORTUNITY TO EDUCATE AND CELEBRATE THE RICH HERITAGE AND TRADITIONS OF ASIAN CULTURE & HERITAGE.

FOR ANY QUESTIONS, CONTACT EDITOR-IN-CHIEF, ANTHONY NGUYEN AT OUAASA.GENSEC@GMAIL.COM

Like a lot of other Asian Americans in Oklahoma, I grew up in a town that didn't have too many Asian Americans within it. Although I wasn't necessarily ashamed of my Vietnamese culture, I'd ask my mom to buy me Lunchables since I didn't want to stick out as the only kid eating out of a thermos at lunch in elementary school. I wasn't ostracized for being Asian, but I always felt an awkward rift between myself and my classmates.

Coming into OU, however, I found a community of people, with who I stumbled upon a "home away from home" People who had similar stories as me, coming together to celebrate our culture as Asian Americans.

We, at AASA, hope to provide a similar experience to our members, where we are able to help facilitate this process of reconnecting with our Asian American heritage. So, to everyone reading this. We love you. Unconditionally.

Sincerely, AASA

Clasped Hands

by Nate ReeseFor "Clasped Hands," I was inspired by the way I see humanity’s struggle as a chain of common experiences. Our struggle and our success from that struggle are through our common experiences and our cooperation through that struggle. I believe if we power through these experiences, such as lack of meaning, poverty, and discrimination, with our “hands clasped” and fully united as humanity, we can eliminate our suffering.

Our hands clasped, You, my voice when I speak in rasp. Our claps a roar and our clasp a chain, Together there is no pain

Our chant is not in vain, A melody of gain. Of our fore sought change, Of an arranged peace. Grab my face, And give me a kiss of grace, To last a lifetime. And give me a bell to chime, Till the end of time. That we are clasped hand, For life's climb

Talking Body: Tattoo Art as Cultural Rebellion and Reconciliation

By Caitlin Le

Tattoo artist Seoyeon on parental approval, cultural stigmas, and the ways young Asian artists are breaking down barriers.

That very belief inspires all of my tattoos, in fact, with every piece as a bridge between tradition and rebellion. All of my body art connects back to my Vietnamese heritage, simultaneously indulging in and challenging what it means to be “Asian”.

New York tattooist Seoyeon, 24, knows this struggle well The Korean born, NYC raised artist has grown from 5,000 to 50,000 Instagram followers in the past 5 months, garnering praise for her East Asian inspired style. A lover of “all things pink, anime, cats, fashion, drawing, and hanbok,” Seoyeon might live at the very intersection between cultural rebellion and reconciliation. Twenty three days.

That’s how long it took for my mother to notice my first tattoo Once the long sleeves grew unbearable and my right arm was free for viewing, the hellscape began.

“That better be henna,” she cried, trying to convince herself of something we both knew was untrue She thought I would know better, really better than to defile my own body with such permanence. While the lotus flower drawing was beautiful, illustrating both my Vietnamese heritage and my birth month of July, it was wrong.

One year, two disappointed parents, and three tattoos later, I’ve come to terms with this belief

@tattooist yeonnie

@tattooist yeonnie

How did you get into tattoo art? W do you love it?

I’ve been drawing my whole life a even have a BFA in animation decided it wasn't for me, thou career wise. I love tattooing because very different from the art I’m used making. My main hobby in creat semi realistic digital illustrations w lots of rendering and detail. This ta forever but with tattoos, I mostly w small only a few inches and with cu simple subjects. I love the tattoo sty have going on right now with all sparkles

Since a lot of those designs revo around Asian culture, like anime, pop, cute and colorful characters, you feel in touch with your Kore culture there? How so?

My parents forced me to go to Korean school as a kid on Saturdays. I hated it then, because I just wanted to play on the weekends instead of going to more school. But as an adult, I’m really grateful for it since I’m nearly fluent in reading, working, and speaking I’m obsessed with Korean traditional clothing, accessories, and architecture, so I watch a lot of historical dramas. This led me to learn more about my country’s history. I think that’s very important: to know where you can from, and to know what your predecessors lived through I enjoy all the modern stuff too, of course, like K fashion and K pop!

Korea’s Constitutional Court reaffirmed tattoo art’s illegality. Do you feel the effects of this stigma here in New York? How so?

A lot of my friends are Asian, and their parents are immigrants I feel like older Asian people still stigmatize tattoos because of their history tattoos being used as a form of punishment or branding, affiliations with crime, et cetera. I don't think younger people have as much of a problem with tattooing though, even in Asia. Korea reaffirmed illegality of tattoos but the people running the court and the government are ... older folks.

I see. Speaking of older folks, though, how does your family feel about your job?

I like tattooing and it's my job. I made it clear to them I'm not seeking their approval, and they got over any issues they had with it pretty fast. Now they are extremely proud and supportive of me and my work.

I’m glad! My parents weren’t exactly happy about my tattoos, even after I explained their meanings do you get any backlash as an artist for your work, whether from clients or unhappy guardians?

I just have one tattoo and my family is

first represents the national flower of Vietnam, the second is a play on my Vietnamese name, and the third depicts symbols from a traditional Lunar New Year game. Do you feel like you get a lot of these? Clients using body art as a way to connect with their culture, I mean.

Sometimes! I think about half the people get tattoos that connect back to their identity, culture, or family. The other half just get designs they like aesthetically, or their favorite characters. It doesn't always have to have meaning!

What’s something you wish more people knew before getting their first tattoo?

I wish people would stop assuming color tattoos automatically fade and disappear after a year or two. That is just not the case. All tattoos fade a bit post healing, as fresh colors are very vibrant. But beyond that initial dulling, it won't deteriorate extremely fast unless it’s on the fingers!

Finally, what’s something you want to say to aspiring Asian tattooists or anybody wanting your tattoos?

@tattooist yeonnie

If tattooing is what you love, don't let your disapproving family or anyone stop you! It's a very fun and rewarding career. And thank you to everyone for letting me tattoo cute sparkles, flowers, and characters on you!

Surviving The Tiger

I remember when I told my father that I got a B on my chemistry exam:

“How are you so far away from an A?"

“Why didn’t you study harder?”

“How do you think you are going to get into college with a B?”

He never considered that the teacher sucks at her job, we were limited to less than 30 minutes, and a B was still higher than the class average. Or how I would lock myself in my room after school for hours, just to do my homework and study.

I could no longer use the same old excuse of “I don’t understand what the teachers are saying since English isn’t my native language,” because I’ve been in this country for so long now that I don’t even buy the excuse myself.

In his eyes, his children were never enough Not smart enough Not hard working enough. Not good enough.

He always said, “I don’t expect you to be the valedictorian of your class. The least you can do is to not disappoint me with your grades. When I was your age, I was doing hard labor in rough environments back in our rural village in Asia Do you know how many of your cousins want to be in your shoes right now?"

Afterwards, I never told him my grades unless I knew they met his expectations. Even then, he’d always tell me to not get a big head, since there were always other kids who were better than me.

drawn by Yuko Shimizu"If you stayed there, you would have never even made it to college because the competition over there is more than someone of your typical intellectual level could handle.”

I became more introverted and insecure, compared to my childhood days when I wasn't living with my dad. He would always find time to bash what I am doing if I was not staring into a book or doing schoolwork. When I managed to accomplish something that was “expected” of me, he would somehow turn it into a pep talk about how other people could do it better or faster. No matter how hard I may try, I knew I would never satisfy him.

To think that all of my hard work will turn into scars for the next generation of kids disgusts me. The last thing I want to be is “that kid,” who they will be ruthlessly compared to. In a way, it feels like Asian children are treated as trophies to be displayed and compared with each other

But every night, I watch both of my parents go to work early in the morning and return late at night, exhausted. And gradually, I understand why.

I’m not a genius, like some of those kids constantly brought up by family friends. Those “perfect kids,” who all happen to be valedictorians, 4.0 pre meds, engineers who have companies lining up to them, or girls who get good grades and can cook and clean for their families. In fact, I don’t even know nor care about them, but I’m already sick of being compared to them all the time.

And in a vicious cycle, my accomplishments will be spread in his social circle of other Asian parents.

Coming into a foreign country with little money and a language barrier, it can change a person. The first generation gets hit the hardest, and they believe education can break the cycle, especially in America the land of “freedom and opportunity.” However, they tend to be blinded by this mindset that they never realize how much pressure they are putting onto their children As a part of the 15 generation of immigrants who came to America during childhood, I understand why they made these decisions. At the same time, however, I know to never follow in their footsteps.

A Place for Us:

A Novel by Fatima Farheen Mirza

by Ryna Zubair

by Ryna Zubair

A Place for Us unfolds the lives of an Indian American Muslim family, gathered together in their Californian hometown to celebrate the eldest daughter Hadia's wedding, a match of love rather than tradition It is here, on this momentous day, that Amar, the youngest son, reunites with his family for the first time in three years. Their parents, Rafiq and Layla, must now face the choices and betrayals that lead to their son's estrangement, the reckoning of parents who strove to pass on their cultures and traditions to their children, and the struggle of children to balance authenticity in themselves with loyalty to the home they came from. Rafiq and Layla barely knew one another when they immigrated to the United States, but they were aligned in their goal of starting a devoted family Their story is just one example of an immigrant story in that long line of American experiences about religious parents battling to uphold tradition in the face of a secular world, meant to lead their children astray.

Mirza, however, adds an element of real commitment that makes it impossible for the parents to abandon their faith, complicating the repetitive tale

Hadia and her sister feel constrained by their parents' rigid expectations and have no intention of consenting to arranged marriages or lives of

servitude and upholding honor. However, they too receive the Prophet's message and experience the same currents of faith. The sole distinction is their determination to pioneer a new Muslim lifestyle in the West.

Amar becomes the family's open sore He is energetic and impulsive, but inquisitive Hadia believes that in any other family, "a young man acting like a young man would not be a problem." But in this household, the teenager's spirit clashes with Islamic laws, and the result is rebellion and guilt.

As he struggles to find his place in the family, the novel explores how we show empathy or unfulfillment, and the things and words that get lost or remain unsaid

Part of what makes Mirza’s novel captivating is her ability to shift between contrasting perspectives. She depicts the panic of Amar’s parents as they struggle to find some effective balance between discipline and indulgence along with the torment of Amar’s conviction that he doesn’t belong or deserve the blessing of salvation or that he’s not a Muslim. Yet the real agony, which Mirza plumbs with such heart breaking sympathy, is Amar’s incurable longing for the balm of belief and the embrace of his devout parents.

Each of the characters also contends with how their traditions and customs conflict with modern realities in various ways.

In gentle prose, Mirza traces those twined strands of yearning and sorrow that faith involves. She writes with a mercy that encompasses all things. If the demands of Islam make Rafiq behave strictly toward his only son, those same demands eventually inspire a confession of affection that is touching. Reading her novel made it easy to dwell among these people, to fall back under the gentle light of Mirza’s words.

"That was my fight: to continue to do little things for people around me, so no one would find fault in my demeanor and misattribute it to my religion."

Renewed Pride

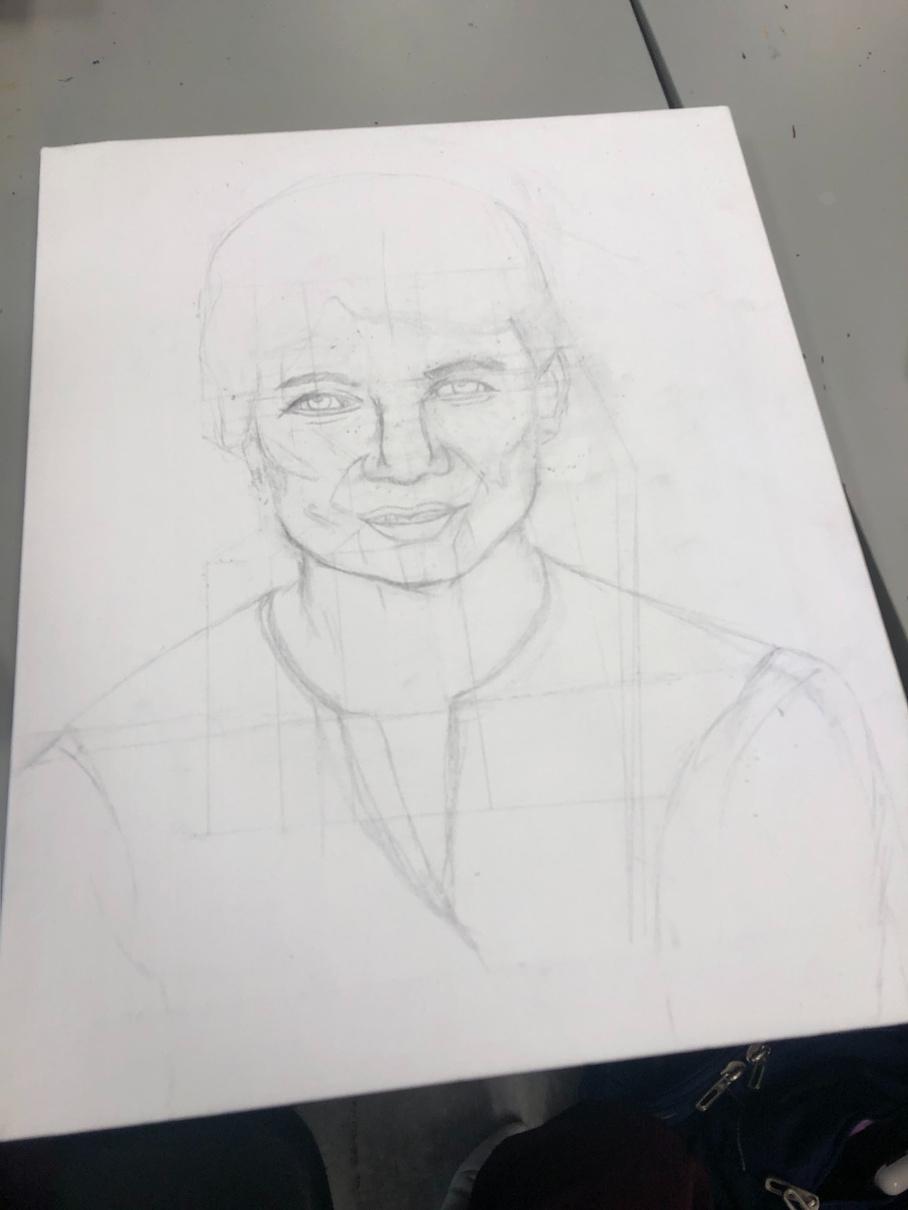

by Amelia Torrevillas BrownDuring my sophomore year of high school, I found an expression of love through painting, along with a desire for connection to individuals so distant in time and location. I challenged the isolation brought upon growing up in Oklahoma, and as I progressed onto these artistic projects, I revived insecurities about my cultural identity

I warded off these weary feelings by incorporating sentimental themes of my Asian heritage into my paintings My Filipino American childhood experiences were shaped by my angered mentality of living in Oklahoma. After all, I was furthest from my mother’s family, and all attempts at finding a Filipino community to learn and thrive from were diminished

In result of this cultural absence, I returned to photo albums of my Filipino ancestors. Reading through these pages, I saw myself regretting things, like never visiting my late Lola in the Philippines at an age that I could remember.

As I flipped through this extensive documentation of my mother’s past, I felt a longing to travel in time, wanting to see what it’d be like to physically be with them. I projected how I felt to my mother, as her eyes glossed with reflection on the twenty eight years without her family by her side. I watched her sink into a heartbreaking abyss of memories, and I instantly understood her feelings of loneliness in Oklahoma. Within this acknowledgment of my mother’s vulnerability was a drive to hone a symbol of her Filipino home A drive for me to dismantle my own perceptions of what it truly meant to live so far from the 50% of who I am.

I brought this determination to fruition when I was presented with an opportunity: a new class project that was “freestyle.” No prompts or rules, a completely independent creation, and with that, I found a route to reconnecting with both my Lola's and my mother’s past. I made a blueprint for an oil painting filled with burnt umber, sienna, ochre, phthalo green, and dark phthalo blue to pair with a beautiful photograph of my cheerful Lola. After gathering these materials, I got to work sketching and carefully planning, fearing that one small

mistake would curse my painting. Although time felt nonexistent, I completed the portrait quickly, but before I could gift it, I realized the impact this piece had on me. It was as if Lola's presence was there, cheering on the grandchild she would never see past the age of eight while simultaneously being brought to life permanently on my mother’s wall.

On my mother’s birthday, I placed the delicate portrait in the family room. Tightly embracing me, my mother’s hug symbolized a sense of love for a heritage she longed to embed into our family ever since she arrived in Oklahoma in 1994.

As I reconcile my cultural insecurities, I am reminded of how necessary vulnerability and empathy are when reflecting upon my childhood and my mother. My time with my Lola was short and consisted of phone calls that I now wish could last ages, and letters every month begging my mother to visit her homeland. Yet, I have found growth through these memories and the beauty of my mother’s strength I no longer exhibit disdain for my mother choosing to raise a family in Oklahoma; I have found perseverance from painting my Lola. This project rekindled memories of what an apo is to be: a permanent bridge between generations of love for a legacy, and pride of a culture I am no longer secluded from but finally the closest

Such representation of my American experiences offered a reflection into who I descend from, connecting a passion for art and a desire for a stronger cultural identity. It formulated dreams that one day, my experiences of growing up in Oklahoma would ease the cultural dysphoria that seeped my mind and would influence how I defined myself as the future of my heritage.

MEET THE MA

Anthony Nguyen Caitlin Le

Christine Nguyen Emma Nguyen

Anthony Nguyen Caitlin Le

Christine Nguyen Emma Nguyen

GAZINE TEAM

Ivan Ma Nate Reese

Kelvin Yang Amy Nguyen

Ivan Ma Nate Reese

Kelvin Yang Amy Nguyen

Duong Thach (Cody)

AASAADVISOR Daniel Li STUDENTASSISTANT Xian Lai

Duong Thach (Cody)

AASAADVISOR Daniel Li STUDENTASSISTANT Xian Lai

Lana Nguyen

GRAPHICDESIGNER

Amelia Torrevillas-Brown

HISTORIAN

Bella Pham

OUROYALTY

Lina Thai

FRESHMANREP

Paul Nguyen

FRESHMANREP

Maria de Asis

LIVEMUSICNIGHTCHAIR

Dim Zuun

FRESHMANREP

Annie Nguyen VPEXTERNAL

Sydney Wong VPINTERNAL

Oliver Wu

PRESIDENT

Margaret Le DIRECTOROFPHILANTHROPY

Brittney Luong

LUNARNEARYEARCHAIR

Syeda Sayera

ASIANFOODFAIRCHAIR

Sana Arshad

FRESHMANREP

Ryna Zubair

Lana Nguyen

GRAPHICDESIGNER

Amelia Torrevillas-Brown

HISTORIAN

Bella Pham

OUROYALTY

Lina Thai

FRESHMANREP

Paul Nguyen

FRESHMANREP

Maria de Asis

LIVEMUSICNIGHTCHAIR

Dim Zuun

FRESHMANREP

Annie Nguyen VPEXTERNAL

Sydney Wong VPINTERNAL

Oliver Wu

PRESIDENT

Margaret Le DIRECTOROFPHILANTHROPY

Brittney Luong

LUNARNEARYEARCHAIR

Syeda Sayera

ASIANFOODFAIRCHAIR

Sana Arshad

FRESHMANREP

Ryna Zubair

A S A E X E C O F F I C E H O U R S

9:00am

9:30am 2:30pm 3:00pm 3:30pm 4:00pm 4:30pm 5:00pm 5:30pm

MONDAY

DANA

THE UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA ASIAN AMERICAN STUDENT ASSOCIATION

Connection