Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia

Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia

“We are such extraordinary and inexplicable creatures. We come out of nothingness into the world and then disappear into nothingness, leaving no trace of where we’ve gone. Throughout our short lives we are always in the middle of the mystery of who we are and where we come from. The only thing I know is that we are meant to act, and we are meant to act through love.”

Mary Holmes

New York City

CONTENTS 9 FOREWORD REGGIE WATTS 10 INTRODUCTION ADDI SOMEKH 38 WHAT IS LAUGHING? AN INTERNATIONAL SURVEY 90 THE ROAD TO TIMBUKTU A. G. VERMOUTH 156 THE EMOTIONAL HISTORY OF THE HEADDRESS A CONVERSATION WITH MARY HOLMES 204 STORIES AND TRAVELOGUES ADDI SOMEKH AND CHARLES ECKERT

Maharatasan, Thailand 8

FOREWORD

REGGIE WATTS

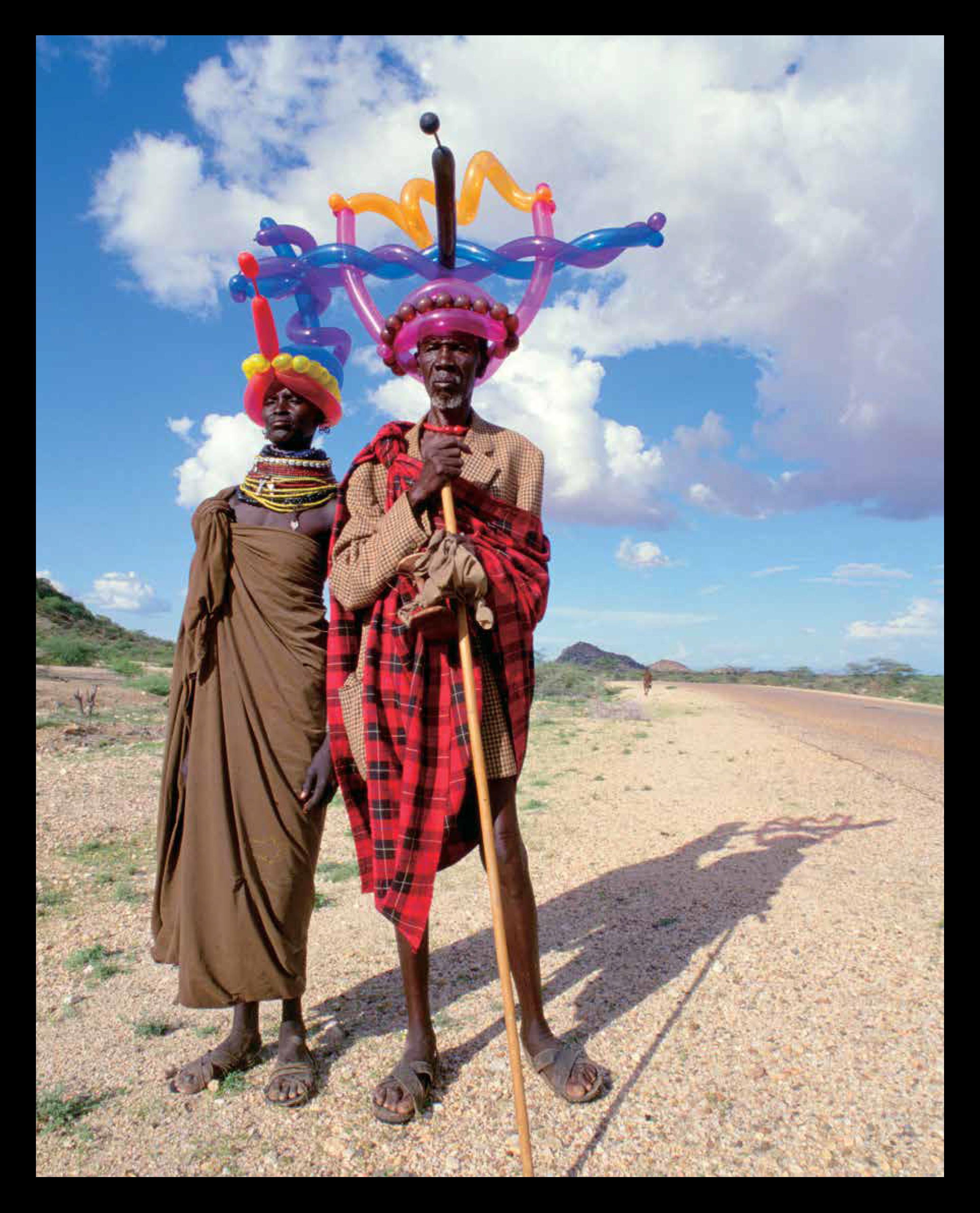

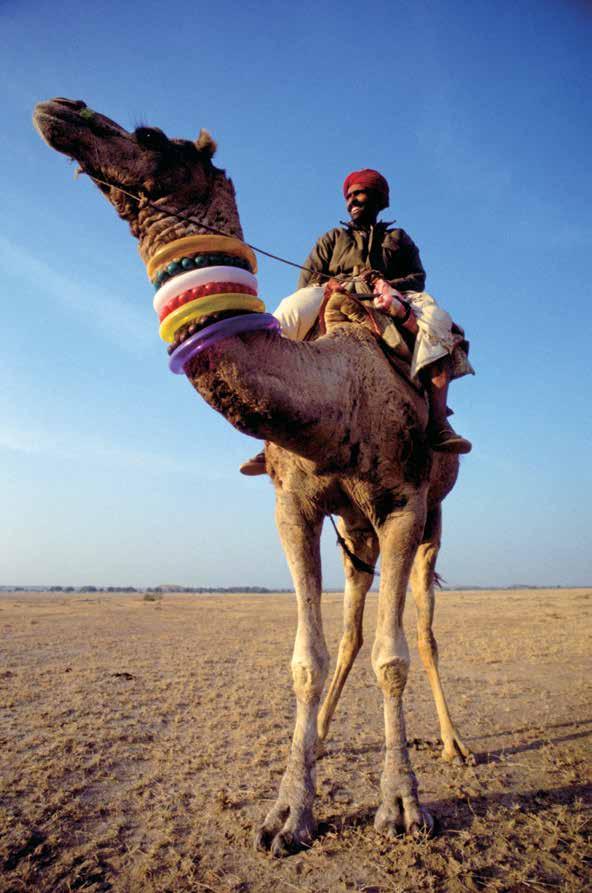

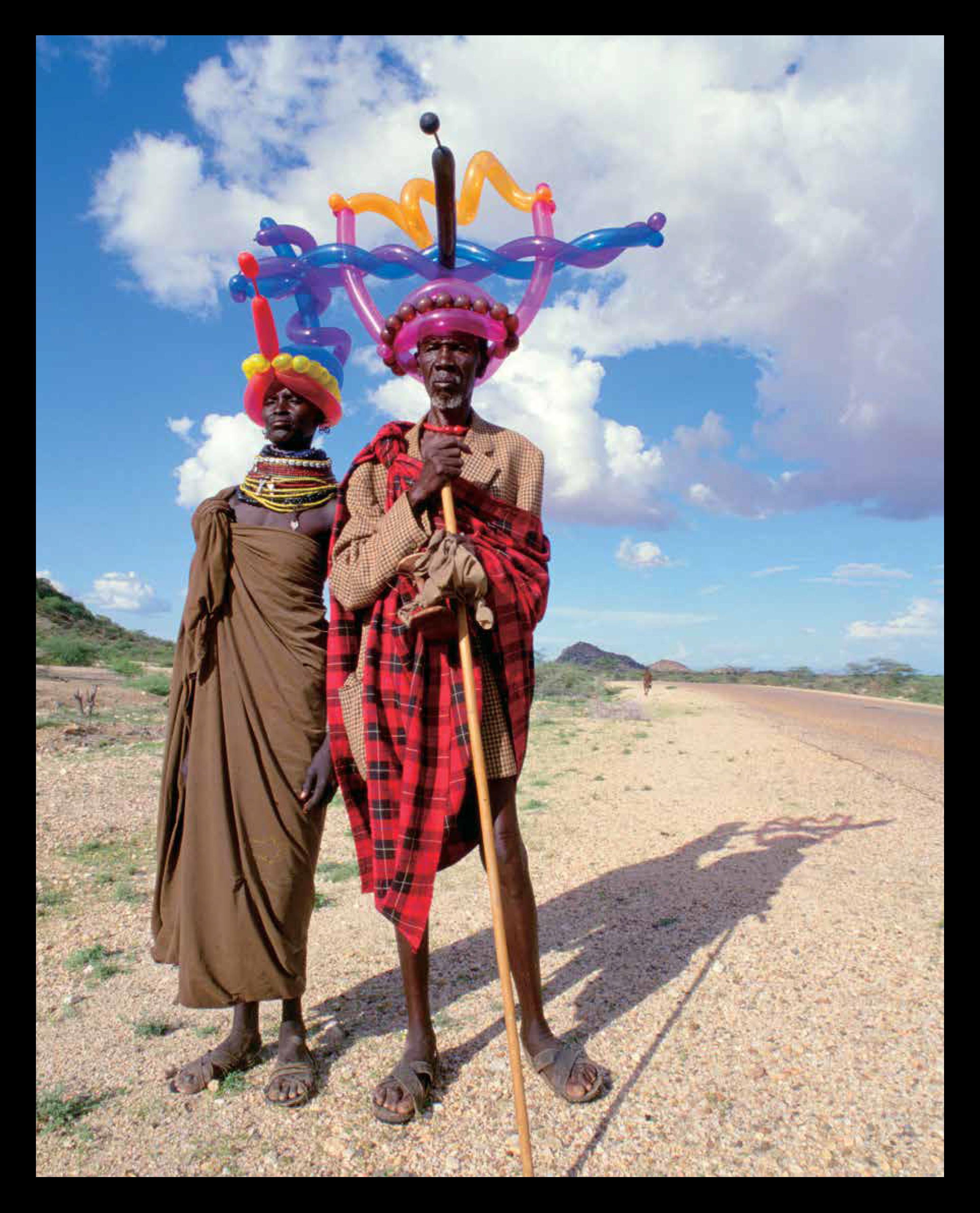

THE POWER OF A BALLOON comes from its vulnerability: there is only a thin layer of rubber between its life and death. The fact that a balloon can pop at any moment, even under the most favorable conditions, forces people to be in the moment. Unconsciously, we know we are looking at something that is here only right now, and we feel that more than we think it. Add some crazy improv-twisting to this already mesmerizing matter and we cross into the realm of the fantastic and surreal. Addi’s hats are part performance art, part engineering, part magic.

Despite having zero long-term commercial value, his creations are invaluable in their ability to surprise, delight, and communicate to humans of all ages and languages. There is a beauty in the fact that a cheap, disposable party novelty in the hands of a well-trained and well-intentioned practitioner has the power to bring out and display the personality of a complete stranger. And Charlie’s photos don’t merely capture the smiles and laughter; they illuminate an aura, revealing in a frozen moment in time the dignity at the core of a person’s soul.

Taken as a whole, these photos show us a paradox of simplicity and complexity so many people, cultures, aesthetics, politics, and belief systems, with one indelible thread of joy unifying them all.

And what is this thing we call “joy”? A mysterious force from somewhere in the universe: primal, elusive, and totally absorbing when it hits. Joy cannot be summoned, nor can it be prevented. The energy from joy can recharge us. When reality is at its most harrowing and heartbreaking, joy can bring the counterbalance that reminds us life is worth living.

Our lives as human beings on this planet are not a whole lot longer than the life of a balloon hat—compared to the Grand Canyon, we are balloons! So with our brief time here, may we rejoice in the unexpected, the colorful, and the ephemeral. May we remember that simple acts can produce the most profound connections. And, most important, may we all cultivate and share the signal, in order to survive within the static.

INTRODUCTION

ADDI SOMEKH

A WELL-MADE BALLOON HAT seems to have magical powers.

For a start, it transcends language barriers. It can create laughter without words. Its ephemeral nature makes people feel grounded in the moment. A balloon hat has no long-term value, making it not worth stealing or hoarding. And it’s a powerful social lubricant that doesn’t produce a hangover.

But most important, a balloon hat can make people happy while sparking connection between complete strangers.

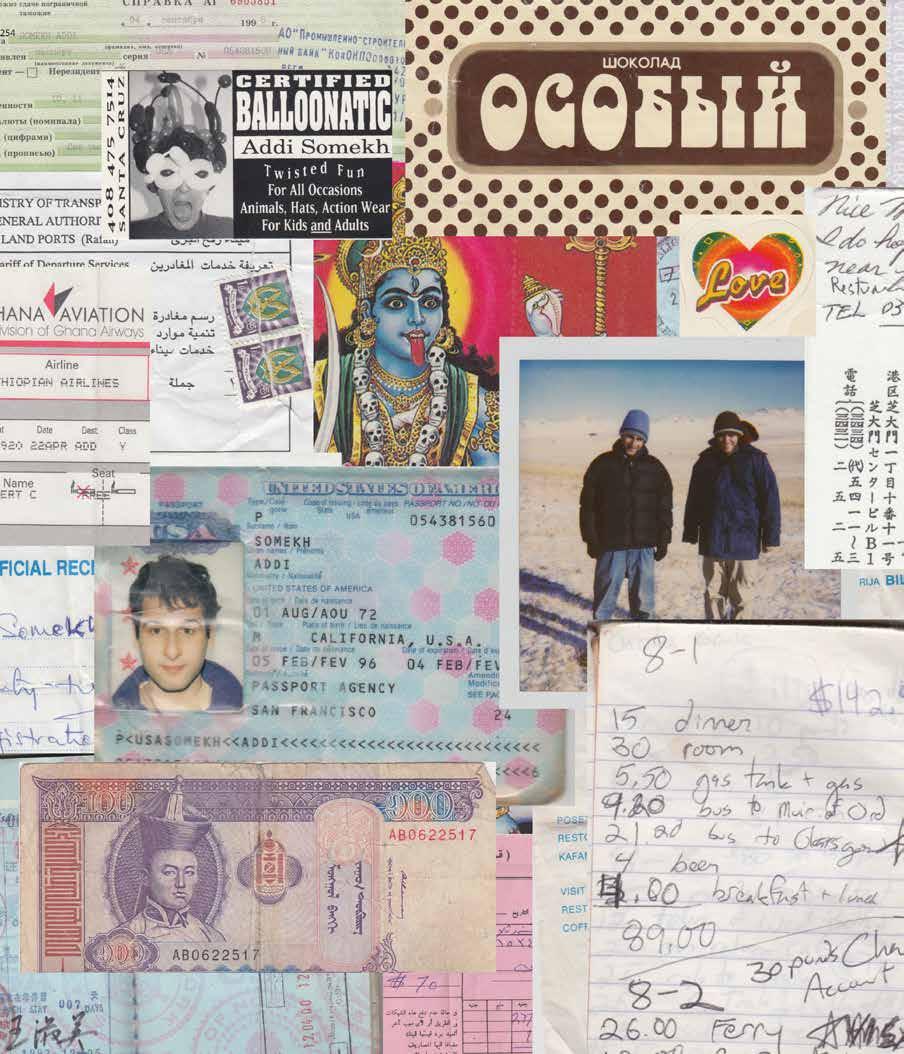

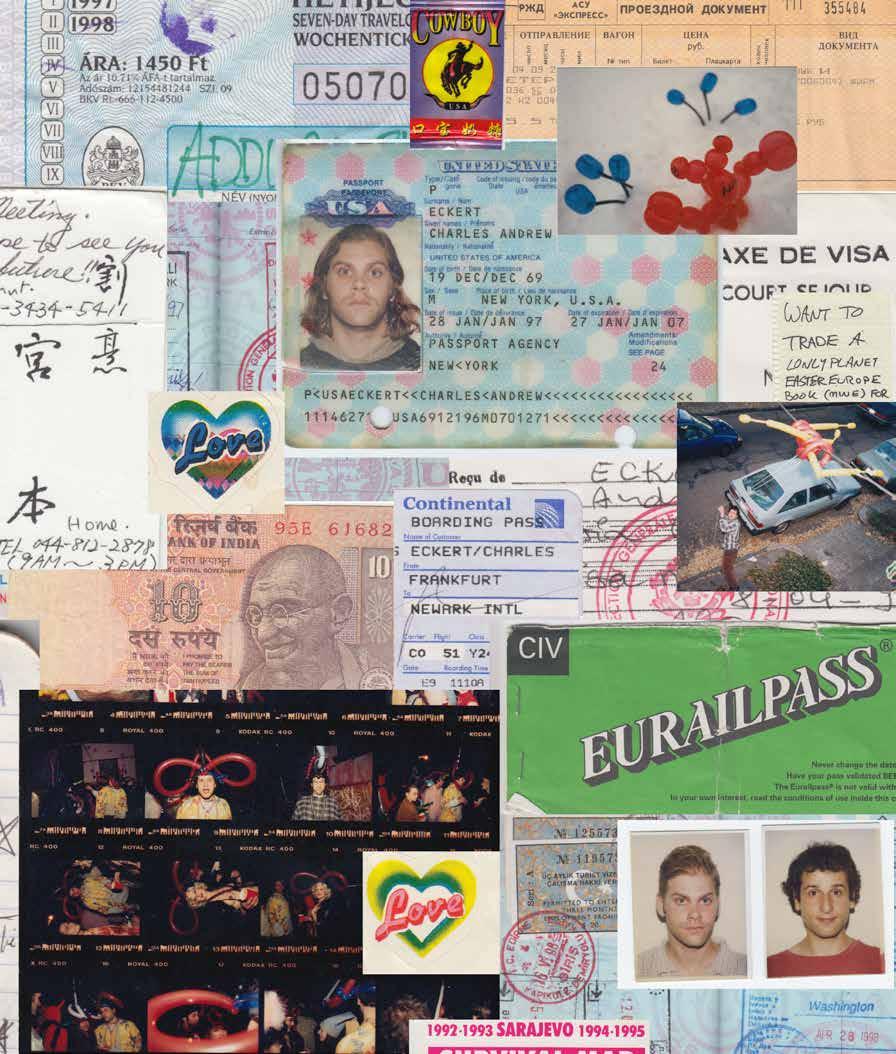

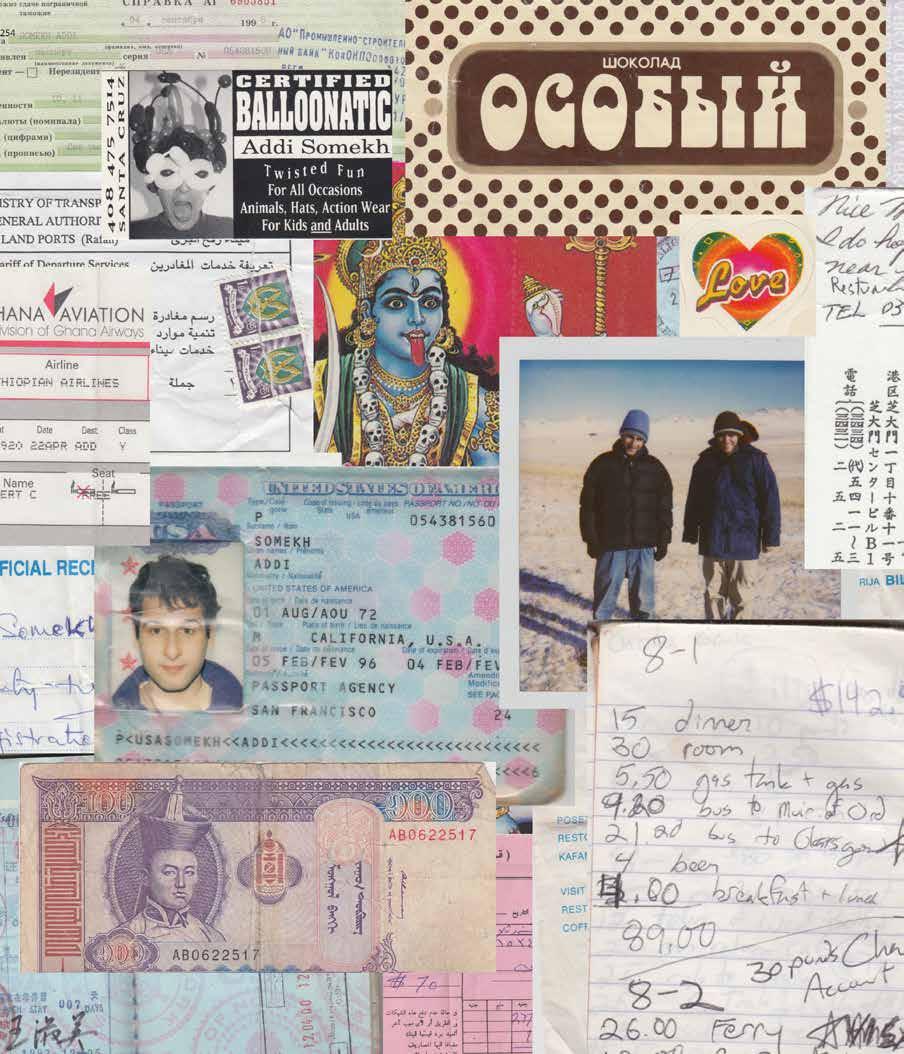

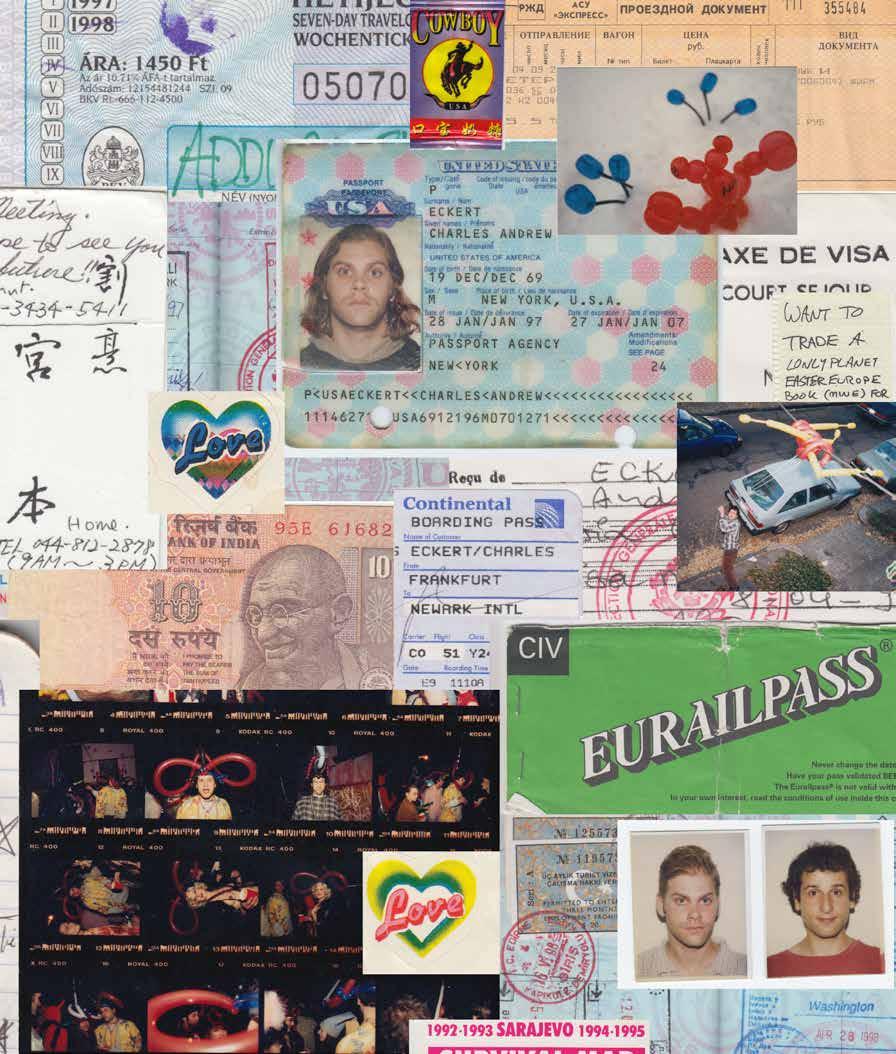

This book is the product of a long-running series of balloon hat experiments in cross-cultural communication. Between 1996 and 2002, photographer Charles Eckert and I got to perform these experiments in 35 countries. We used more than 100,000 balloons and shot more than 10,000 photographs on slide film.

Our modus operandi was to travel far off the beaten path, surprise people with custom-made balloon hats, and document their reactions in pictures. The key was to show up with good intentions, connect, and improvise.

This simple approach yielded an astonishing variety of results. And our random international sharing of ephemeral balloon art opened a portal to cultures and personalities, serendipity and joy.

It was Charlie who came up with the idea of doing this project, though he said it as a lark, and since it

was only the second time we had ever met, he didn’t think I would take him seriously.

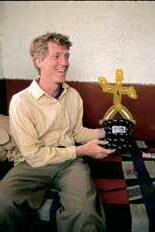

The year was 1994, in New York City. I was finishing up graduate school without even a vague idea of what to do next. Though I had a natural talent for making balloon hats that captured people’s intangible energy, I also felt shame and embarrassment over the fact that my only real talent in life was essentially being a novelty act.

Charlie was living a much more mundane and repetitive existence, working in Manhattan and commuting from Queens, assembling shelving in people’s closets (or as he says it, “organizing their useless crap so they had more room to buy more useless crap”).

Our paths crossed thanks to our mutual friend Jason Brown. I remember Jason telling me that though Charlie had never studied photography, he was taking unique and beautiful photos of people and landscapes. But Charlie was the opposite of a self-promoter, and the only way one could see his photos (this was before the wide use of the Internet or digital photography) was to go to his house in Queens to view the leather-bound portfolio that sat on his desk. When I finally made it out to his place and picked up the portfolio, I was mesmerized by his raw, emotionally complex imagery.

A few weeks later, Charlie and I met again, this time in my apartment in the middle of Manhattan, on Halloween. Charlie and Jason knew about a cool

party, but we needed costumes to get in. I said, “I make balloon hats. Don’t worry, we’ll get in.” I quickly busted out some hats, and we put them on and headed downtown.

On the way there, people on the street started clapping as we walked by. For Charlie, born and raised in New York City, this was a revelation. “You could be bleeding on the sidewalk and people would just walk right past you,” he told me later. “I had never experienced people actually clapping before.”

As fate would have it, Charlie missed the last train back to Queens that night, so he wound up crashing on the floor of my apartment. The next morning, the conversation quickly turned to the strange effect the balloon hats had had on habitually cynical and dismissive New Yorkers. “If those balloons affected people here like that,” Charlie said, “it would be amazing to go around the world and make balloon hats for people and take photos of them.”

I knew at that moment we needed to try this idea.

It didn’t matter if we had only a one-in-a-billion chance to make it work. At least we had to try. While the idea might sound like a wild dream, actually making it happen involved a lot of practical planning and the nuts and bolts of mundane logistics. We knew the why, but everything else was unknown. Where do we go? When do we go, and how do we get there? What do we do once we’re there? What kind of equipment do we need? How

many balloons do we take? And how many rolls of film? And, maybe most dauntingly, what do we do with all the photos when we get back?

Working in our favor was the fact that, though we barely knew each other, we realized we could agree on aesthetics, which was vital. We were both selftaught and both improvisers, so though we worked with different media, we thought a lot alike.

As things became more real, we agreed on three working principles that would set the foundation of our collaboration:

1. I stick to the balloons, and Charlie sticks to photography.

2. We split money and responsibilities 50/50.

3. We don’t fall in love with the same woman.

Next, we needed to test the idea to see if it had legs. Charlie’s mom was a flight attendant who was able to get us free plane tickets, and I cashed bar mitzvah money that had been sitting in the bank since I was thirteen. Again, we turned to our practical sides to come up with some simple criteria for success:

1. Will people like the balloons?

2. Will people like the photos when we come home?

3. Will we get along and be able to work together?

If—and only if—all three answers were yes, we would keep going.

We decided that our first trip, in the spring of

11

1996, should be to Central America. It was relatively easy to get to, and between the two of us we knew enough Spanish to be able to get by. We flew to Guatemala City and then traveled by land through Honduras and Nicaragua. We were on the road for a total of five weeks.

As with almost everything in life, mistakes are your best teachers, and our whole first trip was one giant learning process. But Charlie and I had a genuine chemistry, and we stuck to the three principles we had agreed upon. It was heartwarming to see that, everywhere we went, people loved receiving balloon hats and treated us with kindness and gratitude.

We returned home with 26 rolls of film, and with profound anticipation we waited for them to get developed so we could see the fruits of our labor. We edited them down to our favorites and shared them with friends and family to gauge their reactions as our final test for whether we should continue. Everyone was shocked and moved when they saw the photos—even my parents, who up until then had been our biggest skeptics.

With our test run deemed a success by all, it was time to take off the training wheels and go hard, all

over the world. Our second trip was to Europe, Scandinavia, and Russia. Then Africa, west and east. Our fourth trip was the longest: three months in Asia, where we visited Japan, Vietnam, China, Mongolia, Thailand, and India. Next were the Balkans and the Middle East. Our sixth trip was back home, driving to more than 30 states in my old Volvo station wagon. And our last trip was to the homeland of the latex rubber tree, the Amazon rainforest in Brazil in the winter of 2002. Because we shot everything on film, we would go out on a trip and then return to New York, where we would develop and edit the film. We were a stripped-down, two-man crew with no manager to tell us where to go, no security guard to manage the crowds or ward off thieves, no intern to help us find a place to sleep or eat. The logistics of travel were so time-consuming and overwhelming that the actual twisting and shooting took up only a tiny percentage of our time. We both carried two backpacks, a large camping bag, and a smaller day-trip bag. My bag at the beginning of every trip weighed 60 pounds, from all the balloons I brought—two bags of every color. Minor things like clothes and hygiene supplies were stuffed into as small a space as possible.

Addi improvising a necklace in Pokot, Kenya

12

Charlie carried not only all of his camera equipment but all the film as well. This was of major significance. Digital cameras had been invented, but cost in the thousands. Therefore, this entire project was shot old school on two manual Nikon cameras and slide film.

Working with film was undoubtedly one of the biggest challenges we faced. Charlie had to shoot strategically and sparingly to make sure our supply lasted the entire trip. But even more concerning, we had to guard with our lives all of the rolls that he shot, because if someone stole the camera bag, our work would also be gone.

The balloons I made for people were always free —even if a tip was offered, we wouldn’t accept it. We did, however, accept a ride, a meal, a place to sleep, a connection to another town, and any other form of support. (This wasn’t just appreciated; it was vital for us to survive and thrive in foreign lands.) If someone wanted a balloon hat but didn’t want the photo taken, that was completely fine by us, though to the best of my recollection it only happened twice in 35 countries. And for all the photos we shot of kids, their parents were off frame and gave their consent.

Charlie and I walked around the world together, and are thankful we always got along. We were in our mid-20s when we did the balloon hat trips, but unlike many rock bands who are full of ego and light on perspective, we were always gratefully cognizant of how fortunate we were. We witnessed much human suffering and poverty, which gave us some real perspective. No matter how much our quirks might annoy each other, we knew we were there in service of a larger purpose. No matter how exhausted or irritated we might have been at any moment, we were a team. The most important thing was to stay focused on the mission to make people happy, document these instances, and come home alive.

On our third trip, the one to Africa, we met Andy Vermouth at the airport in Accra, Ghana, and he decided to tag along on our adventure. I guess Fate knew that the joy and chaos that balloon hats would bring to the Africans we met would overpower our two-man crew. In addition to being an invaluable source of support, Andy took copious notes from his own unique vantage point. Those notes eventually became his story in this book, “The Road to Timbuktu.”

Charlie trying to get his camera back from a kid in Fort Collins, Colorado

13

We began this project with the idea that all humans today are more similar than they are different from one another. That is, with all the various languages, religions, politics, aesthetics, and values, it often feels that suspicion and miscommunication are the natural order of things. While it is certainly true that fear and tribalism are hardwired into the human brain, there is something bigger.

What we saw over and over again in our travels was that laughter sounds the same in every language; that there is no culture in the world that does not know laughter; that, unlike reading and arithmetic, people do not have to go to school to learn how to laugh; and that the ability to laugh and experience joy is a fundamental aspect of human life.

When it comes to the power of the balloons to get people to quickly open up and connect, there was one day in Southeast Asia that stands out in my mind.

We were visiting Buon Ma Thout, a mediumsized city in the Central Highlands of Vietnam. Our close friend Bill had fought there 25 years previously in the Vietnam War (or the American War, as they call it in Vietnam). Bill had told us many harrowing stories of his time there, and we were curious to see the city with our own eyes.

Our day began just as any other on the road— wake up, organize our balloons and camera gear, find a small local restaurant for breakfast, and, with

the help of a balloon flower for the waitress, begin our recon to figure out which direction we should head. On this day, we decided the best course of action was to rent a couple of mopeds and drivers so we could visit different parts of town.

After a full, fun, and productive day, we found ourselves catching the final golden afternoon light while twisting for an extended family in front of their homes. About 15 balloon hats in, I noticed an older man off to the side, squatting in a sitting position and smoking a cigarette, as is a common practice for Vietnamese men. He was watching the entire scene transpire, occasionally nodding his head in approval. Suddenly, all the kids began to shout that the old man needed a hat too; he lit another cigarette and nodded once more. What came out was a sleek, spider-like crown, unlike anything I had made before. I put it on his head as he continued squatting and smoking, and the entire family exploded in laughter and applause.

We were told that he was one of the family’s grandfathers, and that he had been a Vietcong general. I couldn’t help wondering if he and our friend Bill might have been on opposite sides in the same battle, in this same city, 25 years earlier.

The old man stood up and invited us into his home. It was a small hut with a corrugated tin roof and a cement floor. His daughter explained that it is customary to share rice wine and song in a show of gratitude and friendship. Within minutes, the old

14

man—who told us to call him Charlie—and I were sitting on the floor, using long bamboo straws to sip from a three-foot-tall ceramic vase full of the homemade wine. We didn’t need to speak. The grandfather/general began singing us traditional Vietnamese folk songs, still wearing his balloon crown, as we continued to sip away, sitting in a circle around the vase, which was by now crawling with myriad ants, some of which we drank down too.

Later that night, we returned to the same restaurant we’d visited that morning—for some beer, dinner, and decompression from the day’s adventures and ironies. Suddenly, a British man in his 50s spotted us from across the room, rushed to our table, and grabbed a seat. “So, you are the balloon guys,” he said. “I heard about you chaps, and I saw what you’ve been doing. I am an anthropologist and have been living here for six months. I have to say, you two gentlemen have gotten deeper into this culture in one afternoon than I have in half a year—just because you made people laugh with those balloons.”

15

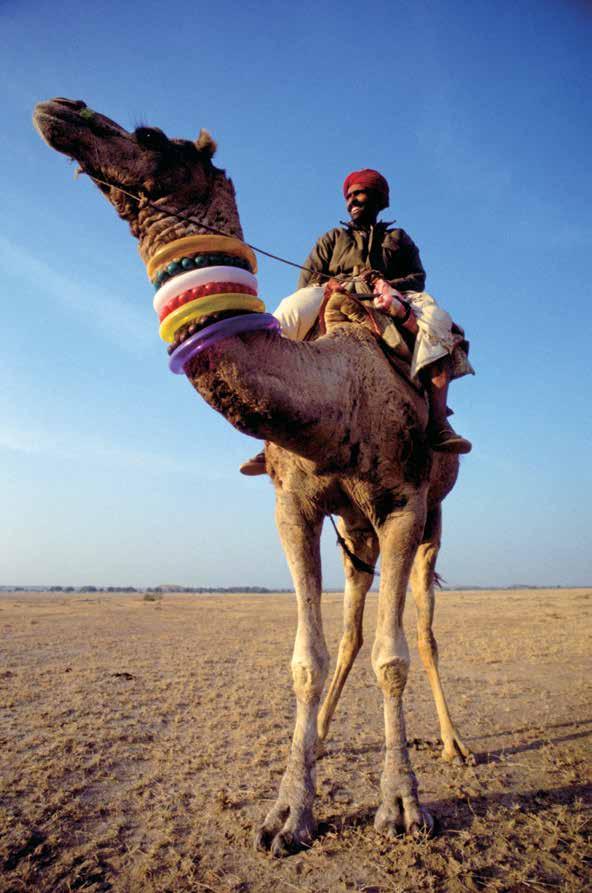

Rajasthan Desert, India

Rajasthan Desert, India

16

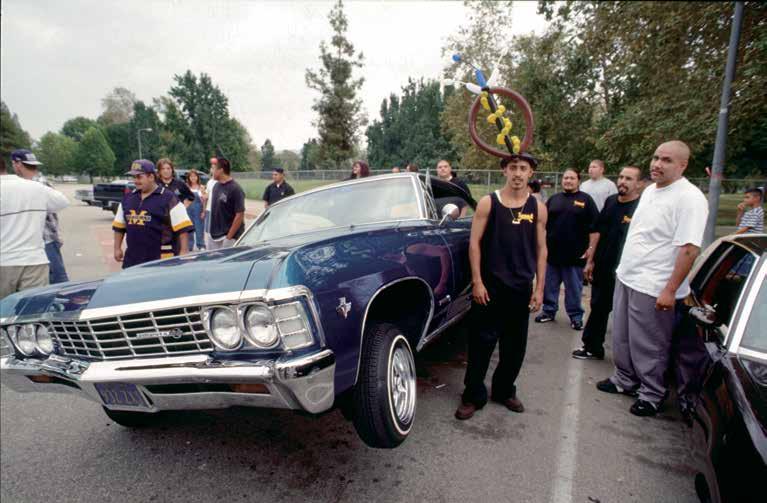

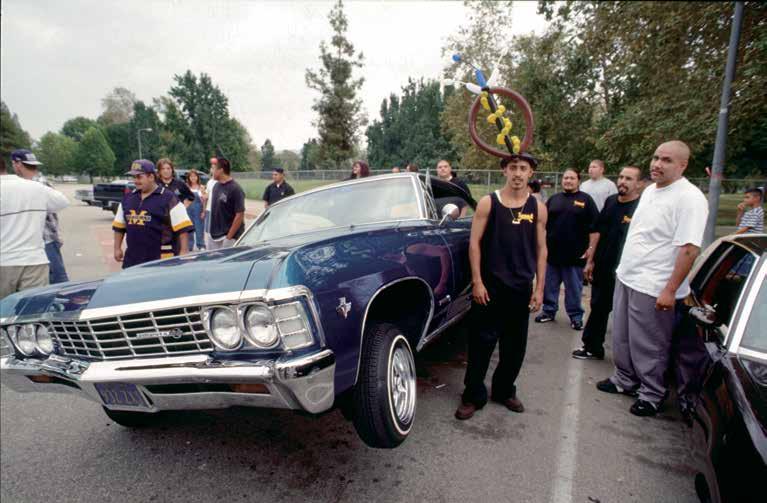

East Los Angeles

East Los Angeles

17

Somewhere in Mongolia

21

WHAT IS LAUGHING?

We asked people around the world, “What is laughing?”

Where does it come from, and what does it mean?

Here are a few of the answers we received.

AN INTERNATIONAL SURVEY

39

“Laughing is a celebration of the good, and it’s also how we deal with the bad. Laughing, like crying, is a good way of eliminating toxins from the body. Since the mind and body are connected, you use an amazing amount of muscles when you laugh.”

Gerry Fialka , Venice, California

40

Chanchla Yadar , Varanasi, India

Chanchla Yadar , Varanasi, India

“I happy on you.”

41

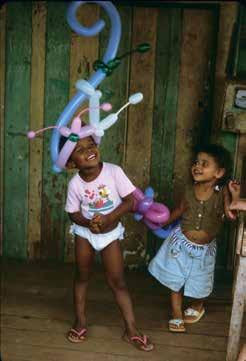

Springfield, Nebraska 73

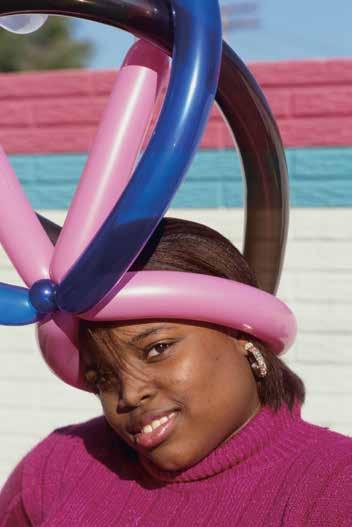

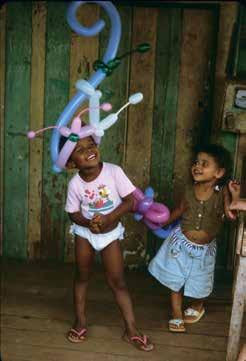

Clockwise from top left: Sarajevo, Bosnia; Bluefields, Nicaragua; Miami; London 86

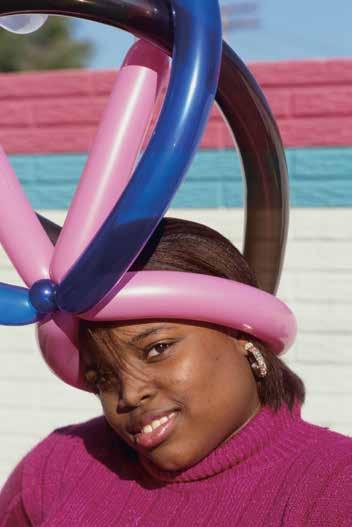

Clockwise from top left: Palo Alto, California; Detroit; Shenzhen, China; Wichita, Kansas

Clockwise from top left: Palo Alto, California; Detroit; Shenzhen, China; Wichita, Kansas

caption 87

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

FROM THE MOMENT this project was conceived, we began asking for favors and help from old friends and total strangers. Thank you to all the people who fed us, gave us places to sleep, gave us rides, and offered help, advice, and encouragement.

Guatemala: Todos Santos Cuchumatán Proyecto Linguístico Español/Mam, Juan Ramirez. Nicaragua: Mr. “Lingo” Alvin Hing, Corn Islands Peace Corp Crew. England: Pipa Galea, Emeka Onono. Scotland: Mary Smith and Gowanbank Barn. Ireland: l Mairaead and San DeLaney and family, Wessy Kasa. Northern Ireland: Peter Worth. France: Kevin O’Brien. Germany: Thomas Grigat. Denmark: Mille Mapjka. Holland: Woucha Swets and Kalai Herrick, Homegrown Fantasies. Norway: Knut Hohle, Ingvald Guttorn, Karajok Bareskole. Finland: Iina Olinki and Riku Puustilli. Russia: Sergei Nikitan in Moscow, Tatiana Kobalenko and Kira Levina in St. Petersburg. Poland: Wiesiq Lpib, the mysterious English girl with the luscious lips. Prague: Katka Zapletalova. Ghana: Henry Neiboi Odoi, the Royal Princes Crown Hotel crew, Big Andy, Little Andy. Burkina Faso: Bruno, Jean Luc, Antoine Bamara, Batiano “Vincent” Manore. Mali: Noufou for only getting us stranded in the desert once. Kenya: The great Dr. Donald S. Gilchrist, Dr. Tony Barrett, John Ebenyo Kawaltathe. Japan: Ono San, Akasaka San, Soto San, Rita Kanda, Hirokazu Sugiyama and family, Kenji Kowamoto. Vietnam: Phil Dolan and Hein Nguyen, Luc the Driver, Wendy Madrigal, Josh and Nancy Gnass. China: Ming Chi Bao, a big, big thank you to Tom Kirkwood and Cowboy Candy, Jeff Keidel, Shahin Kianpour and Kirsha Kaechele (for much needed doses of sanity), the always impressive Anna Shields, Travis Hicks, Erwin Zaat, Louis Jenseny. Mongolia: our man in Mongolia Mr. Bold, Gotoff (for not beating Addi to a pulp that morning), Odbileg and Gerelma, Ch. Nuamdorj, Roger Gruys, Didi Kalika and the Lotus Children’s Center, Perenlei Sendzoo, Doripalam, Junji Masuda. Thailand: the amazing people who drove us around and introduced us to everyone in Maha Sarakham, Weerachon Puttpradit. India: Ian Winn, Barry and Lars, Mr. John Major. Hungary: Monika Muranyi. Bosnia: Sean Moffatt and everyone at IRC, Nadja Karahmet. Serbia: Dragan Radenovic, Natasa and

Jelena, Ana, Zoran, Nikoli, Zorana, Ivana, Studio B, and Bora for the homemade plum wine. Bulgaria: Rossen Roussev. Turkey: Hale Ozen in Sinop, Nilgün Eke in Instabul. Israel: Yuda and Drora, Aviram Gavish, Rachel Somekh, Oliva Garcia, and the essential help of Professor Sasson Somekh. Palestinian Authority: Hassan and Wali Asous and Pizza Inn. Egypt: Mohamed Waly. California: Tiarra Car Club, Alberto Michel, Joe Roma, Krissy Ramirez, Don and Ruby Brown, Gerry Fialka and Suzy Williams, Nissan and Carmela Pardo, Anh Vi Dao, Dr. Paul and Charlene Lee, Lloyd Mooney and Around the World Books for the ethically dubious hookups, Antoinette Maillard, Besedka Johnson, Fred Burke, Fred Drake, Bruce Cantz, Hamid Ezzatyar, Katherine Beiers, Woutje Swets, Harrod Blank, Marie Mandoli, Jeremy Townsend, Kathy Rose and Paul Schoellhamer, Jim and Angie Christman. Nevada: Heidi, Phil, Martin, Felice. New Mexico: Nancy Evans of Shiprock, DVS, Castillo Brothers Barber Shop, Albuquerque International Balloon Fiesta, Balloon mister Alan Rector, Gay Jensen James, Debbie Fowler. Texas: Mark Granoff, the Street of Lights on 37th Street in Austin, Amarillo Helium Facility. Colorado: Brendan and Katie McGivney. South Dakota: Ronette Kirk Walton, Joseph Shields, Oliver Sully. Wyoming: the Currachett family—Alnina, James and Jamie. Kansas: the boys at Fire Station 13B in Wichita. Nebraska: Kevin Welsh and family, the Ludz brothers (Dwayne, Dwight, Gordon, and Jerry). Indiana: Ken and Phyllis Martin, Dana Williamson, Glen’s Barbershop in Royal Center. Ohio: Dr. Dave and Margo Smart, the Cleveland Museum of Art, Tom Welch. Illinois: Martin Hallanger, Cabrini Green Youth and Family Services, Jimmy Fitzgerald. Wisconsin: Zav Leplae and the whole Pumpkin World Crew.

Addi’s mom, Eta, sewing his balloon apron (reenactment)

Jason Brown, the homie who introduced Addi and Charlie

Dr. Noah Thomas bonds with the natives

Michigan: Professor Arwulf Arwulf, Matt Camp, Ana Furioso. New York: Ashlynn, Sarah, Charlotte, and Aidan Moran (and of course Sean and Gerry), Gennie and Manny, Yudi Soffer, Bob and Judy Goldman, Penny Peters, Shirley and Matthew Gabriner, Debra Goldman, Werner and Helen, the always entertaining Brendan Burt, Iceberg Athletic Club, Joe Lazzaeo, John Sineno, David Stanford. Florida: Uncle Charlie Barbash and Aunt Ruth, Marty and Ann Robinson, Lisa at the Tallahassee YMCA. New Orleans: Ann Mari Coviello and the Box of Wine Krewe (Long Live Dr. Larry), Sean McNally and Jen Knox, Ray “Rowdy” Sibley, Clara Connell, Villa Feliciana Medical Complex, New Orleans Klezmer All Stars for the parade that started it all.

On the book and business side, we are stoked to have met and worked with: Gordon Goff, Kirby Anderson, and Goff Books; Phil Freshman; Ali Davis; Carrie Paterson; Reggie Watts; Jaime Alyse Andrews; Tim Young; David Tenzer; Rosanna Bilow; Lisa Lytton; Alice Gabriner; Greg Apodaca; and, of course, Ted and Betty Vlamis, Dan Flynn and Pioneer Balloon Company for making the organic latex balloons that worked all over the planet, from scorching-hot Africa to freezing Mongolia.

Charlie would like to thank: All the people who were kind enough to share their time with us and pose for a photo; Eta, Sass, and Talli Somekh; Jennifer Maloney and Beatrice Eckert; Charles William Eckert; Adrienne Eckert; Todd Eckert and his boys; Jim Borrelli; Tom Muchowski; Herbie Meier; Seamus the Famous Swimmer and all my four-legged friends that came before and after him.

Addi would like to thank: My nuclear family (Eta, Sass, and Talli) for the high-quality love and support, Pearl and Tim O’Brien, all my peoples at 89.7 FM KFJC at Foothill College, the Penny University in Santa Cruz for the legit education, Mary Holmes for her never-ending inspiration and insights, Master C. K. Chu and Chu Tai Chi in NYC (without whom I would not have been able to carry 60 pounds of balloons on my back around the world), Jim Borrelli for always telling it like it is, Adrienne and Todd Eckert, Galen Rosenberg, Stefanie Elkin, Jeff Teicher, Nick Cain, Michael Rosenberg, Gideon Rappaport, the always lovable and hilarious Christine Ventenilla, everyone who has ever taught me something useful, Tracy Hunter for the initial glow of inspiration and magic which started this whole ball rolling, Miriam Hunter for holding down the fort, Bill Tracey, Faye Crosby for the opportunity and the mentoring, all my students at UC Santa Cruz, Cernesto, Jeff Wilson, David Bossi, April Doby, Kristie Lowrance, Nancy Luna, Alice and Alana Lin, Dominic Poccia, Danish Renzu, Henry “Red”

Griffin, Torwa Joe, the creative mind of Brian Knappmiller, The Unpoppables = Brian Asman + Katie Balloons + Rob Balchunas, Leo Verlinden for mussels and Duvels, Guido Verhoef, Micha De Haan, Dave Brenn, Molly Balloons, Finn Thompson, the entire balloon art community (past, present, and future), Sean Rooney for inventing and sharing the balloon bass, Joey Maramba, Arlynn Page, Gabriel Rowland, Danny Frankel, and all the other incredible musicians I get to make noise and bond with, Sex Mob (Steven Bernstein, Briggan Krauss, Tony Scherr, and Kenny Wollesen) for showing me how to be tight and loose at the same time, the steady and heavy blasts of inspiration from Jimi Hendrix, Nels Cline, John Zorn, Greg Cohen, Stephen Ulrich, J. J. Cale, Dave Alvin, Nirvana, Charles Dickens, Christopher Hitchens, and James Nachtwey, Slocum Hewson and Amaru Spirit for the heroic doses, the super soul of Zochada Tat, you (the discriminating reader) for checking out our book, and most important: the mysterious muse that whispered all the balloon designs into my ear. Thank you.

A. G. Vermouth, man of many talents and awards

Mr. Bold, our main man in Mongolia

Jan and Jerry James, for the Santa Cruz crash pad and unlimited servings of medieval oxtail stew

A. G. Vermouth, man of many talents and awards

Mr. Bold, our main man in Mongolia

Jan and Jerry James, for the Santa Cruz crash pad and unlimited servings of medieval oxtail stew

251

252

253

Published by Goff Books, an imprint of ORO Editions

Executive publisher: Gordon Goff www.goffbooks.com info@goffbooks.com

© 2021 Addi Somekh

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including electronic, mechanical, photocopying of microfilm, recording, or otherwise (except that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of United States Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press) without written permission from the publisher.

You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover, and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Graphic designer: A. G. Vermouth

Text and images: Addi Somekh, Charles Eckert, A. G. Vermouth, Noah Thomas, Reggie Watts Copy editor/proofreader: Phil Freshman

Goff Books project coordinator: Jake Anderson

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 First Edition

Library of Congress cataloguing data available upon request. World Rights: available.

ISBN: 978-1-951541-15-6

Color separations and printing: ORO Group Ltd. Printed in China.

International distribution: www.goffbooks.com/distribution

Goff Books makes a continuous effort to minimize the overall carbon footprint of its publications. As part of this goal, Goff Books, in association with Global ReLeaf, arranges to plant trees to replace those used in the manufacturing of the paper produced for its books. Global ReLeaf is an international campaign run by American Forests, one of the world’s oldest nonprofit conservation organizations. Global ReLeaf is American Forests’ education and action program that helps individuals, organizations, agencies, and corporations improve the local and global environment by planting and caring for trees.

Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia

Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia

Rajasthan Desert, India

Rajasthan Desert, India

East Los Angeles

East Los Angeles

Chanchla Yadar , Varanasi, India

Chanchla Yadar , Varanasi, India

Clockwise from top left: Palo Alto, California; Detroit; Shenzhen, China; Wichita, Kansas

Clockwise from top left: Palo Alto, California; Detroit; Shenzhen, China; Wichita, Kansas

A. G. Vermouth, man of many talents and awards

Mr. Bold, our main man in Mongolia

Jan and Jerry James, for the Santa Cruz crash pad and unlimited servings of medieval oxtail stew

A. G. Vermouth, man of many talents and awards

Mr. Bold, our main man in Mongolia

Jan and Jerry James, for the Santa Cruz crash pad and unlimited servings of medieval oxtail stew