Following the Nicola River from Merritt to These less travelled natural sanctuaries are

Saving

Following the Nicola River from Merritt to These less travelled natural sanctuaries are

Saving

NOTHING MAKES YOU feel the passage of time like seeing other people’s children. Those with kids may not notice them getting bigger and maturing when they are around them every day, but you sure notice the changes in other children when you see them once or twice a year.

I think the same applies to the communities right under our noses. Old shops close down, new ones open up, old buildings get demolished and new developments take their place. You notice each individual event while it’s happening but it’s hard to feel the full impact of these changes over time in your own community. And just like it is with kids, the changes you notice when you take a familiar road trip can be striking.

This phenomenon is something that makes road trips special. Sure, you can always fly somewhere new and get new experiences, but there’s something comforting about driving to a familiar spot and visiting that same restaurant or coffee shop you enjoyed last time, and noticing when something has changed. Part of the appeal, I think, is how it gives you a little taste of what it’s like being a local in a community that’s not your own. There’s something fun and worldly in recommending your favourite coffee shop in some far-off destination, and you feel like a real insider when you can remember how things were in “the old days.”

One of our goals with each issue of British Columbia Magazine is to bring this familiarity of place to all our readers, whether you live in the province or visited it long ago. It is satisfying to hear a reader enjoying or reminiscing

about one of the attractions, destinations or businesses they read about in these pages. We feel we’ve done our job if you can visit a place mentioned in a story and feel like it’s familiar, even if it’s the first time you’ve been there. It’s happened to me many times over the years. Most recently, during my visit to the town of Gold Bridge that I mentioned last issue.

This issue, however, has taken a bit of a different angle on this theme. Instead of focussing on destinations, we’ve got several stories focussing on the places between the destinations—highways.

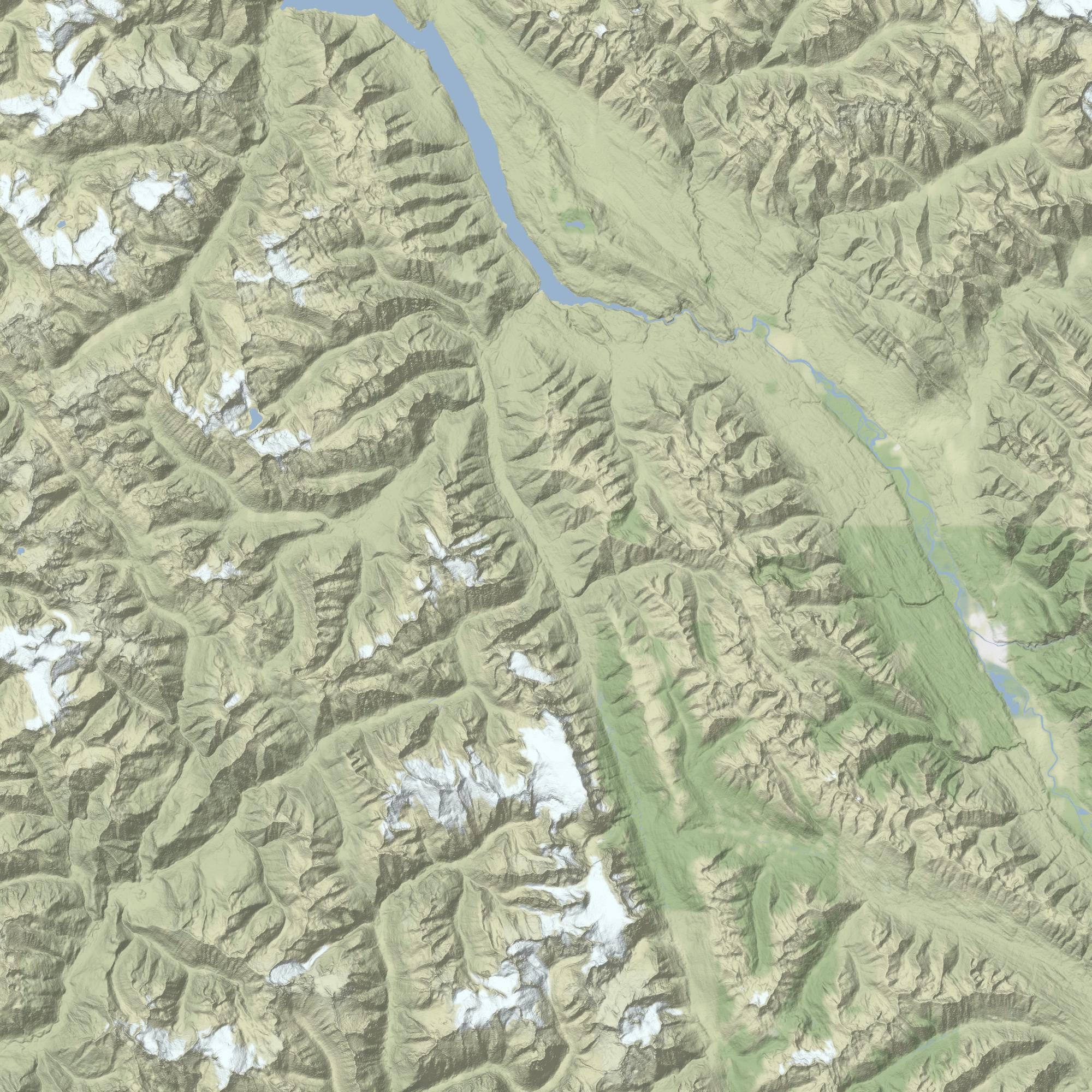

These features each tell about the history and the highlights of these storied roadways, starting with the remote Alaska Highway on page 30, the famous Rogers Pass on page 40 and the troubled Highway 8 on page 54. Learn how these highways connect communities for both business and pleasure, how they are intertwined with the history and development of our province, and how they too have changed over the years.

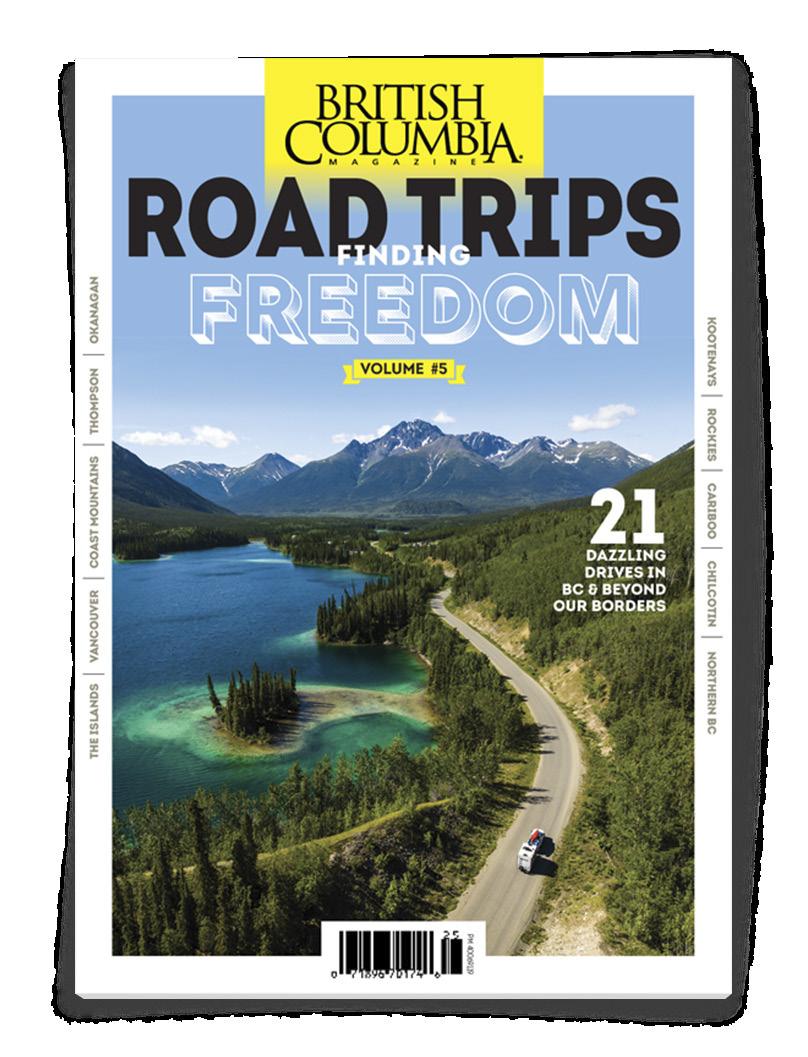

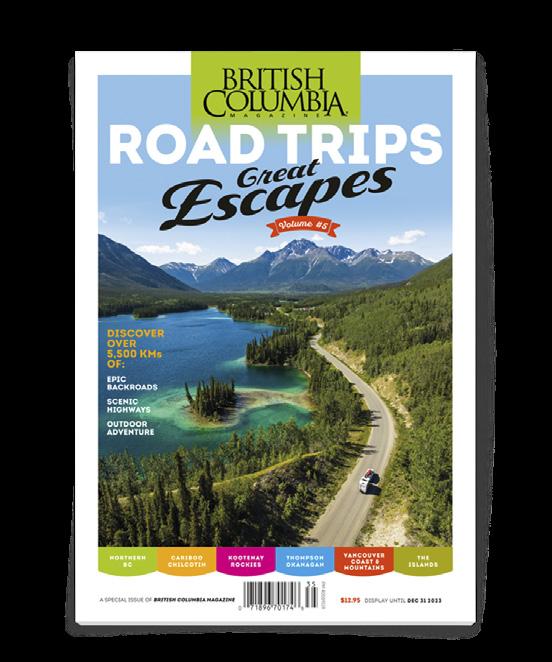

For a more traditional take on road trips, our latest edition of the annual Road Trips Guide: Volume 5 is available on newsstands now or available online at bcmag.ca/roadguide. This guide takes a region-by-region look at all the amazing hot spots, getaways and attractions our province has to offer, from the old to the new, and hopefully with something for every reader.

Summertime is the best time to hit the road in search of something familiar, something new and hopefully something you’ll want to make familiar in the future. Happy trails

—Dale Miller

EDITOR

Dale Miller editor@bcmag.ca

ART DIRECTOR Arran Yates

ASSOCIATE EDITOR Sam Burkhart

GENERAL ADVERTISING INQUIRIES 604-428-0259

ACCOUNT MANAGER Tyrone Stelzenmuller 604-620-0031

ACCOUNT MANAGER (VAN. ISLE) Kathy Moore 250-748-6416

ACCOUNT MANAGER Meena Mann 604-559-9052

ACCOUNT MANAGER Katherine Kjaer 250-592-5331

PUBLISHER / PRESIDENT Mark Yelic MARKETING MANAGER Desiree Miller GROUP CONTROLLER Anthea Williams

ACCOUNTING Angie Danis, Elizabeth Williams

DIRECTOR - CONSUMER MARKETING Craig Sweetman CIRCULATION & CUSTOMER SERVICE

Roxanne Davies, Lauren McCabe, Marissa Miller

SUBSCRIPTION HOTLINE 1-800-663-7611

SUBSCRIBER ENQUIRIES: cs@bcmag.ca

SUBSCRIPTION RATES

FREE with your subscription: the British Columbia Magazine wall calendar. 13 months of glorious landscape and wildlife photography.

1 year (four issues): $19.95 / 2 years: $34.95 / 3 years: $46.95

Add $6 for Canadian, $10 for U.S., or $12 for International subscriptions per year for P&H.

Newsstand single-issue cover price: $8.95 plus tax.

Send Name & Address Along With Payment To: British Columbia Magazine, 802-1166 Alberni St. Vancouver, BC, V6E 3Z3 Canada

British Columbia Magazine is published four times per year: Spring (March), Summer (June), Fall (September), Winter (December)

Contents copyright 2023 by British Columbia Magazine. All rights reserved.

Reproduction of any article, photograph or artwork without written permission is strictly forbidden. The publisher can assume no responsibility for unsolicited material.

ISSN 1709-4623

802-1166 Alberni Street Vancouver, BC, Canada V6E 3Z3

PRINTED IN CANADA

Missed the Spring issue?

Buy it here.

The latest British Columbia Magazine with the editorial “Gold Fever” caught my wife and I close to home. We enjoyed the same area you describe [The Bridge River Valley] back in the 1960s driving only a VW Beetle. It was a four-wheel challenge then and we made the trip with our VW. Now 60 years later, we still enjoy the area since we loved it so much, and we bought at Gun Lake and eventually lived there. I discovered the area in ’63 as a student working for the summer at the Bralorne Mine (a gold mine). I came back a few years later, married now, to purchase a spot on the lake. Gun Lake has the clearest water in North America and is featured in the BC Lake Stewardship Society “Secchi Dip-in” results each year [an international effort to collect water clarity data from lakes,

rivers and streams all around North America]. We would love to show you gold we have panned in the area and share stories about gold mining. We raised three daughters at the lake while having a very fun life.

Terry & Cathy Thiessen, Gun Lake, BC

Terry & Cathy Thiessen, Gun Lake, BC

We’d love to hear those stories too! The “Tales of BC” column at the back of the magazine would be a great place to share one of your Gun Lake / gold panning adventures, and we are always looking for submissions. It doesn’t have to be funny, but it helps, and it should be around 600 words showcasing some fun or insightful look at living or visiting British Columbia. Looking forward to it. —Eds.

I enjoyed and was interested to read the article about cormorants in the Winter edition of British Columbia Magazine.

I was surprised to see that the author states that cormorants are sometimes called shags in Britain, which in fact is not true. The European shag is a different bird called P aristotelis, so it is always called a shag in Britain. The cormorant found in BC is P carbo, which is a different species. I found this information in the Birds of Ocean and Estuary, from Orbis Publishing and Reader’s Digest Field Guide to the Birds of Britain.

As always we enjoyed British Columbia Magazine.

Michael and Rachel Wilson, Dalkeith, Midlothian, ScotlandI read with great interest the story about Port Alice. I was born there in 1945. My dad and mom lived in Holberg where dad worked as a logger. When mom got close to her due date, she had to wait for a ride down the Quatsino Sound on a tugboat pulling a log boom. I can’t even imagine what that journey was like. She stayed by herself at Port Alice until she gave birth. This winter issue arrived just two days after my 78th birthday.

Alexis Hendricks, San Francisco, CA

There will be danger when wrestling with barbed wire and Eddie, aka Mike Becherer.

“Y’ALL

yells the MC. “Hell yeah,” the audience whoops back. “We’re gonna rumble” barks the MC again, as he whips the crowd into a frenzy. The referee enters the ring to a chorus of “Ref, you suck!” While Eli Surge—decked out in tinfoil—slips under the ropes and chants his mantra along with the audience: “Birds aren’t real, Birds aren’t real,” interspersed with “I hope he rips your head off” and “Put him in a body bag!” A row of kids wrapped in tin foil blankets hoot while

BY JANE MUNDY

BY JANE MUNDY

old timers decked in black leather holler, and hipsters rub shoulders with mothers wearing tin foil hats—this is Eli’s fan club. It’s a family affair tonight, and 365 Pro Wrestling is sold out at the White Eagle Polish Hall in Victoria.

The ring is decorated with barbed wire (I touched it, it’s real), and more barbed wire is nailed to a scary plywood board next to a trash can. The ref announces the rules to the four wrestlers—you have to be pinned or submit in the ring, oth-

er than that there are no rules— and in a flash, Eddie Osbourne gets smashed onto the mat that shakes and sags on impact. I’m laughing and screaming at the same time, it’s like riding the roller coaster. Eddie gets slammed again and is somehow wedged under the barbed wire board. There is blood.

“Yeah, I was bleeding, it happens sometimes,” says Eddie, aka Mike Becherer, Victoriabased 365 Pro Wrestling’s owner and operator.

So wrestling isn’t all fake? “Just fall in the ring once… Sometimes we get a few broken

bones and concussions but we work hard to keep each other safe,” says Mike. “We have to be in good shape and know how to take the falls, and you have to practice.”

You also need charisma. “Wrestling is like theatre; we try to be bigger than life, and project that image to the back row,” says Mike. “You could just get your opponent in a quick headlock but we draw it out so everyone can see, so our story is believable.”

When female pro wrestler Rose struts onstage the crowd goes wild and the ring is littered with artificial roses. But she’s the real deal. “Train with us for 30 minutes and then say it’s fake,” says Rose.

The audience throws their support behind her and good guys Haviko and Crofton, and dutifully boo the bad guys. Tonight, the most villainous are Devonshooter and Stein. “Crofton is the everyday man;

he goes to work and wrestles at night and people identify with him,” Mike explains. “Haviko is a superhero with his cartoon mask and high-flying flips from the ropes, people love how he twirls his opponent and takes them down.”

Mike started his wrestling career in high school. With his family’s support he trained at a pro wrestling school in Ontario for two years—although his mum thought it was just a phase and kept his room. But Mike didn’t move back home. He has been a pro wrestler for over 20 years and recently opened a wrestling school in Campbell River. Mike’s parents are proud of him. “My parents are incredibly supportive and proud,” says Rose, age 27. “Whenever possible they come to my events, wear my merchandise and show family and their friends my videos. They’re really involved in my career and I’m very lucky.”

Rose had never been to a live wrestling event before she started training with Mike/Eddie just one year ago. “Before I opened his door, I heard loud thumps on the mat and almost turned back—what was I getting myself into?” says Rose. “But ever since watching wrestling on TV as a kid I wanted to be in the ring. It was stupid to walk away. And getting out of your comfort zone was important to me so I took a deep breath and opened the door to six guys and Nicole, in full gear. I had never even worn knee pads.”

Rose caught on fast, but she had to find the courage to endure three months of training that was “super scary” before her first match. “I got squished,” she says, laughing. “Eddie won the match but he got booed and everyone cheered me except the little boys, because they love Eddie so much, and now see me as their evil big sister. That match

started my own fan base.”

Some people who have never been to a live event might look down on female wrestling but for Rose and her female colleagues, it is empowering. Her persona is a feisty woman defending people who can’t defend themselves. “It’s about showing young girls—through my athletic skills—that they too can be fierce and at the same level as men,” says Rose. Women and kids see her wrestle guys and win and they also see empowerment. “We have been taught that you have to be pretty and act a certain way to be accepted and succeed; we are scared to show our fierce spirit. But I’m not scared and I get to show my spirit in the ring.”

Not everyone, however, is supportive. “Some venues I try to book will say wrestling is too violent, but in the same breath they will say it’s fake. But it is definitely entertainment,”

Mike quips. Like ancient theatre. Remember that scene in Gladiator when Russel Crowe’s character Maximus yells, “Are You Not Entertained?” Sure, the audience loves that element of danger and kind of wants to see someone get hurt, but these guys are professionals and they excel at throwing insults at each other rather than punches.

“I didn’t expect that level of showmanship—combining acrobatics, gymnastics and old-time carnival theatrics. And the creative costumes—they really get into it,” says Robb Johnstone, age 59, after attending his first event. “I joined the audience’s gasps, oohs and aahs as wrestlers dropped from 10 feet in the air and piled on top of each other. It’s like Jackie Chan choregraphed the show.”

Jakob Svorkdal, age 21,is also a fan. “The interactive show, where audience and performers yell at each other, is terrific. Even my female friends enjoy yelling; everyone pretends it’s real, but we all know the birds aren’t real,” says Svorkdal, laughing. “Eli has a good gimmick, he nails the comedy angle.” (FYI, the tinfoil keeps ‘them,’ aka birds, from spying on us. That’s one conspiracy theory put to good use.)

Why do British Columbians go bonkers for wrestling? You get to grab a bevvie, yell and scream and laugh your head off. “Pro wrestling is magic; you can be a kid again, get outside of yourself and no worries for a few hours,” says Mike. I concur. A measly 20 bucks for more than three hours of the best live theatre in a small BC town is a great way to spend an evening. I’m hooked.

IN SEPTEMBER 2022, a new reconciliation agreement between Stz’uminus First Nation and British Columbia set out a plan that provides $10 million over five years to support Stz’uminus-led remediation in areas of Ladysmith Harbour with the goal of supporting the nation’s land acquisition and management plans within the harbour. Not long afterward, the Ladysmith Maritime Society (LMS), a nonprofit organization that manages and operates Ladysmith Community Marina was informed by the Town of Ladysmith that they need to vacate the site and remove their infrastructure by the end of December 2023.

Richard Wiefelspuett, executive director of LMS, says the Ladysmith Maritime Society fully supports reconciliation and the transfer of the water lot (which has not yet occurred) to the Stz’uminus First Nation. He also believes the interests of all parties are best served with a strong working relationship between SFN and LMS. However, the society’s current agreements to use the water lot and the town's current lease weren’t set to expire until 2029, and a new operating arrangement between SFN’s Coast Salish Development Corp. and the society has not yet been reached.

The complex but important work of reconciliation that includes LMS will be precedent setting. This is all the more reason to work through the process in a slow and methodical way, to ensure that everyone’s rights are respected says Wieflespuett.

The water lot in question has $5 million worth of docks and other infrastructure, which have been added to over the years through donations and grants and worked on by volunteers. According to Wiefelspuett, it’s also a thriving community hub; and is home to multiple liveaboards and provides annual and transient moorage to a wide range of locals and visitors. A recent open house hosted by the society attracted an estimated 800 people—and while LMS had few answers, their presentation reiterated their support of the water lot transfer and the hope that it can be done in a way that respects their rights as a society.

Stz’uminus First Nation chief John Elliot also met with Ladysmith Mayor Aaron Stone and Kelly Daniels, president of LMS to discuss the issues. Chief Elliot, who was recently re-elected along with a new council, says the nation needs more time to get caught up in order to get the right information out to the community.

Diane Selkirk

LATE OCTOBER starts the truffle season and the lagotto romagnolos, the breed known as the Italian truffle dog, are back at work on Pete and Virginia Brietzke’s truffle farm in Parksville. Truffles have been harvested in Italy and France for thousands of years, and recently British Columbia has become fertile territory for cultivating the Périgord black truffle. After all, the Cowichan Valley is known as Canada’s Provence. Key to any successful truffle harvest, however, is a well-trained truffle hunting dog.

“Dogs are more reliable and faithful than fickle truffles that have minds of their own,” quips Pete. While growing truffles may be a labour of love, breeding truffle-hunting dogs is a sure thing—and the Brietzkes do both.

Pete leashes Katie and one of her pups in-training, and they head into the orchard for a two-to-three-hour hunt. This is not a nature walk. Pete leads them to a row of 50 oak trees with the dogs walking tail up, nose down and the command is “find.” Yesterday evening

was Yemma’s turn to hunt truffles under a row of hazelnut trees. “I’m looking for their ‘nose to ground’ cues; they scratch the earth under a tree, indicating where to dig,” explains Pete, who is looking for indicators like the absence of grass or a crack in the ground. He delicately scrapes the earth with a three-prong rake as the truffles can be small, and gently digs. “We typically bring back one or two—or none. Sure, it’s disappointing when you don’t find something but that’s part of the payoff when you hit the jackpot.” But Pete and Virginia

haven’t hit the truffle jackpot yet, which can mean yields up to 60 kilograms per hectare and thousands of dollars per kilogram.

What’s so special about these Périgord black truffles? The ancient Greeks and Romans called them the Food of the Gods, and they rank with other elite foods such as caviar and saffron. The French gastronome Jean Brillat-Savarin in 1825 claimed it “the jewel of the kitchen” and an aphrodisiac. The English poet Lord Byron reportedly kept a truffle on his desk, believing its fragrance

would stimulate creativity and attract the muses. The taste is earthy and nutty, rich and deep, with a sensual, musky aroma. Add to that its scarcity and that’s why this sought-after delicacy is known as the “black diamond.”

For centuries wild truffles grew only in Europe, but truffle cultivation, which has been around since the early 19th century, has enabled this delicacy to be farmed in new places, such as the Pacific Northwest. Cultivation comprises inoculating the roots of oak and hazelnut trees with truffle spores. According to Dr. Shannon Berch, president of the Truffle Association of BC, there’s science behind the difficult work of creating a cultivated truffle industry, and you have to make a truffle orchard specifically; you can’t create one after the fact. Successful truffle production requires a symbiotic relationship between Tuber Melanosporum and its host tree so that the fungus envelops the tree roots and provides mineral ions, phosphorus in particular. (A truffle is the fruiting body of a fungus—a tuber—that grows underground.) In return, the fungus that will grow up to be black Périgord truffle receives carbohydrates. But this association needs to be nurtured, and it takes time.

Virginia’s parents imported their first inoculum from Europe in 2003 and now the family is growing and marketing truffle trees inoculated with French black Périgord spores. Pete and Virginia inoculated their Garry oak and hazelnut trees 15 years ago and they now have five acres of inoculated trees. But there are also several factors involved for a successful harvest. Soil pH level is key, along with everything else that dictates growth. The estimated time to the first truffle harvest is five to nine years, like most fruiting trees. And truffles are tasty to pretty much all wildlife. With so many challenges, why bother buying inoculated trees?

“Our customers are mostly interested in doing something different—their green thumbs want a challenge,” says Pete. “European customers buy trees because they want a bit of home and Americans buy our dogs to find truffles,” says Pete, “but most folks purchase several inoculated hazelnut trees because they are guaranteed to get nuts and truffles later— can’t lose.”

Berch has a truffle dream for BC that includes “professional truffle dog teams working with truffle growers to ensure that all cultivated truffles harvested in BC are at the peak of ripeness and build a first-rate reputation for cultivated culinary BC truffles.”

Lagotto romagnolo truffle dogs originated in the Romagna region of Northern Italy in the 1300s. The first Cana-

dian litter from working truffle lagottos were born at Virginia’s parents’ Parksville farm in 2008. They typically have just three mothers who will have only three litters in their lifetime, so some people wait years for puppies.

Truffle detection is pretty much the same as finding anything else, like beagles finding narcotics at airport terminals. Virginia starts training the lagottos by spritzing truffle on Mum’s teats when her pups are suckling. “Then we put truffle shavings in rice caches tied with an 18-inch string and bury underground but with the top of the string marking the spot,” she says. “We walk the puppy past the spot a few times and they are rewarded with treats and hugs when they find the cache.”

Italians describe them as “carino,” meaning cute. But those

teddy-bear looks are deceiving as they are durable workers, known for their strength and endurance—everything you want as a pet and truffle hunter. “We’ve been breeding Laggotos for 10 years and Pete still gets teary-eyed when they are adopted, but we know they will be taken care of, mainly to families and often people with allergies,” says Virginia. “As well, because the dogs are so quiet, they are great with autistic kids and they’re therapy dogs; you can train them to sniff anything, from drugs to diabetes.”

While dogs and trees are Pete’s passion, Clarence, the family’s mini-pig has his snout out-of-joint because truffles are his passion and the dogs are hunting while he stays home. Pete says Clarence finds truffles easily and he’s faster than the

dogs, but he needs restraining, otherwise he’ll eat them. That’s the tough part—some Italians are missing fingers. (Truffle pigs were banned in Italy in 1985.)

“Clarence is mostly an ornament now and he doesn’t play well with others, but he has an iron will and I only get truffles out of his mouth with a lot of protest and loud squealing,” says Pete, with all his fingers. While the cultivated truffle industry in BC is just starting to take off, there are many native species on the island. We don’t know much about what kinds of truffles are here, unlike foragers in Europe. However, Berch told the Vancouver Island Free Daily that, “We have some good, trained truffle dogs, they’re out in the woods finding them. I suspect we’ll find hundreds [of species]… The dogs have just revolutionized truffles.”

PAT DEMEESTER, a Powell River-based angler and flyfishing guide, says he first noticed farmed fish swimming wild in Lois Lake more than a decade ago. Now he catches them almost every time he casts a line into Lois and Khartoum lakes—some of them up to 30 pounds.

Lois is the first in a 57-kilometre-long, five-portage, eight-lake chain popular with paddlers, anglers and campers. It’s called the Powell River Forest Canoe Route and it travels through a working forest crisscrossed with logging roads and cut blocks. The tree stumps on Lois Lake’s shoreline tell the story. The lake was formed in the late 1940s following the construction of a dam to store water for a hydroelectricity power plant downstream in Stillwater, a rural community 20 kilometres south of Powell River.

There’s been a fish farm and hatchery on Lois Lake for more than 30 years. It’s run by West Coast Fishculture, a subsidiary of AgriMarine Holdings Inc. In 2013 AgriMarine, then based in Vancouver bought West Coast Fishculture for $5.2 million with plans to install its proprietary

fibreglass semi-closed containment technology at the Lois Lake site. A year before buying the Lois Lake operation, AgriMarine hit the headlines when a pilot semi-closed floating fish tank farm near Campbell River was damaged in a storm, releasing thousands of farmed chinook salmon into the Salish Sea.

Demeester says he’s been watching the Lois Lake fish farm for years and fears that escaped fish have taken hold in the wild. He calls them “30-pound kokanee-eating machines.” He’s particularly concerned about the impact on the blue-listed endemic cutthroat trout as well as kokanee salmon that are important feed fish for wild cutthroats.

“It’s not just a few rainbows that have escaped, it’s hundreds and thousands of them. What is the impact of all this biomass on other species?” Demeester says.

“This farm is flying under the radar and nobody seems to be doing anything about it.”

That’s not all he’s concerned about. According to Demeester this past winter Styrofoam and other debris from the fish farm was littering the shore and

surface of Lois Lake. Furthermore, he claims the farm halted the required practice of marking farmed fish (by clipping their adipose fins), making it hard for anglers to identify them.

In a statement dated April 14, 2023, Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) spokesperson Jennifer Young confirmed the federal government “is aware of compliance concerns at the AgriMarine operation on Lois Lake.”

“The facility is currently being investigated by fishery officers from DFO’s Conservation and Protection Aquaculture Unit. As this is an ongoing investigation, it would be inappropriate to comment further at this time,” Young wrote in the response.

Stan Proboszcz, senior scientist with the Watershed Watch Salmon Society, was alerted about Lois Lake early in 2023. In April, he travelled to the Sunshine Coast to check it out and captured video of fish farm infrastructure, including pipes and tubes leading from the shore to the fish farm. He also saw escaped farmed trout rolling around on the surface

of the lake. Proboszcz says his visit confirmed what he saw on an aerial photo located on iMAPBC, a provincial database of all provincial tenures on Crown land, that clearly shows the Lois Lake fish farm operating outside of its 40-acre tenure.

This isn’t news to regulators. A document obtained by Proboszcz through a freedom of information request confirms government officials have been talking about problems at Lois Lake for almost two years.

“… Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) has determined that the new infrastructure placement at the facility is not located within the associated [Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations] Crown land tenure and is therefore in non-compliance,” states the internal Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Fisheries document dated July 21, 2021.

Demeester believes a big part of the problem is that regulation of freshwater fish farms involves a number of different government agencies “that aren’t talking to each other.”

DFO is responsible for licensing and regulating salt and freshwater fish farms. It’s up to them to ensure a company meets the conditions of its license. DFO last issued a license to West Coast Fishculture in 2016 and it’s set to expire next June.

One fact is clear—fish escapes and effluent issues at Lois Lake are now squarely on the provincial government’s radar. Last December, the Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Strategy issued a warning to West Coast Fishculture for failing to meet discharged water quality standards. Water samples revealed levels of coliform, ammonia, nitrate, nitrite, as well as dissolved aluminium, zinc and copper that exceeded British Columbia Approved Water Quality Guidelines. Then in early 2023, the Ministry of Forests said on its website that it was pondering a daily catch quota of six rainbow trout, including a maximum of two wild rainbows. As rationale, the ministry highlighted “an immediate threat posed by the escaped, non-sterilized rainbow trout from the Lois Lake aquacul-

ture facility which have the potential to hybridize with resident cutthroat trout populations and compete for resources.”

Several calls to West Coast Fishculture’s Powell River office asking for comment from operations manager Jeff Robins were not returned. A phone number for the parent company AgriMarine Holdings in Vancouver is out of service.

While DFO is keeping tightlipped about its investigation, it’s business as usual at Westcoast Fishculture. At the same time, the company’s product continues to appear on the menus of BC restaurants with the Ocean Wise label. For example, Cactus Club Café is serving “Grilled Dijon Salmon” described on the menu as “Ocean Wise Lois Lake steelhead,” despite the fact that fish currently being farmed at Lois Lake are rainbow trout. Ocean Wise is the Vancouver Aquarium’s seafood rating system, which is based on 10 environmental impact criteria

ranging from chemical use and waste effluent to disease and introduced species escapes.

Mike McDermid, director of Ocean Wise, says he first heard about allegations of problems at Lois Lake last year. Consequently, in November 2022 Ocean Wise put Lois Lake rainbow trout officially “under review,” but the fish emerged with their rating intact.

“After reviewing all of the information it was deemed that the farm was still operating in accordance with the original assessment and the Ocean Wise recommended status was reinstated,” McDermid says. “We know that all food production is going to have some impact, so the goal here is to mitigate impact on the ocean and drive continuous improvement.”

According to McDermid, the problems at Lois Lake are more regulatory in nature than environmental and notes that Lois Lake is part of an unnatural chain of lakes created by a

hydro dam project.

“If they’re going rogue and dropping their environmental standards then yes, this will be a concern for us. But at this point there doesn’t appear to be any environmental problems at this operation,” he says. “We found no evidence of fish escapes in the last five years.”

The fact that Lois Lake and its farmed trout still fly with the Ocean Wise banner puzzles both Demeester and Proboszcz.

“I have to say, I’m a bit surprised, given it appears the province acknowledges the threat of the marked fish escapes on natural populations in the lake,” says Proboszcz.

Demeester is out on the lake chain almost everyday and says McDermid is dead wrong about fish escapes.

“This is what we’re dealing with up here.” says Demeester. “I’m not an anti-aquaculture guy. But I think this fish farm should be shut down until they’re in compliance.”

The 2023 British Columbia Magazine Photo Contest is now live! Go to bcmag.ca/ photo-contest for rules and regulations and to find more information on how to enter. Deadline for this year’s contest is July 21. Good luck!

Whiffin Spit and its little lighthouse.

Whiffin Spit and its little lighthouse.

IIn the not-too-distant past, Sooke wasn’t much more than a haven for hippies and commercial fishers. There wasn’t much to do. Now it’s a magnet for lightweight adventurers. And with great food, three brew pubs and lux accommodations, this little town 45 minutes west of Victoria is a perfect getaway where you can unwind and get outdoors.

Circle routes are more interesting than driving the same stretch of road twice. So, adding another half hour from Victoria to bucolic Cobble Hill, we were just in time for lunch at Merridale Ciderworks. (If you’re coming from the mainland, either catch the ferry to Nanaimo from West Vancouver (Horseshoe Bay) or avoid

the Malahat and board the ferry from Brentwood Bay to Mill Bay—close to the Swartz Bay ferry terminal.) After a stroll in the orchard with 20 apple varietals—keep going to the end and the faerie mine, which is fascinating not only for kids—Chelsea guided us through the cider tasting experience, including traditional “Scrumpy” with its huge tannins to a Margarita-style Jalisco cider. Merridale has come a long way since selling cider from soda pop coolers. Sample their Aura Gin, a gorgeous magenta colour and so smooth, even at high noon. Speaking of gin, Sheringham Distillery recently moved from Sooke to Langford and you can’t miss it on this route.

To get the lay of the land in the Sooke area, we hopped on e-bikes provided by Palli Palli (delivery and pickup included in rental), ideally suited for the famous 56 kilometre Galloping Goose converted railway trail. You can pedal the trail in three hours and be back without breaking a sweat, with a pit stop at the Sooke Potholes, so pack your bathing suit. Hiking at Sooke Potholes Provincial Park is also not to be missed— even on a gloomy day.

Well-maintained trails lead down to pools and potholes naturally carved into the bedrock of the Sooke River with crystal clear water. Hands down—and handsfree—pedaling with West Coast Outdoor Adventure was one of my best (AKA relaxed and easiest) kayak trips ever. Our guide Allen briefly explained the fast and stable foot-powered Hobie kayak and we zipped past Sooke Harbour and Whiffin Spit in no time. We paddled through kelp gardens with water so clear we could see purple and pink sea stars and a world of marine life far below. Coming back, we zig-zagged under the old wooden boardwalk and under the watchful eyes of harbour

seals lolling on the dock. And a molting elephant seal was snoozing on the pebbly beach at Wiffen Spit, and cordoned off with yellow warning tape, thanks to the parks board. The 1.3-kilometre flat walking trail, which is suitable for wheelchairs and strollers and dogs on leashes, is flanked by park benches and driftwood, and divides the calm waters of Sooke Basin with the frothy Juan de Fuca Strait.

All that walking and paddling required a bevvy. With three microbreweries and only about 15,000 residents, you’ll likely grab a table, along with a stellar view, at award-winning Sooke Oceanside Brewing. Owner Ryan Orr started brewing from his garage and expanded to a gas station in 2016. “When you don’t have money you get resourceful—it’s called West Coast Funky,” says Orr, laughing. “We sold out of beer one day after we opened and now SOB beer sells in 150 stores throughout Vancouver Island.” Go for the flight, a great way to sample six brews and delivered in a gorgeous flight board design of Vancouver Island.

After a morning soak in the Prestige Oceanfront Resort’s hot tub followed with coffee on our expansive balcony overlooking Whiffin Spit, we were stoked for a zip with Adrena LINE Zipline Adventure Tours—talk about exhilarating! A short drive from our hotel, we were soon soaring through the forest canopy on the new 2,400-footlong “Big Zip,” eye-level with raptors and the Olympic Mountains in the distance. I’ve experienced several ziplines, including a few near-death zips that involved stopping at the end by smashing into the platform at the speed of light. But these trolleys have magnets that allow for a soft and gentle landing and a back-up brake system is a heavy-duty spring pack—clearly no expense has been spared on safety.

Combine the Big Zip with the twohour guided forest canopy on eight different ziplines, ranging from 45 to 305 metres in length. “An 86-year-old wore her sticks until the very top. She zipped with her granddaughter and

last year an ‘active seniors’ group was here—they’ll be back,” says Scott McQueen, Adrena LINE director. “Zip lining appeals to adventurous people and it doesn’t require any aptitude. Our goal is to be wheelchair accessible.” After the first zip we were in competitive mode and with bodies in torpedo shape (flat) we clocked in at 66 kph. Heehaw!

Back at the luxurious Prestige with its beachy-Miami decor, we didn’t have to leave the building for outstanding local cuisine. The bucket of shrimp and calamari were both perfectly cooked and the huge plate of burrata with tomatoes made it back to our balcony. A few locals said they come here for the best smoked

salmon and crab cake bennys, and I agree. On par with the West Coast Grill is Wild Mountain. Chef Oliver’s menu showcases the local community of fishers, foragers, farmers, brewers and bakers, including pizza sliding out of the new wood-fired pizza oven (the crust is made with locally grown and milled wheat). We scarfed down a second order of the crispy polenta and pickle dip and outrageous chocolate pudding back on our balcony, listening to the last cry of seagulls and faint snorts of seals as the sky turned pink and purple and everything was right with the world.

Stay Prestige Oceanfront Resort offers luxury, an indoor pool, hot tub and spa for guests. prestigehotelsandresorts.com

Eat The West Coast Grill in the Prestige Hotel offers a great Ocean Wise menu. westcoastgrill.ca

Best to make a reservation at the wildly popular Wild Mountain, open Thursday to Sunday. wildmountaindinners.com

Drink

Sooke is home to three microbreweries—Sooke Brewing Company, Bad Dog Brewing and Sooke Oceanside Brewing. sookebrewing.com baddogbrewing.ca sookeoceansidebrewery.com

Play Kayak with West Coast Outdoor Adventure. westcoastoutdoor.com

Palli Palli delivers e-bikes and paddleboards to your location. pallipaddle.com

AdrenaLine zipline adventures provides guided canopy tours. adrenalinezip.com

“LET US BREAK BREAD TOGETHER.”

BY M arianne S cottTThis is one of the many sayings about bread, a fundamental staple food that provides 20 percent of calories consumed by humans. All the world’s countries produce some kind of bread, ranging from fluffy loaves to baguettes to bagels to flatbreads of every kind. Bread permeates history and cultures—even revolutions. The phrase “Let them eat cake,” attributed to Marie Antoinette, refers to peasant-led bread riots which helped launch the 1789 French Revolution.

A recent archeological find in Jordan revealed that hunter-gatherers made bread from wild wheat, wild barley and plant roots around 14,000 years ago. Bread became widely available when various grains were domesticated, millstones ground grain into flour, and settled agriculture spread around the globe. And since man cannot live by bread alone, pastries became common after world exploration made sugarcane more available after 1500.

In the last decades, bread and pastries have seen a renewal in North America, changing from mass-produced, generic, soft bread to many varieties of artisanal loaves. Vancouver Island’s bakeries have some of the most original specialties whose descriptions make our mouths water—a caramel macchiato bun, a chocolate cake with peanut butter mousse and a French buttercream and ganache top, or a Belgian chocolate berry torte. So for us breadwinners, here are six south Vancouver Island bakeries that bring joy.

Wayne Sawchuk

Wayne Sawchuk

This bakery has operated in downtown Victoria for 31 years and its breads, pastries and pies—both sweet and savoury—trigger line-ups outside its unpretentious premises every weekend. Operated by the gregarious Daniel Vokey, it’s an institution where several generations have ordered cakes to celebrate births, baptisms, birthdays and weddings. “When people order for a special event, you’re part of the celebration,” Daniel said. He wears a smile as he works from a table near the cash register and greets his customers, old and new. He chats with people ranging from artist Robert Bateman to those down-on-their-luck who hang out in the

neighbourhood. “Some people come in every day,” he said.

His bakery is festooned with two kinds of kitchen tools: cutting boards and rolling pins. A thousand wooden boards form an odd kind of wallpaper— their many shapes and colours cover the walls; the rolling pins hang in rows in the shop’s front windows forming unusual curtains. “One customer gave us a cutting board, then another brought a rolling pin and these started both traditions,” said Daniel. “Each item has a story.”

Daniel hails from Montreal and started baking with his uncle at a St. Rémy hotel. During a Victoria holiday, he

noted a scarcity of bakeries, presenting a business opportunity. After arriving in BC’s capital, he began making pastry in Murchie’s venerable tearoom, but in 1992 he launched his own bakery. The mostly sourdough breads he and his crew of 22 bake every day are sought after, brioche and croissants are favourites, and I swooned over florentines made of honey, almonds and chocolate. The website description and photo of the Pamona—“light vanilla sponge cake perfumed with orange brandy, orange zest, sliced pears with a delicate pastry cream, decorated with marzipan fruits” makes me salivate. His cakes can be prepared to be gluten-free, vegetarian or vegan. His savoury lamb pie takes four days to make.

“What’s your favourite bakery item?” I asked Daniel. “Happy customers,” he said, smiling

Pandora Avenue, Victoria

Tara Black, who owns Origins in Victoria, grew up in Sparwood, BC, and took cooking classes in high school. She moved to Courtenay at 19, apprenticing in several restaurants. “It turned out I just didn’t like line cooking,” she said. “Too repetitive, but I loved the pace of pastry making. It’s a special kind of chaos, never boring.

“At home my mum, grandmother and aunt savoured healthy, slow food,” she said. “They gave me the foundation for making and sharing food.” After relocating to Victoria, she trained with Patisserie Daniel. Then she saw an opportunity: baking gluten-free products for an underserved group—those with celiac disease and those who’re glutensensitive.

Before opening a formal bakery, Tara and a then-partner tested the market for gluten-free baked goods with a stall at the historic Bastion Square Market. Would customers buy their wheat-free items? Indeed, so many people bought

their GF products they were able to open a storefront called Origins within six months. Tara says her premises are absolutely gluten-free, even the cutting boards, mixers and knives that cut dough. “I sell doubt-free safety,” she says.

To achieve a pristine environment, Origins uses a variety of globally sourced gluten-free grains including sorghum, amaranth, millet, buckwheat and tef. Traditional sourdough bread, vegan chocolate cake and carrot cake are the most popular fare, but seasonal specials such as an Easter nest cake with lemon curd and buttercream, topped with toasted coconut and meringue eggs fly off the shelves.

Origins has opened another bakery in Langford and now ships products across Canada. Tara prizes her team of bakers, which includes two daughters. “Running bakeries is hard work,” she says. “We begin at 5:00 a.m., but it’s worth it. It’s so good to see people, even those who cannot digest gluten, enjoy breads and pastries.”

Tara Black of Origins.

Tara Black of Origins.

Quadra Street, Victoria

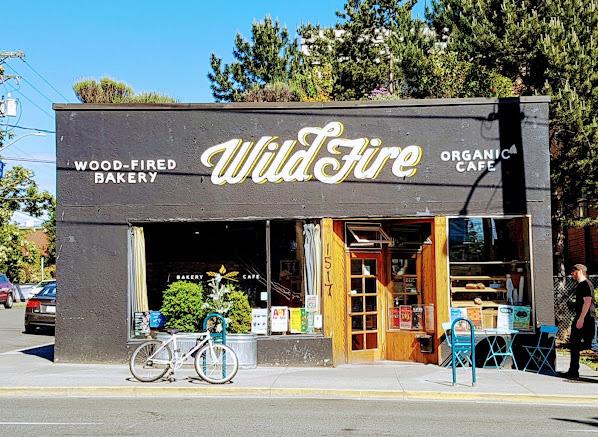

To ensure her breads and pastries use the right organic grains, Wildfire Bakery owner Erika Heyrman opened the Nootka Rose Milling Company in Metchosin, BC. The mill stone-grinds fresh BC-grown grains such as barley, spelt, einkorn and other forms of ancient wheat. Other local bakers buy their organic flours from Nootka.

Erika has run her bakery for 25 years,

starting with a brick oven on her driveway and selling her products at the weekly Moss Street Market. “We had a very reliable demand,” she says, “there weren’t many artisan bakers around then. We then moved to our permanent location, once a 1950s small grocery, where we produce everything by hand and from scratch.” A variety of regional supermarkets also carry her breads.

“Baking is a demanding profession,” she tells me. “Our staff ranges from 15 to 24 and work on rotating shifts. Prep takes place during the day and evening, and then at 4:00 a.m. we fire up the ovens. Bread is our top seller with rustic

white sourdough being the most popular.” She notes that vegan chocolate cake is in demand, and the bakery also makes cakes to order. Her own favourites are a hazelnut-pear tart and three-seed sourdough that includes sesame, sunflowerand flax seed.

Asked what advice she has for aspiring bakers, she mentions that they should be transparent about the ingredients used, but also have a business sense. “Profit is low,” she said, “and the work can be physically taxing, with lots of lifting and repetitive motions. But I’m proud of literally feeding my community with genuine products. It’s super valuable.”

Josh Houston is surrounded by black plastic boxes in which he transports his breads and pastries to a Victoria institution—the Saturday Moss Street Market—where he sells his baked goods each week. When I arrive at his stall at noon, he’s nearly sold out. (Fortunately, he still had a maple-pecanbutterscotch cookie I demolished.) His unique products include herb-and-seasalt focaccia, smoked sprouted-rye sourdough and, just to make it really sour, sauerkraut rye sourdough. His loaves bake in cast-iron Dutch ovens on Friday night.

He differs from other bakers in that he’s home-based—his converted garage in Sooke is a full-fledged bakery, where he feeds his sourdough and bakes while listening to podcasts and music.

He spends his week getting ready for the market—his only outlet except for special orders. The slim 42-yearold once worked as a chef but when he and wife Christine started their family, Josh realized a chef’s life was incompatible with family life. He then taught culinary arts—especially baking—at Esquimalt High School. In 2018, he began home baking as a hobby. Then Covid-19 shut the schools and the demand for his baked goods exploded. “Many older people didn’t go out shopping and I delivered,” he said. “I’d bake between 150 and 200 loaves a week.”

Today, he continues to bake solo to a schedule he keeps in his head, although his daughter (five) pitches in and son (nine) has his own business taking care of the chickens and eggs. His organic, locally grown grains—rye, red fife wheat, oats, barley, einkorn, emmer and spelt— are milled at Metchosin’s Nootka Rose Mill while his white flour originates in Saskatchewan. Asked what he’d like to be doing in five years, he answered, “exactly what I’m doing today.”

When I enter True Grain in Cowichan Bay, the heady scent of baking bread and pastries is pervasive. I inhale deeply; it smells like home and comfort. Racks laden with loaves of all kinds, including organic red fife cracked grain, khorasan and others encrusted with seeds line up behind the counter. Trays with scones, croissants, thickly frosted cinnamon buns and butterfly pastries entice the constant flow of customers. Baguettes and German pretzels are also on the menu.

True Grain co-owner and president Bruce Stewart fuses his baking philosophy with environmental practices. The multiple grains they use are organic and stone

ground at the bakery. No additives, sugar or oil. “Our bakers are craftsmen,” he said.

“We mix everything by hand. The baker has a relationship handling the dough that can’t be replicated by a machine. Our dough is allowed to rest so the flavours can develop. We have 12 to 15 bakers depending on the season and they’re cross-trained on bread and pastries.” Bruce’s wife Leslie co-owns the business and their two young daughters, Monica and Fiona, “help dad stack stuff and see how hard everyone works.”

Bruce heads the Italian-founded movement “Cittaslow,” an organization inspired by the slow food movement. Its goals focus on high-quality local food and drink, while opposing “fast food anywhere North America.”

Bruce previously bought Saskatch-

ewan grain, but judged the diesel used to deliver it too polluting. His biodegradable bread bags cost five times plastic ones. Today all grain comes from BC’s organic farmers, which includes khorasan, spelt, emmer, einkorn and rye. Those who wish to bake their own bread can purchase ingredients in berry or milled form, as well as pasta, nuts and seeds.

Covid shut down in-store tables, but True Grain opened a café next door. Bruce shares his business savvy with other small businesses. “We support bread entrepreneurs with our products, knowledge and solutions,” he said. “We are mentors and our partnerships with younger people help support BC farmers.”

The Cowichan area has adopted the slogan, “Slow Down, Savour Life.” The True Grain bakery is an example of that philosophy.

Whenever we travel “up island” past Ladysmith, stopping by the Old Town Bakery is a requirement. Located in the heart of the historic downtown, their multiple varieties of cinnamon buns require early attendance, especially after Times Colonist readers voted their buns to be the best on Vancouver Island. As a result, they’ve expanded their gourmet bun varieties to include cream cheese and sliced almond, blueberry almond, blackberry apricot ginger, even peanut butter cream cheese.

In 1999, Kate Cram launched the Old Town Bakery with her parents, then

moved to its present location in 2002 where a bakery had existed since 1932. Husband Geoff Cram joined in 2005. Kate had always felt passionate about cooking and baking, so her dad arranged for her to attend the New York-based Culinary Institute of America, where she spent two-and-a-half years perfecting her gastronomic art. Geoff came from a graphic design background and learned baking by doing.

The bakery’s philosophy is straightforward: to create delicious items from scratch using traditional wheat. Kate adds that their secret ingredient is “love.” Some breads use sourdough

starter, others are yeast-based. “We don’t follow trends,” Geoff told me, “just oldfashioned baking, with special cakes for baby showers and weddings.” That said, the pair did expand down the street with a gluten-free restaurant, closed by Covid-19, but reopened as a grocery with GF products. They added the space next door and scoop tasty gelato there. A total staff of 68 are employed by the three stores—significant for a town the size of Ladysmith.

The bakery itself has a public section with display cases and tables, but its other side, recently renovated by son Seth, shows the long table where dough is prepared. It’s visible to the public. Like the other bakeries, crew arrive between 2:00 and 5:00 a.m. The most popular breads? Plain or seeded sourdough.

I asked Geoff for his favourite confection. “It’s an old prairie mainstay,” he said. “It’s a confetti square with marshmallow, peanut butter, butterscotch chips and cornflakes. It’s ridiculously sweet.”

BY RICK HUDSON

BY RICK HUDSON

Summer’s coming, and that means it’s time to hit the road again. And what road is more iconic, more panoramic, and more majestic than the Alaska Highway? It’s long, it’s remote, and it has an aura about it that deserves its reputation as one of the great road trips of North America. Archie says it might be the greatest of them all, but then Archie’s like that at times.

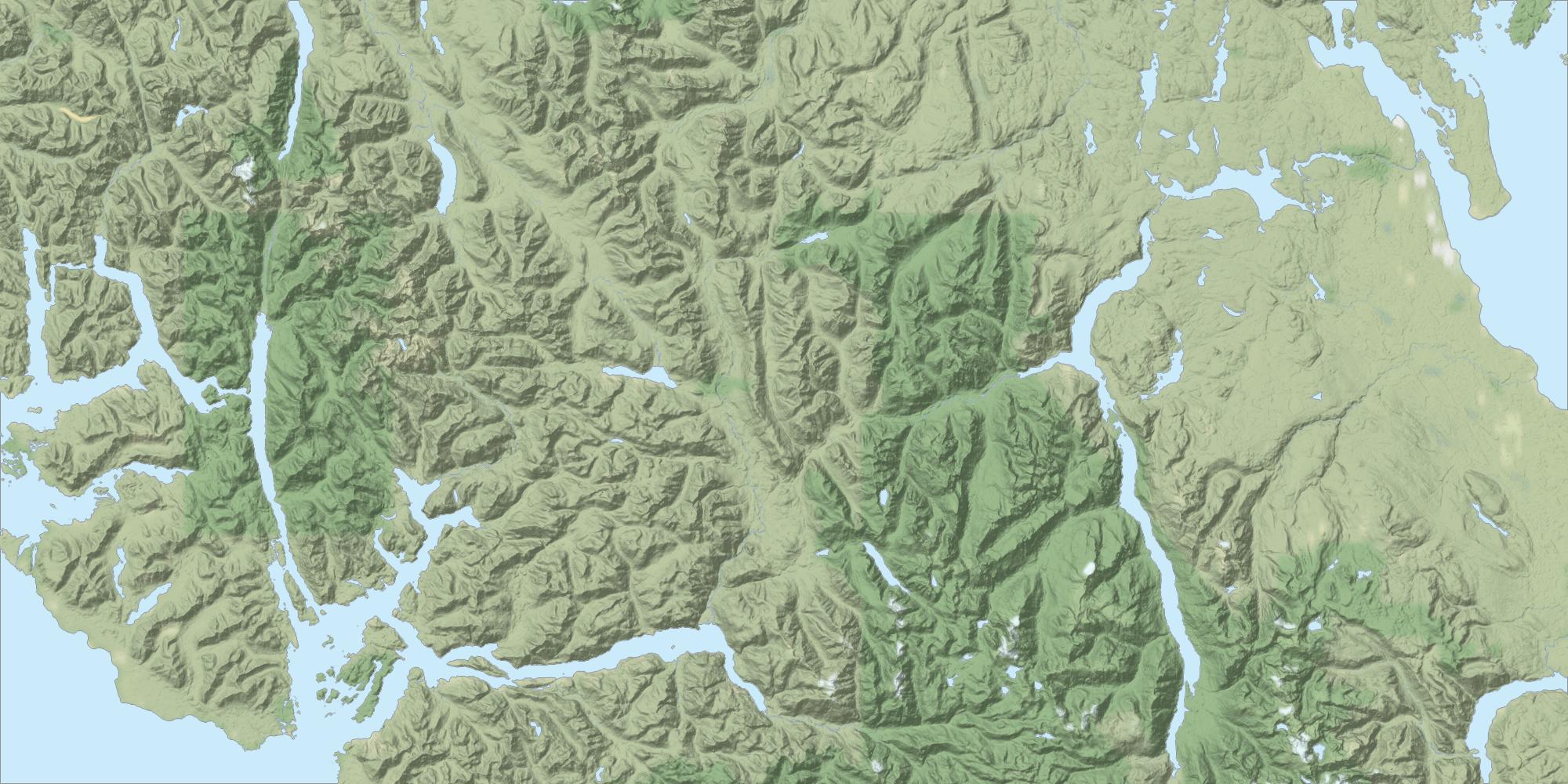

The driving is huge, as you’d expect in a province that’s bigger than France and Germany combined. Put another way, you could drop California, Oregon and Washington into BC and still have room for Maine. So, driving the highway north is a big commitment and shouldn’t be taken lightly. Spring storms can linger into June, and fall whiteouts can start as early as September.

So, most summer visitors tend to push it, anxious to cover the long distances in the shortest time. The highway’s official start is Dawson Creek (named for the Canadian geologist George Dawson). That’s ‘Mile 0’ or ‘Km 0’. There’s almost 1,000 kilometres on Highway 97 to the Yukon border. From there it becomes Highway 1 for a further 930 kilometres to the Alaska border. And from there… well, it’s a long way to anywhere, depending on your plans. Overall, it’s 2,400 kilometres or 1,500 miles from Dawson Creek to Fairbanks.

All of which explains why most folk just put the pedal to the metal and in doing so, miss a lot of interesting side trips. Archie wants to expand our minds and is encouraging us to slow down and smell the roses. Or balsam fir. Care to tag along?

The Alaska Highway was built in a rush by the US Army Corps of Engineers in 1942 in response to the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941. There was an imminent

Sthreat of a Japanese invasion through the Aleutian Islands in Alaska, and the traditional sea route from Seattle to Anchorage was threatened by enemy submarines.

Given the limited construction time, it was an engineering feat of staggering proportions—1,478 miles (2,365 kilometres) of gravel laid in two years at a cost of close to $123 million, or $83,000 per mile. And those were real dollars back then.

The route chosen was neither the cheapest, the best surveyed, nor the easiest. It was the route that linked the most airfields, which were of strategic value to the allies during the Second World War. They had been built in 1941 to provide air support to the Soviet Union, which had already opened an Eastern Front against Japan.

The highway and associated infrastructure (buildings, bridges, airstrips, etc) were sold to Canada at war’s end for $108 million and taken over by the Canadian Army in 1946. Substantially re-built, it was opened to the public in 1948 and paved end to end in 1992.

North of Mile 0 the road empties. The oil and gas service trucks dwindle and it’s just the RV crowd and an occasional long-haul tractor-trailer. The boreal forest appears as the wheat and canola fields disappear. From Fort Nelson the highway turns west and starts to get interesting. Because we’re in BC, the distance posts are in kilometres, which don’t quite match the old milepost signs, partly because the road has been shortened periodically, and partly because although Mile 0 is at Dawson Creek, the kilometre posts were installed starting at the Yukon border and working backwards. “Isn’t that just like a government?” asks Archie rhetorically.

Passing Tetsa Lodge (Kilometre 572) on the river of the same name (‘best cinnamon buns in the galaxy’) the watercourse splits and the highway follows the North Tetsa River upstream. The road tops out at Summit Lake (Kilometre 598), the highest point on the Alaska Highway. We’re at 1,300 metres (4,250 feet) above sea level. Archie has a warn-

ing. “Came here one May,” he says, “and the lake was frozen solid. The wind came through that gap in the mountains like a freight train. It’s not a good place to be caught in bad weather.”

Nevertheless, he advises we’ll be stopping for a few days. Why not? The

campground (28 sites) is next to the lake, close to the highway, and surrounded by superb hills and snowcapped peaks. There are water taps, picnic tables, fire rings and outhouses. It’s open May 1 to September 16. Today the sky is blue, the lake’s surface unruffled by breeze. There’s a concrete boat launch if you’re interested in rainbow

and lake trout and mountain whitefish. Archie has more energetic pastimes in mind. Across the highway is the Summit Peak Trail, opposite the campground. There are three options. If your energy level is low, it’s worth hiking half a kilometre into the valley. The trail climbs out on the opposite bank and follows the edge of a forest. There are numerous places where

you can drop down to the river, to smooth limestone rock slabs to sunbathe out of the wind, or swim in the pools.

For the more energetic (“Let’s keep going,” shouts Archie from the back) the trail clears the pines after a kilometre and starts to climb. The path is obvious and once out of the trees the viewscape opens up. It’s no wonder this is one of the

most popular hikes along the highway.

There’s no cell coverage at Summit Lake campground, but about halfway up the ridge there’s a spot next to a rock wall where, curiously, all our phones go ping! We pause to catch our breath and reach out to someone far away. Then it’s back on the trail, gaining height steadily. The distance to the first high point (1,981 metres) is 3.5 kilometres one way from the road, with about 700 metres elevation gain. Happily, because it’s so open, you can turn around anywhere without losing much in terms of a view.

Near the top, the limestone is so pure that perfectly formed calcite (the basic building block of limestone) lies in the path in crystal shape, like Lego blocks. At the first high point, most sensible folk turn around, says Archie. The true summit of Mount Saint Paul (2,125 metres) is still a long way off, although it looks deceptively close. Ahead is an undulating ridge forming a giant U to the top, but is still four kilometres away with a 350-metre gain.

To discourage any thoughts in that direction, Archie draws our attention to the view back over the highway to Mount Saint George (2,256 metres) beyond Summit Lake. It’s a great panorama. Positioned as we are just off the main line of the Northern Rockies, there’s a broad perspective of this end of the range stretching almost 5,000 kilometres from New Mexico in the south to just north of us.

The following morning, we hike the gravel road that leads south from near the campground. The road is gated but mountain bikers can bypass it and ride to the microwave tower about six kilometres away. Much of the terrain is low alpine bush, so views are good.

Archie has other plans. We pass the gate and walk about two kilometres up the road to the Flower Springs trailhead at the first hairpin. There’s a registration desk and a path leading southwest up the valley towards the mountains. After another three kilometres, we reach Flower Springs Lake. In early summer (late June to early July) the flora in the valley and around the lake are spectacular. By midAugust the meadows start to put on their autumn colours of gold, yellow and red,

and the valley is equally colourful.

Archie will have none of this glorified shrubbery. We must go further. The valley beyond the lake divides. The left arm terminates below impressive cliffs of an unnamed peak (2,384 metres). Taking the right arm leads to two small lakes and a waterfall under the slopes of Mount Saint George.

Stone Mountain Provincial Park is a tiny northern add-on (257 square-kilometres) to the much bigger Northern Rocky Mountains Park (6,660 square-kilometres). This is untracked wilderness with barely a road anywhere, apart from the highway. The region comprises tilted sedimentary rocks, mostly dolomite (calcium magnesium carbonate), that formed underwater in the Pacific Ocean during the Devonian Period (360 to 420 million

to show us McDonald Valley tomorrow. It’s just a few kilometres downhill to the west from Summit Lake, and comes into view on the left beyond Mount Saint George. The valley is extraordinarily wide for such a small creek, until Archie points out that it’s the remnant of an ancient glacier that once filled the entire basin. What we are seeing is the ghost of a giant that drained the mountains over Summit Lake and down the North Tetsa River. Archie waxes eloquent about the good old days, when ice was real ice, and it took a week to trot a polar bear across those glaciers.

For a short walk (one-kilometre round trip), stop four kilometres west of Summit Lake campground at Kilometre 603 (Mile 376). Pull off next to a small lake on the left-hand side of the road. The Erosion Pillar Trail begins on the opposite (north) side, marked by a rock cairn and winds gently through trees. Near the end it climbs a short incline to the base of a 10-metre-high rock pillar that closely resembles a giant phallus. From beyond the pillar there are good views with Mount Saint George in the background.

years ago) and was then uplifted in the Cretaceous (80 to 90 million years ago). Keep an eye open for fossils.

Stone Mountain Park is named for the Stone Mountain sheep that you may see along the highway’s verges. Periods of glaciation have ground the dolomite bedrock into ‘flour’ comprising calcium, magnesium, sulphur, phosphorous and sodium. Hoofed animals such as moose, buffalo, caribou, goats and sheep need these elements to grow strong bones, teeth and hair.

Stone mountain sheep were named for Andrew J. Stone, an American hunter and explorer. They differ from the more common dall sheep of the Yukon, and the bighorn sheep found further south. Stone sheep are best identified by their horns— they are smaller and narrower than their cousins. For that reason, they are sometimes referred to as “thinhorns.” Bighorn sheep, famously seen in Jasper and Banff National Parks, are seldom found north of the Peace River.

Back at the campground, Archie is keen

For a slightly longer hike, from Summit Lake campground go eight kilometres west on the highway, where at Kilometre 607 there’s a pullout on the north side, with parking. There, a trail leads upstream into Baba Canyon, labeled on a rock. Depending on the river level, there may be some boulder hopping involved, but the steep sided valley has photogenic limestone walls and easy hiking. In early spring there are many wildflowers, notably lady slipper orchids. There’s not much height gain initially, and you can go just as far as you choose. The first viewpoint is a 5.5-kilometre round trip, the second is 11 kilometres there and back.

Top: Wood bison are common along the highway at all times of the year. With little traffic sense, in winter and poor visibility they are the cause of numerous accidents. Drive with caution!

Bottom: It’s a long day hike, but Forlorn Canyon on the Hokkpash River is lined with hoodoos topped with balancing boulders the size of small cars. Hokkpash Lake is just visible beyond.

The valley is wide for such a small creek, until Archie points out that it’s the remnant of an ancient glacier

Archie tolerates our interest in these short hikes, but promises bigger things ahead. We are going to explore the Wokkpash River Valley—specifically Forlorn Canyon and its hoodoos. At Kilometre

619 (Mile 382), One Thirteen Creek crosses the highway, and a gravel road descends two kilometres to McDonald Creek. There’s no longer a bridge as the Churchill Copper Mine closed years ago, but at low water levels (late summer and early mornings) the river is knee deep and may be crossed with a 4WD. Warning: The region is subject to rainstorms with rapidly rising water levels. Archie reminds us we have to get back too.

On the south side, a 20-kilometre road of varying grade with washouts leads to the Wokkpash River, descending in two big hairpin bends. Just before the descent, there’s a lake on the right that provides a roadside camping area.

From the trailhead above the river, a 70-kilometre backcountry trail leads upriver, across tundra, over mountain

passes, and back to the highway on upper McDonald Creek. It takes four to five days and offers a glimpse of what this incredible region can offer—wildlife (caribou, elk, moose, bear, deer, martens, wolverines and porcupine), wilderness, peaks and river crossings.

Archie has more modest ambitions. It’s possible, he advises, to camp at the little lake next to the mine road. In the morning we’ll do a fast and light dash up the Wokkpash River for 12 kilometres to Forlorn Canyon.

Starting at the trailhead kiosk, the path drops to the river and runs upstream on a bench, staying mostly level before climbing and dropping on the second half of the distance. Forlorn Canyon is a fivekilometre-long gorge lined by 150-metre-

high hoodoos on either side. Hard upper cap stones protect the softer lower strata, creating impossibly tall, narrow spires of crumbly conglomerate that seem in imminent likelihood of collapse. It’s a crazy world of balancing boulders that offers photo opportunities all the way. Although a long hike in and out, it’s so worth it.

If you’re feeling really energetic, Archie says, there’s Wokkpash Lake just beyond, where the fishing is good for dolly varden and bull trout. We decide that’s too ambitious. We return to camp at twilight. Early next morning the river crossing at McDonald Creek is shallow. The 4WD climbs to Highway 97, turning west again. The paving feels wonderfully smooth after the mine road.

There’s a large RV site and fuel stop at Toad River (Kilometre 647/Mile 405), with a path along the reservoir next to the campground. The highway here runs east to west, and some distance to the north is Toad River Hot Springs Provincial Park. Archie asks around. There’s a 12-kilome-

tre trail to hike in, or you can take horses, but there have been washouts along the trail. Alternatively, you might find a river boat to take you down the Racing River and then up the Toad River about a kilometre. The hot springs are on the true left hand side and comprise several pools. There’s a muddy field. Someone advises the mineral lick draws moose and other ungulates. No-one is very sure about the details. Someone else says the hot springs aren’t that great. Maybe next year.

By the time we reach Muncho Lake, the highway has swung south to north. Muncho means ‘big lake’ in the local Kaska

language. It’s one of the largest natural lakes in the Canadian Rockies and is said to be over 200 metres deep in places. The jade-green colour is reported to be from copper minerals.

Along the 11-kilometre shore there’s the Northern Rockies Lodge (Kilometre 708/Mile 442) and two nice provincial campgrounds (Strawberry and McDonald). Even as late as Victoria Day the lake can have ice cover. Other years it clears by early April. From the red roofed lodge, there are flights in the summer to Virginia Falls on the Nahanni River 300 kilometres to the north. It’s a long flight, but as Archie points out, it saves a lot of driving to Fort Simpson in the NWT, which is

the traditional access point to those iconic northern falls.

All along the highway we see wildlife on the verges—stone sheep and caribou in the drier regions, herds of wood bison and the occasional scuttling porcupine in the grassier sections. Early in the year the bison look scruffy as their winter coats peel off. They seem placid enough as they graze on the sweet spring grasses that grow close to the road. But looks are deceiving. Large males are over two metres tall at the shoulder and can weigh over 900 kilograms. In winter, in poor light, they are a serious highway hazard, and as many as 15 are killed in road accidents annually. The Department of

Highways is trying to reduce those collisions by plowing escape alleys off the highway for them, with some success. “Bison aren’t the sharpest tacks in the mammal pyramid,” says Archie.

We stop at the Trout River mineral lick and walk through flats filled with flowering anemones to the overlook. The river here has exposed a high bank of fine clay, the remnant of a past glacier. Rich in minerals, it’s a draw for animals in the early mornings and late evenings.

As you approach Kilometre 763 you see the stately Lower Liard River Bridge, the only suspension bridge on the highway. (There was another across the Peace River, but it failed in 1957.) Built in 1943 as part of the frantic Alaska Highway construction, this elegant 307-metre-long steel bridge forced the engineers of the time to abandon their usual multi-post construction, because of the river ice. Another curiosity is that it was fabricated from recycled steel— not uncommon in wartime—from the much longer Tacoma Narrows Bridge, built in 1940. That structure collapsed four months after opening to the public. Thanks to rare film footage taken as it happened, the failure is one of those seminal moments in North American engineering and was a lesson to civil engineers worldwide about bridge resonance caused by wind.

Today, the recycled steel stands firm as we cross to the north bank and turn in at Liard Hot Springs. No first trip along Highway 97 should miss this popular destination. There’s a day use fee or overnight camping charge. Both include access to the pools. Archie’s only advice is to avoid long weekends. Despite being a very long way from Fort Nelson and Watson Lake, the place is popular with locals and fills up quickly. You can book online now, and it’s open year-round. If full, there’s always the less interesting overflow parking across the highway.

West of the hot springs, the Smith and Liard Rivers meet (Kilometre 793/Mile 495) at Fort Halkett Provincial Park.

Close to the Liard River on the west bank of the Smith River is an old Hudson’s Bay trading post, now part of the park. Back on Highway 97 and just 300 metres west of the bridge over Smith River is a gravel road leading 2.5 kilometres north to a viewpoint over Smith

Right next to the highway are the second largest natural hot springs in Canada, formed by warm water that emerges at between 42 and 52°C (108 to 126°F). Known for millennia by the Kaska Dena First Nations, they were noted in the diary of Robert Campbell of the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1835 while looking for a trade route into the region. (The Liard River was later abandoned due to rapids in the upper sections.)

The first access path

and pool were built by the US Army in 1942, and there have been steady upgrades ever since. Today a long boardwalk leads across warm wetland to modern pool buildings with change rooms and toilets. There are two pools, the upper one being warmer than the lower. On cold days, sitting neck deep in hot water while watching snow fall is one of nature’s great treats.

The hot springs have created a unique habitat where temperate plants and animals survive.

Ostrich fern and cow’s parsnip grow tall, giving the area a tropical feel amid the black spruce forest. The warm microclimate and rich nutrients feed many mosses and wildflowers.

At the Hanging Gardens above the main pool, look for lobelias, primroses, fleabanes and monkey flowers that wouldn’t normally be seen this far north. Fourteen different orchids survive here, as do several rare frogs and a warm water snail that is found nowhere else in the world.

River Falls. There, the river plunges 35 metres in two steps through a narrow canyon and is most photogenic. A short trail leads to the foot of the falls. Fishing on Smith River is reported to be good.

Continuing west, Coal River Lodge (Kilometre 823/Mile 514) offers fuel, camping, a playground, an airstrip and bison burgers. You choose. Or if tumbling water is your thing, pull off on the left of the highway near Skooks Landing for Whirlpool Canyon (Kilometre

832/Mile 519), upstream of where the Rabbit River comes in from the south. A mile (1.6 kilometres) beyond that side road, another road leads down to a fine beach exposed at low water levels. To the right are swim pools in an old oxbow that warm up nicely in the summer. From the main beach you can watch the silty Kechika River merging with the clear Liard just upstream.

Less than seven kilometres further, past Fireside (Kilometre 839/Mile 525) are the Cranberry Rapids—an-

other reason why the Hudson’s Bay Company didn’t take to the Liard River. A huge wildfire came through here in 2009, jumping the highway. Finally, at Allen’s Lookout (Kilometre 880/ Mile 551) there’s a large gravel carpark and good views of the river below.

Shortly after Allen’s the highway makes the first of six crossing into and out of the Yukon over 17 kilometres. “Can’t make its mind up,” is how Archie puts it. But BC is over, and so is this story. But what a road, eh?

HIKING TRIPS ON EITHER SIDE OF ROGERS PASS REVEAL THE DIFFERENT FACES OF MOUNT SIR DONALD

STORY & PHOTOS BY LESLIE ANTHONY

From Bald Mountain in the Purcells, Mount Sir Donald stands out as the high point in the Selkirks' wall of rock and ice.

From Bald Mountain in the Purcells, Mount Sir Donald stands out as the high point in the Selkirks' wall of rock and ice.

TO THE Nłeʔkepmxc First Nation, everything in nature is interconnected. So, it makes sense that this is an overlying theme as nation-member Tim Patterson of Zucmin Guiding leads us on a journey of understanding through the forests of Rogers Pass. As the sun bends its way down through the trees, the warming in open spaces is met by zephyrs of cool air that swirl over lingering snow patches. With airborne phenols from spruce, fir and cedar stirred in, the overall effect is one of marching through a giant cosmic air freshener.

As an ACMG hiking leader, master educator with Leave No Trace, field instructor with the Outdoor Council of Canada, a MA in environmental education, and Indigenous interpretive guide specializing in mountain environments, Tim is deeply knowledgeable and has much to share about Indigenous use of various tree species—whether for cleaning, sustenance or other purposes. He quietly passes on his greatest reverence, however, for “the boss tree”—the interior douglas-fir used in culinary, medicinal, cultural and technological applications. Not to overlook that these sentinels are also, as always, the most impressive, neck-craning arbour in the forest. Even smaller versions, as here, growing at the erstwhile foot of one of western Canada’s most iconic glaciers—an ice flow once impressive enough to be called The Great Glacier, a template for geological, human and, eventually, climate stories.

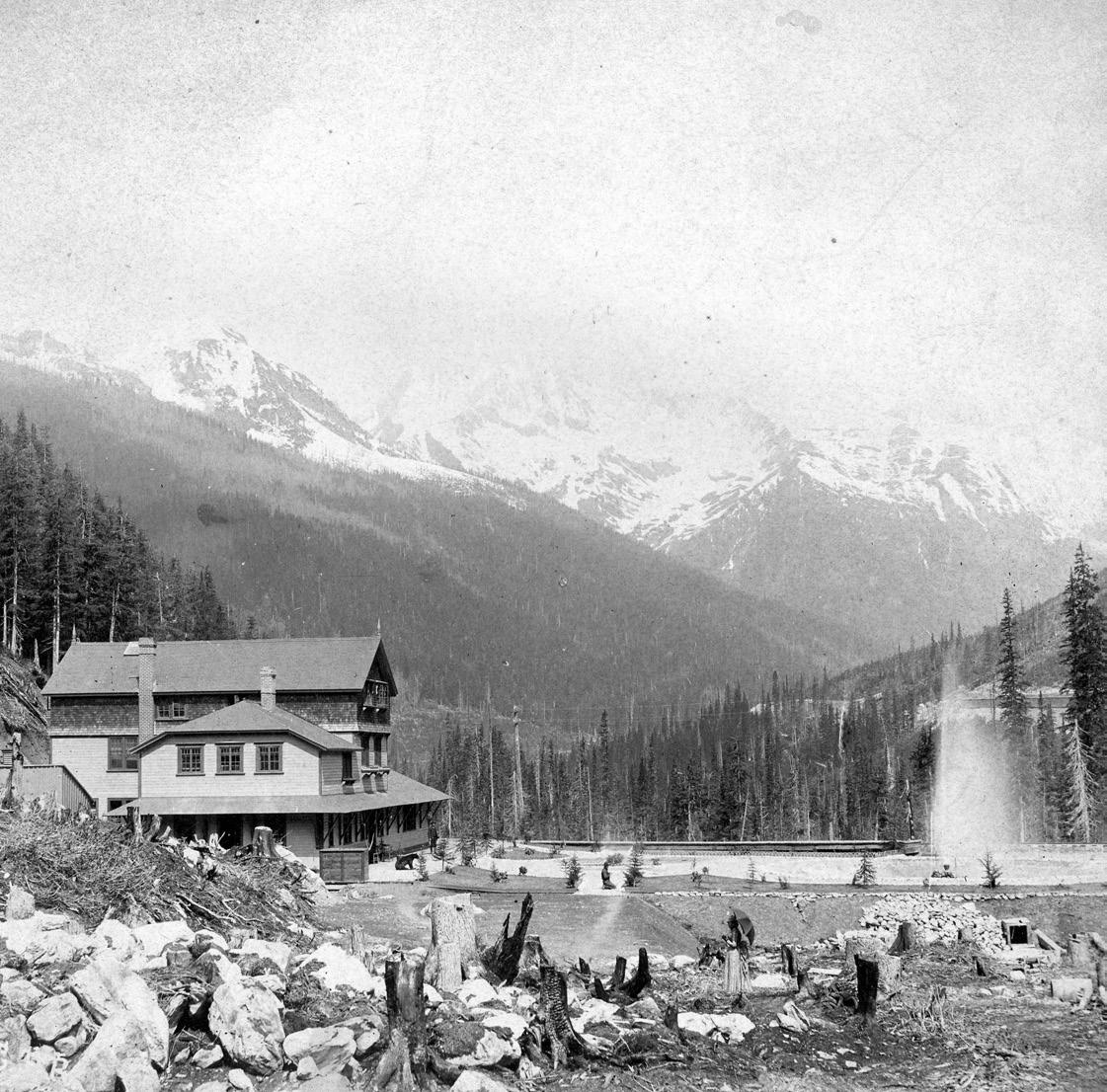

Although several local First Nations tapped the area we’re forging into for resources, they never actually occupied it, sticking to the valleys on either side of the pass given, as Tim explains, the difficulty of its steep terrain, dense vegetation, prodigious snows, thundering avalanches and tricky glaciers descending almost to the river valleys. A more recent, European history of the area kicks off with Major A.B. Rogers, a surveyor employed by the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) who discovered this much-sought singular way through the Selkirk Mountains. When the transcontinental railway was completed in 1885, Rogers Pass became one

of western Canada’s first tourist destinations. Glacier National Park was opened in 1886, and Glacier House, a small hotel, sprang up on the rail line near the glacier’s terminus, expanding in both 1892 and 1904. Swiss guides were brought in to lead hotel guests to the ice, which, by 1907, was the “most visited glacier in the Americas.”

Initially labelled The Great Glacier by Barnum & Bailey-inspired CPR promoters, the Interior Salish word Illecilliwaet (“big water”) was already in use to describe the glacier’s meltwater river, and gradually replaced the former appellation for the ice itself before being officially adopted by Parks Canada in the 1960s. The influx of visitors over the years has included both mountaineers and glaciologists, and thus, though they are sparse by European standards, studies made of the Illecilliwaet Glacier are among the most detailed available for North America. This proved fortuitous given a rapid retreat of the ice that began almost as soon as tourists arrived, pulling it back several kilometres over the course of a century. With the hotel’s raison d’être in slowmotion jeopardy, the CPR’s decision in 1911 to re-route its rail line to make it less vulnerable to avalanches (over 250 people died during construction and the years following) put a final nail in the attraction’s coffin. Glacier House officially closed in 1925, after which it was decon-

structed down to the foundations.

Beginning the hike, we’d walked the abandoned rail bed past the hotel’s historic remains, turning onto a path that guests would stroll after dinner to get a look at the ice. From that same gravel-bar lookout, we now ascend beside the Illecilliwaet River, the forest constellated with house-sized glacial erratics and stranded mounds of rock and till—a Pleistocene

souvenir of the glacier’s profound effect on the land. Above us, from every angle it seems, lords 3,284-metre Mount Sir Donald, the sharp, Matterhorn-like peak whose imposing presence in many ways defines Rogers Pass.

The mountain was originally named Syndicate Peak in honour of the group that had arranged financing for the completion of the CPR. Fortunately,

sober second thought saw it renamed for Donald Smith, 1st Baron Strathcona and Mount Royal, who led the effort. The peak’s good rock quality and classic shape had already made it popular among alpinists. Since the first ascent in 1890 by Swiss guides Emil Huber and Carl Sulzer, and their porter Harry Cooper, three or four parties a year were tackling Sir Donald by the time Glacier

House packed it in. Today, the route up the Northwest Arete is included in the popular book Fifty Classic Climbs of North America.

Eventually leaving the river and forest behind, we labour up a steep, alderchoked slope where the substrate turns to fine dust mixed with gravel—the remains of a towering lateral moraine. If nothing else, the retreating ice has rendered this

hike an excellent Glaciology 101. Rockhopping a small stream flowing off the remaining ice—still high above us and out of sight—we step across glacier-polished rock whose iron content sees it rusting in the air, and lunch where the glacier once sat as recently as my teenage years. In fact, I’d first glimpsed the Illecilliwaet from the window of a van headed west to Whistler from Toronto, and though my memory of an alabaster cascade is all that remains of the ice at this location, I

log a night at the infamously decrepit mega-A-frame known as Glacier Park Lodge for ski-touring. Seeing the waypoints of the pass on the ground like this is a whole new ball game, and hiking them to learn how the area’s Indigenous, European, geological and climate histories weave together vastly enriches my perspective.

The ice might be gone, but fascination with the pass doesn’t change. Later, as our group settles into chairs with cocktail in

ting. And it worked. Even as the ghost hotel and the increasingly ghostly glacier it shilled for pass into the mists of time, interest in the hiking and climbing they inculcated has only increased. You can still access “luxury” lodges in the mountains of western Canada to have similar experiences, but nowadays you can’t just step off a train; instead, depending on the setting, you drive or fly to them.