VICTORIA’S CASTLES

TASTE OF SPRING FIVE FORAGING FAVOURITES SPOTTING GIANTS WHALE WATCHING 101 BCMAG.CA DESTINATION GREENWOOD SPRING/2024 THE NISGA'A POLE RETURNS HOME

A TOUR BACK TO BC'S AFFLUENT PAST

A

TAKE

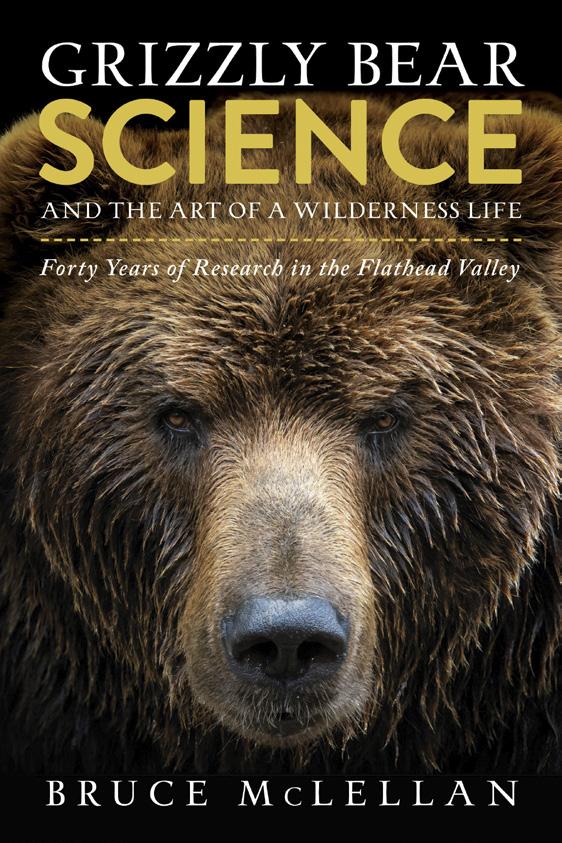

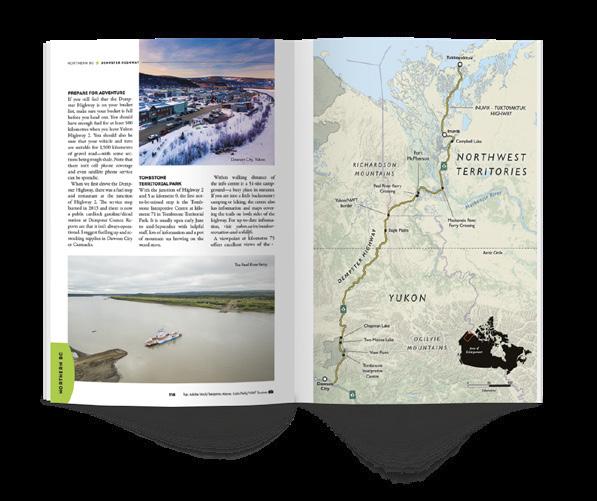

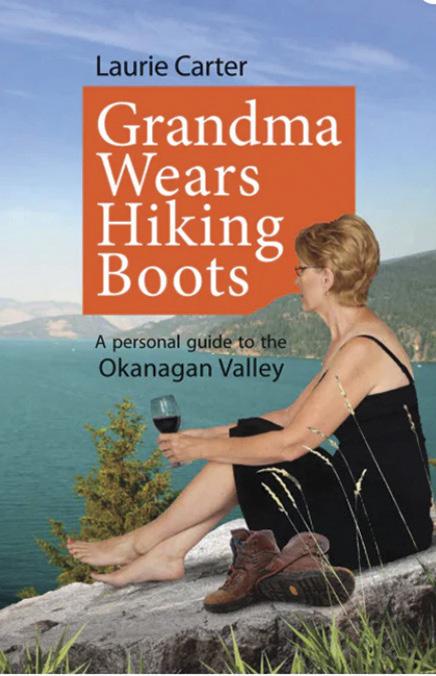

Outdoors LOCAL AUTHORS • LOCAL TOPICS Family Adventures Nature Hotspots Whimsical Fishing Because you Love British Columbia Magazine, you may also enjoy these titles: W Harvest BC A FORAGER’S GUIDE TO EDIBLE PLANTS OF BRITISH COLUMBIA 71 71 W ild Harvest BC BY LINDA GABRIS $24.95 ISBN: 978-1-7778764-2-5 www.opmediagroup.ca Linda Gabris has been venturing into the outdoors to harvest wild edibles for over 60 years. The lessons taught to her by her grandparents, of responsibility, sustainability and a connection to the land are as important today as they were then. This book shares those lessons as well as tips and practical advice in personal, easy-to-read style. Combined with scientific field guide, Wild Harvest BC is the perfect companion book to take with you on your outdoor adventures. Over 70 recipes ranging from Wild Cream of Asparagus Soup to Hazel’s Hazelnut Brittle will help you turn your foraging finds into delicious, hearty meals. So get out there and enjoy the bounty of Mother Nature. Wild Harvest BC thebookshack.ca Visit Our Bookstore For More Great Reading! 1-800-663-7611 NEW

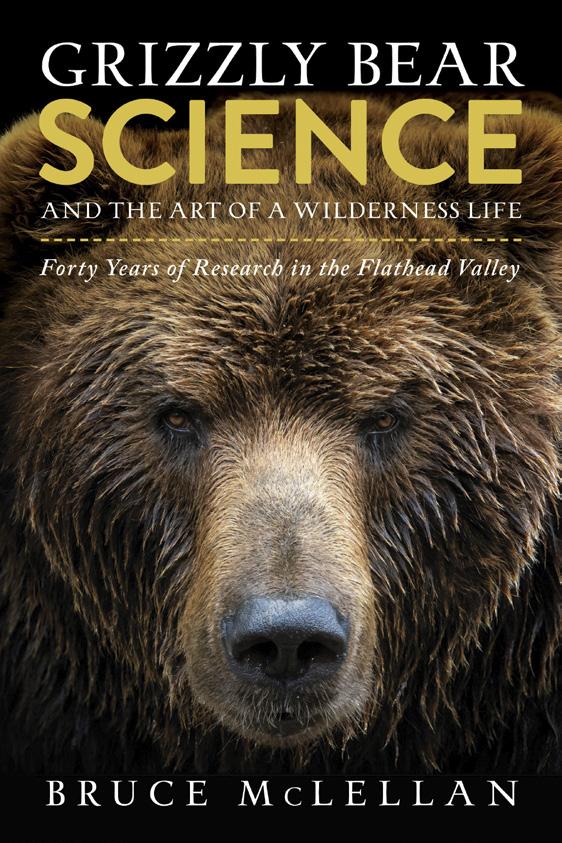

BC MAG • 3 Contents 24 Gulf Island Goodies Jump on the Gulf Islands ferry and treat yourself with this unique dine-around adventure, featuring six delights that you won’t find in the city 30 Spotting Giants A guide to whale watching in BC 42 The Long Journey Home After being stolen and sent to a Scottish museum in 1929, the Ni’isjoohl Memorial Pole makes its long way home to the Nass Valley 50 Ready for Ts’zil Two Indigenous BC teens ski a mountain that defines their people 58 BC’s Top Five Forageable Foods of Spring A beginner’s guide to foraging 66 Hummingbirds at Risk The flying jewels of British Columbia are on the decline, but there are things you can do to help 4 Editor’s Note 6 Mailbox 8 Due West 16 Destination Greenwood 74 Person and Place Bruce McLellan 82 Tales of BC A Dogfish Bonanza IN EVERY ISSUE Cover Photo Anna70/Wirestock Creators/Adobe Stock VOLUME 66 - ISSUE 01 SPRING 30 Hatley Castle FEATURES 16 10 24 50 42 14

EDITOR’S NOTE

THIS PAST MONTH we’ve received letters from residents in a remote valley expressing concern over visitors to their area not respecting private property. Specifically, some residents experienced visitors entering their yards, wandering through their homes and taking pictures. This is of particular concern to the owners of properties devastated by wildfire, who are worried that they will see more of the same on their properties this upcoming summer.

I think everyone can agree that nobody has the right to enter someone’s home or property without permission, especially if it’s clearly livedin or recently used. I’m honestly shocked to hear that someone would have the gall to enter a person’s yard or home in the middle of a community and start taking pictures.

even so, should you do it?

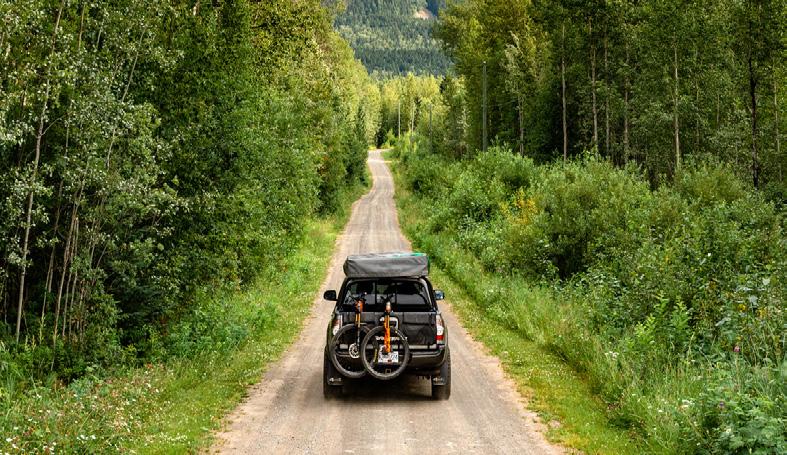

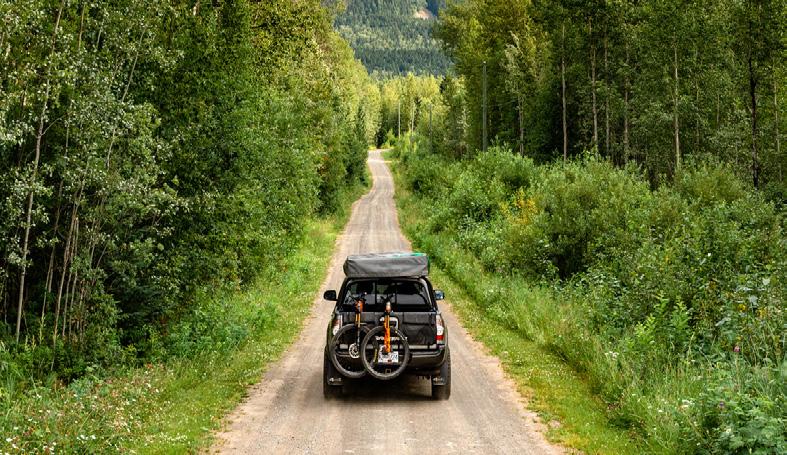

One of the many charms of travelling the backroads of BC is checking out abandoned sites. Whether they are marked on a map, or just something you stumbled across, these sites can be the highlight of any road trip. But like with everything in the great outdoors, there is an unwritten rule to take only pictures, and leave only footprints. That is, go ahead and look but leave it exactly how you found it.

This rule has generally worked for generations. Certainly, the more accessible sites will get vandalized and wrecked by partiers, but the really remote stuff is most often treated with respect and common sense.

But what about a remote cabin that is falling down and clearly abandoned. Or the ruined foundations of a building and an overgrown mine site in the middle of a forest. What if there are no fences or signs? Is this private property, and if you visit these sites, is that considered trespassing? This is where things get a little more complicated.

I’m not going to pretend to know all of the laws here, and please send us a letter to correct what I write next, but the BC Trespass Act defines a trespasser as “A person found inside enclosed land without the consent of its owner, lessee or occupier.” Enclosed land being defined as surrounded by a natural boundary or lawful fence, or having posted signs prohibiting trespass. So, by this legal definition, checking out an old building along a trail or public road is not, in fact, considered prosecutable trespassing. But

Recently though, with the huge uptick in people exploring the more remote parts of BC since Covid and with the advent of social media, it’s easy to see how this “unwritten rule” is no longer being followed in bold and disturbing ways, and how these once secret and remote sites are now being overrun with tourists.

So what can we do about it? I honestly don’t know. Unfortunately, along with the masses also come the people who lack common sense and respect for other people’s stuff, and there’s not much we can do about that except lead by example and call out bad behavior when we see it.

But I am curious to hear what our readers have to say on the subject. This is clearly an issue for residents in remote communities and is only going to get more serious. And if things don’t improve, then our opportunities to explore remote areas is only going to become more restricted. And nobody wants that.

—Dale Miller

4 • BC MAG The Concept of Private Property SPRING EDITOR Dale Miller editor@bcmag.ca ART DIRECTOR Arran Yates ASSOCIATE EDITOR Sam Burkhart COPY EDITOR Margaux Perrin GENERAL ADVERTISING INQUIRIES 604-428-0259 ACCOUNT MANAGER Tyrone Stelzenmuller 604-620-0031 ACCOUNT MANAGER (VAN. ISLE) Kathy Moore 250-748-6416 ACCOUNT MANAGER Meena Mann 604-559-9052 ACCOUNT MANAGER Katherine Kjaer 250-592-5331 PUBLISHER / PRESIDENT Mark Yelic MARKETING MANAGER Desiree Miller GROUP CONTROLLER Anthea Williams ACCOUNTING Angie Danis, Elizabeth Williams DIRECTOR - CONSUMER MARKETING Craig Sweetman CIRCULATION & CUSTOMER SERVICE Roxanne Davies, Lauren Novak, Marissa Miller DIGITAL CONTENT COORDINATOR Mark Lapiy SUBSCRIPTION HOTLINE 1-800-663-7611 SUBSCRIBER ENQUIRIES: cs@bcmag.ca SUBSCRIPTION RATES FREE with your subscription: the British Columbia Magazine wall calendar. 13 months of glorious landscape and wildlife photography. 1 year (four issues): $19.95 / 2 years: $34.95 / 3 years: $46.95 Add $6 for Canadian, $10 for U.S., or $12 for International subscriptions per year for P&H. Newsstand single-issue cover price: $8.95 plus tax. Send Name & Address Along With Payment To: British Columbia Magazine, 802-1166 Alberni St. Vancouver, BC, V6E 3Z3 Canada British Columbia Magazine is published four times per year: Spring (March), Summer (June), Fall (September), Winter (December) Contents copyright 2024 by British Columbia Magazine. All rights reserved. Reproduction of any article, photograph or artwork without written permission is strictly forbidden. The publisher can assume no responsibility for unsolicited material. ISSN 1709-4623 802-1166 Alberni Street Vancouver, BC, Canada V6E 3Z3 PRINTED IN CANADA Canadian Publications Mail Product Sales Agreement No. 40069119. Return undeliverable Canadian addresses to Circulation Dept., 7261 River Pl. #201A, Mission, BC V4S 0A2 Tel: (604) 428-0259 Fax: (604) 620-0245 WWW.BCMAG.CA

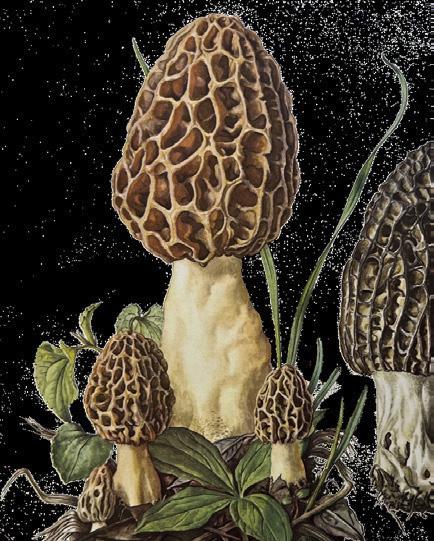

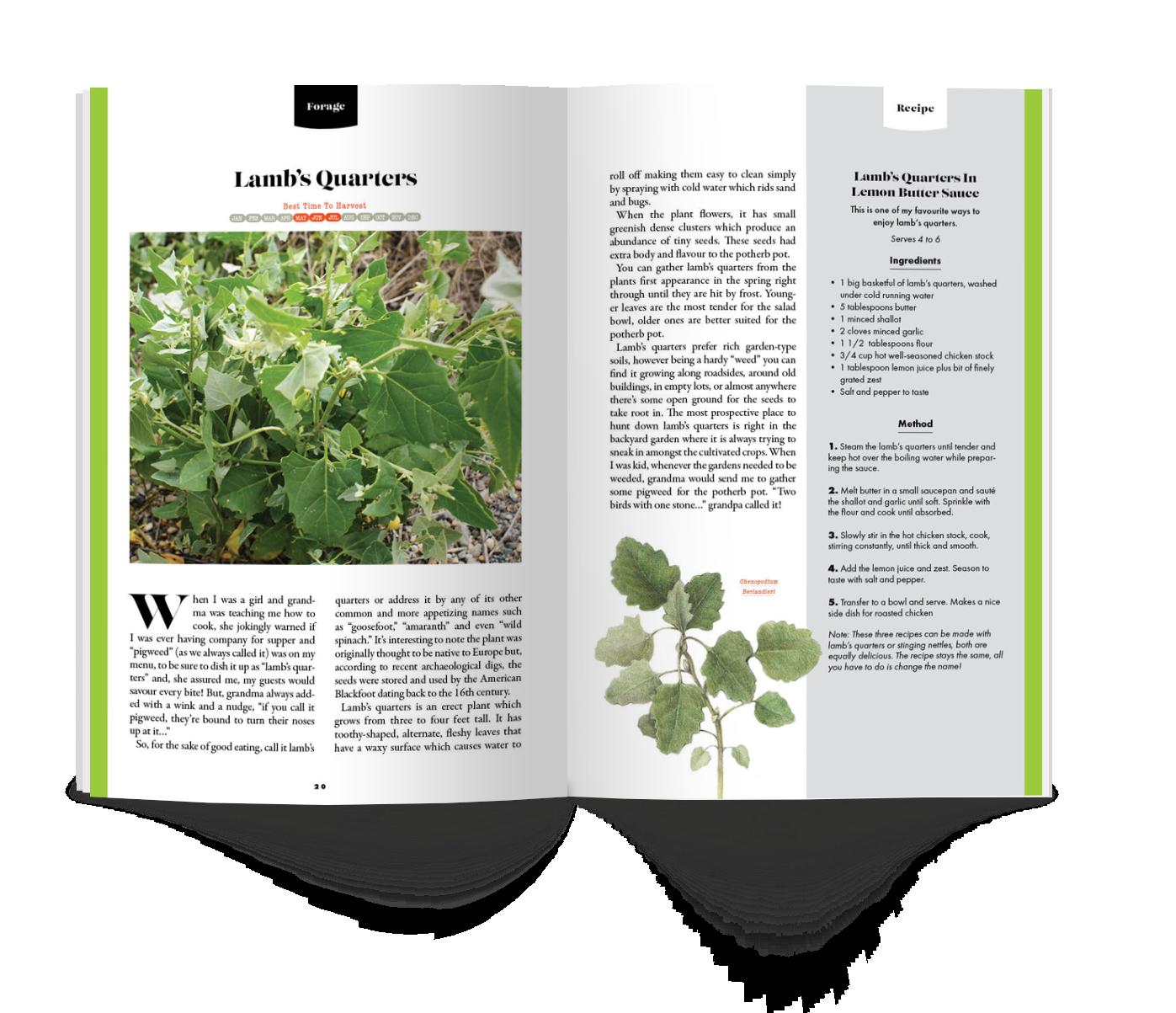

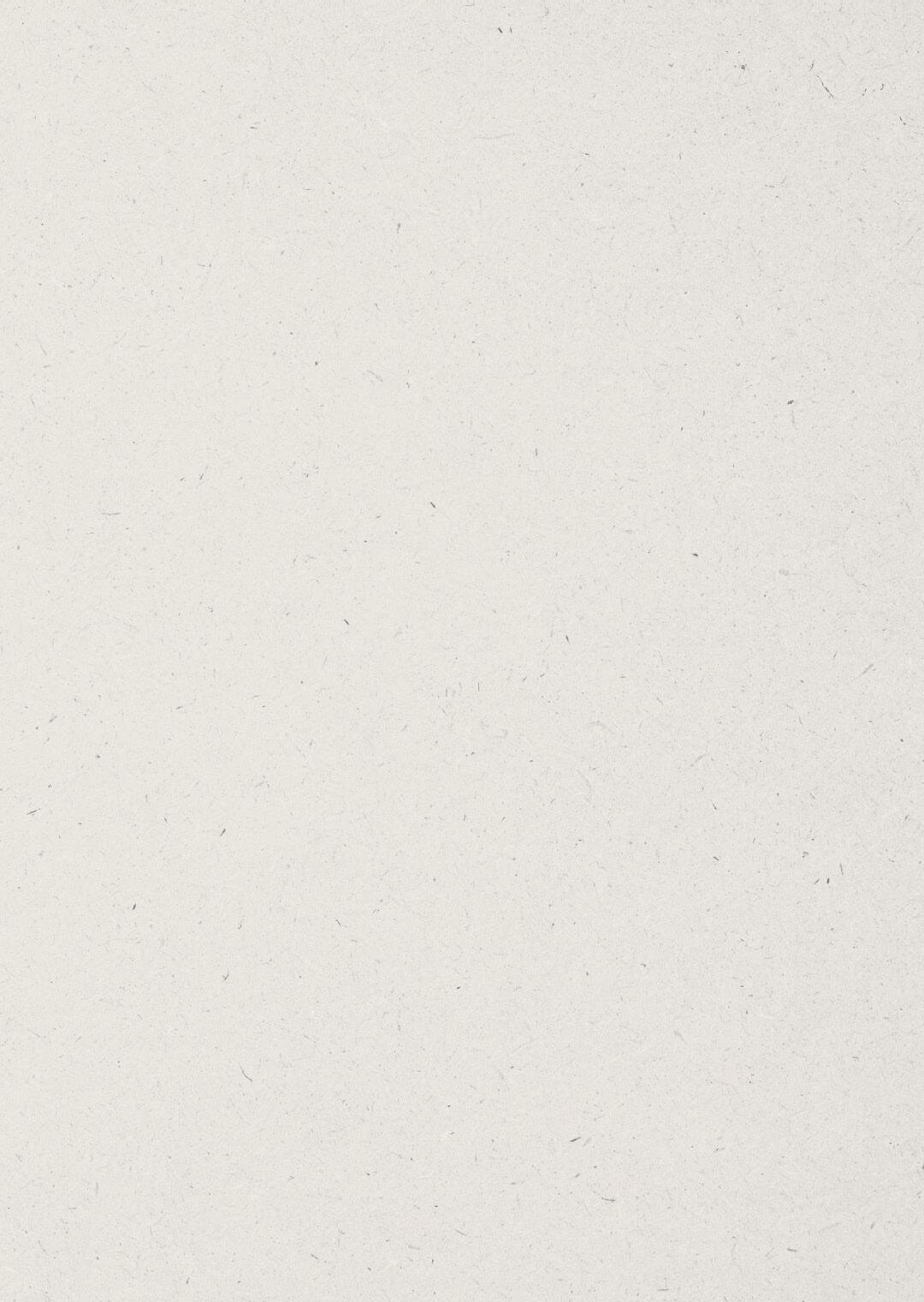

WILD HARVEST

A forager’s guide to edible plants of British Columbia

By Linda Gabris

Linda Gabris has been venturing into the outdoors to harvest wild edibles for over 60 years. The lessons taught to her by her grandparents, of responsibility, sustainability and a connection to the land are as important today as they were then. This book shares those lessons as well as tips and practical advice in a personal, easy-to-read style. Combined with a scientific field guide, Wild Harvest BC is the perfect companion book to take with you on your outdoor adventures. Get

BC A FORAGER’S GUIDE TO EDIBLE PLANTS OF BRITISH COLUMBIA 71 71 71 W ild Harvest BC BY LINDA GABRIS $24.95 ISBN: 978-1-7778764-2-5 www.opmediagroup.ca has been venturing into the outdoors to edibles for over 60 years. The lessons taught grandparents, of responsibility, sustainabiliconnection to the land are as important today as then. This book shares those lessons as well as practical advice in a personal, easy-to-read style. with a scientific field guide, Wild Harvest BC companion book to take with you on your adventures. Over 70 recipes ranging from Wild Asparagus Soup to Hazel’s Hazelnut Brittle turn your foraging finds into delicious, So get out there and enjoy the bounty of Nature.

BC INCLUDES OVER 70 RECIPES

W Harvest

Wild Harvest

$24 95 SHOP NOW NEW RELEASE

your copy from our online bookstore: thebookshack.ca Call1.800.663.7611

Mailbox

MAP MISTAKE

I have been enjoying reading your latest issue of British Columbia Magazine and the article on Nelson was very informative. However, I felt it my duty, in the interest of accuracy, to point out that your map on page 27 has Nelson marked in two places.

I suspect the inhabitants of Golden have already pointed this out to you. Imagine being wiped off the map.

I love your magazine. Keep up the good work.

W. J. Ross, Nanaimo

ARSON LOCATION CORRECTION

While reading the article “Doukhorbors In The Kootenays,” I noticed an error or misprint on page 77. It stated that Mary Braun was charged in 2001 with setting fire to Selkirk College in Castlegar, BC. In fact, she set fire to the Learning Centre of Selkirk College which was located in a portable that is the property of the Crescent Valley Community Hall Society in Crescent Valley, BC.

After Mary Braun set the fire, she knocked on my dad’s door to tell him that she had set the fire. Richard Carl Catton lived at the time next door to the Crescent Valley Community Hall.

Elizabeth Ellis

POWDER HIGHWAY MAP

Always enjoy my time with the magazine and I LOVE the Kooteneys! Thanks for highlighting this part of our beautiful province… especially in the winter.

I believe there is an error in your Powder Highway article, the map of the loop specifically. You have only seven resorts captured and Nelson’s is of course Whitewater with Kicking Horse outside of Golden, which actually isn’t on the this map.

I am sure you will have several folks

who will spot & alert you to the omission/error.

Cheers for a wonderful “snow fun filled holiday season.” Keep the great outdoors just that for us all to explore and enjoy in 2024.

Sue Kennedy

LACK OF RESPECT FROM VISITORS

We appreciate travel media writing about our area very much, particularly now that we are contending with recovering from the Downton Lake wildfire.

That said, the piece on the “Backroads of the Bridge River Valley” on your website has many of the same challenges for our community that many similar blogs/ articles by travel media do.

To give some sense of what we mean:

Description of the historic nature of the town, some of the aspects of that history and then this statement accompanied by a photo of Bradian.

Quote: “Of particular interest for us was the ghost town of Bradian (which lies close to Bralorne and is currently for sale) and the old Pioneer Mine. We spent a couple hours exploring these sites and the surrounding areas.”

Because these travel writers tend to have rose coloured glasses on and want to write an interesting story, they do not think twice about the fact that when

they are exploring the old mine site or the Bradian property, they are actually on private property, it is not a matter of looking for No Trespassing signs, it is about understanding property in our area belongs to someone, it is not all public land.

I do not go to Vancouver and walk all over a property without permission of the owner that may have buildings in disrepair because I know they are private property.

The challenge we have with this sort of thing is that, for example, private property owners of houses in Bralorne actually find people in their yards, wandering around houses and taking pictures! There just seems to be some kind of illinformed attitude because they appear to be in wilderness they can do stuff they would never think of doing in a city or town. We have a similar issue on Gun Lake, where people in boats putt around at slow speed and gawk at our property and us. This year that activity is going to be painful for the 56 properties that lost their structures in the Downton Lake Wildfire, who have had their burnt trees removed and now own a moonscape exposed to dust, their neighbours, noise and disrespectful lookie loos.

What this sort of behavior leads to is a real “anti tourism” feeling with residents

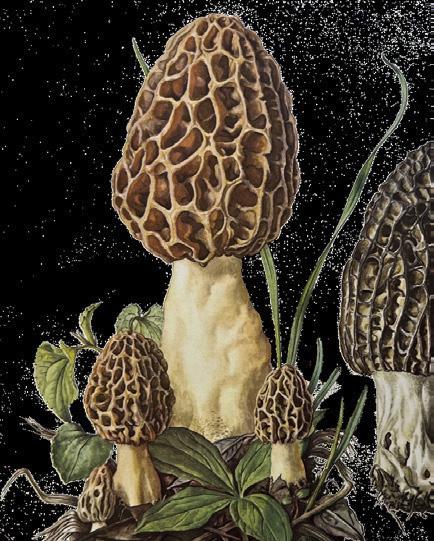

6 • BC MAG 6 MAILBOX SPRING

The abandoned townsite of Bradian is now for sale.

and that also hurts our community by creating division and impacting other sectors so important to our area economically such as mountain biking and tourism.

We simply must get through to the travel media sector they need to actually demonstrate themselves appropriate respectful behavior in areas that are very different for example than large and small markets and also translate that into their writing.

From our side of it, we continue to communicate with visitors and I thought when I read this, I think we need to res urrect our Respect for the BRV program from the Covid period, and use various ways and means to get through to visitors how to properly visit our community.

We love this attention by writer/maga zines but we just need to get through

that that travel articles without the proper demonstration of respectful behaviors cause much distress and impact in terms of the individual community members attitudes to tourism and to be fair, the impact on community members themselves of the disrespectful behavior.

Debbie Demare

Thanks for the note Debbie, we absolutely agree on the need to respect private property when exploring BC. The article you mentioned has a note saying that if you choose to explore abandoned sites, to respect all

body of water, though there is a difference between peacefully enjoying it and gawking at people on the shore. Unfortunately there are always going to be some who lack common sense. —Eds

Send

BC MAG • 7

British Columbia Magazine

EMAIL US

email to mailbox@bcmag.ca or write to

, 1166

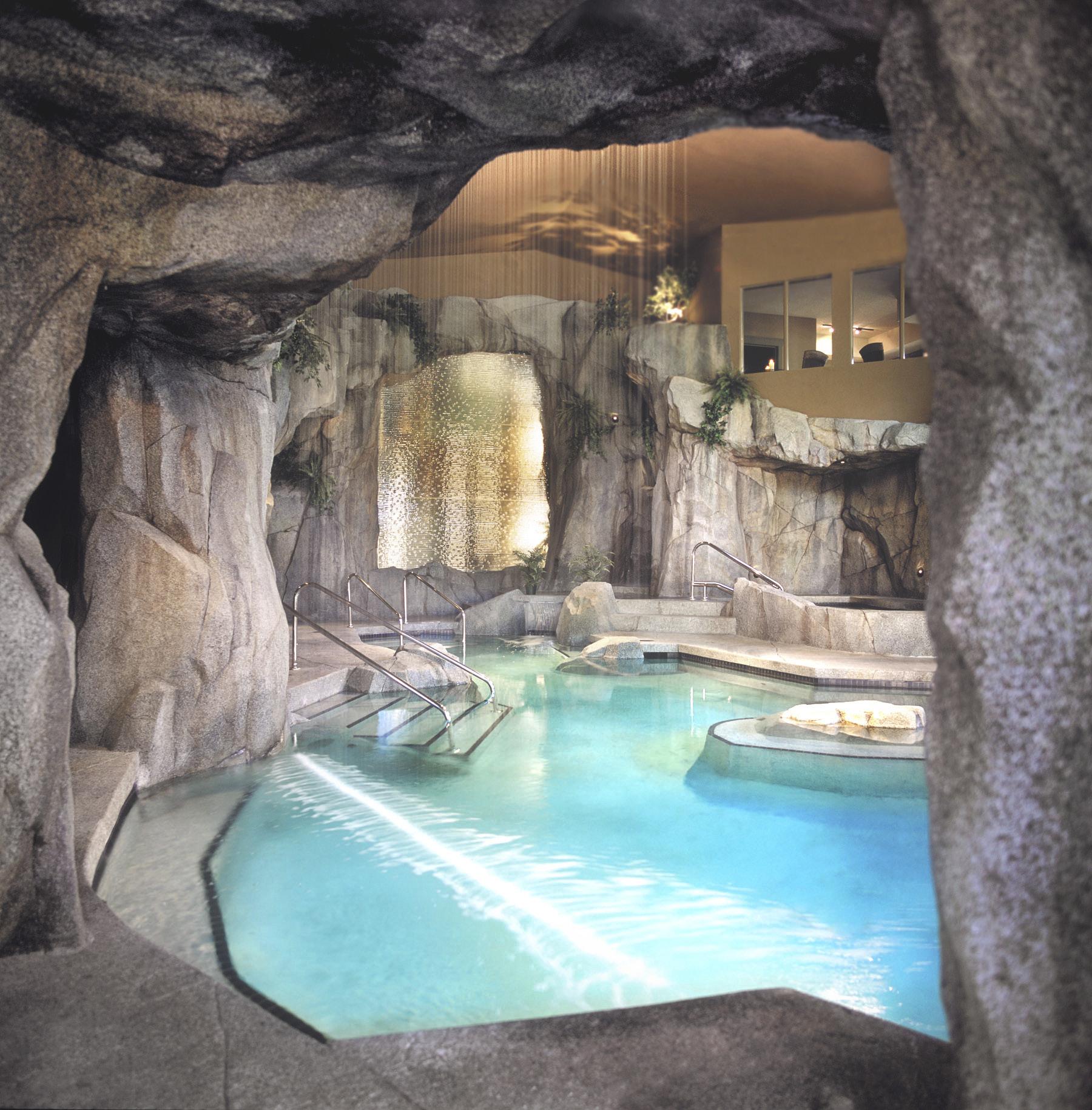

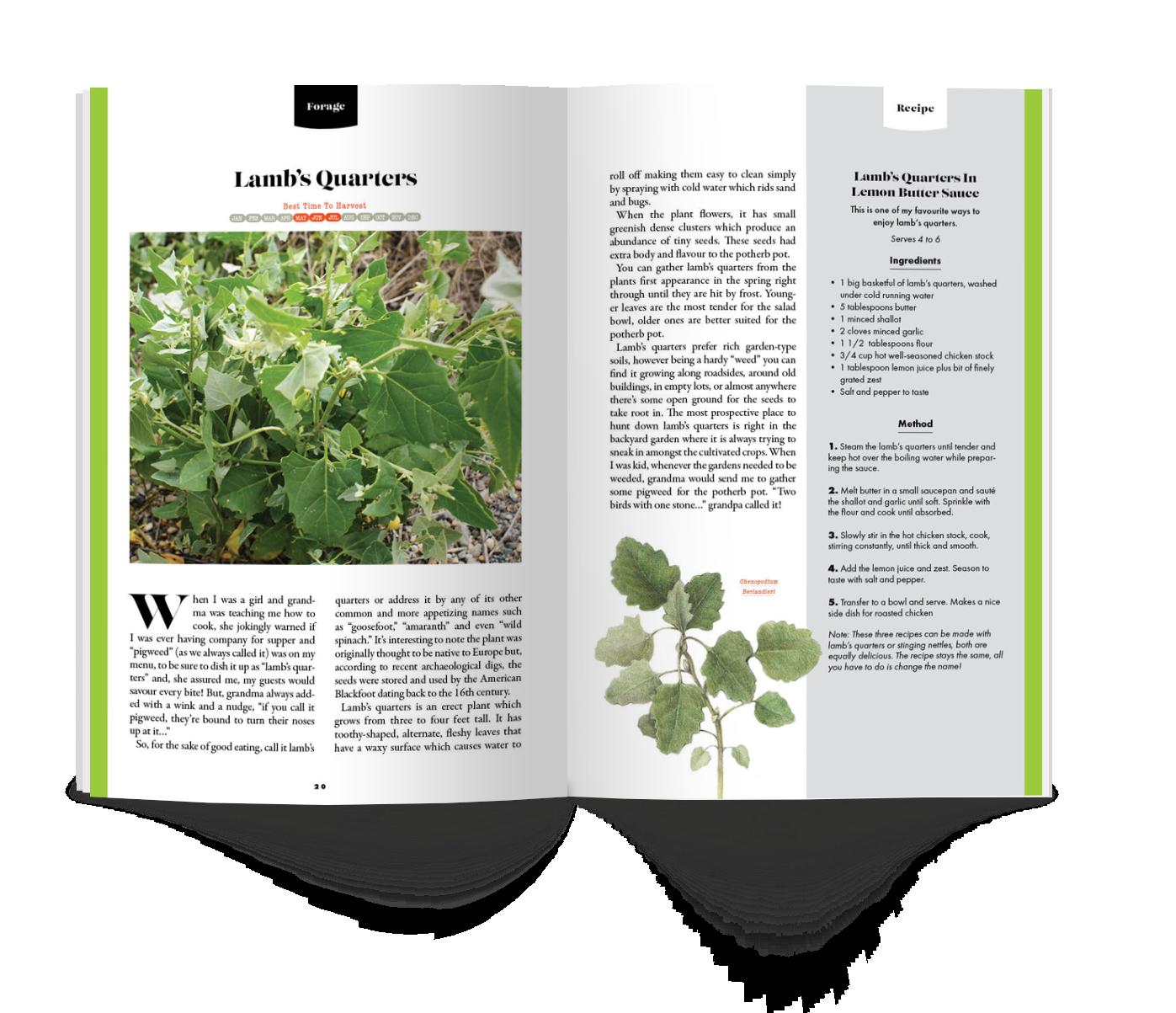

250-248-1838 | Grottospa.com | Embark on a 2-hour journey through the new cedar barrel sauna patio, the warm inviting mineral pool, invigorating waterfalls, and soothing whirlpool. Enhance your visit with spa treatment(s) and our one-of-a-kind tapas dining. Reach out today to book your Grotto experience.

Due West

SPORTS

SPORTS

Spring Skiing

BY LESLIE ANTHONY

ALTHOUGH MANY skiers and snowboarders see winter powder days as a ne plus ultra, most rank spring conditions second—some even elevating it to top choice. That’s because something magical happens to the snowpack this time of year—the phenomenon of “corn snow.” This glorious, ego-boosting surface of sifting beads is formed by snow

crystals that melt during warm, sunny days then re-freeze during cold, clear nights. When this vernal weather loop sets in many are hooked for life. But just so you don’t completely lose the powder plot, March in Interior BC still sees plenty of storms and late-season pow days.

I’ve been a spring-ski aficionado since my teen years

in Ontario, where the moment local lifts shuttered we headed for the larger closed ski areas of Quebec and New England to climb and ski moguls—which were generally abundant, large and delightfully soft. One of my main reasons for moving to Whistler was being able to ski somewhere that reliably stayed open until late May, shut down for a couple weeks,

8 • BC MAG

DUE WEST

Tourism Thompson Okanagan

then re-opened for summer glacier skiing (back when the glacier was still there…).

I’ve also spent a lot of time spring skiing abroad. While most in North America are done with sliding by April, the circumpolar season is just beginning, and international airports bustle with folks dragging ski bags northward for ski touring, boat-based skimountaineering and heli-skiing in Baffin Island, Greenland, Iceland, Sweden and Norway, lured by something captured in the delightful Swedish term vårvinter (or “spring-winter,” pronounced vōar-vinter). Emblematic of the far north, this long, slow dissolve from one season to another is also loosely seen in the alpine areas of most BC mountain ranges—a definitive transition time that sees no prolonged typical winter weather, yet no prolonged spring weather either, making for a happy set of alternating conditions. Sweden’s national weather service even celebrates vårvinter as a de facto fifth season. You can experience your own version by getting into the high-alpine or backcountry with friends or even by heli-skiing at one of BC’s two-dozen operations, where prices often come down for spring sessions.

But back to BC’s resorts

Did we mention impeccable grooming? Spring skiing is possible—indeed made more fun—by resorts’ teams of expert snowmakers and cuttingedge technology. Speaking of which, should you be so disposed spring is also prime time in the terrain park. With dialed features and forgiving landings, laps in the park are de rigeur

Because soft snow tends to harden-up overnight and require morning sun or warmer temps to soften, you should always consider when and where sun hits different aspects of the mountains and follow it like a puppy. Depending on the location, elevation and size of the resort, spring skiing in BC

lasts into mid-April and even late-May at Whistler Blackcomb (this year, in a reversal of the usual, Whistler Mountain will stay open until season end as work commences on a new chairlift on Blackcomb). Of course, good skiing extends into June on the summits and backcountry glaciers around Whistler, though climate change has made that window much smaller.

People often forget about the deeply discounted accommodation at ski resorts in spring popping up through the snow like crocuses, but they shouldn’t, for these are the ways and means to enjoy a surprising range of activities. After all, the snow still stands at winter depths so dog-sledding, snowshoeing and cross-country skiing have yet to be shoved away in a closet with Arctic-rated down puffies. For cross-country skiers and snowshoers spring is the perfect time to take advantage of trails, track-set or otherwise. Late-season also offers the opportunity for snow-free springtime valley activities like mountain biking or golf.

When it comes to après, the Austrian Alps might have a stranglehold on the global prize for oompah madness, but BC resorts have an abundance of patio real estate given over to the pursuit of more civilized gemütlichkeit. More importantly are the growing raft of springtime events in ski country (see sidebar: Spring Flings), a mix of music, art, family fun and long-running local favourites like slush-cups and pond-skims featuring costumes, t-shirts and even bathing suits to help chase away winter’s blue-toe blues.

With the closing bell at many resorts extending to 4:00 p.m. in spring, you can make the most of that warm, afternoon alpenglow no matter how you’ve spent the day, kicking back with a cold one and surveying the mountain realm you’ve just enjoyed. The kind of sunset activity that makes for alpine memories.

SPRING FLINGS

Whistler — The benchmark World Ski & Snowboard Festival (April 8 to 14) includes onsnow competition like the Saudan Couloir Race Extreme, the steepest ski and snowboard race in the world, and a costumed Slush Cup. Music, art, nightlife and some of the best skiing and après in the province combine with signature photo/film events like Intersection, 72-hour Filmmaker’s Showdown, and Sea to Sky Photo Challenge to make the WSSF a must-do.

Sun Peaks — The new Sip, Savour & Ski Sun Peaks Culinary Festival (March 28 to 31), features a full slate of events with dishes crafted with locally sourced ingredients paired with artisanal brews, cocktails and wines. It joins the Hub International Nancy Greene Festival (March 23, 24), “What the Huck” Knuckle Huck and Rail Jam (March 22), Easter Eggsgtravaganza (March 31), and season-closing Wonder Weekend (April 6, 7).

Revelstoke — Watch great deeds of alpine derring-do during the King & Queen of the Mountain competition (March 31) then say sayonara to winter at the Revy Beer Festival (April 5, 6).

Kicking Horse — The Whitetooth Grill Live Concert Series runs throughout March and April, and other events include the Marc Andre Memorial Banked Slalom (March 30, 31), the mountain’s first snowboardonly event, and 2024 Sunsplash Funkfest Dummy Downhill & Slush Cup (April 13, 14).

Silver Star — Seismic Fest (March 29 to April 7)

is a 10-day celebration of mountain culture with live music, art, craft, culinary and family-friendly activities, plus skiing and boarding events.

Big White — AltiTunes Music Festival (April 5, 6) is Canada’s biggest après ski music festival, a weekend that features live music, skiing, snowboarding and an array of outdoor activity.

RED Mountain — Kickoff spring at the Canadian National Alpine Championships (March 15 to 21) then roll right into the third annual Wiener Takes All dog race (April 1), Slush Cup (April 6) and Retro Day Deck Party (April 7), fuelled by live bands, cold beer and local mountain legends.

Fernie — The annual Fernival (April 13, 14), commemorates the resort’s final weekend of skiing and riding with blow-out live rock concerts, wacky contests, and silly costumes.

Whitewater — Check out the Blast Beerfest (March 23, 24), Passholder Appreciation Day (April 6) and Beach Party Sunday (April 7).

Panorama — Swing into spring with Panorama’s first-time Pride & Ski Fesitval (March 22 to 24) and events like the 2024 NORAM Cup (April 1 to 11). Then send off the season with a splash at the Red Bull Slopesoakers rail jam and pond skim (April 13) and Superhero Pond Skim (April 14).

Mt. Washington

— Schuss or cross-country in the morning and golf in the afternoon. Otherwise, end the season with a Dummy Downhill (April 6) and Slush Cup (April 7).

BC MAG • 9

DUE WEST

CULTURE

Victoria’s Castles

BY JANE MUNDY

THINK ABOUT CASTLES

and maybe fairy tales come to mind. Or perhaps you dream of exploring an ancient Scottish fortress or an opulent Bavarian palace. But you don’t have to travel far to visit castles: Victoria is home to three grand buildings, rich with history and architecture, thanks to a19th century mania for castle-building that captured Canada’s affluent elite. They are all open to the public and are a fascinating glimpse into Canadian history, particularly with a guided tour.

Craigdarroch Castle

Built as a comfy, albeit extravagant home for the Dunsmuir family, Craigdarroch towers over Rockland, a residential neighbourhood in Victoria. Just a 30-minute walk (some of it uphill) from Victoria’s Inner Harbour will transport you back in time to the late 1800s, when coal baron Robert Dunsmuir built this massive estate.

Most of the estate was sold in 1908 but some furnishings and knick-knacks (many bought back via auction records) and windows are original, as is the exterior. Before starting the guided tour, we were instructed to scrape our shoes on the carpet next to the antique shoe cleaner and warned not to touch anything, including original oak walls and staircase.

There’s a button under the

dining room carpet to press with your foot to call servants, or yell orders from one of 12 speaking tubes throughout the house—a step up from Downton Abbey’s bells. Other labour-saving devices include a laundry chute and dumbwaiter (note to self, is that PC?) More obvious signs of wealth are mounted elk, goat and deer heads throughout the castle, and PETA would not approve of the taxidermy squirrel perched above a bed. Creepy. And the massive English billiards table on the fourth floor must have cost a pretty penny. Here too is the dance hall: perhaps because guests had to walk through the house to get way up here, Joan Dunsmuir had an opportunity to show off all their stuff.

During the Victorian era it was believed that home interiors could “exert moral influences on the inhabitants,” and Joan was likely a believer: the library speaks volumes, and the fireplace in the entry hall has a quote carved into it: “Reading maketh a full man.”

10 • BC MAG

Location Craigdarroch Castle, 1050 Joan Crescent (named after Joan Dunsmuir). thecastle.ca

Courtesy Craigdarroch Castle X3; Right: Tourism Vancouver Island

Well, maybe not the smoking room, featuring Sir Walter Raleigh in stained glass. Each room is staged with Victorian accessories and a few mannequins—it’s like Scottish Baronial style meets Gothic Revival architecture—think Harry Potter.

The castle was later converted into a military hospital, college and music conservatory before being restored to what it is today—a National Historic Site of Canada. What isn’t on display is how the Dunsmuir fortune was built on deadly mine conditions and racist fearmongering. It was the miners who called Robert the “robber baron.”

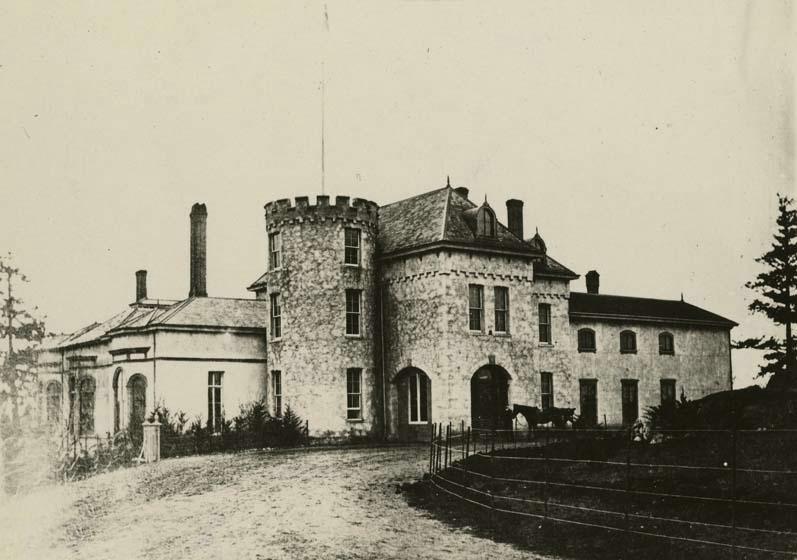

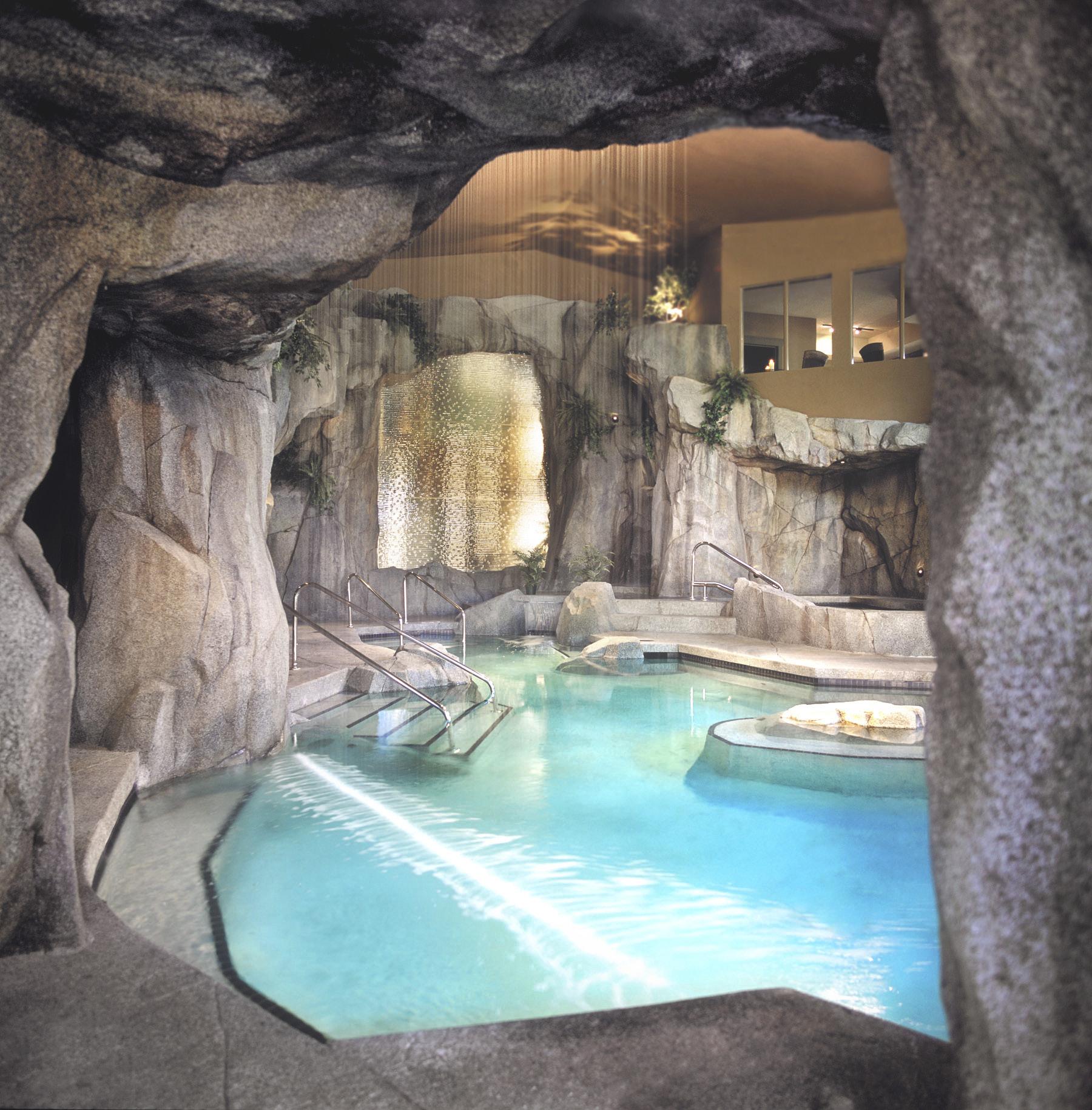

Hatley Castle

James Dunsmuir tended the fortune amassed by his father. He was BC’s premier (19001902) and lieutenant governor (1906-1909) and spared no expense building the lavish Hatley Castle. A combina-

tion of Norman and Renaissance styles, this 15th-century Edwardian manor designed by Victorian architect Samuel Maclure comprises 40 rooms with views of Esquimalt’s seaside lagoon, old growth forests and palatial gardens—565 acres in total.

In 1995 the entire mansion was designated a National

Historic Site of Canada. These days, Hatley Park (named in the tradition of the private estates of Britain and Europe) is associated with Royal Roads University, so it doesn’t get as many visitors as Craigdarroch, but you may have seen it on the silver screen. Hatley Castle made its film debut over 80 years ago and was featured in

“The X-Men” movie series, as Professor Xavier’s School for Gifted Youngsters.

Hatley Castle offers guided tours of just a few rooms on the first floor, but ghosts have a free pass everywhere: A strong smell of cigar smoke can be sensed while inside, according to Erin Limacher, Royal Roads University spokesperson. According to reviews on

Finding yourself at the edge of the world is surprisingly easy, leaving here is much harder.

BC MAG • 11 Accommodations Restaurant + Café Golf Course Local Adventures

hekatesretreat.ca

Location

Hatley Castle, 2005 Sooke Road. hatleycastle.com

DUE WEST

Location

The Empress Hotel, 721 Government Street. fairmont.com/ empress-victoria

Tripadvisor, the tour isn’t worth the price of admission, but you can view the exterior’s ornate stone masonry work, extensive use of battlements and elaborate gardens from 10:00 a.m. to dusk. And like Craigdarroch’s dining room, a tiny little metal lever on the dining room floor was used by Laura Dunsmuir to summon kitchen help. There is also a secret passage in the castle, which husband James purportedly used to escape his guests.

Time it right and you could stroll parts of the grounds surrounding Hatley Castle without a soul in sight, even though these fine Edwardian gardens have been around for almost a century. While most visitors come to see the castle and maybe stroll the Italian and Rose Gardens, venture further to the Japanese Garden, the woodland garden and down a path flanked by 26 elms to the lower lake and the bog garden. The gardens remain largely intact since designed in 1913. “I don’t care what it costs, just build it,” said James, referring to his gardens and Hatley Castle.

Location Government House, 1401 Rockland Avenue. ltgov.bc.ca

The Empress Hotel

Designed by architect Francis Rattenbury and built by a division of the Canadian Pacific Railway, the Empress Hotel opened her doors in 1908 as a “luxury castle on the coast.” Now, the chateau-style Fairmont Empress—in recognition of her architectural and historical importance—is a designated National Historic Site. Named after Queen Victoria, as the ‘Empress of India,” her Edwardian-era exterior boasts intricate stonework, decorative moldings and beautiful

12 • BC MAG

Empress in 1910.

Top: Courtesy Empress Hotel; Above Courtesy Government House X2; Right: Royal BC Archives

stained-glass windows.

Inside, start at the reception lobby. In 2017, the hotel underwent a $60-million-dollar renovation including a chandelier comprising 250,000 crystal beads finely woven together to refract light in rainbow colours. It makes for a grand entrance. Ask the concierge for directions to the “Heritage Hall,” which is

reminiscent of a train caboose. Its walls are lined with vintage photographs capturing the hotel’s early days and a timeline of construction. Back upstairs, check out the magnificent stained-glass ceiling dome in the Palm Court and next door, the ladies at the little Fairmont store will gladly share stories about famous events held

there. Not to be missed are the huge pop art-style portraits of Queen Victoria in the Q Bar. Its makeover in 2017 perfectly balances Edwardian architecture with modern design and best viewed with a Martini Royale made with Empress 1908 gin.

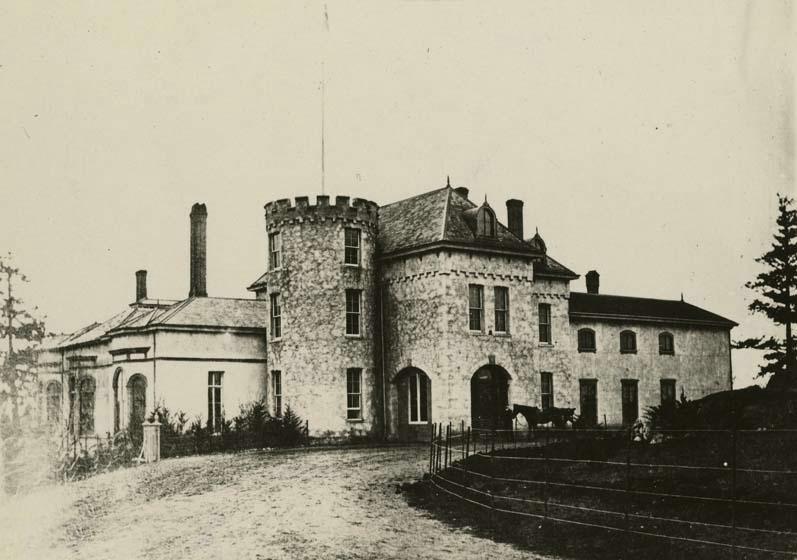

Government House

The official residence of the Lieutenant Governor and the ceremonial home of all British Columbians, the third Government House opened in 1959—the two previous buildings were destroyed by fire. Cary Castle, the first official residence, was built in 1859 but only stood for 40 years. Architects Francis Rattenbury and Samuel Maclure were hired to design a new house on the same site and it opened in 1903. The only remaining structure after it too succumbed to fire is the stone porte-co-

chere at the front entrance. The latest home has an interesting architectural style, fondly described as “Mad Men meets Downton Abbey” with Victorian décor and 1950s style bathrooms complete with ballerina wallpaper (most popular for selfies) in the basement.

The building is huge: 55,000 square feet spread over four stories and an attic. Sign up for a free tour beforehand as guides ask that you please don’t just show up. There’s a lot to see, including the dining room, ballroom, drawing room and a French drawing room, hallway and foyer. You’ll learn a smattering about history and architecture, art and artists, including a collection of First Nations art and other BC artists,such as Bill Reid. The grounds and gardens are open from dawn to dusk, 365 days a year. Be sure to visit the rose garden and when combined with Rudi’s tea room, you’ll be transported back in time to Victorian England.

BC MAG • 13

Cary Castle was destroyed by fire in 1899.

Knocking Haida Gwaii off the Bucket List

DAWN POSTNIKOFF

Haida Gwaii has always seemed slightly out of reach as a travel destination. In my mind it was difficult to get to, complicated to get around and a destination reserved primarily for fishing or high-end boating expeditions. In fact, my daughter worked for several years on a ship which sailed through Gwaii Haanas National Park Reserve, helping visitors to explore the beauty, culture and abundant wildlife of the region.

And yet, little did I know!

When the opportunity finally came for my husband and I to visit Hekate’s Retreat on Haida Gwaii, we weren’t quite sure what to expect.

For starters, it’s actually quite easy to get to. Air Canada has daily flights directly from Vancouver into K’il Kun (Sandspit) on Moresby Island, which is only a few minutes from Hekate’s Retreat. Pacific Coastal

also flies to Haida Gwaii, landing at the Masset airport on the north tip of Graham Island.

We arrived in Sandspit on a sunny Friday afternoon and rented a car right at the airport. My expectations so far had been easily exceeded. After a short drive through town and a pit-stop to grab some snacks and a bottle of wine for later, we found our way to Hekate’s Retreat. Originally a sheep and cattle farm owned by the Mathers family in the late 1800’s, the homestead was converted to the Willows Golf Course in 1972.

And what a beautiful course it is—nine holes with 18 tee boxes, located on the edge of the Pacific Ocean with incred-

ible views and challenging fairways. The course has been refurbished over the past few years, and is getting attention from across the province as a new destination golf experience. The newly renovated clubhouse restaurant offers casual bistro-style fare and

local Haida Gwaii specialties, with fresh seafood a regular feature on the menu. In fact, as we found out the following day, if you happen to bring some fresh salmon back after a day on the water, the chef will happily cook your catch for you.

We were able to tour the original Homestead House and would love to return with our families to stay there. It has been completely refurbished and is available as a vacation rental for small groups.

Our home-away-from-home was a modern cabin, located alongside the first fairway with a stunning view of the Pacific Ocean. The cabin was so cozy, and perfectly equipped for the two of us.

The thing we loved most about Hekate’s Retreat was the central location. Located at the north end of Moresby Island, it served as the perfect basecamp for all our adventures. We drove down to Gray Bay one day for a picnic, joined a fishing charter from the Sandspit marina, and jumped on the BC ferry to explore the rest of Haida Gwaii. So much to explore and so little time. We had three full days, and it wasn’t nearly enough.

If you’re interested in visiting Haida Gwaii, you can learn more about Hekate’s Retreat at hekatesretreat.ca.

14 • BC MAG

DUE WEST TRAVEL

The links / hybrid-style Willows Golf Course features 6,220 yards on nine holes and 18 tee-boxes.

X

Courtesy Hekate’s Retreat

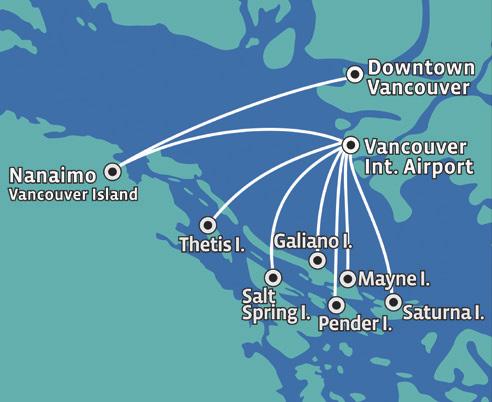

CHARTERS

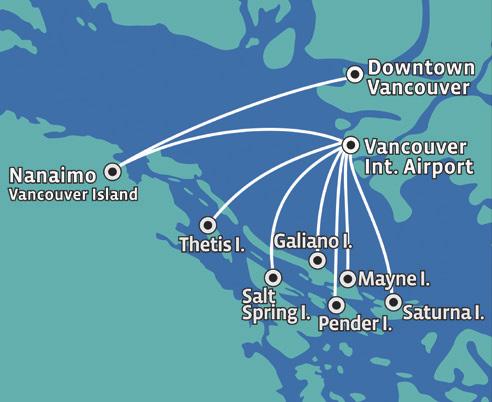

Seaplane Charters to Anywhere on the British Columbia Coast

SCENIC TOURS

Unique Experiences in Amazing Places

SCHEDULED

Up to 32 Flights Daily to Nanaimo and the Gulf Islands from Vancouver

Seair Seaplanes provides you with professional and personalized service specializing in flying charters and scheduled flights throughout Coastal British Columbia.

Seair Seaplanes are leaders in providing fast, safe, and convenient transportation from the busiest urban centres to your favourite great escape. Celebrating over 30 years of operating Canada’s fastest, quietest and most modern seaplane fleet.

BC MAG 15

| 604-273-8900 | seairseaplanes.com

1-800-447-3247

DESTINATION GREENWOOD

Canada’s biggest small city has lots of history and charm

BY JANE MUNDY

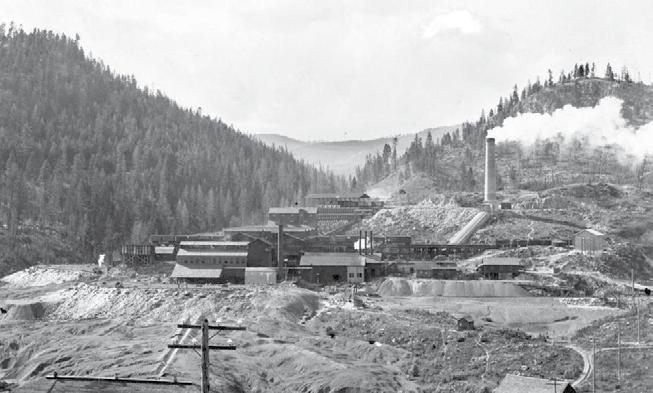

GGreenwood may be Canada’s smallest city, but its roots are huge. Nestled in Boundary Country in south central BC, Greenwood can trace its history back to the 1800s, when it hosted prospectors and miners. Its population soared again when 1,200 Japanese were interned here, and it skyrocketed in 1999 when a film crew arrived to shoot “Snow Falling on Cedars.”

Greenwood holds the title of Canada’s smallest city because it was incorporated in 1897 and its population peaked two years later with over 3,000 habitants, most of whom came here for copper mining and smelting.

The little city decided not to morph into a town or village, even though only 700 people reside here year-round these days, along with a few ghosts.

There’s nothing about Greenwood that Doreen MacLean doesn’t love, so it’s fitting

16 • BC MAG DESTINATION SPRING

X

Copper Eagle Bakery & Cappuccino—a favourite stop on Copper Street.

Adobe Stock/edb3_16

Copper Eagle Bakery & Cappuccino—a favourite stop on Copper Street.

Adobe Stock/edb3_16

that she works at the museum. I was told that she has been instrumental in development of both the museum and the community, but she won’t admit to it. “My grandfather bought the Windsor Hotel during Greenwood’s diminished mining boom and my family ran it until the 1950s,” she says. “Prospectors had no place to go so they lived in the hotel and ate at the hotel’s café—a captive audience.”

MacLean was born in Vancouver and worked in the big city until she was 26 years old. “I’m not a big city girl, so I moved back to Greenwood to be with my family and worked at the sawmill in Midway, just down the road.” Now, she’s a small city girl.

When you visit, don’t be put off by its suburb’s name: Anaconda. The local newspaper Midway Advance wrote in December 1896: “Greenwood City and Anaconda are booming. New buildings are being built daily. Newcomers are arriving every week, and

several families are camping near the town in tents...” Back in its heyday, Anaconda boasted four hotels, two general stores, a post office, bakery, shoemaker, sawmill, lawyer and its own newspaper, the Anaconda News. Anaconda’s name has nothing to do with snakes. Rather, it was named after the huge Anaconda copper mine and smelter in Montana. According to another newspaper, the Nelson Star, Anaconda’s streets were named after English authors and the avenues were named after smelters, such as Butte, Everett and Denver. The street names didn’t survive. “Lots of Americans came here prospecting for copper and to a lesser extent gold and silver, and

Right: The Greenwood Courthouse served as the Supreme Court of Yale from 1902 to 1953. Below: The Greenwood Museum and Visitor Centre, where a warm welcome awaits all visitors.

18 • BC MAG

DESTINATION

a smelter was here too,” says MacLean, “all the trade came through Spokane because the road to Vancouver didn’t exist; the stage lines went north-south until the Columbia and Western Railway came here and trade travelled east to west.” The railroad was crucial to move the ore and to this day “junior” mining companies are still exploring the area, but it costs a lot of money— and a large deposit—to put a mine into production. The city boomed with a smelter but after the First World War, the price of copper dropped and it shut down.

JAPANESE INTERNMENT

Chuck Tasaka is another resident. His parents were interned here after Pearl Harbor was bombed and they lived in an old abandoned hotel—not the Windsor—along with 200 Japanese internees. There was one stove and one toilet per floor and they had a 10x10foot room to accommodate his mother and three young daughters. Greenwood Mayor W.E. McArthur requested that 300 Japanese move to Greenwood to help revive the local economy. He wasn’t expecting 1,200, but they saved Greenwood from becoming a ghost town (more about ghosts later.)

BC MAG • 19

Greenwood was chosen as the location for the 1999 movie Snow Falling on Cedars

Ciel Sander X2

“Dad was sent to forced labour camps but because he was a barber, classified an essential service, he returned to Greenwood and lived in a house with two other families,” says Tasaka. In January 1942, all male Japanese Canadians between the ages of 18 and 45 were taken to road camps in the interior.

“My brother Seiji was born in December 1942. It was one of the coldest winters in that area, reaching -39ºF in February 1943. My mother told me that a kind gentleman friend scoured all over town to find scraps of coal and wood to keep the place warm so that a six-week-old baby would not freeze to death.”

“By 1944, dad rented a house in Midway—nine miles west of Greenwood—shared with just one family, and I was born the following year,” Tasaka adds. “Dad took the bus or train to Greenwood to cut hair and after the war he set up a barber shop here. Even though the feds disallowed Japanese Canadians to own a business, Mayor McArthur allowed it and after the war the mayor and the Greenwood community encouraged their Japanese friends and neighbours to stay. The town thrived, with over 50 percent owned and operated by Japanese Canadians.” Today, many of them or their descendants call Greenwood home.

Tasaka has fond memories of his childhood. “Greenwood was one big outdoor playground. At Sacred Heart school, the Franciscan Sisters of the Atonement never had a clock, so kids had to go outside and check at the post office clock to call lunch and recess time,” he remembers. “Because there were 364 students in four-rooms, children had to attend school in shifts. We made skis out of kindling and candlewax and played hockey on Government Street in the winter, marbles in the spring. And we loved fishing along Boundary Creek…”

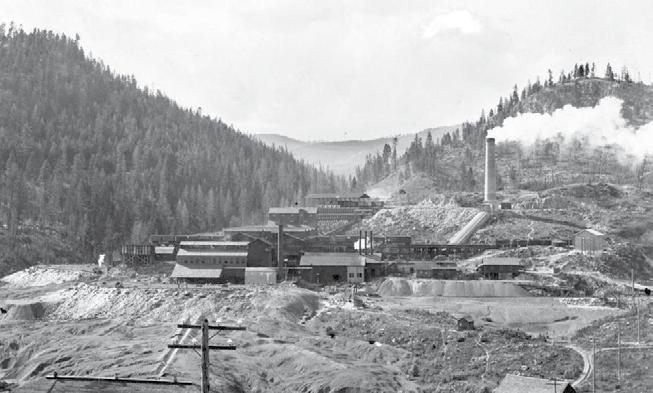

The BC Copper Company smelter stack, standing 36 metres tall, was the highest chimney in the province when built in 1904. Made from 250,000 bricks.

20 • BC MAG

DESTINATION

Top: Royal BC Museum E-03983141

Left: What remains of the BC Copper Company smelter building, a Greenwood icon. Below: Nikkei Legacy Park.

Fast forward to 2014. Tasaka discovered Ohairi Park, which amounted to a picnic area with a little wooden bridge and a Japanese lantern representing the Japanese internment history. He had to do something. “I wanted to emphasize integration and harmony and change the name to Nikkei, which means ‘of Japanese lineage’. He started the Nikkei Legacy Park project that includes family plaques. Tasaka now has over 100 plaques, most of which are internment families. And when he wasn’t combing Boundary to find each and every living surviving senior, in his spare time Tasaka wrote two books on Greenwood.

GHOSTS

Maureen Grant’s grandparents came to Greenwood in the late 1890s. Her grandfather was superintendent of the Sunset Copper Mine and her father was born here. “I spent three summers in Greenwood working at the Pacific and Windsor Hotels, and during that time discovered a rich history, more relatives, and a few ghosts,” says Grant.

With so many tales and anecdotes to tell, she began Greenwood Tours, including “The Ghosts of Greenwood” walking tour. “Charlie hangs out at City Hall and a lot of people see him coming and going. Some janitors who work there see a little girl on the stairs. A girl was killed when a rock from the mine fell on her house and we thought it could be her but the True North Paranormal TV Show came here and said the girl was older. The janitors left toys for her and they move around at night. I leave a toy on my tour.”

Grant believes in ghosts ever since people told her about their ‘experiences’ at the Windsor Hotel. “All the doors had been removed during a restoration project, but a workman kept hearing a door slamming. Ghosts are mischievous, they can come and go and hang out where they feel most

BC MAG • 21

Ciel Sander X3

comfy,” quips Grant. As part of her tour, she takes you into the courthouse, built in 1903 and now the City Hall, and downstairs to the jail cells.

“There were three separate murder trials held in the courthouse and one of the murderers, Joshua Bell, lived with his paramour Annie Allen in Spokane. He stabbed her there and did time for it, and she moved to Grand Forks. Bell followed her, but Allen left him to work in a bawdy house in Phoenix, a few days before he killed her in the street. Bell tried to escape south of the border but he was hanged and his bones were given to the University of the North and used for god-knowswhat…” Ghost tours this year start in May through September.

AND THERE’S MORE to do in Greenwood, especially if you like the great outdoors. There’s golf, fishing, hiking and biking, an outdoor swimming pool and a lake nearby in the summer. In the winter, there’s ice fishing, downhill skiing and cross country, and there’s the Trans Canada trail to snowshoe. Doreen MacLean says put your skis on at your front door. Her neighbour circles around the ball field and she is good at it.

And if you want to live here, MacLean says Greenwood is a wonderful place to grow up, where people are kind to each other. “In our small community you drive by and wave to everyone—it’s also a great place to retire and we have some snowbirds six months a year,” MacLean adds. “Real estate is reasonable although it went up like everywhere else. The climate is not harsh but it helps to like winter sports.

“We have three motels and encourage tourists to stay for at least a few days to explore old mine sites and of course the museum where you’ll find me seven days a week from May 1 to October 31,” says MacLean. There’s a lot to keep you active, but I’m waiting for the indoor and outdoor pickleball courts.

22 • BC MAG

DESTINATION Top: Courtesy Phoenix Mountain Ski Area

Right: In the winter season, good skiing can be found at nearby Phoenix Mountain.

IF YOU GO

STAY

Evening Star Motel Just a 15-minute drive from Jewel Lake Provincial Park, Evening Star Motel offers a family-friendly environment just minutes away from Downtown Greenwood. eveningstarmotel.net

Barrel Cabins at Jewel Creek

Organic Farm Located 1.6 kilometres outside of Greenwood, these charming and rustic cabins are the perfect option for the outdoorsy visitor.

Greenview Motel & RV Park Set conveniently in central Greenwood, Greenview Motel & RV Park is one of Greenwood’s three motels. greenviewmotel.com

EAT & DRINK

Keg & Kettle Grill A short 10-minute drive outside of Greenwood, you will come across Keg & Kettle Grill where you can find staple meals such as burgers and soups that won’t disappoint. keg-kettle-grill.business.site

Copper Eagle Cappuccino & Bakery Enjoy a warm cup of coffee and a sweet treat at this hidden gem located in one of the town’s heritage buildings. yelp.ca/biz/copper-eagle-cappuccino-and-bakery-greenwood

PLAY

BC Copper Company Smelter Built in 1901 and used until 1918, the BC Copper Company Smelter has been abandoned ever since but still offers an impressive site with its tall brick chimney. greenwoodcity.com/city-info/ project-heritage-smelter-preservation/

Jewel Lake Provincial Park

Enjoy a walk and a swim at Jewel Lake Park, located east of Greenwood. bcparks.ca/boundarycreek-park/

Greenwood Tours Take one of Maureen’s tours through town to learn more about Greenwood’s history and its ghosts! greenwoodtours.ca

BC MAG • 23

Ciel Sander X3

GOODIES Gulf Island

JUMP ON THE GULF ISLANDS FERRY AND TREAT YOURSELF WITH THIS UNIQUE DINE-AROUND ADVENTURE, FEATURING SIX DELIGHTS THAT YOU WON’T FIND IN THE CITY

BY Cherie Theissen

BY Cherie Theissen

24 • BC MAG

Galiano Island’s Woodstone Inn

European luxury

No, we’re not in Europe, although the 12-room boutique hotel radiates that certain glow. Located on nine acres and overlooking pastures where horses graze, the inn originally opened in 1992 and was recently renovated by third owners Stephan and Roxanne Orlitzky, who bought it in 2017. Although it closes for the winter season, the opening of the inn and its sumptuous dining room

is always eagerly awaited. The Orlitzkys, who are world travellers, have been generous with sharing the antiques they have acquired on their travels. The bar in

the dining room was originally a French side buffet from San Diego and the nearby six-foot cloisonné vase is from China, to mention only a few notables.

The menu itself is not to be upstaged by the elegant surroundings. I added prawns to my golden beet carpaccio salad while my partner David opted for a caesar salad and a seafood-laden cioppino, both of which were further enhanced by glasses of crisp sancerre. While menus will change in the upcoming season, there is every reason to believe the chefs will continue to outdo themselves and the old-world ambience and charm will never go away. Check their website for opening dates and special events. Brunches can sometimes be on offer too. By the way, inn staff will pick up diners to and from the ferry.

woodstonegaliano.com

BC MAG • 25 MP Studio

1

Top: Liam/Adobe Stock; Courtesy of Woodstone Inn

X5

Galiano Island

X

Mayne Island’s Montrose Local

Fun and games

Good news travels fast in the Gulf Islands, so when Stephanie McBurney and Jeff McPherson opened up Montrose Local in Mayne’s Fernhill Centre two years ago, we were there for lunch. Now it’s one of our regular trips and with a BC Ferry cruise through the Salish Sea and the Gulf Islands thrown in, what’s not to love?

Can you imagine coming into a place, choosing some music you like, sitting down with the chef and discussing food issues and then letting the culinary team go to work to prepare the whole experience from start to finish? This unique idea has now appeared on the menu under Chef Experience, a multi course dinner for those who can’t decide or love the idea of being surprised.

Chef McPherson, who has a long history in the culinary arts, says he loves creating different ethnic

foods with his two other chefs, Mike Smith and Jan Gumbmann, ensuring that the dishes are constantly changing. “I have an outstanding team. We have a lot of fun in the kitchen and there’s a lot of collaboration. We feature freshness and quality—everything comes in fresh except for the prawns and everything is made from scratch.”

I’d swear that the fun they have in the kitchen finds its way into the food too.

The owners are always coming up with fun themes like their popular family nights, for example. “We’d never tackle this in the city,” MacPherson laughs. “But it works here. And the culinary theme nights, where our chefs collaborate, is very popular.”

This is always going to be a place for families, locals and visitors with local knowledge to hang out, and when the warm ambience is paired up with food that will probably never be tasted again, we think it’s a very good thing.

facebook.com/themontroselocal

Galiano Island’s Babes in the Woods

Pizza queen

Since 2014, a determined single mother of two has been creating culinary magic and the locals can’t get enough. It’s a love affair that’s reciprocated. “Galiano kept me and my family safe. I don’t know how the story will end but that’s OK when you can trust and lean into the community around you,” Lisa Gauvreau says as she sprinkles cilantro over caramelized red onions, her own barbecue sauce and roasted chicken.

This is my pizza I’m talking about, and I won’t be sharing with my companions either. A peanut satay pizza with curried vegetables is waiting in the warming oven and the barbecue salmon will be next up.

Because she has recently moved locations and now cooks up a storm in her own building, there are currently no indoor din-

ing facilities. However, there are lots of comfortable tables outdoors, or you can always do what we did and feast in your car at the ferry. The surroundings may not be classy, but this pizza eclipses any background.

Hard to believe this pizza queen does it all, with a very busy Warren Arcand at front of house and two occasional helpers.

And to make it all the more amazing, it’s not just out of this world pizzas she creates. Islanders have been ordering soups, salads, dijon glazed salmon dinners, tacos, and appies since we arrived. Definitely Gauvreau’s 35 years in the food business is a big asset, but it’s still awesome.

She tells me she makes 10,000 pizzas a year and trust me, it is honestly worth the ferry trip just to have one of them. (Babes in the Woods is only a block away from the terminal too.)

facebook.com/babesinthewoodseatery

26 • BC MAG

Galiano Island X

X 2 3

Mayne Island

Left: Cherie Theissen; Above: Hans Tammemagi

Pender Island’s Slow Coast Coffee

If you bake it, they will come

It isn’t easy for small businesses to survive on the Gulf Islands, with their small permanent populations and seasonal summer visitors, but given the fact that Alison Feargrieve and her partner Rob McCallun have operated this 300 square-foot Pender Island hub in North Pender’s Medicine Beach for more than 10 years, you know they have to be doing something right.

was comfortable and cozy and welcoming for folks to come.” They must really love what they do because even with the capable help of an assistant baker and assistant barista, they still can’t manage to take a twoweek holiday.

They survived Covid because they’re small, says Feargrieve, and because the locals refused to let

them die, ordering from the window and mingling and munching at the sheltered picnic table outside while also enjoying the Bedwell Harbour views. They also survived because they are just darn good at what they do! McCallun serves up lattes and cappuccinos that

look too good to drink, while his partner bakes delectable goodies like my favourite pecan toffee squares. “The relationship with Slow Coast and the community was cemented fairly quickly,” says the latter, “and that’s good because we both love community and wanted a great creative space that

Slow Coast opens early and closes mid-afternoon, which is just as well because the baking is pretty much gone by then. While Feargrieve says many locals come for the coffee and goodies, there is always a faithful crowd who wait for the ever-changing luncheon special. Today, we’ve been enjoying the popular buddha bowl but savouries like dosas, quesadillas and crepes are always on hand daily. Slow Coast cooks have dietary restrictions in mind so there are lots of vegan choices too.

Come in on a Sunday afternoon and you will be really into Gulf Island vibes. That’s when local talented musicians get together to jam in the cozy adjoining ‘reading room.’

facebook.com/PenderislandSlowCoastCafe

BC MAG • 27

X

Pender Island

4

Top: Liam/Adobe Stock; Above: Cherie Theissen

Salt Spring Wild Cider

Celebrating the apple in style

Production manager, Jesse Scott, is our server today. He has been here seven years and remembers those early days when he was virtually a ‘Boy Friday’, doing everything from greeting guests, bottling brew and selling ciders in what used to be the horse barn. We look out on fields, fruit trees, firs and tables adorned with colourful but droopy umbrellas, awaiting spring’s warmer weather. The ample choice of award-winning ciders ranges from rhubarb to rosemary, Saskatoon berry to scrumpy, elderberry to

pear. We order a generous platter of charcuterie accompanied by a large flight of ciders while we enjoy the fully enclosed and warmly heated pergola that has recently been snugly enclosed. Wild

Cider is open year-round and is family and pet friendly. Seniors are treated pretty royally too.

Gerda Lattey, co-owner with Mike Lachelt, tells us there are more than 450 varieties of apples grown on Salt Spring, some over 100 years old. They won’t be running out of product any time soon then and that’s a really good thing.

saltspringwildcider.com

28 • BC MAG

X

Salt Spring Island

5

Stock

Courtesy of Salt Spring Wild Cider X2; Above: edb3_16Adobe

Saturna Island’s Feral Goat Bistro at Sage Hayward Vineyards

Grape meets gourmet

After sitting idle for three years, this 70-acre property with its 40 acres of grape vines was purchased by long-time Saturna islanders, Anne and Doug Hayward, along with Doug’s brother Ian and Ian’s wife, Wendy Sage-Hayward. There was much to be done, but luckily the combined family is a large one with multi talents; it was done and in a big way. We think one of

the best things they’ve done is to renovate and re-open the tasting room and bistro, bringing it back from its early days of dreaming big. When the original winery, which opened in 1995, started having its annual Harvest Festival, we would come by every third week-

end of September because we knew Saturna’s own food guru, Hubertus Surm, would be cooking magical dishes like his signature mussels in a tomato lime leaf curry. Surm’s culinary skills are a legend, and we’ve been forever grateful to Saturna for enticing him there

from Isadora’s on Vancouver’s Granville Island where he was executive chef. Surm thought the Saturna move was semi-retirement, but no chance. He was soon managing chef at the Saturna Café in the General Store as well as cooking up a storm for winery events and the local inn.

On the day we sail over from Pender Island, we sit outside absorbing the views over Plumper Sound while enjoying a flight of the winery’s offerings, finally deciding on a bottle of pinot gris to go with our lunches of scallop ceviche followed by a shared mezze platter. (House made pakoras, potato cakes and hummus served with tandoori chutney and pickled vegetables and crackers to scoop it all up.)

The scenery and ambience is 10 out of 10 and when you can get such a choice of wine and food like this on a small Gulf Island, why wouldn’t you come?

The bistro closes for the winter but will be opening on Mother’s Day and then operating Thursday thru Monday. West Coast dinners on Saturday and Sunday nights are highly recommended, but if you can only make it to Saturna once this year, definitely come by on August 31 when the Harvest Festival returns. It’s another experience you can only have on a Gulf Island.

sagehaywardvineyards. com

BC MAG • 29

X 6

Saturna Island

Courtesy of Feral Goat Bistro X3

GIANTS SPOTTING

A GUIDE TO WHALE WATCHING IN BC

BY MARGAUX PERRIN

Destination BC/Garry Henkel

Orca breaching off the coast of Vancouver Island.

WWhales may be the largest animals on earth, but they disguise themselves from the surface impeccably. However, once in a while they rise up to inhale a breath of fresh air, and that is when lucky eyes can spot them and admire them from a safe distance.

Wilma Fuchs has been a professional whale spotter, more commonly known as a whale watching tour guide, or naturalist, at Prince of Whales for more than a decade. Prior to joining Prince of Whales, she volunteered for the Vancouver Aquarium for six years, which is where she fell in love with marine mammals. Determined to pursue a career that would allow her to work with marine mammals, she turned to whale watching companies. “12 seasons and 11 years later, I am still working on a whale watching boat and absolutely loving it!” says Fuchs.

Simon Pidcock, captain and owner of Ocean Ecoventures, is another person who was destined to have a career in the marine industry.

“Being able to spend time on the wa-

ter exploring the Salish Sea, seeing the waters around Vancouver Island and photographing the wildlife made me realize what a unique ecosystem and what an amazing place in the world that we live in, and I realized that I could actually share those experiences and the wildlife with people all around the world,” says Pidcock, who grew up in a wooden shipyard and got his first boat at four years old. “I really felt that it was a great way to inspire people to make personal change, to look after our local environment, and not even just our local environment, but as we see people from all around the world, really inspire them to try to make a difference in their daily actions.”

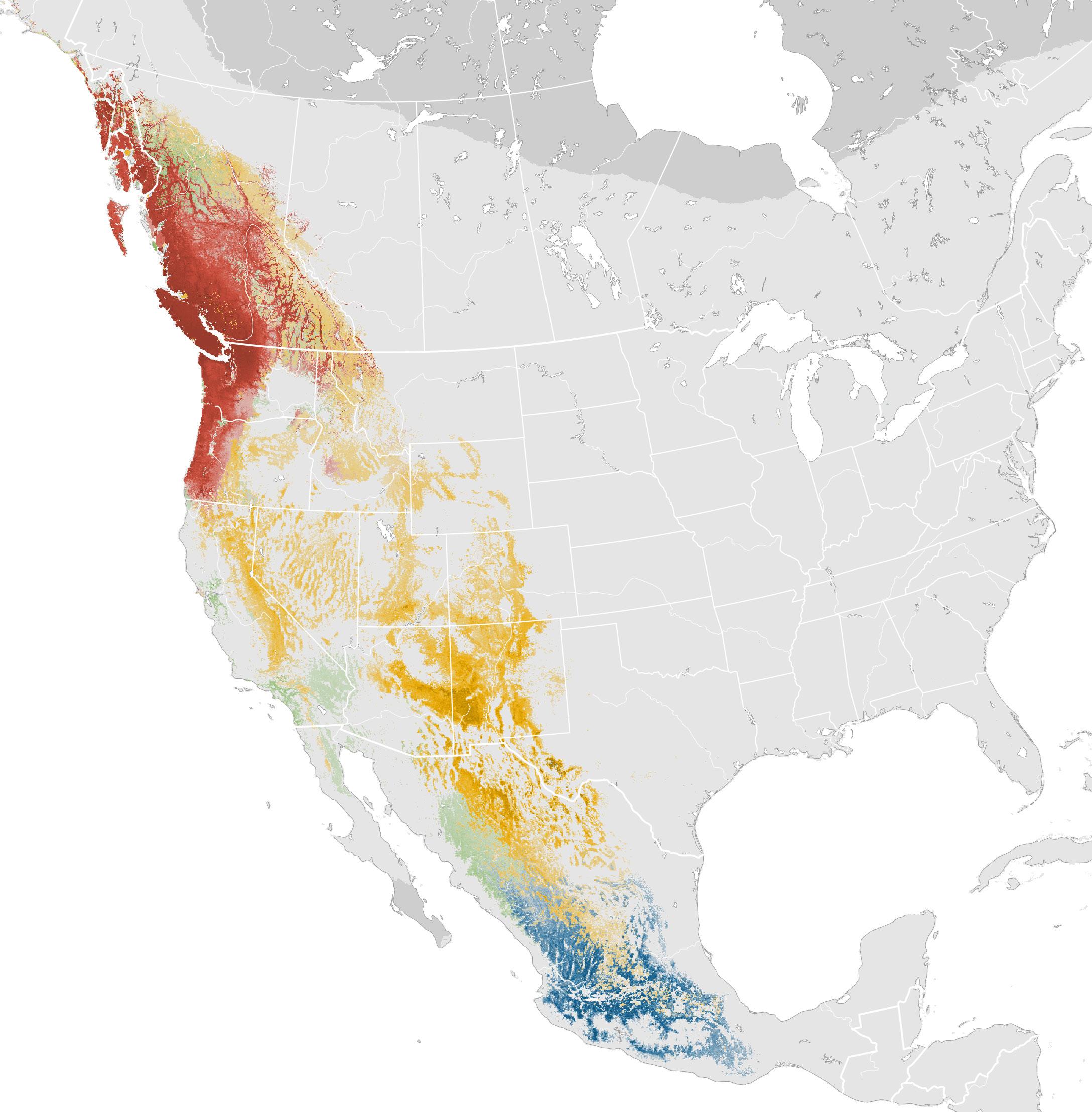

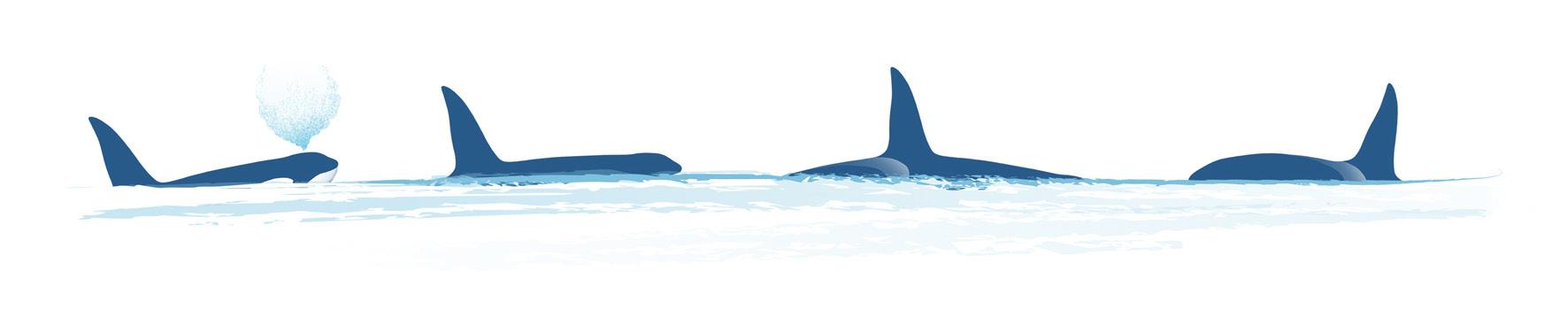

Whale watching is a popular and educational activity in several areas of the BC coast, where there are three distinct whales commonly found: resident and transient killer whales from the orca family, and humpback whales.

RESIDENT KILLER WHALES

Mysterious and breathtaking, resident killer whales rely on their family to survive. In each family group, the female assumes the leadership role as matriarch. Each family of whales is classified into pods, or groups, and in almost all cases, residents spend their whole lives attached at the fins of their family members. They are also on a strict fish-diet, composed mainly of salmon. Resident killer whales can be

32 • BC MAG

Destination BC/Jordan Dyck

A pod of Orcas swimming off the shoreline in Victoria.

A humpback whale breaching.

Although the specific reason for why the humpbacks perform this spectacular move is not clear, there are a few possible explanations such as a way to communicate, to attract eligible mates or simply to have fun!

divided into two communities in BC; northern and southern residents. The northern residents are the most common types of whales in Alaska and the northern part of the BC coast. However, as a whale watching tour guide around Vancouver, Fuchs has only spotted a small group of northern residents twice in her career.

Since 2001, the northern residents have been listed as threatened, while southern residents have been listed as endangered. “Over the last 10 years, we witnessed a decrease in the numbers of southern residents killer whales” says Fuchs. “One reason we know of is the decrease in chinook salmon runs, returning to spawn in the Fraser River. Orcas are forced to travel further to find food.”

Pidcock says that for his first 12 years as a whale watching operator, he saw a lot of southern residents. He once had a 126-day long streak where he saw them every single day. “It shifted all of the sudden and we started encountering more and more Bigg’s killer whales or transient orcas,” he adds.

TRANSIENT KILLER WHALES

Although transient killer whales, also known as Bigg’s orcas, are cousins of the resident killer whale, these two branches of the family do not interact. A major difference between these two species is that transient whales will feed exclusively on marine mammals, such as harbor seals and sea lions. To sustain that diet, they have been increasingly roaming around the Salish Sea, as it has recently become more and more abundant with prey. As a result, Wilma and Simon both mentioned there has been an increase in numbers of transient whales over the last 10 years.

34 • BC MAG

Prince of Whales/Seanie Malcolm

“It’s really neat to be able to individually identify [these transient whales] and watch them as they grow up and go through all the stages,” says Pidcock.

Last August, Pidcock had spent a day out on the water where he and his team saw about 25 transients. After finishing up their last tour of the day at sunset, they returned to the water to continue watching the group of transient whales, even after the sun had set and it was nearly impossible to see in the darkness.

“It was mostly auditory, but we were still able to track them,” says Pidcock. “And then the bioluminescence came out and we were actually able to watch them swim and watch them travel.”

Although he has had many incredible encounters throughout the years, he says this one was special. “There’s stars above us and it looked like they were swimming through stars from all the bioluminescence. It was an amazing night.”

Capable of holding up to 95 guests onboard, this is one out of the 15 boats that Prince of Whales operates. Engineered in Canada, it was made specifically for the purpose of whale watching in British Columbia.

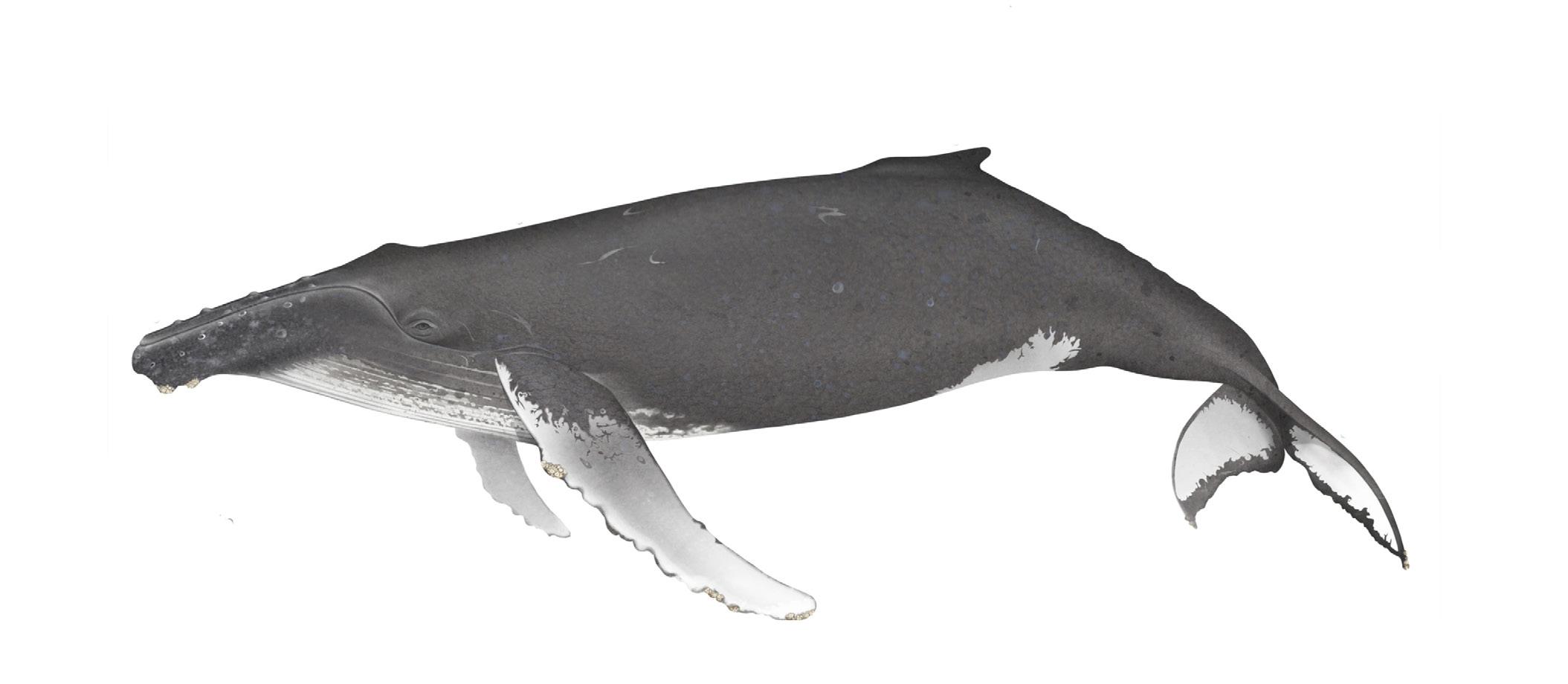

HUMPBACK WHALES

You can spot humpback whales all year round in BC, although they tend to be most common in April to November. These majestic creatures have a sad history, as in the late 1800s to 1965 they were commercially hunted, and approximately 28,000 were captured in the North Pacific. It is not until recently that they started to come back to BC and are now no longer labeled as “threatened.”

According to Fuchs, these whales have become the most common ones to spot while whale watching. Over the

years, they have also become her favourite type of whale to observe.

“My favourite used to be the southern resident killer whale when I just started whale watching because that is all I had seen, but now with having humpback whales in larger numbers, I have switched my allegiance!” says Fuchs.

One of her favourite facts about humpback whales is that whale mothers communicate with their calves in a frequency out of range of transient orcas, who happen to be their main predators; this phenomenon is called a “whale whisper.”

WHEN ASKED WHAT her most unique experience was throughout her whale watching years, Fuchs shared the incredible story of two passengers she had in her second year of whale watching. They were with a small group aboard the vessel that day, so Fuchs got

36 • BC MAG

Destination Vancouver/Prince of Whales Whale Watching

the chance to talk to each passenger a little more in depth, including two women who were sitting at the back of the boat. “I learned they had been diagnosed with terminal cancer, both of them, and were given one year to live,” Fuchs adds, “their lifelong dream was to see orcas.”

Determined to see whales, they looked extra hard, but unfortunately there seemed to be none in sight that day. At last, as the day was coming to an end, they heard on the radio that a nearby boat had spotted humpback whales. As they arrived on the site, they were stuck behind six other vessels and had no choice but to wait their turn. It was getting late and they were running out of time, so the captain decided to move the boat about 100 metres away from the rest of the lot to see what would happen. They waited there for a few minutes until suddenly, they heard a loud exhale at the back of the boat, where the two women were sitting. “The humpback lifted his head up and looked right into their eyes, check-

ing them out and almost touching the boat,” says Fuchs. “Then they dove right underneath the boat, only to surface on the other side at the back. This went on for about 25 minutes, with some of the passengers being moved to tears.”

Aside from orcas and humpback whales, there are a few other types of whales you might get lucky to see on your outing. For both Wilma and Simon, the rarest species of whale they had encountered while watching was the fin whale.

RULES TO FOLLOW

Although seeing whales up-close is thrilling, whale watching tour operators must follow the Marine Mammal Regulations under the Government of Canada’s Fisheries Act as well as the rules of the Pacific Whale Watch AsMinke whales frequent the Pacific Northwest during spring and fall.

sociation (PWWA) that have outlined clear guidelines on maintaining safe distances. For most whales in the Salish Sea, including humpback whales, gray whales and minke whales, the viewing distance is 100 metres. The viewing distance in BC for whales who are resting or with calves is 200 metres, and the distance for all killer whales in inland waters in BC is 400 metres.

Some strict “don’ts” when whale watching include positioning your vessel between the food source and whales and flying drones around whales. More on guidelines can be found at pacificwhalewatchassociation.com/regulations and the Fisheries and Oceans Canada website.

Whale watching offers the opportunity to gain insight on these magical creatures that roam our oceans. Not only will you get the opportunity to see whales in person (likely), you will also get to learn a whole lot on whales and other marine mammals from passionate whale watching experts like Wilma and Simon (guaranteed).

BC MAG • 37

Abode Stock/Jay S

grahof_photo

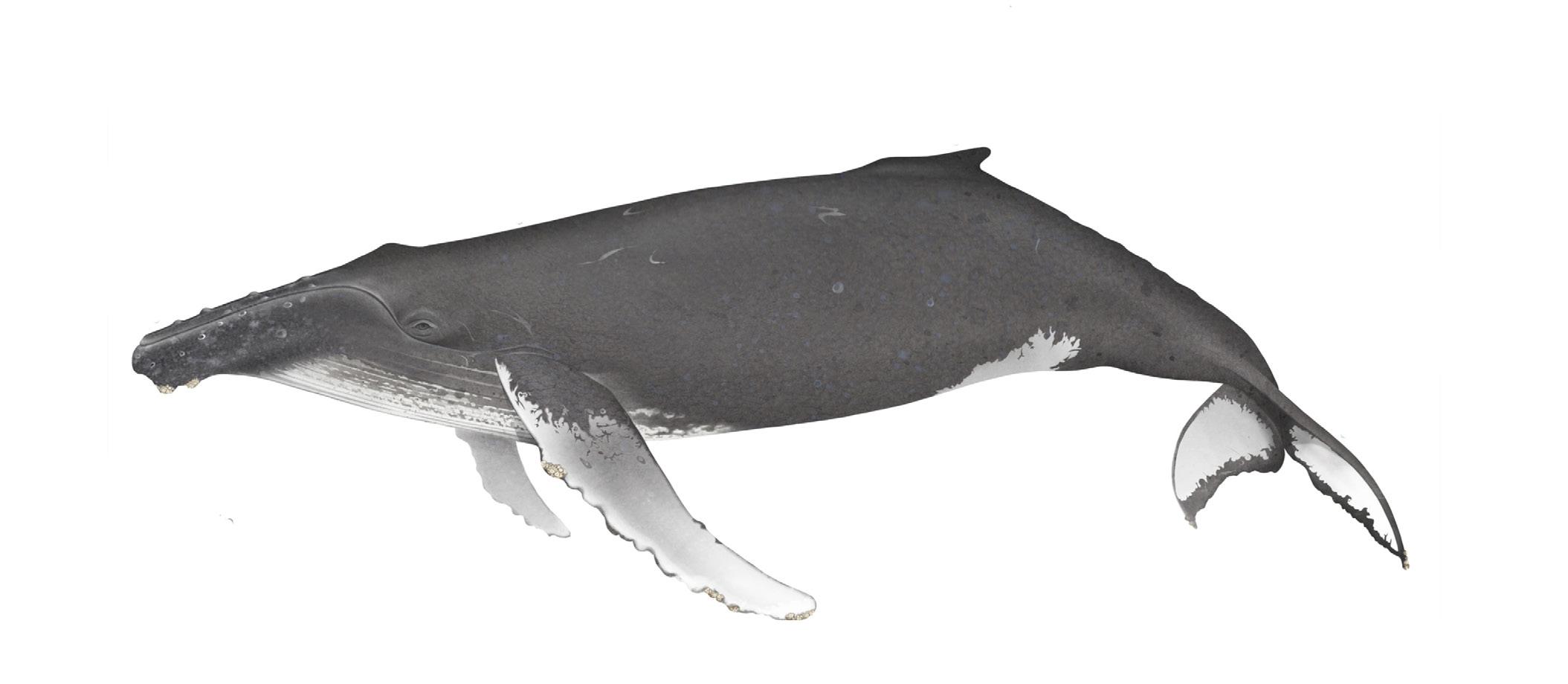

Knobs on top of head and lower jaw.

WHAT TO LOOK FOR

Humpback Whale

Adult length: 11.5-15m • Adult weight: 25-30 tonnes

Low, often stubby dorsal fin with broad base and “hump”: can be highly variable shape. Dark grey to blue-black colouration on upper side.

Tail flukes are broad and usually serrated on the trailing edges. Dark on top and can vary from black to white underneath.

Rounded protrusion at tip of lower jaw.

Long flippers - up to 1/3 of body length with knobs on leading edges. White underneath, but can be black, white or mottled on top varying by population or individual.

Although females are on average larger than males, the only way to distinguish the sexes is by the presence of a grapefruit-sized lobe at the rear of the genital slit or presence of a calf (female) or the detection of singing (male).

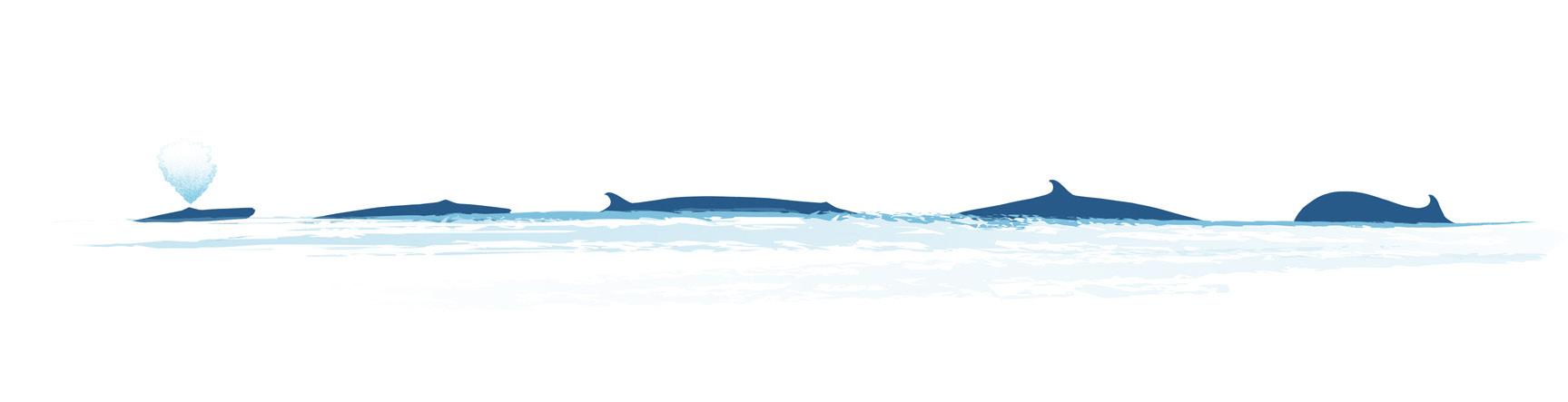

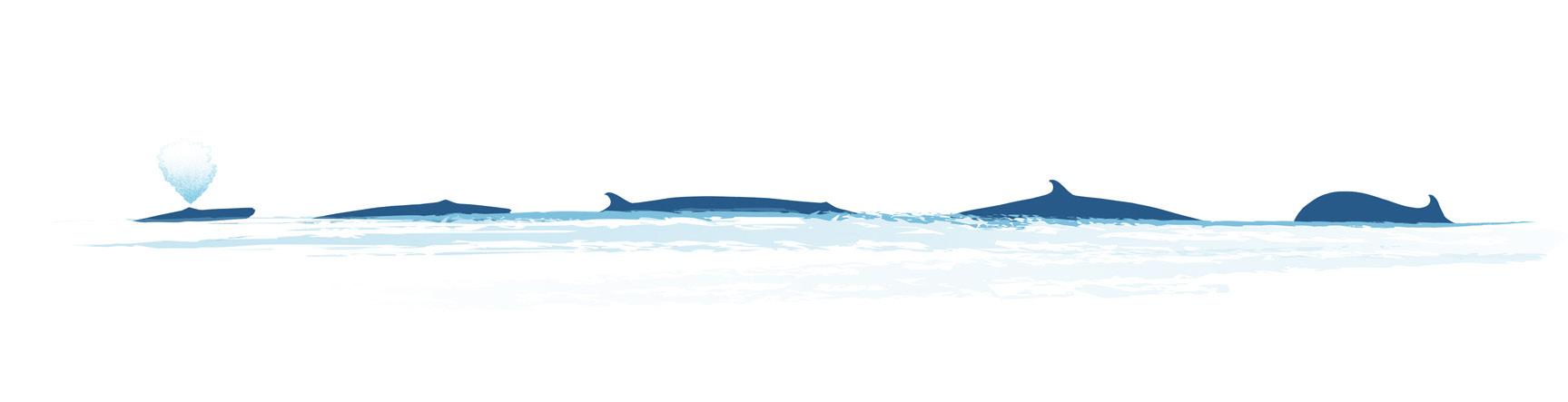

Gray Whale

Adult length: 11-15 m• Adult weight: up to 45 tonnes

Blowholes located in a shallow dip on the top of the head.

Narrow, triangular head that slopes and arches between the blowhole and the snout. Patches of whale lice and barnacles are usually present on the head. Broad paddle-shaped flippers.

Dorsal fin is only a low hump.

Visible ‘knuckles’ or fleshy knobs between the dorsal hump and the tail flukes (varies between individuals).

Dark grey skin is covered with light coloured blotches and white, yellow, or orange patches of whale lice and barnacles.

Flukes are mottled with ragged edges, and pointed tips, and oftern bear scars from killer whale attacks.

40 • BC MAG

Info courtesy IWC (International Whaling Commission)

Minke whale

Adult length: up to 8.8m (female) • Adult weight: up to 9 tonnes (female)

Curved and pointed dorsal fin located roughly 2/3 of the way between the head and tail.

Flattened head.

Sharply pointed snout.

Tail flukes are black on top and pale underneath.

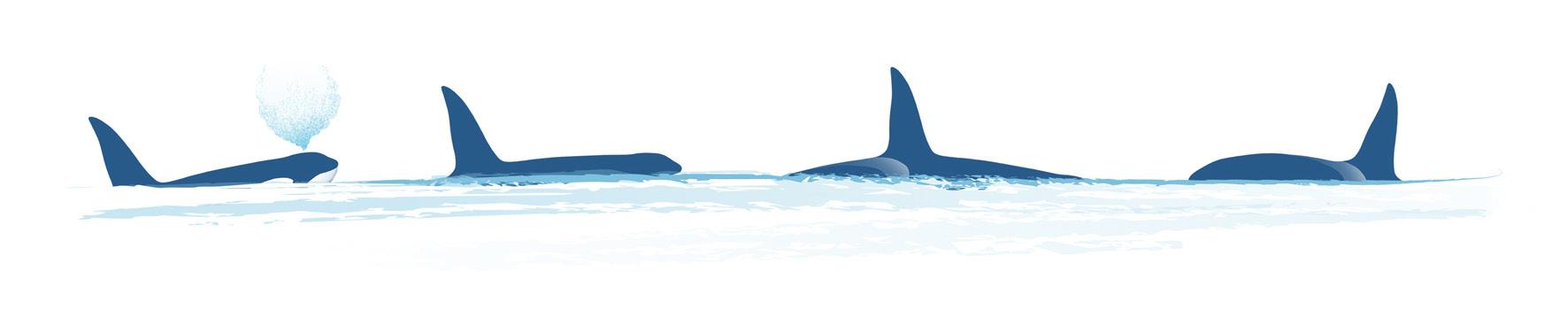

Orca

Adult length: up to 9.8m (male)/8.5m (female) • Adult weight: up to 10 tonnes (male)

Adult males have an unmistakably tall (up to 2m) triangular dorsal fin. Females and juveniles have smaller sometimes curved dorsal fins. Transient orcas often have a more sharply pointed tip to their dorsal fin.

WHALE WATCHING COMPANIES

Prince of Whales

Vancouver /Victoria/ Telegraph Cove

Toll Free: 1-888-383-4884

Local: 1-250-383-4884 princeofwhales.com

Wild Whales

Granville Island, Vancouver, 604-699-2011 whalesvancouver.com

Steveston Seabreeze Adventure

Vancouver (Richmond) 604-272-7200 seabreezeadventures.ca

Campbell River Whale

Watching and Adventure Tours

Campbell River

Toll Free: 1-877-909-2667/

Local: 1-250- 287- 2667

Ocean Ecoventures

Vancouver Island (Cowichan Bay & Parksville)

Toll Free: 1-866-748-5333

Local: 1-250-748-3800 oceanecoventures.com

Vancouver Island Whale Watch Vancouver Island (Nanaimo)

1- 250-667-5177 vancouverislandwhalewatch.com

Pale grey saddle patch, variable between individuals and populations.

Tail flukes are black on top and very pale to white underneath.

Eagle Wing Tours

Vancouver Island (Victoria)

Toll Free: 1-800-708-9488/

Local: 1-250-384-8008 eaglewingtours.com

Orca Spirit Adventures

Vancouver Island (Victoria)

Toll Free: 1-888-672-6722/

Local: 1-250-383-8411

Jamie’s Whaling Station

Tofino

Toll Free: 1-800-667-9913

Local: 250-725-3919 jamies.com/whale-watching/ tofino-whale-watching/

Prince Rupert’s Adventure Tours

Prince Rupert

Toll Free: 1-800-201-8377

Local: 1-250- 624-8199 adventuretours.ca/tours/ whale-watching-tour/

BC MAG • 41

50-70 throat grooves.

Small, slender, pointed flippers with distinctive white band.

White, pale grey or pale brown underside.

White chest.

Large, wide paddle-shaped flippers – up to 1/5 of body length in adult males.

White patch extending from belly up the sides.

Oval shaped white patch behind each eye (variable).

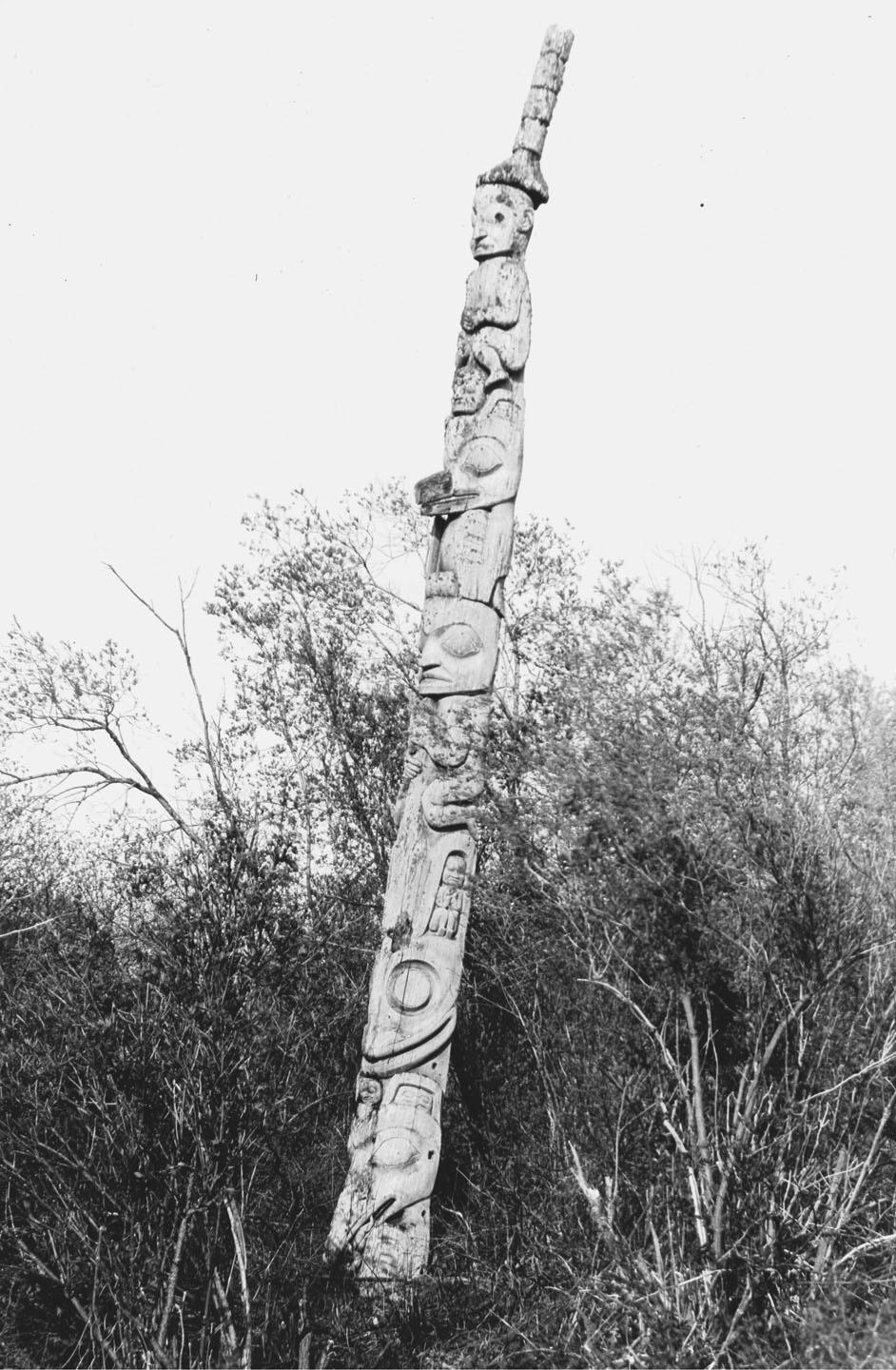

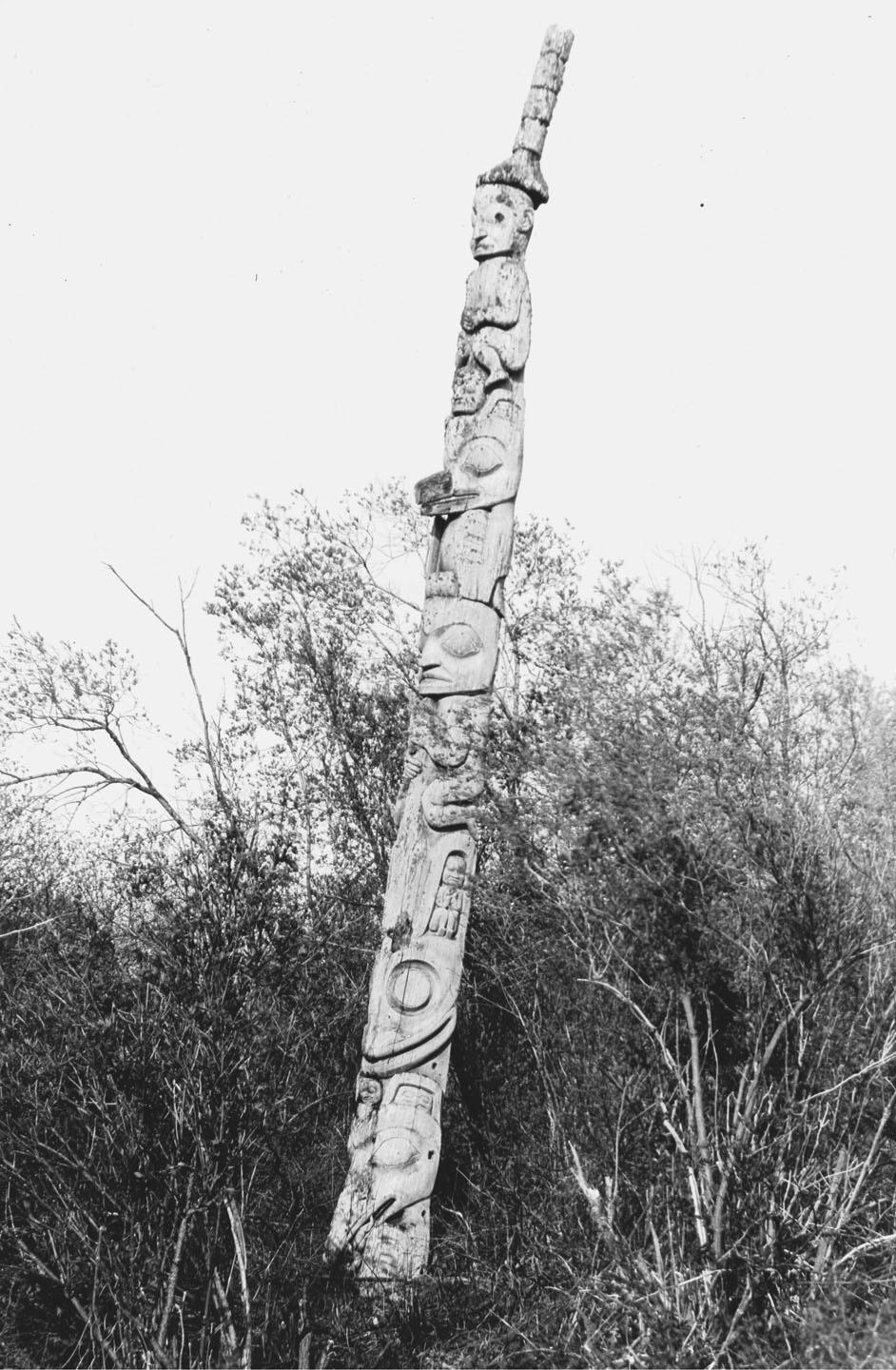

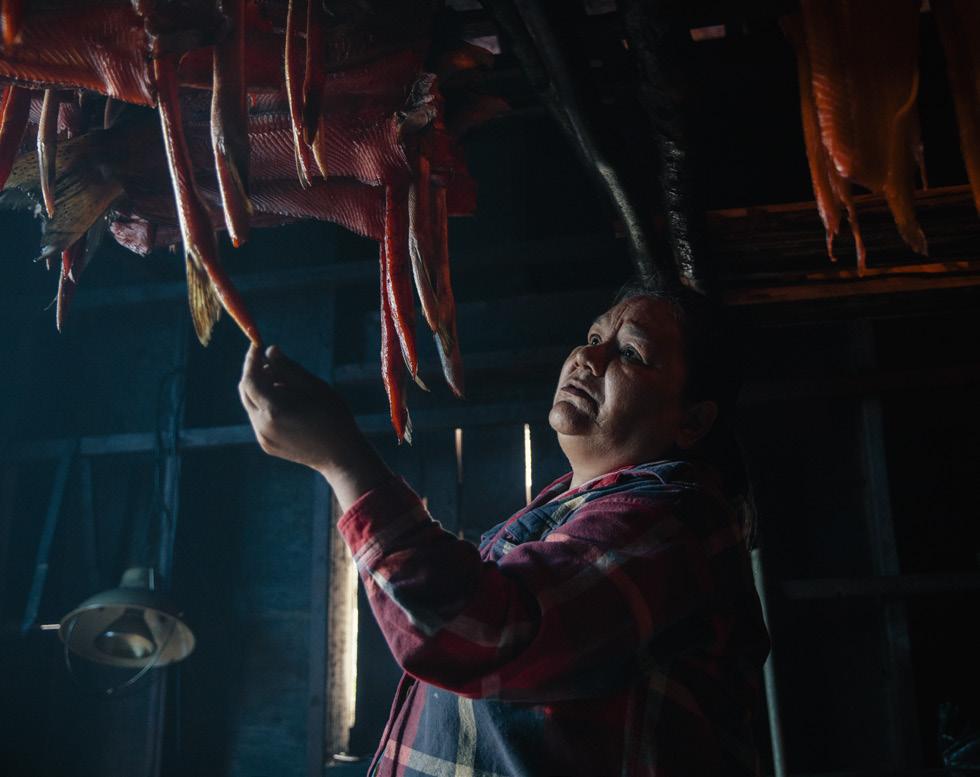

THE LONG JOURNEY HOME

AFTER BEING STOLEN AND SENT TO A SCOTTISH MUSEUM IN 1929, THE NI’ISJOOHL MEMORIAL POLE MAKES ITS LONG WAY HOME TO THE NASS VALLEY

BY DIANE SELKIRK

BC MAG • 43

Left: Diane Selkirk

The Nisga’a delegation went to Scotland to request the return the Ni’isjoohl Memorial Pole.

SStanding at the lookout at Ksi Wil Ksi-Baxhl Mihl or Crater Creek, it’s hard not to feel awe as I gaze over a landscape of lava fields framed by the snow-capped Hazelton Mountains and Kitimat Range. This vast expanse of volcanic rock is the result of Canada’s most recent volcanic activity. Around 1690 CE, the Tseax Cone erupted, spilling hot lava into the Tseax River and forming a dam that created Lava Lake. Then, the lava flowed northward toward the Nass River, covering the valley floor, destroying at least two Indigenous villages and claiming an estimated 2,000 lives through fires and what Nisga’a Elders called “poison smoke.”

Stretching 32 kilometres across the valley, I’m surprised by the diversity in the volcanic plains. In one area, there are imposing heaps of metres-high rubble, while in another, the basalt flow takes on the smooth appearance of a paved parking lot. At Dihlaa N ’ iiBax-hl Aks Sbayt-G-an, the Drowned Forest, it forms deep potholes that fill with clear, aquamarine river water. At

Wil Luu-g-alksi-mihl G-an, the Tree Cast, I notice that much of the volcanic rock is covered in vibrant gold lichen and mosses. In some places, soil has even formed and small trees have sprouted—almost as though the land is healing itself.

Continuing along Nisga’a Highway 113 toward the seaside village of Gingolx, the radio station fades out just as the lava field ends and the dense green forest begins. Searching for a new station, I find CNFR, Canada’s First Nation’s Radio. Driving along the braided tributaries of the Nass River, I listen as the broadcaster recounts how almost 100 years ago, the Ni’isjoohl Memorial Pole was stolen from the village of Ank’idaa and floated away down the Nass. Reaching the bridge, I slow my car to look down at the churning waters below.

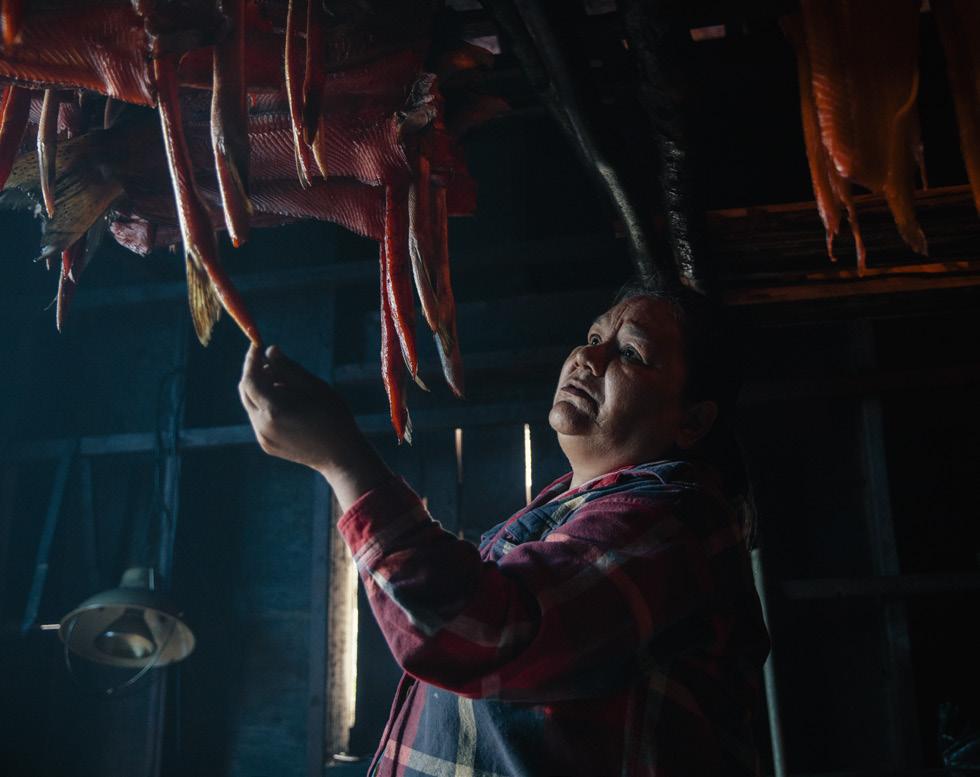

While the Nass Valley is stunning, my focus this visit is not just the scenery. A little over a year ago, I visited the carving shed in the village of Laxg alts’ap and met master carver Calvin McNeil. He was working on a replica of the Eagle-Halibut Pole of Laay, a pole currently housed in the Museum of Anthropology in Vancouver. As McNeil demonstrated how he recreates the crests using historic and modern photographs, he explained the original pole is considered an ancestor. It was one of several brought to life in the mid-1800s by legendary Nisga’a carver Oyay, which later went on to be

stolen for museums around the world. But, McNeil said, a Nisga’a delegation was about to go to Scotland to request the return of one of his ancestors, the Ni’isjoohl Memorial Pole.

TO UNDERSTAND HOW the Ni’isjoohl Memorial Pole ended up in Scotland, I’m told you need to start with Lisims, the Nass River. Flowing from its headwaters in the glaciers of the Skeena Mountains, the Nass meanders southwesterly for 380 kilometres before draining into Portland Inlet and the Pacific Ocean. Surrounded by

44 • BC MAG

glacier-capped mountains and flanked by meadows thick with soapberry, salmonberry and kinnikinnick as well as forests of hemlock, spruce and redcedar—the Creator placed the Nisga’a People in villages along the river. Guided by the belief that everything is interdependent, the people followed a sophisticated code of laws and customs to maintain balance in the community and ecosystem.

Toward the end of this era of balance, Oyay emerged as a master carver renowned for crafting pts’aan, totem or crest poles, which intricately detailed

a family’s history and their ties to the land and other families. Around 1860, Joanna Moody, a 25-year-old matriarch in the village of Ank’idaa, commissioned Oyay and his assistant Gwanes to carve a pole in memory of Ts’wawit, a warrior in line to be chief until he fell in battle. Utilizing a redcedar tree that had been girdled and dried for years in the forest, the carvers dedicated almost a year to breathing life into the pole. Then, with great ceremony, the pole was raised with an elaborate feast (often referred to as a potlatch).

Standing, the pole took its place

alongside Crane and Grizzly, Bear Mother, the Shaking Pole of Kw’axsuu, and a dozen others that collectively held the community’s accumulated knowledge. The Ni’isjoohl pole was intended to ensure the transmission of knowledge and protocol to future generations, but rapid change had already arrived in the Nass Valley. Captain George Vancouver became the first European to record encountering the Nisga’a while charting the Pacific Coast from 1791-95. Then the fur trade got underway. As new settlers were drawn to the region, diseases

BC MAG • 45

Duncan McGlynn

followed. No one is certain how many Nisga’a died over the decades, but by 1889 many of the large, traditional villages had emptied, and the Northwest Coast Indian Agency census counted just 805 survivors.

WIDESPREAD DEATH LED to the loss of familial lines, cultural leaders and traditional stories. Then, beginning in 1882, the nation’s school-aged children were taken to St. Michael’s in Alert Bay or St. George’s in Lytton. Not long after this, the Potlatch Ban was enacted, outlawing the practices that wove the Nisga’a together. Meanwhile, missionaries pushed the Nisga’a to convert to Christianity, warning their attachment to ‘pagan’ beliefs could only bring tragedy.

Under cultural assault, Indigenous people faced a significant threat to their heritage. Anthropologists of the time believed that Indigenous cultures would vanish. In the period just before and after the First World War, a move-

ment now known as salvage archaeology began. Ethnographic expeditions set out across Canada with the goal of collecting and preserving whatever material culture remained before it was too late.

In 1927, Marius Barbeau, an anthropologist with the National Museum of Canada, renowned for gathering and recording narratives from Quebecoise and Tsimshian cultures, set out for the Nass. His field notes from that time detail an encounter with a Nisga’a chief from the village of Git’iks. Barbeau, aiming to acquire an impressive pole now known as the pole of Sag aw'een, attempted to purchase it from Chief Sag aw'een, promising to display it in the Royal Ontario Museum. Rejecting the monetary offer, the chief defiantly suggested a trade. “Give me the tombstone of Governor James Douglas,” he said, “I will give you the totem of my grand-uncles.”

Barbeau left the Nass without poles, but the following year, artist Em-

ily Carr made a trip to Laxg alts’ap and Ank’idaa to paint. Anticipating the impending loss, Carr wrote that the poles she’d painted would soon be “carried away to museums” where “they would be labelled as exhibits, dumb before the crowds who gaped…” She feared the poles’ value would be misunderstood, “because the white man did not understand their language.” As predicted, Barbeau returned in 1929. Using photos he took in 1927, he had pre-sold Nisga’a poles to museums around the world and, it seems, devised a new approach. Offering money to an extended relative of Chief Sag aw'een, he secured ‘permission’ to take the pole. Then he continued to Ank’idaa.