PHOTO CONTEST WINNERS REVEALED

PHOTO CONTEST WINNERS REVEALED

THE STORY OF British Columbia’s communities is one of life, death and rebirth. From First Nations villages, fur trade outposts, gold rush towns, logging camps and fishing communities of the past, to the modern villages, towns and cities they evolved into, the last 200 years of BC history has seen an incredible amount of change in how and where people live. As old ways of life fade away, new ones emerge and the cycle continues.

Most recently, this is a trend we’ve seen in many of the former resource towns who are blessed to be surrounded by amazing recreational opportunities. Communities in the Sea-to-Sky corridor, the Comox Valley and the Kootenays have successfully transformed themselves from once-rough, resourceextraction towns to world-renowned destinations for skiers, climbers, hikers, kayakers and mountain bikers. And communities around the province have taken note.

This fall issue features a destination piece on one of the communities that is currently undergoing their own recreational renaissance, Port Alberni. Much like the Comox Valley before it, Port Alberni has long had a somewhat colourful reputation as a rough and ready town of hard-working British Columbians. The amazing outdoor opportunities it offers both hunters and fishers is no secret to anyone, but those looking for hikes, art galleries and craft beer often passed it by in favour of Tofino and Ucluelet, just a couple hours down the Pacific Rim Highway.

Even though the Port Alberni Paper Mill is still up and running as a major employer in the area, the city’s government and businesses have made a concerted effort to diversify their local economy and attract new people to the

town, both to live and to visit. It’s exciting to see passionate folks changing their own stars, and I’m looking forward to my next visit.

Another feature in this issue focusses on the growing mountain bike communities on Vancouver Island. Anyone familiar with mountain biking in BC knows how important volunteer organizations are to the sport. Without people willing to spend their free time negotiating land use agreements, maintaining trails, digging out berms and building wooden features in the forest, there simply wouldn’t be anywhere for people to ride.

Interestingly, it isn’t just mountain bike enthusiasts banding together to create new trail networks, but rather local government and businesses working with them to make their task easier and also boost local economies in the process. It’s this kind of forward-thinking, coordinated effort that creates real, lasting change for the better.

I recently bought a used mountain bike so I could see what all the fuss is about, and let me tell you it’s been an eye opener. I had no idea how many trail networks there were around the province, and how many opportunities there are to discover new areas of BC while using mountain biking as a catalyst. It’s a stark contrast to activities like hiking and fishing, which seem to get more difficult each year.

In many ways, this new-found hobby of mine is a product of all the hard work that mountain biking groups have put in around the province. And go figure. Show people how much fun their sport can be, open opportunities for them to try it and watch your sport (and the tourism dollars) grow.

Dale Miller

Because you Love British Columbia Magazine, you may also enjoy these titles:

Wild Harvest BC

Tips and practical advice, combined with a scientific field guide, Wild Harvest BC is the perfect companion book to take with you on your outdoor adventures.

This is your guide to dozens of spectacular and often hidden beaches on the eastern coast of Vancouver Island between Qualicum and the Malahat.

Popular Day Hikes in South-Central Okanagan describes 35 accessible treks from Kelowna to Osoyoos.

Terry Nelson’s richly illustrated field guide and big tree compendium is filled with fascinating facts and highlights of his adventures from remote backroads of BC.

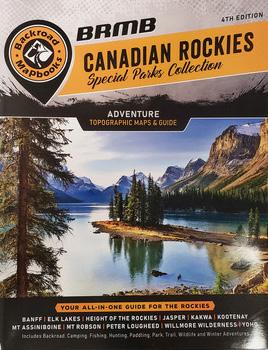

Backroad Mapbooks, Canadian Rockies, Special Park Collection 4th edition

Backroad Mapbooks feature Canada’s most detailed topographic maps and outdoor recreation information.

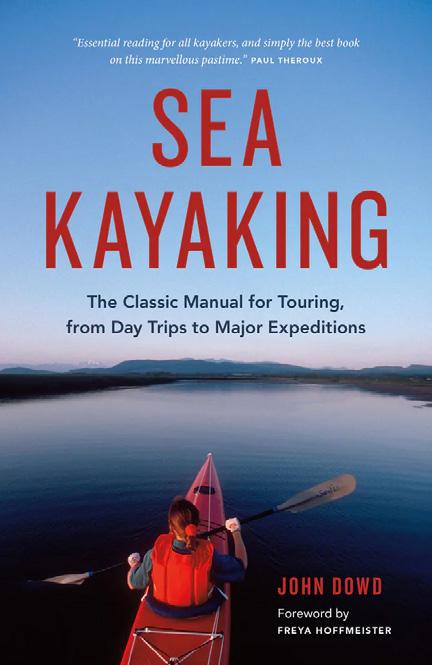

The Classic Manual for Touring from Day Trips to Major Expeditions Still regarded as “the bible” for both new and experienced kayakers after more than 30 years in print and 60,000 copies sold.

Growing up, I remember my parents and grandparents proudly wearing Cowichan sweaters they got from the Duncan area on Vancouver Island in the 1970s. The article in the spring issue brought back lots of memories, not the least of which was the pleasant “sheep smell” that the sweaters had that never went away. Thanks for the memories, I think might find one for myself, but will be careful about who to buy from!

Tom Jeffries, Markham, ON

Thank you for the interesting article about the artists and art in British Columbia (Summer 2024 issue). It is fascinating to discover the variety of artists

and the source of their inspiration, from the whimsical to the spiritual. I would like to tell your readers they can also take selfguided tours of Vancouver’s arts district that is located around Main Street. These art galleries offer a diversity of art that is sure to appeal to the discerning art lover. Learn more and download the map at vancouverartwalk.com.

My family has been subscribing to British Columbia Magazine for more than 20 years and we look forward every season to learn something new about this province. Keep up the good work!

Emilie Davies, North Vancouver

Here in England we enjoy reading British Columbia Magazine, which reminds

us of our many visits to beautiful BC. In the spring issue Jane Mundy worries that the term dumb waiter may not be Politically Correct. In British English dumb means unable to speak. In North American English it means stupid, possibly derived from the biblical phrase “dumb animals,” which correctly means that animals do not use language (at least any words we can understand), but which has become corrupted to mean not intelligent. Jane can rest assured that in the context of the Victorian times in which it was installed, the term dumb waiter is entirely correct.

Dr

Peter

Burdett-Smith, Malvern, England

Wholeheartedly agree with the summer issue editorial on backcountry access in BC. I remember the days when you could drive up to the Squamish Valley or southern Vancouver Island and pick a backroad to drive down on an adventure. I used to take my old Jeep out for the day and check out an old mine site, have lunch and head home. Now we are lucky to have just a handful of roads that are un-gated close to Vancouver or Victoria, and even those are at risk of being gated up. If you want to have a true adventure like the old days you have to drive for hours, which is fine when you’ve got a long weekend but tough when you just want to get out of town.

Bill Jones, Langford, BC

My husband and I have loved all of the foraging stories you’ve been running over the past year or so. It’s turned into a bit of a hobby for us to go out and try and find some forest delicacy to take home and cook a meal with. We were most scared about mushrooms, since we’ve heard there are lots of poisonous ones out there, but reading these articles gave us the confidence to try them out. Having a good reference guide helps too!

Jody Miller, Chilliwack, BC

Glad to hear it Jody, we have been inspired by Linda’s stories as well and have a few favourite items we look for each time we’re out in the forest. Make sure to check out Linda’s new book Wild Harvest BC, which is available at the BC Magazine bookstore at thebookshack.ca. —Eds

Send email to mailbox@bcmag.ca or write to British Columbia Magazine, 1166 Alberni Street, Suite 802, Vancouver, BC, V6E 3Z3. Letters must include your name and address, and may be edited and condensed for publication. Please indicate “not for publication” if you do not wish to have your letter considered for our Mailbox.

We’ve put together a few handy tips from area locals to encourage sustainable travel to our beautiful home. Take the pledge now and learn how you can North Shore, Like a Local.

www.northshorelikealocal.com

BY DIANE SELKIRK

LIKE MANY BRITISH Columbians, I have an old picture of a Martin Mars water bomber in my photo album. It was taken while we were camping at Sproat Lake Provincial Park. The quiet had just been shattered by the thunderous roar of aircraft engines, and my husband and I rushed our preschool daughter to the lake’s edge to see the enormous Martin Mars bomber gliding across the serene water. My own parents had taken my sisters and me to see these same planes. I still recall the thrill of hearing them rumble to life and gasping in awe as they skimmed the lake’s surface, scooping up thousands of litres of water before flying off to fight fires. Before that, my grandfather had taken my mum and her siblings to see the mighty planes—my mum still talks about how exciting it was to go onboard.

With the Hawaii Mars taking flight for a new life as the flagship of a wildfire aviation exhibit at the British Columbia Aviation Museum in North Saanich, I’m probably not alone in reminiscing about these historic planes. But despite their deep connection to our province’s history, perhaps the most remarkable thing about the Martin Mars is that they became our planes at all.

In 1941, just weeks before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, aviation pioneer Glen L. Martin unveiled a prototype for a largescale flying boat to the US Navy. Christened the Martin Mars after the Roman god of war, the plane was originally designed as a long-range bomber but quickly proved more valuable for its transport capabilities. Impressed with the huge seaplane’s ability to fly to Europe and back on a single tank of gas, the Navy ordered 20 of the craft. They took possession of the Hawaii Mars on July 21,

Coulson Aviation

1945, but less than two weeks later it crashed during the test flight on Chesapeake Bay. The US Navy used the event to reduce its order from 20 planes to 11 and then to five. Over the next year, the Philippine Mars, Hawaii II Mars, Marianas Mars, Marshall Mars, and Caroline Mars were launched.

During the final days of the Second World War and the years that followed, the five Mars planes transported troops and cargo between California, Hawaii and the South Pacific, safely flying more than 200,000 passengers and carrying over 20,000 tons of high-priority cargo over a distance equivalent to 23 round trips to the moon. During the Korean War, Hawaii Mars became the world’s largest air ambulance. But by 1959, their role was done, and the US Navy sold the four remaining Martin Mars flying boats for scrap.

At this same time, a group of BC lumber companies (MacMillan Bloedel, TimberWest, and Pacific Forest Products) were grappling with how to manage forest fires. Joining forces, they formed Forest Industries Flying Tankers (FIFT) and found the four Martin Mars when they were searching for large flying boats to turn into water bombers. They bought the four aircraft for $25,000 each, and with a stroke of foresight, they also bought every spare part they could find, including several crates of US Navy factory-new spares.

The Marianas Mars was the first of the four to be adapted for firefighting. FIFT engineers removed military equipment, installed water tanks and added the famous retractable scoops that allowed it to fill its water

tanks while skimming across the water. In May 1960, reporters and onlookers in Sidney watched as the newly outfitted Marianas flew across the ocean at 120 kilometres per hour, scooped up 27,000 litres of water and dumped it in front of the crowd—demonstrating the capacity to fight fires like never before. Sadly, two of the four aircraft were soon lost: the Marianas in a crash in 1961, taking the lives of all four crew members, and the Caroline Mars was damaged beyond repair during a 1962 storm. Despite the rough start, FIFT pushed on, and the Philippine and Hawaii II were soon cloaked in their distinctive red and white paint and sent into action from their new base at Sproat Lake.

The planes performed what many called miracles. In 1998, during the Silver Creek Fire in Salmon Arm, 7,000 people were forced from their homes in the largest civil evacuation in BC’s history (to that point). Locals still recall how reassuring it was to see the massive airboats arrive and how they learned to tell the identical planes apart: Philippine Mars

had a white tail while Hawaii Mars had a red one. Every day, from August 3rd until August 15th, the big planes fought to save the town and surrounds. But on their final day, they circled Salmon Arm, scooped up water from the lake, flew up the valley to the fire site, and then returned to dump their loads back into Shuswap Lake. This was the signal to the community that the fire was out.

With the forestry industry changing, the Coulson Group acquired the planes in 2007. But the Martin Mars were aging, and those spare parts were beginning to run out. Firefighting tactics had also shifted; the focus became less on dousing a fire completely and instead aimed to contain them and keep them away from structures. The forest was left to burn as it would naturally. When the bombers were needed, the Mars’ incredible size also restricted their operational range; BC doesn’t have enough large lakes in the right places. The province ended its Martin Mars contract with Coulson in 2013.

The final flight of Hawaii

The Hawaii Mars Exhibit will officially open Saturday, September 28, 2024. Visitors to the BC Aviation Museum at 1910 Norseman Rd, North Saanich will be able to explore inside the aircraft and even climb four stories above ground to sit in the pilot’s seat.

Mars was over a year in the making. To get from Sproat Lake to Sidney and the museum, Coulson Aviation enlisted five former maintenance engineers and four flight crew to complete about 10,000 hours of aircraft preparation and flight retraining over six months.

Wayne Coulson, CEO of the Coulson Group of companies, said in a statement he was pleased to partner with the BC Aviation Museum in the “important endeavour” of preserving the plane. “The Hawaii Martin Mars water bomber is an amazing aircraft,” Coulson said. “You will probably never see one fly again.”

The province also contrib-

uted a one-time grant of $250,000, with Lana Popham, minister of tourism, arts, culture and sport, calling the aircraft a proud symbol of BC’s ingenuity and innovation. “We recognize the value the Hawaii Martin Mars water bomber holds for many people and have heard their desire to have it protected as an important piece of our province’s history,” she said.

Now, as the Hawaii Mars begins its new chapter at the museum, I can’t help but recall the distinctive sound of her engines as she rumbled overhead, and the relief in knowing she’d come to help. The nostalgia feels bigger than a memory of watching a giant plane scoop up water and take flight—and different than an appreciation for innovation or engineering. It’s more like that sense of affection and connection that we hold for an old sailing ship; the kind we know can weather storms and keep us safe at sea. It’s comforting to know that future generations will have the chance to create their own memories and marvel at this remarkable aircraft, just as we did.

THERE ARE NOW designated spaces on the upper outer decks of the Spirit of British Columbia and Spirit of Vancouver Island on the Tsawwassen and Swartz Bay route. Dogs on leashes and cats in carriers, accompanied by their owners, can now enjoy the outdoor area.

“These new pet areas mean extra comfort for canine and feline friends and family members—and their people—through the peak season and beyond,” says Melanie Lucia, vicepresident of customer experience at BC Ferries. “Transport Canada regulations are clear that our customers can’t stay in their vehicles when they’re parked on

an enclosed car deck. By growing the number of safe, accessible pet spaces on our biggest ships, we are also providing a better experience for pet parents parked on our lower car decks so they have the choice to get outside with their animals.”

There are regulations to take note of while utilizing the area; dogs must be kept on a one-metre leash at all times, cats must be in a travel carrier, and pets with owners are to remain in the designated area. As well, waste bags and water bowls are provided and the area will be cleaned regularly.

For more information on travelling with pets, visit bcferries.com.

by Jan Garnett

WHAT DO Canada’s Gulf Islands, humpback whales, the RCMP witness protection society, landscaping design, a movie star, a kayak and a decommissioned lighthouse share with Kathleen (Kot) Cafferty? They are all under the covers of No Safe House, a debut mystery by Pender Islander, Jan Garnett.

Shortlisted for the 2023 Crime Writers of Canada Best Unpublished Manuscript Award, this mystery packs in a lot of explosive action and draws together three resilient females, two of whom you could say are

in over their heads. That would be 12-year-old Camus, a First Nations girl who, in escaping her abusive stepfather, is washed ashore on a Gulf Island, near that decommissioned lighthouse, and Kot Cafferty who witnessed a shooting of her married boyfriend in the Port of Vancouver and then found herself encapsulated in a safe house without knowing what was going on, and Kot’s best friend, Mich, who never does realize her role in enabling the reluctant hired killer to find Kot a second time.

The first time was, of course, in the safe house, when our heroine escaped a powerful blast that demolished the home and sent her scarpering to safety in a kayak with her dog, Medley.

This is where it starts to get fun because west coast readers will recognize many of the places

where Kot and Camus wind up. Who knows what island almost came to a civil war over a millionaire showing up on the island with his helicopter? Or what island has a decommissioned lighthouse? Or what marina has cabins to rent out? Recognizing the places and sometimes even the people is part of the game. Some of the islands, like D’Arcy for example, are identified by

their real names, but then you have Atticus, which is not. So guess away!

A kayaker herself, Garnett did a fairly hefty amount of research on drug dealing through the Port of Vancouver, but came by her knowledge of landscaping and her knowledge of the Nature Conservancy of Canada through her various professional careers.

How much research did she do on whales? Well, enough to discover a few amazing things about these gargantuan mammals, but that would be giving away the ending.

It’s a rollicking read.

—Cherie Thiessen

(Available in e-book, or soft or hard cover at many island bookstores, or go to the author’s website to order. jangarnett.com).

TO PREVENT THE spread of invasive whirling disease parasites, as well as zebra and quagga mussels, BC’s chief veterinarian has issued a new rule making it illegal to transport watercraft with the drain plug still in place.

Whirling disease is caused by a microscopic parasite (Myxobolus cerebralis) that infects both fish and freshwater worms during different phases of its lifecycle. First, the worms develop triactinomyxon, which then infect fish, eventually causing their spine’s cartilage to deform and making the fish “whirl” while swimming. The disease can attack and kill many of the young populations

of trout, salmon and whitefish, among other species. No treatment is currently available to eradicate whirling disease.

The ministry states there are no health concerns for people swimming in or drinking water that contains whirling disease.

The invasive zebra and quagga mussels are also a threat. They can significantly change aquatic food webs and bundles of them can clog water intakes and pipes of hydro facilities, agricultural water mains and city water systems. In the ocean, they filter plankton out of the water, which depletes it as a food source for native species. They can also glom onto your boat and cut your

feet when they attach to rocks and beaches.

These invasive mussels can survive for several weeks outside of the water if left in a cool and moist environment. Just one litre of water can contain 9,000 microscopic free-swimming larvae that can survive for several weeks, and those

attached to boats or equipment can survive a trip between different bodies of water. That’s why it is crucial to eliminate standing water. So pull the plug on your boat and clean and dry internal compartments, ballasts, bilges and live wells when on dry land.

—Marianne Scott

ATTRACTION

A museum like no other

BY CHERIE THIESSEN

WHEN JIM SHOCKEY

bought the old elementary school where his two children had gone to school years earlier, no one really noticed. When he opened the old 17,000 square-foot building as a museum in 2018, no one really noticed. That was fine with Shockey. A sole billboard upon entering the Vancouver Island town of Duncan advertises his passion, but that’s pretty much it. Unlike the man himself, the museum’s birth and existence is surprisingly low keyed. Since he was 10, Jim Shockey wanted to open a

museum—no being a fireman or ship’s captain for him. He held fast to that dream. “If you drive somewhere for 50 years and don’t take any sideroads, you wind up somewhere, and this is where I wound up.” That ‘somewhere’ is in the small community of Maple Bay near Duncan where despite the lack of advertising, his museum is becoming a serious attraction, attracting over 1,000 visitors annually from all over the world.

Open 365 days a year, The Hand of Man Museum is a warren of surprises that will intrigue even restless children.

Where else are they going to be dwarfed by prehistoric creatures? The anatomically correct casts of dinosaur skeletons take centre stage in the gym, and the 20,000-yearold white tusk and femur bone

of a woolly mammoth are definitely not what you would expect to see in an out-ofthe-way small town museum. It sets the stage, though, for other remarkable exhibits, like the showcase of first edition books, one of them signed by Sir John Franklin and another that dates back to 1507! How the ‘curator’ acquired these objects is another story altogether. A world traveller, photographer, big game outfitter and filmmaker, he spent 52 years collecting artifacts: taxidermy animals, prehistoric skeletons, tribal artifacts, art, instruments, all are carefully

preserved in room after room. I’m constantly reminded that this was once a school as I wander in and out. Turns out that a disused elementary school is actually a terrific venue for a museum like this. While he emphasizes that this is not a hunting museum, visitors should be aware that many of the animals they’ll see here are going to look suspiciously like trophies from someone who Outdoor Life once called the most accomplished big game hunter of the modern era. However, it would be a mistake to dismiss Hand of Man because of this. There are treasures here well worth seeing and more and more visitors are arriving these days to see them.

handofmanmuseum.com

No longer just a mid-island resource town, Port Alberni is changing its own fortune and open for tourism

BY JANE MUNDY

Most people on their way to Tofino and Ucluelet have stopped in Port Alberni—for gas. Years ago, they drove through the smelly slate-grey town at break-neck speed toward the west coast’s pristine beaches. Nowadays the “build it and they will come” adage applies to this former mill town— “they” being tourists and young families.

Originally named for the 18th century Spanish military commander Don Pedro de Alberni, Port Alberni, situated at the end of Vancouver Island’s Alberni Inlet, is shaking off its roots as just a logging, milling and fishing hub and evolving into a destination for culture and history lovers. In fact, its dining scene beats Tofino— since it’s affordable and you can actually get a seat. Oh yeah, the town is surrounded by several lakes, has incredible hiking and biking trails and fishing—convinced yet?

Scott Lemkay moved here five years ago, when he saw PA as a “diamond in the rough.” Since then, he and many residents, along with mayor Sharie Minions, have polished their town into a gem. “Our mayor forced a logging company to sell off a big chunk of land, and now old factory buildings are being demolished to make way for walkway paths and mixed income living spaces,” says Lemkay. “Revitalization projects are attracting small business and making our town affordable.” (The City of Port Alberni recently bought the 43acre waterfront property, formerly the Somass sawmill site.)

One of those projects is a four-kilometre pathway connecting Harbour Quay to Victoria Quay along the waterfront. The pathway will also be routed through, and to, other major Port Alberni destinations such as Roger Creek Park, Somass Lands, and the historic train station (which is being restored and runs until Labour Day) at Harbour Road and Argyle Street. It will be completed this fall. Minions’ goal is to preserve the community’s waterfront access forever.

“Key is to keep a working waterfront and not hide the fascinating shipbuilding industry,” says the 35-year-old mayor.

Minions is quick to list off-season attractions. “ROAV is a mountain biking non-profit organization that is building and maintaining multi-use trails outside city limits—we’re working on signage. And there’s stormwatching here too.” Take a day trip on the Frances Barkley, a historic working ship that delivers and picks up mail and supplies to tiny communities on its way up the inlet to Bamfield—watch the crew take death-defying leaps to flimsy docks. It leaves the harbour at 7:30 am and returns down the inlet around 5:00 pm.

Lemkay describes a perfect day. “At sunrise and a six-minute drive from town to a peaceful wilderness forest I hit the trails with my dogs for bear

watching and berry picking. It’s the Quay for breakfast, an oceanside stroll and if it’s Saturday morning, Spirit Square Market draws a few hundred shoppers. Then I head to the lake with my boat before watching the sun fall behind the mountains.”

“True story—my friends in Campbell River come here to fish because hands down we are the salmon capital of the world,” says Mike Lambert, who owns and operates three boats with Action Packed Charters along with his First Nations partner Carla Halverson. Campbell River might disagree, even though Lambert boasts that your chance of catching a fish (which could include catch-and-release) is 99 percent. Regardless, you’re “guaranteed a blast” and there’s awesome scenery.

“Guests from the mainland one afternoon caught over a dozen catchand-release, kept five sockeye, a spring salmon, a rock cod and sea bass—it’s all about timing,” he added. You can buy a license online but Lambert says it’s easier at Gone Fishing, the local sporting goods store.

The city boundary sits within the traditional territories of the Hupačasath and Tseshat First Nations. The Hupačasath invite visitors with traditional male and female welcome figures at Victoria Quay and the Alberni Valley Museum houses an extensive collection of First Nations art and artifacts. This fall the museum showcases an aquaculture installation including Indigenous components such as clam gardens and kelp farming.

Step back in time to almost a century ago at McLean Mill. A private 90-minute tour with historic interpreter Elliot Drew will give you the full story of this family business that ran from 1926 until 1965 but you’re welcome to explore the preserved sawmill and camp where loggers and millers lived. This 13-hecatre forested area comprises of 35 buildings, engines and cars surrounding a steam powered sawmill and mill pond. At the Maritime Discovery Centre,

While tubing the Stamp River, I reverted back to my childhood. We started out just past the falls, inching our way at first into jadegreen pools bursting with salmon. The river was warm as bath water, and relaxing, but we actually shot a few rapids! Interspersed with a Huck Finn-like nonchalance was roller-coaster hysteria as we clung, white-knuckled, to our life support inner tubes (with a few inches of water below us in most places, but part of the fun was screaming). Then back to another leisurely float to the next set of ‘rapids’. Downriver we waved to the locals in their backyards, gawked at eagles and listened to nothing but gurgling water and bird calls. It was four hours of sheer fun.

guide Faith Sutton tells me that her family has been here four generations. “I’ve heard so many stories from visitors sharing their marine history and realize we have so much in common,” she says. “We live in such a great place with boats constantly coming into the harbour,” says guide and sea cadet Sarah Whitehouse, age 19. “I have a perfect job here, meeting people who grew up on boats, and they help me appreciate our coast.” Kids love this place—just about everything is touchable, so much so that one kid pulled down the rigging while another was turning the wheel on the bridge. I could have spent more than an hour perusing the displays, pulling the steam whistle on the Swan (amazing story about her resurrection) and walking around the lighthouse.

DINING I sidled up to the bar at Antidote Distillery, ordered a black gin fizz, and gave my head a shake: how had I landed in NYC or Vancouver? And what the heck is black gin, besides smooth, earthy and delicious?

“A local company called ‘Forest for Dinner’ forages mushrooms, juniper and spruce tips that go into my gin,” says owner Nilo Du Plessis, “and the blue oyster mushrooms are produced at Port Alberni Shelter Farm.” Du Plessis also

The Hole in the Wall was once a shortcut for the town’s water supply back in 1915, and you can still see remnants of the old pipeline. A 15-minute drive gets you to Coombs Country Candy, and the trail starts across the street at the “Mosaic private property” sign. From there it’s a 15-minute walk down a gentle incline, turn right at the first intersection and veer to the left. There is no signage except near the trail end—I relied on Google Maps. Kids love this spot so go early and bring a bathing suit.

supports local breweries and wineries, bakeries and butchers. There’s a food truck inside this gastro pub serving up the best burgers (according to the locals at the next table). “You can have a fancy night here but if you’re a White Spot fan the food truck could be welcoming and you can come in wearing flip flops.”

Like Lemkay, Du Plessis moved here six years ago and saw Port Alberni on the knife edge of explosion or slumber, then Covid hit. “We saw an influx of young professionals who could afford a house and work remotely and suddenly felt a change. Another brewery and Broken Bow restaurant opened and my wife and I wanted to be part of this growth. We fell in love with PA. ”

On Mayor Minion’s advice (she needs the huevos rancheros at least once a week) I had breakfast at Broken Bow at the Harbour Quay and it didn’t disappoint. If you can’t decide on the eggs benedict or waffles, combine both. The entire menu is gluten-free, as is Bare Bones Fish House & Smokery, housed in a former 1950s church. I had the freshest halibut cloaked in crispy tempura batter and my server said the seafood is locally sourced pretty much year-round. My next stop was Dog Mountain Brewing, with the only roof top patio in town, and next door is their coffee roasting company.

Before leaving town, I was told that nobody can resist a salted caramel at the iconic Donut Shop. True. Then I

If You Go

Eat and Drink: The Broken Bow, 5405 Argyle St. 778-421-7542 for takeout

Antidote Distillery antidotedistillingco.com

Wildflower Bakeshop & Café cafewildflower.ca

Bare Bones Fish House & Smokery barebonesfishhouse.ca

Dog Mountain Brewing dogmountainbrew.com

grabbed a gourmet pastry and espresso at Wildflower café and bakery, looked at the menu and the outdoor patio packed with young families. Note to self: have lunch and dinner here next visit. Everything eating and drinking is within walking distance—and you’re guaranteed to get a seat, even when the cuisine rivals that other place. And it’s affordable.

“You build a community for people to live and tourism will follow,” says Mayor Minions. “We are working on a hotel joint venture with three First Nations, and the waterfront development will include mixed use commercial and residential and a brewery district. It’s exciting to see younger people moving here, buying an affordable house and investing in business: we feel the vibe, we feel momentum and change happening.”

CATEGORY: ADVENTURE

Garrett Jung

Location: Stave Lake, Mission

Congratulations to all the winners and runners-up in the 2024 British Columbia Magazine Photo Contest. The staff at British Columbia Magazine were once again thrilled to check out each and every entry we received.

At BC Magazine we see the photo contest as an annual celebration of all the things that make our province great, and a chance to share the excitement of discovery with others. From amazing drone-footage landscapes to iconic urban scenes, all kinds of stunning wildlife and even underwater photography, we are excited to share this year’s selection of amazing BC images with our readers.

We have tried to include camera and photo data along with the images, which will hopefully inspire some of you when taking your own shots.

We hope you enjoy this year’s selections as much as we do, and we look forward to next year’s entries!—Eds

Honourable Mention

Jake Huang

Location: False Creek, Vancouver

Honourable Mention

Carol Horn

Location: Kelowna

IPHONE X5: 1/1800 SEC | F/1.8 | ISO 25

Category:

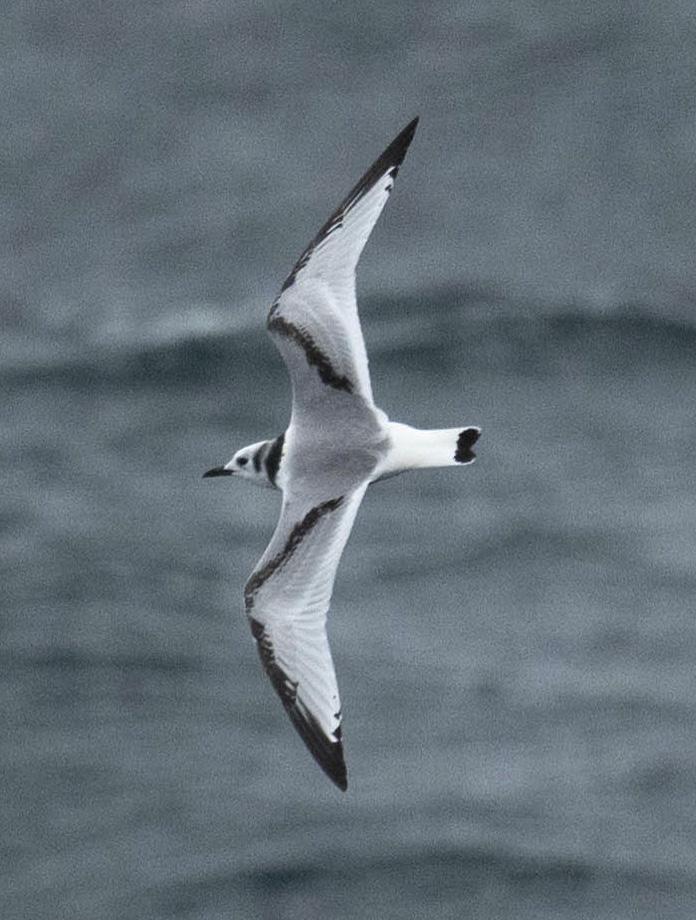

CATEGORY WINNER

Aiden Conners

Location: Barkley Sound, Vancouver Island

SONY ILCE-7RM4: 1/200 SEC | F/8 | ISO 800

Location: Gabriola Island SONY ILCE-7RM4: 1/1000 SEC | F/6.3 | ISO 320

Location: Jericho Beach, Vancouver

PENTAX K-1: 1/800 SEC | F/81 | ISO 800

Category: SCENIC

Raj Deepak

Location: Sandcut Beach, Vancouver Island

SONY ILCE-7M3: 260 SEC | F/1.8 | ISO 4000

Honourable Mention

Kevin Dahl

Location: Cox Bay, Tofino Category:

Honourable Mention

Darcy Monchak

Location: Bugaboo Provincial Park

Visiting sawmill ghost towns and lingering villages along Northern BC’s East Line

BY LINDA GABRIS

IfIf you want to travel back in time, tracing the heavily-trodden steel rail tracks of our forefathers, taking the nostaligic East Line may be just the ticket. This road trip takes you through the old sawmill ghost towns and lingering historical villages dotting a relatively short but very memorable stretch of the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway (GTP).

The East Line, as it is dubbed, refers to the GTP rail line of today’s Canadian National Railway (CNR), which runs parallel to and never strays far from the Fraser River. It makes its way through backcountry from Prince George to McBride, surrounded by towering mountains and gullied by the renowned waterway which served Indigenous people, explorers, trappers, traders, steamboaters, railroaders, lumberjacks and settlers throughout history.

Until the tracks of the East Line were laid, the only mode of transportation through this remote stretch of the Rocky Mountain trench was the Fraser River, so there were few footprints into the rugged country. However, as the GTP tracks forged westward they allowed easy access into the vast expanses of virgin timberlands and with the growing demands for lumber needed for the hundreds of miles of railway ties still waiting to be laid ahead, the boom was on and springing up almost magically overnight, were swarms of sawmill towns buzzing along the tracks.

But the boom busted within a hundred years, leaving a slew of scattered

ghost towns and a few lingering villages along the tracks. You can visit the majority of these historical sites by touring the drivable portion of East Line, the main route, which can be done as a day trip, beginning in Prince George and ending in Penny (130 kilometres). If you wish to have more leisurely time to poke around the ghost towns and stroll through the countryside, hike, bike, fish, kayak, paddle and picnic (yes, take along food because there’s only two spots to buy eats) then turning it into overnighter is the way to go and, good news is, there’s some peaceful, self-maintained forestry campgrounds along the way for pitching camp.

Prime seasons for touring the East Line are summer and fall as the unpaved portion of the road can be very muddy and almost impassable in the spring. The East Line dishes up endless opportunities for winter sports including ice-fishing, cross country skiing and snowmobiling but be sure to go prepared for rural winter driving.

Leaving Prince George on the Yellowhead Highway 16 East, you’ll cross the modern-day Fraser River Bridge. Downriver sits the beautiful Lheidli T’enneh Memorial Park (previously known as Fort George) and short distance upriver spans the GTP truss rail bridge built in 1914, a year before the founding of the City of Prince George. In the early days, this old bascule bridge (meaning the middle span opened to allow shipping on the river) was one of the longest railway bridges in Canada.

When my family moved to BC from Ontario in 1970, we lived in several different sawmill villages along the East Line so coming to town meant crossing the old bridge, which was usually congested and a little nerve-wracking, feeling the overloaded steel bridge vibrating under the weight of the train. Today I am happy to salute the old bridge for its many years of service, but from a safe distance away!

SHELLEY The first stop on the East Line is Shelley (about 21 kilometres) which was a thriving sawmill town until the mill closed in 1990, causing a loss of 100 jobs and a dwindling population. Shelley is home to the Lheidli T’enneh Nation who were relocated to this site from their ancestral home in 1913, after the explorer Simon Fraser set up a bustling

fur trading post in 1807, on the banks of the Fraser River, overtaking the longsettled Lheidli T’enneh village.

After the band was moved to the Shelley reservation, the fur-trading site became known as Fort George, which later grew into Prince George. In more recent years, Fort George was renamed the Lheidli T’enneh Memorial Park to pay tribute to the “people of the land.” While passing through Shelley, be sure to visit the Tano Fuel Station which is a boost to the band’s economy and a friendly place to chat with the locals while picking up some treats before venturing onward.

Leaving Shelley, instead of backtracking, take the graveled Beaver Forestry Service Road (BFSR), a short jaunt out to the paved Upper Fraser Road (UFR).

At the junction there’s a must-see sidetrip so cross the main road and continue on the BFSR for about another 10 kilometres, which delivers you to a lofty logging bridge over the Willow River, a major tributary of the Fraser. The high,

narrow bridge offers a bird’s-eye view of the river which has raging rapids and huge outcropping slabs of bedrock.

WILLOW RIVER Backtrack to the UFR, and continue to the community of Willow River (about 20 kilometres). This pretty village sits at the confluence of the Fraser and Willow rivers. The willow flats and marshes around the merging rivers are popular with big game hunters, especially those hoping to set their sights on moose, so have your camera ready.

During the boom, Willow River boasted a population of 1,500, but today it houses about 150 residents. Be sure to pop into the historical Willow River General Store, still flaunting its original Telegraph and Cable Sign on the front porch (a reminder of how busy this town once was) and if you need food or fuel this is the last stop for tanking up. And if you’re there on a Sunday in summer you can visit the farmer’s market offering

produce, homemade preserves, handicrafts and a concession stand… so don’t leave empty-handed!

GISCOME Ten kilometers further is the remnants of Giscome, one of the last mills in the area running on its own steam and also one of the longest surviving mills on the East Line. Sitting on the nose of Eaglet Lake, this was a lively sawmill town from 1914 to 1975, and, I’m happy to say, my family enjoyed living in Giscome from 1970 until the mill closed down at which time we, like many other families whose livelihoods revolved around the lumber industry, packed up and followed the flow of millworkers further along the East Line.

The foundation of the giant Cant/ Swede Gang Saw marks the spot where the mill once stood, a silent reminder of days gone by. Giscome has a spread of rich farmland, a few private homes and a newly erected schoolhouse serving Willow River and remaining communities

along the line. There’s an old church sitting in the valley, and if you’re a movie buff take note, this forlorn church earned fame in 1999 when it was featured in the final scene of the motion picture, Reindeer Games.

Onward, the UFR hugs the shoreline of Eaglet Lake for about eight kilometres. There’s a couple pull-overs along the lake where small craft can be launched. Long strings of boxcars and freight carriages constantly chug along the East Line on the far side of the lake proving the rail is as important today for trade and commerce as it was since the tracks were first laid! Along the roadside is a steep rocky

cliff that’s popular with amateur climbers and towering in the distance are the majestic McGregor Mountains, wearing their year-round snow-caps.

Before steering away from the lake you can rest up at the Harold Mann Regional Park, named after the pioneer credited with introducing logging trucks to the region, making the days of skidding logs with a team of horses a thing of the past. The well-groomed day-use park offers picnic tables, firepits, outhouses and covered shelter for picnicking on rainy days.

NEWLANDS The next GTP station is Newlands, established in 1928 with in-

tentions of drawing settlers into the area to break ground farming, because with the rapid growth in population along the East Line there was a shortage of food supplies. When the 1930 depression hit, it put a damper on farming and even though a sawmill sustained the area for a number of years, all that remains today is a spread of agricultural land, a few old buildings and a road sign marking the site. The road is fringed with Saskatoon brushes and, in fruiting season, you can almost always find a black bear gorging on the berries, a sight that never loses its thrill! And it’s common to see herds of deer, browsing knee-deep in the hayfields along the UFR.

NEWLANDS Up the road and around the bend, is Aleza Lake, the town whose sawmill cut the majority of railways ties for the GTP. The feature attraction here is a 9,000 hectare parcel of land which makes up the Aleza Lake Forestry Research Station (watch for the sign) used by the University of Northern BC, as well as other educational groups studying ecosystems within the Sub-Boreal Spruce Zone. The reserve is open to the public and there is a kiosk at the visitor centre where you’ll find an information board and trail maps for some scenic hikes.

UPPER FRASER Back on the road, a few kilometres further, brings you to Upper Fraser, sitting on the banks of the river. This site housed the most modern, largest and one of the longest surviving mills on the East Line, holding ground until 2003. During its years of operation, Upper Fraser Sawmill was also the largest lumber producer in the province. My family made our home in Upper Fraser for more than 10 years and loved the easy access to all kinds of year-round outdoor sports and recreation.

All that’s left of the townsite today is the cement silo burner still towering in the millyard, a few private homes and tumbling shacks. In 1969, Northwood, a company owned by Noranda Mines, took over the sawmills that were still operating on the East Line, and in 1999, Canfor purchased the Northwood holdings that included Upper Fraser. In 2003, the Upper Fraser sawmill closed down permanently and the company owned townhouses were demolished.

HANSARD Leaving Upper Fraser, you’re 90 kilometres from the starting point in Prince George and this is where the paved road ends. Following the gravel road, you’ll cross the Fraser River over the new bridge built in 2004. Up until that point, traffic and trains shared the old GTP Hansard Bridge, built in 1914, which was one of only two bridges of its kind still operating in Canada before the new bridge was erected. You can see the historic bridge upriver, twinning the new bridge and still serving the CNR.

After crossing the bridge, you’ll come to two junctions marked with forestry service road signs offering exciting sidetrips should you have the time to stray from the main route. Pointing north are three secluded lakes—Amanita, Boundary and Freya which have forestry campgrounds offering canoeing, fishing and swimming. This North Fraser Logging Road is an alternate route leading out to the John Hart Highway, exiting about 40 kilometres north of Prince George, not far from the historic Huble’s Homestead, worth keeping in mind should you decide to make a circle tour homeward instead of backtracking on the UFR.

MCGREGOR On the sign, pointing in the opposite direction is Pass Lake (great for canoeing) and McGregor River (popular with fishermen and big game hunters), scenic Kittil Falls and the challenging Red Mountain Trail, which winds through 800 year old cedar stands, affording views of Robson Valley to the south. The McGregor Road also leads to the Torpy River which used to be a major salmon spawning ground but, judging from our last few visits to view the spectacular sight, the numbers of spawners had greatly declined.

This road also leads to the Evanoff Park where you’ll find the trailhead for the Fang Cave complex, which includes the Tooth Decave and Window on the West. These captivating caves have gained recognition on the Cavers Map as being the ninth longest cave system in Canada and recommended for experienced spelunkers and climbers only. There are scenic trails in the park so pick up a map before venturing into these remote woodlands and be cautious because you’re in grizzly bear country now so keep your bangers and spray handy.

Sticking to the main East Line route, continue to drive past the McGregor Logging Road junction where you’ll be astonished to see mountainous piles of logs covering the old townsite of McGregor, which at one time was a booming sawmill community. Today, the massive amount of logs piled in the landing for as far as the eye can see is testimony to the fact that the lumber industry still

plays a major role in the economy of Northern BC.

SINCLAIR MILLS Follow the sign to Sinclair Mills. During the building of the GTP, this area was dubbed “Mile 180,” being the distance, by rail, to the Alberta border. Sinclair Mills was a thriving sawmill town until the operation shut down in 1966. A few years

later the entire town was sold to a local entrepreneur, a skilled chef named Ervin who turned the old bunkhouse into a restaurant called The Hideaway Inn that had enough clientele scattered along the East Line to keep it running for several years. My family went there often from Upper Fraser, crossing the old Hansard bridge, for a Saturday night dance or a Sunday night dinner. The establishment burnt down in 1989 but the memories of good food and great entertainment will always be remembered by many of us “East-Liners.”

LONGWORTH Ten minutes further is Longworth, which had its first mill in 1915, and by the 1920s, it was running double-shifts, producing an astonishing 18,000 board feet of lumber a day. By 1924, Longworth, like many of the other sawmill towns along the line, had a school, church, dancehall, general store,

post office and some loyal residents who had fallen in love with the area and, instead of moving onward after the mill closed down, they stayed in the fertile Fraser River Valley and turned to farming for a living. Today it is a peaceful little village scattered with pretty country homes and gardens.

Friendly local folks will welcome you to their community centre to visit and even shop for some beautiful handicrafts such as patchwork quilts, aprons, pillows and homemade preserves, and during the summer you can even buy fresh produce, baking and other goodies before saying goodbye and taking off to the end of the “drivable” portion of the line.

And I stress the word “driveable” because the road to Penny, another sawmill town that boomed before busting, is often impassable, especially in off-seasons. When the road is ser-

viceable, you will find a community hall and a village with about 20 residents. With the coming of “back-tothe-land” movement that peaked in the 1970s, tree planting companies and fire suppression crews made up of mostly hippies (US draft dodgers) lived commune-style in what was dubbed the “Buffalo Wallow.” As the movement died down, so did the town.

The last time I drove down the Penny Access Road to the Fraser River a few years ago, the old beehive burner was still standing on the far side of the river.

Now it’s time to backtrack the UFR to the starting point. At the junction of the Yellowhead Highway 16 East you

More

Eat

Joe Boo’s Fast and Fresh Mobile Eatery beside the Dome Creek turn-off, dishing up great food, good prices, friendly service and the only eatery between McBride and Prince George.

See

have the option of heading west to return to Prince George or continuing east to visit the last few remaining historical sites on the East Line.

These were all once booming sawmill towns but today, like most of the others along the tracks, they have dwindled to a few homesteads, scattered farms and summer cottages, but logging continues intermittently in the region. A local lodge at Crescent Spur offers year-round outdoor sports and recreation including heli-skiing and snowmobiling. From the “Spur” it’s a short drive to McBride so why not venture on into town and shop around before heading homeward.

MCBRIDE Unlike most of the other dwindling settlements along the East Line, McBride continued to grow and flourish with its livelihood mostly revolving around agriculture in the rich fertile Robson and Fraser river valleys

and year-round tourism. McBride is a very important stop for travellers going west as there is no gas and only one food service on the 400 kilometre highway to Prince George.

While in town be sure to visit the McBride Heritage Railway Station, built in 1919, featuring an art gallery displaying works of local artists. You can pick up brochures and maps for area attractions and there’s a new “Beanery,” which in the early days of railroading referred to a “cheap eatery” that only served beans. I once heard a hardy old timer’s joke, “there were always plenty enough blasters on an old tin plate to blow you away…”

Leaving McBride, it’s time to head back to Prince George, the original direction in which the East Line tracks were laid. But don’t come down from that Rocky Mountain “high” just yet because there’s still some points of interest (see sidebar) which are not considered to be part of the East Line tour but well worth jotting down on the agenda.

The Ancient Forest which is a unique ecosystem and part of what is believed to be the only inland temperate rainforest in the world. There are boardwalks for leisurely walks which lead through a breathtaking stand of giant 1,000-year old cedar trees.

Watch for the Chun T’oh Whudujut Provincial Park sign, on the left side of the road, just a little further down the highway from the Ancient Forest where the sign announces the Driscoll Ridge Trail, 15.6 kilometres. This challenging trail is loaded with breathtaking views of mountains and the famed river. It is a rather steep loop trail through the deep wilderness so study the map before taking off.

Heading homeward, you’ll cross bridges over the Bowron and Willow rivers. You’ll find a rest stop at the Willow River alongside a 19 kilometre interpretive trail, an easy nature hike where you can admire some of the area’s flora and fauna before enjoying the rest of the short ride back to Prince George.

Vancouver Island towns see a sustainable future in mountain biking and trails

STORY RYAN STUART

PHOTOS DAVE SILVER

It’s just a bump in the trail, but to Chad Hendren it’s an excuse to fly. Pedalling his mountain bike down the Found Link trail in the Cumberland trail network he goes from adhering to the rules of gravity to being four feet in the air. Following behind, my bike barely bumps over his launch pad.

Such is the talent of gifted mountain bikers, like Hendren. They see trails in a third dimension—an avian one—that I will never understand. I console my ego with the knowledge that Hendren lives on a bike. He raced mountain bikes in the 1990s and has been working in the industry ever since.

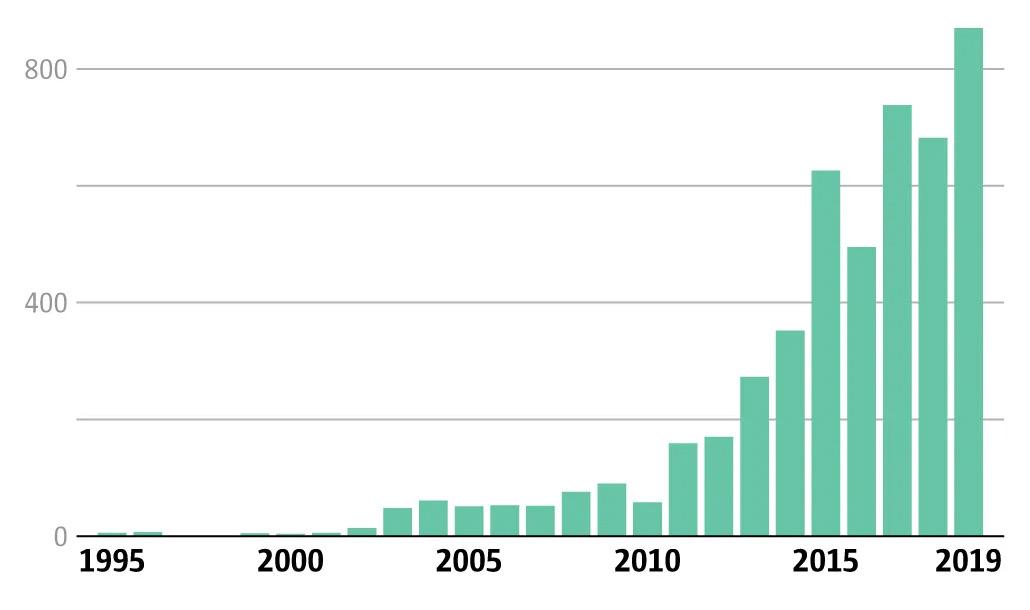

I signed up to this humbling experience in an effort to understand how trails can turn into cents. Over the last few years bike clubs, economic development organizations and tourism promotion companies have been spending millions of dollars building mountain bike networks on Vancouver Island, sometimes from scratch. They believe investing in trails is a path to healthy communities and a sustainable economy. The case study they’re following is the village of Cumberland and Hendren is part of the proof.

Twenty five years ago Cumberland was a resource town suffering a prolonged bust. Dunsmuir Avenue, the main street, was mostly boarded up buildings. But living there was cheap and the forest started two blocks from downtown. Skiers and mountain bikers moved in. Visionary locals started building trails for their own enjoyment. Little did they know they were changing the town’s fortunes, one shovel of dirt, one wooden bridge at a time.

The mountain bike trails attracted more riders, who drank more coffee, ate more pizza and bought more things. The more trails they built, the more riders came, the more businesses opened, the more people that moved to town, who built more trails. The cycle kept spinning.

Eight years ago, Hendren and his partner CJ moved to the Comox Valley on

Vancouver Island’s east coast from Whistler. They started riding Cumberland’s emerging world class trail network and realized no one was offering kids mountain bike camps. They started Gravity MTB, a training and coaching academy. They train some of the top junior mountain bikers in the country. Last year the couple expanded their operation by opening Gravity Garage. It’s like a mountain bike community centre with merchandise, bike demos, a fitness facility, suspension service and an event space. Gravity Garage is part of Cumberland’s booming trail-driven economy. An economic impact study in 2016 found visiting mountain bikers spent an average of $93 per person, per day on food, accommodation, souvenirs, and so on. in Cumberland and area. According to TrailForks, a mapping app, Cumberland is the fifth busiest mountain biking trail network in North America.

That peddles a lot of business. There are two bike shops in the village of 3,700 people and four others within a 15-minute drive. A running shop is about to open, joining two others in nearby Courtenay. In 2018, Owen Pemberton launched Forbidden Bike Co., a bike manufacturer. Opening in the village allowed him to test new bike designs and go for lunchtime rides without driving anywhere. And last summer Western Bike Company opened, adding highend bike-wheel manufacturing to the eclectic selection of village businesses.

On a sunny October weekend, before my ride with Hendren, I take a walk down Dunsmuir. I pass a Japanese food truck, a brewery, a Mexican take out joint and vegan cafe. The shops are equally varied: Moons Records sells souvenir T-shirts and hard to find vinyl; a chocolate shop serves handmade truffles and micro-roasted coffee; there are artisans and consignment shops. The road is busy with a steady stream of cars loaded with bikes. Families stroll past on their way to buy a Cumberland donut or grab a coffee at one of the cafes. While not everyone

Stopping for a rest beside a salmon spawning pool in the Cowichan Lake Trail Blazers Society's network of trails.

is a mountain biker, the trails are the reason it’s all here, says Hendren.

“Cumberland wouldn’t be Cumberland without mountain bikes and trails,” he says.

It’s a pretty compelling business case for the power of trails. Other towns on Vancouver Island are taking notice.

NOWHERE HAS INVESTED as heavily as Langford.

I’ve got my head down, eyes on the ribbon of dirt in front of me, so I don’t notice the million-dollar view until the trail turns to rock and I have to look around to find its route forward. When I do, I skid to a stop. In front of my knobby tire the hillside tumbles away revealing an aerie over all of Victoria.

The snow topped Olympic Mountains loom to the south and the Mount Baker snow cone is in the distance to the east. In between I can pick out the towers of downtown, the cranes at the Esquimalt harbour and the hump of Mount Douglas. It’s shocking not just for the pretty view. I had forgotten I was in the city at all.

The viewpoint is one of the highlights of the Jordie Lunn Bike Park and attached Gravity Zone, a built-fromscratch trail network of trails on the edge of Langford, a city suburb of Victoria.

With its mild climate and abundance of bike paths, Victoria is synonymous with bike culture. But with most of the land privately owned, there’s never been a lot of mountain bike trails. What ex-

isted tended to be difficult and illegallybuilt on private land. As the city, and Langford in particular, grew, development gobbled up the trails. Mountain bikers were left with long commutes.

At the same time, the mayor of Langford wanted to turn the city into a sports tourism destination. When a group of bike race organizers approached the city with a humble idea for a mountain bike park, the mayor realized the sport had as much potential as soccer, hockey and baseball. They took the original concept and blew it up into a world class facility, with a progression of trails from beginner to an expert jump line, a slick bike park and a clubhouse. Total budget: $1.4-million. The only thing missing was a name.

Jordie Lunn grew up in Langford, BMX and mountain biking racing. He eventually found his niche in freeride mountain biking and became one of the top athletes, winning contests and filming all over the world.

“Jordie was always really invested in the community and getting kids into the sport,” says Craig Lunn, Jordie’s brother. “He had a huge impact on BC mountain biking and riding in Langford.”

Jordie tragically died in a mountain bike crash in 2019. He became the logical namesake and the Jordie Lunn Bike Park opened in 2020. The Gravity Zone, the neighbouring trail network that now includes two climbing trails and six descents, opened a year later.

My visit to the bike park begins among a pack of teens that make me look like I have training wheels on. I find the fastest route away, weaving down a rubbery path through berms and rolls. At the bottom I follow a beginner path through the forest and then turn onto Initial Attack, which crosses the bottom of the network on a wide, smooth trail, before I climb Slow Burn to the top of the hillside. Mid-way a middle-aged couple zips by me on their e-bikes. On the Rocks tumbles me down rock bluffs, past several beautiful vistas. Then it’s another climb and a fast and fun descent back to the parking lot.

It’s a compact area, but surprisingly diverse and well laid out. Most of the time I feel like I’m in the middle of nowhere, not five minutes from the Trans Canada Highway. And the network fills an important hole in the mountain biker infrastructure around Victoria, says Craig Lunn.

The bike park and trails have created an easily accessible place for a beginner rider to get a taste for mountain biking and then build their skills right up to expert.

“The level of progression is unparalleled on the island,” says Lunn. “E-bikes, kids, people of any age can get comfortable there and take those skills to bigger mountain bike networks.”

It’s already paying off economically. For the last three years the Jordie Lunn Bike Park has hosted the Langford Bike Fest, which has generated more than $500,000 of economic activity in food, accommodation and other spin-offs every year.

AN HOUR NORTH and west of Langford, the town of Lake Cowichan is working on its own trail legacy.

“I’m a firm believer that people need to get off the couch and do stuff,” says Bob Day, the former mayor of the town in the Cowichan Valley. “As a community we need to have access to the forest to be happy in life.”

For a long time that was hard for locals to do. Surrounded by some of the most productive forest lands in the country, Lake Cowichan has long been a hub for the logging industry. But it’s also blessed with hot summers, an expansive lake and the lazy, warm waters of the Cowichan River. Come July and August, tourists and cottagers inundate the area to boat, float and swim. But not mountain bike.

The town is surrounded on three sides by forest that climbs into the surrounding hills and mountains. But it’s all privately owned, mostly by Mosaic, a large forest land management company. Trail building was illegal and locals found it difficult to access the forests. A downturn in logging left the community searching for an alternative economic driver, particularly outside the busy summer season.

“Anyone can see it: why don’t we have more hiking and biking trails here?” says Cathy Robertson, the general man-

You don't build a trail network to attract tourists, build it for the locals

Lake Trail Blazers Society. The club signed a land use agreement with Mosaic, CFC applied for grants and the locals started building trails on the Fairservice Fun trail network.

Day is now the president of the Trail Blazers and I meet him at one of his favourite corners of the network. In one direction is a trail along an overgrown logging railway. In the other

5 ways to be a good mountain bike tourist

With a little thought and planning a travelling mountain biker can leave a positive legacy in the communities and trail networks they visit. It starts with acting respectfully and conscientiously and extends to travelling with intention.

•Visit a local bike shop. There’s no substitute for local knowledge and bike shop employees always know about new trails, any guidance on etiquette and, of course, recommendations on what trails to ride.

•Donate to the local bike club. They’re the ones that pay for maintenance and organize volunteer diggers. The trails wouldn’t be there without them, so show your appreciation. Most have a donate button on their website or ask in a local shop (see #1).

•Visit outside of peak season. Travelling in fall or spring not only means quieter trails and lower costs at ferries, accommodation and restaurants, it also injects money into the economy when it’s more needed.

ager of Community Futures Cowichan (CFC), a federal government-funded organization with the mandate of business and economic development.

There was interest in trail building, but a grassroots effort would take volunteers a decade or more to win grants and develop a trusting relationship with the landowner. The CFC’s backing opened doors. In 2018, Robertson helped local hikers and bikers form the Cowichan

•Brag about being a mountain biker. You don’t have to wear your helmet into the grocery store, but be open about the fact you’re in town to ride. It will help build support for trails and ensure the riding only gets better.

•Leave the trails better than you found them. That could mean stopping to move a branch off a trail, picking up garbage, or showing up for a trail maintenance event.

direction, Layer Cake is a new purposebuilt mountain bike path that climbs into the woods. And just off to the side is a bench overlooking a salmon spawning bed.

“You’re really in the wilderness out here,” Day says as we dig in a new signpost. “We see elk and bears all the time.”

We don’t see any wildlife while I’m there, but we also don’t see another mountain biker in two hours of pedalling. Linking sections of single track with old logging road we climb onto a plateau above town and then grunt up a steep hillside. A hang-on descents drops us back to the plateau, where we fly along more trails and double track. Mostly it’s cross country rambling close to town.

Early on, Robertson hired a mountain bike consulting firm to develop a trail master plan. They gave her some important advice: don’t build a network to attract tourists; build it for the locals.

“He told me to focus on what the locals want because they are the ones that will build the bike culture,” she said. “Everything, from people travelling here to an outdoor rec economy, will grow from the locals loving their trails and loving where they live.”

For some that means puckering downhills. For others, like Day, it’s going for an easy ride through the forest and stopping for a break to watch salmon spawning.

“Even with this big fancy trail plan and all the agreements, the trail building is still going to happen organically,” says Day.

THIS IS A STORY repeating across Vancouver Island. In Sooke the mountain bike club has worked hard with the Capital Regional District to make its trail network better and more sustainable. Now mountain bikers rub shoulders with Galloping Goose cyclists and surfers on the brewpub patios. In Campbell River, the club has spent almost $800,000 renovating trails in the Snowden Demonstration Forest to make them more accessible and inclusive. BC Parks has opened Partridge Hills near Sidney to mountain biking, increasing the options for Victoria area riders. And Nanaimo continues to build an impressive system of trails.

All the communities see mountain biking, trail running, hiking and horseback riding as a path to happier residents, a way of attracting and retaining professionals, and a mechanism to diversify their economies. Maybe most importantly they see a path to a better future.

Back in Cumberland with Chad Hendren, we end our ride at the Riding Fool Hostel, a bike focused accommodation. Over a beer and a bike wash, the owner Jeremy Grasby provides a fatherly perspective on the benefits that mountain biking has brought to town. He’s proud of the success of his business, but more he’s excited about the opportunities Cumberland’s mountain bike economy has created for the next generation.

“My two daughters work at businesses that didn’t exist when they were born,” he says. “That’s because of the trails and mountain biking. For a parent, that’s huge.”

Mountain Bike BC has a section devoted to Ride Island, it’s nickname for a Vancouver Island road trip. mountainbikingbc.ca

Tourism Vancouver Island is the go-to place for finding accommodation and learning about what to do. It also has guidelines for being a good visitor. vancouverisland.travel

Around the province, communities come together to help juvenile western toads beat the odds of… well… being squashed

OBY LESLIE ANTHONY

n a steamy afternoon in early August, I’m one of thousands swarming the beach at Whistler’s popular Lost Lake Park. But it’s not as bad as it sounds. Only about a hundred of those are people lounging on towels, tossing frisbees or barbecuing. The rest of the crowd is somewhat less obvious: behind a shin-high barrier on a marshy corner of the beach, multitudes of newly metamorphosed western toads, each smaller than a fingernail, are exiting the water to take their first tentative steps on land. Having spent the past few months wriggling through water as tadpoles, the new environment—not to mention novel acts of breathing air and using legs—takes getting used to. The emerging toadlets appear to pause and consider this trope of rebirth, a poignant echo of the water-toland transition pioneered by amphibian ancestors in the Devonian Period. There are 370 million years of evolution packed into the DNA of these tiny titans—and plenty of instinct. With a new range of predators rendering the beach even more

perilous than the lake, toadlets are quick to get moving again, driven to reach the cover of vegetation.

Over the next 48 hours they’ll follow a several-hundred-metre route shaded by quarter-round plastic fencing, employing nascent hopping skills to gain the forest in which they’ll either prosper or perish. By design, nature has favoured the latter; indeed, fewer than one percent of these determined emigrants will make it to adulthood. And the gauntlet starts along the fence, where potential death awaits from heat, desiccation or disease, and predation by gartersnake, crow or shrew—each of which patiently awaits this emergence to gobble their fair share. Be that as it may, the fencing obviates a far larger threat: humans. With the odds already against them, the added mortality of busy roadways, trails and lawns can tip the balance for a local toad population. And for years here, there was indeed cause for worry: each summer, thousands of toadlets were squashed by people, bikes and cars as they struggled toward the forest. It wasn’t malicious— they were just too small and the rest of the world too big and indifferent. And

Rachel Shephard of the Squamish Environment Society searches for newly hatched western toad tadpoles along the shoreline of Fawn Lake in Alice Lake Provincial Park. She will conduct counts and take measurements to document growth. so, for several weeks, visitors would be treated to constellations of tiny carcasses underfoot. The optics were bad, the biodiversity impacts worse.

After experimenting with several approaches, the Resort Municipality of Whistler installed fencing to direct forest-bound toadlets away from high-risk areas. In addition, it protected breeding and tadpole habitat adjacent to the beach, installed interpretive signage and constructed permanent underpasses to funnel toadlets beneath busy trails along several preferred routes (these can change year to year) to the forest. Now, when toadlet emergence is nigh, temporary fences, signs and boardwalks are also added, and the access road and parking lot closed; those wishing to use the park take a shuttle from Whistler village then hoof it half a kilometre. During this time, volunteers dressed like crossing guards in hi-visibility vests patrol the area, answering questions (there are plenty) and politely asking visitors to watch their step or walk their bikes. They also scoop up errant toadlets that may have found their way around barriers, ferrying them in plastic cups to the safe side of the fence.

Today I’m a toad “crossing guard.” Several years have passed since I last did this and I notice two related things: buy-in from park users, who now seem more interested than inconvenienced—and far fewer dead toads. Something is working.

As I answer a query about why toadlets often pile up together (a way to pick up warmth amidst the safety of numbers), two young kids tear across the lawn between beach and forest. The older, a girl, holds a cup at arm’s length, trailed by her excited younger brother. A frazzled voice in the distance pleads for them to stop running. “But mom—we’re saving toads!”

With the western toad listed as a Conservation Concern in BC and of Special Concern under the federal Species at Risk Act, it’s great to see this happening in my hometown. Better still to know that similar efforts are underway across the province.

YOU NEVER KNOW who you’ll run into in the bush. But when it comes to amphibians you can be sure they’ll be more surprised than you are. Whether it’s small size, cryptic colouration, or secretive ways, amphibians are masters of not being seen. Still, of BC’s 13 species of anurans (frogs and toads), the wideranging western toad, Anaxyrus boreas, found in 80 percent of the province, is the most likely to say hi.

Adult toads are stocky, 5.5 to 14.5 centimetres nose-to-butt, with short, stout legs. Unlike frogs, their skin is dry and bumpy (these are keratinized tubercules, not warts as folklorists aver) and colouration ranges from pale green to grey, dark brown, even reddish, often with a visible light stripe down the back. Males are generally smaller and have dark pads on their thumbs to help cling to females during mating. Behind each eye rises a kidney-shaped parotid gland that exudes a milky mix of nasty alkaloid neurotoxins when a toad is threatened. Depending on time of year and weather, adult toads can be active day or night, dining on flying insects, ants, beetles, spiders, centipedes, slugs and earthworms. Indeed, the vast number of invertebrates they consume make toads ecologically important; ditto that they, in turn, feed otters, minks, raccoons, snakes, herons, owls, crows and other birds as an important link in the transfer of energy from freshwater to terrestrial ecosystems.

Adults migrate to wetland breeding sites in spring, where males court females, clasping them from behind with their thumb pads, a configuration known as amplexus. The eggs—fertilized as they’re deposited in the water—resemble tiny black pearls strung single file in jelly. With females averaging 12,000 eggs, that’s a lot of fertilizing—and hanging on.

The eggs hatch in three to 12 days, depending on temperature. Tadpoles are dark-coloured (making it easier to absorb heat) and swarm in large schools through the warmest near-shore shallows, feeding on aquatic plants, detritus, algae and even pollen grains. After six to eight weeks of dodging fish, birds and predatory insects like dragonfly larvae,

tadpoles transform into six-millimetre toadlets and forsake their watery nursery; varying with altitude and location, this can be anywhere from mid-June to mid-August.

Although the western toad is highly threatened across much of its US range, population declines in BC—primarily due to habitat loss from development— have mostly been noted from Vancouver Island and the Lower Mainland. Such impacts aren’t uncommon for amphibians that require both aquatic and terrestrial habitats to complete their life cycle; anything that separates these is a threat.

“Toads follow very directional routes toward overwintering and breeding sites,” says Elke Wind, a Nanaimo-based amphibian biologist. “So anything that gets in the way causes attrition over time.”

Meaning that if a developer tries to protect habitat and wildlife by putting a road around a wetland versus through it, they’re still causing a lot of harm. For animals like amphibians, that have multiple migration events to or from wetlands each year, roads are a death sentence. Instead, what’s needed is landscape-level planning and mitigation earlier in the process—a costlier, lengthier, but ultimately more sound approach.

Even parks, where nature is supposedly protected and celebrated, can have a negative effect in the often-shortsighted drive to create recreational space.

RACHEL SHEPHARD WALKS FAST. Even faster when she’s talking about the project she manages for the Squamish Environment Society (SES)—monitoring western toads at Fawn and Edith lakes in Alice Lake Provincial Park.

Populations here were well-known to locals—mostly because the area surrounding the lakes is interlaced with trails where, each summer, the ground came alive with toadlets swarming from the lakes, many to suffer the wrath of hikers and mountain bikers unaware of their presence. Some years saw more toadlets, other years less, and it was recognized that no one knew anything about these populations, whether they were doing well or in decline. The SES thought it

might be a good idea to collaborate with BC Parks to get that beta, and parks agreed. “We figured we could learn more than just the anecdotal information we were getting from hikers,’” Shephard tells me as we stroll under a canopy still wet from rain on an overcast May morning. At Fawn Lake, few tadpoles are visible in the first embayment we check, and they’re noticeably small. Shephard manages to bend close enough to measure one with a hand-held ruler. “Looks like about 100 millimetres,” she notes, recording it on a data sheet fixed to a clipboard.

Volunteers like Shephard keep an eye

on tadpole growth and development and, when the animals finally exit the lake, conduct toadlet counts—dead or alive—at various transects. “We want to know if they’re crossing trails and where, and the level of mortality,” she says.

The data helps visualize hotspots, information that can then be used to site temporary elevated boardwalks which allow toadlets to pass safely beneath— and hikers and bikers less guiltily above.

“We’re basically eyes on the ground, gathering all sorts of data relevant to the health of the population,” she says of parameters like the date of first arrival for adults, onset of amplexus, start and end of egg-laying, days to hatching and first metamorphosis—not to mention daily counts of males and females during peak breeding days, the peak number of individuals or pairs, and overall totals.

Such long-term monitoring and data-gathering are the two most important things in the conservation game, as they inform what type of mitigation efforts to employ, and how adaptive those need to be. Sadly, such practices are the least-likely to be funded by municipal or regional governments with limited means who prefer quick solutions that make them look good. It can turn even the most noble conservation effort into a best-guess scenario. And toads are notorious for keeping people guessing.

“On the mainland toads breed in a variety of aquatic habitats, including temporary ponds like ditches and road ruts. But on the South Coast they are only found in larger, permanent water bodies,” says Wind. It’s unclear why toads aren’t using ephemeral water bodies on the South Coast, especially because larger water bodies are often stocked with fish, a major amphibian predator. “Studies have shown that toad tadpoles are unpalatable to fish,” she notes.