how long does it last?

how long does it last?

from David Campany’s essay in Singular Images: Micro or macro Dust Breeding resembles, to borrow the French title of another Man Ray image, a terrain vague. It looks like a waste ground or disused area, perhaps the overlooked edge of a city. It is an indoor image alluding to the outside, particularly when titled View from an Aeroplane. Modern Europe saw the terrain vague as a site of anxiety: ‘I will show you fear in a handful of dust’ warned T.S. Eliot in The Wasteland In North America there is more terrain vague than anything else. There, it appears more as a motif of boredom or entropy. Dust has a place in both schemes. It is abject, liminal, bodily stuff that threatens the modern and rational order. It is also a sign of dead time passing.

https://davidcampany.com/dust-breeding-man-ray-1920/

Elévage de Poussière (Dust Breeding) is attributed to Man Ray and Marcel Duchamp, 1920. Image found in Sophie Howarth, editor, of Singular Images. London: Tate Publishing, 2005

Elévage de Poussière (Dust Breeding) is attributed to Man Ray and Marcel Duchamp, 1920. Image found in Sophie Howarth, editor, of Singular Images. London: Tate Publishing, 2005

masthead: how we operate

A fragmentary introduction

Beyond Throwaway Achitecture. Time as a political act

The Afterlives of Temporary Architecture

Flowers in the Snow. Architecture, entropy and temporariness

What We Build Together. Material expression of ritual and care in southern Chile

Temporary Engaging with difficulty: Building Critique

Formalising Tirana

Architecture Passes. Noticing entropy, anxiety and indeterminacy

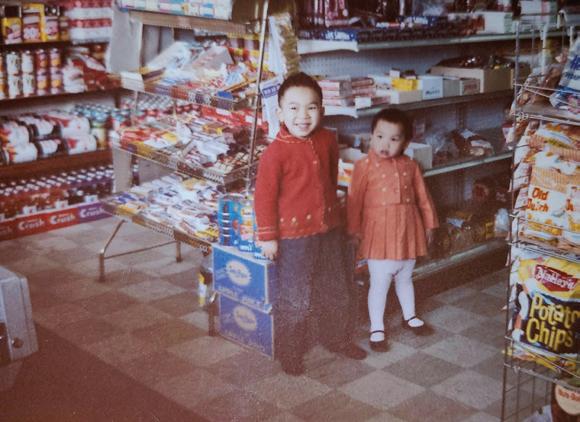

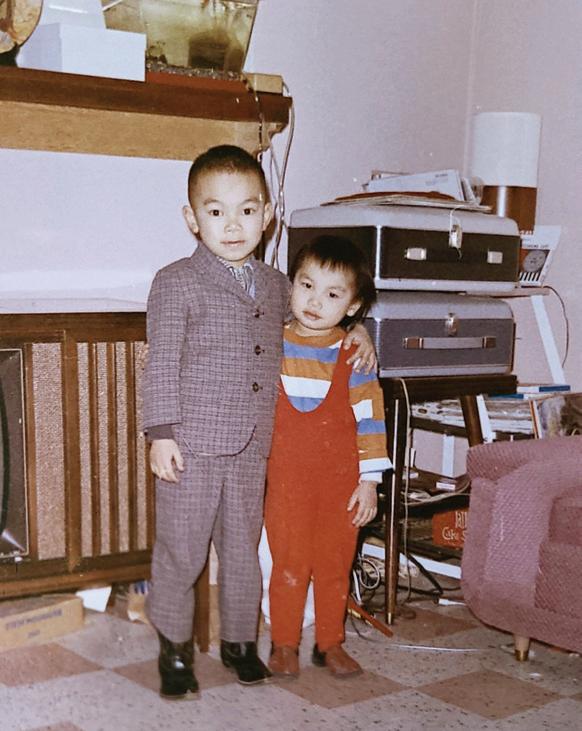

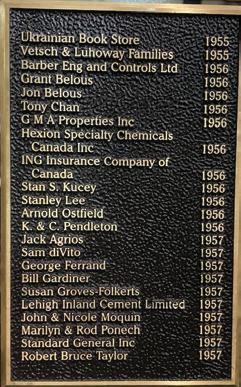

Lee’s Food Market, an unlikely story of longevity

The Ethics of Lasting. Middleton Inn revisited

45 High Street, Reading Massachusetts

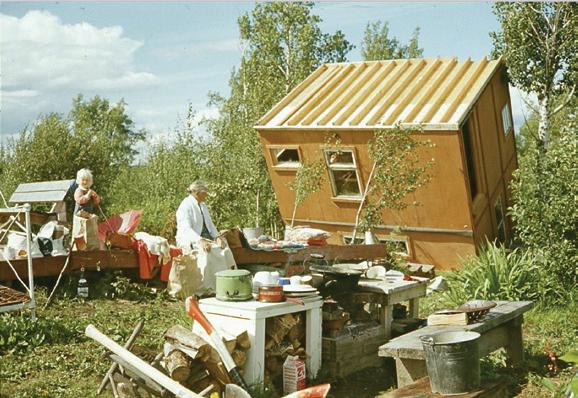

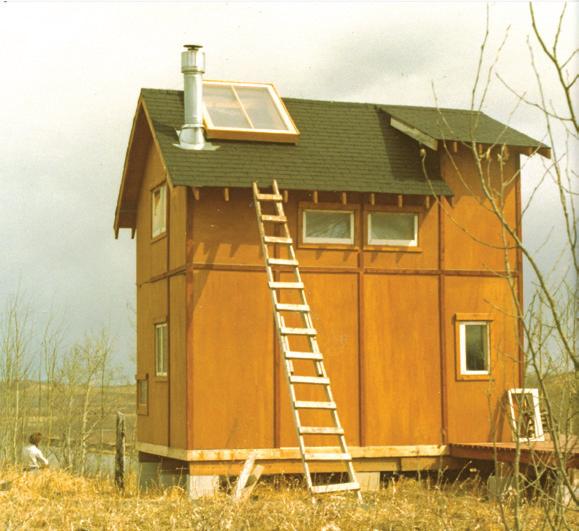

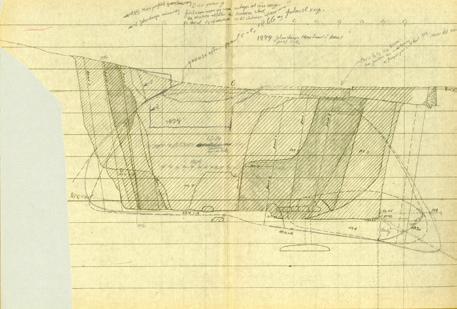

The Short Life of Two Tiny Buildings

On a lighter note

On Site review 44: PLAY

On Site review is published by Field Notes Press, which promotes field work in matters architectural, cultural and spatial.

Always quite liked that for Abbé Laugier, the muse of architecture was female, and there she is, holding her divider, classical architecture in ruins at her feet. For us, it is not the primitive hut that is interesting, it is the water tower.

For any and all inquiries, please use the contact form at https://onsitereview.ca/contact-us

ISSN 1481-8280

copyright: On Site review. All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopied, recorded or otherwise stored in a retrieval system without the prior consent of the publisher is an infringement of Copyright Law Chapter C-30, RSC1988.

back issues: https://onsitereview.ca

these are listed in the website menu in three groupings: issues 5-16, 17-34 and 35-39.

editor: Stephanie White

design:

Black Dog Running

printer: Mitchell Press, Vancouver BC

subscriptions:

libraries: EBSCO On-Site review #3371594 at https://ebsco.com

individual: https://onsitereview.ca/subscribe

This issue of On Site review was put together in Nanaimo on unceded Coast Salish territory, specifically the traditional territory of the Snuneymuxw Peoples who continue to live on this land.

both Alessio Mamo/The Guardian https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/apr/01/ ukraine-rebuild-bucha-prompts-corruption-reconstruction

Two images from The Guardian of April 1, 2023, the top a church in Dolina after Russian bombing, and above, the ongoing mending of bombed apartments, this one in Kharkiv, at the beginning of the invasion.

Two significant typologies, both buildings from previous eras, the pre-soviet and the soviet, both damaged. The church can be reconstructed, in the way carpet-bombed Dresden was after WWII, but there is a political question whether future resources will be spent in this kind of reconstruction of a past that Ukraine wishes to leave behind: its historic, oft-unwilling, affiliation with the Russian Empire in its many guises. Given the schism between the Ukrainian and Russian Orthodox Churches, perhaps the rebuilding of a church on the site will be a different expression of faith.

The apartment building isn’t being reconstructed as an iconic building, rather it is being mended immediately. This is the difference between houses and housing. Houses come and go; housing is eternal. The two have entirely different time frames. g

This issue started by thinking about architecture through the Annales School lens of history: the longue durée, cultural history factored by land, geology and climate (where structural questions arise about architecture’s longevity – is it all temporary?); histoire événementielle, a series of events (in architecture particular buildings have long been the subject of most critique – how long does this famous building actually live for?); and the formation, development and demise of social movements – a middle ground between spectacular events and millennial histories: the long era of modernism, for example.

This last one I am most interested in terms of the instant recognisability of late colonial architecture. I was reading about E R Braithwaite and his 1959 autobiographical novel To Sir, with Love, and found he had attended Queen’s College in Georgetown, Guyana, then still a British colony. And there was the building: a white, brise-soleiled, low horizontal stamp of indubitable tropical colonialism.

What exactly is modernity in the context of de-colonisation? It became an imperative in Africa and the Caribbean for public housing, schools, administration buildings – a sort of cheap, egalitarian architecture for institutions; a casting-off of hierarchies, whether colonial or social or ancient. Jane Drew and Maxwell Fry were the exemplars of this kind of postwar architecture: rather than the bludgeoning architecture of empire, they turned to the environment: weather, climate, materials. The AA had a department of Tropical Studies within it, revisited at the 2023 Venice Biennale. Kenneth Frampton’s critical regionalism of the 1980s continued this direction. Admittedly influenced by the Frankfurt School and its critique of capitalism and globalisation, he proposed an architecture of place, culture, climate: more direct responses to locale than theoretical approaches to society, politics and capital economic contingency. An architecture of place, culture and climate sits in the Annales sense of a longue durée, where architecture concerns itself with material fundamentals that transcend both events and social movements, no matter how new or old they might be.

Now, forty years since critical regionalism was floated, it seems to divert architecture’s possible response to division and strife. We cannot ignore the state of the world in 2023. We can no longer rely on climate as a touchstone. The neo-colonialism of trade pacts and treaties work much as did the old colonialism. Any idea of a social contract is near extinction.

What is the architecture for this?

Most empires start to have qualms at a certain point; their end beckons, and there are various remedial attempts to re-frame the colonial enterprise. The high point of British Empire was achieved towards the end of the reign of Queen Victoria, but it had started four hundred years earlier with Queen Elizabeth I, covering civil war, the industrial revolution and the rise of global capitalism. WWI, The Great War, dealt imperial hubris a death blow. By the end of the Second World War the process of literal decolonisation had begun, resulting in bloody wars of resistance: resistance to colonial status in the colonies, and resistance to this resistance on the part of Great Britain, eventually re-naming its empire The Commonwealth, and tying negotiations for independence to the Queen and to resource extraction, the main reason for having colonies in the first place.

At this point, just as my fingertips were touching what I thought was critically momentous, all the critically momentous essays for this issue of On Site review came in and I got totally distracted as I read, edited and conducted much, no doubt annoying, correspondence with the contributors. Now that the layout is done, I return to my introduction to this issue.

Time, being a concept deep and fathomless, has in this issue become largely a discussion of the temporary: whether it is achieved or resisted, whether it is a valid direction for architecture or simply cheap. Is time an eternal background factor to all we do, or is it a series of events we can control? There is something for every position here. Is architecture itself a series of events over a long history of civilisation? or is architecture a rather monotonous background to other more vital forms of civility and incivility? or, is architecture the face of social and political movements and revolutions: an evolutionary flag?

These are not rhetorical questions, rather they are topics addressed in this issue. Each contributor has sent us a very specific discussion, either of specific buildings or building systems. Collectively they speak about architecture’s place in a series of endings, from climate to political systems, from cultural hegemonies to a misplaced trust in globalisation.

In a recent article published on the Italian magazine Casabella1, Vittorio Magnago Lampugnani summarises the current debate on reuse and sustainability in architecture in a paradigmatic case study: the refectory of the New College in Oxford, originally opened in 1376. The refectory has a generous roof, whose timber carpentry was built with oak beams – 60 by 60 centimetres in section and 13 metres long. Around the year 1860, it became clear that the wood had been attacked by insects and needed to be replaced; the problem was to find a sufficient number of exceptionally thick, long beams. At first this seemed to be impossible, and that the building would be doomed to demolition. Then someone recalled that the College owned wooded estates, and an inquiry was made regarding large oak trees. Soon it turned out that there was an entire forest planted 500 years earlier, precisely to provide the timber needed for the replacement of the roof structure. The original builders had foreseen the deterioration of the wood and prepared for its reconstruction.

Magnago Lampugnani’s anecdote isn’t meant as a nostalgic celebration of the good old days, nor is an invitation to think of architecture as something necessarily ever-lasting. On the contrary, the refectory project is first of all a metaphor of the inextricable connection between architecture and time – the unstable tension between duration and decay, permanence and disappearance, firmness and fragility. Over the centuries, such tension has translated into different (built) forms: spoliation, appropriation, ruination, the quest for the ephemeral or for continuous change. In late antiquity, for example, most of the buildings erected in Rome were made almost entirely from spolia of other constructions – not only plundered artworks, but also reused building components such as columns, capitals, arches, etc. The act of spoliation was not simply driven by pragmatic reasons – to save labour, or scarcity of materials. Spoliation was also ideological, in the sense that appropriators of stones from the Roman Empire considered themselves as the prosecutors of that imperial glory: stones were the symbol of the past but also the foundations of the future.

For millennia appropriation has represented a less violent but more systematic way of incorporating the old into the new: Rome’s Theatre of Marcellus of 13 BC was first transformed into a medieval fortress and later converted into a palazzo for the Savelli family in the 16th century. Or, to remain in Italy, Rimini’s Tempio Malatestiano, designed by Leon Battista Alberti between 1450 and 1460 as a mausoleum for Sigismondo Malatesta and his lover, built by wrapping a 13th century Gothic church with a new façade which could counterbalance and partially hide the ‘uncivilised’ language of the Gothic elevation.

Appropriation, however, is not something only belonging to the past: in 1977 Frank Gehry transformed a 1920 detached house in Santa Monica by deforming its original configuration, and hybridising its image with a new disruptive lexicon. More recently, the 2004 Pavilion for Vodka Ceremonies designed by Alexander Brodsky consisted of 83 windows recuperated from a demolished factory. In their variety, all of these examples describe the ingenuous and sometimes desperate attempt made by humans over the centuries to deal with time: by celebrating it, denying it, dilating it or simply acknowledging it. Because facing the problem of time in architecture means, by extension, facing the problem of human caducity in its physical and symbolic expression.

The refectory of New College, Oxford also serves as a pretext to investigate the relationship between time and architecture today, in the general context of the current capitalist development. What does durable mean for architecture? What are the social and environmental costs associated to its durée? How does time affect the design of space?

Terms such as sustainability, circularity, reuse, upcycle have become commonplace: they not only influence the architectural discourse, but also suggest a wider paradigm shift in the role of the architect and their ethos. Such a shift manifests itself at various levels, from governmental initiatives – see the plan of the Dutch Cabinet to develop a circular economy in the Netherlands by 2050 and to achieve a 50% reduction in the use of primary raw materials (minerals, fossil, and metals) by 2030 – to the proliferation of architectural and curatorial projects on those topics – see Open for Maintenance, an exhibition/installation at the German Pavilion of the 2023 Venice Architecture Biennale. In this project, curated by ARCH+, SUMMACUMFEMMER, and Büro Juliane Greb, the German Pavilion is displayed as a series of maintenance works which include not only Germany’s contribution to the Biennale Arte from last year, but also leftover materials from over 40 national pavilions showcased at the same Biennale’s edition.

https://hicarquitectura.com/2022/12/frank-gehry-house-gehry/

Despite the always present risk of reducing complex phenomena to fashionable trends, the German Pavilion and other similar projects pose urgent questions about the impact of architecture on the built environment. They do that by investigating the temporality of architecture as a material, conceptual and ideological practice, and by addressing the question of durée from a different perspective, one which refuses a vision of architecture as a mass-consumption, disposable, a-critical spectacle. In other words, opposed to so-called throwaway architecture which oft-times replaces buildings with devices, aesthetics with experience or the public with individualism, a variegated set of design positions have progressively emerged.

If in the 1960s, Archigram responded to the ‘irreversible escalation in the day-to-day demands of ordinary people for greater access to goods, services, and culture’,2 by imagining ever-changing cities (Plug-In Cit y, 1964), nomadic units (The Cushicle, 1966), or inflatable structures (Blow-out Village, 1966), today the idea of a durée for architecture is articulated as a political vector to address societal and ecological issues. This approach produces architectures that are different in scope, scale and premises, but that all share some common points: a critical awareness of the need to optimise existing resources and reduce waste, a total disinterest in dramatic gestures or formal acrobatics, and an emphasis on public instances. Most importantly, these architectures, and the body of ideas connected to them, all engage with time directly.

Yury Palmin, Divisare October 27 2016

https://www.labiennale.org/en/architecture/2023/germany

Radical in its intentions – to offer an alternative to the current processes of urban development triggered by the so-called Bilbao effect – and provocative in its formal outcome – a synthesis of artistic performance and typological innovation – is the work of the Berlin-based office Brandlhuber+, founded by Arno Brandlhuber. Over the years, Brandlhuber+ has developed a unique trajectory in which the peculiarity of the decisions informing their projects – lack of thermal insulation, exteriorisation of interior circulation, formal indifference – matches with the interest in the work of artists such as Rachel Whiteread or Gordon Matta-Clark. This combination of heterogeneous references and positions finds full expression in Brandlhuber+’s architecture, which explores the intrinsic potential of existing buildings to resist over time and generate new unexpected meanings. Coherently, Brandlhuber+’s message involves not only the design of space but also its representation. The visual body of drawings produced by the office, for example, depict a clear understanding of the role played by time in their work, especially when it comes to the dialogue between old and new elements in both 2D and 3D visualisations. Among the several projects developed recently, two are emblematic of Brandlhuber+’s inquiries: Antivilla (2010-15), and San Gimignano Licthenberg (2012).

Antivilla is located at the Krampnitz Lake, southwest of Berlin, and is the transformation of a former warehouse, built in the 1980s, which used to store lingerie produced by a nearby East German factory. The challenge of this project was to prove that empty buildings in risk of demolition can be made usable again. So, rather than demolishing it and replacing it with a single-family home, Brandlhuber+ decided to keep the existing load-bearing structure, and to remove only a few interior partitions. More specifically, the design process was informed by a series of different steps: first, the existing asbestos-contaminated globe roof was dismantled and replaced with a flat concrete roof, whose presence was emphasized by a sculptural waterspout. Second, inside the empty shell of the building, a functional load-bearing core containing kitchen, bathroom, fireplace, and sauna was inserted. Then, the existing façade was perforated by irregular holes which allowed the house to have a view of the lake.

Through a sequence of simple but bold moves, Brandlhuber+ presents us with an artificial ruin, a vacant building which has been given a new meaning and transformed into a domestic shelter. The ruin is at the same time romantic but blunt, intriguing but repelling, comfortable but extreme.

Similarly, the San Gimignano project in Lichtenberg, Berlin, gravitates around the transformation of two existing towers – a silo and a circulation tower used in the past as central production sites for a large graphite factory. The only remnants of a larger industrial complex, these towers remained abandoned due to high demolition costs. Brandlhuber+ takes advantage of the existing situation to preserve their industrial character: one of the two towers serves as a workshop for different industries such as 1:1 prototyping of architectural units; the other tower works as a warehouse – an unheated storage space up 22m high. The silo tower only contains two floors: the ground floor and the first floor at 31.63m. By focusing attention only on those floors, the need for extensive technical equipment (ventilation and exit doors) shrinks and additional costs are avoided. Brandlhuber+ restored all original apertures of the tower and left them open, turning the interior into a semioutdoor space. Overall, Brandlhuber+ reduced their intervention to the minimum: an additional floor in one of the towers as well as an external staircase to provide access.

In using the framework of existing buildings and regulations as point of departure, Brandlhuber+ investigate new forms of interaction between public and private in contemporary cities; their projects explore radical forms of living and working via site-specific, acupunctural interventions in the urban fabric.

Different in formal expression but equally compelling, is the dialogue with the existing built environment which characterises the work of several architecture firms based in Barcelona. One of those is HArquitectes. The Centre Cívic Lleialtat Santsenca 1214, designed in 2017, is in fact based on the transformation of a 1928 working class cooperative building. The project develops across the definition of an interior urban void – an atrium that allows for the encounter between the old decayed structures and the new intervention. The role of this urban void is to celebrate the heterogeneity of the separate parts constituting the building and, at the same time, to ideally bridge past and future. The atrium is the moment where differences juxtapose and interact: the patina of the existing walls and the new polycarbonate roofs coexist in the same environment. In the progression of the spaces designed as well as in the overall process of mending, an overlap of textures, patterns, and colors take place. One may say therefore that the whole project is an example of assemblage as it is compact and finite in its multiplicity; all its different layers morph into a visual and functional unity.

https://floresprats.com/archive/sala-beckett-project/

A few years earlier in 2014, also in Barcelona, Catalan architects Flores & Prats worked on an analogous project of adaptive reuse: Sala Beckett. In rehabilitating a former social club used in the past for family celebrations, memory is the red thread connecting old and new, on the verge between nostalgia and experimentalism. The building is transformed into a theatre and a dramaturgy school.

Instead of accommodating the new program in one specific and well-defined area, the architects fragment the program and diffuse it over every corner of the building. The building itself becomes the theatre: materials, decorations, object trouvé and interior vistas shape the main theatrical activity. The intervention in the old building reveals itself as a process of anastylosis where existing and new fragments are re-composed in a novel fashion. Notions of legibility and atmosphere regulate the relation between old and new, and connect the interiors to the history of the surrounding neighbourhood. Sala Beckett as well as the Lleialtat Santsenca Civic Centre are not questioning ideas of image and function. They constitute a composite artifact: a combination of old and new patterns, entropic relations, interior and urban components.

The 2021 Pressens hus, by Atelier Oslo + KIMA Arkitektur, Oslo, follows a similar design strategy as the one employed in the Lleialtat Santsenca Civic Centre by H Arquitectes. The project consists in the transformation of two nineteenth century listed buildings located in the centre of Oslo. The new program – spaces for media and press activities, conference rooms, studios, café/restaurant – develops across two atriums. Around these two voids, the building reveals the passing of time and the dialogue between the existing vocabulary of steel beams and brick buildings and the new vertical order of posts and beams in laminated timber. The geometry of these two orders overlaps, revealing the continuity of past and future in the same building.

In going over these examples, it is clear that differences in formal vocabulary, materials and building techniques characterise their configuration. Nevertheless, when it comes to the overall relationship between time and architecture, all those projects address a similar concern: all of them question the socially and culturally acceptable durée for architecture, against and beyond market-driven interests. The way they do it is by being aware that architecture is not only about space, but is above all a matter of time – whether time is interpreted as a scar of the past (Flores & Prats), as a design material (H Architectes), or as a conceptual scaffold for future interventions (Brandlhuber+). Only by facing, embedding and interpreting time in all its manifestations, architecture can play a different and less invasive role in the built environment. Reusing rather demolishing, repairing rather than discarding, updating rather than replacing; this is what architecture can do to act as a catalyst for new collective and urban instances. g

STEFANO CORBO is an architect and educator at TU Delft – Chair of Public Building – where he also serves as MSc Coordinator. In 2012 Corbo founded SCSTUDIO, a multidisciplinary network practicing public architecture. www.scstudio.eu

Temporary constructions are an increasingly common part of contemporary architectural production. They range from short-term pavilions, installations and exhibitions to building-performance mockups and urban placemaking events. They offer architects a much greater degree of design freedom than full-fledged permanent structures, in that they are often smaller, less expensive and inherently less burdened by regulation and the obligations of long-term durability. As such, architects routinely use temporary projects as laboratories for testing new materials and exploring alternative approaches to fabrication and assembly, or as trial balloons to shape or activate space in unconventional and creative ways.

More recently, as the discipline’s commitment to ecological engagement has grown, the temporary structure in its various forms has also become a site for progressive experiments in architectural recycling and reuse. No longer content to turn a blind eye to the widespread but wasteful practice of demolition and disposal, the designers of temporary projects are widening their attention spans to account for what comes before and after a temporary project’s limited run. Some of these architects build their short-term structures out of scrap materials or other byproducts of construction activities such as construction shoring

and lumber off-cuts. In these cases, the reappropriation of waste often constitutes a clever response to limited budgets, as in the common refrain, ‘one man’s trash is another man’s treasure’. Other designers work to ensure their temporary projects will have a second life—either as raw material for future constructions, or in their entirety as relocatable structures that live again in service to other communities—thus, widening the project’s circle of beneficiaries. Either way, efforts to account for the past, present and afterlives of temporary constructions hold valuable lessons for architecture more broadly. Despite being implemented at a limited scale and in the short-term, these efforts constitute valuable rehearsals in radical architectural resourcefulness, and they point the way toward more sustainable and impactful life cycles of use and reuse.

Through case studies, I offer three ways of thinking about the role of life-cycle design in temporary architectural projects: recovery of waste, preemption of waste, and extension of scope. Each of these approaches is illustrative of an entrepreneurial strategy I call piggybacking—where one project’s resources are opportunistically leveraged to the benefit of some greater, often public, good; where architects tease out hidden value from within the gaps of a market economy notoriously characterised by exploitation, inequality and waste.

First, temporary projects that build from waste, or that redirect their own waste streams or byproducts toward subsequent projects. In Germany, artists Folke Köbberling and Martin Kaltwasser took this approach to extremes in a range of temporary public structures they designed and built from salvaged materials during the early 2000s. Their projects were often visually striking; they made a conspicuous display of their salvaged components. Construction pallets, wood sheathing and discarded doors used as ad hoc cladding-framed legible public narratives around waste and reuse. Working with whatever unused materials they were able to scavenge from construction sites and city streets required that they develop a somewhat improvisational design process—one that allowed them to modify their designs in real-time during construction. This way of working brought challenges as well as pleasures: as their projects became more public and more permanent, the artists found that municipal authorities were often not amenable to changes made on the fly. Ultimately, their open and improvisational approach proved to be fundamentally incompatible with a public review process that demanded predetermination and certainty. As a result, Köbberling and Kaltwasser shifted their attention away from architectural installations and back toward the relative freedom of art practice.

Working with the irregularities of miscellaneous scrap materials is one of the key challenges in waste-recovery design projects. Jessica Colangelo and Charles Sharpless, of the architectural practice Somewhere Studio, tackled this challenge with a temporary pavilion as part of the Biomaterial Building Exposition at the University of Virginia in 2022. Their pavilion, called Mix and Match, was developed in response to the large quantities of waste lumber – offcuts, overages and

temporary shoring—generated by conventional housing construction in the United States. Somewhere Studio’s approach foregrounded the inherent inconsistencies of salvaged wood as features of the pavilion’s design: pieces were stacked in a vertical gradient from tallest to shortest, and half-lap joints constituted a visually expressive connection detail that accommodated dimensional irregularities. In developing Mix and Match in this way, Somewhere Studio leveraged design to highlight both the opportunities and challenges presented by salvaged materials in architecture.

Meanwhile, in a different corner of the building industry, large-scale commercial developments produce waste from short-term constructions in the form of construction mock-ups. For example, full-scale façade mock-ups up to one-story tall have increasingly become de rigueur among New York City’s newest high-rise projects. They allow design and construction teams to research, test and control for technical performance and design quality, and are typically discarded upon a building’s final completion (figure 1) Testbeds, a project by Ivi Diamantopoulou and Jaffer Kolb of New Affiliates, in collaboration with Samuel StewartHalevy and the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation, captures and redirects this waste stream for public reuse. Their project— they describe it as akin to a rescue operation1—is to reconfigure these discarded assemblages as the basis for any number of local community garden structures: sheds, shade structures, casitas, greenhouses or raised beds (figure 2). Much more than a simple reuse of raw materials, they aim to bring the ‘image of the growing city down to the ground’, recontextualizing the mock-ups while ‘humanizing the scale of the skyline’.2 New Affiliates completed a Testbeds pilot project in 2022 for the Garden by the Bay in Edgemere, Queens, currently featured in MoMA’s New York New Publics exhibition.

1. Akiva Blander. ‘From Playful Products to Clever Urban Interventions, New Affiliates Distills Design to Its Essence’. Metropolis, June 5, 2019. https://www.metropolismag.com/architecture/newaffiliates-firm-profile/pic/56480/ Accessed Oct 13, 2019.

2. Testbeds, New Affiliates, https://new-affiliates.us/Testbeds. Accessed June 22, 2023.

The next two projects exhibit a similarly resourceful disposition, but they also go one step further—demonstrating how, through borrowing, temporary projects might eliminate waste before it is created. Peter Zumthor’s iconic design for the Swiss Pavilion at Expo 2000 in Hannover, Germany, exemplifies this approach, both conceptually and practically. Designed to resemble stacks of wood temporarily set out to air dry, Zumthor’s pavilion was made of nearly one hundred vertical stacks of dimensional pine lumber arranged in something of a maze-like configuration (figure 3). To facilitate eventual disassembly, these stacks of lumber were held together without screws, nails, glue or conventional fasteners; instead, small wooden spacers were placed between each wood member and a custom-designed assembly of steel plates, rods and springs held each wall together in tension. Each pile of wood was inherently dynamic; as the wood shrank over time, the tension rods were adjusted accordingly. The pavilion, formally called the Swiss Sound Box, but which Zumthor referred to informally as the wood yard, effectively held these materials in trust for the duration of the exposition. Having spent several months air drying (and increasing in market value), the entire pavilion was carefully disassembled—almost as if it was never there—and the dimensional lumber was sold-off for use in subsequent construction projects.

Foregrounding a similarly logistical approach, Shelf Life, LeCavalier R+D’s proposal for the 2018 MoMA P.S.1 Young Architects Program, also borrows the bulk of its material resources to temporarily construct a series of labyrinthine spaces for public enjoyment. According to Jesse LeCavalier, the project’s designer, Shelf Life ‘intervenes in the material systems of logistics to recontextualize a major but invisible part of many people’s daily lives: the industrial pallet rack.’3 In a nod to the spaces

and furnishings of warehouses and big-box stores, standardised pallet racks were arrayed throughout the P.S.1 courtyard in tall stacks outfitted with seating, shading, misters and conveyance systems to serve the needs of MoMA’s summer-event programming. Instead of buying raw materials and reselling them on the open market, as was the case with Zumthor’s Swiss pavilion, Shelf Life involved a literal borrowing; the design team secured an agreement from an industrial shelving supplier to lend the 140 pallet racks needed for the installation. After the summer, the racks were set to be disassembled, returned to the supplier and re-dedicated to their customary service in warehousing and retail operations. Cleverly, borrowing these components instead of buying them allowed the designers to stretch MoMA’s notoriously small project budget in support of a larger and more immersive installation than would have otherwise been possible.

By borrowing construction components to preempt waste, these two resourceful projects demonstrate another way by which architectural materials might be given multiple lives: they deploy shrewd logistical manoeuvres to piggyback on – and briefly insert themselves into –existing supply chains. There are lessons here that can be applied to the design of less temporary buildings as well. Proponents of such an approach seek to address the much longer lifespans of permanent architecture — they research design for disassembly in which materials and components only temporarily coalesce into architectural form. In design for disassembly, after a building’s useful life is exhausted, it is to be carefully taken apart, returning all, or most all, materials and components to their original state, available for future uses. This is a simple idea in theory, but unsurprisingly, design for disassembly remains a wickedly complex problem in practice. We can therefore expect further experiments with small-scale, temporary pavilions and installations to play a role in the advancement of this work for some time to come.

Re cycling and disassembly processes that break products down into raw materials or constituent parts pose a particular challenge to designers in that they typically obscure linkages between waste and reuse, making it very difficult for consumers to see and understand lifecycles of production, consumption, waste and reuse — think of those tote bags announcing in bold typeface that they ‘used to be a plastic bag’. Each of the projects discussed so far engage this challenge in different ways through design. In contrast, the waste-stream piggybackings we now turn to intervene in advance of disassembly to capture not only the raw materials but also the embodied energy and social histories of designed artifacts. These next projects call our attention to instances of architectural reuse by creating legible narratives around these efforts and by challenging architects to anticipate and design for a project’s afterlife at the very outset of design—effectively doing double duty as two projects in succession.

Holding Pattern, Interboro’s 2011 project for the MoMA P.S.1 Young Architects Program, is notable for the way it enlarged the ambitions and possibilities of an ephemeral urban construction. More than merely fulfilling MoMA’s project brief of providing a dynamic stage for a summer festival, Interboro designed their installation with the project’s afterlife in mind. The needs of MoMA patrons were overlapped with the needs of a diverse array of neighbourhood organisations by designing for both groups simultaneously (figure 4). At the end of the installation’s time at P.S.1, the seventy-nine objects that Interboro designed and the eighty-four trees they planted were all given new homes among fifty local community organisations for long-term use and enjoyment. Through a process of extensive community outreach and inventive design work, Interboro leveraged the commission to realise not one but two projects: the first for P.S.1, and the second for the local community. Every element of the installation was uniquely charged and enriched by the designers’ ambition to leverage the project budget to serve not just a single institutional client for one summer, but a whole community of clients over the longer term.

The Jarahieh School for Refugees is the result of another resourceful effort to make two projects from one temporary-pavilion commission. Crossing continents and cultures, it captured the architectural by-products from an international exposition and put them to use serving refugee children in Lebanon. The project began its life in Italy: the Milan Expo of 2015 consisted of seventy temporary pavilions that amounted to an expenditure of 13-billion euros. Intent on putting this massive, short-term investment to longer term use, Save the Children Italy, working with the design practice AOUMM, made a commitment to the architectural reuse of its own expo pavilion in support of its larger philanthropic mission (figure 5)

During the design process the organisation connected with London-based CatalyticAction to plan for and implement the pavilion’s afterlife as a semipermanent school for Syrian refugees in Lebanon. CatalyticAction adapted the pavilion’s modular design, reconfiguring its six independent frame structures to support the needs of both the school and the larger community of the settlement (figure 6). After being disassembled and shipped from Italy to Lebanon, the structure was reassembled, insulated and clad by residents of the Jarahieh settlement working alongside the design team from CatalyticAction, who tapped into local skill sets and material knowledge as the basis of an inherently participatory process. The result is a multi-purpose school and community centre that leverages underused international resources with local skills and materials to improve the quality of life in the Jarahieh settlement –benefits made possible by piggybacking one project upon another.

Drawing by Brian Holland and Kayla Ho.

figure 6 (facing page): CatalyticAction, Jarahieh School for Syrian Refugees

Save the Children Pavilion reconfigured as school.

Drawing by Brian Holland and Kayla Ho.

In these examples of recovering waste, temporary architectures extend the impact of discarded resources and provide those materials with a second life—piggybacking on the waste of prior constructions. Each of these temporary projects illuminates a promising form of social and ecological entrepreneurialism in contemporary architecture. Conceptually and practically, they point toward a more robust form of sustainability than is often considered in practice. They close loops to eliminate material waste, yes, but they also go further than that: by reusing waste, borrowing resources or doing double duty, they leverage one project’s resources in the service of another. In radically resourceful ways, their designers extend the tangible investments of their various stakeholders – clients, builders, designers and communities – across a project’s past, present and afterlife to serve multiple and often underserved constituencies. They demonstrate how, through practices of piggybacking, environmental sustainability might be made to dovetail with social sustainability.

What is certain is that any attempt to carry forward the lessons learned from these small, temporary architectures will face significant practical challenges when measured against the demands of larger, longer-lasting buildings. Nevertheless, given the magnitude of present environmental and social crises, we must continue to try. Design experiments like those reviewed here are tremendously promising as ‘generative demonstrations’4 providing legible examples of life-cycle design that could help transform industry practices of waste recovery and preemption, and suggest a hopeful future where buildings are made of recycled materials, designed to be disassembled, and planned for extended lives of environmental and social impact. g

BRIAN HOLLAND is an assistant professor of architecture at the University of Arkansas, and the creator and organizer of the Piggybacking Practices research project, which launched online in 2021. https://piggybackingpractices.com/

tim ingleby

tim ingleby

The Swiss engineer Heinz Isler was a pioneer in the field of thin shell structures. He developed a series of form-finding methods that have informed the design of hundreds of reinforced concrete shells. Isler prototyped the most influential of these by taking advantage of his homeland’s frigid alpine winters: hanging sheets of saturated fabric overnight and returning to frozen forms that inverted became freestanding free-form shells.

A little-known footnote to this story is that Isler also pioneered several other structural types using fabric and ice. Perhaps the most enigmatic of these ‘playful experiments’ as Chilton called them, is the flower form. I have looked at this structural type, the flower form, in a series of self-built experimental structures of fabric and ice. Knowingly ephemeral, the only certainty is their demise which occurs not to a planned timescale but to the caprices of the weather. Such structural entropy makes further study and understanding inherently difficult but it can start to formulate ways of embracing and addressing temporariness in architectural construction.

That could stay, not forever, because we believe that nothing exists that is forever, not even the dinosaurs, but if well maintained, it could remain for four to five thousand years. And that is definitely not forever.

— attributed to ChristoIn Christo’s terms, all architecture is temporary. In anticipating their demise, works of temporary architecture are unusually candid. Rarely is this strength exploited. By using principally fabric and ice, the story of my constructions is one of a death foretold. Although highly specific and undoubtedly quixotic by nature, to extend their lifespans offers three lessons that may benefit other architectures that also acknowledge their temporariness.

Architecture is rarely temporary by choice. Planning laws, land-ownership models and rising real estate values — bureaucratic and/ or economic imperatives, impinge upon the durée of buildings far more frequently than a building’s physical capacity to remain.

Over the last century, art rather than architecture has found ways to exist within, embrace, or subvert, the rules and regulation of such systems. The subway drawings of Keith Haring, Banksy’s murals, the (pseudo) anarcholibertarianism of Atelier Van Lieshout, Yona Friedman’s quest to free and empower nonspecialists – all offer insights into agile guerrilla tactics. These modus operandi question, resist or exploit such state-imposed strictures.

*

Built on a frozen lake in Val-des-Monts in Québec, Orko is a modest act of subversion. It shares some formal similarities to lávvu –temporary tented shelters used by nomadic Sami people following their reindeer herds, stable enough to withstand the winds of treeless plains in the higher arctic regions. However, Orko has no structural frame. Fabric is propped or suspended to create a thin skin which is then saturated using water pumped from beneath the ice. The fabric freezes, fixing the form; props and ties are removed, leaving a self-supporting structure.

Such an agile architecture designed to exist only for a short time, might exploit a grey area where planning permits and building codes are side-stepped, and land-ownership claims are difficult to enforce. Such acts of resistance, although anarchistic, need not necessarily result in anarchy. Nor need they preclude an architecture from ‘gathering the properties of the place’ as Norberg-Schulz wanted, with built forms retaining the capacity to respond to or reflect cultural, historical or material qualities of place.

Some burlap cloth, a macramé ring, a reel of cotton, an ice auger, a kayak bilge pump, a telescopic swimming pool pole, some nylon cord, a snow shovel, and a backpack cropsprayer.

This inauspicious collection of everyday items could be an inventory of objects dragged from the dark recesses of a garage blinking into the light of a yard sale. It is, in fact, an exhaustive list of items used in the construction of Orko; a testament to adhocism where ‘everything can always be something else’. Improvising with what is at hand rather than things devised for a particular purpose is to construct as a bricoleur rather than as architect or engineer.

Levi-Strauss observes that ‘the ‘bricoleur’ also, and indeed principally, derives his poetry from the fact that he does not confine himself to accomplishment and execution: he ‘speaks’ not only with things … but also through the medium of things: giving an account of his personality and life by the choices he makes between the limited possibilities. The ‘bricoleur’ may not ever complete his purpose’.

In this spirit Orko is a beginning rather than an end. As temperatures rose above freezing, the structure failed as it melted. Doubling down, the construction principles, structural strategy and materials were reclaimed and re-deployed to create a new structure, assuming its own distinct form in a new location. Oculus, a small shelter for two people, is a bricolage of bricolage.

To the bricoleur, temporary architecture is not an immutable object but a materials bank. Through architectural and structural strategies with multiple potential outcomes, and assuring the integrity of materials and components are preserved, shapeshifting reinvention is possible. Looseness and imprecision can extend an architecture’s life, albeit in a form that little resembles the original and may not have been fully designed at the outset.

A common measure of well-engineered architecture is efficiency. David Billington elegantly outlines efficiency in this sense as ‘the search for forms that use a minimum of materials consistent with sound performance and assured safety …’. Frei Otto’s theory of minimal structures is yet more expansive, ‘an attempt to achieve, through maximum efficiency of structure and materials, optimum utilization of the available construction energy’. The ice surface structures described here, even for someone with little or no construction skills or experience, are fast to construct, use cheap, readily at hand materials and are only a few millimetres thick. Despite no calculations having been made, they are highly efficient in their use of structure, materials and constructional energy.

Yet their virtues are also their vulnerability. Even at sub-zero temperatures, they are susceptible to structural failure. Sublimation – the state-change process of ice becoming vapour without first becoming liquid – poses the same threats as ice melt. At such minimal thicknesses, even a small loss of ice quickly causes buckling and structural failure. Attempts to mitigate this by increasing Oculus’ thickness by spraying it with frigid water proved largely futile as despite air temperatures approaching -10ºC much of the water ran off before it could freeze.

Two years later Oculus was reprised. Opportunely constructed before a heavy snowstorm, the ice-fabric form was engulfed overnight by a blanket of snow over 10cm deep, which was further thickened and compacted manually. Adding more material rather than using less might seem counterintuitive, however this additive redundancy enabled Oculus 2.0 to survive several weeks of fluctuating weather, including multiple spells in which conditions for sublimation or ice melt occurred that would have resulted in the collapse of a thinner version. The snow layer not only stabilises but insulates, making temporary occupation of these forms a more viable proposition.

For architecture that is intended to be permanent, additive redundancy would be materially and economically perverse. Where an architecture’s duration is constrained, particularly by entropy, additive redundancy becomes an interesting and valid proposition. Paired with the lesson of adhocism – that everything can indeed always be something else – additive redundancy through, for instance, oversizing components, materials or structure may further extend possibilities for reuse. Oculus was realisable because Orko contained a greater amount of fabric than its footprint strictly required. Extending this logic, a simple beam intentionally oversized for its first life could be subsequently re-used over a larger span or to take a heavier load in a second or even third life. From a strategy of additive redundancy a constructional grammar – oversailing beams, projecting columns, gathered fabric, and so on - may arise for a work of temporary architecture.

“I think it’s more important to make .., a lot of different things and keep coming up with new images and things that were never made before, than to do one thing and do it, do it well. They come out fast, but, I mean, it’s a fast world.”

— Keith Haring, 1982, CBS Sunday MorningThe world is still fast, but the term increasingly has negative connotations. From food to fashion, ‘fast’ is all but synonymous now with convenience, cheapness and disposability. Fast might be accused of creating or displacing as many problems as it proffers to solve. Temporary architecture is not immune to such charges. These are serious issues, but fast remains an indelible reality of our time. The structures described here are also fast. Even with little or no construction skill they can be made in a matter of minutes, conditions permitting. The artist and social innovator Theaster Gates has spoken of his belief that “most things have a second life, that there is a value in the discarded, and that objects and buildings can be reactivated and redeployed to serve a purpose beyond what they were originally intended for”.

A melted ice/fabric structure’s second life – if not already the product of something else – may assume either its original form or a new one, never made before. Work continues on finding ways these playful experiments might also directly offer utility. Preliminary measurements taken from Oculus 2.0 offer encouragement that the snow blanket may not only make such structures more resilient in unstable frigid climates, but may also help create stable internal environments potentially suitable for temporary occupation, akin to an igloo yet a distinct structural morphology. For now, situated between the philosophies of Haring and Gates, these modest constructions perhaps offer some clues as to how temporary architecture can accentuate the positives of ‘fast’, while ameliorating some of the issues of disposability and waste associated with it.

Though derived from an esoteric form of construction and structural type, the lessons of agility, adhocism and additive redundancy, are generalisable, applied alone or in combination with other architectures, but especially those with limited lifespans, such that like certain forms of art practice, they might question, resist, or exploit circumstances that would otherwise curtail their permanence. The lessons invite us to find ways of building more freely but still responsively and responsibly. They invite us to contemplate reframing the task of designing temporary architecture as an act of designing systems with multiple possible outcomes and lives, as opposed to a singular defined presence. In so doing, constructional grammar(s) may emerge that enable temporary structures to acknowledge and celebrate their transience, thereby architecturally distinguishing them from those which are to remain uncertainly. g

Billington, David. The Art of Structural Design: A Swiss Legacy. Princeton, 2003

CBS Sunday Morning. ‘From the Archives: Keith Haring Was Here’. YouTube, 28 Mar. 2014

www.youtube.com/watch?v=W04j0Je01wQ.

accessed 19 January 2023

Chilton, John. Heinz Isler (Engineer’s Contribution to Architecture) Thomas Telford Ltd., 2000

Garlock, Maria Moreyra, and David Billington. Félix Candela: Engineer, Builder, Structural Artist. Yale UP, 2008.

Glaeser, Ludwig. The Work of Frei Otto, Museum of Modern Art, Greenwich, 1972

Jencks, Charles, and Nathan Silver. Adhocism: The Case for Improvisation. Expanded,updated ed., MIT Press, 2013.

Levi-Strauss, Claude. Savage Mind. University of Chicago Press, 1968.

Norberg-Schulz, Christian. Genius Loci: Towards a Phenomenology of Architecture. Rizzoli, 1979.

Tsui, Denise, et al. “Theaster Gates on Driving Community Transformation With Art.” COBO Social. 18 Apr. 2020.

www.cobosocial.com/dossiers/theaster-gatescommunity-transformation

accessed 19 January 2023

All constructions and photography by Team HILL (Hockett/Ingleby/Lawes/Leeson)

TIM INGLEBY is an architect and an assistant professor of architecture. His teaching and research interests lie in contemporary architectural design, allied with novel formfinding methods, innovative structural systems, and the principles of construction.

brittany giunchigliani

brittany giunchigliani

Water, an omnipresent element within our bodies and the environment, holds a wealth of dynamic and collaborative qualities that are often overlooked in architecture and landscape architecture. In this line of work, the mechanics of water is inherently entangled with our material choices but is often over-simplified and undervalued. Critical geographer Jamie Linton argues that our perception and understanding of water has been reduced to a measurable unit – H2O, stripping away its inherent connection to bodies and the environment. Within spatial design, this process of modernising water has led to a rigid and impermeable built environment.

Beyond the abstracted understanding of how water affects the world around us lies an opportunity to reconceptualise the ways in which water shapes us. It degrades. It brings life. It is scarce. Its behaviours are versatile. If we give more attention to the movement, dissolution, transformation and interactions of water, the body and our environments, if we embrace a notion of wateriness in practice, might our work become more flexible, nimble and intentional? Thinking this way challenges the prominent western paradigm of self sufficiency, individualism and excess as we look to watery logics for inspiration. This inquiry invites us to look beyond our profession and explore strategies of artisanal fishers who intimately work with and in the sea.

In February 2023, I conducted field research in small coastal towns within the Los Ríos and Los Lagos regions of southern Chile. There, I had the opportunity to engage with a diverse group of artisanal fishers who rely on the sea for their livelihoods. From seaweed harvesters to crabbers to fisherpeople, each person’s relationship to the water was illuminated through different strategies of ritual and care. These were often shaped by wisdom passed down through generations within their close-knit communities and the specific demands of their respective trades. Consequently, this interweaving of knowing a place and professional necessity manifested in deliberate and meaningful material expressions along the shoreline.

Working with water has its own temporality - a diurnal and seasonal rhythm that requires one to be responsive with intention. Within these two rhythms there are different rituals: daily routines such as harvesting at specific times during the day depending on the tides, and seasonal tasks such as mending and replacing tools. These activities vary by fishing village and that which is being harvested. Each system, catch, place requires its own material approach, cared for not only by the individuals using them, but also the web of people that interact within this waterscape.

Public

Luga Roja drying in the sun on the beach, Playa Chauman, Ancud, Chiloé Island, Chile

At Playa Chauman I met a family of seaweed collectors who harvest each morning at the public beach. When the tide begins to return, the mother and her two older children passively collect Luga Roja (Sarcothalia crispata) in the small, protected cove at the end of the beach. They use plastic woven sacks, a material that can be seen everywhere around the island, recycled from various other uses to hold their harvest. The bags are light, permeable and can hold roughly 25 kilos of wet seaweed. Once filled, they are carried from the shore up the beach to the warm sand where the seaweed is laid out to dry under the sun. After drying, the seaweed is loaded back into the bags and are transported to market and sold. When the bags start to break down, they are used at home until they deteriorate completely. Here, the rhythm of the sea and the bodies’ ability to carry are in constant conversation

In the small town of Pupelde on Chiloé Island, wooden stakes are spaced out along the beach — a passive, tidal collection system to capture Pelillo (Gracilaria chilensis), a common seaweed harvested in the estuaries of southern Chile.

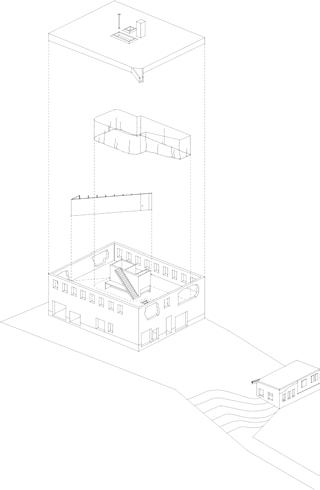

These micro-installations of the fishing community’s daily operations are nimble, intentional and in conversation with the environment. Here, architecture does not serve as the foundation, nor does it act as the saviour; and in some towns such as Los Molinos where communal dinghies and wooden pallets are left on the shore, it is not even necessary. Instead, architecture is just one voice engaged in a dialogue with fishers, the sea, materials and the day’s catch. Architecture’s significance is small in scale, discreet and relational; capable of being adjusted, removed or replaced.

While different artisanal groups often use trade-specific tools and work in distinct coastal areas, there are similarities in the southern Chilean fishing landscape they all share — access to certain materials, how goods are bought and sold, climate, sense of place and a shared cultural identity. Chilean industrial and mechanised fishing industries use permanent piers and warehouses developed and maintained solely for that industry. In contrast, many artisanal fishers, such as seaweed harvesters or individual pescadores, rely on access to public beaches or local paths that lead to the water. The responsibility for maintaining access points – to take care of them – is shared. The line blurs between the individual and the collective as multiple families, ages, and professions collaborate to maintain communal tools, manage beaches, and generate income.

Co-management of this waterscape reveals a particular intimacy – one where the environment and the fishers are in constant dialogue. The market is not necessarily the driver of how and where the days’ catch is offloaded rather it’s the shape of the beach, the depth of the bay, the materials used to stack, store and move the goods from boat to shore; a dialogue observed through small, fluid, site-specific material choices. For instance, .

Even though the customary materials have changed over time, from jute and wood to plastics and styrofoam, many of the tools are still fastened, affixed, or used as they were by grandparents: knowledge is passed down, along and through time, to people young and old, and assumes a material form through these micro-installations that are cared for by the artisanal fishers and their families. The techniques of harvest and collection embed the strategies of those who came before and ways of working that will guide those who come after.

It is through these material expressions in the coastal towns of southern Chile that offer insight into qualities of wateriness that are applicable to our practice as designers. Working closely with the sea, artisanal fishers have honed their craft through generations, weaving together traditions, materials, and a deep sense of place. Water’s influence imbues a greater need for adaptability and resourcefulness that can be observed in these quotidian rituals of care. It is not through the simplification of these approaches that we are able to gain insight but rather through water’s synergetic nature that we can better learn to build together.

BRITTANY GIUNCHIGLIANI, a Baltimore-based landscape designer, explores embodiment in the landscape through a feminist lens. Brittany holds a Master’s in Landscape Architecture from Harvard Graduate School of Design.

www.littlejonquil.com and @ourbodiesmadeofwater on Instagram.

Online Etymology Dictionary

temporal (adj.)

late 14c., ‘worldly, secular’; also ‘terrestrial, earthly; temporary, lasting only for a time’, from Old French temporal ‘earthly’, and directly from Latin temporalis ‘of time, denoting time; but for a time, temporary’, from tempus (genitive temporis) ‘time, season, moment, proper time or season’, from Proto-Italic *tempos- ‘stretch, measure’, which according to de Vaan is from PIE *temp-os ‘stretched’, from root *ten- ‘to stretch’, the notion being ‘stretch of time’. Related: Temporally.

Yona Friedman. ‘Guidelines for People’s Architecture’, Mobile Architecture, People’s Architecture. Rome: MAXXI | Museo nazionale delle arti del XXI secolo, 2017

I am interested in the etymology, origin and meaning of words. I can get lost in an old fashion paper dictionary, and the Online Etymology Dictionary can be a serious work disrupter. The whole question of temporary architecture raises many, many questions: who decides what is temporary? Is it a political decision, driven by commerce, the politics of capitalism, or by fashion?

Temporary: Are refugees camps temporary architecture? This camp could be any camp.

One of the oldest camps is Cooper’s Camp in West Bengal, India, opened after partition in 1947. Made up of mostly Hindus living in mainly Muslim East Bengal who fled across the border. After 70 years Cooper’s Camp is still home to some 7,000 people. From Kenya to Palestine to Turkey.

Tents fill the outskirts of Dagahaley refugee camp in Kenya’s Dadaab refugee complex on July 24, 2011. The United Nations refugee agency, UNHCR, estimates Dadaab is receiving 1,300 new arrivals each day, adding to the numbers in the already drastically overpopulated camp. Dadaab was opened twenty years ago, with a capacity of 90,000 people. Current estimates place the refugee population here at around 380,000 people. The European Union aid commissioner vowed yesterday to do all that is possible to help 12 million people struggling from extreme drought across the Horn of Africa, boosting aid by 27.8 million euros ($40 million).

temporary (adj.)

‘lasting only for a time’, 1540s, from Latin temporarius ‘of seasonal character, lasting a short time’, from tempus (genitive temporis) ‘time, season’ (see temporal, late 14c., which was the earlier word for ‘lasting but for a time’).

The noun meaning ‘person employed only for a time’ is recorded from 1848. Related: Temporarily; temporariness.

The Palestinian camps/temporary homes began to appear in 1940: temporary shelters, temporary architecture. Not all look like tent cities, some are more like shanty towns.

Politically, camps are always temporary, even if they are 70 years old.

Though we have seen amazing architecture structures over the years, people are still living in tents. disposable: ‘that may be done without, makeshift: ‘the nature of a temporary expedient.

short-lived: ’having a brief existence’. provisional: ’as a temporary arrangement, provided for present need or occasion’

Prospector’s tent on waterfront, Dawson, Yukon, Territory, 1899, these camps were not temporary structures but portable, when the prospectors moved on they struck camp. These tents were also used by geologists and archaeologists.

Temporary employment, like temporary architecture, is taking on a whole new meaning, as workers are fighting back at being temporary or considered disposable.

homeless (adj.) ‘having no permanent abode’, 1610s, from home (n.) + -less. Old English had hamleas, As a noun meaning ‘homeless persons’, by 1857.

1680s, ‘one who flees to a refuge or shelter or place of safety; one who in times of persecution or political disorder flees to a foreign country for safety’, from French refugié, a noun use of the past participle of refugier ‘to take shelter, protect’, from Old French refuge ‘hiding place’, from Latin refugium ‘a taking refuge; place to flee back to’, from re - ‘back’ (see re-) + fugere ‘to flee’ (see fugitive (adj.)) + -ium , neuter ending in a sense of ‘place for’.

http://www.shigerubanarchitects.com/works/2020

2020 South Kyushu Flooding / Paper Partition System. Voluntary Architects’ Network (VAN) and Shigeru Ban Architects provided 1300 units of Paper Partition System (PPS) as a relief to support for flooding in southern Kyushu, Japan.

temporary = political = disposable temporary = social = memories

www.shigerubanarchitects.com/SBA_NEWS/2022_ukraine/ VAN+ Shigeru Ban Architects provide the Paper Partition System (PPS) for shelters of the increasing number of refugees staying in neighbouring countries of Ukraine. This is a simple partition system to ensure privacy for inhabitants and has been used in numerous evacuation centers in regions hit by disasters, such as the Great East Japan Earthquake (2011), Kumamoto Earthquake (2016), Hokkaido Earthquake (2018), and torrential rain in southern Kyushu (2020). above, PPS system in a college gym, Uman.

Shigeru Ban Architects and Ikea: life in a box without the Allen Wrench — temporary privacy screens at the Hoita Elementary School Ukraine Refugee Assistance Project Slovakia, is a project supported by IKEA (the mega centre for disposable items).

The question is why temporary?

Foster+Partners has designed two residential towers on Al Reem Island, UAE, currently under construction close to the north eastern coast of Abu Dhabi city. When complete in 2024 it will house 280,000 residents, as well as providing schools, medical clinics, shopping malls, restaurants, sports facilities, hotels, resorts, spas, gardens and beaches.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cyclone_Mocha

One million Rohingya refugees live in Cox’s Bazaar, Bangladesh, fleeing persecution, widespread violence and human rights violations in Myanmar.

makeshift: an interesting word, make shift:

makeshift, adj., 1680s, ‘of the nature of a temporary expedient’, which led to the noun sense of ‘that with which one meets a present need or turn, a temporary substitute’ (by 1802).

permanent, adj.

‘enduring, unchanging, unchanged, lasting or intended to last indefinitely’, early 15c., from Old French permanent, parmanent (14c.) or directly from Latin permanentem (nominative permanens) ‘remaining’, present participle of permanere ‘endure, hold out, continue, stay to the end’, from per ‘through’ + manere ‘stay’ (from PIE root *men-(3) ‘to remain’).

— Nikolaus Pevsner, An Outline of European Architecture. London: John Murray, 1943

This might explain why we have an abundance of churches that are not temporary or disposable.

Kumbha in Kumbh Mela literally means ‘pitcher, jar, pot’ in Sanskrit. It is found in the Vedic texts often in the context of holding water or in mythical legends about the nectar of immortality...The word mela means ‘unite, join, meet, move together, assembly, junction’ in Sanskrit, particularly in the context of fairs and community celebration. (from wikipedia)

Who decides what is temporary? Have you gone for a walk in your neighbourhood, and find there is something missing — a whole community missing, buildings and stores, and wondered where all the people have gone? In their place a hole, and soon another glass tower.

What is possible

What is possible!

Tens of millions of pilgrims attend Kumbh Melas every three to four years, praying the holy waters will free them from the cycle of rebirth. The Kumbh Mela is planned/ designed to be erected and inhabited as soon as the monsoon season ends and the riverbanks emerge from the water, and then dismantled before the flood waters return.

Who decides what is temporary and makeshift? If a structure no matter how temporary or makeshift can be constructed to accommodate 200 million people, does that not suggest the possibility of creating many small permanent communities?

Canada’s national database estimates that there are approximately 235,000 homeless people across the country.

What if – the planning and management model for a Kumbh Mela, one of the wonders of modern management, and, say, Foster+Partners with their global and political clout, collaborated to build permanent shelter, not for money, but for humanity?

Maybe it is just magical thinking.

Imagine what is possible. g

‘Nearly everything that encloses space on a scale sufficient for a human being to move in is a building; the term architecture applies only to buildings designed with a view to aesthetic appeal.’from the series, Walking Toronto ANNE O’CALLAGHAN uses a range of media to emphasise the idea behind an artwork over how it is made or what it is made from. O’Callaghan and lives and works in Toronto.

The week before she died, in September 2022, Hilary Mantel wrote ‘what makes craft into art is the margin left for contingency, the space made for ambiguity’.1

Dennis Rovere2 sent me a book last spring: Building Critique. Architecture and its discontents3, which asks ‘Can architecture be critical despite its interdependent relationship with power and profit?’ and then answers with eleven essays that range from theory to activism. The editors’ introduction, ‘A Critique of Practice or a Practice of Critique’ lays out the issues: as critique is at the centre of progressive thought, it was long thought that deconstruction of certain practices revealed structural weaknesses that were either naturalised ideology, unsustainable hierarchy or myth. Critical architecture of the 1970s and 1980s meant to translate largely academic critical theory into design work: projects themselves illustrated disjunctions between social reality and capitalism with which the practice of architecture is indubitably intertwined. Commercial and institutional architecture was untouched by this critique which became increasingly de-politicised and ineffective. Post-criticality engages a different set of social parameters, casting architecture as a way to propose alternatives to socially weak critical architecture which was difficult to apply to practice.

The essays in Building Critique are characterised by what the editors call ‘gradual openings’ to other lines of influence, mainly sociology and geography, poststructuralism, feminism, postcolonial theory and media studies. The very fact that we are in an era of global migration means that the direction of thought is no longer solely from the global north to the south, or from the centre to the periphery, but is multi-directional: the global south is arriving in the north with different, no less sophisticated, spatial and social understandings.

The basic referents are neither new, nor surprising. Manfredo Tafuri’s Architecture and Utopia: Design in Capitalist Development came out in 1978. Henri Lefebvre’s The Production of Space in 1974, and The Critique of Everyday Life in 1988. Bourdieu’s conception of habitus was articulated in lectures at the Collège de France in 1982-3. Out of these seminal texts comes the sense that a critical spatial practice is a mode of action, an engagement with hegemonic structures, not a withdrawal from them.4

Lisa Fior’s essay in this book, ‘Don’t make it sound heroic; that’s why we have put the keynote last’ states at the very beginning:

Since muf started working together in the mid-1990s, we have been trying out ways to expand a project brief in order that it reflects more than the source of funding and the limited indicators of success. This way of working includes the acceptance of compromised briefs and then expanding their scope through a willfully literal interpretation. Often , this also means working for free and then making it sound better by calling it ‘unsolicited research’.

And a bit later:

We wedge the door open for other people and other agendas so that they can enter and complete the brief in ways that are sometimes obvious and sometimes less so. We describe this as ‘unsolicited research’, the extra work necessary to make a project both meaningful and bearable.

1 cited by Gaby Wood in The Guardian, 25 Sep 2022

2 On Site review 40 contributor, and author of The Xingyi Quan of the Chinese Army, Penguin Random House, 2008

3 Gabu Heindl, Michael Klein, Christina Linortner, editors. Building Critique. Architecture and its discontents. Leipzig: Spector Books, 2019

4 Chantal Mouffe, ‘Critique as Counter-Hegemonic Intervention’. EIPC European Insititue for Progressive Cultural Policies, 2008 http://eipcp.net/transversal/0808/mouffe/en

Clearly this is a long and fairly subversive process, to leave hidden directives and clues to future designers of public spaces, for that is muf’s terrain – the public spaces of London, and for the public filling such spaces. The process starts before design, continues during construction and is active after the project is signed off, supposedly complete. Fior calls it wedging open a door by degrees. She cites Ruskin Square beside the East Croydon train station, meant to fit into a masterplan by Foster+Partners, masters at ensuring the clarity of their projects. Wilfully literal, quotes from Ruskin justify design moves: ‘A healthy manner of play is necessary for a healthy manner of work’ framed the site as a garden with sports facilities: not the British obsession with football, but for Afghan refugees fostered in the community who play cricket. The garden, a temporary re-wilding of a derelict site, introduced ground rules – landscapes can host young people, that the formal next to the wild is a design language, and that Ruskin’s epigrams are references for future design decisions by the developer and other designers. Termporary moves, over time, come to be seen as embedded and logical. A Ruskinian ‘festival of toil’, part of a requisite art strategy for planning permission, was developed by muf’s Katherine Clarke and a local organisation that works with young men, who ultimately made their own work clothes, a clay oven, cast aluminum tools and built furniture from site hoardings. This material making and un-making of a site is a strategy that seeds its future. g

When many people think of temporary architecture they conjure images of camping tents, perhaps a pop-up market stall or food truck. But the temporary is also often conflated with informality in what are preferably called ‘self-built communities.’ An example of this is the neighbourhood of 05 Maji (5th of May) on the northern peripheries of Tirana, Albania, originally self-constructed by rural migrants arriving at the capital in the early 1990s following the collapse of Enver Hoxha’s communist regime. For decades, residents have established inter-generational roots and supported the city’s socio-economic activity, despite their neighbourhood being unrecognised, and often erroneously framed as ‘impermanent’ or

‘temporary.’ There are deeper historical reasons behind Tirana’s property informality, driven by a nationwide post-communist politico-economic crisis resulting in long periods of legal ambiguity and entire city districts being frozen in ad hoc and contingent bureaucracy. In the decades since the 1990s, residents and their advocates have worked to register, or formalise property, including following an April 2006 law on the legalisation, urbanisation and integration of unauthorised constructions — with varying degrees of success depending largely on the politicians in office and their plans for transforming the city.

On 31 January 2020, the Council of Ministers solidified 05 Maji’s temporary designation by declaring it a ‘forced development area.’ The government claimed such redevelopment was necessary following damage from a 2019 earthquake, and the relocation of residents from other earthquake-effected areas. Yet, schematic proposals to re-develop the district date back to 2012, following the forcible eviction of 21 Roma families in August 2006, leaving 109 people homeless.1 Now, a fresh round of mass evictions, land seizures and demolitions of approximately 400 residential buildings aim to make way for a new neighbourhood of the future: the iconic Tirana Riverside Project, a 29-hectare ‘smart city,’ ‘pandemic-proof’ eco-district for 12,000, designed by the famous Italian firm Stefano Boeri Architetti. The Tirana Riverside Project was proposed as a key component of Prime Minister Edi Rama’s vision to rebrand the Albanian capital, in turn attracting greater tourism and investment to the city. It is connected to the larger TR2030 Masterplan also by Stefano

1. Centre on Housing Rights & Evictions (COHRE). Global Survey on Forced Evictions: Violations of Human Rights. 2006 https://www.hlrn.org/img/violation/GLOBAL%20SURVEY%202003-2006.pdf Accessed 10 May 2023.

Boeri Architetti, with both iconic proposals held up as evidence that the government is improving Tirana, in turn increasing voter popularity. Yet, in Albania’s flawed democratic context with chronic corruption, concerns these initiatives are greenwashing a type of urban development propelled by money laundering put designers like Boeri in an awkward position and belie their claims that their work is headed toward a more habitable and inclusive future.