Vice President

Sarah MacDougald (‘25)

Head of Writing

Melina Traiforos (‘25)

Head of Photography

Blythe Green (‘27)

Head of Design

Oliver Hale (‘25)

Editors

Breanna Laws (‘25)

Maddie Stopyra (‘25)

Design

Claire Bedley

Oliver Hale

Chloe Han

Elizabeth Hodges

Grace Schuringa

Photographers

Madison Burba

Mary Chura

Blythe Green

Kait Sharkey

Writers

Tabitha Cahan

Adam Coil

Lydia Derris

GK Duncan

Aria Heyneman

Carolyn Malman

Virginia Noone

Molly Steur

Hope Zhu

It is seemingly impossible to imagine what life at Wake Forest would be like without Reynolda. For so many students, it provides an escape from the stressors of campus life, an opportunity to get in touch with nature and a nice diversion during lulls in our schedule. But oftentimes, it is the very things we are accustomed to seeing every day that we cannot fully appreciate without taking a closer look.

As you will discover in this issue, the story of Reynolda is much more than the story of the Reynolds family and Tobacco Road wealth. It is a tale told by a wide array of peoples that stretches across multiple centuries — at times a tale of exploitation and violence but also, crucially, one of empowerment, spiritual revival, community, joy and aesthetic beauty. Our goal in this edition is to reckon with some of the history of the land that Wake Forest is built on, while also celebrating what it means to so many people today.

I hope that by reading about all of the individuals who have shaped Reynolda over the years, as well as the

opportunities that it provides for people of all ages, you will be better equipped to appreciate what it has to offer. Reynolda is a place for reflection, and by documenting stories that have been unfolding here for decades, we hope that you will be able to see your time on this land in a new light. Questions are still unanswered and history is still unfolding — it is our responsibility to make meaning out of it all.

I want to thank everyone who shared their stories and their time to make this edition possible, as well as all of those individuals whose contributions have brought The Magnolia to this point. In particular, I want to thank the former presidents of The Magnolia — Selinna Tran, Cooper Sullivan and Maryam Khanum — each of whom I have looked up to and learned so much from over the years.

We remain, in the words of Tommy Priest, a “small experiment with radical intent.”

One man. 65 beehives and counting. Over 2,000 pounds of honey.

Curiosity grows into lifelong passion and career opportunities at stArt Gallery.

American art has evolved since the Reynolda House museum of American Art opened. How has it adapted?

The university’s path from Wake Forest to Winston-Salem spans over 70 years and 100 miles. 26

Get to know the people behind your favorite small businesses in Reynolda. 32

Students and faculty alike find peace, reflection and answers in the comfort of Reynolda. 36

Learn about one local teacher’s efforts to enhance education at its roots. 40 An Ode to the

How many college students get to say, “Hey, wanna go hang out by the waterfall?”

Wake Forest confronts its problematic history as it seeks a path forward.

If you were to drive the 9.4 miles down Silas Creek Parkway, a colorful blur of trails, schools and businesses would whiz past your window as you neared Wake Forest University’s campus. Although at times scenic, the parkway would be unremarkable to the driver, who has no way of knowing the history they are driving over.

A history that has been paved over with cement, asphalt and an ignorance of Winston-Salem’s complicated past.

Still, They Rise continues on page 44.

Less than 70 years ago, driving to “Wake Forest” would have taken you to both the home of the Demon Deacons and a city 100 miles east of the current campus. The story of the town of Wake Forest and the university’s transition to Winston-Salem has been continuously reshaped and rediscovered. Yet, it is a story that connects the university to a complicated history. This land, that of Winston-Salem and Wake Forest, N.C., has become a forgotten witness to the tale of the oppressed and privileged alike. This land, divided between two cities, shares a history defined by those who have occupied it. The land’s story deserves to be told through a more truthful lens to ensure that our expressed institutional progress is not in vain. This is a narrative of human experience defined by its relationship to Indigenous communities, to the horrific institution of slavery, to a religious minority seeking a safe haven and to one of the wealthiest families in the North Carolina’s history. So, while this is a story about land, it really isn’t. This is more so a story about these people and how they shaped this community — unearthing the context in which pro humanitate must be understood.

This is Not About Land: Grounding Wake Forest’s History continues on page 20.

Do you know where your honey comes from?

By Tabitha Cahan

Photos by Blythe Green

The steady hum of bees fills the air as I stand beside David Link, a seasoned local beekeeper. Red, yellow and blue boxes are stacked atop one another — each its own hive. At first, I felt nervous, given that the hive of bees was mere inches from my face, but David’s calm demeanor immediately rubbed off on me.

“We’re standing right here behind these hives, and they could care less we’re here,” he reassures me. “They’re just checking you out.”

Link has been beekeeping for about 15 years. He’s managed over 100 hives, 65 of which are still thriving. They span the entirety of Winston-Salem, from Reynolda to Campus Gardens to Pilot Mountain. He teaches with the Forsyth County Beekeepers Association, which be-

gan in 1973. For Link, beekeeping is much more than just a hobby; it is about working with nature, and understanding that, like communities of people, each hive is different.

Link’s beekeeping journey was born out of necessity — his vegetable garden was struggling due to a lack of pollinators. A classmate at Forsyth Tech introduced him to beekeeping, and soon he had two small hives in his backyard. He initially started with Italian honey bees, given that they are more popular and readily available. However, despite seeing his garden flourish that spring, the bees didn’t survive.

He decided to switch to Russian honey bees, having learned that they are the best breed for North Carolina. Originating in the Primorsky Region of Russia, these bees can with-

stand cold temperatures, and even fly through the rain. They are also resistant to Varroa and tracheal mites, allowing him to refrain from using chemicals to keep them healthy. Chemical treatments cut a queen’s life short, making it more difficult to sustain the hive. Link is committed to beekeeping in its most natural form, with minimal intervention. It takes patience to cultivate the right conditions for the hive, and he finds fulfillment in watching them thrive. In the coming spring, he is planning to expand his hive count to 120.

Link is not alone in his beekeeping endeavors, however. He takes on mentees, guiding them through the complexities of hive management. This mentorship is something that he is deeply passionate about; it allows him to share his experience with

others and prepare them for managing the hives on their own.

“Beekeeping has shown me that I’m a homebody,” he said, “and beekeeping has shown me a lot that I wouldn’t have seen without it.”

Link approaches his hives with care and respect, but also a level of distance, treating them as though they are wild colonies that he’s providing a home. His philosophy is simple: give the bees the space and resources they need to thrive, and only intervene when necessary. Working with the bees, hands bare in the hive, is meditative for Link. His bees are very docile, allowing him a rare, profound connection to these hives. By

giving them space and respecting their instincts, Link demonstrates that less interference allows the hives to flourish naturally, a lesson in humility and trust in nature’s rhythms.

One way Link ensures his bees are healthy is by leaving enough honey in each hive during the winter. Rather than relying on sugar or corn syrup, he allows the bees to feed on the honey they produce because it is far more beneficial for their health.

For Link, the most rewarding aspect of beekeeping is performing a physical split on his hives, a process where a hive — home to just one queen — is divided into two. While one side of the split keeps the exist-

ing queen, the other half must raise a new one.

The satisfaction comes from seeing these hives grow into what Link lovingly refers to as “monster hives”. These massive colonies can get taller than him, with colorful boxes stacked atop one another. This process is not just about productivity, but preventing swarming. If the bees swarm, half of the hive could fly away. By managing the instinct to swarm, Link can maintain a healthy, thriving colony.

From the way Link talks about his bees, his genuine love for beekeeping shines through. He is so at ease as he describes this process, but also equally excited to share it with me. His

voice lifts with excitement as he describes these intricacies of hive management, and it is clear that nothing brings him more joy.

As more land is cleared for housing and farming, there is a decline in native bee populations. Managed honeybees have become crucial to sustaining our food supply, as native pollinators have become too few to handle the task.

Link stresses the need for bees that can care for themselves. Breeds like Russian and Carniolan bees offer hope, given that they are self-sustaining. For Link, it’s not just about honey production, but the joy of seeing hives thrive — knowing they are contributing to something larger.

Link urges people to be careful with pesticide use because many don’t realize that pesticides harm the delicate ecosystem inside a hive, especially the fungi. Honeybees do not have their own immune system. Instead, they rely on fungi within the hive to create a layer of protection that keeps them healthy. Without these fungi, bees become more vulnerable, so it is important to pay attention to what we spray and where.

Link uses hives as a valuable educational tool. Students and volunteers regularly visit the hives, learning about the role that honeybees play in our environment. Once, he demonstrated honey extraction to a junior high class and let the students manually crank the extractor and bottle the honey. According to Link, the more people know about the importance of bees, the better we can protect them.

“Link approaches his hives with care and respect, but also a level of distance, treating them as though they are wild colonies that he’s providing a home.”

By GK Duncan

Photos by Blythe Green

StArt Gallery creates a space where student potential can explode and lifelong connections can be made.

Maggie Hodge

Abuzz emits from the stArt Gallery in Reynolda Village. When you walk into a reception here, you never know who you’ll see — your faculty fellow from freshman year, a professor from your art divisional, a classmate from semesters past or community members from outside of the Wake Forest bubble — but what these people have in common is a shared appreciation for student creativity.

Friends of Amelia Dunat roam around the gallery, celebrating the time and dedication to her project, “Torn Together.” Over a charcuterie board and Trader Joe’s Raspberry Heart Cookies, attendees discuss their favorite

of Dunat’s works. For those who know Dunat in passing, a new side of her is unveiled.

Dunat is a senior at Wake Forest who has worked at stArt Gallery since 2023. “Torn Together” creates a conversation between her own artworks and those of alumni. It has always been a dream of hers to exhibit her art in a gallery, and stArt has given her the opportunity to do so.

“The buzz and energy within stArt is contagious,” said Dunat. “Everyone’s happy to be there, and it’s a special feeling to have all of my hard work paid off… the support of my friends and professors at the reception holds a special place in my heart.”

Dunat transferred to Wake Forest her junior year, and she feels that stArt was a catalyst for feeling a sense of belonging on campus and developing skills for her future career in a gallery.

“StArt bridges the artist with peers on campus and emphasizes community,” she said.

Maggie Hodge, a senior who exhibited her solo show “Going Through The Motions” during the fall of 2024, agrees that the gallery has brought a sense of belonging to her time at Wake Forest.

“Having a place where any student can exhibit their art is powerful and promotes a community around art,” she said. “It’s a great place to build confidence as a young artist.”

StArt Gallery, which is managed by the Wake Forest Fellows Program, opened its doors in 2009, providing an interdisciplinary space for learning outside of the classroom. It pushes current art students to build confidence and competency in the art world by granting them pre-professional opportunities and allows alumni to work on campus after graduation, feeding back into the Wake Forest arts community.

Hodge, like myself and many other students, was introduced to stArt Gallery in a studio art course during her freshman year. Her professors urged students to submit work to stArt Gallery’s inaugural “Let It Show.”

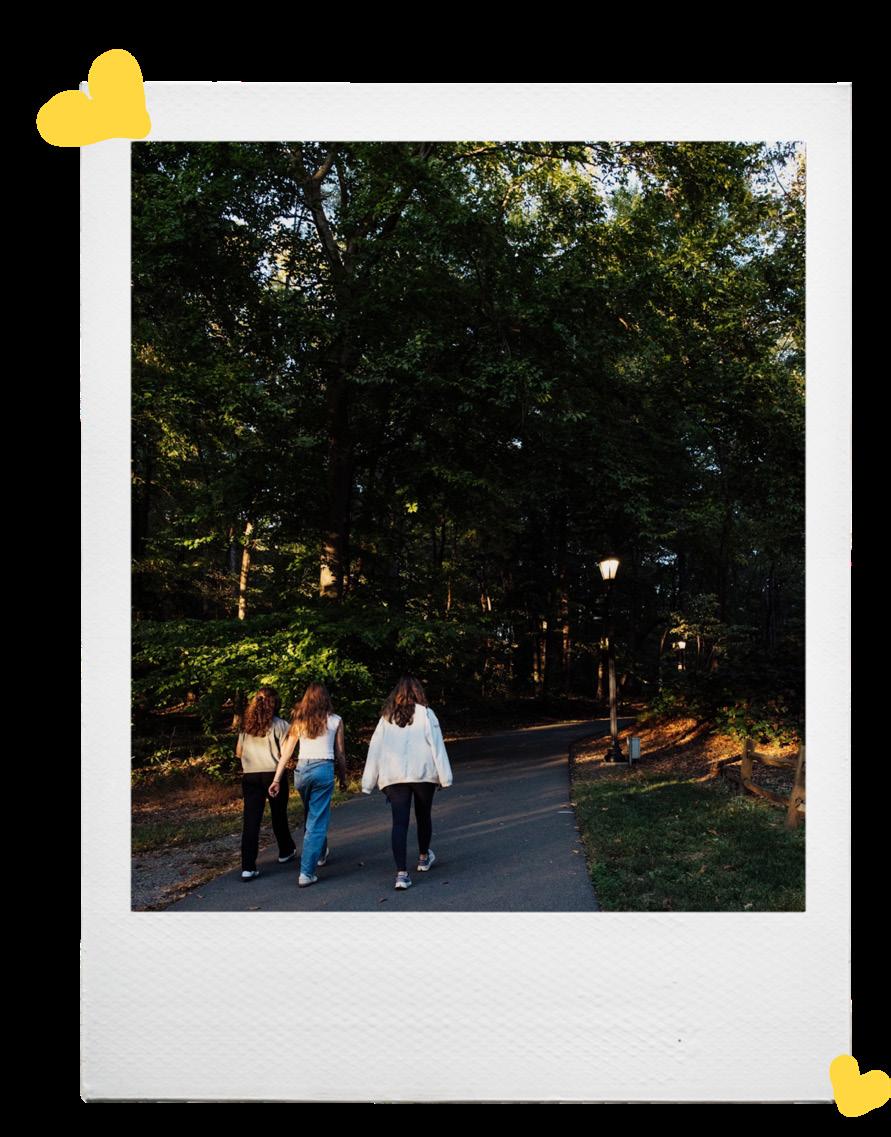

It was this semester, Hodge’s and my freshmen fall, that our friendship first formed. Walking through Reynolda Trail on our way back from the “Let It Show” exhibition, we shared our support for each other’s artistic endeavors. Hodge’s joy from the reception lingered all the way back to South Campus.

The stArt Gallery’s main physical space lies in the former blacksmith’s house of the Reynolds Estate in Reynolda Village. It is easily accessible from campus, just a short walk along the Reynolda Trail. As visitors follow this path away from the bustling campus, their journey to stArt becomes an extension of campus life — a space where the noise of “Work Forest” fades away.

At a secondary location, stArt Downtown, art and science intersect. STEM students interact with the artwork on their way to engineering, chemistry and biology laboratories, creating conversation outside of the usual chatter of the next exam, or lab practical.

For Audrey Knaack, a senior who has worked at stArt Gallery since her freshman year, the gallery is a part of her “self-care routine.” Biking to work through Reynolda Village, grabbing a coffee at Dough Joe’s and welcoming visitors into an intimate setting of student expression is an essential part of her wellbeing.

“The magic at stArt Gallery is infectious,” she said, “even noticed by visitors outside of the Wake Forest community that come inside and experience the exhibitions.”

At the gallery, the focus on art offers a momentary es-

cape from the academic pressures at Wake Forest. Knaack describes this journey from campus as an “approachable adventure” because students, regardless of their former knowledge about art, can take something away from their visit.

Working at stArt Gallery has been incredibly meaningful for Knaack, as she feels empowered as an artist, and brought her hands-on experience as a student entering the art world.

“Working with StArt Gallery taught me the steps of an exhibition,” said Jane Alexander, a senior who held her solo exhibition “mtf.zip” in the Spring of 2024. “Their help with writing an artist statement gave me strength as an artist to foster dialogue, and learn curatorial skills.”

Working at stArt, Dunat has also gained confidence and feels well-equipped to handle the responsibilities of a gallery setting. The lessons she has learned cannot be taught in a classroom but only through hands-on work experience.

Wake Forest alumna Maya Whitaker (’23), the current stArt gallery manager, believes that student artwork deserves the same care as those at a high-level museum.

She honors that sentiment as she trains the students who work at stArt Gallery.

“When installing an exhibition, we treat student work with the same respect as the Picassos hanging in Benson,” she said.

During my sophomore year, anxious to build experience in the art world, I worked as the Business & Communications Intern at stArt Gallery and exhibited my own work. I have vivid memories of how giddy I was getting ready for my first headshot as an intern, hugging my friends who came to support me at receptions and creating Instagram posts for @stArtgallerywfu. Instilling a sense of self-worth through uplifting the creative ventures of my peers was an experience unlike any other.

Stepping into stArt my freshmen year, on the night of “Let It Show,” and making new friends by just talking about the artwork made by our peers was the first time it really clicked that I had a community on campus.

The magic that radiates from stArt Gallery doesn’t appear out of thin air — it is continuously regenerated through the vibrancy of those who love, support and visit stArt Gallery.

By Lydia Derris

At the turn of the century, all the elusive promises of the great American myth appeared to have been realized. A high society propped up by wealth, draped in minks and glinting with diamonds, had heightened the allure of American enterprise. The success stories of the Vanderbilts, the Carnegies and the Rockefellers, affirmed the American Dream to stake your claim and strike it rich. This mythos, too, orients the history of Reynolda House. Built in 1917, the once private estate of R.J. and Katharine Reynolds remains today both a celebration and self-critique of its gilded past.

The estate, with its sprawling grounds, was built on the success of the R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company. But in its construction, Katharine Reynolds insisted on something more homey than extravagant. She instructed her architects to create a “squatty house” — a white, bungalow-style home with low green tile rooflines, sweeping porches and solid columns, according to Deputy Director of Reynolda House, Phil Archer. It wasn’t about gran-

deur for grandeur’s sake. It was about creating a space that embraced comfort while quietly commanding respect. Today, that same ethos persists at Reynolda House Museum of American Art. Though its purpose has evolved, the museum retains its sense of intimacy and approachability.

Barbara Babcock Millhouse, R.J. and Katharine’s granddaughter, was the driving force in transforming the home into the Reynolda House museum. She opened its doors to the public in 1967 with just nine works of art. From these modest beginnings, it has grown into a collection of more than 200 works.

Babcock Millhouse has been an integral part of the museum’s milestones, including its affiliation with Wake Forest University in 2002, and the successful restoration efforts that have preserved the house’s historic interiors. Her ongoing efforts ensure that Reynolda House remains not only a premier museum destination but also a space where American art and the Reynolds legacy nourish each other in creative symbiosis.

Each individual piece of the museum’s collection has an immense artistic range, from 18th-century portraiture to 19th-century Hudson River School landscapes to 20th-century abstraction. This dynamism is “a testament to Barbara’s incredible versatility and eye and her focus on getting the best American art that she can get,” says Allison Slaby, the museum’s current curator.

Susan Sontag argues in her Against Interpretation that while content is often privileged in discussions of art, it can be a hindrance, a philistinism that traps us in reductive thinking.

Art, she suggested, must transcend its content to engage viewers on a deeper, visceral level.

This is what Reynolda does best.

Winter trudges on and the days grow shorter, and by mid-afternoon, the violet hour approaches. The sun is

down and there’s just a little bit of light left in the sky. On those dark, short winter days, the main reception room glows softly with lamplight and the sconces on the wall illuminate the art.

It’s almost like the room, quietly guarded by the monolithic masterworks, wraps its arms around you and keeps you safe. Frederic Church’s “The Andes of Ecuador” envelops you in its sublime grandeur, the peaks dissolving into mist and mystery. The painting and the house feel almost alive, the dramatic light and shadows build into catharsis: a serene moment of reverence — a reminder of nature’s capacity to dwarf human ambition.

Hanging above the balcony, pulling your eyes heavenward, Albert Bierstadt’s “Sierra Nevada” commands the space with its vast, glowing mountain range cascading into infinity. These Hudson River School landscapes transport you into the uncharted wilderness of 19th-century America, a world teetering between discovery and conquest.

Babcock Millhouse’s acquisition of these early works in 1966 closely coincided with the museum’s opening in 1967. In many ways, it’s hard to determine whether Babcock Millhouse was projecting an ambitious, untapped vision into these early acquisitions, or if these early acquisitions were informing her vision of the untapped field of American art collection.

The collection is continuously modernizing with time as it expands to include bold contemporary art. Babcock Millhouse began purchasing such as Georgia O’Keeffe’s “Pool in the Woods, Lake George” and Stuart Davis’ “For Internal Use Only.”

Shortly after purchasing the work by Davis, Babcock Millhouse relays that, “The archivist comes up to me and says, ‘Barbara, you need to come and look at some papers that I have in the archives, some papers of your mother’s,’ and there was a box of papers and inside this box was a full page color, illustration of “For Internal Use Only” that have been in Life Magazine in 1945 or ‘46, about the time the painting was actually done.”

This discovery led Babcock Millhouse to reflect on the subtle influence her mother may have had on her collecting instincts and, perhaps more profoundly, the intersections of the lives of women — artists and collectors alike.

Corey D.B. Walker, Dean of Wake Forest University School of Divinity, interprets this as part of a broader issue: “The norm has been a very narrow understanding of what constitutes art, a very narrow understanding of who constitutes the artist and a very narrow understanding of what art should contribute.”

This narrowness, Walker suggests, is not unique to Reynolda but emblematic of American art institutions. Even still, Reynolda’s role is a microcosm of the vast sets of questions around art and what constitutes the criteria of good art, making it an ideal stage for grappling with these questions. One example of such interrogation is Fred Wilson’s famous 1992 exhibit, “Mining the Museum” at the Maryland Center for History and Culture.

Many of Reynolda’s new acquisitions are by contemporary Black artists, such as the 2022 “Black Is Beautiful: The Photography of Kwame Brathwaite” and his piece “Untitled (Garvey Day Parade - Harlem).”

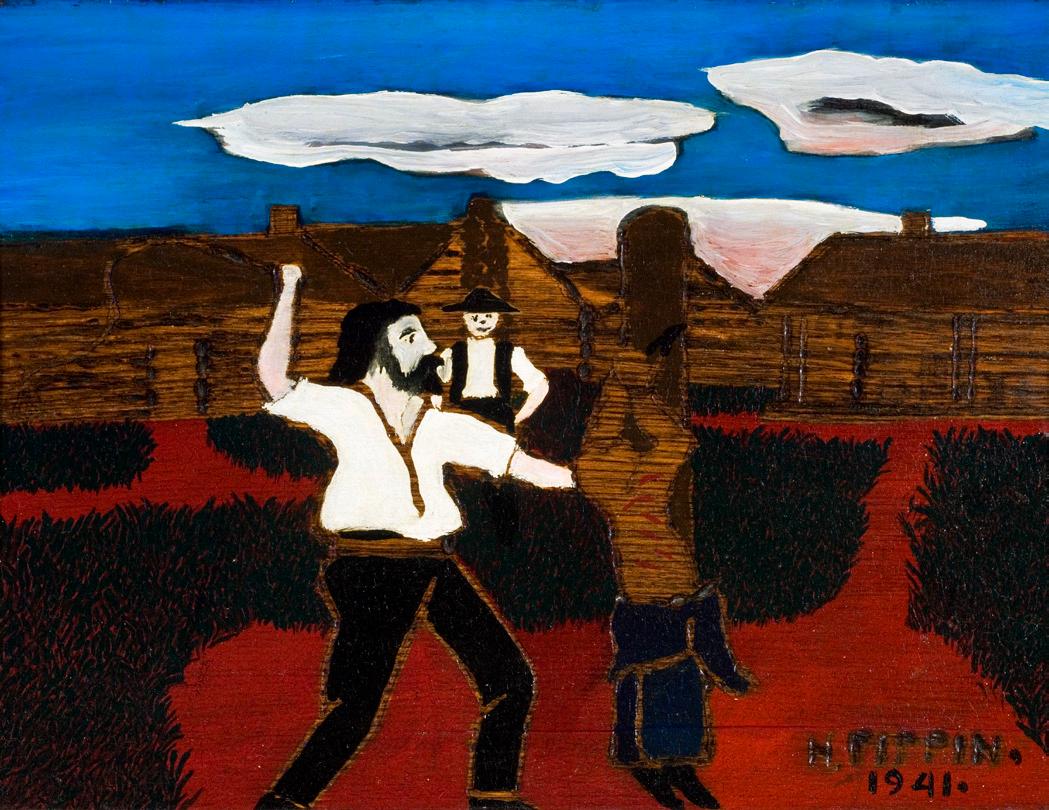

Yet when the museum began, its walls held no works by Black artists, reflecting the narrow definitions of American art at the time. Bari Helms, the museum’s historian, relayed that Reynolda House didn’t receive its first work by a Black artist until 1973 when Horace Pippin’s “The Whipping” was donated to the museum — with perhaps a subtle critique of the museum in its brush strokes.

This occurred five years after the museum opened because a Winston-Salem citizen called the then executive director Nicholas Bragg and challenged the collection, asking, “How can you say you represent American art when the collection doesn’t feature any works by a person of color?”

As Walker explains, “The exhibit showcased all these things that African Americans had created,” but they were everyday items: some ironwork, some woodwork. He asks, “At what point does it belong in a museum? We have to think about the production and politics of a museum. The answer to those questions can’t be assumed a priori. The conversations have to be much more involved, especially when we’re speaking on oversights. It could be that there’s already so much art in Reynolda and what we need is a Fred Wilson-type mining exhibit. Because, if we’re talking about the workers at Five Row and all of the ways in which they worked at Reynolda House, then it becomes the very idea of Reynolda House that is unable to exist outside of these communities.”

Walker referenced Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello, saying, “You can’t think of that outside of those hundreds of enslaved workers, working there each and every day, creating the very Monticello that we now walk through as a museum. The museum does not exist in a certain sense, and it cannot exist outside of Black art. There’s a work of trying to make Reynolda House exist outside of Black art.”

The earliest theory of art, that of the Greek philosophers, proposed that art was mimesis — an imitation of reality. This pretext suggests that art’s power lies in its ability to reflect life’s peculiarities, textures and soft

rhythms. American art is a lone branch of art where this mimesis grasps and claws in a vain attempt for any one movement, style or artist to immortalize the undulating, nonlinear essence of the nation. A country in flux decorated with shifting identities and walking contradictions.

Babcock Millhouse is something of a prophetic visionary for her foresight at a time when “collecting American art was a really forward-thinking way of collecting.” When she started collecting in the 1960s, American art wasn’t even taught at the college level. In many ways, Babcock Millhouse determined, at least for the greater Winston-Salem community, what American art is while she occupied the frontier of an emerging art movement. Perhaps this mimetic nature is why American art allows for the tumultuous realism depicting roiling gray clouds above a withering sapling in George Inness’ “The Storm” to hang mere feet away from the stark non-representation that is Lee Krasner’s “Birth.” By art’s very

terms, it challenges art to justify itself. What is it that you’re looking for, what is it that you’re assuming? These works commune and clash in the velvet extravagance that is the historic wing of the museum.

This juxtaposition is both startling and inevitable. Both works are truths of the American experience — grandeur meets rawness, precision meets chaos and the tension electrifies the space.

“Barbara’s vision was to showcase American art, but also to maintain the house’s role as a cultural and creative mine for the community,” said Slaby. Reynolda has upheld this vision, continuing to serve as an arts and cultural hub for the broader Winston-Salem community. Current and upcoming exhibitions such as Wake Forest professor Leigh Ann Hallberg’s “Phenoms” and “Andrew Wyeth at Kuerner Farm: The Eye of the Earth” highlight Reynolda’s growing influence in the art world, where America’s origins collide with its multiple horizons.

By Molly Steur

Continued from page 7

This story begins with a 617-acre plot of land.

This plot would later become the town of Wake Forest, and it was initially owned by David Battle, who sold it to a man named Calvin Jones for $4,000 in 1821. Jones was born in Massachusetts, moving to North Carolina in 1795 and later marrying a planter-class woman named Temperance. In the antebellum United States, the planter class was a racial and economic caste that indicated inclusion in the Southern white aristocracy for those who owned at least twenty enslaved individuals and several hundred acres of land. From his marriage to Temperance, Jones came into possession of several enslaved people, and he purchased Wake Forest in hopes of starting a successful plantation.

Within a “fine grove of oaks,” Jones built his farm — cultivating corn, wheat, cotton, hay, vegetables, fruit and brandy. He and his family, as well as the enslaved people and their families, lived and worked together on this land for 13 years, their living quarters not 100 feet from each other. When Jones attempted to sell the land several times throughout the 1820s, he described the plantation as “well-ordered,” with all the necessary buildings. The main house, he wrote, had a “portico,…[five] rooms with fireplaces, [three] lodging rooms without and garrets and good cellars, the whole decently furnished and in good repair,” as well as outhouses, garden, barns and blacksmith and carpenter houses. He did not, however, mention the seven slave dwellings in his advertisement, which were blocked from view of the main house by a five-foot-high stretch of corn.

In 2019, Matthew Capps performed the first formal study of the Calvin Jones plantation and the nineteenth-century Wake Forest College campus. While most of the material was readily available, no one bothered to put it together in an analytical study until Capps’ work as a part of the broader Wake Forest Slavery, Race, and Memory Project. According to Capp’s report, Wake Forest students later lived in those slave cabins — walls that once reinforced the bonds of slavery became the backdrop of the path to the economic freedom that a college education offered.

Although Jones attempted to sell the land several times,

he was unsuccessful until 1832 when the North Carolina Baptist Convention offered to buy it for $2,000, half of what he originally paid. Jones and his wife moved with about 20 enslaved people to Tennessee where Jones had purchased more land, leaving the “Forest of Wake” to other stewardship.

The Wake Forest Manual Labor Institute opened its doors in 1834, providing a religious and agricultural education for just $60. A student’s duties were not just academic because, in those early days, everyone had to lend a hand in the manual labor required to keep the property functioning. However, the students grew weary of such “dirty work,” so the faculty brought more enslaved people to work on the campus. It is important to note that the university at this point was deeply reliant on the institution of slavery. Though this was not unordinary for the time, as the university was participating in “the southern culture of slavery,” its commitment to pro humanitate must be read against a past dependence on forced labor.

In 1835, the students founded Wake Forest Baptist Church following a religious revival. According to the Wake Forest Historical Museum, the church’s services were originally segregated, with early records suggesting that “a white minister led services for white congregants in the morning and Black congregants in the afternoon.” About 15 years later, the Black congregants separated and formed their own church with elected Black deacons called the “African Church” or “African Chapel.”

The university did not accept Black students until 1962, but Black people were always present on campus. In fact, Wake Forest was never a completely white space at any point in its history. Black persons were not treated equally in any regard, unable to earn an education at the university but still crucial to the functioning of the university through their work as forced laborers and later as employees. The exclusion of Black persons from academic spaces until 1962 has modern-day implications: fewer Black applicants can be deemed “legacy students” because their ancestors were denied an education at Wake Forest for 128 years, which is roughly double the amount of time since desegregation.

The town of Wake Forest, literally incorporated as the “Town of Wake Forest College” in 1880, grew with the school, which rechartered as Wake Forest College in 1838. “There is no town of Wake Forest without the college,” explains Wake Forest historian Dr. Sarah Soleim. According to Soleim, the existences of the two are intertwined and inseparable. The town developed to cater to the college, as the downtown store’s primary patrons were students. Outside of the college, the town was predominantly home to scattered farming families and their small estates.

Although the cotton mill was a major employer of the town separate from the college, the Wake Forest economy was largely dependent on business from the school. The town continued to grow alongside the school, reaching a peak population of 3,704 in the early 1950s. The 1946 move from Wake Forest to Winston-Salem was devastating to the town’s economy, especially downtown. While the seminary school moved to Wake Forest in 1951, those students were not actively patronizing the area because their primary residences were not on campus. They were older, they had families and they worshiped and led services at home churches outside the city lines of Wake Forest. In the years following the school’s move, the town of Wake Forest annexed many smaller communities around it, including the mill town, which increased the net tax revenue it could receive and ultimately kept it afloat. Even with the annexations and the addition of the seminary, the town’s population dipped significantly, not reaching its peak population again until the 1980s.

Earliest known photograph of Wake Forest College, pre-1880

Photo courtesy of Wake Forest Historical Museum

For a campus that is now so beloved, it’s a little bit ironic that alumni of the original location needed convincing of the move. However, pamphlets were sent out to persuade them to support the transition through monetary donations, suggesting they were not immediately on board. They were curious about what Winston-Salem was like, what the new campus would be like and who this Reynolds family was who so generously offered land for the purpose of scholarship.

Currently, few people know about the depth of the connection between the town of Wake Forest and Wake Forest University — how the town would not exist without the university that once resided within its borders. It seems like even fewer students have ever been to the original campus. Prospective students hear about it when they first tour, but rarely ever again. To most, Wake Forest University is the new campus in Winston-Salem. It’s where so many people grew up coming to football games, where the last 70 classes graduated, and where a lot of alumni consider “home.” However, the Wake Forest community must recognize that the university is also all of the original buildings in Wake Forest, N.C. — it is all of the people who worked and taught and studied and lived there. It is the town that grew to support it and stayed when it left.

While the school’s history is split between two distinct locations, its past is not so bifurcated. Its influence remained beyond the day it left the town of Wake Forest, and it appeared in Winston-Salem long before classes actually started.

***

Despite their fame and influence in the area, Winston-Salem’s history did not begin with the Reynolds family. In fact, evidence of indigenous presence in Forsyth County dates back at least ten thousand years. The first archaeologist in Forsyth Country was Moravian

Reverend Doug Rights, who was the founding member of the Archaeological Society of North Carolina in 1933 and discovered thousands of Native artifacts in the area. Andrew Gurstelle, professor and academic director of the Lam Museum of Anthropology, explained in an interview how in the 1980s, Wake Forest was given 15,000 Native artifacts that Rights collected, which kickstarted the school’s archaeological work and understanding of the history of its land. A portion of that collection is on permanent display at the museum. This land, he explained, is important to several Native groups, namely the Catawba Nation, the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, the Coharie, the Tutelo, the Sappony and the Lumbee. The museum has worked to maintain connection and conversation with those groups through many pathways.

While several departments and disciplines at Wake Forest have made an effort to incorporate Indigenous Studies into the course curriculum over the years (for example in English, Religion, Linguistics, History and Archaeology), currently only one course is devoted specifically to Native history: Lisa Blee’s “Modern Native American History” course. While numerous courses integrate elements of Indigenous studies, students may not develop a deep understanding of the historical and current issues facing Indigenous people and their communities during their time at Wake Forest. The university released a land acknowledgment five years ago, on Nov. 4, 2019, claiming Wake Forest “continues to be a place of learning and engagement for Indigenous students, faculty, and staff regionally, nationally, and globally.” Acknowledgment is surely much better than erasure. However, there is still much to be done for this statement to reflect a truly continuous effort. The prioritization of

connection with local native communities, the hiring of staff for that purpose — and Native staff members in general — within specific departments, and increasing momentum within the student body to push for more courses on Native history will bring this campus closer to living up to its promises.

Acknowledgement is surely much better than erasure. However, there is still much to be done for this [land acknowledgement] to reflect a truly continuous effort.

Gurstelle went on to describe how the European history of Forsyth County begins with the Moravians, a religious minority group in Pennsylvania who sought economic security to support their faith community. After purchasing land from the governor of North Carolina, Lord Granville, they came to Forsyth County and settled in Bethabara. When the Moravians arrived at Forsyth, it was empty. But just a few years earlier, in the late 1600s, German explorer John Lederer came through the area, and he described the Saura (sometimes spelled Cheraw), a native group who lived in the area, in his catalog of adventures aptly named “The Discoveries of John Lederer.” However, the Saura decided to move south, joining forces with the Catawba nation after European disease and warfare made the land in Forsyth County inhospitable. Just 60 years before the Moravians arrived, the Saura were working and living in Bethabara — this European story was separated from the Indigenous one by time only.

When the Moravians first arrived, they lived out of a pre-existing barn. Although this structure signaled they were not the first Europeans in the area, they were, indeed, the first major European settlement group. Lord Granville’s only claim to the land he sold the Moravians was that it was within the drawn borders of North Carolina. Other colonists had not marked the area with anything of note, and it had not been bought from anyone as it was largely unoccupied. It was just there.

This stretch of land was considered the Western colonial frontier. The Moravians wrote a daily entry of the town occurrences, which cataloged their interactions with Cherokee, who moved in and out of the area frequently. Gurstelle explained, “Quickly one of their most lucrative trades [was] with Indigenous people.” Therefore, while the Moravians and Cherokee weren’t next-door neighbors, they were never truly separate. The Moravian’s success as a settlement was largely thanks to their close working proximity to these Indigenous persons. Gurstelle, describing the story of the settlement of Forsyth and the broader colonial project, explained, “This was not a story of replacement.” Instead, it is a story of overlapping lives, which deserves recognition when discussing past and ongoing relationships and interactions.

The Moravians continued to build their settlement in Bethabara. Some moved to what would later become Bethania in 1759, and they broke ground on their permanent settlement in Salem in 1766. When R.J. Reynolds arrived in Winston-Salem in 1874 to establish his tobacco factory, many farmers in the area were already cultivating the plant as a cash crop. Thus, there was already a rich tradition of tobacco to draw on and use as a resource when he came. Reynolds married Katherine Smith, his first cousin once removed, in 1905.

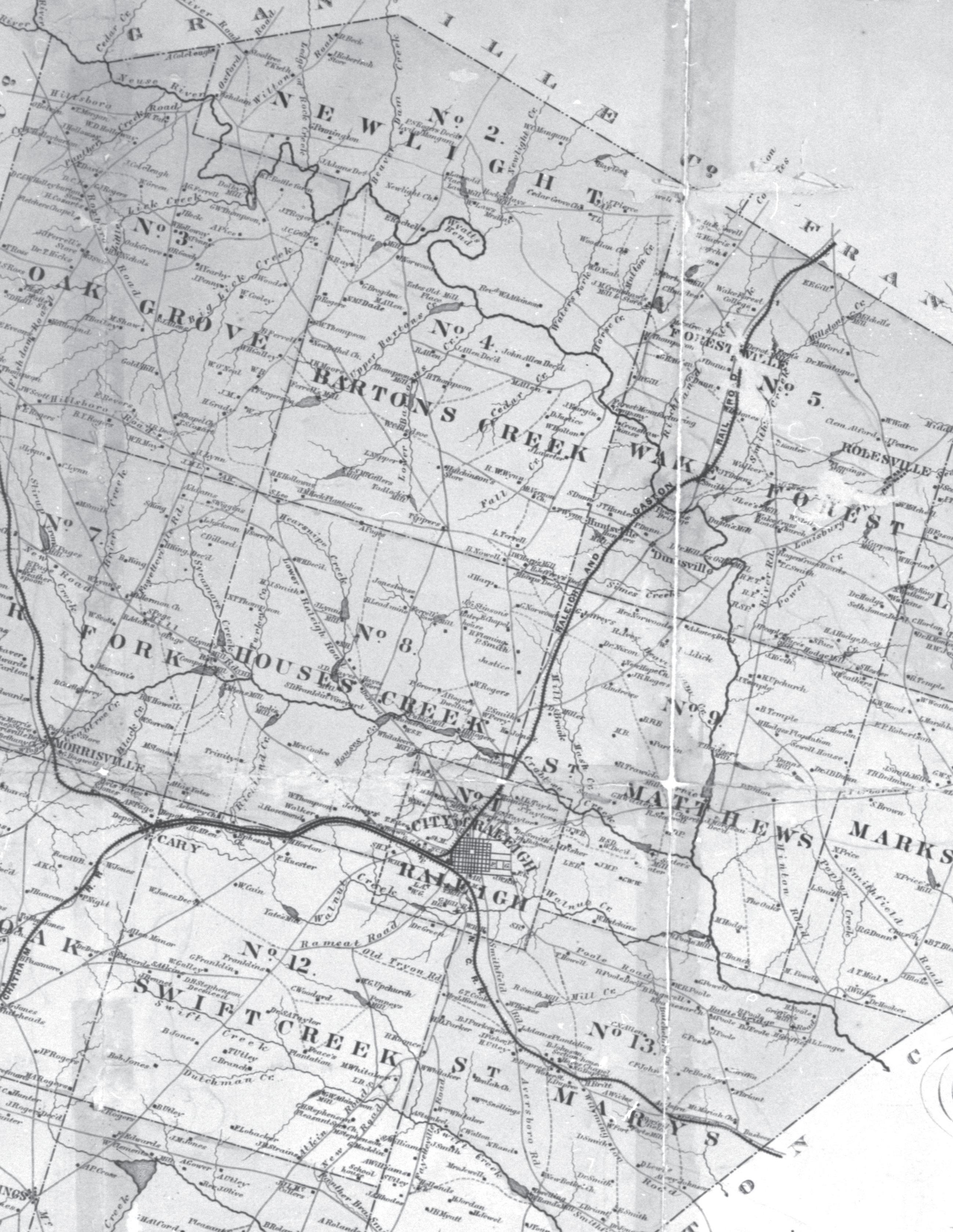

Katherine was a huge proponent of the expansion of Reynold’s property. According to the Reynolds Foundation, she made 27 land acquisitions over the next 13 years, which became the Reynolda estate. The acquisition of the Reynolds’ land was not one collective purchase but several purchases from small landholders and churches in Forsyth County. The land was mapped out through sketches on bits of paper and attached to the deeds, marking the rough size of the plot and the streets or notable landmarks that surrounded it. The Reynolds farm was self-sufficient, eventually spanning 1,003 acres and growing many types of vegetables and cultivating a remarkable garden and greenhouse. Those on the estate also raised hens, cows, hogs and horses. In 1917, Reynolda was described as “a happy community” of “about twenty resident families.”

The land that the university now occupies was largely part of the orchard section of the Reynolds farm. After the tragic and sudden passing of Z. Smith Reynolds in 1932, the Smith Reynolds Foundation was established to support “educational and charitable organizations throughout North Carolina.” The estate’s land at that point was divided amongst the Reynolds heirs, and Mary Babcock Reynolds and her husband purchased the land from her siblings so the estate was cohesively under their authority. The couple wanted to expand the legacy of the Reynolds family and their foundations. So, in 1946, they wrote to the trustees of Wake Forest College and made them an offer they couldn’t refuse: a proposed relocation to 300 acres of their estate as well as $350,000 per year in perpetuity.

It was surprising and generous — so much so that there was a significant question over if the proposed contract could legally be upheld. How could this agreement be enforced or even promised forever? The contract went to the State Supreme Court for a declaratory judgment. The statement from Reynolds Foundation v. Trustees of Wake Forest decided that it didn’t matter where the university was located. They could still educate and

pursue their mission Pro Cristo et Humanitate in Forsyth County. The State Supreme Court wrote, “We would not deny to this great institution and to those whose faith and good works have made it possible, this vista of a new dawn and this vision of a new hope.”

The contract was deemed legal, so efforts to transition the campus to Winston-Salem began. With this gift from the Reynolds Foundation, the school ranked in the top ten percent of all American colleges in regard to endowment. Wake Forest Medical School announced its move to Winston-Salem in 1939, so the transition was not unprecedented, but it still rocked the community of Wake Forest, N.C.

On Oct. 15, 1951, President Harry Truman broke ground on this “new dawn” for the college. The university didn’t officially transition until the summer of 1956 when construction was finished. Since then, Winston-Salem has been its home, and the connection to Wake Forest, N.C. has faded in all but name.

The history of Wake Forest, of the land that it now occupies, is complicated. It is a story of agriculture and ministry, enslavement and wealth and two towns over a hundred miles apart. It is a story of land that has been walked by people for thousands of years. This place, while it feels permanent and rich with tradition, is incredibly new — in both the life of the college and in the span of human presence in Forsyth Country. Yet, how often do visitors think of who laid the bricks they stroll across, of who walked the earth beneath those bricks before they were laid? Do students ever think of the alumni who came before them? How often is Wake Forest, N.C. mentioned outside of a quick fun fact on a college tour?

Only in the last few years has this history been publicly unpacked and examined. But, if the origin of the school has been so easily forgotten, how much more is the legacy of forced labor, religious minorities and the help of indigenous persons swept under the rug to promote a more appealing narrative of academic excellence and philanthropy? While Wake Forest has failed to live up to its motto in the past, a new commitment to exploring and doing justice to its history will bring the school closer to living out and understanding what it means to be “for humanity.”

Below: President Harry Truman breaks ground on new Winston-Salem campus, 1951

Photo courtesy of Wake Forest Historical Museum

Take a walk through Reynolda Village with senior Hope Zhu as she gets to know the local business owners and the stories behind their products.

Annie Ewell relishes whipping up crepes. As she stands over the griddle, the pale yellow batter splays out and the edges start to curl, turning a golden-brown color. Spatula poised, she readies to flip, knowing the hungry diners on the other side of the arched glass might just as well be waiting to pounce on the finished product.

It is 11 a.m., and the lunch rush at Penny Path Café is starting to form — girls in Wake Forest University sweatshirts, old couples with golden retrievers and parents wrangling their energetic kids through the door. Once inside, the kids crouch to study a winding pattern of copper coins on the floor. The green and white cottage is where Ewell has spent the last four years serving up hot coffee and fluffy crepes.

“We cook the sweet and savory crepes at the same time, the smell of drying beans and fresh espresso mixed with the well-seasoned mushrooms,” Ewell said, her voice dreamy as she described the kitchen in the morning. “It is amazing.”

When Wake Forest University acquired Reynolda Village in 1965, the university welcomed small businesses into R.J. Reynolds’ old backyard. The corn crib, which held sun-drenched cobs, now houses a dumpling shop offering delicate dim sum. The old power plant, once rattling with machinery, is now filled with books and chatter about poetry.

Penny Path’s wooden name plate rests near the outdoor seating area: a steampunk rendering of Abraham Lincoln on a penny hints at treasures inside. On weekdays, five young employees work through a steady line, handing out crepes stacked with ice cream and sugar. The cafe’s crowd reflects owner Miro Buzov’s knack for business: He’s served diners in three North Carolina cities — High Point, Winston-Salem and Blowing Rock — winning them over with ease.

Buzov opened his small, 600-square-foot creperie on a quiet street in downtown Winston-Salem, laying a winding floor made of pennies by hand. After this initial location’s success, Buzov sought a second location in Winston-Salem, settling in Reynolda Village. The 17-seat nook grew to 60 seats, drawing students and visitors to enjoy stuffed crepes in this calm, tucked-away spot.

“We hoped people would beat a path made with pennies from our doorway to our register,” he said.

“Can I get three orders of pork dumplings?”

It’s a slow afternoon for Karma Tsering, who took only a half-dozen orders, nearly all dumplings. A green poster taped to the white cabin where he works says “May Way Dumpling” — a phonetic twist on the Chinese word for “delicious.”

Students cram into the narrow waiting area by the kitchen window, nudging each other. Which dumplings are you getting?

The menu plastered on the window reveals steamed veggie buns, cold noodles, soups and 20 flavors of boba tea. This was Tsering’s vision when he joined May Way in 2015: a handmade menu highlighting their secret sauce and a fusion between Indian and Chinese dishes. He crafted the cold noodles with mala sauce, cucumbers and carrots, along with a one-of-a-kind pork curry born from a customer request for a weekend special.

The sweet soy sauce is one of his proudest creations. It’s so popular they can sell seven liters in a day.

“You cannot find this … sauce anywhere in the United States,” Tsering insisted, gesturing to the rich, dark sauce that keeps customers coming back. “We created the secret recipe.”

All three workers at May Way are Tibetan immigrants. Tsering came to the U.S. in 1993 after teaching Hindi in India. Tsering knows the restaurant industry is no quick profit, but like many immigrants, it is a solid way to gain a foothold in a new country. He’s dabbled a bit in the restaurant industry, having opened eateries near Virginia Tech and another in Charlottesville.

“I suggest not starting very big,” Tsering said. “You cannot manage; you need to hire people. It’s too much. Every time you run the restaurant, you look at each other, and it’s just unhappiness.”

If Tsering hadn’t found happiness in his previous ventures, he has now, standing behind a modest counter beneath a kitchen hood that pulls in the scents of leek and ginger. Here, he sticks to his philosophy: everything must be fresh and high-quality. Buns take 15 minutes because they’re steamed on site — no microwaves, which he despises. Dumplings get their first steam in the morning, then are fried on the spot. And the boba? Pure tapioca starch, never the watered-down, wholesale version.

The COVID-19 pandemic sent ingredient prices

through the roof, and Tsering’s already drooping eyebrow furrowed even further as the cost of soy sauce forced him to change the spice-to-sauce ratio in his prized recipe. Yet, May Way kept its affordable prices: six dumplings for $4.95, buns at $2.60 each, and filling soups for under $10.

“That’s what consumers want,” he explains. “This isn’t the kind of work where you’ll be a billionaire in a year, but it’ll stick around for a long time.”

At 4:00 p.m., Tsering settles into his corner desk. The kitchen hood buzzes above, foreshadowing the busy hours ahead. Soon, the phone will ring, and the space will fill with hungry people. ***

“It Doesn’t Feel Like Work”

An hour later, Meghan Brown opens the door to the brand-new Bookhouse, just a year old. Her day at General Electric is over, and now the fun begins — working at the bookshop she has always dreamed of owning.

Brown strides past the front shelves, filled high with new releases from romantasy like “Fear the Flame” to gripping nonfiction such as “Targeted: Beirut.” Each is handpicked according to customer feedback, social media trends and her own taste. In the middle, six more rows offer an even spread of genres that fall within general fiction.

The bookstore is not only a dream of her own, but also shared by her sister, Tara Cool, who works here full-time during the day. Their reading tastes balance one another: Cool is the extrovert who digs sci-fi, while the more introverted Brown loves anything to do with history. Since their childhood, they have dreamed of owning a cozy bookshop and serving coffee.

“It was one of those dreams you don’t think is actually going to happen,” Brown said. “Then, a few months later, we are opening!”

The first year at the Bookhouse overflowed with events the sisters hoped would catch on: open mic nights, Monday morning children’s book readings and “blind dates with a book,” where they wrap books in brown paper and write clues about the plot for readers to select based on their curiosity.

Their main goal, however, is to make Bookhouse a true gathering place, a space where people can grab coffee, hear live music and discover the book that starts a lifelong love of reading.

“I love helping the kids find that book that opens that world for them,” Cool said.

Adults, too, come in searching for the perfect book, usually as a gift, and ask Cool for her top pick.

“I am just like, “Demon Copperhead!” It was so good, but it is a little heavy,” Cool said, describing the gritty story of addiction and poverty.

She usually pivots to “Theo of Golden,” a more heartwarming tale of a mysterious stranger in a southern city. For those seeking history or memoirs, she sends them to Brown, who, while not a people person, enjoys helping readers discover their next great read.

In an age when Amazon dominates the market, running a local bookstore is tough. Luckily, having a sister as a business partner means they always look out for each other.

Through refining their weekly events, the sisters found their efforts met with enthusiasm. Homegrown musicians like Mike Coia and Spencer Aubrey have become regulars at Wine Down Wednesday, while local authors like Tina Firesheets have hosted talks and signings at the store. Remote workers pop in for meetings over lattes, and guys gather at the bar to chat.

In April, the Bookhouse launched a Poetry Slam, drawing a tight-knit group of ten who craved the community connection they had missed during the pandemic. This year, Cool and Brown decided to expand the poetry slam into a three-part series starting in November.

“It doesn’t feel like work,” Brown said proudly. “It’s like raising a baby. You’re helping it grow.”

By 8:00 PM, the Bookhouse settles into quiet. Brown cleans the bar, shuts off the coffee machine, and locks the door.

“A Wonderful Anomaly”

Across the street in a cleared grove, Theodore’s Bar & Market enters the night’s final round, flickering warmly under the chandelier. The lobby evokes a European estate, with an embroidered carpet rolled out beneath a long communal wooden table that straddles the breezeway of the Reynolda Village barn. To the left, the bar serves craft cocktails, beer and mocktails. To the right, shelves overflow with rolling pins, cutting boards and Red Tail Grains.

In the evenings, the bartender takes charge, and tonight, it’s Sam Miller. She slides behind the polished mahogany counter, fetches a coupe glass and pours a rich espresso martini. With a tilt, pumpkin latte ale spills over the surface of the drink.

At 27, the round-faced woman with piercing blue eyes has tended bars for almost half her life.

A Winston-Salem native, Miller started bartending at 17 in a downtown brunch spot, mastering basics like Bloody Mary, Peach Bellini and Mimosa. She loved it so much she moved to Austin to launch her bartending career at 18.

Miller soon discovered that the service industry is not very friendly, and even less so toward women. Though she serves and bartends, she prefers the latter; the bar provides a shield from patrons who might dish out harassment.

Tending a bar at an Austin airport, frustrated travelers would often ask her for directions. “I can’t tell you where the plane is, I’m just bartending,” she would say. There, she trained a whole staff who were clueless about proper cocktail crafting for over two years.

“I was one of those psycho bartenders who worked 70 hours a week,” she said. “I was in the right place at the right time.”

Yet Miller grew exhausted as the money poured in. At 20, she worked 30 hours straight at a crowded Austin café, eventually passing out. Her manager waited until she woke, passed her water, and said she needed to get back to work.

Tired of corporate culture, Miller started thinking about moving back to the Tar Heel State. She returned to Winston-Salem with her fiancé in June of 2024, interviewed at Theodore’s and was hired. She loves the aesthetic of the space; as a lifelong bartender, she cherishes the chance to work with crafted beer sans the suffocating rush of a high-volume Texas bar.

“It’s steady, it’s structural, it’s alive,” she said. “It’s that kind of environment where people can be chatting and relax.”

Customers love Miller. Sheryl and Bill Bowman, who’ve worked in restaurants since the 90s, sat with her at the bar during brunch. They chatted about how service jobs are viewed as unserious, yet workers hustle twice as hard as most.

“You are a wonderful anomaly,” the Bowmans told Miller.

At the moment, Miller is creating a winter drink series for Theodore’s: one that grasps the full essence of the season, not just a nod to Christmas. She is after that perfect first sip that brings the warmth and celebration of winter days. She’s weighing two ideas: a Ginger Old Fashioned with hints of ginger syrup, bourbon and ginger bitters, or a cozy mocha cider, layered with dark chocolate.

Miller hasn’t given up on the contract business. Someday, she might go back, but right now, she’s all in for the Wake Forest crowd: Students, parents and locals drop by her bar for a drink on gameday. She wants to make sure they have a great time.

Her schedule is still full, but it’s less hectic now that she works from noon until 9:00 PM. With little free time on her hands, she has yet to see other spots around the village. However, she’s heard about a place called Penny Path, a creperie nearby that supposedly serves up the best European-style sweets in town. She intends to visit soon and taste for herself.

By Carolyn Malman

Photos by Blythe Green

It’s a Tuesday around five o’clock. My classes are over, and I’ve decided to take a long walk in Reynolda. Preparing for the brisk chill of the autumn air, I put on a long-sleeved top, lace up my sneakers and grab my bag. Starting at Davis Residence Hall and passing Scales Fine Arts Center and the commuter parking lot, I eventually reach the two stone pillars that frame the start of the walking trail.

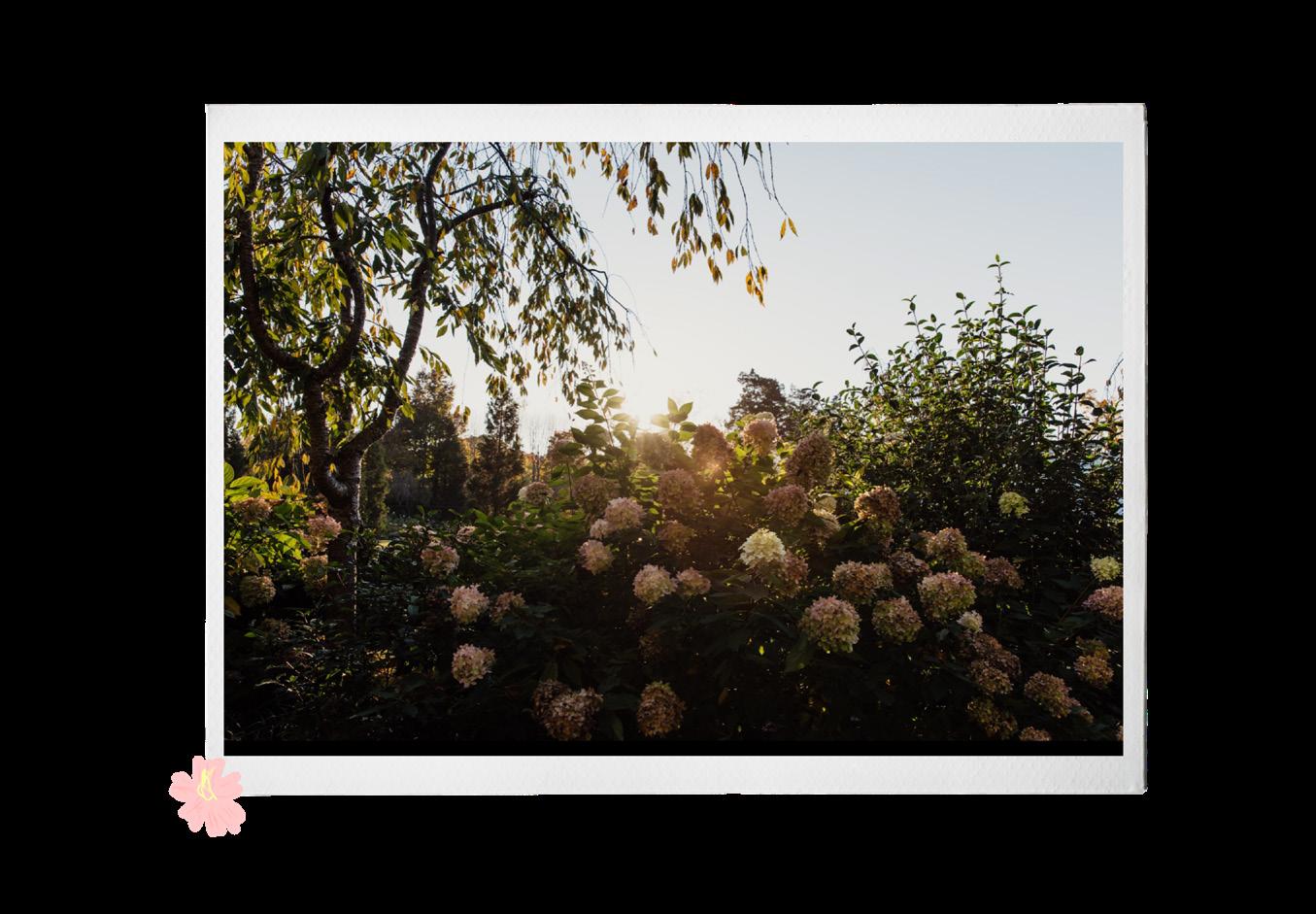

I never fail to admire the magical quality that the trails possess — the canopy of trees blocking out the sun, the stillness of the forest and the smoothness of the paved road under your feet. Fall is my favorite time of year to walk in Reynolda. The leaves reveal beautiful hues signifying the end of one season and the beginning of another. Walking in Reynolda, you feel connected to the world around you.

“Reynolda provides a safe space for Michelle to process complicated emotions, including ‘joy, sorrows and grief.’”

The evolving seasons reassure me that change is natural and inevitable.

Reynolda has been a special place from the moment I stepped on campus. It’s the first place I called my mom when I got to school freshman year, the spot where I spend the most time with friends and where I go when I need to think through all of the complicated emotions associated with being in college. Reynolda is the bridge between the Wake Forest bubble and the outside world. It’s where we can explore ourselves while still being in the safe proximity of campus.

On this particular day, I have just finished my shift as an Office Assistant at the Dean of Students Office in Benson. Like most days, I spent it conversing with Michelle Zhan, Case Manager and Coordinator for Chinese Student Life. We share a love of walking, and as if by fate, I see her walking towards me now. We talk about what a gorgeous day it is, and then we laugh about how we always see each other walking on the trails.

Our brief meeting on the trail reminds me of many

conversations we have had about what Reynolda means to Michelle. When I agreed to write this article, Michelle was the first person I thought of. I prompted her with a simple question: Describe your relationship with Reynolda Village.

In 2017, Michelle moved to Winston-Salem from China to pursue her master’s degree in Interpreting and Translation Studies. As a graduate student, Michelle would often take walks in Reynolda.

“As I was jogging, I had a fleeting thought that I could be here for a long time,” she said.

While navigating the trails of Reynolda, Michelle dreamt about a future in the United States. She reflected on her passion for helping students, and she imagined building a life for herself in Winston-Salem by working for Wake Forest University.

A few days later, Michelle received a call from her employer at the university…

“I got a call from the dean, and I was so overjoyed that they asked me to stay.”

Michelle’s reflective moment in Reynolda turned into a reality — the university asked her to work full-time after her graduation from graduate school and help students assimilate into the Wake Forest community after she completed her graduate program.

Michelle left her family for almost five years to pursue a career and life in Winston-Salem — she loves this place and the work she does here. It hasn’t been easy, but her “connection with Reynolda allowed [her] to build [her] relationships with friends and with God,” which has helped her gain the courage to tackle these challenges. When Michelle had problems renewing her visa, she again turned to the comforting trails of Reynolda to process her emotions.

“I was so worried that I would have to leave my job,” she said.

Michelle prayed that she would be able to stay at the job that she loves. While walking, she had a strong and sudden premonition that her boss would call her with good news. Later that week, the university helped her regain her work visa allowing her to stay at Wake Forest.

Reynolda provides a safe space for Michelle to process complicated emotions, including “joy, sorrows and grief.” Michelle replaces anxiety about her future with action, and the quiet reflection helps her stay grounded. She knows that everything happens for a reason, and she often relies on her time in Reynolda to remind her of this truth.

As a junior, I face an uncertain, and exciting, future. A few months ago I made a decision that felt monumental: stay at Wake in the spring to pursue an opportunity here or go abroad to London. I agonized over this decision for weeks until I called a friend in Reynolda.

She told me to take a step back. To breathe. To go against the part of myself telling me to make a pros and cons list, and just live — the act of living would bring me to my answer. I sat on a bench beside a pond surrounded by tall trees. I watched the stillness of the water and the reflection of the trees on the surface. I remembered to trust myself.

A life away from Wake Forest felt unimaginable only months ago, but now it’s exciting to imagine where my next chapter might be. My heart yearns for growth in a new city filled with endless possibilities. Instead of becoming paralyzed in fear, I embrace my future and even run towards it.

Life changes, and we are forced to cope with the ever-changing world around us. With courage, Michelle faces her future. She inspires me to do the same.

By Aria Heyneman

In the heart of Reynolda, Janie Bass has created a new curriculum to teach local children the wonders of the great outdoors.

When Janie Bass left her position at Redeemer School in 2020, her friends and colleagues told her she was crazy. But ever since she arrived in Winston-Salem from rural Virginia in 2000, when her husband took a job with the Wake Forest athletic department, the walking paths of Reynolda Gardens have been her safe haven. While working at the private school in southwest Winston-Salem, she was spending hours on the trails, soaking up slices of nature in the heart of her new city.

So when she got the offer to be the Coordinator of Early Childhood Education at Reynolda House and Gardens, she saw the chance to spend every day in her sanctuary as an opportunity that she “couldn’t pass up.”

During the 2020-21 school year, the United States Department of Education reported that 43 schools in Forsyth County had school-wide Title I programs, meaning they receive supplemental financial assistance due to a high percentage of students from low-income families. Whether it is the location of their home or the constraints of their parents’ work, many of these students do not have the opportunity to spend time outside in nature.

As a teacher and administrator in Forsyth County public schools for eight years, Bass is painfully aware of the lack of funds for student field trips. These trips are missed opportunities for students to have profound experiences interacting with nature. It took Bass leaving the school system to change that.

Bass’s mission, supported by the director of Reynolda Gardens, Jon Roethlin, its dedicated horticulturalists, and the many community members who volunteer in the gardens and trails, is to bring children outside.

“For a lot of these kids, the happiest place they ever go is school,” said Bass. “To spend a day out here really is a gift.”

The Reynolda House and Gardens offers free field trips to the schools they serve. Bass knows the state public school learning standards as well as the student population of Forsyth County. She understands how difficult it is to run field trips because of the cost barrier and has alleviated this burden. She levels her years of past experience in education, providing the context and compassion required to bridge the gap between Reynolda leadership

and the school district in order to make this program as impactful and rewarding as possible for students. Reynolda is “truly a new destination for them.”

Bass offers a green space to children in the Forsyth community who do not have access to one. Her hope is that, once kids go to Reynolda and they see the meadow, woods, and wetlands, they will know that this public space is there for them — for free — every single day. She hopes that eventually, they will bring their parents and siblings.

Bass builds the curriculum for her field trips by walking around the trails with a printed-out copy of state science standards in her hands, checking things off and deciding which of the trail’s natural features future students could benefit from. Her eyes light up when she talks about the magic of a “living classroom.”

The programs are centered around both students and nature with an emphasis on hands-on experiences. She teaches her students about sound-mapping, inviting them to simply exist — in silence — with the plants, bugs and wildlife around them. Students mark where they hear sounds. This type of experiential learning allows students to relate classroom lessons to real-world situations, expanding their vocabulary, strengthening critical thinking skills, and exposing them to new career possibilities.

“The county has a high rate of kids struggling with literacy concepts and this exercise ties in literacy language arts standards,” said Bass.

Other activities prompt students to go through four different stations depending on their grade level. They track “signs of the beaver,” conduct soil experiments, identify plants, and learn about planting patterns in the children’s garden. Bass prioritizes “inquiry and interactive learning.”

As a teacher, she knows how much time kids spend sitting at their desks. The 90 minutes they get in Reynolda allows for a different kind of education, one they can take with them and share with their loved ones.

Bass doesn’t have to reach out to schools — her field trips have a waitlist. On average, 150 students come to Reynolda every year during the warmer months.

Bass is a champion for the children of the Forsyth County community, and she has big plans for the future of her program. One of her dreams is to gain the funding required to offer stream experiences for children from Title I schools, complete with water gear and boots. She envisions children from schools across Winston-Salem immersed in a natural playground — the streams and trails of Reynolda. It’s a different play space than the mulched playgrounds they see every day. She already has the support from Wake Forest biology professors, her own team at Reynolda, and a wonderful group of committed volunteers.

Most importantly, Bass has a passion for change.

By Adam Coil

Photos by Blythe Green

The Reynolda waterfall is the first thing I remember seeing when I came to visit Wake Forest in the spring of 2021, a few weeks before I finally committed. At the time, I wasn’t thrilled about the idea of attending Wake Forest. I thought of it primarily as the school that my sister and mother went to — not for me. Instead of excitement, there was a looming sense of inevitability pulling me to Winston-Salem. It was not until I walked through Reynolda Village with my mom and we stopped on the bridge above the waterfall to discuss her time at Wake Forest that I began to see things differently. Recognizing the waterfall as something truly special that Wake Forest had to offer, I felt all of a sudden like I was choosing my future, and it made me excited to move to Winston-Salem. After all, how many college students can say they have a waterfall on their campus?

Now an iconic Wake Forest symbol, the Reynolda waterfall began more or less as an afterthought in the construction of Lake Katherine. It was originally designed as a two-arch dam to stop the flow from Silas Creek, creating the lake that Katherine Reynolds saw as the key to her and her husband’s future.

Reynolds was determined to construct a lake as early as 1910, before her family bungalow had even been built, let alone lived in. Where others saw an unruly wetland, Reynolds envisioned a sixteen-acre body of water that would one day be at the heart of the estate. It would assist the complex irrigation system necessary to sustain the gardens and the fields. Fishing in its depths would provide both sustenance and a diversion for workers. It would be the perfect site for boating and garden parties, for conveying to their guests the splendor and magnitude of their novel wealth.

It was the picturesque and the practical that Reynolds was after, and it was both she would have: over only a few years and at the expense of nearly $400,000 in today’s money, her extravagant dream was realized. A page in the October 1917 issue of House Beautiful Magazine was set aside to celebrate the lake’s completion, reporting that “sixty thousand dandelion bulbs were naturalized around this lake, and in blossoming time the place is thronged with visitors.”

The lake soon became a pillar of the community. As Camilla Wilcox writes, “It seems that almost everyone

who lived in Winston-Salem during that time has some special memory of the lake.” These memories range from the everyday to the momentous. For example, on May 25, 1921, “an estimated 5,000 people, seated on the slope from the main house,” gathered to watch local children stage a pageant on the shore of the lake. The Winston-Salem Journal described the performance as “one of the most beautiful outdoor events in the history of Winston-Salem.” Or on July 5, 1932, when a birthday party hosted at the Lake Katherine Boathouse ended with the still unsolved death of Zachary Smith Reynolds.

Of course, the Lake Katherine that was so beloved in its Roaring Twenties glory is almost unrecognizable in the wetlands it has become today. This regression was a natural, inevitable process that would have required constant maintenance to counteract. As soon as the lake was completed, it was already slowly filling up with silt and sediment deposited by Silas Creek and other waterways flowing into it. When Wake Forest University arrived in the 1950s, extra runoff from campus construction exacerbated the existing disregard for the preservation of the lake. By the 1960s, it was full of mud, and nature has reigned supreme ever since. ***

There is no waterfall in Reynolda without Lake Katherine, and yet the waterfall alone remains, essentially unchanged. From that first visit, it has continued to be a temporal landmark that helps me keep my memories in order. When I first got to Wake Forest, I would only encounter it in passing, in the middle of my runs through the Reynolda trails, or when my friends and I would go to Reynolda Village for boba tea. During my sophomore year, however, I began to appreciate it much more. I would walk to the waterfall late at night, especially on weekends, where I could sit and let its roar drown out my anxious thoughts. At night, there is a lethargic magic resonant in the waterfall’s hum, and I have drifted off to it on multiple occasions.

mation of human construction and nature’s will had won me over. This monument — somehow rooted in history and yet convincingly timeless, always rippling movement and yet going nowhere — had taught me so much. But it was time to go home, and then to go abroad in the spring. I spent much of my last night in North Carolina at the waterfall. I shed painful tears when I had to say goodbye, not just to the waterfall but all that it represented at the time.

I have had some of the most important conversations of my life there — topics ranging from quantum mechanics and neuroscience to Bob Dylan and The Beats, from nostalgic recapitulations of the past to shared fears for the future. Awkward silences are wonderfully nullified in the calming presence of the waterfall. Walls are set aside, at least for a moment. Language sprouts unexpectedly in the cracks that are normally sealed off by conventions and time constraints. Wide distances in background and opinion are collapsed, and memories imprint themselves in strange ways.

It is a place for everyone: for lovers and for loners; for grandparents and for toddlers; for the stoned and the sloshed; for the brokenhearted and the triumphant; for me and for you.

*** Wake Forest is saturated with natural beauty. I love how the light sifts through the trees during golden hour, spreading a soft blanket of sun on the Davis Field grass. The dramatic sunsets to the tune of roaring cicadas, the white blooms of the Magnolia trees, and falling leaves — all of this beauty is, for me, distilled in the waterfall, which is the epitome of our unique blessings as Wake Forest students.

It is a place for everyone: for lovers and for loners; for grandparents and for toddlers; for the stoned and the sloshed; for the broken-hearted and the triumphant; for me and for you. Since it was built in 1912, it has been a place where employees on the Reynolda estate could swim and fish, where college students can go for a little solace and where families can enjoy nature with their children.

According to Bari Helms of the Reynolda House, it was used by members of the church at Five Row to perform baptisms. During my junior year, I began to see the space as hallowed ground as well, inextricably linked to some of the most important people in my life and to the spiritual growth I had achieved as a person. This confusing amalga-

I have fallen asleep to the melody of the cascading water. I have waded in its pools and let its current crash over me in the moonlight. I have written countless awful poems sparked by a moment of strange illumination sitting on that bench sinking in the sand. I have made the most of some of the best that Wake Forest has to offer. Whether it be a waterfall or a fallen log, I encourage you to find your nook in Reynolda and make it your home.

By Virginia Noone

The once-thriving community of Five Row was buried underneath Silas Creek Parkway. The lives of the enslaved people who built the original Wake Forest campus were forgotten, their names were nearly lost. Part of Wake Forest’s long, complicated history is a history of erasure. A century later, people are trying to recover and untangle these histories and the stories of the Black experiences that shaped our campus and community today.

Originally consisting of five wooden houses lined in a singular row, the segregated community of Five Row rested parallel to Silas Creek and was positioned just out of view of Reynolda from the 1910s through the 1950s. Unseen from the Reynolda House and Village buildings, Black farm workers on the estate, along with their families, built a space where children’s education and community values were prioritized during a time when very little opportunity existed for minorities in the city.

Black families and workers in Five Row did not have access to running water and were forced to use kerosene lamps for light and coal heaters for warmth, unlike white workers who lived in the village. Despite these disparities in living conditions between Black and white workers, Black workers were still drawn to the estate. Katharine Reynolds believed in building an ethical workplace, offering higher wages and additional resources to her Black workers. Her vision for the farming community was progressive for its time.

Soon, the community expanded from only five houses to ten houses, a boarding house, a school and a church. It became a compelling place for Black families to live. The Pledger family came to Five Row because of the high wages and improved conditions Katharine Reynolds offered her employees.

“I loved it, I loved it,” Flora Pledger, a laundress and maid who lived in Five Row, said in a 1980 interview for the Reynolda Oral History Project. “And if it had the water and electricity that I’ve got now — I’d rather be there than anywhere that could be.”

Reynolda itself existed, in many ways, as an oasis, located just outside of Winston-Salem’s city lines and thus

out of reach of the tobacco city’s bustle, grit and legislative jurisdiction. This distinction would prove to be important. Winston-Salem was one of the first cities in America to enact block-by-block segregation in 1912. Later ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in 1914, the segregation ordinance made it illegal for any Black person to occupy a residence on a street between two majority-white streets, in addition to other race-based housing restrictions.

Meanwhile, north of city limits in the Reynolda estate, the children of Black and white farm workers employed by Katharine Reynolds would play together, despite Jim Crow laws segregating most Black and white children throughout the South. The Black community of Five Row was close-knit and committed to giving their children the best education possible.

Although they attended a separate school from the white children, the children of Five Row were given access to the same schoolbooks. Five Row’s school offered the best education for Black children in Winston-Salem as it had college-educated teachers, course materials that were equal to white students’ and an academic calendar consisting of nine months rather than the typical six months, according to Phil Archer, deputy director of the Reynolda House Museum of American Art.

Harvey Miller, whose father was hired as a mule teamster for the estate, was a student at the school and remembers his community with fondness:

“Well, we all were raised with white kids and Black kids in this community,” Miller said in a 1980 interview. “We all played together, used to go to church together, we played ball together, would eat at each other’s houses when lunchtime come. There’s not a house hardly that I haven’t had dinner or something at...”