Kevin Yu Katie Fox Lucius You Evan Harris

Video Maryam Khanum Photography

Staff Writers Cooper Sullivan Christa Dutton Prarthna Batra Sara Hagiwara Adam Coil Contributors Celina Seo Sarah MacDougald

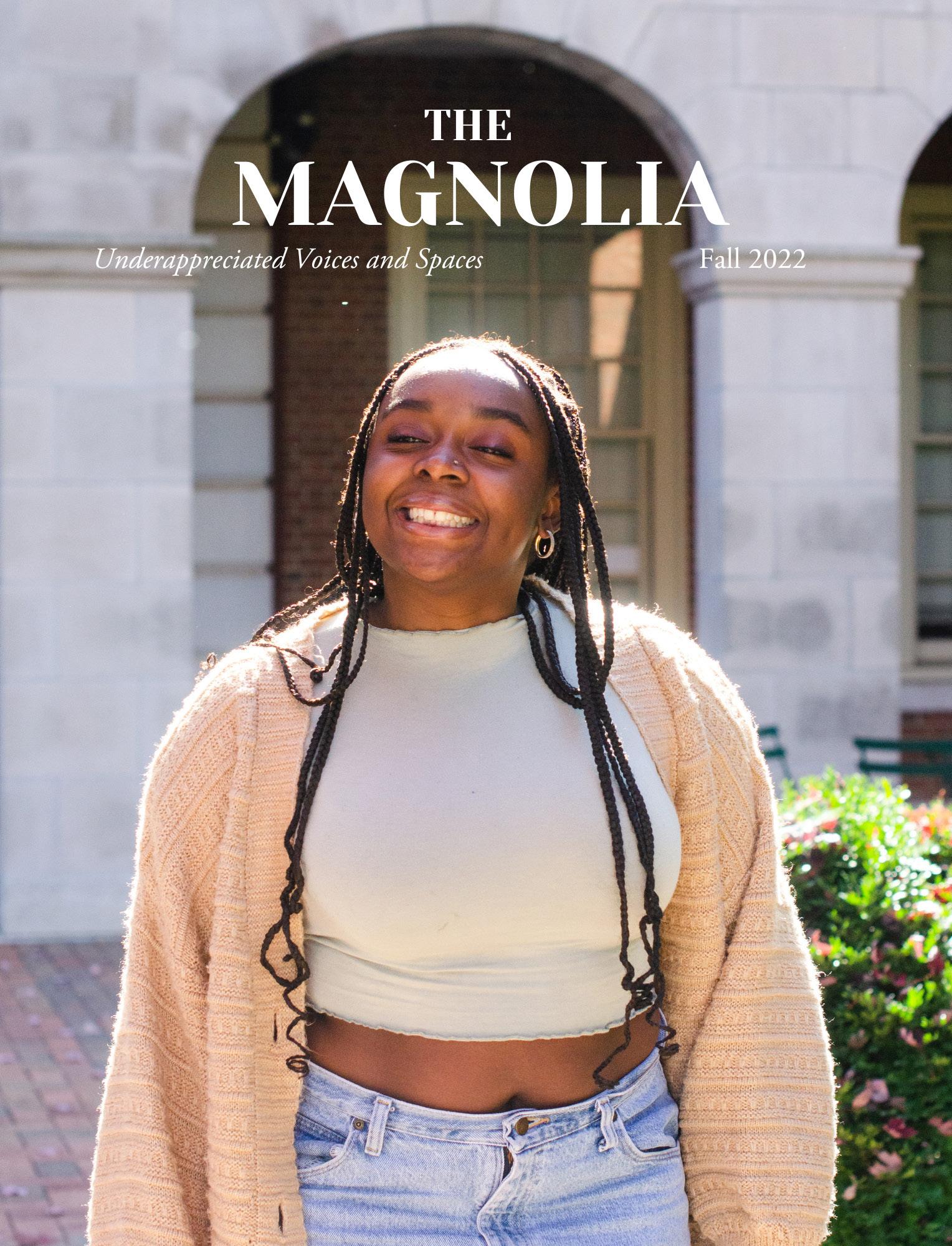

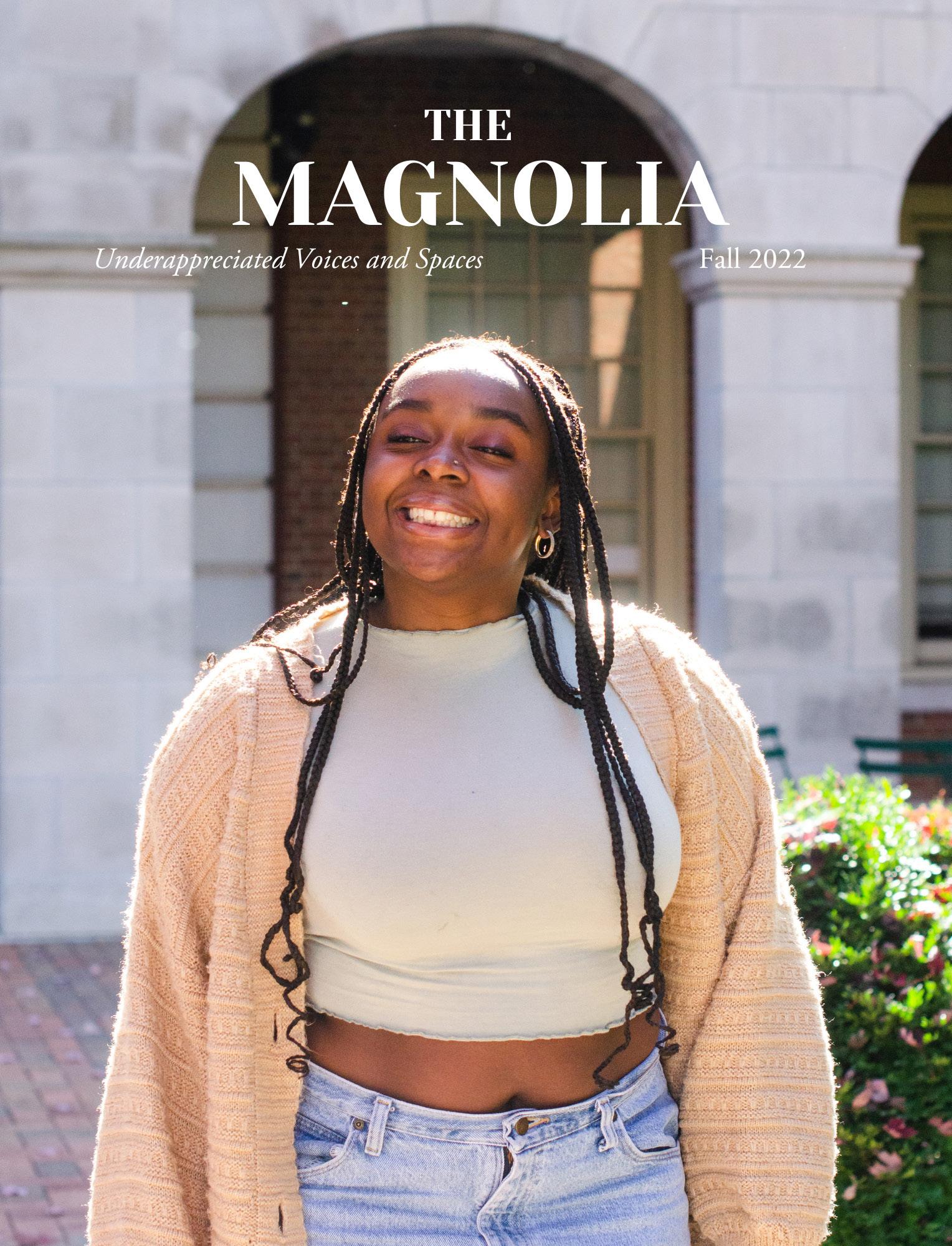

LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT

Iwant to start with giving tremen dous appreciation to all of the love and support received on the first edi tion of the magazine. It is not easy to start something from scratch and it would not have been done without the amazing team that I get to work with. Thank you to everyone who has contributed to this, big or small, your impact and contribution is so incred ibly crucial.

In this edition of the magazine, I wanted to, ambitiously, increase the amount of stories and increase the amount of pages — while still main taining the integrity of the magazine, which is to be an arts and culture magazine that shines light on com munities that don’t frequent the spot light.

As a result, the content of this edi tion spans the stories of people, com munities and organizations on cam pus that are overlooked. Stories span from the profile of a Benson employ ee to taking a deep dive into the com munity of black women in the field of STEM.

The stories featured not only shed light onto these communities, people and spaces, but also humanize those around us.

To better understand and be a part of the Wake Forest community, it is important to understand all walks of life that are a part of our campus. I hope that this edition of The Mag nolia provides a glimpse into the lives of the people that make up the cam pus we love. I also hope to continue to cover and provide a platform for these voices to be heard. Cheers!

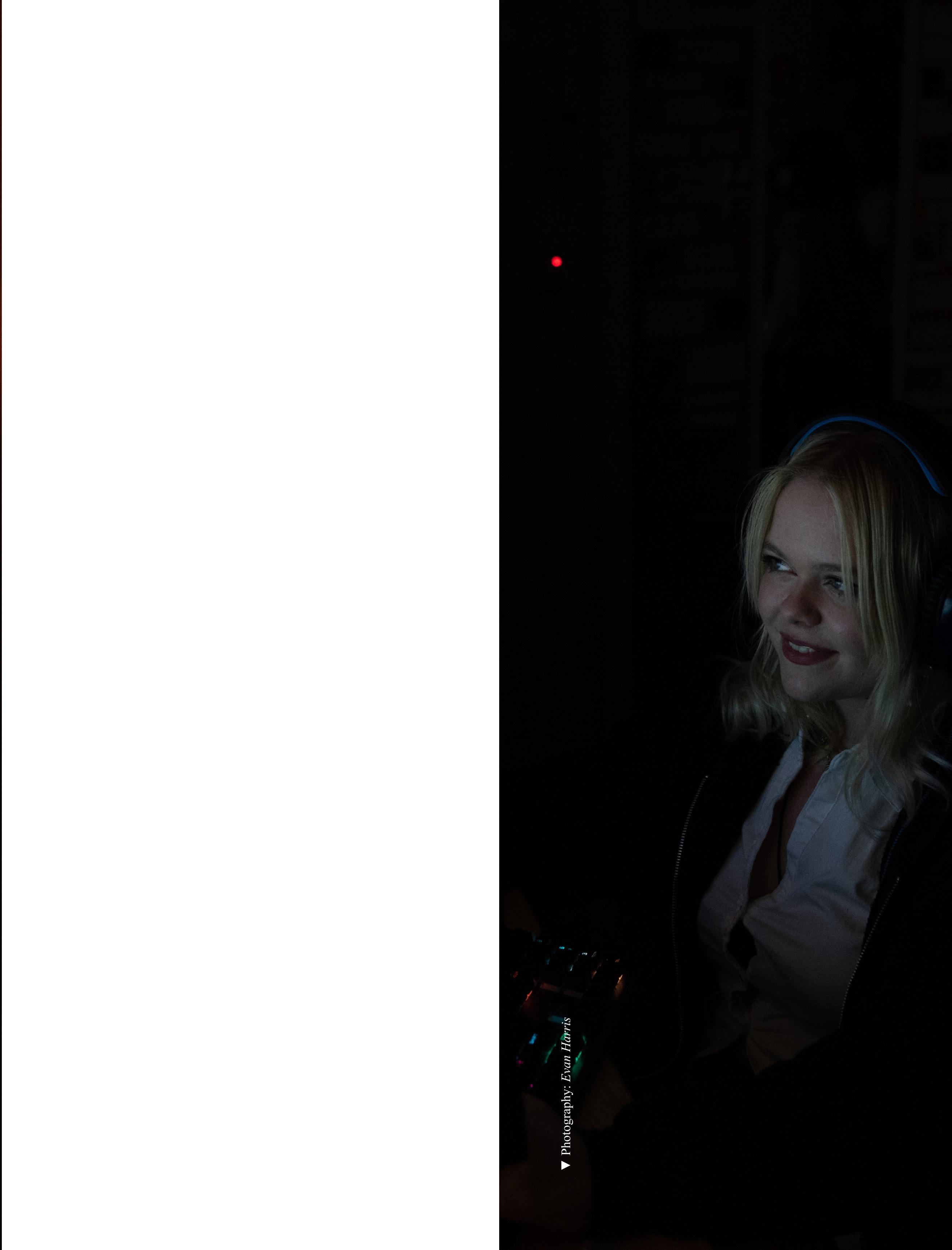

6 THE MAGNOLIA • Girls in Gaming

IN

GIRLS GAMING

Christa Dutton (‘24)

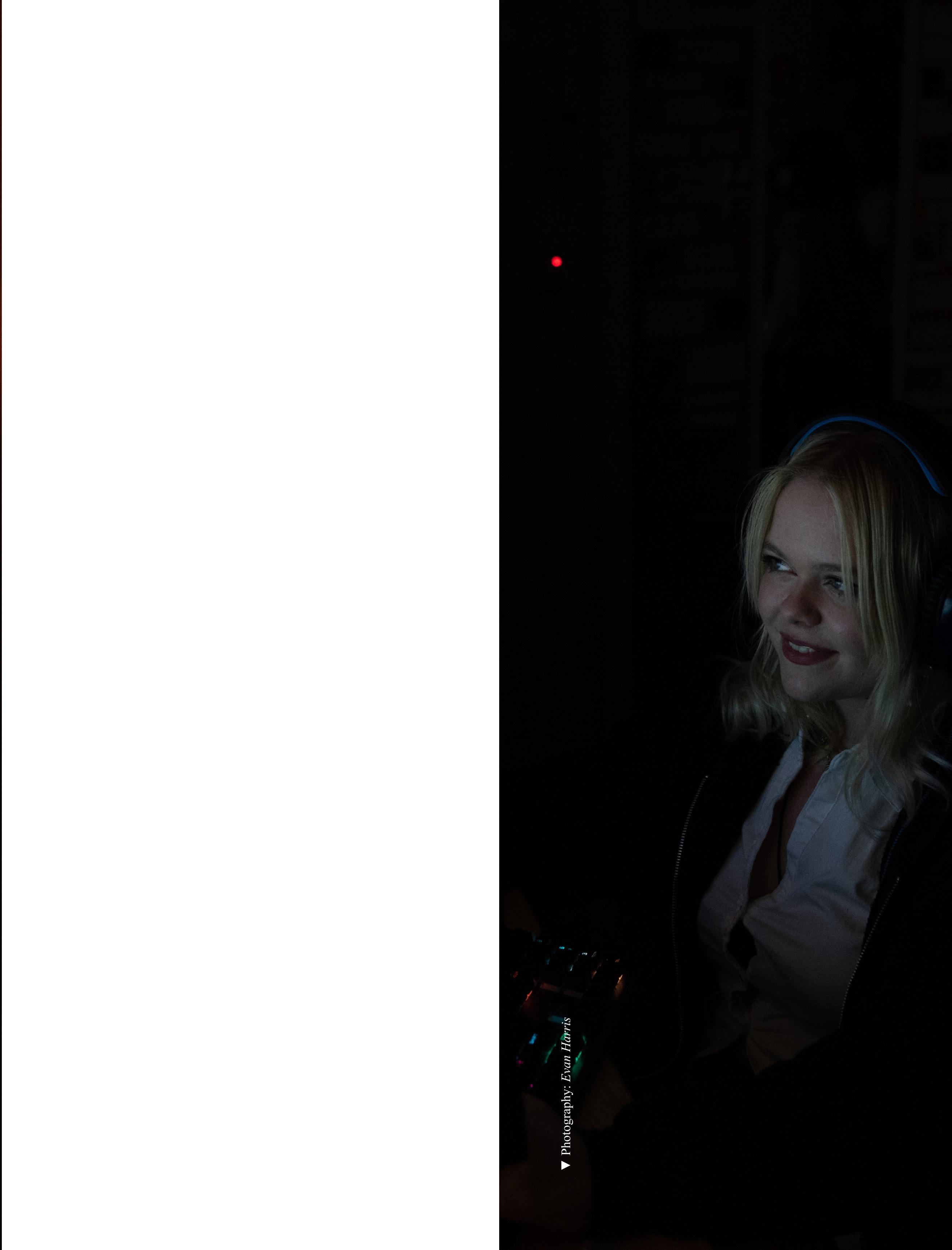

Rylie Torgussen — screen-name “ryles” — is a soph omore from Sioux Falls, South Dakota, a political sci ence major and a very good Valorant player.

Valorant is a 5v5, first-person hero shooter game. Players can play as any one of 19 “agents”, or char acters. Agents are divided into four roles — Duelists, Sentinels, Initiators and Controllers. Torgussen is an initiator, which means she plans out offensive attacks and provides crucial information on the enemy’s lo cation while on defense. She’s captain of the Valorant “A” team in the Wake Forest Esports Club. On a team of 10 people, not only is Torgussen captain, but she’s the only girl. When Torgussen games, she does so in style. Her dorm room is, for lack of a better word, cool. Or may be that’s the perfect word. Her bed is covered with oversized stuffed animals. Posters, photos, sheet music and records adorn her wall. Purple string lights give the space a soothing ambience. At her desk, the key board and PC have tasteful red, green and blue light ing.

After a long day of classes, Torgussen likes to come back to her room in Davis Residence Hall and play Valorant, her favorite game. She puts on her headset that, of course, lights up, and begins a game with four of her esports teammates.

Before she came to college, Torgussen played video games casually. She got her start playing games like Minecraft when she was younger, until a friend intro duced her to first-person shooter (FPS) games. She ar rived at Wake Forest last year and heard about the Esports club. That’s when her interest in gaming piqued. Since then, she’s strengthened her skills, now rank ing at the Diamond — only 10.1% of Valorant players are at this rank; it’s the fourth highest level out of nine.

In a recording of one game Torgussen has played, you can see her make a clutch play, taking out an agent from the other team. In the background, you hear her teammate say, “Sheeeeesh.”

“Oh my gosh, you’re crazy,” another teammate says. Most of the time, however, reactions to her game play aren’t as positive.

As a girl in the gaming community, Rylie has faced both conscious and unconscious sexism.

Conscious examples include players making insen sitive, inappropriate or just straight-up mean com ments.

Fall 2022 THE MAGNOLIA 7

8 THE MAGNOLIA • Girls in Gaming

She’s heard people scream “E-GIRL, E-GIRL, E-GIRL” into the mic as soon as they discover she’s a girl — which doesn’t take long in Valorant because the game re quires voice communication.

Men have said “fuck you” and force-quit ted the game just to get into another one without a girl. On occasion, she gets un warranted sexual comments.

Torgussen says the response of some men to female gamers is either one of two ex tremes.

“Either guys see you as a girl involved in gaming, and their reaction is negative — they associate you with all these negative stereotypes of girls playing games — or they see you as something they can make sexual comments about,” Torgussen said. “It’s just a very odd dynamic.”

For Torgussen, unconscious sexism typi cally takes the form of backhanded compli ments and backseat gaming.

She’s taken less seriously by her male counterparts and sometimes, people as sume that her successes are the result of being “boosted” or “carried” by a male player. Male players tell other male players that they should be embarrassed that they were killed by a girl. Similarly to backseat driving, guys will often engage in backseat gaming, telling Torgussen how to play, as though she isn’t one of the highest ranks in the game.

People also assume that female players only play certain characters, often ones with healing powers.

“It’s definitely not true,” Rylie said. “[Women play] kickass duelists or people who actually need kills to be good at their [roles].”

And of course, there’s always the com ment: “You’re pretty good, for a girl.”

“It isn’t just sexism,” Torgussen said. “I’ve seen other sorts of discrimination, wheth er that be blatant racism, homophobia or transphobia — all that stuff exists within this sphere and makes it pretty hostile for people, especially if they don’t know how to navigate their way through that sort of environment for the first time.”

Fortunately for Torgussen, most of this toxicity takes place online and not on her team at Wake Forest. She described the few jokes her teammates make as “harmless” and says her male teammates will stand up for her if another player online says some thing inappropriate. They respect her.

“[My male teammates] never make it awkward for me,” Rylie said. “They just treat me as any other player.”

Still, they’ll never know what it’s like to be a girl in gaming.

Fall 2022 THE MAGNOLIA 9

“They’ll just say: ‘Oh, get over it. It’s not a big deal. They’re just joking,’” Torgussen said. “But deep down, you know that they don’t understand the implications of those comments.”

It’s tough out there in the male-dominated commu nity, and the toxicity only makes the community more exclusive.

“That’s one of the biggest reasons why [gaming] is male-dominated, because non-male players — includ ing non-binary and trans women — feel discouraged to join because they know the toxicity exists,” Torgus sen said.

When asked what would change the culture of the gaming community, Torgussen said there needs to be a mindset shift more than anything.

“People just need to drop the idea that girls can’t be at the same level as guys in a male-dominated activi ty,” Torgussen said. “People need to be more receptive to girls playing, or there needs to be harsher penalties when people get reported for inappropriate behavior on games.”

To address these issues, Torgussen is a part of a col legiate gaming think tank called gameHERs, a group that provides “a safe, inclusive space for collegiate women and femme- identifying humans who game and/or have a desire to work in the gaming industry,” according to its website.

Not only are girls in gaming overlooked, but so is the entire Wake Forest Esports Club, says Torgussen. This became all the more apparent to her this semester when the team played in a tournament at the Univer sity of Kentucky.

UK’s Esports lounge is located in one of the univer sity’s most elaborate, innovative buildings called “The Cornerstone.” The lounge features 50 PC gaming stations, three console gaming areas and a multi-use, 100-seat theater that can host 6v6 Esports tourna ments.

Another example of a university who is investing in the rising popularity of gaming is North Carolina State University, which received $16 million this year from the state government to fund an Esports facility and esports truck, according to its student newspaper, the Technician.

“Esports is up and coming,” Torgussen said. “It hasn’t even hit its peak of popularity.”

While other schools have their state funding and fancy lounges, Wake Forest Esports players will con tinue to play in their rooms, physically apart but to gether online and in spirit.

One of Torgussen’s favorite memories from her time on the team was when she got to meet everyone in person last year. She has played so many games with these people but had never met them in person until then. Now, they are some of her best friends.

10 THE MAGNOLIA • Girls in Gaming

Fall 2022 THE MAGNOLIA 11

Photography Kevin Yu

Photography Kevin Yu

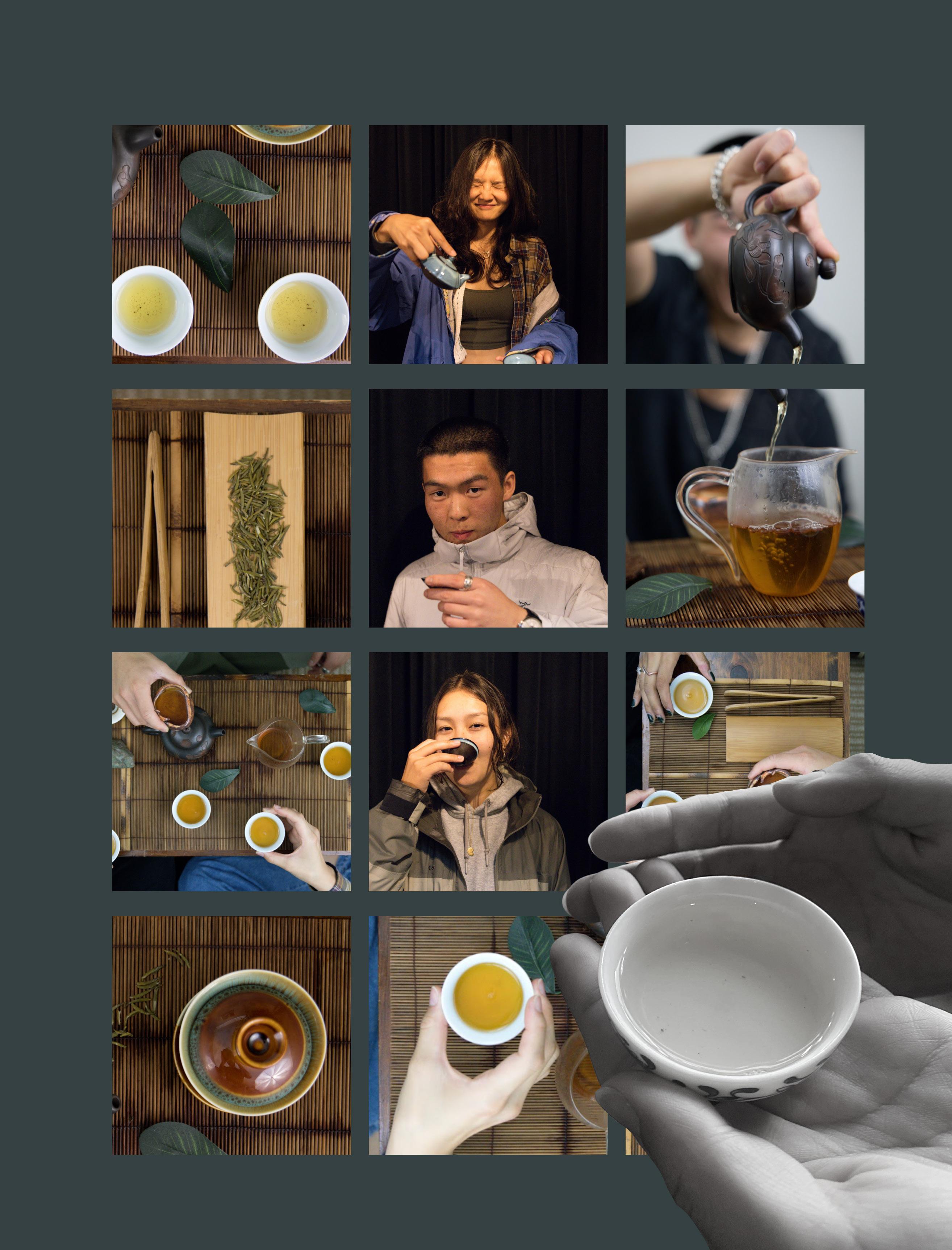

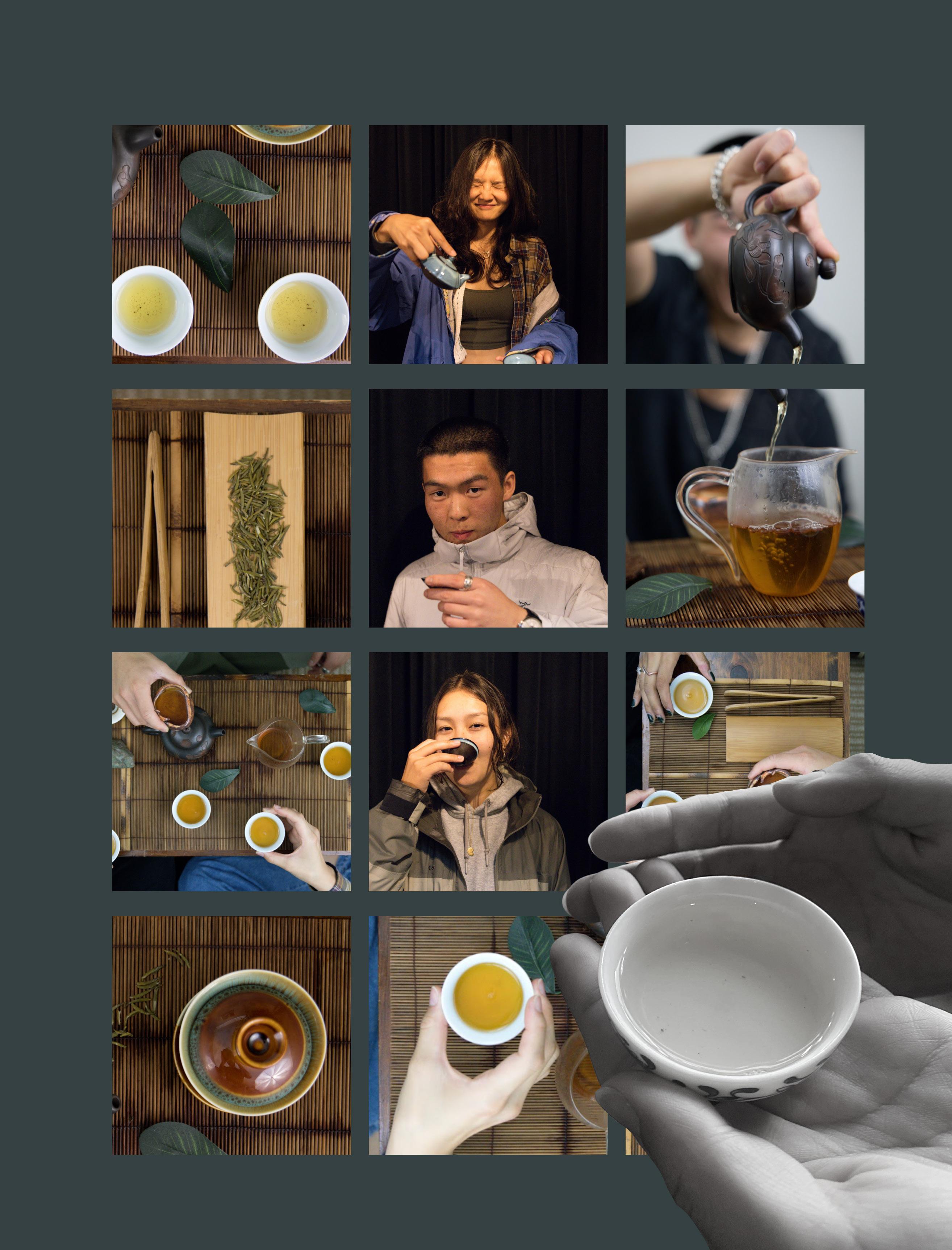

EXPLORING TEA, CULTURE AND IDENTITY

William Liu (‘23)

Tea became significant in my life during my senior year of high school when my South-American friend introduced me to yerba maté, a plant native to South America, where people in a group all share it out of one straw. I never drank tea before then; in fact, I disliked tea because I thought it was essential ly just hot water that was flavored. However, when my friend intro duced me to tereré, which is a cold yerba maté, I realized that tea held an important connection to culture and nationality. Tea transcends cultures because different cultures around the world all have their unique way of consuming tea. And the only thing that remains consis tent about tea in different cultures is that tea is something that brings people together.

Fast forward to my freshman year at Wake Forest, when I found my self disoriented with my identity as a Chinese-Canadian. Born and raised in Canada with first generation Chinese immigrant parents, I had to explore my own Chinese culture from a third-culture perspective. I

was simultaneously navigating my way through Wake Forest’s intricate campus while navigating my own cross-cultural identity. I realized that growing up, I had partly ne glected my Chinese identity and at times was even ashamed of it. However, the older and more mature I became, the more I realized that connecting with my cultural roots was essential. Therefore, I wanted to learn more about Chinese culture and become more connected to it. During winter break freshman year, I found myself sitting for an entire afternoon around a large wooden tea table sculpted from a single tree trunk at a tea shop, sampling a va riety of Chinese teas and visiting traditional teahouses in China with my mom. This was my first intro duction to traditional Chinese tea culture, and I was instantly hooked. From the wooden architecture and traditional design to the buzz I was feeling from all the teas consumed, I came back from my China trip knowing that this was the thing I was going to invest all my time and effort into learning.

What began as a journey to con nect with my cultural roots has now

evolved into incorporating the art and practice of tea into all aspects of my life. I seek to share the tea ex perience with everyone around me. I am passionate about the world of tea and re-introducing the culture and perspective of artisanal tea culture to the modern world.

About World Tea Association

Tea transcends culture and peo ple. It is a social lubricant and a tool to cultivate ourselves. There is also great evidence supporting the beneficial aspects of consuming tea for the mind, body and soul. The World Tea Association was born out of the idea to share tea with students on campus. Our mission is to explore the world of tea from a variety of cultures. Curiosity and community are at the core of the World Tea Association. We are ded icated to learning about tea together through a cultural, historical and physical perspective through our events and weekly tea sessions. We host multiple weekly tea sessions where anyone is welcome to join for good company, good conversation and good tea.

Fall 2022 THE MAGNOLIA 15

Brew Nature in

A Haiku

by William Liu

Sounds of birds chirping Grounded in the humble roots

This brew is pleasant

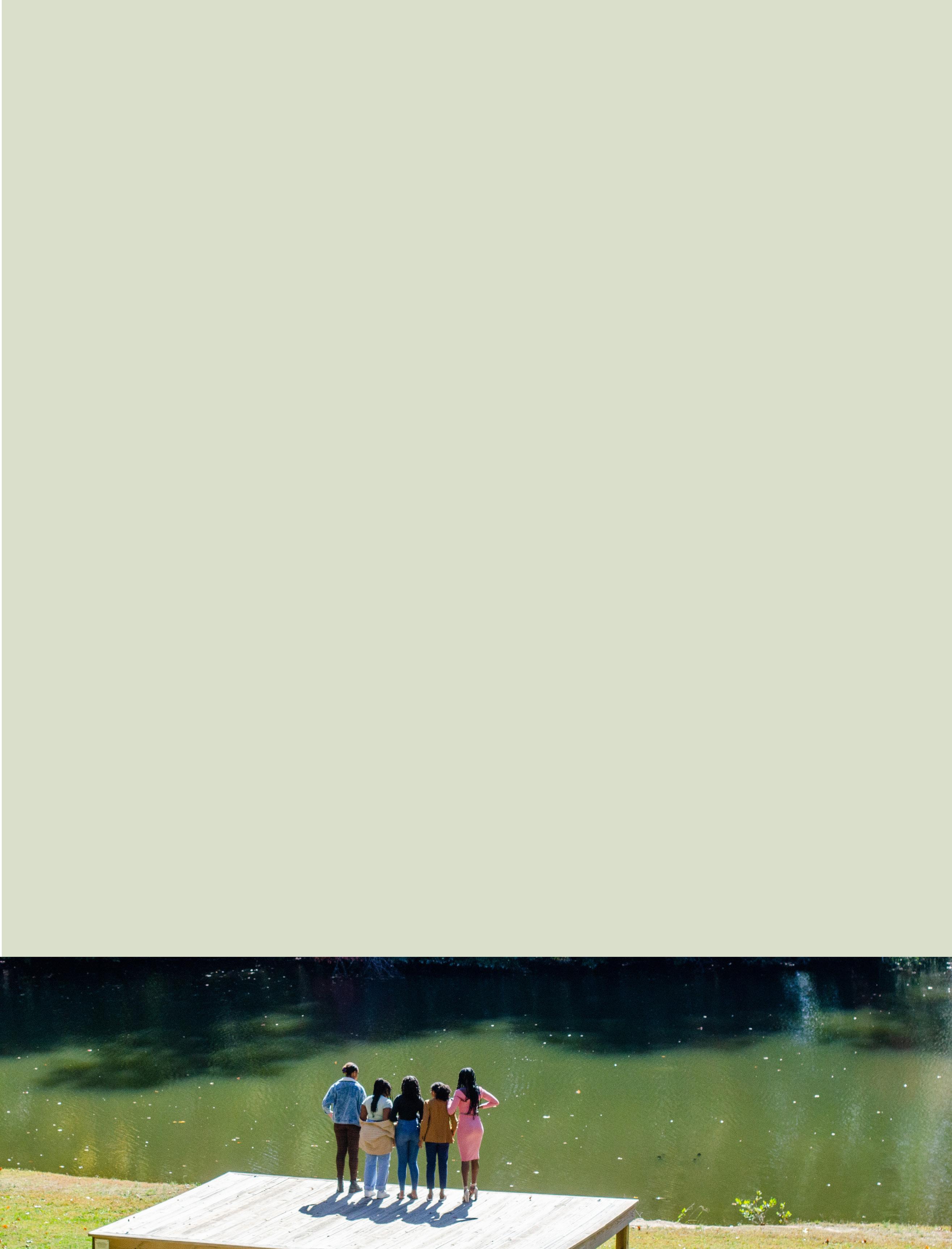

As consumers, we often don’t think enough about how the products we interact with every day get to us. Tea is a plant grown naturally outdoors. Before people began cultivating the tea plant, Camellia sinensis, tea trees were found in the wild. Enjoying tea outdoors in nature connects us to our most natural state and to the environment in which the tea plant is grown. Brewing tea outdoors allows us to sit with the brew while observing the beauty of nature. When I brew in nature, I often find myself observing the details of nature; from looking at how the trees have been shaped by wilderness to listening to the sounds of birds nearby. When we consume tea in a mindful way, our senses are heightened, allowing us to become more sensitive to our surroundings in nature. This experience is indeed one that is peaceful and pleasant.

16 THE MAGNOLIA • World Tea Association

Fall 2022 THE MAGNOLIA 17

Upon seeing my commitment to Wake, my sister sent me paragraphs detailing her resent ments and reassured me that transferring is al ways an option, but was ultimately excited for me to come. I knew from the start that I would al ways hesitate to say that I’m fully happy here. It’s always been hard for me to connect to my Thai side, but on a campus with virtually no South east Asian students, I felt completely alone.

Joining World Tea was something I did to hu mor my parents. They saw me wallowing in the Bostwick mold and told me nothing would get better if I didn’t at least try. Tea club was hosting a trip to Asheville that October, and I figured this was the perfect opportunity to show that I could do more than just stew in my bed. It was there that I met people of similar backgrounds with similar animosity towards Wake. In a day, I had a friend group. World Tea was diverse both racially and in personality.

Meeting people from so many different back grounds facing the same challenges made it eas ier to forgive myself for standing out. It took me a while, but I was finally able to understand why my sister was eager for me to join her. I have a newfound love for milk oolong and Will’s moodbased pu’ers, and a rea son to be excited to come back. Wake has pock ets of diversity, and the best one I’ve found is in World Tea.

18 THE MAGNOLIA • World Tea Association

Fall 2022 THE MAGNOLIA 19

To be multicultural means to live in ambi guity. I have lived many identities but somehow never ful ly one or the other. I was born in Nairobi, Kenya, to a half-Singapor ean and half-Kenyan father and an ethnically Korean mother who was adopted by white Americans. Even within my immediate family, I was a mix. My mother toted an Amer ican passport. My father, a Kenyan and New Zealand passport. I was born Kenyan and American, having both nationalities and passports.

I moved from Nairobi to the suburbs of Georgia when I was just a toddler and then to Boston, Massachusetts for a brief year before moving back to Nairobi to complete middle school and high school. Throughout my upbringing in the United States, perhaps due to youth or naivete, I did not think of my identity much. It was not un til I moved back to Nairobi, Kenya during the already confusing years of adolescence that I became pain fully aware of my identity, or lack thereof.

I went to a missionary board ing school in a place called Kijabe, a small town about an hour and a half outside of Nairobi. There, the majority of the student body was comprised of three nationalities respectively, Americans, Koreans and Kenyans. At an early stage during my time in boarding school, I real ized how homogenous Korean and Asian society is as a whole. Many Asians react with shock when I tell them that I am mostly Asian. After I told one Korean that I am half-Korean, she responded with a flat, “No you’re not.” This simple, almost comical denial is hurtful, and sometimes I think of my cous ins growing up in Singapore, speak ing Mandarin fluently — as we are Hokkien — and wonder what my life could have been had I gone to highschool in Singapore instead of Kenya. However, since I grew up in

Kenya, most of the interactions I have had center on my Kenyan identity.

During my sophomore year of high school, I worked on the pro duction line at my Guka’s (grand father) maize factory for a couple of weeks. My job included mindless ly scooping maize into paper bags, measuring the weight, or sometimes sticking my bare hands into a cup of glue and sealing the bags closed. I worked with many other Kenyan women, and since I did not speak Swahili fluently, I already felt oth ered, but this was normal. I would hear whispers behind my back as I glued paper maize packages closed. I overheard the women workers call me a “Mzungu,” meaning “foreign er”, which is commonly associat ed with white people in Kenya. I whipped my head around, knowing that my understanding of that word meant they would stop speaking about me so freely behind my back. As I stared at them, I felt a small pang in my heart. These women and I shared a passport and a home, yet they saw me as immutably dif ferent than them.

This is not uncommon and I do not blame all the people who have othered me by calling me half-cast, shouting random Chinese words at me or pulling their eyes tightly to mimic my own. I’ve come to accept that I cannot control how people see me. I remember the day I moved from Nairobi to Winston-Salem, North Carolina to attend Wake Forest University. I was at an airport security check and a guard stopped me. I asked him what he wanted from me and told him that I had no cash to give him. He looked dis appointed that I had made that as sumption and adamantly said that he did not want any money. In stead, for my continued passage to the airport, he said, “Tell me a story, I want to laugh”. I racked my brain for what I could possibly tell this man that could make him laugh. Then, I thought of a single sentence that some Kenyans never ceased to

find funny. “I’m Kenyan,” I replied to him seriously. The security guard erupted into uncontrollable laugh ter. I smiled and proceeded to tell him about myself. I told him that my family is from Nyeri, a rural but booming town north of Nairobi. To his dismay, we were both from the same tribe, Kikuyu. When we spoke, we learned we had a lot more in common than either of us would have thought before. In this way, I have learned to connect with peo ple.

I am grateful for all of my expe riences because they have formed in me a desire to understand and for mally study why some people hold so tightly to some identities and why others do not.

This passion has taken the form of my major, sociology, where I can freely learn about humans, our messy interactions and where my own identity fits into it all.

I want to point out that I would never want to change my multicul tural identity. I absolutely love all of the varying cultures I can relate to, and I have, in many ways, ben efited greatly from understanding so many different types of people globally. Most people are receptive to my complex identity.However, it has been a struggle for me to continue to embrace myself as I have never felt fully affirmed by any of my identities.

All of my life, I have had peo ple tell me that I am not Kenyan. They have said that I am not Kore an, nor Singaporean. These people are right, I’m not. I am all of these identities combined, and I believe that nuance is part of what makes me human.

24 THE

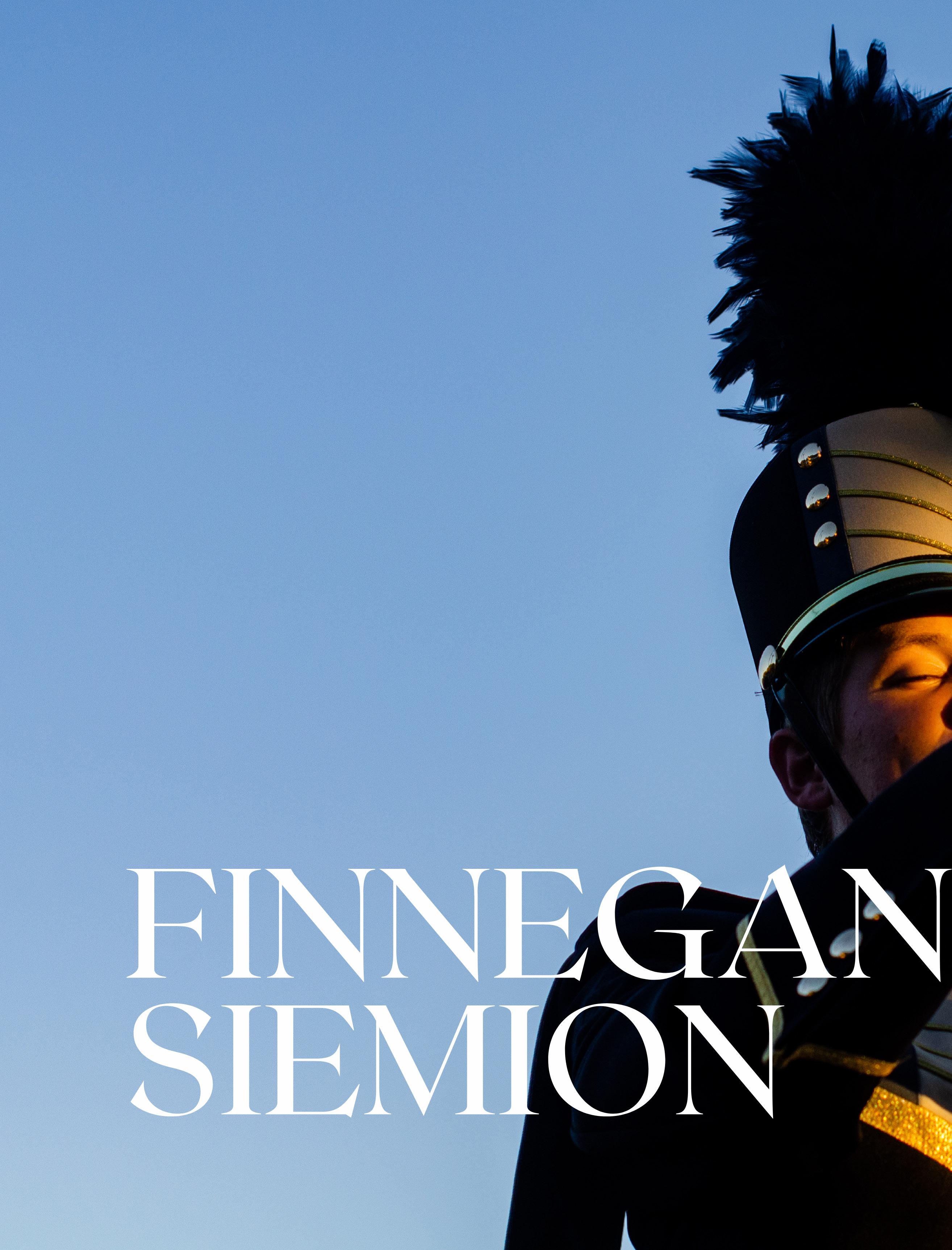

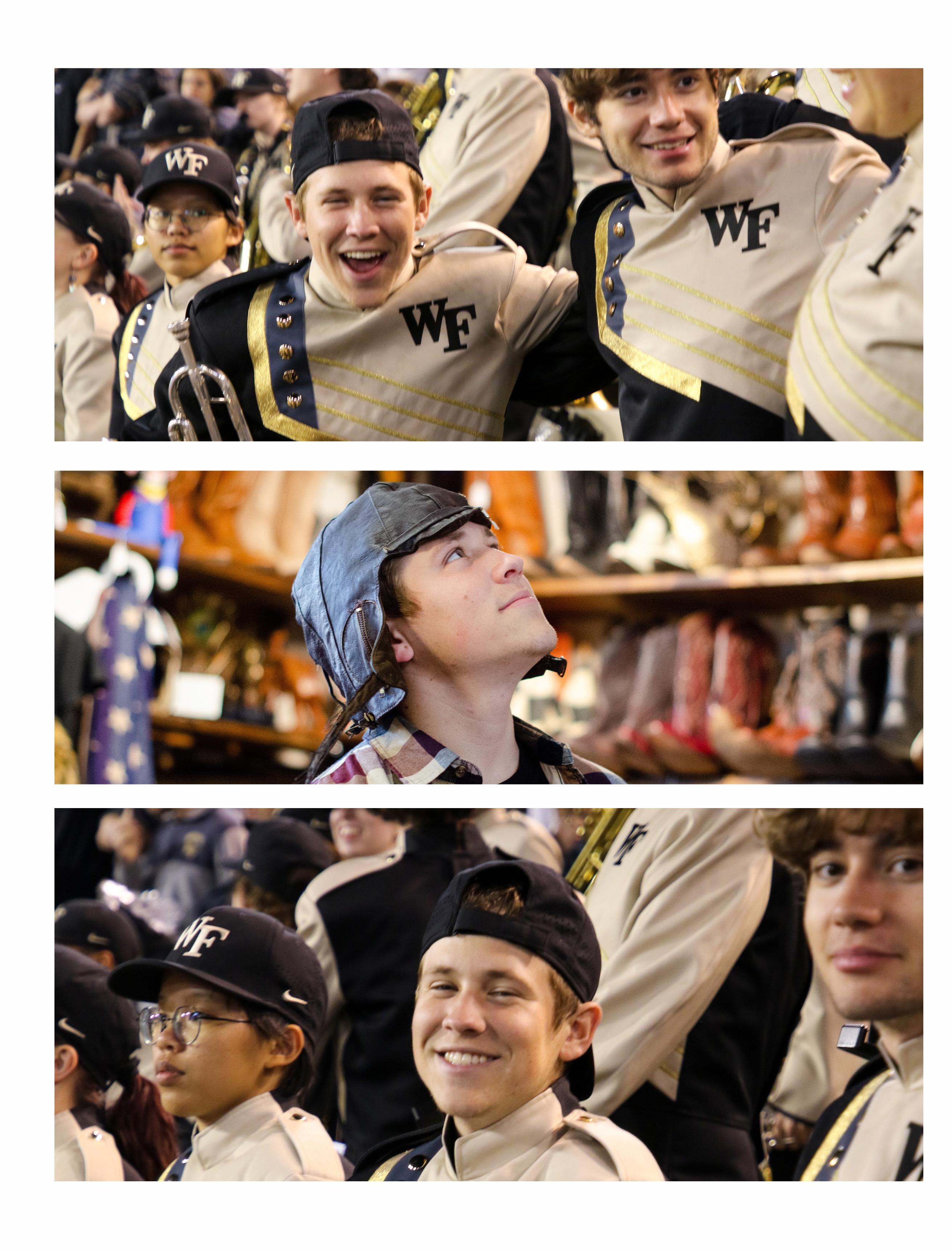

MAGNOLIA • Spirit of the Old Gold & Black

Fall 2022 THE MAGNOLIA 25

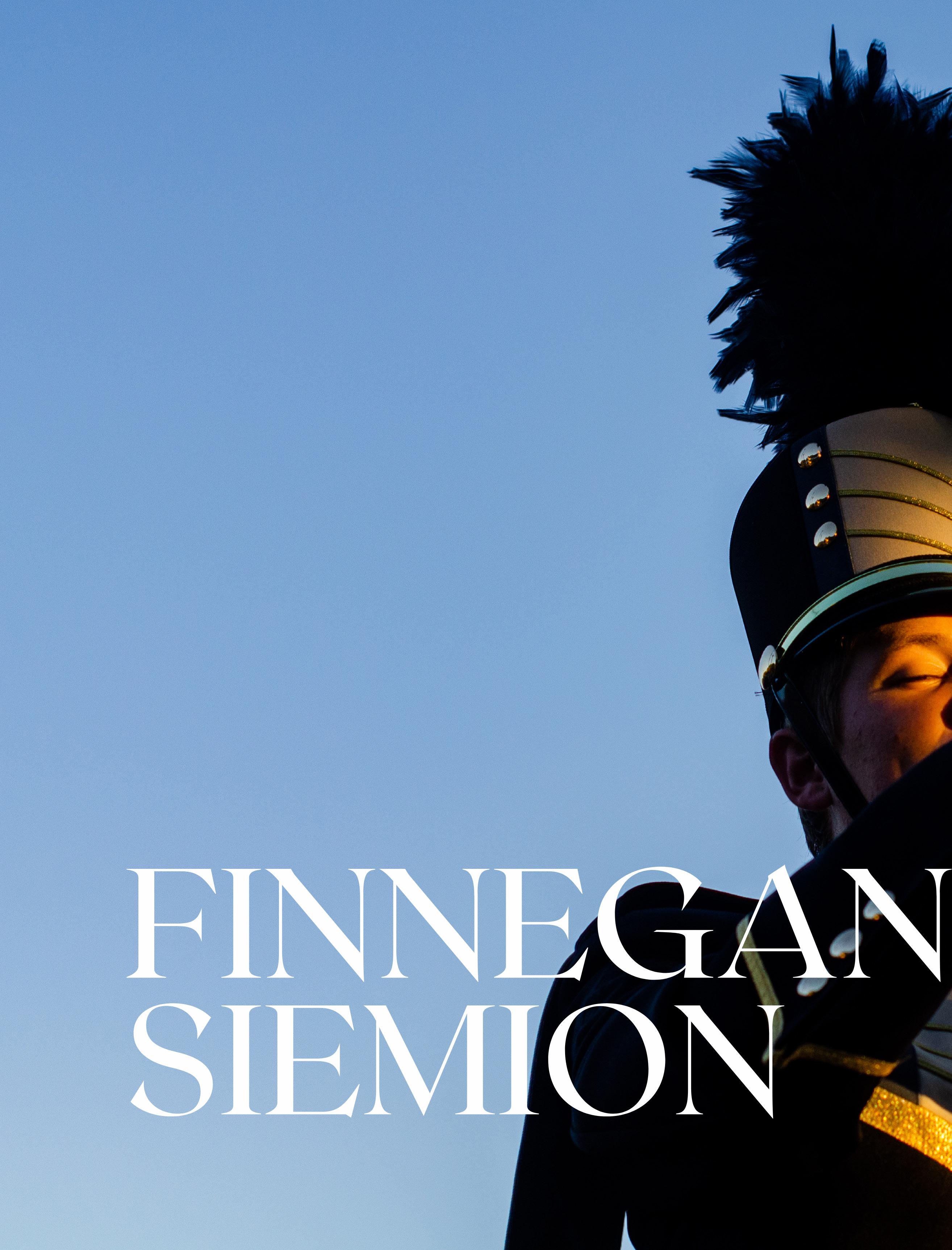

Photography Katie Fox, Finnegan Siemion pictured at Design Archives in downtown Winston-Salem.

Photography Katie Fox, Finnegan Siemion pictured at Design Archives in downtown Winston-Salem.

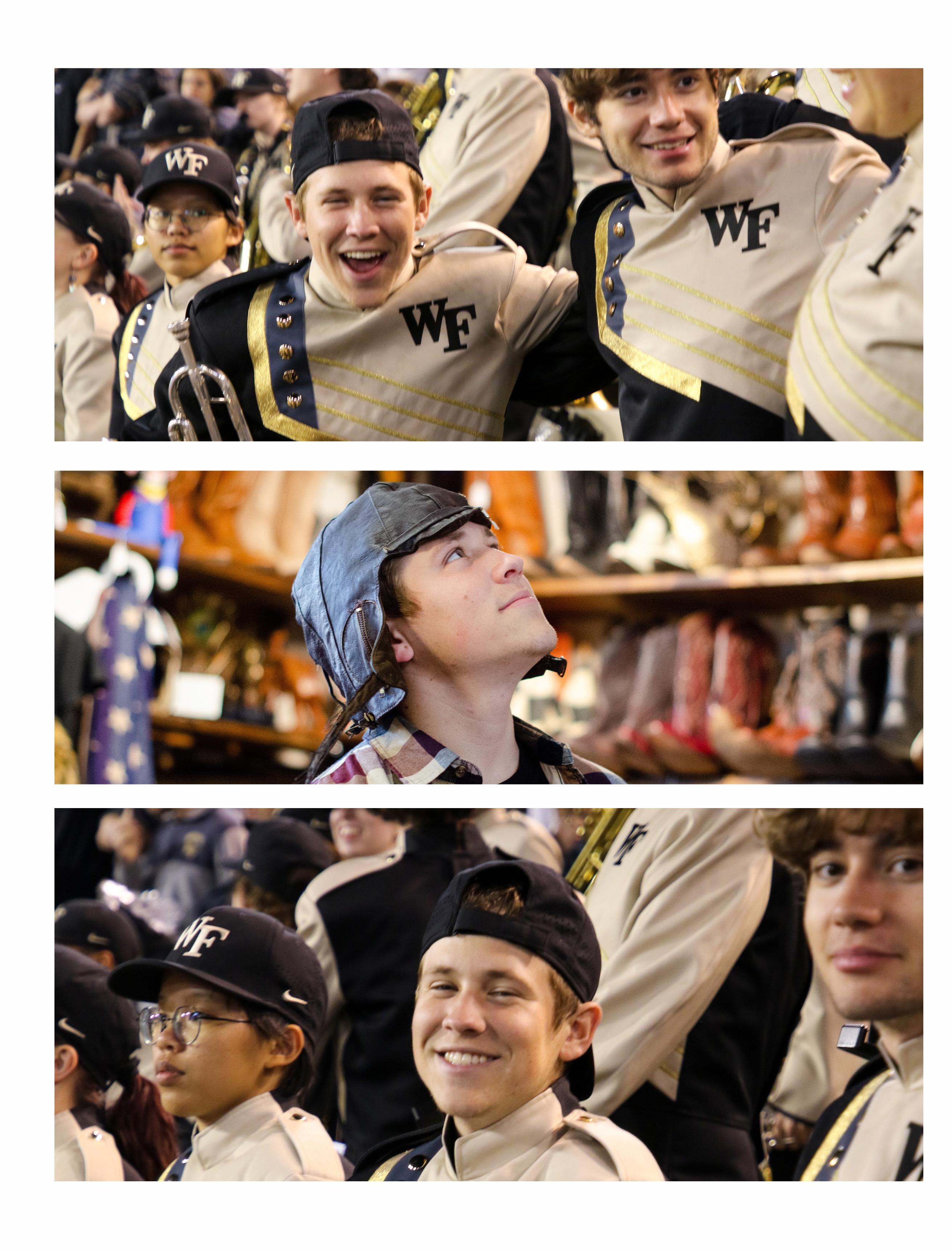

An Interview with Finnegan Siemion

By Sarah Hagiwara

Finnegan Siemion is a soph omore who plays the trum pet for the Spirit of the Old Gold & Black (SOTOGAB), Wake Forest’s marching band. Siemion, who has played in a marching band since 7th grade and has played the trumpet since he was in 5th grade, spoke with The Magnolia about his experience in SOTOGAB and how the marching band is perceived on campus. The in terview below has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Sarah Hagiwara: What drew you to SO TOGAB?

Finnegan Siemion: I was always involved in band stuff. It’s kind of expected, like one of those things you’ve always done so you’re go ing to keep doing it.

SH: How has your experience been in SO TOGAB?

FS: I’ve liked it. I love the stuff we get to do. I stay in it for the experiences, being able to travel with the team and go to places like Charlotte and Jacksonville. It’s not some thing that a lot of kids get to do. I remember when we went to Clemson last year. Being a part of the band, we didn’t have to wonder if we could go to the game, it was a given that we were going. That’s pretty special to me. Obviously, it’s a lot of commitment because we do all of the sports games. It becomes more of a heavy load at some points in the semester, especially during midterms and fi nals. For me, at least, on game days, that’s when it’s worth it. When you’re all dressed up, and you think ‘Wow I am at a college football game, and I am in the college band,’ that’s what makes it special.

Fall 2022 THE MAGNOLIA 27

FS: I think it is somewhat underappreci ated. Since most people aren’t involved in the band and never have been, they don’t really know a lot about it. But when they do see the marching band, they always get super hyped. Whenever we play the drum cadences at the football games, I’ll always see students dancing.

I know we are appreciated, but also we are a band, and bands are usually over looked. The reality of the university, with respect to funding, is that people are go ing to prioritize football or other sports — something that people connect with more than bands. Even though we usually are present, we are definitely overlooked. But to say that we’re underappreciated would be an overstatement. I feel like it’s a bit weird because I remember when my brother was a freshman, the band was very small. Obviously COVID-19 played a role in that, but even before COVID-19, the band was a lot smaller than it is now, even though we’re still generally pretty small. Being in a small band, especially

when your football team isn’t doing par ticularly well, means that a lot of people aren’t really going to the games and seeing some of the stuff you do outside of the stands.

It’s interesting that now that our foot ball team’s actually really good, the band is starting to get more attention. Obvi ously, it just comes down to finances. If something’s doing well, you invest in it, and the band is a part of that. I don’t think that the band should be getting more recognition because the football team is doing better. It shouldn’t be the reason why you’re paying more atten tion to SOTOGAB. When it comes to sports, programs and extracurriculars, the most rewarding aspect of that is gain ing income, traction, reputability, news and media. When we’re a top-15-ranked football school – technically, right now – you’re going to be earning more mon ey, putting in more money, because it is becoming a bigger and more recognized program. Anything that involves football also involves cheer, dance and the march ing band. You can’t have one without the other two, so it’s always going to have an effect.

SH: Do you think SOTOGAB is over looked or underappreciated at this campus?

It builds such a strong sense of communi ty because everyone doesn't have to be there, everyone doesn't even just want to be there. It’s almost the feeling that they need to be there because no one else will.

“

FS: I think for me, especially join ing as a freshman, it does. I got here on campus at least a week before the other freshman. You’re on campus essentially by yourself, except for these 60 other band kids who you’re going to be spending 12 hours a day with. From the get-go, you’re in troduced and start interacting with these people who are similar to the people you probably were friends with in high school.You tend to find a similar group to those you’d been a part of in high school. Everyone has those band friends. And, like I said earlier, it takes a lot to be in SO TOGAB. You really have to be com mitted and you really have to want to do it because you don’t really get a lot out of it other than the experi ence. [This] sometimes can be over looked when you’re stressed or don’t have a lot of time on your schedule. School’s enough as is, so you really have to be committed to be a part of SOTOGAB, and that results in a

group of kids that are committed to SOTOGAB. They are really genuine people, because they understand why they’re there, they understand what they’re doing and they understand why they enjoy it. Every single one of them. It’s not like a club that meets for an hour once a week. You have to bond with each other. When you meet each other from week one, and you’re going to be spending all year with them — maybe four years with them — you’re going to bond. That’s going to be automatic. When you add that extra level of commitment, it makes that bond stronger. I know I’ve only been in it for just more than a year, and I know if there’s anything that would happen where I need to fall back on somebody, I’d just pick one of the 70 from SOTOGAB, and any one of them would be able to support me . Obviously, there are times [when] it gets stressful and you might not appreciate stuff as much as you usually would, but you still know at the end of the day, you al ways have people to fall back to. I think it is special.

What is one aspect of SOTOGAB that is unique to the group and members?

BS: I would just reiterate the fact that it is such a commitment. It builds such a strong sense of com munity because everyone doesn’t have to be there, everyone doesn’t even just want to be there. It’s al most the feeling that they need to be there because no one else will.. Numbers are low as it is — it’s such a struggle to find people. While they want to be there, there’s also the feeling that they have to be there. If there are only four flute players — which there are only four flute players — if you make that decision [and don’t commit to SOTOGAB], there is no one. This isn’t Ohio State, where you have a 300-person band with 200 people on deck where people are begging to be a part of the band. There is no one lined up, so you have to be su per committed and super invested. It’s incredibly different from a lot of other stuff on campus.

SH: Does SOTOGAB give you a sense of community?

Fall 2022 THE MAGNOLIA 29

Photography Katie Fox, Finnegan Siemion (‘25) pictured with SOTOGAB members at the Wake vs Army football game.

AN INTERVIEW WITH BRUCE SONG

By Prarthna Batra (‘26)

Bruce Song is a 21-year-old se nior from Shanghai, China, majoring in accounting and computer science. The Magnolia spoke with Song about his memories at Wake Forest, culture shock and what has made him feel at home here in the United States. The interview below has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Prarthna Batra: Why did you choose to study accounting and computer science ?

Bruce Song: I chose to major in account ing because it is a pretty basic skill when you are looking into business. It can really help with a lot of projects to be knowledge able about a skill like that. Similarly, com puter science is very important nowadays, and there’s nothing you can really do with out the involvement of technology.

PB: What was the process that went be hind picking a college so far away from home and why not a college back in China?

BS: The mindset of wanting to study abroad and pursue my education in the United States started for me when I was 12 years old. That was when I traveled to the United States for the first time, for a summer camp. My first experience being here was so refreshing, and every time I came back for that summer camp, I had a great experience.That is what made me make up my mind that I wanted to pur sue my undergraduate degree here. It was just exciting to experience a different way of life, and the quality of life was definitely enhanced, too. The education is more ad vanced, and you have more options to ex plore before you make a decision on what you really want to pursue.

PB: What are some of your interests and hobbies? How do you like to spend your free time?

BS: Surprisingly, I do have a lot of time during the week. I usually like to hangout with my friends and just relax by listening to music. Recently, I’ve been loving to collect re cords as well. My favorite artists are basic but classic. I love to listen to The Beatles, and I love classic rock as a genre. I do love to spend my time at the gym and working out as well.

PB: How do you feel about the fact that Wake Forest does have a large community of Chinese international students and does it make you feel involved and represented?

BS: I don’t really spend a lot of time with the Chinese community, but it is nice to hang out with them once in a while because it is comforting to know that we all come from the same culture, and it helps in having a sense of belonging. But I do like to be in tune with American culture and learn to fully em brace it.

Photography: Lucius You

PB: When you first moved to the Unit ed States for college, was there any culture shock you faced?

BS: About family life, it’s been really hard in the sense that COVID has made it really hard to get back to my family in Shanghai because I have to quaran tine for a month everytime I try to go back. While it is improving now, it is still pretty hard to find flights. I Facetime my family once a week and that helps being so far away from home, but that is about the only interaction I have with them. Another change I feel in the sense of family life is that people here have a lot of siblings and big families, but that is strange to me because I grew up as an only child.

Another cultural change I noticed between the United States and China is that I think Asian parents put more pressure on their children to succeed. Academic pressure is everywhere, and all parents want their children to succeed, but it is definitely more prominent in Asian countries.

One advantage in terms of cultural dif ferences I noticed when I moved here was the fact that I’m not a religious minority anymore. I’m now a part of the religious majority. I’m a Christian and back home in China, since the majority of the pop ulation is Buddhist, you always had to be secretive about your religion if you were a Christian and had to go to these Chinese underground churches. There is a safe space for free expression of your religious identity [in America], and I feel relieved here about the freedom of ex pression of my Christianity.

In terms of the education system, the courses here encourage discussion, ex pressing your own opinions and critical thinking. Back in China, it was more of taking exams and getting a good grade. Getting good grades is obviously very important here too, but there are a lot more components that contribute to it. I did feel pretty well prepared to tackle the education system because I went to an international school in China and took some AP courses back in high school. It wasn’t that much of a jump from high school to freshman year of college, but now as I progress in my major, it keeps getting harder.

PB: Is English your first language? And if not, have there been any bar riers you’ve faced related to language since you’ve been here?

BS: English isn’t my first language. I’m from the mainland in Shanghai, which is a primarily Mandarin-speaking area.

I have been learning English since ele mentary school, and even though I’m not a native speaker, the only struggle I have faced is during classes. Sometimes during classes it is hard for me to speak out loud, but I’m making progress and trying to overcome that because at the end of the day, it is a much bigger deal in our heads than it is to others. People don’t care that much about accents.

PB: What has been the hardest part of being away from home for you?

BS: Being homesick and missing family and friends is undoubtedly the hardest part of being away from home. The only way I can talk to them is through Face time, and I miss them a lot.

PB: What was the process that went behind picking a college so far away from home and why not a college back in China?

BS: The mindset of wanting to study abroad and pursue my education in the United States started for me when I was 12 years old. That was when I traveled to the states for the first time. My first experience being here was so refreshing, and every time I came back for that sum mer camp, I had a great experience.That is what made me make up my mind that I wanted to pursue my undergraduate degree here. It was just exciting to ex perience a different way of life, and the quality of life was definitely enhanced too. The education is more advanced, and you have more options to explore before you make a decision on what you really want to pursue

PB: What has been your favorite memory since you have been here at Wake Forest?

BS: My favorite memory since I’ve been at school is when I bought the company “University Storage Solutions”. During my freshman year, I heard about it from my friend, and we both decided to buy some shares in it. Due to COVID-19, it wasn’t doing well, and it just picked up this past summer because my friend and I started advertising our company. We got the opportunity to collaborate with other students at Wake Forest, and it was a wonderful experience. I really got a sense of accomplishment after achiev ing that. I learned how a business works and how to communicate with people in a professional setting. It has been a really meaningful experience that I am lucky to have been a part of, and it brought me a lot of great memories.

32 THE MAGNOLIA • Nathaniel Holiday

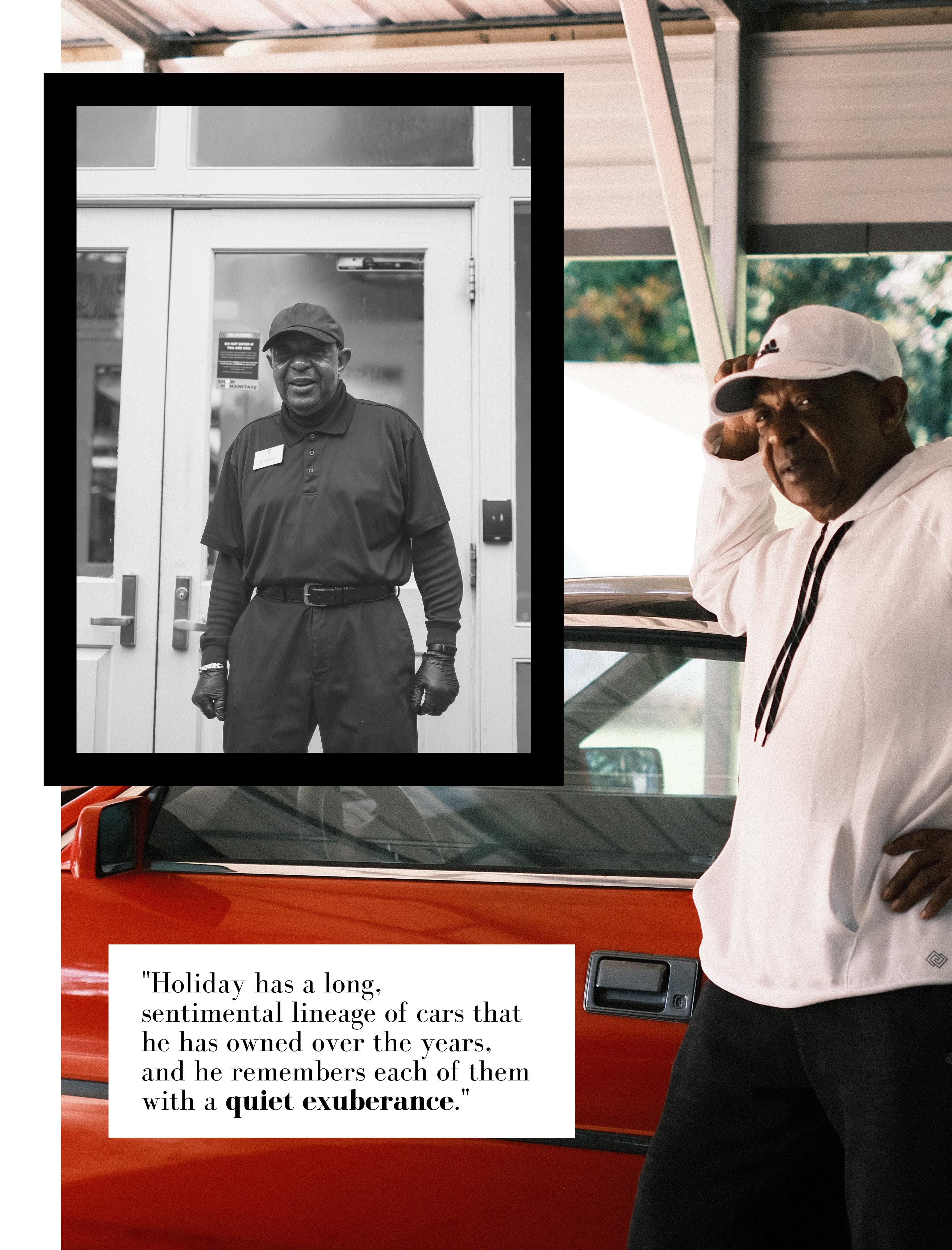

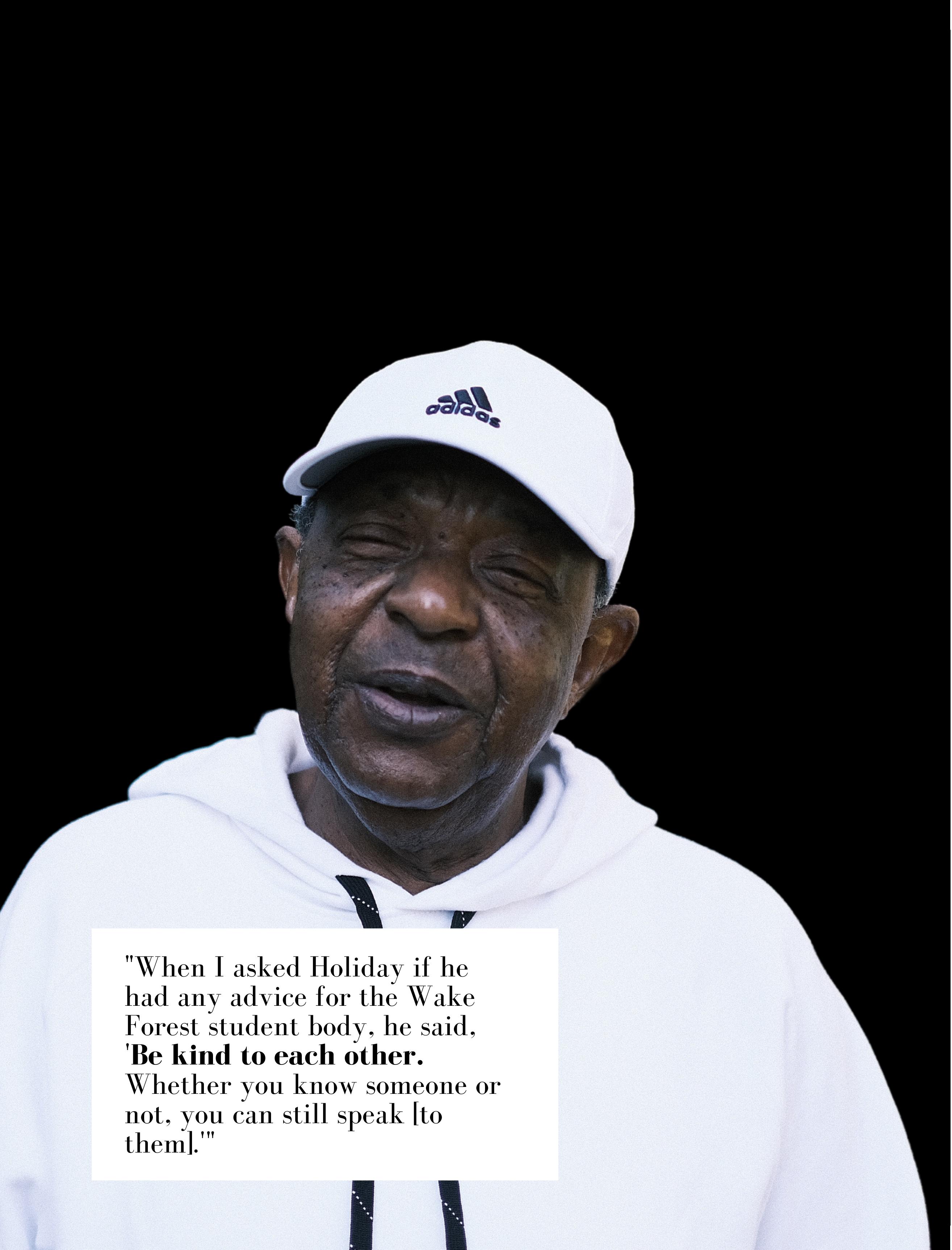

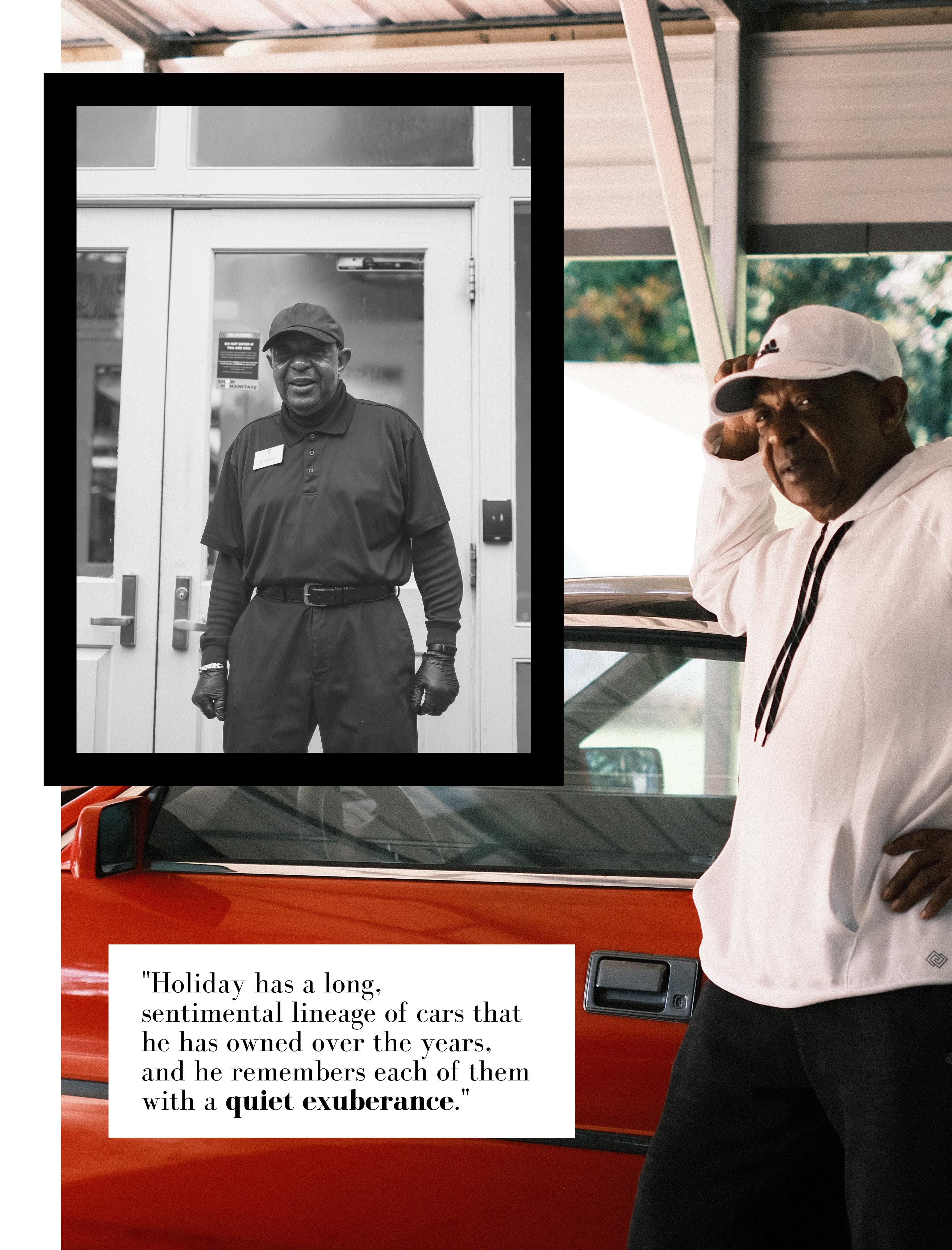

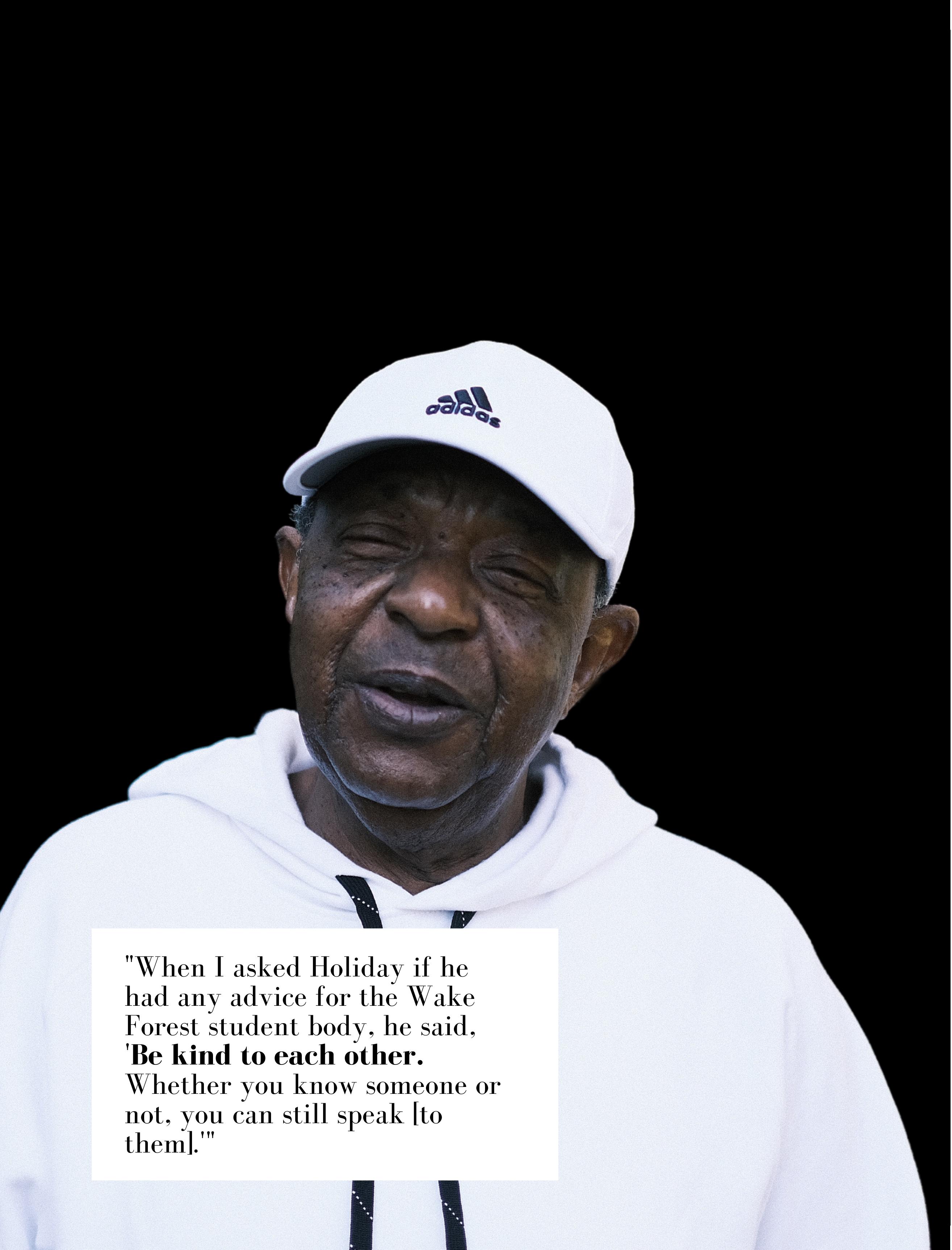

Beyond Benson, a conversation with Nathaniel Holiday

Adam Coil (‘25)

Adam Coil (‘25)

Making his rounds in the Benson University Center, long-time Wake Forest custodian Nathan iel Holiday is so good at his job, you can al most miss that he’s there. Almost. With an endearing smile and a warm, inviting person ality, Holiday has been a crucial member of the Wake Forest community since the 1960s. Not only is he a highly respected and dili gent employee, he’s also been a much-needed friend to Wake Forest students of multiple generations, passing on his kindness and wis dom to those who need it.

Fall 2022 THE MAGNOLIA 33

“Holiday has a long, sentimental lineage of cars that he has owned over the years, and he remembers each of them with a quiet exuberance.”

A Winston-Salem native, Holiday has been an enthusiastic sports fan for his entire life, eventually displaying his talents at Atkins High School. He grew up playing games whenever and wherever he could with his friends.

“Oh, yeah, I could run that ball,” he said. “I played football, basketball and I ran track through the ninth grade.”

With the intense rivalries between the lo cal schools back then, the stakes on the field were always high. “Football, you know, I took that seriously. You had to be good, and Atkins was the best.” Once he got his driver’s license, though, his interests started to change, and his love for cars began to take up more and more of his free time.

“I always did love them cars. Always. I couldn’t wait to get my license. I didn’t care what I was driving — it could’ve been a truck, as long as I was driving,” he said.

Holiday has a long, sentimental lineage of cars that he has owned over the years, and he remembers each of them with a quiet exuber

ance.

“My first car was a ‘57 Chevy, and it was nice. Then, I went to a 1964 [Pontiac] Tem pest. Then I got a ‘67 [Pontiac] GTO 400/360, black on black, and I had it built…They tried to get me for racing, but they couldn’t prove it, so I never did get convicted.”

Holiday attended Atkins during the day and worked at Wake Forest in the afternoons. “I’d leave school at probably 3 o’clock,” he said, “and then I’d have to be [at Wake Forest] at around four o’clock, and then I’d finally get off at about nine or ten o’clock.”

With how much time he was putting into his first job and taking care of his cars, Holiday had little time and energy left for academics. Holiday reflected, “When them cars came around, school kind of went away for me… Back in the day, if you worked for RJ Reynolds, you didn’t even need to finish school… you could go there and make all kinds of mon ey. These days, it’s different — you need that education.”

Photography Katie Fox

“Holiday has a long, sentimental lineage of cars that he has owned over the years, and he remembers each of them with a quiet exuberance.”

Because he started working for the University in the ‘60s, Holiday has been witness to a lot of change, espe cially at the Pit, where he first worked.

“Everything was good back in the day. They had whole steaks, home made pie, sweet potato pie... mhmm. I love sweet potatoes.”

Holiday also noted the infrastruc ture changes that dining has under gone. A football player-only dining section in the Pit has been removed, and a multi-floor conveyor belt for washing dishes has been added. He is a living testament to the micro and macro evolutions of this university.

In between his two stints working for Wake Forest, Holiday spent 42 years at Sara Lee, a textile factory in Winston-Salem. At Sara Lee, Holiday

“Yeah, we had a ball,” Holiday said in refer ence to his time there. “We’d bring our own music, put it on the machine. It was nice.”

was in charge of a compactor machine within the factory, and he was also re sponsible for training new employees.

“We had a ball,” Holiday said of his time there. “We’d bring our own music, put it on the machine. It was nice.”

Holiday is a lifelong fan of jazz and RnB music. Listing his favorite artists, Holiday mentioned Najee, in particu lar — a saxophonist and flute player who broke onto the jazz scene in the 1980s.

“I like all kinds of music. I got a camera full of music. Old school stuff, yeah,” he said.

Holiday then returned to Wake For est in 2008 after a brief interlude of retirement.

“My wife said, ‘You can’t play golf every day,’ and so I had a buddy work ing up in the Pit who told me to put in an application. They hired me on the spot, just like that.”

Holiday was quickly moved to the Benson Center — where he has worked to this day — there, he mops all of the floors, replaces all of the

trash bins, takes care of the soda ma chine, wipes the tables and vacuums the floor, among other things.

When asked about the best part of his job here, Holiday said, “Every day is different. It’s lowkey today, but to morrow it’ll all change… It’s a good place to work, you know, and people know I do a good job.”

Outside of work, Holiday spends a lot of time taking care of his yard, relaxing in his entertainment center and spending time with his wife, Patricia.

“Me and my wife, we go walking in the neighborhood. We like the quiet, it’s no-nonsense.”

Also, when they have the time, they like to unwind up in the mountains.

“We got another house in the mountains… It’s real nice and lowkey… We just go up there to chill out, go to some different places and visit people.”

Holiday also enjoys the relationship he has with the student body, and he appreciates everyone he interacts with during the day.

“[Students] come and talk to me all the time,” he said, “A bunch of them. They’ll come over and touch me on the shoulder and say hi.”

When I asked Holiday if he had any advice for the Wake Forest student body, he said, “Be kind to each other. Whether you know someone or not, you can still speak [to them].” Indeed, that’s exactly the kind of person Hol iday is — somebody who’s constantly looking to brighten someone else’s day through conversation and compan ionship, even if that person is a com plete stranger.

It’s difficult to know how much lon ger the Wake Forest community will have the pleasure of Holiday’s pres ence. In reference to a potential retire ment, Holiday said, “I might give it up next year… but I like to be busy. I can’t just sit around the house and do nothing.”

I encourage everyone to stop and chat with Holiday if given the oppor tunity. He is an instrumental part of the Wake Forest community, someone who can offer comfort, advice or even the simple pleasure of polite conversation. It is for those reasons, in particu lar, that Holiday is much, much more than a custodian to Wake Forest.

Fall 2022 THE MAGNOLIA 37

Marina Velasco is a 21 year old junior from Lima, Peru. She is majoring in Politics & International Af fairs with minors in Art History and global trade and commerce.

Velasco spoke with The Magnolia about navigating cultural differences as an international student. The interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

AN INTERVIEW WITH MARINA VELASCO

By Prarthna Batra (‘26)

By Prarthna Batra (‘26)

Prarthna Batra: How did you end up choosing to study what you chose?

Marina Velasco: I picked politics and international affairs because I want to be a writer at some point and write books and be a published author. I don’t know if it made sense to pick this major over something like English,but I felt like picking something like that might limit what I could pursue as a career. I picked political science because I wanted to study something that integrated most of my interests as much as possible. A humanities-heavy major like politics and international affairs also involves a lot of writing, which is very useful for the kind of career I want to pursue.

PB: What are some of your interests and hobbies and how do you like to spend your free time?

MV: My primary hobby is writing, I love to write. I write a lot of poetry because I think it is easy to write while you’re on the go. You can just take out a little notebook and jot down a few lines and later on that can turn into whatever you want it to be. I also love to play the guitar and listen to music. Music and art fascinate me and are my biggest hobbies and interests. That’s why I’m studying art history to nurture those interests. I love to learn about art and create art in its different forms such as drawing, painting and sculpting. I’m also really interested in spirituality. I don’t see it as a hobby or an interest but more as a way of living my life. I like to feel connected to everything, wherever I go. I love to spend my time around nature and work on making our way of living a more sustainable way. I have a very curious mind and I love seeing everything around me.

PB: When you moved here, what were some of the culture shocks you faced?

MV: The first thing that I noticed immediately when I moved here, was the fact that the kind of preoccupations people have were very differ ent from mine. It felt like everyone had a high school mentality of being very aware of others’ opinions and what they think of you. Maybe this is more of a personal difference, than a cultur al difference but maybe I was just really lucky to have amazing people surrounding me back home. I have amazing friends here too, but I think sometimes people here can be very pre occupied with others opinions, while I just go about life carefree. I think what people think of you is considered very important here, and I feel like that perpetuates the barriers between peo ple.

Another huge culture shock for me was the fact that I come from a culture that is extreme ly warm and affectionate and very expressive about emotions. The experiences I had here pointed to the direction that people here aren’t as affectionate, and culturally, everyone seems to be very detached from each other. Everyone has the mentality that they are just fending for them selves here and that just isn’t something that I can relate to. I think being vulnerable and open ly expressive of your emotions and specifically intense emotions like love, affection, sadness and anger aren’t accepted with open arms here. I see these patterns a lot in the way I interact with other people. Back home, the way I greet a friend is by giving them a big hug and a kiss on the cheek. This may not be something that is accepted in a post-COVIDworld, but that’s all I’ve known and that’s how I’ve been raised in my culture. It makes me feel connected to the person I’m talking to when there is that physical connection and intimacy. Here, I’m always so conscious of the way I greet people because I never want to make anyone uncomfortable.

I feel that being vulnerable, being emotional and being expressive of your love and appreci ation and admiration for others is so valuable. It is such a valuable quality to have as a person and there is so much power in doing that un ashamedly. One of the biggest cultural clashes for me was how different it is to say I love you to someone here.it is considered such a big deal. I say it casually, but I don’t think that reduces the meaning of it. Me telling someone that I love them often is just because I mean it that much every single time I say it.

My friends have gotten used to me express ing my love for them because I do it so often and I absolutely love to do it. I’m just used to speaking my mind, without any filter. Even if it is something as simple as having a great conver sation with my friend, I’m going to tell them that

I love them and how proud of them I am. I’m go ing to tell you how much I admire you because expressing your feelings and admiration isn’t a sign of weakness, even if some people view it like that. It is extremely important to me to make the people around me feel loved and appreciated and expressing my gratitude and admiration for them.

I grew up in an all-girls school in Lima, so the idea of sisterhood and lifting each other up, be ing in it together, taking care of each other and caring for each other was a very huge part of my upbringing. I went to that school all my life, from the age of six, until I was 19 and I spent my entire childhood growing up with the same 80 girls. They taught me what it is to care for each other and I am always going to love them.

I hope nobody is ever deterred from express ing their love or the fact that they care for some one. You should always be able to speak your truth and express your admiration for the people you love and if they don’t want to take it and digest it and appreciate it, that’s okay and that is on them.

The culture shock that I faced in terms of fam ily life was also massive. It's very common to move out at 18 in a lot of places, but back home, even after you move out, family life is so important. I’ve noticed that people here are a lot more individualistic. The culture here is very much focussed on productivity and hustle cul ture and focussing only on yourself. For me, that is a representation of a fight-or-flight mentality. It is a response that doesn’t allow you to see the world in all its colors and feel emotions in all their depth. I do want to step out in the world, be productive and be my own person and that is definitely part of my motivation. But at the same time, another huge motivating factor is my family and making sure they are okay, and in the hope of providing something better for the people behind me and the people that might be in front of me. My family is always in my head, in regard with every action I take. I think not from the standpoint of an individual, but I think of all the people in my family that I love and care about. My family is a big part of me, and I really want to make them proud but that isn’t a mindset that a lot of people that grow up in the United States have.

Read the rest of Marina’s story online.

40 THE MAGNOLIA • Marina

Velasco

Fallenius Clara

AN INTERVIEW WITH CLARA FALLENIUS

By Prarthna Batra (‘26) Read Clara’s full story on the website

Clara Fallenius is a 19-year-old fresh man from Stockholm, Sweden. Falle nius is on the Wake Forest women’s track and field team and plans to ma jor in Health and Exercise Science (HES). The Magnolia spoke with Fallenius about her interests, talents and her Wake Forest experi ence thus far. The interview below has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Prarthna Batra: Why do you want to major in HES?

Clara Fallenius: I’m really fascinated by the human body and how it works, so this major seems to be a great fit for my interests. There are also several athletes who are pursuing the same major, so if they can do it, so can I.

PB: What are some of your interests and hobbies? How do you like to spend your free time?

CF: Obviously, track. I love being a part of the track team, but when I’m not busy doing that, I love to read. When I’m reading, it is with the aim of get ting my mind off of stressful things so it is usually genres like romance, fantasy and some contempo rary novels. My favorite latest read was ‘The Seven Husbands of Evelyn Hugo’ by Taylor Jenkins Reid. She is one of my favorite authors, along with Adam Silvera. Another thing I really love to do is cook, and I basically have a whole kitchen in my tiny Collins dorm room. My favorite dish to make from scratch if

I have all day is chicken tikka masala accompanied with some naan, but if I am looking for a quick reci pe, it is usually some kind of pasta.

PB: How did you get into track and when did you start?

CF: I’ve been doing track since I was 10 years old, so it’s been almost 10 years now. My dad was a high jumper when we was younger, and that drew me to track as a sport. At age 10, I started training in a track group, with him as my coachThen I just started going to summer track events, and it was so much fun and I absolutely loved it. My dad has been my coach ever since, and it’s been so nice to have all this time together when we have gone to athletic camps together. He is my biggest supporter.

PB: How did you end up choosing Wake Forest?

CF: Back home in Sweden, school and sports are two completely different worlds; they aren’t affili ated or combined in any way at all. If I had chosen to go to school in Sweden, I would have had school, and then after that, I would have had practice sepa rately. I always had to travel an hour to track practice after already having a long day at school. Instead, I just decided to take one 10 hour flight to Wake For est, where school and track coexist, rather than stay and have to drive 45 minutes daily. It is so nice to have everything in the same place. Sometimes, it's crazy to believe. The facilities here are so nice, it is not comparable to what we had back in Sweden.

AN INTERVIEW WITH CLAYTON BI

By Prarthna Batra (‘26)

Read Clayton’s full story on the website

By Prarthna Batra (‘26)

Read Clayton’s full story on the website

Clayton Bi is a 20-year-old junior at Wake Forest University from Chengdu, China, with a double major in computer science and studio art. Clayton shares his interest in architecture and pho tography as well as what it has been like to be an international student at Wake Forest.

Prarthna Batra: What is the hardest part of being away from home?

Clayton Bi: I would say the disconnect from authentic Chinese food is the hardest part of be ing away from home for me. There are so many dishes that I love to cook and eat at home that I am not able to eat over here. I have been pretty good at adapting to the food culture the United States has to offer, but I miss spicy Chinese food and I am still trying to overcome that challenge.

PB: What has been your fondest memory since you have been at Wake?

CB: My favorite memory of being at Wake For est so far is a fairly simple weekend I spent. Af ter I was done with my computer science home work, I went out to lunch and then spent the rest of the day by myself at the Scales center. I was working on my studio art project. It was a really beautiful and peaceful day on campus and work ing on something that I am so passionate about just gave me such a strong sense of satisfaction. At that moment, I felt most like myself. I was so happy to be doing what I love and was real ly enjoying myself. There is so much beauty in simple and mundane moments like those.

PB: Is English your first language? If not, were there any language related barriers you faced since the time you moved here?

CB: English isn’t my first language, Mandarin is. But in our school curriculum, from the very beginning of primary school, we have been in contact with English and we have always had the opportunities to explore the language more. I feel like if I am an international student, it is our responsibility to make an effort and learn more about the language. There were definite ly some challenges after coming here, like not being able to understand some local phrases and slang. There have been instances where I hav en’t been able to understand something that my professor is trying to explain in a class setting. If that happens, I just ask because I know it is ok to do so. I have the right to not know everything about the language, and the challenges that come with understanding English are just a part of the process of fitting in.

PB: What are some of your interests and hobbies? How do you like to spend your free time?

CB: I spend the majority of my free time pursu ing photography. I really love to try and capture the beauty of the moment. I’m mostly interest ed in artistic and experimental films and images over commercial ones. I like to pursue photogra phy when it offers some artistic value over sole ly aesthetic value. I have really been trying to imitate a few of my favorite photographers and recreate their style. Apart from that, in my free time, I just like to browse through architecture magazines and books so that I can stay up to date with the world of architecture.

I use my free time after I’m done with all my major-related work to try and broaden the hori zon of architecture in my mind, just so I can gain more knowledge. All this information is in a way preparing me for the future so that I can focus on my own style in the future and gradually build my own skill set.

44 THE MAGNOLIA • Clayton Bi

By Cooper Sullivan (‘24)

By Cooper Sullivan (‘24)

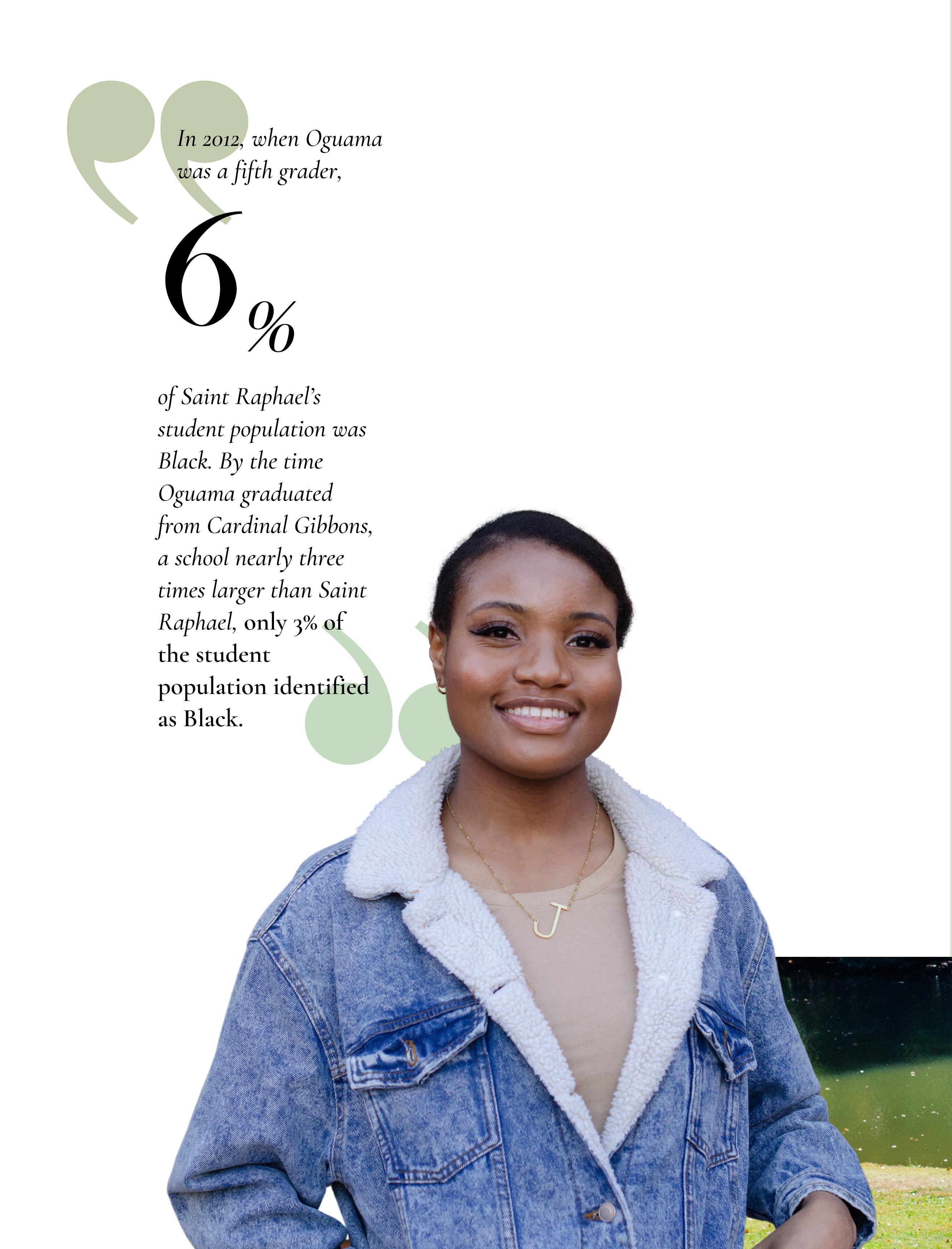

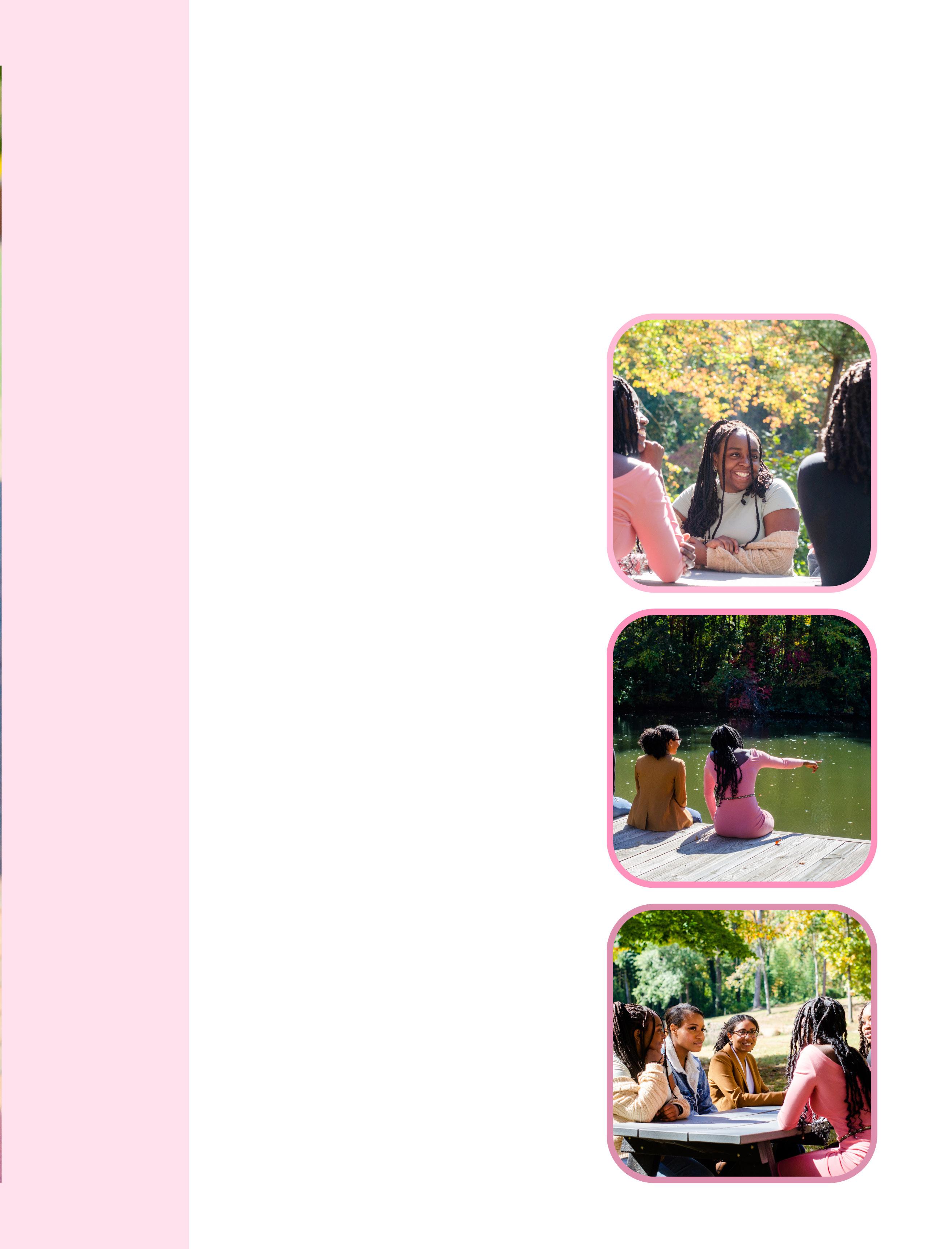

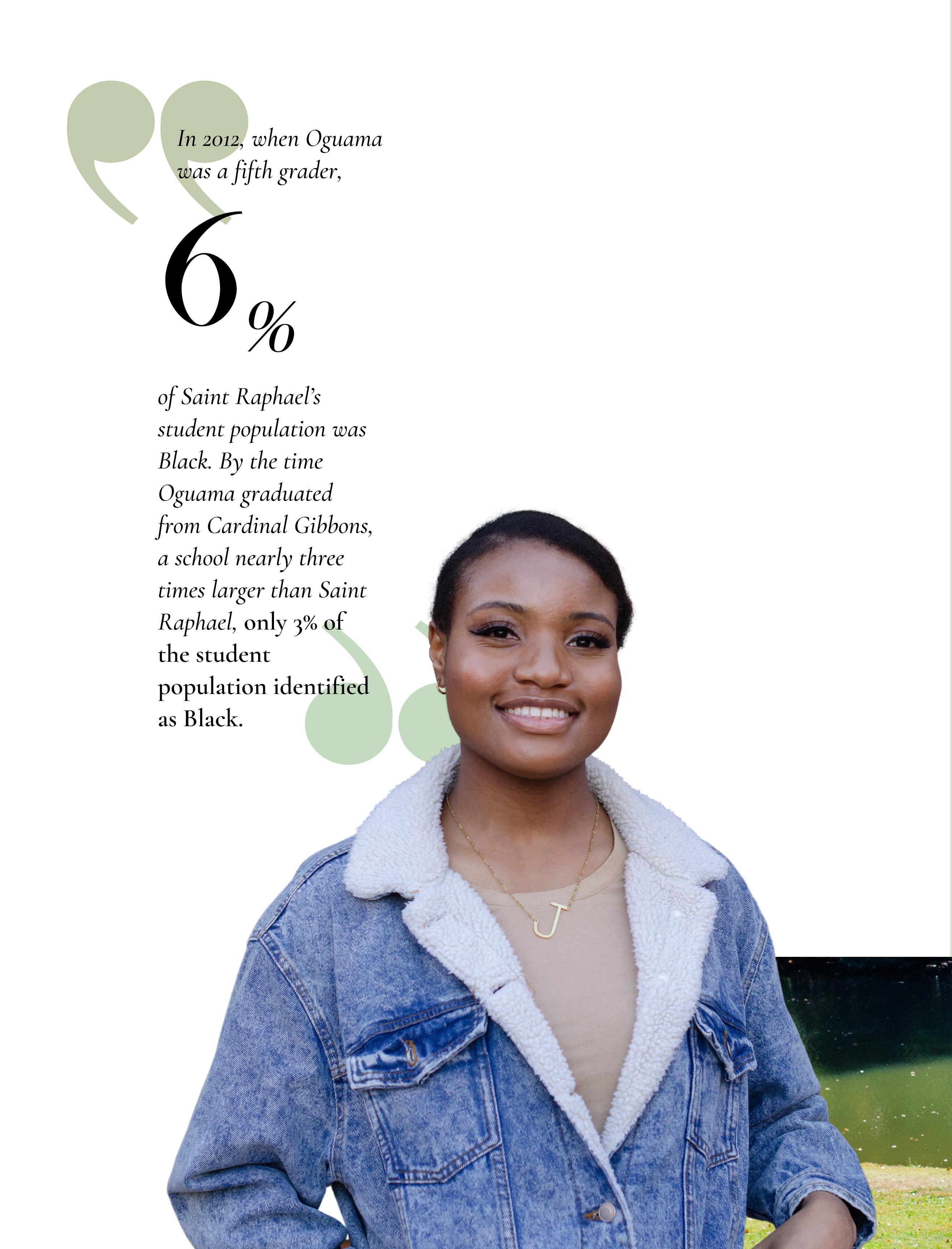

Joy Oguama has attended three schools during the last sixteen years — Saint Raphael Catholic in North Ra leigh for kindergarten through eighth grade, Cardinal Gibbons in West Ra leigh for four years of high school, and Wake Forest for the last three-and-ahalf years of college. There are many similarities between the three schools. They are all in North Carolina, they are all private schools and they are all primarily white insti tutions (PWIs).

“I kind of knew how to navigate being a minority and being marginalized [in the academic setting],” Oguama said. “I was kind of used to it.”

In 2012, when Oguama was a fifth grader, 6% percent of Saint Raphael’s student population was Black. By the time Oguama graduated from Cardinal Gibbons, a school nearly three times larger than Saint Raphael, only 3% of the student population identified as Black.

Even though she was used to being one of the few Black students in her class es, Oguama still experienced a culture shock when she arrived at Wake For est. Not only was the now-senior biol ogy major and statistics minor not pre pared for being one of the only, if not the only Black woman in her STEM classes, but it was the way everyone else interacted with her that stood out.

“It’s almost like I don’t know if some of these people have actually interacted with Black people before,” Oguama said. “I don’t know if they see me as their equal.”

Oguama is not the only Black woman pursuing a degree in the STEM fields to feel this way.

Chi Nwakuche, a senior computer science major, constantly deals with assumptions that her appearance, and not her intelligence and academic record, was the reason she got into Wake Forest . Alex Labady, a senior majoring in sociology with a concentration in health and wellbeing on the pre-med track, says she often gets confused for being an athlete. Maahla Fofack, a senior biochemistry and molecular biology major, calls the need to always prove her knowledge, her worth and herself morally discouraging. Sheevanie Casimir, a senior health and exercise science (HES) major, calls the constant justification exhausting. Sabrina Jeancharles, a sophomore HES major, is questioning if she even wants to continue down the STEM path, something she’s loved since middle school.

They become numb to feelings of discomfort, frustration, and otherness because there is something more important than feeling welcomed, valued, and celebrated — their futures.

Of the 5,447 undergraduate students enrolled at Wake Forest in the Fall 2022 semester, 342 individuals identify as Black, or 6.2% of the current undergraduate population. This mark is consistent with the proportions of Wake Forest’s six previous fall terms, but matched up against national averages — Wake Forest falls well short.

In the Fall 2019 semester — when Oguama, Fofack, Labady, and Casimir started their freshman year at Wake Forest — 13% of the student population at 4-year, private, not-forprofit colleges or universities across the nation identified as Black. That same semester in Winston-Salem, only 6.5% of the undergraduate population and 8% of the entire student population identified as Black.

It’s not just those that sit in the classroom seats either that are dealing with underrep resentation. In the College of Arts and Sciences, 5% of last year’s faculty identified as Black as opposed to a nationwide 7%. There are 193 professors in the biology, chemistry, computer science, engineering, HES, mathematics, physics, and statistics departments. A person wouldn’t even need a second hand to count the number of Black women teaching in those departments.

There are

five.

Sheevanie Casimir notices the fact that there aren’t a lot of Black women on campus — 181 or 3.3% of the undergraduate class to be exact. It’s hard not to notice when you walk into an organic chemistry class and no one looks like you.

“I wish there was definitely more representation. I definitely wish there were more professors that we could turn to and talk to you. I wish the class rooms weren't like just me and another person or just me by myself and a sea full of white classmates. But, I mean, that's just how it is when you go to an institution like Wake Forest.”

It is hard not to become distracted, but Casimir’s ultimate blinder is keep ing her eyes pointed toward the future. Her interest in kinesiology and anato my combined with her caretaking abilities — Casimir spent the entire soph omore year remotely to help her family take care of her brother with spastic quadriplegic cerebral palsy — has her poised to become a doctor.

Plus, this is what the real world is going to be like, she says. She wishes it weren’t, but she’s been aware of discrimination and underrepresentation since elementary school. It’s exhausting.

Sabrina Jeancharles has yet to have any Black pro fessors, and although she says “it is what it is”, there are strong signs of discontent with this fact.

Hailing from Orlando, FL, Jeancharles was a part of the Medical Magnet program at Jones High School. The pro gram was majority Black stu dents, but the nurses teaching were white. This forced many of the students, including Jeancharles, to advocate for themselves, explaining their backgrounds and situations to their instructors in order to bridge the gap of misunder standing.

Jeancharles not only saw it necessary to do so, but it was relatively easy. This program was the only thing that got her out of bed in the morn ings, and she was determined to get the absolute most out of it. It also helped to have a class full of other Black women feeling the same way. Here at Wake Forest, it feels like there is no strong support system to help or guide her along the pre-health track.

Her former STEM advisor in the Office of Academic Advising, Bert Ellison, left his position in August of this year to spend more time with his family. Without a dedi cated individual or a general sense of community and be longing helping her along the path, Jeancharles is weighing if the pre-medicine track is something she even wants to continue following.

“Who am I supposed to go to? I feel like I don’t have somebody to fall back on,” she said.

Who am I supposed to go to? I feel like I don’t have somebody to fall back on. “

Dr. Lauren Lowman is a professor in the Wake Forest engineering and phys ics departments — one of the five Black STEM professors mentioned earlier.

As a Black woman in STEM who wasn’t surrounded by other Black women in or in front of the classroom seats, Lowman is very conscientious of what she can do for other underrepresented students. She has experienced firsthand the importance of gender and racial representation in en gineering.

“I definitely gravitated towards female faculty members that I had as an under grad, and I did not have many. I did not have many, even in public policy [Low man’s major at the time]. Actually, I think all of my faculty members in public policy were men. I didn't have a single female faculty member teaching any of my classes, except for one elective that I took. I really enjoyed it and I did actually connect with her.”

Lowman’s advisor for her master’s de gree in engineering was a woman for this reason. Her previous advisors were both men — and they were both great she adds — but this time she would have someone guiding her, who knew where the obsta cles were and how to get around them.

“Coming here I've recognized how im portant for some students just having that visual connection, be it that I’m a woman, be it that I'm Black, makes them per haps be more approachable to me. So yes, I always welcome students to my office if they want to talk about anything. My door is open. It’s an open-door policy.”

Maahla Fofack grew up in a family of doctors. Her mother is one, her aunt is one, so is her other aunt and don’t for get about the other, other aunt. In terms of visibility, Fofack believes she has it based on gender. Most of the STEM teachers and professors she has had since high school have been women. But out side of her family, the number of Black

women she sees in these positions is hard to come by.

“When you are the only one in a space, it’s very clear,” says Fofack. “Obvious ly you are going to feel like the one who doesn’t belong.”

When professors like Lowman, or in Fofack’s case, Dr. Diana Arnett of the bi ology department or Dr. David Wren of the chemistry department make this em phasis, it goes noticed.

“All your professors want you to do well, but when you approach them about it, and they're extremely reciprocal. Like, you can tell that they're honest in their intentions and their presentations, and in their responses to me. That just warms my heart,” says Fofack.

“When you are the only one in a space, it’s very clear.”

Photography Katie Fox Dr. Lauren Lowman pic tured in front of Reynolda Hall

Photography Katie Fox Dr. Lauren Lowman pic tured in front of Reynolda Hall

Alexchandra Labady is also un sure if the campus has become more accepting or welcoming over her four years here because she is in her own lane. She quickly dis covered how worrying about ev eryone else was leading her down the road to a quick burnout.

It took a talk with Dr. Nate French, Labady’s advisor, for her to recognize that comparing time lines and forgetting about differ ent starting points or advantages would cause the soon-to-be soph omore to overwork herself.

Now a senior, the hyper-com petitive STEM classes still stress her out, but much less so. It often takes a while for her classmates to acknowledge Labady’s abilities, but she has become more comfort able advocating for herself and her brain.

Because she is focused on her own goal of going to medical school, it is hard for her to say if the right university and department efforts are being made to increase inclusion, but that doesn’t stop La bady from advocating for it herself. She offers guidance and advice to Jeancharles, who she knew in high school, about what the sophomore can do to navigate being Black in a PWI’s STEM classes.

Chi Nwakuche hasn’t always been at a PWI. Nwakuche’s strug gles with mental health forced her to put academics on the back burn er, and in doing so she was placed on academic suspension. Instead of stopping, she was determined to push forward and keep learning. She withdrew from Wake Forest and enrolled at Winston-Salem State, an HBCU, for the 2021-22 academic year.

Before the switch, Nwakuche had never been taught computer science by a Black professor. At WSSU, the majority of her profes sors were Black, as well as multiple female faculty members. Now back at Wake Forest, Nwakuche is the only person of her complexion in the department.

She’s cognizant of it, but she tries not to let it define her. Otherwise, days would become very exhausting.

“I used to feel like I needed to prove something to someone. I used to feel like I could only speak if I had something extremely intelligent to say. I used to feel like I wanted to be accepted and fit in. And I think now I feel more accepted because I refuse to be unaccepted. I refuse to be ignored. I don't care to fit in. I don't care to assimilate. I am who I am. That's just how I go.”

As a computer science major, Nwakuche is a big fan of data. Especially when she can use numbers to help the way people think about systemic is sues revolving around race. While in high school, she created a model that analyzed national incarceration rates using census data. Proving racism to white people is one of the things that makes her feel important and is a big joy in her STEM career.

“I can change how you think. And maybe I can change how you talk to your friends and talk to their friends and maybe change how you vote. And maybe if you educate enough people, maybe we can make a ripple effect and change some things, change the waters, change people's lives.”

No one enjoys the feelings of dis comfort, the feelings of isolation, the backhanded remarks, the overt ly racist phrases, the preconceived notions of doubt, the lack of com munity, the list could go on. Joy Oguama, Sheevanie Casimir, Sabrina Jeancharles, Dr. Lau ren Lowman, Maahla Fofack, Alex Labady, Chi Nwakuche, and every other Black woman on Wake Forest’s campus — regardless of major — don’t enjoy it either.

They have done everything they can to ignore, deflect, look past, and push forward. They all hope that future classes will not have to endure what they did, but from what they have heard from un derclassmen still, that hope seems unsure. One person can only do so much to achieve that hope.

Wake Forest Demographic Statistics courtesy of the Office of Institutional Research

All other national or institutional demographics courtesy of National Center of Education Statistics and Pew Research

Photography Katie Fox

Photography Katie Fox

Photography Katie Fox

Photography Selinna Tran Adam Coil (‘25) and Na thaniel Holiday pictured in front of Holiday’s car

Photography Selinna Tran Adam Coil (‘25) and Na thaniel Holiday pictured in front of Holiday’s car

Photography Kevin Yu

Photography Kevin Yu

Photography Katie Fox, Finnegan Siemion pictured at Design Archives in downtown Winston-Salem.

Photography Katie Fox, Finnegan Siemion pictured at Design Archives in downtown Winston-Salem.

Adam Coil (‘25)

Adam Coil (‘25)

By Prarthna Batra (‘26)

By Prarthna Batra (‘26)

By Prarthna Batra (‘26)

Read Clayton’s full story on the website

By Prarthna Batra (‘26)

Read Clayton’s full story on the website

By Cooper Sullivan (‘24)

By Cooper Sullivan (‘24)

Photography Katie Fox Dr. Lauren Lowman pic tured in front of Reynolda Hall

Photography Katie Fox Dr. Lauren Lowman pic tured in front of Reynolda Hall

Photography Katie Fox

Photography Katie Fox

Photography Selinna Tran Adam Coil (‘25) and Na thaniel Holiday pictured in front of Holiday’s car

Photography Selinna Tran Adam Coil (‘25) and Na thaniel Holiday pictured in front of Holiday’s car