The Oklahoma Historical Society

The Oklahoma Historical Society (OHS) is a private membership organization and state agency. The mission of the OHS is to collect, preserve, and share the history and culture of the state of Oklahoma and its people. Organized in 1893 by a group of territorial journalists, it has developed into one of the nation’s largest and most innovative historical agencies. Today the OHS operates museums and historic sites; publishes a historical journal, newsletter, electronic publications, books, and brochures; encourages and assists with historic preservation; and maintains several renowned research libraries.

The Chronicles of Oklahoma, published quarterly by the OHS, is distributed to subscribers and all OHS members. Each issue contains historical articles, photographs and illustrations, book reviews, notes and documents relative to the preservation of our history, and OHS Board of Directors meeting minutes.

Membership

Membership in the OHS is open to anyone who wants to share the excitement and wonder of state and local history. Annual dues are Basic $40, Family $75, Friend $100, Associate $250, Fellow $500, Director’s Circle $1,000, Partner $2,500, and Benefactor $5,000. Membership includes a subscription to The Chronicles; Mistletoe Leaves, the OHS bimonthly newsletter; and EXTRA!, the OHS email newsletter; as well as other benefits.

Membership applications and subscriptions should be mailed to: Membership Coordinator, Oklahoma Historical Society, 800 Nazih Zuhdi Drive, Oklahoma City, OK 73105-7917. Memberships also can be purchased online at okhistory.org/join.

Single copies of The Chronicles cost $7 each plus shipping (and tax for Oklahoma residents). Single copies may be ordered by calling 405-522-5214 or emailing museumstore@history. ok.gov.

Reprints

Requests to reprint copyrighted material from The Chronicles of Oklahoma must be submitted in writing to the editor. In some cases, permission also must be obtained from the author of the article for which the reprint is requested.

This publication, printed by Southwestern Stationary and Bank Supply, Inc., is issued by the Oklahoma Historical Society as authorized by Section 19, Title 53, O.S. A total of 2,800 copies have been printed at a cost of $8,645. Copies have been deposited with the Publications Clearinghouse of the Oklahoma Department of Libraries.

The Chronicles of Oklahoma (ISSN 0009-6024) is published quarterly by the Oklahoma Historical Society, 800 Nazih Zuhdi Drive, Oklahoma City, OK 73105-7917. Periodicals postage paid at Oklahoma City, OK.

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to The Chronicles of Oklahoma, 800 Nazih Zuhdi Drive, Oklahoma City, OK 73105-7917.

Responsibility for statements of facts or opinions made by contributors in The Chronicles of Oklahoma is not assumed by the Oklahoma Historical Society.

Copyright 2025, Oklahoma Historical Society

Editor: Anna L. Davis

Volume CIII Number 3 Fall 2025

Contents

An Improbable Story: The History of the Oklahoma History Center

BY BOB L. BLACKBURN

On November 16, 2005, the Oklahoma History Center officially opened its doors to the public. The opening marked a long journey of collaboration between state officials and workers at the Oklahoma Historical Society, with many highs and lows. Blackburn reflects on the history of building a new home for Oklahoma’s history on the twentieth anniversary of the building and the people that played a role in bringing the plan to life.

248

“Let My People Have a Right:” The Native Activism of Arapaho Chief Paul Boynton

BY CHRISTIANNA STAVROUDIS

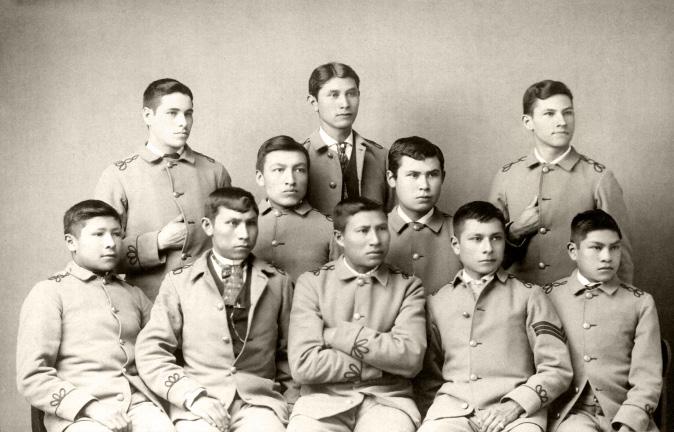

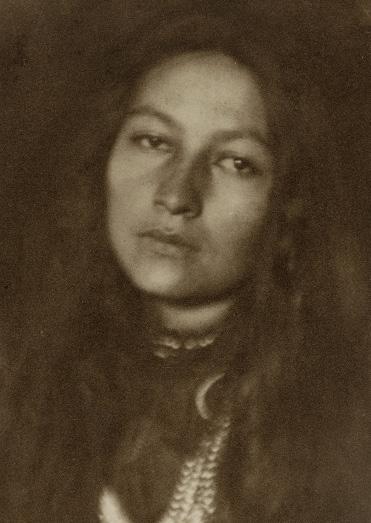

In the early twentieth century, various Native American leaders championed the use of peyote as their right to the US government. One of the most vocal proponants of peyote was Paul Boynton, an Arapaho chief and alumni of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School. Boynton championed the use of peyote for all tribal members and strove to show that Native Americans were capable of handling their own affairs. Stavroudis worked with Boynton’s descendents to bring new research about his life and work to light.

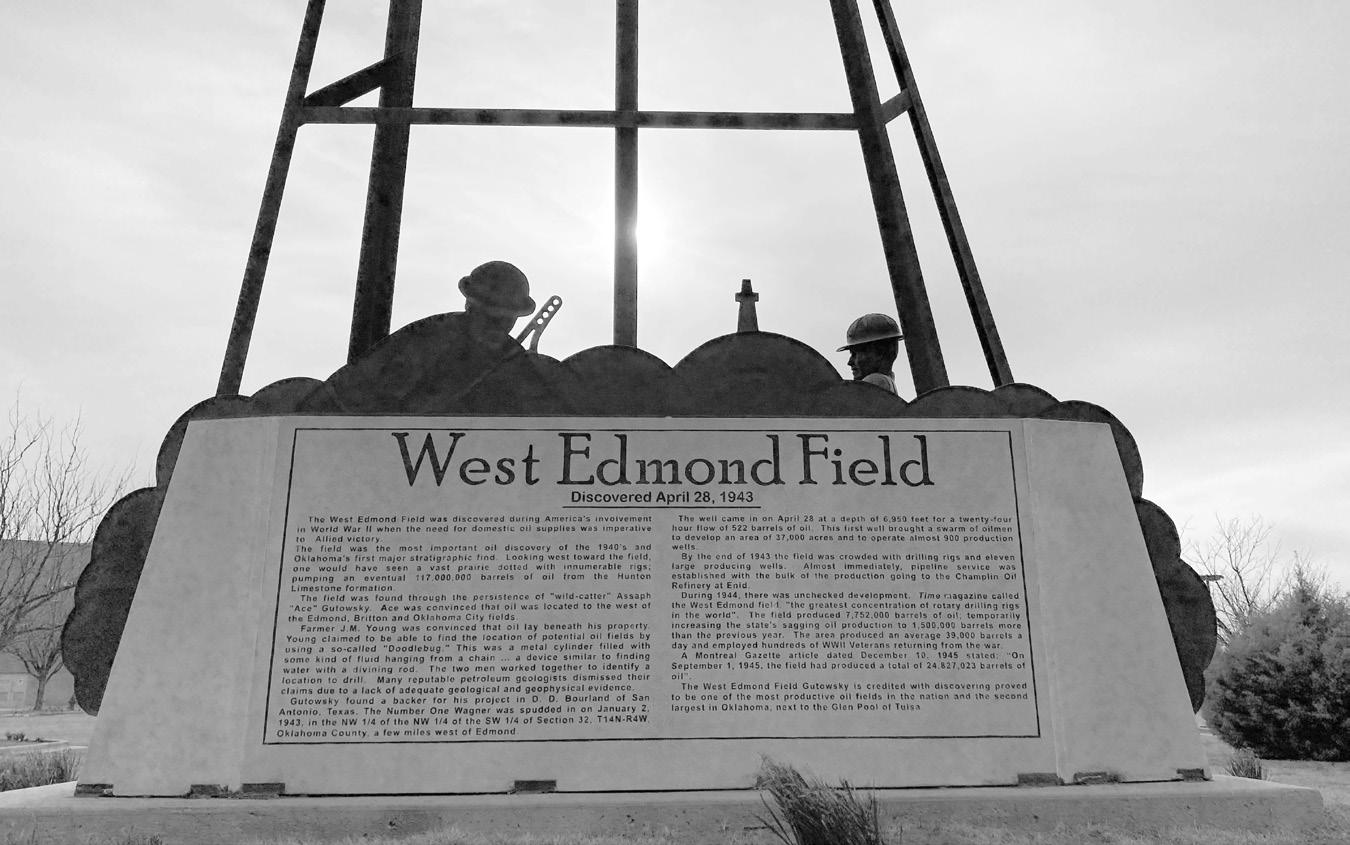

Wildcatter “Ace” Gutowsky Strikes Oil West of Edmond

BY LARRY C. FLOYD

291

During World War II, the West Edmond Oil Field became one of the largest producers of oil in the United States’ war effort. With a war being waged by tank and by air, oil became an urgent commodity. The discovery of oil came at the hands of Assaph “Ace” Gutowsky, a Ukrainian emigrant, who had long believed that the Oklahoma oil industry would be revitalized if drilling happened in Canadian County. Floyd recounts the exploits of the famed wildcatter and his controversial doodlebugging that helped the United States win the war.

319

Volume CIII Fall 2025

Beck, David R. M., Bribed With Our Own Money: Federal Abuse of American Indians Funds in the Termination Era, reviewed by Joshua Clough

Maraniss, David, Path Lit By Lightning: The Life of Jim Thorpe, reviewed by Matthew Pearce

Nagle, Rebecca, By the Fire We Carry: The Generations-Long Fight for Justice on Native Land, reviewed by Grace Ellis

For the Record

Minutes of the OHS Quarterly Board Meeting, May 2, 2025

345

Minutes of the OHS Board of Directors Meeting of the Membership, May 3, 2025

Minutes of the OHS Board of Directors Organizational Meeting, May 3, 2025

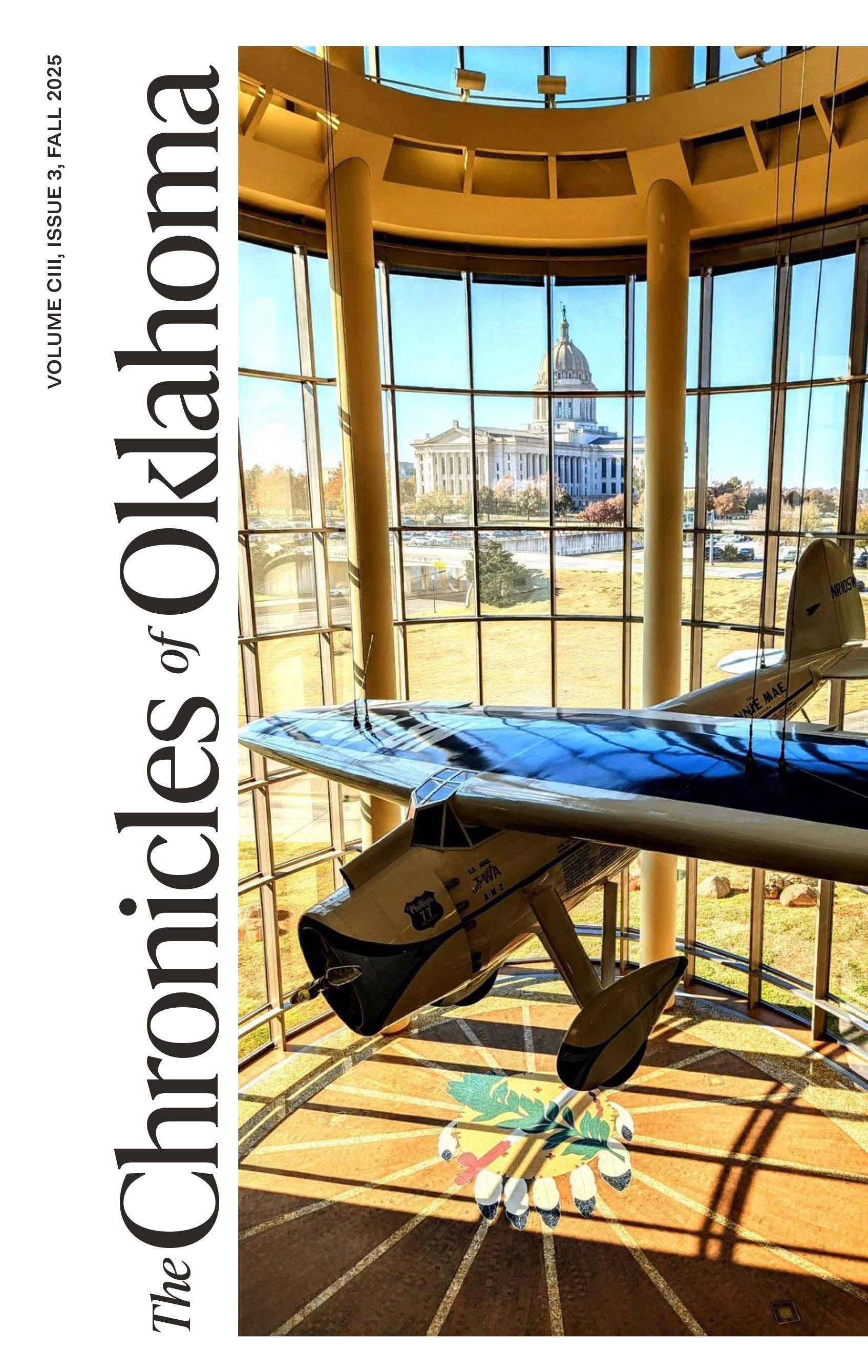

The Winnie Mae in the Devon Great Hall (image taken by Trait Thompson).

An Improbable Story: The History of the Oklahoma History Center

By Dr. Bob L. Blackburn*

Twenty years ago, on November 16, 2005, the doors of the Oklahoma History Center opened with a grand ceremony. For most people, it was a day to celebrate and look ahead to years of an improved ability to collect, preserve, and share Oklahoma history. For some of us, it was a day to look back on the twists and turns, the successes and setbacks that led to that celebrated day. This is a short history of that improbable story.

I use the word improbable because in 1997, when this story begins, no one would have expected a young conservative state with a small population and low tax base to build a $62 million, 215,000-squarefoot museum and archival masterpiece that would achieve status as both an affiliate of the Smithsonian and an affiliate of the National Archives. As with many turning points that make Oklahoma history so

fascinating, the only way to understand the story is to interweave opportunities seized and challenges overcome.1

The key to seizing opportunities is to be prepared, and we were in 1997 after a decade of raising standards, launching new projects, and assembling a leadership team that included members of the Oklahoma Historical Society (OHS) Board of Directors, staff, and volunteers who shared a passion for Oklahoma history. Leading the charge was J. Blake Wade, a retired US Army officer from Lawton who became OHS executive director in 1989. Blake brought to the table a take-charge personality, a problem-solving grasp of politics, and a willingness to share authority, which he did when he asked me to be his deputy executive director as a partner. I brought to the table my PhD as a published historian, my passion for historical collections, and a deep understanding of OHS institutional history dating to our founding by the Oklahoma Press Association in 1893. At our sides were empowered leaders on the staff, including Melvena Heisch in historic preservation, Kathy Dickson and Dr. Bill Lees in museums and sites, Sandy Stratton in special projects, Whit Edwards in living history, Bill Welge in research, Georgianna Rymer in administration, and Billy Nichols in finance. To use a sports cliché, we had a deep bench.2

For decades, OHS leaders had asked for better space to store collections and share Oklahoma’s story with the public through modern exhibits and enhanced research. The Wiley Post Historical Building, completed in 1930, was a beautiful neoclassical icon across from the State Capitol, but its casement windows, small galleries, light wells, temperamental heat, and humidity controls made it an ancient relic that had long outlived its purpose. Attempts to build an addition on the east side of the building failed first in 1982 and again in 1992. History would prove both failures providential.

As the OHS leadership team built credibility with constituents, legislators, reporters, and leaders in both the business and philanthropic communities, the planets aligned to open a new door of opportunity. Supreme Court Justice Yvonne Kauger, the godmother of the Sovereignty Symposium, Red Earth, and other historical ventures, cast her eyes on the OHS building as a perfect place to house the Oklahoma Supreme Court. A similar transformation had already been accomplished in Minnesota, where the state historical society received legislative funds to build a new museum and research center, and the

THE CHRONICLES OF OKLAHOMA

The Wiley Post Historical Building, completed in 1930 as the headquarters of the Oklahoma Historical Society, was designed with casement windows and light wells for air flow during summers and steam boilers and radiators for heat during winters. Although a beautiful neoclassical structure with marble floors and WPA murals, the building no longer served the needs of a modern research and museum organization by the 1980s. (22055.13305, Ray Jacoby Collection, OHS).

Supreme Court Judge Yvonne Kauger was an early champion for a new OHS museum and research center, in part to improve efforts to collect, preserve, and share history, but also to retrofit the Wiley Post Historical Building for the expanding appellate court system. (2012.201.B0323.0092, Oklahoma Publishing Company Photography Collection, OHS).

OKLAHOMA HISTORY CENTER

courts renovated and moved into their former historical society building. Justice Kauger’s vision got the ball rolling when she earned the support of Senate Pro Tem Stratton Taylor, a master dealmaker from Claremore, Oklahoma.

Adding momentum for a capital investment deal was Senate Appropriations Chairman Kelly Haney, a Seminole artist and tribal leader who wanted state support for what eventually would be named the First Americans Museum. According to Blake and Justice Kauger, Senator Haney believed his best chance to get a new Native American museum was to link it with a new building for the OHS. In the Oklahoma House of Representatives, which typically opposed anything originating in the Oklahoma Senate, support came from Speaker Lloyd Benson and Appropriations Chairman Jim Hamilton, who wanted state funding to acquire land north of the State Capitol to construct office buildings for state agencies, then leasing space elsewhere in Oklahoma City.

Rounding out the capital investment cheering section was Governor Frank Keating, a self-described history buff who told me when we first met in 1995 that he had spent most weekends while in Washington, DC, visiting museums and historic sites. Governor Keating also wanted a dome for the Capitol and a mini-urban renewal program around Lincoln Boulevard and Northeast Twenty-Third Street. The governor’s right-hand man working on a package to do all the above was Secretary of State Tom Cole, a historian with a PhD and a friend of mine since graduate school days.

Fortunately for our ambitions, state revenues exceeded expectations in 1997, so the legislature passed Senate Bill 175, creating a capital improvements revolving fund with $2 million for planning, land acquisition, and architectural concepts. Senator Haney was named chairman of the Long Range Capital Improvement Authority.3 When the Authority granted $200,000 to the OHS, Blake asked me and my right-hand partner, Sandy Stratton, to develop a plan for a new history center using the best consultants. On October 22, 1997, the OHS Board of Directors approved a plan to hire local architectural firm Glover-Smith-Bode to help us conduct a comprehensive national study to assess best practices, space needs, possible locations, costs, and themes for a new museum and research center.4

The planning process started with staff members. At the time, the State Historic Preservation Office was located in leased space in the

251

THE CHRONICLES OF OKLAHOMA

old Shepherd Mall. Melvena outlined a plan to bring staff, working files, and archival collections back into an OHS headquarters building. Working with the shorthanded staff in the State Museum, Sandy calculated space needed for exhibits, collections, and office space for an expanded staff. I worked with Bill Welge in the Indian Archives and Connie Shoemaker in the Library and Newspaper Room to anticipate storage needs for growing collections, more microfilm readers, and the onrushing transition to digital preservation and access.

While staff members worked on divisional plans, I drafted concepts for museum exhibits, and Sandy and the consultants reached out to constituents to determine top priorities. Focus group meetings included educators, journalists, family historians, and elected officials. We conducted a telephone survey of five hundred families, two hundred in the Oklahoma City metropolitan area and three hundred across the state, including Tulsa. As we gathered data, we presented suggestions to the various committees of the OHS Board of Directors. We followed with field trips for board members to trend-setting museums and libraries across the country, including the Atlanta Heritage Center, the Minnesota Historical Society, and the South Carolina State Archives. Each trip, each meeting with administrators, historians, educators, and archivists who had gone through a similar planning process, helped us focus on what might work best in Oklahoma.5

In February of 1998, just as the legislative session began, we released details of the plan at a press conference in a cramped gallery of the old Historical Building that clearly illustrated the need for more and better space. OHS Board president Dr. Marvin Kroeker, a history professor at East Central Oklahoma State University, described the importance of collections and ended with a call for action. “We will need the support of all Oklahomans if we are to be successful,” he said. “Saving our priceless heritage is too important for us not to.” Blake added that we were gaining support at the State Capitol. “We represent all seventyseven counties in the state,” he said, “and I believe we’re going to get a lot of support from legislators and Governor Keating.”6

With Marvin and Blake at my side, I presented a summary of the plan contained in two volumes filled with details. We needed approximately two-hundred-thousand square feet of space, at least eight acres of land for parking, and a bond issue for funding if we wanted to open the new facility by the centennial of statehood. I then provided

details, such as the need for eighty microfilm readers, two classrooms, forty thousand square-feet of collections storage, and museum exhibits that spanned all themes of Oklahoma history with an emphasis on Oklahomans at war, free enterprise, farm and ranch, the struggle for civil rights, American Indians, and cultural icons. The anticipated cost would be $46 million in state funding for the land, building, and environmental systems, with another $10 million in privately raised funds for museum exhibits and artwork. One reporter noted in her column that I repeatedly used terms and phrases such as “emotional connections” and “individual stories” to describe themes and “alive” and “dynamic” to describe design. That same reporter noted that I added a cautionary warning, “The OHS plan is an ambitious one.”7

It was ambitious, considering the political obstacles ahead of us. As we had learned many times over the preceding decades, political dealmaking behind closed doors can go in any direction with unanticipated surprises. For example, in 1992, on a Wednesday night during the last week of the legislative session, the OHS was on a list to get $10 million for an addition to the east side of the Historical Building. The next morning, that money was split between the University of Oklahoma and Oklahoma State University. With political factions fighting for their own priorities, final deals rarely end where they begin.

As the 1998 legislative session got underway, our team hit the speakers’ trail, sharing the story of what we needed and why. Blake continued his dialogue with Justice Kauger, a bulldog armed with homemade cookies on a quest to get our building, and Senator Haney, determined to get initial funding for his Native American museum. I spent many hours in the office of Secretary of State Tom Cole, a sympathetic supporter and close ally of Governor Keating, who had a seat at the table as negotiations advanced on several issues, including a possible bond issue.

I also roamed the legislative halls, where I had come to know many representatives and senators, as I sought funding for OHS field sites and museums and special projects in their districts. On the last day of the legislative session, a bill authorizing the sale of $320 million in revenue bonds passed the House and Senate, soon to be signed by Governor Keating. In it was $32 million for a new History Center. Although it was less than we needed, Senator Haney and Governor Keating pledged to do their best to get more funding during the next legislative session.8

THE CHRONICLES OF OKLAHOMA

Bond funds triggered a number of initiatives we had anticipated. Knowing we needed to raise millions in private funding, I recruited friends to create a 501(c)3 nonprofit support group that could accept and spend donations. I wanted the foundation not so much to raise money, but to convince people in the business and philanthropic communities that we had their peers on our team. On April 30, 1998, I met with Cliff Hudson, CEO and chairman of the board for Sonic: America’s Drive-in, and asked him to be the founding president. He agreed. Then I called on other friends, such as Charles Wiggin, a real estate developer; John Yoeckel, an oil and gas entrepreneur; and Jay Hannah, a banker and chairman of the Cherokee Constitutional Convention. The list initially grew to more than a dozen community leaders across the state.

The most critical decisions before us were where to build the History Center and who to design it. The plan approved by the OHS Board of Directors included three possible sites: one adjacent to the Harn Homestead on Lincoln Boulevard, a site near Lake Arcadia on I-35 offered by the City of Edmond, and land along the banks of the North Canadian River near the intersection of I-35 and I-40 offered by the city of Oklahoma City. After the bond issue was approved, the OHS Board of Directors added a fourth option, an eighteen-acre site on the northeast corner of Northeast Twenty-Third and Lincoln Boulevard across the street from the Governor’s Mansion. After Sandy and I presented a detailed analysis of each site with advantages and disadvantages, the OHS Board of Directors unanimously selected the site closest to the State Capitol across the street from the Governor’s Mansion.9

Selection of architects was a more complicated task dictated by a statutory selection process managed by the Construction and Properties Division of the Oklahoma Department of Central Services, a separate state agency. Blake, Sandy, and I wanted a competition, which had never been done under state law. When I explained the reasons to Robert Thomas, director of Construction and Properties, he called in his agency’s attorney, and they found a way to make a competition possible.

The OHS Board of Directors interviewed seven teams and selected three finalists to submit conceptual designs. Because we wanted to own rights to any part of the proposed designs that might be useful, we offered $35,000 stipends to each firm and gave them eight weeks to come back with a conceptual design and model. The winning team,

OKLAHOMA

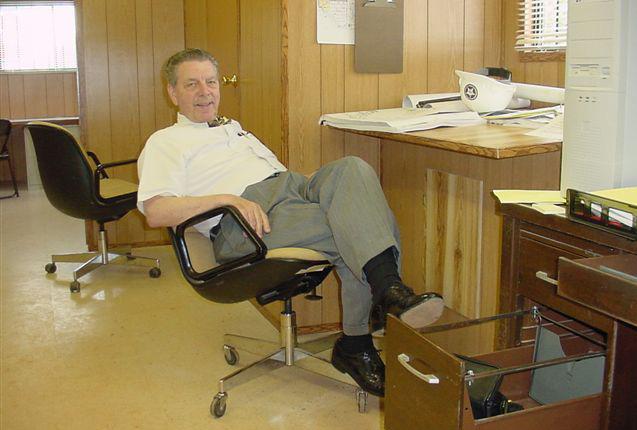

Among the many recruits who helped design, construct, and occupy the new Oklahoma History Center were Bill Moore (above), who expanded the film collection, produced many of the videos featured in the museum, and served as a “glue guy” in the words of Bob Blackburn, and Robert Thomas (below), the OHS deputy director who applied his architectural skills to making sure the “once in a lifetime” project was successful. (photos provided by the Oklahoma Historical Society Research Division).

THE CHRONICLES OF OKLAHOMA

selected by a blue ribbon panel and approved by the OHS Board of Directors, was a partnership between Beck Associates, an experienced library design firm based in Oklahoma City, and HOK, an international firm led by Gyo Obata, who had designed the Smithsonian’s Air and Space Museum; the Lincoln Memorial in Springfield, Illinois; the Missouri Historical Society in St. Louis; and the Museum of Science and Technology in Chicago.10

Blake and I knew we needed a proven leader who could work daily with the architects and exhibit consultants while we concentrated on getting a second bond issue, raising private funds, bringing in new collections, and launching additional projects that had to be ready by the time we opened the History Center to the public. From a strong field of candidates, we selected Dan Provo, who brought seventeen years of experience in museum design, construction, and management. An additional asset was his commitment to education and telling every part of the story. “We’re going to look into everything that went into the development of Oklahoma,” he told one reporter, “the good things and things that are more difficult . . . We can’t ignore any part of the picture.”11

With pieces of the planning puzzle dropping into place, Blake announced he was taking on a new challenge as director of the recently created Oklahoma Centennial Celebration Commission. As he expected, the OHS Board of Directors selected me to take his place and push the History Center to the finish line. I gladly accepted. On August 1, 1999, I became executive director of the Oklahoma Historical Society, the public/private organization I had served since 1979.

The smooth transition was fortunate because we had to make a critical decision before we signed contracts with the architects. When we received the $32 million bond issue on the last day of the 1998 legislative session, Governor Keating and Senator Haney reassured us they would help get us the other $14 million to pay for the History Center as conceptualized by Don Beck and Gyo Obata. True to his word, the governor asked for the money in his executive budget in 1999, but the legislature did not act on it. When the last gavel ended the session in May, we were still $14 million short.

On November 11, 1999, after a few months of considering options with our team, I drove to Frederick to confer with Speaker of the House Benson. He confided that there would not be any more funding.

One of the first historians hired by Bob Blackburn was Bruce Fisher, who opened many doors to underserved communities throughout the state as planners tried to represent all themes and geographical sectors in the new research and museum facility. (photo provided by the Oklahoma Historical Society Research Division).

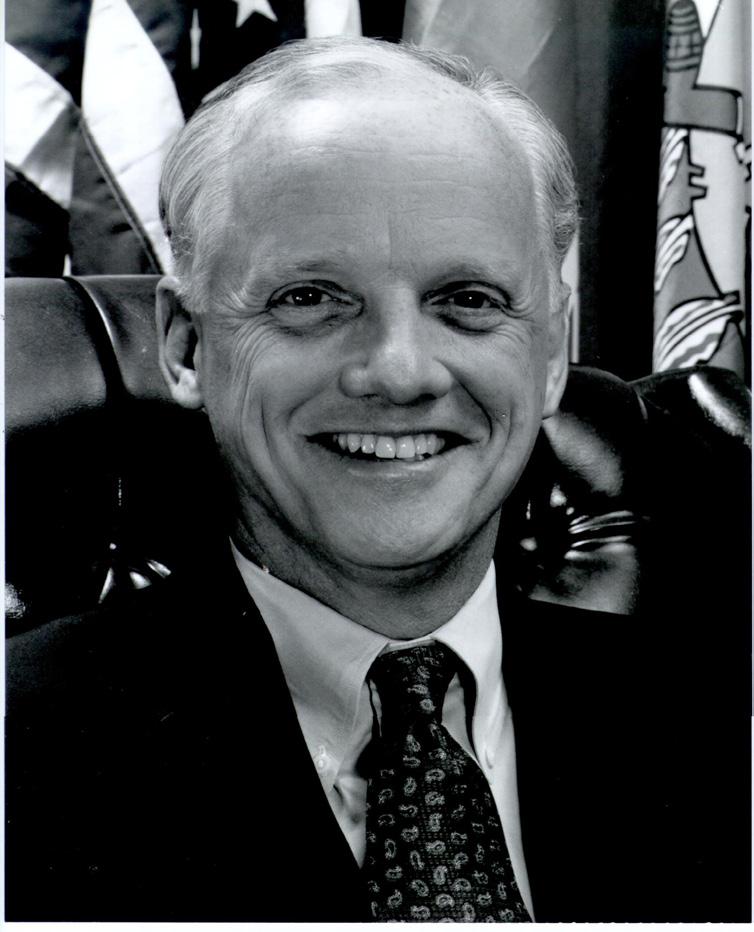

Governor Frank Keating introduced himself to Bob Blackburn as a “history buff” who wanted a first class History Center that would rival any museum and research center in the fifty states. (21596, Oklahoma Historical Society Photograph Collection, OHS).

THE CHRONICLES OF OKLAHOMA

His advice was to scale down the size and build something with $32 million. Although I did not like the message, I appreciated his honesty when it would have been easy for him to string me along. He was and is an honorable public servant.

I talked to Governor Keating about what to do. With his naturally positive enthusiasm and love of history, he said go for the full package with Smithsonian-sized ambitions. He said he still had two more years to help get us the money. I briefed the full OHS Board of Directors, shared with them my meetings with the speaker and governor, and told them I recommended that we stay on course, start planning for a $46 million construction budget, and split the project into two phases, the first to get an enclosed building for less than $30 million and a second to finish the interior. Board members asked questions, discussed the issue, and made a bold decision. We would not compromise and reduce the size or cost of the History Center. Without knowing what was over the next hill, we charged ahead.

Our decision to take a chance was based partly on the expanded leadership team we had assembled by that time. With Dan Provo and Sandy Stratton already on board, we needed a deputy director with complementary skills for a once-in-a-lifetime construction project. We needed someone who could stand toe-to-toe with architects,

258

Former Governor and US Senator Henry Bellmon (left), standing in front of educators Bruce Fisher (center) and Whit Edwards (right), spoke at one of the many dedication ceremonies for the Oklahoma History Center. After his death, Governor Bellmon’s family donated his collections to the OHS. (photo provided by the Oklahoma Historical Society Research Division).

engineers, and construction supervisors as they turned our dreams into reality. I wanted someone who knew the state system of consultant selection and contracts and had enough self-confidence and creativity to get things done without blaming bureaucratic red tape for lack of action. I chose Robert Thomas, an experienced architect who had led his own firm before taking the job as director of Construction and Properties for the state. He agreed to accept my offer after a luncheon meeting at the Faculty House on July 9, 1999.

We also needed specialists with experience and connections in their professions. Bill Moore, a film and video producer who had made a series of historical documentaries while working full-time at the Oklahoma Department of Transportation, came onto the team and proved to be what I call a “glue guy,” a person who brings divergent opinions together and finds a way to finish complex projects. I recruited Bruce Fisher, a historian and son of Ada Lois Sipuel Fisher, the civil rights icon who had broken segregation in Oklahoma higher education. Bruce was respected in the African American community and anxious to bring in collections and content specialists. Others rising to the challenge from the existing staff included Laura Martin and Chad Williams in the library and archives, Jeff Briley and Mike Atkins in the State Museum, Max Nichols in public relations, and Terry Howard in finance. With Sandy, Dan, and Robert as corps commanders, we moved out like an army on the march.12

In keeping with the military metaphor, the OHS Board of Directors played the role of civilian control of all action on the battlefield. Throughout the planning and development phases, we reported monthly to the OHS Executive Committee and quarterly to the full board of twenty-five members. Typically, the senior team and I described what had happened, explained where we were in the process, and sought advice and approval about moving forward. The constant interaction with board members not only gave our team a chance to assess progress across divisional lines every month but also tapped into the combined experience and wisdom of board members from across the state. A complete list of the board members from 1997 to 2005 is included in the endnotes.13

Reading the minutes of those meetings reminds me that the History Center was not the only major project needing our attention and resources from 1999 to 2005. Anticipating increased funding rising from

THE CHRONICLES OF OKLAHOMA

Manhattan Construction Company, the oldest corporation in state history, began excavation for the History Center in 2000. Among the many challenges faced during construction was the discovery of several uncapped oil wells. In the image above, notice the scaffolding around the new Capitol Dome then under construction. (photos provided by the Oklahoma Historical Society Research Division).

the enthusiasm for the upcoming state centennial, we spent an entire year assembling master plans for each of our thirty-two museums and historic sites, which required my attendance at community meetings and constant interaction with Kathy Dickson, Bill Lees, and Whit Edwards. We jumped at the opportunity to investigate, raise money, and recover remnants of the steamboat Heroine at an underwater archeological site where it sank in the Red River in 1838. With a federal grant, we started work on a new road, a bridge over Elk Creek, trails, and interpretive markers within the Honey Springs Battlefield.

Tapping the creativity of Dr. Dianna Everett, we launched a multiyear effort to research, write, and publish The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. We managed the Tulsa Race Riot Commission, with me as chairman and Larry O’Dell as my right-hand man, coordinating a steady stream of special projects legislators funded with additional appropriations. A few of the most time consuming were Hackberry Flats Interpretive Center, a lease to develop a new museum complex in Frederick, and plans for a museum in Grove dedicated to my childhood hero, Mickey Mantle. Then there was the full cycle of legislative hearings, budget preparations, and the lecture circuit where I was giving eighty to ninety speeches a year. It took time and energy folded into the daily tasks needed to keep the OHS running smoothly.14

The pace quickened after a groundbreaking ceremony on Statehood Day, November 16, 1999. Looking back on that ceremony filled with big band music, historians in period clothing, and speakers, perhaps the most important words were delivered by Mennonite minister and Cheyenne Peace Chief Lawrence Hart, who solemnly blessed the occasion. We needed the help. That month we added to the list of History Center deadlines when we were notified we had won a $588,000 federal grant through the Oklahoma Department of Transportation to build what we called The Red River Journey, an outdoor landscaped interpretive park that spanned two blocks north of the Governor’s Mansion.15 The project not only added to the list of deadlines we had to meet, but also required more fundraising to meet a twenty percent match.

By April of 2000, while Sandy planned a series of fundraising events across the state, Robert reported that the architects had completed the schematic design. Dan announced that he had moved his growing

THE CHRONICLES OF OKLAHOMA

museum staff of twelve people into a former bowling alley on North Lincoln Boulevard. The successful search for a museum exhibit design firm was announced that same month. The new partner was Haley-Sharpe Design, Inc., a British firm that had recently entered the Canadian and United States markets. The previous year, they had competed for four projects in North America, and won all of them. The creative director assigned to the History Center was Alisdair Hinshelwood, a gifted designer and strategist who was destined to be an important part of the OHS’s future for more than two decades by assisting with master plans for the Will Rogers Memorial Museum and the Oklahoma Museum of Popular Culture in Tulsa. In many ways, he became our team’s mentor in exhibit design.16

For the next six months, after an initial weeklong brainstorming session with senior staff, Alisdair and his associates communicated with Dan’s team through emails and conference calls to build on themes approved by the OHS Board of Directors. As they narrowed the focus to thirty-seven exhibit components in four large galleries, they worked on adjacencies based on subject matter and design elements. For consistency, Alisdair suggested a text panel template with a title, main message, secondary story, and tertiary additions such as photographs, captions, and sidebars. As the process progressed, Dan assigned each exhibit component to a staff member who would serve as lead curator. Even though I was busy with administrative duties, I asked to be the lead curator for four topics. In my mind, I was still a historian and anxious to learn a new skill.

While Dan’s and Alisdair’s teams focused on exhibits, the architects worked on construction documents, adding details to the conceptual design. As conceived by Don Beck and Gyo Obata, the History Center consisted of four separate structures, each with its own specific characteristics under one roof, connected by public spaces, an auditorium, and a grand atrium. The northwest three-story structure was for OHS staff with offices, board room, meeting spaces, and classrooms. The northeast three-story structure was for the library and archives, with the reading room on the ground floor and collections and staff offices above.

Facing the southwest were two two-story structures for museum galleries, connected to the other structures by a grand atrium topped by a dome, a flat-floor auditorium seating 240 people at eight-person

262

OKLAHOMA HISTORY CENTER

tables, a cafe, a second-floor bridge, and floor-to-ceiling hallways flooded with natural light during the day. Both ends of the hallway were enclosed by glass curtain walls, and the atrium featured a semicircular glass wall framing a view of the State Capitol, which we called Artifact Number One. Underneath most of the building was a thirty-foot-deep basement for collections, workspace, and mechanical equipment.

A challenge for the architects creating detailed construction documents was the overall footprint of the History Center. As they often commented, there was not a straight line anywhere. The two museum galleries were curved like arms embracing the State Capitol. The research and staff wings were also curved, but in a lazy S-shape configuration that anticipated future expansion. The exterior facade facing the Capitol featured neoclassical columns with backlit onyx curtain walls that radiated a warm golden hue at night. The rest of the building was clad with precast stone panels punctuated by bands of windows, giving the north facade strong horizontal lines with a main entryway distinguished by a covered portico off a circular drive.

Bridging the gap between form and function was more than just an architectural challenge; it was a communication challenge between us on the OHS staff, who knew what we wanted, and Beck Associates and HOK, who worked with architects and engineers to translate that

The architectural team of HOK and Beck Associates designed an S-shaped building that consisted of four large museum galleries on either side of a domed atrium (top of the structure), a wing for research collections (left), and a wing for a variety of meeting spaces, classrooms, and offices (right). (photo provided by the Oklahoma Historical Society Research Division).

THE CHRONICLES OF OKLAHOMA

into lines, shapes, and lists of materials. Fortunately, we had Deputy Director Robert Thomas as an intermediary who sat in all our planning meetings, knew the language of architecture and engineering, and had the courage to use his red pen for corrections and changes. With that advantage, Richard Ford on Beck’s staff met his construction document deadlines of thirty percent in October of 2000, sixty percent in January of 2001, and completion in May of 2001. The next step was getting the plans distributed that summer to solicit construction bids.17

Eight firms bid for the high-profile project, but the lowest and best came from Manhattan Construction Company, a family-owned firm that had started in Chandler in 1896 and moved to Muskogee where it became the first corporation to file papers with the new state in 1907. When Manhattan became our partners, Francis Rooney had his headquarters in Tulsa and offices in various cities across the west and south. Fortunately for us, John Jamison, a Manhattan project manager already working on the Capitol Dome, was named supervisor of History Center construction. His team started with demolition of the remaining homes on the site and started excavating the basement. By January of 2002, they had already hauled off six hundred truckloads of dirt and the big hole in the ground was only forty percent complete.18

Construction kept everyone on their toes. Robert hired experienced architect Jerry McKinney to be our eyes and ears on the ground at the site with our own trailer where we could hang our OHS hard hats. When there were questions or surprises, Robert was only a five-minute drive away, so he was a frequent visitor at least twice a day engaged in finding solutions. He made most decisions working with Beck’s and HOK’s team, but a few he kicked upstairs to me. I will never forget the day he came to my office and said excavators had found two oil wells that had never been capped. What should they do? I called the Corporation Commission and found out they could do nothing to help. I called the Oklahoma Energy Resources Board, and they said they could not do remediation on state land. When Robert told me it would cost $20,000 apiece to cap, I said do it. We would find the money later.

Manhattan proved to be an excellent partner. They kept the project on schedule and brought in the best subcontractors. Less that nine months after Manhattan crews moved onto the site, they had completed excavation, poured eighty-eight percent of all basement walls, and sunk piers for support columns. They found a firm in Arkansas to produce

264

the durable pre-cast stone and tapped W & W Steel of Oklahoma City to fabricate the $4.29 million worth of steel for the framework and dome. “I’ve been in this business for nineteen years,” said Bert Cooper, CEO and chairman of W & W Steel. “We’ve never seen anything like it . . . It’s pretty unique.”19

As designed by Beck and HOK, the sixty-five-foot by forty-five-foot dome was tilted toward the State Capitol, asymmetrical with horizontally concentric bands of steel tubes that weighed forty tons. “I don’t know that we’ve ever come across such a complex design,” said Cooper. To bend the steel tubes to precise curves, they engaged a roller coaster fabrication firm in Salt Lake City. They then assembled the pieces at their plant on West Reno Avenue in Oklahoma City using piano wire to ensure the beams were aligned correctly. When it was finished, the OHS leadership team was invited to view what looked like a contemporary work of sculptural art. Later, it was taken apart, shipped to the site, and reassembled one hundred feet off the ground, never to be seen again underneath metal roofing above and ceiling tiles below.20

As the superstructure rose from the red dirt, our hope for a second bond issue sank under the pressure of declining state revenues and budget cuts. During the 2002 legislative session, with the request for a bond issue included in Governor Keating’s executive budget for the third time, the pendulum swung the other way with a 4.75 percent cut in operating funds that a House staff member erroneously applied to the annual appropriation to make monthly payments on the first bond issue. Compounding both setbacks, our legislative appropriation subcommittee placed a hold on our verbal agreement to add $200,000 annually to the OHS base budget to ramp up for staff to run the History Center. The year before, the fourth installment had been reduced to $62,500.21

As we successfully fought to retrieve full funding to make our bond payments, all state agencies faced a series of budget cuts during the 2003 legislative session. On top of the $499,475 cut imposed at the beginning of the year, we were hit with two successive revenue shortfalls of $184,015 and $141,975 as legislative leaders warned agency directors that funding cuts the following year would likely be in the ten percent range. Reluctantly, the OHS Board of Directors approved my plan to freeze all hiring with forty-seven vacancies on a staff of 151 people, delay projects, close the OHS library to walk-in patrons, and declare an agency furlough for all employees, including me and Robert Thomas.22

THE CHRONICLES OF OKLAHOMA

Dr. Bob Blackburn (above) gave many hardhat tours of the History Center while under construction as the OHS team kept the governor, legislature, press, and potential donors up to date on needs and progress. (photo provided by the Oklahoma Historical Society Research Division).

Looking down into the central atrium from the balcony, stacks of wood flooring were ready for installation. (photo provided by the Oklahoma Historical Society Research Division).

I saw my career coming to an end as Manhattan crews neared the end of Phase I construction. The History Center looked impressive, but there were no interior walls, finished flooring, furniture, fixtures, or exhibits. Within months, the construction site would have to be shut down, adding another $2 million to the final cost and derailing the fundraising drive that was just getting underway to pay for exhibits. Other than faint optimism, the only advantage we had was a steady stream of great press coverage over the previous two years that kept the History Center before elected officials and the public.23

On December 9, 2002, I took a chance and sent letters to all state senators and representatives describing the coming crisis if another bond issue was not forthcoming. The response was a deafening silence. I followed that with a series of meetings with Senate Pro Tem Cal Hobson on December 17, Senate Chair of Appropriations Mike Morgan on January 13, 2003, Speaker of the House Larry Adair on January 15, and House Minority Leader Todd Hiett on February 26. The story was the same each time. They were sympathetic but pointed out that the state was facing a $350 million revenue shortfall, a bankrupt Rainy Day Fund, and teachers about to be furloughed without pay across the state. They gave me little hope.

The only ray of sunshine at that low point was a meeting on January 15 with recently elected Governor Brad Henry and Scott Meachum, his director of state finance. I went to their office armed with a stack of evidence to lay before them. Before I got started, Scott in his best banker’s voice said, “Bob, relax, you can share your information, but we support another bond issue to keep construction going.” They agreed to put the recommendation in their executive budget.

As if schizophrenic, I started living two lives. While stalking the hallways of the Capitol in desperation and commiserating with staff who were being furloughed, we were at a critical point of fundraising. From January to May, 2003, I put on a happy face and stayed on the donation trail, meeting with Bill and Bob Ross at the Inasmuch Foundation on January 14, ONEOK officers on March 27, Tom Price at Chesapeake Energy on March 28, Walt and Peggy Helmerich on April 23, Larry Nichols at Devon Energy on April 28, and officers with the 1889ers Society on May 22. All would eventually make large lead gifts.

Renewed hope came on March 3, 2003. Armed with a new strategic plan, I got follow-up appointments with Senate Pro Tem Hobson,

THE CHRONICLES OF OKLAHOMA

Senate Appropriations Chair Morgan, and House Speaker Adair. I told them we did not need cash this year or the next if the legislature authorized another bond issue. As the hard-working state bond advisor Jim Joseph had taught me, we could capitalize interest accrued since the first bonds were sold and make payments on a new $18 million bond issue for more than two years. I suggested the burden of funding a second bond issue would be shifted to a future time and a future legislature when state revenues were in better shape, giving them a chance to claim at least one immediate victory on the battlefield of bad news. They did not like the optics of taking on new debt while furloughing teachers.

I went home that night, ran three miles trying to shake the blues, and retreated to my front porch, where I popped a beverage and started thinking about finding a job in higher education when I was fired for failure. Then my mobile phone rang. I answered, and it was Senator Morgan. “Bob,” he said, “we will give you a chance at a bond issue with three conditions . . . what you said about capitalizing interest has to be true and there cannot be any logrolling with other projects added to the bill.” Then he added the zinger. “You also have to get two-thirds of all members in both the House and Senate to sign a pledge to vote for the bill, which includes a majority of Republicans so this will not become a political campaign issue.” I distinctly remember that the second the conversation ended, I knew we would get the bond authorization. If I have ever had one, that was a vision.24

I lived at the State Capitol for the next two months from noon Monday to noon Thursday. I started with the leadership on both sides of the aisle, including Todd Hiett, minority leader in the House, and Jim Williamson, minority leader in the Senate, to let them know what I was doing. I then went to known supporters and legislators I had worked with, briefed them on the plan, and asked them if I could place a “yes” by their names on my roll call sheet. Most said yes, but some said no, the timing was not right. During my laps on the third, fourth, and fifth floors of the Capitol, I came to appreciate the role of legislative assistants in managing time. Some would put me on the schedule, tell me where I could intercept their boss, or encourage me to keep coming back. Some were hostile, which probably reflected their boss’s opposition, which I noted. Although he said he could not vote for a bond issue, Senator Willamson gave me a chance to speak to his caucus behind closed doors. I will never

268

forget a senator from the south side of Oklahoma City who stood up after my presentation and encouraged his colleagues to vote for it. By late May, I returned to a surprised Senator Morgan and showed him the roll call sheet with all my notes and pledges. I had the two-thirds he wanted in the House and Senate, plus five extras in case a member buckled at the last minute and withdrew their pledge. He said they would draft the bill and bring it to the floor for a vote the last week of the session. With only days left before adjournment, I was called into the office of the Senate’s legal counsel, who was drafting the bill. He told me there was a problem. The director of Central Services told him we could not capitalize interest on one bond to make payments on a second bond. I asked if I could call Jim Joseph, the bond advisor, or the bond attorney, Gary Bush. He said yes. I called Gary, who luckily answered, and asked him to tell the attorney what he and Jim had told me. He did, and the bill was drafted and submitted to the General Appropriations Committee before going to a vote on the floor. It passed both chambers with hours to spare.25

In the time I had spent chasing bond authorization, Robert Thomas, Dan Provo, Sandy Stratton, and their crews had never slowed efforts to keep the History Center project on schedule. With the bond money available in September of 2003, Robert used a new state statute to extend Manhattan Construction’s involvement through a construction management contract that opened the door to a more collaborative partnership, seeking subcontractors, with Manhattan earning a fixed percentage of each contract. Without that flexibility to respond to market conditions and monthly price fluctuations, we never could have brought the project in under budget.

The construction management contract helped Dan as well. As designed, the four exhibit galleries were big black boxes, each with approximately 8,200 square feet of space and twenty-five-foottall ceilings. All work on the walls, partitions, floors, light grids, and cases typically would have been bid out, a lengthy and timeconsuming process, but with the construction management contract, Manhattan hired each of the subcontractors after Dan and Haley-Sharpe provided construction drawings. When bids came in too high for some projects, Manhattan used their own crews and adjusted plans on the run while working with Dan and Robert.

269

THE CHRONICLES OF OKLAHOMA

The Red River Journey, stretching east and west along the south side of Northeast Twenty-third Street, created an outdoor classroom with historical markers, crushed red granite representing water, and topographical features such as Mount Scott, the Arbuckle Mountains, and the Winding Stair Mountains. (photo provided by the Oklahoma Historical Society Research Division).

An early addition to the original plans for the History Center was an oil patch exhibit with historic drilling rigs, production equipment, and transportation. Devon Energy stepped up as the major sponsor. (23389.520.157, Jim Argo Collection, OHS).

To help visualize the use of horizontal and vertical space with topical adjacencies and shared design features, Alisdair and his associates at Haley-Sharpe created three-dimensional physical models of each gallery with moveable components that could shift as needed. By mid-2003, Dan’s team had divided the four galleries into more than fifty thematic zones and subzones. On the ground floor, one gallery was dedicated to the image of Oklahoma, with artifacts and interpretation from radio, television, movies, the arts, sports, and Wild West shows. The opposing gallery was dedicated to the story of American Indians in Oklahoma, with themes of tribal origin stories, spirituality, language, dwellings, lifeways, and notable leaders.26

Upstairs, one gallery included themes such as oil and natural gas, military history, transportation, and the story of African Americans in Oklahoma history. The facing gallery covered land runs, farms and ranches, domestic life, weather, law and order, schools, and government. Additional themes were addressed outdoors. The Red River Journey, combined themes of transportation, geography, and historical events as viewed in one region of the state. At the head of the river outside the glass partition at the south end of the grand hallway was a fountain surrounded by red granite boulders excavated from OHS board member Jack Haley’s ranch on the western slope of the Wichita Mountains. Those boulders also recreated a scaled version of Mount Scott, the highest mountain in the Wichita Mountains Wildlife Refuge.27

The largest outdoor exhibit, located next to the main entry onto the History Center grounds, was dedicated to oil and natural gas. The concept started when we saved two derricks from the Capitol complex. One was an oversized drilling derrick located behind the Wiley Post Historical Building that had to be removed during the Supreme Court’s expansion. After we stored it on the new site, Senate Pro Tem Stratton Taylor told me they needed to remove one of the work-over derricks on the west side of the Capitol. I asked for it, and Senator Taylor included funding to move and reassemble it on our new site. When word spread that we were developing an oil and natural gas outdoor exhibit, Sherman Smith, a veteran in the oil patch, offered to donate a portable drilling rig he had designed in 1947. Other donations followed, including the world’s tallest “Christmas Tree” of control valves donated by Gene Downing and a modified oil tank truck donated by John Groendyke.28

THE CHRONICLES OF OKLAHOMA

Many collections came in as we researched stories. Marvin Jirous, president of Sonic: America’s Drive-in in the 1970s, donated one of the four original Sonic signs after I interviewed him. Dr. Kenny Brown, a professor at the University of Central Oklahoma, found out we were assembling an exhibit on voting and convinced the university to donate a large collection of ballot boxes from every corner of the state. Currie Ballard, a collector who had loaned us many objects of African American history over the past decade, donated his entire collection.

One of the most significant donations came during planning meetings with a group of tribal elders funded through a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. After a planning session to develop themes, Otoe elder Joan Aitson told us she had her grandmother’s trunk of family keepsakes. Along with a buckskin dress and other personal items was a small piece of paper pressed between two pieces of cedar. When we looked at it, we discovered it was a Thomas Jefferson Certificate of Friendship given by Lewis and Clark to one of Joan’s ancestors as the explorers ascended the Missouri River in 1803. When she saw our reaction, she said she and the family would donate it. Dan had it appraised and found it was one of only two that had survived that perilous peace-keeping mission. It appraised for $1.2 million. We returned to Joan, a retired state employee, and said we would return the gift now that she and the family realized its value. The Smithsonian and National Archives contacted her with an offer to purchase the document. In an impressive act of generosity, she and her family said no, it should be in the History Center, where it could illustrate the story of two cultures advocating peace during turbulent times.

Several artifacts came in as long-term loans. As curator of the sports exhibit, I wanted a large object to pull visitors into the story.

272 Since 1997, we had been branding the Oklahoma History Center as an opportunity to expand collections. We did not have to wait long. One of the first major gifts was the Kilgen Theatre Organ and all of its pipes that had been purchased by E. K. Gaylord for WKY radio in 1937. We did not know what we might do with it, but we knew we wanted it. On September 23, 1998, soon after legislative approval of the first bond issue, I met with Stanley Lee, the former CEO of Leeway Freight Lines, to discuss a new home for his collections, then on display at a small museum in Oklahoma City. He donated the entire collection, including several trucks and hundreds of artifacts dating to the company’s founding by his father, Whit Lee, in 1931.

When I told a car collector I wanted a race car, he said I needed to talk to Jack Zink in Tulsa. I called him, joined him for lunch, and accepted an invitation to tour the Zink Ranch. He eventually agreed to loan us his car, which had won the Indianapolis 500 in 1956. Another nationally significant loan came in through the efforts of General Tom Stafford, the legendary astronaut from Weatherford. When Dan and Bill Moore told him we wanted a flown spacecraft, he used his connections and influence to get the Smithsonian’s Air and Space Museum to loan us the Gemini 6 capsule in which he had conducted the first rendezvous, a critical steppingstone to the Apollo mission to the moon.

Bruce Fisher, curator of the African American exhibit, established a lasting friendship with Clara Luper, who had led a series of sitins from 1958 to 1964 in the fight against racial segregation. As we earned her trust, she and her children donated her collections, including personal objects such as the eyeglasses she wore at the first sit-in at Katz Drug Store. An industrial artifact from the same period was donated following a meeting with Ed Malzahn, a founder of an international firm based in Perry, who had invented a small trencher called the Ditch Witch. When asked if he would loan us one of the original models, he said he would donate one and restore it.

The architectural plan for the History Center included a temporary gallery where the staff displayed race cars and motorcycles loaned to the museum from Jack Zink and his son Darton of Tulsa. (photo provided by the Oklahoma Historical Society Research Division).

THE CHRONICLES OF OKLAHOMA

In 2007, with the History Center as an appropriate stage for state centennial events, the OHS sponsored an exhibit about governors and hosted an opening reception attended by seven former and present governors and their first ladies. The governors, from left to right, were David Boren, David Walters, David Hall, Brad Henry, George Nigh, Frank Keating, and Henry Bellmon. (photo provided by the Oklahoma Historical Society Research Division).

The American Indian Gallery was designed around themes suggested by a committee of tribal elders. The themes included origin stories, lifeways, spirituality, homes, and language. (photo provided by the Oklahoma Historical Society Research Division).

By the time we received the second bond issue, curators were working on more than fifty exhibit topics with 220 interactive elements. Some were computer-based learning tools, while others were video features that supported labels on artifacts and copy on exhibit panels. Some were hands-on stations where students could sit on a saddle or solve a puzzle. “We’re very determined to make this space alive,” Dan told one reporter, “where people can come every month of the year and find something new . . . we are already planning the replacements of the exhibits that will be installed when the museum opens.”29

Work on the History Center also attracted new archival collections. One of the largest single collections came from former Governor George Nigh, who said he had all his papers from a long career as governor, lieutenant governor, and university president. It is now one of the largest collections in the OHS archives. Bill Moore, who joined the staff in 1999, used his connections in the television community to bring in the WKY-TV film archives dating to the 1950s, including original film footage shot in the early 1900s, news features, and documentaries made by Emmy-winning producer Bob Dotson, who started his career at WKY-TV before going to NBC. Paul Strasbaugh, my coauthor on a book about the State Fair of Oklahoma and a former director of the Oklahoma City Chamber of Commerce, helped me bring in the chamber’s archival collection dating to 1898. The seven hundred volumes of source material collected under the watchful eye of Stanley Draper traced the economic history of the state.

With news of the History Center splashed across headlines, I got a call one day from John Dunning, a friend, well-known collector, and antique dealer, who said he wanted to show me his collection of political memorabilia scattered in three different locations. After convincing him to consolidate the collection in one room at the old Wiley Post Historical Building, John and I were surprised that it consisted of more than twenty thousand items dating to the 1890s, spanning topics from tribal elections and political buttons to banners, Bibles, and brochures. We purchased half of the collection with a grant from Aubrey McClendon, and John donated the rest. This one collection served as the heart of an exhibit on Oklahomans’ willingness to serve in government. The newfound success in aggressively seeking collections extended to fundraising. Throughout the 1990s, despite our rising ambitions, the ability to raise money in the private sector had been minimal. There

THE CHRONICLES OF OKLAHOMA

We sprinted off the starting line with grants from the federal government, the one area of fundraising that had been successful in the 1990s. Among those achievements, in addition to $700,000 for the Oklahoma Route 66 Museum, were grants for Honey Springs Battlefield, Forts Washita and Towson, the US Newspaper Project, and The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. After the first bond issue was approved in 1998, we applied for and won two grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities to bring in scholars and tribal elders to help develop a plan for the American Indian gallery. With Governor Keating’s help and his secretary of transportation, Neal McCaleb, we won several federal grants for a transportation exhibit, The Red River Journey, the excavation, conservation, and display of the shipwrecked Heroine, and the outdoor oil patch. McCaleb helped again when the Oklahoma Department of Transportation paid for traffic signals and turn lanes at the corner of Laird Avenue and Northeast Twenty-Third Street, which would have depleted $580,000 from our construction budget.30

As construction and exhibit planning started, Sandy staged a series of living history fundraising events designed to raise money and promote public awareness of the History Center project. The first, in April of 2001, was held on Northeast Second Street, the traditional commercial center of the African American community in segregated Oklahoma City. The Deep Deuce music event raised about $45,000 and generated newspaper headlines. The other two events staged later that year were held at the restored Harvey House in Waynoka and the historic Ambassador Hotel in Tulsa. Sandy and Whit Edwards recreated a USO show from World War II. A memorable highlight of that event was retired Air Force General Jay Edwards singing a song made famous by Bing Crosby. At retired General Billy Bowden’s suggestion, we served fried Spam as a historic appetizer.

Raising $10 million for exhibits and collections was a daunting challenge. Seeking advice on launching that effort, on March 20, 2001, I met with Lou Kerr, a family friend and philanthropist who knew the

276 were a few success stories, such as raising more than $300,000 in Clinton in 1993 to match a federal grant to build the Oklahoma Route 66 Museum, but more reflective of our shortcomings was the inability to raise enough money to match John Kirkpatrick’s offer of $20,000 for our endowment at the Oklahoma City Community Foundation. The History Center changed that dynamic.

landscape of foundations, corporations, and individuals who could make significant grants. I told her we had two options. One was to hire a fundraising firm to bring experience to the table but siphon off part of the proceeds as their fee and take their connections with them when they walked away. The other option was to conduct the campaign on our own. She said, “Bob, you can do this on your own and you need to transform the image of the OHS as a cultural facility worthy of grants long after construction.” To encourage us to take that leap, she directed me to a new foundation with funds to share.

After the collapse of the oil and natural gas industry in the mid-1980s, which brought chaos to the banking and real estate communities, the economy was improving after innovators in the oil patch developed new tools such as horizontal drilling and high-pressure hydraulic fracturing, just as the prices of oil and natural gas were rising. This time, instead of oil executives in New York City, Los Angeles, Houston, and Amsterdam leading the charge, the energy revolution was started and sustained by native Oklahomans such as Harold Hamm, Larry Nichols, Tom Ward, and Aubrey McClendon. Riding on the shoulders of the energy boom from 1998 to 2008, banks were prospering, and real estate developers were transforming the urban landscape. It was a fertile field for fundraising.

Lou told me to call Bill Ross, an attorney who was just then organizing two foundations funded by the late Edith Kinney Gaylord. I called and got an appointment at his historic First National Bank Building office. After OHS board member Denzil Garrison and I showed him the plans and images for the History Center, exhibits, and collections, he said he was a history buff and wanted to help. Still, the new foundations could not give money directly to a government agency. I said no problem; by statute, the OHS was a public/private organization with a 501(c)3 nonprofit support group that could receive the funds. After I made a presentation to his board of directors and got to know his son and future foundation president, Bob Ross, the Inasmuch Foundation made one of the first $500,000 donations we needed to switch the campaign from silent to public stages.

We decided to cap the kickoff grants at $500,000 instead of going for a seven- or eight-figure grant that might include a request for naming rights. The name of the new museum and research facility was going to be the Oklahoma History Center, plain and simple, owned by

THE CHRONICLES OF OKLAHOMA

We settled on seven $500,000 major naming rights because we had four museum galleries, one auditorium, one grand atrium, and a new street with a new mailing address. Each gift required numerous meetings, especially with corporations that needed buy-in from staff and board members. The quickest and most enthusiastic response came from Aubrey McClendon, cofounder of Chesapeake Energy and a man destined to change the philanthropic culture of Oklahoma City. He pledged $500,000. More deliberate but just as enthusiastic was Larry Nichols, CEO and cofounder of Devon Energy, who would later transform the shape of downtown Oklahoma City by constructing a fifty-four-story skyscraper and more than $110 million invested in surrounding public byways and parks. He pledged $500,000.

Another energy giant making a $500,000 pledge was Kerr-McGee Energy, led by Luke Corbett, who later facilitated the donation of all Kerr-McGee archival collections to the OHS when a Houston firm absorbed the company. One of our most structured pursuits focused on ONEOK, the parent company of the historic Oklahoma Natural Gas Company, headquartered in Tulsa. Starting with Ginny Creveling, ONEOK’s director of community relations, we worked our way up the corporate ladder to vice presidents, CEO David Kyle, and his board of directors. Their $500,000 pledge was the largest gift in the history of ONG or ONEOK. The last pieces of the major gift puzzle were provided by the Noble Foundation, based in Ardmore, and Dr. Nazih Zuhdi, whose name would thereafter be used as the address of the History Center: 800 Nazih Zuhdi Drive.

The quiet phase of fundraising also included several $100,000 gifts, some with naming rights. Martha Williams and her brother, Chuck Vose Jr., placed their father’s name, Charles Vose, on the north wing hallway. The south wing hallway was named the West Family Gallery with a donation from Elk City oilman J. Cooper West. Former Governor

278 and dedicated to the people of the state, past, present, and future. The History Center’s major components, indoors and outdoors, could be named for donors who contributed between $100,000 to $500,000. Naming rights for smaller donors were available by sponsoring $35 bricks on the grounds, $1,000 limestone pavers outside the entryway, $1,000 leaves on a sculptural piece of art mounted near the entry to the Research Center, and $5,000 limestone pavers inside the entryway. All donors giving $1,000 or more would be recognized by name on a permanent display on the third-floor bridge. It is still there today.

OKLAHOMA HISTORY CENTER

Bob Blackburn (right) with Dr. Nazih and Annette Zuhdi announced the naming of a new street and circle drive leading guests into the History Center. Their donation helped complete the $12 million fundraising drive for exhibits. (photo provided by the Oklahoma Historical Society Research Division).

Since completion, a recurring event in the History Center has been a series of concerts featuring the historic Kilgen Theatre Organ, a rare organ restored and played through the generous leadership of Dusty Miller and Kimray Industries. (photo provided by the Oklahoma Historical Society Research Division).

THE CHRONICLES OF OKLAHOMA

With funding from John Groendyke, Enid-based artist Harold Holden created the Monarch at Rest sculpture that sits by the front entryway into the History Center. (23389.520.256, Jim Argo Collection, OHS).

Unconquered, a monumental sculpture created by Indigenous artist Allan (Haozous) Houser (Chiricahua Apache) (1991–1994). The piece was acquired through a grant from the Inasmuch Foundation and mounted on a native stone pedestal funded by Cliff and Leslie Hudson. (photo provided by Trait Thompson).

David Walters and First Lady Rhonda Walters pledged $100,000 and earned naming rights to the plaza surrounding the headwater fountain of the Red River Journey. The Kirkpatrick Family Fund, led by Joan Kirkpatrick and Chris Keesee, offered a $100,000 gift to name the Research Reading Room for John and Eleanor Kirkpatrick.

The temporary exhibit gallery was named in honor of E. L. and Thelma Gaylord with a gift from the Gaylord family. Major gifts of more than $100,000 without naming rights came from John Zink, Marvin and Barbara Jirous, and Ed Malzhan. The Oklahoma City Federation of Women’s Clubs donated $110,000 to match the federal grant funding the Red River Journey. Walt Helmerich of Tulsa contributed $200,000 to pay for a full-scale replica of Wiley Post’s airplane, the Winnie Mae, which still hovers over guests in the Devon Great Hall. Other donors giving over $100,000 included the Oklahoma Energy Resources Board, Oklahoma Gas and Electric Company, and Garman Kimmell.

Several donors came back with major gifts time and again. Devon Energy invested another $500,000 to earn naming rights on the outdoor oil and natural gas park. The Ethics and Excellence in Journalism Foundation, endowed by Edith Kinney Gaylord and led by Bill and Bob Ross, added another $500,000 in multiple grants for the Research Center. Aubrey and Katie McClendon gave numerous personal gifts totaling almost $500,000 in addition to grants from Chesapeake Energy. The Inasmuch Foundation, the single largest donor during the campaign, came back with another $750,000 donation to acquire Unconquered, a monumental bronze sculpture created by native Oklahoman Allan Houser. John Groendyke of Enid added to the artwork greeting guests when he donated $100,000 to create Monarch at Rest, a bronze buffalo sculpted by Harold Holden, low enough with horns tucked into its mane so an entire class of first graders could sit on its back.

OHS board and staff members showed their personal commitment with donations. The children of longtime OHS board member Dr. LeRoy Fischer donated $50,000 for a specially crafted boardroom table and earned naming rights for their father. Chuck Wiggin and Chip Fudge, original members of the History Center foundation, each gave $40,000. In addition to Sonic’s gifts, Cliff and Leslie Hudson donated $25,000 to pay for the customized sandstone pedestal for the Unconquered statue. John Mabrey, an OHS board member from Tulsa, gave $25,000 to pay for the Oklahoma Family Tree. Other gifts contributing

THE CHRONICLES OF OKLAHOMA

to the cause included $10,000 from Barbara and Ralph Thompson, $10,000 from me and Debbie, $5,000 from Aulena and Gib Gibson, $5,000 from Bill Welge, and $1,000 gifts from several staff and board members. By the end of the campaign in 2005, more than five thousand people and organizations had donated more than $12 million in grants and gifts to the History Center, fulfilling the commitment made when the first bond issue was authorized in 1998.31 This confirmed my belief that generosity is one of the key attributes describing the character of Oklahoma’s people.

With money from the second bond issue for construction and raised funds for exhibits, it was a sprint to the opening ceremonies scheduled for November 13, 2005. Kyle Nelson of Manhattan Construction was a critical player down the home stretch. He worked with Dan and his staff to stage subcontractors for walls, light grids, flooring, and cases, often as changes were made on the run. He worked with Robert and Don Beck’s team to bring the building under budget. He also worked with my new fundraising director, Dr. Tim Zwink, and me as we led a seemingly endless parade of donors, reporters, and legislators through the construction site. I still have my well-worn hard hat hanging in my office at home.32

Those attending the grand opening of the History Center Research Center included, from left to right, Speaker of the House Lloyd Benson, architect Don Beck, OHS board members Billie Fogarty and Leonard Logan, Bob Blackburn, former Governor George Nigh, donors Christian Keesee and his mother, Joan Kirkpatrick, and Research staff and volunteers including Laura Martin, Bill Welge, and Chester Cowen. (photo provided by the Oklahoma Historical Society Research Division).

One disappointment in the summer of 2005 was a shortfall in legislative funding for staff members. When the project began in 1997, I made a deal with Senator Rick Littlefield, chairman of our appropriation subcommittee, to add $200,000 a year to our base appropriation to pay for the additional staff we needed to run an expanded operation. That worked for two years, followed by a couple of reduced amounts, totaling approximately $600,000, short of the $1,000,000 we needed for museum and research staff, housekeeping, and maintenance specialists. As a result, in July of 2005, we announced that the Research Division would remain in the Wiley Post Historical Building until the spring or summer of 2006. We eventually plugged the funding gap by transferring marketing funds to staff support and tapping the revenue earned for some operational expenses.33

A tidal wave of enthusiastic press coverage pushed aside that disappointment. Even before the opening was announced, the Daily Oklahoman ran a multipage story about the History Center titled “Black History in Oklahoma,” with subtitles such as “Blacks Due Historical Honor” and “Civil Rights History Told.” By summer, statewide newspapers carried stories with headlines such as “History Museum Needs Volunteers,” “Racing into the Past,” “Museum to Open Near State Capitol,” “Winnie Mae Rises Again,” “Oklahomans Honor Civilian Conservation Corps,” “New $54 million Center Tells State’s Story,” “History an Attraction to OKC,” “History Center Park Offers Oil and Gas Insights,” “Home on the Range,” “History Center to Open with Treasures of State Heritage,” “USS Oklahoma Remembered,” and “Historical Society Prepares for Opening.” Capturing the entire odyssey of developing the History Center from first steps to opening night was an eight-page insert in the Daily Oklahoman newspaper.34 The pull-out tab was titled “Embracing our Past: Opening Oklahoma’s Temple to History.” The coverage included photographs ranging from aerial views of the site and building details to artifacts and gallery diagrams. There were lists of donors, a short history of the OHS, verbal descriptions of all galleries, and an entire section called “Cool Stuff” that featured artifacts such as the Gemini 6 capsule, the Zink Indy race car, Mary Kay Place’s cowgirl outfit worn when she was Loretta Haggers on television, Woody the Birthday Horse from the Foreman Scotty Show, the world’s first parking meter, and the Osage war shield depicted on Oklahoma’s state flag.35

THE CHRONICLES OF OKLAHOMA

The History Center grand opening included tours, acknowledgements, videos, fine dining, music, and fireworks staged from the south side of the State Capitol visible through the glass curtain wall of the Devon Great Hall. (photo provided by the Oklahoma Historical Society Research Division).

To help plan the opening ceremonies, we partnered with J. Blake Wade, executive director of the Oklahoma Centennial Commission, and Lee Allan Smith, his fundraising and event planning specialist. With a healthy budget matching their spectacular dedication of the Capitol Dome in 2002, Lee Allan and his team created a keepsake invitation, chose the best caterers, commissioned ice sculptures in the shape of the History Center, and booked musical entertainers. The night before the opening ceremonies, our OHS curators, educators, maintenance staff, and administrators, including me and Dan, feverishly installed the last artifacts and rushed to clean cases and galleries.

On November 16, 2005, after eight years of planning, funding, and building the History Center, we hosted what reporter Joan Gilmore called a “glorious night.” Historical interpreters dressed as soldiers, pioneers, fancy dancers, and entertainers greeted guests at the front door along either side of a red carpet. Inside were tables of food piled high, beverages served in glassware engraved with the words “Oklahoma History Center,” and musical entertainment provided by Oklahoma opera singer Leona Mitchell, big band leader Al Good’s orchestra, the Ambassadors Concert Choir, classical guitarist Edgar Cruz, and the Oklahoma City University Choir. After I offered a welcome to the guests and thanked the many people and groups who had made the History Center a reality, a fireworks display began that framed the State Capitol seen from the Devon Great Hall beneath the Winnie Mae. As one reporter described the event, “Oklahoma’s Past Has a New Home.”36

The story of the Oklahoma History Center does not end there. As we had anticipated, the new temple of history changed our brand, supercharged our ability to collect, preserve, and share collections, and proved the success of our evolving business model based on a combination of state support, private fundraising, and earned revenue. By the time the History Center opened, we already had more than two hundred events booked for the coming year, a trend that would accelerate until we were booking more than four hundred events a year and generating more than $400,000 a year in revenue.

The brand of the OHS was enhanced as people and organizations recognized our insistence on higher standards, which we applied across the board at statewide museums and historic sites and to public programs and educational outreach. A symbol of that success was

THE CHRONICLES OF OKLAHOMA

being named a Smithsonian Affiliate, the first in Oklahoma, a special category of museums across the country that met the standards of our national museum flag bearer. Our national status was further enhanced as an affiliate of the National Archives, making the Oklahoma History Center the only institution in the nation that shared both honors. With the History Center experience fresh in our minds, bringing in and processing collections became our obsession, especially in the Research Division. Large donations included the Kerr-McGee Collection, more than one-hundred-thousand items, including public relations records, scale models of drilling rigs, corporate records, maps, and photographs. Even larger was the photographic archives of the Oklahoma Publishing Company, with more than one million images dating from the late 1920s to the late 1990s, each image with a caption taped to the back and a reference to the story it illustrated. Just as valuable were small collections ranging from political campaign materials and family movies to organizational scrapbooks and tribal records. With the ability to raise money for investments, we rushed headlong into the information age by scanning and adding search functions to collections in what we called the Gateway to Oklahoma History. Jennifer Towry, a new staff member of the Research Division, created a new, more useful OHS website.

The facade of the History Center facing the State Capitol was a blend of neoclassical columns, backlit curtain walls, and Indigenous motifs on either side of the central atrium dome. (23389.23.457, Jim Argo Collection, OHS).