Editor: Anna L. Davis, MA

Volume CIII Number 2 Summer 2025

Would Americans Tolerate Sonic Booms? Oklahoma City’s Role in the Failed Effort to Develop a Supersonic Transport Aircraft

BY THOMAS A. WIKLE

In 1964, Oklahoma City became the testing ground for a government experiment. The Federal Aviation Agency had chosen Oklahoma City as the site of sonic boom testing to see if citizens could live with the sounds produced by supersonic passenger transportation. While these experiments intended to create safe, quiet, and efficient supersonic aircraft, the outcome involved protests and accusations of property damage. Wikle writes about the government program that earned Oklahoma City the nickname "Boomtown."

126

"Bullheaded Resistance": Choctaw Nation Political Responses to the Euro-American Cattle Market and the Act of 1899

BY TARYN M. DIXON

In the nineteenth century, the Choctaw Nation's cattle business provided for many tribal citizens. However, as Indian Territory was open for white settlement, they were forced to fight for their tribal autonomy. To protect their cattle business, the Act of 1899 was passed, attempting to protect tribal livestock operations. Dixon (Choctaw) explores the history of the Choctaw cattle industry, their traditional ranching practices, and how they fought to maintain their tribal control during the Allotment era.

BY MICHELLE JALUVKA

150

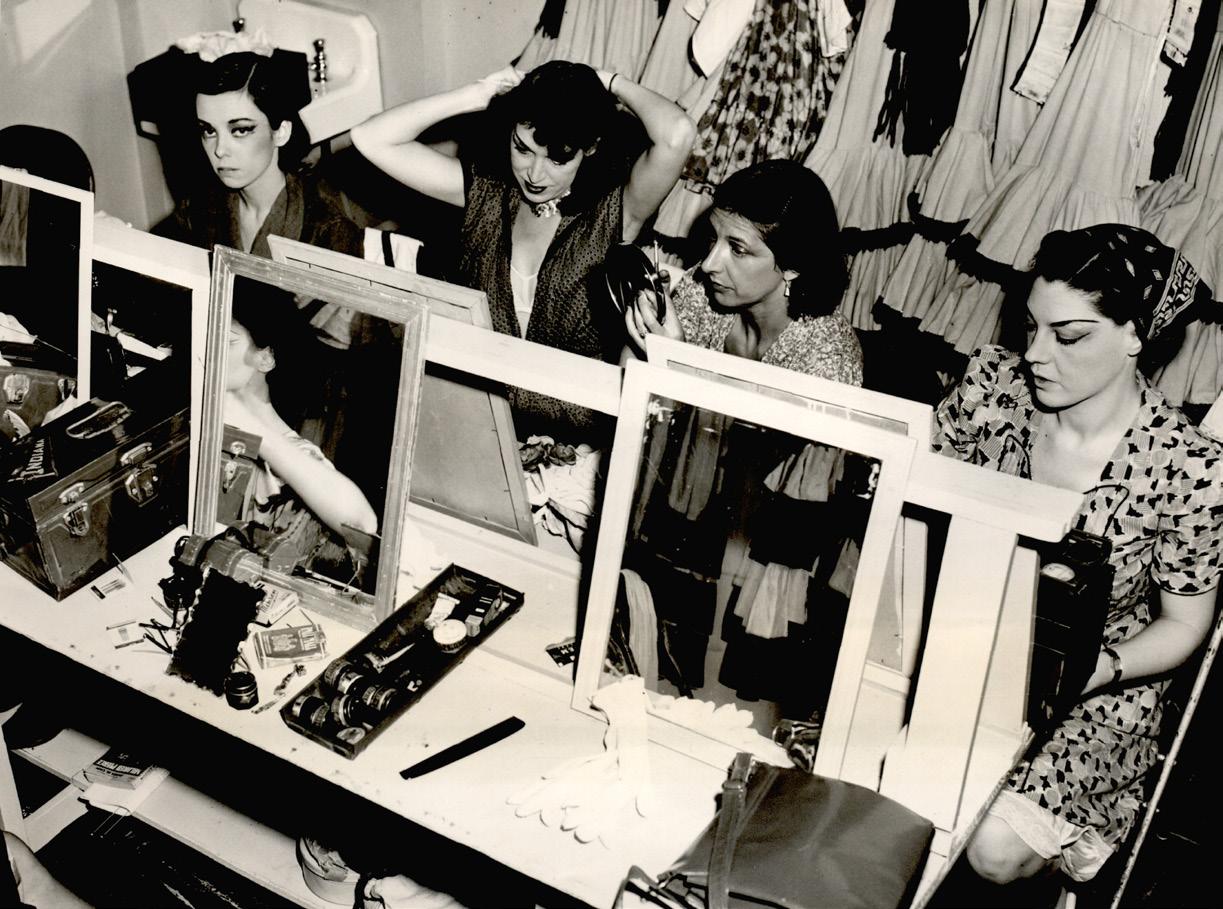

Opera as an artistic medium in the United States has often been categorized as high-brow entertainment. As the city of Tulsa grew, so too did the art scene. The opera in Tulsa started as a local grassroots movement featuring local talent. However, as the demand for bigger productions began, Tulsa citizens banded together to bring top talent from the New York Metropolitan Opera. Through the 1950s and 1960s, these singers would shape Tulsa's opera scene. Jaluvka looks at the prima donnas who brought national esteem to the Tulsa opera. 171

BY D. SCOTT PETTY

Black, Jennifer M., Branding Trust: Advertising and Trademarks in Nineteenth Century America, reviewed by Loren Gatch Bruning, John R., Fifty-Three Days on Starvation Island: The World War II Battle That Saved Marine Corps Aviation, reviewed by Thomas A. Wikle Kiser, William S., Illusions of Empire: The Civil War and Reconstruction in the U.S.-Mexico Borderlands, reviewed by Collin Karst Puglionesi, Alicia, In Whose Ruins: Power, Possession, and the Landscapes of American Empire, reviewed by Kathleen Wilson

Minutes of the Special Meeting of the Board of Directors, December 18, 2024 Minutes of the OHS Quarterly Board Meeting, January 22, 2025

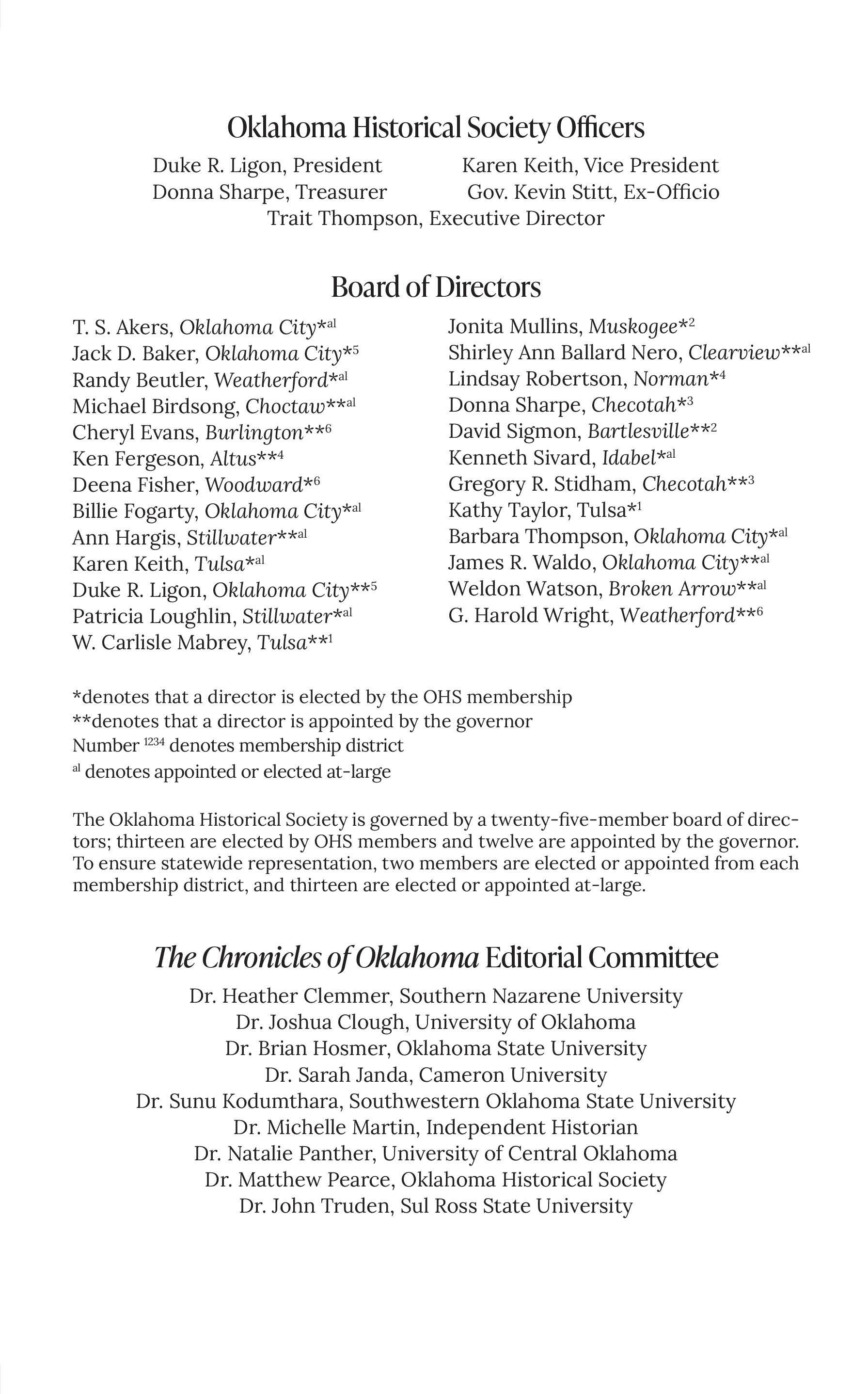

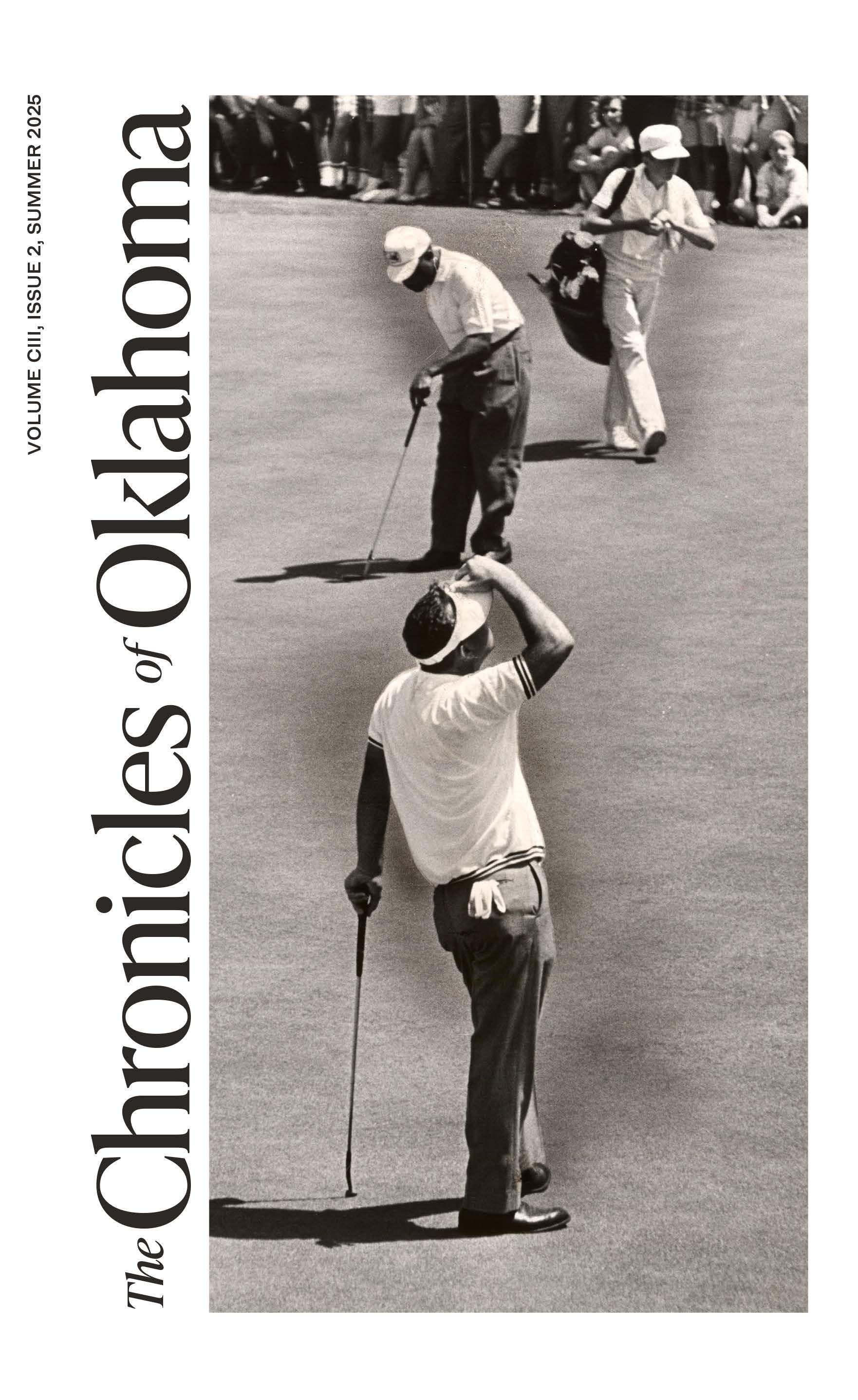

ON THE COVER

Arnold Palmer pauses while waiting for a sonic boom, 1964 (2012.201.OVZ001.3534, Oklahoma Publishing Company Photography Collection, OHS).

By Thomas A. Wikle*

On February 3, 1964, residents of Oklahoma City and surrounding communities were startled by a loud bang that shook windowpanes and rattled dishes. Some likened the sound to a bomb exploding. Visiting her mother in Oklahoma City, Bridget Meadows remarked, “I didn’t know what it was at the time—it literally shook the house . . . the kids ran crying.”¹ More booms were heard by residents the next day, and within less than a week, the booms grew in frequency to eight each day. Buildings sustained minor damage, mostly fallen mirrors, broken windows, and cracked plaster. Although some residents were unaware of their cause or purpose, the booms had been announced in advance in Oklahoma City area newspapers and other

news outlets. Commissioned by the Federal Aviation Agency (FAA; now the Federal Aviation Administration) and involving the National Aeronautical and Space Administration (NASA) and the US Air Force, the blast-like noises were part of a project to assess how the US population would react to regular sonic booms produced by a future fleet of commercial airliners traveling faster than the speed of sound. Created by military aircraft, the booms were slated to last six months. Although most business owners and civic leaders supported the test, opposition grew each week, as demonstrated by complaints directed at FAA officials, city and state leaders, and the Air Force. Seven years after its conclusion, the sonic boom test over Oklahoma City became a key factor in the government’s decision to cancel funding for American-built supersonic passenger aircraft.

The 1960s was a decade shaped by rapid technological change. In 1961, US scientists and engineers successfully launched an astronaut into space, and commercial jets recently replaced propeller-driven aircraft for carrying passengers over long distances. With American companies leading the world in aircraft design and construction, US leaders envisioned a future with faster aircraft. Following test pilot Charles “Chuck” Yeager’s achievement in exceeding the speed of sound in 1947, the US military began building supersonic aircraft, including the US Navy’s D-558-2 Skyrocket, which flew at Mach 2.0 (twice the speed of sound) in March 1953. By the early 1960s, ten military aircraft were capable of supersonic flight.² For many, a supersonic commercial airliner was the next logical objective for the US aircraft industry.

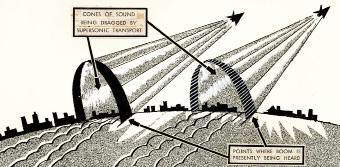

Air Force and Navy engineers knew that aircraft exceeding the speed of sound (approximately 678 miles per hour at 30,000 feet) created an unpleasant experience for people on the surface. A sonic boom happens when sound waves ahead of a supersonic aircraft become compressed, producing a noise with the intensity of a shotgun blast or mild thunderclap.³ Rather than creating a single loud noise, the disturbance sweeps over the ground like a broom in a continuous motion. A typical sonic boom’s intensity of about 110 decibels is greater than a passing train (eighty-nine to eighty-five decibels), but less intense than nearby thunder (165 to 180 decibels).

Hoping to influence public opinion about the need to endure sonic booms, the US military commissioned short films such as Mission

Sonic Boom (1959) and Strategic Air Command (1955), narrated by actor and Air Force Reserve Colonel Jimmy Stewart.⁴ Magazine advertisements portrayed the booms as a “thundering signal of aviation’s progress for national defense” or reminded readers that the military pilots who create booms, “Are patriotic young Americans affirming your New Sound of Freedom.”5 Anticipating damage claims, the Air Force distributed brochures to explain how booms were created and who to contact about property damage.6

Meanwhile, the race was on to build a supersonic transport (SST) airliner. In the early 1960s, the United Kingdom and France began a joint venture to develop the Concorde, an airliner that could carry one hundred passengers at speeds between 1,500 to 2,000 miles per hour. Whereas a conventional commercial jet could travel between New York and London in seven hours, the Concorde would complete the journey in just two hours.7 The Soviet Union also developed a supersonic transport called the TU-144.8 Initially, President John F. Kennedy was not in favor of the US investing in the development of a supersonic airliner. However, a 1963 decision by Pan American World Airways President Juan Tripp to purchase six Concordes was a major setback to American aviation leadership.9 Speaking during a graduation ceremony at the US Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs on June 5, 1963, Kennedy announced that the US would initiate its own program to build a commercial supersonic transport (SST) and pledged $750 million of the estimated $1 billion needed for research and development.10 Soon after, Burbank-based Lockheed, Seattle-based Boeing, and Los Angeles-based North American Airlines submitted SST plans. Ultimately, Boeing’s design, the 2707, won.11 Powered by four turbofan jet engines, the Boeing 2707 would carry 240 passengers at three times the speed of sound.12 To withstand tremendous heat flying at high speeds and altitudes, the aircraft’s exterior would be made of titanium.13

With SST development underway, government officials questioned how the public might react to regularly occurring sonic booms. Estimates suggested that when SSTs began regular flights in the late 1970s, 65 million people would be subjected to ten daily booms.14 Additional information came from scientists and economists. A technical paper written by a NASA scientist in 1960 warned that shock-wave noise pressures from sonic booms could damage buildings and annoy people on the ground.15 A December 1963 report to President Kennedy,

coauthored by Eugene R. Black, former head of the World Bank, warned, “the sonic boom gives all who are working on the supersonic transport the most worry.”16

In March 1961, John F. Kennedy appointed FAA Administrator Najeeb Halaby to lead development of SST policy. Having previously served as a test pilot, Halaby knew that public acceptance of low-intensity sonic booms would be critical to the success of the SST Program.17 A preliminary study of sonic boom acceptance over St. Louis, Missouri, in 1961–62, called Operation Bongo, had demonstrated that the public was not pleased with regularly occurring booms. One hundred fifty flights by Air Force B-58 Hustler bombers yielded five thousand complaints and 1,624 damage claims.18 Following the St. Louis test, Halaby directed FAA officials to search for a city suitable for a long-term study of boom impacts on structures and people. Oklahoma City appeared to meet Halaby’s criteria. The city had relatively flat terrain and residential buildings of various types and ages. In addition, the city’s “air-minded” and “progressive” residents seemed likely to be accepting of sonic booms given the large number of people employed at nearby Tinker Air Force Base and the FAA’s Aeronautical Center located at Will Rogers Airfield.19

Slated to extend from February 3–August 3, 1964, Operation Bongo II involved eight sonic booms each day created by Air Force jets flying between 21,000 and 50,000 feet. In preparation for the test, the Air Force invited thirty-nine school administrators, city officials, police and fire department representatives, and insurance executives to attend a sonic boom demonstration at Clinton Sherman Air Force Base on January 14, 1964.20 In addition to notifying news outlets, the FAA distributed brochures explaining benefits of the SST Program and the purpose of the test over Oklahoma City. The brochure listed questions the FAA hoped to address including, “How do people feel about hearing booms over or near their communities?” and, “At what levels are booms annoying to most people?” A statement on the brochure provided assurance that people and animals would not be harmed.21 Although the FAA held discussions with city leaders, the plan to subject residents to a six-month sonic boom test was never put to a vote by city council members or the public.22 When newspapers announced that Oklahoma City would host the test, the city’s chamber of commerce held a celebratory dinner.23

130 The FAA rented test houses on 91st Street, Kenilworth Road, Northeast 24th Street, and Southeast 16th Street. The house on Kenilworth Road was almost directly below the planned flight path. Accelerometers and strain gauges were installed by the FAA on each house’s rafters, studs, and doors, while seismic sensors were buried outside to measure boom-related movement. Microphones were positioned within and outside each house to capture the intensity of booms.24 Inside, technicians installed mirrors on walls and placed bric-a-brac on shelves. Photographs were taken by the agency to evaluate house exteriors before and after exposure to booms.25 The plan called for booms created during the initial twelve weeks of the project to be limited to 1.0 to 1.5 pounds per square foot (psf) of overpressure (pressure greater than atmospheric pressure). Overpressures would increase to 1.5 to 2.0 psf for the subsequent fourteen weeks of the project.26 To assess public perceptions and attitudes, the FAA contracted with the University of Chicago’s National Opinion Research Council. A group

of three thousand Oklahoma City residents would be surveyed three times during the six-month test period.27 In a television interview, Halaby explained that they sought the views of average people, whose feelings about the booms fell somewhere from “curious” to “furious.”28

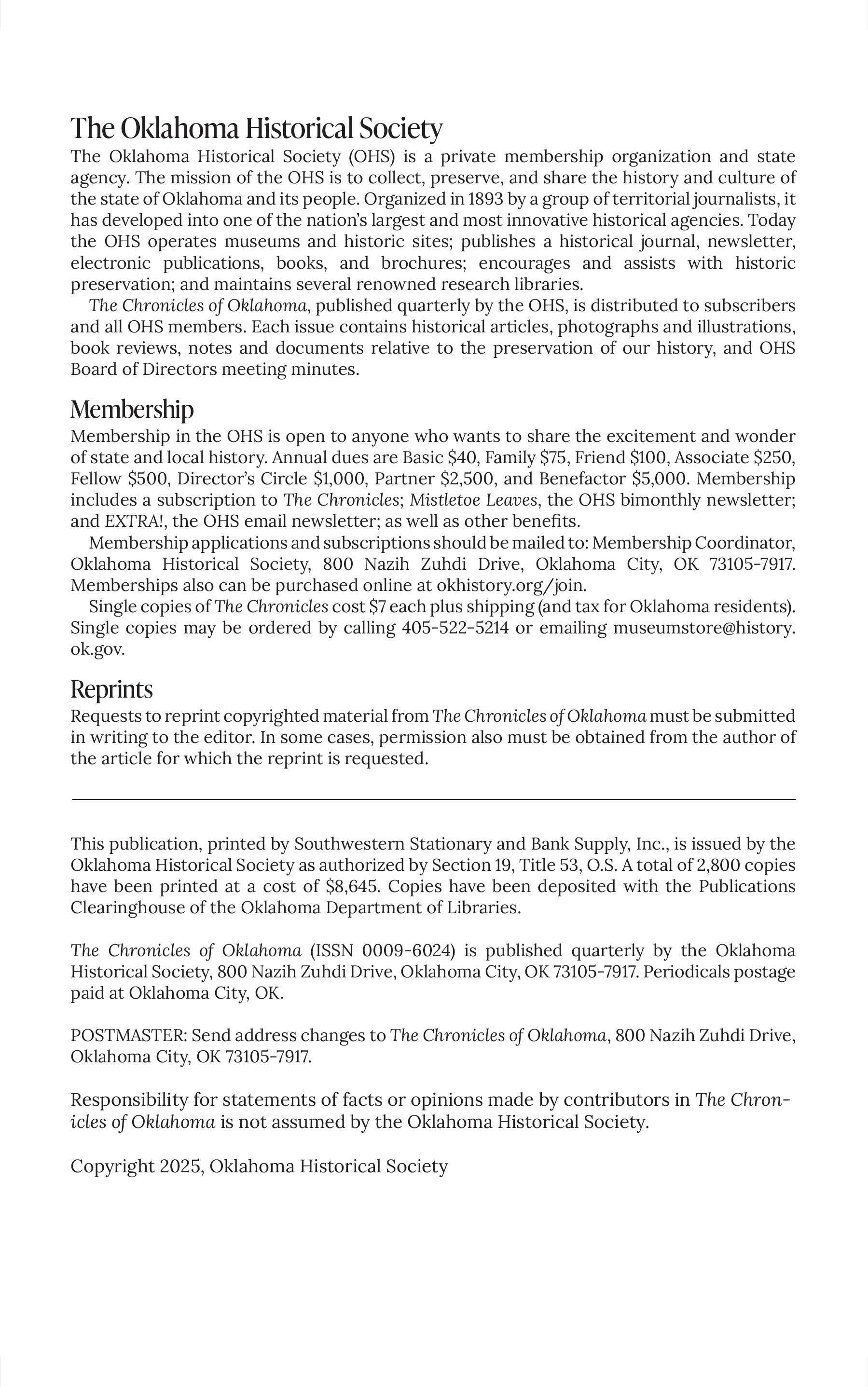

The plan called for aircraft departing Tinker Air Force Base to fly over the Wichita Mountains and Fort Cobb before turning northeast. On reaching 30,000 feet, test aircraft would start to accelerate. Each supersonic run would begin eighteen miles west of downtown Oklahoma City. The route passed over shopping centers, parks, industrial buildings, and a mixture of newer neighborhoods and older subdivisions. Crossing the southeast corner of Yukon, the route passed Bethany, Warr Acres, and the southeast tip of Lake Hefner. Continuing northeast, the transect continued over The Village and Nichols Hills. On reaching Arcadia, test aircraft would decelerate to subsonic speed as they passed Luther, Wellston, Carney, and Agra. At Cushing, the aircraft would turn southwest for the return to Tinker.29 Remarkably, the

The sonic boom flight path, 1964 (2012.201.OVZ001.2714, Oklahoma Publishing Company Photography Collection, OHS).

thirty-mile supersonic portion of the route would be completed in less than two minutes.

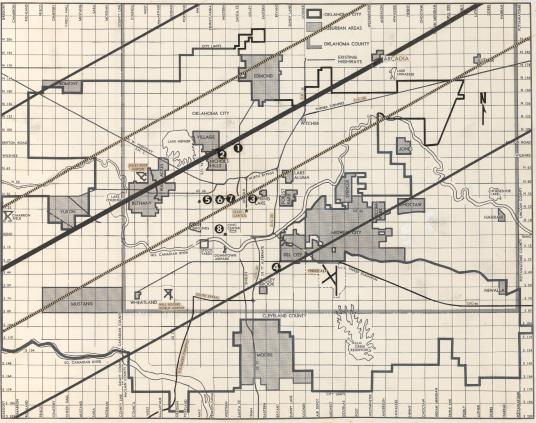

Although the Air Force planned to use several types of aircraft to make the flights, including F-101 Voodoos, F-106 Delta Darts, and fourengine B-58 Hustlers, most flights were made in F-104 Starfighters. Designed by the legendary engineer Clarence “Kelly” Johnson, the F-104’s slender body and stubby wings contributed to its nickname “missile with a man in it.” Powered by a single Pratt and Whitney J75 engine, the F-104 could fly at Mach 2.0 (twice the speed of sound) and could climb at the astonishing rate of 48,000 feet per minute.30 The F-104 was flown “clean,” meaning without fuel tanks or ordinance mounted on its wings. Speaking about boom tests over Oklahoma City, Air Force Lt. Col. Jack Price noted, “although the supersonic transport will be bigger and fly faster, the F-104s duplicate the airliner booms by flying lower.”31

The first flight over the city took place on February 3. Taking off from Tinker at 10:05 a.m., the F-104 became supersonic at 10:21 a.m., with the boom audible to Oklahoma City residents at 10:27 a.m. Technicians estimated the plane’s speed to be 1,210 miles per hour and the boom’s intensity to be 0.785 psf of overpressure.32 Flights were made at prearranged times announced in advance. A typical schedule called for booms at 7:00 a.m., 7:30 a.m., 9:30 a.m., 10:00 a.m., 1:30 p.m., 2:00 p.m., 4:00 p.m., and 4:30 p.m.33 Although Easter Sunday was planned as the only “boomless” day during the six-month project, there were days when weather prevented flights.34 For people on the ground, the full effect of each boom could be felt within four miles on each side of the aircraft’s flight path. A visiting writer for Popular Mechanics magazine wrote, “I was brushing my teeth when the first one came over. There was a loud crack; the bathroom window rattled, and it seemed the floor and walls shook. . . . Twenty minutes later, while eating breakfast in the motel restaurant, it happened again. . . . If you’re used to it, you can almost ignore it. I wasn’t and I didn’t.”35 Besides Oklahoma City, the flight path crossed in close proximity to the towns of Washita, Anadarko, Gracemont, Minco, and Union City.36 Although much lower in intensity, the booms could be heard up to twenty miles away. By late afternoon on February 3, the FAA had received seventytwo complaints.37

Within a week of the first flight, the FAA had recorded 655 complaints.38 After a total of thirty-four booms, FAA engineers reported

no damage to the test houses, with one technician suggesting that the structures would experience more significant strain from a passing freight train or the slamming of a bedroom door.39 However, there were reports of damage to other structures, including the city’s two tallest buildings, which sustained 147 broken windows.40 Angry citizens sent letters to Oklahoma City Mayor Jack Wilkes, FAA Administrator Halaby, Oklahoma Senator Mike Monroney, and Lyndon B. Johnson.41 Senator Monroney wrote back to every person who contacted his office, whether in favor or in opposition to the booms. A few residents sent letters to local newspapers, such as Lester W. Ellis, who wrote, “I knew before last week started that I wasn’t going to like sonic booms. Nothing has happened to change my mind.”42 A letter to the editor published on February 13, 1964, noted, “Perhaps the booms don’t seem to bother downtown, but you should come out to Lake Hefner area and take a listen . . . I submit that these tests are a public nuisance in the legal concept of a gross invasion of privacy by any standard.”43 Another boom opponent wrote, “Why six months? You have already gotten reactions. Is it inefficiency which requires that much time, or just purposeful irritation?”44 Others wrote in support of the booms, including bankers, business owners, medical doctors, insurance executives, and church pastors.45 One stated that the “minority” of people opposed to the booms, were “against anything that is progressive.”46

Among the F-104 pilots who made runs over Oklahoma City was twenty-seven-year-old First Lieutenant Edward “Ted” Hopkins. A recent US Air Force Academy graduate, 1st Lt. Hopkins was part of the 331st Fighter-Interceptor Squadron based at nearby Webb Air Force Base in Big Springs, Texas. Hopkins came to Tinker on a temporary assignment with thirty enlisted airmen and four other officers.47 He was selected for sonic boom missions, in part, because more senior officers considered the straight and level flights to be unglamorous.48 Each aircraft was maintained by a crew chief and two assistants. To acknowledge their new mission, ground personnel stenciled “Sooner Boomer” on the fuselage of each plane, just above the wing. As Hopkins explained, after his F-104 completed its ground roll, it accelerated rapidly using afterburner. Often flying through clouds, Hopkins and other pilots relied on navigation instruments as well as radar guidance from controllers on the ground. The F-104s could make two sonic boom runs on one tank of fuel with each boom created according

to a precise schedule. After completing the first two runs of the day, Hopkins would return to refuel in preparation for runs three and four. The process continued for a total of four sets of two runs. Between each pair of booms, he would find an altitude to loiter before returning to the starting point for his next run.49 Air Force Captain Samuel H. Fields was another pilot who flew sonic boom missions over Oklahoma City. Fields discovered that pitching the nose of his F-104 down just before breaking the sound barrier would produce an extra “pop” in the boom.50 Fields could not hear the noise made by his aircraft since a sonic boom cannot be heard inside the airplane that creates it.51 Another pilot was thirty-three-year-old Captain Richard Durant. An Oklahoma City native, Durant had already logged 130 hours flying F-104s before he began making boom runs.52

Unable to see the small fighter aircraft flying high over the city, most Oklahoma City residents believed the flight path was directly

over their homes. One Sunday afternoon, Hopkins was asked to fly the route “low and slow” so that residents and members of the media could see his aircraft and flight path. It was necessary to pitch the 104’s nose up to a high angle to stay airborne while flying at a slow speed. As Hopkins exited his aircraft after the demonstration, he saw two Air Force colonels and two men in civilian clothing walking toward him. One of the colonels asked if he was okay and if the aircraft had sustained damage. After inspecting his F-104 and reporting no damage, Hopkins was told that at least two people on the ground had fired guns at his plane during the demonstration flight. He also learned that the men in civilian clothing were Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) agents.53

Some residents were not bothered by the booms. Jimmie Sorrells noted, “My family didn’t mind it one bit. In downtown Oklahoma City, in the Skirvin Tower where I work, we could hardly hear or feel the booms.”54 Others became accustomed to the precise schedule maintained by the Air Force, with workers at one construction site using booms to signal breaks.55 Ron Roby, who worked for Gulf Oil, remarked, “you could set your watch by the time you would hear the booms pass over the office.”56 Others were less enthusiastic, such as a farmer who complained that the noise caused his cows to stop producing milk.57 One woman claimed that the booms made her furniture shrink. Another said they caused her electric clock to run backwards.58 Northwest Oklahoma City resident H. M. Bickel noted, “The booms are hard on anyone who hasn’t had Marine basic training.”59 After three weeks of booms, the League of Women Voters voiced opposition.60 Media outlets outside the state also took notice. An editorial in The New Republic stated, “Not since 1884, when land ‘boomers’ from the East had to be repulsed by US troops, has this city been so up in arms.”61 Some local anti-boom groups, including Ban the Booms, argued that people’s constitutional rights were being taken away by the government.62

While some residents came out in opposition, most state and civic leaders spoke in favor of testing. Known locally as Mr. Chamber of Commerce, Stanley Draper referred to the booms as “the sound of the future.”63 In February 1964, Oklahoma Governor Henry Bellmon went on record in support of the tests, saying, “My position is that the booms have not been a serious problem to Oklahoma City or its residents and I feel it would be a serious mistake to take action that would

to reporters, 1964 (2012.201.B1192.0121, Oklahoma Publishing Company Photography Collection, OHS).

cause these tests to be cancelled.”64 Pro-boom groups emerged under names such as Citizens for the Advancement of Oklahoma City.65

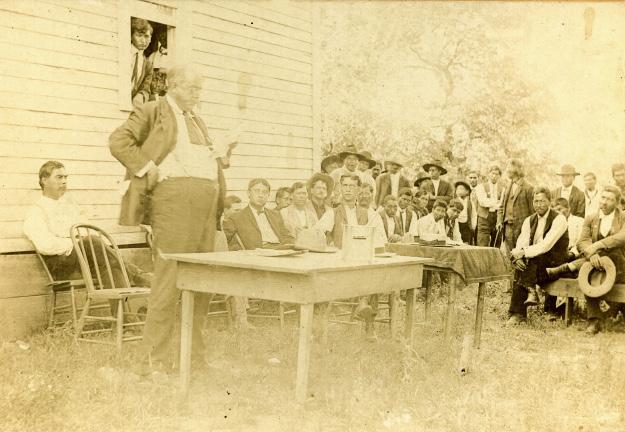

Before the end of February 1964, supporters and opponents began flooding Oklahoma City Council meetings.66 Recalling the council chamber packed with pro-boomers and anti-boomers, news reporter Kay Dyer remarked, “The city council meetings during those days lasted for hours, and hours, and hours.”67 Facing a backlash of boom opposition, the Council met on February 25 and voted 7–0 in favor of a resolution to ask the FAA for a three-month suspension of the tests to allow an assessment of boom impacts on people and property.68 The next day, Gordon Bain, FAA deputy director in charge of the tests, told a reporter that his agency would consider suspending the project if the city council sent a formal request to Washington, DC.69 FAA Administrator Halaby weighed in during a television interview on February 27, saying, “If the people here do not want the tests, we will revise or discontinue them.” In the same interview, he noted that other cities had expressed interest in hosting the project.70 The day after the vote, The Daily Oklahoman published an editorial saying that the city council’s decision did not reflect the sentiment of the whole community and that the resolution jeopardized the city’s “favorable impression as a forward looking aviation center.”71 On February 28, the Northwest Oklahoma City Chamber of Commerce, the Yukon Chamber of Commerce, and the Del City Chamber of Commerce went on record in favor of continuing the test.72 Not wanting to appear unsupportive, the Oklahoma City Council voted to rescind its earlier resolution.73

Pressure on the Oklahoma City Council continued into early March. Boom supporters attending council meetings wore blue cards featuring the letters SST, while opponents wore cards that said “Stop Sonic Tests” or “Ban the Boom.”74 At one meeting, a representative of an anti-boom group presented council members with a petition containing 704 signatures from people opposed to the test.75 Among them was Ward One City Councilman William C. Kessler, who argued, “people’s basic human rights are being ignored. We’re being used as human guinea pigs.”76 The pro-boom Oklahoma City Chamber of Commerce came out with its own petition signed by 16,758 citizens favoring a continuation of the tests.77 Later that month, the Council voted 5–2 in favor of a statement saying that it had no authority or jurisdiction over the test.78

138 While the City Council attempted to address citizen concerns, the FAA received a steady stream of damage claims. Among them were a $15,000 request by a farmer whose chickens had stopped laying eggs and a claim by a man whose seeing eye-dog was too frightened to perform its responsibilities. While the vast majority of claims were modest—broken windows or cracked ceilings—a few involved potentially life-threatening situations, such as a six-year-old who narrowly escaped being hurt when the ceiling of his home collapsed.79 Reacting to requests for compensation, an FAA engineer suggested that the city was filled with substandard dwellings that did not meet building codes.80 The FAA made it known that the burden of proof fell on residents to demonstrate that booms had damaged their property. Nearly ninetyfive percent of claims submitted were rejected.81 Some whose claims were turned down complained to their representatives in Congress. Displeased with FAA’s manner of dismissing claims, Senator Monroney wrote to FAA Deputy Director Bain with a copy of a damage claim denial shared by one of his constituents, noting, “Absolutely no explanation is given as to how the decision to deny the claim was reached.” Monroney’s letter also noted that he hoped that “procedures will be set up to guarantee that all citizens submitting claims for property damages will be treated fairly and their claims given careful consideration.”82

In May 1964, a group of anti-boomers attempted to stop the test in state court. After seeing the evidence presented by the plaintiffs, Oklahoma State Judge Boston W. Smith granted a temporary restraining order on May 13, directing Halaby, Air Force Chief of Staff General Curtis LeMay, and twenty other FAA and Air Force officials to halt the tests. On the day the restraining order was issued by the court, Halaby contacted representatives of the National Academy of Sciences with an urgent request to form an advisory panel of scientists who would provide guidance on boom research.83 One day after it was issued, the restraining order was rescinded by US Federal Judge Stephen Chandler.84 Soon after, an editorial appearing in the Saturday Review argued, “If the people of Oklahoma City cannot obtain the help of the law to save themselves from being used as subjects of an experiment by a distant government, can any American citizen anywhere feel secure against invasion of his body and mind at any official’s whim?”85 Another editorial published in The New York Times suggested, “never were so

An Oklahoma City Council meeting, 1964 (2012.201.OVZ001.2707, Oklahoma Publishing Company Photography Collection, OHS).

August C. Carlson was a former boom claim investigator, 1964 (2012.201.B1192.0124, Oklahoma Publishing Company Photography Collection, OHS).

many people bedeviled by so few, as with these new monsters of noise and terror.”86

By July 1964, overpressures produced by the eight daily sonic booms were twice as strong as the ones created in February.87 Concerned about property damage, the FAA requested volunteers to have their homes inspected three times a week for the remainder of the test period.88 Despite the increase in boom intensity, opinions of city residents remained mixed. A July 1964 survey of 250 residents by The Oklahoma City Times found 118 respondents supportive of the test and ninety-one opposed. Comments ranged from, “I hate them if that’s plain enough for you,” to “anything that is going to be helping our country is fine with me.”89 Individuals and anti-boom organizations continued to pressure city council members and politicians to demand that the FAA stop the test. Mark Weaver, the FAA’s public relations officer assigned to the project, received death threats and was burned in effigy.90 Oklahoma City Council and Chamber of Commerce members also received threats.91

On July 28, the Oklahoma City Council voted 4–3 to ask the FAA to stop the test. The request was submitted five days before the sixmonth project was scheduled to end.92 On July 30, the FAA terminated the sonic boom test over Oklahoma City, with the final boom flight taking place that day at 1:20 p.m. Flying in an F-101 Voodoo, the project’s last run was made by Captain Robert C. Mali.93 The FAA reported the total cost of Operation Bongo II to be $1,039,000 (about $10 million in 2025).94

Soon after announcing the completion of the test, FAA Administrator Halaby presented citations acknowledging the efforts of city and state officials in “contributing significantly to the future of aviation in the United States.”95 An FAA statement noted, “in the years ahead the citizens of Oklahoma will take pride in their participation and contributions to the national supersonic transport development program.”96 Halaby made stops in Oklahoma City to visit people who had complained about property damage. Among them was Helen Waddy, who showed the administrator a five-foot hole in the ceiling of her bungalow on Northwest 15th Street. Mrs. Waddy remarked, “I don’t think they should do this to another community, I really don’t.” As Halaby left, Mrs. Waddy asked how his name was pronounced, to which the administrator replied, “Well, in Oklahoma City, it’s mud.”97 Over the testing period,

A diagram of the cones of sound generated by the supersonic planes, 1964 (2012.201. B1192.0120, Oklahoma Publishing Company Photography Collection, OHS).

the FAA and Air Force received 15,116 telephone calls and letters complaining about the booms. Of these, 9,594 alleged property damage.98 With testing complete, FAA analysts began reviewing structural data from test houses and interviews with residents. One finding was that weather conditions caused the intensity of booms to be greater on cool, moist days and less severe on hot, dry days.99 The survey of residents was also revealing. Although research showed no significant damage to test houses, forty percent of respondents believed their homes had been damaged.100 The duration of the test and the increased overpressure in later weeks may have contributed to a decline in the percentage of people who could accept the booms. At the end of the first eleven weeks, ninety percent of respondents felt that they could accept eight daily booms. However, that number dropped to eighty-one percent at the end of the next eight-week period and seventy-three percent during the final week of the test. During the final week, twenty-seven percent said they could not live with sonic booms.101 Also noteworthy was that many of those interviewed believed there was little point in complaining.102

With test houses showing little significant damage and the public opinion survey suggesting that most people could live with sonic booms, FAA Administrator Halaby urged the federal government to continue the SST Program.103 Despite his enthusiasm, some newspapers took a dim view of the motivations behind the test. A February

1965 issue of The Saturday Evening Post speculated that the booms in Oklahoma City, “will turn out to have been not a test of the possible but a conditioning for the inevitable.”104 The FAA continued collecting data in the months following the Oklahoma City test. Twenty-one buildings at White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico were subjected to sonic booms between November and February 1965 using boom overpressure intensities as high as 5.0 psf to provide more conclusive evidence of potential structural damage.105 Hoping to mitigate complaints from the Oklahoma City test, the Air Force flew twenty-two sonic boom missions over Chicago in February and March 1965, resulting in tens of thousands of dollars in additional damage claims.106

On July 1, 1965, Najeeb Halaby stepped down as FAA administrator. Speaking at the swearing-in ceremony for his successor, President Johnson reaffirmed the nation’s commitment to move forward with the SST Program, noting that he would ask for $10 million over eighteen months to support research and development for supersonic passenger aircraft.107 The campaign to project a positive image of the program continued with Boeing Aircraft distributing the film You and Me and the SST, narrated by journalist Bob Considine.108 With more frequent conversations about how to cope with sonic booms, Popular Mechanics published an illustration showing a "boom proof" house featuring extra-small windowpanes.109

To expedite the processing of Oklahoma City area damage claims, the FAA hired the Remmert Adjustment Company.110 As of August 1964, 208 of 4,202 claims had been deemed to have merit. Most of these were small, averaging only $50. By June 1965, the FAA had paid just $16,597 for property damage caused by booms, including $1,890 to repair broken glass in St. Patrick Catholic Church, located on North Portland Avenue.111 With the FAA unwilling to provide compensation for the vast majority of claims, a few residents filed lawsuits, including a one billion dollar claim against President Johnson for “mental, physical, and nervous” damage.112 Judge Chandler dismissed two federal lawsuits on the grounds that a federal agency could not be sued without its consent.113 A few individual suits were successful. In mid-February 1967, a federal court awarded $10,000 to Bailey Smith for damage to his Oklahoma City home located on Northeast 67th Street.114 Another ninety-seven claims went to trial in federal court in mid-April 1967.115 After waiting more than four years, many city residents received compensation in 1969 when the government lost a class action suit.116

By the late 1960s, public enthusiasm for the SST Program faded. Noting delays and cost overruns, two reviews commissioned in 1969 questioned the financial viability of the SST Program and recommended an end to public funding.117 Anti-boom organizations had also begun emerging from within the growing environmental movement. Among them was Citizens League Against the Sonic Boom, organized by Harvard University physicist William A. Shurcliff.118 Another factor was growing fear about unknown environmental impacts associated with supersonic aircraft, such as damage to the atmosphere’s ozone layer.119 In 1971, both houses of Congress voted to halt funding for the SST Program. Overnight, 120 orders for Boeing 2707s were canceled, resulting in the loss of tens of thousands of jobs.120 Two years later, the FAA banned non-military supersonic flights over the US.121

For its part, the FAA’s supervision of the sonic boom test over Oklahoma City demonstrated that the agency was not prepared to oversee research involving human subjects. The agency also did a poor job handling complaints, addressing legal claims, and dealing with the public. Following the test, the FAA returned to its role as a regulatory agency. The Oklahoma City sonic boom test also represented the nadir of FAA Administrator Najeeb Halaby’s influence over the SST Program. Following the test, management of the program shifted from Halaby and the FAA to the President’s Advisory Committee on Supersonic Transport, chaired by Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara.122 McNamara’s skepticism for the program could be seen during the committee’s first meeting on April 13, 1964, when he noted, “the figures that I have been presented to date show the unprofitability of the supersonic to be so great that I have no confidence that following down this course of design development will ever lead to a profitable airplane.”123

In hindsight, the battle over sonic booms was a significant triumph for the environmental movement, which popularized the notion of noise as a form of pollution. Restricted from flying over the US mainland, the Concorde carried passengers from 1976 to 2003. With a oneway ticket between Washington, DC, and London, costing 431 Francs in 1976 (about $2,800 today), the Concorde was never affordable, nor was it profitable for its owners. When retired for financial reasons by British Airways and Air France in 2003, the fleet of Concordes amounted to just twelve aircraft.124

Several factors contributed to the federal government’s decision to end funding for the US SST, including technical challenges, high costs,

and negative public opinion. Without question, the sonic boom test in Oklahoma City helped tip the scales against the SST by presenting an unfavorable vision of day-to-day life with low-intensity booms. Some viewed the decision as a lost opportunity and setback to progress. Writing about the project, author Jim Eckles stated, “The United States was probably very lucky it didn’t build the SST . . . It could have bankrupted many an airline and required huge subsidies.”125 Others suggested that the program’s high cost outweighed its benefits. As noted in an editorial published in the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, “The proposed demand for supersonic transport planes (four hundred airliners between 1970 and 1990) seems altogether out of proportion to the imposition on society which it would entail.”126 Today, the 1964 sonic boom test is an event remembered by longtime residents of the Oklahoma City area. We should be thankful for the sacrifices they made. By serving as test subjects for six months, residents of Oklahoma City and surrounding communities helped save tens of millions of fellow Americans from a future shaped by an endless succession of annoying booms.

* Thomas A. Wikle is a retired professor of geography at Oklahoma State University and the author of several previous articles published in The Chronicles of Oklahoma that explore Oklahoma’s rich aviation history. In his spare time he works as a commercial pilot and flight instructor at Stillwater Regional Airport.

The photograph on page 126 shows sonic boom protestors at an Oklahoma City city council meeting, 1964 (2012.201.B1192.0109, Oklahoma Publishing Company Photography Collection, OHS).

1 Ken Raymond, “Jets Broke Speed Barriers—and Tempers,” The Daily Oklahoman, September 18, 2006.

2 Eli Dourado and Samuel Hammond, Make America Boom Again: How to Bring Back Supersonic Transport (George Mason University, 2016), 9.

3 “Sonic Boom Test in Oklahoma City,” The New York Times, January 14, 1964.

4 Mission Sonic Boom, US Air Force film, PF No. 19704, 1959, posted July 10, 2021, by Periscope Films, Youtube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q5BUVPTEEns.

5 “Freedom Has a New Sound,” Flying, September 1955, 5; “Sonic Boom,” Air Force, July 1954, 33.

6 Sonic Boom (United States Air Force Office of Information, 1966).

7 Salman Baig, “Why You Never Got to Fly the American Concorde: The Boeing 2707 SST Story,” Medium.com, January 7, 2024, https://medium.com/@salman12788/ why-you-never-got-to-fly-the-american-concorde-the-2707sst-story-009217e6b871.

8 David Schneider, “The New Supersonic Boom,” IEEE Spectrum, August 16, 2021, https://spectrum.ieee.org/the-new-supersonic-boom.

9 David Susman, “The Oklahoma City Sonic Boom Experiment and the Politics of Supersonic Aviation,” Radical History Review 2015, no. 121 (January 2015), 175.

10 Susman, “The Oklahoma City Sonic Boom,” 176.

11 “What Happened to the American SST?” The NDC Blog, January 28, 2017, https://declassification.blogs.archives.gov/2017/07/28/what-happened-to-the-american-sst/.

12 Baig, “Why You Never Got to Fly.”

13 “Jets Broke Speed Barriers.”

14 Karl Kryter, “Sonic Booms from Supersonic Transport,” Science, January 24, 1969, 359.

15 Matthew Hudson, “Will We Ever Fly Supersonically Over Land?” The New Yorker, June 25, 2021, https://www.newyorker.com/tech/annals-of-technology/will-weever-fly-supersonically-over-land.

16 “SST Report Stresses Role of Boom Testing,” The Daily Oklahoman, March 3, 1964.

17 Robert Burkhardt, “Sonic Boom Town,” The New Republic, August 22, 1964; “Sonic Boom Test in Oklahoma City,” The New York Times, January 14, 1964.

18 Osita Nwanevu, “Boom and Bust,” Slate, July 29, 2014, https://slate.com/technology/2014/07/oklahoma-city-sonic-boom-tests-terrified-residents-in-1964.html.

19 “City’s Boom Dispute Strays Off Course, FAA Official Claims,” The Daily Oklahoman, March 4, 1964.

20 “Persons Attending Sonic Boom Demonstration at Clinton Sherman Air Force Base,” folder 3, box 47, January 14, 1964, Monroney Collection: General Correspondence,

1962–68, Sonic Booms, Carl Albert Congressional Research and Studies Center, University of Oklahoma (hereafter cited as Monroney Collection).

21 Sonic Boom Brochure 6 (Federal Aviation Agency Office of Public Affairs, 1964).

22 John Skow, “The Sound of Progress,” The Saturday Evening Post, February 13, 1965, 25–6; “City No Volunteer as Site of Test, Air Official Says,” The Daily Oklahoman, February 28, 1964.

23 Nwanevu, “Boom and Bust.”

24 "Support Sought for Boom," The Chickasha Daily Express, February 26, 1964; “Cost’ll Shake You,” The Oklahoma City Times, January 31, 1964.

25 “FAA to Take City’s Pulse,” The Oklahoma City Times, January 14, 1964.

26 “MMAC Celebrates 75 Years—From Sonic Boom Studies to Emergency Evacuation Safety,” Monroney News vol. 7, no. 5, https://www.esc.gov/MONRONeYnews/archive/ Vol_7/CB/05_1.asp.

27 Paul Borsky, “Community Reactions to Sonic Booms in the Oklahoma City Area,” National Opinion Research Center Report, No. 101, (University of Chicago, February 1965): 13, https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/tr/pdf/AD0625332.pdf.

28 “Sonic Boom,” WKY Television news clip, posted May 16, 2014, by the Oklahoma Historical Society, Youtube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q5BUVPTEEns https:// www.youtube.com/watch?v=7XIVeTUZoKs.

29 “Boom Study to Start Monday,” The Chickasha Daily Express, July 31, 1964.

30 “Missile With a Man In It—the F-104 Starfighter,” Duotech, https://duotechservices. com/missile-with-man-on-it-f104-starfighter.

31 “Sonic Boom,” Changing Times: The Kiplinger Magazine, May 1961.

32 “Boom or Bang, Sonics Are Popping in the Sky Over City,” The Daily Oklahoman, February 4, 1964.

33 “Here’s the Boom Schedule,” The Daily Oklahoman, February 11, 1964.

34 “Sonic Booms End in Oklahoma City,” The New York Times, August 1, 1964.

35 Kevin Brown, “Ready for Your Daily,” Popular Mechanics, October 1964, 112–13.

36 “Boom Study to Start Monday,” The Chickasha Daily Express, July 31, 1964.

37 “Boom or Bang, Sonics Are Popping in the Sky Over City,” The Daily Oklahoman, February 4, 1964.

38 Nwanevu, “Boom and Bust.”

39 “Test Site Unhurt by Sonic Booms,” The Daily Oklahoman, February 11, 1964; Joseph Power, “Some Results of the Oklahoma City Sonic Boom Tests,” Materials Research and Standards 4, no. 11 (November 1964): A65.

40 Miguel Ortiz, “That time the Air Force bombarded Oklahoma City with sonic booms,” March 14, 2023, https://www.wearethemighty.com/mighty-history/ that-time-the-air-force-bombarded-oklahoma-city-with-sonic-booms.

41 Susman, “The Oklahoma City Sonic Boom Experiment,” 180.

42 “Who Needs Super Planes, Anyway?”, The Oklahoma City Times, February 14, 1964.

43 Robert Varga, “He Finds Sonic Booms Serious,” Oklahoma City Advertiser, February 13, 1964.

44 A. G. Dill to the Federal Aviation Administration, folder 5, box 47, March 18, 1964, Monroney Collection.

45 Mike Monroney to city and business leaders, folder 4, box 47, June 1964, Monroney Collection.

46 Dency Henley to Senator Mike Monroney, folder 6, box 47, June 8, 1964, Monroney Collection.

47 “F-104s Great Sonic Boomer,” Abilene Reporter-News, May 17, 1964.

48 Edward “Ted” Hopkins, interview by Thomas A. Wikle, May 31, 2024.

49 Hopkins interview.

50 “Samuel H. Fields ’54,” Grip Hands, Summer 2012, https://www.usma1954.org/grip_ hands/memorials/20052shf.htm

51 John Kelly, “Remembering the Boom in Sonic Booms that Once Shook the USA,” The Washington Post, June 6, 2023.

52 “City Pilot to Fly in Boom Testing,” The Daily Oklahoman, January 15, 1964.

53 Hopkins interview.

54 “Who Wants to Fly at 2,000 MPH?” Oakland Tribune, January 17, 1965.

55 Rachard Clark, “Mysterious ‘Boom’ Comes 50 Years after Infamous Oklahoma Sonic Boom Study,” Newson6, January 2, 2014, https://www.newson6.com.

57 “Sonic Boom Tests,” September 17, 2007, posted November 29, 2017, by The Oklahoman Video Archive, Youtube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vc_2sgS1VcU

58 Nwanevu, “Boom and Bust”

59 Ed Dycus, “You Didn’t Miss a Thing,” Oklahoma City Advertiser, February 13, 1964.

60 “Boom Opponents Regrouping Forces,” The Chickasha Daily Express, February 27, 1964.

61 Burkhardt, “Sonic Boom Town,” 5.

62 “Ban the Booms,” folder 4, box 47, Monroney Collection.

63 Pendleton Woods, Historic Oklahoma County: An Illustrated History (Historic Publishing Network, 2002), 52.

64 “Support Sought for Boom,” The Chickasha Daily Express, February 26, 1964.

65 Dave Klement, “Boom Forces Clash Today,” The Daily Oklahoman, March 3, 1964.

66 “To Boom or Not to Boom,” The Sapulpa Daily Herald, February 27, 1964.

67 “Sonic Boom Tests.”

68 “City Council’s Boom Letter Ready, The Oklahoma City Times, March 4, 1964.

69 John Lear, “The Era of Supersonic Morality,” Saturday Review, June 6, 1964.

70 “Sonic Boom,” WKY Television news clip.

71 “Bowing to Pressure,” The Daily Oklahoman, February 26, 1964.

72 “Support for Boom Tests Growing,” The Daily Oklahoman, February 28, 1964.

73 Lear, “The Era of Supersonic Morality,” 50.

74 “Tension Marks Boom Crowd,” The Oklahoma City Times, March 3, 1964.

75 “City Council to Send ‘Neutral’ Boom Letter,” The Oklahoma City Times, March 3, 1964.

76 “Jets Broke Speed Barriers.”

77 “City Council to Send ‘Neutral’ Boom Letter,” The Oklahoma City Times, March 3, 1964.

78 “Council Denies Any Authority for Objection,” The Daily Oklahoman, March 4, 1964.

79 "Ceiling Tumbles In; Owners Blame Booms," The Oklahoma City Times, March 20, 1964; Nwanevu, "Boom and Bust."

80 “City’s Homes Substandard, FAA Claims,” The Oklahoma City Times, June 19, 1964.

81 Ortiz, “That time the Air Force bombarded Oklahoma City.”

82 Mike Monroney to Gordon M. Bain, folder 4, box 47, July 13, 1964, Monroney Collection.

83 Lear, “The Era of Supersonic Morality,” 50.

84 Lear, “The Era of Supersonic Morality,” 50.

85 Lear, “The Era of Supersonic Morality,” 50.

86 “Sonic Boom,” Air Force, 33.

87 Susman, “The Oklahoma City Sonic Boom Experiment,” 169.

88 “Our Sonic Booms Involve ‘Voodoo’ Now,” The Oklahoma City Times, May 15, 1964.

89 “City Boom Reaction Mixed,” The Oklahoma City Times, July 31, 1964.

90 Skow, “The Sound of Progress,” 26.

91 Dan Verano, “People Are Being Subjected to Sonic Booms to See If The Rich Get Supersonic Planes Again,” BuzzFeed, November 9, 2018, https://www.buzzfeednews.com/ article/danvergano/supersonic-planes-nasa-sound-experiment.

92 “City Asks Boom Halt,” The Oklahoma City Times, July 28, 1964.

93 “Booms Ending, But Not Echo,” The Daily Oklahoman, July 31, 1964; Ortiz, “That time the Air Force bombarded Oklahoma City.”

94 Lawrence Benson, “Quieting the Boom: The Shaped Sonic Boom Demonstrator and the Quest for Quiet Supersonic Flight,” National Aeronautical and Space Administration, 2013, 18, https://www.nasa.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/QuietingtheBoomebook.pdf; “Aeronautics: Boom or Bust,” Time, December 11, 1964, https://time.com/ archive/6832415/aeronautics-boom-bust/.

95 “First Sonic Boom Test is Completed in Oklahoma City,” FAA Aviation News 3, no. 5 (September 1964), 3.

96 Burkhardt, “Sonic Boom Town,” 5.

97 “10 to 20% Object to Sonic Booms: FAA Gives Early Results of Oklahoma City Test,” The New York Times, August 4, 1964.

98 Jim Eckles, “How a Sonic Boom Study at WSMR Helped Kill Supersonic Transports,” Hands Across History, May 2010, 6.

99 Burkhardt, “Sonic Boom Town,” 6.

100 Borsky, “Community Reactions.”

101 Andrea O’Sullivan, “How the FAA Killed Supersonic Flight—And How it Can Revive it,” Reason, July 26, 2016, https://reason.com/2016/07/26/how-the-faa-killed-supersonic-flight/.

102 Borsky, “Community Reactions to Sonic Booms in the Oklahoma City Area,”

103 “SST Spurred by City Boom Test Findings,” The Daily Oklahoman, April 25, 1965.

104 Skow, “The Sound of Progress,” 26.

105 “MMAC Celebrates 75 Years.”

106 Benson, “Quieting the Boom”; “Aeronautics: Boom or Bust.”

107 Lyndon B. Johnson, Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States: Lyndon B. Johnson, Book One (Government Publishing Office, 1965), 714.

108 “You and Me and the SST,” Boeing Supersonic Transport SST Promotional Film 72732, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=730hKzBgu6c&t=1s

109 Brown, “Ready for Your Daily,” 116.

110 Larry Levy, “FAA Hires Experts to Probe All Claims of Boom Damage,” Oklahoma City Times, March 11, 1964.

111 “SST Spurred by City Boom Test Findings,” The Daily Oklahoman, April 25, 1965.

112 Nwanevu, “Boom and Bust”

113 Lear, “The Era of Supersonic Morality,” 49.

114 “$10,000 Boom!” The Daily Oklahoman, February 18, 1967.

115 “Judge Chandler Orders 97 Sonic Boom Cases to Trial,” The Daily Oklahoman, April 1, 1967.

116 “MMAC Celebrates 75 Years.”

117 Baig, “Why You Never Got to Fly the American Concorde.”

118 Lear, “The Era of Supersonic Morality,” 50.

119 David Kurlander, “You, Me and the SST: The Ozone Layer, Technological Noises, and Supersonic Transports,” Café.com, September 21, 2021, https://cafe.com/article/ you-and-meand-the-sst-the-ozone-layer-technological-noises-and-supersonictransports/

120 Baig, “Why You Never Got to Fly the American Concorde.”

121 Nwanevu, “Boom and Bust”

122 Mel Horwitch, “The Role of the Concorde Threat in the US SST Program,” Working Paper WP1306-82, Alfred P. Sloan School of Management, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, May 7, 1982, 6.

123 “What Happened to the American SST?” The NDC Blog, January 28, 2017, https://declassification.blogs.archives.gov/2017/07/28/what-happened-to-the-american-sst/.

124 Schneider, “The New Supersonic Boom.”

125 Eckles, “Sonic Boom Study,” 6.

126 L. Douglas DeNike, “Sonic Booms,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, November 1965, 25.

By Taryn M. Dixon*

“In 1902 it seemed to me that cattle ranching on a big scale was doomed but today ranching has returned under different conditions, and is a leading industry.”1 Writing in a 1959 The Chronicles of Oklahoma article, J. B. Wright reminisced about his youth in Indian Territory. Before statehood, Indian Territory was a cattleman’s haven, comprised of luscious plains filled with blooming prairie grass. In the mid-1800s, this land fed hordes of cattle as cowboys wrestled them up trails toward cattle markets in the north. At the same time, prospective settlers joined land runs, encouraging thousands of westward immigrants to establish homesteads. From a 1902 viewpoint, the land upon which the forty-sixth state would soon reside was prime ranching land. Why,

then, did a young J. B. Wright fear the downfall of cattle ranching and what were these different conditions that existed in Indian Territory?

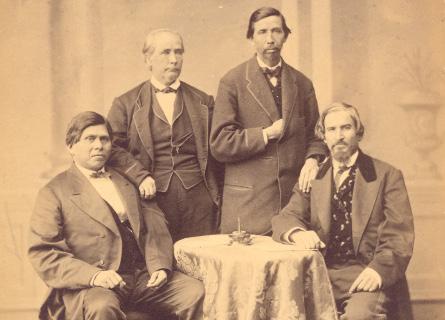

The answer resides not only in J. B.’s childhood exposure to cattle, but also in his citizenry.2 James Brookes Wright was the last child of Allen Wright, the principal chief of the Choctaw Nation from 1866-1870.3 In 1878, two years after J. B.’s birth, Allen lost his final campaign for chief.4 After his political career ended, Allen invested most of his time in his ministry studies and his ranching pursuits.5 It was here among his father’s livestock that J. B. understood cattle’s place in Indian Territory. In his eyes, and the eyes of numerous Choctaws in the late nineteenth century, the cattle industry was a tenet of the Choctaw Nation economy, and—even more importantly—the Choctaw Nation ran the cattle economy.6 Their legislation determined who could access land, who could introduce and sell cattle, and who could run cattle operations. Government intervention within the cattle industry promoted a staunchly anti-settler policy to aid internal economic development. This well-crafted legislation peaked at the very end of the nineteenth century when pressure from invasive settlers and US law resulted in the Choctaw Nation’s last effort to preserve the cattle market for its citizens: the Act of 1899. By the birth of the twentieth century, the world of cattle ranching in Indian Territory was defined by political negotiation and resistance.

Much of the scholarship analyzing the Choctaw Nation in the mid-to-late nineteenth century presents this period as marred with “federal complicity,” where the Choctaw government was intentionally referential to US powers.7 In her exceptional ethnography of the Choctaw Nation, Valerie Lambert depicts the very end of the 1800s as the beginning of the tribe’s demise—a “dismantling” of national sovereignty.8 It was an era of survival against the amalgamation of socio-political threats facing the Choctaws.9 The Act of 1899 was a moment of experimental nation-building in which the Choctaw Nation used the cattle industry to assert its sovereignty in response to threats of US governmental oversight, the invasive international cattle market economy, and settler intrusion.

To understand the significance of cattle as a mode of Native American resistance to colonization, we must understand cattle not only as resources but as representations of European expansion. Colonial settlers on the North American continent practiced raising livestock for

sustenance and profit. Furthermore, livestock raising also held ideological symbolism as a representation of civilization.10 Europeans believed their cattle embodied a sociocultural superiority over societies that did not practice similar livestock raising techniques. By the seventeenth century, cattle represented domestication, husbandry, and individual land use on which cattle could graze. In the Euro-American consciousness, all these patterns conveyed civilization. Thus, the acceptance of cattle in a society represented the civilizing of the cattle owner.11 Despite this expectation, the Choctaws—alongside many other Native groups throughout the continent—redefined the cattlehuman relationship.

Choctaws first acquired cattle through trade networks with Indigenous groups in the Gulf region. James Taylor Carson speculates that most Choctaw cattle in the early colonial period were from the Caddoans, who themselves got cattle from trade with the Spanish.12 The breed of cattle the Choctaws acquired at this time is unknown, though we may speculate that they were likely Spanish longhorn. Early colonial encounters tell us that “cattle were becoming a regular fixture on the Choctaw landscape” by the early eighteenth century.13 The acceptance of cattle into Choctaw society was by no means uncontentious— Choctaws likely began to slowly explore livestock raising as increased colonial presence led to decreased hunting availability and environmental effects. Cattle raising eventually became a substitute for wild meat.14 If cattle came to replace deer, their role within the community in the early colonial period more closely resembled wild grazers than European domesticates. As livestock became mainstays, Choctaws found that ranching fit within their gendered conceptions of society. In a society where farming and planting were women’s work, the Choctaw dismissed cattle raising as a solely male occupation. Historical analysis indicates livestock raising was a mixed-gender practice, with women milking and cooking the meat and men slaughtering them.15 Because cattle grazing required significantly less labor than arable farming, the supervision of livestock was often allotted to men.16

The ranging practices of these Choctaw cattle hardly met the standard of livestock raising as practiced by colonialists.17 Furthermore, cattle were raised on tribal lands rather than individual lots. Comparatively, in England, cattle required their owner to retain land for pasture. By bypassing the need for privatized land, small-scale cattle

ranching guaranteed Choctaw citizens could have access to the benefits of the market economy without slicing up their territory. Up through the early nineteenth century, cattle raising grew as a reliable form of economic stability and was standardized as a form of surplus production. As James Taylor Carson states, “Choctaw men and women relied extensively on livestock to put the nation back on a sound economic footing. Stock raising, after all, fit perfectly within the regional market economy of the Lower Mississippi Valley and within the marketplace economy of the Choctaws.”18

By the end of the colonial period, cattle were common in Choctaw society. However, cattle practices differed from those observed in Euro-American settlements. Cattle within Choctaw society represented what Virginia DeJohn Anderson refers to as “selective acculturation.”19 Cattle served as means of market interaction and resource access, aligning with their use in European ideologies. Richard White conducted significant research on how the tribe responded to cattle in various ways across their landholdings in the southeast. This included stealing cattle from settler herds for food, as well as

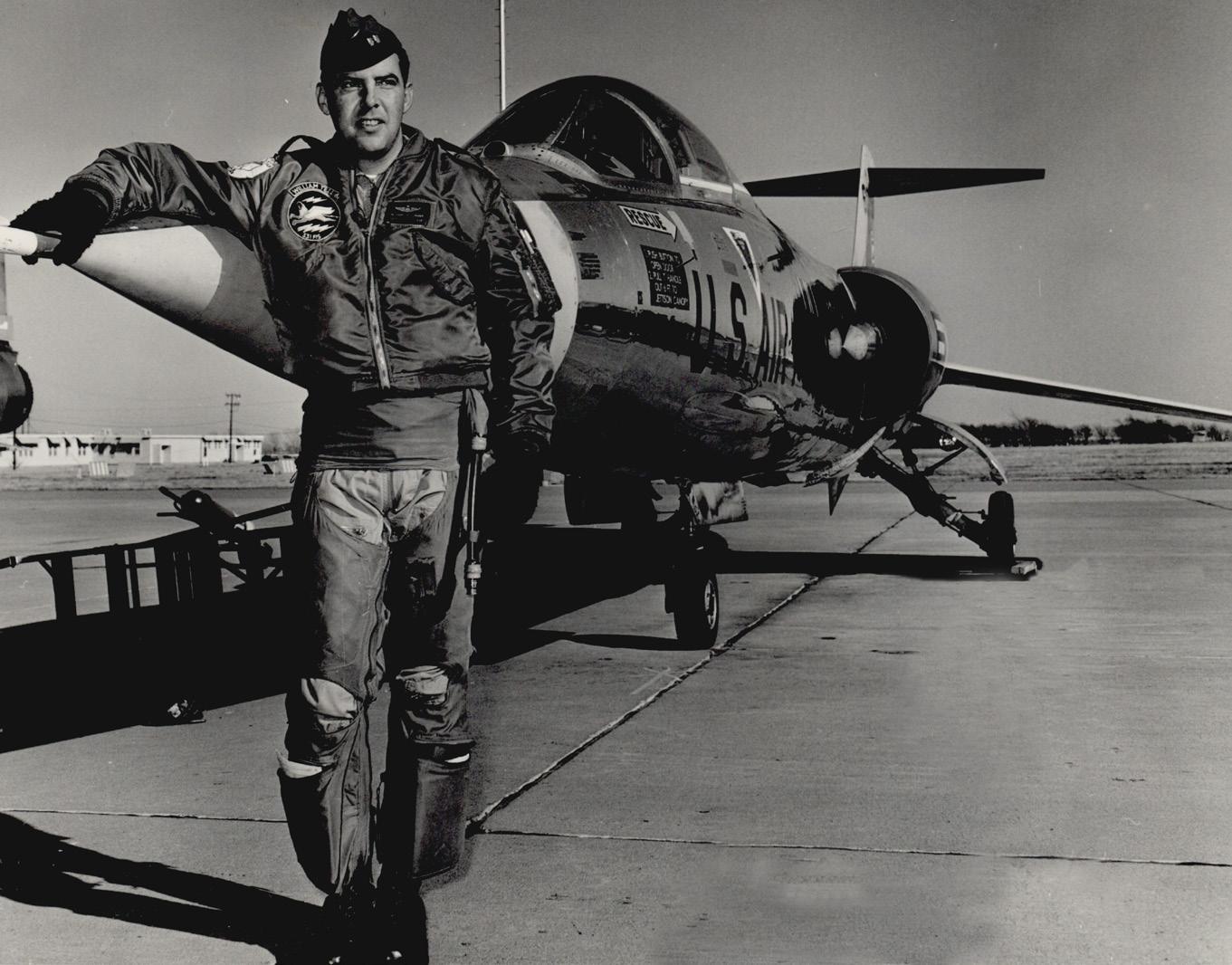

Allen Wright’s home in Boggy Depot, Indian Territory, c. 1890 (6222.2, Oklahoma Historical Society Photograph Collection, OHS).

The Wright family at the Allen Wright home, 1941 (13736, Oklahoma Historical Society Photograph Collection, OHS).

predominantly mixed-blood or intermarried white citizens establishing ranching practices in peripheral areas of the Choctaw homeland by the nineteenth century.20 This diverse adaptation method meant that some groups in Choctaw society engaged more closely with the cattle market.

The Indigenous practice of selectively acculturating colonial domesticates resulted in tension between settlers and Natives. In the Choctaw case, where cattle were tucked into social norms, settlers realized “that Indians intended to pick and choose among the items on the English agenda for native cultural transformation. Owning cows did not make them Christians, much less Englishmen.”21 The failure to make Choctaws, or any other Indigenous people, into Euro-Americans resulted in a revamped settler project: relocation.

Fifty-six years after his people’s relocation to Indian Territory, J. B. Wright was born in the far western stretches of the Choctaw Nation. He grew up in Boggy Depot, a bustling town a few miles southwest of modern-day Atoka. His hometown was located near the Military Road, which connected Fort Washita in the Choctaw Nation to Fort Gibson in the Cherokee Nation. Along this route, immigrants, traders, and cattle drivers kicked up clouds of red dirt as they passed from places like St. Louis and Kansas City, Missouri, towards Dallas or Austin, Texas. His father was a busy man in that corner of Indian Territory, but he always had a ranch venture on the side. Such practice was standard for many economical Choctaws, though most farmers could not afford significant operations like the elder Wright. In this land, where water drained into the Red River, where citizens spoke Indigenous languages, and where the range was open, cattle was king.

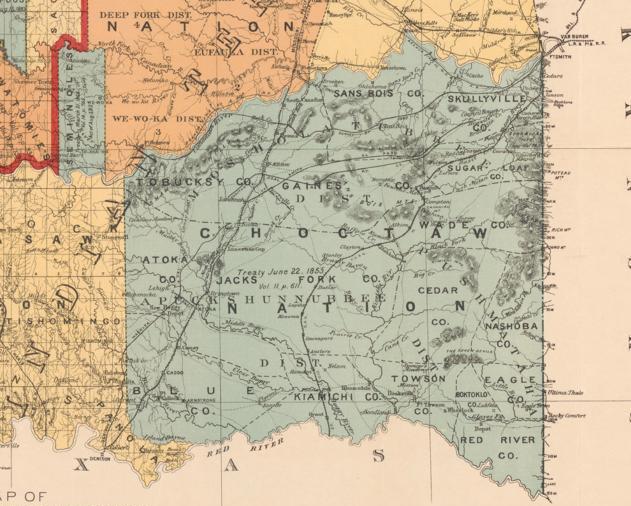

The land of the Choctaw Nation was held in communal ownership, as had been the practice in their ancestral homelands.22 Indian Territory (or, at least, the portion that the Nation controlled) was perfect grazing land. Citizens raising cattle could turn their heads on the open range, where they free grazed on natural hay: “Most of the whole country was outside land with immense canebrakes and [cattle would] forage in all the valleys and on the creeks between the mountains, and . . . would live and do well all winter,” a white settler reminisced.23 As J. B. noted, “I well recall when the western part of the Choctaw Nation and bordering parts of the Chickasaw Nation was mostly prairie with free, open range and grass growing belly deep to a horse.”24 All citizens,

including J. B. Wright, saw cattle stray from their owners’ ranch with minimal hindrances.25 These cattle would be branded and moderately supervised until roundup. Roundups were large-scale collections of livestock that were joyous, weeks-long affairs comprised of numerous teams working independently or as hired hands.26 Cattle were rarely penned, and often only for branding purposes. Some range cattle had horns, making adult cattle branding a dangerous work that required a skilled cowboy to rope a specific head out of a group. When working for his father or other ranching family members, J. B. preferred branding calves, since their youth was not a threat. He would grab the calf around its neck, shove his knee into its underbelly to hitch it up, and wrestle it to the ground.27 Without a doubt, ranching was laborious business, and many Choctaw citizens were uninterested or incapable of dedicating their full time to ranch maintenance. Many hired settlers as workers to watch over their property, including J. B.’s father: “When [dad] first established the ranch, he hired a white man, Walter van Hoosier, as foreman to look after the livestock, and he himself worked on a salary to carry on the ranch business.”28 The cattle produced from ranching operations might be sold within the Nation, but the best profits came from northern markets. Reportedly, Choctaw cattle “brought top prices on the Kansas City, Chicago, and Saint Louis markets.”29

Unfortunately, the profitability of the nation’s farming and livestock resulted in threats from outsiders, who wished to extract the benefits of the carefully curated cattle market. The Choctaw Nation had the unfortunate luck of being well-situated between two cattle-centric economies. To the south, the Spanish heritage of the Texas borderlands resulted in numerous prosperous ranchos; to the north, an expanding US economy meant a rise in beef demands in growing population centers. Prospecting ranch owners settling near the Texas-Mexico border hungrily eyed Indian Territory as a tunnel for hired cowboy outfits to transport their property to markets in the Midwest.30 On their drives, cowboys could easily feed their wares on open-access tribal lands from the Red River to the Kansas-Missouri border. Although the financial benefits of such drives were occasionally profitable, many Choctaw citizens were frustrated with the trampled, overgrazed fields that foreigners created with their hundreds of heads of cattle. Worse still, many Texas herds transmitted tick-borne diseases

that infected local cattle herds.31 Thus, cattle trails such as the Military Trail resulted in non-citizens using national graze lands for their cattle—in other words, an invasion.

The accessibility of land bolstered non-citizen settlement as well. Emphasizing Indian Territory as a resource was perhaps the best way to express its value to prospective settlers. As iterated repeatedly in first-hand accounts, the land the Choctaw Nation was luscious, composed of fields blossoming with wild grasses and creek beds, from which alluvial soils nourished a plethora of viable food for livestock. For enterprising men coming in from the far eastern stretches of the US, the short, mild winters of Indian Territory and the proliferation of grasses were a majesty of nature.32 To speculating westward immigrants, the unfenced plains of prairie grass of the Choctaw Nation appeared unclaimed. Many settlers easily claimed unoccupied portions of land through the payment of quaint sums.33 One Virginian named Richard Morgan relocated to Durant, Indian Territory, in 1893, with funds earned while working in the cattle business in Texas. His new operations north of the Red River were centered in what he called, “the heart of the finest grazing country I had ever seen, with good pens and yards for shipping cattle.”34

By the 1890s, non-citizens could not operate businesses within the Choctaw Nation and the only way to gain citizenship was through marriage, which Morgan promptly did.35 His wife, Loerna (née Nail), was a Choctaw woman from a well-educated family. Loerna’s paternal grandfather was Robert Nail, a chairman of the Rabbit Creek Colony and a Choctaw interpreter. Despite his white heritage, Morgan was proud of his community and believed himself to be accepted into it. When Morgan arrived at the Caddo Courthouse in 1898 to receive his and his wife’s allotment, the Choctaw registers joked that they would permit him to file for his parcel—but not another intermarried white man who accompanied him.36 Like many other intermarried citizens, Morgan based his capital on ranching. His hometown of Durant had easy access to the railroad, and he made multiple trips up the Kansas, Missouri, and Texas railway (later renamed to the Missouri Pacific Railway) to sell cattle at auction in St. Louis.37 It was not only individuals who staked their familial and financial claims in Native lands: corporations and businesses rushed into Indian Territory as well. One 1888 Cherokee Nation newspaper emphasized cattle syndicates’

“cupidity” for Native-held land.38 By 1890, only one in four individuals in the Choctaw Nation were citizens.39

The Choctaw Nation’s transition into a settler-dominated space with widespread practices of capital accumulation through private venture was a systematic and well-curated strategy of the settler state to pressure assimilation.40 Economic dependency and settlement patterns were not directly controlled by the US Federal government, but they were developments born out of intentional practices of jurisdictional claiming and legislative encouragement to privatize. Because US legislation portrayed Indian Territory as a region under US oversight, and because land use practices of the Choctaw and the other Five Tribes did not abide by Euro-American standards of ownership, westward migrating settlers inevitably viewed settling Native-owned land as legally permissible. Through the nineteenth century, the Choctaw government had been forced to accede to US expectations, reinforcing a paternalistic relationship with the federal government that had been steadily rising. The 1898 Curtis Act is one such example. This US statute erased Choctaw and Chickasaw sovereignty by abolishing their courts and requiring US executive approval for all tribal laws.41 The Curtis Act was born out of the 1887 Dawes Allotment Act, which was intended to parcel land to enrolled tribal citizens to enforce individualized land use.42 The implementation of Allotment represented an oppressive form of federal oversight, demanding that Native nations across the continent abide by Western civilization land use practices, further incentivizing individual involvement in economic forms, specifically capitalism. Despite the introduction of these federal laws, citizens of Indigenous nations responded in complex, diverse forms. Thus, the effectiveness of Allotment and its effect on the Choctaw Nation social and cultural perceptions is unknown and requires more historical study.

The intrusion of the foreign cattle market (and foreigners at large) was not met with total complicity from the Choctaw government. Throughout the 1880s and 1890s, the Choctaw National Council continuously passed bills that asserted administrative control over the cattle market and those non-citizens who abused it. The most significant of these bills came in 1885 when it became illegal for Choctaws to hire non-citizens to “take charge of their cattle.”43 This bill was one in a series that obstructed foreigners from locating work in the Nation

while increasing the number of jobs available to legal residents. Over time, the regulations for cattle grazing became stricter. Within two years, it would be illegal for individuals, citizens or otherwise, to graze their cattle on the public range outside of the winter grazing period.44 Another bill would forbid running herds on Sunday.45 The passage of these bills indicates that the Choctaw economy had a significant stake in its cattle market and that the government was willing to define the extent of its jurisdictional control by regulating it. Based on the nature of laws aiming to retain the cattle market as a resource for Choctawonly labor and preserving national resources the intention of the legislature was not to eradicate the cattle economy, but rather to mediate non-citizen profit. These late nineteenth-century legislations were protective of social patterns that would have been largely promoted by Euro-American society, i.e. ranching for purposes of individual profit or sustenance. However, and most critically, the acts were enacted to preserve the Choctaw economy and citizen prosperity, thereby undermining reliance on US markets. Moreover, the implications of controlling the cattle industry could be applied to numerous other industrial

labor fields developing within the region at the same time, such as the expansive coal industry operating in northern Choctaw Nation by the 1870s and the lumber industry operating in the central portion of the Nation thereafter. Throughout the latter end of the nineteenth century, US business methods were becoming increasingly vital to the Choctaw economy, and maintaining some method of control would have been a major concern for the legislature at the time.

It was this heavy-handed assertion of internal control that led to the Allotment Act having critical effects. Early negotiations between Choctaw delegates and the federal government guaranteed parceling, as stipulated in the Dawes Act, would not apply to the Choctaw Nation. By 1897, relentless pressure from the US government and the Dawes Commission resulted in the acceptance of Allotment for both the Choctaw and Chickasaw Nations.46 This implementation was a crisis for the Choctaw. Traditional land use was made unsustainable, a cataclysmic development for many citizens who still heavily relied on the standardized communal land use that their ancestors had practiced. For some citizens, especially more progressive individuals who sought US acculturation, Allotment appeared as a moment to assimilate into a society already suffocating their lifeways. For the cattle case specifically, this meant more Choctaw citizens would be pressured to raise penned livestock on small farms, a form of sustenance that encroaching settlers were familiar with and could usurp. Despite decades of legislation intended to empower Choctaw ranchers and farmers and to disenfranchise settlers, the suffocating prospect of forced land privatization demanded quick and decisive action from the Choctaw Nation.

With these uncertainties overhead, the Choctaw National Council passed its Act of 1899. We know that the severance of land directly caused the Act of 1899, as it is written into the document: “the allotment of our lands in severalty and the taking of each citizen of his rightful share, which must of necessity break up the holding of large bodies of land in pastures, is under the Agreement in the near and immediate future, therefore—.” This law made the introduction of foreign cattle into the Nation by any individual, citizen or otherwise, outside of the grazing period of November and December, illegal. Any cattle introduced during such time were required to be penned, and any individual not penning legal cattle or abiding by the regulations would be fined. Here is the first indication of the act’s intention to promote

citizens’ economic development by determining who could access land resources. The document defines “foreign cattle” as cattle from any “State or surrounding Nations.” These foreign cattle, as outlined previously, were the property of settlers and speculators who “run at large on the public domain and to drift [unattended], and thus drifting carry the small herds of cattle away from their ranges causing great loss and inconvenience to the citizens.”47

Based on its language, this law was intended to preserve quality land for citizen-owned cattle. At the time of the document’s publication, Allotment was imminent but not active. The public range, at least temporarily, was off-limits only to foreign cattle, retaining its use and the benefits for Choctaw citizens and their businesses. Furthermore, any individual whose illegal cattle were found grazing on public land would be fined five dollars per head of cattle. If the fine was not paid within ten days, the sheriff of the county would collect the cattle and perform a public sale, of which legal Choctaw residents could purchase and expand their cattle holdings.48

Not only did this act forbid non-citizens access to the range, but any individual caught doing so would be “prosecuted under the laws of the United States.” Any instance of illegal activity practiced as defined within the Act would be reported to the local Indian agent and the US commissioner.49 Such an announcement instilled that settlers were under foreign protection and effectively stated that the US must uphold the Nation’s law. No longer would cattle drivers or foreign settlers have unbridled access to the resources of the Nation. By setting such strict mandates, the government ensured its citizens would have great access to land resources for their cattle, easier access to purchase and expand their cattle holdings, and would set up a strict penalty system that thwarted non-citizen business competitors. Further still, the Choctaw Nation placed the work of policing non-citizen illegal activity into the hands of the US government.

The Act of 1899 benefited Choctaws, at least for a short period. It allowed many citizen cattle ranchers to dispossess their direct competitors, and citizens outed illegal activity if its existence threatened their operations. W. F. Choate of Canadian, a town in northern Choctaw Nation, wrote to Chief Green McCurtain in May of 1903 to complain: “There is about a thousand head of cattle held in the vicinity of Choate and Indianola upon the range and in pasture. My purpose of addressing you is to know whether or not these parties can not be dealt

with or handled, and their stuff removed from the Choctaw Nation.”50 As stipulated in the Act of 1899, addressing unauthorized land use by non-citizens was to be enforced by federal agents. McCurtain’s executive office regularly forwarded requests such as Choate’s to the corresponding federal jurisdiction. In this case, Johnson Frazier, sheriff of Calvin, Indian Territory, was instructed to investigate the incident. It would take several months for the investigation to unfold, largely due to the sheriff claiming illness.51 Presuming that Choate’s original statement was accurate, as Frazier was ordered to assist US Indian Policemen to remove cattle and collect illegal hay royalties in August of that same year.52 Choate’s incident was one of the numerous investigations in the Choctaw Nation that followed the passage of the Act of 1899, though not all were as successful at clearing the land of illegal cattle herds. When claims of illegal activity were investigated and found true, the Choctaw Nation had to make extravagant payments to the US government to enforce the law. In November 1903, a single operation of cattle removal cost the Nation over $1,500.53

Having the US government enforce the Choctaw Nation’s law was not an unprecedented choice, and the decision was born out of a contentious debate concerning jurisdictional control and authority over settlers. Federal courts established along the borders of the Choctaw Nation, specifically Fort Smith, were known to “exceed [their] legitimate authority and jurisdiction” on matters of internal Choctaw operations.54 Whereas these US-based operatives pushed for control over Indian Territory, the Choctaw Nation saw their role as mere enforcers of tribal law. Although the US Commissioner of Indian Affairs, the Secretary of the Interior, and the Indian Agents were foreign actors, they were, by design, working on behalf of the Choctaw Nation. The Choctaw legislators’ expectations for US agents are reminiscent of a foreign trade monitor, in that they were expected to work as inspectors, revenue collectors, and policy enforcers.55 US agents were also expected to track illegal international markets like the liquor trade.56 It comes as no surprise, then, that legislators in 1899 would place monitoring of illegal cattle exchanges into the hands of US entities, seeing as such a practice had been well-established. Based on previous statutes, such as an 1882 bill that set more strict protocols on settlers requesting citizenship, it appears that US-affiliated settlers were largely uninterested in making sure they abided by the laws of the Choctaw Nation. Regulations set to ensure occupants of the Nation

were legal residents could never be fully enforced because outsiders greatly outnumbered citizens, and the US government and its agents on the ground were largely uninterested in upholding such laws. Choctaw legislators realized that the influx of foreigners on their land largely identified as US citizens, and therefore, only complied with US-enforced laws. This is not to indicate that these alien occupants were outside the Choctaw jurisdiction, for the Treaty of 1855 stipulated that the Nation had “unrestricted right of self-government and full jurisdiction over persons and property within [its] limits.”57 Rather, the Choctaw administration’s assertion that US agents must police their citizens on foreign land as a better guarantee that the laws would be upheld while simultaneously proving that the US worked for the Choctaw Nation.

The Act of 1899 had profound effects on who could raise stock in the Choctaw Nation, especially in promoting capital growth for tribal citizens by erasing competition. Alongside preceding cattle-centric laws, the government could ensure that its citizens did not outsource labor and that non-citizens could not lay claim to resources or opportunities within the Choctaw Nation. Perhaps more importantly, the act reinforced the Nation’s foreign sovereign power over the US by requiring the federal government to enforce tribal law. The Act of 1899 was a strategy of nation-building that incentivized capital development through ranching and investment in the cattle economy and enforced jurisdictional control over economic developments. Through the act’s implementation, we see decisive legislative responses to federal and US-citizen threats undermining the Choctaw Nation’s political autonomy.