LUMEN

OHIO HUMANITIES MAGAZINE

VOLUME I

Lumen is a publication of Ohio Humanities, a nonprofit dedicated to sharing stories, sparking conversations and inspiring ideas.

Lumen aims to build and foster community through thoughtfully curated storytelling that shows the humanities at play today, highlights noteworthy humans throughout Ohio and dares to examine big questions and ideas.

It is an annual, free publication available at organizations statewide and by subscribing at ohiohumanities.org. All rights reserved.

Ohio Humanities

541 West Rich St., Columbus, Ohio 43215

614.461.7802 • ohc@ohiohumanities.org • ohiohumanities.org • @ohiohumanities

Ohio Humanities is the state-based partner of the National Endowment for the Humanities. Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in publication do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

LET’S CONNECT

LUMEN OHIO HUMANITIES MAGAZINE

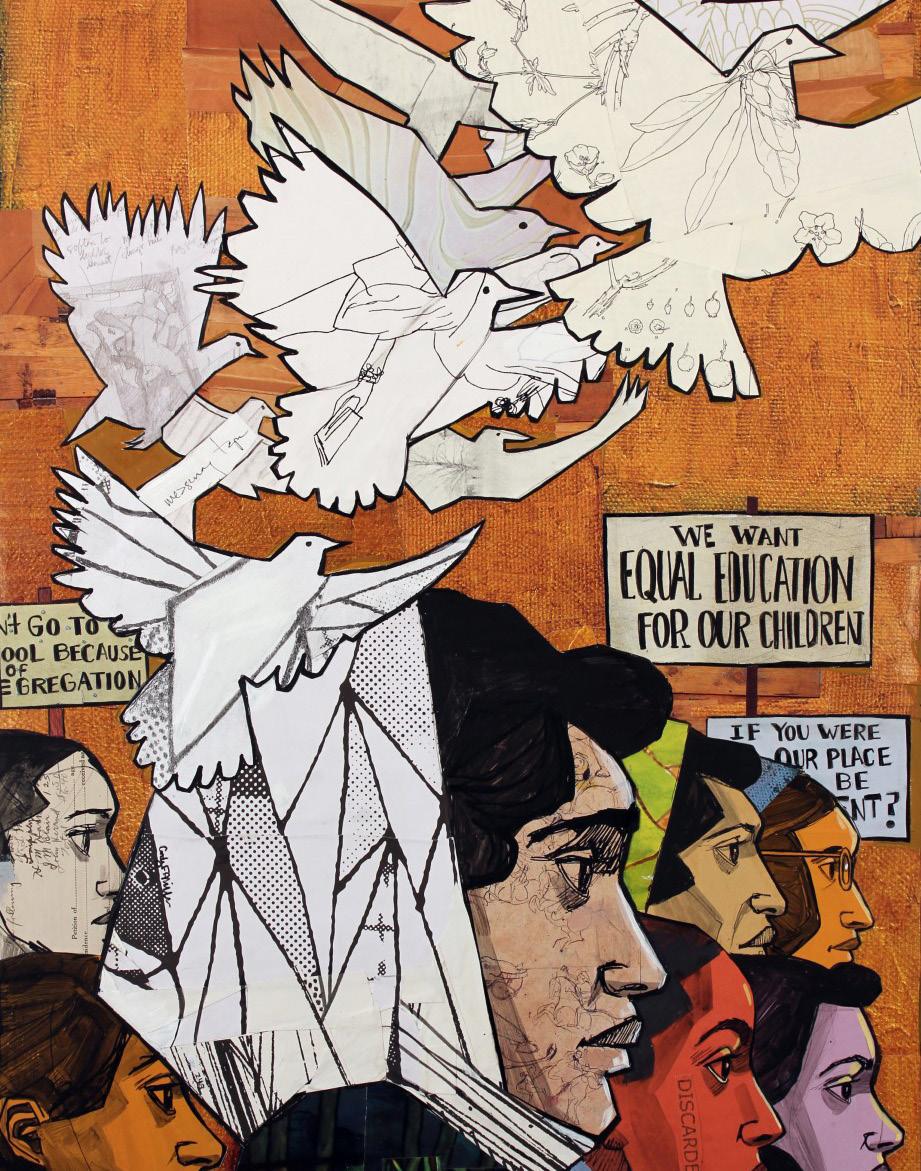

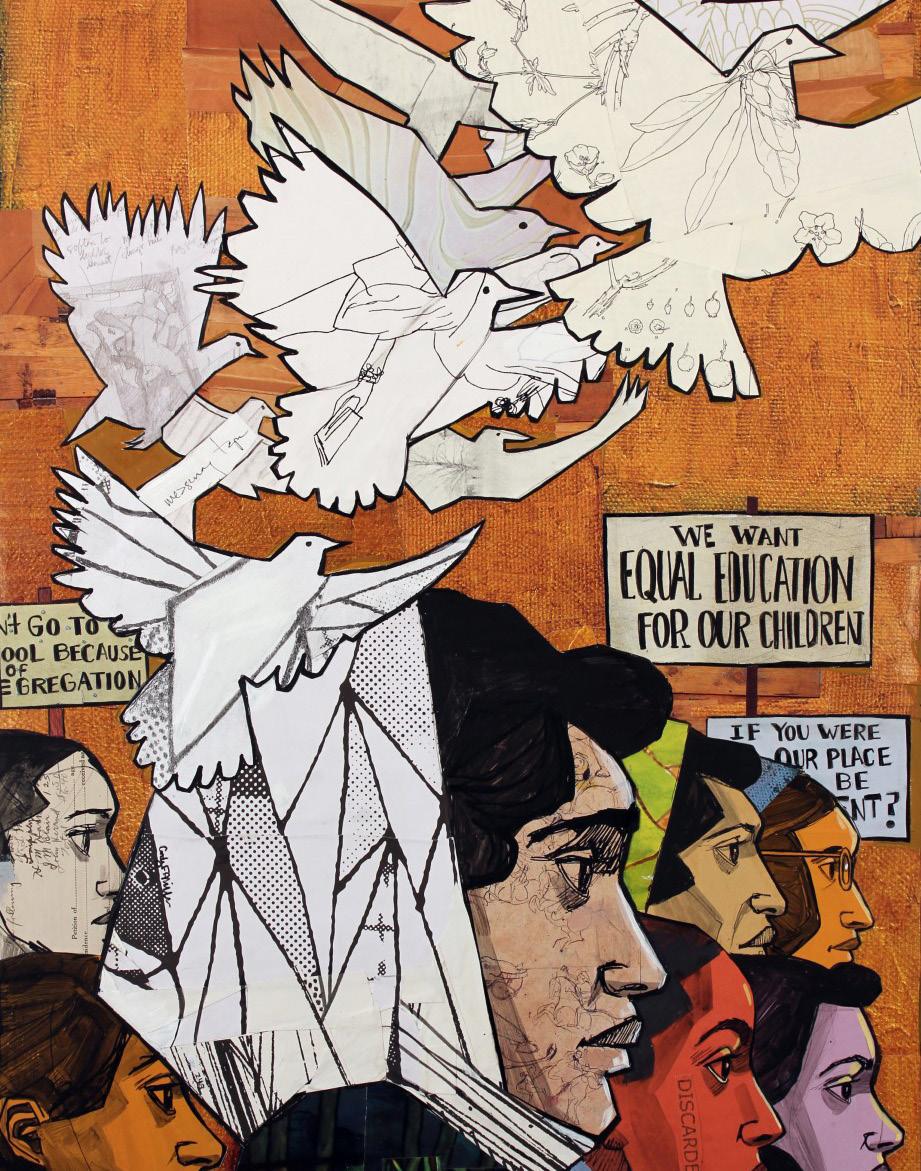

COVER ART BY CODY F. MILLER

CONTENTS

THE POWER OF PERSPECTIVES

by Rebecca Asmo

HUMANITIES AT PLAY

by Kristy Eckert

THE STORYTELLERS

by Taylor Starek

COMPLICATED IMAGINATION

by tt stern-enzi

MARCHING ON

by Aaron Rovan and Melvin Barnes

SOME KIND OF WONDERFUL

by Melanie Corn

HOMETOWN JUXTAPOSITION

by Amanda Page

ALMOST HOME

by Ruth Chang

BUILT ON BROKEN PROMISES

by Rebecca S. Wingo

MAKING HEROES SUPER

by Vera Camden and Valentino Zullo

MEET

THE

TEAM

02 52 04 54 16 56 24 58 26 60 64

THE POWER OF PERSPECTIVE

02 | LUMEN 2023

PHOTO BY KILEY KINNARD

After Brown v. Board of Education was decided in 1954, a group of Black mothers in southern Ohio marched their children to the white school, demanding admission. After being rejected, they woke up the next morning and marched again. And again. And again. For two years, they marched.

Even when those children were admitted, of course, nothing was easy. They endured ongoing racism from both teachers and students. Their story is compelling, and their perspective is critical.

Sharing stories and understanding different perspectives help us learn and grow as individuals and a community. For 50 years, Ohio Humanities has invested in both by supporting storytellers statewide, from museums to journalists to documentary filmmakers. It’s a legacy we are excited to carry on with Lumen. And it’s why we’re focusing on the power of perspectives in this inaugural edition.

Diversity encourages conversation and allows us to think critically about our own points of view. What I find most fascinating is how often I find commonality and connection within our differences.

Within these pages, you will meet an array of people—many whose work Ohio Humanities is helping fund. You will also find an array of perspectives from several fascinating Ohioans.

Melanie Corn, for example, writes about wrestling with desire and what it meant for a queer teen growing up in the Midwest. And tt stern-enzi shares how he marveled at “E.T.” as a child—while simultaneously wondering what the movie would be like if his Black face was inserted. Because of their columns, I will take a different approach to a casual conversation about a movie or where someone is from.

I hope that this publication provokes critical thinking for you, too. I hope it helps you feel a deeper connection with someone you know. I hope it prompts you to share a story or start a conversation.

And above all, I hope that it inspires empathy. Because the world could use a whole lot more of that.

Rebecca Brown Asmo Executive Director, Ohio Humanities

p.s.—Are you an Ohio storyteller looking for a grant to support your work? Whether you’re a scholar, journalist, documentary filmmaker, museum leader or someone else sharing compelling stories, we’d love to know what you’re doing and how we might help. Visit us at ohiohumanities.org/grants or start a conversation at ohc@ohiohumanities.org.

LUMEN 2023 | 03

04 | LUMEN 2023

HUMANITIES AT PLAY 3 PEOPLE TO KNOW

There are thoughtful, brilliant humanities experts sparking conversations and inspiring ideas statewide. Here, get personal with three of them.

By Kristy Eckert

LUMEN 2023 | 05

ALEXANDRA NICHOLIS COON

ALEXANDRA NICHOLIS COON

As a young girl hiding from the horrors of the Holocaust, Nelly Toll turned to art. She spent the better part of 18 months holed up in the bedroom of a tiny apartment, using painting as a source of distraction and therapy. After surviving the war, she moved to America, earned her PhD and became a professor, author, artist and speaker. Massillon Museum Executive Director Alex Coon first met Dr. Toll when she visited Massillon Middle School to share her story. “Her message of hope,” Coon said, “has tremendous power to heal.” Coon and colleagues were moved to produce a traveling exhibition of Toll’s artwork to convey how transformative art can be during the darkest of times. Ohio Humanities helped fund the project—an example of Coon’s innovative work. Here, the North Canton mother of twins gets personal.

06 | LUMEN 2023 IMAGE

COURTESY ALEXANDRA NICHOLIS COON

WHAT LIGHTS YOU UP?

Connecting people to opportunities that allow their talents to shine.

WHAT FRUSTRATES YOU?

People who resist making time to listen, resist communicating in a civil manner and resist personal growth.

WHAT MAKES YOU LAUGH?

I often laugh at myself and am drawn to people who are able to do the same.

WHAT PROFESSIONAL JOURNEY ARE YOU ON?

My professional journey involves connecting people to educational and ultimately life-changing narratives that expand our understanding of the world. I seize every opportunity to foster dialogue between people, places and things where capacity exists to deepen an experience.

WHAT PERSONAL MISSION ARE YOU ON?

My personal mission is to be present where I am most needed, and to do so in places from which I can draw energy and inspiration and am able to grow.

WHY IS HUMAN CONNECTION SO IMPORTANT?

Human connection reminds us to see the world through different lenses.

WHAT IS A DEFINING MOMENT FROM YOUR CHILDHOOD?

I have vivid memories of my childhood, so singling out just one while scanning the files of my consciousness is difficult. For some reason, rising to the surface this very moment is a memory of attending my first all-class sleepover in fourth grade, where the host was celebrating a birthday. After playing video games, singing and dancing, opening presents and eating cake, a dozen or so girls had settled into our sleeping bags. As the lights turned out, an anonymous voice called out, “Goodnight everybody” in an exaggerated and halted manner to mock one of the girls in attendance known for having a pronounced stutter. Tears and bickering ensued. The lights came back on. And the party was brought to a screeching halt, with parents coming to retrieve children in the middle of the night, as things had grown so uncomfortable. That kind of bullying was not identified as such when we were children. But I recognized the taunting as dangerous and always strived to counter such behavior. To this day, I can feel the pit in my stomach when recalling that incident, sympathizing with my classmate’s pain and failing to understand how and why such cruelty could exist at the expense of others. I would, of course, learn that much of it stemmed from insecurity, pain, ignorance and perhaps the absence of being taught how to exercise compassion. Nevertheless, that moment and the heartache I felt for my classmate reminds me to this day how important it is to recognize and address bullying and its destructive patterns and to seek remediation.

LUMEN 2023 | 07

WHO MADE A POWERFUL MARK ON YOUR LIFE, AND HOW?

I model the way I treat people and my work ethic after my grandfather’s actions. A sheet metal worker who valued precision and quality, he taught me how to exercise patience and thoughtfulness when approaching any project. There were few school posters and projects of mine that didn’t bear marks of his guidance. He ensured I was always armed with a ruler and a pencil (as he knew mistakes were inevitable), and he leveraged this skill to help me understand the importance of planning well in advance and that “haste makes waste.” My grandfather was the person who welcomed door-to-door solicitors of all kinds into his home. Who drove all of his neighbors to doctor appointments. Who would help any stranger who approached him in a public place. Who returned any stray article of clothing or retail item he encountered in a store that had fallen onto the floor back to its rightful rack or shelf. And who provided each trick-or-treater with not one but two king-sized Hershey bars and two apples. He had the most pleasant, trusting disposition of anyone I have ever known. His compassion, selflessness and lack of judgement are tenets I hold dear and carry with me.

WHO DO YOU LOVE TO LEARN FROM?

I love learning from people who are passionate and derive joy from their calling—and who have devoted copious amounts of time putting their craft into practice to the point where the skill appears effortless.

WHY DO YOU LOVE OHIO?

I love Ohio for its beautiful and varied scenery and rotation of seasons that inspire both romantic and angst-riddled poetry. For its history rich in change makers, visionaries and artists. And for its capacity to inspire a sense of community. I also recognize its imperfections but believe strongly in the power of placemaking. Each of us has the ability to incite change in the places we live and work to help shape these spaces.

WHAT ONE PERSON DO YOU WISH EVERY OHIOAN KNEW?

I wish everyone knew the story of Nelly Toll, a young girl of eight who harnessed the power of art to imagine a world beyond war.

WHAT ARE YOU CERTAIN IS TRUE?

I am certain one cannot fight fire with fire— and also that complacency yields nothing. It is by way of respectful conversation and a willingness to reserve judgement until listening to all sides of a story that resolution can be found.

IF THERE IS A SINGLE MISSION YOU COULD MOBILIZE PEOPLE AROUND, WHAT WOULD IT BE?

Inclusion.

IF PEOPLE DEFINED YOU WITH ONE WORD, WHAT DO YOU HOPE THAT WORD IS?

Genuine.

“ 08 | LUMEN 2023

EACH OF US HAS THE ABILITY TO INCITE CHANGE IN THE PLACES WE LIVE AND WORK TO HELP SHAPE THESE SPACES.” –ALEX COON

MARILYN MOBLEY

MARILYN MOBLEY

Race. Gender. Class. Social justice. Diversity and inclusion. They’re topics that author, speaker, educator and community activist Marilyn Mobley, 70, has been talking about for decades. Mobley—who earned a bachelor’s degree from Barnard College of Columbia University, a master’s degree from New York University and a PhD from Case Western Reserve University—is an international thought leader on race who has presented her research in Kenya, Italy, France, Russia and beyond. She founded the African American Studies program at George Mason University and served as Vice President for Inclusion, Diversity and Equal Opportunity at Case Western, among many roles in higher education. She also is a noteworthy Toni Morrison scholar who is a founding member and former president of the Toni Morrison Society. Mobley—a mother, grandmother and great-grandmother who lives in Cuyahoga Falls—is an ordained associate minister in Akron and a board member at the Cleveland Institute of Music and Ohio Humanities.

LUMEN 2023 | 09

IMAGE COURTESY MARILYN

MOBLEY

WHAT LIGHTS YOU UP?

Doing FaceTime calls with my sons and grandchildren. My grandchildren know I am happiest when they share what they’ve been reading, especially if they’re reading books I sent or recommended to them!

WHAT FRUSTRATES YOU?

I am very frustrated about the ways in which our society is devaluing children, elders and fellow humans in ways that demonstrate a lack of care and concern. I’m particularly frustrated by the ways in which bigotry and injustice of all kinds are tearing at our humanity and the fabric of our democracy.

WHAT MISSION ARE YOU ON?

To find as many tangible ways as possible to express my faith and commitment to justice in the way I live and treat others on a regular basis. I’m always looking for ways to spread joy, because I know how discouraging life can be when people hit obstacles they did not anticipate. Even though I have lived my life as a scholar, I wrote my spiritual memoir The Strawberry Room, and Other Places Where a Woman Finds Herself to encourage other women dealing with the grief that comes from divorce and other family losses.

WHAT IS A DEFINING MOMENT FROM YOUR CHILDHOOD?

One of the most memorable moments of my childhood was being with my parents at an NAACP rally in Akron when I was around 7 or 8. There was music, food and speeches about our community. My dad was publicity chair, and my mom helped with membership. I learned from my parents and other leaders the importance of thinking not only about your own wellbeing but also that of your neighbors and your community. Because my dad was an educator and public-school administrator, and because my mom was a Head Start teacher, I learned early how ideas circulate, can be taught and can influence change.

WHO MADE A POWERFUL MARK ON YOUR LIFE, AND HOW?

My mother taught me to read and write two years before kindergarten. I began school with confidence that I was smart, with evidence that I could learn and with a positive attitude about life. Everything that I have accomplished always goes back to my beginning of having a praying mother who believed in me from the time I was born until her death in 2014. Even when family and friends in Akron questioned why my mother would allow me to go to college in NYC rather than stay closer to home in Akron where I was raised, my mom believed in me. Barnard College helped me continue on the path of knowing myself as a woman with the capacity to learn and lead in ways that would make a positive difference for others. My mom did not have a college education, but she knew how to leverage what she had to help me learn to do the same.

I AM CERTAIN THAT LOVE IS THE MOST RADICAL EMOTION ON EARTH... AND THAT SOCIAL JUSTICE IS WHAT IT LOOKS LIKE IN ACTION.” –MARILYN MOBLEY

“

WHAT WORK THAT YOU’VE DONE ARE YOU MOST PASSIONATE ABOUT, AND WHY?

Being the founder of African American Studies at George Mason University was one of the most important moments in my life. As an interdisciplinary academic field of study, African American Studies enriched my own intellectual life and helped me do the same for hundreds of others. In every endeavor, I have been able to draw on my preparation and education in the humanities to make a difference, to make connections and to grow as a person.

WHO DO YOU LOVE TO LEARN FROM?

I love learning from my 92-year-old mother-sister-friend Dr. Patricia Stewart and other scholars, especially scholar activists, whose teaching and scholarship is changing the way people think and interact with one another. I am a Toni Morrison scholar, because I believe with every novel she wrote, every speech she gave and every opportunity she had, she was using the power of language and narrative to make a difference. What happens to me inside the covers of a book written by Toni Morrison is magical, because she connects the human experience with the moral imagination, and at that intersection is where transformation happens. As a minister, I’m always drawn to the narratives that shape the Holy Bible and theologians like Howard Thurman who offer powerful ways of thinking about life and living over and above what can bring us despair.

WHY DO YOU LOVE OHIO?

I love all the attractions that are in Ohio, from the parks to the museums to the colleges and universities. Despite our complaints about the weather, Ohio is a national treasure! More than anything, I love the history we have of producing such great literary figures as Toni Morrison, Rita Dove, Langston Hughes, Sherwood Anderson, Charles Chesnutt, Paul Laurence Dunbar, Hart Crane and others.

WHAT ARE YOU CERTAIN IS TRUE?

I am certain that love is the most radical emotion on Earth and in the human spirit— and that social justice is what it looks like in action, as Cornel West and bell hooks taught us.

IF YOU COULD MOBILIZE PEOPLE AROUND A SINGLE MISSION, WHAT WOULD IT BE?

I would mobilize people around knowing that they were loved so well that they would not be the least inspired to do harm to themselves or one another. Such love would free them to live, learn and love like never before.

IF PEOPLE DEFINED YOU WITH ONE WORD, WHAT DO YOU HOPE THAT WORD IS?

Joyful!

LUMEN 2023 | 11

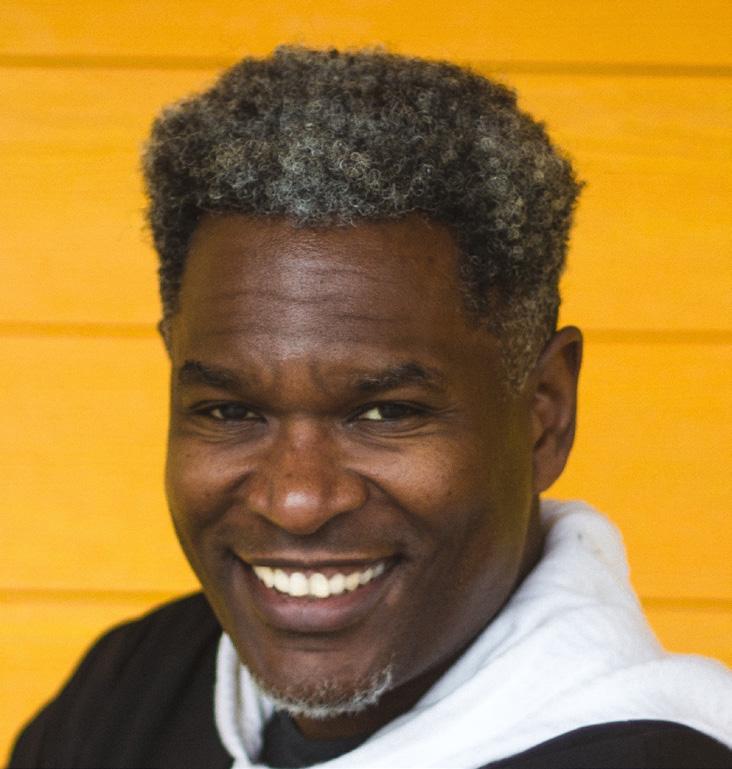

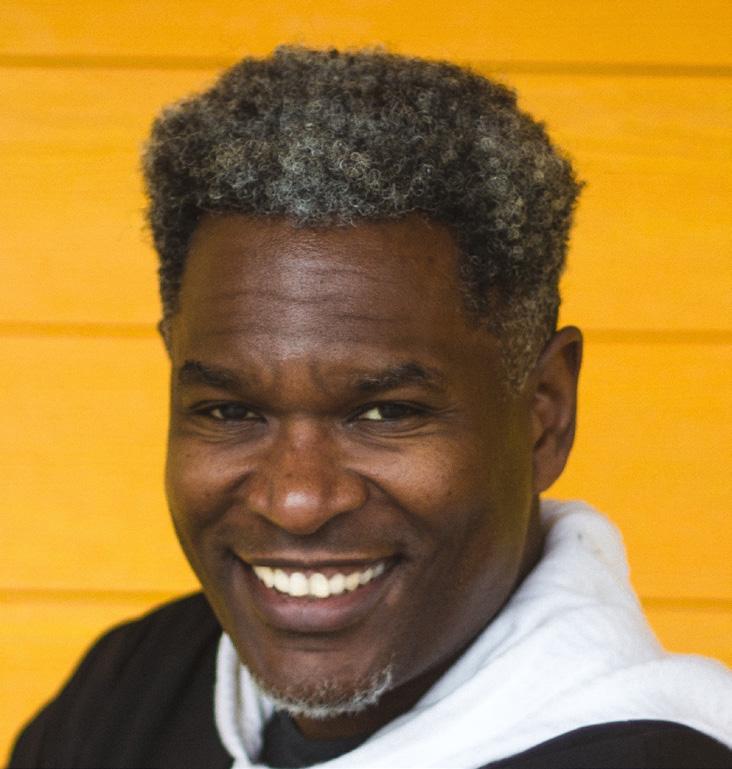

DAVID BROWN

DAVID BROWN

For David Brown, it’s not about the power play but the passion play. And his passion for people—connecting them, loving them and lifting them—has manifested as a nonprofit that has inspired people not just around Ohio but also across the nation. Brown founded Columbusbased Harmony Project in 2009 to bring people together to sing, share and serve. In the years since, he has grown it into a national model that brings diverse people together through song and innovative programs in schools, shelters and prisons. Ohio Humanities helped fund a prison choir program. Brown has shared the stage with Grammy-, Tonyand Academy Award-winning artists. And his work has been featured on “The Today Show,” “Good Morning America” and “CBS Sunday Morning.” Here, meet the 58-year-old single father of two adopted sons.

12 | LUMEN 2023 IMAGES

COURTESY DAVID BROWN

WHAT LIGHTS YOU UP?

People accomplishing something they previously thought impossible.

WHAT FRUSTRATES YOU?

Inequality, and the idea that one group of people can determine the trajectory for another group based on position, power and resources.

WHAT MAKES YOU LAUGH?

A naughty joke, going down memory lane with close friends and when I make a complete fool of myself.

WHAT PROFESSIONAL MISSION ARE YOU ON?

To connect people who likely would not have interacted because of spiritual or political beliefs, geographic locations, social, economic and cultural barriers, or indifference.

WHAT PERSONAL JOURNEY ARE YOU ON?

To have done more good than bad when it’s all over.

WHY IS HUMAN CONNECTION SO IMPORTANT?

Our human-to-human connection is pre-programmed: a newborn infant will instinctively grasp a finger that touches their hand. In music, harmony exists only when there is more than one note. It works the same for humans. We require one another’s different notes to live in social harmony.

WHAT IS A DEFINING MOMENT FROM YOUR CHILDHOOD?

We moved to a very small town in Louisiana when I was 16. I had to figure out new friends, a new routine and learn how to navigate the new bullies. I was perhaps the most depressed I had ever been as a teenager. But on a trip to the mall, I dropped into a poster shop and spent a few bucks on a couple of posters. My friends were buying posters of rock stars, but I went my own way. On the east wall of my bedroom, I put up the poster of the New York City skyline and on west wall, a poster of the Los Angeles skyline. I would imagine myself living in those cities, even though I had no idea how that could possibly happen. But I continued to believe and continued to work and persevere, and 20 years of my life were spent living in both of those cities. The lesson: You don’t need the answers, you just need the dreams.

WHO MADE A POWERFUL MARK ON YOUR LIFE, AND HOW?

The late Dr. Arthur Caliandro—a boss, mentor and father figure who taught me to find a way to “yes.” He didn’t like hearing “no.” He recognized that in me as well. He taught me that although “no” is unavoidable, there is almost always a pathway to “yes.” Keep seeking, and keep the faith.

LUMEN 2023 | 13

WHAT WORK THAT YOU’VE DONE ARE YOU MOST PASSIONATE ABOUT, AND WHY?

I am passionate about results. It is a group of high school students who thought they were incapable of bringing an audience to its feet, then finding themselves singing in front of thousands in Times Square. It is a group of people serving time who bought into the definition of “inmate” and learned through music that where they are does not define who they are. It is hundreds of people coming from every corner of a community to empower their individual voices by joining with others. I am passionate about people finding their voices and using them for something greater.

WHO DO YOU LOVE TO LEARN FROM?

People who have made a lot of mistakes, because that means they’ve lived.

WHY DO YOU LOVE OHIO?

In full transparency, I am struggling with this question right now. There are only a few places in our state where I feel safe and comfortable—mostly mid-sized to larger cities. Urban areas. My sons and I have experienced racism and homophobia while traveling throughout the state. I am aware that this isn’t an “Ohio” issue, but it does seem that Ohio is trending in what I believe is the wrong direction. However, the reason I stay is because of the love I have for the people who share Ohio with me.

WHAT ONE PERSON DO YOU WISH EVERY OHIOAN KNEW?

The one person would be a man named Dave, who I was first privileged to work with a decade ago when we launched a program for people living in supportive housing—folks who could not care for themselves on their own. Dave spent his entire life in caregiver facilities or institutions. He rarely engaged socially, keeping to himself. Dave discovered his voice in the program, and it’s a great voice! Now, he sings wherever he goes. He accepts all people, loves all people and exudes empathy for others. He’s the best of us. If we could all channel a little bit of Dave every day, life would be better.

WHAT ARE YOU CERTAIN IS TRUE?

That no religion has a monopoly on truth.

IF THERE IS A SINGLE MISSION YOU COULD MOBILIZE PEOPLE AROUND, WHAT WOULD IT BE?

Equality.

IF PEOPLE DEFINED YOU WITH ONE WORD, WHAT DO YOU HOPE THAT WORD IS?

Human.

14 | LUMEN 2023

YOU DON’T NEED THE ANSWERS, YOU JUST NEED THE DREAMS.”

–DAVID BROWN LUMEN 2023 | 15

“

16 | LUMEN 2023

THE STORY TELLERS

From murder mysteries to music, these artists are telling stories in powerful ways.

By Taylor Starek

LUMEN 2023 | 17

OHIO DOCUMENTARY FILMMAKERS TO WATCH

FOR THE LOVE OF THE TRUTH

Everyone told Shawn Rech it wouldn’t work in Cleveland. He couldn’t be a filmmaker here—he’d have to go to Hollywood.

Rech was unphased. His first project, a local TV program, focused on unsolved crimes.

“People told us we’d never have the production values,” he said. “[They said] we’d never get it on TV.”

Rech’s program not only got on TV, but it also led to tips that solved 10 murders and won nine regional Emmy awards. Soon, several top-20 markets were calling, asking Rech to bring the show to their city. From there, he gained momentum.

Today, Rech, 56, has directed films such as “A Murder in the Park” and “White Boy,” which explore themes of wrongful convictions and over-sentencing. He also directed “American Gospel: Christ Alone,” an in-depth look at the negative effects of the prosperity gospel. Each has found a home on Netflix, and Time named “A Murder in the Park” one of the 15 most fascinating true crime stories ever told.

Those who have watched Rech’s films might be surprised to learn that he didn’t become a director and producer until the age of 43.

18 | LUMEN 2023

Once the founder of a laser engraving company, he moved on to sell educational software, followed by a few years as the editor of a trade magazine. But then, he got the entrepreneurial bug.

“I thought, ‘If I’m going to start something and make it, or possibly fail, then it’s going to be something that I’ve always wanted to do and that I love,’ ” he said.

So he and Ralph McGreevy co-founded Transition Studios, an award-winning documentary production company based in Cleveland.

“A Murder in the Park” is their most recognized film. It examines the conviction of a man who served more than 15 years in prison for a double homicide after a false confession. It’s a convoluted journey, broken down with mind maps, interviews and dramatic reenactments.

These types of stories appeal to Rech, he said, because of his devotion to justice and his qualms with journalism. His films often document people he sees as overzealous storytellers who try and fit the facts of a situation into a narrative they already crafted. In “A Murder in the Park,” for example, a journalism professor hires an aggressive private investigator to get a forced confession from someone who was innocent.

“I think you can consider us journalism critics,” he said. “What draws me is educating the public on how [some journalists or other storytellers] got it wrong. And to be leery of storytelling.”

But he and his team often look beyond true crime. Rech has more recently directed “Unsanctioned,” a miniseries about the struggle of sanctioning high school girls wrestling.

He also directed a historical series called “People in the Pictures,” which tracks down individuals captured on camera opposing the civil rights movement in hateful or violent ways to see if, and how, they’ve changed. The project, he said, has been both enlightening and encouraging.

“I’m not trying to be too self-important,” he said. “But I see [this] as cathartic for our country. We’re understanding that people can change.”

“People in the Pictures” will premiere on TruBlu, a boutique streaming service with factual programming that Rech is launching. TV personality Chris Hansen is collaborating with Rech and Transition Studios on content for the platform—and yes, they’re doing it from Cleveland.

Although he travels for meetings and to film his pieces (he said he knows Beverly Hills as well as he knows his hometown of North Olmsted), he’s been able to make a lot of meaningful work in Ohio. And he’s proud of that.

“There’s been a myth since I was in high school: Go west and make your dreams come true,” he said. “You don’t have to do that anymore.”

LUMEN 2023 | 19

SHAWN RECH IMAGE COURTESY SHAWN RECH

BEYOND THE SURFACE

Amanda Page didn’t set out to be a filmmaker.

The 46-year-old is a Columbus-based writer and founder of Scioto Literary, a nonprofit that supports storytellers in Scioto County. She found her way to filmmaking thanks to a case of writer’s block.

She was struggling to pen an essay on her hometown of Portsmouth, located in southern Ohio, when she came across the PBS documentary “Moundsville.” That film traces the history of Moundsville, W.V., through the rise and fall of industry.

Page was inspired.

“I’ve always enjoyed learning about what makes a place a place,” she said, “and what

20 | LUMEN 2023

PAGE &

BERNABO PHOTO

AMANDA

DAVID

BY BENTLEY VISUAL STORYTELLING

creates a sense of belonging to the people who live there.”

She connected with David Bernabo, who co-directed “Moundsville” with writer John Miller, and told him, in so many words: Let’s do it for Portsmouth. Bernabo, a 39-year-old Pittsburgh-based filmmaker, was on board.

Together, the two created “Peerless City.” It’s a documentary that looks past the surface-level narratives often told by politicians and parachute reporters— think Trump, opioids and poverty— and highlights the nuanced history of Portsmouth through the lens of its many slogans. A grant from Ohio Humanities helped to fund the making of “Peerless City.”

The film has no narrator, instead letting the voice of residents lead the way. A story of resilience unfolds.

“What we’re trying to convey is the diverse range of experiences that exist in a city,” Bernabo said. “And how nothing’s simple. Everything’s nuanced and complicated. Things change over time, and contexts change.”

“Peerless City” premiered first in Portsmouth in March 2022 and will continue to screen at festivals around the state. A PBS edit is in the works as well.

Now that the film is out in the world, both Page and Bernabo are wont to keep those threads of community, empathy and hope in their projects moving forward.

Alongside her work as a writer, Page is set to direct another film about the struggle for retention in Appalachian communities and the role that plays in economic and workforce development.

And Bernabo, who works in the Oral History Program at Carnegie Mellon, launched a podcast called “Cut Pathways” with his colleague Katherine Barbera, which details the diverse journeys of students and faculty through higher education.

Both also see “Peerless City” and “Moundsville” as a template—something that might inspire a movement of future makers to tell the stories of their communities with compassion.

“This is kind of a cool model for people to look at their own towns,” Bernabo said, “and their own experiences.”

LUMEN 2023 | 21

AMANDA PAGE & DAVID BERNABO IMAGE COURTESY AMANDA PAGE

PHOTO BY DAVID BERNABO

PASSION PLAY

Secret American lives.

That’s what Yemi Oyediran calls the oftenoverlooked experiences of racial and cultural minorities. And those stories matter.

So Oyediran, the child of immigrants from Nigeria, co-founded a company to tell them.

Oyediran—alongside friend and business partner JP Leong, who is Chinese American—runs AfroChine, a production company that not only partners with Cincinnati arts organizations on multimedia projects and events, but creates its own meaningful works of art as well.

“We are more apt to look beyond the surface and ask deeper questions and expose deeper experiences of our community,” Oyediran said. “That’s really what we do and what we’re passionate about.”

A true Renaissance man, Oyediran, 41, actually has many passions, and he pursues them all with unabashed enthusiasm.

For example, his day job as a software developer with the National Institute for Occupational Safety & Health led him to pursue his PhD in computer science. As he works toward his degree, he’s also teaching as an adjunct lecturer at the University of Cincinnati and at Xavier University. He’s an accomplished jazz musician, too, playing with many bands and configurations around the Queen City.

22 | LUMEN 2023

YEMI OYEDIRAN IMAGES COURTESY YEMI OYEDIRAN

Oyediran combined many of his loves to create the documentary “Queen City Kings,” an AfroChine project funded in part by an Ohio Humanities grant.

The film explores the legacy of King Records, a Cincinnati-based label founded in 1943 by Syd Nathan. It’s known for launching the career of legendary artist James Brown. It also blended country, bluegrass and R&B—an amalgamation that many say led to the birth of rock ‘n’ roll. And it was among the first companies with a racially integrated staff.

It’s an archetype, Oyediran argues, for how to celebrate people’s differences.

“We believe if we look at the model of King Records,” he said, “it gives us a model for understanding how to address racial issues, both in the Cincinnati area and nationwide, by being able to say, ‘Look, there are differences. How do we now benefit from these cultural differences?’”

An early version of the documentary was shown to a small audience in Cincinnati in

2018. AfroChine has been polishing a final version for wider distribution, and PBS is planning to distribute it nationally.

But the question of how to celebrate the region’s cultural nuances is one Oyediran is committed to asking long after the completion of “Queen City Kings.” And AfroChine is the vehicle for that quest.

The company also helps to produce Urban Consulate, a series of conversations around racial disparities, how to address them and, ultimately, how to build more equitable communities. It’s also working with various arts organizations and Asian American and Pacific Islander groups to help celebrate the stories of Asian Americans around the city.

These projects are a perfect fusion, Oyediran said, of their interests and their talents, and that’s what keeps them going.

“AfroChine gets to be the expression of our emotions, of our passions,” he said. “Our motivation is our passion.”

LUMEN 2023 | 23

COMPLICATED IMAGINATION

I am a child of the 1980s. I fully moved into the second decade of my life at the start of the 80s. One of my first film experiences with a childhood friend was a matinee screening of “E.T.” I remember marveling at the wondrous adventure unfolding before us along with a full audience.

By tt stern-enzi

But as much as I wanted to be young Elliot (Henry Thomas), I was already working through a peculiar narrative rewrite to insert my Black face and history into those frames.

I was raised by a single mother and grandmother somewhat adjacent to the suburbs in Asheville, North Carolina. But I knew that my version of Elliot’s life would have not been the same. It was a fact that I carried into every movie I watched.

It is only over the past few years that I realized this is how much of my critical thinking was born. It’s because I have been developing and flexing critical and analytical muscles throughout my lifetime as a Black man. For far too long, for instance, coming-of-age stories—whether in print or onscreen—featured white male protagonists and their white female love interests. There might have been a token Black best friend with little or no sense of agency or backstory beyond their connection to the protagonist. But that was it. So I not only consumed stories, but I also then imagined how those stories might play out for me.

Fast forward to today’s cultural landscape, widen the perspective, and there is a fascinating lesson for audiences from marginalized communities. Thanks to an industry that has completely embraced the format options now available— streaming has revolutionized narrative storytelling in ways that television and even cable couldn’t have—we’re no longer limited to only telling one perspective’s story at a time. Opportunities abound to create richer, more dynamic and powerfully inclusive worlds, to the point that storytellers can dare to reimagine and reconfigure the past with an authenticity rooted in purpose and intention.

A film festival artistic director and longtime entertainment critic reflects on why inclusive filmmaking matters.

24 | LUMEN 2023

Consider “Hollywood,” the 2020 mini-series created by Ryan Murphy and Ian Brennan. It delves into an alternative postWorld War II City of Angels where a diverse group of aspiring actors and filmmakers dreamed of making it big and forced the industry to bend to their will. Or check out how the mini-series adaptation of the graphic novel Watchmen repositioned its take on masked vigilantes within the context of Tulsa, Oklahoma, and introduced audiences to the Tulsa Race Massacre, a dark piece of American history that is rarely, if ever, discussed (and certainly not as part of genre storytelling).

These two examples, among a growing number of others, spotlight how this current generation will not have to exercise the same critical and creative muscles I had to back in the 1980s.

This mattered, especially to me, because at the start of this movement, I feared that the gatekeepers would merely remake the old stories and insert Black and other marginalized folks into those worlds without recontextualizing the social and cultural realities.

To be completely honest, I longed for white audiences to have to switch places with me, to do the same heavy lifting I have always done. What would it be like for others to have to imagine themselves in these worlds, to figuratively walk in someone else’s shoes for a moment?

That is the ultimate superpower of the arts—a muscle that we will hopefully continue to flex to create reflections that won’t require the same level of critical effort I have exerted for so long.

tt stern-enzi is artistic director of the Over-theRhine International Film Festival. It’s an Ohio Humanities-backed Cincinnati event that curates a mix of narrative and documentary features as well as short programs across five pillars: freedom, diversity, disability, faith and identity. He is also the film critic for Fox19 Cincinnati and a member of the Critics Choice Association.

LUMEN 2023 | 25

26 | LUMEN 2023

Lincoln School Marchers carry signs while walking to Webster Elementary in Hillsboro, Ohio in the mid 1950s. Photo by Getty Images

MARCHING ON

After Brown v. Board of Education was decided in 1954, a group of Black mothers in Southwest Ohio dressed up their children and marched them to the white school, demanding admission. Upon being rejected, they woke up the next morning and marched again. And again. And again. For two years, they marched. Even their eventual win came at a cost. Theirs is a story of pain. Of passion. Of determination. And of love.

Story By Aaron Rovan and Melvin Barnes

Photos By Shellee Fisher

LUMEN 2023 | 27

Athunderclap roused Dana Fields from a deep sleep. It was the middle of the night, but an acrid stench permeated the air. As a lightning flash cast shadows through the room, he heard a frantic commotion in the kitchen. The 5-year-old boy wandered from his bed to find his parents.

“No,” his dad said. “It’s not here.”

“I know I smell smoke,” his mom insisted.

A sudden spark drew the family’s attention outside. Ten-foot flames licked the darkness as they engulfed the windows of Lincoln Elementary—the school and social hub for the small town’s vibrant Black community. A lightning streak threw the rest of the building into grotesque relief. As the ensuing thunder rumbled through Hillsboro—a small town tucked into the Appalachian foothills of southwest Ohio— Dana stood, entranced.

Perhaps the man who set the building aflame was running. Or maybe he was watching it burn from a nearby hilltop perch he had escaped to.

Regardless, he was already gone.

When Hillsboro residents awoke on July 5, 1954, the summer storm had passed, but the damage to Lincoln Elementary was permanent. Gossip skittered through the small town. Who had set the fire? For what reason? And, most importantly, where would the young Black students go to school in the fall?

For a select few in town, the answer to the latter question was simple: the schools would be integrated.

Just six weeks earlier, the nation had held its collective breath as Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren took the center chair in the nation’s highest courtroom. America’s system of racial segregation hung in the balance as he prepared to read the Court’s unanimous opinion in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka. “Separate but equal,” he read, “has no place in the Constitution.”

School segregation was now, in theory, illegal. But as the Black community in Hillsboro knew, theory and practice are two dramatically different things.

28 | LUMEN 2023

but

Lincoln Elementary School in Hillsboro, Ohio, was built in 1864. It served as the primary school for local Black children and doubled as a social hub for the Black community. Image Courtesy Highland County Historical Society

“Separate

equal has no place in the Constitution.”

LUMEN 2023 | 29

—Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren, in the Brown v. Board of Education ruling

The Brown decision changed everything and nothing, said Dr. Jessica Viñas-Nelson, a professor of African American History at Arizona State University and an expert on desegregation.

“The Brown decision is this thunderclap,” she said, especially in terms of legal precedent. But lived experiences of people in the mid-1950s, she noted, were far less dramatic. “Brown did not fix anything. You had a slow walk all across the country to end school segregation. And it was almost harder to dislodge in the North.”

Hillsboro was one of those Northern towns where officials approached integration cautiously after the Supreme Court decision. Although the community’s high schools were integrated by 1946, the elementary schools were still racially segregated. Black students attended Lincoln, and white students went to Webster and Washington. After the Brown decision, the school board announced that they would integrate the elementary schools only after they were finished remodeling the Washington school building, which they projected would take two years.

That kind of stalling tactic was typical in the months and years immediately following the decision, thanks to vague language around the enforcement of integration. “The Court said you should desegregate ‘with all deliberate speed,’” Viñas-Nelson said. “And that was interpreted by opponents of Brown in a very liberal sense.”

Although Hillsboro’s school officials were comfortable delaying integration, the Highland County engineer—a white man who believed segregation was wrong—was furious about the injustice. The week before the fire, Philip Partridge listened to his Presbyterian minister preach in defense of

those who break the law in pursuit of just reforms. Partridge considered his options. If there is no school for Black children to attend, he surmised, then the white schools must allow the Black children in.

He acted in the early morning hours of July 5. This, he believed, was an act of patriotism. As little Dana Fields and his family slept soundly across the street, Partridge clawed through the weeds of an abandoned alley up to the isolated school. Wielding a crowbar, he broke the padlock of Lincoln Elementary, doused newspapers in oil and gasoline and struck a match.

Partridge was eventually found guilty of arson and served nine months in prison. But he always defended his actions as justified. “We can’t wait five or 10 or 20 years for progress,” Partridge later wrote for the Cleveland Call and Post, a Black newspaper. “We may not be a free nation that long.”

Partridge, it turns out, had ignited not just a structure but also a movement that would eventually place this quiet, rural town at the epicenter of the battle to desegregate schools nationwide.

Sunlight dappled Joyce Clemons’ face as she hid behind the tree in her front yard. Like many young girls, Joyce was curious, particularly about the conversations among adults. On that day near the end of July in 1954, Joyce was eavesdropping on her mom as she talked with their neighbor, Miss Imogene, over the fence. The tree’s rough bark rubbed uncomfortably under Joyce’s palms as she steadied herself to peek across the yard. As the mothers hung laundry, Joyce caught snippets of their conversation.

30 | LUMEN 2023

IGNITING A MOVEMENT

After his arrest for setting Lincoln Elementary on fire, Philip Partridge wrote a column for the Cleveland Call and Post published on October 16, 1954, excerpted here.

I thought of the many things that needed to be done in the world and how little I had done. I thought about the school problem in Hillsboro and our comfortable home and yard and me sitting in a rocking chair year after year waiting for death and the problem going on and on. I thought of my four years here during which time I had hoped that desegregation in our organization was accomplished—and then two nights before the picnic with everybody present except our Negro employees. I felt the bitterness of watching this go on without doing anything about it. Experience had taught me that, for me at least, the surest way to get answered on the prongs of public opinion and slowly scorched to death was to try to talk and argue this sort of thing. I am blunt and not tactful. This pretty much made up my mind to go ahead. I did not dare think of my family and boys. This thing looked bigger than Hillsboro—maybe it involved millions of boys.

LUMEN 2023 | 31

Fire. School. Unsafe. Not fit for our kids. We have to do something.

“You know, really,” Joyce remembers, “kids weren’t supposed to listen to grown-ups back then.” Nonetheless, she later gathered the gumption to ask about the words she overheard.

“You wasn’t supposed to be listening, Joyce,” Gertrude Clemons scolded her, then softened her tone. “But I will explain it to you.”

Despite the Brown decision and Partridge’s arson, which had irreparably damaged Lincoln, Hillsboro’s school board still planned to keep Lincoln open for the

town’s Black elementary students. The school board made minor repairs, slapped on a fresh coat of paint and declared Lincoln Elementary ready to welcome Black students for the year. Their intentions, said Highland County historian Kati Burwinkel, were obvious. “The school board wanted to make sure there were no illusions,” Burwinkel said, “that the Black students were coming to the white school.”

To many in the Black community, that was unacceptable. So they strategized a plan.

On August 9, Imogene Curtis, Clemons’ neighbor, and other members of Hillsboro’s Black community delivered a petition to the Hillsboro School Board signed by 225 Black residents demanding immediate integration. The board members’ shock was palpable.

“We have been good to our colored people,” one defensive board member said.

“Wonderful,” Curtis responded sharply. “Like if you have a second-hand suit, instead of throwing it away, you give it to colored people.”

The school board refused to budge on its decision to keep Lincoln open. This news didn’t necessarily surprise Curtis, Clemons or the other Black parents. Lincoln had historically lacked the resources of

“ Brown did not fix anything. You had a slow walk all across the country to end school segregation.”

32 | LUMEN 2023

—Jessica Viñas-Nelson, desegregation scholar

Washington and Webster. Lincoln was crowded, with first-, second-, and thirdgrade students all taught in one room. In the winter, the second floor was difficult to heat, so class was often moved to the basement—that is, until the boiler would overheat, sending steam and children streaming upstairs.

As August waned, Curtis and Clemons continued chatting across the fence as they hung their laundry. Why would they send their children into a fire-damaged building with fewer educational resources when the highest court in the land had declared school segregation illegal? They, the mothers decided, would not.

Curtis, Clemons and a few other Black parents enrolled their children into Webster for the start of the 1954-1955 school year. And to Webster their children went. But the first week of classes wasn’t even over before the school board held a special meeting to discuss the “forced integration” of the schools.

“We still believe we made a reasonable request in asking them [the Black students] to use Lincoln School for two more years,” one board member said.

The school board hastily drew up three new school zones. The Washington and

Webster zones were essentially split by the town’s north-to-south thoroughfare, High Street. Conspicuously, however, the school board carved a third school district out of two predominantly Black neighborhoods located in the Washington school zone. The students in this third zone were to attend Lincoln.

The school board maintained that they constructed the school zones “strictly on residential lines.” But Washington and Webster remained overwhelmingly white, and Lincoln remained all Black. In practical terms, this meant that some Black students had to walk past one of the white schools to attend Lincoln. All students were instructed to report to their newly zoned schools on Friday, September 17.

Curtis and Clemons had had enough.

On Friday morning, Clemons dressed Joyce in her Sunday best—pretty dress, neatly folded socks, fancy shoes. Next door, Curtis similarly dressed her son John in dapper trousers and a carefully pleated shirt. A handful of other Black mothers across town did the same with their children. Many congregated in the street for a milelong walk to Webster Elementary. Others joined along the journey. By the time they arrived at the school, there were a few dozen in the group.

LUMEN 2023 | 33

Several mothers accompany Black school children to Webster Elementary School in an attempt to demand that the youngsters be admitted. Photo by Bettmann of Getty Images

—A white employer, after discovering Carolyn Steward’s mother, Elsie, was an integral figure among the marchers

“I thought Elsie was better than that.”

34 | LUMEN 2023

Webster’s school bell rang at precisely 9 a.m. Joyce, John and the other Black children ran through the open doors as they had been doing for the past two weeks. As the mothers milled around on the sidewalk, school officials sent the children back out.

The principal walked out and apologized, explaining that these students were no longer on the roster for the Webster school.

“The nation’s highest court says our children must be allowed to learn with yours,” Curtis argued, her figure casting an imposing shadow on the sidewalk beside the principal.

“I understand,” he assured her. But he still insisted that there was no room for the children. They would have to go to Lincoln. He walked back in.

Clemons and Curtis exchanged glances, turned to their children, and in unison, sent them back in.

The Black children pulled the door open and marched back through. But moments later, they returned. After a third failed attempt, the mothers wearily turned their backs on Webster and shepherded their children back home.

At the end of the school day, the superintendent announced that any child, regardless of race, who did not attend their assigned school on Monday would be considered truant. The school district, he warned, would mete out the appropriate consequences.

Clemons, Curtis and the other Black families were not deterred.

The Lincoln School marchers were just getting started.

Carolyn Steward carefully chose her dress for the day, as she did every school day. She brushed her hair, ran down the steps and sidled up to the breakfast table, just like the day before. The sun was starting to peek through the windows as she heard her mom run through the morning ritual: Eat breakfast, put your school clothes on, don’t forget your shoes.

They were running late, as usual. But with seven siblings, Carolyn was used to it. She left the house with her mom and a few siblings, including older sister Virginia and younger brother Ralph. They walked down Collins Avenue, over to North West Street and then to the Church of Christ. Carolyn had the route memorized. They had, at this point, been walking it daily for well over a year, every school day. In their original route, they had walked past the Washington Elementary construction zone, but men working on the building would wait until the mothers and children got close and then drop their pants. So they adjusted to this less obscene path.

At the church, they met up with their friends Joyce Clemons, John Curtis, Teresa Williams and Myra Cumberland. The group of mothers and children was 50 people strong and stretched half a block as they marched down the sidewalk. A few marchers carried carefully crafted signs above their heads.

“I can’t go to school because of segregation,” one said.

“Our children play together. Why can’t they learn together?” said another.

Carolyn noticed Joyce with a grin on her face and a spring in her step. But Teresa wasn’t enjoying herself one bit; she had

LUMEN 2023 | 35

broken her hip when she was attending Lincoln, and it still hurt to walk. So went these daily marches—for some, they were an adventure. For others, they were nothing more than tedium or, worse, blisterinducing rituals. Either way, they always ended the same.

After another couple blocks, Webster finally came into view.

Carolyn looked for the window. Right on cue, as she and the other Black children approached, a gaggle of children waved to them with their small white hands. Carolyn waved back. Maybe today would be the day she could join them.

Suddenly, a long white arm reached toward the window’s center, and the blinds crashed down. As Carolyn and the others reached the steps of the school, the principal walked out.

“Sorry, folks,” he said. “Nothing has changed.”

After being turned away, the group walked another mile back to the east side of town, and the children divided into several houses based on age. In a gesture of mutual aid, the mothers set up learning centers in their homes to ensure that their children’s education wouldn’t lag behind their grade level. They called them kitchen schools.

Each school day was carefully structured. The day started with lessons prepared by volunteer teachers from nearby Wilmington College. Then the children enjoyed a short recess. “They’d give you a little time to run out and play for a minute,” Carolyn remembers. “You weren’t out there very long, and it was time to come back in. So you didn’t have very much play time.” After another stretch of lessons, the children ate lunch—a highlight of the day. “Whatever

house we were in, they had a lunch for us,” Carolyn recalls. “We didn’t go hungry while we were there. You know, because it did turn out to be a long day.”

The boycott of the local school district was only one aspect of the Black community’s protest. They were also guiding a civil lawsuit through the federal court system.

On September 22, 1954—just five days after they were initially turned away from Webster—the mothers filed a lawsuit against the Hillsboro School District with the help of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). At age 12, Joyce Clemons was among the oldest marchers so was chosen as lead plaintiff. The case would become known as Clemons v. Board of Education.

The timing of the case was ideal for the NAACP. The organization and its chief counsel Thurgood Marshall—who would later become a Supreme Court Justice himself—were in search of cases to test the scope of the Brown decision and clarify how the law would work in practice. How, for example, would people interpret “all deliberate speed?”

In Hillsboro, the NAACP filed a temporary injunction requiring integration to begin immediately while the case was tried, but the move was blocked by a federal judge.

Marshall and the NAACP enlisted the help of Constance Baker Motley, a high-profile strategist in the civil rights movement who eventually won several landmark civil rights cases and later became a federal judge. Although Motley was the face of the case in the courtroom, the mothers and their families carried the bulk of the case’s burden.

36 | LUMEN 2023

“Our children play together. Why can’t they learn together?”

—A marcher's sign

The five plaintiffs and their attorneys stand in court on Sept. 29, 1954 while on their precedent-shattering mission. Front row, left to right: Plaintiffs Elsie Steward, Roxie Clemons, Zella Cumberland and Gertrude Clemons. Back row, left to right: Attorney Russell L. Carter, plaintiff Norma Rollins and attorneys Constance Baker Motley and James H. McGee. Photo by Harvey Eugene Smith of AP

LUMEN 2023 | 37

Sallie Williams, Seleicka Dent, Joan Zimmerman and Gertrude Clemons stand with children inside Webster Elementary School on April 3, 1956. The day before, the Supreme Court refused to intervene in the Marching Mothers’ case, thereby rendering as valid the lower court’s ruling to integrate the school. But Principal Harold Henry once more denied the Black children permission into classrooms, saying the district was awaiting official notification of the court’s decision.

Like millions of Black women at the time, many of the marching mothers worked as domestic helpers in white homes. Elsie Steward, Carolyn’s mother and a widowed mother of nine, risked her employment to serve as a plaintiff on the case. One day, her employer found out that she was a key figure in the marches and resulting trial. “Well,” her white employer lamented, “I thought Elsie was better than that.”

In the face of threats and risks to their livelihoods, the mothers persevered for almost two years as the case wound its way through the legal system—becoming experts in legalese while marching every school day, regardless of scorching heat or freezing rain.

The case included three critical junctures. In the first, a federal judge in Cincinnati ruled in favor of the Hillsboro School Board, arguing that the plan to integrate the elementary school in two years was sufficient. Then the mothers and NAACP appealed that decision to the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals, who sided with the mothers and instructed the original judge to order integration. With high hopes, the school board appealed that decision to the Supreme Court.

Finally, in April 1956, the Supreme Court declined to review the case, effectively agreeing with the second decision and forcing the Hillsboro school board to integrate immediately.

38 | LUMEN 2023

Photo by Bettmann of Getty Images

The Lincoln School mothers had won.

The case the marchers fought so diligently to win had far-reaching implications. Hillsboro became a source of inspiration for other Ohioans fighting for integration. It also laid the groundwork for subsequent legal battles in places as far away as Texas.

But while the case inspired change nationally, the celebration in Hillsboro was muted. The Hillsboro School Board ensured the Black families paid a hefty price for their actions. While the board agreed to fully integrate schools in the fall of 1956, all but one of the student marchers were held back one or even two grade levels.

“The mothers get the success and the kids go into the school,” said Burwinkel, the local historian. “But now the kids pay the price.”

Myra Cumberland sat in a circle with her new classmates, filled with nervous excitement despite being forced to re-do the same grade she had already completed in her kitchen school. It was the fall of 1956, and reading class was about to start. Myra was especially delighted with her dress—a purple skirt with a white bodice and purple dots. Her toes wiggled nervously inside her shoes as the teacher began the lesson, but she remained quietly attentive.

Myra glanced at the two girls beside her, whose whispered chatter distracted her. Then she turned back to the teacher sitting beside her. The teacher’s thick-soled shoes, inches from Myra’s dress, also tapped nervously. Suddenly, in one swift motion, the teacher’s head turned toward Myra, and she struck Myra’s dress with her shoe.

SHARING THIS STORY

The story of the Lincoln School Marchers is an important one in America’s fight for racial justice. For years, it went largely untold. Ohio Humanities is proud to share this story in myriad ways, including helping fund “The Lincoln School Story,” a 20-minute documentary film. Ohio Humanities has also created a discussion guide for book clubs, film clubs, community groups, nonprofits and families to prompt learning and thoughtful discussion. Access the documentary film, discussion guide and more by using this QR code or visiting ohiohumanities.org.

Two Black children sit in the rear row of a third-grade classroom in Webster Elementary School. Photo by AP

Two Black children sit in the rear row of a third-grade classroom in Webster Elementary School. Photo by AP

“Now the kids pay the price.”

40 | LUMEN 2023

—Kati Burwinkel, Hillsboro historian

“Be quiet!” she hissed at Myra. “It’s people like you…”

Myra, introspective, stifled her tears as she looked at the shoe print that now marred her dress.

Later, during art time, the teacher circled the room as students practiced drawing shapes. One of the chatty girls from the reading circle was seated at a desk beside Myra. They were each drawing stars. The teacher walked past, lingering over Myra’s classmate and praising her art. When she turned to Myra, her demeanor shifted.

“See what she can do?” the teacher said. “She drew a star. That’s something you will never be able to do.”

Despite that specific teacher, Myra found allies in some of her white classmates. Once, in a different class, Myra stood up to sharpen a pencil when that teacher briefly left the room. “Don’t touch me,” one boy nastily said as Myra passed him. Two of Myra’s friends—both white boys—took the bully by the leg and hung him out of the window on the second floor until he apologized. By the time the teacher returned, the boy was back in his seat but flushed. “What’s wrong?” the teacher asked. The bully had, apparently, learned his lesson. “Nothing,” he said.

Myra, along with the other Black students attending Webster, now faced many of the same discriminations inside of the school that they had faced outside of it.

“It was really tough for the Black students,” said Viñas-Nelson, the desegregation scholar. “The school board had spent years saying that it was the children’s fault and their parents’ fault for causing useless controversy. Teachers and their classmates had been told the same things. And now they are looking at these kids that are two years older than them in their classrooms.”

The student marchers faced verbal and emotional abuse by classmates and teachers alike.

One child was forced to practice her drums in a school closet while the white children attended class in the music room.

Another was assigned a seat by the bathroom door—the worst spot in the classroom.

A third remembers simply being alone. In a room full of children, not one made him feel welcome.

The trauma from those consequences lingers.

“With every good thing that’s accomplished, there’s always a cost,” observes Eleanor Curtis Cumberland, the older child of Imogene Curtis. Although she was in high school by the time the march started, she watched her mother sacrifice herself for the sake of social justice. “You know, it wasn’t all sunshine and blue skies and happy days. They’re still living with some of the repercussions from this fight— memories that they can’t shake.”

LUMEN 2023 | 41

Eleanor Curtis Cumberland sat against a window in the cramped Highland County Courthouse, the faint spring sunlight glancing across her neck. As commissioners took their seats at the front table, Cumberland readied herself for a fight.

It was March of 2022, and the commissioners, she thought, needed a reprimand. Her mother’s fight for equality was not to be dismissed; it was to be celebrated.

In 2020, a small group of dedicated residents erected a marble bench on the courthouse grounds in honor of the marchers’ tenacity. Just the act of erecting the bench took perseverance. The materials for the bench were donated by a local business, but collecting the names of all 55 marchers—18 mothers and 37 children— was tedious work for Shawn Captain, the grandson of a student marcher.

While county officials welcomed the idea of installing a bench on the courthouse grounds, they originally wanted it to face a side street. “I didn’t want it there,” Cumberland said. “I wanted it on the front street where it could be displayed and seen.” Cumberland and Captain successfully lobbied officials to cement it in a place of prominence.

Now, less than two years later, county commissioners were entertaining the possibility of removing the memorial bench from the front of the courthouse to make space for an extended seating wall that would complement a nearby fountain.

Cumberland gathered at the meeting with other members of Hillsboro Against Racial Discrimination (HARD), an organization that works for a more just

and equal community. As the meeting was called to order, Cumberland voiced her concerns. Today, the bench remains in its place of prominence facing Hillsboro’s main thoroughfare.

Cumberland is still an active part of Hillsboro’s vibrant Black community. She is not only a member of HARD, but also a central part of a small group of former Lincoln School students who are committed to keeping the story of the march, and their mothers, alive. Together with Joyce Clemons Kittrell, Carolyn Steward Goins, Virginia Steward Harewood, Myra Cumberland Phillips and Teresa Williams, all of whom are in their 70s or 80s, Eleanor regularly travels around southwestern Ohio to share the story of the Lincoln School marchers.

The former Lincoln school students talk often about the love, pride and appreciation they have for their mothers.

“I know who wrote the letters,” Eleanor Curtis Cumberland said. “I know who made the phone calls. I know who the newspapers contacted during this fight. My mom fought for other people’s rights ‘til the day she died. That’s just who she was.”

For these women, the story is as much about the present as it is about the past, both locally and nationally. Clemons thinks of the story as a powerful reminder of how children can be led to understand racial differences. “We have to be able to explain to kids that you may be a little light, you may be a little brown, but you’re all the same. We have to get that into their heads.”

Other women speak with humility about the important role they and their mothers played in the Civil Rights Movement.

42 | LUMEN 2023

“Back then, I probably didn’t think I was part of the Civil Rights Movement,” Myra Cumberland Phillips said. “But now, yes, I do.”

Their mission is to celebrate their mothers’ central role in the Civil Rights Movement in the public discourse.

To Viñas-Nelson, the story of the Lincoln School marchers is really a story about the power of small groups in establishing profound, lasting change. Local people and local leaders drove the Civil Rights Movement, she said—a realization she hopes can shift the paradigm of how social change happens today.

“If you think you have to be a Martin

Luther King or a Rosa Parks to lead a civil rights movement, no one’s ever going to lead a civil rights movement, because the movements didn’t start from those high pillars,” she said. “All of these movements happen by local people starting them.”

The marchers hope that sharing their story inspires others to remember their mothers and continue the work they started.

“My mom couldn’t have done it without the other mothers,” Eleanor Curtis Cumberland said.

“So that’s my purpose—to see that my mama’s work isn’t lost. And that this fight goes on, that this story goes on.”

Marchers Joyce Clemons Kittrell, Myra Cumberland Phillips, Teresa Williams, Carolyn Steward Goins, Eleanor Curtis Cumberland and Virginia Steward Harewood stand present day in Hillsboro, Ohio—two of them holding medals from the induction of the Lincoln School Marchers into the Ohio Civil Rights Hall of Fame. They travel around the community, hoping to keep alive their mothers’ legacy of bravery and tenacity.

LUMEN 2023 | 43

MEET THE MARCHERS

ELEANOR CURTIS CUMBERLAND, 79

Mother: Imogene Curtis

“People would come to my mother for a lot of different things, like if they were having housing discrimination or job discrimination or even problems with the courts. My mom wrote letters to prisons and lawyers and to judges on people’s behalf. So I know what my mom did. With every fight, you have to have somebody leading it.”

44 | LUMEN 2023

JOYCE CLEMONS KITTRELL,

80

Mother: Gertrude Clemons

“At that time, the parents were very strict about learning. My dad always told me, ‘You do 100%. If you can do 150%, you do it.’ And so that kind of helped a lot, you know? We knew we had to do it because we’d have been right back where we were before if we didn’t—not allowed to go places and not allowed to do things.”

LUMEN 2023 | 45

MYRA CUMBERLAND PHILLIPS, 74

Mother: Zella Mae Cumberland

“We’ve still got a long way to go, but I hope children today learn what we actually, really went through. And really, I never sat down and explained it all to my boys until after this (documentary) film came out. I didn’t think they would be interested. I never did explain it to them when they were little. I just would say, ‘You better get an education.’”

MEET THE MARCHERS 46 | LUMEN 2023

TERESA WILLIAMS, 79

Mother: Sallie Williams

“I have often been asked, how did we get along with kids after we got into Webster School. We would tell the difference from the kids who knew about the desegregation problem in Hillsboro. Because the kids who didn’t have a problem playing with us, it wasn’t being talked about in their homes. The kids who had a problem with the Black students knew about the desegregation problem in Hillsboro.”

LUMEN 2023 | 47

VIRGINIA STEWARD HAREWOOD, 76

Mother: Elsie Steward Young

“I mean, two or three months (of marching) was something. But we went for two years every day, rain or shine. I thought, ‘Why do we have to continue to do the same thing over and over when we knew they weren’t going to let us in?’ So, at 8, you can imagine what that was like.”

MEET THE MARCHERS 48 | LUMEN 2023

CAROLYN STEWARD GOINS, 74

Mother: Elsie Steward Young

“(Being held back) wasn’t nice. It wasn’t fun at all. We already knew all that we had learned from the kitchen schools when they put us back. So we knew everything they were trying to teach us. It still bothers me. It makes me mad. But, you know, we met so many nice people. I wasn’t fond of going back to school, but I enjoyed all the kids that I got acquainted with.”

RALPH STEWARD, 72

Mother: Elsie Steward Young

“I appreciate everything my mother did, because she made it easier for the Black kids to go to school. And we’ve had several that have graduated college. And it all stems from what happened in ‘54 to ‘56. I don’t want people to feel sorry for me, but sorry for the way that we were treated. There’s so many things we were not able to do because of our skin color. And it’s not right. I would hope that they wouldn’t ever want to go backward. We need to continually go forward.”

LUMEN 2023 | 49

THE ART OF

50 | LUMEN 2023

PERCEPTION

Portrayals in films, on TV shows, in magazines and across other media can dramatically affect how humans see themselves and each other. We asked three different Ohioans to share how media portrayals impacted their own sense of identity.

LUMEN 2023 | 51

SOME KIND OF WONDERFUL

BY MELANIE CORN

As a Gen-X kid, popular culture—Saturday morning cartoons, music videos on MTV, Atari and mixtapes—was a defining framework of my youth.

Melanie Corn, PhD is president of Columbus College of Art & Design, where she has strengthened the school’s role as a leading cultural institution while building its national reputation.

And certain movie characters helped me understand who I wanted to be and who I didn’t as I was coming of age— none more than those created by filmmaker John Hughes. His films documented and influenced a generation of (white and suburban) cynical teenagers who seemed to have more anxiety about their futures and distrust of authority than their relatively privileged lives should warrant. In short, they hit home.

Not all of Hughes’ teen movies stand the test of time, with trite social-class conflicts and punch lines that rely on sexism, homophobia and racism. But my favorite Hughes film was “Some Kind of Wonderful” (1987). Drummer Watts (Mary Stuart Masterson) and artist Keith (Eric Stoltz) are childhood best friends and high school outsiders from the wrong side of the tracks. Watts is in love with Keith. Keith is oblivious and has his eyes on Amanda (Lea Thompson), who runs with the rich kids but is actually from the same working-class neighborhood as Keith and Watts. By the end of the antics and romance, Keith realizes he does love Watts, while Amanda is happily on her own.

52 | LUMEN 2023

The film’s strong character development, comedic asides and killer soundtrack compensate for its predictability. Most importantly, Hughes makes the outsiders the heroes. Keith defies his overbearing father by choosing art school rather than majoring in business at the university. And in the end, the soft-spoken, artsy Keith and short-haired, no-nonsense Watts stop worrying about societal expectations and choose each other for who they are.

For me, “Some Kind of Wonderful” was personal. It came out at the moment when I was starting to figure out my queer identity, and Watts was my first crush. Growing up in the 1980s meant not having a lot of clearly identified LGBTQ+ characters in popular culture to emulate, so for many of us, that meant finding the “queerness” in purportedly straight characters.

Throughout the movie, Watts’ sexuality is questioned because of her gender presentation. One character says she looks like a guy but has “a little bit too much up front,” so she must be a lesbian. And when Watts encourages Keith to practice his kissing on her before his big date with Amanda, she tells him to “pretend I’m a girl.”

As a young person, I understood the problematic nature of these homophobic stereotypes: Women must be hyperfeminine to be attractive, all masculine women are lesbians, and lesbians are bad. And yet each moment of calling attention to Watts’ genderqueerness was an affirmation of my own identity and desire. Though negative, stereotypes can also cue recognition. When your identity is taboo, there is an excitement in feeling like you are part of a secret club who can pick up on signs of otherness and queerness that are just under the surface of “straight” characters and their love stories.

At 13, I simultaneously wanted to be Watts and be with Watts. Thirty-some years later, I’m still grateful for Watts— and Duckie, Allison “The Basket Case” Reynolds, and other queer/not queer characters created by Hughes—who helped me see what my life might look like in a time before “Will & Grace” and “Ellen.” The only better ending for “Some Kind of Wonderful” than Watts and Keith finally getting together might have been for Watts to sweep Amanda off her feet. Or better yet, for Watts to break the fourth wall, and with a knowing wink, beckon me into her 1980s-cool world to be my punk rock girlfriend.

LUMEN 2023 | 53

ALMOST HOME

BY RUTH CHANG

“4 5 ‘00.”

In a photograph, my father, my mother, my brother and I sit smiling on the concrete steps of our apartment. We live within earshot of I-75, located at the periphery of a quiet Ohio town, corn fields just beyond. Above us, an American flag softly waves, afloat for the moment.

Ruth Chang is the co-founder of Midstory, a nonprofit media thinkhub supported by Ohio Humanities with a mission to uplift the Midwest narrative through storytelling and research. She was born in Taiwan and grew up in Northwest Ohio. Ruth holds a BA in Architecture from Princeton University, and a Master in Architecture from Harvard University.

In the late 1990s, TV stations began introducing Japanese animated shows on Saturday mornings to youth audiences. Rustling my brother awake at 5 a.m., I’d switch on channel 36. Shows like “Yu-Gi-Oh!,” “Pokémon” and “Sailor Moon” were like me: jarringly dubbed over, a bit of foreign on a white canvas. My childhood years happened at the cusp of change, when globalization catalyzed a slow but steady transformation that resulted in American society waking up to the other side of the world.

Just as Japanese TV shows infused millennials’ childhoods, the American Midwest powerfully shaped me—its rurality, sparseness, coolness. It meant accepting myself as a pebble, to be humbled and rounded, but always distinct. When people asked, “Where are you [originally] from?” I would respond, “Ohio.” It was a rebuff, besting the questioner at their own game. But it was also becoming more and more the truth.

54 | LUMEN 2023

Now, you can buy mochi from the local Kroger and stream all the Sailor Moon your heart desires. But back then, the closest thing to East Asia was a language arts unit on “tolerance” and The Joy Luck Club taught freshman year of high school. Tolerance couldn’t describe the loneliness and boredom to be found here, or the joy in rooting for Michelle Kwan as she competed for gold on screen. It did not justify my silent ambitions to go to Yale’s architecture school after watching a documentary about the Chinese American architect Maya Lin, who herself hails from Ohio, in the seventh grade. Her masterful design for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial brought on national controversy over her race, gender and age. Such stories of celebrations and struggles gifted me with possibilities of where I could go and who I could be.

In 2021, “Minari,” an American film that featured an immigrant family in the rural Midwest, won the year’s Best Foreign Language Film Award. Its successes are applauded—but only as foreign. This is not only the controversy at the Golden Globes, but also that of people who grew up across cultures everywhere. In high school, a teenage boy came up to me on the playground to provoke a baffling debate:

“Do you know how to speak English?”

“Yes.

“No, you don’t.”

“Yes I do.”

“No, you don’t know how.”

“Well, I’m speaking it now.”

He was affronted not just by my English fluency, but by the idea that being American could mean something more than just speaking English, or looking like someone who does.

The media portrayal of the “whitebread,” agrarian ideal might still drive people’s concept of the Midwest, but on the ground, the region has always fostered its own nuances and complexities. It might surprise some to hear I feel more kinship to postindustrial Ohio than Shanghai or NYC. After a decade roaming elsewhere in the world, I’ve now chosen to return to this place—unabashedly underrated, deceptively flat on a globalized landscape. But for my Saturday morning fix, I don’t watch TV. Instead, we opt to drive out for freshly sliced sashimi and red bean buns filled with whipped cream. It is not confusing to me to be in between, born out of cultural tensions and the American Dream. It is where I am almost home.

LUMEN 2023 | 55

HOMETOWN JUXTAPOSITION

BY AMANDA PAGE

Life magazine reporter Peter Meyer arrived in Portsmouth, Ohio, in 1989 to write about the extended family at 215 Washington Street, a two-story dwelling that tilted a bit and was rumored to be former slave quarters. He barely noticed the Ramada Inn across the street.