LUMEN

OHIO HUMANITIES MAGAZINE Volume II

VOLUME II

Lumen is a publication of Ohio Humanities, a nonprofit dedicated to sharing stories, sparking conversations and inspiring ideas.

Lumen aims to build and foster community through thoughtfully curated storytelling that shows the humanities at play today, highlights noteworthy humans throughout Ohio and dares to examine big questions and ideas.

It is an annual, free publication available at organizations statewide and by subscribing at ohiohumanities.org. All rights reserved. LET’S

Ohio Humanities

541 West Rich St., Columbus, Ohio 43215

614.461.7802 • ohc@ohiohumanities.org • ohiohumanities.org • @ohiohumanities

Ohio Humanities is the state-based partner of the National Endowment for the Humanities. Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in publication do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

CONNECT

LUMEN OHIO HUMANITIES MAGAZINE Volume II

COVER IMAGE BY DE’SHAUNAE MARISA

KEEPING THE FAITH

by Rebecca Brown Asmo

HUMANITIES AT PLAY

by Kristy Eckert

THE STORY OF CORY

by Joe Blundo

A QUIET FAITH

by Lucy Enge

GOD HAUNTED

by Joe Mackall

NEVER LOST, ALWAYS FOUND

by Ashton Colby

FAITH AS A COMPASS

by Ismail Mohamed

IF I AM CATHOLIC

by David Merkowitz

THE FILM FELLOWS

by Taylor Starek

BEHIND THE STORY

03 57 05 59 19 61 53 63 55 69 70

OHIO HUMANITIES BOARD & TEAM CONTENTS

Keeping the Faith

When our team was introduced to Cory United Methodist Church in Cleveland’s historic Glenville neighborhood, we were wowed.

Wowed by its size—an entire city block. Wowed by the majesty of its sanctuary and stained-glass windows. Wowed by its diverse history as a center of life for both Jewish and Black communities. We kept

talking about Cory and its history, which includes world-changing speeches from civil rights legends like Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X.

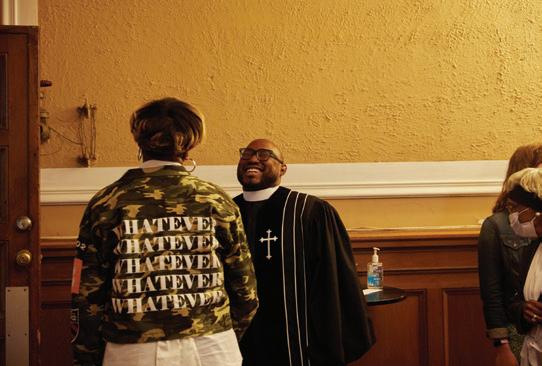

We all are moved by Cory’s passionate and entrepreneurial pastor, Rev. Gregory Kendrick Jr., who arrived at the dilapidated Cory building in 2019 on a temporary assignment and asked to stay.

3 | LUMEN 2024

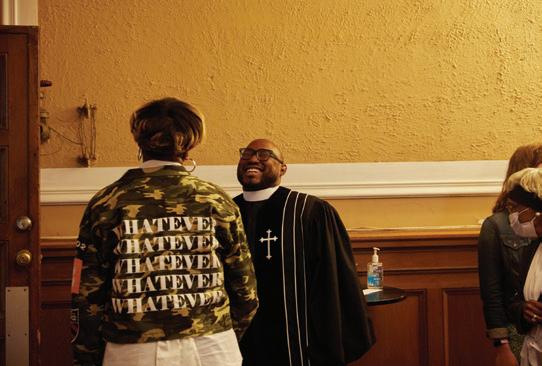

PHOTO BY KILEY KINNARD

Over the next few months, whenever I met someone from Cleveland, I would tell them about Cory, its history and Rev. Kendrick. I soon found that many people had their own unique Cory story. They swam at the pool, or went there for a community festival, or had family members who attended church there. I came to understand that Cory was not just a place, but a nexus of human connection.

Cory and the work of Rev. Kendrick are a perfect example of why the humanities matter. In its 140-year history, Cory has hosted some of America’s most consequential historical moments and social justice movements, but it has also served to connect individuals and communities in the smaller moments that make up their everyday lives.

Cory’s story is undoubtedly important, but the building, the congregation and the community it serves are facing an existential crisis today. One that has been exacerbated by systemic injustices like redlining and the changing demographics of religious institutions.

As you read about Cory, I hope you are inspired by Rev. Kendrick. He’s not working to keep the church alive just for the sake of preserving history. He’s also working to evolve the space into one that can continue serving its community in the way it always has—as a place that brings people together.

Community and connection are vital. In 2023, the U.S. Surgeon General issued an advisory that warned of the ill effects of what he called our nation’s epidemic of loneliness.

“Loneliness and isolation represent

profound threats to our health and wellbeing,” Surgeon General Dr. Vivek H. Murthy wrote in the report. “But we have the power to respond. By taking small steps every day to strengthen our relationships, and by supporting community efforts to rebuild social connection, we can rise to meet this moment together.”

The humanities, it turns out, are exactly what the nation needs. Because the humanities, at their core, connect people and foster community. They are not trival; they are central to our very survival.

I hope that this issue of Lumen helps you connect to your Ohio community, whether it’s by introducing you to new people and perspectives or by giving you a reason to start a meaningful conversation you otherwise wouldn’t have had.

I also hope that you will see the same connective tissue within these pages that I do: faith. Everyone we feature here, I noticed, has faith in something—and that goes beyond religion. Yes, some have faith in a higher power. But they also have faith in education. Faith in the creative process. Faith in humanity.

Rev. Gregory Kendrick doesn’t know how Cory’s story ends, and neither do I. What I do know is that we are proud to be supporting him in his work to resurrect it.

It’s an honor to share his story—and the stories of so many others—with you.

Here’s to building community—and keeping the faith as we do.

Rebecca Brown Asmo Executive Director, Ohio Humanities

LUMEN 2024 | 4

HUMANITIES AT PLAY

There are thoughtful, brilliant humanities experts sparking conversations and inspiring ideas statewide. Here, get personal with three of them.

By Kristy Eckert

5 | LUMEN 2024

3 PEOPLE TO KNOW

LUMEN 2024 | 6

7 | LUMEN 2024

DR. CARLOTTA PENN

WHAT LIGHTS YOU UP?

Love is the most brilliant light. The love I feel for my children, spouse and family. God’s love. My love for good food and for acting on creative inspirations. The love I see exchanged among people in my community. The experience of entering a community far away and different from my own. So many lights.

WHAT FRUSTRATES YOU?

The too-fast pace of U.S. society, and the feeling of time passing by.

WHAT MAKES YOU LAUGH?

The group chat. My text message

Carlotta Penn is a creator—an author, a songwriter and a poet. She’s a learner—a thirsty student with a bachelor’s degree in communication, a master’s degree in comparative studies and a doctorate in education. She’s an educator—a longtime teacher who is now a senior director at The Ohio State University, overseeing partnerships and engagement activities in the Office of Equity, Diversity and Global Engagement at the College of Education and Human Ecology. And she is also a mother who wants her three young children to see themselves in the books they read. It’s a conviction that led her to found Daydreamers Press, which publishes children’s content highlighting multicultural perspectives. The 42-year-old’s most recent project is a collaboration with Ohio Humanities—a children’s book about the Lincoln School Marchers, a group of Black mothers in southern Ohio who were civil rights heroes. The Columbus dynamo opens up here.

conversations with family and friends bring spontaneity and laughter to each and every day. I will always love the company of my dearest friends and family face to face, but the digital bonds cannot be discounted!

WHAT IS YOUR PROFESSIONAL MISSION?

Daydreamers Press seeks to carry on the legacy of Black storytelling, art and advocacy for representation and justice. We publish content that highlights perspectives and knowledges of multicultural communities. We honor the work of those Black writers and creators who have come before Daydreamers Press and that of our extraordinary contemporaries.

LUMEN 2024 | 8

LOVE IS THE MOST BRILLIANT LIGHT.

WHAT IS YOUR PERSONAL MISSION?

To be the best I can wherever I am, and to do the best I can with what I’ve been given. I really just want to make the most of my brief time on earth.

WHY IS HUMAN CONNECTION SO IMPORTANT?

Collectively, we need each other, and any given community is best when united. But on the interpersonal level, I know from history and experience that even brief human encounters can change the course of someone’s life for the better.

WHAT IS A MEMORABLE TIME FROM YOUR CHILDHOOD?

My siblings and I spent lots of time with our cousins growing up. I remember long days outside finding furry caterpillars at my grandparents’ home. Some of the best times were writing and performing skits for the grown-ups. These are defining experiences because those relationships are some of the best I have. And I’m still writing and sharing stories.

WHO MADE A POWERFUL MARK ON YOUR LIFE?

My father, Gary Penn Sr., led an inspirational life that integrated family, faith, entrepreneurship, blue collar work, service and arts. I learned from him to pursue dreams and listen to God’s voice in our lives, in the midst of both ease and adversity.

9 | LUMEN 2024

—CARLOTTA

” ”

PENN

DAYDREAMER

WHAT ACCOMPLISHMENT ARE YOU MOST PASSIONATE ABOUT?

I have two. First, I co-produced a documentary about the experiences of millennial Black women in Columbus during the 2020 pandemic. The Black Women Story Project is so in line with my professional mission to listen, share and honor the lives and knowledge of Black women. I had the joy of working on this with my friend and co-producer Donna Marbury, who is a writer and creative in Columbus. Second, working with Ohio Humanities and the women of Hillsboro, Ohio, on the Lincoln School Marchers story has been amazing. Publishing a picture book about Black mothers, children and a community advocating for justice is an extra-special honor.

WHO DO YOU ENJOY LEARNING FROM?

James Baldwin’s essays and interviews are always worth taking in. He was brilliant and compassionate, and his confident, easygoing demeanor in the midst of conflict is aspirational. Virginia Hamilton’s essays and speeches are also especially meaningful to me now, since she wrote many of my favorite children’s books.

WHY DO YOU LOVE OHIO?

I love Ohio because it holds the people I love most. But there’s more to love about Ohio—the changing of seasons, the parks and libraries. And so many talented artists of all sorts came to brilliance here.

WHAT ONE PERSON DO YOU WISH EVERY OHIOAN KNEW?

In 1947, my grandfather Thomas O’Rare Penn and a co-worker, Muriel McMullen, helped rescue four people who had fallen into the Scioto River when lightning struck the Broad Street Bridge. They weren’t thanked or recognized until 1990, when City Council honored them. Though there was also a white man who helped in the rescue, it’s believed their bravery went unrecognized because, as my grandfather said, “Back in those days, Black people didn’t get recognized unless they killed somebody.” I share this story as an example of the role everyday people play in shaping our communities.

WHAT ARE YOU CERTAIN IS TRUE?

Every day is a new chance to start again. It’s worth it to just keep going.

IF THERE IS A SINGLE MISSION YOU COULD MOBILIZE PEOPLE AROUND, WHAT WOULD IT BE?

I wish we would all take good care of ourselves and each other.

IF PEOPLE DEFINED YOU WITH ONE WORD, WHAT DO YOU HOPE IT IS?

Daydreamer, of course!

LUMEN 2024 | 10

11 | LUMEN 2024

DR. CLAY JOHNSON

WHAT LIGHTS YOU UP?

I love it when a volunteer or a volunteer committee celebrates their sense of accomplishment. Our organization relies on so many dedicated volunteers. Without their hard work, it would be challenging for us to thrive as we do.

WHAT FRUSTRATES YOU?

Closed-mindedness creates barriers. The increasing political polarization is adding an additional layer of challenges to our limited resources.

American sharpshooter Annie Oakley was born in Darke County, Ohio—a rural spot nestled against the Indiana border along the state’s western edge. Preserving her legacy is, among other things, Clay Johnson’s job. He is the first professionally trained CEO of the Garst Museum, home of the National Annie Oakley Center. The tasks before him were daunting, including creating and managing significant institutional policies on everything from collections to security to disaster plans. But a dozen years later, Johnson—with the support of dedicated volunteers—has reimagined what’s possible. From the Gathering at Garst event to a grant-based school tour program, Johnson is making history compelling and accessible. In short, he is using all three of his history degrees—a bachelor’s, a master’s and a doctorate—to help preserve and share the stories of the community he loves. Here, the 60-year-old husband and motorcycle enthusiast talks politics, Scouting and more.

WHAT IS YOUR PROFESSIONAL MISSION?

A passion of mine is to provide awareness through knowledge. Since a museum’s primary mission is to educate, I believe we can provide the necessary tools to inform about our past through interpretation. These efforts will hopefully lead to a better understanding and respect for our cultural heritage while building unity in our community.

WHAT IS YOUR PERSONAL MISSION?

A personal goal of mine is to absorb all that our rural material culture has to offer.

WHAT MAKES YOU LAUGH?

Am I still allowed to laugh at the style of humor I enjoyed as a teenager? Because I still do!

LUMEN 2024 | 12

IT IS CRITICAL FOR PEOPLE ADAGE THAT HISTORY CAN —CLAY JOHNSON ” ”

WHY IS HUMAN CONNECTION SO IMPORTANT?

It takes humanity to facilitate change.

WHAT IS A MEMORABLE TIME FROM YOUR CHILDHOOD?

Becoming an Eagle Scout has had a positive and lasting impact on my life. Growing up in Beavercreek, Ohio, I was fortunate to have an active and attentive Boy Scout troop. The values I learned and the acquired outdoor skills are still treasured today. My Eagle Scout project was to restore two local cemeteries, and I am happy to say that after 44 years, parts of my project still survive.

WHO MADE A POWERFUL MARK ON YOUR LIFE?

I was raised by a single mother struggling to put herself through college while raising two active teenage boys. She succeeded in excelling in her new career despite challenges. Witnessing her sacrifices for her family gave me a deep respect for so many other families striving to succeed. Unfortunately, she succumbed to a terminal illness at an early age, but seeing her happiness and success gave me the drive to return to school to pursue my passions.

WHAT ACCOMPLISHMENT ARE YOU MOST PASSIONATE ABOUT?

During the first month of my employment at the Garst Museum, I met with a creative and dedicated community volunteer who had the drive to help create a wonderful community event. The result was the Gathering at Garst. The Gathering’s mission is to promote awareness and appreciation of those who made unique contributions to the culture of Darke County and to celebrate the local heritage in a familyoriented and educational atmosphere. The highly-anticipated festival is held in July and features a Living History Encampment and a venue for performers and artists. Through the Living History Encampment, visitors learn of the cultural contributions that indigenous and pioneer settlers made in developing the area now known as Darke County. The encampment village, representing life from 1750 to1865, is designed to engage the entire family while promoting a rich sense of community.

WHO DO YOU ENJOY LEARNING FROM?

I enjoy learning from those who are unafraid to get their hands dirty.

13 | LUMEN 2024

WHY DO YOU LOVE OHIO?

I love the Ohio rural landscape. Since my teenage years, I have enjoyed riding my motorcycle and getting lost on our winding backroads. These trips are always enlightening and a great way to observe Ohio’s natural beauty, regional cultures and changing landscapes. Unfortunately, however, over the last few years of my travels, I have noticed a concerning increase in Confederate flags and other divisive and hurtful signs. In fact, a couple of years ago, I even had Ku Klux Klan propaganda thrown in my yard. Hopefully, in the coming years, our picturesque rural landscape will no longer be blighted by these pockets of hate.

WHAT ONE STORY DO YOU WISH EVERY OHIOAN KNEW?

The story of Chief Little Turtle of the Miami tribe is often overlooked as part of our regional history. Little Turtle’s leadership resulted in the destruction of two American armies in the Ohio territory, but

he later became a staunch ally. After signing the Treaty of Greene Ville on August 3, 1795, he pledged that although he was the last to sign the treaty, he would also be the last to break it. He held to his word and dissuaded many Indians from joining the British side during the War of 1812 despite his declining health.

WHAT ARE YOU CERTAIN IS TRUE?

Despite their challenges or obstacles, people can change.

IF THERE IS A SINGLE MISSION YOU COULD MOBILIZE PEOPLE AROUND, WHAT WOULD IT BE?

It is critical for people to understand the time-tested adage that history can repeat itself. Otherwise, we may relive some of our past ugly experiences or hardships.

IF PEOPLE DEFINED YOU WITH ONE WORD, WHAT DO YOU HOPE IT IS?

Steadfast.

TO UNDERSTAND THE TIME-TESTED REPEAT ITSELF. STEADFAST

LUMEN 2024 | 14

15 | LUMEN 2024

DR. JEREMY TAYLOR

WHAT LIGHTS YOU UP?

As an educator, I am passionate about seeing students transform from first-year students into professionals. It inspires me to see them learn, question and grow throughout their four undergraduate years.

WHAT FRUSTRATES YOU?

It frustrates me when people lack compassion. Many people today get caught up in ideological beliefs without taking the time to understand others’ perspectives. Rather than jumping to conclusions about one’s circumstances, I wish people would start from a place of understanding and compassion.

Dr. Jeremy Taylor is a longtime history professor who holds bachelor’s, master’s and doctorate degrees in history—and who has compiled an armful of awards in his career across Texas, Arkansas and Ohio. At Northwest Ohio’s Defiance College, he garnered accolades by helping create Jacket Journey (named after Defiance’s mascot, the yellow jacket), an innovative, interactive career-readiness program. Now, he’s the school’s vice president of enrollment management. Here, the husband and father of two young adults, who serves on the Ohio Humanities Board of Directors, talks about the value of a liberal arts education, an ancestor’s inspiring evolution from slave to business owner and more.

WHAT MAKES YOU LAUGH?

I love slapstick comedies. I grew up watching Airplane, Police Academy, Spaceballs and many others. I’m really easily entertained.

WHAT IS YOUR PROFESSIONAL MISSION?

I want every student in America to know that college can be an option for them. There is a common misconception that colleges—particularly small, liberal arts colleges—are too expensive and not worth the investment. A college degree is one of the best drivers for social and economic mobility. Also, students gain invaluable skills that employers often identify as desirable: critical and creative thinking, oral and written communication, problem solving and many more.

LUMEN 2024 | 16

WHAT IS YOUR PERSONAL MISSION?

My personal mission is to simply be kind. I try to put others before myself and do a little bit of good every day.

WHY IS HUMAN CONNECTION SO IMPORTANT?

Human connection is important because we, as a species, are not meant to live in isolation. We need to speak, talk, touch and interact with other humans. Human connection allows one to move beyond themself and learn from others.

WHAT IS A MEMORABLE MOMENT FROM YOUR CHILDHOOD?

My most memorable moment from childhood was when I read my first book by myself. I can remember the feeling of accomplishment that I had. This was defining because reading opened up the world to me.

WHO MADE A POWERFUL MARK ON YOUR LIFE?

I have never met the person that made the most powerful mark on my life. His name is Sip Mills, and he was my great, great, great grandfather. He was born into slavery but managed to become a land and business owner in segregated, 19thcentury Alabama. His ability to adapt and overcome enormous odds has always been an inspiration to me.

WHAT ACCOMPLISHMENT ARE YOU MOST PASSIONATE ABOUT?

I had the pleasure of helping to create and implement the Jacket Journey program at Defiance College. This is a required, fouryear career-readiness program designed to help students find their calling and prepare for their career. Jacket Journey is fun, interactive and embedded into the curriculum. It was great to work with stakeholders from across campus and the community to develop the program.

WHO DO YOU LOVE TO LEARN FROM?

I love learning from my students. Although I don’t teach as much as I used to, I generally learn just as much from my students as they do from me.

WHY DO YOU LOVE OHIO?

I love Ohio because of the people. I moved to Ohio from the great state of Texas (by way of Arkansas) about 10 years ago, and I have developed great friendships with people from all walks of life. Ohio is a great place to live.

17 | LUMEN 2024

KIND

WHAT ONE STORY OR PERSON DO YOU WISH EVERY OHIOAN KNEW?

I did my dissertation research on the relationship between Johnson’s Island Confederate prison camp in Lake Erie and the city of Sandusky during the Civil War. This is a fascinating tale of civil-military relations and is full of interesting, relatively unknown characters.

WHAT ARE YOU CERTAIN IS TRUE?

I have the best job in the world.

IF THERE IS A SINGLE MISSION YOU COULD MOBILIZE PEOPLE AROUND, WHAT WOULD IT BE?

I would mobilize people to help improve educational opportunities for all students. Education is the key to solving many of the world’s problems.

IF PEOPLE DEFINED YOU WITH ONE WORD, WHAT DO YOU HOPE IT IS?

Kind.

LUMEN 2024 | 18

EDUCATION IS THE KEY TO SOLVING MANY OF THE WORLD’S PROBLEMS.

”

—JEREMY TAYLOR

”

The Story of Cory

Cleveland’s Cory United Methodist was born a Jewish synagogue and community center. Then, it evolved into a Christian church and became one of the nation’s most noteworthy centers of civil rights activism. Now, led by a passionate young pastor, the landmark that hosted crusaders from Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. to Malcolm X is fighting not for equality but for its life.

Story

by Joe

Blundo

Photos by De’Shaunae Marisa

19 | LUMEN 2024

LUMEN 2024 | 20

21 | LUMEN 2024

Rev. Gregory Kendrick Jr. was 12 years old when he preached his first sermon on a neighbor’s front porch.

He grew up on Chicago’s West Side in a neighborhood with gangs and gunfire but also guardians, sanctuaries, places of grace. The Pleasant Ridge Missionary Baptist Church—where Kendrick learned how to pray, how to dance and how to distinguish a salad fork from a dinner fork—was steps away from his home. And a neighbor, Rev. Janey Rucker, held a Bible study on her small, enclosed front porch once a week for kids who were interested.

“We went there for the snacks, and in the midst of getting snacks, we were able to grow and understand what love really meant,” Kendrick said. “It was almost as if we were in this sacred, holy place.”

It was the first place where Kendrick preached—where he publicly proclaimed his faith—although he can’t remember what he said.

“I’m sure it wasn’t good,” he joked, and then reconsidered. “No, I’m sure it was good for its time and its place. I was 12.”

Two decades later, on Cleveland’s East Side, Kendrick, 35, is the pastor of a church in a neighborhood not unlike the one where he grew up. Like Kendrick’s childhood church, Cory United Methodist Church in the Glenville neighborhood of Cleveland is a place where kids learned to pray and dance. It’s also a place where civil rights history was made.

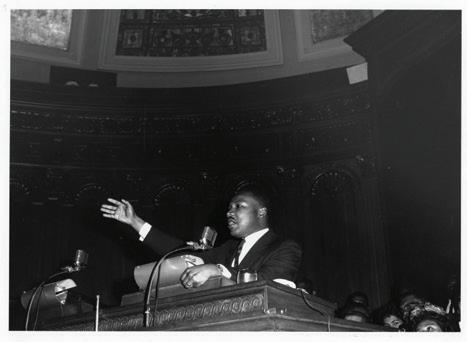

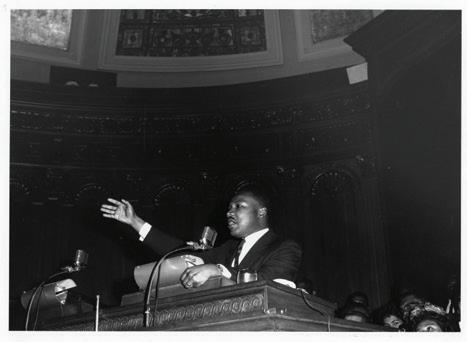

Just days after being released from the Birmingham Jail, for example, Martin Luther King Jr. came to Cleveland to address an overflow crowd at Cory. “We will meet physical force,” he said to thousands, “with soul force.”

Less than a year later, it was from Cory’s pulpit that Malcolm X first delivered his The Ballot or the Bullet speech, often found on lists of the most noteworthy addresses of the 20th century.

LUMEN 2024 | 22

“This place is worth cherishing. This place still has value to offer to the world.”

—Rev. Gregory Kendrick Jr., Cory pastor

23 | LUMEN 2024

It’s no coincidence that both civil rights leaders came to Cleveland at important moments in the struggle for equality. The city was a center of civil rights activism in the North. And, in coming to Cory in particular, King and Malcolm X were following in the footsteps of writer W.E.B. Du Bois and Chief Justice Thurgood Marshall, who also spoke at the church.

“During the 1950s and ’60s, it was the site for civil rights activities,” said Margaret Lann, director of preservation services and publications for the Cleveland Restoration Society, which works to ensure the preservation of significant buildings.

Once one of Cleveland’s largest Black churches, Cory, so dedicated to the civil rights struggle, is now in a struggle of its own. Its aging membership has dwindled to about 150—and only a fraction of them show up each Sunday. Funding is a struggle. And the coronavirus pandemic shuttered most of the social programs for which it was well known.

But even as churches close at an alarming rate nationwide, there are reasons to hope that this church—whose walls have echoed with so much history—will endure.

Two years ago, it was the first site named to Cleveland’s African-American Civil Rights Trail, a collection of important locations in the fight for equality. Cory has also attracted a few grants to preserve its distinctive building. And, perhaps above all, it has Gregory Kendrick Jr.

LUMEN 2024 | 24

Rev. Gregory Kendrick preaches at Cory on a spring Sunday in 2023

Synagogues and Superman

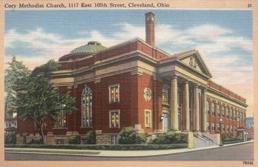

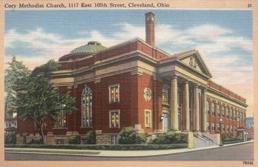

Cory stretches the length of an entire block on East 105th Street in Glenville, a predominantly Black neighborhood on Cleveland’s East Side.

Glenville was founded as an independent village in 1870. It was known for its farms, its horse-racing track and, on its northern edge, its opulent summer residences near Lake Erie. It grew quickly and developed into a thriving, middle-class Jewish community often called the Gold Coast, with 105th Street the thriving heart of a bustling commercial strip.

One of its claims to fame: In the 1930s, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, both Glenville

High School students and the sons of Jewish immigrants, dreamed up a comic strip hero called Superman. Siegel’s home, on the National Register of Historic Places, still stands on Kimberly Avenue.

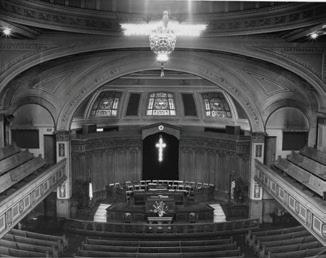

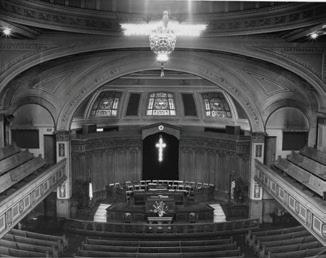

The building now known as Cory was originally constructed as a synagogue and community center by the Jewish congregation Anshe Emeth Beth Tefilo, which moved into the facility in 1921 and renamed itself the Cleveland Jewish Center. Such combination synagogues and community centers were something of a trend at the time, as congregations looked for ways to attract and retain members and to provide recreational and social opportunities that were often denied Jews elsewhere due to discriminatory practices.

The structure was called the largest Jewish center west of the Allegheny Mountains. Its fluted columns, supporting a pediment

25 | LUMEN 2024

Cory in June 1975 / The Michael Schwartz Library at Cleveland State University

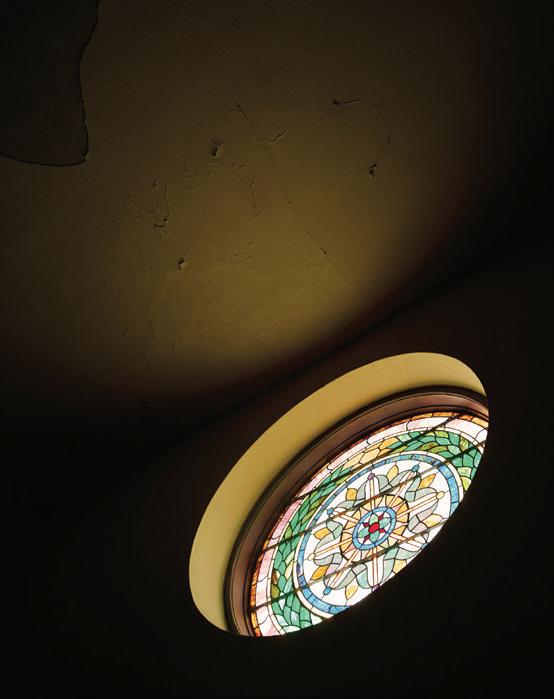

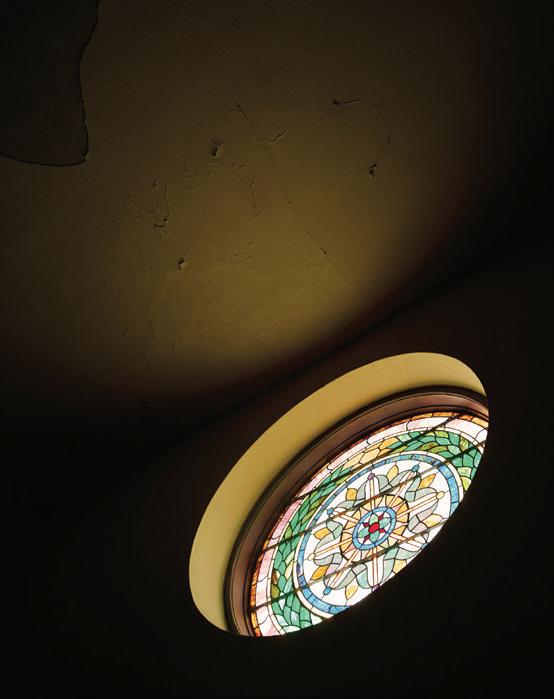

with Hebrew inscriptions, loom over 105th Street. The names of Old Testament prophets are carved into the cornices of the building. The synagogue was built with elegant stained-glass windows, seating for 2,400 people, a large ballroom, a gymnasium and a swimming pool. It was one of many synagogues in Glenville at the time.

Then, in 1946, the Cleveland Jewish Center congregation followed its members to the suburbs. The building was sold to the Cory congregation, which moved to Glenville from a site closer to the center of Cleveland.

In the late 1940s, after the Second World War, many Black families migrated from the South to the North. Black citizens came seeking better opportunities and less oppressive social conditions. It dramatically shifted the demographics of Cleveland neighborhoods.

“The transformation of Glenville was very quick,” Lann said.

In 1940, Black people constituted about 2 percent of the neighborhood. By 1950, the Black population had reached 50 percent and continued to grow rapidly through the decade. Now, it stands at more than 90 percent.

Housing discrimination restricted most Black families to living on the East Side. Glenville quickly became overcrowded, with many of its large houses converted into rental units. Multiple families sometimes shared space, crowding together so they could afford shelter.

Increasingly weighed down by problems of poverty, crime, blight and racism, Glenville was convulsed by violence in July 1968. A gun battle between Cleveland police officers and Black nationalists, dubbed the Glenville Shootout, killed three officers, three nationalists and one civilian and wounded others. Several days of rioting followed.

Efforts to improve the neighborhood have had limited success. While the southern part of Glenville has been attracting new investment and has higher home ownership rates, the northern section, where Cory is located, continues to struggle.

More than 60 percent of Glenville’s population lives in or near poverty, according to research by the Center for Community Solutions in Cleveland. The neighborhood also has higher infant mortality rates and higher unemployment than other parts of the city. Glenville’s population fell from 27,000 in 2010 to 21,000 in 2020, according to Census data.

Cleveland City Councilman Kevin Conwell, whose district includes much of Glenville, said major infrastructure improvements and a business-incubator

LUMEN 2024 | 26

“It’s a real neighborhood. There’s a community. People look out for each other.”

—India Pierce Lee, Glenville resident

program are among recent efforts to improve the neighborhood. But change, he said, will take time.

India Pierce Lee, executive vice president and chief strategy officer at Cuyahoga Community College, swam in the Cory pool as a child and has lived in Glenville much of her life. She acknowledges Glenville’s problems but fiercely defends it. “It’s a real neighborhood,” she said. “There’s a community. People look out for each other.”

Although it’s technically illegal for lenders to let racial considerations influence their decisions, redlining still happens in Glenville, she said. People with great credit scores have trouble securing mortgages. It’s one of the factors holding the community down.

“But we’re committed to staying in this community as long as God allows,” Pierce Lee said. “As far as I know, I’m going to stay here until they carry me out.”

Gregory Kendrick’s father drove trucks, and his mother did clerical work—a fortunate working-class family in a neighborhood with a high poverty rate. His parents expected Kendrick to excel at school and attend college.

Kendrick discovered Denison University—a small, private college in Granville, Ohio— through the Posse Foundation. It’s a nonprofit organization that identifies promising students from the same area and awards them scholarships to attend a college as a group. They find diverse young leaders like Kendrick who might be missed by traditional admissions criteria.

In 2006, Kendrick, arrived at Denison with his best friend Joseph and eight other Chicagoans. They were met with warm welcomes—and the occasional racial slur.

The campus was beautiful, and most people were kind and accommodating, Kendrick said. Yet there were pockets of hostility. “It smells like (racial slur) in here,” someone once yelled when his best friend walked by. There was also a fraternity Halloween party with blackface, noose symbols thoughtlessly employed for humor, the casual use of slurs.

Back home, Kendrick’s half-sister was shot and killed by an assailant who apparently mistook her for someone else.

His faith and his friends sustained him through it all.

“The community of faith in some ways was tangible evidence of God’s presence,” he said. “In the end, my experience at Denison was the most transformative experience of my life.”

27 | LUMEN 2024

LUMEN 2024 | 28

Cory’s once-gleaming exterior, shown in an old postcard at left, is now undergoing renovations thanks to a few grants it has secured

Alabama North

The Christian congregation that bought the Cleveland Jewish Center in 1946 remodeled the building but kept the Jewish iconography. There are menorahs on the walls of the sanctuary and a Star of David chandelier.

Kendrick smiles about it now. “I often joke and say Cory moved here and just put up a cross and went right to work,” Kendrick said.

There was a lot of work to do.

In the 1950s, the church had a membership of more than 3,000, according to the Encyclopedia of Cleveland History. More than a church, it was a bustling

center of community life, much as it had been when it housed a synagogue— packing in guests for not just Sunday sermons but also community dances, festivals and more.

The church continued to operate the gym and swimming pool that came with the building. In 1961, the city of Cleveland rented the part of the building containing the pool and gym and declared it an official city recreation center. It remains so to this day.

Charles Williams, who has been a Cory church trustee since 1979, said the recreation opportunities were a lifeline for him when he moved to Cleveland with his family as a teenager in the 1950s. It gave him a place to belong when he didn’t know many people.

29 | LUMEN 2024

Martin Luther King Jr. speaks from Cory’s pulpit in the ’60s / The Western Reserve Historical Society, Cleveland, Ohio

“Man,” said Williams, 84, “it was like a second home to me.”

It wasn’t the only lifeline that Cory extended to its neighbors.

The church established a credit union in 1958, at a time when getting loans was especially difficult for Black people. (It operated until 2016, when it merged with another credit union.) Cory also organized youth sports leagues, offered dance and music lessons, formed its own community library and housed a day-care center.

But Cory’s most significant legacy involves opening its doors to civil rights organizers and activists. In addition to the high-profile speakers it attracted, Cory was a regular meeting place for rallies, discussions, voter registration drives and strategy sessions. In the 1960s, one of its pastors, Rev. Sumpter Riley, served as president of the United Freedom Movement, a union of 34 organizations, including the NAACP, the Congress of Racial Equality and many other groups that battled school segregation, discriminatory hiring practices and police brutality in Cleveland.

Many of the Black people who migrated to Cleveland from the South after each world war hailed from Alabama.

“It was not uncommon to refer to Cleveland as ‘Alabama North,’ ” said Ohio author James Robenalt in his book Ballots and Bullets: Black Power Politics and Urban Guerrilla Warfare in 1968 Cleveland.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was locked behind bars for leading those demonstrations. While sitting in his cell, he wrote his famous Letter from Birmingham Jail, which contains one of his most-quoted lines. “Injustice anywhere,” he wrote, “is a threat to justice everywhere.”

So in 1963, when Bull Connor, the notorious Birmingham, Alabama, safety commissioner, unleashed his police dogs and fire hoses on Black civil rights demonstrators—many of them children— the pain cut deep in Cleveland.

LUMEN 2024 | 30

“We will meet physical force with soul force.”

—Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. in a 1963 speech at Cory

Glenville is a neighborhood on the East Side of Cleveland, about five miles from Downtown

Emmitt Theophilus Caviness, who has been senior pastor at Cory’s neighbor, Greater Abyssinia Baptist Church, since 1960, knew Martin Luther King Jr. well. He said King told him many times how fondly he regarded Cleveland. “King was very much at home here,” said Caviness, 95.

The news that King, fresh from that Birmingham jail, would be coming to Cleveland on May 14,1963, to speak at Cory was met with great excitement. “Thousands began lining up outside Cory Methodist Church early in the day, though King was not scheduled to speak until 7:30 p.m.,” Robenalt wrote, “and traffic backed up for miles around the church.” The crowd around Cory became so congested that King postponed his 7:30 p.m. speech until 8:45

so that he could make appearances at three other Black churches in the neighborhood to accommodate all who wanted to hear him. When he finally arrived to speak at Cory, the sanctuary was packed with 4,000 people, and another 5,000 listened outside through speakers.

31 | LUMEN 2024

“King was very much at home here.”

—Emmitt Theophilus Caviness, senior pastor at Greater Abyssinia Baptist Church, Cory’s neighbor

Rev. Kendrick shows a banquet photo from Cory’s heyday

“The walls were bulging,” reported the Call and Post, Cleveland’s Black-owned newspaper.

King called it the most enthusiastic welcome he’d ever seen.

In his Cory speech, King reiterated his determination to pursue justice through nonviolent protest. “We will meet physical force with soul force,” he said. “I am committed to nonviolence as a way of life.”

He called segregation a cancer.

“There comes a time when people get tired of being trampled over by the iron feet of oppression,” he said. “A time when people get tired of being pushed out of the glittering sunlight of life’s July and left standing in the chill November of an alpine winter.”

The Call and Post said King was repeatedly interrupted by thunderous applause. The baskets that were passed around the pews to collect bail money for jailed protesters in Birmingham raised $12,000, according to one account. “One group, unable to pass their contribution to Birmingham down from the crowded balcony, wrapped it in a silk scarf and tossed it down,” the newspaper reported.

A young girl, touched by the idea of kids facing the brutality of Bull Connor, donated the $50 her parents had gifted for her 12th birthday.

“I’m giving this money,” she said, “to the children of Birmingham.”

As a college student, Kendrick had several potential career paths in mind: politics, community advocacy, business entrepreneurship, higher education. He always knew he wanted to be engaged in ministry, but he thought he’d do it as “the world’s greatest tither”—a lay person with a healthy bank account who could financially support the work of a church. After growing up in an impoverished neighborhood, he joked, making money might be nice.

But as a rising senior at Denison, Kendrick, who had been active in a campus ministry called Agape, saw a need.

The campus chaplain was expecting twins with his wife. The additions would give the family four children under 4. The balancing act, the chaplain knew, could be tenuous.

“Hey, why don’t I help you out?” Kendrick suggested. “I could be like a student chaplain.”

Kendrick spent his senior year helping lead chapel services and organize activities.

“I realized maybe there might be something in ministry,” he said, “that could be more a part of my daily life.”

LUMEN 2024 | 32

33 | LUMEN 2024

LUMEN 2024 | 34

“I realized maybe there might be something in ministry that could be more a part of my daily life.”

—Rev. Gregory Kendrick Jr., Cory pastor

Ballots or Bullets

In the months between King’s May 1963 speech at Cory and Malcolm X’s April 1964 speech there, much happened. Civil rights activist Medgar Evers was assassinated in June 1963 in Mississippi. The March on Washington in August 1963 attracted 250,000 people and culminated in King’s I Have a Dream speech. A month later, four Black girls were killed in the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham.

The alternating cycles of peaceful protests and violent backlash raised doubts about King’s tactics of nonviolent resistance. Among his most vocal doubters, few stood out like Malcolm X.

“Whereas Dr. King was a Christian, committed to nonviolence and in favor of integration, Malcolm X was a Muslim, committed to armed self-defense, and a separatist who espoused Black nationalism and a separate state,” Robenalt wrote.

Malcolm, who had joined the Nation of Islam (Black Muslims) in the 1950s, had a fiery personality that made him a celebrity in the early 1960s with frequent TV appearances. His rising profile led to tensions with his mentor, Elijah Muhammad. Muhammad was founder of the Nation of Islam who preached total separation of the races and a ban on participating in politics or even voting.

Just as his fame was reaching its zenith, Malcolm came to Cleveland to support a

35 | LUMEN 2024

Methodist church leaders gather at their national church convention at Cory in July 1960 / The Michael Schwartz Library at Cleveland State University

heated campaign against de facto segregation of Cleveland’s public schools. Black students in Cleveland attended schools in their neighborhoods, which were almost entirely Black because of redlining, deed restrictions and other discriminatory practices that restricted where Blacks could live. Although a separatist, Malcolm had lately grown more willing to participate in such integration battles as he distanced himself from Elijah Muhammad.

Leonard N. Moore, a professor of history at Louisiana State University who wrote a 2002 article on the Cleveland school struggle in the Journal of Urban History, summed up the grievances Black parents cited in complaining about the educations their children were receiving: “Inferior teachers, teacher segregation, a lack of remedial teachers, low teacher expectations, few Blacks in administrative positions, high student-teacher ratio, poor physical plant, inadequate social services and a severe lack of vocational courses. In comparison, schools on the all-white West Side had the most experienced teachers, the best services, the most attractive buildings and a low studentteacher ratio.”

City officials responded to the protests by planning to bus Black children to white neighborhoods, which had surplus classroom space. But the officials assured white parents that there would be no sharing of facilities: The Black students would be strictly segregated, with Black teachers brought in to instruct them.

the school board in fall 1963 to promise true integration by the next year. But the board was in fact planning to build new schools in Glenville, which would return students to segregated classrooms.

Protesters were further inflamed when Ralph McAllister, the white school board president, publicly declared that Black children were “educationally inferior” to white students.

A protest at Murray Hill School in the white neighborhood known as Little Italy had barely gotten underway on January 30, 1964, when violence erupted. Gangs of young white men beat several Black people; threw rocks, bricks and bottles; and even attacked some police officers and news reporters. Leaders of the United Freedom Movement, which had been coordinating the civil rights demonstrations, abruptly halted the protest to avoid further violence.

It was into this tense atmosphere that Malcolm X, at the invitation of the Congress of Racial Equality, arrived at Cory to speak on April 3, 1964.

The arrangement infuriated Black parents. They responded with demonstrations, marches, picketing and sit-ins, finally leading

LUMEN 2024 | 36

“During the 1950s and ’60s it was the site for civil rights activities.”

—Margaret Lann, Cleveland Restoration Society

An estimated 3,000 people showed up at the church that night. The evening was billed as a debate between the radical Malcolm and the more mainstream activist Louis Lomax, a Black writer who had coproduced a documentary on the Nation of Islam.

It was not a back-and-forth discussion. Lomax spoke first, followed by Malcolm X, who launched into a blistering indictment of American society.

“The question tonight, as I understand it, is ‘Where Do We Go From Here?’ ” he began. “In my humble little way of understanding it, it points toward either the ballot or the bullet.”

He predicted that 1964, a presidential election year, would be “the most explosive year” in American history. “Why? It’s also a political year,” he said. “It’s the year when all of the white politicians will be back in the so-called Negro community jiving you and me for some votes. The year when all of the white political crooks will be right back in your and my community with their false promises.”

He then reviewed how neither political party had delivered anything remotely resembling equal rights to Black people, including the right to vote in Southern states.

after they get it, the Negro gets nothing in return.”

Malcolm claimed he wasn’t advocating violence, just self-defense.

“Let them know your eyes are open,” he said. “It’s got to be the ballot or the bullet. The ballot or the bullet. If you’re afraid to use an expression like that, you should get on out of the country; you should get back in the cotton patch; you should get back in the alley. They get all the Negro vote, and

“I’m nonviolent with those who are nonviolent with me. But when you drop that violence on me, then you’ve made me go insane, and I’m not responsible for what I do. And that’s the way every Negro should get.”

He told audience members that, yes, he’d work with them on school boycotts. “We will work with anybody, anywhere, at any time, who is genuinely interested in tackling the problem head-on, nonviolently as long as the enemy is nonviolent, but violent when the enemy gets violent.”

The Call and Post said most of the 3,000 listeners at Cory were “brought to their feet” by the speech. Malcolm X would repeat the speech 10 days later in Detroit.

The school protests that brought Malcolm X to Cleveland in early April 1964 continued after he left. On April 20 that year, Cory opened its doors to some of the 60,000 students, most of them Black, who participated in a citywide school boycott despite threats from school officials to take harsh action against them.

37 | LUMEN 2024

“It’s got to be the ballot or the bullet.”

—Malcom X in a 1964 speech at Cory

Cory Pastor Sumpter Riley hoped his church had made a statement. “Let no one go home and say that churches are remaining silent or inactive,” he said, “for we are doing our part.”

Less than a year later, Malcolm X, while preparing to speak in New York City, was shot multiple times and killed. Three men, all members of the Nation of Islam, were convicted in the killing. But the convictions of two of them were reversed years later, and mystery continues to surround the crime.

King, who would return to Cleveland many times, was assassinated in 1968 in Memphis, where he had traveled to support a strike by city sanitation workers. James Earl Ray pleaded guilty to King’s murder in 1969, but King’s family has long maintained the crime sprang from a conspiracy and that Ray was a scapegoat.

As for school integration in Cleveland, it would be late 1979 before court-ordered busing would achieve it.

After graduating from Denison, Kendrick took a job in multicultural recruitment at Ohio Northern University and then entered the Methodist Theological School in Ohio (MTSO).

He expected to graduate as a Baptist pastor. But a stint as a student minister at Broad Street United Methodist in Columbus changed his heart.

John Wesley, founder of Methodism, once wrote: “The gospel of Christ knows of no religion, but social; no holiness but social holiness. Faith working by love, is the length and breadth and depth and height of Christian perfection.”

Kendrick found the emphasis on community captivating.

The husband and father of two began serving Methodist churches in Columbus and Cleveland.

Cory’s sanctuary, shown here in March 1958, has remained largely intact / The Michael Schwartz Library at Cleveland State University

LUMEN 2024 | 38

39 | LUMEN 2024

LUMEN 2024 | 40

Cory has nearly 100,000 square feet of space, and Rev. Kendrick is trying to figure out how to use it to best serve the community

‘I Need to Stay’

Kendrick is somewhat soft-spoken for a preacher. It’s hard to imagine any hellfire and brimstone coming from his pulpit. He’s warm but maintains a certain reserve—especially for making anything, including conversation, about himself. There is, however, a quiet firmness, a directness and a thoughtfulness to the way he expresses himself that leaves little doubt about his convictions.

Kendrick arrived at Cory in late 2019, on what was supposed to be a temporary assignment. “The goal,” he said, “was that I would be here for 3 months to try to figure some things out.”

He began hearing talk of two major challenges: First, the massive building—95,000 square feet—needed too much repair. Second, the small congregation—it averages perhaps 40 worshippers on a typical Sunday—was dwindling too quickly to justify keeping the building open.

The building, Kendrick acknowledges, needed—and still needs—work. “There would be weeks on end when I would come in,” he said, “and my main job was to see what was leaking today.”

Then, in early 2020, the coronavirus pandemic hit.

41 | LUMEN 2024

Rev. Kendrick laughs with a congregant after a Sunday service at Cory in May 2023

But Kendrick felt called to counter pessimism about the church’s future. The biblical prophet Nehemiah, he said, was his inspiration. When Nehemiah hears of the desolation and poor conditions of his people, he weeps—and then prays to God that he may have the blessing and strength to work for the collective good of his people. “When I saw what people were experiencing and how greatly they were being affected in the early pandemic,” Kendrick said, “I had a similar prayer to God.”

Kendrick went to his bishop.

“I need to stay,” he said.

Kendrick immediately faced COVIDinduced, gut-wrenching choices.

Cory had provided the neighborhood with food for 50 years through hot meals and a free pantry. But some of the food was unhealthy or low-quality. Other food came from agencies requiring Cory to collect income information from recipients, a practice Kendrick disliked. And keeping up with growing demand was pushing volunteers to a physical breaking point. After wrestling with the decision for months, Kendrick closed the pantry and stopped serving hot meals. “There was disappointment, shock,” Kendrick said. “People still ask when we will open again.”

But the church’s goal, he noted, was never to be a grocer. “The vision,” he said, “was always a sovereign and sustainable community that had everything it needed within it to be successful.” Kendrick is planning to realize that vision by partnering with local farmers to supply fresh food

that will be distributed to neighbors in need. “It’s more sustainable,” he said. “It allows us to make connections with folks who are local. It allows us to provide more nutritious food.”

Then, 2021 brought a bright spot: Cory became the first site designated as a spot on the Cleveland African-American Civil Rights Trail—a project funded in part by Ohio Humanities that denotes locations important to the civil rights movement.

Cory has also attracted more than attention for its significant history: It’s attracted grants that have kept it at least temporarily afloat. Among its gifts: About $1million from the National Park Service for building preservation; $150,000 from the African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund for the same purpose; $25,000 from the Northeast Ohio Regional Sewer District for a green infrastructure project to install permeable pavers in its parking lot and to harvest rainwater from its roof; and $10,000 in private philanthropy funds from Ohio Humanities.

LUMEN 2024 | 42

“Churches aren’t just religious institutions, they’re also places where people find fellowship, leadership.”

—Aaron Fountain, National Museum of African American History and Culture

Kendrick’s vision for continued survival is to take advantage of the building’s size and amenities—it has two commercial kitchens and much empty space—to create opportunity for neighborhood residents.

Can it be an entrepreneur incubator? he wonders.

Can Cory offer a commercial kitchen where an aspiring restaurateur who is working on some recipes in their home can level up?

Can it be a place where an aspiring saxophonist can come to practice and even host a recital?

“We have these spaces,” Kendrick said. “How do we create the vehicle where those things can happen?”

Kendrick knows exactly why he stayed: the Cory stories. There were so many stories, he said. And there could be so many more.

People shared tales of how Cory affected them—how they learned to swim at Cory, or ski through Cory, or met with the Boy Scouts inside Cory. They echoed some of Kendrick’s own experiences growing up with a church just down the street as a place of comfort, refuge and inspiration.

“When people began to tell me their own narratives of joy, of helpfulness, I realized, ‘Oh there’s something here,’ ” he said. “It was people telling me this place is worth cherishing and that this place still has value to offer to the world.”

43 | LUMEN 2024

LUMEN 2024 | 44

The Resurrection

As Cory eyes its future, it is looking to lock arms with the congregation that preceded it.

The two congregations—one Jewish, one Christian—that have worshipped at 1117 East 105th Street have forged new ties in recent years.

The Jewish congregation that built Cory is now known as Park Synagogue and is located in the Cleveland suburb of Pepper Pike. In 2016, it received a grant to locate two Little Free Libraries—the tiny, houseshaped book cases that have popped up in many cities—wherever it chose. Park chose to put them both at Cory.

The synagogue had no ongoing relationship with the church back then, said Ellen Petler,

Park’s program and volunteer director. Given their historical connection, she thought it was time they developed one.

The library project was well-received by both congregations and led to regular events between the two. There have been joint choir concerts, Martin Luther King Jr. Day observances, a Passover seder recognizing the enslavement suffered by both the Hebrews of the Bible and the Africans brought to America in chains, and conversations about the twin evils of racism and anti-Semitism.

Petler told a TV interviewer in 2022 that she found the Seder particularly poignant.

“It was a beautiful event that helped people from both congregations see that being free is something we shouldn’t take for granted,” she said. “That both of our peoples came

45 | LUMEN 2024

Outside the church, Rev. Kendrick discusses preservation efforts on a spring Sunday in 2023

from a history of slavery to freedom and we have to continue to work every day to make sure all people are free.”

There are no lack of voices expressing respect and affection for Cory, the contributions it has made in the fight for racial justice and the way it has cared for its neighbors in Glenville. The grants it has attracted and the honors it has received speak to the importance of ensuring its survival, said Lann of the Cleveland Restoration Society.

Losing it would leave both a literal and a spiritual hole in the neighborhood, said Aaron Fountain, who worked as a researcher on the Civil Rights Trail project and is now web content editor for the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C.

“You (would) lose a sense of community,” Fountain said. “Churches aren’t just religious institutions, they’re also places where people find fellowship, leadership.”

Case Western Reserve University professor John Grabowski, a respected scholar of Cleveland history, said that in many ways, places provide tangible evidence of the past that can evoke individual and community memory. And in an increasingly virtual world, he noted, losing places like Cory would create a void.

life. The tangible is increasingly important in a world consumed by and, to some extent, ruled by the virtual. To lose a structure such as this would create a vast void in personal and communal memory.”

“It is not only the site of major events in the history of Cleveland’s African American community, it is also a site with deep religion connections, both to the Jewish and Christian communities,” Grabowski said. “It has hosted weddings, wakes, bar mitzvahs and the religious services which underpin and outline the cycle of human

Charles Williams, the long-serving Cory church trustee, was in the midst of remodeling a church bathroom with another volunteer when asked his opinion about Cory’s future.

“I got this hope in my heart and mind that at some point we will have some young people that will come back and will want to do something good in Cory and in Glenville. I think if Glenville thrives, Cory will thrive,” he said. “I still feel that if you do all that you can, then God will take care of the rest. And that’s why I’m in that bathroom right now, trying to make it look nice.”

Methodist officials recently took another step toward ensuring that Cory will continue to be a beacon in Glenville. The church is teaming up with St. Matthew United Methodist in the neighboring Hough community of Cleveland to share resources—including some funding.

LUMEN 2024 | 46

“To lose a structure such as this would create a vast void in personal and communal memory.”

—John Grabowski, Cleveland scholar

47 | LUMEN 2024

“It is another predominantly Black congregation that was actually birthed out of Cory in the late 1940s,” Kendrick said. “The goal is to create a cooperative between the two to share resources that allow each to continue to be deeply rooted and committed to their respective neighborhoods.”

Kendrick said he agrees with Williams that Cory’s future is tied to Glenville’s future. But, like the civil rights leaders who saw the obstacles ahead and kept moving forward anyway, he is determined to carry on.

He knows there are questions about the church’s survival.

But for him, it’s a matter of faith.

“I’m not naive or Pollyanna. I know the lifecycles of churches,” Kendrick said. “I am, however, a person of resurrection. That’s what we believe. Whether literal or symbolically, we believe that resurrection is possible.”

Interested in supporting Cory? Contact ohc@ohiohumanities.org.

LUMEN 2024 | 48

“I got this hope in my heart and mind that at some point we will have some young people that will come back and will want to do something good in Cory.”

—Charles Williams, Cory church trustee

Cleveland’s Civil Rights Trail

The African-American Civil Rights Trail in Cleveland, which was funded in part by Ohio Humanities, is a route that ushers visitors past significant locations in the struggle for equal rights. Here, learn about the nine current sites.

Cory United Methodist Church

1117 E. 105th St.

Constructed between 1920 and 1922 as the Cleveland Jewish Center and Anshe Emeth Beth Tefilo Synagogue, the building was purchased by Cory Methodist in 1946. (Cory added “United” to its name in 1968 when the worldwide Methodist church joined with the Evangelical United Brethren denomination to form the United Methodist Church.) In the 1950s and 1960s, it became a center of grassroots organizing for the civil rights movement and a venue for appearances by leading civil rights figures, including W.E.B. DuBois, Thurgood Marshall, Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X. It has also served its neighborhood as a recreation center, food pantry, credit union and Head Start site.

African American Cultural Garden

890 Martin Luther King Jr. Dr.

Between 1926 and the early 1940s, the Cleveland Cultural Gardens allowed many ethnic groups to establish gardens celebrating their heritage. But inclusion was denied to African Americans. A protracted struggle to include an African American garden began in 1961 and finally succeeded in 1977 with the dedication of the African American Cultural Garden.

Ali Summit and Negro Industrial and Economic Union

10501 Euclid Ave.

In June 1967, athletes and activists held a press conference to support boxer Muhammad Ali’s refusal to be drafted into the military during the Vietnam War. Jim Brown and several other former and current players on the Cleveland Browns participated, along with basketball stars Lew Alcindor and Bill Russell and future mayor of Cleveland Carl Stokes. The summit was held at the headquarters of the NIEU, which was founded by several Browns players and promoted racial liberation through entrepreneurship.

49 | LUMEN 2024

Carl Stokes (Cleveland City Hall)

601 Lakeside Ave. E.

Stokes became the first Black to rise to the office of mayor of a major American city when he was elected in 1967. He also served as an Ohio legislator and as a municipal court judge in a long political career. As mayor, he established an anti-poverty program, insisted the Black businesses get city contracts and pushed for fair-lending practices by banks. His mayoral campaigns were copied by Black people seeking similar offices in other cities.

Glenville High School

650 E. 113th St.

In the wake of the Hough Uprising and on the eve of Cleveland electing its first Black mayor, Martin Luther King Jr. came to Glenville High School on April 26, 1967 and delivered his “Rise Up” speech. He urged the students to convince their parents of the importance of voting to bring about social change. It marked the beginning of his drive to elect to public office Black people who would address the issues of systemic racism in Northern cities.

Greater Abyssinia Baptist Church

1161 E. 105th St.

The United Freedom Movement, a Cleveland umbrella organization for groups fighting to end segregation in the city’s schools in the 1960s, had its headquarters at Abyssinia. The church’s longtime pastor, Emmitt Theophilus Caviness, 95, has been both an activist and a public official. He was elected to Cleveland City Council in 1974 and was appointed chair of the Ohio Civil Right Commission during the administration of Gov. George Voinovich.

Ludlow Community Association

13601 Corby Rd.

In 1956, a bomb exploded in the garage of a home under construction for a Black family that had been warned not to move into a Shaker Heights neighborhood. The incident led to the founding of the Ludlow Community Association, which worked to maintain a wellbalanced, integrated community for decades. Still in existence, it focuses on community programming and neighbor events.

Olivet Institutional Baptist Church

8712 Quincy Ave.

Olivet pastors Oddie Hoover Jr. and Otis Moss Jr. were civil rights activists and supporters of Martin Luther King Jr. Hoover accompanied King to Oslo in 1964 when King was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. When Olivet opened the O.M. Hoover Christian Community Center, King dedicated the building. Moss succeeded Hoover as Olivet pastor, founding a community development corporation to help the Fairfax neighborhood. He also promoted gender equality in ministry.

The Hough Uprising

E.79th

St. and Hough Ave.

A dispute in a neighborhood bar is said to have been the spark that led to days of violence that ended with four people dead, 50 injured and 275 arrested, along with extensive property damage. But issues of poverty and racism were the fuel for what has been called Cleveland’s most significant urban uprising.

For more information, visit clevelandcivilrightstrail.org.

LUMEN 2024 | 50

Profiles

51 | LUMEN 2024

in Faith

The number of places of worship nationwide is decreasing, but faith remains. What role does faith play in the modern world? We asked five Ohioans to share what it means in their daily lives.

LUMEN 2024 | 52

Lucy Enge is a member of Wilmington Friends Meeting and a graduate of Wilmington College, where she concentrated in food policy and nonviolence. An enthusiastic eighth-generation Ohioan, she currently works in government and is an aspiring theologian and future farmer. She lives in Columbus, Ohio.

A Quiet Faith

By Lucy Enge

When my parents left the Catholic Church and decided to start attending a Quaker Meeting, my devoutly Catholic grandmother, who would only find religious tolerance years later through the Baptist music ministry at her nursing home, thought we were becoming Amish.

I was five then and was shocked—after only knowing the unmarried priests of our Catholic parish—that our new Quaker pastor had a wife. But, despite a lack of acceptance from their families, my parents’ choice for their faith to reflect the world they saw and wanted was one of the best things that has ever happened to me.

Quakerism, or the Religious Society of Friends, dates back to 17th-century England. What set early Friends apart were their deeply entrenched commitments to equality and simplicity. They were known for their belief in “The Light”— seeing that of God in every person. And, in worship, they practiced waiting in silence for God to speak to them.

53 | LUMEN 2024

Today, Quakerism is not a monolithic faith. Friends range from atheists to evangelicals. Meetings, as Quaker churches are commonly called, can be like those of early Friends practicing unprogrammed (silent) worship or can be programmed like a traditional Christian service with a sermon and hymns interwoven with periods of waiting worship.

Now, 17 years after my family began attending our small, welcoming and theologically-diverse programmed meetings, I cannot imagine my life without my faith.

The silence of waiting worship that used to pain me is now welcome and needed in my life, and I often wish it would last longer. Some of my most treasured memories of being a child in the Meeting are the picnics and potlucks, youth pageants and Sunday school shenanigans that made me feel a part of the community.

My parents always let religion be my choice, and, after learning about world religions in middle school, I almost decided to become a Buddhist. But what made me decide to remain a Quaker, and later officially become a member of my Meeting, were the Quaker Testimonies that centered my life: peace, integrity, community, equality, stewardship and simplicity. And, most importantly, in Quakerism, there was space for faith to be a journey of questioning and challenging.

I ended up deciding to go to the Quaker college in my hometown, thanks to the encouragement of a professor who attended my Meeting. While I considered myself Quaker, I had long been very troubled by the evangelical nationalism so many Christian denominations preached that seemed rooted in hatred and fear. Through my coursework, I was introduced to the writings

of progressive theologians. As I read and studied, I witnessed how the Christianity of the early church had been lost in our world of consumerism and co-opted to lay a moral ground far from Jesus’ teachings. I saw a broader loving Christian community of thought that I wanted to be a part of. I realized the importance of both my Quakerism and my Christianity.

Yet, what can living a faithful life as a Quaker look like in our ever-connected and loud world?

I have come to understand that simplicity cannot coexist with inauthenticity, for simplicity means removing all the junk and focusing on what makes us whole and gives thoughtful meaning to our lives. My mom instilled in me that we vote not only at the polls but also with our money. This knowledge has led me to focus on the impact of my purchases and to constantly work towards living a mindful and minimalist life. My current personal challenge, as a lifelong vegetarian, is to be vegan and eat more locally to care for both myself and the planet.

As a Quaker, I am a pacifist who also cares deeply about our veterans. I have focused my energy on politics and building consensus based on shared values. I have lobbied my elected officials on issues including ending gun violence and addressing the climate crisis, and in school, I organized with my fellow students to raise wages for our beloved professors and staff.

My life has been changed by serving nights at a women’s shelter and refreshed by visiting Friends in Costa Rica.

For me, faith is not public words of declaration. Rather, it is an inward reflection that is a catalyst for a transformative life of faithful action and witness grounded in community and love.

LUMEN 2024 | 54

Joe Mackall is the author of The Last Street Before Cleveland, Plain Secrets: An Outsider Among the Amish and Yesterday’s Noise. He’s an emeritus professor of English and creative writing at Ashland University, and he is co-founder and co-editor of River Teeth: A Journal of Nonfiction Narrative. He lives in West Salem, Ohio.

God Haunted

By Joe Mackall

Not long ago I was outside chopping wood just after dusk, knowing that with a forecast of heavy snow and single-digit temperatures, I’d be feeding the fire for hours. In the middle of lifting logs to my chest to carry inside, I glanced in the front window of our house, and I saw my wife smiling. In the next instant I felt a chill up my neck, and it wasn’t caused by the weather. I nearly sank to my knees in gratitude for the life I have lived, for the gift of love that has been given to me by this exceptional woman, who gravitates to her faith the way water seeks its level. And then, inexplicably, I looked away.

I’d like to say that I heard a sound, or I dropped a log, but nothing distracted me. When my gaze returned to the inside of my house on an ordinary winter evening, my wife was gone, nothing left but the yellow light of an empty kitchen. Snow still covered the ground and the roof; smoke rose from the chimney. Although my wife was no farther away than another room, I felt a bit of sadness for a moment that was. I had turned away from

55 | LUMEN 2024

the moment of joy, and then the moment had passed. And yet faith helps me understand that the moment of joy that I experienced then, and many times since, did not spring from fallowness. The moment contained a world of living. C.S. Lewis believed these moments occur when eternity pierces time.

That moment alone contained within it nothing less than love, marriage, a joyful wife’s smile, wood smoke, snow, fire and light—all gifts, all worthy of my attention—and yet I turned away.

I’m not known as an upbeat, glass-is-half-fullkind of guy. I’m more of the glass-is-shatteredand-flecks-of-skin-and-spots-of-blood-cover-theshards-of-glass-kind of guy. For me it’s far easier dwelling in the darkness than living in the light. Perhaps it’s my upbringing or my disposition. I’ve always subscribed to what Robert Duvall’s character says at the end of the movie Tender Mercies: “I never did trust happiness.” However, I don’t trust myself without my faith. I just run too dark for that.

I wish I could give testimony to inspire nations, but instead I’m left with nothing more than a longing for some stillness at my aching center.

I’ve always been what the writer John Updike called “God-haunted.” I’ve been haunted by his existence and his nonexistence. I’ve lived haunted by the need to believe and the penchant

to doubt. Although I grew up a cradle Catholic and attended Catholic schools until college, the faith never took. I let dogma beat me down. For years after eschewing the faith of my youth, I gave myself to literature, whose stories served as secular scripture. I worshipped in its riotous quietude. And yet my devotion to literature failed to remedy the roiling alchemy of fear and sadness, the twin pillars of my existence.

I don’t get through a day without moments of doubt. I turn to Christ all the time, and it’s not because I want to. I need to. I need the help. I need the story. I need it to be true.

As each morning breaks heavy with beginning, I wake up and remind myself that I have chosen to believe. Updike said he wrote to give the “mundane its beautiful due.” I begin the day by clawing my way up and through layers of dark matter, igneous rocks of remorse, sedimentary stones of sin and guilt to rise up and pay heed to what is ordinary and holy.

I seek whatever is true and noble and lovely. I strive to live out these feelings, but I fail way too often. I ask for help. I come in need and wonder and awe. I often leave sated, which forces me to remain alert for shoots of joy, tendrils of grace.

I need to welcome and witness these timepiercing moments and give them their due. Not even I can deny the beauty and truth of it.

LUMEN 2024 | 56

Ashton Colby is a trans spirituality advocate, keynote speaker and the founder of Gender YOUphoria, a social enterprise on a mission to shift the global and interpersonal disempowering narratives about transgender people. He lives in Columbus, Ohio.

Never Lost, Always Found

By Ashton Colby

I found pure joy in the trees and lakes at various nondenominational Christian summer camps, from Ohio to Virginia to upstate New York.

Each summer from elementary to high school, you could find me in cargo shorts and tie dye, singing songs about Jesus led by the acoustic guitars our college-age counselors carried around.

I was born in a girl’s body. But I loved those cargo shorts, which were from the boy’s section at Kmart. I could talk my mom into buying them if they were for a week spent hiking the woods at church camp.

The summer between 7th and 8th grade, I stole my dad’s Speed Stick deodorant to wear to camp. Twice a day, I would rummage through my duffle bag under the bottom bunk and pop off the minty green cap. I’d apply it to my underarms, inhale deeply and exhale a sigh of relief.

57 | LUMEN 2024

I felt like I was wearing a superhero’s uniform under my clothes, one that only I knew about. I was energized to spring into action at a moment’s notice, like Clark Kent in pedestrian clothes.

For me, it was a rite of passage to smell like what I learned men smell like—much like a hug from my dad in his crisp white dress shirt, softened by a long day of working at the office.

Today, at age 31 and now 11 years into my physical gender transition, I see the man I have always known myself to be staring back at me in the mirror. I’m finally living my childhood dream.

I buy my own men’s deodorant, my own men’s clothing. And it still brings me the same sigh of relief I experienced when I was 13.

Because despite being a young girl in the eyes of others back then, the feel of my cargo shorts and the smell of that deodorant were potent reminders that I knew who I was. And I knew God loved who I was.

Of course, over the years and increasingly so today, the very same teachings I learned at summer camp are often used to try to separate me from God and the wholeness I felt in those quiet moments.

As a trans advocate and a person of faith, I’m often met with disdain. Sharp words about my gender transition, like abomination, test my resolve and threaten my peace. They tell me I’m lost, or that I’ve strayed.

It’s a strange thing—the constant pressure to prove God loves me when I already feel God’s love. I watch the same people questioning my salvation search and strive for joy, peace and a sign of God’s acceptance, and I know I’ve found it. I still feel it with my entire being.

I found it at 13, as a kid singing praises in cargo shorts and my dad’s deodorant. And I find it today, living as a man and praying to a God that transcends gender.

In fact, I’ve never been lost. I’ve always been found.

LUMEN 2024 | 58

Ismail Mohamed is an Ohio State Representative and the first Somali-American attorney to practice in Ohio. A refugee from Somalia, he lives in Columbus and owns his own legal practice specializing in personal injury, immigration and criminal law.

Faith as a Compass

By Ismail Mohamed

My faith is something that advises me when I need help, guides me when I am lost. To me, faith is about being compassionate and inclusive and should never be used to exclude people.

I was born in Somalia, a country in the horn of Africa, into a big family in the Muslim community. When I was 5, as a civil war raged, my family fled the country. We went to Ethiopia, then Kenya. Finally, when I was 12, we immigrated to the United States.

Columbus has the country’s second-largest Somali population, so it’s a natural place for other Somali refugees to land. As immigrants, there’s a tendency to stick together, and extended families, like mine, often stay close.

During my 18 years in Columbus, I’ve seen a big change in terms of Muslims being able to be more open about their faith. More mosques and religious centers are being built throughout the city.

59 | LUMEN 2024

We live in a very welcoming city where you’re not shunned because of your faith.

Faith is a big part of my life. I’m not the most religious person in the world, but I grew up in my faith, and I pray five times a day. I look to my faith as a guiding principle in terms of what’s acceptable and what’s not in terms of values. I don’t belong to any specific mosque—I go to any mosque around me.

As the Ohio State Representative for District 3, I am also one of the first Somali Muslims elected to the Ohio General Assembly. Rep. Munira Abdullahi, from Ohio House District 9, is also a Somali Muslim elected this year. It is my goal that we use our roles as elected officials to focus on being inclusive.

The Ohio Statehouse has held many religious gatherings, but until recently, never for iftar, which is a fast-breaking dinner during the holy month of Ramadan. In 2023, I hosted the Statehouse’s first iftar celebration attended by several elected officials, interfaith community leaders and community members. People were excited and want to be a part of it going forward. It sends a message that the Statehouse is the people’s house, that everyone is invited, that all communities are welcome.