Authors: Irene Kingma, Paddy Walker

Published: September 2021

Suggested citation: Kingma, I.,Walker, P. 2021. Was Article 11 of the CFP doomed to fail? Report produced by Ocean Future Collective for Oceana. Amsterdam, The Netherlands. 53 pp.

DOI number: 10.5281/zenodo.5503739

Report commissioned by Oceana

Editorial review: Nicolas Fournier, Vera Coelho, and Allison Perry – Oceana

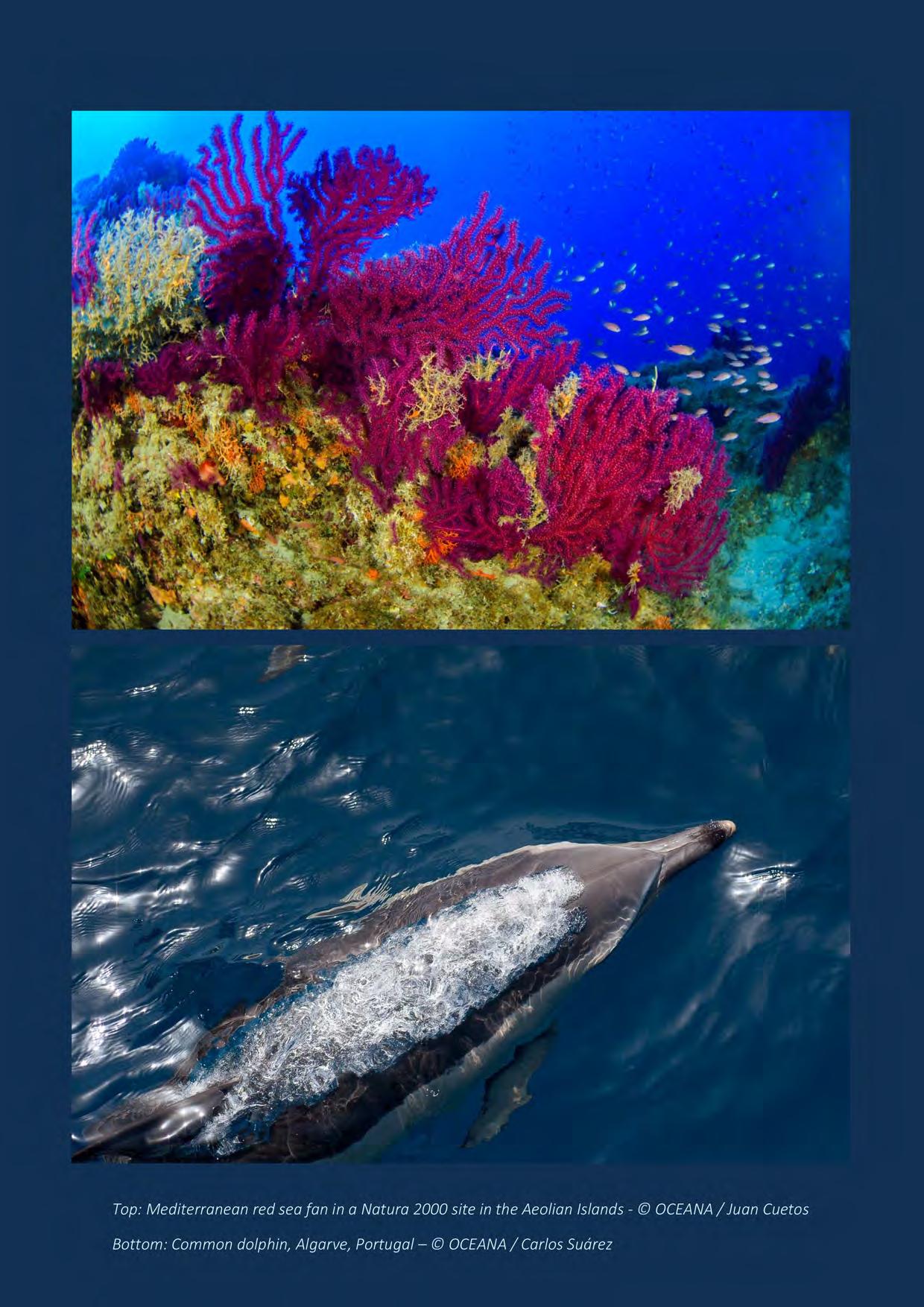

Cover photo: Yellow gorgonian in a Natura 2000 site in the Aeolian Islands. © OCEANA / Juan Cuetos

The contents of this document are the sole responsibility of OCEANA and the views expressed in it do not necessarily reflect the official position of the European Commission. The European Commission is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained in this document

2

WAS ARTICLE 11 OF THE CFP DOOMED TO FAIL?

A review of the progress in applying fisheries measures in Natura2000 sites within a regional context

Contents

Rationale for protecting Marine Areas ........................................................................................ ....... 7 Background on Marine Protected Areas in Europe ............................................................................ 8 Fisheries and Natura 2000 ..................................... .............. 9

Implementation of Article 11 .................................. ........... 14

Process in Initiating Member States ........................... ............................................................... ....... 19 Member States with fishing interest and Regional Groups .............................................................. 20

Role of scientific underpinning ............................... ........... 24

Role of the Commission ........................................ ............. 26

Recommendations ............................................... ............................................................... .................. 30 Clarity on process & timelines ................................

ANNEX 1: Case Studies ......................................... .................. 35

Case study: Sweden ............................................ ................... 35

Case study: North of Scotland.................................. ............................................................... .............. 38

Case study: Belgium ........................................... ............................................................... .................... 42

Case study: Dogger Bank .......................................

ANNEX 2 Interview Outline .....................................

3

Executive summary ............................................. ................. 4 Background .................................................... ............................................................... .......................... 7 Introduction .................................................. ............................................................... ....................... 7

Other relevant policy processes ............................... ......... 15 Methods ....................................................... ............................................................... .......................... 18

Review ....................................................................................................................... ............................ 19

...............................................................

...............................................................

........... 30 Arbitration & conflict resolution ............................. ............................................................... ........... 31 Transparency & accountability .................................

......... 31 Conclusions ................................................... ......................... 34

............................................................... ................. 45

............................................................... ............... 50 References ................................................................................................................... ......................... 51

Executive summary

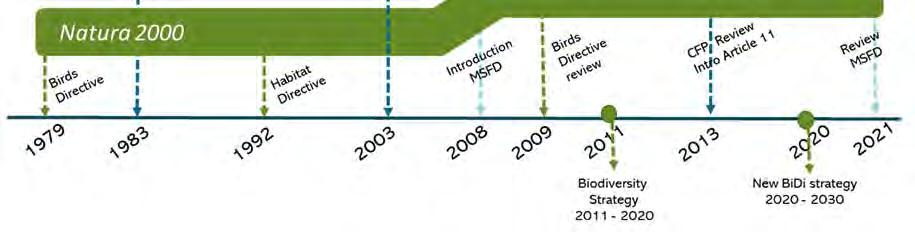

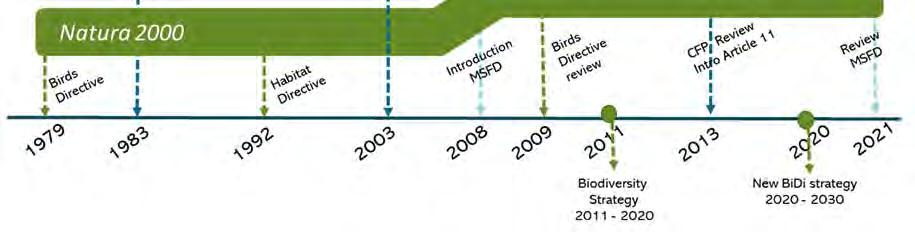

1. The EU has set out strong objectives for marine protection in its waters. This began with the adoption of the Habitats Directive in 1992 and has been continually re‐emphasised in later policy outlines, the latest being the 2030 Biodiversity Strategy which sets a target of protecting 30% of the marine habitat with 10% being strictly protected.

2. When it comes to setting fisheries measures in areas outside the 12 nautical miles zone, where multiple countries have fishing interests, measures have been developed for very few Marine Protected Areas (MPAs). Most of the areas that have been designated as MPAs have no measures implemented.

3. In the CFP reform of 2013, Article 11 was introduced which sets out the process for Member States to adopt a Joint Recommendation for fisheries measures within MPAs in a regional set‐up, which is then transposed into a Delegated Act by the Commission.

4. In the eight years since its adoption only three delegated acts related to Article 11 have come into force. All the areas concerned, found within existing MPAs, are small in size and only have two Member States (the initiating Member State and one other) with significant fishing interests in the designated area.

5. Even though the CFP allows the Commission to take short‐term emergency measures within Natura 2000 sites when there is an urgent conservation need and no measures are taken by Member States, there are no cases of this happening.

6. This report reviews the challenges faced in implementing Article 11 through specific case studies and though interviews with stakeholders (from policy, the fishing industry, and NGOs) to pinpoint where improvements can be made.

7. We recommend focusing on three distinct areas of improvement: clarity on process & timelines, arbitration & conflict resolution, and transparency & accountability. All three areas require improvements at Member State, regional and Commission level.

8. Clarity on process & timelines: the legal text in the CFP leaves room for interpretation on the roles and responsibilities of the different parties, which can be used to stall or derail the process. The initial phase in which the initiating Member State drafts a basic document to share with the regional group has no timeline or formal end point and neither does the deliberation phase in the regional group; information provided needs to be ‘sufficient’ without a definition of what constitutes sufficient information.

9. Clarity on process & timelines: the responsibility for development of measures in MPAs is shared between environment and fisheries departments, which tend to operate very differently. Fisheries departments are focused on sustainable extraction of marine resources with their environmental counterparts working to protect (certain elements) of the marine ecosystem. As Article 11 is within the realm of the CFP but the outcomes need to adhere to

4

the EU Nature Directives and the Marine Strategy Framework Directive there is a clear mismatch in how to manage these sites.

10. Arbitration & conflict resolution: if parties cannot agree on a joint way forward the whole process can become blocked with no way to move ahead. There is no mechanism to have parties take ownership of the conservation needs. Objectives are often watered down to appease Member States or stakeholders (at a national level) with no way to prevent that from happening if the initiating Member State is not in a capacity to invest political capital in the outcome of the process.

11. Arbitration & conflict resolution: a legal interpretation of the relationship between the CFP and the Nature Directives has never been performed. It is unclear how the environmental goals are embedded in the CFP and how the environmental and fisheries legislation are aligned. As the EU legislators are hesitant to take steps in this, the route through the European Court of Justice is a good option to create jurisprudence.

12. Arbitration & conflict resolution: the timing of the scientific advice from STECF is late in the process, by which time conflicts may have occurred. As it is not the role of science to solve these conflicts, the process could be strengthened by including a scientific check at an early stage of the Joint Recommendation to review if the proposal meets the environmental objectives, and then suggest improvements and clarifications which can be accommodated in the Joint Recommendation within the agreed time frame.

13. Transparency & accountability: the process has very few checks and balances to allow scrutiny of the decision being made. It is left up to the discretion of the initiating Member State to consult with stakeholders at a national level. Regional groups are, at best, only partly open to observers. Advisory Councils have to be consulted but their advice can be put aside with no explanation and the Commission only provides minimal information once it has received the Joint Recommendation.

14. We conclude that the current legislative and policy framework as expressed in Article 11 has the potential to reach the EU’s environmental objectives, but that the implementation can be improved by better understanding of the environmental goals embedded in the CFP, in order to align the environmental and fisheries legislation. Moreover, it is essential to create clarity on the roles and responsibilities of all actors in the process and to improve transparency in order to ensure a collective ownership for a successful outcome.

15. In future, the legislator, in particular the Commission, can utilise the upcoming opportunities, for example the revision of Multiannual Plans, as well as the further roll out of the Biodiversity Strategy in the form of the EU Action Plan to conserve fisheries resources and protect marine ecosystems or, at a later date, an EU restoration law. By using these political opportunities to set hard targets for implementation and put clear restrictions on practices allowed within MPAs, a better balance can be found among the different interests at play. In this way the implementation deadlock, that many of these areas are in now, can be broken.

5

Background Introduction

Protected areas (PA) are the fundamental tool for global biodiversity protection and Europe is among the regions with the largest share of territory protected on paper. At the International Our Ocean conference in 2018, the EU proudly stated that 10.8% of its waters were designated as MPAs1. To ensure that conservation and restoration targets for ecosystems are met, and to halt the loss of biodiversity, MPAs need to be effectively managed. This is clearly recognised by the EU and strongly emphasised in the new 2030 EU Biodiversity Strategy2 which highlights the importance of healthy marine ecosystems and the role in that regard of effectively managed marine protected areas (MPAs), with clearly defined conservation objectives and measures.

In 2013 the EU introduced a regionalised process for introducing fisheries management measures in MPAs in the revised Common Fisheries Policy (CFP)3. CFP Articles 11 and 18 were designed to guide Member States in setting measures for areas in which fishing interests of several Member States were represented.

CFP Article 11 is a potentially powerful instrument in the protection of the marine environment. It allows Member States to designate specific fisheries and spatial measures for the conservation of marine biological resources or the marine ecosystems in their waters. Successful implementation of this article is essential for the role of the CFP in marine conservation. But is it fit for purpose? Eight years after it came into force, about forty relatively small areas, found within 18 Natura 2000 sites in the North Sea and the Baltic Sea have successfully completed an Article 11 procedure, with the bulk of other MPAs designated in the EU still waiting for measures to be introduced4

The aim of this study is to assess the uptake and effectiveness of Article 11 of the CFP in introducing management measures in MPAs in the context of obligations under relevant marine conservation legislation, as well as to point out the shortcomings and pitfalls which impede effective implementation of this tool. The study had three parts: it started with a literature review on the background of marine spatial policy as a preparation for the second step of four analytical case studies of Article 11 procedures, and thirdly a series of interviews with key stakeholders from policy, NGO and the fishing industry.

We conclude with an overview of the main learning points from our research and recommendations on how the process for introducing fisheries measures in MPAs can be improved. Learning from past successes and mistakes will provide a basis for the future development of well‐managed protected areas.

Rationale for protecting Marine Areas

The regional seas surrounding Europe include vast, open oceans as well as almost entirely landlocked seas. These seas are home to a diverse range of habitats that sustain thousands of species of plants and animals, a biodiversity which is the foundation for marine ecosystems and their capacity to deliver the services from which we benefit. In addition, more than 5 million Europeans depend on the sea, its ecosystem services and its resources to support their daily livelihoods as well as those working in the recreation and leisure industry.

In spite of the sea's key role, human activities in the marine environment are jeopardising the state of marine ecosystems. Moreover, land‐based activities are also impacting the sea. Scientists — both globally, and within Europe — have observed an accelerated rate of biodiversity loss through

7

(ecological) extinctions and extirpations of marine species. Biodiversity loss is caused by multiple human activities burdening ecosystems with different pressures: damage and loss of habitats, extraction of resources, introduction of non‐indigenous species, pollution and the effects of climatic change. The cumulative effect of these pressures is damaging the state of marine ecosystems5

Well placed MPAs are a key policy measure and management tool for addressing these increasingly complex threats to marine ecosystems. By protecting key features and biodiversity hotspots of an ecosystem they can function as a refuge for the surrounding areas that will also benefit from the stability MPAs provide. MPAs — and networks of MPAs spanning large areas — are a key mechanism to safeguard biodiversity and increase the resilience of ecosystems to unwanted change6.

Background on Marine Protected Areas in Europe

A range of pressures is affecting Europe's seas, their biodiversity, and the services they provide for human use. These pressures stem directly and indirectly from human activities. Moreover, the prospect for improving this situation in the near future is uncertain at best, given the expected increase of human activities and the systemic nature of pressures and impacts affecting ecosystems7

To address these sustainability issues, an ecosystem‐based approach to management (EBM) was introduced in key EU policies and legislation: the Integrated Maritime Policy (based on the communication An Integrated Maritime Policy for the European Union; the Common Fisheries Policy (CFP), the 2020 EU Biodiversity Strategy (based on the communication Our life insurance, our natural capital: an EU biodiversity strategy to 2020; and the Marine Strategy Framework Directive (MSFD)8 EBM works by striking a balance between continuing to manage the complex relationship between human and natural systems and safely adapting to change9.

Introduction of Natura2000

The Natura 2000 network is the most extensive protected area system in the world, comprising more than 27,300 sites covering approximately 18% of the EU land area. It consists of Special Protection Areas (SPAs) and Special Areas of Conservation (SACs), classified under the EU Birds and Habitats Directives respectively. The SPAs and SACs, forming the Natura 2000 network, should contribute to the maintenance and restoration of favourable conservation status of the habitats and species listed in the annexes of the Habitats and Birds Directives (known together as the EU Nature Directives)10

In parallel with global processes, in 1992 the EU adopted the Habitats Directive, which aims to protect vulnerable natural habitats and wild fauna and flora including those considered rare and/or endemic. Together with the Birds Directive, which had been in use for creating Special Protection Areas (SPAs) since 1979, it remains at the core of EU nature conservation efforts. A central component of these directives is the use of special conservation areas to help achieve their objectives, through a 'coherent European ecological network' (Natura 2000) covering both land and sea11.

As the Natura 2000 network is meant for both protection of vulnerable nature on land and in the sea, it also includes an extensive amount of Marine Protected Areas – currently it has over marine 3,000 sites covering over 318,133 km2, corresponding to just over 10% of EU seas. These areas are designated by Member States based on their importance for marine biodiversity and protection of vulnerable and threatened species12

Despite providing, in principle, a coherent approach to the protection of seabirds, turtles and marine mammals, the Nature Directives provide limited possibilities for the protection of marine fish and invertebrate species and marine habitats. The directives thus exclude significant aspects of the marine ecosystem from formal protection schemes. This is especially obvious for offshore habitats, for example sandbanks below 20 m or soft‐bottom habitats, and the associated communities of fauna

8

and flora. This shortfall is apparent from the distribution of the Natura 2000 network, in which the majority of protected areas are situated within coastal regions

In response, the EU produced new legislation: in particular, the Marine Strategy Framework Directive (MSFD) aims to launch measures for achieving or maintaining Good Environmental Status (GES) in the marine environment by 2020. One of the measures to be implemented is the use of 'spatial protection measures' contributing to the creation of coherent and representative networks of MPAs, adequately covering the diversity of the constituent ecosystems. Furthermore, Directive 2014/89/EU establishing a framework for maritime spatial planning is to contribute to the effective management of maritime activities and the sustainable use of marine resources in the marine environment.

Fisheries and Natura 2000

When first introduced, the Natura 2000 legislation had no immediate effect on fisheries management through the CFP because Member States initially saw their obligations restricted to territorial waters (i.e., areas 12 nautical miles from the baselines, where the CFP applies only under certain conditions).

The Commission consistently challenged this interpretation of the Habitats Directive and this opinion was confirmed by the European Court of Justice in 2005 (case C‐6/04 of 20 October 2005). For Member States, a new deadline to report site nominations was then set for September 2008. Most Member States complied with this and designated sites within their waters. However, to date, very few were able to set fisheries measures within them13

Until the reform of the CFP in 2013 there were only soft law guidelines for fisheries measures for marine Natura 2000 sites; under the 2003 revision of the Common Fisheries Policy there was an option to facilitate the process of restricting harmful fishing methods in MPAs. The process started with an application by the Member States for measures in their MPAs to the Commission, sometimes followed by advice from the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES) or a stakeholder opinion through the then newly formed Regional Advisory Councils (RACs). The Member States then had to find a way to coordinate their management plans with other Member States, but no framework existed to facilitate this. Overall, the procedure was lengthy, unclear and in need of major revision, there was ambiguity on which route to follow to implement measures in marine Natura 2000 sites and, as a result, very few of the sites designated had measures introduced. This was a concern that was addressed in the revision of the Common Fisheries Policy in 2013.

9

10

CFP Article 11

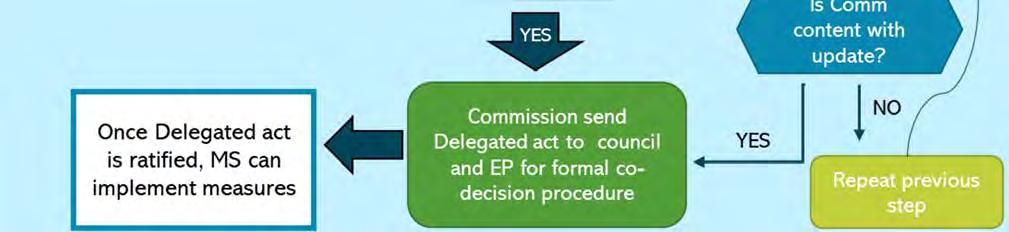

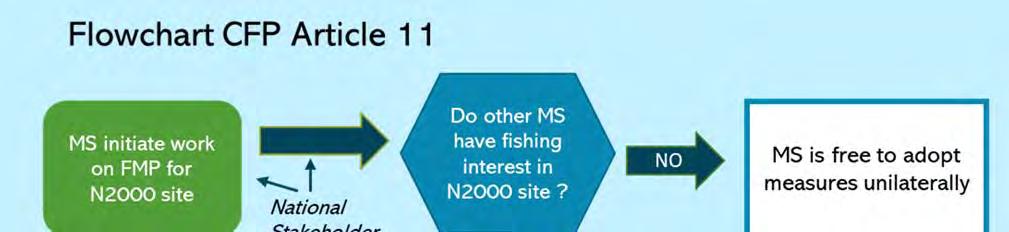

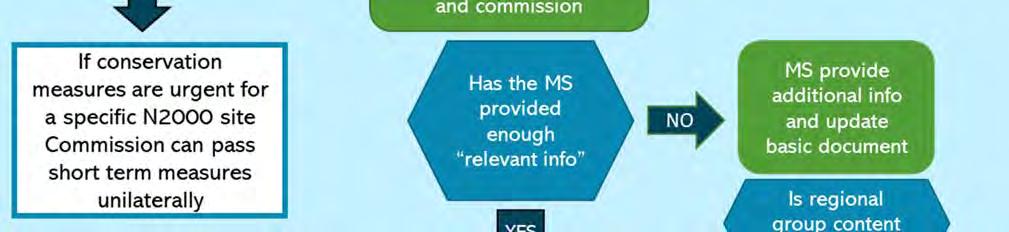

Within the CFP reform of 2013 legislators adopted new wording that was meant to provide clarity for Member States on the procedural steps to follow in order to adopt conservation measures to meet environmental obligations within their Marine Protected Areas, related specifically to Article 6 of the Habitats Directive, Article 4 of the Birds Directive and Article 13(4) of the Marine Strategy Framework Directive. The new CFP Articles (11 and 18) were part of a new regionalised approach to fisheries management where Member States ranging on the same sea basin work together on setting measures that are relevant to their area. Member States can present proposals for measures to the European Commission in the form of a Joint Recommendation which then becomes part of EU law through a Delegated Act.

The key changes after the 2013 reform for setting fisheries measures within MPAs in the 12 nautical mile zone were:

Article 11 (hard law) on introducing fisheries conservation measures in MPAs;

The group of Member States expanded from neighbouring /initiating ones to include those with a direct management interest within a defined regional sea;

Measures can now only be decided on through a consensus‐based system by the regional Member States (which created the risk, which was to prove high, of Member States struggling to reach agreement on a Joint Recommendations);

The role of Advisory Councils was included as part of regional cooperation (Art 18).

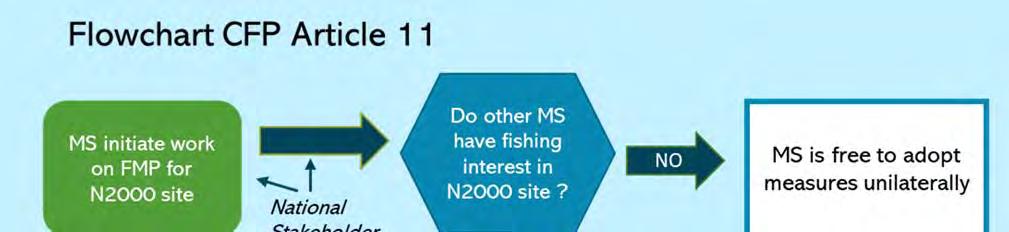

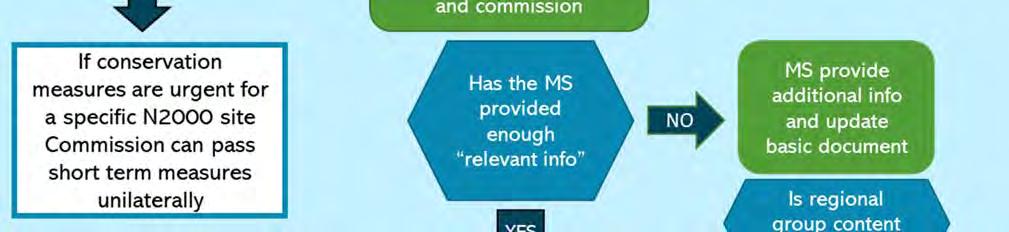

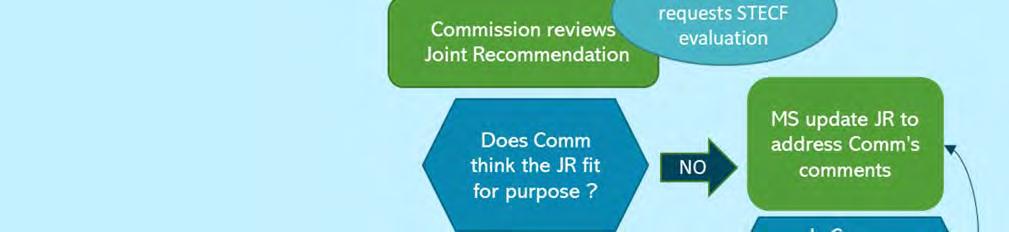

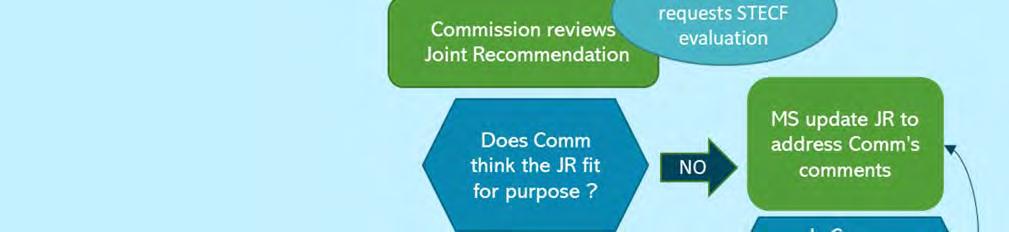

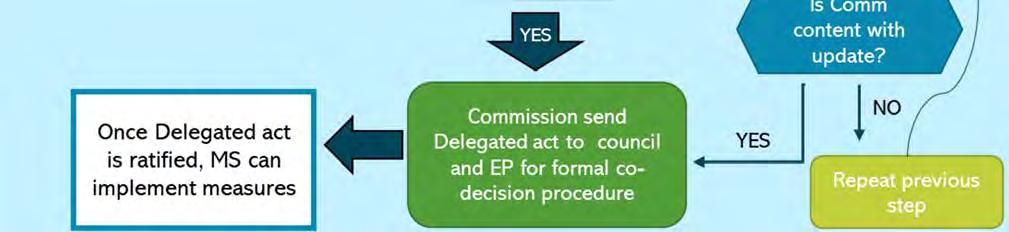

Article 11 sets out three options for implementing fisheries management measures in MPAs. The first deals with the setting of conservation measures where the measures in question do not affect other Member States’ fishing vessels (Article 11.1), in which case the initiating Member State has the sole competence to adopt measures. The second option is for situations where one or more Member States have fishing interests in the proposed area. In this case the initiating Member State drafts a proposed Fisheries Management Plan (FMP) and consequently Member States should work together in drafting a Joint Recommendation (through the regional process outlined in Article 18 of the CFP) that they present to the European Commission. If approved by the European Commission, the Joint Recommendation is then transposed into law through a Delegated Act which has to be officially approved by Council and Parliament. (Article 11.2 and 11.3). The third option is meant for cases where urgent action is needed and allows for the European Commission to take emergency measures (Article 11.4 and 11.5)14

11

The Scientific, Technical, Economic Committee on Fisheries (STECF)

Under Article 18 the legislators can obtain an interpretation on the best available science related to the MPA under discussion. In practice this means that the Commission asks the Scientific, Technical, Economic Committee for Fisheries (STECF) to review Joint Recomm endation proposals once they are received.

The STECF is a group made up of 30‐35 members who advise the Commission in implementing fisheries policy: “to implement Union policy in the area of fisheries and aquaculture, the assistance of highly qualified scientific experts is required, particularly in the application of marine and fisheries biology, fishing gear technology, fisheries economics, fisheries governance, ecosystem effects of fisheries, aquaculture or similar disciplines, or in the field of collection, aquaculture data. (para (2) of Commission Decision (2016/C 74/05)).” Members of STECF are appointed by the Director‐General of DG Maritime Affairs and Fisheries.

The STECF group may set up sub‐groups to examine specific questions on the basis of the terms of reference defined by the Commission. The sub‐groups consist of at least two STECF members and external experts (including a chair), who are chosen by the STECF chair and members. Sub‐groups report to STECF within a given time frame in accordance with those terms of reference. The report is presented to the STECF Plenary by the chair and STECF formulates its own conclusions. Such sub‐groups are disbanded as soon as their mandate is fulfilled. (Article 6.4 of Commission Decision (2016/C 74/05)). Since 2011 specific working groups of the STECF are labelled as Expert Working Groups (EWG) with a clear and concise title.

Regional seas conventions

Within the different regional seas surrounding Europe, the Regional Sea Conventions (RSCs) engage neighbouring countries for the conservation of their common marine environment. Their work areas cover maritime activities and pressures resulting from them, as well as biodiversity and ecosystem protection. The RSCs implement coordinated monitoring programmes in the regional sea basins and perform joint assessments of the state of the environment. Article 6 of the MSFD requires EU Member States to use existing institutional cooperation structures such as the RSCs in order to implement the marine strategies in the most coherent way at the regional level15

Four RSCs have been established in Europe: OSPAR for the North‐East Atlantic; HELCOM for the Baltic; the Barcelona Convention for the Mediterranean; and the Bucharest Convention for the Black Sea.

RSCs play an important role in agreeing and streamlining environmental measures within their regions and in setting objectives for marine protection.

But as fisheries are not part of their remit, they cannot play an active role in setting fisheries measures in MPAs; this instead falls under the Regional groups that operate in parallel to the RSCs.

Map of Regional Seas Convention Areas in Europe (source: Europe's Seas, EEA)

12

Regional groups

The 2013 CFP review introduced the process of regionalisation, as before there was no formal EU process at a regional level to take decisions on fisheries measures. The CFP calls for the set‐up of regional cooperative management structures in which governments work together to prepare proposals for the implementation of EU legislation in the form of Joint Recommendations that the Commission then turns into delegated acts, which makes them legally binding. Member States had to begin organising themselves in regional groups that could take decisions jointly. In total eight groups were founded:

‐ Baltfish for the Baltic Sea ecoregion

‐ Scheveningen group for the North Sea

‐ North Western Waters regional group for West of Scotland, Irish Sea, Celtic Sea and Channel

‐ South Western Waters regional group which deals with Atlantic waters from the Bay of Biscay to the Strait of Gibraltar

‐ The Mediterranean has three groups for different regions (Pescamed for the West, Sudest‐med for the South and a group for the Adriatic)

‐ Black Sea regional group

As there is no formal guidance for the organisation of these groups, there is great variety between groups in their remit and workplans. The eight Baltic Member States were the only ones who already had an organisation in place, as Baltfish had been active for several years (it was initiated in 2009). This served as a model for other Member States to organise themselves. They all have a two‐tiered system where proposals are prepared in a working group and decision are taken in a High Level Group (HLG) in which fisheries directors of ministries and the European Commission sit and the secretariat rotates between Member States.

However, where Baltfish allows active stakeholder participation in the working group (the Baltfish Forum), all the other groups are opaquer in the way their work is organised and decisions are taken. Most are informal in character and kept outside EU transparency regulations, so observers are not allowed to participate, except when specifically invited for part of the meeting, and the minutes are classified.

13

Implementation of Article 11

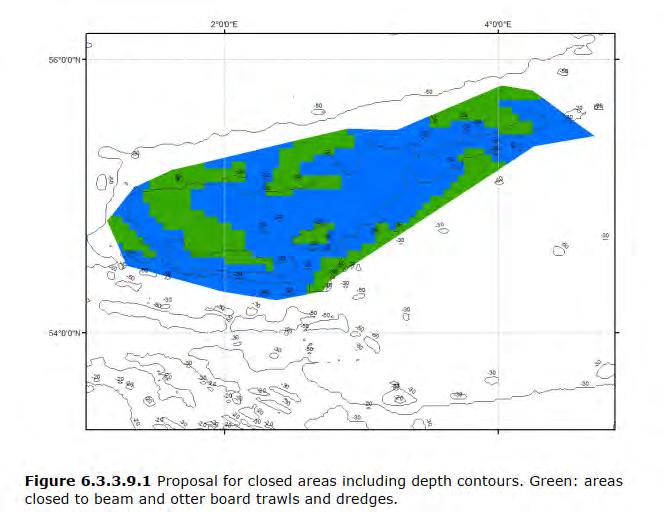

All regional groups are active in drafting Joint Recommendations for annual Discard Plans associated with the implementation of the Landing Obligation (Articles 15 and 16 of the CFP) but only a few have worked on Article 11 processes. In the eight years after the adoption of Article 11, Baltfish, the Scheveningen group, and the North Western Waters regional group have initiated discussions on Article 11 procedures for Natura 2000 sites where multiple Member States have fishing interests, but to date only Denmark and Sweden have managed to conclude the full Article 11 process for a limited number of sites, and only a few habitats types (e.g., reefs). Two delegated acts (one in 2016 and the other in 2019), were adopted for a total of 18 MPAs in the Danish EEZ and one for Sweden16

To organize themselves in the process of drafting Joint Recommendations, in 2014, the Scheveningen High Level group, for example, adopted Terms of Reference (ToR) for regional coordination in relation to Articles 11 and 18.The ToR allows for the establishment of ad‐hoc groups within the regional group to deal with specific fisheries management proposals with representatives from Member States having direct management interests in the conservation measures expected to participate in the ad‐hoc groups. It is unclear if such groups have ever been formed.

In 2018 the European Commission published a Commission Staff Working Document17 on the establishment of conservation measures under the Common Fisheries Policy for Natura 2000 sites and for Marine Strategy Framework Directive purposes. This document was drafted by DG MARE in close coordination with DG Environment as a guidance for those implementing Articles 11 and 18.

The aim of the document “is to describe good practices on the elements to be considered by the Member States when preparing Joint Recommendations for the adoption of conservation measures under the Common Fisheries Policy (CFP) to comply with their obligations pertaining to Article 6 of the Habitats Directive, Article 4 of the Birds Directive and Article 13(4) of the Marine Strategy Framework Directive (MSFD). It aims to recall the rules and procedures relating to the submission of a Joint Recommendation by the Member States, in order for the Commission to adopt conservation measures by means of a delegated act pursuant to Articles 11(2) and 11(3) of the CFP.”

The working document was presented to all regional groups and widely distributed to all stakeholders. But as it is a guidance document it has no formal status within EU legislation; its use is optional and the recommendations within it need not be followed

In November 2020 the European Court of Auditors (ECA) published a comprehensive review of the EU’s progress in the implementation of its targets for the protection of marine ecosystems and resources under the title: Marine environment: EU protection is wide but not deep18. The conclusions are quite damning on the progress made in protecting European Seas:

“EU protection rules have not led to the recovery of significant ecosystems and habitats. The network of marine protected areas was not representative of the EU’s diverse seas and sometimes provided little protection. In practice, the provisions to coordinate fisheries policy with environmental policy had not worked as intended”

Interesting to note is that in this report the Member States interviewed who mainly represented countries in the south of Europe indicated they had no interest in starting Article 11 processes for designating fisheries measures within MPAs as they viewed the process as complicated and cumbersome and expected it could lead to watering down of protection measures needed.

14

Other relevant policy processes

Green Deal

To deal with the global challenge of climate change as well as the biodiversity crisis the European Commission announced a Green Deal for Europe in 2020. The Green Deal serves as a roadmap for making all processes in the EU sustainable, and it will work through a framework of strategies, regulations and legislation setting clear overarching targets. One of the strategies introduced shortly after the Green Deal was announced is the updated Biodiversity Strategy that extends to 2030, which replaces the previous Biodiversity Strategy which ran from 2010 to 2020.

Biodiversity strategy 2010 to 2030

The EU recognised that the loss of biodiversity was continuing, and also that this loss was posing a major threat to long‐term sustainable development, both within the EU and beyond. To address this challenge, and reflecting global commitment to the same cause, the EU has launched a series of action plans and strategies, starting with the EU Biodiversity Action Plan in 2006 (EC, 2006), followed by the EU Biodiversity Strategy to 2020 (EC, 2011) which was updated last year to the EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 (EC,2020).

If they were fully implemented, the Habitats Directives (from 1992) and the Birds Directive (from 2009) would provide more than enough legal backing to safeguard marine biodiversity in the EU. However, the EU acknowledged that implementation had been slow and incomplete. The Commission is still reviewing the effect of the Biodiversity Strategy to 2020 but for the marine Natura 2000 areas the conclusion can be that little progress was made. The reasons for not reaching the strategies objectives were similar to those identified in 2010 as the main blockages to progress then:

Insufficient sense of urgency in implementing environmental and nature legislation

Lack of coordination with other policy areas (fisheries, transport, energy, etc.)

Lack of financial resources

Concerning Protected Areas, and the Natura 2000 network in particular, the new Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 observes that the: “protection has been incomplete, restoration has been small‐scale, and the implementation and enforcement of legislation has been insufficient”.

Among the objectives of the Biodiversity Strategy, the European Commission wants to “improve and widen our network of Protected Areas and develop an ambitious EU Nature Restoration Plan.” The strategy further states that the EU should:

Build a coherent Trans‐Europe Nature Network.

Legally protect a minimum of 30% of the EU’s land areas and 30% of the EU sea area and integrate ecological corridors. (This means an extra of 4% of land and 19% for seas areas as compared to today)

Strictly protect one third of protected areas, covering 10% of EU land and 10% of EU sea. (Today, only 3% of land and less than 1% of marine areas are under strict protection.)

Although these are strong objectives, a considerable effort will have to be made to implement the Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 when it comes to MPAs. Only a very small fraction (+/‐ 0.5%) of MPAs provide full protection against all extracting activities19. These fully protected or no‐take MPAs are of great importance for marine biodiversity and are also more likely to be successful in reaching the conservation objectives set20. Many MPAs in Europe are multiple‐use MPAs in which many activities are permitted. A recent study assessed 727 MPAs designated in the EU and found that commercial

15

trawling was happening in the majority of these MPAs (59%). The data also demonstrated that trawling intensity was actually higher inside MPAs, in comparison to non‐protected areas21. Major shipping lines may also intersect MPAs. For example, in the Baltic Sea, some major shipping lines go through MPAs or are very close to MPAs and fishing activities take place within MPAs.

Action plan to conserve fisheries resources and protect marine ecosystems

As part of the new Biodiversity Strategy for 2030, an Action Plan to conserve fisheries resources and protect marine ecosystems is to be developed, and should be published before the end of 2021. The plan will address the by‐catch of sensitive species and adverse impacts on sensitive habitats by introduced measures to limit the use of fishing gear most harmful to biodiversity, including on the seabed. It will also look at how to reconcile the use of bottom‐contacting fishing gear with biodiversity goals. Interestingly, the Roadmap for the Action Plan22 specifically mentions the need to link this strategy to the implementation of the Bird and Habitats Directives, in this way allowing spatial measures to be incorporated.

Multiannual Plans

As part of the Regionalisation process introduced in the CFP reform, from 2013 the obligation for Regional Member State Groups to develop Multiannual Plans (MAPs) was introduced. In these plans Member States active in a certain sea basin were tasked to create a tailor‐made plan relevant to the local conditions that set out how the CFP objectives on fisheries (e.g., MSY) are to be obtained for the region. This can include fishing effort restrictions and contain specific control rules and technical measures.

Although spatial management is not specifically mentioned in the articles related to the Multiannual Plans, Article 9.5 does have scope for spatial measures to be incorporated as it relates to the ecosystem approach, which in an EU context is developed under the Marine Strategy Framework Directive (Article 9.5): “Multiannual plans may contain specific conservation objectives and measures based on the ecosystem approach in order to address the specific problems of mixed fisheries in relation to the achievement of the objectives set out in Article 2(2) for the mixture of stocks covered by the plan in cases where scientific advice indicates that increases in selectivity cannot be achieved. Where necessary, the multiannual plan shall include specific alternative conservation measures, based on the ecosystem approach, for some of the stocks that it covers.”

The first Multiannual Plan (for the Baltic Sea) was agreed in 2016, the plans for the North Sea in 2018, and for Western Waters and for the Mediterranean in 2019. None of the current plans incorporate technical measures, as the focus lies on fishing limits and flexibilities in mixed fisheries. These plans will need to be revised in the near future, and the first steps for the revision of the Baltic Sea MAP have already been taken with a review of the implementation of this plan published by ICES in 201923

16

Top: Grey seal in the northern North Sea – © OCEANA / Juan Cuetos

Bottom: Marine life in an Aeolian Islands Natura 2000 site – © OCEANA / Juan Cuetos

17

Methods

Interviews

Participants were selected from a list with key stakeholders from policy, fishing industry, and NGO backgrounds and efforts were made to have a geographical spread in the interviewees. A total of eight interviews were conducted between May and June 2021. The in‐depth semi‐structured interviews were conducted through video calls based on a protocol that divided the interview in two parts:

The first part dealt with EU MPA policy in general, with attention on the following topics:

‐ the perception of the implementation of Article 11 in general

‐ the role of the Commission, Member States and stakeholders in the process

‐ the content of the EC staff working document

In the second part, respondents were asked in detail about specific Article 11 procedures they had worked on, both in terms of the broad outlines of the process and also specific examples of things that worked very well or not at all.

The route to a fisheries management plan for an MPA roughly breaks down into four phases:

1. First exploration/draft within Member State

2. Collecting information/stakeholder consultations

3. International alignment towards Joint Recommendation

4. Review by European Commission (+ request STECF) towards Delegated Act

In the interviews, these phases were used as a guideline to ensure that cases from different countries could be compared. All interviewees provided consent for the recording on the basis of anonymity in the report. The interviews were recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analysed using a general inductive approach. All quotes were anonymised using standard practice removing names and locations. The outline of the interview can be found in Annex 2.

Case studies

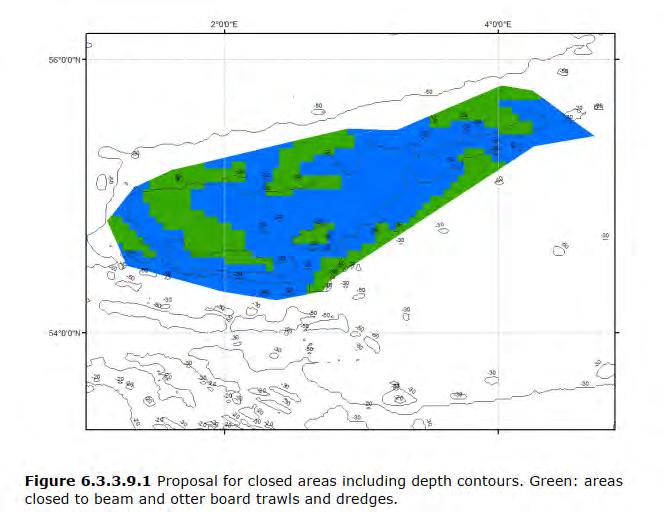

Four cases where Member States implemented or tried to implement an Article 11 process were selected. (1) Sweden – Kattegat / Skagerrak MPAs; (2) Scotland – North of Scotland, North Sea MPAs; (3) Belgium – Belgian North Sea; and (4) Germany, Netherlands, UK – Dogger Bank.

The case studies consist of a summary and map of the process, a detailed overview of the content of the proposal and the policy process towards a delegated act and end with an appraisal of the strengths and weaknesses in both the proposal and the process.

Information for the case studies came from publicly available sources, supplemented with intelligence provided by the respondents to the interviews. Initially Denmark was supposed to be one to the case studies, as this is this is one of the few examples of a completed Article 11 process, but no respondents could be found from this county. In three cases contact was also sought with experts that were not part of the interview pool to check certain elements of the case studies.

Results

Findings were captured in overarching themes: (national process, regional process, role of stakeholders, role of scientific underpinning, role of the Commission and use of the Staff Working Document) that emerged in the interviewing process as well as the case studies.

18

Review

Process in Initiating Member States

Art 11 3. The initiating Member State shall provide the Commission and the other Member States having a direct management interest with relevant information on the measures required, including their rationale, scientific evidence in support and details on their practical implementation and enforcement

The first phase of designing fisheries measures for the conservation measures within an MPA starts within the initiating Member State. Under the Habitats Directive as well as the MSFD, each Member State must define the conservation objectives and develop strategies for its own waters. In all of the case studies reviewed, Member States chose to develop their initial proposal on their own and only present to the wider regional group once they had a proposal ready.

Measures relating to the implementation of the CFP fall within the remit of the fisheries department within the Member State whilst the protection of the marine ecosystems and species falls within the environment department. In many countries these are part of different ministries which leads to confusion about the type of measures that can be taken and how to propose them.

“The ministry is responsible both for fisheries and for marine protected areas. …I understand that in many Member States the knowledge of people who have to work with marine conservation about the tools [available through the CFP] are not so very well developed…. So I think there is a need to share information with the people working more on conservation on these tools, to make it more effective.”

The fisheries department policy objectives will, in most cases, be worded about sustainable use of marine resources whilst the narrative from their environmental counterparts will be more centred around preventing harm to species and habitats. This can lead to diverging interpretations of what consists of relevant measures for a certain area.

For example, in the Belgian case, even though the federal environmental department is responsible for the MPA, the negotiations were led by the regional (Flemish) fisheries department in close coordination with the Belgian industry. If this is compared to the Swedish case where the drafting was driven by the nature department, the initial ambition for the protection was much higher than in the Belgian case. Sweden consistently based its proposal on the precautionary approach (under the MSFD) which enabled it to set quite stringent measures when it came to disturbance.

This discrepancy in defining the path to management measures is clear in the official texts. CFP Article 11.3 refers to “direct management interest” (of the Member State), which is further elaborated on in the Staff Working Document as “this direct management interest consists of either fishing opportunities or a fishery taking place in the exclusive economic zone of the initiating Member State.” Management in the context of the Habitats Directive Article 6.1 is conservation management (ecological requirements) and Article 13.4 of the MSFD does not mention management, only (spatial protection) measures. In the interviews we heard that from a fisheries perspective the goal would be to develop measures to move towards sustainable fisheries, whereas those speaking from a nature conservation point of view, or applying the precautionary approach, were working towards goals as defined in the national legislation for the Birds and Habitat Directives and MSFD. This is an inconsistency which echoes throughout the whole process giving scope for fisheries and conservation to be played out against each other. This happens despite the perception of the Commission, which is

19

that measures taken under the CFP Articles contribute to meeting environmental objectives. This discrepancy has to be addressed.

“As a Member State you have to make a trade‐off between achieving goals on the one hand and the economy on the other. And certainly in the case of fishing with a certain gear. But we as a Member State have not said we are going for a total ban on gear, not anywhere. So that's one reason those goals aren't being met.”

CFP Article 20

Aside from Article 11 of the CFP, Article 20 also provides Member States with the opportunity to adopt conservation measures within their 12‐mile zone. Measures taken have to be non‐discriminatory, applying to all operators active in the area. Article 20 differs from Article 11 in that where the latter forces the proposing Member State to seek consensus with all other Member States with a fishing interest in the area, under an Article 20 procedure the proponent only has to inform other Member States and the relevant Advisory Council(s).

Some of the respondents thought that this option was under‐utilised by Member States as it provides a much simpler process for the adoption of measures.

"Article 20, as far as it applies, is simply an easy way out that Member States do not really dare to use, because they are unfamiliar with it. But it's really simple and some of the areas that can be registered that are within 12 miles and that can just be done in a very simple procedure of Article 20. But the Commission does not encourage that because the Article 20 procedure largely sidelines the Commission."

Whilst others pointed out that Article 20 can be viewed as a blunt instrument as it bypasses all discussion and can lead to opposition form affected Member States on other measures. They therefore only thought it was useful for small areas where there was hardly any fishing interest form outside the proponent’s country.

“When it comes to implementing measures which affect other Member States, having buy in from the other fisheries is essential. So this [using Article 20] is not the way for us.”

Member States with fishing interest and Regional Groups

Staff Working Document. 3.1. Preparing a Joint Recommendation

In preparing a Joint Recommendation, the following steps should be envisaged.

Identifying other Member States concerned

It is the responsibility of the initiating Member State to determine whether the measures may affect fishing vessels flying the flag of other Member States or which other Member States have a direct management interest in the fishery to be affected by measures it intends to adopt. Pursuant to Article 4(1)(22) of the CFP, this direct management interest consists of either fishing opportunities or a fishery taking place in the exclusive economic zone of the initiating Member State. A broad and transparent approach in consulting the other Member States may help to identify which Member States have a direct management interest in the fishery to be affected. It is highly recommended that the relevant national authorities engage in early cooperation at Member State level between fisheries and nature conservation authorities, as well as other relevant departments (e.g., fisheries control, marine, etc.).

20

The regionalisation process was hailed as a great improvement after the 2013 CFP reform by policymakers. This would allow targeted measures that were tailored to the specific situation in each sea basin, something for which both Member States and some stakeholders had advocated for years. Nearly a decade after the introduction of Articles 11 and 18, more and more stakeholders are concluding that the regionalisation process is not delivering on its objectives of setting fisheries measures in MPAs.

“I don’t know how you could claim that Article 11 as it’s currently been operationalised has been successful. We've seen maybe 5 or 6 Joint Recommendations that have been sent to the Commission and led to delegated conservation measures since 2013 and I imagine it would cover a very small area [of marine Natura 2000 sites] and presuming the goal would have been that fishery management measures would have been in place for all of these Natura2000’s sites”

The CFP calls for establishing specific, EU‐only, regional management bodies, which are the regional management groups consisting of a high level and working group, whilst the coordination of environmental issues happened under Regional Sea Conventions. So from the onset there was a disjointed approach to policy coordination and integration.

Regional Groups setup

The CFP only stipulates that the Regional Groups shall be set up but does not add guidance on their organisation. As outlined in the dedicated section in the first chapter of this report, there is great variety between groups in their remit and workplans and the level of stakeholder participation allowed. Some groups allow stakeholders to join at a working group level, although that is mostly though the Advisory Councils, whilst others only allow minimal participation. In all regional groups the meetings of the High Level Group (HLG, in which fisheries directors of ministries and the European Commission take final decisions) are closed to outside participation. In general, there are no notes of these meetings available and the agenda is not public.

“What I'm saying is there is very little transparency happening with the high‐level groups when they sit around to negotiate or they actually want to agree on for the Joint Recommendation. That’s a problem for the stakeholder consultation and it’s probably also a problem for figuring out who’s responsible when the measures are watered down; to try to pinpoint who’s the responsible party for doing this”

Harmonisation of approach

Harmonising implementation of different EU policies at the regional level also faces a number of challenges. There is a mismatch of scales between the design and focus of the different EU policies and the implementation modes. In order for policy implementation to be harmonised between coastal states it helps for legal scales to be aligned. In the case of setting fisheries measures in MPAs, this is not the case. On the one hand, the CFP is a regulation and under European law its measures take immediate effect, whilst on the other hand the Habitats, Birds, and Marine Strategy Framework Directives require Member States to prepare a national implementation plan within their own remit. As a result, governance systems and structures, management measures, and even the indicators used to measure the level of implementation and success differ among Member States and so hamper the overall effective operationalisation.

21

This was apparent in the case study of the Dogger Bank process (also see Dogger Bank Case Study) where different interpretations of the Habitats Directive led to the three initiating Member States having differences in formulating their objectives for the habitat in the area even though they all agreed on its unfavourable status.

The mismatch is further exacerbated by the fact that, in most countries, the CFP lies within the competence of fisheries ministries whilst implementation of the environmental directives is handled by the environment ministries. Or as one respondent reflected on the objectives of the Habitats Directive vs the CFP:

“It might not be about the habitat but maybe it’s about the gear. The fishers are not forced into a permanent process of becoming more sustainable this way and that’s a shame.”

Timelines and pathways

Art 11 3. The initiating Member State and the other Member States having a direct management interest may submit a joint recommendation, as referred to in Article 18(1), within six months from the provision of sufficient information

Art 18 2. (Regional cooperation) For the purpose of paragraph 1 (Ed. MS agree to submit JR), Member States having a direct management interest affected by the measures referred to in paragraph 1 shall cooperate with one another in formulating joint recommendations. They shall also consult the relevant Advisory Councils. The Commission shall facilitate the cooperation between Member States, including, where necessary, by ensuring that a scientific contribution is obtained from the relevant scientific bodies.

Article 11.3 of the CFP provides a crucial element of the implementation process as it contains the only clear timeline that Member States need to adhere to within the process. When assessing the uptake of Article 11, it is clear that the provisions in this article are not enough to prevent confusion on the process and bad actors to be effective in causing delays or even blocking the whole process.

In three of the four cases reviewed, the process from the initiating Member State starting discussion within the Regional Group to the Joint Recommendation being finalised was the longest part of the process. The only initiating Member State that managed to prevent this was Sweden. However, in that case only one other Member State (Denmark) had a strong fishing interest in the area.

The term sufficient information is not defined within the context of Article 11, which can lead to confusion and unwanted delays whilst there is disagreement if the knowledge base is strong enough to go forward.

“More often than not asking for more additional information is a delay tactic. And I think if there could be clear guidelines that if the proposal is put forward, if there are objections then within X days the country objecting has got to list its objections and the reasons as to why it's objecting. And then if there's new information to be provided it's got to be done similarly within a set number of days. “

22

The way in which Article 11.3 is worded technically gives any Member State with fishing interest a veto on the process, and there are ample examples of this happening. This can be done actively, as happened for example when the Dutch parliament voted against the fisheries measures proposed for the Dogger Bank SAC, after which the whole process had to be redone. But Member States can also passively block progress, as they did in the case of the Scottish Joint Recommendation proposals whereby by simply refusing to engage in the process, due to concerns around Brexit, all progress was blocked.

“it becomes highly politicised and as we have seen, and the Member States seem to be impotent to prevent that or to have some sense of balance and say well… you know I hear what you say but we have to press on with this… so I mean it is almost laughable. You end up with this incredibly torturous process where the environment loses out, you know, still no protection after 10 years”

Several respondents pointed to the need to have more clarity on roles and responsibilities and a way to bring in arbitration in the Article 11 process, to ensure the process is concluded in a timely manner and that the ambition is not watered down.

“The problem with Article 11 is that in normal circumstances it’s quite easy to pinpoint if the Member State is at fault for not complying with the European laws, because it’s just one Member State. It’s their responsibility to take action in the protected sites, so that’s quite clear, but under Article 11 it becomes a lot more complicated with other Member States being involved”

“Sweden has very strong political willingness internally to do this and have a relatively easy situation in relation to their own fisheries sector. And still it took them years to put through a Joint Recommendation that is protecting relatively small areas. So when is France ever going to protect its massive MPA in the French Atlantic? It's huge, and they designated it but there is not a single measure in that MPA and there's Spanish boats in there. When is that ever going to happen without binding legislation that says you've got to stop”

Role of Stakeholders

Neither Article 11 nor Article 18 give clarity on how the Regional Group should engage with the Advisory Councils or other stakeholders. Article 18.2 merely states that, in cooperating with one another in formulating Joint Recommendations, Member States having a direct management interest ‘shall consult the relevant Advisory Councils’. This is frustrating according to some respondents as it is quite unclear how and if advice is taken on board and how stakeholders can participate.

“an issue of you have the advisory council giving advice to the high level group, and to what sense that advice is taken on board as well. There is very little transparency happening with the high‐level groups when they sit around to negotiate to agree on for the Joint Recommendation, and that’s a problem for the stakeholder consultation”

Article 11 is descriptive on the issue of regional cooperation in agreeing conservation measures but does not stipulate how much say in the process stakeholders get. Article 18 also gives no guidance on the specific consultation requirements.

This has led a lack of uniformity in the approach taken by different Member States. This was apparent in all the processes reviewed as case studies in this report. In the case of the Dogger Bank, Member

23

States tried to have a stakeholder‐driven approach at first, asking the North Sea Advisory Council to come up with a zoning plan that would form the basis of the Joint Recommendation. But this approach was later abandoned when the stakeholders could not find agreement. After the introduction of Article 11, the North Sea Advisory Council advised several times on the progress on the Dogger Bank but they were quite frustrated in the lack of response they got on their advice from both the Member States and the Commission24. Sweden made sure stakeholders were fully informed of every stage of the process but opted not to give them a say in the setting of measures, as that was fully aligned to national policy. In the case of Belgium, lack of stakeholder involvement at the Joint Recommendation stage led to them coming in at the last minute to instigate a block of the Delegated Act at a European Parliament level.

Role of scientific underpinning

Art 11 3. The Commission shall adopt the measures, taking into account any available scientific advice (= STECF), within three months from receipt of a complete request.

Art 26. Consulting scientific bodies. “The Commission shall consult appropriate scientific bodies. STECF shall be consulted, where appropriate, on matters pertaining to the conservation and management of living marine resources, including biological, economic, environmental, social and technical considerations. Consultations of scientific bodies shall take into account the proper management of public funds, with the aim of avoiding duplication of work by such bodies.”

The role of scientific expertise, although specifically referred to in the CFP legal text, is not interpreted in the same way by all parties within the process. Although all agree that it is a role of importance, the timing and role of scientific grounding is not defined.

STECF advice in the Article 11 process

The role of the EU Scientific, Technical, Economic Committee for Fisheries (STECF) in the Article 11 process is an evaluation of proposed fisheries measures. STECF reviews the content of the Joint Recommendation after submission and is asked to indicate if proposed measures will contribute to the goals under the relevant directive(s) for the area. If the information is found to be insufficient or does not support the goals, this it reported to the Commission.

Some interviewees thought that the STECF role could be improved if more scientists with a thorough understanding of the functioning of marine ecosystems and nature conservation were added to the panel, as the majority of members are experts in fisheries and economics.

“I think someone like STECF should be advising on what are the scientific impacts or what are the environmental, ecological impacts of fishing. And the problem is once they make a reference to socio‐economic factors that just undermines all of the work. It gives governments a free reign to not implement measures that are needed.”

From STECF Plenary reports, it is clear that STECF often does not have much time to evaluate the Joint Recommendations received through the Article 11 process. Considering the specific nature of Article 11 Joint Recommendations, taking these requests out of the regular work of the STECF might give the members more time to address them.

“They’re given a very short period of time to provide advice. It’s matter of days on joint recommendation and they can only do so much in that period of time…”

24

Timing of scientific input in the Article 11 process

As stated above, the STECF is only consulted by the Commission after the Joint Recommendation is submitted by the relevant Member States. If the information in the proposal is found to be insufficient or does not support the goals for the MPA, then the Commission can opt to request the proposing Member States to address the concerns or provide additional information. This means that any comments, criticisms and suggestions for improvement made by STECF and to be addressed by the initiating Member State come once the Joint Recommendation process has already been concluded. This leads to delays and irritation.

Sometimes the STECF advice includes suggestions to increase gear exclusion zones (Belgium (STECF 2017) and Germany (STECF 2019)), or has comments on lack of a monitoring programme, etc. If these issues were flagged at an earlier stage, then solutions might have been possible. For Kattegat (STECF 2021 – Sweden. Denmark) STECF detailed comments and positive outcomes for each of the Terms of References. In 2016, there was an STECF written procedure on the four Danish N2000 areas in the Kattegat, based on the information supplied by Denmark. Germany and Sweden. Some of these areas were later included in the Swedish Joint Recommendation for the Kattegat.

Many of the respondents agreed that it would make sense to have this scientific check, or a similar one, earlier in process, or to carry out a screening of the draft Joint Recommendation before it has been submitted, or to even have a request to ICES from the regional Member State groups on the basic document submitted by the initiating Member States.

“About the basic document then, that would be possible. Also, because they then receive a fairly recent document and not two or three years later. Because as a Member State, you cannot of course predict how quickly the process will go, even if you want to go as quickly as possible. But now perhaps the basic document could also be reviewed by STECF”

Scientific expertise in the Article 11 process

Article 26 of the CFP states that the “Commission shall consult appropriate scientific bodies” which opens up the possibility that a forum other than STECF could be consulted. For the Dogger Bank, a Special Request was sent to ICES in 2012 by Germany, the Netherlands, and the UK as follows: “ICES is requested to advise on the degree to which the implementation of the proposed fisheries measures in the Presentation Paper will contribute to the achievement of the established conservation objectives, taking into account the wish of the Dogger Bank states to consider the Dogger Bank as one ecosystem.” The headline conclusion was: “ICES considers that the diversity, and ambition, of the national conservation objectives makes development of a single management approach complicated and difficult.” The main criticism pointed out by ICES was that each of the countries had a different (conservation) goal in their particular part of the Dogger Bank, which would complicate any attempt at a joint management approach. Taking heed of this initial advice provided by ICES back in 2012 could have saved time and prevented the reiterations of the same criticism by STECF when it was asked to review the Joint Recommendation in 2019.

25

Role of the Commission

Process

Articles 11 and 18 of the CFP define a specific role for the Commission at different steps in the process.

Art 18 2. (Regional cooperation) For the purpose of paragraph 1 (Ed. MS agree to submit JR), Member States having a direct management interest affected by the measures referred to in paragraph 1 shall cooperate with one another in formulating Joint Recommendations. They shall also consult the relevant Advisory Councils. The Commission shall facilitate the cooperation between Member States, including, where necessary, by ensuring that a scientific contribution is obtained from the relevant scientific bodies.

There is also an overarching role for the Commission in ensuring that the EU’s objectives for the Birds and Habitat Directives, the MSFD, the Biodiversity Strategy for 2030, and other global and regional conservation commitments are met as was pointed out in the European Court of Auditors report from 2020 (see section on this special report in the first chapter of this report).

According to the Commission itself, the responsibility for the Article 11 process lies with the Member States under regionalisation. The interpretation of the Commission of their facilitation role within the process is fulfilled by providing information such as the Staff Working Document, by organising workshops and seminars, and by attending meetings of the Regional Groups. They do not take an active role when negotiations are stalled or there is disagreement between Member States.

“And I think if there could be clear guidelines that you know... that the proposal is put forward, if there are objections then within 14 days the country objecting has got to list its objections and the reasons as to why it's objecting. And then if there's new information to be provided it's got to be done similarly within 14 to 28 days... but then there's got to be some way of arbitration, you can't have nothing happen in the absence of an agreement…So, I think there's got to be a clear timeline and pathway for situations where there is an objection.”

Interpretation of the role of the Commission

Articles 11 and 18 set out a clear role for the Commission in the designation process, but most of those interviewed were quite critical of the efficacy of the Commission and most found the Commission to be lacking in leadership or coming to the process too late. Looking at the reactions of the interviewees, it is clear that the expectations of the role the Commission should play do not tally with the perception of the Commission. Improving this pattern would be beneficial.

“We felt a bit abandoned because no one from the Commission reacted to our requests.“

“.. the guardian is the Commission. The Commission has to put its first on the table and say, enough, we have to make progress on this JR. You have three months to give us a proposal that responds to the requirements of this and this and that and such. And if you don't, we will open infringement procedures against your country”

In this respect it would be advisable to clarify the roles of DG Environment vs DG MARE.

26

Interviewees were quite sceptical of the balance between the two DGs and pointed out there was ample room for improvements.

“.. it ties up with all of this due diligence… a much stronger and more integrated role of DG Environment. I mean they are the protectors of the Nature Directives and frankly their involvement in all the processes they have been involved in has been minimal and highly ineffective really… I just don’t feel they have their finger on the pulse of these things … I think DG MARE rules the roosts… “ “... the guardian is the Commission. The Commission has to put its first on the table and say, enough, we have to make progress on this JR. You have three months to give us a proposal that responds to the requirements of this and this and that and such. And if you don't, we will open infringement procedures against your country”

Article 18.2 states that the Commission shall facilitate cooperation between Member States, but opinions differ strongly on what this facilitatory role should be. In a legal briefing developed briefing developed by Client Earth on Article 1125, they stressed that as Article 18.2 refers to cooperation in relation to implementation and enforcement of the measures adopted under Article 11.2‐11.4 and Article 11.6 which are linked to the EU’s environmental law, it should be DG Environment that has the primary responsibility for overseeing the processes described in Article 11. This interpretation is not followed by the Regional Groups, that hold that the process is within the remit of the fisheries departments as they are the bodies tasked with the implementation of the CFP.

However, in general all interviewees agreed that the facilitation of cooperation by the Commission was limited and only took shape late in the process after it had become politicised.

“And so, we were happy that DG MARE got involved, but it would have been so much better that I'd gotten involved much, much earlier because you don't want to waste all of this time for anyone. You know, it's such a bad use of civil servants time as well.”

Both from the case studies and the interviews it is clear that there is great frustration with the length of the processes. Even the measures for the relatively simple areas in the Skagerrak and Kattegat took over a decade to materialise. Even though this was already apparent during the CFP reform from 2013, Articles 11 and 18 do not provide a way to take action if processes are stalled and no sanctions are levied if deadlines are missed or exceeded, even for places where there is wording in Article 11 to facilitate this.

“It is really hard for say the European Commission to pinpoint one particular actor... and be like well, you’re responsible for this... you’re not in compliance with European environmental law we’re going to take infringement action against you. At the moment just none of this accountability is happening and so we see that is a huge non‐compliance with the Habitats Directive but just nobody’s been held accountable for that at the moment. That's the big problem.”

An interesting observation is that even though the Commission has the option to take emergency measures within Natura 2000 sites when no measures are taken by Member States, there are no cases of this happening. There are some cases where emergency measures were taken to protect species (e.g., sea bass, Baltic cod) but the Commission never used its capacity to force action within an MPA to prevent further damage.

27

Functioning of Article 11

The reactions to the existence and working of Article 11 were varied. Several of the respondents pointed to the importance of having Article 11 in existence as a means to align legislation and include environmental considerations in the CFP.

“But I guess as a member of a club you need club rules. And that's what it (Art. 11) did. It formalized the behaviors... that each of us should adopt you know.”

“So, we think that Article 11 and regionalisation process is a very good step forward. We have the tools in Article 11. Absolutely, in connection with Article 18.”

Others were more critical about the efficacy of Article 11 and found that it did not provide enough (legal) background for successful implementation.

“it is safe to say that Article 11, even in legal terms, is insufficient.”

“Article 11 is just not enough to guide the civil servants who have to do this job of reconciling fisheries management and nature protection, it is just one article with four paragraphs.”

All those interviewed expected a stronger role by the Commission as far as guiding the process and keeping to the timeline of the Article 11 process is concerned. Once a Joint Recommendation has been submitted, the Commission could have a checklist to see if the information provided is adequate/fit for purpose. Perhaps some sort of risk assessment should be carried out by the Commission at this point.

“… I can see the justification in… you need to have some outsid e sort of arbitration on whether the Joint Recommendation is fit for purpose…”

Most of those interviewed felt there should be a clear mandate and responsibilities for DG Environment and DG MARE, as well as alignment of the two departments. The Commission appears to have the same ambition for alignment and it is hoped that this will improve with the current Commissioner, who has both departments as his responsibility.

“…it may not be possible in the long run, because it’s the Commission… is that DG Environment take the lead in all of these matters, regarding Article 11… but even if that were not possible, they need to be structurally much more involved than they are. It’s just because it’s fisheries… you know that not enough… without DG MARE’s business it’s an environmental business, first and foremost. “

“But in the end the decision power lies with the marine department. And if they were aligned the environment department and the marine department that doesn’t have to hurt, but you can imagine... I know at a Commission level there is quite some com petition between ENVI and MARE“

Some of those interviewed suggested taking the Commission to the European Court of Justice in order to provide clarity on the implementation of Article 11 and supply jurisprudence. This would

28

provide a means of putting pressure on Member States that have made little progress in establishing fisheries management measures in their MPAs.

“.. until we have proper jurisprudence from the European Court of Justice, we won't know which way to go or how to apply it (Art. 11).”

“.. so this whole big problem about who’s legally responsible u nder Article 11.”

Staff Working Document (SWD)

In 2018, the European Commission brought out a Commission Staff Working Document (SWD) on the establishment of conservation measures under the Common Fisheries Policy for Natura 2000 sites and for Marine Strategy Framework Directive purposes. The document states that “the good practices described in this document are for information purposes only, and are without prejudice to the interpretation of the Court of Justice and the General Court or decisions of the Commission.” This suggests that this document does not have formal status. Most of the interviewees were familiar with the document and appreciated the information presented, but were unsure of its status and use.

“Art. 11 is complemented by a guidance document, but because the article itself is relatively vague, there's so much that the guidance document could do and say, but it cannot be more prescriptive because the guidance document is not the legislation.”

In the SWD are listed ten “Elements of good practice regarding the information to be provided by the Member States with the submission of the Joint Recommendations” but because the status of the document is unclear this information unfortunately does not seem to be used.

“How much do we rely on this sort of wish list of the staff working document guidance? And how much of that should be hardwired into the legislation and potentially a revision of the common fisheries policy or something.”

The Commission has distributed the document widely and sees the availability of the document and the information presented therein as a way of facilitating the Article 11 process. This sentiment is not shared by all recipients. Many interviewees pointed out that a SWD is a weak tool that is of little use when there is a bad actor blocking progress on a file. An improvement could be to incorporate elements of the SWD into legislation so that they become fixed guidelines for the process and prevent unwanted delays or watering down of objectives.

In addition, the Commission needs to better identify who the document is aimed at, and ensure all recipients have the same level of understanding of both fisheries and environmental policy and legislation. In this respect, it is important to include all those involved in the negotiations from both

“And it just seems too much take or leave… basically what I’m saying is that you know, there really needs to be a kind of triage exercise to see which elements of the staff working documents should be incorporated into the articles themselves, rather than being left to… it’s a sort of soft guidance…”

environment and fisheries departments at the European Commission level and even more so in the Member States and Regional Groups.

29

Recommendations

In the analysis it became clear that the barriers to the successful implementation of Article 11 can be separated in three distinct areas of improvement: clarity on process & timelines, arbitration & conflict resolution and transparency & accountability. All three areas require improvements at Member State, regional and Commission level.

Clarity on process & timelines