A MELODIOUS HOMECOMING:

A MELODIOUS HOMECOMING:

AT OBERLIN, WE’VE LONG BELIEVED THAT PROTECTING THE ENVIRONMENT is an intentional and shared responsibility. From the significant to the small, thoughtful things we do, it can all make a difference globally.

Perhaps it’s biking from South Campus to an 8 a.m. class in the Science Center or carrying a sticker-covered water bottle everywhere. Maybe it is sorting lunch scraps at Stevie, finding a perfect sweater at the Free Store, or driving less.

Over the past four years, Oberlin quite literally laid the groundwork for the college’s future: transitioning our historic campus from a 19th-century reliance on fossil fuels to a 21st-century geothermal system that heats and cools our buildings using energy drawn from the Earth itself.

This work represented a crucial step in fulfilling the promise we made more than two decades ago: to achieve carbon neutrality by 2025.

Of course, the true measure of our commitment to sustainability—and the promise it holds—extends well beyond what we achieve on campus. We benefit the world through the impact of our graduates, who demonstrate the courage to imagine the possible and pursue it with integrity.

In this special issue focused on sustainability, you’ll learn how we achieved carbon neutrality—the Oberlin way.

You’ll also read about the impact of the Adam Joseph Lewis Center for Environmental Studies, the many ways sustainability shows up on campus today, and how faculty research and academic programs such as food studies are helping Obies change the world.

And, of course, you’ll meet alums applying Oberlin values in farms, offices, businesses, and kitchens around the world, advancing a more sustainable future in their own ways.

Yes, there is much to celebrate—but there also is much still to do. I am proud of how Obies embrace this world of ours, giving their energy, intellect, and optimism to improve it day by day. After all, each of us has the power to do good in this world, to make a difference.

Carmen Twillie Ambar President, Oberlin College and Conservatory

Send letters to the editor, story tips, and pitches to alum.mag@oberlin.edu. If you are submitting a letter to the editor, please specify that your note is for publication and include your class year, location, and how your name should appear in print.

Editor

Annie Zaleski

Art Director

Nicole Fansler

Magazine Designer

Lesley Busby

Graphic Designer

Nick Giammarco

Director of Content and Social Media Strategy

Mathias Reed

Photo Coordinator and Project Manager

Yvonne Gay

Executive Director, Office of Communications

Kelly Viancourt

Vice President for Communications

Josh Jensen

The Oberlin Alumni Magazine (ISSN 0029-7518), founded in 1904, is published by Oberlin’s Office of Communications and distributed to alumni, parents, and friends of Oberlin College.

Office of Communications

247 W. Lorain St., Suite C Oberlin, OH 44074

Phone: 440.775.8182 Fax: 440.775.6575

Email: alum.mag@oberlin.edu www.oberlin.edu/oam

Oberlin Alumni Association

Dewy Ward ’34 Alumni Center 65 E. College St., Suite 4 Oberlin, OH 44074

Phone: 440.775.8692

Fax: 440.775.6748

Email: alumni@oberlin.edu www.oberlin.edu/alumni

POSTMASTER

Send changes to Oberlin College, 173 W. Lorain St., Oberlin, OH 44074

THE RAINBOW CONNECTION

It is awesome to see in the cover photo that Montana Levi Blanco [“Treasure Hunting,” Spring 2025] organizes his books according to color! Alternatively, things spontaneously organize themselves by color whenever Montana is around, which is just as great! Bravo to the photographer Samantha Jane!

Jennifer Kahle ’85

San Diego

HISTORY LESSONS

I was moved by the article “The Body, The Host” on art and HIV in the Spring 2025 issue. Since graduating from Oberlin and moving to Boston in 2004, I’ve worked in HIV care and services—a path sparked by a class called STDs: Biology/History/Misery that was taught by the late biology professor Richard Levin. That course, and the stories of radical activism by marginalized communities fighting to save their friends, left a lasting impression. It’s heartening to see that new generations of Obies are learning this powerful and ongoing history, especially as familiar threats to this community reemerge.

Rachel Weidenfeld ’04

Boston

RADIO, RADIO

Your article about Obies taking the lead in podcasting [“A Pipeline to Podcasts,” Spring 2025] is also an appropriate way

to celebrate WOBC’s 75 years of broadcasting. Having graduated in 1968, I am aware that both Michael Barone ’68 and Robert Krulwich ’69 got their start at WOBC. The first time I heard their voices on the air, I recognized them and that they were fellow Obies. If I am remembering correctly, Robert was part of a group of us who had a comedy show on the air, with silly fake news and weather reports. I played “Mia Nice, the Weather Girl.” (Yes, those were the days when women were denied adulthood by being called “girl,” and before meteorolo gists regularly gave accurate weather reports on air.) We also performed Dylan Thomas’ A Child’s Christmas in Wales, more of a literary nature. I was a speechlanguage pathologist for 50 years, so the experience on air served me well! Here’s to 75 more years of WOBC!

Tawn Reynolds Feeney ’68 Conesus, N.Y.

ON THE COVER: THE BURST

To commemorate Oberlin becoming a carbon-neutral campus in 2025, the Office of Communications’ design team led the creation of a distinctive brand mark: the Burst.

At the heart of the mark is a solid yellow circle representing the sun—an homage to Oberlin’s solar arrays, which supply roughly 12 percent of campus electricity. Sixteen angular petals radiate from this core at equal intervals, their form inspired by the distinctive pointed windows of Bibbins Hall. The gaps between petals subtly mirror the network of underground geothermal piping that now heats and cools campus buildings. By combining a floral form with architectural geometry, the design offers a fresh, nontraditional take on sustainability symbolism—one that feels rooted in Oberlin’s creative, free-spirited ethos rather than generic “green” clichés.

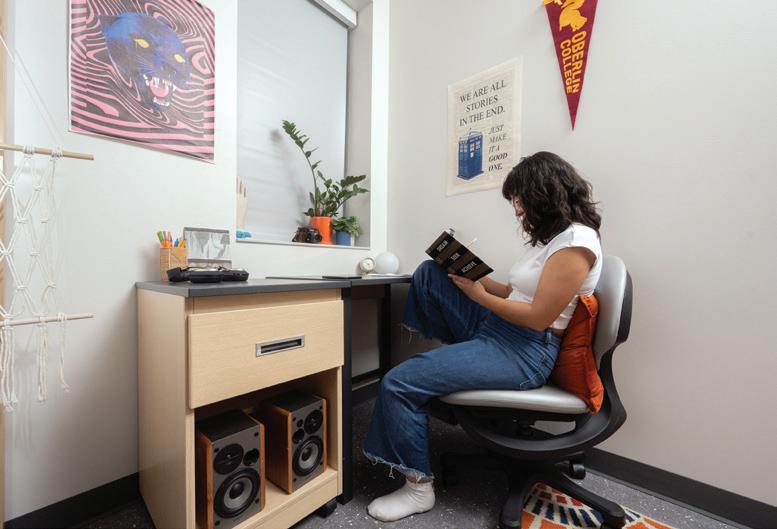

WELCOME HOME! In fall 2025, 402 Obies moved into Woodland Hall, a brand-new building that’s now the largest residence hall on campus. Located on Woodland Street near the north end of campus and conveniently situated between the Science Center and the athletics complex, Woodland is built with sustainability at the forefront: Designed to meet LEED Gold standards, the building is tied into the college’s geothermal heating and cooling system and features electric vehicle charging stations. Residents enjoy access to lounges and meeting rooms in addition to acoustically optimized music practice rooms and outdoor gathering spaces. A plaque installed in the courtyard pays tribute to the late Michael Kamarck ’73, a former trustee and biotechnology and pharmaceutical industry executive.

Starting in June 2027, students in Oberlin’s BA+BFA in Integrated Arts program will spend their fifth and final year living and working at a newly renovated collaborative space called Park Arts. Located at the historic Park Synagogue in Cleveland Heights, Ohio, Park Arts gives students 24-hour access to studios, rehearsal spaces, theaters, and production facilities. These amenities will enable Obies to fulfill their degree requirements by creating a large-scale, public-facing project, such as a performance, exhibition, or installation.

“This move provides an essential bridge from student life to professional careers in the arts,” says Julia Christensen, program director and Oberlin’s Eva & John Young-Hunter

Professor of Integrated Media.

Sustainable Community Associates (SCA), a Cleveland-based team of Oberlin alums Ben Ezinga ’01, Josh Rosen ’01, and Naomi Sabel ’02, is leading the redevelopment in partnership with Friends of Mendelsohn, a nonprofit that seeks to preserve the historic campus. SCA purchased the site in 2023 and spent over 18 months working with

the congregation, the local Jewish community, area residents, and city leaders to shape the future of the space. Construction is currently underway.

Oberlin’s newly launched BA+BFA in Integrated Arts program is designed with collaboration in mind: Students work with visiting artists, faculty mentors, and Cleveland arts organizations through internships, commissioned works, and public programming. Park Arts also places Oberlin students near some of the region’s most distinguished cultural institutions, as well as Cleveland’s renowned performance venues and galleries.

“For artists, community connections are invaluable,” Christensen says. “Collaborating with Cleveland’s arts organizations, securing internships, and being immersed in a thriving cultural district will be transformative. At the same time, these emerging artists will bring fresh perspectives and energy to the broader Cleveland arts scene. It’s an exciting exchange.”

In the last few years, several alums have made gifts to Oberlin to sustain language study at the college.

When Dr. Dorothy Koster Washburn ’67 was in her second year at Oberlin, she overheard two classmates talking about going on an archaeological dig in Wyoming. Her ears perked up: As a child, she was fascinated with an exhibition of ceramics she saw in Mesa Verde National Park. Emboldened, she asked if she could come on the dig, which was run by National Geographic and Harvard University’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology.

“I applied, and that summer, I was on the train going out [there],” Washburn recalls. “It was in 1965—and I have never looked back.” She earned a doctorate in anthropology at Columbia University and spent her career studying geometric design on pottery and other decorated artifacts using mathematical principles.

Through this work, she met Emory Sekaquaptewa, a Hopi scholar who introduced her to the Hopi language and Katsina songs. Studying these texts “brought front and center how important language is to people,” Washburn says. “Emory always said, ‘When a culture loses its language, it loses its culture, so you have to preserve these languages.’” In a nod to the importance of languages, Washburn gave Oberlin generous gifts for programming in Middle East and North Africa Studies (MENA) and a faculty position, the Dorothy Koster Washburn ’67 Endowed Lecturer in Arabic Language. Read a longer profile: go.oberlin.edu/dorothy-washburn

From a very young age, Edith Clowes ’73 was good at languages. “I was always imitating people without knowing what they were saying,” she says. “And my mother was a language wiz. She just adored learning languages.” Clowes followed in her footsteps, first learning

Update Your Address

Have you recently moved?

Share your new contact info online: go.oberlin.edu/oam-address-update

Submit a Class Note

You can now submit a class note (along with a photo) online: go.oberlin.edu/submit-class-notes

French and later German. Upon arriving at Oberlin, she packed a whole first-year Russian course (and part of the secondyear course) into a “very intensive” fall semester and Winter Term. She later earned a doctorate at Yale and taught Russian language, literature, and culture at the college level, eventually becoming the Brown-Forman Chair in the Humanities in the Slavic languages and literatures department at the University of Virginia. In 1998, Clowes helped start the Oberlin Center for Russian, East European, and Central Asian Studies (OCREECAS). This led to a scholarship to support Oberlin students studying Russian language and, as of fall 2025, the Edith W. Clowes Endowed Professorship in Russian. “[Language training is] a very intensive process, but also extremely exciting,” she says. “[It] changes a person for the better in terms of expanding their understanding of themselves and their opportunities in life.” Read a longer profile: go.oberlin.edu/edith-clowes

The late Harry “Pat” L. Patterson ’61 majored in math and earned a master’s in teaching. Education was his calling: He taught math at the International School Bangkok for nearly three decades. In 2025, Pat’s sister, Sue A. Bielawski ’56, honored her brother’s life and career with an endowed East Asian Studies support fund, which goes toward student instruction in a language within the East Asian Studies department.

Connect on Social Media OberlinCollege oberlincon groups/oberlin.alumni oberlincollege oberlincon oberlin-college

BY ANNIE ZALESKI

An interview with Jon Seydl, the new John G.W. Cowles Director of the Allen Memorial Art Museum

Over the summer, Oberlin welcomed Jon Seydl as the new John G.W. Cowles Director of the Allen Memorial Art Museum. Seydl, who previously worked for the Cleveland Museum of Art and came to Oberlin after serving as director of the Krannert Art Museum at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, was already familiar with the Allen. He’s always had a “soft spot” for self-portraits by Michael Sweerts and William Hogarth in the museum’s collection. Years ago, he and the Allen’s former director, Andria Derstine, also worked on a project together that involved museum staff and Oberlin students. “They were so creative and hardworking and really imaginative,” he recalls. “It was a revelation.”

Seydl earned a bachelor’s degree in art history at Yale University and a doctorate at the University of Pennsylvania in early modern Italian ar t history, giving him a strong background in art from the Renaissance to 1800. “But the older I get—and the more I spend time in museums—I now tend to go to the things I know least about,” he says. “I’m always learning something brand new.”

Once Seydl began to settle in at Oberlin, both on campus and in the city—he says people recognize him by his adorable 30-pound dog, Lenny, a mutt “with a heavy dose of pit bull”—he took time to answer questions about his career and what he hopes to bring to Oberlin.

What drew you to the Allen Memorial Art Museum and Oberlin? I mean, who wouldn’t be drawn to the Allen? [Laughs.] There are a whole

bunch of reasons. I love university museums. I find them genuinely liberating places to work. You never have to make an excuse for research because research is actually valorized in an academic setting. The fact that you can work with faculty across disciplines is amazing. And Northeast Ohio was a draw for us.

The intense work the Allen does with students and faculty, along with the use of the collection, is incredible. In the summer, I was meeting faculty who were telling me about their work

with the museum. And it comes from so many different disciplines. The museum’s not just there for art history or studio art; it’s for the whole campus. What happens at all academic museums happens so much more deeply here, with such a high level of quality and diverse touch points. It’s really dazzling.

What drew you to this line of work? When I was a kid, my sister was the one with artistic talent, not me, and she took art lessons. This was in Lehigh Valley, Pennsylvania, and the only place to go

was the Allentown Art Museum. It was far enough away from our house that it wasn’t a drop-off/pickup situation; we had to stay. While we were waiting, we only had two options: One was to stay in the museum, and the other was to go shopping. I hated the shopping option— and I loved the museum environment.

It took me outside of myself into a completely different world. I loved the focused, contemplative environment, but also the one where I was interacting with my parents. We were all looking at things together and learning from scratch. Fundamentally, as a visual person, it was a great place in general. That always stuck with me. I interned at a local museum in high school and college, and I had a job at the campus art museum.

I’m old enough that mental health was not really a topic you talked about a lot in college. But in retrospect, I realized I was using time in the two campus museums at Yale as a way to rest, restore, heal, and pull myself out of ordinary life and step back and reflect. That’s a really important role for museums—what I often call sanctuaries. And it’s something I always want to emphasize to students, faculty, and really anybody who visits: Think of your museum as a site for mental health and wellness.

Don’t get me wrong: I also love coming into a museum when it’s incredibly lively and noisy and there’s a lot going on. These spaces—and the Allen is a really great example of that too—can go from calm to bustling to calm again in a really healthy and important way.

What do you want to bring to your position at the Allen?

Like any wise leader, you spend a lot of time observing first. The thing that I’m observing is that there’s some areas where it’s best in business, best in class, and it runs like clockwork. One area for growth I see for the Allen is community engagement. We do incredible work with the college, and we’re a really important part of the city of Oberlin. But I also recognize that we

are the museum for Lorain County, which is a place that is underserved by arts organizations. And I know there are ways that we could be a much stronger partner across the county. I have experience in precisely that work. It’s something I’ve done in my previous position. Opening the museum up in a more active way to a bigger community is something I’m really, really excited about.

As we like to say, “Art is for everybody.” You never know who’s going to see something in a museum that’s going to change the course of their life or give them a spark to think that they can be something unexpected. It’s so powerful. Literally inscribed into the frieze on the entrance to the building is, “The Cause of Art is the Cause of the People,” that William Morris quotation. I take that incredibly seriously. That really is like my guide stone. That’s what the building and the collection was created to be, to have that social importance for a much wider group.

And the thing that I like best is developing longer-term partnerships with community groups—to develop something that can be on a three-tofive-year arc, at the very least. That involves a really intense phase of trust-building in the beginning. But the museum can play a really important part in connecting students to the broader community. Our Gallery Guide program, for example, is one obvious way to do that.

What else do you want people to know about you?

I want to know people. I want them to introduce themselves to me. I don’t want the director’s office to feel like a thing that’s completely apart. I deliberately chose to live in the city of Oberlin. I loved living in Cleveland, but I really want to be here, and I want to be an active part of the community. It’s been great. And I feel like having a dog in Oberlin is the key to everything. You just meet everyone.

In 2025, Oberlin reached its ambitious goal of achieving carbon neutrality, in large part by replacing the college’s century-old, fossil fuel-based heating system with geothermal energy. Call it the Oberlin Way: Sustainability isn’t just something we do during a certain month or in one building. Instead, it’s built into our everyday campus lives, through research, academics, student life, and more. Because of this supportive community, our alums are well-prepared for careers in sustainability, the environmental sciences and beyond. At Oberlin, we’re making the world a more resilient place, one thoughtful gesture at a time.

BY DYANI SABIN ’14

How infrastructure, partnerships, and student involvement helped Oberlin achieve carbon neutrality.

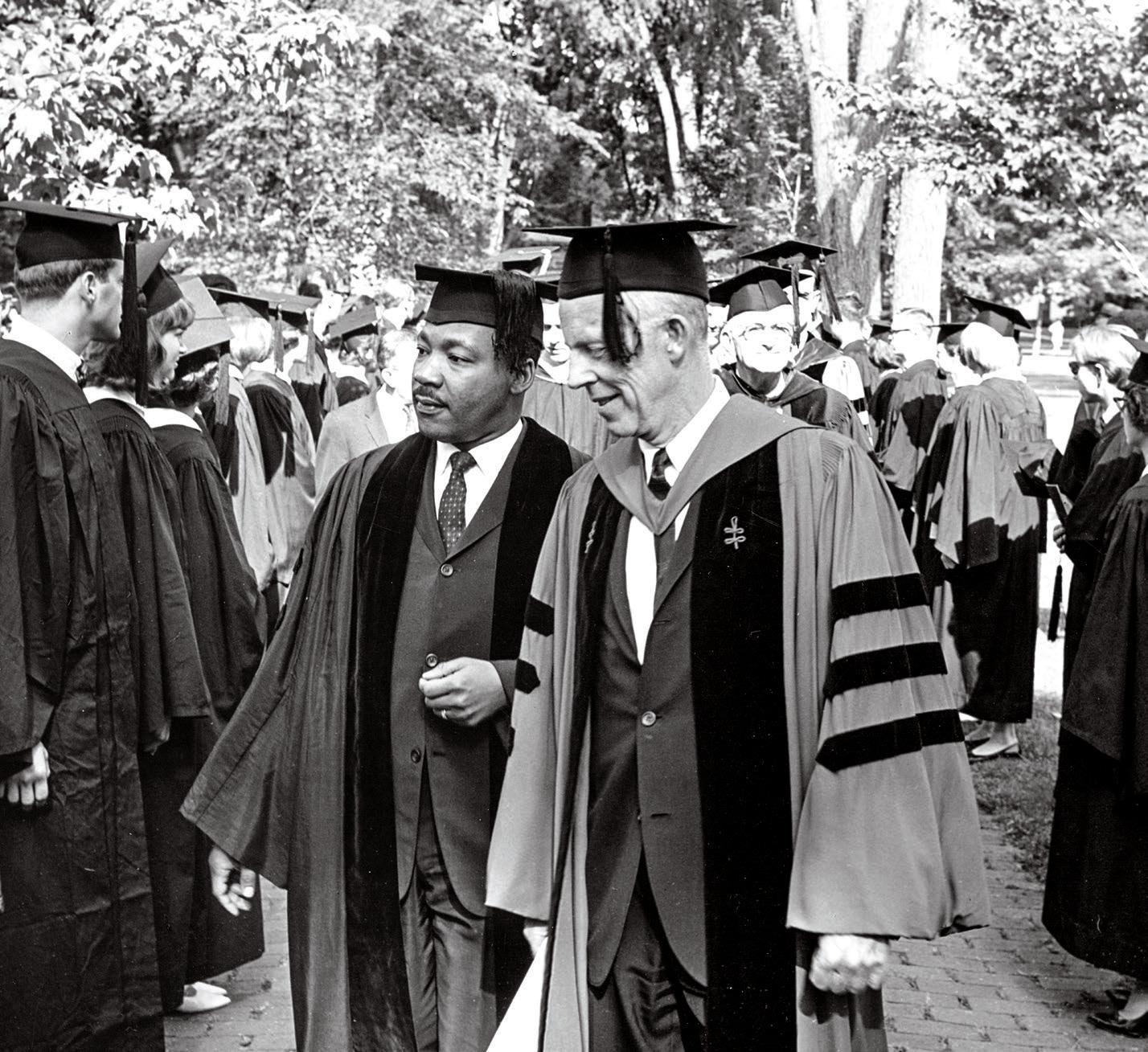

LONG BEFORE GLOBAL leaders started to take climate change seriously, Oberlin was paying attention. In January 1978, Karen Florini ’79 took the Winter Term intensive Humankind Tomorrow. Each day, students heard lectures on different aspects of sustainability and the broad impact of climate change. “[This] really set the course of my life’s work,” says Florini, a former Oberlin trustee who’s also worked as a deputy special envoy for climate change at the U.S. Department of State. “I was already somewhat on that path, but that experience of that class ensured that I could never consider doing anything else.” Decades later, Oberlin’s early

warnings about climate change look increasingly prescient. Research showed that 2024 was the hottest year on record since scientists started recording temperature measurements in 1880—continuing a warming trend that’s accelerated markedly in the last decade. Climate change is driven by human-created carbon emissions, with electricity, transportation, and industrial production being the largest sources. The more carbon that’s released into the atmosphere, the bigger the impact: These atmospheric greenhouse gases trap heat, which warms the Earth’s surface. At our current rate of emissions, the temperature of Earth is expected to rise by at least 3 degrees Fahrenheit in the next few decades.

“The one thing that really matters most in addressing climate change [is] reducing emissions, because the only thing that matters to the atmosphere is tons of carbon pollution,” says Florini, a strategic advisor at the nonprofit C-Change Conversations.

Failing to reduce carbon emissions, she adds, has massive negative impacts on food and water systems and increases geopolitical tensions and the number of destructive global weather events. “It’s a pretty ugly picture,” she says, “including extreme heat, wildfires, droughts, and floods—with all the resulting impacts on health and the economy—all occurring with increasing severity and cascading into one another.”

Florini says the way to combat climate change is by taking action. In late 2024, Oberlin announced it was on track to reach a milestone almost 25 years in the making: achieving carbon neutrality by 2025. This milestone reflects a steadfast commitment to sustainability projects on the part of three college presidents and multiple city leaders, as well as collaborations with the city of Oberlin and student involvement.

“We know what to do to avoid these horrible outcomes; we just have to do it,” Florini says. “And Oberlin has done it— and that is why Oberlin should be very proud of what it has accomplished here.”

“Energy isprobably one of the single most—if not the single most—critical emission source to figure out how to transition to net zero.”

What put Oberlin over the top was the Sustainable Infrastructure Program (SIP)—the transformation of the college’s 100-yearold steam-heating system into a geothermal heating and cooling system that connects 60 campus buildings. Although Oberlin switched its energy source from coal to natural gas in 2014, the college’s central heating plant was still the largest source of on-campus emissions. Finding an alternative energy source was a crucial next step.

“Energy is probably one of the single most—if not the single most—critical emission source to figure out how to transition to net zero [carbon neutrality],” says Lyrica McTiernan ’04, a sustainability consultant who formerly worked on Facebook and WeWork’s sustainability teams and originally decided to attend Oberlin because of the Adam Joseph Lewis Center for Environmental Studies (AJLC).

The geothermal system is an underground roller coaster of pipes that transports water around campus and through the college’s central heating plant in order to heat and cool buildings and provide hot water. Creating the closed-loop system involved digging 850 geothermal wells beneath one of the practice fields on north campus. These wells, which drop 600 feet into the Earth, allow water in the pipes to pull heat from the Earth in winter and shed it in the summer. No matter the season, the temperature of the Earth remains the same, so the water leaving this field is approximately 55 degrees Fahrenheit. The central heating plant then uses heat pumps to chill or warm the water, which circulates through campus before reaching the field, where the loop repeats.

Geothermal energy is one of several

Over the last 25 years, Oberlin became a national leader in campus-community sustainability partnerships, culminating in the college achieving carbon neutrality in 2025.

sustainable energy sources Oberlin is using to reduce emissions; for example, the college also has multiple solar arrays. While McTiernan stresses that a small amount of greenhouse gas emissions are inevitable even with alternative energy—among other things, you might still need to use backup generators in extreme weather—Oberlin has been successful using infrastructure to neutralize its carbon output. All told, the college has reduced roughly 90 percent of campus’s total emissions by switching to alternative energy sources.

“[Oberlin has] taken on the hardest part of the work by actually reimagining some of the most greenhouse gasintensive systems in their footprint and fundamentally redoing them in such a way that deeply decreases emissions,” McTiernan says. “That is the way to do it.”

To reach 100 percent carbon neutrality, institutions typically purchase carbon offsets, a transaction that involves paying another entity to reduce or remove a quantifiable amount of greenhouse gas emissions. Making sure that the offsets are high-quality is essential, says Claire Jahns ’03, whose

FROM THE GROUND UP The foundation of Oberlin’s new on-campus heating and cooling system is 850 geothermal wells.

Under the leadership of Professor David Orr, then the director of the environmental studies program, Oberlin initiates a major study on the feasibility of campus carbon neutrality. The resulting report outlined ways to achieve this goal.

The city of Oberlin adopts a Sustainability Resolution, preparing the way for concerted sustainability actions in the community.

Oberlin’s Board of Trustees adopts a comprehensive Environmental Policy; in response, Oberlin pledges to use more renewable resources and prioritize environmental impact in campus decision-making.

Oberlin is one of the first U.S. colleges to sign the American College and University Presidents’ Climate Commitment, which advocates for carbon neutrality and emphasizes higher education’s role in shaping a sustainable society.

Oberlin adopts its initial Climate Action Plan, which outlines the college’s goal of achieving carbon neutrality by 2025.

background is in climate economics. “Offsets should be quantifiable, measurable, and verifiable; otherwise, they’re not good offsets.”

Oberlin partnered with its natural gas supplier to purchase high-quality offsets from a third party to cover things like gas used for on-campus buildings not connected to SIP. To account for things like employee travel (e.g., business trips and daily commutes) that contribute to the college’s total emissions, Oberlin chose the offsets provider Tradewater, which captures and destroys potent greenhouse gases like refrigerants and plugs up abandoned oil and gas wells that leak methane gas. In other words, these offsets are actively, permanently removing carbon emissions.

Thanks to the college’s extensive, upfront infrastructure work, Oberlin had to purchase only a very small number of carbon offsets—far fewer than many other colleges and universities that have reached carbon neutrality. This impressed Bridget Flynn, a former sustainability officer at the college, now a climate programs senior manager at Second Nature, a nonprofit that works with Oberlin and other higher education institutions on carbon neutrality and resilience. “Oberlin is an example that other campuses will be able to use,

Oberlin College, the city of Oberlin, and local stakeholders team up to launch the Oberlin Project. The partnership establishes a blueprint for sustainable development, climate resilience, and community engagement.

A 2.27-megawatt solar array is installed on campus; it produces about 12 percent of the college’s electricity usage.

demonstrating tangible decarbonization on campus is possible.”

Further analysis indicates that Oberlin’s geothermal system not only reduces carbon emissions, but also saves 5 million gallons of water and 4 million gallons of sewage simply because steam isn’t leaking from old pipes. That’s another reason a major infrastructure project like this is so important, says Gavin Platt ’06, vice president of design at Acuity, which creates sustainable building management systems.

“Physical buildings and their supporting infrastructure don’t change very often,” Platt says. “How we manage our buildings and optimize their performance is usually the biggest and only lever we’ve got.” Greater change is possible when you have more levers, he adds: “Sustainability is both technical and cultural. It’s about infrastructure and policy, but it’s also about people and behavior.”

A great example of that is the relationship between the college and the city of Oberlin. “The city’s climate action

The campus energy system becomes coal-free by replacing its coal-fired boilers with natural gasfired ones.

plan is, in effect, the college’s climate action plan,” says Chris Norman, the college’s senior director of energy and sustainability. The college contributes about 25 percent of the city of Oberlin’s total greenhouse gas emissions, so the two entities have been intentionally working together on sustainability projects for decades. Among other things, this included the Oberlin Project, an early—and catalytic— town-gown partnership on sustainability; additionally, the city sold all of its renewable energy credits to the college in 2005. [See timeline for more.]

Committing to green energy has required taking risks; for example, in 2008, Oberlin City Council voted down a new coal plant contract and started sourcing contracts for alternative energy. “Doing the SIP and getting to carbon neutrality would have been really difficult without the city’s carbon-free electricity,” says Heather Adelman, the college’s sustainability manager and an associate director of the Oberlin Project. “The leadership it took on the

2016

Oberlin finalizes a tangible plan to achieve carbon neutrality.

part of the city, where they made longterm commitments to green energy, was crucial.”

“How we ma nage our buildings and optimize their performance is usua lly the biggest and only lever we’ve got ”

That relationship is key, says Brian Pugh ’08, the mayor of Croton-onHudson, New York, a village about the size of Oberlin, which he has led to become the No. 1 clean energy community in New York state. “The fact that a village of a little over 8,000 people is able to do things like this shows that it can be done,” Pugh says. “Oberlin would probably say the same thing—if a small liberal arts college in the Midwest can do this, maybe some of the mighty universities of the East and West with multibillion-dollar endowments could do the same.”

For a small town, having a large stakeholder like a college interested in purchasing green energy creates essential financial backing for sustainability projects. Pugh’s village works with Columbia University; Oberlin College, meanwhile, was that anchor for the city of Oberlin’s first renewable energy credits. It’s a mutually beneficial

In collaboration with the college, the city of Oberlin approves a revised Climate Action Plan that includes a commitment from the city to provide 100 percent carbon-free electricity.

The Board of Trustees approves a new oncampus energy system that replaces the century-old fossil fuel-based system.

relationship: The college ensured that its electricity came from a renewable source; in turn, this helped the city invest in long-term renewable energy contracts for electricity.

Jahns had been pushing for renewable energy credits decades ago while still a

student. She was at Oberlin right after the signing of the Kyoto Protocol, the first international agreement for nations to reduce carbon emissions. In response, Jahns formed a student activist group, Climate Justice, and worked with the campuswide sustainability group to get

The Board of Trustees approves geothermal energy for heating and cooling on campus.

Construction begins on the Sustainable Infrastructure Program (SIP), a four-year project to upgrade and modernize the college’s energy system.

After upgrading the energy system on South Campus in 2021, construction begins on North Campus buildings and a distribution pipe that will link to a geothermal well field.

Oberlin begins construction of a geothermal well field with 850 wells.

the college to reduce emissions.

“One of my final memories of Oberlin is when I graduated in 2003,” she says. “I walked across the stage to accept my diploma, and I shook [then-Oberlin president] Nancy Dye’s hand, and she said to me—while handing me my diploma—‘We’re going to go ahead and buy those renewable energy credits,’ which is something Climate Justice had been really pushing for.”

Jahns, who founded the climate change strategy consulting firm Scale, is impressed with how the college has continued that commitment, which had seemed almost “pie in the sky” then. That Oberlin partially funded SIP using green energy bonds—becoming only the second higher education institution approved to use them to fund sustainable infrastructure—impresses her even more.

“Oberlin can teach other small and medium-sized institutions about how to leverage investor interest and climate finance to make really clear and permanent emission reductions possible,” Jahns says. “To see this massive investment in infrastructure— really transformational for the college’s infrastructure, period, but also for student life—the contributions that can have to student educations at Oberlin and careers afterwards is monumental.”

The geothermal heating and cooling system comes online, and SIP concludes on schedule, with Oberlin installing 13 miles of heating and cooling pipe and connecting 60 campus buildings to the new energy system.

Oberlin achieves carbon neutrality, fulfilling its decades-long goal.

The impact of what happens next at Oberlin is hard to quantify, but having this project physically on campus is important, says Justin Mog ’96, director of sustainability initiatives at the University of Louisville. “Oncampus things always have to be the first priority,” he says. “That’s where you discover these things and learn to care about them. It’s not just about the infrastructure of the campus; it’s the infrastructure of our minds.”

Mog emphasizes that having buy-in over time from the college administration also helped Oberlin achieve carbon neutrality. “It makes all the difference in the world,” he says, although he also credits the constant push of Oberlin students toward sustainability as one thing that shapes how the college reached its goals.

As a student, Platt was integral to the development of the technology that now drives the Environmental Dashboard, a campuswide energy monitoring system that shows electricity and water usage in real time.

“The overall idea was to make energy use more visible so students could connect their daily choices to Oberlin’s broader sustainability goals,” he says, noting that this experience led to his career in sustainable management systems. “It taught me that even small shifts in awareness can ripple outward and support larger systemic changes. As a student, I didn’t fully understand just how difficult these things were to pull off, and it’s humbling now to know how slow change could be. Looking back, I’m glad to have played a small part in it.”

“Oberlin is a laboratory for the future. Smaller institutions like Oberlin can be test beds for innovation. ”

Current students can take a

course with Professor of Psychology and Environmental Studies Cindy Frantz called Advanced Methods in Community-Based Social Marketing. As part of the class, students design and evaluate programs to promote sustainable behaviors like using cold water to wash clothes and taking shorter showers. Their research has led to tangible, campuswide programs, Adelman says, like stickers explaining when it’s efficient to have windows open, and a ban on single-use plastic water bottles. Moving forward, Oberlin has more work to do with the geothermal system, including connecting additional buildings and optimizing the system for efficiency. In the future, the college plans to transition the rest of the maintenance fleet to electric vehicles and imagine campus landscaping for biodiversity and resilience in extreme weather. Meanwhile, the city of Oberlin is talking about building an eco-industrial park with a geothermal

system built in from the start.

Starting in mid-October, UL Verification Solutions (UL Solutions) also embarked on a third-party review of Oberlin’s carbon-neutral status for 2025. This verification ensures the college continues to be on track with its sustainability goals—and going forward will be a model for other places to replicate.

“Oberlin is a laboratory for the future,” Platt says. “Smaller institutions like Oberlin can be test beds for innovation. That’s what we did there. And as it turns out, what happens on campus doesn’t stay on campus. Students carry those lessons into the world, and other schools and communities notice.”

And, as Florini notes, having realworld examples makes all the difference —“especially in responding to people who say it can’t be done,” she says. “The best response is to say, ‘Well, actually—we just did it.’”

Freelance science journalist Dyani Sabin ’14 is an author of speculative fiction and one of the first residents of the Kahn Sustainable Living Dorm.

How

In true liberal arts fashion, at Oberlin, sustainability isn’t just a topic covered in the environmental studies program. Students can study how it intersects with history (You Are What You Eat and Wear: Global Crops), politics (Environmental Policy), and music (Making a Sustainable, Inclusive, and Just Future: The New Industrial Revolution). Another popular class, Environmental Economics, explores how to use economic tools to understand the root causes of environmental problems, as well as potential policy solutions. “Environmental economics integrates ecological realities with economic decision-making frameworks,” says

“Environmental economics integrates ecological realities with economic decision-making frameworks.”

BY ANNIE ZALESKI

Associate Professor of Economics and Environmental Studies Paul Brehm, who teaches the class. “As a result, we can find policies that maximize social welfare—a combination of prosperity and sustainability.”

Students interested in gaining environmental experience can intern with Oberlin’s Office of Energy and Sustainability (OES) on various teams that align with their interests (e.g., zero-waste, policy, and green grounds). The Resource Conservation Team is another popular internship option: This group oversees sustainability-geared initiatives the Free Store, Oberlin Food Rescue, the J-House Garden, and Big Swap, all of which emphasize the value of reducing waste and making resources available to the college and surrounding communities.

Each residence hall has an EcoRepresentative (EcoRep), who is like “a green ambassador,” says sustainability manager Heather Adelman. “They’re meant to provide peer-to-peer support and interactions between students on sustainability topics.” In addition to hosting sustainability awareness events such as trivia nights or “Eco Jeopardy,”

they monitor buildings to make sure recycling and composting is being done correctly, helping students change their behavior to reduce water and energy use.

No car on campus? No problem! The college has a free Saturday shopping shuttle that stops at major stores, while the city of Oberlin offers a free electric bus during the week

that makes a loop around major places. All-electric CarShare vehicles are also available for students to rent. For those who prefer two wheels, OES is also partnering with the Bike Co-op to hire bike mechanics so they can bolster the bike rental program.

At the start of this academic year, all incoming first-year and transfer students went through mandatory sustainability training to learn about the college’s commitment to carbon neutrality; how to get involved in oncampus sustainability efforts; and how their day-to-day behavior choices make an impact on Oberlin resource use.

Staff at Oberlin take care of campus from the ground up—literally. The grounds services team is looking

Launched in 2006, the two-week Ecolympics competition challenges buildings on campus and in the city of Oberlin to lower their carbon footprint. During Ecolympics, people who live or work in these buildings are encouraged to put extra thought into their electricity and water consumption, like shutting off lights when not in use or turning off the faucet when brushing teeth. Ecolympics exemplifies how individual behaviors add to our collective impact and contribute to our overall carbon neutrality. “We’ve even found that resource use stays lower after Ecolympics because people are creating new behaviors,” Adelman says.

SUSTAINABLE EFFORTS A student goes shopping for treasure in Oberlin’s oncampus Free Store (top); an environmental orb gives green guidance (above).

for opportunities to reduce synthetic fertilizers on grass that needs to look perfect, like in Wilder Bowl and Tappan Square. Current pilot projects at the latter places showed so much promise that this work is expanding to the athletic fields and the lawn at President Carmen Twillie Ambar’s house. Several times a year, a flock of sheep arrives on campus to graze on

the solar array; consider them ecofriendly lawn mowers.

Established in 2008, the Green EDGE Fund is a student-run organization to support sustainability projects for the college and surrounding areas. The fund administers efficiency loans (earmarked for on-campus projects) and sustainability grants (for community or city projects). Over time, these grants have funded water refill stations on campus and materials for Ecolympics, along with solar installations at Oberlin Community Services and Oberlin City Schools.

First-year students in Kahn Hall apply to live there and pledge to make sustainability part of their everyday life; among other things, they try to conserve water and energy, reduce waste, avoid bringing cars to campus, and minimize their negative impact on the environment. As of this year, Adelman is Kahn’s residential hall advisor, overseeing a variety of activities with and for students. First up: an invasive species removal from the woods behind the dorm.

Located in all large residential houses, Oberlin’s environmental orbs use pulsing and changing patterns of color to communicate each building’s current level of water and electricity usage. The real-time feedback communicates the dynamic nature of resource consumption and raises awareness about conservation.

Additional reporting by Lucy Curtis ’24

BY GINGER CHRIST

As the Adam Joseph Lewis Center for Environmental Studies turns 25, our world-changing alums carry its impact forward.

BEFORE A VISITOR EVER steps foot inside the Adam Joseph Lewis Center for Environmental Studies (AJLC), the building’s ties to the natural world are clear. On the south side, a seasonal sundial set to mark solstices and equinoxes stretches out before the glassencased atrium. On the southeast side, a restored wetland is visible from a stone amphitheater.

Inside, a welcome sign displays the Environmental Dashboard, which shows real-time data on resource consumption, and a 100-square-foot water sculpture rises to the ceiling. The sound of trickling water echoes through the plantladen two-story lobby.

Opened in 2000, the solar-powered AJLC, which Building Design + Construction magazine once named one of 52 “game-changing buildings” alongside the Gateway Arch in St. Louis and London’s Savoy Theatre, is considered a pioneer of the green campus movement. The space laid the groundwork for a one-of-a-kind experiential learning experience and the future of green building.

The AJLC also launched Oberlin’s sustainability journey and cemented the college as a leader in environmental innovation. For example, Oberlin achieved carbon neutrality thanks to its groundbreaking Sustainable Infrastructure Program, which involved replacing aging infrastructure with an eco-friendly system powered by 850 geothermal wells.

“[The AJLC] opened a door that a lot of people have walked through since,” says Lindsay Baker ’04, CEO of the International Living Future Institute, a nonprofit committed to advancing regenerative design.

Baker says that prior to the AJLC’s construction, there was an assumption that the built environment couldn’t be changed or influenced by new ideas—especially from students. “That building and the way that it was designed, built, and then

operated really busted that myth for a lot of undergraduates at Oberlin. We were told, ‘It’s possible to run buildings in a different way, to build them in a different way.’”

It all started with a rainstorm—or a few of them.

David Orr, who is now the Paul Sears Distinguished Professor of Environmental Studies and Politics Emeritus, had an office in the basement of Rice Hall, which flooded every time it rained.

“We had to build a building to get out of the wetland,” he quips.

With a grant from the George Gund Foundation to assess the possibilities for an environmental studies center on campus, Oberlin launched what amounted to a full-year building course. The college brought in a dozen well-known architects from across the country to present architecture and landscape concepts to students.

None of the options for using existing buildings panned out, so Orr and the students worked with the design team at William McDonough + Partners to create their vision for what would eventually become the AJLC.

“That building and the way that it was designed, built, and then operatedreally busted that myth for a lot of undergraduates at Oberlin.”

Orr, who envisioned using architecture as a tool to teach environmental lessons, saw the building as an opportunity for students to be involved in every step of the process, to help craft the very place where future students would learn.

For example, undergraduates have opportunities to oversee the Living Machine, which filters and recycles the

building’s wastewater by mimicking natural wetlands. The building also incorporates natural lighting and ventilation and employs a ground-source heat pump system.

“You don’t stop to say, ‘Can it be done?’ You say, ‘Should it be done?’” Orr says. “The thing I’m most proud of about the building is that it drove green building in higher education and elsewhere.”

Sadhu Johnston ’98, who now consults on green building and climate readiness, couldn’t agree more. “That whole experience really shaped my passion and interest in green buildings and green building policy,” he says. “It had a fundamental impact on my career path.”

Johnston and his now-wife, Manda Aufochs Gillespie ’97, were involved in the building during the design and construction phase; Orr later tapped the couple to lead a sustainable community symposium tied to the AJLC’s creation. Even after the building opened, they gave tours and engaged with donors and prospective students.

“At that time, the building was this kind of living experience that we were having,” Johnston says, comparing it to a physical manifestation of what was being taught in the classroom.

tools,” says Baker, whose organization currently leads the certification program. “We work with a variety of different organizations around the country to use their buildings in the way that the [AJLC] does.”

The AJLC’s influence can be seen not only in physical buildings, but also from the impact graduates of the environmental studies program—and the college—have had in the world.

Historically, Oberlin has attracted students who “want to make a change in the world” and “want to be agents of change,” says John Petersen ’88, the Paul Sears Distinguished Professor of Environmental Studies and Biology.

“The thing I’m most proud of about the building is that it drove green inbuilding educationhigher and elsewhere.”

Today, he says the right metaphor to show the building’s influence is to imagine someone dropping a stone into a still pond and seeing the ripples spreading across the water.

Baker notes that the AJLC was a living building before the existence of the Living Building Challenge, which recognizes buildings that are net positive in terms of their energy and water; are free of toxic chemicals; and have shown positive impacts on the community.

“One of the handful of ways that the [AJLC] has had a lasting impact is that it has inspired and helped to fuel the growth of this program that we run that is designed to help people design and build and then operate and use these kinds of buildings as teaching

“Everything we are here at this institution today—and not just this institution, but the [Oberlin] community as a whole—can be traced back to the AJLC and the ripples going out,” Petersen says. Through the building, the college was able to show “what it means to create something that’s truly novel and innovative” and “to attract creative, smart, entrepreneurial people.”

Baker, a leader in the green building movement, has used her experience at Oberlin with the AJLC to create market and regulatory mechanisms to change how buildings are built in this country and around the world.

“ Fundamentally, I would never have

understood the power of buildings to influence how we see the world if I hadn’t been in [the AJLC],” Baker says. “I got to learn that firsthand, and it’s enabled me to go and teach that lesson to many people.”

Baker’s work began right out of college, when she landed a position at the U.S. Green Building Council and helped create Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED)

standards. Those standards are the most widely accepted green building rating system and assess a project’s energy and water usage, materials selection, waste management, and indoor environmental quality.

After graduating from Oberlin, Johnston was unsure if he wanted to attend graduate school and turned to Orr, his advisor, for advice.

“He gave me this poke in the chest

and said, ‘We don’t have time for you to go to graduate school. Get out there and start working,’” Johnston says. “That really had an influence on me; I could continue to learn in school or continue to learn on the job.”

Johnston moved to Cleveland and launched a speaker series, “Redesigning Cleveland for the 21st Century,” that brought thinkers, leaders, and architects involved in the AJLC to

the city to speak at City Hall and in meetings with business leaders.

The series aligned with the creation of the Cleveland Green Building Coalition, where he served as founder and executive director. The group spearheaded a LEED-certified renovation of the Lorain Avenue

Savings & Loan Building in Ohio City, a nearly 100-year-old building that was retrofitted with geothermal heating and cooling, solar panels, and a green roof.

Johnston went on to work as chief environmental officer for Chicago and a city manager for Vancouver, British Columbia, before launching his consultancy.

Today, he’s focused on bringing those green building concepts to smaller communities. Through a contract from the federal government with the Canadian Urban Institute, he works with communities to integrate climate readiness into their infrastructure. He’s also dedicated to green housing and implementing solar design and rainwater capture, which he first learned about in the AJLC design.

“Throughout my career, I’ve definitely anchored back to those experiences and lessons learned at Oberlin and, in particular, with the building,” Johnston says.

Grant Sheely ’19, who minored in environmental studies, was encouraged by Petersen to work at the AJLC while he studied at Oberlin. Sheely became a Living Machine operator, where he helped monitor the solar panels and meters and ensure the building was operating at net zero. At the same time, he did greenhouse gas accounting for the college and presented data and suggestions on how to reduce emissions.

That experience propelled Sheely into a career involved in buildings and their environmental impact. He worked as sustainability coordinator for a real estate company before training to award LEED and Energy Star certifications to buildings being constructed. He now works for the New Buildings Institute, which does building code development and helps jurisdictions achieve their goals.

“This whole path of buildings being my focus truly originated at the AJLC,” Sheely says. “There’s no way I would have been like, ‘Buildings are cool,’ without one of the coolest ones ever.”

Being an environmental educator involves teaching students the often hard truth about the problems plaguing the world, but also showing them a path to make that truth better and giving them hope, Petersen says. “Hope is about rolling up your sleeves and getting something done. I think that’s what this building has been so good at.”

Through the AJLC, Oberlin has been able to show students firsthand systems thinking—understanding the complexity of the world through the relationships among its parts.

“The thing that you try to teach students is that yes, there are a lot of problems to solve in the environment, but if you solve those problems right, you can solve them across society,” Petersen says.

At one point, the AJLC and adjacent solar parking pavilion comprised the largest solar array in Ohio. “Today, this building has a solar array that is dwarfed

A BRIGHT FUTURE Today’s Oberlin students continue to study and work in (and learn from) the AJLC (left and below).

by the solar array we have on the north end of campus,” Petersen says. “That’s how far we’ve come in these 25 years.”

Petersen and others have recently engaged in a series of envisioning sessions about the future of the AJLC, coined AJLC 2.0. They’ve identified physical things that need to be addressed, from heating to plumbing to electrical problems, and are considering how the building can inspire the next quarter century.

As Orr notes, the idea is to keep the vision not just going, but growing.

Having achieved carbon neutrality, Oberlin has an opportunity to build on the seeds planted by the AJLC, show others what is possible, and inspire the next generation of students to come to Oberlin, Petersen adds.

In other words, the true legacy of the AJLC is what change it brought about—and the trajectory it put the environmental community and Oberlin on, as he puts it.

“We have a unique moment right now,” Petersen says. “Oberlin is offering some hope right now with what we’ve done.”

Ginger Christ is a freelance journalist in Northeast Ohio.

BY ANNIE ZALESKI

Every day, Oberlin’s faculty and students produce scholarly work that uncovers new insights into how we understand the world, particularly in sustainability and the environment.

WHEN PROFESSOR of Chemistry and Biochemistry

Matt Elrod started studying pollutants, the major topics of conversation in his field were the detrimental health effects of ozone pollution (e.g., smog). Today, he says, the research is focused on small particles—for example, the pollutants produced by wildfire smoke or industrial processes. “Particle pollution is now understood to be a big public health problem around the world,”

“Particle pollution is understoodnow to be a big publicproblemhealtharound the world.”

Elrod says. “[In my Environmental Chemistry class] I talk about it in terms of, ‘There are multiple threats in the air that we breathe.’ The smallparticle kind of air pollution kills many more people worldwide than ozone pollution.”

One mystery is how these pollutant particles end up in the atmosphere. Not all of the gases produced by industrial plants are dangerous. Instead, chemical processes happening in the air transform these harmless substances into damaging ones. But how exactly does this happen? It’s a question Elrod posed in a 2025 ACS Earth and Space Chemistry article based on six years of research that looked at how a chemical emitted by trees “interacts with acids which humans have added to the atmosphere and creates these particles,” he explains.

Working in tandem with Associate Professor of Chemistry and Biochemistry Jason Belitsky and student researchers—including Rebecca Fenselau ’22, Ali Alotbi ’23, Caroline Lee ’24, Julia Cronin ’25, and Daniel Hill ’21—Elrod discovered something surprising. “The chemicals that come from trees can cause pollution, but only in combination

with human-added chemicals,” he says. That’s where the acids come in: They are a by-product of energy production with fuels containing sulfur. “Sulfur leads to acid formation—and acid formation is what allows these particles to form from natural chemicals.” In other words, he notes, this pollution is a “human-caused problem”—and any regulation taking aim at particle formation needs to target things that produce acids.

Solving this problem led Elrod and his lab to solve another problem related to how human-caused nitrogen pollution leads to particle formation; they published their findings in August 2025 in ACS ES&T Air. Three alums from the first paper were coauthors, alongside Molly Foley ’26, Serena Gaboury ’27, Daniel Pastor ’25, Drew Dansby ’23, and Galen Brennan ’17. Elrod notes that it can take years for research to impact policy, but his lab’s discoveries have the potential to make a difference in the future.

Associate Professor of Geosciences Rachel Eveleth grew up on Lake Michigan seeing how much people rely on the Great Lakes for things such as drinking water. At Oberlin, she saw an

opportunity to expand the research on these crucial bodies of water.

“People weren’t thinking as much about the climate impacts on the Great Lakes,” she says. “They were more focused on harmful algal blooms themselves rather than the interactions with climate and carbon.”

Given her background in oceanography—she earned a doctorate in Earth and ocean sciences at Duke University—Eveleth began to apply some of the methods she was using in the open ocean to a system that “had more immediate, direct human impact,” she says. “Big picture, my research program is looking at interactions between climate and water, and mostly that looks at carbon cycling.”

Among other things, Eveleth and several other institutions have worked on a NOAA-funded collaborative project on the potential effects of the acidification of the Great Lakes. Her

research also examines the impact of the decline in ice coverage over the water during the winter. “There’s variability from year to year, but the trend is downward, and [the expectation is] that this will continue,” she says. “What does that mean for the ecosystem? What does that mean for the chemistry of the water, the water quality?”

Getting water samples via field work is key; for example, this could include going on boats on the western basin of Lake Erie. As part of a group called the Great Lakes Winter Network, Eveleth and her research collaborators f rom U.S. and Canadian institutions (including student Nyrobi Whitfield ’26) have also come together to do a series of “winter grabs” of samples. The Oberlin team augured through the ice off a dock in the Lorain Harbor.

The goal is to determine a baseline to inform research going forward. “We don’t know what the carbon budget

Are there ways to leverage advertising psychology for the good of the planet? Professor of Environmental Studies and Biology John Petersen ’88 and Professor of Psychology and Environmental Studies Cindy Frantz say yes: The pair coauthored a field study in the journal Sustainability that demonstrated digital signs were effective in fostering positive environmental norms and behaviors. Read more about their work: oberlin.edu/news/ marketing-good

looks like for Lake Erie, and we’re starting to put that together and figuring out what that means for longterm trends,” Eveleth says, noting that the algae blooms in particular affect whether the lakes are emitting or absorbing carbon dioxide.

Based on the carbon budgets they’ve seen so far, Lake Erie is “acting as a sink, so it’s taking up carbon dioxide from the atmosphere rather than releasing it,” Eveleth says, even in the winter. “How we put these carbon dynamics from the lake into large-scale climate models can impact what future climate projections look like. But it also can change our future predictions about pH.”

For more incredible research conducted by Oberlin’s faculty, read Volume 1 of the Oberlin Research Review, available at: oberlin.edu/research-review

BY ANNIE NICKOLOFF

Oberlin’s academic offerings and Northeast Ohio’s unique agriculture scene are havens for students passionate about food studies.

AT VILLAGE FAMILY FARMS in Cleveland’s Hough neighborhood, peppers, tomatoes, green beans, and herbs flourish on the lots that once housed apartment complexes for the community. Bees buzz around the site’s hives while, just a few blocks away, traffic rumbles in and out of the city’s east side.

Last summer, Vic Zuno ’26 sank his hands in the dirt here, contributing to the farm’s day-to-day operations and assisting founder Jamel Rahkeera with the property as part of an internship centered on food justice, fulfilling the experiential requirement of Oberlin’s food studies integrative concentration.

But Zuno’s focus went deeper than the topsoil. Working with neighborhood teens, he created a new summer youth curriculum, designed to explore the intersections of urban farming, the environment, societal issues like redlining, and food sovereignty.

Zuno, who’s from Chicago. “I come from an area where there’s a lot of obstacles you have to jump over to get what should be given to you—like a good education, healthy food options, and safety in general. These kids have their own testimonies and their own struggles that they’ve overcome or are going through.”

The experience made a mark on Zuno. After graduating, he plans to look for similar opportunities in his career, working with sustainable organizations like Village Family Farms as a consultant in business development or community engagement.

“It’s been really powerful for students to be getting engaged in the local area beyond the town of Oberlin.”

“It took me back to my roots,” says

“It was a transformative experience,” he says about both Village Family Farms and food studies.

The integrative concentration is about more than food. Often, it’s about community. Since launching in 2023, the food studies program has empowered students to get involved with grassroots local organizations, kick-started entrepreneurial incubation projects on Oberlin’s George Jones

Memorial Farm, and strengthened connections between Oberlin and Lorain County Community College.

“It’s been really powerful for students to be getting engaged in the local area beyond the town of Oberlin,” says Jay Fiskio, professor of environmental studies and comparative American studies. “Students do get a lot of opportunities to do stuff in Oberlin if they want, but we have a lot of community partners in Lorain, Elyria, and Cleveland. That’s been really great.”

Oberlin’s approach to food studies is broad and interdisciplinary, focusing on history, foodways, and even neuroscience in addition to food justice and equity. The latter topics are important to Northeast Ohio communities. According to 2023 data compiled by Feeding America, Lorain County has a 15.4 percent food insecurity rate, and adjacent Cuyahoga County, where Cleveland is located, has a rate of 16.6 percent; both are above the national average of 14.3 percent. Locally, the nonprofit Healthy Northeast Ohio found that those rates increase in Black and African American communities (33 percent in Cuyahoga County, 32 percent in Lorain County) and in Hispanic communities (29 percent in both Cuyahoga and Lorain Counties).

At Oberlin College and in Northeast Ohio, the study of food is about more than just flavor: It’s about the systems and stories behind each bite.

Rolling fields of towering cornstalks and lush, green soybeans surround Oberlin with typical Lorain County farmland. It’s quite different from Gavriella Perez ’25’s urban and suburban hometown of Pennsauken, New Jersey, seven miles from Philadelphia. Perez says healthy food wasn’t always accessible in their community, though credits her parents with showing how to source nutritious groceries and meals.

When Perez came to Oberlin in September 2022, the quiet, rural campus felt like “a complete 180” from their hometown. But there was some overlap. According to 2019 USDA food access research, which analyzed food access with and without a vehicle, much of Oberlin lacks easy access to nutritionally dense food—even with all the surrounding farms of corn and soy.

“Here we are in a county that is very food production heavy, but it’s very cash-crop heavy,” they say. “Corn, for the most part, most of it isn’t for human consumption. You will never eat that corn. That corn is going, maybe, 100 miles away.”

and agriculture, and even a French class where students sample wine and cheese.

In addition to her food studies classes, Perez completed an internship with chef Shontae Jackson’s Steel Farm and Gardens in Lorain in the summer after their second year. There, on land that once held an abandoned house, Jackson has regenerated and returned nutrients into the soil to grow things such as fruit trees, berries, and cacti in Northeast Ohio’s often unpredictable climate.

“She’s someone I’ve admired for years, and so being able to work with her was honestly a dream,” Perez says. “She’s also an amazing chef, and she’s able to also foster that, helping me actually work in kitchens, working in food service, being able to see what it’s like to be on the executive side of that culinary world.”

“Those decades and decades of connection and community created this fabric that enriched the soil in which the local food movement in Clevelandoutgrewof.”

Initially drawn to Oberlin for its environmental studies program, Perez quickly jumped into the food studies integrative concentration when it became available during their sophomore year because of her passions for culinary and agricultural studies. “It aligned with every interest I have,” Perez says.

Food studies includes a range of classes on healthy eating, Lorain County foodways, the Great Lakes’ Indigenous nations, restaurant labor, colonization

Perez used their experiences at Steel Farm and Gardens to research Northeast Ohio’s food ecosystem, and that segued into their capstone project, which analyzes Puerto Rico’s farming history and culture and the impacts of American imperialism. She hopes to continue her research in a graduate program.

“[Oberlin’s] a completely different food scene,” Perez says. “I was able to take the ways that food exists in Ohio as a whole and just transplant different ways of thinking to it.”

Plenty of Obies found passions for sustainability and agriculture on campus before the food studies program was established. So far, only two classes have graduated with the concentration as an option, says Fiskio.

“The food studies program is really new, but we’ve had students doing agriculture and food work for years before there was a program,” Fiskio says. “And that gives a better sense of what the f ield is—that it’s very interdisciplinary. It

stretches in all kinds of directions, and it’s really up to the students to direct where they want it to go.”

Sitting on the patio to George Jones Memorial Farm’s straw bale house, Leah Finegold ’20’s energetic dog Squash leaps jubilantly through the grasses near a garden’s rows of blossoming flowers.

Finegold found their way to a community-supported agriculture program thanks to their early experiences at Oberlin. As an

undergraduate, they were a part of the Oberlin Student Cooperative Association (OSCA) and worked as a food security associate for Oberlin Community Services. After graduation, Finegold worked at Bellwether Farm in Wakeman, Ohio, and for a low-income housing program for the city of Cleveland.

Today, they work at City Fresh, a nonprofit that sells locally grown produce boxes to Northeast Ohio community members at a reasonable price. The organization was another perfect fit for Finegold’s interests—and was just a mile away from Oberlin. (The college owns George Jones Memorial Farm and rents space to City Fresh.) Finegold is the program director of the organization’s farm box program, a

subscription of in-season, locally grown produce shares delivered weekly to various pickup stations in Northeast Ohio.

“I came to Oberlin knowing that I wanted to do at least something with environmental studies,” they say. “I explored a lot of facets of environmentalism during my time at Oberlin and really found food to be a connector of all of them and just something that I loved.”

In addition to City Fresh, George Jones Memorial Farm hosts a regular crew of student workers from Oberlin and a new incubator farm program with six farmers using land to work on agriculture projects. And, for the past decade, visiting environmental

studies lecturer Brad Melzer can often be seen out on the farm with his class of agroecology practicum students.

Depending on the season, the group builds garden beds, plants seeds, crafts water systems, and harvests crops— all while exploring the sciences of sustainable agriculture and ecology. Field trips bring students to urban farms in Cleveland, like Rid-All Green Partnership in the Kinsman neighborhood and the Ben Franklin Community Garden in Old Brooklyn.

These spaces spurred the local food movement in Northeast Ohio— something that’s reflected in some of the region’s most popular farm-to-table restaurants today, Melzer says.

“Ohio is an agricultural state as it is, but those community gardens, especially on [Cleveland’s] East Side, just have really deep roots of community,” Melzer says. “Those decades and decades of connection and community created this fabric that enriched the soil in which the local food movement in Cleveland grew out of.”

Small, biodiverse farms such as George Jones, along with the urban lots peppering Lorain and Cuyahoga County, are the future of the agriculture industry, Melzer says—and by experiencing these spaces firsthand, students create pathways for careers in fields like mycology, horticulture, environmental policy, and more.

Their work gives back to the land, too.

“It’s exciting because we’re just at the beginning of this programming,” Melzer says, “and certainly it’s created a renaissance here at the farm.”

Annie Nickoloff is a Cleveland-based journalist who has written for a variety of local and national publications. She enjoys taking care of her small garden, checking out live music, and playing pinball.

Oberlin alums are building sustainability into successful careers in fashion, jewelry, business, and more.

MI LEGGETT ’17 LINED up outside of the Allen Memorial Art Museum for Art Rental every semester with one piece in mind: a Keith Haring. The art history major wanted Haring’s art in their space as a tool of inspiration: As a fashion designer creating pieces in their dorm roomturned-studio, Leggett was deeply influenced by Haring’s ability to use commercial objects to make explicitly political and queer high art accessible to the broader public.

Over the years, Leggett had remarkable luck with Art Rental, scoring pieces by Picasso, Jasper Johns, and Barbara Kruger. However, the Haring work evaded them each semester—until the spring of 2017, when they finally scored the piece they had waited for, Haring’s Untitled 1, from the series Untitled 1-6. The timing was perfect; by this point, Leggett had started Official Rebrand, an anti-waste,

gender-free fashion line.

Official Rebrand’s lines are full of inventive, one-of-a-kind hand-painted garments and custom layered pieces made from upcycling fabric. Imagine a skirt made entirely from discarded skirt hems that were stitched together, or a tank top patterned with a scan of a box of testosterone. Or you might pair a tank top ripped into something resembling a rib cage with a jacket covered in an abstract swan painting.

“Berlin has a culture of leaving outside,clothes much like Oberlin’s free bins and free store, providing me with endless material to play with.”

To date, Official Rebrand’s designs have received attention from publications such as the New York Times, Teen Vogue, Elle, GQ, and Them. “Creating upcycled, gender-free clothing is what I am meant to do and truly the best way for me to positively impact my community,” Leggett says.

At Oberlin, they began as an environmental studies major but as a first-year student quickly fell in love with the art history and studio art departments after taking an abstract painting class with then-YoungHunter Professor of Art John Pearson. “It rocked my world,” Leggett says. “It was a challenging time for me, socially

and emotionally, so having that studio space to retreat into was really important for me.”

As a student, they also found solace in their on-campus job at the ’Sco. “You have to make your own fun at Oberlin, so I was involved in a lot of event coordinating,” Leggett notes. “It taught me about production and logistical planning, which became really helpful later on as an independent artist. Be the party you wish to see in the world.”

This event planning experience led to involvement in Berlin’s queer arts communities during semesters abroad.

Official Rebrand—the name began as “an Instagram handle joke about me rebranding from liberal arts college girl to genderqueer artist in Berlin,” Leggett playfully recalls—began during that time of exploration, when they were collaborating with all kinds of artists.

This included an independent avantgarde fashion designer whose approach to reconstructing clothing inspired Leggett’s own wardrobe and outfits as they explored their gender identity. “I hadn’t come out as nonbinary yet, but I didn’t feel comfortable or like I fit into preordained gendered clothing,” Leggett says. “Berlin has a culture of leaving clothes outside, much like Oberlin’s free bins and free store, providing me with endless material to play with.

“I could limitlessly take things apart and put them back together, painting things as I went,” they continued. “I was playing around and figuring out what made me feel good. Making crazy outfits helped me develop a sense of how I wanted to show up in the world.”

Leggett turned this individual experimentation and expression into the more developed artistic practice that sustains Official Rebrand. They wrote a senior honors thesis on the brand and held an accompanying fashion show in the Hales Gymnasium locker rooms. Not long after, Official Rebrand was recruited to participate in an independent designer fashion show— Leggett’s first time showing their work outside of Oberlin and DIY art spaces in Berlin.

This led to running events for an art magazine, which Leggett says “set off a chain reaction” and led to the busiest year of their life. What had been planned as a post-graduation year of rest and generation quickly became a year of career acceleration: They hosted events at the acclaimed international art fair Art Basel, began working with individual clients, and eventually were scouted by the Council of Fashion Designers of America to be in a New York Fashion Week show.

Over the years, Official Rebrand has collaborated with the music platform Soundcloud to raise money for the trans support organization and crisis hotline Trans Lifeline; teamed up with Penguin Random House to create merchandise in support of a book release; and released a collaborative fashion collection with Arianna Gil ’17’s skateboard collective Brujas.

Leggett says they think fondly of those first years out of Oberlin when they were so green and excited by every opportunity that they said yes to all of them, whether they were ready or

not. “In retrospect, I was very glad I did [the New York Fashion Week show],” they say. “I didn’t know enough to know I wasn’t ready. I’m still learning how to be a proper designer now because I’m just doing things my own way. I am doing things that haven’t been done in the industry, which is what set me apart when I was starting out.”

Leggett also believes their art history and queer theory background helped them stand out amongst a sea of fashion school graduates vying for

attention in New York’s scene. Their ambition to take on opportunities has led them to a busy period of collaborations and new work projects, including as a visiting educator at Cooper Hewitt, the Smithsonian Design Museum.

Leggett says they draw energy from working collaboratively toward designing a better, more inclusive, and sustainable world. “It brings me a lot of joy to help people create outfits they do want to wear and feel like themselves in,” Leggett says. “I’ve had some existential crises—[like] maybe I should’ve been an

immigration lawyer or not dropped out of my environmental classes. But these days I’m sure that channeling my antiwaste design methods to help people express their interior selves and show up in the world how they want to is my calling.” —Serena Zets ’22

places. But while handling precious metals up close, they found themselves drawn to the same question. Where did these materials come from?

Given that the pair had both studied environmentalism in college, not knowing the answer “felt like a big disconnect,” Neal says. “Particularly knowing that the jewelry industry has been historically damaging to people and the environment.”

After the Oberlin alums reconnected at the wedding of a mutual friend, Kathryn Jezer-Morton ’04, their shared passion for sustainable jewelry became the company Bario Neal, which was founded in 2008 with locations in Philadelphia and New York City and has been featured in Vogue, the New York Times, and the Wall Street Journal