Oak

Farm Montessori

The Power of Language in a Montessori Education

Language is at the heart of human connection. It allows us to express our thoughts, share our stories, and understand the world around us. In a Montessori environment, language is not just another subject—it is an essential tool for learning, discovery, and self-expression.

The Montessori language curriculum is thoughtfully designed to nurture language development at every stage of a child’s journey. Beginning in the Preparatory Stage, young learners build the foundation for communication through spoken language, vocabulary enrichment, and phonemic awareness. This stage is critical, as it aligns with a child’s natural sensitivity to language during their early years.

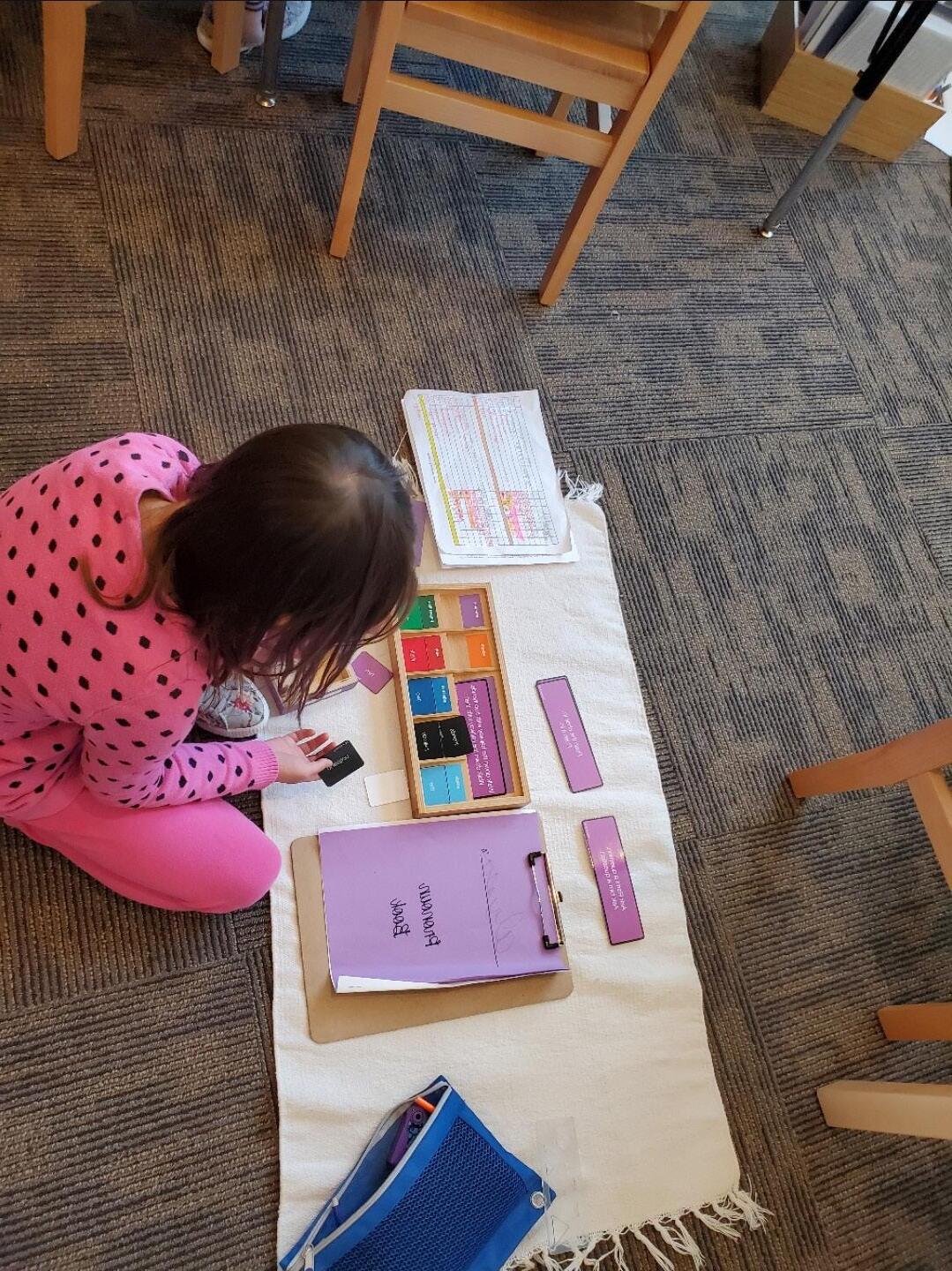

As children progress to the Symbolic Stage, they explore the relationships between sounds, symbols, and meaning. Through hands-on materials such as sandpaper letters and the movable alphabet, students make the exciting transition from recognizing sounds to forming words. This stage lays the groundwork for reading and writing, empowering children to become independent thinkers.

In the Reading and Writing Stage, children refine their skills and deepen their understanding of language. Montessori classrooms offer a rich literacy environment, where students are encouraged to read a variety of texts, engage in storytelling, and express themselves through writing. The study of grammar, word structure, and syntax is introduced through interactive lessons, making abstract concepts more accessible and engaging.

By the time students reach the secondary level, language becomes a tool for critical thinking, self-expression, and academic inquiry. Middle and high school students refine their writing skills, engage in literature studies, and explore the power of dialogue. They learn to articulate their ideas confidently, analyze complex texts, and develop a command of grammar and vocabulary that will serve them well beyond their years at Oak Farm Montessori.

Montessori education recognizes that language is not simply a subject to be memorized—it is a living, evolving skill that empowers students to communicate, create, and contribute to their world. Through a carefully structured curriculum that respects each child’s pace and abilities, we cultivate a love for language that extends far beyond the classroom.

As we celebrate this month’s theme of Language, I invite you to observe the incredible ways in which your children are discovering their voices. Whether they are sounding out their first words, composing a thoughtful essay, or engaging in meaningful discussions, they are on a lifelong journey of communication and connection.

HEAD OF SCHOOL

Language in Lower Elementary

Abby Roughia, LE4 Teacher

Since the Coming of Man humans have had a need to communicate. In order to do that more effectively, utterances turned to word labels which turned into symbols from which eventually a variety of early civilizations developed language. Maria Montessori highlights in “The Absorbent Mind” that children possess an extraordinary capacity for absorbing language during their early years, with the “child’s sensibility to absorb language [being] so great that he can acquire foreign languages at this age” (birth to three).

Reading, Writing, and Speaking are integral to all subjects in the Montessori environment. It is through this that the children pursue interests and satisfy their curiosities. The Montessori Language curriculum has an incredible impact on their intellectual, emotional, and social growth. The Montessori method, grounded in the belief that children learn best through hands-on experiences, provides a rich, dynamic environment in which language acquisition is not only nurtured but celebrated. Through this approach, children are empowered to discover their love for language and gain essential skills that will serve them for a lifetime.

The Montessori Language curriculum is designed to cater to each child’s individual needs, allowing them to progress at their own pace. Beginning with the exploration of phonetics, children engage with materials that make abstract concepts concrete. They learn to connect sounds with symbols and use this foundation to build words and sentences. The emphasis on sensory learning through hands-on activities, such as movable alphabets, ensures that children internalize these concepts deeply. This method not only builds foundational reading and writing skills but also fosters a profound understanding of how language works, giving them the confidence to use language in a variety of contexts.

As your child grows, the curriculum expands to incorporate more complex aspects of language, such as grammar, sentence structure, and composition. Through the use of materials like the Grammar Symbols and Sentence Analysis, children develop an understanding of the rules that govern

language. This deeper engagement with language helps to build critical thinking and problem-solving skills, as they are asked to analyze, construct, and deconstruct language in creative ways. The Montessori approach encourages children to express themselves through both written and spoken language, cultivating a sense of ownership over their communication and enabling them to articulate their thoughts and ideas with clarity.

The benefits of the Montessori Language curriculum extend beyond academic skills. Language is also a tool for social development and emotional intelligence. In the classroom, children work collaboratively, discussing and sharing their ideas, which strengthens their interpersonal skills and enhances their ability to listen and empathize with others. The integration of storytelling, poetry, and creative writing into the curriculum also fosters imagination and emotional expression. Through these activities, children not only gain technical language skills but also learn how to use language to connect with others on a deeper level.

The Language Bridge: Montessori Connections

Amber Coss, Upper 1 Teacher

In the Montessori upper elementary environment, language is more than just a subject; it serves as a bridge connecting all areas of learning. Language is interwoven into every subject and activity, from mathematics and geometry to history and science. Children ages 9-12 are developing abstract and critical thinking skills, fueling their curiosity to explore deeper layers of communication and expression. Lessons and assignments are hands-on and interactive, often using stories and history to spark students’ imagination and engage critical thinking.

Word study, which includes etymology, Latin and Greek roots, and spelling patterns, deepens students’ understanding of vocabulary. By studying the origins and meanings of words, they expand their vocabulary and develop the ability to decode unfamiliar terms in both spoken and written language. Advanced grammar symbols and sentence analysis allow students to examine the language of others. Items parsed or analyzed are often pulled from history or science lessons, literature circle books, or quotes from people who have made significant contributions or have positively impacted the world. Upper elementary students crave meaningful work which considers their interests and connects them to the world. This is an age where children start to take a greater interest in current events. Encourage thoughtful discussions and critical thinking about not only what’s happening in their own lives, but also in the world around them.

Writing in all its forms begins to take center stage as students learn to express themselves persuasively and creatively. The combination of their imagination and increased writing stamina leads to long and elaborate stories. Research writing, often linked to the cultural curriculum, taps into their natural curiosity about the world and their desire to explore topics in-depth. The culmination of these research projects in oral presentations offers students the chance to practice public speaking in the supportive environment of their classroom community. Parents can support this learning by engaging in discussions, visiting the library, and helping students navigate online research.

Shared reading also plays a crucial role at this stage. Literature circles give students the opportunity to discuss, debate, and explore complex topics, fostering a deeper connection with the material and their peers. Encourage your child to share book suggestions and challenge yourself to read along with them. Share your favorite books from their age and your connected memories. Don’t miss out on these powerful opportunities for discussion and connection! Ultimately, language in the Montessori upper elementary classroom is more than a tool for communication—it is the bridge that connects ideas, nurtures creativity, and empowers students to engage with the world around them.

Cultivating Collaboration Through Seminar

Chea Parton, Middle School Language and Humanities Teacher

In the third developmental plane, adolescents are all about figuring out how to be social successfully. Much of their learning and energy is spent figuring out how to interact with others productively. Figuring out how to divide their time between the socializing they crave and the meaningful work present in our middle school curriculum and Erdkinder is big work at this level. Seminar is one aspect of the curriculum that brings their big social and academic work together.

What is a Seminar?

Sometimes called Socratic Seminar, Socratic Circle, and Paideia Seminar, a Seminar is a place where students come to discuss a text that they have read and annotated. The structure looks like this:

• Students come to Seminar with annotations and choose to sit in the inside circle or outside circle.

• Once everyone is seated, we review our guiding principles for discussion: (A) Be actively engaged. Your perspective matters; (B) Bring annotations, thoughts, and questions; (C) Cite the text to support your ideas; (D) Disagree with thoughts/statements not people; (E) Share your perspective and invite others to share theirs.

• I start by asking a reflective question to get them thinking about the major ideas and themes of the text. For example, we recently read a text about a Harvard student who faced the consequences of unintentional/ accidental plagiarism, and I invited them to think about a time they did something unintentionally harmful and the consequences they faced.

• Students in the inside circle then discuss the text, relying on their annotations to support their ideas and points. While they’re talking, the outside circle pays attention to their talk, considering what conversational moves are successful and which aren’t.

• After the inside circle finishes their discussion, the outside circle reports “glows and grows” of the conversation–where they did well and what could use some growth.

• Then they switch and the outside circle becomes the inside circle, discussing the text to expand and build upon the ideas presented in the first conversation, while the original inside circle becomes the outside to monitor the discussion.

• Once both groups have been both on the inside and outside, students complete a self-assessment rubric where they list personal and group goals for the next Seminar.

What does a Seminar do?

This one activity involves each of the major areas of Language (reading, writing, speaking, and listening) as well as opportunities for connections to history, geography, civics, science, and math. It is also metacognitive in that it invites students to think about their own thinking and conversational moves while conversation is happening. It is collaborative, and it asks students to learn how to express themselves, question themselves and one another, and disagree in civil and productive ways.

In its versatility, Seminar covers a broad range of academic skills and content in a way that allows students to collaborate and cooperate as they work to cultivate a community that thoughtfully and critically considers different ideas and perspectives as well as learn how to coexist peacefully with others even when they know they disagree on some things. Chat with your young person at home to learn more about Seminar and ways to support their growth in the principles that guide us in learning through conversation.

The Importance of Language Work in High School Learning

Amy Norton, High School English Teacher and Capstone Advisor

Although our high school adolescents are not in a sensitive period for language, they ARE in a sensitive period for discovering how they can be accepted into the world: and language gives them the means to communicate those needs. Oak Farm Montessori High School students engage deeply with what the education world refers to as Tier 3 vocabulary words—these are specialized, low-frequency terms that are crucial for understanding concepts in various academic subjects. This content specific vocabulary is essential for their academic work and helps ouro adolescent students develop a deeper comprehension of subject matter.

Montessori Language Acquisition and the Third Plane of Development

In Montessori education, language acquisition for younger children follows three key steps: naming, recognition, and recall. This process helps students internalize new vocabulary through structured lessons, conferencing, nomenclature cards, and other hands-on activities.

Additionally, our elementary students receive The Fourth Great Lesson, “The Story of Writing,” which unveils the fascinating journey of how humans developed the incredible ability to communicate their thoughts through written symbols.

At the high school level we build upon the ideas of communication from the three period lessons and the Fourth Great Lesson: this active engagement with new vocabulary remains essential, as students need to internalize specialized language to explore subjects in great depth. Because high school projects demand deep learning, students must fully grasp the meanings of these Tier 3 words to complete their work effectively and transmit the information within our community and beyond.

Some key ways our Oak Farm Montessori High School students engage with specialized vocabulary include:

• National History Day projects

• Socratic Seminars

• Shelf work in subjects like English, Biology, Environmental Science, and Anatomy & Physiology

• Capstone projects

National History Day: Deep Learning Through Research

All students participate in National History Day, an annual project centered around a historical theme. They conduct historical research, interpret findings, and creatively express their understanding within this theme. This project requires deep learning and engagement with historical vocabulary, as students analyze primary sources filled with complex, subject-specific language.

Socratic Seminars: Practicing Critical Thinking and Expression

Socratic Seminars provide students with the opportunity to think critically, discuss complex ideas, and articulate their thoughts using precise vocabulary. Through teacher-selected texts—chosen in part for their rich vocabulary—students engage in meaningful discussions about philosophical and moral questions. They learn to express their views clearly, challenge ideas respectfully, and consider multiple perspectives, all the while using that rich vocabulary present in the text.

Shelf Work: Reinforcing Specialized Vocabulary

High school teachers design shelf work that allows students to practice technical language in subjects such as English, Biology, Environmental Science, and Anatomy. These activities help reinforce subject-specific vocabulary, ensuring students can use and understand complex terms in their academic work. Whether sorting rhetorical modes, or constructing and labeling the parts of a cell, students are engaging with technical language that they will then use as they do their own meaningful work.

Capstone Projects: Mastering Academic Language

Capstone projects push students beyond the classroom, requiring them to conduct independent research, write literature reviews, analyze data, and present their findings in a formal academic thesis. This experience immerses students in research methodologies and peer-reviewed journals, exposing them to sophisticated academic language.

By the time students present their work, they have fully internalized specialized vocabulary related to their field of study, allowing them to communicate confidently and articulately.

Conclusion: Preparing Students for Lifelong Learning

Through deep academic engagement, structured discussions, and independent research, Oak Farm Montessori High School students develop a strong command of Tier 3 vocabulary. These learning experiences not only enhance their subject knowledge but also equip them with the language and critical thinking skills necessary for success in higher education and beyond. By actively working with specialized vocabulary, students become confident speakers, thoughtful learners, and adaptable thinkers—ready to navigate the complexities of the world.

Congratulations to the Class of 2025!

How Reading Specialists Help Students Develop Strong Reading Skills

Lisa Bockelman, Reading Teacher

Reading is a fundamental skill that supports success in all areas of learning. For some students, reading comes easily, while others need extra support to build their skills and confidence. This is where reading specialists play a crucial role. Reading specialists are trained educators who work with students at different reading levels to help them develop essential literacy skills. They use research-based strategies to support struggling readers, reinforce classroom instruction, and guide students toward reading success.

Reading specialists begin by identifying each student’s strengths and areas for improvement. Through assessments, they determine a student’s reading level, comprehension skills, and specific challenges, such as decoding words or understanding text. Reading specialists create personalized learning plans once a student’s needs are identified. In kindergarten and lower elementary, they use phonics instruction, fluency practice, and comprehension strategies to help students improve. Small-group and one-on-one sessions allow for focused learning and individual attention.

The focus of instruction shifts as students move into the upper grades. A strong vocabulary and the ability to understand what is read are key components of upper reading skills. Reading specialists introduce students to new words, teach them how to use context clues, and help them make connections between ideas in a text.

Reading specialists also foster a sense of collaboration with classroom teachers and parents. They work together to ensure students receive the support they need both at school and at home. By providing strategies and resources that help reinforce reading skills in everyday life, they empower educators and parents to be active participants in their students’ literacy development.

One of the most important roles of a reading specialist is to instill a positive attitude toward reading in students. By selecting engaging books and using interactive strategies, they make reading an enjoyable and rewarding experience. This approach not only builds students’ confidence but also fosters a love for reading that can last a lifetime. Reading specialists play a vital role in helping children become strong, confident readers, and their expertise and dedication ensure that every student has the opportunity to reach their full potential in literacy and beyond.

“Our family’s lives would not be the same without her life’s work.” (A Parent’s Perspective)

Kim Davidson, Director of Strategic Partnerships

Having been a Montessori parent for 25 years, it’s easy to reflect on how our family’s lives would be vastly different without Oak Farm Montessori School and Lorene’s vision. This impact is evident in our children, their friends, and their passions, to name just a few. But the reach extends beyond our children and who they have become. I can say, without hesitation, that my husband and I have become better parents because of the influence and education we’ve received along the way.

We were blessed to have Nancy Hathaway, one of the first employees at the school, as the Lead Primary Teacher for three of our four children. Nancy’s advice and guidance would often sting a bit, but she helped us understand how our lives, schedules, and moods impacted our child’s day. When our children struggled at school or acted out, we learned that it was our responsibility, as adults, to determine what had changed in our child’s environment and how we could reset and provide the right environment for them to thrive.

What I’ve learned over the years is that Montessori is a way of life. It’s difficult to have your children thrive in a Montessori learning environment when the philosophy is not evident at home. As Oak Farm Montessori parent April Reinhard, mother to Bo and DaisyMay, shared, “When my husband and I first made the decision for our children to attend Oak Farm, we saw it as our gift of love to them. However, as we attended parent events, invested in Positive Discipline practices, and read books on Maria Montessori’s life and the impact of her work, it wasn’t long before we realized we were growing, too!”

To embrace and practice Montessori outside the prepared learning environment is not always easy, especially when family and friends do not understand or subscribe to the same principles. Having a strong support system is fundamental to a family’s success with Montessori at home. Anne Bao, parent of Annika and Emily, shares, “As parents, we appreciate the continued involvement through celebratory, educational, and volunteer opportunities. This provides a strong sense of community, and the ability to consistently meet with other parents and teachers who share the same interests and passions has been wonderful.” Anne continues, “The Montessori emphasis on self-reliance and self-determination, paired with a culture of helping one another, has also made home and sibling life easier. We feel we can enjoy family and personal time better, and our two children seem to get along as well as any two sisters can.”

In summary, the reflection that April shared regarding parenting and the Montessori philosophy resonates with me, as I’m sure it will with other parents on this shared Montessori journey, “I’ve discovered that the Montessori philosophy is not only a whole-child approach, but a whole-parent approach as well. It has led me on a journey that—although challenging at times—has helped me grow beyond the limiting narratives I once lived by. We now say that a Montessori education is a gift we’ve given to our children and to ourselves. Thank you, Maria, for this foundation and Lorene for your vision!”