About Global- is-Asian

As we celebrate the 20th anniversary of Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy (LKYSPP) in 2024, we also celebrate two decades of thought leadership. Global-is-Asian has been one of the central platforms for us to drive this, capturing necessary discussions on public policy. So, it is timely to reflect on the evolution of governance, a cornerstone of LKYSPP. In our early years, good governance primarily revolved around excellence within our own borders. It was about getting public service right, ensuring meritocracy by placing the most capable individuals in roles that best suited their talents, and prioritising the welfare of individuals in society. This approach established a robust foundation and contributed significantly to our nation’s success. However, the path forward demands a broader conception of governance. Today, good governance extends beyond our immediate surroundings. It necessitates a commitment to uplifting everyone within our community and recognising that our well-being is interlinked with the well-being of others. This ethos of mutual upliftment is now essential not just within Singapore but also across nations in our interconnected world. By supporting and elevating those around us, we, in turn, elevate our own society and nation. This expanded vision of governance, rooted in empathy and collective progress, will guide us through the next decades, ensuring that we not only thrive as a nation but also contribute meaningfully to the global community.

IF YOU ARE

A CURRENT OR PROSPECTIVE STUDENT AN ALUMNUS

A MEMBER OF THE MEDIA

INTERESTED IN MAKING A DONATION

INTERESTED IN EXECUTIVE EDUCATION

INTERESTED IN OUR PUBLIC EVENTS

INTERESTED IN A CAREER WITH US

LOOKING FOR GENERAL ENQUIRIES OR FEEDBACK

lkypostgrad@nus.edu.sg lkysppalumni@nus.edu.sg media.point@nus.edu.sg givelkyspp@nus.edu.sg

lkysppoe@nus.edu.sg lkyschoolevents@nus.edu.sg lkysppjoinus@nus.edu.sg

lkyspp@nus.edu.sg

Conflict

GOVERNANCE

As the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy celebrates its 20th anniversary, we reflect on the enduring principles that have shaped governance across nations. At its core, governance is an act of public service — a collective endeavour to improve lives, resolve conflicts, and build a more just and equitable society. This section of our commemorative magazine explores the intricate interplay between governance and public service, showcasing insights from two distinguished contributors.

This article, “How Fear, Luck and Golf Brought ASEAN Together” (March, 2017) written by Professor Kishore Mahbubani (Dean of LKYSPP 20024 – 2017), underscores the critical role of governance in fostering regional stability. Mahbubani’s narrative is a compelling reminder of ASEAN’s improbable success — a “miracle” born of pragmatism and collaboration amid historical tensions. He likens ASEAN to a protective umbrella shielding Singapore and its neighbours from geopolitical storms, cautioning against complacency or neglect. His reflections challenge us to appreciate and strengthen the institutions that safeguard our collective well-being, highlighting governance as both a stabilising force and a strategic tool.

In As a Small Country, Soft Power is Particularly Important for Singapore, Associate Professor Terence Ho examines how governance shapes a nation’s brand and influence. Professor Ho’s insights on Singapore’s soft power — a blend of its economic strategies, cultural capital, and global reputation — illustrate how governance transcends borders. By fostering inclusivity, innovation, and sustainability, Singapore exemplifies how small states can amplify their impact through thoughtful policy and visionary leadership.

Together, these articles remind us that governance is not an abstract concept but a lived experience, intimately tied to the aspirations and resilience of communities. Whether through regional cooperation or soft power projection, governance reflects the values and priorities of those it serves.

As we honour two decades of nurturing leaders in public policy, let these thoughts inspire a renewed commitment to governance as a noble pursuit, rooted in service to others and dedicated to the common good. May these reflections guide us as we navigate the challenges and opportunities of an increasingly interconnected world.

At its core, governance is an act of public service — a collective endeavour to improve lives, resolve conflicts, and build a more just and equitable society.

How fear, luck and golf brought ASEAN together

Asean provides an important security umbrella for Singapore and the region. People, stop poking holes in this umbrella.

Imagine Singapore in December. The north-east monsoon is approaching. Heavy rains are coming. Someone has gifted you a strong umbrella. The rational thing to do would be to preserve and protect this umbrella. The irrational thing to do would be to poke holes in this umbrella.

Yet, many Singaporeans today are doing this irrational thing. They have been gifted a wonderful geopolitical umbrella. It is called Asean.

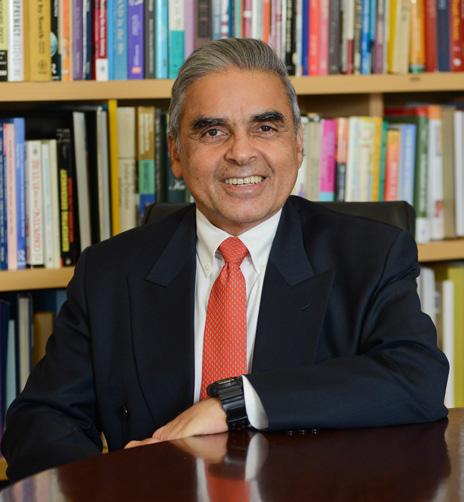

Featured Faculty Kishore Mahbubani

Founding Dean (2004 – 2017)

“In an era of growing cultural pessimism, where many thoughtful and influential individuals believe that different civilisations — especially Islam and the West — cannot live together in peace, ASEAN provides a living laboratory of peaceful civilisational coexistence.”

Kishore Mahbubani & Jeffery Sng

Instead of strengthening it, they are poking holes in it. And they are poking holes just as new geopolitical storms are coming to our region, in the form of enhanced US-China rivalry.

Why are Singaporeans behaving irrationally? The simple answer is ignorance. Any simple survey would show that most Singaporeans know next to nothing about Asean. Many can’t recognise the Asean flag.

President of the Institute of Singapore Chartered Accountants Gerard Ee was dead right when he said at a recent panel discussion that Singaporeans should understand the region better. Singaporeans, he said, “do not understand the cultures and values of different people in the region that we are trying to form a bond with, and we might inadvertently end up making enemies rather than friends. So, I wish all the schools would go back to teaching the history of all the Asean countries so that we appreciate where they’re coming from.”

Even more sadly, the little that Singaporeans know about Asean comes from the usual jaundiced Anglo-Saxon media coverage of Asean.

To combat this ignorance, a childhood friend of mine, Jeffery Sng (whom I grew up with in Onan Road in the 1950s and 1960s) and I decided to publish a book on Asean to coincide with Asean’s 50th anniversary on 8 Aug this year. It is called The Asean Miracle: A Catalyst For Peace, and it has been published by NUS Press this month. The goal of this article is to provide a flavour of the book.

One simple way of understanding Asean is to apply the 3M formula. 3M here does not refer to the Minnesotan manufacturer of sturdy products. The three “M” words to understand Asean are Miracle, Mystifying, and Money.

Asean miracle

Why is Asean a miracle? First, when it was born in 1967, everyone expected it to fail. Its two predecessors, ASA (Association of South-east Asia) and Maphilindo (MalayaPhilippines-Indonesia), died within two years. No one dreamt in 1967 that Asean would hit 50. But it has.

Second, all the five founding members had bilateral disputes with each other in 1967. Indonesia had confronted Malaysia. Singapore had just had a bitter separation from Malaysia. The Philippines claimed Sabah from Malaysia and the south Thailand insurgency was brewing on the Thai-Malaysia border.

Third, the region was in turmoil. Communist parties were active. The Vietnam War was gaining momentum. The Tet Offensive took place five months after Asean’s birth.

Fourth, Southeast Asia is the most culturally diverse region on planet Earth. If you were looking for a place to start regional cooperation, the last place you would pick is South-east Asia. In short, there were many reasons why Asean should have failed. And I could give a few more. This is why Asean’s success is a true miracle.

“Why is Asean deprived of resources?

The simple answer is that the total size of the Asean budget is determined by the capacity to pay of the poorest member of Asean. This is a result of Asean’s insistence on the principle of equal payments from all 10 countries. This principle is manifestly absurd as it says that large and rich member states should pay the same as small and poor member states.”

Fear, not love, brought Asean together

Yet, this miracle is also mystifying. No one really understands why Asean has emerged as the world’s most improbable success story. Our book cannot possibly provide a definitive explanation. Future historians will have to do this. Nonetheless, we try to provide a theory on why Asean succeeded. This theory is based on a few four-letter words. The first begins with “f“. It is fear.

Given the major bilateral disputes they had with each other, it was not love that brought together the five founding members, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand. It was fear of communist expansion. Indeed, these five countries were often referred to as the noncommunist “dominoes“ waiting to fall in the face of communist expansion. As Jeffery and I both lived through this period, we experienced this fear. It was real.

The second four-letter word is luck. Asean was lucky on several counts, especially in the 1980s. After Vietnam defeated the United States in 1975, it became arrogant. It invaded Cambodia in 1978. This triggered a geopolitical alliance between the US, China and Asean. The three worked closely together. I experienced it at first-hand when I served as Singapore’s Ambassador to the United Nations from 1984 to 1989. This strengthened Asean considerably. It was geopolitical luck that drew us together.

Asean was also lucky to have unusually strong leaders, especially in the 1980s, including Indonesia’s Suharto, Singapore’s Lee Kuan Yew and Malaysia’s Mahathir Mohamad. Strong leaders don’t have to worry unduly about domestic political pressures — they can focus on doing the right thing for the region. Indonesian leadership was key. Suharto wisely decided that the best way for Asean to grow was for Indonesia to take a back seat. It allowed smaller countries, like Malaysia and Singapore, to play a stronger role. As our book documents, it was also Suharto who made the fateful decision that Indonesia should join the rest of Asean in opposing the Vietnamese invasion. If Indonesia had vacillated, Asean would not have succeeded. In short, Asean avoided many potential disasters. It was lucky.

The third four-letter word will make you laugh. It is golf. When I mention the role of golf, many in the West think I am joking. Yet, I am dead serious. Multilateral negotiations are inherently messy. If you want to argue about texts of documents, you can go on for hours. Yet, somehow, after a golf game with my then Asean senior official counterparts in the 1990s, we would have a beer and reach agreements very quickly. The camaraderie produced by golf did the trick.

One recent miracle Asean achieved was the conclusion of the Asean Charter in about a year in 2007. This achievement should be recorded in the Guinness Book of Records. And how was this agreement reached so quickly? Former deputy prime minister S. Jayakumar was a member of the Eminent Persons Group that was set up to begin the discussions of the charter. In our book, we quoted him as saying: “It helped that Ramos, Ali Alatas, Musa, Jock Seng and I had also been long-time golf buddies!“ These were Fidel Ramos of the Philippines, Ali Alatas of Indonesia, Musa Hitam of Malaysia, and Lim Jock Seng of Brunei.

More resources needed

Yet, even though Asean has succeeded in many ways, it continues to face many perils. Our book documents many of these, especially the geopolitical perils. But one peril that it faces can be solved quite easily. This peril is the lack of money. For reasons I still don’t fully understand, the Asean Secretariat has been deprived of the resources that it needs to grow to a healthy state.

To understand the scale of the problem, just compare the budgets of the world’s most successful regional organisation, the European Union, with the budget of the world’s second-most successful regional organisation, Asean. The EU’s annual budget was 145.3 billion Euro (S$219 billion) in 2015. Asean’s was US$19 million (S$26 million). The EU budget is 8,000 times larger than Asean’s. Yet, the combined gross domestic product of the EU is not 8,000 times larger. It is only six times larger.

Why is Asean deprived of resources? The simple answer is that the total size of the Asean budget is determined by the capacity to pay of the poorest member of Asean. This is a result of Asean’s insistence on the principle of equal payments from all 10 countries. This principle is manifestly absurd as it says that large and rich member states should pay the same as small and poor member states. Virtually no other credible international organisation (IO) uses this formula. Instead, all credible IOs, like the UN, use the principle of “capacity to pay“. Rich countries pay more. Poor countries pay less.

This is why one bold recommendation that our book makes is for Singapore to take the lead in arguing for the UN-style “capacity to pay“ system to apply to Asean. Why should Singapore take the lead? Singapore should because it is the single biggest beneficiary of the magnificent Asean geopolitical umbrella. Singapore’s trade to GDP ratio is the highest in the world at 300 per cent. No other Asean country came close to this ratio. A lot of Singapore’s $1.2 trillion in trade could shrivel up if Asean broke up and South-east Asia once again became a region of turmoil, as it was in 1967.

This is what I meant when I said that Singaporeans were poking holes in the geopolitical umbrella gifted to us. We should do our best to strengthen this umbrella. Let’s start by paying more to it. We can afford it.

GLOBAL-

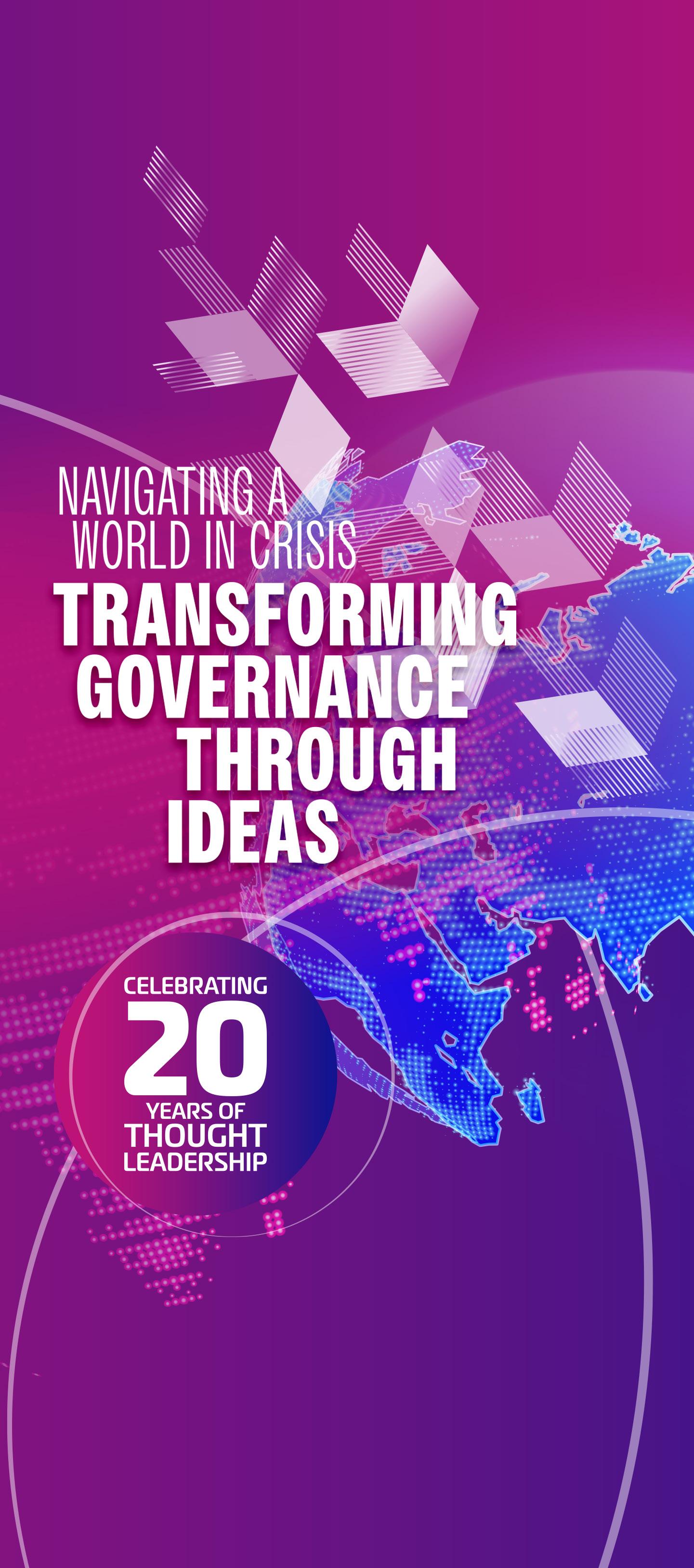

Featured Faculty

Terence Ho

Adjunct Associate

Professor

Research Areas:

• Economic, Labour and Education Policy

• Fiscal Policy

• Public Sector Management and Organisation

• Social Security, Inequality and Social Mobility

As a small country, soft power is particularly important for Singapore

SINGAPORE: In his book in 1990, American political scientist Joseph Nye popularised the concept of “soft power”, referring to a nation’s international influence arising from attractiveness or appeal, in contrast to “hard power” rooted in military or economic strength.

While every nation seeks hard power in a turbulent world marked by trade and military conflict, there is much to be said for soft power which enables countries to project influence without force. The latter is closely associated with a nation’s brand strength, or how a nation is perceived by the global public.

As a small state, soft power and branding are particularly important for Singapore as commanding global mindshare is necessary to attract visitors, investment and talent, as well as for the country to exercise influence in the international arena.

The recent 2024 edition of Brand Finance Global Soft Power Index saw Singapore slip one place to 22nd among 193 nations ranked, although its absolute score improved 3.4 points to 54.4. This indicates that other nations are not standing still. To avoid being overtaken, Singapore must strive to make its mark in new ways that complement existing strengths.

However, in terms of Nation Brand Strength, Singapore still punches well above its proverbial weight, moving up to 10th place in the ranking.

According to the Brand Finance report, Singapore “serves as the business hub of Southeast Asia and is renowned for its world-class education, healthcare, transport, and low crime levels. These factors, paired with the nation’s unwavering political stability and commitment to its economic strategy, firmly position Singapore among the world’s strongest Nation Brands”.

The story of Singapore

Much of Singapore’s brand is tied to its remarkable economic success, which many developing countries around the world are keen to emulate. Singapore’s infrastructure, governance, cleanliness and public safety are also much admired worldwide.

Furthermore, Singapore has in recent years established itself as a vibrant global city hosting high-profile sporting events such as the Singapore Grand Prix and concerts by top global artistes. Who can forget the buzz surrounding Taylor Swift’s concerts in Singapore in 2024

Futuristic architecture including the Marina Bay Sands hotel tower and the Supertrees at Gardens by the Bay have captured global attention, putting Singapore on the bucket list of many a globetrotter. This reputation has in turn made Singapore a preferred venue for international meetings and conferences.

Still, Singapore has the potential to significantly enhance its soft power and branding in several ways.

Having more recognisable corporate brands and innovations that are closely associated with Singapore would make a difference, as would having more Singaporeans globally recognised for their achievements in various domains. Finally, Singapore can become an exemplar for inclusive development and social cohesion, inspiring societies across the world.

Building Singapore’s brand

While a handful of corporate brands such as Singapore Airlines are worldrenowned, Singapore has fewer well-recognised commercial brands compared with other small countries such as Sweden and Switzerland. One reason is the relative dearth of Singapore companies in consumer-facing sectors.

This, however, is changing. Today, we have the likes of Charles & Keith, Razer and Grab, prominent brands whose companies are headquartered here.

A stronger association of such brands with Singapore would boost the nation’s own branding, in turn benefitting all firms that ride on the Singapore brand. It is important for Singapore to develop clusters of successful firms, as it may take more than one world-class company for a country to gain recognition in a particular industry or sector.

Innovations, too, can enhance national branding across a wide variety of domains.

Governance

For instance, “Singapore Math” - an approach to teaching mathematics — has gained traction in the United States and other countries. Singapore’s Electronic Road Pricing system (ERP), the world’s first congestion pricing system of its kind, has served as a blueprint for similar initiatives in other cities, including London and Stockholm. These innovations have put Singapore at the forefront of pedagogy and traffic management, burnishing its reputation as an innovative country.

With the world facing an existential climate crisis, there is an opportunity for Singapore to be at the forefront of sustainability innovation through a whole-of-nation effort spanning private, public and people sector innovations. There are industry players investing in energy transition projects, low carbon technologies and biofuels; regulatory innovations around green finance and carbon offset schemes; as well as grassroots and non-profit initiatives such as Zero Waste SG.

In particular, Singapore is well-positioned to be a test-bed for innovations that require complex regulatory coordination, given its size and administrative efficiency. Major innovations developed here can be adapted and implemented in other cities, enhancing Singapore’s reputation for leading-edge innovation.

Singaporeans on the global stage

A country’s soft power is also reflected in its leading personalities, be they cultural or sporting icons, industry titans, political leaders, or leading thinkers. Smaller nations, in particular, can gain outsized mindshare from such personalities. For instance, Serbian tennis star Novak Djokovic and Lord of the Rings filmmaker Peter Jackson from New Zealand have raised the international profile of their respective countries.

While Singaporeans like TikTok CEO Chew Shou Zi have made their mark internationally, there is certainly potential for more Singaporeans to rise to the top of their professions as Nobel Prize winners, Fortune 500 CEOs, Olympic champions, bestselling authors and chart-topping artistes.

This requires years of continual investment to build strong ecosystems and talent pipelines in various domains, so that the stars who emerge are not just the occasional flash in the pan.

Singapore may not have the scale and depth of overseas ecosystems such as the American collegiate sports system or the Korean pop music industry, but we can strengthen the linkages between our domestic ecosystems

and their overseas counterparts to facilitate talent flow in both directions.

This would provide more pathways for Singaporeans to rise to the top of their vocation, while also nurturing our domestic ecosystems. Successful Singaporeans can be both role models and mentors for the next generation of sports stars, musicians, entrepreneurs and academics.

Singapore’s economic and social inclusiveness

While Singapore is often lauded for its economic success, its social achievements have been no less remarkable. Investment in education, public housing and healthcare have laid strong foundations for inclusive growth over the decades. With Singapore now among the most expensive cities in the world, sustaining inclusive growth requires new policies to strengthen social assurance and keep social mobility going.

In many advanced economies, unfettered globalisation has widened inequality over the years and provoked a reaction from the economically disenfranchised. As a result, right-wing populism is on the rise and countries are turning insular.

By stepping up social investment and support, Singapore can be a paradigm for inclusive growth and development, where economic gains are spread across society, with opportunities for all to move up in life.

Inclusivity amid diversity should become a hallmark of the Singapore identity. As a nation with immigrant roots that experienced communal riots in the 1960s, Singapore has always prioritised racial and religious harmony. Today, we need to extend the concept of inclusivity by making new immigrants and migrant workers feel welcome and part of our community, so that all can flourish under the Singapore tent.

At a time where the excesses of political partisanship are eroding social cohesion in many countries, Singapore has the opportunity to show the way in political discourse that is informed and respectful, and political competition that strengthens rather than divides society.

Singapore is already widely known and admired abroad, but its soft power can be significantly enhanced through stronger corporate brands, innovations, and personalities, along with a reputation for inclusivity.

Further progress in each of these areas will allow Singapore to exert greater influence as a nation that inspires people and societies around the world.

NAVIGATING GEOPOLITICS

As we celebrate two decades of thought leadership, the articles we have produced on geopolitics remind us of the persistent and evolving challenges that define our geopolitical landscape. There have been significant shifts in the global order between 2004 and 2024. From a unipolar global order dominated by the United States, the landscape has evolved dramatically, influenced by the rise of emerging economies, the proliferation of technology, and shifting alliances.

A significant change has been the rise of China as an economic and military powerhouse. This shift has altered the balance of power, creating a more multipolar world where influence is distributed among several key players, including the European Union, India, and Russia. Additionally, technological advancements have created new dimensions of geopolitical competition, from cyber warfare to space exploration. The global economy has also seen supply chain disruptions and trade tensions redefining international relationships.

From rising nationalism and terrorism to the unpredictability of rogue state actors, the pressures on global conflict resolution and negotiation are immense. Globalisation, while connecting economies and cultures, has also heightened the stakes of transnational disputes. The article in this section, “Conflict Resolution and Negotiation in an Era of Growing Uncertainty” (Aug 2017), adeptly addresses these dynamics, emphasising the need for leaders to engage constructively, foster cross-cultural collaboration, and cooperate with peacebuilding institutions. These strategies are essential for maintaining the fragile balance of peace in an increasingly volatile world.

Meanwhile, “The Geopolitics of Populism” (Aug 2018), takes us into the heart of one of the most consequential phenomena that exists even today — the surge of populist movements. This trend, as the article illuminates, is not merely a reaction to economic inequality but a reflection of deeper anxieties about lost control in a rapidly shifting global order. These populist waves, exemplified by Brexit and the Trump presidency, underline a critical challenge for policymakers worldwide: addressing the discontent of those who feel left behind in the modern, interconnected age.

There have been significant shifts in the global order between 2004 and 2024. From a unipolar global order dominated by the United States, the landscape has evolved dramatically, influenced by the rise of emerging economies, the proliferation of technology, and shifting alliances.

As these articles suggest then, and is still true now, the future of geopolitics will be shaped by our ability to navigate uncertainty with foresight, empathy, and cooperation. Institutions like LKYSPP play a crucial role in equipping future leaders with the skills to resolve conflicts, bridge cultural divides, and respond to the anxieties of globalisation’s discontents. The challenges ahead demand innovative thinking, grounded in an appreciation of history and an unyielding commitment to peace and progress.

Conflict resolution and negotiation in an era of growing uncertainty

Rising nationalism, persistent threats of terrorism and North Korea’s unpredictability are just some of the issues that have contributed to growing international tension in recent times. This has put increased pressure on world leaders to engage in effective conflict management to ensure peace.

Conflict has always been present in one form or another, from the devastating international World Wars of the 20th century to subnational and regional conflicts that persist today. Although wars in the past few decades have generally been contained within countries and states, a US intelligence report predicts dark times ahead for the world, with rising nationalism, anti-globalisation and terrorism all increasing the risk of conflict that could potentially alter the global landscape.

The possibility for disputes has been further increased by globalisation, which has resulted in higher levels of connectivity that drive interactions across economic, political and social dimensions. Transnational conflict has also become more prevalent due to people fleeing unsafe conditions by crossing borders.

It is hence becoming increasingly important to focus on finding solutions through conflict management, which looks at constructive ways to transform disputes. Political leaders and public administrators have to be particularly skilful in conflict management to ensure that things run smoothly. Here are three ways in which leaders can resolve conflict and engage in effective negotiation.

1. Engage, not isolate

In order to negotiate successfully, political leaders have to learn how to engage the opposing party in a constructive manner. One of the biggest current threats to global peace is terrorism. Francesco Mancini, Vice Dean (Executive Education) and Associate Professor in Practice at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, said in an interview with Global-isAsian: “Disenfranchised societies and groups within countries can become easy prey (for) radical groups. The more you marginalise these groups, the more radicalisation is likely to happen”. This accurately sums up the issue with current approaches in the West — countries and societies tend to isolate populations at risk instead of engaging them.

In the Philippines, however, President Rodrigo Duterte has established relationships with the Moro Islamic Liberation Front and Moro National Liberation Front in order to achieve productive dialogue with them. With the Philippine army still battling Islamic State (ISIS)-affiliated militants in Marawi, this is important in preventing the spread of ISIS propaganda. Addressing widespread poverty and youth unemployment by educating the next generation of Muslim youth will also help integrate them into society instead of leaving them vulnerable to radicalisation.

Apart from terrorism, the other huge threat to geopolitical stability is the unpredictability of rogue nations such as North Korea. Heavy sanctions and increasingly numerous country alliances with the US have not halted North Korea’s nuclear weapons programme. In fact, the programme has developed at a faster rate over time. Instead of President Trump’s approach of threatening fire and fury, emphasising diplomacy whilst maintaining sanctions could deescalate tensions and preserve the potential for a halt on its nuclear weapons development.

2. Seek cross-cultural collaboration that addresses the needs of all parties

In regions where there is great diversity, conflicts such as territorial struggles or secessionist movements are common if various groups feel that their interests are not adequately addressed. When it comes to separatist movements or protests, governments tend to respond with force, such as the Myanmar army’s crackdown on the Rohingya Unfortunately, violence ultimately reinforces oppression of the minority.

On the other hand, peaceful crosscultural negotiation can be a way to ensure that the needs of all parties are met. For example, despite the immense diversity of Southeast Asia, leaders in the region have managed to successfully cooperate by adopting the ASEAN way, which is often lauded for reaching consensus through establishing common interests. Though some criticise it as being slow in achieving progress, it has resulted in positive results, such as the endorsing of the framework for a code of conduct in the South China Sea territorial dispute

Research has shown that negotiating across cultures tends to lead to less favourable outcomes as we are inclined to rely on stereotypes or interpret behaviour through our own lens of culture. To avoid misunderstandings, collaboration has to take into account cultural barriers.

Another important aspect of crosscultural negotiation is how leaders

verbally address the issue. It is important to avoid exclusionary language in conflict resolution. It may appear simplistic to say that words such as “them” encourage divisions whereas words such as “us” encourage inclusion, but these nonetheless have an impact on our resolve to seek mutual understanding and respect. Therefore, leaders should be careful about their choice of words when engaging in negotiation.

3. Cooperate with peacebuilding institutions

Peacebuilders are institutions that help mediate conflict between groups and organisations. Some of the betterknown institutions include the United Nations (UN), International Committee of the Red Cross, and International Crisis Group.

In instances of armed conflict, the UN has carried out numerous peacekeeping missions. Although a

few were considered failures, such as those in Rwanda and Somalia, other missions have been considered more successful, such as Sierra Leone’s. If a country wishes to settle a dispute by arbitration, there are mechanisms such as the International Court of Justice and International Criminal Court, which provide advisory opinions or mediation services.

Despite the existence of these numerous peacebuilding institutions that have proven themselves to be capable of effecting change, countries do not engage them often.

This is likely due to the importance that states attach to sovereignty in international affairs, especially for larger powers that perceive themselves as independent actors in the global order.

For such peacebuilding institutions to be effective, it is therefore essential that leaders embroiled in disputes seek and accept assistance from them. In the aforementioned interview with Mancini, when asked about the capability of the UN to resolve conflict, he stated that the UN can get teeth if stronger member states give them teeth.

Maintaining an equilibrium

Hard and soft power, cultural differences and peacebuilding initiatives are just some of the factors that influence conflict management. There are also other approaches that have been studied in depth. Examples include structural prevention, which focuses on institutionalising rules to strengthen nonviolent channels for dispute resolution; or normative change that sees the development and institutionalisation of principles, such as non-interference, to create a new context for managing conflict.

“Ultimately, leaders need to navigate each situation carefully to find the best possible way to address the concerns of all parties and maintain the delicate balance of peace in this increasingly volatile world.”

This piece was written by Prethika Nair based on an interview given by Francesco Mancini, Vice Dean (Executive Education) and Associate Professor in Practice at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy

The Geopolitics Of Populism

The big question in Asian countries right now is what lesson to take from Donald Trump’s victory in the United States’ presidential election, and from the United Kingdom’s Brexit referendum, in which British voters opted to leave the European Union. Unfortunately, the focus is not where it should be: geopolitical change.

“Trump won 53% of white male college graduates, and 52% of white women (only 43% of the latter group supported Clinton).”

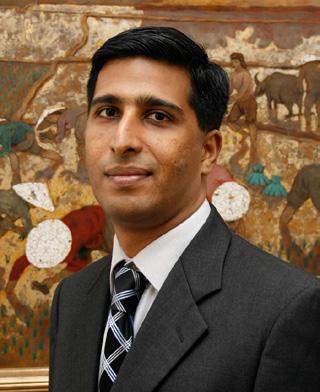

Featured Faculty

Danny Quah Dean and Li Ka Shing Professor in Economics

Research Areas:

• Applied Timeseries Econometrics

• Economic Growth and Development

• International Economics

• World Order; Models of Global Power Relations

Instead, for the most part, economic narratives have prevailed: globalisation, while improving overall wellbeing, also dislocates workers and industries, and generates greater income disparity, creating the anxious electorates that backed Brexit and Trump. An alternative narrative asserts that technological advances, more than globalisation, have exacerbated economic inequalities, setting the stage for political disruptions in developed countries.

In either case, policymakers in emerging countries have identified inequality as a major problem, and rallied around efforts to improve social mobility, lest globalisation and new technologies displace their middle and working classes, and clear a path for their own versions of Trump and Brexit. For Asian countries, the policy prescription is clear: take care of disadvantaged populations and provide retraining and new employment opportunities for displaced workers.

Of course, all societies should look out for their poorest members and maximise social mobility, while also rewarding entrepreneurship and challenging people to improve their lot. But focusing on such policies would not address the public disaffection underlying the populist uprising, because inequality is not its root cause. Feelings of lost control are.

Even if countries closed their domestic income and wealth gaps and ensured social mobility for all their citizens, the forces fuelling public dissatisfaction around the world today would remain. Consider the US, where the inequality narrative’s poster child has become the displaced, older, less-educated, white working-class male. Many people credit these voters for Trump’s victory, but the poster-child cohort did not actually have the biggest impact on the election outcome.

According to exit polls, Trump won 53 per cent of white male college graduates, and 52 per cent of white women (only 43 per cent of the latter group supported Clinton); he won 47 per cent of white Americans between the ages of 18 and 29, compared to 43 per cent for Clinton; and he beat Clinton by 48 to 45 per cent among white college graduates overall. These Trump supporters do not fit the stereotype at the centre of the economic narrative. Meanwhile, more than half of the 36 per cent of Americans who earn less than USD $50,000 annually voted for Clinton, and of the remaining 64 per cent of voters, 49 per cent and 47 per cent chose Trump and Clinton, respectively. Thus, the poor were more favourable toward Clinton, and the rich toward Trump. Contrary to the popular narrative, Trump does not owe his victory to people who are most anxious about falling off the economic ladder.

A similar story unfolded in the UK’s Brexit vote, where the Leave campaign asserted that the EU’s supposedly burdensome regulations and exorbitant membership fees are holding back the British economy. This hardly amounts to an agenda to fight economic inequality and exclusion, and it is revealing that rich businessmen wrote the largest cheques to support Leave.

Moreover, the street-level emotions that contributed to Leave’s victory were not rooted in income inequality or the 1%: alienated poor voters directed their anger at other alienated poor people particularly immigrants not at the rich. The Mayor of London’s office reported a 64% increase in hate crimes in the six weeks after the referendum, compared to the

The Globalisation Lift : Emerging countries’ combined GDP as a share of G7 GDP

six weeks before it. So, while income equality may have been a part of the Brexit campaign’s background noise, it was not the first issue on Leave voters’ minds.

What unites Trump and Leave supporters is not anger at being excluded from the benefits of globalisation, but rather a shared sense of unease that they no longer control their own destinies. Widening income inequality can add to this distress, but so can other factors, which explains why people at all levels of the income distribution are experiencing anxiety. Indeed, many people in Eastern Europe felt a sense of lost control during the harsh socialist experiments of the post-war era, as did many Chinese during the Cultural Revolution, and these societies had minimal visible income inequality.

The effects of globalisation

Paradoxically, Brexit and Trump supporters might be feeling the effects of globalisation because overall inequality has actually declined. Globalisation’s largest effect has been to lift hundreds of millions of people in emerging economies out of poverty. Throughout the 1990s, emerging countries’ combined GDP (at market exchange rates) amounted to barely one-third of the G7 countries’ combined GDP. By 2016, that gap had essentially vanished.

Low international income inequality, rather than growing income inequality in individual countries, is putting unprecedented stress on the global order. There is a growing mismatch between what Western countries can provide, and what emerging economies

This piece first appeared in Project Syndicate on 9 December 2016.

are demanding. The power of the transatlantic axis that used to run the world is slipping away, and the sense of losing control is being felt by these countries’ political elites and ordinary citizens alike.

Trump and the Leave campaign appealed to voters by raising the possibility that transatlantic powers can reassert control in a quickly changing world order. But with the geopolitical rise of emerging economies, especially in Asia, that order will have to achieve a new equilibrium, or global instability will persist. Closing the income gap can help the poor; but, in the developed countries, it will not alleviate their anxiety.

SOCIAL COHESION

In the past, social cohesion often implied a sense of unity and shared values within relatively homogenous communities. Today, this has broadened to encompass inclusivity, diversity, and the welfare of the entire society, including its most vulnerable members.

Amid rapid technological advancements, economic shifts, and geopolitical changes, societies worldwide are grappling with issues of inequality and social fragmentation. Are we paying enough attention to the welfare of society as a whole? While we have made significant strides in promoting social cohesion through policies aimed at education, healthcare, and housing, there is always room for improvement.

The pandemic years have been a stark reminder of the inequalities that divide us, as vividly examined in “Inequality: A Tale of Three Countries” (Feb 2021). This article underscores how the pandemic widened existing gaps between the haves and the have-nots. Yet, it also points to an important distinction: inequality itself is not always the central problem — it is the lack of adequate resources and opportunities for upward mobility that truly threatens social cohesion. This thought-provoking piece challenges us to focus on empowering the disadvantaged, not only by redistributing wealth but by creating pathways for sustainable growth and inclusion.

On the ground, the experiences of the marginalised are brought to life through “Delving into the Lived Experiences of Singapore’s Homeless” (Dec 2022). This research shines a light on the realities of housing insecurity, where stories of strained family ties, precarious employment, and systemic barriers paint a picture of resilience amidst adversity. The findings highlight the importance of inclusive policies that address not just immediate needs but also the underlying causes of housing instability. Complementing this, “Homeless During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Singapore” (Dec 2022) reveals how the crisis reshaped homelessness, prompting a surge in temporary shelters and a shift in the geography of vulnerability. Together, these articles call for sustained efforts in providing accessible housing and a robust safety net to prevent and alleviate homelessness.

Lastly, “High Time We Stopped Worrying About Global Rankings” (Dec 2016) offers a refreshing perspective on progress. It argues that our fixation on rankings and metrics can distract from the broader goal of fostering innovation, creativity, and meaningful growth. True cohesion stems from a society that values qualitative transformation over quantitative competition, one that invests in people and nurtures a spirit of collective betterment.

May these articles inspire reflection on the pathways to a more cohesive and equitable society.

Amid rapid technological advancements, economic shifts, and geopolitical changes, societies worldwide are grappling with issues of inequality and social fragmentation. Are we paying enough attention to the welfare of society as a whole?

Inequality: A tale of three countries

During the coronavirus pandemic, a poignant global narrative on inequality has been told. Rich families have had a good pandemic. They found it easy to navigate circuit breakers and lockdowns as they could afford the space and technology for parents to work from home.

In contrast, low-paid physical labourers could not work when they were told to stay home. The poor therefore suffered further falls in already meagre incomes. Disadvantaged children from low-income households were photographed studying on borrowed laptops set on cardboard boxes. This unfortunate “us versus them” narrative breeds class envy and is distracting. It is a narrative that diverts us from a genuine social problem.

Featured Faculty

Danny Quah

Dean and Li Ka Shing Professor in Economics

Research Areas:

• Applied Timeseries Econometrics

• Economic Growth and Development

• International Economics

• World Order; Models of Global Power Relations

The inadequate resource challenge

While it is true that the pandemic has wrought terrible suffering on the poor, the low-paid and the disadvantaged, the problem here lies not so much with inequality per se as the inadequate resources those groups have been able to command to control their own destiny and environment. To put it differently, the many difficulties poor families face in coping with the fallout of the pandemic would exist even in the absence of the well-off. Of course, we can alleviate the plight of the poor by redistributing resources from the rich. But simply imposing equality — however that might be achieved — will not deliver a cohesive society, not least if that society is egalitarian because everyone in it is equally poor.

Tensions can be rife in poor egalitarian societies for many reasons, among them people needing to skip meals to pay bills or fretting over having just enough to survive. This is not to say inequality is inconsequential. Excessive income disparity can give rise to political conflict as feelings of discontent among the poor will be sharpened by the knowledge that others have more than them.

For the rich, the reward to suppressing change, too, rises with ever higher inequality. An angry, divided society is no good for anyone. But when will the inequality problem be taken as solved, when envy might arise over all kinds of characteristics, not just income disparity? In the longer term, should policy seek to shift people away from falling easily to envybased discontent? Call the group of policy problems emerging from this collection of inequality-driven effects the “disparity challenge”.

Social Cohesion

Solutions for Policymakers

Between the inadequate resource and disparity challenges, which of these should public policy address? If policymakers had unlimited resources, the answer, of course, is to tackle both problems. In reality, however, especially during the pandemic and its aftermath, resources are severely limited. The focus should be on the inadequate resource challenge — on lifting the weak and disadvantaged in society.

In a zero-sum game, pure redistribution to address the inadequate resource challenge is politically impractical. A better solution should do two things simultaneously: First, raise average incomes, so that the game can be positive-sum; second, build pathways so that those at the bottom of the income distribution see prospects for continual improvement.

Are these steps possible? I examine alternative solutions, using the World Inequality Database and measuring incomes in local currencies deflated by inflation. Call inequality the money amount separating the average incomes of the top 10 per cent and bottom 50 per cent in society. This measure of inequality directly addresses the disparity challenge. Use the average income of the bottom 50 per cent as a measure of the resources available to the weak and disadvantaged. Call it upward mobility when the bottom 50 per cent see average incomes rise; the rate of increase then also provides an index of upward mobility. The higher this index is, the more successfully the inadequate resource challenge of the poor is being addressed.

My calculations show that in Singapore, in the two decades between 2000 and 2019, inequality increased by 85 per cent. However, the bottom half of Singapore’s population also had average incomes rise by 55 per cent. These last 20 years, therefore, saw upward mobility of 2.3 per cent a year. In other words, even as disparity increased, Singapore’s weak and vulnerable steadily gained ever greater control over real resources.

Taking the longer time horizon that began in 1980, by 2019 the average income of Singapore’s bottom half had increased to more than three times

its earlier level, even as inequality increased to nearly 580 per cent of what it used to be. Upward mobility in Singapore over these last four decades occurred at 3.1 per cent a year. Therefore, in this account, yes, Singapore’s inequality rose.

But all segments of Singapore society have seen their economic well-being improve, along with consistent and significant upward mobility among the bottom 50 per cent. These past four decades therefore saw Singapore successfully address the inadequateresource challenge among its poor, at the same time that inequality increased. The rise in inequality was no barrier to improving the well-being of the poor.

A cross-country perspective is useful for comparison. China saw inequality increase an astonishing nineteenfold between 1980 and 2019, but its bottom 50 per cent also saw their incomes increase a remarkable sixfold. Inequality rose, but China’s poor became much, much better off at the same time, with an upward mobility index of 4.6 per cent. What we have seen of China and Singapore, however, is far from automatic or universal.

Consider the United States. Between 1980 and 2019, America’s bottom 50 per cent saw their average incomes rise 33 per cent; between 2000 and 2019, just 10 per cent. These correspond to dismal upward mobility indexes of only 0.7 per cent and 0.5 per cent, respectively.

In contrast to the marked improvement in economic well-being of China and Singapore’s bottom 50 per cent, America’s underclasses have seen their circumstances hardly budge. Indeed, between 2000 and 2010, in inflation-adjusted terms, the average incomes of America’s bottom 50 per cent fell. In that terrible decade, the poor in America became, in absolute terms, even poorer.

To further calibrate how well Singapore’s and China’s bottom halves have fared, between 2000 and 2019, the US’ top 10 per cent had their average incomes rise at 1.4 per cent a year. Compare this with Singapore’s and China’s upward mobility indexes over this same time period of 2.3 per cent and 6.4 per cent, respectively.

Lessons from Singapore, China and the US

Over these last two decades, Singapore’s and China’s poor have seen average incomes rise faster than those of America’s rich, at rates from 1.5 times to 5.5 times the average incomes of America’s wealthy. The US, these last two decades, saw inequality rise 32 per cent — a rate lower than Singapore’s and China’s. But America’s lower increase in inequality did not benefit its poor.

Instead, the opposite: America’s bottom 50 per cent have not fared nearly as well as Singapore’s or China’s. Upward mobility of the poor in Singapore and China has been strong, despite the increases in inequality in both societies. In sharp contrast, America’s poor have stagnated; and indeed over significant time periods have actually grown poorer. How much of the world is more like Singapore and China than like the US?

My research documents show, in reality, most economies in the world have seen their poor rise, even as inequality increased. In other words, Singapore’s and China’s inequality and upward mobility experiences are also the world’s — America’s, not so. The data shows that however income inequality evolves, a broad spectrum of possibilities is possible for the wellbeing of society’s weak and vulnerable.

The conclusion is that inequality simply does not shed light on the inadequate-resource challenge, and therefore does not reveal what happens to the weak and vulnerable in society. In popular thinking, inequality carries associations that go beyond the inadequate-resource challenge that upward mobility addresses. Policy conversations often surface issues, not about economic resources, but instead about human dignity and social cohesion. These are obviously greatly consequential.

However, from the lens of the pandemic, where the inadequateresource challenge is paramount, such problems are also separate, and should not be conflated with COVID-19’s effects on the weak and vulnerable in society. Human dignity and social cohesion — or generally a broader line of concern over inequality — are often said to be about more than economics.

Certainly, these challenges need to be carefully addressed. Just as all nations report national income numbers, policymakers around the world might consider providing a dashboard to track improvement or deterioration over time of these imprecise but important variables. But given that these problems are non-economic, we should be clear that they will not be dealt with effectively by a purely economic solution.

Reducing income inequality through, say, a minimum wage, will not solve challenges of human dignity and social cohesion. If the problem is not about economics, then economics cannot be the solution, and policymakers should not dissipate society’s finite resources to alter economic outcomes, to try and counter broader social discontent. Inequality might well be one such distraction from real social problems. For sure, however, inequality is no sufficient statistic.

“Human dignity and social cohesion — or generally a broader line of concern over inequality — are often said to be about more than economics.”

This article was first published on The Straits Times on 20 May 2024.

High time we stopped worrying about global rankings

We fixate on the quantitative because it is an easier game to play, or at least it was a game we played well. But as the Committee on the Future Economy pointed out, the big prizes are now to be sought in the qualitative: The entrepreneurial mindset, the innovative ethos and the spirit of learning. These call for a different game to be played.

Featured Faculty

Dr Adrian W J Kuah

Former Head (Case Studies Unit) & Senior Research Fellow

GLOBAL-IS-ASIAN

The sky is falling. No, not really. But for a country so accustomed to being ahead of a chasing pack, Singapore’s recent slide down various global competitiveness rankings and tables must surely feel like it. One can imagine the consternation and hand-wringing behind closed doors in government and business circles.

But as our policymakers and industry leaders grapple with how to climb back up the rankings, it is worth reflecting on our obsession with rankings and its implications.

Let us pre-empt criticism by saying we are not advocating defeatism, fatalism or taking our foot off the gas. Neither is it a case of sour grapes at being dislodged in the rankings. By all means, we must retain a culture of excellence and constant striving. But there is a difference between reaching ahead out of passion and courage, and being driven by obsession over relative scores.

There are three observations we want to make.

One, our obsession with rankings reflects a long-standing emphasis on tangible and measurable key performance indicators (KPIs) such as the ease of doing business, cost competitiveness, attraction of foreign direct investment and talent and so on.

This is explained by the fact that Singapore’s success is defined primarily in material terms. It is natural to tout rankings when we do well in them.

We fixate on the quantitative because it is an easier game to play, or at least it was a game we played well.

But as the Committee on the Future Economy pointed out, the big prizes are now to be sought in the qualitative: The entrepreneurial mindset, the innovative ethos and the spirit of learning. These call for a different game to be played.

Our obsession with the things that can be counted blinds us to other qualities that count but may not register on the rankings we place such importance on.

Two, the over-emphasis on rankings can thwart our attempts to reinvent our economy. Indeed, the focus on and attainment of rankings is a natural outcome of a policy-making ethos defined in terms of “quick wins” and “plucking low-hanging fruit”.

Every KPI can become gamed and eventually, the KPI becomes an end in itself.

The consequence then is that the economy remains firmly stuck in the prevailing albeit disintegrating paradigm as the longer-term strategic goal of fundamental transformation is sacrificed to quick wins in the rankings game.

On the other hand, if we successfully transform our economy along the lines of start-ups, innovation and creativity, we should expect our rankings in the traditional tables to tank in the transition phase. We would then be succeeding in areas for which rankings have not yet been developed.

And finally, our fixation on rankings reveal how we wrongly frame economic development as a zero-sum game. It is not. Just because another economy becomes cheaper or better than Singapore, or both, it does not mean we are worse off. In fact, it may make us better off because that economy can afford to buy more goods and services from us.

As the economist David Ricardo pointed out two centuries ago, what matters is not what our “competitors” do, but what we do. Are we becoming more productive? And are we becoming more innovative?

As long as we are constantly improving on these fronts, it does not really matter that other economies are catching up with us. Our own improvements matter far more than our relative standing in international league tables.

So long as we are still growing the economy — even if it is at a slower rate — businesses will still find it worthwhile to invest here.

While there are a few things which exhibit winner-take-all dynamics (i.e., either we are number one in the region or we are nothing at all), these tend to be the exception to the rule that development is not zero-sum.

Being the sea and air hub of the region, or the financial centre of Southeast Asia, are examples of such exceptions; there can only be one regional hub in each of these.

But in these domains, Singapore is still very much ahead of regional competitors. In the main, therefore, focusing on the competition is mostly unnecessary.

To illustrate this last point, consider China’s rapid growth in the last 30 years. This has been the most remarkable story of economic catchup in the modern age.

Has China’s catch-up been to Singapore’s benefit or detriment? Clearly, it has been the former.

There is an old joke about how a policeman found a drunk man on his hands and knees searching for his lost keys under a street light. When asked by the policeman if he dropped his keys there, the drunk man replied, “No, but this is where the light is.”

If we look away from established and conventional global competitiveness tables and rankings, even the ones we continue to do well in, we might discover new capabilities that need to be developed, and anticipate or even create new areas we could excel in.

Delving into the lived experiences of Singapore’s Homeless

Featured Faculty Ng Kok Hoe

Senior Research Fellow, Head of Case Insights Unit & Social Inclusion Project

Research Areas:

• Ageing and poverty

• Community-based social interventions

• Old-age pensions and income security

• Public housing policy

• Social housing

Featured Faculty Jeyda Simren

Sekhon Atac

Former Research Assistant in the Social Inclusion Project

The Social Inclusion Project (SIP) is a research programme dedicated to analysing the role of public policies in creating an open, diverse and inclusive society, where people have opportunities for participation. Its activities aim to influence policy development, promote policy literacy and enable engagement. The SIP is committed to independent and transparent research on overlooked and emerging social problems, with a focus on empirical work with practical impact.

In 2021, researchers from the Social Inclusion Project carried out indepth interviews with 51 shelter residents in Singapore, both female and male, whose ages range from 31 to 79. This qualitative component of the study was concurrent with Singapore’s second nationwide homelessness street count and helped the research team to better understand homeless persons’ trajectories into housing insecurity.

While the pandemic triggered some homeless persons’ admission into shelter, it was not the dominant cause of housing insecurity in Singapore. Undoubtedly, because of COVID-19, many jobs were lost, borders were closed and rough sleeping became unlawful. However, the social context, economic circumstances and institutional barriers related to participants’ housing insecurity had been present even before COVID-19 hit. Through interviews conducted, the researchers were also able to draw lessons from participants’ lived experiences.

Three distinct groups

Over the course of the research and analysis, three distinct groups of homeless persons were identified. The first is long-term homeless persons who had experiences of rough sleeping prior to the pandemic.

The second, newly homeless persons, refers to those who had not slept in public places before the pandemic.

The third, transnational homeless persons, was Singaporeans living in Malaysia or Indonesia who frequently travelled to Singapore before the pandemic for work or visa renewal, and were displaced by border closures in 2020.

Commonalities across the three groups

Across the three groups, the dynamics of their housing insecurity had much in common.

For many, family conflicts had directly contributed to their loss of housing. These took many forms: from failed marriages to being kicked out by siblings. Through the in-depth interviews, the researchers noted that the participants spoke of these as painful experiences and breakages which felt irreversible. This meant that even in times of crisis like the pandemic, families were no longer able to stay together.

Another important factor was longdrawn irregular work and in-work poverty, the result of low pay and unstable hours. This meant that participants’ financial resources were insufficient to meet basic needs, including housing.

Depending on relatives and friends for shelter was not an ideal nor long-term solution. The participants talked about these stays being terminated due to conflict or inability to make financial contributions.

Failure to obtain public rental housing, along with negative experiences as tenants under the Joint Singles Scheme, was common in the housing histories of long-term homeless persons. A requirement for applicants to pair up created both barriers to access and potential for conflict among tenants, often leading to exit from public rental housing.

For those who then slept rough, conditions of rough sleeping were harsh and meeting basic needs remained difficult. Meals and safety were not guaranteed, which often had detrimental impact on physical and mental health. For female rough sleepers, as safety was of particular concern, they would often sleep in public places with security officers in view or other members of public around.

While the pandemic saw an unprecedented level of state and community resources utilised to provide support to those experiencing housing insecurity, there were also lessons to be learnt.

Firstly, the efficient mobilisation of frontline officers at the height of COVID-19 showed the efficacy of a consistent whole-of-government approach in responding to homeless persons when they interact with government agencies. Secondly, exit from homelessness depends on accessible and adequate housing options. This requires us to put in place fairer eligibility requirements and better rental housing conditions for those most vulnerable to homelessness. Thirdly, for income security, recently announced plans to extend wage protection for lowincome workers must be closely watched. Fourthly, provisions of public financial assistance must account for health needs, and the additional needs of those unable to find work because of health issues. Finally, ongoing research that feeds into policymaking must account for different forms and levels of housing insecurity, and not just rough sleeping alone.

Homeless during the COVID-19 pandemic in Singapore

Featured Faculty

Ng Kok Hoe

Senior Research Fellow, Head of Case Insights Unit & Social Inclusion Project

Research Areas:

• Ageing and poverty

• Community-based social interventions

• Old-age pensions and income security

• Public housing policy

• Social housing

Featured Faculty

Jeyda Simren

Sekhon Atac

Former Research Assistant in the Social Inclusion Project

Between February and April 2021, researchers from the Social Inclusion Project carried out Singapore’s second nationwide homelessness street count. This was the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic and a time when homelessness spiked in many countries due to an increase in unemployment, poverty and evictions. The aim of the study was to capture the state of homelessness in Singapore in this exceptionally challenging time. As a follow-up to the first nationwide street count in 2019, it draws methodological lessons from the earlier study and extends the line of enquiry through three research strategies in 2021:

1

2

Nationwide street count using the same cumulative count method as in 2019.

Combination of administrative data on temporary shelter occupancy with street count figures to produce, for the first time, an estimate of the total homeless population.

3

In-depth qualitative interviews with shelter residents to document long-term experiences of homelessness and housing insecurities during the pandemic.

Street homeless figures are based on nationwide street counts conducted in 2019 and 2021. Shelter figures are averages of month-end occupancy numbers in each period provided by MSF

Findings from street count and shelter data

Despite intense state intervention and massive economic disruptions during the pandemic, the scale of homelessness did not change significantly between 2019 and 2021. The combined street homeless and temporary shelter populations declined by just 7 per cent, from 1,115 before COVID-19 to 1,036 in 2021.

However, the form of homelessness had changed, because primary homelessness declined and secondary homelessness rose. The number of street homeless persons dropped 41 per cent, from 1,050 in 2019 to 616 in 2021. Meanwhile, occupancy in temporary shelters increased more than sixfold, from 65 to 420.

Considering strict regulations about residing indoors during the circuit breaker and greater public watchfulness about people sleeping in common spaces, the sharp decline in street homelessness was expected. Meanwhile, growing shelter occupancy reflects the dramatic initial expansion of shelter capacity in response to large numbers of homeless people seeking help around the time of the circuit breaker, followed by a steady rate of exits from the shelters after that period.

Analysis of the street count data found that the situation in 2021 was comparable to 2019 in several ways:

• Street homelessness remained geographically widespread and was observed in all 25 districts covered by the study.

• There was close correlation in the geographical distribution of street homelessness. Higher-count districts in 2019 continued to account for more homeless persons in 2021.

• More street homeless persons were found in larger, older and poorer neighborhoods.

• The most common profile was older Chinese men.

The main deviation is a deconcentration of homelessness from the City district to residential districts. Although the City district still accounted for the largest number of homeless persons, its share of the total fell from 23 per cent in 2019 to 12 per cent in 2021. Instead of commercial buildings, homeless persons were also more likely to be found in locations within residential neighbourhoods.

ENVIRONMENT & SUSTAINABILITY

As we look back at the discussions over the last two decades, we reflect on whether the global conversations are tackling issues related to the environment, such as climate change and sustainability, seriously enough. Despite growing awareness and numerous international agreements, the pace of change often falls short of what is necessary to avert catastrophic consequences. The urgency of the situation demands action that is both immediate and far-reaching.

The articles in this section encapsulate both the urgency and the opportunities inherent in tackling one of the greatest challenges of our time. From the devastating trajectory of climate-related disasters to the innovative policy responses necessary to counter them, the conversation is rich, complex, and essential.

In “Climate Action Must Be Part of National Plans” (Jan, 2017), the authors vividly illustrate the alarming rise in climate-related disasters and their far-reaching economic and social impacts. The analysis underscores the need for nations to mainstream climate mitigation and disaster risk management into economic planning. The article calls for valuing natural capital, rethinking economic models, and transitioning to low-carbon economies through concerted global and local efforts. This approach is especially critical for Asia-Pacific nations, where urbanisation and geographical vulnerabilities intensify the stakes.

Meanwhile, “Why Singapore’s Climate Policies Are Likely to Be Durable and Effective” (May 2024) offers a compelling case study of Singapore’s innovative and anticipatory policy designs. From the Singapore Green Plan 2030 to the progressive carbon tax and pioneering climate finance mechanisms, the article highlights how foresight and meticulous governance enable the city-state to chart a sustainable path. Singapore’s success is not merely in policy innovation but in integrating technical expertise with trust and legitimacy, offering valuable lessons for global climate governance.

As we delve into these articles, it becomes clear that addressing climate change demands more than technological advances or financial investment. It requires a paradigm shift in policymaking — one rooted in long-term vision, inter-disciplinary collaboration, and a commitment to equity and resilience.

Small states like Singapore play a crucial role in driving the conversation on climate change. While it may seem that larger nations bear the brunt of responsibility, small states can lead by example, demonstrating that sustainable practices are achievable and beneficial. Singapore, with its innovative approaches to urban planning, water management, and green technology, serves as a model for others. By investing in renewable energy, reducing waste, and promoting green buildings, small states can significantly impact global sustainability efforts.

Despite growing awareness and numerous international agreements, the pace of change often falls short of what is necessary to avert catastrophic consequences. The urgency of the situation demands action that is both immediate and far-reaching.

Climate Action must be part of national plans

As president country, China can help the BRICS bloc deepen cooperation to meet global challenges and uncertainties.

Featured Faculty

Vinod Thomas Former Visiting Professor

GLOBAL-IS-ASIAN

Climate-related disasters are on an alarming trajectory. Great floods in China, India and Thailand, super storms in the Philippines and the United States, and summer heat waves in the Northern Hemisphere in recent years are manifestations of this trend.

The 2010s may well go down as the decade when the trendline of these events headed aggressively north after a noticeable rise in their intensity and frequency since the 1970s. The underlying link to all this is climate change.

Scientists have been cautious about linking a particular climatic episode to climate change, but they are now beginning to attribute extreme weather in various instances to climate change. For example, scientific evidence points to global warming for making Japan’s unusually hot summer this year 1.5 to 1.7 times more likely. A consensus, too, is building that climate change has roots in human actions that not only influence people’s exposure and vulnerability to

calamities but also the intensity and frequency of the hazards themselves.

This understanding will profoundly affect how countries handle disaster risk reduction, requiring climate mitigation be given far greater prominence. But the implications are much wider. Climate change will alter the very economic models being used to promote strong and sustained economic growth, as countries strive to leave a lighter carbon footprint.

To do this, policymakers will need good data and forecasting techniques to plan for lower-carbon growth. Right now, however, few of the forecasts being made by government and private think tanks for global and country-level growth take into account the impacts of climate change that are already evident, or the massive investment and resources that will need to be mobilised for climate action. Such forecasting is needed for a truer picture of short and long-term growth prospects. And it is certainly missing from the current estimates for global growth of around 3.0–3.5 per cent in 2017, and 5.5–6 per cent for Asia and the Pacific.

Climate change will threaten the economic performance of countries just as surely as the 2008-2009 global financial crisis did. Floods and storms in recent years inflicted sizable economic losses in Australia, China, Indonesia, South Korea, Thailand and Vietnam. After the financial crisis, governments and multilateral institutions intensified their efforts to anticipate future crises, carrying out stress tests of the vulnerability and resilience of their banking systems, as the Bank of England did in 2016. In the same way, we now need stress tests of how well countries can withstand the impact of rising natural disasters.

The Sustainable Development Goals and the Paris agreement on climate change showcase the importance of a less environmentally-destructive pattern of growth and climate action. For that, we need to value all three forms of capital — physical, human and natural. Government spending and private investment have long been skewed towards the first two forms of capital, with natural resource management getting short shrift in development programmes.

Yet, a country’s natural capital — its stock of natural assets — is essential for the pace and quality of growth. Estimates of growth rates that take into account the destruction of natural capital are far lower than those that do not. With the rising climate threat, sustainable land use and agricultural practices, and forest and coastal management, need far greater emphasis, for instance, in South-east Asia.

Valuing natural capital also means that countries must commit to phasing out the use of fossil fuels that present the greatest danger to our environment. International agreements to transition to lower-carbon economies and to mitigate climate change are putting the world on the right course, but unilateral country actions are also essential. Global actions will not suffice for the highest-risk countries, many of which are located in Asia and the Pacific region.

A country’s own actions have a great rationale, especially when local gains are clear. When it comes to pollution control, there is an overlap between the global and local good. Reducing black carbon emissions that blight so many cities such as Beijing and New Delhi is a case in point.

“Climate change will alter the very economic models being used to promote strong and sustained economic growth, as countries strive to leave a lighter carbon footprint.”

India and Indonesia recently slashed fossil-fuel subsidies, a politically courageous move that requires confronting opposition from powerful interest groups. Reducing these subsidies, amounting to some US$500 billion, needs to become widespread. Investments in solar photovoltaics in China and Japan, and in onshore wind energy across Europe, are pointing the way for increased use of renewable energy.

The five cities most vulnerable to natural hazards are all in Asia: Bangkok, Dhaka, Jakarta, Manila and Yangon. All of them are overcrowded and in geographically fragile settings. Asia’s growth has been characterised by increasing urbanisation, making it imperative that climate-friendly urban management becomes a strategic thrust in growth plans. And because the poor are hit harder by the effects of climate change than the rest of the population, building resilient communities will be an essential element of poverty reduction strategies.

The overriding message is that the mindset that natural disasters are oneoff occurrences rather than a systemic

problem must change. Disaster risk management needs to be understood as an investment, going beyond relief and reconstruction to a dual approach of prevention and recovery. Japan invests some 5 per cent of its national budget in disaster risk reduction, and this has been shown to reduce human and economic losses when disasters strike.

High returns on preventive efforts are also evident even where the total spending is not as high as in Japan. In the Philippines, the effects of flooding in Manila after heavy monsoon rains in August 2012 contrasted strongly with the devastation caused by Tropical Storm Ketsana in 2009, after the authorities instituted preemptive evacuations and better early warning systems.

The new development paradigm, if it is to deliver sustained growth and prosperity, needs to value natural capital, recognise the human hand in climate change, and take preventive action against climate-related calamities.

Why Singapore’s climate policies are likely to be durable and effective

Featured Faculty

Benjamin William Cashore

Li Ka Shing Professor in Public Management and Director, Institute for Environment and Sustainability (IES)

Research Areas:

• Comparative Policy Analysis

• Corporate Social Responsibility

• Environment and Climate Change

• Global Environmental Governance

• Private Governance

• Public Management

“I have been studying global environmental governance for over three decades. What struck me when I moved here four years ago was the dizzying array of domestic and global climate and sustainability initiatives that the Singapore Government was in the middle of unleashing. Many of these efforts have been shepherded through the Singapore Green Plan 2030, which details the country’s path towards meeting its Paris Agreement commitments.”

This journey includes a progressive carbon tax — the first of its kind in South-east Asia — as well as climate adaptation through coastal protection and flood resilience.