Chapter 1 Introduction

In an era increasingly shaped by technological innovation, heritage both tangible and intangible is being reimagined through digital tools. From 3D laser scanning and Building Information Modelling (BIM) to Virtual Reality (VR), Augmented Reality (AR), immersive media, and even video games, the ways in which we access, interpret, and interact with heritage have expanded dramatically. These tools are not merely enhancing preservation; they are fundamentally reshaping our perception of heritage’s social, historical, and commercial value. This research critically explores the central question: how are new digital tools changing our perception and experience of heritage?

Three interrelated themes emerge in response to this question.

First, digital technologies increase the affection, visibility, and accessibility of heritage. They make previously remote or fragile sites viewable in high-definition detail from anywhere in the world, allowing broader audiences to engage with heritage in meaningful ways. This visibility fosters new forms of emotional and cultural connection, especially among digitally native generations.

Second, these technologies have made heritage easier to reproduce, simulate, or even remix, which invites debate about the authenticity and authority of digital reconstructions. While reproduction can democratize knowledge and preserve endangered heritage, it also risks reducing complex cultural artefacts to consumable and sometimes commodified experiences.

Finally, digital heritage generates new forms of emotional attachment and interaction, as immersive environments provoke visceral, embodied reactions not commonly associated with traditional museum or archive visits. These reactions often blur the line between past and present, user and subject, rendering heritage a lived experience rather than a distant memory.

The central research question of this study is: How are new digital tools changing our perception and experience of heritage? This question necessitates a multidisciplinary exploration of heritage through the lenses of architecture, technology, sociology, and economics. On a social level, digital heritage facilitates emotional engagement and collective memory. On a historical level, it ensures the preservation and documentation of at-risk or damaged structures. Commercially, it creates new opportunities for tourism, gaming, education, and branding. Each of these dimensions is essential for understanding the value digital tools add to heritage in the 21st century.

Several emerging technologies have already begun reshaping our interaction with heritage. For instance, immersive exhibitions such as those developed by the Louvre and the British Museum allow visitors to explore ancient ruins through interactive digital displays and VR headsets12. Video games like Assassin’s Creed Origins, which recreated ancient Egypt based on archaeological evidence, have popularized the concept of "playable heritage" and expanded historical awareness through gamification3. Meanwhile, open-access online

1 Louvre Museum. Mona Lisa: Beyond the Glass.

2 Smith. Uses of Heritage:

3 Ubisoft. Discovery Tour: Ancient Egypt

archives, such as UNESCO’s Digital Archives platform, provide remote access to endangered documents and artefacts, fostering global scholarly collaboration and public learning4

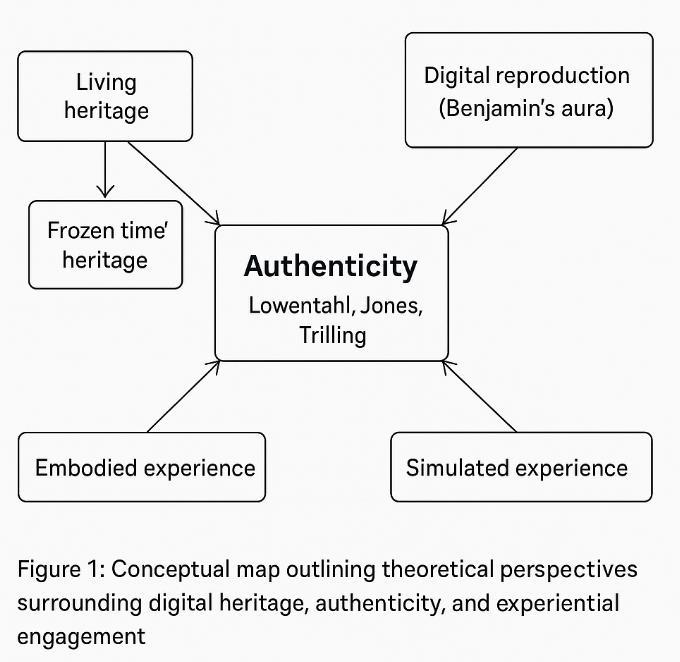

Above all, the concept of authenticity has become a focal point in the debate surrounding digital heritage. To better illustrate how the authenticity is being preserved and challenged by the digitalization, Traditional conservationists argue that a digital replica cannot replace the materiality and context of a real structure5. However, others suggest that digital heritage may constitute a form of heritage in its own right, especially when the original is lost due to war or decay6 . On a deeper level, it shows deeper questions as to how society values cultural artifacts, and if emotional, symbolic, and experiential aspects are equal to physical presence.

This research stems from one of the major motivations of the research itself, that is, the rising vulnerability of heritage sites, especially in areas that are bathed in violence and/or developing lands. As an example, in Syria or in Afghanistan, historical monuments have been damaged or destroyed by the war, which is raising a global level of concern for the loss of identify. Both CyArk and UNESCO have begun using 3D laser scanning and drone photography to develop digital archives of these endangered sites78. Firstly, such efforts help preserve information for future generations, and secondly, they help with future restoration projects. Digital heritage is thus a tool between memory and resilience.

This research further argues that digital heritage does not only serve as a tool of conservation but also as a site of conflict. Consequently, it is a product of contradictory imperatives: memory vs marketability; access vs control; authenticity vs innovation. For instance, while the National Digital Preservation (NDP) model provides a strategic, systematic approach to securing the shelf life of digital archives, it also subconsciously predetermines how the heritage is saved and catalogued, favouring the dominion over community memory of an institution. Immersive simulations and virtual heritage environments have recently been used in the realms of education and have shown promise in promoting deep learning with regards to architectural history and cultural context9. On the other hand, such applications present a problem in regard to pedagogical ethics of teaching 'place' without embodiment and 'culture' without lived experience.

These dynamics complicate further the commodification of digital heritage. With the onslaught of the COVID-19 pandemic, virtual heritage tours, online exhibitions and gamified experiences have proliferated, creating new revenue streams for museums and governments while shifting public perception on what heritage is and how it should be consumed10. Mobile AR apps or historically inclined video games give younger audiences the opportunity to learn cultural narratives without trying to, by making border between education and entertainment blurry. But in doing so, this playfulness can trivialise trauma, aestheticise conflict, or reduce the sacred places to pixelated spaces to be navigated.

4 UNESCO. UNESCO Digital Archives

5 Sally M. Foster and Sian Jones, “The Untold Heritage Value and Significance of Replicas,”

6 Enrico Bertacchini and Federico Morando, “The Future of Museums in the Digital Age,” 161.

7 CyArk. Mission and Projects

8 Sin-wai, C., Kin-wah, M., & Ming, L. S. (2024). Routledge encyclopedia of technology and the humanities Routledge.

9 Alonzo Addison, “Emerging Trends in Virtual Heritage,”

10 Brendan Ciecko, “Virtual Reality and Digital Heritage during COVID-19.”

With the aim to understand the multiple dimensions of value of digital heritage, this research will consider three case studies: (1) preserving war damaged sites in Syria, (2) reviving Afghanistan’s architectural landmarks and (3) the use of immersive digital tools in the educational environment through the NDP model. Through each case, technology will be shown to increase visibility, emotional connection and sustainability of heritage even as it brings up ethical questions such as replication, ownership, and authenticity.

The research will be methodologically conducted using this qualitative approach, including document outline, Digital project analysis, and comparative case study. It is to examine what we do, not simply understand the technologies and practices but also these means within a socioeconomical and emotional framework: how they could influence the perception and the institutionalize of the public. This process will further the understanding of why digital heritage reconfigures our relationship with the past and why it should be strategically harnessed into conservation, education, and have cultural industries. This dissertation contributes original insight by foregrounding the emotional, ethical, and pedagogical implications of digital heritage, rather than focusing solely on technological innovation. It situates digital tools not just as methods of preservation, but as active agents in reshaping how heritage is perceived, experienced, and valued. By drawing out tensions between authenticity and reproduction, simulation and embodiment, education and commodification it reframes digital heritage as a contested cultural field rather than a neutral solution. Unlike existing literature that often celebrates digital access or laments the loss of “aura,” this study explores the grey zones where digital reconstructions evoke both connection and critique. Through comparative case studies including Notre-Dame’s digital resurrection this research reveals how digital heritage can become a space of affective engagement, ethical negotiation, and cultural redefinition. The dissertation thus adds a nuanced, interdisciplinary perspective that challenges binary narratives and calls for more critical reflection in heritage discourse.

The central idea of this document is that digital heritage is not a passive recapitulation of the past, but a constitutive recreation of cultural memory. It dictates how we remember, by whom, and what. It is an extension into time and space of heritage beyond the temporal and spatial dimensions known historically but, at the same time, it raises issues of new ethical, ontological, and epistemic challenges. With increasing integration of digital heritage into conservation and cultural policy and education, it is imperative to ask: what do we preserve, for whom and at what cost?

These researches ultimately seek to illuminate both the transformative potentials and contentious terrains of digital heritage. The study draws on critical examination of discourses and projects about the real world in order to deepen our understanding of how digital tools are reshaping these relationships (both in form and in meaning, value and practice).

2.1. Introduction

The digital revolution has profoundly transformed how cultural heritage, particularly architectural heritage, is documented, preserved, and interpreted. As heritage sites face increasing threats from urban development, environmental degradation, and conflict, the use of digital technologies has emerged as a significant means of conservation and engagement.11 This literature review explores key academic discussions surrounding digital heritage, architectural preservation, and the theoretical constructs of cultural memory and authenticity that underpin contemporary practices.

2.2. Digital Heritage: Concepts and Approaches

Digital heritage exists as the application of digital technology toward preserving as well as interpreting and distributing cultural materials that include both tangible and intangible heritage items. According to the UNESCO Charter on the Preservation of Digital Heritage 2003, digital heritage encompasses "resources of human knowledge and expression" that are created digitally or converted to digital form.12 Among the digital heritage tools are digital reconstructions in addition to virtual reality (VR) environments and 3D models and GISbased mapping applications.

According to Champion digital heritage exceeds mere digitization because it enables users together with experts to develop stories and interactions which promote enhanced comprehension.13 For instance, through virtual models of ancient cities like Rome and Palmyra researchers gain academic opportunities while global users across the world achieve heritage accessibility despite their physical distance.14 Digital media has provoked public discourse about narrative control because of rising participatory heritage activities according to Chiara Bonacchi, Mark Altaweel, and Marta Krzyzanska.15

Digital heritage also plays a crucial role in risk preparedness. Projects such as CyArk’s digital documentation of at-risk heritage sites use laser scanning and photogrammetry to create resilient digital archives.16 These methods offer a form of "digital insurance" BentkowskaKafel, Denard and Baker describe this process as "digital insurance which maintains architectural data from destruction by natural disasters and political turmoil.17

11Alonzo Addison, “Emerging Trends in Virtual Heritage,”

12 UNESCO World Heritage under threat

13 Champion. Critical Gaming:

14 Maurizio Forte, Virtual Archaeology: Reconstructing the Past through Immersive Technologies

15 Chiara Bonacchi, Mark Altaweel, and Marta Krzyzanska, “Digital Heritage Research Re-Theorised: Ontologies and Epistemologies in a World of Big Data,”

16 CyArk. Mission and Projects

17 Baker, Drew, Anna Bentkowska-Kafel, Hugh Denard, and John Beardsley. "Alfano, Veronica and Andrew M. Stauffer, eds. Virtual Victorians: Networks, Connections. 117.

2.3. Architectural Preservation in the Digital Age

Architectural preservation has traditionally relied on physical conservation techniques. However, digital technologies have increasingly been integrated into preservation strategies, providing new methodologies for recording, analysing, and disseminating architectural heritage. 3D scanning, Building Information Modelling (BIM), and Augmented Reality (AR) have become essential tools in modern preservation practice.18

Digital reconstruction of historic structures such as the Parthenon or Notre-Dame Cathedral allows for both visualisation and hypothetical restoration, addressing the temporal and physical limitations of traditional preservation.19 Moreover, such reconstructions can simulate various historical epochs, enabling comparative and evolutionary analyses of architectural styles and techniques.20

BIM, in particular, offers a dynamic way to model heritage buildings with embedded historical data and metadata. According to Murphy, McGovern and Pavia, Heritage-BIM (HBIM) achieved development for integrating historical information within digital models which strengthens heritage preservation activities while broadening their educational reach.21

These technologies face various critical challenges that obstruct their smooth implementation. The long-term usefulness of digital records faces challenges caused by data precision problems together with high implementation costs and the need for extended digital storage solutions and the risk of technological system decay.22 Furthermore, debates persist about whether digital replicas can ever fully substitute the ‘aura’ of the original Benjamin, a concern that leads into broader theoretical discussions of authenticity and cultural memory.23

2.4. Theoretical Frameworks: Cultural Memory and Digital Mediation

The notion of cultural memory provides a valuable theoretical lens through which to understand the role of digital heritage in architectural preservation. Assmann, defines cultural memory as the collective understanding and transmission of knowledge, identity, and heritage across generations.2425 In this context, architecture functions as a tangible vessel of memory, encoding cultural values and historical narratives within physical space.

Digital representations of architecture, then, can act as new repositories of cultural memory. As Holtorf argues, digital media allow for the "mediation of memory," whereby archived visuals, texts, and simulations construct a collective remembrance that transcends physical location.26 The accessibility and interactivity of digital heritage platforms enhance the

18Ibid.

19 Lefteris Kastanis, Authenticity in Digital Archaeological Reconstructions:

20 Yastikli, Naci. "Documentation of cultural heritage using digital photogrammetry and laser scanning." 437\

21 Maurice Murphy, Eoin McGovern, and Sara Pavia, “Historic Building Information Modelling (HBIM),”

22 Jeffrey. Challenging heritage visualisation

23 Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,”

24 Jan Assmann, “Collective Memory and Cultural Identity,”

25 Jan Assmann, Cultural Memory and Early Civilization: Writing, Remembrance, and Political Imagination

26 Cornelius Holtorf, “On Pastness: A Reconsideration of Materiality in Archaeological Object Authenticity,”

participatory dimension of memory-making, allowing diverse audiences to engage in dialogue with the past.27

However, this digitization also introduces tensions. Critics such as Nora warn against the "outsourcing" of memory to external devices, arguing that digital archives may commodify heritage and diminish its lived, experiential dimension.28 This concern is echoed by Smith, who critiques the "Authorised Heritage Discourse" (AHD), suggesting that institutionalised forms of digital documentation may impose rigid narratives, marginalising alternative or subaltern voices.29

2.5. Authenticity in Digital Heritage

The concept of authenticity is central to debates on digital heritage. Building maintenance policies over the past fifty years often start from authentic material qualities of constructions as specified in heritage documents such as the Venice Charter from 1964. However, the rise of digital heritage necessitates a more nuanced understanding. The authors Jones and Yarrow assert that authenticity needs to extend beyond physical elements to include elements of social structures and emotional character in addition to performance aspects.30 Digital reconstructions develop their own forms of authenticity when they demonstrate accurate historical legacy combined with accurate aesthetic attributes and accurate symbolic meanings of heritage sites. Virtual reality systems enable discussions of

27 Elisa Giaccardi, ed., Heritage and Social Media: Understanding Heritage in a Participatory Culture

28 Nora, Pierre. “Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire.” Representations 26 (1989): 7.

29 Smith , Laurajane. Uses off Heritage.

30 Siân Jones and Thomas Yarrow, “Crafting Authenticity: An Ethnography of Conservation Practice,” (2013)

ancient rituals or public events that allow users to experience intangible cultural aspects through multisensory immersion.31

People continue to express uncertainty about how digital representations compare to authentic reality. The argument based on Baudrillard’s simulation theory, asserts that digital copies could produce false authentication perceptions which obscure reality from reconstruction.32 The ethical problems surrounding authorship definition together with interpretation and historical accuracy become major issues thanks to the work of Denard.33

People engaged in digital heritage work need to document their reengineering sources alongside methods and restrictions according to both the London Charter 2009 and the Seville Principles 2011.34 A digital artifact attains “discursive authenticity” Graham when it uses its ability to encourage well-informed critical analysis as its primary value instead of attempting illusionistic realism.35

2.6. Integration of Theory and Practice

The interplay between theory and practice is increasingly evident in interdisciplinary heritage projects. For instance, the EU-funded INCEPTION project (2015–2019) integrated HBIM with semantic web technologies to enable inclusive access to cultural heritage, embedding user-generated content and personal narratives within digital reconstructions.3637 Such initiatives demonstrate how theoretical frameworks like cultural memory and authenticity can inform the design of technologies that are socially responsive and epistemologically transparent.

Moreover, the convergence of digital heritage and architectural preservation aligns with broader shifts in museology and heritage studies toward more inclusive, dialogic, and participatory practices.38 This signals a paradigmatic shift from preservation as a purely technical endeavour to one that is also ethical, social, and political.

Chapter 3 Digital Interventions and Their Impact on Architectural Heritage

3.1 Technology in Heritage Preservation: BIM, VR/AR, and Immersive Media

The incorporation of digital technologies such as Building Information Modelling (BIM), Virtual Reality (VR), Augmented Reality (AR), and immersive media has increasingly transformed the way cultural heritage is documented, preserved, and experienced. In particular, BIM has been regarded as an indispensable instrument for architectural heritage

31 Louvre Museum. Mona Lisa: Beyond the Glass

32 Jean Baudrillard, “Simulacra and Simulations (1981),”

33 Hugh Denard, “A New Introduction to the London Charter,”

34 Ibid

35 Brian Graham, “Heritage as Knowledge: Capital or Culture?”

36 Mincolelli, Giuseppe, G. I. A. N. Giacobone, Silvia Imbesi, and Michele Marchi. "Inception. Inclusive (2020).

37 INCEPTION: Inclusive Cultural Heritage in Europe through 3D Semantic Modelling

38 Simon Nina. The Participatory Museum

conservation since it makes it possible to produce very detailed 3D models and store metadata that illustrate historical building structures and materials. In this regard, the research by Murphy, Maurice, Eugene McGovern, and Sara Pavia. proves the role that BIM plays in doing accurate preservation planning by merging architectural structure data with its structural and material details in a dynamic model. By using digital reconstructions, restoration management planning can be used and architectural and conservation specialists, archaeologists and other scholars can cooperate multi-dimensionally.

Virtual, Augmented Reality provide new dimensions for heritage interpretation, and public engagement. By constructing immersive environments users have the possibility to experience past forms and cultural landscapes inaccessible due to deterioration or destruction. The immersive storytelling offered by the VR/AR leads to a more presence and empathy experienced, which hyperbolizes user engagement with historical narratives: Champion.39 It allows for the reconstruction of ancient sites such as the Roman forum or Pompeii through VR technologies, where in traditional museum exhibitions cannot be fully reproduced, audiences walk through temporally accurate reconstructions that can almost never be experienced.40

Platforms such as Ubisoft’s Assassin’s Creed: Discovery Tour mode are an example of how accurate digital reconstructions of historical cities can be incorporated into mainstream popular entertainment within the domain of video games and gamified heritage. Historical research is combined with interactive technologies in these representations and thus provides users with opportunities for educational engagement in informal and exciting settings. Mol, Angenitus Arie Andries, Csilla E. Ariese-Vandemeulebroucke, Krijn Boom, and Aris Politopoulos, argue that such digital environments encourage historical literacy of younger audiences and the design of cultural heritage through experiential design.41

Democratizing cultural access has spurred on immersive media including 360 degree videos, mixed reality installations and digital projections. These technologies have been adopted by institutions such as the British Museum and the Smithsonian who have used them to create virtual environments in which the audiences can access artifacts and architectural spaces in remote, virtual conditions, especially during such periods in which physical access was restricted.42

However, their arrival carries with it both innovation and major problems: authenticity, historical accuracy, and bias from the curator. For reconstructions based on data, often there are speculative additions thrown in. However, Gillings exposes how we can create such reconstructions which can be dangerous if these reconstructions are being used as authoritative, hence creating misleading historical interpretations.43 Therefore, digital heritage projects should, therefore be transparent about assumptions, methodologies and design choices so as to achieve scholarly accountability and user awareness.

39 Erik Champion, “Applying Game Design Theory to Virtual Heritage Environments,”

40 Mulugeta K. Bekele et al., “A Survey of Augmented, Virtual, and Mixed Reality for Cultural Heritage,”

41 Angela A. A. Mol et al., The Interactive Past: Archaeology, Heritage & Video Games

42 Erik Champion, Rethinking Virtual Places

43 Mark Gillings, “Landscape Phenomenology, GIS and the Role of Affordance,”

Chapter4 Research Methodology

4.1

Research Approach

This study adopts a qualitative, interpretive research approach to critically examine how new digital tools are transforming public perception and experience of architectural heritage. Rather than measuring quantifiable outcomes, this research explores the socio-cultural and affective dimensions of digital heritage through case studies, theoretical literature, and contextual analysis. The focus is not solely on technological application but on how these tools shape meanings, emotions, and ethical relationships with the past.

The methodology is grounded in critical heritage studies and digital humanities frameworks, which position heritage as a socially constructed and politically mediated process.50 Within this lens, digital heritage is not just a technical artefact but a site of cultural negotiation raising questions about authenticity, authority, access, and value.

4.2

Case Study

To explore how digital technologies, reshape heritage experience, the study employs a comparative case study design, incorporating three carefully selected examples that reflect diverse yet interconnected applications of digital heritage.

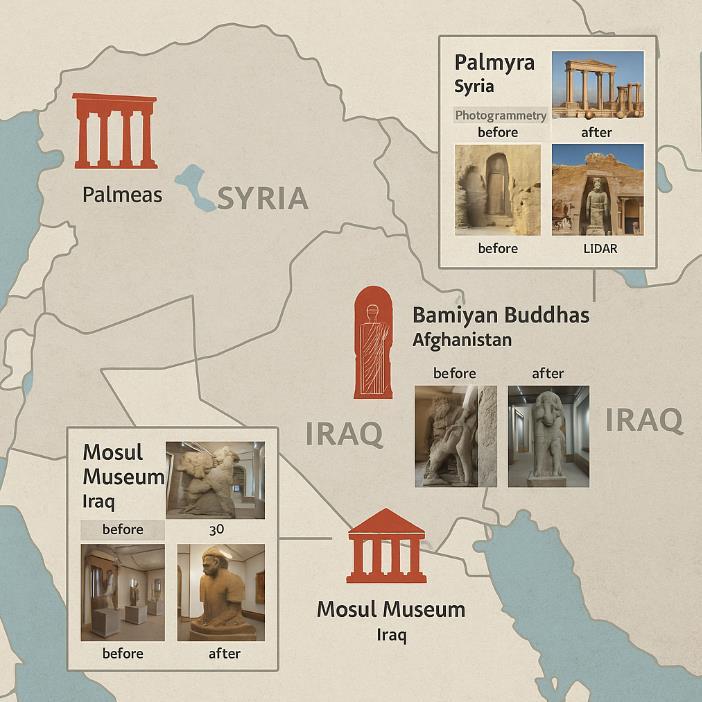

1. Case Study 1: Palmyra, Syria – Heritage at Risk

This case investigates how 3D modelling and photogrammetry were used to digitally reconstruct the ancient city of Palmyra following its destruction by ISIS in 2015. It explores how digital surrogates function as tools of memory, global awareness, and symbolic restoration.

2. Case Study 2: Buddhas of Bamiyan, Afghanistan – Cultural Loss and Digital Representation

Focuses on the 3D and virtual reconstructions of the Buddhas after their destruction by the Taliban. It critically examines issues of authenticity, institutional power, and the ethics of digital preservation when local voices are marginalised.

3. Case Study 3: Notre-Dame de Paris – Digital Resurrection and Experiential Heritage

Analyses how immersive technologies, including 3D scans, VR simulations, and game environments (e.g., Assassin’s Creed Unity), transformed Notre-Dame into a globally accessible digital experience after the 2019 fire. The case highlights tensions between emotional engagement, authenticity, and commodification in digital heritage.

Together, these cases offer contextual variety ranging from post-conflict reconstruction to digital spectacle and enable cross-analysis of how digital tools affect public understanding, emotional connection, and perceptions of authenticity.

4.3

Methods of Data Collection

Data is drawn from three interconnected methods: document analysis, digital archives, and multimedia reviews.

50 Elisa Giaccardi, ed., Heritage and Social Media: Understanding Heritage in a Participatory Culture

1. Document Analysis

This includes formal reports, international conventions (e.g., The Hague Convention), humanitarian policy documents, mission statements from NGOs, and strategic evaluations by organizations such as UNESCO, UNHCR, and the World Bank. For Syria and Afghanistan, post-conflict assessment reports and field evaluations are central sources. For the NDP Model, policy frameworks, stakeholder agreements, and educational development plans are reviewed.

2. Digital Archives

Archives such as ReliefWeb, the UNESCO Observatory of Destroyed Cultural Heritage, and Open Access Afghanistan provide timely and historical records on cultural destruction, humanitarian interventions, and reconstruction efforts. Visual and interactive databases, such as Google Arts & Culture’s Syria initiative and the Digital Silk Road archive, are consulted for mapping heritage loss.

3. Multimedia Review

A curated review of films, interviews, online exhibitions, humanitarian campaign videos, and educational webinars is conducted to capture public and institutional narratives. This is particularly useful in assessing how crises are represented, how audiences engage with cultural loss, and how recovery initiatives are communicated. For example, video documentation of the destroyed Aleppo souk or community storytelling projects in Kabul provide alternative voices often excluded from official reports.

All sources are thematically coded using a qualitative data analysis tool (e.g., NVivo), allowing the researcher to identify key patterns, discursive contradictions, and evolving interpretations across the three cases.

4.4 Case Study

4.4.1 Case Study 1: Syria – Heritage at Risk Facing War

4.4.1.1 Description of Threatened Heritage

Syria is home to some of the most ancient and diverse cultural heritage in the world, including archaeological sites, religious monuments, traditional architecture, and intangible cultural practices. The country’s long history as a cradle of civilisation has left behind remarkable cultural landmarks such as the ancient city of Palmyra, the Old City of Aleppo, the Umayyad Mosque, and the Crac des Chevaliers. These sites embody not only the local and national identity of Syria but also carry global cultural significance, having been inscribed as UNESCO World Heritage Sites due to their outstanding universal value.51

51 UNESCO. World heritage under threat.

Figure 2. Palmyra, the Old City of Aleppo, the Umayyad Mosque,

However, since the outbreak of civil war in 2011, Syria’s heritage has come under severe threat. Armed conflict, political instability, and targeted attacks by extremist groups such as ISIS have resulted in the destruction, looting, and illegal trafficking of cultural artefacts. Notably, the ancient city of Palmyra once a flourishing trade hub in the Roman Empire suffered immense damage between 2015 and 2017 when ISIS destroyed the Temple of Bel, the Arch of Triumph, and numerous other monuments.52 Similarly, Aleppo, one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world, saw widespread devastation, including the burning of its famed souks and the destruction of the Umayyad Mosque’s minaret.53

Such loss foregrounds a critical dimension of digital heritage: when the physical is destroyed, what remains of our relationship with the past? This case illustrates how perception of heritage is transformed in response to violence and absence, demanding new tools for preservation and meaning-making.

4.4.1.2 Role of Digital Tools in Preservation and Global Visibility

On the other hand, digital technologies have evolved into powerful tools for documentation, preservation and dissemination of Syria’s cultural heritage, in response to these threats not only in preserving knowledge, but in reframing how we experience endangered heritage remotely.

The Syrian Heritage Archive Project is one of the most prominent and represents a work of collaboration between the Museum of Islamic Art and the German Archaeological Institute. Part of the project has been to create a digital archive of over 150,000 photographs, architectural plans, and historical papers concerning Syrian heritage sites.54 The digital records act as important blueprints for subsequent restoration efforts, and are an academic resource for researchers, heritage professionals and policymakers.

52 Salam Al Quntar and Brian Daniels, “Responses to the Destruction of Syrian Cultural Heritage,” 227.

53 Jesse Casana, “Satellite Imagery-Based Monitoring of Archaeological Site Damage in the Syrian Civil War,”

54 Schäfer, Erich. Lebenslanges Lernen. Berlin: Springer Berlin Heidelberg,

Figure 3: 3D reconstruction of the Arch of Triumph in Palmyra

Culturally, digital storytelling and VR have also reconnected Syrian refugees to lost sites through diaspora engagement platforms. This redefines heritage not as static ruins, but as lived, affective memory deepening emotional connections even in displacement.58

However, digital preservation introduces new frictions. Replicas may preserve form, but not materiality, ritual, or sacred meaning. Questions of data ownership, platform control, and digital colonialism remain unresolved especially when reconstructions are mediated through Western institutions.59 Perception is shaped not only by what is represented, but by who controls the narrative.

Thus, Syria reveals both the potential and paradox of digital heritage: it preserves cultural memory in crisis, reshapes public experience, and reframes loss as resistance but only when inclusively designed and ethically implemented

4.4.2 Case Study 2: Afghanistan (Cultural Loss and Recovery)

The destruction of cultural heritage in Afghanistan, particularly the obliteration of the Bamiyan Buddhas by the Taliban in 2001, is one of the most devastating instances of cultural loss in recent memory. Carved in the 6th century, these monumental statues once stood as emblems of Afghanistan’s Buddhist past and were globally recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Their destruction, widely condemned by the international community, marked a turning point in global awareness of the fragility of heritage under ideological and military threat.

58 Lynn Meskell, A Future in Ruins: UNESCO. 2018.

59 David I. Jeffrey, “Relational Ethical Approaches to the COVID-19 Pandemic,”

Figure 5: 3D reconstruction of the Arch of Triumph in Palmyra

4.4.2.1

Digital Tools and the Reimagining of Heritage

In response, digital technologies have redefined how heritage can be preserved and experienced. Projects by the Institute for Digital Archaeology (IDA) and UNESCO employed 3D modelling, drone imagery, and archival data to reconstruct the Buddhas virtually. The Million Image Database, for instance, empowers local volunteers to document at-risk sites using low-cost cameras, helping to build a collective digital memory.60

Perhaps most striking was the 2015 holographic projection of the Buddhas at their original site a digital resurrection that sparked global discourse on memory, loss, and authenticity.61 Through virtual reality (VR), mobile apps, and online platforms, the Buddhas have become globally accessible once again, transforming public perception from irreversible loss to symbolic recovery. This increased visibility and accessibility contribute to the emotional reattachment of both local and global communities to what was once physically inaccessible or lost entirely.

Digital archives, including the Digital Bamiyan Project, have also used pre-destruction photographic and archaeological data to reconstruct highly accurate 3D models, even simulating colour and texture.62 These tools allow viewers to not only see the Buddhas, but to interact with them redefining heritage as an experience rather than a static object.

Critically, however, this case raises complex philosophical and ethical questions about the status of digital replicas. Can a digital replica carry the same cultural, historical, and spiritual weight as the original? While critics worry about the trivialisation or commodification of such reproductions, others like Holtorf argue that digital replicas contribute to a “new authenticity,” where the value of heritage is not only in the material original but also in the meanings, memories, and emotions it evokes.63 Digital tools here do more than document; they challenge what it means to "experience" heritage in the absence of physical form.

60 Stone, Peter. "Protecting cultural property in the event of armed conflict:. (2019).

61 Rosen. The Return of the Bamiyan Buddhas in Hologram.

62 Armin Grün, Fabio Remondino, and Liang Zhang, “Photogrammetric Reconstruction of the Great Buddha of Bamiyan, Afghanistan,”

63 Cornelius Holtorf, “On Pastness: A Reconsideration of Materiality in Archaeological Object Authenticity,”

Figure 6: Bamiyan Buddhas (Afghanistan)

Figure 7: Projection of the Bamiyan Buddhas (Afghanistan)

Crucially, these reconstructions are not just about visibility. They reshape public engagement offering interactive, participatory experiences and inviting users to be cocurators of memory.64 However, the ease of reproduction also opens heritage to risks of commodification or trivialization, where digital replicas may be consumed without context or reverence. Raising ethical questions: Who controls these digital narratives? How are local voices involved, or excluded?

In the case of Afghanistan, digital technologies have become powerful mediators between absence and remembrance. They allow heritage to persist beyond destruction, reshape how it is perceived, and redefine how it is experienced transforming it from static monument to interactive, living memory. In doing so, they urge us to reconsider what constitutes heritage today: not simply what remains, but what can be digitally reimagined, emotionally reconnected, and collectively shared.

4.4.3 Case Study 3: NDP Model– The Fire, Digital Resurrection, and Experiential Heritage

The 2019 fire that ravaged Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris marked a symbolic rupture not only in architectural continuity but in the global public’s emotional relationship to heritage. The event catalysed a remarkable digital response that redefined how heritage can be preserved, experienced, and understood in a post-material context. This case exemplifies what this study defines as the New Digital Preservation (NDP) model, in which immersive technologies, open-source reconstructions, and virtual engagement reframe heritage not as fixed artefact, but as interactive, emotionally charged experience.

Drawing on high-resolution laser scans by Andrew Tallon originally intended for academic analysis developers rapidly mobilised digital reconstructions to shape restoration strategies and offer public access to the cathedral in virtual form.65 Ubisoft’s Assassin’s Creed: Unity, with its detailed 3D rendering of the cathedral, became an unexpected medium for public exploration. Adapted for VR and educational platforms, the model allowed users to engage with Notre-Dame as both historical monument and digital experience.66 These technologies

64 Erik Champion, Critical Gaming: Interactive History and Virtual Heritage

65 Eugene Ch’Ng et al., “The Effects of VR Environments on the Acceptance, Experience, and Expectations of Cultural Heritage Learning,”

66 Sin-wai, Chan, Mak Kin-wah, and Leung Sze Ming. Encyclopedia of Technology and the Humanities. 2024.

Figure 8: Notre-Dame de Paris 3D Fixture

confirms that such participatory methods enhance learning outcomes and deepen public understanding.72

At the same time, Notre-Dame’s transformation into a digital spectacle raises important critiques. The gamification and commercialization of its virtual forms risk reducing a sacred, historically layered site to a visual commodity, designed for entertainment rather than reflection. Moreover, the ease of reproduction inherent in digital media introduces concerns about cultural dilution and aesthetic flattening the possibility that uniqueness and aura might be lost in the process of infinite replication.

In sum, the Notre-Dame case demonstrates how digital heritage technologies can reshape public perception by shifting emphasis from preservation of the tangible to the production of experience. It challenges us to rethink whether heritage resides in physical form, or in the emotions and interactions it inspires even in virtual space. Might digital heritage be more than a tool for preservation might it be the future of heritage itself?

4.4.4 Global South & Grassroots Digital Heritage Initiatives

While this dissertation has focused on prominent examples, it's crucial to acknowledge that digital heritage is not solely the domain of institutions or Western-led initiatives. In the Global South, grassroots and community-led projects have increasingly leveraged digital tools for local empowerment and cultural resilience. Projects like Map Kibera in Nairobi, Kenya, using open-source GIS and participatory mapping, have empowered local residents to map their communities using open-source platforms, enhancing visibility and access to services in previously undocumented areas.73 Similarly, in Iraq and Yemen, local scholars and volunteers have collaborated with digital archaeologists to build decentralized archives of war-damaged heritage using smartphones and open platforms.74 Similarly, the Digital Benin project has created an online database, reuniting over 5,000 artefacts from 131 institutions across 20 countries, thereby restoring cultural connections and promoting transparency.75 These initiatives exemplify how community-driven digital heritage projects can decentralize authority, challenge dominant narratives, and foreground local knowledge systems

4.4.5 Cross-case Synthesis

Together, the three case studies reveal how digital tools are not merely preservation technologies but powerful agents reshaping how heritage is perceived, experienced, and emotionally engaged with. In Syria and Afghanistan, digital reconstructions serve as acts of resistance, enabling cultural continuity in the face of physical destruction. In contrast, the Notre-Dame case shows how digital heritage can amplify global emotional resonance and educational engagement, even when the original remains partially intact. Across all cases, digital tools challenge traditional boundaries between original and replica, material and virtual, memory and simulation. They open new modes of access, yet also introduce tensions

72 Maria Economou and Eleni Meintani, “Promising Beginning? Evaluating Museum Mobile Phone Apps,”

73 Erica Hagen, Open Mapping from the Ground Up

74 Naser, Revealing the collective Memory

75 Solomon, Tessa. “Thousands of Looted Benin Bronzes Scattered in Museums Worldwide Are Now Listed in an Online Database.”

around authenticity, ownership, and commodification. While the contexts differ conflict zones versus global urban spectacle the digital turn consistently repositions heritage as a dynamic, affective, and participatory process. These case studies thus lay the groundwork for the critical discussion that follows, where the social, historical, and commercial implications of digital heritage are explored in greater depth.

Cross-Case Comparison

The following table summarises key similarities and differences across the three case studies, highlighting how different socio-political and technological contexts shape the perception and experience of digital heritage.

Table: Comparative Analysis of Digital Heritage Interventions

Aspect Syria (Palmyra & Aleppo) Afghanistan (Bamiyan Buddhas)

Context of Loss

Primary Digital Approach

Perception Shift

Critical Tension

Educational & Experiential Value

War-driven destruction, looting, and ideological targeting

Archival digitisation, 3D reconstructions (#NewPalmyra), satellite monitoring

From heritage as national identity to global symbol of resilience

Digital colonialism and outsider-led narratives vs. community voice

Low formal use; symbolic resistance via digital storytelling

Notre-Dame de Paris (NDP Model)

Iconoclasm and symbolic erasure by Taliban Fire damage; partial material survival

VR projections, 3D modelling, opensource photo archives

From tangible absence to virtual represence; focus on affect/memory

Ethical debates on authenticity and cultural agency

Holograms and VR used for public empathy and memory recovery

5 Critical Analysis of Perceptions and Impacts

5.1 Social Value

Pre-fire laser scans, VR exhibitions, and gaming reconstructions

From religious monument to a globally shared immersive experience

Gamification vs. sanctity; experience vs. spectacle

High use in immersive education and emotional reattachment

Digital heritage technologies are transforming heritage from an elite, site-bound experience into a socially accessible, affective, and participatory practice. Yet, this democratization is not without tensions while it amplifies visibility and emotional connection, it also risks superficial engagement and cultural misrepresentation.

5.1.1 Digital Accessibility and Public Engagement

One of the most significant contributions of digital heritage tools lies in their capacity to expand access to cultural sites. Digitization initiatives such as online exhibitions, 3D reconstructions, and virtual reality (VR) experiences allow users to engage with heritage regardless of geographic or political barriers. In conflict-affected regions such as Syria, where the Temple of Bel and other historical monuments were destroyed during armed conflict, digital reconstructions have provided a means for displaced populations and global audiences to re-engage with lost heritage. For example, virtual reconstructions exhibited in European museums and online platforms have been credited with maintaining the visibility of Palmyra’s cultural identity in global consciousness. Such efforts support the social function of heritage as a site of collective memory and identity, particularly among diaspora communities.

However, this digital accessibility is not without limitations. Critics have noted that removing heritage from its physical, geographical, and cultural context can lead to what Yehuda Kalay, Thomas Kvan, and Janice Affleck, describe as “placeless heritage.”76 In this sense, digital reconstructions risk flattening the complexity of lived historical environments, reducing heritage to a set of visual and interactive features devoid of their original significance. Moreover, questions arise around the authenticity of these representations and whether they genuinely reflect the cultural narratives of the communities they purport to serve.

In contrast, the New Digital Pedagogies (NDP) model used in educational settings seeks to enhance students’ access to architectural heritage by integrating digital heritage tools into the classroom. These models allow students to explore reconstructed historical environments, enriching their understanding of distant or destroyed sites. While the pedagogical benefits are evident, such implementations must be critically examined to avoid presenting oversimplified or decontextualized versions of heritage that fail to communicate the full scope of its cultural relevance.

5.1.2 Emotional Engagement and Affective Value

Beyond access, digital heritage tools also have the potential to generate emotional responses and foster affective relationships with historical sites. Immersive technologies, including augmented reality (AR) and 3D audio-visual experiences, allow users to navigate virtual heritage environments and emotionally connect with spaces they might never physically visit. In the context of Afghanistan, the temporary digital resurrection of the Buddhas of Bamiyan through projection mapping and 3D modeling served as a symbolic act of cultural resilience. This event was met with significant public interest and emotional resonance, particularly among local communities and diaspora populations.77 For many, these digital renderings act as surrogates for cultural continuity in the face of irreversible destruction.

Nevertheless, the emotional power of these reconstructions can complicate users’ perceptions of authenticity and historical truth. While immersive experiences can inspire empathy and

76 Yehuda Kalay, Thomas Kvan, and Janice Affleck, eds., New Heritage: New Media and Cultural Heritage 77 Breen, Colin. Conflict, cultural heritage and peace: an introductory guide. Routledge, 2023.

engagement, they may also risk turning cultural heritage into a consumable spectacle valued more for its visual and emotional appeal than its cultural or historical depth. As Champion argues, digitally mediated encounters with heritage may encourage a passive form of interaction that emphasizes entertainment over critical understanding.78 The tension between emotional engagement and historical authenticity is thus a critical dimension of digital heritage’s evolving social value.

5.1.3 Inclusion, Ownership, and Digital Representation

Digital heritage tools also introduce the possibility of more inclusive and participatory models of representation. By enabling the integration of diverse narratives such as oral histories, indigenous perspectives, and community memories digital platforms can support a more pluralistic view of heritage. In educational contexts, the NDP model promotes this inclusive approach by incorporating multi-vocal narratives into digital exhibitions and lesson plans. However, these initiatives often rely on institutional curation, which can marginalize or exclude local voices if not designed in collaboration with source communities.

Furthermore, issues of ownership and control over digitized heritage remain unresolved. The majority of digital reconstructions from conflict zones like Syria and Afghanistan are hosted and maintained by institutions based in the Global North. This raises concerns of digital colonialism, where Western institutions become the custodians of cultural data belonging to communities in the Global South.79 The power to interpret, display, and monetize digital heritage frequently lies outside the communities to which the heritage originally belonged.

These power dynamics challenge the assumption that digital tools inherently democratize heritage. While they may expand access and visibility, they can also reinforce historical inequalities in cultural representation and control. As such, the social value of digital heritage must be critically assessed not only by its reach and interactivity, but also by whose narratives are included, and who benefits from their circulation.

5.2 Historical Value

The historical value of architectural heritage is tied to its ability to document the past and preserve cultural memory. With the advent of digital tools, heritage is no longer limited to its physical presence. Technologies such as Building Information Modelling (BIM), 3D scanning, immersive exhibitions, and virtual reconstructions are increasingly used to record, disseminate, and reinterpret historical knowledge. Digital heritage technologies are transforming heritage from an elite, site-bound experience into a socially accessible, affective, and participatory practice. Yet, this democratization is not without tensions while it amplifies visibility and emotional connection, it also risks superficial engagement and cultural misrepresentation. This evolution raises critical questions about the fidelity, authority, and ethics of digitised heritage, especially in post-conflict or culturally sensitive contexts

78 Erik Champion, “Applying Game Design Theory to Virtual Heritage Environments,”

79 Elisa Giaccardi, ed., Heritage and Social Media: Understanding Heritage in a Participatory Culture

5.2.1 Enhancing Documentation and Preservation

Digital documentation methods like 3D scanning and BIM create extraordinarily detailed archives of at-risk heritage. For instance, the 3D model of Palmyra, captured before ISIS’s 2015 destruction, enabled partial reconstruction and continues to serve as a learning and planning resource. Such interventions offer a form of “rescue heritage,” especially in conflict zones where the physical site may no longer exist.

However, these digitised forms pose ontological challenges. Benjamin’s critique of mechanical reproduction is especially resonant: can a digital model, detached from its temporal and spatial aura, still be considered "authentic"?80 Critics argue that digital heritage often flattens complexity turning multi-layered, lived spaces into static visual records. This is evident in the case of the Buddhas of Bamiyan, where reconstructions often prioritise visual fidelity over cultural nuance, prompting debates among Afghan scholars and international preservationists.81

Stakeholders:

Local communities often feel alienated when digital preservation is externally driven.

Governments and NGOs may prioritise symbolic visibility over local agency.

Tech developers, while skilled, may unintentionally aestheticise trauma.

Thus, preservation becomes a paradox: what is digitally "saved" may be physically and emotionally displaced. Nevertheless, scholars like Champion contend that interactive digital heritage can evoke emotional engagement, creating “new forms of aura” that offer meaningful connections, especially when originals are inaccessible.82 In contrast to the original, lived experience of a space, these digital representations often provide only a fragmented and sanitized version of history, devoid of the nuances that come with real-world engagement.

Moreover, the digitization process itself introduces issues of fidelity and authority. In the case of Afghanistan’s Buddhas of Bamiyan, the digitization process has sparked a debate about the extent to which these digital reconstructions reflect the intent of the original creators or the beliefs of the local communities. Should these reconstructions reflect historical accuracy, or should they prioritize symbolic and emotional meaning?

5.2.2 Facilitating Historical Research and Education

Digital tools make architectural heritage accessible and pedagogically rich. The NDP model, for example, uses gamified storytelling to teach students architectural history, promoting emotional and critical engagement.83 This creates a participatory, multisensory way of “learning through experiencing.”

80 Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,”

81Rodney Harrison, Nélia Dias, and Kristian Kristiansen, eds., Critical Heritage Studies and the Futures of Europe

82 Erik Champion, “Applying Game Design Theory to Virtual Heritage Environments,” 2016

83 Huriye Ayshan, Video Game Trailers

Yet immersive platforms can prioritise emotional affect at the expense of critical history. Reconstructions of Palmyra rarely address the political violence or cultural trauma behind their destruction, opting instead for visual splendour. This echoes Laurajane Smith’s view that heritage is not neutral but actively constructed often sanitised in digital form for broader appeal.84 The "Disneyfication" of history Urry & Larsen, risks replacing rigorous interpretation with spectacle.85

In education, the NDP model fosters inclusive engagement; in conflict zones, the same tools may obscure painful histories under a glossy interface. The context in which digital heritage is used thus fundamentally shapes its interpretive outcomes. Importantly, there is a growing push towards community-led digital heritage, where local stakeholders shape how their cultural memory is digitised and shared. Initiatives in Syria and Iraq have involved local youth and artisans in the digital reconstruction process,86 challenging the dominance of Western institutions and offering more pluralistic accounts of history.

5.2.3 Ownership, Control, and Ethical Dilemmas

Digitised heritage complicates questions of ownership and control. Who owns the data? Who decides how it's presented or monetised? In the Bamiyan case, international bodies digitised the site post-destruction, but local Afghan voices were excluded from decisions about how digital replicas were used and exhibited.87 This reveals a neo-colonial dynamic: Western institutions may control narratives about non-Western heritage.

In Syria, digitisation was driven by external actors (e.g., ICONEM), highlighting tensions between global visibility and local voice. Whereas in NDP-based classrooms, the issue becomes pedagogical ethics: who frames the historical story? What narratives are

84 Laurajane Smith. Uses of Heritage.

85 Urry, John, and Jonas Larsen. "The tourist gaze 3.0." (2011): 1-296.

86 Rodney Harrison, Nélia Dias, and Kristian Kristiansen, eds., Critical Heritage Studies and the Futures of Europe

87 Rodney Harrison, Nélia Dias, and Kristian Kristiansen, eds., Critical Heritage Studies and the Futures of Europe

Figure 10: Map of Syria showing Heritage Before and After Digitalization

emphasised? As Smith notes, the digital reproduction of cultural heritage is fraught with power dynamics, where the dominant stakeholders control the narrative, often sidelining local perspectives.88 As Harrison notes, digitisation can reinforce colonial or neo-imperial power structures, where Western agencies decide what is preserved and how.89 Even when intentions are restorative, digital reproductions may reproduce historical imbalances, especially when local voices are excluded.

The case of the Buddhas of Bamiyan is particularly illustrative of these issues. The Afghan government, which initially welcomed international efforts to digitally preserve the statues after their destruction by the Taliban, later found itself excluded from decision-making processes regarding how the digital replicas were to be displayed and interpreted. This raises important questions about the extent to which digital heritage can be a tool for preserving historical value if the stakeholders most invested in that heritage are not included in its digital reproduction.

While digitisation is often portrayed as objective, the processes are inherently curated. As Macdonald notes, heritage in digital form is shaped as much by absence as presence what is left out matters as much as what is included.

5.2.4 From Documentation to Experience: A Shift in Historical Value

Digital heritage is no longer only about recording the past it is about producing experience. Virtual reality allows users to “walk” through ancient spaces, altering how historical value is constructed. This experience-driven model enhances public connection, but also shifts authority from historians and communities to tech platforms.

The digital resurrection of Notre-Dame (though not a core case here) showed how VR can become an emotional surrogate for loss. Similarly, in NDP classrooms, students build emotional connections to heritage through interactive design sometimes without understanding the material constraints or historical contexts.

If the emotional experience of a digital model can replace the physical encounter, what then becomes of the original? Holtorf suggests that we are moving toward a future where digital heritage may itself be accepted as heritage not a proxy, but a primary experience.90

5.3 Commercial Value

Digital heritage increasingly functions not just as a tool for preservation or education, but as a cultural commodity. Immersive exhibitions, gamified reconstructions, and branded digital content are transforming heritage into a marketable experience. This commercialisation brings financial and educational benefits but also raises deep concerns about ownership, authenticity, and who controls the narratives of heritage in digital form. The commercialisation of digital heritage through tourism, branding, and gamification

88 Smith, Laurajane. Uses of Heritage. London: Routledge, 2006.

89 Rodney Harrison, Nélia Dias, and Kristian Kristiansen, eds., Critical Heritage Studies and the Futures of Europe

90 Cornelius Holtorf, “Embracing Change: How Cultural Resilience Is Increased through Cultural Heritage,” 550

consideration of who benefits from the economic opportunities and who is excluded from the decision-making process. In both Palmyra and Bamiyan, external organisations played central roles in digitisation efforts. This raises issues of data sovereignty: who owns these representations? Who profits? These questions are not just technical, but ethical and political.

5.3.3

Market Logics and Educational Tools: The Case of NDP

The NDP model illustrates how digital heritage can be used commercially in education. Immersive storytelling platforms engage students emotionally and cognitively, helping them connect with complex histories.95 Some tools developed for education are also monetised through app stores or licensing creating a symbiotic relationship between cultural content and commercial viability.

However, as educational platforms become part of the heritage-tech market, they may be designed to prioritise entertainment, gamification, and retention over historical complexity or critical thinking. Developers often curate simplified narratives that align with institutional or commercial goals rather than plural histories. In the classroom, NDP enhances engagement but risks superficial learning if content is oversimplified. Additionally, in conflict zones, digital heritage may be used to promote national recovery or donor interest, often without critical engagement with the politics of destruction or cultural trauma.

5.3.4 Ethical

Concerns in Commercializing Digital Heritage

Commercialisation raises urgent questions about ownership and control. In Syria and Afghanistan, much of the digitisation has been led by international NGOs, Western institutions, or private tech firms, creating asymmetries in access, voice, and benefit. Local communities whose heritage is being digitised are often excluded from decision-making and receive little benefit from commercial use.

As Harrison and Smith argue, the commodification of digital heritage often reflects institutional priorities, not the lived realities of affected populations.9697 Even well-meaning digitisation efforts can reproduce colonial dynamics, where Western actors curate and capitalise on non-Western heritage under the banner of preservation.

5.3.4.1 Reflections on Authenticity and Digital Replicas in Heritage Experience

The emergence of digital heritage has fundamentally disrupted traditional notions of authenticity, which have long been anchored in material presence and historical continuity.98 High-fidelity digital replicas, immersive reconstructions, and interactive platforms now mediate how people access and experience heritage, raising a central question: can a digital object be considered heritage in its own right?

95 Huriye Ayshan, Video Game Trailers: How Storytelling Is Used to Create Identification and Appeal with Audiences

96 Rodney Harrison, Nélia Dias, and Kristian Kristiansen, eds., Critical Heritage Studies and the Futures of Europe

97 Smith, Laurajane. Uses of Heritage. London: Routledge, 2006.

98 Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” 230.

This tension reflects a shift from material to experiential authenticity. While digital models may lack original substance, scholars such as Holtorf and Champion argue that they often succeed in evoking emotional resonance, immersive engagement, and narrative meaning qualities that shape public perception of heritage.99100 A 3D model of Palmyra’s ruined structures, for instance, may lack original material but still foster cultural memory and emotional connection, especially for those unable to physically access the site.

Moreover, digital heritage invites a redefinition of authenticity through participation. Laurajane Smith’s critique of the "Authorized Heritage Discourse" highlights how digital platforms challenge expert-dominated narratives by enabling vernacular contributions, family archives, and user-generated content.101 Community-led digitisation projects such as indigenous virtual museums or diaspora memory archives demonstrate how heritage is increasingly defined through cultural relevance and social use rather than permanence or age.

However, this democratisation comes with contradictions. The ease of reproduction risks reducing heritage to disembodied simulations visually compelling but historically decontextualized. Digital surrogates may serve commemorative or pedagogical functions, yet when produced without local consent or contextual framing, they risk becoming commodified artifacts rather than heritage.102

Whether a digital replica becomes heritage depends on its function, intent, and embeddedness. In conflict zones like Syria and Afghanistan, digital reconstructions often

99 Cornelius Holtorf, “On Pastness: A Reconsideration of Materiality in Archaeological Object Authenticity,”

433

100 Erik Champion, Rethinking Virtual Places

101 Smith, Laurajane. Uses of Heritage. London: Routledge, 2006.

102 Rodney Harrison, Nélia Dias, and Kristian Kristiansen, eds., Critical Heritage Studies and the Futures of Europe

Figure 11: Digital Replica Heritage Venn Diagram

assume symbolic authority in the face of physical destruction. The Palmyra Arch replica, for example, circulated as a global symbol of resilience but also sparked criticism for being detached from the site's lived reality. As Giaccardi argues, heritage is not merely inherited it is performed, contextual, and relational.103

Digital heritage thus transforms our experience from passive observation to active participation, reframing heritage as something we engage with rather than simply visit. Yet it also raises ethical questions about who defines, curates, and owns these new forms. In the digital age, heritage is no longer solely material it is increasingly relational, experiential, and contested.

Limitations of the Study

While this study provides meaningful insights into how digital tools are reshaping perceptions and experiences of heritage, it is not without limitations. First, the research relies on a selective range of case studies (e.g., Syria, Afghanistan, the NDP model) which, while diverse, may not fully represent global practices or localised responses to digital heritage. Additionally, the study focuses more on theoretical and visual analyses rather than empirical fieldwork or large-scale survey data, which could limit the generalisability of findings. Lastly, the rapid pace of technological innovation means that tools and platforms discussed may evolve or become obsolete, thus requiring continuous reassessment of their impact on heritage discourse

Conclusion

This research has critically explored how emerging digital tools such as immersive exhibitions, online archives, VR, and photogrammetry are transforming the ways we perceive, access, and experience architectural heritage. These tools expand the social value of heritage by making it more accessible and emotionally resonant for diverse global audiences, while enhancing historical value through detailed documentation and new modes of scholarly engagement. The commercial implications from virtual tourism to branding and gamification further illustrate the dynamic intersections between culture, technology, and economy.

However, these developments raise significant questions. As we’ve seen, authenticity in a digital age is no longer confined to materiality; rather, it is being redefined through emotional connections, interactivity, and community co-creation. Under certain conditions particularly when replicas are used for education, memory preservation, or community identity digital

103

Elisa Giaccardi,

ed., Heritage and Social Media: Understanding Heritage in a Participatory Culture

reproductions can indeed be considered heritage. Yet, concerns around commodification, detachment, and politicisation remain central to debates on digital heritage.

Ultimately, this study argues that technology is not simply a tool but a transformative agent that reconfigures our relationship with heritage from static monuments to dynamic, participatory, and sometimes contested digital experiences. The paradox lies in how digital tools both democratise and destabilise heritage: they broaden access and redefine value, but also risk diluting context or privileging certain narratives over others. Recognising these tensions is essential as we navigate the future of heritage in a rapidly digitising world.

Digital heritage is not merely a preservation tool but a dynamic medium that shapes cultural narratives and identities. Moving forward, policymakers should develop inclusive digitization policies that prioritize community engagement and equitable representation. Educators are encouraged to integrate digital heritage into curricula, fostering critical thinking and cultural awareness among students. Conservationists must adopt participatory approaches that value both tangible and intangible heritage aspects, ensuring that digital reproductions do not overshadow the cultural significance of original artefacts. By embracing these strategies, stakeholders can ensure that digital heritage serves as a platform for inclusive dialogue, cultural resilience, and shared human experience.

Ch’Ng, Eugene, Yiekai Li, Shihui Cai, and Feng Tian Leow. “The Effects of VR Environments on the Acceptance, Experience, and Expectations of Cultural Heritage Learning.” Journal on Computing and Cultural Heritage 13, no. 1 (2020): 1–21.

Champion, Erik. Critical Gaming: Interactive History and Virtual Heritage. London: Routledge, 2015.

Champion, Erik. “Applying Game Design Theory to Virtual Heritage Environments.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 22, no. 3 (2016): 166–177.

Champion, Erik. Rethinking Virtual Places. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2021.

Ciecko, Brendan. “Virtual Reality and Digital Heritage during COVID-19.” MuseumNext 2020. https://www.museumnext.com

CyArk. “Mission and Projects.” 2020. https://www.cyark.org. Accessed April 16, 2025.

CyArk. “3D Documentation Projects and Virtual Tours.” Digital Preservation Projects. 2020. https://www.cyark.org/projects

Denard, Hugh. “A New Introduction to the London Charter.” In Paradata and Transparency in Virtual Heritage, 57–71. 2012.

Economou, Maria, and Eleni Meintani. “Promising Beginning? Evaluating Museum Mobile Phone Apps.” Museums and the Web 2011. 2011.

Economou Maria, and Laia Pujol. “Evaluating the Impact of New Technologies on Cultural Heritage Visitors.” In Technology Strategy, Management and Socio-Economic Impact, Heritage Management Series 2 (2007): 109–121.

Forte Maurizio. Virtual Archaeology: Reconstructing the Past through Immersive Technologies. Cham: Springer, 2021.

Foster Sally M., and Sian Jones. “The Untold Heritage Value and Significance of Replicas.” Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites 21, no. 1 (2019): 1–24.

Graham Brian. “Heritage as Knowledge: Capital or Culture?” Urban Studies 39, no. 5–6 (2002): 1003–1017.

Giaccardi Elisa, ed. Heritage and Social Media: Understanding Heritage in a Participatory Culture. London: Routledge, 2012.

Gillings Mark. “Landscape Phenomenology, GIS and the Role of Affordance.” Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 19 (2012): 601–611.

Louvre Museum, “Mona Lisa: Beyond the Glass – The Louvre’s First Virtual Reality Experience,” 2022, https://www.louvre.fr/en/explore/life-at-the-museum/mona-lisa-beyondthe-glass.

Macdonald, Sharon. Memorylands: Heritage and identity in Europe today. Routledge, 2013.

Meskell, Lynn. A future in ruins: UNESCO, world heritage, and the dream of peace. Oxford University Press, 2018.

Mincolelli, Giuseppe, G. I. A. N. Giacobone, Silvia Imbesi, and Michele Marchi. "Inception. Inclusive Cultural Heritage in Europe through 3D Semantic Modelling." In 100 anni dal Bauhaus. Le prospettive della ricerca di design, pp. 128-135. SID-Societa Italiana di Design, 2020.

Mol, Angenitus Arie Andries, Csilla E. Ariese-Vandemeulebroucke, Krijn Boom, and Aris Politopoulos, eds. The interactive past: Archaeology, heritage & video games. Sidestone Press, 2017.

Murphy, Maurice, Eugene McGovern, and Sara Pavia. "Historic building information modelling (HBIM)." Structural Survey 27, no. 4 (2009): 311-327.

Naser, Sahar Riyadh. "REVEALING THE COLLECTIVE MEMORY IN THE DIGITAL RECONSTRUCTION OF THE LOST CULTURAL HERITAGE–EXAMPLE OF AL-NURI MOSQUE IN MOSUL." EFFECTS OF WAR TRAUMA ON STUDENTS FROM WAR AREAS HERITAGE DESTRUCTION AND COLLECTIVE MEMORY.

Nora, Pierre. "Between memory and history: Les lieux de mémoire." representations (1989): 7-24.

Parry, Ross. Recoding the museum: Digital heritage and the technologies of change. Routledge, 2007.

Parry, Heather. “A Sense of Place: A Scenographic Interpretation of Place and Community Engagement.” PhD diss., University of Brighton, 2022.

Rosen, Armin. “Holographic Resurrection: The Return of the Bamiyan Buddhas.” The Atlantic, June 11, 2015. https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2015/06/bamiyanbuddhas/

Schäfer, Erich. Lebenslanges Lernen. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2017.

Simon, Nina. The participatory museum. Museum 2.0, 2010.

Sin-wai, Chan, Mak Kin-wah, and Leung Sze Ming. Routledge Encyclopedia of Technology and the Humanities. Routledge, 2024.

Smith, Laurajane. Uses of Heritage. London: Routledge, 2006.

Solomon, Tessa. “Thousands of Looted Benin Bronzes Scattered in Museums Worldwide Are Now Listed in an Online Database.” ARTnews, 2022.

Stone, Peter. "Protecting cultural property in the event of armed conflict: The work of the blue shield." In Contested Holy Cities, pp. 147-168. Routledge, 2019.

Terras, Melissa. "Crowdsourcing in the digital humanities." A new companion to digital humanities (2015): 420-438

Ubisoft. Discovery Tour: Ancient Egypt. 2022 https://www.ubisoft.com/enus/game/assassins-creed/discovery-tour

UNESCO. World Heritage under Threat. 2021. https://whc.unesco.org/en/activities/493/

UNESCO. “African World Heritage Day 2022: Youth and Digital Technologies for the Promotion and Safeguarding of African Heritage.” 2022. https://whc.unesco.org/en/news/2439/

UNESCO. UNESCO Digital Archives. 2023. https://www.unesco.org/en/archives

Urry, John, and Jonas Larsen. "The tourist gaze 3.0." (2011): 1-296.

Yastikli, Naci. "Documentation of cultural heritage using digital photogrammetry and laser scanning." Journal of Cultural heritage 8, no. 4 (2007): 423-427.