ABSTRACT

Religious heritage management in China varies across regions, influenced by policy, social change, and economic factors. Existing studies largely focus on well-known religious sites in major cities, lacking systematic research on religious heritage management in marginal cities. This study is motivated by the phenomenon of closure in religious heritage buildings in Hancheng, revealing its unique management mode and exploring the policy, social, and economic factors shaping it, examining different management modes across China and their formation mechanisms.

Through case analysis, four main modes of religious heritage management are identified: completely closed, passively open, cultural tourism-oriented, and community-engaged. In the completely closed mode, buildings are inaccessible due to religious restrictions or government policies. Passively open sites allow public access but prohibit religious practice, weakening cultural meaning. The tourismoriented mode transforms sites into attractions, prioritizing historical value over religious use. In contrast, the community-engaged mode retains religious function and fosters cultural continuity, allowing religious architecture to serve an active social role.

Practices in France, Japan, and Singapore also offer insights for China through models of community participation, secular adaptation, and policy design. The research contributes by identifying management typologies, analyzing causes of functional closure, and proposing a policy-society-economy framework. It offers guidance for policymakers, scholars, and practitioners seeking more inclusive and sustainable heritage conservation.

Key words: Religious heritage, Heritage management, Functional closure

This year passed faster than I could have imagined, yet every moment remains vivid in my memory. I remember the days of laughter in classrooms, chit-chatting in the cafeteria, and the way we all fought all night for the design studio’s final reviews. I loved the sunlight in Singapore every morning, soft and reassuring, gently waking me into a new day. Although I used to count over and over again in my mind "How long will I be able to go home", I know that on one of the future mornings when I am

commuting in China, I will surely think of the clear sky here, the lizards walking past the roadside, and myself who was struggling to grow up in the hot and humid air.

Perhaps no amount of words will ever be enough to contain everything I feel. This year was more than a degree it was a season of my life that shaped me in ways I’m only beginning to understand. It may be over now, but it will remain one of the most precious memories I carry with me, always.

LIST OF FIGURE

Figure 1 Aerial photo of the Guandi Temple

(Source: Author's photograph, March 05, 2024.)

Figure 2 Iron gate of the Guandi Temple

(Source: Author's photograph, March 05, 2024.)

Figure 3 Iron gate of the Huayan Temple

Figure 4 Aerial photo of the Huayan Temple

(Source: Author's photograph, March 05, 2024.)

Figure 5 Signboard at the entrance of Xingshan Temple

(Source: Xiaohongshu, March 21, 2025.)

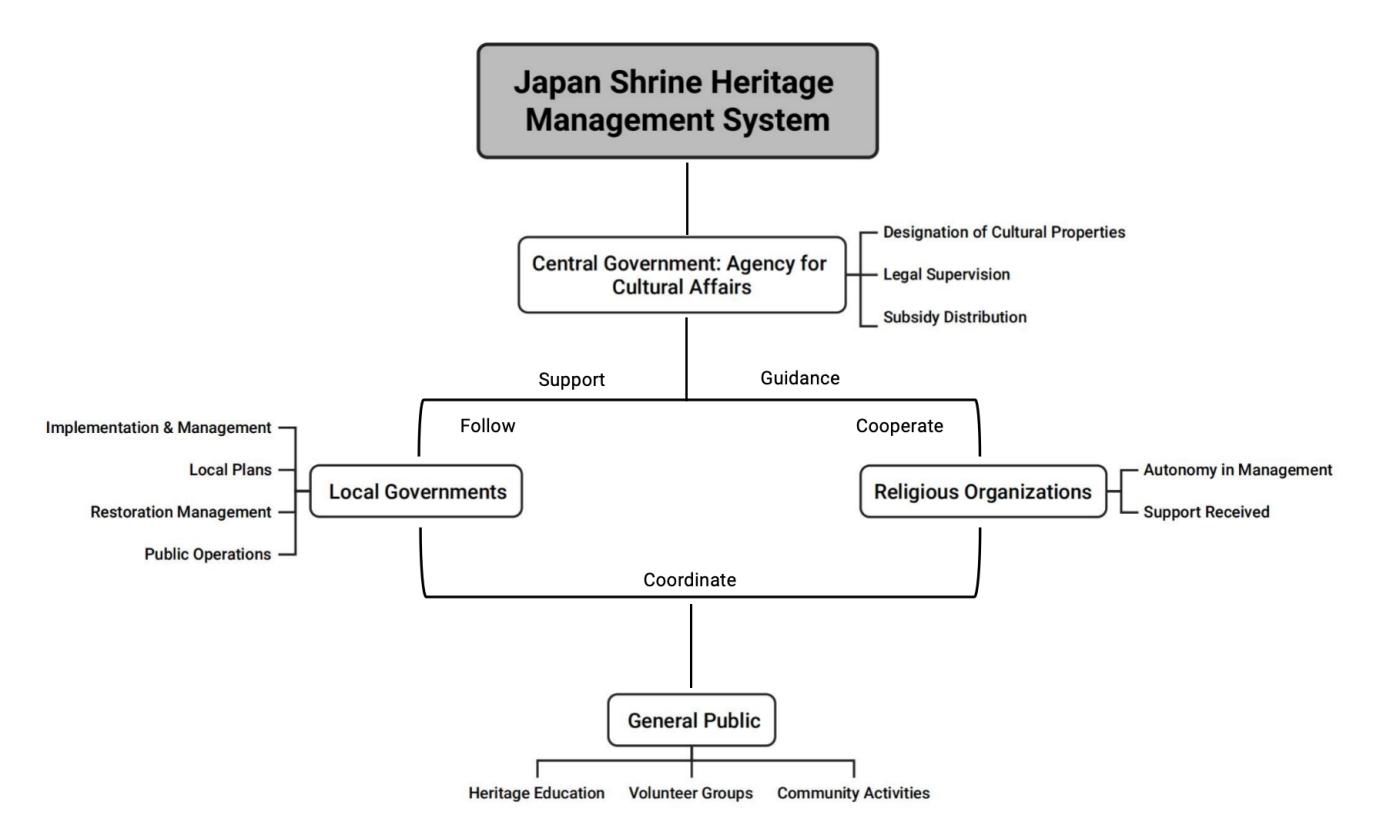

Figure 6 Japan Shrine Heritage Management System

(Source: Author's own creation, April 9, 2025.)

, Baijiahao, February 05, 2021)

physically conserved, their social function and community connection are gradually weakened, and even disconnected from the lives of residents.

This phenomenon has triggered deep thinking on the management mode of religious heritage buildings. In traditional management systems, the social function of religious buildings and their interaction with local communities are often neglected. Some local governments manage religious heritage buildings as mere cultural relics resources, lacking effective opening and social interaction mechanisms, resulting in these heritage buildings isolated. At the same time, although the national policy on cultural relics protection has gradually improved, the insufficiency of relevant policies and management modes still makes many religious heritage buildings fail to realize their potential in modern society.

The management mode of religious buildings is also influenced by both policy orientation and economic pressure. At the policy level, although the state emphasizes, in practice, local governments dilemma between conservation and development. Religious heritage buildings as cultural heritage need to be strictly protected; Local governments hope to promote local economic development by exploiting these resources, particularly in light of the rapid growth of tourism 2 This contradiction has led to some religious buildings being "closure" in the gray area between protection and development after conservation, which can neither give full play to their social functions nor integrate into the economic system of modern society. For example, in some areas, religious heritage buildings are converted into tourist attractions to generate economic gains by attracting tourists. However, this tourism-oriented management model often ignores the cultural and religious values of religious heritage buildings, resulting in their function gradually changing from a

2 Xijia Huang and Zhijun Chen, "The Multi-Dimensional Value of Religious Tourism and Its Development and Utilization,"Religious Studies Research 1 (2009): 143-147.

place for religious activities to a space for cultural display. Alleviating the problem of insufficient funds, it also brings negative effects such as the weakening of religious functions and the loss of cultural connotations.3

Therefore, this research will explore the diversity of management modes of religious heritage buildings in China, especially analyze the reasons for the formation of the closed management mode of Hancheng and the social, cultural and policy factors behind it. Explore religious heritage building management in different regions, assess the impact of various management models on and public access, and consider how to better socialize and revitalize religious heritage. This research aims to provide a new perspective for the sustainable use and living conservation of China's religious heritage.

1.2 Literature Review

1.2.1 Distribution and Status of Religious Heritage in China

Religious architectural heritage in China can be broadly categorized by location: one group in economically developed urban areas, the other in underdeveloped rural regions. The latter, often vernacular village temples, receive less attention and remain in weaker conservation states. Yet these structures are integral to the evolution of regional history and cultural continuity.4

In Shaanxi, half of the protected religious sites are rural.5 Compared with the urban religious architectural heritage, this village-type architectural heritage has a longer period and more abundant types, and some buildings dates back to the Ming and Qing dynasties or even earlier historical periods. They not only bear witness to the

3 Huang and Chen, "The Multi-Dimensional Value of Religious Tourism," 143-147

4 Zheng, “Sociological Study on the Protection of Village-type Religious Architecture Heritage.”

5 ibid.

evolution of Chinese religious culture but also are an important part of maintaining the integrity of China's architectural heritage protection system.

Since the 1980s, attention to rural religious heritage has increased alongside broader efforts to preserve ancient villages. However, scholarly research still tends to focus on protection theories, architectural styles, and regional features. Few studies approach these sites from a sociological perspective, especially regarding their community functions and how to reconnect them with local society in the context of social change.

1.2.2 The Phenomenon of "Closure" of Religious Heritage in China Zheng Jiandong (2014) noted that many village-type religious heritage buildings have transitioned from community belief centers to symbolic cultural relics, often losing their social function in the process. Though physically conserved, many become disconnected from daily life, turning into passive “decorations.”6

Although these buildings are key national cultural relics protection units, they are faced with insufficient funds, chaotic management, and low community participation problems,7 they are only conserved for "protection", and the actual functions of the buildings are ignored.

Not only that, urbanization has an impact on villages, and the disintegration of such social structures also indirectly leads to the weakening of the use function of religious heritage. 8 In other words, if the people of the village left, the religious heritage buildings, even if they were well-conserved, would be difficult to reuse.

This is the loss of believers.

6 Zheng, “Sociological Study on the Protection of Village-type Religious Architecture Heritage.”

7 Junmin Liu and Jiandong Zheng, “A Study on the Current Situation, Issues, and Countermeasures for the Protection of Village-type Religious Architecture Heritage: A Case Study of the 'Four Temples of Han Cheng'” Journal of Northwestern University (Natural Science Edition) 44, no. 6 (2014): 983987, https://doi.org/10.16152/j.cnki.xdxbzr.2014.06.024

8 Xueting Chen, Analysis of the Phenomenon of Abandonment in Traditional Villages in the Han Cheng Region and Research on Protection and Development Strategies (Master's thesis, Xi'an University of Architecture and Technology, 2017).

Some studies try to explore the community function of buildings. After the introduction of community management and cultural activities, the activation and utilization effect of historical buildings in Hancheng is significantly better than a single government-led model,9 which indicates that community participation is an important factor for the functional regeneration of heritage buildings.

However, existing studies discuss the functional decline and management challenges of religious heritage, but they rarely examine the “closed” phenomenon in Hancheng. Moreover, they often adopt a single-dimensional approach and overlook the intersection of cultural relics protection policies, social changes and economic factors, thus the need to address this research gap.

1.2.3 Religious heritage management models in China

The cultural tourism-oriented management model is currently prevalent model in the management of China's religious heritage This model brings problems such as excessive commercialization and weakening of religious functions. For example, the conservation of the Chongsheng Temple in Dali is a typical case. To develop the cultural tourism industry, the Dali Prefecture government supported enterprises to restore and rebuild the Chongsheng Temple and gifted it to a religious organization for management. This mode of government guidance, enterprise investment, and Buddhist management has led to local economic development in the short term, but it has also led to many problems. Firstly, during the process of temple conservation, the commercialized operation of enterprises has led to the gradual reduction of religious places to tourist attractions and the loss of their original religious functions. Second, admission tickets are priced by the government and monopolized by enterprises, further exacerbating the commercialization tendency of

9 Fuyiao Lv, Research on the Revitalization and Adaptive Reuse of Historical Buildings in the Han Cheng Ancient City Xuexiang (Master's thesis, Chang'an University, 2023), https://doi.org/10.26976/d.cnki.gchau.2023.000526

religious heritage, making it difficult to satisfy the spiritual needs of the believers.10 This pattern reflects the profound contradiction between economic growth and the safeguarding of religious functions in cultural tourism-oriented management.

Passive openness models are formally open to the public and allow tourists to visit them, but the practice of religion is strictly limited, and the government usually does not allow official religious activities to be held; thus, while these buildings remain in existence, their core religious cultural and belief values are virtually lost. China's religious policy has long taken an evasive attitude towards religion and minimized the publicity of religious activities, especially in the emergence and expansion of some emerging religions, the government has taken tight monitoring and restrictive measures, resulting in an increasingly shrinking space for religious practices.11 In addition, many people enter religious sites only for social and traditional reasons, engaging in superficial acts of "worship" rather than out of a genuine belief in the religion and an in-depth understanding of its teachings. According to the Pew Research Center, China has one of the lowest rates of religious affiliation in the world, with about 10 percent of adults identifying themselves as religious. However, when considering behavior that involves participation in religious activities or holding certain religious beliefs, the percentage can be as high as 50 percent.12 This suggests that many people may be involved in religious activities in terms of their behaviors but are not faithful believers in terms of their faith identity.

The formation of a management model for religious heritage is influenced by a combination of policy and legal, socio-cultural, and economic factors. Policies and laws are important mechanisms for the formation of management models. However, the legal system for the

10 Yalan Chen, “On the Government Regulation of the Development of Religious Cultural Heritage Resources” Yunnan Social Sciences 1 (2012).

11 Qun Lu, “On the Specificity of Religious Cultural Heritage and the Construction of Its Management System” Journal of Huaihua University 10 (2008), https://doi.org/10.16074/j.cnki.cn43-1394/z.2008.10.005

12 "Research: More Chinese People Do Not Identify as Religious," ABC News (Australia), September 8, 2023, https://www.abc.net.au/chinese/2023-09-08/pew-china-religion-research-identity-question/102828678.

protection of religious and cultural heritage in China is not yet perfect, and there is an obvious gap compared with developed countries. France, Japan, South Korea, and other countries have established a complete legal system for the protection of religious heritage and have achieved remarkable protection results. In contrast, China's legislation for the protection of religious cultural heritage is lagging. Legislation for the protection of religious and cultural heritage in China is still lacking, relying more on policies, regulations, ordinances, and even executive orders and administrative measures formulated by governments at all levels. This lack of legislation leads to a low degree of rule of law and institutionalization by the government, and policy implementation is often subject to frequent changes or inconsistencies, which is not conducive to the long-term protection of religious heritage ;13For example, regulatory legislation on religious cultural heritage often has obvious industry and sectoral characteristics and fails to form a unified legal framework, further exacerbating the confusion in management.

Sociocultural factors also have a profound impact on the management model. First, China has very diverse types of religions, especially multi-ethnic primitive religions, which have diverse forms of beliefs, flexible rituals, and are closely related to daily life. These characteristics make the management of religious heritage complex and difficult to manage with uniform standards.14 Second, the relationship between religion and social stability has also had an important impact on the management model. In the past, religious management in China was often an afterthought, meaning that measures were taken only after problems arose, without a preventive mechanism. Such a management style is passive and tends to lead to the manipulation of religious power by a few people and may even pose a threat to social stability. 15 In addition, the close connection between religion and community is also an important factor affecting the management model. Primitive religions

13 Chen, “On the Government Regulation of the Development of Religious Cultural Heritage Resources”

14 Lu, “On the Specificity of Religious Cultural Heritage and the Construction of Its Management System” 15 ibid.

built religious heritage and the unique challenges it faces. Thus, the gaps in the existing literature are mainly characterized by a lack of in-depth exploration of the types of religious architectural heritage in China and their specific influencing factors, and in particular a lack of a comprehensive understanding of the specific conservation needs and management modes faced by different regions and types of religious buildings.

1.3 Research Gap

Existing literature focuses on big cities or well-known religious buildings but lacks systematic research on religious heritage in marginal cities such as Hancheng in Shaanxi Province, where “closed management” is practiced. Although these buildings are listed as national cultural heritage units, they have been in a state of “closure” for a long time, and their formation mechanism and social impact have not been fully explored.

Most studies analyze the management model from a single dimension (e.g., policy or tourism economy), failing to integrate the policy, social, and economic dimensions to build a systematic analysis framework. At the same time, there is a lack of typology summarizing the management models of China's religious heritage.

Existing international studies have failed to consider the constraints imposed by China's unique institutional system on the management models, which has made it difficult for their experiences to be directly applied to Chinese practice. This institutional difference makes the existing international comparative studies have limited guiding value for the management of China's religious heritage.

1.4

Research Question

The study will explore the types of religious heritage management models in different regions, analyze how these models are affected by policy, social, cultural, and economic factors, and

examine the reasons for forming different management models in different contexts. To address this issue, the following questions must be clarified:

Firstly, how did the "closure" of the religious heritage of Hancheng come about? And how did the policy, social, cultural, and economic factors behind it work together to form this management pattern?Secondly, what are the types of architectural management models of China's religious heritage?Finally, what is the logic of the formation of architectural management models of religious heritage in different contexts?

How is the formation of architectural management models of religious heritage in different regions influenced by local policies, social changes, cultural attitudes, economic development, and other factors? How do these factors interact with each other to drive the formation of different models?

1.5 Research Scope

This study focuses on the management modes of China's religious heritage, emphasizing the types of management modes of religious heritage buildings in different regions and their logic of formation. Taking the "closed" management model of Hancheng as a starting point, the study analyzes the influence of policy, sociocultural, and economic factors on the management model in the context of typical cases in other regions of China. At the same time, the study will further explore the diversity and complexity of the management of religious heritage through the analysis of international cases.

The geographical scope of this study is China's religious heritage, especially those that are included in the national or provincial cultural relics protection system. The study takes the Hancheng area as the core case, while other representative areas are selected as supplementary cases to reflect the diversity of China's religious heritage

management.In the part of international analysis, the study will select cases of religious heritage management in Singapore, France and Japan.

The study mainly focuses on heritage buildings with explicit religious functions such as temples, churches, and mosques, etc. in religious buildings, excluding other types of cultural heritage (e.g. folk houses, palaces, etc.). In addition, the study focuses on religious buildings that are included in the heritage protection system, while religious buildings that are not included in the system (e.g., small folk temples) are not included in the main discussion of this study.relationship between economic factors and the maintenance of religious functions provides a reference.

This study mainly analyzes the logic of the formation of the architectural management model of religious heritage from the macro level of policy, socio-cultural, and economic aspects, and does not deal with the details of specific engineering techniques or architectural restoration. In addition, the study will focus on the social function and cultural value of the management model rather than the physical characteristics or artistic style of the building itself.

The analysis of international cases is mainly used to provide references and insights, rather than directly applying their management models. Due to the differences in cultural backgrounds, policy environments, and social structures, the applicability of international experiences in China needs to be further explored. Therefore, this study will focus on the theoretical level of reference in the international comparison part, rather than direct application at the practical level.

1.6 Research Methods

The study utilizes textual analysis, field investigations, comparative studies, and case studies to examine the diversity of China's religious heritage management modes from a multi-dimensional perspective.

Case study is one of the core methods of this study. The study takes the national religious heritage building in Hancheng as the main case and analyzes in depth the formation mechanism of its "closed" management mode. At the same time, the study selects Singapore's joint temples (government-led multi-religious model), France's religious heritage (secularization and cultural heritage protection), and Japan's shrine management (maintenance of religious functions in the context of urbanization), to reveal the diversity of the management models of religious heritage and their formation logics in different contexts through horizontal comparisons.

textual analysis is an important supporting method for this study. By systematically combing the literature related to the protection and management of religious heritage at home and abroad, the study focuses on key factors such as policies and regulations, social and cultural backgrounds, and economic development patterns, and analyzes how these factors affect the management patterns of religious heritage. In addition, the study will combine textual information such as local records, government reports, and cultural heritage protection plans to provide richer historical and policy background support for the case studies.

By observing the physical state of the building, its openness, and its interaction with the community, the study will provide insight into the actual use of the building and its social function.

1.7 Research Significance

At the theoretical level, the study breaks through the limitations of the traditional single perspective and innovatively constructs a three-dimensional analytical framework of “policy-society-economy”, which not only examines the relationship between cultural relics protection policies and religious management policies, but also analyzes in-depth the impacts of the changes in community structure on the

functions of religious buildings in the context of urbanization, providing a more systematic theoretical tool for understanding the management of religious buildings in China.

In terms of typology research, this study is the first to systematically sort out and categorize the management practices of religious architectural heritage in China, identifying four typical modes and establishing the corresponding evaluation dimensions. This classification system makes up for the shortcomings of existing studies and provides an operational analytical framework for subsequent studies. It is especially worth emphasizing that, in analyzing international cases, this study focuses on the specific measures taken by different countries in response to community participation, secularized culture, and policy regulation, which provides new perspectives on the sustainable use and living conservation of China's religious heritage and offers theoretical support for future policy adjustments and management practices.

1.8 Chapter Layout

This dissertation systematically explores the management of religious architectural heritage in China through five main chapters. The first chapter establishes the research background, core issues, and analytical paths, reveals the important gaps in the existing research in terms of geographical coverage, theoretical framework, and international comparison through literature review, and explains in detail the research methodology and significance of the research.

Chapter 2 focuses on the case study of Hancheng, analyzing the specific manifestations of the phenomenon of “closed” religious heritage in this region and its formation mechanism through field research and policy analysis. The chapter systematically examines how multiple factors have jointly shaped this unique

management model from three dimensions: policy management system, community social change, and economic development planning.

The third chapter turns to a nationwide typology study, which, based on detailed case studies, categorizes China's religious architectural heritage management models into four typical categories: completely closed, passively open, culturaltourism oriented, and community-participation oriented. Each type is explained in detail through characterization and typical cases (e.g. Xi'an Xingshan Temple, Songshan Shaolin Temple, Quanzhou Guanyue Temple).

Chapter 4 explores in depth the influencing factors of management mode selection, analyzing the causal mechanisms of different management modes from four key dimensions. Meanwhile, through the comparative study of international cases such as Singapore's United Temples, France's religious heritage and Japan's shrine management, it provides a more complete theoretical framework and reference for understanding Chinese practices.

Chapter 5 concludes with a systematic summary of the findings, outlining the theoretical contributions and practical insights of this study, and objectively pointing out the limitations of the study.

development, and in December 1986 was named as the national historical and cultural city.18

There are many different types of religious heritage in Hancheng, and different types of religious architectural heritage had different functions in the society at that time and served different groups of people. They constituted a multi-level and extensive interactive social and cultural system. However, today's closed state limits their function as a center of cultural and social activities, unable to serve as a spiritual center in the community and enhance the cohesion of the community as in the past, resulting in the gradual loss of their original social functions and cultural values.

2.1.2 The Closure Phenomenon in Hancheng

In field research, it was observed that religious heritage buildings in Hancheng's traditional villages are uniformly managed by the local scenic area management committee. Each village’s cultural relics administrator is responsible for safeguarding the keys. To access a temple for investigation or activities, an application must first be submitted to the committee, which then instructs the village staff to open the gate. While this system ensures the safety of cultural relics, it also limits daily accessibility, further weakening the buildings’ role within the community.

The first case is Guandi Temple in Liuzhi Village, the first batch of provincial traditional villages. Guandi Temple is located near the center of the village, as the eighth batch of national key cultural relics protection units, the temple was built in the Yuan Dynasty, and has since been conserved four times. And the Guandi Temple consists of several folk heritage buildings.

18 Chi Chen, Ruo Shui Li, Guang Yang, and Yu Xi Zhu, Map of Ancient Architecture in Shaanxi (Beijing: Tsinghua University Press, 2021).

From the observation of the scene, the Guandi Temple is currently surrounded by walls and iron gates and is completely closed. The current Guandi Temple(see Figs.1. and 2)retains the appearance after conservation in 2016, but its closed state makes it inaccessible to the public. Guandi Temple is a complex of buildings, there is a large open space in front of the temple, villagers can observe the situation inside the courtyard through the gap of the iron gate, but the actual use of the temple has been absolutely limited.

Figure 1.Aerial photo of the Guandi Temple. Figure 2.Iron gate of the Guandi Temple.

Source: Author's photograph, March 05, 2024.

According to villagers' accounts and historical records, Guandi Temple was used as a village primary school after the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949. From 1958 to 2018, Guandi Temple underwent six conservation projects. 19 The temple has been closed since 2016 and is not open to the public. Although the Guandi Temple is currently closed, the large open space in front of its Hall of Offering still provides a space for villagers to observe and reminisce.

Due to the extremely important geographical location of Guandi Temple in Liuzhi Village, it is located in the center of the village, previously, as a spiritual place, it was

19 Yubin Xu, “The Path of Villagers' Participation in the Regeneration of Traditional Settlements from the Perspective of Dominance: A Case Study of the Guandi Temple in Liuzhi Village” Architectural Heritage 2 (2022), https://doi.org/10.19673/j.cnki.ha.2022.02.014

From the observation of the scene, the Huayan Temple is currently surrounded by walls and iron gates and is completely closed(see Figs.3.). After the front gate was removed, the entrance was rebuilt in the southeast corner of the courtyard. Now the entrance is extremely hidden in the corner next to the residential houses, and completely closed with iron doors, so that the villagers cannot observe the situation in the courtyard.

Figure 3. Iron gate of the Huayan Temple. Source: "韩城市马庄村:寻访华严寺,曾经是一座小学 校," Baijiahao, February 05, 2021, https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1772844447585732608.

According to villagers' accounts and historical records, Huayan Temple was used as a village primary school after the founding of New China in 1949. In 2019, it was included in the eighth batch of national key cultural relics protection units; In 2022, Huayan Temple underwent a large-scale conservation project. 23 Huayan Temple has been closed to the public since the closure of the village primary school, and now its interior no longer bears any social or cultural functions.

At that time, most villagers had limited awareness of architectural heritage conservation and almost no systematic concept of conservation at that time. As a result, the buffer zone of Huayan Temple was extremely imperfect, and the

23 “Mazhuang Huayan Temple.”

courtyard walls were surrounded by dense residential buildings, some of which even directly connected with the heritage buildings(see Figs.4.). This situation not only destroyed the original spatial pattern of the temple, but also caused a serious impact on the heritage itself. Moreover, it is precisely because of the construction of these adjacent residential houses that Huayan Temple is completely hidden in the village, losing its due spatial independence and recognition. In the field investigation, it was found that most of the villagers in the village did not even know the existence of the Huayan temple, which further reflected that Huayan Temple was not only covered by the physical space, but also its cultural and historical value was gradually faded in the villagers' cognition.

Figure 4.Aerial photo of the Huayan Temple. Source: Author's photograph, March 05, 2024.

2.2 Factors Shaping Hancheng's Mode

2.2.1 Policy and Management System

The current "scenic area management committee - village cultural conservator" management model in Hancheng City has resulted in the limited use of cultural relic sites. According to the field survey, in this management system, the management committee of the scenic spot is responsible for the overall management decisions, while the village cultural conservator only undertakes the daily maintenance duties.

Although the village cultural conservator holds the key to the heritage building, any open use must be approved by the management committee of the scenic spot. This process is often complicated and time-consuming.

This mode of management reflects two major contradictions: first, the national policy direction of "conservation first" has been simplified in actual implementation into a management mode of "closure"; and second, although villagers have actual needs for the use of these cultural heritage buildings, the lack of a smooth application channel has made it difficult to realize their wishes for their use.

From the policy level analysis, in 2019, the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development and the State Administration of Cultural Heritage's circular criticism of Hancheng City pointed out that there were problems of destroying the landscape environment pattern of the ancient city, which reflected that there was a lack of clarity in the management responsibilities and coordination between cultural relics protection and urban development.

24 In 2022, the cultural relics protection promotion meeting held in Hancheng City emphasized that it was necessary to "explore the rationalization of the systematic mechanism of protection and management as soon as possible".25 This indicates that the existing management mechanism is inadequate and needs to be further improved.

The Guidelines for the Management of Cultural Relics Collections in Shaanxi Province stipulate that cultural relics in collections shall not be lent out or used for commercial purposes at will and that they shall be managed in strict accordance

24 Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development and National Cultural Heritage Administration, Notice on the Inadequate Protection of Certain National Historical and Cultural Cities, March 14, 2019, https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2019-09/29/content_5434593.htm?utm_source

25Hancheng City Culture and Tourism Bureau, Hancheng City Holds a Meeting to Promote Cultural Relics Protection Work, April 12, 2022, https://wwj.shaanxi.gov.cn/sy/dtyw/wbyw/202204/t20220412_2217176.html?utm_source

traditional temples, which used to serve as centers of socialization and belief, have been replaced by party service centers that provide free Wi-Fi and square dance venues.

Analyzed at the macro level, this phenomenon is related to multiple social factors.

First, the process of urbanization has accelerated changes in the demographic structure of villages. Many young adults have gone out to work or settled in cities, leading to the increasingly prominent problem of the aging of the population left behind. 28 This population mobility changes the age structure of the countryside and cuts off the chain of cultural inheritance between generations, gradually weakening the emotional connection of the younger generation to traditional historical buildings.

Second, the modernization and transformation of the grass-roots governance system has reshaped the pattern of rural public space. The establishment of new types of public facilities, such as party service centers, has objectively formed a substitute for traditional public space through the provision of standardized modern services. This substitution reflected in physical functions, and the deeper involvement of State power in rural social life, leading to the gradual marginalization of traditional forms of social organization.

Thirdly, the focus on rural construction policies has affected the functional positioning of historic buildings. The current policy orientation focuses more on physical construction, such as infrastructure improvement and environmental remediation, and provides relatively little support for cultural projects, such as the revitalization of cultural spaces. 29 This tendency in resource allocation makes it

28 Chen, Analysis of the Phenomenon of Abandonment in Traditional Villages in the Han Cheng Region

29 Hancheng City Housing and Urban-Rural Development Bureau, Hancheng City Historical and Cultural City Protection Affairs Center, April 18, 2024, http://www.sxbb.gov.cn/site-sxdjgl/yearlyReport_view/261430

difficult for historic buildings, although conserved, to find a suitable functional position in modern community life.

These macro-social changes have led to the predicament of "well-conserved physical space but continued weakening of social functions" of the historical buildings in Hancheng. To solve this dilemma, it is necessary to rethink the positioning and value of traditional architecture in modern rural society from the perspective of social transformation.

2.2.3 Economic Development and Government Planning

Hancheng City is facing serious financial difficulties in the conservation of religious heritage temples. Currently, the conservation work mainly relies on government financial inputs and external financial support, and the villages themselves lack sustainable economic blood-supporting capacity. Although tourism development is seen as a potential solution, there are objective difficulties in integrating into the mainstream tourism market for villages that are remotely located and lack distinctive tourism resources.

Although the state has invested a large amount of money in conserve works for historic buildings, the subsequent operation and maintenance funds are seriously insufficient. Taking Hancheng City Historical and Cultural City Protection Center as an example, its available funds at the end of 2024 will only be 127,500 RMB, which is difficult to support the daily maintenance work.

30 This mode of fund allocation has led to many conserved buildings being abandoned again due to the lack of follow-up investment. Secondly, in the context of local financial constraints, the potential cultural value of cultural heritage often gives way to short-term economic

30 Hancheng City Housing and Urban-Rural Development Bureau, Hancheng City Historical and Cultural City Protection Affairs Center

more comprehensively the spectrum of practices of cultural heritage conservation in China and provide references for the optimization of the Hancheng model.

TYPOLOGIES

3.1 Fully Closed Model

This type has been mentioned in Chapter 3 of the research and refers to some religious sites or historical buildings that have been closed to the public for a long period. At this time, the place no longer conducts any religious activities or social services and is used only for heritage conservation. This phenomenon is more common in the city of Hancheng in China.

3.1.1 Feature Analysis

In this model, the heritage building would be closed off and not accessible to the public. Only specific managers or conservators would have access to the building.In addition, religious ceremonies or community activities are no longer conducted in these places, and they only serve to conserve historical heritage. The original religious and social functions cease, and the building becomes a purely heritage conservation site.Management is usually the responsibility of the Government's heritage conservation department. The opening of these sites is subject to layers of approvals, and only authorized persons are allowed to enter, making the management stringent and the procedures complex.

3.2 Passively Open Model

Passively open models are religious sites that are formally open to the public, allowing visitors to enter and visit, but severely restricting religious practice. These buildings usually maintain their original religious appearance and basic functions, but the government imposes severe restrictions on formal religious activities.

heritage" or "historical sites" management model to downplay their religious functions so that they are viewed more as cultural heritage than as centers of faith.

3.2.2 Typical Case : Xingshan Temple in Xi'an Xingshan Temple in Xi'an is a historical Buddhist temple. Although the temple is still open to the public in terms of physical space and allows visitors to worship, its religious activities are strictly limited, especially in terms of some of the traditional religious ceremonies and activities with a high level of popular participation.

Recently, the Xingshan Temple in Xi'an announced that it had suspended traditional religious activities such as drawing lots for fortune, and a notice posted at the entrance(see Figs.5.) to the temple made it clear that believers and tourists would no longer be allowed to participate in these activities,36 which had once been part of a temple fair or religious experience. This move has directly affected the religious atmosphere of the temple, transforming it from a place of religious worship to a cultural attraction with religious elements. The change in the content of the announcement reflects the government's increased regulation of religious activities, especially in large religious events, where restrictions on popular participation are gradually increasing.

Figure 5.Signboard at the entrance of Xingshan Temple. Source: Xiaohongshu, March 21, 2025. http://xhslink.com/a/74IGcZhqZ028

36 Xiaohongshu, "Daxingshan Temple Stops Issuing Talismans," accessed April 19, 2025, https://www.xiaohongshu.com/discovery/item/67dd27f8000000001c001e23

Although temples are open to the public and tourists can still worship and visit them, these activities are more limited to the level of cultural consumption rather than indepth religious experience. Traditional religious practices such as drawing lots and praying for blessings have been strictly compressed, and the core function of religious belief has been marginalized and gradually transformed into venues for tourism and commercial experiences.

3.2.3 Policy Restriction

China's religious policy is not a direct ban on religious activities, but rather a systematic policy to squeeze the space for religious practice and make it naturally shrink.

The Regulations on Religious Affairs (State Council Decree No. 426) explicitly require that religious venues be subject to government supervision and that any large-scale religious activities require approval, which hinders the normal operation of religious spaces.

37 The ban on minors (Circular on Further Control of Illegal Religious Activities) stipulates that minors are not allowed to participate in religious activities,38 resulting in the transmission of religious beliefs of the new generation being artificially blocked.

3.3

Cultural and Tourism-Oriented Model

Cultural tourism-oriented models are religious sites that deeply integrate religious functions with tourism. In this model, religious activities are often replaced by commercialization and tourism, and the function of core religious activities is weakened and replaced by a variety of activities aimed at attracting tourists. The management of religious heritage is usually dominated by tourism enterprises or

37 Ministry of Justice of the People’s Republic of China, Regulations on Religious Affairs, January 12, 2025, https://www.moj.gov.cn/pub/sfbgw/flfggz/flfggzbmgz/202401/t20240112_493489.html

38 Lushan County People’s Government, Notice on Further Rectifying Illegal Religious Activities, March 18, 2023, https://www.hnls.gov.cn/contents/43251/364826.html

local governments, which reach agreements with religious groups on the distribution of benefits.

3.3.1 Feature Analysis

These religious buildings are integrated into the tourism industry chain, with ticket sales, performance programs, and souvenir sales becoming the main sources of income, and the proportion and influence of religious activities gradually being marginalized.To attract more tourists, religious ceremonies and activities are often simplified or transformed into activities of a performative nature, and the role of monks or clergy is gradually changing to that of participants in cultural presentations and tourist activities.

Management and operation are dominated by local governments or tourism companies, and benefit-sharing agreements between religious groups and other management entities have led to a greater focus on the commercialization of religious buildings.

3.3.2 Typical Case : Shaolin Temple in Songshan

The Shaolin Temple in Songshan, Henan Province, is a typical representative of cultural tourism-oriented religious buildings. As a world-renowned Buddhist temple, Shaolin Temple has become a very commercialized and tourist-oriented religious site because of its close connection with martial arts and strong cultural tourism resources.

The main sources of income for the Shaolin Temple include ticket sales, sales of peripheral merchandise, and income from martial arts performances. According to a study in the Journal of Geographical Studies, the annual number of visitors to the Shaolin Temple has exceeded 5 million, of which more than 90% come mainly to experience martial arts culture and participate in tourism activities rather than

This model usually maintains operations through donations and small-scale business activities. Such religious buildings not only undertake religious ceremonial functions but also integrate multiple functions, such as community deliberation and cultural inheritance, emphasizing community participation and the spirit of shared governance.

3.4.1 Feature Analysis

Community members are a key force in management and development. Management decisions are not determined solely by government or religious institutions, but through extensive community consultation and participation. The views and needs of the community play an important role throughout the management process. This model ensures that religious heritage sites are close to the lives of the local population and are better integrated into everyday social functions.

This type emphasizes the participation of various groups, including residents, believers, volunteers, and relevant social organizations and civic groups. These groups are usually involved in various aspects such as planning of religious activities, education on cultural heritage, maintenance of facilities and daily management. Multiple participation ensures comprehensive management work and feedback from multiple perspectives, which helps to improve social acceptance of heritage conservation.

In the community participatory model, residents support the sustainable development of religious heritage by establishing network relationships, and cooperative mechanisms, pooling funds for donations, or providing voluntary services. This spontaneous social participation not only brings economic support to religious sites but also promotes the spread of community culture and cohesion.

3.4.2 Typical Case : Guanyue Temple in Quanzhou

The faithful have been central to the restoration of Guanyue Temple. 40 The conservation of Guanyue Temple was not solely led by the government but was gradually carried out with the voices of the faithful and the support of the community, reflecting their high recognition of the cultural value and their strong desire for conservation. This shows that the recognition and support of the faithful and the community for the historical, cultural, and religious significance of the temple is the core driving force for its operation.

The then Minister of the United Front Work Department of the Quanzhou Municipal Party Committee commissioned the principal of the Kaiyuan Primary School to preside over the conservation of the Tonghuai Guanyue Temple and set up the "Board of Directors for the Protection of the Monuments of the Tonghuai Guanyue Temple in Quanzhou".41 This shows that the active involvement of local leaders and community elites was central to the process of temple restoration. Community organizations undertook the actual work of temple conservation and ensured the cultural and religious legacy of the temple through interaction with the government and the faithful.

The donations and participation of the faithful enable the temples to carry out social services and cultural activities on a larger scale, thus enabling the temples to form a unique social function in the community and become an important carrier of local cultural identity and community cohesion.42 The participation of the faithful is not only reflected in monetary donations but also in the formation of the temple's social capital through their social connections and networking. The economic

40 Jianmei Xiao, “A Study on the Contemporary Development of Folk Belief Temples: A Case Study of Tonghuai Guanyue Temple in Quanzhou,” Cultural Heritage, no. 2 (2016).

41 ibid.

42 ibid.

development of Guan Yue Temple is deeply intertwined with the extensive support of the community within the temple, and this support increases the economic

income of the temple and provides a stable foundation for its further development.

Category Fully Closed Model Passively Open Model

Accessibility

Primary Function

Management Body

Fully closed to the public

Heritage conservation only

Government heritage

Typical activities None

Revenue Source Government funding

Policy Constraints

Case Example

All activities banned

Physically open, religious acts restricted

Nominal religious function(de facto tourism)

Government-controlled, limited religious input

Tourist visits,passively worship

Tickets, minor donations

religious ceremonies restricted

Cultural-Tourism Oriented Model

Community-Engaged Model

Fully open, highly commercialized Open, community centric

Religious role marginalized; tourism dominates

Government/tourism companies + religious groups

Performative acts

Tickets, merchandise performance

Commercial compliance checks

Closed sites in Hancheng Xingshan Temple in Xi’an Shaolin Temple in Songshan

Public participation None

Religious Vitality

Fully extinct

Low(passive tourist engagement)

Symbolically preserved

High(active tourist consumption)

Religious, social, and cultural integration

Local clans, NGOs, believers

Rituals, community deliberation, cultural events

Donations, community fundraising, small business

Community selfgovernance rules

Guanyue Temple in Quanzhou

Very high(community cocreation)

Performative preserved Substantively sustained

Table 1. Management Models of Religious Heritage in China (Compiled by the author)