CONTENTS: A. Abstract

B. Acknowledgements

C. Methodology

i. AimsofDissertation

ii. ResearchQuestions

iii. ResearchScope

iv. LimitationsofStudy

D. Introduction

1. Background: Contemporary Challenges facing Traditional Crafts

1.1 IssuesfromtheLackofRecognitionofIntangibleHeritage

1.2 MarginalisationofTraditionalCraftsandInadequatePolicyFrameworks

1.3 IsthereanAbsenceofTraditionalCraft?

2. Importance of Material and Tangible Heritage Conservation

2.1 EvolutionofConservationPrinciples

2.2 TowardsConservationPrinciplesofModernistHeritage

3. Contextualising Singapore

3.1 SingaporeConservationPrinciples

3.2 PerspectivesfromLocalBuilders

4. Is a Revival of Traditional Crafts Possible?

4.1 TheArtisan,TheCraftsmanandTheBuilder

4.2 WorkmanshipasaMentality

4.3 Conclusion

E. List of Figures

F. Bibliography

A. Abstract Thisdissertationinvestigatesthedecliningtraditionalbuildingcraftskillswithin thefieldofbuilt-heritageconservation,emphasisingtheircriticalrolein conservationinterventions.Theresearchemploysaqualitative,mixed-method approach,combiningarchivalresearchandsemi-structuredinterviewstoexplore thecontradictionsinthedemandandsupplyoftraditionalcraftskills.Archival researchanalysestheevolutionofconservationapproaches,particularlytheshift fromRuskinianoriginstomodern20th centuryprinciples,whilesemi-structured interviewsgatherinsightsfromlocalbuildersandcraftsmenabouttheirchallenges andreservationsregardingconservationwork.Akeyfindingofthisresearchisthe persistentgapbetweenthought-basedandmotor-basedlabourinheritage conservation,wheretheexpertiseofcraftspeopleisoftenmarginalisedinfavourof abstracttheoreticalframeworks.Thisdividehasledtothedevaluationof intangibleculturalknowledgeandskillsoftraditionalcraftsmen,resultingintheir exploitation.Furthermore,thestudyrevealsthattheexclusionofcraftspeople fromdecision-makingprocessesandtherelianceonstandardizedarchitectural drawingshaveexacerbatedthisdisparity,oftenleadingtoinappropriate interventionsthatcompromisetheintegrityofheritagesites.Toaddressthese challenges,thedissertationproposesstrategiestobridgethethought-basedand motor-basedgap,includingtheintegrationofcraftspeople'sexpertiseinto conservationframeworksandthedevelopmentofinternationaleducational platformstorevivetraditionalcraftsmanship.Byhighlightingtheimportanceof workmanshipandtheembodiedknowledgeofcraftspeople,thisresearch advocatesforamoreinclusiveapproachtoheritageconservationthatvaluesboth tangibleandintangibleculturalheritage,re-establishingthevitalrolethatlocal buildersandcraftspeopleplayintheconservationprocess.

B. Acknowledgements I am deeply grateful for the invaluable support received during my Masters of Architectural Conservation program this past year. My heartfelt thanks go to Dr. Ho Puay Peng for his dedicated supervision and for sharing his extensive knowledge both in Singapore and overseas. I am equally thankful to Dr. Nikhil Joshi for his trust in developing my conservation capabilities and for connecting me with passionate professionals, academics, and craftsmen in the field.

Special thanks to my classmates who offered thoughtful suggestions and lent sympathetic ears as we shared our challenges together. I particularly want to acknowledge Jackson, Ben, Kojio-san, and Derrick for generously providing valuable industry insights about construction and craftsmanship through our interviews.

Finally, I extend my deepest gratitude to my fiancé for providing the space and support needed to pursue architectural conservation. Your presence has helped me approach this new chapter with greater objectivity and pragmatism.

ii. Research Questions 1. Fromanalysisofvariousinternationaldoctrinaldocumentson conservationapproaches,howhavetheyfailedtohighlightthe valueofexpertise,knowledgeandskillofcraftspeopleinthe successfulexecutionofconservationinterventions?

2. Howistraditionalcraftstillrelevantandintegraltoconservation worktoday?

3. Inafast-pacedandmodernisedeconomylikeSingapore,howcan decliningandabsenttraditionalcraftmanshipberevalorisedand revivedinanauthenticmannerwhilestayingrelevantand functioningsustainability?

iii. Research Scope Theresearchscopeofthisstudyisfocusedoninvestigatingthe declineoftraditionalbuildingcraftskillswithinthecontextofbuiltheritageconservationinSingapore.Thestudyaimstoaddressthe growingissuesofdecliningtraditionalcraftskillsbyexploringtheir importanceinconservationinterventionsandidentifyingthe challengesfacedbylocalbuildersandcraftspeople.Theresearchis geographicallylimitedtoSingapore,withaspecificfocusonthe urbansettinganditshighlyregulatedconstructionindustry.The paperwillnotattempttoproposenewframeworksandpolicy reforms,andwillonlysuggestpossibleavenuesforallowing traditionalbuildingcrafttoberevivedwithinthedefinitionsof conservationprinciples.

iv. Limitations of Study TheresearchislimitedtothecontextofSingapore,whichmaynotbe representativeofotherregionswithdifferentcultural,economic, andpolicyframeworks.Whilethefindingsmayhaveimplicationsfor similarurbanizedandmodernizedeconomies,theymaynotbe directlyapplicabletoothercontexts.Thesemi-structuredinterviews withlocalbuildersandcraftspeopleconductedmaynotbe representativeoftheentirepopulationofstakeholdersinvolvedin heritageconservation.Thesamplesizeandselectioncriteriamay limitthebroaderapplicabilityofthefindings.Lastly,thestudy examinesthelimitationsofexistingconservationpoliciesand guidelinesbutmaynotproposecomprehensivepolicyreformsor practicalinterventionsforaddressingtheselimitations.

E. Introduction Inmanypartsoftheworld,traditionalbuildingcraftshavebeenstrugglingto maintaintheirrelevanceinthemodernworld.Theskillsandexpertiseof craftspeoplehavebeeninsteadydeclineduetoincreasingglobalisationand industrialisationofmoderneconomicstructures 1 WhilesomenationslikeJapan stillmanagetoretaintheirprideincraftskills,traditionalbuildingcraftskillsin Singaporestandatthebrinkofcollapse.TheSingaporegovernmenthasbeen acutelyawareofitserodingnationalandculturalidentitysincethe1980s.2 Rapid modernisationhasprioritisedredevelopmentattheexpenseofbuilt-heritageand itssupportingintangiblecultures.

AlthoughconservationinitiativesexistthroughagenciesoftheSingapore governmentsuchastheNationalHeritageBoard(NHB)andtheUrban RedevelopmentAuthority(URA),theseconservationguidelinesandpoliciesare mainlyfocusedontechnicalmaterialimplementations.TheConservation principlestheyhaveadoptedfromICOMOSandUNESCOonlyaccountsforthe tangibleaspectsofheritageconservation.Moreover,conservationguidelinesand recommendationsarealsolimitedinscope,coveringonlyurbansettingsand domestictypologiesintheformsofconservationdistricts,historicshophouses, andhistoricbungalows.Despitegreateremphasisonlocalheritageawarenessas highlightedinthenew Our SG Heritage Plan 2.0 initiativebyNHBin2023,an absenceintheacknowledgementandsupportforlocaltraditionalbuildingcraft skillsandknowledgehasfailedtoinstilconfidenceinourlocalcraftsmanand builders.3 Thiscreatesacircularproblem:alackofpublicawarenessofbuilt heritageconservationleadstolowdemandforconservationwork,complicatedby itscomplexityandhighcosts.Thislimiteddemandandawarenessresultinweak conservationpoliciesandminimalgovernmentsupport,discouraginglocal buildersfromdevelopingconservationexpertise.(Figure1)Today,manyofthem continuetodistancethemselvesfromthecomplexitiesofconservationwork.

1 Partarakis et al., “A Review, Analysis, and Roadmap to Support the Short-Term and Long-Term Sustainability of the European Crafts Sector.”. P. 2

2 Yeoh and Huang, STRENGTHENING THE NATION’S ROOTS? HERITAGE POLICIES IN SINGAPORE P. 201

3 NHB, “Our SG Heritage Plan 2.0.”

1. Background: Contemporary Challenges facing Traditional Crafts TheroleoftraditionalcraftsisfundamentaltoHeritageconservation.Thework andpracticecarriedoutbytraditionalcraftspeopleembodybothtangibleand intangibleculturalheritagethroughcenturiesofaccumulatedknowledge,skills, andculturalsignificanceessentialforinformedandsensitiveconservation practices.However,thedeclineofthesecraftsposesacriticalthreattothequality andauthenticityofheritageconservationwork.Traditionalcrafts,particularly traditionalbuildingcrafttrades,facemountingsocial,economicandsystemic resistanceacrosstheworld.Ourmodernsocietyhassteadilyevolvedfromthe industrialmechanisationandmanufacturing,tothemodernisedknowledge-based anddigitaltechnology-centriceconomyoftoday.Associetyembracesthe conveniencesandspeedofmodernisation,theresultantforcesofglobalisationand industrialisationhaveprofoundlyimpactedtraditionalcrafts.Mass-produced productsnowdominatethemarkets,offeringcheaperalternativesthat overshadowthemorehuman-centricvaluesinherentintraditionalcraft techniques 5

Adominanceofindustrialisedconstructionpracticesandthecommercialisationof heritageconservationhasresultedinanincreasingemphasisoneconomic efficiencyandcost-cuttingmeasures.Thishomogenisationofconsumerculture, combinedwithhighproductioncosts,andlimitedmarketsaccess,diminishesthe demandfortraditionalcraftsandcontributestotheundervaluationof craftsmanshipinourfast-pacedconsumerlandscape.Partarakisetal.(2025)argue thatthepressuresofglobalisationundermineeffortstowardspreserving traditionalcrafts,whicharevitalformaintainingculturaldiversityandidentityin conservationpractices.6 Therelianceonindustrialisedproductsinconservation interventionsoftencompromisesthequalityofconservationwork,resultingin diminishedauthenticityandculturalsignificance.Whentraditionalcraftsmanship isnotrecognizedasvaluableassets,thenecessarysupportforpreservingthese

5 Schultz, “Traditional Arts and Crafts for the Future.”. P. 56–63.

6 Partarakis et al., “A Review, Analysis, and Roadmap to Support the Short-Term and Long-Term Sustainability of the European Crafts Sector.” P. 2

skillsdiminishes,resultinginalossofexpertisethatiscriticalforsensitive conservationpractices.

However,evenasinvaluablecontributorsofculturalandmaterialauthenticityin conservationinterventions,theeconomicrealitiesofconservationworktendto undervaluetraditionalcraftsmanship,exploitingcraftspeopleintheprocess. Norton(2018)highlightsthatthissystemundervaluescraftspeople,viewingtheir workasameanstoanendratherthanavaluedskill,furtherexacerbatingthe challengesthesecraftspeopleface. 7

1.1 Issues from the Lack of Recognition of Intangible Heritage Thepracticeoftraditionalcraftrepresentsaphysicalembodimenta craftsman’stacitknowledge.Itencompassesbothtangibleandintangible valuesofculturalheritage.Inthelaterpartsofthepaperwhereweevaluate theinternationalconservationdoctrinaldocumentstoverifytheiremphasis onmaintainingauthenticitythroughoutallaspectsofconservation interventions,wecontinuetoobservethatintangibleheritage-skill, knowledge,andexpertise-areoftenoverlookedinfavouroftangible heritage-materialoutcome;leadingtoinsufficientsupportforthe preservationandtransmissionoftraditionalcraftskills.Norton(2018) notesthatthislackofrecognitionhasledtothemarginalisationof craftspeopleandtheirexploitationduringtheprocessesofconservation work,fundamentallyunderminingtheirexpertise.8 Thechallengeextends todocumentation,asthecomplexprocessoftranslatingknowledgeand skillintocraftworkprovesdifficulttorecordcomprehensively.Friel(2020) emphasisesthatwithoutadequateinformationaboutthecultural,historical andthetechnicalembodiedskills,itisdifficultformanyconsumersto recognisethevalueandqualitythatcraftmanshipisabletoprovide.9 Bridgingtheawarenessgapregardingthequalityandvalueoftraditional

7 Norton, “Heritage Conservation and the Building Crafts: A Qualitative Study of Yorkshire Craftspeople.” P. 12

8 Ibid. P. 36

9 Friel, “Crafts in the Contemporary Creative Economy.” P. 87

craftsmanshiprequirescomprehensiveeducationforboththepublicand professionals.Withoutproperunderstandingofcraftspeople's contributionstoconservationwork,decision-makersoftengravitatetoward mass-producedsolutions,overlookingtheinvaluableabilityofskilled artisanstoassess,evaluate,andresolvespecificon-sitechallengeswith precisionandexpertise.Craftspeoplenowfaceanuphillbattletosecure adequatefundingandsupportthatreflectstheirdedication.Withoutwhich, theystruggletomaintaintheircredibilityascustodiansofbothculturaland technicalknowledge,hinderstheirabilitytodevelopsustainableand economicallyviablebusinessmodels,andmakesitincreasinglydifficultto attractyoungergenerationsastheygravitatetowardsothermoremodern andfinanciallyrewardingcareers.10

Zbuchea(2022)highlightsthatthislackofinteresthasresultedinthe declineofcraftsmanshipinmanyregions,whichisalarmingfor conservationeffortsthatdependontheseskills.11 InSingapore,the absenceofaneconomicandpolicysupporttowardsestablishingrobust educationalframeworksthatintegratetraditionaltechniqueswithmodern practicesfurtherexacerbatesthisissue,leavingconservationprofessionals withoutthenecessaryexpertisetoexecutesensitiveinterventionsthat adheretoestablishedconservationdoctrinalguidelines.

Thedeclineofapprenticeshipsisparticularlyconcerning,astraditional craftsareoftentransmittedthroughhands-onlearningandmentorship. Withoutsuchopportunities,thenextgenerationofcraftspeoplewilllack theskillsandknowledgerequiredtopreserveculturalheritage.12

1.2 Marginalisation of Traditional Crafts and Inadequate Policy Frameworks Theexclusionoftraditionalcraftspeoplefromheritageconservation decision-makingprocessesisacriticalissueArevealingcasestudyof

10 Cetinkaya, “Challenges for the Maintenance of Traditional Knowledge in the Satoyama and Satoumi Ecosystems, Noto Peninsula, Japan.” P. 27–40.

11 Zbuchea, “Traditional Crafts. A Literature Review Focused on Sustainable Development.” P. 10–27

12 Wallace and Kalleberg, “Industrial Transformation and the Decline of Craft.” P. 307

heritageconservation,ultimatelythreateningtheauthenticityandintegrity ofhistoricalsites.

Though,theinvolvementofarchitectsandheritageprofessionalsinplaying mediatoryrolesinconservationworkaimstobridgebetweenshortagesof skillsandknowledgeofconservationconcepts,italsoservedasacatalystin creatingadividebetweenthethought-basedandmotor-basedworkof professionalsandcraftspeople.15 Thedominanceofheritageexpertsand architecturalframeworksoftenoverlooksthepracticalexpertiseof craftspeople,furtherdiminishingthevalueoftheintangibleknowledge, skill,andtheembodieddecision-makingprocessintraditionalcraft. Themarginalisationoftraditionalcraftsacrossmanynationscanalsobe largelyattributedtothepoorwagesystemsandpoliciesavailableto supporttheindustry.ManycasesinIndiaandChinademonstratethateven small-scaletraditionalcraftbusinesses,particularlythoseresidingin historicurbanareas,mostlyfalloutsidetheradarofeconomicreformsand policies.16,17 ResearchbyPartarakisetal.(2021)revealsthattheaverage degreeofpolicymatchingamongcraftspeopleinTaiyuan,Chinawasan averageof28.5%,withover53%experiencinglessthan20%policy coverage.Thissignificantgapunderminesthecraftindustry'sabilityto competeandthriveinthemoderneconomy.Furthermore,thelowtax reductionpolicymatchingrateof15.15%indicatesthattheintangible culturalknowledgeandvaluesinherentincraftsmanshiparenotproperly recognisedasvitalcontributorstoTaiyuan'seconomicandcultural development.18 Theabsenceofcomprehensivepolicyframeworkspresents amajorobstacletotheevolutionandintegrationoftraditionalcraftsinto contemporarymarkets.Thissystematicundervaluationofcrafts'cultural andeconomicsignificancehasresultedindiminishedpublicinvestmentand

15 Norton, “Heritage Conservation and the Building Crafts: A Qualitative Study of Yorkshire Craftspeople.” P. 222-223

16 Jigyasu, “IMPACT OF URBAN TRANSFORMATIONS ON TRADITIONAL CRAFTS SKILLS: AMRITSAR’S HISTORIC CORE.”

17 Zhu, Tian, and Wang, “Improving the Sustainability Effectiveness of Traditional Arts and Crafts Using Supply–Demand and Ordered Logistic Regression Techniques in Taiyuan, China.”. P. 2-3

18 Ibid. P. 6-12

support,ultimatelycompromisingthequalityofheritageconservation effortsandthreateningthesurvivalofthesevaluableculturalassets.

1.3 Is there an Absence of Tradition Craft? Traditionalcraftsrepresentfarmorethanartisticexpression;theyserveas vitalrepositoriesofspecialisedknowledgeandtime-honouredtechniques indispensableforheritageconservation.Theongoingdeclineofthese traditionalcraftshasresultedinacriticallossofexpertise,severely compromisingourabilitytoexecuteauthenticconservationworkthat meetsinternationalstandardsandprinciples.Recognisingthischallenge, theAgaKhanDevelopmentNetwork(AKDN)hasemergedasaleading advocateandactivefacilitatorforcraftrevivalacrossitsregionsof influence,particularlyinIndia,whereithassuccessfullyimplemented numerouspreservationinitiatives.

Throughapublic-privatepartnership,the Nizamuddin Urban Renewal Initiative tookonthechallengeofrevivingandguidingstrayartisansand youngtalenttowardtheconservationoftheculturalheritageproperties withinthe Nizamuddin Basti Zone. 19 Skillstrainingprovidedincludedthe restorationofMughalTiles,handlinglime,stonecarving,masonry,gilding, coppersmithing,andtimberworkinvolvingawidedisciplineof conservationarchitects,engineers,students,historians,localyouth, landscapearchitects,andscientists.UnderthemainprinciplesoftheVenice Charterof1964,whichemphasisestheimportanceofpreservingthe authenticityofthetangiblematerialandhistoricfabric,theinitiative functionstotraincandidatesinthetraditionaltechniques,materials,and tools;mergingIndianrepairtraditionswithinternationalscientificrigour.20

Singaporefacesasimilar,albeitamorediresituationwithregardstothe supplyoftraditionalbuildingcraftspeople.Ourlossofsuchtraditionalskills andknowledgesignificantlyaffectsthecostinconservingourheritage

19 Nizamuddin Urban Renewal Initiative, “Reviving Traditional Craftsmanship.”

20 Ibid.

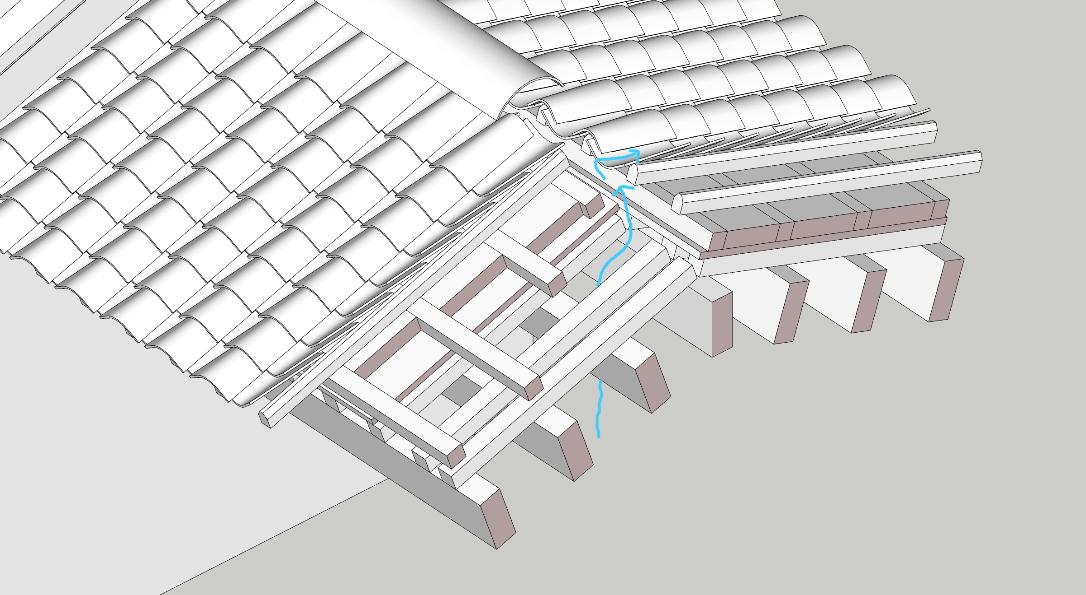

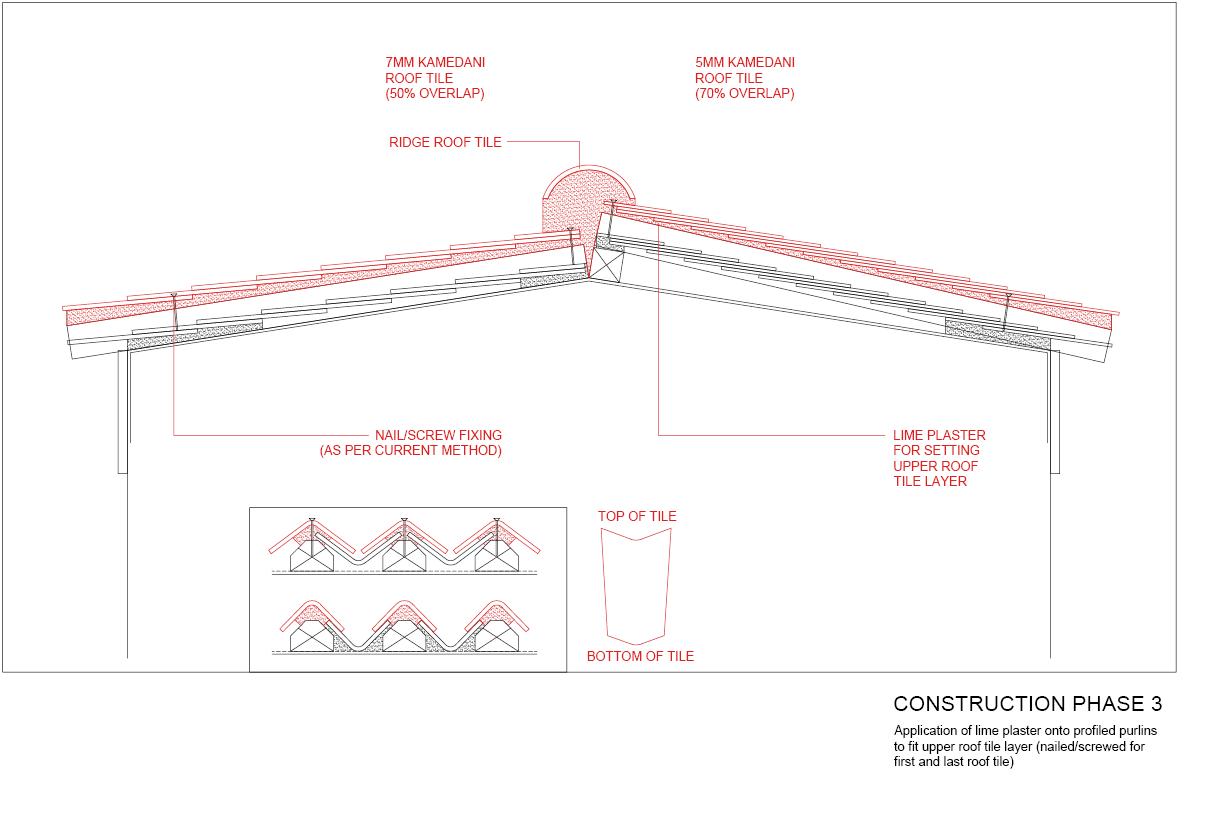

assets.Moreimportantly,itseverelyunderminestheculturalandhistorical integrityofourheritagesites.Whilemajornationalmonuments,suchas Singapore'soldCityHallandSupremeCourt(nowcombinedintoasingle facilityastheNationalGalleryMuseum),receivedsubstantialsupport duringtheirconservation,smallerprojectsstruggletosecuresufficient fundingandtoleranceformoreeffectivecollaborationsbetween craftspeopleandheritageprofessionals.AlongNeilRoad,NUSArCLabfaced challengesreminiscentofthosedocumentedinNorton'sstudyofFountains Abbeystonemasons.Theirmock-upinvestigation,whichsoughttodevelop improvedsolutionsforwatertightnessandheatdissipation,encountered significantresistancefromboththought-basedacademicresearchersand motor-basedtimberroofbuilders.Ononehand,facedwiththeassumption ofworkingwithbuilderswhoarenotwell-versedwithconservation principles,ourheritageprofessionalsdevisedmeansofconveying investigationobjectivesandspecificinstructionsbycreatingdetailed, annotatedspecificationdrawingsliketheonesissuedinFountainsAbbey aroundthe1990s.(Figure2)Asathough-basedacademicendeavour, archivalresearchwasconductedtounderstandroofdetailsofsimilar typologytoNUSArCLab.Throughasequentialprocess,iterationsofroof detailsweredevelopedafterdiscussionsbetweentheteamofheritage professionalsandtimberroofcraftsmen.(Figure2a)Eventuallyafinal conceptualiterationwasproduced(Figure2c).

2b Initial technical drawings produced that utilizes a double layered roof system as compared a single layer in most shophouse typologies in Singapore. The additional layer facilitates air movement freely from the internal to the external through an air-gap at the ridge which will

Figure

then travel along the purlins and released through various gaps between the roof tiles. However, this proposal incurs a lot more cost and weight to the existing roof structure of NUS ArCLab, potentially altering its proportions and overall height as well. (Source: Author)

The final iteration of the roof detailing has reverted to a single layered roof system that sees the introduction of 4mm air-gaps between the plywood substrate that supports the rock wool insultation and waterproof lining. In order to achieve vapour movement between these layers, a new brand of waterproof lining called Tyvek is introduced. This lining is used widely in UK and Japan and its technology allows for vapour movement between the lining while keeping moisture away. It is made possible using a microscopic fibrous membrane that is fine enough to prevent moisture from penetrating through its layers. Compared to bitumen and adhesive waterproof linings used conventionally in Singapore, the use of Tyvek would, in theory, aid in the circulation of air between the roof components and the external surroundings. (Source: Author)

Figure 2c

However,betweentheoryandpractice,therewereunderlyingtensions betweenboththeheritageprofessionalsandthetimberroofcraftsmen.As partoftheteamofheritageprofessionals,Iinitiallyproposedusing architecturaldrawingstofacilitatediscussionsandalignresearch objectiveswithpracticalpossibilities.However,compromisewasnoteasily achievedasthecraftsmenwereaccustomedtotheirowntrialandtested methodsofconstructionusingcorrugatedmetalsheetswhiletheheritage professionalteamopposedthisapproachandcritiquestheimplementation ofcorrugatedmetalsheetswithintheroofstructuresthatpreventedheat fromdissipatingawayfromtheinternalspacesofthebuilding This fundamentaldisagreementcreatedresistancebetweenbothparties, ultimatelyleadingtodeviationsinthemock-updesign(Figure3)To addressthissituation,wedevelopednewdrawingsthatemphasised researchobjectivesratherthanprovidingdetailedconstruction specificationsforthecraftsmen(Figure4)

3

Eventual completed mock-up which deviated from the original proposed drawings. The lack of projected roof overhang serves as a point of vulnerability for the mock-up, potentially allowing water infiltration into the interior of the mock-up structure and the roof components within. The lack of the intended gable-end walls also meant that there will not be

Figure

Figure 4

Technical drawings by convention, are used to convey specific instructions and specifications determined by the architect, they are often incapable of explaining intensions that are more experimental in nature. As the mock-up of NUS ArCLab is experimental in nature and aims to study various ways of achieving the 3 specifications detailed earlier, distributing the construction in phases with clear intents are used in these construction phase drawings to facilitate construction liberty depending on implications faced on-site. As long as theses main objectives can be attained, the builder has freedom to cover gaps of knowledge lacking by more abstract thinkers of institutions. (Source: Author)

TheNUSArCLabcaseclearlyillustratesthedividebetweenintellectualand manuallabour,revealinghowheritageprofessionalsoftenoverlook craftspeople'sintangibleculturalcontributions.Notably,thecentralissue usingcorrugatedmetalsheetsforhistoricbuildingroofs wasoriginallya URAinitiativedesignedtodemonstratetheviabilityofrestoring shophousesforprivateinvestmentduringthe1980s.21 Thelocalbuilders wereinevitablyforcedtoconformwithURA’sdirectivetoimplementsthe useofmetalcorrugatedmetalsheetsbackthen,seeingURAasan

21 URA, “Conservation Guidelines Technical Supplement" Understanding The Roofs.”

conservationmanagingauthority.Consequently,craftspeoplefind themselvescaughtbetweencompetingintellectual,thought-basedforces, effectivelyexcludedfromcrucialdecision-makingprocesses.Thequestion arises:IstraditionalcraftdisappearinginSingapore?Theongoingabstract debatesbetweenpro-developmentgovernmententitiesandheritage professionals whorigidlyenforceinternationalpreservationguidelines withoutempathytothelocalcraftspeopleandcontext mayultimatelyseal thefateoftraditionalcraftsmanship.

2. Importance of Material and Tangible Heritage Conservation Recentcriticalheritagestudieshavebroughtaboutaparadigmshiftintheway authenticityshouldbedefinedandhowitfurthercontributestothewayheritage isbeingreproducedtocapturespecificinterestsandvalues.22,23,24 (Lowenthal, 1985;Herzfeld,1991;Smith,2006)Althoughheritagemanagementand interventionsaregraduallyleaningtowardsvalue-basedapproachesincapturing theintangible,culturalandsocialaspectsoflivingcommunities-cultural landscapesandhistoricurbanlandscapes-subsequentconservationprinciples aftertheNaraDocumentof1994(ICOMOS,1994)stillsuggestsheavyrelianceof preservingthetangible.

2.1 Evolution of Conservation Principles Ruskin’sprinciplesonthebuildingconservationdisciplinethroughhis writtenworkof‘The Seven Lamps of Architecture’in1849,profoundly influencedtheconceptofmaterialauthenticitythatlaterinspiredMorris’ ArtsandCraftmovementandfoundingoftheSocietyfortheProtectionof AncientBuildings(SPAB)in1877.TheinfluencethatSPABhasonthe implementationofhonestyinrepairsemergedasformofresistanceagainst thedestructivestylisticrestorationpracticesofVictorianarchitectsthat resultedinirreparabledamageinthe19th century.25 Overtime,its campaignledtothelandmarkAncientMonumentsAct1881intheUKand subsequentlywentontoinfluencethewayinwhichconservation interventionswerebaseduponandimplementedthroughtheearly internationaldoctrinaldocuments.Recentdevelopmentshaveseenthe conceptofauthenticityundergocriticalevaluation,withscholars recognisingitasdependentonculturallyrelativevaluejudgments.Thishas promptedchallengestothetraditionaldistinctionbetweenoldandnew

22 Lowenthal, The Past Is a Foreign Country - Revisited

23 Herzfeld, “A Place in History: Social and Monumental Time in a Cretan Village.”

24 Smith, Uses of Heritage

25 Slocombe, “SPAB Approach.”

fromadifferenterathatconsidersculturalheritagebeyondancient buildings.Furthermore,asmentionedbyLin,manyofthedocumentsafter theNaraDocument(ICOMOS,1994)takereferencefromavarietyofother documentsthatthemselveshavedifferentprioritiesandagendasspecificto theirownculturalsetting.Likeabrokentelephone,definitionsthatareless clearlydefinedliketheterm“earlierform”fromNewZealandCharteron “Reconstruction”and“earlierstate”fromBurraCharteron“Restoration” and“Reconstruction”bothfailtomentionthecriteriafordecidingonthe said“earlierstateorform”.31,32

AnimportantthingtonoteontheLin’sstudyisthatitonlytookaccountof thevariousinternationaldocumentsthatarewritteninapositivist frameworkfortheprotectionofculturalheritage.Manyoftheconservation conceptspointedoutareundoubtedlyskewedtowardsthesafeguardingof tangibleheritage.Insomecases,theprotectionofintangiblecultural heritagefallsjustshyofrehabilitationorrenewalefforts.Mostcommunities thatrequiresafeguardingoftheirintangibleattributesareusually ostracisedandmarginalisedminoritygroupswhorequirerepresentation morethananyoftheinitialsevenconservationconceptthataremostly outlinedbyinternationaldoctrinaldocuments.Severalkeydocumentshave attemptedtoaddressintangibleculturalheritagepreservation:the ConventionfortheSafeguardingoftheIntangibleCulturalHeritage (UNESCO,2003),theUniversalDeclarationonCulturalDiversity(UNESCO, 2001),andtheYamatoDeclarationonIntegratedApproachesfor SafeguardingTangibleandIntangibleCulturalHeritage(UNESCO,2004). Thesedocumentsprimarilyemphasisetheimportanceofvalue-based

31 ICOMOS New Zealand, “ICOMOS New Zealand Charter for the Conservation of Places of Cultural Heritage Value.”

32 ICOMOS Australia, “The Burra Charter.”

assessmentinincorporatingintangibleculturalattributesandengaging relevantcommunitiestoensuretheirculturalcontinuity.33,34,35

Table 1

Identified attributes to documents. (Source: Lin, 2025)

33 UNESCO, “The Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage.”

34 UNESCO, “UNESCO Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity.”

35 UNESCO, “Co-Operation and Coordination between the UNESCO Conventions Concerning Heritage: The Yamato Declaration on Integrated Approaches for Safeguarding Tangible and Intangible Cultural Heritage.”

whilepermittingnecessarymodificationsforongoingrelevance.

37 Adaptive-reusebecameapredominantstrategythatenablesbuildingsto evolvewhilemaintainingtheirhistoricalvalue,socialandaestheticvalueto thecity.

38

Despitepublicengagementsinrecognizing20th centuryheritage,public supportremainslimited.Modernismisoftenviewedasanoutdated architecturaltrend,perceivedtodayasaneyesoreandirrelevanttourban life.Thisperceptionhindersconservationeffortswhencomparedtothe appreciationforolderheritage.Activistsfortheprotectionand conservationof20thcenturybuildingshavebegunadoptingecological sustainabilityargumentstosupplementtheirclaimsforprotecting significantmodernistbuildings.However,integratingsustainabilityinto conservationpresentschallenges,asgreenstandardscanconflictwith preservingoriginalmaterialsandtheintegrityofdesignintentions.

39 Balancingtheseprioritiesisanongoingresearchfocus.Engagementand ProgramsDevelopingpoliciesfor20th centuryheritageconservationis crucial.Internationalcooperation,likeDOCOMOMO,andinitiativessuchas theConservingModernArchitectureInitiative(CMAI)promotetechnical solutionsandknowledgesharing.

Conservationinpoliciesofthepastthatemphasiseonscientificrestoration ofhistoricbuildingsoftenposedchallengestohighdensitymoderncities likeSingapore.Thesechallengesincludebalancingheritagepreservation withurbandevelopmentneeds,aswellasintegratingmodern infrastructurewhilemaintainingtheculturalsignificanceofhistoricalsites. Manyconservationpoliciesdevelopedforguidingconservationprinciples formodernbuildingsoftentracetheirfoundationbacktoAnti-Restoration philosophiesthatoriginatedfromRuskin'sargumentforminimal interventionandtheretentionofmaterialauthenticityandintegrityas

37 MacDonald et al., “Recent Efforts in Conserving 20th-Century Heritage.”. P. 11

38 Plevoets and Cleempoel, “ADAPTIVE REUSE AS A STRATEGY TOWARDS CONSERVATION OF CULTURAL HERITAGE: A SURVEY OF 19TH AND 20TH CENTURY THEORIES.”.

39 Macdonald, “Materiality, Monumentality and Modernism: Continuing Challenges in Conserving Twentieth-Century Places.”. P. 12

muchaspossible.40 Thedemandsofmoderncitiesandbuildingshavesince shiftedtoadapthighdensitylivingandalesspermanentbuiltenvironment, unlikehistoricbuildingsofthepast.Mostliteratureanddocumentson conservationguidingprinciplesformodernbuildingsoftencalltoattention theneedtoaddressitsstakeholders-architect,owners,patronsofthe building-inordertobettercomprehendthecomplexityofitsdesignintent andsocialsignificance.However,thebuildersbehindthesemodernist buildingsareusuallyleftoutanddeemedtobeeasilyreplaceable.

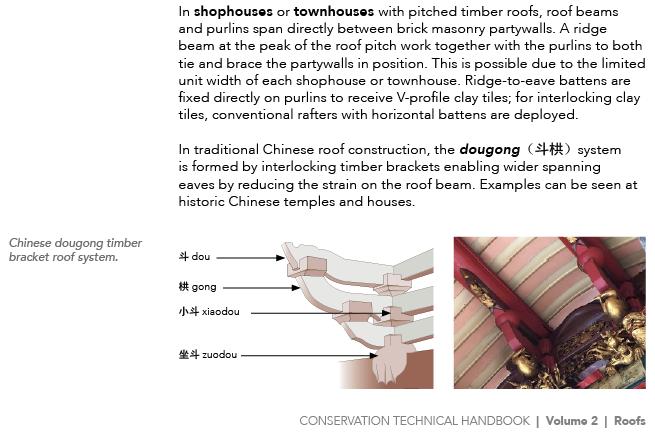

Manyinternationaldoctrinaldocumentshavebeenproducedtopromote,educate, andsafeguardculturalandbuiltheritagethroughtheevaluationoftangibleand intangibleattributes.Whilethesetheoreticalframeworksprovidehelpful guidelinesforustofollow,IwouldarguethatonlyMorris’advocacyeffortshada strongconvictionforthededicationofcraftspeopleandthequalityof workmanshiptheymanagedtoupholdasevidencedbytheenduringmonuments theycreatedthatstoodthetesttime.Theactofconservationisundoubtedlyalso anintimatedialoguebetweenbothmaterialandhand.Thematerialfabricitself revealscrucialevidence-offeringinsightsintohistoricalusagepatterns,activities, traditionaltechniques,andtoolsthatweremoreprevalentinthepast.These materialcluesareessentialinassessingastructure'ssignificance,character,and authenticity.41 DuringadiscussionwithYarrow,Mark,abuilder,mentions:

“Watching him at work, on a domestic renovation, I see how the past is experienced corporeally and viscerally through the materials encountered through building work. On one occasion, he picks up a 19th-century brick from a pile created by the demolition of an internal wall, running his hand over the surface, as he explains how it came to have its distinctive mottled pattern: ‘All the others are flat – you see it was raining on that day.’ Elsewhere, he shows me the back of a cupboard where the plasterwork is noticeably less well finished: ‘That’s where the apprentice would have

40 Rouhi, “Development of the Theories of Cultural Heritage Conservation in Europe: A Survey of 19th And 20th Century Theories.”. P. 5

41 Yarrow, “Where Knowledge Meets: Heritage Expertise at the Intersection of People, Perspective, and Place.”

practised.’ He knows roughly when the building was constructed, but the past disclosed through these encounters is less of a chronologically sequenced ‘history’ than of the more intimate, if more fleeting, sense of connection to those who built it. Mark has no formal training in building conservation but describes how the physical intimacy of working in these buildings engenders a specific way of understanding and caring for their past: ‘There is a big sense of responsibility; you’re making big decisions that have irreversible consequences for the house.’ Working with them intimately, normally only on one at a time, brings a specific kind of responsibility.”42

Despiteadvancesinconservationinterventionconcepts,thereremainsa significantgapinrecognizingboththeintrinsicvalueoftraditionalcraftspeople's workmanshipandtheneedformodernbuilderstodemonstratecomparable responsibilitywhenhandlinghistoricandsensitivebuildings.TheGetty ConservationInstitute'sworkontheEamesHouseexemplifiesthisimportance, whereskilledworkmanshipservedasthecrucialbridgeintransferringknowledge neededtorepairweather-damagedsteelwindows.43 Incontrast,themodern constructionindustryhasstandardisedbuildingmaterialsandapproachesthathas graduallyerodedthespecialisedskillsneededtomitigateagainstthefragilityof oldstructures.Thepreservationofanysensitivehistoricstructurebecomes meaninglessifwefailtomaintainandhonourthetraditionsofexceptional craftsmanshipandworkmanship.44,45

42 Yarrow, “How Conservation Matters.”

43 Normandin, “Conserving the Eames House: A Case Study in Conservation.”

44 Brumann, Tradition, Democracy and the Townscape of Kyoto Claiming a Right to the Past.

45 Yarrow and Jones, “‘Stone Is Stone’: Engagement and Detachment in the Craft of Conservation Masonry.”

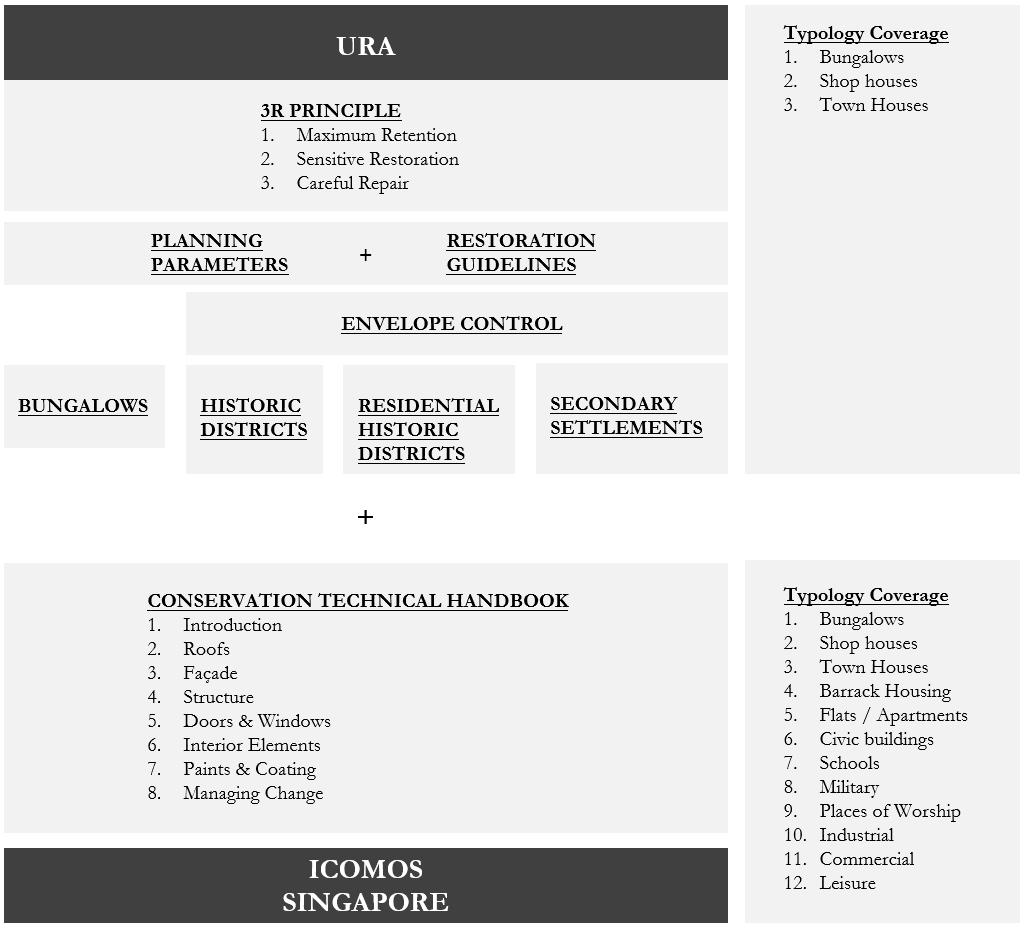

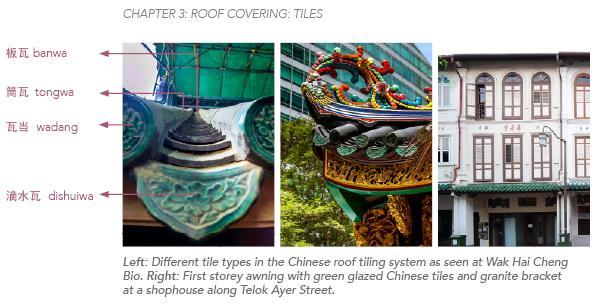

3.1 Singapore Conservation Principles Inthe2023EditionofURA’sconservationguidelines,Singapore’s conservationprincipleswerestillmainlybasedonthe3RPrinciple approach-maximumretention,sensitiverestorationandcarefulrepair. Veryevidently,onecanidentifythattheseconceptsembodymuchof Ruskin’sandMorris’philosophyofminimuminterventionandmaximum retentioninthehonestyofrepairsundertakenwhencarryingout conservationwork.49 UnderURA'sstewardshipofurbanredevelopment, theconservationguidelinesregulatetheoveralldistrictmorphology, aesthetics,buildingandlandusepatterns,andeconomicviabilitythrough carefulplanningparametersandenvelopecontrolmeasures.(Figure5)

49 URA, “Conservation Guidelines.”

Figure 5

Singapore’s conservation principles through URA’s conservation guidelines that controls the overall urban setting of conservation areas and technical handbooks by ICOMOS Singapore that helps manage and guide the local industry towards some understanding of international conservation practices. (Source: Author)

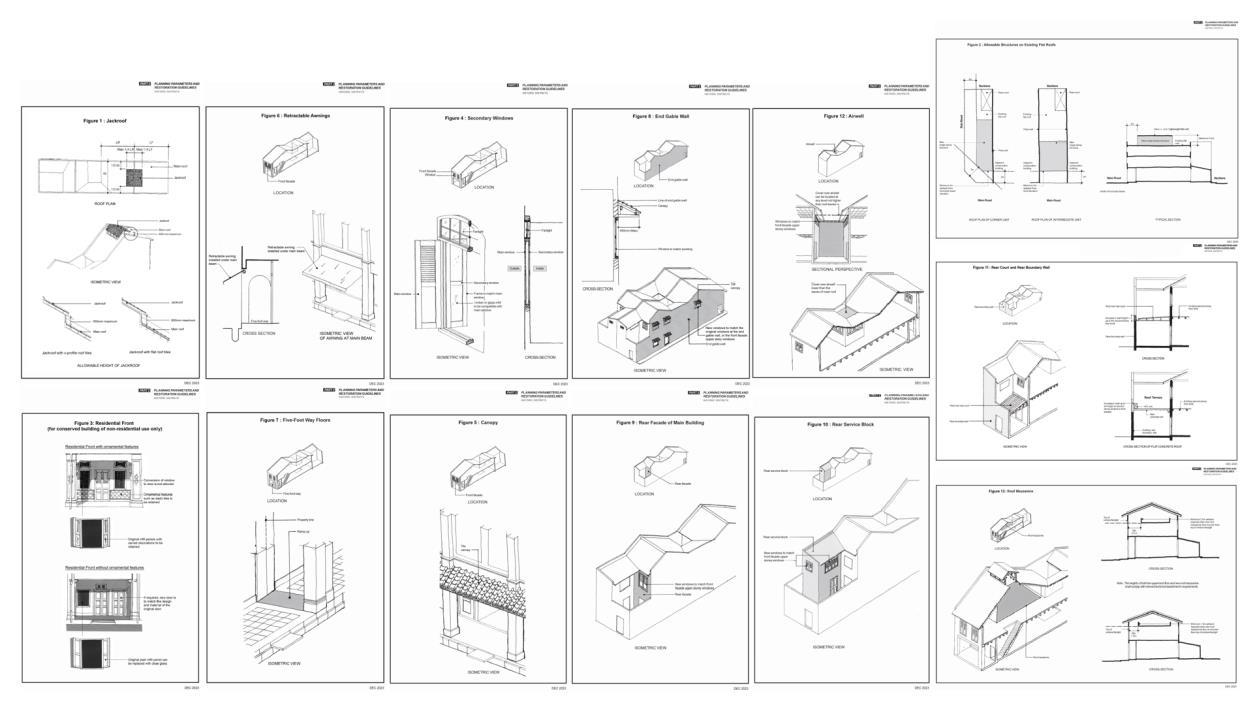

WithinURA’srestorationguidelinesarekeyelementsthattriestomaintain theoverallaestheticsofhistoricshophousesandtownhousesseenfroman urbandesignperspective.Asmostcommunitieswithinconservationareas havebeendisplacedintomodernisedhigh-risedwellings,recreatingthe socialaspectofthesehistoricdistrictsremainsanimpossibletask.Steps weretakentocompensateforthelivingtraditionsthatoncefilledthese historiclandmarks,byattemptingtomaintainthescaleandimageryof thesehistoricbuildingsthatcontributetoitsurbansetting.

Restoration guidelines that detail physical elements of the shophouse that should be respected and maintained in order to recreate its character as a whole historic district. (Source: URA)

Figure 6

Forinstance-theallowableheightofajackroofortheaccessibilityofthe five-footwayasittransitionsbetweeneachhouse-allcontributetowards achievingthesenseandphysicalatmosphereofahistoricshophouseand townhousedistrict.Itsdeploymentassumesthatallshophousesand townhouseshavesimilarcharacter,historyandsignificanceandtakesaway fromtheintimacybehindtheculturalandsocialaspectofthesehistoric districts.

ManyofSingapore’sconservationprojectsstraddlebetweenthe enforcementofthe3Rprincipleandacompleteoverhaulofitsintegrity. Manyshophousestodayhavebeenextensivelyrenovatedintheinterior, reducingthesehistoricalstructurestomereshellsoftheiroriginalform Furthermore,URApermitsupto50%removalofpartywallsbetween adjacentshophousestoallowforthemergingoftwoormoreshophouses.50 (URA,2023)Inthepublic-privatepartnershipbetweenprivatedeveloper FarEastOrganisationandURA,theFarEastSquarehasbeenconstructed whereblocksofshophouseshavebeenguttedandcrudelytransformedinto combinedofficespaces.Theresultingdevelopmentmaintainsonlyapoorly fabricatedfacsimileofshophousefacadesinmannersthatwouldhave drawnfiercecriticismfromconservationtheoristWilliamMorris.51 Yeo (2018)bringsothersimilar,albeit,slightlyless“disney-fied”examplesto callintoquestiontheenforcementandcommitmenttothe3Rprinciples establishedbyURA Healsopointsoutthecontradictioninargumentsand conflictscarriedforwardbyURAandNHBintheexampleofTanSiChong Su,aChineseancestraltemplefortheTanclanconstructedbetween1876 and1878.BeinggazettedasaNationalMonumentin1974,thetemple’s custodianwasprosecutedandfinedforcarryingoutrepairworksand additionofornaments.Whilethetemplecustodianregardedhisactionsas

50 URA, “Conservation Guidelines Technical Supplement" Understanding The Partywalls.”

51 Far East Square was a joint public-private partnership between URA and Far East Organization. More information can be found in: chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.ura.gov.sg//media/Corporate/Get-Involved/Conserve-Built-Heritage/AHA/1999/AHA-1999 Far-East-Square.pdf

TheBurraCharter(1979-2013)

Broadeningofheritagebeyondtangibleandmaterialaspectsof buildingandfocusesmoreonphysicalcontextbeyondthe building.

Addedemphasisonplaceandculturalsignificancetoinclude historicsignificanceintherelationshipbetweenpeopleand place.

TheNaraDocumentonAuthenticity(1994) Addressingtheshiftfromwestern-centricheritage understandingtowardsamoreculturallyrelativeapproachin definingauthenticity.

Focusonmethodsofbuildingandtraditionalcraftsmanship.

Recognisingthatdifferentapproachestoconservationshouldbe consideredindifferentculturalcontexts.

Respectforthelegitimacyoftheculturalvaluesofallparties evenwhereculturalvaluesappeartobeinconflict.

ThechoicesofdocumentschosenintheICOMOStechnicalhandbookscover theimportanceinconservingthetangiblematerialfabricofhistoric structures,italsocoverstheinternationalshifttowardsanemphasisin recognisingthevaluesofintangibleculturalheritageofallstakeholders involved.ApositivestepinaddressingthelimitationsofURA'sconservation guidelines.However,asillustratedinthepreviouschapter,thoughthey highlighttheimportanceoftraditionalcraftmanshipandbuildingmethod, thesedocumentsdoverylittleinaddressingtheimportanceofthe intangibleaspectsofexpertiseandknowledgethatunderpintheexecution ofsuchspecialisedwork.

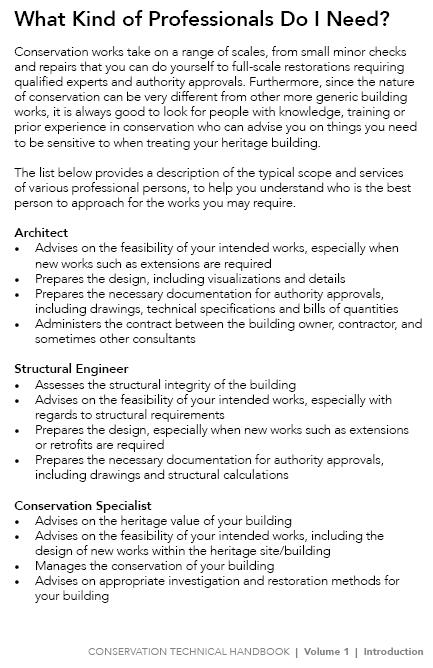

Similarly,whendescribingthemulti-disciplinaryrolesforaconservation project,higheremphasisisgiventothethought-basedprofessional-

Architect,StructuralEngineer,ConservationSpecialist,MaterialSpecialist, andQuantitySurveyor.Thoughthehandbookdescribeshowsearchingfor specialists,skilledworkers,andartisansremainachallenge,evenasit pointsoutthescopeoftheSpecialistBuilder,theyoftenfalloutsideofkey decision-makingandaremadetofollowdetailedspecificationsand drawingssetoutbyArchitectsandConservationSpecialists.(Figure7)Itis onlyinvolume6and7,onInteriorElementsandPaintingsandCoatings respectively,doweseethought-basedprofessionalscedeauthoritytothe skilledmotor-basedartisanswheretheyaregivenlibertyandrecognition asprofessionalartisanspossessingindispensableskilland,particularlyin restoringintricateandcomplexwork.(Figure8)

Excerpts from the Conservation Technical Handbook Volume 1 that mentions the roles involved in conservation work and difficulties in procuring resources. (Source: ICOMOS Singapore)

Figure 7

Figure 9

Excerpts from the Conservation Technical Handbook. (Source: ICOMOS Singapore)

3.2 Perspectives from Local Builders Asemi-structuredinterviewwasconductedtobetterunderstandwhatthe morecrucialfactorsleadingtotheunfavourableperceptionofconservation workinSingaporeamongfivelimitationfactors:

Manpower

Worker skill and knowledge

Legal liabilities

Lack of appropriate materials

Lack of demand

Table 2

Howmuchhavethelimitationsonmanpowernegativelyaffectyour perceptionoftakingonconservationwork?

(1=noconcerns,5=extremelyproblematic)

Whatisthemainproblemyouhavefacedasaresultofmanpower limitation?

Howmuchhavethelimitationsonworkerskill/knowledgenegatively affectyourperceptionoftakingonconservationwork?

(1=noconcerns,5=extremelyproblematic)

Whatisthemainproblemyouhavefacedasaresultofworker skill/knowledgelimitation?

Howmuchhaslegalliabilitiesnegativelyaffectyourperceptionof takingonconservationwork?

(1=noconcerns,5=extremelyproblematic)

Whatisthemainconcernaboutlegalliabilityandresponsibilityyou haveforconservationwork?

Howmuchhasthelackofappropriateconstructionmaterials negativelyaffectyourperceptionoftakingonconservationwork?

(1=noconcerns,5=extremelyproblematic)

Whatisthemainproblemyouhavefacedasaresultofalackof appropriateconstructionmaterialforconservationwork?

Howmuchhasthelackofdemandnegativelyaffectyourperceptionof takingonconservationwork?

(1=noconcerns,5=extremelyproblematic)

Whatisthemainproblemyouhavefacedasaresultofalackof demandforconservationwork?

Interview questionnaire issued to local contractors on the five limitation factors and a short description stating rationale for each factor. (Source: Author)

3.2a Manpower and Worker Skill Bothlimitationfactorsofmanpowerandworkerskillrankedsimilar (3of5scoreonlevelofconcern),showingthatlocalbuildersdonot findtheprocessofbringinginnewmanpowerasamajorissue affectingconservationwork.Thoughbothmanpowerandworker skillrankedthesame,thereisaslightlyhigherconcernwiththe skillspossessedbyworkersthanthequantityofworkerspresent. Betweenbuilderswithandwithoutconservationworkexperience, thelackofinformationandunderstandingofwhatconservation workingeneralentails,havebeenhighlightedasamainconcernfor thebuilderswithoutexperience.Ontheotherhand,thosewithprior experiencefeelthatcurrentworkpermitrestrictionlimitingthelong termstayofworkersarethemainreasonswhyworkerskillsare hardtomaintain.

3.2b Legal Liabilities and the Lack of Appropriate Materials Thelimitationfactorsoflegalliabilitiesandthelackofappropriate materialsreceivedstarklyopposingresults(2of5levelofconcern amongbuilderswithconservationworkexperienceand4of5level ofconcernamongbuilderswithnopriorexperience)withthemain issuesbeingtheexposuretoconservationworkexperience.Other mainconcernsincludethehiddenriskfactorsaccompaniedbyA&A works(AdditionalandAlteration)thatmanybuildersandclients tendtosteerclearoffduetotheunexpectednatureofcomplications thataredifficulttodetect.Otherwise,dependingontheindividual experiencesofeachbuilder,theywilleitherbewellconnectedto legaladvisorsandspecificmaterialsuppliersortheywouldface difficultiessourcingforsuchsupportsforconservationwork.

4. Is a Revival of

Traditional Crafts Possible? Wherevernacularcraftisstillalive,theconservationprocesscouldpossiblybe carriedoutinadivergentperspective.TheCharterontheBuiltVernacular Heritage(ICOMOS,1999)putsfocusontraditionalbuildingsystems:

“The continuity of traditional building systems and craft skills associated with the vernacular is fundamental for vernacular expression, and essential for the repair and restoration of these structures. Such skills should be retained, recorded and passed on to new generations of craftsmen and builders in education and training.”54

Itgivesfullcredibilitytothesocialstructuresandexpertiseoflocaltraditional craftspeople,allowingthemtoparticipateininterventionsinspontaneousways thatreflecttheauthenticmethodsandtechniquesoftheirvernacularpractice. Suchspontaneityhindersmethodicaldocumentationandregulatorycompliance, whichpresentsaconflictwiththeresponsibilitiesofthemodernisedheritage professionalsandregulatoryenforcers.Conservationinacademicsettingsonthe otherhand,outlinedinSingapore’sConservationTechnicalHandbook(ICOMOS, 2017)forexample,outlinestheroleofthespecialistbuilderassomeonewho

“Carries out the works according to the design and conservation programme, in a safe manner”.55

Anapproachthatisevidentlydictatedbyframeworksandsystemsofamorecivil citygovernancewheresafeguardsareputinplacetopreventpoorperformancein environmentsaturatedwithalternativesandoptions.Astarkdifferenceinliberty canbeseenbetweenbothmethodsofconservationprocesseswheretheheritage professionalintervenestofillthevoidwherethepracticeofvernacularcraftsis absent.56,57 (DeaconandSmeets,2013,p.132)(ChirikureandPwiti2008)

Addressingthedeclineoftraditionalbuildingcraftisnosimpletaskconsidering theeffectsofmodernisation.Whileheritageprofessionalsincreasinglyfillthe knowledgegapleftbydwindlingcraftsmen,thistransitioninadvertentlywidens thedividebetweenremainingcraftpractitionersandacademicprofessionals.The IntangibleCulturalHeritageConvention(UNESCO,2012)primarilyaddresses livingheritagepracticesandservestoacknowledgeexistingintangibleheritage withincommunitiesratherthanresurrectlosttraditions.58 (DeaconandSmeets, 2013,p.135)Evidently,thepropositionofrevivingtraditionalbuildingcrafts couldmeetresistancefromdocumentsthatchampionintangibleculturalheritage. Moreover,theveryconceptofrevivalraisescriticalquestions:determiningwhich historicalperiodtoreferencechallengesnotionsofauthenticityandrisks overlookinghowtraditionalcraftswouldandhavehadnaturallyevolvedover time,potentiallyinvalidatingcontemporaryadaptationsofthesepractices.

4.1 The Artisan, The Craftsman and The Builder InanurbansettinglikeSingapore,thehighlyregulatedanddiversifiedroles inabuildingconstructionprocesspartitionsthescopesofworktovarious parties.Whatwouldhavebeenadesignandfabricateroleofanartisanis veryeasilybeenreducedtoacraftsmantoonlyberesponsibleforthe fabricationofdesignconceptsproducedbydesignconsultants.

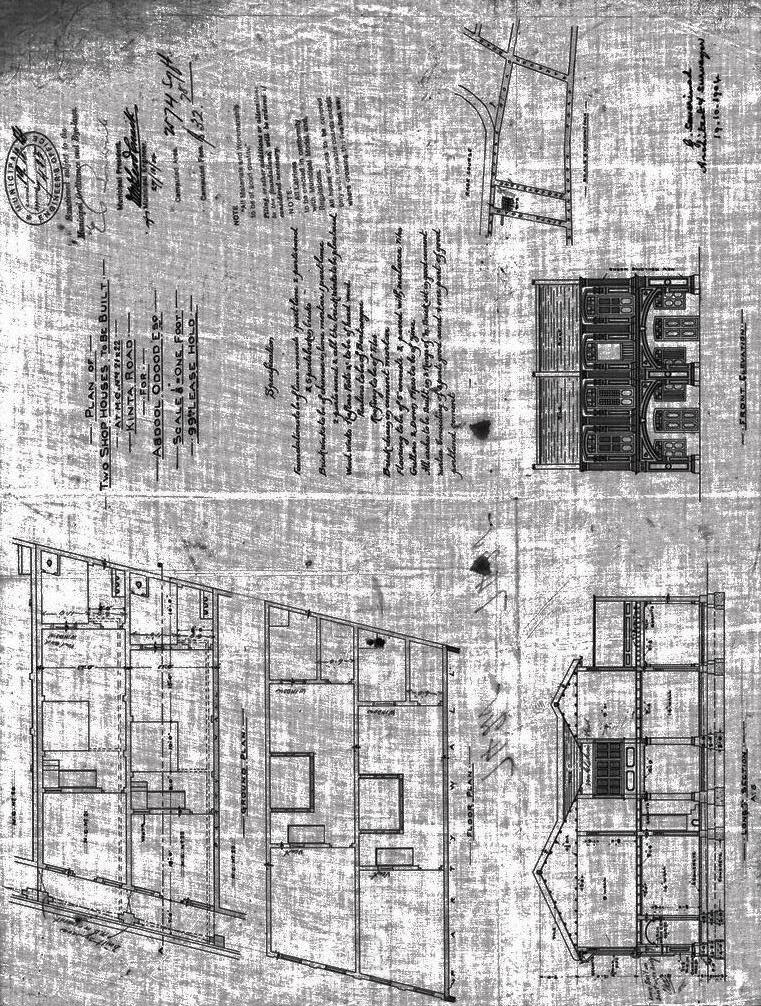

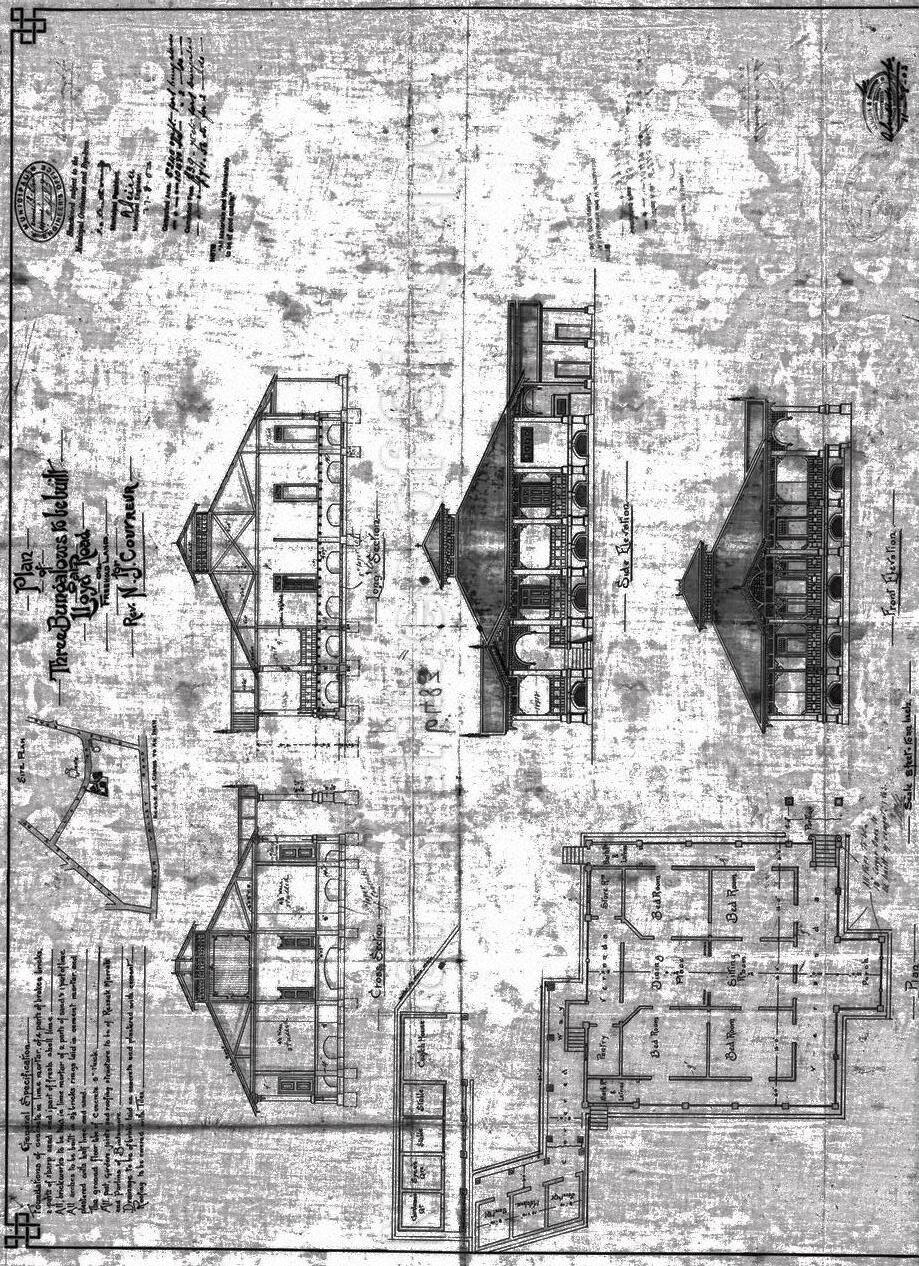

Manyoftheoldshophouseconstructiondrawingsinlater1800sshowed verylittleindicationofornamentations.Intheearly1900s,manyofthe drawingsstartedtoshowalotmoredetailandindicationsofsome embellishmentsonthefaçadeoftheshophouses.(Figures10atoc)Early formatsofsuchconstructiondrawingsoftenhavegenericspecifications accompanyingthedrawingswithdimensionsandmeasurementsofkey elementsofthespaces.Contrasttothehighlydetailedconstructionand shopdrawingsproducedbyarchitectsandmainorsub-contractorsin today’sconstructionregulatoryframeworks,theroleofthebuilderandthe

Drawings by the Public Works Department to the Building Control Division in Singapore for proposed new-built shophouse along Cross Street in 1904 (Source: National Archives of Singapore)

Figure 10b

Drawings by the Public Works Department to the Building Control Division in Singapore for proposed new-built bungalow along Lloyd Road 1903s. (Source: National Archives of Singapore)

Figure 10c

Craftspeopleinthepasthadtheartisticlibertyandthetechnicalprowessto functionasartisans.Withouttoday’sextensiveregulatoryframeworksin theconstructionindustry,theseartisanswereabletoleadtheconstruction process,throughtheircomprehensiveknowledgeandskillenablingthemto makespontaneousdecisionsduringconstruction.Today,theexpertiseof theartisanisoftenobscuredbymultiplelayersofcodecompliances, regulations,andwidecoverageofscopesofamulti-disciplinaryteamof buildingprofessionals.Theroleoftheartisanhasgraduallybeendilutedto aspecialistbuilder(acraftsperson),andinsomecases,tobereplacedby genericbuilderswhentheunderstandingoftheexpertiseandskillofa craftspersonisdownplayed.TheeventualresultleftSingaporewithoutan adequatesupplyoftraditionalbuildingartisansandcraftspeopletoday.

4.2 Workmanship as a Mentality TherecentdevelopmentofSingapore’splantoincorporate27historic structuresasheritagebuildingsintheBukitTimahTurfCity(BTTC)new housingredevelopmentsignalsahopefulshiftinattitudeforSingapore’s historicandmodernheritage.59 Thewindowofheritagecontinuesto expand,andsodoestheopportunitiesforbuilderstodeveloptheircraft skillsonmodernmaterials-concrete,metal,andsteel-thataremore familiartotheircontemporarypractice.CirclingbacktoYarrow’spoint, upholdingworkmanshipremainsacentralandintegralattribute maintainingandbuildingstructures,oldandnewalike.Havingthe sensitivityinapproachinganyexistingheritagestructureallowsthebuilder tostudyandlearnfromthepast,slowlybuildingarepositoryofeducated enquiriesthatallowsthemtobuildupembodiedknowledgeandexpertise whichnootherprofessionalwithintheheritagemanagementecosystem can.

59 URA, “Heritage, Nature and Inclusive Spaces to Anchor New Housing Estate at Bukit Timah Turf City.”

Whenpossible,inter-nationtrainingprogramsserveasvitalplatformsthat enableprofessionalsfromalldisciplinesacrosstheheritageecosystemto strengthentheirknowledgeofconservationprinciplesandtechnical capabilities.Specialisedtrainingandcoursesontraditionalmaterialshelps deepenunderstandingandexpertiseinheritagepreservation.Initiatives liketheConservingModernArchitectureInitiative(CMAI)bytheGetty ConservationInstitute,CommonwealthHeritageSkillsTrainingProgramme provideessentialavenuesforlearningandmasteringtradeskillsofvarious materialsandtheirapplicationsinheritageconservationwork.60,61 In addition,establishinganetworkplatformsimilartoSPAB,thatcreatesand maintainsongoingconnectionsandprovidetechnicalconsultation enhancesthecapacitybuildingoflocalbuildersandinstilsgreater confidenceinfieldconservationwork.62 Itisimperativethatanew generationoflocalbuildersdeveloptheprideandsensitivityfor workmanshipandbeattunedtotheworkthattheyconduct;recognising theiruniqueopportunitytobeexposedtothematerialfabricofbuiltheritage,interwovenbylayersofhistory.

Beyondtechnicalproficiency,thesebuildersmustdevelopathorough understandingofconservationprinciplesandbestpracticestoadvancein thefield.Theevolutionfrombuildertocraftspersonandultimatelyto artisanrequiresnotonlytakingprideinone'sworkbutalsoembracing guidancefromglobalexperts.Thistransformationisessentialfor preservingourarchitecturalheritagewiththehigheststandardsof craftsmanshipandexpertise.

60 Getty Conservation Institute, “Conserving Modern Architecture Initiative.”

61 Commonwealth Heritage Forum, “The Queen Elizabeth II Platinum Jubilee Commonwealth Heritage Skills Training Programme.”

62 SPAB, “Advice.”

CMAIbytheGettyConservationInstituteandSPAB’sopennetworkfor consultationswithresearchersandtechnicalexpertsserveasgoodmodels toallowlocalbuildersandcraftspeopletoskilluptheirknowledgeon technicalskillsandconservationprinciplessothatthegapbetween thought-basedandmotor-basedendeavourscanbebridged.

D. List of Figures Figure1: CirculatoryproblemofHeritageConservationinSingapore (Source:Author)

Figure2a: Exampleofasinglelayeredroofsystemofashophousealong CraigRoadinasubmissiondrawingundertheyear1989. (Source:Author)

Figure2b: InitialtechnicaldrawingsproducedforNUSArCLabmock-up. (Source:Author)

Figure2c: ThefinaliterationoftheroofforNUSArCLabmock-up (Source:Author)

Figure3: Eventualcompletedmock-upwhichdeviatedfromthe originalproposeddrawings.(Source:Author)

Figure4: Simplifiedtechnicaldrawingsshowingresearchobjectivesof NUSArCLab.(Source:Author)

Figure5: Singapore’sconservationprinciplesthroughURA’s conservation.(Source:Author)

Figure6: Restorationguidelinesforshophouses.(Source:URA)

Figure7: ExcerptsfromtheConservationTechnicalHandbookVolume 1.(Source:ICOMOSSingapore)

Figure8: ExcerptsfromtheConservationTechnicalHandbookVolume 6and7.(Source:ICOMOSSingapore)

Figure9: ExcerptsfromtheConservationTechnicalHandbook. (Source:ICOMOSSingapore)

Figure10a: Drawingsforproposednew-builtshophousealongSyed AlweeRoadin1903.(Source:NationalArchivesofSingapore)

Figure10b: Drawingsforproposednew-builtshophousealongCross Streetin1904.(Source:NationalArchivesofSingapore)

Figure10c: Drawingsforproposednew-builtbungalowalongLloydRoad 1903s.(Source:NationalArchivesofSingapore)

Table1: Identifiedattributestodocuments.(Source:Lin,2025)

Table2: Interviewquestionnaireissuedtolocalcontractorsonthe fivelimitationfactorsandashortdescriptionstating rationaleforeachfactor.(Source:Author)

Bibliography Brumann, Cristoph. Tradition, Democracy and the Townscape of Kyoto Claiming a Right to the Past. 1st ed. London: Routledge, 2012.

Cetinkaya, Gulay. “Challenges for the Maintenance of Traditional Knowledge in the Satoyama and Satoumi Ecosystems, Noto Peninsula, Japan.” Human Ecology Review 16, no. 1 (2009): 27–40.

Commonwealth Heritage Forum. “The Queen Elizabeth II Platinum Jubilee Commonwealth Heritage Skills Training Programme,” n.d. https://www.commonwealthheritage.org/heritage-skills-2/

Croft, Catherine, and Elain Harwood. “CONSERVATION OF TWENTIETH-CENTURY BUILDINGS New Rules for the Modern Movement and After?” In Managing Historic Sites and Buildings: Reconciling Presentation and Preservation, 1st ed. Routledge, 2013. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203714652.

Deacon, Harriet, and Rieks Smeets. “Authenticity, Value and Community Involvement in Heritage Management under the World Heritage and Intangible Heritage Conventions.” Heritage & Society 6, no. 2 (November 2013): 129–43. https://doi.org/10.1179/2159032X13Z.0000000009

Friel, Martha. “Crafts in the Contemporary Creative Economy.” Aisthesis, 2020.

Getty Conservation Institute. “Conserving Modern Architecture Initiative,” n.d. https://www.getty.edu/projects/conserving-modern-architecture-initiative/.

Glendinning, Miles. “Heritage in the Age of Globalisation: Post-1989.” In The Conservation Movement: A History of Architectural Preservation, 1st ed. Routledge, 2013.

Herzfeld, M. “A Place in History: Social and Monumental Time in a Cretan Village.” Princeton Studies in Culture/Power/History. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press, 1991.

ICOMOS. “Nara Document on Authenticity.” ICOMOS, 1994.

ICOMOS Australia. “The Burra Charter: The Australia ICOMOS Charter for Places of Cultural Significance 2013.” Australia ICOMOS Incorporated, 2013.

ICOMOS New Zealand. “ICOMOS New Zealand Charter for the Conservation of Places of Cultural Heritage Value,” 2010.

Jigyasu, Niyati. “IMPACT OF URBAN TRANSFORMATIONS ON TRADITIONAL CRAFTS SKILLS: AMRITSAR’S HISTORIC CORE.” Srishti Institute of Art, Design and Technology, 2017.

Lin, Mi, Ivan Nevzgodin, Ana Pereira Roders, and Wessel De Jonge. “The Role of Attributes Defining Intervention Concepts in International Doctrinal Documents on Built Heritage.” Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development 15, no. 1 (February 5, 2025): 4–23. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCHMSD-06-2023-0095.

Lowenthal, David. The Past Is a Foreign Country - Revisited. Revised and Updated ed. Cambridge (GB): Cambridge University Press, 2015.

Macdonald, Susan. “Materiality, Monumentality and Modernism: Continuing Challenges in Conserving Twentieth-Century Places.” Getty Conservation Institute, 2009.

MacDonald, Susan, Sheridan Burke, Sara Lardinois, and Chandler McCoy. “Recent Efforts in Conserving 20th-Century Heritage: The Getty Conservation Institute’s Conserving Modern Architecture Initiative.” Built Heritage 2, no. 2 (June 2018): 62–75. https://doi.org/10.1186/BF03545694

Morris, William. “SPAB Manifesto.” SPAB, 1887. https://www.spab.org.uk/about-us/spabmanifesto.

NHB. “Our SG Heritage Plan 2.0.” National Heritage Board, 2023. https://www.nhb.gov.sg/heritage-plan-2/publication/html5/index.html?pn=77.

Nizamuddin Urban Renewal Initiative. “Reviving Traditional Craftsmanship.” Nizamuddin Urban Renewal Initiative, n.d. https://www.nizamuddinrenewal.org/casestudies/craftsmanship/

Normandin, Kyle. “Conserving the Eames House: A Case Study in Conservation.” Los Angeles, 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P4lS53FjsJU&t=1468s.

Norton, Sophie Catherine. “Heritage Conservation and the Building Crafts: A Qualitative Study of Yorkshire Craftspeople.” University of York, 2018.

Partarakis, Nikolaos, Xenophon Zabulis, Carlo Meghini, Arnaud Dubois, Ines Moreno, Chistodoulos Ringas, Aikaterini Ziova, et al. “A Review, Analysis, and Roadmap to Support the Short-Term and Long-Term Sustainability of the European Crafts Sector.” Heritage 8, no. 2 (February 13, 2025): 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8020070

Plevoets, Bie, and Koenraad Van Cleempoel. “ADAPTIVE REUSE AS A STRATEGY TOWARDS CONSERVATION OF CULTURAL HERITAGE: A SURVEY OF 19TH AND 20TH CENTURY THEORIES,” 2012.

Rouhi, Jafar. “Development of the Theories of Cultural Heritage Conservation in Europe: A Survey of 19th And 20th Century Theories.” Iran, 2016.

Schultz, Kiri. “Traditional Arts and Crafts for the Future.” Museum International Vol LIV, n°1-2 (2002): 56–63.

Slocombe, M. “SPAB Approach,” n.d. https://www.spab.org.uk/campaigning/spab-approach.

Smith, Laurajane. Uses of Heritage. 1st ed. London: Routledge, 2006.

SPAB. “Advice,” n.d. https://www.spab.org.uk/advice

UNESCO. “Co-Operation and Coordination between the UNESCO Conventions Concerning Heritage: The Yamato Declaration on Integrated Approaches for Safeguarding Tangible and Intangible Cultural Heritage.” Paris: UNESCO, 2004. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000137634.

. “The Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage.” UNESCO, 2018. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429507137-9.

. “UNESCO Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity,” Vol. 1. Paris: UNESCO, 2002.

URA. “Bukit Timah Turf City Exhibition,” 2024. https://www.ura.gov.sg/Corporate/Planning/Master-Plan/Draft-Master-Plan-2025/BukitTimah-Turf-City-Exhibition.

. “Conservation Guidelines,” 2023. https://www.ura.gov.sg/Corporate/Guidelines/Conservation/Conservation-Guidelines.

. “Conservation Guidelines Technical Supplement" Understanding The Partywalls.” Urban Redevelopment Authority, 1997.

. “Conservation Guidelines Technical Supplement" Understanding The Roofs.” Urban Redevelopment Authority, 1997.

. “Heritage, Nature and Inclusive Spaces to Anchor New Housing Estate at Bukit Timah Turf City,” May 23, 2024. https://www.ura.gov.sg/Corporate/Media-Room/MediaReleases/pr24-24.

Wallace, Michael, and Arne L. Kalleberg. “Industrial Transformation and the Decline of Craft: The Decomposition of Skill in the Printing Industry, 1931-1978.” American Sociological Review 47, no. 3 (June 1982): 307. https://doi.org/10.2307/2094988.

Yarrow, Thomas. “How Conservation Matters: Ethnographic Explorations of Historic Building Renovation.” Journal of Material Culture 24, no. 1 (March 2019): 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359183518769111

. “Where Knowledge Meets: Heritage Expertise at the Intersection of People, Perspective, and Place.” JRAI 23, no. S1 (2017): 95–109.

Yarrow, Thomas, and Sian Jones. “‘Stone Is Stone’: Engagement and Detachment in the Craft of Conservation Masonry.” JRAI, 2014. https://rai.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1467-9655.12103

Yeo, Kang Shua. “Bridging Positivist and Relativist Approaches in Recent Community-Managed Architectural Conservation Projects in Singapore.” Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia 33, no. 3 (November 30, 2018): 647–76. https://doi.org/10.1355/sj33-3e

Yeoh, Brenda S.A., and Shirlena Huang, eds. STRENGTHENING THE NATION’S ROOTS? HERITAGE POLICIES IN SINGAPORE. Social Sciences in Asia, v. 17. Leiden ; Boston: Brill, 2008.

Zbuchea, Alexandra. “Traditional Crafts. A Literature Review Focused on Sustainable Development.” Culture. Society. Economy. Politics 2, no. 1 (June 1, 2022): 10–27. https://doi.org/10.2478/csep-2022-0002.

Zhu, Bo, Si-Qi Tian, and Chien-Chih Wang. “Improving the Sustainability Effectiveness of Traditional Arts and Crafts Using Supply–Demand and Ordered Logistic Regression Techniques in Taiyuan, China.” Sustainability 13, no. 21 (October 23, 2021): 11725. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132111725.