Vadlakunta

“Once a land of sparks and smoke, Haral is now a land of soil and soul. The bricks we lay today were born from the ashes of yester-

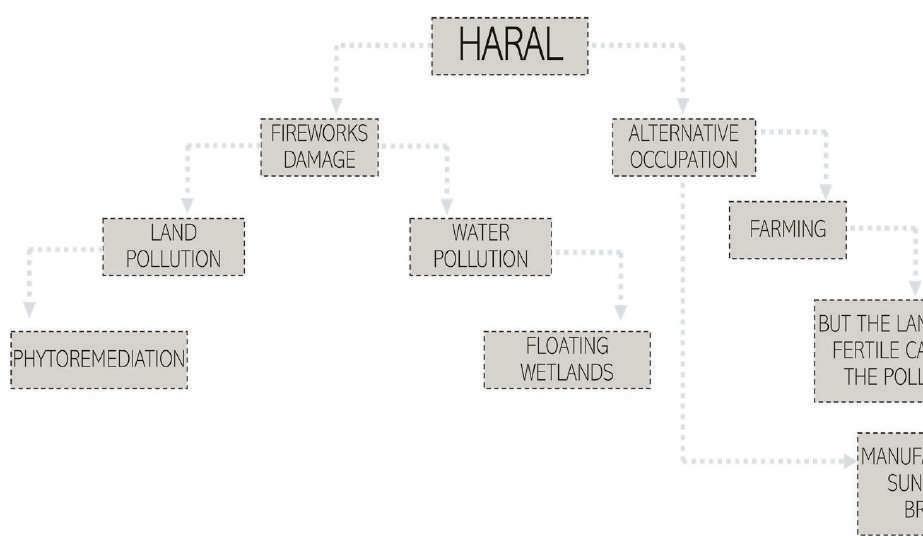

This project, Healed by Time, reimagines Haral—a peri urban district an alternative future which is currently reliant on manufac-

pollution and public health hazards due to widespread usage of chemicals like sulfur, nitrate, charcoal, magnesium, perchlorates illegally or to try to do something else?

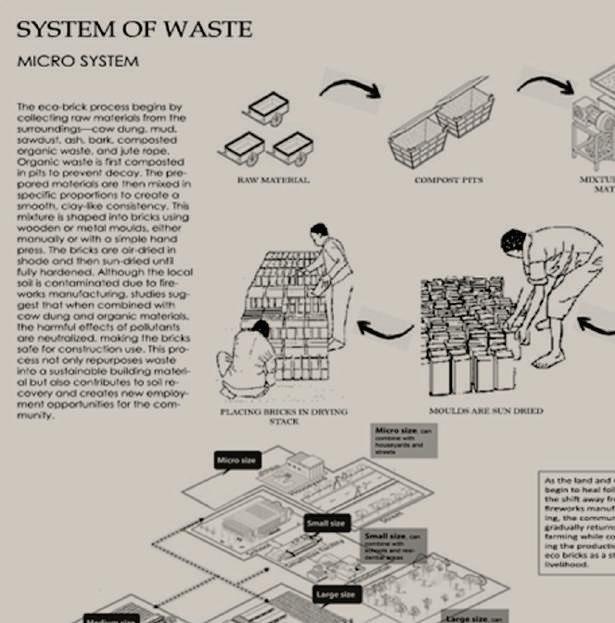

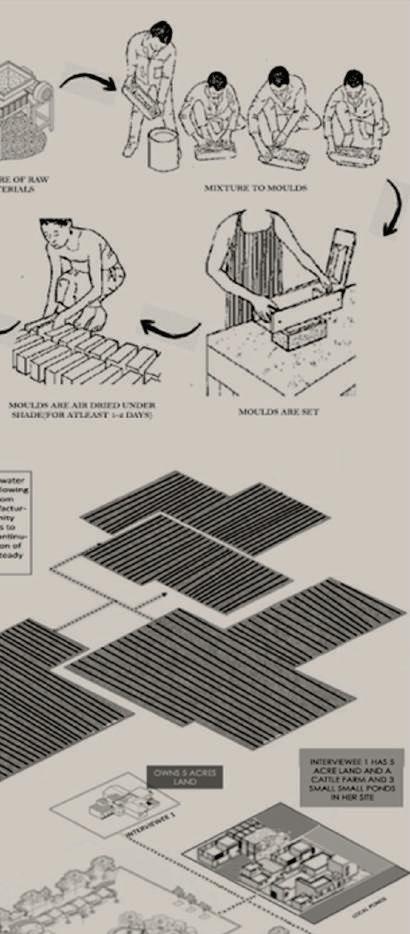

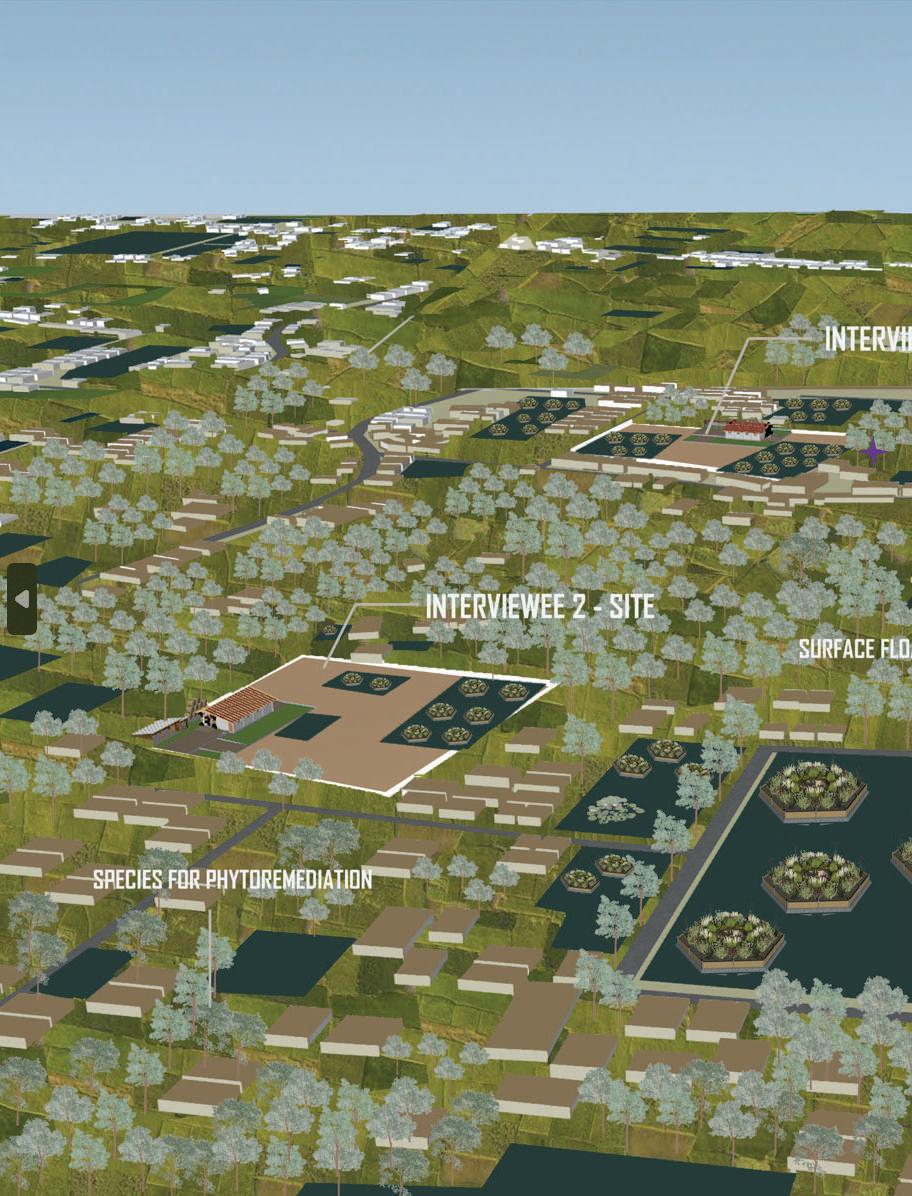

In my response, my project reimagines the landscape of Haral as a brick-scape where slow-time and sun, give form to this peri urban settlement’s future. On one hand I am proposing a new economic model centered on sunbaked bricks, using cow dung, saw dust, tree bark, ash, and pond mud. On the other hand, I am proposing that the landscape itself, be the self – regenerative source and outcome of a peri urban lifestyle and landscape.

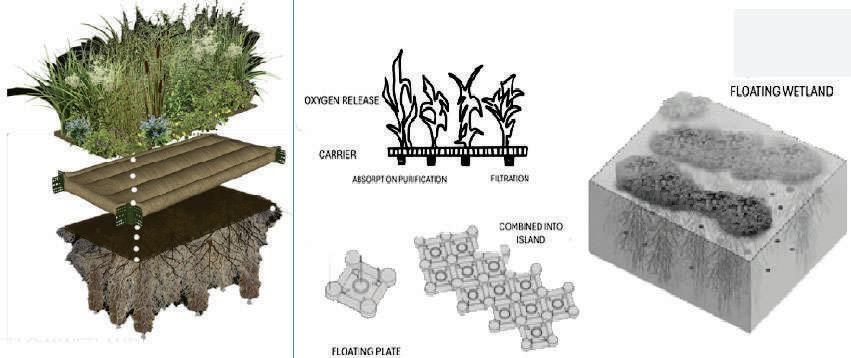

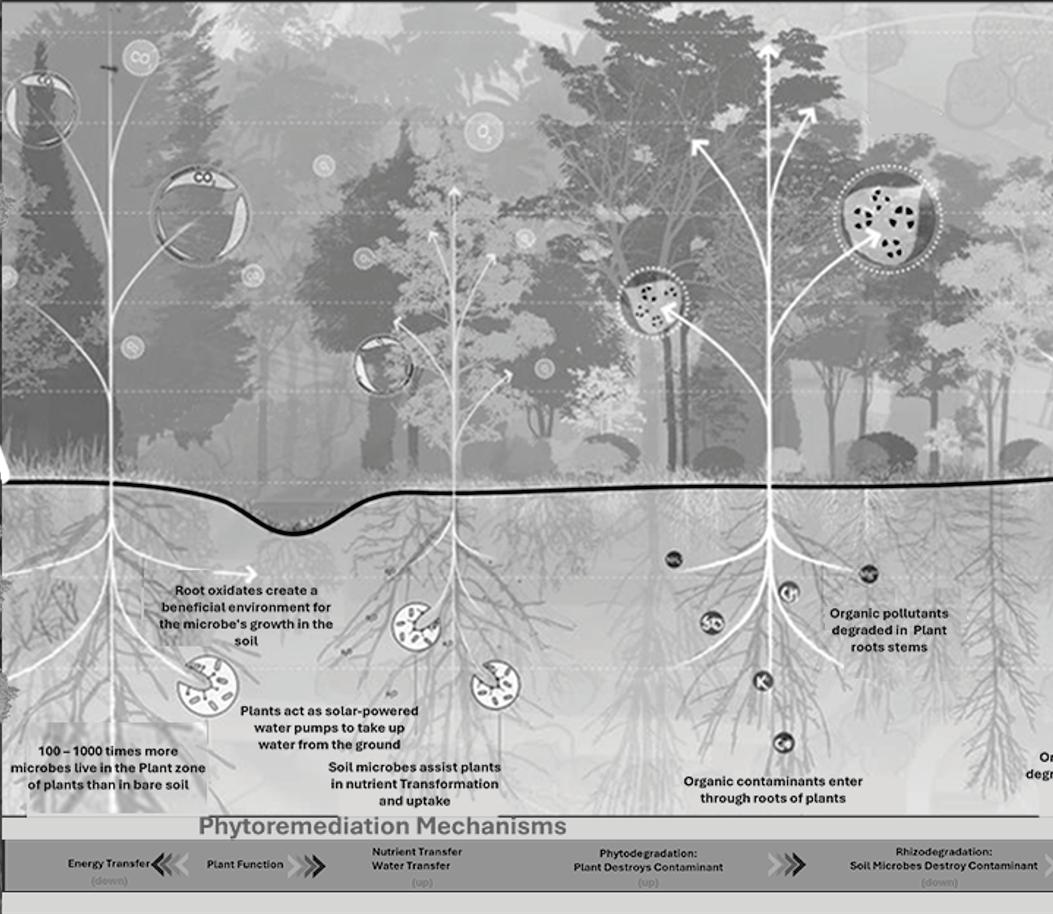

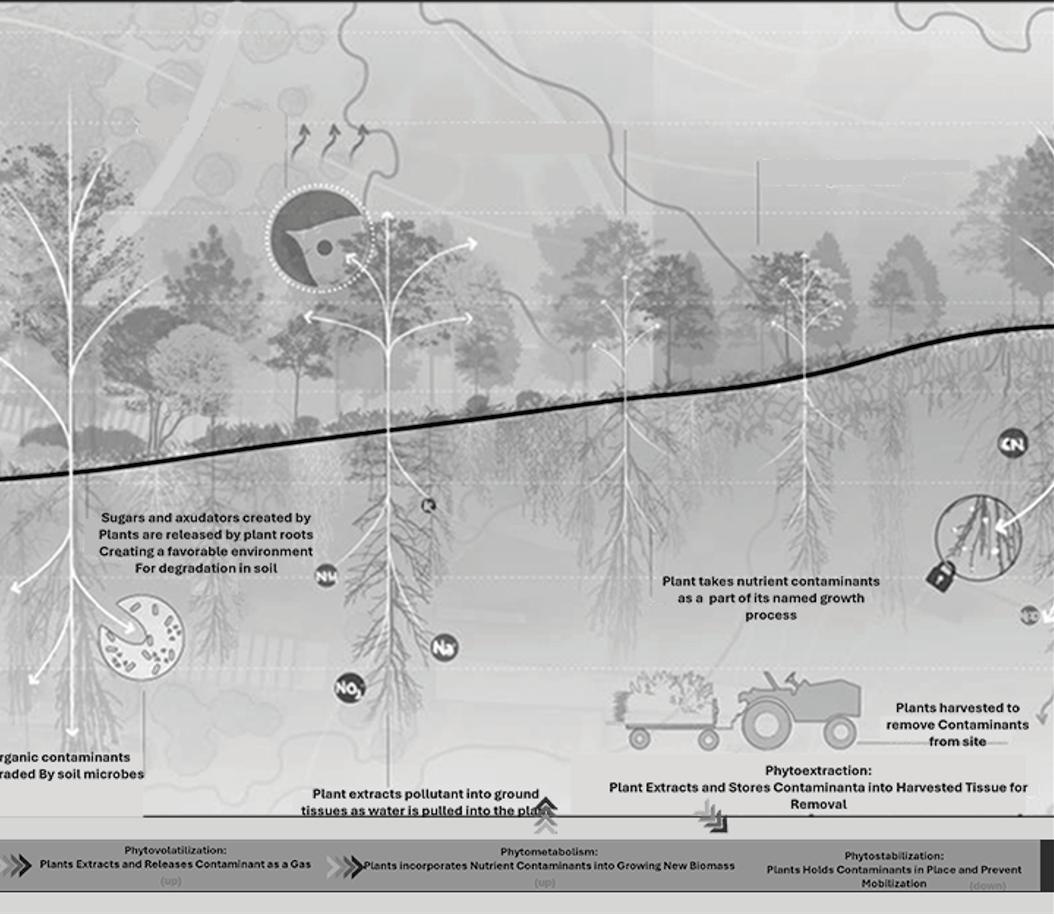

Firstly, the main concern was the renewal of land, water and air. In collaboration with one willing local resident, an existing pond in -

the help of particular species like vetiver and water hyacinth, combined with constructed wetlands. In time, as others transform their farm-land and house-land property in this way, soil remediation is made possible through composting pits and biochar beds that are built using local organic waste.

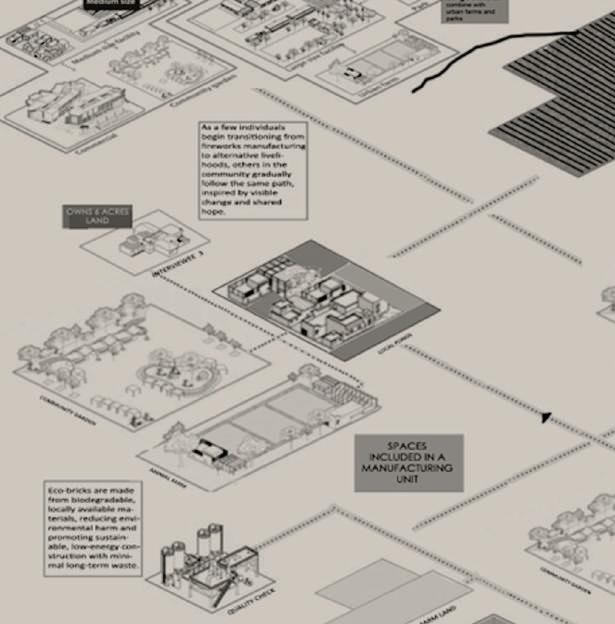

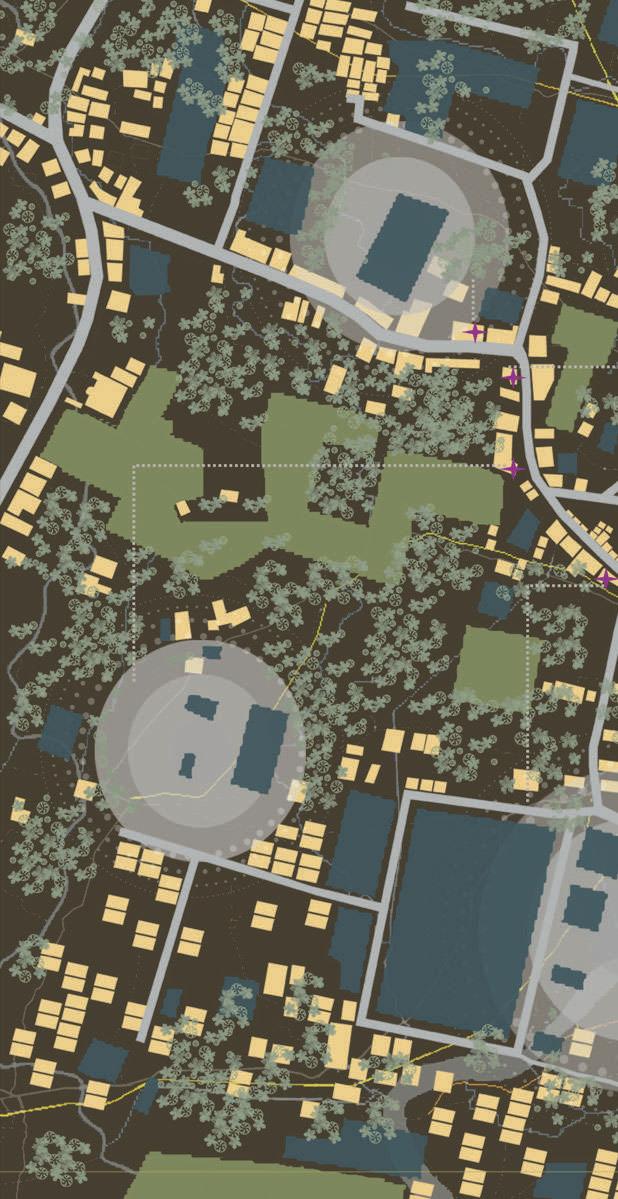

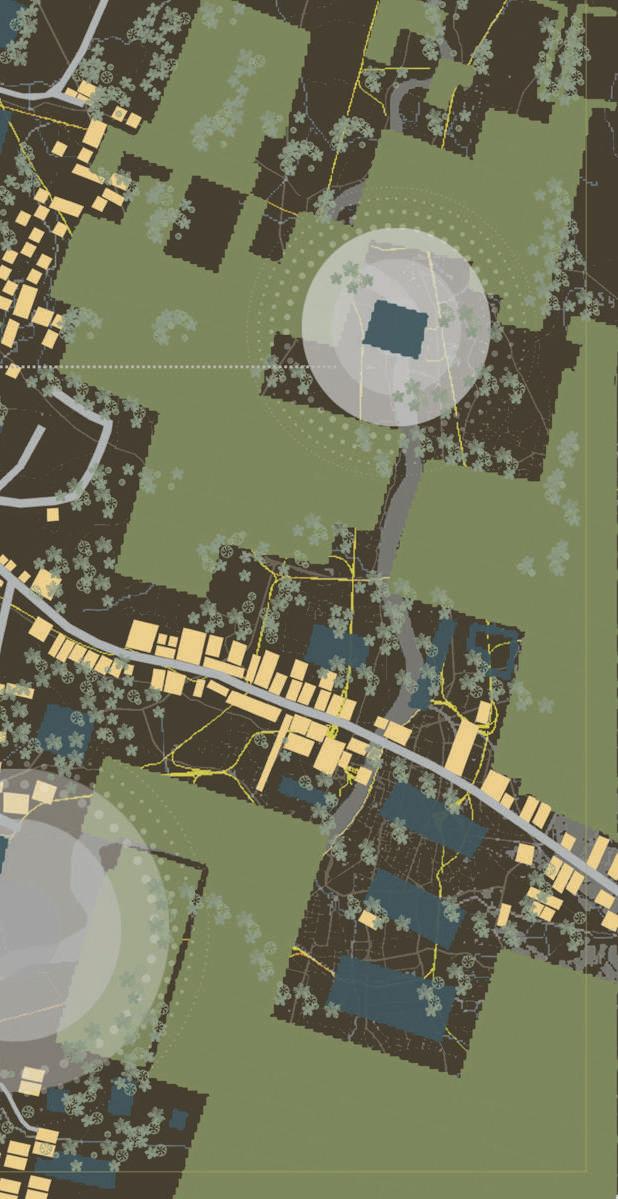

The project develops a scenario of a decentralized constellation of sunbaked brick manufacturing facilities in the locality, forming a landscape pattern, a brick-scape. Designed with the involvement of people, each unit uses low-technology machin-

industry workers coordinate co-operatives to manage production and sales. The bricks are not only used in housing but also in paving roads, sheds, composting toilets, and open markets. Training centers enable skills learning in construction, testing becomes resources, and each brick is witness to empowering —of land, of people, of purpose.

In sum, the project speaks to the agency of of a slow landscape in shaping slowly changing socio-ecological futures. The project transforms power of harmful economic “development” into unharmful economic lifestyle and livelihood - from an explosive nighttime spectacle to a quietly spectacular, daytime, model for other post-industrial-rural periurban areas navigating the complexities of post-rural life and policy inertia.

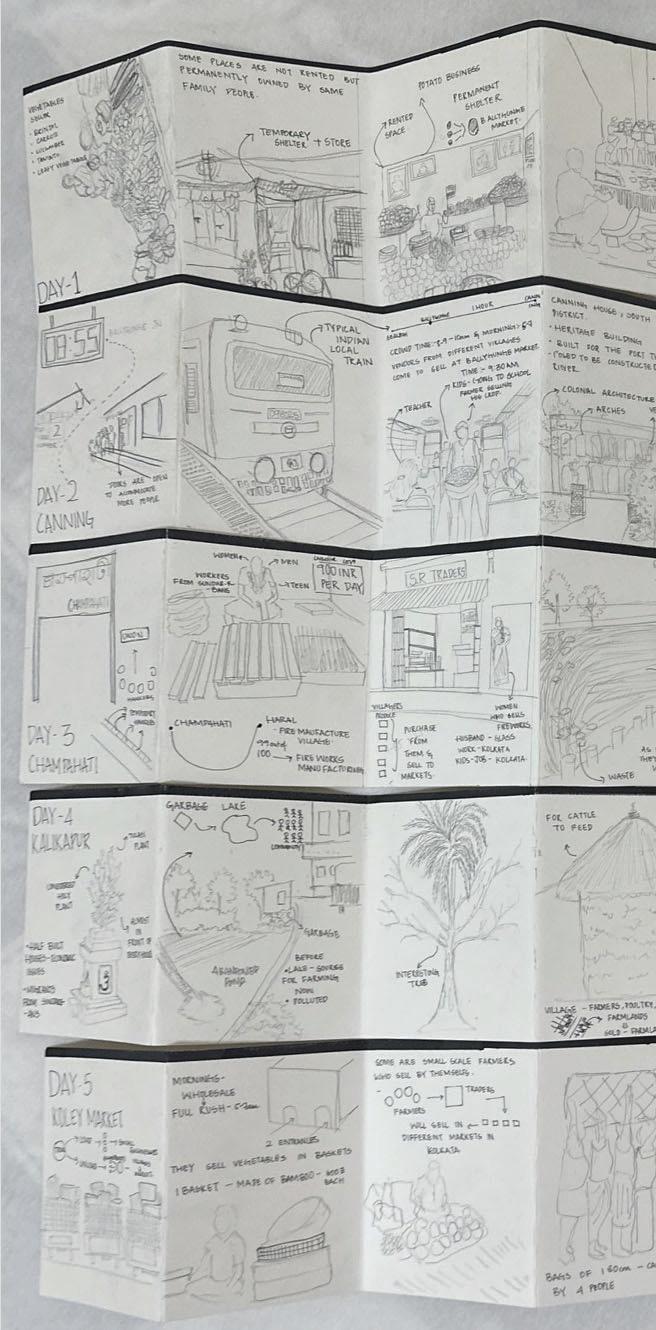

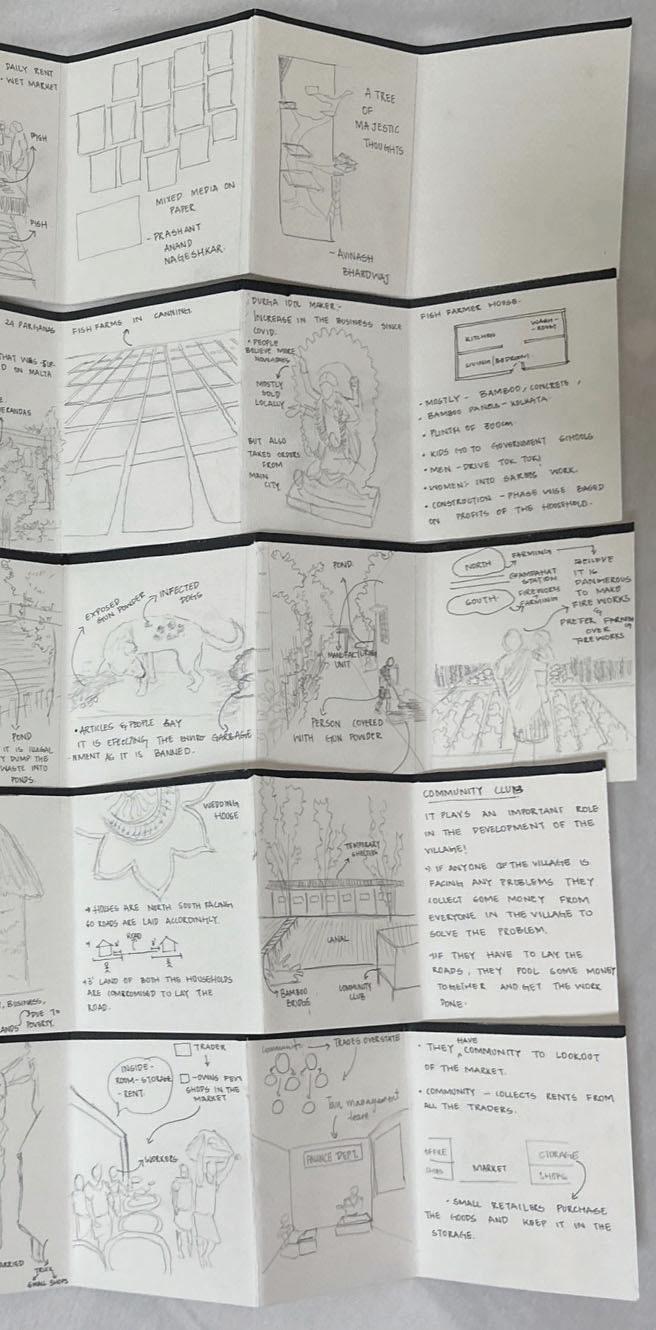

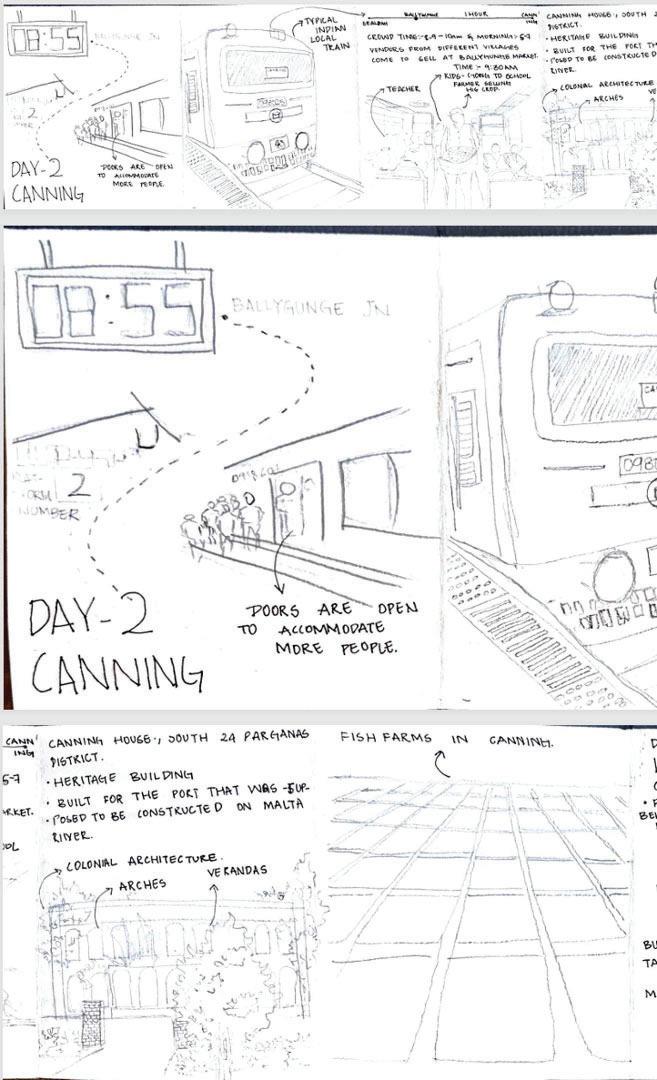

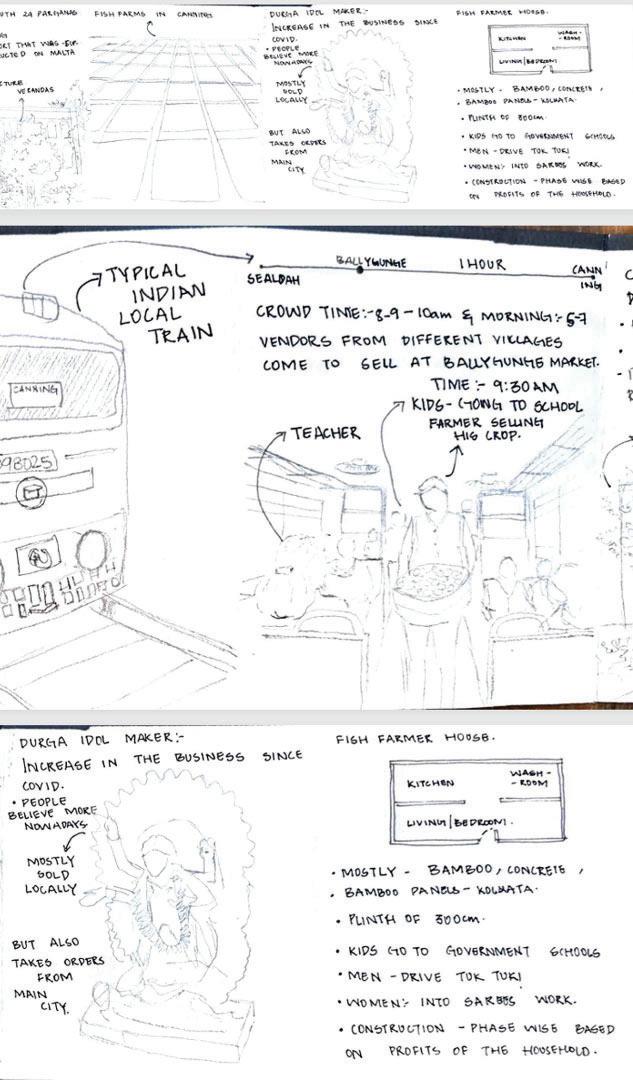

01_Field Sketches

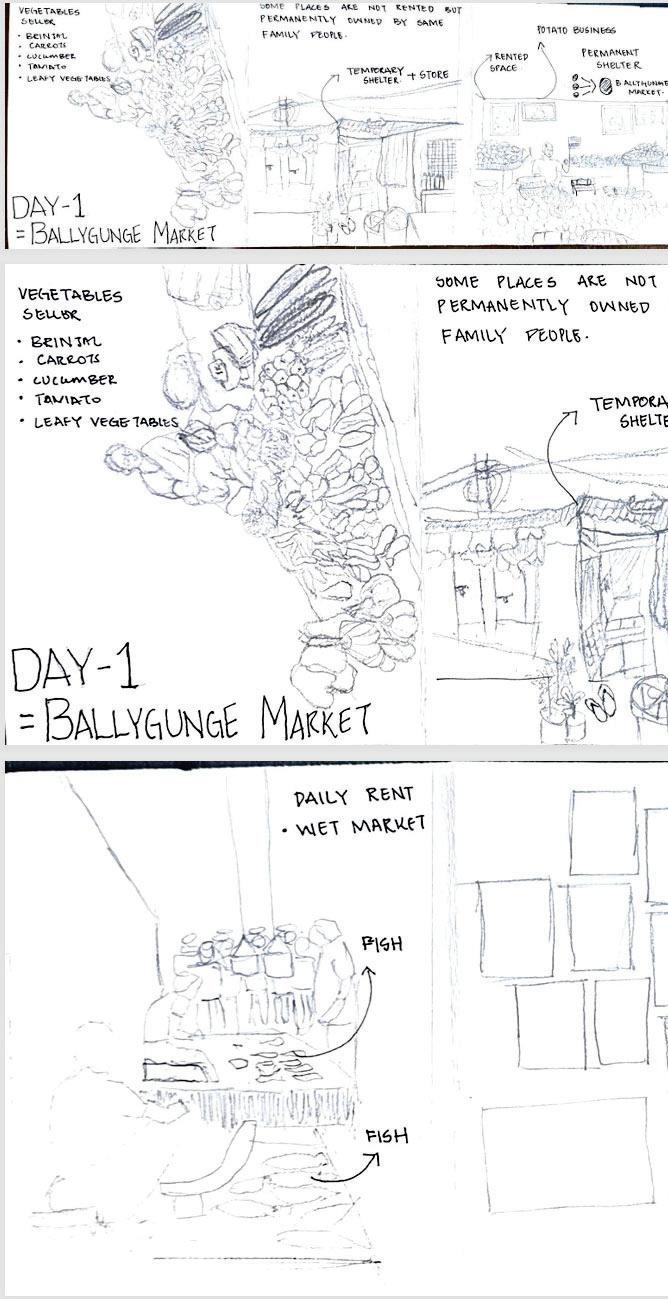

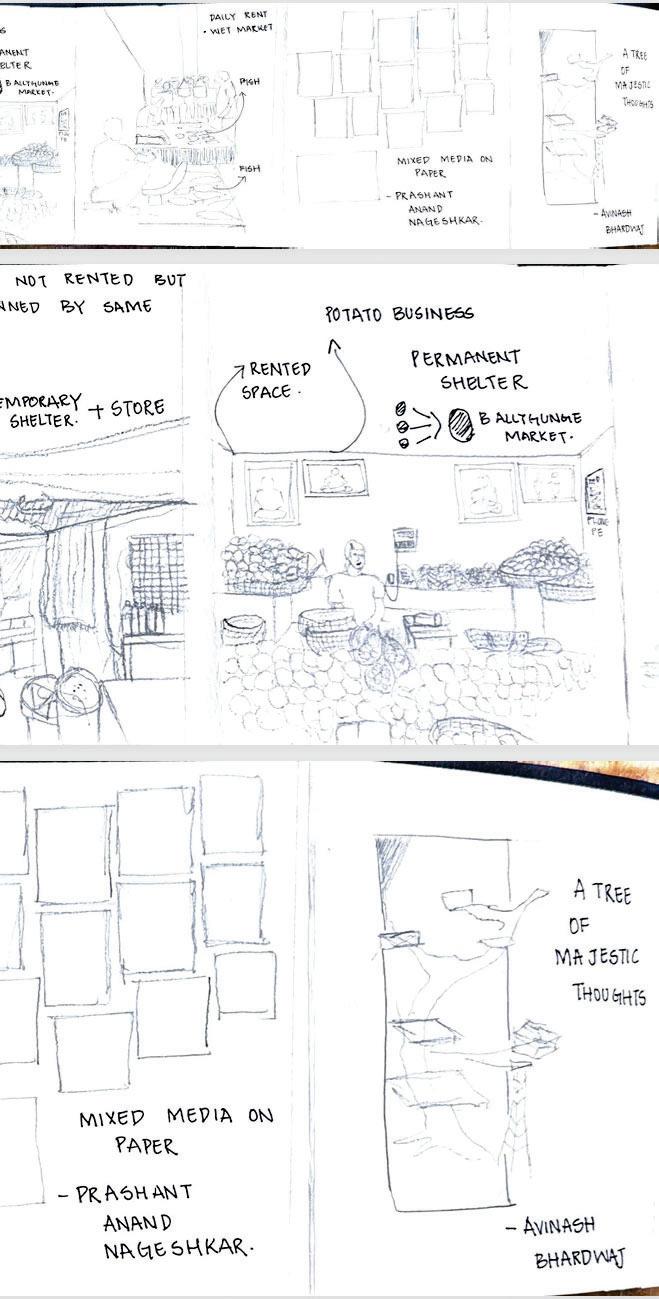

Day 1 - Ballygunge Market

Day 2 - Canning

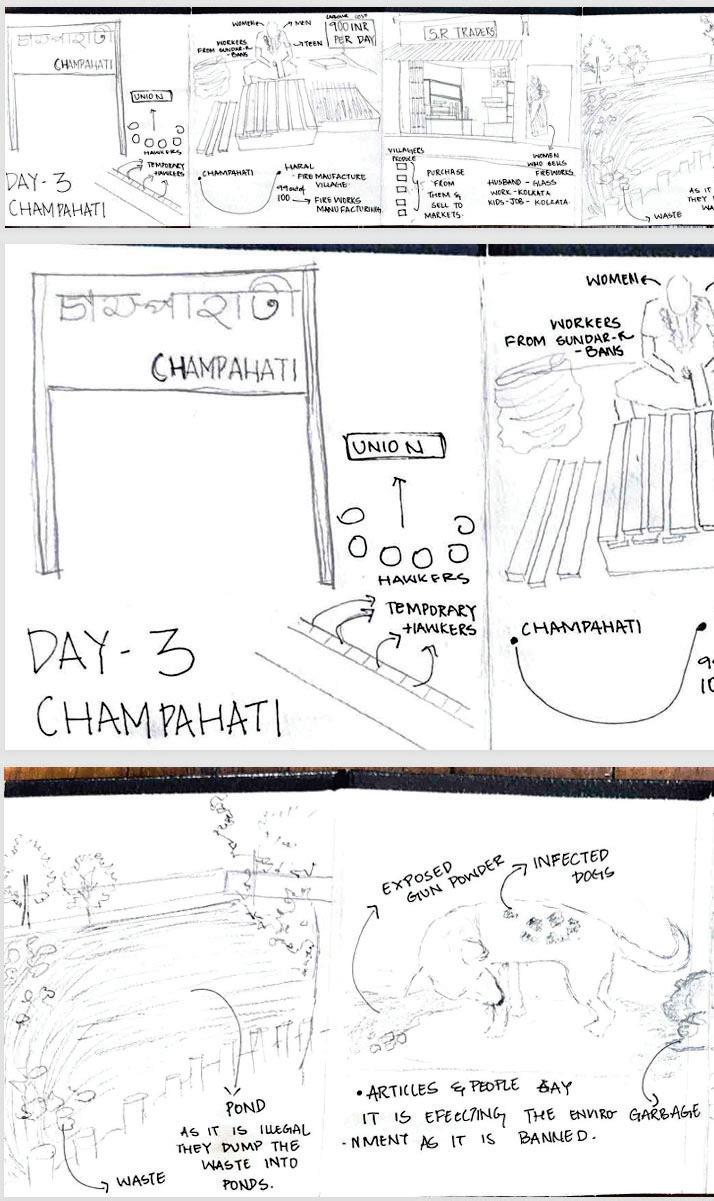

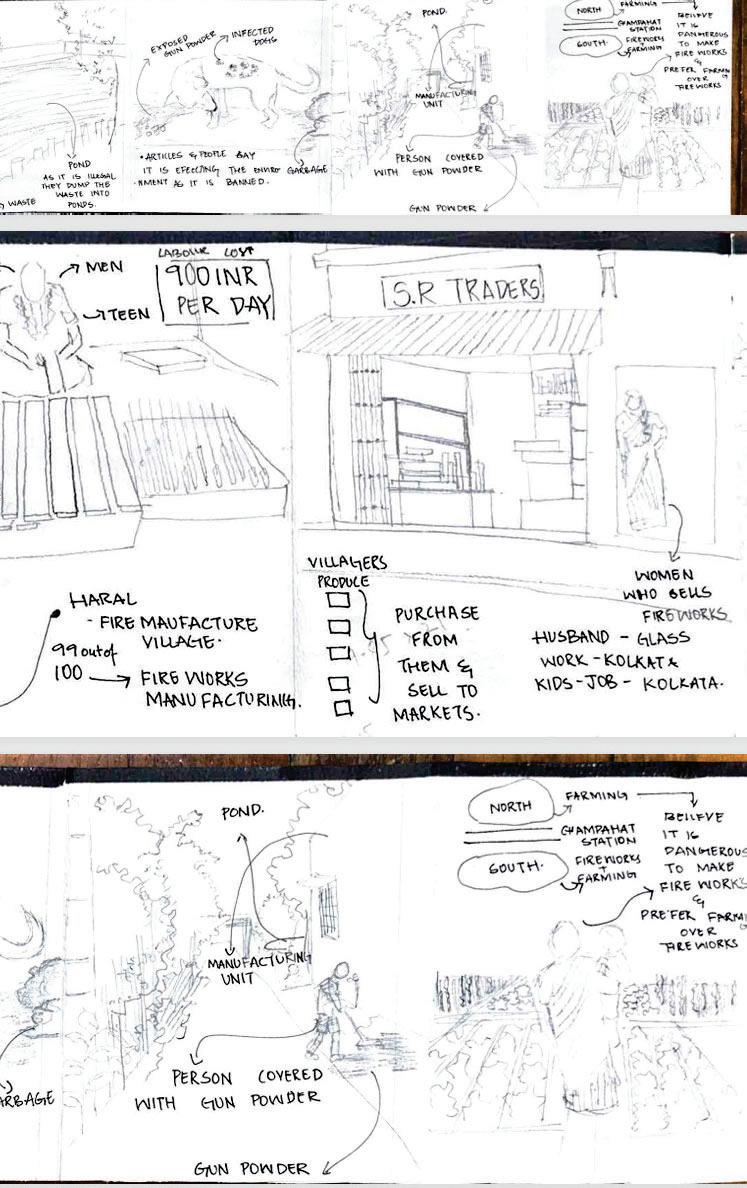

Day 3 - Champahati

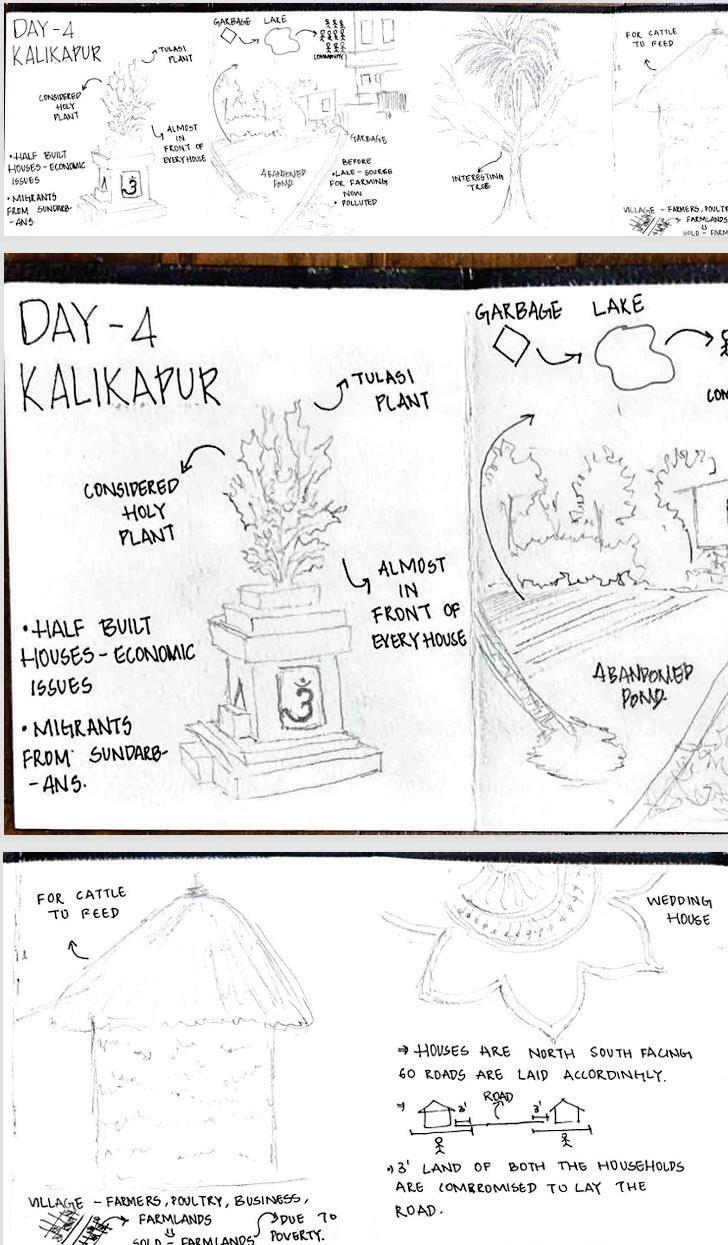

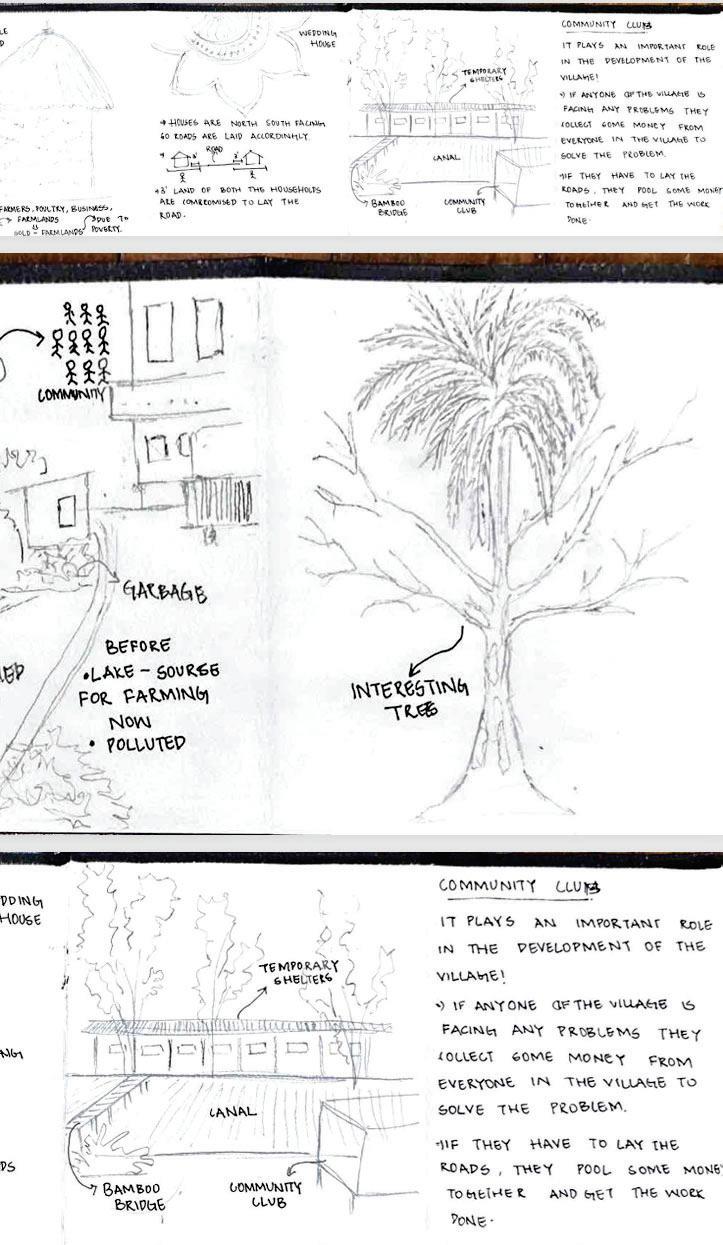

Day 4 - Kalikapur

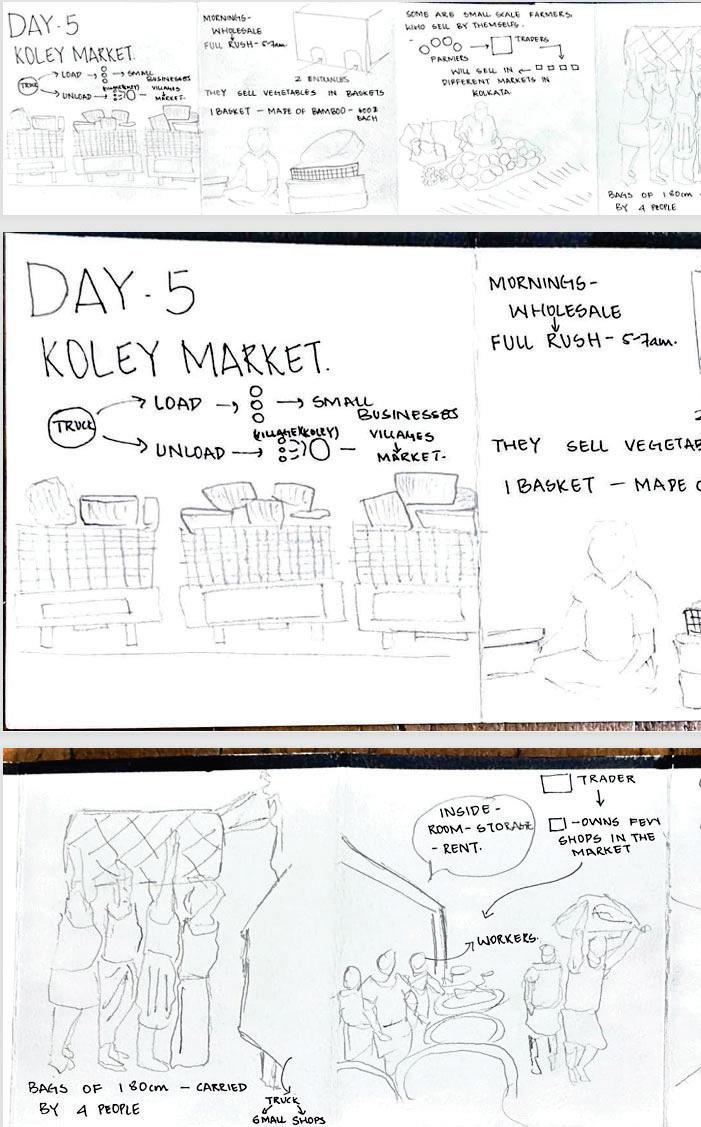

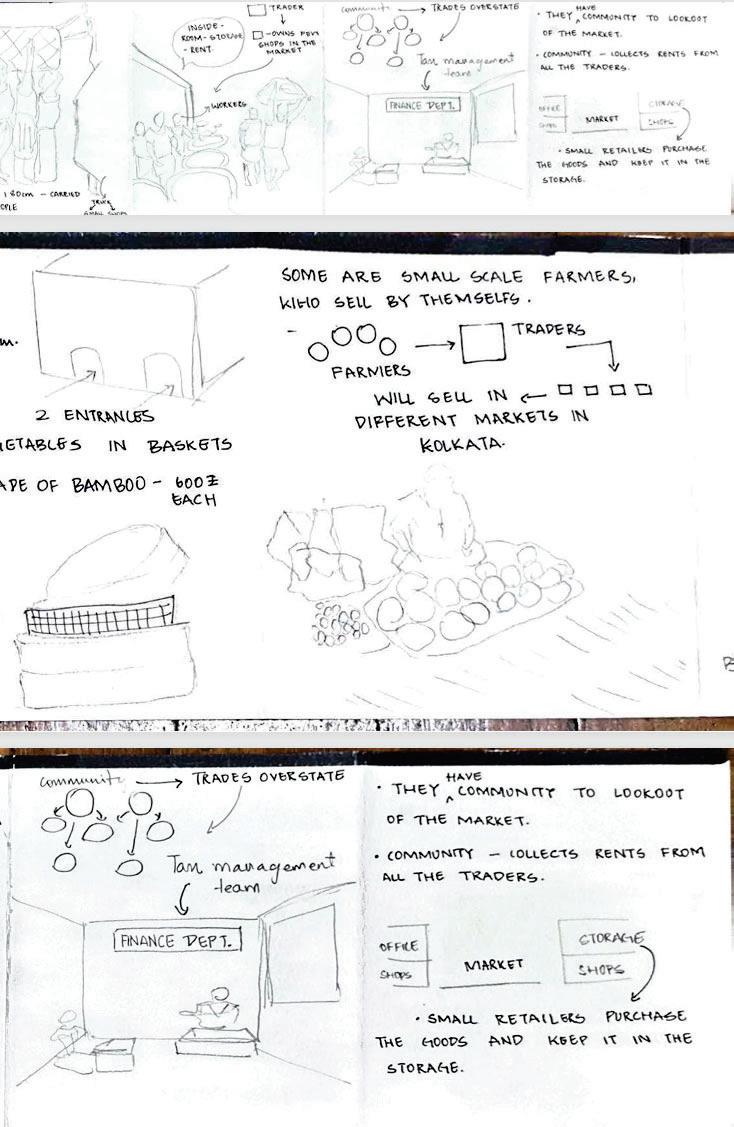

Day 5 - Koley Market

MY STORY OF HARAL-FIREWORKS MANUFACTURING VILLAGE IN CHAMPAHATI

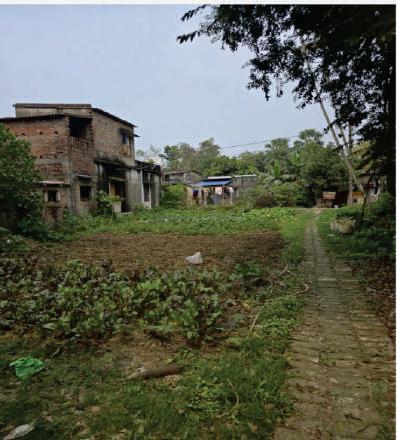

When I embarked on this study trip to Kolkata, I initially thought the fireworks industry was simply an environmental hazard that could be shut down with stricter regulations. I assumed that once the government enforced a ban, the issue would resolve itself, leading to a healthier environment. However, what I found on-site was far more complex. Through interviews with villagers, workers, and farmers, I discovered a deeply intertwined system of economic survival, political influence, and environmental degradation. The ban on fireworks manufacturing did not come with proper waste disposal strategies, leaving the villagers to dump hazardous chemicals into nearby ponds, which then polluted the canals. Furthermore, I learned that fireworks were not a year-round industry but rather a seasonal occupation spanning 4-5 months, while farming sustained them for the rest of the year. However, even agriculture was compromised, as excessive chemical fertilizer use further degraded the already contaminated soil.

This realization advanced my understanding of architecture and landscape beyond just ecological restoration. I began seeing it as a socio-environmental challenge that needed a holistic design and policy-based intervention. The connection between land use, water systems, and economic livelihood became evident. Landscape architecture, in this case, wasn't just about designing green spaces but also about rethinking land management, waste treatment, and alternative livelihoods. The situation forced me to think about sustainable transitions that wouldn't displace people but instead empower them. The possibility of repurposing fallow land, introducing controlled waste management, and transitioning the industry into a safer and regulated framework became central to my thought process. I also started to explore the potential of creating alternative employment opportunities, especially for women, who expressed a willingness to shift professions if viable options existed.

One moment of clarity came when I saw a worker covered entirely in gunpowder, lacking any protective gear, and continuing his work as though it were normal. It struck me how deeply ingrained this industry was in their daily lives. I also met women who had sustained their families for decades through fireworks manufacturing yet now found themselves at a crossroads with no alternative means of income. Some had begun shifting to bidi-making, while others were selling off their last stock with uncertainty about their future. These interactions made me realize that simply removing the industry without an alternative plan would not be a solution—it would only worsen poverty.

Another shift in my perspective came when I understood the role of unions and politics in sustaining this industry. The workers were not just operating independently; they were backed by powerful unions aligned with political interests, making government interventions far more complicated than I had assumed. The system was not just a question of environmental laws but also one of political will and social restructuring.

This led me to rethink my approach. Instead of proposing a complete shutdown of the industry, I started considering a more structured, regulated, and hygienic model of production, ensuring proper waste disposal and safety for workers. I also began exploring ways to introduce alternative industries, such as eco-villages where women could take on roles in land restoration, water purification, or sustainable craft-making. I realized that a well-planned transition, rather than an abrupt ban, would be key to balancing environmental restoration with economic survival.

This study was not just about pollution—it was about people, their livelihoods, and their future. It made me realize that design and planning should always consider the human stories behind the spaces we intervene in. My perspective evolved from seeing fireworks manufacturing as a problem to be eliminated, to viewing it as an opportunity for transformation through inclusive, sustainable, and socially responsive solutions.

02_Research

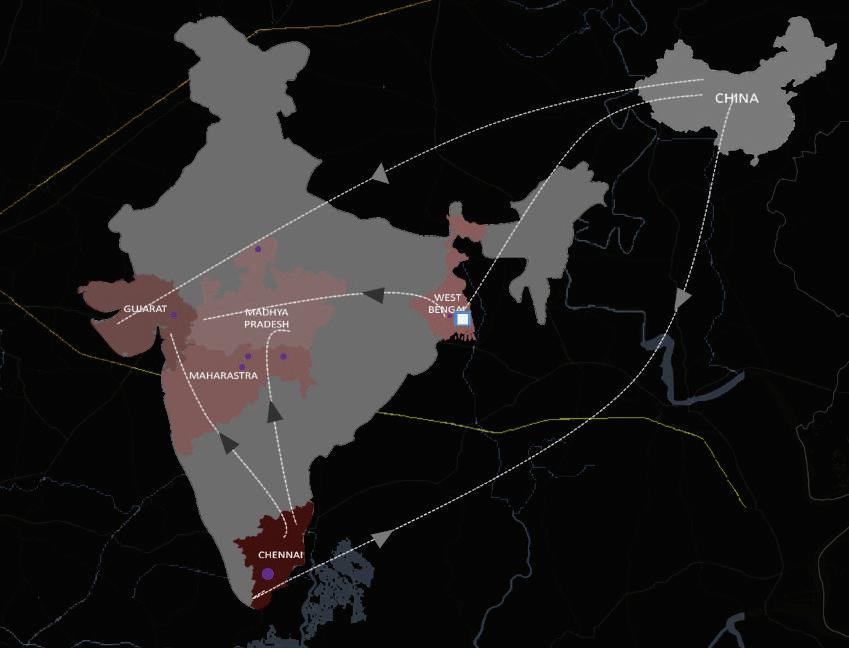

02_01 Fire works distribution in India

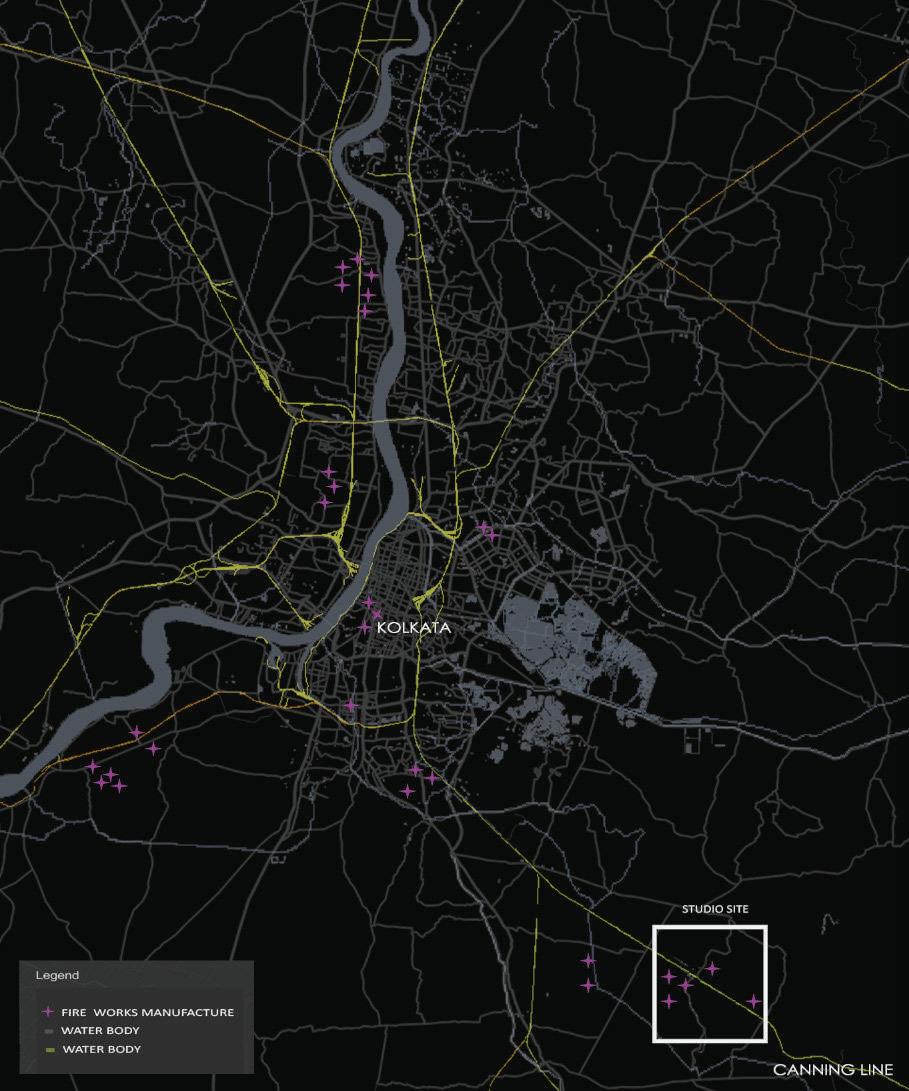

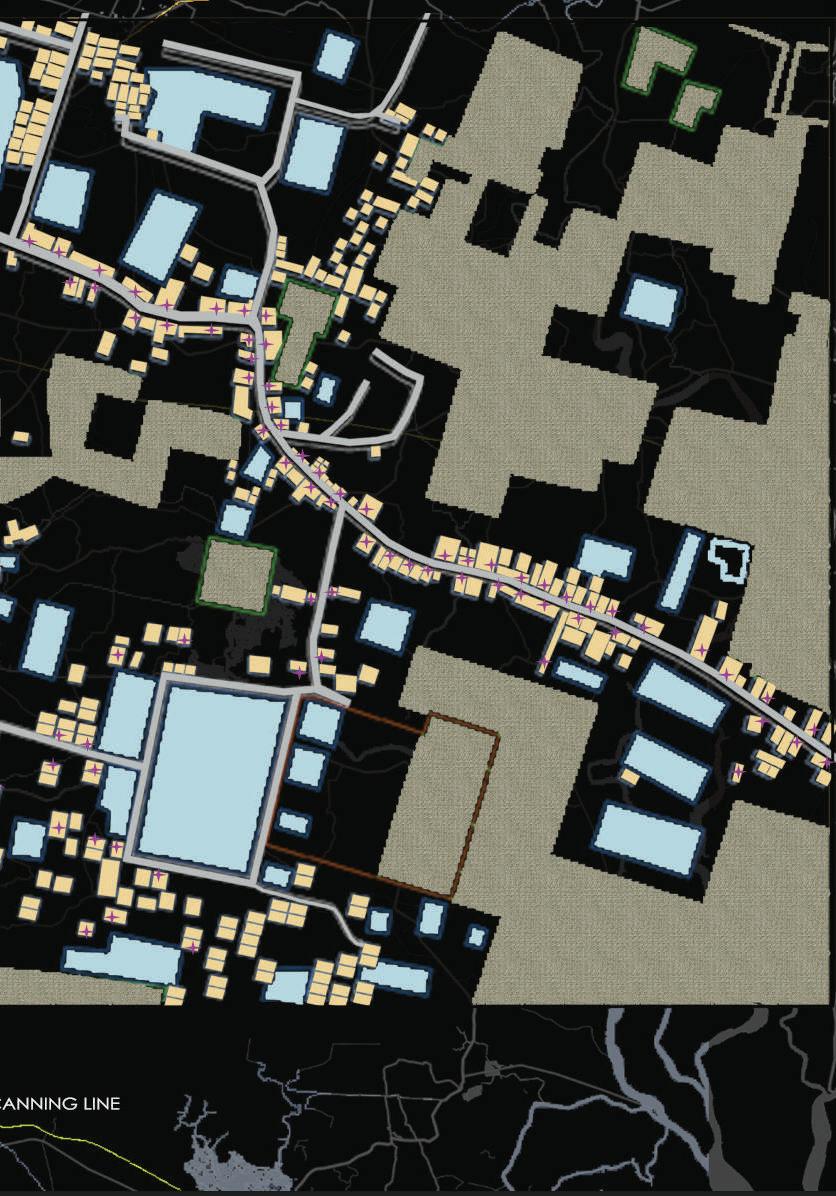

In India, fireworks are used during festivals, weddings, and celebrations. 90% fireworks are made in Sivakasi, Tamil Nadu, but many other places also started making them, including small villages in West Bengal. Haral, near Champahati, began producing fireworks in the 1960s. It gave jobs to many families, but over time, the chemicals used—like sulfur, potassium nitrate, charcoal, and aluminum powder—damaged the soil, water, and people’s health.

To manufacture fireworks, different chemicals like potassium nitrate and sulfur come from Rajasthan and Gujarat. Charcoal comes from Jharkhand. Aluminum and magnesium powders are from Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra. Some materials like coloring powders and special chemicals are also brought from China because they are cheaper.

One such region where fireworks are manufactured is Champahati, Haral district became a prominent local hub for fireworks production starting in the 1960s. The community, dependent on this industry for income, gradually embedded firework making into its everyday life—across homes, courtyards, and even temporary sheds.

HEALED BY TIME

02_02 Fireworks Affects

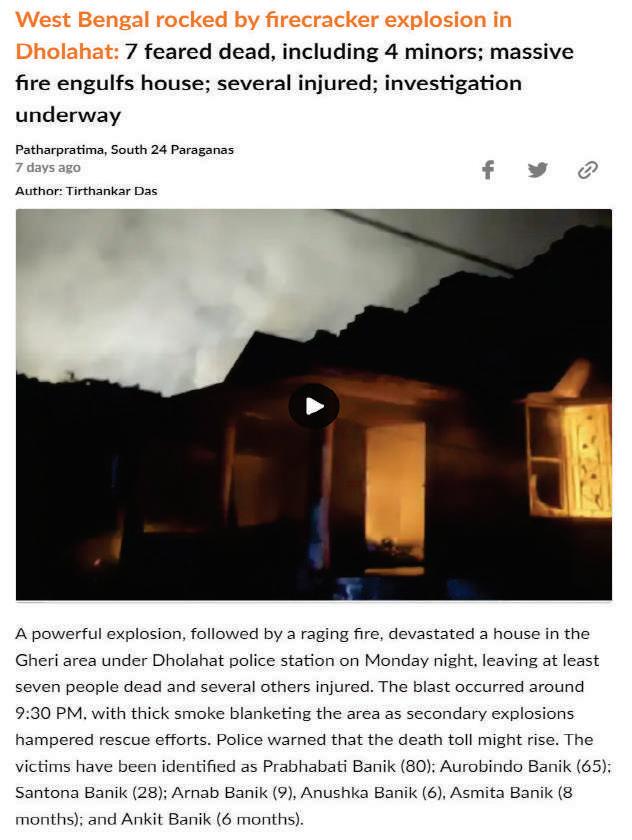

Haral, a village near Champahati, has been deeply affected by decades of fireworks manufacturing, which began in the 1960s. The use of harmful chemicals like nitrates and sulfur led to severe soil, air, and water pollution. Unsafe working conditions caused multiple accidental blasts, resulting in injuries and even deaths of workers, many of whom were women and children. With growing health risks and environmental damage, the West Bengal government officially banned firework manufacturing in 2021. However, illegal production still continues in some areas, putting lives at risk. The community now struggles with both pollution and loss of livelihood.

02_03 Haral Fieldwork

Fireworks seller: The seller has been doing this since past 10-12 years. They have their manufacturing unit inside the village but refused to take us to the manufacturing unit.They have like a fire extinguisher and a small bucket of sand which doesn’t really help incase of the whole shop explosion.They have a union that helps the works survive and do things illegally, the union is mostly takes care of the fireworks manufacturing units in the village and even if the accident did happen they would cover up that news saying that it’s a terrorist attack (this did happen).

Fireworks seller: The seller has been doing this since past 10-12 years. They have their manufacturing unit inside the village but refused to take us to the manufacturing unit.They have like a fire extinguisher and a small bucket of sand which doesn’t really help incase of the whole shop explosion.They have a union that helps the works survive and do things illegally, the union mostly takes care of the fireworks manufacturing units in the village and even if the accident did happen the union would cover up the news saying that it’s a terrorist attack.

This is a stray dog whose body was found covered in gunpowder, likely due to prolonged exposure to nearby fireworks manufacturing units. Unfortunately, many street dogs in Haral suffer from serious skin conditions and other health issues simply because they live in environments where toxic substances, chemical residues, and pollutants are constantly present. These animals have no protection against the harmful materials around them, which leads to infections, burns, and long-term diseases.

02_04 Alternative occupations of the Residents

Residents

-January fireworks manufacturers

Fire works manufacturers

water being contaminated

Dump waste in ponds

January –august farming, other smallscale works

Farming

Use of fertilizers to get more yield

The residents of Haral juggle between seasonal occupations—working as fireworks manufacturers from September to January and turning to farming or other small-scale jobs for the rest of the year. This dual economy, however, comes with consequences: chemical waste from fireworks is dumped into ponds, and overuse of fertilizers in farming further degrades the soil. Interviews revealed that sellers rely on unsafe practices like using only a sand bucket for fire safety. A strong union shields illegal operations, suppressing accidents and framing them as other issues. Despite visible pollution and risks, the community continues in this hazardous yet familiar livelihood cycle.

And one that that can be observed in all the pictures is a common use of material for, footfaths, building blocks, and various other things that is bricks.

03_Projections

HEALED BY TIME

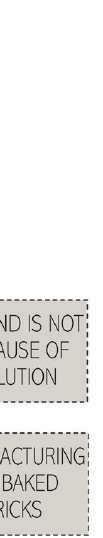

The first frame represents individual agency, where one person takes the initiative to shift towards a cleaner, safer lifestyle, such as adopting eco-friendly practices like composting or switching away from fireworks manufacturing.

This small step inspires neighbors, leading to the second stage — the locality association — where the community begins to come together around shared goals like re-greening spaces or restoring ponds. With growing support, they move towards the sunbaked brick association, a locally driven economic alternative that uses traditional, non-polluting methods for brick making.

Finally, in the last stage, the formation of a union solidifies this collective effort, giving people a stronger voice, protection, and the ability to push for systemic change. The image captures how grassroots efforts can slowly reshape the identity of a place, grounded in care and community.

03_02 SUNBAKED BRICK FRAMEWORK

HEALED BY TIME

03_03 TREATING WATER

03_04 TREATING SOIL

03_05 HEALING THROUGH TIME

HEALED BY TIME

03_06 HEALED BY TIME

HEALED BY TIME