CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION

1.1 Research Background & Rationale

The intersection of nationalism and heritage conservation in contemporary times has been deeply rooted in dismantling the undeniable physical remnants of the colonial past, often leading to the obliteration of trans-colonial urban identities in the postcolonial period this predisposed understanding of the past results in biased principles for contemporary heritage conservation. British imperialism across its colonies played a vital role in shaping health, hygiene, and urban development policies in the late 19th century by establishing City Improvement Trusts to serve broader colonial goals. Understanding the implications of this development in the contemporary trans-colonial context in terms of heritage conservation is crucial. Although there has been significant progress in the discourse of imperial urbanization, in the era of modernization, there is a substantial gap in comprehending the transformation of this colonial development in the postcolonial period. Moreover, addressing this progression through the lens of heritage conservation is crucial. This dissertation aims to address these gaps thematically and to reinvent and reuse colonial legacies to meet current needs through the comparative analysis of the Bombay City Improvement Trust (BIT) and Singapore Improvement Trust (SIT). It is imperative to note that this dissertation is not an attempt to advocate for 'colonization' but rather an exercise to analyze and comprehend all the layers of the colonial legacy without any biases while attempting to set a precedent for contemporary conservation practices for utilitarian heritage.

Why the Comparison between 'Singapore' and 'Bombay' in the

Context of Improvement Trust?

Comparisons between Singapore and Bombay are made to analyze the social stratification strategies through urban planning, urban identities, and transformation in the fabric and the current conservation principles for colonial heritage. Both the city and the nation-state shared similar experiences and colonial narratives with the interrelationship of multiculturalism, trade, and economics due to their geographical setting and socio-cultural context.

Key reasons for a comparative analysis include

1. Urban development under imperialism: Significant changes in urban planning, policy planning, and uniform /broader colonial vision.

2. Port city, trade and commerce: the location of trading ports, the mass migration of the community's squatters, and an unprecedented population explosion in the 1900s.

3. Socio-economic context: economic transformations during the colonial period, social segregation, and change in the morphology of the cities due to demographic shifts.

4. Postcolonial shift of narratives: A shift in the narrative post-independence, nationalism, and development, housing development schemes, and slum redevelopment.

1.2 Aim and Objectives

The project's primary aim is to critically examine the potential of heritage conservation in trans-colonial urban development through the comparative study of utilitarian architecture by BIT and SIT. Additionally, it aims to address this transformation and comprehend a discourse on the appropriate interpretation of the colonial legacies contributing to the preservation of trans-colonial urban identities in the postindependent era. This imperative is because nationalistic narratives of any contentious past often challenge their preservation. The key objectives are-

1. Examine the ideological and morphological framework that characterized the Singapore and Bombay improvement trust.

2. To understand and analyze the influence of policies and planning by improvement trusts in contemporary urban planning and conservation strategies.

3. To undertake a nuanced understanding of trans-colonial urban identities in the postcolonial period by acknowledging the complexities of the past and reinterpreting the beneficial aspects for current and future needs.

1.3 Research Questions

1. How did the Singapore Improvement Trust (SIT) and Bombay City Improvement Trust (BIT) contribute to shaping urban identities across the social classes, and how have they transformed in the postcolonial period?

2. To what extent did the Improvement Trust consider the existing traditional urban fabric during the modernization efforts in Singapore and Bombay? How have they transformed in the postcolonial era?

3. How have the remnants of the development of the City Improvement Trust conserved in Singapore and Bombay? To what extent are the tangible and intangible aspects intact and adaptable for contemporary needs?

1.4 Scope and limitations

The project's scope extends to undertaken a comparative analysis of the Improvement trusts in Bombay and Singapore and it includes examining their planning policies, the architectural integrity of the colonial legacy, and socio-spatial transformations. By analyzing the aforementioned parameters, the study explores how urban schemes have shaped the urban identities and social stratification of respective cities. The research scope will also include their postcolonial transformation and influence on modern heritage conservation principles. A key contribution of this dissertation lies in its exploration of heritage conservation as a reconciliatory tool, proposing methodologies for interpreting colonial-era urban planning principles within modern conservation frameworks. By reinterpreting it away from a nationalist narrative, the study will explore the understanding of contemporary heritage conservation, ensuring an unbiased and informed approach for the present and future generations.

However, the research's extent of study research is subjected to certain limitations. Firstly, this study is confined to a comparative study of the specified Improvement trusts and colonial-urban reformations in Bombay and Singapore and will not extend beyond that. Additionally, the study intends to provide a comprehensive assessment of BIT and SIT's impact; it will rely primarily on archival documentation, secondary sources, openended surveys, and visual analysis, which may limit the research to desktop-based study and archival study in contrast to extensive field study.

These archival materials provide insights into the social, political, and economic motivations behind colonial urban planning and its legacy in both cities. They also serve as a foundation for understanding policy frameworks and decision-making processes influencing built environments.

1.5.3. Visual and Spatial Analysis

This method employs:

• Maps, photographs, and architectural plans from the colonial and postcolonial periods

• Historical cartography and land-use patterns to track urban transformation

• of SIT and BIT housing models, particularly Tiong Bahru and Dadar, as well as SIT

Apartments and BIT Chawls

By analyzing physical remnants, this approach evaluates the continuity and adaptation of colonial structures in contemporary conservation practices.

1.5.4 Open-ended Interviews

The archival study and visual and social analysis will be complemented by open interviews to understand the residents' current social identities and lived experiences.

• Current and former residents of SIT and BIT estates to document personal narratives, housing experiences, and perceptions of heritage

• Local shopkeepers, market vendors, neighborhood associations, and social groups around these estates to understand community interactions

1.5.5. Data Analysis

The dissertation applies thematic analysis, categorizing data into core themes:

• Colonial urban planning models and socio-spatial segregation

• Social stratification and displacement during SIT and BIT projects

• Shifts in identities and conservation approaches post-independence

• Challenges in contemporary heritage conservation of utilitarian colonial architecture remnants of the colonial legacy.

The comparative study of Singapore and Bombay during the colonial period allows for a structured analysis of urban transformation, providing insights into how colonial legacies persist in contemporary cityscapes with respect to heritage conservation Ultimately, the dissertation acknowledges its limitations in comparing across two contexts.

CHAPTER 2. LITERATURE REVIEW

The contradictory discourse is owing to the gap in understanding the transformation and the absence of an appropriate interpretation of the trans-colonial narrative at present. This chapter intends to comprehend the contemporary narrative by exploring the existing body of research on social stratification, urban planning, renewal, and conservation, focusing on the Singapore Improvement Trust (SIT) and Bombay Improvement Trust (BIT). The review highlights the gaps while evaluating the impact of tangible and intangible heritage and reinterpreting the colonial legacy.

2.1. Trans-colonialism

The colonial hegemony over the 18th century Asia had given rise to the trans-colonial legacies that are in dire need of reinterpretation in the context of 21st-century 1 The transcolonial lens would help us understand Singapore and Bombay's shared yet distinct histories and development. 2. Sham (2015) criticizes that the “occidentalist” interpretation of the past has completely omitted the vernacular histories of former colonies. He argues that the reuse/ reinterpretation of the colonial remnants would aid

1 Royal Institute of Art, Decolonizing Architecture: Modernism and Demodernization, accessed April 16, 2025, https://kkh.se/en/education/further-education-in-architecture-and-fine-art/decolonizingarchitecture/

2 Desmond Hok-Man Sham, Heritage as Resistance: Preservation and Decolonization in Southeast Asian Cities (PhD diss., Goldsmiths, University of London, 2015).

Etymology -Trans-colonialism: Trans: Extending across, though, or over; Colonialism: Of or about a colony. Of or about a period when a country or territory was a colony. Of or about the ideals of colonialism. In this context, "Trans-colonialism” literally referred to the ideas/ influence of British colonial rule across two important colonies: Mumbai and Singapore. This was a term that was coined in the 1990s.

in better interpreting the conflicted past instead of completely dismantling or destroying it. While both Singapore and Bombay inherited the urban planning model under the improvement trust, their approach to heritage conservation is significantly distinct. Consequently, the comparative study on the administrative alliance (Improvement Trust) of the British through mass urban planning across the borders of Singapore and Bombay would enable us to better comprehend the vernacular histories and their interpretation in the postcolonial period.

2.2. Colonial Urban Identities and Social Stratification

Response to the congested housing conditions and the outbreak of the disease resulted in the imperial government's establishment of improved trust in Bombay and Singapore. 3. Framed as a positive development, sanitation, de-congestion, health, and hygiene were the primary driving factors with which they envisioned creating social housing for the indigenous working class. However, Hazareesingh's (2001) segregation rather than the welfare of the Indigenous population. The social segregation of the British in the urban context, as discussed by Christopher (1992), validates that "cultural and structural pluralism" was often the basis for the planning of their city. 4. Furthermore, from the physical remnants of the colonies today, one can comprehend that the cultural and physical segregation was the barrier between the rulers and the ruled. However, scholars like King (1976) argue the hierarchy of social stratification predominantly served the Europeans, the urban elites, and the middle class of the indigenous population. The complexity of this stratification substantiates that imperialism created a hierarchy of

3 Alternative Planning History and Theory. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis, (n.d.).

4 A. J. Christopher, “Urban Segregation Levels in the British Overseas Empire and Its Successors, in the Twentieth Century,” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 17, no. 1 (1992): 95–107, https://doi.org/10.2307/622639

social class rather than an absolute dichotomy. Additionally, in Bombay and Singapore, the absence of resettlement further exacerbated the housing crisis for the displaced and the marginalized, resulting in the proliferation of unplanned settlements around these colonial developments 5. Sugarman (2017) highlights how SIT and BIT have undertaken urban development in their respective colonies, which the regional socio-political and economic conditions have influenced. It is imperative to understand the transformation of the development in the present day as scholars like Christopher (1992) and Sugarman (2017) argue that the "demise of colonialism" did not dissolve this social stratification; instead, it just transformed them into new urban identities. 6 .

Therefore, the disparity in the trans-colonial narrative of social stratification due to colonial urbanism requires a more nuanced understanding because of its persistent colonial legacies in postcolonial cities.

2.3. Post-independent Shifts in conservation

Modernist ideologies were disregarded in favor of the distant past, thus resulting in an 'anti-modern' bias. 7. To deviate from the colonial past and undo imperialism's impact, pre-colonial heritage was used to shape the narrative, or new post-modernist buildings were conceived. She further argues that the 19th and 20th-century buildings require a broader framework that continues to address their contemporary relevance by adaptively reusing them, reinterpreting their simple geometries, and adopting

5 Sandip Hazareesingh, “Colonial Modernism and the Flawed Paradigms of Urban Renewal: Uneven Development in Bombay, 1900–25,” Urban History 28 (2001): 235–255, https://doi.org/10.1017/S096392680100205X.

6 Sugarman, Michael William. Slums, Squatters, and Urban Redevelopment Schemes in Bombay, Hong Kong, and Singapore, 1894-1960. PhD diss., Magdalene College, University of Cambridge, 2017.

7 Jain, Priya. 2023. "India’s Modern Heritage: Conservation Challenges and Opportunities." Planning Perspectives 38 (June 20): 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1080/02665433.2023.2224177.

construction techniques. Rather than relying entirely on demolition and new construction, it validates the significance of historic buildings, specifically through examples such as warehouses and the National Gallery in Singapore, which serve as prominent remnants of the colonial past. 8However, conservation efforts must shift from iconic monumental buildings or large-scale buildings to vernacular hybrid buildings. Additionally, social, economic, and cultural attributes must be studied to effectively conserve and reuse colonial heritage.

2.4. Intangible Heritage of SIT and BIT

Current socio-cultural interpretation of the colonial remnants of SIT and BIT are absorbed into the nation-building narrative but Chua, Beng Huat. (1997) contends that it portrays a more pragmatic approach to urban planning 9. This has resulted in the retention of most of the architectural vestiges in Singapore. At the same time, the social and cultural attributes have changed due to the displacement of the communities within the heritage precinct. In contrast, the Chawls in Mumbai, suffering from social-spatial inequalities presently due to the increase in density in the postcolonial period, have very high socio-cultural value, as noted by Solomon Benjamin (2008) 10One can comprehend that these contradictory trajectories of the two former colonies are the interrelationship between the colonial past and the postcolonial aspiration. This further necessitates addressing the gap in understanding the shift in the cultural and social practices shaped by displaced populations during colonial and postcolonial urban planning in the former colonies.

8 Cummer, Katie, and Lynne D. DiStefano, eds. Asian Revitalization: Adaptive Reuse in Hong Kong, Shanghai, and Singapore. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2021. ISBN 978-988-8528-55-4.

9 Chua, Beng Huat. Political Legitimacy and Housing: Stakeholding in Singapore. London: Routledge, 1997.

10 Benjamin, Solomon. “Occupancy Urbanism: Radicalizing Politics and Economy beyond Policy and Programs.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 32, no. 3 (2008): 719–29.

“Improvement schemes include creating housing along modern sanitary lines in older parts of the city, including Nagpada and Agripada.

Street schemes: The construction of broad west–east boulevards to bring healthful ocean breezes from the west into central and east Bombay neighborhoods, such as Nagpada.

Suburbanization: The development of new areas for settlement and urban habitation. These included two kinds of spaces: areas reclaimed from the sea and sparsely populated northern parts of the island, home to rice cultivators, Bhandari toddy-tappers, and Koli fishing communities.” 16

They actively executed the first two schemes between 1898 and 1910 through mass demolition and relocation of the working class population. It is crucial to note that the colonial rule undertook the demolishing in a faster phase than relocation, causing the displaced and working class to seek accommodation with the fringes of their previous settlement inflating the rent prices. This drew criticism from Bombay Municipal Corporation and the urban elite. The urban elites were worried that the central core's proximity and densification would further exacerbate the outbreak. However, the Bombay Improvement Trust came up with two solutions: "to divide the island into natural areas for the accommodation of the upper, the middle and the lower classes with special reference to occupation." 17Secondly, it "was to place the working class as far as possible from their workplace." 18. It is imperative to note that both schemes were fairly received well by the government and the urban elites. The special exclusion as per the class would physically separate the inhabitants and delimit the urban poor away from the

16 Rao, Nikhil. House, But No Garden: Apartment Living in Bombay's Suburbs, 1898-1964. United States: University of Minnesota Press, 2013.

17 Kidambi, Prashant. “Housing the Poor in a Colonial City: The Bombay Improvement Trust, 1898–1918.” Studies in History 17, no. 1 (2001): 57–59.

18 Ibid, [57-69]

main city. Although this was derived from the anxiety of the epidemic, it demonstrated the social stratification encouraged by the colonial and the native elites, thus imposing an identity on the inhabitants through urban planning.

However, even if the social stratification ideology was well received, "by the end of the 1910s, the decisions of the Trust were being challenged at every turn" due to their inability to deliver. The "Government responded to such pressure by creating a new body in 1919, the Bombay Development Directorate (BDD), an entirely executive body and an actual department of provincial government." 19 “The discussion of the worker’s house gradually shifted focus from the morality of ruling elites and civic duty to the potential for profit.”

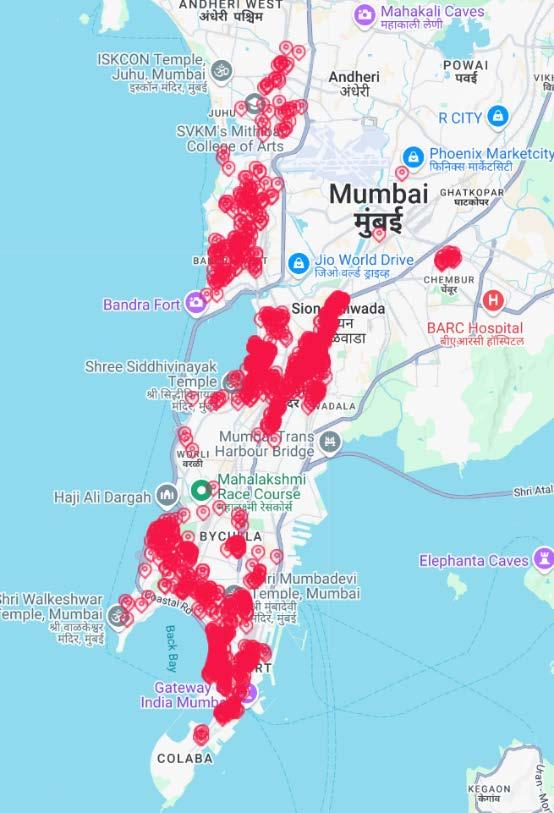

20 The development of suburban in the north of Bombay was conceived as the antithesis of the old inner city; the BDD envisions it to be an 'indirect attack' the slum clearance and rehabilitation as the 'direct attack- mass slum clearance and rehabilitation' had failed. The goal was to attract the migration of the overcrowded south (Present day fort area) to the “new building sites” in the north towards “Matunga – Dadar – Sion," thus forging a new low-middle class identity for the slum dwellers (Refer figure 1) 21 .

19 Karim, Farhan Sirajul. Of Greater Dignity than Riches: Austerity and Housing Design. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2019.

20 Ibid

21 Kamalika Banerjee, Thinking through the Postcolonial Neighbourhood: Jugaad Politics and the Everyday Production of Space in Mumbai (PhD diss., National University of Singapore, 2021), ProQuest (29352889).

Figure 1: A map of Bombay from 1914 that shows the different Trust initiatives. Completed schemes, such as Nagpada, were represented by areas in black; vested in the Trust by areas in blue; and prospective or ongoing Trust schemes by regions in brown.

This was also an important move for the colonial government as they took control of all the land in the north, hoping to promote consistent regulation and connecting the north and south to stabilize the property values. Although suburbanization was a conscious

dwelling unit without veranda (Refer Image 2) in chawls from their three-room kaccha mud houses. Beyond its poor construction quality and design, the tenements could not be filled, causing ‘Industrial housing for the working poor’ to halt The BDD stuck to reclamation projects along the periphery of Bombay until 1929 and absorbed into the revenue department

(Source-

Although it was part of the revenue department's BDD role, which started during the Great Depression (1929), it impacted industrial growth and employment, increasing demand for affordable housing. 25 Activism and tenets movements, led by the Congress Socialist Party, brought together a group of socialists and leftists to form the Bombay Tenants' Central Committee (called BTCC) to protest unfair housing policies. The colonial government was forced to act and increasingly intervened in the housing policies. At the same time, the BDD in the revenue department continued to construct tenement housing,

25 ¹ Art Deco Mumbai, Ideas for the Modern Home, Art Deco Mumbai, accessed March 12, 2025, https://www.artdecomumbai.com/research/ideals-for-the-modern-home

Figure 2: The BDD chawl on DeLisle Road is being built. Take note of the absence of a verandah.

Gammon India.)

primarily in areas like Worli, Naigaon, Sewri, and Chinchpokli amidst the social unrest. 26 Activism leading to political unrest led to the formation of the Rent Control Act of 1939 to protect the tenants from getting exploited by the BDD authorities demanding high rents. The predicament of the BDD worsened after WWII in the 1940s, exacerbating the Socio-economic challenges, and the growing momentum of the independence was closely linked to the housing rights movement. The authorities grew increasingly concerned about the political agitation that this was causing. They resorted to producing mass housing quickly, consequently giving rise to substandard living conditions and deterioration of the older chawls by the independence. 27 Therefore, post-independence, the government, and the municipal corporation focused on redeveloping housing in Bombay (now Mumbai). In order to solve the housing deficit, the Maharashtra Housing Board (MHB) was founded in 1948. In order to supervise the restoration and repair of deteriorating buildings, the Bombay Building Repairs and Reconstruction Board was established in 1971. The Bombay Slum Improvement Board was established in 1974 with the goal of improving living conditions in unofficial colonies. As a result of these initiatives, the Maharashtra Housing & Area Development Authority (MHADA) was established in 1976 to supervise the building, renovation, repair, and redevelopment of subsidised housing in Mumbai following independence 28 .

26 Caru, Vanessa R. "Where is Politics Housed? Tenants’ Movement and Subaltern Politicization: Bombay, 1920–1940." Revue d’Histoire Moderne et Contemporaine 58, no. 4 (2011): 71-95. https://shs.cairn.info/article/E_RHMC_584_0071.

27 Caru, Vanessa R.p.81-85

28 The Maharashtra Housing and Area Development Authority is a statutory authority established under the MHADA Act, 1976

3.3.

CHAPTER 4: SINGAPORE IMPROVEMENT TRUST (SIT)

4.1. Inception, Adoption and development of Singapore Improvement Trust (SIT)

"While the Straits Chinese, immigrant Chinese, Malays, and Indians are subject to malaria, Europeans, it appears, enjoy a comparative immunity. The residential quarters of the latter are generally well away from the massive, and it is to this fact, together with the use of mosquito curtains, test their immunity is more or less attributed; that immunity, however, it is pointed out, is likely to disappear with the encroachment of native houses, especially shop houses, or in other words tenement houses, on those parts of the town now occupied by Europeans. This danger to the European community can easily be prevented when the Municipality is given the power to specify the class of dwelling houses in special districts." 29

An excerpt from the report on the sanitary WJ Simpson (1907) depicts the condition of the Straits settlement in the early 20th century. This is attributed to the social segregation between the white elites and the natives, whose settlements were organically evolving and moving toward the fringes of the non-native settlements. This ubiquitous nature of urban growth, coupled with the anxiety and fear of the colonial settlement disease transmission, was the motivation to initiate the Singapore improvement trust in the 1927s. Their primary concern was not the overcrowding and the rise in the mortality rate of the natives but rather the well-being of the European elites. This portrays the broader objective of the colonial government to protect and control their interest through social order, urbanism, and segregation.

29 Simpson, W. J. Report on the Sanitary Condition of Singapore by Dr. J. Galloway. Straits Settlements Records. National Archives of Singapore Collection, 1907. Microfilm Number: NA 1294. Accessed with permission. P 105

Various Kampongs, like the Kampong Eunos, encouraged the urban growth trends in Singapore along the periphery. As Singapore witnessed unprecedented growth along the edge, it helped build a case for Singapore's improved trust 30. The official mandate only allowed the Singapore Improvement Trust to condemn buildings and declare them inhabitable for living, and housing was never incorporated to keep the costs low

"It should be remembered that the Trust has no obligation to provide houses at all, and what it has done to alleviate the housing situation has been entirely on its initiative and with the help of money borrowed from the Government. Public housing is still nobody's business, and if Singapore wants public housing, the legal, financial, and physical means must be made available to meet the need." 31 .

They also undertook a clearing back lane program to make the space habitable and provide proper sanitation in the overcrowded area. It is crucial to note that after the buildings had been declared inhabitable, the displaced population had to rehabilitate, and the SIT reluctantly accepted the housing mandate but in limited scope to "keep the cost of improvement scheme to a minimum." 32. "During this period, it ran 'Improvement Schemes' including small provisions of low-cost housing along the urban periphery at Balestier Road, Lavender Road, Sago and Smith Streets, Dickenson Hill and Racecourse. Other schemes, like at Bugis Street, were abandoned as the difficult management and financial costs of these improvement schemes emerged." 33One can comprehend that the Singapore model was very similar to the housing model of BDD as they quickly moved towards building low-cost housing along the periphery rather than clearing slums

30 Sugarman 2017, p. 123

31 Singapore Improvement Trust, SIT Annual Report 1951, 1952. p.1.

32 Sugarman, 2017. P. 123

33 Ibid., p. 9-10, 45-6.

The government of Singapore chose to replace SIT with the Housing Development Board (HDB) when the country's political climate changed. A key role in Singapore's public housing system, HDB was formed after extensive talks with the state party and its strong commitment to rehousing and rehabilitation. After the PAP came into power in 1959, they inherited the Planning and Housing and Development Bills passed by Labour. 40. The Planning Bill was passed, and "The Planning Bill additionally enshrined planning powers in a centralized 'competent authority' as part of Government duties overseen by the Minister of Local Government, Lands, and Housing (MLLH)." 41 As the bill implementation was delayed, the SIT was officially replaced in 1960 42. Additionally, "in 1954, the committee was given another assignment. Headed by members Carl Alexander GibsonHill and T.H.H. Hancock – curator of zoology at the Raffles Museum and senior architect of the Public Works Department, respectively – the team was asked to draw up a list of historic sites of Singapore". 43 Interestingly, most of the listed buildings were from the 19th century, and their historical and architectural significance was taken into account. Although the SIT wanted to preserve and conserve these historic sites, it dropped the idea due to insufficient funds.

4.3. Contemporary conservation practices in Singapore

Built heritage conservation in Singapore has transformed over the last three decades, evolving from preserving limited culturally significant monuments to a broader and more integrated approach similar to its Western counterparts. Post-Independence in the 1960s, Singapore prioritized urban renewal efforts that involved slum clearance, mass

40 Singapore Parl Debates; Vol 9 Sitting No.3, Col 1819-1830, 1830-1846; January 26, 1959

41 Ibid,749-752

42 Neo,2021, p. 53

43 Seng. 2019. Brief history of conservation. Urban Redevelopment Authority.Retrieved from the Urban Redevelopment Authority website: https://www.ura.gov.sg/

housing initiatives, and transformation of the central area to accommodate and resettle its vulnerable and displaced population. These instrumental efforts in transforming Singapore into a nation-state have preceded while devising heritage conservation plans on the horizon. Consequently, the establishment of the Preservation Monuments Board (1971), URA (1977), and NHB (1998) formalized the conservation efforts into a comprehensive and strategic conservation framework. "As for the URA, it is continuously identifying new areas to be conserved and updating its conservation guidelines to improve the standard of conservation works. As of 2018, some 7,000 buildings in more than 100 locations have been conserved".

44 The financial landscape in Singapore is largely shaped by land value, as land serves as an asset for revenue generation. Due to high developmental pressure and redevelopment plans, many historic areas and buildings constructed by the Singapore Improvement Trust (SIT) are not protected under the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) guidelines. However, the government has protected areas like Kampong Silat, Tiong Bahru, and various SIT labor quarters. Thus, there is a need for a more comprehensive study and cohesive mandate for their protection.

44 Urban Redevelopment Authority. n.d. Brief history of conservation. Retrieved from the Urban Redevelopment Authority website

human-centric approach grounded in reality that prioritizes long-term development aligned with a master plan. The plan also included urban planning rooted in functional planning and local identity. After this, indirect suburban development away from the city center was envisioned and implemented. They attempted a strategic shift in urban planning, particularly through land acquisition and road planning.

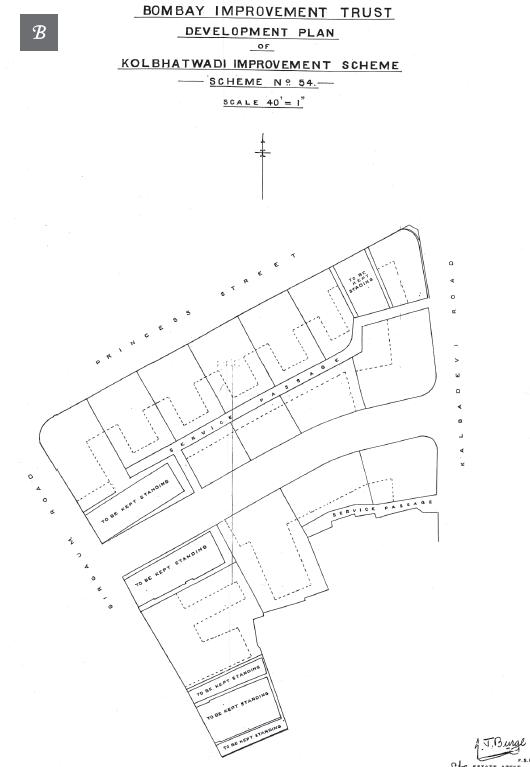

As for SIT (1927-9147), after the initial demolition schemes that was based on the 'general improvement plan,' which predominantly included large-scale demolition back lane development construction of drainage and roads(Refer figure 4 & 5). However, the Zoning responsibilities remained under the Municipality 49 After World War II, the trust replaced the back lane development and rehabilitation with extensive urban renewal as they constructed social housing in various localities like Tiong Bahru and artisans' villas like the Balestier road. Therefore, the macro-level planning of the Trans-colonial settlement was primarily driven by urban health, sanitation, and disease control. However, these functions objectively evolved into comprehensive planning schemes like the garden city, suburbanisation, and social housing. While these interventions addressed immediate public health crises, one can comprehend that the broader colonial agenda of spatial control and social engineering disguised these.

49 Robert Home, Of Planting and Planning: The Making of British Colonial Cities, 2nd ed. (London: Routledge, 2013), [209].

Figure 4: Before (A) and after (B), the Kolbhatwadi Street layout was an older pattern that was forced into orderly growth. BIT, 1918–1919 Annual Administration Report. Maharashtra State Archives provided this image.

Figure 5: Image showing the plans of back lanes of the native settlements that have houses back to back (Source:JW Simpson report)

5.1.2. Social Housing Approach

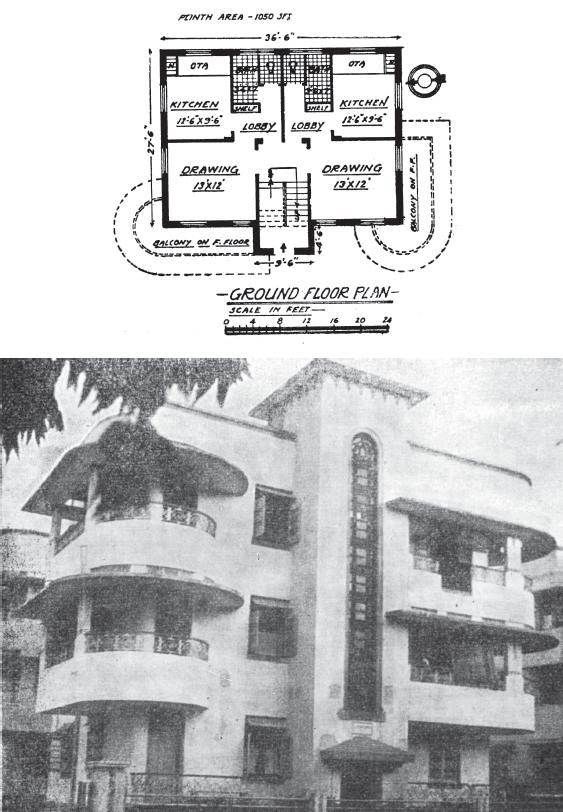

Insights of macro-level urban planning elucidated that it had transformed into microlevel planning at the locality level. Dadar–Matunga–Sion estate in Mumbai was originally planned based on the European "Garden City" model, emphasizing spacious, green, and well-zoned residential areas. The informal settlement and agrarian grounds were cleared and aimed to include a mix of residences for different socio-economic classes, including the spaces for bungle, chawls, and cheap cottages for working-class groups (Refer figure 5) , and open areas like playgrounds and “villages green." Although BIT did not fully enforce this vision, it did construct a few housing blocks to promote social housing development on the premise that the wealthier residents would build their own houses. At the same time, the trust supported the housing needs of the workers. 50. This also marked the shift from traditional building materials like timber to Reinforced cement concrete in the 1920s. Point load construction was adopted for the main skeleton of a building, columns, and beams. Floors and roof were cast in place or pre-casted. This increased the speed of construction and made the overall construction phase costeffective as a result, demand for older housing dropped, affecting property owners who had invested in earlier construction. 51

50 Mariam Dossal, The City in Action: Bombay Struggles for Power (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2010), 154–156.

51 Nikhil Rao, House, but No Garden: Apartment Living in Bombay’s Suburbs, 1898–1964 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013), 144–146.

Figure 6 : BIT's "Workingmen's Cottages" in Scheme 5 (BIT, Annual Administration Report, 1915–1916) (Source: Maharastra State Archives)

Figure 7: Image depicting the plans and view for the new RCC social housing that was constructed. during the late colonial period. (Source: Nikhil Rao)

and basic architectural form. 55. This portrays how colonial urbanism was adopted at the micro-level for social housing and selectively adapted across the trans-colonies.

5.1.3.

Infrastructure Development

Roads were typically carved out of ‘dense urban masses', and the impetus of the colonial government imperial urbanism through the provision of open space through decongestion, laying the drainage system, and designing of access ways to facilitate transit. Stone-hydro pneumatic sewer system had been introduced in Colaba, Mumbai, for the transportation of sewage; it was later proposed that the SIT be adopted in the JW Simpson sanitation report. 56 .

The BIT was predominantly working on an 'Infrastructure Financing model' wherein the cost of Public amenities such as the roads and railways were recovered through the levies imposed on the locality directly benefiting from these improvements, trying to balance the financial burden with the beneficiaries of the development, consequently increasing the cost of living. 57 At the same time, the SIT had borrowed funds from the government for their construction work.

5.1.4.

Social Stratification & Class Distinction

"In the Restoration period, political theorists were exploring new philosophies, and the ruling elite was exploring the new forms of physical planning based upon ordered harmonious principles." 58 . While the dilemma around the political philosophers and the

55 Nikhil Rao, Householders: The Reurbanization of Mumbai and the Making of a Middle-Class Slum, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013), 153–154.

56Simpson, W. J. Report on the Sanitary Condition of Singapore by Dr. J. Galloway. Straits Settlements Records. National Archives of Singapore Collection, 1907. Microfilm Number: NA 1294. Accessed with permission.

57 Robert Home, Of Planting and Planning: The Making of British Colonial Cities, 2nd ed. (London: Routledge, 2013),[207]

58 Ibid,[2-5].

ruling elite persisted, the Bombay Presidency was segregated into ‘White towns’ and ‘Black towns.’While the ruling elites and trader lived in the white town, the native elites were allowed to design their plots and streets (Refer Image 7). 59Interestingly, no provision for the native poor was designed, and they were settled around the periphery of these towns as squatters until the plight of plague hit. In the mid-1700s, when the threat from the rivals loomed over the white town, it was brought closer by fortification, and the ground was cleared and demolished. 60 This ground later became to be known as “maidan." 61 used for recreation for the whites, physically making a clear distinction between races. Munity (1857), the plague epidemic, and industrialization set a new wave of urban planning by BIT (urban planning discussed in sections 3.1 & 5.1.1) based on the pre-existing social stratification in Bombay.

59 Ibid, [76].

60 Tindall, G. City of Gold: The Biography of Bombay. London: Temple Smith, 1982. Pg.76

61 Ibid,76

Since the port of Singapore was established in 1819, a century after the establishment of Bombay port, the self-proclaimed racially superior Imperial government had advanced its hierarchical distinction. Home (2013) describes it as "segregation as taxonomy."

"It can be best characterized as a taxonomist's approach, based on Raffles' hierarchical classification of societies. He reserved separate geographical areas for the different ethnic groups, going beyond a crude division into 'whites' and 'blacks' to distinguish six main

Figure 8: Map demonstrating the town planning of Bombay city in the 1920s (Source- 1920s Bombay, British India. City Plan 1920s).

White Town

In 1989, Dubow 65 concludes that racial segregation was very closely ‘associated with the concept of land-use planning’ as it was initiated with ‘town planning scheme’ and it had been widely accepted from the early 20th century to mid20th century 66But in the global context, due to the imposition of racial segregation and extremism in the Nazi regime, the whole idea was scrutinized, and post-World War II, the colonial government could not be legally associated with it.

However, during the bubonic plague pandemic, the anxiety of the ruling elite amplified, and the public health officials advocated for a morphological divide based on race. While other colonies like Singapore and Bombay Rangoon suffered, a Cape Town medical officer sent a confidential memo stating, "The real object we have in front of us is not to exclude dirty Asiatics 67 and to admit clean ones…but it is to shut the gate against the influx of an Asiatic population altogether." 68 From the aforementioned excerpt, one can comprehend that the need for racial segregation was a public secret strengthening their ideology. Owing to this, it was unanimously integrated into city planning when SIT and BIT were established. Furthermore, the schematic map of segregation by the Lugardian principle was based on urban planning based on race and income, which corroborates the imperial government's aspiration for segregation across trans-colonial borders. 1990). 69

65 Saul Dubow, Racial Segregation and the Origins of Apartheid in South Africa, 1919–36 (London: Macmillan, 1989).

66 Ibid, 76

67 Asiatics in South Africa referred to the immigrant Indian and Chinese settlers. The immigrants, migrant workers, or the natives were perceived as a threat to the Europeans as the disease broke out

68 Denoon, 1988, p. 130

69 Anthony Lemon, Homes Apart: South Africa’s Segregated Cities (London: Paul Chapman, 1991)

Figure 10: Image depicting the map of a schematic diagram developed by the colonial government based on race and Income for the colonies in Cape Town (Source: Lemon, 1990)

5.2. Influence on Contemporary Heritage Policies

5.2.1.

Legal Framework & Policies

SIT and BIT had provisions for conserving built heritage as per the Town Planning Act 1915 mandate, but they were predominantly focused on monumental heritage. In the post-colonial era, the Mumbai Heritage Conservation Committee (MHCC) coordinated with INTACH and UNESCO to protect the legal framework of the city's heritage. While UNESCO is specific to sites/areas inscribed as World Heritage Sites, INTACH has devised a grading system for listing unprotected heritage across Mumbai. Therefore, the MHCC was an SPV constituted to oversee the city's conservation effort. However, in reality, the

planning department often ignores their efforts; this was evident when the city's 70% heritage was left out during the Development Plan (2014–2034). Moreover, statutory discrepancies within the heritage committee cause legal framework and policies oversights. For instance, "clause 8.2 of the Conservation of Heritage Sites Including Heritage Buildings, Heritage Precincts, and Natural Feature Areas states that 'it shall be the duty of the owners of heritage buildings and buildings in heritage precincts or heritage streets to carry out regular repairs and maintenance of the buildings'": the state does not propose to be a centralized conservation body; rather, it decentralizes the authority, shifting responsibility to the homeowners. Non-incentivised listed heritage buildings protected under the Rent Control Act of 1947, with tenements paying rents frozen at 1940s levels, combined with present-day land valuations, pose a huge financial burden to conserve and reuse the structure.

Contrastingly, the remaining vestiges of the SIT construction (SIT apartment, Tiong Bahru, etc.) are centrally protected under the URA. Singapore has stringent, area-based conservation guidelines that homeowners must adhere to, and heritage homeowners are incentivized to undertake additions and alterations to their heritage property. But, while addressing the guidelines through a critical lens, the overarching principles predominantly focus on the architectural attributes and the elements. This results in homogeneous heritage conservation and 'facadism.'

5.2.2.

Urban Identity, Public Engagement, and Awareness

Open-ended interviews were conducted in the SIT and BIT-constructed housing colonies in Singapore and Bombay to comprehend the evolving urban identities. Residents who lived in and around localities like Tiong Bahru, Dhadar, and Matunga offered a layered and deeply personal perspective on the changing dynamics of the identities associated

with the place. The interviews reveal a complex interplay between cultural continuity, collective memory, and a sense of belonging for the community.

The respondents view Tiong Bahru as a transitional space between the old and the new that creates a balanced modernity of the architectural aspects. However, amidst the chaos and cafes with artistic vibes, the older community longs for its quiet past. The older generation said their social anchors have been facing the brunt of gentrification. For instance, the community wants to revive the bird-singing corner that has been replaced by the link hotel, reinforcing the role of place memory in shaping collective identity.

Bombay's urban identity has shifted from colonial-era dominance to post-independence modernization. The older respondents observed the shift from peaceful, communitycentric localities to redeveloped high-rise gated communities. While the infrastructure has been upgraded, many expressed reminiscences of the city's working-class identity and cultural richness. While the Ganesh Utsov, a ten-day festival, still connects the people and allows them to revive their collective memories, the residents feel it is vulnerable to modernization.

While Singapore’s architectural legacy is protected, the public sentiment embodies the nostalgia of community and cultural continuity. With investment in community awareness and public engagement around heritage in Singapore, the community believes that the sense of place could be inculcated through collective memory. On the contrary, Mumbai’s urban transformation in the areas that are not protected by UNESCO is drastic while the cultural attributes still strongly exist. Lack of inclusivity in community awareness leads to growing nostalgia and concern over cultural erasure.

5.2.3. Influence on National Identity

SIT and BIT were pivotal in shaping the pre- and post-colonial urban landscape, which embodied the imperial urbanism of hygiene, sanitation, and British colonial hegemony. Although formulated under colonial governance, these improvement trusts were rudimentary for later expressions of national identity through housing. SIT planning for housing estates symbolized the transition from kampongs to modern living, replicating the aspirations of the state for a disciplined and progressive society 70 . Meanwhile, the embryonic planning by BIT and clearance projects, often criticized for uprooting the communities, proposed the infrastructural blueprint the city would later build upon.

71

At present, perceptions of these developments are mixed, layered with nostalgia and cultural dissonance. Tiong Bahru is viewed as a heritage precinct symbolizing architectural marvel and colonial modernity and harmonizing memories and identity. 72In Mumbai, chawls and apartment housing are frowned upon for their dilapidated state and poor living conditions yet celebrated for forging community resilience and social cohesion. In both contexts, these developments were a milestone for the national progression.

5.3. Lessons for Trans-Colonial Urban Heritage Conservation

5.3.1. Urban Governance & Policy-making

After studying the German and Glasgow cases, the improvement trust was modeled in Bombay. Therefore, the overall planning legislation and governance had evolved based on the local context. Although the colonial government advocated for housing for the poor

70 Limin Hee and Giok Ling Ooi, Public Space in Urban Asia (Singapore: Marshall Cavendish International, 2004), 32–33.

71 Gyan Prakash, Mumbai Fables (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010), 132–135.

72 Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA), Conservation Guidelines for Tiong Bahru Conservation Area (Singapore: URA, 2014), 6–9.

and displaced, the overarching schemes implemented were meant to broaden the colonial narrative across its colonies. Plans and ideas from Bombay influenced the formulation of SIT in 1927; JW Simpson used Bombay as the "Model City" during his investigation and proposal for improvements. 73. Having a preconceived “imperial urbanism” set in place, it is imperative to note that the local adaptation to the Singapore context made formulating its urban governance more nuanced than Bombay.

Mumbai’s (Bombay) postcolonial transformation in urban governance is fragmented due to the multiplicity of statutory stakeholders. The Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai (MCGM) and the Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority (MMRDA), often having overlapping jurisdiction and unpredictable policy implementation, have hindered the overall conservation process in Mumbai. 74

In contrast, before the SIT was established, development governance in Singapore was rudimentary, and the municipal government enforced by-laws to control development on certain roads and shape the urban morphology. 75A Singapore Improvement Ordinance formulated in 1927 marked the inception of SIT, and this improvement trust was entrusted with developing the general improvement plan. Over time, Singapore's governance transitioned into a statutory framework for urban governance through the development of subsequent master plans that have provisions for heritage conservation, particularly under the URA. This top-down governance and policy structure has ensured the effective implementation of urban renewal and heritage conservation efforts, such as the demarcation of historic districts like Chinatown and Little India. 76 .

73 Anthony Lemon, Homes Apart: South Africa’s Segregated Cities (London: Paul Chapman, 1991) 90-100

74 Gupta, N. 2007. The Architecture of Postcolonial Societies in India: Regionalism and Modernity in Bombay

In Scriver, P., & Prakash, V. (Eds.), Colonial Modernities (pp. 95–113). Routledge.

75 Lim, C. 1969. "Planning Law and Processes in Singapore." Malaya Law Review, 11(2), 316–334.

76 Lai, C. 1995. The First Batch: Tiong Bahru and Public Housing in Singapore. Singapore Heritage Society.

5.3.3. Challenges in Heritage Interpretation

Addressing contested heritage in postcolonial settings has always been a challenge because of the enigma associated with the heritage. Understanding that the lived experience is multifaceted and possesses intrinsic tensions is imperative. When we look at the current state of heritage interpretation of the colonial legacies for utilitarian heritage in Singapore and Bombay, we see that it struggles with the complexities of contested heritage and the erasure of Indigenous narratives. For instance, while the buildings protected under the UNESCO World Heritage Site nomination are prioritized, conserved, and celebrated for their architectural legacy of the Art Deco ensemble, the plight of the same utilitarian buildings like the chawls and the apartments in the suburban areas are left to face the brunt of the grappling truth; the truth is that they evoke memories of displacement and imperial domination, creating an ambivalence in their heritage interpretation. 80Moreover, open-ended interviews in these areas revealed that the residents dreaded that the city's redevelopment scheme was in control of most of the buildings, which were left in a state of disrepair and dilapidation.

On the contrary, the interpretation of Tiong Bahru is well-preserved with the narrative of post-war emergencies and the provision of social housing, symbolizing the architectural legacy and urban planning. Open-ended interviews revealed that the interpretations often focused on the aesthetics and nostalgic narratives, downplaying the socio-political context. Critically analyzing the texts of Sugarman (2017), one can understand that the estate was developed for a specific class that aligned with colonial ideas, excluding the marginalized native communities, a typical example of "double-

80 Art Deco Mumbai. “Insights from Practice: The Conservation of Swastik Court near Oval Maidan.” Art Deco Mumbai, June 25, 2018. https://www.artdecomumbai.com/research/lessons-from-the-field-therepair-and-restoration-of-swastik-court-oval-maidan/

edged improvement."

81 Additionally, the residents fear that present-day gentrification and commodification by boutique cafes and curated heritage trials further complicate the heritage reading.

Therefore, in the postcolonial context, both countries, though having made progress, face challenges in crafting narratives that need to move beyond celebratory, partial interpretations and sanitized narratives. There is a need to embrace pluralistic interpretations, acknowledging the complexities that allow for critical reflection and community engagement.

81 Sugarman, 2017, p. 97

CHAPTER 6: DISCUSSION & CONCLUSION

6.1. Discussions:

Sno. Aspects/ Attributes

Comparison

Mumbai (Bombay)Bombay Improvement Trust (BIT)

1. Colonial influence on planning It was strongly influenced by the British imperial vision, and Governor Aungier played a key role. The Improvement Trust model was established in 1898. Focused on destructive demolition and large infrastructure

Singapore –

Singapore Improvement Trust (SIT)

SIT (1927–1947) was modeled after BIT; Governor Raffles viewed city planning as a tool of social control and trade enhancement. Early plans focused on demolition, road widening, drainage, and

Learning and reflections

Imperial urbanism served as a model for dominance and social order through planning and social segregation. Both countries inherited the top-down approach, which prioritized hygiene and sanitation over community needs.

3. Social stratification

4. Urban identity

Binary divisions as ‘white town’ and ‘black town’ for native elites and the native poor.

Refined and defined ethnic zones for the Europeans, Chinese, Malays, Arabs, and Indians.

Planning was racialized and profiled. Cities in the postcolonial period dealt with the aftermath of the ingrained spatial legacies and inequalities.

Urban identities are linked to everyday utilitarian heritage, like the chawls, but they are contested due to mismanagement and neglect of socio-economic attributes.

Incentivized heritage with guidelines for protection to ease the overall process for homeowners. Risk of homogenized narratives and loss of lived experiences in favor of national narrative.

Urban identities are dynamic and should integrate both tangible and intangible heritage. Overinstitutionalising leads to the erasure of community continuity, calling for an inclusive narrative for heritage conservation.

5. Urban governance and Policymaking Fragmented governance with overlapping policies leads to inconsistent policy implementation. Early legislation under the Town Planning Act of 1915 aimed at monumental heritage; the postcolonial framework was led by MHCC in coordination with INTACH and UNESCO.

Top-down governance with structured measures to incorporate heritage conservation into urban planning principles. Early conservation under SIT; current framework managed by URA, with strict centralized authority. Systematic governance of urban policies incorporating heritage conservation within its framework, with phased community engagement, is recommended to complement the

6. Conservation Approach The multiplicity of Statutory bodies and decentralized conservation approach. A systematic institutional framework has been centralized with structured conservation efforts. Both centralized and decentralized conservation approaches have to go hand in hand, leading to conservation-led development.

7. Cross-Cultural Learning Community voices and ethos play a significant role. The top-down approach yields visible results, and civic engagement is less pronounced. Mumbai could learn from Singapore's top-down institutionalized framework, and Singapore could adopt Mumbai's community ethos for community-driven conservation.

8. Heritage interpretation Contested heritage is due to the ambivalence associated with interpreting colonial heritage. The remnants are well preserved and have a strong narrative of the development during the It must go beyond the preservation of physical remnants and include lived experiences and

Table 1: Table depicting the comparative study and the learning outcomes of the SIT vs BIT

6.2. Conclusion:

The legacies of the Singapore Improvement Trust (SIT) and the Bombay Improvement Trust (BIT) mirror the difficult change from colonial rule to postcolonial nation-building. Originally intended to impose order, cleanliness, and control, these housing projects have been reinterpreted over time as basic components of national identity. SIT's Tiong Bahru estate in Singapore now represents early public housing success, reflecting both colonial modernity and national progress. By contrast, BIT chawls in Mumbai, which were first condemned for their crowded shape, are now remembered for their cultural resiliency and close-knit communities.

The idea of adaptive reuse significantly influences the continuous transformation of these areas. Tiong Bahru's effective blending of modern functions with legacy preservation emphasizes the possibility of adaptive reuse in meeting modern demands without destroying the past. Though BIT chawls still house thousands, the need for careful interventions to enhance living conditions in Mumbai remains critical.

Active community involvement will eventually preserve these locations. As a way forward, residents should help shape the future of these areas so they stay vibrant, useful, and linked to the cultural identities they represent. Inclusive conservation techniques help to sustain and reinterpret the legacy of colonial urbanism for future generations. Ultimately, one can comprehend that the postcolonial shift in the narrative between Singapore and Bombay complements each other. Therefore, it is also recommended that the learnings from both the trans-colonial regions be adopted to arrive at a point of intersection that can be selectively adapted within the context.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

• Alternative Planning History and Theory. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis, n.d.

• Art Deco Mumbai. “Insights from Practice: The Conservation of Swastik Court near Oval Maidan.” Art Deco Mumbai, June 25, 2018. https://www.artdecomumbai.com/research/lessons-from-the-field-the-repairand-restoration-of-swastik-court-oval-maidan/

• Art Deco Mumbai, Ideas for the Modern Home, Art Deco Mumbai, accessed March 12, 2025, https://www.artdecomumbai.com/research/ideals-for-the-modernhome

• Asiatics in South Africa referred to the immigrant Indian and Chinese settlers. The immigrants, migrant workers, or the natives were perceived as a threat to the Europeans as the disease broke out

• Banerjee, Kamalika. "Thinking through the Postcolonial Neighbourhood: Jugaad Politics and the Everyday Production of Space in Mumbai." PhD diss., National University of Singapore, 2021. ProQuest (29352889).

• Benjamin, Solomon. “Occupancy Urbanism: Radicalizing Politics and Economy beyond Policy and Programs.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 32, no. 3 (2008): 719–29.

• Caru, Vanessa R. "Where is Politics Housed? Tenants’ Movement and Subaltern Politicization: Bombay, 1920–1940." Revue d’Histoire Moderne et Contemporaine 58, no. 4 (2011): 71-95. https://shs.cairn.info/article/E_RHMC_584_0071.

• Caru, Vanessa R. "Where is Politics housed? Tenants' Movement and Subaltern Politicization: Bombay, 1920–1940." Revue d’Histoire Moderne et Contemporaine, vol. 58, no. 4, 2011, pp. 71–92.

• Christopher, A. J. “Urban Segregation Levels in the British Overseas Empire and Its Successors, in the Twentieth Century.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 17, no. 1 (1992): 95–107. https://doi.org/10.2307/622639.

• Chua, Beng Huat. Political Legitimacy and Housing: Stakeholding in Singapore. London: Routledge, 1997.

• Cummer, Katie, and Lynne D. DiStefano, eds. Asian Revitalization: Adaptive Reuse in Hong Kong, Shanghai, and Singapore. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2021.

• Denoon, David B. "Devaluation under Pressure: India and the International Monetary Fund." ProQuest Dissertations and Theses, 1988. p. 130https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/david-b-h-denoondevaluation-under-pressure-india/docview/1301472045/se-2.

• Dossal, Mariam. The City in Action: Bombay Struggles for Power. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2010.

• Dubow, Saul. Racial Segregation and the Origins of Apartheid in South Africa, 1919–36. London: Macmillan, 1989.

• Enthoven, R. E. Census of India, 1901, Volume IX, Bombay, Part I: Report. Bombay: The Government Central Press, 1901.

• Fraser, 'Work of the Singapore Improvement Trust, 1927-1947', p. 11.

• Gupta, N. 2007. The Architecture of Postcolonial Societies in India: Regionalism and Modernity in Bombay. In Scriver, P., & Prakash, V. (Eds.), Colonial Modernities (pp. 95–113). Routledge.

• Gupta, Narayani. “Historic Neighbourhoods in a Global City: The Case of Mumbai.” In Urban Imaginaries: Locating the Modern City, edited by Andreas Huyssen, 92–108. Duke University Press, 2007.

• Hazareesingh, Sandip. “Colonial Modernism and the Flawed Paradigms of Urban Renewal: Uneven Development in Bombay, 1900–25.” Urban History 28 (2001): 235–255. https://doi.org/10.1017/S096392680100205X.

• Hee, Limin and Giok Ling Ooi. Public Space in Urban Asia. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish International, 2004.

• Home, Robert. Of Planting and Planning: The Making of British Colonial Cities. 2nd ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

• Jain, Priya. 2023. "India’s Modern Heritage: Conservation Challenges and Opportunities." Planning Perspectives 38 (June 20): 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1080/02665433.2023.2224177

• Karim, Farhan Sirajul. Of Greater Dignity than Riches: Austerity and Housing Design. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2019.

• Kidambi, Prashant. “Housing the Poor in a Colonial City: The Bombay Improvement Trust, 1898–1918.” Studies in History 17, no. 1 (2001): 57–59.

• Lai, C. 1995. The First Batch: Tiong Bahru and Public Housing in Singapore. Singapore Heritage Society.

• Lai, Chee Kien. Building Tiong Bahru: The Birth and Death of a Community Housing Project. National University of Singapore, 1995.

• Lemon, Anthony. Homes Apart: South Africa’s Segregated Cities. London: Paul Chapman, 1991

• Lemon, Anthony. Homes Apart: South Africa’s Segregated Cities. London: Paul Chapman, 1991

• Lim, C. 1969. "Planning Law and Processes in Singapore." Malaya Law Review, 11(2), 316–334.

• Prakash, Gyan. Mumbai Fables. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010

• Rao, Nikhil. House, But No Garden: Apartment Living in Bombay's Suburbs, 1898-1964. United States: University of Minnesota Press, 2013.

• Royal Institute of Art, "Decolonizing Architecture: Modernism and Demodernization," accessed April 16, 2025, https://kkh.se/en/education/further-education-in-architecture-and-fineart/decolonizing-architecture/.

• Seng. 2019. Brief history of conservation. Urban Redevelopment Authority.Retrieved from the Urban Redevelopment Authority website: https://www.ura.gov.sg/.

• Sham, Desmond Hok-Man. "Heritage as Resistance: Preservation and Decolonization in Southeast Asian Cities." PhD diss., Goldsmiths, University of London, 2015.

• Simpson, W. J. Report on the Sanitary Condition of Singapore by Dr. J. Galloway. Straits Settlements Records. National Archives of Singapore Collection, 1907. Microfilm Number: NA 1294. Accessed with permission. P 105

• Urban Redevelopment Authority. Pre-war SIT Flats in Tiong Bahru Conservation Area Guidelines. Singapore: Urban Redevelopment Authority, 2021.

https://www.ura.gov.sg/-/media/User-Defined/ConservationPortal/Guidelines/Pre-war-SIT-Flats-in-Tiong-Bahru-Conservation-Area.pdf.

• "'The most filthy and corrupt department,'" July 17, 1959, Straits Times, NewspaperS

12. Would you like to see more historical information or signage around the neighbourhood?

13. Have you ever joined a heritage walk or community history event in Tiong Bahru?

SECTION D: Heritage, Change & the Future

14. Do you feel Tiong Bahru is changing too fast? How do you feel about new developments in the area (like cafes, boutique stores)?

15. Do you believe heritage areas like Tiong Bahru should be protected from major redevelopment?

16. If you had the choice, would you prefer to live in a modern high-rise or a low-rise heritage block like the SIT flats?

17. What do you think Tiong Bahru will look like in 20 years?

18. How important is it to you that future generations know about the history of this place?

19. Do you think your voice matters in decisions about neighborhood changes and preservation?

years?

13. What kind of changes have you noticed?

SECTION C: Urban Identity & Memory

14. What kind of identity do you associate with your neighbourhood?

15. Do you feel that the culture or ‘feel’ of your neighbourhood comes from a particular era?

16. Have you heard stories from your elders about what the neighbourhood used to be like?

17. Can you share one memory or story you’ve heard or experienced about how the place looked or felt in the past?

SECTION D: Heritage, Planning & Urban Futures

18. Do you think buildings from the colonial or pre-colonial period should be preserved?

19.Do you think post-independence housing (like Chawls, LIC colonies, etc.) should be conserved/reused as part of Mumbai’s heritage?

20.Do you feel your neighbourhood is at risk of losing its identity or memory due to redevelopment or gentrification?

21.What are some aspects of your neighbourhood you think should be kept alive for future generations?

22.Do you think the stories of everyday people are as important as famous monuments when we talk about heritage?

SECTION E: Participation & Awareness

23.Have you ever participated in a heritage walk, workshop, or neighbourhood history event in Mumbai?

24.Would you be interested in joining one or sharing your neighbourhood stories in future?

25.Any final thoughts or messages about your neighbourhood and its future?