ABSTRACT

This study examines the cultural landscape narratives embedded in Singapore Chinese literature from1948to1965,atransformativeperiodspanningpost-warreconstructiontoearlyindependence. By systematically analyzing 42 literary works, this research uncovers how literature serves as an alternativearchivefordocumentingheritageelementsthathavesincebeenlostortransformed.

Through thematic analysis and grounded theory, the study identifies three interwoven layers of heritage representation: (1) environmental signatures, including depictions of tropical climate, endemicflora,andnaturalrhythmsshapingdailylife;(2)vernacularbuiltforms,suchasshophouses, kampongs, and marketplaces that defined mid-20th-century Singaporean urbanity; and (3) intangible spatial practices, encompassing street hawking, temple rituals, and everyday sensory experiencesthatsustainedculturalcontinuity.

By linking literary descriptions with heritage discourses, the study highlights literature’s role in encoding traditional ecological knowledge and place identity. The findings contribute to heritage conservationbyoffering:(a)aliterarytaxonomyofmid-20th-centurySingaporeanlandscapes,and (b) a methodological framework for reconstructing cultural landscapes based on textual analysis. This interdisciplinary approach underscores the evidentiary value of literature in heritage studies, demonstrating its potential to complement conventional archival and material records in the preservationofculturalmemory.

Keywords:SingaporeChineseLiterature;CulturalLandscape;HeritageConservation

ListofFigures

Figure1.HistoricalDevelopmentandCharacteristicsofSingaporeChineseLiterature

Figure2.MappingoftheFrequencyofOccurrenceofMentionedLocationsinSingaporeChinese Novels(1948-1965)

ListofTables

Table1.ListofSingaporeChineseLiterature(1948-1965)(tobeadded)

Table2.PlaceFrequencyCountofMappingofMentionedLocationsinSingaporeChineseNovels (1948-1965)

CONTENTS

ABSTRACT

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

ListofFigures

ListofTables

1Introduction

1.1 ResearchBackground

1.2 ResearchProblemandObjectives

1.3 MethodologyOverview

2LiteratureReview

2.1CulturalLandscapeandHeritageValueStudies

2.2LiteratureasaCarrierofHeritage

2.3ResearchonSingaporeChineseLiterature

2.3.1HistoricalDevelopmentofSingaporeChineseLiterature(1948-1965)

2.3.2SingaporeChineseLiteratureandPlaceIdentity

2.4ResearchGapsfromanInterdisciplinaryPerspective

3Methodology

3.1TextSelection

3.2SelectionofLiteraryWorks

3.3AnalyticalMethods

4ResearchFindings:LiteraryConstructionofHeritageValues

4.1BuiltEnvironmentHeritageInterpretedfromLiterature

4.1.1ArchitecturalTypology

4.1.2StreetandAlleySystem

4.1.3InteriorSpaces

4.1.4LandscapeSystem

4.2ClimatePerceptionandAdaptiveResponses

4.2.1HistoricalValueofClimateRepresentation

4.2.2PassiveStrategiesforClimateAdaptation

4.3FolkPracticesandCulturalTransmission

4.3.1FestivalRitualTraditions

4.3.2EverydayFolkPractices

4.3.3IntangibleCulturalHeritage

4.3.4TransnationalCulturalPractices

4.4CommunityandCollectiveBeliefs

4.4.1EthnicSpaceGovernance

4.4.2MutualAidandEthicalResponsibilities

4.4.3Labor,Perseverance,andEconomicAspirations

4.4.4Anti-ViceCampaignsandSocialDiscipline

4.5LinguisticHeritageandDialectalSignificance

4.6MemoryandIdentityNarratives

4.6.1ReconstructingTraumaticMemories

4.6.2TheGenreofInspirationalStoriesandtheMigrantSpirit

4.6.3TheInfluenceofIdeologicalandCulturalTraditionsonMoralNarratives

4.6.4FromDiasporicConsciousnesstoLocalIdentity

5Conclusion

Bibliography Appendix Appendix1.

(WordCount:14563)

1.3 MethodologyOverview

Thisstudyadoptsaqualitativeresearchapproachthatintegratestextualanalysisandheritagevalue interpretation. The research begins with the selection of Singapore Chinese novels from 1948 to 1965, prioritizing works with explicit spatial descriptions, depictions of community life, or references to historical events. Through close reading, passages related to cultural heritage such asarchitecturalfeatures,traditionalcustoms,andnaturallandscapes areidentifiedandannotated. The extracted descriptions are then categorized into tangible heritage, which encompasses architecture,streetscapes,andnaturallandscapes,andintangibleheritage,whichincludesfestivals, dialects, and craftsmanship. This classification allows for a systematic analysis of how literature assigns heritage value to these elements. Certain spaces gain emotional significance through repetitivedescriptions,reinforcingtheirsymbolicimportance,whileothersacquirehistoricalvalue throughtheirassociationwithkeyevents.

To further substantiate the findings, the study interprets the identified heritage values using established cultural heritage frameworks, including historical, social, and identity values. This provides insight into how literary narratives shape readers' perceptions of cultural landscapes and demonstratestheroleofliteratureasanalternativearchive forheritageconservation.Additionally, acomparativeanalysiswithhistoricalrecordsandurbanplanswillhighlightpotentialgapsbetween literary memory and official heritage discourse, revealing overlooked spatial practices or lost landscapesthatcontinuetoholdculturalsignificance.Bysynthesizingtextualanalysiswithheritage studies, this research aims to uncover the implicit heritage discourse within mid-20th-century SingaporeChineseliteratureanddemonstrateitsrelevancetocontemporaryconservationefforts.

2 LiteratureReview

2.1 CulturalLandscapeandHeritageValueStudies

ThegeographerOttoSchlüterfirstformallyusedtheterm ‘culturallandscape’ asanacademicterm atthebeginningofthe20thcentury(Hennon&Harris,1997).AsIckerodt(2006)discusses,cultural landscape as a term has experienced an unusual degree of multidisciplinary popularity in a very shortperiodoftime.

Cultural landscapes, especially in cities with a rich historical and cultural heritage, play a crucial role in enhancing the resilience of local communities (MoussaviA & Lak, 2024). According to Domosh(2001),thetermculturallandscapehastwointerrelatedmeanings:ononehand,itrefersto thethree-dimensionalpatternsinwhichcultureleavesitsmarkontheland,suchasagriculturalfield systems, transport networks, residential and commercial buildings, and urban forms. On the other hand, it also refers to an approach to the study of these forms, one that uses interpretive strategies tounderstandtheculturalmeaningsembeddedinthelandscape.Thismeansthatwecanbreakdown theculturallandscapeintoitselementsonaphysicallevel,orwecanusetheconcepttodigdeeper into the spiritual core of the landscape. In this study, we will use the prism of Singapore Chinese literaturetodiscoverthevariousdimensionsofSingapore'shistoricalculturallandscapeswithinit, andtounpackthespiritofplaceandheritagewithintheculturallandscape. DelaTorreandMason(2002)arguethatvalueshavealwaysbeenthebasisforheritageconservation. Bosetal.(2025)statethattheconceptofvalueisofsuchsignificanceinthetheoryandpracticeof heritage management that all actions to develop the built heritage seem to depend on the value assigned to it. Noteverything in history can be judged asheritage;whatwe can callheritage must

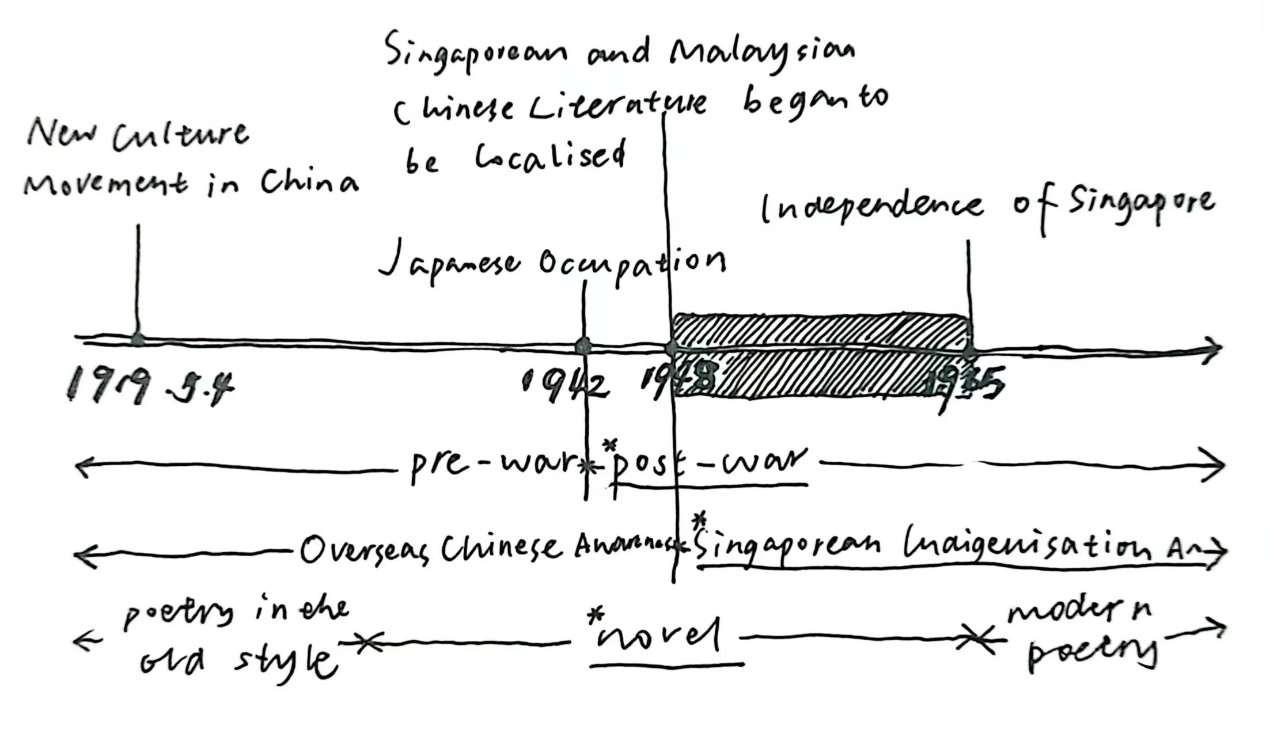

2.3.1 HistoricalDevelopmentofSingaporeChineseLiterature(1948-1965)

AftertheOpiumWar,alargenumberofbankruptChinesepeoplewenttotheSouthSeaseveryyear tomakealiving,formingaChinesesociety.ThebirthofChineseliteratureinSoutheastAsiacame aftertheMayFourthNewCultureMovementinChina.Underitsinfluence,thevernacularlanguage graduallybecamethemainstreamofChineseliteratureinSingaporeinthe1920s.However,before thefoundingofSingapore,thewritingofoldChinesepoemswasstillquiteflourishing(LAMLap, 2018).

Historically,SingaporeandMalaysiawerebothBritishcolonies.Inthebeginning,Chineseliterature in Singapore and Malaysia was full of Chinese diaspora consciousness and had a strong Chinese colour.In1948,becauseofthecontroloftheBritishcolonialgovernmentinMalayaandthereturn of some Chinese writersandthe liberation of mainlandChina, Chinese literaturein Singapore and MalaysiapartedwayswithChineseliteraturefromthenon,identifyingtheroadoflocalisation. In1965,SingaporeseparatedfromMalaya.Generally,whenexploringtheChineseliteraturebefore 1965,itiscustomarytonarrateSingaporeandMalaysiatogether,andSingaporeandMalaysiahave been the best-developed regions in SoutheastAsia for Chinese literature. While after Singapore's independence,theliteraryscenewassilentduetothebusyeconomicconstruction,andlateron Yin (2011) argues that the quality of Chinese novels in Singapore was higher for the preestablishmentperiod.

theAuthor)

Considering the above historical reasons, this study focuses on novels in Singapore's Chinese literature during the period of 1948-1965. In terms of content, this period of Singaporean Chinese literature is atthe highest quality of novels; in termsof theme, this period ofSingaporean Chinese literature is detached from the Chinese diaspora narrative, and is committed to the creation of Singaporeanindigeneity,whichismorecapableofreflectingthespiritoflocalisedplace.

MiaoXiu(1970)saidinhisintroductiontoworksinthisperiod,‘Ifwereviewtheachievementsof Malaysia (and Singapore) Chinese literature in the past today, we have to admit that the most

successful literary genre is fiction. Compared with poetry, prose and drama, Malaysia (and Singapore) Chinese novels can more widely and faithfully reflect the life of all walks of life in society. In view of the poverty of our historical circles, our so-called historians will only immerse themselves in the study of ancient history, ignoring modern history.After a few years, people will understand our times and the social life of our generation, and they may get the information they needfromthesenovels.’Thisisthereasonwhythispaperchoosesnovelsastheresearchobjectof heritage value. The novel is documentary, which well preserves the style of that historical period andprovidesvaluableinformationforexploringtheheritagevalueofSingapore'sculturallandscape.

2.3.2 SingaporeChineseLiteratureandPlaceIdentity

Place identity is an important concept in cultural geography and sociology, referring to an individual's or group's sense of belongingto a particularplace andits culturalsignificance (Relph, 1976; Tuan, 1977). Places are not only physical spaces, but also intersections of social relations, historical memories and cultural symbols. Places are inextricably linked to culture and memory, which characterise cultural landscapes. Tökölyová and Pondelíková (2024) propose cultural landscapes as a basis for national identity. They also argue that cultural landscape is the main reflectionofnationalidentity.

Literature,asanimportantformofculturalexpression,isabletoshapeandstrengthenpeople'ssense of identity with places through narratives, descriptions and emotional projections. According to Tökölyová andPondelíková's(2024)formulationofculturallandscape,itisanideologicalconcept defined as a temporally layered synthesis of the chain ofmemoriesof the generationsliving there, whichareexpressedintheformofarchitecture,paintings,music,landscapesandsoon.Obviously, literature also belongs to this category of expressions of cultural landscapes in the pan-artistic category. We can work backwards from literature to restore the face of the cultural landscape as expressed by the writer. ‘ Place writing ’ in Singapore Chinese literature involves cultural landscapesthatdemonstratetheirsignificanceasnationalidentity.

2.4 ResearchGapsfromanInterdisciplinaryPerspective

Despite the significant progress in the study of Singapore Chinese literature, several key research gapsremain,particularlyintherelationshipbetweenliteratureandheritagepreservation.Oneofthe primary challenges is thedisconnectbetween literary analysis and heritage conservation practices. WhileliteraryworksoffervaluableinsightsintoSingapore’sculturalandhistoricallandscape,they are often studied in isolation from the practical aspects of preserving both tangible and intangible heritage.

This gap between literature and heritage conservation becomes apparent in the lack of interdisciplinary frameworks that connect literary narratives with heritage preservation efforts. Although literature plays a vital role in reflecting the city ’ s evolving identity and urban transformations,itisseldomutilizedtoinformorenhancepreservationpoliciesandurbanplanning.

As a result, the potential of literary works to contribute to heritage conservation remains underexplored, highlighting a significant opportunity for future research to bridge this divide and develop more integrative approaches that combine literary studies with the practice of cultural heritagepreservation.

3 Methodology

These works, written by key authors recognized as significant figures in the development of SingaporeChineseliterature,willformthecorecorpusforthisstudy.

2. ExtractingRelevantPassagesforHeritagePreservation:Inthe secondstep,passagesfrom the selected novels that may contribute to heritage preservation will be identified. These passages will focus on descriptions and representations of cultural landscapes, spaces, and societalelementsthataretiedtoSingapore’sheritage.Thesereferencescouldincludedepictions of specific places, architecture, social interactions, or traditional practices that reflect the culturalandhistoricalidentityoftheregion.

3. Thematic Categorization: The third step involves thematizing the extracted passages into specific thematic categories. These categories will include tangible and intangible aspects of heritage, focusing on elements such as climate, architecture, streetscape, indoor scenes, community, and stories.Additionally, other relevant themes such as cultural practices, social interactions, memory, and place identity may be included. Each theme will act as a thematic repositorywherethepassagesrelatedtothesespecificaspectsare groupedtogetherforfurther analysis.Thesethematiccategorieswillserveasthefoundationforunderstandinghowvarious aspectsofheritagearerepresentedintheliterature.

4. Heritage Classification and Analysis: The final step involves analyzing these themes and categorizingthemaccordingtotheirrelevancetothebroaderconceptofheritage.Thisstepwill consider how each theme corresponds to various aspects of heritage, such as tangible heritage (e.g., architecture, natural landscapes) and intangible heritage (e.g., cultural practices, beliefs, stories).Thegoalistorelatetheliterarydepictionstospecificaspectsofheritage,suchas:

NaturalHeritage:trees,rivers,mountains,climate,etc.

BuiltHeritage:buildings,streets,monuments,traditionalspaces,etc.

CulturalHeritage:communitypractices,stories,rituals,festivals,etc.

IntangibleHeritage:traditions,beliefs,collectivememories,values,etc.

SocialHeritage:thewaycommunitiesinteract,socialstructures,andfamilydynamics. Each thematic category will then be analyzed for its contribution to heritage conservation, providing a deep understanding of how literature functions as a tool for reflecting and preservingculturalandspatialheritageinSingaporeduringthemid-20thcentury.

This qualitative approach allows for a nuanced examination of the texts, where the focus is on interpreting the cultural and historical significance of the representations, rather than quantitative measurements.

3.3AnalyticalApproach

Thisstudyemploysaqualitativeanalyticalapproachtoexaminehowculturalheritageisrepresented inliterarynarratives.

Narrative analysis provides a framework for understanding how spatial and heritage-related meanings are constructed through storytelling. By examining narrative structures, temporal and spatial arrangements, and character portrayals, this approach uncovers how literary texts embed cultural memory within their representations of space. Particular attention is given to how the organization of time and setting contributes to the evocation of historicallandscapesand localized experiences,revealingthewaysinwhichliteratureshapesperceptionsofculturalheritage.

4 ResearchFindings:LiteraryConstructionofHeritageValues

4.1 BuiltEnvironmentHeritageInterpretedfromLiterature

4.1.1ArchitecturalTypology

Architectural typology in Singapore Chinese novels reflects the historical transformation of urban spaces and the lived experiences of different communities. Traditional residences, commercial buildings,andreligiousstructuresformthebackboneofthesenarratives,preservingthememoryof social interactions and spatial adaptations. Pre-war shophouses exemplify mixed-use architecture, showcasing the integration of commerce and residence in a sustainable urban model. Religious buildings, including temples, mosques, and churches, embody the multicultural and multi-faith landscape of Singapore, while their architecturalelements and spatial organization provide insight intoritualpracticesandcommunalactivities.

During that period, there were different residential buildings in Chinese novels in Singapore. Due to the differences in the environment and topography of the base and the differences between the rich and the poor in Singapore society at that time, different residential buildings reflected the national identity, economic status and way of making a living of the residents. For example, the overseas Chinese residence mentioned in Miao Xiu's Waves of Fire is better than those in the Chinatowninmanyarticles:

Vacant rooms are in the mud pond, an ancient single-story overseas Chinese residential building. The newly-repaired, probably long-abandoned, newly-painted white can't cover the true colors of birdblack.There are several"patterns"ofpig's ass printedwith yellow mud on thewall(Miao,n.d.).

The floating-footalcuo in Miao Xiu's On the Beach is a specialfolk house in tropical areas where riversandnetworksareintertwined:

Acrosstheriverisarowoftropicalfloatingfeet,andtheriveroftenrisestothebottomofthese feetduringtheday(Miao,n.d.).

Publicentertainmentbuildingshaveplayedanimportantroleinpeople'surbanlife,andmanynovels havementionedtheimportantintentionof"entertainmentsquare".Forexample,MiaoXiuwrotein Under the Roof of Singapore:

Thegiantwheelofthe"GreatWorld"entertainmentsquare,whichiscoveredwithred,yellow, blue and cyan tubes, slowly circled and painted a beautiful rainbow on the dark blue sky. Wheels take pairs of tourists high into the sky, laughing and rippling in the fresh night sky (Miao,1951).

4.1.2StreetandAlleySystem

The depiction of streets and alleys in literature captures the evolution of Singapore’s urban form, emphasizing mobility, public life, and neighborhood identity. The transformation of pavement materials, from early stone paths to modern roads, signifies shifts in infrastructure and urban planning. The portrayal of nighttime lighting, from oil lamps to electric streetlights, reflects changingsocialrhythmsandtheexpansionofnightlifeactivities.Boundarymarkers,suchasgates,

plaques,andtransitionalspacesbetweenethnicenclaves,playaroleindefiningsocialandcultural boundaries,reinforcingspatialidentitywithinurbannarratives.

The functionofthe streetsystemin MiaoXiu's Under the Roof of Singapore istemporal.Atnight, some back alleys that are normal during the day will be converted into places where prostitutes solicitcustomers:

Duringtheday,blackalleysarelikehundredsofbackalleysinSingapore,andthebackdoors areclosed.Occasionally,somenearbyresidents,greedyforconvenience,takethisbackalley; Butmostofthetimeisdeserted.

But as soon as it got dark, the gas street lamp in the alley turned on, as if it had passed the magic wand of the wizard in the fairy tale, and the black alley immediately changed into anotherappearance.Thedimglowcastbythestreetlamphighlightstheshadowdensityofthis blackalleyandaddstothemysteryofthisblackalley.

Sothebackdoorsthatwereclosedduringthedayopenedoneafteranother.Thosewomenwho have been squashed by life, those who have exchanged their last capital for a meager loaf of bread,haveallappearedinthedarkness.

The air in the back alley is stagnant, and the garbage dump and the blocked clear canal give offamustysmellattheend,andtheyalsohaveaburstofcheappowderincense.

This black alley is slowly busy, and countless shadows float and wander in this black alley, stopping in front of those women who sell their bodies. Countless pornographic eyes are flashinginthedark,greedilytakingobjectsofsexualdesire(Miao,1951).

ZhaoRong's In the Straits of Malacca mentioned theconcentrationcampinYalanduringtheAntiJapaneseWar,andmanytimestherefugeeswererushedtothestreets,whichwasverycrowded:

Undertheeaves,5-foot-way,aplacethatcancoverthewindandrainalittle,arecrowdedwith people(Zhao,n.d.).

4.1.3InteriorSpaces

Interior spaces in literary works reveal the functional and symbolic significance of built environments. Domestic spaces are portrayed through architectural layouts, furnishings, and the divisionofprivateandcommunalareas,illustratingchangingfamilystructuresandlivingconditions. Commercialinteriors,suchastraditionalshopsandpawnshops,highlighteconomicpractices,trade interactions, and the material culture of different historical periods. The classification and organization of stored goods in these spaces reflect systems of value, economic hierarchies, and socialcustomsembeddedineverydaytransactions.

Mr.FanginMiaoXiu's Waves of Fire hastworesidences,oneinChinatownandtheotherinTiong Bahru's"BayaAnsuo,amountainwiththreemonumentsfromhishomeonDapo",whichisusedto escapetheaircrash:

Heglancedatthetemporaryshelterandfoundonlyafewsimplefurnishings:twocanvascamp bedsleaningagainsteachother,estimatedthatalmosta cow'sroomwasleft,andthe restwas

Dashanba,intheimaginationofconstantlychauffeuredpeoplewhoareusedtolivingin cities,isadarkandterribleblackhell,butinfrontofchildrenanddogswhogrowinthewild, itisacoolandquietparadise.TherearedensetreeseverywhereinDabali,mostofwhichare oldandtallbanyantrees,likethebigbrotherintheforest,whichoccupyeveryhill,sloping skinorhill,andtheirkneesarearounditsbranches,likethousandsofpythonsofdifferent sizes,tightlyholdingit,butitislikeakindoldmanwhousesitsbrownlonghairtobrushthe weedsonthegroundinthewind.Thereareallkindsoftreesaroundit,someofwhichare attachedtothedeadbranchesofmanymiserablewhiteandsoftstrawmushrooms,andsome arelightpig-coloredsandalwoodtrees,whichmakeitlookparticularlynobleinthejungle. Therearemilletashighasfivefeet,whichisevenmorearrogant,becausethemostannoying vinecan'tgetaroundit.Inthisdarkforest,mostofthemare"lowly"shortbushes.Theugliest thingisthethornbushescoveredwiththickthorns,andthegreenbristlegrasseverywhere. Occasionally,thereareseveralwildrosesashighasfourorfivefeet.Althoughtheyare overgrownwithbranchesandpricklyleaves,theirpurewhiteorpinkflowerscanattract manybutterfliestoclingtoaroundthem.Itisonlytheserosamultiflorathataddalotofcolor tothisgloomyforest(Luo,n.d.).

MiaoXiu's The Return of the Native describesSingapore'sseaandfreightlandscape:

Whenisthetrainparalleltothecoast?Thedarkgreenseaflashesfromtimetotimethrough thewarehousesandtreespaintedwithochre.Thewaveswerefoaming,andtheshipsatsea farawaybecameblurredintherainandfog(Miao,1957).

WeiYun's Evening on the Crow Hill alsodescribesthesceneryonthesea: Afteracontinuousperiodofrottencoconut.Thecoldcrescentmoononthemistybeach revealsthedarknessofthecowandthecow.Oops,apileofdarkthingsissurgingonthe beach.BrotherJin,theheartoftheoldfishermanwithlong-termexperienceisquitestrong. Therehasjustbeenastorminthisport,andthewavesarestillsurgingwiththedeadleaves ofcoconuttreesonthebeachandthebrokenrottenboardsleftbyMitsubishiShipyardand fallingfromtheunfinishedcave(Wei,n.d.)...

ZhaoRong's Begging for A Letter describestheenvironmentatthejunctionofseaandgrassland: Shelookedoutforthecarandturnedtothefourthpavilion.Shewalkedalongthenarrow paththatpassedthroughBalin,Hougang.Onbothsidesoftheroad,thethatchedgrasswas denselygrown,andthewaveswereringinginthegrass,whichmadepeoplefeellikeYuanYe withhumanandanimaleffects.Veryeasy,throughtheclearwaterflowingunderthesingleplankbridgemadeofcoconuttrees(Zhao,n.d.).

InSingaporeinthe20thcentury,naturalandhumanlandscapesechoedeachother.MiaoXiu's On the Beach showsthegoodrelationshipbetweenarchitectureandenvironment:

Thisevening,theskydarkenedveryquickly,andtheearthsoonbecamehazy,andthickgray cloudsfloodedthewest-slantingsun.Severaltallkapoktreesalongtheriverturneddark

green,whichmadethemparticularlygloomy.Inthedistance,overtheamusementpark, lightsareswaying,andtheshops,foodstallsandtheatersintheparkarealllit,readyto welcometourists(Miao,n.d.).

4.2 ClimatePerceptionandAdaptiveResponses

4.2.1

HistoricalValueofClimateRepresentation

DescriptionsofclimatearepervasiveinSingaporeChineseliterature,appearinginmostnovelsfrom the period. As part of the tropical Southeast Asian environment, the hot and humid climate significantlyshapesdailylifeandservesasanessentialbackdropinliteraryworks.Thesetextsnot only portray monsoons, rainy seasons, and humidity variations in great detail but also emphasize recurring elements such ashigh temperatures, torrentialrains, andmoisture-laden air,constructing adistinctsenseofplace.Climatedepictiongoesbeyondmereenvironmentaldescription;itprovides a historicalrecordof how people perceived and experienced climatic conditionsatdifferenttimes. Particularlyinthepre-urbanizedlandscapeofSingapore,literatureoffersavaluableculturalarchive of past climate conditions, contributing to the study of regional climate history and humanenvironment interactions. By analyzing these literary accounts, researchers can trace how climate shapedsociallifeandunderstandhistoricaladaptationstrategies.

Miao Xiu's work Waves of Fire can feel the hot and humid local climate in Singapore in the title. Thefollowingisadescriptionoftheclimateinthearticle:

The sky is bottomless, and the stars haven't appeared yet. Needless to say, the wind has long since stopped blowing. The whole space is like a solidified body, hot and suffocating (Miao, n.d.).

Miao Xiu's On the Beach describes the humid weather in Singapore, which is largely due to the threesidesoftheoceanandtheinterweavingofrivers:

Awetwindblewonthebeach.Theblackriverwasevaporatedbythesunduringtheday,and astinkingsmellsolidifiedontheriverbegantoblowaway(Miao,n.d.).

There are dry seasons and rainy seasons in Singapore. April-October is the dry season and November-March is the rainy season. In Zheng Yan's President Huang, the rainy season in Singaporewasmentioned:

Marchisstillalive,andApriliscoming,whichistherainyseason.Qingmingrainfallsonthe westcoastalmosteveryday(Zheng,n.d.).

YuMowo's Guest alsodescribesthehumidandrainyclimateinSingapore:

Itisstillraining.

God always lowers his eyebrows and face, as if he had been heavy all his life, and his eyes could never be dragged down.Ah, always sad, the space is always so wet and greasy, like a damploosecloth,whichmakespeoplefeelmoldywhentheytouchitcasually.

.....Ithasbeenrainingfortwodaysandnights(Yu,n.d.).

WeiYun's Wish to Return to the Hometown describes themountain flooddisaster caused byheavy raininrainyseason:

Rain, although this tropical monsoon rain kept dripping in the hills and mountains, the river outside Ba Yuan was shaken by flash floods, but there was a commotion in the Gambang of the late horse in the distance.As the flash floods rushed to this tree potato Ba Lei, LuoYou, who sat staring at the ups and downs outside, seemed to have a shock in his heart. The tiger jumpedup,rantowardsthedoorandstretcheditsneckoutward.

“Oldhuang,someonefellintotheriveragain?”

Every bar that grocery store surnamed Huang's vice-treasurer, is wearing a broken rain hat, from above the river, carrying a foot of red soil, limping back high and limping low, shaking hisheadandsighing:

“A single-plank bridge, the bridge is broken, the son of Sala Don't, fell down, and the flash floodabovewasswirlingunderthebridge,whodaredtosaveit! (Wei,n.d.)”

4.2.2

PassiveStrategiesforClimateAdaptation

Literaryworksalsodocumentvariouspassivestrategiesemployedbycommunitiestocopewiththe challengesposedbythetropicalclimate.Thesestrategies,oftendepictedasingrainedindailylife, reveal how local populations adjusted their behaviors, built environments, and social practices to mitigate the effects of heat and humidity. For instance, narratives frequently illustrate lifestyle patternssuchasthetimingofdailyactivitiestoavoidextremeheat,theuseofnaturalventilationin architecture,andsocialcustomsthatprioritizeshadedorbreezylocationsforcommunalgatherings. Additionally,traditionalclothingchoices,dietaryhabits,andseasonalcustomsreflectedanimplicit understandingofclimaticadaptation.Throughthesedepictions,literaturenotonlycapturesthelived experience of climate responsiveness but also highlights the embedded knowledge systems that governed human interactions with the environment before the advent of modern technological interventions. But on the whole, there is no clear development of building performance and technologytocopewiththehotclimate,whichmaybebecause Singapore,whichjustexperienced thewaratthattime,hasalottodoandhasnotrecoveredfromtheshadowofthewar.

4.3 FolkPracticesandCulturalTransmission

4.3.1

FestivalRitualTraditions

Festivals serve as an essential medium for preserving communal memory and reinforcing social bonds.Literarynarrativesdocumentthespatialorganizationoffestivalactivities,ritualobjects,and their symbolic meanings within the community. These depictions highlight the interplay between religiousbeliefs,socialhierarchies,andlocalcustoms.InSingaporeChinesenovels,therearemany memorials to major festivals in China. Commemorating every traditionalfestival in China is a top priority for Singaporeans. In addition, we can also see that Malay festivals are commemorated in thenovel.

InMiaoXiu's Under the Roof of Singapore,wecanseethegrandoccasionofthe MalayNewYear

children,arealsowatching.Mid-autumnnightismorelivelythanNewYear!

Somepeopleholdaplatewithdozensofwoodenfishbooksonit,holdingtwosticksofincense, appearing in the street, at the end of the street, in the center of the street, and in the corner, singing: "Begging for fortune, hitting your hands!" Moonlight divination, noble! ..... Many pedestrians fell off the horns and took one at random to guess their luck.The ancient legend, guessingluckinthisnight,isthemosteffective(Zhao,n.d.).

In addition to theMid-Autumn Festival mentionedabove, the families inthis article also celebrate the Dragon Boat Festival, the Mid-Autumn Festival, funerals and happy events. Wei Yun's novel Cold Mid-Autumn Festival is also set on the night of the Mid-Autumn Festival. In Xie Ke's Singapore Scenery,itismentionedthatDabotouGonggongperformedChaozhouOpera.

4.3.2 EverydayFolkPractices

Daily customs embedded in domestic and public life reflect traditional worldviews and social structures.Literaturerecordshouseholdrituals,foodpreparationtechniques,andinformaleconomic activities, demonstrating how these practices shape spatial arrangements and interpersonal relationships.Thetransmissionofthesecustomsacrossgenerationsisalsoemphasized,reinforcing theirroleinculturalsustainability.InSingaporeatthattime,people'sliveswereinfluencedbymany racesandbeliefs.Interestingly,every cultureisverytraditionalandnotsomodern, soitiscolorful andfullofflavor.Sometimespeople'sdailybehaviorischaracterizedbyculturalintegration. In Under the Roof of Singapore,ChenWan'sauntisa"nativeNyonya"whoalwayswearsasarong oftheirMalays.

MiaoXiudescribedpeople'sdailyprocurementin After Freedom:

.....Somewomeninthissuburb.WhentheycamebackfromtheBackstreetBazaartobuyfish and vegetables, they bought some spare parts, such as sugar, vermicelli, dried shrimps, soap powderandtoiletpaper,whenpassingbythisJilashop(Miao,1960).

XiaLin's TheTwinsofTabasco alsodepictsthedailylifeofSingaporeansinthissmokyatmosphere: Almost half an hour of picking, big belly Tak and high brother Lin two only bought a few pounds of ‘fish’ and some ‘big uncle male fish’, more than 10 pounds of ‘in the shrimp’ , downhearted out of the door of the Dabasha a look, the sky is still dark, a few stars are also stillin thebirdcloudstwinkle.InfrontofthegateofDabaksha,thereisalreadyadensearray of melons, and hawkersselling laksa, congee and cakes,all with oillamps on, hawking (Xia, n.d.).

InZhaoRong's AskingforALetter,SisterYad'swifehastoperformadailydivinationactivitycalled seekingwordsbeforeshecanbeginhernormalfamilylife.Asitturnsout,theseekingofgodsisfor a kind of gambling, called betting on the twelve branches. Most of the flower questions in it are Chinese proverbs, such as ‘Walking on Horses and Watching Flowers’ , ‘Hopscotch’ , ‘Iron Cock’ , andsoon.

SheaskedthewomanindetailtotakethePasirPanjangbustotherouteoftheLongevityHill,

andthen,yesterday,shedidsingle-mindedlyfastingandbathing,dressedupallshiny,bought fresh peanuts and fruits,Yuanbao candles, to the Longevity Hill to ask for the word, but also plustheintentionofrichlyonthetwobucketsofmoneyontheincenseoil,spentatotaloffive buckets,andhalfaday,sheaskedforafive-eighty-onepairsofwords,carefully,andthefive - eighty-one pairs of words, carefully. Eighty-one pairs of words, carefully written on paper, butalsoafraidofopeningthecrooked,inadditiontobuystraightdown,andbuyrowsandrows ofsitting,andstand-ins,atotaloftenbuckstowrite.Thisbuymethodisverystable,notopen the dooralsoopencrossroadah,randomlyin thatpairofwordsaregood,morethaninhalfa thousand,atleastinthereturnoftwoorthreehundred?SheevenmadeawishinfrontofGod thatifshewontwelveofthem,shewouldimmediatelysendagifttorepayGod'sfavour!How couldsheknowthatshewasstillnotluckyenough(Zhao,n.d.)?

MusicofallgenreswasalsopresentinthelivesofordinarySingaporeansduringthatperiod.InWei Yun's Evening on the Crow Hill,alinefromaMinnandittyisrecorded:

‘O,O,O!......Withoutahusband,yougivebirthtoasonwholoseshisreputation......’ Minnan ditty(Wei,n.d.).

InZhaoRong's Festival therearetwoendsofthespectrumofdepictionsofwomensinging.Oneis the gramophone in a coffee and tea shop playing the Song of the Singing Girl by the Hong Kong ChinesesingerZhouXuan;theotheristheyounggirlwhoputshersistertobedsingingalullaby:

Intheroom,Daju,theunderstandinganddelicategirl,singsalullabyagain,withsuchalong, warmvoice:

“SparrowBoy.

Takethebamboobranch.

I'mlookingatAuntieAsia.

AuntieAsiawearsabasketbasket.

Pickingaredflowerandputtingitinabun.

I'msoproudofyou........”

Woo-ya-Woo-ya-.........Mimi'scryisringingoutagain!

“Hello...hello...hello...hello...hello...hello...hello...hello...hello!

Moonlight.

Shiningontheground.

Onthenightofthe30thdayofthelunarmonth.

Pickingbetelnuts.

Thebetelnutsmellsgood.

MarryErniang.

Erniang'shairhasnevergrownlong......”(Zhao,n.d.)

LuoPing's Children of Mountains describesthedailylifeofafarmerinamountainbar:

The beautiful dream of this workshop became his life force, making him work hard from morningtonightwithoutanycomplaint-cultivatingtheland,weeding,turningthesoil,sowing

seeds,watering......orcuttinggrassforZhangDeji'splasticplantation,andthenburningitone by one on his newly reclaimed land to increase the nutrients of the newly reclaimed land. He would only go to the market in eight or ten days, using his old and cumbersome bicycle to carry eggs and grain to sell, and to buy coconut oil, salt, matches, and cigarettes from the CantonTank.

Sister-in-lawA-Tongueworkedjustashard.Mealsandlaundryweresecondarychores,while the main choreswereraisingchickensand ducks,feedingpigs, choppingbananas, andtaking careofthegarden.Herthirteen-somethingson,Puppy,washerhelper, checkingthe firewood inthebar,pickingandpouringthewaterwashisregularworkinthemorningandevening,and when he was busy, he also had to help his father come to the Xinken land to loosen the soil piecebypiece,orsquattingdowntopickupthesmallstonesortreeroots(Luo,n.d.).

InYuMowo's Guest,hewroteaboutthedailyflowofabusinessmaninanoldfirm: Tick-tock, tick-tock - those few fingers of the shopkeeper Lao San are strangely flexible in playingthebeadsoftheabacus.

The old generation ofbusinessmen, just like this, recognised thatwhenthey smelledthe door in the morning and shook the abacus, their business would always be prosperous for the day (Yu,n.d.).

4.3.3

IntangibleCulturalHeritage

Singapore Chinese literature presents the contemporary legacy of traditional intangible cultural heritage elements in fragmented narratives. Though the texts are often presented as absurd interpretations of lost skills, they reflect the genetic memory and identity confirmation of the Chinese cultural lineage of the dispersed communities through literary mirrors. These intangible culturalheritages, asfigurativesymbolsofculturalDNA,areundergoingadoublewritingprocess ofdeconstructionandreconstructionintheliteraryfield,exposingthedilemmaofinheritanceduring the period of cultural fault line, and at the same time, through creative translation, becoming an importantmediumformaintainingthespiritualtiesofethnicgroups,andcontinuingtoproducethe narrativeenergyofculturalidentityinthecontextofglobalisation.

The continuation of specialized crafts is a recurring theme in literary representations, illustrating how artisanalskills are passed downandadaptedover time.Thesenarratives explorethe selection of materials, modifications to traditional tools, and the hybridization of techniques that respond to local environmental and cultural contexts. The process of skill transmission within families and apprenticeshipsisalsoafocalpoint.

There are depictions of a wide variety of non-fiction in Xiao Cun's The National Martial Artist Therearethe ‘threewars’ ofboxing,PekingOperaandmetaphysics.Althoughthetextcanseethat these inheritorsdo nothaveathickfoundation,orevenonlylearnttheskin,andbecameaharmful liar,butatleastwecanseetheChinesecultureofSingaporeangenes.

He angrily pulled up his cuffs and danced his way to Lei, ‘Look at this: “Chop” , “cut” , “tackle” , “whip”.........Thatstep,well,it'sfromthe “ThreeBattles” thatLeiwastakenoutof the “ThreeBattles” ......... “ThreeBattles” isthemotherofallpunches......

Afterbreakfast,HeHuiboughtafewcopiesoftheXNewspaperandaskedsomeonetogoand

asksomeoftheleadersintheguildtocorrectthem.Hethensatdowninthelitigationroomto read the ‘essence ofboxing’ thathadbeenpurchasedfrom a stall, and almostleaptup with a relaxedheart.Hecouldn'thelpbuthumafewlinesofaBeijingtunethatdidn'tsoundright.

‘Haha......... sang it sowell that the theatre club concubine askedyouto playthe roleof Kung Fu Xiaosheng.’ ‘Iron Steel Knife’ sitting at a desk, while studying ink, while talking to the national artist.According to him, he has a deep understanding of fortune-telling, divination, andevenincantations,andwhenhegotoutofthestatecapitalafterthepeace,herentedastreet intheNationalArtMuseumtohangasigntomakealiving(Xiao,n.d.).

WeiHao's Evening on the Crow Hill alsomentionstraditionaloperas:

AtthestreettheatreinfrontofthetempleatthebackoftheseainPandey,theTaiwaneseclass movedandactedoutthestoryof ‘TheKillingofPanQiaoyunatCuiPingShan’ (Wei,n.d.).

Thepeople'sbeliefinthe Half-Heaven Maiden wasrecordedinXiaoCun's ‘Half-DayMaiden’,but someso-calledclergymenusedthisnametoenrichthemselvesandharmothers:

‘The sky is filled with red gas, the incense is burnt to penetrate the nine heavens, the golden furnace spits out wood cloud smoke, Rabbit's radiance comes from the heavenly gates, the Southern Gods and the Northern Dipper all descend, the five-coloured clouds make a lot of noise,theriverofcompassionisontherightpath,theTaoyuanCaveinvitesallthedeities,and before the altar of the Lady of the Temple of Miriam is told to make three invitations to the Half-DayNyonyatodescend,andthedivinearmyisfiveasiftheywereinalawfulunion.’

After reciting the ‘Invocation Mantra’, her eyes began to roll up in fear and she choked as if shehadbeenfed.Thetwowhitehandsaretwistedtogetherasiftheywerestrungupandrotated inwards,agesturethatindicatesthatthegodhascometopossessthebody.

The altar was setup in the teamroom, where severalplaques with gold characterson a black backgroundwerehung,suchas ‘thespiritofallages’ and ‘protectmychildren’,andNiuTian Niang was seated in the red lacquer, carved gold, green netting kind of account in the nanmu niches,andonbothsides:thepowderbox,paperflowers,handkerchiefs,andfanslinedupfull ofenamels(Xiao,n.d.)......

4.3.4 TransnationalCulturalPractices

Cross-border exchanges influence material culture and social practices, shaping the evolution of traditionsinanewgeographicandculturalcontext.Literaryworksdepictthecirculationofobjects, ideas,andskillsbetweenregions,highlightinghow migration,trade,andcommunication networks contribute to the adaptation and reinterpretation of cultural elements. The situation is vividly depictedinMiaoXiu's Under the Roof of Singapore:

At that moment, four guys came across the table: one Indian, oneWulai oil, two Bali (native Chinese). They are about specialised in doing the brokerage for others, take the ‘Tukou’ (foreignersorgan),sharesachair,theywillbeagurglinghightalkaboutLei,speakingherXixi donotunderstandabitoftheredMaoistlanguage,inthemiddleoftheoccasionalinterspersed with some Malay language. Sisi had just come out from the United Bongsamba, and the

Kampong(Malaycountryside)peopleallspokeMalay,soshewasusedtohearingit,andknew itwell.Butshedidn'thavethetimetolistentowhatpeopleweresaying.

4.4 CommunityandCollectiveBeliefs

4.4.1

EthnicSpaceGovernance

SingaporeanChineseliteraturefrom1948to1965frequentlydepictsthestructuredorganizationof ethnic communities, particularly in the ways they managed shared spaces. Clan associations, religious groups, and trade guilds played a crucial role in maintaining social order and economic stability within their respective enclaves. These institutions not only provided welfare support but alsomediateddisputes,ensuringaharmoniouscoexistenceamongdifferentgroups.Literatureoften portrays the governance of community spaces, such as the hierarchical seating arrangements in mediationhallsortheboundariesmaintainedbetweendifferentdialectgroupswithinneighborhoods. These narratives highlight how physical and social spaces were intricately linked, with spatial organizationreinforcingculturalidentityandsocialcohesion.

After the war, the British army returned to Singapore and Malaysia and continued their colonial instincts by issuing brutal ‘Emergency Ordinances’, launching the scorched earth policy, banning culturalandpublishingactivities,andimplementingeducationalpolicies,allofwhicharousedsocial discontent. The contents of the novels, such asYang Pu's Chamee, Miao Xiu's Under the Roof of Singapore, MaYang's The End of the World, and Li Zao's New Settlement, allreflectthe antipathy towards the British colonial rule, and the demand to break away from it and fight for the independence and freedom of the country. Xia Lin's Quiet Pahang River and Rushing Xie Ming's The Sound of Wind and Rain at Night emphasise racial harmony and the will to develop society together.

4.4.2 MutualAidandEthicalResponsibilities

Mutual aid was a fundamental aspect of community life, ensuring that individuals were supported in times of need. Literary works frequently depict systems of communal assistance, such as cooperative efforts in funerals, childbirth care, and neighborhood maintenance. These portrayals emphasizethemoralobligationsofreciprocity,wheremembersofthecommunitywereexpectedto contributetocollectivewelfare.Theliteraturealsoillustrateshowinformaleconomiccollaborations, such as food-sharing and labor exchange, strengthened social ties and reinforced a sense of belonging. Through these depictions, Singapore Chinese literature reflects the deeply embedded ethicalvaluesthatsustainedcommunityresilienceduringperiodsofhardship. SuchexamplesarecountlessinSingaporeChinesenovels.InZhaoRong's IntheStraitsofMalacca, the Japanese army exclusively captures the Chinese. However, even at the most critical moment, everyonesharestheconsensusofmutualassistanceandhatesthetraitorswhoselloutthepeopleto survive, reflecting the true nobility and goodness of human nature. In Xie Ke's Undercurrent, the tradeunionistsuniteandsupporteachothertohelpthoseintroubleoutoftheirdifficulties,andthey evensay ‘UnityisStrength’,apopularsayingintheChineseRevolution. In Xie Ke's A Little View of Singapore, the two fellows, Zhaodi and Ah Yong, in the face of difficulties from the shopkeeper and his wife, encourage and support each other in the face of difficulties and do not lose their dignity, and finally go out to start their own business to sell kueh kueyteow.

4.4.3 Labor,Perseverance,andEconomicAspirations

The glorificationofhardworkandperseveranceisarecurringthemeinliteraturefromthisperiod, reinforcing the belief that diligence leads to both individual success and collective prosperity. Stories often depict artisans, hawkers, and plantation workers as exemplars of resilience, emphasizing the value of skill, discipline, and endurance. The narratives also highlight the importance of financial prudence, portraying wealth accumulation through careful planning rather thanspeculation.ShameiinMiaoXiu's On the Beach hasbeenrobbedofherbeautybythedaysof pain, but ‘only two large eyes, which sometimes glitter with a touching light, that of sorrow, unwilling to give in completely to the weight of life, and burning with longing for survival’. By linking personal labor to the broader national development narrative, these literary works frame economicaspirationsasacommunalratherthanpurelyindividualpursuit,reinforcingtheideathat hardworkbenefitsnotjusttheindividualbuttheentiresociety.

4.4.4

Anti-ViceCampaignsandSocialDiscipline

The mid-20thcenturysaw strong ideologicalmovementsagainstperceived moralcorruption, with campaigns targeting gambling, prostitution, and extravagant lifestyles. Literature from this period reflects the promotion of frugality and discipline as essential virtues, often contrasting them with thedangersofindulgenceandidleness.Therejectionofbourgeoisleisureandluxuryisaprominent theme, as many narrativesdepictcharacterswho embrace simplicity and industriousness as model citizens. However,some textsalsocritiquethe rigidityof these movements,questioningtheextent to which moral enforcementcould suppress personal freedoms.These portrayals offer insight into the complexdynamicsofsocialdiscipline,illustratingboththe effectivenessandthelimitationsof state-drivenculturaltransformation.

Duringtheanti-vicemovementintheearly1950s,worksthatreflectedstudents'participationinthe anti-colonial and anti-yellow struggles included SongYa's Ah, I am a Youth. Gao Jinglang, in his shortstoriessuchas Youth Song and Green Grass,portrayedanumberofvividimagesofyouthand providedsocietywithhealthyliteraryreadingmaterial.Throughtheseliterarydepictions,Singapore Chinese literature provides a rich account of community structures, ethical codes, and social ideologies that shaped mid-20th-century life. The texts not only document the resilience and adaptability of these communities but also offer a space for critical reflection on the evolving tensionsbetweentradition,modernity,andideologicalinfluence.

4.5 LinguisticHeritageandDialectalSignificance

Singapore Chinese literature from 1948 to 1965 vividly captures the role of dialects in shaping community interactions and cultural identity. During this period, Chinese communities were linguistically diverse, with Hokkien, Teochew, Cantonese, Hakka, and Hainanese being widely spoken in different districts. Hokkien speakers predominantly resided in areas such as Chinatown andTelokAyer,whileTeochewcommunitieswereconcentratedaroundClarkeQuayandBoatQuay due to their historical involvement in river trade. Cantonese was commonly heard in KretaAyer, wheremanyCantoneseoperatroupesandtraditionalmedicineshopswerebased,whileHakkaand Hainanesegroupsoccupiedsmallerbutsignificantenclaves,particularlyintrade-relatedprofessions such as coffee shop owners and innkeepers. These different kinds of dialects are usually used together in a mixed way, for example like ‘拍拖’, ‘沙爹’, ‘丢那媽’, ‘幹汝老母’, ‘自家人’, ‘老

relocations,orthelossoflovedones.Thesenarrativesservenotonlyasdocumentationofhistorical sufferingbutalsoasameansofprocessingcollectivetraumaandreinforcingcommunityresilience. In Miao Xiu's Waves of Fire, which chronicles the policy of relocating people from Ngau Chew ShuitoShanBainTiongBahrutoescapefromtheairraid,thereisalsothetragedybroughtbythe war:

Earlythenextmorning,thepeopleofTiongBahrufoundtheair-raidshelterhadbecomeabig hole,andinsidewasabluroffleshandblood.

Onthebrokenbranchesoftheteaplumtree,hangingonahumanleg,likeapig'shoofhanging fromaporkstall,butalsowearingawhitecanvastreerubber. Take wooden boards, zinc and iron skin built up ‘big uncle Gong’ collapsed on one side, the altartablecameupasmallchild'ssoulcover,cuttingasmalldefence,mixedwitharedband. The scene was so tragic that the hairs on the backs of the heads of the men were all raised (Miao,n.d.).

InMiaoXiu's On the Beach,itiswrittenabouttheendofJapan'swarofaggressionandhowpeople are still cleaning up the wounds from all aspects of the war against Japan. Shamei learnt of her husband Matsuo's death during the war and later moved in with Adai who helped her, but her husbandactuallycamehomealiveafterthewar.Inheranguish,shepreparestocommitsuicide. ZhaoRong's IntheStraitsofMalacca,alsowritesoftheJapanesehittingBukitTimah,PasirPanjang, Serangoon.but,astheoldpeninthetextputsit:

‘ThenewSingapurawasbornoutofthefire.Thatistosay,outofpainnewlifeisbirthed(Zhao, n.d.).’

In the text, we can see how resilientand optimistic Singaporeans of thatera were, andthe old pen adds, ‘Now is the time for testing.’ The writer values dignity as more important than life in his values,whilealsodenouncingthetraitorsthroughthemouthsofhischaracters.

4.6.2 TheGenreofInspirationalStoriesandtheMigrantSpirit

Amajor theme in Singapore Chinese literature of this period is the perseverance of early Chinese migrants, particularly those from South China, in their pursuit of stability and prosperity. Stories oftenportrayindividualswhoarriveinSingaporewithlittleandgraduallyachievesuccessthrough diligence,frugality,andentrepreneurialskills.Thisliterarytraditionechoesthereal-lifeexperiences ofChinesemerchants,artisans,andlaborerswhocontributedtoSingapore’seconomicdevelopment. The emphasis on hard work, self-discipline, and perseverance not only reflects the values of the migrant generation but also shapes the moral expectations for future generations within the community.

4.6.3 TheInfluenceofIdeologicalandCulturalTraditionsonMoralNarratives

Moralstorytellinginthisperiod’sliteratureisshapedbymultipleideologicalcurrents,includingthe legacy of the May Fourth Movement, socialist thought, and traditional Chinese ethics. The May Fourth Movement’s critique of feudal traditions encouraged writers to explore themes of social progress, gender equality, and the need for education.Atthe same time, socialist ideals introduced

conceptsofclassstruggle,collectiveresponsibility,andthedignityoflaborintoliterarynarratives. TheseinfluencesoftenintertwinedwithConfucianmoralteachings,whichemphasizedfamilyduty, honesty,andsocialharmony.Asaresult,manystoriescarriedadidactictone,portrayingcharacters whosemoralchoicesledtoeithersocialupliftmentordownfall,reinforcingethicalandideological valueswithinthecommunity.

4.6.4 FromDiasporicConsciousnesstoLocalIdentity

Duringthisperiod,SingaporeChineseliteratureunderwentatransitionfromadiasporicoutlookto anemerginglocalconsciousness.EarlierworksoftendepictedSingaporeasatemporaryhome,with charactersmaintainingemotionalandeconomictiestoChina.However,asSingaporemovedtoward self-governanceandnationhood,literarynarrativesbegantoreflectashiftinidentity.Writersstarted toportraySingaporenotjustasaplaceofeconomicopportunitybutasahomeinitsownright.The depiction of local landscapes, everyday interactions, and community life contributed to a growing sense of rootedness. This transformation signaled a departure from the traditional "overseas Chinese"mindset,markingthebeginningofadistinctSingaporeanChineseidentity.

Throughreflectionsonmemory,migration,moralvalues,andevolvingidentity,SingaporeChinese literaturefrom1948to1965capturesthecomplexitiesofacommunitynavigatinghistoricalchange. These narratives provide a window into how the Chinese population in Singapore gradually redefined their place in society, shaping a literary heritage that continues to influence cultural identitytoday.

5 Conclusion

ThroughasystematicanalysisofSingaporeChineseliteraturefrom1948to1965,thisstudyreveals the multifaceted value of literary works as carriers of cultural heritage. The findings indicate that literary creations from this period not only document a crucial phase in Singapore’s urban developmentbutalsoconstructadistinctiveheritagevaluesystemthroughrichnarratives. First, on the material level, literary works have meticulously preserved Singapore ’ s built environment, including architectural typology, street and alley systems, interior spaces, and landscape systems. These descriptions not only showcase the adaptive intelligence of architecture andtheenvironmentbutalsoprovidevaluablefirsthandmaterialsforhistoricalbuildingrestoration, spatialreuse,andculturallandscapestudies.Additionally,literaryworksofferdetailedportrayalsof bothnaturalandman-madelandscapes,frequentlyreferencingSingapore’stropicalclimateandthe passive strategies people employed to cope with it. These references further reflect the historical significanceofSingapore’sgreenandclimaticheritage.

The map below (Fig 2) wasdrawn by the author by counting the frequency of each place name in the work, with darker colours indicating more occurrences. From the map, we can see that these locations are mainly concentrated in the south and east of Singapore. Among them, Chinatown, Tanjong Pagar, and Geylang appear very frequently, indicating that they were probably the main gatheringplacesoftheChineseinSingaporeduringthatperiod.

1. Establishing a methodological framework for analyzing the heritage value of literary texts, providingafoundationforfuturestudiesonliteratureandheritage.

2. Unveiling the transformation of Singapore’s heritage characteristics between 1948 and 1965, illustratingtheshiftfromadiasporicconsciousnesstoalocalidentity.

3. Exploring the active role of literature in constructing heritage discourse, demonstrating that literature is not merely a vessel for cultural heritage but also a key agent in shaping heritage perceptions.

The study's limitations lie in its scope of textual coverage and time span. Future research could extendtocomparativeanalysesofSingaporeanChineseliteraturefromdifferentperiodsorexplore parallelswithMalaysianChineseliterature.Intermsofpracticalapplication,thisstudyrecommends thatheritage conservation agencies recognize the spatial memory and culturalvaluesembedded in literary works, incorporating them into heritage planning and cultural education initiatives. This would allow literary heritage to contribute more effectively to cultural transmission and social development.

Bibliography

Bos,M.,Claeys,D.,Stiernon,D.,&Vandenbroucke,D.(2025).ObjectivisingHeritageAssessment with Values: Criteria-Based Grid and Constructivist Approach. Heritage, 8(4), 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8040116

Chen, D. (2023). How Visitors Perceive Heritage Value—A Quantitative Study on Visitors’ Perceived Value and Satisfaction of Architectural Heritage through SEM. Sustainability, 15(11), 9002.https://doi.org/10.3390/su15119002

Cresswell,T.(2004). Place: A short introduction.BlackwellPublishing. de laTorre,M., &Mason,R. (2002).Introduction.In M.de laTorre (Ed.), Assessing the Values of CulturalHeritage:ResearchReport (pp.3–4).GettyConservationInstitute:LosAngeles,CA,USA.

Domosh, M. (2001). Cultural landscape in environmental studies. In Elsevier eBooks (pp. 3081–3086).https://doi.org/10.1016/b0-08-043076-7/04147-4

Duncan,J.,&Duncan,N.(1988).(Re)ReadingtheLandscape. EnvironmentandPlanningDSociety and Space, 6(2),117–126.https://doi.org/10.1068/d060117

Geurts, K. L. (2003). Sensory experience and cultural identity. In University of California Press eBooks (pp.227–250).https://doi.org/10.1525/california/9780520234550.003.0010

Hennon, P., & Harris, A. (1997). Annotated bibliography of Chamaecypans nootkatensis. https://doi.org/10.2737/pnw-gtr-413

Ickerodt, U. (2006). The Term "Cultural Landscape". In: T. Meier (Hrsg.), Landscape Ideologies ArchaeolinguaSeriesMinor.Budapest2006,53-79.

Kou,Y., &Xue,X. (2024).The influence ofrural tourism landscape perception ontourists’revisit intentions—a case study in Nangou village, China. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11(1).https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03129-8 LAM Lap. (2018, July 2). 新加坡华文旧体诗的百年风雅 _光明日报 _光明网 https://news.gmw.cn/201807/02/content_29608063.htm#:~:text=%E2%80%9C%E5%8D%97%E6%B4%8B%E8%89%B2 %E5%BD%A9%E2%80%9D%E4%B8%80%E8%AF%8D%E8%99%BD%E7%84%B6%E6%98 %AF%E7%94%B1%E6%96%B0%E5%8A%A0%E5%9D%A1%E7%9A%84%E7%99%BD%E8 %AF%9D%E6%96%87%E5%AD%A6%E7%95%8C%E6%8F%90%E5%87%BA%EF%BC%8 C%E4%BD%86%E6%97%A9%E5%9C%A8%E4%BB%96%E4%BB%AC%E4%B9%8B%E5% 89%8D%EF%BC%8C%E9%82%B1%E8%8F%BD%E5%9B%AD%E7%AD%89%E6%97%A7 %E4%BD%93%E8%AF%97%E4%BA%BA%EF%BC%8C%E5%85%B6%E5%AE%9E%E5% B7%B2%E6%8A%8A%E5%A4%A7%E9%87%8F%E6%9C%AC%E5%9C%B0%E5%85%83% E7%B4%A0%E8%9E%8D%E5%85%A5%E4%BB%96%E4%BB%AC%E7%9A%84%E4%BD %9C%E5%93%81%E4%B9%8B%E4%B8%AD%E3%80%82%20%E5%9C%A8%E3%80%8A %E6%99%9A%E8%BF%87%E5%98%89%E4%B8%9C%E3%80%8B%E4%B8%80%E8%AF %97%E4%B8%AD%EF%BC%8C%E9%82%B1%E8%8F%BD%E5%9B%AD%E8%BF%99%E 6%A0%B7%E5%BD%A2%E5%AE%B9%E6%96%B0%E5%8A%A0%E5%9D%A1%E7%9A %84%E8%87%AA%E7%84%B6%E9%A3%8E%E5%85%89%E5%92%8C%E5%A4%A9%E6 %B0%94%EF%BC%9A%E2%80%9C%E5%B9%B3%E5%8E%9F%E9%A9%B0%E9%81%93 %E5%B8%A6%E7%96%8F%E6%9E%97%EF%BC%8C%E9%9A%94%E7%BB%9D%E7%82 %8E%E4%BA%91%E4%B8%80%E5%BE%84%E6%B7% Lee,K.Y.(1991). The Singapore story: Memoirs of Lee Kuan Yew.TimesEditions. Lee, K.Y. (1991). 李光耀谈新加坡的华人社会 . 新加坡中华总商会、新加坡宗乡会馆联合总

Appendix

Table1.ListofSingaporeChineseLiterature(1948-1965)(tobeadded)

Title

ChineseName PossibleEnglishTranslation

火浪 Waves of Fire

新加坡屋顶下 Under the Roof of Singapore

挂红 Black and Blue

河滩上 On the Beach

还乡 The Return of the Native

残夜行 Walking in Mid-night

年代和青春 Times and Youth

小城忧郁 Melancholy in a Town

离愁 Departure Sorrow

第十六个 The Sixteenth

边鼓 Border Drum

红雾 Red Mist

人畜之间 Between Human and Animal

恢复自由以后 After Freedom

在马六甲海峡 In the Straits of Malacca

求字 Begging for A Letter

过节 Festival

梦 Dream

阿O正传 A O's Bibliography

Author

ChineseName PossibleEnglishTranslation

苗秀 MiaoXiu

苗秀 MiaoXiu

苗秀 MiaoXiu

苗秀 MiaoXiu

苗秀 MiaoXiu

苗秀 MiaoXiu

苗秀 MiaoXiu

苗秀 MiaoXiu

苗秀 MiaoXiu

苗秀 MiaoXiu

苗秀 MiaoXiu

苗秀 MiaoXiu

苗秀 MiaoXiu

苗秀 MiaoXiu

赵戎 ZhaoRong

赵戎 ZhaoRong

赵戎 ZhaoRong

丘絮絮 QiuXuxu

丘絮絮 QiuXuxu

沉渣的浮起 The Floating of Sinking Dregs 丘絮絮 QiuXuxu

搬家 Moving 丘絮絮 QiuXuxu

荣归 Returning with Honor 丘絮絮 QiuXuxu

学府风光 Academy Vista 丘絮絮 QiuXuxu

在大时代中 In Big Times 丘絮絮 QiuXuxu

房东太太 Landlord's Wife 丘絮絮 QiuXuxu

变 Change 丘絮絮 QiuXuxu

大时代中的插曲 Interlude in the Big Time 丘絮絮 QiuXuxu

坎咪之死 Cammie's Death

四姨太 The Fourth Aunt

小人物地悲喜剧 The Tragedy and Comedy of the Nobody

从黑夜到天明 From Night to Day

赌博世家 The Gambling Family

山野的孩子 Children of the Mountain

体罚 Corporal Punishment

走路 Walking

暗流 Undercurrent

新加坡小景 A Small View of Singapore

他们的世界 Their World

客 Guest

黄校长 President Huang

丘絮絮 QiuXuxu

洛萍 LuoPing

洛萍 LuoPing

洛萍 LuoPing

洛萍 LuoPing

洛萍 LuoPing

洛萍 LuoPing

谢克 XieKe

谢克 XieKe

谢克 XieKe

谢克 XieKe

于沫我 YuMowo

征雁 ZhengYan

Table2.PlaceFrequencyCountofMappingofMentionedLocationsinSingaporeChineseNovels (1948-1965)