nuAZN serenade

Editor in Chief

Kim Jao

Print Managing Editors

Kaavya Butaney, Joyce Li

Creative Director

Gracie Kwon

Assistant Creative Director

Indra Dalaisaikhan

Photo Director

Lianna Amoruso

Publisher

Yinuo Wang

Leisure District Editors

Sarah Lin, Jerry Wu Worldwide Editors

Christine Mao, Shravya Pant, William Tong

Gathering Editors

Yiming Fu, April Li

Copy Editors

Rohan Krishnamurthi, Meryl Li

Styling Director

Julianna Tia

Photographers

Katie Chang, Yulan Guo, Joyce Huang, Cassie Sun, Yujin Tatar

Page Designers

Jessica Chen, Jessica J. Chen, Betty Dong, Jenna Jeon, Allison Kim, Jackie Li, Esther Lian, Xiaotian Shangguan, Esther Tang, Joyce Wang, Allen You, Diane Zhao

Corporate

Ashley Guo, Selina Jiang, Maya Ramaswamy, Lucia Shen, Katie Tsang Contributors

Cate Bikales, Kerrin Cha, Keya Chaudhuri, Yulan Guo, Emily Jiang, Cindy Khuc, Lucas Kim, Abhi Nimmagadda, Katie Tsang, Beatrice Villaflor

Models

Daniela Aves, Toubby Chau, Max Chen, Rita Chen, Conner Dejacacion, Kylie Kim, Sanjana Rajesh, Aditi Ram, Joel Reyes, Julianna Tia, Anna Truong, Shepherd Lee Williams

Editor’s Note

Recall the last time your heart was moved. You might remember music in the air, a quiet song echoing from below like a lover finger-picking melodies to their other half. Perhaps that moment left you changed, rearranged everything you thought you knew. Maybe it was as if a serenade was sung for your ears and your ears only.

In nuAZN’s 31st issue, we explore the forces that push and pull the heart in all directions. From stories of love and loss to reconnection with heritage, we invite you to read about the experiences of others in hopes of finding the tune to your own symphony.

On page 12, read about how Hindu siblings commemorate their relationship with Rakhi. Bask in the joy of self-pleasure on page 17 and listen to the struggles of translating queer identity on page 24. Get swept off your feet with our main shoot on page 20 and savor a love letter to soup on page 33.

I have so much love for the nuAZN team. There are few spaces on campus where we can laugh and commiserate in the parts of ourselves that make us who we are. There are even fewer where we can turn them into stories on a page. From the Slack frenzies and the late hours spent finding every error in the issue, Sunday brunches and the feeling of seeing the centerspread for the first time, making this magazine has been a labor of love. I hope you can feel it emanate through every page.

Kim Jao, Editor in Chief

Kim Jao, Editor in Chief

nuAZN

Table of Contents LEISURE DISTRICT Singing sexism 5 Etched in ink 7 Rajas of rock 8 Reclaiming my inheritance 10 Sibling ties 12 WORLDWIDE The accented tongue 14 Self-serenade 17 Song of life 20 That didn’t come out right 24 Halmeoni, saranghaeyo 27 GATHERING Losing you, in translation/一言难尽 30 In good hands 32 ode to soup 33 On love 34 How to date a ______ 35 Cover by Lianna Amoruso & Gracie Kwon

FREE AND OPEN TO ALL Image: Lhola Amira, IRMANDADE: The Shape of Water in Pindorama, 2018-2020. HD video, single channel sound, film still. Image courtesy of th artist and SMAC Gallery. Actions for the Earth is produced by Independent Curators International (ICI), New York. www.blockmuseum.northwestern.edu Hours: Wed-Fri 12-8PM, Sat & Sun 12-5PM Closed Monday & Tuesday @nublockmuseum January 26–July 7, 2024

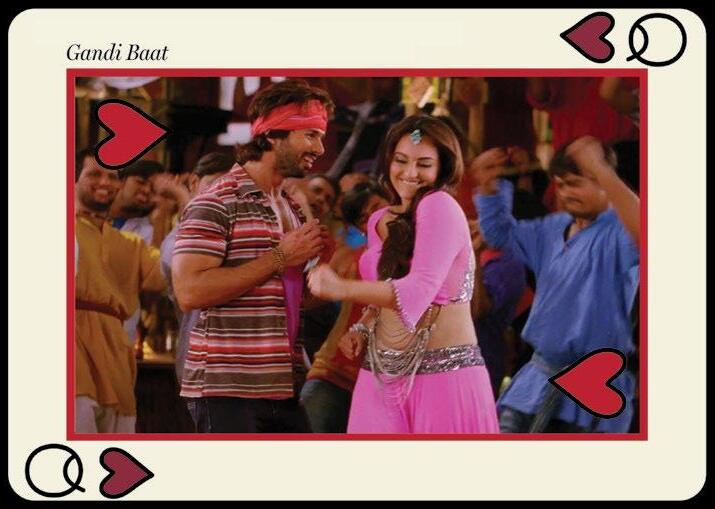

Debriefing Bollywood’s storied history of misogyny.

STORY BY SHRAVYA PANT DESIGN BY ESTHER LIAN

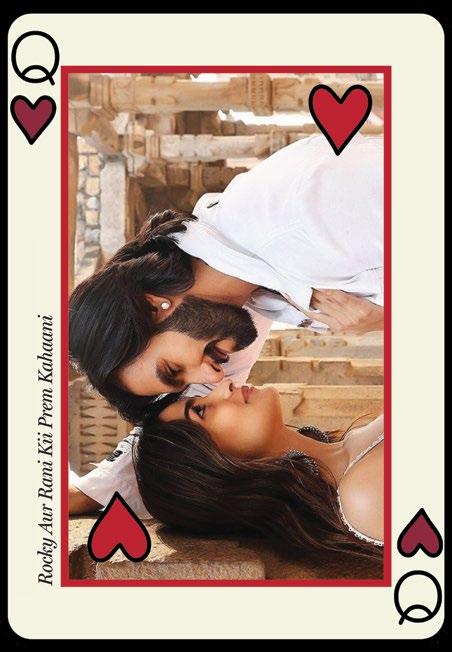

Women twirl in glitzy lehengas, onlookers ogle and a groovy track plays as men attempt to woo their targets with suave lyrics. It’s these colorful choreographies and romantic rhythms — the Bollywood serenades that set box office records. Bollywood has always been about more than just movies. An amalgamation of film, music and obsession with celebrity culture makes it the all-encompassing pop culture industry.

Hindi cinema has dehumanized its female characters for decades. In 1994 “Tu Cheez Badi Hai Mast,” loosely translated as “you are a fun thing,” Bollywood superstar Raveena Tandon dances scantily clad to eyebrow-raising lyrics. As male onlookers ogle while the male lead sings, “tu cheez badi hai mast,” they raise their glasses and blow kisses, while the camera pans to Tandon’s hips and seductive panting.

However, these songs and music videos aren’t innocent musical theater. Themes of harassment and objectification run rampant, with a notable lack of consent reflecting the roots of misogyny in Indian culture. Bollywood’s recent shift toward more equitable gender roles has reshaped the dynamics of the musical tradition, although lingering remnants of persisting misogyny feature in even the most recent blockbusters like 2023 film Rocky Aur Rani Kii Prem Kahaani.

A 2023 study from the Tata Institute of Social Sciences in Mumbai examined the deep patriarchal ties in Bollywood. Researchers analyzed nearly 2,000 on-screen characters and found that women only made up 26% of characters, and only one in 10 held decision-making roles. The study found that despite evolving laws against gender-based violence,

In the mid-2000s, unconventional film Jaane Tu... Ya Jaane Na friendly serenade in “Kabhi Kabhi Aditi.” The comingof-age film is about a college friend group that trades the glamorous dance numbers typical in Bollywood movies for a more intimate, quirky tone. The song plays when female lead Aditi is heartbroken over the death of her beloved cat, while her best friend Jai and the rest of their posse whimsically try to raise her spirits. It’s a more personal type of song, as Jai sings to assure Aditi that “everything’s gonna be okay.”

The song expresses an appreciation for her personality and a desire to emotionally connect with her rather than to make sexual advances. It’s remarkable as up to this point in Bollywood, the serenade rarely veered from its typical motif, with one fan on IMDb writing, “there is freshness in this approach.”

nuAZN LEISURE DISTRICT | 5

PHOTO COURTESY OF ROMANTIC HITS/YOUTUBE

PHOTO COURTESYOF ABPNEWS

PHOTO COURTESY OF BOLLYWOOD HUNGAMA

Baat” from R... Rajkumar, we see Bollywood’s misogyny has not escaped the industry. The male lead, dubbed Romeo, becomes beguiled by Chanda after seeing her once. Romeo persistently courts Chanda, despite her declining interests until she gives in.

The trope of wearing down a woman until she accepts romantic advances is fairly common in Bollywood movies. The song’s lyrics recall Chanda’s rejections of Romeo’s courting attempts, after which he decides he is done with manners, and will only talk dirty — “gandi baat.” During the song, Chanda emerges from water in sultry makeup, Romeo’s friend holds two women on him in what is essentially a lap dance and a man forces a woman to kiss him. Chanda eventually acquiesces, saying she also wants to engage in “dirty talk” with him, as if Romeo’s blatant disregard for her consent does not matter.

Two years later, period drama Bajirao Mastani released with a female warrior as the heroine. Mastani and Bajirao, a leader in the Maratha empire at the time, fall in love after Mastini assists him to victory against Marathi enemies. Mastani’s character defies gender norms with her battlefield prowess and her performance of a female serenade “Deewani Mastani.” Mastani keeps her gaze on Bajirao and sings of becoming mad with love, “deewani,” as soon as she sets her eyes on him, “nazar jo teri laagi.”

“playful,” it still maintains stalkerish themes.

6

nuAZN SERENADE |

ABPNEWS

PHOTOCOURTESYOFLISTOFSUPERHITS/YOUTUBE PHOTOCOURTESYOF

Etched in ink

Unveiling cultural tapestry on skin.

STORY BY KERRIN CHA

DESIGN BY JOYCE WANG PHOTOS BY JOYCE HUANG

Tattoos have a wide variety of cultural connotations across Asia and the Pacific. In the Philippines, tribal tattoos are deeply embedded into Indigenous culture and are prevalently used for tribal identification, charms of protection and aesthetic. In much of East Asia, however, tattoos are socially taboo. In Japan, for instance, people cannot enter hot springs with their tattoos exposed. In South Korea, it is illegal for tattoo artists to practice without a medical license.

For Asian Americans, tattoos vary in meaning from an aesthetic cultural connection to a deliberate choice of rebellion. Take a look at how these Northwestern students choose to etch their Asian heritage into their skin and the unique identities they claim for themselves.

EJEAN KUO

SESP first-year Ejean Kuo’s tattoos stand as testaments to her journey of self-expression. Her left bicep sports a goldfinch in flight above a barbed band, representing her favorite book, The Goldfinch. Growing up in a Christian Chinese household where tattoos were considered inappropriate, she never would’ve expected to get one. However, she says she felt the restrictiveness and despair that many teenagers experienced

JAMES KIM

JAMES KIM

when COVID-19 hit. She decided to get a tattoo on her 18th birthday.

“Being able to make [my] own decision was kind of liberating,” she says.

Kuo’s tattoos are a point of contention between her and her parents.

“My mom didn’t talk to me for a couple of days,” Kuo says. “I really don’t care that much what their expectations are for my own body and my self-expression.”

AIDAN OCAMPO

Weinberg fourth-year Aidan Ocampo says he views his tattoo journey as a means of dismantling colonialism. External copresident of Kaibigan, the PhilippineAmerican student association on campus, Ocampo’s tattoo journey is a reflection of how he has rediscovered his Filipino heritage.

“I wanted to get something that definitely was intrinsic about myself,” Ocampo says.

That’s why he got the stars and sun from the Filipino flag with batok bands wrapped around them tattooed on his back calf.

Ocampo’s tattoos reflect his national pride and are statements toward the Filipino decolonial movement. After coming to Northwestern, he connected with activists engaged in the movement.

Weinberg fourth-year James Kim got one of his tattoos as a celebration of growth in his mental health journey. As a Korean American Christian, he grew up with two cultural narratives that emphasized placing others before yourself — the Korean emphasis on familial community and the Christian values of serving. But after starting therapy in his second year of college, James began to recognize the importance of self-care.

“I realized it’s not completely about depriving yourself, it’s about nurturing

The Philippines’ history with traditional art and methods of tattooing was mostly lost under Spanish rule. Today, many Filipino Americans strive to revive the art to reclaim their cultural history.

Ocampo says these tribal tattoos are unique to certain regions in the Philippines. He continues educating himself and voicing the need for cultural reclamation and decolonization. In the future, he hopes to receive a traditional tribal sleeve on his arm.

“For Filipinos, getting a traditional Filipino tattoo is an action of decolonization, which is really powerful,” he says. “I hope to see more people get more tattoos.”

yourself, taking care of yourself in the way you take care of others,” Kim says. His tattoo of a man watering a plant on his left rib cage stands as a reminder to care for himself. Kim says his parents, who serve in a Christian ministry, have been understanding.

“I realized our parents also live under a certain way they have grown up,” he says, “Once you bring up a change, they also become more open to things, and in a way, more destigmatized by you.”

FRajas of R O C K

Meet the nascent Northwestern student band, Revere.

STORY BY KATIE TSANG DESIGN BY BETTY DONG PHOTO BY YULAN GUO

ingers slide down metal guitar strings, the speaker hums and an electrifying riff cuts through the air before the song kicks off with a piercing scream.

This is Northwestern student band Revere’s practice session in the music fraternity Phi Mu Alpha, where they rehearse and write their original punk rock music.

I got the chance to watch Revere jam out through video and to chat with the band members about their musical journeys. The band consists of vocalist McCormick fourth-year Nabil Hussaini, bassist Weinberg second-year Rohan Subramaniam, lead guitarist Weinberg second-year Zhanran Shi, drummer Weinberg second-year Veer Bathwal and rhythm guitarist McCormick second-year Daniel Killioğlu (who was not present for the interview).

The band describes their sound as a mix of rock, grunge and emo with a touch of “rebellious teen angst.” Each of them has their own taste in music ranging from ’90s-esque Nirvana to boomer rock, which brings a variety of influences into their music.

“Somehow, it works,” Subramaniam says.

The rock genre is dominated by white musicians, including the band members’ favorite artists like Dream Theater and Taylor Hawkins. But the predominantly Asian American band isn’t fazed.

to be a hard rock band, especially if it inspired someone to pick up an instrument.

“I remember one of my older brothers was like, ‘People like us don’t usually make music, and then I think about you,’” Hussaini says.

The formation of the band began two years ago, the summer before four of the five members even arrived at Northwestern.

Subramaniam and Killioğlu found each other on the admitted class Instagram and connected over their similar music tastes. They planned to form a band once they arrived on campus.

Their first task was to find someone for each role. Conveniently, Songwriters Association at Northwestern held a band formation night — an event where student musicians network in a speed-dating style — soon after the school year began. Subramaniam and Killioğlu found Shi and Hussaini at the event. The four immediately bonded over their love for rock.

The final member, however, found them.

“Is anyone a drummer here?” Bathwal recalled hearing from the corner of the room. He raised his hand and walked over. Lo and behold, Revere.

“I don’t think race has anything to do with [music],” Shi says.

Subramaniam noted that his favorite band, Soundgarden, has an Indian American lead guitarist whose family is from Kerala, the same state of India as his family is from. Even with this connection, his interest in Soundgarden started from the music alone.

Yet, Hussaini says one of Revere’s goals is to diversify what it looks like

8 nuAZN SERENADE |

The band has a deep admiration for music and performing, which the name Revere seems to reflect, Hussaini says. In actuality, the band name plays on the drummer’s name, “Veer.”

Although they started out performing covers, the band now has a set list with nine original songs.

Subramaniam says a song usually starts with a riff or an idea on guitar from Hussaini, Killioğlu or himself. Then, the magic happens.

The five musicians get together and work piece by piece to add in each instrument. Bathwal adds a beat with drums while the guitarists work on a melody. Hussaini can craft the lyrics before or after the rest of the instruments are put together.

Hussaini’s favorite original song shows how much heart the band puts into their music.

He wrote it about an ex-girlfriend who dyed his bangs a sunset pink. From dating to friends to falling out of touch, time passed and Hussaini’s natural black hair started to peek through, leading to the song title “Black Clouds in a Pink Sky.” (My heart melted.)

The two were no longer in a relationship but still friends when he heard her sing an original song with the lyrics “heavy lies the crown” at an

writes, “There’s no kingdom to keep safe what’s hidden/No pushing this down/ I’m still waiting.”

As a songwriter, Hussaini says part of his goal is to be heard. He chuckles as he describes the lyrics’ backstory to me.

“I’m actually getting myself out there. I’m not pushing anything down. I felt all the emotions of this, and I made it into lyrics that I sang,” Hussaini says. “It’s very satisfying.”

Several of Revere’s songs are about this mystery girl, who has never heard any of the songs she’s inspired.

Besides songwriting, performing is what the band really loves to do.

“I get really nervous about public speaking and other public performances but not playing bass,” Subramaniam says.

“He does a lot of improvising, which is really impressive because he could whip out totally different versions of the same material and different concepts at different times,” Shi says.

The band has worked with several campus organizations, including Songwriters Association and Nitesckool Productions.

“There’s lots of opportunities going around,” Shi says. “Sometimes, when you’re just too busy with work, playing with people helps you destress.”

Looking forward, the band hopes to record their nine original songs and release them as an album or EP by the end of the school year.

Until then, they’re playing gigs and writing new material.

“Time goes by really quickly, but it’s more about enjoying myself out there.”

—Veer Bathwal, McCormick second-year

With the crowds cheering and adrenaline pumping, Bathwal says the musical set passes in an instant.

“Time goes by really quickly, but it’s more about enjoying myself out there,” Bathwal says.

“I think we’re doing it because we love music,” Bathwal says. “We want to have some platform where we can express ourselves.”

From left to right: Nabil Hussaini, Daniel Killioğlu, Rohan Subramaniam, Veer Bathwal, Zhanran Shi

From left to right: Nabil Hussaini, Daniel Killioğlu, Rohan Subramaniam, Veer Bathwal, Zhanran Shi

STORY BY KAAVYA BUTANEY DESIGN BY ALLEN YOU

STORY BY KAAVYA BUTANEY DESIGN BY ALLEN YOU

Kaavya, samji?” my aunt asked, after a long string of instructions in fluent Hindi. I did not, in fact, samji (understand). Just one quarter into Northwestern’s HindiUrdu sequence, this second-generation Desi disaster was not ready for the big leagues (my cousin’s wedding).

I have parents who don’t speak the same mother tongue, and like many other multi-language households, my family didn’t really strike a balance between my mother’s Tamil and my father’s Hindi. Instead, my brothers and I learned neither and became monolingual disgraces to the subcontinent.

I used to believe that taking Hindi would immediately bring me into the fold of my culture, but one quarter was not enough for me to competently talk to my grandmother in Hindi. Not without wanting to curl up and cry on a carpet, anyway.

Learning the language has never been easy. I mix up के and को all the time, and for a full month, I couldn’t figure out how to describe where I put my shoes.

Still, learning Hindi was satisfying. Struggling in Hindi was a breath of fresh air from my endless organic chemistry memorizations. And I always had a reason to keep going.

SESP third-year Hana-Lei Ji already speaks Japanese, which she learned from her mother. She started learning Korean when she arrived on campus.

“When I started taking Korean, I didn’t know any of the letters, and we had quizzes in the first week about the entire alphabet,” Ji says. “In the beginning, it’s very hard to hear even the difference between the different tones or pronunciation. I just haven’t heard much Korean growing up.”

Learning a new script and language is daunting, but her quarter of Korean provided her with a structure that helped her start from zero. For her, learning Korean is a way to connect with her heritage, even though her Americanborn father does not speak the language.

I found learning the Devanagari script in class was helpful. Although I was initially focused on just learning

phonetics, I realized that learning the script meant I could actually distinguish between sounds that don’t exist in English more easily.

Korean and Filipino SESP third-year Anna Alava also took Korean at NU for a full year. Alava started formally learning Korean at her local community center in high school. Her classmates were mainly adults, many of whom were not Korean.

When she took classes at NU, however, she met many Korean Americans who were also not taught Korean growing up.

“It was an opportunity where I was finally able to relate to other Korean people who were struggling to learn,” Alava says.

My Hindi class is entirely South Asian during both quarters, with people from different backgrounds and countries, but united against a common enemy: spelling English words in the Devanagari script (here’s Northwestern, revel in the horror of it: नॉरथवेसटरन).

But classes alone did not prepare me for the real thing. When I went to my cousin’s wedding, prepped to converse

10 nuAZN SERENADE |

“

in Hindi, I just didn’t. I was too scared to mess up, to say सनना instead of सोना and mangle the pronunciation of घर (ironically, home, ghar).

I’m not the only one. Ji said that she has often been nervous to speak Korean with people she doesn’t know, and Alava has found some Koreans and Korean Americans to be judgmental of her lack of expertise.

Alava also faces challenges communicating with family. Alava’s grandparents both speak English but are more fluent in Korean. She often finds that she can’t always understand exactly what they’re saying.

“I’ll run it through a translator, I’ll send it to my aunts who can tell me more about what they’re saying,” Alava says. “But if I could speak fluent Korean, I bet there’s so much more to them that I could know that I don’t know right now.”

Alternatively, I could get the fuck over it. Hinglish is a beautiful thing. Language is not fixed, and my relationship to my heritage and my father’s language is in my control. Hindi may not always roll off my tongue, but I can read lyrics to my favorite song. Maybe, one day, I can read a book in Hindi. The sky is my limit.

For Alava, when she was able to understand other Korean Americans’ Konglish at a convention, it was a watershed moment.

“It was the first time I felt integrated in the Korean American community properly because they also didn’t point out that I was Filipino or half,” she says.

Last quarter, in between almost being brought to tears by continuously learning and forgetting vocabulary, and struggling with the pronunciation of the four duh sounds (द, ध, ढ, ड), I realized Hindi was never going to be truly intuitive for me.

I had grown up in one language and was going to live in one language — and that was it. I will never be able to truly connect with those who came before me — the generations and generations of Desis speaking their mother tongues, each sound carrying millennia of history and culture.

And I could hate it. I could regret my childhood and resent my parents. And I could stay a pathetic, self-determined beginner forever.

Even though Alava is no longer in class, she’s finding her own ways to keep the language fresh, such as finding textbooks online. Soon enough, she wants to learn Filipino too. I haven’t even really touched on each of our deeper relationships with our family’s other languages, like my mother’s Tamil, which if I hear in public, will instantly make me homesick. Each language has a specific place in our hearts, and each language is part of a different history of our life.

My name is Desi (see: कवया or காவிய), and my face is brown, but my accent screams American. I can’t erase the years of single-language learning, but I can try and work despite it, even if I mess up kaam and kam, even if I can’t find my way to ghar. Mera ghar California mei hai, my home is California. I didn’t grow up with these languages, but I can grow with them. That’s life, baby. Sab theek hai. It’s all good. I just keep trying.

Tips from the classroom

1 — Confidence is key

Chinese language professor Jingjing Ji starts her classes by strengthening her students’ confidence in their existing knowledge and skills.

“Sometimes they do not even realize, ‘Oh, actually, I could express myself or respond to that question in Chinese,’ because in family [sic] they are so used to responding to their parents, probably in English,” Ji says.

Ji says her students’ families in China or Taiwan often laugh at them, although it is not from bad intentions.

“It’s very often they receive such kind of negative feedback, and it’s very true it’s hard to build confidence,” she says.

Ji says she has assignments in which students must talk to native speakers and another where they must talk to international students in particular.

2 — Learning context matters

Ji says that previously, her learning materials for heritage speakers often did not align with their priorities. That’s why she, along with other educators, wrote materials specifically tailored to the Chinese American experience, such as Chinese parenting and different language variations.

She says her students have loved that the material reflects their experience across different cultures.

Ji also says she teaches translanguaging, a less traditional teaching philosophy where professors start with what students want to express in English and use the class’s collective knowledge to express that idea in Chinese.

“We want our heritage students to get connected to their family and community,” Ji says. “That’s their advantage of learning language.”

nuAZN LEISURE DISTRICT |

11

Sibling ti

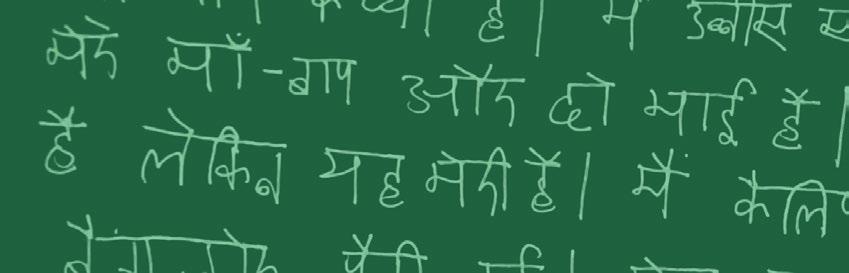

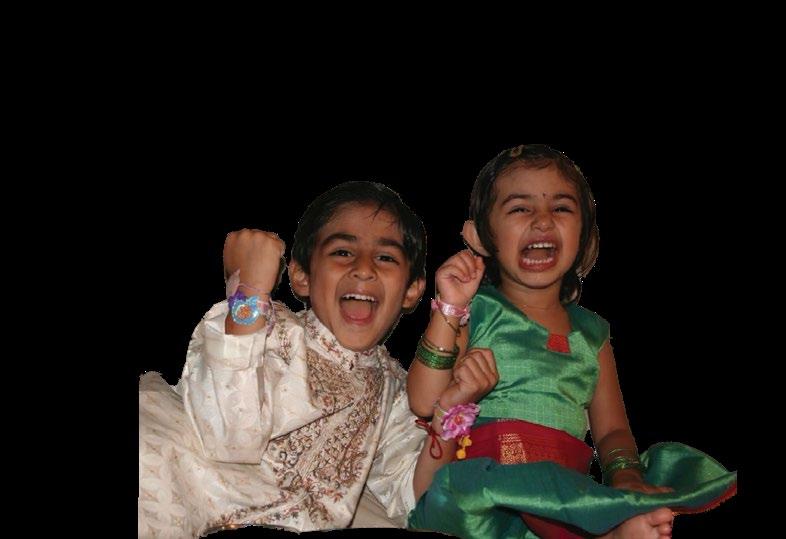

CCelebrations of the Hindu holiday Rakhi reflect what it means to be bonded by blood.

STORY BY KEYA CHADHURI

ommunication first-year Shreya Saini has been celebrating Rakhi for as long as she can remember. Her quintessential Rakhi starts with putting on her lehenga. Then, she puts a tikka on her brother Varun’s forehead with her right ring finger and thumb, marking his ajna chakra as a form of protection. She sprinkles rice on his head as a blessing, then ties a rakhi — a threaded amulet, often red and adorned with gold charms and sacred symbols — on Varun’s right wrist. He gives her cash, always amounts ending in the number one to represent seeds for growth and prosperity. Finally, the siblings feed each other sweets, like laddus or kaju katli.

Hindus from northern and western India and Nepal celebrate Rakhi — also known as Raksha Bandhan, Sanskrit for “bond of protection” — on the August full moon. Its origins are attributed to a multitude of myths, most notably the Mahabharata, where Princess Draupadi ties a piece of her saree fabric to treat Lord Krishna’s bleeding finger. Touched by the gesture, he offers her eternal protection and promises to rescue her in times of need. Over time, the torn saree became the rakhi, which the sister ties around her brother’s wrist for protection.

DESIGN

BY DIANE ZHAO

“It’s like [my brother] gets a thread and I get money,” Saini says jokingly.

Over time, Rakhi has adapted to suit evolving generational values, shifting social landscapes and new perceptions of sibling relationships. Many celebrators shift away from the idea of siblings “protecting” each other and emphasize shared love, respect and joy through transformed traditions.

SESP third-year Isha Bhardwaj has a twin sister at Northwestern and an older brother. Despite her close relationship with her siblings, the foundations of Rakhi did not necessarily reflect the true value of their bonds.

“It’s based on the premise that brothers have to ‘protect’ their sisters, which I find a little outdated and untrue,” Bhardwaj says. “Women and girls can defend

themselves, and everyone is capable of helping each other.”

Saini shares this sentiment. She used to throw tantrums, she says, because she was jealous that her brother got a “pretty bracelet” and she did not.

Instead, Bhardwaj views Rakhi as a chance to have fun.

“It celebrates sibling bonds by affirming my commitment to having a good relationship with my siblings, celebrating our friendship and getting to spend some time together,” she says.

Anthropology and Asian American studies professor Shalini Shankar says that Rakhi bears a special significance for Indian Americans.

“In the U.S., at least, it seems to be about strengthening sibling bonds in a way that I think I’ve heard various

“It celebrates sibling bonds by affirming my commitment to having a good relationship with my siblings, celebrating our friendship, and getting to spend some time together.”

— Isha Bhardwaj, SESP third-year

12 nuAZN SERENADE |

“In the U.S., at least, it seems to be about strengthening sibling bonds in a way that I think I’ve heard various parents express concerns. Who will be there for their kids?”

— Shalini Shankar, Anthropology and Asian American studies professor

parents express concerns,” she says. “Who will be there for their kids?”

In the U.S., many Indian Americans do not have the large network of an extended family to celebrate Rakhi as they would in India. As such, Rakhi holds a special significance for Indian Americans because it fosters interconnectedness within the immediate family, which provides comfort to immigrant families facing the unknown by offering a partnership of shared experiences, Shankar says. In this respect, Rakhi becomes a symbol of strength.

Rakhi still offers a special day of connection even when extended families cannot celebrate together, like Indian Americans whose relatives live in the subcontinent.

Bhardwaj mails rakhis and handwritten notes to her cousins, who she doesn’t see often. Saini makes the time to call her brother-cousins in India late the night before or early

the morning of the holiday to wish them a happy Rakhi. She ties five extra rakhis on her brother every year on her sisters-cousins’ behalf.

“I guess that’s the biggest difference in culture. In India, you consider your cousins like siblings and here there’s like a distinct separation,” Saini says.

There is no word for “cousin” in Hindi — they are the same as sisters and brothers. Rakhi helps legitimize that bond, Shankar says.

“I think that it adds validity to that way that many Indians don’t just say cousin, they’ll say ‘cousin-brother’ or ‘cousin-sister,’ because, in a way, that’s the relationship they’re fostering,” Shankar says.

Rakhi is also one of the easier Indian holidays to celebrate, Saini says, because it is relatively low maintenance. It doesn’t involve the colorful chaos of Holi or the decoration and worship of Diwali. Families also don’t have to celebrate it in one specific way.

“There’s been a lot of room for variation over the years,” she says. “Sometimes there are no Indian sweets and we’ll just feed each other Starbursts, sometimes we’ll just be in normal, everyday clothes.”

Rakhi is not reliant on its specific practices but on values of love and affection. It acknowledges a bond that is rarely attended to — taking the time to convey love to romantic partners and parents is frequent and expected, but sibling ties can often go unappreciated and unacknowledged.

“I feel like just in general, in the U.S., there’s not as much emphasis on sibling relationships,” Saini says. “But there’s appreciation for parents and even grandparents.”

Saini turns to her brother for everything, she says. She sees tying the rakhi as an act rooted in protection, care and her love for him. Even though she feels this every day, Rakhi is an opportunity to verbalize appreciation and be conscious of those, fostered relationships that escape recognition, Saini says.

“[Varun’s] been able to help me so much with things, academically, or just life experiences, and I’m never able to give back,” she says. “And it’s not like he’s ever asking for anything, but it’s just like to me, it means a lot to be able to say ‘Hey, I appreciate you. Thank you for everything you do.’”

nuAZN LEISURE DISTRICT | 13 PHOTO COURTESY BY SHREYA SAINI

Pronunciation carries traces of home.

STORY BY BEATRICE VILLAFLOR DESIGN BY XIAOTIAN SHANGGUAN “

Where are you from?”

I take in a sharp breath. “I grew up in the Philippines, but I live in Hong Kong now — that’s home.” Exhale.

“Oh?” The other person will leer at me, because I’m always an anomaly. “How did your English get so good then?”

Many people will assume it’s the international school I spent my formative years in, but I learned English in a local all-girls Catholic school in Manila.

“English is my first language. I’ve been speaking it since I was little,” is my usual reply, willing the conversation to be over.

“You don’t have an accent!” the well-meaning woman coos. “I had some exchange kids from Hong Kong stay with me, and their English was not so good.”

“But your accent is so perfect,” goes one of the more egregious responses. In those moments, I wish I could be indignant.

“What does ‘perfect’ even mean?” I would hiss. “That I sound like you?”

“It’s a compliment!” is the all-encompassing defense. I do not feel complimented. I feel like a lab specimen examined for cracks in its skin.

I never realized I had an accent until I moved abroad to Hong Kong at 10, and my tongue stumbled over the British pronunciations of toh-mah-to, vit-ah-min and purr-chased (not per-chased).

My accent has taken on many lives. I use it like snakeskin, shedding it at the right time.

Sometimes I am Bea, said like the Bey-yah my parents gave to me. For many years, I was the Bee-yah my friends in Hong Kong adopted. My British teachers called me Bee, an alter-ego I occasionally slip on.

For Asian and Asian American students like me, the art of the accent is a constant consideration as we learn to switch from one intonation to another. First-generation Asian Americans sometimes discard their accents in order to assimilate, as others subconsciously take them as emblematic of one’s cultural citizenship and race. Some experience microaggressions because of the way they speak, but many also take pride in their unique accent — it’s a lot to juggle.

“I’ve never gone a single day here at Northwestern without thinking about my accent and the accent that I put on or put off,” Medill first-year Ashley Wong says.

Wong, an international student, says she’s mastered code-switching — the act of modifying one’s voice in response to certain situations. She describes her accents as a hybrid of American, Singaporean and British.

Code-switching demands a certain degree of mimicry, which can be difficult. Medill and SESP first-year Anavi Prakash, who was born in the U.S. but lived in India from the ages of three to nine, says she “trained” herself to have an American accent as an adolescent because she hated the Indian accent she grew up with.

“Your voice is such a huge part of who you are, but it didn’t match how I saw myself because I saw myself as ‘American first, Indian second,’” Prakash says.

A confidence boost for her thirdgrade self, while she was still attending school in India, was when a teacher asked her if she was an American after hearing her speak. Prakash was proud to be seen as American first, especially when surrounded by other Indians.

ACCENTS AS RACE

The American entertainment industry has manufactured the non-standard Asian accent, dialects with distinct word stress and pronunciations compared to standard American English, as a means to characterize foreignness. It has used the accent for decades, often for a cheap laugh, University of Virginia Media

Studies Professor Shilpa Davé says. An example Davé highlighted isTheSimpsons character Apu Nahasapeemapetilon, who was voiced by Hank Azaria in accented English for 27 years.

One of the few brown-skinned characters in fictional Springfield, Nahasapeemapetilon is an Indian immigrant. Azaria is a Caucasian man speaking what could be called a stereotypical Indian accent, what Davé calls “brown voice.” The actor stepped down from playing the character following public criticism of racial stereotyping in 2020 and apologized “to every single Indian person” a year later.

“It was separating out the visual aspect from the actual vocal aspect and saying, ‘how do we look at race?’” Davé says. “It can’t just be visual. It’s not only visual, there is a particular sonic element to this.”

These non-standard accents emphasize word stress differently than in standard American English, as influenced by sounds and pronunciation learned in other languages.

For example, I adopt a Filipino accent with family, saying sahl-mon and uncom-fort-able. These words are remnants of my mother tongue, Tagalog, a phonetic language where your mouth appreciates each letter in every word.

Davé notes that accents can be a representation of a person’s position in society, whether through location, race or gender.

“Accent is not limited to sound or the performance of brown voice; it can also be defined as an accessory or cultural characteristic that is designed to highlight a dominant look,” Davé writes in a 2017 article about racial accents in Hollywood.

Regarding South Asian culture, this might mean American TV shows amplify “non-standard” cultural practices like arranged marriage.

“Accent is influenced not just by the way in which we talk, but what we talk about as well,” Davé says.

CULTURAL CITIZENSHIP

Davé points out another function of having the standard American accent — acculturation and assimilation.

Davé’s research suggests that fluency in English and having a “standard American English” accent are tied to “cultural citizenship” in the U.S. She writes that speaking standard American English associates someone with class and upward mobility as well as better schools and jobs.

McCormick second-year Emily Ye grew up translating for her father, who immigrated from China about two decades ago and whose English speaking skills are limited. Ye, who grew up in a predominantly white area, served as a translator in everyday locations like the doctor’s office or the grocery store.

Ye’s father failed the written exam twice when trying to renew his driver’s license because he couldn’t read in English, she says.

“I remember he was talking to me and my siblings and just telling us how difficult it was for him,” she says. “Even though he had all this experience driving, he had to prove himself through this exam. And there’s that block of not being able to read the exam and not having any other options like a translator.”

Ye says even when her father might try to interact with someone in English, the other person may defer to her for a response.

“They’ll talk to him like a child, talking loud or talking slower, talking simply,” she says. “If they were talking to me, they wouldn’t be talking that way.”

BLENDING IN

Ye says she does not think that this was intentional, but having these attitudes can appear as if the other person is looking down at her father. She says seeing these interactions happening within her communities can be difficult.

“Because I know these people personally, I know there’s so much more than how they’re being perceived,” she says. “That’s something really important. The way that you speak or if you have an accent does not say anything about you.”

Wong says she will adopt an American accent with strangers, like when she’s ordering food at a restaurant or visiting the Social Security office.

“I use it because I know it gets me places sometimes, and sometimes it gets a foot in the door when I need it to be,” she says.

In her work, Davé says there is a key difference between accent proficiency and performance. Minimizing the role of performance in accent perception would mean renegotiating how we gain regional or cultural markers from the way we pronounce words.

Pui Tak Center program administrator Sarah Swetz Huang has been teaching English as a second language to new immigrants in Chicago’s Chinatown for a decade. She specializes in teaching students who have little to no experience in English, so she says accent reduction has not been the Center’s priority for their students.

“Fluency over accuracy is more important,” Swetz Huang says. “As long as you’re able to successfully communicate your meaning then, I think, especially for the lower level learners, that’s the most important thing.”

For example, Swetz Huang corrects speakers if they cannot pronounce the letter Z in zero, because saying ee-ro changes meaning. However, she says she would not correct “some- sing ” into “some- thing ”.

Swetz Huang says learning English has helped her students improve career prospects and gain greater independence — affording them that “cultural citizenship” that Davé writes about.

RECLAIMING THE ACCENT

While a lot has been done in the last few decades to improve representation for accents in the media, Davé says some accents are still not considered race-neutral.

As the country becomes more multilingual, it’s necessary to consider our personal biases and what it means for an accent to carry “authenticity,” she says.

“We do see many more different types of accents now and not just among Indian Americans, but also among Asian Americans,” Davé says. “It’s not just one accent that’s associated with a particular group, but multiple accents.”

An international student whose first time visiting the U.S. was last fall, Wong acknowledges that being able to mask her accent to her advantage is a privilege.

Still, she says it isn’t her authentic voice: changing her accent erases the traces of her Singaporean identity.

“I understand that this is not the reality for a lot of my international friends who can never get around the accent because they simply cannot,” Wong says. “They lack the ability to camouflage the accent, and sometimes I wonder whether they’re better off than me.”

Wong says she doesn’t want others to misunderstand her intentions — her American accent is not part of her identity. While she’s proud of her native accent, she says it’s easier for those at a café or a train station to understand a more standardized sound.

At NU, Wong says she uses a full Singaporean accent when she’s around

other people from Singapore on campus. In her year, that’s only a few others.

“Whenever I use my [Singaporean] accent, I feel so much more connected to home, especially when Chicago isn’t exactly a good home hub for Southeast Asians or Singaporeans,” Wong says. “I take every chance I can get to be in touch with fellow Singaporeans.”

Similarly, Prakash says she’s realized how important her Indian heritage is after reconnecting with parts of her culture through visiting loved ones in India. Because her American accent slips into her Hindi, she’s pointed out as the “American girl” when she travels to India. Now, she says her Indian identity has “priority” over being “American.”

“What I like to say is: No matter where, sometimes I’ll be in a place and I’ll stand out because of the color of my skin — that’s in America,” she says. “And sometimes I’ll stand out because of the way I sound — my accent — which is in India.”

For many first-generation Asian Americans, reclaiming the accent has inadvertently become a vital part of their identity. Now, my friends say my everyday accent is some curious mixture of standard American with British inflections. NU friends say my voice becomes more English in the classroom — echoes of my time at a British international school.

For a long time, I wasn’t sure how I wanted to be called. What does it matter if it’s Bey-yah, Bee-yah or Bee?

Going by Bey-yah , the way it’s pronounced in Tagalog, has felt like a homecoming.

Even if it gets pointed out often, I love my accent. How could I not?

It was formed in the standstill traffic of Manila, challenged in the tall towers of Hong Kong and rests in the waves along Lake Michigan. It’s the sound of an accented, immigrant tongue: a true amalgamation that intermingles where I used to be and where I am now.

16 nuAZN SERENADE |

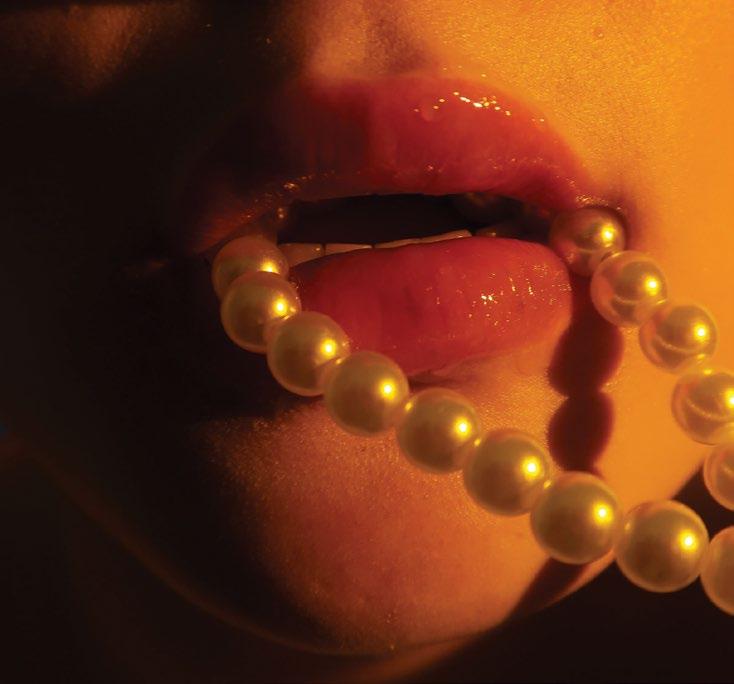

SELF-serenade

Overcoming the embarassment of jerking off.

STORY BY YIMING FU DESIGN BY JACKIE LI PHOTOS BY JOYCE HUANG

Iwanted to slam the MacBook into the ground, shatter the screen with a baseball bat, douse it in gasoline and light it on fire. I read the screen again, my cheeks red hot — The U.S. Department of Homeland Security had fined eighth-grade me $100,000 for illegally downloading child porn. I had to pay it upfront, and I had no other way of leaving the page.

I was dead meat.

Since the pop-up told me I would likely be going to jail, I had no choice but to sheepishly show the computer to

my mom. Maybe she would understand and scrounge up some bail.

“Did you watch porn?” She stared at me with a stone-faced expression.

“Yes,” I barely eked out, wanting to evaporate.

“Don’t do this again.”

My mom did some research on her phone, learned this was a common porn site virus and disabled it on the laptop. She lectured me on a million and one reasons why watching porn is bad for you, which included rotting my brain with depravity, leading to

homelessness, incarceration and ruined career prospects. My mom drove me to a dentist appointment right after. It was the most tense and silent car ride, with me stewing in shame and her stewing in anger. We didn’t exchange any words, but the message was clear: Self-pleasure was an arrestable offense, and I would not disappoint my mother like that.

Everyone gets aroused. Masturbation is one of the best ways to learn about your sexual preferences and take care of yourself. But if you’re anything like me, masturbation is an awkward thing to talk

nuAZN WORLDWIDE | 17

about, more so than crushes, kisses and hookups — the quintessential elements of a gossip session with friends.

“Masturbation is such a scary, huge word,” says Vic Liu, author of Bang! Masturbation for People of All Genders and Abilities. “But at the end of the day, it just means touching yourself. Like that’s the least scary, chillest part of sex, and yet we’re more OK with talking about hookup culture than we are about masturbation, which is so weird to me.”

Masturbatory shame can stem from a variety of sources, including religious stigma, outdated scientific studies that claim masturbation “wastes” sperm and makes men weaker and a general culture that doesn’t talk about it much.

When I was a 10-year-old boy, sex was the butt of every joke. My friend Edwin would run up to people on the playground in fifth grade, screeching “do you MASTURBATE?!?!?!” He would do this for the entire 30-minute recess period, and if you got hit with an Edwin-attack, the best course of action was to shake your head vigorously and deny the allegations until he left. I think all of us were left scandalized by the thought of touching your private parts because it meant you were a lonely, laughable loser who had nothing better to do with your time.

In September 2021, British girl group Little Mix released “Love (Sweet Love),” a lead single about masturbation for their greatest hits album Between Us. I remember feeling confused about why anyone would sing about masturbation for the general public. The topic seemed unrelatable, unglamorous and overtly intimate. “I been spendin’ time on everybody else/ It’s time I did for me/Love, sweet, love, oh, baby,” the lyrics read.

When I look back, there’s nothing scandalous about these lyrics. Perhaps what scared me most was how vain solitary self-pleasure seemed. I didn’t think it was something to be proud of.

Growing up, I used to elevate partnered sex as the symbol of “making it,” especially as a gay Asian American teenager who jealously watched my straight white friends tear through relationship after relationship in high school.

But jerking yourself off isn’t a lonely, sinful or incel activity. It’s powerful. In a world that encourages you to find your “soulmate” amid a flood of love songs, rom-coms and dating apps, I believe finding your own pleasure is an equally valuable pursuit.

Cecilia Villero is a Filipina American sex educator and pleasure activist. She says though her immediate family wasn’t religious, her parents raised her with “traditional” values influenced by Catholicism. She was also discouraged from talking about sex because she grew up with the view that the things you talk about represent and reflect your family.

“One of the things I was told as a kid is you’re not supposed to date until you’re 18, and then from there

it’s essentially like you’re trying to get married,” Villero says. “That certainly affected how I learned about my body and how I learned about pleasure. The omission of information can lead to misinformation and shame.”

Liu says her parents were culturally conservative and never had any conversations about sex.

“It’s not like they were like ‘We believe in Jesus in this household, and that’s why we will never masturbate!’ I don’t think they ever said the word

“At the end of the day, it just means touching yourself.”

Vic Liu, author of Bang! Masturbation for People of All Genders and Abilities

18 nuAZN SERENADE |

masturbate to me,” Liu says. “But it was implied.”

person disease. It’s actually a better way to get to know yourself, your likes and dislikes, and can also lead to better partnered sex, though that doesn’t have to be the primary goal.

But Liu’s parents have turned around. When Liu fundraised on Kickstarter to launch “Bang!” their publisher had reward tiers with different sexual names. She was pleasantly surprised to find her dad donated to the “orgy” tier, which involved buying 10 copies of the book to give away.

My pornography-near-arrest story is the only time I ever breached the conversation of sexuality with my parents. At the time, I felt my slipup jeopardized my family’s future for generations to come.

It blew my mind to learn that most people masturbate. For people aged 20-24, 85.5% of respondents reported masturbating in their lifetime, while 62.8% of male and 43.7% of female respondents reported masturbating in the last month.

Masturbation is not a symptom of lonely

“We’ve been taught that your job is to pleasure your partner. But that’s 100% not true,” Villero says. “They’re not in charge of your pleasure. We’re in charge of our own pleasure.”

For Villero, one way to take charge of your own pleasure is by looking at your body in a mirror and observing what you love. She says she still gets insecure when she does the activity, but she has learned to block out criticisms other people have told her about her body.

“I’ve worked on turning those messages around and thinking, ‘Bitch, you’re so cute,’” Villero says. “Focus on one thing you like about yourself and focus on saying those positive things to the rest of your body. It doesn’t have to be a big thing. And it can be a lifelong thing.”

In my fourth year at Northwestern, I think I’m finally getting there. I used to hinge my worth on validation from others and the ways I could satisfy them, be it with my personality, sense of humor or what my body has to offer.

When I started therapy a year ago, I connected the dots between my personal and professional life and recognized my incessant desire to satisfy someone else while forgetting to listen to what my body was telling me. I found my way back to myself by making lists of things I’m good at, making lists of doing things I liked and then actually going out and doing those things.

I believe everyone needs to intentionally carve out spaces for themselves where they are the sole object of their affection. For me, this looks like buying a bouquet of $5.99 fuchsia roses every time I’m at Trader Joe’s or lighting my candle and journaling at night, writing down what I did during

the day that makes me proud. Sexually, this looks like trying new things when I masturbate, whether I’m reading something, watching something or just using my imagination. It means learning new tricks in books or on the internet and experimenting with duration and touch and other toys to figure out exactly what I like. When I catch myself in the mirror these days, I find myself sexy. Tell me that at any earlier point in my life, and I would’ve straight up laughed at you.

Masturbation is so wonderful because it’s a moment I have all to myself. I get to indulge myself, take care of myself. I know I can count on me every single time, and I know I’m going to deliver exactly what I want because I’m the best at it. That confidence is hard to shake.

“We’ve been taught that your job is to pleasure your partner. But that’s 100% not true.”

Cecilia Villero

Filipina American sex educator and pleasure activist

nuAZN WORLDWIDE | 19

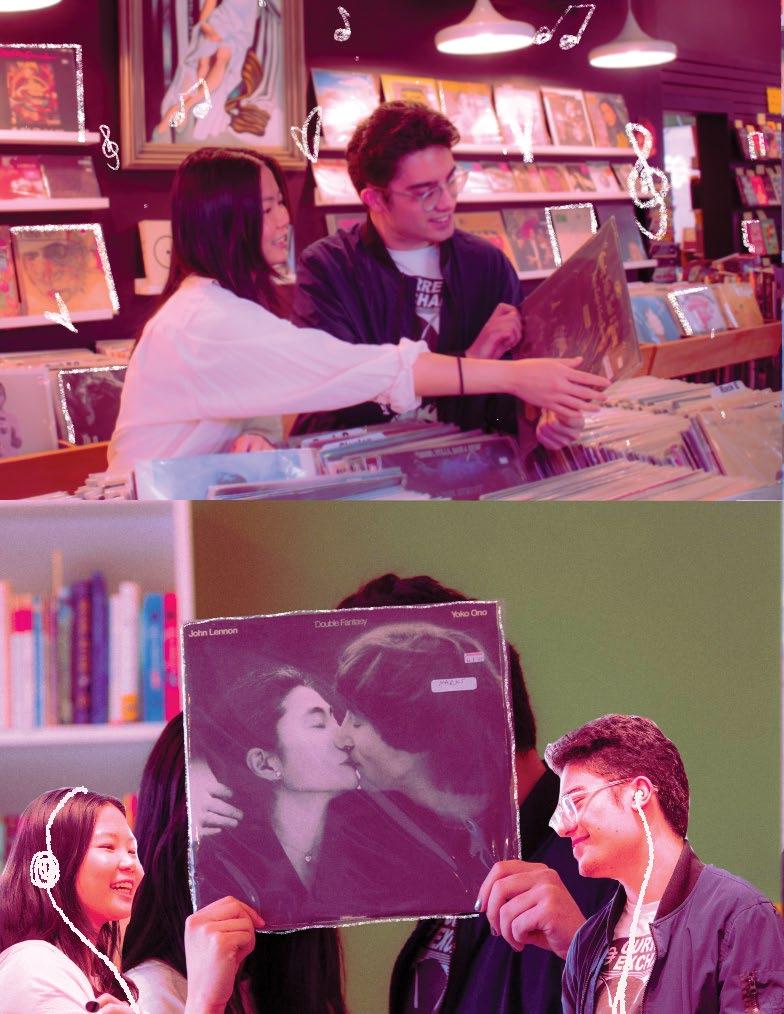

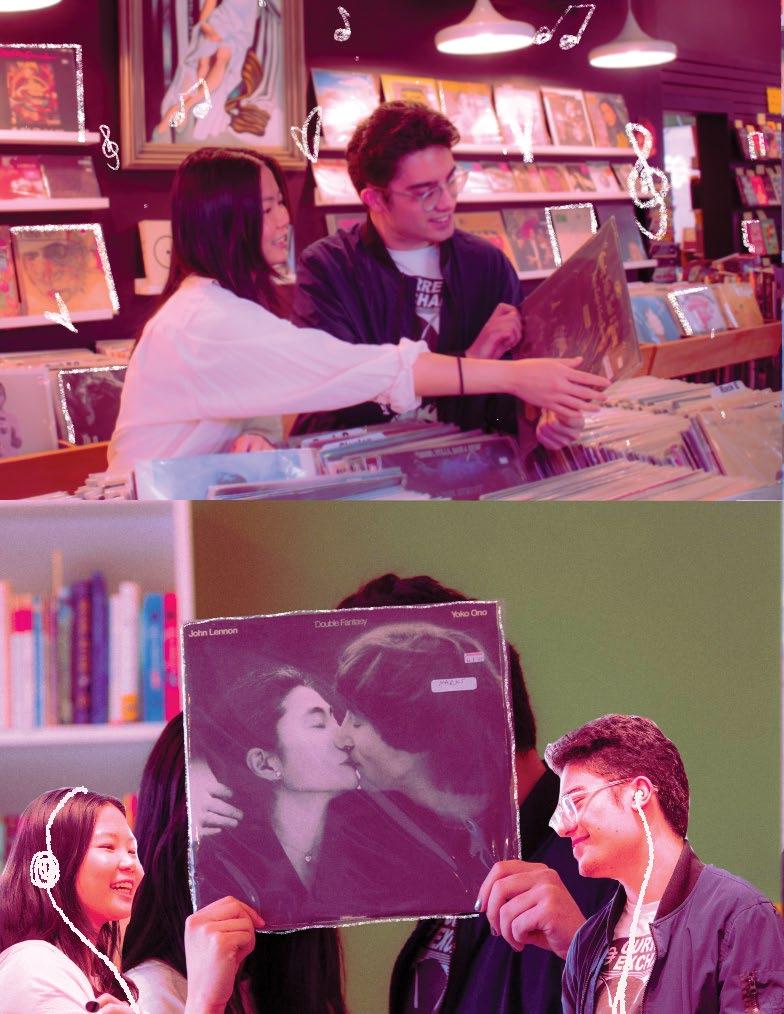

Song of life

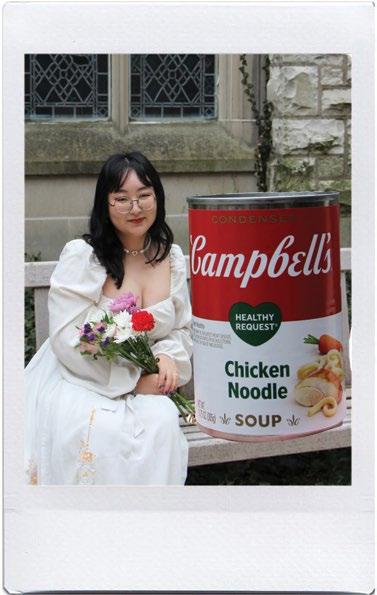

We can find serenades in nearly every facet of our lives — and what better time to meditate on these special moments that make our lives more melodious than the endless cold of the winter months, which most of us spend holed up in our rooms, struggling through assignments. For me, one of the things that enriches life is love: It casts a pinkish, vibrant glow on an otherwise menial existence. Music, too, romanticizes even the simplest commute between classes. And dance, something passed down in my family from my Dida, my maternal grandmother, turns a quiet night on the beach into something magical.

Take a moment to soak in the positivity, love and fun emanating from this quarter’s shoot, and then, don’t forget to serenade your life, too.

— Lianna Amoruso

PHOTOS BY LIANNA AMORUSO

PHOTOS BY LIANNA AMORUSO

That didn’t

come out right

Translating queerness poses challenges for multicultural youth.

STORY BY JOYCE LI DESIGN BY GRACIE KWON PHOTOS BY LIANNA AMORUSO & KIM JAO

Jinan jeon, [jeoneun] yeoja iss-eoss-eoyo. Geuligo oneul, jeoneun namjaaeyo.”

That’s something SESP firstyear Shepherd Lee Williams learned to say after two quarters of Korean classes: Last year, I was a girl. And today, I am a boy.

Williams came out as transgender to his parents in 2021 and began hormone replacement therapy soon

thereafter. Though his appearance and voice have changed, he has yet to come out to his maternal grandparents, who primarily speak Korean.

“I’ve been telling my grandparents that I got COVID, and now I sound like this,” he says. Like many queer Asian Americans, Williams faces a language barrier when talking to his family about his identity. For some, this hurdle is also compounded by the outdated, derogatory or entirely absent vocabulary surrounding same-sex attraction and gender identity in several Asian languages. Williams, who is biracial, says his mother didn’t speak much Korean with him growing up. He says one of the first Korean phrases he taught himself is “jeoneun

teulaenseujendeo imnida” — “I am transgender.” However, he says he isn’t sure his grandparents will know what it means. Like ge-i (gay), reseubian (lesbian) and kwi-eo (queer), teulaenseujendeo is a loanword from English.

“The national conversation [in Korea] around gender and gender identity is still very much less about trans people and more about the feminist movement as a whole,” Williams says. “I do know conversations about transness are starting to happen more often. It’s just kind of complex, so I don’t even know how well they’ll understand.”

The unfamiliarity around queerness in East Asian countries is also why John Lee* (Medill ’23), who says he has been considering coming out to his parents, plans to do so in English. It’s the language he’s more comfortable with — he says he speaks a mixture of Mandarin and English at home but leans heavily on the latter.

“I feel like I would end up having to come out almost entirely in English just to explain what all my positions or beliefs are — concepts that are basic or inherent to me but would probably take a lot of explanation for them to get,” he says.

24 nuAZN WINTER 2024 |

“

“That’s something that they would immediately understand. That’s their language and their worldview.”

— John Lee*, Medill ‘23

Lee* knows the Mandarin word for “homosexual” — tóng xìng liàn — but struggles with its more clinical connotations compared to colloquial English words like gay or queer. Similarly, the most widely used Korean term for homosexuality — donseongaeja, or “person who loves someone of the same sex” — is a neutral term but has taken on negative associations due to widespread homophobic attitudes in Korean society.

When Belle Lu came out over the phone to their dad in Mandarin ahead of their graduation in 2022, they grappled with the same issue. The thenNew York University fourth-year had come out in English to their mother months prior, but their dad speaks mostly Mandarin. If he was going to fly to New York to see them graduate, Lu wanted to know that he was there because he loved them for who they are — not the “lie” they had kept up.

“Hey, I have something important to tell you.”

“Are you doing drugs?”

“No, I —”

But when the time came, the right words still did not. “I’ve labeled myself as ‘queer’ ten thousand times, but I’ve never labeled myself anything in Chinese,” Lu says.

In recent years, LGBTQ+ communities in Asia have developed new slang to describe queerness. Terms like tóng zhì, (used to refer to those attracted to the same sex, literally “comrade”) lā lā (lesbian) and kù’ér (queer) have been adopted by Chinesespeaking online spaces. In Korea, queer people have adopted iban (abnormal person), a playful, ironic subversion of ilban (normal person).

However, for Asian Americans, especially those who grew up outside of their country of origin, vocabulary surrounding queerness can be limited to what they hear at home. Lu says tóng xìng liàn feels inherently shameful to her because she is not involved in Mandarinspeaking queer communities and has only ever heard the term used with negative connotations.

In the end, they steered clear of labels and told their dad “wǒ xǐ huān nü shēng” — “I like girls.” He took it well.

“I think he was glad I wasn’t doing drugs, primarily,” Lu says.

But the conversation ended there. Had she come out in English, Lu says she would have spoken more about her identity, but navigating the conversation

in Mandarin would have required her to take on more labels than she was comfortable with.

Lu acknowledges they eventually want to reclaim tóng xìng liàn. For the time being, though, they prefer not to use it. When they came out to their grandmother months after graduation, they did so by saying that they and their girlfriend “zài jiāo wǎng” — “were dating.”

“In English, I’d probably say I’m gay or I’m a lesbian or I’m queer — I’d be really direct about it,” she says. “But in Chinese, for example, you don’t have to be so direct if you don’t want to put a label on yourself.”

To avoid the more impersonal undertones of tóng xìng liàn, Lee*, whose father is a pastor, says he is considering drawing from queeraffirming theological ideas to help him communicate his identity to his family in Chinese. When he comes out, Lee* hopes to say that God’s love is all-encompassing — that God loves him not despite his queerness, but because he created Lee* that way.

“That’s something that they would immediately understand,” he says. “That’s their language and their worldview.”

nuAZN WINTER 2024 | 25

In some Asian countries, English words and Western cultural references have been adopted by queer communities and serve as shared vocabulary across disparate cultures. Nisha Kommattam, professor of comparative literature at the University of Chicago, says English is used for the sake of practicality in the diverse linguistic landscape of South Asia, where over 600 languages are spoken.

“People who don’t speak English still tend to use the English terms very often, such as ‘gay’ or ‘lesbian,’” Kommattam says.

The word queer has also been adopted by South Asian academics, though its negative connotations sometimes still persist. There’s also the issue of the letter Q doesn’t exist in most South Asian scripts, making the word look “really weird” in writing, Kommattam says.

But Kommattam says some people object to the adoption of English terms to explain queerness. For example, conservatives in India have long argued that homosexuality, along with single parenthood and divorce, is a Western import with no place in Indian societies.

To combat these perceptions, there has been a movement within some activist and academic circles to coin

new terms based on Sanskrit to replace English ones — such as svavargga-laingika, a Sanskrit-derived adjective that translates directly to “same-type sexual” in Malayalam.

Kommattam says she thinks such terms are a good idea in theory, but in practice, they are unlikely to catch on.

“No one wants to say that,” she says. “It sounds medical, it sounds academic, it sounds like using the word ‘heteronormativity’ at a McDonald’s.”

For Kommattam, translating queerness is a multilayered issue: The translation of English terms to local languages overlaps with the translation of academic jargon to everyday speech.

“What I’m trying to do actually in my classes is raise the awareness of how we don’t want to impose possibly colonial legacies, possibly elitist and English-speaking or Western-dominated terminologies, onto local lived existences,” she says.

This year, Lee* will be traveling to Taipei, where his family is from. He says he’s looking forward to immersing himself in Taipei’s gay nightlife scene and queer communities.

he says. “When I look at myself and all I can think about is how I have traits that make me a woman … it makes me unhappy with myself. So in changing these things, I think I am helping myself be a more complete person.”

Williams sees his grandparents less now, partly because he’s been avoiding them. Since he started learning Korean, they’ve stopped speaking English with each other.

“That’s really terrifying,” he says. “But I need to be ready to tell them I am transgender.”

*A name in this story has been changed to anonymize a source who has not come out to his family.

“I feel like I’ll end up absorbing how gay people talk about their own identities,” he says.

For now, Williams says the rudimentary vocabulary he knows doesn’t capture the complexities of how he feels about his identity.

But when his Korean is good enough, he knows what he wants to say.

“Beautiful men can exist, and despite how I was born, I feel like I’m a man,”

26 nuAZN WINTER 2024 |

Halmeoni, saranghaeyo

Remembering my grandmother on her behalf.

STORY BY CATE BIKALES DESIGN BY INDRA DALAISAIKHAN

STORY BY CATE BIKALES DESIGN BY INDRA DALAISAIKHAN

27 WORLDWIDE | nuAZN

“저는 당신의 손녀 케이트입니다. 저를 기억하시나요?”

“I am Cate, your granddaughter. Do you remember me?”

She looked at me with a blank stare, and I felt a piece of my heart break.

For a long time, I denied the signs of my grandmother’s dementia. I refused to believe she could ever forget me — the person who had grown up for the past 20 years right by her side. But the horrible thing about a disease is it can make your worst fears become reality.

In just four months, Maya, as I have always called her, transformed from cheerful and loving, albeit slightly forgetful, into a shell of the woman she once was. She had completely disappeared into her own brain.

As I stared into her hazy eyes at the memory care facility, she felt thousands of miles away. Not only was I losing my best friend and the person I have looked up to my entire life, I felt I was losing a part of myself: my connection to my Korean heritage.

Growing up biracial, I often felt split between my Korean and white self, never fitting fully into one or the other.

I felt too white in affinity groups but also never quite thought my white friends understood me.

It was because of my grandmother that I developed a stronger connection with my Korean identity than my white one.

My family spoke English at home, but because my grandmother never became proficient in the language, I learned how to speak Korean to communicate with her. My speaking ability was elementary at best, but having her around to practice always made it easier to hold onto those basic skills.

Maya also helped me develop an appreciation for traditional Korean food, clothing and music.

Every New Year’s, my brother and I would dress up in our vibrant pink hanboks, adorned with beautifully embroidered flowers and shapes, and bow to our grandmother, wishing her the best for the new year: 새해 복 많이 받으세요 (saehae bok mani

badeuseyo). Afterward, she would fill the dining table with all kinds of Korean delicacies — steaming bowls of kimchi jjigae, plates piled high with soft and chewy tteokbokki — and my family would eat until we felt like our stomachs were going to burst. In a way, she showed her love through that food. Whenever I told her I was full, she always made me eat just one more bite.

Maya’s desire to put family first inspired me to treat those around me with love and respect. I remember the joy I felt each day when I saw her smiling face waiting at the bus stop to pick me up. After we got home, the food would already be waiting for me. Her gimbap was always my favorite, her little handwrapped gifts of flavor.

Every time I looked into her eyes, they would be sparkling with love. All I could see was how proud she was of me.

The rest of the afternoon was always filled with laughter. No matter what we were doing — reading silly Korean books, singing Korean children’s songs, watching meaningless Korean reality TV — my grandmother always reminded me of how important it was to stay connected to that side of myself.

But how do you hold onto a part of yourself that is so strongly tied to a person who is slipping away?

28 nuAZN SERENADE |

PHOTOS COURTESY OF CATE BIKALES

In 2020, the early stages of her dementia began to show. She would misplace her keys, and we would spend hours searching to find that she had left them in the fridge or in the bathroom closet. Sometimes, she would ask me a question and, after I answered, immediately ask it again. I could tell she was frustrated with herself, and it was not her fault, but it was easy for me to get irritated with her behavior.

I started seeing her less as I got busier with school and friends. She would invite me to sleep over at her apartment, and I would choose to stay home and do school work instead. When I became vegetarian, she never really understood what it meant. It often became a point of contention, and when she made me traditional Korean food, which often contains meat, I would eat the leftovers at my parents’ home instead.

I regret it. I wish I had taken advantage of the time I had with my grandmother when she was still mentally present. I wish I had given her the same unconditional love she always showed me.

It hurts to see her face now and realize I did not cherish these last few years. It hurts even more that we no longer share the memories of our years spent side-by-side. It takes losing (or starting to lose) someone to realize how much they truly mean to you.

As she falls away, I grapple with how to hold onto my own Korean identity. With a fading connection to the language and its traditions, how do I stay anchored to that side of myself?

she is not herself mentally, her presence still reminds me of the love and care she has shown me throughout her life. Although it feels like part of my identity is slipping away with her, I realize that losing her does not mean I have to lose what she has taught me. I will still be Korean when she is gone.

I will continue to uphold her treasured values of kindness and family. I will learn the lessons and recipes that she made such a big part of my life

speak English, she was forced to work as a seamstress in a New York City sweatshop to provide for her family. My mom always told me that, through it all, she never complained. She never showed signs of anger.

Now, she continues to fight.

A few days before I left home to return to Evanston, my mom and I once again visited my grandmother in the memory care facility. For the majority of the visit, she was in her own world, talking to her sister on an invisible “cell phone” about how she was going to be killed and insisting that the food we had brought her was poisoned. She looked anxious, almost weak. It pained me to see her in that state. It was hard to imagine she was the same person I had always known — someone who was always so positive and full of life.

so I do not lose it when she is gone. I will keep our memories and my heritage alive, and carry with me the resilience she has shown throughout her life.

In the past year, I have asked myself this question dozens of times. At the beginning, I was often left with a sense of distress. It felt impossible. But now, I realize the best I can do is take advantage of the time I still have with her. Even if

My grandmother has always been a fighter. She left Seoul, South Korea, in 1977 — the only home she had ever known — and immigrated to America to start a better life for her three children. Because she could not

But, there were moments of clarity. As I sat by her side, tears streaming down my face, she took my hands into hers, looked me in the eyes and reassured me: “ 괜찮아요 (gwaenchanhayo)” — “It’s OK.”

In that moment, I was reminded of the timeless nature of love. My grandmother’s love has impacted me in ways that I will carry with me forever. Each day, her memory fades, but my connection to her and all she has taught me grows stronger.

The next time I visit her, I will hold her hand tight and remind her how much she means to me.

Even when she is gone, I will remember her smile. I will remember the way she laughed with me, the way she cried with me, the way she brightened my day. I will hold my grandmother close to my heart and lead a life of courage and love, just as she has.

할머니, 사랑해요 (halmeoni, saranghaeyo). Grandmother, I love you.

29

WORLDWIDE | nuAZN

Losing You, In Translation | 一言难尽

Naming the bruises I didn’t know you left.

STORY BY JOYCE LI DESIGN BY JESSICA CHEN

刺激 (cì ji), n, v, adj. — To stimulate, provoke, upset or excite. As a noun, “刺” means “spike”; as a verb, it can mean “to stab.” 激 also appears in 激动 (emotional), 激 情 (passion) and 感激 (thankful).

In the aftermath, my friends ask me why I stayed. What can I tell them?

That I speak the language of endurance? That patience is in my blood, that blind faith runs through my veins, that I have been taught to survive on it? That my heart had time to break several times before I noticed?

I don’t have answers, just the memories of that long winter when, as a quiet, resolute devotion bloomed like frostbite at my knuckles, I gave myself to you because I didn’t know how else to keep you with me.

对不起 (duì bù qǐ), v. Sorry. Literally, “unable to face.” You had been trying to get me to watch New Girl with you for weeks, and I finally caved. You didn’t warn me, though, that the early seasons had a lot of Asian jokes — one in almost every episode. You’d acknowledge each one with a small “I don’t remember that being in there” and a sudden inability to meet my gaze. Thirteen episodes in, you reached your limit with “take that Chinese head out of your Chinese ass, Ming” and said we didn’t have to keep watching if I didn’t want to, though you promised it would get better.

I told you the show didn’t bother me, that the jokes were too absurd to be offensive. I didn’t know what else I could’ve said, when I saw the way you sang along to its theme song and shrieked with laughter at the one-liners you had memorized, when I recognized every little quirk you’d picked up from Jess Day as a child. I understood that, like her, you existed in a world where jokes like these weren’t worth remembering, where their targets never appeared on screen — and my presence threatened to shatter it all.

This show wasn’t made for me, but it made you who you are, and you were sharing it with me. So I kept watching, and every time your eyes flickered away from the screen like momentary static, I accepted your unspoken apology.

酸 (suān), adj. — Sour, sore or something in between: the sting in the bridge of my nose when I know I’m about to cry (鼻酸) or the twinge of hollowness in my chest afterward (心酸).

I learned what Guinness pie was when your mom made it for us. It was delicious and strangely familiar — the beer-infused concoction uses the same cut of meat my dad puts in his signature braised beef stew. He’d made me three thermoses of the stuff when he drove me down to Illinois that fall.

I didn’t want to like your parents. Something bristled in me every time you’d relay what they said about my family, who I’d lied to so I could come meet yours: how terribly sad it was that I couldn’t come out, how willing they’d be to “adopt” me, even, if I’m ever looking for a “white ass family.” Still, when I reached for your hand under the dinner table and your dad said he was glad you’d met me, my heart threw itself against my rib cage like a hungry dog. Just between us: even after you took it back, I couldn’t forget the taste of acceptance pooling behind my teeth, every mouthful a betrayal.

30 nuAZN SERENADE | AN ENCYCLOPEDIA OF US Vol. 1

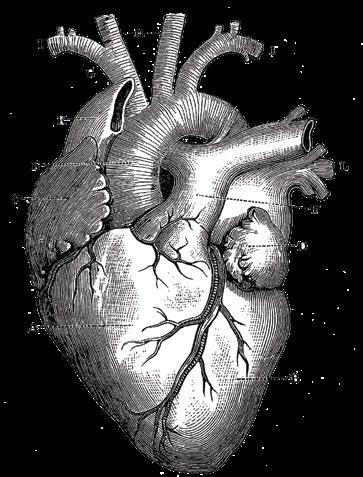

Fig. 1314. Bos Taurus

Fig. 748. Sequoia Sempervirens.

美国 (měi guó), n America. Literally, beautiful country.

You taught me to love California. The orange trees dotting grassy hills in the horizon, defended valiantly by a “do not pick” sign we later ignored. The cluster of deer who judged us from a distance. The smell of damp soil that would cling stubbornly to my clothes weeks after the rain soaked us to the bone in the redwood grove. The shallow creek bisecting a fern-encircled clearing tucked deep in the forest behind your house, where we snuck out to smoke and share secrets. You were proudest of the stars, which shimmered when it got dark like crushed glass.

My fascination amused you. You laughed at my little outbursts of “cow!” out the car window every time I spotted the gentle creatures grazing contentedly on the side of the road — an everyday sighting for you. But later you pointed out a house and told me its residents had moved in recently. “It’s so great that we’re getting more diverse,” you said as we drove past what you later told me was one of the only Black families in the neighborhood.

背影 (bèi yǐng), n. The silhouette of a person from behind. Literally “back-shadow.”

After that, I kept catching myself scanning the sunbleached storefronts of the diners and artisanal shops of your town for faces that looked like mine. I found just one: a woman in the produce section of the town’s only Whole Foods, studying the neatly arranged rows of kale bundles and heirloom tomatoes like there was something else she was hoping to find.

忍 (rěn), v. — To tolerate.

When separated, 刃, the top portion of the character, is “blade.” 心, the bottom portion, is “heart.”

What began as a joke quickly curdled. I stared at my phone, my cursor blinking and blinking beneath your texts as they piled up one by one: I haven’t personally colonized anyone. I’ve been spending a lot of time feeling very shitty about the actions of my ancestors recently, and it feels really gross to be lumped in with them. Go ahead and rag

on white people for being colonizers, but I would prefer it if you didn’t rag on me.

I began to type, as calmly as I could, something about how you couldn’t separate your presence and position in this country from the legacy of colonialism. But angrier words welled up in my eyes and threatened to spill, hot and stumbling and urgent — and futile. I knew nothing I could write would make you understand that this was about more than your guilt, that your guilt was a privilege I could never earn, that it afforded you a distance from the weight of a history I could not so easily shed.

I’m sorry I’m not reacting the way you want me to, came your response. I don’t know why I’m reacting like this. I’ve been crying for like 20 minutes.

Later, in your dorm, you explained as if to a child that I had a right to make these jokes but you’re asking me not to, because you wanted to be better than who you came from. I nodded like I understood and tried to make myself feel sorry I made you cry. You put an arm around me and we watched TV and we didn’t talk about it anymore.

But just then, I thought about leaving you. For a second, I was gone.

养伤 (yǎng shāng), v — To heal. Carries the idea that a wound (伤) must be taken care of or raised (养), like a pet or a child.

In the aftermath, new skin grows to cover what is hurting: the small of my back where you used to hold me, the top of my head I would tuck beneath your chin, and the memory of you, always apologizing, though neither of us had the words to explain what for. It was always easier to forgive you than to pry myself away.

nuAZN GATHERING | 31 AN ENCYCLOPEDIA OF US

Vol. 1

Fig. 555. Brassica Oleracea var. Sabellica

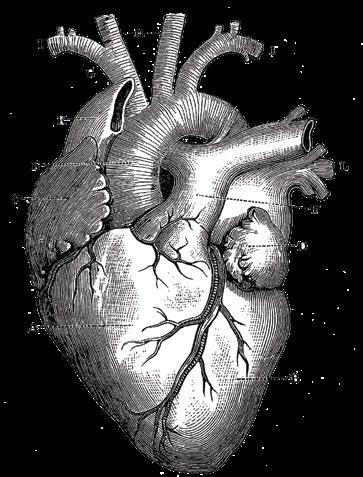

Fig. 520. Myocardium

In good hands

My sweaty palms, to have and to hold.

STORY BY LUCAS KIM DESIGN BY ESTHER TANG

STORY BY LUCAS KIM DESIGN BY ESTHER TANG

Ihave a superpower: I can make my palms sweaty whenever I want. Though it’s not the kind you read about in the comics, I call it my superpower because it seems to be the one thing I can set my mind to and accomplish without fail. In actuality, it’s a condition called focal hyperhidrosis: excessive sweating in one or more parts of the body (for me, my palms and the soles of my feet). It’s said to affect 3% of the population. I don’t go around telling people I have it, though — “superpower” sounds cooler.

I’d estimate my palms are sweaty around 80% of the time. Fortunately, there are no severe medical implications, but that’s not to say my sweaty palms haven’t had their fair share of consequences on my life. No one wants to touch a clammy hand, so all forms of palm-topalm contact are far down on my list of favored ways to greet others. Unfortunately, my preferences fly out of the picture when an acquaintance approaches me in the library with a wide-eyed smile and an extended hand, blissfully unaware of the grave error they’re about to make.