nuAZN

Editor in Chief

William Tong

Print Managing Editors

Cate Bikales

Shravya Pant

Multimedia Managing Editor

Anavi Prakash

Leisure District Editors

Sydney Gaw

Sarah Lin

Katie Tsang

Photographers

Trois Ono

Michelle Sheen

Ashley Zhou

Web Developer

Beatrice Villaflor

Publisher

Selina Jiang

Creative Directors

Jackie Li

Xiaotian Shangguan

Photo Director

Joyce Huang

Worldwide Editors

Kunjal Bastola

Esther Lian

Rachel Yoon

Multimedia Editors

Anita Li

Meryl Li

Misha Manjuran Oberoi

Contributors

Gathering Editors

Ellie Carney Yong-Yu Huang

Multimedia Producers

Kaavya Butaney

Indra Dalaisaikhan

Michelle Sheen

Yitong Zhang

Designers

Jessica Chen, Abigail Jacob, Summer Jeong, Yelim Kim, Gracie Kwon, Jamie Li, Mariana Ma, Michelle Sheen, Serena Song, Yitao Wang, June Woo, Sabrina Zhang

Scott Hwang, Izzie Jacob, Emily Jiang, Medina Miranda, Chloe Park, George Sun

Expect the unexpected. This life lesson often crashes into us when we’re not paying enough attention.

But it’s how we handle surprise, shock and failure that defines us. Every setback is a launchpad for improvement. Every rejection is a chance to chart your own course.

nuAZN 34 encapsulates how members of the Asian diaspora ricochet off unexpected circumstances, whether that’s subverting the boundaries between art forms or bouncing between tough comingof-age transitions. Some surprises are disappointing — others might be pleasant — but each and every one provides a chance to grow.

On page 8, learn how the Metal Gear Solid series has defied stereotypes about Asian video games for decades. Get a taste of how Asian Americans work around allergies and still connect to their traditional cuisine on page 19. In our main photoshoot on page 21, travel from sterile panopticon to brutalist dystopia. And on page 35, learn how to get back at your ex with brutal hexes from across Asian cultures. On our website, nuazn.com, watch our video introducing

Corporate Members

Christine Shin

Lucy Yao

Madelyn Yu Pearl Zhang

Models

Gauri Chugh, Amir Dhami, Jasmine Guo, Nicole Gunawan, Hwirim Jang, Chloe Jung, Ariel Lan, Irene Li, Shahzeb Shah, Edison Tan, Chelsey Tao, Sophia Tay, Chester Wonchoba

Han Training, a queer- and trans-affirming gym in Chicago that channels anguish into motivation.

For me, the last months of 2024 were an emotional rollercoaster, filled with terror, shock, rejection and unexpected trips to the hospital. This issue is part of my personal process of recovery.

Ricochet also continues nuAZN’s post-COVID comeback — it’s a testament to the painstaking effort that current and former editors, reporters, designers, photographers and other staffers have put into our magazine’s rebirth. As you flip from page to page, I hope the stories we share inspire you to find whimsy, duality, perspective and inspiration from life’s unpredictability.

William Tong, Editor in Chief

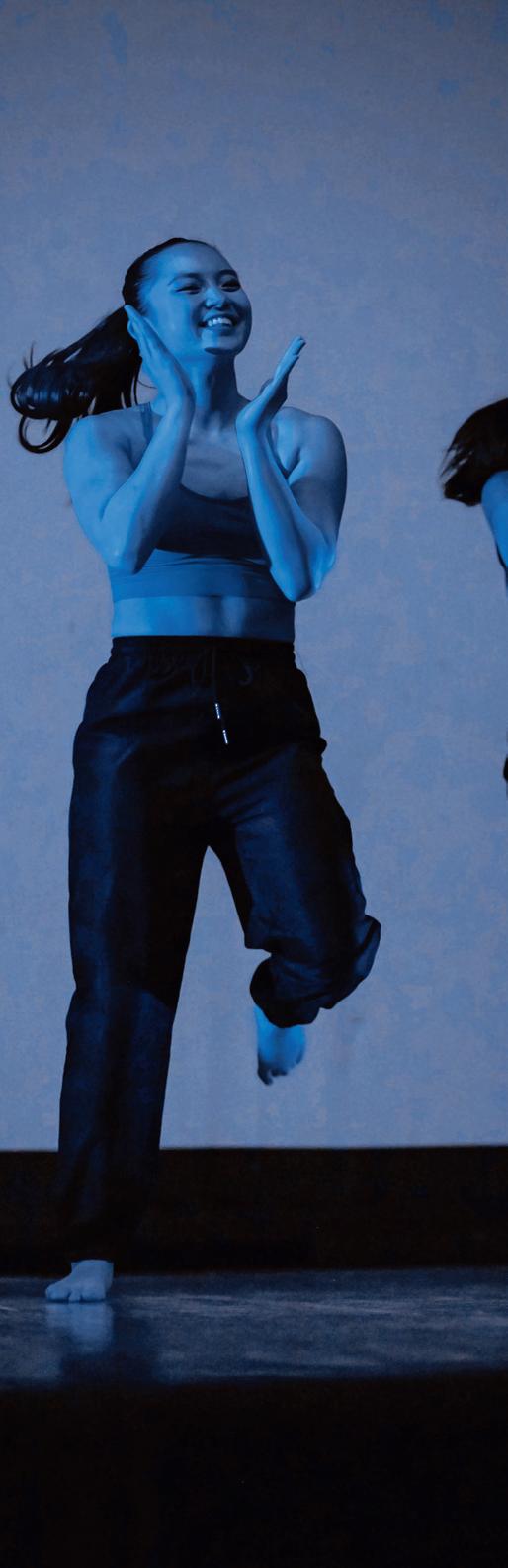

Choreographed to the sharp snaps of long bamboo sticks against SPAC’s studio floor, McCormick fourth-year Sophia Tay teaches fellow dancers routines on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays. The other days, Tay trains to the pulse of Bollywoodfusion medleys amplified onto competition stages.

For Tay, cultural dance is more than performance — it is a bridge to both her own heritage and new traditions. At Northwestern, Tay leaps between Tinikling, a traditional Filipino folk dance, and a fusion of Bollywood and South Asian cultural dances.

“These are two very different groups of people, but they both just share that same commonality of the love of dance,” Tay says.

Born in the Philippines and raised in Singapore, Tay grew up surrounded by a variety of cultures. In her high school’s yearly cultural showcase, she volunteered to participate in Caribbean and Nigerian dance performances.

After coming to NU, Tay immediately felt the shift from being part of the ethnic majority to a minority.

She quickly joined Northwestern’s Filipino organization, Kaibigan, for its warm community and traditional dance workshops.

“When I found out that they do Tinikling, I was honestly surprised because that was something that we did back in my elementary school in the Philippines,” Tay says. “Knowing that my culture was being shared and appreciated here was really great to see.”

Kaibigan’s Tinikling program encourages everyone to audition, regardless of their dance experience. Weekly classes build up to a performance at Kaibigan’s annual Pinoy Show.

This year, Tay is serving her first year as a Tinikling instructor. Her co-dance committee head, McCormick third-year Elizabeth Park, describes Tay as warm, kind and energetic. Park recalls a Kaibigan social event where Tay went out of her way to welcome new members.

“Tay incorporated everyone into our games and animated the atmosphere,” Park says. “She’s bold and confident in herself.”

Tay says Kaibigan played a vital role in helping her find a sense of community at Northwestern. While she cherishes the opportunity to represent her heritage through exploring traditional practices with fellow students, she’s also found a home at Deeva, Northwestern’s audition-based

“These are two very different groups of people, but they both just share that same commonality of the love of dance.”

— Sophia Tay, McCormick fourth-year

Bollywood and South Asian fusion dance team.

“It’s so important to broaden your perspectives and not just stick to your own people,” Tay says.

In her freshman year, Tay attended Deeva’s spring show performance and was inspired by their tight synchrony and close-knit community.

“I wanted to join a team that was a bit smaller — where I could get to know everyone on a deeper level,” Tay says. “They’re like my family here.”

Deeva attends annual state-wide competitions and frequently collaborates with South Asian performance groups from neighboring schools. While Kaibigan prioritizes fostering cultural appreciation, Deeva emphasizes achieving cohesion, Tay says.

Tay says she finds it challenging to switch between the expectations of the two teams.

“I have to restrain myself from correcting people during [Kaibigan] clinics to do things perfectly when that’s not what it’s about,” Tay says.

Additionally, balancing the time commitments of both

teams on top of academics can be strenuous, she says.

Tinikling and Bollywood fusion require intricate hand and footwork, demanding practice outside of meetings.

Between Deeva’s regular rehearsals and Kaibigan’s Tinikling workshops, Tay spends up to 22 hours a week in the studio.

While Deeva trains dancers to perform a blend of South Asian and Western movements, Kaibigan typically teaches Tinikling in its most traditional form.

But this year, Tay is bringing a new spin to Kaibigan’s 2025 Pinoy Show: modern Tinikling.

Tay plans to blend pop music and hiphop elements into her choreography. She says fusion will demonstrate that Tinikling and other cultural dances can evolve over time while preserving their core traditions.

As graduation approaches, Tay says she’s grateful for NU’s opportunities to explore cultural performance and solidify her notion of identity.

“My parents always joke that since I’ve come to Northwestern, I’ve become more Filipino,” Tay says.

STORY BY JACKIE LI DESIGN BY MARIANA MA X

As snow flurries drift across the frigid Alaskan landscape, security cameras whir. Guards march back and forth. You have 12 hours to prevent a terrorist nuclear launch and save the world.

With the clock ticking, the mission falls to four buttons, an analog stick and your expert control over Solid Snake, the legendary hero and main character of the video game Metal Gear Solid

>> SOLID SNAKE >> ./info/snake

* Born in 1972

* Nationality: USA

* Height: 6’0” (182 cm)

Created by game developer Hideo Kojima, the seven-part Metal Gear Solid collection, released from 1998 to 2015, directs its characters through solo infiltration quests to destroy the titular Metal Gear, a nuclear tank created for catastrophic warfare. While it has the makings of a generic action-adventure narrative, the franchise’s greatest strength is how it surprises audiences, both in the nuance of its subversive anti-military messaging and its push for Asian gaming, culture and characters to be taken more seriously.

As Japan — home to titles like Super Mario Bros. and Pokémon — pioneered the game industry, the country built a positive reputation for its games. Japanese franchises are often tied to adorable avatars and colorful gameplay as a result of the Cool Japan movement, an attempt by the government to distance the country from violent parts of its past.

“Characters like Hello Kitty, Pikachu and Mario were explicitly mascots for that effort and to represent an image of Japan that

was cuter, more humane and more friendly,” Asian American Studies Prof. Tara Fickle says.

However, departing from the animated look of Nintendo and the cyberpunk fantasies that Western films like Blade Runner (1982) expect Asian aesthetics to embody, Metal Gear Solid’s gritty realism and explicit conversations about war and violence align more with Hollywood’s action blockbusters and other military games. Though its American characters and setting might seem like an unconscious way to make the game more palatable to the West, Metal Gear Solid manages to retain its unique Japanese identity. From mecha-inspired, pilotable robots to subtle nods to Buddhist and Shinto philosophy, Kojima weaves homages to Japanese culture into the very DNA of his franchise.

Metal Gear Solid also utilizes its character design and narrative choices to make two important points about masculinity. It undermines the emasculation of Asian men we see in Western spaces and dismantles society’s ideal of masculinity to broaden its definitions of what makes someone “man enough.”

Western society’s perceptions of manhood often rest on pillars of dominance, detachment and selfsufficiency. Traditionally, to be a man was to be as physically fit as you were mentally and socially capable, never swayed by emotions or any other

human shortcomings. Heterosexuality and attractiveness, too, have historically been tied to masculinity; if you couldn’t get a girl or simply didn’t want to be with one, you were painted as inferior. Through adverse portrayals in American media as nerdy, sexless, awkward and feminine, Asian men came to take on a subordinate status. Cisgender heterosexual white men were viewed as the standard, while Asian men found themselves struggling for the same kind of respect.

Metal Gear Solid seems like it would easily lend itself to that Western male standard. In the first game, the seemingly impossible premise of saving the world falls on the main character Solid Snake, who is tall, muscled and stoic. These traits conveniently fall in line with what modern masculinity idolizes: heroism and strength. While the game does center itself on these two concepts, it’s much more effective in shattering the illusion of traditional masculinity.

Where we might look up to Solid Snake for being a self-sufficient and independent man, the game underscores that his self-chosen solitude and nihilism come from deepseated trauma and misery — instances of emotional weaknesses that are commonly seen as “feminine.” Where we want him to continue walking this path of being a deadly, domineering soldier-turned-mercenary for the sake of heroism, the game counters that mold by highlighting how much he’s been dehumanized while trapped in the makings of war. According to the game, the masculinity that Snake

seemingly represents is nothing more than a curse and a myth. When showing his so-called weaknesses and breaking away from his macho actionhero archetype, he’s portrayed as no less of a man.

It goes beyond a single game, too. When fans wanted Snake to return for the sequel, Kojima instead made a new main character, Raiden, whose soft voice, slim waist and feminine features completely disrupted the “manly” precedent Snake had set before. These decisions force us to interrogate society’s obsession with upholding toxic masculinity and, by extension, its racial exclusivity, especially when we begin to take Snake’s identity into consideration.

Snake, as we come to find out, is actually biracial, which takes on a new edge depending on which context his character is played in. When American fans play the Metal Gear Solid collection, Snake’s Asian American identity subverts the classic preconceptions they may have about Asian masculinity. Audiences are forced to divorce ideas of race and manliness when Snake proves that being of Asian descent can coexist with being respected as a man.

We shouldn’t ignore gaming’s massive presence and impact. It’s an industry with an estimated worth of $184 billion in 2022 — nearly seven times that of its movie counterpart. Yet analyzing its influence is all the more important when it comes to the massive contradiction existing at the heart of the gaming community: Video games are “the most advanced in terms of graphics and processors, but the most regressive in terms of social representations,” Fickle says.

When playable power is vested in the audience’s hands, it matters who these milliondollar franchises frame as protagonists we idolize and enemies we vilify. In a sphere where vestiges of Orientalism, toxic masculinity and swaths of

bigotry still persist, it’s important that we have games willing to push back, rather than playing to stereotypes and the repression of diverse identities.

The subversion in Metal Gear Solid breathes life back into characters who, in other circumstances, may have just been vessels for harmful rhetoric and shallow stereotyping. After nearly 27 years, the games leave behind a unique legacy that stands out amidst the spectacles of its action-adventure peers, preserving the humanity of both its in-game characters and the real communities they represent.

>> RAIDEN >> ./info/raiden

* Born in 1983

* Nationality: Liberian

* Height: 5’10” (178 cm)

STORY BY GEORGE SUN DESIGN BY JAMIE LI PHOTOS BY TROIS ONO

Three hundred and fifty-one miles per hour. That’s the top speed McCormick secondyear Ryan Liu’s shuttlecock could fly at. On the court, he meticulously plans his every step, his squeaky shoes marking the gym floor as he jumps in the air for a smash.

Northwestern’s Badminton Club is thriving. Twice a week, the lineups

This year, Liu leads the club. His journey with the sport started in high school after he quit track and field.

“I didn’t feel like [track] was something I wanted to continue,” Liu says. “I needed to pick up a new sport, so I turned to badminton.”

After coming to Northwestern and joining the club his freshman year, Liu says he has become a part of a tight-knit community that is competitive yet fun.

Edison Tan, Weinberg fourth-year

grow and the courts fill up as dozens of members meet to play at Blomquist Recreation Center. It reflects a broader trend in the badminton community: The sport is growing, and Asians are at the forefront. At the 2024 Badminton World Federation Finals, competitors from Asian teams won four out of the five events.

“We all really just love to play,” Liu says. “Everyone’s always smiling.”

The club’s welcoming atmosphere draws everyone from undergraduate students to Ph.D. candidates. It’s not just a place to compete; the club turns into a social hub every night where friendships form. There’s a sense of community between each rally and game.

“Before I start a match, I usually get to know the people that I’m playing with,” Weinberg second-year Tolu Onitilo says.

Members not only join to improve their skills but also to enjoy the social atmosphere. As a result, the club has thrived, growing each quarter as newcomers turn into regulars.

Badminton originated in the mid1800s, when British military officers stationed in India modified the racket game poona by adding a net. Now, the sport has evolved. Every member of the 2024 U.S. Olympic badminton team was Asian American.

“It’s such an East Asian dominated sport,” Bienen and Weinberg second-year Dhruva Balan says.

However, Southeast and South Asians are making their mark, too.

In many Asian countries, sports — including badminton — are a way out of poverty. In Indonesia, for example, national team members earn about 10 times the average income. Many individuals raised in the rural countryside see sports as a way to lead a better life and financially support their families. As Asians emigrate out of their home countries,

“We all really just love to play. Everyone’s always smiling.”

— Ryan Liu, McCormick second-year

their passion for badminton diffuses into their new communities. With more Asians moving to Australia for example, badminton participation numbers have grown from 226,000 in 2020 to 311,000 in 2022.

At Northwestern, badminton is played out of passion and curiosity. For some, picking up the sport came with an element of surprise. Balan started playing badminton through a high school physical education class.

“I discovered that I’m kind of good at it,” Balan says. “And so, that’s kind of how I started.”

For others, it came later. Weinberg fourth-year Trevor Chau began after arriving at Northwestern. Having played tennis for most of his life, he was looking for a form of cardio that he could do year-round. He landed on badminton.

Chau says that, for the most part, skills carry over between the two racket sports. Coming from Wisconsin, where the Asian population is just 3.3%, Chau says he experienced a culture shock after coming to Northwestern.

“We had a decent mix of representation on my tennis team,” Chau says. “In comparison, here there’s a lot more Asians.”

Chau says given the slim Asian representation in his hometown, his school wasn’t able to garner enough interest to start a badminton club. Stories like these are not uncommon.

“I went to high school in Connecticut,” Weinberg fourth-year Neha Navrange says. “There aren’t many Asians who play badminton, so there was no team.”

Instead, Navrange played softball and field hockey in middle school, two sports traditionally dominated by white players. Navrange says it was difficult to gel with people given her limited shared experiences and backgrounds with them.

At Northwestern, the club has seen a growing trend toward diversity, especially with the club exploding in popularity the past few years. Meanwhile, the sport is growing on a global scale. According to the International Olympic Committee, more than 330 million people play

WSTORY BY KATIE TSANG

hen Chen, a former member of the K-pop boy band EXO, announced his marriage in 2021, Weinberg second-year Yujin Tatar* remembers his fans growing furious online and demanding he leave the group.

Chen’s marriage quickly became major news in South Korea. Reports said fans felt disappointed and disconnected from him because of the announcement. Tatar says she was shocked to see how public figures in South Korea could not have a private life.

“People seem like they feel entitled to have a say in how the idols live their life,” Tatar says. “They’re commodities.”

Cancel culture is prevalent in both Western and Eastern media and can have far-reaching implications, from online and in-person harassment to limited future job opportunities. However, Asian entertainment, especially K-pop, can cultivate an even more intense

continue to appear in movies or release music after getting canceled, Korean idols are more often forced to leave their careers behind or disappear from the public eye altogether. Not everyone can survive the media storm and fan outrage.

“They want the entire celebrity’s life to be catered towards the fans, and so if they can’t maintain this perfect image, then that’s where the criticism starts to come into play,” McCormick third-year Nayeon Kim says.

With the release of Squid Game ’s second season in December 2024, fans saw former K-pop star T.O.P return to the spotlight as Thanos after an eightyear hiatus. In 2017, a South Korean court charged T.O.P for marijuana usage, which is illegal and highly stigmatized in South Korea.

KWON

Following the indictment, T.O.P repeatedly expressed how sorry he felt and committed to improving himself before disappearing from the spotlight. This is a common response for many Asian celebrities after getting canceled. Korean stars will issue handwritten public apologies for their actions, then take hiatuses from their public careers ranging from a couple weeks to several years. Giving fans enough time to forget about the scandal, then re-garnering support, is key.

Weinberg first-year Jackie Le says T.O.P managed to recover after his drug scandal because his former K-pop group, Big Bang, retains established influence across the world.

“I think it’d be different if he was a newer idol,” Le says. “He’s very well established. At this point, I think people disapprove or they look down upon it. Maybe they’ll shit talk him. But otherwise, it’s like, ‘Whatever we move on with our day.’”

Kim says from an American perspective, smoking marijuana should not stop a celebrity from continuing their career. She says the Squid Game 2 role served as a good opportunity for T.O.P’s comeback.

“I feel like it was him just being

Asian media outlets often scrutinize celebrities for behavior that their Western counterparts deem normal, such as talking about mental health or being a feminist. Despite varying legal statuses, drugs like marijuana are somewhat normalized in America, with references appearing in popular songs, movies and music videos. South Korea and other Asian countries do not tolerate drug use.

In October 2023, Studio XU dropped Lee Sun-kyun, best-known for his role as Mr. Park in the Oscarwinning film Parasite , from the project No Way Out following a police investigation into his alleged use of marijuana and ketamine. Despite denying the claims and never being formally charged, brands pulled his face from advertisements. He disappeared from public view as fans and trolls bashed him online. Soon after, he died by suicide, drawing the world’s attention to the intense cancel culture in Korea.

“It’s just so unfortunate that that’s a rising conclusion that a lot of people in entertainment in Asian media are coming

“They’re not just this fantasy figure in your brain that you can project yourself onto and whenever you want.”

In contrast, Western audiences tend to tolerate — even support — celebrities facing fire for drug use, Kim says. She uses Demi Lovato as an example of an American star known for overdosing and doing drugs in the past who has continued their career.

“In America, I feel like it’s more focused on the recovery and how they get over that addiction,” Kim says. “Meanwhile, in Korea it’s just focusing on the fact that they did it.”

On whether cancel culture is justified or if it’s gone too far, Le

“They’re not just this fantasy figure in your brain that you can project yourself onto and whenever you want,” Le says. “They have needs, they have wants and they should be allowed those needs and wants.”

* Tatar previously contribued to nuAZN.

LEISURE DISTRICT — Jackie Le, Weinberg first-year

STORY BY RACHEL YOON DESIGN BY MICHELLE SHEEN

ChatGPT’s linear algebra answers weren’t satisfying Communication third-year Muse Miao. The computations were sometimes wrong and the explanations unclear. With her midterm approaching, Miao needed a solution. She heard DeepSeek was stronger in logical thinking.

“I just opened DeepSeek and let it do some mathematical proofs for me,” Miao says. “I think it’s really helpful. The explanation is really clear, so whenever I want to solve math problems, I just go to DeepSeek instead.”

DeepSeek, an AI company based in China, released its problem solving model R1 in late January. Its reasoning was comparable to OpenAI’s ChatGPT o1 and cheaper, despite the company not having the same access to materials under U.S. export sanctions on computer chips.

Some Northwestern students say it signals new and more accessible opportunities in the AI world.

McCormick second-year Evan Chen first heard about DeepSeek from a friend who was using it for an assignment. Later, he saw the news about chip manufacturing giant Nvidia’s share prices plummeting about 17% following DeepSeek’s release.

“I think that it really alerted a lot

of the top AI companies like OpenAI to start being more efficient with their production output,” Chen says.

Proponents of DeepSeek note the caliber of its logic and problem-solving models as well as its open source code, which allows programmers to access and manipulate the software to fit their own projects. OpenAI has not released its code.

Weinberg third-year Ronit Mehta is interested in OpenAI’s next steps.

“With DeepSeek being open source, if people can go and see what goes into that, the draw to ChatGPT goes away a little bit,” Mehta says.

Weinberg second-year Nandan Dhanesh says he’s excited for the widespread accessibility of open source code from quality AI models like R1 or Meta’s Code Llama.

While programming for Slow, an AI journaling app he co-founded, Dhanesh drew on Llama to develop user-facing advice.

“The cost of the actual AI part of your service is so low and everyone has access to a model of equivalent quality,” Dhanesh says. “It really becomes about building things that people want on top of the AI.”

While DeepSeek’s entrance has shocked the market, it probably won’t take OpenAI’s spot anytime soon. A few days after DeepSeek released R1, OpenAI bounced back with o3-mini,

which is vastly cheaper than their popular o1 model and “optimized for STEM reasoning,” according to a press release. Comparisons of the two show that the o3-mini was faster in solving problems. R1 has also shown weak spots in answering controversial questions about the Chinese government and other censored topics in China, according to users.

Dhanesh doesn’t see DeepSeek replacing ChatGPT. He prefers the more established service for most tasks.

“It can do 95% of the things I need it to pretty quickly,” he says. “It gives me a pretty concise answer. I rarely have to prompt it twice to do the things that I want it to do.”

01111001

McCormick fourth-year Sabian

Atmadja has won what many Northwestern students strive for every year: a full-time offer with management consulting firm Bain & Company.

Atmadja, who is originally from Indonesia, hopes to work in the U.S. after graduation — but that’s not up to him. To stay in the country long-term, Atmadja will have to obtain an H-1B visa.

“If I get it, then I can work at that company indefinitely, and if I don’t get it, I’m probably going to be sent back home,” Atmadja says. “So there’s a lot of uncertainty on that front.”

Most international students seeking work in the U.S. after graduation find themselves confronting the unpredictable H-1B visa process — filled

with logistical hurdles, random chance and rules that could change any year. Ongoing debate within President Donald Trump’s political circles surrounding specialized immigrant workers has only compounded the uncertainty.

For some NU international students, that means entering the job search with concerns and priorities in mind, including why they want to stay and work in the United States.

Atmadja is focusing on higher pay and work culture as he starts his career.

He worries about work-life balance and rigid hierarchical dynamics back home in Asia.

“It’s very much like the boss tells you what to do, and you have to follow what the boss does, no matter what you do,” Atmadja says.

The H-1B visa allows foreign workers in “specialty occupations” — those requiring “highly specialized knowledge” and the equivalent of a bachelor’s degree, according to the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) — to live in the U.S. for up to three years after graduation. The visa can extend to six years. Obtaining an H-1B is a complicated process. Before applying for the visa, an applicant must find an employer willing to sponsor them.

That requirement was a factor that made consulting companies an appealing choice for Atmadja.

“They are quite generous with sponsorships,” Atmadja says.

Not all companies will extend that courtesy. McCormick and Bienen fourth-year Evan Chen says needing sponsorship can make companies less likely to hire international students — even if their websites don’t explicitly say so.

“If I ticked that box, there are many times where, literally 30 seconds after I submitted the application, I would get the rejection letter, which made me pretty pissed off because they could’ve just told me and not wasted my time,” Chen says.

Increased discourse around H-1Bs has reduced that problem somewhat, he adds.

The annual visa cap presents another hurdle for international students.

According to USCIS, a student who found a willing sponsor joined 758,994 eligible entries for 65,000 available slots in 2024 — a spike in applications from previous years, when applicants had a roughly 25-40% chance of winning the lottery. Data from 2025 shows eligible registration numbers dropped back down to about 470,000.

This means that international students are acutely aware that, even after securing a post-graduation job offer, nothing is guaranteed.

Weinberg third-year Tanat Chavapokin, an international student from Thailand, plans on working in finance after graduation. According to him, employers in the finance industry will typically move people who don’t win an H-1B visa to a regional office outside of the U.S. temporarily before trying again. That is what Chavapokin expects to happen if he secures a full-time offer after graduation but doesn’t win the H-1B lottery.

If that doesn’t work, Chavapokin might pursue an MBA. Otherwise, he would return to Asia to seek other options there. However, he prefers to stay in the United States.

“The opportunities here are the highest,” Chavapokin says. “It is the finance capital of the world.”

How the Trump administration may change the H-1B program is not clear. During his first term, Trump criticized the system for displacing American workers and issued an executive order targeting the program. H-1B rejection rates rose from 6% in 2016 to 15% in 2019, plummeting to 2% in 2024.

Vivek Ramaswamy, have argued the United States does not produce enough talented engineers and should expand the H-1B program.

Some conservatives disagree. Elizabeth Jacobs, director of regulatory affairs and policy at the right-leaning Center for Immigration Studies, says the program needs significant changes.

At the start of his second term, Trump has expressed support for the H-1B program, backed by leaders in the tech industry who have become some of his close political allies — but others in his base are still calling for more restrictive policies.

Debates over bringing overseas workers to the United States aren’t new. The 20th century saw a gradual shift in U.S. immigration policy away from national origin quotas and toward visa limits that prioritized relatives of U.S. citizens, refugees and specialized foreign workers.

The H-1B emerged toward the end of this shift. In 1990, the government created the visa for 65,000 annual workers.

The policy tried attracting highskilled labor with protections for American workers. To maintain domestic wage levels, Congress mandated that H-1B recipients could not be paid below the prevailing wage for similarly employed workers. Meanwhile, the growing tech industry lobbied to raise the cap, according to the Migration Policy Institute, a centrist immigration think tank.

Debate over the balancing act has continued. Supporters of Trump’s second term in the tech industry — most notably Elon Musk, the CEO of Tesla and owner of the social media platform X — have advocated for the persisted use of the H-1B program. Musk lamented the shortage of engineering talent on X in late 2024.

“The reason I’m in America along with so many critical people who built SpaceX, Tesla and hundreds of other companies that made America strong is because of H-1B,” Musk said in another X post.

He, along with fellow Trump ally and former Republican presidential candidate

“With the majority of H-1B employers or employers who seek to petition for H-1B workers, there’s actually no requirement to demonstrate to the to hire an American worker,” Jacobs says. Some employers dependent on H-1B workers or who have previously violated H-1B rules can be required to make those demonstrations, however.

Jacobs, who worked in the Department of Homeland Security under the last Trump administration, would like to see the current government “revive” two regulations for H-1Bs from the end of the first Trump term that former President Joe Biden’s administration didn’t implement.

First, she says the government needs to increase wage rates — appropriate salary levels based on region and occupation — for H-1B recipients. That way, employers can’t use low-cost

international labor to replace American workers, Jacobs says.

The second regulation would replace the current lottery with a system that prioritizes wage rates. Jacobs says this policy would be an improvement, as wage rates are a reasonable proxy for the “value” that a worker contributes to the company and the overall economy.

“We view [these] regulations as being pro-worker,” Jacobs says. “And that means pro-worker in terms of beneficial to American workers and to foreign workers.”

“If I ticked that box, there are many times where, literally 30 seconds after I submitted the application, I would get the rejection letter.”

— Evan Chen, McCormick and Bienen fourth-year

talk about the current people in the Trump administration also supporting H-1B so there’s some kind of divide in there.”

Jacobs also raises concerns with the misuse of the H-1B program by companies that use to work in the country, she says.

With so much uncertainty surrounding their futures, many international students look for strategies to maximize their chance of successfully passing through the H-1B pipeline.

After graduation, students on an F-1 student visa are eligible for work directly related to their major on a 12-month Optional Practical Training (OPT) period, which can serve as a stepping stone to an H-1B visa. Students with STEM degrees can receive an extra 24-month STEM OPT extension — meaning more chances to win the lottery without having to leave the country.

This is why having a governmentdesignated STEM degree is so important for international students. The U.S. government updates the list of eligible degree fields, most recently adding Environmental/Natural Resource Economics to the list in July 2024.

Chen says he’s unsure if he’d be allowed to be sponsored by two places at once.

“Not only has that affected the career that I chose, anything else that I pick other than that is also kind of affected by that choice,” he says.

The H-1B also makes it difficult to switch employers. If a worker decides to accept a job offer from a different company, their new employer must file again for a new H-1B. Although this transfer does not require reentering the H-1B lottery, it still deters workers from changing jobs, tying people to the sponsoring company for visa stability.

Depending on a student’s nationality, the H-1B may not be the only option to stay in the United States. Chen holds a Canadian passport, meaning he’s eligible for the TN visa, a different working visa open to Canadian and Mexican nationals that does not involve a lottery.

In late 2024, Trump appears to have sided with Musk and Ramaswamy, expressing support for H-1B to The New York Post. Nevertheless, the future of the program under his administration is far from clear, adding uncertainty to the plans of the hundreds of thousands of international students hoping to work in the United States.

For Chavapokin, the political uncertainty is confusing.

“I heard they want to reduce the number of people they take for H-1B each year,” Chavapokin says. “But I also heard a lot of

Chavapokin is currently pursuing a double major in economics and statistics.

“I got scared [that] my econ major might be removed from STEM OPT,” he says. “That’s why I added stats as well.”

Other students like Chen have to balance chasing their passions with more feasible H-1B routes.

As a student studying both violin and computer science, Chen has considered pursuing both interests; he has a full-time software engineering role lined up after graduation and is also auditioning for a seat in the Civic Orchestra of Chicago.

But employers are often unfamiliar with alternatives to the H-1B. Chen says the company he plans to work for after college grouped him in the H-1B category, and he had to convince staff he was in a different situation.

“I wouldn’t say it’s that different from the H-1B, except that you’re not on the track to get a green card, which I don’t mind because I don’t intend on staying in the U.S. forever,” Chen says.

Getting an H-1B is far from the end for international students and workers.

Applications for green cards, which allow people to live and work in the U.S. without a time limit, also face a decade-long backlog.

While the national origins quotas of the early 20th century are gone, green cards are still broadly capped, with no more than 7% of visas going to people from any one country. This presents issues for people from applicant-heavy countries like India, China, Mexico and the Philippines seeking to move from a temporary H-1B to a more permanent option.

Anam Khan, who went to college in Bangalore, India, graduated from NU in 2020 with a master’s in computer science. Encyclopedia Britannica offered her a full-time job, and she transitioned from OPT to an official work visa after winning the H-1B lottery in 2021.

“It is not a fun position to be in,” Khan says. “If I had the forethought when I was younger to actually foresee and think that I was going to stay somewhere long term, I would probably pick something that was less stressful than this.”

Now, Khan is in the fourth year of her H-1B visa, and her current extension will expire in 2027. If her employer doesn’t file for a green card petition to extend her status beyond six

years, Khan will have to move out of the country. Even once it is filed, she knows she will probably be waiting years for a green card. With an H-1B visa, nothing is certain.

Several students say they were unaware of just how difficult it is to stay in the U.S. after graduation as an international student. Khan says she didn’t initially plan to stay and work after graduation. But after finishing her internship at Britannica and receiving a full-time return offer, she began to see a future here.

Even though she has an H-1B visa, she is still unable to call the U.S. her permanent home.

“Security and stability is just what I want right now,” Khan says. “It’s so dicey and it’s so scary, and even switching careers with the visa, with the sponsorship, right? Because if I lose my job, then I have three months to find employment. If not, then you need to leave the country, which is so daunting and so scary, and yeah, that does make you second-guess every decision.”

Her current contingency plan is to move to another country, perhaps the U.K. or somewhere else in Europe, where the culture would be more similar to what she has become accustomed to in the U.S. as opposed to India. Khan hopes that her computer science degree and work experience will make things easier.

“As I’ve learned from being in the U.S. for three and a half years now, you just have to take it one day at a time and just hope for the best.”

— Sabian Atmadja, McCormick fourth-year

For Atmadja, the uncertainty is something he has come to terms with.

“As I’ve learned from being in the U.S. for three and a half years now, you just have to take it one day at a time and just hope for the best,” Atmadja says.

STORY BY MEDINA MIRANDA DESIGN BY JESSICA CHEN

It’s Christmas Eve, and my stomach rumbles as I eye my grandmother’s dining table. It’s piled high with traditional Filipino dishes, and steam fills the room as I scoop colorful stews onto my plate and dig in — Mangan na! Let’s eat!

But after one bite, my throat tightens, my skin erupts in hives and my cousins watch in confusion as I wheeze. I glance down at my plate.

What looked like chicken was actually shrimp — one of my worst allergens.

Food facilitates cultural connection, but allergies can complicate that relationship. I can’t try the recipes my grandparents depended on when they emigrated to California in the 1970s. I can’t eat ginisang sardinas, my mom’s favorite childhood dish, since it contains fish. Most importantly, I can’t visit my family in the Philippines, since my food allergies are too much cause for concern.

This disconnect isn’t unique to my experience. In the U.S., food allergies and other immune conditions like asthma and eczema disproportionately affect Asian populations, though the reasons remain unclear. A 2021 Johns Hopkins study suggests different environmental factors between Asia and the U.S. may contribute to rising allergy rates. Because of these differences, newer generations might be at higher risk, which could explain why my brother and I have food allergies while our parents don’t.

Asian students at Northwestern are working to raise awareness and maintain connections to their heritage through food. From scientific research to ingredient substitutions, Northwestern’s food allergy community balances advocacy with everyday challenges, seeking both safety and cultural belonging.

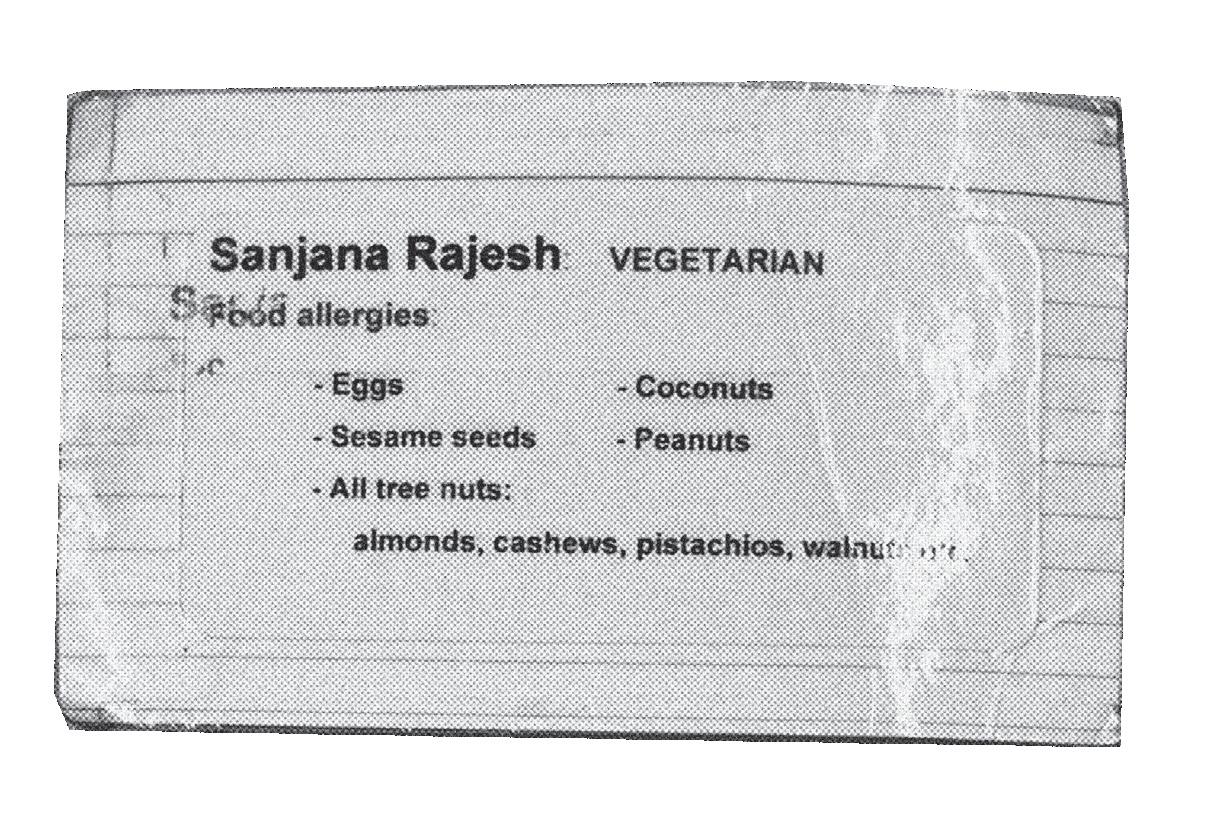

Like me, Weinberg fourth-year Sanjana Rajesh has had to navigate food allergies since the age of 4. Developing allergies changed her relationship with South Indian cuisine, both in America and India. Although her immediate family accommodates her dietary restrictions, Rajesh says many South Indian dishes include her allergens, like coconut and egg. As a result, she says food is a point of tension in her family.

“Going to India is really hard because people don’t know that allergies exist,” Rajesh says. “They don’t know how to deal with it.”

At Northwestern, Rajesh often feels like a “Debbie Downer” when choosing restaurants with friends because she limits their options. But she’s found ways to advocate for herself. She carries allergy identification cards she laminated with packing tape, keeping some in each of her bags.

“It’s nice to hand it to a server,” she says. “I’ve even sent these to friends, because it’s so much easier to have things written out.”

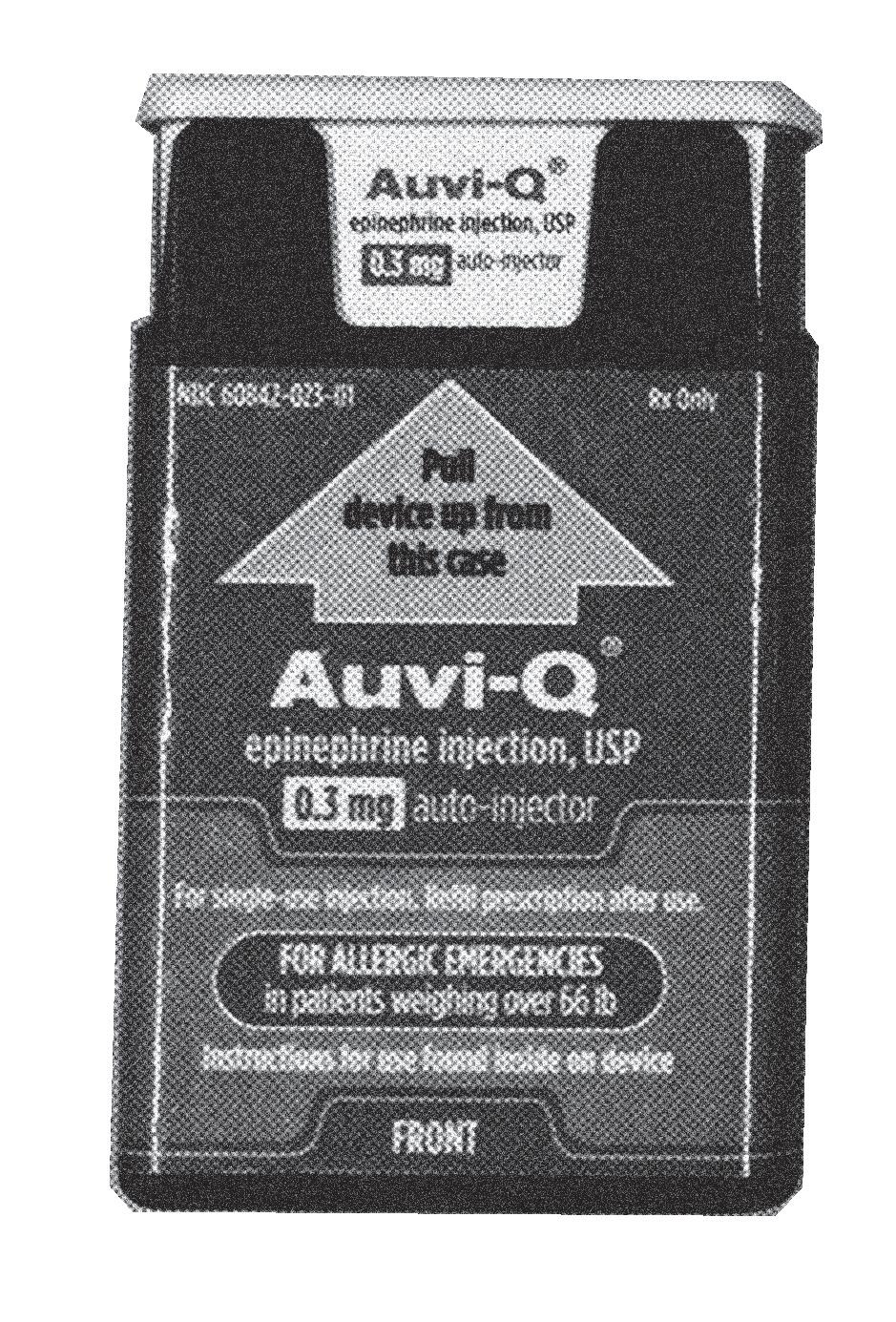

Rajesh has been using the cards since 2021. She also carries both an Auvi-Q and an Epipen, handheld devices ready to administer a life-saving dose of epinephrine — a stimulant that relaxes airway muscles — if needed.

Northwestern offers other food allergy resources for students without these devices. Rajesh receives allergy shots from Northwestern Medicine Student Health Service, and Weinberg third-year Preena Shroff says her close bond with NU’s previous dietitian has helped her feel safer in dining halls.

Off-campus cooking gives students like Shroff and Rajesh the freedom to experiment with different ingredients.

“I can make [food] exactly how I want, even if it doesn’t taste the best,” Rajesh says.

Shroff shows me her Indian spice tray, which she uses as a flavor base to make dishes like muthia, a flour-based dumpling that can be steamed or fried. She appreciates the control that comes with off-campus cooking.

“If I’m cooking, I can make what I want to eat,” she says. “I can also make what everyone else will also enjoy eating.”

Shroff is a student researcher at the Center for Food Allergy and Asthma Research (CFAAR) at Northwestern’s Feinberg School of Medicine. She recently examined 217 colleges’ allergy safety measures, finding that only four schools stock emergency epinephrine in dining halls.

This March, Shroff will present her research at the annual American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology and the World Allergy Organization Joint Congress in San Diego.

“I’m really excited. I’m going to be talking to a lot of healthcare providers and physicians, because the number of people entering college with food allergies is increasing,” Shroff says.

In NU’s chapter of College Advocates for Food Allergy Awareness & Education, Shroff and other NU students have created digital resources to help fellow students adjust to Northwestern and Evanston dining.

Sometimes, having a support system is all it takes for allergies to not feel so burdensome. Sharon Wong, a research

associate at CFAAR, started Nut Free Wok, an allergy-friendly Asian recipe blog, after both of her children were diagnosed with severe food allergies over a decade ago. Through a rigorous testing process, she develops practical allergenfree recipes, fine-tuning them using her mother’s sense of taste.

“I ask, ‘What do you think, Mom?’ and if she likes it, then I know it tastes good. And if I’m willing to make it, I know it’s very easy,” Wong says, laughing.

Wong says dim sum dishes like cheung fun, a traditional Chinese steamed rice roll, can be adapted by substituting the traditional shrimp filling for other ingredients. Families tell Wong that her recipes help kids feel included at meals.

“It makes me super, super happy that these kids have this way to eat, enjoy their foods and partake in their family dinners,” Wong says. “They can share the recipes with their aunties and their grandmas.”

Thirteen years have passed since that fateful Christmas Eve, and I’ve learned a lot. Now, I ask my family to swap shrimp for tofu and crab for chicken. I confidently ask wait staff for allergy accommodations. And as I hunt for apartments with my future roommates, we’re excited to stock our kitchen with food we love — and can safely eat.

PHOTOS BY JOYCE HUANG & ASHLEY ZHOU

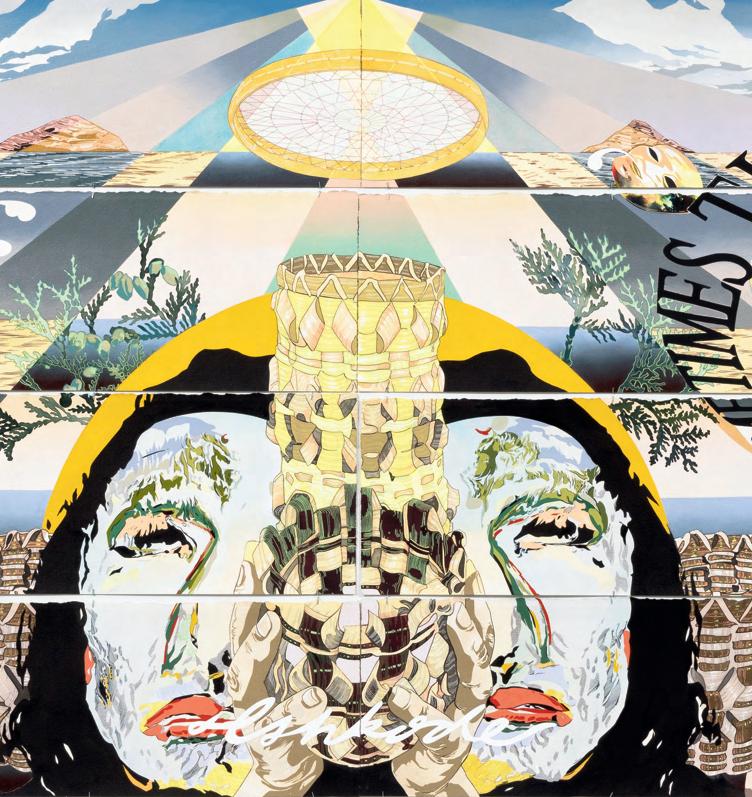

This quarter has been a period of growth and exploration for me, as I am sure it has been for many of our readers. I took on more classes and projects, forged new relationships and stepped into a new role as nuAZN’s Photo Director. In this photoshoot, I want to focus on setting ourselves free from the boundaries we create for ourselves, propelling us into another reality even if we eventually have to leave. As you flip through these pages, I hope it inspires you to find your spark and forge your own path.

STORY BY CHLOE PARK

he summer before he started college, McCormick third-year Taewon Yoon joined Instagram and Discord communities to meet fellow incoming students. Unlike most of his classmates, he faced a daunting dilemma — deciding when to fulfill his mandatory military service back home in South Korea.

According to Yoon, most South Korean students enlist in the military after their first or second year of college. His plans shifted when the COVID-19 pandemic hit. Rather than enrolling in online classes for a year before taking time off, he decided to enlist before he started college, from September 2020 to March 2022.

When he returned as a first-year, the friends he had made online were already two years ahead.

“It was definitely sad not being able to meet them,” Yoon says. “But as I look

back, I think I made the right choice. Especially for my grade, the COVID year, because the first couple of years were done online, a lot of my friends that went to the military after a year or two in college don’t have a lot of friends after coming back.”

While South Korea currently mandates a year and a half of military service for male citizens, conscription processes across Asia do not consistently follow the same protocol. Places like Singapore, Myanmar and Taiwan have shifting expectations based on their geopolitical conditions. For example, Myanmar’s junta enforced a once-dormant conscription law in early 2024 amid battles with ethnic militias and anti-coup fighters.

With governments continuing their service requirements, international students face disruptions to their education and social lives as they are called home to serve overseas.

McCormick fourth-year Dylan Wu says the draft has at times been uncertain, and in his last months at NU, he’ll have to readjust to student life. Though he left for Taiwan in the spring of 2024 and plans to return next quarter, marking a full year off campus, he only served for a fraction of his time off, starting in September.

The conscription age in Taiwan is 18, but students pursuing higher education are often granted deferments from the draft. Regardless, most men must complete their service by 36.

Born in 2003, Wu was only required to serve for four months. Taiwanese citizens born after 2005 are now required to serve for one year.

This change is part of a broader evolution in Taiwan’s conscription politics. In the 1950s, tensions with China led to strict military service requirements. Citizens were expected to

“It’s definitely putting a lot of strain on my friendships in Northwestern.”

— Dylan Wu,

McCormick fourth-year

serve for two to three years until martial law was lifted in 1987 and the length of conscription was gradually reduced to four months. However, then-President Tsai Ing-wen announced in 2022 that Taiwan would extend its compulsory military service to a full year starting in 2024 due to growing pressure from the Chinese military in recent years.

“Four months is really limited time, so there isn’t really a whole lot of things they could teach you,” Wu says. “And the fact that they’re also doing two months of deployment — it’s not all boot camp. We basically learned how to shoot a rifle and that’s kind of it, and the rifle is like 50 years old.”

Wu says the role of military service becomes more important as the service period increases. He says he started his service thinking it could be an opportunity to learn, but after four months, it started to feel like a waste of time.

As a senior who has already secured his post-graduation plans, Wu’s concerns about returning to Northwestern primarily revolve around reintegrating into college social life.

“It’s definitely putting a lot of strain on my friendships in Northwestern because a lot of my friends are actually graduating early,” Wu says. “When I left, it was basically the last time that I’ll get to see them unless after graduation.”

When he returns, Wu aims to rejoin the organizations he was a part of before leaving for military service, such as Northwestern’s Develop and Innovate for Social Change club. In his last quarter at Northwestern, he hopes to connect with friends who are still on campus and keep in contact with them once they graduate.

Wu is not the only student who sees military service as a disruption to his social and academic life. Yoon says losing two years of his life to military service has made him feel like he had a slow start to college compared to his peers.

“I’m already 23 and now I’m a junior,” Yoon says. “All my friends have already graduated a couple years ago and they’re already working. I’m still in college.”

While he acknowledges the value of compulsory service given South Korea’s ongoing military standoff with North Korea, he

says his personal experience was largely unproductive, as COVID-19 restrictions prevented him from participating in military exercises, leaving him with excessive free time.

Yoon says feeling too old is common among those who have returned from military service. His roommates, who also served in South Korea at different times, avoid attending some parties or events because they worry about being surrounded by students who are “too young.”

“A lot of people don’t know about it, but there is a small community of ex-military people,” Yoon says. “And I feel like we bond along together based on our similar factors.”

SESP first-year Joseph Oh, who plans to enlist in the South Korean military in the fall, also relies on such communities to cope with the challenges of military service.

“I have friends who will be returning with me to Northwestern, so I think that’ll definitely help with re-adjusting and being part of a social scene,” Oh says.

Oh shares Yoon and Wu’s sentiments, saying that military service can feel burdensome, particularly as

most of his peers are not required to serve. Still, he says military service is his obligation as a South Korean citizen and even sees it as an opportunity to live in the moment.

“Even if I join a really selective club, there’s a chance that I have to reapply or adjust to the club atmosphere from the start again once I’m back from military service,” Oh says. “So I think it’s rather allowing me to slow things down and really enjoy my first year.”

Weinberg second-year Josh Lake says Singapore’s compulsory military service is an important opportunity to develop discipline, accountability and resilience. Like Yoon, Lake enlisted in the military after graduating high school and before attending Northwestern.

Because of its strained ties with its neighbors, Malaysia and Indonesia, Singapore placed a heavy emphasis on self-defense. Its parliament passed the National Service (Amendment) Bill in 1967, requiring all eligible male citizens to serve in the military soon after they complete secondary education, with limited flexibility in choosing the date of service.

learning to persevere through the rigor alongside teammates.

Lake served in the National Service for 22 months before attending Northwestern, where his younger sister is now a grade ahead of him, despite being a year younger. Though he dubs this arrangement “unconventional,” Lake says he values his post-high school progression.

“Having an extra two years to think longer and harder about what you want to do and what you value and find meaningful is a huge opportunity,” Lake says.

Lake says he learned more social and life skills from his first three months at basic training than he did during high school, as he was introduced to draftees from all different backgrounds.

He specifically recalls undertaking field exercises in the jungle and

“You can’t just take out your phone and call someone,” Lake says. “When you’re in the field, you don’t have anyone else to carry you through the situation other than yourself and your peers.”

For Lake, serving in National Service imbued him with a sense of national pride and self-fulfillment. The draft didn’t affect his outlook on future plans. Rather, it taught him that life is not a race and to treasure his family, friends and time.

Military service can feel like an interruption to students’ academic and social aspirations. But students like Yoon, Wu, Oh and Lake have found ways to navigate its challenges — whether by forming supportive

communities, building resilience or learning to cherish their education and future. As they return to familiar faces and classes, they carry with them a newfound clarity and appreciation for what matters most.

“It changed my outlook for the better,” Lake says. “There are challenges, but no bad experiences.”

PShifting Hindu sentiments may coincide with conservative momentum.

STORY BY IZZIE JACOB DESIGN BY XIAOTIAN SHANGGUAN

urnima Nath (Kellogg ‘17) lost the Republican primary for Wisconsin’s 4th U.S. House district last August. The Republican base in her district, which represents Milwaukee, River Hills and additional suburbs, instead chose to put Tim Rogers on the ticket.

Then, on Election Day 2024, the district voted overwhelmingly Democrat. Nath was inspired to run in her district because Hindus have “always been a micro minority, no matter which part of the world we have belonged to,” she says.

She decided to run as a Republican because she agreed with the party’s policy beliefs. She also says the Democratic party is not for Hindus, and that the political left is too aligned with cancel culture and tries to “dump” their

Indian Americans joined Congress. Nearly 50 are in state legislatures, according to The New York Times. In the 2024 election cycle, Kamala Harris, Nikki Haley and Vivek Ramaswamy — three Indian Americans — ran for president.

Nath’s decision to run represents a larger trend: More South Asian Americans are entering politics. In 2023, five

While Indian Americans seem to remain committed to the Democratic Party, their attachment has declined, according to a Carnegie Endowment for International Peace survey conducted in late 2024. Of those surveyed, 47% identified as Democrats, compared to 56% in 2020. Hindus were 8% more likely to vote for Donald Trump than non-Hindu Indian Americans (35% and 27%, respectively). Data on non-Hindu Indian Americans were not specific and did not distinguish between religious minorities like Muslims, Jains or Sikhs.

Nath, who got into politics during President Donald Trump’s first campaign, says she was attracted to his policies regarding national security, border security and inflation. A campaign issue Nath and Trump share similar views on is illegal immigration. One of Nath’s campaign slogans was “legal immigrant.”

“It is important for me that this country is actually open to legal immigrants at this point in time,” Nath

immigrants like her, deeming it unfair.

Still, Nath doesn’t predict Indian Americans will make a major shift to the Republican Party anytime soon and recognizes that Indian Americans still tend to lean Democratic as a whole.

The Carnegie study showed that 58% of Hindus surveyed said they voted for Harris.

Pushkar Sharma is co-founder of the South Asian American Coalition to Renew Democracy (SACRED), an organization working to fight Hindu supremacy in American politics and other forms of hate within the South Asian community. He says he cannot come to any conclusions regarding a shift in political allegiance given that data on the 2024 presidential election is so new.

Nonetheless, he says South Asian American leaders in the Republican Party have pushed a conservative narrative, especially within the Hindu American community.

“I think there is clearly a very strong narrative and leaders pushing community members within faith-based Hindu American communities,” Sharma says. “We can focus on groups like the Republican Hindu Coalition, but also leaders like Vivek Ramaswamy, Tulsi Gabbard and Kash Patel, three individuals who have been floated as appointments to the current Trump administration.”

Since nuAZN spoke with Sharma, Patel has been appointed to serve as the director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Gabbard was also confirmed as Director of National Intelligence.

own religious community.

“For some paradoxical reason, [they] support an anti-secular stance in this country and support a Christian nationalist agenda in this country,” Sharma says.

That kind of contradiction is not new, Sharma says. In the 1930s, an extremist group formed in colonial India called the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS).

The RSS looked up to fascist Italy, Nazi Germany and other supremacy ideologies that paralleled their own. Even today, the RSS continues to

a trend that we’ve seen historically,” Sharma says. “The relationship between

“It is people like us who actually, on a grassroot level, campaigned and communicated that the Republican Party is actually good for us for various reasons.”

— Purnima Nath, Kellogg ‘17

not American enough?”

Nath asks. “Just because we speak for Hindus doesn’t mean we’re not American enough.”

these types of supremacist ideologies is not new.”

Sharma says there are connections between far-right Hindu ideology and white supremacist notions that some South Asian Republicans seem to align with. Additionally, Sharma says political candidates’ outward expressions of their wealth may also make them attractive to South Asian American voters.

“I think we have to look at things through a racial lens but also an economic lens — look at things in an intersectional way [to see] how wealth can have white adjacency,” Sharma says.

According to the Carnegie Endowment Survey, 64% of Indian Americans with a median household income below $50,000 voted for Harris. On the other hand, 58% of Indian Americans with a median household income over $100,000 voted for her.

Some South Asian students who lean towards the left, like Communication second-year Asha Navaratnasingam, condemn her community’s possible shift towards the right.

Navaratnasingam has not noticed a change among her peers at NU. Still, she has heard more South Asians say they’re not included in anti-immigrant and racist rhetoric often spread by Trump, she says.

“I think a lot of POC and South Asians that support Trump and are Republican have this tendency to think

that they’re not going to be affected in the same way that other groups are going to be affected because they’re Republican,” Navaratnasingam says. “They can be like, ‘Deporting isn’t going to affect me because I’m a Republican citizen who supports Trump,’ and they just don’t really realize that it will still affect them.”

Navaratnasingam says this is why many of them think anti-immigration rhetoric won’t hurt them. She also says the Republican Party may look more South Asian than it actually is.

“I think that the Republican Party has this tendency to boost the voices of marginalized people that are Republican if it helps their cause, because then they can be like, ‘Look, we’re diverse,’” Navaratnasingam says.

That benefits the party more than the marginalized people whose voices the party is amplifying, she adds.

Though Nath says she aligns with the Republican Party, she hasn’t felt fully accepted because of her Hindu and Indian identity, especially after online debates regarding H-1B visas. Many Trump supporters argue that American jobs shouldn’t go to those coming from outside of the United States. This debate has made her question her American identity.

“If I was an Indian American and I’m a naturalized citizen to America and I have my ethnicity as an Indian, does it mean I’m

Nath also says the Republican Party does not reach out to her community enough. She adds that the only reason there has been a slight increase in Hindu voters supporting Republicans is because of organizing within the Indian American community.

Nevertheless, she wants to continue to fight from the right.

“It is not the Republican Party who brought us to the Republican Party,” Nath says. “It is people like us who actually, on a grassroot level, campaigned and communicated that the Republican Party is actually good for us for various reasons.”

STORY BY SARAH LIN DESIGN BY SABRINA ZHANG

PHOTOS BY MICHELLE SHEEN

Iam Shui Feng, Northwestern’s premier fēng shuǐ consultant! I’ve graciously extended my services to help young clients ward away evil spirits in shabby dorm rooms and even shabbier apartments for better harmony, happiness and sleep. And no, I’m not another wannabe student consultant, nor am I the middle-aged white man with a Ph.D. teaching your “Intro to Buddhism” class. I actually have qualifications — see the Coursera certification on my LinkedIn

This bedroom has balance, but not harmony. There looks to be many light sources, but not a single one of them is soothing or natural. We get it, you bleed purple. How come you and every fraternity brother insist on hanging dinky lights above your sleeping space? So inauspicious. What about your love life? Is it harmonious right now? I thought not. You definitely wake up on the wrong side of the bed every morning with your clingy hookup. After all, your bed’s headboard is a brick wall you share with hundreds of Plex residents, so you’re basically absorbing the yin (or dead energy) from the snoring guy next door. Prepare for your own diagnosis of sleep apnea soon.

Assessment: Chi can be remediated, but your love life? Maybe not.

Gone are the frat lights, but did you know that clutter attracts stale energy and makes you depressed? I’m sure the rack you spent on male figurines and yuri art gives you some sort of gratification, but it’s not conducive to your long-term success in sleeping well or in pretending to be a normal member of society. Plus, the angry and abrasive shadowy artwork above your bed is certain to invite bad chi into your bedroom. Are you frequently bitter and complaining about your stupid baka life? If so, putting away your dirty laundry will help lighten your emotional baggage and subdue negative energy, but seeing a therapist might help more.

Assessment: Does this room even spark joy?

Unlike our last client’s room, this bedroom has cleanliness, purpose and direction. Yet, the room is slightly unsettling. Could it be the bare bed frame you got for free from a former bachelor pad? Instability disturbs chi, and I know that bed frame is rickety from years of … usage. Could it be the ceiling’s singular, protruding boob light? Wait. It’s definitely the coats hanging on the same wall as the bed. Uh oh. That’s where the evil spirits hide.

Assessment: Sleep paralysis demons.

STORY BY ELLIE CARNEY

hen I was 14, my friend told me she liked how “masc” I was. Until then, I never thought of myself as anything but feminine. Sure, I had a deeper voice, my handwriting was messy like a boy’s and I didn’t like to wear skirts and dresses, but that didn’t make me “masc.”

Did it?

In high school, almost half of my grade identified as queer. Liking girls made you “cool,” especially if you looked the part. My friend calling me “masc” was like an invitation into a club that I didn’t know I could join.

I got a wolf cut. I started slouching. I bought three baggy button-down shirts from the H&M boy’s section. The cool gay people started talking to me and having crushes on me. I was frustrated that I didn’t have the guts to chop my hair off completely or shop exclusively in the men’s section like I wanted to, but I maintained hope that with the freedom of college, I’d finally assimilate into a fully masculine gender expression.

“So, what were your first impressions of me like?” I remember asking my friends a month or so into freshman fall. Three words came up again and again: Wasian, Bostonian and bisexual. At the time, I enjoyed hearing I looked queer — it meant I still had an invite to the club I was sure existed at Northwestern.

I never found that club. When you’re not at a tiny high school where everyone knows everyone’s business, it’s hard to tell who’s queer and who thinks gay people are weird. A bigger place also means first impressions are often people’s only impression of you. Was I okay with “gay” or “masc” being my primary identity?

There were other factors too. I went from only having one close Chinese friend in high school to being in a mostly Chinese friend group at Northwestern. I joined various Asian affinity clubs. As much as I dislike thinking about stereotypes, being in these heterosexual,

Asian-dominated spaces reminded me that East Asian women are often expected to be hyper-feminine. If standing out for being “white-presenting” wasn’t enough, I also felt like my white appearance was compounding my lack of femininity.

I tried to go back. I replaced my button-down shirts with tank tops adorned with bows. I grew out my wolf cut. I started twirling my hair, covering my mouth when I laughed and sitting upright.

But I can’t change my messy handwriting, my low voice or my aversion to skirts. When I’m at a Chinese Students Association party and I’m reminded of these things, I realize no matter how many hair twirls I practice, I will never be as naturally feminine as the girls around me.

There’s a lot of pressure on queer people to be pioneers for our community — to be strong, to fight for acceptance, to be comfortable standing out.

But it’s just hard. It’s hard when a person I think is straight sits next to me in class and I worry about whether they’re judging my appearance. It’s hard when I go to a party and wonder if my tank top will be enough to disguise all the parts of me that don’t fit in. It’s hard when I follow the boy I like on Instagram and see that the girls he hangs out with are all naturally feminine, fully Asian with long, silky hair and delicate features.

It’s OK to feel that way. I’ve come to realize that I don’t need to choose between femininity or masculinity. I’ve settled on a place in-between. Button-downs and bows — there’s room in my wardrobe for both.

STORY BY CATE BIKALES

WDESIGN BY YELIM KIM

hen it comes to insults, creativity knows no bounds — especially across different languages. While English has its fair share of colorful jabs, many Asian languages take insults to another level, blending humor, cultural context and sheer linguistic flair. From sharp-witted to affectionate, these insults reveal how language shapes the way we tease, criticize and express frustration. Hopefully you can add some new insults to your verbal artillery!

dol-dae-ga-ri (stone

Weinberg fourth-year Jamie Kim first encountered the insult 돌대가리 while watching The Penthouse: War in Life, a K-drama that follows a group of rich families living together in a fancy penthouse in Seoul who scheme and sabotage to maintain power. The insult, flung with perfect fury, was both unfamiliar and instantly amusing — something about the rhythmic four characters made it extra satisfying. Despite never having the perfect opportunity to use the insult in real life (yet), Kim still occasionally revisits clips from the show just to relive the magic. After all, there are many ways to call someone dumb, but 돌대가리 brings a unique creativity that elevates the art of the insult.

Japanese Chinese Korean Hindi

xiao lan zhu (lazy little pig)

Weinberg third-year Skyla Kiang has been called a 小懒猪 more times than she can count. When she would sleep in on weekends in high school (as one does), her mom would bust open her door and, without fail, declare the phrase. Despite the “pig” part, it’s not an insult to take seriously — it’s more of a playful nudge, like being called a sleepyhead. In her groggy state, Kiang barely registered it anyways. She was too busy trying to wake up and find caffeine. If anything, she knew it was just her mom’s way of teasing her for loving sleep a little too much. And honestly, who wouldn’t want to be a cozy, well-rested 小懒猪 on the weekends?

Aren’t owls supposed to be wise? It turns out owls are associated with ill-gained wealth and foolishness in India, making

का

a go-to phrase for calling someone an idiot in the most delightfully absurd way possible. Weinberg third-year Ishani Pidara has heard this insult countless times, especially when her mom is driving down the busy streets of Chicago and gets cut off by a driver. In her family, the insult isn’t dramatic or harsh but a light-hearted way to express mild frustration (or pure exasperation). For Pidara, it’s just one of those silly insults that somehow never gets old, no matter how many times she hears it.

kimi

君, one of three ways to address someone, is considered the casual form of “you.” あなた (anata) is the most neutral and polite form, while お前 (omae) is considered very informal and rude.

The Japanese language doesn’t use explicit swear words in the same way that English does, but word choice can still pack a punch — especially when it comes to how you address someone. Japanese is a tiered language, with different levels of formality depending on to whom you’re speaking. Even the word “you” has variations. So, when Weinberg fourthyear Lilly Tokoro’s supervisor at her summer internship in Japan casually addressed her as 君, it came by surprise. Although the word itself isn’t rude, people rarely use it in professional settings. Hearing it directed at her felt strangely condescending. In a language where subtlety is everything, even a simple “you” can carry a lot of weight!

STORY BY EMILY JIANG

DESIGN BY JUNE WOO

a lot of things have changed.

i hope you’re well. the years have flown, haven’t they? since i last saw you eight years ago when i left, we were best friends.

some have stayed the same.

i invited you to my going-away party.

i brought you a gift, my favorite book.

back then, even now, eight years away from that summer evening.

i didn’t realize how much i meant to you. i was focused on my new life in the big city.

i didn’t realize how much you meant to me. i was trying to forget missing you.

but i’m thinking about late night conversations from our flip phones, playing games and bonding over webtoons and anime and yeah,

maybe distance makes the heart grow fainter.

maybe you left me behind.

i remember when we had that big performance in seventh grade — in another county, for an award.

we were dressed up in black suits and pants. you sat close to me on the bus ride back.

your hair was slicked back. you wished me good night when we left.

are you still performing? getting dolled up and kissing your bandmates goodnight? or was that just for me?

because i know it’s been us since i moved into town. two chinese kids floundering in a sea of otherness.

i took italian. i already knew mandarin.

sit next to me again, and ask me is it ài or ái?

i remember when they made us choose a language for school, do you still feel like you can’t find your place?

your parents didn’t let people over but i didn’t care. you talked about comics and idols during late nights in the band room and you were my anchor — magnetic, grounding. are you still into computer science?

but i wanted to learn my mother tongue. i wanted an excuse to practice chinese with you.

i can still write the characters for you and me. but i stopped learning after you left.

you confided in me about your parents’ expectations, how you were always so busy. and instead of homework we watched music videos and i wanted to hold onto you but you were like a dream — unreal, fleeting.

but that was eight years ago. how are you now?

i got my old phone back, and i looked at our texts.

are you pursuing your artistic aspirations? maybe you think you abandoned me. but i’m stronger than before.

and i’m sorry we stopped talking.

i still have that ring you gifted me.

i haven’t forgotten you.

in my head, you’re still the same as always, waiting for me to come home.

in my head, you’re a stranger, someone completely new. and we’ve both grown.

but like two butterflies floating side by side, a week into spring for a few years we were together, you and me, so beautiful.

i hope you’re well.

STORY BY XIAOTIAN SHANGGUAN DESIGN BY YITAO WANG

Despite his grotesque appearance from chronic sleep deprivation and his exponentially decreasing wealth, he somehow still pulls so many baddies. In Korean culture, gifting your girlfriend shoes signifies that they will walk out of your life. For the next curse, I delivered all of his girlfriends shoes under his name so they would immediately dump him. The curse has worked wonders. Every time I spotted him with a new girl, I did a bit of research, sent her some nice heels and she was on her way out! In the most recent case, I had to hold in a laugh as I watched a girl dump him in Tealicious because she “had a sudden realization of how hideous he truly was.”

It was a shame I couldn’t stay long. I wanted to relish in the streaks of pain streaming down his cheeks from being dumped so suddenly. Even though he was distressed, I couldn’t help but want to enact the final part of my plan. In Hindu mythology, the demon king Hiranyakashipu, who thought he was invincible, was slain by the god Vishnu under the arch of a doorway, making the area a place of extreme vulnerability. I returned to my ex’s dorm and poured a puddle of Super Glue right under his door frame. Stressed from his boba outing, he planted both feet into the puddle, leaving him permanently stuck under the door frame. Immediately, he transformed into a new person. He fell on his butt, clawing at the door frame in an attempt to get himself out. He tried screaming, yelling and begging each of his dormmates for help. They all avoided him, fearing his bulged eyes and crazed expression. His sleep-deprived appearance did little to help.

is not liable for any damages that may occur if you attempt these hexes yourself, such as (but not limited to) missing limbs, failing kidneys, aorta chunks in vomit or the gorgeous rush of schadenfreude.

As the campus Asian-interest magazine, we simply want to share the diverse voices in our communities, even those crazy psychos, you know? Also, if you happen to suddenly experience extremely poor sleep or exponentially worsening events happen to you like clockwork, you probably deserve it! Toodaloo!